Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Filter-Based Feature Selection Framework to Detect Phishing URLs Using Stacking Ensemble Machine Learning

1 Faculty of Computer Science and Engineering, GIK Institute of Engineering Sciences and Technology, Topi, 23640, Pakistan

2 Department of Computing, Hamdard University Islamabad Campus, Islamabad, 44000, Pakistan

3 Department of Computer Networks and Communication, College of Computer Science and Information Technology, King Faisal University, Al-Ahsa, 31982, Saudi Arabia

4 Department of Computer Science, King Khalid University, Abha, 61421, Saudi Arabia

5 Department of Operations and Information Management, Aston Business School, Aston University, Birmingham, B4 7ET, UK

6 Institute for Analytics and Data Science, University of Essex, Colchester, CO4 3SQ, UK

* Corresponding Authors: Asma Patel. Email: ; Insaf Ullah. Email:

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(1), 1167-1187. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.070311

Received 13 July 2025; Accepted 22 August 2025; Issue published 30 October 2025

Abstract

Today, phishing is an online attack designed to obtain sensitive information such as credit card and bank account numbers, passwords, and usernames. We can find several anti-phishing solutions, such as heuristic detection, virtual similarity detection, black and white lists, and machine learning (ML). However, phishing attempts remain a problem, and establishing an effective anti-phishing strategy is a work in progress. Furthermore, while most anti-phishing solutions achieve the highest levels of accuracy on a given dataset, their methods suffer from an increased number of false positives. These methods are ineffective against zero-hour attacks. Phishing sites with a high False Positive Rate (FPR) are considered genuine because they can cause people to lose a lot of money by visiting them. Feature selection is critical when developing phishing detection strategies. Good feature selection helps improve accuracy; however, duplicate features can also increase noise in the dataset and reduce the accuracy of the algorithm. Therefore, a combination of filter-based feature selection methods is proposed to detect phishing attacks, including constant feature removal, duplicate feature removal, quasi-feature removal, correlated feature removal, mutual information extraction, and Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) testing. The technique has been tested with different Machine Learning classifiers: Random Forest, Artificial Neural Network (ANN), Ada-Boost, Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), Logistic Regression, Decision Trees, Gradient Boosting Classifiers, Support Vector Machine (SVM), and two types of ensemble models, stacking and majority voting to gain A low false positive rate is achieved. Stacked ensemble classifiers (gradient boosting, random forest, support vector machine) achieve 1.31% FPR and 98.17% accuracy on Dataset 1, 2.81% FPR and Dataset 3 shows 2.81% FPR and 97.61% accuracy, while Dataset 2 shows 3.47% FPR and 96.47% accuracy.Keywords

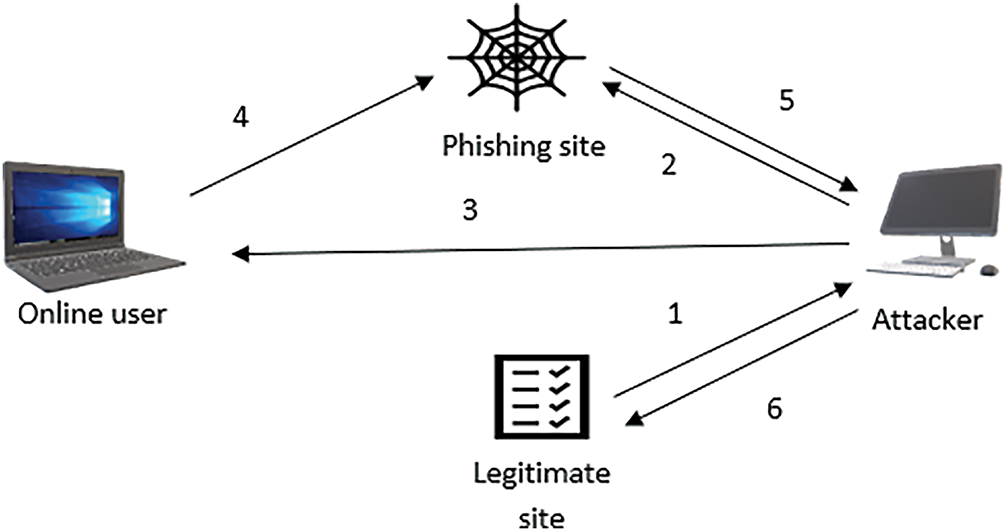

Web-based services such as online banking, social networking, online education, entertainment, and software downloads are growing rapidly. Phishing is a form of cyber fraud that combines social engineering and technical deception to steal personal and financial information [1]. Victims believe they are dealing with a good and trustworthy group through deceptive email messages and social engineering techniques. Customers are redirected to fake websites to obtain financial information such as passwords and usernames. These attacks may involve malware infections, credential-stealing applications, or redirection to fake websites Fig. 1. In 2020, cyber attackers carried out COVID-19-themed phishing attacks on healthcare systems, a sign that phishing attacks are on the rise. In 1996, the term “phishing” was introduced by a group of hackers who gained access to an account of America Online (AOL) [2]. The attacker creates a page of phishing attacks identical to the real one and then sends the phishing websites to victims via email or other communication links. Such messages often create a sense of urgency or fear—offering rewards or threats—to manipulate users into taking immediate action. According to the Federal Bureau of Investigation(FBI), over 100 phishing complaints were recorded in 2018. The most frequently targeted sectors included healthcare, air travel, and education, resulting loss of 100 million USD. Phishing emails were used to get employees’ information. These credentials were then used for logging in to the system, and the phishers modified the company’s rules so that workers would not receive account updates [3]. According to the Anti-Phishing Working Group(APWG) 2021 fourth quarter [4], in December 2021, APWG recorded 316,747 attacks, the greatest monthly number in the organization’s history. Since early 2020, the number of current phishing attacks has tripled that of observed attacks. In December, 16,461 phishing e-mail attacks were registered. And 521 brands were attacked. The financial institute is 23.2%, Webmail at 19.5%, and eCommerce at 17.3% are the three most targeted industries, in which 20% are manufacturing,13% retail and wholesale, and 12% are business services.

Figure 1: An illustrative figure related to the phishing detection framework

The type of phishing attack depends on the target and what the attacker wants to achieve. Phishing attack types can be categorized based on their targets and objectives [5,6] on the information the attacker wants to obtain from the victim. The first type of phishing attack is social engineering. Short Message Service (SMS) phishing, known as smishing, is the most common method of sending SMS to the user, pretending as a trusted authority such as a bank. The second approach is to send a malware-embedded SMS. Another type of phishing attack is Vishing. The most used phishing attack is email phishing [7]; e-mail is widely used and does not reveal the sender’s geographical location. Another method of a Phishing attack is launched by generating a fake one similar to the real web page. The second type of phishing attack is a technical trick. Phishing attacks are also carried out using technical tricks. Technical phishing methods include malware, trojans, and session hijacking, etc. Malware is a very useful piece of software designed to retrieve and collect credentials. A keylogger is a feature that records the keystrokes of every user on the user’s computer. The attacker tricks the user into creating a session in session hijacking, i.e., H. The user is notified that their account is locked, and when the user authenticates to log in, the session begins and The attacker then uses the victim user’s session ID or secret key to gather credentials. The web trojan appears on the website screen, and the user thinks they are entering details on the website they are opening, but they are entering the details in the hacker’s pop-up window. Pharming installs code on a user’s computer that unknowingly drives traffic to a website. Experts have proposed several techniques to identify phishing attempts in recent years. However, phishing attempts continue to be a problem, and building an effective anti-phishing strategy has proven difficult. Furthermore, most anti-phishing systems have a high rate of false positives and are unable to detect a zero-hour attack. There are many ML algorithms [6–8] for phishing attack detection which achieves the best accuracy on a given dataset, but the problem which is faced by their method is high FPR (false positive rate), Because of the high FPR, phishing websites are mistakenly perceived as real, resulting in significant losses for the person who visits the site. The most challenging aspect of this research is that while many solutions for phishing attack detection are available, phishing attacks remain a problem. Initially, our motivation was to detect phishing URLs effectively. However, during our investigation, we identified a critical challenge—high false positive rates—which guided the direction of this research: a high false-positive rate of anti-phishing systems. This challenge serves as our motivation for this research. If a person visits a phishing website after verifying that it is legitimate using a phishing detection method, they will suffer a significant loss. As a result, none of the phishing websites are identified as legitimate by our system. Most phishing detection approaches employ irrelevant features to detect phishing attacks, resulting in a high false-positive rate. As a result, we encourage feature selection algorithms to pick relevant features. The major objective of this study is to develop a framework for detecting phishing URLs using machine learning. Numerous solutions have been presented in recent years. The existing techniques still lag in detecting phishing URLs, as they have a high FPR and are unable to detect new attacks. This research aims to develop a time-efficient and accurate phishing detection model with reduced false positives. For this purpose, this research concentrated on creating a unique combination of a filter-based feature selection system. This feature selection method contains the removal of constant, quasi, and correlated variables. Duplicate attributes and applying the ANOVA test and mutual information gain on the dataset can help select the most significant feature for the classification and result in effective detection.

The contribution of our research is

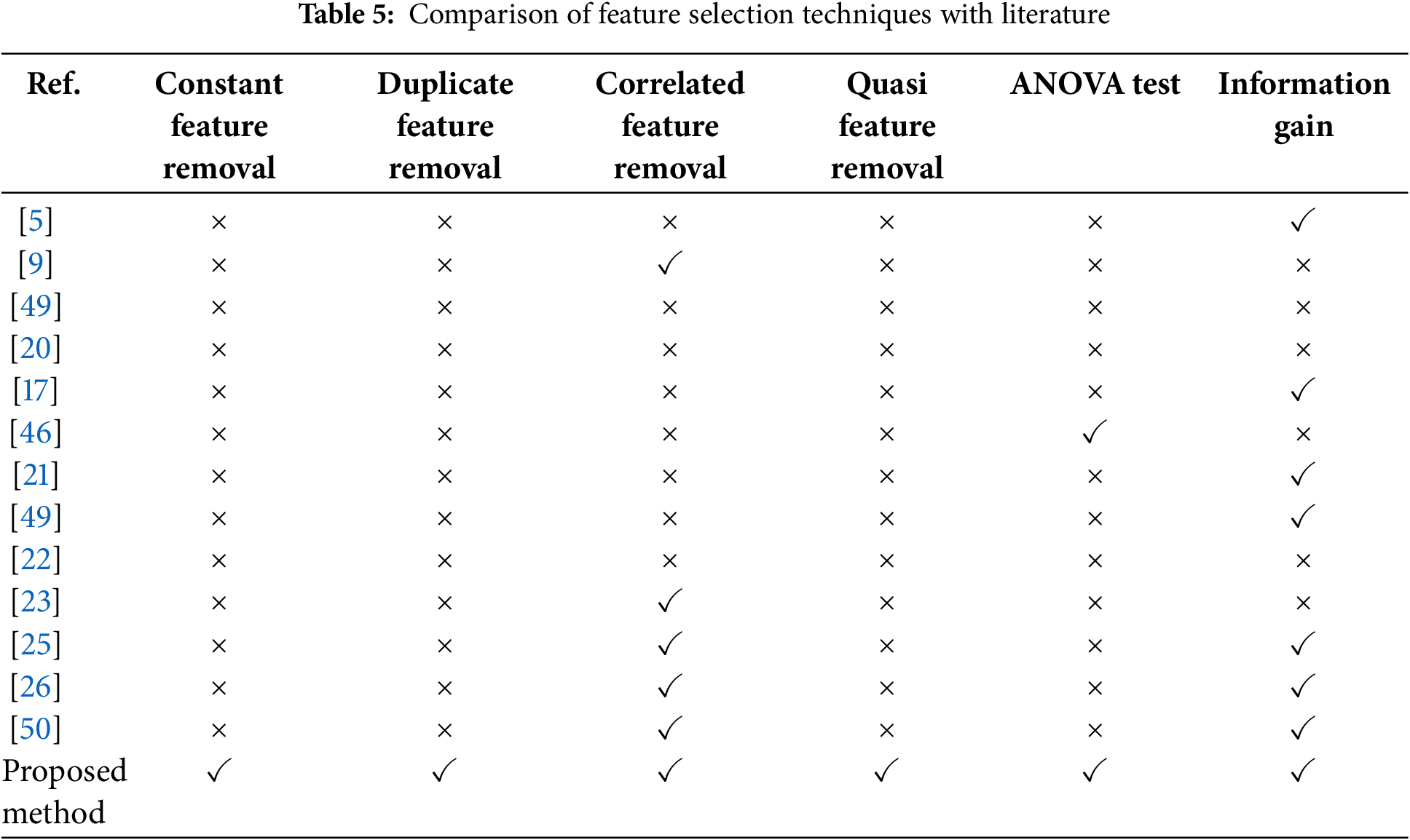

• We use a broader set of filter-based feature selection techniques than previous work to identify the most relevant features for phishing detection.

• A novel combination of filter-based feature selection methods is used, which includes constant feature removal, duplicate feature removal, quasi-constant feature removal, correlated feature removal, the ANOVA test, and Mutual Information Gain.

• Eight machine learning classifiers are applied to the proposed model to find the best three performing classifiers.

• To improve predictive performance and reduce false positives, ensemble learning techniques such as stacking and majority voting are applied to the top-performing classifiers (SVM, Random Forest, and Gradient Boost).

• We test real-time detection by inputting new URLs to classify them as phishing or legitimate.

The main emphasis of this research is on machine learning algorithms, 8 of which introduce and compare different feature sets from the website URL. The different datasets are tested on the proposed feature selection combination and selected machine learning algorithm, and a combination of machine learning voting and stacking. The rest of the paper contributions are as follows: Section 2 reviews the literature, Research Methodology is presented in Section 3, results are discussed in Section 4. The conclusions and future works are discussed in Section 5.

This section is based on a literature review. Phishing attacks are proliferating. Owing to online enterprises, financial transactions, and e-commerce websites, Spear Phishing, Tax Scammers Phishing, Iterative campaigns phishing, and Pharming Phishing are some of the latest tactics used by Phishers. Common phishing techniques include malicious emails, zero-day phishing, and deceptive tactics.

2.1 Content Phishing Detection

This method detects phishing attacks using the website’s content [9,10] analysis, which necessitates some features from the URL, text content, and image, such as password, grammar, and spellings checks, visual similarity tests between URL features, website, and so on.

1. URL analysis: This analysis can be achieved by checking the Internet Protocol (IP) address, a suffix, @, number of dots (.) in the URL, hexadecimal, Hypertext Transfer Protocol Secure (HTTPS) port, and URL length. Machine learning [11] and Rule-based approaches [12] analyze web text content and the content of a URL using specific heuristics.

2. Image analysis: To distinguish a phishing webpage from a legitimate webpage, this method [13] examines photographs, logos, screenshots of the website, and Completely Automated Public Turing test to tell Computers and Humans Apart (CAPTCHA).

3. Text analysis: This method examines the webpage text content [14], such as keywords, whether Secure Sockets Layer (SSL) is allowed or not, and so on. Text analysis makes spotting phishing scams easy. Text analysis solutions, rule-based approaches, similarity-based approaches, and ML are used for text analysis.

2.2 Non-Content Phishing Detection

This type of detection focuses on features other than content.

1. Black/white list: The blacklist [15] stores the known phishing URLs list, and if the currently accessed URL is on this list, it is categorized as a phishing URL, and users are notified if the URL matches. This list-based solution is simpler and faster to develop because it verifies whether the URL is mentioned or not. It does not, however, detect URLs that are not blacklisted, which is known as “zero-day phishing,” and slight URL modifications can bypass blacklist-based methods.

2. DNS-based approach: This technique uses Domain Name System (DNS) data to assess the legitimacy of IP addresses and domain names connected with them to detect phishing [16].

3. User website rating: The legitimacy of a website is determined based [17] on user reviews and other features. Customers must rate the site’s trustworthiness when they visit it so that the site can be classified as a phishing website or not, depending on the user’s response.

4. Domain popularity: This approach [18] determines the trustworthiness of a website based on domain information like domain registration information, certificate authority, certificate details, and so on.

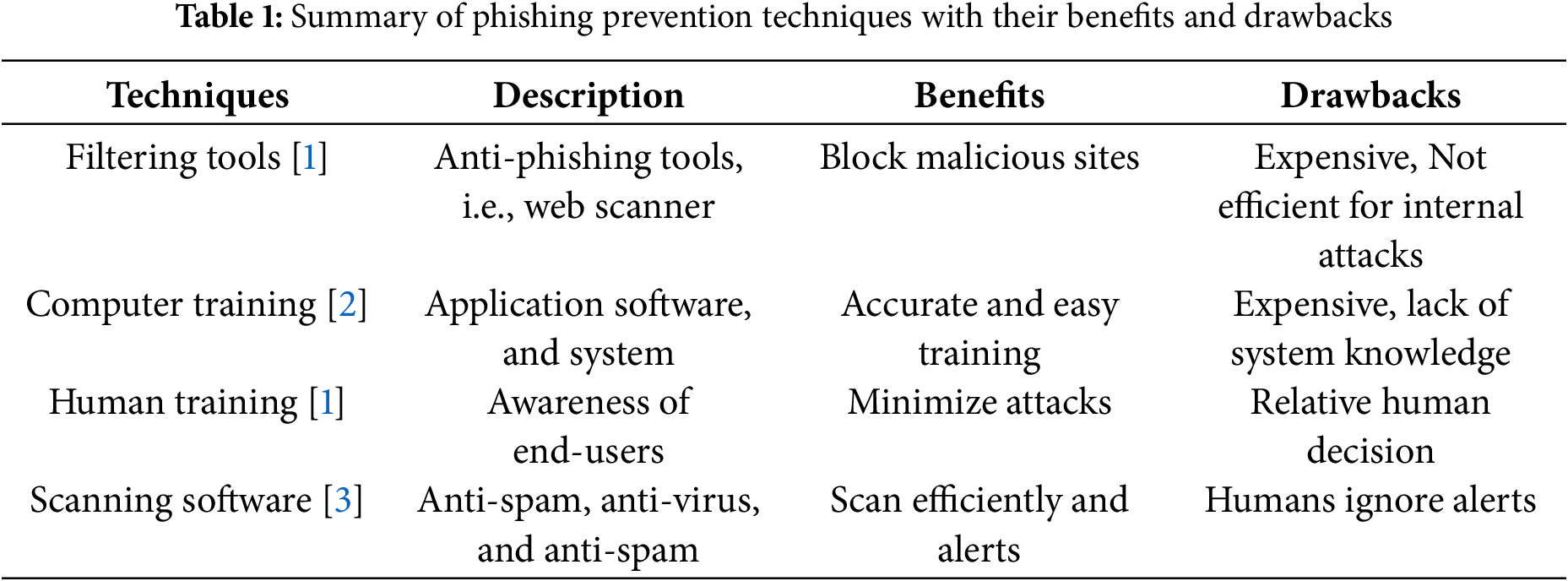

Table 1 summarizes phishing prevention [9] and analyzes it based on benefits and drawbacks, and Table 2 shows the drawbacks of phishing website detection.

Many researchers used ML methods to detect phishing attacks. For phishing identification, the paper [19] used ML techniques. They used the Logistic Regression (LR), K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Ada-boost, Support Vector Machine (SVM), Random Forest (RF), and Artificial Neural Network (ANN), and the random forest algorithm provided good accuracy. A variety of ML algorithms have been used to detect phishing attacks [20]. For better results, they used Natural Language Processing (NLP) techniques. They were able to achieve reasonable accuracy using SVM and NLP techniques. Support vector classifiers, decision trees, and RF models were used to detect phishing web pages [21] and found that their model had a high level of accuracy. ML learning models for phishing attacks are applied in [21] and found that a random forest algorithm provided good accuracy. In [22], the researcher examined various phishing attack detection strategies, opportunities, patterns, and challenges. The Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) model is highly successful in detecting new phishing websites based on the findings of comprehensive studies [23]. A deep learning model that can solve regression and classification problems is the Artificial Neural Network. There is no need to use any feature selection techniques in ANN. Neural networks will extract features for you automatically. Some researchers used artificial neural networks to detect phishing sites. Other advanced approaches, such as the BERT and CNN-based computational model, have also been proposed for phishing detection in enterprise systems [24]. ML techniques were used to detect phishing websites [25] and got 89 percent accuracy using a naive Bayes classifier and an ANN. A survey of phishing detection using ML methods is presented in [26]. SVM and RF classifiers to detect phishing attacks [27] used two different data sets. Reference [28] compared ML techniques and concluded that ML is a good way to identify phishing websites. Reference [28] used a variety of classification models to identify phishing websites. Decision Tree, RF, SVM, and Logistic Regression were used. They used Logistic Regression to achieve reasonable accuracy with 1200 URLs. However, when Logistic Regression was applied to 12,000 sites, they found that it was less accurate. They inferred from the experiments in the Decision Tree performs best regardless of dataset size. CNN uses several measures to solve classification problems. It resembles an ANN after flattening. Aljofey et al. [29] proposed a deep learning model for detecting phishing sites. They used CNN at the character level and got good results.

A phishing detection model based on Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BLSTM) [7], which plays an important role in network security, achieves an accuracy of 95.47% using a dataset with 11,000 URLs and 30 functions. Wu created a URL-based recognition system [30] with only seven features. Machine learning methods, datasets, number of legitimate and phishing sites, number of features extracted, feature selection methods, and accuracy using machine learning methods are compared in [31] to perform. Almseidin used a feature selection method [32] to reduce the number of features from 48 to only 20, resulting in the best results. The model was built in 2.44 s and performed with a 98.11 percent accuracy rate. Gutierrez created SAFE-PC, A system that extracts features [33], some of which are elevated to higher-level features, to bypass typical phishing e-mail detection tactics. Unnithan focuses on feature engineering; the Doc2Vec [34] format is used for identifying and classifying phishing and legitimate e-mails. Korkmaz et al. [35] uses eight machine learning classifiers and three datasets with good active accuracy, with 5.79 FPR. Shikalgar et al. [36] and Butnaru et al. [37] use only nine features to predict Phishing URLs.

Recent research has focused on enhancing phishing URL detection through advanced machine learning techniques. Tamal et al. [38] developed an optimal feature vectorization algorithm with supervised machine learning, achieving 97.52% accuracy using random forests. Sankaranarayanan et al. [39] proposed a stacking-based ensemble classifier integrating multiple algorithms, resulting in 96.8% accuracy for multi-class URL classification. He et al. [40] introduced a tiny-Bert stacking model, which achieved 99.14% accuracy by combining semantic feature extraction with a stacked classifier. Urmi et al. [41] evaluated feature selection techniques for cyber-attack detection, demonstrating that Recursive Feature Elimination with a stacked ensemble approach achieved up to 100% accuracy for certain attack types. Alshdaifat et al. [42] developed DaE2, an ensemble framework integrating AdaBoost, Bagging, Stacking, and Voting, achieving 98.7% accuracy on a dataset of 11,055 URLs with 30 features. Nayak et al. [43] used deep learning models to achieve 94.46% accuracy with only 14 features from a dataset of 58,645 URLs. Setu et al. [44] proposed the RSTHFS method, based on Rough Set Theory, maintaining 95.48% average accuracy while reducing features by 69.11% across three datasets. Rao et al. [45] developed the Phish-Jam super learner ensemble model for mobile phishing detection, achieving 98.93% accuracy by combining predictions from various ML algorithms.

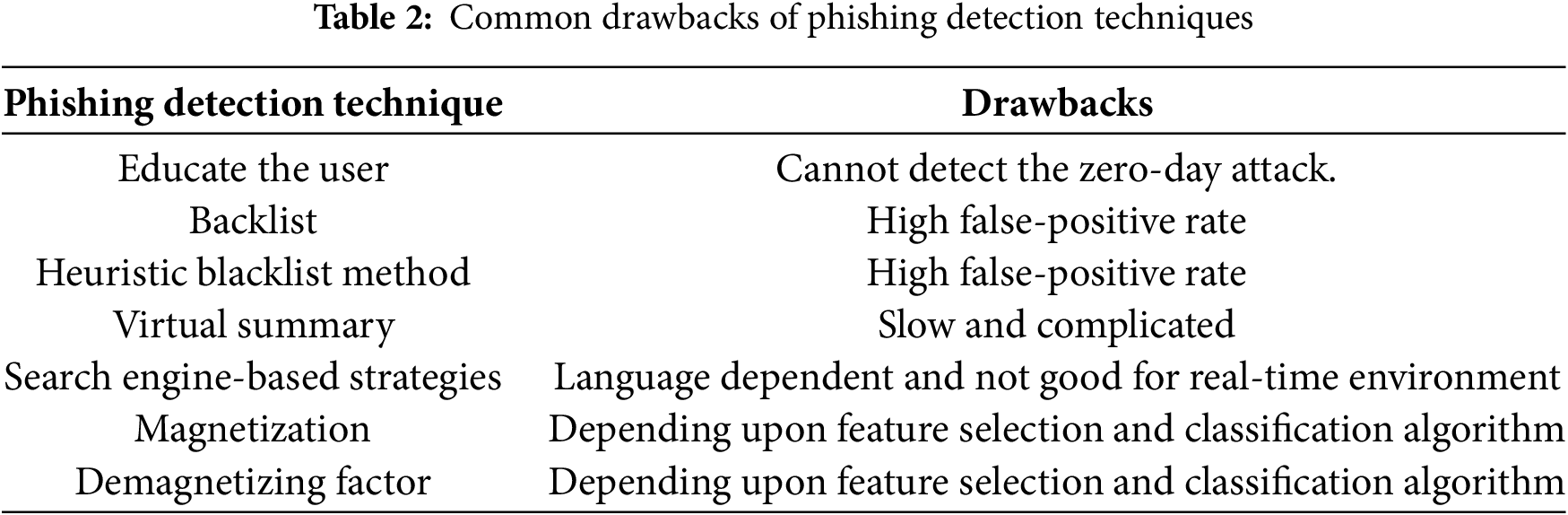

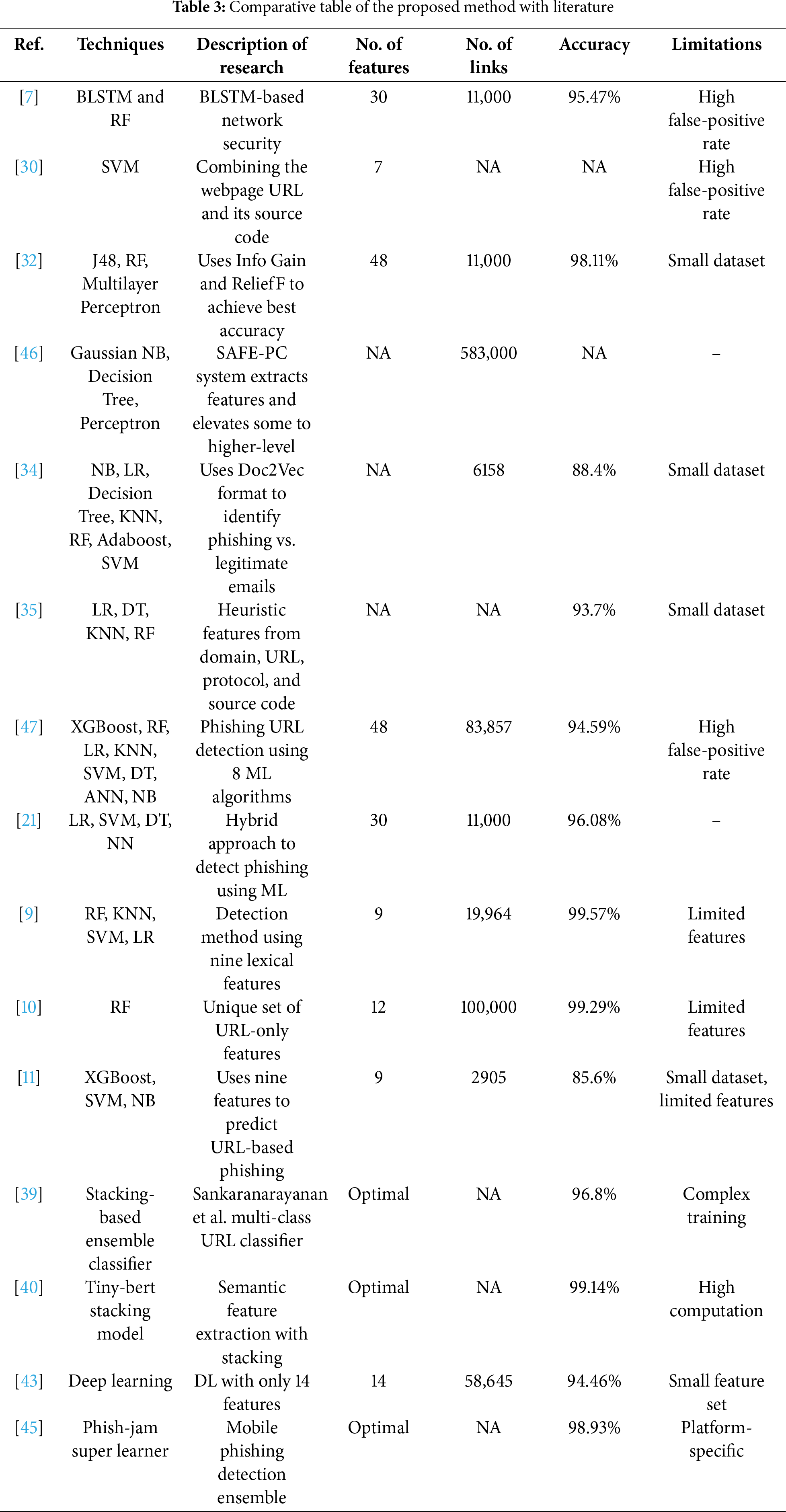

Table 3 reviews the literature in terms of techniques, description, number of features and links, accuracy, and limitation, while the comparison of the proposed method with existing methods in terms of feature selection, feature extraction, datasets, and ensemble method is shown in Table 4.

Most previous phishing detection approaches make use of either stacking or feature selection, but not both in combination. Some use wrapper-based selection methods, which are computationally expensive and less scalable, while others rely entirely on Mutual Information or ANOVA. Our method combines six lightweight filter-based techniques (constant, duplicate, quasi, correlated feature removal, ANOVA, and mutual information gain) to refine feature sets, and then applies ensemble models to only the best-performing base classifiers. Layered optimization of features and classifiers improves performance and reduces FPR, which is often overlooked in previous studies.

URLs are commonly exploited to deceive users to take advantage of a user’s vulnerability. This study focuses on determining the outcomes of a variety of machine learning classification techniques, including Decision Tree, Random Forest, XGBoost, KNN, Ada-Boost, Gradient Boost, logistic regression, and SVM, or whether a URL is benign or harmful. It also examines to detect unsafe websites from the Open phishing domain; the best-performing classifier is used. The proposed methodology is shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Proposed methodology

The four phases of the proposed methodology are given below.

Phishing and legitimate URLs are collected from various sources such as PhishTank and Open Phish throughout the data collection phase. Different features are taken from the URL, and the URL is labeled as phishing or legitimate based on these features.

3.2 Phase 2 (Feature Selection)

Feature selection aims to improve training speed and model performance by reducing irrelevant input data. Machine learning models’ input variables are termed features. Each data column is a feature. To train an optimal model, simply use the necessary features. Too many features can make the model learn from noise and uninteresting patterns. Feature Selection chooses our data’s relevant parameters. We can expect garbage output if we feed our model junk. Noise in data reduces model performance. A considerable amount of the data obtained is noise, and several columns of our dataset may not contribute significantly to model performance. Having a lot of data can also slow down the model’s training. The model may potentially be wrong from irrelevant data. According to Guan et al., most studies have focused on using different filter-based feature selection methods to generate different feature subsets. In our study, we focus on filter metrics that require significantly less computation and are therefore more suitable for feature selection, as shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Feature selection technique

3.2.1 Constant, Duplicate, Quasi, and Correlated Feature Removal

Constant features are those features in the dataset that have constant values (i.e., only one value for all outputs or goal values) [18]. The quasi feature means all of the records have the same value; duplicate features are those that occur twice, and correlated features are those highly dependent on other features, offering little unique information in numerous datasets, which indicates they are somewhat linearly dependent on other features. These properties have a minor impact on output prediction, but they raise the computational cost. The target feature receives no information from these features. These are duplicate data found in the dataset [48]. Because the presence of this feature does not affect the target, it’s best to eliminate it from the dataset. The filter method of Feature Selection Methods is used to remove these features and preserve only the relevant features in the dataset.

Mutual information gain is then applied to the selected features. Elimination methods aim to reduce the size of the input feature set while preserving the class-discriminating information for classification problems [19]. Mutual information (MI) is an asymmetric and non-negative measure of how much information exists. Swap two random variables. It can be zero if and only if the variables are independent.

ANOVA test is applied to the dataset. ANOVA is a parametric statistical hypothesis test that assesses whether the means of more than one sample of data are of the same distribution or different distributions [20].

Normalization is a scaling technique that rescales and shifts values to a range between 0 and 1. It is also known as Min-Max scaling. The proposed feature selection techniques are compared with the literature work, which is given in Table 5.

3.3 Phase 3 Machine Learning Techniques

After feature selection, the data set is split into test and train sets, and all simple machine learning Classifiers (Random Forest, KNN, Logistic Regression, Decision tree, SVM) and Boosting classifiers (Ada-boost, XGBoost, Gradient boost Classifier) and ensemble model (Majority voting) are trained on train data to identify the three best performance classifiers.

3.4 Phase 4 (Stacking Ensemble)

The best 3 classifiers from the Previous phase are selected for stacking. In the ensemble model, Stacking is applied to achieve a Low False positive rate and high accuracy. The best-performing classifier was saved for deployment. For further use. In the Stacking ensemble, we use Gradient Boost and Random Forest as a base classifier and SVM as a meta classifier, shown in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: Stacking ensemble model

3.5 Phase 5 (Real-Time Manual Detection)

After training the model, the most accurate model, which has a low positive rate, is selected for manual URL classification. A URL is an input to the proposed model, and then Features are extracted from the input URL using a Python-based feature extractor [51]. Feature extraction is utilized in our research to extract features from website URLs, suffixes, prefixes, sub-domains, and so on. Feature extraction from a URL is done using Python. After extracting, all features are then cleaned, normalized, and converted to binary using one-hot encoding. Then that binary will be given to the trained model, and the URL will be classified as legitimate or phishing, shown in Fig. 5.

Figure 5: Manual testing of URL

The result of our experimentation is presented in this section. To begin our experimentation discussion, we will go through the main requirements for effectively implementing our proposed approach, as well as quickly examine all of the phases’ Results.

4.1 Measures for Evaluating Performance

On the phishing site data set, many Performance Evaluation Measures Performance Evaluation Measures (PEMs) are used to estimate classifier accuracy. The accuracy, False positive rate, precision, and recall metrics are in Eqs. (1)–(4).

TP (True Positives) are the correctly identified phishing URLs. TN (True Negatives) events that the model accurately anticipated as negative, and FP for false-positive outcomes. FN stands for false negatives and has been forecasted mistakenly as a positive class. As a negative class, the events that the model anticipated were wrong.

Our environment is based on Google Colab, a notebook environment for Jupyter notebooks. It is a Google-provided free source where we can write and run programs. We can utilize Google Colab in the same way as we can use local Jupiter with simplicity. Google Colab comes with 12 GB of RAM and 358.27 GB of storage space. For the implementation and execution of training and testing scripts for machine learning models, we used Python version 3.8.

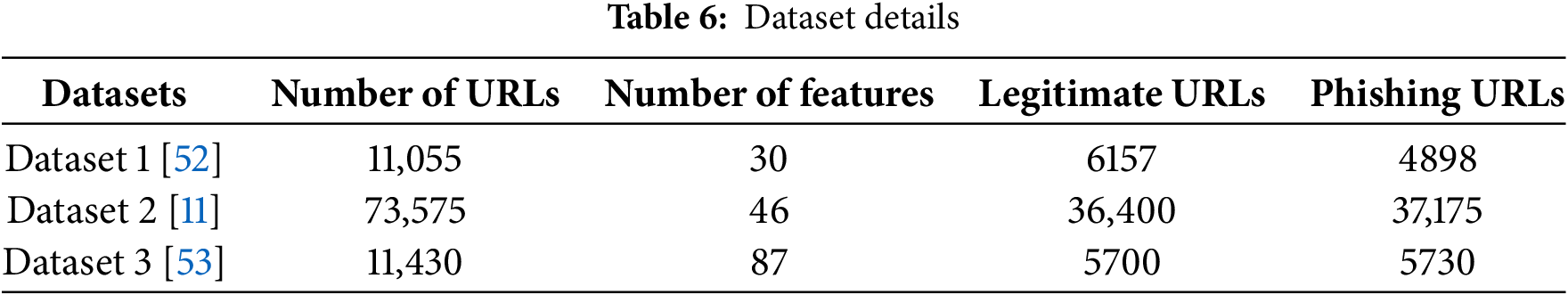

The data for this research was collected from different sources, including datasets containing phishing and legitimate URLs, and labeled features of phishing URLs. Three datasets are selected for this research, which are various in the number of URLs and Features, as shown in Table 6.

Dataset 1 is taken from Mohammad et al. [52]. The dataset has 4898 phishing URLs with 11,055 data points. Each data point is subdivided into the following three categories with 30 features: 1) URL having derived features 2) Source page and source code-based features 3) Domain-based features

Buber collects [11] Dataset 2, which has 73,575 URLs. There are 36,400 authentic URLs and 37,175 phishing URLs in this sample. From phishing links, 46 Features are extracted.

A. Hannousse collected Dataset 3 [53]. There are 11,430 URLs in the dataset, with 87 retrieved features. The dataset is intended to serve as a benchmark for phishing detection systems that use machine learning. The dataset is balanced, with exactly half of the URLs being phishing and half being legitimate.

4.4 Feature Selection Evaluation

First of all, each dataset is subjected to a proposed filter-based feature selection combination in this section. We dropped the correlated, duplicate, quasi, and constant features after applying feature selection algorithms to the datasets. These attributes generate noise in the data sets, reducing our accuracy and increasing our false positive rate.

4.4.1 Dataset 1 Feature Selection

There are 30 features in total in dataset 1, including 0 constant features, 0 quasi-constant features, four duplicate features, and 0 correlated features. We have 26 features after applying mutual information gain and the ANOVA test, after eliminating the four characteristics.

4.4.2 Dataset 2 Feature Selection

There are 46 features in total in Dataset 3, including 0 constant features, five quasi-constant features, two duplicate features, and six correlated features. We have 33 features after applying mutual information gain and the ANOVA test after eliminating the 13 characteristics.

4.4.3 Dataset 3 Feature Selection

There are 87 features in total in Dataset 3, including seven constant features, 17 quasi-constant features, 0 duplicate features, and three correlated features. We have 61 features after applying mutual information gain and the ANOVA test after eliminating the 26 characteristics.

4.5 Machine Learning Model Prediction Evaluation

The non-relevant features are dropped from the data sets, and the experimentation is done on the remaining features, which are the most important for phishing detection. All the machine learning and boosting classifiers were trained and tested on the best features in terms of accuracy and false-positive rate. Then, the best-performing algorithms from all data sets were selected for ensemble techniques. The majority of voting and stacking applied to the best-performing models. Results of all classifiers compared with each other on separate data sets. Python and Google Collaboratory are used for implementation. The following are the results.

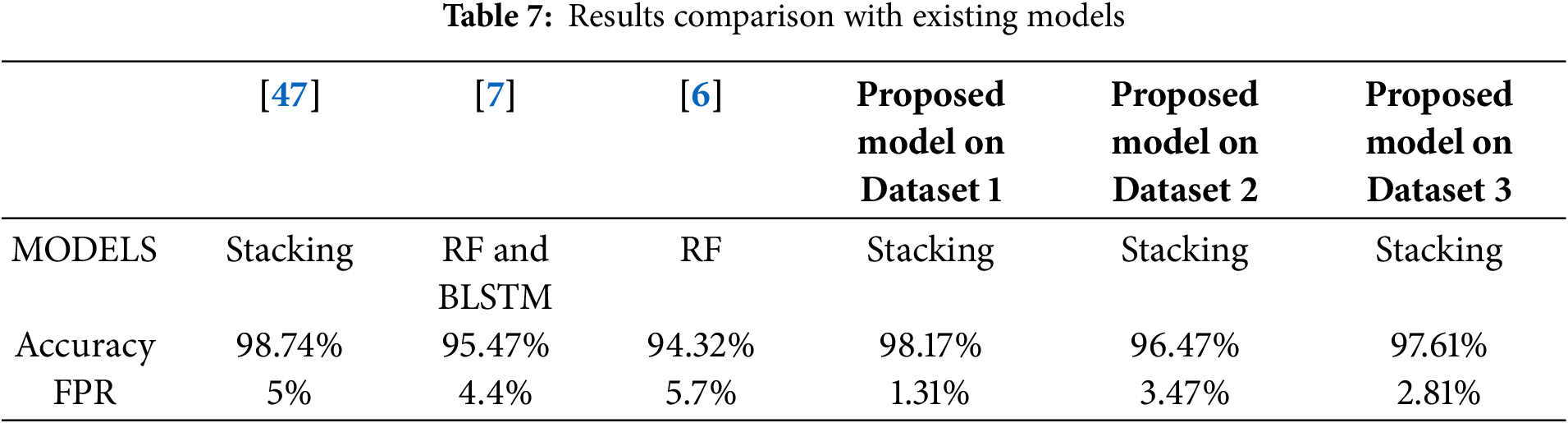

4.5.1 Comparison of False-Positive Rate

In the model we’ve proposed, many machine learning models have a low false-positive rate. SVM, gradient boost, majority, and stacking obtain 1.31%, 1.9%, 2.16%, and 3.1%, respectively, on Dataset 1. Gradient boost, SVM, and stacking on Dataset 2 accomplish 3.47%, 3.75%, and 3.86%, respectively. On Dataset 3, gradient boost, SVM, stacking, majority voting, and random forest obtain 2.1%, 2.86%, 2.91%, 3.29%, and 3.71%, respectively. Our proposed method, FPR, is lower than the existing techniques shown using a comparative graph in Fig. 6. Most machine learning classifiers perform well across datasets thanks to our effective feature selection techniques. For example, SVM had the lowest FPR on Dataset 1, gradient boost worked best on Dataset 2, and stacking ensemble methods performed well consistently across all datasets. This suggests that, while individual models advantage from high-quality feature sets, ensemble methods such as stacking and majority voting provide robust performance across a range of data characteristics.

Figure 6: Comparison of ML classifiers on the different datasets for FPR

4.5.2 Comparison of Accuracies

The proposed models achieved high accuracy, ranging from 96.47% to 98.17% across datasets, presented in Fig. 7. As we know, SVM is the most popular method in machine learning for classification. So when we use SVM as a final decision classification model in the boosting technique, it will get more accuracy than other methods present in our experiments. If we change one of the boosting models, we can achieve even better results using different combinations.

Figure 7: Comparison of ML classifiers on the different datasets for the accuracy

4.5.3 Comparison of Accuracy and FPR with Base Models

The proposed model results are compared with existing models in terms of false-positive rates and accuracies. The proposed method FPR is lower than the existing techniques shown using a comparative graph in Fig. 8.

Figure 8: Proposed model comparison with other models. Other models are from [6,7,47]

The comparison of the proposed model with existing models is given in Table 7. In Table 7, the comparison parameters are accuracy and false-positive rate.

The confusion matrix in Fig. 9 highlights the classification results of the stacking ensemble model, with or without normalization. It displays the number of true positives (TP), true negatives (TN), false positives (FP), and false negatives (FN) in the test results. The normalized version has better TP and lower FP, indicating that normalization helps to reduce misclassification. This supports our claim that preprocessing improves model performance.

Figure 9: Stacking confusion matrix

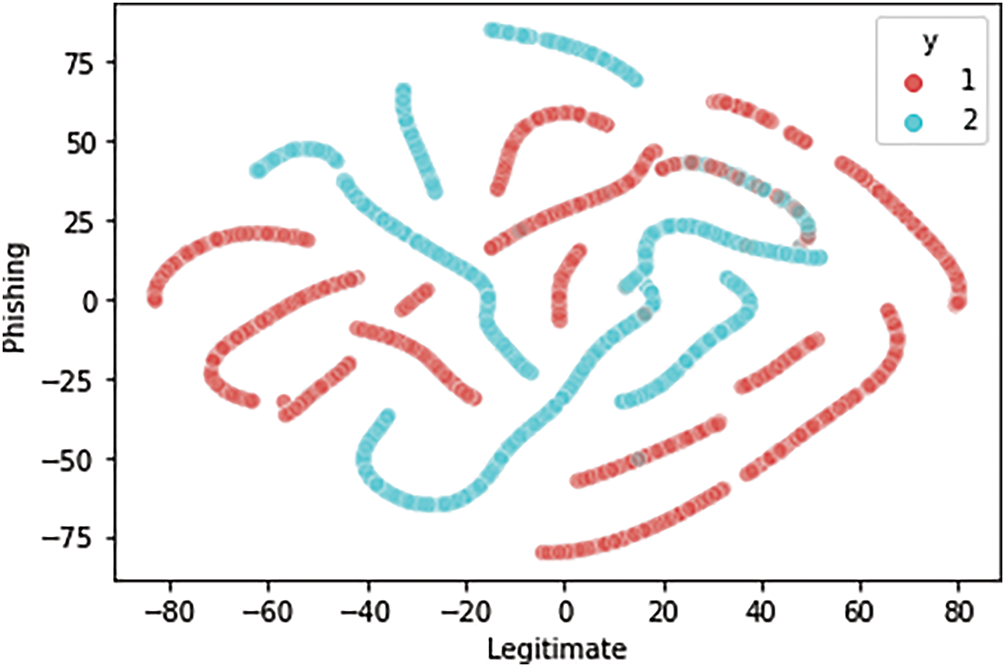

4.5.5 T-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (T-SNE)

The t-SNE analysis requires reflection and insight. This t-SNE visualization in Fig. 10 shows how the stacking ensemble model clusters phishing and legitimate URLs. As shown, there is a clear distinction between the two classes, indicating that the selected features and model successfully captured the underlying patterns in the data. This visualization backs up our claim that the feature selection phase helps significantly improve class separability and reduce false positives.

Figure 10: The t-SNE analysis of the final stacking ensemble model

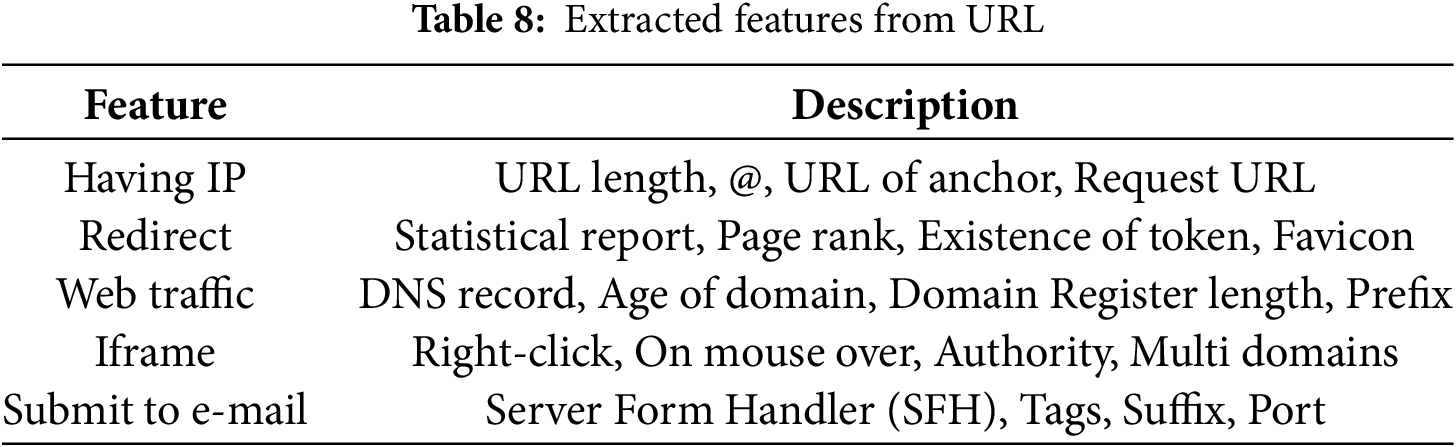

For manual URL classification, we choose SVM, which has high accuracy and a low false-positive rate on Dataset 1. The suggested model receives a URL as input and then performs feature extraction. All features are cleaned, normalized, and transformed to binary using one-hot encoding after extraction. The binary will then be sent into the trained SVM model, which will classify the URL as legitimate or phishing. To extract features, feature extraction is used [51]. Feature extraction is utilized in our research to extract features from website URLs such as suffixes, prefixes, sub-domains, and so on. A Python script is used to extract features from the URL, and the selected features are given in Table 8.

We investigated the most influential features selected during feature engineering, shown in Fig. 11. The presence of IP addresses in URLs, abnormal URL lengths, use of “@” symbols, suspicious subdomains, and domain age was consistently ranked as important. These features are consistent with common phishing techniques like obfuscation, redirection, and newly registered malicious domains.

Figure 11: Top features contributing to phishing detection based on feature importance

The majority of anti-phishing solutions achieve maximum accuracy on a particular dataset. Still, their technology often yields a high number of false positives and is unable to detect zero-hour attacks. Feature selection is critical when designing a phishing detection technique. While a good feature selection can aid accuracy, repeated features can add to the noise in a dataset, lowering the algorithm’s accuracy. Constant feature removal, Duplicate feature removal, Quasi feature removal, Correlated feature removal, Mutual information Gain, and ANOVA test are among the filter-based feature selection strategies offered for detecting phishing attempts. To obtain a low false-positive rate, this technique was tried on ML classifiers, Random Forest, KNN, Adaboost, XGBoost, Logistic Regression, Decision Tree, Gradient Boost Classifier, SVM, and two forms of ensemble models: Stacking and Majority Voting. The stacking ensemble classifier (Gradient Boost, Random Forest, SVM) achieved 1.31% FPR and 98.17% accuracy on Dataset 1, 2.81% FPR and 97.61% accuracy on Dataset 3, and 3.47% FPR and 96.47% accuracy on Dataset 2. The experimental results show that our novel feature selection framework and ensemble learning strategy improve phishing detection accuracy while lowering false positive rates across all datasets. Notably, the proposed method performed consistently regardless of dataset size or feature variety, demonstrating the strength and generalizability of our approach. These findings demonstrate that careful pre-processing and optimal classifier selection can result in highly effective phishing detection models.

Future work includes datasets, where a hybrid feature selection can be used to identify more relevant characteristics. A large dataset with a large number of URLs can be used to improve accuracy and further reduce the false positive rate.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank to University of Essex and the Deanship of Scientific Research and Graduate Studies at King Khalid University under research grant number (R.G.P.2/21/46).

Funding Statement: This research was financially supported by the Deanship of Scientific Research and Graduate Studies at King Khalid University under research grant number (R.G.P.2/21/46) and in part by the Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia, under Grant KFU253116.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Nimra Bari; Methodology, Nimra Bari; Software, Nimra Bari; Validation, Nimra Bari, Abdulmohsen Algarni; Formal Analysis, Nimra Bari; Data Curation, Nimra Bari, Munam Shah; Writing—Original Draft, Nimra Bari; Writing—Review & Editing, Munam Shah, Tahir Saleem, Asma Patel, Insaf Ullah; Investigation, Munam Shah; Resources, Tahir Saleem; Supervision, Munam Shah, Asma Patel, Insaf Ullah; Project Administration, Asma Patel, Insaf Ullah; Funding Acquisition, Asma Patel. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets used in this study are publicly available from the following sources:

• Dataset 1: Sourced from Mohammad et al. (2012) and available at the UCI Machine Learning Repository, https://archive.ics.uci.edu/ml/datasets/Phishing+Websites (accessed on 21 August 2025).

• Dataset 2: Sourced from Buber (2019). The data was collected from PhishTank and Open Phish, which are publicly accessible platforms. https://www.phishtank.com/ (accessed on 21 August 2025) and https://openphish.com/ (accessed on 21 August 2025).

• Dataset 3: Sourced from Hannousse (2021). This dataset is a benchmark for machine learning-based phishing detection and is available for research purposes. 10.1016/j.engappai.2021.104347 (accessed on 21 August 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Li Y, Yang Z, Chen X, Yuan H, Liu W. A stacking model using URL and HTML features for phishing webpage detection. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2019;94(11):27–39. doi:10.1016/j.future.2018.11.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Tayyab S, Masood A. A review: phishing detection using URLs and hyperlinks information by machine learning approach. Int J Comput Sci Mob Comput. 2019;8(5):345–51. [Google Scholar]

3. Alassaf M, Alkhalifah A. Exploring the influence of direct and indirect factors on information security policy compliance: a systematic literature review. IEEE Access. 2021;9:160947–69. doi:10.1109/access.2021.3132574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. APWG. APWG phishing trends report 2nd quarter 2021 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 21]. Available from: https://docs.apwg.org/reports/apwg_trends_report_q2_2021.pdf. [Google Scholar]

5. Chen J, Guo C. Online detection and prevention of phishing attacks. In: First International Conference on Communications and Networking in China; 2006 Oct 25–27; Beijing, China. p. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

6. Rao RS, Vaishnavi T, Pais AI. CatchPhish: detection of phishing websites by inspecting URLs. J Ambient Intell Humaniz Comput. 2020;11(2):813–25. doi:10.1007/s12652-019-01311-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Wang S, Khan S, Xu C, Nazir S, Hafeez A. Deep learning-based efficient model development for phishing detection using random forest and BLSTM classifiers. Comput Intell Neurosci. 2020;2020:8839862. doi:10.1155/2020/8694796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Jain AK, Debnath N, Jain AK. APuML: an efficient approach to detect mobile phishing webpages using machine learning. Wirel Pers Commun. 2022;125(4):2465–85. doi:10.1007/s11277-022-09707-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Abuzuraiq A, Alkasassbeh M, Almseidin M. Intelligent methods for accurately detecting phishing websites. In: 11th International Conference on Information and Communication Systems (ICICS); 2020 Apr 7–9; Irbid, Jordan. p. 85–90. [Google Scholar]

10. Castaño F, Fidalgo E, Alegre E, Chaves D, Sanchez-Paniagua MJ. State of the art: content-based and hybrid phishing detection. arXiv:2105.02249. 2021. [Google Scholar]

11. Sahingoz OK, Buber E, Demir O, Diri B. Machine learning-based phishing detection from URLs. Expert Syst Appl. 2019;117(4):345–57. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2018.09.029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Faruk N, Jimoh RG. Hybrid rule-based model for phishing URLs detection. In: Emerging Technologies in Computing: Second International Conference, iCETiC 2019. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2019. p. 119–28. [Google Scholar]

13. Afroz S, Greenstadt R. PhishZoo: detecting phishing websites by looking at them. In: IEEE Fifth International Conference on Semantic Computing; 2011 Sep 18–21. Palo Alto, CA, USA. p. 368–75. [Google Scholar]

14. Adebowale MA, Lwin KT, Sanchez E, Hossain M. Intelligent web-phishing detection and protection scheme using integrated features of Images, frames, and text. Expert Syst Appl. 2019;115(12):300–13. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2018.07.067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Tan CD. Phishing dataset for machine learning: feature evaluation; 2018 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 21]. Available from: https://www.kaggle.com/competitions/phishing-detection. [Google Scholar]

16. Sun B, Wen QY, Liang XY. A DNS based anti-phishing approach. In: Second International Conference on Networks Security, Wireless Communications and Trusted Computing; 2010 Apr 24–25; Wuhan, China. p. 262–5. [Google Scholar]

17. Chanti S, Chithralekha T. Classification of anti-phishing solutions. Int J Comput Appl. 2020;1(1):1–18. doi:10.1007/s42979-019-0011-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Kumar R, Vishal M, Singh Y, Chouhan AS. Relative study of machine learning and deep learning algorithms for URL-based phishing identification. arXiv:2004.02683. 2020. [Google Scholar]

19. Rashid J, Mahmood T, Nisar MW, Nazir T. Phishing detection using machine learning technique. In: 2020 First International Conference of Smart Systems and Emerging Technologies (SMARTTECH); 2020 Nov 3–5; Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. p. 43–6. [Google Scholar]

20. Kumar GR, Gunasekaran S, Vignesh ASV. URL phishing data analysis and detecting phishing attacks using machine learning in NLP. Int J Eng Appl Sci Technol. 2018;3(8):70–5. doi:10.33564/ijeast.2019.v03i10.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Alswailem A, Alabdullah B, Alrumayh N, Alsedrani A. Detecting phishing websites using machine learning. In: 2019 2nd International Conference on Computer Applications and Information Security (ICCAIS); 2019 May 1–3; Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

22. Basit A, Zafar M, Liu X, Javed AR, Jalil Z, Kifayat K. A comprehensive survey of AI-enabled phishing attacks detection techniques. Telecommun Syst. 2021;76(1):139–54. doi:10.1007/s11235-020-00733-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Yerima SY, Alzaylaee MK. High accuracy phishing detection based on convolutional neural networks. In: 2020 3rd International Conference on Computer Applications and Information Security (ICCAIS); 2020 Mar 19–21; Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

24. Gupta BB, Gaurav A, Arya V, Attar RW, Bansal S, Alhomoud A, et al. Advanced BERT and CNN-based computational model for phishing detection in enterprise systems. Comput Mater Contin. 2024;141(3):2165–83. [Google Scholar]

25. Satapathy SK, Mohapatra S, Sarangi SK, Dash S, Pattnaik S, Mishra SK. Classification of features for detecting phishing websites based on machine learning techniques. In: International Conference on Machine Learning, Big Data, Cloud and Parallel Computing (COMITCon); 2019 Feb 14–16; Faridabad, India. p. 425–30. [Google Scholar]

26. Almomani A, Gupta BB, Atawneh S, Meulenberg A, Almomani E. A survey of phishing e-mail filtering techniques. IEEE Commun Surv Tutor. 2013;15(4):2070–90. [Google Scholar]

27. Kulkarni AD, Brown LLIII. Phishing websites detection using machine learning; 2019 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 21]. Available from: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/cs_f_p/1/. [Google Scholar]

28. Nandal R, Joshi K. Phishing URL detection using machine learning. In: Advances in communication and computational technology. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2021. p. 547–60. doi:10.1007/978-981-15-5341-7_42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Aljofey A, Jiang Q, Qu Q, Huang M, Niyigena JP. An effective phishing detection model based on character level convolutional neural network from URL. Electronics. 2020;9(9):1514. doi:10.3390/electronics9091514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Wu CY, Kuo CC, Yang CS. A phishing detection system based on machine learning. In: 2019 International Conference on Intelligent Computing and its Emerging Applications (ICEA); 2019 Aug 30–Sep 1; Tainan, Taiwan. p. 28–32. [Google Scholar]

31. Bari N, Shah MA. Securing digital economies: detection of phishing attacks using machine learning approaches. In: Competitive Advantage in the Digital Economy (CADE 2021). London, UK: IET; 2021. p. 105–11. [Google Scholar]

32. Almseidin M, Zuraiq AA, Al-Kasassbeh M, Alnidami N. Phishing detection based on machine learning and feature selection methods. arXiv:1901.05907. 2019. [Google Scholar]

33. Gutierrez CN, Al-Sarem M, Al-Mekhlafi ZG, Mohammed BA, Al-Hadhrami T, Saeed F. Learning from the ones that got away: detecting new forms of phishing attacks. IEEE Trans Dependable Secure Comput. 2018;15(6):988–1001. doi:10.1109/tdsc.2018.2864993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Unnithan NA, Harikrishnan N, Vinayakumar R, Soman K, Sundarakrishna S. Detecting phishing E-mail using machine learning techniques. In: Proceedings of the 1st Anti Phishing Shared Pilot at 4th ACM International Workshop on Security and Privacy Analytics (IWSPA 2018); 2018 Mar 21; Tempe, AZ, USA. p. 51–4. [Google Scholar]

35. Korkmaz M, Sahingoz OK, Diri B. Detection of phishing websites by using machine learning-based URL analysis. In: 2020 11th International Conference on Computing, Communication and Networking Technologies (ICCCNT); 2020 Jul 1–3; Kharagpur, India. p. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

36. Shikalgar MS, Sawarkar S, Narwane MS. Detection of URL based phishing attacks using machine learning; 2019 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 21]. Available from: https://www.ijert.org/research/detection-of-url-based-phishing-attacks-using-machine-learning-IJERTV8IS060560.pdf. [Google Scholar]

37. Butnaru A, Mylonas A, Pitropakis N. Towards lightweight URL-based phishing detection. Future Internet. 2021;13(6):154. doi:10.3390/fi13060154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Tamal MA, Islam MK, Bhuiyan T, Sattar A, Prince NU. Unveiling suspicious phishing attacks: enhancing detection with an optimal feature vectorization algorithm and supervised machine learning. Front Comput Sci. 2024;6:987654. doi:10.3389/fcomp.2024.1428013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Sankaranarayanan S, Dhavachelvan P, Arun K, Dhanya M, Ramprasath A. A stacking-based ensemble classifier for multi-class URL classification. PLoS One. 2024;19(4):e0302196. [Google Scholar]

40. He D, Lv X, Choo KKR, Sun X, Zhang J, Guo M. A method for detecting phishing websites based on tiny-bert stacking. IEEE Int Things J. 2024;11(2):1200–10. doi:10.1109/jiot.2023.3292171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Urmi WF, Uddin MN, Imran F, Sifat S, Karim A, Al-Otaibi AM, et al. A stacked ensemble approach to detect cyber attacks based on feature selection techniques. Int J Chem Chem Eng. 2024;12(4):345–59. doi:10.1016/j.ijcce.2024.07.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Alshdaifat N, Mohammad S, Alshurideh M, Al-Hamad A, Al-Kaabi A, Al-Rjoub M, et al. DaE2: a diverse and efficient ensemble framework for real-time phishing URL detection. J Posthumanism. 2025;5(3):234–50. doi:10.63332/joph.v5i3.854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Nayak GS, Muniyal B, Belavagi MC. Enhancing phishing detection: a machine learning approach with feature selection and deep learning models. IEEE Access. 2025;13(12):124567–78. doi:10.1109/access.2025.3543738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Setu JH, Halder N, Amin MA. RSTHFS: a rough set theory-based hybrid feature selection method for phishing website classification. IEEE Access. 2025;13(27):123456–67. doi:10.1109/access.2025.3561237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Rao RS, Kondaiah C, Lee B. A hybrid super learner ensemble for phishing detection on mobile devices. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):12345. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-02009-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Reddy JM, Rao KV, Prasad GLV. An approach for detecting phishing attacks using machine learning techniques. J Crit Rev. 2020;7(18):321–4. [Google Scholar]

47. Al-Sarem M, Saeed F, Al-Mekhlafi ZG, Mohammed BA, Al-Hadhrami T. An optimized stacking ensemble model for phishing websites detection. Electronics. 2021;10(11):1285. doi:10.3390/electronics10111285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Zeydan HZ, Selama A, Salleh M. Survey of anti-phishing tools with detection capabilities. In: 2014 International Symposium on Biometrics and Security Technologies (ISBAST); 2014 Aug 26–27; Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. p. 214–9. [Google Scholar]

49. Jain AK, Gupta S. Phishing detection: analysis of visual similarity-based approaches. IEEE Access. 2017;5:2777–93. [Google Scholar]

50. Jagadeesan S, Chaturvedi A, Kumar SP. URL phishing analysis using random forest. Int J Eng Adv Technol (IJEAT). 2019;8(5):4159–63. [Google Scholar]

51. Nandhini S, Vasanthi V. Extraction of features and classification on phishing websites using web mining techniques. International Journal of Adv Res Comput Sci Softw Eng. 2017;5:1215–25. [Google Scholar]

52. Mohammad RM, Thabtah F, McCluskey L. An assessment of features related to phishing websites using an automated technique. In: 2012 International Conference for Internet Technology and Secured Transactions (ICITST); 2012 Dec 10–12; London, UK. p. 492–7. [Google Scholar]

53. Vrbancic G, Fister IJr, Podgorelec V. Datasets for phishing websites detection. Data Brief. 2020;33(6):106438. doi:10.1016/j.dib.2020.106438. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools