Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Numerical Modeling of Bubble-Particle Attachment in a Volume-of-Fluid Framework

Department of Mechanical Engineering, Pohang University of Science and Technology, Pohang, 37673, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Donghyun You. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Modeling and Applications of Bubble and Droplet in Engineering and Sciences)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(1), 367-390. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.071648

Received 09 August 2025; Accepted 19 September 2025; Issue published 30 October 2025

Abstract

A numerical method is presented to simulate bubble–particle interaction phenomena in particle-laden flows. The bubble surface is represented in an Eulerian framework by a volume-of-fluid (VOF) method, while particle motions are predicted in a Lagrangian framework. Different frameworks for describing bubble surfaces and particles make it difficult to predict the exact locations of collisions between bubbles and particles. An effective bubble, defined as having a larger diameter than the actual bubble represented by the VOF method, is introduced to predict the collision locations. Once the collision locations are determined, the attachment of particles to the bubble surface is determined using a novel numerical algorithm based on collision/induction times. The proposed numerical method is validated through simulations of a rising bubble moving through a layer of particles. The validity of the collision detection algorithm is examined by comparing the collision probability predicted by the present numerical method with that predicted from a theoretical relationship based on bubble/particle diameters. The attachment probability predicted by the present algorithm is found to agree well with that of an experiment.Keywords

Gas bubbles are widely used to capture particles in various industrial applications, such as recovery of coal and minerals from ores, de-inking in paper recycling, and inclusion removal in steelmaking processes [1]. In particular, inclusion removal using gas bubbles is a key technique for producing ultra-clean steel, where micro-sized inclusions are collected on bubble surfaces by injecting gas at various locations [2]. Numerical simulations of particle attachment to bubble surfaces are valuable for improving these applications. However, predicting particle attachment requires an understanding of complex three-phase flow, which makes it challenging to determine the optimal locations for gas injection and improve inclusion removal efficiency.

Particle attachment to a bubble surface is governed primarily by three phenomena: oscillating collision, liquid film formation, and sliding. When a flow-driven particle contacts a bubble, oscillations occur due to the particle inertia and surface tension. Meanwhile, a thin liquid film forms between the particle and the bubble surface, causing the particle to slide downward. The particle may continue sliding and eventually detach, or it may attach to the bubble when the liquid film ruptures. This attachment process can be characterized by three timescales corresponding to each phenomenon: collision time, induction time, and sliding time. The collision time corresponds to the duration of the oscillating collision, for which a mathematical expression was proposed by Evans [3]. The induction time denotes the lifetime of the liquid film from formation to rupture. Finally, the sliding time characterizes the interval during which the particle slides over the bubble surface. This phenomenon was modeled by adopting experimental results [4,5] under the assumptions of inertialess particles and potential flow [6].

Recent efforts have examined bubble-particle interactions using advanced CFD and modeling approaches. Liu et al. [7] and Li et al. [8] reported particle-scale insights into fluidization and phase distribution, while Wang et al. [9] reviewed CFD applications in flotation. Chan et al. [10] investigated bubble-particle collisions under turbulence, and Zheng et al. [11] proposed a model for predicting collision efficiency. In parallel, Szmigiel et al. [12] highlighted the role of machine learning in flotation process optimization. These studies underscore recent progress, though attachment and detachment dynamics remain insufficiently addressed. Many researchers have studied bubble–particle attachment phenomena using numerical methods. To predict collision efficiency and attachment probability, hydrophobic forces acting on particles near a stationary bubble have been modeled [13–15]. It was concluded in the previous work that the force acting on particles near a bubble has a significant impact on predicting bubble–particle interactions. Although these studies have simulated particle motions near bubble surfaces based on attachment physics, only the particle dynamics are solved without consideration of the dynamics of the flow field. Some studies have incorporated flow field results to estimate collision efficiency [16–19]. To better capture particle behavior around deformable bubble surfaces, the volume-of-fluid (VOF) method has been employed to model the phase interface in gas-liquid-solid systems [20–22]. Further advances extended this approach to multiscale and coupled DEM-VOF methods [23,24]. More recently, particle-bubble interactions near solid boundaries have also been investigated using VOF-based simulations [25]. However, the detailed physics of particle attachment at the bubble surface has not been considered in these studies.

Despite numerous theoretical models on attachment physics, it has been difficult to apply them to practical numerical methods for multiphase flow such as those based on a VOF method. Liu et al. [26] provided a detailed assessment and analysis of five different phase-change models for simulating vapor bubble condensation within a VOF framework. Although bubble-particle interactions were not considered in this study, the method integrated physical bubble models with the VOF method. To accurately predict attachment, the three characteristic times related to bubble-particle interaction must be accounted for. Especially, calculating the induction time has been difficult because modeling the physics of the liquid film is complex. According to Nguyen et al. [27], the characteristic times can be alternatively interpreted as the relative position between a particle and a bubble. By adopting the concept of a critical angle, induction and sliding times can instead be represented by geometric relations between a particle and a bubble. In this model, the collision location of a particle to the bubble surface must be known a priori. However, when the bubble interface and the particles are represented in a distinct Eulerian–Lagrangian framework, the accuracy of the interface reconstruction is affected by grid resolution [28]. For this reason, precise determination of the collision location is technically difficult.

In the present study, bubble-particle attachment is modeled by considering both the attachment physics and the dynamics of the bubble surface. To apply the theoretical relationship developed by Nguyen et al. [27] to an Eulerian-Lagrangian framework based on a VOF method, an effective bubble is introduced to predict the collision locations. A method for computing the bubble-particle angle is devised to determine the three characteristic times: collision, induction, and sliding times, during bubble-particle interaction. Numerical algorithms are developed to incorporate both the VOF method and the relationship proposed by Nguyen et al. [27].

Numerical methods for simulating gas-liquid-solid flows are described in Section 2. The physical background and numerical algorithms for bubble-particle interaction are presented in Sections 3 and 4, respectively. Results of validation simulations using the present numerical method are discussed in Section 5, followed by concluding remarks in Section 6.

Gas-liquid flow is governed by the Navier-Stokes equations with surface tension. The one-fluid formulation is adopted, in which the total density and total dynamic viscosity are used instead of solving the governing equations separately for each phase. The incompressible variable-density Navier-Stokes equations in Cartesian coordinates are given as follows:

where

where

Numerical schemes for solving Eqs. (1) and (2) are described in [29]. The Crank–Nicolson scheme is employed for time advancement, and a Newton-iterative method is applied to solve the nonlinear terms. A second-order central-difference scheme is used to discretize the spatial derivative terms. The fractional-step method and an approximate factorization technique [30] are then applied to the discretized equations. Finally, the Poisson equation for pressure is solved using an algebraic multigrid method [31].

The motion of a solid particle is predicted within a Lagrangian framework. The governing Lagrangian equations for the particle motion are expressed as follows:

where

where

where

The gas and liquid phases are distinguished by the volume fraction, which is advected using the VOF method. The advection equation for the volume fraction

A piecewise linear interface calculation (PLIC) approach [33] is used to solve Eq. (9). In this approach, the phase interface in each cell is represented by a line or a plane equation. The VOF/PLIC method consists of two steps. First, the interface is reconstructed from the volume fraction

where

The surface tension force

where

3 Physics of Bubble-Particle Interaction

3.1 Mechanisms of Sliding and Attachment of a Colliding Particle

Numerical modeling of bubble-particle interaction requires understanding how a particle moves on a bubble surface. In this study, the case where the particle size is much smaller than the bubble size: the particle diameter

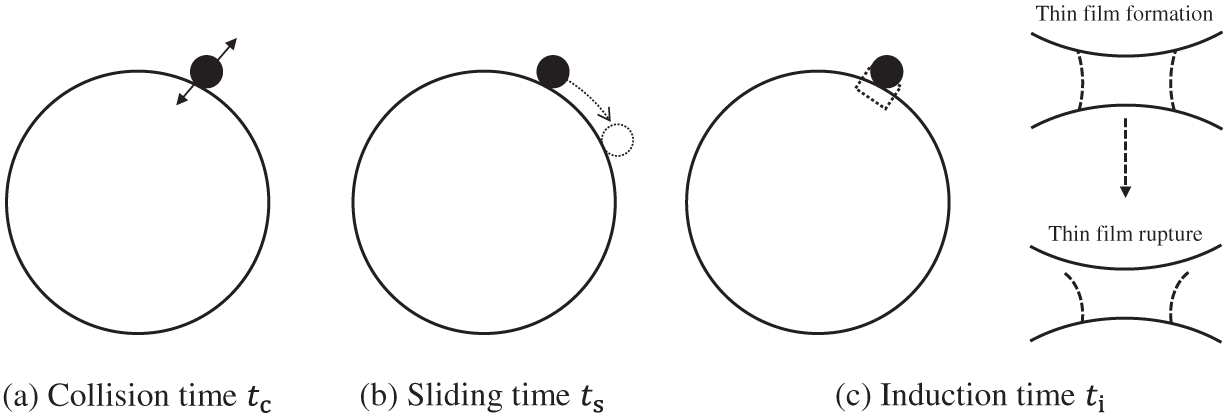

The motion of particles on the bubble surface can be characterized by three characteristic timescales, as illustrated in Fig. 1. These times determine whether a particle attaches or slides away after collision. The collision time

Figure 1: Schematic illustration of the three characteristic times which determine particle motions on a bubble surface: (a) collision time

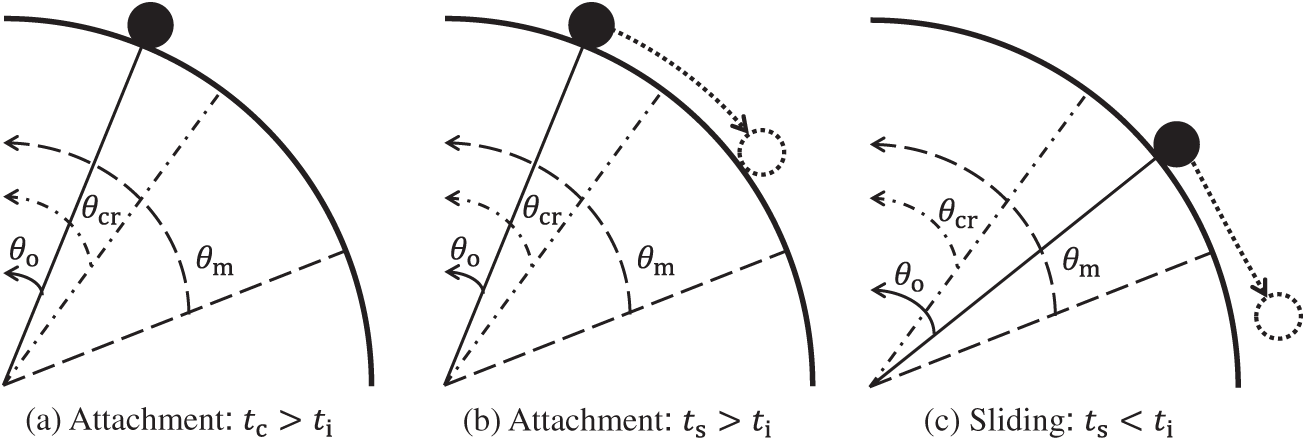

Particle motions on the bubble surface can also be described in terms of the relative position between the bubble and the particle. The relative position is represented by the angle measured from the stagnation point (the top position of a rising spherical bubble) to the point of particle contact. Three possible outcomes after particle collision are illustrated in Fig. 2 based on the angle criteria. Three characteristic angles are used to determine particle motions. The bubble-particle angle

Figure 2: Schematic illustration of three types of particle motions after collision: (a) attachment during oscillation; (b) attachment during sliding; and (c) sliding over a thin liquid film

In the present model, both time and angle criteria are used to determine the particle motion. The calculation procedures for the collision angle

3.2 Collision and Attachment Probabilities

Based on particle motions on the bubble surface, the number of colliding and attached particles, and thereby the probabilities of collision and attachment are determined. The collision probability

where

where

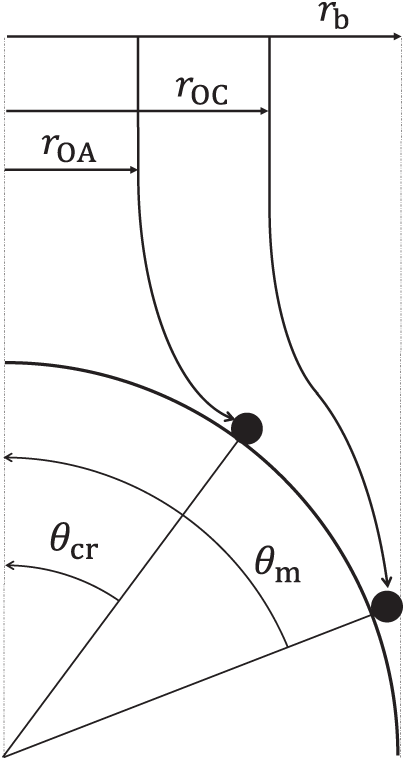

Figure 3: Definitions of the collision radius

The collision probability

where the dimensionless parameters X, Y, C, and D are defined as follows:

where

The particle velocity can also be determined using the formula of Oeters [43], as follows:

where

The attachment probability

where

where

In the present study, the attachment probability

where the model constants

where

4 Numerical Modeling of Collision, Sliding, and Attachment

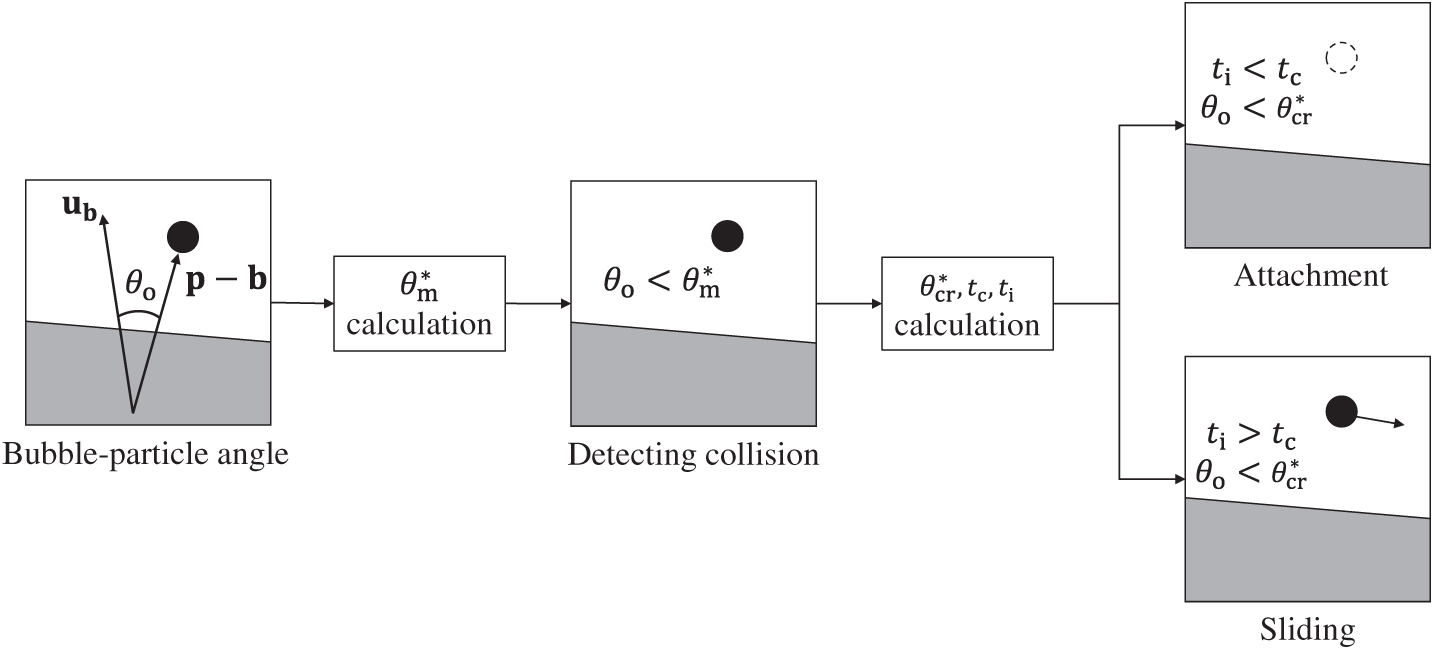

In the present numerical method, particle motions including collision, sliding, and attachment, are predicted using time and angle criteria derived from empirical relationships. The numerical method consists of two steps: first, detecting particle collisions near the bubble surface; second, determining whether the colliding particle slides or attaches. Fig. 4 schematically illustrates the procedure for modeling bubble-particle interaction. The detailed algorithms and methodology are presented in the following subsections.

Figure 4: Procedure for modeling bubble-particle interaction. The method of calculating the bubble-particle angle

4.1 Relative Position and Angle between a Bubble and a Particle

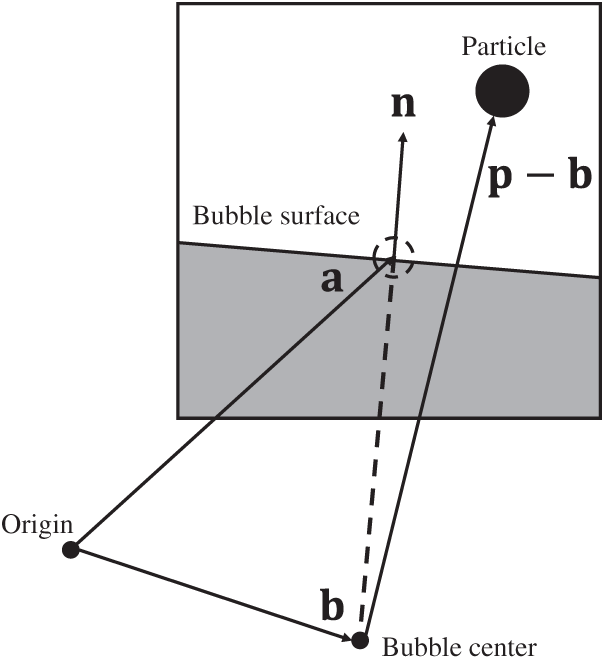

As mentioned in Section 3.1, angle criteria are used to determine particle motions on the bubble surface. To apply these criteria, the bubble-particle angle

Figure 5: Position relationships between a bubble and a particle.

First, the normal vector of the bubble surface

where

Finally, the particle position vector relative to the bubble center

Determination of particle attachment on the bubble surface begins with detecting bubble-particle collisions, since attachment is examined only for colliding particles. A collision occurs when the particle is in physical contact with the bubble surface. In other words, the collision condition is satisfied when the bubble-particle distance equals the particle radius. The bubble-particle distance

where

However, a new definition of collision is required because the exact collision location cannot be easily determined: the bubble surface represented in a computational domain is not explicitly defined in the VOF method. Instead, the interface is reconstructed from the volume fraction in an Eulerian framework. Since the particle size is smaller than the grid size, calculating the exact distance between the particle center and the bubble surface is not straightforward.

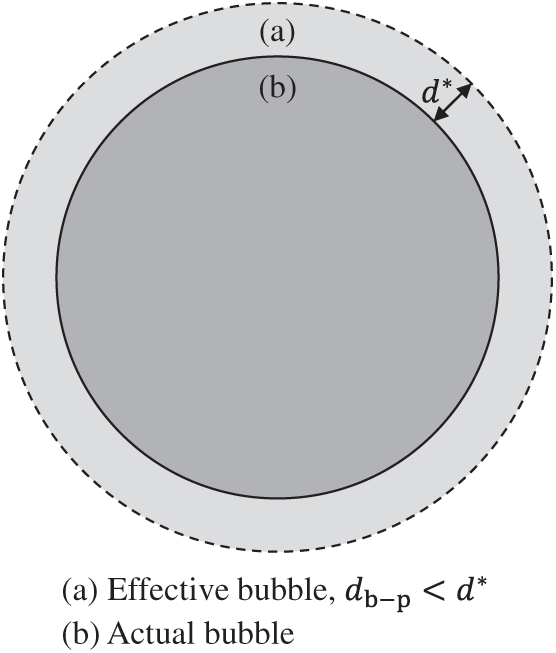

In the present method, the concept of an effective bubble is introduced to address the difficulty of determining the collision location. The effective bubble is defined as having a larger diameter than the actual bubble but the same center. Fig. 6 illustrates the regions of the actual and effective bubbles. The circle with a solid line represents the actual bubble with the diameter

Figure 6: Definitions of (a) the effective bubble and (b) the actual bubble.

Instead of predicting the exact collision on the actual bubble surface, which is difficult to determine precisely, a collision is assumed to occur when a particle is located within the region between the effective and actual bubble surfaces. Thus a particle positioned between the solid and dashed lines in Fig. 6 is considered a candidate for collision with the actual bubble. For such colliding particles, the bubble-particle angle

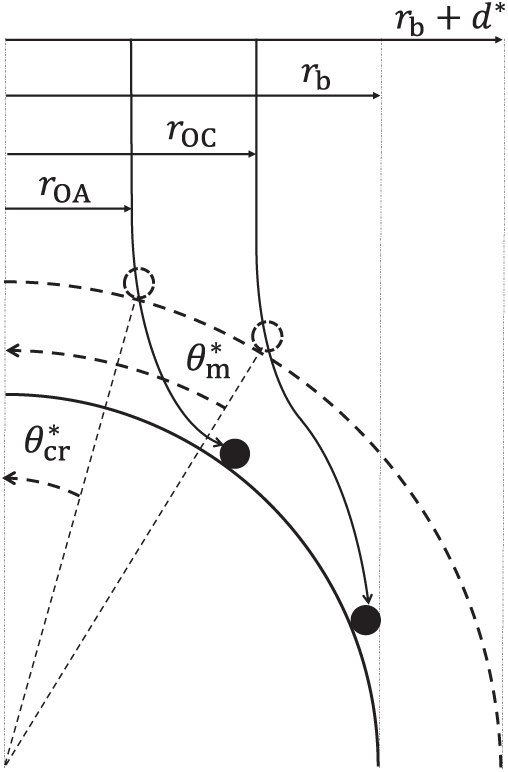

4.3 Effective Collision and Critical Angles

As mentioned in the previous section, collision and attachment are determined when a particle crosses the surface of the effective bubble. Since the collision point shifts from the actual bubble to the effective bubble, the collision and critical angles must be adjusted. Fig. 7 shows the geometric definitions of the effective collision angle

Figure 7: Effective collision angle

Details of the effectiveness factors

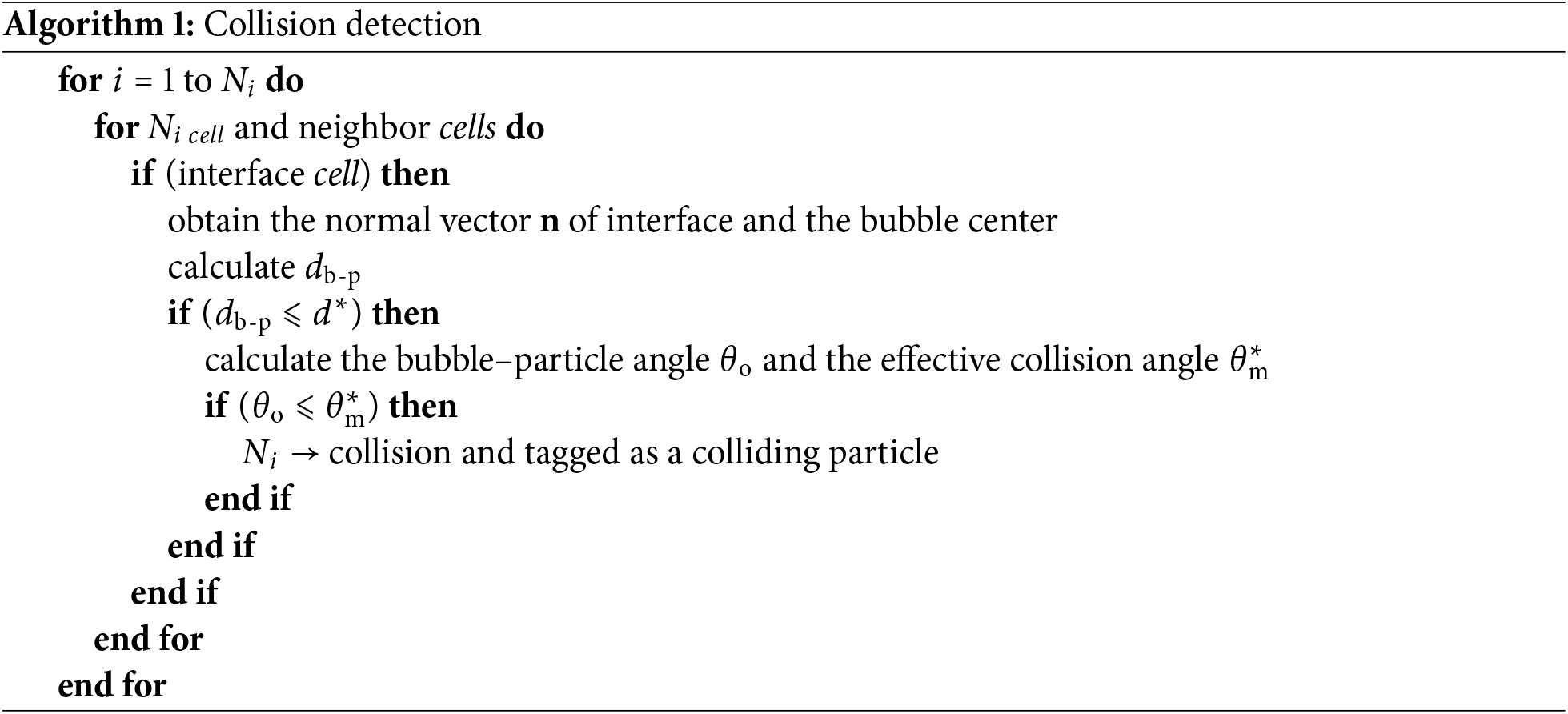

The algorithm for collision detection in the VOF method is summarized in Algorithm 1. An interface cell is defined as a cell with volume fraction

4.5 Determination of Sliding or Attachment

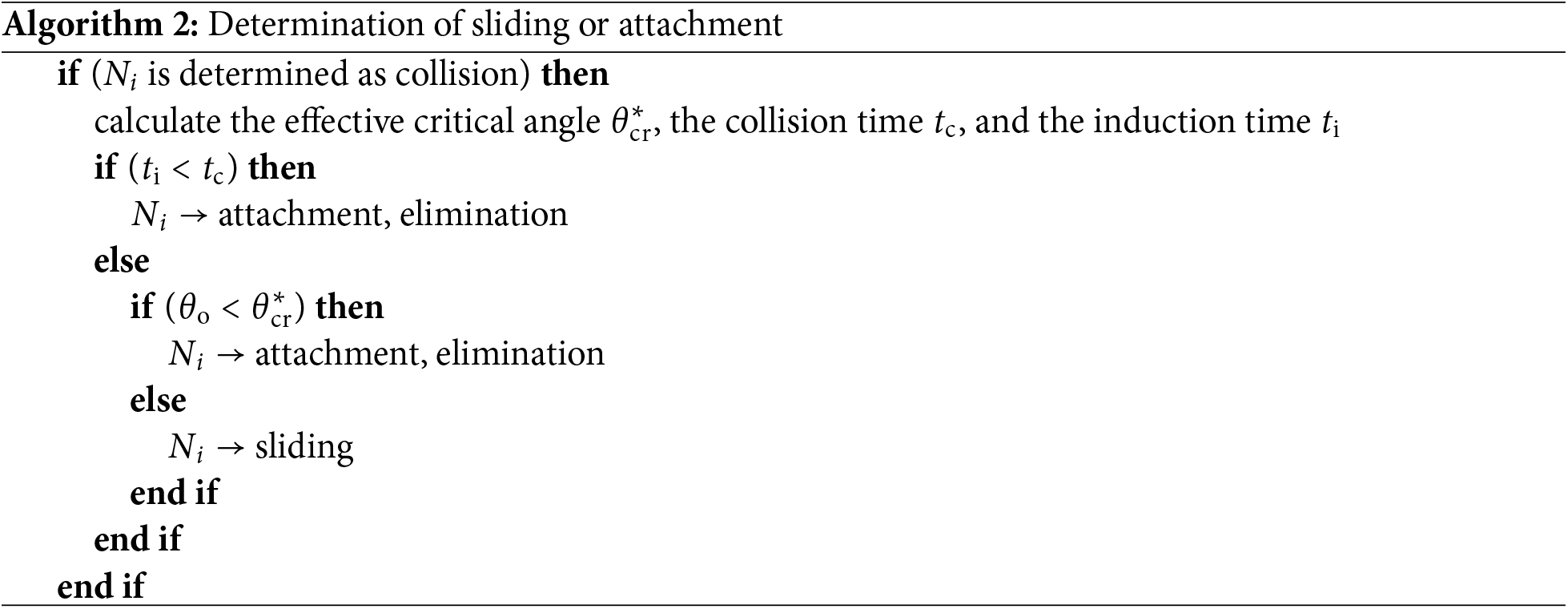

After detecting a collision, the final step is to determine whether the colliding particle slides off or attaches to the bubble surface using the time and angle criteria. First, the collision time

This timescale represents the duration of oscillation following particle collision. The induction time

where the dimensionless parameters A and B are given by

where X and Y are defined by Eqs. (15a) and (15b), respectively. The effective critical angle

The procedure for determining sliding or attachment is summarized in Algorithm 2. As discussed in Section 3.1, if

5.1 A Rising Bubble through a Layer of Particles

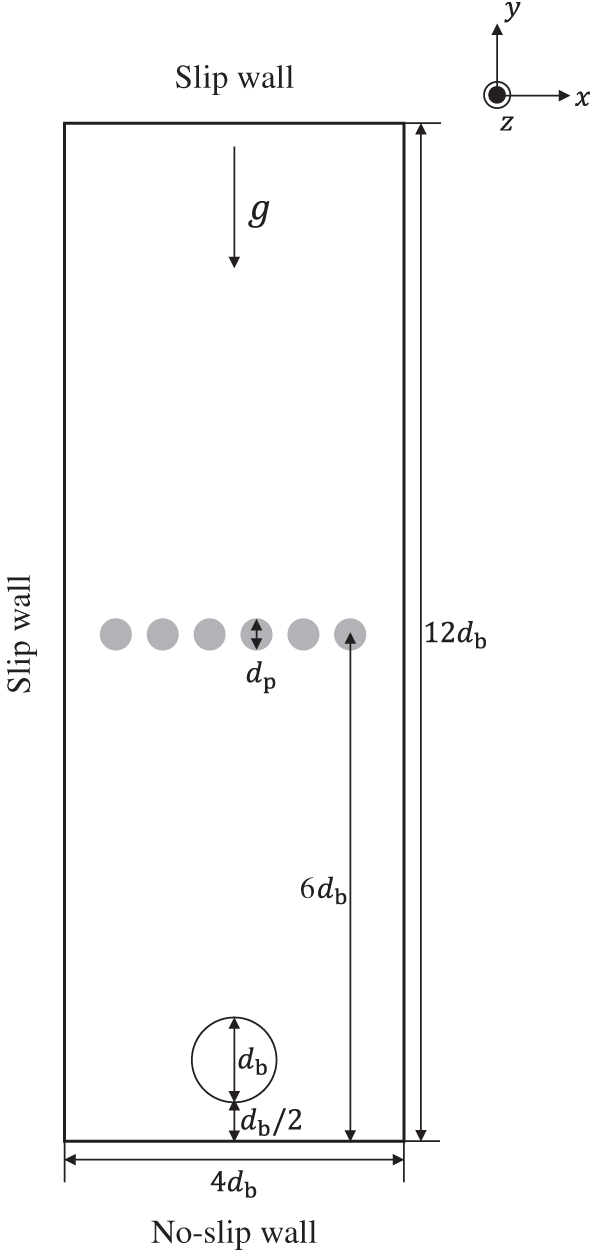

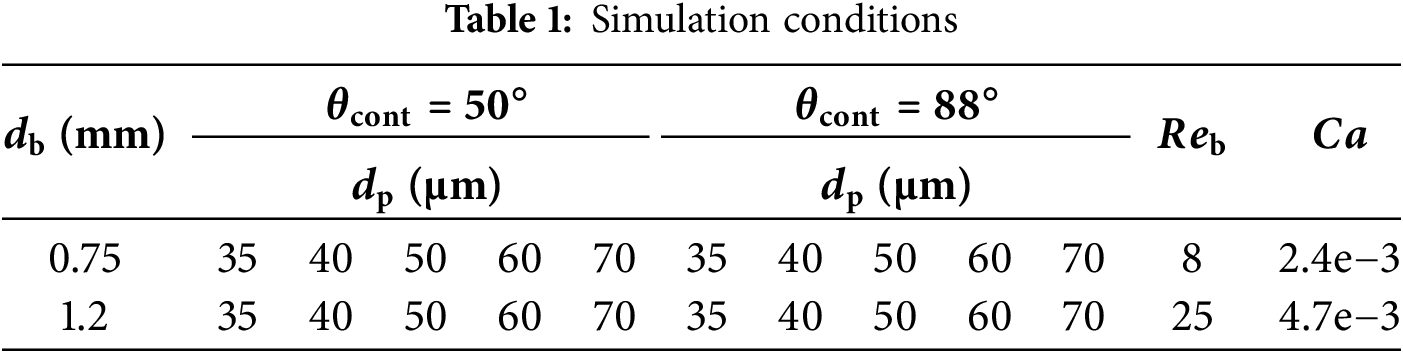

Numerical simulations of a rising bubble moving through a layer of many particles, as configured in Fig. 8, are conducted to present gas–liquid–solid flow method together with the bubble–particle attachment model. Simulation results are compared with the experimental data of Hewitt et al. [44]. The computational domain is

Figure 8: Computational setup for numerical simulations of a rising bubble moving through a layer of particles

A stationary spherical bubble is initially placed at the center of the domain, positioned one bubble diameter

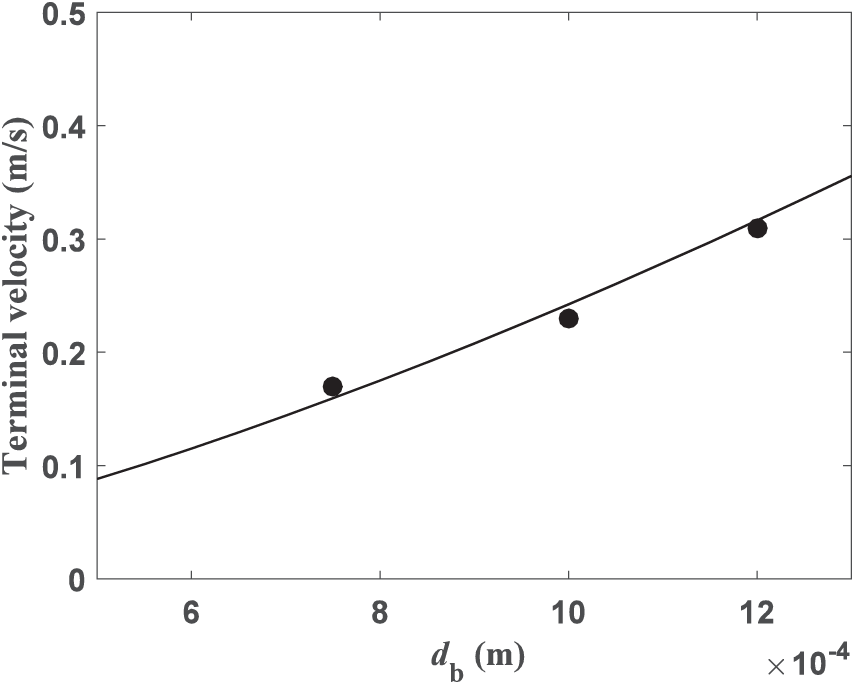

Before validating the present bubble-particle attachment algorithm, the terminal velocity of a rising bubble without particles is compared with the empirical relation given in Eq. (16). The terminal velocity, determined from the velocity of the bubble center, shows good agreement with the empirical value, as illustrated in Fig. 9.

Figure 9: Terminal velocity of a rising bubble as a function of the bubble diameter

5.1.1 Collision Probability and Collision Diameter

The collision probability (Eq. (12)) obtained from the present simulation is compared with that predicted by the theoretical relationship (Eq. (14)). To calculate the collision probability in the simulation, the ratio of the ideal to the actual number of colliding particles is required. From the definition in Section 3.2, the ideal number of colliding particles

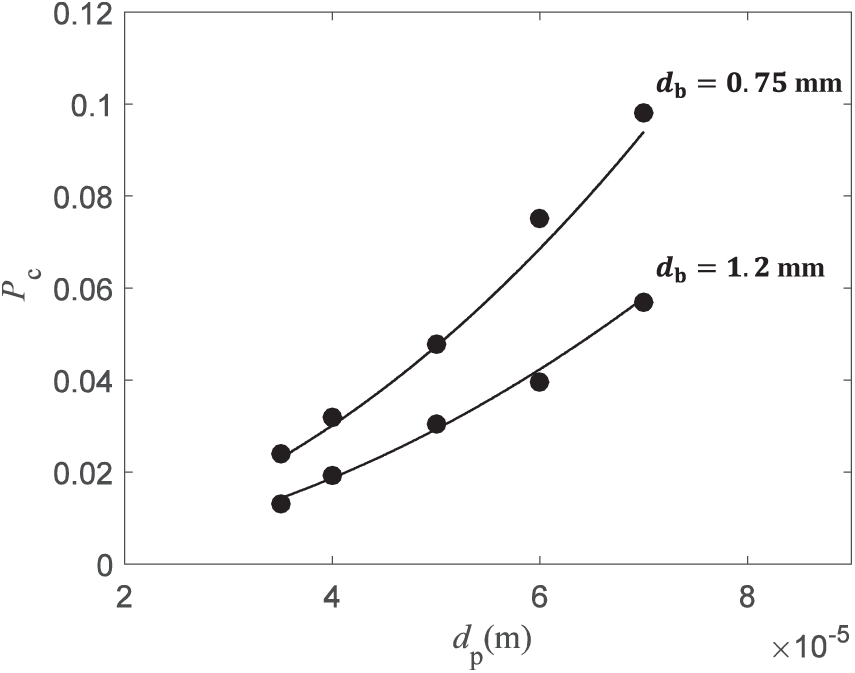

Figure 10: Collision probability

The collision diameter

Figure 11: Collision diameter

5.1.2 Attachment Probability and Attachment Diameter

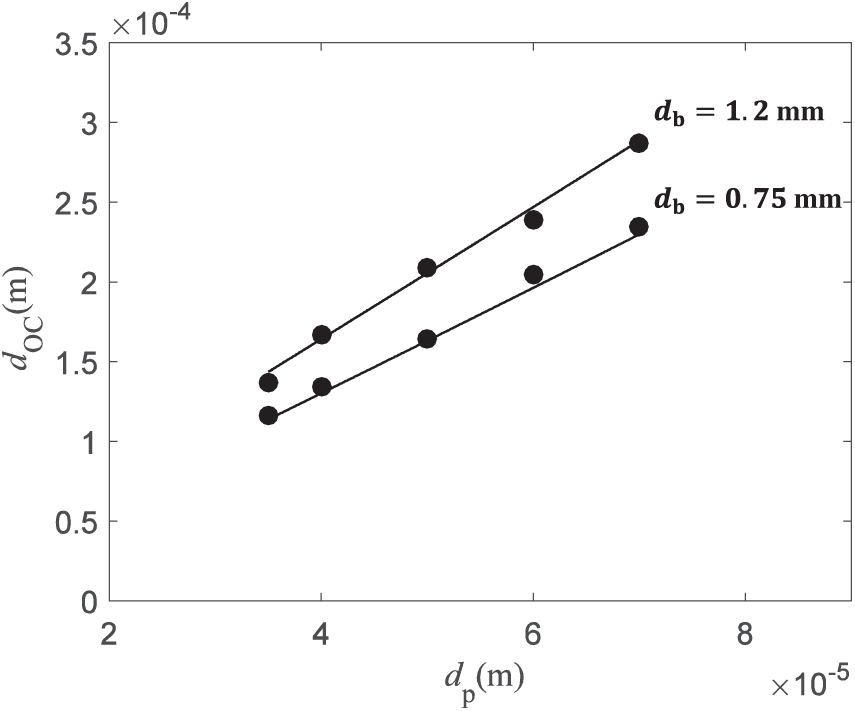

The attachment probability and attachment diameter are compared with theoretical and experimental results [44]. In the present simulation, the attachment probability is estimated using Eq. (18). The total number of attached particles

Figure 12: Attachment probability

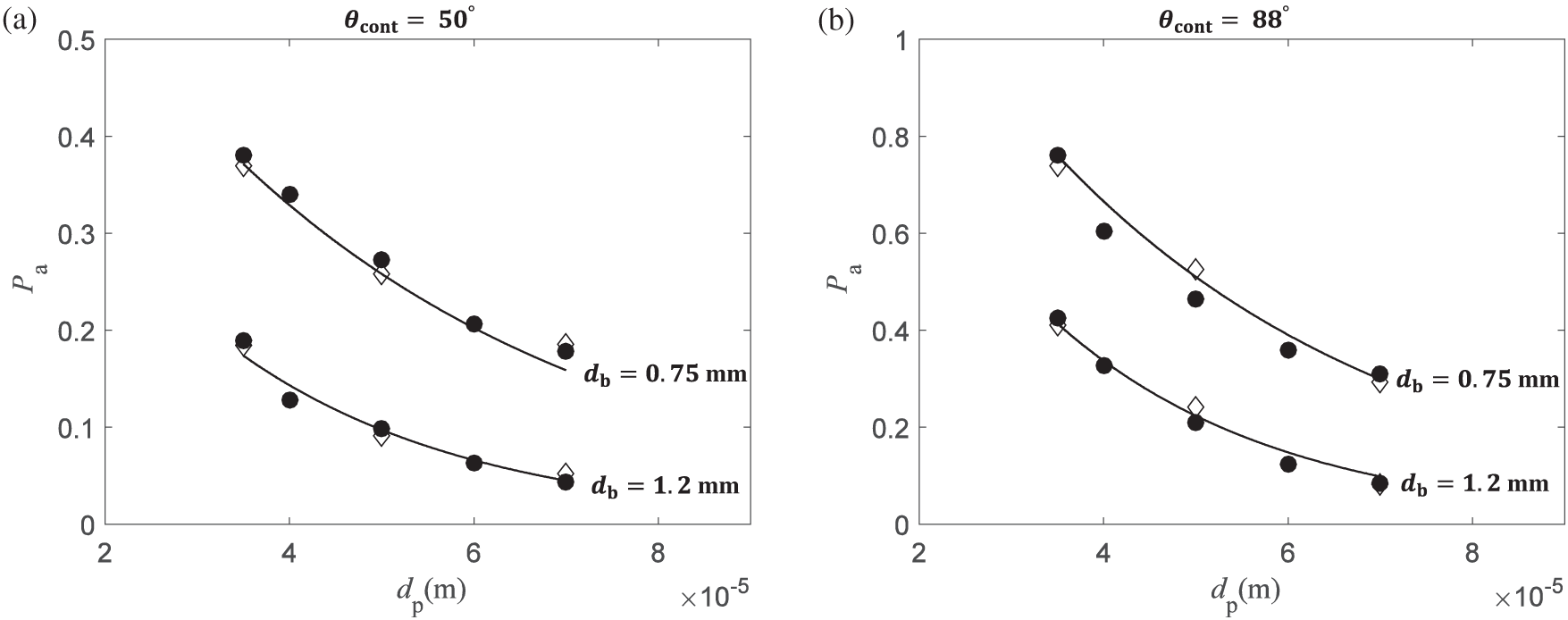

The attachment diameter is calculated as

Figure 13: Attachment diameter

This tendency arises from the product of the collision probability and the attachment probability:

where P is referred to as the flotation probability [27] or total attachment probability [2]. The probability corresponds to the ratio of attached particles to the ideal number of colliding particles. The relation indicates that the attachment diameter

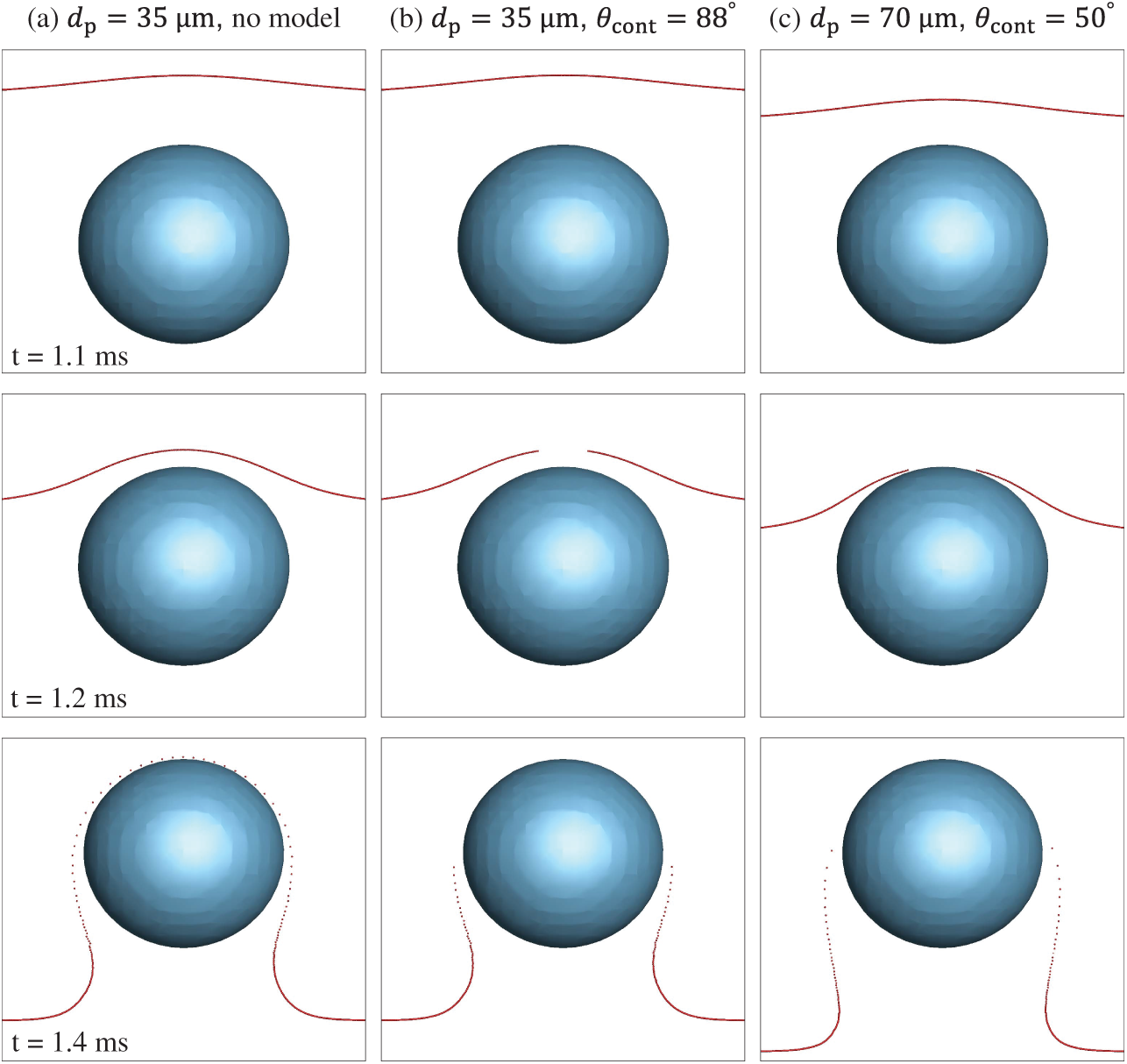

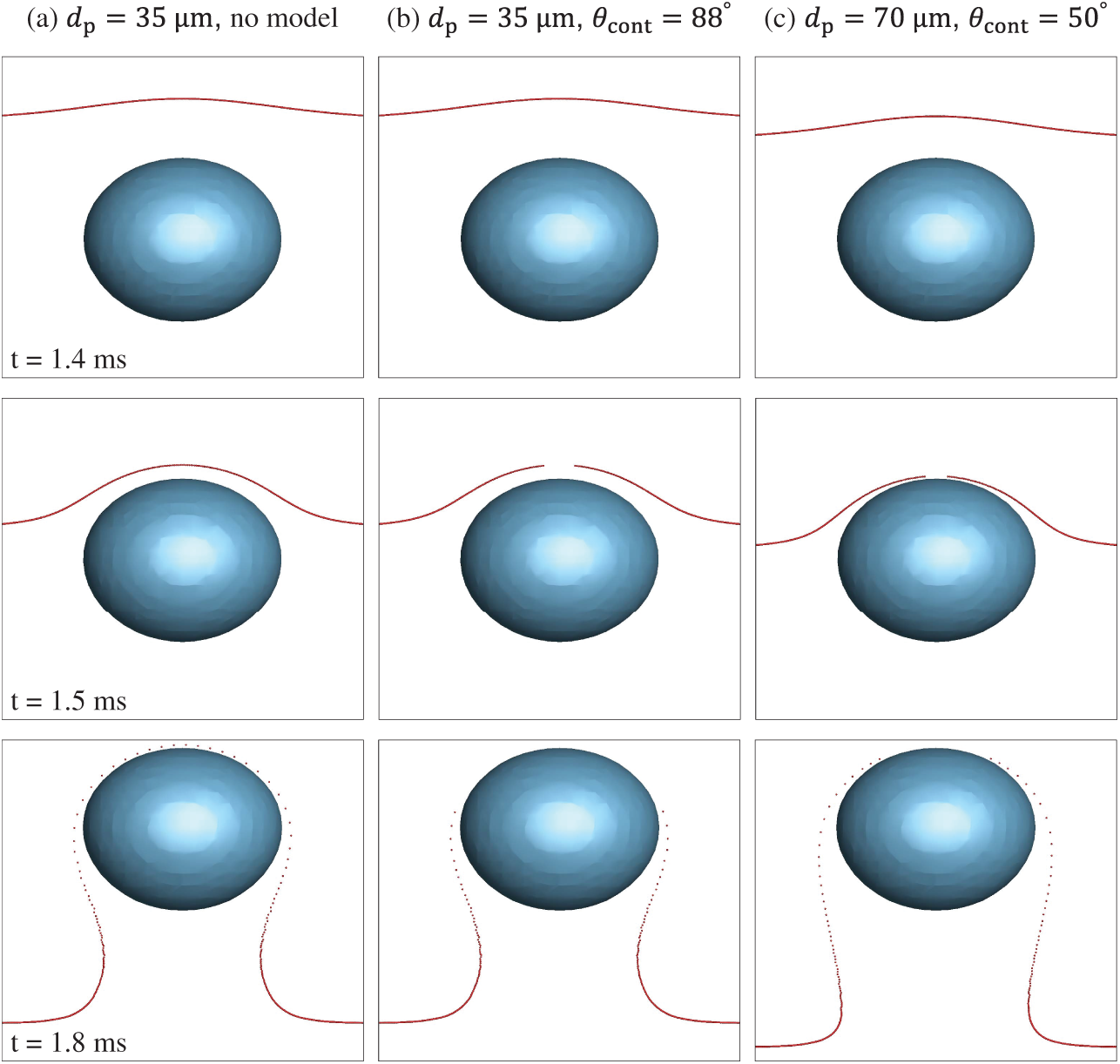

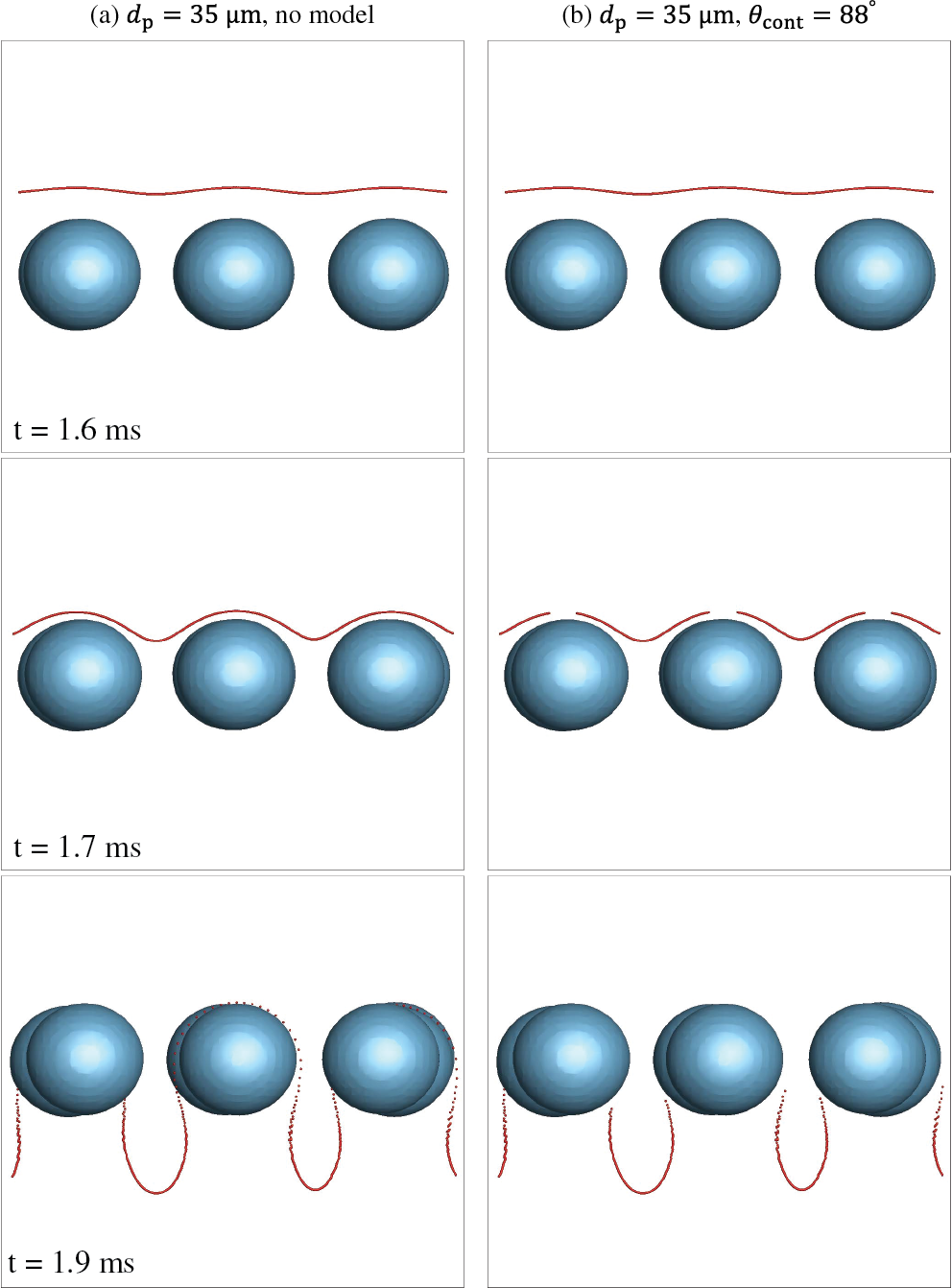

The present method distinguishes between sliding or attachment of colliding particles, thereby enabling observation of particle motions near the bubble surface, as shown in Figs. 14 and 15. Bubbles are represented by iso-surfaces of the volume fraction

Figure 14: Visualization of a layer of particles interacting with a bubble with

Figure 15: Visualization of a layer of particles interacting with a bubble with

As discussed in Section 4.5, attached particles are eliminated on the effective bubble before making contact with the actual bubble surface. The bubble surface is reconstructed from the VOF method in an Eulerian framework, while the particle size is smaller than the grid size, making the prediction of the exact collision location difficult. Therefore, sliding and attachment are determined on the effective bubble surface, which is larger than the actual bubble. For the bubble with a diameter of 0.75 mm, the number of attached particles is nearly identical for both

Similarly, Fig. 15 shows the case of a bubble with diameter 1.2 mm. The number of attached particles in Fig. 15b is greater than in Fig. 15c, because the attachment diameter in the former case is 90

5.2 Multiple Rising Bubbles through a Layer of Particles

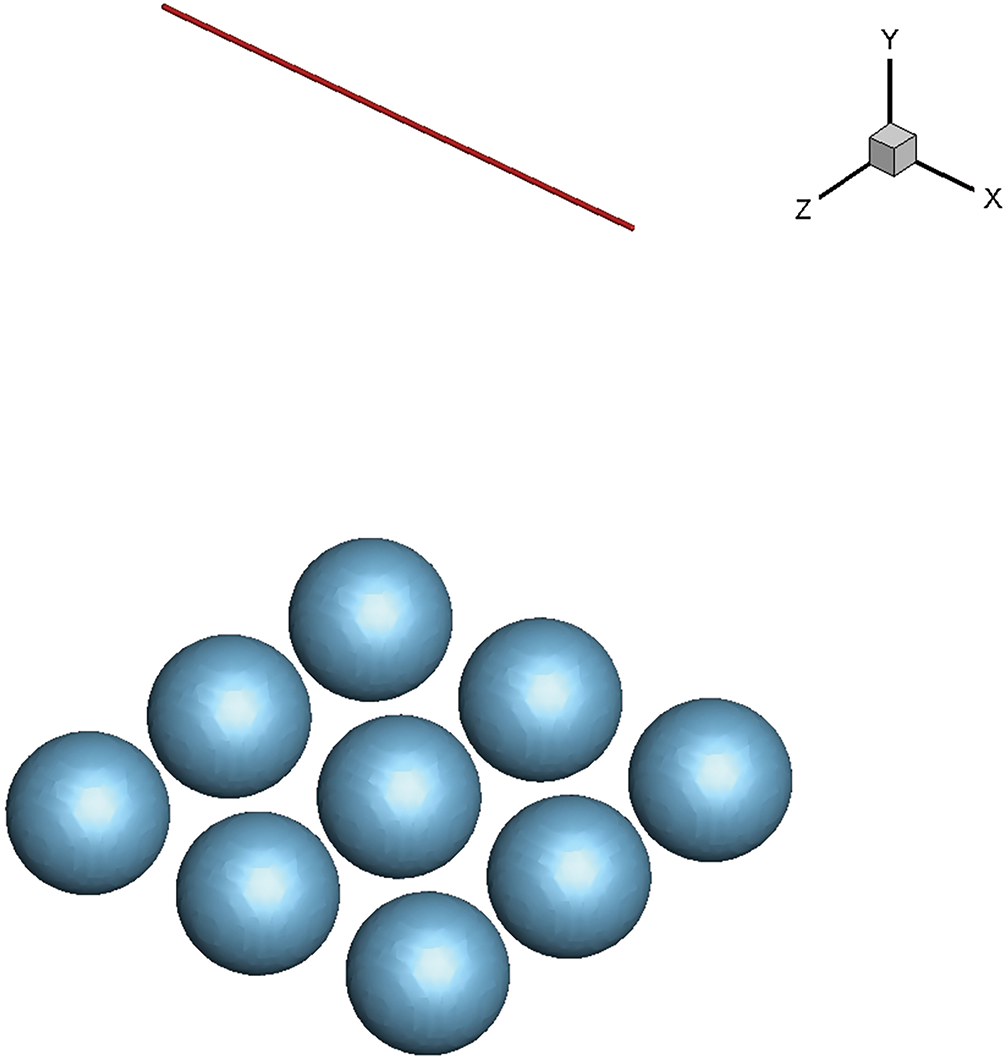

The present bubble-particle attachment method can be extended to interactions involving multiple bubbles and particles. The computational domain is the same as in the single bubble case presented in Section 5.1, except that periodic boundary conditions are applied to the side walls instead of slip conditions. Fig. 16 shows

Figure 16: Initial configuration of multiple bubbles and a layer of particles.

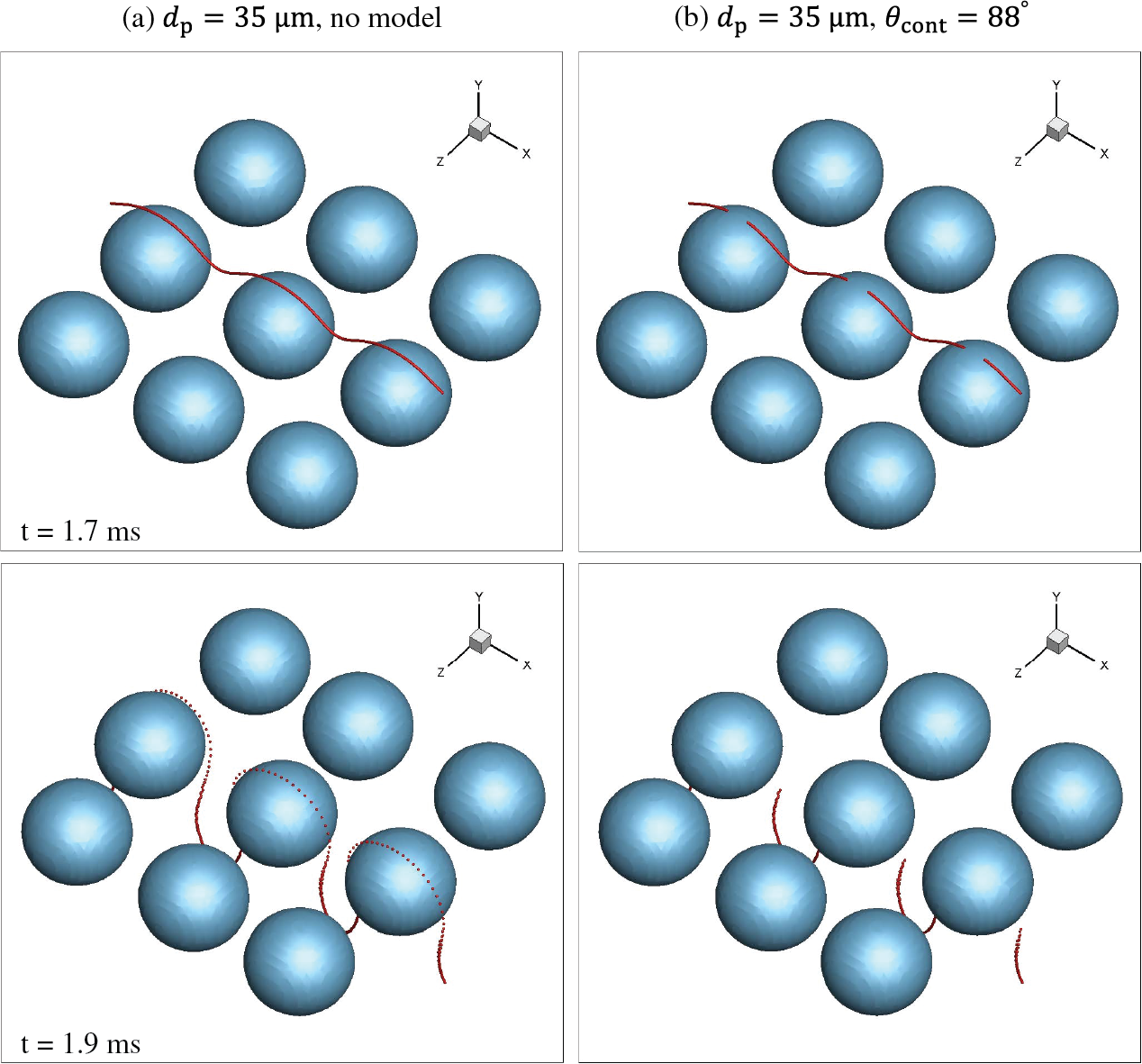

For the multiple-bubble case, tilt and side views are visualized to illustrate interactions between bubbles and a layer of particles, as shown in Figs. 17 and 18. Without the attachment model, no particles adhere to the bubble surface as shown in Figs. 17a and 18a. In contrast, with the attachment model, attached particles are eliminated on the bubble surface as shown in Figs. 17b and 18b.

Figure 17: Multiple rising bubbles through a layer of particles. (a) Without the attachment model and (b) with the attachment model.

Figure 18: Side views (

A numerical method for simulating gas-liquid-solid flows, including bubble-particle attachment, has been developed. Phase interfaces are described and advected using a geometrical conserving VOF method, while particle dynamics are solved in a Lagrangian framework. The bubble–particle attachment is modeled in the VOF framework using the concept of an effective bubble together with the theoretical relationships of Nguyen et al. [27].

The present numerical method consists of two steps: collision detection and sliding/attachment determination during bubble-particle interaction. It requires evaluation of the angle between two vectors: the bubble velocity vector and the vector of the particle position relative to the bubble center. A method for calculating this angle in the geometric VOF framework is proposed. Since the exact collision location cannot be easily resolved in the VOF framework, collisions are defined to occur when a particle lies between the surfaces of the actual bubble and an effective bubble with a larger radius, introduced to account for grid-resolution limits.

The present numerical method has been validated by reproducing experimental cases. Simulations of a rising bubble moving through a layer of particles, for a range of bubble diameters, particle diameters, and contact angles, demonstrated that the present numerical method accurately predicts collision and attachment probabilities. The efficacy of the present attachment model is further confirmed through visualizations of the simulated particle dynamics. Finally, the applicability of the present method to complex industrial problems has been illustrated by simulating multiple rising bubbles interacting with a layer of many particles.

The present numerical method successfully simulates bubble-particle attachment, yet several limitations remain. First, because it relies on the concept of an effective bubble and grid resolution, the precise collision location and the detailed physics of liquid film formation and rupture are simplified. Second, complex physical factors such as particle hydrophobicity/hydrophilicity, surface roughness, and turbulent flow conditions are not fully considered. Future work should therefore aim to incorporate more detailed models, such as molecular dynamics or continuum-scale coupling, to better capture film physics.

Acknowledgement: The authors gratefully acknowledge Sanghyun Ha and Jeongbo Shim for their constructive comments on this work.

Funding Statement: The work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) under the Grant Numbers NRF-2021R1A2C2092146 and RS-2023-00282764.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Hojun Moon and Donghyun You; methodology, Hojun Moon; software, Hojun Moon; validation, Hojun Moon; formal analysis, Hojun Moon; investigation, Hojun Moon and Donghyun You; resources, Donghyun You; data curation, Hojun Moon; writing—original draft preparation, Hojun Moon; writing—review and editing, Donghyun You; visualization, Hojun Moon; supervision, Donghyun You; project administration, Donghyun You; funding acquisition, Donghyun You. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Appendix A Tuning of the Effective Collision Angle and the Critical Angle

In the present numerical method, collisions are defined using both the actual and effective bubble surfaces. The effective collision angle

where

where the coefficients

The coefficients in Eqs. (A1) and (A2) are determined as follows. First, the effectiveness factors

References

1. Nguyen AV, Schulze HJ. Colloidal science of flotation. Vol. 118. In: Surfactant sciences series. 1st ed. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

2. Zhang L, Taniguchi S. Fundamentals of inclusion removal from liquid steel by bubble flotation. Int Mater Rev. 2000;45(2):59–82. doi:10.1179/095066000101528313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Evans LF. Bubble-mineral attachment in flotation. Ind Eng Chem. 1954;46(11):2420–4. [Google Scholar]

4. Dobby GS, Finch JA. A model of particle sliding time for flotation size bubbles. J Colloid Interface Sci. 1986;109(2):493–8. doi:10.1016/0021-9797(86)90327-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Dobby GS, Finch JA. Particle size dependence in flotation derived from a fundamental model of the capture process. Int J Miner Process. 1987;21(3–4):241–60. doi:10.1016/0301-7516(87)90057-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Sutherland KL. Physical chemistry of flotation. XI. Kinetics of the flotation process. J Phys Chem. 1948;52(2):394–425. doi:10.1021/j150458a013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Liu L, Zhan M, Wang R, Liu Y. Three-dimensional VOF-DEM simulation study of particle fluidization induced by bubbling flow. Processes. 2024;12(6):1053. doi:10.3390/pr12061053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Li X, Hao Y, Zhao P, Fan M, Song S. Simulation study on the phase holdup characteristics of the gas–liquid-solid mini-fluidized beds with bubbling flow. Chem Eng J. 2022;427(31):131488. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2021.131488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Wang H, Yan X, Li D, Zhou R, Wang L, Zhang H, et al. Recent advances in computational fluid dynamics simulation of flotation: a review. Asia Pac J Chem Eng. 2021;16(5):e2704. doi:10.1002/apj.2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Chan TTK, Ng CS, Krug D. Bubble–particle collisions in turbulence: insights from point-particle simulations. J Fluid Mech. 2023;959:A6. doi:10.1017/jfm.2025.10405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Zheng K, Yan X, Wang L, Zhang H. Predictions of particle–bubble collision efficiency and critical collision angle in froth flotation. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp. 2024;702(Part 1):134985. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfa.2024.134985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Szmigiel A, Apel DB, Skrzypkowski K, Wojtecki L, Pu Y. Advancements in machine learning for optimal performance in flotation processes: a review. Minerals. 2024;14(4):331. doi:10.3390/min14040331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Maxwell R, Ata S, Wanless EJ, Moreno-Atanasio R. Computer simulations of particle–bubble interactions and particle sliding using discrete element method. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2012;381(1):1–10. doi:10.1016/j.jcis.2012.05.021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Moreno-Atanasio R. Influence of the hydrophobic force model on the capture of particles by bubbles: a computational study using discrete element method. Adv Powder Technol. 2013;24(4):786–95. doi:10.1016/j.apt.2013.05.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Moreno-Atanasio R, Gao Y, Neville F, Evans GM, Wanless EJ. Computational analysis of the selective capture of binary mixtures of particles by a bubble in quiescent and fluid flow. Chem Eng Res Des. 2016;109:354–65. doi:10.1016/j.cherd.2016.01.035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Sarrot V, Guiraud P, Legendre D. Determination of the collision frequency between bubbles and particles in flotation. Chem Eng Sci. 2005;60(22):6107–17. doi:10.1016/j.ces.2005.02.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Nadeem M, Ahmed J, Chughtai IR, Ullah A. CFD-based estimation of collision probabilities between fine particles and bubbles having intermediate reynolds number. The Nucleus. 2009;46(3):153–9. doi:10.71330/nucleus.46.03.940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Koh PTL, Schwarz MP. CFD modelling of bubble–particle collision rates and efficiencies in a flotation cell. Miner Eng. 2003;16(11):1055–9. doi:10.1016/j.mineng.2003.05.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Koh PTL, Schwarz MP. CFD modelling of bubble–particle attachments in flotation cells. Miner Eng. 2006;19(6–8):619–26. doi:10.1016/j.mineng.2005.09.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Li Y, Zhang J, Fan LS. Numerical simulation of gas–liquid–solid fluidization systems using a combined CFD-VOF-DPM method: bubble wake behavior. Chem Eng Sci. 1999;54(21):5101–7. doi:10.1016/s0009-2509(99)00263-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Chen C, Fan LS. Discrete simulation of gas-liquid bubble columns and gas-liquid-solid fluidized beds. AIChE J. 2004;50(2):288–301. doi:10.1002/aic.10027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Xu Y, Ersson M, Jönsson PG. A numerical study about the influence of a bubble wake flow on the removal of inclusions. ISIJ Int. 2016;56(11):1982–8. doi:10.2355/isijinternational.isijint-2016-249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Pozzetti G, Peters B. A multiscale DEM-VOF method for the simulation of three-phase flows. Int J Multiphase Flow. 2018;99(15):186–204. doi:10.1016/j.ijmultiphaseflow.2017.10.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Zhao N, Wang B, Kang Q, Wang J. Effects of settling particles on the bubble formation in a gas-liquid-solid flow system studied through a coupled numerical method. Phys Rev Fluids. 2020;5(3):033602. doi:10.1103/physrevfluids.5.033602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Teran LA, Rodriguez SA, Laín S, Jung S. Interaction of particles with a cavitation bubble near a solid wall. Phys Fluids. 2018;30(12):123304. doi:10.1063/1.5063472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Liu H, Tang J, Sun L, Mo Z, Xie G. An assessment and analysis of phase change models for the simulation of vapor bubble condensation. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2020;157(Part A):119924. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2020.119924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Nguyen AV, Ralston J, Schulze HJ. On modelling of bubble–particle attachment probability in flotation. Int J Miner Process. 1998;53(4):225–49. doi:10.1016/s0301-7516(97)00073-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Lecrivain G, Yamamoto R, Hampel U, Taniguchi T. Direct numerical simulation of a particle attachment to an immersed bubble. Phys Fluids. 2016;28(8):083301. doi:10.1063/1.4960627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Moon H, Hong S, You D. Application of the parallel diagonal dominant algorithm for the incompressible Navier-Stokes equations. J Comput Phys. 2020;423(2):109795. doi:10.1016/j.jcp.2020.109795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Kim J, Moin P. Application of a fractional-step method to incompressible Navier-Stokes equations. J Comput Phys. 1985;59(2):308–23. doi:10.1016/0021-9991(85)90148-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Henson VE, Yang UM. BoomerAMG: a parallel algebraic multigrid solver and preconditioner. Appl Numer Math. 2002;41(1):155–77. doi:10.1016/s0168-9274(01)00115-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Crowe CT, Schwarzkopf JD, Sommerfeld M, Tsuji Y. Multiphase flows with droplets and particles. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

33. Scardovelli R, Zaleski S. Direct numerical simulation of free-surface and interfacial flow. Annu Rev Fluid Mech. 1999;31(1):567–603. doi:10.1146/annurev.fluid.31.1.567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Aulisa E, Manservisi S, Scardovelli R, Zaleski S. Interface reconstruction with least-squares fit and split advection in three-dimensional Cartesian geometry. J Comput Phys. 2007;225(2):2301–19. doi:10.1016/j.jcp.2007.03.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Scardovelli R, Zaleski S. Analytical relations connecting linear interfaces and volume fractions in rectangular grids. J Comput Phys. 2000;164(1):228–37. doi:10.1006/jcph.2000.6567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Weymouth GD, Yue DKP. Conservative volume-of-fluid method for free-surface simulations on Cartesian-grids. J Comput Phys. 2010;229(8):2853–65. doi:10.1016/j.jcp.2009.12.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Brackbill JU, Kothe DB, Zemach C. A continuum method for modeling surface tension. J Comput Phys. 1992;100(2):335–54. doi:10.1016/0021-9991(92)90240-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Popinet S. An accurate adaptive solver for surface-tension-driven interfacial flows. J Comput Phys. 2009;228(16):5838–66. doi:10.1016/j.jcp.2009.04.042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Francois MM, Cummins SJ, Dendy ED, Kothe DB, Sicilian JM, Williams MW. A balanced-force algorithm for continuous and sharp interfacial surface tension models within a volume tracking framework. J Comput Phys. 2006;213(1):141–73. doi:10.1016/j.jcp.2005.08.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Nguyen AV. New method and equations for determining attachment tenacity and particle size limit in flotation. Int J Miner Process. 2003;68(1–4):167–82. doi:10.1016/s0301-7516(02)00069-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Nguyen AV. The collision between fine particles and single air bubbles in flotation. J Colloid Interface Sci. 1994;162(1):123–8. doi:10.1006/jcis.1994.1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Clift R, Grace JR, Weber ME. Bubbles, drops, and particles. New York, NY, USA: Academic Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

43. Oeters F. Metallurgy of steelmaking. 1st ed. Düsseldorf, Germany: Verlag Stahleisen; 1994. [Google Scholar]

44. Hewitt D, Fornasiero D, Ralston J. Bubble–particle attachment. J Chem Soc Faraday Trans. 1995;91(13):1997–2001. doi:10.1039/ft9959101997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Bná S, Manservisi S, Scardovelli R, Yecko P, Zaleski S. Numerical integration of implicit functions for the initialization of the VOF function. Comput Fluids. 2015;113:42–52. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools