Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

How Robust Are Language Models against Backdoors in Federated Learning?

1 Department of Information and Communication Engineering, Chosun University, Gwangju, 61467, Republic of Korea

2 Department of Artificial Intelligence and Software Engineering, Chosun University, Gwangju, 61467, Republic of Korea

3 Department of Artificial Intelligence, Kongju National University, Cheonan, 31080, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Hyunil Kim. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(2), 2617-2630. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.071190

Received 01 August 2025; Accepted 23 October 2025; Issue published 26 November 2025

Abstract

Federated Learning enables privacy-preserving training of Transformer-based language models, but remains vulnerable to backdoor attacks that compromise model reliability. This paper presents a comparative analysis of defense strategies against both classical and advanced backdoor attacks, evaluated across autoencoding and autoregressive models. Unlike prior studies, this work provides the first systematic comparison of perturbation-based, screening-based, and hybrid defenses in Transformer-based FL environments. Our results show that screening-based defenses consistently outperform perturbation-based ones, effectively neutralizing most attacks across architectures. However, this robustness comes with significant computational overhead, revealing a clear trade-off between security and efficiency. By explicitly identifying this trade-off, our study advances the understanding of defense strategies in federated learning and highlights the need for lightweight yet effective screening methods for trustworthy deployment in diverse application domains.Keywords

Modern Natural Language Processing (NLP) has advanced dramatically with the advent of Transformer-based Language Models (TbLMs) [1], in particular the Autoencoding and Autoregressive architectures. Because the Transformer architecture comprises millions to billions of parameters, these models necessitate an extensive corpus of training examples to learn diverse patterns and contextual relationships. Such rich and varied data distributions are essential for the self-attention mechanism to capture complex inter-token interactions and enhance generalization performance. In regimes of data scarcity, models are prone to over-fitting, leading to a precipitous decline in predictive accuracy on novel sentences or unseen domains.

Historically, to meet the demand for large-scale training data, it has been common practice to collect and centrally process user data on a dedicated server. However, this paradigm conflicts with strengthened privacy regulations such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) [2] and confronts significant practical limitations. In particular, the GDPR’s purpose-limitation and data-minimization principles, which entered into force in May 2018, explicitly prohibit the large-scale aggregation and retention of raw user data, thereby engendering a fundamental tension with centralized model training.

Under these constraints, federated learning (FL), a distributed optimization framework [3], emerges as an effective solution to address this challenge. In FL, each client trains a model locally on its raw data and shares only the resulting model parameters with a central server, thereby preserving data privacy while collaboratively improving a global model. This approach has proven useful in pre-trained FL settings [4], particularly for TbLMs.

However, the distributed nature of FL gives rise to several security issues by providing malicious or compromised participants with opportunities for attack [5]. A representative threat is the backdoor attack, where a malicious client uses an update trained on poisoned data to cause the global model to output a specific, incorrect prediction for a certain input. Such attacks can severely undermine model reliability.

Notably, backdoor attack techniques validated in standalone TbLMs environments are theoretically effective in federated learning contexts as well. In this study, we empirically evaluate these techniques under various attack modalities and defense mechanisms in practical FL scenarios.

In this way, Ensuring robustness is an essential research topic for the safe and widespread adoption of FL-based language models. Indeed, various defense mechanisms have been proposed to counter threats such as the backdoor attacks described previously. However, there is a lack of systematic research comparing the performance of these existing defenses under key attack scenarios, specifically when applied to autoencoding and autoregressive-based language models.

Bridging this gap is essential, as the inability to defend against such attacks undermines the trustworthiness of FL as a privacy-preserving framework. This challenge is extends beyond NLP; it is a posing critical implications in other privacy-sensitive domains like IoT and edge computing, where resource constraints are also paramount [6]. Likewise, in the healthcare domain, where sensitive patient data and strict privacy regulations further accentuate the necessity for secure and reliable FL frameworks [7]. Collectively, these applications highlight the urgent need for robust and secure FL systems.

The key contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

• We provide a systematic evaluation of both classical and advanced backdoor attacks in FL environments with transformer-based language models.

• We conduct a comparative analysis of perturbation-based, screening-based, and hybrid defense mechanisms against these attacks.

• We validate the results across both autoencoding (BERT) and autoregressive (GPT-2) paradigms, ensuring broad applicability.

• We identify the trade-off between defense effectiveness and computational efficiency, offering insights for the design of lightweight yet robust defenses.

This paper aims to contribute to the development of trustworthy FL-based NLP systems. To this end, we experimentally evaluate both classical and advanced backdoor attack methods, as well as representative defense mechanisms in FL environments, across two paradigms—autoencoding (BERT) and autoregressive (GPT-2). Based on these results, we analyze and compare the performance of defense mechanisms against major backdoor attacks, thereby providing an empirical basis for selecting appropriate defense strategies for specific threats. To the best of our knowledge, no prior work has systematically compared backdoor defense effectiveness in FL-based NLP systems employing TbLMs.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the background of our work. Section 3 introduces representative backdoor attack methods for TbLMs. In Section 4, we describe the aggregation methods designed for robust FL-based NLP, and Section 5 presents experimental results under representative attack scenarios. Section 6 discusses key findings and their implications, and Section 7 concludes with a summary and directions for future research.

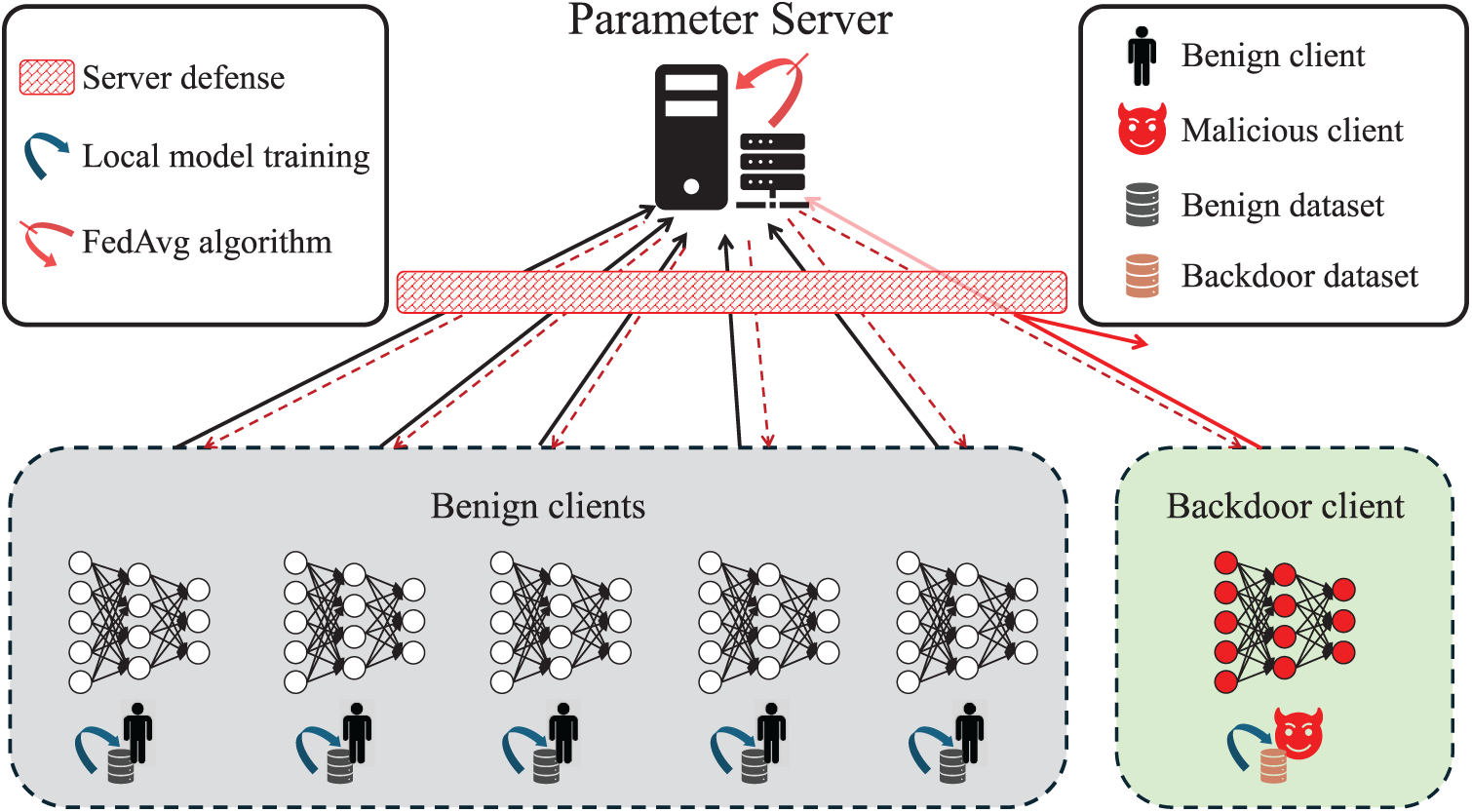

FL [3] is a decentralized learning paradigm proposed to protect user privacy by allowing each client to train a model locally on its own data, rather than transmitting raw data to a server. This approach enables effective model training in distributed environments while complying with strict data protection regulations such as the GDPR [2]. This entire process is visually summarized in Fig. 1. The most widely used algorithm in FL is FedAvg [3], which proceeds as follows: (1) the server initializes the global model and distributes it to the clients; (2) a subset of clients is randomly selected to participate in training, and each selected client updates the received model using its own local data; (3) the locally updated model parameters are then sent back to the server; and (4) the server aggregates these updates using a weighted average based on the data size of each client to produce a new global model. FedAvg is formally defined as follows [3]:

where

Figure 1: Federated learning architecture

2.2 Transformer-Based Language Model

The Transformer architecture processes contextual information through attention mechanisms while eliminating recurrence, enabling parallel computation and efficient training [1]. The attention mechanism assigns weights based on token-to-token relevance, and the multi-head attention structure performs these operations across multiple representation subspaces in parallel, allowing the model to effectively capture complex linguistic patterns.

The Transformer structure is divided into encoder and decoder. Each input token

Subsequently, the hidden state is iteratively updated through repeated application of attention and MLP layers, combined via residual connections and layer normalization [1]:

The computation of the attention output

The encoder integrates contextual information from the entire input length T, whereas the decoder references only the first

Autoencoding models such as BERT [8] are trained to reconstruct masked tokens within an input sequence and are commonly used for natural language understanding tasks such as sentiment analysis and sentence classification. Autoregressive models such as GPT-2 [9], on the other hand, are trained to predict the next token based on prior context and are well-suited for tasks involving next token prediction.

This study utilizes BERT and GPT-2 as representative models of the autoencoding and autoregressive paradigms, respectively, to construct backdoor attack and defense scenarios in federated learning (FL) environments, and empirically evaluates the success rates of the attacks and the effectiveness of the corresponding defense mechanisms.

Backdoor attacks are an insidious threat that embed malicious behaviors into a model, which are activated only by specific triggers without degrading general performance. These attacks become a particularly severe security vulnerability in the FL environment, where the central server cannot validate client data to preserve privacy. This section, therefore, systematically analyzes backdoor attack methodologies, categorizing them into traditional and advanced approaches. These attack methods are summarized in Table 1.

This section introduces classical backdoor attacks, the pioneering methods that established the foundational threat model. These attacks are primarily characterized by their use of a fixed, static trigger, a pre-defined, unchanging pattern embedded into training data via poisoning. While this reliance on a static trigger makes them less stealthy and more susceptible to detection compared to advanced techniques, their direct methodology proves highly effective in creating a compromised model. We will now describe representative examples of this category, namely BadNet and RIPPLe.

BadNet [10] is a foundational backdoor attack that utilizes data poisoning. In the NLP domain, this involves injecting a pre-defined, static trigger into a portion of the training sentences and altering their labels to a single target class. This trigger can be a specific word, phrase, or a seemingly meaningless character sequence (e.g., “cf”, “mn”). The model is then trained on this mixed dataset, embedding the malicious trigger-label association.

The resulting poisoned model exhibits a high attack success rate for inputs containing the trigger, while its accuracy on benign, trigger-free data remains largely unaffected. Although its use of a conspicuous trigger makes it less stealthy, BadNet’s effectiveness and simplicity make it a standard baseline for demonstrating backdoor vulnerabilities.

The RIPPLe [11] attack is designed for greater persistence and robustness against fine-tuning compared to foundational methods like BadNet. Its primary innovation is a mechanism to mitigate the conflict between learning the main task and the backdoor task. This is achieved during the fine-tuning data poisoning process by imposing a constraint that the dot product of the main task loss gradient (

Advanced backdoor attacks represent a significant evolution from the classic methods, designed primarily to enhance stealth and evade detection. Their core innovation lies in moving beyond simple, static triggers to more dynamic and imperceptible triggers that blend into the natural data distribution. Furthermore, their methodologies are often more intricate, such as by manipulating gradient updates or targeting specific parameter subsets, going beyond simple data poisoning. We will now explore BGMAttack and Neurotoxin as prime examples of these sophisticated strategies.

The BGMAttack [12] is a sophisticated text backdoor attack that leverages an external Large Language Model (LLM) to generate stealthy triggers. The attack poisons a dataset by creating natural, semantic-preserving paraphrases of benign sentences and relabeling them to a target class. A model fine-tuned on this data learns to misclassify any input that exhibits the subtle statistical patterns of the generator LLM, while maintaining its accuracy on clean samples.

The key advantage of this method is its high stealth. By using implicit triggers derived from the generator’s conditional probability distribution, rather than conspicuous, fixed keywords, BGMAttack can create effective backdoors that are robust against a wide range of detection techniques.

Neurotoxin [13] is a highly persistent model poisoning attack designed for federated learning. Its core strategy involves embedding the backdoor into a sparse subset of model parameters that are rarely updated by benign clients. By isolating the malicious update to these non-overlapping parameters, Neurotoxin prevents the backdoor from being diluted or overwritten during the server aggregation process. This results in exceptional durability where even simple triggers remain potent, a significant improvement in robustness achieved with minimal implementation effort. This strategic targeting of under-utilized parameter spaces allows Neurotoxin to act as an adaptive adversary, effectively tailoring its poisoning strategy to the aggregation dynamics of federated learning.

In the federated learning process, since each client trains its own local model, the defense mechanisms originally designed for a single centralized model are unlikely to be effective. Consequently, federated learning environments require the adoption of defense mechanisms specifically tailored to the federated learning paradigm. We analyze defense mechanisms in federated learning environments by classifying them according to their mechanisms into perturbation-based and screening-based Approach. These defense mechanisms are summarized in Table 2.

This method uniformly applies each client’s local updates without regard to whether they are benign or adversarial. Because it does not distinguish between benign clients and adversarial clients, it predominantly employs more conservative defense mechanisms, as illustrated in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Adversarial vectors according to the defense approach

This method computes the squared

In the subsequent aggregation process, the global model is updated by adding the average of the adjusted updates

4.1.2 Weak Differential Privacy

This method [14,15] enhances the final aggregation stage of federated learning by adding small Gaussian noise

Here,

This approach introduces a screening phase prior to update aggregation to detect potentially malicious contributions. Screening is performed conservatively to preserve the integrity of benign training, and for updates flagged as suspicious, proactive defense actions—such as removal, scaling, or sanitization—are applied to safeguard overall model stability. This process of identifying and excluding malicious updates is visually outlined in Fig. 2.

Multi-Krum [16] is an extended version of Krum that enables a trade-off between Byzantine robustness and convergence speed by aggregating multiple vectors rather than selecting just one. The procedure is defined as follows [16]:

For each client

FLAME is an integrated hybrid defense framework that primarily relies on clustering-based screening, while also incorporating perturbation techniques such as adaptive clipping and adaptive noise injection to defend against backdoor attacks [17]. In the screening phase, the cosine distance between each pair of client update vectors

HDBSCAN with a minimum cluster size of

where

with

The experimental evaluation is designed to assess the effectiveness of the aforementioned defense strategies against various attack scenarios. To quantitatively evaluate performance, we adopt the Attack Success Rate (ASR) as the key metric. ASR measures the effectiveness of a backdoor and is defined according to the model architecture as follows:

• For autoencoding models (e.g., BERT), ASR denotes the proportion of trigger-injected inputs that are misclassified into the attacker’s target label.

• For autoregressive models (e.g., GPT-2), ASR refers to the proportion of trigger-injected inputs that generate attacker-intended next tokens.

Our experimental settings for backdoor attacks consist of 100 clients in total, with a participation fraction of 0.1 (10 clients selected per round). The adversarial presence is simulated within a specific window, from round 10 to round 30. To analyze the impact of varying threat levels, we conducted experiments with adversarial client rates of 10% and 20% in separate runs.

To evaluate the robustness of the autoencoding model, we conducted experiments using BERT on the SST-2 [18] dataset, a standard benchmark for sentiment analysis. The evaluation focused on the performance of various defense mechanisms against classical attacks (BadNet and RIPPLE) and an advanced attack (BGMAttack) in a federated learning environment. For BGMAttack, which uses natural paraphrases as triggers in a binary sentiment analysis task, the probabilistic baseline for ASR is 50%. Therefore, we establish a stringent success criterion: an attack is considered successful only if its ASR consistently exceeds this 50% threshold, providing clear evidence that the model has learned the malicious trigger-label association rather than making random classifications.

As shown in Fig. 3, perturbation-based defenses demonstrated limited efficacy and were largely unable to withstand the attacks. For instance, under Norm-clipping, BadNet’s ASR reached 50% immediately after the attack’s onset, while RIPPLE’s ASR surpassed 90% after round 15. Weak DP offered even less resistance, with both classical attacks achieving a 100% ASR almost immediately after insertion. Notably, the advanced BGMAttack also circumvented both defenses, maintaining an average ASR of 61% throughout the attack phase, confirming its significant threat. This threat was further amplified when the adversarial client rate was increased to 20%.

Figure 3: Attack success rate (ASR) of various backdoor attacks and defenses in the autoencoding model (BERT). The left and right columns of graphs correspond to scenarios with 10% and 20% adversarial clients, respectively

In stark contrast, screening-based defense mechanisms delivered outstanding performance. Multi-Krum and FLAME successfully neutralized both classical attacks, suppressing the ASR for BadNet and RIPPLE to below 10% throughout the experiment. These defenses also effectively contained the advanced BGMAttack, consistently keeping its ASR below the 50% success threshold.

These findings reveal a clear performance disparity between the two defense philosophies. Screening-based methods, which proactively identify and exclude malicious updates, demonstrated far superior robustness compared to perturbation-based techniques, which apply uniform constraints to all client updates.

Experiments on the next-token prediction (NTP) task were conducted using the GPT-2 Medium model with the Shakespeare [19] corpus. There are plans to extend the benchmarks to WikiText-103 for practical applications. The attack methods included a BadNet variant optimized for autoregressive models and two versions of the Neurotoxin backdoor attack. The BadNet variant was designed to produce biased content or false information upon activation by a designated trigger. To analyze the impact of trigger design, the Neurotoxin attack was implemented in two versions: ‘Rare trigger’ and ‘Sentence trigger’. The ‘Rare trigger’ employs rare tokens, whereas the ‘Sentence trigger’ uses sentences containing profanity and hate speech. This design ensures that malicious updates are statistically similar to benign ones, allowing them to evade detection by defense mechanisms. Notably, due to its nature and the constant mitigation effect from benign client updates in the FL environment, the ASR for the Sentence trigger struggles to reach 100%. However, an ASR of around 70% is sufficient to severely compromise the model’s integrity and achieve the attacker’s objectives.

As the experimental results in Fig. 4 demonstrate, perturbation-based defense mechanisms were largely ineffective against most attacks. For instance, with a 10% adversarial client rate under Norm-clipping, attacks based on rare triggers (BadNet and Neurotoxin Rare trigger) achieved a 94% ASR within 12 rounds of attack initiation, while the Sentence-trigger-based Neurotoxin attack reached an ASR of 68.4% in just 10 rounds. Under the Weak DP setting, rare-trigger-based attacks also recorded an ASR of 90% within 17 rounds. Furthermore, when the adversarial client rate was increased to 20%, all successful attacks surpassed a 90% ASR in less than five rounds, highlighting the insufficiency of both defense mechanisms in thwarting these attacks.

Figure 4: Attack success rate (ASR) of various backdoor attacks and defenses in the autoregressive model (GPT-2). The left and right columns of graphs correspond to scenarios with 10% and 20% adversarial clients, respectively

In contrast, screening-based defense mechanisms demonstrated varied performance depending on the attack trigger’s design. Multi-Krum and FLAME completely mitigated attacks using rare triggers, such as BadNet and the Neurotoxin (Rare trigger), maintaining their ASR at 0%. However, against the statistically stealthy ‘Sentence trigger’ employed by Neurotoxin, both defenses failed, with the ASR climbing to 70% in under 10 rounds from the attack’s commencement.

These results indicate that the effectiveness of a defense mechanism is highly contingent on the sophistication of the attack, particularly the design of its trigger. Specifically, while rare and explicit triggers can be easily filtered by screening methods, implicit triggers designed to mimic the distribution of benign data can circumvent even robust defense strategies, such as screening-based methods, which incur substantial computational overhead.

Figs. 3 and 4 demonstrate a clear performance disparity between defense strategies. Perturbation-based defenses, such as norm clipping and weak DP, largely failed to suppress the ASR, with their ineffectiveness becoming more pronounced as attack sophistication increased. In contrast, screening-based defenses like Multi-Krum proved highly effective, particularly against rare trigger-based attacks where they maintained a 0% ASR. However, this superior security comes at a significant cost. Focusing on the aggregation phase for the 355-million-parameter GPT-2 Medium model, a screening-based method required 27.03 s, while a perturbation-based method took only 3.9 s—a nearly seven-fold difference in computational overhead. We anticipate this overhead will grow exponentially for state-of-the-art models with billions of parameters, highlighting a critical trade-off between security and efficiency.

Thus, while screening-based defense methods deliver superior protection, we confirmed that they incur relatively high overhead in aggregation computations. Moreover, as attacks become more sophisticated, some malicious vectors may still survive the screening stage. To fully suppress these residual threats, it may be beneficial to adopt a hybrid defense that follows the initial screening phase with a lightweight perturbation based mechanism. The FLAME framework, as previously described, likewise employs a three-stage hybrid defense—comprising clustering, adaptive norm clipping, and adaptive noise injection—but incurs, on average, an aggregation time of 63.20 s—approximately 2.3 times the overhead of alternative approaches. Consequently, to realize a more lightweight hybrid solution, it is worth investigating a scheme founded on Multi-Krum.

However, it is crucial to acknowledge that even robust screening-based defenses like Multi-Krum and FLAME can be circumvented under certain sophisticated attack scenarios. As highlighted in prior work [13], when the attack vector itself is composed of sentences containing profanity and hate speech, the resulting malicious updates may not be markedly different from benign ones. This statistical similarity makes it significantly easier for adversaries to evade detection, posing an ongoing challenge for even advanced defense mechanisms.

This paper presents a critical evaluation of applying existing defense strategies to TbLMs within FL environments, representing a crucial step in understanding their practical security implications. Our comprehensive analysis of perturbation-based and screening-based defense mechanisms revealed a significant trade-off between defensive performance and communication efficiency.

Perturbation-based methods, which introduce noise or constraints, were consistently characterized by their low computational overhead across both models. This makes them easily integrable into existing systems. However, our evaluation uniformly showed that they struggle as a robust defense, with the ASR remaining considerably high.

In contrast, screening-based methods demonstrated a considerably higher rate of defense in our experiments. By actively identifying and excluding suspicious components, these techniques effectively neutralized backdoor threats in both model environments. Despite this high efficacy, however, there was a clear drawback of high overhead, consuming intensive computation and resources that were more than double those of perturbation-based methods.

Ultimately, overcoming this defensive performance-communication efficiency trade-off is a key challenge for future work. Specifically, research is urgently needed to achieve the high security performance of screening-based defenses at a realistic computational cost. Reducing the computational overhead while maintaining a high level of defense is the essential next step toward deploying truly trustworthy machine learning systems in a wider range of environments. This challenge is not limited to text-based FL systems but also extends to multimodal AI models, where adversarial robustness remains an open research problem [20].

Future research needs to be concretized along two complementary directions. First, perturbation-based defenses should maintain their inherently low overhead while improving their currently modest defense rate. Second, screening-based defenses must focus on reducing overhead while sustaining strong robustness. Since most of the overhead arises from pairwise comparisons across client updates, strategies to reduce the number and cost of these comparisons are essential. Finally, Neurotoxin [13], examined in this study, serves as a representative example of an adaptive adversary, underscoring the need for future defenses to address not only traditional backdoors but also adaptive and evolving attack strategies. In this regard, exploring more advanced and durable attacks such as SDBA [21], as well as recent defense mechanisms applied in image-based FL models [22], will be crucial for assessing their applicability and effectiveness in TbLMs.

While this study primarily focuses on the technical robustness of federated learning (FL)-based language models, we acknowledge that the deployment of FL systems in sensitive domains (e.g., healthcare, finance, education) raises important ethical considerations. These include issues of fairness, accountability, potential misuse, and the unintended amplification of biases. Although these concerns fall outside the direct scope of our experiments, addressing them is essential for safe and trustworthy real-world adoption of FL systems. We encourage future research to incorporate both technical defenses and ethical safeguards.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by a research fund from Chosun University, 2024.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Gwonsang Ryu and Hyunil Kim; methodology, Hyunil Kim; software, Seunghan Kim and Changhoon Lim; validation, Seunghan Kim; formal analysis, Seunghan Kim; investigation, Seunghan Kim, Changhoon Lim and Hyunil Kim; resources, Gwonsang Ryu; data curation, Changhoon Lim; writing—original draft preparation, Seunghan Kim and Changhoon Lim; writing—review and editing, Gwonsang Ryu and Hyunil Kim; visualization, Seunghan Kim; supervision, Hyunil Kim; project administration, Hyunil Kim; funding acquisition, Hyunil Kim. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are openly available at https://github.com/ICT-Convergence-Security-Lab-Chosun/fl-lm-backdoor-robustness (accessed on 12 September 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Vaswani A, Shazeer N, Parmar N, Uszkoreit J, Jones L, Gomez AN, et al. Attention is all you need. Vol. 30. In: Advances in neural information processing systems. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

2. Voigt P, Von dem Bussche A. The eu general data protection regulation (gdpr). 1st ed. Vol. 10. In: A practical guide. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2017. p. 10-5555. [Google Scholar]

3. McMahan B, Moore E, Ramage D, Hampson S, Arcas B. Communication-efficient learning of deep networks from decentralized data. In: Singh A, Zhu J, editors. Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics. Vol. 54. Westminster, UK: PMLR; 2017. p. 1273–82. [Google Scholar]

4. Tian Y, Wan Y, Lyu L, Yao D, Jin H, Sun L. When federated learning meets pre-training. ACM Trans Intell Syst Technol. 2022;13(4):66. doi:10.1145/3510033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Nguyen TD, Nguyen T, Nguyen PL, Pham HH, Doan KD, Wong KS. Backdoor attacks and defenses in federated learning: survey, challenges and future research directions. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2024;127(7):107166. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2023.107166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Mali S, Zeng F, Adhikari D, Ullah I, Al-Khasawneh MA, Alfarraj O, et al. Federated reinforcement learning-based dynamic resource allocation and task scheduling in edge for IoT applications. Sensors. 2025;25(7):2197. doi:10.3390/s25072197. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Vajrobol V, Saxena GJ, Pundir A, Singh S, Gaurav A, Bansal S, et al. A comprehensive survey on federated learning applications in computational mental healthcare. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2025;142(1):49–90. doi:10.32604/cmes.2024.056500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Devlin J, Chang MW, Lee K, Toutanova K. BERT: pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In: Burstein J, Doran C, Solorio T, editors. Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies. Vol. 1. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2019. p. 4171–86. [Google Scholar]

9. Radford A, Wu J, Child R, Luan D, Amodei D, Sutskever I, et al. Language models are unsupervised multitask learners. OpenAI Blog. 2019;1(8):9. [Google Scholar]

10. Gu T, Liu K, Dolan-Gavitt B, Garg S. Evaluating backdooring attacks on deep neural networks. IEEE Access. 2019;7:47230–43. doi:10.1109/access.2019.2909068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Kurita K, Michel P, Neubig G. Weight poisoning attacks on pre-trained models. In: Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2020. p. 4931–7. [Google Scholar]

12. Li J, Yang Y, Wu Z, Vydiswaran VGV, Xiao C. ChatGPT as an attack tool: stealthy textual backdoor attack via blackbox generative model trigger. In: Proceedings of the 2024 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (Volume 1: Long Papers). Stroudsburg, PA, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2024. p. 2985–3004. [Google Scholar]

13. Zhang Z, Panda A, Song L, Yang Y, Mahoney M, Mittal P, et al. Neurotoxin: durable backdoors in federated learning. In: International Conference on Machine Learning. Westminster, UK: PMLR; 2022. p. 26429–46. [Google Scholar]

14. Sun Z, Kairouz P, Suresh AT, McMahan HB. Can you really backdoor federated learning? arXiv:1911.07963. 2019. [Google Scholar]

15. Abadi M, Chu A, Goodfellow I, McMahan HB, Mironov I, Talwar K, et al. Deep learning with differential privacy. In: Proceedings of the 2016 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, CCS ’16. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; 2016. p. 308–18. doi:10.1145/2976749.2978318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Blanchard P, El Mhamdi EM, Guerraoui R, Stainer J. Machine learning with adversaries: byzantine tolerant gradient descent. In: Guyon I, Luxburg UV, Bengio S, Wallach H, Fergus R, Vishwanathan S, et al. editors. Advances in neural information processing systems. Vol. 30. Red Hook, NY, USA: Curran Associates, Inc.; 2017. p. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

17. Nguyen TD, Rieger P, Chen H, Yalame H, Möllering H, Fereidooni H, et al. FLAME: taming backdoors in federated learning. In: 31st USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 22). Boston, MA, USA: USENIX Association; 2022. p. 1415–32. [Google Scholar]

18. Socher R, Perelygin A, Wu J, Chuang J, Manning CD, Ng A, et al. Recursive deep models for semantic compositionality over a sentiment treebank. In: Proceedings of the 2013 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2013. p. 1631–42. [Google Scholar]

19. Karpathy A. char-rnn; 2015 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 20]. Available from: https://github.com/karpathy/char-rnn. [Google Scholar]

20. Cho HH, Zeng JY, Tsai MY. Efficient defense against adversarial attacks on multimodal emotion AI models. IEEE Trans Comput Soc Syst. 2025. doi:10.1109/tcss.2025.3551886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Choe M, Park C, Seo C, Kim H. SDBA: a stealthy and long-lasting durable backdoor attack in federated learning. IEEE Trans Dependable Secure Comput. 2025. doi:10.1109/tdsc.2025.3593640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Xu J, Zhang Z, Hu R. Detecting backdoor attacks in federated learning via direction alignment inspection. In: Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2025 Jun 10–17; Nashville, TN, USA. p. 20654–64. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools