Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

An Impact-Aware and Taxonomy-Driven Explainable Machine Learning Framework with Edge Computing for Security in Industrial IoT–Cyber Physical Systems

1 Faculty of Information Technology, L.N. Gumilyov Eurasian National University, Astana, 010000, Kazakhstan

2 Department of Computer Engineering, Astana IT University, Astana, 010000, Kazakhstan

3 Department of Computer Science and Information Technology, Hazara University, Mansehra, 21300, Pakistan

4 Higher School of Information Technology and Engineering, Astana International University, Astana, 010000, Kazakhstan

* Corresponding Authors: Zulfiqar Ahmad. Email: ; Nurdaulet Karabayev. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Next-Generation Intelligent Networks and Systems: Advances in IoT, Edge Computing, and Secure Cyber-Physical Applications)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(2), 2573-2599. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.070426

Received 16 July 2025; Accepted 11 October 2025; Issue published 26 November 2025

Abstract

The Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT), combined with the Cyber-Physical Systems (CPS), is transforming industrial automation but also poses great cybersecurity threats because of the complexity and connectivity of the systems. There is a lack of explainability, challenges with imbalanced attack classes, and limited consideration of practical edge–cloud deployment strategies in prior works. In the proposed study, we suggest an Impact-Aware Taxonomy-Driven Machine Learning Framework with Edge Deployment and SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP)-based Explainable AI (XAI) to attack detection and classification in IIoT-CPS settings. It includes not only unsupervised clustering (K-Means and DBSCAN) to extract latent traffic patterns but also supervised classification based on taxonomy to classify 33 different kinds of attacks into seven high-level categories: Flood Attacks, Botnet/Mirai, Reconnaissance, Spoofing/Man-In-The-Middle (MITM), Injection Attacks, Backdoors/Exploits, and Benign. The three machine learning algorithms, Random Forest, XGBoost, and Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP), were trained on a real-world dataset of more than 1 million network traffic records, with overall accuracy of 99.4% (RF), 99.5% (XGBoost), and 99.1% (MLP). Rare types of attacks, such as injection attacks and backdoors, were examined even in the case of extreme imbalance between the classes. SHAP-based XAI was performed on every model to help gain transparency and trust in the model and identify important features that drive the classification decisions, such as inter-arrival time, TCP flags, and protocol type. A workable edge-computing implementation strategy is proposed, whereby lightweight computing is performed at the edge devices and heavy, computation-intensive analytics is performed at the cloud. This framework is highly accurate, interpretable, and has real-time application, hence a robust and scalable solution to securing IIoT-CPS infrastructure against dynamic cyber-attacks.Keywords

The Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) is a disruptive paradigm that integrates the technologies of advanced sensing, data analytics, and connectivity to industrial systems [1–3]. It brings the essential concepts of the general Internet of Things (IoT) to the industrial sectors of manufacturing, energy, transportation, oil and gas, and utilities. IIoT is based on a system of intelligent sensors, actuators, and edge devices installed in the machinery and infrastructure to collect huge volumes of real-time data [4–7]. This information is therefore transmitted and processed in order to improve decision-making, automate the processes, and enhance efficiency in operations. IIoT is mission-sensitive and focuses on reliability, safety, and high availability [8–11]. Some of its most important applications include real-time monitoring and predictive maintenance, where an organization can detect problems before they translate into costly breakdowns. With cloud services and edge computing, IIoT systems enable distributed and heterogeneous environments to connect seamlessly and be smart [12,13]. IIoT is the foundation of smart factories and Industry 4.0 programs because industries are becoming more data-driven [14–16].

Cyber Physical Systems (CPS) involve a combination of computation and networking with physical processes [17]. Embedded computers and networks in CPS monitor and control physical processes, and frequently physical processes have feedback loops in which these physical processes influence computations. CPS has been a gateway to automation in contemporary industry and facilitates not just reactive systems but also predictive and responsive systems. Autonomous cars, smart grids, industrial robots, and medical surveys are examples of CPS [18,19]. CPS enables intelligent interaction between machines and digital platforms within an industrial environment to qualify intelligent control, automation, and optimization. These systems are characterized by strict timing, safety-critical results of the operations, and the need to coordinate the single work of the physical resources and the cyber ones. As industries become more connected and automated, CPS acts as the system that connects IIoT devices and smart software to enable real-time decision-making and independent operations in complicated environments [20–23].

With IIoT and CPS being more and more a part of industrial infrastructure, cybersecurity cannot be overestimated [17,24]. With the integration of operational technology (OT) and information technology (IT) that IIoT and CPS bring, the integration has brought about new vulnerabilities that the current security models might not be sufficient. What was once a closed and privately controlled industrial system is now open to public and corporate networks and can be attacked, hacked, and otherwise messed with by cybercriminals [25–27]. The effects of cyber threats in the IIoT-CPS environment may be disastrous and result in physical destruction of property, destruction of essential services, loss of money, and even harm to human beings [28–30]. Real-world implications of insecure industrial systems have been experienced through attacks like Stuxnet, Triton, and ransomware attacks in manufacturing plants [31,32]. Thus, cybersecurity in IIoT-CPS is not only a technical issue but an essential prerequisite of trust, resilience, and safe working in the contemporary industry [33,34]. Protecting IIoT-CPS environments should be done in a multi-layered manner that includes secure communication protocols, identity and access management, anomaly detection, and real-time threat mitigation [35–37]. These systems are complex and dynamic; hence, rule-based security solutions may prove inadequate, and more intelligent, adaptive, and explainable approaches must be given attention [38–40]. In order to meet the dynamically changing nature of cyber threats in IIoT and CPS, the incorporation of state-of-the-art technologies has been essential. These include machine learning (ML), clustering methods, taxonomy-based methods, and XAI, which provide a complete set of tools for creating powerful and smart cybersecurity systems [41,42]. ML algorithms have the potential to analyze and learn on high volumes of IIoT data to identify patterns and detect anomalies, and predict cyberattacks, even those that have never been seen before (zero-day attacks) that are otherwise missed by traditional rule- or signature-based systems [43,44]. Moreover, clustering methods make unsupervised learning possible, enabling the system to segment similar data elements and reveal hidden attack patterns without preceding annotation, which is particularly necessary in dynamic and unlabeled IIoT conditions [2,45]. Behind the strength of ML, there is one main issue: the need to comprehend and trust decisions made by it. This is why XAI, especially such frameworks as SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations), is such an important factor here. XAI renders ML decisions clear by explaining how each feature contributes to the output of the model. This interpretability is essential to the operators and cybersecurity analysts in the safety-critical IIoT-CPS systems to confirm the alerts, hold people accountable, and make informed decisions in real time. Cumulatively, the technologies provide a comprehensive approach to increasing cybersecurity in IIoT-CPS settings. Organizations can implement resilient, proactive, and explainable defense systems by combining taxonomy-driven models, pattern discovery clustering, ML predictive intelligence, and XAI interpretability. Besides, edge deployment of such capabilities improves responsiveness to low latency, local decision-making, and resistance to new threats in distributed industrial environments. The main contributions of the research work are as follows:

• We proposed a Taxonomy-Driven ML Framework for improving the cybersecurity of IIoT-CPS, integrating edge computing and SHAP-based XAI.

• We designed and defined a taxonomy-driven approach for attack classification, incorporating impact levels to better understand and prioritize cyber threats.

• We applied and compared multiple clustering techniques, including K-Means with Elbow Curve for optimal cluster selection, K-Means with Principal Component Analysis (PCA) for dimensionality reduction and visualization, and DBSCAN with PCA for identifying dense attack clusters and handling noise in the dataset.

• We implemented and evaluated three ML models, i.e., Random Forest, XGBoost, and Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP), for attack detection and classification, and conducted a comprehensive performance comparison.

• We applied SHAP-based Explainable AI to each ML model to provide transparent, interpretable insights into the model decisions and feature contributions.

• We presented a practical mechanism for integrating edge computing into the proposed framework, enabling real-time, low-latency threat detection suitable for deployment in resource-constrained IIoT environments.

We organized the remaining part of the paper as follows: Section 2 describes the related work. Section 3 employs a system design and model. Section 4 presents a performance evaluation, and, finally, Section 5 concludes the article with several future directions.

We reviewed the literature review with respect to industrial IoT, CPS, and taxonomy approaches for cybersecurity. The article in [8] investigates the process of integrating real-time communication technology in the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) networks regarding the growing requirements of flexibility, reliability, and mixed-criticality data transmission in the present industrial systems. The authors examine the use cases of IIoT and compare the real-time needs through evaluation of peer-reviewed publications and existing networking tools, specifically the embedded systems and controllers. Their results emphasize that although real-time is essential to IIoT applications, especially with the merging of OT and IT, the discipline does not have standard and widely accepted communication protocols, especially in wireless contexts. The paper [2] provides a detailed survey of the approaches to IIoT reference architecture, comparing conceptual models and experimental ones to state the most important architectural requirements, such as scalability, interoperability, security, privacy, reliability, and low latency. To support these needs in IIoT systems, the authors reveal the application of new technologies such as edge/fog computing, ML, blockchain, Software-Defined Networking (SDN), 5G, and wireless sensor networks. They dwell on the complexity of the architecture and the need to possess integrated and layered solutions to support the evolution of industrial processes. Our study is consistent with this one, as the authors in this study identify ML and edge computing as key to the construction of secure and scalable IIoT frameworks.

The authors in [17] critically assess the cybersecurity threat of the emergence of interconnectivity in Industrial CPS. They reference the growing attack surface and the existence of vulnerabilities as a result of weak boundary protections and lax security policy. Unlike the earlier literature, which focused on Intrusion Detection System or anomaly detection, this article suggests a multi-dimensional adaptive taxonomy of attacks to measure real-world cyber attacks in Industrial Cyber-Physical Systems (ICPSs), consequently bridging a major gap between empirical reports on vulnerabilities and theoretical research. The article in [46] addresses the detection of Advanced Persistent Threats (APTs) in CPS systems that are also linked to the IIoT and outlines the fact that conventional ML fails to detect covert and highly intelligent attacks. To overcome these barriers, the authors propose a model that is grounded on the Graph Attention Network (GAN) capable of learning the sophisticated behavioral patterns in the shape of masked self-attentional layers, which is better than deep learning that operates based on convolution. Their model has impressive detection rates of 96.97 and 95.97 percent on two benchmark datasets, and its inference time is also competitive. It is obvious, because of this aspect that adaptive, context-aware ML must be applied in IIoT-CPS security.

The authors of [47] suggest the use of ICS-ADD, a large open-source dataset that is specifically aimed at Industrial Control Systems (ICS) anomaly detection to enable developing and benchmarking new and advanced cybersecurity mechanisms. The data will include raw network traffic information within various simulated cyberattacks, such as DoS, MITM, and malware incidence, and the results of the OSSIM (Open Source Security Information Management) and Suricata detection. The two-layered approach offers a strong foundation on which to evaluate the reliability of the existing security equipment and identify the security breach gaps. The work highlights the heterogeneity and complexity of contemporary industrial cyber threats and the significance of such high-fidelity, realistic datasets as ICS-ADD toward security research. In the article discussed in [48], the authors focus on the changing nature of the deployment of ICPSs within the paradigm of cloud-fog-edge computing and the increasing use of edge-based analytics as an attempt to overcome the drawbacks of bandwidth and latency associated with cloud-based computing. The authors present a vulnerability-aware microservice orchestration framework, which improves security in edge computing systems, especially in heterogeneous industrial environments and their specific challenges. Their work combines a trust model to identify behavioral anomalies in microservices, thus enhancing resilience and adaptive security in the decentralized systems.

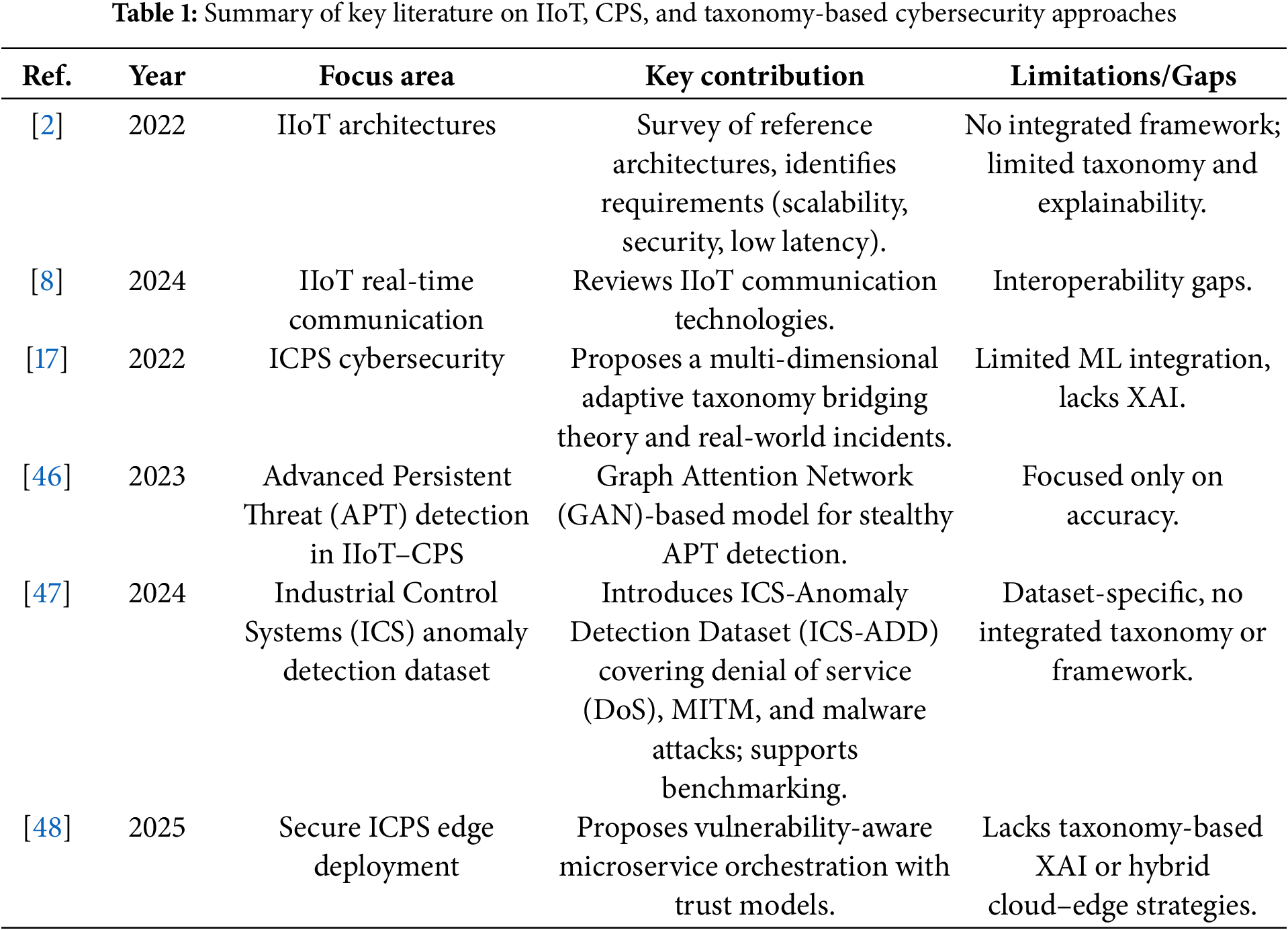

Table 1 provides a comparative summary of key recent studies on IIoT, CPS, and taxonomy-based cybersecurity approaches. There are some important research gaps in the area of security in the IIoT and CPS. Although some of the available literature offers valuable architectural knowledge or addresses how to deploy new technologies such as edge computing, fog computing, and microservices, they do not necessarily present a complete end-to-end cybersecurity framework that may present real-time threat identification and explainable decision-making. The other major gap includes the low application of integrated taxonomies that consider the influence and activity of attacks. Whereas taxonomic classifications or anomaly detection have been proposed in some work, not many combine this with supervised ML to simultaneously detect an attack and classify the impact. Moreover, current solutions to ML problems are usually based on high accuracy without considering interpretability, which is essential in the industrial context where actionable insights and a clear understanding of the model are essential. XAI is very sparsely studied in combination with taxonomy-aware frameworks, especially SHAP-based interpretations. Finally, even in the works that explore edge-based security, they usually do not consider the practical aspect of distributing the workload between edge and cloud tiers in order to achieve scalable, low-latency detection of attacks in IIoT systems. Such gaps point to the necessity of a comprehensive, interpretable, and results-oriented security system that makes use of the edge integration in IIoT-CPS environments as well as explainable ML.

In contrast to prior studies that have primarily focused on flat attack classification, single-model explainability, or cloud-only deployments, our work advances the state of the art through several distinctive contributions. We introduce an impact-conscious taxonomy-based framework, according to which we classify 33 fine-grained attack types in seven high-level categories and indicate their severity in IIoT-CPS applications. Unlike studies limited to supervised learning, we combine clustering with taxonomy-based classification, which allows the identification of hidden traffic patterns and resistance to new attacks. We perform the full SHAP-based explainability of several models (RF, XGBoost, and MLP) to achieve transparency and validate the model-agnostic features. To make it more realistic, we propose an effective edge-cloud hybrid deployment plan, which compromises between lightweight edge inference and cloud-based analytics to detect real-time using resources. We directly deal with uncommon and skewed classes of attacks, including injection and backdoor attacks, and thus, are robust in highly heterogeneous industrial environments.

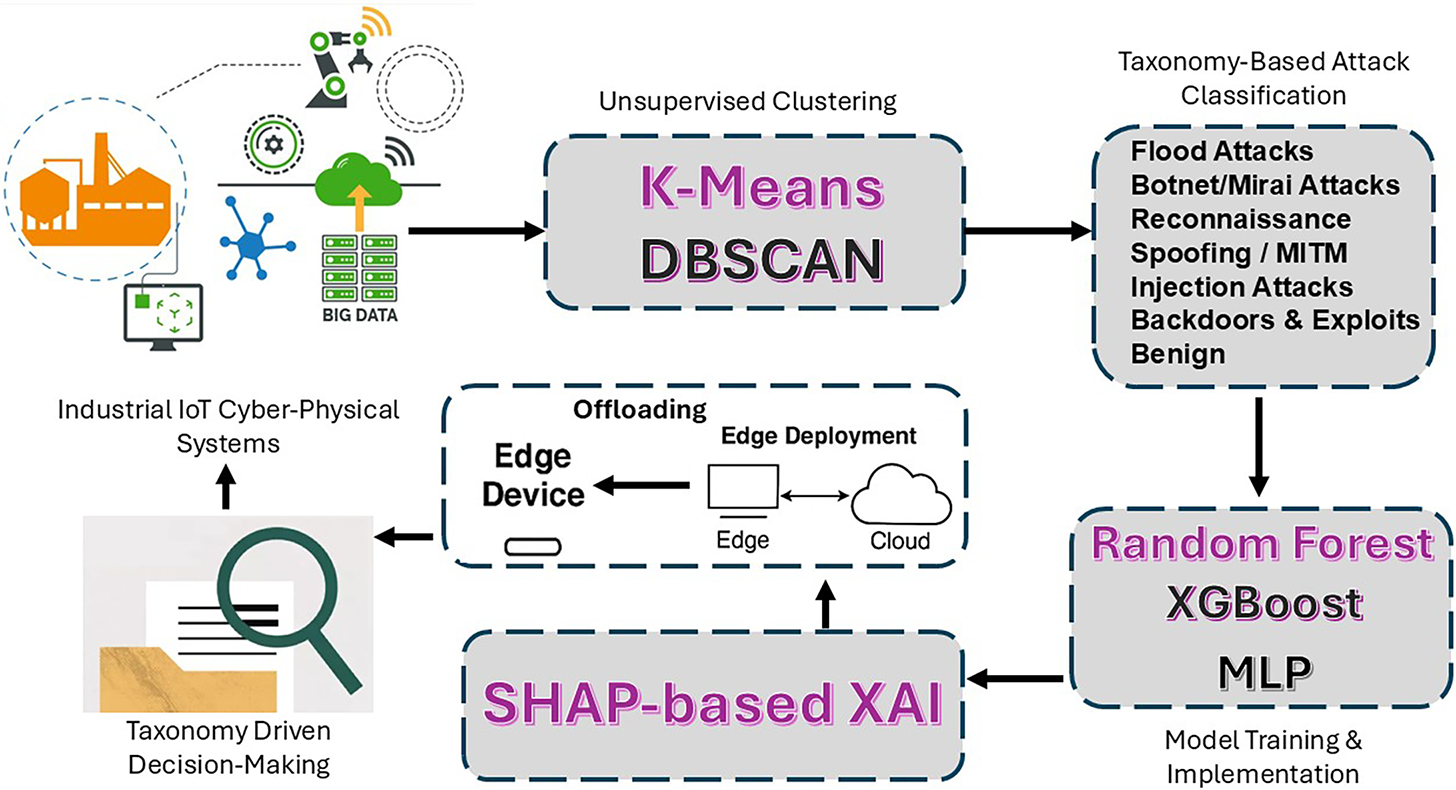

We present a Taxonomy-Driven ML Framework for enhancing the cybersecurity of IIoT-CPS, incorporating edge computing and SHAP-based XAI, as illustrated in Fig. 1. The framework is designed to provide a comprehensive, intelligent, and interpretable solution for detecting and classifying cyber-attacks in complex industrial environments.

Figure 1: Taxonomy-driven ML framework for IIoT-CPS cybersecurity

The center of the framework is the CPS environment as part of IIoT that is naturally exposed to a variety of cyber risks because it is interconnected and heterogeneous. The data related to sensors and the operational measures are constantly gathered about units of the CPS and are undergoing data preprocessing operations such as normalization, cleaning, and transformation in order to make the data ready to be processed. After preprocessing, the framework carries out clustering-based analysis to investigate the latent structure of the data and possible groupings of attack patterns. To identify natural clusters and separate anomalies in an unsupervised way, techniques like K-Means (with Elbow Curve), K-Means with PCA, and DBSCAN with PCA have been used. The key component of the system is a taxonomy-based approach, in which a taxonomy map of cyberattacks is created. This classification system groups the attacks according to their characteristics, which include type, behavior, and impact. The taxonomy supports and improves the work of the ML models, i.e., Random Forest, XGBoost, and MLP, that are involved in the classification and detection of the attacks. The framework uses SHAP-based XAI to provide interpretability and trust in the decision-making process. This module also offers a clear interpretation of model prediction by measuring the proportion of each feature to the classification output so that the operators and analysts can interpret and verify the reactions of the system. In addition, the proposed framework presents a realistic idea of the integration of edge computing. The data preprocessing, initial anomaly detection, and other lightweight operations are performed on edge devices, thus providing a low-latency response and minimizing bandwidth requirements. In the meantime, computationally intensive tasks such as training models and SHAP analysis are outsourced to cloud data centers, with the scalability and efficiency that such a solution provides.

Algorithm for the Proposed Framework

The suggested algorithm (Algorithm 1) proposes a Taxonomy-Driven ML Framework that helps to improve the cybersecurity of IIoT-CPS by integrating clustering algorithms, ML models, XAI using SHAP, and edge computing implementation. The framework begins by taking real-time sensor and system data from CPS components. This data, referred to as D (Data), is preprocessed through cleaning and normalization to ensure quality and consistency. Cluster methods such as K-Means and Elbow Curve, K-Means and DBSCAN with PCA are utilized in order to identify underlying attack patterns and cluster similar data points. They are useful in the discovery of known and unknown threats in a non-supervised fashion.

After clustering, a taxonomy-based approach is adopted to organize and categorize cyberattacks according to the established semantic classes and the level of impact. This taxonomy talks about training various ML models, such as Random Forest, XGBoost, and Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP), on the labeled data to do the attack detection and classification. All models are tested on the usual performance measures to determine the best classifier.

The chosen model is combined with SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) to improve interpretability, as this tool can explain each prediction on a feature level. This enables operators to know the logic of decisions made on models, which enhances their trust and allows them to respond to threats intelligently. Lastly, the algorithm takes into account a feasible edge-cloud computing plan in which the computational tasks are examined and dynamically distributed according to the resource requirements. Tasks that require less compute, like preprocessing and preliminary anomaly detection, can be performed on the edge devices to reduce latency, whereas more compute-intensive tasks, like model training and SHAP calculations, can be offloaded to data centers in the cloud, making them efficient and scalable across industrial settings. More specifically, the distributed task computing is carried out at the edge layer instead of depending on centralized cloud servers alone, which distributes the computation over multiple edge devices, including routers, gateways, and fog nodes. There are several intermediate processing edge nodes, which analyze and execute the tasks to the data source and, thus, reduce the latency and response time for security threats.

We conduct simulations and evaluate the performance of the proposed framework to assess its effectiveness in detecting and classifying cyber-attacks in industrial environments.

We evaluated the performance of the methods and models implemented in the proposed framework using the silhouette score, accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score [11,49,50]. We calculated accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score based on the following terms:

• True Positives (TP): The number of correctly identified positive instances.

• True Negatives (TN): The number of correctly identified negative instances.

• False Positives (FP): The number of incorrectly identified positive instances.

• False Negatives (FN): The number of incorrectly identified negative instances.

We have utilized the dataset called “IoT Intrusion Detection” [51,52], which is publicly available on the Kaggle platform. The data has high volumes of network traffic, as represented by 47 features. Such attributes encompass a large set of packet-/flow-level features, such as source and destination Internet Protocol addresses/ports, protocol types, packet sizes, flow time, statistical indicators (e.g., mean packet size, inter-arrival time), and diverse flags. This makes them a good source of information to discover cyber-attacks in industrial IoT settings. The data set has both benign and various types of attacks, and thus it is good to be used in supervised classification. Since it is large and diverse in features, it provides solid training and validation of the clustering algorithms, ML models, and explainable AI techniques such as SHAP. Also, a high-dimensional feature set allows doing dimensionality reduction (e.g., PCA) and feature importance analysis, which is essential to clustering accuracy and interpretability. In the preprocessing stage, the raw features are cleaned up, normalized, and encoded so that they match, and anomalies are eliminated. The labels are then further subdivided based on the proposed impact-aware taxonomy, where each instance is labeled as low, moderate, or high impact depending on the nature and severity of the underlying attack.

The experiments were performed by implementing two clustering methods, K-Means [53,54] and DBSCAN [55] and three ML models, Random Forest [39,56,57], XGBoost [50,58,59] and MLP [60,61]. All experiments are implemented in Python in a GPU-based environment. Predefined ML packages and libraries, including Pandas, Numerical Python (Numpy), Seaborn, Sklearn, LabelEncoder, OneHoTencoding and Matplotlib have been used.

The IoT Intrusion dataset, which comprises 1,048,575 records and 47 characteristics, was loaded in Pandas to perform pre-processing and exploration data analysis. The data has a broad set of flow-level and statistical network characteristics that are of interest in intrusion detection in IIoT scenarios. The most important libraries in Python were imported, including NumPy, Scikit-learn, XGBoost (Extreme Gradient Boosting), Light Gradient Boosting Machine, and SHAP, in order to preprocess the data, scale the features, cluster, train the models, and explain the results.

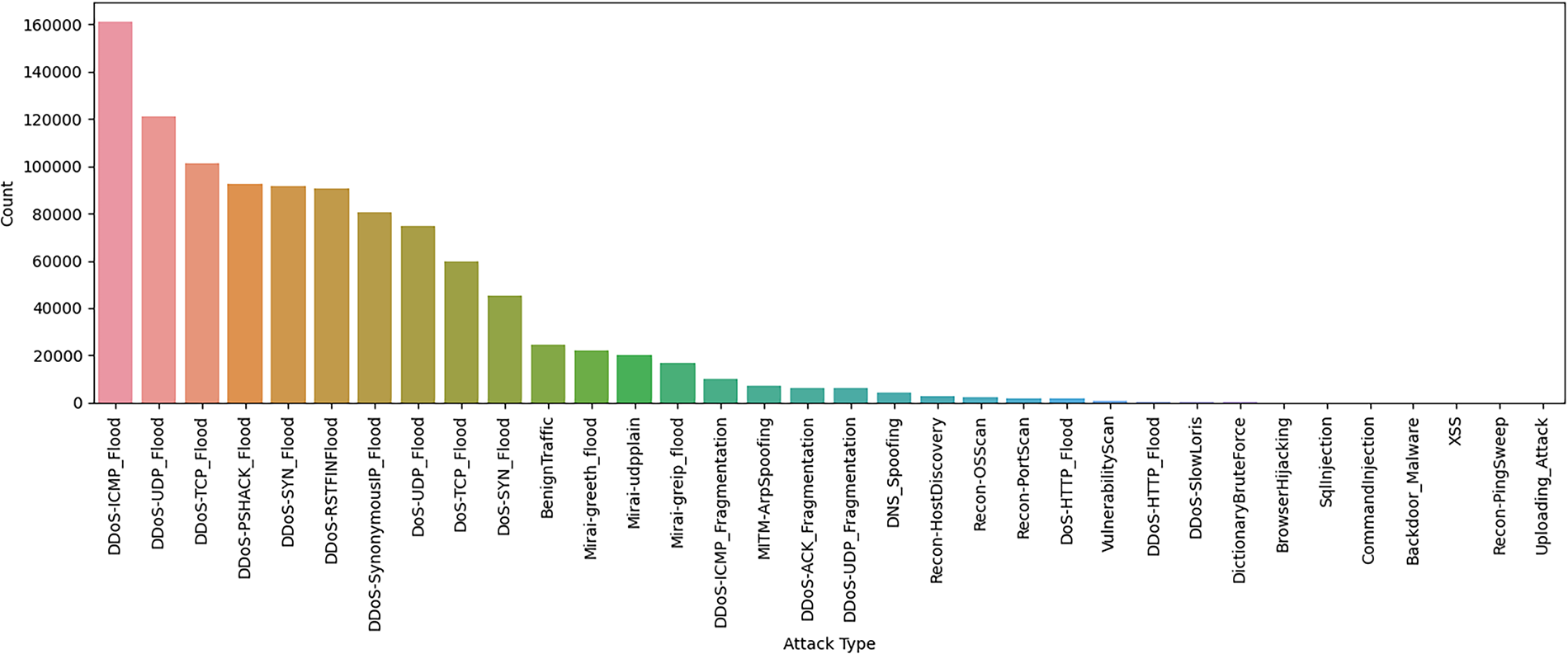

Preliminary analysis revealed the presence of high-dimensional data that can be used in supervised and unsupervised ML. In order to obtain an initial impression of the distribution of classes in the dataset, we studied the frequency of every kind of attack with the help of a bar plot. The column denoting the type of network activity (benign or the classes of attack) was the label column, and a count of values in each category was generated. The resulting distribution is shown in Fig. 2, which indicates a large degree of class imbalance, as is typical with intrusion detection datasets. Several attack types are vastly more common than others and may be used to bias model training and degrade the effectiveness of classifiers unless addressed properly. Hence, this knowledge was used to guide subsequent preprocessing procedures like resampling or taxonomy-based categorization to even the score.

Figure 2: Distribution of attack types in the dataset

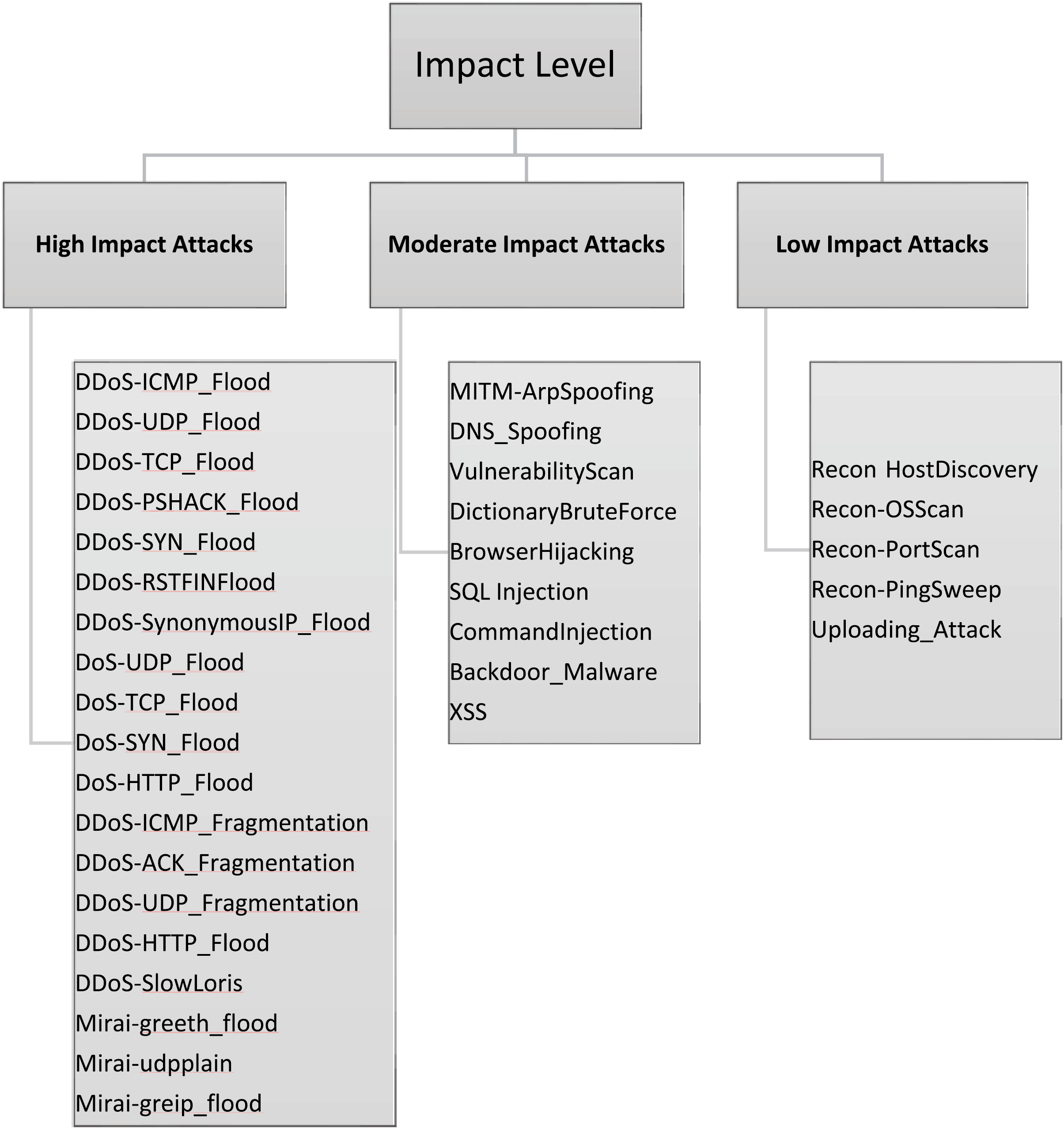

4.5 Categorization of Attacks for Impact-Aware Taxonomy

In order to suit the proposed impact-aware taxonomy, labels of all attacks in the IoT Intrusion dataset were divided into three separate impact levels: high, moderate, and low, as demonstrated in Fig. 3. This categorization was informed by prior studies discussed in Sections 1 and 2, which analyze the nature and severity of different attack types. This classification indicates the possible threat and operational risk of each type of attack in the IIoT-CPS.

Figure 3: A three-level impact-aware taxonomy of cyberattacks targeting industrial IoT CPS

The classification facilitates focused analysis and training of models, as it is possible to examine threats in order of their criticality.

• High-impact attacks encompass different denial-of-service (DoS) and distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks, including but not limited to DDoS- User Datagram Protocol (UDP)_Flood, DDoS- synchronize (SYN)_Flood, and Mirai-greeth_flood, which have the potential to significantly impair system availability or functionality. These were the most common attacks in the dataset and present a serious threat to IIoT-CPS settings.

• Moderate impact attacks include such threats as MITM-Address Resolution Protocol Spoofing (ArpSpoofing), Domain Name System (DNS)_Spoofing, Structured Query Language Injection (SQL Injection), and Backdoor_Malware, which may violate data integrity or confidentiality. These attacks do not necessarily result in failure of the system immediately, but they have the potential of causing long-term effects when they are not detected.

• Low-impact attacks, i.e., recon-port scan, recon-host discovery, and uploading attacks, are majorly reconnaissance-based operations. Although they are possible precursors to more serious intrusions, they have a direct, limited effect.

4.6 K-Means Clustering (k = 10) Interpretation with Elbow Curve

In order to use the dataset with unsupervised clustering, the column with the target label (label) was dropped so that the process of clustering can be based only on the input features. A check was done to ensure that the rest of the features were numeric. The StandardScaler tool was then used to normalize the feature set so as to reduce all features to the same scale. This standardization is necessary in achieving fair performance of clustering algorithms that are prone to feature magnitude variations.

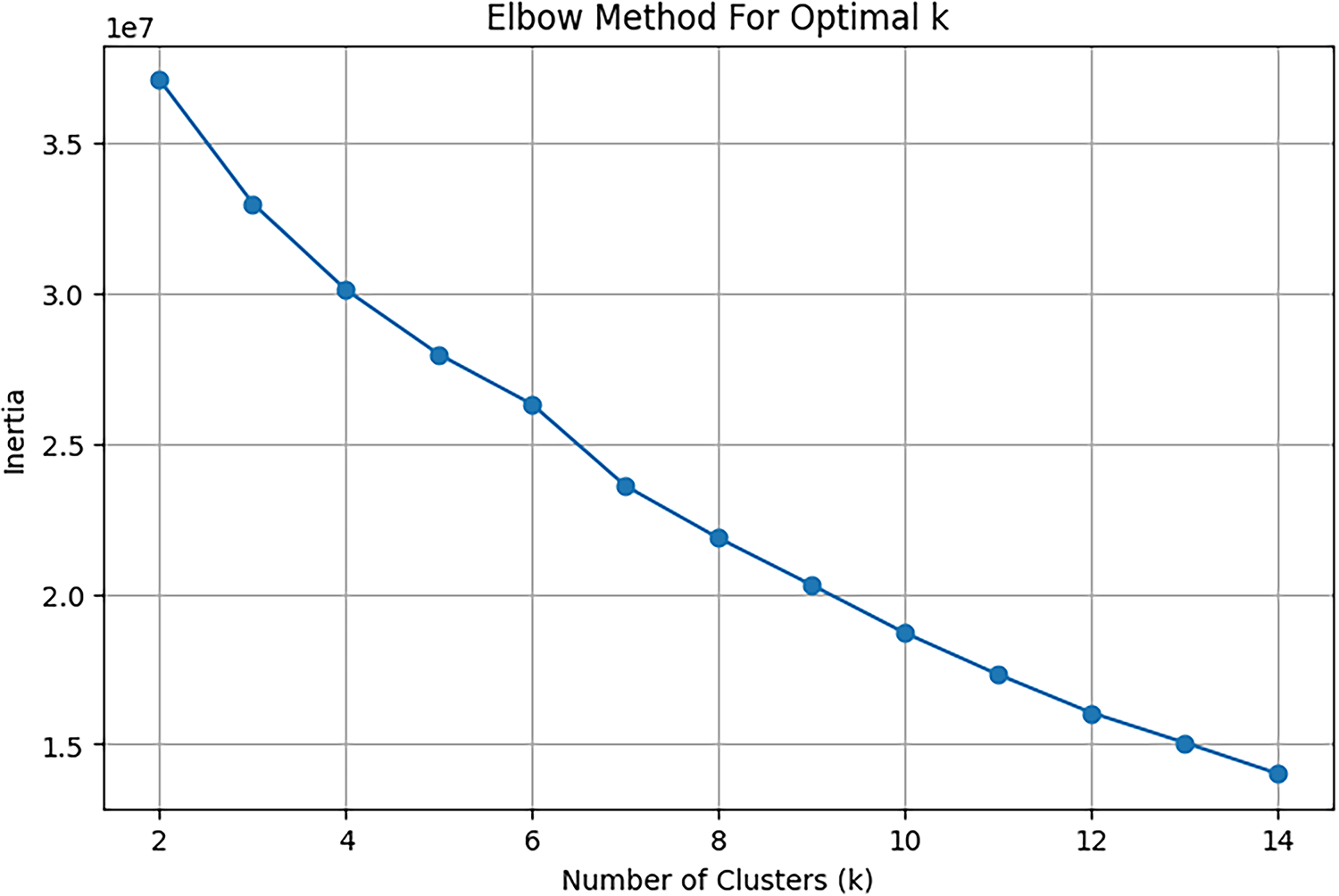

We used the Elbow Method to identify the optimum number of clusters in k-Means in an effort to measure the performance of various clusters with different cluster values of k = 2 to k = 14. The inertia (i.e., the within-cluster sum of squared distances) of the model (at each k) was computed and plotted. The plot also allows determining what is called the elbow point, i.e., the point at which the rate of decrease in inertia subsides significantly, indicating that there is likely to be a reasonable balance between risking underfitting and overfitting (Fig. 4). Final clustering is then conducted by using this optimum k value. The Elbow Method can assist in determining the optimal number of clusters; this is determined by noticing when the within-cluster sum of squares (inertia) starts to flatten out, which means that there are diminishing returns on the clustering performance. The elbow occurs at k = 6 or k = 7, in our case, the rate of decrease in inertia slows dramatically. After k = 7, any additional gain in cluster number creates only minimal decreases in inertia, indicating possible overfitting or granularity that is too fine. Thus, we chose K-Means optimal number of clusters k = 7, since it is a sufficiently practical compromise between the resolution of clustering, the cost of operations, and the generalization of the model.

Figure 4: Elbow curve for determining optimal number of clusters in K-Means

4.7 K-Means Clustering (k = 7) Visualization with PCA

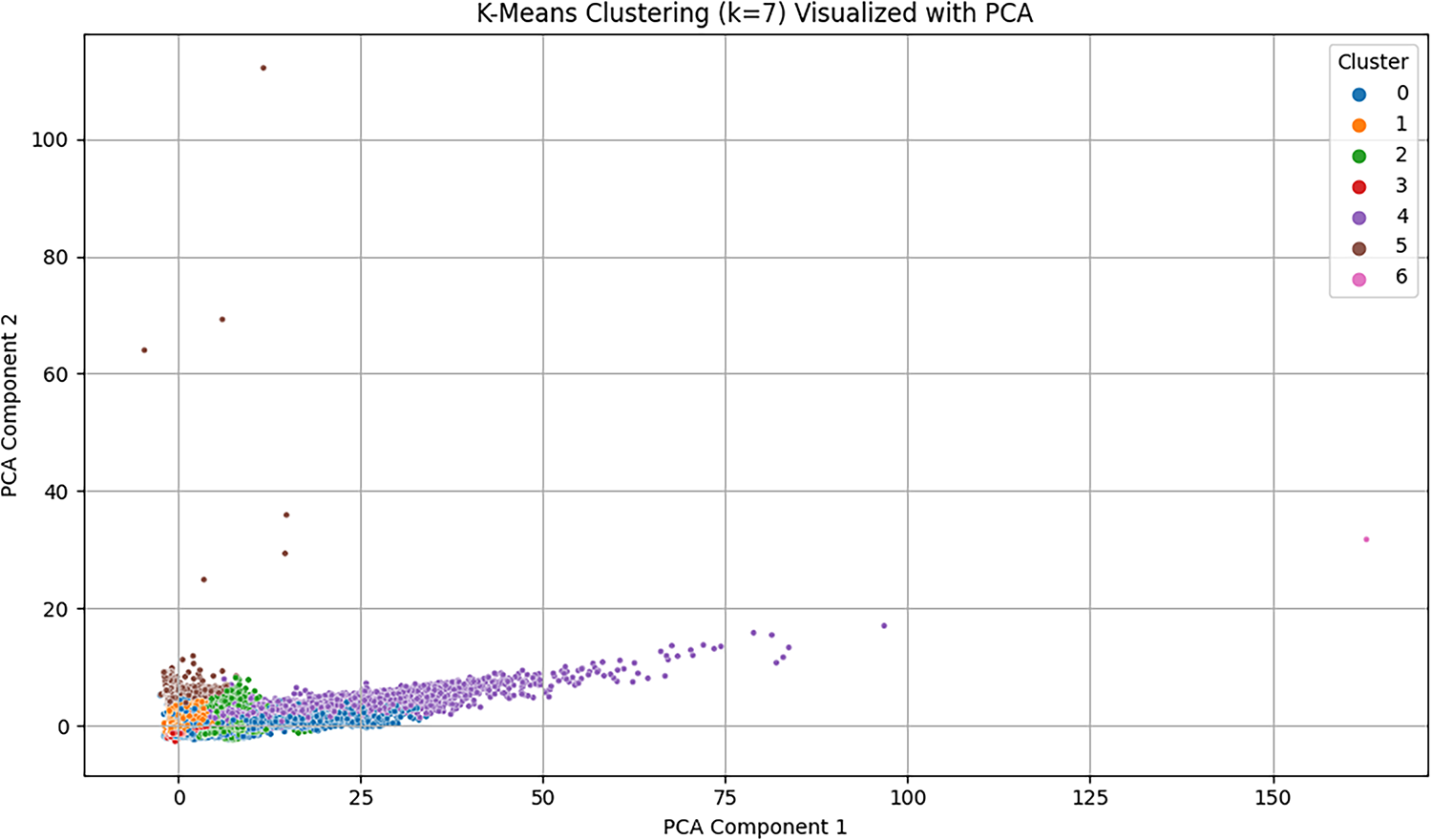

Having determined that the smallest number of clusters is k = 7 by applying the Elbow Method, we went ahead and clustered the scaled data by implementing K-Means. The cluster names that were obtained were added to the dataset to be used in an analysis that follows. In order to have a visual representation of the clustering structure, we reduced the high-dimensional feature space to two principal components.

As depicted in Fig. 5, the individual data points are presented on the reduced 2D space and colored depending on the allocated cluster. This visualization gives a simple visual understanding of the way the clustering algorithm has separated the data, which can clearly show groupings and intersections. Although PCA is not able to record all variance in 2 dimensions, the 2D plot can provide a good insight into the distribution, separation, and tightness of the formed clusters. The K-means clustering model usage, which can be visualized with the help of PCA, demonstrates that the data is naturally split into seven behavioral clusters, without any predetermined labels whatsoever. Every cluster (numbered 0 to 6) has distinct structural properties in the lower-dimensional feature space.

Figure 5: PCA-based visualization of K-Means clustering results (k = 7)

Visually, clusters (4, 5) are long and broad, which means that they have an increased intra-cluster variance and can be complex in their behavioral patterns that the traffic represented by those clusters follows. On the contrary, clusters 3 and 6 have a higher level of vertical stretching or horizontal stretching that can be an indication of outliers or exotic behavior of attacks. These clusters provide an easy-to-understand separation among the large traffic types, e.g., DDoS floods vs. DoS attacks or normal vs. anomalous traffic. Low and less frequent clusters (e.g., 3 or 6) probably represent non-frequent but highly effective attacks, such as Cross-Site Scripting (XSS), SQL injection, or malware that are usually underrepresented but very effective. This early clustering forms a good base to map the cluster groups to classes of the taxonomy (e.g., flood attacks, reconnaissance, exploits, malware) and assist in building a taxonomy-based intrusion detection framework.

4.8 Map Cluster Identifiers to Attack Types

To explain the behavioral composition of every cluster, we reviewed the most common types of attacks in each of the 7 clusters produced by K-Means. This action links the unlabeled clusters with the known threats and provides a semantic context and ground on which to align taxonomies.

The most prevailing trends are noted as follows:

• Cluster 0 is a mixed cluster in which Benign Traffic is dominant, followed by MITM-ArpSpoofing, DNS Spoofing, and Reconnaissance. This is an implication that Cluster 0 might be low- to moderate-impact behavior, such as normal and stealthy threats.

• Cluster 1 consists largely of high-volume DDoS flood attacks, such as Internet Control Message Protocol (ICMP), TCP, PSH-Push + ACK-Acknowledge (PSHACK), and SynonymousIP floods (a DDoS attack pattern involving spoofed or repeated IP addresses to evade detection), and, thus, is a solid representative of high-impact DDoS behavior.

• Cluster 2 is mostly composed of Mirai-based attacks like Generic Routing Encapsulation (GRE) flood, UDP-based flood, and fragmentation-based DDoS, which shows a specific botnet-related cluster.

• Cluster 3 indicates a combination of DDoS-UDP floods and DoS-UDP floods, with a slight proportion of benign and spoofing traffic, which means a combination of volumetric UDP attacks.

• Cluster 4 is similar to Cluster 0 in that these segments are dominated by Benign Traffic and reconnaissance/MITM attacks, implying another group of low-to-moderate threat behavior, possibly recorded under different feature space attributes.

• Cluster 5 is dominated by DDoS-RST + FINinish Flood (RSTFINFlood), to the extent of 99 percent, and also DoS- HyperText Transfer Protocol (HTTP) Floods, another high-impact cluster of volumetric attacks.

• Cluster 6 is highly sparse and contains small numbers of Benign Traffic, DNS Spoofing, and Reconnaissance Ping Sweep, presumably containing outliers or low-volume rare attacks.

The clustering outcomes indicate a significant and clear distinction between various kinds of network behaviors in the data, which is in line with the attack styles and mechanics. In particular, active flood attacks (including different types of DDoS and DoS traffic) prevail in clusters 1, 3, and 5, and these are high-volume, high-impact threat groups. Conversely, clusters 0, 4, and 6 predominantly include passive or stealthy actions, such as recon, spoof, and benign traffic, which are generally less voluminous but essential when trying to intrude at an earlier phase. Cluster 2 is specifically unique, with almost all of the Mirai-based botnet attacks demonstrating activity trends that are particular to IoT-focused malware. Such a distinct separation between clusters can prove the efficiency of unsupervised learning to differentiate behavioral patterns in IIoT-CPS settings and represent a reliable basis of impact-aware taxonomy-based classification.

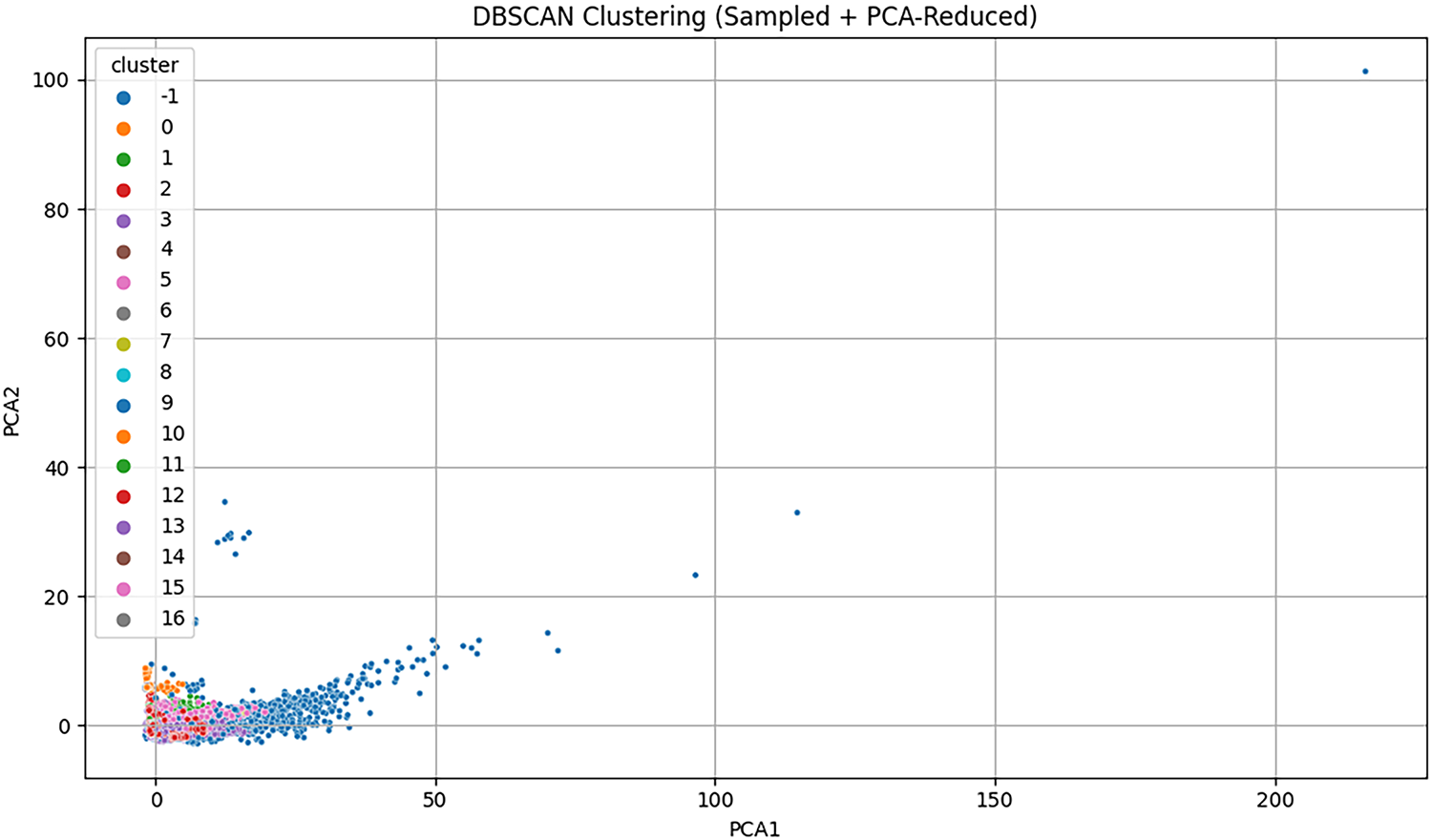

4.9 DBSCAN Clustering with PCA

In order to assess the clustering behavior with a density-based method, we used DBSCAN on a subset of 100 k records of the standardized dataset to improve run-time. As DBSCAN works best when the dimensionality is lowered, we used PCA to preserve 15 principal components with the largest share of variance and the fewest number of noises. The clusters thus obtained were visualized as projected onto two principal components. As Fig. 6 indicates, DBSCAN has the advantage of being able to identify dense clusters of similar behavior and assigning sparse regions or outliers to −1. The technique has complementary views with K-means, such as detecting non-globular groups and raising the warning of anomalies that might not conform to regular traffic patterns. There are 17 clusters that were formed by the DBSCAN clustering method with label range 0–16, and there is a label -1 representing outliers or noise. Label -1 is present in large quantities, and it takes up many of the data points, which is an anticipated result in density-based clustering, more so in high-variance network traffic data. The rest of the clusters seem to be fairly small and distinct, and this is one of the strengths of the DBSCAN since it is capable of detecting dense areas as well as effectively isolating sparse or anomalous patterns that do not belong to any cluster.

Figure 6: Visualization of DBSCAN clustering on PCA-reduced sampled data

To investigate how well K-Means and DBSCAN clustering algorithms perform on a large-scale IoT intrusion detection dataset with 1,048,575 records and 46 numerical characteristics, we used the two algorithms to cluster it. The aim was to discover the latent behavior patterns in network traffic through clustering of similar instances, which could be used to explore taxonomy-based classification and anomaly detection. In spite of the efficiency of these methods, a number of problems exist in the dataset. It is worth noting that its dimensionality is quite high, and thus the clusters based on distance lack cohesiveness, and the huge class imbalance, where the most common types of attacks, e.g., DDoS-ICMP_Flood, have over 100,000 samples, whereas the rarest, e.g., XSS or Uploading_Attack, have fewer than 100, makes uniform clustering difficult. Furthermore, the similarity of feature distributions of benign and attack traffic, the noise of data because of spoofing, fragmented packets, and Mirai-like behavioral patterns make the clustering more complex. To measure the quality of clustering, we took the Silhouette Score as a performance measure. K-means clustering of k = 7 gave a silhouette score of 0.3519, whereas DBSCAN gave a score of 0.3088 using an epsilon of 2.5 and min_samples = 10. Both clustering algorithms yielded semantically meaningful and practically effective groupings. Particularly, K-Means demonstrated that it is possible to cluster and, therefore, increase the interpretability and security insights of IIoT-CPS environments by offering clear and distinct clusters with flood attacks, Mirai-based botnet activity, and reconnaissance behavior.

4.10 Taxonomy Driven Detection and Classification with ML

After the clustering-based analysis, we move forward to taxonomy-based attack detection and classification, followed by supervised ML models. This step is going to use the labeled data and the created taxonomy to correctly identify and classify various kinds of cyberattacks in the IIoT-CPS environment. The three models that we use are common and have proven to be effective and are Random Forest, XGBoost, and Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP). The models are selected based on their capacity to deal with high-dimensional information, deal with the imbalances of the classes, and their capacity to identify intricate associations between features and types of attacks. The labeled dataset is used to train each of the models using the features extracted from the IoT traffic, and the performance of each model is evaluated by detecting frequent as well as rare attacks as defined in the impact-aware taxonomy. To make the interpretability higher and align attack prediction with cyber threat intelligence, we suggested a taxonomy-based approach to attack classification. In order to enhance semantic knowledge and decision-making, we designed a taxonomy map where all 33 types of attacks were categorized into 7 broad categories:

• Flood Attacks

• Botnet/Mirai Attacks

• Reconnaissance

• Spoofing/MITM

• Injection Attacks

• Backdoors & Exploits

• Benign

This mapping was considered directly on the labeled dataset to create a new column, taxonomy_label, so that supervised classifiers can forecast not only on the exact type of attack but also on the higher classification of impact. As anticipated, flood attacks occupied the majority of the dataset (more than 920,000 cases), and botnet/Mirai and benign traffic were in the second and third places, respectively. More important but rarer classes, such as Injection Attacks and Backdoors & Exploits were also retained to test the performance on the classes that are imbalanced but high-risk. Under the proposed environment, the classification of attacks into three levels is based on their impact, i.e., high, moderate, and low. The most dangerous threat is high-impact attacks like flood attacks or botnet/Mirai-based intrusions that target the availability of the system and may lead to massive service interruption, data loss, or industrial production stoppages. Medium-level attacks such as spoofing, MITM, and reconnaissance attacks usually pave the way for further serious attacks by collecting intelligence information or interfering with communications, thereby damaging any confidentiality and trust of the systems. Low-impact attacks are inside the group of injection-based attacks (e.g., SQL Injection, XSS), backdoors, and exploit attacks, which, although critical in nature, are less likely to happen and may require extra phases to increase their threat level. Such an impact-sensitive categorization informs defense mechanism prioritization and resource distribution to achieve resilient cybersecurity within IIoT-CPS environments.

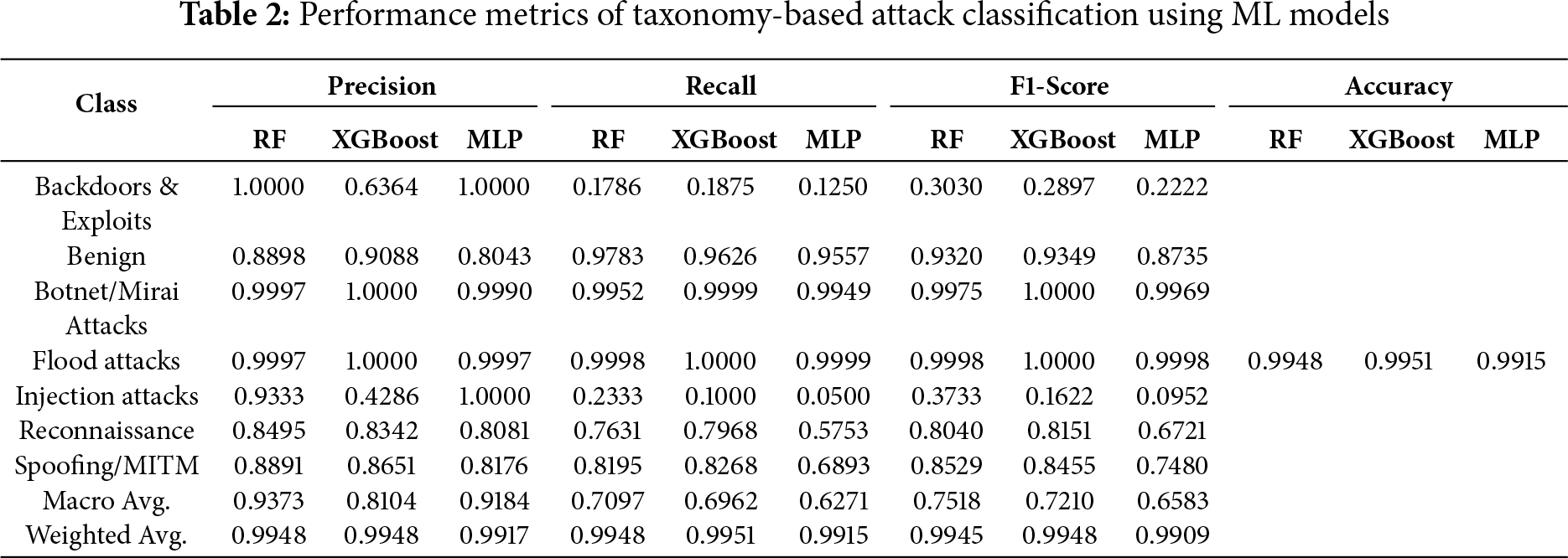

We compare the three models, Random Forest (RF), XGBoost, and MLP, to test the effectiveness of our taxonomy-driven ML classification method. To analyze the evaluation, four major metrics, including precision, recall, F1-score, and overall accuracy, are used on all seven specified taxonomy classes, which are flood attacks, botnet/Mirai attacks, reconnaissance, spoofing/MITM, injection attacks, backdoors & exploits, and benign. The models performed extremely well on the majority of classes, including flood attacks, botnet/Mirai attacks, and benign traffic, as Table 2 reveals. In these high-frequency classes, precision, recall, and F1-scores were close to perfect in all models. As an example, Random Forest and XGBoost managed to score an F1 score of 1.000 on flood attacks and more than 0.99 on botnet/Mirai classes. The performance of the Benign class was also steady and significant, with F1-scores of the models varying between 0.87 and 0.93. These findings correspond to the fact that the models generalize well when they have enough data to train.

The minority classes, e.g., injection attacks and backdoors & exploits, were performing worse, especially in recall. As an example, Random Forest and MLP showed precision of 1.000 and 1.000 in Backdoors & Exploits, respectively, whereas the recall decreased to 0.1786 and 0.1250, respectively. Such a difference between precision and recall shows that the models have been very precise when they do make predictions on these low-frequency classes, but miss out on a lot of true predictions, an effect that can be explained by the extreme imbalance in the classes in the data set. The two classes contained fewer than 600 samples compared to flood attacks that contained more than 920,000 records. On the same note, injection attacks had poor recall scores, although the precision was moderate to high. In all classes, the macro-averaged results were smaller than the weighted averages, which gives an advantage to the majority classes. This gap showcases the inability of the models to capture minority patterns, even though they perform well on the major ones. The random forest model performed better among the three so well that it balanced high- and low-frequency classes. Its improved macro-averaged recall and F1-score imply that it is more appropriate in imbalanced classification tasks in complex and real-world datasets in cybersecurity.

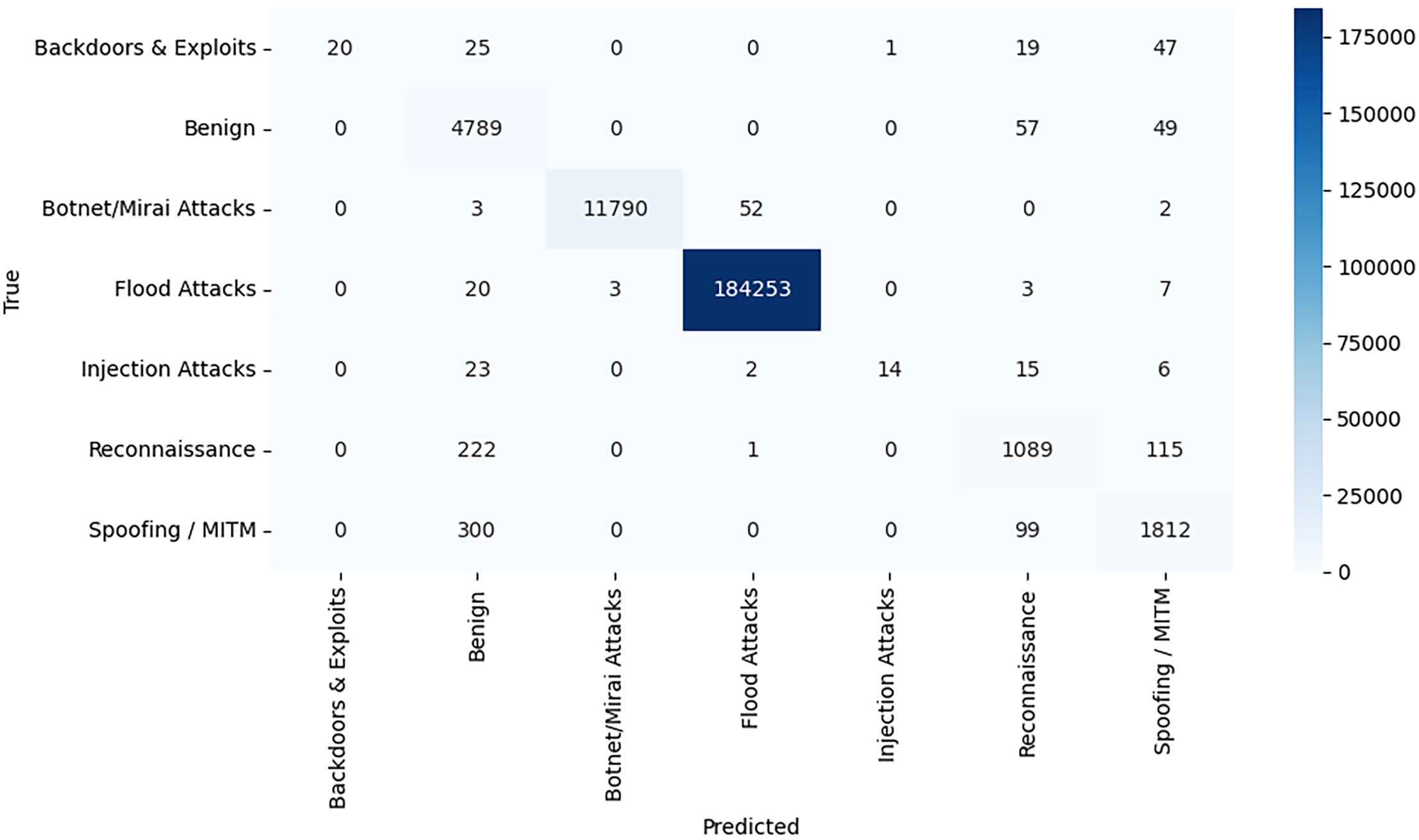

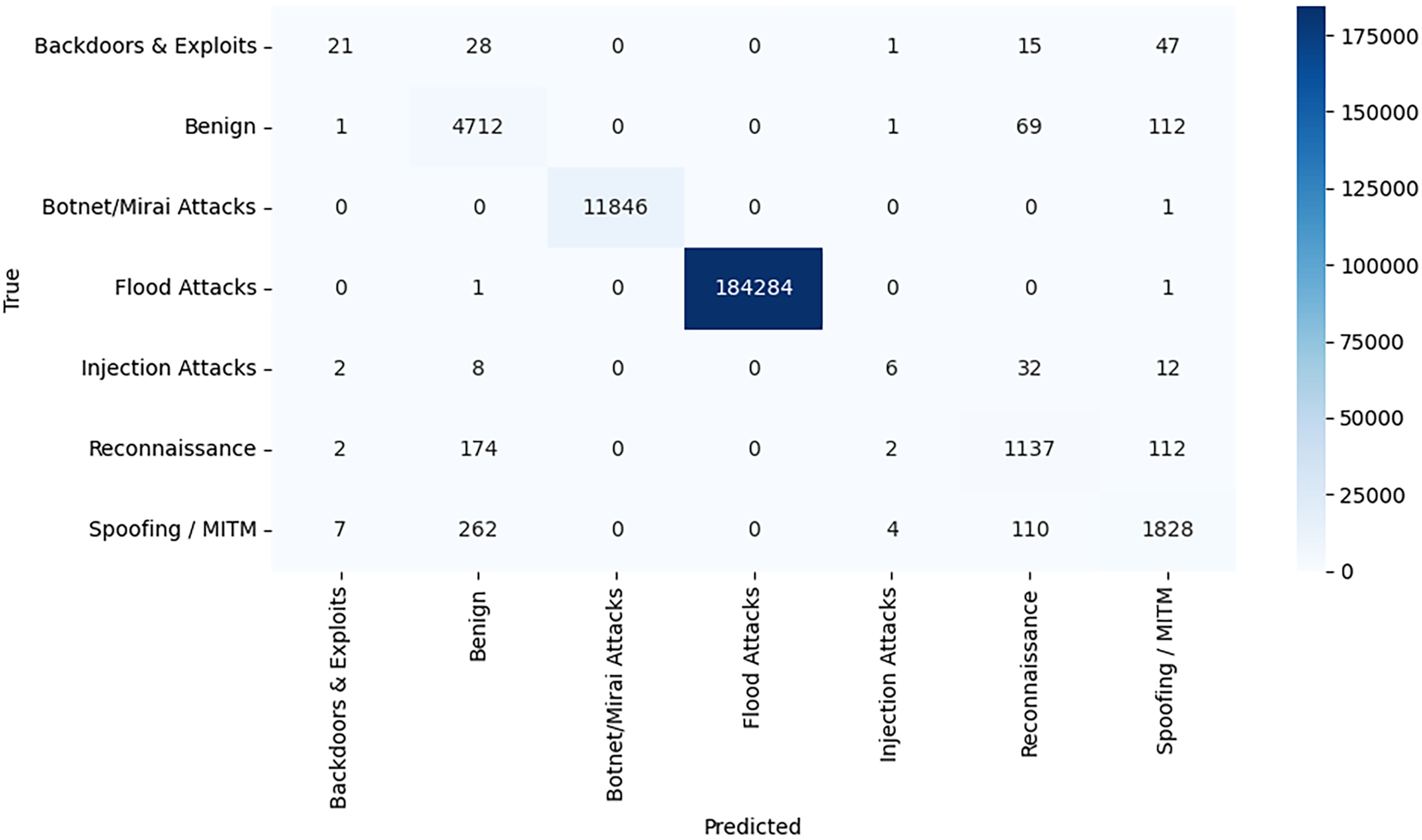

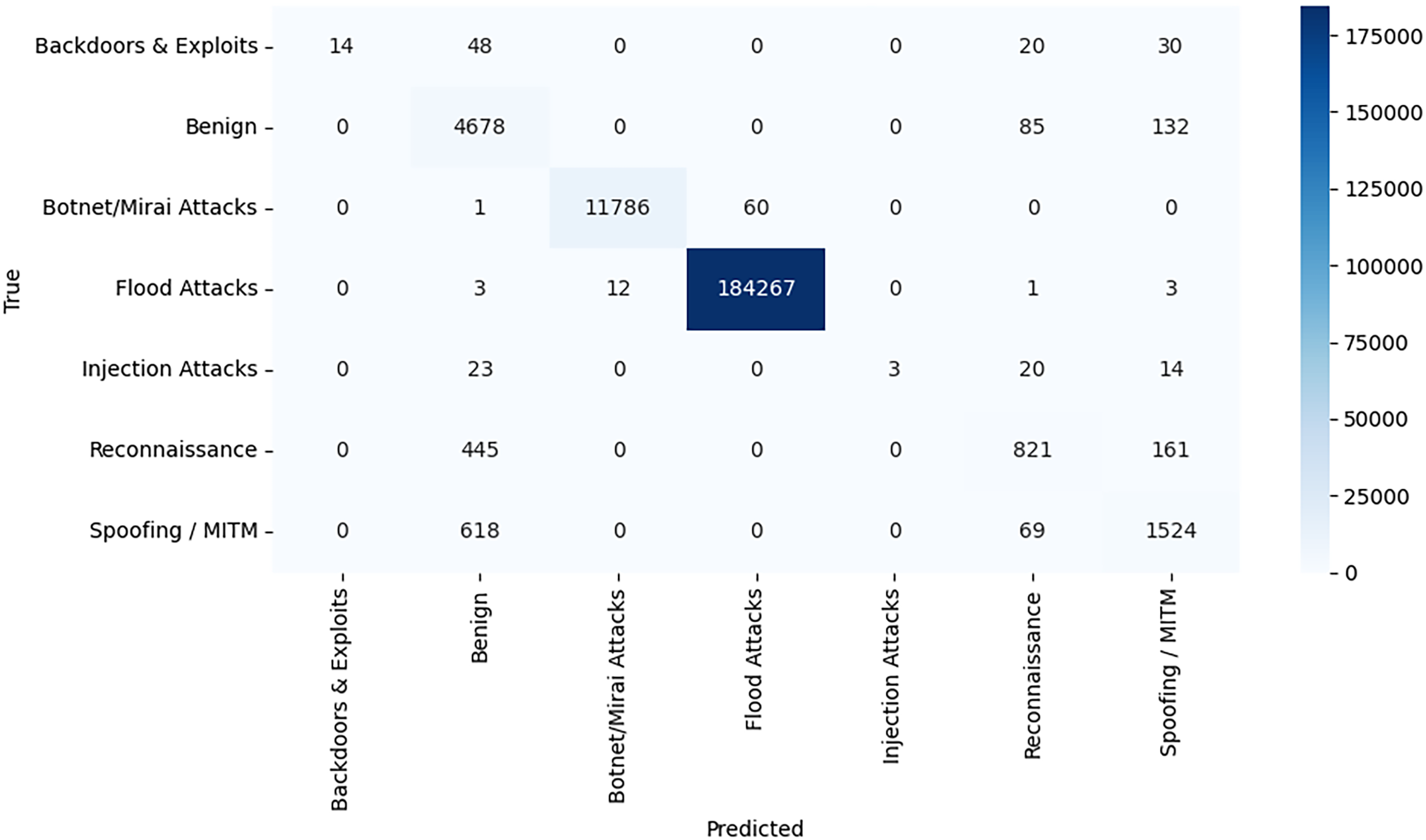

Fig. 7 (Random Forest), Fig. 8 (XGBoost), and Fig. 9 (MLP) provide the confusion matrices allow getting a better understanding of how each of the models is capable of differentiating between the taxonomy-based classes of attacks within the IIoT-CPS dataset.

Figure 7: Confusion matrix-random forest

Figure 8: Confusion matrix-XGBoost

Figure 9: Confusion matrix-MLP

The random forest model shows good results in terms of classification, especially in the cases of flood attacks and botnet/Mirai attacks. As an example, 184,253/184,286 flood attack samples are rightly categorized, and there is very little confusion with other classes. In the same regard, benign traffic is mostly well detected, with a total of 4789 correct predictions. Nevertheless, in spoofing/MITM and reconnaissance, some misclassifications can be observed when a considerable number of samples (e.g., 300 and 222, respectively) are mistaken for benign. The Backdoors & Exploits and Injection Attacks categories are still difficult to quantify because of their rarity, which is manifested as low diagonal numbers, as well as substantial dispersion into the wrong classes.

The Flood Attacks (184,284 correct) and Botnet/Mirai Attacks (11,846 correct) belong to the key categories that are perfectly detected by XGBoost. Benign samples are also processed well, but a little bit more are misclassified than with Random Forest. Among the positive changes, it is possible to note a more distinct difference between flood attacks and spoofing/MITM, with fewer false positives and false negatives in these two categories. Nonetheless, injection attacks and backdoors & exploits are still struggling—this can be seen by low true positive numbers and more predictions scattered into benign and other majority classes. However, XGBoost demonstrates a slightly better accuracy in a number of minority groups than RF.

The MLP model proves to have generally satisfactory performance, with flood attacks being once again well supported (184,267 correct classifications) but confused slightly more at neighboring categories (Botnet/Mirai and Benign). Benign traffic is not forecasted easily, and this is proven by 85 and 132 incorrectly classified samples into reconnaissance and spoofing/MITM, respectively. Backdoors & Exploits and Injection Attacks fared worst on the model, and this was probably because these two categories are either confused with Reconnaissance or Spoofing/MITM, perhaps because of similar traffic patterns or perhaps because there were insufficient training examples. The same is true of Reconnaissance and Spoofing/MITM, with both displaying worse misclassification than RF and XGBoost, showing MLP does not isolate low-frequency attacks as well.

4.11 Explainable AI with SHAP for Model Interpretation

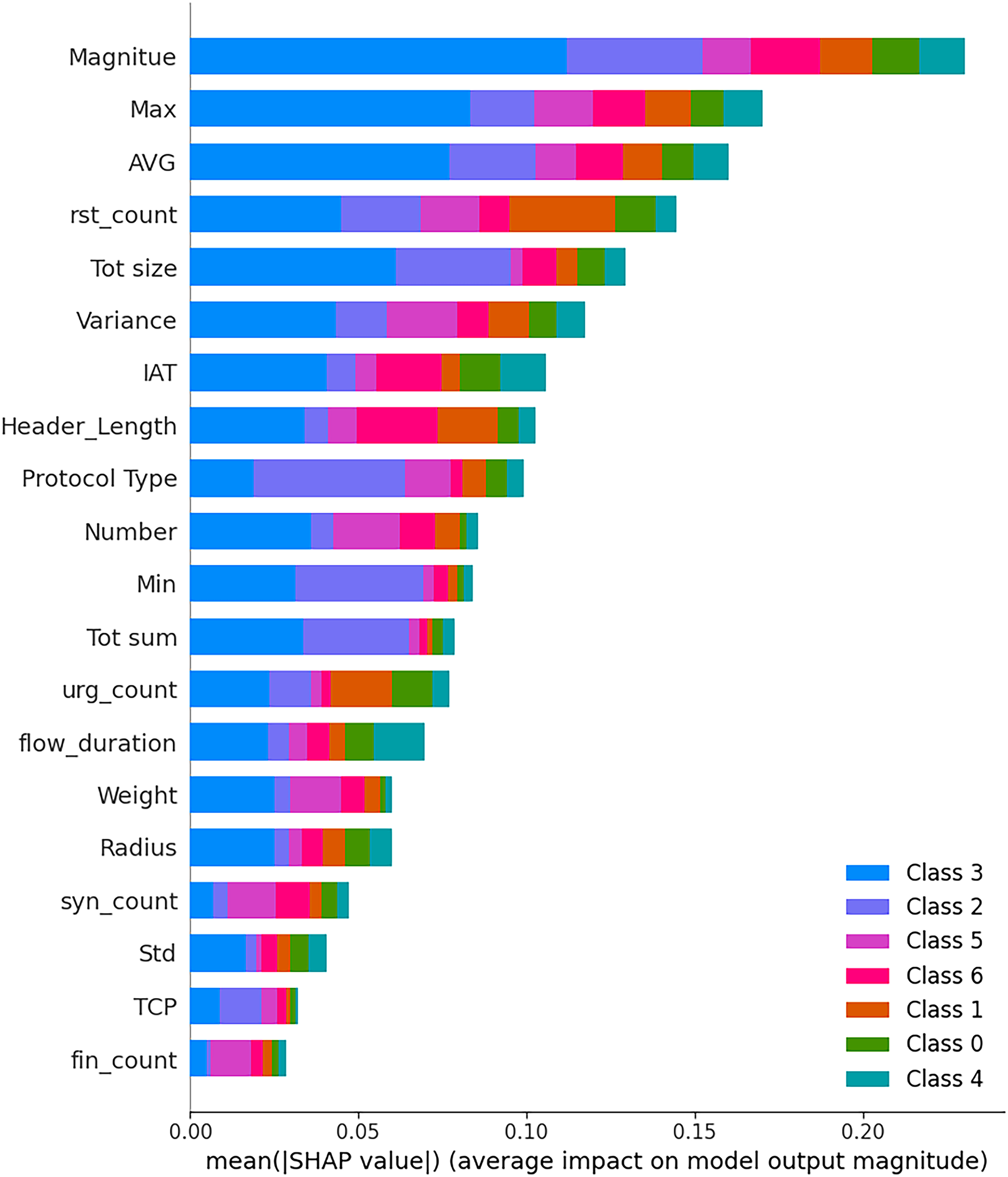

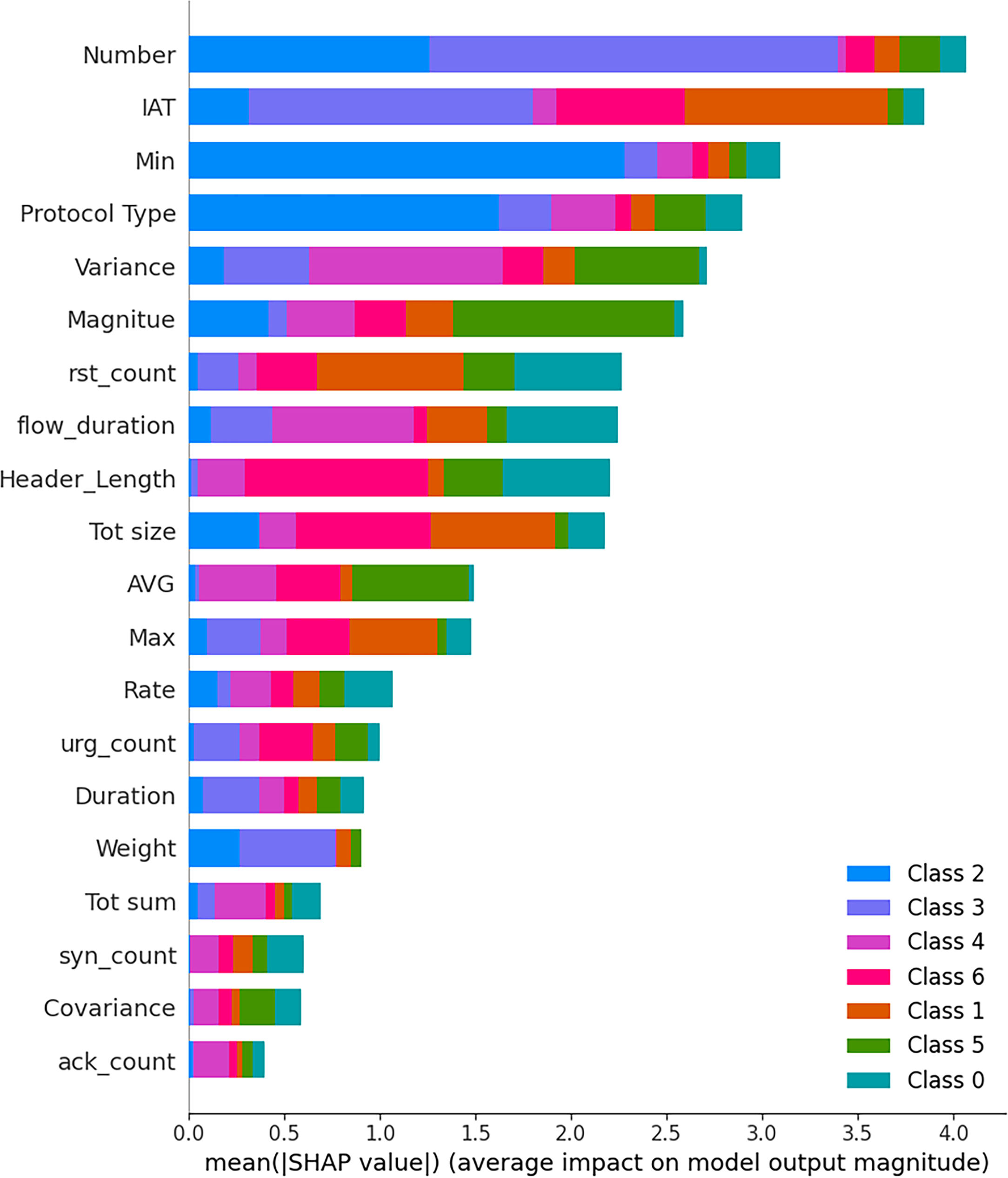

In order to gain insight into the internal decision-making process of the RandomForest model utilized to classify taxonomy-driven attacks in IIoT-CPS, we used SHAP as a method of local and global interpretability. SHAP-based explanations play an important role in assisting operators with real-time decision-making. By highlighting the features that most strongly influence the prediction of the model, operators gain actionable insights into why a given flow is flagged as malicious. This transparency increases trust in the automated system as well as enables faster incident triage. In real-time scenarios, such interpretability ensures that operators can respond promptly and confidently. The SHAP summary plot shown in Fig. 10 gives a visual representation of the contribution of each feature to the model output, summarized over a sample of 1000 instances of the test set. Every point of the plot is a Shapley value of a feature in a single prediction and plotted in a range of colors (blue to red) by the value of that feature.

Figure 10: SHAP summary plot for RandomForest–Taxonomy-based classification

On the list of feature importance, magnitude is positioned in the first place as the total volume of the information transferred during a session or flow. This is especially effective in differentiating flood attacks and botnet/Mirai activities, which are typified by large quantities of traffic. The model has been trained to correlate such volumetric characteristics with high-impact cyber threats, which makes magnitude a prevailing decision-making characteristic. Right behind these are Max and AVG, which are the maximum and average of traffic flows. These characteristics assist in distinguishing between aggressive, bursty behaviors that are characteristic of denial-of-service attacks and more steady patterns that exist with benign or reconnaissance traffic. The fact that they occupy the leading positions implies that the RandomForest model can be effectively used to identify the behavioral anomalies by using statistical profiling. TCP RST (Reset) packet counts (rst count), total size, and variance also assist the detection abilities of the model at the TCP/session level. Large numbers in such features usually indicate abnormal termination of sessions or payload discrepancies that occur in spoofing, fragmentation, or malformed packet attacks. The time-based metric Inter-Arrival Time (IAT), which refers to the intervals between subsequent packets, also makes it among the highest features. IAT is important, though not as crucial as in other models, such as XGBoost, in providing the means of detecting time-based anomalies like slow-rate DDoS or stealthy botnets.

Protocol-specific features such as Protocol_Type, Header_Length, and Number provide critical insight into how different layers of the network stack are utilized or abused in attacks. These features help differentiate between TCP, UDP, and ICMP-based attack strategies and reflect structural variances in how packets are constructed. While not in the topmost ranks, features such as syn_count, psh_flag_number, and fin_count still contribute meaningfully, particularly when identifying rare or subtle attack classes like Backdoors, MITM, or Injection Attacks. The SHAP analysis reveals that the RandomForest model employs a broad spectrum of feature types, including:

• Statistical attributes (Magnitude, AVG, Max, Variance),

• Behavioral indicators (rst_count, IAT),

• Protocol-level characteristics (Protocol_Type, Header_Length, TCP flags).

This well-distributed reliance across diverse feature domains makes the RandomForest model robust and adaptable to various attack vectors. It does not overly depend on a narrow set of features, which can be advantageous in environments with high variability and evolving threat patterns, such as IIoT-CPS.

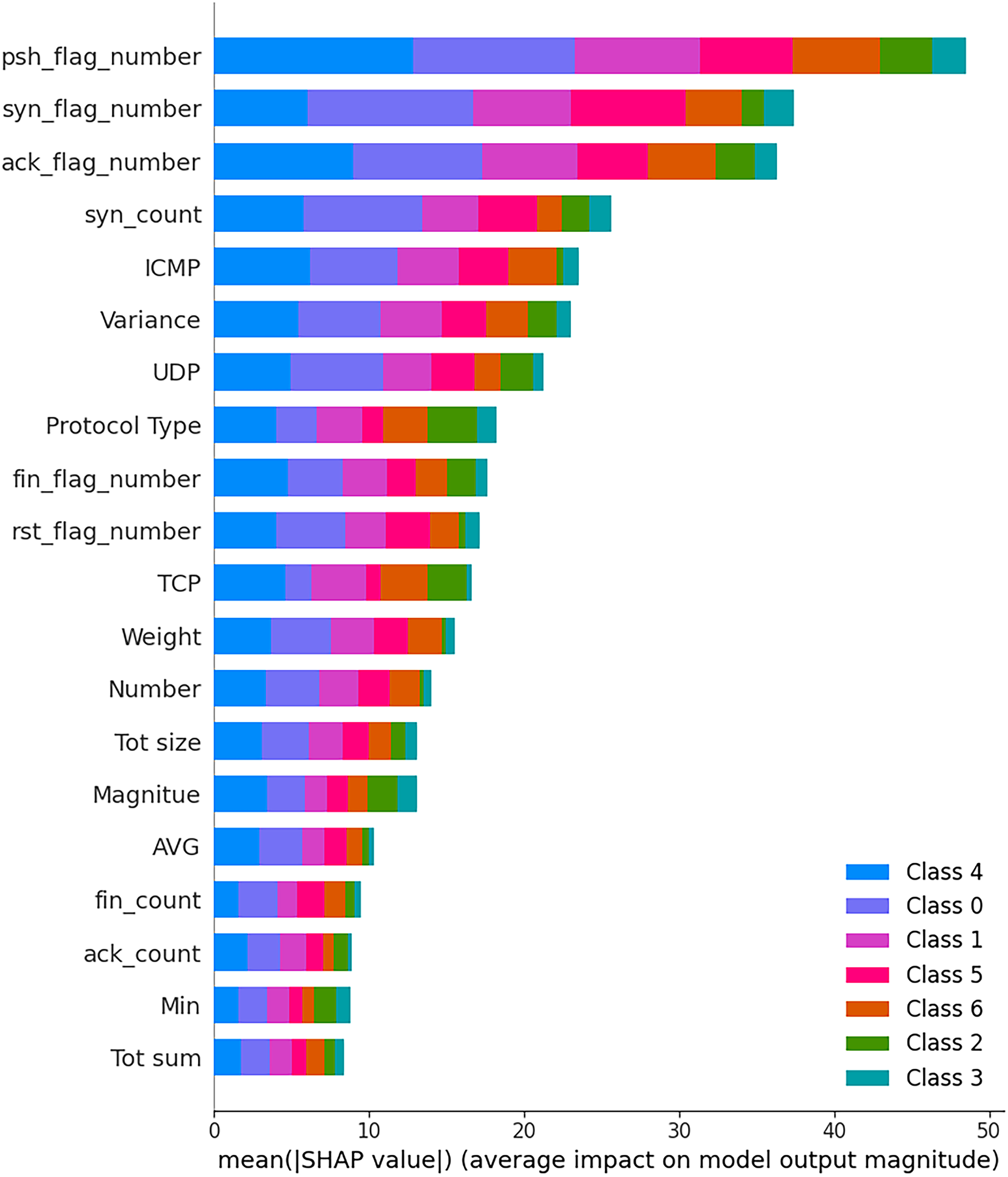

In order to further explain the choice made by the XGBoost classifier that was used in the taxonomy-driven detection framework, we leveraged SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations). Fig. 11 shows the SHAP summary plot of a sample of 1000 test instances, in which the contribution of the different input features to the predictions of the different attack categories is shown. SHAP analysis on XGBoost shows a very steep distribution of feature influence. The XGBoost model contrasts with the RandomForest model because it concentrates on a small set of key features that overpower its predictive abilities. By far the most significant of the features is Number, which probably refers to the number of packets in a flow or equivalent session-level measure. Its high SHAP value in all samples indicates that the model was highly dependent on the volume of the flows to identify high-traffic-based attacks such as flood attacks and botnet/Mirai intrusions. Inter-Arrival Time (IAT) has also been another feature that is of utmost importance, as it takes into account the time gaps between packets. Flooding attacks or stealthy probing are common to have high or irregular IAT, and XGBoost leverages this characteristic as a major indicator to separate good and bad bursts.

Figure 11: SHAP summary plot for XGBoost–Taxonomy-based classification

Such statistical properties as Min, AVG, and Variance are also significant. These assist the model in identifying irregular or inconsistent flows that are frequent in DoS/DDoS and backdoor/malware activities. There is definite variation in these metrics displayed in SHAP values, demonstrating that they have the potential to reflect dynamic behaviors across taxonomy classes. Protocol_Type is categorical and is used to identify the type of traffic by the protocol family it belongs to—TCP, UDP, or ICMP. This helps in separating attacks like DDoS-ICMP floods from TCP floods or spoofing attacks. In the same way, flow_duration and Header_Length play a further semantic role by characterizing the life and structure of traffic sessions. The TCP flags and session-level behaviors are linked to lower-ranked features, which are urg_count, ack_count, and syn_count.

The SHAP-based summary plot in Fig. 12 provides a window into how the MLP model internally makes decisions when classifying network traffic into impact-aware taxonomy categories. Unlike traditional tree-based models, the MLP captures nonlinear and deeper interactions between features, and the SHAP plot reveals which of those it prioritizes. The MLP model exhibits a strong preference for TCP flag-based features, particularly:

Figure 12: SHAP summary plot for MLP–Taxonomy-based classification

• psh_flag_number

• fin_flag_number

• ack_flag_number

These flags form the focus of TCP session management and are usually tampered with in spoofing, scanning, or handshake-based assaults. The large SHAP scores of most of the classes demonstrate that the MLP has learned that such flag patterns are relevant pointers to malicious actions, particularly where spoofing, MITM, or backdoors may be involved. Next in line are the identifiers of the protocols: ICMP, TCP, and UDP. Their impact highlights the ability of the MLP to differentiate between the protocol-specific attack types—ICMP floods, UDP-based denial of service, and TCP handshake abuse. Such categorical protocol inputs are necessary in categorizing traffic patterns within taxonomy labels. Interestingly, there is a stable impact of such characteristics as variance, protocol type, and syn_count, which indicates the model’s focus on the variability and structural abnormalities at the level of sessions. These characteristics facilitate the detection of bursty behaviors or irregular session formations that many times preface an attack, such as botnet commands or reconnaissance scans. In contrast to the tree-based models (such as RandomForest or XGBoost), the MLP does not focus on high-level volume indicators: magnitude, AVG, or number. It is, instead, biased toward lower-level, protocol-specific signals and so suggests a more precise understanding of session dynamics and flag behaviors, as opposed to the aggregate traffic characteristics.

In a nutshell, this study presents an end-to-end, impact-aware cybersecurity framework with Industrial Internet of Things-Cyber Physical Systems (IIoT-CPS) in context. Since such interconnected industrial environments are complex and vulnerable, our aim was to create an intelligent and sensible solution that is interpretable and would identify and classify cyberattacks on the basis of behavior and effect. We started with the analysis of a real-world intrusion detection dataset that is large-scale and contains more than one million records of network traffic with 33 different types of attacks. To learn the underlying structure of natural groupings and latent groupings of the data, we used unsupervised learning techniques defined as unsupervised clustering, such as K-Means (with PCA and the elbow method) and DBSCAN, which allowed us to identify the intrinsic traffic patterns and provided the basis of semantic grouping of attacks. Continuing this, we have presented a taxonomy-based approach, where the 33 different types of attacks are classified into seven broad categories: flood attacks, botnet/Mirai attacks, reconnaissance, spoofing/MITM, injection attacks, backdoors & exploits, and benign. We used supervised ML models, Random Forest, XGBoost, and Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP), to classify attacks based on taxonomy. These models were tested with standard performance measures, and their performance showed high precision, especially for dominant types of attacks. We considered that the performance of underrepresented classes would be degraded by imbalance, but kept them complete and covered critical risks. We incorporated XAI using SHAP in order to have transparency and interpretability. SHAP analysis helped us to visualize and interpret the model’s decision-making. As we have noticed, XGBoost depends on the statistics of the traffic volume and timing. Random Forest had more dispersion in structural and statistical characteristics. MLP also concentrated on protocol-level flags and session behavior and was therefore more sensitive to the subtle and stealthy attacks.

The study proposes a new ML framework based on taxonomies where the taxonomies are impact-aware, with the aim of achieving a cybersecurity boost to the Industrial IIoT-CPS. Since we are aware of the growing maturity and complexity of cyber threats in industrial settings, our framework incorporates several state-of-the-art components such as unsupervised clustering, taxonomy-based classification, supervised ML, SHAP-based XAI, and edge computing deployment. We started with the analysis of the attack behavior based on clustering methods such as the K-Means and DBSCAN in order to find natural groups in network traffic. On the basis of this analysis, we have created a taxonomy that classifies 33 attack types into seven comprehensible classes based on behavior and impact. The taxonomy forms the foundation of another classification system that is more interpretable and more structured. In order to identify and label these attacks, we used and compared the functionality of Random Forest, XGBoost, and Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) classifiers. Both had high accuracy, particularly on the dominant classes, and fairly good performance on the less represented and risky attack types. SHAP enabled us to explain the decisions of the models, to see which features had the most effect on the predictions, and therefore enhance trust and responsibility in high-stakes industrial use cases. Lastly, we discussed real-life deployment issues by including a feasible edge computing strategy, making our solution not only precise and explainable but also scalable and adaptive in dynamic IIoT settings.

In the future, we aim to combine continual learning with adaptive models that guarantee the system grows with new attack patterns, zero-day exploits, and network behavior changes without a complete retraining of the system. Although the dataset is rich and diverse, it is still captured in controlled conditions and may not fully reflect the dynamic heterogeneity of traffic in real industrial environments. Thus, we plan to validate the framework on additional benchmark datasets and, where possible, on real IIoT testbed traffic to further strengthen its generalizability and industrial applicability. Also, multi-modal data sources, e.g., logs, sensor anomalies, and device telemetry, will be used to provide better context to attacks and to detect multi-stage complex intrusions.

Acknowledgement: The authors extend their appreciation to the Committee of Science of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan for funding this work through Research Grant No. AP23489127.

Funding Statement: This research has been funded by the Committee of Science of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan (Grant No. AP23489127).

Author Contributions: Tamara Zhukabayeva, Zulfiqar Ahmad, Yerik Mardenov, and Nurdaulet Karabayev contributed to conceptualization, software, validation, and writing original draft. Nurbolat Tasbolatuly, Makpal Zhartybayeva, and Dilaram Baumuratova performed formal analysis, supervision, project administration, and review and editing article. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The “IoT Intrusion Detection” [51,52] dataset available on Kaggle platform has been used in this research work.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Ni C, Li SC. Machine learning enabled industrial IoT security: challenges, trends and solutions. J Ind Inf Integr. 2024 Mar;38:100549. doi:10.1016/j.jii.2023.100549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Mirani AA, Velasco-Hernandez G, Awasthi A, Walsh J. Key challenges and emerging technologies in industrial IoT architectures: a review. Sensors. 2022 Aug;22(15):5836. doi:10.3390/s22155836. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Xu G, Wang L, Chen S, Zhu L, Guizani M, Shi L. MPAEE: a multipath adaptive energy-efficient routing scheme for low earth orbit-based industrial Internet of Things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025 Sep;12(17):34793–805. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2025.3581314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Sun G, Liao D, Zhao D, Xu Z, Yu H. Live migration for multiple correlated virtual machines in cloud-based data centers. IEEE Trans Serv Comput. 2018 Mar;11(2):279–91. doi:10.1109/TSC.2015.2477825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Song L, Sun G, Yu H, Niyato D. ESPD-LP: edge service pre-deployment based on location prediction in MEC. IEEE Trans Mob Comput. 2025 Jun;24(6):5551–68. doi:10.1109/TMC.2025.3533005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Wu T, Li M, Qu Y, Wang H, Wei Z, Cao J. Joint UAV deployment and edge association for energy-efficient federated learning. IEEE Trans Cogn Commun Netw. 2025. doi:10.1109/TCCN.2025.3543365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Xu F, Yang H-C, Alouini M-S. Energy consumption minimization for data collection from wirelessly-powered IoT sensors: session-specific optimal design with DRL. IEEE Sens J. 2022 Oct;22(20):19886–96. doi:10.1109/JSEN.2022.3205017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Behnke I, Austad H. Real-time performance of industrial IoT communication technologies: a review. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024 Mar;11(5):7399–410. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2023.3332507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Pop P, Zarrin B, Barzegaran M, Schulte S, Punnekkat S, Ruh J, et al. The FORA Fog computing platform for industrial IoT. Inf Syst. 2021;98:101727. doi:10.1016/j.is.2021.101727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Alwakid G, Humayun M, Ahmad Z, Shaheen M. Development of a sustainable and optimized energy ecosystem with real-time monitoring through innovative IoT-based actuator design for human-centric security in smart cities. Human-Centric Comput Inf Sci. 2025;15:2. doi:10.22967/HCIS.2025.15.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Balaji BS, Paja W, Antonijevic M, Stoean C, Bacanin N, Zivkovic M. IoT integrated edge platform for secure industrial application with deep learning. Human-Centric Comput Inf Sci. 2023;13:19. doi:10.22967/HCIS.2023.13.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Chen P, Luo L, Guo D, Wu J, Chi K, Yan C, et al. QoS-oriented task offloading in NOMA-based Multi-UAV cooperative MEC systems. IEEE Trans Wirel Commun. 2025. doi:10.1109/TWC.2025.3593884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Li Y, Yi Z, Guo D, Luo L, Ren B, Zhang Q. Joint communication and offloading strategy of CoMP UAV-assisted MEC Networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025 Oct;12(19):39788–802. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2025.3588840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Kumar S, Mallipeddi RR. Impact of cybersecurity on operations and supply chain management: emerging trends and future research directions. Prod Oper Manage. 2022 Dec;31(12):4488–500. doi:10.1111/poms.13859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Shafique K, Khawaja BA, Sabir F, Qazi S, Mustaqim M. Internet of things (IoT) for next-generation smart systems: a review of current challenges, future trends and prospects for emerging 5G-IoT Scenarios. IEEE Access. 2020;8:23022–40. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2970118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Jiang H, Cai J, Xiao Z, Yang K, Chen H, Liu J. Vehicle-assisted service caching for task offloading in vehicular edge computing. IEEE Trans Mob Comput. 2025 Jul;24(7):6688–6700. doi:10.1109/TMC.2025.3545444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Kayan H, Nunes M, Rana O, Burnap P, Perera C. Cybersecurity of industrial cyber-physical systems: a review. ACM Comput Surv. 2022 Jan;54(11s):1–35. doi:10.1145/3510410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Ding F, Liu Z, Wang Y, Liu J, Wei C, Nguyen A-T, et al. Intelligent event triggered lane keeping security control for autonomous vehicle under DoS attacks. IEEE Trans Fuzzy Syst. 2025;33:1–13. doi:10.1109/TFUZZ.2025.3597276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Alazeb A, Chughtai BR, Al Mudawi N, AlQahtani Y, Alonazi M, Aljuaid H, et al. Remote intelligent perception system for multi-object detection. Front Neurorobot. 2024 May;18:3782. doi:10.3389/fnbot.2024.1398703. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Singh H. Big data, industry 4.0 and cyber-physical systems integration: a smart industry context. Mater Today Proc. 2021;46:157–62. doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2020.07.170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Cao K, Hu S, Shi Y, Colombo A, Karnouskos S, Li X. A survey on edge and edge-cloud computing assisted cyber-physical systems. IEEE Trans Ind Informatics. 2021 Nov;17(11):7806–19. doi:10.1109/TII.2021.3073066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Mahmud R, Ramamohanarao K, Buyya R. Application management in fog computing environments: a taxonomy, review and future directions. ACM Comput Surv. 2021;53(4):1–43. doi:10.1145/3403955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Akbarzadeh A, Erdodi L, Houmb SH, Soltvedt TG. Two-stage advanced persistent threat (APT) attack on an IEC 61850 power grid substation. Int J Inf Secur. 2024 Aug;23(4):2739–58. doi:10.1007/s10207-024-00856-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Mullet V, Sondi P, Ramat E. A review of cybersecurity guidelines for manufacturing factories in industry 4. 0. IEEE Access. 2021;9:23235–63. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3056650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Corallo A, Lazoi M, Lezzi M, Pontrandolfo P. Cybersecurity challenges for manufacturing systems 4.0: assessment of the business impact level. IEEE Trans Eng Manage. 2023 Nov;70(11):3745–65. doi:10.1109/TEM.2021.3084687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Shen X, Li L, Ma Y, Xu S, Liu J, Yang Z, et al. VLCIM: a vision-language cyclic interaction model for industrial defect detection. IEEE Trans Instrum Meas. 2025;74:1–13. doi:10.1109/TIM.2025.3583364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Liu Y, Dong X, Zio E, Cui Y. Active resilient secure control for heterogeneous swarm systems under malicious cyber-attacks. IEEE Trans Syst Man, Cybern Syst. 2025 Oct;55(10):7195–204. doi:10.1109/TSMC.2025.3580940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Qiao Y, Lü J, Wang T, Liu K, Zhang B, Snoussi H. A multihead attention self-supervised representation model for industrial sensors anomaly detection. IEEE Trans Ind Inform. 2024 Feb;20(2):2190–9. doi:10.1109/TII.2023.3280337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Yue M, Yan H, Han R, Wu Z. A DDoS attack detection method based on IQR and DFFCNN in SDN. J Netw Comput Appl. 2025 Aug;240:104203. doi:10.1016/j.jnca.2025.104203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Ouyang S, Liu X, Liu L, Wang S, Shao B, Zhao Y. An efficient and provably secure SM2 Key-insulated signature scheme for industrial Internet of Things. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2024;138(1):903–15. doi:10.32604/cmes.2023.028895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Zhang J, Sui H, Sun X, Ge C, Zhou L, Susilo W. GrabPhisher: phishing scams detection in ethereum via temporally evolving GNNs. IEEE Trans Serv Comput. 2024 Nov;17(6):3727–41. doi:10.1109/TSC.2024.3411449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Jin J, Wu M, Ouyang A, Li K, Chen C. A novel dynamic hill cipher and its applications on medical IoT. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025 May;12(10):14297–308. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2025.3525623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Gao H, Xin R, Chen P, Li X, Lu N, You P. Memory-augment graph transformer based unsupervised detection model for identifying performance anomalies in highly-dynamic cloud environments. J Cloud Comput. 2025 Jul;14(1):40. doi:10.1186/s13677-025-00766-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Zheng W, Liu C, Deng P, Chen X, Wu X. Enhancing concurrency vulnerability detection through AST-based static fuzz mutation. J Syst Softw. 2025 Apr;222:112352. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2025.112352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Shen X, Liu J, Ren Y, Jiang L, Wang L, Zhao H, et al. A task-oriented physical collaborative network for pipeline defect diagnosis in a magnetic flux leakage detection system. Comput Ind. 2025 Aug;169:104290. doi:10.1016/j.compind.2025.104290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Wang P, Song W, Qi H, Zhou C, Li F, Wang Y, et al. Server-initiated federated unlearning to eliminate impacts of low-quality data. IEEE Trans Serv Comput. 2024 May;17(3):1196–211. doi:10.1109/TSC.2024.3355188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Liu Y, Li S, Wang X, Xu L. A review of hybrid cyber threats modelling and detection using artificial intelligence in IIoT. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2024;140(2):1233–61. doi:10.32604/cmes.2024.046473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Nankya M, Chataut R, Akl R. Securing industrial control systems: components, cyber threats, and machine learning-driven defense strategies. Sensors. 2023 Oct;23(21):8840. doi:10.3390/s23218840. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Alrashdi I, Alqazzaz A, Aloufi E, Alharthi R, Zohdy M, Ming H. AD-IoT: anomaly detection of IoT cyberattacks in smart city using machine learning. In: Sharma K, editor. 2019 IEEE 9th Annual Computing and Communication Workshop and Conference, CCWC 2019; 2019 Aug. p. 305–10. doi:10.1109/CCWC.2019.8666450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Dalal S, Lilhore UK, Faujdar N, Simaiya S, Ayadi M, Almujally NA, et al. Next-generation cyber attack prediction for IoT systems: leveraging multi-class SVM and optimized CHAID decision tree. J Cloud Comput. 2023 Sep;12(1):137. doi:10.1186/s13677-023-00517-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Wood NG. Explainable AI in the military domain. Ethics Inf Technol. 2024;26(2):1–13. doi:10.1007/s10676-024-09762-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Lundberg H, Mowla NI, Abedin SF, Thar K, Mahmood A, Gidlund M, et al. Experimental analysis of trustworthy in-vehicle intrusion detection system using eXplainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI). IEEE Access. 2022;10:102831–41. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3208573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Gurrapu S, Kulkarni A, Huang L, Lourentzou I, Batarseh FA. Rationalization for explainable NLP: a survey. Front Artif Intell. 2023 Sep;6:1955. doi:10.3389/frai.2023.1225093. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Zhang K, Wang H, Chen M, Chen X, Liu L, Geng Q, et al. Leveraging machine learning to proactively identify phishing campaigns before they strike. J Big Data. 2025 May;12(1):124. doi:10.1186/s40537-025-01174-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Gang Q, Muhammad A, Khan ZU, Khan MS, Ahmed F, Ahmad J. Machine learning-based prediction of node localization accuracy in IIoT-based MI-UWSNs and design of a TD coil for omnidirectional communication. Sustainability. 2022 Aug;14(15):9683. doi:10.3390/su14159683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Javed SH, Ahmad MB, Asif M, Akram W, Mahmood K, Das AK, et al. APT adversarial defence mechanism for industrial IoT enabled cyber-physical system. IEEE Access. 2023;11:74000–20. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3291599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Gaggero GB, Armellin A, Portomauro G, Marchese M. Industrial control system-anomaly detection dataset (ICS-ADD) for cyber-physical security monitoring in smart industry environments. IEEE Access. 2024;12:64140–9. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3395991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Mahmud R, Jin J, Kua J, Afrin M, Mistry S, Krishna A. Trusted microservice orchestration for secure edge computing in industrial cyber-physical systems. IEEE Netw. 2025;39:1. doi:10.1109/MNET.2025.3541032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Yafooz WMS, Bakar ZBA, Fahad SKA, Mithon AM. Business intelligence through big data analytics. Data Min Mach Learn. 2020;1016:217. doi:10.1007/978-981-13-9364-8_17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Kumari A, Patel RK, Sukharamwala UC, Tanwar S, Raboaca MS, Saad A, et al. AI-empowered attack detection and prevention scheme for smart grid system. Mathematics. 2022;10(16):1–18. doi:10.3390/math10162852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Kaggle. IoT Intrusion Detection [Online]. [cited 2025 May 20]. Available from: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/subhajournal/iotintrusion. [Google Scholar]

52. Neto ECP, Dadkhah S, Ferreira R, Zohourian A, Lu R, Ghorbani AA. CICIoT2023: a real-time dataset and benchmark for large-scale attacks in IoT environment. Sensors. 2023 Jun;23(13):5941. doi:10.3390/s23135941. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Singh V, Gupta I, Jana PK. A novel cost-efficient approach for deadline-constrained workflow scheduling by dynamic provisioning of resources. Futur Gener Comput Syst. 2018 Feb;79:95–110. doi:10.1016/J.FUTURE.2017.09.054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Matni N, Moraes J, Oliveira H, Rosário D, Cerqueira E. Lorawan gateway placement model for dynamic internet of things scenarios. Sensors. 2020;20(15):1–18. doi:10.3390/s20154336. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Deng D. DBSCAN clustering algorithm based on density. In: 2020 7th International Forum on Electrical Engineering and Automation (IFEEA); 2020 Sep. p. 949–53. doi:10.1109/IFEEA51475.2020.00199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Shah K, Patel H, Sanghvi D, Shah M. A comparative analysis of logistic regression, random forest and KNN models for the text classification. Augment Hum Res. 2020 Dec;5(1):12. doi:10.1007/s41133-020-00032-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Farnaaz N, Jabbar MA. Random forest modeling for network intrusion detection system. Procedia Comput Sci. 2016;89:213–7. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2016.06.047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Chen Z, Li Z, Huang J, Liu S, Long H. An effective method for anomaly detection in industrial Internet of Things using XGBoost and LSTM. Sci Rep. 2024 Oct;14(1):23969. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-74822-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Venkatesan VK, Ramakrishna MT, Izonin I, Tkachenko R, Havryliuk M. Efficient data preprocessing with ensemble machine learning technique for the early detection of chronic kidney disease. Appl Sci. 2023 Feb;13(5):2885. doi:10.3390/app13052885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Khater BS, Abdul Wahab AW, Idris MYI, Hussain MA, Ibrahim AA, Amin MA, et al. Classifier performance evaluation for lightweight ids using fog computing in IoT security. Electron. 2021;10(14):1633. doi:10.3390/electronics10141633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Wang Z, Wang C, Li X, Xia C, Xu J. MLP-Net: multilayer perceptron fusion network for infrared small target detection. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2025;63:1–13. doi:10.1109/TGRS.2024.3515648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools