Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Advancing Radiological Dermatology with an Optimized Ensemble Deep Learning Model for Skin Lesion Classification

1 Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, COMSATS University Islamabad, Wah Campus, Wah Cantonment, 47040, Pakistan

2 Department of Information Systems, College of Computer Engineering and Sciences, Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University, Al-Kharj, 16273, Saudi Arabia

3 Department of Information Technology, College of Computer and Information Sciences, Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, P.O. Box 84428, Riyadh, 11671, Saudi Arabia

4 Informatics and Computer Systems Department, King Khalid University, Abha, 62217, Saudi Arabia

5 Department of Computer Science, College of Computer Engineering and Sciences, Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University, Al-Kharj, 16273, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Author: Ghada Atteia. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Machine Learning and Deep Learning-Based Pattern Recognition)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(2), 2311-2337. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.069697

Received 28 June 2025; Accepted 09 October 2025; Issue published 26 November 2025

Abstract

Advancements in radiation-based imaging and computational intelligence have significantly improved medical diagnostics, particularly in dermatology. This study presents an ensemble-based skin lesion classification framework that integrates deep neural networks (DNNs) with transfer learning, a customized DNN, and an optimized self-learning binary differential evolution (SLBDE) algorithm for feature selection and fusion. Leveraging computational techniques alongside medical imaging modalities, the proposed framework extracts and fuses discriminative features from multiple pre-trained models to improve classification robustness. The methodology is evaluated on benchmark datasets, including ISIC 2017 and the Argentina Skin Lesion dataset, demonstrating superior accuracy, precision, and F1-score in melanoma detection. The proposed method achieved a classification accuracy of 98.5%, evaluated using an LSVM classifier on the Argentina Skin Lesion dataset, underscoring the robustness of the proposed methodology. The proposed approach offers a scalable and computationally efficient solution for automated skin lesion classification, thereby contributing to improved clinical decision-making and enhanced patient outcomes. By aligning artificial intelligence with radiation-based medical imaging and bioinformatics, this research advances dermatological computer-aided diagnosis (CAD) systems, minimizing misclassification rates and supporting early skin cancer detection. The proposed approach provides a scalable and computationally efficient solution for automated skin lesion analysis, contributing to improved clinical decision-making and enhanced patient outcomes.Keywords

Skin lesions pose a significant challenge in dermatology due to their potential to develop into severe conditions and life-threatening forms, including malignant skin cancers. These lesions result from the abnormal and uncontrolled proliferation of skin cells, which can metastasize to other parts of the body if not detected and treated early [1]. A primary contributing factor to their development is prolonged exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation, leading to DNA damage and uncontrolled cell growth [2]. Skin lesions are broadly classified into benign and malignant types, where squamous cell tumors and basal cell malignancies are the most common benign lesions that do not metastasize. In contrast, melanoma is a highly aggressive and malignant form of skin cancer that arises from melanocytic cells, responsible for skin pigmentation, and is often characterized by an irregular mole that appears dark brown or black [3–5].

Skin melanoma lesion spreads rapidly throughout the body and are the deadliest skin lesions, with lethal statistics increasing worldwide during recent decades [6]. A benign melanoma mole is a non-cancerous skin growth that does not pose a significant health risk. According to a national report from the National Skin Cancer Institute, skin cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer, with the highest incidence reported in the United States [7,8]. Melanoma ranks among the leading causes of cancer-related mortality worldwide [5,9]. Compared to other forms of cancer, skin cancer accounts for approximately 1% of all cases of skin; it has one of the highest mortality rates. Melanoma is classified into four main stages, ranging from Stage I, where the cancer is localized and confined to the skin, to Stage IV, where it has metastasized to distant organs such as the liver, lungs, or brain. The prediction of melanoma significantly worsens as it advances through these stages. Stage I melanoma has a five-year survival rate of nearly 96%, while Stage II and Stage III involve increasing tumor thickness and lymph node involvement, reducing survival rates. When melanoma reaches Stage IV, the five-year survival rate drops drastically to approximately 5% [10].

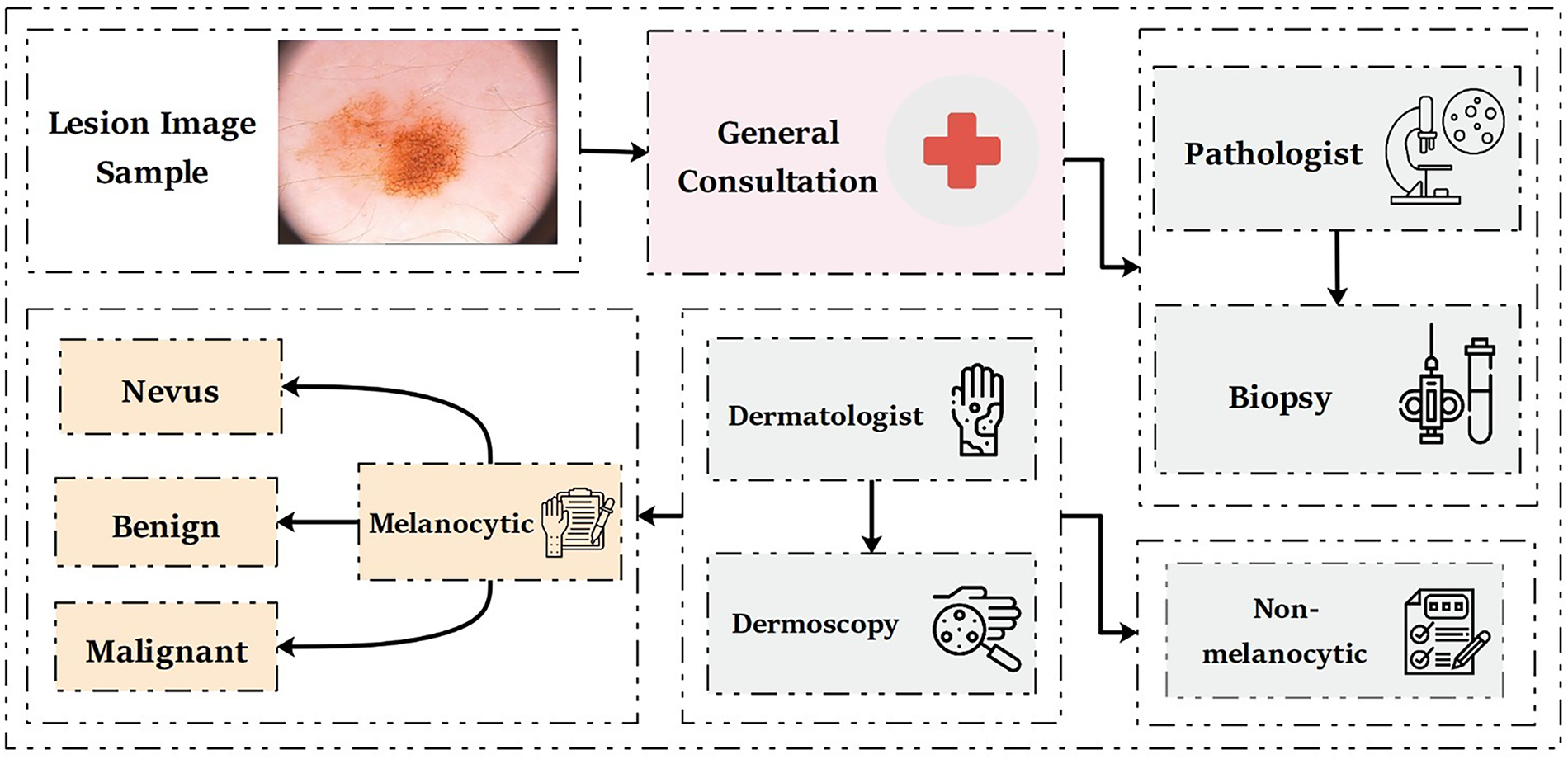

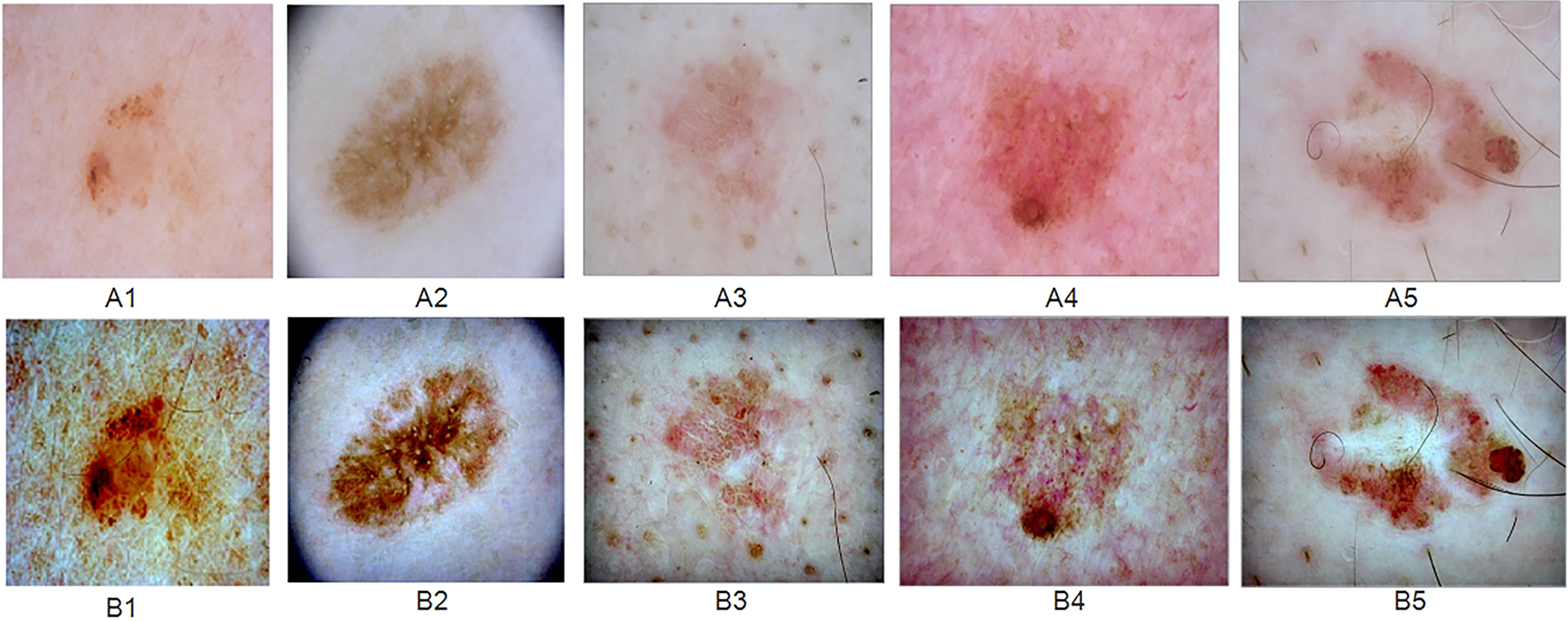

To make a final diagnosis, a pathologist removes a sample of skin tissue from the affected area to perform a biopsy and the final results typically take between 3 and 12 weeks. Dermatologists use highly magnified images of the affected skin along with dermoscopic techniques such as ABCDE (Asymmetry, Border, Color, Diameter, and Evolving), CASH (Color, Architecture, Symmetry, and Homogeneity), the 7-Point Checklist, and Menzies’ method to identify skin abnormalities [11], as illustrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Traditional clinical approaches for skin lesion diagnoses

However, dermoscopic analysis presents significant challenges due to the distinct characteristics of melanocytic and non-melanocytic skin lesions [12–14], including variations in skin texture and the presence of injuries. Even for experienced dermatologists, achieving accurate skin lesion diagnosis is a complex task. Diagnostic accuracy largely depends on the expertise and experience of the dermatologist, which can vary between 75% and 85% [15,16].

To overcome these limitations, medical researchers have developed computer-aided diagnosis (CAD) models based on deep learning (DL) and machine learning (ML). The CAD-based skin lesion diagnosis process begins with dataset creation, which involves the acquisition of skin lesion images. Once the dataset is prepared, DL models are trained to analyze these images. This training process includes feature extraction and selection, where relevant patterns and characteristics of the skin lesions are identified. Finally, the extracted features are used to classify skin lesion types, enabling the system to distinguish between different categories of skin lesions with high accuracy [17]. However, when dealing with large-scale datasets, classification becomes computationally expensive. To address this issue, the removal of redundant or irrelevant features, a process known as feature selection, plays a crucial role. Feature selection reduces the data’s dimensionality, decreases the model’s learning time, and improves classification accuracy. Over the past decade, several feature selection algorithms have been proposed in ML and DL research [18,19].

Among the proposed algorithms, metaheuristic techniques have demonstrated essential advantages in solving feature selection problems. Notable metaheuristic feature selection models include genetic algorithms (GA) [20,21], ant colony optimization (ACO) [22], particle swarm optimization (PSO) [23,24], firefly algorithm [25], artificial bee colony (ABC) [26], grasshopper optimization algorithm (GOA) [27], evolutionary gravitational search (EGS) [28,29]. Among these techniques, differential evolution (DE) has gained attention due to its simplicity and efficiency in feature selection [30,31]. Brest et al. [32] proposed an adaptive differential evolution model with the name of jDE to improve the performance of continuous optimization problems.

Emerging quantum deep learning (QDL) approaches, including hybrid quantum-classical convolutional neural networks (QCCNN) used for breast cancer diagnostics [33], quantum dual-branch neural networks (QDBNN) for skin cancer classification [34], and comprehensive reviews highlighting QSVM and QCNN architectures [35], have shown promise, but they remain largely experimental and constrained by current quantum hardware and encoding challenges. Moreover, existing methods, including CNN-based classifiers and transfer learning frameworks, have demonstrated promising results on benchmark datasets such as ISIC. However, most approaches rely on single-model architectures that may not generalize well across diverse datasets and skin types.

In this study, we propose an optimized ensemble deep learning framework, with SLBDE optimization, leveraging widely available conventional GPU infrastructure and facilitating reproducibility. This makes them a more practical and robust choice for dermatological diagnostic applications.

The key contributions of this paper are as follows:

• We design an ensemble deep learning framework that combines transfer learning with a customized DNN for robust skin lesion classification.

• We introduce the SLBDE algorithm that is directly embedded into the feature fusion stage of an ensemble deep learning model.

• We validate the proposed system on two benchmark datasets (ISIC 2017 and the Argentina skin lesion dataset), achieving superior accuracy and statistical significance compared to state-of-the-art models.

Unlike previous studies where SLBDE has been primarily applied as a standalone optimizer or limited to traditional feature selection tasks, our work incorporates a customized SLBDE mechanism directly into the feature fusion stage of an ensemble deep learning pipeline. In our proposed framework, SLBDE is not only used to reduce feature dimensionality but also to optimize the fusion of heterogeneous deep features from multiple networks. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first application of SLBDE for ensemble-level feature selection and fusion in dermatological image analysis.

By explicitly aligning advanced optimization techniques with medical imaging, this work contributes a practical solution for improving automated melanoma detection and supporting dermatologists in early diagnosis. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews relevant literature work. Section 3 details the proposed methodology, including the feature selection algorithm and the customized DL model. Section 4 presents the mathematical details and development of the proposed (SLBDE) feature selection algorithm. Section 5 provides an analysis of the proposed model, followed by a discussion in Section 6. Finally, Section 7 concludes the article.

Various methods and techniques have been developed for the detection and classification of skin lesions. Most CAD-based techniques use ML algorithms and computer vision (CV) tools. The CAD-based skin lesion detection process generally follows a standardized pipeline, including image enhancements, lesion segmentation, feature extraction and selection, and ultimately classification [36]. In [37], supervised ML and DL algorithms were employed for skin lesion segmentation and classification. Similarly, a pre-trained AlexNet DL model was used for feature extraction for SVM-based skin lesion classification [38].

To enable automated skin lesion segmentation and classification, a convolutional neural network (CNN)-based mutual bootstrapping network was proposed in [39]. Both skin lesion segmentation and classification have shown significant performance across multiple datasets using the bootstrapping network. The deep residual network was used in [40] for deep feature extraction combined with SVM and chi-square analysis for melanoma skin lesion detection and classification. For performance evaluation, the ISBI 2016 skin lesion dataset was used. Similarly, in [41], Hawas et al. introduced a Graph-Cut algorithm for efficient skin lesion segmentation and classification. Mask recurrent neural network (Mask-RNN) was used for efficient skin lesion segmentation. Resnet50 was used to extract features, followed by a Softmax classifier for skin lesion classification. For performance evaluation, the HAM10000 skin lesion dataset was utilized.

In [42], a novel cascaded DL architecture was proposed for skin lesion identification. To address class disparity removal, data augmentation was adopted. The proposed model was evaluated against state-of-the-art (SOTA) skin lesion classification and segmentation. Improved skin lesion segmentation results were achieved through feature derivation by integrating segmentation and registration [43]. In [44], efficient skin lesion segmentation and classification were achieved through DL networks. In [45], a deep learning-based feature selection pipeline is developed to segment skin lesion from dermoscopic images. The ISIC skin lesion dataset was used to evaluate and compare performance.

Since malignant melanoma is characterized by irregular borders, asymmetric shapes with narrow diameters, and rough edges, feature extraction and selection are crucial for accurate detection. Therefore, in precise skin lesion classification, handcrafted image features, such as shape, color, and texture, are as important as statistical features (e.g., histogram, texture, contour) and dermoscopic features (e.g., ABCD, structure, pattern). However, selecting a minimal yet optimal set of image features that ensures high computational efficiency, accuracy, performance, and reduced complexity remains a challenge [46–48]. Among these features, color and skin texture are the most significant properties for identifying skin lesions [49] as variations in skin color serve as the primary distinction between benign and malignant melanoma lesions in dermoscopic images [50,51].

Although ML and DL techniques have shown significant improvements in skin lesion detection accuracy compared to conventional methods, detection performance accuracy can be further improved by integrating multiple pre-trained models through ensemble learning. Ensemble-based skin lesion detection has been widely studied and has demonstrated superior performance compared to single techniques [51].

This article introduces an innovative ensemble learning approach that integrates pre-trained and customized DNN with an optimized SLBDE algorithm, along with a novel feature reduction technique, to improve accuracy while minimizing computational complexity. Before feature extraction, all images underwent a standardized preprocessing workflow to ensure consistency and reliability of the input data. This process involved systematic adjustments to normalize image characteristics, removal of common artifacts, and preparation of the dataset to reduce potential sources of noise and imbalance. In addition, data expansion strategies were applied to improve the diversity of training samples and to strengthen the robustness of the model against variations in acquisition conditions. These steps collectively enhanced the quality of the dataset and contributed to more reproducible experimental results.

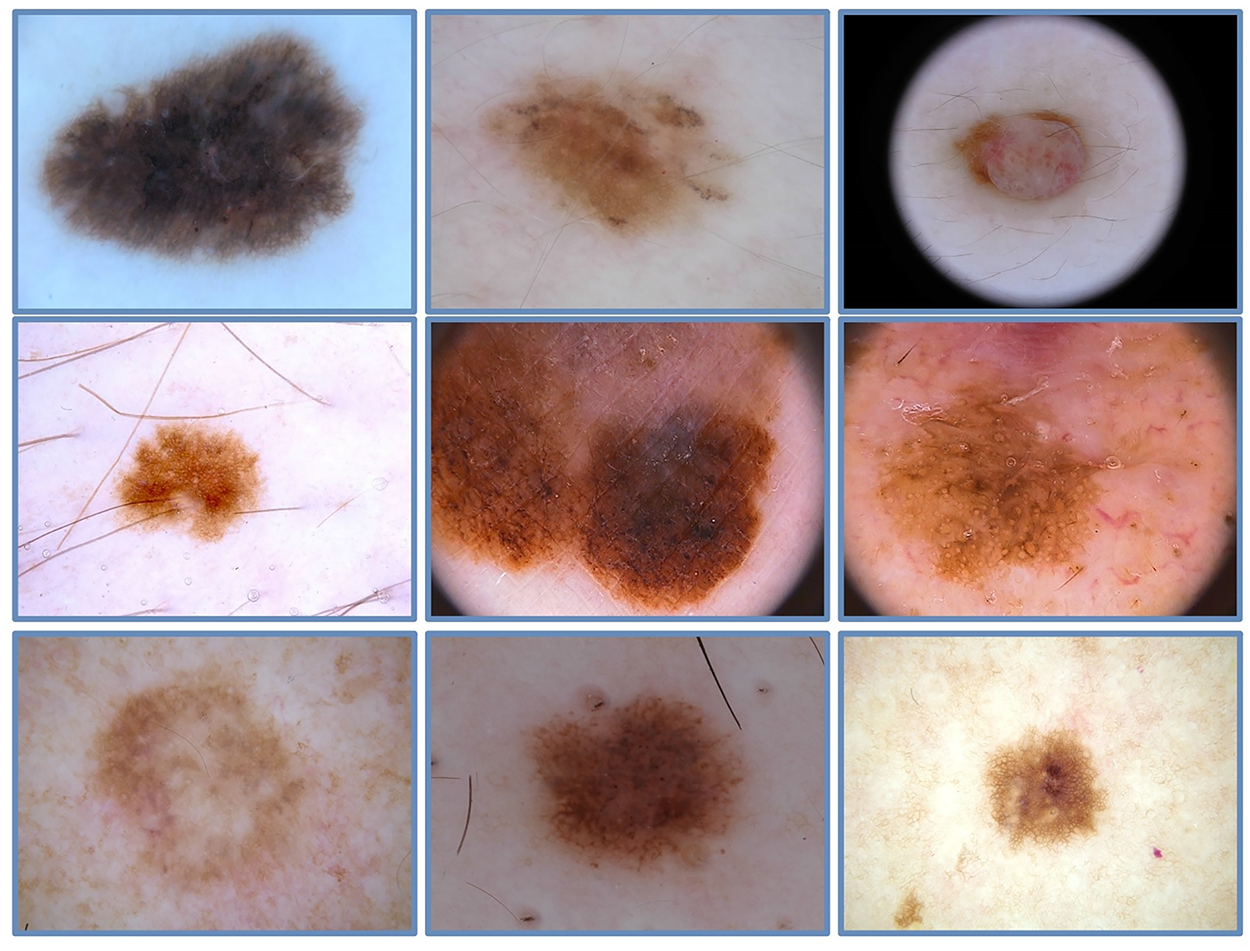

Datasets play a crucial role in the training, evaluation, and validation of DNN. This study used multiple skin lesion databases, including ISIC2017 [52] and the Argentina skin lesion [53] datasets. The International Skin Imaging Collaboration (ISIC) is a fundamental resource that provides expertly annotated digital skin lesion image datasets, facilitating the development of automated CAD systems for melanoma and other skin cancers. Additionally, ISIC organizes annual skin lesion challenges to encourage research advancements, improve the accuracy of CAD algorithms, and raise awareness of skin cancer detection. The ISIC2017 dataset comprises approximately

Figure 2: A few image samples from ISIC-2017 skin lesion dataset

In addition to widely used datasets, this study employed a less common skin lesion database [53], the first publicly available dermoscopy and clinical image database from Argentina. The database comprises 1616 images corresponding to 1246 distinct skin lesion images collected from 623 patients. As specified by the data collection team, all patients included in this database had undergone at least one consultation with professionals at a hospital in Buenos Aires, Argentina.

3.2 Pre-Trained Models for Feature Extraction

This sub-section provides a detailed exploration of pre-trained DL models employed for feature extraction in the proposed framework. These models that are trained on large-scale datasets have proven to be highly effective in learning rich and diverse features, often outperforming traditional hand-crafted techniques. Pre-trained models effectively capture low-level features, such as edges and textures, and higher-level abstract information, depending on the task. Additionally, their ability to generalize across different domains minimizes the dependence on large task-specific datasets, thereby reducing computational complexity and training time.

1. ResNet-50

ResNet-50 is a powerful DL model with residual connections, making it highly effective for extracting discriminant feature information. Initially introduced by He et al. in [54], ResNet-50 won the ILSVRC (ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge) in 2015, showing remarkable performance. ResNet-50 consists of 50 layers with learnable weights, which are set up in a pre-defined manner to add residual learning. This resolves the problem of gradients disappearing in very deep networks. The key innovation in ResNet-50 lies in its residual connections, also known as ‘skip connections.’

2. VGG-16

VGG-16 is a highly influential and widely used DL model for image classification tasks, initially proposed by Karen Simonyan and Andrew Zisserman from the University of Oxford [55]. VGG-16 consists of 16 layers with learnable weights, including 13 convolutional layers and 3 fully connected layers. The VGG-16 architecture employs small receptive fields (3 × 3 filters) with a stride of 1 and uses padding to maintain the image’s spatial resolution. Additionally, the VGG-16 deep network employs max-pooling layers with a 2 × 2 filter and a stride of 2 to reduce the spatial dimensions.

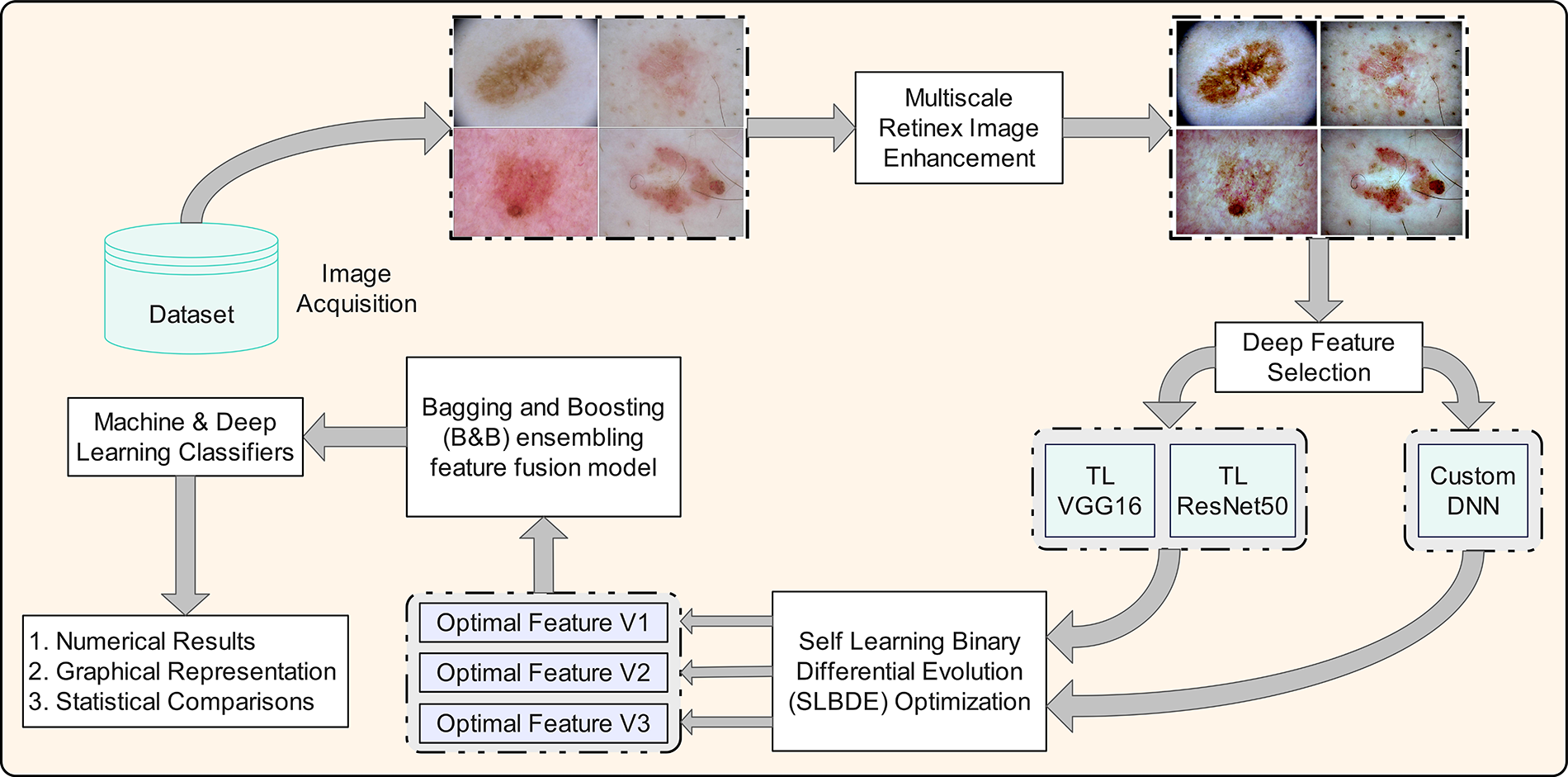

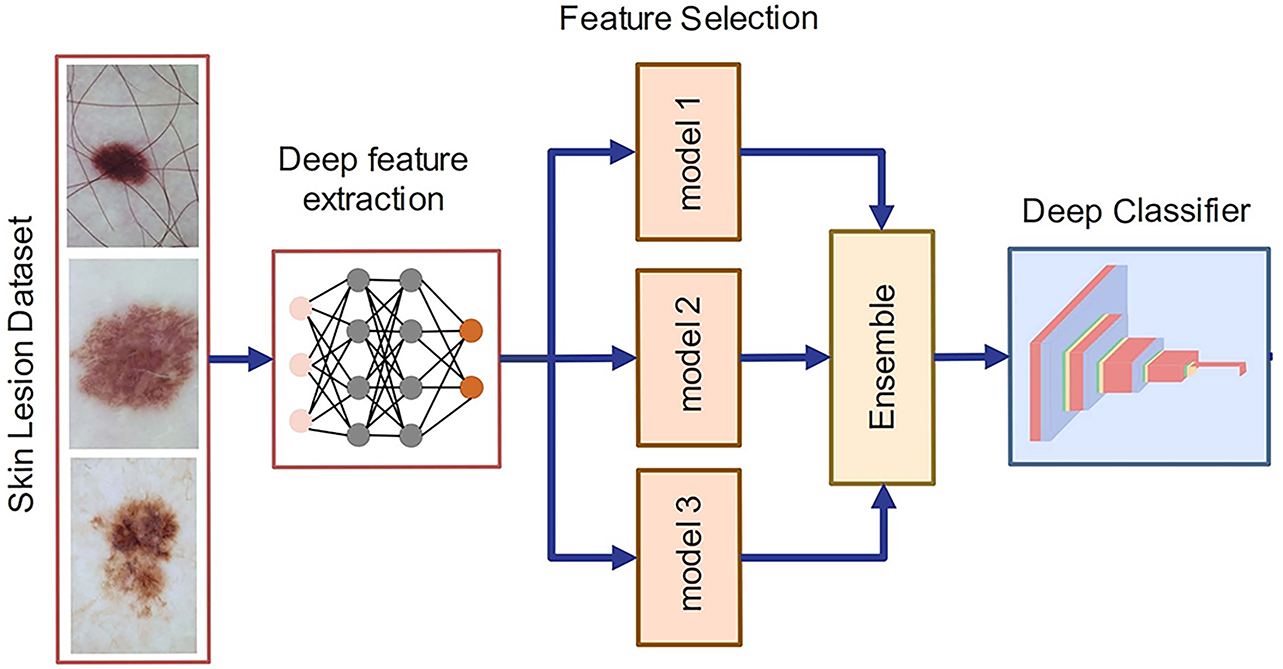

3.3 Proposed Feature Selection and Fusion Framework

This section presents a novel comprehensive ensemble learning technique combining pre-trained and customized DNN along with SLBDE, as well as a novel feature reduction algorithm, to reduce computational load and improve accuracy. The flowchart of the proposed methodology is shown in Fig. 3. The proposed model comprises several key stages, including image enhancement, feature extraction using transfer learning with ResNet-50 and VGG16, feature selection using the SLBDE algorithm, and ensemble learning via Baggigng and Bosting (B&B) to integrate selected features from both pre-trained and customized DNN. Ultimately, the refined features are used to classify skin lesions. The details of each step are presented in the following sections.

Figure 3: Proposed feature selection and fusion framework for skin lesion classification

The skin lesion datasets comprise dermoscopic images of skin lesions captured using various dermatoscopes and camera devices, each differing in sensor quality and resolution. Additionally, these images are acquired under diverse environmental conditions, all of which can impede the accurate identification and classification of skin lesions in automatic computational models. The presence of artifacts such as hair occlusions, low contrast, and the resemblance between healthy skin and affected areas further complicates the effectiveness of CAD algorithms. Therefore, preprocessing techniques, including color normalization and illumination correction, are crucial for improving the accuracy of automated classification models. Several algorithms have been proposed in the literature to address these challenges and improve skin lesion images [56].

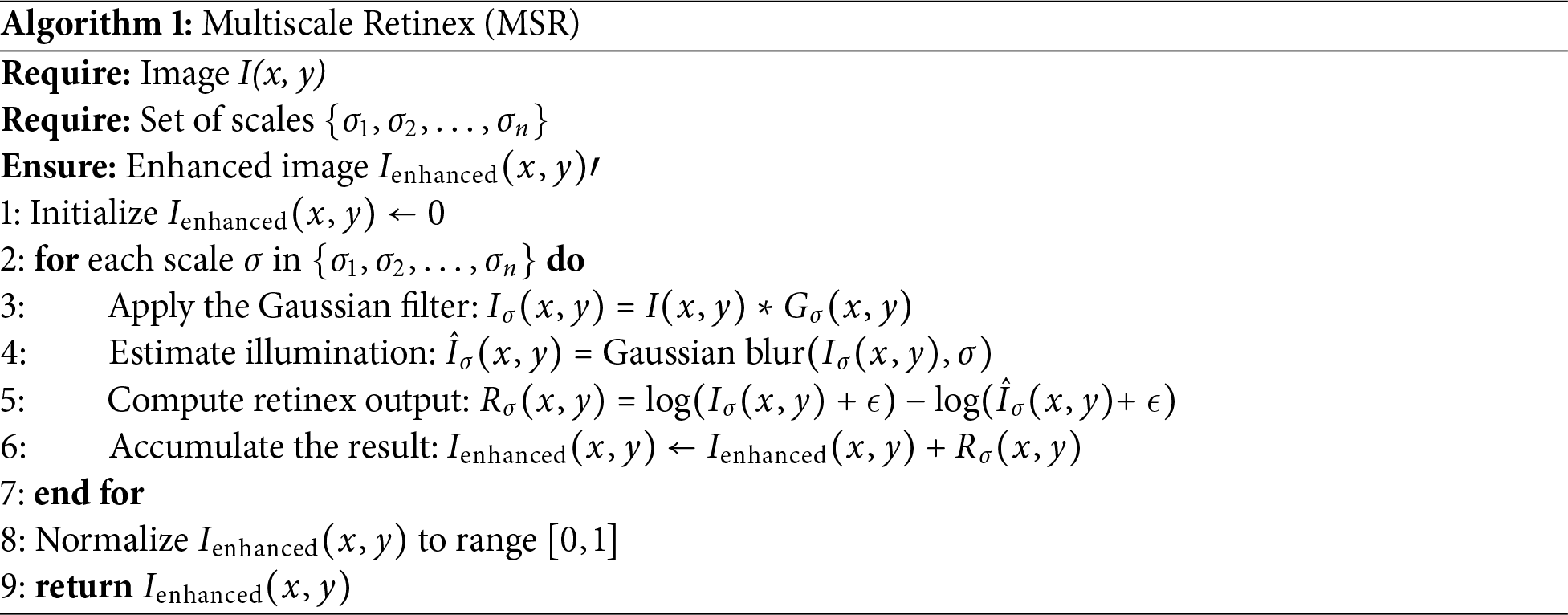

To improve the effectiveness of the proposed skin lesion classification method, this study employs an adaptive multiscale retinex model. The original multiscale retinex algorithm, introduced in [57], was proposed to minimize the disparity between color images and human perception by improving color accuracy and spatial contrast. This algorithm separates an image into multiple scales, allowing for independent processing of different frequency ranges to improve visual quality. Although this technique was initially developed to augment human visual perception and interpretation, it can also improve the quality of dermoscopic images for better performance in CAD systems by optimizing the overall illumination and local contrast, thereby improving classification performance.

Mathematically, the multiscale retinex algorithm can be expressed as:

• The process initiates with the multiscale decomposition, in which the input image

• To estimate the global illumination, enhance each scale

• Combine the enhanced scales to generate the final image:

Adjustments could be made to scale up the contributions at different levels based on their priority or perceptual relevance. The complete algorithmic pseudocode of MSR is provided in Algorithm 1.

Some improved skin lesion dermoscopic images are shown in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: “Random samples from the ISIC 2017 skin lesion dataset: (A) original dermoscopic images, (B) MSR-enhanced images”

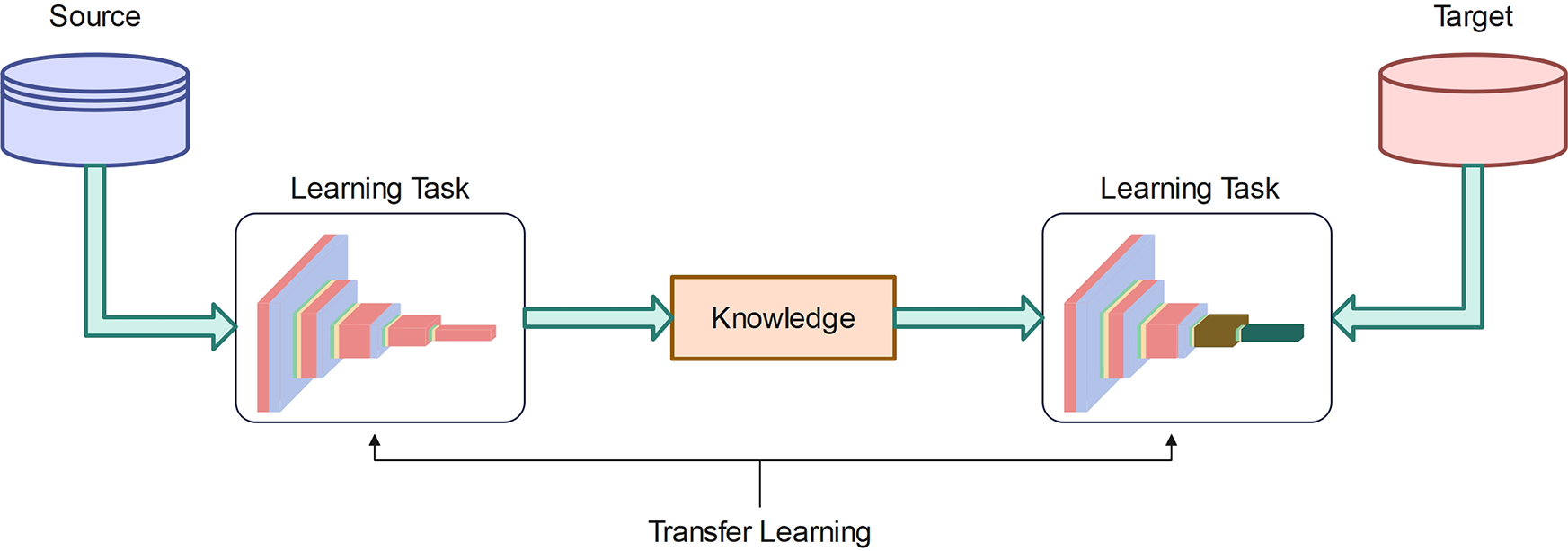

3.3.2 Deep Networks Transfer Learning

Transfer learning has emerged as a crucial technique in ML to address the fundamental challenge of limited training data. Its primary objective is to transfer knowledge from a source domain to a target domain, thereby relaxing the requirement that training and test data must be independent. This technique has significantly impacted various domains, particularly those constrained by the scarcity of labeled training data. In DL, an untrained model typically starts with randomly initialized weights for its nodes. During the computationally intensive training process, these weights are iteratively adjusted using an optimization algorithm tailored to the specific task or dataset. Research has shown that initializing weights with a pre-trained network, even when trained on a significantly different dataset, improves training performance compared to random initialization [58]. Deep transfer learning (DTL) differs from semi-supervised learning in that the source and target datasets in DTL may have different distributions but remain related. In contrast, semi-supervised learning assumes that both labeled and unlabeled originate from the same dataset, with the key distinction being that the target dataset lacks labels.

Definition 1: Let

Definition 2: Consider a transfer learning function defined by

Figure 5: Deep network transfer learning

DTL is categorized into instance-based deep transfer learning and mapping-based deep transfer learning. DTL takes the knowledge gained from one task and a dataset, even if they are not closely related, to improve learning efficiency for a new task. In many ML applications, gathering a large amount of labeled data is not feasible, which is essential for most DL models. An untrained DL model that starts from scratch assigns weights randomly to its nodes. Throughout the extensive training process, these weights are gradually adjusted to optimal values using an optimization algorithm tailored to a specific task or dataset. Studies have shown that initializing these weights using a pre-trained network, even when the pre-training dataset is only loosely related to target domain, significantly improves training performance compared to random initialization [58].

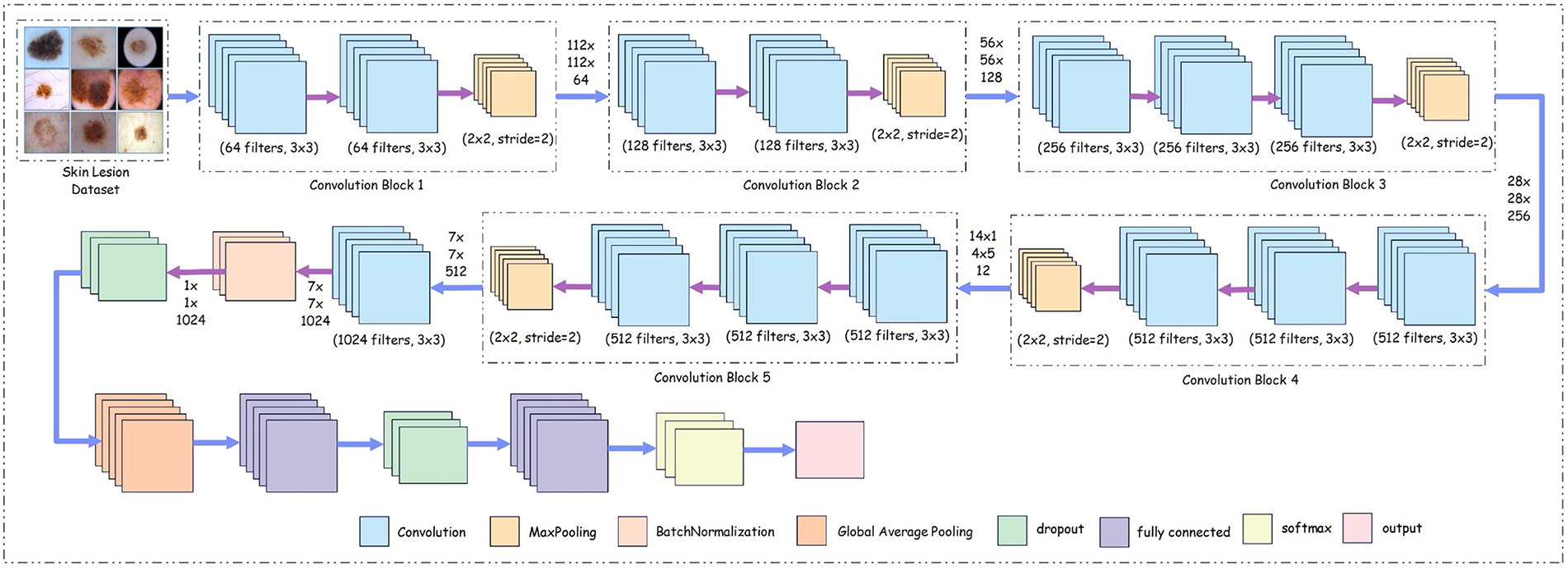

The customized CNN, shown in Fig. 6, is specifically designed for skin lesion classification. The deep architecture is divided into multiple stages, each contributing to the gradual extraction and refinement of the features for classification.

Figure 6: Proposed customized deep neural network architecture

The core architecture of the network comprises five convolutional network blocks. Each block contains convolutional layers with progressively increasing filter counts, allowing the network to learn both low-level and high-level features. In the initial block, 64 filters with a kernel size of 3

To improve the stability of the network and speed up the training process, batch normalization layers are employed after the convolutional operations. These layers normalize the output activations, ensuring that the input to subsequent layers has a consistent scale, thereby mitigating the internal covariate shift during training. This normalization also acts as a form of regularization, reducing overfitting and improving the generalizability of the network. Mathematically, the model is described layer-by-layer—starting from the image acquisition step with the input image defined as

where

3.3.4 Feature Fusion and Selection

Fig. 7 presents an overview of the simultaneous feature fusion and selection process using the SLBDE algorithm. Simultaneous feature fusion and selection, when applied to extracted features from multiple pre-trained deep networks, offers several key advantages that improve both the productivity and performance of ML models. By fusing features from multiple pre-trained models, the combined features capture diverse and complementary aspects of the data. Applying feature selection alongside fusion ensures that only the most relevant and informative features are retained, removing redundant or noisy information. This selective technique results in more compact yet richer information, improving the model’s ability to generalize across different tasks. Feature fusion combined with selection filters out irrelevant or low-importance features, reducing data dimensionality and minimizing the risk of overfitting. By focusing on the most impactful features, the model can achieve higher accuracy with less computational overhead, improving both speed and performance on downstream tasks.

Figure 7: Ensemble learning for skin lesion classification

Simultaneous feature fusion and selection, applied to extracted features from ResNet-50 and VGG-16 models retrained on skin lesion datasets like ISIC2017 and ISIC2018, provides significant advantages in medical image analysis. By fusing the features from these two pre-trained deep networks, the model benefits from the complementary strengths of both architectures. ResNet-50, known for its deep residual connections, captures high-level features with a strong focus on deep, hierarchical representations, while VGG-16, with its simpler, sequential layers, excels at capturing fine-grained textures and patterns. Fusing features from these two networks allows the model to generate a comprehensive representation of skin lesions, capturing both high-level and fine-grained details, crucial for accurate lesion classification and diagnosis. In parallel, feature selection plays a crucial role by filtering out irrelevant or redundant features from the combined set. While ResNet-50 and VGG-16 extract a large number of features, not all are equally relevant to the task of skin lesion classification. ResNet-50’s deep layers provide robust high-level representations of lesion structures, which are often crucial for identifying malignant patterns, while VGG-16 captures finer texture and color variations, helping with the detection of subtle differences between benign and malignant lesions. By applying feature selection during the fusion process, the model can retain only the most informative features from each network, improving both accuracy and computational efficiency. This ensures that the fused model can effectively focus on the critical aspects of the lesion, such as color, texture, and edge patterns, while discarding noise or uninformative data that might otherwise hinder performance.

In this article, we adopt the SLBDE algorithm for simultaneous feature fusion and selection. The integration of SLBDE for simultaneous feature fusion and selection, using features extracted from ResNet-50 and VGG-16 models, provides a sophisticated optimization framework for improving skin lesion classification tasks on datasets such as ISIC2017 and ISIC2018. SLBDE is an advanced evolutionary algorithm that optimizes both feature fusion and selection processes, making it ideal for combining features from ResNet-50 and VGG-16, two pre-trained networks with different strengths in feature extraction.

The SLBDE algorithm simultaneously performs both feature fusion and selection by optimizing which features from ResNet-50 and VGG-16 should be retained. Using evolutionary strategies, SLBDE evaluates different combinations of features, progressively refining its selection to keep only those that contribute most to classification accuracy. This helps to eliminate noisy, irrelevant, or redundant features, resulting in a more compact and discriminative feature set. By focusing on the most informative features from both networks, SLBDE significantly improves the model’s ability to differentiate between benign and malignant lesions. SLBDE intelligently selects the optimal subset of these features, ensuring that the model benefits from both the depth of ResNet-50 and the granularity of VGG-16 without suffering from the curse of dimensionality. This results in a more accurate classification model, particularly in complex tasks like differentiating subtle patterns in skin lesions. A detailed discussion of SLBDE is provided in Section 4.

3.3.5 Skin Lesion Classification

The final step of the proposed methodology involves the classification of skin lesion images by first training the system using a selected feature set. By fusing features from both ResNet-50 and VGG-16, the model employs the complementary strengths of these architectures. To improve classification accuracy, an ensemble-based classification technique is employed to improve classification accuracy by combining the strengths of multiple classifiers. To address the challenge of an imbalanced dataset problem, where certain classes significantly outnumber others, the choice of ensemble technique can significantly play a crucial role in improving classification accuracy, especially for the minority class. Therefore, the Bagging & Boosting ensemble technique is adopted. The rationale for integrating both bagging and boosting lies in their complementary strengths. Bagging reduces variance by training multiple weak learners on bootstrapped subsets, thereby stabilizing predictions. However, bagging alone may underperform in highly imbalanced datasets such as ISIC, where malignant cases are underrepresented. Boosting, on the other hand, sequentially emphasizes hard-to-classify samples, improving sensitivity to minority classes. By combining both mechanisms within our ensemble pipeline, we ensure balanced performance: bagging provides robustness and stability, while boosting enhances discrimination of challenging lesion categories. This hybrid strategy, to the best of our knowledge, has not been previously integrated with SLBDE-driven feature fusion for skin lesion classification.

To benchmark the effectiveness of the proposed SLBDE-based feature optimization, we evaluated a set of widely used classifiers, including Support Vector Machine (SVM), Random Forest (RF), k-Nearest Neighbors (kNN), Gradient Boosting (GB), and Logistic Regression (LR). These classifiers were selected due to their established role in medical image classification and their frequent use in dermatological studies for baseline evaluation [59–61]. Prior research has shown that SVM and RF are effective for handling high-dimensional features extracted from skin lesion images, while boosting methods such as GB are particularly useful in capturing complex nonlinear patterns. By including these classifiers, we ensure that the comparison with and without feature optimization is grounded in well-validated baselines from the literature.

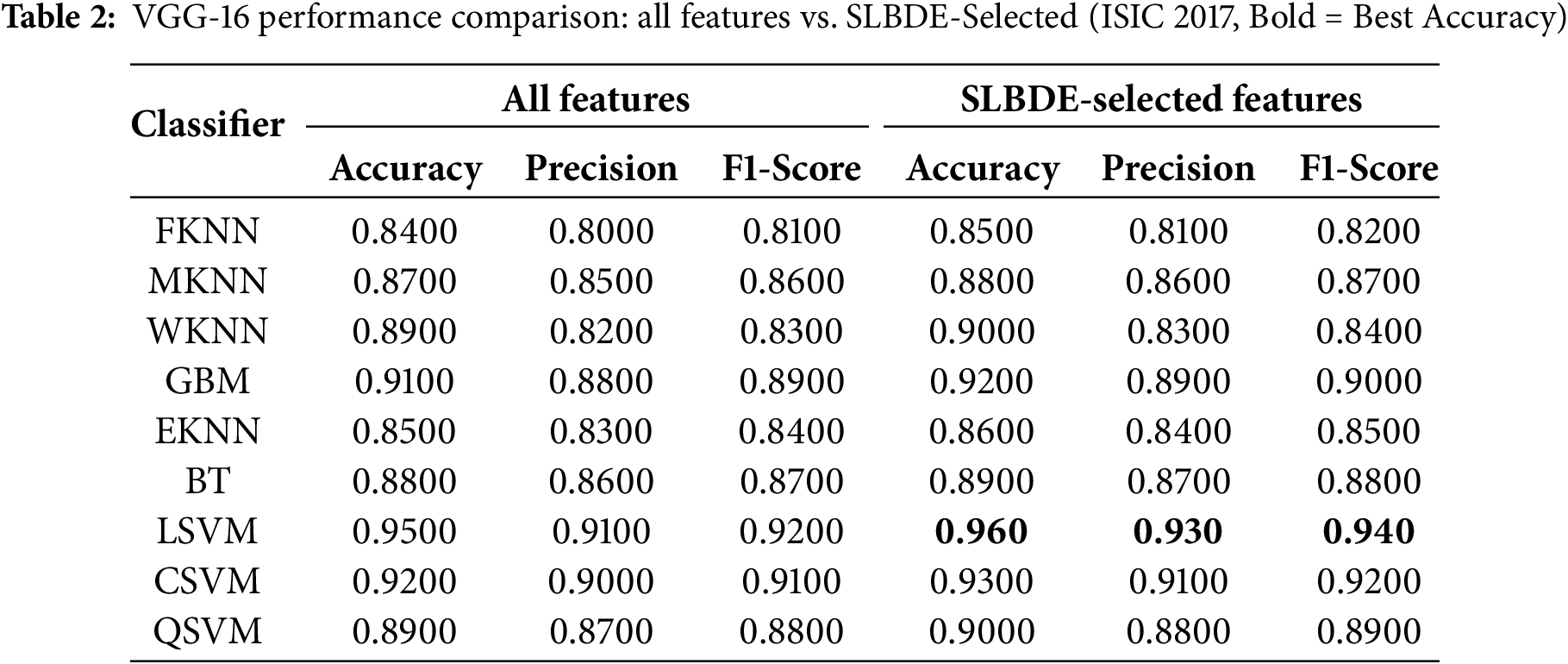

4 Self-Learning Binary Differential Evolution (SLBDE)

In the standard DE algorithm, each member represents a potential solution to the optimization challenge. For a population of N individuals, the DE method begins by generating N random target vectors. Each target vector undergoes mutation and crossover operations to produce a corresponding trial vector. The DE algorithm processes each individual through these operations, generating trial vectors from the original target vectors. A new parent generation is then formed through the selection operator, which evaluates both target and trial vectors.

In this section, we describe our binary differential evolution algorithm that employs a self-learning strategy to improve SLBDE performance. This work introduces self-learning search as a key strategy to improve SLBDE efficiency. The proposed technique features an optimized selection method that combines non-dominated sorting together with a crowding strategy. The latest binary mutation method is based on high probability changes, helping the algorithm achieve better convergence while maintaining strong global search abilities. The new mutation operator selects the strongest among three random vectors as a base molecule, applying vector differences between the remaining two as mutation chances on this base vector to generate a mutation vector for subsequent crossover procedures.

Consider that the population in the algorithm is represented by

1. Initialization:

The population

where

2. Mutation:

Mutation generates a new mutant vector

where

3. Crossover:

A crossover operation generates the trial vector

where

4. Selection:

The trial vector

where

5. Self-Learning Mechanism (Adaptive F and CR):

The self-learning mechanism dynamically adjusts the parameters F and CR based on the success of mutations and crossovers in previous generations. Let

where

where

To analyze the performance of the proposed system model, multiple performance metrics are evaluated using several classifiers, including SVM, BT, GDM, and KNN, for both the complete feature set and the selected feature set. First, the performance metrics are explained, followed by the presentation of the results. All experiments were implemented in Python using TensorFlow and PyTorch frameworks. Standard scientific computing libraries such as NumPy, OpenCV, and scikit-learn were utilized for preprocessing and evaluation. Training and testing were conducted on a workstation equipped with a CPU and 32 GB RAM.

Accuracy, Precision, and F1-score are used to evaluate the performance of the proposed framework.

1. Accuracy: Accuracy is a widely used metric in DL. It represents the proportion of correct predictions out of the total predictions made by a classifier. Accuracy is a crucial metric in applications where errors are critical or costly, such as medical diagnostics or fraud detection. In these cases, achieving high accuracy ensures trust and reliability in the model’s predictions. Mathematically,

2. Precision: Precision is a key performance metric used to assess the accuracy of a model’s positive predictions in DL applications. It is the proportion of accurate positive predictions relative to the number of positive predictions made by the DNN model. Precision is critical in applications such as medical diagnostics, where minimizing false positives is vital. Mathematically,

where TP represents the true positive and FP represents the false positive.

3. F1-Score: The F1-score is a performance metric that represents the harmonic mean of precision and recall. It is calculated as follows:

The F1-score ranges from 0 to 1, with values closer to 1 indicating a more optimal balance between precision (the accuracy of positive predictions) and recall (the ability to identify all positive samples). Unlike standard accuracy, the F1-score provides a comprehensive metric that simultaneously accounts for precision and recall, making it particularly valuable in scenarios where relying on either metric alone would be insufficient.

5.2 ISIC2017 Skin Lesion Dataset

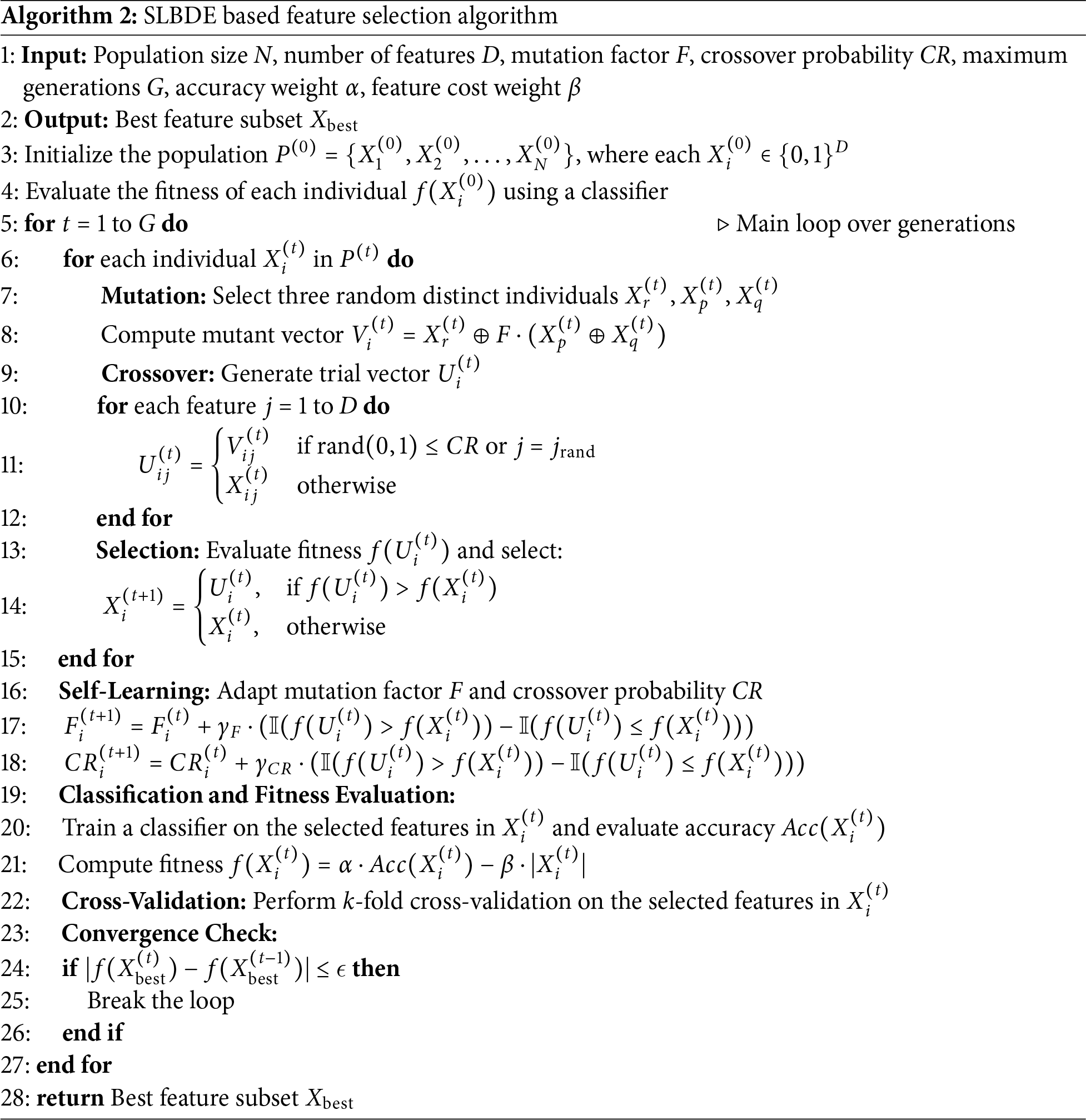

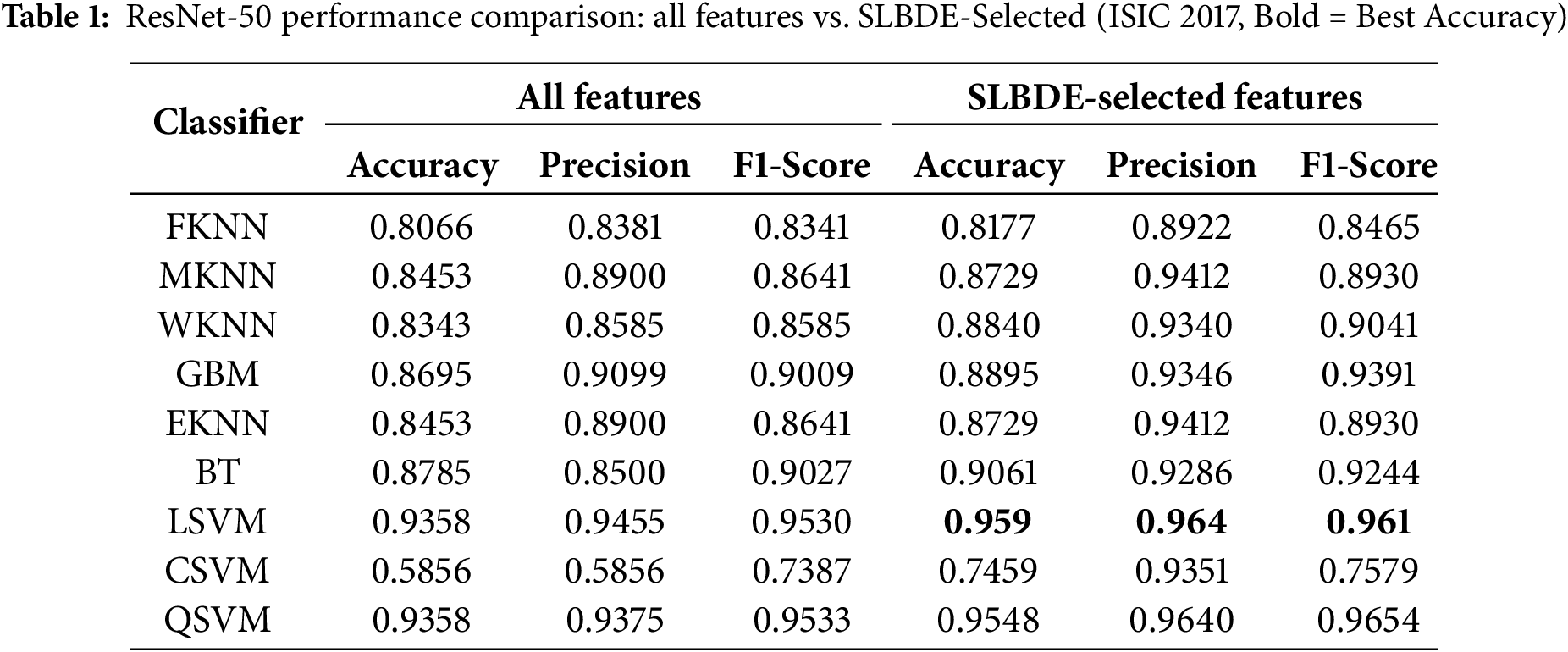

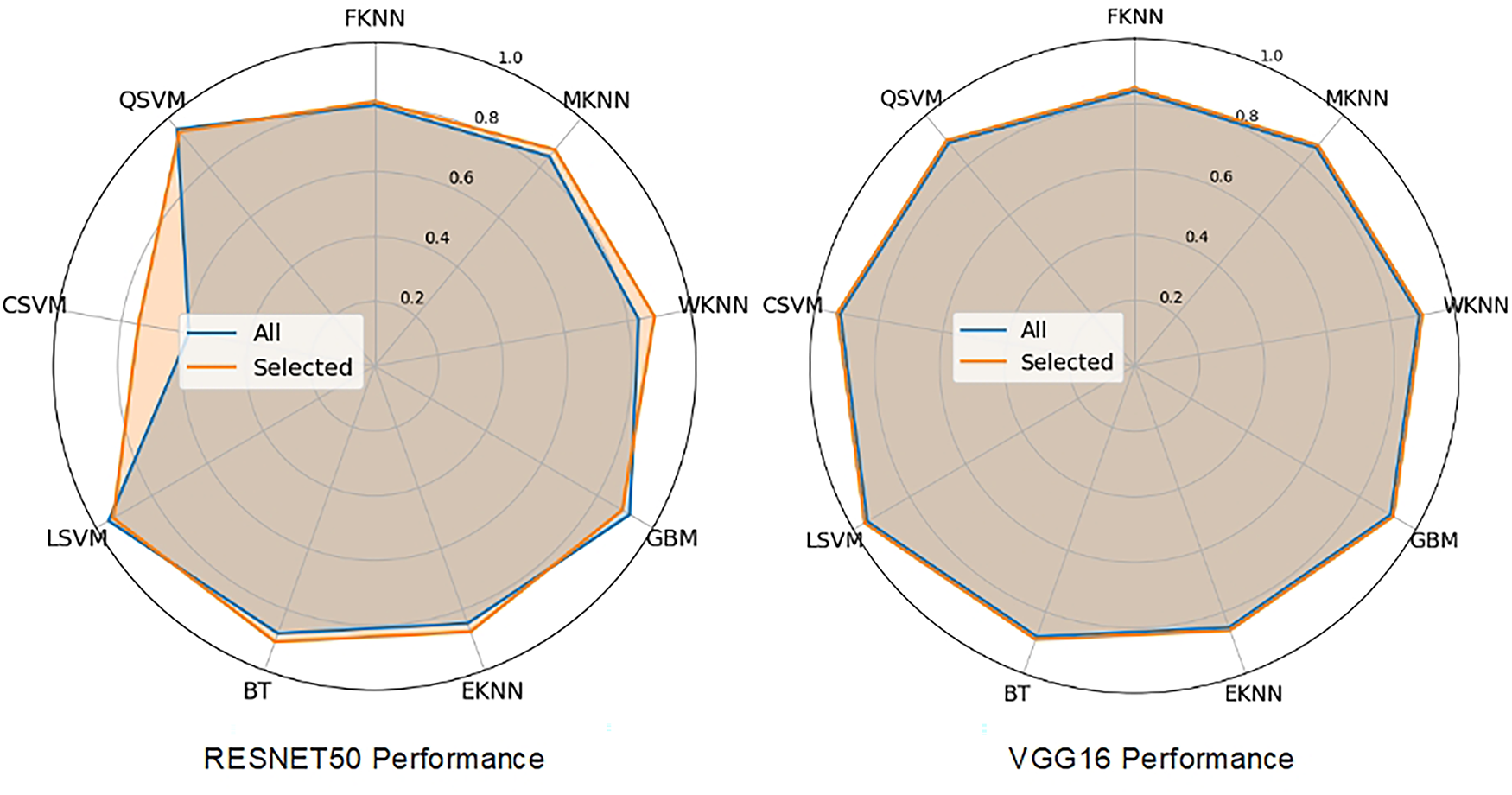

Table 1 presents a comparative performance of various classifiers applied to skin lesion features extracted from the pre-trained ResNet-50 model. These classifiers are evaluated for the classification of skin lesions when trained using the complete feature set and the selected feature set. The results are evaluated using three key metrics: accuracy, precision, and F1-score, which are essential for evaluating the effectiveness of medical image analysis. Multiple classifiers, including FKNN (Fuzzy k-Nearest Neighbor), MKNN (Modified k-Nearest Neighbor), WKNN (Weighted k-Nearest Neighbor), GBM, EKNN (Enhanced k-Nearest Neighbor), BT, LSVM (Linear Support Vector Machine), CSVM (Cubic Support Vector Machine), and QSVM (Quadratic Support Vector Machine), are evaluated. These classifiers differ in their ability to model complex feature relationships for skin lesion classification. The results show that SLBDE feature selection improves the performance of most classifiers. Fig. 8 highlights the importance of selecting the most relevant features, as it improves the performance of weaker classifiers and strengthens the robustness of top-performing classifiers. Moreover, to ensure the robustness and generalizability of the proposed model, a k-fold cross-validation was conducted on the LSVM classifier, yielding a mean accuracy of 96.4% with a 95% confidence interval ranging from 0.95 to 0.98.

Figure 8: ResNet-50 metrics comparison for all and selected features

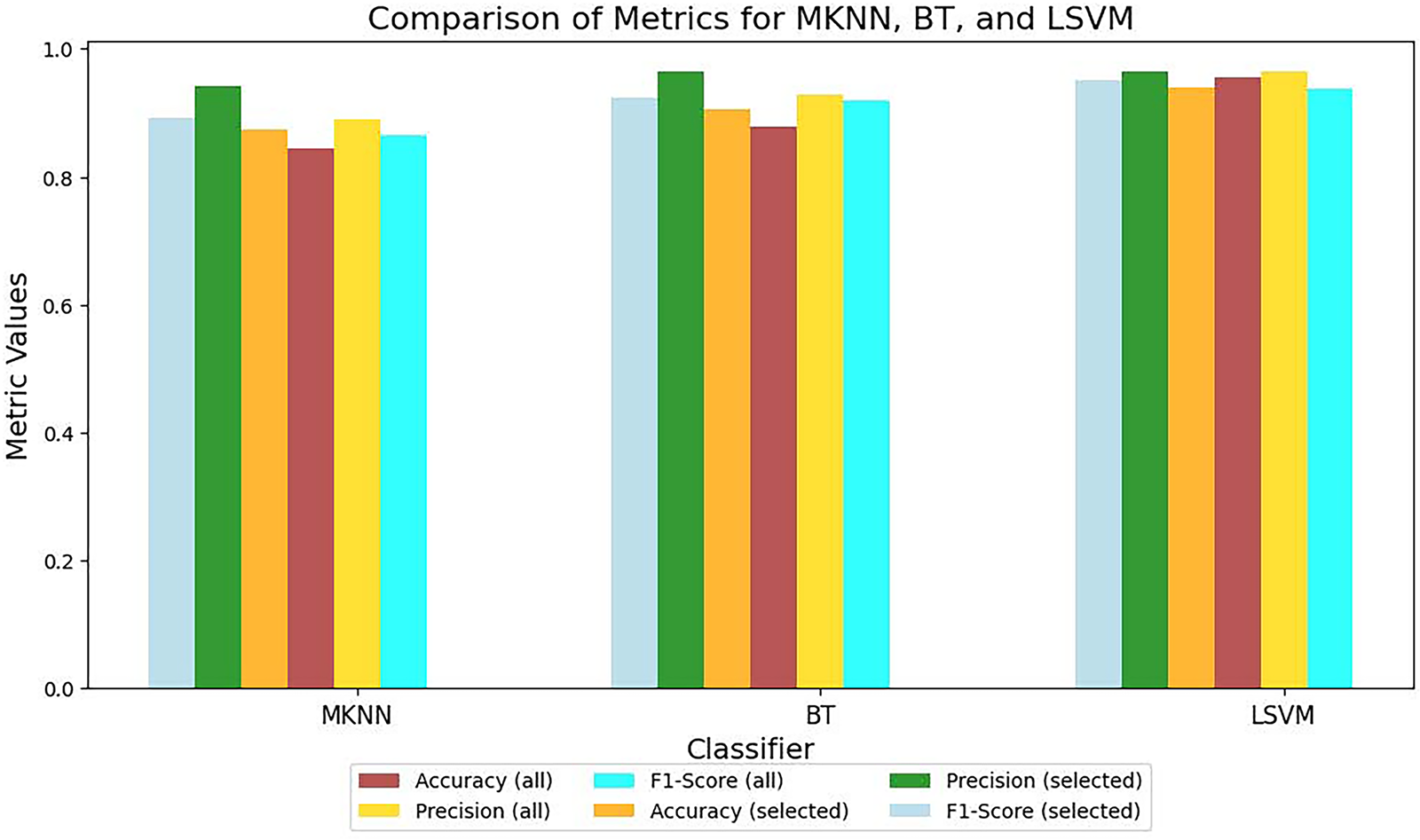

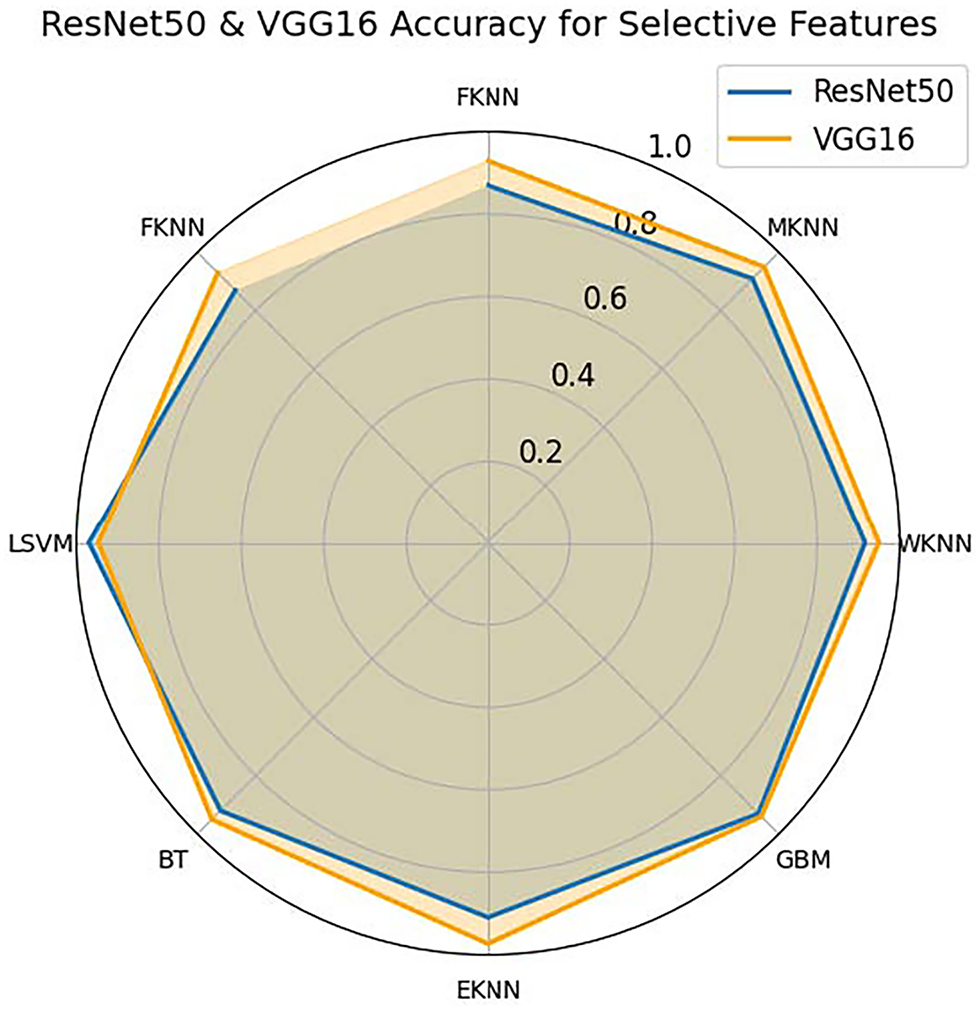

Table 2 evaluates the results for ISIC2017 skin lesion extracted features from a pre-trained VGG-16 model for different classifiers. The results clearly demonstrate that selecting a subset of relevant features improves the performance of almost all classifiers. In order to attain the generalization, k-fold cross-validation was performed for LSVM over VGG-16 extracted features using the ISIC2017 dataset, yielding a 95% confidence interval from 0.947 to 0.987. However, comparison of results from ResNet-50 and VGG-16 for skin lesion classification highlights the differences in feature extraction capabilities and performance across various classifiers as depicted in Fig. 9. ResNet-50 demonstrates better generalization and classification performance, particularly in terms of F1-score, which is critical for medical applications.

Figure 9: Classifier performance on all and selected features

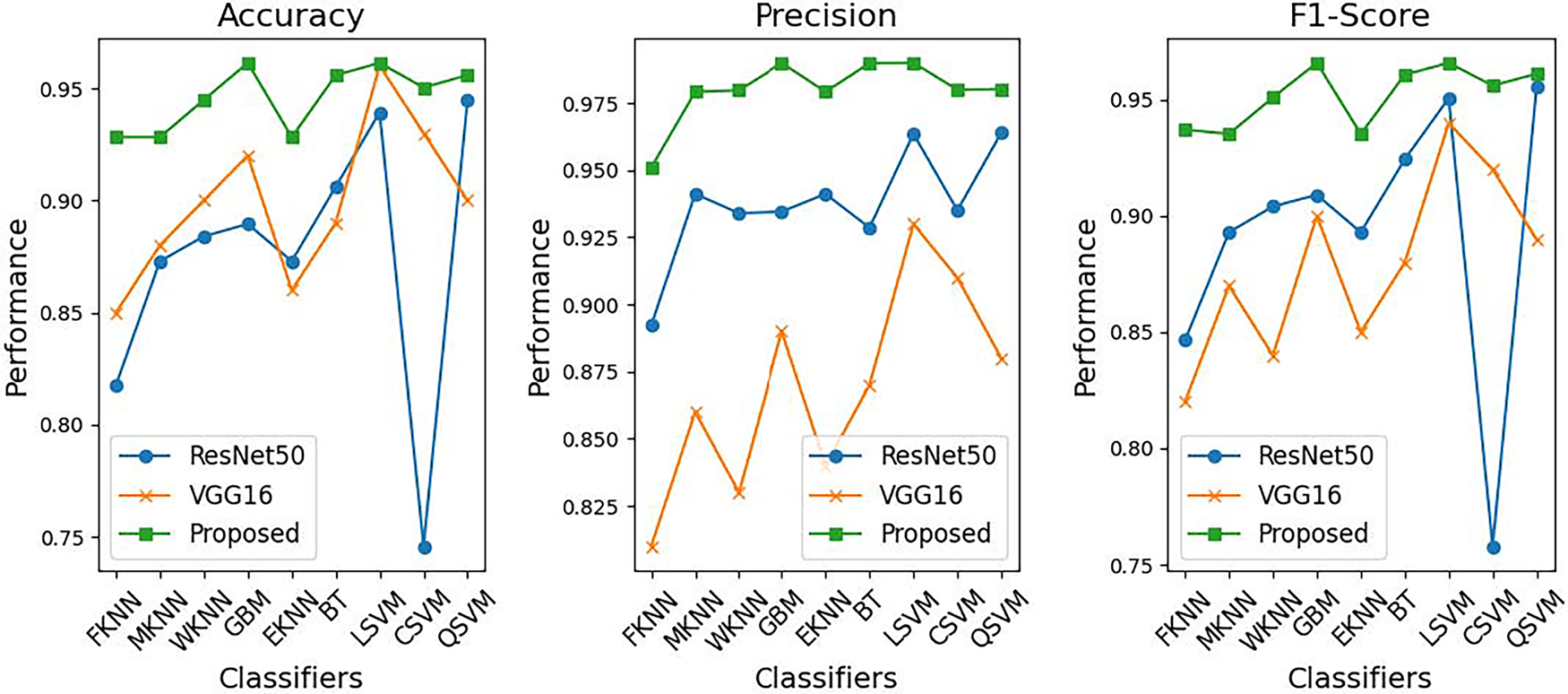

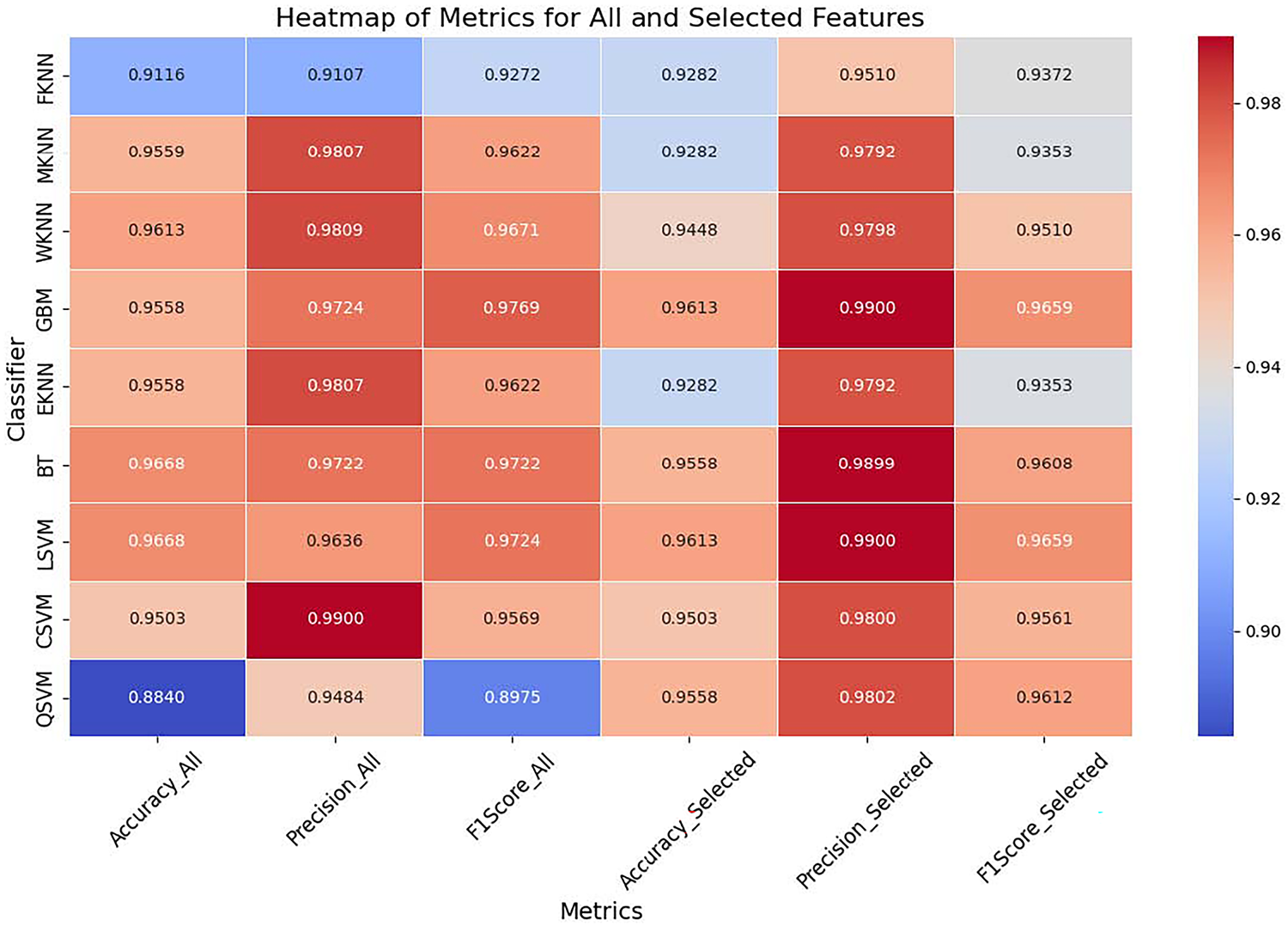

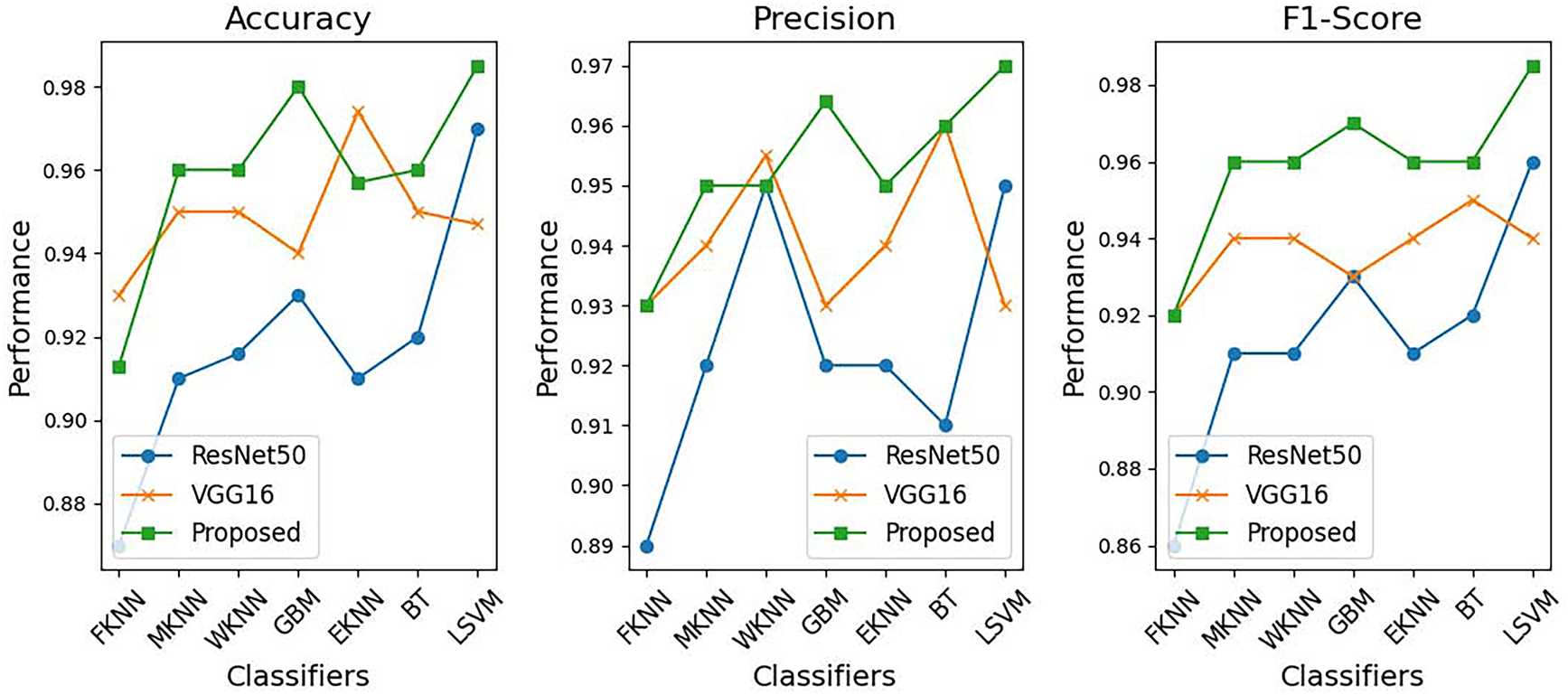

Fig. 9 illustrates the classifier performance on ResNet-50 extracted features. Fig. 10 provides a comparative analysis between the proposed method, ResNet-50, and VGG-16 across various classifiers, and Fig. 11 presents the heatmap showcasing the comparison between the complete and selected set of features.

Figure 10: Proposed Method vs. ResNet-50 and VGG-16: performance comparison across classifiers

Figure 11: Heatmap of complete vs. selected set of features

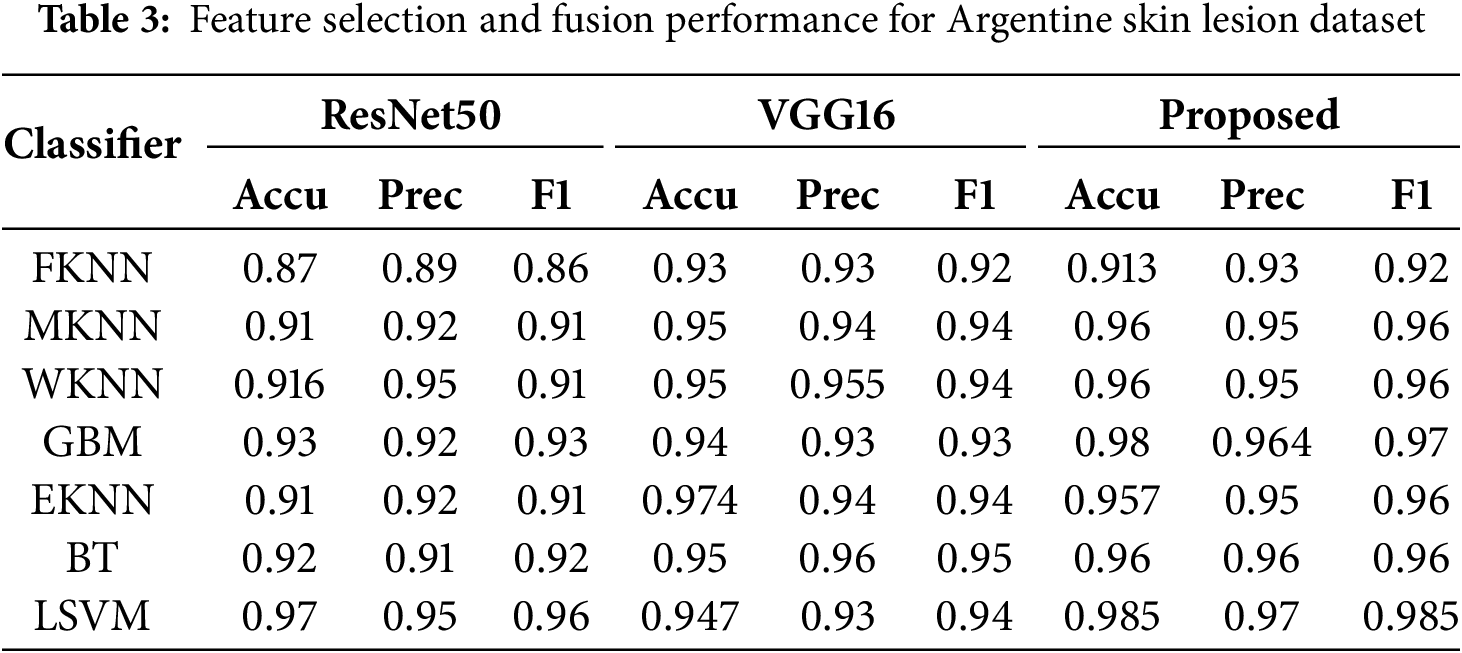

5.3 Argentina Skin Lesion Dataset

Table 3 presents a comparative analysis of classifier performance in the Argentina Skin Lesion dataset using three feature extraction methods: ResNet-50, VGG-16, and the proposed method. The evaluated classifiers include FKNN, MKNN, WKNN, GBM, EKNN, BT, and LSVM. The proposed method improves MKNN and WKNN, which leads to outstanding performance, although FKNN remains at moderate results among classifiers. GBM and EKNN exhibit strong performance across all methods, with significant gains in the proposed approach. The classifiers BT and LSVM reached the top ranks, while LSVM achieved the highest performance, attaining an accuracy of 0.985 along with precision and F1-score improvements. Through its ensemble technique, the proposed method successfully increases classification performance by combining features from multiple DL models and implementing optimized feature selection. These findings demonstrate how the proposed model’s robustness benefits both LSVM and BT models, resulting in substantial classification performance improvements across numerous evaluation criteria.

Fig. 12 shows a comparison of the accuracy across various classifiers—FHKN, MKNN, WKNN, GBM, EKNN, BT, and LSVM—using feature sets selected by SLDBE from the ResNet-50 and VGG-16 models. The visualization shows the classifier results for ResNet-50 in blue and VGG-16 in orange. VGG-16 demonstrates better classification performance across all tested classifiers compared to ResNet-50 when features are chosen by SLBDE-based selection, although the advantage remains relatively small. Among the evaluated classifiers, both WKNN and BT delivered high results, while LSVM achieved exceptional performance across all the methods tested. In contrast, FKNN shows lower accuracy scores than all other classifiers investigated. The analysis highlights stable performance metrics for both techniques while demonstrating the slight advantage of VGG-16 over ResNet-50 in improving classification accuracy with selected SLBDE features.

Figure 12: Accuracy comparison of SLBDE-Based feature selection on Argentina Skin Lesion Dataset using VGG-16 and ResNet-50

Fig. 13 provides a comparative analysis of the performance of different classifiers: FKNN, MKNN, WKNN, GBM, EKNN, BT, and LSVM-based on precision, recall, and F1 score, using three feature extraction techniques: ResNet-50, VGG-16, and the proposed method. Through self-learning binary differential evolution-based feature selection, the proposed method consistently outperforms ResNet-50 and VGG-16 across all three performance metrics. The proposed method demonstrates the best accuracy across different classifiers, particularly with LSVM and BT achieving remarkable performance scores. In addition, it delivers superior precision by effectively minimizing false positives across all classifiers. The proposed method also excels in F1-score evaluations, as it optimally balances precision and recall to produce superior classification results. When evaluating the performance of the model across different datasets, the proposed method consistently surpasses both VGG-16 and ResNet-50. The study results presented in Fig. 13 demonstrate that the proposed technique provides effective and robust improvements in the classification performance metrics for multiple classifiers.

Figure 13: Feature selection performance for Argentine skin lesion dataset

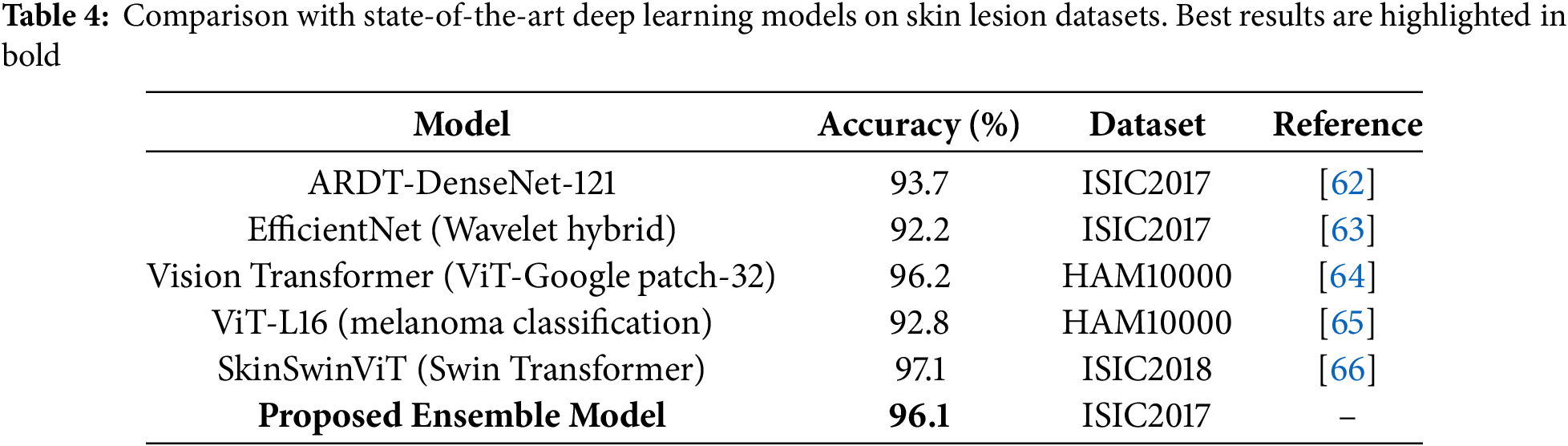

Compared to recently reported state-of-the-art methods such as EfficientNet, DenseNet, and Vision Transformers, our proposed ensemble approach demonstrates competitive or superior results (Table 4). While ViT-based architectures achieve high accuracy, they typically require large-scale datasets and extensive computational resources. In contrast, the proposed model achieves statistically significant improvements while maintaining computational efficiency, making it more suitable for practical deployment in clinical decision-support systems.

The proposed ensemble-based classification framework outperforms integrating SLBDE for feature selection from ResNet-50, VGG-16, and a customized DL architecture. The proposed model demonstrates improved classification metrics by combining different architectural strengths to surpass traditional standalone feature extraction methods across several classifiers. This model combines the feature hierarchy capabilities of ResNet-50 with the detailed texture examination of VGG-16 for skin classification using their ensemble technique that achieves robust lesion representation.

The tests show that the proposed model exceeds the existing performance benchmarks across the ISIC2017 and the Argentina Skin Lesion dataset. LSVM achieved a success rate of 98.5% on the Argentina dataset, outperforming both ResNet-50 and VGG-16, while BT also exhibited strong evaluation metrics. The SLBDE algorithm proves to be essential for selecting the most relevant features by eliminating duplication and improving classification performance.

The study demonstrated that ensemble-based classification systems are particularly effective in handling imbalanced data challenges. In medical imaging, misclassification of the minority class is a critical concern, especially when diagnosing malignant skin lesions. By integrating bagging & boosting algorithms, the proposed technique mitigates this issue, ensuring accurate detection of malignant cases while maintaining high precision through improved recall performance. The reported experimental results directly support our claims of robustness and improved performance. Specifically, the integration of SLBDE-driven feature fusion with bagging and boosting consistently yielded higher accuracy, sensitivity, and F1-scores compared to baseline ensembles. These improvements validate the effectiveness of our hybrid approach in addressing variance reduction and minority class detection challenges, thereby confirming the proposed contributions.

Previous studies displayed performance limitations when applied to diverse datasets or when maintaining generalization across multiple lesion types. The study’s simultaneous feature fusion and selection technique effectively addresses these challenges by retaining only the most discriminative features, thereby improving both model scalability and robustness.

The research findings highlight how integrating ensemble learning with sophisticated feature selection techniques opens new possibilities for developing CAD systems that specifically detect skin lesions. Melanoma detection through the proposed model demonstrates a reliable but efficient technique that delivers essential early detection to improve patient treatment outcomes. Future work will focus on further validation using larger and more diverse datasets, as well as real-world clinical applications, to refine the model and improve its practical applicability.

Recent developments in QDL—including hybrid quantum-classical networks in cancer diagnostics [33], quantum dual-branch architectures for skin lesion analysis [34], and broader evaluations of QML methods for medical imaging [35], highlight exciting future directions. However, these models are limited by reliance on specialized quantum hardware, simulation environments, and reproducibility issues under noisy conditions. By contrast, our ensemble deep learning framework offers strong classification performance, statistical robustness, and full compatibility with existing clinical pipelines. We suggest that hybrid quantum-classical approaches may become viable in the future as quantum hardware matures, but currently, ensemble DL remains the most practical high-performance approach for clinical CAD systems.

Although our evaluation relies on the ISIC2017 and Argentina datasets, which are standard benchmarks in dermatological image analysis, these datasets remain essential for ensuring comparability with state-of-the-art models. Standardized datasets enable consistent and fair benchmarking across studies, thereby allowing researchers to validate methodological improvements under identical conditions. We acknowledge that exclusive reliance on benchmark datasets may limit generalizability to broader populations and clinical settings. Future work will extend validation to diverse, multi-ethnic datasets and real-world clinical images, which will further establish the practical applicability of the proposed system.

Despite the strong performance demonstrated, several limitations of this study must be acknowledged. Pre-trained models may introduce biases from their original training data, which can affect the generalization of this technique. Although the ISIC2017 and Argentina datasets provide valuable benchmarks, they still suffer from class imbalance, with malignant cases underrepresented compared to benign lesions. While our ensemble framework with boosting mitigates this issue to some extent, future work should explore advanced imbalance handling techniques such as focal loss, class-balanced reweighting, or synthetic data generation (e.g., GAN-based augmentation). External clinical validation remains an important next step. The current evaluation relied on publicly available datasets, and prospective testing in real-world dermatology workflows is essential to confirm robustness, interpretability, and physician acceptance. Future research should also focus on developing lightweight optimization techniques that employ domain knowledge, enabling improved performance while reducing computational demands.

In this work, we proposed an ensemble DL model supported by Self-Learning SLBDE to improve the accuracy of skin lesion classification. The proposed approach integrates feature representations extracted from ResNet-50 and VGG-16, along with a customized CNN, employing an optimized feature fusion and selection strategy. The incorporation of SLBDE enables simultaneous feature refinement, ensuring that only the most relevant information is used for classification, thereby minimizing redundancy and improving computational efficiency. Comprehensive experiments carried out on benchmark datasets, including ISIC2017 and the Argentina Skin Lesion dataset, demonstrate the superior performance of the model compared to conventional DL architectures. The ensemble-based classification framework, which incorporates ML classifiers such as SVM and BT, achieved state-of-the-art results in terms of accuracy, precision, and F1-score, where the LSVM classifier attained an impressive classification accuracy of 98.5% on the Argentina dataset, underscoring the robustness of the proposed methodology. These results highlight the effectiveness of integrating multiple feature extraction techniques with an optimized evolutionary search algorithm. In general, this technique strengthens CAD systems by providing a reliable and efficient framework for the early detection of malignant skin lesions. By facilitating early-stage melanoma diagnosis, this study holds significant promise for improving clinical outcomes and patient survival rates. Future work may involve validating the model on larger and more diverse datasets as well as integrating real-time deployment strategies to improve its applicability in practical medical settings. Future research will focus on addressing dataset imbalance through advanced sampling strategies, validating the model across a more diverse range of skin types, and exploring lightweight optimization for deployment in real-time clinical settings. Moreover, prospective studies in collaboration with dermatologists will be critical to ensure clinical translation of the proposed framework.

Acknowledgement: We would like to thank Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R748), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, for funding this research. The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Research and Graduate Studies at King Khalid University for funding this work through the Large Research Project under grant number RGP2/283/46.

Funding Statement: The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Research and Graduate Studies at King Khalid University for funding this work through the Large Research Project under grant number RGP2/283/46. This research was funded by Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R748), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Adeel Akram, and Tallha Akram; methodology, Adeel Akram, Ghada Atteia, and Faisal Mohammad Alotaibi; software, Tallha Akram, and Adeel Akram; validation, Ayman Qahmash, Sultan Alanazi, and Faisal Mohammad Alotaibi; formal analysis, Tallha Akram, and Ghada Atteia; investigation, Adeel Akram, and Ayman Qahmash; resources, Adeel Akram, Tallha Akram, and Ghada Atteia; data curation, Adeel Akram, and Tallha Akram; writing—original draft preparation, Adeel Akram, and Tallha Akram; writing—review and editing, Tallha Akram, Ayman Qahmash, Sultan Alanazi, and Faisal Mohammad Alotaibi; visualization, Tallha Akram; supervision, Ghada Atteia; funding acquisition, Ghada Atteia, and Ayman Qahmash. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets used in this study are publicly available. The ISIC2017 Skin Lesion Dataset can be accessed at ISIC2017. The Argentina Skin Lesion Dataset can be accessed at Argentina Skin Lesion Dataset. Both datasets are available for public use under the respective terms and conditions of the ISIC Archive.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Strzelecki MH, Stra̧kowska M, Kozłowski M, Urbańczyk T, Wielowieyska-Szybińska D, Kociołek M. Skin lesion detection algorithms in whole body images. Sensors. 2021;21(19):6639. doi:10.3390/s21196639. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Dong Y, Wang L, Cheng S, Li Y. Fac-net: feedback attention network based on context encoder network for skin lesion segmentation. Sensors. 2021;21(15):5172. doi:10.3390/s21155172. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Benyahia S, Meftah B, Lézoray O. Multi-features extraction based on deep learning for skin lesion classification. Tissue Cell. 2022;74(22):101701. doi:10.1016/j.tice.2021.101701. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Shetty B, Fernandes R, Rodrigues AP, Chengoden R, Bhattacharya S, Lakshmanna K. Skin lesion classification of dermoscopic images using machine learning and convolutional neural network. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):18134. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-22644-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Sulthana R, Chamola V, Hussain Z, Albalwy F, Hussain A. A novel end-to-end deep convolutional neural network based skin lesion classification framework. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;246:123056. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2023.123056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Hatem MQ. Skin lesion classification system using a K-nearest neighbor algorithm. Visual Comput Indus Biomed Art. 2022;5(1):7. doi:10.1186/s42492-022-00103-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Ayas S. Multiclass skin lesion classification in dermoscopic images using swin transformer model. Neural Comput Appl. 2023;35(9):6713–22. doi:10.1007/s00521-022-08053-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Popescu D, El-Khatib M, Ichim L. Skin lesion classification using collective intelligence of multiple neural networks. Sensors. 2022;22(12):4399. doi:10.3390/s22124399. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Qian S, Ren K, Zhang W, Ning H. Skin lesion classification using CNNs with grouping of multi-scale attention and class-specific loss weighting. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2022;226(3):107166. doi:10.1016/j.cmpb.2022.107166. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Omeroglu AN, Mohammed HM, Oral EA, Aydin S. A novel soft attention-based multi-modal deep learning framework for multi-label skin lesion classification. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2023;120:105897. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2023.105897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Menzies SW, Ingvar C, McCarthy WH. A sensitivity and specificity analysis of the surface microscopy features of invasive melanoma. Melanoma Res. 1996;6(1):55–62. doi:10.1097/00008390-199602000-00008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Foahom Gouabou AC, Damoiseaux JL, Monnier J, Iguernaissi R, Moudafi A, Merad D. Ensemble method of convolutional neural networks with directed acyclic graph using dermoscopic images: melanoma detection application. Sensors. 2021;21(12):3999. doi:10.3390/s21123999. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Attique Khan M, Sharif M, Akram T, Kadry S, Hsu CH. A two-stream deep neural network-based intelligent system for complex skin cancer types classification. Int J Intell Syst. 2022;37(12):10621–49. doi:10.1002/int.22691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Zhao F, Zhou H, Xu T. A self-learning differential evolution algorithm with population range indicator. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;241:122674. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2023.122674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Chanda D, Onim MSH, Nyeem H, Ovi TB, Naba SS. DCENSnet: a new deep convolutional ensemble network for skin cancer classification. Biomed Signal Process Control. 2024;89(2):105757. doi:10.1016/j.bspc.2023.105757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Sharma S, Guleria K, Kumar S, Tiwari S. Benign and malignant skin lesion detection from melanoma skin cancer images. In: 2023 International Conference for Advancement in Technology (ICONAT); 2023 Jan 24–26; Goa, India. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

17. Khan MA, Muhammad K, Sharif M, Akram T, Kadry S. Intelligent fusion-assisted skin lesion localization and classification for smart healthcare. Neural Comput Appl. 2024;36(1):37–52. doi:10.1007/s00521-021-06490-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Peng H, Fan Y. Feature selection by optimizing a lower bound of conditional mutual information. Inform Sci. 2017;418:652–67. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2017.08.036. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Raza MS, Qamar U. An incremental dependency calculation technique for feature selection using rough sets. Inform Sci. 2016;343:41–65. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2016.01.044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Das AK, Das S, Ghosh A. Ensemble feature selection using bi-objective genetic algorithm. Knowl-Based Syst. 2017;123(1):116–27. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2017.02.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Eroglu DY, Kilic K. A novel Hybrid Genetic Local Search Algorithm for feature selection and weighting with an application in strategic decision making in innovation management. Inform Sci. 2017;405(1):18–32. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2017.04.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Tabakhi S, Moradi P. Relevance-redundancy feature selection based on ant colony optimization. Pattern Recognit. 2015;48(9):2798–811. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2015.03.020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Chen K, Zhou FY, Yuan XF. Hybrid particle swarm optimization with spiral-shaped mechanism for feature selection. Expert Syst Appl. 2019;128:140–56. [Google Scholar]

24. Zhang Y, Gong DW, Cheng J. Multi-objective particle swarm optimization approach for cost-based feature selection in classification. IEEE/ACM Transact Computat Biol Bioinform. 2015;14(1):64–75. doi:10.1109/tcbb.2015.2476796. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Zhang Y, Song XF, Gong DW. A return-cost-based binary firefly algorithm for feature selection. Inform Sci. 2017;418(3):561–74. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2017.08.047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Zhang Y, Cheng S, Shi Y, Gong DW, Zhao X. Cost-sensitive feature selection using two-archive multi-objective artificial bee colony algorithm. Expert Syst Appl. 2019;137(1):46–58. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2019.06.044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Mafarja M, Aljarah I, Heidari AA, Hammouri AI, Faris H, Ala’M AZ, et al. Evolutionary population dynamics and grasshopper optimization approaches for feature selection problems. Knowl-Based Syst. 2018;145(2):25–45. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2017.12.037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Barani F, Mirhosseini M, Nezamabadi-Pour H. Application of binary quantum-inspired gravitational search algorithm in feature subset selection. Appl Intell. 2017;47(2):304–18. doi:10.1007/s10489-017-0894-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Taradeh M, Mafarja M, Heidari AA, Faris H, Aljarah I, Mirjalili S, et al. An evolutionary gravitational search-based feature selection. Inform Sci. 2019;497:219–39. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2019.05.038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Al-Ani A, Alsukker A, Khushaba RN. Feature subset selection using differential evolution and a wheel based search strategy. Swarm Evolution Computat. 2013;9:15–26. doi:10.1016/j.swevo.2012.09.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Baig MZ, Aslam N, Shum HP, Zhang L. Differential evolution algorithm as a tool for optimal feature subset selection in motor imagery EEG. Expert Syst Appl. 2017;90(1):184–95. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2017.07.033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Brest J, Greiner S, Boskovic B, Mernik M, Zumer V. Self-adapting control parameters in differential evolution: a comparative study on numerical benchmark problems. IEEE Transact Evolution Computat. 2006;10(6):646–57. doi:10.1109/tevc.2006.872133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Xiang Q, Li D, Hu Z, Yuan Y, Sun Y, Zhu Y, et al. Quantum classical hybrid convolutional neural networks for breast cancer diagnosis. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):24699. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-74778-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Sun Y, Deng X, Shao H. Quantum dual-branch neural networks with transfer learning for early detection of skin cancer. American J Translat Res. 2025;17(5):3357. [Google Scholar]

35. Radhi EA, Kamil MY, Mohammed MA. Quantum machine and deep learning for medical image classification: a systematic review. Iraqi J Comput Sci Mathem. 2025;6(2):9. [Google Scholar]

36. Abbas N, Saba T, Mohamad D, Rehman A, Almazyad AS, Al-Ghamdi JS. Machine aided malaria parasitemia detection in Giemsa-stained thin blood smears. Neural Comput Appl. 2018;29:803–18. doi:10.1007/s00521-016-2474-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Sumithra R, Suhil M, Guru D. Segmentation and classification of skin lesions for disease diagnosis. Procedia Comput Sci. 2015;45:76–85. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2015.03.090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Attia M, Hossny M, Zhou H, Nahavandi S, Asadi H, Yazdabadi A. Digital hair segmentation using hybrid convolutional and recurrent neural networks architecture. Comput Meth Prog Biomed. 2019;177:17–30. doi:10.1016/j.cmpb.2019.05.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Cheerla N, Frazier D. Automatic melanoma detection using multi-stage neural networks. Int J Innovat Res Sci, Eng Technol. 2014;3(2):9164–83. [Google Scholar]

40. Khan KA, Shanir P, Khan YU, Farooq O. A hybrid Local Binary Pattern and wavelets based approach for EEG classification for diagnosing epilepsy. Expert Syst Appl. 2020;140:112895. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2019.112895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Hawas AR, Guo Y, Du C, Polat K, Ashour AS. OCE-NGC: a neutrosophic graph cut algorithm using optimized clustering estimation algorithm for dermoscopic skin lesion segmentation. Appl Soft Comput. 2020;86:105931. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2019.105931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Hajiaghayi M, Kortsarz G, MacDavid R, Purohit M, Sarpatwar K. Approximation algorithms for connected maximum cut and related problems. Theoret Comput Sci. 2020;814:74–85. doi:10.1016/j.tcs.2020.01.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Pour MP, Seker H. Transform domain representation-driven convolutional neural networks for skin lesion segmentation. Expert Syst Appl. 2020;144:113129. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2019.113129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Ahn E, Bi L, Jung YH, Kim J, Li C, Fulham M, et al. Automated saliency-based lesion segmentation in dermoscopic images. In: 2015 37th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC); 2015 Aug 25–29; Milan, Italy. p. 3009–12. [Google Scholar]

45. Khan MA, Akram T, Sharif M, Javed K, Rashid M, Bukhari SAC. An integrated framework of skin lesion detection and recognition through saliency method and optimal deep neural network features selection. Neural Comput Appl. 2020;32:15929–48. doi:10.1007/s00521-019-04514-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Yousuf M, Mehmood Z, Habib HA, Mahmood T, Saba T, Rehman A, et al. A novel technique based on visual words fusion analysis of sparse features for effective content-based image retrieval. Math Probl Eng. 2018;2018:2134395. doi:10.1155/2018/2134395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Alkawaz MH, Sulong G, Saba T, Rehman A. Detection of copy-move image forgery based on discrete cosine transform. Neural Comput Appl. 2018;30(1):183–92. doi:10.1007/s00521-016-2663-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Khan MA, Sharif M, Akram T, Raza M, Saba T, Rehman A. Hand-crafted and deep convolutional neural network features fusion and selection strategy: an application to intelligent human action recognition. Appl Soft Comput. 2020;87:105986. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2019.105986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Oliveira RB, Pereira AS, Tavares JMR. Computational diagnosis of skin lesions from dermoscopic images using combined features. Neural Comput Appl. 2019;31(10):6091–111. doi:10.1007/s00521-018-3439-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Shahsavari A, Khatibi T, Ranjbari S. Skin lesion detection using an ensemble of deep models: SLDED. Multimed Tools Appl. 2023;82(7):10575–94. doi:10.1007/s11042-022-13666-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Tamoor M, Naseer A, Khan A, Zafar K. Skin lesion segmentation using an ensemble of different image processing methods. Diagnostics. 2023;13(16):2684. doi:10.3390/diagnostics13162684. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Codella NCF, Gutman D, Celebi ME, Helba B, Marchetti MA, Dusza SW, et al. Skin lesion analysis toward melanoma detection: a challenge at the 2017 international symposium on biomedical imaging (ISBIhosted by the international skin imaging collaboration (ISIC). arXiv:1710.05006. 2018. [Google Scholar]

53. Ricci Lara MA, Rodríguez Kowalczuk MV, Lisa Eliceche M, Ferraresso MG, Luna DR, Benitez SE, et al. A dataset of skin lesion images collected in Argentina for the evaluation of AI tools in this population. Sci Data. 2023;10(1):712. doi:10.1038/s41597-023-02630-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. He K, Zhang X, Ren S, Sun J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In: Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 770–8. [Google Scholar]

55. Simonyan K, Zisserman A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv:1409.1556. 2014. [Google Scholar]

56. Shobana P, Deny J. Image fusion based removal of color artifacts for the enhancement of dermoscopy images. In: 2022 International Conference on Smart Technologies and Systems for Next Generation Computing (ICSTSN). Villupuram, India: IEEE; 2022. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

57. Jobson DJ, Rahman Zu, Woodell GA. A multiscale retinex for bridging the gap between color images and the human observation of scenes. IEEE Trans Image Process. 1997;6(7):965–76. doi:10.1109/83.597272. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Yosinski J, Clune J, Bengio Y, Lipson H. In: How transferable are features in deep neural networks? In: Advances in neural information processing systems. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press; 2014. Vol. 27. [Google Scholar]

59. Esteva A, Kuprel B, Novoa RA, Ko J, Swetter SM, Blau HM, et al. Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks. Nature. 2017;542(7639):115–8. doi:10.1038/nature21056. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Tschandl P, Rosendahl C, Kittler H. The HAM10000 dataset: a large collection of multi-source dermatoscopic images of common pigmented skin lesions. Sci Data. 2018;5(1):180161. doi:10.1038/sdata.2018.161. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Trigka M, Dritsas E. A comprehensive survey of deep learning approaches in image processing. Sensors. 2025;25(2):531. doi:10.3390/s25020531. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Wu J, Hu W, Wen Y, Tu W, Liu X. Skin lesion classification using densely connected convolutional networks with attention residual learning. Sensors. 2020;20(24):7080. doi:10.3390/s20247080. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Aboulmira A, Hrimech H, Lachgar M, Hanine M, Garcia CO, Mezquita GM, et al. Hybrid model with wavelet decomposition and EfficientNet for accurate skin cancer classification. J Cancer. 2025;16(2):506. doi:10.7150/jca.101574. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Himel GMS, Islam MM, Al-Aff KA, Karim SI, Sikder MKU. Skin cancer segmentation and classification using vision transformer for automatic analysis in dermatoscopy-based noninvasive digital system. Int J Biomed Imaging. 2024;2024(1):3022192. doi:10.1155/2024/3022192. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Flosdorf C, Engelker J, Keller I, Mohr N. Skin cancer detection utilizing deep learning: classification of skin lesion images using a vision transformer. arXiv:2407.18554. 2024. [Google Scholar]

66. Tang K, Su J, Chen R, Huang R, Dai M, Li Y. SkinSwinViT: a lightweight transformer-based method for multiclass skin lesion classification with enhanced generalization capabilities. Appl Sci. 2024;14(10):4005. doi:10.3390/app14104005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools