Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Predictive and Global Effect of Active Smoker in Asthma Dynamics with Caputo Fractional Derivative

1 Faculty of Arts and Sciences, Department of Mathematics, Near East University, TRNC, Mersin 10, Nicosia, 99138, Turkey

2 Research Center of Applied Mathematics, Khazar University, Baku, AZ-1096, Azerbaijan

3 Jadara University Research Center, Jadara University, Irbid, 21110, Jordan

4 Department of Mathematics, University of Education, Lahore, 54600, Pakistan

5 Department of Mathematics, College of Science and Humanities in Al Kharj, Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University, Al Kharj, 16277, Saudi Arabia

6 Hourani Center for Applied Scientific Research, Al-Ahliyya Amman University, Amman, 19328, Jordan

7 Faculty of Engineering and Natural Sciences, Istanbul Okan University, Istanbul, 34959, Turkey

8 Faculty of Engineering and Quantity Surveying, INTI International University Colleges, Nilai, 71800, Malaysia

9 Faculty of Mangement, Shinawatra University, Pathum Thani, 12000, Thailand

* Corresponding Author: Muhammad Farman. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Analytical and Numerical Solution of the Fractional Differential Equation)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(1), 721-751. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.069541

Received 25 June 2025; Accepted 03 September 2025; Issue published 30 October 2025

Abstract

Smoking is harmful to the lungs and has numerous effects on our bodies. This leads to decreased lung function, which increases the lungs’ susceptibility to asthma triggers. In this paper, we develop a new fractional-order model and investigate the impact of smoking on the progression of asthma by using the Caputo operator to analyze different factors. Using the Banach contraction principle, the existence and uniqueness of solutions are established, and the positivity and boundedness of the model are proved. The model further incorporates different stages of smoking to account for incubation periods and other latent effects, enhancing the accuracy of system dynamics. Within this Fractional operator framework, key analyses are performed, including the identification of equilibrium points, computation of the basic reproduction number, sensitivity analysis, and assessment of local and global stability with the Lyapunov function. Additionally, chaos stability employing linear response regulation is implemented mathematically, and the effect of the compartment shows through simulations. A numerical iterative method employing Newton polynomial interpolation is used to illustrate the effectiveness of the suggested model, and numerical simulations reveal its enhanced efficiency at various fractional orders. The fractional-order framework offers a more realistic representation than classical integer-order models.Keywords

Asthma is a chronic disease that causes difficulty breathing by affecting the inner walls of the airways. Breathing difficulties and shortness of breath when exhaling are symptoms of the chronic illness asthma. Although there is no particular treatment, symptoms can be tracked. Patients should speak with medical professionals who can modify their treatment according to the patient’s condition. Chest tightness, discomfort, coughing, wheezing, respiratory system infections, dyspnea, and trouble sleeping are some of the symptoms. Children with asthma frequently exhibit wheezing during exhalation, which causes breathing problems. Asthmatic patients may have severe symptoms such as chest pain and loss of consciousness due to a shortage of oxygen.

According to reports, cigarette smoke can also cause asthma in addition to air pollutants such hexachloroplatinates and di-isocynates [1–3]. Smoking is harmful to the lungs and has numerous effects on our bodies. This leads to decreased lung function, which increases the lungs’ susceptibility to asthma triggers. Cigarette smoke contains high levels of irritants such as formaldehyde, ammonia, acrolein, and nitrogen oxides. The expert maintained that smoke which enter the host through a close smoker in the community, can harm the lungs. As a result, when someone inhales tobacco smoke, these disagreeable chemicals may trigger an asthma attack. Over 1,000,000 children with asthma worsen after being exposed to secondhand smoke, and over 15 million children are exposed to smoke every day [4,5]. Asthma is also caused by airborne pollutants, including dust from open-pit coal mining, coal-fired cement, and other operations, heavy metal cocktails from Solid Liquid Fuel (SLF) burning cement, and vanadium and nickel particles from power plants and oil refineries [6–8]. As a result, a susceptible population develops asthma as a result of ongoing exposure to air pollutants. To investigate the patterns of transmission of infectious diseases [9–12] and generate vital data regarding disease dynamics for control and prevention [13,14], mathematical models are crucial. Researchers have created a variety of numerical techniques to study disease dynamics. Researchers have recently examined the dynamics of asthma from a variety of angles in their study [15,16]. It is well known that ongoing smoking exposure is a major factor in the onset and progression of asthma.

Because fractional calculus is inherited and uses memory-based depictions, it is a flexible framework that provides accurate results in science and technology [17–19]. Using its derivative for a constant being zero, Caputo’s fractional derivative enables the solution of problems using conventional beginning and boundary conditions [20–22]. Nonlinear functional integral equations can now be solved with a variety of fractional operators (see [23,24]) thanks to new advances in fractional calculus. Dinku et al. [25] used various kernels of fractional differential equations to examine the effect of smoking on the development of cancer. To take into consideration the periodic impacts of smoking, they included a periodic function. For a variety of fractional-order derivatives, the study examined chaotic behavior, such as high smoking frequency and absence of immunological flux under low host cell starting circumstances. The goal of the study [26] was to compare the outcomes with conventional models by using fractional calculus to investigate adsorption and extraction processes. Equations were solved using the Caputo derivative, and processes such as the extraction of maize antioxidant compounds with varying solvent amounts and the adsorption of biodiesel glycerol at varying temperatures were examined. First-order and So and MacDonald’s models were used to compare the extraction of antioxidant chemicals. The diagnosis and therapy of lung cancer in patients with compromised immune systems utilizing cytokines and anti-PD-L1 inhibitors was investigated by Nisar et al. [27]. In addition to identifying early lung cancer management by cytokines and anti-PD-L1 inhibitors, which promote the generation of anti-cancer cells, they verified immune-mediated compartment linkages. IABNs were developed by Mukhtar et al. [28] to solve fractional order Parkinson’s disease scenarios. Through evaluations with regard numerical solutions and simulations, the IABN was examined. An excellent method for forecasting significant deformations of amorphous polymers is the variable order fractional parametric model, which was refined in [29]. It characterizes the mechanical behavior of polycarbonate at various temperatures. Using a fractional-order system, Farman et al. [30] demonstrate how decreased resources from forests affect toxin activity and fire caused by humans. These steps are intended to confirm that resource depletion has been resolved. In ecological modeling, fractional calculus is crucial for comprehending and overseeing maintaining forests in the face of human pressures, according to the study. Using GA, Adak et al. [31] optimized a SIR fractional order model that included medication, the media, and vaccine controls. The order of fractional derivatives was shown to affect the ideal management parameter values. The fractional operator in the Caputo sense was used by Bansal et al. [32] to create a mathematical model for studying the dynamics of transmitting monkeypox in both humans and other species.

Traditional integer-order differential equations have been widely used to model the dynamics of asthma and its association with environmental pollutants, including tobacco smoke [33]. Incidents of asthma are closely related to environmental variables such as smoking, pollution in the air, and allergens. However, breathing difficulties can be reduced with medication-based therapy and limiting exposure to asthma triggers. Recent advancements have introduced fractional-order derivatives to better capture memory effects and hereditary properties inherent in biological systems [34,35]. Inspired by the debate above, we create a novel model in this work to examine the dynamics of different smoker classes that have the potential to spread asthma. As far as we are aware, this effort is novel and will investigate further perspectives on the problem. Furthermore, because fractional-order models better capture the intricate physical processes, we used the Caputo fractional operator rather than integer-order. The investigation of dynamical behavior throughout the entire time span and its precise mathematical characterization are currently the main challenges. The intricate dynamical processes found in smoking-induced asthma disease can be better described by fractional-order models.

The structure of this manuscript is as follows: A brief description of the fractional operator utilized in the suggested model is given in Section 2. The fractional-order-based smoking-induced asthma model is the main topic of Section 3, and a thorough examination of the generated model is included in Section 4. Section 5 explores the system’s stability using the Lyapunov stability approach. Inside the practicable spectrum, Section 6 examines the model’s performance under chaotic circumstances; Section 7 displays the numerical outcomes derived from the system; Section 8 supplies an in-depth analysis of the outcomes, and delivers a summary of the most significant results and the ultimate findings.

2 Formulation of Dynamical Model for Smoking-Induced Asthma

In this work, we developed a new model of smoking-induced asthma disease flow chart shown in Fig. 1. Smokers are divided into three classes as:

Figure 1: The flow chart of dynamical system

•

•

•

Smoking-induced asthma population is categorized as follows:

•

•

•

•

• Active smokers

• The class

• The class

• The class

• The class

A variable’s rate of change in classical modeling using ordinary differential equations is entirely dependent on its existing state. These models’ basic presumption that the system is memoryless restricts their capacity to represent biological processes impacted by prior actions. The Caputo fractional-order derivative presents a memory-dependent paradigm in which the system’s current state is impacted by every condition in the past via a weighted history. This characteristic is especially crucial for long-term respiratory disorders like asthma, where the effects of environmental exposures, like smoking, take time to manifest. Because the Caputo operator makes the switch from classical to fractional modeling more natural by allowing the integration of beginning conditions in the same form as classical derivatives, it is particularly well-suited for modeling such memory effects. A more realistic depiction of the disease’s course is achieved by incorporating the memory feature into the model, which successfully captures inflammatory accumulation, delayed immune responses, and residual smoking-related harm. Therefore, in comparison to conventional Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs), the fractional-order model with the Caputo derivative offers a more thorough and biologically compatible approach.

There are numerous uses for fractional calculus. In contrast to other derivatives of non-integer orders, the Caputo fractional derivative is a fundamental idea in fractional calculus that finds practical tractability in problem modeling, providing rich and precise information. A possible physical manifestation of real-life phenomena, such the memory of smoking-induced asthma that explains a system’s behavior in the past, is the arbitrary fractional order. Here, we are discussing some fundamental findings that are essential to our work.

Definition 1. [36] For a continuous function

Definition 2. [36] The Caputo derivative operator of order

where

Consequently, by improving the data fitting versatility, the fractional order parameter makes it possible to describe the asthma disease system using the Caputo derivative structure in an extra adaptable way.

with initial condition

2.3 Positiveness and Boundedness of Solutions

In this part, we find the conditions ensuring the poistivity of the solutions, which are crucial for representing real-world scenarios. For

This holds for all

Notably, when dealing with classical derivatives, these properties hold for all

While the positivity of system solutions in terms of Caputo derivative is defined by

2.4 Positively Invariant Region

Lemma 1. For the remainder of the time span, assuming the nonnegative starting conditions, the solutions of the system (9) remain in the confined positive region

Proof. We obtain the following:

Now, we sum up the all equations in (9). Then we obtain

This yields

Thus, we can conclude that

is a positively invariant region.□

By setting the system’s left side to zero, this part offers a thorough examination of equilibrium locations. Let there are no active smokers and in the absence of asthma we get the points free of disease as

The asthma-persistent equilibrium is given by

where

In order to find the reproductive number, we consider the system:

The matrices F and

Then, the reproduction number is obtained as

In the parameters model, the reproduction number

then, we calculate the sensitivity of

An increase in that parameter’s value will result in an increase in the related reproductive number since a positive value is directly proportional to related reproductive. Relative to related reproductive, a negative value is inversely proportional, meaning that if we raise the value of that parameter, the related reproductive number will fall. Sensitivity of these reproductive numbers with respect to these parameters is depicted in Figs. 2 and 3.

Figure 2: The sensitivity analysis of

Figure 3:

3 Existence and Uniqueness Analysis

This study highlights the distinctiveness of the suggested Caputo model, which is founded on the Banach contraction principle and guarantees its existence and dependability in forecasting the dynamics of smoking-induced asthma. To enhance clarity and simplicity, we first assume the following four kernals:

Applying the fractional-order Caputo operator to Eq. (16), we obtain

where

Theorem 1. The aforementioned kernals system

Proof. First, we justify the Lipschitz condition for the kernel

where

The subsequent recursive formula for (29) is the result of the Caputo model having at least one solution.

The positive initial conditions are the first iterative values. Then

It is important to note that

Then, we have

By applying the triangle inequality, the above equation can be reduced

Following from Eq. (29), the kernel

We can simplify the above inequality as follows:

□

Theorem 2. Given the condition:

The fractional-order smoking-induces asthma system has an analytical solution at

Proof. Following from the recursive relation, we observe that the all state variables are bounded functions, confirming that the Lipschitz criteria.

Although the solutions listed are legitimate, we take into consideration the following to make sure the functions listed accurately reflect the suggested model:

This implies that

Using the Lipschitz condition,

This yields,

Next, at

When

In the same direction, we may deduce

We must examine an other solution

Utilizing the norm in Eq. (54), we obtain

□

Theorem 3. In the following circumstance, the analytical solution for the Caputo fractional model is unique, which is:

Proof. Note that (56) is equivalent to (55) so that

Thus,

This suggests that the solution is distinctive and is therefore

Also, we have

□

Theorem 4. The endemic equilibrium points

Proof. Let us represent the Lyapunov function:

Then, we have

From (9), we can write as

Replacing

after some computations, we have

where

It follows that if

□

Here, we discuss the use of linear feedback control method to stabilize system (9) at its equilibrium points, specifically focusing on the fractional-order system in its controlled form.

where

where

With the chosen values

Furthermore, the computed characteristic roots are:

Since all eigenvalues have negative real parts, the equilibrium point

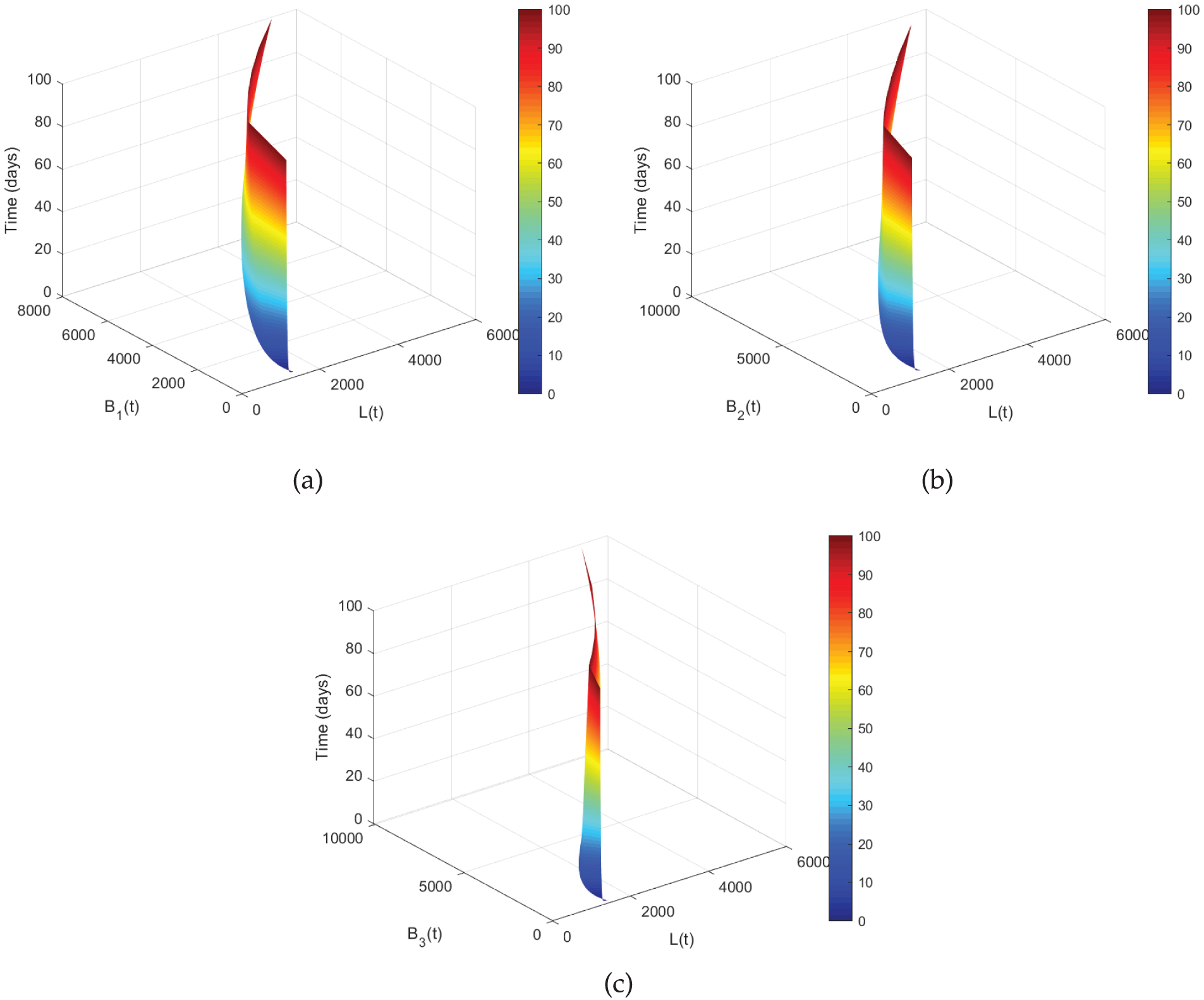

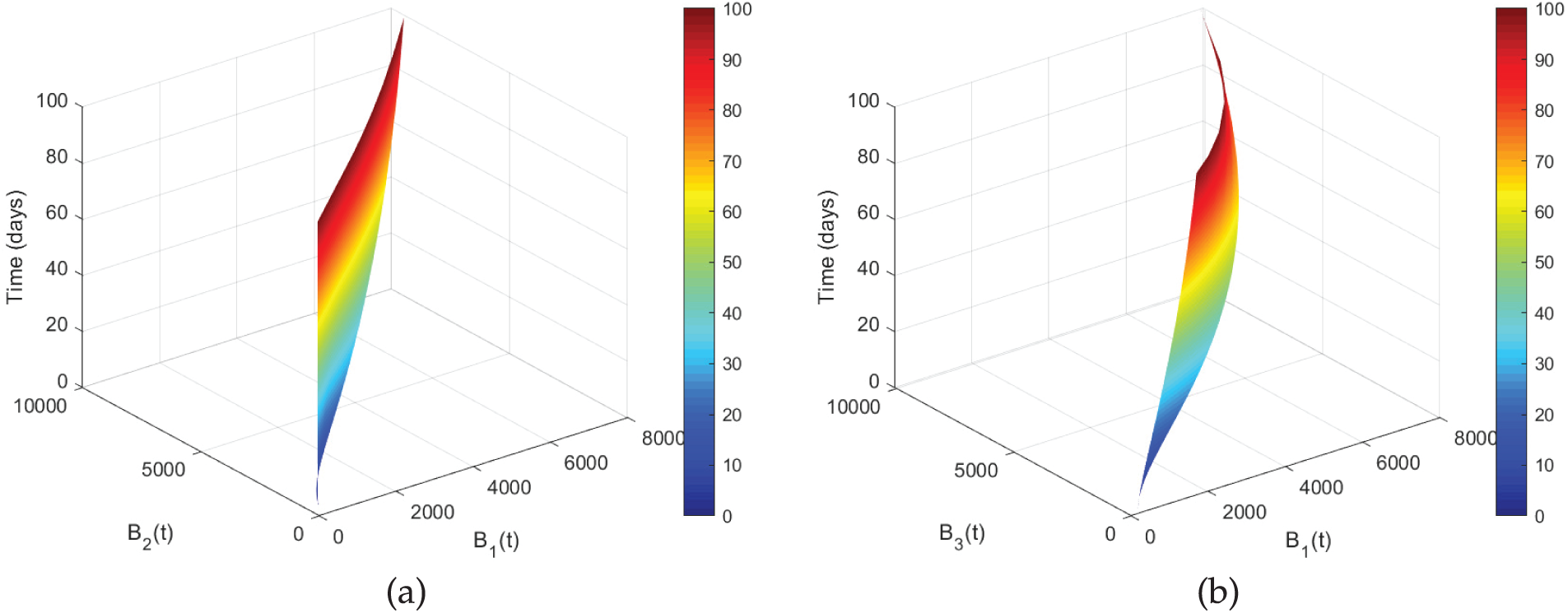

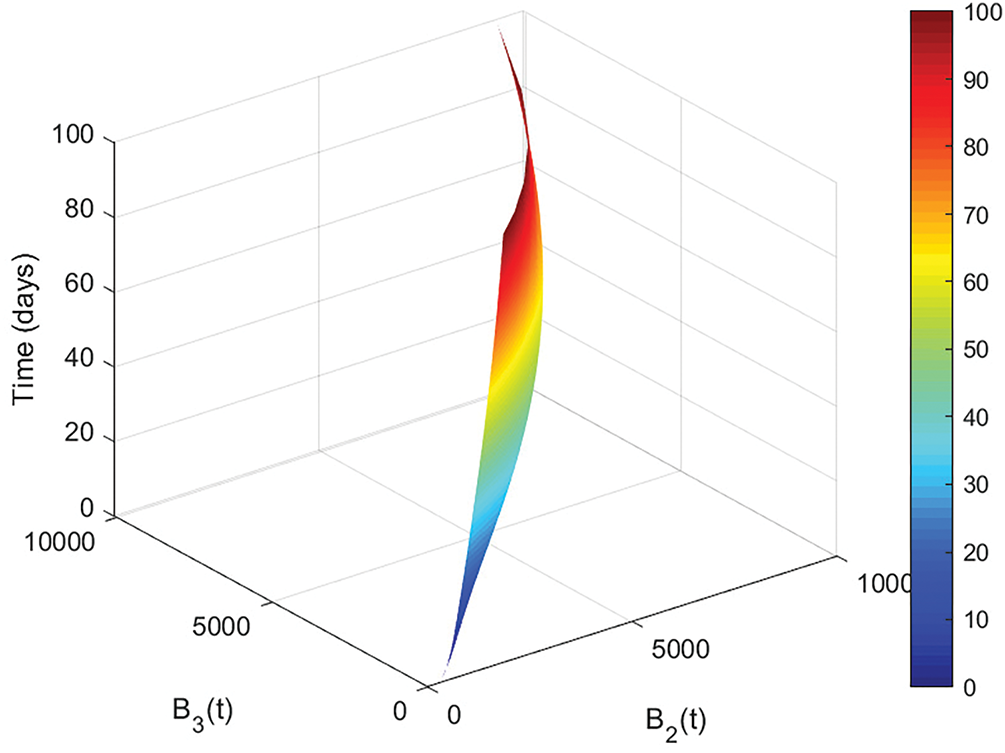

Figure 4: Co-relation between

Figure 5: Co-relation between

Figure 6: Co-relation between

Figure 7: Co-relation between

Figure 8: Co-relation between

Fig. 4 displays a set of graphs that show the co-relation between

The co-relation between the exposed class

The interactions between the asthmatic class and other disease-related groups are depicted in Fig. 6. In Fig. 6a, the exposed class initially maintains expansion as the number of asthmatic individuals rises. More bronchial respiratory damage results from a larger prevalence of asthma, as shown in Fig. 6b. The gradual but steady increase of

The interaction between the population with initial asthma and other illness states throughout time is depicted in Fig. 7. There is a strong positive association shown in Fig. 7a; as

The intermediate stage, where asthma functions are compromised, is the subject of Fig. 8. There is a definite monotonic increase:

To approximate the Caputo fractional system, we employ the Newton-polynomial based scheme for the proposed model (9) originally introduced by [30]. To simplify the explanation, we can represent the previously mentioned system as follows:

At

Above equation can be modified by using the Newton polynomial as

We get finally the following:

The proposed dynamical model (9) depicts the interplay between smoking and asthma as a nonlinear dynamical system. This section of the article presents the results and analysis for the analytical solution of the suggested fractional equations. After a small number of repetitions, it is believed that the predicted results, as stated in the section above, quickly approach the precise solution. We used MATLAB for numerical simulations by choosing appropriate initial conditions and parameter values. These values are suggested on the previous works done in [33–35]. The parameters values used in numerical simulations are as follows:

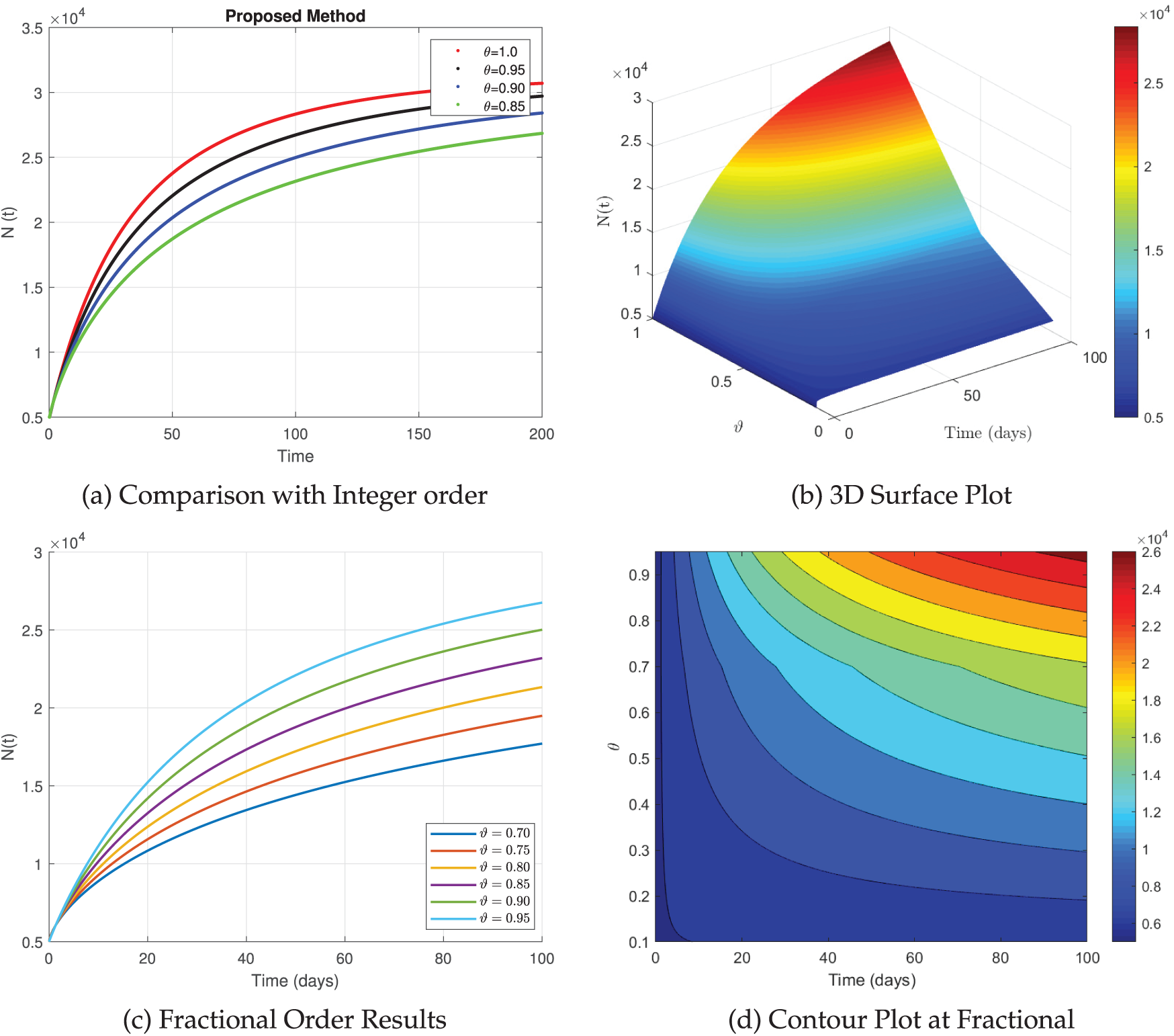

The set of graphs presented in Fig. 9 illustrates the behavior of

Figure 9: The simulation of

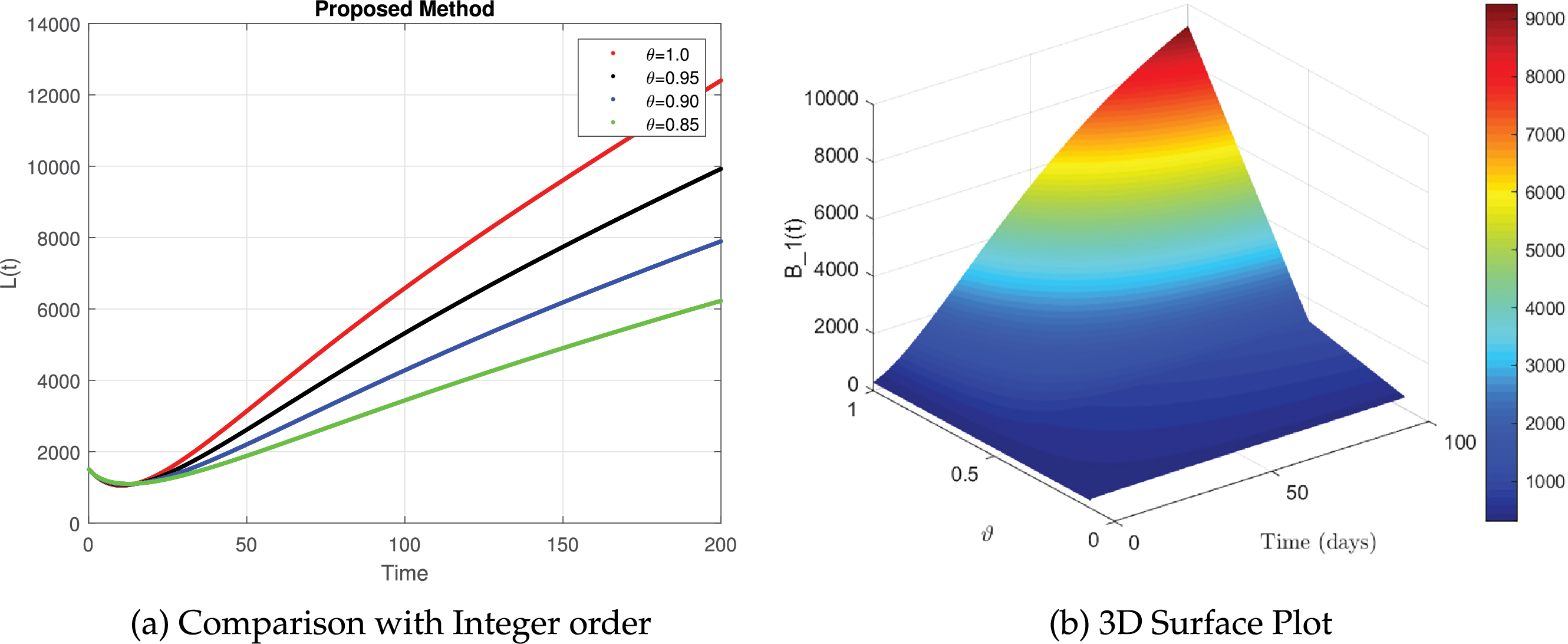

Fig. 10, in Fig. 10a the integer-order model

Figure 10: The simulation of

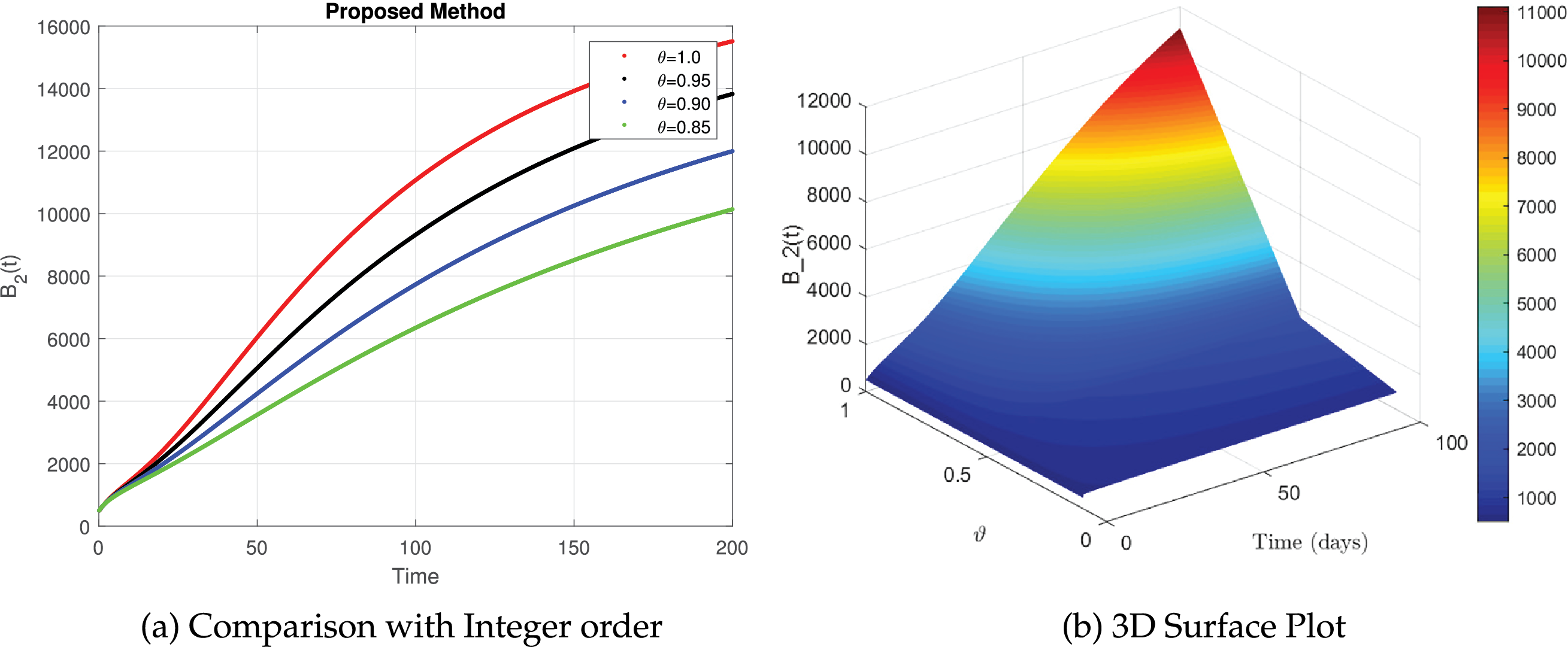

In Fig. 11a, the integer-order model shows a fast progression of lung damage cases. Fractional models demonstrate a slower onset due to memory effects. Fig. 11b depicts the gradual accumulation of lung damage over time. The peak suggests that lung damage worsens before stabilizing. In Fig. 11c, a higher fractional order leads to a more rapid increase in lung damage. Lower orders indicate a slower progression, which aligns with real-world cases where damage accumulates gradually. Fig. 11d represents different intensity levels of lung damage. The color variations highlight how the disease progresses under different fractional orders. These results highlight the importance of fractional calculus in modeling asthma and lung damage, capturing real-world memory effects and delayed responses in disease progression.

Figure 11: The simulation of

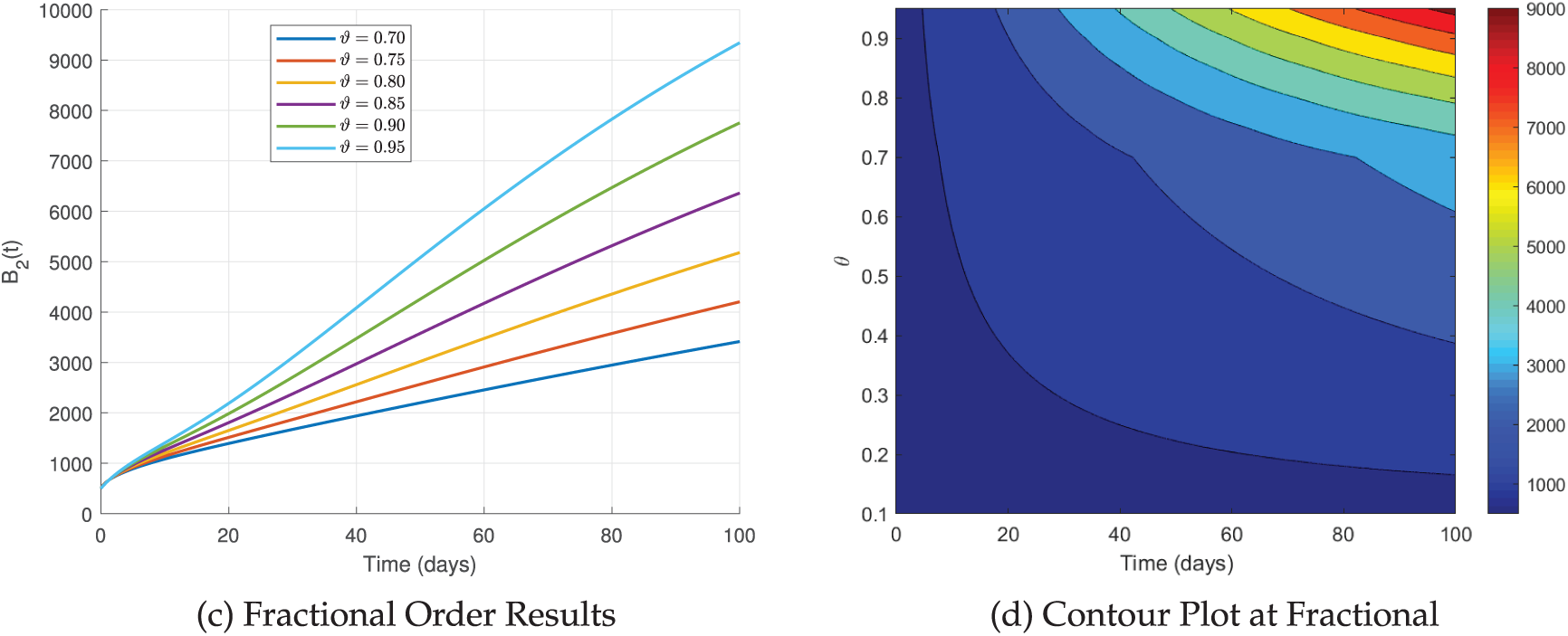

Fig. 12a, the integer-order model

Figure 12: The simulation of

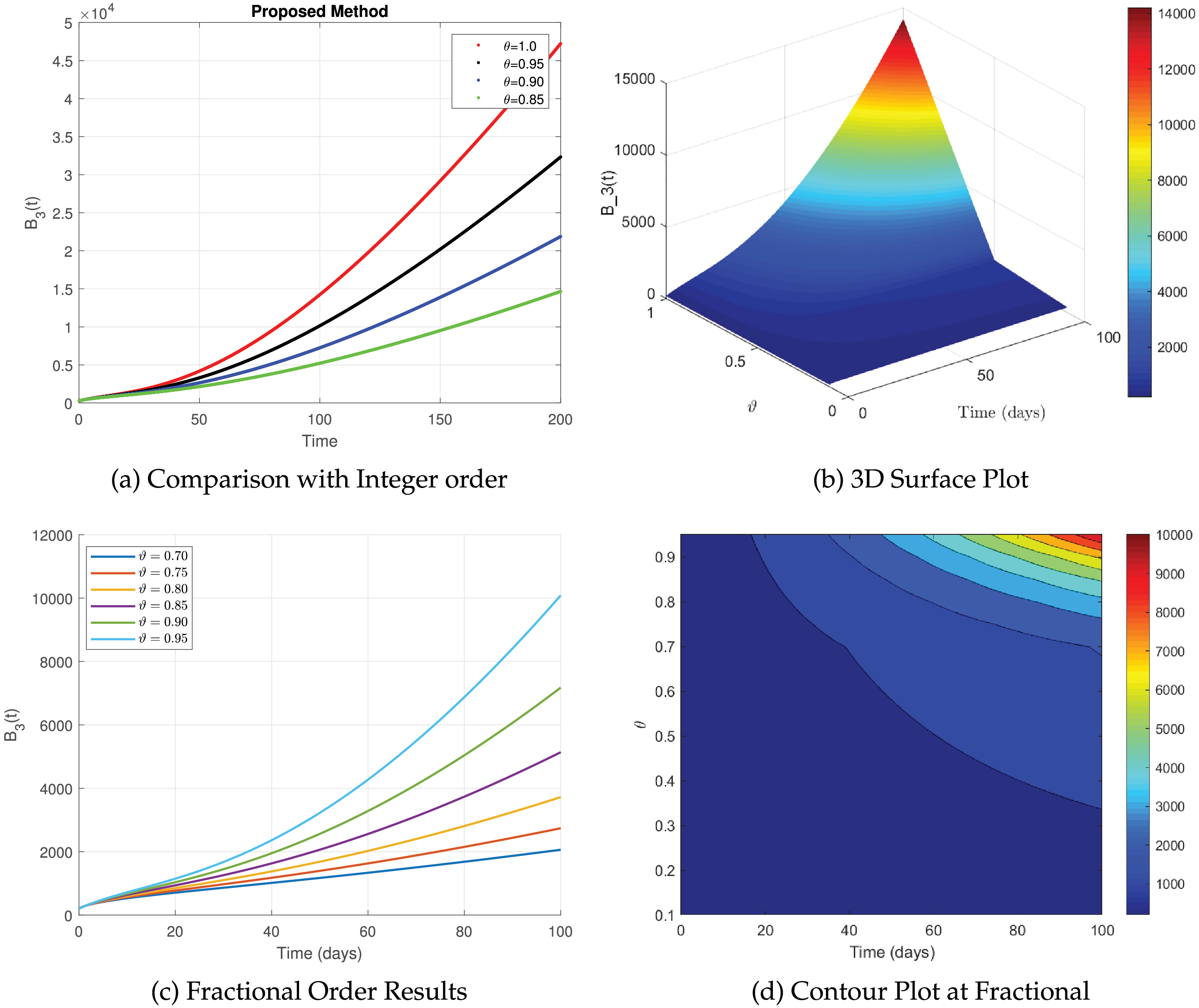

Fig. 13 provides a detailed description of the simulated dynamics of

Figure 13: The simulation of

Fig. 14a shows the dynamics of the

Figure 14: The simulation of

This study used a fractional-order mathematical model to examine how smoking affects the development of asthma. To establish unique solutions and validate positivity and boundedness, the Banach contraction principle was applied. Asthma disease transmission among smokers was evaluated using the fundamental reproductive number

The suggested model ignores natural demographic shifts and other environmental triggers and is based on the supposition that smoking is the main factor influencing asthma dynamics in a population. Predictive accuracy may be limited by the literature-based parameters that were employed. In order to evaluate the effects of different memory kernels on the progression of asthma, future research may concentrate on applying optimal control techniques for assessing smoking cessation policies and expanding the framework by comparing different fractional operators, such as Caputo-Fabrizio and Atangana-Baleanu derivatives.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: This research received no external funding.

Author Contributions: The contributions of each author to this research are as follows: Conceptualization, Muhammad Farman, Noreen Asghar and Kottakkaran Sooppy Nisar; methodology, Muhammad Farman, Noreen Asghar and Muhammad Umer Saleem; software, Noreen Asghar and Muhammad Umer Saleem; validation, Kamyar Hosseini and Mohamed Hafez; formal analysis, Muhammad Umer Saleem; investigation, Muhammad Farman, Muhammad Umer Saleem and Kottakkaran Sooppy Nisar; resources, Kamyar Hosseini; data curation, Mohamed Hafez; writing—original draft preparation, Muhammad Farman and Noreen Asghar; writing—review and editing, Muhammad Farman, Noreen Asghar, Muhammad Umer Saleem, Kottakkaran Sooppy Nisar; visualization, Muhammad Farman and Kottakkaran Sooppy Nisar; supervision, Kamyar Hosseini and Mohamed Hafez; project administration, Muhammad Farman. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All data analyzed and generated during this study are included in this article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Ghosh M. Industrial pollution and Asthma: a mathematical model. J Biolog Syst. 2000;8(4):347–71. doi:10.1142/s0218339000000225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Polosa R, Thomson NC. Smoking and asthma: dangerous liaisons. Eur Respir J. 2013;41(3):716–26. doi:10.1183/09031936.00073312. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Strachan DP. The role of environmental factors in asthma. Br Med Bull. 2000;56(4):865–82. doi:10.1258/0007142001903562. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Driscoll AJ, Arshad SH, Bont L, Brunwasser SM, Cherian T, Englund JA, et al. Does respiratory syncytial virus lower respiratory illness in early life cause recurrent wheeze of early childhood and asthma? Critical review of the evidence and guidance for future studies from a World Health Organization-sponsored meeting. Vaccine. 2020;38(11):2435–48. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.01.020. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Canadian Medical Association. Secondhand cigarette smoke worsens symptoms in children with asthma. Section on Allergy, Canadian Paediatric Society. CMAJ. 1986;135(4):321–3. [Google Scholar]

6. Collishaw NE, Kirkbride J, Wigle DT. Tobacco smoke in the workplace: an occupational health hazard. Can Med Assoc J. 1984;131(10):1199. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

7. Dockery DW, Pope CA, Xu X, Spengler JD, Ware JH, Fay ME, et al. An association between air pollution and mortality in six US cities. New Engl J Med. 1993;329(24):1753–9. doi:10.1056/nejm199312093292401. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Utell MJ, Looney RJ. Environmentally induced asthma. Toxicol Lett. 1995;82:47–53. doi:10.1016/0378-4274(95)03467-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Jan R, Xiao Y. Effect of partial immunity on transmission dynamics of dengue disease with optimal control. Math Methods Appl Sci. 2019;42(6):1967–83. doi:10.1002/mma.5491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Akinyemi ST, Idisi IO, Rabiu M, Okeowo VI, Iheonu N, Dansu EJ, et al. A tale of two countries: optimal control and cost-effectiveness analysis of monkeypox disease in Germany and Nigeria. Healthcare Analytics. 2023;4:100258. doi:10.1016/j.health.2023.100258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Sohaib M. Mathematical modeling and numerical simulation of HIV infection model. Res Appl Mathem. 2020;7(41):100118. doi:10.1016/j.rinam.2020.100118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Attaullah RJ, Jabeen A. Solution of the HIV infection model with full logistic proliferation and variable source term using Galerkin scheme. Matrix Science Mathematic. 2020;4(2):37–43. doi:10.26480/msmk.02.2020.37.43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Jan R, Xiao Y. Effect of pulse vaccination on dynamics of dengue with periodic transmission functions. Adv Differ Equ. 2019;2019(1):1–17. [Google Scholar]

14. Mahmoudi MR, Baleanu D, Band SS, Mosavi A. Factor analysis approach to classify COVID-19 datasets in several regions. Results Phys. 2021;25:104071. doi:10.1016/j.rinp.2021.104071. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Baskonus HM, Hammouch Z, Mekkaoui T, Bulut H. Chaos in the fractional order logistic delay system: circuit realization and synchronization. AIP Conf Proc. 2016;1738(1):290005. doi:10.1063/1.4952077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Slowikowska M, Bajzert J, Miller J, Stefaniak T, Niedzwiedz A. The dynamics of circulating immune complexes in horses with severe equine asthma. Animals. 2021;11(4):1001. doi:10.3390/ani11041001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Khan D, Ali G, Khan ZA. Heat transfer capability analysis of hybrid Brinkman-type fluid on horizontal solar collector plate through fractal fractional operator. Opt Quantum Electron. 2025;57(2):154. doi:10.1007/s11082-024-08025-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Farman M, Xu C, Shehzad A, Akgül A. Modeling and dynamics of measles via fractional differential operator of singular and non-singular kernels. Math Comput Simul. 2024;221(1):461–88. doi:10.1016/j.matcom.2024.03.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Mohamed Hafez, Faisal Alshowaikh, Betty Wan Niu Voon, Shawkat Alkhazaleh, Hussein Al-Faiz. Review on recent advances in fractional differentiation and its applications. Progr Fract Differ Appl. 2025;11(2):245–261. doi:10.18576/pfda/110203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Awadallah M, Hannabou M, Zaway H, Alahmadi J. Applicability of Caputo-Hadmard fractional operator in mathematical modeling of pantograph systems. J Appl Math Comput. 2025;71:4971–86. doi:10.1007/s12190-025-02421-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Farman M, Nisar KS, Shehzad A, Baleanu D, Amjad A, Sultan F. Computational analysis and chaos control of the fractional order syphilis disease model through modeling. Ain Shams Eng J. 2024;15(6):102743. doi:10.1016/j.asej.2024.102743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Madani YA, Ali Z, Rabih M, Alsulami A, Eljaneid NH, Aldwoah K, et al. Discrete fractional-order modeling of recurrent childhood diseases using the caputo difference operator. Fract Fraction. 2025;9(1):55. doi:10.3390/fractalfract9010055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Farman M, Akgül A, Conejero JA, Shehzad A, Nisar KS, Baleanu D. Analytical study of a Hepatitis B epidemic model using a discrete generalized nonsingular kernel. AIMS Math. 2024;9(7):16966–97. doi:10.3934/math.2024824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Matouk AE, Botros M. Hidden chaotic attractors and self-excited chaotic attractors in a novel circuit system via Grünwald-Letnikov, Caputo-Fabrizio and Atangana-Baleanu fractional operators. Alex Eng J. 2025;116(2):525–34. doi:10.1016/j.aej.2024.12.064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Dinku T, Kumsa B, Rana J. A mathematical approach to cancer growth: the role of smoking through fractional order models with Mittag-Leffler kernels. Alex Eng J. 2025;124(4):46–65. doi:10.1016/j.aej.2025.03.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Ferrari AL, Gomes MCS, Aranha ACR, Paschoal SM, de Souza Matias G, de Matos Jorge LM, et al. Mathematical modeling by fractional calculus applied to separation processes. Sep Purif Technol. 2024;337:126310. doi:10.1016/j.seppur.2024.126310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Nisar KS, Kulachi MO, Ahmad A, Farman M, Saqib M, Saleem MU. Fractional order cancer model infection in human with CD8+ T cells and anti-PD-L1 therapy: simulations and control strategy. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):16257. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-66593-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Mukhtar R, Chang CY, Raja MAZ, Chaudhary NI, Shu CM. Novel nonlinear fractional order Parkinson’s disease model for brain electrical activity rhythms: intelligent adaptive Bayesian networks. Chaos Soliton Fract. 2024;180:114557. doi:10.1016/j.chaos.2024.114557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Sun L, Cheng G, Barriere T. Investigation of temperature-dependent mechanical behaviours of polycarbonate with an innovative fractional order model. Mat Res Proc. 2024;41:2174–81. doi:10.21741/9781644903131-239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Farman M, Jamil K, Xu C, Nisar KS, Amjad A. Fractional order forestry resource conservation model featuring chaos control and simulations for toxin activity and human-caused fire through modified ABC operator. Math Comput Simul. 2025;227(2):282–302. doi:10.1016/j.matcom.2024.07.038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Adak S, Barman S, Jana S, Majee S, Kar TK. Modelling and analysis of a fractional-order epidemic model incorporating genetic algorithm-based optimization. J Appl Math Comput. 2025;71(1):901–25. doi:10.1007/s12190-024-02224-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Bansal J, Kumar A, Kumar A, Khan A, Abdeljawad T. Investigation of monkeypox disease transmission with vaccination effects using fractional order mathematical model under Atangana-Baleanu Caputo derivative. Model Earth Syst Environ. 2025;11(1):40. doi:10.1007/s40808-024-02202-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Naresha R, Tripathi A. A nonlinear mathematical model for asthma: effect of environmental pollution. Iranian J Optimizat. 2009;1:24–56. [Google Scholar]

34. Jan R, Yüzbaşi S, Attaullah A, Jawad M, Jan A. Fractional derivative analysis of asthma with the effect of environmental factors. Sigma J Eng Nat Sci. 2024;42(1):177–88. doi:10.14744/sigma.2023.00098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Tuza FADA, de Sá PM, Castro HA, Lopes AJ, de Melo PL. Combined forced oscillation and fractional-order modeling in patients with work-related asthma: a case-control study analyzing respiratory biomechanics and diagnostic accuracy. Biomed Eng Online. 2020;19:1–30. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-31314/v2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Padder A, Almutairi L, Qureshi S, Soomro A, Afroz A, Hincal E, et al. Dynamical analysis of generalized tumor model with Caputo fractional-order derivative. Fract Fraction. 2023;7(3):258. doi:10.3390/fractalfract7030258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools