Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Efficient Malicious QR Code Detection System Using an Advanced Deep Learning Approach

1 Department of Information Systems, Faculty of Computing and Information Technology, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, 21589, Saudi Arabia

2 Department of Cybersecurity, Faculty of Computer & Information Technology, Jordan University of Science and Technology, P.O. Box 3030, Irbid, 22110, Jordan

3 Department of Information Technology, Faculty of Computing and Information Technology, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, 21589, Saudi Arabia

4 Department of Networks and Communications Engineering, College of Computer Science and Information Systems, Najran University, Najran, 61441, Saudi Arabia

5 Department of Computer and Information Technology, The Applied College, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, 21589, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Author: Qasem Abu Al-Haija. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Next-Generation Intelligent Networks and Systems: Advances in IoT, Edge Computing, and Secure Cyber-Physical Applications)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(1), 1117-1140. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.070745

Received 23 July 2025; Accepted 28 September 2025; Issue published 30 October 2025

Abstract

QR codes are widely used in applications such as information sharing, advertising, and digital payments. However, their growing adoption has made them attractive targets for malicious activities, including malware distribution and phishing attacks. Traditional detection approaches rely on URL analysis or image-based feature extraction, which may introduce significant computational overhead and limit real-time applicability, and their performance often depends on the quality of extracted features. Previous studies in malicious detection do not fully focus on QR code security when combining convolutional neural networks (CNNs) with recurrent neural networks (RNNs). This research proposes a deep learning model that integrates AlexNet for feature extraction, principal component analysis (PCA) for dimensionality reduction, and RNNs to detect malicious activity in QR code images. The proposed model achieves both efficiency and accuracy by transforming image data into a compact one-dimensional sequence. Experimental results, including five-fold cross-validation, demonstrate that the model using gated recurrent units (GRU) achieved an accuracy of 99.81% on the first dataset and 99.59% in the second dataset with a computation time of only 7.433 ms per sample. A real-time prototype was also developed to demonstrate deployment feasibility. These results highlight the potential of the proposed approach for practical, real-time QR code threat detection.Keywords

Quick response (QR) codes became one of the most used machine-readable codes in daily life [1]. They are a two-dimensional matrix form of barcode initiated by the Denso Wave company based in Japan in 1994 [2]. This two-dimensional barcode can encode several data types, including binary data, symbols, characters, letters, numbers, etc. The QR codes are used to display text, have wireless connection details, or want to access a uniform resource locator (URL) linked to a web source [3]. The QR codes are used in different domains, including identifying products, advertisements, payments, and tracking [4].

The popularity and wide usage of QR codes can create security issues. This has attracted cyber attackers to start looking for methods and ways to misuse them for attack purposes [2,5]. The attackers started attacking the QR codes in 2011, and one of the first attempts was a malicious attack at the end of September 2011 [6]. Attackers use QR codes integrated with malicious links to route users to malicious websites [2]. Some internet users do not have the skills to access the internet safely; they cannot differentiate between safe and malicious links and websites [7]. The attackers succeeded by using the QR codes in their attacks because of the unreadability of the code by humans, as they needed QR code scanners to scan the code [8,9]. The link in the QR code redirects the user to a site that has been altered by attackers who aim to steal the important information of the victims [10]. Recently, there has been a rise in QR code phishing attacks. The H1 2024 threat intelligence report from Abnormal Security states that approximately 89.3% of QR code phishing attacks are designed to obtain user credentials, with the C-suite being 42 times more likely to be the target than the typical employee [11]. These attacks are often hidden as communications from reliable platforms, like Microsoft. Furthermore, Keepnet Labs noted that in 2023, the number of QR-based phishing incidents increased by 587%. The fraudulent QR codes are also placed on parking meters, EV charging stations and restaurant tables that redirect users to malicious websites or prompt them to download malware.

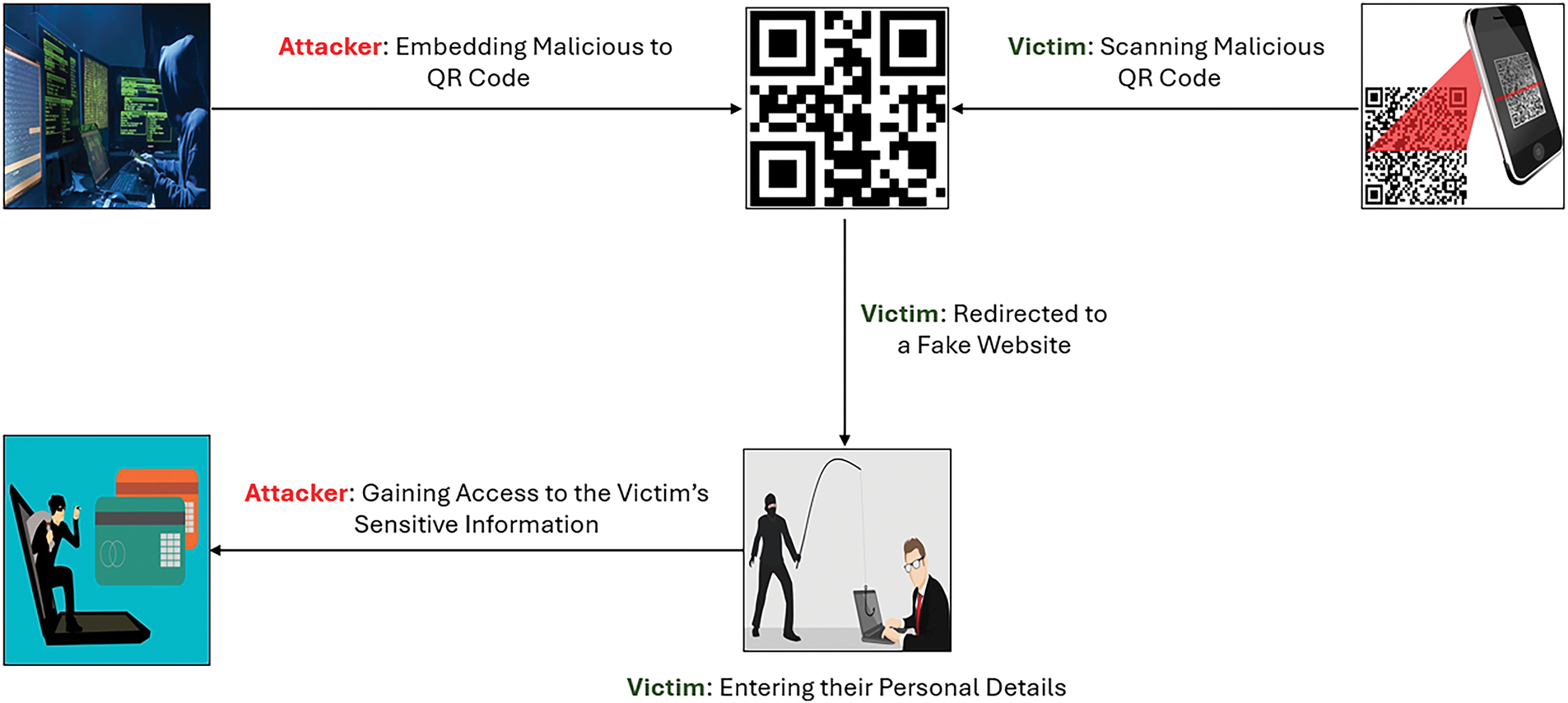

Several possible attack scenarios can occur depending on whether an automated program or a human operates the QR reader. These attacks include command injections, SQL injections, malware propagation, and phishing. Additionally, there are other types of attacks on QR codes, namely barcode tampering and counterfeiting, barcode-in-barcode attacks, cross-site scripting attacks (XSS), and reader applications attacks [12,13]. Also, it is possible to have attacks on the scanner application [14,15]. There are many phishing attacks where the attackers encode a phishing link in a QR code [16]. Phishing can be considered a common attack when using QR codes, where the user reads the QR code using a scanner on their mobile. They navigate to a seemingly authentic phishing link, which aims to obtain the user’s crucial data, including login credentials and potentially financial details like credit card numbers and expiration dates [17]. Attackers often use malicious links when delivering malware to software, and the adoption of QR codes with malware propagation is becoming a growing concern [2]. Attackers can infect users’ systems for harmful purposes, including worms, Trojan horses, botnets, spyware, ransomware, and viruses [18]. Fig. 1 depicts an attack targeting a QR code, illustrating the steps involved in a typical QR code phishing attempt.

Figure 1: Malicious QR codes attack flow

The process begins with the attacker generating a malicious QR code and embedding a phishing website. When a victim scans the malicious QR code using their mobile device, they are redirected to a fake website created by the attacker. The victim is then tricked into entering their personal information on the fake website, such as their username, password, and bank account details. Consequently, the attacker accesses the victim’s sensitive information [19].

The available security techniques for identifying QR with malicious URLs focus on web browsers’ security. The accuracy and effectiveness of the systems are based on the web browser’s ability to detect malicious URLs [20]. Simple detection browsers’ methods focus on an approach called blacklisting [21], which is a common approach, but it has limitations as it cannot identify the newly generated malicious URLs. Recently, some scanners started using machine learning methods to detect malicious URLs [2]. In addition, adversarial works often simulate cyberattacks against available deep learning methods, including AlexNet, LeNet, VGG, ResNet, and Inception [22]. In addition, various datasets have been used, including the ImageNet dataset, CIFAR dataset, and MNIST dataset. ImageNet has been used in most literature experiments because of the dataset’s volume, which comprises around 14 million images and 1000 classes [22]. Therefore, there is a need for a solution that uses the power of deep learning models to detect malicious activity while maintaining the computation process, as the models might require high computation process.

This research proposes a deep learning model that integrates AlexNet, principal component analysis (PCA), and recurrent neural networks (RNNs) to detect malicious activity in QR code images. Unlike prior CNN–RNN studies in general cybersecurity domains, our work is novel in that it directly addresses QR code security. The key novelty of the proposed approach lies in its ability to combine efficient feature extraction with reduced computational overhead while maintaining high classification accuracy. The main contributions of this study are as follows:

– We extract critical features from QR code images using the pre-trained AlexNet model to capture meaningful visual patterns.

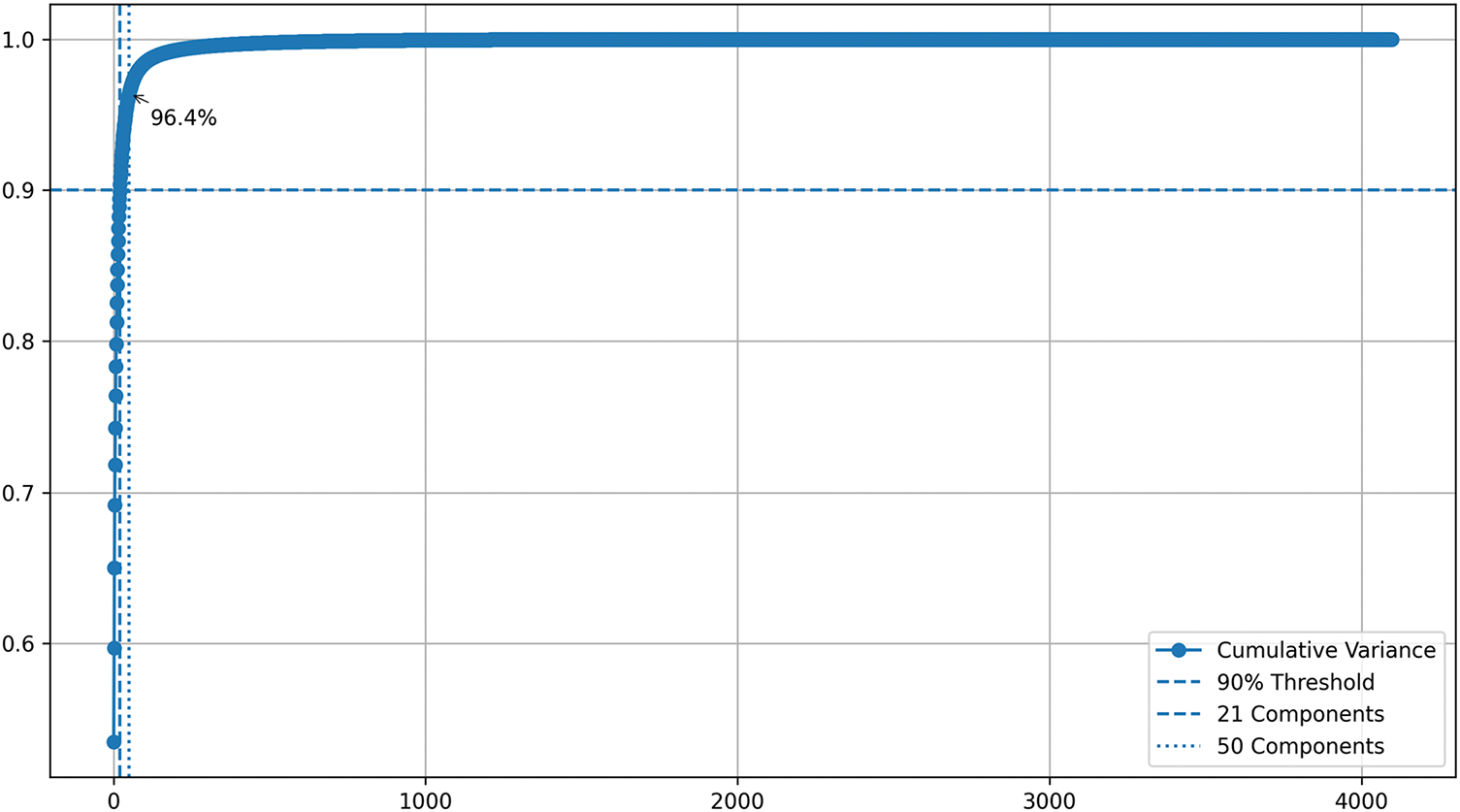

– We apply PCA to reduce the dimensionality of the extracted features, ensuring a compact and informative feature set. Therefore, combining PCA with AlexNet reduces 4096-dimensional feature vectors to 50 components, preserving ≈96.4% of the variance. This design achieves high accuracy while significantly lowering computational cost.

– We evaluate the gated recurrent unit (GRU) and long short-term memory (LSTM) against end-to-end CNN models and traditional machine learning baselines, highlighting the advantages of sequential modeling on compact feature sequences.

– GRU achieved 99.81% of classification accuracy on the first dataset and 99.59% on the second dataset outperforming LSTM and traditional classifiers, while maintaining an average inference time of 7.433 ms per sample.

– We develop a real-time web-based prototype using Streamlit, and discuss the challenges of robustness against adversarial, noisy, or distorted QR codes.

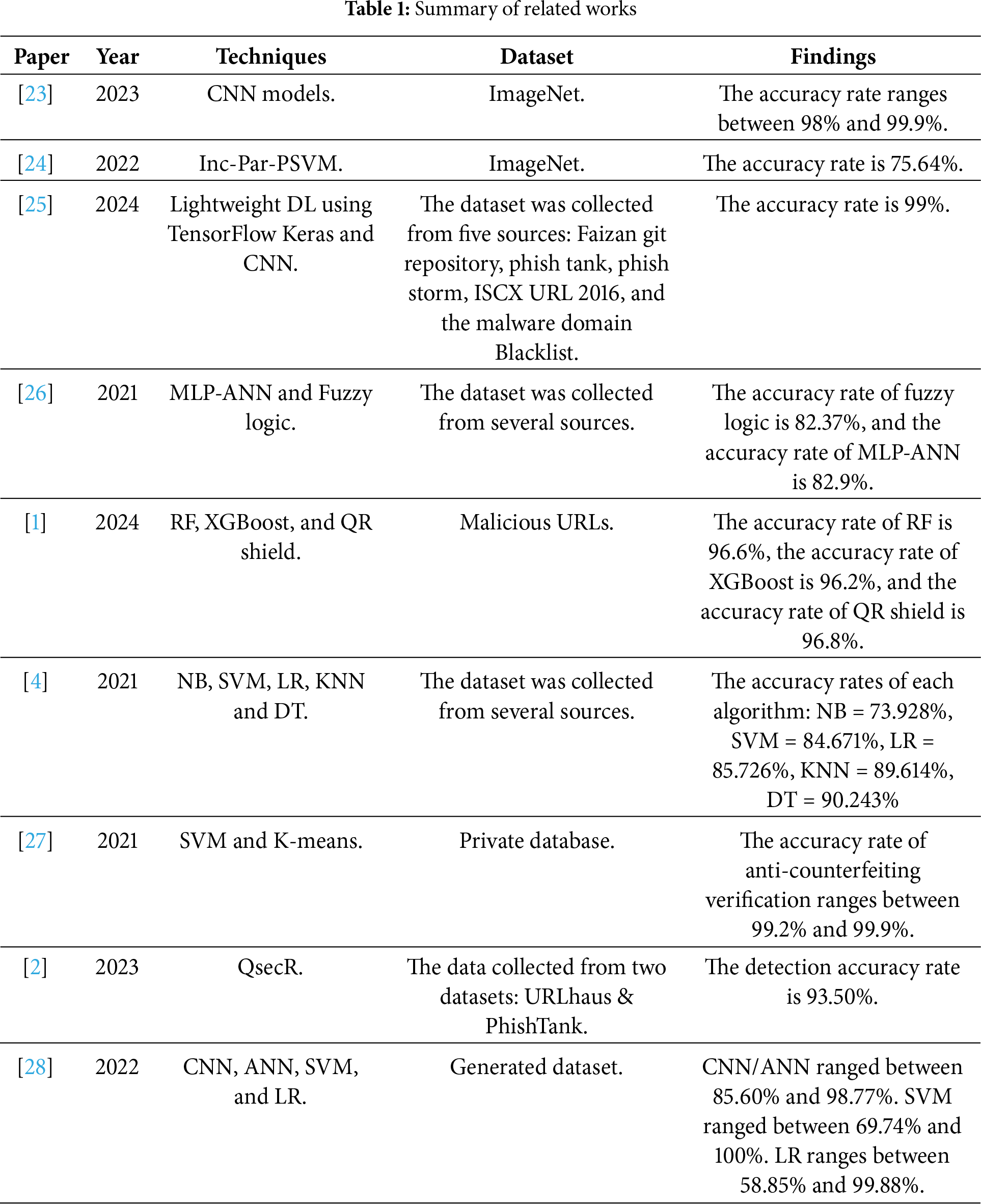

This section will present related research on cybersecurity methods, frameworks, and techniques for detecting abnormalities in QR codes, including those involving malicious URL links. Several papers have been reviewed to explore the ideas in the field and the strategies used when detecting and classifying cybersecurity threats. The discussion also includes the datasets used in the literature, along with the findings from these research works. The authors in [23] implemented several types of CNN architectures, including VGG16, ResNet, MobileNetv2, GoogleNet, DenseNet201, AlexNet, and other pre-trained CNN models to evaluate their model’s ability to predict the QR codes source of the printer while maintaining a high rate of accuracy. Their pre-trained CNN models have been tested and trained on a dataset called ImageNet. They used three optimizer types: Adam, RMSprop, and SGDM. According to their results, they achieved the highest accuracy rate with MobileNetv2 using RMSprop, which was 99.9% with color QR.

The researchers in [24] suggested a new method called Inc-Par-PSVM to train a proximal support vector machine that can work with large image data on small devices like Jetson Nano. They tested their method using the ImageNet dataset and found that the Inc-Par-PSVM algorithms on edge devices performed better than linear SVM algorithm run on personal computers. Their model achieved an accuracy of 75.64%.

The work in [25] proposed a method to help secure the codes utilized for identification and advertisements. They explored utilizing a lightweight DL model to identify attacks built into the QR codes. Their model classified the QR codes into malware, phishing, and normal. They collected data from several sources, including Faizan’s GitHub, Phish Tank, and phish storm, ISCX URL 2016, malware domain Blacklist. They achieved an accuracy of 99%. The findings of the work show that their model effectively differentiates phishing and normal QR codes from malicious ones.

The researchers in [26] proposed a method for identifying malicious URLs in QR codes. Their dataset has 90 thousand malicious and benign URLs gathered from several sources. In addition, two classifiers are applied and compared, such as a multilayer perception and artificial neural network (MLP-ANN) on the dataset. Based on the results, MLP-ANN has outperformed the fuzzy logic classifier and achieved an accuracy rate of 82.9%, which is higher than the fuzzy logic, which achieved an accuracy rate of 82.37%.

The authors in [1] introduced a shield for QR codes; they designed a model based on two machine learning algorithms, Random Forest and XGBoost, to detect cybersecurity vulnerabilities embedded in QR codes. Their shield of QR utilizes ML algorithms to detect and identify malicious that are in QR codes accurately. They have used a benchmark dataset called Malicious URLs. Their results show that their model has achieved an accuracy of 96.8%. The QR shield has outperformed the accuracy of RF, XGBoost, and existing works. The study in [4] introduced an approach to identify malicious URLs embedded in QR codes, two-dimensional codes, and one-dimensional barcodes. They proposed an attack that depended on the counterfeiting of the barcode, which might be utilized in performing attacks online. They collected a dataset from several sources. They utilized various classifiers, including Naive Bayes (NB), support vector machine (SVM), logistic regression (LR), k-nearest neighbors (KNN), and Decision Tree (DT). Their results indicate that DT has outperformed other algorithms with an accuracy of 90.243%.

The work in [27] presented an anti-counterfeiting model for the Internet of Things (IoT) that utilizes a QR code combined with visual features. Visual features are important for ensuring the authenticity of goods that use QR codes for tracing and tracking. Their model uses statistics and machine learning algorithms, including SVM, Mahalanobis distance, Otsu, and K-means. Their model integrates all the statistics and machine learning algorithms for anti-counterfeiting. They have used a private database to collect data in an industry based on real-life products. Their model achieved the highest accuracy rate of 99.9%.

The authors in [2] proposed a framework for detecting malicious URLs called QsecR, a private and secure QR-code scanner. They implemented the framework in Android as a QR code scanner application depending on already defined feature classification by using 39 classes, including content-based features, host-based features, lexical, and blacklist. They used a dataset with around 4 thousand real URLs collected from PhishTank and URLhaus. They used supervised batch and online machine learning classifiers, although they mentioned the methods they used directly in the paper when referring to previous papers.

The researchers in [28] started their approach by generating a dataset that comprised 10 thousand QR code pictures of various sizes. Next, they introduced various types of noise, including Gaussian, local variance, salt, Poisson, speckle, pepper, and a combination of salt and pepper, resulting in a dataset that contained 80 thousand images. They have used classifiers, including logistic regression (LR), SVM, and CNN, to detect noisy images and differentiate them from the original. Then, they integrated an analysis of histogram density to find the most important features: 256, followed by artificial neural networks (ANN), SVM, and LR. Their experiments included 4 classes, 6 classes, and 8 class classification problems. According to the results, histogram analysis was useful in improving the accuracy of classifiers, particularly SVM, which has achieved an accuracy of 100% with 4 class and 6 class problems. Table 1 shows the summary of related works mentioned above, including paper references, techniques used in the paper, the datasets used, and the findings.

The study in [29] allocated priority coefficients and feature evaluation techniques to introduce a framework for malicious URL detection based on preset static feature categorization. Their feature classification includes 42 classes, such as content-based, host-based, lexical, and blacklist characteristics. In order to validate their model, they gathered a dataset from dataset 1 and dataset 2 [29] and from malware and phishing websites such as PhishTank and URLhaus. They used three supervised machine learning techniques namely Bayesian Network (BN), Random Forest (RF) and SVM to evaluate the performance of proposed framework. Their framework achieved an accuracy of 98.95% and it shows that their framework outperforms the above-mentioned three supervised ML approaches. The authors in [30] proposed URLNet that is an end-to-end deep learning system that uses the URL itself to build a nonlinear URL embedding for malicious URL detection. The URL is embedded in a jointly optimized framework; they used Convolutional Neural Networks on the URL strings’ words and characters. Also, they proposed sophisticated word embeddings to address the issue of an excessive number of uncommon terms. They carried out comprehensive experiments on a sizable dataset with a large corpus of labeled URLs that are collected from VirusTota [31] (antivirus group) and demonstrated a notable improvement in performance over current techniques. Additionally, they conducted tests to assess the functionality of different URLNet components. Researchers in [32] proposed a malicious URL detection model using a dynamic CNN (DCNN) that improves feature extraction based on input length and depth by adding a folding layer and substituting k-max pooling for conventional pooling. A stacked CNN, a DCNN, and a DCNN with field extraction were the three classifiers that were put into the experiment. They gathered datasets from Alexa, GitHub, UCI, and Kaggle. DCNN, with field extraction produced the best performance results with an accuracy rate of 98.7%.

Most of the literature focused on detecting malicious activity of QR codes and did not focus on the computational process of QR codes. The computational process of the QR code is critical as the QR code image is in a 2D form, which makes it computationally complex. This can be more challenging when an image is transmitted over the network or when a system requires a fast response from the user, so it will take time to analyze and provide the results. However, in our proposed model, we addressed this issue by transforming the 2D image into a 1D form, which is less complex, and dimensionality reduced without compromising the classification accuracy of identifying malicious QR activity.

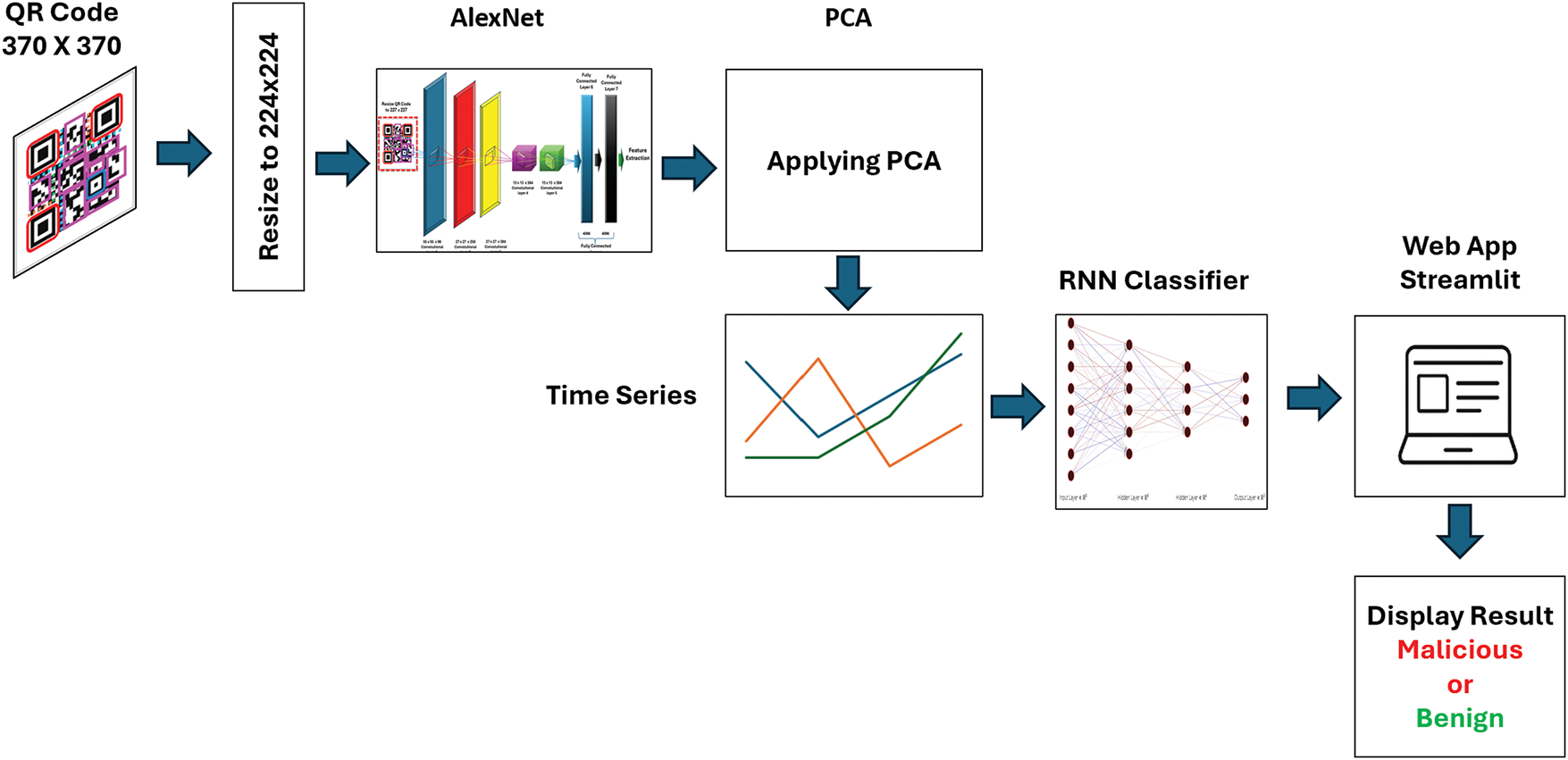

This section presents the research methodology. The primary objective of this study is to propose an efficient deep learning-based model that can extract trend features from QR codes and then detect malicious activity using RNNs such as GRU and LSTM. Notably, GRU and LSTM use input in the form of time series, which is 1-dimensional data, and the QR code is in 2-dimensional form. Therefore, features from the QR code need to be extracted in a form acceptable for the GRU and the LSTM models. Also, to take advantage of processing reduced data in a 1-dimensional rather than a 2-dimensional format, since 2D is more complex. This section starts by presenting the entire architecture of the proposed model to outline the key components and workflow. Next, it provides information about the structure of the QR code. After that, it discusses using AlexNet networks to extract features from the QR code. Then, it shows the use of the PCA technique to reduce the dimensionality of the extracted features. Finally, a real-time web-based application was implemented using Streamlit to explore the potential of the model for real-world deployment scenarios.

3.1 Proposed Model Architecture

The overall architecture of the proposed model is illustrated in Fig. 2. The figure shows the entire process of the proposed model. Initially, the QR code with a size of 370 × 370 is resized to 224 × 224 to be fed to the AlexNet model, which retrieves important information from the QR code. The output of AlexNet is the extracted features, which have a size of 1 × 4096. These features are passed into the PCA model, which is responsible for reducing the dimensionality of the data that AlexNet processed. The output of PCA is reduced by data with the size of 1 × 50, as the number of PCA components defined is 50. Then, the reduced data is formed to the time series format before passing it to RNN models. Time series classification is a specialized data mining task involving categorizing time-dependent sequences. Unlike traditional classification, where individual features are treated independently, the temporal order of data points in time series is crucial. Time series classification assigns a label to a given time series by training a model on a labeled dataset. Performing classification using time series data provides valuable insights for informed decision-making by identifying patterns and trends within the data [33]. This work utilizes LSTM and GRU models that accept time series data as input. LSTM is a recurrent neural network that efficiently handles sequential data. LSTM captures long-term data dependencies; therefore, LSTM is effective with time series analysis and image processing. LSTM combines cells of memory and mechanisms of gating. LSTM is utilized in many applications because it manages long-term dependencies and processes sequential data [34]. GRU is another recurrent neural network alternative to LSTM. In GRU, LSTM’s architecture is simplified by reducing the number of gates and parameters. Thus, GRU has faster training and less computational costs [35]. The output of RNN classifier is displayed in a Streamlit web prototype and labeled as benign or malicious.

Figure 2: The entire architecture of the proposed model

We used two datasets to evaluate our work. The first dataset is a balanced dataset containing 200,000 QR codes, downloaded from Kaggle [36]. This dataset has equal parts benign (100,000) and malicious (100,000) QR codes, representing real URLs. The malicious QR codes represent a broad range of real-world attack vectors and are linked to potentially harmful sites, including phishing sites, malware distribution platforms, and other cybersecurity threats. For this research, the first 10,000 URLs from each class, benign and malicious, were selected randomly to ensure class balance and consistency. The QR codes are version 2, and the size of each image is 370 × 370. The Kaggle dataset has been used in recent research by Alshaya et al. [37].

The second dataset is also balanced and is published on Mendeley [38]. It contains a total of 1000 QR code images, 500 malicious and another 500 are benign. The QR codes are version 1. The malicious QR codes are linked to verified harmful URLs associated with phishing sites, malware distribution platforms, and other cyber threats. However, the benign QR codes point to safe and trusted domains, primarily drawn from Alexa’s top-ranked websites, which helps guarantee the reliability of the non-malicious samples.

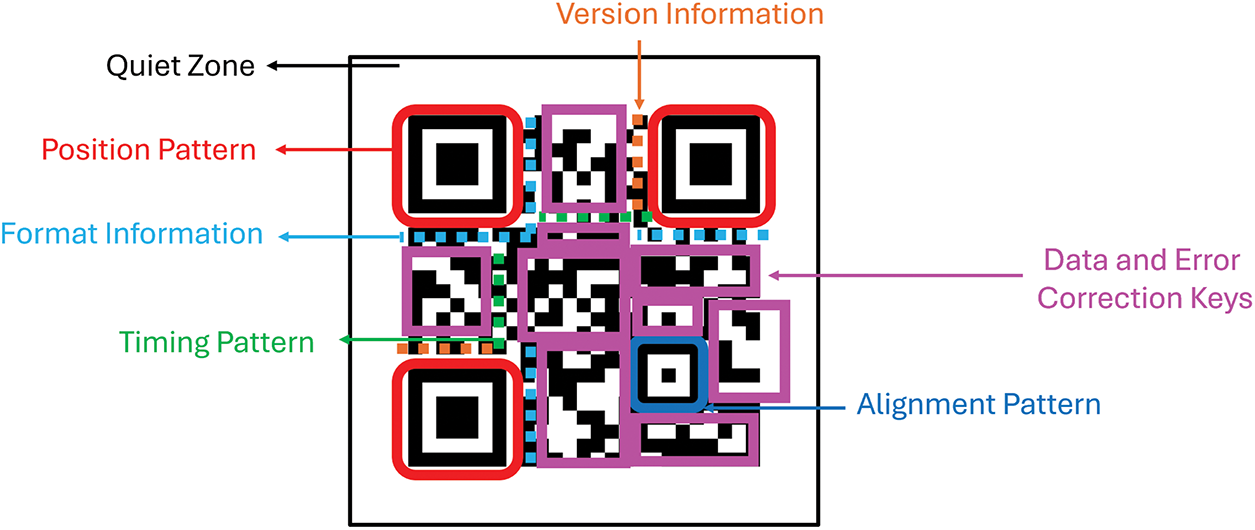

The fundamental components of QR code are illustrated in Fig. 3. It comprises information, timing patterns, data, and error correction keys, position patterns, quiet zones, format information, and alignment patterns [39,40]. There are 40 different QR code versions, each identified by specific markers. However, versions 1 through 7 are the most commonly used. Timing patterns help identify potential distortions in a QR code, which determines the number of columns and rows and measures the module size. Data and error correction keys are used to store all the data and include error correction blocks, which allow the code to remain functional even if up to 30% is damaged. Position patterns are distinctive in three of the QR code’s corners. They help scanning devices understand the code’s position and direction. The quiet zone is a blank space surrounding a QR code, free from structures or patterns that might confuse readers. Format information includes essential details for decoding a QR code, such as the mask pattern (chosen from 7 options) and the error correction level (selected from 4 options). Alignment Patterns help the scanning device detect any perspective distortion in the QR code image. Several or no alignment patterns may exist depending on the QR code version.

Figure 3: QR code structure

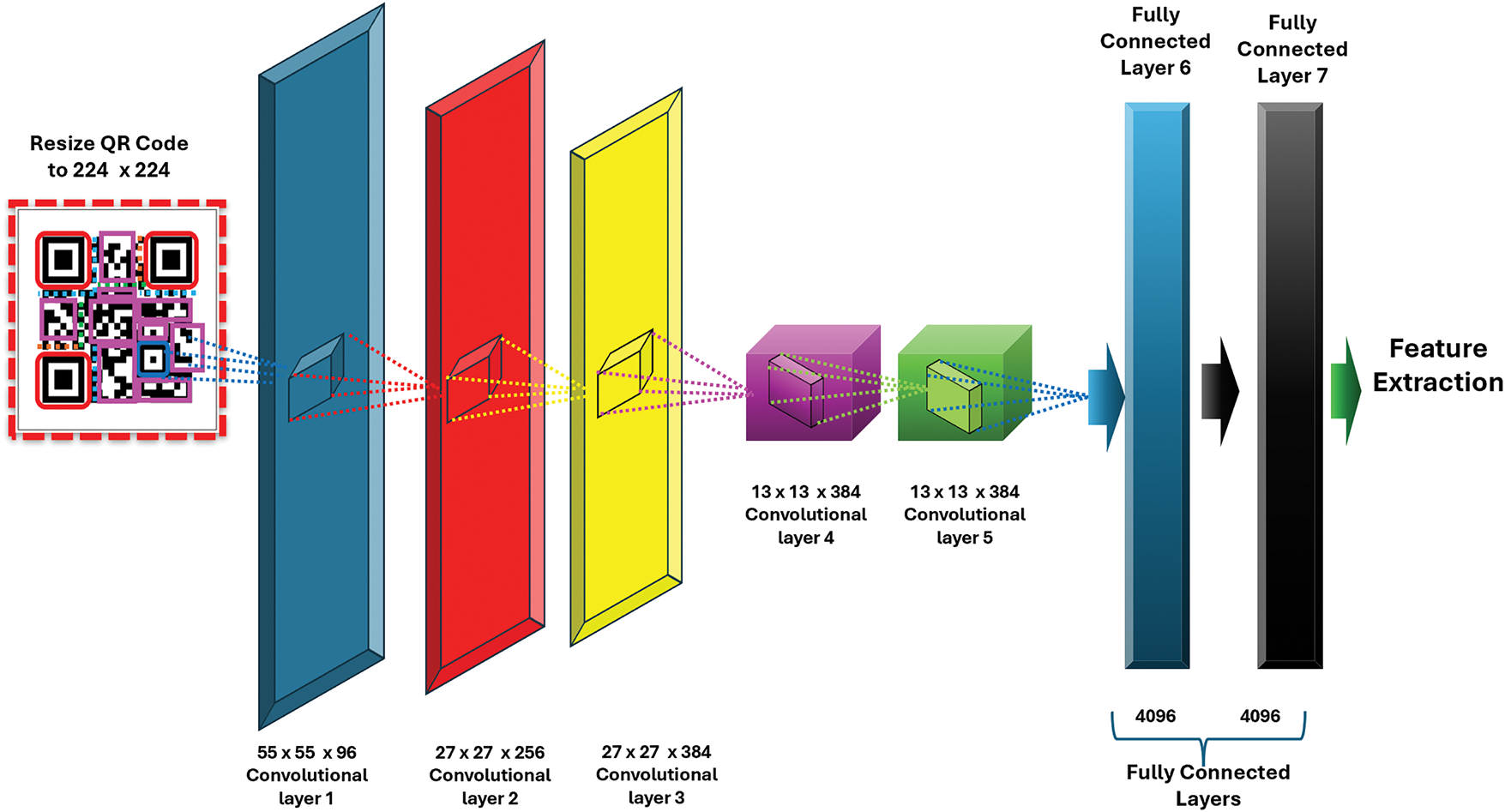

Due to their outstanding results, pre-trained neural networks are well-known models for classifying images [41,42]. The ImageNet dataset [42], which consists of over 14 million images labeled in 21,000 classes, was used to train most of these models. AlexNet is one of these pre-trained models [31] and was also trained on a portion of the ImageNet dataset [43]. Despite using only part of the ImageNet dataset for training, AlexNet became well-known for its exceptional results in numerous classification challenges [44]. Therefore, AlexNet is used in this research to extract features from QR codes. AlexNet utilizes local response normalization (LRN), which has eight layers. The normalization method LRN aims to maximize neighboring neurons’ activation. The AlexNet architecture is shown in Fig. 4. It has three fully connected layers and five convolutional layers. Its first convolutional block has the size of 11 × 11 convolutional layers with 96 filters. It is followed by the max pooling layer, which contains a pool size of 3 × 3 and a normalization layer. The second convolutional block has 256 filters of size 5 × 5 convolutional layer, a max-pooling layer, and a normalization layer. Convolutional layers 3, 4, and 5 use 3 × 3 filters with 384 and 256 filters, respectively. Following these convolutional layers are two fully connected layers, each containing 4096 neurons and incorporating dropouts [45,46].

Figure 4: AlexNet for extracting features from QR codes

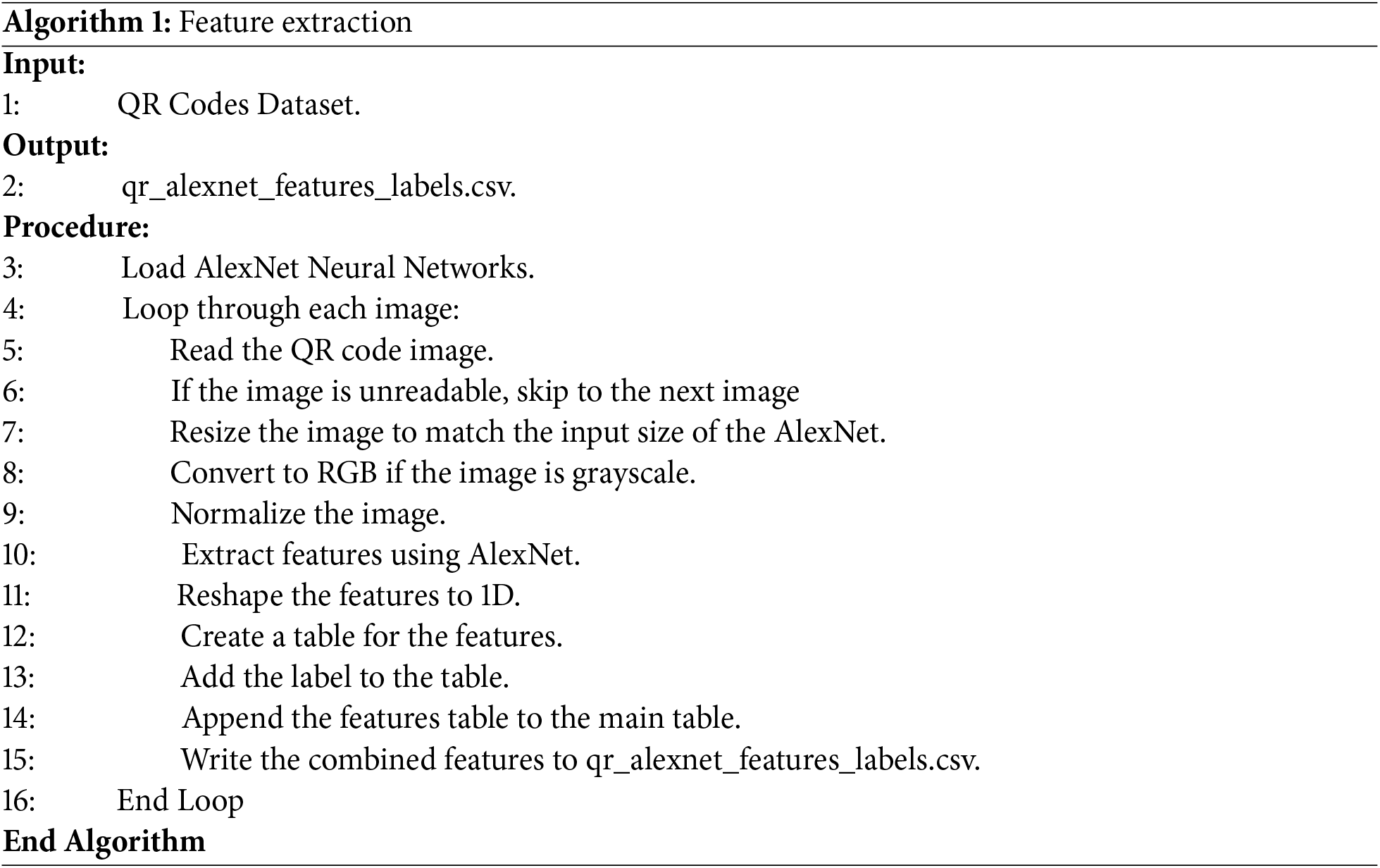

Algorithm 1 demonstrates the feature extraction technique used in this study. It comprises three components to define the model’s functionality: input, output, and procedure. The algorithm takes the QR code images from the dataset directory as input. The dataset’s root directory includes two subdirectories containing malicious and benign images. The algorithm’s output is the extracted features from the QR codes with labels in CSV file format. The procedure begins with loading the AlexNet neural network, which extracts features from QR code images. The main functionality of Algorithm 1 is shown in the loop, which starts from image 1 to the last image in the two subdirectories. Initially, the QR code is read, then unreadable or corrupt images are skipped using a check. Next, the QR image is resized to fit the input parameter of AlexNet, which is 224 × 224. Next, the model checks whether the QR code image is in RGB format; if not, the image is converted to RGB format. The reason is that AlexNet does not accept grayscale images as input. After that, the image is normalized by dividing by 255 so it is scaled from the range [0, 1]. It is worth noting that in the case of a binary image with the value 0 or 1, there is no need to normalize it, as the data would be distorted.

The output of AlexNet consists of the extracted 4096-dimensional features produced by the “fc7” layer, the seventh layer, and part of the fully connected section of the AlexNet architecture. The extracted features are reshaped into one-dimensional array (4096 values). These feature arrays are then organized into a table, where each row corresponds to a single QR code image, and columns. The corresponding label is added to each record, indicating whether the image is benign or malicious. Each features table is appended to the main table during the loop. The loop iterates over all QR code images in the dataset. Finally, the combined feature dataset is saved to a CSV file named qr_alexnet_features_labels.csv, ready to be used for training various machine learning classifiers that accept one-dimensional data.

3.5 Principal Component Analysis and Recurrent Neural Network

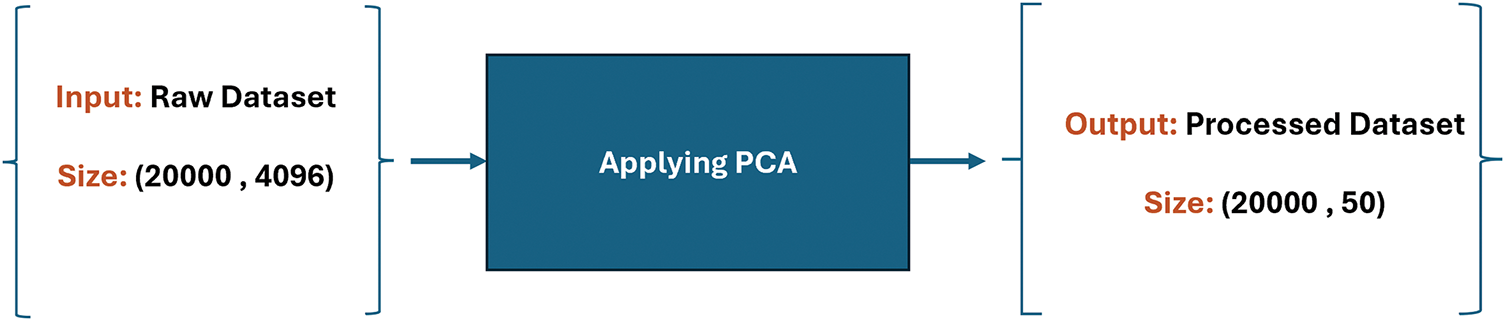

PCA is a method that simplifies complicated data by reducing the number of features while maintaining most of the important information. It achieves this by rotating the original variables to align with new axes representing the maximum variance directions. This transformation results in a more efficient representation of the data. PCA is widely used in various fields, such as image processing, gene analysis, and facial recognition. The first principal component captures the greatest variation in the data, with each subsequent component progressively capturing less of the remaining variation [47]. PCA reduces data complexity by translating it into a new coordinate system with maximum variance. The number of factor groups is calculated by examining the eigenvalues, which show how important each factor is in explaining the variance of the examined variables. As illustrated in Fig. 5, the QR code images, which AlexNet processed sized at (20,000, 4096), are reduced to a more compact representation of (20,000, 50) after applying PCA. This transformation allows the data to be processed more efficiently while preserving its essential structure. This mapping preserves the key features of the data, allowing for quicker and more efficient processing [48]. Therefore, our work used PCA to determine the most significant features in the QR codes by focusing on those contributing significantly to total variation. By maximizing the variance explained by the principal components, PCA identified and retained the most valuable and relevant features for the analysis. This strategy helped us remove insignificant features, improving model performance and interpretability.

Figure 5: PCA procedure

We selected the top 50 principal components based on a variance–efficiency trade-off observed in the PCA analysis of the 4096-dimensional features extracted from AlexNet. The first 21 components already exceeded the 90% cumulative explained variance threshold, while 50 components captured approximately 96.4% of the variance, as illustrated in Fig. 6 using the first dataset. The top 50 components preserved nearly all of the essential information while substantially reducing computation compared with the original 4096-D space.

Figure 6: Cumulative explained variance of PCA on AlexNet features

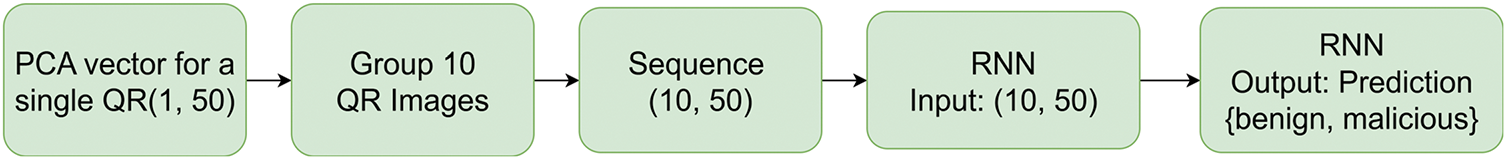

Fig. 7 shows the process of sequence construction for RNN. After performing PCA, each QR code is represented by a 50-dimensional feature vector, which preserves about 96.4% of the original variance. That means each image is stored as a vector of size (1, 50). To train the RNN, we needed to organize the data into sequences by grouping every 10 consecutive QR codes into one sequence. Each sequence therefore has 10 steps, and at each step the RNN receives one 50-dimensional vector (the PCA features of a single QR code). This means each input sequence has the shape (10, 50), corresponding to 10 QR images with 50 features each. Finally, the RNN model predicts the classification of the QR code which is either benign or malicious.

Figure 7: Sequence construction for RNN

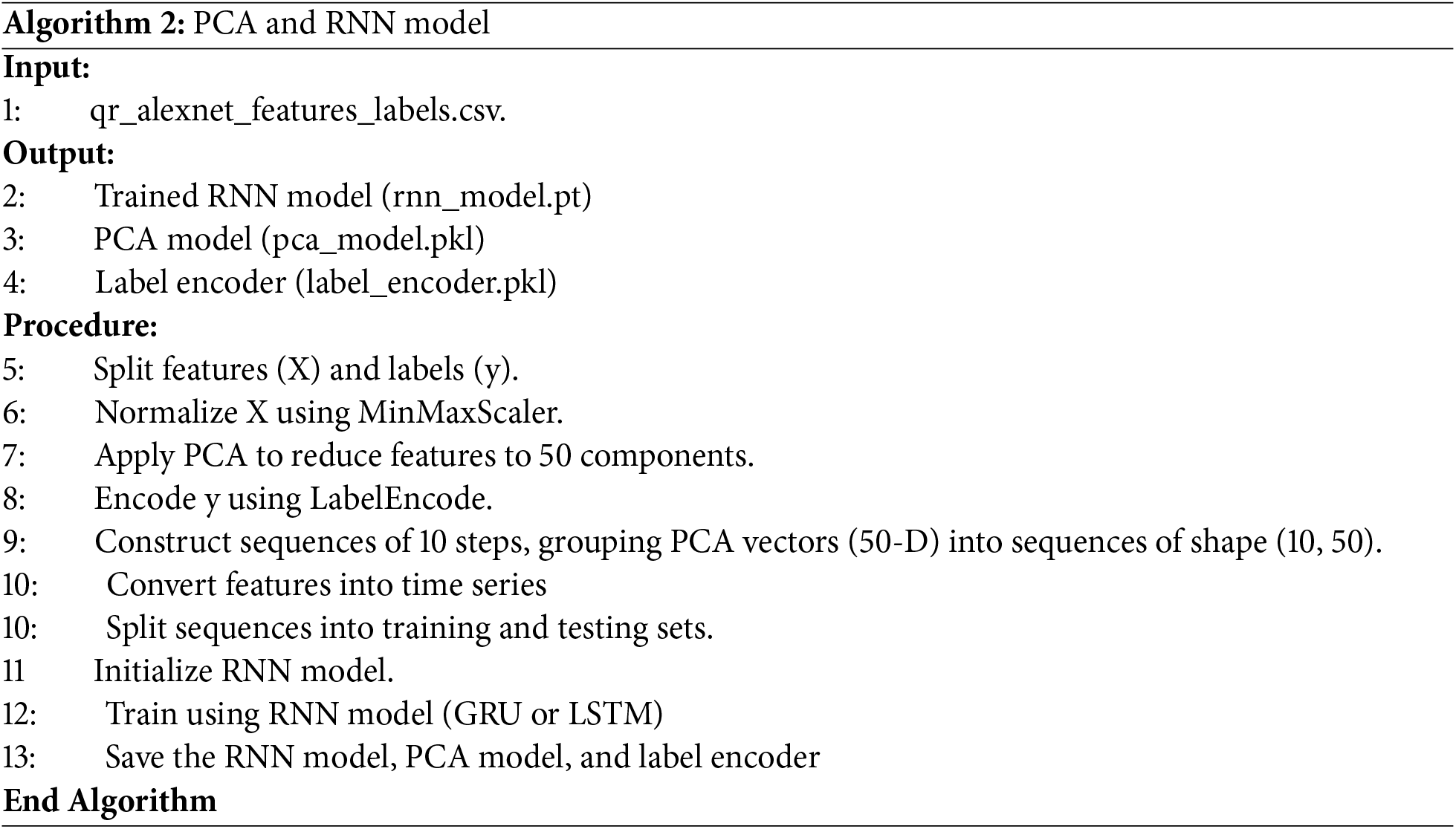

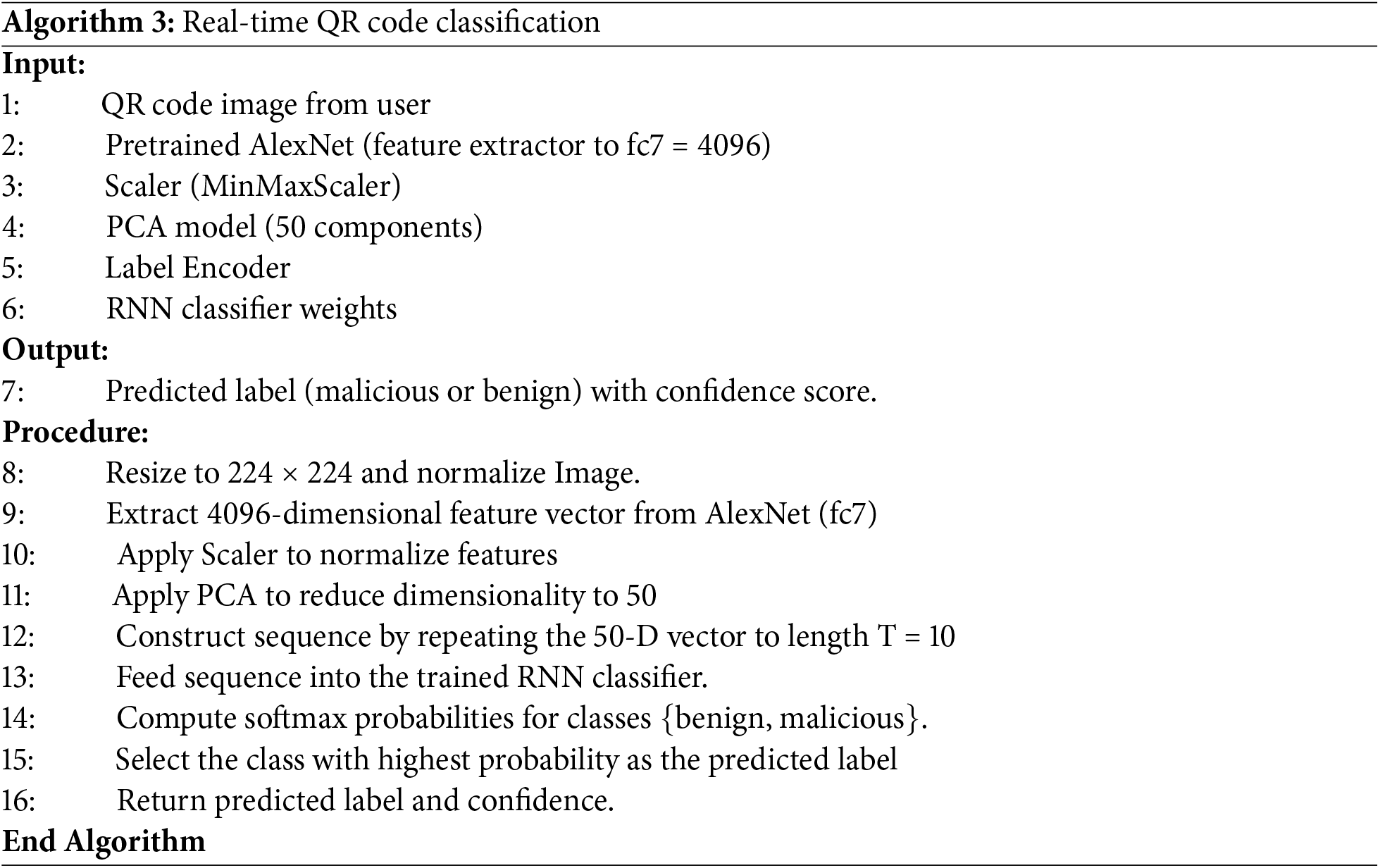

Algorithm 2 demonstrates the steps involved in applying PCA and RNN models. It basically begins from the output of Algorithm 1, the qr_alexnet_features_labels.csv file. To enable efficient and accurate classification, the extracted features from the QR codes are first split into features (X) and labels (y). The features are then normalized using MinMaxScaler, ensuring that all feature values lie within a comparable range. Subsequently, PCA is applied to reduce the dimensionality of the data while preserving the most significant variance, allowing the model to learn from a compact and informative feature set. After normalization and dimensionality reduction, the labels (y) are encoded using LabelEncoder to convert categorical class names into numerical format. Next, the data is organized into sequences of 10 steps, grouping PCA vectors (50-D each) into sequences of shape (10, 50). These sequences are then used to train RNN model, such as GRU or LSTM, both of which are well-suited for learning dependencies in sequential data. The RNN is configured with two layers, dropout and L2 weight decay to prevent overfitting. The training process includes early stopping based on validation loss to ensure generalization. Finally, the trained RNN model, PCA transformer, and label encoder are saved for to be used in Algorithm 3.

3.6 Real-Time Prototype Implementation

A real-time web-based prototype was developed using Streamlit in order to validate the practical use of our proposed model. Basically, the user is able to upload an QR code image in web-based interface then the implemented prototype can predict if the QR code is benign or malicious. Streamlit [49] is an open-source Python framework designed to simplify the development of interactive web applications for machine learning and data science projects. It enables developers and researchers to create visually appealing and highly functional interfaces with minimal code, using only Python without needing HTML, CSS, or JavaScript. Streamlit supports various interactive widgets such as sliders, file uploaders, and buttons, making it ideal for building dashboards, model deployment tools, and real-time data analysis applications. The application allows users to upload QR code images, automatically extract features using pretrained AlexNet model, apply PCA for dimensionality reduction, and classify the image as malicious or benign using a trained classifier. The prototype runs locally and provides near-instant classification, highlighting its potential for real-time QR security monitoring in desktop environments.

Algorithm 3 presents the real-time prototype for classifying QR code security status. A lightweight web-based application was developed using Streamlit, and it loads all trained parameters produced in Algorithm 2, including the RNN classifier, the PCA transformer, the MinMaxScaler, and the label encoder.

The process begins when a QR code image is uploaded through a Streamlit-based user interface. The uploaded image is resized to 224 × 224 pixels and normalized by ImageNet standards to match the input requirements of the AlexNet model.

The pretrained AlexNet is used to extract from the QR image. Specifically, the convolutional features are flattened, and the fc7-level 4096-dimensional feature vector is obtained. These raw features are first scaled using the saved MinMaxScaler and then reduced to 50 principal components using the pretrained PCA model, ensuring both dimensionality reduction and preservation of discriminative information. The reduced feature vector is replicated into a fixed-length sequence (T = 10) to match the input requirements of the RNN classifier. The RNN processes this sequence and outputs logits, which are transformed into class probabilities via softmax.

The predicted class index is mapped back to the original categorical label (benign or malicious) using the saved label encoder. Finally, the result is displayed to the user along with the associated confidence score, providing instant QR code threat detection in a transparent and user-friendly manner.

This section presents and discusses the experimental results obtained from this research. It begins with the setup parameters for training the GRU, LSTM, and CNN models. Each model’s classification performance and computation time are then evaluated and compared. Next, we compared the classification performance of the proposed model with traditional machine learning models such as support vector machine (SVM), random forest, eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), and decision tree (DT) in identifying malicious QR code activity. The traditional machine learning models were tested as baselines further to validate the classification performance of the deep learning approaches.

In addition, we provide a comparative analysis between our proposed model and related baseline studies in the domain of QR code security and broader cybersecurity detection systems. A real-time classification example using the developed prototype is also included to demonstrate the model’s feasibility when working in real-time setting. The experimental findings are organized into four subsections: Section 4.1 details the setup parameters for each deep learning model. Section 4.2 evaluates the models’ ability to identify malicious QR codes. Section 4.3 examines the computational performance of the models and Section 4.4 provides insights into real-time prototype and considerations.

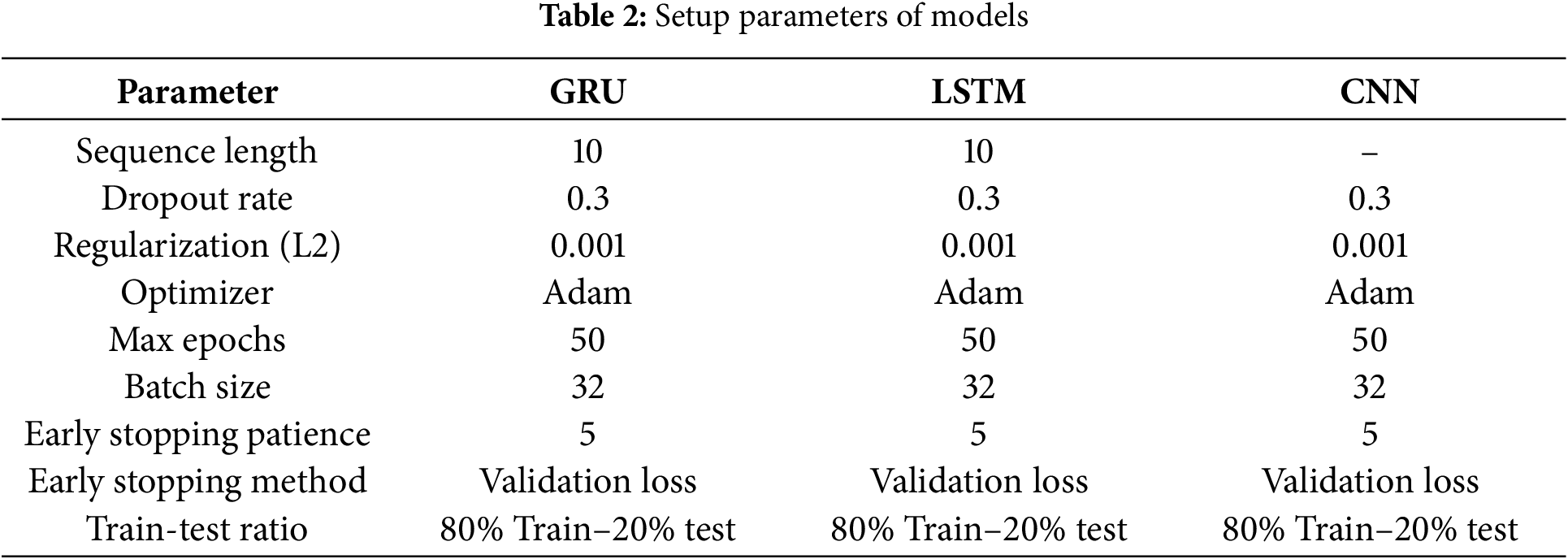

4.1 Setup Parameters of Deep Learning Models

The setup parameters of the DL models used in this research are listed in Table 2. The parameter setup is being shown to confirm that the three DL models were treated equally during training. These parameters were selected based on thorough experimentation. The sequence length refers to the number of previous steps the model uses when predicting [50]. Here, the sequence length is set to 10. The dropout rate is set to 0.3, meaning 30% of the neurons are randomly dropped in each training iteration. This forces other neurons to learn to prevent overfitting. In addition, regularization (L2) balances each DL model’s weight and helps eliminate overfitting [51]. Adam is the optimizer algorithm used to train each model. The max epoch is set to 50, while the early stopping method, based on validation loss, determines when to stop the training. The early stopping patience is set to 5, which means the training continues with 5 more epochs before the training ends [52]. The batch size is 32, and the default value is [53].

4.2 Evaluation of Malicious QR Code Detection

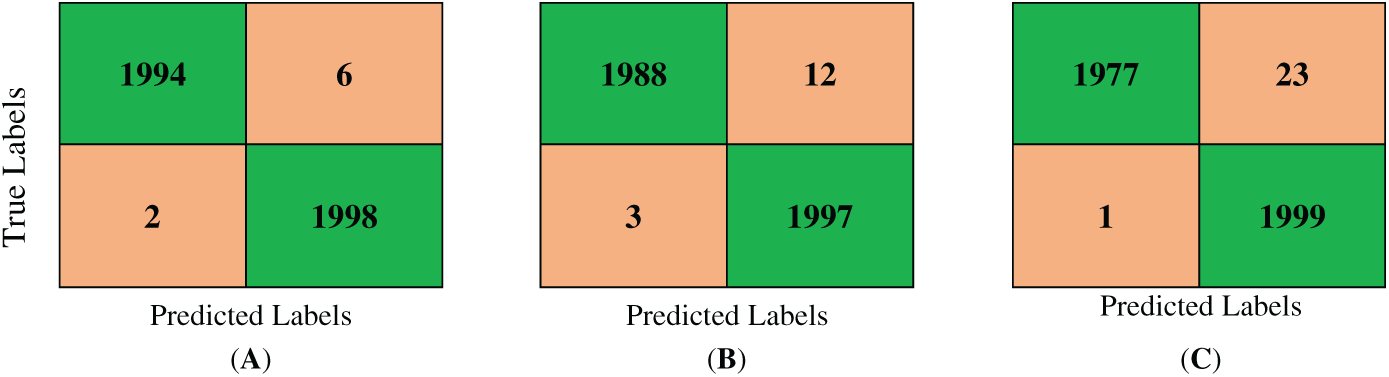

The GRU, LSTM, and CNN classification performance evaluations concerning the confusion matrix (CM) and accuracy metrics are discussed. Each model was trained with 80% of the dataset and tested with the rest 20%. The total number of images used in this experiment is 20.00, in which 10.00 belong to the benign class and 10.00 to the malicious class. The size of the test data used in CM is 4000, which is 2000 for benign and 2000 for malicious. The CM of each model is illustrated in Fig. 8A–C, which shows the performance of a binary classification task using the first dataset. Each model recorded the following parameters: true negatives (TN), true positives (TP), false positives (FP), and false negatives (FN). Those parameters will be used to calculate accurate metrics. The GRU model correctly classified 1994 benign cases (TN) and identified 1998 malicious cases (TP). Meanwhile, 6 benign instances were misclassified as malicious (FP), and the model misclassified 2 malicious instances as benign (FN). The LSTM model correctly identified 1988 benign samples as benign (TN) and predicted 1997 malicious samples as malicious (TP). However, 12 benign samples were misclassified as malicious (FP), and 3 malicious samples were incorrectly classified as benign (FN). The CNN model predicted 1977 benign samples as benign (TN) and 1999 malicious samples as malicious. However, 23 benign samples were falsely classified as malicious (FP), and only 1 malicious sample was misclassified as benign (FN). The GRU model is best for correctly identifying benign samples (TN) as benign. The CNN model outperformed other models, correctly predicting malicious samples as malicious (TP).

Figure 8: (A) CM of GRU model; (B) CM of LSTM model; (C) CM of CNN model

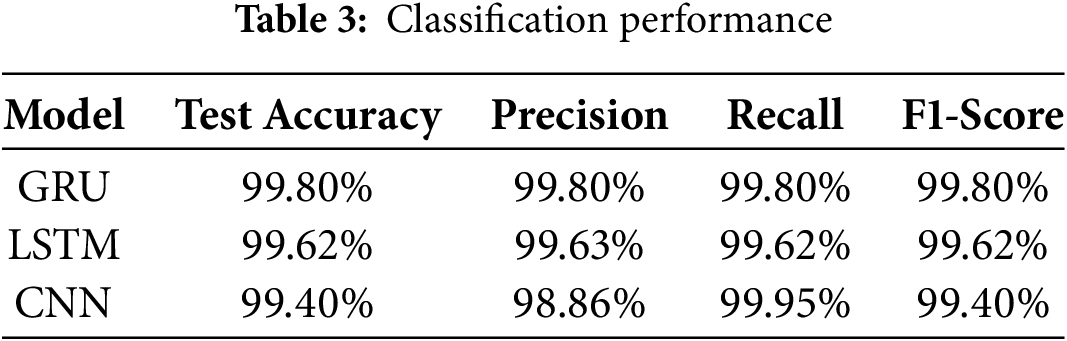

Table 3 lists the evaluation metrics, precision, recall, and F1-score, for assessing the classification performance of the GRU, LSTM, and CNN models using the first dataset based on the testing approach. The reason is to analyze and compare the classification performance of each deep learning model when identifying malicious QR code activity. This ensures a comprehensive evaluation that includes false positives (FP) and false negatives (FN), particularly critical in cybersecurity applications. According to the table, the performance of the GRU model is stable across all evaluation metrics at 99.80%. This indicates that GRU balances the tradeoff between TP, TN, FP, and FN, which is essential for reducing potential misclassifications in cybersecurity contexts. LSTM model also shows a strong performance, with slightly lower scores around at around 99.62%, which maintained balance across all metrics. In contrast, the CNN model demonstrates the highest recall at 99.95% and precision at 98.86%, highlighting its strong sensitivity to detecting malicious instances but with a trade-off in precision. This reveals that using the GRU model to detect malicious QR codes accomplishes acceptable classification performance compared with the CNN model, a well-known approach in classifying 2D data.

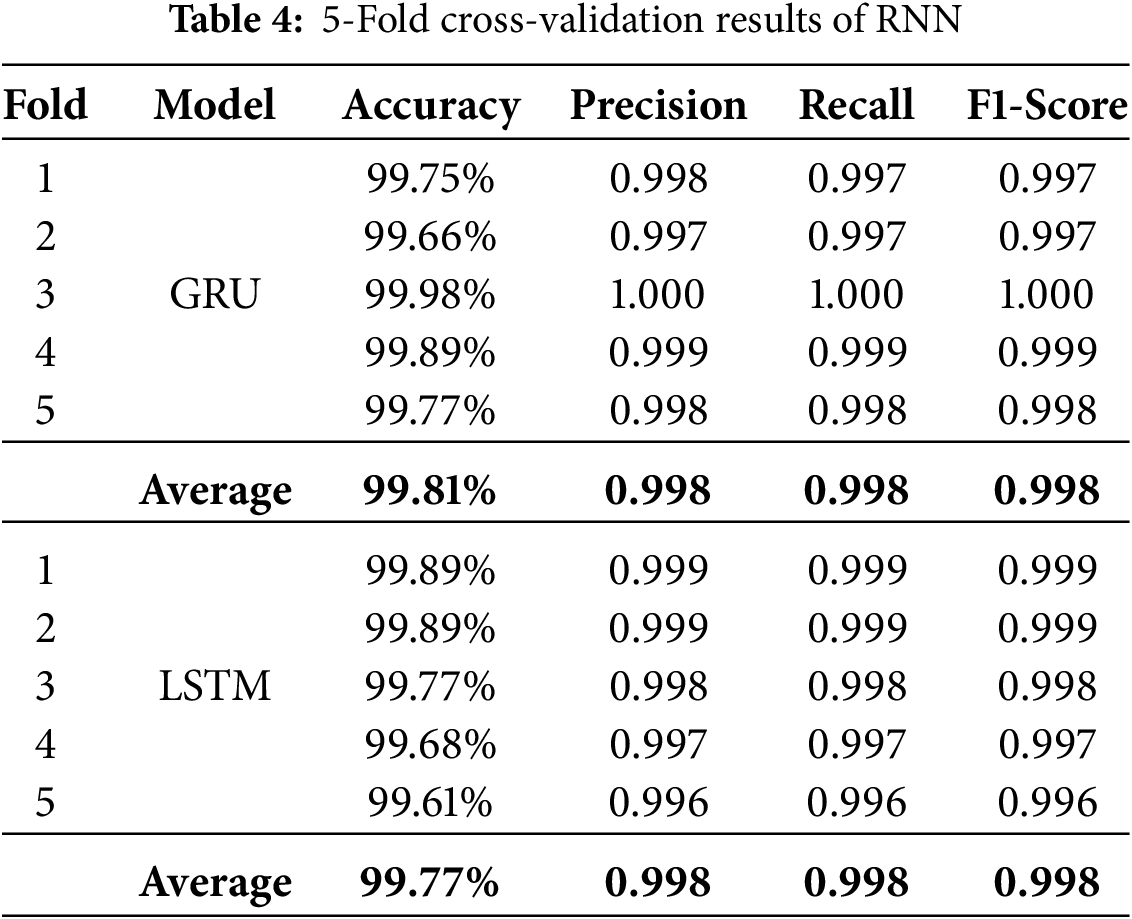

The results in Table 4 reflect the performance of GRU and LSTM models on the first dataset using 5-fold cross-validation setting. Both models demonstrated high accuracy and consistency across all folds. This indicates their robustness and reliability for QR code classification. The GRU model achieved fold accuracies ranging from 99.66% to 99.98%, with an overall average accuracy of 99.81%. In comparison, the LSTM model exhibited slightly lower but still excellent fold accuracies ranging from 99.61% to 99.89%, with an average of 99.77%.

Both models’ precision, recall, and F1-score metrics are consistently high across all folds. GRU recorded an average precision, recall, and F1-score of 0.998, reflecting a near-perfect balance between correctly identifying benign and malicious QR codes. Similarly, LSTM yielded identical averages 0.998 for all three metrics, which indicates its strong generalization performance. Notably, GRU slightly outperformed LSTM in average accuracy, suggesting it may offer a marginal edge in classification reliability in this context. Both RNN variants performed comparably well, with GRU having a slight advantage in fold accuracy stability. These findings confirm the effectiveness of sequential learning methods in QR code security classification tasks.

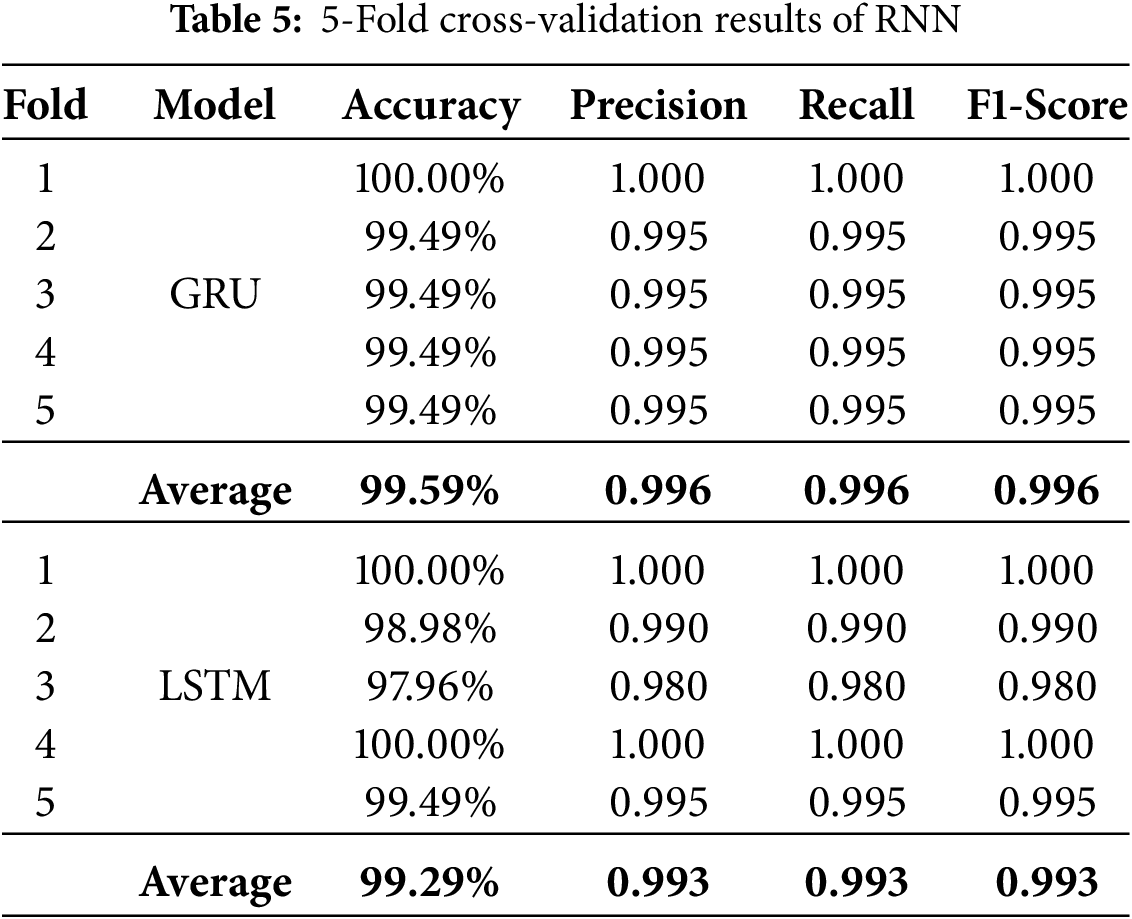

The results in Table 5 present the evaluation on the second dataset, again using 5-fold cross-validation. GRU maintained strong and stable performance, achieving 100% accuracy in the first fold and ≈99.49% in the remaining folds, yielding an overall accuracy of 99.59% with precision, recall, and F1-score values of 0.996. LSTM also recorded perfect accuracy in two folds, but displayed greater variability, with accuracy dropping to 97.96% in one-fold. Its average accuracy was 99.29%, with precision, recall, and F1-score averaging 0.993.

Together, the results from both datasets in Tables 4 and 5, demonstrate the effectiveness of RNN-based models in QR code security classification. While both GRU and LSTM achieve near-perfect performance, GRU consistently provides slightly higher average accuracy and greater fold-to-fold stability, making it the more reliable candidate for deployment in real-time environments.

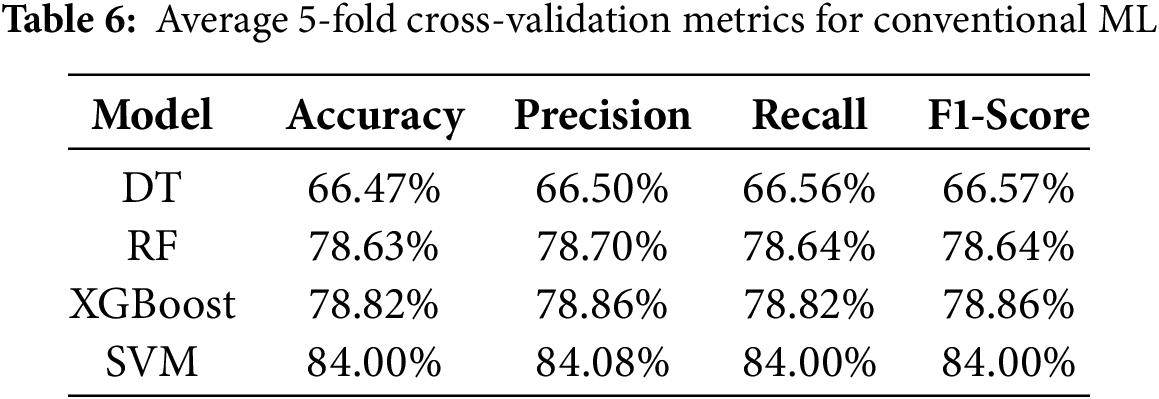

To strengthen the evaluation of the proposed model, 5-fold cross-validation experiments were conducted using traditional machine learning classifiers trained on the PCA-reduced features extracted from QR code images. Table 6 summarizes the average results across folds for Decision Tree (DT), Random Forest (RF), XGBoost, and Support Vector Machine (SVM) in terms of accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score using the first dataset. The SVM classifier achieved the highest accuracy of 84.00%, outperforming XGBoost at 78.82% and Random Forest at 78.63%, while DT scored the lowest performance at 66.47%. In contrast, the proposed GRU-based deep learning model consistently outperformed these conventional classifiers with an average accuracy of 99.81%. This substantial performance gap highlights the effectiveness of sequential deep learning architectures for capturing complex patterns within QR code data, providing strong justification for employing RNN-based models in QR code security applications.

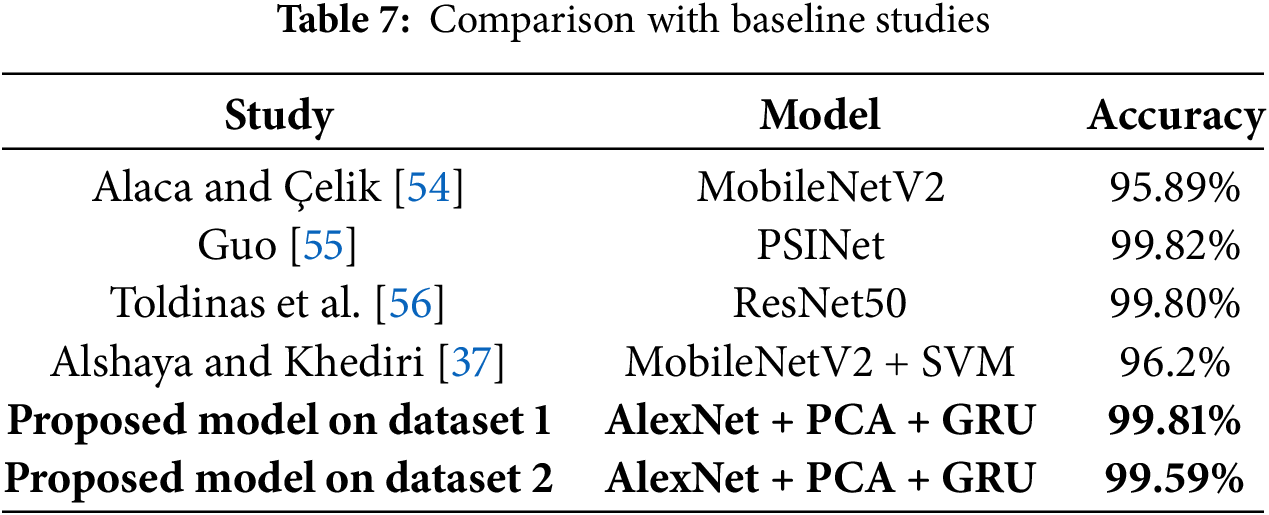

To confirm the validity of the proposed model, Table 7 presents a comparison of the proposed model with other baseline studies in the field of QR code security and related cybersecurity detection systems. The studies include Alaca and Çelik [54], Guo [55], Toldinas et al. [56], and Alshaya and Khediri [37], each employing different models and achieving varying levels of accuracy. For instance, Alaca and Çelik used MobileNetV2, achieving 95.89% accuracy on QR code images. Guo and Toldinas et al. used PSINet and ResNet50, respectively, reporting high accuracies of 99.82% and 99.80%. Alshaya and Khediri combined MobileNetV2 with SVM, achieving 96.2% accuracy. In comparison, the proposed model, which integrates AlexNet for feature extraction, PCA for dimensionality reduction, and GRU for sequential classification, achieved 99.81% accuracy. This performance maintains the highest baseline results while offering a more computationally efficient that is suitable for real-time QR code security applications.

4.3 Evaluation of Computation Performance

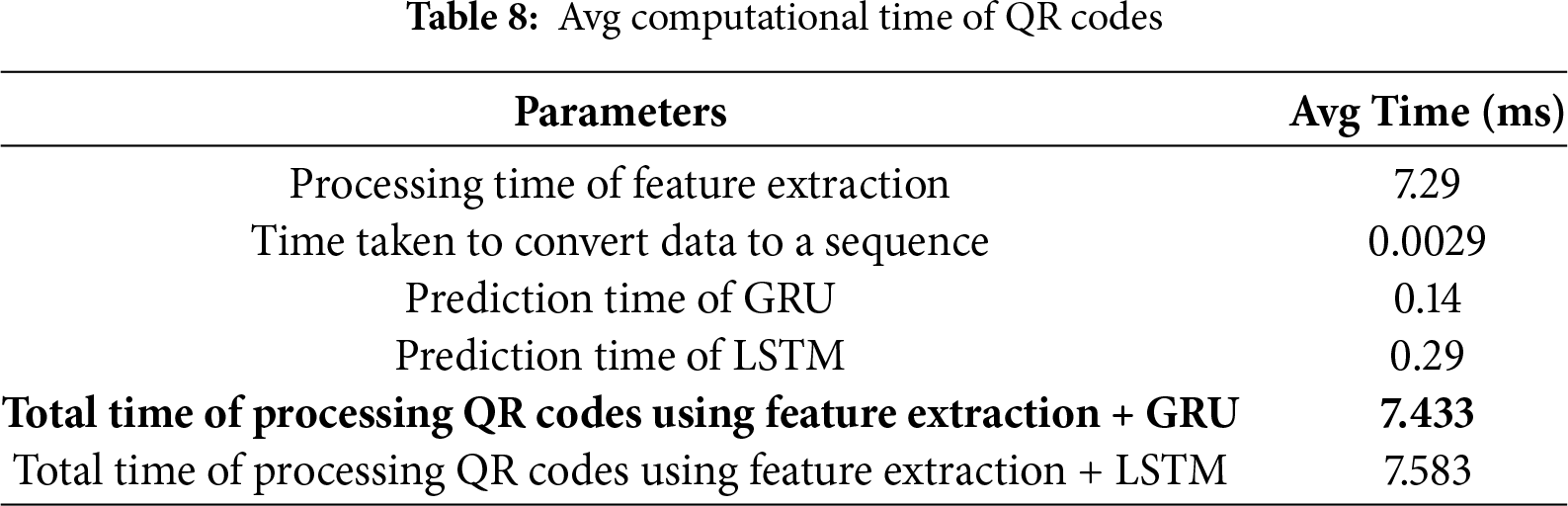

The result of computation performance measuring the time taken to process the proposed model with the GRU and LSTM models is reported in Table 8. We computed the elapsed time> in milliseconds (ms) of processing the average QR codes, starting from reading the image to the prediction result. The average processing time for extracting features from QR codes is 7.29 ms. This step involves obtaining important information from the QR code data. The average time needed to convert extracted data to sequence data from the QR codes is 0.0029 ms. This step is important to prepare the data to be used by GRU and LSTM models. The GRU model shows a faster average computation time in predicting QR codes than the LSTM model. Therefore, the average time to process QR codes using feature extraction with the GRU model is slightly faster than the LSTM model. Based on the discussion mentioned above, GRU has the best performance. Therefore, it is selected as an optimal model for classifying QR codes.

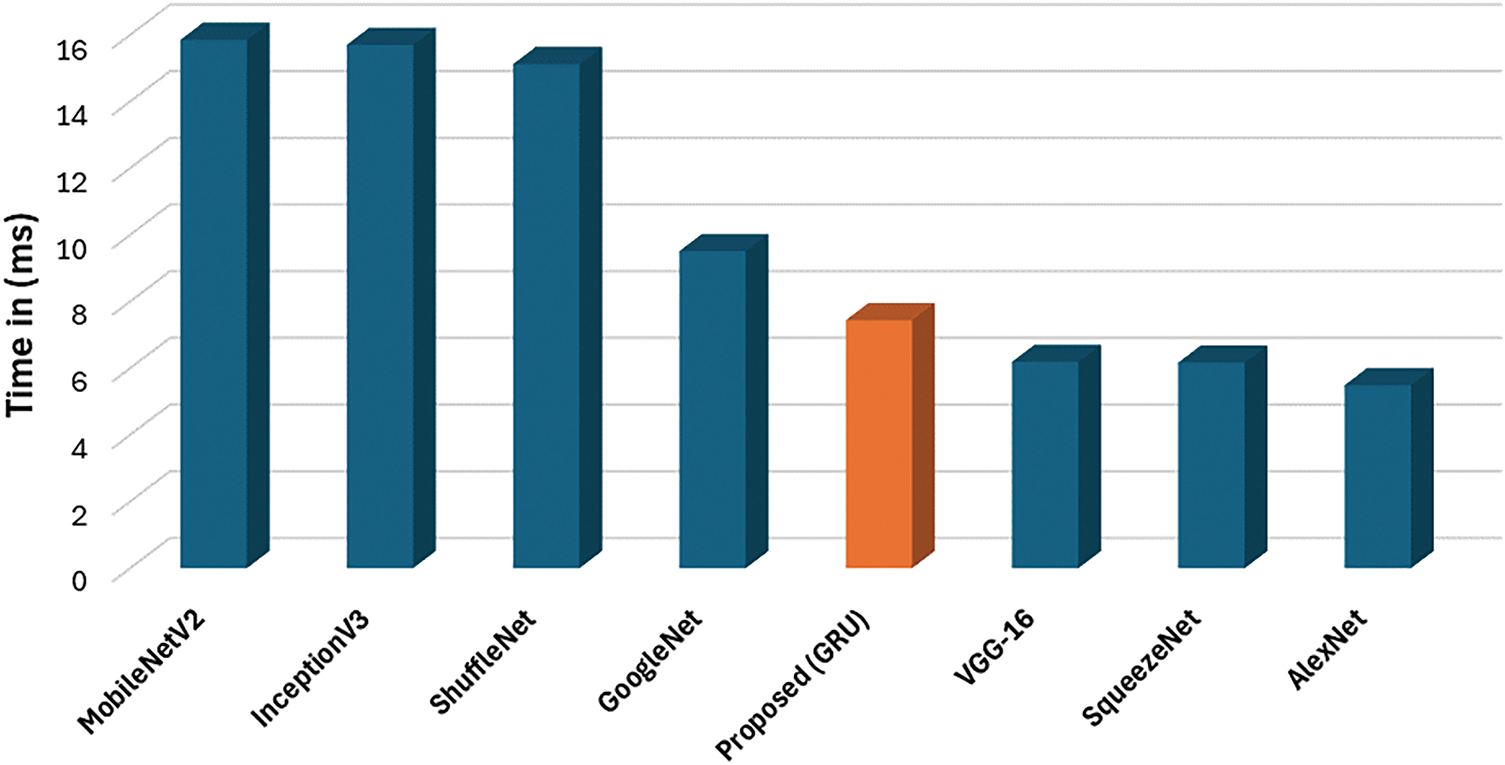

We compared the computational time of the proposed GRU-based model with well-known pre-trained neural networks, which are MobileNetV2, InceptionV3, ShuffleNet, GoogleNet, VGG-16, SqueezeNet, and AlexNet. The reason for making this compression is to validate the computational performance of the proposed model against popular models that handle image classification. In addition, it ensures that the computation time of the proposed model is within the acceptable range. As shown in Fig. 9, models such as MobileNetV2, InceptionV3, and ShuffleNet showed the highest computation times compared with other models, averaging around 16 ms. This may be due to the high number of layers in those models. GoogleNet has moderate performance around just above 8 ms. In contrast, GoogleNet demonstrated moderate performance with an average slightly above 8 ms. The proposed GRU-based model outperformed GoogleNet in terms of computation time and achieved processing times comparable to lighter models such as VGG-16, SqueezeNet, and AlexNet. Therefore, we can conclude that the proposed model has an acceptable computational time while the process data size is 1 × 321 (1D data). However, the other models used the original QR code image with a process data size of 370 × 370 (2D data).

Figure 9: Comparison of the computation time in (ms)

4.4 Real-Time Prototype and Considerations

An example of the real-time prototype classification result is shown in Fig. 10. The QR code classifier integrates AlexNet, PCA, and GRU models, all developed in Python with the assistance of Streamlit. In this case, the uploaded QR code was correctly classified as malicious with a confidence of 98.5%. This demonstration highlights both the potential and the challenges of deploying machine learning models in real-world environments. While offline experiments achieved 99.81% accuracy using 5-fold cross-validation on a balanced dataset, real-time performance can vary due to factors such as QR code design variations, noise, distortions, or input quality differences. In particular, the classifier’s accuracy may deteriorate when QR codes undergo pixel-level changes caused by adversarial perturbations, low resolution or blur. Under such conditions, the features extracted by AlexNet may be distorted, which in turn affects the performance of PCA and ultimately leads to incorrect classification.

Figure 10: QR code classification using streamlit interface

Misclassifications may arise when QR codes are subjected to pixel-level tampering (adversarial perturbations), low resolution, blur, or partial occlusion. Such distortions can alter the extracted convolutional features, leading to degraded PCA representations and, consequently, incorrect classification. Future improvements will focus on robustness-oriented strategies, including adversarial training, augmentation with distorted QR codes, and hybrid deep learning approaches (e.g., ensembles or transformer-based architectures). These measures are expected to enhance generalization and make the classifier more reliable under challenging real-world conditions.

These differences underscore that while offline evaluations are useful for benchmarking, real-time performance can fluctuate, and models may not always replicate their test set results when encountering unseen inputs.

In conclusion, our study contributes significantly toward the security of QR code technology by proposing a robust and computationally efficient system for detecting malicious QR codes. Conventional methods to detect malicious activity on QR codes generally depend on analyzing the URLs and 2D images. This study introduces an advanced deep learning approach to detect malicious QR code activity by combining pre-trained neural networks with RNN models. Specifically, AlexNet is employed to extract high-level features from QR code images. At the same time, PCA reduces the dimensionality of these features, converting them into one-dimensions sequences suitable for classification by RNN architectures. The performance of GRU and LSTM models was compared to determine the optimal approach for binary classification of QR codes as either malicious or benign. Based on five-fold cross-validation, the experimental results demonstrated that the GRU model outperformed LSTM, achieving an average classification accuracy of 99.81% compared to 99.77% for LSTM. Furthermore, the GRU model exhibited efficient computational time, with an average inference time of 7.433 ms, making it suitable for real-time applications. To explore the practical use of the proposed model, a real-time web-based prototype was developed using Streamlit, enabling users to upload QR code images and receive instant predictions. While offline experiments demonstrated high accuracy under controlled conditions, the real-time prototype highlighted potential variations in performance due to unseen QR code designs or distortions, emphasizing the need for continual model validation and calibration when deployed in real-world scenarios. For future research, we recommend exploring adversarial attacks on QR codes, where small modifications could compromise the model’s predictions, and apply defense techniques to improve the model’s robustness against such threats. Additionally, we recommend focusing on retraining the model with real-world QR codes that include distortions and design variations to improve robustness in real-time environments.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research is funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR) at King Abdulaziz University Jeddah, under grant no. (GPIP: 1168-611-2024). The authors acknowledge the DSR for financial and technical support.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Abdulaziz A. Alsulami, Qasem Abu Al-Haija, Badraddin Alturki, and Ali Alqahtani; methodology, Abdulaziz A. Alsulami, Ayman Yafoz, and Ali Alqahtani; software, Abdulaziz A. Alsulami, Qasem Abu Al-Haija, Badraddin Alturki, Ayman Yafoz, Ali Alqahtani, Raed Alsini, and Sami Saeed Binyamin; validation, Abdulaziz A. Alsulami, Badraddin Alturki, Ayman Yafoz, Ali Alqahtani, Raed Alsini, and Sami Saeed Binyamin; formal analysis, Abdulaziz A. Alsulami, and Badraddin Alturki; investigation, Ayman Yafoz, Ali Alqahtani, and Sami Saeed Binyamin; resources, Abdulaziz A. Alsulami, Raed Alsini, and Sami Saeed Binyamin; data curation, Abdulaziz A. Alsulami, Ayman Yafoz, Ali Alqahtani, and Raed Alsini; writing—original draft preparation, Abdulaziz A. Alsulami, Badraddin Alturki, Ayman Yafoz, and Ali Alqahtani; writing—review and editing, Abdulaziz A. Alsulami, Badraddin Alturki, Ayman Yafoz, and Ali Alqahtani; visualization, Raed Alsini, and Sami Saeed Binyamin; supervision, Abdulaziz A. Alsulami; project administration, Abdulaziz A. Alsulami, Qasem Abu Al-Haija, and Ali Alqahtani; funding acquisition, Abdulaziz A. Alsulami, Ayman Yafoz, and Raed Alsini. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data presented in the study are contained in the article and openly available at https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/samahsadiq/benign-and-malicious-qr-codes (accessed on 28 April 2025) and https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/cmhh7744sp/1 (accessed on 30 August 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Almousa H, Almarzoqi A, Alassaf A, Alrasheed G, Alsuhibany SA. QR Shield: a dual machine learning approach towards securing QR codes. Int J Comput Digit Syst. 2024;15(1):887–98. doi:10.12785/ijcds/160164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Rafsanjani AS, Kamaruddin NB, Rusli HM, Dabbagh M. QsecR: secure QR code scanner according to a novel malicious URL detection framework. IEEE Access. 2023;11:92523–39. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3291811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Ozturkcan S, Kitapci O. A sustainable solution for the hospitality industry: the QR code menus. J Inf Technol Teach Cases. 2023;15(1):2–7. doi:10.1177/20438869231181599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Al-Zahrani MS, Wahsheh HAM, Alsaade FW. Secure real-time artificial intelligence system against malicious QR code links. Secur Commun Netw. 2021;2021:1–11. doi:10.1155/2021/5540670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Yao H, Shin D. Towards preventing QR code based attacks on android phone using security warnings. In: Proceedings of the 8th ACM SIGSAC Symposium on Information Computer and Communications Security; 2013 May 8–10; Hangzhou China. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2013. p. 341–6. doi:10.1145/2484313.2484357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Kaspersky. Malware in september: the fine art of targeted attacks [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2024 Sep 26]. Available from: https://www.kaspersky.com/about/press-releases/malware-in-september-the-fine-art-of-targeted-attacks. [Google Scholar]

7. Mondal DK, Singh BC, Hu H, Biswas S, Alom Z, Azim MA. SeizeMaliciousURL: a novel learning approach to detect malicious URLs. J Inf Secur Appl. 2021;62:102967. doi:10.1016/j.jisa.2021.102967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Chou GJ. Wang RZ The nested QR code. IEEE Signal Process Lett. 2020;27:1230–34. doi:10.1109/LSP.2020.3006375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Zhou A, Su G, Zhu S, Ma H. Invisible QR code hijacking using smart LED. Proc ACM Interact Mob Wearable Ubiquitous Technol. 2020;3(3):1–23. doi:10.1145/3351284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Chimuco FT, Sequeiros JBF, Lopes CG, Simões TMC, Freire MM, Inácio PRM. Secure cloud-based mobile apps: attack taxonomy, requirements, mechanisms, tests and automation. Int J Inf Secur. 2024;22(4):833–67. doi:10.1007/s10207-023-00669-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Abnormal AI. H1 2024-phishing frenzy: C-suite receives 42× more QR code attacks than average employee [Internet]; 2023 [cited 2024 Sep 26]. Available from: https://intelligence.abnormal.ai/resources/h1-2024-report-qr-code-phishing-attacks. [Google Scholar]

12. Wahsheh HAM, Luccio FL. Security and privacy of QR code applications: a comprehensive study general guidelines and solutions. Information. 2020;11(4):217. doi:10.3390/info11040217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Ndia J, Njuguna D. Quick response code security attacks and countermeasures: a systematic literature review. J Cyber Secur. 2024;7(1):1–20. doi:10.32604/jcs.2025.059398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Averin A, Zyulyarkina N. Malicious QR-code threats and vulnerability of blockchain. In: 2020 Global Smart Industry Conference (GloSIC); 2020 Nov 17; New York, NY, USA. doi:10.1109/GloSIC50886.2020.9267840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Chiramdasu R, Srivastava G, Bhattacharya S, Reddy PK, Gadekallu TR. Malicious URL detection using logistic regression. In: 2021 IEEE International Conference on Omni-Layer Intelligent Systems (COINS); 2021 Aug 23; New York, NY, USA. doi:10.1109/COINS51742.2021.9524269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Thomopoulos GA, Lyras DP, Fidas CA. A systematic review and research challenges on phishing cyberattacks from an electroencephalography and gaze-based perspective. Pers Ubiquit Comput. 2024;28(3):449–70. doi:10.1007/s00779-024-01794-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Yong KSC, Chiew KL, Tan CL. A survey of the QR code phishing: the current attacks and countermeasures. In: Proceedings of the 2019 7th International Conference on Smart Computing & Communications (ICSCC); 2019 Jun 28–30; Sarawak, Malaysia. doi:10.1109/ICSCC.2019.8843688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Aslan Ö, Aktuğ SS, Ozkan-Okay M, Yilmaz AA, Akin E. A comprehensive review of cyber security vulnerabilities threats attacks and solutions. Electronics. 2023;12(6):1333. doi:10.3390/electronics12061333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Heartfield R, Loukas G. Protection against semantic social engineering attacks. In: Conti M, Somani G, Poovendran R, editors. Versatile cybersecurity. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2018. p. 99–140. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-97643-3_4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Song J, Gao K, Shen X, Qi X, Liu R, Choo K-KR. QRFence: a flexible and scalable QR link security detection framework for Android devices. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2018;88:663–74. doi:10.1016/j.future.2018.05.082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Tian Y, Yu Y, Sun J, Wang Y. From past to present: a survey of malicious URL detection techniques, datasets and code repositories. Comput Sci Rev. 2025;58:100810. doi:10.1016/j.cosrev.2025.100810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Chindaudom A, Siritanawan P, Sumongkayothin K, Kotani K. Surreptitious adversarial examples through functioning QR code. J Imaging. 2022;8(5):122. doi:10.3390/jimaging8050122. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Tsai M-J, Lee Y-C, Chen T-M. Implementing deep convolutional neural networks for QR code-based printed source identification. Algorithms. 2023;16(3):160. doi:10.3390/a16030160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Do T-N. Incremental and parallel proximal SVM algorithm tailored on the Jetson Nano for the ImageNet challenge. Int J Web Inf Syst. 2022;18(2/3):137–55. doi:10.1108/IJWIS-03-2022-0055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Sarkhi M, Mishra S. Detection of QR code-based cyberattacks using a lightweight deep learning model. Eng Technol Appl Sci Res. 2024;14(4):15209–16. doi:10.48084/etasr.7777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Wahsheh HAM, Al-Zahrani MS. Secure real-time computational intelligence system against malicious QR code links. Int J Comput Commun Control. 2021;16(3):4186. doi:10.15837/ijccc.2021.3.4186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Yan Y, Zou Z, Xie H, Gao Y, Zheng L. An IoT-based anti-counterfeiting system using visual features on QR code. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021;8(8):6789–99. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2020.3035697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Rasheed J, Wardak AB, Abu-Mahfouz AM, Umer T, Yesiltepe M, Waziry S. An efficient machine learning-based model to effectively classify the type of noises in QR code: a hybrid approach. Symmetry. 2022;14(10):2098. doi:10.3390/sym14102098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Rafsanjani AS, Binti Kamaruddin N, Behjati M, Aslam S, Sarfaraz A, Amphawan A. Enhancing malicious URL detection: a novel framework leveraging priority coefficient and feature evaluation. IEEE Access. 2024;12:85001–26. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3412331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Le H, Pham Q, Sahoo D, Hoi SCH. URLNet: learning a URL representation with deep learning for malicious URL detection [Internet]; 2018. [cited 2024 Sep]. Available from: http://arxiv.org/abs/1802.03162. [Google Scholar]

31. VirusTotal; 2005 [cited 2024 Sep 26]. Online. Available from: https://www.virustotal.com/gui/home/upload. [Google Scholar]

32. Wang Z, Ren X, Li S, Wang B, Zhang J, Yang T. A malicious URL detection model based on convolutional neural network. Secur Commun Netw. 2021;2021:1–12. doi:10.1155/2021/5518528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Li T, Zhang Y, Wang T. SRPM-CNN: a combined model based on slide relative position matrix and CNN for time series classification. Complex Intell Syst. 2021;7(3):1619–31. doi:10.1007/s40747-021-00296-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Mohammadi Foumani N, Miller L, Tan CW, Webb GI, Forestier G, Salehi M. Deep learning for time series classification and extrinsic regression: a current survey. ACM Comput Surv. 2024;56(9):1–45. doi:10.1145/3649448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Wang J, Wang P, Tian H, Tansey K, Liu J, Quan W. A deep learning framework combining CNN and GRU for improving wheat yield estimates using time series remotely sensed multi-variables. Comput Electron Agric. 2023;206:107705. doi:10.1016/j.compag.2023.107705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Malibari S. Benign and Malicious QR Codes [Internet]; 2024 [cited 2024 Aug 25]. Available from: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/samahsadiq/benign-and-malicious-qr-codes. [Google Scholar]

37. Alshaya R, Khediri SEL. Optimizing cybercrime detection: a hybrid deep learning approach for enhanced intrusion detection systems. Peer Peer Netw Appl. 2025;18(3):145. doi:10.1007/s12083-025-01933-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Galadima S. Dataset of 1000 images of malicious and benign QR codes 2025. Mendeley Data [Internet]; 2025 [cited 2024 Sep 05]. Available from: https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/cmhh7744sp/1. [Google Scholar]

39. Karrach L, Pivarčiová E, Božek P. Identification of QR code perspective distortion based on edge directions and edge projections analysis. J Imaging. 2020;6(7):67. doi:10.3390/jimaging6070067. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Tribak H, Gaou M, Gaou S, Zaz Y. QR code recognition based on HOG and multiclass SVM classifier. Multimed Tools Appl. 2023;83(17):49993–50022. doi:10.1007/s11042-023-17398-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Shafique S, Tehsin S. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia detection and classification of its subtypes using pre-trained deep convolutional neural networks. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2018;17:153303381880278. doi:10.1177/1533033818802789. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Deng J, Dong W, Socher R, Li L-J, Li K, Fei-Fei L, et al. ImageNet: a large-scale hierarchical image database. In: Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2009 Jun 20–25; Miami, FL, USA. New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2009. p. 248–55. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2009.5206848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Russakovsky O. ImageNet large scale visual recognition challenge. Int J Comput Vis. 2015;115(3):211–52. doi:10.1007/s11263-015-0816-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Putzu L, Piras L, Giacinto G. Convolutional neural networks for relevance feedback in content based image retrieval. Multimed Tools Appl. 2020;79(37–38):26995–7021. doi:10.1007/s11042-020-09292-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Han X, Zhong Y, Cao L, Zhang L. Pre-trained AlexNet architecture with pyramid pooling and supervision for high spatial resolution remote sensing image scene classification. Remote Sens. 2017;9(8):848. doi:10.3390/rs9080848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Tiwari V, Joshi RC, Dutta MK. Deep neural network for multi-class classification of medicinal plant leaves. Expert Syst. 2022;39(8):e13041. doi:10.1111/exsy.13041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Elhaik E. Principal component analyses (PCA)-based findings in population genetic studies are highly biased and must be reevaluated. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):14683. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-14395-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Setiawan RF. Analysis of factors affecting the interest of people to use DANA application using principal component analysis method (PCA). Int Res J Adv Eng Sci. 2024;5(1):226–32. doi:10.5281/zenodo.3712102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Streamlit. A Faster Way to Build and Share Data Apps [Internet]; 2025 [cited 2024 Apr 11]. Available from: https://streamlit.io/. [Google Scholar]

50. Keras. Timeseries Data Loading [Internet]; 2024 [cited 2024 Aug 10]. Available from: https://keras.io/api/data_loading/timeseries/. [Google Scholar]

51. Alsulami AA. Exploring the efficacy of GRU model in classifying the signal to noise ratio of microgrid model. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):15591. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-66387-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Keras. EarlyStopping [Internet]; 2024 [cited 2024 Aug 10]. Available from: https://keras.io/api/callbacks/early_stopping/. [Google Scholar]

53. Keras. Input Object [Internet]; 2024 [cited 2024 Aug 10]. Available from: https://keras.io/api/layers/core_layers/input/. [Google Scholar]

54. Alaca Y, Çelik Y. Cyber attack detection with QR code images using lightweight deep learning models. Comput Secur. 2023;126:103065. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2022.103065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Guo Z. Digital forensics of scanned QR code images for printer source identification using bottleneck residual block. Sensors. 2020;20(21):6305. doi:10.3390/s20216305. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Toldinas J, Venčkauskas A, Damaševičius R, Grigaliūnas Š., Morkevičius N, Baranauskas E. A novel approach for network intrusion detection using multistage deep learning image recognition. Electronics. 2021;10(15):1854. doi:10.3390/electronics10151854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools