Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Towards Secure and Efficient Human Fall Detection: Sensor-Visual Fusion via Gramian Angular Field with Federated CNN

1 Department of Information and Computer Science, King Fahd University of Petroleum & Minerals, Dhahran, 31261, Saudi Arabia

2 Interdisciplinary Research Center for Intelligent Secure Systems (IRC-ISS), King Fahd University of Petroleum & Minerals, Dhahran, 31261, Saudi Arabia

3 SDAIA-KFUPM Joint Research Center for AI and Interdisciplinary Research Center for Bio Systems and Machines, King Fahd University of Petroleum & Minerals, Dhahran, 31261, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Author: Md Mahfuzur Rahman. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Exploring the Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Healthcare: Insights into Data Management, Integration, and Ethical Considerations)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(1), 1087-1116. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.068779

Received 06 June 2025; Accepted 22 September 2025; Issue published 30 October 2025

Abstract

This article presents a human fall detection system that addresses two critical challenges: privacy preservation and detection accuracy. We propose a comprehensive framework that integrates state-of-the-art machine learning models, multimodal data fusion, federated learning (FL), and Karush-Kuhn-Tucker (KKT)-based resource optimization. The system fuses data from wearable sensors and cameras using Gramian Angular Field (GAF) encoding to capture rich spatial-temporal features. To protect sensitive data, we adopt a privacy-preserving FL setup, where model training occurs locally on client devices without transferring raw data. A custom convolutional neural network (CNN) is designed to extract robust features from the fused multimodal inputs under FL constraints. To further improve efficiency, a KKT-based optimization strategy is employed to allocate computational tasks based on device capacity. Evaluated on the UP-Fall dataset, the proposed system achieves 91% accuracy, demonstrating its effectiveness in detecting human falls while ensuring data privacy and resource efficiency. This work contributes to safer, scalable, and real-world-applicable fall detection for elderly care.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Human fall detection is a growing concern due to its potential to cause serious health complications, including fatal injuries. World Bank data indicates that 10% of the population is over 651. This demographic trend highlights the urgent need for effective fall detection systems to protect the elderly population. Therefore, the design and development of efficient and reliable fall detection systems is critical to ensure the safety and well-being of a large number of elderly people, especially those living alone. Modern healthcare systems can play a significant role in detecting falls early and enabling rapid response. Early fall detection can greatly reduce injuries and improve the quality of life for elderly individuals.

Fall detection systems have recently been developed using sensors [1,2], vision-based approaches [3–5], and multimodal methods [6,7]. Despite their advances, these systems face critical challenges such as privacy concerns, high false detection rates, and inconsistent performance across varying environments. Privacy is especially critical in vision-based systems, where video data can inadvertently expose sensitive personal information [8–10]. Another major issue is the occurrence of false positives and false negatives, which compromise the reliability of these systems [5–7]. Multimodal approaches—such as combining video with sensor data—offer improved accuracy by capturing complementary features, but they often require substantial computational resources. Recently, federated learning methods with enhanced feature extraction have shown potential in mitigating these limitations by enabling decentralized and efficient learning [11,12]. Federated learning (FL) is a distributed machine learning paradigm in which models are trained across multiple devices holding local data samples—without transferring raw data to a central server. FL is particularly suitable for privacy-sensitive applications, as it preserves data locality and prevents exposure of personal information. It also supports scalability by utilizing the computational resources of distributed client devices. This makes it an excellent candidate for privacy-preserving applications, such as fall detection in elderly care, where devices can continuously learn personalized patterns without compromising privacy.

In this research, we propose a privacy-aware fall detection framework based on federated learning. Each elderly individual’s device (e.g., wearable sensors or smart home cameras) locally collects and processes motion data, keeping all raw data on-device. Importantly, only the model updates (e.g., gradients or weights) are transmitted to the central server for aggregation. To support practical deployment, we also design a resource-aware optimization strategy that adapts the training workload to each client’s computational capacity, ensuring efficiency without sacrificing privacy. In summary, while significant progress has been made in fall detection technology, key issues such as data privacy, detection accuracy, and computational feasibility remain open. This study aims to address these challenges through a synergistic combination of multimodal data fusion, deep learning, federated training, and resource-aware optimization. The main contributions of this research are summarized below:

• This study integrates sensor and visual data using Gramian Angular Field (GAF) encoding to enhance feature extraction and improve fall detection accuracy.

• A secure learning framework is designed to retain all raw data on local devices, sharing only model updates to preserve privacy during distributed training.

• A lightweight convolutional neural network (CNN) is developed to process fused multimodal inputs, capturing spatial and temporal features for accurate fall classification.

• A Karush-Kuhn-Tucker (KKT)-based optimization strategy is employed to ensure efficient task allocation and balanced training load across heterogeneous devices.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 reviews the related work on fall detection, multimodal fusion, and privacy-preserving techniques. Section 3 presents the proposed methodology. Section 4 discusses the experimental results. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper and outlines future research directions.

The fall detection research field has been developed by researchers over time. In this section, we have reviewed articles covering multimodal data fusion, federated learning, convolutional neural network (CNN)-based models, and resource optimization in distributed environments. The researchers investigated these techniques to enhance fall detection accuracy and adaptability in different real-world scenarios.

Multimodal data fusion is becoming a handy technique to improve fall detection accuracy by integrating data from different sources. Auvinet et al. proposed a multiple camera-based occlusion-resistant fall detection technique using 3D silhouette vertical distribution [13]. Though they achieved a good score of 99.7%, their method performed poorly in challenging environments like varying lighting conditions. Another work, skeleton-based data fusion to improve fall event classification, was proposed by Xie et al. [14]. However, their proposed method needs high-quality skeleton data for reliable detection. Qi et al. [6] proposed the FL-FD model, which integrates federated learning with multimodal data fusion for human fall detection. Their approach uses input-level fusion of GAF-encoded time-series data and grayscale images derived from visual frames, and a 3-layer CNN is used as the local model to reduce communication cost. Each user is treated as a private client in the FL framework, preserving data privacy by training locally and only sharing model updates. While their model achieves strong performance, it does not consider resource heterogeneity or task scheduling across devices. In contrast, our method not only adopts a privacy-preserving federated architecture and input-level multimodal fusion but also incorporates KKT-based optimization for resource-aware task allocation. This makes our approach better suited for deployment in real-world, resource-constrained environments. Furthermore, our proposed model employs a deeper CNN with enhanced feature extraction and dropout layers for robustness, contributing to improved generalization.

Several techniques are used to transform data/signals from one format into another, which is essential for fusion. Wang et al. proposed that Gramian Angular Field (GAF) is capable of extracting both temporal and structural information where other methods fail [15]. Spectrogram-based approaches are useful for frequency domain analysis but have phase loss issues. As a result, these methods lack in identifying subtle motion variations [16,17]. Though wavelet transforms are good at capturing multi-resolution patterns, they fail to provide the structured patterns required for efficient detection [18,19]. On the other hand, recurrence plots illustrate the recurrence dynamics but cannot capture continuous angular relationships [18,20].

Fall detection accuracy in different challenging environments can be improved using convolutional neural networks (CNNs). Bo Luo presented a fall detection system for smart homes using YOLO networks and achieved 95% [21]. However, his proposed system performs poorly in low-light and complex settings. Another study mentioned that their model is effective across different lighting conditions, including low light [22]. Their proposed model struggles in an environment with cluttered backgrounds and camera angle variations. Another recent study proposed an enhanced feature extraction method from multiple datasets, but it requires a high computational cost, which limited its applicability in real-world scenarios [4].

Federated learning (FL) leverages privacy-preserving fall detection by facilitating model training without collecting data on a central server. Ma et al. proposed an enhanced FL security using multi-key homomorphic encryption [23]. To address non-IID (independent and identically distributed) data issues, their method needs to upload partial data to the central server for synchronization. Another study used an Extreme Learning Machine (ELM) with FL for fall detection [11]. They achieved promising results but suffered from mislabelling errors in manual feature labelling. Beyond standard federated learning (FL), recent advancements in privacy-preserving techniques include secure aggregation using homomorphic encryption and hybrid methods combining differential privacy (DP) with secure multiparty computation (SMC). Miao et al. [24] proposed a blockchain-integrated FL framework that uses fully homomorphic encryption to securely aggregate model updates, offering robustness against Byzantine attacks. While highly secure, such techniques often introduce heavy computational and communication overhead, making them less feasible for real-time, edge-based fall detection. In contrast, our lightweight FL framework balances privacy and efficiency for deployment on resource-constrained devices. Similarly, Truex et al. [25] introduced a hybrid DP+SMC model that adds noise to shared updates while coordinating secure computations, effectively defending against inference attacks. Although such methods provide enhanced theoretical guarantees, our work prioritizes practical trade-offs suited for scalable, multimodal fall detection scenarios.

In the FL environment, computational resources must be optimized to deploy fall detection models in practical settings. Liu et al. presented primal-dual algorithms for convex optimization problems in imaging systems [26]. Another study focuses on the application of KKT-based optimization techniques to gradient flows in noisy ReLU networks [27]. However, the authors did not adequately consider the constraints of federated learning in a real-world setting. While KKT conditions are appropriate for our formulation, we acknowledge that other optimization techniques may also be applicable depending on system objectives and constraint complexity. For instance, evolutionary algorithms such as Genetic Algorithms (GA) have shown promise in distributed FL for balancing communication delay and data privacy in vehicular networks [28]. Reinforcement Learning (RL) approaches can adaptively optimize computation offloading and resource scheduling in dynamic mobile edge environments [29], while Simulated Annealing (SA) has been effectively applied to offloading tasks in UAV-assisted MEC networks [30]. Additionally, greedy heuristics have shown success in client selection and scheduling under constrained FL settings [31]. These alternative approaches are promising in scenarios involving non-convex, non-differentiable objectives or environments with dynamic topologies and intermittent connectivity.

Despite developments in the field of fall detection, several challenges remain unaddressed. One of the major issues is that the effectiveness of the model is still questionable in challenging environments like lighting variations, cluttered backgrounds, and diverse camera angles [21,22,32]. High computational demands of CNN-based models are another crucial problem, which limits real-world applicability [4]. Lastly, distributing the tasks based on resource constraints in federated learning environments needs to be addressed [11,23]. It is essential to address these challenges to ensure efficient, scalable, and real-world applicable fall detection systems.

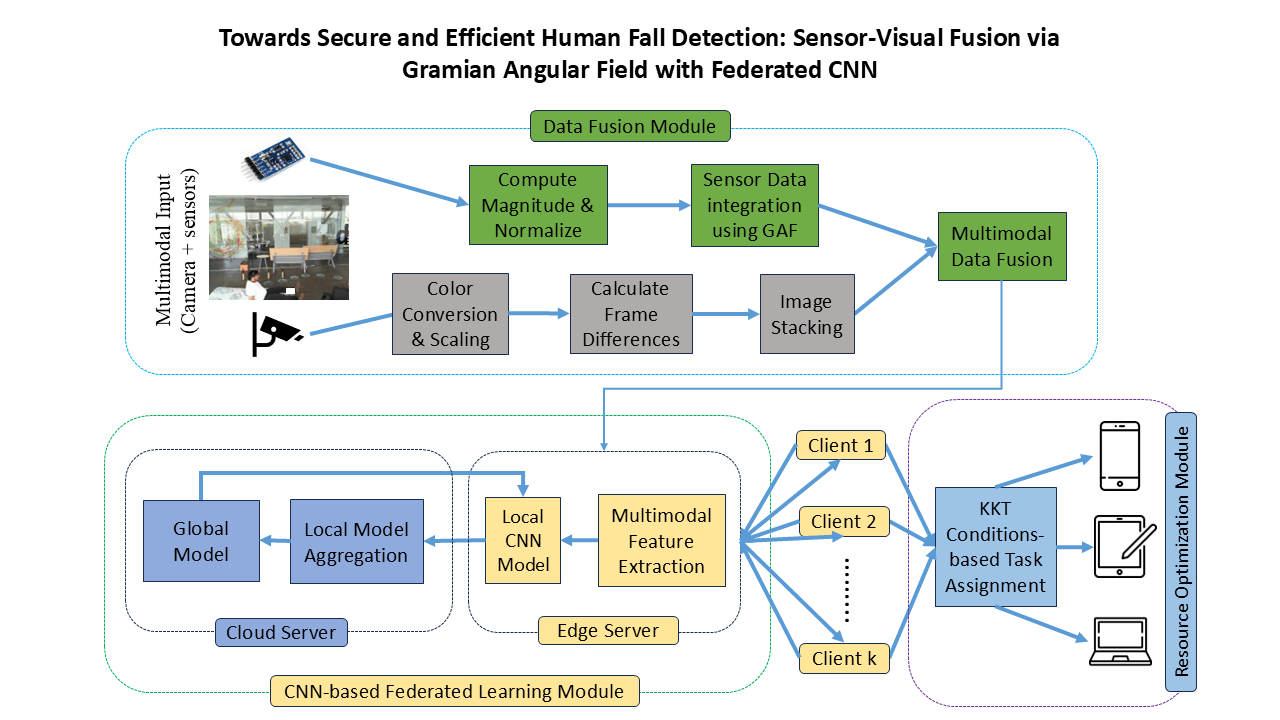

The proposed methodology for privacy-preserving human fall detection using federated learning is shown in Fig. 1. This architecture comprises three key modules: multimodal data fusion, CNN-based federated learning, and KKT-driven resource optimization, working together to address privacy and efficiency in fall detection.

Figure 1: Proposed privacy-preserving fall detection framework integrating multimodal data fusion and CNN-based federated learning. The architecture includes resource-aware task optimization (via KKT) and illustrates how all client devices operate identically—each extracting features and training local models before contributing updates to a global model without sharing raw data

The pipeline begins with multimodal inputs (sensor and camera), where sensor signals undergo normalization and transformation via Gramian Angular Field (GAF), and visual data is processed through color scaling and motion-aware frame differencing. Both streams are stacked and fused to generate enriched multimodal representations. In the federated learning module, each client device hosts a local CNN model that extracts features from the fused data and transmits model updates—not raw data—to a central server. The server aggregates updates and redistributes the refined global model back to the clients. Cloud and edge servers collaborate in this decentralized training. Simultaneously, a resource optimization module utilizes Karush–Kuhn–Tucker (KKT) conditions to allocate training workloads across edge clients (e.g., smartphones, tablets, laptops) based on their current computational state. This end-to-end setup ensures both privacy preservation and resource-aware efficiency, making the model practical for deployment in real-world edge environments. The individual modules—data fusion, federated CNN training, and task allocation—are discussed in more detail in the following subsections.

In the data fusion module, we collected heterogeneous data from wearable sensors and cameras, as diverse modalities provide relevant information required for comprehensive and accurate detection. The sensor and camera data are integrated using the input-level multimodal data fusion technique. The sensor data processing part includes several steps: computing magnitudes, normalizing sensor data, and integrating processed data using GAF. In the case of visual data, we apply color conversion and scaling techniques, calculate frame differences, and create image stacking. The result from both modalities is fused to enhance the representation, which assists in identifying the critical features required to detect human falls.

This fusion is designed to preserve complementary information from both sources: GAF-encoded sensor data captures body movement dynamics (e.g., acceleration, rotation) across multiple anatomical locations, while the grayscale visual input encodes contextual scene and motion boundary information. Their combination enables the network to detect subtle motion variations and environment-sensitive cues, improving fall discrimination robustness. We further validate the benefit of this fusion through an ablation study in Section 4.3, which shows that individual modalities (sensor-only or camera-only) perform significantly worse compared to the fused configuration. This confirms that each channel contributes complementary information critical to accurate fall recognition.

3.1.1 Transforming Time Series Data to Image

We used Gramian Angular Field (GAF) to integrate sensor data with visual data as it offers notable advantages over other time-series conversion techniques such as spectrograms, wavelet transforms, or recurrence plots (RP). The concept of GAF to convert time series data to visual data was introduced by Wang and Oates in 2015 [15]. Integration of images achieved from sensor-based accelerometer and gyroscope signals with RGB data allows the model to learn multi-modal features more effectively. We integrated multimodal sensor data (accelerometer and gyroscope) from wearable sensors located at the ankle, right pocket, belt, neck, and wrist. Data from these body locations captures the scenarios that contributed to falls. We summarize the mathematical steps of GAF to process sensor data in the next section (Algorithm 1).

Initially, the raw time-series data,

The camera frames pass several preprocessing stages before fusing with GAF images obtained from time-series data to enhance fall detection effectiveness, shown in Fig. 2. To ensure consistency in different image sources, initially, the raw frames are resized to 140

Figure 2: Processing steps of camera data, illustrating grayscale frame extraction, frame differencing to highlight motion, and summation of normalized differences

Figure 3: Concatenation of multi-sensor (Ankle, Right Pocket, Belt, Neck, Wrist) Gramian angular field (GAF) images and camera data, integrating acceleration, angular velocity, and visual inputs

3.1.3 Fusion of Sensor and Camera Data

GAF images from sensor data are combined with camera-based motion features into a unified three-channel representation. A 3-channel RGB-like image is produced by stacking the GAF acceleration, GAF angular velocity, and camera grayscale image (Fig. 3). These fused images facilitate capturing human motion dynamics by extracting both spatial and temporal dependencies. The linear human motion variation is encoded into the GAF acceleration channel. On the other hand, the rotational dynamics are presented by the GAF angular velocity channel. The time series perspective on movement patterns from these two channels is crucial to differentiate between fall and non-fall activities. The generated grayscale image provides visual context by highlighting the human silhouette and movement boundaries. Each channel contributes distinct types of motion information—linear force (acceleration), rotational movement (angular velocity), and silhouette-based scene dynamics (visual channel)—enabling the network to learn from spatial and temporal interactions across modalities. The proposed CNN model learns cross-domain features. Thus the model becomes more generalized in different environments, such as sensor noise and varying lighting conditions.

3.2 Federated Deep Learning Module

In this module, high-dimensional spatial-temporal features are extracted from the multimodal fused input using a custom convolutional neural network (CNN), optimized for fall detection tasks. A Federated Learning (FL) framework is adopted to preserve data privacy and enable distributed training across edge devices. This setup eliminates the need to transfer raw sensor or camera data to the server. Each client trains its own local model on fused sensor-camera data, keeping all user data on-device while learning personalized fall-related patterns. After local training, only the model weight updates are shared with a central server, which performs model aggregation using Federated Averaging (FedAvg) to build a global model. This global model is then broadcasted back to all clients for the next training round, continuing iteratively until convergence.

3.2.1 Data Partitioning Assumption in FL Setup

Our current federated learning setup assumes an IID (Independent and Identically Distributed) data distribution across clients by randomly sampling from the global training pool. This simplifies convergence and enables controlled performance comparisons across model variants. However, it does not reflect real-world non-IID scenarios where client data distributions vary by user or context. Although our work prioritizes privacy-preserving training and multimodal fusion, evaluating performance under non-IID conditions remains a key direction for future research.

3.2.2 Proposed CNN Architecture

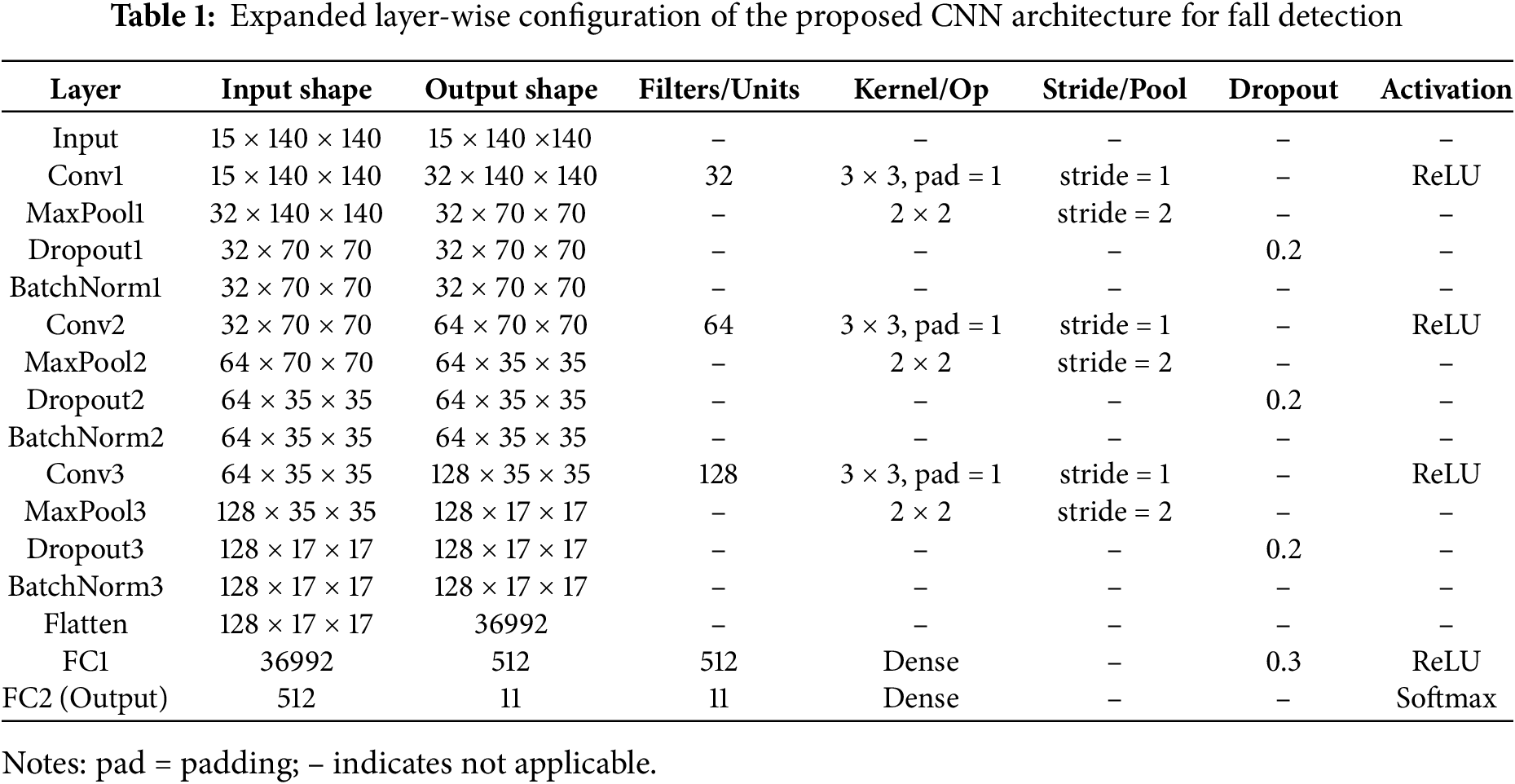

While popular architectures like ResNet and MobileNet were evaluated in our benchmarks, we found that adapting them to handle fused 15-channel multimodal input in a federated setup led to suboptimal convergence and lower accuracy. To address these shortcomings, we designed a lightweight CNN tailored for spatial-temporal feature extraction from fused sensor and camera modalities, with layers configured for robustness under FL constraints.

Our proposed convolutional neural network (CNN) architecture is capable of processing multimodal data to enhance detection accuracy (Fig. 4). By extracting spatial and temporal motion features from fused data, the network effectively learns hierarchical characteristics. After feature extraction using convolutional layers, fully connected layers efficiently classify fall and non-fall activities. Three channels, namely GAF acceleration, GAF angular velocity, and camera grayscale motion images, are provided as input to the CNN model. They supply complementary information to the model, such as capturing motion intensity, rotational movement, and visual motion boundaries. Several convolutional layers are used to process the multimodal data to reduce spatial dimensions and extract high-level patterns related to human movement.

Figure 4: Block diagram of the proposed CNN architecture illustrating the transformation of multimodal input (sensor + visual) through convolutional and dense layers

The network starts with an input volume of 15 channels, corresponding to the 3

The final feature maps (128 channels of size 17

By combining deep feature extraction with multimodal fusion, the CNN architecture enhances fall detection robustness, ensuring improved recognition accuracy across diverse real-world scenarios. The model leverages the strengths of both sensor-based motion analysis and vision-based detection, making it highly effective in detecting human falls under varying environmental conditions.

3.2.3 CNN-Based FL Implementation

The Federated Learning (FL) algorithm ensures privacy preservation by decentralizing model training, allowing clients to train locally on their own datasets without transmitting raw data to the central server (Algorithm 2). In each communication round, a subset of K clients is randomly selected (Line 3) to participate in training, reducing computational overhead while maintaining model generalization. Each client downloads the current global model (Line 5) and trains it locally using its multimodal dataset, computing gradients from mini-batches (Line 9) and updating the local model parameters (Line 10). Once training is completed, the clients send only the updated model weights

This iterative process enables the model to learn from decentralized data sources while preventing sensitive information from being exposed. Additionally, the resource optimization module (Fig. 1) utilizes KKT-based task assignment to efficiently allocate computational resources, balancing workload among clients and minimizing communication overhead. By integrating CNN-based local training with FL, the system effectively extracts spatial and temporal multimodal features while preserving user privacy and optimizing network efficiency.

3.3 Task Assignment Using KKT Conditions

The use of Karush–Kuhn–Tucker (KKT) conditions in our resource-aware task distribution module is driven by their proven ability to handle nonlinear constraints in convex optimization problems. This makes KKT especially well-suited for federated learning (FL) applications involving edge devices with heterogeneous computing and energy capabilities—common in fall detection scenarios for elderly care. In such domains, strict latency and real-time requirements exist, while devices may vary significantly in processing power. KKT’s analytical formulation allows us to formally enforce constraints such as task size, device capacity, and processing overhead, enabling efficient and balanced workload distribution.

However, we acknowledge that our current implementation assumes static device availability, fixed task profiles, and no communication loss. While the method has demonstrated favorable results under controlled conditions, real-world FL deployments may face client dropout, bandwidth fluctuations, or network delays. We now explicitly recognize these factors as limitations of the current system and highlight them as targets for future research.

3.3.1 Optimization Problem Formulation

This section presents the task assignment optimization problem using the Karush-Kuhn-Tucker (KKT) approach. The optimization objective and constraints are detailed below.

Objective Function. The optimization aims to minimize the total computational cost, which includes both the task-specific computational cost and a fixed overhead cost. The objective function is formulated as:

where

Constraints. The following constraints must be satisfied to ensure feasible task assignments.

Task Completion Constraint. Each activity must be assigned to exactly one device, ensuring that no task is left unallocated or assigned to multiple devices:

Capacity Constraint. The total workload assigned to a device must not exceed its available computational capacity:

Here, T represents the task size,

Binary Constraint. The task assignment variable

The task assignment optimization follows an iterative process where tasks are allocated based on adjusted costs, and dual variables

To achieve optimal resource allocation, Algorithm 3 leverages Karush-Kuhn-Tucker (KKT) conditions to balance task assignments while respecting device capacity constraints. Algorithm 3 initializes task allocation variables (

Once tasks are assigned, the algorithm updates dual variables to enforce constraints dynamically. The first dual variable update (Line 7) ensures that each task is assigned to exactly one device while penalizing over-allocation using the learning rate

This approach optimally distributes computational tasks across heterogeneous devices while enforcing resource constraints through KKT conditions. By dynamically adjusting dual variables, the method efficiently balances the workload, preventing overloading and ensuring smooth execution.

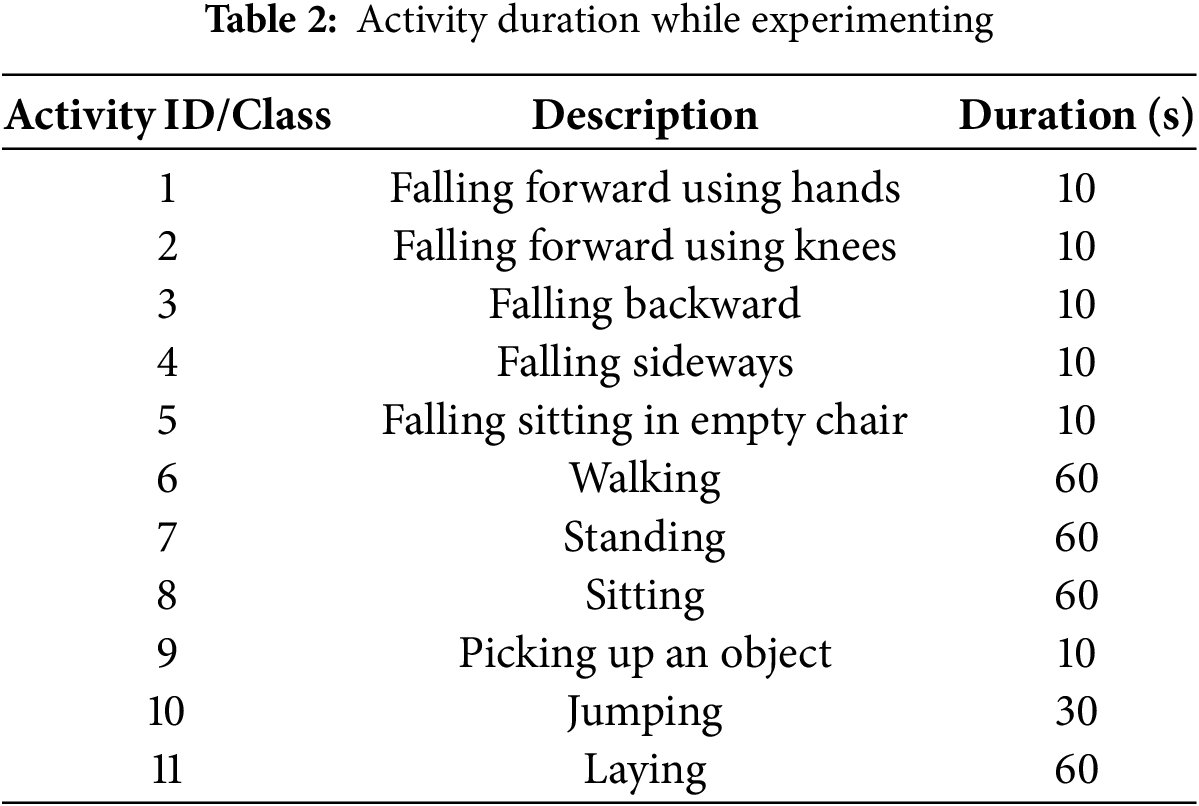

The UP-Fall Detection Dataset is a comprehensive multimodal dataset designed for fall detection research, capturing fall-related and daily activities performed by multiple subjects. The dataset includes 11 activities categorized into falling scenarios (e.g., falling forward using hands/knees, falling backward, sideways, and sitting falls) and daily activities (e.g., walking, standing, sitting, object pickup, jumping, and laying), as detailed in Table 2. To enable robust analysis, the dataset was collected using a combination of wearable sensors, environmental sensors, and cameras. Fig. 5 illustrates the data collection setup, highlighting the sensor placement on the body and the camera views used for visual data acquisition. The UP-Fall dataset includes accelerometers, gyroscopes, environmental sensors, and EEG headsets to capture multimodal information. In this study, however, we used only wearable sensor and camera data for fusion and model training.

Figure 5: Dataset collection setup: (a) Infrared sensors and camera views; (b) Sensor orientation (wearables and EEG headset) (adapted from [33])

Fig. 6 provides a visual representation of each recorded activity in the dataset, demonstrating the diversity in movement patterns across different actions. Additionally, Fig. 7 illustrates the process of tracking a single activity composed of multiple poses, emphasizing the dataset’s granularity in capturing continuous motion sequences. The duration of activities varies from 10 to 60 s, ensuring sufficient data for training robust machine learning models. This dataset serves as a valuable resource for researchers focusing on computer vision, deep learning, and sensor-based fall detection, contributing to the development of automated fall detection systems for elderly and at-risk individuals.

Figure 6: Example of each activity in the UP-fall dataset

Figure 7: Tracking a single activity composed of several poses

The experiments were conducted on a local machine (HP Victus Gaming 16-r0007nx), featuring the following hardware specifications: 13th Gen Intel Core i7-13700H processor (2.40 GHz), 32 GB DDR5-5600 MHz RAM (2

4.3 Evaluation of the Proposed System

This section presents a comprehensive evaluation of the proposed fall detection system, focusing on quantifying the contribution of each key module. We perform ablation studies to analyze the impact of multimodal data fusion (sensor and camera), the proposed federated learning (FL) framework vs. centralized training, and the effectiveness of KKT-based resource optimization. Each subsubsection presents both quantitative metrics and visualizations to demonstrate improvements in accuracy, generalization, and deployment efficiency.

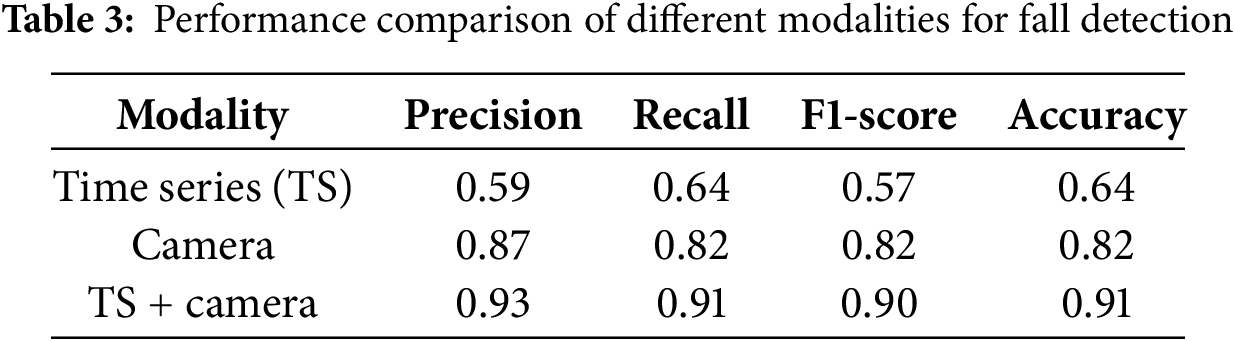

4.3.1 Performance of Different Modality Data

The performance comparison of different modalities for fall detection is analyzed through the confusion matrices (Fig. 8) and performance metrics table (Table 3). The confusion matrices in Fig. 8 illustrate the classification results for different input modalities: time series, camera, and their combination (TS + Camera). From the individual confusion matrices (Fig. 8a and b), it is evident that both the time series and camera data alone lead to significant misclassification across different classes, resulting in scattered off-diagonal values. However, when both modalities are combined (Fig. 8c), the confusion matrix becomes more diagonal dominant, indicating improved classification performance.

Figure 8: Confusion matrix for different modalities: (a) Time series; (b) Camera; (c) Time series + camera

The performance comparison in Table 3 further supports this observation. Using a single modality, the performance is limited: the time series (TS) data achieves a precision of 0.59, recall of 0.64, F1-score of 0.57, and accuracy of 0.64, while the camera modality alone improves performance to a precision of 0.87, recall of 0.82, F1-score of 0.82, and accuracy of 0.82. However, when both modalities are combined (TS + Camera), the model demonstrates a substantial improvement across all metrics, achieving a precision of 0.93, recall of 0.91, F1-score of 0.90, and accuracy of 0.91. This significant improvement highlights the advantage of multimodal fusion, as the combined data captures complementary features, leading to more robust and reliable fall detection. Overall, the results demonstrate that integrating both time series and camera data enhances model performance, making it a more effective solution for accurate fall detection.

4.3.2 Centralized vs. Federated Training

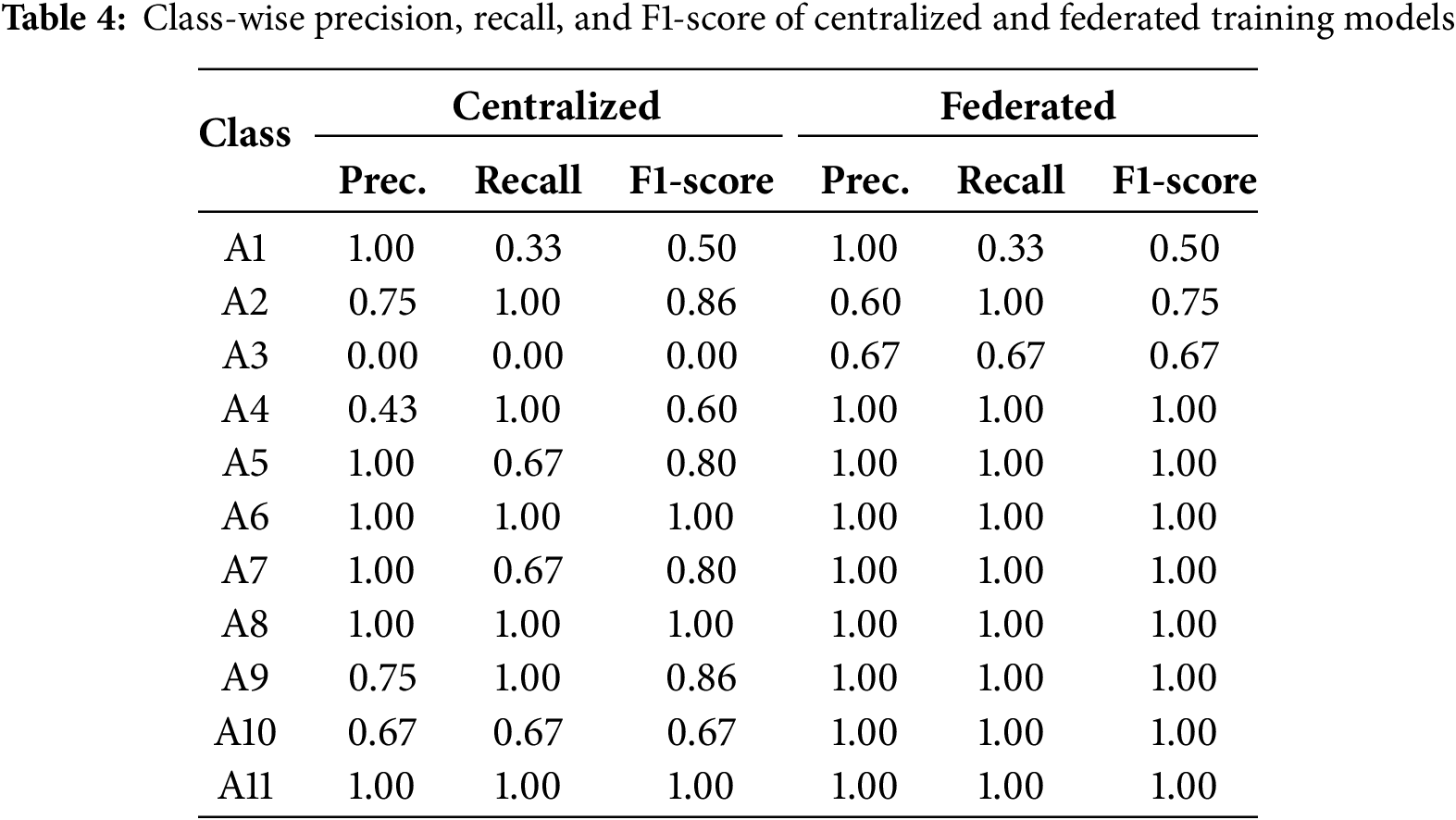

To assess the effectiveness of our federated learning (FL) framework, we conducted an ablation study comparing the proposed CNN model’s performance under two training settings: centralized training and federated training. Both settings used the same multimodal inputs (sensor + camera), CNN architecture, and hyperparameters on the UP-Fall dataset to ensure fairness. Fig. 9 shows the comparative results across four performance metrics. The federated model outperforms the centralized one in every aspect, achieving 93.3% precision, 90.9% recall, 90.15% F1-score, and 90.91% accuracy—compared to 78.1%, 75.8%, 73.5%, and 75.8%, respectively, in the centralized case. These improvements confirm that federated learning not only preserves data privacy but also enhances generalization across distributed devices.

Figure 9: Overall performance comparison between centralized and federated training

To provide further insight, Table 4 reports the class-wise precision, recall, and F1-score for both models. The federated model shows consistently higher scores across all activity classes—including challenging fall classes such as A3, A4, and A5—where the centralized model either failed completely (A3) or struggled (A5). These findings highlight the federated model’s superior robustness in learning discriminative features across a broader distribution of user data. These class-wise improvements demonstrate that federated training is not only advantageous in preserving data privacy but also leads to better learning of fall-specific motion patterns across a diverse subject population.

4.3.3 KKT-Based Optimization for Resource Utilization

The experiment was conducted with three subjects performing eleven activities, distributed across ten computational devices. Each subject had a predefined computational capacity ranging from 100 to 120 processing units, with an initial load of 20 to 30 units per device. The task size was set to 15 units, and each task had a processing duration of 1 s with an overhead cost of 2 s per assignment. The goal was to evaluate task assignment efficiency with and without KKT-based optimization. The primary assumption in this study is that each device operates under resource constraints, meaning tasks must be assigned efficiently without exceeding device capacity. Additionally, it is assumed that all tasks must be completed within the available computational resources. The optimization aims to minimize divergence time while ensuring balanced workload distribution.

The results demonstrate that KKT-based optimization significantly improves resource utilization. The number of iterations required for task allocation decreased from three (without KKT) to just one (with KKT), ensuring faster task execution (Fig. 10a). Without KKT, task assignments led to bottlenecks and inefficient workload balancing, resulting in a higher divergence time of 102.0001 s. In contrast, KKT-based optimization reduced this to 100.0047 s by optimally distributing tasks across available devices (Fig. 10b). Although the total computational cost remained the same (495 GFLOPS), KKT optimization ensured efficient task execution, reducing idle time and unnecessary delays. This is crucial for privacy-preserving federated learning applications, particularly for human fall detection, where timely inference and efficient model updates are essential.

Figure 10: Results of KKT conditions-based resource optimization: (a) Required number of iterations; (b) Divergence time

In summary, KKT optimization improves efficiency by reducing divergence time, minimizing iterations, and ensuring optimal resource utilization. This makes real-time federated learning more practical in resource-constrained environments, enabling faster and more reliable fall detection while maintaining privacy.

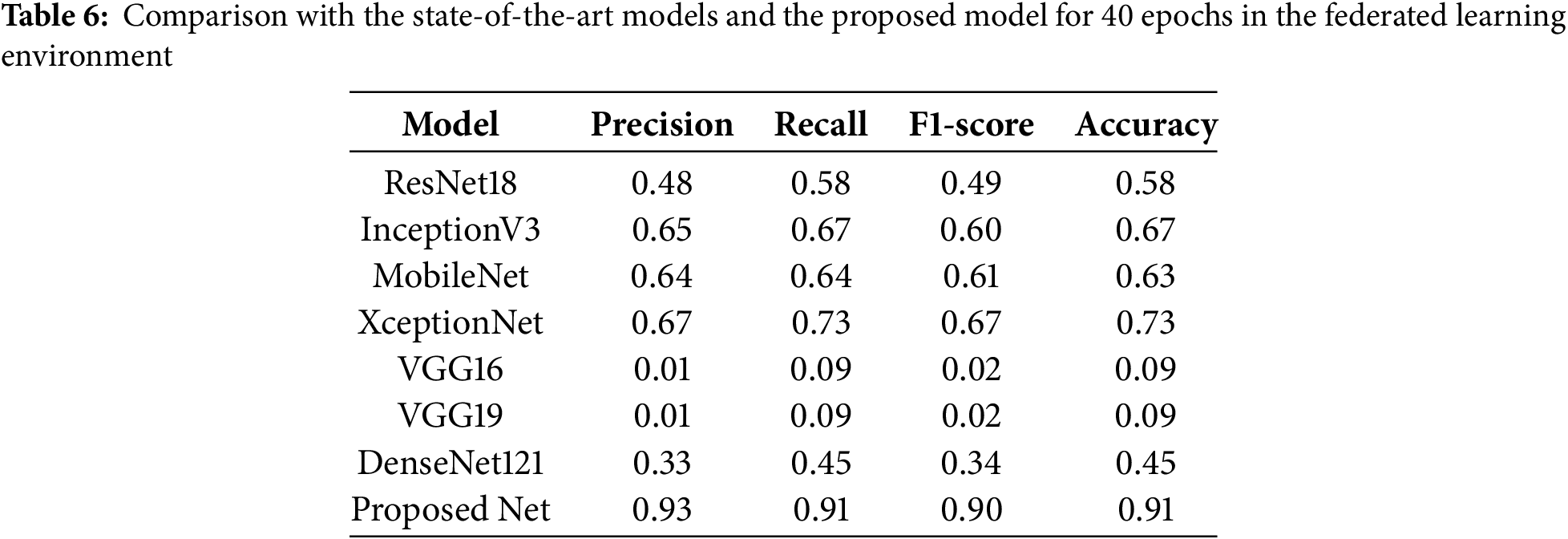

The training loss analysis in Fig. 11 offers insights into model convergence under a federated learning (FL) setting for multimodal fall detection. The proposed model consistently achieves the lowest and most stable training loss across all 40 epochs, reflecting efficient learning even under decentralized data conditions. Compared to the proposed model, other CNN-based architectures demonstrate varied performance. ResNet18, InceptionV3, and DenseNet show volatile loss curves with several spikes, suggesting unstable convergence in the FL context. MobileNet converges more consistently but to a higher final loss. XceptionNet performs competitively in later epochs. In contrast, VGG16 and VGG19 exhibit extremely poor results (both 9% accuracy), as these architectures are primarily designed for single-modal image classification and failed to converge effectively under our multimodal FL setup. This highlights the need for customized architectures tailored to fused multimodal data.

Figure 11: Training loss curves (log scale) across 40 epochs for various CNN-based models in a federated learning environment

To ensure a fair and consistent evaluation, all baseline models (e.g., ResNet18, MobileNet, VGG16) were initialized with pretrained ImageNet weights to leverage transferable visual features. Each model was modified to accept 15-channel multimodal input by inserting a 1

The proposed model incorporates convolutional layers specialized for fused sensor-visual input, along with batch normalization and dropout, to ensure stable convergence and prevent overfitting in a federated setting. Its performance reflects strong generalization across decentralized clients while preserving data privacy. Overall, these results emphasize the importance of architectural customization when training on multimodal inputs under federated constraints. The proposed model consistently maintains lower training loss and higher stability, reinforcing its effectiveness for real-world, privacy-aware fall detection systems.

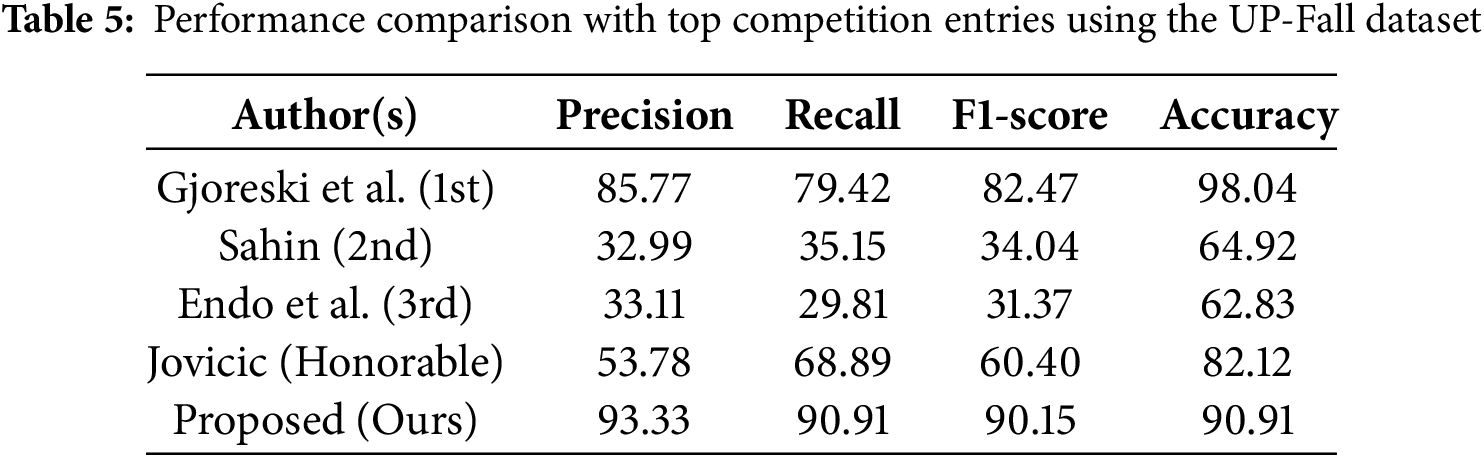

4.5 Benchmarking against UP-Fall Competition Winners

To ensure a fair and domain-specific benchmark, we compared our proposed system with the top-ranking models from the Challenge UP–Multimodal Fall Detection competition2. All models were evaluated on the UP-Fall dataset using a 1-second sliding window classification task [34]. The first-place model by Gjoreski et al. used a Random Forest classifier trained solely on wearable sensor data and achieved an F1-Score of 82.47% and an exceptionally high accuracy of 98.04%. Sahin (2nd place) utilized a 1D CNN with data from sensors, EEG, and ambient sources but only achieved 34.04% F1-Score and 64.92% accuracy. Endo et al. (3rd place) implemented a BiLSTM using wearable data and reported even lower performance (F1-Score: 31.37%, Accuracy: 62.83%). The honorable mention by Jovicic reached an F1-Score of 60.40% and accuracy of 82.12%, though implementation details were not disclosed.

In contrast, our proposed method achieves strong and balanced performance across all evaluation metrics, with 90.15% F1-Score, 90.91% accuracy, 93.33% precision, and 90.91% recall. While Gjoreski et al.’s model reported a slightly higher accuracy (98.04%), our approach provides superior precision, recall, and F1-Score, reflecting more consistent detection capability. These gains are driven by two key design choices: (1) the fusion of visual and sensor modalities using Gramian Angular Field (GAF) encoding to jointly capture spatial and temporal dynamics, and (2) the integration of a privacy-preserving Federated Learning (FL) framework, which none of the benchmarked methods employed. Together, these features validate the strength of our system not only in accuracy but also in robustness, fairness across metrics, and secure, real-world deployment potential. Table 5 summarizes the performance comparison, demonstrating the superiority of our approach over existing top-ranked models from the UP-Fall detection benchmark.

4.6 Comparison with SOTA Models

Table 6 presents a comparative analysis of the proposed model against several state-of-the-art (SOTA) deep learning architectures, all of which were trained in a federated learning environment using the same multimodal dataset and experimental setup. The evaluation metrics include Precision, Recall, F1-Score, and Accuracy, providing a comprehensive assessment of classification performance. The proposed model achieves the highest accuracy of 91%, along with superior F1-Score (0.90), Precision (0.93), and Recall (0.91), outperforming all other models. Compared to the proposed model, the FL-adapted versions of ResNet18, MobileNet, and InceptionV3 perform moderately, achieving accuracies of 58%, 63%, and 67%, respectively. XceptionNet achieves competitive performance with 73% accuracy. In contrast, VGG16 and VGG19 exhibit extremely poor results (both 9% accuracy), while DenseNet121 performs marginally better at 45%. These results reflect clear disparities in model adaptability to the federated multimodal context.

The poor performance of several well-known architectures can be attributed to their design limitations. Most, including ResNet18, DenseNet, and InceptionV3, were originally optimized for single-channel image classification (e.g., RGB or grayscale images) and lack mechanisms for handling fused multimodal inputs. Consequently, they struggle to capture the complex spatial-temporal correlations present in Gramian Angular Field (GAF)-based sensor features combined with visual motion data, leading to unstable convergence and suboptimal classification. From an implementation perspective, the proposed model is specifically designed for multimodal feature extraction. It effectively utilizes convolutional layers to capture spatial and temporal patterns in the fused input, while batch normalization and dropout mechanisms enhance generalization, reducing overfitting. In addition, the proposed model also supports privacy-aware processing by leveraging local sensor fusion without centralized raw data transmission, making it more suitable for deployment in real-world edge environments.

Overall, the proposed model provides an optimal balance between privacy preservation, computational efficiency, and classification accuracy. The results highlight the necessity of custom architectures tailored for multimodal federated learning tasks, rather than relying solely on standard deep learning models designed for unimodal vision applications.

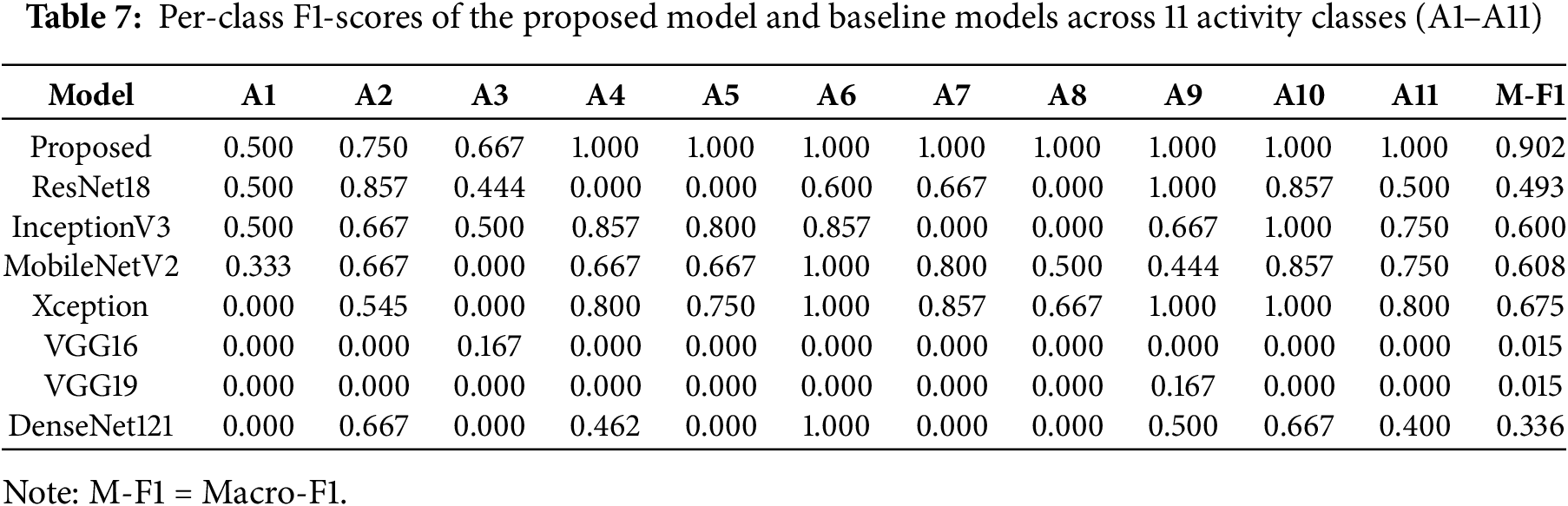

4.7 Statistical Significance Testing

To rigorously assess the superiority of our proposed model, we conducted a paired t-test [35] on the per-class F1-scores (A1–A11) obtained from the proposed model and each baseline. This test, originally introduced by Gosset under the pseudonym “Student”, evaluates whether the means of two related samples differ significantly. Since all models are evaluated over the same set of 11 activity classes, the paired t-test is appropriate for comparing these matched observations.

Table 7 presents the detailed F1-scores across all classes along with the macro-averaged F1. The proposed model consistently achieves near-perfect results, whereas models such as ResNet18, InceptionV3, MobileNetV2, and Xception show moderate performance. VGG16 and VGG19 perform poorly and fail to generalize in a multimodal federated setting, while DenseNet121 performs better but still trails the proposed approach. To formally assess the performance differences, we conducted paired t-tests on the per-class F1-scores (A1–A11) of the proposed model compared to each baseline. Table 8 reports the mean improvements (

The results confirm that the proposed model achieves statistically significant improvements over all baselines (

In conclusion, the results in Tables 7 and 8 provide robust evidence that the proposed model delivers consistent and significant performance improvements over both classic and modern CNN baselines. This supports its claim as a state-of-the-art solution for multimodal federated fall detection.

4.8 Comparative Analysis of Benchmark Approaches

This section presents a two-part comparative analysis. First, we examine neural network-based multimodal fall detection methods, regardless of deployment settings. Then, we focus on approaches leveraging federated learning (FL) to ensure data privacy and distributed intelligence. Both categories use the UP-Fall dataset, a widely accepted benchmark in fall detection research.

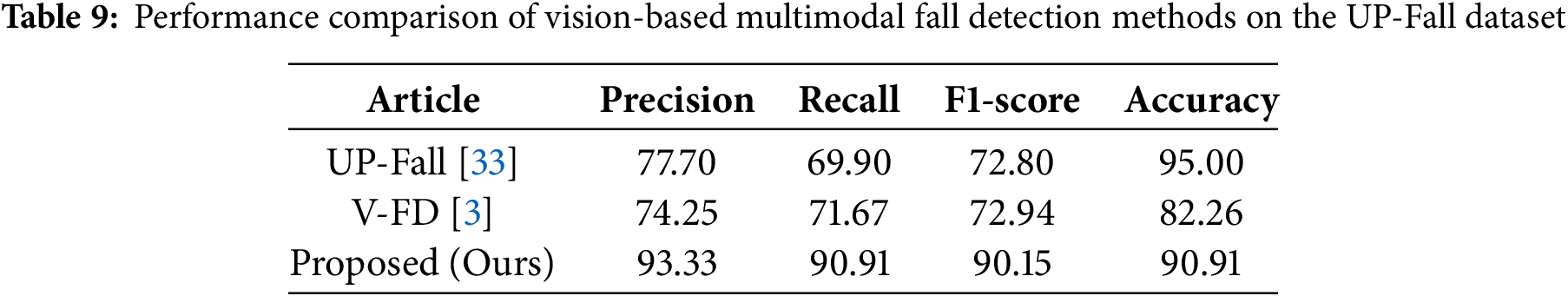

4.8.1 Vision-Based Multimodal Fall Detection Methods

Table 9 summarizes the performance of state-of-the-art multimodal neural architectures that do not adopt FL. Martinez-Villasenor et al. [33] employed a simple MLP using fused IMU, EEG, and dual-camera modalities, achieving 95.00% accuracy. However, the recall remained at 69.90%, reflecting the risk of undetected fall events. Espinosa et al. [3] developed a CNN-based vision-only method (V-FD), reporting modest gains in F1-score (72.94%) without leveraging sensor data or privacy mechanisms.

In comparison, our proposed model integrates Gramian Angular Field (GAF) encoding, deep CNNs tailored for multimodal spatio-temporal data, and resource-aware training mechanisms. It achieves 93.33% precision, 90.91% recall, 90.15% F1-score, and 90.91% accuracy, surpassing all vision-based models while preserving real-time applicability and scalability.

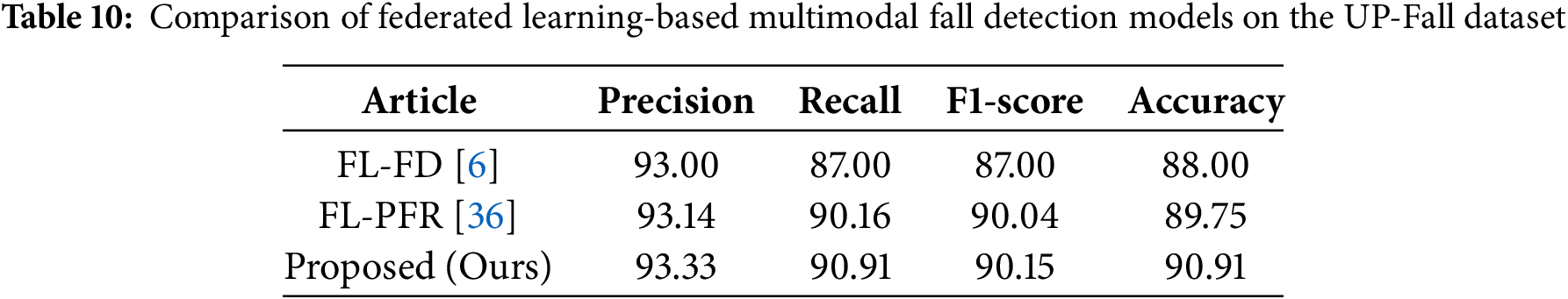

4.8.2 Federated Learning-Based Multimodal Fall Detection

Table 10 compares FL-enabled fall detection systems. Qi et al. [6] introduced FL-FD, using CNNs with sensor-visual inputs in a federated setup. It achieves 87.00% F1-score and 88.00% accuracy, demonstrating the promise of privacy-preserving fall detection. Kim et al. [36] proposed FL-PFR, which uses a hybrid of GAT (Graph Attention Network) and LSTM layers to model spatial-temporal dependencies from CCTV streams. Their design emphasizes real-world road surveillance and achieves 90.04% F1-score and 89.75% accuracy using the UP-Fall dataset. Our proposed system, when tested under a similar FL setup, delivers superior performance with 93.33% precision, 90.91% recall, 90.15% F1-score, and 90.91% accuracy. It also incorporates a KKT-based optimization module for resource-aware task distribution—a feature absent in FL-FD and FL-PFR. These findings highlight the competitive advantage of our model in both predictive accuracy and practical deployment in distributed, privacy-critical environments.

5 Conclusion and Future Research Directions

This research presents a privacy-aware and resource-efficient fall detection framework that combines multimodal sensor and visual data fusion with federated deep learning. By encoding accelerometer, gyroscope, and camera inputs using Gramian Angular Field (GAF), the system captures spatial-temporal patterns crucial for robust fall classification. A custom CNN architecture is proposed to process the fused input within a federated learning (FL) setup, ensuring that raw data remains on-device and privacy is preserved. Additionally, the system incorporates Karush–Kuhn–Tucker (KKT)-based optimization to intelligently distribute training workloads across edge devices based on computational capacity. Evaluated on the UP-Fall dataset, the framework achieves a 91% accuracy, outperforming several baseline and competition models. These results confirm the effectiveness of our integrated approach in delivering accurate, secure, and scalable fall detection suitable for real-world deployment in elderly care. Moreover, comparative evaluations and ablation studies validate the robustness and generalizability of our multimodal fusion approach under federated constraints.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

Despite these achievements, several future research directions can further enhance the system’s real-world feasibility, accuracy, and deployment scalability. Although the UP-Fall dataset provides a rich multimodal benchmark, it represents a single controlled environment. In future work, we plan to evaluate the model’s generalizability using other publicly available datasets such as DR Fall [37] and UR Fall [38], which capture more realistic or varied deployment settings.

Another limitation of this study is the assumption of an IID data distribution across clients in the federated learning setup. In real-world deployments, user devices typically contain non-IID data based on activity type, subject variability, or sensor noise. In future work, we plan to simulate non-IID conditions—such as subject-wise or activity-wise data partitioning—to evaluate model robustness under realistic heterogeneity and personalization scenarios. Moreover, our current implementation relies on synchronized sensor-visual data collected under controlled laboratory conditions. Such a setup may not reflect challenges in real-world deployment, such as missing data, environmental noise, or asynchronous sensor streams common in home environments. To address this, future work should explore robustness under partial modality availability, variable lighting, and layout diversity.

While our CNN is lightweight and KKT optimization improves task distribution, we acknowledge that GAF transformations and CNN inference can be demanding for low-power edge devices. Future work will explore model compression (e.g., quantization, pruning) and offloading GAF preprocessing to edge gateways to enhance real-world feasibility without compromising privacy. Additionally, investigating fall detection on encrypted data using Homomorphic Encryption can enhance privacy without compromising model performance. Recent advancements in secure aggregation and differential privacy combined with secure multiparty computation (DP+SMC) offer promising avenues for stronger privacy guarantees in federated learning. Although our current system relies on a standard FL setup without cryptographic overhead, future extensions could explore integrating these techniques to protect against adversarial inference or collusion risks. Incorporating secure aggregation via homomorphic encryption or hybrid DP-SMC strategies would further enhance privacy at the cost of computational complexity, which should be carefully balanced for edge deployment feasibility.

To strengthen deployment readiness, future efforts should include testing across home environments with variable lighting, background clutter, and natural occlusions to ensure robust inference in unconstrained conditions. In future work, we aim to extend the proposed KKT optimization strategy by integrating it with dynamic system feedback, including latency monitoring, device dropout handling, and task reallocation in real time. Additionally, we plan to investigate alternative optimization techniques such as Genetic Algorithms, Reinforcement Learning, and Simulated Annealing to complement or enhance scheduling robustness under non-convex and dynamic scenarios.

Lastly, future work can extend this research toward proactive fall prevention by leveraging sequential visual and sensor data to predict imminent falls before they occur. This would enable early warnings and preventive interventions, advancing the system from detection to prediction. Altogether, these additions will help validate the model’s performance beyond a single dataset and foster trust in its generalizability across unseen domains. Addressing these practical limitations will also bridge the gap between laboratory performance and real-world usability. These advancements will further refine the fall detection framework, making it more adaptable, secure, and effective in real-world scenarios.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research is based upon work supported by King Fahd University of Petroleum & Minerals, Dhahran, 31261, Saudi Arabia. The authors at KFUPM acknowledge the Interdisciplinary Research Center for Intelligent Secure Systems (IRC-ISS) for the support received under Grant No. INSS2516.

Author Contributions: Md Sabir Hossain: Writing—original draft, review & editing, visualization, validation, coding, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, data curation, conceptualization. Md Mahfuzur Rahman: methodology, conceptualization, review & editing. Mufti Mahmud: methodology, conceptualization, review & editing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The dataset used in this study is publicly available at https://sites.google.com/up.edu.mx/har-up/ (accessed on 21 September 2025). To promote reproducibility and transparency, we provide detailed methodological explanations in the manuscript, including preprocessing steps, multimodal fusion, CNN architecture, training routines, and evaluation protocols. The code used in this study is available from the authors upon reasonable request for academic and non-commercial purposes.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Appendix A Statistical Testing Procedure:

To formally validate the superiority of our proposed model, we conducted paired statistical tests on the per-class F1-scores of all models. The following steps were applied:

Appendix A1 Data Preparation:

For each model M, we extracted the per-class F1-scores across all 11 activity classes

Appendix A2 Paired Differences:

For each class

The mean difference is given by

where

Appendix A3 Paired T-test:

The paired t-test statistic is calculated as:

where

The corresponding two-tailed

Appendix A4 Multiple Comparisons Correction:

Since the proposed model was compared against seven baselines, we corrected for multiple hypothesis testing using:

• Bonferroni correction:

• Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) correction: False discovery rate control was applied by ranking the

Appendix A5 Effect Size:

We also report Cohen’s

A

Appendix A6 Implementation:

All computations were implemented in Python using the numpy and scipy.stats libraries, ensuring reproducibility. Scripts used for significance testing will be shared upon request for academic use.

Appendix A7 Example Calculation (Proposed vs. ResNet18)

As an illustrative example, we detail the paired t-test calculation for the comparison between the proposed model and ResNet18.

Step 1: Extract per-class F1-scores. From Table 7:

Step 2: Compute paired differences.

Step 3: Mean and standard deviation of differences.

Step 4: t-statistic.

Step 5: p-value (two-tailed). With

Step 6a: Bonferroni correction (FWER). For

Step 6b: Benjamini-Hochberg correction (FDR). Assuming the ranked

Step 7: Effect size.

Interpretation. The proposed model improves mean per-class F1 by

1https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.65UP.TO.ZS (accessed on 21 September 2025)

2Official competition link: https://sites.google.com/up.edu.mx/challenge-up-2019/overview (accessed on 21 September 2025).

References

1. Lian J, Yuan X, Li M, Tzeng NF. Fall detection via inaudible acoustic sensing. Proc ACM Interact Mob Wearable Ubiquitous Technol. 2021;5:1–21. doi:10.1145/3478094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Momin MS, Sufian A, Barman D, Dutta P, Dong M, Leo M. In-home older adults’ activity pattern monitoring using depth sensors: a review. Sensors. 2022;22(23):9067. doi:10.3390/s22239067. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Espinosa R, Ponce H, Gutiérrez S, Martínez-Villaseñor L, Brieva J, Moya-Albor E. A vision-based approach for fall detection using multiple cameras and convolutional neural networks: a case study using the UP-fall detection dataset. Comput Biol Med. 2019;115(11):103520. doi:10.1016/j.compbiomed.2019.103520. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Gunale KG, Mukherji P, Motade SN. Convolutional neural network-based fall detection for the elderly person monitoring. J Adv Inf Technol. 2023;14(6):1169–76. doi:10.12720/jait.14.6.1169-1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Y. MA, Tang L, Liu J. Elderly fall detection method using threshold based method and transfer learning. In: Frontiers in artificial intelligence and applications. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: IOS Press BV; 2024. p. 542–9. doi: 10.3233/faia231339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Qi P, Chiaro D, Piccialli F. FL-FD: federated learning-based fall detection with multimodal data fusion. Inf Fusion. 2023;99(9):101890. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2023.101890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Jiao S, Li G, Zhang G, Zhou J, Li J. Multimodal fall detection for solitary individuals based on audio-video decision fusion processing. Heliyon. 2024;10(8):e29596. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e29596. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Mobsite S, Alaoui N, Boulmalf M, Ghogho M. A privacy-preserving AIoT framework for fall detection and classification using hierarchical learning with multi-level feature fusion. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024;11(15):26531–47. doi:10.1109/jiot.2024.3398782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Asif U, Mashford B, Von Cavallar S, Yohanandan S, Roy S, Tang J, et al. Privacy preserving human fall detection using video data. In: Machine learning for health workshop. Westminster, UK: PMLR; 2020. p. 39–51. [Google Scholar]

10. Naser A, Lotfi A, Mwanje MD, Zhong J. Privacy-preserving, thermal vision with human in the loop fall detection alert system. IEEE Trans Human-Mach Syst. 2022;53(1):164–75. doi:10.1109/thms.2022.3203021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Yu Z, Liu J, Yang M, Cheng Y, Hu J, Li X. An elderly fall detection method based on federated learning and extreme learning machine (fed-elm). IEEE Access. 2022;10:130816–24. doi:10.1109/access.2022.3229044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Xiao Z, Xu X, Xing H, Song F, Wang X, Zhao B. A federated learning system with enhanced feature extraction for human activity recognition. Knowl Based Syst. 2021;229(5):107338. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2021.107338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Auvinet E, Multon F, Saint-Arnaud A, Rousseau J, Meunier J. Fall detection with multiple cameras: an occlusion-resistant method based on 3-D silhouette vertical distribution. IEEE Trans Inf Technol Biomed. 2010;15(2):290–300. doi:10.1109/titb.2010.2087385. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Xie L, Yang Y, Zeyu F, Naqvi SM. Skeleton-based fall events classification with data fusion. In: 2021 IEEE International Conference on Multisensor Fusion and Integration for Intelligent Systems (MFI); 2021 Sep 23–25; Karlsruhe, Germany. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

15. Wang Z, Oates T. Encoding time series as images for visual inspection and classification using tiled convolutional neural networks. In: Workshops at the Twenty-Ninth AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2015 Jan 25–30; Austin, TX, USA. Vol. 1, p. 91–6. [Google Scholar]

16. Guendel RG, Fioranelli F, Yarovoy A. Phase-based classification for arm gesture and gross-motor activities using histogram of oriented gradients. IEEE Sensors J. 2020;21(6):7918–27. doi:10.1109/jsen.2020.3044675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Averbuch G. The spectrogram, method of reassignment, and frequency-domain beamforming. J Acoust Soc Am. 2021;149(2):747–57. doi:10.1121/10.0003384. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Wang Z, Li X, Duan H, Zhang X, Wang H. Multifocus image fusion using convolutional neural networks in the discrete wavelet transform domain. Multimed Tools Appl. 2019;78(24):34483–512. doi:10.1007/s11042-019-08070-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Yang Y, Jiao L, Liu X, Liu F, Yang S, Li L, et al. Dual wavelet attention networks for image classification. IEEE Trans Circuits Syst Video Technol. 2022;33(4):1899–910. [Google Scholar]

20. Wendi D, Marwan N. Extended recurrence plot and quantification for noisy continuous dynamical systems. Chaos: An Interdiscip J Nonlinear Sci. 2018;28(8):085722. doi:10.1063/1.5025485. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Bo L. Human fall detection for smart home caring using yolo networks. Int J Adv Comput Sci Appl. 2023;14(4):59–68. doi:10.14569/ijacsa.2023.0140409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Kan X, Zhu S, Zhang Y, Qian C. A lightweight human fall detection network. Sensors. 2023;23(22):9069. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

23. Ma J, Naas SA, Sigg S, Lyu X. Privacy-preserving federated learning based on multi-key homomorphic encryption. Int J Intell Syst. 2022;37(9):5880–901. doi:10.1002/int.22818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Miao Y, He W, Wang C, Yang Q. Privacy-preserving byzantine-robust federated learning via blockchain systems. IEEE Trans Inf Forensics Secur. 2022;17:2848–61. doi:10.1109/tifs.2022.3196274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Truex S, Baracaldo N, Anwar A, Steinke T, Ludwig H, Zhang R, et al. A hybrid approach to privacy-preserving federated learning. In: Proceedings of the 12th ACM Workshop on Artificial Intelligence and Security; 2019. p. 1–11. doi:10.1145/3338501.3357370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Liu X, Ratnarajah T, Sellathurai M, Eldar YC. Adaptive model pruning and personalization for federated learning over wireless networks. IEEE Trans Signal Process. 2024;72:4395–411. doi:10.1109/tsp.2024.3459808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Chambolle A, Pock T. A first-order primal-dual algorithm for convex problems with applications to imaging. J Math Imaging Vis. 2011;40(1):120–45. doi:10.1007/s10851-010-0251-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Erel-Özçevik M, Özçift A, Özçevik Y, Yücalar F. A genetic optimized federated learning approach for joint consideration of end-to-end delay and data privacy in vehicular networks. Electronics. 2024;13(21):4261. doi:10.3390/electronics13214261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Chen J, Xing H, Xiao Z, Xu L, Tao T. A DRL agent for jointly optimizing computation offloading and resource allocation in MEC. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021;8(24):17508–24. doi:10.1109/jiot.2021.3081694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Hsu CK. An adaptive simulated annealing-based computational offloading scheme in UAV-assisted MEC networks. Comput Commun. 2024;224(1):118–24. doi:10.1016/j.comcom.2024.06.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Hu G, Lu J, Han J, Cao S, Liu J, Fu H. TRAIL: trust-aware client scheduling for semi-decentralized federated learning. In: Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2025 Feb 25–Mar 4; Philadelphia, PA, USA. p. 13935–43. [Google Scholar]

32. Hossain MS, Rahman MM. Human fall detection in poor lighting conditions using CNN-based model. In: Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (ICT4AWE 2025); 2025 Apr 6–8; Porto, Portugal. p. 414–20. [Google Scholar]

33. Martínez-Villaseñor L, Ponce H, Brieva J, Moya-Albor E, Núñez-Martínez J, Peñafort-Asturiano C. UP-fall detection dataset: a multimodal approach. Sensors. 2019;19(9):1988. doi:10.3390/s19091988. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Ponce H, Martínez-Villaseñor L. Approaching fall classification using the UP-fall detection dataset: analysis and results from an international competition. In: Challenges and trends in multimodal fall detection for healthcare. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2020. p. 121–33. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-38748-8_6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Student. The probable error of a mean. Biometrika. 1908;6(1):1–25. [Google Scholar]

36. Kim B, Im J, Noh B. Federated learning-based road surveillance system in distributed CCTV environment: pedestrian fall recognition using spatio-temporal attention networks. Appl Intell. 2025;55(6):1–16. doi:10.1007/s10489-025-06451-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Frank K, Vera Nadales MJ, Robertson P, Pfeifer T. Bayesian recognition of motion related activities with inertial sensors. In: Proceedings of the 12th ACM International Conference Adjunct Papers on Ubiquitous Computing-Adjunct; 2010 Sep 26–29; Copenhagen, Denmark. p. 445–6. [Google Scholar]

38. Kwolek B, Kepski M. Human fall detection on embedded platform using depth maps and wireless accelerometer. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2014;117(3):489–501. doi:10.1016/j.cmpb.2014.09.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools