Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Deep Learning in Medical Image Analysis: A Comprehensive Review of Algorithms, Trends, Applications, and Challenges

1 Symbiosis Artificial Intelligence Institute, Symbiosis International (Deemed University), Pune, 412115, Maharashtra, India

2 Department of Electronics and Communication Engineering, Faculty of Engineering & Technology, Marwadi University Research Center, Marwadi University, Rajkot, 360003, Gujarat, India

3 Faculty of Engineering, Sohar University, Sohar, 311, Oman

4 Centre for Research Impact & Outcome, Chitkara University Institute of Engineering and Technology, Chitkara University, Rajpura, 140401, Punjab, India

5 College of Technical Engineering, The Islamic University, Najaf, 54001, Iraq

6 Department of Computer Science and Information Technology, Siksha ‘O’ Anusandhan (Deemed to be University), Bhubaneswar, 751030, Odisha, India

7 Department of Biotechnology, University Centre for Research and Development, Chandigarh University, Mohali, 140413, Punjab, India

* Corresponding Author: Dawa Chyophel Lepcha. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Artificial Intelligence Models in Healthcare: Challenges, Methods, and Applications)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(2), 1487-1573. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.070964

Received 28 July 2025; Accepted 24 October 2025; Issue published 26 November 2025

Abstract

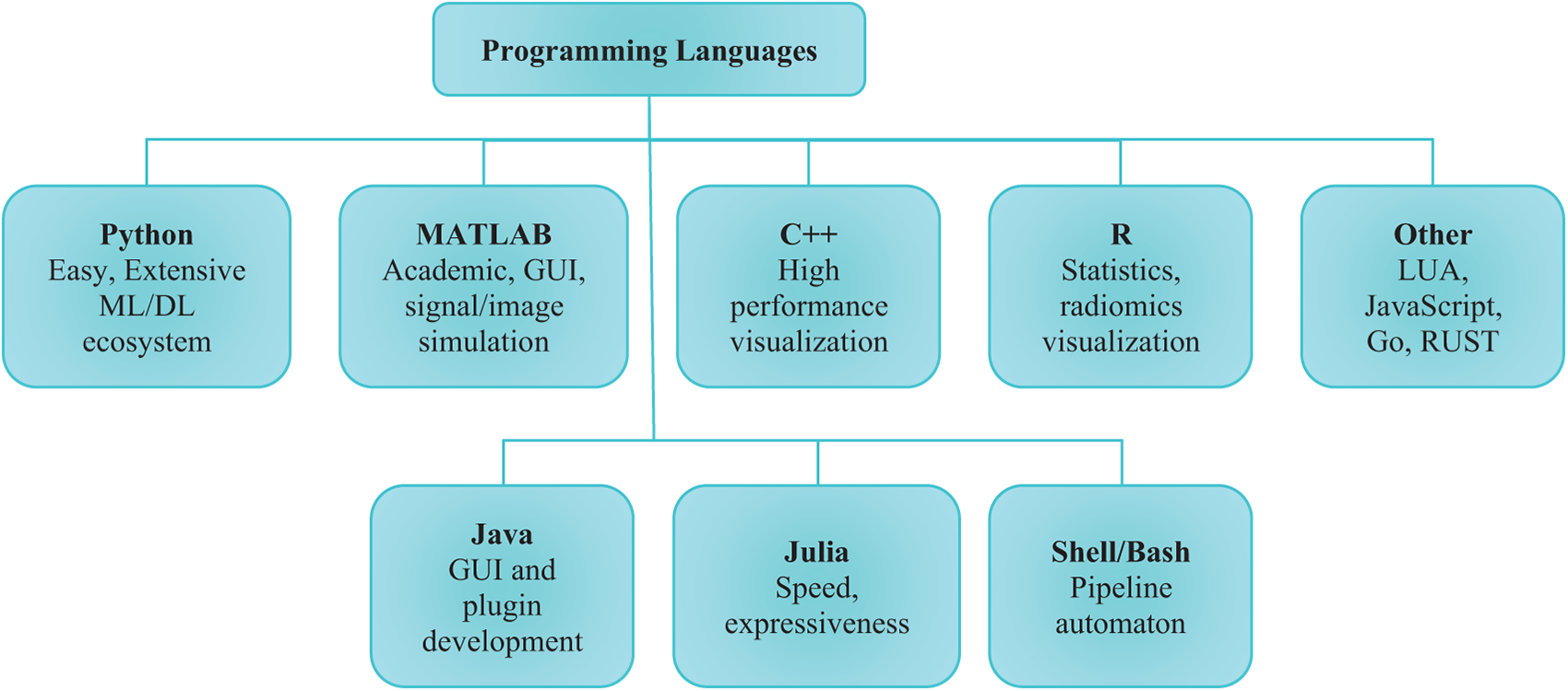

Medical image analysis has become a cornerstone of modern healthcare, driven by the exponential growth of data from imaging modalities such as MRI, CT, PET, ultrasound, and X-ray. Traditional machine learning methods have made early contributions; however, recent advancements in deep learning (DL) have revolutionized the field, offering state-of-the-art performance in image classification, segmentation, detection, fusion, registration, and enhancement. This comprehensive review presents an in-depth analysis of deep learning methodologies applied across medical image analysis tasks, highlighting both foundational models and recent innovations. The article begins by introducing conventional techniques and their limitations, setting the stage for DL-based solutions. Core DL architectures, including Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), Vision Transformers (ViTs), and hybrid models, are discussed in detail, including their advantages and domain-specific adaptations. Advanced learning paradigms such as semi-supervised learning, self-supervised learning, and few-shot learning are explored for their potential to mitigate data annotation challenges in clinical datasets. This review further categorizes major tasks in medical image analysis, elaborating on how DL techniques have enabled precise tumor segmentation, lesion detection, modality fusion, super-resolution, and robust classification across diverse clinical settings. Emphasis is placed on applications in oncology, cardiology, neurology, and infectious diseases, including COVID-19. Challenges such as data scarcity, label imbalance, model generalizability, interpretability, and integration into clinical workflows are critically examined. Ethical considerations, explainable AI (XAI), federated learning, and regulatory compliance are discussed as essential components of real-world deployment. Benchmark datasets, evaluation metrics, and comparative performance analyses are presented to support future research. The article concludes with a forward-looking perspective on the role of foundation models, multimodal learning, edge AI, and bio-inspired computing in the future of medical imaging. Overall, this review serves as a valuable resource for researchers, clinicians, and developers aiming to harness deep learning for intelligent, efficient, and clinically viable medical image analysis.Keywords

In modern clinical practice, the accuracy of cancer and other disease detection and diagnosis relies on the expertise of particular clinicians (e.g., radiologists, pathologists), leading to significant inter-reader variability in the interpretation of medical images [1]. To handle and resolve this clinical dilemma, many computer-aided diagnosis (CAD) systems [2] have been developed and evaluated with the intention of assisting physicians in understanding medical images more efficiently and making diagnostic decisions with greater accuracy and objectivity [3]. This practice is scientifically justified as it enables computer-aided, objective analysis of image features which can address several challenges in clinical practice, including the shortage of skilled clinicians, the risk of fatigue among human experts and the limited availability of medical resources [4]. While initial computer-aided diagnosis systems were established in the 1970s [5], advancements in CAD systems have accelerated since the mid-1990s due to the incorporation of more sophisticated machine learning practices into these systems [6–8]. Traditional CAD practices typically involve a three-step development process: image segmentation, feature computation, and disease classification. For example, Sahiner et al. [9] devised a CAD system for facilitating mass categorization on digital mammograms [10]. The regions of interest comprising the object masses were initially classified from the background utilizing a modified active contour system.

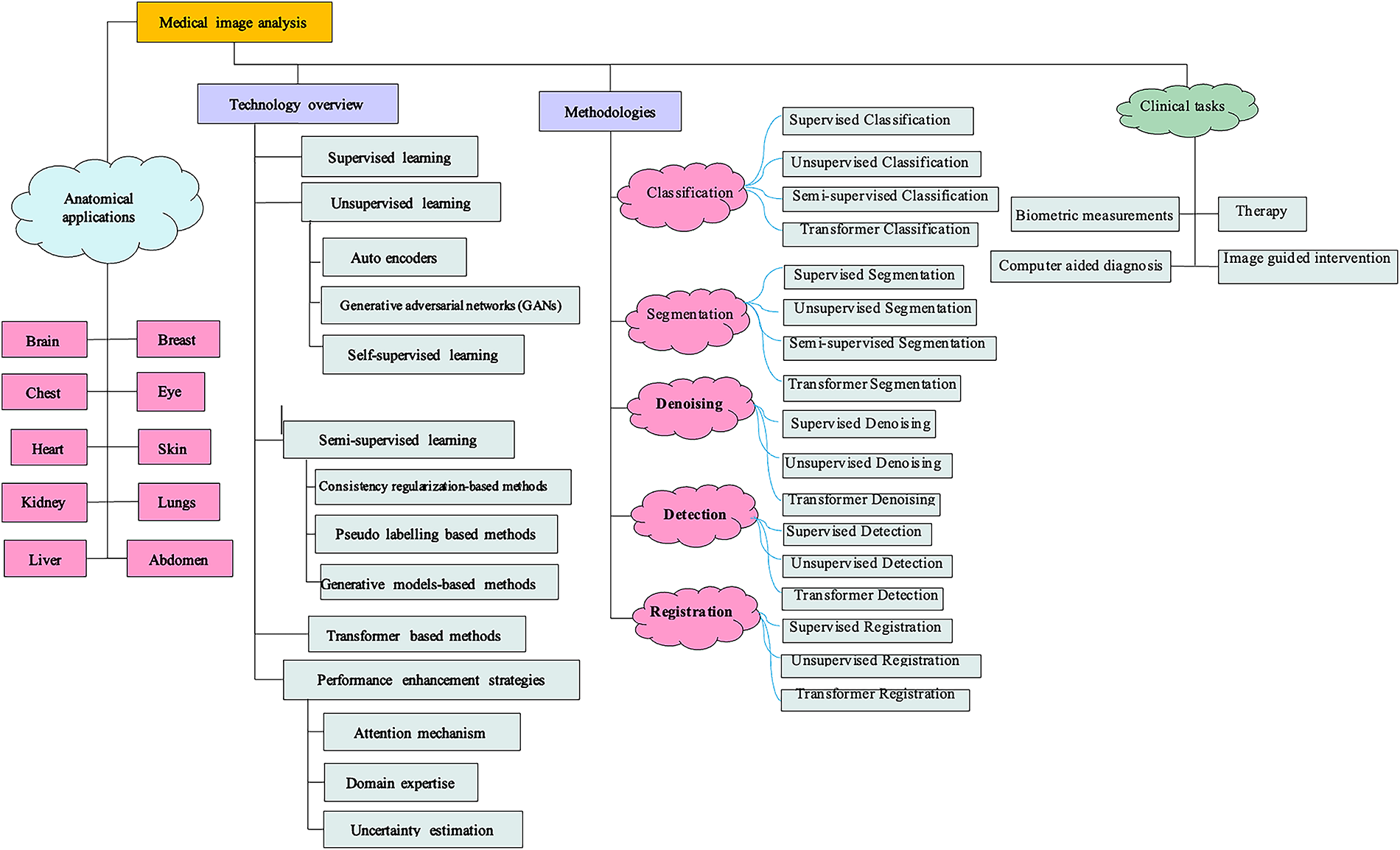

A substantial array of imaging elements was utilized for computing the lesions characteristics in terms of dimension, morphology, margin geometry, texture, and other factors. Thus, the unprocessed pixel data are transformed into a vector of representative characteristics. A classification model based on linear discriminant analyses (LDA) was ultimately employed on the feature vector to ascertain bulk malignancy. In contrast, deep learning models progressively identify and learn hidden patterns within regions of interest using the hierarchical structure of deep neural networks [11]. Throughout the process, significant characteristics of the input image will be progressively recognized and enhanced for specific tasks (e.g., detection, classification) while unnecessary features will be reduced and eliminated. An MRI image illustrating questionable liver lesions consists of a pixel array [12] with each entry serving as an individual source feature for the deep learning model. The initial layers of the design may acquire fundamental lesion information, including tumour morphology, position, and orientation [13]. The subsequent layer batch may identify and maintain traits consistently associated with lesion malignancy, while ignoring unimportant fluctuations. Relevant features will undergo additional processing and integration by following high levels in a more intangible manner. Increasing the numbers of layers enhances the feature representations level [14–18]. Throughout the complete process, significant attributes hidden within the raw input are identified by the general neural network structure in an unsupervised manner, eliminating the necessity for manual feature extraction [19–21]. Alom et al. proposed an improved U-Net architecture that maintains the same number of network parameters while achieving superior performance in medical image segmentation. The model was evaluated on multiple benchmark datasets, including blood vessel segmentation in retinal images, skin cancer segmentation, and lung lesion segmentation. Experimental results demonstrated its enhanced segmentation accuracy compared to existing models such as U-Net and residual U-Net (ResU-Net). The study presents an optimized architecture that achieves optimal performance without increasing network complexity. Due to its significant advantages, deep learning methodologies have emerged as the predominant technology in the CAD domain and have been extensively utilized across various tasks, such as disease classification, region of interest (ROI) segmentation, medical object detection, and image registration [22–25]. Supervised learning was the initial deep learning technique utilized in medical image analysis [26–28]. Despite its successful application in numerous contexts [29,30], the broader implementation of supervised algorithms in various scenes is significantly hindered by the limited dimension of several medical datasets. In contrast to traditional datasets in computer visions, the dataset typically comprises a limited number of images, with only a negligible portion of these images annotated by specialists. Fig. 1 depicts the taxonomy of deep learning methods, applications, and challenges in medical image analysis.

Figure 1: Overall taxonomy of this study outlining deep learning methods, applications, and challenges in medical image analysis

To address these restrictions, unsupervised as well as semi-supervised learning models have garnered significant attention in the past few years, enabling (1) the generation of additional labelled images from model optimisation, (2) the extraction of significant hidden information from unlabelled image data, and (3) the creation of pseudo labels for the unlabelled data. The number of outstanding survey publications summarizing deep learning usages in medical image analysis presently exist. References [31,32] examined early deep learning methodologies, primarily grounded in supervised procedures. Recently, References [33,34] examined the use of GANs in several medical imaging tasks. Reference [35] examined the application of semi-supervised learning and multiple instance deep learning in segmentation tasks. Reference [36] examined various methods to address dataset constraints (e.g., limited or inadequate annotations) specifically in image segmentation. These points echo earlier discussions, as they remain fundamental barriers for applying supervised learning at scale.

This study aims to elucidate how the medical image analysis domain, sometimes limited by scarce annotated data, may benefit from recent advancements in deep learning. Our study is notable from recent publications by its comprehensiveness and technical alignment. Firstly, we emphasize the applications of many promising methodologies under the machine learning paradigms, encompassing self-supervised, unsupervised, and semi-supervised learning simultaneously. Secondly, instead of focusing just on a particular task, we present the applicability of the above-mentioned learning methodologies across several important medical image analysis techniques. We precisely studied deep learning in detail, which is a topic that is hardly addressed in recent survey articles. We concentrated on the utilization of chest X-rays, mammograms, CT scans, MRI, PET images, and so on. All these image types share numerous common properties, which are analysed by radiologists within the same department (Radiology). We also referenced some general methodologies utilized in other image domains (e.g., histopathology, skin lesion, ultrasound, Dermoscopy, pneumonia, etc.) that may be applicable to radiographic or MRI images. Third, existing models for these techniques are explained thoroughly. We precisely examine the recent advancements in machine learning paradigm methodologies. This survey may benefit a broad audience, including researchers specializing in deep learning, big data, artificial intelligence, machine learning, and physicians or medical researchers.

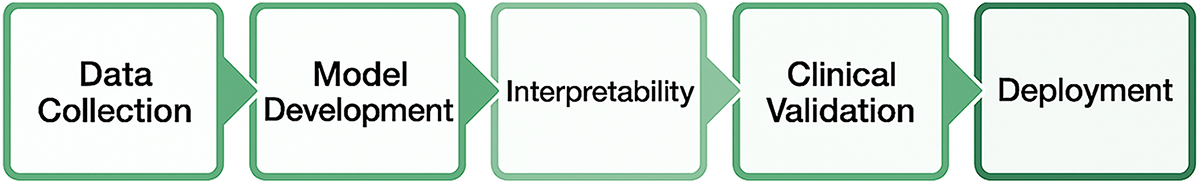

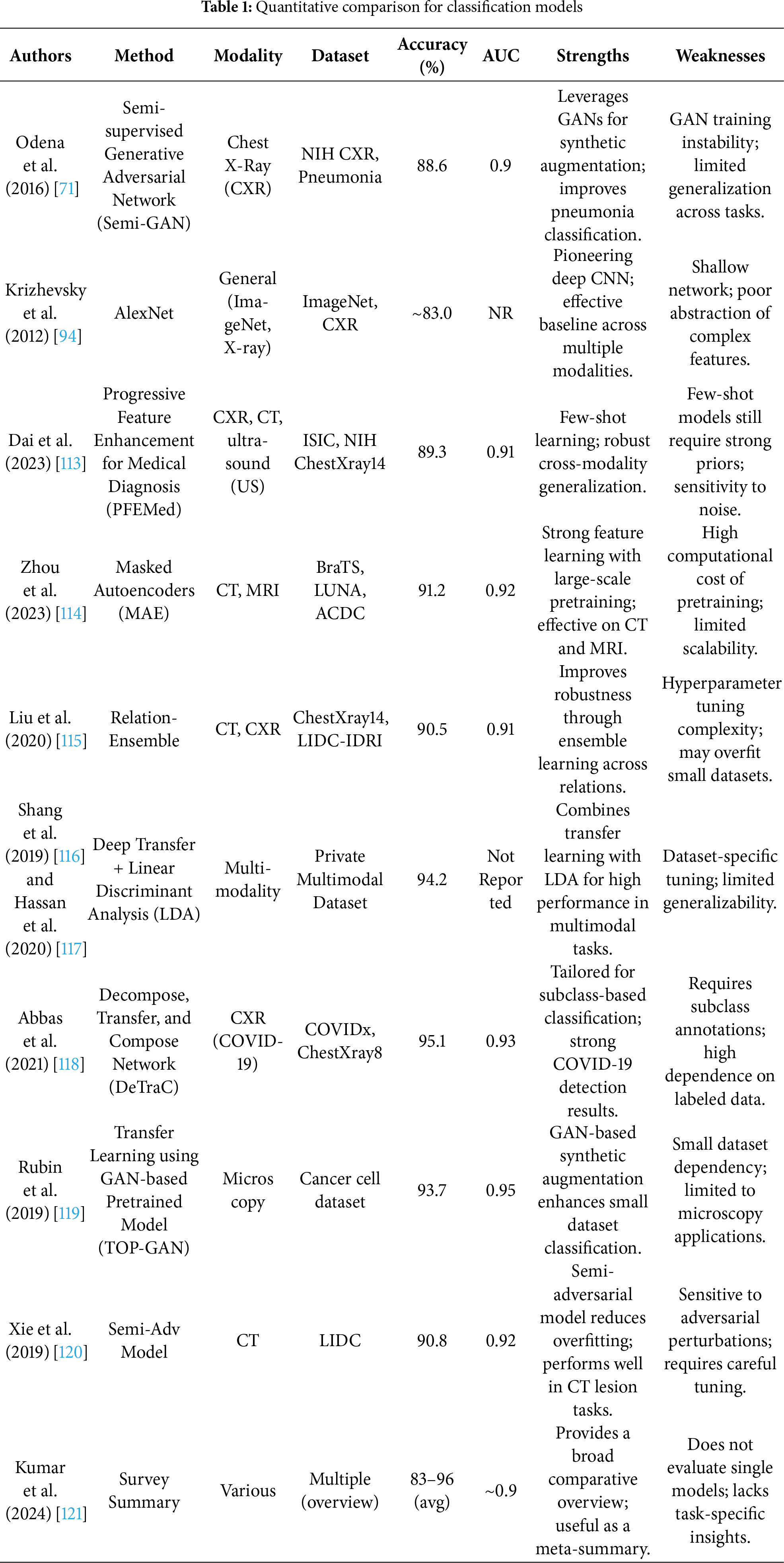

The remainder of the article is structured as follows: Section 2 outlines the research process in medical image analysis. Section 3 presents deep learning paradigms relevant to medical imaging, while Section 4 offers a critical evaluation of prominent DL models. Section 5 explores clinical suitability and adoption barriers of emerging techniques. Section 6 emphasizes scalability and generalizability beyond benchmark datasets. Section 7 discusses evaluation metrics, regulatory frameworks, and interpretability. Section 8 introduces model maturity mapping for clinical readiness. Sections 9 and 10 address the research–clinic gap and deployment best practices. Sections 11 to 14 analyze model validation, clinical trends, dataset challenges, and security concerns. Finally, Sections 15 to 18 present open challenges, discussion, future directions, and the conclusion.

This study meticulously examined relevant documents that generally investigated the application of deep learning models in medical image analysis. This section thoroughly covers the domain of medical image analysis by using the systematic literature review exercise. This study involves a thorough evaluation of all research conducted on a pivotal topic. The study concludes with a comprehensive analysis of machine learning models in the domain of medical image analysis. The reliability of the research selection procedures is examined. The subsequent subsections contain further information regarding research methodologies, including selection criteria. The primary objectives of the research are to discover, evaluate, and distinguish all significant publications in the domain of deep learning systems for medical image analysis. The practice of systematic literature review can be employed to analyse the components and attributes of methodologies for achieving the specified objectives. Besides, a systematic literature review enables the attainment of a deep understanding of the critical issues and obstacles in this field.

2.1 The Process of Paper Analysis

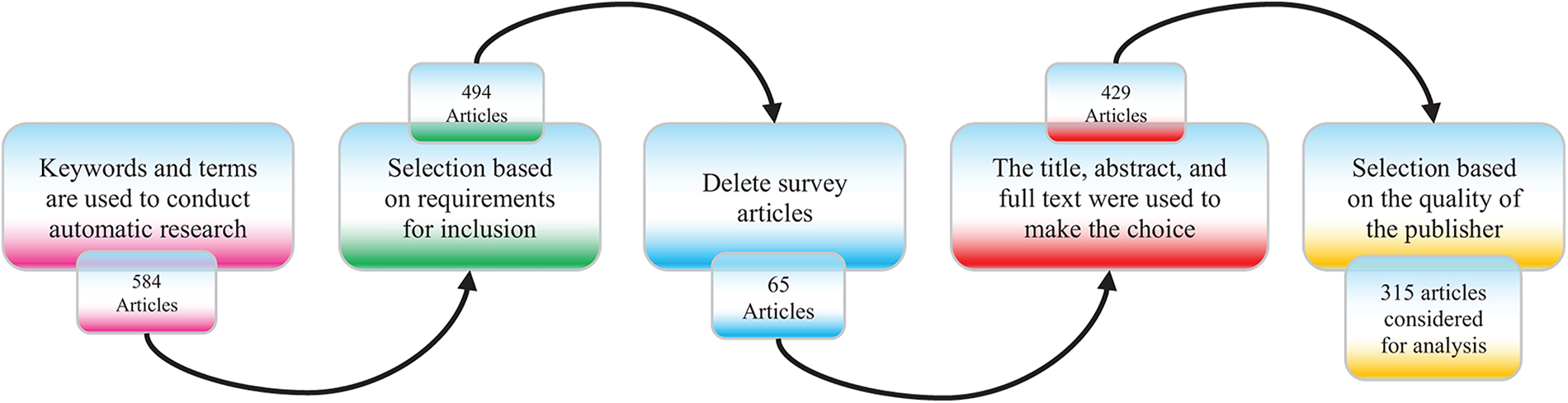

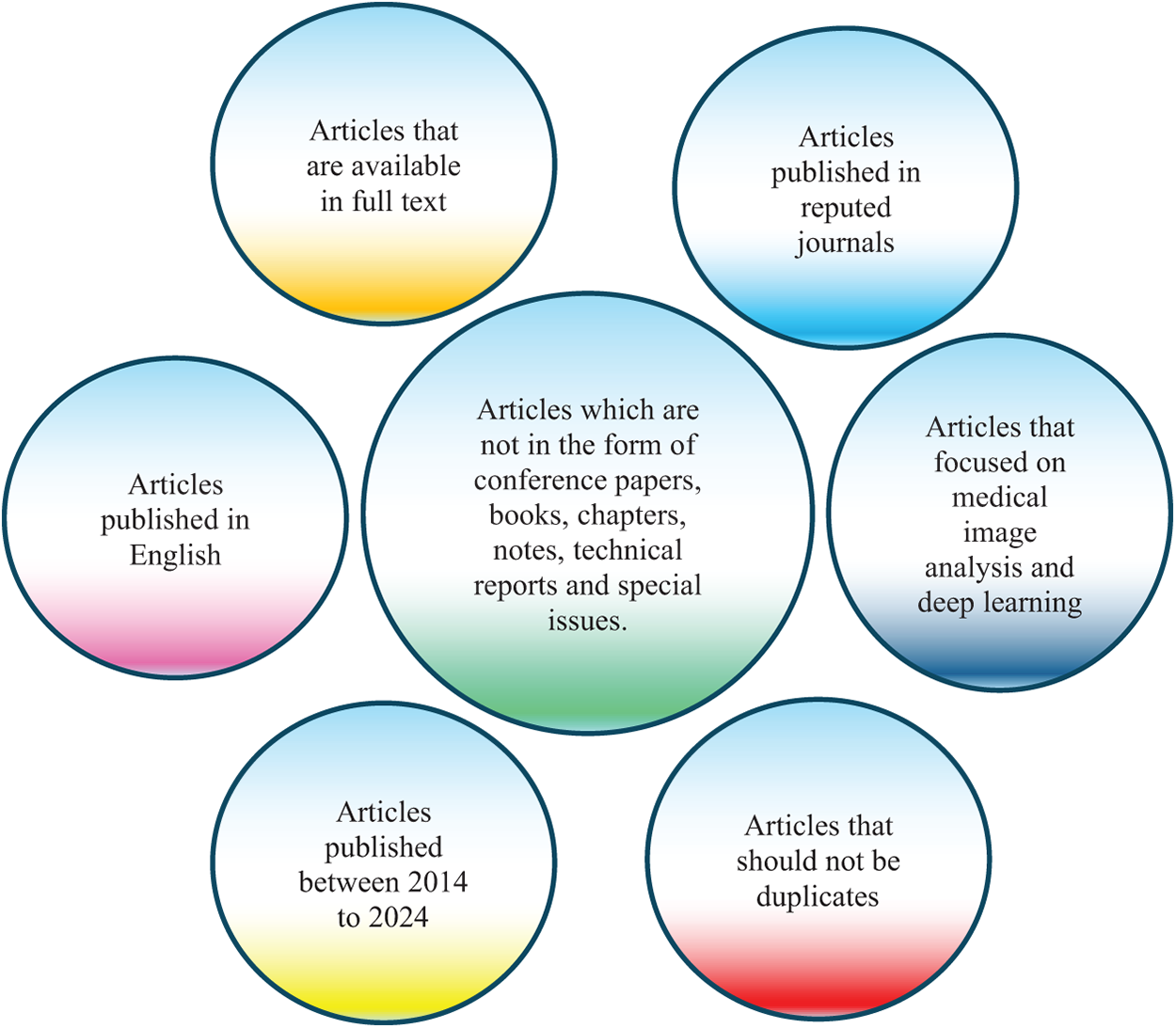

The search and selection processes used in this inquiry are divided into five stages, as shown in Fig. 2. The total of 584 papers is obtained by using an electronic database to retrieve relevant materials such as journals, chapters, technical studies, notes, conference papers, and special issues. Following a thorough analysis of these papers in accordance with a set of predefined criteria, only those that satisfied the requirements shown in Fig. 3 are selected for additional assessment. Fig. 2 displays the distribution of publications in this first phase. There were 494 articles remaining at the end of the first phase. The titles and abstracts of the selected papers were carefully studied in the following step with an emphasis on the methodology, analysis, discussion, and conclusion of the publications to make sure they were pertinent to the research. Following this stage, only 429 papers were kept, and 315 papers were further processed and selected for a more thorough assessment with the final goal of selecting publications that satisfied the predefined parameters of the study.

Figure 2: Phases of the article searching and selection process used in the systematic literature review

Figure 3: Criteria for inclusion in the article selection process used for identifying relevant studies

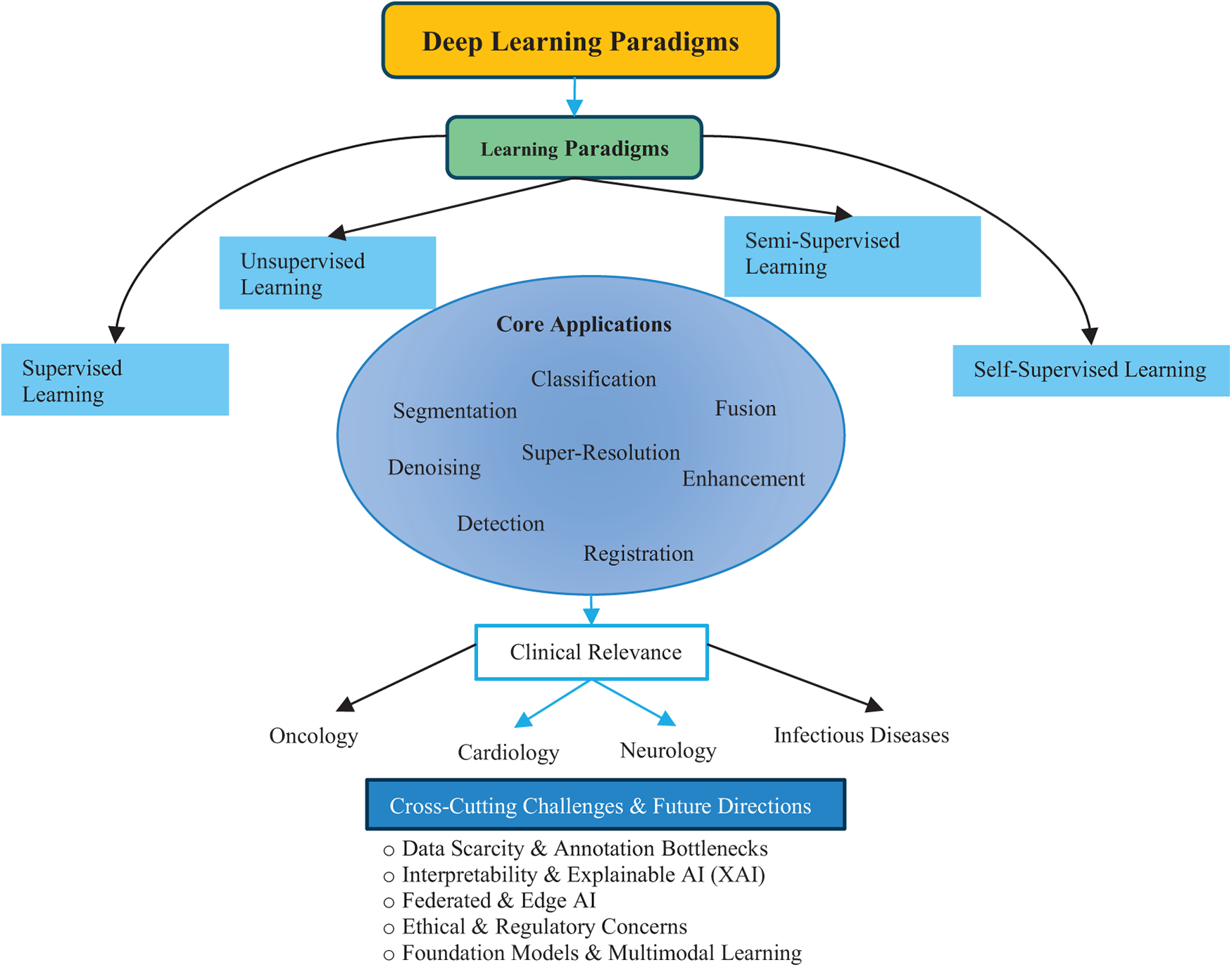

Fig. 4 provides a top-down roadmap of the study. The central theme of Deep Learning in Medical Image Analysis is first expanded into four major learning paradigms. These paradigms support a range of medical imaging applications, which are further contextualized in clinical domains such as oncology, cardiology, neurology, and infectious diseases. At the foundation, key challenges and future directions highlight emerging issues such as data scarcity, interpretability, federated and edge AI, ethical concerns, and the role of foundation models. Together, this overview helps readers navigate the structure and flow of the review.

Figure 4: Overview of the review structure illustrating the relationship between deep learning paradigms, applications, and clinical domains

3 Deep Learning Paradigms in Medical Imaging

Deep learning (DL) has profoundly transformed medical image analysis, offering powerful tools for disease diagnosis, prognosis, and therapeutic planning; however, its methodological landscape encompassing supervised, unsupervised, semi-supervised, and self-supervised learning necessitates a critical examination not only of their theoretical formulations but also of their limitations, real-world relevance, and potential for generalization. Supervised learning remains the most established approach in the field, particularly through the use of Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) [37], which excel at hierarchically extracting features from images and yielding highly accurate classification and segmentation outputs when large, annotated datasets are available. Nonetheless, the dependence on extensive, high-quality labelled data severely restricts the scalability of this paradigm, especially in medical domains where data annotation demands expert radiologists, incurs high costs, and raises privacy concerns. In addition, CNNs are prone to performance degradation under class imbalance, a common issue in rare disease datasets, and often suffer from poor generalization to out-of-distribution data, thus undermining their utility in diverse clinical settings. Furthermore, their fixed receptive field size and pooling operations can result in the loss of subtle anatomical details that are critical for accurate medical interpretation, exacerbated by their black-box nature, which complicates clinical trust and transparency. In contrast, unsupervised learning offers an alluring promise of label-free discovery by modeling underlying data distributions using techniques such as autoencoders (AEs) [38], stacked autoencoders (SAEs) [39], and various regularized variants including sparse [40], denoising [41], and contractive autoencoders [42], which aim to extract compact and generalizable latent features. Yet, these models often fail to yield clinically useful representations without extensive tuning, and while deep generative frameworks like Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) [43] and their extensions using Gaussian mixture priors [44] or conditional architectures [45] attempt to address expressiveness, they struggle with reconstructing sharp and realistic medical images, undermining diagnostic reliability. Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) [46] represent a more expressive alternative and are widely applied for image synthesis, domain translation, and augmentation, yet they are notoriously difficult to train, with frequent issues such as mode collapse and sensitivity to hyperparameters, although architectural innovations like Wasserstein GANs (WGANs) [47], conditional GANs (cGANs) [48], and auxiliary classifier GANs (ACGANs) [49] have significantly improved training stability and controllability. Nevertheless, the metrics typically used to evaluate these models’ reconstruction error or adversarial success do not always align with clinically meaningful performance, and as a result, their adoption in medical pipelines remains limited due to concerns around interpretability and reliability. Meanwhile, self-supervised learning (SSL) emerges as an innovative middle ground by automatically generating supervisory signals (pseudo-labels) from unlabelled data using pretext tasks such as image inpainting [50], colorization [51], relative patch prediction [52], jigsaw puzzle solving [53], and rotation recognition [54] inspired by its success in natural language processing with models like Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) [55]. Among SSL techniques, contrastive learning frameworks such as Momentum Contrast for Unsupervised Visual Representation Learning (MoCo) [56] and Simple Framework for Contrastive Learning of Visual Representations (SimCLR) [57] have gained significant traction by training models to maximize agreement between different augmented views of the same image while minimizing agreement with views from other images, using Information Noise-Contrastive Estimation (InfoNCE) loss [58] and projection heads to create well-separated latent spaces. However, while contrastive SSL has shown promise in natural image tasks, its application in medical imaging is still in its infancy, constrained by domain-specific challenges such as limited variability in anatomical structures, class imbalance, and the need for clinically appropriate augmentations. Recent studies highlight the potential of hybrid approaches that combine SSL with classical machine learning classifiers. Such frameworks can improve robustness and interpretability compared to fully end-to-end deep learning pipelines. For instance, a study demonstrated that SSL features coupled with conventional classifiers achieved superior performance in biomedical image analysis tasks [59,60]. These results suggest that hybrid SSL–Machine Learning (ML) paradigms may serve as strong alternatives in scenarios with limited labeled data and the need for greater interpretability.

Furthermore, the potential of SSL remains largely untapped in medical applications due to a lack of large-scale domain-specific studies and benchmark datasets, although it holds significant promise in overcoming annotation bottlenecks that plague other learning paradigms. Semi-supervised learning (also abbreviated as SSL) offers a practical compromise between supervised and unsupervised approaches by combining small labeled datasets with abundant unlabelled data, thus reducing the dependency on expert annotation. Early criticisms, such as those highlighted in [61], which demonstrated that unlabelled data could degrade performance, are now being revisited in light of more sophisticated deep semi-supervised architectures that consistently outperform their supervised counterparts in medical imaging tasks [62]. Consistency regularization methods, including Π-model and temporal ensembling [63], as well as ladder networks [64], enforce stability under perturbations by minimizing the difference in model outputs when noise or augmentation is applied to the same input, while mean-teacher models [65] improve robustness through a student-teacher framework optimized with dual loss components. Pseudo-labelling strategies [66], which generate soft labels for unlabelled data based on model confidence, are further enhanced through Mixup augmentation [67], unsupervised data augmentation (UDA) [68], and co-training techniques [69], each helping to refine model predictions iteratively with minimal supervision. Meanwhile, semi-supervised extensions of generative models, particularly GANs adapted for classification tasks [70,71], and the more modular Triple-GAN [72], show considerable promise in integrating both generative fidelity and discriminative accuracy, although training these multi-objective architectures remains challenging and computationally intensive. Across all paradigms, enhancing deep learning models for medical use necessitates strategic architectural interventions, such as attention mechanisms that enable models to focus on salient regions of interest. These mechanisms, inspired by visual cognition [73] and widely applied in NLP [74,75] have found success in vision tasks like image captioning [76–78], object recognition, and medical image segmentation [79,80] with specific implementations like spatial attention [81], channel attention [82], self-attention [83], and the hybrid convolutional block attention module (CBAM) [84,85] each offering tailored benefits in highlighting diagnostic features. The Transformer model built entirely on self-attention layers, epitomizes the trend towards attention-dominant architectures, although its high computational demands and dependency on large training corpora remain barriers to adoption in medical imaging. Furthermore, attention mechanisms, while improving localization and interpretability, add architectural complexity and are often dependent on large datasets to learn meaningful attention maps, which can limit their application in resource-constrained healthcare environments. Another crucial area is the integration of domain expertise, as many pre-trained models derived from natural images perform poorly on medical data due to limited texture diversity, subtle inter-class differences, and smaller dataset sizes. Effective DL applications in medicine often involve embedding anatomical priors [86,87], 3D spatial dependencies, and multimodal metadata [88] into network architectures, either via auxiliary channels, feature fusion, or custom loss functions; for instance, radiomic features and pathology reports can provide complementary information that boosts model performance and interpretability. While these integrations improve clinical relevance and model accuracy, they often require highly specialized architectural designs and limit cross-domain generalizability. Finally, the estimation of predictive uncertainty is essential for clinical trustworthiness, especially in high-stakes domains like oncology, where decisions based on erroneous predictions can have life-threatening consequences. Bayesian deep learning methods, such as Monte Carlo dropout (MC-dropout) [89], approximate posterior distributions over network weights to quantify uncertainty, while model ensembles [90] capture variance across independently trained models to provide robust confidence estimates. These uncertainty estimation techniques, although computationally expensive, enable critical functionalities such as error detection, selective prediction, and triage decision support [91], helping bridge the trust gap between AI systems and clinical practitioners. Despite their theoretical appeal, the practical implementation of uncertainty-aware models is still rare in deployed systems due to added computational burden, interpretability challenges, and a lack of standardized evaluation protocols. In conclusion, the landscape of deep learning for medical image analysis is marked by both remarkable progress and persistent challenges, with supervised learning offering strong performance under ideal data conditions, unsupervised learning pushing the boundaries of label-free modeling, semi-supervised learning providing data-efficient compromises, and self-supervised learning presenting a new frontier for leveraging unlabelled data through creative supervisory signals. Enhancing these paradigms through the strategic use of attention mechanisms, domain-specific features, and uncertainty estimation not only improves accuracy and generalization but also fosters clinical acceptance by addressing the foundational concerns of trust, transparency, and reproducibility. As the field evolves, a hybrid methodology that dynamically integrates these learning strategies in a modular, data-aware, and context-specific manner is likely to drive the next wave of breakthroughs in medical AI, moving beyond algorithmic performance metrics to prioritize real-world utility, ethical compliance, and patient safety. Bio-inspired models, including swarm intelligence and evolutionary algorithms, are increasingly applied in medical imaging. These approaches can optimize feature extraction, segmentation, and classification processes while offering improved adaptability to complex datasets. Recent works demonstrate their effectiveness in medical domains, reinforcing their role as complementary paradigms alongside conventional deep learning [92].

4 Critical Evaluation of Deep Learning Models

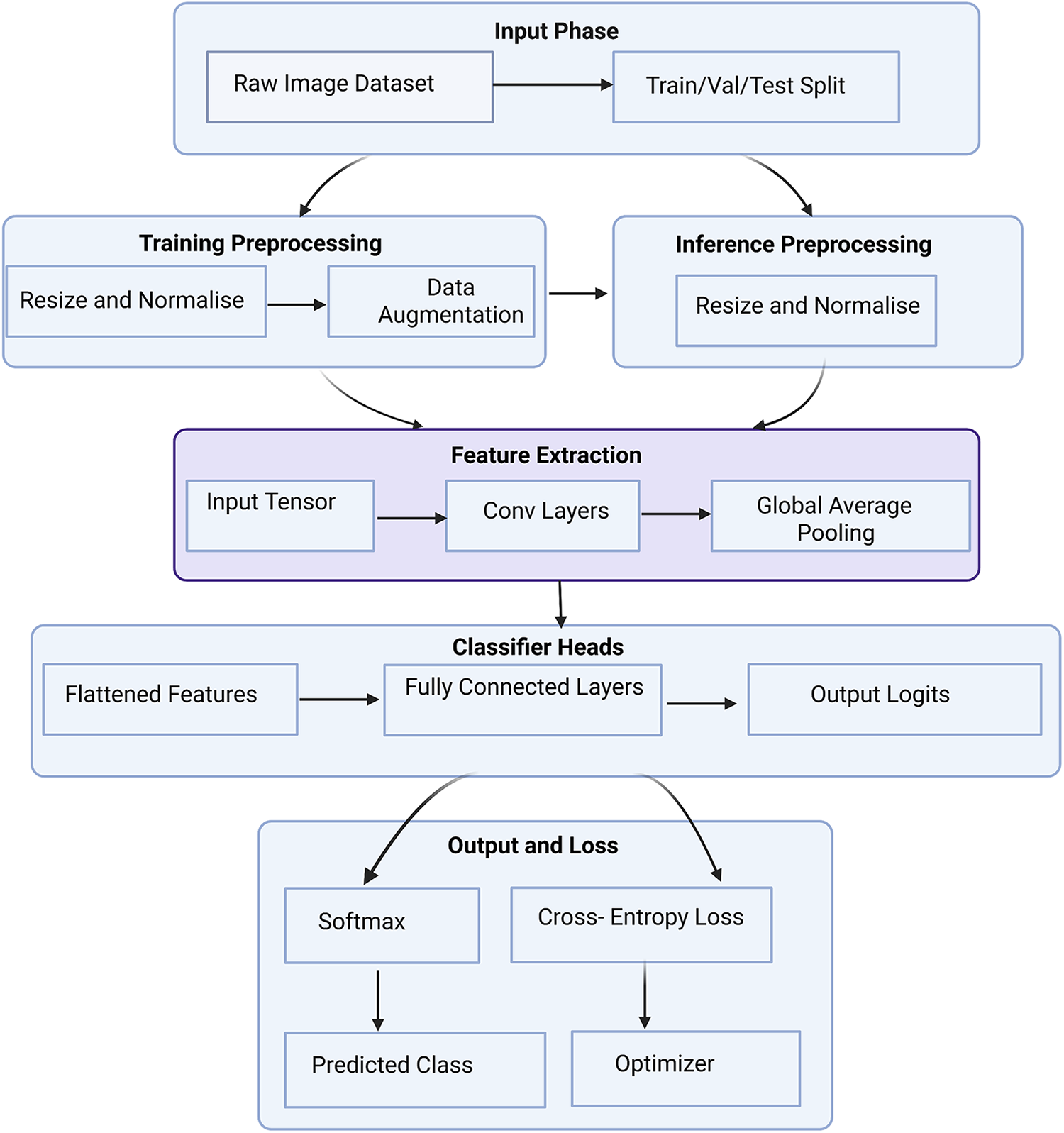

Deep learning-based classification in computer-aided diagnosis (CADx) has made significant strides in disease identification and lesion characterization from medical images [93]. However, rather than presenting a purely descriptive overview, it is critical to assess these methods in light of their performance bottlenecks, data dependencies, and clinical reliability, especially when deployed in diverse, real-world healthcare settings. Supervised learning models, such as AlexNet [94], Visual Geometry Group (VGG) [95], GoogleLeNet [96], ResNet [97], and DenseNet [98] have become foundational in CADx. These architectures provide deep hierarchical representations that excel in capturing complex spatial features in medical images. However, their reliance on extensive, high-quality annotated datasets poses a significant barrier, particularly in domains like 3D MRI and CT imaging, where expert-labeled data is scarce and difficult to acquire due to clinical workload, patient privacy, and cost [99,100]. Transfer learning has emerged as a practical solution to this challenge. By leveraging pretrained weights from large-scale datasets like ImageNet [101] or domain-specific medical image datasets, models can be effectively fine-tuned for target clinical tasks with significantly fewer training examples, consistently outperforming models trained from scratch [102]. These strategies have proven particularly effective across modalities such as CT [103], MRI [104], mammography [105], and X-ray [106], and are further enhanced by attention mechanisms [107–109] which enable models to focus on the most diagnostically relevant regions. For instance, Huo et al.’s Hierarchical Fusion Network (HiFuse) [110] employs a hierarchical multi-scale fusion of local and global features using an adaptive fusion block to improve representational power and classification accuracy across diverse imaging conditions. Fig. 5 demonstrated schematic flow diagram of a deep learning–based image classification network.

Figure 5: Schematic flow diagram of a deep learning–based image classification network

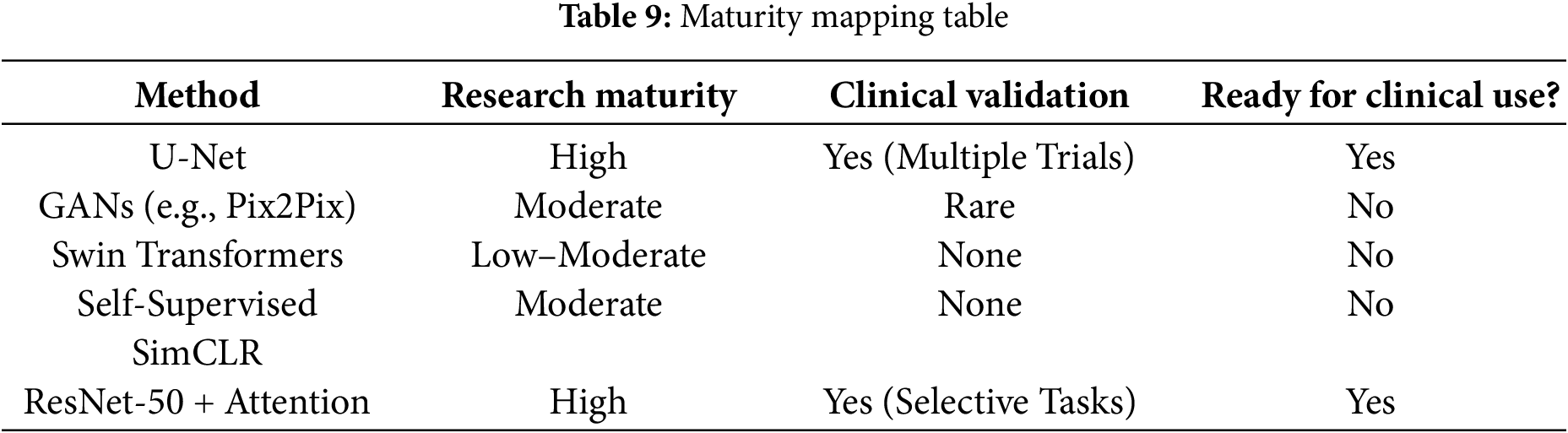

The supervised models dominate clinical research, while unsupervised methods are gaining grip for their potential to reduce dependency on labeled data. Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) have been extensively explored for data augmentation, offering the ability to synthesize realistic pathological variations. Frid-Adar et al. [111] demonstrated improved liver lesion classification performance using Deep Convolutional Generative Adversarial Network (DCGAN)-generated samples, later extending to ACGAN [17] for class-conditional generation, though with mixed results. Similarly, conditional GANs have been used in mammogram classification to generate lesion-specific samples with marginal accuracy improvements [112]. Complementing GANs, few-shot learning approaches like PFEMed [113] use dual-encoder strategies and Variational Autoencoders to extract both general and task-specific features, enhancing classification with limited samples. In addition to GANs and VAEs, diffusion models have emerged as powerful generative tools for medical imaging. These models are capable of synthesizing high-fidelity medical images, enabling data augmentation, anomaly detection, and simulation of rare conditions. Their integration into generative frameworks enhances the ability to train robust models under limited data conditions. Table 1 summarizes the quantitative performance of different classification models.

More recently, self-pretraining using Masked Autoencoders (MAE) [114] has shown promise in vision transformer (ViT)-based architectures, where models learn to reconstruct missing image regions, leveraging contextual relationships inherent in medical images. Self-supervised learning (SSL) has also emerged as a transformative approach. Frameworks like MoCo [15,56], SimCLR [122] and others [123–127] rely on contrastive learning or pretext tasks to extract robust representations from unlabelled data, significantly boosting classification performance in tasks like diabetic retinopathy, chest X-ray analysis [128], and COVID-19 detection [129]. These models benefit from clever pretraining strategies such as Rubik’s cube recovery [130,131], rotation prediction [132], and context restoration [133], which enhance the feature extraction process and improve transferability to downstream tasks. Efficient hybrid models like Eff-CTNet [134] and CNN-transformer frameworks [135] combine global attention with local texture learning while mitigating computational burden and vulnerability to adversarial attacks. In parallel, semi-supervised learning methods such as consistency regularization via Mean Teacher [65], semi-supervised GANs [115,121], and knowledge-aware SSL frameworks like Unsupervised Knowledge-guided Self-Supervised Learning (UKSSL) [136] integrate unlabeled and labeled data for performance gains. UKSSL incorporates Medical Contrastive Learning of Representations (MedCLR) and Unsupervised Knowledge-guided Multi-Layer Perceptron (UKMLP) modules for feature extraction and classification using only 50% labeled data while achieving near state-of-the-art accuracy on diverse benchmarks. Taken together, while supervised models provide a strong baseline, unsupervised, self-supervised, and semi-supervised methods critically address data limitations and generalizability challenges, establishing themselves as vital components in the future of CADx-driven medical image classification. Yang et al. [137] present MedKAN, a medical image classification framework built upon KAN and its convolutional extensions. MedKAN features two core modules: The Local Information KAN (LIK) module for fine-grained feature extraction and the Global Information KAN (GIK) module for global context integration. Lai et al. [138] proposed a new Multi-instance Learning (MIL) framework integrating CNN Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) and Broad Learning Systems (BLS). Hussain et al. [139] present Efficient Residual Network-Vision Transformer (EFFResNet-ViT), a novel hybrid deep learning (DL) model designed to address these challenges by combining EfficientNet-B0 and ResNet-50 CNN backbones with a vision transformer (ViT) module. The proposed architecture employs a feature fusion strategy to integrate the local feature extraction strengths of CNNs with the global dependency modeling capabilities of transformers. Regmi et al. [140] uses different CNNs and transformer-based methods with a wide range of data augmentation techniques. We evaluated their performance on three medical image datasets from different modalities. We evaluated and compared the performance of the vision transformer model with other state-of-the-art pre-trained CNN networks.

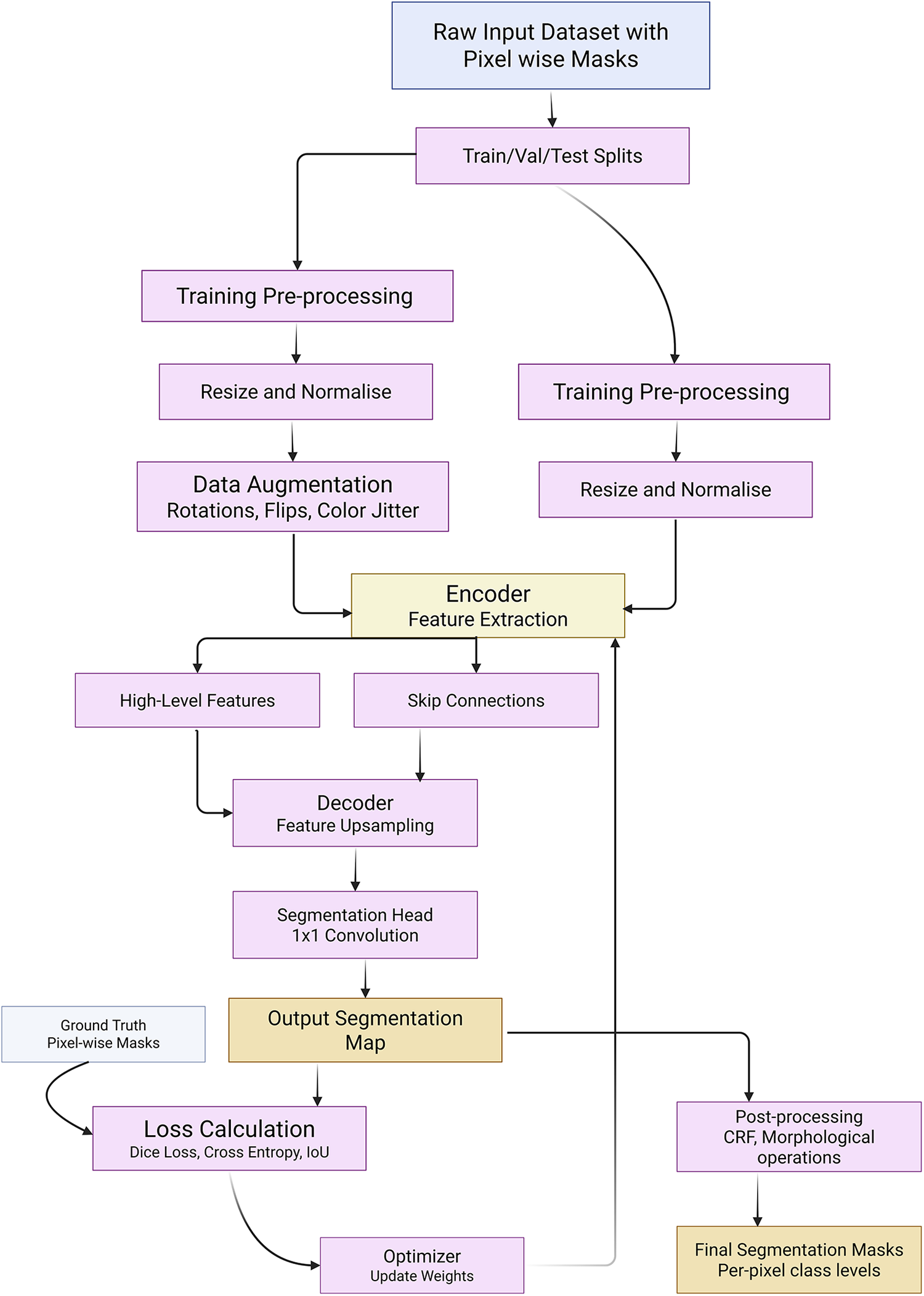

Medical image segmentation [1], a fundamental step in quantitative medical analysis, involves delineating organs, lesions, and tissues from complex imaging backgrounds [31,141,142]. While early studies often emphasized descriptive overviews of architectures such as U-Net [143], a critical evaluation is warranted to assess limitations, innovations, and the broader clinical applicability of recent advances. Segmentation tasks pose unique challenges, demanding pixel- or voxel-level precision, and thus requiring substantial annotated datasets for supervised models [36]. The original U-Net, designed for biomedical image segmentation, relies on an encoder-decoder architecture with skip connections [143], which enhance localization by fusing low-level and high-level features. However, traditional U-Net struggles with deeper semantic understanding and long-range dependency modeling, especially in high-resolution and 3D applications [144,145]. To address these, U-Net++ [146] introduced nested skip connections, improving feature propagation and semantic fusion, while 3D U-Net [147] extended the architecture to volumetric data. V-Net [148] advanced this further by incorporating residual units and proposing a Dice-based loss to tackle class imbalance. The Dense V-Net [149] improved multi-organ segmentation by integrating dense blocks, yielding superior Dice scores in abdominal CT scans. Hybrid networks, like the RU-Net [19] fused residual mappings from ResNet [97] and Recurrent Convolutional Layers (RCLs) from Region-based Convolutional Neural Network (RCNN) [150], improving training stability and segmentation accuracy. Attention U-Net [151] utilized attention gates to suppress irrelevant features, enhancing pancreas segmentation in CT. GAN-based adversarial training [152,153] and uncertainty quantification using variational autoencoders [154–156] further enhanced segmentation reliability and robustness. Recent works have leveraged Transformer-based models to overcome CNN limitations in capturing global context. Transformer-based U-Net (TransUNet) [157] pioneered the integration of CNNs with Transformer encoders, using self-attention to model long-range dependencies while maintaining spatial precision through skip connections. This hybrid approach achieved competitive results on multi-organ CT segmentation. Transformer-Fusion Network (TransFuse) [158] employed a parallel CNN-Transformer design, enhancing performance by fusing local and global features at multiple scales. Convolutional Transformer Network (CoTr) [159] adopted deformable self-attention to reduce computational complexity in 3D segmentation. Swin UNet [160], a pure Transformer model, replaced convolutions with hierarchical Swin Transformer blocks [161], offering high-resolution feature representation with low computational overhead. These Transformer-based models demonstrate improved generalization, though many rely on pretraining on large external datasets [162,163] which raises concerns regarding data leakage and generalization to unseen modalities. Mask R-CNN [164], originally developed for object detection, has been adapted for instance-level medical segmentation. It incorporates Region of Interest Alignment (RoIAlign), Feature Pyramid Network (FPN) [165], and a segmentation mask branch, providing multiscale representations. Volumetric adaptations with attention modules [166] improved contextual awareness and reduced false positives.

The Mask R-CNN++ [146] hybrid, combining UNet++’s nested skip connections yielded state-of-the-art results in complex segmentation tasks. In unsupervised settings, GANs and generative models were initially used to augment datasets [86,167], but self-supervised and semi-supervised approaches have emerged as more scalable alternatives. TransUNet [157] was extended with modality-agnostic 3D adapters (MA-SAM) [168], preserving pretrained weights while adapting to volumetric inputs. Vision Mamba U-Net (VM-Unet) [169] introduced a Vision Selective Scan (VSS) block and asymmetric architecture to enhance contextual understanding in ISIC and Synapse datasets. Self-supervised methods using pretext tasks, such as semantic inpainting [50], anatomical position prediction [125], and metadata integration [170] have demonstrated robust representation learning. Fig. 6 demonstrated schematic flow diagram of a deep learning–based segmentation network.

Figure 6: Schematic flow diagram of a deep learning–based segmentation network

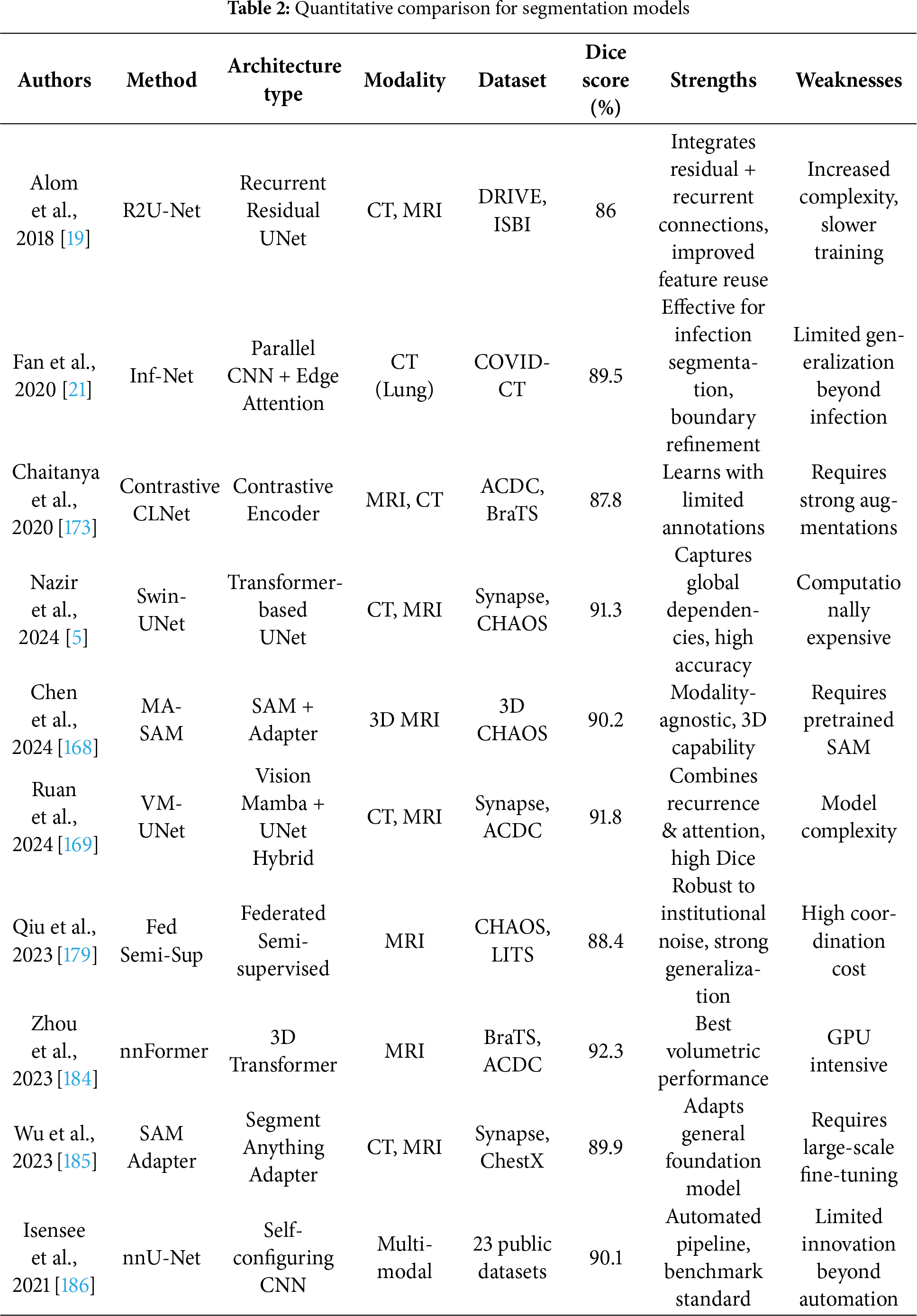

Adaptations of 2D tasks (e.g., jigsaw, rotation) to 3D segmentation [171] have improved generalization, even surpassing supervised pretraining. Contrastive learning variants [172] have also emerged, with methods like local contrastive loss [173] capturing pixel-wise distinctions vital for segmentation. These techniques benefit from data augmentations like Mixup [67] to further enhance robustness. Semi-supervised segmentation strategies like Mean Teacher [20,174] leverage teacher-student frameworks with uncertainty modeling to guide learning from unlabeled data. COVID-19 segmentation tasks [175], utilized pseudo-labeling and iterative self-training in architectures like Semi-supervised Inf-Net (Semi-InfNet) incorporating reverse attention (RA), edge attention (EA), and parallel partial decoder (PPD) [176–178]. Federated semi-supervised learning (FSSL) [179] with pseudo-labeling addressed data heterogeneity across institutions. Dual-VAE frameworks [180] combined latent representation learning and mask prediction, while shared-encoder models reconstructed both foreground and background separately to enhance attention-based segmentation. Domain priors, such as anatomical [181], atlas [182], and topological [183], further refined segmentation consistency. Advanced architectures like nnFormer [184] used volume-aware attention with skip-attention mechanisms for 3D segmentation. Table 2 summarizes the quantitative performance of different segmentation models.

While H2Former [187] combined CNNs, multiscale attention, and Transformers to outperform existing models. Wu et al. [188] extend the adaptation of SS2D by proposing a High-order Vision Mamba UNet (H-vmunet) model for medical image segmentation. Among them, the H-vmunet model includes the proposed novel High-order 2D-selective-scan (H-SS2D) and Local-SS2D module. Zheng et al. [189] proposes an asymmetric adaptive heterogeneous network for multi-modality image feature extraction with modality discrimination and adaptive fusion. For feature extraction, it uses a heterogeneous two-stream asymmetric feature-bridging network to extract complementary features from auxiliary multi-modality and leading single-modality images, respectively. Iqbal et al. [190] propose a novel deep learning architecture for medical image segmentation, which takes advantage of CNNs and vision transformers. Our proposed model, named Transformer-Based Convolutional Long Short-Term Memory Network “TBConvL-Net”, involves a hybrid network that combines the local features of a CNN encoder–decoder architecture with long-range and temporal dependencies using biconvolutional long-short-term memory (LSTM) networks and vision transformers (ViT).

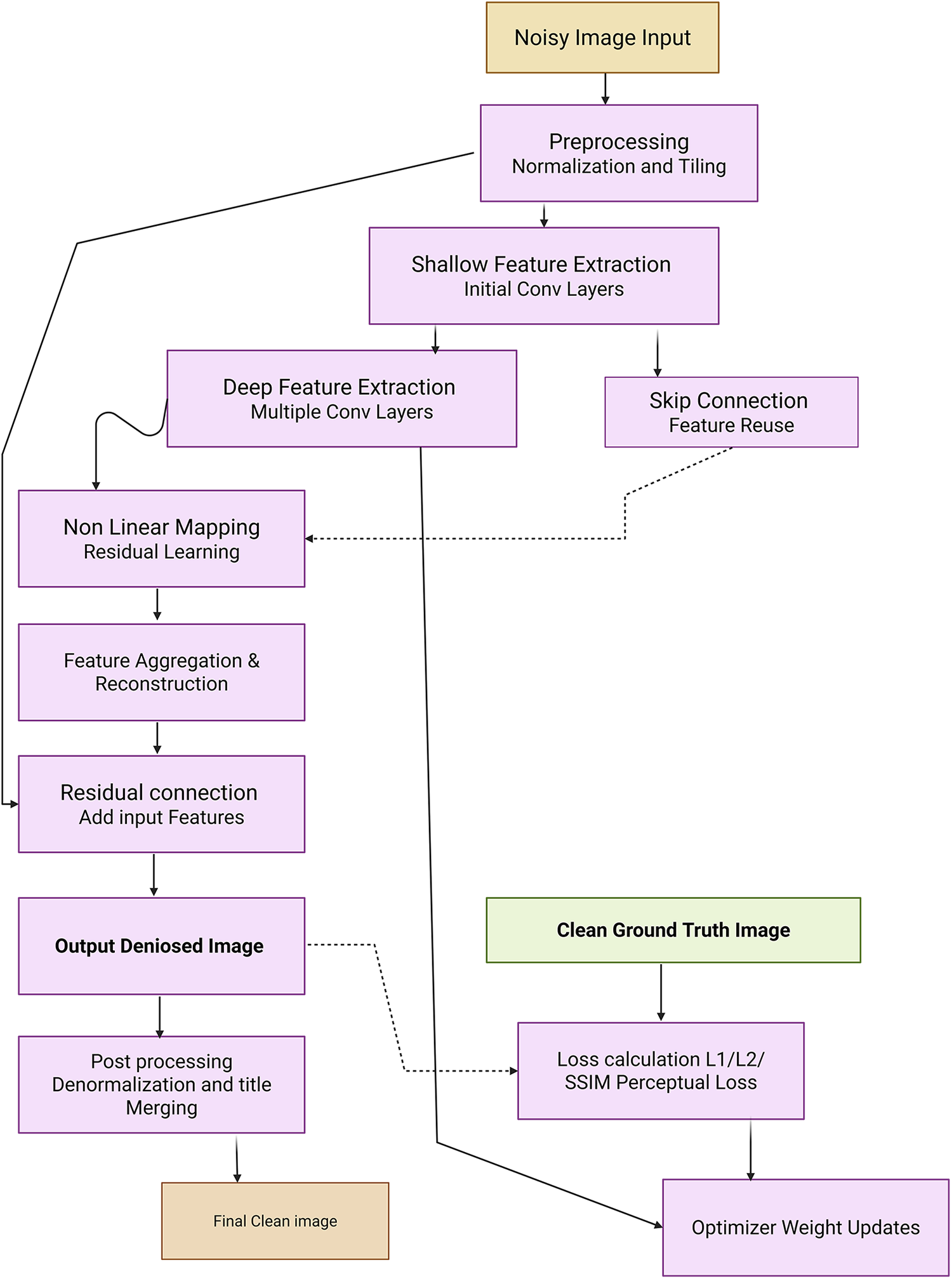

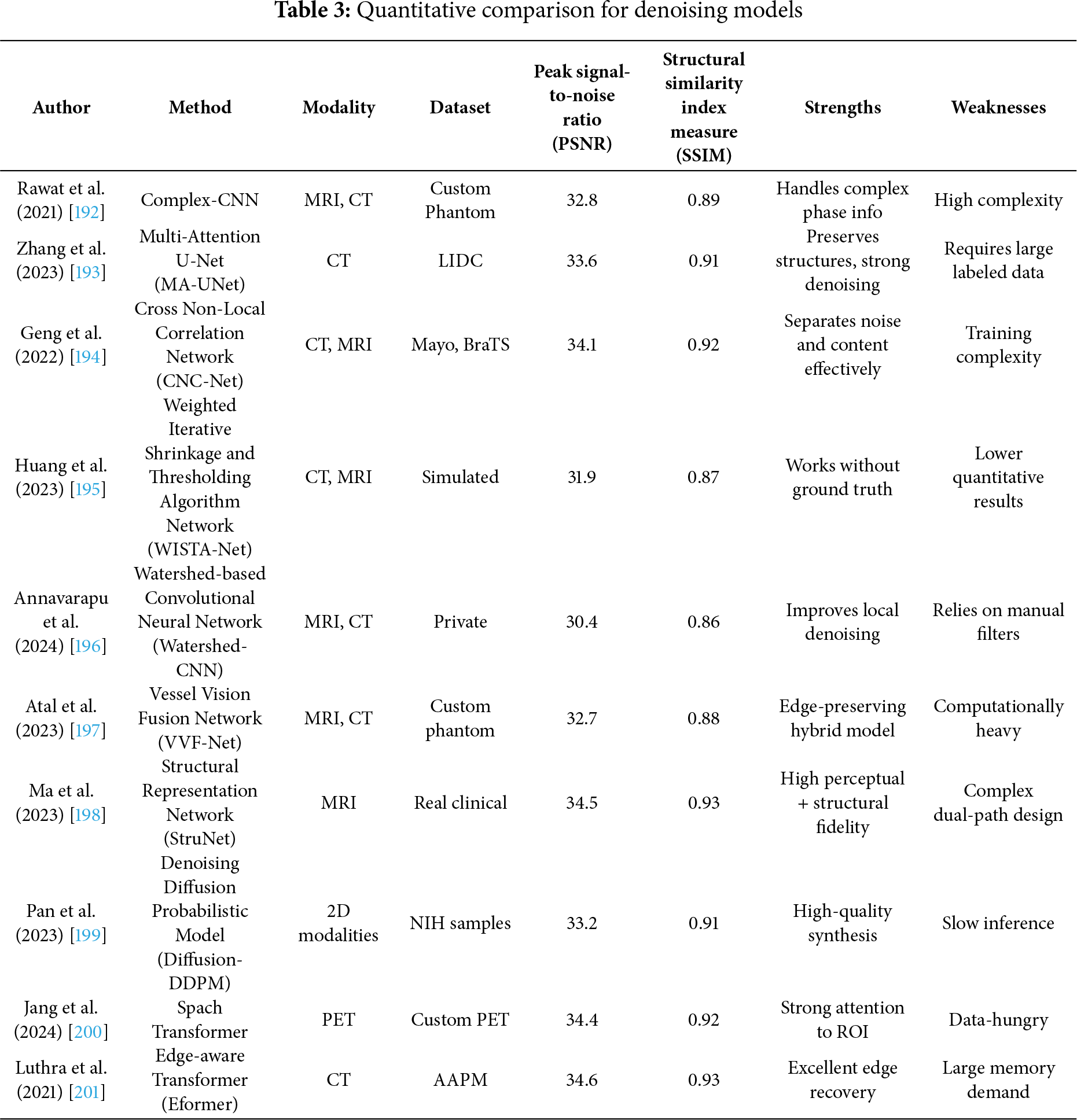

Medical image denoising remains a critical preprocessing step in diagnostic pipelines for modalities such as CT, MRI, X-rays, and ultrasound, which are frequently corrupted by noise, leading to potential misdiagnoses [5]. Traditional reliance on radiologist interpretation has evolved with the integration of intelligent deep learning-based systems [191]. However, a critical evaluation of modern denoising techniques reveals both advancements and ongoing challenges. Rawat et al. [192] proposed CVMIDNet, a complex-valued CNN leveraging residual learning and CReLU activations to predict residual noise from chest X-rays rather than estimating the clean image directly, thereby reducing signal distortion. Similarly, attention-based U-Net architectures, like that of [193] integrated local, channel, and task-adaptive attention mechanisms to better localize features and suppress irrelevant noise in CT images. Geng et al. [194] demonstrated that adversarial frameworks like Content-Noise Complementary Learning (CNCL), when combined with base models such as Universal Network (U-Net), Denoising Convolutional Neural Network (DnCNN), and Super-Resolution Dense Network (SRDenseNet), improved denoising across Computed Tomography (CT), Magnetic Resonance (MR), and Positron Emission Tomography (PET) data. While generative approaches provide flexibility, they often require extensive computational resources. In contrast, self-supervised sparse coding methods such as Weighted Iterative Shrinkage and Thresholding Algorithm (WISTA) and its deep-learning counterpart WISTA-Net [195] achieved competitive denoising without ground-truth images by exploiting lp-norm constraints and Deep Neural Network (DNN)-based parameter updates. Annavarapu et al. [196] introduced a denoising pipeline incorporating CNNs with adaptive watershed segmentation and contrast enhancement, validated on MRI and CT images, though their performance gains were limited by dependence on manually designed filters. Atal et al. [197] addressed CT noise using a hybrid approach that combines a deep CNN with an optimization-based vectorial variation filter, where pixel-wise noise maps are identified and cleaned using the Feedback Artificial Lion (FAL) algorithm. Fig. 7 demonstrated schematic flow diagram of a deep learning–based image denoising network. The hybrid learning-optimization method improved accuracy but introduced higher computational complexity. Ma et al. [198] advanced denoising via a dual-path encoder-decoder utilizing Swin Transformer blocks and residual units in parallel. This design effectively captured local and global features, while low-rank regularization and perceptual loss preserved feature consistency and structural fidelity. Transformer-based innovations have further proliferated. Pan et al. [199] employed a Swin-transformer-driven diffusion model for denoising and image synthesis across multiple imaging modalities. This model generated realistic synthetic images, verified using Inception Score (IS), Fréchet Inception Distance (FID), and visual Turing tests, and showed that synthesized data could complement real data in downstream classification tasks. Jang et al. [200] presented the Spach Transformer, validated across multiple PET tracers, and reported improved quantitative performance over leading networks. Meanwhile, Eformer by Luthra et al. [201] introduced a Transformer-based denoising network integrating learnable Sobel-Feldman edge enhancement operators to retain critical edge features while employing non-overlapping windowed self-attention for computational efficiency. These methods, although promising, highlight ongoing tensions between denoising performance, computational burden, and data requirements. Many approaches lack generalizability across modalities or underperform in low-signal to noise (SNR) settings without modality-specific tuning. Additionally, few studies assess clinical applicability through radiologist-in-the-loop evaluations or real-time performance metrics. A critical path forward will involve designing lightweight, explainable, and generalizable denoising models that balance accuracy, speed, and interpretability across diverse clinical environments.

Figure 7: Schematic flow diagram of a deep learning–based image denoising network

Demir et al. [202] propose Diffusion-based Denoising Network (DiffDenoise), a powerful self-supervised denoising approach tailored for medical images, designed to preserve high-frequency details. Chen et al. [203] propose a task-based regularization strategy for use with the Plug-and-Play Learning Strategy (PLS) in medical image denoising. The proposed task-based regularization is associated with the likelihood of linear test statistics of noisy images for Gaussian noise models. Kathiravan et al. [204] proposed a hybrid approach to image denoising that makes use of elements of EfficientNetB3 and Pix2Pix models. The EfficientNetB3’s efficient scaling and feature extraction capabilities, combined with the Pix2Pix’s image-to-image translation capabilities, enable the model to effectively remove noise while preserving essential image features. And Table 3 summarizes the quantitative performance of different denoising models.

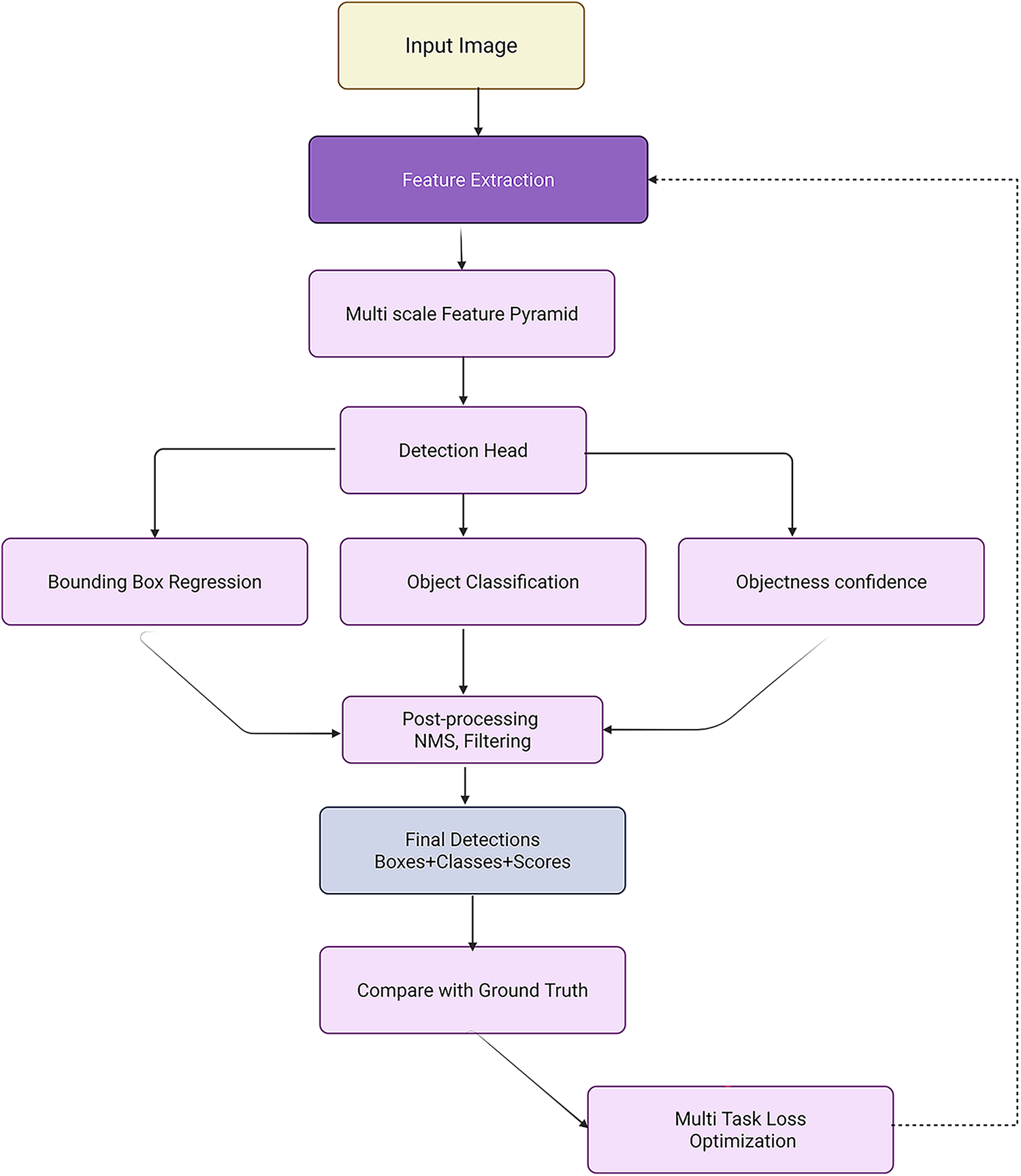

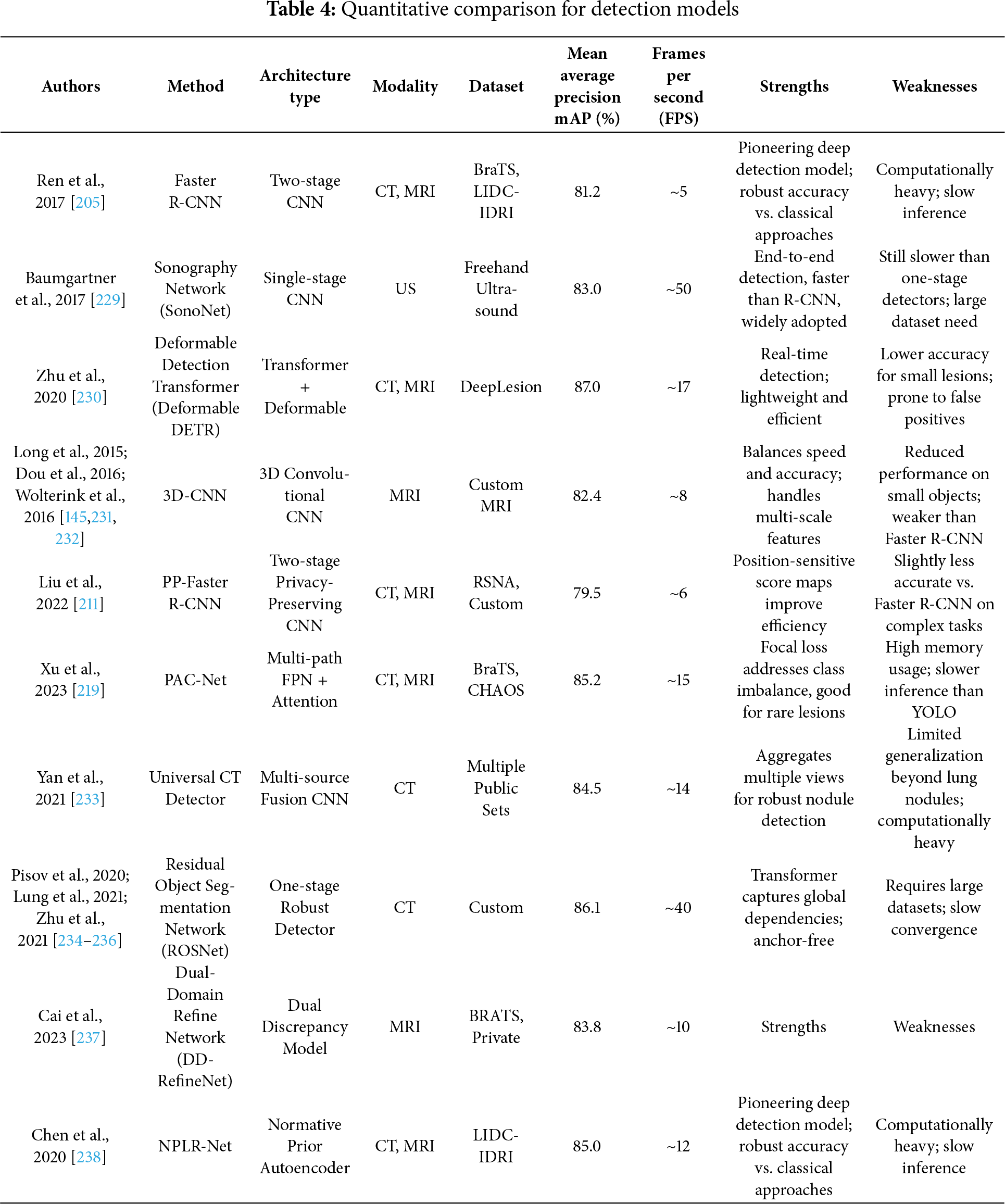

The evolution of object detection in medical imaging from classic region-based methods like RCNN [205] and OverFeat [206,207] to advanced CNN-based and Transformer-based models demands a critical re-evaluation of detection frameworks tailored for the complex structure of medical data. While general object detectors, such as Faster Region-Based -CNN [205], You Only Look Once (YOLO) [208], and RetinaNet [209] brought considerable improvements in efficiency and accuracy over their predecessors, their clinical deployment in computer-aided detection (CADe) remains constrained by domain-specific limitations like lesion size, variability, and class imbalance. Two-stage detectors, particularly Faster R-CNN [205,210], revolutionized medical image detection by introducing a Region Proposal Network (RPN) for efficient anchor-based region generation. Despite notable improvements, its dependency on anchor design and computational bottlenecks in ROI pooling persisted. To address privacy concerns, Liu et al. [211] extended Faster R-CNN into a secure detection framework (SecRCNN) that leverages secret sharing in edge environments, ensuring patient data confidentiality. Mask R-CNN [164], a derivative of Faster R-CNN, enhanced performance through instance segmentation using FPN [165], further improving object delineation in cluttered medical backgrounds. However, computational expense and limited real-time capability restrict its scalability. In contrast, YOLO [208], as a one-stage detector, gained popularity for its simplicity and speed, although with suboptimal accuracy in small lesion detection. Later YOLO iterations, including YOLOv2 and YOLO9000 integrated fine-grained features, anchor optimization, and multiscale training to alleviate initial weaknesses [208]. Fig. 8 demonstrated schematic flow diagram of a deep learning–based detection network. RetinaNet [209] addressed class imbalance in one-stage detectors via focal loss, boosting sensitivity to hard examples and improving detection rates. Nevertheless, the extensive use of anchor boxes across these models introduced challenges such as hyperparameter tuning, redundancy, and positive-negative imbalance. Anchor-free models like Corner-based Object Detection Network (CornerNet) [212,213] and CenterNet [214] emerged to address these issues, leveraging keypoint detection strategies, although CornerNet’s performance suffered due to weak regional context modeling. CenterNet improved upon this with triplet key points and contextual reasoning. For lesion-specific detection, especially of sclerosis lesions [24] and pulmonary nodules [215,216] and breast tumors [217,218], standard detectors struggled due to the subtle nature and size of lesions. Xu et al. [219] proposed Pyramid Attention and Context Network (PAC-Net), a multi-pathway FPN with position-attention-guided connections and vertex distance Intersection over Union (IoU) loss to increase sensitivity in universal lesion detection. Incorporating domain-specific adaptations, including 3D convolutional layers [220,221], deconvolution layers for resolution recovery [222] and spatial context aggregation, substantially enhanced nodule recognition accuracy, exemplified by 3D Faster R-CNN ranking first in LUNA16 [223,224]. In histopathology, streamlined YOLOv2 versions [208], modified for whole-slide lymphocyte detection that improved speed and F1 score but remained inferior to U-Net-based pixel-wise methods. Semi-supervised approaches including Mixed Sample Data Augmentation Technique (Mixup) [67], MixMatch Semi-Supervised Learning Framework (MixMatch) [225], and focal loss extensions [226] that improved generalizability with minimal labeled data. For instance, the PAC-Net’s modified focal loss and pseudo-labeling with Mixup led to substantial accuracy improvements in 3D lesion detection. Uncertainty estimation methods like MC dropout and predictive entropy [24,227,228] enhanced confidence calibration in detecting ambiguous small lesions, proving critical for sclerosis or tumor boundary remains in label completeness and cross-domain variability. Contextual and spatial attention modules [84,85,210] further enriched features by weighting informative slices and regions. Table 4 summarizes the quantitative performance of different detection models.

Figure 8: Schematic flow diagram of a deep learning–based detection network

Furthermore, methods incorporating radiologist-style window reweighting [239] improved interpretability and alignment with clinical practice. Meanwhile, unsupervised lesion detection methods primarily reconstruction- and restoration-based models’ normal anatomy to highlight anomalies. Anomaly Generative Adversarial Network (AnoGAN) [240], with iterative latent optimization using residual and discrimination losses, was effective but slow. Fast Anomaly Generative Adversarial Network (f-AnoGAN) [241] and AnoVAE-GAN [242] introduced encoders for rapid inverse mapping. Evidence Lower Bound (ELBO) approximation inaccuracies [243] were addressed by local gradient corrections, while 3D modeling improved spatial coherence. Additionally, Conditional Variational Autoencoder (CVAE) [244] incorporated spatial priors for delineation. Predecessor such as 3DCE [220] has been outperformed by Universal lesion detectors like ULDor [245] and MULAN [246] built upon Mask R-CNN with multitask learning integrated classification, segmentation, and detection. However, the challenge is the more precise segmentation of anomalous regions. Self-supervised detection models, such as One-Class Self-Supervised Learning (OC-SSL) with Dual-Domain Anomaly Detection (DDAD) [237] utilized reconstruction discrepancies across normal and unlabelled data to define anomaly scores, pushing unsupervised frameworks closer to supervised benchmarks. Altogether, while supervised detectors dominate clinical pipelines, their dependence on annotated data and sensitivity to domain shifts remain bottlenecks. Semi- and self-supervised frameworks, augmented with uncertainty quantification, task fusion, and Transformer attention, offer scalable, robust alternatives. As detection models evolve toward unified, anchor-free, and 3D-aware architectures, critical integration of clinical priors, interpretability tools, and multi-institutional datasets will be essential to drive real-world CADe adoption and effectiveness. Bi et al. [247] propose a novel unsupervised anomaly detection framework based on a diffusion model that incorporates a synthetic anomaly (Synomaly) noise function and a multi-stage diffusion process. Synomaly noise introduces synthetic anomalies into healthy images during training, allowing the model to effectively learn anomaly removal. Hoover et al. [248] investigate the robustness of pre-trained deep learning models for classifying bone fractures in X-ray images and seeks to address global healthcare disparity through the lens of technology. Lab-on-a-chip technology offers high-throughput, automated data generation that addresses the major bottleneck of AI [249]. The study explores the emerging synergy of ‘AI on a chip,’ highlighting key advances, challenges, and future opportunities.

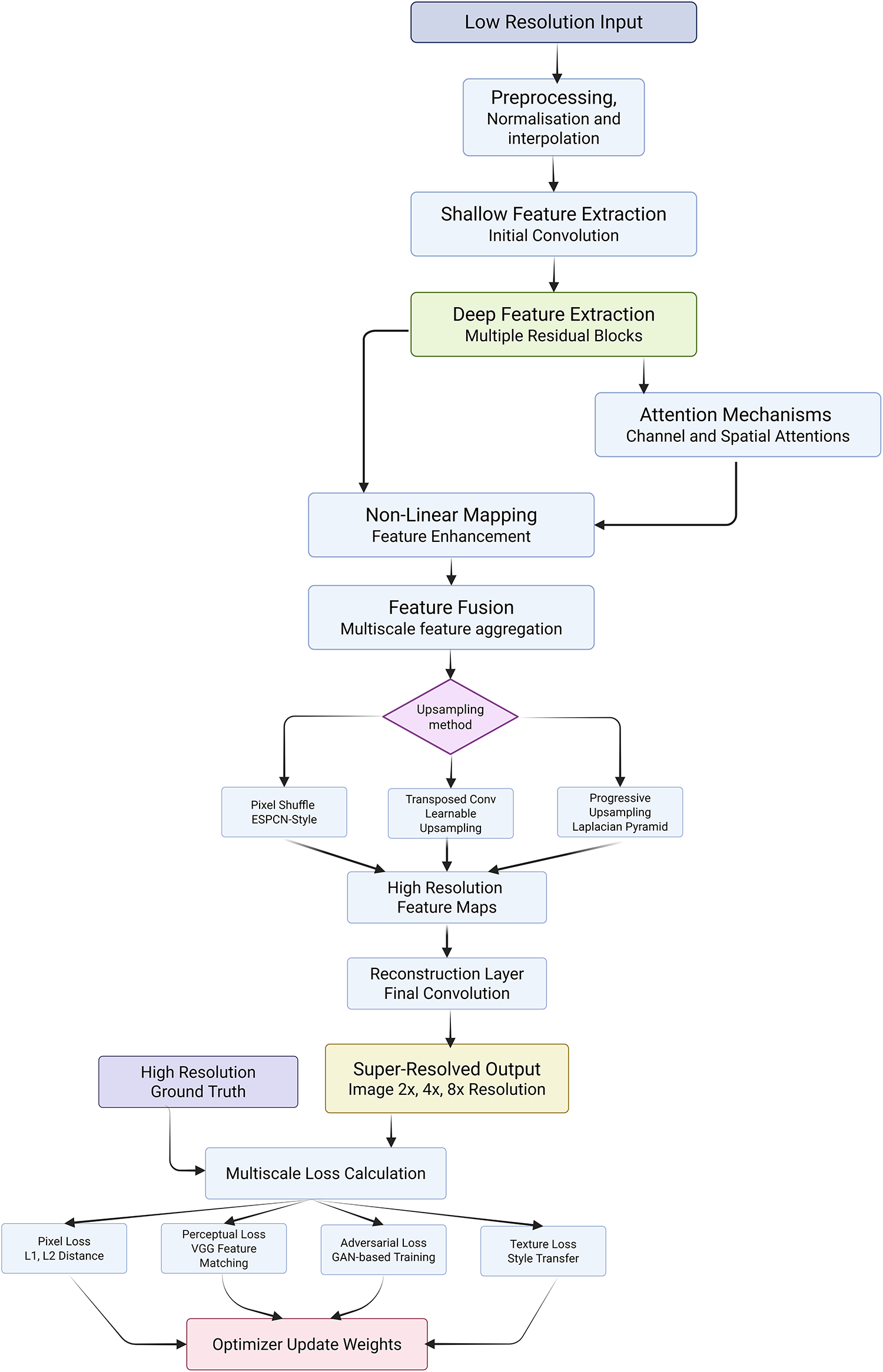

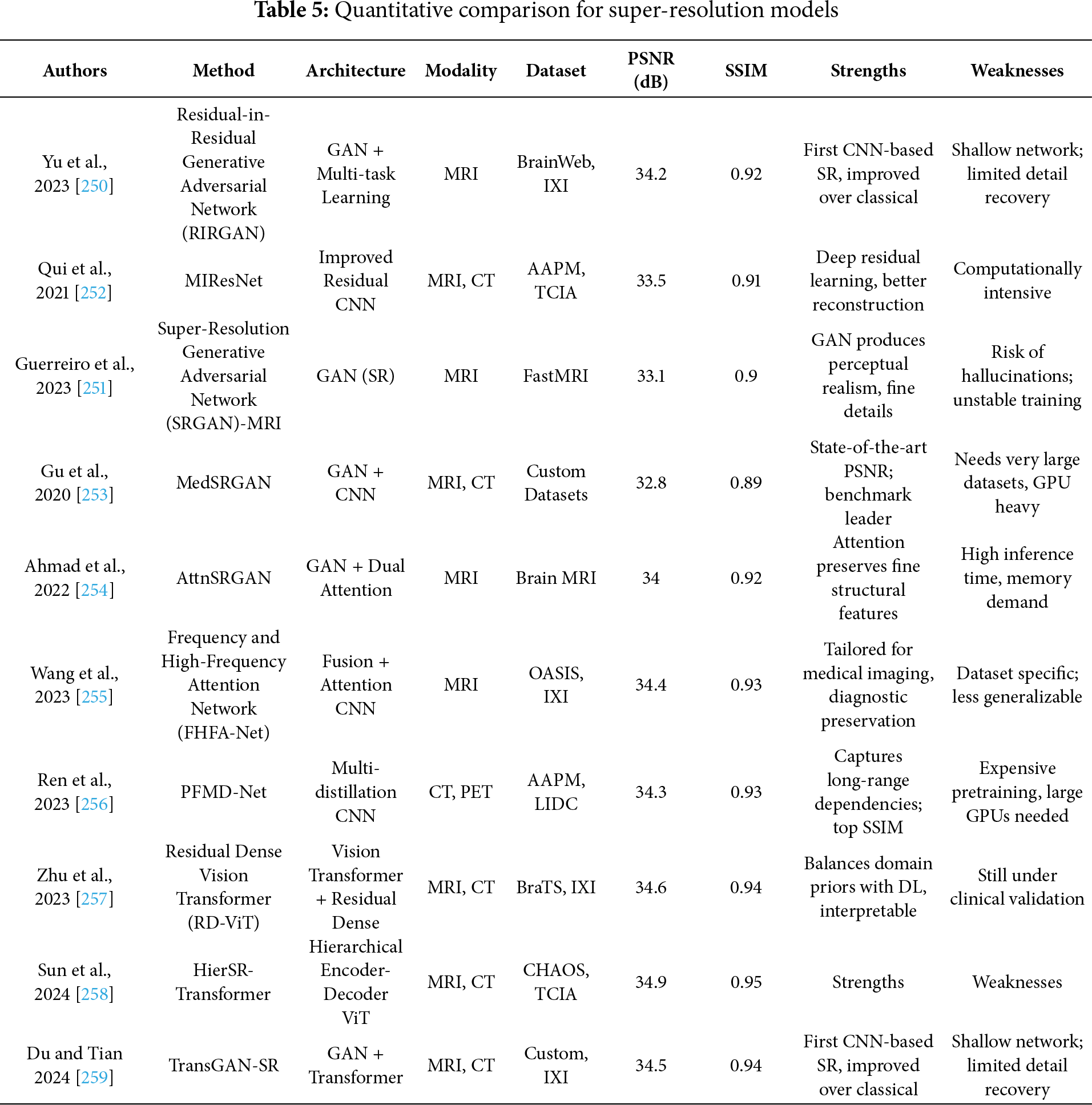

In medical imaging, the challenge of improving the resolution of diagnostically critical images without compromising accuracy or introducing artifacts has led to the rapid development of advanced super-resolution (SR) models. However, critical analysis reveals that while multiple architectures have demonstrated promising results, their applicability in real-world clinical settings remains bounded by computational complexity, generalization capacity, and integration with diagnostic pipelines. The strengths of Transformers are reiterated here to underline their significance across various imaging modalities and tasks. Yu et al. [250] proposed RIRGAN, a multi-task GAN using Residual-in-Residual (RIR) blocks for simultaneous denoising and super-resolution. While the model’s long skip connections facilitate deeper architectures to learn high-frequency information, the complexity of tuning adversarial losses and ensuring convergence remains a limitation. The reliance on relativistic average discriminators enhances realism but also increases training instability. Guerreiro et al. [251] introduced a perception consistency method using cycle-GANs to enforce reconstruction from LR-SR-LR (Low-Resolution → Super-Resolution → Low-Resolution) paths, eliminating the need for HR labels. This self-supervised method offers robustness but can be limited in datasets with significant anatomical variation. Similarly, the Multiple Improved Residual Network (MIRN) proposed by Qiu et al. [252] addresses residual feature correlation using deep skip connections; however, its dependence on adaptive learning schedules and complex residual aggregation raises questions about scalability. Gu et al. [253] developed MedSRGAN using a Residual Whole Map Attention Network (RWMAN) for channel-wise feature emphasis. Despite high performance, training with multiple adversarial and feature loss functions add complexity and computational overhead. Ahmad et al. [254] proposed a three-stage GAN model employing ResNet34 and multi-path extraction. While incremental upscaling addresses gradient propagation and authenticity, its deeper architecture may be unsuitable for low-resource clinical environments. Wang et al. [255] introduced a fuzzy hierarchical attention model with fuzzy logic integration. This hybrid model innovatively addresses pixel uncertainty but may overfit in diverse image scenarios due to the handcrafted fuzzy membership logic. Ren et al. [256] designed a pyramidal multi-distillation network incorporating entropy-based attention and gradient map supervision. Though perceptually effective, integrating multiple supervision paths increases inference time. Zhu et al. [257] introduced perceptual loss from a pretrained segmentation U-Net into super-resolution networks, including CNNs and Transformers. While the segmentation-aware supervision improves semantic preservation, it can bias models toward overfitting on the pretraining domain, especially in heterogeneous datasets. Transformer-based models like Transformer-based Hierarchical Encoder–Decoder Network (THEDNet) by Sun et al. [258] offer multi-scale attention via Exponential Moving Average (EMA) modules to extract global dependencies. However, Transformers demand high memory and are often over-parameterized for limited medical datasets. Du et al. [259] combined Transformers and T-GANs for texture-aware reconstruction using weighted multi-task loss. While effective in preserving texture details, balancing the trade-off between content and adversarial losses remains a challenge. Collectively, these models highlight the evolving landscape of SR in medical imaging; yet, their critical deployment demands addressing generalizability, interpretability, and efficiency. While adversarial and Transformer-based approaches enhance visual fidelity, their integration into practical CAD systems must consider training complexity, reproducibility, and dataset variance. Furthermore, benchmark datasets and standardized evaluation metrics are essential to avoid overclaiming model robustness. Ultimately, although numerous SR frameworks have improved medical image resolution across CT, MRI, and X-rays, critical bottlenecks persist in balancing visual enhancement with diagnostic reliability, especially in edge-device and real-time settings where resource constraints and model transparency are paramount. Fig. 9 demonstrated schematic flow diagram of a deep learning–based super-resolution network.

Figure 9: Schematic flow diagram of a deep learning–based super-resolution network

Goyal et al. [260] proposed an SR method that integrates multiscale CNNs with weighted least squares optimization (WLSO), leveraging wavelet decompositions. Although effective in capturing multiscale contextual information, wavelet-based models can struggle with learning fine semantic details across modalities. Lu et al. [261] propose a novel sparsity-guided medical image SR network, namely SG-SRNet, by exploiting the spatial sparsity characteristics of the medical images. SG-SRNet mainly consists of two components: a sparsity mask (SM) generator for image sparsity estimation, and a sparsity-guided Transformer (SGTrans) for high-resolution image reconstruction. Pang et al. [262] present Neural Explicit Representation (NExpR) for fast arbitrary-scale medical image SR. Our algorithm represents an image with an explicit analytical function, whose input is the low-resolution image and output is the parameterization of the analytical function. Ji et al. [263] propose a self-prior guided Mamba network with edge-aware constraint (SEMambaSR) for medical image super-resolution. Recently, State Space Models (SSMs), notably Mamba, have gained prominence for the ability to efficiently model long-range dependencies with low complexity. Li et al. [264] develop a Self-rectified Texture Supplementation network for Reference-based Super-Resolution (STS-SR) to enhance fine details in MRI images and support the expanding role of autonomous AI in healthcare. Our network comprises a texture-specified self-rectified feature transfer module and a cross-scale texture complementary network. Table 5 summarizes the quantitative performance of different super-resolution models.

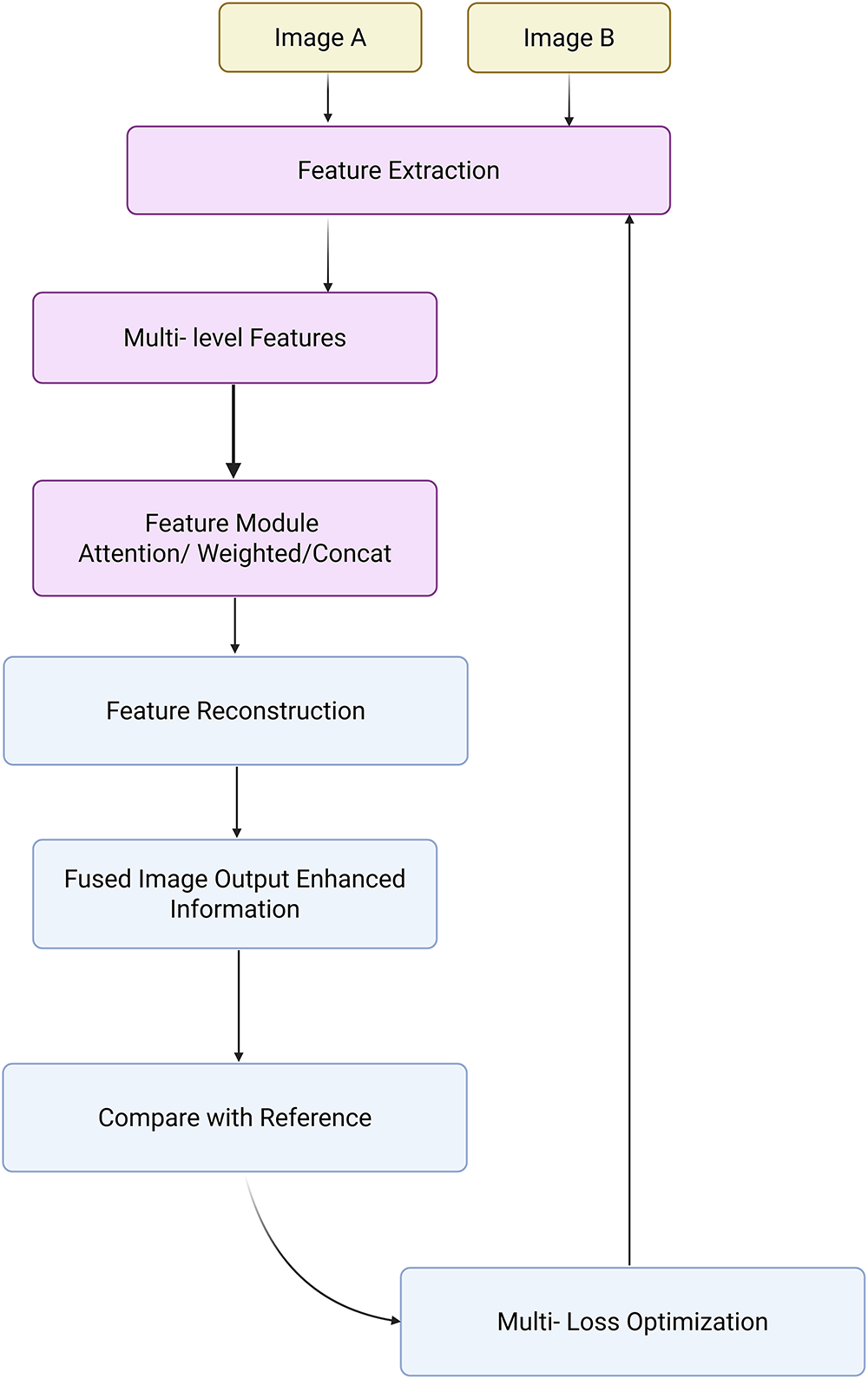

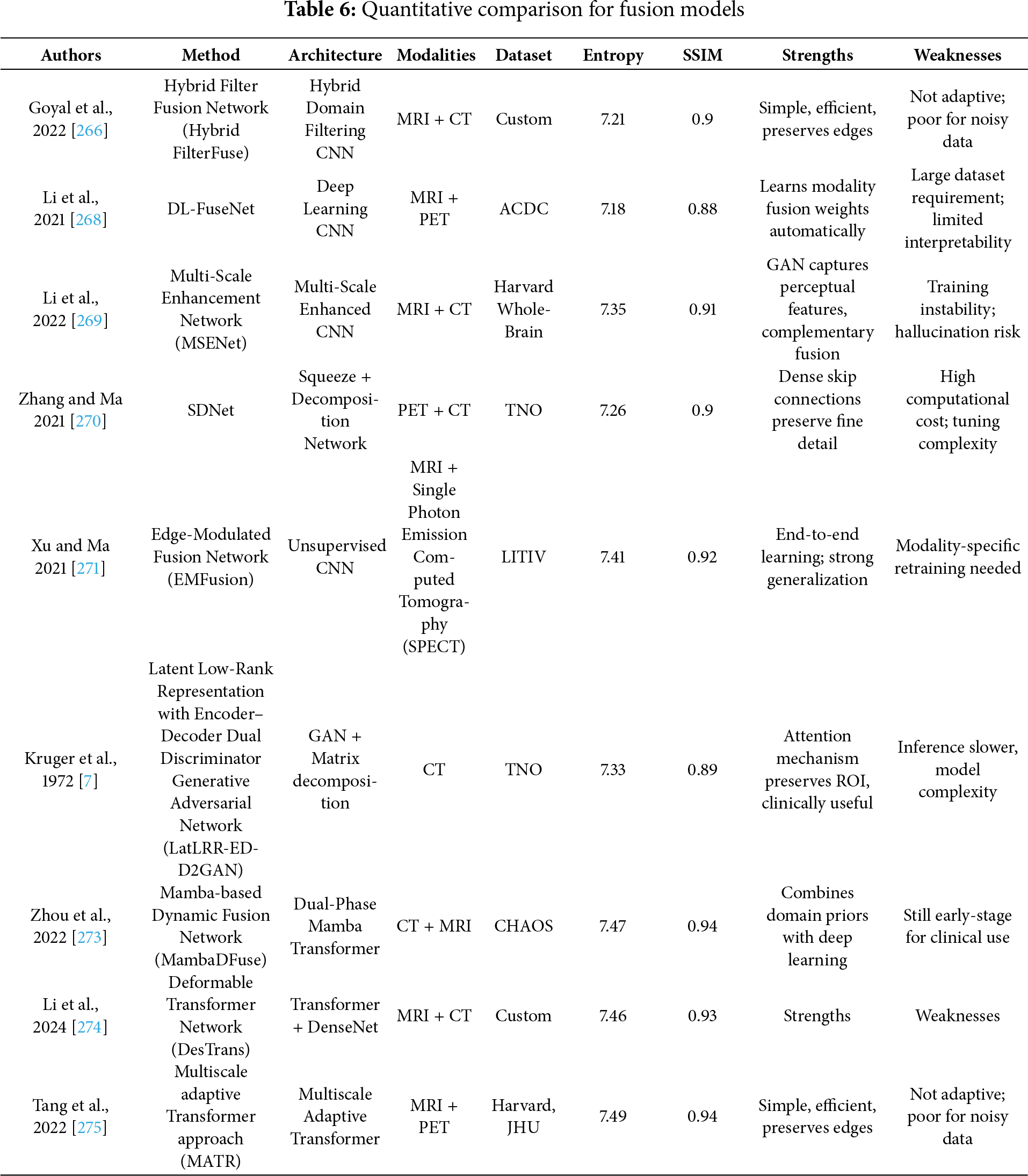

Recent advances in medical image fusion have led to numerous innovations, yet a critical evaluation reveals considerable variance in effectiveness, generalizability, and interpretability across supervised, unsupervised, and transformer-based approaches. Traditionally, fusion strategies aimed to combine information from different modalities (e.g., MRI, CT, PET) or from different focal lengths to reduce the fragmentary nature of clinical data and enhance visualization [265–267]. While supervised fusion frameworks such as the one proposed by Li et al. [268] utilize Deep Boltzmann Machines (DBM) to learn fusion mappings, the requirement of extensive labeled datasets and perfect image registration limits scalability in clinical applications. Likewise, the Multi-Scale Enhanced Network (MSENet) [269] and Saliency-Driven Network (SDNet) [270] introduce modular enhancements like dilated convolutions, unique fusion modules, and gradient-intensity decomposition but their dependency on hand-crafted scoring metrics and fixed architectural assumptions may limit adaptability to new modalities or diagnostic contexts. In contrast, unsupervised fusion techniques attempt to bypass the annotation bottleneck but often sacrifice interpretability or robustness. Xu et al. [271] combine surface-level and deep constraints in an unsupervised setting but may be sensitive to feature extraction biases from pre-trained encoders. The Foveation-based Differentiable Architecture Search Framework (F-DARTS) framework by Ye et al. [272] innovatively leverages human visual saliency via a foveation operator and multi-component loss functions, but the computational overhead and lack of end-user transparency present hurdles for clinical integration. Similarly, LatLRR-GAN [273] incorporates Latent Low-Rank Representations with a dual discriminator GAN for detail preservation in low-rank regions, yet suffers from dependency on optimal thresholding and network tuning. MambaDFuse [274] attempts to balance shallow and deep fusion using Mamba blocks and CNNs, but the integration of long-range dependencies through channel exchange raises questions about feature redundancy and optimization stability. The MATR [275] refines semantic extraction through adaptive convolutions and regional mutual information loss, showcasing state-of-the-art performance in unsupervised multimodal fusion. However, its reliance on complex objective functions and multiscale learning complicates training convergence and practical deployment. Overall, while the field has progressed from early rule-based strategies to sophisticated deep and Transformer-based architectures, limitations persist in terms of scalability, interpretability, and the balance between global semantic context and local detail preservation. A critical takeaway is the need for future frameworks that are not only robust across diverse modalities but also interpretable, computationally efficient, and capable of adapting to varying levels of supervision without compromising diagnostic accuracy or clinical utility. Fig. 10 demonstrated schematic flow diagram of a deep learning–based fusion network.

Figure 10: Schematic flow diagram of a deep learning–based fusion network

Table 6 summarizes the quantitative performance of different fusion models. In the context of Transformer-based fusion, recent models like the enhanced DenseNet-Transformer hybrid by Song et al. [276] present promising improvements in minimizing feature loss and edge blurring, but Dense concatenation architectures can be memory-intensive and may face difficulties in generalizing to smaller datasets. He et al. [277] propose a novel invertible fusion network (MMIF-INet) that accepts three-channel color images as inputs to the model and generates multichannel data distributions in a process-reversible manner. Specifically, the discrete wavelet transform (DWT) is utilized for downsampling, aiming to decompose the source image pair into high- and low-frequency components. Li et al. [278] propose an unaligned medical image fusion method called Bidirectional Stepwise Feature Alignment and Fusion (BSFA-F) strategy. PH Dinh [279] propose a novel medical image fusion method that combines the strengths of Bilateral Texture Filtering (BTF) and transfer learning with a modified ResNet-101 network (M_ResNet-101). The method begins with the application of BTF to decompose the input images into texture and detail layers, preserving structural integrity while effectively separating relevant features. Liu et al. [280] propose a novel salient semantic enhancement fusion (SSEFusion) framework, whose key components include a dual-branch encoder that combines Mamba and spiking neural network (SNN) models (Mamba-SNN encoder), feature interaction attention (FIA) blocks, and a decoder equipped with detail enhancement (DE) blocks.

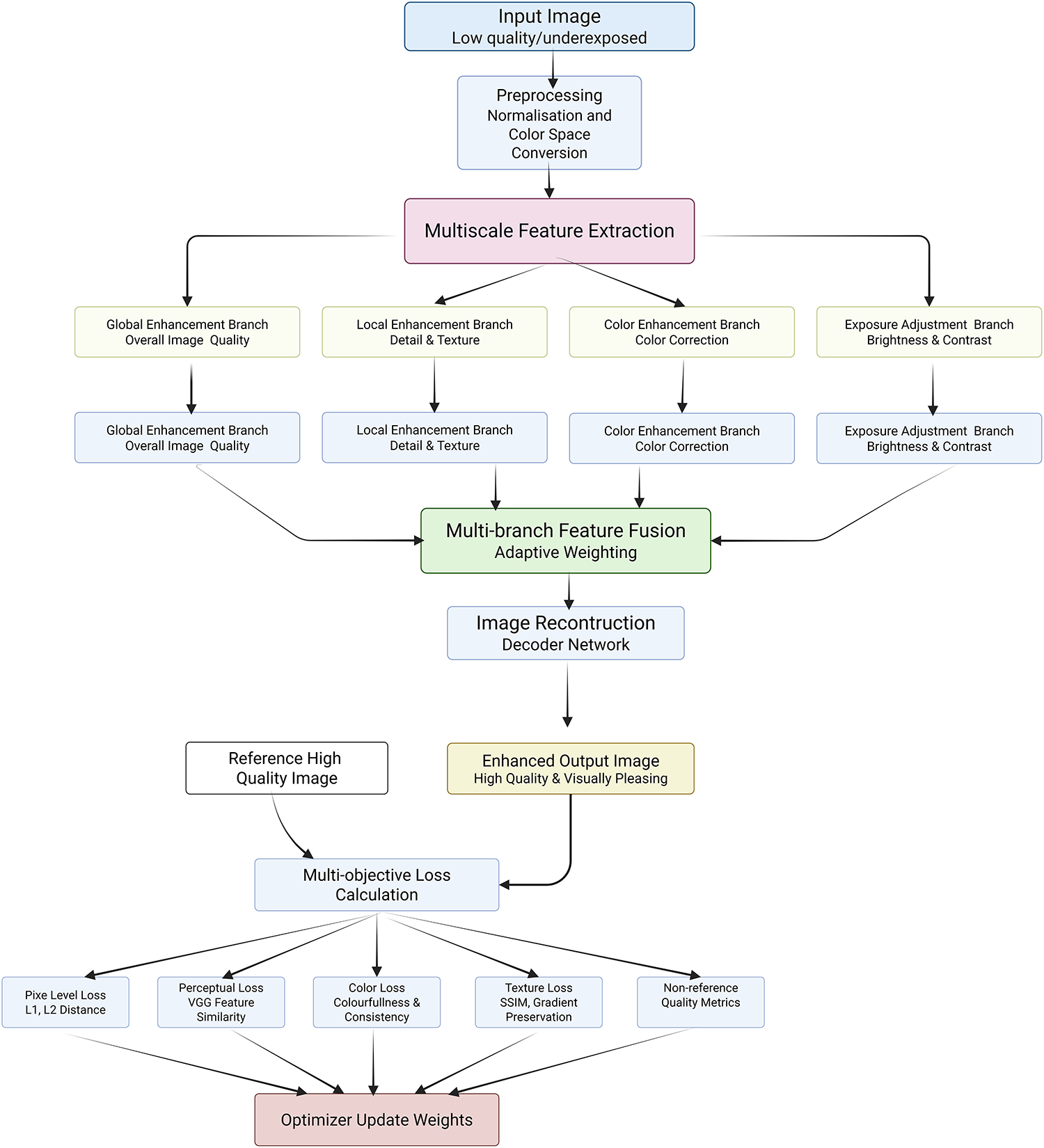

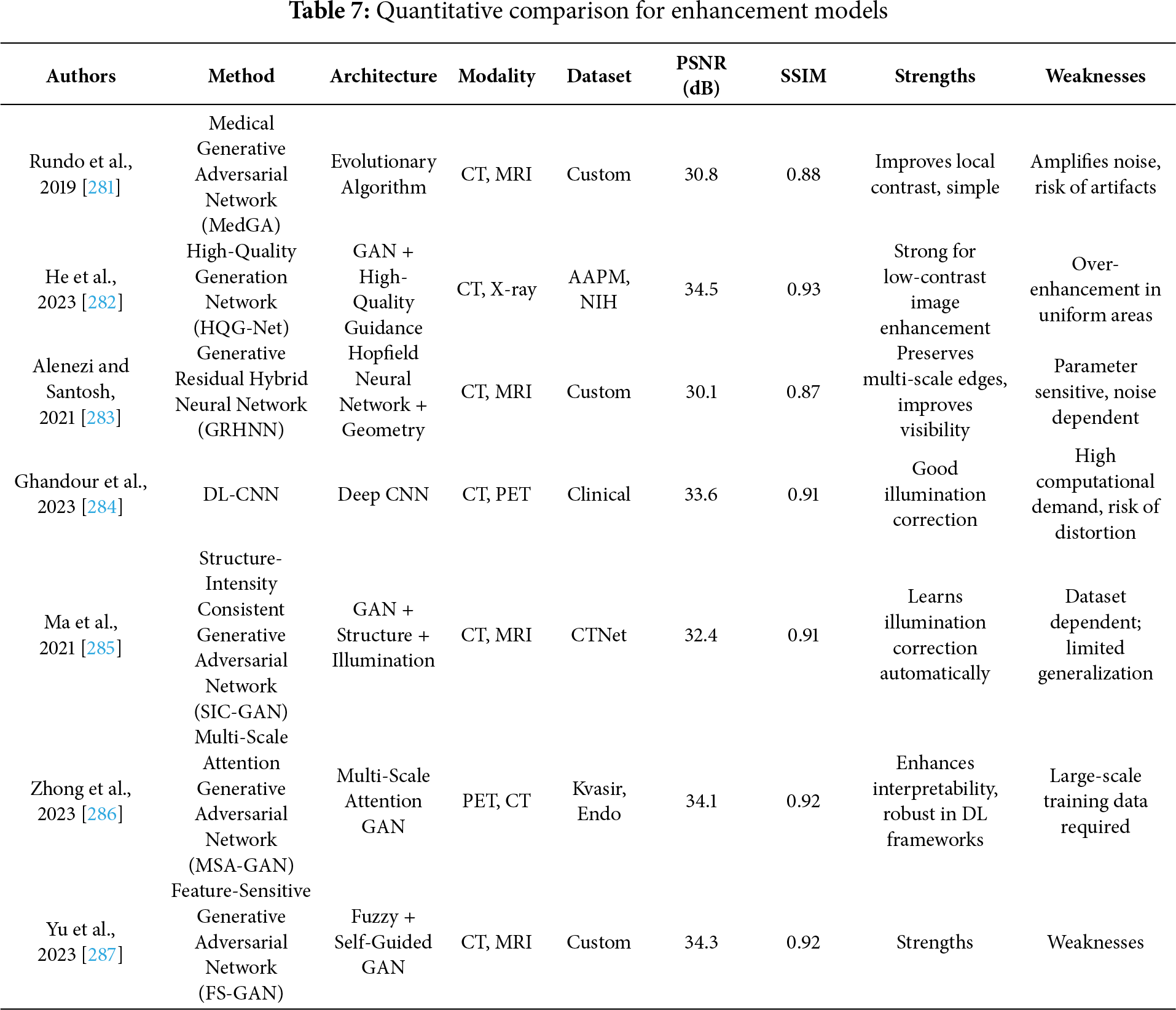

Medical image enhancement has become an indispensable pre-processing step to augment the visibility of anatomical and pathological details across imaging modalities such as CT, MRI, and X-ray, thereby assisting radiologists and automated systems in accurate interpretation and diagnosis. However, a critical evaluation of the enhancement methods reveals several methodological strengths, algorithmic limitations, and practical challenges that persist in clinical application. While traditional enhancement algorithms focus on improving global contrast or noise suppression, recent approaches based on supervised deep learning exhibit improved robustness through learning complex intensity transformations. Rundo et al. [281] proposed MedGA, which leverages genetic algorithms to enhance images with bimodal gray-level histograms, demonstrating clinical applicability in contrast-enhanced MRI. However, its reliance on predefined histogram properties restricts adaptability across diverse image contexts. He et al. [282] tackled cross-domain enhancement through the Unsupervised Multi-domain Image Enhancement (UMIE) strategy, integrating high-quality guidance into low-quality image transformation via variational modelling. This framework addresses the domain gap between low- and high-quality image distributions but depends heavily on the availability and representativeness of high-quality prompts. Alenezi et al. [283] introduced a modified Hopfield Neural Network (MHNN) under cohomological constraints to regulate gradient vector flow, thus enhancing local-global feature correlations. Although theoretically promising, MHNN’s computational demands and convergence guarantees warrant further empirical validation. Ghandour et al. [284] evaluated feature-level fusion in Deep Learning–based Medical Image Fusion (DLMIF) using pretrained CNNs for enhancement without ground-truth supervision, highlighting CNN feature reliability but also underlining limitations in control over fused feature distribution due to static pretrained layers. Unsupervised strategies, while more flexible, present their own trade-offs between realism and interpretability. Structure and Illumination–aware Generative Adversarial Network (StillGAN) [285] exemplify GAN-based enhancement techniques treating image quality as a domain transfer task. StillGAN’s bi-directional architecture integrates structural and illumination priors, addressing both global coherence and local fidelity. Nevertheless, the training instability of GANs and the reliance on handcrafted domain constraints remain pertinent drawbacks. Similarly, Multimodal Adversarial Generative Adversarial Network (MAGAN) [286] exploits multi-scale attention mechanisms in an adversarial setting to capture feature hierarchies but inherits the GAN framework’s susceptibility to mode collapse. FS-GAN [287] innovatively employ a fuzzy domain discriminator and structure-retention modules to refine nerve fiber imagery and light distribution. While promising in preserving structural integrity, the fuzzy domain formulation may vague interpretability and reproducibility in clinical settings. Moreover, Transformer-based enhancement techniques are gaining traction due to their capability to model global dependencies. Fig. 11 demonstrated schematic flow diagram of a deep learning–based enhancement network.

Figure 11: Schematic flow diagram of a deep learning–based enhancement network

Xia et al. [288] observed that the previous models necessitate large training data and complex tuning, making their deployment in data-constrained scenarios challenging. Thus, despite notable progress, critical gaps remain in generalizability, real-time processing, interpretability, and integration with downstream diagnostic tasks. Enhancement models must be evaluated not only based on visual quality but also on their impact on clinical decision-making and compatibility with classification, segmentation, and detection pipelines. Continued development of hybrid models combining CNNs, Transformers, and domain adaptation strategies, along with the adoption of evaluation metrics that reflect diagnostic relevance, is essential to transition from visually plausible to diagnostically reliable enhancement solutions in medical image analysis. Lei et al. [289] propose a general framework called Contrast-Driven Medical Image Segmentation (ConDSeg). They develop a contrastive training strategy called Consistency Reinforcement. It is designed to improve the encoder’s robustness in various illumination and contrast scenarios, enabling the model to extract high-quality features even in adverse environments. Table 7 summarizes the quantitative performance of different enhancement models.

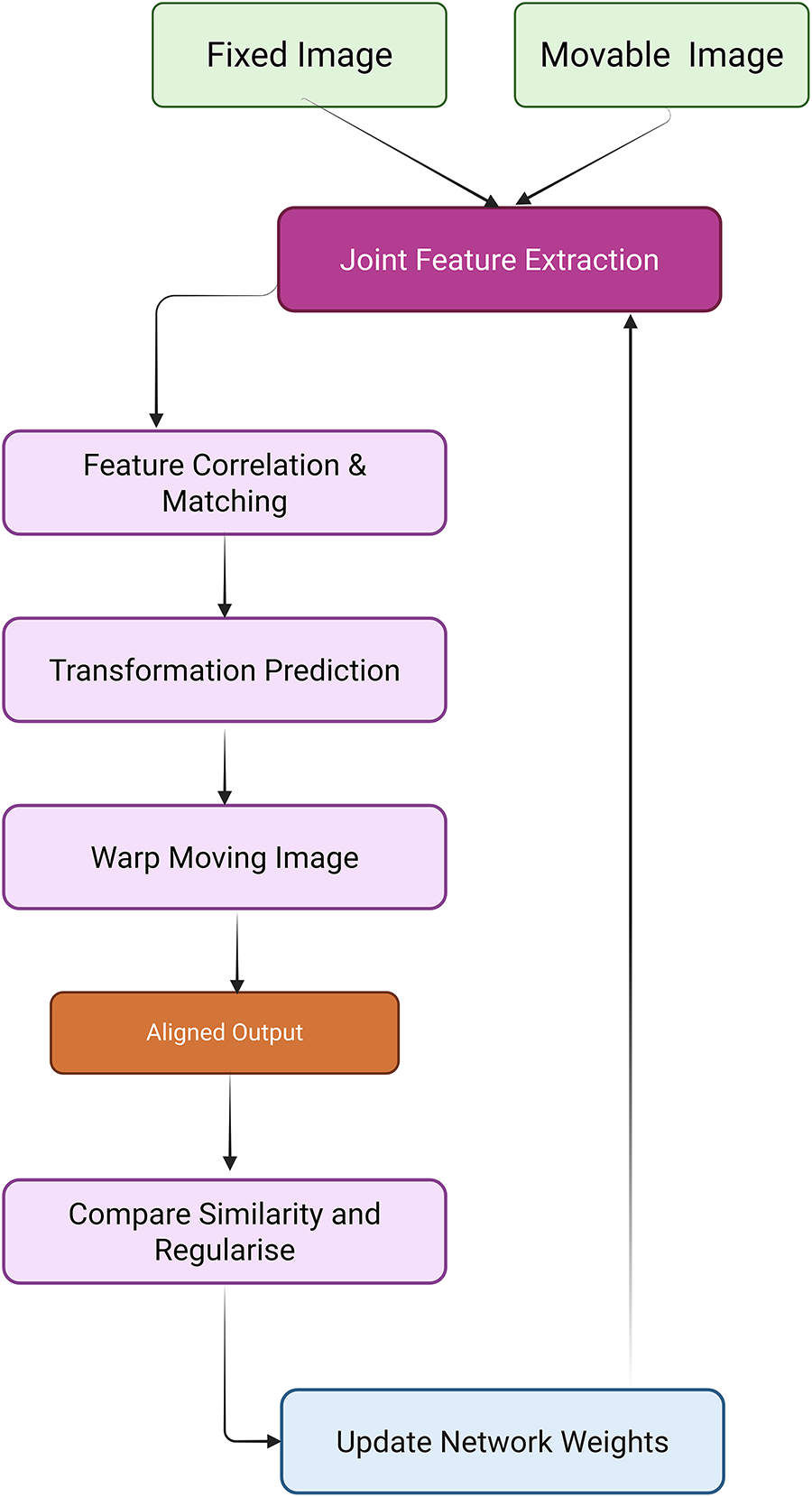

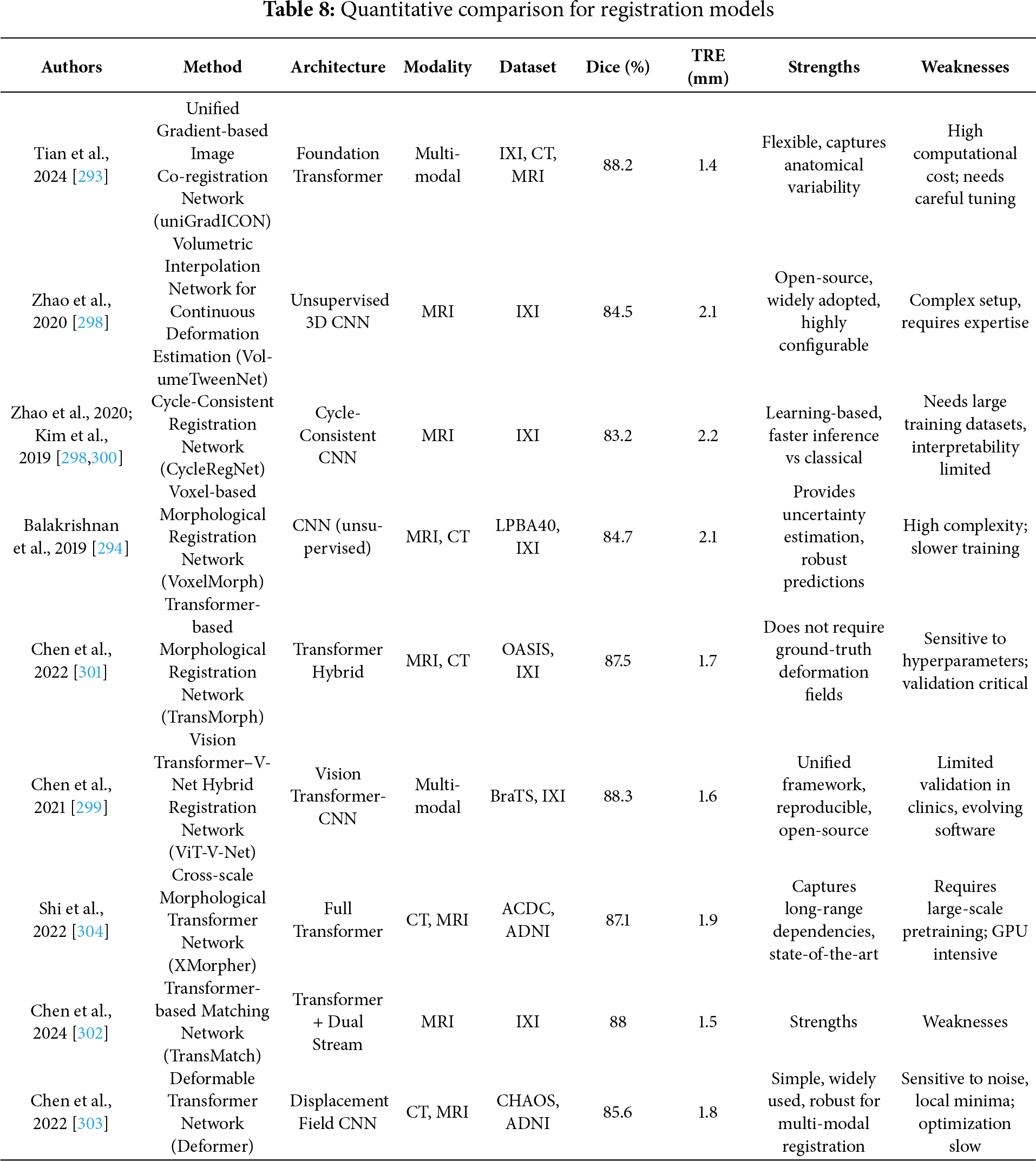

Image registration plays a pivotal role in medical image analysis by aligning images within a common coordinate space for accurate diagnosis and treatment planning [2]. However, the effectiveness of current deep learning-based registration methods must be critically evaluated across supervised, unsupervised, and Transformer-based paradigms. Traditional rigid registration techniques that apply consistent transformations lack adaptability in modeling patient-specific deformations, while deformable (non-rigid) registration allows localized spatial alignment but increases computational complexity and model instability. The deep iterative registration paradigm attempts to overcome limitations of handcrafted similarity metrics by learning task-specific similarity measures through CNNs. Yet, the robustness of such learned metrics across image modalities is inconsistent. For instance, CNN-based metrics [26] that outperformed mutual information in aligning T1-T2 MRI scans showed reduced performance when applied to anatomically dissimilar modalities like Magnetic Resonance–Transrectal Ultrasound Fusion Imaging (MR-TRUS) [290]. Additionally, these learned metrics are computationally expensive as they still require integration with classical iterative optimization algorithms. In supervised deep learning approaches, models like the multiscale CNN proposed in [27] effectively predict dense vector fields (DVFs) in one pass, reducing time complexity. However, this gain in efficiency comes at the cost of requiring large labeled datasets of ground truth deformation fields, which are often generated via traditional registration algorithms, thereby limiting their generalization potential [291,292]. While dual-supervision models, such as the one described in [292], provide performance boosts via complementary loss constraints, they remain data-hungry and constrained to specific modalities and deformation scenarios. The uniGradICON [293] is a foundation model for medical image registration that unites the speed of deep learning with the versatility of traditional methods, enabling cross-dataset performance and zero-shot generalization. While extensions of VoxelMorph that integrate anatomical [294] and weak supervision [295,296] improve performance and these additions often reintroduce domain-specific bias and complicate training. The foundation models like uniGradICON [295] demonstrate promise in zero-shot settings, but such methods still face interpretability issues and lack consensus in standardizing evaluation benchmarks across diverse medical datasets. On the other hand, unsupervised registration frameworks such as VoxelMorph [28], which utilize spatial transformer networks and CNNs to jointly predict and apply deformation fields without labeled data, represent a scalable solution for clinical use. However, their reliance on fixed similarity metrics (e.g., MSE or cross-correlation) in loss functions may degrade accuracy in multimodal settings. Moreover, adversarial frameworks [294] incorporating GANs for similarity estimation offer better cross-modality generalization, but they introduce training instability and require careful calibration of generator-discriminator dynamics. The Deep Learning Image Registration (DLIR) framework [297], with its progressive affine-to-deformable stages, exemplifies modularity and hierarchical refinement, yet its performance is sensitive to hyperparameter tuning across each stage, and it lacks robustness in handling large-scale variability across patients. A similar limitation exists in Volume Twinning Networks (VTN) [298], where cascaded architecture and invertibility constraints enhance alignment quality but may result in diminishing gains with each added stage. In terms of Transformer-based registration, architectures like ViT-V-Net [299] leverage global attention to capture long-range spatial dependencies. Fig. 12 demonstrated schematic flow diagram of a deep learning–based registration network.

Figure 12: Schematic flow diagram of a deep learning–based registration network

Kim et al. [300] present an unsupervised cycle-consistent CNN for fast and accurate 3D deformable medical image registration, achieving precise alignment on multiphase liver CT images for improved cancer size estimation. TransMorph [301] further enhance this approach by effectively modeling large deformations, addressing the limitations of CNNs. Despite their superior performance across multiple benchmarks, these models often require substantial computational resources and pretrained weights to avoid overfitting. TransMatch [302] and Deformer-based multi-scale frameworks [303] refine displacement prediction using hierarchical matching, yet they often necessitate multiscale ground truth data for effective supervision and have yet to demonstrate consistent improvements across multimodal domains.

Models like XMorpher [304] and C2FViT [305] that use cross-attention or hierarchical feature alignment strategies exhibit better registration for high-resolution 3D images but lack robustness in low-resolution or sparse anatomical datasets. Overall, the field is rapidly evolving with hybrid approaches combining CNNs and Transformers, but most existing models struggle to balance precision, speed, generalizability, and interpretability. Furthermore, benchmarking remains inconsistent across datasets, making fair comparison difficult. While supervised methods provide high accuracy in controlled settings, they are data- intensive and prone to overfitting. Unsupervised methods offer scalability but struggle with multimodal alignment without additional anatomical priors or adversarial constraints. Transformer-based solutions provide a compelling direction but require significant computational overhead and careful architectural design. Critical gaps remain in generalization across imaging modalities, robustness in real-world clinical scenarios, and standardized evaluation protocols. Future research must prioritize model interpretability, cross-domain generalizability, and computational efficiency to transition these methods from proof-of-concept to practical clinical deployment. Meng et al. [306] propose an Automatic Fusion network (AutoFuse) that provides flexibility to fuse information at many potential locations within the network. A Fusion Gate (FG) module is also proposed to control how to fuse information at each potential network location based on training data. Chen et al. [307] propose a new method called Multi-scale Large Kernel Attention UNet (MLKA-Net), which combines a large kernel convolution with the attention mechanism using a multi-scale strategy, and uses a correction module to fine-tune the deformation field to achieve high-accuracy registration. Meyer et al. [308] proposed a hyperparameter perturbation approach to estimate an ensemble of deformation vector fields for a given computed tomography (CT) to cone beam CT (CBCT) Deformable Image Registration (DIR). For each voxel, a principal component analysis was performed on the distribution of homologous points to construct voxel-specific DIR uncertainty confidence ellipsoids. Jiang et al. [309] introduce Fast-DDPM, a simple yet effective approach capable of simultaneously improving training speed, sampling speed, and generation quality. Unlike DDPM, which trains the image denoiser across 1000-time steps, Fast-DDPM trains and samples using only 10-time steps. Table 8 summarizes the quantitative performance of different registration models.

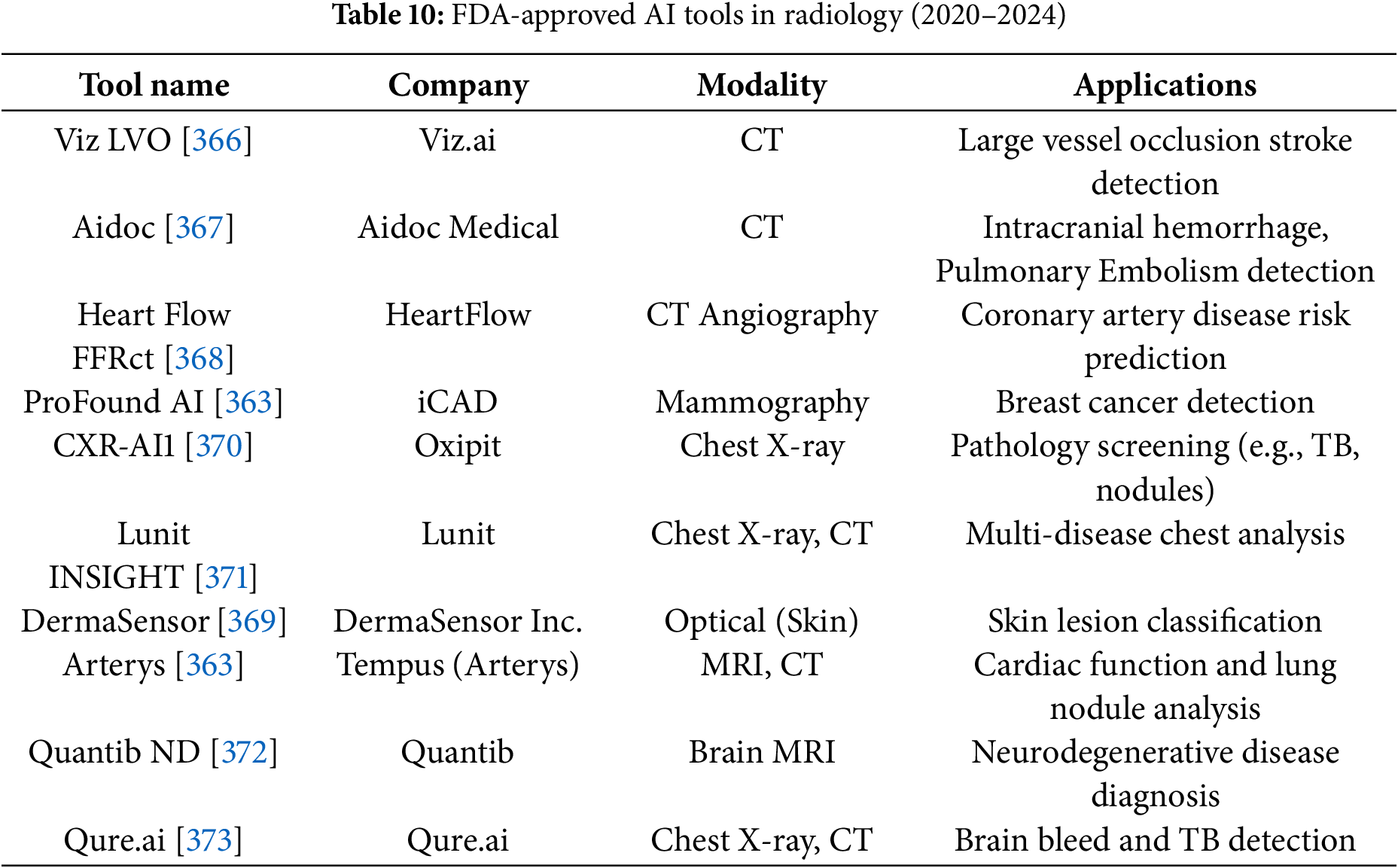

5 Clinical Suitability and Adoption Barriers of Emerging Techniques