Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Quantum Genetic Algorithm Based Ensemble Learning for Detection of Atrial Fibrillation Using ECG Signals

1 Department of Electrical Engineering, Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU), Riyadh, 11432, Saudi Arabia

2 Department of Creative Technologies, Faculty of Computing and Artificial Intelligence, Air University, Islamabad, 44000, Pakistan

3 Department of Computer Science, Bahria School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, Bahria University, Islamabad, 44000, Pakistan

4 Computer and Information Sciences Research Center (CISRC), Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU), Riyadh, 11564, Saudi Arabia

5 Department of Computer Engineering, Bahria School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, Bahria University, Islamabad, 44000, Pakistan

6 Computer Science Department, College of Science and Humanities, Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University, Jubail, 31961, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Author: Shehzad Khalid. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Machine Learning and Deep Learning-Based Pattern Recognition)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(2), 2339-2355. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.071512

Received 06 August 2025; Accepted 23 October 2025; Issue published 26 November 2025

Abstract

Atrial Fibrillation (AF) is a cardiac disorder characterized by irregular heart rhythms, typically diagnosed using Electrocardiogram (ECG) signals. In remote regions with limited healthcare personnel, automated AF detection is extremely important. Although recent studies have explored various machine learning and deep learning approaches, challenges such as signal noise and subtle variations between AF and other cardiac rhythms continue to hinder accurate classification. In this study, we propose a novel framework that integrates robust preprocessing, comprehensive feature extraction, and an ensemble classification strategy. In the first step, ECG signals are divided into equal-sized segments using a 5-s sliding window with 50% overlap, followed by bandpass filtering between 0.5 and 45 Hz for noise removal. After preprocessing, both time and frequency-domain features are extracted, and a custom one-dimensional Convolutional Neural Network—Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (1D CNN-BiLSTM) architecture is introduced. Handcrafted and automated features are concatenated into a unified feature vector and classified using Support Vector Machine (SVM), Random Forest (RF), and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) models. A Quantum Genetic Algorithm (QGA) optimizes weighted averages of the classifier outputs for multi-class classification, distinguishing among AF, noisy, normal, and other rhythms. Evaluated on the PhysioNet 2017 Cardiology Challenge dataset, the proposed method achieved an accuracy of 94.40% and an F1-score of 92.30%, outperforming several state-of-the-art techniques.Keywords

Cardiovascular disease is an imminent threat to life and health today, and it is becoming more common each year. The diagnosis and prevention of cardiovascular disease must therefore be a top priority. Cardiac problems can be analyzed using Electrocardiogram (ECG) signals. Atrial Fibrillation (AF) is a type of heart arrhythmia in which a patient undergoes an irregular heartbeat. If untreated in a timely manner, this AF can lead to heart failure in the worst case. According to the published guidelines on AF set forth by the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) [1], implementing a rhythm control strategy in conjunction with rate control can significantly improve symptoms. In remote areas, where only a few radiologists are available and there is a lack of sufficiently experienced cardiologists, automated detection of AF becomes extremely important. Researchers [2–4] have proposed different methods for automated detection of AF and other arrhythmias. With timely detection of AF, therapeutic measures can be taken for the prevention of heart attacks [5,6].

Most of the current research focuses on a binary classification between healthy participants and AF subjects. It is projected that more than 12 million people in Europe and America have AF, and that number is expected to increase in the following 30 to 50 years [7]. Despite the scale of the issue, AF detection is still a challenge since it may be episodic. AF detectors may be thought of as falling into one of two categories, having approaches based on ventricular response analysis or atrial activity analysis. The examination of the lack of P waves or the presence of fibrillation f waves in the TQ interval is the foundation for atrial activity analysis-based AF detectors. The R-peak, which has a highly noticeable large amplitude as a feature in the ECG and whose detection can be much more noise-resistant, is where RR intervals are formed. Therefore, this method could be more suited for automated, real-time AF detection [8–11]. A variation of the peaks (P, Q, R, S, and T) or inconsistency in the ECG signals or segment intervals indicating an irregular ECG leads to Cardiovascular Diseases (CVD) [12,13]. The P waves in the ECG signal during AF degrade into a string of weak fibrillation f waves [14,15].

Researchers [16–20] have proposed various machine learning and deep learning techniques for AF prediction using heart ECG signals. These techniques include Bandpass/Bandstop filters [21–23], Butterworth filter [24], Wavelet transform [25], Fourier transform [24], and the Pan–Tompkins algorithm [21,25] for QRS detection from ECG signals. Zhang et al. [24] applied a Butterworth filter for preprocessing to flatten the frequency in the passband and zero out responses in the stopband. Zhang et al. [24] used the Fourier Transform for non-periodic signals and for transforming the signal from the time domain to the frequency domain. The Bandpass filter is used to limit the range of frequencies that may pass through, since the Low-Pass Filter’s (LPF’s) cutoff frequency is greater than the High-Pass Filter’s (HPF’s) cutoff frequency in [21–23]. Hernandez et al. [25] used the technique of wavelet transformation to create a representation of the signal in the temporal domain. Handcrafted features include temporal features [21,22,26] and spectral features [21,27]. Multiple frequency bands have been extracted as features by dividing ECG signals [25–28]. Zhao et al. [29] used Long Short-Term Memory Units (LSTMs) and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), while Hong et al. [28] and Mukherjee et al. [23] used ensemble learning to differentiate between the classes. Support Vector Machine (SVM) was used for classification by García et al. [22]. Multiple classes were also classified using dense networks, CNNs, and Random Forest (RF) models [21,26,27,30].

Recent studies using the same PhysioNet/CinC 2017 single-lead dataset have pushed performance with diverse pipelines. Zhao et al. [29] fused Temporal Convolutional Networks with ResNet backbones for single-lead AF detection and reported strong accuracy and F1 scores on the CinC-2017 setting. Zhang et al. [24] investigated overfitting suppression strategies in deep learning-based AF detection using the same dataset. For robustness and deployment, Soleimani et al. [31] trained on CinC-2017 and showed that test-time data augmentation (TTA) improves generalization under cross-domain shifts to a distinct wearable dataset. These works strengthen the empirical context for AF detection on CinC-2017 and motivate our hybrid feature extraction method and QGA-optimized ensemble direction.

Automated detection of AF from ECG signals faces multiple challenges. The presence of noise due to body movements, electrode impedance, and external interference often distorts the ECG signals. Narrow differences between AF and other cardiac rhythms further hinder reliable detection, especially in multiclass scenarios. Many existing methods focus only on binary classification. Moreover, existing methods rely only on on either handcrafted or deep features that limits the ability to capture the full complexity of ECG signals. Feature level fusion and ensemble classification methods remain underexplored, whereas, most models lack optimization strategies that effectively combine multiple classifiers. Unlike existing approaches that rely only on handcrafted features or deep learning models, our work introduces a hybrid feature extraction strategy and a quantum-optimized ensemble. We performed feature level fusion by concatenating handcrafted statistical and morphological features with machine learned features extracted using a customized 1D CNN-BiLSTM. Furthermore, we apply a Quantum Genetic Algorithm (QGA) to dynamically optimize classifier weights a novel contribution not yet reported in the AF detection literature. Finally, we extend beyond binary AF detection by addressing four clinically important classes (normal, AF, noisy, and other rhythms), enhancing practical applicability in real-world and remote healthcare scenarios. The specific contributions of the proposed work are as follows:

• Hybrid feature extraction pipeline: Feature level fusion of handcrafted features with deep CNN-BiLSTM features for AF detection.

• QGA-optimized ensemble classifier: Novel application of Quantum Genetic Algorithm for assigning optimized weights of SVM, RF, and LSTM outputs.

• Multi-class classification: Unlike prior binary AF methods, our framework classifies four rhythms (normal, AF, noisy, and other arrhythmias).

• Clinical robustness: Demonstrate state-of-the-art accuracy (94.40%) and F1-score (92.30%) on PhysioNet 2017 dataset.

In this research, we propose a novel QGA based ensemble method for the automated detection of AF using single-lead ECG signals. Our proposed method includes data acquisition, preprocessing of ECG signals to remove multiple types of noise, feature extraction of both types, i.e., handcrafted as well as automated machine learned features, and ensemble classification among AF, noisy, normal, and other rhythms.

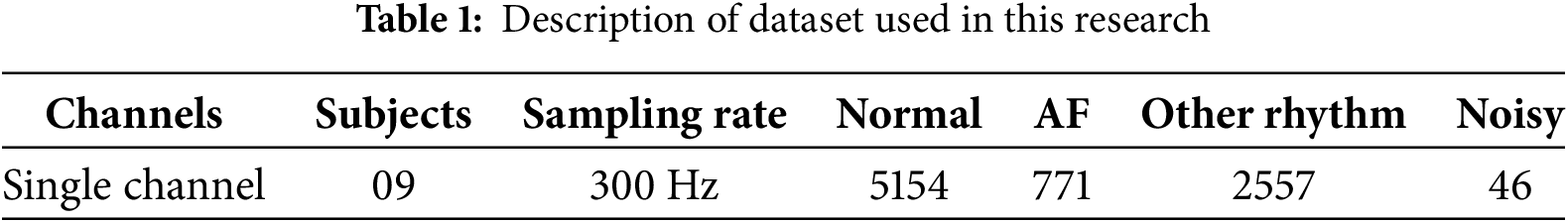

We used the publicly available PhysioNet/Computing in Cardiology Challenge (CinC) 2017 dataset in this research. The dataset contains 12,186 single-lead ECG recordings, whereas, each recording lasts for 9 to 61 s. ECG signals have been sampled at 300 Hz, and annotated by clinical experts into four categories, i.e., Normal (5154 recordings), Atrial Fibrillation (771 recordings), Other Rhythms (2557 recordings), and Noisy signals (46 recordings). The CinC dataset is imbalanced, with the AF and noisy classes being significantly smaller than the normal class. To address this and ensure fair evaluation, we used the overlaping window with 50% overlap for segmentation of ECG signals into equal length segments. We used

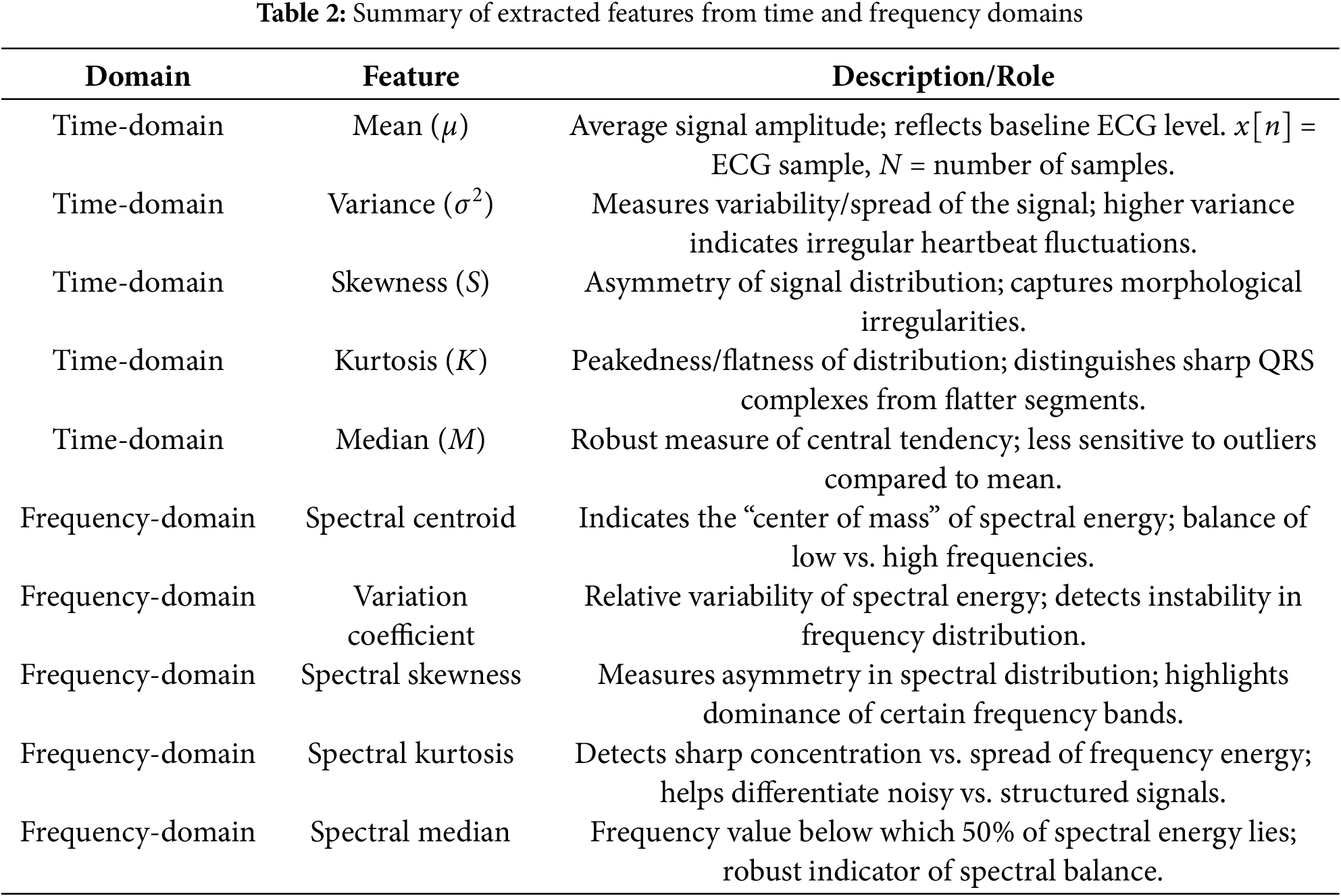

After data acquisition, we segmented ECG signals into equal-length samples using an overlapping window of 5 s with an overlap of 2.5 s. A second-order Butterworth bandpass filter was then applied with cutoff frequencies of 0.5 and 45 Hz to remove the high-frequency components that are susceptible to noise and to eliminate power line interference from the ECG signals. The Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) was then applied to convert the time-domain signals into frequency-domain signals. A comprehensive feature vector was extracted by concatenating features from a customized one-dimensional CNN architecture and statistical features in both the time and spectral domains. This feature vector was then passed to three classifiers, including SVM, LSTM, and RF. The QGA was employed to assign weights to the outputs of these three classifiers for the final decision among four classes, i.e., AF, normal, noisy, and other rhythms. Fig. 1 shows the flow diagram of the proposed novel method for the classification of AF, normal, other rhythms, and noisy classes in ECG signals.

Figure 1: Flow diagram of the proposed novel method for classification of atrial fibrillation, normal, other rhythms and noisy classes in ECG signals

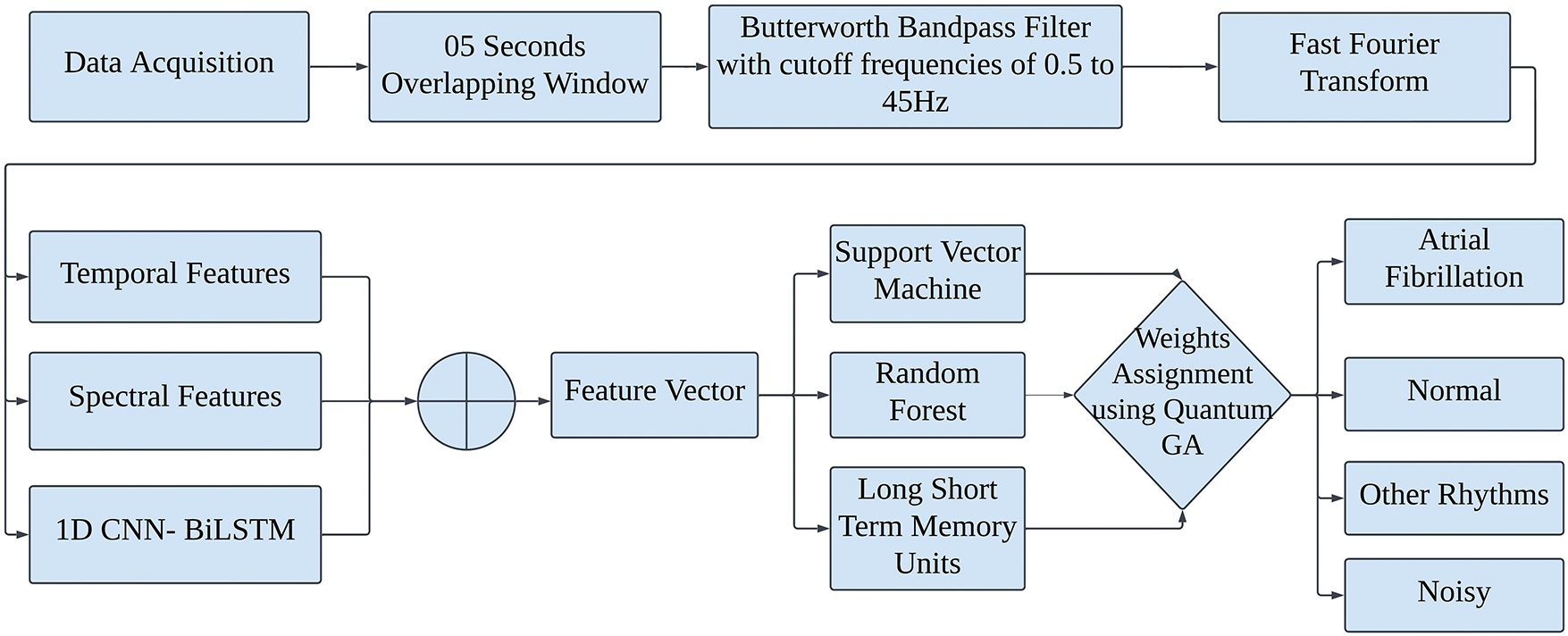

ECG signal

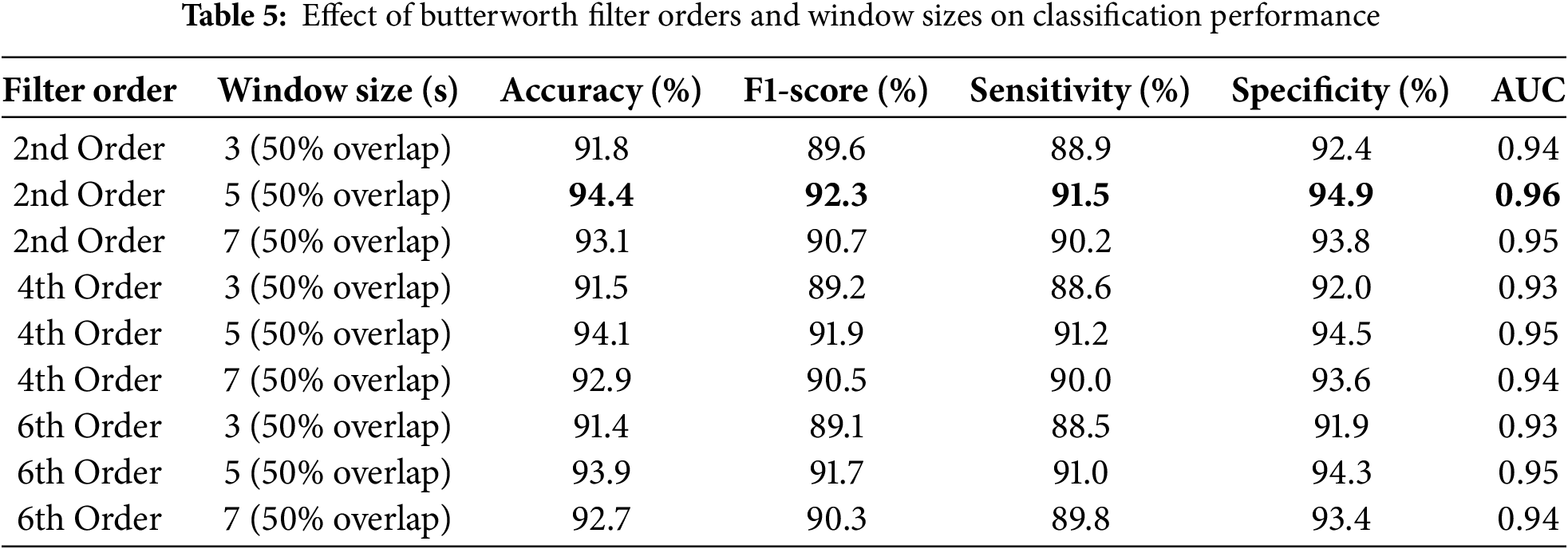

There are 9000 and 18,000 samples in each signal, due to having a different number of signal lengths, preprocessing mandatory in such situations. Due to the difference in each signal length, we have applied the Butterworth filter and segmentation to gain the right and equal lengths. For this purpose, we take both the order of 2 and 4, but their results are not that much different except for the computational time. To systematically validate this choice, we conducted additional experiments varying both the filter order (

Figure 2: Filtered ECG signal

The FFT operates on

To recover the original signal in the time domain from its spectral components, the inverse FFT is applied, defined as:

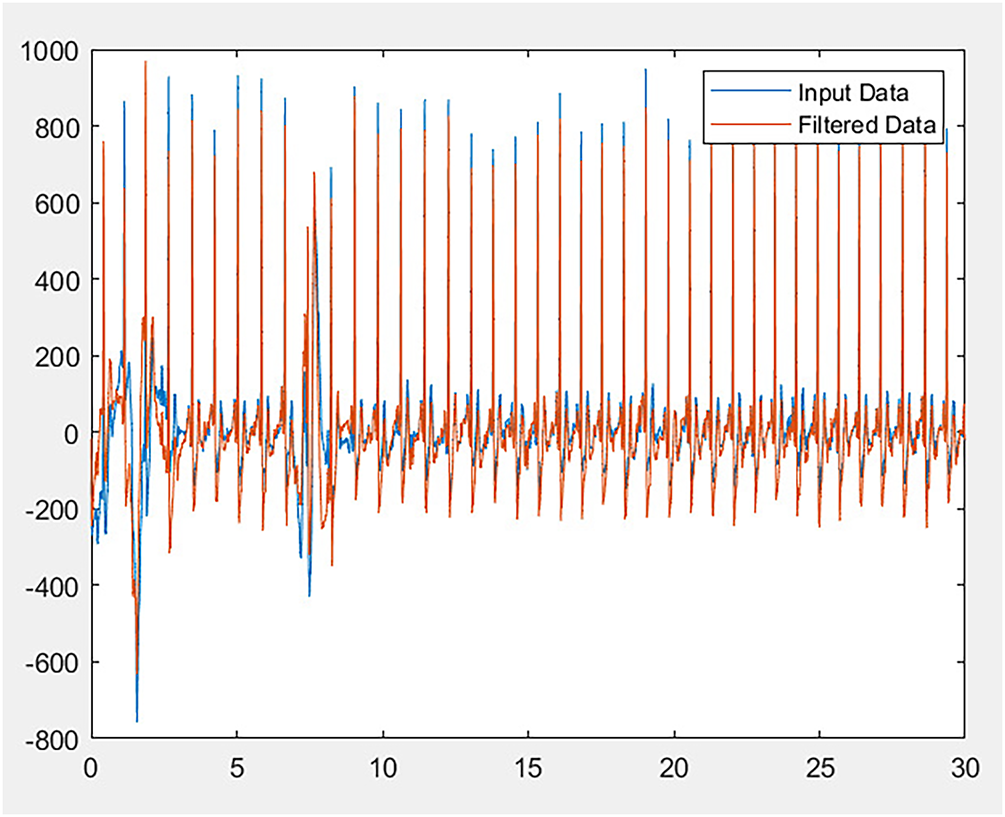

We compute statistical measures including mean, standard deviation, and degree of peakness or flatness, skewness, and kurtosis. These calculations are very helpful for detecting irregular heart rhythms, known as cardiac arrhythmia. To detect cardiac muscle injury, the morphological parameters of ECG signals can be extracted, such as the area, perimeter, and compactness of the QRS complex. Time-domain research analyze signal fragments in the time-domain directly. Frequency-domain features are extracted after conversion of time-domain signals to frequency-domain signals using the Fourier transform. Techniques for morphological feature extraction are peak detection, for example, recognizing peaks, troughs, and other noteworthy ECG waveform features, and template matching to extract distinguishing characteristics and compare the ECG waveform with established templates. Moreover, segment the ECG waveform into separate sections to illustrate the various components.

Assume

Handcrafted features provide important information for classification between different classes used for AF detection. The mean amplitude reflects the baseline ECG level and can indicate signal shifts due to electrode placement or noise. Variance/ standard deviation capture beat-to-beat variability, which is often increased in case of atrial fibrillation due to irregular ventricular response. Skewness and kurtosis measure the asymmetry and peakedness of the ECG waveform distribution. Abnormal values of skewness and kurtosis may correspond to distorted QRS complexes or the absence of distinct P-waves. Similarly, in the frequency domain, the spectral centroid reflects the average frequency content, which tends to shift upward in noisy or fibrillatory signals. Spectral skewness and spectral kurtosis provide irregular distributions of frequency energy, commonly observed when AF disrupts normal periodicity. The spectral median provides a robust marker of frequency balance and helps in classification between different rhythms and AF. These features are concatenated together and provide morphological and spectral fluctuations that help in classification of atrial fibrillation and other arrhythmias. A summary of the extracted features and their diagnostic roles is provided in Table 2.

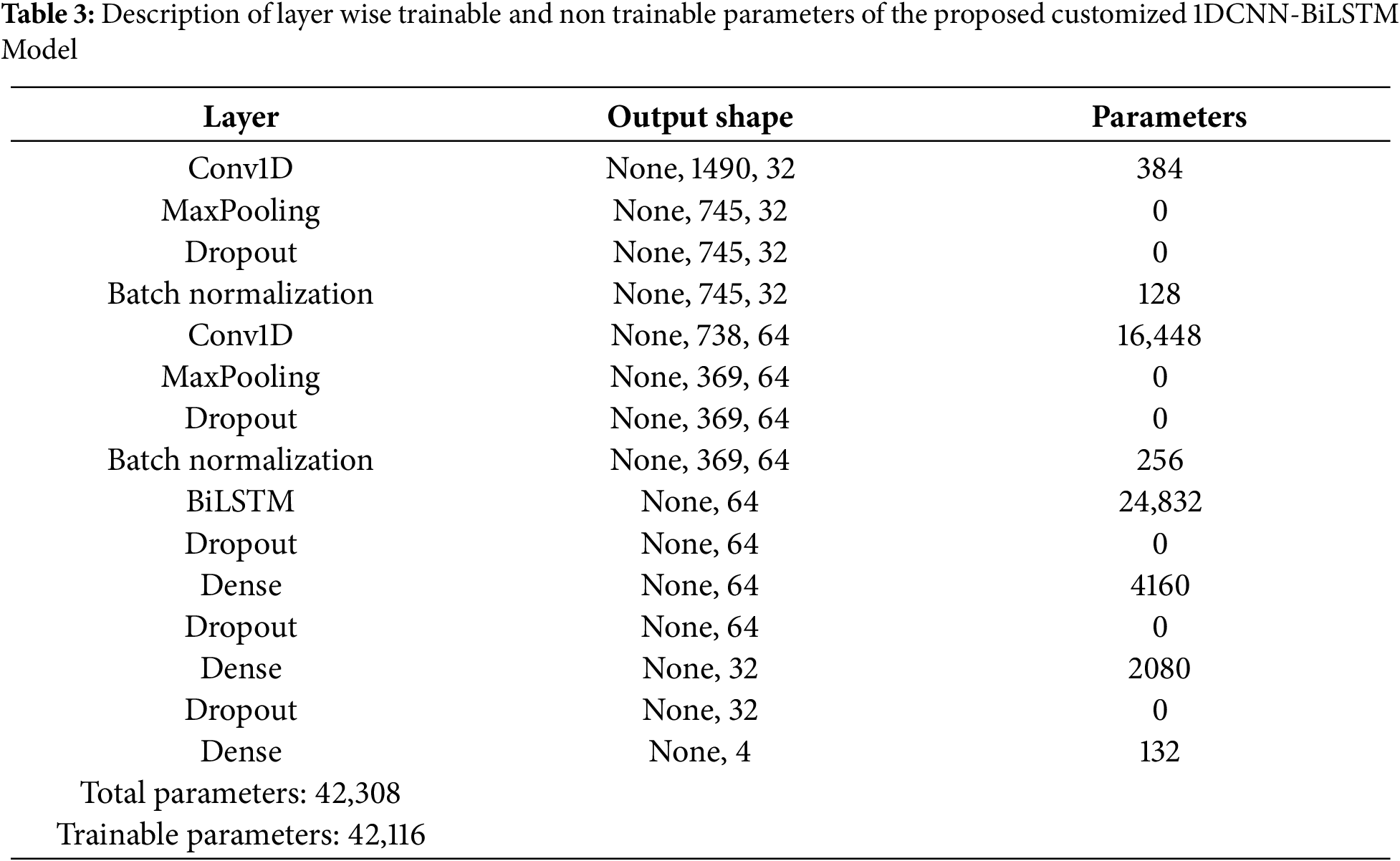

To overcome the challenges presented by low ECG data signal’s verbose nature in time series analysis, we propose a model utilizing both deep convolutional strategies and BiLSTM models to produce effective feature extraction. Architecture of the proposed custom CNN-BiLSTM list of trainable and non-trainable parameters is shown in Table 3. In a CNN, there are shared weights across local receptive fields. Gaussian noise is added to the training set, in order to improve accuracy, so it will perform well if the outlier arrives on the testing set and to enhance the accuracy and resilience of the proposed classifier, various techniques have been employed.

where

The LSTM network operations for a given time step

Forget gate:

Input gate:

Cell state update:

Output gate:

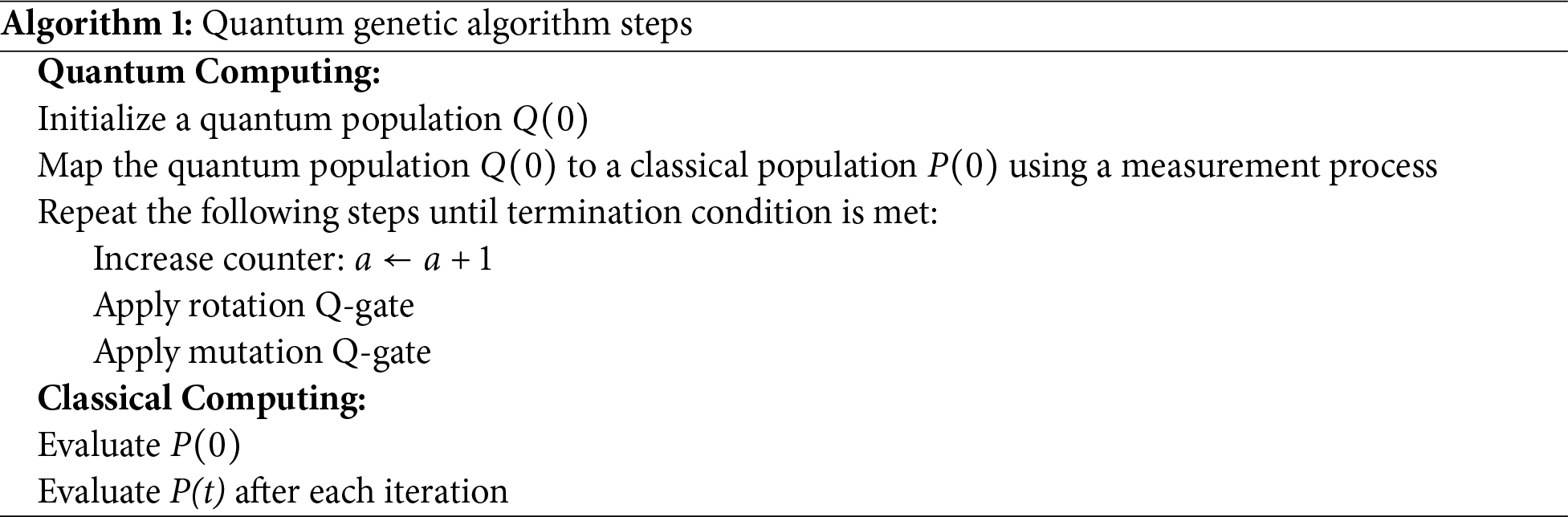

After feature extraction, we passed the feature vector to three different classifiers including SVM, LSTM and RF. Output of these classifiers is then assigned a unique weight using QGA to classify the segments into four classes. Classical Genetic Algorithms (GA) are widely used for optimization problems, but they often suffer from premature convergence and slow exploration of large solution spaces. The Quantum Genetic Algorithm (QGA) enhances GA by introducing principles of quantum computing. In QGA, each gene is represented as a qubit that can exist in a superposition of states, allowing multiple potential solutions to be explored simultaneously. Quantum operations such as rotation gates and probability amplitude updates adjust the qubits adaptively, ensuring a more diverse search and reducing the risk of being trapped in local optima. This global search capability makes QGA particularly suitable for complex optimization problems such as assigning optimal weights to ensemble classifiers. QGA is a probabilistic search algorithm for optimization that is more intelligent, efficient, and adaptive. The optimization involves using qubits to characterize genes, utilizing quantum information to make all possible information exist, and incorporating quantum concepts such as quantum states, quantum revolving gates, quantum state characteristics, and probability amplitudes into fundamental genetic algorithms. Among the genes expressed by qubits, it possesses strong uncertainty, compensating for low randomness and tendency to fall into the local optimum of common genetic algorithms.

Often, complex problems that would take a lifetime to solve, can be solved with the help of Genetic Algorithms (GAs) to obtain optimal or nearly optimal solutions. In research and machine learning, as well as in solving optimization problems, these are widely employed. Finding the input values so that we obtain the ”best” output values is referred to as optimization. Although the term ”best” has different meanings for different problems, in mathematics it means maximizing or minimizing one or more objective functions by changing the input parameters. Similarly to classical genetic algorithms, QGA has the advantage of utilizing quantum principles for more effective solution space exploration, and QGA can be used to solve classification problems. The classifier serves as the fitness function after the population has been initialized and decoded. The solution’s individual is put through a crossover mutation process called selection.

The primary procedures and characteristics of their non-quantum equivalents are shared by quantum evolutionary algorithms. In machine learning, weights are frequently connected to a model’s parameters. GA uses selection to enhance populations, while QGA uses rotation to change individuals towards best fitter states. Some QGA use roulette or elite selection to avoid premature convergence. Taking advantage of quantum parallelism, QGA computes multiple outcomes at once. This is helpful when solving optimization problems. The same set of problems that the traditional genetic algorithm can be used to solve can also be solved with this algorithm, but because of quantum parallelization and quantum state entanglement, the evolutionary process can be accelerated considerably. A global search for a solution with a fast convergence and a low population value is made possible by the evolutionary algorithm and the probabilistic mechanism of quantum computations. The efficiency of these algorithms has been shown to resolve issues in signal processing, image processing optimization, combinatorial and functional optimization, and many other areas. Algorithm 1 presents all the steps performed by QGA. In our framework, QGA is used to dynamically optimize the weights assigned to the outputs of SVM, RF, and LSTM classifiers. Instead of relying on static or heuristic weight assignment, QGA adaptively learns the optimal combination that maximizes classification performance across all four classes (AF, normal, noisy, and other rhythms). This ensemble classification using QGA based optimized weights enable the use of strengths of the base learners resulting in improved accuracy and robustness against noise. The quantum population size in the proposed GQA was set to 40 individuals, each represented by qubits. The maximum number of generations was fixed at 100, or earlier if convergence occurred. The quantum rotation angle

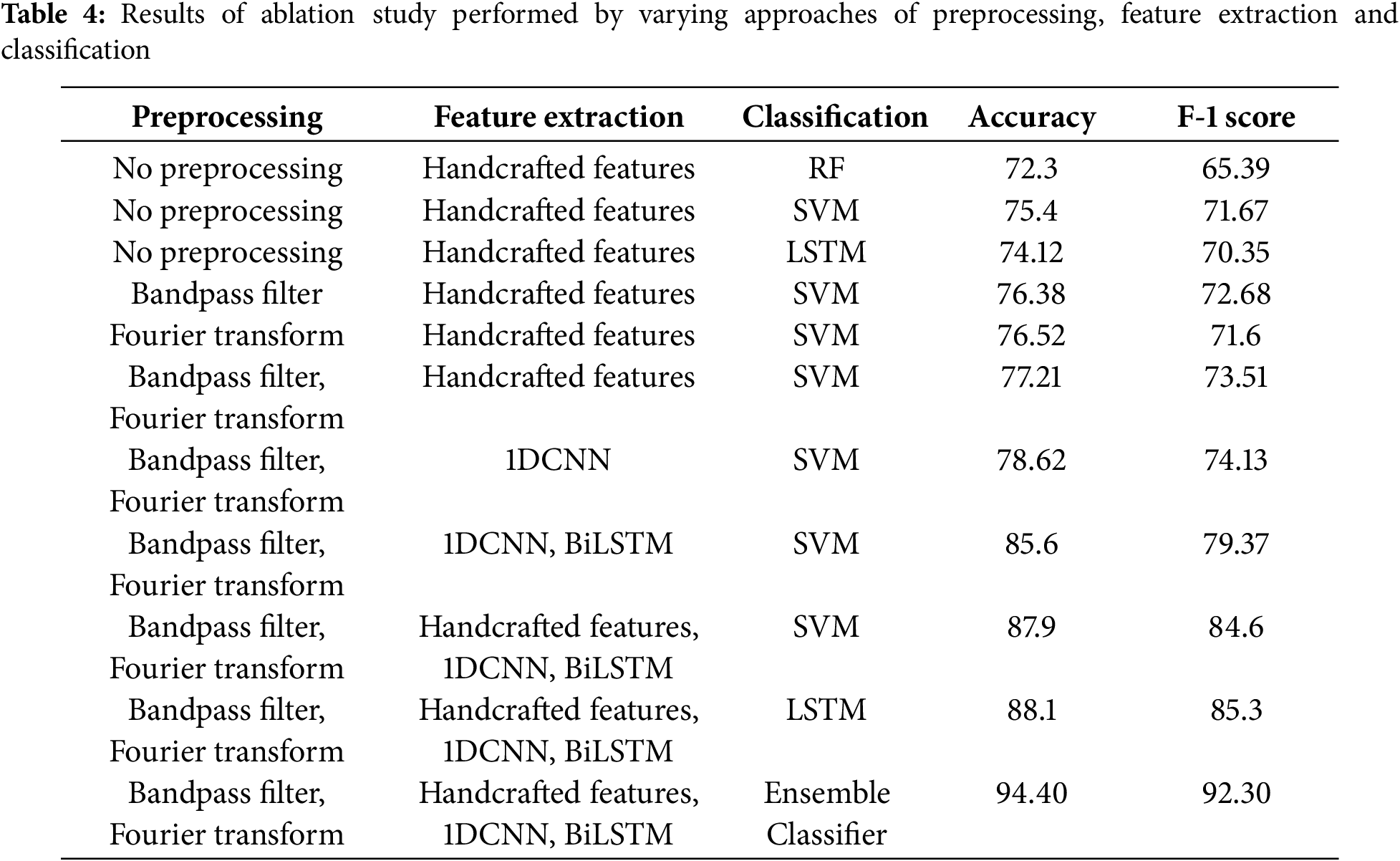

In this research, we performed experiments on the Physionet CniC 2017 dataset. Table 4 presents the ablation study performed by varying different approaches of preperocessing, feature extraction and classification. In the ablation study conducted for the detection of heart disease using ECG signals, a systematic evaluation of various preprocessing, feature extraction, and classification techniques was performed. Results presented in the Table 4 shows the performance of experiments with varying approaches of preprocessing, feature extraction and classification. It can be observed from the results obtained from the experiments that no preprocessing resulted in lower classification performance with the baseline classification models like RF, SVM, and LSTM. When combining with preprocessing, these models achieved modest accuracy and F1 scores using the handcrafted features which shows that handcrafted features can provide discrimination between different classes for AF detection. Introducing bandpass filtering as a preprocessing step resulted in a improved accuracy and F1 score when used with an SVM classifier. This indicates that bandpass filter increases the signal to noise ratio by removing noise from ECG signals. In this way, more distinct features can be extracted that provides high interclass variance for classification between different classes. Inclusion of Fourier transform along with bandpass filter improved the performance of classifier.

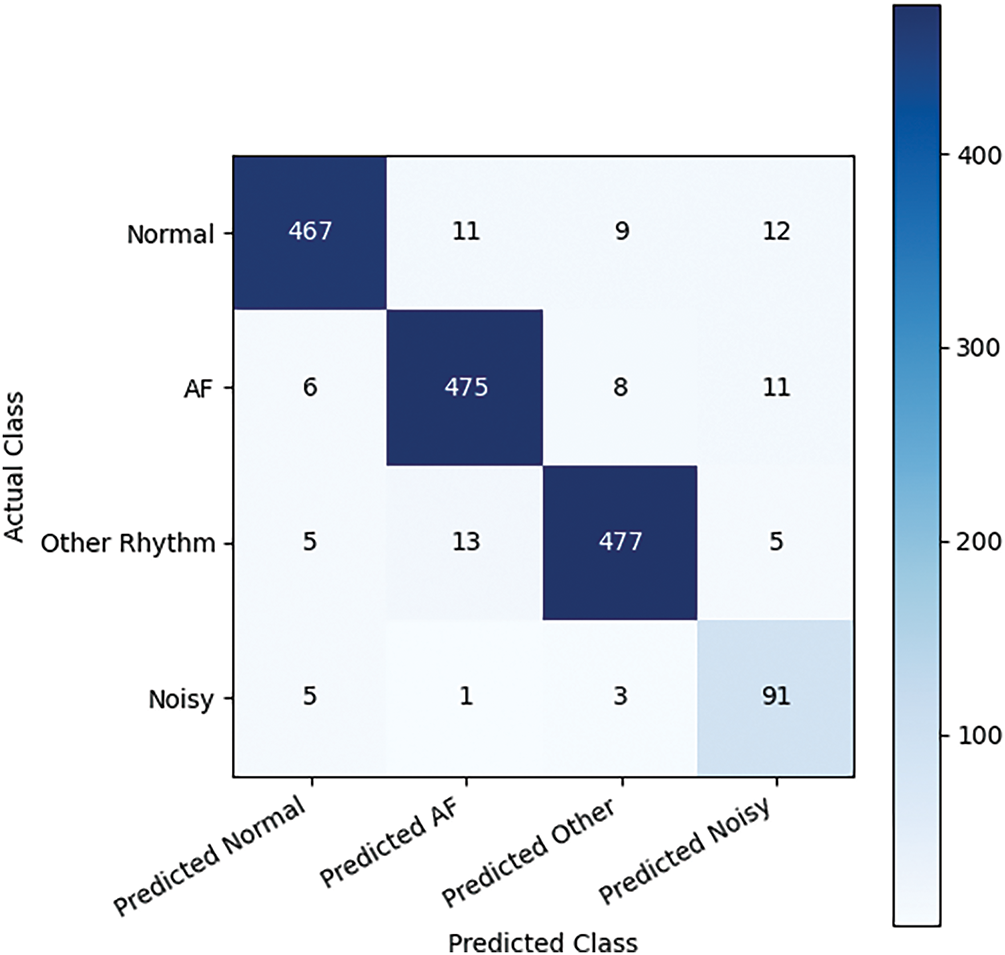

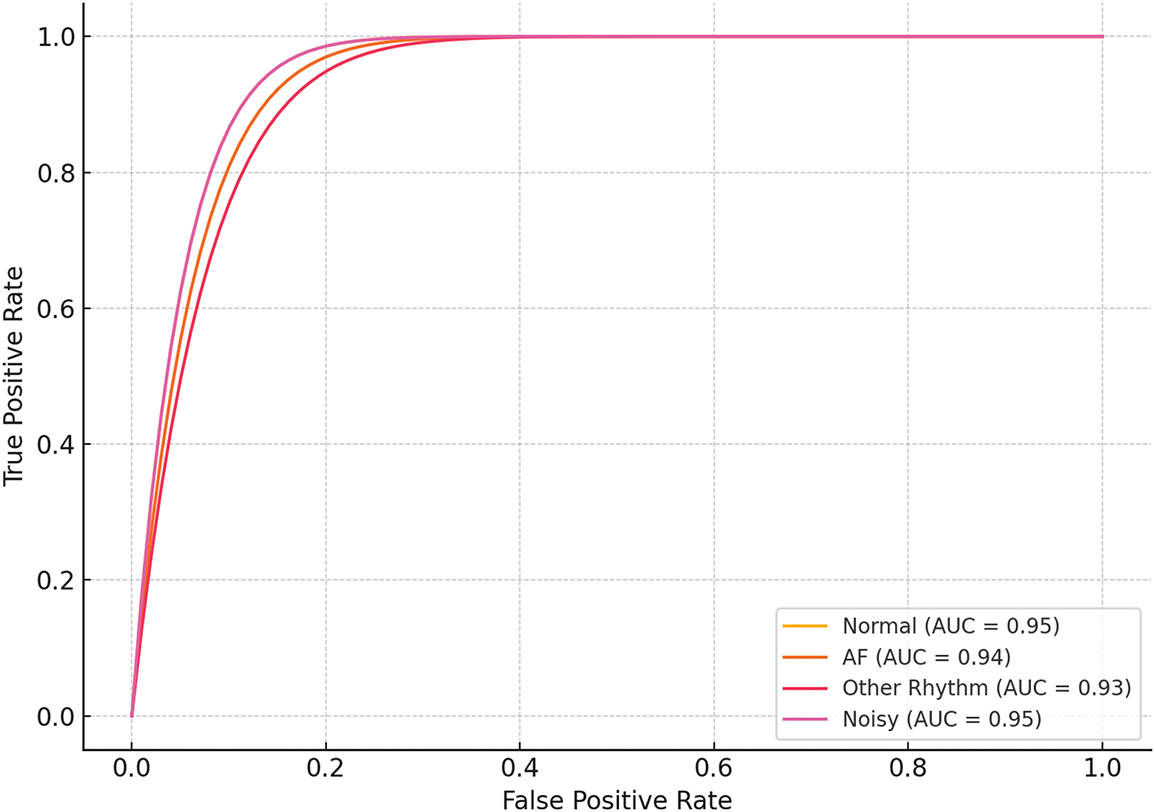

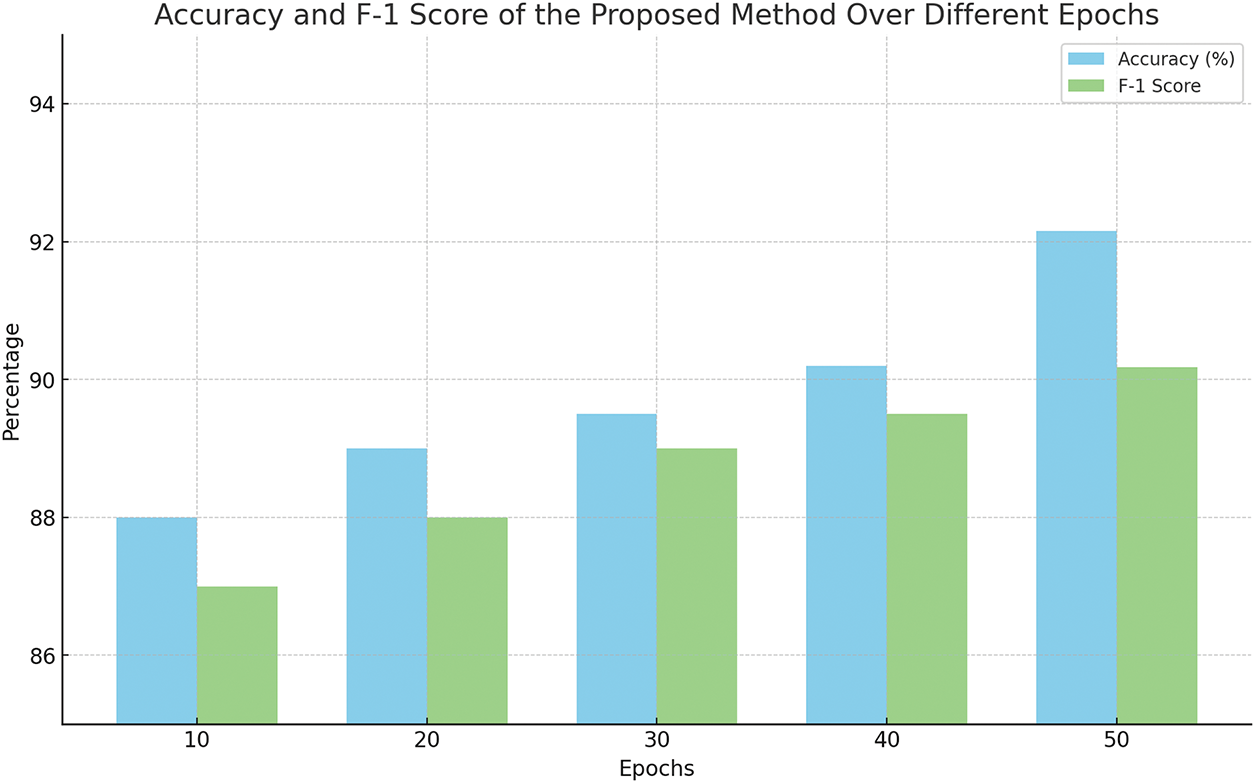

The combined preprocessing method and handcrafted features with SVM classifier outperformed the other experiments with no preprocessing. This underscores the complementary nature of the time-frequency domain transformations in capturing salient features of the ECG signals. Table 5 presents the ablation studies performed by varying different order of filters and window length. The 2nd-order Butterworth filter with a 5-s overlapping window achieved the better accuracy. Fig. 3 shows the confusion matrix of the proposed method. ROC curve of four classes is presented in Fig. 4 whereas, Fig. 5 presents results obtained by varying the number of epochs. After performing the ablation study, we propose a hybrid feature vector that concatenates both handcrafted features and automated features extracted from a custom 1DCNN-LSTM architecture. This comprehensive feature set consists of high interclass variance, therefore, helps in accurate classification between AF and normal rhythms than traditional single-method approaches. The integration of SVM, RF, and LSTM into a single ensemble classifier, optimized by a QGA also contributes towards accurate classification. The QGA uses principles of quantum computing to efficiently explore and optimize the solution space, enhancing the ensemble’s decision-making capabilities. This optimization allows the ensemble to effectively combine the strengths of its constituent classifiers, leading to higher accuracy and stability across varied test conditions.

Figure 3: Confusion matrix of proposed method

Figure 4: ROC of the proposed method

Figure 5: Results with difference Epochs

The proposed 1D Convolutional Neural Networks (1DCNN) for automated feature extraction from the flatten layer and classification with SVM showed an improved performance over handcrafted features. This shows that the automated features extracted from 1DCNN have increased interclass variance than handcrafted features. A significant improvement in performance was observed with the combination of bandpass filtering, Fourier Transform, and the integration of both 1DCNN and BiLSTM as feature extractors, followed by classification with SVM. The BiLSTM likely captured temporal dependencies in the ECG signals, providing a more comprehensive feature set for the SVM classifier to operate on. The highest accuracy and F1 score were achieved by the ensemble classifier that utilized all the combined preprocessing and feature level fusion of handcrafted and automated features. This concludes the benefit of combining multiple models and techniques, which can capture a broad range of signal characteristics and reduce the likelihood of overfitting to noise or specific artifacts within the ECG data.

To assess the computational feasibility of our framework, we analyzed both the theoretical time complexity and practical runtime. The preprocessing stage, including bandpass filtering and FFT/iFFT transformations, operates in

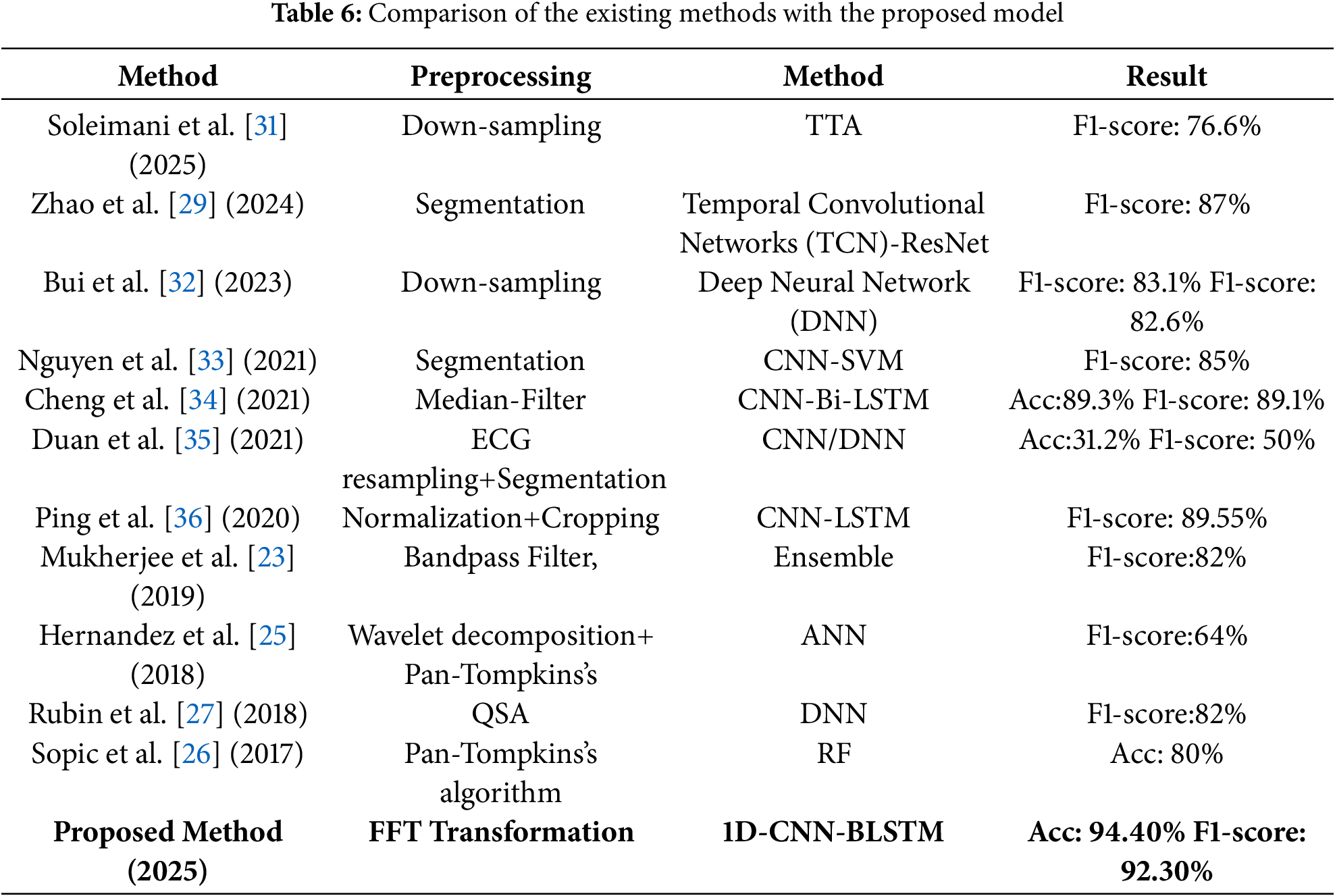

Table 6 presents the comparison of the results achieved by the proposed method with state of the art methods of AF detection using ECG signals. The proposed method outperforms in terms of both accuracy, F1 score and ROC curves than existing models. The robustness of this method suggests it could be highly effective in clinical settings, providing reliable AF detection crucial for timely and accurate diagnosis and treatment. The proposed method could be utilized in real time settings as well for wearable devices of AF detection. This capability could transform how cardiac conditions like AF are managed, enabling early intervention and ongoing patient monitoring in everyday settings. It is important to note that, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first work applying QGA-based optimization to ensemble AF detection. Moreover, the combination of handcrafted and a cutomized 1DCNN for automated features within a multi-class classification framework further distinguishes our approach from prior binary AF models.

Despite its strengths, the method requires further validation on larger, diverse datasets for real time applications. Additionally, considerations for computational efficiency and the practical implementation of QGA in wearable devices need to be addressed in future developments. This study sets a new standard for AF detection through its innovative use of hybrid feature extraction and quantum-optimized classification. Its implications for enhancing diagnostic accuracy and expanding the capabilities of wearable cardiac monitors highlight its significant impact on the field of cardiac health monitoring and patient care.

4 Conclusion and Future Directions

In this research, we propose a novel ensemble learning method for classification of ECG signals for AF detection. The proposed algorithm efficiently removes noise from ECG signals and extracts meaningful features, enabling reliable classification. Our proposed method integrates handcrafted features with a CNN-BiLSTM architecture and demonstrated improved classification performance, achieving an accuracy of 94%. It can be used for multiple applications, including wearable devices such as pacemakers and portable ECG monitoring stations, for analyzing data in real time to support timely medical interventions. While CNN-based architectures are effective, they involve parameter tuning and computational cost. Hybrid models may provide more accurate solutions but require further optimization for resource-constrained devices. Future research will focus on testing these models on larger datasets to evaluate their robustness over extended periods. Expanding the classification framework to include a wider variety of arrhythmias, with appropriate subclassification by medical experts, would further improve diagnostic capability. Moreover, the use of deeper architectures, transfer learning, and real-time monitoring systems integrated into wearable technology may advance AF detection and continuous patient monitoring, thereby improving clinical outcomes.

Acknowledgement: This work was supported and funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU) (grant number IMSIU-DDRSP2501).

Funding Statement: This work was supported and funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU) (grant number IMSIU-DDRSP2501).

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Yazeed Alkhrijah, Marwa Fahim, Syed Muhammad Usman, and Haya Aldossary; methodology, Yazeed Alkhrijah, Marwa Fahim, Syed Muhammad Usman, Haya Aldossary, and Qasim Mehmood; software, Yazeed Alkhrijah, Marwa Fahim, Syed Muhammad Usman, and Qasim Mehmood; validation, Syed Muhammad Usman, Shehzad Khalid, Haya Aldossary, and Mohamad A. Alawad; formal analysis, Shehzad Khalid, Syed Muhammad Usman, and Qasim Mehmood; investigation, Yazeed Alkhrijah, Marwa Fahim, Syed Muhammad Usman, Haya Aldossary, and Qasim Mehmood; resources, Syed Muhammad Usman, and Shehzad Khalid; data curation, Yazeed Alkhrijah, Marwa Fahim, and Qasim Mehmood; writing—original draft preparation, Yazeed Alkhrijah, Marwa Fahim, and Syed Muhammad Usman; writing—review and editing, Shehzad Khalid, Syed Muhammad Usman, Haya Aldossary, and Mohamad A. Alawad; visualization, Yazeed Alkhrijah, Shehzad Khalid, and Syed Muhammad Usman; supervision, Syed Muhammad Usman, and Shehzad Khalid; project administration, Syed Muhammad Usman, Haya Aldossary, and Mohamad A. Alawad. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets generated and/or analyzed during this study are available in the Physionet Cardiology Challenge 2017 repository at https://archive.physionet.org/challenge/2017/ (accessed on 22 October 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Hohnloser SH, Kuck KH, Lilienthal J. Rhythm or rate control in atrial fibrillation—Pharmacological Intervention in Atrial Fibrillation (PIAFa randomised trial. The Lancet. 2000;356(9244):1789–94. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(00)03230-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Goette A, Borof K, Breithardt G, Camm AJ, Crijns HJ, Kuck KH, et al. Presenting pattern of atrial fibrillation and outcomes of early rhythm control therapy. J Am College Cardiol. 2022;80(4):283–95. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2022.04.058. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Bittner A, Mönnig G, Zellerhoff S, Pott C, Köbe J, Dechering D, et al. Randomized study comparing duty-cycled bipolar and unipolar radiofrequency with point-by-point ablation in pulmonary vein isolation. Heart Rhythm. 2011;8(9):1383–90. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2011.03.051. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Zylla MM, Brachmann J, Lewalter T, Hoffmann E, Kuck KH, Andresen D, et al. Sex-related outcome of atrial fibrillation ablation: insights from the German Ablation Registry. Heart Rhythm. 2016;13(9):1837–44. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2016.06.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Hindricks G, Potpara T, Dagres N, Arbelo E, Bax JJ, Blomström-Lundqvist C, et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTSThe Task Force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(5):373–498. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa612. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, Calkins H, Cigarroa JE, Cleveland JC Jr, et al. AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American heart association task force on practice guidelines and the heart rhythm society. Circulation. 2014;130(23):2071–104. doi:10.1161/cir.0000000000000040. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Savelieva I, Camm J. Update on atrial fibrillation: part I. Clin Cardiol. 2008;31(2):55–62. doi:10.1002/clc.20138. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Carrara M, Carozzi L, Moss TJ, De Pasquale M, Cerutti S, Ferrario M, et al. Heart rate dynamics distinguish among atrial fibrillation, normal sinus rhythm and sinus rhythm with frequent ectopy. Physiol Meas. 2015;36(9):1873. doi:10.1088/0967-3334/36/9/1873. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Andrade J, Khairy P, Dobrev D, Nattel S. The clinical profile and pathophysiology of atrial fibrillation: relationships among clinical features, epidemiology, and mechanisms. Circ Res. 2014;114(9):1453–68. doi:10.1161/circresaha.114.303211. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Stewart S, Murphy N, Walker A, McGuire A, McMurray J. Cost of an emerging epidemic: an economic analysis of atrial fibrillation in the UK. Heart. 2007;93(11):1472–2. doi:10.1136/hrt.2002.008748. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Mackay J, Mensah GA. The atlas of heart disease and stroke. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2004. [Google Scholar]

12. Dey M, Omar N, Ullah MA. Temporal feature-based classification into myocardial infarction and other CVDs merging CNN and Bi-LSTM from ECG signal. IEEE Sens J. 2021;21(19):21688–95. doi:10.1109/jsen.2021.3079241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Gerc V, Masic I, Salihefendic N, Zildzic M. Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) in COVID-19 pandemic era. Materia Socio-Med. 2020;32(2):158–64. doi:10.5455/msm.2020.32.158-164. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Huang C, Ye S, Chen H, Li D, He F, Tu Y. A novel method for detection of the transition between atrial fibrillation and sinus rhythm. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2010;58(4):1113–9. doi:10.1109/tbme.2010.2096506. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Tateno K, Glass L. A method for detection of atrial fibrillation using RR intervals. In: Computers in Cardiology 2000; 2000 Sep 24–27; Cambridge, MA, USA: IEEE. Vol. 27 (Cat. 00CH37163). p. 391–4. [Google Scholar]

16. Phan T, Le D, Brijesh P, Adjeroh D, Wu J, Jensen MO, et al. Multimodality multi-lead ecg arrhythmia classification using self-supervised learning. In: 2022 IEEE-EMBS International Conference on Biomedical and Health Informatics (BHI); 2022 Sep 27–30; Ioannina, Greece: IEEE. p. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

17. Krupa AJD, Dhanalakshmi S, Sanjana N, Manivannan N, Kumar R, Tripathy S. Fetal heart rate estimation using fractional Fourier transform and wavelet analysis. Biocybernetics Biomed Eng. 2021;41(4):1533–47. doi:10.1016/j.bbe.2021.09.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Allam JP, Samantray S, Sahoo SP, Ari S. A deformable CNN architecture for predicting clinical acceptability of ECG signal. Biocybernetics Biomed Eng. 2023;43(1):335–51. doi:10.1016/j.bbe.2023.01.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Acharya UR, Hagiwara Y, Koh JEW, Oh SL, Tan JH, Adam M, et al. Entropies for automated detection of coronary artery disease using ECG signals: a review. Biocybernetics Biomed Eng. 2018;38(2):373–84. doi:10.1016/j.bbe.2018.03.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Shahid AH, Singh M. Computational intelligence techniques for medical diagnosis and prognosis: problems and current developments. Biocybernetics Biomed Eng. 2019;39(3):638–72. doi:10.1016/j.bbe.2019.05.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Mahajan R, Kamaleswaran R, Howe JA, Akbilgic O. Cardiac rhythm classification from a short single lead ECG recording via random forest. In: 2017 Computing in Cardiology (CinC); 2017 Sep 24–27; Rennes, France: IEEE. p. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

22. García M, Ródenas J, Alcaraz R, Rieta JJ. Atrial fibrillation screening through combined timing features of short single-lead electrocardiograms. In: 2017 Computing in Cardiology (CinC); 2017 Sep 24–27; Rennes, France: IEEE. p. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

23. Mukherjee A, Choudhury AD, Datta S, Puri C, Banerjee R, Singh R, et al. Detection of atrial fibrillation and other abnormal rhythms from ECG using a multi-layer classifier architecture. Physiol Meas. 2019;40(5):054006. doi:10.1088/1361-6579/aaff04. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Zhang X, Li J, Cai Z, Zhang L, Chen Z, Liu C. Over-fitting suppression training strategies for deep learning-based atrial fibrillation detection. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2021;59:165–73. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

25. Hernandez F, Mendez D, Amado L, Altuve M. Atrial fibrillation detection in short single lead ECG recordings using wavelet transform and artificial neural networks. In: 2018 40th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC); 2018 Jul 18–21; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 5982–5. [Google Scholar]

26. Sopic D, De Giovanni E, Aminifar A, Atienza D. Hierarchical cardiac-rhythm classification based on electrocardiogram morphology. In: 2017 Computing in Cardiology (CinC); 2017 Sep 24–27; Rennes, France: IEEE. p. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

27. Rubin J, Parvaneh S, Rahman A, Conroy B, Babaeizadeh S. Densely connected convolutional networks for detection of atrial fibrillation from short single-lead ECG recordings. J Electrocardiol. 2018;51(6):S18–21. doi:10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2018.08.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Hong S, Zhou Y, Wu M, Shang J, Wang Q, Li H, et al. Combining deep neural networks and engineered features for cardiac arrhythmia detection from ECG recordings. Physiol Meas. 2019;40(5):054009. doi:10.1088/1361-6579/ab15a2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Zhao X, Zhou R, Ning L, Guo Q, Liang Y, Yang J. Atrial fibrillation detection with single-lead electrocardiogram based on temporal convolutional network-resnet. Sensors. 2024;24(2):398. doi:10.3390/s24020398. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Zhou X, Zhu X, Nakamura K, Mahito N. ECG quality assessment using 1D-convolutional neural network. In: 2018 14th IEEE International Conference on Signal Processing (ICSP); 2018 Aug 12–16; Beijing, China: IEEE. p. 780–4. [Google Scholar]

31. Soleimani M, Toosi MH, Mohammadi S, Khalaj BH. Using test-time data augmentation for cross-domain atrial fibrillation detection from ECG signals. arXiv:2503.13483. 2025. [Google Scholar]

32. Bui TH, Hoang VM, Pham MT. Automatic varied-length ECG classification using a lightweight DenseNet model. Biomed Signal Process Control. 2023;82:104529. doi:10.1016/j.bspc.2022.104529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Nguyen QH, Nguyen BP, Nguyen TB, Do TT, Mbinta JF, Simpson CR. Stacking segment-based CNN with SVM for recognition of atrial fibrillation from single-lead ECG recordings. Biomed Signal Process Control. 2021;68:102672. doi:10.1016/j.bspc.2021.102672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Cheng J, Zou Q, Zhao Y. ECG signal classification based on deep CNN and BiLSTM. BMC Med Inform Decis Making. 2021;21:1–12. doi:10.1186/s12911-021-01736-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Duan H, Fan J, Xiao B, Bi X, Zhang J, Ma X. A branched deep neural network for end-to-end classification from ECGs with varying dimensions. In: 2021 Computing in Cardiology (CinC); 2021 Sep 13–15; Brno, Czech Republic: IEEE. Vol. 48, p. 1–4. doi:10.23919/cinc53138.2021.9662727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Ping Y, Chen C, Wu L, Wang Y, Shu M. Automatic detection of atrial fibrillation based on CNN-LSTM and shortcut connection. Healthcare. 2020;8(2):139. doi:10.3390/healthcare8020139. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools