Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

A Review of Modern Strategies for Enhancing Power Quality and Hosting Capacity in Renewable-Integrated Grids: From Conventional Devices to AI-Based Solutions

1 Electrical Engineering Department, Faculty of Engineering, Menofia University, Shebin El-Kom, 32511, Egypt

2 Electrical Engineering Department, Faculty of Engineering, Kafrelsheikh University, Kafrelsheikh, 33511, Egypt

3 Sustainability Competence Center, Széchenyi István University, Egyetem square 1, Gyor, H-9026, Hungary

4 Electronics Engineering Department, Higher Institute for Engineering and Technology, Manzala, 35642, Egypt

5 South Delta Electricity Distribution Company, Shibin El Kom, 32621, Egypt

* Corresponding Author: Ragab A. El-Sehiemy. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advanced Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Methods Applied to Energy Systems)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(2), 1349-1388. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.069507

Received 25 June 2025; Accepted 23 October 2025; Issue published 26 November 2025

Abstract

Distribution systems face significant challenges in maintaining power quality issues and maximizing renewable energy hosting capacity due to the increased level of photovoltaic (PV) systems integration associated with varying loading and climate conditions. This paper provides a comprehensive overview on the exit strategies to enhance distribution system operation, with a focus on harmonic mitigation, voltage regulation, power factor correction, and optimization techniques. The impact of passive and active filters, custom power devices such as dynamic voltage restorers (DVRs) and static synchronous compensators (STATCOMs), and grid modernization technologies on power quality is examined. Additionally, this paper specifically explores machine learning and AI-driven solutions for power quality enhancement, discussing their potential to optimize system performance and facilitate renewable energy integration. Modern optimization algorithms are also discussed as effective procedures to find the settings for power system components for optimal operation, including the allocation of distributed energy resources and the tuning of control parameters. Added to that, this paper explores the methods to maximize renewable energy hosting capacity while ensuring reliable and efficient system operation. By synthesizing existing research, this review aims to provide insights into the challenges and opportunities in distribution system operation and optimization, highlighting future research directions that enhance power quality and facilitate renewable energy integration.Keywords

The integration of renewable energy sources (RESs) into distribution systems has led to considerable challenges in maintaining power quality and grid stability. Unlike traditional power systems, which are unidirectional and centrally controlled, modern distribution networks are evolving into complex, bidirectional systems due to the high penetration of distributed generation [1]. This transformation complicates power flow management, voltage regulation, and fault detection. As the variability and uncertainty of RESs increase, ensuring stable and high-quality power delivery becomes more difficult [2]. Consequently, there is a growing need for advanced monitoring, control, and optimization techniques, particularly those driven by artificial intelligence and machine learning, to address these challenges and enhance hosting capacity.

1.1 Distribution Grids in the Global Renewable Energy Era

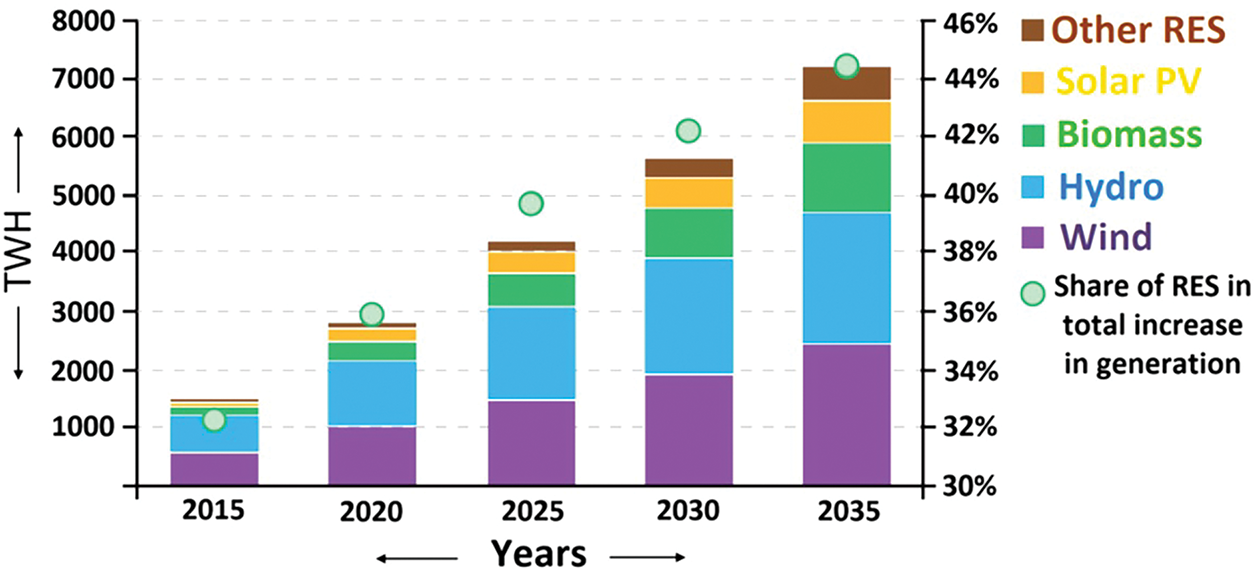

The projected growth of RESs in global electrical generation from 2015 to 2035 is illustrated in Fig. 1 [3]. This illustrates the expected sight of how the global energy is gradually transitioned toward sustainability with steady and significant increase over time involving the various types of renewable sources such as wind, hydro, biomass, solar PV, and other types of RESs [4]. As shown, wind and hydro sources dominate early on, while solar PV and biomass also show notable growth, especially after 2025. The penetration of RESs in power systems rises from around 32% in 2015 to over 44% by 2035. This upward trend not only highlights technological advancement and policy support but also reflects a global commitment to reducing carbon emissions and embracing cleaner, greener energy sources, as RESs could play a central role in meeting future energy demands [5]. The most common key phrases used in the research with this topic from 2019 to 2023, according to [6], are illustrated in Fig. 2 in numerous subject areas as shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 1: Incremental global RESs penetration in power systems [3]

Figure 2: Common key phrases [6]

Figure 3: Subjects areas [6]

1.2 Power Quality and Hosting Capacity: Concepts and Impacts

Maintaining power quality (PQ) is one of the most critical operational requirements of modern distribution systems [7,8]. PQ is a major concern in this transition. Renewable output variability, inverter harmonics, and load variability all create the risk of voltage time variation, which can cause voltage instability and therefore damage equipment [9]. Utilities need to embrace advanced controls and PQ management to support grid reliability [10].

Power quality in renewable-integrated systems is a multifaceted challenge involving harmonics, voltage fluctuations, and unbalances, necessitating both device-level and AI-driven mitigation [11]. Poor PQ causes inefficient operation, damage to equipment, and can result in unacceptable system stability. Some of the specific PQ issues include harmonics. Harmonics are caused by non-linear loads. These non-linear loads include devices such as inverters and electric vehicle chargers. Harmonics distort the voltage waveform and can cause heating of equipment and operational problems. Also, voltage fluctuations and flicker are from PQ issues. Sudden increases or decreases in generation or load can trip relays, which can cause flicker on sensitive devices and equipment [12]. Voltage sags and swells are momentary deviations of voltage that can cause disruption and/or damage to electronic systems. For example, lightning and switching operations may cause transients that can induce voltages on electrical lines from 0 to 2000 volts (V). Frequency Variations: Frequency variation indicates that there is a difference in generation and loading, resulting in an imbalance in the generation and load [13]. Frequency variations may cause generation units to trip and harm synchronous motors [14]. High PV penetrations worsen these challenges. The PV output is intermittent, and reverse power flows during high generation create the potential for overvoltages. Inverters create harmonics, and this variability makes balancing generation and load even more difficult. The collective effects of these issues include grid instability, higher operating costs, damage to equipment, and potential service interruptions [15].

Hosting Capacity (HC) denotes the ability of a distribution system to accommodate DERs without breaching key operational limits—mainly voltage, thermal, and stability—thus serving as a critical indicator of grid flexibility under renewable integration [16]. Traditional power is a one-way street, and as such, traditional grids aren’t designed to handle the dynamic system operation of DERs; key issues related to HC are [17]:

• Reverse power flow—causes voltage rise and trips protection devices

• Transformers—distribution equipment typically is not designed for high input from DERs, which can lead to transformers overheating and/or failures.

• Balance of grid—the generation of behind-the-meter solar or wind generation can be so unpredictable and rapid that it can create deviations in voltage and frequency.

Upgrading distribution systems will increase HC [18]. This means adding new modernized systems that allow utilities to create smart inverters, energy storage, and advanced voltage regulation [19]. New infrastructures aren’t necessarily cheap; however, they promote the flexibility of the grid and help meet longer-term decarbonization goals. Historical evolution shows that there was a systemic evolution from centralized to decentralized energy systems, which should highlight the importance of HC in grid planning and operations [20].

1.3 AI and Machine Learning in Modern Distribution Systems

Many utilities are now investing in smart grid-related technology involving a combination of dynamic monitoring systems, automation, and advanced metering to address these emerging challenges. Once installed, the smart grid technologies provide near real-time applications to dynamically monitor and control grid voltage and frequency, enhancing the overall stability of the grid [21]. Energy storage systems such as batteries and pumped hydro are critical to our present and future energy supply in managing surpluses from annual solar charging that will need to be stored for future use [22].

There are various grid challenges arising due to the changes in our modern power grid brought on by the inclusion of DERs such as PV systems [23]. One of the biggest changes occurring is due to the way DERs have changed how energy is moving: normally, the power grid is regulated as unidirectional or one-way flow of energy from the producer to the end user; with the inclusion of these DER’s it becomes bi-directional as energy flows in through the grid. Other challenges will develop in the grid with increasing amounts of PV integration and include, but are not limited to, voltage regulation, reverse power flow (the electricity is moving in the wrong direction), and unpredictability in both load and power generation patterns [24]. Utilities are investing in technologies: ’smart grid’ adoption (“dirt and dynamic demand”) that are essentially smart grid-related technologies that will involve dynamic monitoring systems, automation, and advanced metering [25].

In recent years, artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) have emerged as powerful tools for addressing complex challenges in modern power systems that are difficult to resolve using conventional methods [26]. These techniques provide advanced capabilities in forecasting, classification, and intelligent optimization, leveraging the vast volumes of real-time data generated by smart meters and distributed control devices [27]. Moreover, AI- and ML-based models enhance grid adaptability and responsiveness through predictive and adaptive modeling, thereby supporting efficient and reliable system operation [28]. AI/ML applied to distribution system operations is another powerful model in the evolution toward self-healing, resilient, and future-proof smart grids that maintain PQ and achieve greater HC sustainability. Ref. [29] integrates a dual-phase Universal Power Quality Conditioner (UPQC) controlled by adaptive dynamic neural networks (ADNN) and a PI controller optimized via a krill herd algorithm. It discussed Voltage sags/swells, current and voltage harmonics, and voltage imbalance from PQ problems. It found that robust disturbance detection and compensation with enhanced DC link regulation under varying conditions. Ref. [30] combines Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) for feature extraction with Long Short Term Memory (LSTM) networks for time-series PQ prediction. It discussed PQ Problems like Multi-indicator power quality forecasting and early warning in active distribution grids with distributed generation and the outcome from it is improved accuracy in predicting PQ disturbances compared to baseline control models [31] used Hilbert Huang Transform (HHT) to decompose the signal into Intrinsic Mode Functions, feeding these features into a Support Vector Machine (SVM) classifier. It discussed the classification of disturbances such as harmonics, voltage sags, swells, and transients affecting induction machines. It found that real-time detection with 97.2% classification accuracy. Recent research has shown growing interest in developing computational models based on AI and ML to improve power quality and hosting capacity in renewable-integrated distribution systems. These models include optimization algorithms, load profile forecasting techniques, fault detection models, and adaptive voltage and frequency control schemes. Integrating such models within the digital infrastructure of smart grids provides a more flexible and efficient mechanism for grid operation and management.

The placement and sizing of DERs, capacitors, and energy storage systems are important to properly utilize resources while maintaining efficiency, stability, and minimizing costs [32]. Important optimization objectives include minimizing power losses, improving voltage profiles, improving resilience, and minimizing operating costs [33]. Traditional optimization methods (i.e., Linear and Nonlinear Programming) are suitable for small, deterministic systems, but they do not address the increased complexity of modern environments with uncertainties [34].

Recent heuristic optimization algorithms such as Genetic Algorithms (GA), Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), and Ant Colony Optimization (ACO) are more applicable to large-scale, non-linear optimization problems with multiple objectives [35]. However, they may require a lot of computational effort and tuning. Multi-objective Optimization (MOO) methods can assist in finding balance among conflicting objectives (e.g., cost and reliability through Pareto fronts), allowing a stakeholder to make a selection given the realistic trade-offs [36]. Uncertainty in demand, output from renewables, and market conditions can be treated using different methods, including Stochastic Optimization, which uses probabilistic models, Robust Optimization, which focuses on the worst-case performance, and Fuzzy Logic, which deals with imprecise or vague information [37]. For example, the topological configuration of a PV power station is illustrated in Fig. 4 with the systematic arrangement of PV panels, inverters, cables, and connection buses [38]. Power generation is facilitated by solar panels, which are interconnected in series and parallel combinations to achieve desired voltage and current levels. The generated DC electricity is transmitted to inverters, where it is converted into AC power suitable for grid integration or local consumption, as shown in the schematic diagram in Fig. 5 [39]. Each component within the configuration is strategically placed to optimize efficiency, minimize losses, and ensure reliability. Electrical connections are designed to support redundancy and maintain operational stability under varying load and environmental conditions. Through this topology, scalability and ease of maintenance are also enhanced, allowing the PV power station to be adapted to different capacities and site requirements [40].

Figure 4: Systematic arrangement of PV panels to the power grid

Figure 5: Topological configuration of PV power station

Although notable progress has been made in power quality improvement and grid-modernization technologies, several challenges still limit widespread adoption. High costs remain a major concern, as devices such as DVRs, STATCOMs, and AI-driven monitoring platforms require substantial investment and ongoing maintenance. Interoperability limitations persist, with diverse equipment, vendor-specific standards, and compatibility issues complicating smooth integration. In parallel, cybersecurity risks are growing as digitization and communication-based control expand potential vulnerabilities in smart grids. Additionally, the integration of modern solutions with legacy infrastructure is often difficult, given that many existing systems were not designed to accommodate advanced, intelligent devices. Addressing these gaps will require research into cost-effective technologies, standardized protocols, resilient cybersecurity frameworks, and strategies for phased integration with older systems. Future work should prioritize scalable, secure, and interoperable solutions that are both technically feasible and economically viable.”

1.5 Research Objectives and Scope of Review

This paper comprehensively reviews power quality enhancement strategies in renewable-integrated distribution systems. It aims to provide a structured synthesis of both conventional PQ mitigation techniques and emerging artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML)-based models. The study addresses a critical research gap, as existing literature often discusses these approaches in isolation without a unified comparison of their performance, limitations, and practical applicability. The key contributions of this review are fourfold:

1. Categorizes and analyzes the spectrum of PQ disturbances in renewable-rich grids.

2. Evaluates the effectiveness and limitations of traditional mitigation devices alongside advanced computational methods such as optimization algorithms and ML models.

3. Identifies challenges in real-world implementation, including cost, scalability, and robustness under dynamic conditions.

4. Proposes a set of actionable research directions to bridge the gap between theoretical advancements and practical deployment.

The implications of this work lie in providing researchers, engineers, and policymakers with a consolidated framework to guide the selection and integration of PQ enhancement solutions, thereby supporting the stability, reliability, and scalability of future renewable-integrated power distribution systems.

2 Power Quality Challenges in Renewable-Integrated Distribution Systems

Power quality (PQ) is a pivotal aspect in modern distribution networks, ensuring the efficiency and reliability of the delivered power. The increasing penetration of renewable energy sources (RESs), combined with uncertainties in climate conditions and load variations, has intensified PQ challenges [41]. These challenges manifest in several forms, each with distinct impacts on system stability and equipment performance. As illustrated in Fig. 6, the effects of power quality problems for different voltage events vary considerably [42].

Figure 6: Some effects of power quality problems for the different voltage events

One of the most critical issues is harmonics, which are commonly induced by renewable interfacing converters and degrade power quality by distorting waveforms. Their mitigation is essential to ensure grid compatibility and protect sensitive loads. Non-linear loads such as inverters, arc furnaces, rectifiers, and variable speed drives are major contributors [43]. Harmonics can result in overheating, interference with communication circuits, equipment maloperation, increased losses, and reduced device lifespan. Standards such as IEEE 519 and IEC 61000-3-6 provide acceptable thresholds for total harmonic distortion (THD) [44]. Voltage fluctuations, including sags, swells, and flickers, are also common PQ issues. Sags occur during capacitor or heavy load switching, while swells may arise from system faults or load imbalances. Flickers, often caused by abrupt renewable output or load variations, lead to visible light fluctuations, equipment malfunctions, and shortened device lifespan [45]. Additionally, the Power factor directly affects the operational efficiency of distribution systems. In renewable-integrated grids, maintaining a high power factor is critical to minimizing losses and enhancing voltage stability. Non-linear loads are a primary reason for degraded power factor values, leading to higher losses and possible penalties from utilities [46].

The integration of RESs, particularly photovoltaic (PV) systems, further complicates PQ by introducing voltage variability due to intermittent solar irradiance and changing weather conditions. PV inverters, if not adequately filtered, can exacerbate harmonics and create voltage unbalance, especially when single-phase systems are unevenly distributed across three-phase networks. These challenges stress voltage stability and necessitate careful reactive power management [47,48]. Similarly, load variability, such as the starting of large motors or abrupt demand changes, triggers sags or swells, while extreme temperatures increase demand from air conditioning, stressing voltage stability. Sudden shifts in solar irradiance likewise impact PV plant output and cause further fluctuations [49]. To mitigate these challenges, various strategies have been developed [46]:

• Harmonics Mitigation: Passive LC filters [50]; Active power filters [51]; Phase-shifting transformers [52]; K-rated transformers [53]; Multi-pulse rectifiers [54].

• Voltage Fluctuation Control: Static VAR Compensators (SVCs) [55]; Flicker mitigation systems [43]; Soft starters and VFDs [56]; Dedicated feeders [57].

• Power Factor Improvement: Capacitor banks [58]; Synchronous condensers [59]; Automatic Power Factor Correction (APFC) [60]; VFDs [56].

• Voltage Unbalance Mitigation: Load balancing [61]; Tap-changing regulators [62]; Phase balancers [48]; Coordinated PV re-phasing [63].

• Load Variability Management: Energy Storage Systems (ESSs) [64]; Demand Side Management (DSM) [65]; Load forecasting tools [66]; Smart grid automation [67].

• Climate Variability Adaptation: Weather-resilient infrastructure [68]; Advanced forecasting tools [69]; Hybrid renewable integration [70]; Microgrids and smart grids [71].

Table 1 provides a comprehensive overview of common power quality issues in power systems, detailing their causes, impacts, mitigation strategies, and evaluating their real-world applicability through key performance indicators such as classification accuracy, computational efficiency, and latency.

3 Conventional and Custom Power Devices for PQ Improvement

3.1 Conventional Harmonic Mitigation Techniques

To mitigate harmonic contents and improve power quality in distribution networks, numerous techniques can be employed, such as passive and active filters, Phase-shifting and K-rated transformers, and utilizing multi-pulse rectifiers as shown in Fig. 7.

Figure 7: Commonly widespread harmonics mitigation techniques

Passive filters are one of the commonly utilized techniques for harmonic mitigation in distribution power networks. These filters consist of passive components such as inductors, capacitors, and resistors. The elements are designed to present low-impedance ways for definite orders of harmonic contents. Hence, the unwanted harmonic currents are diverted away from the sensitive device. Passive filters can be practically tuned to eliminate dominant lower-order harmonics as the 5th, 7th, and 11th, via parallel connection with the load. These filters are widely spread for their simplicity, low cost, and ability to improve power factor besides reducing harmonic contents [50].

Nonetheless, passive filters are further fit for networks with moderate harmonic distortions. Because these filters are tuned to eliminate specific frequencies and may be ineffective or even problematic at varying the load conditions. Additionally, they may introduce resonance issues at interacting with power network impedance or associating with other filters. Despite these limitations, passive filters remain a cost-effective and practical solution for harmonic suppression in industrial and commercial applications where load profiles are predictable [50].

The connection of RESs with the grid through passive filters is shown in Fig. 8 [73]. As illustrated, there are three options for connecting the passive filters in the system. The first connection is the L filter, which is considered a traditional type due to its simple construction. While this type of passive filter could not meet the guidelines of IEEE standard 1547, besides its bulkiness and inefficiency [74]. The second connection is the LC filter, which indicates an improved damping performance. This makes it rather more cost-effective as well as efficient compared to L-type filters [75]. The third connection is the LCL filter, which has better current ripple attenuation despite the small values of inductive reactors. Therefore, this type does not need a high switching frequency of the inverters [75]. Therefore, LCL-type passive filters are considered cost-effective for a suitable size. However, it could result in both dynamic and steady-state distortions because of resonance [76].

Figure 8: Connection of RESs with grid involving different types of passive filters

Active power filters are regarded as advanced harmonic mitigation devices that can detect and compensate unwanted harmonic contents dynamically in real time. Unlike passive filters, power electronic devices as IGBTs, are employed in active power filters. Furthermore, the controllers are employed with these power filters to regulate the load current and extract harmonic components, then inject equal and opposite currents that are back into the network to cancel these harmonics. This technique qualifies the active power filters to be highly effective across a wide range of harmonic orders and could be adaptable to the changes of load conditions [51]. The connection of active power filters is illustrated in Fig. 9 [77]. Such filters can be configured in networks as shunt, series, or hybrid, while the shunt configuration is the most common. Moreover, active power filters could correct the improper values of power factor, mitigate the unbalanced loads and voltage flicker, then improving the overall power quality. Therefore, active power filters can be utilized in applications with uncertainty or non-linearity, such as RESs, and highly electronic-based components where the precision is considered a critical requirement [51].

Figure 9: Connection of active power filter

Despite the numerous advantages of these filters, they come with certain limitations. Their costs are relatively high due to the use of sophisticated power electronics devices and control systems. Moreover, proper design and periodic maintenance are required for these filters to avoid instability or interaction with other equipment. Furthermore, active power filters could introduce electromagnetic interference in the networks. This interference needs suitable shielding to be prevented. Nonetheless, dynamic conditions of loads require high-performance harmonics mitigation devices. Thus, active power filters are among the most effective and reliable solutions to improve the power quality in such cases [51].

3.1.3 Phase-Shifting Transformers

Phase-shifting transformers are a harmonic mitigation technique that works by altering the phase angle of input voltages to cancel specific harmonic currents generated by power electronic-based loads. This control in phase difference leads to cancel the harmonic components at the point of common coupling. As a result, lower-order harmonics such as the 5th and 7th are significantly reduced or eliminated, thereby improving overall power quality without the use of external filters [52].

Consequently, phase-shifting transformers are mainly applied in large industrial settings where high-power drives, furnaces, compressors, and other systems that operate with electronics-based devices are found. These systems are particularly beneficial where continuous operation and compliance with harmonic standards (e.g., IEEE 519) are critical [44].

However, there are some limitations to consider these types of harmonics mitigation techniques. For instance, phase-shifting transformers are physically large, heavy, and expensive compared to conventional transformers. Moreover, their installation requires careful planning, and the harmonic content cancellation effect is only effective when load balance and transformer loading are well controlled. Additionally, this technique does not respond dynamically to load changes and may not be able to compensate for all harmonic orders. Despite the existence of these constraints, the phase-shifting transformers technique is still regarded as a robust solution for mitigating harmonics in many applications.

K-rated transformers are introduced to handle the thermal stresses that are caused by harmonic contents in distribution networks. Unlike conventional transformers, K-rated transformers have enhanced winding and core designs, larger conductors, and improved insulation to manage the additional heat produced by harmonic currents without de-rating or premature failure. The K-rating value indicates the level of harmonic order that can be handled safely by the transformer. K-1 rating refers to conventional transformers, which are designed for fundamental conditions. While K-rated transformers with values K-4, K-9, K-13, K-20, K-30, K-40, and K-50 can handle the loads that generate harmonic contents with these specified orders. Therefore, K-rated transformers are considered a vital technique in harmonics mitigation strategies, especially in distribution networks where harmonic currents are unavoidable. As K-rated transformers, ensuring that the transformer could be operated reliably and efficiently under distorted conditions [53]. Applications of K-rated transformers are widespread in commercial and institutional buildings where non-linear loads dominate, such as in office environments with large numbers of light-emitting diode (LED) lighting, data centers, and uninterruptible power supplies (UPSs). Hence, K-rated transformers could be utilized to ensure safe operation under heavy electronic-based loading.

However, there are some limitations of using such types of transformers as the inability to actively reduce the harmonic distortions, because these transformers are only designed to withstand harmonic effects without addressing the main causes of the problem. Additionally, K-rated transformers have high costs compared to conventional transformers due to their enhanced construction. Even so, K-rated transformers require complementary harmonic mitigation techniques such as filters or multi-pulse rectifiers to mitigate the harmonic contents. Despite these challenges, K-rated transformers could be an effective solution for overheating in transformers and energy losses due to their capabilities of withstanding harmonic effects.

Multi-pulse rectifiers are regarded as an effective harmonics mitigation strategy that could be employed for reducing the harmonic contents, unlike the conventional rectification process. The principle of operation of these rectifiers depends on using multiple rectifier bridges fed by specially designed phase-shifting transformers, such as in 12-pulse or 18-pulse configurations. The key principle behind this technique is harmonic cancellation by supplying the rectifiers with input voltages that are phase-shifted. Hence, the harmonics generated by each rectifier are out of phase and could be controlled to cancel each other. As a result, multi-pulse rectifiers significantly reduce lower-order harmonics, minimizing THD and improving overall power quality without the need for external filtering [54].

Accordingly, multi-pulse rectifiers are commonly utilized in industrial power settings where large VFDs are employed to comply with the acceptable standards of harmonics levels. However, there are limitations to this technique. For instance, multi-pulse systems require complex and costly transformer arrangements, which increase the overall system troubles. They are also less effective under unbalanced load conditions or when the rectifiers are not equally loaded. Despite these constraints, their ability to reduce harmonic content at the source makes them a preferred choice for high-performance, high-reliability industrial applications.

From the previous survey, it is noticed that Passive filters have low cost and are suitable for specific harmonics, but are not adaptable. On the other hand, active power filters offer better performance and adaptability but at a higher cost. Phase-shifting transformers and multi-pulse rectifiers are effective in high-power and fixed-load applications. While K-rated transformers could not mitigate harmonic contents, they could be effectively employed for withstanding the consequences that are caused by these harmonics. A comparison between these techniques is stated in Table 2.

3.2 Power Quality Enhancement Using Custom Power Devices

The new concept of advanced power electronic-based Custom Power Devices has emerged, featuring innovative solutions such as Distributed Static Synchronous Compensators (D-STATCOM), Dynamic Voltage Restorers (DVR), and Unified Power Quality Conditioners (UPQC), designed to overcome the limitations of traditional compensation devices in effectively mitigating power quality disturbances [78]. Power quality disturbances, including voltage imbalances, harmonic distortions, flicker, voltage sags, and swells, can significantly impact the quality of voltage and current waveforms [79]. These issues can lead to a range of problems, including increased energy losses, equipment malfunction or damage, electromagnetic interference, and other operational disruptions. To mitigate these issues, power electronic-based Custom Power Devices, such as D-STATCOM, DVR, and UPQC, can be employed to provide effective solutions and enhance power quality [80]. Despite their technical effectiveness, devices such as STATCOMs and DVRs can pose high deployment costs and integration complexities, limiting their feasibility in resource-constrained or legacy distribution networks.

Custom Power Devices (CPDs), including D-STATCOMs, DVRs, and UPQCs, are part of the Active Power Filter (APF) family, configured in shunt, series, or hybrid arrangements to effectively mitigate various power quality issues [81,82]. Unlike passive filters, CPDs offer superior performance, avoiding drawbacks like instability, fixed compensation, and resonance [78,83]. However, their high rating requirements, often approaching full load capacity, make them a costly solution for power quality enhancement [84,85].Thus, CPDs like DVRs and DSTATCOMs are conventional hardware solutions for localized power quality issues. However, their effectiveness can be enhanced by integrating data-driven control methods.

3.2.1 Categorization of Custom Power Devices

Custom power solutions fall into two main categories: network reconfiguration type and compensation type. Fig. 10 illustrates the different types of Custom Power Devices, their classifications, and a diagrammatic representation for each type.

Figure 10: Categorization of custom power devices

Key network reconfiguring custom power devices comprise solid-state current limiters, static transfer switches, static breakers, and UPS systems [86]. Solid-state current limiters mitigate high fault currents by dynamically inserting and removing a limiting inductor. Static transfer switches safeguard sensitive loads by seamlessly switching to an alternate source during primary source disruptions. Static breakers minimize electrical faults and protect against excessive currents. UPS systems ensure uninterrupted operation by maintaining a stable load voltage using battery power during voltage fluctuations or outages.

On the other hand, compensating custom power devices play a crucial role in enhancing power quality through active filtering, load balancing, voltage regulation (mitigating sags and swells), eliminating harmonics, and correcting power factors [87]. Different configurations of DSTATCOM, DVR, and UPQC are employed to address power quality disturbances in distribution systems, and these can be classified based on converter design or supply system topology [88]. The following is a concise description of the three types:

• D-STATCOM: It is a crucial shunt-connected custom power device that plays a vital role in regulating system voltage, improving voltage profiles, reducing harmonics, mitigating transient voltage disturbances, and compensating loads [82]. By injecting a precise current, it effectively eliminates harmonics generated by nonlinear loads.

• DVR: It is a custom power device that utilizes power electronic converters to shield sensitive loads from supply-side disturbances, excluding outages [89]. By injecting a voltage of the necessary magnitude and frequency, the DVR restores the load-side voltage to its desired level and waveform, even in the presence of unbalanced or distorted source voltage.

• UPQC is a universal power quality solution that integrates series and parallel active power filters to provide comprehensive protection for sensitive loads [90]. It offers flexible compensation for various power quality disturbances, addressing both voltage and current-related issues simultaneously.

These custom power devices (D-STATCOM, DVR, UPQC) utilize various inverter topologies, including VSI, CSI, and Z-source [91]. VSI-based topologies offer several advantages over CSI-based topologies, including lower costs, greater control flexibility, elimination of blocking diodes, and multilevel operation capabilities [92]. However, CSI topologies provide enhanced reliability and fault tolerance due to the series inductor’s current-limiting effect during faults [93]. CSIs suffer from increased losses due to inductive energy storage, making VSIs a more popular choice for D-STATCOM, DVR, and UPQC applications, thanks to their capacitive energy storage advantages.

The converter topology of compensating custom power devices is typically composed of various configurations, including but not limited to, dual H-bridge inverters, half-bridge inverters, or 3-leg inverters, which provide the necessary flexibility and functionality to effectively compensate for power quality issues as shown in Fig. 10 [94].

Compensating custom power devices can be categorized based on supply system topology, which includes single-phase two-wire, three-phase three-wire, and four-wire configurations. Fig. 11 shows that this classification applies to devices like UPQC, with D-STATCOM and DVR being subsets focusing on shunt and series compensation, respectively [95].

Figure 11: Classification of custom power devices based on supply system topology

3.2.2 Control Techniques for Custom Power Devices

The control technique is crucial to the performance of D-STATCOM, DVR, and UPQC devices. While simple systems use open or closed-loop control, advanced systems employ sophisticated methods like sliding mode control, LQR, and Kalman filters [96]. Modern devices leverage complex algorithms, including fuzzy logic, neural networks, and genetic algorithms, enabled by microprocessors and microcontrollers, to enhance dynamic and steady-state performance [97]. Control strategies typically involve frequency or time-domain correction techniques to generate reference signals [83].

To improve Custom Power Devices, researchers are optimizing control techniques to achieve reduced ratings, enhanced performance, and increased efficiency [80]. This involves minimizing losses, reducing component count, and eliminating harmonics. The current research focus is on developing multifunctional control strategies that can effectively optimize device performance [98].

4 Modern Grid Technologies and Intelligent Monitoring Tools

The integration of information and communication technology has transformed the power sector, revolutionizing generation, transmission, distribution, and operations [99]. This shift has enabled market participants to leverage diverse energy sources and technologies, enhancing the reliability, resilience, security, and economic viability of the electric utility industry [100].

Modernizing the distribution grid involves creating a smart, reliable, and secure network that empowers consumers to engage with diverse market opportunities [101]. This intelligent grid requires a strong foundation, advanced monitoring, protection, automation, and control capabilities, extending to the grid edge, surpassing traditional distribution grid functionalities [102]. Fig. 12 demonstrates the evolution of a centralized system into a hybrid model, combining centralized and decentralized elements, as communication and computing capabilities advance.

Figure 12: Evolution of the electric power systems

Successful grid modernization requires a multifaceted approach, including new infrastructure, updated processes, and regulatory frameworks [103]. It also involves embracing distributed energy resources, energy storage, and secure communication networks to safeguard against cyber threats and facilitate efficient grid operations [104].

4.1 Key Technologies Driving Distribution Grid Modernization

4.1.1 Advanced Metering Infrastructure (AMI)

Smart metering technology enables two-way communication, providing utilities and customers with detailed insights into energy usage [105] and supporting pricing models that can lower peak demand by 10%–15% [106].

4.1.2 Distribution Automation Systems

These advanced technologies improve grid reliability through automated fault management, reducing outage times by up to 55% and yielding significant SAIDI improvements of approximately 35% [107].

4.1.3 Distributed Energy Resource Management Systems (DERMS)

(DERMS) help utilities manage the increasing number of customer-owned energy resources, ensuring grid stability even with high levels of distributed solar and storage [108].

4.1.4 Advanced Distribution Management Systems (ADMS)

Advanced Distribution Management Systems (ADMS) provide a comprehensive software solution that integrates previously isolated utility operations, leading to substantial cost savings [109].

4.1.5 Grid-Edge Sensors and IoT Devices

The rapid proliferation of grid-edge sensors and Internet of Things (IoT) devices has revolutionized the way distribution networks operate, providing unprecedented visibility into previously “blind” or unmonitored sections cite dutta2025harnessing. However, implementing IoT in smart grids faces challenges related to data transmission quality, security, and protocol selection. Future developments will focus on advancing communication protocols, enhancing cybersecurity, and improving the integration of renewable resources to create a more sustainable and efficient power system.

Battery technologies are multifunctional, supporting various grid operations simultaneously. Notably, front-of-meter deployments have experienced rapid growth, with a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 42%.

Microgrids play a vital role in modernizing the distribution grid by providing localized, reliable, and efficient energy solutions. They enable the integration of renewable energy sources, enhance grid resilience, and support critical infrastructure. As the grid evolves, microgrids offer a promising path forward for creating a more sustainable and reliable energy system [110].

5 Optimization Techniques for Power Quality Enhancement

Nowadays, various optimization algorithms gain widespread attention in power quality enhancement studies. This spread is due to their ability to handle the most complex, non-linear, and multi-objective problems, which are inherited in power networks. Generally, optimization algorithms could mimic the natural behavioral processes to obtain the optimal results, making them suitable for power quality applications involving uncertainties and dynamic conditions. The commonly employed techniques in optimization studies of power quality include: classical, nature-inspired, and artificial intelligence (AI)-based algorithms.

Linear programming (LP) and mixed-integer programming (MIP) are involved in optimization studies as classical methods.While, the traditional methods such as linear and non-linear programming often fall short in modern distribution systems due to their inability to cope with high dimensionality, dynamic uncertainties, and nonlinearities inherent in renewable energy integration. However, there are nature-inspired algorithms such as genetic algorithms (GA), particle swarm optimization (PSO), differential evolution (DE), and grey wolf optimizer (GWO) that are newer than classical methods. These algorithms enable adaptive and intelligent decision-making, which is critical for maintaining voltage stability, mitigating harmonics, and improving power factor. Recently, AI-based techniques such as artificial neural networks (ANNs) and fuzzy logic controllers (FLCs) have become very widespread [111]. In the next lines, a comparison between numerous optimization algorithms in power quality studies is demonstrated. Then, the most common applications of optimization techniques are overviewed for power quality improvements. After that, the challenges and opportunities are introduced.

5.1 Comparison of Different Optimization Algorithms in Power Quality Studies

In power quality studies, different optimization algorithms offer unique strengths in solving related problems based on their convergence speed, accuracy, complexity, and ability to handle non-linear, multi-objective, and uncertain cases. The classical algorithms, such as LP [112,113] and MIP [114], are suitable for problems that are structured by well-defined constraints. However, such algorithms may struggle with the non-linearity and the uncertainty issues of these problems.

On the other hand, the metaheuristic algorithms as GA [115–117], PSO [118,119], DE [120,121], and GWO [122,123] are more suitable in handling more complex power quality problems taking into account non-linearity and uncertainty issues. The common applications of such algorithms in power quality studies include: optimal placement of filters and capacitor banks, besides the allocation of distributed generator (DGs) sources to effectively solve issues as voltage fluctuations and harmonics mitigation in power networks. Although metaheuristic optimization techniques like GA, PSO, and ACO are widely used, their real-time deployment is constrained by intensive computational requirements and sensitivity to parameter tuning.

Nowadays, AI-based algorithms such as ANNs [124] and FLCs [125] have caught the attention of researchers to be employed in power quality studies due to their learning capabilities, besides their adaptability. These techniques are effective in dynamic environments where system conditions can change rapidly. For example, ANNs are excellent at pattern recognition and learning from historical data, this merit making them ideal for power quality event detection and could be trained to detect and classify the power quality disturbances. In a related context, FLCs could provide smoother decision-making and provide a robust methodology to handle the imprecise information and take effective decisions even if there are uncertain conditions. However, these AI-based techniques often require large learning datasets to operate effectively [126]. A comparison of the strengths and weaknesses points, besides the common applications of the various optimization techniques in power quality studies, is summarized in Table 3. Moreover, Table 4 presents a comparative analysis of three uncertainty handling methods; Stochastic optimization, robust optimization, and fuzzy logic. The comparison highlights the differences between the methods in terms of uncertainty type, computational complexity, data requirements, adaptability, robustness, scalability, and key limitations within power system applications.

Consequently, the choice of the most suitable optimization algorithm depends on various factors. The complexity of the studied network, availability of data and resources, besides the nature of the power quality issue which needs to be handled, are regarded as the most common factors to be considered at selecting the optimization algorithm.

5.2 Applications of Optimization Techniques in Power Quality Enhancement

For mitigating the power quality issues in distribution networks, optimization techniques could be applied in various applications to enhance the power quality of such networks. For example, optimization algorithms can be utilized for determining optimal placements of filters in distribution power networks. Furthermore, optimization algorithms could be involved in tuning the control parameters of the compensating devices in these networks. In addition, the optimal integration of RESs and ESSs in distribution networks requires the involvement of such algorithms for appropriate management.

5.2.1 Optimal Placements of Filters

Filters are considered a key approach for improving power quality in modern distribution networks. Consequently, optimization techniques that involve finding the optimal placements of filters play a vital role in the distribution of power networks. As is known, harmonic distortions caused by non-linear loads could degrade equipment performance and reduce overall network efficiency. Thus, optimization algorithms could be employed to identify the most suitable locations and sizes for passive and active power filters in networks to address this issue. These algorithms aim to minimize the THD and voltage deviations while maintaining network limitations at their limits. Utilities operators could guarantee more benefits by applying these methods, such as improving overall performance and compliance with the standards [134].

5.2.2 Tuning of Control Parameters

One of the remarkable applications of optimization algorithms in research is the tuning of the control parameters of power quality enhancement devices. These devices such as dynamic voltage restorers (DVRs), distribution static synchronous compensators (STATCOMs), and unified power quality conditioners (UPQCs). Such devices require precise tuning of their controllers as proportional-integral (PI), proportional-integral-derivative (PID), and fuzzy logic-based control systems. The tuning aims to maintain the voltage stability and fast response for the system during disturbances [135]. Therefore, optimization techniques automate the tuning process by adjusting controller gains to enhance performance characteristics such as settling times, overshoots, and steady-state errors. Proper tuning of these controllers results in improvements in transient response and better handling of voltage sags, swells, and flicker in distribution networks [135].

5.2.3 RESs and Energy Storage Integration

Nowadays, the optimal penetration of RESs and ESSs in distribution networks aims to enhance operational efficiency, reliability, and sustainability, which are considered critical issues in modern networks. Therefore, optimization techniques could help in determining the best allocations for RESs and ESSs to minimize power losses, improve voltage profiles, and minimize cost. As modern distribution networks are regarded as complex systems with multiple objectives and constraints, optimization approaches can effectively balance trade-offs between cost, efficiency, and stability. These approaches aid the operators in network planning, especially under high penetration of uncertain RESs [136].

Moreover, the optimized penetration of RESs and ESSs facilitates the energy management processes and ensures network flexibility by guaranteeing the ratio between the generated power and load demands. Moreover, by optimally managing ESSs, the excess generation could be absorbed during low-demand periods and released during peak hours. Through this process, the load curve would be flattened and the dependence on conventional fossil fuel plants could be reduced. Furthermore, the advanced optimization techniques could be incorporated in uncertainty studies related to RESs generation and load forecasts. This incorporation could framework the essential support for transitioning toward smarter distribution networks [137].

6 AI and ML Models in Power Quality Analysis and Harmonic Mitigation

As discussed earlier, conventional mitigation strategies as passive filters, active filters, and other compensation techniques, are widely used for addressing the problem. However, these approaches are often constrained by their dependence on system parameters and their fixed configurations, which could not behave optimally especially at the rapid change of networks conditions [138].

In recent years, a growing emphasis is placed on integrating intelligent technologies into power systems. Machine learning is considered as a subfield of artificial intelligence that has an ability to handle complex problems, learn from historical data, and has an adaptivity to real-time changes. Thus, machine learning could be involved in distribution networks as an advanced technology for solving power quality issues especially, harmonic distortion mitigation [139]. Therefore, machine learning technique could help in overcoming the limitations of conventional harmonic strategies [140,141].

Machine learning encompasses various approaches, including supervised learning, where models learn from labeled data for tasks like classification and regression. Unsupervised learning involves discovering patterns in unlabeled data through clustering and dimensionality reduction. Reinforcement learning optimizes decisions through trial and error, while semi-supervised learning combines labeled and unlabeled data for training. Active learning selects the most informative data points to improve model performance. These diverse techniques enable machine learning models to tackle a wide range of applications and challenges. Fig. 13 illustrates the primary classifications of machine learning.

Figure 13: The classifications of machine learning

To apply machine learning for power quality analysis, a comprehensive approach is required, involving data collection on disturbances, thorough data preprocessing, feature extraction to identify key characteristics, selection of a suitable algorithm based on problem requirements, model training using labeled data, and model evaluation and deployment for real-time power quality analysis with ongoing refinement to adapt to changing conditions and improve performance. Fig. 14 illustrates the machine learning steps for power quality analysis.

Figure 14: The machine learning steps for power quality analysis

Table 5 provides illustrative examples of how different machine learning (ML) techniques are applied in renewable energy and power quality (PQ) systems. The table links each ML method with its typical application domain, highlighting their roles in forecasting, classification, clustering, and optimization tasks.

There are many approaches of machine learning are utilized for harmonic mitigation. In [142], power line frequency detection is employed with support vector machine approach to analyze signals through intrinsic mode functions while preserving signal’s characteristics at finding the lineaments associated with harmonic distortion from lighting sources. In [143], artificial neural networks are proposed to estimate the individual harmonic components using minimal inputs. The process of this approach depends on extracting and analyzing characteristics of harmonic component magnitudes acquired from the inspection of a region via real-time measurements.

In [144], K-Means clustering approach is introduced and adaptive density peak clustering is presented for enhancing its performance. This approach is precise in tracing analysis in scenario of enormous harmonic causes because it depends on recognizing local locations of multi-harmonic sources. Thus, it could decrease large scale orders of harmonic. In [145], an approach based on component analysis is presented to estimate the harmonic transfer impedances in power networks with multiple harmonic causes. The approach is applied to determine Norton equivalent to calculate harmonic transfer impedance.

In [146], deep reinforcement learning-based is utilized with proportional-resonant controller for enhancing the stability of distribution network. The controller is trained by minimizing the total harmonic distortion of injected current from battery energy storage system to the grid. Then, the approach is employed with filters controller. In [147] and [148], decision trees and random forest are used for harmonic classification, respectively. Table 6 gives a brief overview of machine learning approaches and their applications in harmonic mitigation.

Despite the advancements of machine learning technology, there are certain challenges remain. For instance, data scarcity in low-instrumented grids, the interpretability of complex models, and the computational demands of real-time deployment continue to pose obstacles. However, the ongoing evolution of smart sensors, edge computing, and hybrid modeling frameworks is expected to further enhance the integration of machine learning in harmonic mitigation. Moreover, while machine learning approaches are designed to be adaptive and data-driven, human oversight ensures their safety, and reliability. Thus, a human-in-the-loop concept is often retained throughout the machine learning processes. This is essential for effective feature selection, model validation, and result interpretation.

7 Comparative Analysis and Performance Evaluation

The classification of harmonics in power systems is critical for effective monitoring, diagnosis, and mitigation of power quality issues. As artificial intelligence techniques gain traction in this domain, Support Vector Machines (SVMs) and Neural Networks (NNs) are emerged as two of the most widely applied classifiers. Therefore, a detailed comparative evaluation of these methods is carried out to aid in model selection and practical deployment decisions.

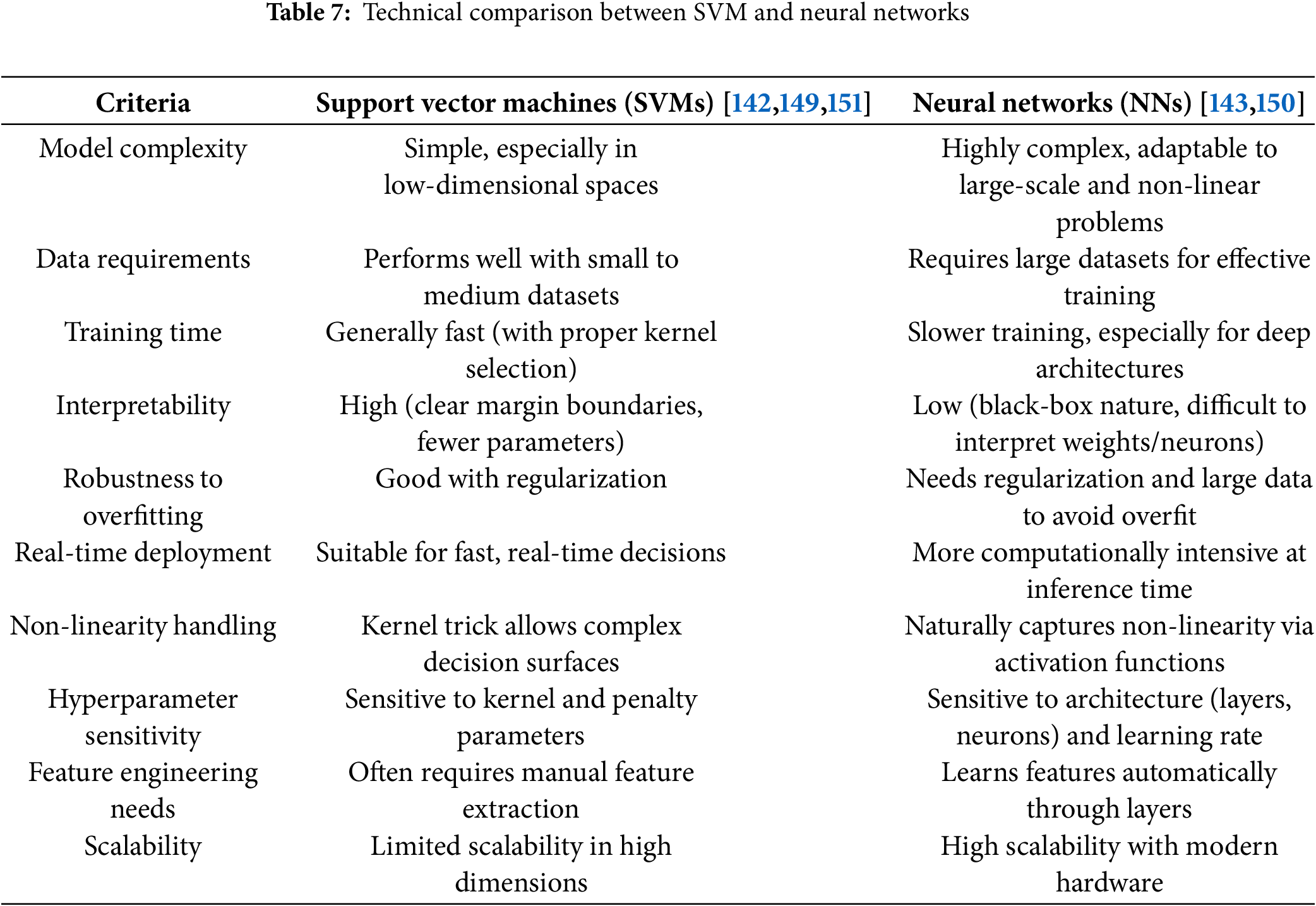

7.1 Theoretical and Computational Characteristics

SVMs are founded on the principle of maximizing the margin between classes in a transformed feature space, enabled by kernel functions. Their strength lies in handling structured data with clear decision boundaries, often requiring only modest training data [149]. On the other hand, neural networks (NNs) operate through multiple non-linear transformations, automatically extracting features and uncovering complex patterns across layers. However, this comes with increased computational demands and data requirements [150]. Table 7 outlines a direct comparison of core characteristics of SVMs and NNs in terms of model behavior, training complexity, and generalization.

7.2 Functional Capabilities and Application Suitability

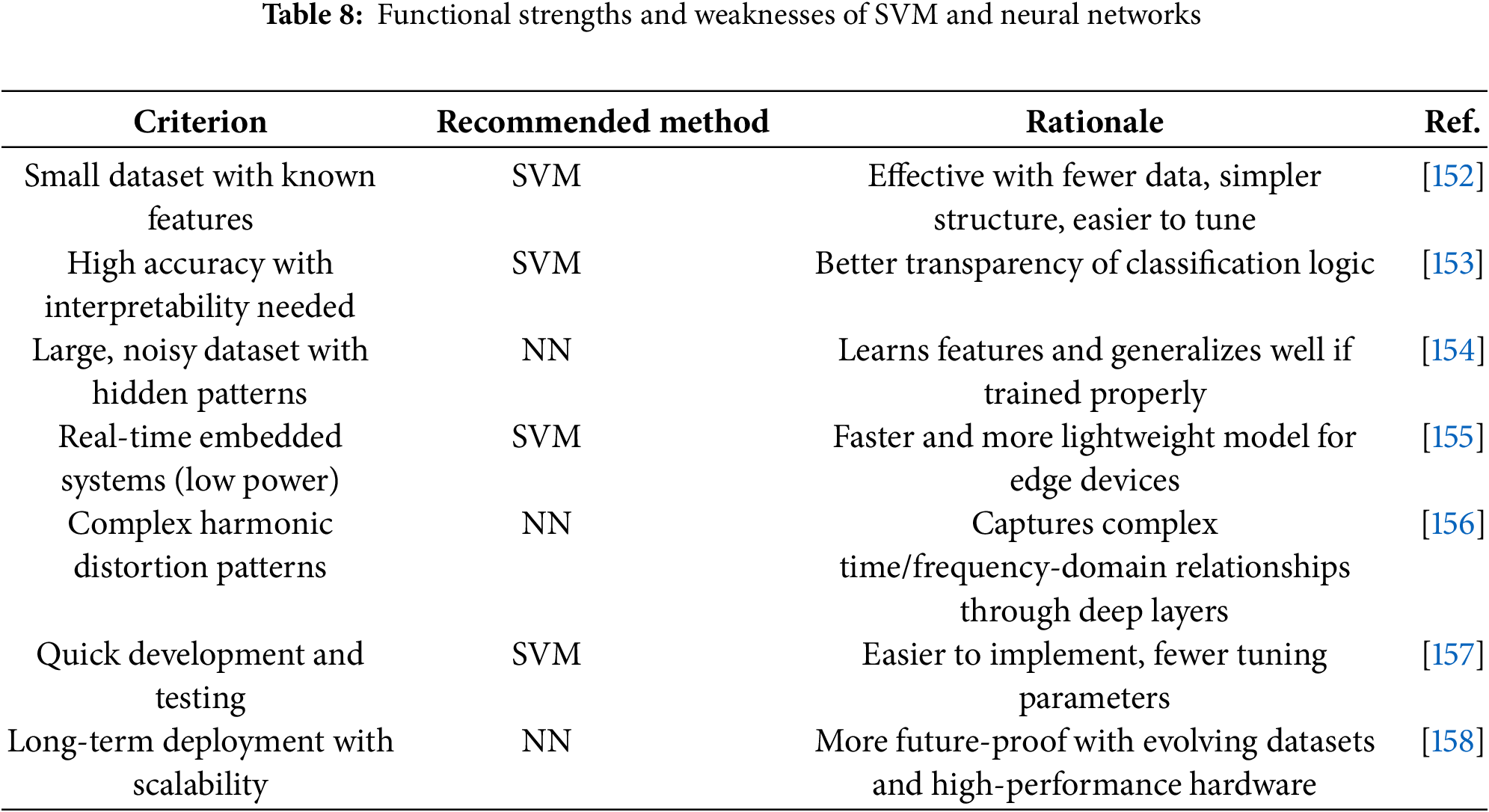

Beyond theoretical attributes, practical concerns such as real-time operation, model interpretability, and ease of deployment play a significant role in method selection. SVMs excel in scenarios where computational efficiency and explain ability are essential, such as embedded grid sensors or mobile platforms. In contrast, neural networks shine in cloud-based platforms or control centers where complex harmonic distortion patterns must be modeled in detail. Table 8 expands on these functional characteristics, highlighting where each method is most suitable based on application-specific priorities.

7.3 Key Comparative Attributes and Remarks

The presented holistic perspective can guide researchers and engineers in selecting the most appropriate model for a given harmonic classification scenario. This comparative study demonstrates that no single model universally outperforms the other across all harmonic classification tasks. Instead, model selection should be guided by data availability and dimensionality, deployment context as real-time or offline, interpretability needs, and scalability and resource constraints.

Therefore, in many real-world applications, hybrid approaches may prove beneficial. For instance, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) can be used for automatic feature extraction from harmonic waveforms, while SVMs can serve as final classifiers to maintain decision boundary interpretability and computational efficiency. Such integrations offer a balanced trade-off between accuracy, speed, and practicality, and warrant further investigation in future work.

Based on the previously discussed types of custom compensation devices, Table 9 presents a quantitative comparison based on the performance of various enhancement technologies and devices. From this table, the performance insights are presented as follows: for Voltage Sag Mitigation: DVR: the most effective; restores load voltage to nearly 97% within 10 ms. STATCOM: Achieves 40%–80% sag mitigation with new controllers. Passive/APF: Minimal impact on sags.

8 Challenges, Implementation Barriers, and Future Prospects

There are many technical challenges facing the application of optimization techniques in power quality enhancement studies. One of these challenges is maintaining the network’s stability while operating the networks at their acceptable limits. Furthermore, power systems currently should meet the growing penetration of RESs with their inherent uncertain nature, besides the complexity of load balancing, voltage regulation, harmonic contents, and other power quality issues. Therefore, optimization algorithms should be operated in real-time with the grids to ensure voltage stability, frequency regulation, and minimal harmonic distortion. However, modeling these dynamic systems accurately remains a complex task, especially at designing robust algorithms that could be adapted to the changes in grid conditions, particularly when high-speed data processing and system responsiveness are required [159].

Moreover, the protection coordination across distribution networks is also considered another technical challenge for optimization techniques. Optimization techniques should adjust the parameters of protection devices as relays and circuit breakers, dynamically. While the conventional coordination strategies are designed for fixed operational conditions, which is not suitable for dynamically changing conditions. The failure to handle such protection schemes may lead to maloperations and delays in power systems. Therefore, developing adaptive protection schemes that integrate seamlessly with optimization frameworks becomes an essential challenge that should be treated [160]. Also, the robustness of machine learning and Al models under rapidly changing grid conditions (e.g., load spikes, intermittent PV output) remains an open challenge. Moreover, the risk of overfitting in limited-data scenarios calls for cautious model validation and generalization strategies.

8.2 Economic and Regulatory Challenges

The implementation of advanced optimization techniques for power quality improvement requires a high upfront investment from an economic perspective. This high cost is due to the increased charges of the components required to match the prevailing modern networks. For example, hardware upgrades, intelligent sensors, communication infrastructure, besides software platforms are ones of the high-cost required elements. Moreover, when the benefits like improved power quality or reduced losses are difficult to quantify in monetary terms, the cost-benefit analysis of such investments would be more complicated. Additionally, the operators of distribution networks may face other struggles, such as the constraints of the budgets. So, without clear financial incentives or returns on investment, the adoption of these challenges becomes more complicated [161].

On the regulatory side, the absence of consistent policy frameworks hinders the broader deployment of optimization-based solutions. Therefore, the lag of regulatory compared to the rapid technical advancement in optimization techniques may prevent the utility operators from applying the advanced optimization techniques. Thus, providing supportive regulations could help in innovation growth and encourage more employment of these advanced technologies in power systems [162].

8.3 Opportunities for Innovation and Growth

Despite the challenges of involving optimization techniques in power quality enhancements, the ongoing development of smart grids offers a substantial opportunity for innovation in such techniques. Smart grids incorporate monitoring and automated control, which provide the appropriate environment for implementing the advanced optimization algorithms. These algorithms can manage load profiles, compensate, the reactive power with high precision, and mitigate the harmonic contents. As smart grid technologies become more prevalent, the interaction between real-time data analytics and optimization techniques releases new avenues for the customized power quality solutions [163].

Furthermore, the penetration of ESSs with optimization techniques presents a promising growth research area that needs further study. ESSs can mitigate the fluctuations of RESs, reduce peak demand, provide ancillary services, besides other benefits such as voltage strengthening and harmonics filtering. Optimization techniques can be employed to manage the charging and discharging cycles of these storage units in a way that maximizes their benefits to the overall power quality. As battery technologies become more affordable and regulations evolve to support storage participation in network operations, the combination of optimization techniques and ESSs becomes a cornerstone of future power quality enhancement strategies [164].

8.4 Actionable Research Gaps and Proposed Roadmap

This review has provided a comprehensive analysis of power quality (PQ) enhancement techniques and hosting capacity (HC) optimization in renewable-integrated distribution systems. It has discussed conventional methods, grid modernization technologies, and Al/machine learning-based approaches in the context of harmonic mitigation, voltage regulation, and power factor correction. While significant progress has been achieved in recent years, several critical gaps remain in the literature as follows:

• Lack of comparative evaluation: Few studies offer systematic comparisons of AI and ML models in terms of accuracy, computational cost, and adaptability in real-time environments.

• Underexplored hybrid models: Limited attention has been given to combining traditional optimization algorithms with Al-based techniques to enhance PQ metrics dynamically.

• Insufficient empirical validation: Many models are evaluated on simulated data; real-world deployment and testing are still rare.

• Narrow focus on individual PQ issues: Most studies target single PQ issues, neglecting interdependencies (e.g., voltage instability due to harmonic distortion).

• Outdated literature citations: Some reviews heavily rely on pre-2020 studies, missing recent advancements in Al-driven grid solutions. The proposed future research roadmap can be illustrated in the following points:

• Combine rule-based methods (e.g., fuzzy logic) with ML (e.g., reinforcement learning or federated learning) for real-time PQ control to develop adaptive hybrid models.

• Employ explainable AI frameworks to increase trust in decision-making systems and improve interpretability of Al models.

• Use hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) testing and digital twins to verify Al models on actual distribution systems and validate in real-world scenarios.

• Adopt multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) integrated with ML models to manage harmonics, voltage, and power factor simultaneously for optimizing multi-objective PQ issues.

• Leverage edge devices and lot sensors for collecting real-time grid data to enhance ML training to expand data sources.

Thus, the actionable research recommendations for future studies include designing of benchmarking datasets for fair comparison of PQ mitigation methods. Moreover, studies should encourage interdisciplinary approaches, combining power engineering, Al, and cybersecurity, furthermore, propose standardized frameworks for evaluating Al-based PQ models across various geographic and operational contexts.”

The increasing integration of renewable energy sources, particularly photovoltaic systems and other distributed energy resources, continues to challenge the stability and reliability of modern distribution networks. This review has provided a comprehensive analysis of the challenges raised, emphasizing key issues such as power quality disturbances, voltage regulation, hosting capacity limitations, and system efficiency. A structured evaluation was presented, bridging traditional enhancement techniques with advanced AI- and ML-based models, offering comparative insights into their accuracy, adaptability, and computational efficiency. The study further highlighted the role of optimization algorithms in addressing harmonics, voltage fluctuations, and reactive power management under renewable-rich conditions. Despite the progress achieved, several research gaps remain, including the need for real-time validation frameworks, scalable and cost-effective deployment strategies, and enhanced resilience under dynamic grid conditions.

Future research should prioritize intelligent, adaptive, and integrated solutions capable of supporting the growing share of renewables while ensuring robust and sustainable grid performance. By consolidating insights from both conventional methods and cutting-edge AI-driven approaches, this review provides a practical roadmap to advance power quality management and hosting capacity in renewable-integrated distribution systems. The growing penetration of renewable energy sources, particularly photovoltaic systems and other distributed energy resources, has created significant challenges in maintaining power quality, voltage regulation, and system reliability in modern distribution networks. This comprehensive review examines these challenges while exploring the opportunities and solutions available to enhance power quality and hosting capacity. Also, the review provides a structured evaluation of existing PQ enhancement techniques, bridging traditional methods with emerging AI- and ML-based models. The study categorizes and critically analyzes harmonics mitigation, voltage regulation, and power factor correction methods, highlighting their strengths, weaknesses, and applicability under renewable-rich conditions. Furthermore, comparative insights are drawn regarding computational efficiency, accuracy, and adaptability of optimization algorithms and AI-driven approaches. The review identifies current research gaps, such as the lack of real-time validation and cost-effective deployment strategies, and proposes future directions for practical implementation.

Acknowledgement: The authors thank Menoufia University for supporting this work.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study

Author Contributions: Consceptual: Eman S. Ali, Ragab A. El-Sehiemy and Abdallah Nazeh; methodology, Eman S. Ali and Abdallah Nazih; validation, Ragab A. El-Sehiemy and Adel A. Abou El-Ela; formal analysis, Asmaa A. Mubarak and Ragab A. El-Sehiemy; investigation, Eman Salah, Ragab A. El-Sehiemy and Abdallah Nazeh; resources, Asmaa A. Mubarak and Adel A. Abou El Ela; writing—original draft preparation, Eman Salah, Asmaa A. Mubarak and Abdallah Nazih; writing—review and editing, Adel A. Abou El-Ela, Ragab A. El-Sehiemy and Abdallah Nazih; supervisors: Ragab A. El-Sehiemy and Adel A. Abou El-Ela. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All requested data about this study is included in the text and can be requested from the corresponding author at elsehiemy@eng.kfs.edu.eg.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Varshney G, Chauhan DS, Dave MP. Evaluation of power quality issues in grid connected PV systems. Int J Electr Comput Eng. 2016;6(4):1412. doi:10.11591/ijece.v6i4.pp1412-1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Al-Shetwi AQ, Hannan MA, Jern KP, Alkahtani AA, PG Abas AE. Power quality assessment of grid-connected PV system in compliance with the recent integration requirements. Electronics. 2020;9(2):366. doi:10.3390/electronics9020366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Chao P, Li W, Peng S, Liang X, Zhang L, Shuai Y. Fault ride-through behaviors correction-based single-unit equivalent method for large photovoltaic power plants. IEEE Trans Sustain Energy. 2020;12(1):715–726. [Google Scholar]

4. Bhattacharya I, Deng Y, Foo SY. Active filters for harmonics elimination in solar photovoltaic grid-connected and stand-alone systems. In: 2nd Asia Symposium on Quality Electronic Design (ASQED); 2010 Aug 3–4; Penang, Malaysia. p. 280–4. doi:10.1109/ASQED.2010.5548252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Du Y, Lu DD, James G, Cornforth DJ. Modeling and analysis of current harmonic distortion from grid connected PV inverters under different operating conditions. Sol Energy. 2013;94:182–94. doi:10.1016/j.solener.2013.05.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Diaz Schery CA, Caiado RG, Corseuil ET, Neves H, Weibull JK. Multilevel analysis of the scientific trajectory of BIM: insights from SciVal and cumulative capability development perspective. Eng Constr Archit Manage. 2025. doi:10.1108/ECAM-05-2024-0688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Yan Y, Chen K, Geng H, Fan W, Zhou X. A review on intelligent detection and classification of power quality disturbances: trends, methodologies, and prospects. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2023;137(2):1345–79. doi:10.32604/cmes.2023.027252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Zanib N, Batool M, Riaz S, Afzal F, Munawar S, Daqqa I, et al. Analysis and power quality improvement in hybrid distributed generation system with utilization of unified power quality conditioner. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2023;134(2):1105–36. doi:10.32604/cmes.2022.021676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Haji A, Bonneya MF. Assessment of power quality for large scale utility grid-connected solar power plant integrated system. J Tech. 2021;3(3):20–30. doi:10.51173/jt.v3i3.336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Liang X. Emerging power quality challenges due to integration of renewable energy sources. IEEE Trans Ind Appl. 2017;53(2):855–66. doi:10.1109/TIA.2016.2626253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Ortega MJ, Hernández JC, García OG. Measurement and assessment of power quality characteristics for photovoltaic systems: harmonics, flicker, unbalance, and slow voltage variations. Electr Power Syst Res. 2013;96:23–35. doi:10.1016/j.epsr.2012.11.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Sami FP. Techno-economic analysis of grid connected photovoltaic systems under Sahelian climate: the case of Burkina Faso. [Ph.D. thesis]. Nairobi, Kenya: University of Nairobi; 2024. [Google Scholar]

13. Urbanetz J, Braun P, Rüther R. Power quality analysis of grid-connected solar photovoltaic generators in Brazil. Energy Convers Manage. 2012;64:8–14. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2012.05.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Sun X, Fan T, An S, Zhang Q, Zhang B. An improved grid-connected photovoltaic power generation system with low harmonic current in full power ranges. In: 2014 International Power Electronics and Application Conference and Exposition; 2014 Nov 5–8; Shanghai, China. p. 423–8. doi:10.1109/PEAC.2014.7037893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Paukner FL, Carati EG, Cardoso R, Stein CMO, da Costa JP. Dynamic behavior of the PV Grid-connected inverter based on L and LCL filter with active damping control. In: 2015 IEEE 13th Brazilian Power Electronics Conference and 1st Southern Power Electronics Conference (COBEP/SPEC); 2015 Nov 29–Dec 2; Fortaleza, Brazil. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/COBEP.2015.7420108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Liu Y, Wu W, He Y, Lin Z, Blaabjerg F, Chung HSH. An efficient and robust hybrid damper for LCL-or LLCL-based grid-tied inverter with strong grid-side harmonic voltage effect rejection. IEEE Trans Ind Electron. 2015;63(2):926–36. doi:10.1109/tie.2015.2478738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Koran A, Sano K, Kim RY, Lai JS. Design of a photovoltaic simulator with a novel reference signal generator and two-stage LC output filter. IEEE Trans Power Electron. 2010;25(5):1331–8. doi:10.1109/TPEL.2009.2037501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Turitsyn K, Sulc P, Backhaus S, Chertkov M. Options for control of reactive power by distributed photovoltaic generators. Proc IEEE. 2011;99(6):1063–73. doi:10.1109/JPROC.2011.2116750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Jha RR, Dubey A. Local smart inverter control to mitigate the effects of photovoltaic (PV) generation variability. In: 2019 North American Power Symposium (NAPS); 2019 Oct 13–15; Wichita, KS, USA. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/naps46351.2019.9000321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Akdogan ME, Ahmed S. Control hardware-in-the-loop for voltage controlled inverters with unbalanced and non-linear loads in stand-alone photovoltaic (PV) islanded microgrids. In: 2020 IEEE Energy Conversion Congress and Exposition (ECCE); 2020 Oct 11–15; Detroit, MI, USA. p. 2431–8. doi:10.1109/ecce44975.2020.9235913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Honrubia-Escribano A, García-Sánchez T, Gómez-Lázaro E, Muljadi E, Molina-García A. Power quality surveys of photovoltaic power plants: characterisation and analysis of grid-code requirements. IET Renew Power Gener. 2015;9(5):466–73. doi:10.1049/iet-rpg.2014.0215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Dahmani A, Himour K, Guettaf Y. Optimization of power quality in grid connected photovoltaic systems. J Eur Des Systèmes Autom. 2023;56(6):1095–103. doi:10.18280/jesa.560619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Ali Alhussainy A, Alquthami TS. Power quality analysis of a large grid-tied solar photovoltaic system. Adv Mech Eng. 2020;12(7):1687814020944670. doi:10.1177/1687814020944670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Elbaset AA, Hassan MS. Power quality improvement of PV system. In: Design and power quality improvement of photovoltaic power system. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2016. p. 73–95. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-47464-9_4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Hamid AK, Mbungu NT, Elnady A, Bansal RC, Ismail AA, AlShabi MA. A systematic review of grid-connected photovoltaic and photovoltaic/thermal systems: benefits, challenges and mitigation. Energy Environ. 2023;34(7):2775–814. doi:10.1177/0958305x221117617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Ibrahim MS, Dong W, Yang Q. Machine learning driven smart electric power systems: current trends and new perspectives. Appl Energy. 2020;272:115237. [Google Scholar]

27. Ukoba K, Olatunji KO, Adeoye E, Jen TC, Madyira DM. Optimizing renewable energy systems through artificial intelligence: review and future prospects. Energ Environ. 2024;35(7):3833–79. [Google Scholar]

28. Chen M, Zhao Q, et al. Recent advances in reinforcement learning and deep learning for adaptive control in smart grids. Energy Inform. 2025;8:45–62. [Google Scholar]

29. Singh AR, Dashtdar M, Bajaj M, Garmsiri R, Blazek V, Prokop L, et al. AI-enhanced power quality management in distribution systems. Artif Intell Rev. 2024;57:1769. doi:10.1007/s10462-024-10959-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]