Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Hybrid Meta-Heuristic Feature Selection Model for Network Traffic-Based Intrusion Detection in AIoT

1 Department of Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence, Dongguk University, Seoul, 04620, Republic of Korea

2 Department of Police Administration, Dongguk University, Seoul, 04620, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Young-Sik Jeong. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Machine learning and Blockchain for AIoT: Robustness, Privacy, Trust and Security)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(1), 1213-1236. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.070679

Received 21 July 2025; Accepted 10 September 2025; Issue published 30 October 2025

Abstract

With the advent of the sixth-generation wireless technology, the importance of using artificial intelligence of things (AIoT) devices is increasing to enhance efficiency. As massive volumes of data are collected and stored in these AIoT environments, each device becomes a potential attack target, leading to increased security vulnerabilities. Therefore, intrusion detection studies have been conducted to detect malicious network traffic. However, existing studies have been biased toward conducting in-depth analyses of individual packets to improve accuracy or applying flow-based statistical information to ensure real-time performance. Effectively responding to complex and multifaceted threats in large-scale AIoT environments is challenging. This study proposes a hybrid multivariate network traffic (HyMNeT) feature-based intrusion detection system that applies a hybrid meta-heuristic feature selection approach to create a secure and efficient AIoT environment. The HyMNeT system selects critical features by applying mutual information maximization (MIM) and the maximal information coefficient (MIC) based on statistical features of the network traffic flow and raw packet features. This system employs the reference vector-guided evolutionary algorithm to search for optimal thresholds that maximize MIM scores while minimizing MIC scores. An evaluation of the selected multivariate network traffic feature set using four machine learning models on the BoT-IoT and ToN-IoT datasets resulted in average accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score values of 0.9844, 0.9897, 0.9844, and 0.9859, respectively. This work demonstrates that HyMNeT performs detection consistently and stably across all models.Keywords

With the acceleration of digital transformation, diverse industrial sectors (including manufacturing, urban planning, and healthcare) have employed the artificial intelligence of things (AIoT) to enhance system efficiency. The AIoT integrates artificial intelligence (AI) technology into existing internet of things (IoT) environments, enabling data collection, real-time analysis, prediction, and autonomous decision-making. Recent studies on AIoT have demonstrated effectiveness not only in anomaly detection for smart industries but also in detecting malicious network traffic in cybersecurity applications [1,2]. Furthermore, the importance of IoT devices in smart industries has significantly increased with the emergence of the sixth-generation (6G) network technology, supporting the real-time transmission of massive data and simultaneous connection of billions of IoT devices [3,4].

Moreover, 6G technology enables more sophisticated and rapid AIoT services (e.g., autonomous driving, robotic control, and large-scale real-time sensor network management) via an ultrareliable, ultra-low latency, and enhanced mobile broadband. As the demand for AIoT devices rises with the advancement of 6G network technology, massive volumes of data are collected, stored, and processed over networks. In this 6G-enabled AIoT environment, the ultra-low latency characteristics enable malicious network traffic to propagate in real time. This renders each device a potential attack target and amplifies potential vulnerabilities during data transmission processes [5,6].

In AIoT environments, sensitive and critical information (e.g., control data from smart factories, public infrastructure information from smart cities, and personal lifestyle pattern data) is collected and stored. However, IoT devices have limited memory capacity and low-power processors; hence, adding powerful security capabilities is challenging [7,8]. Additionally, due to the low-cost design and short development cycles, security testing for IoT devices is insufficient, resulting in security vulnerabilities. Attackers target these AIoT devices as primary attack vectors, creating various cyber threats, including taking control of industrial facilities, paralyzing critical urban infrastructure, and stealing corporate confidential information or sensitive personal data [9,10].

Numerous studies have been conducted to detect malicious network traffic in AIoT networks to protect sensitive information from various cyber threats. Packet-based intrusion detection techniques analyze individual packets in network traffic to detect malicious network traffic. These techniques can accurately detect security threats by analyzing diverse types of detailed information (e.g., packet headers, payloads, and protocol fields). However, all packets generated during communication processes must be analyzed in real time; hence, high computational costs and analysis complexity occur in massive-scale traffic environments. Additionally, some new applications use dynamic instead of fixed ports or employ encrypted traffic, making direct network traffic analysis challenging.

Flow-based intrusion detection techniques group network traffic into flow units over specific periods, then collect and analyze statistical data (e.g., the number of packets and bytes for each session) to detect malicious network traffic. A network flow unit comprises a series of packets with the same source and destination internet protocol (IP), source and destination ports, and protocols. These flow-based intrusion detection techniques require fewer computational resources than techniques that analyze all individual packets, allowing them to process massive-scale network traffic in real time. However, detection performance is lower because they rely only on statistical characteristics without analyzing detailed information from individual packets. Furthermore, it is challenging to understand the overall context of network traffic and analyze encrypted network traffic.

Session-based intrusion detection techniques analyze network traffic in connection units between network endpoints to detect malicious network traffic. Such techniques employ combinations of specific source IP, destination IP, source ports, destination ports, and protocols to reconstruct network traffic flows and analyze interactions between clients and servers in detail. The context of network traffic can be understood through these reconstructed sessions. Malicious network traffic is accurately detected by capturing state changes and the overall flows of each session. However, such session-based intrusion detection techniques are challenging for analyzing massive-scale network traffic in real time because the process of reconstructing simultaneously generated sessions or tracking their status is complex.

This study proposes a hybrid multivariate network traffic (HyMNeT) feature-based intrusion detection method to provide a secure and efficient AIoT communication environment. HyMNeT applies mutual information maximization (MIM) and maximal information coefficient (MIC) techniques to construct critical feature subsets. These subsets consider both the correlation with labels and the redundancy between features from statistical and packet header information. The reference vector-guided evolutionary algorithm (RVEA) is employed to set optimal thresholds that maximize MIM scores and minimize MIC scores. The selected multivariate feature set is trained on traditional machine learning (ML) models, including the decision tree (DT), gradient boosting machine (GBM), extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost), and random forest (RF) methods, to detect malicious network traffic.

The HyMNeT method can analyze detailed network traffic characteristics and the overall flow simultaneously by considering packet headers and flow-level features. The experiments confirm that high detection performance is maintained with only a few features. The primary contributions of this study are as follows:

• We propose HyMNeT, which detects malicious network traffic operating in 6G-enabled AIoT environments.

• Hybrid feature selection based on MIM and MIC values improves detection accuracy by increasing the correlation with labels while reducing feature redundancy.

• Automatically adjusting MIM and MIC thresholds via RVEA ensures objectivity in the feature selection process and optimal multivariate network traffic feature sets.

• The consistent performance with few features across traditional ML models demonstrates the effectiveness of the multivariate feature set construction of HyMNeT.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the existing studies, and Section 3 proposes the overall scheme for HyMNeT. Next, Section 4 implements HyMNeT and evaluates the intrusion detection performance. Finally, Section 5 summarizes the research and presents future research directions.

Studies have been conducted on intrusion detection, analyzing network traffic in real time to detect malicious network traffic in AIoT environments. Recently, intrusion detection techniques using ML and deep learning (DL) models have been researched to enhance performance. This section describes these techniques, which are categorized into packet-based, flow-based, and session-based intrusion detection approaches according to their network traffic analysis methods.

2.1 Packet-Based Intrusion Detection

Packet-based intrusion detection identifies malicious network traffic by analyzing detailed information from individual packets, including packet headers and payloads. This enables accurate detection of various security threats.

Luo et al. [11] proposed BITization to analyze encrypted traffic by converting the bytes of each packet (including headers and payloads) into the binary format and encoding with one, two-, four-, and eight-bit representations, then combining the encoded results to generate a single feature vector. The generated feature vectors were trained on ML models to detect the maliciousness of the encrypted network traffic.

Hassan et al. [12] proposed PayloadEmbeddings to address header-based intrusion detection, which does not consider payloads, by generating embedding vectors for payloads. They applied shallow neural networks to generate vector representations of payloads and trained them using k-nearest neighbor classifiers to distinguish between normal and anomalous packets.

Xu et al. [13] proposed FastTraffic, a lightweight intrusion detection technique, to address the problems of fixed input sizes causing information loss and overhead in existing DL-based traffic classification. They applied N-gram embedding to tokenize the header of the input packet and a three-layer multilayer perceptron to classify the encrypted network traffic.

Packet-based intrusion detection in AIoT environments requires high computational resources because it individually analyzes massive volumes of packets and examines various packet fields. This method has limitations due to the limited computing power in IoT devices and their real-time processing requirements.

2.2 Flow-Based Intrusion Detection

Flow-based intrusion detection analyzes network behavior patterns by analyzing the continuous packet flow. This approach enables efficient malicious network traffic analysis by considering the overall characteristics of grouped network flow units rather than individual packets.

Huoh et al. [14] proposed a graph neural network (GNN)-based method for encrypted network traffic classification, addressing the information loss problem in high-dimensional flow data that occurs in most DL-based detection techniques, using a convolutional neural network (CNN) and a recurrent neural network. They mapped the raw bytes, metadata, and interpacket relationships of network traffic flow units into graph structures and employed an encoder-decoder structured GNN model to detect encrypted network traffic.

Zhou et al. [15] addressed the problem of redundant or irrelevant data among high-dimensional network traffic flow features, which interferes with classification, by combining correlation-based feature selection with the bat algorithm to select optimal feature sets from network traffic flow units. They proposed an ensemble classifier that employs RF, C4.5, and forest PA using a rule voting approach based on the average of the probabilities to detect intrusion.

Jia et al. [16] proposed a deep belief network (DBN)-based approach to address the problem of reduced generalizability and efficiency, as the optimal parameters of the DL-based approach are determined by trial and error. Moreover, they applied information gain to reduce the dimensionality of high-dimensional features and remove redundant characteristics. Additionally, they employed information entropy to select optimal features from network traffic flow units and trained them on DBN models to detect malicious network traffic.

However, flow-based intrusion detection in AIoT environments is challenging to configure effectively due to the mix of protocols and communication patterns. Furthermore, it is difficult to extract features from long-term flow units.

2.3 Session-Based Intrusion Detection

Session-based intrusion detection identifies malicious network traffic by analyzing complete communication sessions between network endpoints. These techniques perform detection by considering the overall context of the network traffic via a detailed analysis of client-server interactions.

Davis et al. [17] converted raw packet capture (PCAP) files into images to use all the information without loss and trained them on CNN models. They selected 50 packets from each network traffic session and generated

Lin et al. [18] proposed a hybrid DL network structure combining the CNN and bidirectional gated recurrent unit (Bi-GRU) methods to extract high-dimensional data characteristics by learning the temporal and spatial features of traffic data. After segmenting network traffic into session units, they removed the data link layer information and the domain name system (DNS) protocols. The selected features were trained on CNN and Bi-GRU to detect encrypted network traffic.

Wang et al. [19] proposed SessionVideo based on the 3D-CNN to employ the temporal features of traffic payloads. They converted network traffic sessions into

Session-based intrusion detection techniques enable accurate attack detection by considering the complete communication contexts but require a significant amount of time and computational resources for analysis. In particular, in the massive-scale traffic environments of AIoT, storing and processing all packet information in real time is challenging, and an immediate threat response is difficult because analysis proceeds after session completion.

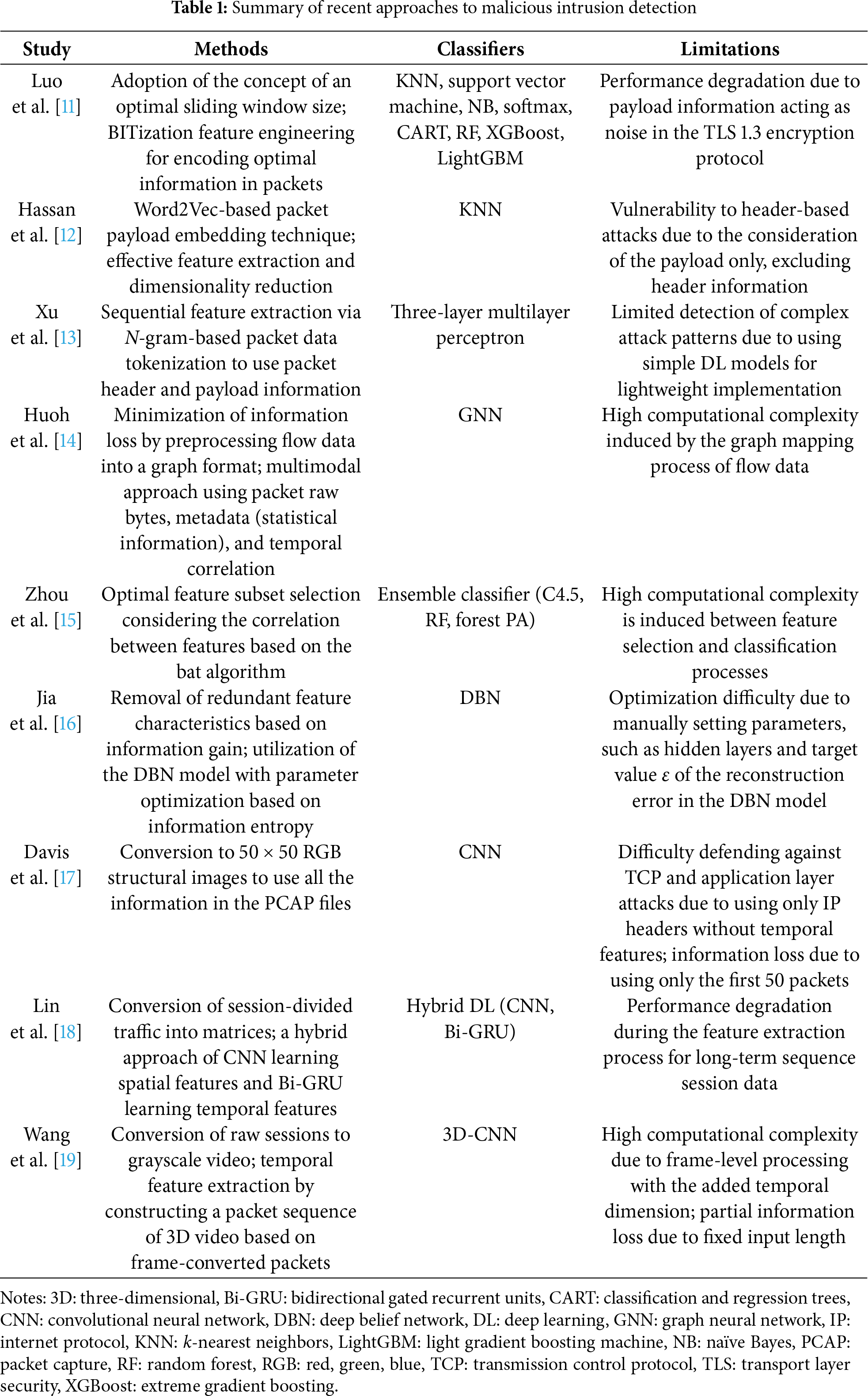

The HyMNeT method proposed in this study selects critical features from IP packet header information and flow-level features, then generates multivariate feature sets. This approach selects only the primary features with low redundancy that are crucial for detecting malicious network traffic. Moreover, HyMNeT enhances detection performance by analyzing long-term patterns of malicious network traffic and unique characteristics of packets in detail. Table 1 summarizes existing studies that analyze network traffic in IoT environments and perform intrusion detection based on this analysis.

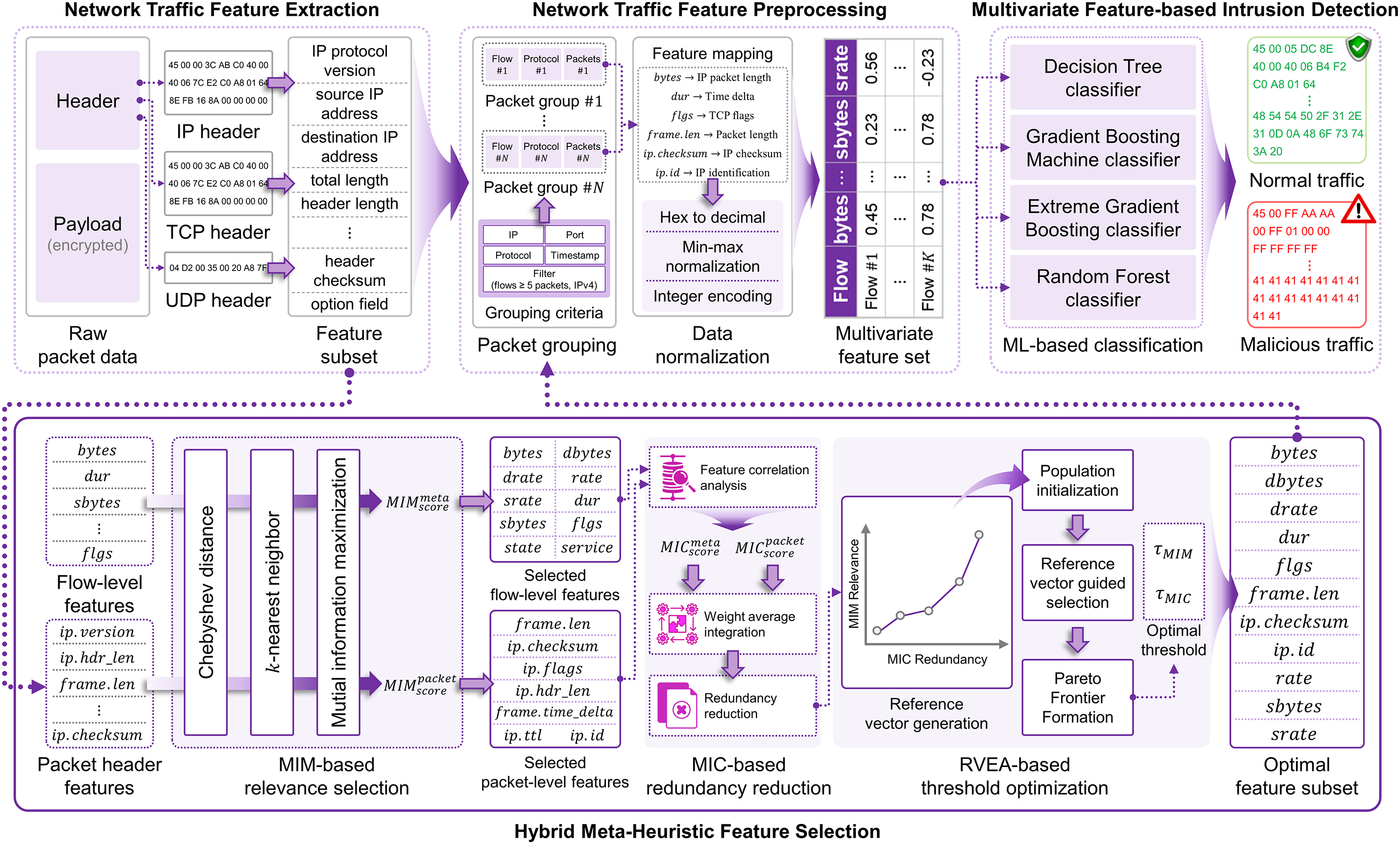

This study proposes HyMNeT, which detects malicious traffic patterns using multivariate network traffic features selected using a hybrid meta-heuristic approach to protect 6G-enabled AIoT environments from diverse cybersecurity threats. The HyMNeT method comprises network traffic feature extraction, network traffic feature preprocessing, and multivariate feature-based intrusion detection stages. Fig. 1 illustrates the overall scheme.

Figure 1: Intrusion detection scheme based on multivariate network traffic features

3.1 Network Traffic Feature Extraction

The network interface is configured in promiscuous mode to sniff all packets on the network to detect malicious traffic on AIoT networks. Packets received through the network interface are stored in memory in PCAP file format. These PCAP files contain detailed information about packets, including the capture time, payload, and actual packet length.

The HyMNeT framework extracts raw packet data from PCAP files to analyze network traffic patterns in detail. The raw packet data comprise hexadecimal packet headers and payloads. As the importance of privacy protection has increased, most packets are transmitted in an encrypted format. Encrypted payloads are challenging to analyze, and excessive computing resources are consumed during decryption [20,21]. In contrast, most packet headers are not encrypted, and even if they are tampered with by malware, integrity checks can detect the tampering [22].

Therefore, HyMNeT extracts packet header information from raw packet data to construct the initial feature subset. Packet headers contain control information related to networks, with major fields including the IP protocol version, source IP address, destination IP address, total length, header length, service type, identification, flag, fragment offset, protocol, time-to-live, header checksum, and option fields. These features are input during the hybrid meta-heuristic feature selection stage and network traffic feature preprocessing stage.

3.2 Hybrid Meta-Heuristic Feature Selection

Network flow-level features comprise multiple records in the form of statistical summaries of individual packet transmission events. In flow-level features include various statistical-based metadata, including the number of packets per source IP, the number of packets per second for the same source IP and protocol, and the flow connection status. In this study, flow-level features and packet header information are analyzed to select features with a high correlation to malicious network traffic patterns, enhancing the performance of malicious intrusion detection. Flow-level features and packet header features are integrated and defined as network traffic features.

First, HyMNeT employs MIM [23] to select critical network traffic features with a high relevance to labels. Such MIM effectively identifies nonlinear dependencies between data and enhances feature representation by maximizing mutual information between individual features and labels [24]. Before estimating

Mutual information between

where

The HyMNeT scheme employs the MIC [25] to select the final network traffic features, analyzing the similarities between network traffic features selected using MIM and removing redundancy. First, to analyze dependencies between features, MIC calculates the probability distributions for features, as in Eq. (4), to compute mutual information

The maximum

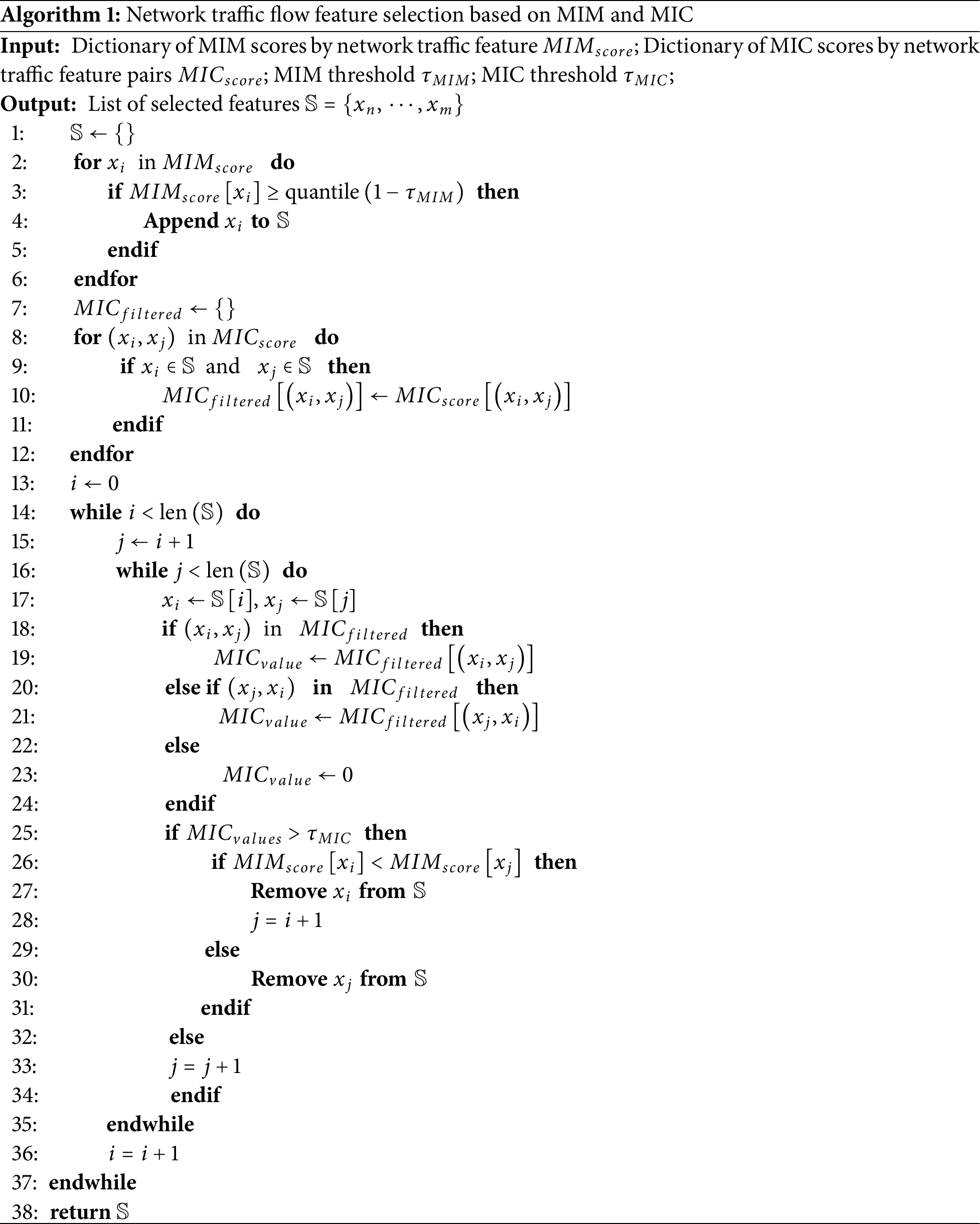

Algorithm 1 presents the process of selecting critical network traffic features based on

The optimal thresholds

3.3 Network Traffic Feature Preprocessing

The feature subset derived from the hybrid meta-heuristic feature selection stage comprises packet headers and summary information. Moreover, HyMNeT performs preprocessing to train these features in the intrusion detection model. First, HyMNeT groups packets based on the identical source IP, destination IP, source port, destination port, and protocol, arranging them in numerical order. The packet sequences generated in this manner are employed as network traffic features.

Network traffic features contain several data types and value ranges, requiring consistent normalization and encoding processes. First, features (e.g., packet identification and checksum) are expressed in the hexadecimal format and are converted to decimal numbers ranging from 0 to 255. Then, min-max normalization is applied to numerical features (e.g., the header length, Ethernet frame length, and duration), along with the converted decimal features, scaling them to a range of

3.4 Multivariate Feature-Based Intrusion Detection

The HyMNeT method trains the selected multivariate feature set on several ML models. This evaluates the effectiveness of hybrid meta-heuristic feature selection by comparing intrusion detection performance against malicious network traffic. The DL models require considerable computational resources and complex hyperparameter tuning. Analyzing the direct influence of feature selection is challenging due to the nonlinear and multilayer feature representations. Therefore, this study employs ML classifiers (e.g., DT, GBM, XGBoost, and RF).

First, DT [30] is an ML model that branches based on the information gain of features, exhibiting superior performance when the correlation between features and labels is high. This approach aligns with that of HyMNeT, which selects features with high relevance to labels based on

The boosting-based GBM [31] sequentially trains multiple DTs and compensates for the prediction errors of previous models. When redundancy between features is high, the model becomes sensitive to noise during the boosting process, leading to overfitting [32]. Therefore, GBM is employed to evaluate the influence of the feature subset of HyMNeT (which removes redundant features based on

The XGBoost [33] method is an extended form of GBM that prevents overfitting via regularization and provides stable performance even for sparse features, using sparsity-aware splits. Therefore, XGBoost is applied to evaluate detection performance on the feature subset of HyMNeT, which has high importance and low redundancy.

Finally, the RF [34] bagging-based ensemble model trains multiple DTs on feature subsets, providing excellent generalization performance via feature combinations. The RF method is introduced to evaluate whether the hybrid meta-heuristic feature selection for HyMNeT operates robustly under diverse conditions.

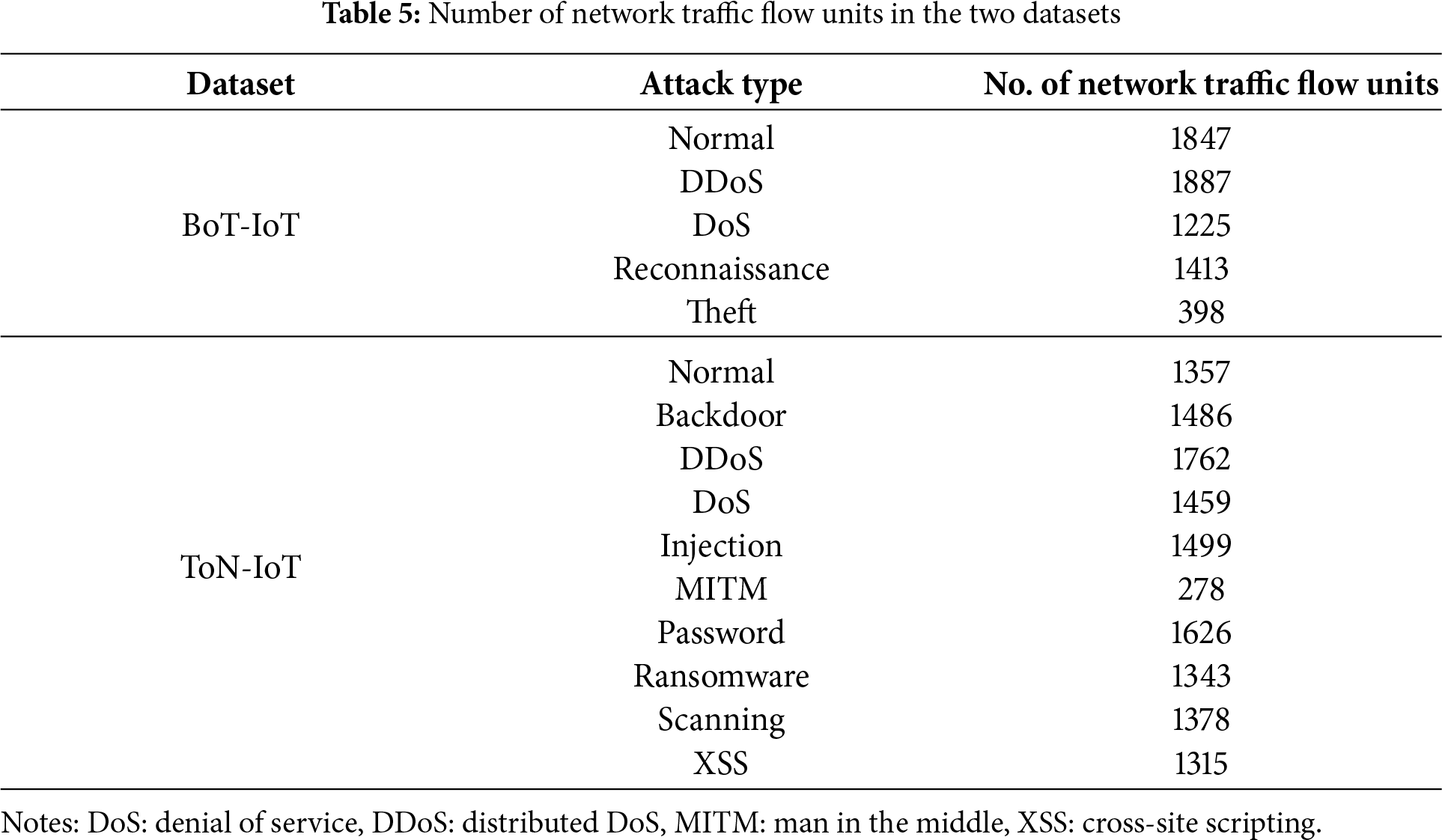

This study employs the BoT-IoT [35] and ToN-IoT datasets [36], which were collected from real IoT networks and simulation environments. The BoT-IoT dataset provides metadata for regular network traffic and four types of botnet-based malicious traffic. The malicious network traffic types consist of denial of service (DoS), distributed DoS (DDoS), reconnaissance, and information theft (referred to as theft throughout).

The ToN-IoT dataset comprises multiple attack simulation results, including logs from Windows and Linux systems, IoT device status data, and network traffic. Among these, the attack types for network traffic are broadly categorized into nine types: backdoor, DoS, DDoS, injection, man-in-the-middle attacks, password, ransomware, scanning, and cross-site scripting.

Both datasets provide metadata on network traffic flow and PCAP files. This study employs 394 PCAP files (excluding corrupted PCAP files) to generate multivariate network traffic features.

This study implements HyMNeT using an Intel Core i9-10800K processor and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3090 graphics card. This work evaluates the performance of malicious network traffic detection using a selected multivariate feature set.

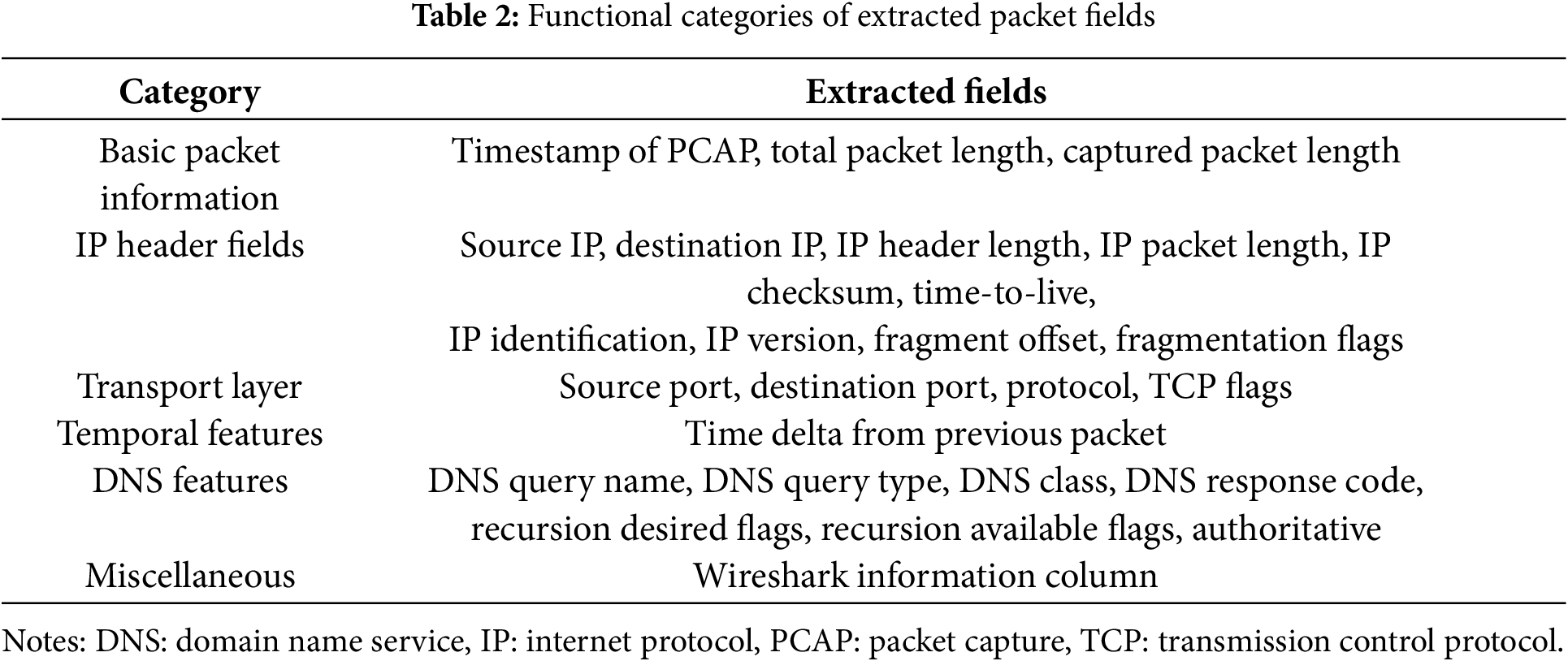

4.2.1 Network Traffic Feature Extraction

In the network traffic feature extraction stage, HyMNeT uses the Tshark tool [37] to extract monitored raw packet data from PCAP files and stores them in comma-separated value format. Table 2 lists the primary extracted fields classified by functionality. The Wireshark information column provides a comprehensive summary of information for each packet, describing the transmission protocols and communication states.

These fields reflect the network traffic characteristics, including temporal patterns, packet sizes, transmission structures, and DNS operations. We use these characteristics as foundational data for the quantitative analysis of diverse traffic types.

4.2.2 Hybrid Meta-Heuristic Feature Selection

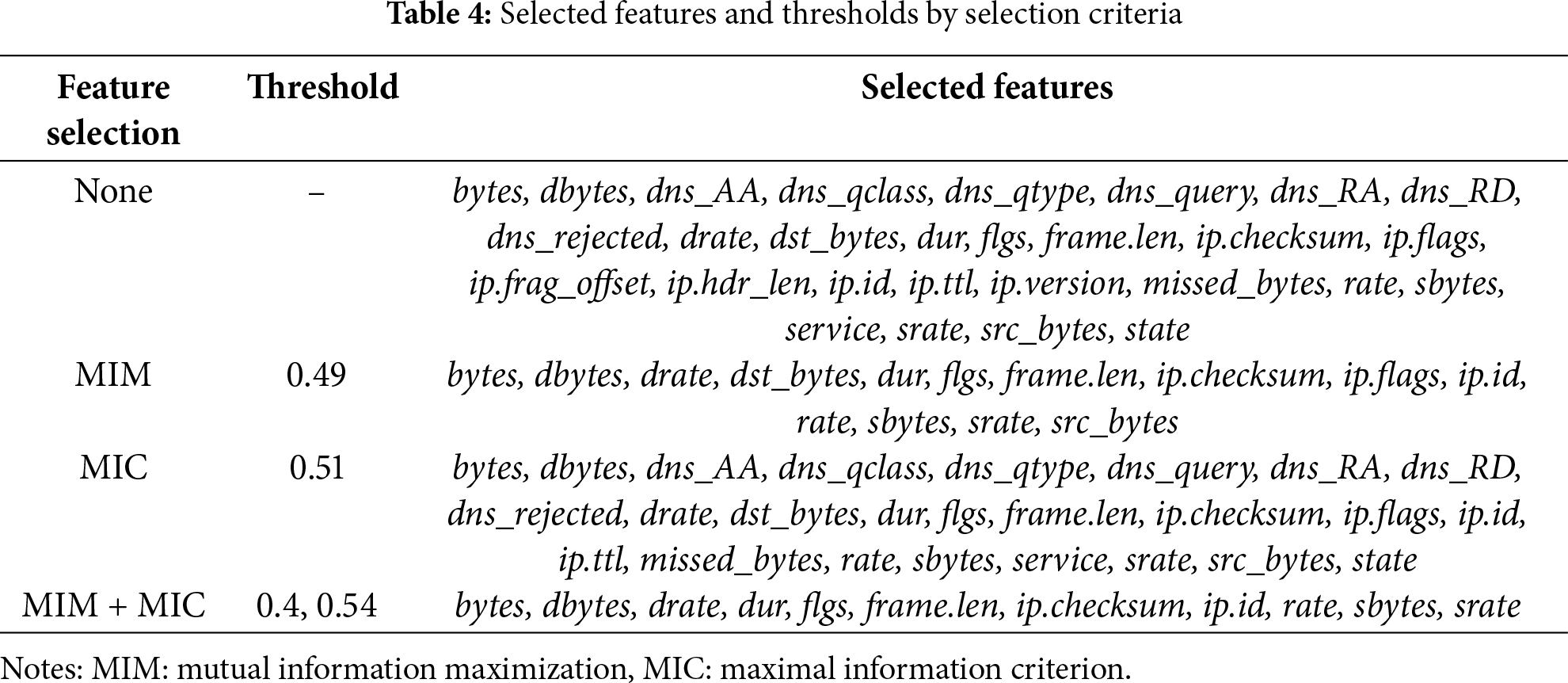

In the hybrid meta-heuristic feature selection stage, HyMNeT analyzes the importance and correlation of network traffic-related features using metadata files provided by the BoT-IoT and ToN-IoT datasets. Prior to calculating these metrics, features that were unnecessary for analysis or could adversely influence model performance were removed.

In the BoT-IoT dataset, stime and ltime (the start and end times of the network flow) and the subcategory, which indicates detailed attack types, were excluded. Additionally, pkSeqID, a unique identifier distinguishing network traffic flow, was removed because it is unrelated to traffic patterns. For the ToN-IoT dataset, the label field was excluded, and type was applied as the final label.

The source and destination IP addresses have low direct correlation with network traffic patterns [38]. When intrusion detection models are trained with a bias toward specific IP addresses, they fail to detect identical malicious traffic from different IP addresses accurately, resulting in degraded generalization [39,40]. Therefore, this study excludes the source IP, destination IP, source port, destination port, and protocol from network traffic features in both datasets. Furthermore, this work also excludes statistical features that are difficult to derive directly at the packet level, including features related to packet counts and those with value distributions biased toward 0%.

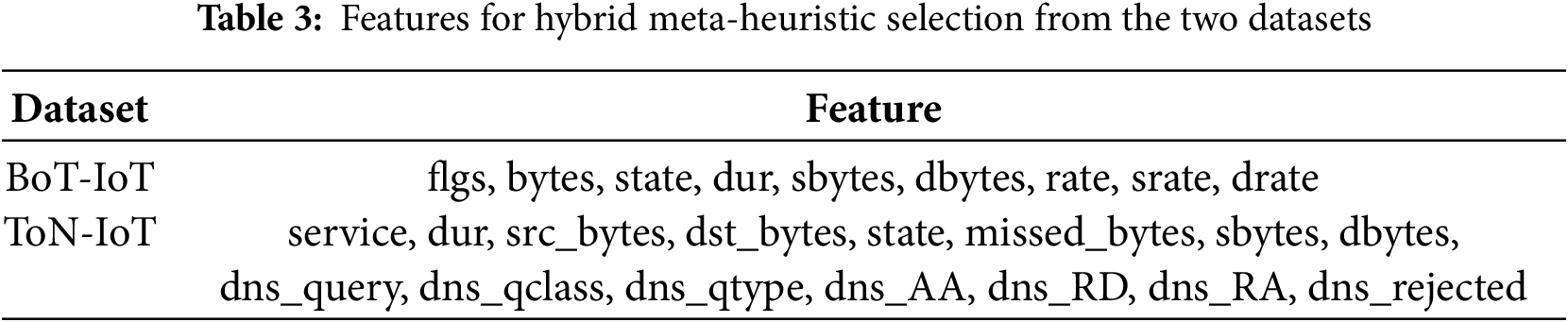

We unified features that had identical meanings but different names to address differences in feature naming between datasets. Table 3 presents the features for hybrid meta-heuristic feature selection in the BoT-IoT and ToN-IoT datasets.

The metadata primarily contain flow-level statistical information; therefore, we extracted IP header-related fields from raw packets to apply as network traffic features. The added fields include the IP version, header length, IP packet length, IP identification, fragment offset, fragmentation flags, time-to-live, IP checksum, time delta from the previous packet, and total packet length.

First, HyMNeT calculates the

Next, we performed a first integration by applying a weighted average proportional to the number of features for each raw packet feature and metadata feature

Finally, HyMNeT applies RVEA to search for the optimal balance point between

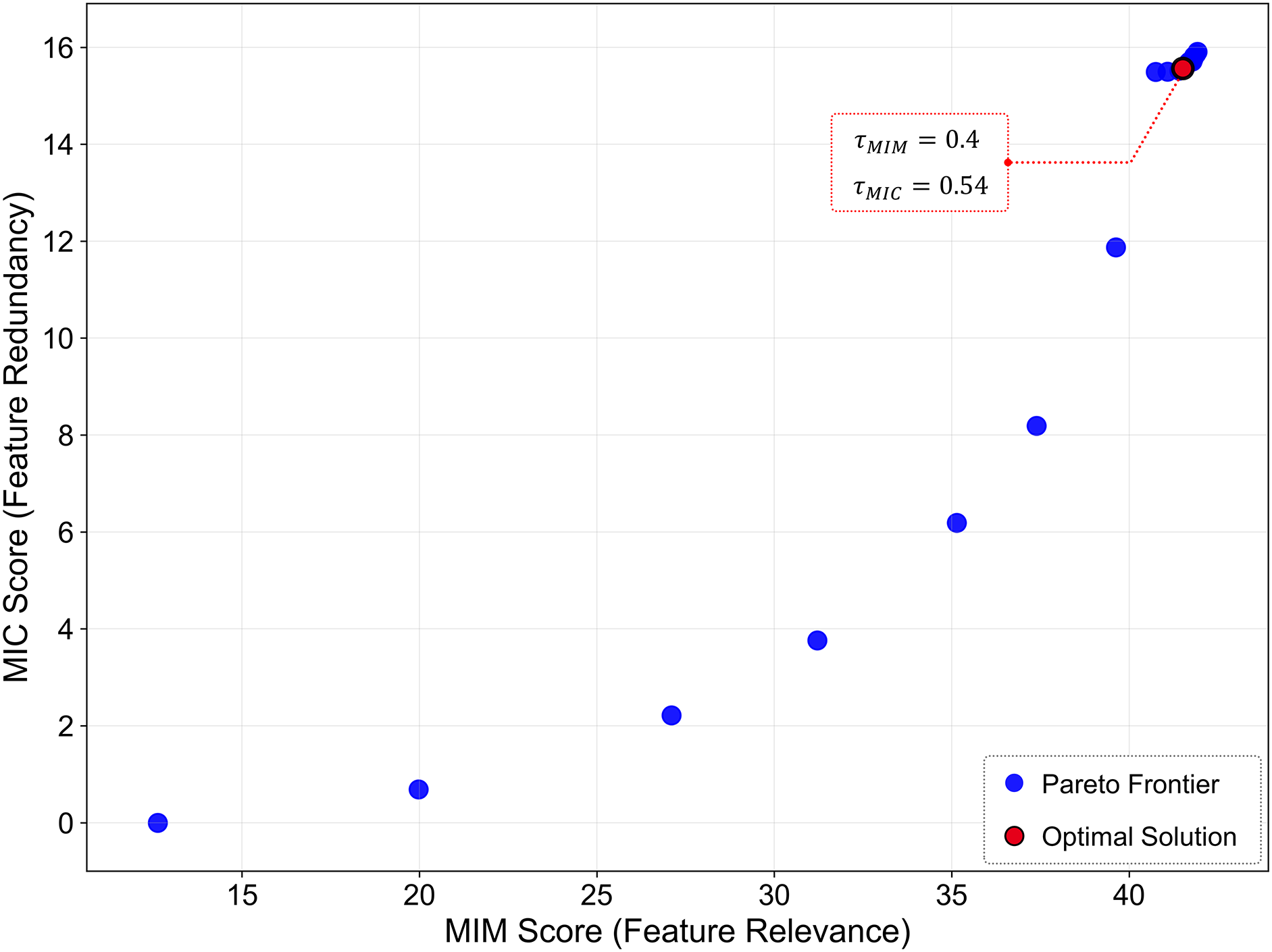

Fig. 2 visualizes the Pareto frontier calculated using RVEA, where each point represents the results for one threshold combination. The x-axis represents the feature relevance for label predictions based on

Figure 2: Pareto frontier for threshold combinations of MIM and MIC scores

The lower left area on the Pareto frontier represents cases with low MIM relevance and low redundancy, indicating relatively low information content and minimal overlap between features. In contrast, points in the upper right area have high MIM relevance and high redundancy, meaning abundant information content but redundant features. An analysis of the Pareto frontier results based on median values revealed that, when

4.2.3 Network Traffic Feature Preprocessing

The HyMNeT method constructs the final feature set based on the raw packet data extracted in the network traffic feature extraction stage, according to the selected network traffic feature subset. First, packets are grouped by source IP, destination IP, source port, destination port, and protocol, then sorted by timestamp to reconstruct the flow-level network traffic features. At this stage, some network traffic flows are short due to temporary connection attempts and transmission errors. This not only includes data unrelated to network usage patterns, but also causes additional overhead during network traffic pattern analysis [41]. Accordingly, we regarded short-term flow instances with fewer than five packets as noise and removed them. Additionally, most network environments operate based on IPv4 due to the high costs and compatibility problems associated with the IPv6 transition; thus, we excluded IPv6-related features from the analysis. The HyMNeT method maps raw packet data to the selected network traffic feature subset. Bytes correspond to the IP packet length, dur to time delta from the previous packet, flgs to TCP flags, frame.len to the total packet length, ip.checksum to IP checksum, and ip.id to IP identification. In contrast, rate represents the packet arrival frequency per unit time and is calculated as the reciprocal of the time delta from the previous packet. Moreover, sbytes, dbytes, srate, and drate are features that reflect the communication directionality and represent the number of bytes transmitted between the client and server and the transmission speed. This study generates features by distinguishing the communication direction based on well-known port numbers. Next, hexadecimal ip.id and ip.checksum were converted to decimal form, and min-max normalization was applied to all feature sets, scaling them to a range of

Table 5 reveals the number of network traffic flow units by attack type generated from the BoT-IoT and ToN-IoT datasets. A total of 6770 network traffic flow units were extracted from the BoT-IoT dataset, and 13,503 were from the ToN-IoT dataset. The length was limited by calculating the weighted median based on the frequency of the overall flow distribution, and the maximum flow length was set to 59 according to the ToN-IoT dataset, which had a lower weighted median.

4.2.4 Multivariate Feature-Based Intrusion Detection

The HyMNeT method detects malicious network traffic using multivariate network traffic features as input for four ML models. We evaluated the detection performance of the selected feature set using the DT, limited to a maximum tree depth of 10, whereas GBM employed 100 weak learners with a learning rate of 0.1. For XGBoost, the number of boosting rounds was set to 100 with a learning rate of 0.1, and RF was configured with 100 trees, each with a maximum depth of 10. All ML models employed cross-entropy loss as the loss function during training and validation processes to minimize errors.

This work employs accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score as evaluation metrics to assess the detection performance of HyMNeT, where TP, TN, FP, and FN represent the true positive, true negative, false positive, and false negative, respectively [42]. Accuracy evaluates whether HyMNeT correctly classifies malicious network traffic by attack type, as presented in Eq. (6):

Precision represents the ratio of correctly classified cases from the malicious network traffic predicted by HyMNeT, as in Eq. (7):

Recall represents the ratio of correctly predicted cases by HyMNeT from actual malicious network traffic, calculated in Eq. (8):

The F1-score evaluates the balance between the precision and recall, which have opposing characteristics, as in Eq. (9):

4.4 Intrusion Detection Results for the BoT-IoT Dataset

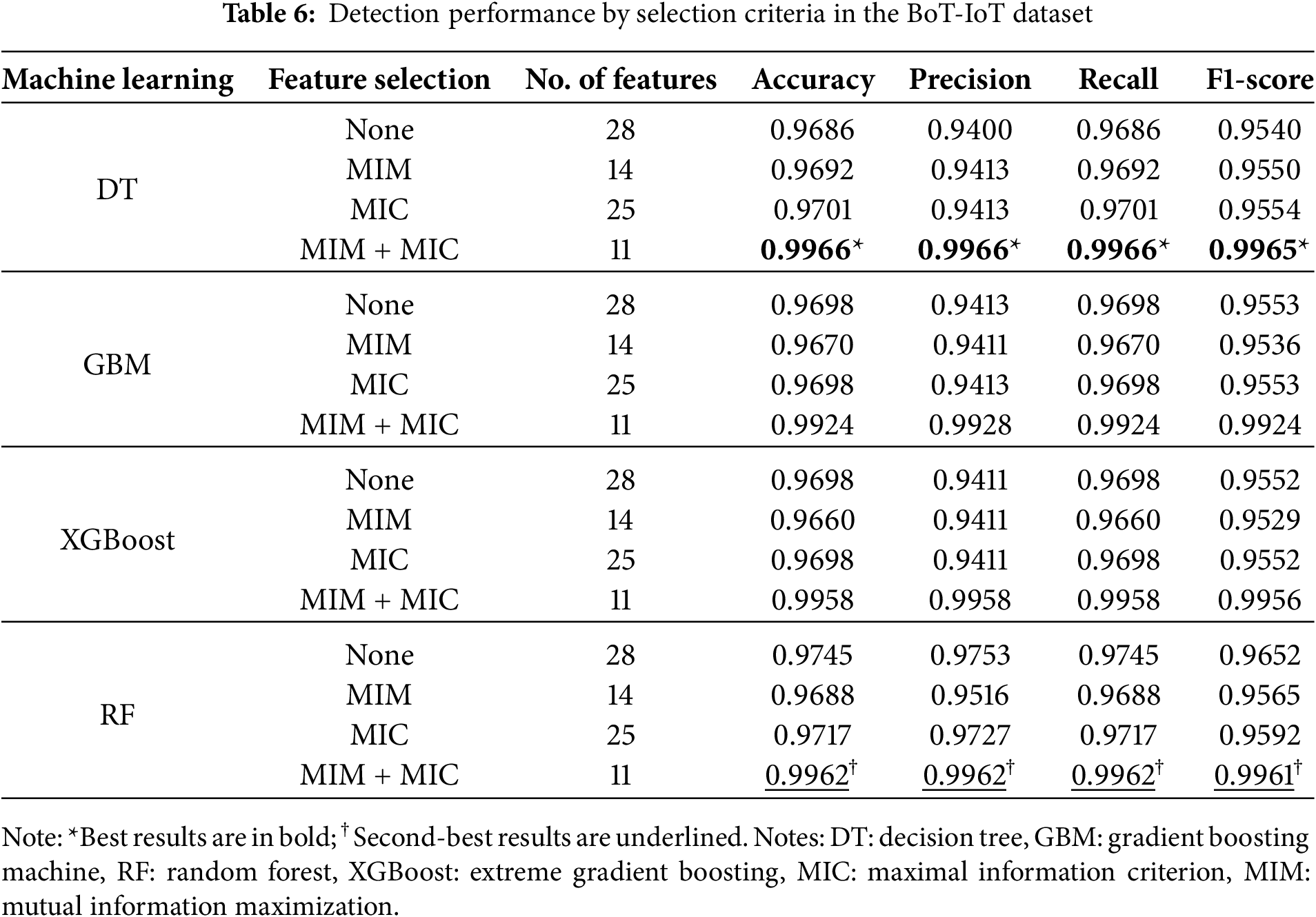

This section presents the detection results for HyMNeT on the BoT-IoT dataset. Among the 6770 network traffic flow units extracted in the network traffic feature preprocessing stage, 5416 were restructured as the training dataset, 677 as the validation dataset, and the remaining 677 as the testing dataset. Table 6 compares the detection performance for the DT, GBM, XGBoost, and RF methods according to the selection criteria.

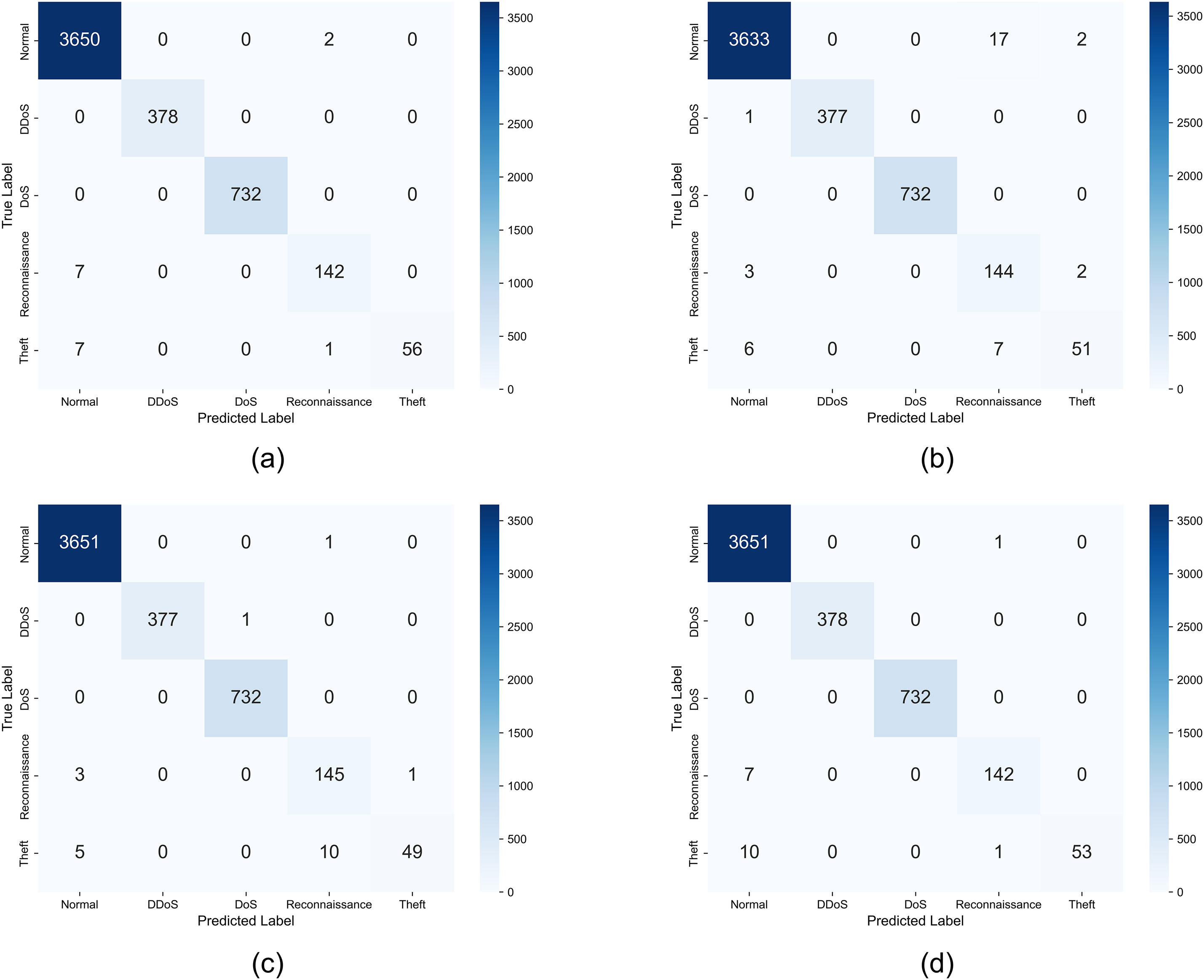

Overall, the MIM with MIC-based feature subsets demonstrated superior detection performance compared to the other selection criteria, as they simultaneously consider correlations between labels and feature redundancy. For the DT method, applying only the MIM-based feature selection improved performance compared to the baseline while reducing the total number of features by half. When MIM with MIC was applied, the model demonstrated excellent performance across all evaluation metrics. This result confirms that DT responds sensitively to features highly correlated with labels and that the feature selection approach of HyMNeT is effective. The performance of GBM and XGBoost degraded when there were many redundant features. When only MIM was applied, performance was lower than the baseline; however, when only MIC and MIM with MIC were applied, performance was maintained or significantly improved. The XGBoost method outperformed GBM because it reflects feature importance via regularization and sparsity-aware splits. The RF method performed best when using the MIM with MIC-based feature subsets, indicating robust operation via effective learning of combinations based on high-quality features. Fig. 3 visualizes the detection results by classifier for each label represented as confusion matrices after applying the MIM with MIC-based selection criteria to the BoT-IoT dataset.

Figure 3: Confusion matrix for BoT-IoT dataset: (a) decision tree, (b) gradient boosting machine, (c) extreme gradient boosting, and (d) random forest

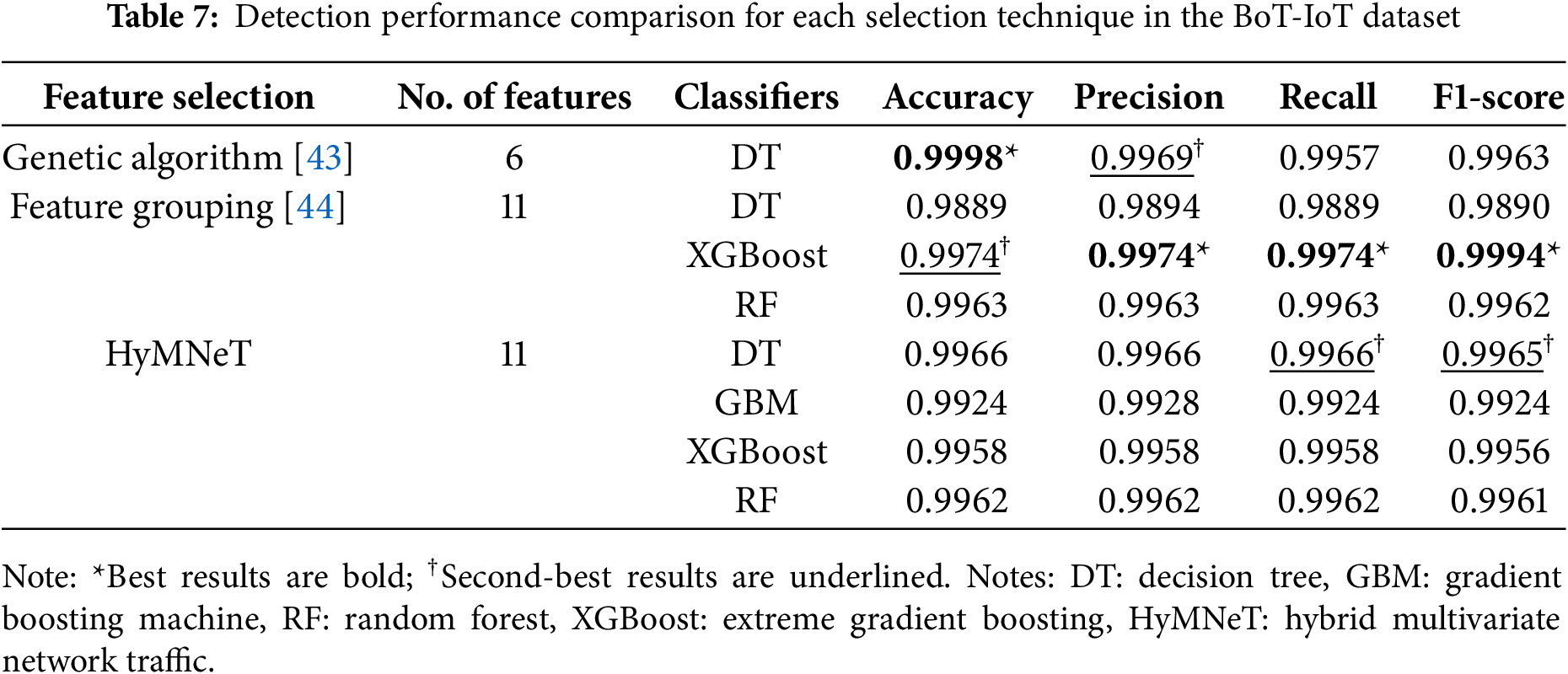

Each classifier demonstrated high detection rates for attack types with clear patterns and high traffic volume (e.g., DDoS and DoS). Particularly, DT and RF produced minimal false-positive rates for classifying normal traffic as malicious traffic, demonstrating high stability. Although reconnaissance and theft attacks with small sample sizes were partially classified as other malicious labels, all classifiers performed intrusion detection effectively. Table 7 compares the detection performance results between HyMNeT and existing studies that have employed the BoT-IoT dataset for intrusion detection.

The genetic algorithm-based [43] DT model achieved an accuracy of 0.9998 using six features selected from statistical information from network traffic flow units. Although this represents excellent results for DT-based detection models, the HyMNeT-based DT model demonstrated higher performance in terms of the recall and F1-score, achieving 0.9966 and 0.9965, respectively. This result indicates that HyMNeT constructed feature subsets capable of detecting attack types in a more balanced manner.

Feature grouping [44] selects only meaningful features. When applied to DT, feature grouping displayed lower detection performance than HyMNeT, indicating that HyMNeT selects effective features by simultaneously considering the label relevance and feature redundancy more effectively than existing techniques. Conversely, when XGBoost and RF were applied, the performance of the feature grouping technique was higher than that of HyMNeT, suggesting that some performance degradation occurred due to the limited feature combination diversity in tree-based models, as HyMNeT employed feature subsets with interfeature redundancy removed.

In the BoT-IoT dataset, HyMNeT demonstrated consistent superior performance across all ML classifiers by simultaneously optimizing feature-label correlation and inter-feature redundancy. Compared to existing studies, HyMNeT achieved stable detection performance with fewer features regardless of classifier type. Particularly, the balanced performance between recall and F1-score validates consistent effectiveness across various attack types.

4.5 Intrusion Detection Results for the ToN-IoT Dataset

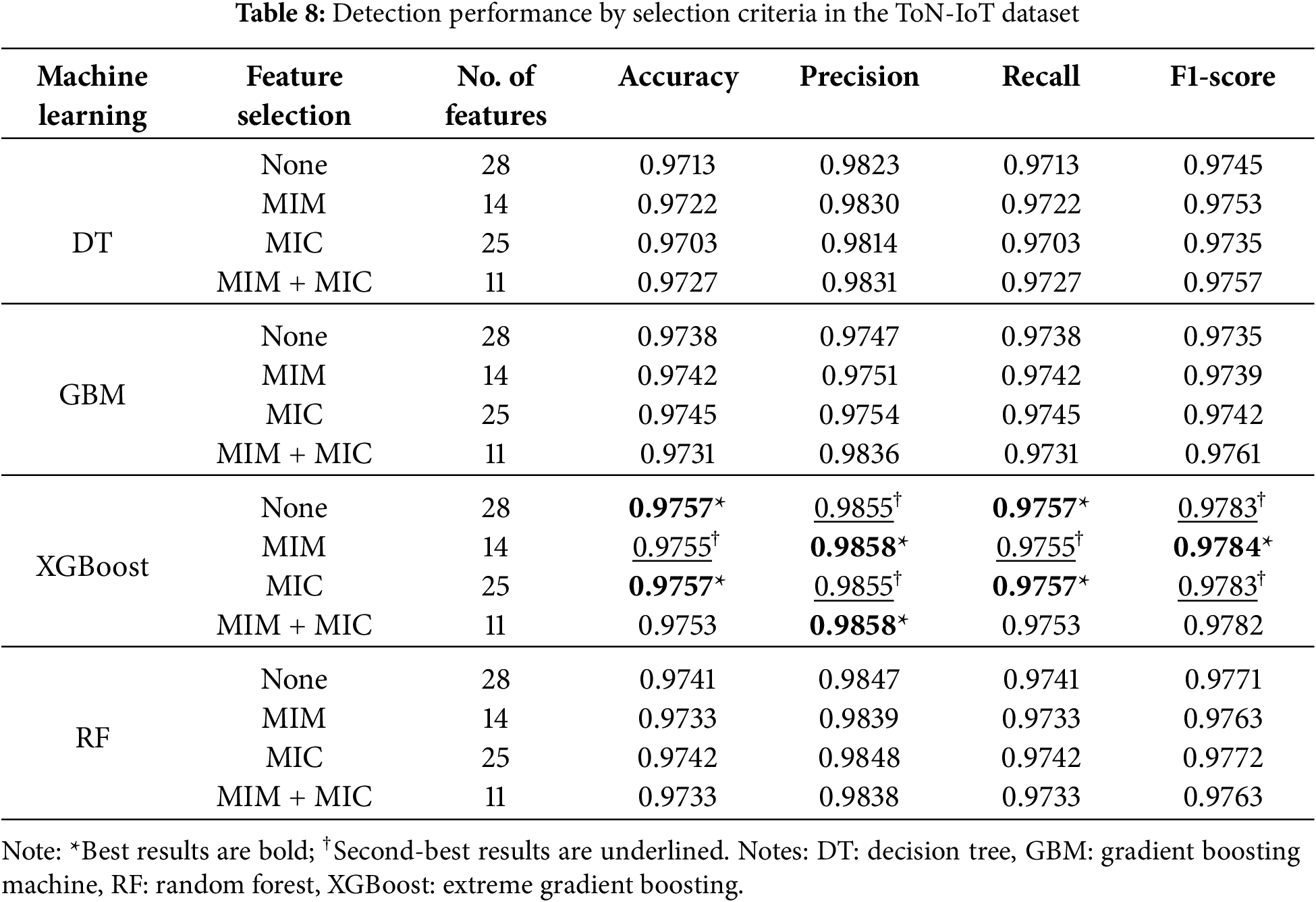

This section evaluates detection performance by restructuring 13,503 network traffic flow units extracted from the ToN-IoT dataset into 10,799 for the training dataset, 1352 for the validation dataset, and 1352 for the testing dataset. Table 8 compares the detection performance of each ML model by selection method (e.g., none, MIM, MIC, and MIM with MIC).

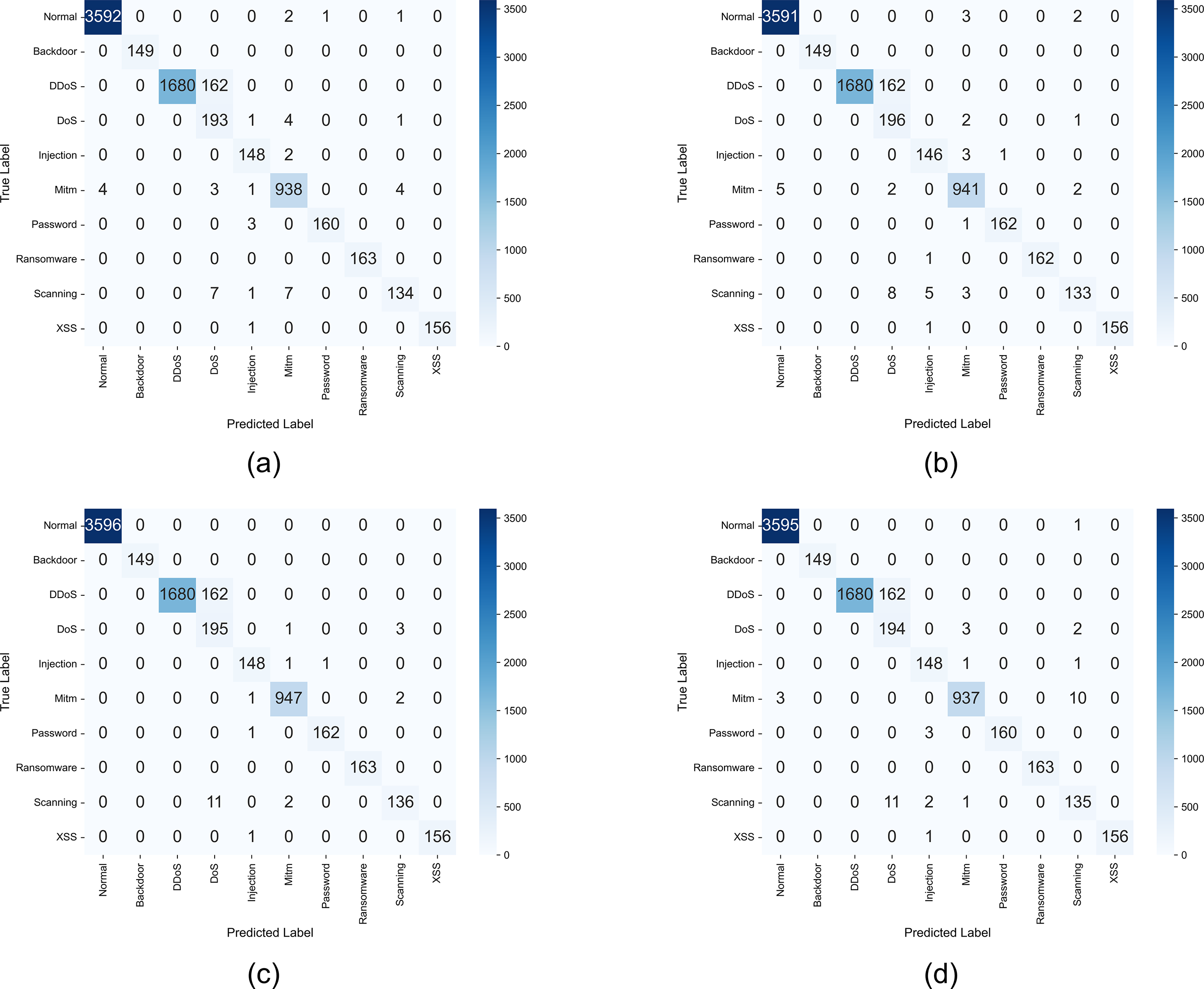

For DT, when MIM with MIC was applied, the overall detection performance was higher than that of MIM, as it considered feature importance and redundancy together. For GBM, when MIM with MIC was applied, accuracy and recall were low, but precision and F1-score were high. This result indicates that, although the overall accuracy was low due to class imbalance and diverse attack types in the ToN-IoT dataset, the detection was more balanced across classes based on the F1-score criteria. The XGBoost and RF methods with the MIC and the none criteria outperformed MIM with MIC in detection. Both models are tree-based ensemble structures that internally evaluate feature importance while optimizing splits, resulting in higher performance with the MIC and none-based feature subsets that have more features. In contrast, MIM with MIC was relatively low for XGBoost and RF because the number of features was limited to 11. Overall, MIM with MIC performed similarly to other selection criteria in most models while using relatively few features. Fig. 4 illustrates confusion matrices of the detection results by classifier for the ToN-IoT dataset with MIM with MIC-based selection criteria applied, facilitating a detailed examination of the results.

Figure 4: Confusion matrix for the ToN-IoT dataset: (a) decision tree, (b) gradient boosting machine, (c) extreme gradient boosting, and (d) random forest

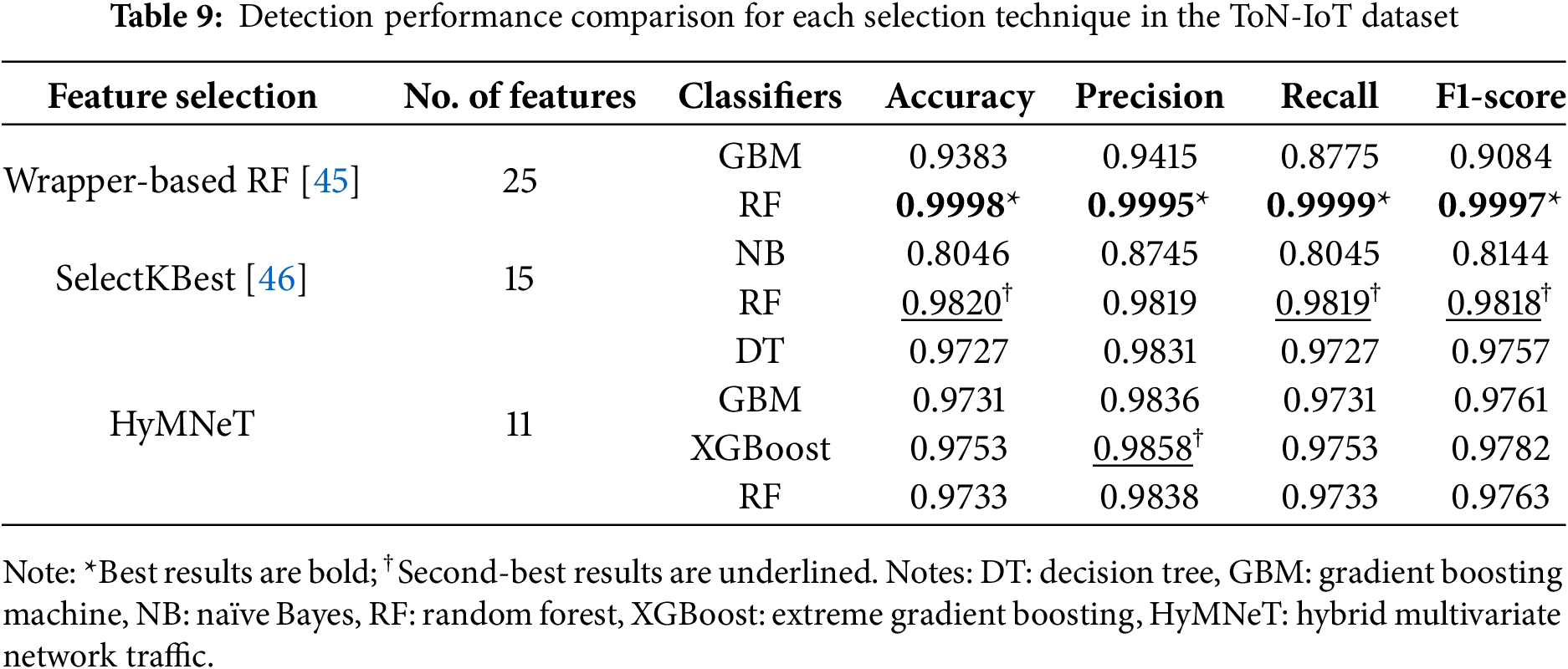

Analysis of the confusion matrices confirms the overall high accuracy, as most attack types were successfully classified. Notably, XGBoost displayed the most robust performance by learning while compensating for errors. This performance confirms that boosting-based models effectively detect complex network traffic patterns. Each classifier misclassified some scanning attacks as other types of attacks; however, overall, XGBoost demonstrated effective attack detection performance. Table 9 compares the performance of HyMNeT with existing studies that have performed malicious network traffic detection using the ToN-IoT dataset.

The wrapper-based RF technique [45] demonstrated excellent detection performance with an accuracy of 0.9998 and F1-score of 0.997 in the RF model using 25 features. However, when the same feature subset was applied to the GBM model, its performance was lower than that of the HyMNeT-based DT. Particularly, recall was low at 0.8775, indicating that detection bias occurred for some attack types.

The SelectKBest technique [46] selected 15 features and applied them to naïve Bayes (NB) and RF; however, in NB, the overall accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score were all below 0.9, indicating low detection performance. Conversely, when RF was applied, the model demonstrated excellent performance with an F1-score of 0.9818.

Despite the increased complexity and class imbalance in the ToN-IoT dataset, the HyMNeT-based models achieved F1-scores of 0.975 or higher in all DT, GBM, XGBoost, and RF methods with only 11 features, revealing consistent overall detection performance. Although the detection performance was lower than that of the SelectKBest-based RF [46], the fact that F1-scores of 0.97 or higher were maintained with a small number of features confirms that the feature selection technique of HyMNeT constructed efficient feature subsets relative to detection performance. Furthermore, in terms of computational efficiency, HyMNeT achieved fewer features compared to existing studies, enabling operation in resource-constrained AIoT environments.

This study proposes HyMNeT, a hybrid meta-heuristic approach that selects meaningful features and detects malicious network traffic to protect AIoT environments from network attacks. The HyMNeT method selects the top 40% of features with high correlation to the label through MIM and applies MIC to select only features with a similarity of 51% or less between features, constituting 11 multivariate network traffic feature sets. This multivariate feature set was trained on the DT, GBM, XGBoost, and RF algorithms to evaluate the intrusion detection performance on the BoT-IoT and ToN-IoT datasets. The experimental results demonstrated consistent and high detection performance, with average accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score values of 0.9952, 0.9953, 0.9952, and 0.9952, respectively, on the BoT-IoT dataset, and 0.9736, 0.9841, 0.9736, and 0.9766, respectively, on the ToN-IoT dataset.

HyMNeT achieved high detection performance with only a few features. This was accomplished by effectively selecting features of high importance and low redundancy from both raw packet data and statistical flow information. The experimental validation confirmed that flow-level extracted features, when fused with packet-level features, contribute to enhanced intrusion detection performance.

However, certain flow-level statistical features (e.g., mean packet size and number of flows with the same source IP) were excluded from this study due to the computational difficulty of the direct calculation at the packet level. Such a limitation can lead to a partial loss of feature information, potentially causing performance degradation in classifiers (e.g., XGBoost and RF). Additionally, further research is needed to address newly emerging sophisticated threats in rapidly evolving AIoT environments. To overcome these limitations, future research should extend the study by applying lightweight feature abstraction techniques with DL approaches. This integration would enable real-time estimation of flow-level statistical information while enhancing detection capabilities for novel attack patterns in dynamic AIoT environments.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was partly supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (RS-2023-00267476) and by the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy (MOTIE) and the Korea Institute for Advancement of Technology (KIAT) through the International Cooperative R&D program (No. P0028271).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Jueun Jeon; method, Jueun Jeon and Seungyeon Baek; investigation, Seungyeon Baek, Byeonghui Jeong and Jueun Jeon; software, Seungyeon Baek and Byeonghui Jeong; validation, Seungyeon Baek, Byeonghui Jeong, Jueun Jeon and Young-Sik Jeong; data curation, Seungyeon Baek and Jueun Jeon; writing—original draft preparation, Jueun Jeon and Seungyeon Baek; writing—review and editing, Seungyeon Baek, Byeonghui Jeong and Young-Sik Jeong; supervision, Young-Sik Jeong; project administration, Young-Sik Jeong. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are openly available from the Cyber Range Lab of the Center of UNSW Canberra Cyber at https://research.unsw.edu.au/projects/bot-iot-dataset (accessed on 01 January 2025) and https://research.unsw.edu.au/projects/toniot-datasets (accessed on 01 January 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Fu H, Rao J, Deng F, Wang Y, Zhao B, Liu Z, et al. AIoT: artificial intelligence and the Internet of Things for monitoring and prognosis of systems and structures. IEEE Trans Instrum Meas. 2025;74:9700232. doi:10.1109/TIM.2025.3557124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Nguyen-Da T, Nguyen-Thanh P, Cho MY. Real-time AIoT anomaly detection for industrial diesel generator based an efficient deep learning CNN-LSTM in industry 4.0. Internet Things. 2024;27:101280. doi:10.1016/j.iot.2024.101280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Son BD, Hoa NT, Chien TV, Khalid W, Ferrag MA, Choi W, et al. Adversarial attacks and defenses in 6G network-assisted IoT systems. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024;11(11):19168–87. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2024.3373808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Jeon J, Jeong B, Baek S, Jeong YS. TMaD: three-tier malware detection using multi-view feature for secure convergence ICT environments. Expert Syst. 2025;42(2):e13684. doi:10.1111/exsy.13684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Kil YS, Jeon YR, Lee SJ, Lee IG. Multi-binary classifiers using optimal feature selection for memory-saving intrusion detection systems. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2024;141(2):1473–93. doi:10.32604/cmes.2024.052637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Baek S, Jeon J, Jeong B, Jeong YS. Two-stage hybrid malware detection using deep learning. Hum-Centric Comput Inf Sci. 2021;11:1–14. doi:10.22967/HCIS.2021.11.027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Jeon J, Jeong B, Baek S, Jeong YS. Hybrid malware detection based on Bi-LSTM and SPP-net for smart IoT. IEEE Trans Ind Inform. 2022;18(7):4830–7. doi:10.1109/TII.2021.3119778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Jeon J, Park JH, Jeong YS. Dynamic analysis for IoT malware detection with convolution neural network model. IEEE Access. 2020;8:96899–911. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2995887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Alsoufi MA, Siraj MM, Ghaleb FA, Al-Razgan M, Al-Asaly MS, Alfakih T, et al. Anomaly-based intrusion detection model using deep learning for IoT networks. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2024;141(1):823–45. doi:10.32604/cmes.2024.052112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Jeon J, Baek S, Jeong B, Jeong YS. Early prediction of ransomware API calls behaviour based on GRU-TCN in healthcare IoT. Connect Sci. 2023;35(1):2233716. doi:10.1080/09540091.2023.2233716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Luo P, Chu J, Yang G. IP packet-level encrypted traffic classification using machine learning with a light weight feature engineering method. J Inf Secur Appl. 2023;75:103519. doi:10.1016/j.jisa.2023.103519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Hassan M, Haque ME, Tozal ME, Raghavan V, Agrawal R. Intrusion detection using payload embeddings. IEEE Access. 2022;10:4015–30. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3139835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Xu Y, Cao J, Song K, Xiang Q, Cheng G. FastTraffic: a lightweight method for encrypted traffic fast classification. Comput Netw. 2023;235:109965. doi:10.1016/j.comnet.2023.109965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Huoh TL, Luo Y, Li P, Zhang T. Flow-based encrypted network traffic classification with graph neural networks. IEEE Trans Netw Serv Manage. 2023;20(2):1224–37. doi:10.1109/TNSM.2022.3227500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Zhou Y, Cheng G, Jiang S, Dai M. Building an efficient intrusion detection system based on feature selection and ensemble classifier. Comput Netw. 2020;174:107247. doi:10.1016/j.comnet.2020.107247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Jia H, Liu J, Zhang M, He X, Sun W. Network intrusion detection based on IE-DBN model. Comput Commun. 2021;178:131–40. doi:10.1016/j.comcom.2021.07.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Davis RE, Xu J, Roy K. Classifying malware traffic using images and deep convolutional neural network. IEEE Access. 2024;12:58031–8. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3391022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Lin CY, Chen B, Lan W. An efficient approach for encrypted traffic classification using CNN and bidirectional GRU. In: 2022 2nd International Conference on Consumer Electronics and Computer Engineering (ICCECE); 2022 Jan 14–16; Guangzhou, China. doi:10.1109/ICCECE54139.2022.9712708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Wang H, Xu T, Yang J, Wu L, Yang L. Sessionvideo: a novel approach for encrypted traffic classification via 3D-CNN model. In: 2022 23rd Asia-Pacific Network Operations and Management Symposium (APNOMS); 2022 Sep 28–30; Takamatsu, Japan. [Google Scholar]

20. Xiao P, Yan Y, Hu J, Zhang Z. HMMED: a multimodal model with separate head and payload processing for malicious encrypted traffic detection. Secur Commun Netw. 2024;2024(1):8725832. doi:10.1155/2024/8725832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Cui S, Liu J, Dong C, Lu Z, Du D. Only header: a reliable encrypted traffic classification framework without privacy risk. Soft Comput. 2022;26(24):13391–403. doi:10.1007/s00500-022-07450-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Munshi A. Hybrid detection technique for IP packet header modifications associated with store-and-forward operations. Appl Sci. 2023;13(18):10229. doi:10.3390/app131810229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Peng H, Long F, Ding C. Feature selection based on mutual information: criteria of max-dependency, max-relevance, and min-redundancy. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2005;27(8):1226–38. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2005.159. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Zhou K, Wang H, Zhao WX, Zhu Y. S3-rec: self-supervised learning for sequential recommendation with mutual information maximization. In: d’Aquin M, Dietze S, Hauff C, Curry E, Cudré-Mauroux P, editors. Proceedings of the 29th ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management; 2020 Oct 19–23; Virtual. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2020. p. 1893–902. doi:10.1145/3340531.3411954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Sun G, Li J, Dai J, Song Z, Lang F. Feature selection for IoT based on maximal information coefficient. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2018;89:606–16. doi:10.1016/j.future.2018.05.060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Cheng R, Jin Y, Olhofer M, Sendhoff B. A reference vector guided evolutionary algorithm for many-objective optimization. IEEE Trans Evol Comput. 2016;20(5):773–91. doi:10.1109/TEVC.2016.2519378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Velliangiri S, Bhuvaneswari Amma NG, Baik NK. Detection of DoS attacks in smart city networks with feature distance maps: a statistical approach. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023;10(21):18853–60. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2023.3264670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Ding Z, Zhong G, Qin X, Li Q, Fan Z, Deng Z, et al. MF-Net: multi-frequency intrusion detection network for Internet traffic data. Pattern Recognit. 2024;146:109999. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2023.109999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Jiang X, Zhang HR, Zhou Y. Multi-granularity abnormal traffic detection based on multi-instance learning. IEEE Trans Netw Serv Manage. 2024;21(2):1467–77. doi:10.1109/TNSM.2023.3322152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Quinlan JR. Induction of decision trees. Mach Learn. 1986;1(1):81–106. doi:10.1007/BF00116251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Friedman JH. Greedy function approximation: a gradient boosting machine. Ann Stat. 2001;29(5):1189–232. doi:10.1214/aos/1013203451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Adler AI, Painsky A. Feature importance in gradient boosting trees with cross-validation feature selection. Entropy. 2022;24(5):687. doi:10.3390/e24050687. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Chen T, Guestrin C. XGBoost: a scalable tree boosting system. In: Krishnapuram B, Shah M, Smola AJ, Aggarwal C, Shen D, Rastogi R, editors. Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; 2016 Aug 13–17; San Francisco, CA, USA. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2016. p. 785–94. doi:10.1145/2939672.2939785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Breiman L. Random forests. Mach Learn. 2001;45(1):5–32. doi:10.1023/A:1010933404324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Koroniotis N, Moustafa N, Sitnikova E, Turnbull B. Towards the development of realistic botnet dataset in the Internet of Things for network forensic analytics: Bot-IoT dataset. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2019;100:779–96. doi:10.1016/j.future.2019.05.041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Moustafa N, Ahmed M, Ahmed S. Data analytics-enabled intrusion detection: evaluations of ToN_IoT linux datasets. In: Wang G, Ko R, Bhuiyan MZA, Pan Y, editors. 2020 IEEE 19th International Conference on Trust, Security and Privacy in Computing and Communications (TrustCom); 2021 Dec 29–Jan 1; Guangzhou, China. p. 727–35. doi:10.1109/TrustCom50675.2020.00100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Wireshark. Tshark(1) manual page. [cited 2024 May 5]. Available from: https://www.wireshark.org/docs/man-pages/tshark.html. [Google Scholar]

38. Hu Y, Zeng Z, Song J, Xu L, Zhou X. Online network traffic classification based on external attention and convolution by IP packet header. Comput Netw. 2024;252:110656. doi:10.1016/j.comnet.2024.110656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Kong X, Zhou Y, Xiao Y, Ye X, Qi H, Liu X. iDetector: a novel real-time intrusion detection solution for IoT networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024;11(19):31153–66. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2024.3416746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Nie F, Liu W, Liu G, Gao B. M2VT-IDS: a multi-task multi-view learning architecture for designing IoT intrusion detection system. Internet Things. 2024;25:101102. doi:10.1016/j.iot.2024.101102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Lv S, Wang C, Wang Z, Wang S, Wang B, Zhang Y. AAE-DSVDD: a one-class classification model for VPN traffic identification. Comput Netw. 2023;236:109990. doi:10.1016/j.comnet.2023.109990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Jeon J, Jeong B, Baek S, Jeong YS. Static multi feature-based malware detection using multi SPP-net in smart IoT environments. IEEE Trans Inf Forensics Secur. 2024;19:2487–500. doi:10.1109/TIFS.2024.3350379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Liu X, Du Y. Towards effective feature selection for IoT botnet attack detection using a genetic algorithm. Electronics. 2023;12(5):1260. doi:10.3390/electronics12051260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. He M, Huang Y, Wang X, Wei P, Wang X. A lightweight and efficient IoT intrusion detection method based on feature grouping. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024;11(2):2935–49. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2023.3294259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Moustafa N. A new distributed architecture for evaluating AI-based security systems at the edge: network TON_IoT datasets. Sustain Cities Soc. 2021;72:102994. doi:10.1016/j.scs.2021.102994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Almotairi A, Atawneh S, Khashan OA, Khafajah NM. Enhancing intrusion detection in IoT networks using machine learning-based feature selection and ensemble models. Syst Sci Control Eng. 2024;12(1):2321381. doi:10.1080/21642583.2024.2321381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools