Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Non-Newtonian Electroosmotic Flow Effects on a Self-Propelled Undulating Sheet in a Wavy Channel

1 Department of Mathematics and Statistics, International Islamic University, Islamabad, 44000, Pakistan

2 School of Mechanical Engineering, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN 47907, USA

3 Department of Mathematics and Sciences, College of Humanities and Sciences, Prince Sultan University, Riyadh, 11586, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Author: Zeeshan Asghar. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Mathematical Modeling: Numerical Approaches and Simulation for Computational Biology)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(1), 753-778. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.069177

Received 16 June 2025; Accepted 11 September 2025; Issue published 30 October 2025

Abstract

The objective of this work is to investigate the dynamics of a self-propelled undulating sheet in a non-Newtonian electrolyte solution inside a wavy channel under the electroosmotic effect. The electrolyte solution, which is non-Newtonian, is modeled as a Carreau-Yasuda fluid. The flow generated by a combination of an undulating sheet and electroosmotic effect is obtained by solving the continuity and momentum equations. The electroosmotic body force term is derived using the Poisson-Boltzmann equation for the electric potential. A fourth-order ordinary differential equation for the stream function is solved under the Stokes flow regime. The dynamics of the undulating sheet’s speed and the energy dissipation it, are investigated. The combined effects of electroosmosis and the viscoelastic properties of the ambient fluid on the undulating sheet are discussed.Keywords

Motility refers to the intrinsic ability of an organism or cell to move autonomously, which is vital for numerous biological processes, including reproduction, nutrient acquisition, immune responses, and tissue repair. In microorganisms such as bacteria and spermatozoa, motility is achieved through mechanisms like flagella, cilia, or shape modulation, which convert chemical or mechanical energy into directed motion. Understanding these mechanisms is essential not only in biology but also in engineering applications, as the swimming strategies of microorganisms have inspired the design of micro- and nano-robots capable of navigating complex environments within the human body for tasks such as drug delivery, medical imaging, and microsurgery [1,2]. Since the seminal work of Taylor [3,4], who modeled a microorganism as an infinitely long sheet propagating transverse waves in a viscous fluid, the study of microorganism motility has been a central topic in fluid mechanics. Taylor’s analytical framework enabled the computation of swimming velocity and power dissipation using lubrication approximations and perturbation techniques. Subsequent extensions considered cylindrical filaments, finite-length sheets, and more complex fluid environments. Lauga [5] revisited Taylor’s approach in viscoelastic fluids, demonstrating that fluid elasticity affects swimming kinematics and energy expenditure, often reducing speed relative to Newtonian conditions. Teran et al. [6] further highlighted the role of elastic stress relaxation in enhancing propulsion efficiency, while Dasgupta et al. [7] quantified how shear-thinning and constant-viscosity viscoelastic fluids modify swimming speed. A comprehensive review by Li et al. [8] outlines developments in microswimming models, emphasizing cilia, flagella, and helical propulsion in complex fluids.

The interaction between microorganisms and boundaries also plays a crucial role in motility. Studies have shown that fluid elasticity, near-wall confinement,viscosity gradients, and Brinkmann layer can significantly alter swimming speed and direction. For instance, Ives and Morozov [9] showed enhanced swimming velocity of a Taylor sheet near a rigid wall in a viscoelastic fluid, whereas Jha et al. [10] highlighted the impact of soft boundaries on energy dissipation and swimming efficiency. Harsh Soni [11] investigated swimming in smectic-A liquid crystals, revealing faster locomotion due to the elastic layered structure. More recently, Ali and Sajid [12], Asghar et al. [13], and Shah et al. [14] have explored inertial effects, bounded flows, and complex rheological responses, further demonstrating the intricate interplay between fluid mechanics and microorganism motility. The research [15] investigates how cilia motion in the cervical canal influences electroosmotic flow to aid sperm transport. The study uses mathematical modeling to analyze this biomechanical process within human reproductive fluid dynamics. Further, transient and unsteady swimming phenomena have also been studied extensively. Pak and Lauga [16] examined the startup behavior of a waving sheet, revealing time-dependent effects on propulsion and net flow. Ali and Ardekani [17] extended this to non-Newtonian fluids, showing significant influence of viscoelasticity on transient swimming. Gaojin Li [18] investigated the role of fluid and swimmer inertia, identifying velocity overshoots and enhanced burst performance under strong inertial conditions. Alternative models, such as squirmers, have been used to study nutrient uptake, hydrodynamic interactions, and wall effects in Newtonian and non-Newtonian fluids [19–26]. These studies collectively underscore the sensitivity of swimming dynamics to fluid rheology, swimmer type, and environmental confinement. Beyond purely mechanical effects, external fields (magnetic and electric fields) offer unique opportunities to control and enhance microswimmer propulsion. Magnetic microswimmers have been extensively studied, demonstrating precise steering and speed modulation [27–30]. In contrast, electrokinetic effects, particularly electroosmosis, present a distinct approach for manipulating microscale flows. Electroosmosis arises when an applied electric field drives the motion of ions in an electrolyte solution, creating a net fluid movement.

The classical electroosmotic flow (EOF) in microchannels was first analyzed by Burgreen and Nakache [31] and Rice and Whitehead [32], who derived velocity profiles under the Debye-Hückel approximation. Later studies extended this analysis to two-dimensional rectangular microchannels [33–36] and thermal flow conditions [37]. This phenomenon has been widely exploited in microfluidic systems, including lab-on-a-chip devices, chromatography, and drug delivery applications. In recent years, the focus has shifted to non-Newtonian electroosmotic flows. Analytical and numerical studies have considered power-law [38–41], two-fluid stratified [42], and viscoelastic Phan-Thien-Tanner (PTT) fluids [43–45] under combined pressure-driven and electrokinetic forces. These works demonstrated that non-Newtonian rheology, wall zeta potential, and memory effects significantly influence flow profiles, pressure distribution, and pumping efficiency. For example, Akhtar et al. [46] showed that fractional Maxwell fluids exhibit slower flow due to strong memory effects, while Sangeetha et al. [47] highlighted the benefits of variable viscosity and electroosmotic forcing on mechanical efficiency and reduced trapping in peristaltic flows.

Theoretical modeling of physiological and bio-inspired systems, such as seminal fluid transport via metachronal waves, is explored in studies like [48], microfluidic pumping with surface roughness [49], and electroosmotic flow in wavy channels [50–56]. These studies collectively indicate that electrokinetic forces, combined with non-Newtonian fluid properties, enable precise control over micro-scale transport and swimmer propulsion. The integration of electroosmosis with motile surfaces provides a powerful framework to study electrically modulated swimming. Electric fields can enhance or suppress locomotion depending on fluid properties, boundary conditions, and channel geometry. For instance, electroosmotic-peristaltic flows have been shown to improve pressure rise, reduce trapping, and optimize energy efficiency in biorheological fluids [57–59]. Such insights are relevant for biomedical applications, including micro-robotics, drug delivery, and artificial cilia-based pumps. These studies analyze how the undulating or peristaltic motion of a channel’s walls influences the swimming mechanics and speed of self-propelling spermatozoa and microorganisms. They focus on hydrodynamic interactions, wall effects, and the impact of mechanical peristalsis on propulsion. References [60–63] explore how viscoelasticity (the property of fluids like biological gels that are both viscous and elastic) impacts micro-swimmer locomotion. They find that fluid elasticity can enhance propulsion speed for small-amplitude and flexible swimmers, challenging the notion that complex fluids always hinder movement. Shah et al. [64] analyzed shear-thinning slime layers beneath active bacterial surfaces, showing that local viscosity variations significantly affect swimming velocity and energy dissipation. Similarly, Asghar et al. [65] studied microswimmers in viscoelastic biofluids within complex cervical geometries, demonstrating that fluid elasticity and confinement strongly influence propulsion efficiency. Building on these findings, the present study examines an electrically actuated undulating sheet in a shear-thinning non-Newtonian electrolyte within a wavy channel. Unlike [64] and [65], which focused on passive or purely mechanical interactions, our work incorporates electroosmotic forcing, allowing exploration of how electric fields combined with complex fluid rheology impact propulsion, energy dynamics, and microscale transport in confined environments.

Motivated by these observations, the present study focuses on the swimming dynamics of an electrically controlled undulating sheet in a non-Newtonian electrolyte solution confined within a wavy channel. The electrolyte solution is modeled using the Carreau–Yasuda rheology, capturing shear-thinning behavior under creeping flow and long-wavelength approximations. We derive the governing equations, nondimensionalize them, and analyze the resulting system to investigate propulsion and energy characteristics. The novelty of this work lies in combining (i) electroosmotic forcing, (ii) complex non-Newtonian rheology, and (iii) confinement effects in a wavy geometry. By doing so, we aim to bridge biological relevance (e.g., cilia-driven transport in reproductive or respiratory tracts) with engineering applications (e.g., electrokinetically actuated microfluidics and soft robotics). Our findings are expected to provide theoretical insights into fluid–structure–field interactions at the microscale, with implications for both natural and artificial swimmers.

2 Basic Equations and Model Description

A diagram illustrating the physical model is presented in Fig. 1. It shows the swimming of a self-propelling undulating sheet in a non-Newtonian incompressible electrolyte solution flowing through a planar channel with flexible walls. Peristaltic waves of finite amplitude are imposed along the flexible walls of the channel.

Figure 1: Self-propelled undulating sheet centered in a wavy microchannel with Carreau–Yasuda flow under an external electric field

The deformations of upper and lower walls are represented by functions

The wave profiles at the upper

It’s important to note that the net speed of the sheet relative to the inertial frame is

We consider that the flow is driven by the combined action of the self-propelling undulating sheet, peristaltic walls, and the electroosmotic body force. The non-Newtonian fluid within the channel, modeled by the Carreau-Yasuda equation, is considered an electrolyte solution that reacts to an externally imposed electric potential across the channel’s length. When the negatively charged channel walls interact with the electrolyte solution, an electrical double layer is formed inside the flow field. Typically, the electrical double layer (EDL) comprises two sub-layers. The first zone, known as the “Stern layer,” contains ions that are closely attached to the charged surface. The second zone, called the “diffuse layer,” has ions that are more spread out and move freely in the surrounding area. When an external electric field is applied tangentially to the electric double layer, the counter-ions migrate and drag the surrounding solvent molecules by viscous interactions. This phenomenon gives rise to an electroosmotic flow. This flow can interact with the undulating sheet, altering its propulsion dynamics. Depending on the direction and magnitude of the electric field, electroosmosis can either enhance or hinder the sheet’s movement. The electroosmotic flow can act in synergy with the self-propulsion mechanism of the sheet, increasing its speed and providing additional control over its trajectory. Alternatively, if the electric field opposes the direction of the sheet’s motion, it can resist its movement and potentially impede its propulsion. Thus, the interplay between electroosmosis and the undulation of the swimming sheet in a wavy microchannel introduces complex and intriguing dynamics that warrant further exploration for applications in microfluidics and bioengineering.

In the inertial frame, the kinematic boundary conditions at the boundary walls are specified as follows:

here

The self-propelled massless sheet is force-free [60]:

In the above Eq. (7),

The fundamental equations that govern the flow are:

Continuity equation:

Navier-Stokes equation:

where

In the above equation,

Let’s define the Galilean coordinate transformations:

where

The velocity field associated with the flow resulting from the combined action of an undulating sheet, active channel walls, and electroosmotic body force is characterized as

where:

where:

Several studies have examined the axial force distribution in electroosmotic flows. For instance, reference [40] analyzed velocity and wall shear stress in microchannels, while reference [46] highlighted the influence of non-Newtonian rheology. The effects of pulsatile forcing were reported in [47], and memory-dependent viscoelastic behavior was described in [48]. More recently, reference [49] addressed the role of surface roughness, and reference [50] investigated two-phase systems. Based on these contributions, the force distributed along the axial direction can be described as:

In the equation above,

The Poisson equation is denoted as [46–49,53,56]:

where

The expression of

where

where

The following dimensionless quantities are defined to render the previous equations in normalized form:

where

Since the Reynolds number in such analysis is of

Similarly, the Nernst–Planck equation reduces to:

where

For Eq. (26), the bulk conditions are [46–49,53,56]:

The solution of Eq. (26) using condition (27) yields:

Solving Eqs. (25) and (28), we obtained the following equation:

By invoking the linearization approximation [46–49,53,56], Eq. (29) reduces to:

Solving Eq. (30) using the conditions

By symmetry, the potential for the upper region is:

By using dimensionless quantities and parameters defined in Eq. (24), Eq. (13) is found to hold true, while Eqs. (14)–(19) become (neglecting the asterisk):

After applying the Stokes flow approximations, i.e.,

These results, when integrated with simplified Eq. (33), yield:

By eliminating the axial pressure gradient from simplified Eqs. (33) and (34), we get the following result:

The dimensionless boundary conditions in the wave frame are listed as:

The rate of flow is:

After employing the long-wavelength approximation, the force equilibrium condition results in [60,64,65].

Performing integration of the second term, we get

For the free channel case:

The energy loss by the undulating sheet against viscous forces per unit depth is:

where

Using Eqs. (44) and (45), the above formula reduces to:

4.1 Newtonian Case: Closed-Form Solution

To begin the analysis, we consider a special case where the fluid behaves as Newtonian. This is achieved by taking

Stream function in the upper region and lower regions:

Pressure gradient in upper and lower regions:

Stress component in upper and lower regions:

where:

For a Newtonian fluid, the equilibrium conditions used to calculate the unknowns

Substituting Eqs. (50)–(55) into Eqs. (56) and (57), it becomes evident that analytical integration is not feasible due to the nonlinear nature of the resulting algebraic equations. Therefore, a numerical root-finding method is necessary to compute the unknowns

However, in the absence of an electric field

Finally, the solution reduces to a system of two algebraic equations with two unknowns, yielding closed-form expressions for

These expressions perfectly match the results previously reported by Shack and Lardner [60], confirming that our formulation is consistent and in agreement with well-established published studies.

4.2 Numerical Technique: Modified Newton-Raphson Technique

In this section, we describe the procedure to calculate

The governing differential Eq. (41) with the corresponding boundary conditions (specified in Eq. (42)) has six dimensionless parameters, i.e.,

5.1 Undulating Sheet Speed and Energy Loss

In Fig. 2, we present the relationship between the speed of the undulating sheet

Figure 2: Effect of Deborah number

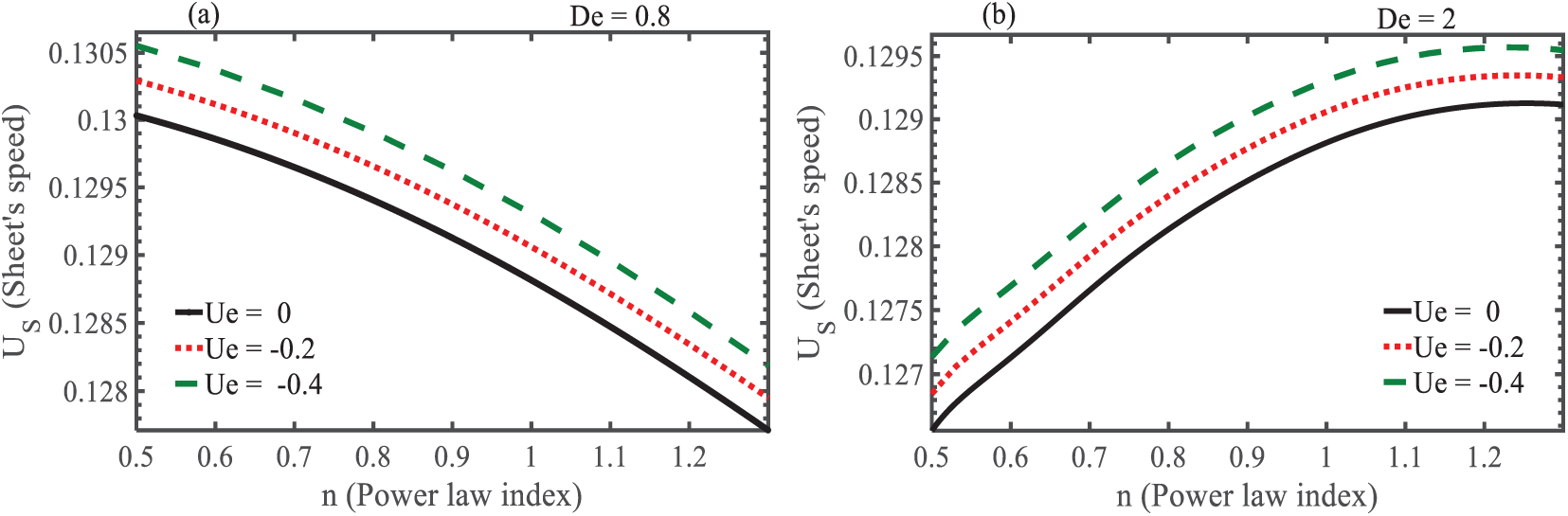

Fig. 3a,b shows the behavior of undulating sheet speed against the power law index

Figure 3: Effect of power law index

Fig. 4 shows combined profiles of the speed against

Figure 4: Combined profiles of the undulating sheet speed

Fig. 5 illustrates the impact of the occlusion parameter

Figure 5: Effect of occlusion parameter

Fig. 6 explores how energy loss

Figure 6: Variation of energy loss

Mathematically, this behavior can be expressed as:

This relationship underscores the significant influence of both the channel occlusion and the Helmholtz-Smoluchowski velocity on the energy dissipation by the undulating sheet. Specifically, higher values of

The findings elucidated herein underscore the importance of fluid rheology in controlling the speed of an undulating sheet, which may be associated with biological propulsion mechanisms. In biological systems, like sperm motility, the viscosity of the fluid around it and the elasticity of the environment affect how well it moves. For shear-thinning fluids, whose viscosity goes down with strain rate, movement is enhanced, simulating how spermatozoa pass through cervical mucus, where the fluid becomes less resistive under strain. In contrast, shear-thickening fluids, whose viscosity rises with strain rate, resemble environments where higher elasticity assists in propulsion, similar to the enhanced elastic recoil found in cilia-driven motion in reproductive or respiratory systems. Our results reveal that, like biological swimmers, the speed of artificial microswimmers can be optimized by adjusting fluid properties such as viscosity and elasticity, especially under controlled electroosmotic forces. Additionally, the finding indicates that occlusion parameter similar to physical confinement in biological channel may have a considerable impact on swimming speed, with increasing occlusion resulting to faster propulsion, particularly when combined with negative Helmholtz-Smoluchowski velocities. These findings are consistent with biological mechanisms in which confinement in narrow channels, such as the fallopian tubes, or fluid interactions in small regions may influence swimmer efficiency. This study therefore fills a gap between theoretical fluid dynamics and biological applications by providing a framework for enhancing microswimmer efficiency in biomedical technologies such as targeted drug delivery and micro-robotic surgery.

The streamlines of the Carreau-Yasuda fluid, depicting the flow behavior under various parameter settings, are illustrated in Figs. 7 and 8. Fig. 7 specifically compares the streamline patterns in both rigid and wavy channels, considering three distinct values of the occlusion parameter

Figure 7: Streamlines of flow in both rigid

Figure 8: Streamlines of flow in wavy

The analysis of streamline patterns depicting the flow of Carreau-Yasuda fluid surrounding an undulating sheet in the context of active channels with varying Helmholtz-Smoluchowski velocities is illustrated in Fig. 8a–c. A detailed examination of these figures reveals that as the values of Helmholtz-Smoluchowski velocity

These findings have significant implications for biological flow systems where peristaltic pumping occurs. The occlusion parameter

5.2 Energy Loss for the Undulating Sheet

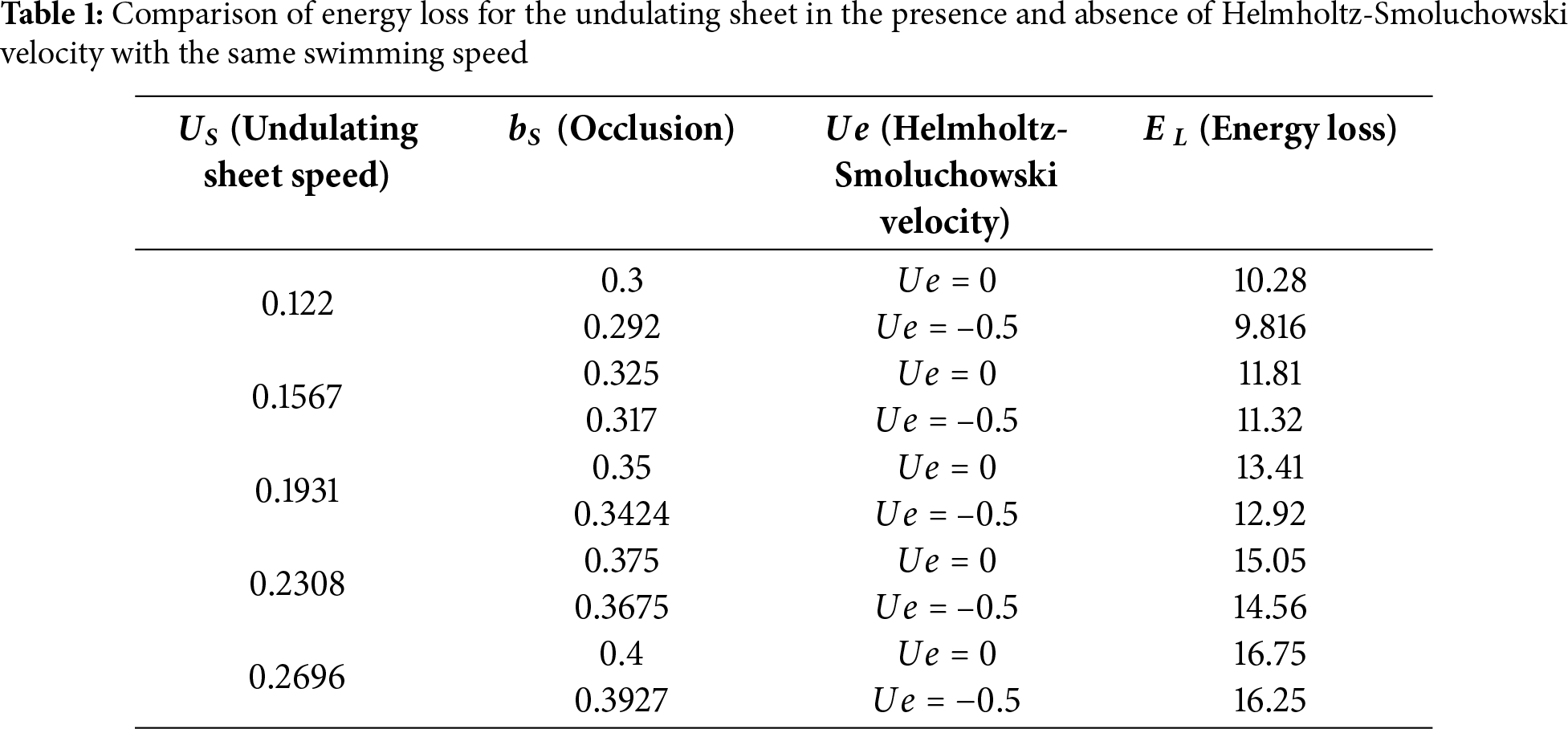

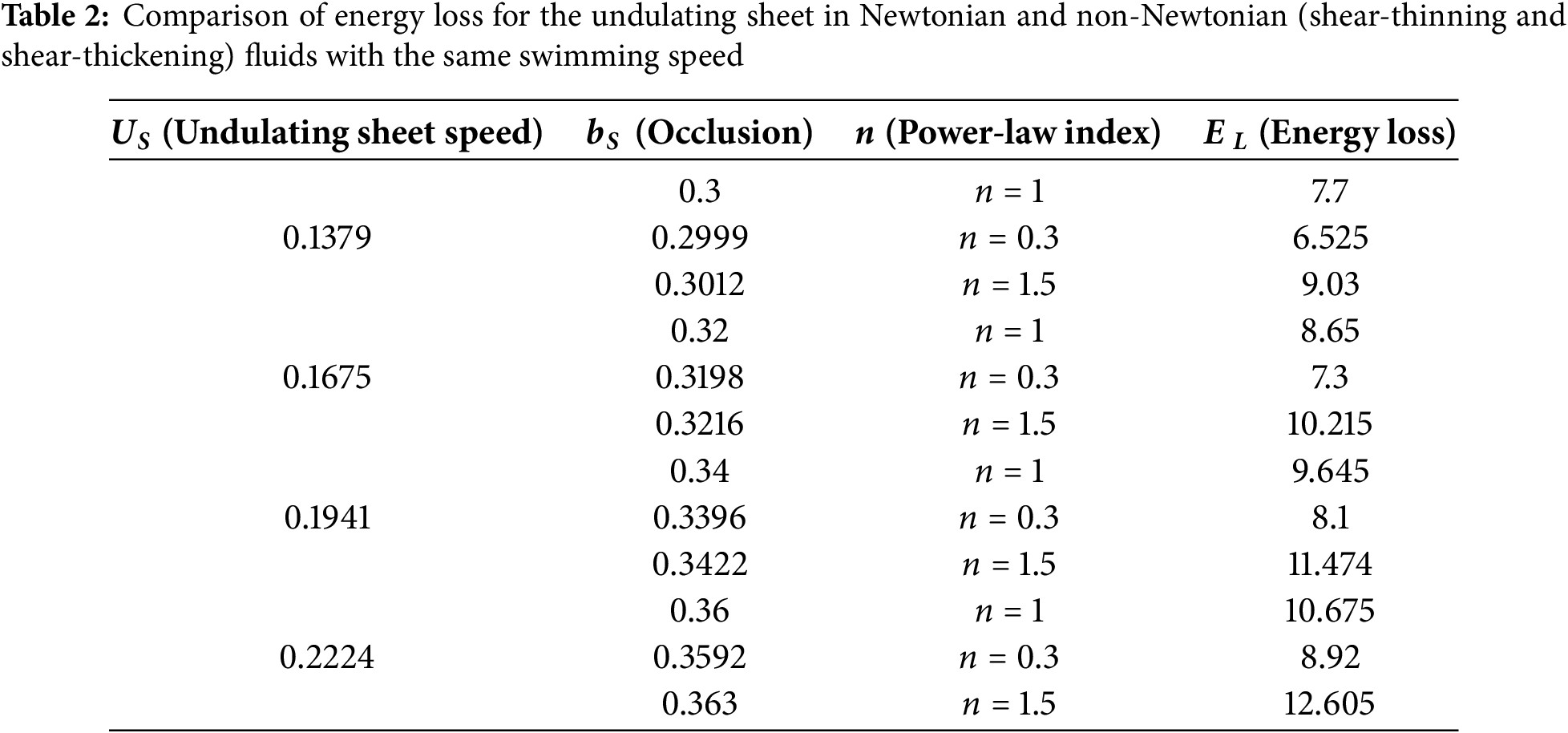

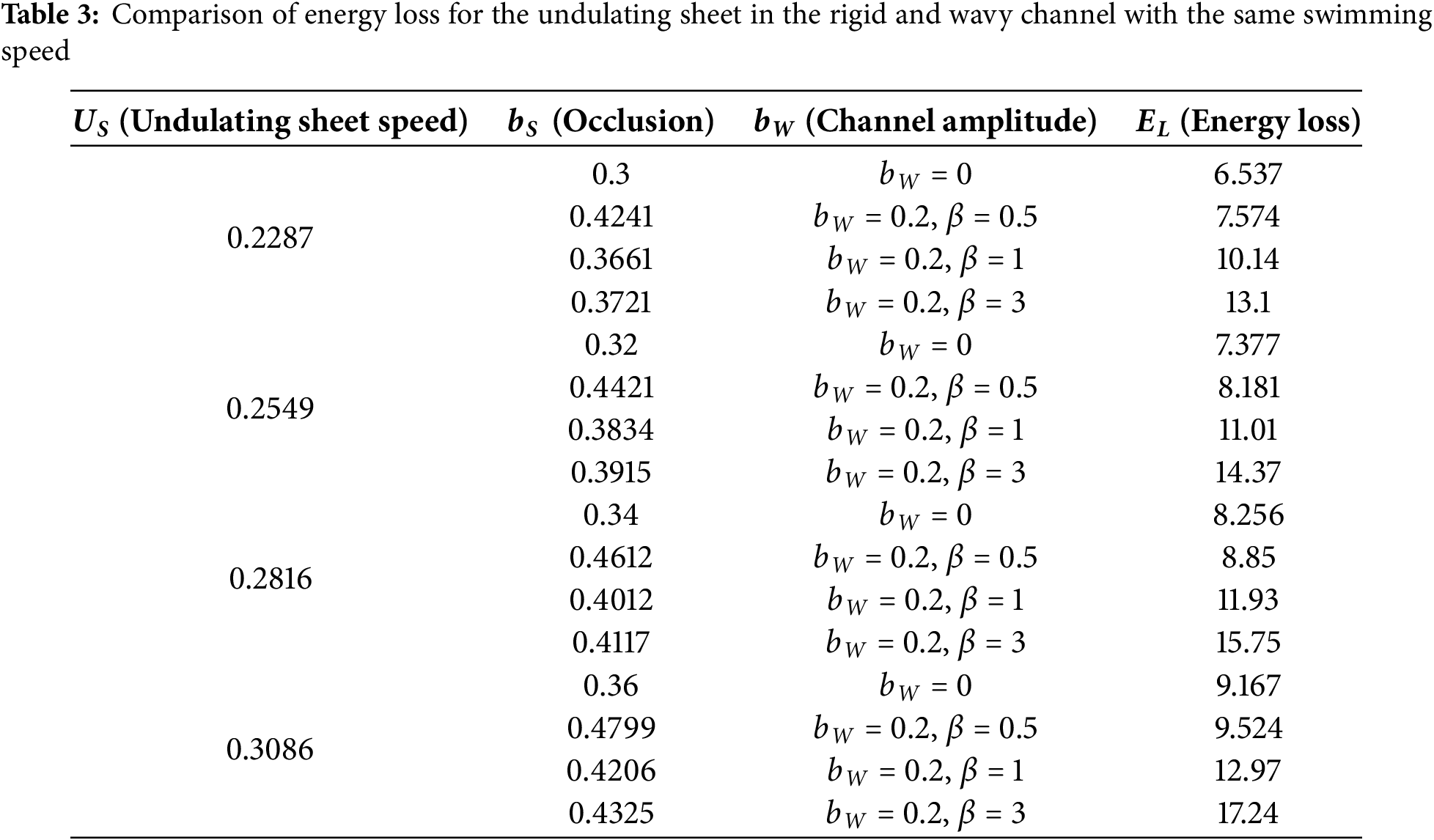

The optimal scenario for an undulating sheet is to sustain a maximum speed while minimizing energy consumption. Therefore, it is more suitable to compare energy loss by the undulating sheet in different scenarios while swimming at the same velocity. Therefore, we have examined four different options for energy comparison:

i. Swimming of an undulating sheet in the absence

ii. Swimming of an undulating sheet in Newtonian

Swimming of an undulating sheet in rigid

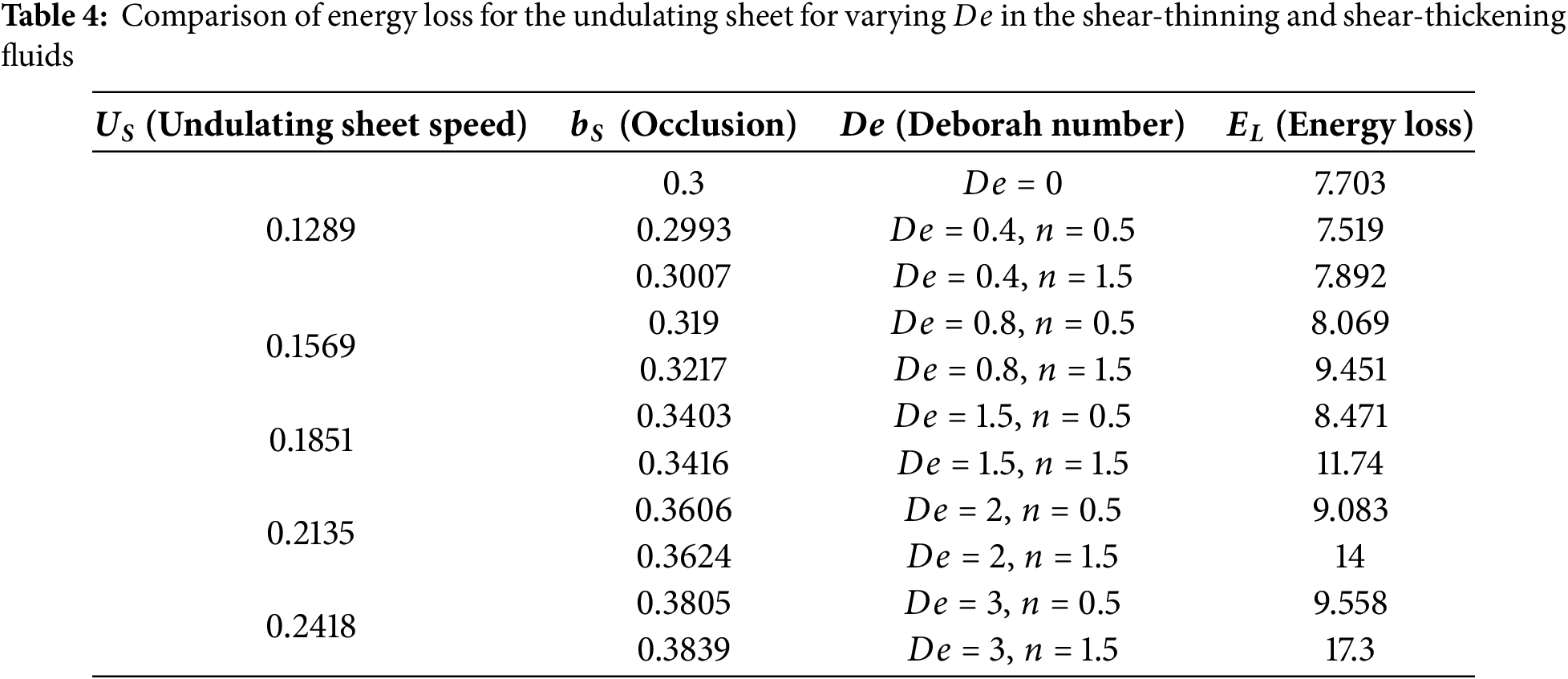

Swimming of an undulating sheet for varying Deborah number

The first case is shown in Table 1. It is observed that energy loss by the undulating sheet is smaller in the presence of the Helmholtz-Smoluchowski velocity. Table 2 reveals that altering the rheology of the surrounding liquid is another way to reduce energy losses. In this context, the shear-thinning characteristics are especially suitable to attain the desired result. In shear-thinning fluids, viscosity decreases with increasing shear rate, allowing the sheet to move more easily and consume less energy. In contrast, shear-thickening fluids have increasing viscosity with the shear rate, requiring more energy for movement. Newtonian fluids have a constant viscosity regardless of shear rate. This difference in viscosity behavior explains the varying energy consumption despite the same sheet speed.

Table 3 highlights that the nature of the channel is also another way to reduce energy consumption. The data demonstrates that the undulating sheet undergoes greater energy dissipation in a wavy channel than in a rigid channel. Here, we have discussed three conditions in connection with

Our energy-loss analysis directly relvant to biological system, as sperm attempt to move quickly while losing as lower energy as possible. When comparing equal-speed scenerios, we find that an applied electric field and shear-thinning medium (like healthy mucus) allow the swimmer to attain the same speed with minimum energy loss, but shear-thickening media increases loss. Flat, straight channels also reduce loss compared with wavy confinement, and a larger mismatch between wall undulations and beat wavelength increases loss. Finally, choosing a Deborah number that matches beat timing to fluid relaxation lowers energy loss and can improve speed. These links show how our results translate to sperm-driven transport and to guided microrobots that target fast motion with minimal energy loss.

6 Conclusions and Future Directions

An attempt is made to investigate the influence of electroosmotic forces on the swimming dynamics of an undulating sheet in a wavy channel. The speed of the undulating sheet and energy loss by it are evaluated by solving the hydrodynamical equations for the fluid motion based on the Carreau-Yasuda constitutive equation. The derivation of the aforesaid equations is carried out under the assumptions of long wavelengths, low Reynolds numbers, and the linearization approximation of the Debye–Hückel theory, with numerical solutions obtained via MATLAB’s bvp5c routine using a modified Newton-Raphson method. A detailed parametric study is performed to estimate the impacts of the Carreau–Yasuda fluid’s rheological properties, electroosmotic forces, and the amplitude ratio on both the propulsion speed and energy loss of the undulating sheet.

The primary findings of this study highlight the pivotal role of electroosmotic effects and fluid rheology in governing the propulsion of the undulating sheet. Electroosmotic forces, when applied in the negative axial direction, assist the sheet’s propulsion, enhancing its speed while simultaneously reducing energy loss. The results underscore a rheological crossover: in shear-thinning fluids, lower Deborah numbers promote faster swimming speeds, while in shear-thickening fluids, higher Deborah numbers lead to better performance. This shift is tied to the fluid’s elastic response and its ability to support momentum transfer, especially in the high-elasticity regime where shear-thickening fluids outpace Newtonian counterparts. The study also reveals that the amplitude of undulation plays a significant role in enhancing the sheet’s speed, with larger amplitudes resulting in faster propulsion. Additionally, it was observed that the undulating sheet consumes less energy in a rigid channel compared to a wavy channel, emphasizing the importance of channel geometry in optimizing energy efficiency. Similarly, the presence of the Helmholtz–Smoluchowski velocity reduces energy loss, indicating the significance of electrokinetic effects in minimizing energy dissipation. Altogether, the findings indicate that the undulating sheet’s motion can be effectively enhanced in three primary ways: by adjusting the amplitude of surface waves, by tuning the rheological properties of the surrounding non-Newtonian fluid, and by utilizing electroosmotic effects to minimize resistance and energy expenditure.

This study is motivated by a deep intellectual curiosity and a desire to better understand the physics of self-propelling undulating sheets in complex fluids. The results demonstrate that electroosmosis can significantly influence sheet propulsion, offering new insights for controlling microscale transport and locomotion. These findings carry important implications for the design and optimization of artificial microswimmers across various fields, including medicine, biotechnology, and environmental monitoring. Moreover, the outcomes of this research are potentially valuable in the development of biomimetic mechanical crawlers and soft robotic devices, where fluid–structure interaction plays a pivotal role in achieving effective and energy-efficient movement.

The current model is based on a two-dimensional undulating sheet in a generalized Newtonian fluid, which captures shear-thinning and thickening behavior but does not account for fluid elasticity. Incorporating viscoelastic models in future work would allow for a more complete understanding of stress memory and elastic effects. The formulation also assumes a simplified geometry. Extending the analysis to three-dimensional filaments or sheets would help represent more realistic configurations. Additionally, replacing wavy walls with rough or actively controlled surfaces could uncover new flow behaviors relevant to microchannel transport.

This work also omits magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) effects, porous media, thermal effects, nature of walls, and the time dependency of sheet movement, which are important in many engineering systems. Including these factors could enhance the model’s applicability to smart microfluidics and thermal-electrokinetic transport.

Acknowledgement: Zeeshan Asghar would like to thank Prince Sultan University for their support through the TAS research lab. Rehman Ali Shah gratefully acknowledges the support of the Higher Education Commission (HEC) of Pakistan through the International Research Support Initiative Program (IRSIP) for enabling a six-month research exchange at Purdue University, USA.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: conceptualization and formulation of research goals: Zeeshan Asghar, Arezoo Ardekani; methodology and model development: Zeeshan Asghar, Arezoo Ardekani, Rehman Ali Shah; software implementation and data analysis: Rehman Ali Shah, Chenji Li; validation and formal analysis: Zeeshan Asghar, Rehman Ali Shah; investigation and data collection: Rehman Ali Shah, Chenji Li; visualization and draft manuscript preparation: Rehman Ali Shah, Zeeshan Asghar; writing—review and editing: Zeeshan Asghar, Arezoo Ardekani, Nasir Ali; supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition: Zeeshan Asghar. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Nomenclature

| Undulating sheet and wall amplitude | |

| Mean distance of the sheet from the wavy walls | |

| Speed of an undulating wave | |

| Velocity vector of the fluid | |

| Cartesian coordinates for a fixed frame | |

| Cartesian coordinates for wave frame | |

| Velocity components in a fixed frame | |

| Velocity components in wave frame | |

| Extra stress tensor | |

| Pressure in a fixed frame | |

| Pressure in wave frame | |

| Components of the extra stress tensor | |

| First Rivlin-Ericksen tensor | |

| Deborah number | |

| Reynolds number | |

| Pe | ionic Peclet number |

| Sc | Schmidt number |

| Helmholtz-Smoluchowski velocity | |

| Boltzmann constant | |

| Dimensionless flow rate | |

| Power law index | |

| Material derivative | |

| Undulating sheet’s speed | |

| Energy expended by the undulating sheet | |

| Fluid forces acting on the upper and lower surfaces of the sheet | |

| Unit vector normal to the swimming sheet | |

| Wave number | |

| Greek Letters | |

| Wavelength | |

| Fluid density | |

| Pressure rise per wavelength | |

| Zero shear-rate viscosity | |

| Infinite shear-rate viscosity | |

| Ratio of infinite to zero shear-rate viscosity | |

| Characteristic time scale | |

| Dimensionless wave number | |

| Stream function | |

| Elementary charge | |

References

1. Liu J, Fu Y, Liu X, Ruan H. Theoretical perspectives on natural and artificial micro-swimmers. Acta Mech Solida Sin. 2021;34(6):781–782. doi:10.1007/s10338-021-00260-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Teng X, Qiao Z, Yu S, Liu Y, Lou X, Yang W. Recent advances in microrobots powered by multi-physics field for biomedical and environmental applications. Micromachines. 2024;15(4):492. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

3. Taylor GI. Analysis of the swimming of microscopic organisms. Proc R Soc Lond A. 1951;209(1099):447–61. doi:10.1098/rspa.1951.0218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Taylor GI. The action of waving cylindrical tails in propelling microscopic organisms. Proc R Soc Lond A. 1952;211(1105):225–39. doi:10.1098/rspa.1952.0035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Lauga E. Propulsion in a viscoelastic fluid. Phys Fluids. 2007;19:083104. [Google Scholar]

6. Teran J, Fauci L, Shelley M. Viscoelastic fluid response can increase the speed and efficiency of a free swimmer. Phys Rev Lett. 2010;104(3):38101. [Google Scholar]

7. Dasgupta M, Liu B, Fu HC, Berhanu M, Breuer KS, Powers TR, et al. Speed of a swimming sheet in Newtonian and viscoelastic fluids. Phys Revi E—Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys. 2013;87(1):13015. [Google Scholar]

8. Li G, Lauga E, Ardekani AM. Microswimming in viscoelastic fluids. J Non-Newton Fluid Mech. 2021;297:104655. [Google Scholar]

9. Ives TR, Morozov A. The mechanism of propulsion of a model microswimmer in a viscoelastic fluid next to a solid boundary. Phys Fluids. 2017;29(12):121612. doi:10.1063/1.4996839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Jha A, Amarouchene Y, Salez T. Taylor’s swimming sheet near a soft boundary. Soft Matter. 2025;21(5):826–34. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

11. Soni H. Taylor’s swimming sheet in a smectic-A liquid crystal. Physical Review E. 2023;107(5):055104. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

12. Ali N, Sajid M. Inertial swimming in an Oldroyd-B fluid. Eur Phys J E. 2025;48(4):1–14. [Google Scholar]

13. Asghar Z, Khan MWS, Ali N, Waqas M. On IFDM simulation of Oldroyd 8-constant fluid flowing due to motile microorganisms. Chin J Phys. 2025;93(3):158–71. doi:10.1016/j.cjph.2024.11.033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Shah RA, Asghar Z, Ali N. Mathematical modeling related to bacterial gliding mechanism at low Reynolds number with Ellis Slime. Eur Phys J Plus. 2022;137(5):1–12. [Google Scholar]

15. Abdelsalam SI, Zaher AZ. On behavioral response of ciliated cervical canal on the development of electroosmotic forces in spermatic fluid. Math Model Nat Phenom. 2022;17:27. doi:10.1051/mmnp/2022030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Pak OS, Lauga E. The transient swimming of a waving sheet. Proc Royal Soc A Math Phys Eng Sci. 2010;466(2113):107–26. [Google Scholar]

17. Ali N, Ardekani AM. Transient swimming of an undulating sheet in a second-order fluid. J Non-Newton Fluid Mech. 2025;105435. doi:10.1016/j.jnnfm.2025.105435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Li G. Transient motion of a swimming sheet in the inertial regime. J Fluid Mech. 2025;1011:A2. doi:10.1017/jfm.2025.382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Lambert RA, Picano F, Breugem WP, Brandt L. Active suspensions in thin films: nutrient uptake and swimmer motion. J Fluid Mech. 2013;733:528–57. [Google Scholar]

20. Magar V, Pedley TJ. Average nutrient uptake by a self-propelled unsteady squirmer. J Fluid Mech. 2005;539:93–112. [Google Scholar]

21. Lin Z, Thiffeault JL, Childress S. Stirring by squirmers. J Fluid Mech. 2011;669:167–77. [Google Scholar]

22. Wang S, Ardekani AM. Inertial squirmer. Phys Fluids. 2012;24(10):101902. doi:10.1063/1.4758304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Doostmohammadi A, Stocker R, Ardekani AM. Low-Reynolds-number swimming at pycnoclines. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 2012;109(10):3856–61. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

24. Li G, Ardekani AM. Hydrodynamic interaction of microswimmers near a wall. Phys Rev E. 2014;90(1):013010. [Google Scholar]

25. Papavassiliou D, Alexander GP. The many-body reciprocal theorem and swimmer hydrodynamics. Europhys Lett. 2015;110(4):44001. [Google Scholar]

26. Lintuvuori JS, Brown AT, Stratford K, Marenduzzo D. Hydrodynamic oscillations and variable swimming speed in squirmers close to repulsive walls. Soft Matter. 2016;12(38):7959–68. doi:10.1039/c6sm01353h. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Gutman E, Or Y. Simple model of a planar undulating magnetic microswimmer. Phys Rev E. 2014;90(1):13012. [Google Scholar]

28. Asghar Z, Ali N, Sajid M, Bég OA. Magnetic microswimmers propelling through biorheological liquid bounded within an active channel. J Magn Magn Mater. 2019;486(475):165283. doi:10.1016/j.jmmm.2019.165283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Temel FZ, Yesilyurt S. Confined swimming of bio-inspired magnetic microswimmers in rectangular channels. Presented at the 67th Annual Meeting of the APS Division of Fluid Dynamics; 2014; San Francisco, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

30. Yamanaka T, Arai F. Electroosmotic self-propelled microswimmer with magnetic steering. IEEE Robot Autom Lett. 2023;9(1):747–54. [Google Scholar]

31. Burgreen D, Nakache FR. Electrokinetic flow in ultrafine capillary slits. J Phys Chem. 1964;68(5):1084–91. [Google Scholar]

32. Rice CL, Whitehead R. Electrokinetic flow in a narrow cylindrical capillary. J Phys Chem. 1965;69(11):4017–24. [Google Scholar]

33. Dutta P, Beskok A. Analytical solution of combined electroosmotic/pressure driven flows in two-dimensional straight channels: finite Debye layer effects. Anal Chem. 2001;73(9):1979–86. doi:10.1021/ac001182i. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Arulanandam S, Li D. Liquid transport in rectangular microchannels by electroosmotic pumping. Coll Surf A Physicochem Eng Aspects. 2000;161(1):89–102. [Google Scholar]

35. Wang C, Wong TN, Yang C, Ooi KT. Characterization of electroosmotic flow in rectangular microchannels. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2007;50(15–16):3115–21. [Google Scholar]

36. Wang X, Chen B, Wu J. A semianalytical solution of periodical electro-osmosis in a rectangular microchannel. Phys Fluids. 2007;19(12):127101. doi:10.1063/1.2784532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Zade AQ, Manzari MT, Hannani SK. An analytical solution for thermally fully developed combined pressure-electroosmotically driven flow in microchannels. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2007;50(5–6):1087–96. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2006.07.037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Das S, Chakraborty S. Analytical solutions for velocity, temperature and concentration distribution in electroosmotic microchannel flows of a non-Newtonian bio-fluid. Anal Chim Acta. 2006;559(1):15–24. doi:10.1016/j.aca.2005.11.046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Chakraborty S. Electroosmotically driven capillary transport of typical non-Newtonian biofluids in rectangular microchannels. Anal Chim Acta. 2007;605(2):175–84. doi:10.1016/j.aca.2007.10.049. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Srinivas B. Electroosmotic flow of a power law fluid in an elliptic microchannel. Coll Surf A Physicochem Eng Aspects. 2016;492(1):144–51. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfa.2015.12.034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Afonso AM, Alves MA, Pinho FT. Electro-osmotic flow of viscoelastic fluids in microchannels under asymmetric zeta potentials. J Eng Math. 2011;71(1):15–30. doi:10.1007/s10665-010-9421-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Dhinakaran S, Afonso AM, Alves MA, Pinho FT. Steady viscoelastic fluid flow between parallel plates under electro-osmotic forces: phan-Thien-Tanner model. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2010;344(2):513–20. doi:10.1016/j.jcis.2010.01.025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Afonso AM, Alves MA, Pinho FT. Analytical solution of mixed electro-osmotic/pressure driven flows of viscoelastic fluids in microchannels. J Non-Newton Fluid Mech. 2009;159(1–3):50–63. doi:10.1016/j.jnnfm.2009.01.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Park HM, Lee WM. Helmholtz-Smoluchowski velocity for viscoelastic electroosmotic flows. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2008;317(2):631–6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

45. Qi C, Ng CO. Electroosmotic flow of a FENE-P fluid in a slit microchannel with gradually varying channel height and wall potential. Eur J Mech-B/Fluids. 2015;52:160–8. doi:10.1016/j.euromechflu.2015.03.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Akhtar S, Jamil S, Shah NA, Chung JD, Tufail R. Effect of zeta potential in fractional pulsatile electroosmotic flow of Maxwell fluid. Chin J Phys. 2022;76:59–67. [Google Scholar]

47. Sangeetha J, Ponalagusamy R, Selvi RT, R. T. Electroosmotic peristaltic flow of thixotropic-Newtonian fluids in a circular tube: effect of variable viscosity co-efficient of core fluid. Chin J Phys. 2024;92(2):470–93. doi:10.1016/j.cjph.2024.06.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Khan MWS, Asghar Z, Shatanawi W, Gondal MA. Cilia-assisted flow for the Johnson-Segalman fluid inside a convergent complex wavy passage with the magnetic field, hall effect, and porous medium. Kuwait J Sci. 2025;53(1):100480. doi:10.1016/j.kjs.2025.100480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Vaidya H, Prasad KV, Choudhari RV, Tripathi D, Naganur M. Surface roughness impact on bioinspired rhythmic contractile microfluidic membrane pumping mechanism: a computational analysis. Phys Fluids. 2025;37(6):061901. doi:10.1063/5.0261414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Arcos J, Bautista O, Méndez F, Peralta M. Analysis of an electroosmotic flow in wavy wall microchannels using the lubrication approximation. Revista Mexicana de Física. 2020;66(6):761–70. [Google Scholar]

51. Tripathi D, Prakash J, Gnaneswara Reddy M, Kumar R. Numerical study of electroosmosis-induced alterations in peristaltic pumping of couple stress hybrid nanofluids through microchannel. Indian J Phys. 2021;95(11):2411–21. doi:10.1007/s12648-020-01906-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Asghar Z, Saeed Khan MW, Gondal MA, Ghaffari A. Channel flow of non-Newtonian fluid due to peristalsis under external electric and magnetic field. Proc Instit Mech Eng Part E J Process Mech Eng. 2022;236(6):2670–8. [Google Scholar]

53. Kumar A, Tripathi D, Tiwari AK, Seshaiyer P. Magnetic field modulation of electroosmotic-peristaltic flow in tumor microenvironment. Phys Fluids. 2025;37(4):043109. doi:10.1063/5.0261414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Ponalagusamy R, Murugan D. Transport of a reactive solute in electroosmotic pulsatile flow of non-Newtonian fluid through a circular conduit. Chin J Phys. 2023;81:243–69. doi:10.1016/j.cjph.2022.11.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Ali N, Hussain S, Ullah K. Theoretical analysis of two-layered electro-osmotic peristaltic flow of FENE-P fluid in an axisymmetric tube. Phys Fluids. 2020;32(2):023105. doi:10.1063/1.5132863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Hussain S, Ali N, Ullah K. Peristaltic flow of Phan-Thien-Tanner fluid: effects of peripheral layer and electro-osmotic force. Rheologica Acta. 2019;58(9):603–18. doi:10.1007/s00397-019-01158-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Shukla JB, Chandra P, Sharma R, Radhakrishnamacharya G. Effects of peristaltic and longitudinal wave motion of the channel wall on movement of micro-organisms: application to spermatozoa transport. J Biomech. 1988;21(11):947–54. doi:10.1016/0021-9290(88)90133-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Philip D, Chandra P. Self-propulsion of spermatozoa in microcontinua: effect of transverse wave motion of channel walls. Arch Appl Mech. 1995;66(1-2):90–9. doi:10.1007/bf00786692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Radhakrishnamacharya G, Sharma R. Motion of a self-propelling micro-organism in a channel under peristalsis: effects of viscosity variation. Nonlin Anal Model Control. 2007;12(3):409–18. doi:10.15388/na.2007.12.3.14703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Shack WJ, Lardner TJ. A long wavelength solution for a microorganism swimming in a channel. Bull Math Biol. 1974;36(4):435–44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

61. Riley EE, Lauga E. Small-amplitude swimmers can self-propel faster in viscoelastic fluids. J Theor Biol. 2015;382:345–55. doi:10.1016/j.jtbi.2015.06.045. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Espinosa-Garcia J, Lauga E, Zenit R. Fluid elasticity increases the locomotion of flexible swimmers. Phys Fluids. 2013;25(3):031701.doi:10.1063/1.4795166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Salazar D, Roma AM, Ceniceros HD. Numerical study of an inextensible, finite swimmer in Stokesian viscoelastic flow. Phys Fluids. 2016;28(6):063101. doi:10.1063/1.4953376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Shah RA, Asghar Z, Waqas M, Gondal MA. Mathematical analysis of the Shear-thinning slime layer flowing beneath an active bacterial surface. Multi Multidis Model Exp Des. 2025;8(2):154. doi:10.1007/s41939-025-00746-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Asghar Z, Rehman KU, Shatanawi W, Khan MWS. Efficiency optimization of micro-swimmers in viscoelastic bio-fluids within complex cervical environments. Chin J Phys. 2025;96(1099):664–77. doi:10.1016/j.cjph.2025.06.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools