Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Energy Transfer during Strong Oscillations of a Spherical Bubble with Non-Ideal Gas Equations of State

1 Center for Fluid Mechanics, School of Engineering, Brown University, Providence, RI 02903, USA

2 Department of Data Science, Ewha Womans University, Seoul, 03760, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Jenny Jyoung Lee. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Modeling and Applications of Bubble and Droplet in Engineering and Sciences)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(1), 345-366. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.070524

Received 18 July 2025; Accepted 16 September 2025; Issue published 30 October 2025

Abstract

Spherical bubble oscillations are widely used to model cavitation phenomena in biomedical and naval hydrodynamic systems. During collapse, a sudden increase in surrounding pressure initiates the collapse of a cavitation bubble, followed by a rebound driven by the high internal gas pressure. While the ideal gas equation of state (EOS) is commonly used to describe the internal pressure and temperature of the bubble, it is limited in its capacity to capture molecular-level effects under highly compressed conditions. In the present study, we employ non-ideal EOS for the gas (the van der Waals EOS and its volume-limited case) to investigate bubble oscillations with a focus on energy redistribution. Bubble oscillation is modeled in two phases: collapse, described by the Keller−Miksis formulation, and rebound, where peak shock pressure is estimated using similitude-based relations. To assess the role of EOS in energy redistribution, we introduce a framework that quantifies energy components in the bubble−liquid system while conserving total energy, tailored to each EOS. Using this framework, we evaluate energy concentration, acoustic radiation, and shock propagation and statistically analyze their dependence on both the driving pressure and the EOS of gas. We statistically derive scaling relations of key bubble dynamics quantities, energy concentration and radiation, and shock pressure using the driving pressure ratio. This work provides a generalizable framework and set of scaling relations for predicting bubble dynamics and energy transfer, with potential applications in evaluating the impacts of cavitation phenomena in complex practical systems.Keywords

Cavitation bubbles play a key role in various industrial and biomedical applications, including naval hydrodynamic machinery [1–3], histotripsy [4], lithotripsy [5,6], chemical processing [7], cancer ablation [8], and coated micro-bubbles for drug delivery [9,10]. When subjected to high ambient pressure compared to the gas pressure inside the bubble, it undergoes rapid oscillations that may emit shock waves into the surrounding medium. These shocks can induce localized high-pressure and stress regions, which may potentially induce damage on nearby objects or the medium [11–13]. Such effects can be harnessed for beneficial outcomes in targeted applications such as breaking kidney stones, ablating cancer cells, or initiating chemical reactions; but they may also be detrimental. In naval machinery, repeated bubble collapses near solid objects can cause erosion, ultimately reducing the structural integrity [1,14].

A cavitation bubble behaves asymmetrically when located near a solid surface [15]. While the bubble dynamics are nearly spherical in the early stages of collapse, asymmetries rapidly develop due to imbalances in mass and momentum transport near the boundary. This results in non-spherical bubble deformation and the formation of a high-speed re-entrant jet directed from the side farther from the boundary toward the side close to the boundary [16,17]. When the jet impacts the opposite side of the bubble near the boundary, a water-hammer shock is generated, further compressing the bubble and emitting secondary shock waves [13]. These shocks induce localized high pressures and stresses on nearby surfaces, potentially causing material damage and surface erosion—a common source of wear in engineering systems [18]. Despite its importance, simulating these phenomena still remains challenging due to the complexity of bubble-boundary [19–22] and bubble-bubble [23,24] interactions.

A spherical bubble setting is often used as an idealized framework that captures key features of non-spherical bubble dynamics [25–27]. Under symmetric conditions, the bubble collapses and rebounds spherically. During collapse, the potential energy stored in the surrounding liquid is transferred into kinetic energy, which is ultimately concentrated into the bubble as internal energy. While this energy redistribution process is well understood in the incompressible limit, it remains less explored when compressibility and the associated wave generation are taken into account [28,29]. In particular, for strong oscillations, compressibility effects become increasingly significant and must be incorporated to accurately describe energy transfer and energy radiation via waves.

Under such oscillations, the gas behavior inside the bubble deviates significantly from ideal gas assumptions, making molecular effects non-negligible. As the driving pressure increases, the bubble undergoes more violent collapse, enhancing the influence of intermolecular forces and finite molecular volume. These non-ideal gas effects are particularly important in sonochemistry and sonoluminescence, both of which require large compression ratios to initiate chemical reactions and light emission [7,30,31]. During the turnaround from collapse to rebound, the bubble reaches extreme conditions: pressures on the order of 4,000−8,000 atm and temperatures approaching 15,000 K for argon, with several molecular emission estimates suggesting peaks near 30,000 K [32,33]. For Ar−Ne mixtures, the sonoluminescence temperature is reduced to around 1,500 K [34]. Although these extreme conditions last only

To model non-ideal gas effects, various equations of state (EOS) have been employed to describe the gas pressure inside a collapsing bubble. For low-to-moderate amplitude oscillations, the ideal gas law is typically sufficient [35–37]. However, under strong oscillations, the van der Waals EOS is often used to account for intermolecular attractive forces and finite molecular volume, both of which become significant during violent collapse [31]. As an alternative, the ideal gas law with a volume cutoff has been applied to approximate the effects of the van der Waals core volume [30,38]. These EOS formulations are commonly coupled with Rayleigh−Plesset-type equations [15,39,40] to model the evolution of pressure and temperature inside the bubble during oscillations. However, the energy transfer associated with different EOS models has not been thoroughly investigated.

In the present study, we develop an energy budget framework for bubble oscillations, particularly under strong oscillations, tailored to different EOS while ensuring conservation of total energy in the bubble−liquid system. We specifically investigate how non-ideal EOS (van der Waals and its volume-limited form) affect bubble compression, energy redistribution, and shock emission. By combining this framework with statistical analysis, we establish new scaling relations linking driving pressure to bubble dynamics, energy concentration, and shock pressure. These contributions provide new insights into the role of molecular effects in cavitation dynamics and offer predictive tools for assessing cavitation-induced energy transfer in practical applications. The article is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the EOS and bubble dynamics models. Section 3 introduces the energy budget framework, which is applied in Section 4 to analyze bubble dynamics and energy redistribution. Section 5 summarizes the overall findings of the present study, discusses the limitations of the framework, and outlines potential directions for future research.

In this section, we introduce the EOS and bubble dynamics model used to simulate spherical bubble oscillations under varying driving pressures.

2.1 Equation of State for the Gas inside the Bubble

We employ three different EOS to investigate molecular effects on bubble dynamics, as well as the resulting energy redistribution, acoustic radiation, and shock wave emission. First, we use the full van der Waals EOS [31]:

where

where

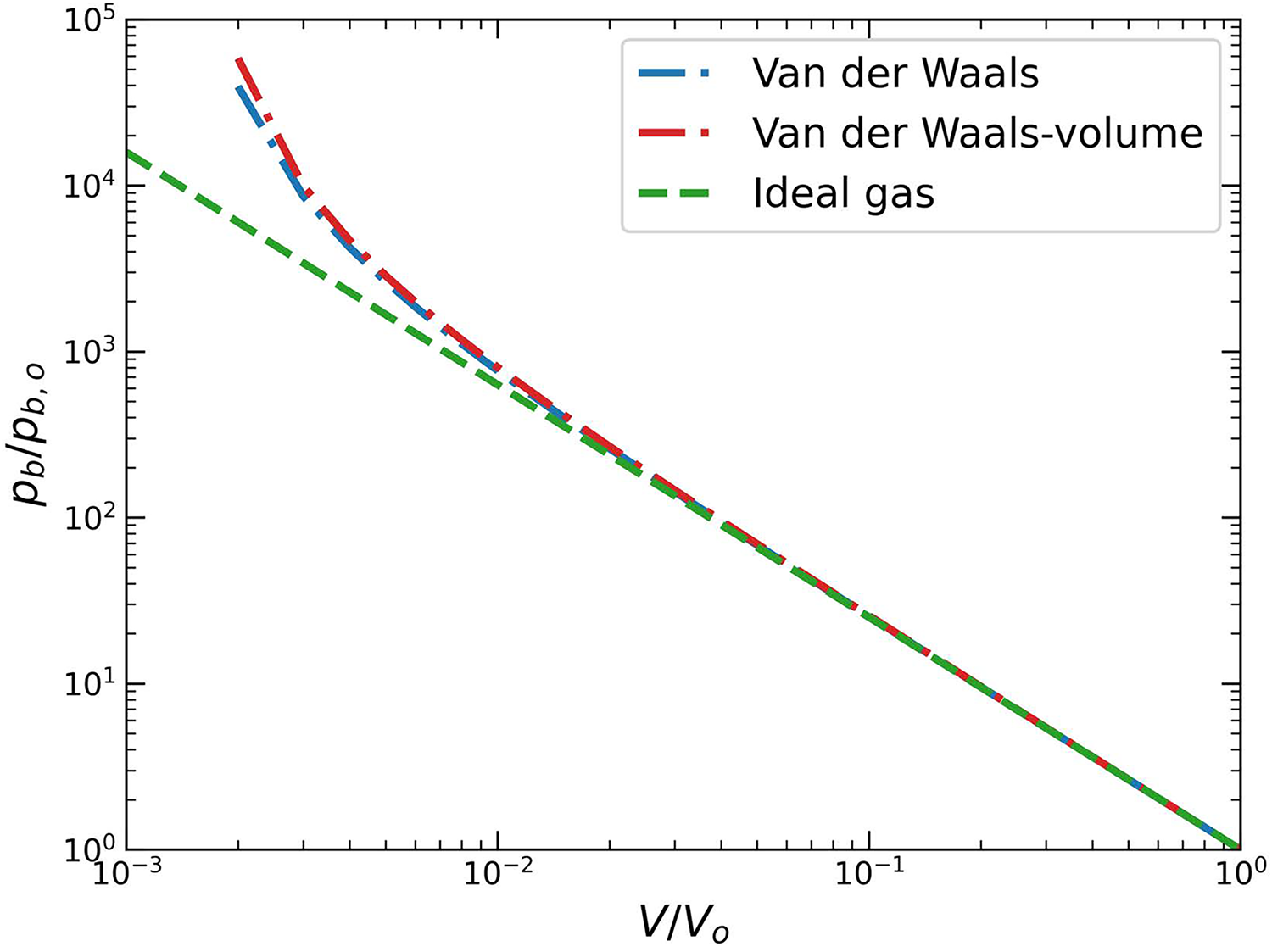

We compare bubble pressures predicted by the three EOS models across a range of bubble volumes starting from the initial volume and decreasing toward smaller values (Fig. 1). For larger bubble volumes, corresponding to the early stages of collapse, all three models yield nearly identical pressures. However, as the bubble compresses to around 2 % of its initial volume, the van der Waals EOS shows higher pressures than the ideal gas law. This can be attributed to the finite molecular volume core becoming significant relative to the total bubble volume, increasing the effective pressure compared to the ideal gas case that neglects this volume. At volumes below 1 % of the initial value, the full van der Waals EOS begins to show lower bubble pressures than the volume-limited version, as intermolecular attractive forces reduce the overall gas pressure.

Figure 1: Pressure inside a bubble as a function of bubble volume for different equations of state: (blue dash-dotted line) van der Waals equation, (red dash-dotted line) volume-limited van der Waals equation, and (green dashed line) ideal gas law

During oscillations, the bubble pressure is assumed to follow an adiabatic law, which is appropriate for violent collapses where the timescale of thermal diffusion is orders of magnitude longer than that of the bubble collapse [42–44]. For each EOS, the corresponding adiabatic relation can be expressed as:

for the full van der Waals EOS, and

for the volume-limited van der Waals EOS, where

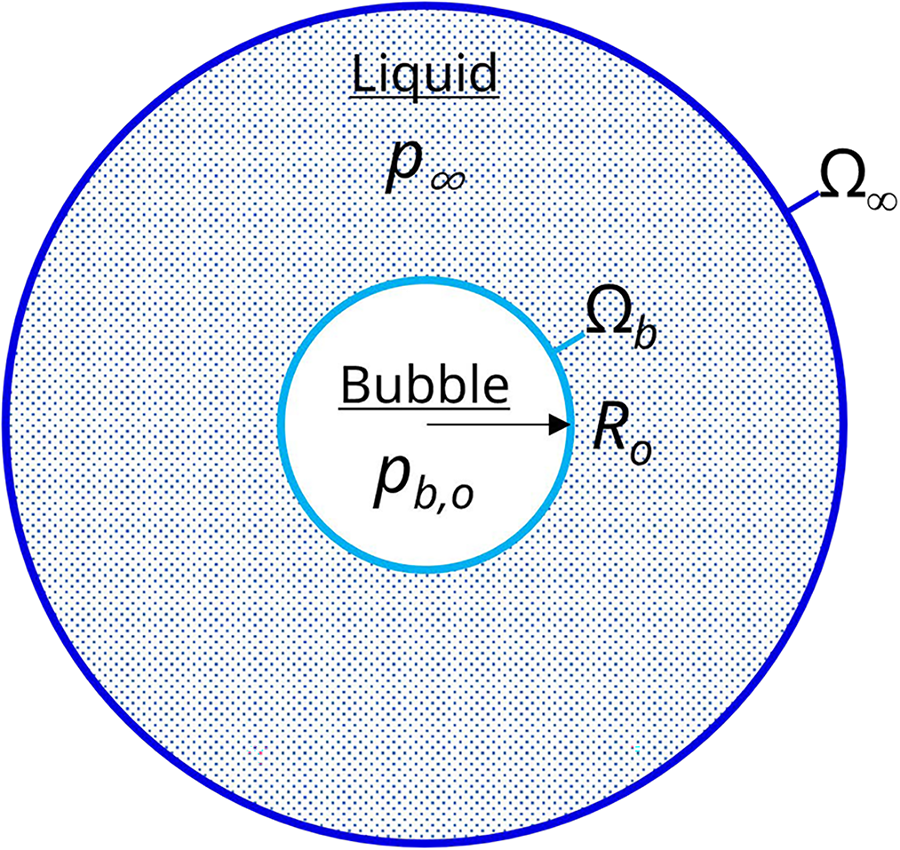

A spherical bubble with an initial radius

where R is the bubble radius, the dot operator is the time derivative,

Figure 2: Schematic of the initial configuration for the bubble collapse problem

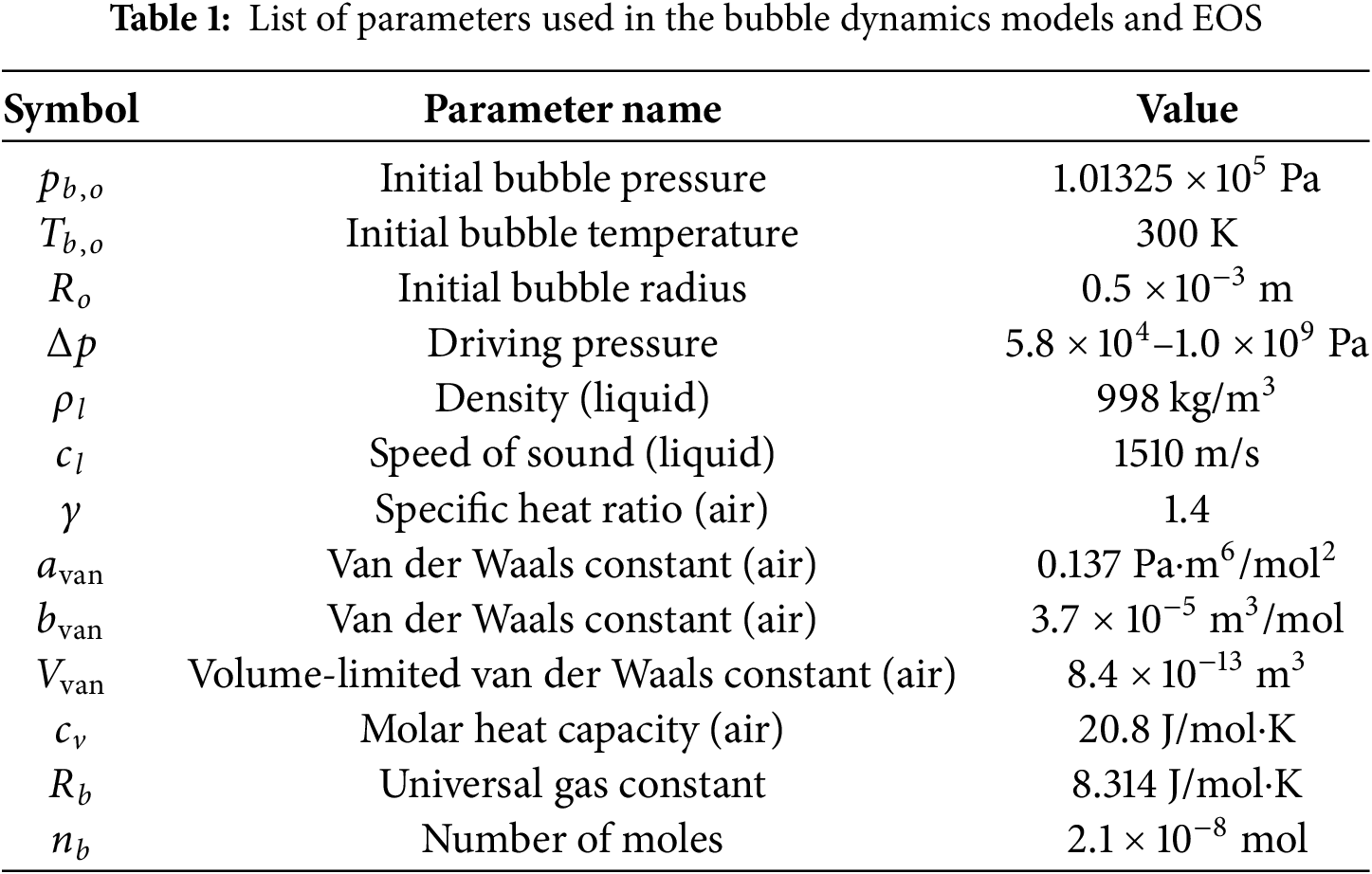

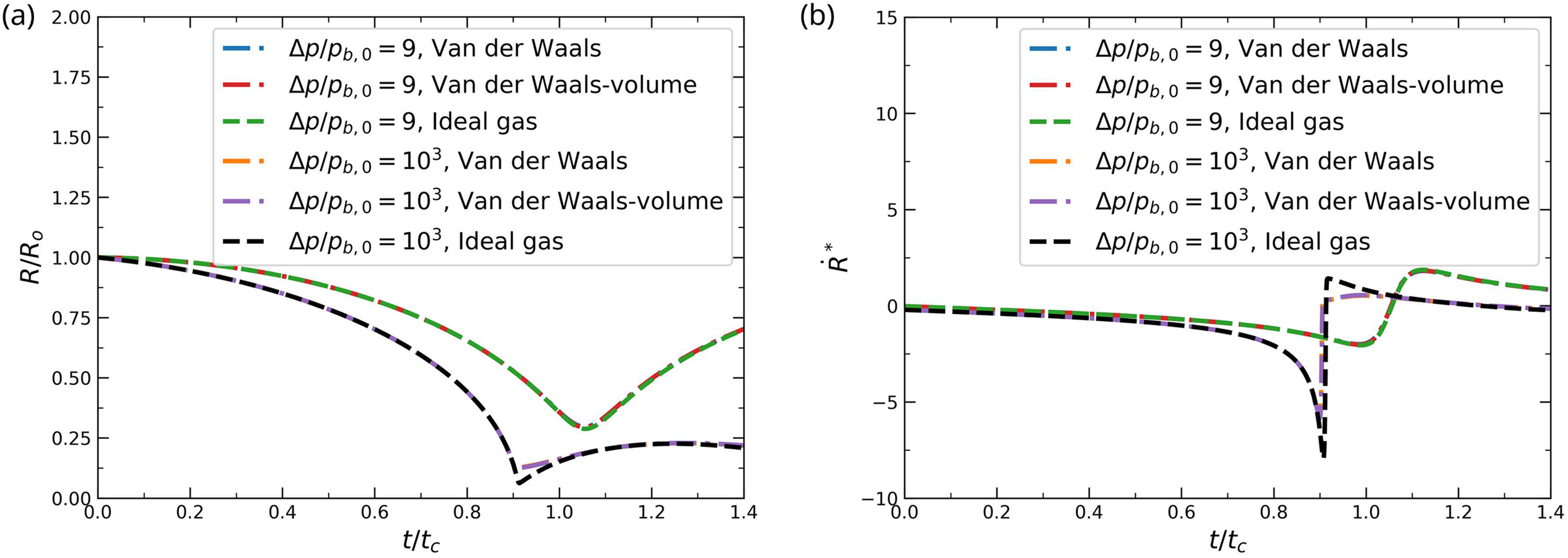

Bubble dynamics exhibit distinct behaviors at high driving pressure ratios depending on the EOS considered. Fig. 3 presents the time evolution of the normalized bubble radius

Figure 3: Time evolution of (a) normalized bubble radius and (b) normalized bubble-wall velocity for the full van der Waals EOS, the volume-limited van der Waals EOS, and the ideal gas EOS at different driving pressure ratios of

3 Energy Component Quantification in the Bubble−Liquid System

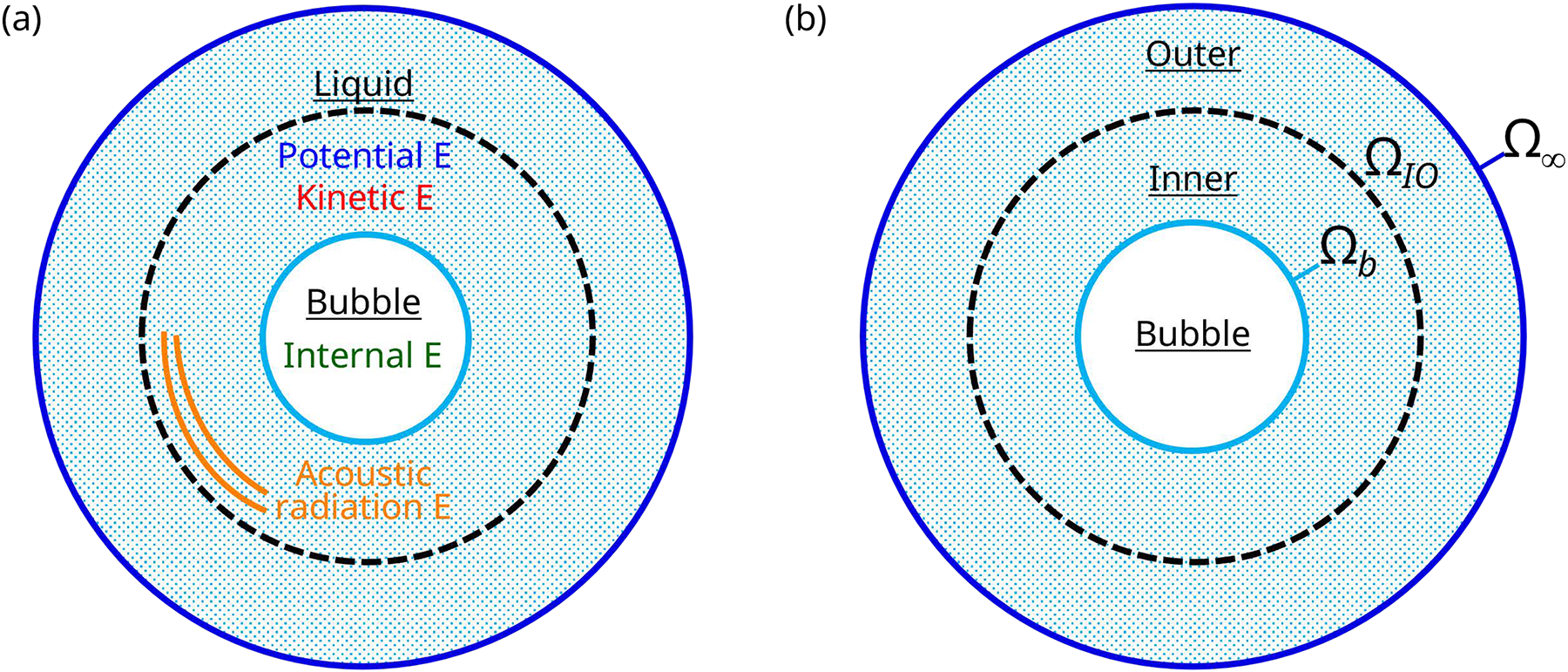

We quantify the energy components of the bubble−liquid system for different EOS. We specifically focus on ensuring conservation of total energy for different EOS cases by accurately computing the bubble internal energy and the radiated energy during bubble collapse and rebound. In the current bubble dynamics model, four energy components are considered: internal energy of the bubble (

Figure 4: Schematics of the energy budget framework: (a) energy components in the bubble−liquid system and (b) inner and outer regions of the weakly compressible liquid

The internal energy of the bubble is defined as

and for the volume-limited van der Waals EOS:

for the ideal gas EOS, the volume correction vanishes, i.e.,

We quantify the energy radiated acoustically during bubble oscillations in a weakly compressible liquid based on the first-order theory by [51], extended to the energy budget framework in [28,29]. In a weakly compressible liquid, the liquid domain can be divided into two sub-regions based on characteristic length scales. The inner region, enclosed by

where

The radiated energy via acoustic waves is then calculated at the outer boundary of the inner region, which is assumed to be sufficiently far from the bubble:

where

The potential energy of the liquid, associated with the far-field pressure, is given by [55]:

which reflects energy stored in the system due to a conservative force field, independent of the bubble oscillation history. The kinetic energy of the liquid in the inner region can be expressed as [56]:

where

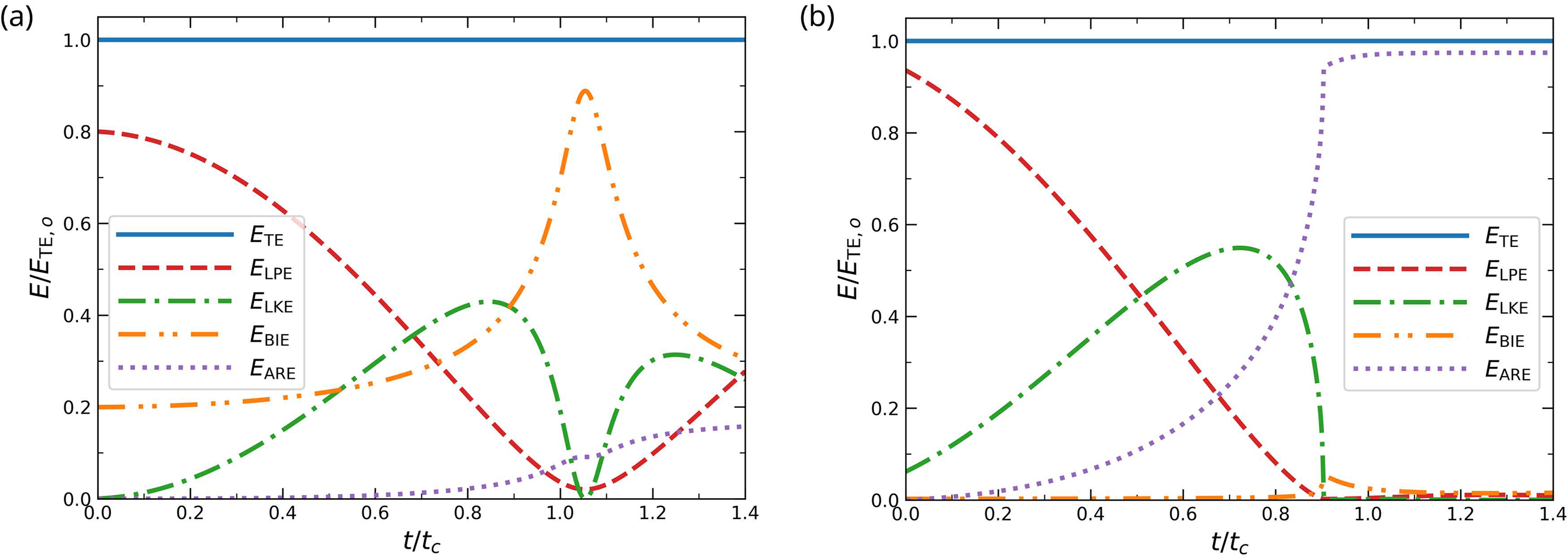

We analyze the time evolution of energy components at

Figure 5: Time evolution of energy components, normalized by the initial total energy

In this section, we model bubble oscillation as comprising two phases: (i) the collapse phase, during which the bubble compresses from its initial state to its minimum radius, and (ii) the rebound phase, during which shock waves are emitted and propagated outward. The Keller−Miksis formulation is employed during the collapse phase to evaluate energy concentration and redistribution as a function of the driving pressure ratio. During the rebound phase, we estimate shock propagation using a theoretical relation based on the Kirkwood−Bethe hypothesis [57], which relates the bubble pressure and radius at the instant of collapse to the shock properties. Based on this relation, we analyze the relationship between the peak shock pressure and the driving pressure ratio.

We compare the collapse and rebound phases for different EOS over a wide range of driving pressure ratios. Based on this comparison, we statistically classify low and high driving pressure regimes that lead to different behaviors in bubble dynamics, energy transfer, and shock propagation. We fit linear regression models relating key bubble and shock quantities to the driving pressure ratio and assess how these trends differ statistically across EOS cases.

4.1 Bubble Dynamics during the Collapse Phase

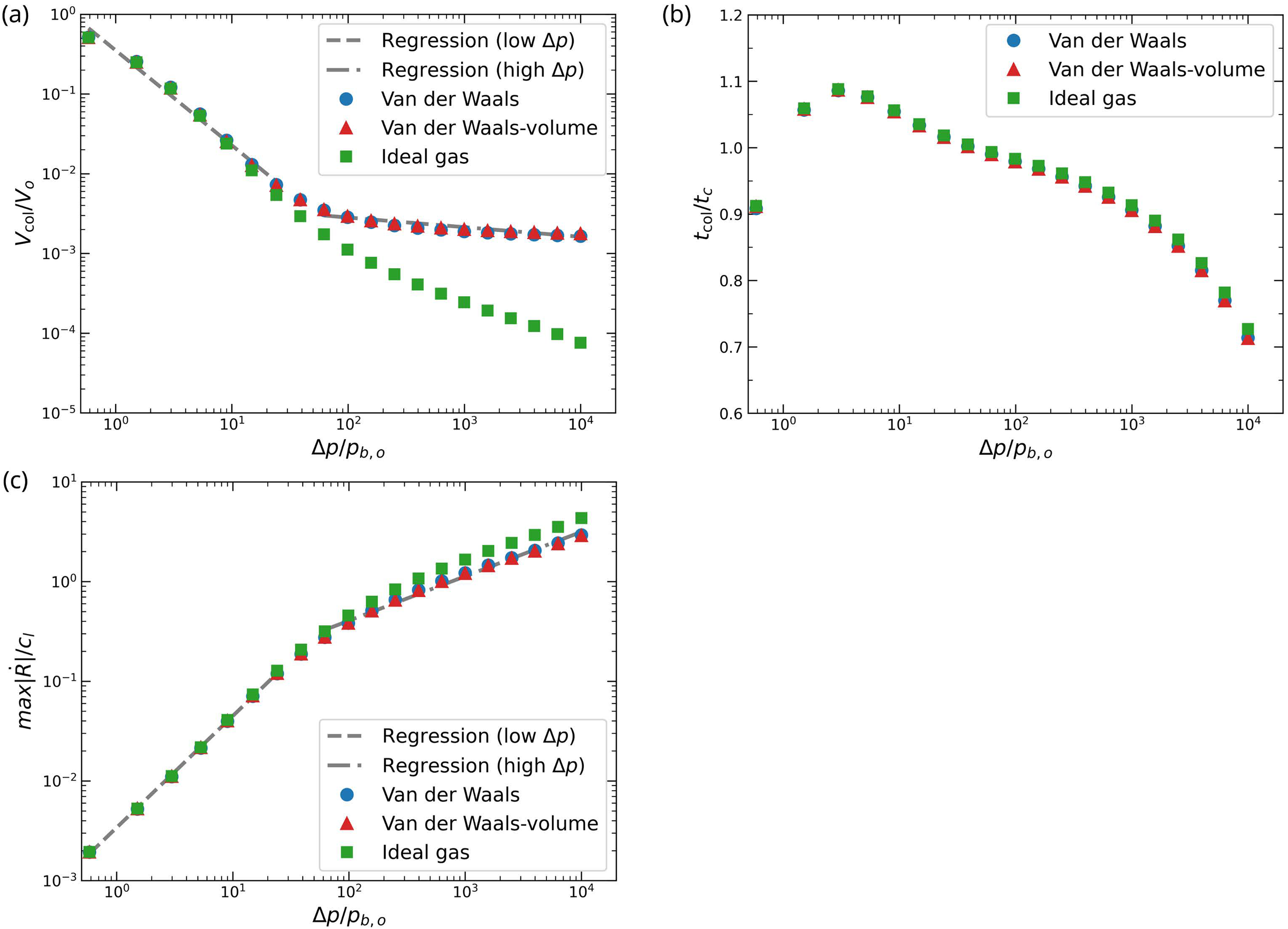

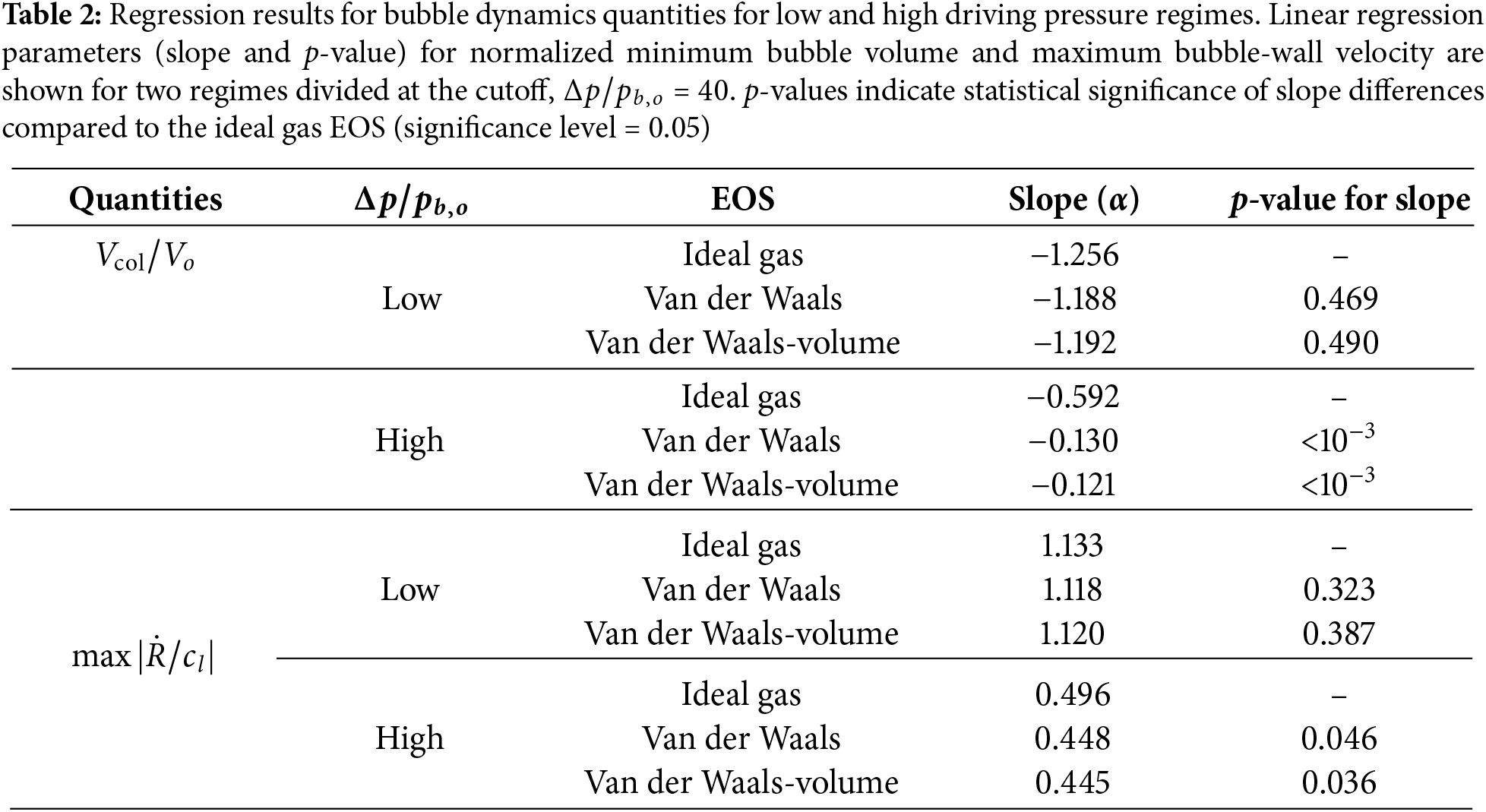

We analyze the bubble volume at collapse, collapse time, and maximum bubble-wall velocity for different EOS cases (Fig. 6). In all cases, these bubble quantities exhibit similar trends at low driving pressure ratios up to

Figure 6: Bubble dynamics at collapse under different driving pressure ratios for the van der Waals and ideal gas EOS. (a) Minimum bubble volume at collapse, normalized by the initial volume, (b) collapse time, normalized by the estimated collapse time, and (c) absolute value of the maximum bubble-wall velocity, normalized by the speed of sound in the liquid. (Blue circles) full van der Waals EOS, (red triangles) volume-limited van der Waals EOS, and (green squares) ideal gas EOS. Fitted linear regression lines for the volume-limited van der Waals EOS case are shown as dashed (low driving pressure regime) and dash-dotted (high driving pressure regime) lines, respectively

We conduct a statistical analysis to identify the regimes where finite molecular volume effects become important. A cutoff at

Separate regressions for the volume-limited van der Waals EOS above and below the cutoff are shown in Fig. 6a and Fig. 6c. The cutoff data point, located near the transition, is excluded to improve the accuracy of the regression models. Both the normalized bubble volume and bubble-wall velocity scale with the driving pressure ratio as

We observe that the slopes across EOS cases remain similar at low driving pressures but diverge at high pressures, particularly for the minimum bubble volume. Specifically, we observe statistically significant differences in slope between the van der Waals EOS cases and the ideal gas EOS at the high pressure regime, but only minor differences at low driving pressures, as summarized in Table 2. For

4.2 Energy Concentration and Radiation during the Collapse Phase

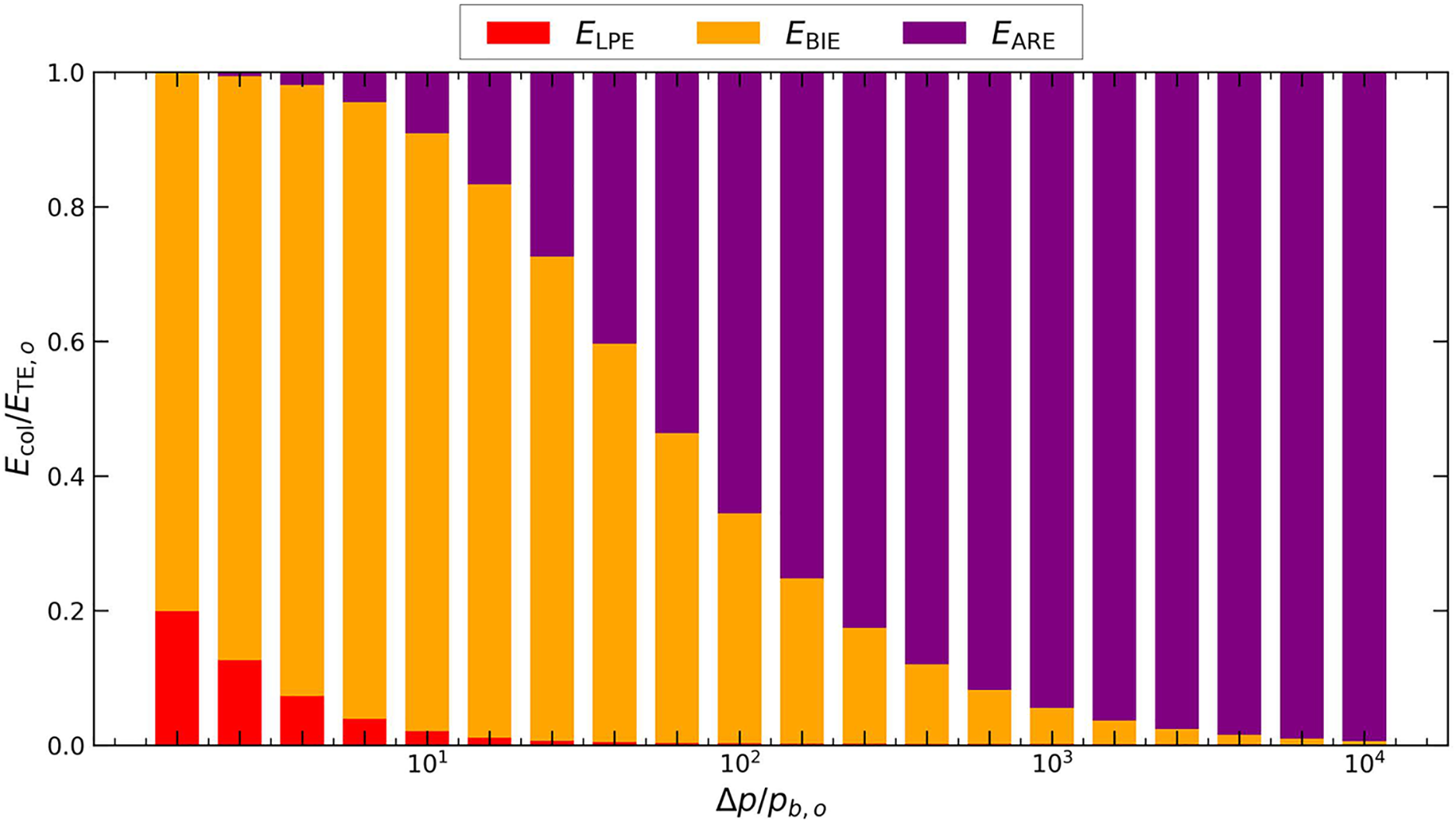

Following the analysis of bubble dynamics, we examine the energy partition at collapse to understand trends in energy concentration and radiation for different driving pressure ratios (Fig. 7). We focus on the volume-limited van der Waals EOS case, which is very similar to the full model. At

Figure 7: Energy partition at collapse for different driving pressure ratios using the volume-limited van der Waals EOS: (red bars) liquid potential energy (Eq. (11)), (orange bars) bubble internal energy (Eq. (7)), and (purple bars) acoustic radiation energy (Eq. (10))

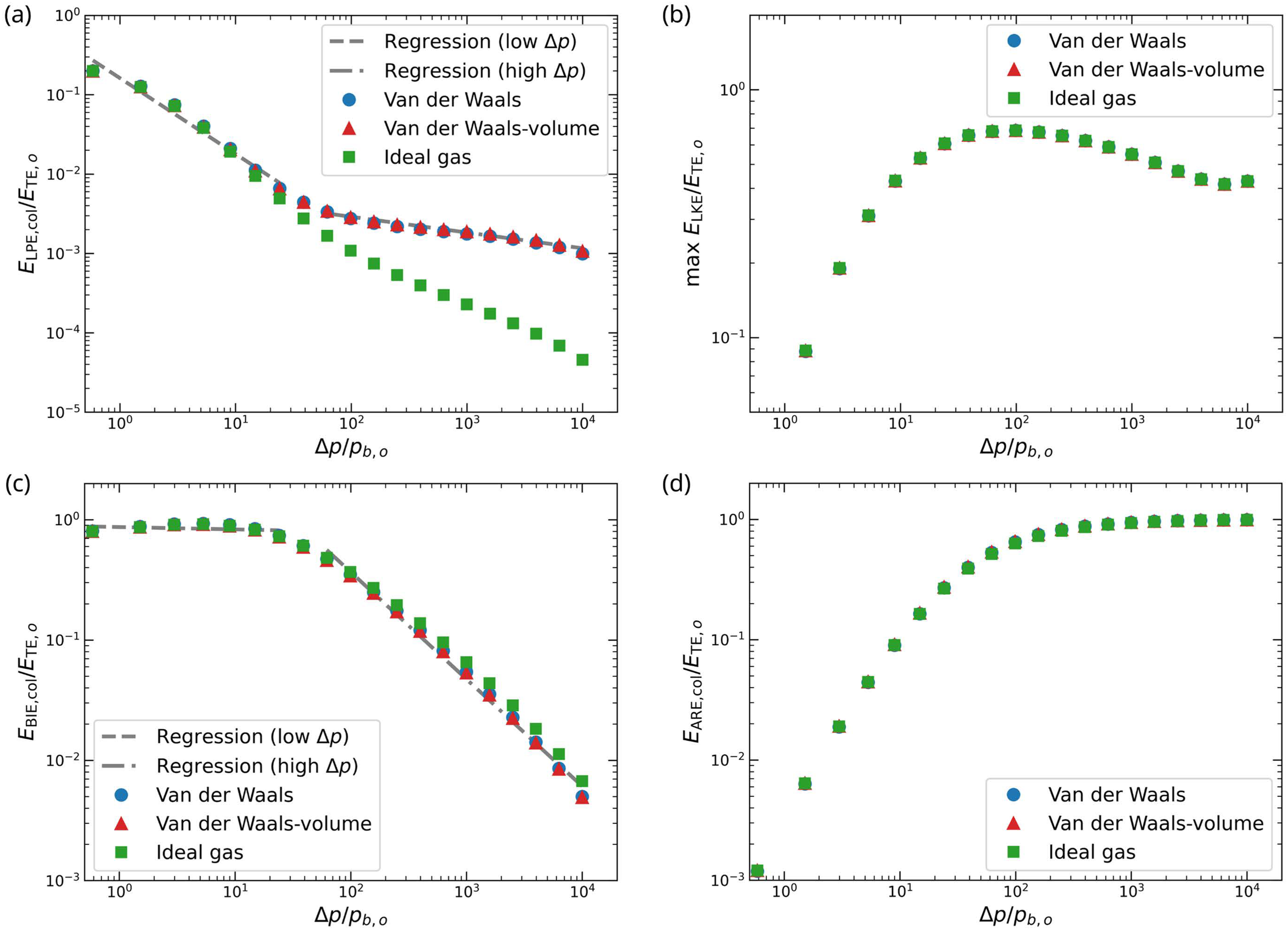

We compare each energy component at collapse for different EOS models (Fig. 8). Overall, these models show similar trends across different driving pressure ratios: as the driving pressure increases, both the liquid potential energy (Eq. (11)) and the bubble internal energy (Eq. (6) or (7)) decrease, while the acoustic radiation energy (Eq. (10)) increases. This trend can be attributed to stronger compressibility effects at higher driving pressures (or more intense bubble oscillations), as discussed with Fig. 7. At low driving pressure ratios, all EOS models behave similarly. However, at high driving pressure ratios, notable differences emerge between the van der Waals EOS cases and the ideal gas EOS. These differences are especially pronounced in the liquid potential energy, which becomes larger in the van der Waals cases due to the bubble being less compressed as a result of finite molecular volume. Thus, less potential energy is transferred to other components (Fig. 8a), and correspondingly, less energy is concentrated in the bubble (Fig. 8c). All EOS models exhibit similar maximum liquid kinetic energy (Eq. (12)) during collapse (Fig. 8b), since this peak occurs before the bubble is strongly compressed and finite molecular volume effects become important. Additionally, the acoustic radiation energy at collapse is comparable among the three EOS models (Fig. 8d), as the radiated energy exceeds 95% at this high driving pressure regime, despite differences in the bubble-wall Mach numbers (Fig. 6c).

Figure 8: Energy components at collapse under different driving pressure ratios for the van der Waals and ideal gas EOS. (a) Liquid potential energy (Eq. (11)) at collapse, (b) maximum liquid kinetic energy (Eq. (12)) during collapse, (c) bubble internal energy (Eq. (6) or (7)) at collapse, and (d) acoustic radiation energy (Eq. (10)) at collapse for the (blue circles) full van der Waals EOS, (red triangles) volume-limited van der Waals EOS, and (green squares) ideal gas EOS. Fitted linear regression lines for the volume-limited van der Waals EOS case are shown as dashed (low driving pressure regime) and dash-dotted (high driving pressure regime) lines, respectively. All energy components are normalized by the total energy

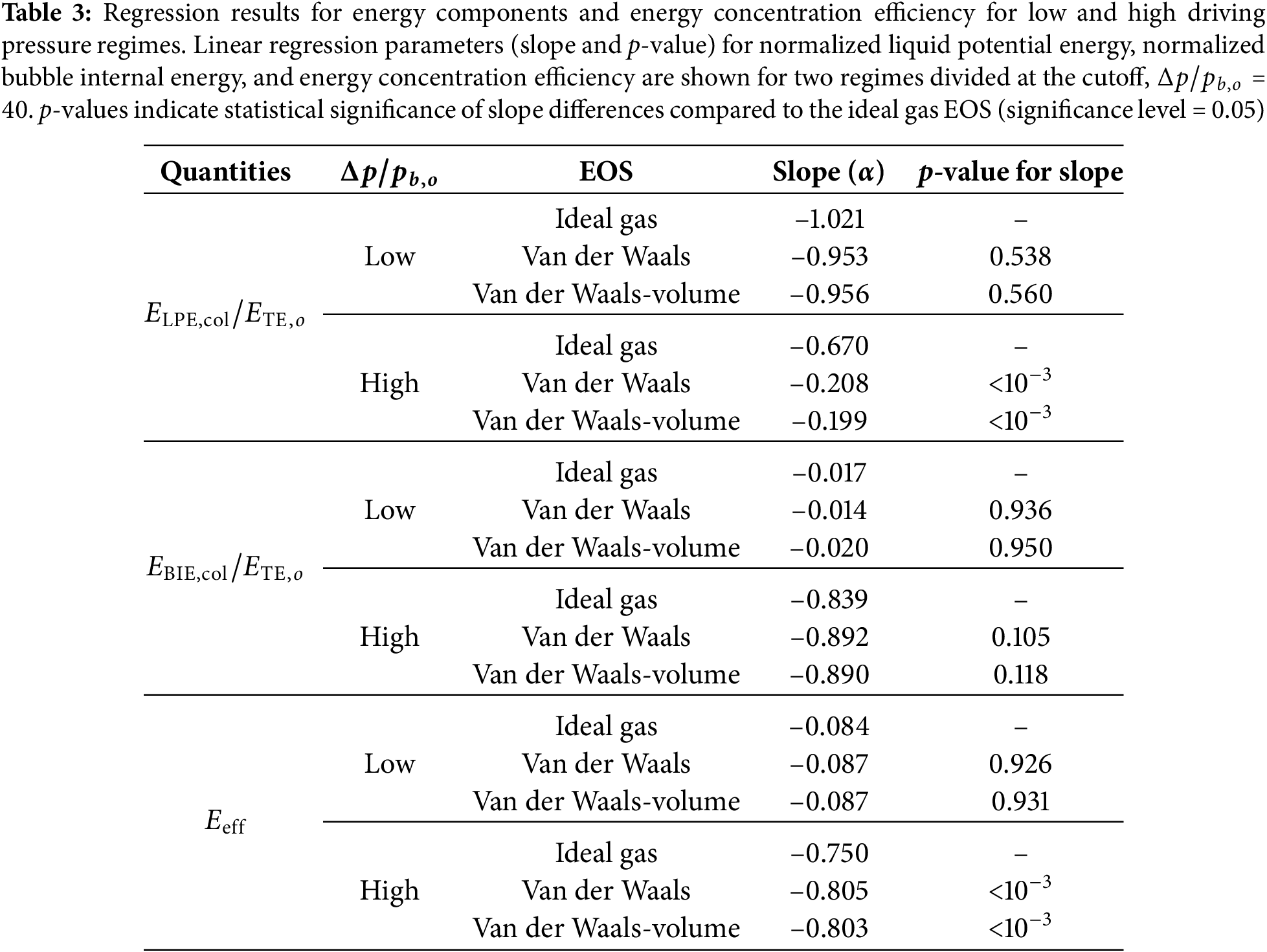

Following the regression analysis used for bubble dynamics, we apply the same approach to the energy components at collapse (Table 3). Consistent with the bubble dynamics results, we find statistically significant differences in slope between the van der Waals EOS cases and the ideal gas EOS in the high driving pressure regime, particularly for the liquid potential energy. For

Both the liquid potential energy and bubble internal energy at collapse scale with the driving pressure ratio according to a power-law relation of the form:

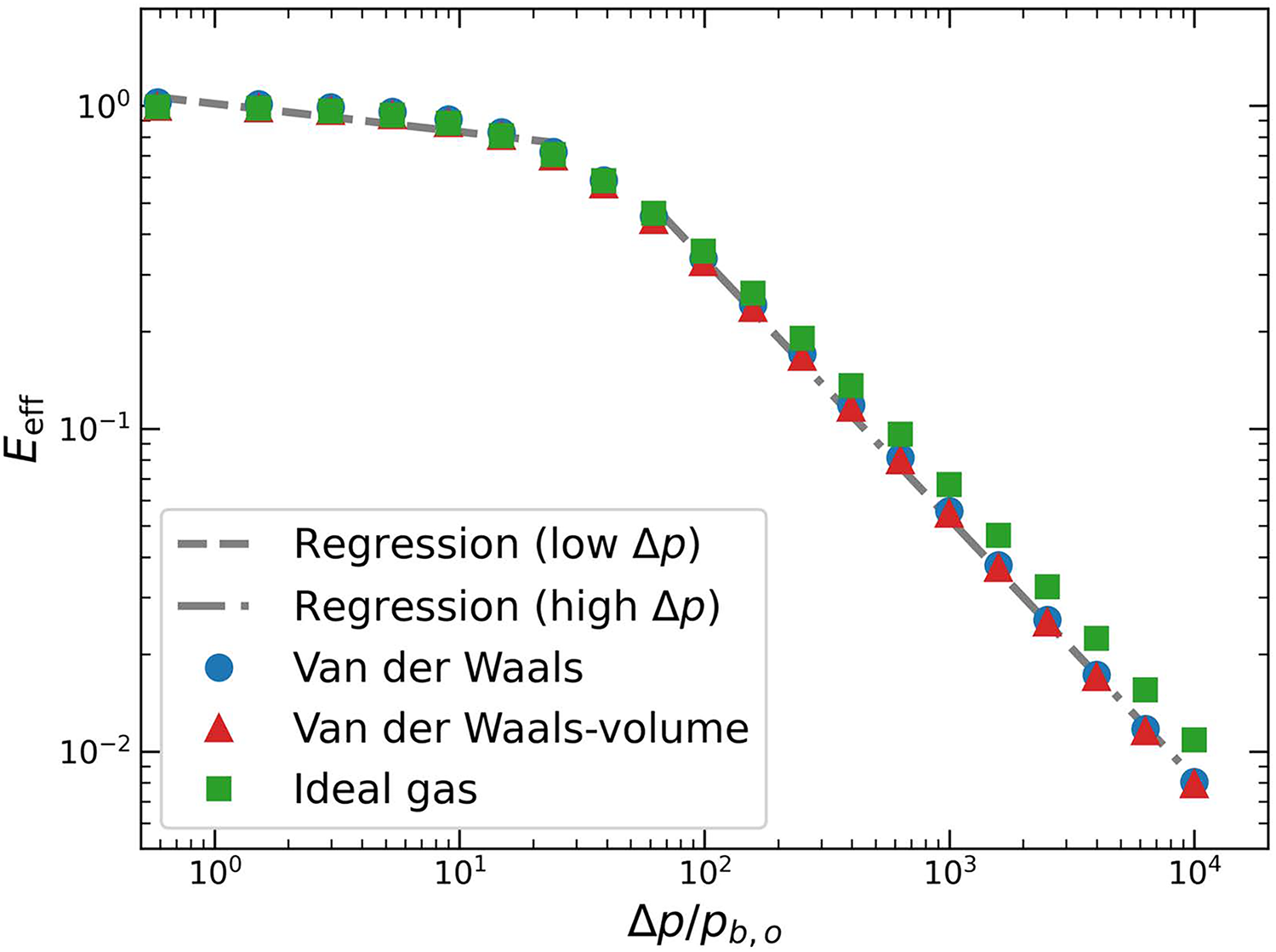

We quantify the energy concentration efficiency, shown in Fig. 9, defined as

Figure 9: Energy concentration efficiency at collapse as a function of driving pressure ratio for different EOS models: (Blue circles) full van der Waals EOS, (red triangles) volume-limited van der Waals EOS, and (green squares) ideal gas EOS. Fitted linear regression lines for the volume-limited van der Waals EOS are shown as dashed (low driving pressure regime) and dash-dotted (high driving pressure regime) lines, respectively

We scale the energy concentration efficiency in the high driving pressure regime for different EOS cases to examine its dependence on the initial problem parameters. For the volume-limited van der Waals, the efficiency can be expressed as:

We apply the same regression analysis used for the energy components to determine the relationship between energy concentration efficiency and the driving pressure ratio. The estimated slopes and corresponding p-values for each driving pressure regime are summarized in Table 3. As with the energy components, no statistically significant differences are observed between van der Waals EOS cases and the ideal gas EOS in the low driving pressure regime (

4.3 Shock Propagation during the Rebound Phase

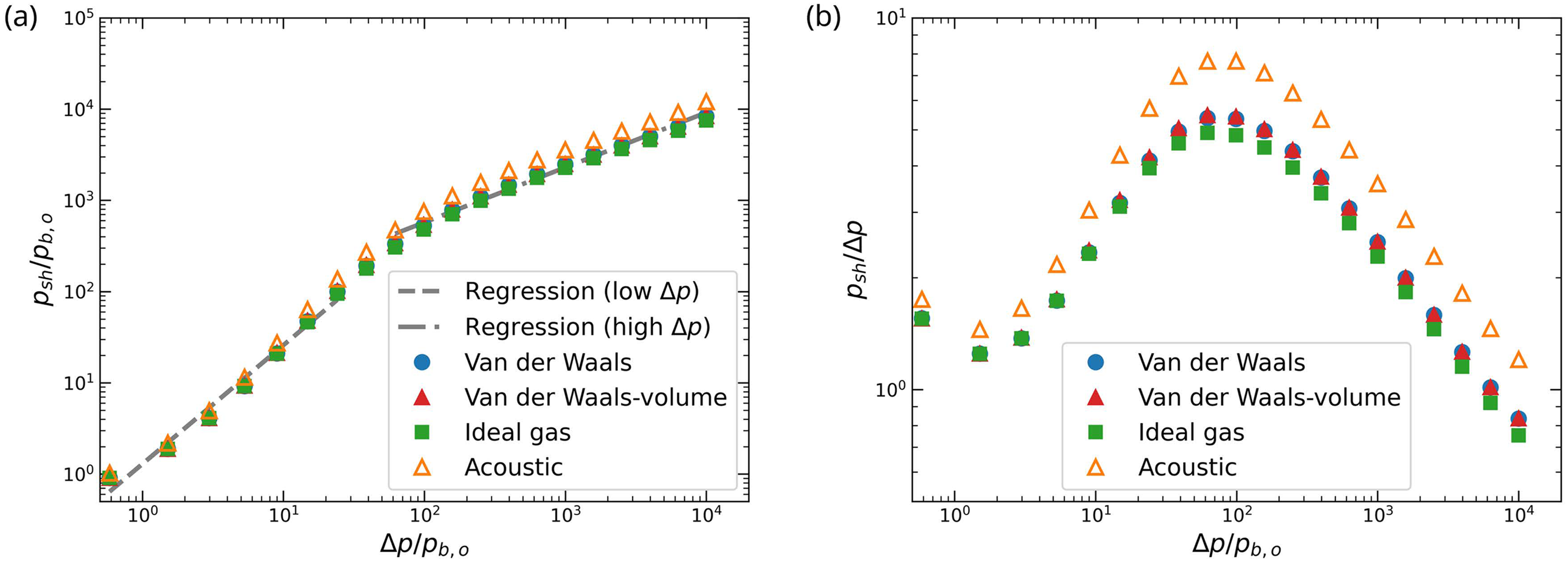

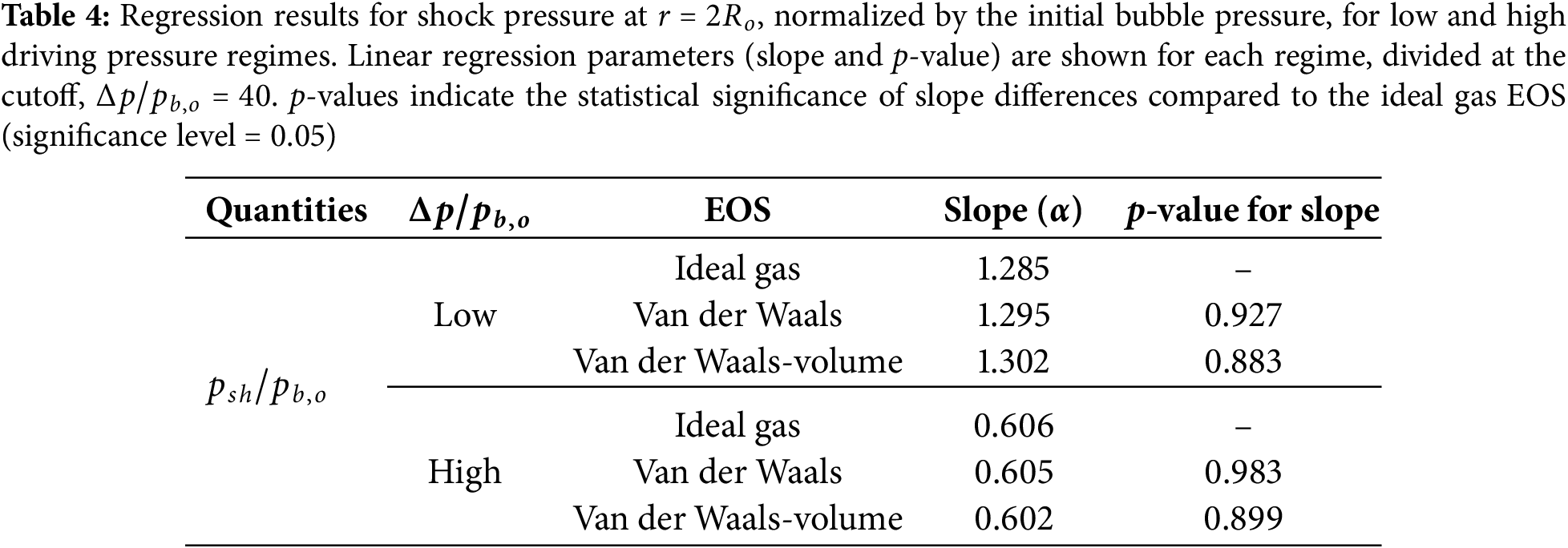

We model the propagation of the shock during the rebound phase to investigate the relationship between the peak shock pressure and the initial driving pressure (Fig. 10). The shock pressure is estimated based on its decay rate as a function of radial distance. During strong oscillations, the rapid deceleration of the bubble wall in the final stages of collapse produces a region of very high pressure in the surrounding liquid. Such pressure leads to an outward-propagating compression wave that can steepen into a shock, followed by another compression wave during rebound due to the outward acceleration of the bubble wall [27,58]. As these waves travel outward, more recently emitted waves overtake earlier ones and eventually merge into a single shock wave, which has been observed experimentally [26,59,60]. The shock decays faster than

Figure 10: Estimated shock pressures at

The shock pressure normalized by the initial bubble pressure shows very similar trends across all EOS models (Fig. 10a), whereas noticeable deviations arise when the shock pressure is normalized by the driving pressure (Fig. 10b). This difference is due to the choice of reference for normalization: the initial bubble pressure is much smaller than the shock pressure, which masks differences between the van der Waals EOS cases and ideal gas EOS in Fig. 10a. However, when normalized by the driving pressure, these differences become more pronounced (Fig. 10b).

We perform a statistical analysis for

We propose a novel energy budget framework to evaluate the energy components of the bubble−liquid system during strong oscillations of a spherical bubble, where molecular effects become important. We derive expressions for the internal energy of the bubble and the corresponding acoustic radiation energy, both of which strongly depend on the choice of EOS, while ensuring strict conservation of total energy in the system. This framework enables, for the first time, a systematic comparison of how non-ideal EOS (the van der Waals and its volume-limited form) alter bubble compression, energy redistribution, and shock emission relative to the ideal gas EOS. By modeling an oscillation in two stages, the collapse phase (from the initial state to the minimum radius) and the rebound phase (including shock generation), we link EOS-dependent energy transfer directly to peak shock pressures. Through statistical analysis across a wide range of driving pressures, we further identify distinct low- and high-pressure regimes and characterize the differences in behavior between the van der Waals EOS and the ideal gas EOS in these regimes. We also establish new scaling relations that connect the driving pressure ratio to bubble dynamics, energy concentration, and peak shock pressure. These contributions provide new insights into the role of molecular effects in cavitation dynamics and deliver predictive tools for anticipating cavitation-induced energy transfer in practical applications.

We observe significant differences between the van der Waals and ideal gas EOS cases at high driving pressure ratios, where intense compression leads to strong finite molecular volume effects. Compared to the ideal gas EOS, the van der Waals EOS cases exhibit much less compression, by orders of magnitude, along with lower bubble-wall velocity (and bubble-wall Mach number), indicating reduced compressibility effects. To quantify these differences, we conduct statistical analyses for both low and high driving pressure regimes, separated by a cutoff pressure ratio of 40. The resulting p-values reveal substantial differences between EOS models in the high driving pressure regime, particularly in the bubble volume at collapse.

We quantify the energy components of the bubble−liquid system using our energy budget framework, tailored to each EOS model. At low driving pressure ratios, most of the initial energy is concentrated to the bubble, whereas at high driving pressures, the majority of the energy is radiated away as acoustic waves. In the van der Waals EOS cases, a smaller portion of the potential energy is transferred to other energy components, resulting in reduced energy concentration to the bubble. We also compute the energy concentration efficiency, which is consistently lower for the van der Waals EOS cases, especially at higher driving pressures. Both the full and volume-limited van der Waals EOS models yield similar results, suggesting that intermolecular attractive forces play a minor role in bubble dynamics and energy transfer within the given driving pressure range. In addition, we estimate the shock peak pressure at a fixed radial distance from the bubble center. This pressure increases when normalized by the initial bubble pressure but decreases when normalized by the driving pressure at high driving pressure ratios, due to reduced energy concentration in the bubble. Finally, we derive scaling relations using linear regression for key quantities, including minimum bubble volume, bubble-wall velocity, liquid potential energy, bubble internal energy, energy concentration efficiency, and shock pressure, as functions of the driving pressure ratio. These relations provide practical insights for predicting cavitation bubble dynamics, energy concentration, and shock pressure in simulations and applications.

In the present study, the liquid is modeled as weakly compressible using the Keller−Miksis formulation, which captures first-order compressibility effects with the small dimensionless parameter

The developed energy budget framework has potential to be applied to a variety of complex bubble−liquid systems, including bubbles near boundaries with geometric constraints [19,68–70], thermodynamic effects [71], bubble clouds [23,24,72], and viscoelastic media [73,74]. In particular, under strong oscillations, the non-ideal gas formulation could be extended to incorporate thermal effects and phase change, enabling a more comprehensive quantification of energy transfer. These effects may interact nontrivially with non-ideal EOS behavior, especially at high pressures; while violent (or inertial) collapse occurs too rapidly for significant vapor diffusion or condensation [43], the extreme temperatures reached [7,32] suggest that thermal conduction and phase change could still influence energy redistribution. The framework can also be extended to account for viscous dissipation at the bubble wall, which becomes significant for larger bubbles with slower growth and collapse. In such regimes, the work done by the pressure difference across the interface is dissipated through normal viscous stresses, contributing to energy loss. In addition, the developed framework can be applicable to the weakly non-spherical bubble oscillations [52]. In this case, the bubble internal energy still follows Eqs. (6) and (7), since it depends on the total bubble volume, whereas both the liquid kinetic energy and the acoustic radiation energy would need modification due to perturbation in the velocity potential [75]. The framework may further be applied to spherical bubble-bubble interactions, which are especially relevant in bubble cloud dynamics. In addition, the spherical formulation can be adapted to non-spherical bubble oscillations, where asymmetry becomes pronounced, affecting the energy transfer. By incorporating the elastic energy stored in the surrounding medium, the framework can also be extended to quantify energy modes in viscoelastic environments. In this context, this work lays a foundation for elucidating energy transfer, concentration, and radiation in bubble dynamics problems under more realistic settings.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by Institute of Information & Communications Technology Planning & Evaluation (IITP) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. RS-2022-00155966, Artificial Intelligence Convergence Innovation Human Resources Development (Ewha Womans University)).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Minki Kim, Jenny Jyoung Lee; methodology, Minki Kim, Jenny Jyoung Lee; software, Jenny Jyoung Lee; validation, Minki Kim; formal analysis, Minki Kim, Jenny Jyoung Lee; investigation, Minki Kim; writing—original draft preparation, Minki Kim; writing—review and editing, Minki Kim, Jenny Jyoung Lee; supervision, Jenny Jyoung Lee; project administration, Jenny Jyoung Lee; funding acquisition, Jenny Jyoung Lee. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The simulation data that support the findings of this study, along with the R code used for statistical analysis, are openly available in the GitHub repository: https://github.com/mkkim400/Regression-analysis-bubble-dynamics (accessed on 15 September 2025). The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Arndt RE. Cavitation in fluid machinery and hydraulic structures. Annu Rev Fluid Mech. 1981;13(1):273–326. doi:10.1146/annurev.fl.13.010181.001421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Yang J, Lee KH, Lee CH. Research on cavitation characteristics and influencing factors of herringbone gear pump. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2024;139(3):2917–46. doi:10.32604/cmes.2024.046740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Peng D, Chen G, Yan J, Wang S. Numerical investigation of the Angle of Attack effect on cloud cavitation flow around a Clark-Y hydrofoil. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2024;139(3):2947–64. doi:10.32604/cmes.2024.047265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Khokhlova VA, Fowlkes JB, Roberts WW, Schade GR, Xu Z, Khokhlova TD, et al. Histotripsy methods in mechanical disintegration of tissue: towards clinical applications. Int J Hyperthermia. 2015;31(2):145–62. doi:10.3109/02656736.2015.1007538. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Johnsen E, Colonius T. Shock-induced collapse of a gas bubble in shockwave lithotripsy. J Acoust Soc Am. 2008;124(4):2011–20. doi:10.1121/1.2973229. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Brennen CE. Cavitation in medicine. Interface Focus. 2015;5(5):20150022. doi:10.1098/rsfs.2015.0022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Suslick KS, Flannigan DJ. Inside a collapsing bubble: sonoluminescence and the conditions during cavitation. Annu Rev Phys Chem. 2008;59(1):659–83. doi:10.1146/annurev.physchem.59.032607.093739. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Mauri G, Nicosia L, Xu Z, Di Pietro S, Monfardini L, Bonomo G, et al. Focused ultrasound: tumour ablation and its potential to enhance immunological therapy to cancer. Br J Radiol. 2018;91(1083):20170641. doi:10.1259/bjr.20170641. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Man VH, Li MS, Derreumaux P, Wang J, Nguyen TT, Nangia S, et al. Molecular mechanism of ultrasound interaction with a blood brain barrier model. J Chem Phys. 2020;153(4):045104. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

10. Nguyen PH. Modeling stable cavitation of coated microbubbles: a framework integrating smoothed dissipative particle dynamics and the Rayleigh-Plesset equation. J Chem Phys. 2024;161(6):64110. doi:10.1063/5.0220395. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Vogel A, Lauterborn W, Timm R. Optical and acoustic investigations of the dynamics of laser-produced cavitation bubbles near a solid boundary. J Fluid Mech. 1989;206:299–338. doi:10.1017/s0022112089002314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Tomita Y, Robinson P, Tong R, Blake J. Growth and collapse of cavitation bubbles near a curved rigid boundary. J Fluid Mech. 2002;466:259–83. doi:10.1017/s0022112002001209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Beig S, Aboulhasanzadeh B, Johnsen E. Temperatures produced by inertially collapsing bubbles near rigid surfaces. J Fluid Mech. 2018;852:105–25. doi:10.1017/jfm.2018.525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Karimi A, Martin J. Cavitation erosion of materials. Int Met Rev. 1986;31(1):1–26. [Google Scholar]

15. Plesset MS, Prosperetti A. Bubble dynamics and cavitation. Annu Rev Fluid Mech. 1977;9(1):145–85. doi:10.1146/annurev.fl.09.010177.001045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Zeng Q, Gonzalez-Avila SR, Dijkink R, Koukouvinis P, Gavaises M, Ohl CD. Wall shear stress from jetting cavitation bubbles. J Fluid Mech. 2018;846:341–55. doi:10.1017/jfm.2018.286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Zeng Q, An H, Ohl CD. Wall shear stress from jetting cavitation bubbles: influence of the stand-off distance and liquid viscosity. J Fluid Mech. 2022;932:A14. doi:10.1017/jfm.2021.997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Blake JR, Gibson D. Cavitation bubbles near boundaries. Annu Rev Fluid Mech. 1987;19(1):99–123. doi:10.1146/annurev.fl.19.010187.000531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Rodriguez MJr, Beig SA, Barbier CN, Johnsen E. Dynamics of an inertially collapsing gas bubble between two parallel, rigid walls. J Fluid Mech. 2022;946:A43. doi:10.1017/jfm.2022.571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. White W, Beig SA, Johnsen E. Pressure fields produced by single-bubble collapse near a corner. Phys Rev Fluids. 2023;8(2):23601. doi:10.1103/physrevfluids.8.023601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Nguyen VT, Sagar HJ, el Moctar O, Park WG. Understanding cavitation bubble collapse and rebound near a solid wall. Int J Mech Sci. 2024;278:109473. doi:10.1016/j.ijmecsci.2024.109473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Nguyen QT, Nguyen VT, Sagar H, Moctar O, Park WG. Effects of oscillating curved wall on behavior of a collapsing cavitation bubble. Phys Fluids. 2025;37(1):013312. doi:10.1063/5.0245434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Ando K, Colonius T, Brennen CE. Numerical simulation of shock propagation in a polydisperse bubbly liquid. Int J Multiph Flow. 2011;37(6):596–608. doi:10.1016/j.ijmultiphaseflow.2011.03.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Maeda K, Colonius T. Bubble cloud dynamics in an ultrasound field. J Fluid Mech. 2019;862:1105–34. doi:10.1017/jfm.2018.968. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Holzfuss J. Acoustic energy radiated by nonlinear spherical oscillations of strongly driven bubbles. Proc R Soc A Math Phys Eng Sci. 2010;466(2118):1829–47. doi:10.1098/rspa.2009.0594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Tinguely M, Obreschkow D, Kobel P, Dorsaz N, De Bosset A, Farhat M. Energy partition at the collapse of spherical cavitation bubbles. Phys Rev E. 2012;86(4):46315. doi:10.1103/physreve.86.046315. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Liang X-X, Linz N, Freidank S, Paltauf G, Vogel A. Comprehensive analysis of spherical bubble oscillations and shock wave emission in laser-induced cavitation. J Fluid Mech. 2022;940:A5. doi:10.1017/jfm.2022.202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Kim M. Energy transport during growth and collapse of a cavitation bubble [Ph.D. thesis]. Ann Arbor, MI, USA: University of Michigan; 2022. [Google Scholar]

29. Kim M, Beig SA, Johnsen E. Energy concentration and release during the inertial collapse of a spherical gas cavity in a liquid. Phys Rev Fluids. 2025;10(9):214. doi:10.1103/bqyr-5c1d. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Löfstedt R, Barber BP, Putterman SJ. Toward a hydrodynamic theory of sonoluminescence. Phys Fluids. 1993;5(11):2911–28. doi:10.1063/1.858700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Kerboua K, Hamdaoui O. Computational study of state equation effect on single acoustic cavitation bubble’s phenomenon. Ultrason Sonochem. 2017;38:174–88. doi:10.1016/j.ultsonch.2017.03.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Didenko YT, Suslick KS. The energy efficiency of formation of photons, radicals and ions during single-bubble cavitation. Nature. 2002;418(6896):394–7. doi:10.1038/nature00895. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Flannigan DJ, Hopkins SD, Camara CG, Putterman SJ, Suslick KS. Measurement of pressure and density inside a single sonoluminescing bubble. Phys Rev Lett. 2006;96(20):204301. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.96.204301. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Flannigan DJ, Suslick KS. Plasma formation and temperature measurement during single-bubble cavitation. Nature. 2005;434(7029):52–5. doi:10.1038/nature03361. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Brenner MP, Hilgenfeldt S, Lohse D. Single-bubble sonoluminescence. Rev Mod Phys. 2002;74(2):425. doi:10.1103/revmodphys.74.425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Brennen CE. Cavitation and bubble dynamics. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

37. Leighton TG. An introduction to acoustic cavitation. In: Ultrasound in medicine. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press; 2020. p. 199–224. [Google Scholar]

38. Lu X, Prosperetti A, Toegel R, Lohse D. Harmonic enhancement of single-bubble sonoluminescence. Phys Rev E. 2003;67(5):56310. doi:10.1103/physreve.67.056310. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Rayleigh L.VIII. On the pressure developed in a liquid during the collapse of a spherical cavity. Phil Mag Or Philos Mag. 1917;34(200):94–8. [Google Scholar]

40. Keller JB, Miksis M. Bubble oscillations of large amplitude. J Acoust Soc Am. 1980;68(2):628–33. doi:10.1121/1.384720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Lauterborn W, Kurz T. Physics of bubble oscillations. Rep Prog Phys. 2010;73(10):106501. [Google Scholar]

42. Storey BD, Szeri AJ. Mixture segregation within sonoluminescence bubbles. J Fluid Mech. 1999;396:203–21. doi:10.1017/s0022112099005984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Storey BD, Szeri AJ. Water vapour, sonoluminescence and sonochemistry. Proc R Soc A Math Phys Eng Sci. 2000;456(1999):1685–709. doi:10.1098/rspa.2000.0582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Barajas C, Johnsen E. The effects of heat and mass diffusion on freely oscillating bubbles in a viscoelastic, tissue-like medium. J Acoust Soc Am. 2017;141(2):908–18. doi:10.1121/1.4976081. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Hickling R, Plesset MS. Collapse and rebound of a spherical bubble in water. Phys Fluids. 1964;7(1):7–14. doi:10.1063/1.1711058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Ohl C, Ikink R. Shock-wave-induced jetting of micron-size bubbles. Phys Rev Lett. 2003;90(21):214502. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.90.214502. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Cole RH. Underwater explosions. Princeton, NJ, USA: Princeton University Press; 1948. [Google Scholar]

48. Hunter KS, Geers TL. Pressure and velocity fields produced by an underwater explosion. J Acoust Soc Am. 2004;115(4):1483–96. doi:10.1121/1.1648680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Qin Y, Wang Y, Wang Z, Yao X. The influence of various structure surface boundary conditions on pressure characteristics of underwater explosion. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2021;126(3):1093–123. doi:10.32604/cmes.2021.012969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Cash JR, Karp AH. A variable order Runge-Kutta method for initial value problems with rapidly varying right-hand sides. ACM Trans Math Softw. 1990;16(3):201–22. doi:10.1145/79505.79507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Prosperetti A, Lezzi A. Bubble dynamics in a compressible liquid. Part 1. First-order theory. J Fluid Mech. 1986;168:457–78. doi:10.1017/s0022112086000460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Plesset M. On the stability of fluid flows with spherical symmetry. J Appl Phys. 1954;25(1):96–8 doi: 10.1063/1.1721529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Burke WL. Runaway solutions: remarks on the asymptotic theory of radiation damping. Phys Rev A. 1970;2(4):1501. doi:10.1103/physreva.2.1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Templin JD. Radiation reaction and runaway solutions in acoustics. Am J Phys. 1999;67(5):407–13. [Google Scholar]

55. Arons AB, Yennie D. Energy partition in underwater explosion phenomena. Rev Mod Phys. 1948;20(3):519. doi:10.1103/revmodphys.20.519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Wang Q. Local energy of a bubble system and its loss due to acoustic radiation. J Fluid Mech. 2016;797:201–30. doi:10.1017/jfm.2016.281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Kirkwood JG, Bethe HA. The pressure wave produced by an underwater explosion. In: OSRD report. Washington, DC, USA: USA Office Sci Res Dev; 1942. [Google Scholar]

58. Yasui K. Acoustic cavitation. In: Acoustic cavitation and bubble dynamics. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2017. p. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

59. Holzfuss J, Rüggeberg M, Billo A. Shock wave emissions of a sonoluminescing bubble. Phys Rev Lett. 1998;81(24):5434. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.81.5434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Garen W, Hegedűs F, Kai Y, Koch S, Meyerer B, Neu W, et al. Shock wave emission during the collapse of cavitation bubbles. Shock Waves. 2016;26(4):385–94. doi:10.1007/s00193-015-0614-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Geers TL, Hunter KS. An integrated wave-effects model for an underwater explosion bubble. J Acoust Soc Am. 2002;111(4):1584–601. doi:10.1121/1.1458590. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Aganin AA, Mustafin IN. Outgoing shock waves at collapse of a cavitation bubble in water. Int J Multiph Flow. 2021;144(5):103792. doi:10.1016/j.ijmultiphaseflow.2021.103792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Yeats E, Lu N, Sukovich JR, Xu Z, Hall TL. Soft tissue aberration correction for histotripsy using acoustic emissions from cavitation cloud nucleation and collapse. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2023;49(5):1182–93. doi:10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2023.01.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Isselin JC, Alloncle AP, Autric M. On laser induced single bubble near a solid boundary: contribution to the understanding of erosion phenomena. J Appl Phys. 1998;84(10):5766–71. doi:10.1063/1.368841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Gilmore FR. The growth or collapse of a spherical bubble in a viscous compressible liquid; Pasadena, CA, USA: California Institute of Technology; 1952. Report No.: 26–4. [Google Scholar]

66. Denner F, Schenke S. Modeling acoustic emissions and shock formation of cavitation bubbles. Phys Fluids. 2023;35(1):12114. doi:10.1063/5.0131930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Denner F. The Kirkwood-Bethe hypothesis for bubble dynamics, cavitation, and underwater explosions. Phys Fluids. 2024;36(5):051302. doi:10.1063/5.0209167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Zeng Q, Gonzalez-Avila SR, Ohl CD. Splitting and jetting of cavitation bubbles in thin gaps. J Fluid Mech. 2020;896:A28. doi:10.1017/jfm.2020.356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Bhola S, Rodriguez MJr, Beig SA, Barbier CN, Johnsen E. Inertial collapse of a gas bubble in a shear flow near a rigid wall. J Fluid Mech. 2025;1004:A3. doi:10.1017/jfm.2024.1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Nguyen QT, Kadivar E, Phan TH, Nguyen VT, el Moctar O, Park WG. Effects of free surface on dynamics of a laser-induced cavitation bubble near horizontal rigid wall. Ocean Eng. 2025;319(3):120258. doi:10.1016/j.oceaneng.2024.120258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Mancia L, Rodriguez M, Sukovich J, Xu Z, Johnsen E. Single-bubble dynamics in histotripsy and high-amplitude ultrasound: modeling and validation. Phys Med Biol. 2020;65(22):225014. doi:10.1088/1361-6560/abb02b. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Bryngelson SH, Schmidmayer K, Colonius T. A quantitative comparison of phase-averaged models for bubbly, cavitating flows. Int J Multiph Flow. 2019;115(6):137–43. doi:10.1016/j.ijmultiphaseflow.2019.03.028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Murakami K, Gaudron R, Johnsen E. Shape stability of a gas bubble in a soft solid. Ultrason Sonochem. 2020;67:105170. doi:10.1016/j.ultsonch.2020.105170. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Murakami K, Yamakawa Y, Zhao J, Johnsen E, Ando K. Ultrasound-induced nonlinear oscillations of a spherical bubble in a gelatin gel. J Fluid Mech. 2021;924:A38. doi:10.1017/jfm.2021.644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

75. Harkin AA, Kaper TJ, Nadim A. Energy transfer between the shape and volume modes of a nonspherical gas bubble. Phys Fluids. 2013;25(6):62101. doi:10.1063/1.4807392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools