Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

GWO-LightGBM: A Hybrid Grey Wolf Optimized Light Gradient Boosting Model for Cyber-Physical System Security

1 Sirindhorn International Institute of Technology, Thammasat University, Pathum Thani, 12120, Thailand

2 Department of Software and Communications Engineering, Hongik University, Sejong City, 30016, Republic of Korea

3 Department of Computer Science, GC University, Lahore, 54000, Pakistan

* Corresponding Author: Byung-Seo Kim. Email:

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(1), 1189-1211. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.071876

Received 14 August 2025; Accepted 24 September 2025; Issue published 30 October 2025

Abstract

Cyber-physical systems (CPS) represent a sophisticated integration of computational and physical components that power critical applications such as smart manufacturing, healthcare, and autonomous infrastructure. However, their extensive reliance on internet connectivity makes them increasingly susceptible to cyber threats, potentially leading to operational failures and data breaches. Furthermore, CPS faces significant threats related to unauthorized access, improper management, and tampering of the content it generates. In this paper, we propose an intrusion detection system (IDS) optimized for CPS environments using a hybrid approach by combining a nature-inspired feature selection scheme, such as Grey Wolf Optimization (GWO), in connection with the emerging Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LightGBM) classifier, named as GWO-LightGBM. While gradient boosting methods have been explored in prior IDS research, our novelty lies in proposing a hybrid approach targeting CPS-specific operational constraints, such as low-latency response and accurate detection of rare and critical attack types. We evaluate GWO-LightGBM against GWO-XGBoost, GWO-CatBoost, and an artificial neural network (ANN) baseline using the NSL-KDD and CIC-IDS-2017 benchmark datasets. The proposed models are assessed across multiple metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, with an emphasis on class-wise performance and training efficiency. The proposed GWO-LightGBM model achieves the highest overall accuracy (99.73%) for NSL-KDD and (99.61%) for CIC-IDS-2017, demonstrating superior performance in detecting minority classes such as Remote-to-Local (R2L) and Other attacks—commonly overlooked by other classifiers. Moreover, the proposed model consumes lower training time, highlighting its practical feasibility and scalability for real-time CPS deployment.Keywords

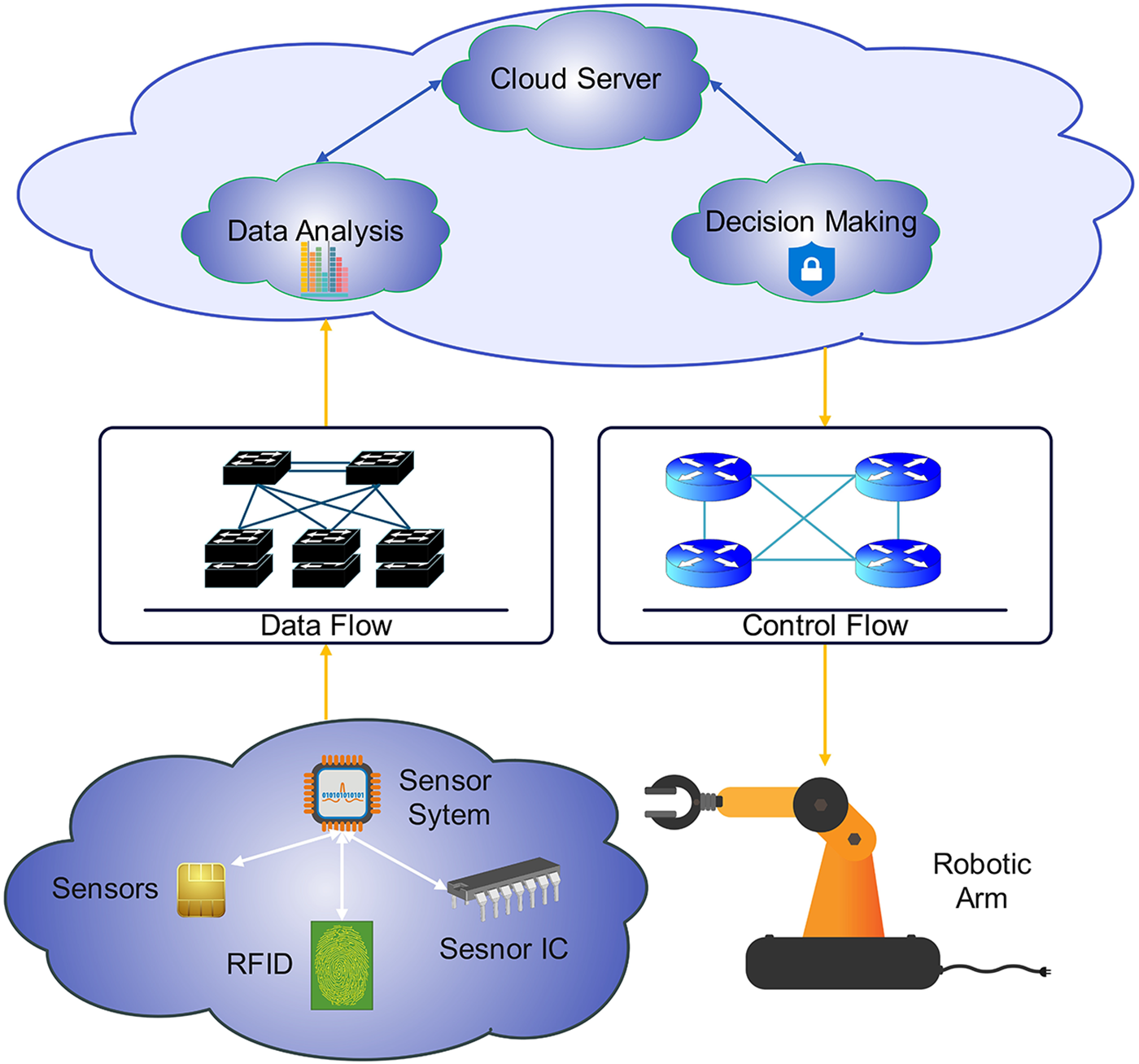

The integration of sensing, computing, and communication technologies has enabled the development of Cyber-Physical Systems (CPS), which form the foundation of Industry 4.0 by facilitating autonomous decision-making, real-time monitoring, and intelligent control of physical processes [1,2]. CPSs have also catalyzed advancements in robotics by minimizing human intervention, thereby enhancing operational performance and enabling ultra-reliable outcomes. These capabilities underscore the importance of robust security frameworks that can adapt to diverse physical environments and real-time operational constraints. According to the U.S. National Science Foundation, CPS are systems comprising tightly integrated physical and software components designed to monitor and control physical processes. This integration necessitates a robust interconnection between the cyber and physical domains to optimize system functionality, as depicted in Fig. 1 [3–5].

Figure 1: Cyber physical system architecture

The physical components of these CPSs are interconnected through wireless communication networks, providing extensive internet connectivity across heterogeneous geographic locations and incorporating capabilities for data sharing among users. However, CPSs also present several challenges, including management complexities, maintenance requirements, provision of seamless internet connectivity, and most critically, cybersecurity vulnerabilities against malicious attacks [6]. These systems become increasingly susceptible to network intrusions when deployed in high-risk facilities such as national security offices, air bases, hospitals, and government institutions. Therefore, there is a critical need for lightweight, intelligent detection systems that can respond promptly and accurately to anomalous behaviors.

The CPSs exhibit considerable vulnerability to cyber-attacks, as malicious intrusions can result in significant operational degradation or complete system failure. The most prevalent forms of such attacks include Denial of Service (DoS) and its variants, Probe attacks, Remote to Local exploits, User to Root escalations, and false data injection. DoS attacks, in particular, can severely compromise system functionality by preventing legitimate requests from being processed, thereby rendering the CPS incapable of executing critical control actions at designated intervals [7,8].

Historically, CPSs have experienced numerous cyber-attacks across various global locations, resulting in substantial damages, including data breaches, financial extortion, service disruptions, and complete system shutdowns. Notable incidents include the 2022 cyber-attack on the Guardian in the United Kingdom, which completely shut down their internal systems. Similarly, Australia experienced a significant breach that compromised 2.1 million customer identities. In 2023, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) suffered a cyber-attack that caused widespread disruption to air travel throughout the United States. Additionally, in 2014, the US healthcare system faced a ransomware attack that resulted in a complete nationwide shutdown of healthcare services [9].

CPS has demonstrated significant impact across various domains, including smart grids, healthcare, transportation, and unmanned aerial systems (drones), highlighting their relevance to a wide range of modern applications. A distinctive feature of CPS is its generation of specific digital content, which necessitates dedicated protection against unauthorized access. This area of research is formally referred to as Digital Content Protection (DCP). The importance of DCP becomes particularly critical when the protected content involves command and control logs. In such real-world scenarios, the deployment of a robust Intrusion Detection System (IDS) is essential to safeguard digital content from threats related to unauthorized access, manipulation, and mismanagement [10].

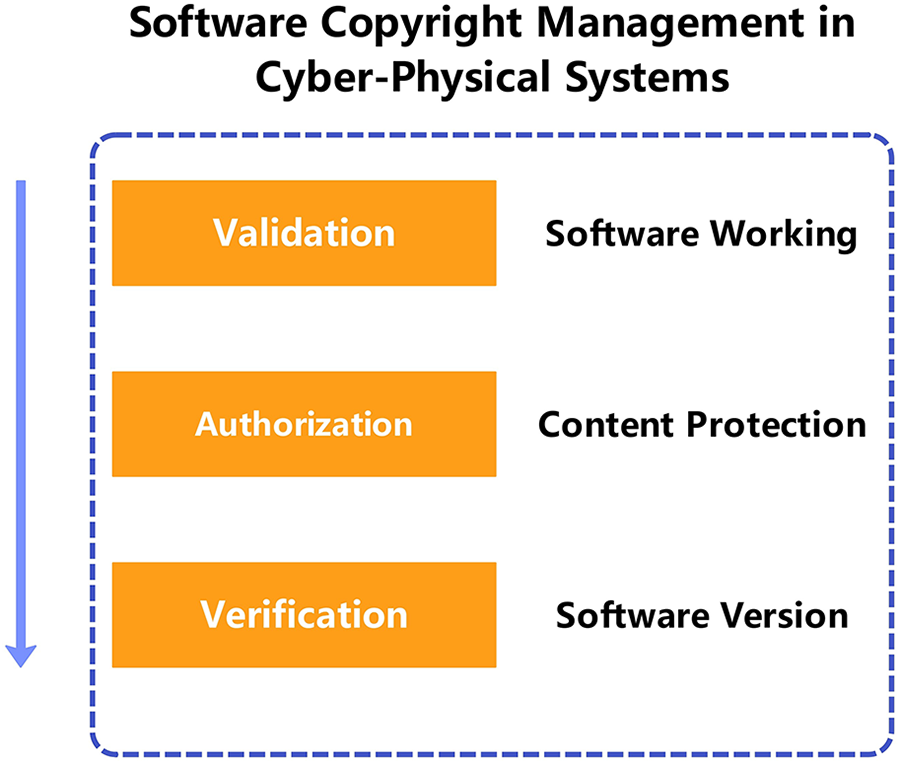

Another critical dimension of CPS is software control, which is deployed across CPS units, and the associated protection of the intellectual property embedded in that software. This concern is particularly significant for CPS stakeholders, who are highly sensitive to the safeguarding of such digital content. Machado et al. [11] highlight the issue of intellectual property leakage and propose a two-party fingerprinting scheme to ensure the digital protection of CPS content and embedded software. Fig. 2 illustrates the fundamental concept of the software control mechanism, which consists of three key components: validation, authorization, and verification. Among these, software authorization plays a critical role in protecting digital content and ensuring copyright compliance.

Figure 2: Copyright management for cyber-physical system security

Most existing studies demonstrate a profound inclination toward developing secure communication systems for CPS, accompanied by resilient cybersecurity solutions. These cybersecurity solutions, commonly referred to as network intrusion detection systems (NIDS), are specifically engineered to identify and mitigate unforeseen cyber-attacks [12]. NIDS primarily encompass network traffic analysis, threat detection, and mitigation protocols. To conduct comprehensive network traffic analysis, NIDS continuously collect network data streams over extended periods and employ diverse methodologies to differentiate between legitimate network communications and malicious attack patterns [13,14]. Historically, detection methodologies incorporated deep packet inspection (DPI), energy-based analysis, entropy calculations, and various statistical approaches. However, contemporary detection techniques have experienced substantial advancement through the integration of artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning (ML), and deep learning (DL) algorithms [15,16]. ML algorithms have introduced sophisticated classification frameworks that effectively distinguish cyberattacks from legitimate network traffic, thereby establishing robust mechanisms for threat detection, including signature-based and anomaly-based detection [17].

The main contributions of this study are as follows:

• We propose a hybrid intrusion detection system for CPS systems, which incorporates the feature selection mechanism using the Grey Wolf Optimization and cyber traffic classification using the LightGBM classifier.

• We incorporate class-weighted sampling and optimized hyperparameters to significantly detect the rare and critical attacks, which enhance recall for minority classes.

• To ensure the effectiveness of the proposed GWO-LightGBM model, the proposed model’s performance is compared with the GWO-XGBoost, GWO-CatBoost, and an artificial neural network (ANN) as a benchmark classification scheme using the NSL-KDD and CIC-IDS-2017 datasets.

• Finally, the proposed hybrid GWO-LightGBM-based framework achieves state-of-the-art performance, including 99.73% overall accuracy for NSL-KDD and 99.61% for CIC-IDS-2017, and illustrates the fastest training time among all models, demonstrating its practical viability for scalable, low-latency IDS deployment in CPS environments.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides a comprehensive review of recent advancements in the design of IDS for the CPS. Section 3 details the proposed methodology comprising GWO-based feature selection, and LightGBM-based classification for detecting cyber-attacks targeting CPS. Section 4 presents the simulation environment, dataset description, results, and corresponding analysis. Section 5 discusses the evaluation metrics, model performance overview, overall accuracy, comparative performance analysis, and key findings in depth. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper and outlines potential directions for future research.

This section presents an overview of existing methodologies and outlines our contributions to the design of an IDS framework specifically developed for detecting malicious traffic within network environments.

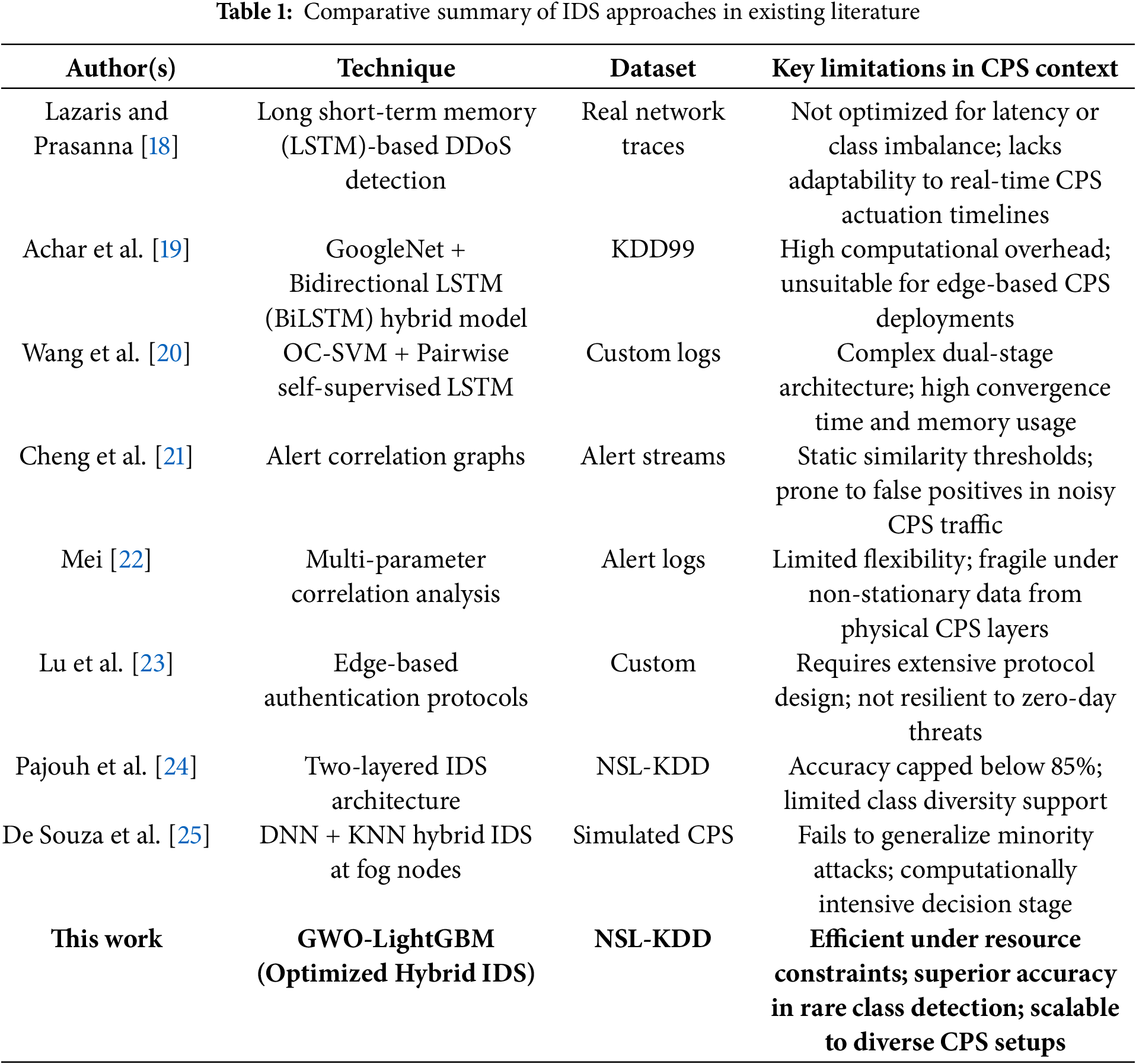

Lazaris and Prasanna [18] employed a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) classifier to detect DDoS attacks in real network traces, achieving a significantly reduced error rate while maintaining rapid prediction capabilities. Subsequently, Achar et al. [19] developed a hybrid model that integrates GoogleNet and BiLSTM architectures to identify cyber-threatening activities. Nevertheless, their proposed approach exhibits substantial computational complexity, rendering it impractical for deployment on resource-constrained devices. While these methods improve detection in general-purpose networks, they lack adaptation mechanisms for CPS-specific operational constraints such as actuation latency and energy limitations.

In a different approach, Wang et al. [20] introduced a framework that combines One-Class Support Vector Machine with Pairwise Self-supervised LSTM components. The rationale behind this integration lies in the segregated detection methodology: the former classifier identifies benign traffic patterns, whereas the latter specializes in recognizing malicious traffic signatures. Although these sophisticated schemes demonstrate enhanced detection capabilities, they concurrently introduce increased computational overhead, thereby limiting their feasibility for deployment on edge devices and other computing environments with restricted resources. Moreover, the separate treatment of benign and malicious streams results in longer convergence times, making them unsuitable for latency-sensitive CPS deployments. Table 1 summarizes the comparative findings of these methods, highlighting the datasets used, key techniques, and their limitations in CPS environments.

Lu et al. [23] proposed an edge-based authentication scheme to secure CPS from unauthorized access and resource overburdening, particularly for resource-constrained devices. The proposed scheme primarily comprises security operations and handshake protocols implemented at edge devices, such as routers. This approach achieves significant performance improvements by leveraging edge computing resources and implementing intelligent authentication processes. Furthermore, the authors in [26] developed a DL-based security mechanism for mobile edge computing within CPS-enabled transportation environments. Their proposed framework efficiently detects cyber-attacks initiated through various threat vectors. The proliferation of such cyber threats stems primarily from increased communication traffic and the extensive interconnectivity among mobile edge computing (MEC) devices.

Yan et al. [27] proposed a multi-model deception attack by incorporating different probabilities instead of relying on a single model. The approach employs a fuzzy proportional–integral estimator, which effectively reduces redundant transmissions in wind turbine systems. This improvement addresses the deterministic fluctuations in wind turbines that often trigger unnecessary events. In [28], the authors proposed an intrusion detection system (IDS) designed to mitigate false data injection attacks in communication networks by employing T–S fuzzy modeling and a radial basis function neural network-based estimator. Furthermore, they compared the performance of the proposed memory-based attack controller with that of a memoryless controller in terms of attack signal estimation, insulin infusion rate, and blood glucose regulation.

Digital twin (DT)-based intrusion detection frameworks also blueillustrate robust detection performance for various modern applications such as internet of things (IoT) and CPS, however often lack the flexibility to adapt to evolving threat landscapes without extensive model recalibration. In contrast, data-driven solutions such as the proposed GWO-LightGBM framework provide a scalable, architecture-agnostic approach capable of learning attack patterns directly from network traffic, thereby offering greater generalizability and deployment feasibility.

DL-based approaches, combined with Natural Language Processing (NLP) and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN), have transformed classification tasks by delivering robust performance. Additionally, machine learning (ML)-based solutions have contributed substantially to IDS development. To comprehensively detect various cyber-attacks, the proposed work incorporates diverse datasets encompassing approximately 15 distinct features. These datasets capture packet-level, network-level, and access-level information to identify cyber threats [29,30]. Despite these advances, many DL-based models exhibit high training complexity and require extensive labeled data, which may not be readily available in real-time CPS deployments. Moreover, models trained on general-purpose datasets often exhibit limited detection capability for infrequent or context-specific attacks in CPS. To address these challenges, our approach integrates GWO-based feature selection with the LightGBM classifier, yielding high accuracy and efficiency, even under conditions of class imbalance and constrained computational resources.

Pajouh et al. [24] proposed a two-layered intrusion detection system (IDS) to classify cyber-attacks. The proposed system primarily focuses on generating alerts for user-to-root (U2R) and remote-to-local cyber threats. The classification mechanism achieved an accuracy of 84.86%. To evaluate the system’s performance, the authors utilized the NSL-KDD dataset. In IDS design, certain datasets require the handling of missing and incomplete values. To address this challenge, a study [31] proposed employing a conditional variational autoencoder, which effectively processes missing and incomplete information, thereby achieving enhanced performance. The proposed approach attained a classification accuracy of 85.97% on the NSL-KDD dataset.

In [32], the authors detect true and false data samples to enhance the security of CPS. Their proposed scheme is based on a learning mechanism that employs generators and discriminators to minimize data loss. The approach was evaluated in a real-time scenario and demonstrated significant performance, reducing data loss to 1% while maintaining an efficacy of 97%. Similarly, Rao et al. [33] propose an intrusion prevention system for SCADA-based industrial IoT, termed CyberFortis. This system leverages a deep Q-Network for feature extraction and attack detection. Furthermore, the authors employ the PopHydra optimizer to improve convergence, achieving a prediction accuracy of 97.5%.

Most existing IDSs are designed with centralized architectures in mind, where model training is performed at a central location, thereby overlooking the significant advantages offered by distributed architectures. The authors in [34] proposed a distributed model that performs training at fog servers, wherein neighboring fog nodes collaborate by sharing training parameters. Their proposed scheme demonstrates advantages in detecting cyber-attacks more rapidly while achieving substantial reductions in traffic flow toward the cloud infrastructure. However, the proposed approach incurs a higher training time overhead.

Another study proposed a fog-based distributed environment that employed online sequential extreme learning schemes. The performance of this approach was evaluated using the NSL-KDD dataset. The proposed methodology demonstrated superior detection capabilities, achieving 25% higher performance compared to conventional systems deployed on cloud servers [35]. The authors proposed a CNN-based IDS that primarily comprises channel boosting and residual learning components. The author, retain the original features using Stacked Autoencoder (SAE). This also enhances detection capabilities with prediction accuracy of 87.28% [36].

In this section, we will provide comprehensive details on the integration of feature selection using GWO and a classification approach using the LightGBM model.

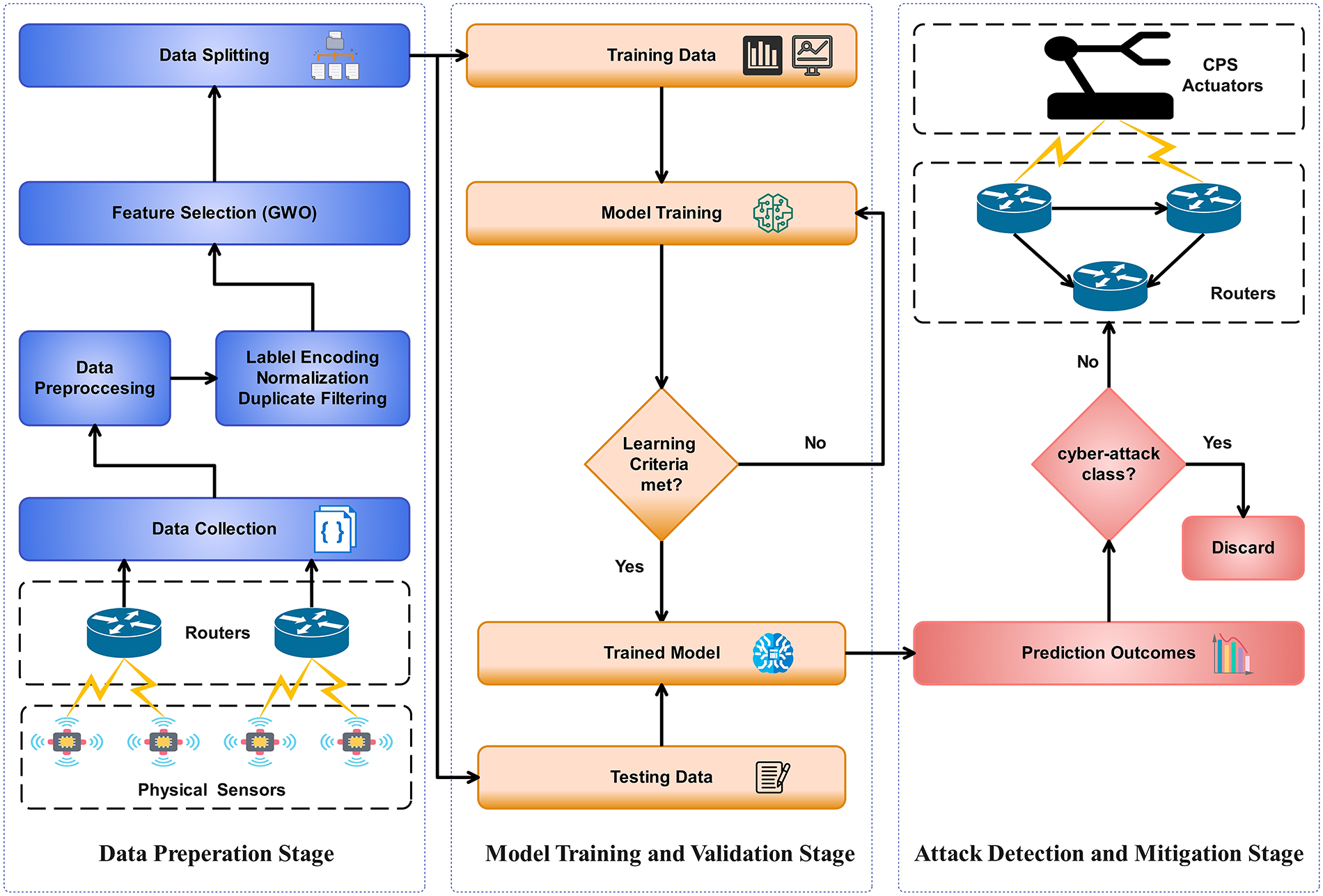

An IDS for CPS consists of multiple stages, each involving specific actions, as illustrated in Fig. 3. The initial stage of such an IDS involves data acquisition, which pertains to collecting log information from network traffic generated by physical sensors and transmitted to the CPS actuators to perform designated physical tasks. In this study, we utilize the publicly available NSL-KDD dataset [37] and CIC-IDS2017 [38]. These datasets primarily consist of raw data, which must undergo preprocessing before it can be used in any AI-based learning model. To prepare the data, we apply label encoding to classify each network traffic record into a specific attack category, thereby facilitating effective model learning. During the preprocessing phase, all feature values are normalized to confine them within a specific range. Furthermore, duplicate filtering is employed to eliminate redundant entries from the dataset, ensuring the integrity and quality of the training data.

Figure 3: GWO-LightGBM model for intrusion detection system for the cyber-physical system

Bio-inspired algorithms such as ant colony optimization (ACO), and particle swarm optimization (PSO) utilize natural intelligence in addressing dynamic and complex problems, including locating food sources, organizing social structures, and facilitating collaborative communication. Among various bio-inspired algorithms, the Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO) is a prominent example that emulates the social hierarchy and hunting behavior of Grey wolves to effectively solve multidimensional optimization problems [39].

GWO emulates the leadership hierarchy and cooperative hunting behavior of wolves to conduct a global search across a solution space. This nature-inspired strategy is particularly well-suited for feature selection tasks in IDS, where the objective is to identify the most relevant features that maximize classification performance while minimizing redundancy and dimensionality. However, the LightGBM model employs a greedy approach when selecting a subset of features for training, which often leads to being trapped in local minima and producing suboptimal prediction outcomes. In addition, LightGBM tends to overlook the dimensionality aspect during training, thereby requiring exploration of a larger search space to identify the optimal solution. To address these limitations, GWO is incorporated for feature selection, providing an optimal subset of features that enhances the efficiency of the proposed hybrid model in terms of both improved classification accuracy and reduced training time. Moreover, GWO offers a global search capability, which ensures optimal feature selection—an advantage not present in the standalone LightGBM model.

After applying the data preprocessing techniques, the datasets were partitioned into training and testing subsets using a standard 80/20 split. The training set was used to train several ML classifiers, including the proposed GWO-LightGBM model. The training process was conducted until the learning convergence criterion was satisfied.

During the training phase, the GWO algorithm iteratively selected feature subsets by minimizing a fitness function derived from classification error. This mechanism ensured that only the most informative attributes were retained for subsequent modeling. The rationale for selecting the GWO over other nature-inspired schemes, such as ACO or PSO, is that these alternatives typically demand higher computational resources to balance the exploration and exploitation phases and are often prone to premature convergence. By integrating this process with LightGBM, we achieved a tightly coupled feature selection and classification pipeline optimized for CPS intrusion detection.

Upon completion of training, the performance of the trained model was assessed using the held-out testing set. Each test instance was passed through the model, and predictions were generated and evaluated against ground-truth labels. Model effectiveness was quantified based on discrepancies between predicted and actual attack classes using precision, recall, F1-score, and accuracy. The final classification outcome was then subject to an operational rule: if the model identified the instance as malicious, the corresponding network packet was dropped; otherwise, the packet was forwarded to the CPS actuator to initiate the intended physical operation. This decision architecture, shown in Fig. 3, ensures that CPS operations are protected from cyber threats in real-time, thereby enhancing system resilience and operational continuity.

The Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO) provides a robust feature selection mechanism by mimicking the social hierarchy and hunting behavior of Grey wolves, which primarily consists of three phases: encircling, hunting, and attacking the prey. In GWO, the wolf pack is categorized into four hierarchical levels based on dominance, namely Alpha (

The encircling phase begins by identifying the position of the prey and subsequently updating it. Initially, the distance between the grey wolf pack and the prey is calculated using Eq. (1). To introduce randomness into the algorithm, the coefficient vector

The updated position of the prey, which can be calculated using Eq. (3) as shown below. In this equation,

During the hunting phase, the Alpha wolf reaches the optimal position, while the Beta and Delta wolves also track the prey’s location. The best solution is estimated by averaging the optimal positions of the top search agents Alpha, Beta, and Delta as shown in Eq. (5).

The positions of the best search agents—Alpha, Beta, and Delta—can be determined using Eqs. (6)–(8), respectively. These positions are represented by the vectors

The binary decision of whether to select a feature is determined by applying an activation function, such as the sigmoid function, to the position vector, as shown in Eq. (9). Here,

3.1.2 LightGBM Based Classification

LightGBM, a gradient-boosting machine learning algorithm developed by Microsoft, is designed for supervised learning tasks including regression and classification [41]. The key distinguishing feature of LightGBM compared to conventional algorithms such as XGBoost and Gradient Boosting Machines (GBM) lies in its tree construction methodology. Specifically, LightGBM employs a Gradient-based One-Sided Sampling (GOSS) scheme to build decision trees. This innovative approach strategically selects critical data points during tree construction, thereby significantly reducing both training time and computational space complexity. A comprehensive explanation of the LightGBM framework is presented below.

Eq. (10) defines the loss function

LightGBM optimizes the classification process through iterative ensemble learning of decision trees. The algorithm constructs a decision tree, denoted as

To update the model in each iteration, LightGBM computes the negative gradient of the loss function with respect to the previous prediction

Once the ensemble model is trained, LightGBM generates predictions using the weighted average of outputs from all decision trees, as shown in Eq. (13). In this equation, T denotes the total number of trees,

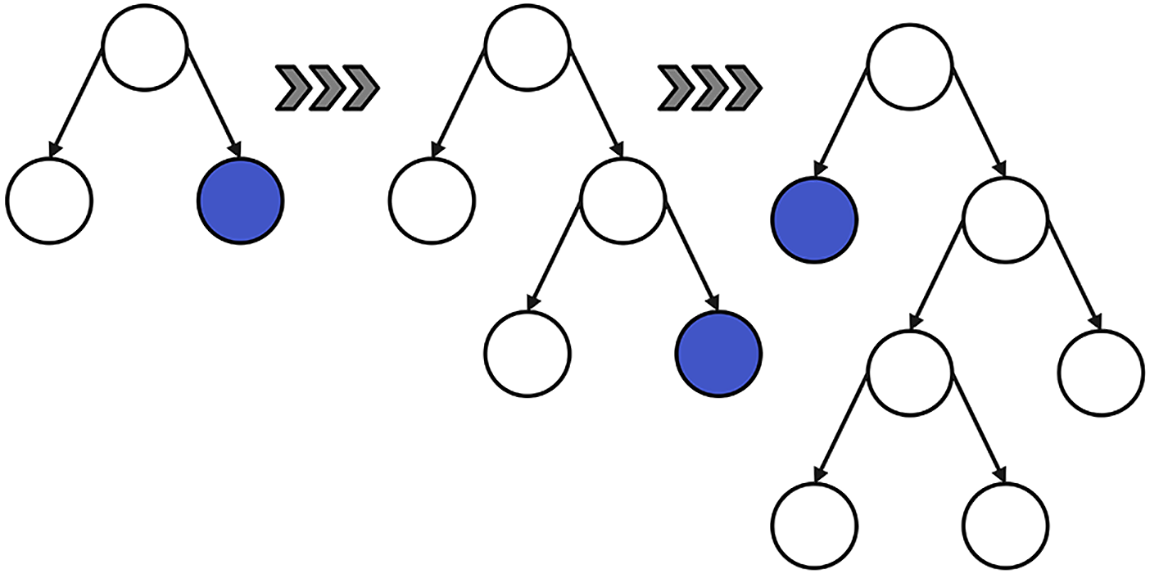

The main principle of LightGBM can be articulated as follows: it constructs decision trees on training subsets that grow in a leaf-wise manner, as illustrated in Fig. 4, utilizing the Gradient-based Decision Tree (GBDT) algorithm. The GBDT algorithm selects features based on the lowest loss function values at each iteration. The ensemble process continues iteratively until a predefined stopping criterion is satisfied, such as reaching the maximum number of trees or achieving a minimum validation error. The rationale for selecting LightGBM for classification tasks stems from its capacity to deliver robust predictive performance. The fundamental strength of LightGBM lies in its sequential ensemble of decision trees, wherein each successive tree rectifies the prediction errors of its predecessors. Furthermore, LightGBM demonstrates superior performance compared to traditional Random Forest classifiers by supporting parallel computation, which enables faster convergence and improved scalability. It is widely recognized for its computational efficiency, often outperforming conventional algorithms such as Support Vector Machines (SVM) and other gradient boosting methods in both training speed and predictive accuracy, particularly when applied to large-scale datasets.

Figure 4: LightGBM leaf-wise tree generation

In these subsections, we will provide a detailed overview of the experimental setup, dataset description, preprocessing steps, and model configuration.

All experiments were conducted using Visual Studio Code (VS Code) as the integrated development environment on a Windows 11 system featuring an Intel Core i5-12500H processor operating at 2.50 GHz, 8 GB of RAM, and a dedicated 4 GB graphics processing unit. The experimental implementation utilized Python 3.11, incorporating essential libraries such as scikit-learn, LightGBM, XGBoost, CatBoost, and PyTorch for machine learning operations, alongside seaborn for data visualization and statistical plotting.

4.2 Dataset Description and Preprocessing

This study employed the NSL-KDD [42] and CIC-IDS2017 [38] datasets as a benchmark for training and evaluating the intrusion detection models. NSL-KDD represents a refined iteration of the original KDD’99 dataset, specifically engineered to eliminate duplicate records and reduce data redundancy, thereby enhancing model generalization capabilities and training stability. The dataset comprises samples characterized by 41 distinct input features, encompassing both continuous variables (e.g., duration, count, src_bytes) and categorical attributes (including protocol_type, service, flag). Each sample is accompanied by a corresponding label that denotes the classification category of the respective network connection. The CIC-IDS2017 dataset comprised 52 network features with 6 distinct classes.

To ensure effective model training and optimal performance, the dataset underwent several preprocessing operations as outlined below:

• Categorical variables were transformed into numerical representations through label encoding, ensuring compatibility with both tree-based algorithms and neural network architectures.

• Numerical features underwent standardization via z-score normalization to maintain consistent scaling across all variables.

• Target labels were systematically consolidated into five distinct categories, facilitating multi-class classification while enhancing model interpretability and addressing class imbalance issues.

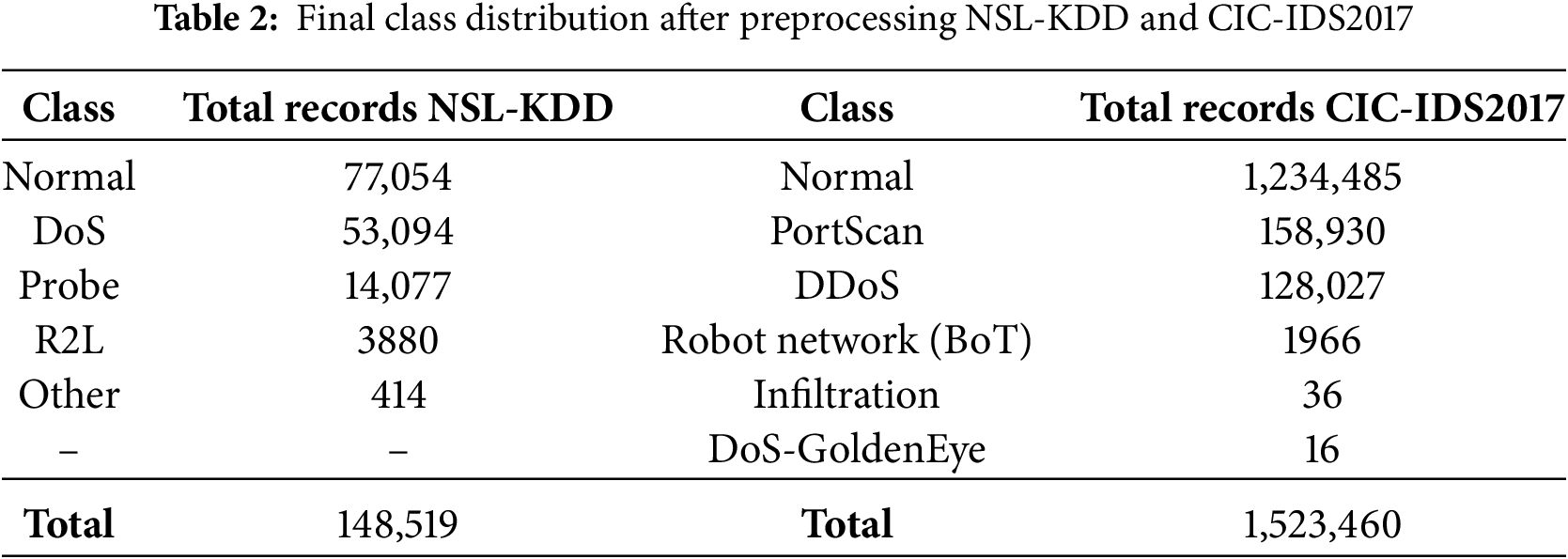

Following preprocessing, data grouping, and feature selection using GWO, the final NSL-KDD dataset comprised 148,519 records, of which 118,815 were allocated for training and 29,704 for testing. Likewise, after applying the same operations to the raw CIC-IDS2017 dataset, a total of 1,523,460 samples were retained for model training. The NSL-KDD dataset was partitioned into training (118,815 records) and testing (29,704 records) subsets, while the CIC-IDS2017 dataset was divided into three subsets: training (80%), validation (10%), and testing (10%). The detailed distribution of records across classification categories for both datasets is presented in Table 2.

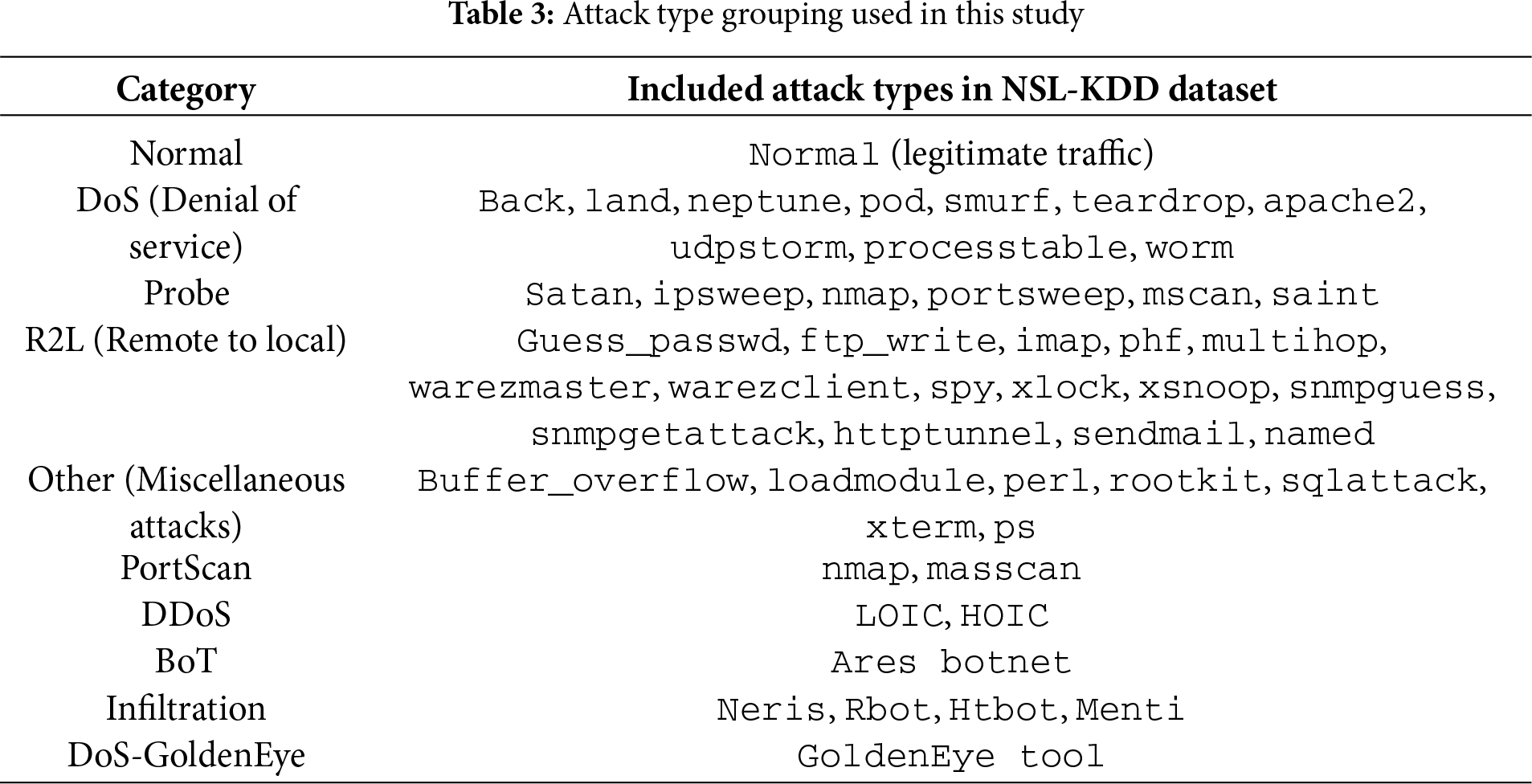

Given the substantial class imbalance—particularly for the Other class, which comprises less than 0.3% of all records—weighted sampling was implemented during the training phase in the NSL-KDD dataset, and BoT, Infiltration, and DoS-GoldenEye in the CIC-IDS2017 data. Each sample was assigned a weight inversely proportional to its corresponding class frequency, thereby enabling underrepresented classes to contribute more equitably to the training objective. This methodology proved essential for enhancing recall performance on minority classes, which are frequently overshadowed by predominant classes. Table 3 illustrates the systematic categorization of various attack types into five comprehensive high-level categories employed throughout this study.

4.3 Model Configuration Summary

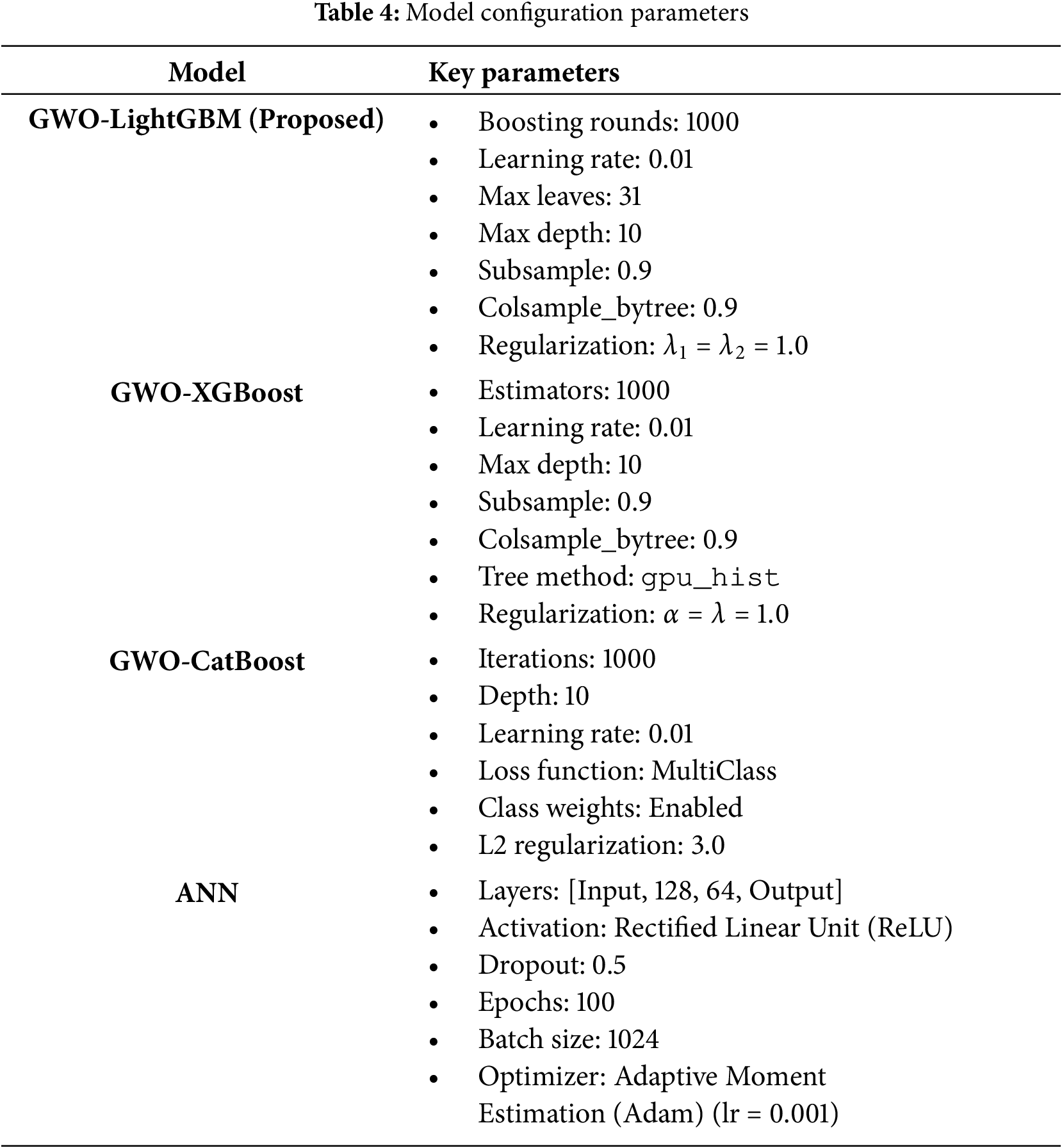

In this study, we propose a GWO-LightGBM-based framework for multi-class intrusion detection utilizing the NSL-KDD and CIC-IDS2017 datasets. LightGBM was selected as the primary algorithm owing to its exceptional computational efficiency, superior scalability, and demonstrated robustness when processing structured datasets characterized by high-dimensional feature spaces. To comprehensively assess the model’s efficacy, we conducted comparative analyses against three established baseline approaches: GWO-XGBoost, GWO-CatBoost, and a fully connected ANN implemented through the PyTorch framework.

All models underwent systematic hyperparameter tuning following a unified training methodology with equivalent parameter configurations, thereby ensuring rigorous and unbiased comparative evaluation. The inherent class imbalance present in the dataset was systematically addressed across all architectures through the implementation of sample weighting techniques and internal class balancing mechanisms. Furthermore, the proposed GWO-LightGBM model was strategically optimized through regularization techniques, subsampling methodologies, and shallow tree architectures to enhance generalization capabilities while preserving high recall performance across all classification categories. The comprehensive configuration parameters for all evaluated models are detailed in Table 4.

This section highlights the evaluation metrics, a discussion of model performance, a comparison of various performance metrics, and a brief comparison with the existing schemes.

To comprehensively assess model performance, we employed four standard classification metrics: accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score. These metrics are mathematically defined as follows:

Here, TP, TN, FP, and FN denote true positives, true negatives, false positives, and false negatives, respectively. All evaluation metrics were calculated on a per-class basis employing macro averaging to ensure equitable representation across both majority and minority classes.

5.2 Model Performance Overview

The proposed GWO-LightGBM model underwent comparative evaluation against three baseline models: GWO-XGBoost, GWO-CatBoost, and ANN implemented through PyTorch. All models were trained and validated using the NSL-KDD and CIC-IDS2017 datasets, employing an 80/20 stratified partitioning approach to ensure representative data distribution. To address inherent class imbalance within the dataset, sample weighting techniques were systematically applied across all experimental configurations.

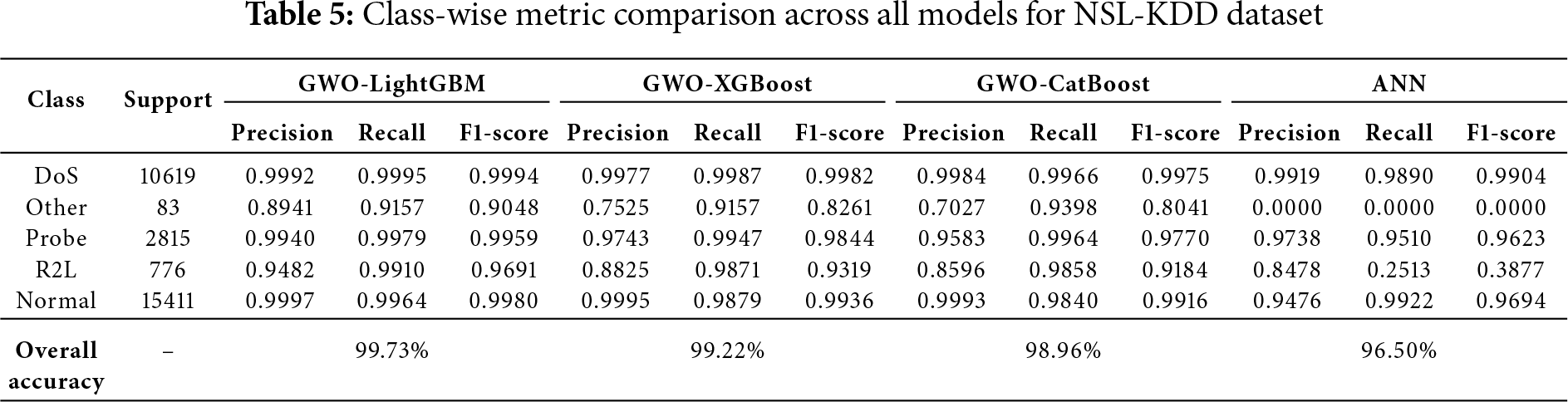

5.3 Class-Wise Metric Comparison for NSL-KDD Dataset

Table 5 presents the precision, recall, and F1-score metrics for each class across all evaluated models. GWO-LightGBM demonstrated superior performance compared to other algorithms across all categories, exhibiting particularly strong effectiveness in detecting minority classes such as Other and R2L. While GWO-XGBoost and GWO-CatBoost achieved robust overall performance, both models exhibited diminished efficacy in minority class identification. Conversely, the ANN model encountered significant challenges with class imbalance, completely failing to detect instances of the Other class.

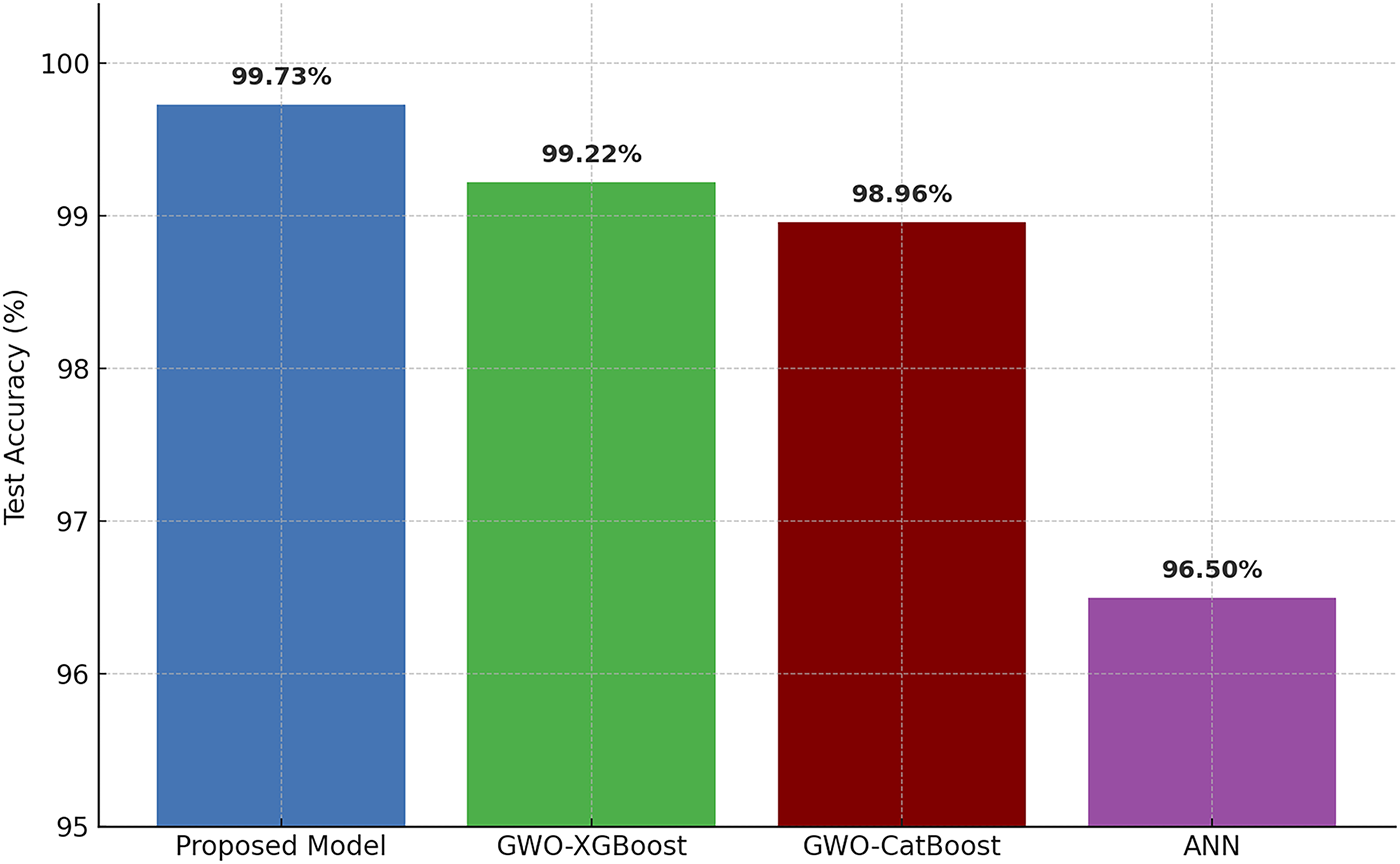

Fig. 5 presents a comprehensive summary of the overall classification accuracy across all evaluated models for the NSL-KDD dataset. The GWO-LightGBM model demonstrated superior performance, achieving the highest test accuracy of 99.73%, while GWO-XGBoost attained 99.22% and GWO-CatBoost reached 98.96%. In contrast, the ANN model exhibited substantially lower performance with an accuracy of 96.50%, primarily attributed to systematic misclassification errors in rare categorical instances.

Figure 5: Test accuracy comparison of all models for NSL-KDD dataset

5.5 Confusion Matrix Evaluation

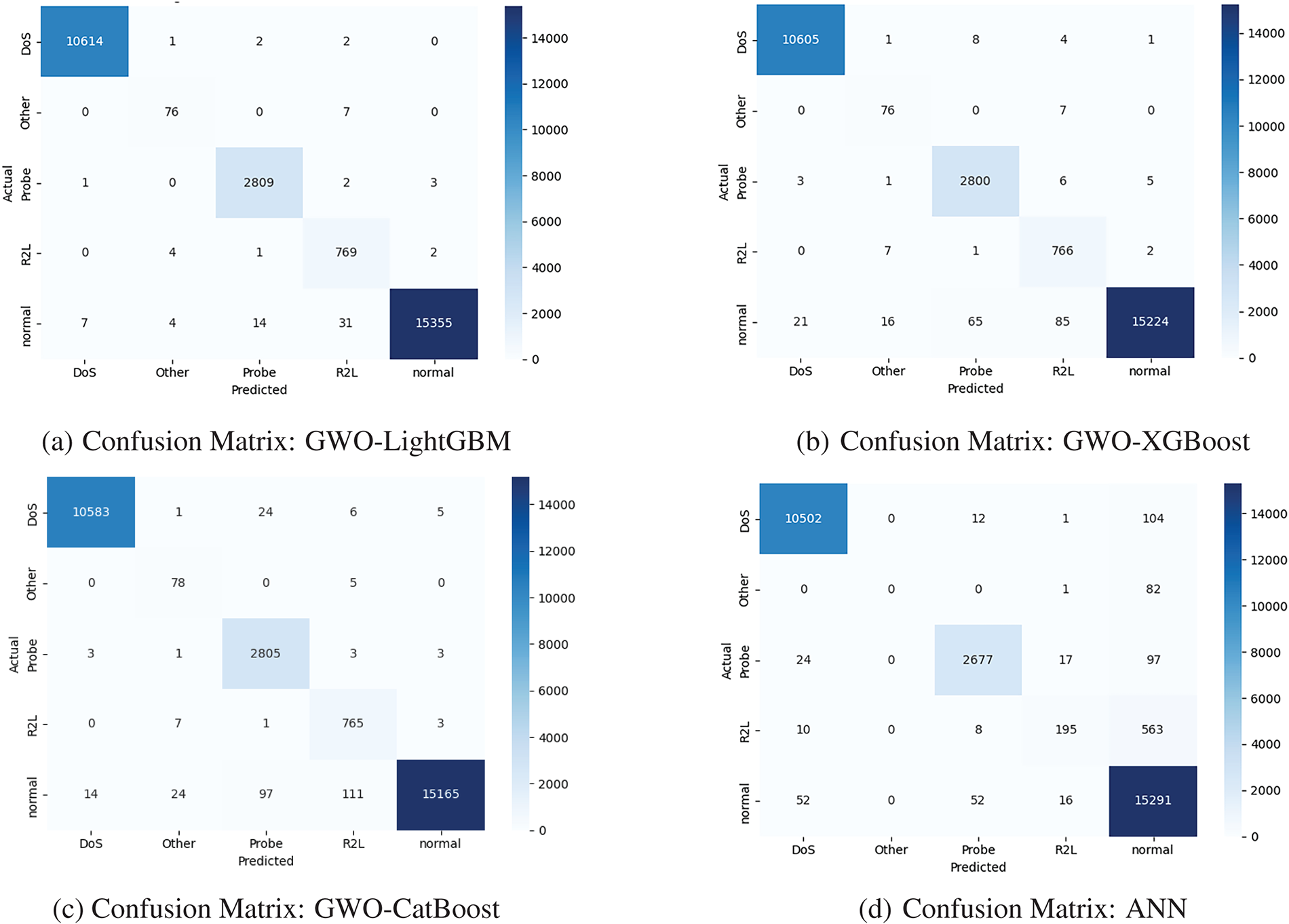

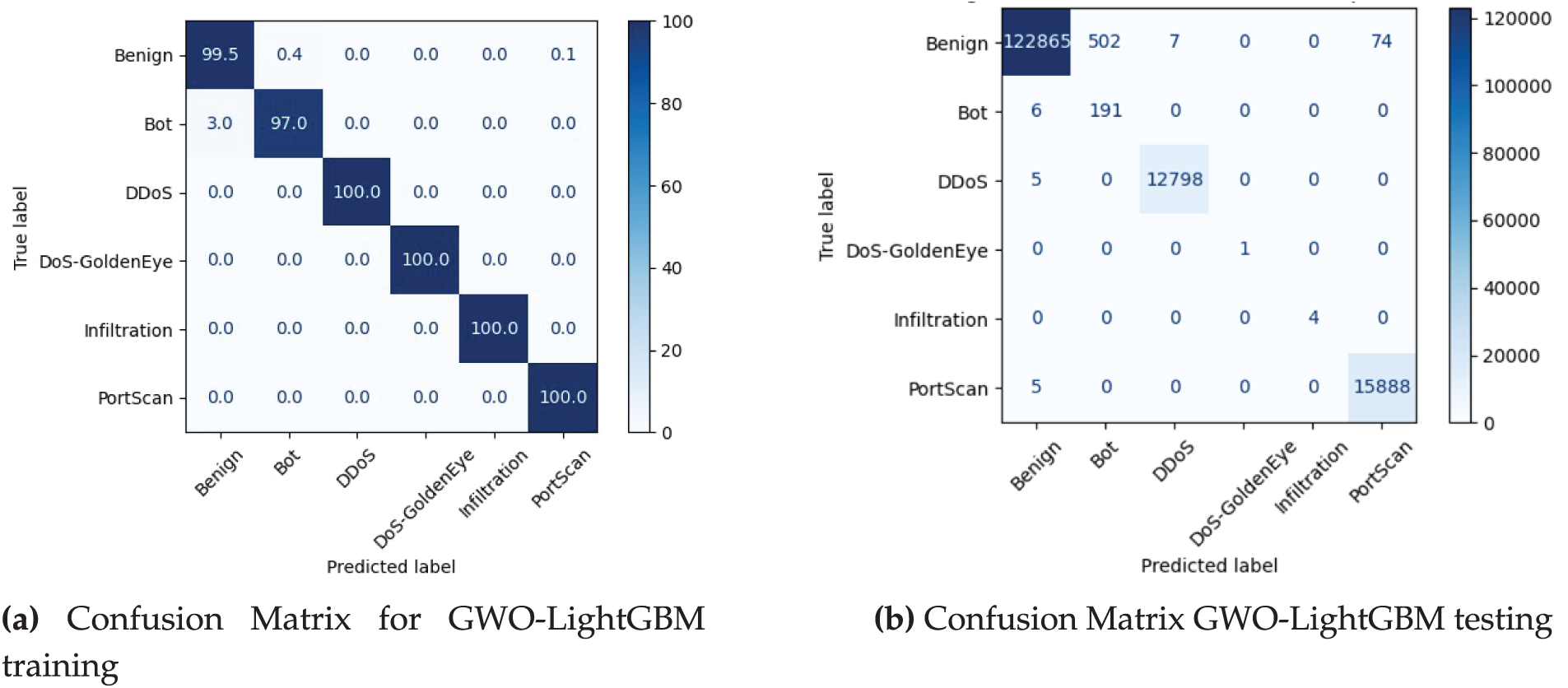

Fig. 6a–d presents the confusion matrices for all evaluated models for the NSL-KDD dataset. The GWO-LightGBM model demonstrates exceptional classification accuracy with minimal inter-class confusion and robust performance across minority classes. Conversely, the ANN model exhibits significant classification challenges, particularly with the R2L and Other categories, frequently misclassifying these instances as normal or DoS attacks. Fig. 7a,b illustrates the confusion matrix of the proposed GWO-LightGBM model for training and testing using another benchmark dataset named CIC-IDS2017, respectively. The confusion matrix in Fig. 7a,b shows the achieved validation accuracy of 98.25%, and testing accuracy of 99.61%.

Figure 6: Confusion matrix of ML-based classifiers for NSL-KDD dataset

Figure 7: Confusion matrix of ML-based classifiers for CIC-IDS2017 dataset

5.6 Per-Class Performance Distribution

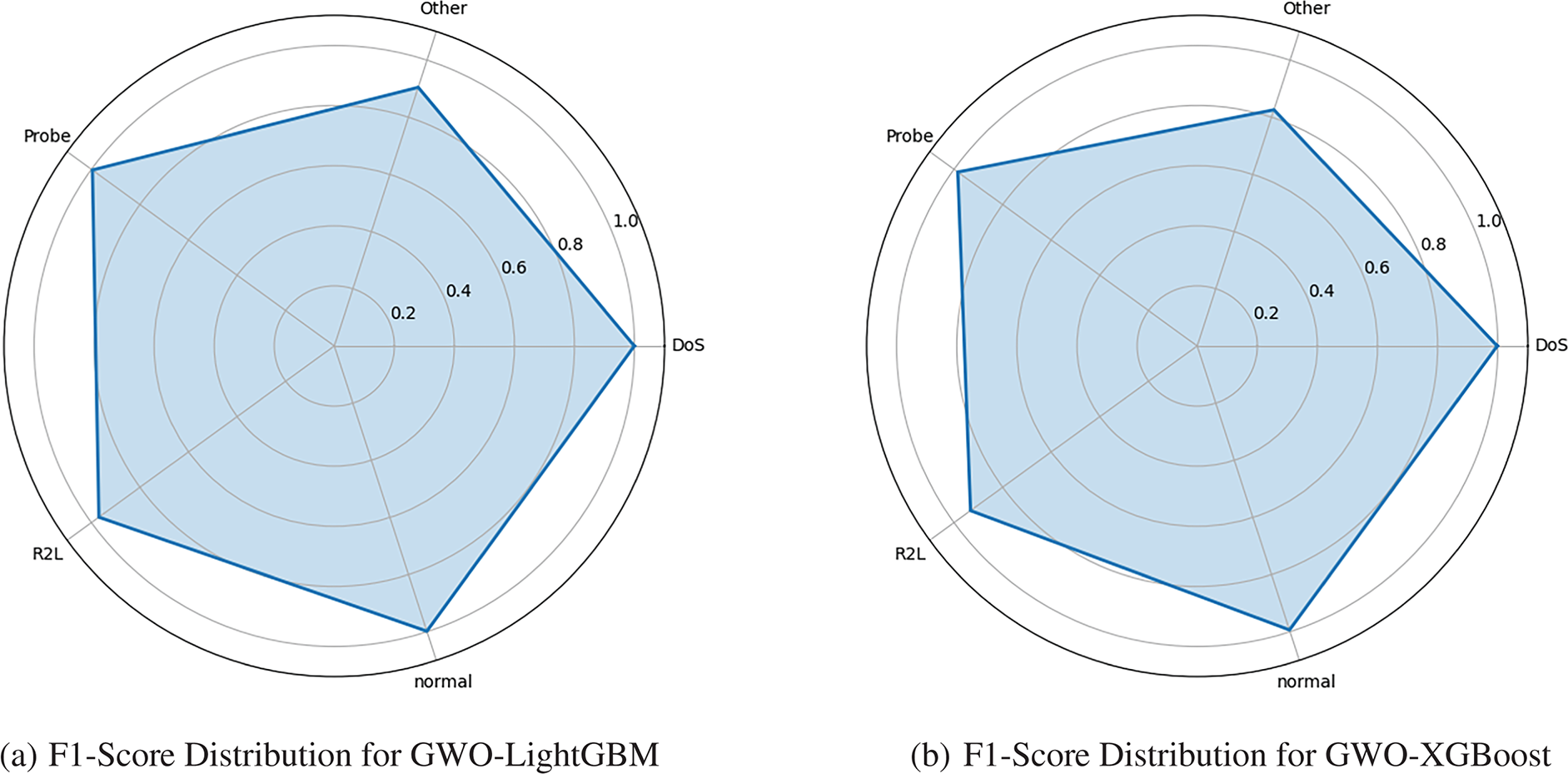

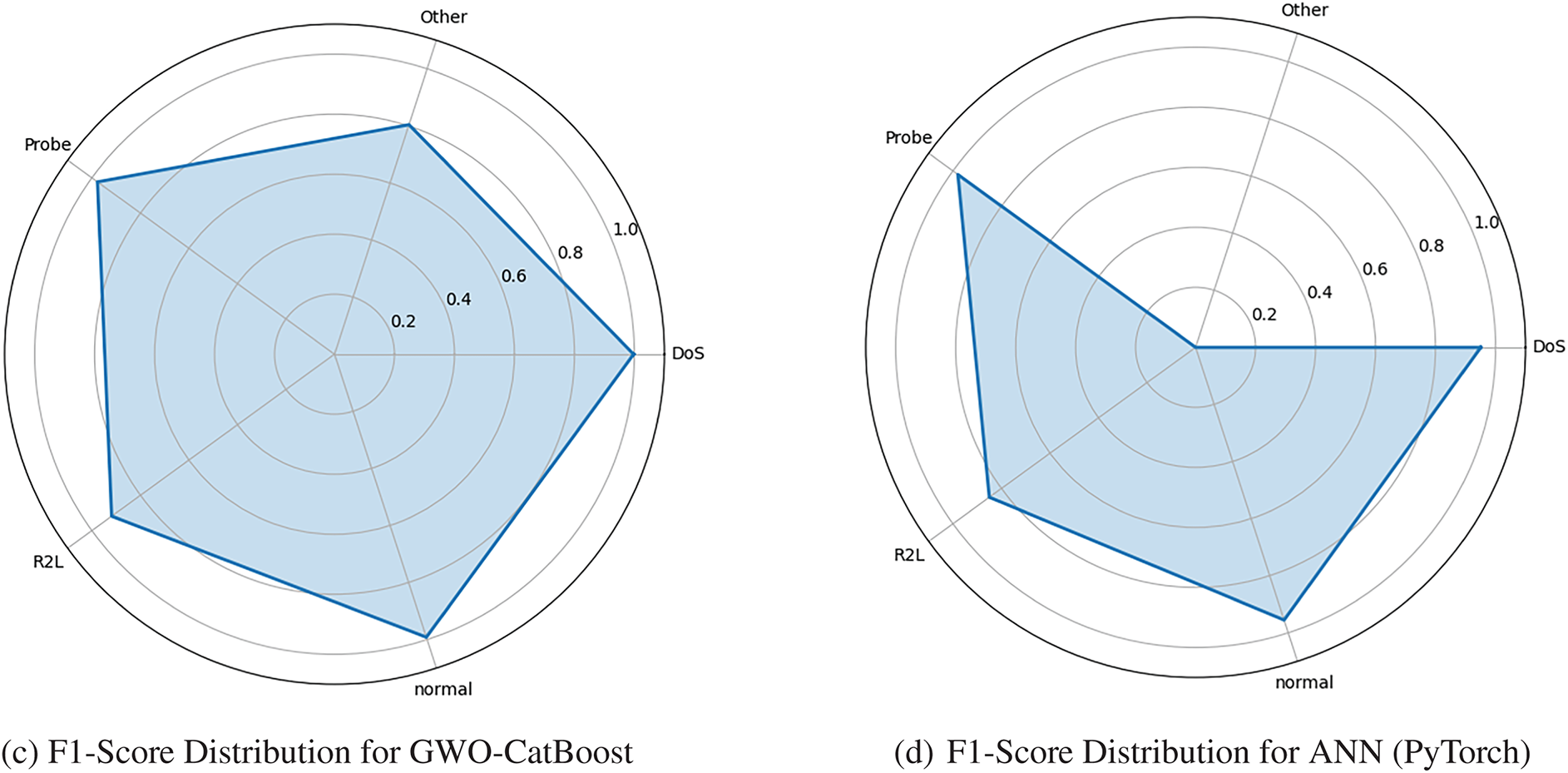

To further assess model consistency, Fig. 8a–d demonstrates the F1-score distribution across all five classification categories. GWO-LightGBM exhibits consistently high F1-scores with minimal variance between classes, indicating robust performance stability. Similarly, GWO-XGBoost and GWO-CatBoost demonstrate reliable performance metrics, albeit with marginally greater fluctuation across categories. In contrast, the ANN model displays considerable performance instability, particularly pronounced when processing underrepresented classes.

Figure 8: F1 score of each ML-based classifier for NSL-KDD dataset

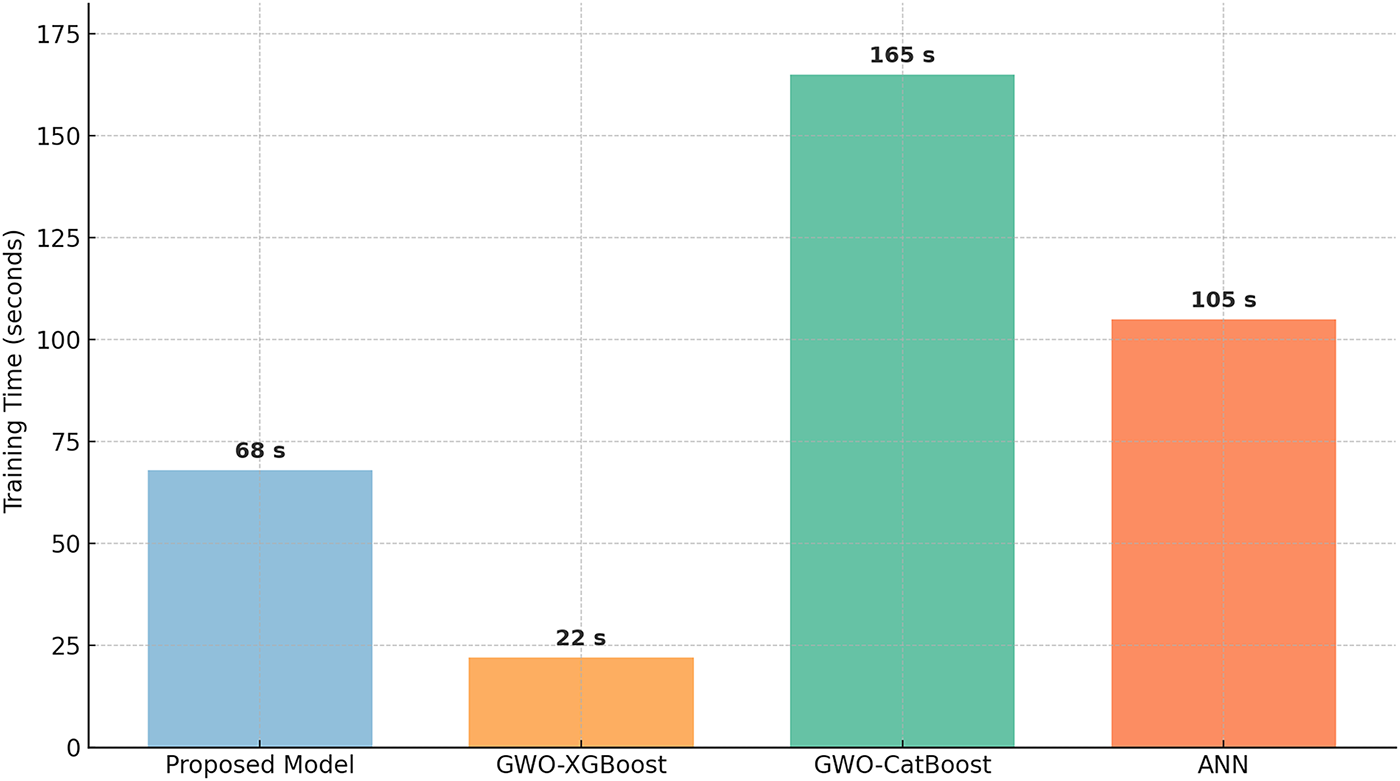

Beyond classification performance, we assessed the computational efficiency of each model by measuring total training time under identical hardware conditions. As depicted in Fig. 9, GWO-LightGBM demonstrated an optimal trade-off between accuracy and computational speed, completing training in approximately 68 s. While GWO-XGBoost exhibited the fastest training time at around 22 s, it yielded marginally inferior performance compared to LightGBM. Conversely, GWO-CatBoost, though achieving satisfactory accuracy, demanded substantially longer training duration (exceeding 165 s), presumably attributable to its sophisticated categorical feature processing and extensive regularization mechanisms. The PyTorch-implemented ANN model attained reasonable performance; however, its convergence required over 100 s, rendering it computationally less efficient than the gradient boosting algorithms in this experimental context.

Figure 9: Training time comparison across models for NSL-KDD dataset

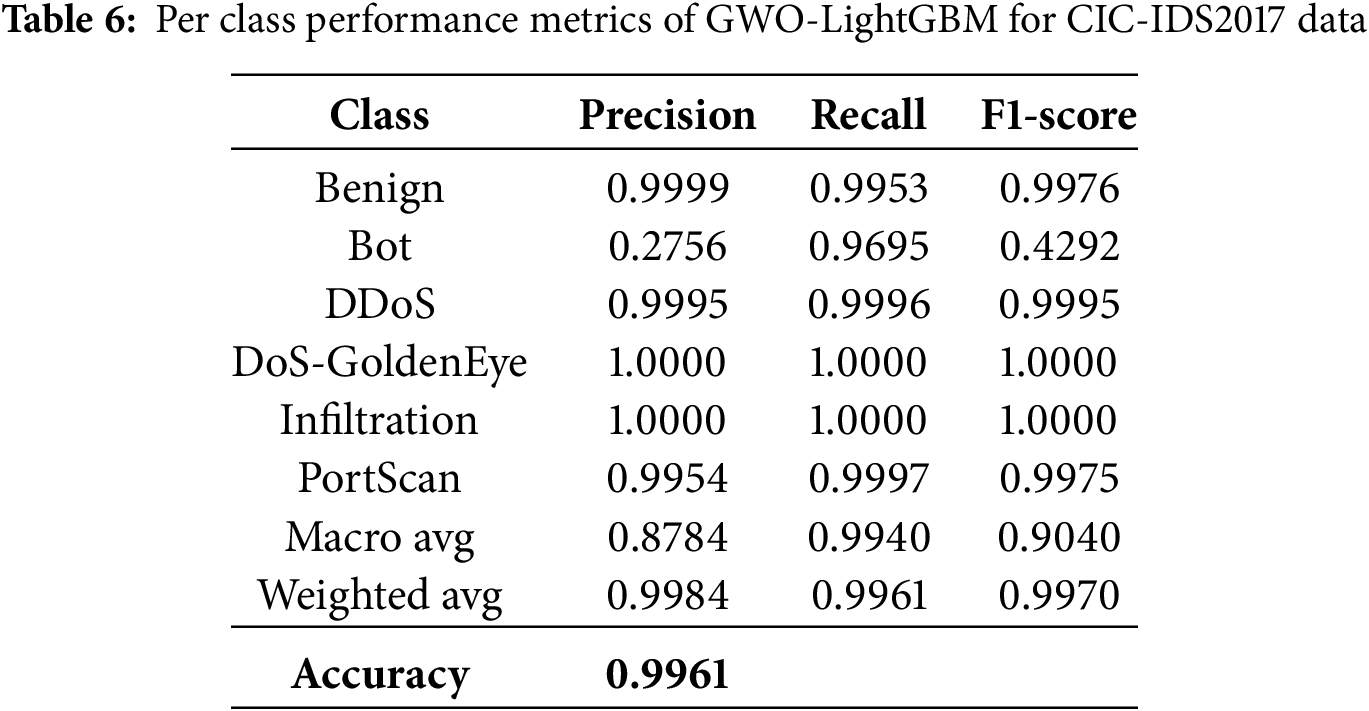

Table 6 presents the testing performance of the proposed hybrid GWO-LightGBM model on the CIC-IDS2017 dataset, demonstrating its robust capability in predicting various cyber threats. The model effectively classifies normal traffic, DDoS attacks, and PortScan attacks with the highest precision, whereas its performance is relatively lower for Bot attacks. This lower precision can be attributed to a higher false positive rate, as the model occasionally misclassifies normal traffic samples as Bot attacks. In contrast, the Infiltration and DoS-GoldenEye categories achieved 100% prediction accuracy, primarily due to the extremely small number of samples for these attack types in the dataset.

5.7 Comparative Performance Analysis

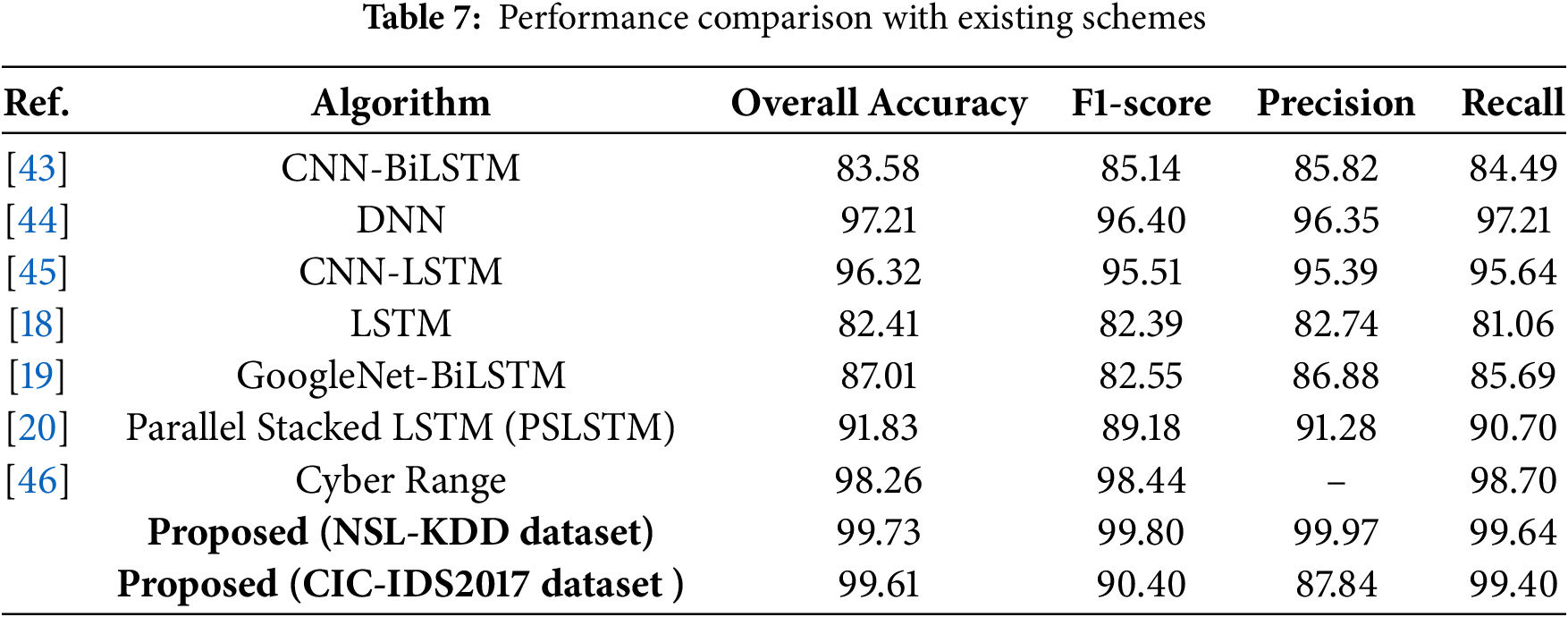

To contextualize the effectiveness of the proposed GWO-LightGBM-based model, a comparative analysis is conducted against several state-of-the-art intrusion detection frameworks reported in recent literature. Table 7 presents a detailed performance comparison that includes overall accuracy, F1-score, precision, and recall metrics for each referenced approach.

As shown in the Table 7, the proposed model consistently outperforms other techniques across all evaluation criteria. Notably, it achieves the highest accuracy of 99.73%, with exceptional precision (99.97%) and robust recall (99.64%). These results underscore the superior classification capability of GWO-LightGBM, particularly in correctly identifying both frequent and infrequent attack categories.

The comprehensive evaluation results affirm the robustness and effectiveness of the proposed GWO-LightGBM-based intrusion detection framework. GWO-LightGBM consistently outperformed the baseline models—including GWO-XGBoost, GWO-CatBoost, and an ANN across all performance metrics: overall accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score. A particularly notable strength of the proposed model is its ability to accurately detect rare and underrepresented attack categories, such as R2L and Other, which are frequently misclassified by conventional classifiers. Class-wise performance metrics presented in Table 5 indicate that GWO-LightGBM maintains uniformly high precision and recall across all categories. In contrast, the ANN model demonstrated significant performance degradation, especially when handling minority classes. These findings are further corroborated by confusion matrix visualizations, which reveal minimal inter-class confusion and strong predictive accuracy for GWO-LightGBM. Additionally, F1-score radar plots illustrate that GWO-LightGBM exhibits balanced performance with minimal variance across different attack types, highlighting its generalization capability and resistance to overfitting despite substantial class imbalance.

In terms of computational efficiency, GWO-LightGBM strikes an optimal balance between training time and predictive accuracy. As illustrated in Fig. 9, while GWO-XGBoost achieves marginally faster training, it underperforms in detecting minority classes. GWO-CatBoost, though comparable in detection accuracy, incurs significantly higher training time.

As summarized in Table 7, the proposed GWO-LightGBM framework outperforms a variety of existing models in the literature, including hybrid DL architectures and sequence-based classifiers. These results confirm GWO-LightGBM’s practicality for deployment in real-world IDSs, particularly in resource-constrained or latency-sensitive environments. Collectively, the findings position GWO-LightGBM as a highly reliable and balanced classifier suitable for modern network security applications. The proposed schema further demonstrates its generalization capability by exhibiting remarkable predictive performance on external datasets, such as CIC-IDS2017.

This study proposed an advanced ML-based IDS framework for CPS, employing the GWO-LightGBM classifier to address evolving cybersecurity threats. Evaluated using the NSL-KDD and CIC-IDS datasets, the proposed model was benchmarked against established ML techniques, including GWO-XGBoost, GWO-CatBoost, and ANN. Performance was assessed using standard classification metrics: accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, alongside per-class analysis and training time comparisons. The GWO-LightGBM model demonstrated state-of-the-art performance, achieving a test accuracy of 99.73%, F1-score of 99.80%, precision of 99.97%, and recall of 99.64% for NSL-KDD dataset and 99.61% overall accuracy, 90.40% F1-score, 87.84% precision and 99.40% for the CIC-IDS2017 dataset. Notably, it exhibited superior capability in detecting minority classes such as R2L and Other, which are commonly misclassified by traditional classifiers. The confusion matrices and radar plots highlighted consistent detection quality across all attack categories, and the model maintained computational efficiency, balancing predictive performance and execution speed more effectively than competing models. Despite the remarkable performance of GWO-LightGM in detecting various types of cyberattacks in CPS, the GWO-Light model suffers from two main limitations. The first limitation concerns transparency and explainability, as the model lacks the ability to provide clear justifications for its predictive behavior. The second limitation relates to the general applicability of the model, which primarily relies on nature-inspired optimization. Such an approach may not consistently deliver comparable performance under different conditions, for example, when applied to validation datasets with varying parameters.

In comparison to existing models, including deep learning and hybrid models, the proposed GWO-LightGBM-based IDS outperformed in both overall and class-specific detection metrics, affirming its robustness and suitability for deployment in CPS environments where accuracy and response latency are critical. Future research will explore adaptive ensemble strategies and real-time learning mechanisms for dynamic network environments. Additionally, incorporating federated and distributed learning paradigms will enable scalable, privacy-preserving intrusion detection solutions for next-generation CPS architectures.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research was supported by Culture, Sports and Tourism R&D Program through the Korea Creative Content Agency grant funded by the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism in 2024 (Project Name: Global Talent Training Program for Copyright Management Technology in Game Contents, Project Number: RS-2024-00396709, Contribution Rate: 100%).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Adeel Munawar and Muhammad Nadeem Ali; methodology, Adeel Munawar and Muhammad Nadeem Ali; software, Adeel Munawar and Awais Qasim; validation, Adeel Munawar, Muhammad Nadeem Ali and Awais Qasim; formal analysis, Awais Qasim and Byung-Seo Kim; investigation, Muhammad Nadeem Ali and Byung-Seo Kim; resources, Byung-Seo Kim; data curation, Muhammad Nadeem Ali; writing—original draft preparation, Adeel Munawar and Muhammad Nadeem Ali; writing—review and editing, Awais Qasim and Byung-Seo Kim; visualization, Adeel Munawar and Muhammad Nadeem Ali; supervision, Byung-Seo Kim; project administration, Awais Qasim and Byung-Seo Kim; funding acquisition, Byung-Seo Kim. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: NSL-KDD dataset https://www.unb.ca/cic/datasets/nsl.html (accessed on 10 June 2025), and CIC-IDS 2017 https://www.unb.ca/cic/datasets/ids-2017.html (accessed on 10 June 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Zhang XM, Han QL, Ge X, Ding D, Ding L, Yue D, et al. Networked control systems: a survey of trends and techniques. IEEE CAA J Autom Sin. 2019;7(1):1–17. doi:10.1109/jas.2019.1911651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Lu Z, Guo G. Control and communication scheduling co-design for networked control systems: a survey. Int J Syst Sci. 2023;54(1):189–203. doi:10.1080/00207721.2022.2097332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Chae J, Lee S, Jang J, Hong S, Park KJ. A survey and perspective on industrial cyber-physical systems (ICPSfrom ICPS to AI-augmented ICPS. IEEE Trans Ind Cyb-Phy Sys. 2023;1(1):257–72. doi:10.1109/ticps.2023.3323600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Lou S, Hu Z, Zhang Y, Feng Y, Zhou M, Lv C. Human-cyber-physical system for Industry 5.0: a review from a human-centric perspective. IEEE Trans Autom Sci Eng. 2024;22:494–511. doi:10.1109/tase.2024.3360476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Brighente A, Conti M, Di Renzone G, Peruzzi G, Pozzebon A. Security and privacy of smart waste management systems: a cyber–physical system perspective. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023;11(5):7309–24. doi:10.1109/jiot.2023.3322532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Peng C, Sun H, Yang M, Wang YL. A survey on security communication and control for smart grids under malicious cyber attacks. IEEE Trans Syst Man Cybern Syst. 2019;49(8):1554–69. doi:10.1109/tsmc.2018.2884952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Hu S, Ge X, Chen X, Yue D. Resilient load frequency control of islanded AC microgrids under concurrent false data injection and denial-of-service attacks. IEEE Trans Smart Grid. 2022;14(1):690–700. doi:10.1109/tsg.2022.3190680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Ge X, Han QL, Wu Q, Zhang XM. Resilient and safe platooning control of connected automated vehicles against intermittent denial-of-service attacks. IEEE CAA J Autom Sin. 2022;10(5):1234–51. doi:10.1109/jas.2022.105845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Lian Z, Shi P, Chen M. A survey on cyber-attacks for cyber-physical systems: modeling, defense and design. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025;12(2):1471–83. doi:10.1109/jiot.2024.3495046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Humayed A, Lin J, Li F, Luo B. Cyber-physical systems security—a survey. IEEE Internet Things J. 2017;4(6):1802–31. doi:10.1109/jiot.2017.2703172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Machado RCS, Boccardo DR, Sá VGPD, Szwarcfiter JL. Software control and intellectual property protection in cyber-physical systems. EURASIP J Inf Secur. 2016;2016(1):8. doi:10.1186/s13635-016-0032-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Sun HT, Peng C, Shen Y. Attack-detection-based event-triggered transmission scheme for stabilizing cyber-physical systems under denial of service attacks. IEEE Trans Ind Cyb-Phy Sys. 2024;2:176–84. doi:10.1109/ticps.2024.3419057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. He K, Kim DD, Asghar MR. Adversarial machine learning for network intrusion detection systems: a comprehensive survey. IEEE Commun Surv Tutor. 2023;25(1):538–66. [Google Scholar]

14. Ullah MU, Hassan A, Asif M, Farooq M, Saleem M. Intelligent intrusion detection system for apache web server empowered with machine learning approaches. Int J Comput Innov Sci. 2022;1(1):21–7. [Google Scholar]

15. Farooq MS, Khan S, Rehman A, Abbas S, Khan MA, Hwang SO. Blockchain-based smart home networks security empowered with fused machine learning. Sensors. 2022;22(12):4522. doi:10.3390/s22124522. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Alsoufi MA, Siraj MM, Ghaleb FA, Al-Razgan M, Al-Asaly MS, Alfakih T, et al. Anomaly-based intrusion detection model using deep learning for IoT networks. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2024;141(1):823–45. [Google Scholar]

17. Kumar G, Alqahtani H. Machine learning techniques for intrusion detection systems in SDN-recent advances, challenges and future directions. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2023;134(1):1–31. doi:10.32604/cmes.2022.020724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Lazaris A, Prasanna VK. An LSTM framework for modeling network traffic. In: 2019 IFIP/IEEE Symposium on Integrated Network and Service Management (IM); 2019 Apr 8–12; Arlington, VA, USA. p. 19–24. [Google Scholar]

19. Achar S, Faruqui N, Whaiduzzaman M, Awajan A, Alazab M. Cyber-physical system security based on human activity recognition through IoT cloud computing. Electronics. 2023;12(8):1892. doi:10.3390/electronics12081892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Wang D, Li F, Liu K, Zhang X. Real-time cyber-physical security solution leveraging an integrated learning-based approach. ACM Trans Sens Netw. 2024;20(2):1–22. doi:10.1145/3582009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Cheng Q, Wu C, Zhou S. Discovering attack scenarios via intrusion alert correlation using graph convolutional networks. IEEE Commun Lett. 2021;25(5):1564–7. doi:10.1109/lcomm.2020.3048995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Mei HB, Gong J, Zhang MH. Research on discovering multi-step attack patterns based on clustering IDS alert sequences. J China Inst Commun. 2011;32(5):63–9. [Google Scholar]

23. Lu Y, Wang D, Obaidat MS, Vijayakumar P. Edge-assisted intelligent device authentication in cyber–physical systems. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022;10(4):3057–70. doi:10.1109/jiot.2022.3151828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Pajouh HH, Javidan R, Khayami R, Dehghantanha A, Choo KKR. A two-layer dimension reduction and two-tier classification model for anomaly-based intrusion detection in IoT backbone networks. IEEE Trans Emerg Top Comput. 2016;7(2):314–23. doi:10.1109/tetc.2016.2633228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. De Souza CA, Westphall CB, Machado RB, Sobral JBM, dos Santos Vieira G. Hybrid approach to intrusion detection in fog-based IoT environments. Comput Netw. 2020;180(7):107417. doi:10.1016/j.comnet.2020.107417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Chen Y, Zhang Y, Maharjan S, Alam M, Wu T. Deep learning for secure mobile edge computing in cyber-physical transportation systems. IEEE Netw. 2019;33(4):36–41. doi:10.1109/mnet.2019.1800458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Yan S, Yang X, Park JH. Outlier-removal memory-event-triggered proportional-integral state estimation for wind turbine systems under multimodal deception attacks. IEEE Trans Autom Sci Eng. 2025;22:17790–800. doi:10.1109/tase.2025.3585410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Yan S, Ding L, Cai Y. Memory-based attack-tolerant TS fuzzy control of networked artificial pancreas system subject to false data injection attacks. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2025;518(3):109486. doi:10.1016/j.fss.2025.109486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Kandhro IA, Alanazi SM, Ali F, Kehar A, Fatima K, Uddin M, et al. Detection of real-time malicious intrusions and attacks in IoT empowered cybersecurity infrastructures. IEEE Access. 2023;11(6):9136–48. doi:10.1109/access.2023.3238664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Farooq MS, Abbas S, Sultan K, Khan MA, Mosavi A. A fused machine learning approach for intrusion detection system. Comput Mater Contin. 2022;74(2):2607–23. doi:10.32604/cmc.2023.032617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Yang Y, Zheng K, Wu C, Yang Y. Improving the classification effectiveness of intrusion detection by using improved conditional variational autoencoder and deep neural network. Sensors. 2019;19(11):2528. doi:10.3390/s19112528. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Selvarajan S, Manoharan H, Abdelhaq M, Khadidos AO, Khadidos AO, Alsaqour R, et al. Diagnostic behavior analysis of profuse data intrusions in cyber physical systems using adversarial learning techniques. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):7287. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-91856-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Rao KS, Kotoju R, Reddy BR, Al-Shehari T, Alsadhan NA, Singh S, et al. Unveiling CyberFortis: a unified security framework for IIoT-SCADA systems with SiamDQN-AE FusionNet and PopHydra optimizer. Comput Mater Contin. 2025;85(1):1899–916. doi:10.32604/cmc.2025.064728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Diro AA, Chilamkurti N. Distributed attack detection scheme using deep learning approach for Internet of Things. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2018;82(6):761–8. doi:10.1016/j.future.2017.08.043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Prabavathy S, Sundarakantham K, Shalinie SM. Design of cognitive fog computing for intrusion detection in Internet of Things. J Commun Netw. 2018;20(3):291–8. doi:10.1109/jcn.2018.000041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Chouhan N, Khan A, Khan HUR. Network anomaly detection using channel boosted and residual learning based deep convolutional neural network. Appl Soft Comput. 2019;83(11):105612. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2019.105612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Umar MA, Chen Z, Shuaib K, Liu Y. Effects of feature selection and normalization on network intrusion detection. Data Sci Manag. 2025;8(1):23–39. doi:10.1016/j.dsm.2024.08.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Sharafaldin I, Lashkari AH, Ghorbani AA. CIC-IDS2017. Kaggle; 2022 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 23]. Available from: https://www.kaggle.com/dsv/4059877. [Google Scholar]

39. Lu Y, Yu X, Hu Z, Wang X. Convolutional neural network combined with reinforcement learning-based dual-mode grey wolf optimizer to identify crop diseases and pests. Swarm Evol Comput. 2025;94(12):101874. doi:10.1016/j.swevo.2025.101874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Al-Wajih R, Abdulkadir SJ, Aziz N, Al-Tashi Q, Talpur N. Hybrid binary grey wolf with Harris hawks optimizer for feature selection. IEEE Access. 2021;9:31662–77. doi:10.1109/access.2021.3060096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Ke G, Meng Q, Finley T, Wang T, Chen W, Ma W, et al. LightGBM: a highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree. In: Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems; 2017 Dec 4–9; Long Beach, CA, USA. Red Hook, NY, USA: Curran Associates Inc.; 2017. p. 3149–57. doi:10.5555/3294996.3295074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Tavallaee M, Bagheri E, Lu W, Ghorbani AA. NSL-KDD dataset: an improved KDD 99 intrusion detection benchmark; 2009 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jun 20]. Available from: https://www.unb.ca/cic/datasets/nsl.html. [Google Scholar]

43. Jiang K, Wang W, Wang A, Wu H. Network intrusion detection combined hybrid sampling with deep hierarchical network. IEEE Access. 2020;8:32464–76. doi:10.1109/access.2020.2973730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Vishwakarma M, Kesswani N. DIDS: a deep neural network based real-time Intrusion detection system for IoT. Decis Anal J. 2022;5(1):100142. doi:10.1016/j.dajour.2022.100142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Abdallah M, An Le Khac N, Jahromi H, Delia Jurcut A. A hybrid CNN-LSTM based approach for anomaly detection systems in SDNs. In: Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Availability, Reliability and Security; 2021 Aug 17–20; Vienna, Austria. p. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

46. Wei S, Jia Y, Gu Z, Shafiq M, Wang L. Extracting novel attack strategies for industrial cyber-physical systems based on cyber range. IEEE Syst J. 2023;17(4):5292–302. doi:10.1109/jsyst.2023.3303361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools