Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

DDNet: A Novel Dynamic Lightweight Super-Resolution Algorithm for Arbitrary Scales

1 School of Automation, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, Chengdu, 610054, China

2 School of Electronic Engineering, Xidian University, Xi’an, 710071, China

3 Department of Geography, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843, USA

4 School of the Environment, The University of Queensland, St Lucia, Brisbane, QLD 4072, Australia

5 School of Artificial Intelligence, Guangzhou Huashang College, Guangzhou, 511300, China

6 Department of Hydrology and Atmospheric Sciences, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721, USA

* Corresponding Authors: Wenfeng Zheng. Email: ; Lirong Yin. Email:

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(2), 2223-2252. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.072136

Received 20 August 2025; Accepted 15 October 2025; Issue published 26 November 2025

Abstract

Recent Super-Resolution (SR) algorithms often suffer from excessive model complexity, high computational costs, and limited flexibility across varying image scales. To address these challenges, we propose DDNet, a dynamic and lightweight SR framework designed for arbitrary scaling factors. DDNet integrates a residual learning structure with an Adaptively fusion Feature Block (AFB) and a scale-aware upsampling module, effectively reducing parameter overhead while preserving reconstruction quality. Additionally, we introduce DDNetGAN, an enhanced variant that leverages a relativistic Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) to further improve texture realism. To validate the proposed models, we conduct extensive training using the DIV2K and Flickr2K datasets and evaluate performance across standard benchmarks including Set5, Set14, Urban100, Manga109, and BSD100. Our experiments cover both symmetric and asymmetric upscaling factors and incorporate ablation studies to assess key components. Results show that DDNet and DDNetGAN achieve competitive performance compared with mainstream SR algorithms, demonstrating a strong balance between accuracy, efficiency, and flexibility. These findings highlight the potential of our approach for practical real-world super-resolution applications.Keywords

Single Image Super Resolution (SISR) represents a pivotal area within the field of computer vision, focusing on enhancing the resolution of an image from a single low-resolution (LR) input. The essence of SISR lies in its ability to reconstruct a high-resolution (HR) image that is both visually appealing and rich in detail, effectively bridging the gap between the captured image and the desired image quality [1–4]. This technology holds the promise of recovering intricate details lost during the image capture process due to factors like sensor limitations, compression artifacts, or suboptimal imaging conditions.

Given its broad applicability and potential to revolutionize fields reliant on image analysis, SISR has garnered substantial interest within the academic and industrial research communities. The continuous advancement in SISR algorithms, driven by the integration of deep learning techniques and novel neural network architectures, aims to achieve more accurate and realistic image reconstructions. The ongoing research endeavors are dedicated to overcoming challenges such as handling varying degrees of image degradation, maintaining textural integrity, and reducing computational demands for real-time processing applications.

The first deep learning-based super resolution convolutional neural network algorithm, SRCNN, was proposed by Dong et al. [5] in 2014, and became a landmark of the super resolution algorithm based on a deep convolutional neural network. This has entered a period of rapid development. Recursive networks can greatly reduce the amount of model parameters, but the computational complexity is not reduced, and DRRN [6] combines recursive networks and residual learning to achieve good performance. DRCN [7] applied the existing recurrent neural network structure to the super-resolution problem for the first time and implemented a recursive-based SR algorithm, which effectively reduced the number of parameters of the model. Lai et al. [8] proposed the LapSRN network, which uses the Laplace pyramid idea to enable a single model to reconstruct SR images of multiple scales simultaneously, and this framework is often referred to as the cascaded upsampling in SR algorithms. To address the problem of poor generalization ability of super-resolution algorithms and realize the extraction of differentiated feature information according to different input image information and scale information, Yin et al. [9] proposed a lightweight adaptive feature fusion module named AFBNet. This module includes dynamic convolution with scale information, the channel spatial attention mechanism combined with multi-feature fusion, and the pixel-based gating mechanism. By improving the structure, different feature information was extracted, more important feature information was retained, and the adaptability of the modules has been further enhanced.

To reconstruct more accurate and realistic images, the Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) proposed by Goodfellow et al. [10] has been widely studied [11–13]. The idea of the generator-discriminator game enables the generator to eventually generate more realistic images. Therefore, it is natural to combine GAN with SISR technology to further enhance the quality of images [14,15]. The training of GAN makes the hyper-resolution images with more texture details and more realistic display effects [16,17]. Ledig et al. [18] first applied generative adversarial networks to super-resolution image reconstruction and proposed SRGAN, a super-resolution algorithm based on generative adversarial networks. Prior to this, the super-resolution algorithm basically used L1 loss and L2 loss as loss functions. Although they obtained good results in reconstruction accuracy, they also ignored the intrinsic relationship between pixels, so the reconstruction effect looked distorted (lack of high-frequency information and excessive smoothing). SRGAN employs a perceived loss for generator loss, which consists of content loss and adversarial loss. The ESRGAN [19] algorithm has made some improvements on the basis of SRGAN, first using different generators to extract feature information, and then introducing the idea of relative GAN.

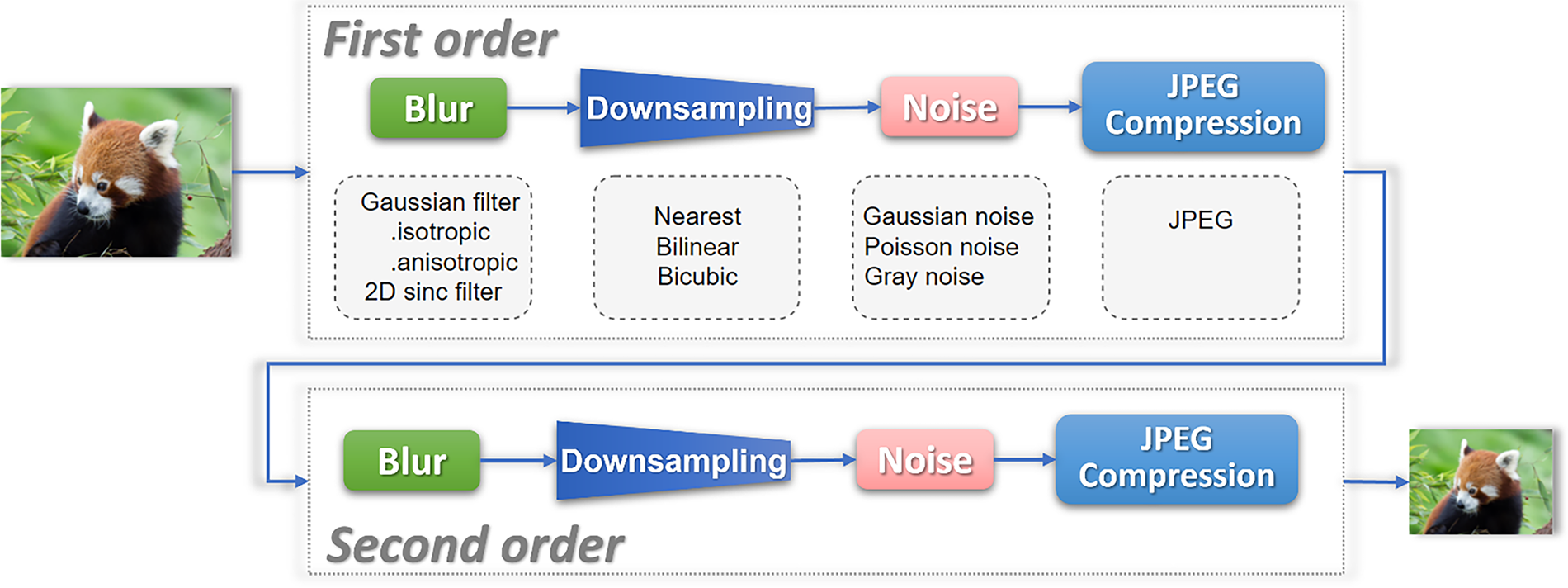

However, most of the super-resolution algorithms used bicubic interpolation, blurring, adding noise, and compression to simulate the image degradation process, but the degradation process of images in the real world is more complex, and a single method can only simulate a limited range of real situations. To address this problem, Real-ESRGAN [20] is proposed and uses second-order degradation models to simulate the degradation process of the real world to achieve a better reconstruction effect than the real data. Real-ESRGAN combines limited methods of simulating image degradation with repeated operations, as shown in Fig. 1. Each order of the degradation model consists of different degradation methods, such as blur, downsampling, noise, and JPEG compression. For each degradation method, one of the rules is randomly selected; for example, rules such as nearest neighbor interpolation, bilinear interpolation, and bicubic interpolation can be selected for downsampling.

Figure 1: The second-order degradation process for image generation in Real-ESRGAN

Recent advances in SR research reflect a shift toward lightweight and adaptive architectures. For example, Gendy et al. [21] designed EConvMixN, a pure convolutional network that replaces attention mechanisms with extended convolution mixers, combining dilated, depthwise, and pointwise convolutions to reduce complexity while maintaining reconstruction fidelity. To exploit long-range dependencies more efficiently, hybrid CNN-Transformer structures have been proposed. Fang et al. [22] introduced HNCT, which integrates Transformer-style blocks with CNN-based local modeling and enhanced spatial attention, striking a balance between performance and model size. Similarly, Gendy et al. [23] proposed STSN using Conv2Former, a lightweight convolutional modulation block that simulates attention using only convolutions and Hadamard products. Meanwhile, Lu et al. [24] adopted a GAN-based approach and integrated Inception blocks into the generator design to achieve better structural representation with fewer parameters. This improves both PSNR/SSIM and inference speed, offering a lightweight generative solution. In another direction, Guo et al. [25] proposed a dual regression learning strategy that jointly learns both SR (LR→HR) and reverse (HR→LR) mappings, effectively reducing the SR solution space and enhancing training stability. This method highlights a trend toward embedding explicit structural constraints into lightweight SR networks.

Beyond algorithmic innovations, the exploration of super-resolution techniques has expanded into concrete application domains. In IoT scenarios, where devices are constrained by limited memory and computational power, Mardieva et al. [26] proposed a lightweight deep residual feature distillation network, incorporating multi-kernel depthwise separable convolution. The model significantly reduces resource consumption while preserving SR quality, making it suitable for real-time deployment on embedded terminals. In the field of medical imaging, Umirzakova et al. [27] developed DRFDCAN, a deep residual feature distillation channel attention network, which effectively enhances high-frequency details essential for clinical diagnosis while maintaining computational efficiency. These application-driven studies illustrate that SR research is no longer confined to algorithmic design alone but is increasingly tailored to domain-specific requirements.

Most of the current research on SISR algorithms focuses on fixed-size upsampling, where each network model can only improve the resolution at a certain fixed number of scales, which lacks flexibility in practical usage. Therefore, many researchers have shifted their direction to SR at arbitrary scales. In addition to the research in enhancing image texture details, the arbitrary-scale-based upscaling algorithms have gained more and more attention to meet the realistic needs in general scenarios. Hu et al. [28] first proposed Meta-OverNet, a single model to achieve arbitrary-scale (including non-integer multiples) upscaling for Meta-SR, which mainly consists of a feature learning module and a Meta-upscale upsampling module. As a lightweight arbitrary-scale overscaling algorithm, it achieves arbitrary-scale overscaling through an overscaling Module and interpolation downsampling. Considering the influence of scale information on arbitrary overscaling and asymmetric arbitrary scale overscaling, a new arbitrary scale overscaling model with a scale sensing function called ArbSR [29] was proposed. ArbSR has two plug-and-play modules: scale-aware feature adaptation and scale-aware upsampling for sensing scale information and implementing arbitrary size (both symmetric and asymmetric scales) upsampling. The plug-and-play modules can be embedded and used as sub-structures in some classical SR networks. However, the number of parameters of arbitrary multiples of SR algorithms is significantly larger than that of SR algorithms with fixed scales. Therefore, lightweight SR algorithms of arbitrary multiples are needed further research.

To address the aforementioned challenges in existing super-resolution methods—such as fixed scaling factors, poor adaptability to input variance, and computational inefficiency—we propose a dynamic, lightweight, and flexible SR framework. Unlike prior arbitrary-scale SR approaches such as ArbSR and MetaSR, which primarily rely on meta-upscaling or kernel prediction, our design introduces dynamic convolution combined with an adaptively fusion feature block (AFB). This enables more effective feature extraction and scale-aware reconstruction with substantially fewer parameters. Our goal is to balance high-resolution reconstruction quality with low parameter overhead and enable arbitrary-scale upsampling for real-world deployment.

For this study, the main contributions are as follows:

1. We propose DDNet, a novel dynamic lightweight super-resolution architecture designed for arbitrary scaling factors. It integrates adaptive dynamic convolution, residual connections, and scale-aware modules for efficient feature extraction and reconstruction.

2. We design an Adaptively Fusion Feature Block (AFB), which incorporates attention mechanisms and pixel-based gating, allowing the network to dynamically adjust to varying input and scale conditions with minimal parameter cost.

3. We introduce DDNetGAN, a variant of DDNet based on a relativistic GAN framework. It incorporates an improved VGG-based discriminator for arbitrary-scale image evaluation and significantly enhances texture realism in reconstructed images.

4. We conduct extensive experiments, including ablation studies and comparisons with mainstream SR methods on standard datasets (DIV2K, Flickr2K, Set5, Urban100), showing that our method achieves a balance between visual quality, reconstruction accuracy, and computational efficiency.

2.1 Datasets and Preprocessing

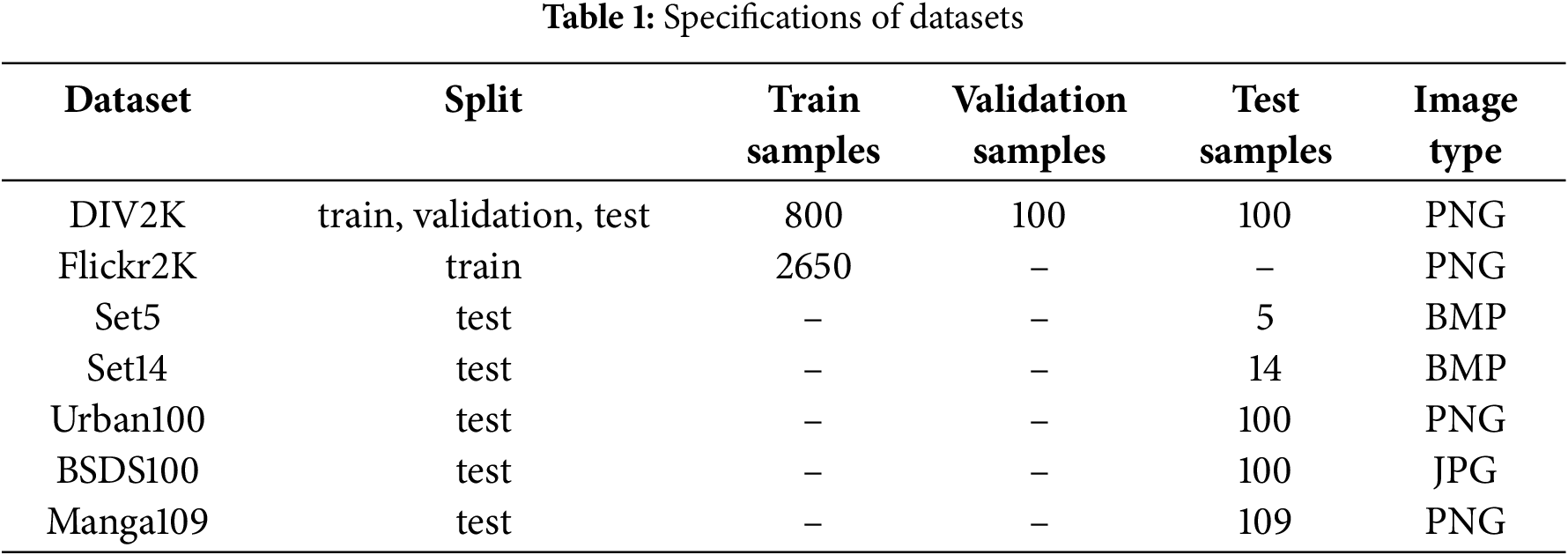

The super-resolution algorithm dataset can be mainly divided into the training set, validation set, and test set. Training sets are mainly used for supervised deep learning super-resolution algorithm training. DIV2K [19] and Flickr2K datasets [30] are the most used super-algorithm training datasets at present, so they were used for training in this paper. Testing sets are used to test the performance of the super-resolution algorithm, and the Set5 [31], Set14 [32], Urban100 [33], BSDS100 [34], and Manga109 [35,36] datasets were used for test comparison. Table 1 Specifications of Datasets shows the specific information of these datasets.

To improve data utilization and enhance the performance of neural networks, we perform data augmentation techniques on the training datasets. Take DIV2K as an example, it contains high-resolution images with dimensions of 1920 × 1920 pixels. The following data augmentations are adopted to preprocess the images:

1. Image Segmentation. We reduced the dimensions of each image to create more training samples. For instance, the image with dimensions of 1920 × 1920 pixels was segmented into 16 smaller images, each measuring 480 × 480 pixels. This process increases the number of training images, yielding approximately 32,096 samples from the original 800 images.

2. Random Cropping and Augmentation. We applied random cropping to these 480 × 480 pixels images, extracting smaller sections (e.g., 50 × 50 pixels) and employing augmentations to the cropped images, such as adding Gaussian noise and blur.

By the above data augmentations, we generate suitable low-resolution (LR) and high-resolution (HR) image pairs for training. It is crucial that the positional correspondence between LR and HR images remains accurate to avoid negatively impacting the model’s learning and overall performance. For instance, in a 2-fold upsampling scenario, an HR image is downsampled by a factor of two to generate the LR counterpart, typically using bicubic interpolation. It’s important to ensure that the dimensions of the HR image are even; otherwise, the upsampled LR image may not accurately match the original HR dimensions.

2.2 Training Data Processing for SR Algorithms at Arbitrary Scales

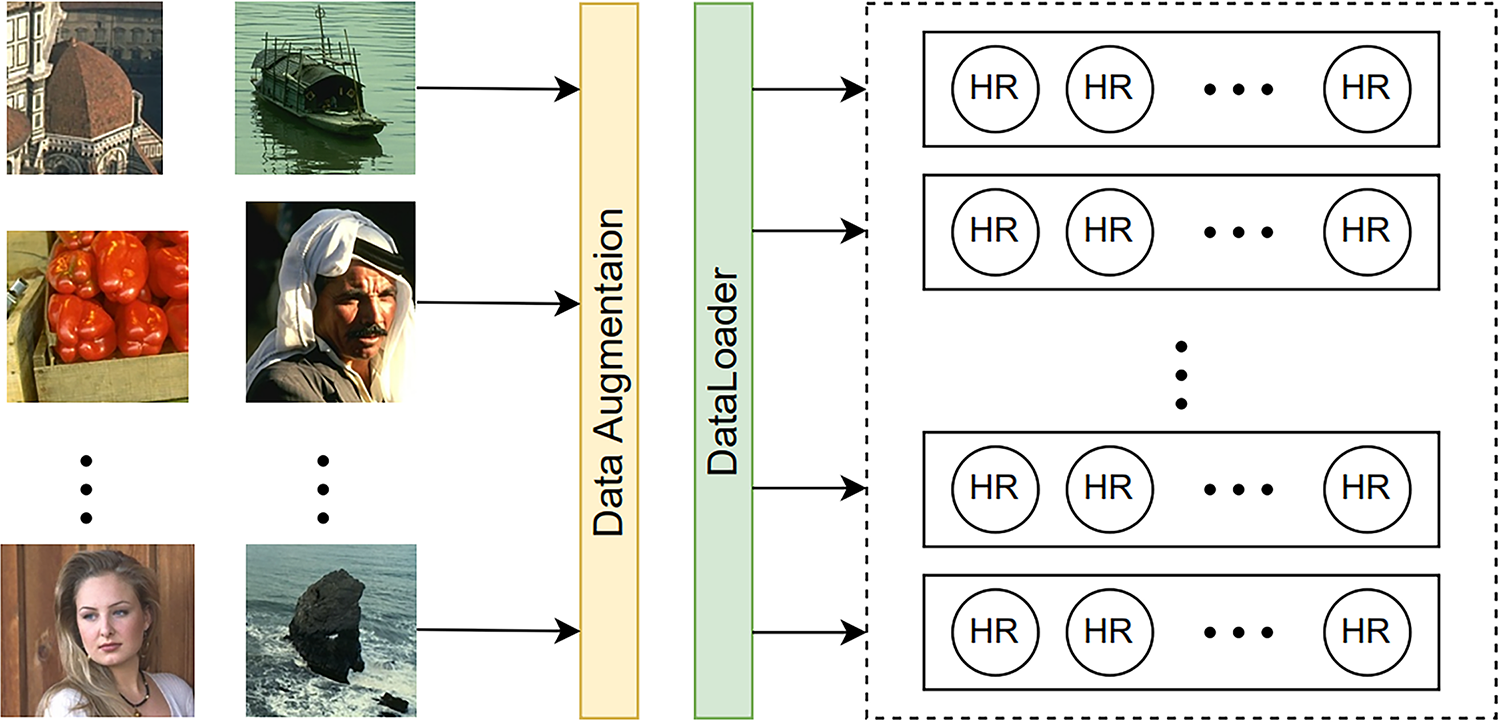

Besides the basic data augmentations, the training data needs further processing to batch images with different scales for the training of SR algorithms. Specifically, for fixed-scale super-resolution model training, when the batch size is set, all data within a batch have the same format size. However, in the training of a SR algorithm capable of handling various scaling factors, it is impossible to fuse multiple images of different sizes into one batch for training. To address this problem, we adopt the following steps:

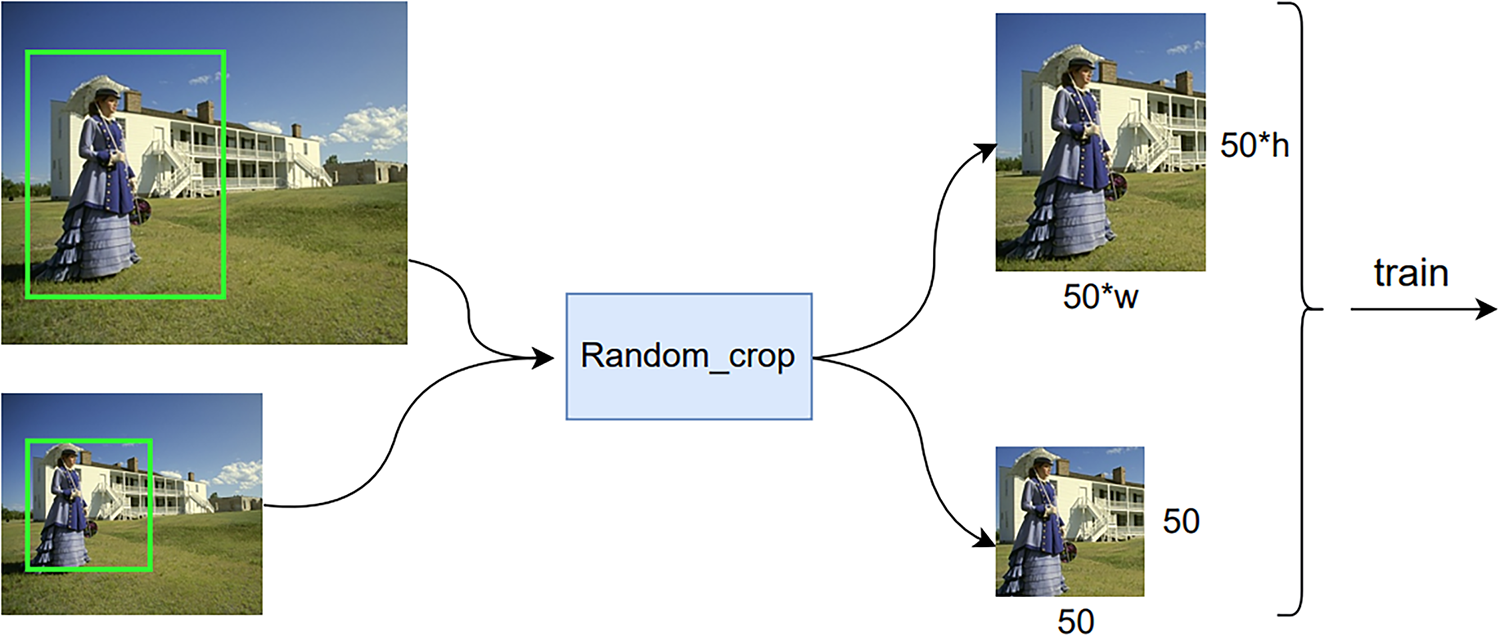

(1) The data returned by the DataLoader in Pytorch is set to contain only HR sample image data, and the data enhancement process, such as random rotation and flip, is completed in the data loading session. Because the DataLoader only returns HR data, the batch processing still ensures that all data formats are of the same size. Fig. 2 shows the flowchart.

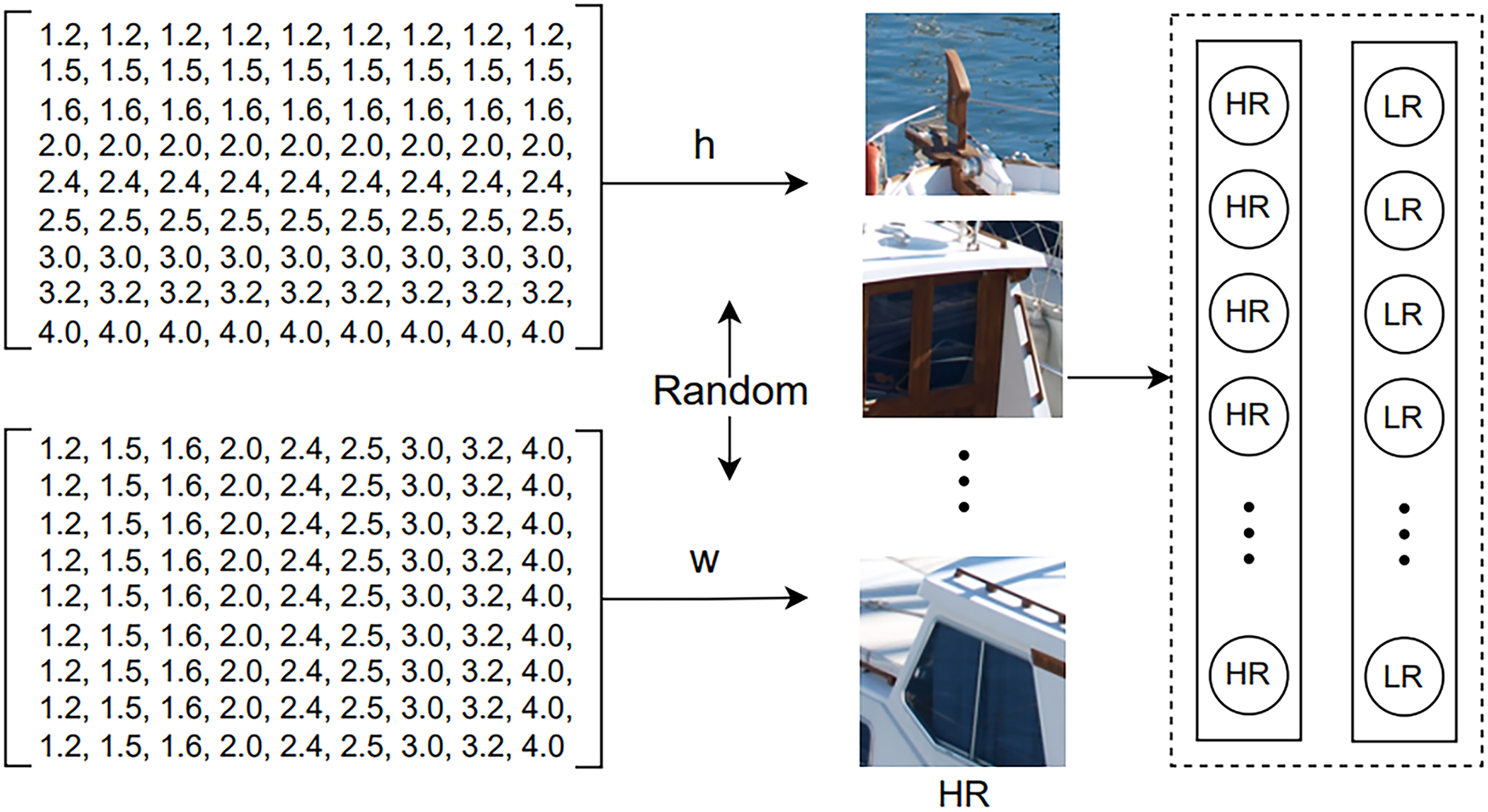

(2) We apply the same upsampling multiplier for each batch of HR images, where a scaling size h and w are randomly selected for height and width. The scaling size data will be saved in an array in advance. Then we perform the same downsampling operation for all image data of a batch to get LR image data, which ensures that the images of a batch have the same size, and the size of image data from different batches can be different. The step is shown in Fig. 3.

(3) After obtaining the LR-HR image data pair according to the selected scaling size, a window size of 50 × 50 is randomly applied to crop the LR images, and a window size of

Figure 2: The flowchart of HR data returning

Figure 3: The diagram of obtaining the LR-HR image data pairs from the HR data

Figure 4: Various random cropping methods on HR and LR images, respectively

When pre-determining the scaling size, we also need to pay attention to the fact that the patch size and the scaling size of the images loaded into the model training should be set reasonably. It should be ensured that the effective receptive field can be approximated by multiplying the patch size with the scaling factor, which determines the coverage of the reconstruction.

3.1 Dynamic Lightweight SR Algorithm at Arbitrary Scale

In this section, we first introduce a dynamic and lightweight super-resolution algorithm at arbitrary scale: DDNet (Dynamic in Dynamic Network for Single Image Super Resolution). To further improve the texture representation capability of the model, we integrate the relative GAN with DDNet and propose DDNetGAN.

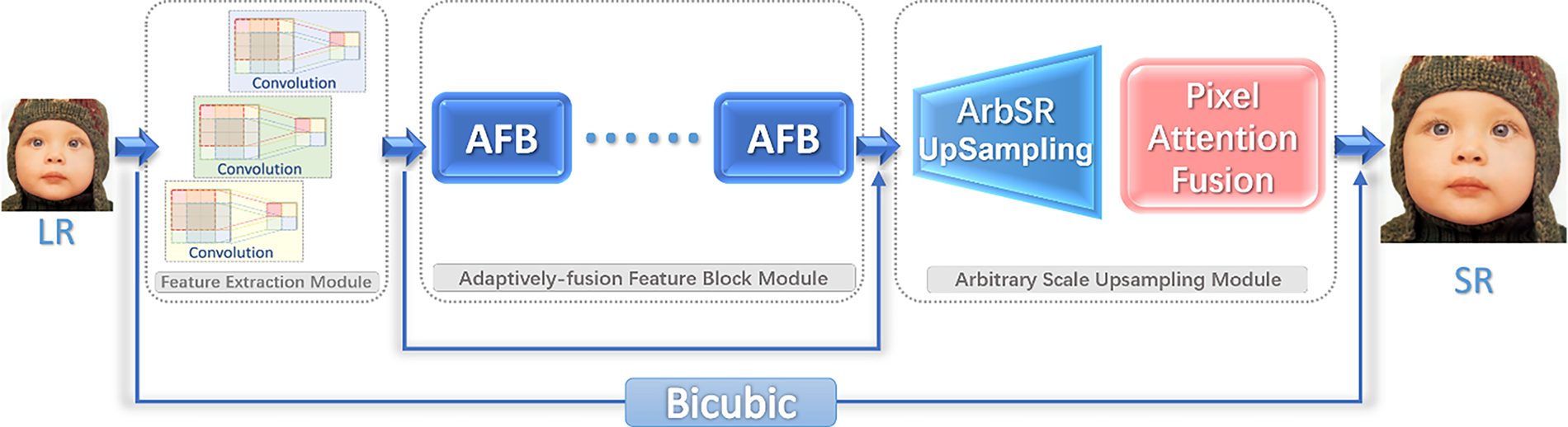

In this section, we first introduce the DDNet Architecture. DDNet consists of three major modules: the feature extraction module, the AFB module that enables the network to better utilize the input and scale information to reconstruct the image at each stage, and an arbitrary scale upsampling module that upscales the input to an arbitrary scale. The DDNet architecture is shown in Fig. 5.

Figure 5: DDNet architecture

As shown in Fig. 5, a low-resolution (LR) image as the input first goes through a feature extraction module consisting of dynamic convolution, which is composed of three or more static convolutions and adaptively extracts the corresponding initial feature information according to different types of input images. Then it is passed through the AFB (Adaptively-fusion Feature Block) module. Each AFB module consists of an attention mechanism and a dynamic convolution, and the AFB module further extracts feature maps for the upsampling. Each dynamic convolution accepts scale information as input. Finally, there is the arbitrary scale upsampling module, which consists of the ArbSR upsampling module and the pixel attention fusion module. Furthermore, there are two more directly connected paths in the network, so the network learns the residuals of the real features, which also makes the network training easier. The bicubic interpolation is used as the upsampling method for the direct connection. The network can be represented as follows.

where

where

After the first dynamic convolution, there is a series of AFB modules, which are the backbone of feature extraction and are given by the following equation.

where

We set d = 16. Before entering the upsampling module, the AFB module output features

After the feature extraction, the upsampling module follows to produce the final output features, given by:

where

3.1.2 Arbitrary Scale Upsampling Module

Arbitrary scale-up upsampling modules are more in line with the needs of practical scenarios and are the key component of the proposed DDNet. At the early stage of the development of the upsampling algorithm, arbitrary-scale upsampling can be easily achieved by pre-interpolation upsampling, but such a method is computationally intensive. Therefore, following arbitrary-scale upsampling algorithms mainly use post-upsampling methods to achieve this, such as MetaSR [28], ArbSR [37], and OverNet [38]. Moreover, the training process for arbitrary-scale upsampling methods is different from the training of fixed-scale upsampling. In this paper, the implementation of arbitrary-scale upsampling mainly adopts the upsampling module of ArbSR.

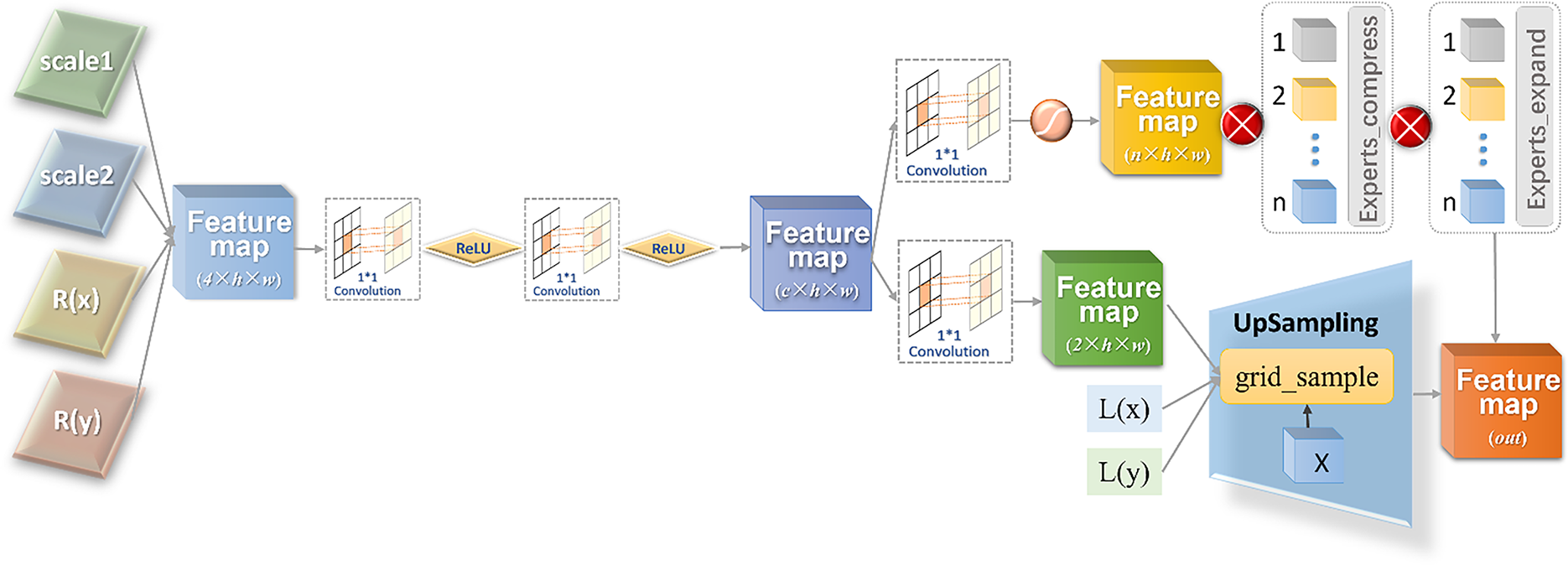

Fig. 6 shows the structure of the arbitrary-scale upsampling module. First, the coordinate information of each pixel of SR is obtained based on the size of the output feature map in the previous stage and the input scale factors: scale1 and scale2. The relative distances

where

Figure 6: Architecture of an arbitrary-scale upsampling module

Feature maps are passed through two fully-connected layers to obtain two-dimensional features with channel

After combining the feature map with channel number 2 with

where

The compressed convolution and expanded convolution are combined with

where

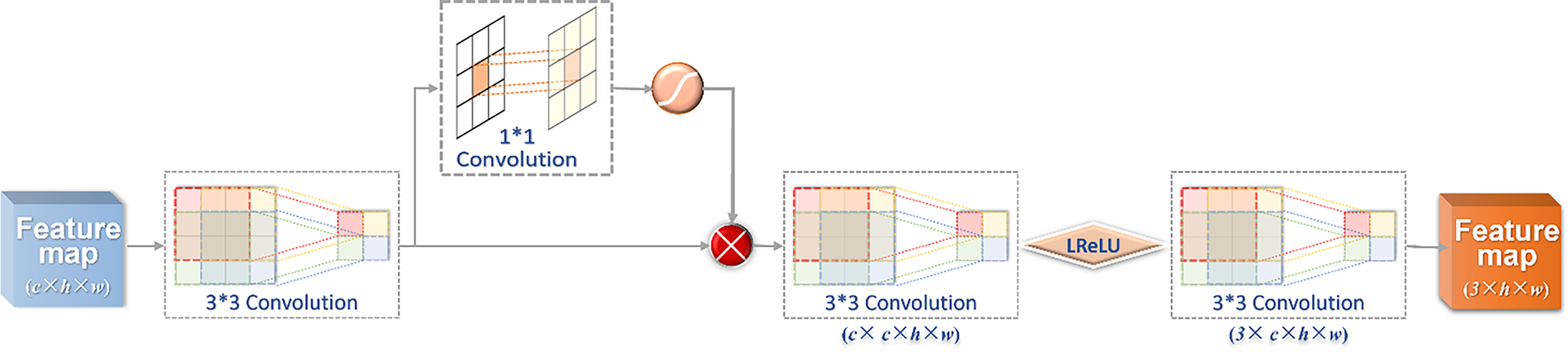

The feature information obtained after upsampling needs to be further fused to generate the final image with the same size as the input. The architecture of pixel attention fusion in DDNet is shown in Fig. 7.

Figure 7: The architecture of pixel attention fusion

Fig. 7 shows that the DDNet network has to go through the process of fusion reconstruction after upsampling to get the final output feature map, and the whole process can be denoted by (16).

where

where,

where

With the pixel attention and reconstruction module, the DDNet network can better fuse the feature information of different channels, which helps to improve the network’s expression ability. At this point, the reconstruction process of the whole network is completed, and some post-processing is needed later to display the reconstructed images. It should be noted that the network involves many residual paths, which is beneficial to the learning of the network.

3.2 DDNetGAN Based on Relative GAN

GAN-based SR algorithm can reconstruct more realistic images. In order to further improve the texture representation capability of DDNet, we propose a GAN-based DDNet network, named DDNetGAN. The generator of the network adopts the DDNet network, which helps to extract richer feature information. In this section, we present the details of the improved VGG model [39] for the feature extraction of arbitrary-scale images and the GAN-based adversarial training.

3.2.1 Improved VGG Discriminator Network

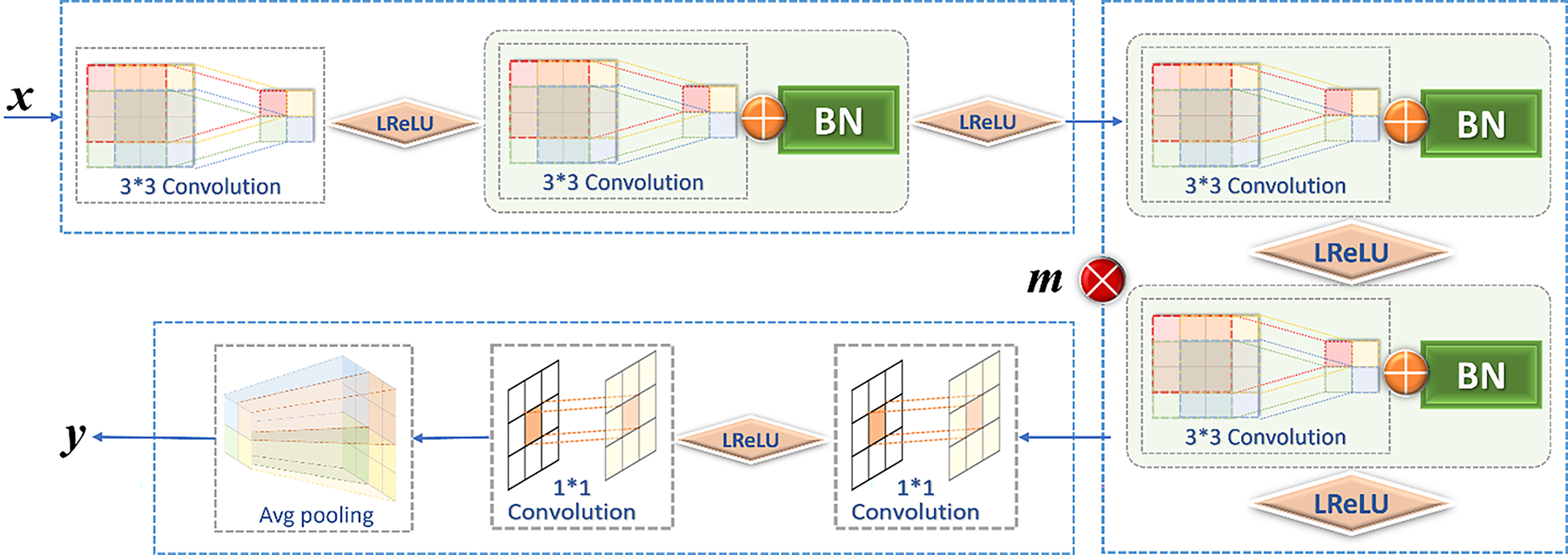

Some previous discriminators mostly target fixed-scale input images, while the proposed DDNet is an arbitrary-scale SR algorithm. Since the size of the image is constantly changing, it requires that the discriminator can not only discriminate a fixed-size input image, but also discriminate an arbitrary-scale input image. To address this problem, we propose an improved VGG discriminator network, as shown in Fig. 8.

Figure 8: The architecture of the improved VGG network

To be able to discriminate the input image of arbitrary size, the modified VGG network removes the original linear connection layer and replaces it with an Avg-pooling layer, where m = 4. As can be seen in Fig. 8, the input image is first passed through the first module, combining a convolution and a batch normalization (BN) layer, and then the output result is passed through the Avg-pooling operation.

Specifically, the input image is first passed through the first module, which consists of two 3 ∗ 3 convolutions and BN, and the number of channels is changed from 3 to 64, given in (19).

where

The next step is to go through four identical modules, each consisting of two 3 ∗ 3 convolution kernels and two BN layers, and the number of channels of the feature map increases by a factor of two for each module, i.e., the number of channels becomes 128, 256, 512, 512 after four modules.

Following four identical convolutional modules, there are two 1 ∗ 1 convolutional layers, which are used to replace the original linear connection layer. The two 1 ∗ 1 convolutional operations are mainly used to reduce the dimensionality, reducing the original 512-channel feature map to 100 channels and then to 1 channel, after global average pooling. Then the output is obtained.

By the above operation, we can get the discriminative result of any input scale image. By combining the improved VGG discriminator with DDNet as the generator, we can get the DDNetGAN to generate images with more realistic texture through adversarial training.

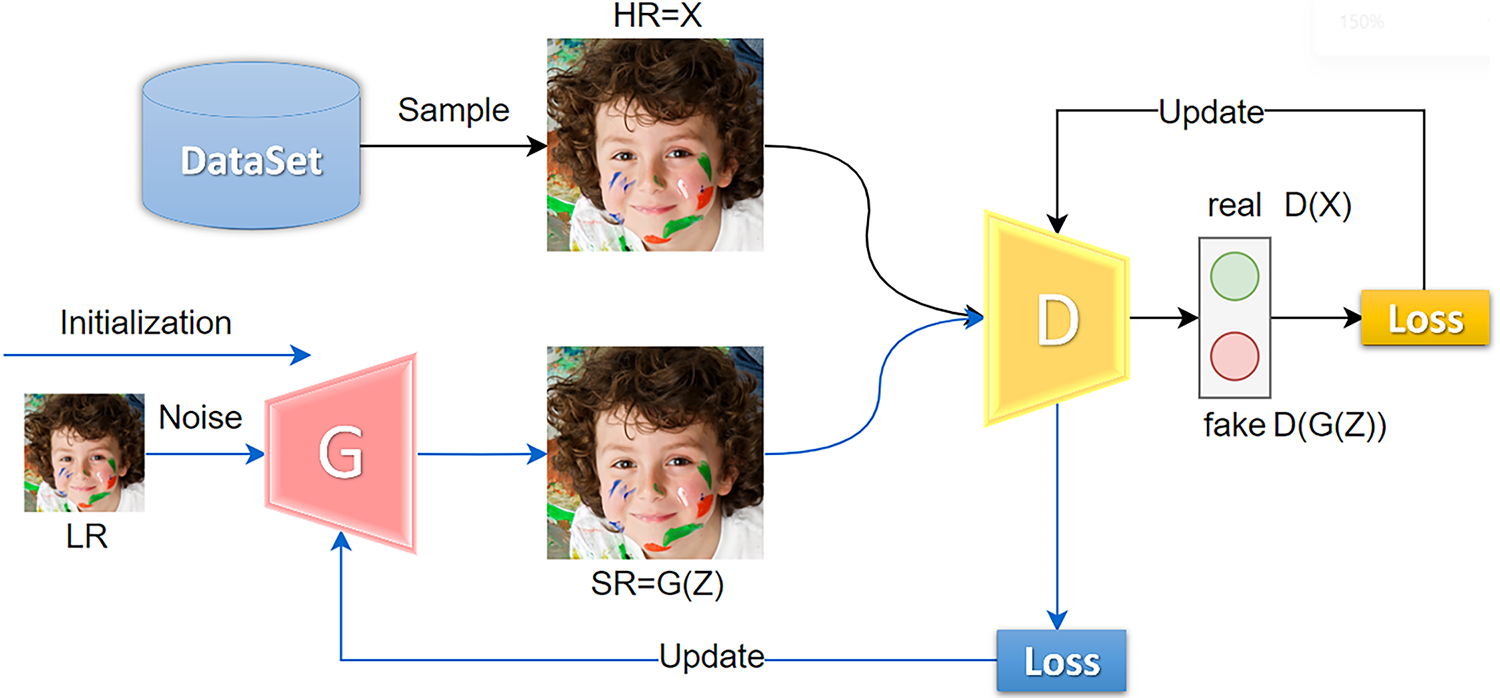

3.2.2 Adversarial Training Strategy of DDNetGAN

In addition to the selection of discriminators, adversarial training also requires the design of the corresponding adversarial loss as a way to interact the information between the generator and the discriminator. Here, the adversarial loss in ESRGAN [19] is chosen for GAN training, and the relative discriminator idea of ESRGAN has been illustrated earlier; its basic representation is as follows.

where

Eq. (24) shows that the more accurately the discriminator determines, the closer the log is to 1, the closer the loss is to 0. E denotes the expectation value of the current batch size. The generator fights against the loss as follows.

It shows that the more accurate the discriminator judgments are, the less capable the generator is; the generated images are easily distinguishable, and therefore the losses are larger, which will urge the generator to generate more realistic images. The total loss of the final DDNet generator is the adversarial loss, the perceptual loss, and the content loss (L1 loss).

where

Besides the design of the discriminator and the design of the loss, how to train the GAN is also important, since the adversarial training is prone to being unstable. For the training of DDNetGAN, the generator DDNet will be trained first, which is able to generate good, high-resolution images. Fig. 9 shows the training process of DDNetGAN. The training is iteratively performed between the training of the discriminator and the generator. For the discriminator training, it is better to be able to discriminate true from false quickly and accurately, i.e., to discriminate true HD images from real HD images and discriminate HD images generated by the generator from false ones. Therefore, we combine the loss function of the discriminator based on ESRGAN and use the generator to complete the update of the discriminator. For the generator, the more accurate the discriminator is, the greater the loss will be, which in turn will motivate the generator to generate more realistic images.

Figure 9: The training diagram of the DDNetGAN network

The learning ability of the discriminator and the generator should be continuously adjusted during the training process. Neither side should be too strong nor too weak; it should be a dynamic game process. For example, if the discriminator is too strong, this will result in the loss of the generator being always large, and the generator cannot use the information of the discriminator, leading to the inability to learn the correct reconstruction effect. If the discriminator is too weak, it cannot distinguish between true and false, which also leads to the network not learning stably. Therefore, it is necessary to continuously adjust the learning ability of the discriminator and the generator during training, so that they can promote each other and achieve the goal of eventually making the generator generate more realistic images of textures.

In order to evaluate the reconstruction performance of the proposed DDNet and DDNetGAN models, comprehensive experiments are conducted in this section. We first evaluate the reconstruction performance of DDNet by comparing it with multiple light SR models and SR models for arbitrary scales. Then we conduct a series of ablation studies to evaluate the impact of each module on the performance.

DDNet is designed for a better balance between the number of network parameters and reconstruction accuracy. In order to show the performance of DDNet more comprehensively, the experiments consist of the following parts. Firstly, DDNet is compared with some existing lightweight SR algorithms, and then DDNet is compared with some classical SR large models. Because DDNet is an arbitrary scale SR algorithm, it is also compared with several existing arbitrary scale SR algorithms separately.

The test sets used in the experiments are Set5, Set14, Urban100, Manga109, and BSDS100, which have been introduced previously. Peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR) and structural similarity index measure (SSIM) are adopted as the evaluation metrics. Baselines for lightweight SR algorithms include SRCNN [5], FSRCNN [40], DRRN [6], VDSR [41], IMDN [42], A2N [43], and DRCN [7]. Baselines for traditional SR methods include Bicubic, EDSR [44], RDN [45], and RCAN [46]. Baselines of SR models for arbitrary scales are MetaRDN [28], ArbEDSR [29], and ArbRDN [29].

Performance comparison with lightweight SR algorithms: DDNet’s parameter count is notably higher than that of typical lightweight super-resolution methods, yet it remains significantly lower—by an order of magnitude—compared to advanced networks like RDN and EDSR. This places DDNet’s complexity in the middle ground, offering a balanced consideration for practical applications based on specific requirements. Our comparison focuses on upscale factors of 2, 3, and 4, with performance evaluated through PSNR (Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio) and SSIM (structural similarity index measure) metrics across various test datasets. The hyperparameters of the experiments are set to D = 3, C = 64, G = 16. We utilized the Adam optimizer, a batch size of 16, and a learning rate of lr = 5e−4. The training protocol commenced with an initial 10 epochs at upscale factors of 2, 3, and 4, succeeded by an extensive 200 epochs to refine performance.

Table 2 demonstrates that DDNet secures superior outcomes with a modest augmentation in parameter count compared to certain lightweight SR algorithms. The inherent dynamic and adaptive qualities of the DDNet SR algorithm contribute to notable enhancements in performance across specific test datasets and scaling factors.

Performance comparison with large models of SR algorithm: While DDNet demonstrates a notable improvement over some classic lightweight SR models, it inherently possesses a higher parameter count. This aspect may not fully showcase DDNet’s advantages. To better illustrate DDNet’s efficacy, we compare it against larger SR models such as EDSR, RDN, and RCAN. This comparison aims to highlight how DDNet maintains competitive performance with these larger models while significantly reducing the parameter count. Additionally, we incorporate results from bicubic interpolation at scale factors of 2× and 3× to underscore the improvements attributed to the SR algorithms. It’s important to note that these models do not offer hyper-resolution at arbitrary scales; thus, we only evaluate PSNR (Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio) and SSIM (structural similarity index measure) metrics at specific integer scale factors. In the experiments, parameters are set as follows: D = 3, C = 64, G = 16, using Adam optimizer, batch_size = 16, and an initial learning rate lr = 5e−4, which is reduced by half every 50 epochs. Training commences with 10 initial epochs at scale factors of 2, 3, and 4, followed by 200 epochs on the Div2K dataset. Subsequently, the model undergoes an additional 100 epochs of training on a combined dataset of Div2K and Flickr2K to further refine its performance.

Table 3 reveals that the DDNet network, despite a reduction in its parameter count by an order of magnitude, achieves results comparable to, and in some cases surpasses, those of competing models across various scales. This underscores DDNet’s advancement in the field of lightweight model design, enhancing the feasibility and application of SR algorithms in practical engineering scenarios.

Performance comparison with SR algorithms for arbitrary scales: This section showcases the advantages of the DDNet network by comparing it with several leading SR algorithms that support arbitrary scaling, namely MetaRDN, ArbEDSR, and ArbRDN. The core strength of the DDNet network lies in its innovative architecture, which includes a sampling module designed for arbitrary scale adaptation, aligning with the approach taken by ArbSR models. For comparison purposes, we focus on PSNR metrics at scale factors of 2, 3, and 4. The experimental setup for this comparison adheres to the same parameters used in the analyses with large SR models.

Table 4 demonstrates that DDNet achieves results that are comparable to, or even exceed, those of other methods like MetaSR and ArbSR across various superscaling factors, while significantly reducing the number of parameters.

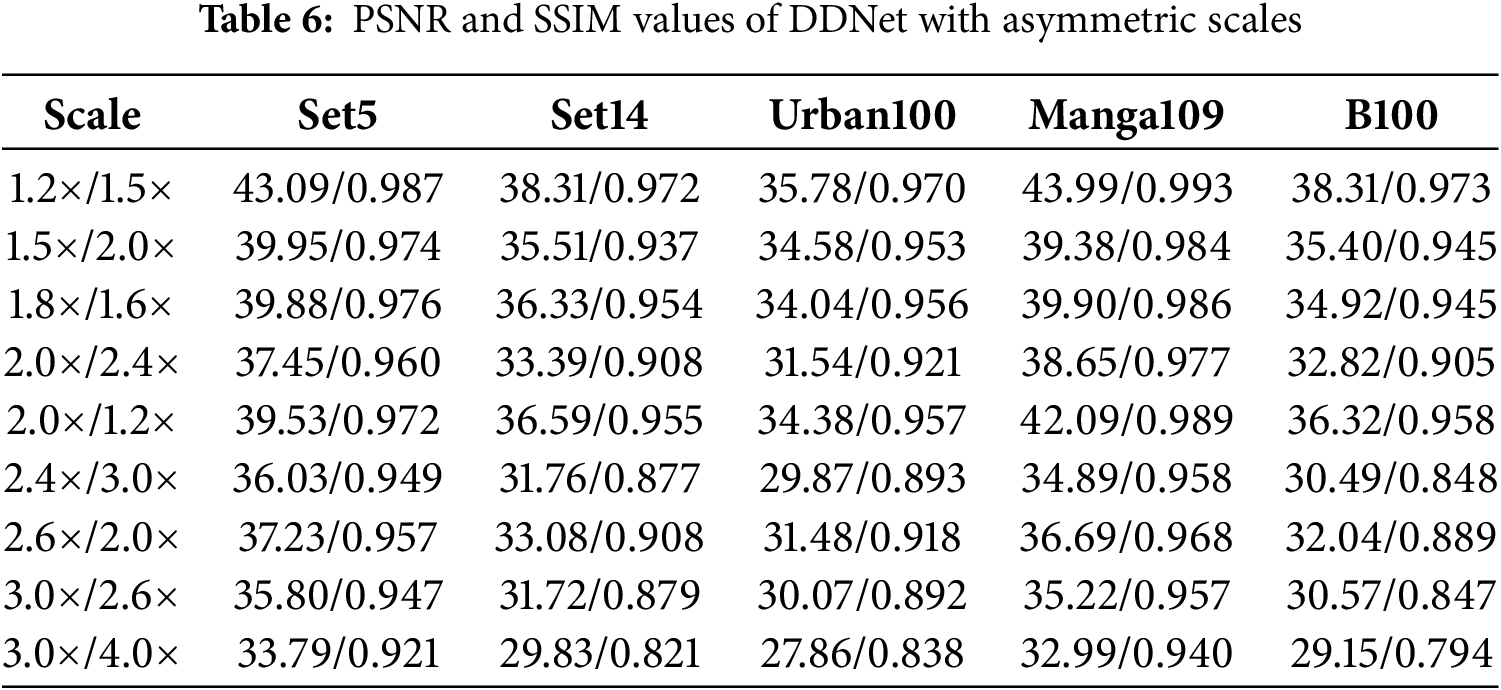

Additional results showcasing the performance of DDNet across various datasets are presented, with both PSNR and SSIM metrics calculated. Table 5 details the PSNR and SSIM values achieved by the DDNet algorithm at different symmetric scales, where both the length and width of the image are scaled at identical ratios. Conversely, Table 6 examines the performance of DDNet at asymmetric scales, where the length and width of the image are scaled at differing ratios. This table’s “Scale” column specifies the distinct scaling ratios for length and width, providing insights into DDNet’s versatility in handling various scaling challenges.

The DDNet architecture incorporates several key components, including a dynamic convolutional structure (DC) informed by scale information, a pixel-based gating mechanism (GM), an attention structure (AB) for multi-feature fusion, an AFB module, and an upsampling module. The primary variables include the number of dynamic convolutions (D), the number of feature channels (C), and the number of AFB modules (G). To assess the DDNet model’s performance and the efficacy of its individual modules, extensive ablation and comparison experiments were conducted. These experiments aimed to validate the network structure’s design choices and achieve a balance between computational complexity and accuracy.

Experimental setup and configuration: We predominantly utilized the DIV2K dataset for training, supplemented by a combination of the DIV2K and Flickr2K datasets to enrich the training data. Initially, all high-definition images from the DIV2K training set were cropped to a uniform size of 480 × 480 pixels. These images were then further subjected to random cropping to serve as network inputs. Super-resolution magnifications were set at varied scales, including 1.2, 1.5, 1.6, 2.0, 2.4, 2.5, 3.0, 3.2, and 4.0, with the training network receiving input images of 50 × 50 pixels. Initial training was conducted over 10 epochs at integer multiples of 2, 3, and 4, followed by training at all specified multiples, employing bicubic interpolation downsampling for model degradation.

Ablation study on dynamic convolutions: DDNet integrates large-sized dynamic convolutions at the network’s inception and within each AFB module throughout the architecture. This strategic incorporation ensures that the network optimally leverages differentiated information from various input images, aiming for high-precision reconstruction of super-resolved images. Given the intrinsic limitations in feature extraction capabilities of lightweight models, these experiments highlight the benefits of the Dynamic Convolution (DC) structure within the DDNet algorithm through a comparative analysis. Our experiments were designed to evaluate the impact of including dynamic convolutions in the DDNet network. When dynamic convolution was incorporated, the configuration was set to D = 3, with all other parameters, including C = 64 and G = 16.

Table 7 illustrates the variations in PSNR values for the DDNet network, comparing configurations with and without the DC module across 2×, 3×, and 4× upsampling factors. The data reveals an approximate difference of 0.15 dB in the average PSNR after training for 200 epochs under identical conditions. This discrepancy underscores the benefit of incorporating the DC feature, highlighting its effectiveness in enhancing the network’s super-resolution performance.

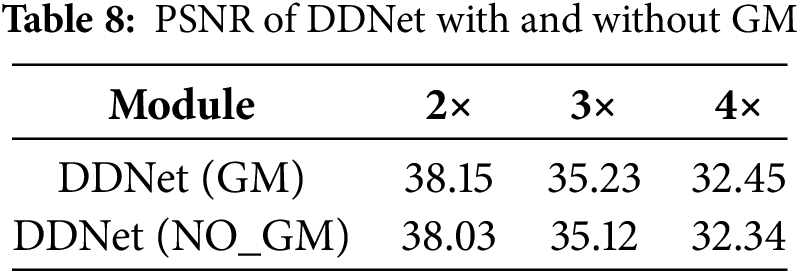

Ablation study on the pixel-based gating mechanism: The pixel-based gating mechanism (GM) can be described as a pixel-based weight filter, which helps to improve the adaptiveness of the network. In order to verify the effectiveness of the GM structure and the ability of adaptive feature information extraction, we conduct an ablation study.

Table 8 shows that the average peak signal-to-noise ratio of the DDNet network with the addition of the GM structure increases by about 0.11 dB. The GM structure is able to adaptively assign different weight values to each pixel of each channel of the feature maps obtained from both DC and AB structures, which further reflects the dynamic nature of the DDNet network.

Table 8 indicates that the inclusion of the GM structure in the DDNet network results in an average increase of approximately 0.11 dB in the PSNR. The GM structure’s ability to adaptively allocate distinct weight values to each pixel across all channels of the feature maps, derived from both DC and AB structures, further emphasizes the dynamic and adaptable nature of the DDNet network.

Ablation study on the AFB module:

The AFB module is pivotal in the DDNet network’s feature extraction process, primarily leveraging dynamic convolution and attention structures to harness diverse features. The AFB module enables the network to selectively concentrate on different aspects of the input: on one hand, it focuses on the differential feature information, and on the other hand, it emphasizes the high-frequency components of the features. By integrating these aspects through the GM structure, the network attains adaptively differentiated feature information tailored to the specific input. To facilitate more efficient information fusion, the AFB module employs 1 × 1 convolution operations both prior to and following the feature combination process. Moreover, it introduces a direct linkage branch, allowing the seamless transition of feature information from one layer to the next by amalgamating the input and extracted features. This architecture not only ensures the module’s lightweight nature but also maximizes the retention of essential feature information, striking a balance between complexity and performance. The number of parameters in a convolution kernel can be calculated as follows.

where

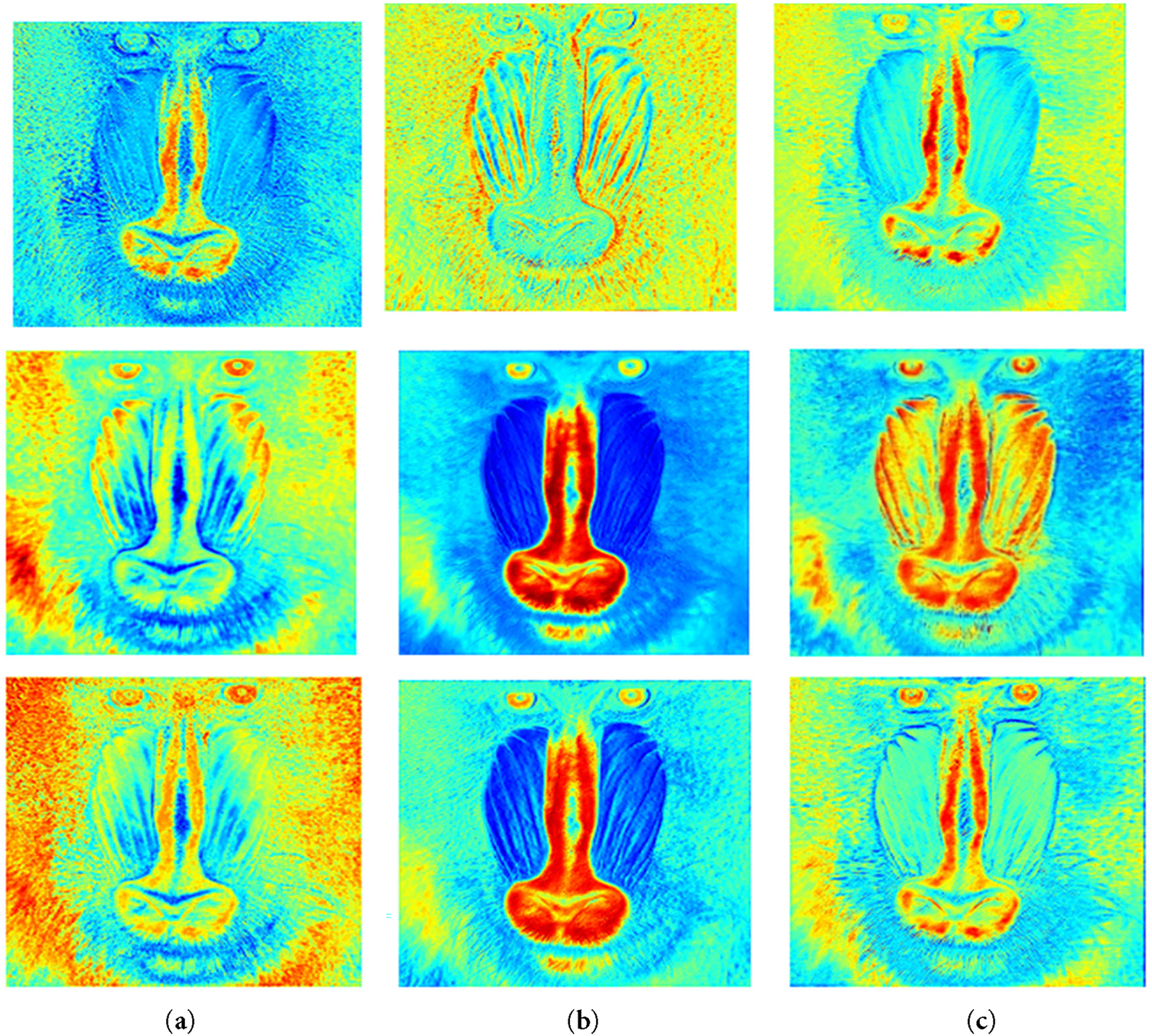

The calculated result is about 0.24 M, while the number of parameters of RDB is about 1.36 M. It can be seen that the number of parameters of the AFB module is reduced by an order of magnitude compared to that of the RDB module. To further understand the expressiveness of the AFB module in the DDNet network, Fig. 10 presents a visual inspection through the heatmap of feature maps extracted by the AFB module.

Figure 10: Heat map of feature information extracted by the AFB module with (a) 16th, (b) 32nd, and (c) 48th channels

In Fig. 10, columns (a), (b), and (c) display the feature maps for the 16th, 32nd, and 48th channels, respectively. The top row illustrates heatmaps generated by the AB component, highlighting the extraction of prominent high-frequency features. The middle row shows heatmaps from the DC component, which captures both high and differentiated low-frequency information. The bottom row presents the combined effect of AB and DC through the GM, illustrating the integrated channel outcomes. According to Fig. 10, it is evident that the AB component predominantly focuses on crucial high-frequency details, whereas the DC component additionally identifies varied low-frequency elements.

Ablation study on the upsampling module with arbitrary scale:

The study explores the functionality of the upsampling module capable of accommodating arbitrary scaling factors, comparing two distinct approaches: the method employed in ArbSR and the upsampling technique utilized in OverNet. The ArbSR method integrates specific scale information into the upsampling process, tailoring inputs according to different magnification levels, whereas the OverNet approach leverages preceding feature data for scale-agnostic upsampling. These methodologies are evaluated for their efficacy.

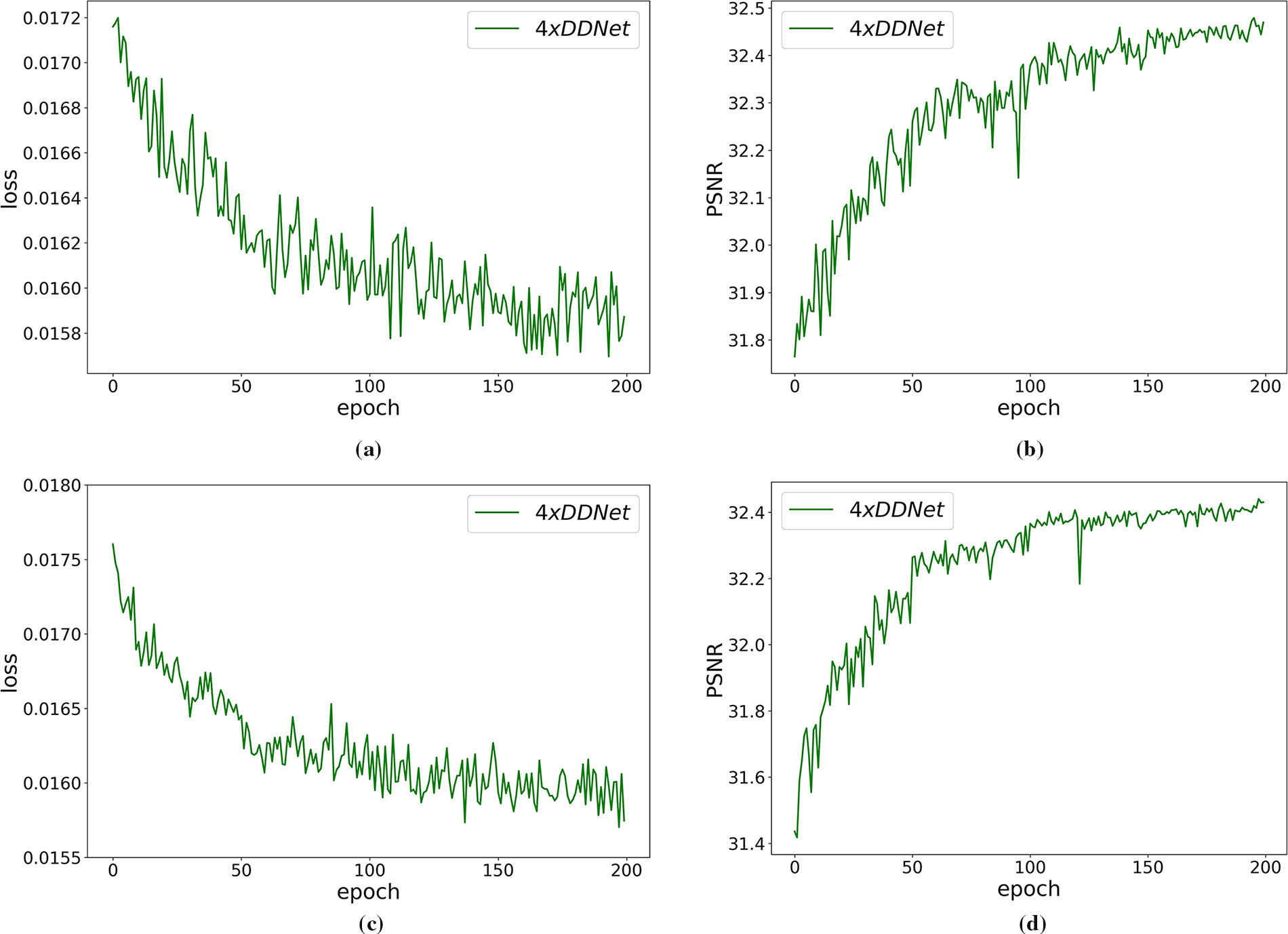

Fig. 11 displays the outcomes of incorporating DDNet with the ArbSR upsampling module in (a) and (b) and the OverNet upsampling in (c) and (d). The comparison reveals that the DDNet architecture, when combined with the ArbSR module, not only achieves superior results but also maintains a leaner parameter profile. This efficiency stems from the OverNet method’s reliance on subpixel convolutional upsampling, which inherently increases the parameter count. Consequently, the experimental evaluation led to the selection of the ArbSR upsampling module for the DDNet algorithm, prioritizing both performance and model compactness.

Figure 11: Training results of DDNet with different upsampling approaches. (a,b) show the results when using ArbSR upsampling. (c,d) show the results when using OverNet upsampling

Ablation study on feature map:

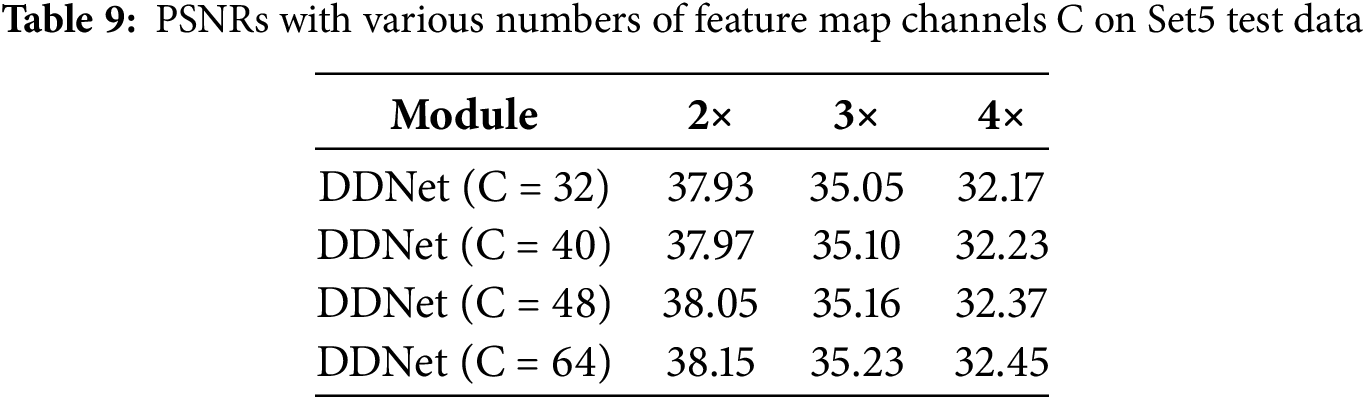

This study examines the optimal number of channels to achieve a trade-off between the richness of feature information and model size. While more channels can enhance the network’s ability to capture valuable information, they also significantly elevate the number of parameters. Channel counts of 32, 40, 48, and 64 are evaluated to discern their impact, yielding insights from the conducted experiments.

Table 9 indicates that as the number of feature map channels (C) increases, PSNR improves correspondingly. Given the objective to maintain the model’s lightweight design, PSNR evaluations for configurations with C values exceeding 64 were not pursued further.

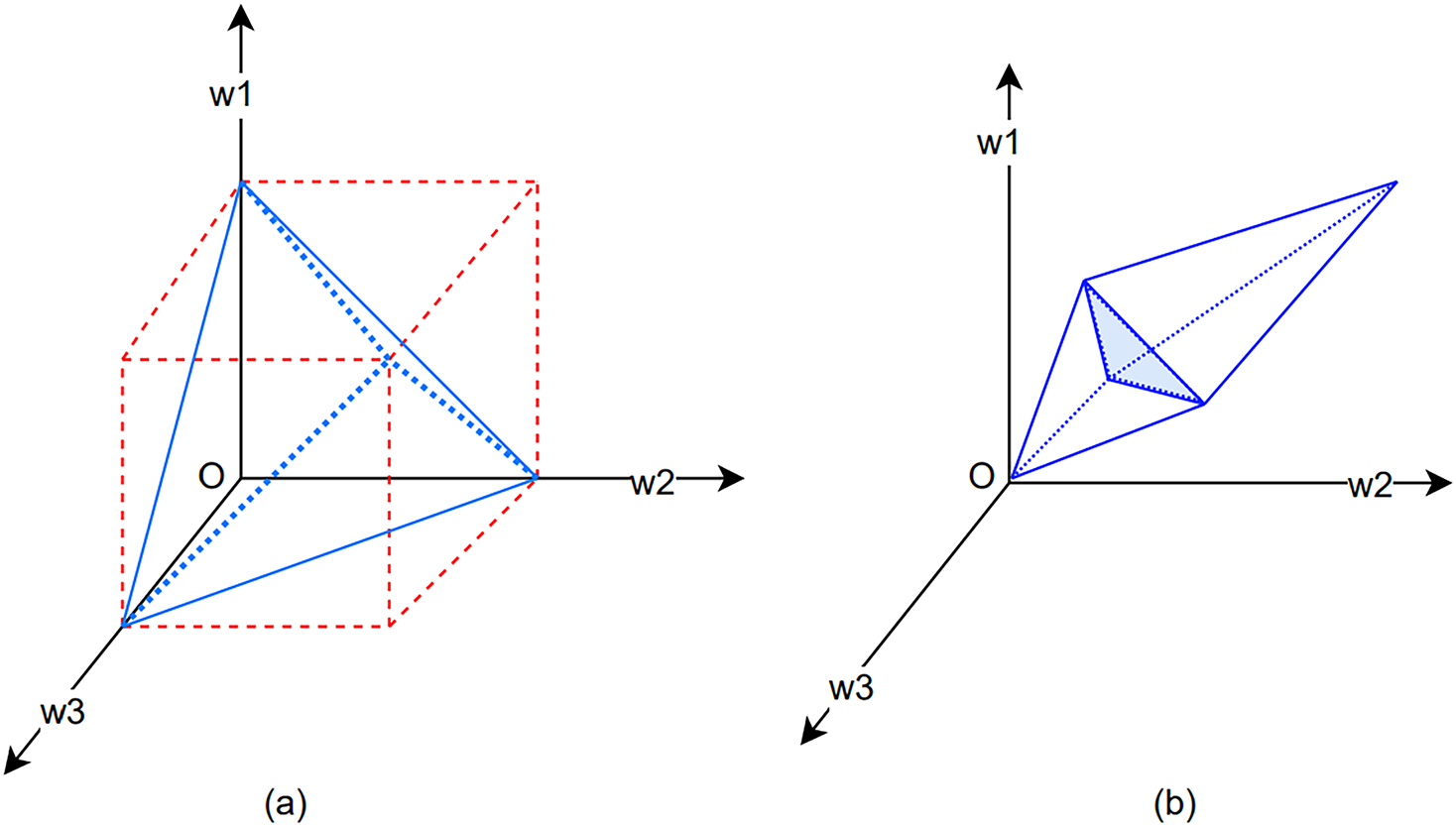

Ablation Study on the Number of Convolutions in Dynamic Convolution: The essence of training dynamic convolution involves the simultaneous learning of the attention module alongside multiple static convolutions. As the network’s complexity increases, the training process becomes more challenging, necessitating a simplification of the learning mechanism. This study employs three static convolutions to demonstrate their combined impact. By normalizing the weights of each static convolution within a 0–1 range, their cumulative effect, when constrained within two trigonometric cones, is depicted in Fig. 12a. Further, when the weights of all static convolutions are adjusted to fall within the 0–1 interval and their sum is normalized to 1, their aggregate impact is represented within a triangular domain, as illustrated by the blue area in Fig. 12b. This approach significantly simplifies the learning process for dynamic convolution.

Figure 12: Diagram of static convolution weight scaling. (a) parameter illustration and (b) confined cumulative value

Fig. 12 illustrates the role of parameters

Table 10 indicates that an increase in the number of convolutions within the dynamic convolutional process complicates the learning. This complexity not only hampers the quality of super-resolved reconstruction outcomes but also leads to an escalation in the model’s parameter count.

Ablation study on the number of AFB modules: More AFB modules can bring stronger generalization ability, but also greatly increase the number of model parameters. In order to set the appropriate number of G, we evaluate the values of G: 8, 16, 24, and 32. The results are given as follows in Table 11.

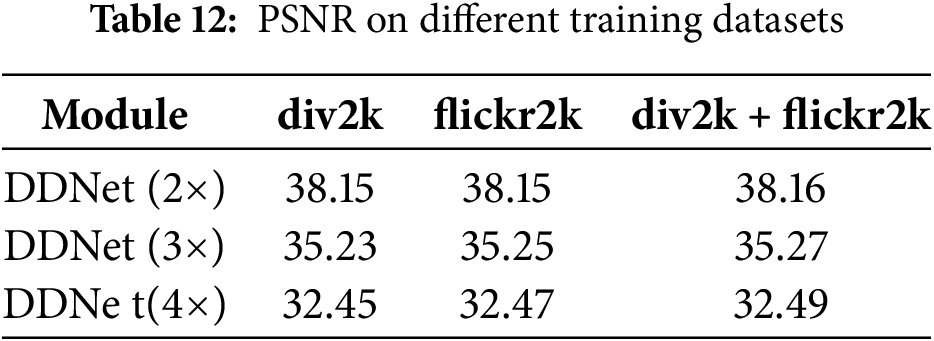

Ablation study on training datasets: To evaluate the effect of data size on model performance. We train the model on div2k, flickr2k, and div2k + flickr2k. The experimental results are shown as follows (Table 12).

Table 12 illustrates that network performance improves with increasing dataset size. This underscores the principle that training with a larger dataset can improve the network’s generalization capabilities. However, it’s important to note that larger datasets not only require more resources to collect and organize but also extend training durations and elevate costs. Therefore, model training must be pragmatically aligned with available resources, and data augmentation techniques may be employed to enhance training efficiency without excessively inflating the dataset size.

By comparing DDNet with lightweight SR methods, we show that DDNet showcases a high degree of effectiveness in image upsampling tasks, balancing model complexity and image quality, making it a competitive option for lightweight super-resolution applications. Its performance is particularly notable in cases where maintaining a lower parameter count is crucial without significantly compromising on the quality of the upsampled images. Moreover, by comparing with large SR models, DDNet consistently achieves high PSNR values with significantly fewer parameters, especially on the Manga109 dataset, known for its complex textures and fine details.

Through a comprehensive series of ablation studies targeting the critical components of DDNet, we have conducted an in-depth analysis of key architectural decisions, specifically evaluating the number of dynamic convolutions (D), the number of feature channels (C), and the number of Adaptive Feature Blending (AFB) modules (G). The findings from these experiments not only corroborate the architectural choices made during the design of DDNet but also illustrate the delicate equilibrium the network maintains between computational demands and the precision of super-resolution outcomes. The insights from these studies are instrumental in refining the network’s efficiency, paving the way for achieving superior image super-resolution with judicious computational expenditure.

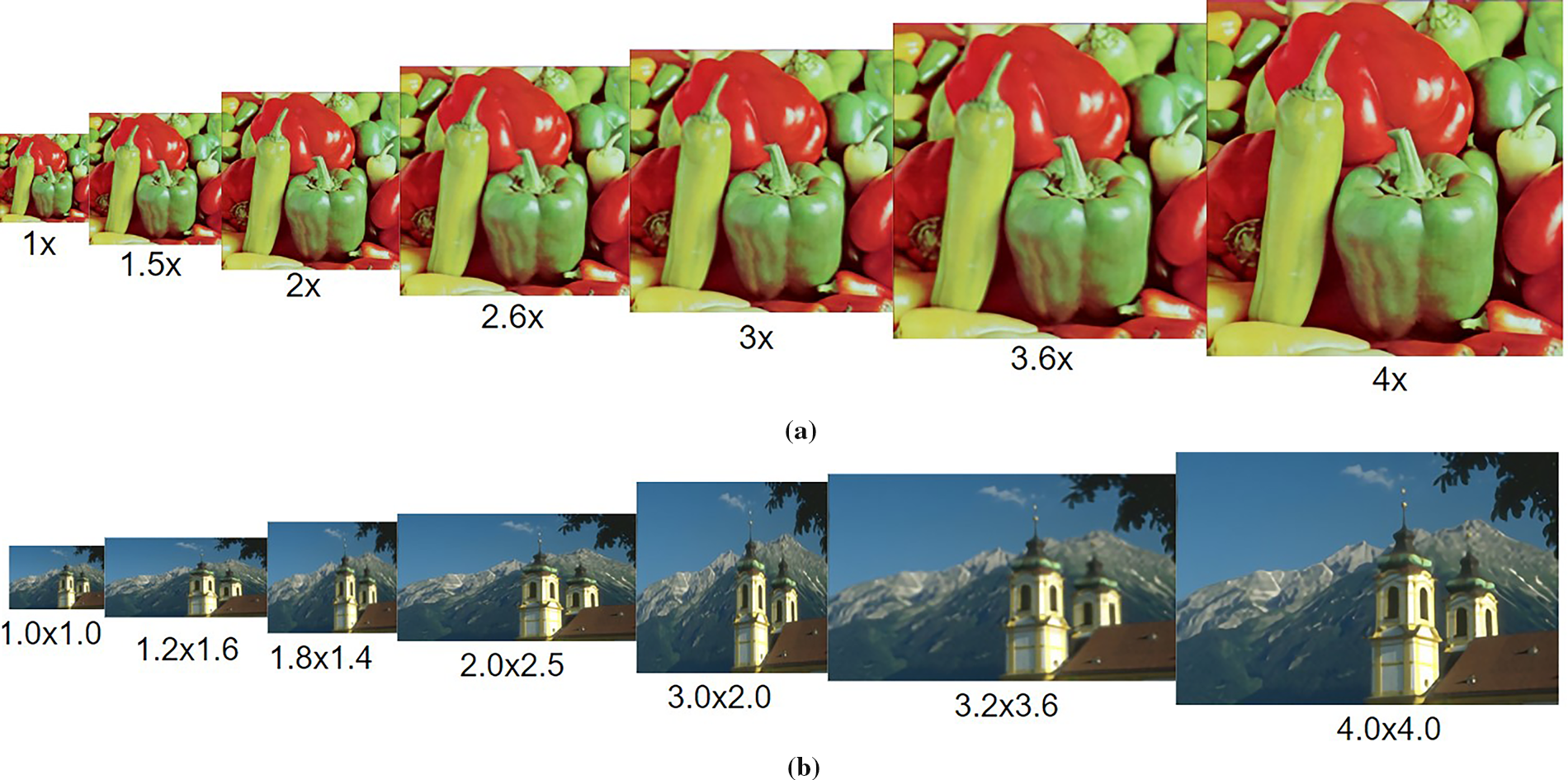

To better demonstrate the actual upsampling quality of DDNet, we provide some case studies of the reconstructed images from different SR methods. Fig. 13 demonstrates several reconstructed images of the DDNet at different scales, including the upsampling of symmetric scales and asymmetric scales.

Figure 13: Demonstration of the reconstructed images of the DDNet algorithm with different scales (a) symmetric reconstraction and (b) asymmetric reconstaraction

Fig. 13a,b displays the reconstruction quality for symmetric and asymmetric scales, respectively. Initially, the original image undergoes downsampling using bicubic interpolation, followed by upscaling at various upsampling scales through the DDNet. The illustrations affirm that the DDNet algorithm consistently delivers impressive visual results across all scaling factors, thereby reinforcing its capability for arbitrary scale enhancement. This is showcased through separate depictions of symmetric and asymmetric scale enhancements, underlining the adaptability and effectiveness of the DDNet in diverse scaling scenarios.

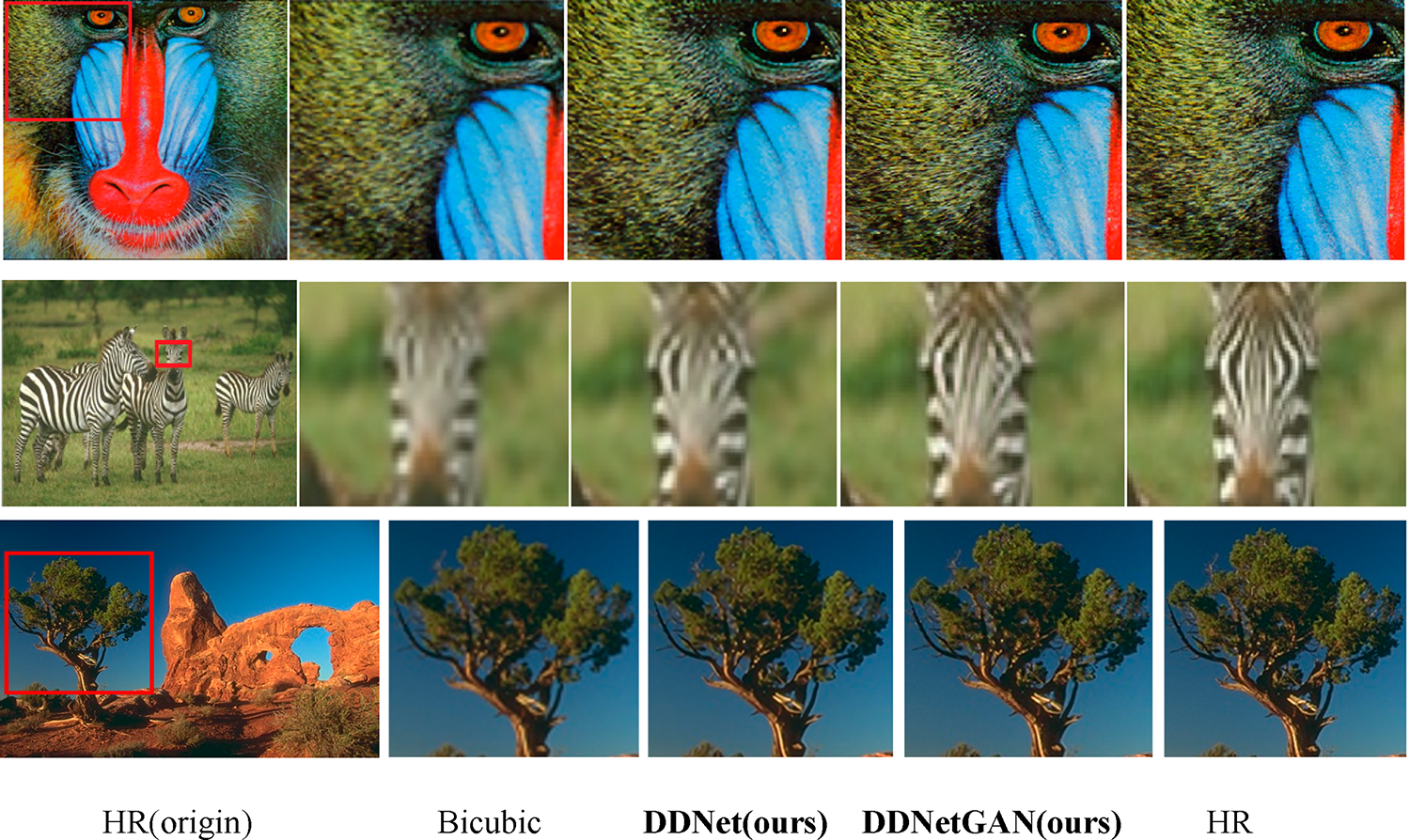

More reconstructed images among bicubic interpolation, DDNet, and DDNetGAN are shown in Fig. 14. From left to right, Fig. 14 shows the original image, the reconstructed image by bicubic, DDNet, and DDNetGAN, and the ground truth-high resolution (HR) image. The scale factor is set to 2. It shows that the visual quality of images by bicubic interpolation is inferior to the SR methods of both DDNet and DDNetGAN. Moreover, by incorporating GAN training into the process, the SR outcomes from DDNetGAN exhibit a more realistic appearance and a richer texture detail than those from DDNet. This highlights the effectiveness of GAN-based training in enhancing the perceptual quality of super-resolved images, offering a notable improvement over DDNet in terms of texture and detail reproduction.

Figure 14: Reconstructed images of different SR methods with scale factor 2

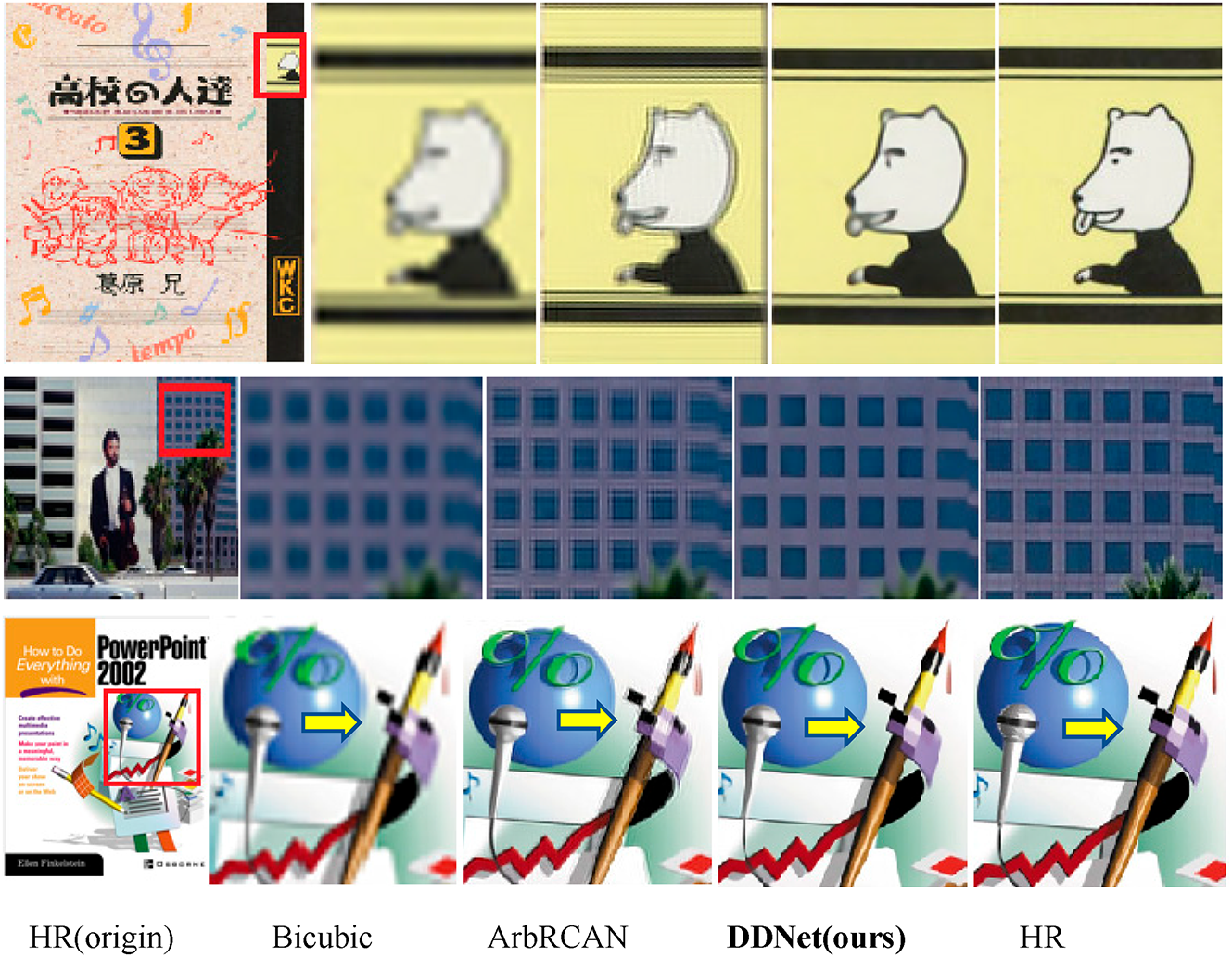

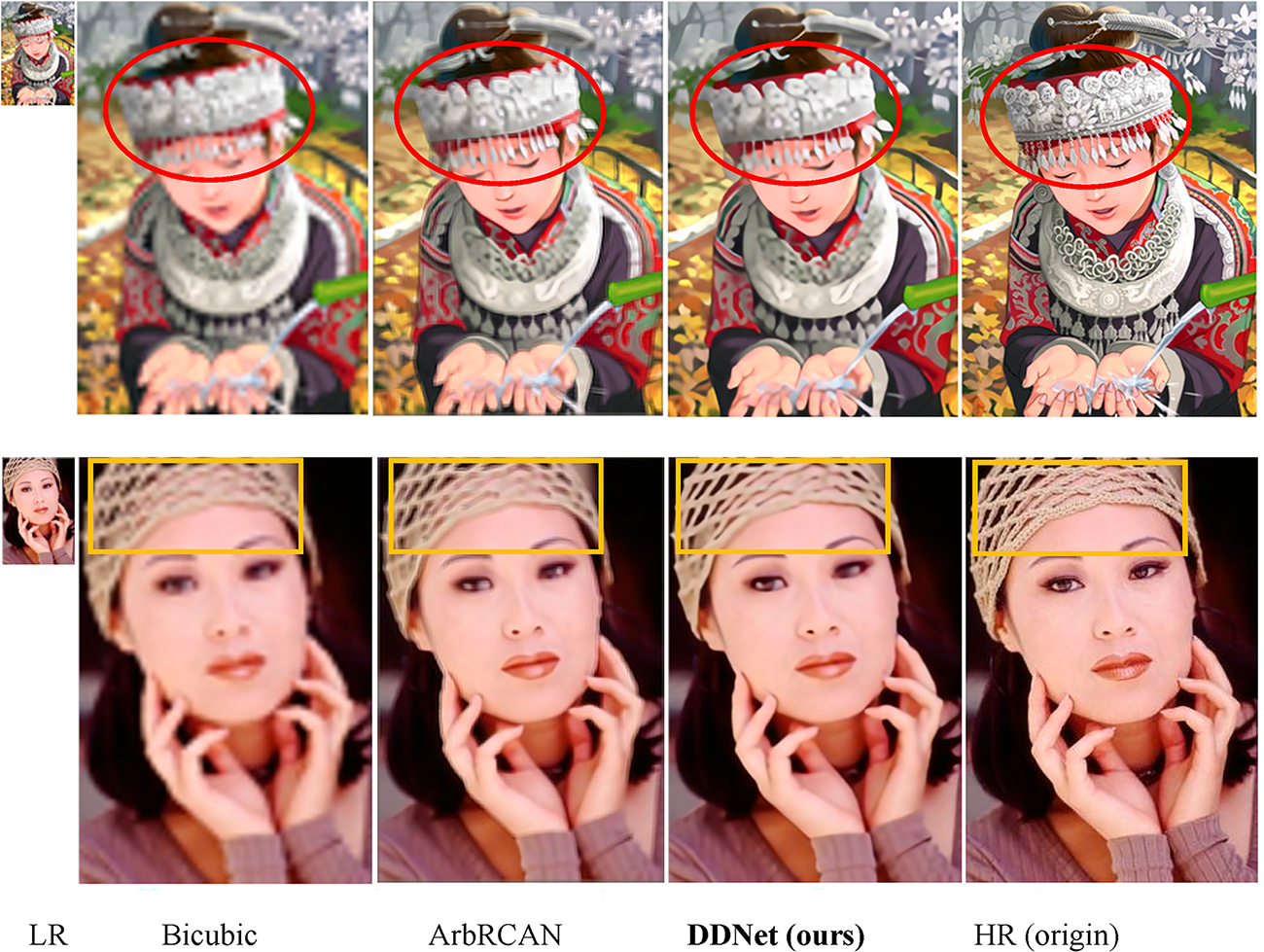

The following comparison of the effect of different SR algorithms to achieve 4-fold SR is shown, because DDNet is an arbitrary scale hypersorting algorithm, so the visual effect is mainly compared with ArbRCAN here. ArbRCAN upsampling, DDNet upsampling, and partial interception of the original image, because considering the large display area of the original image, only the local area of the image after upsampling is extracted for comparison.

Fig. 15 shows reconstructed images of different SR methods with a scale factor of 4. ArbRCAN is compared with DDNet. The figure clearly illustrates that images upsampled using traditional bicubic interpolation appear blurred. Comparing ArbRCAN and DDNet, it’s observable that ArbRCAN’s upsampling results tend to exhibit more artifacts and blurriness at the edges. In contrast, DDNet’s upsampling outcomes are sharper, with edges more distinctly defined, leading to a visually more pleasing overall effect. This comparison highlights DDNet’s superiority in preserving detail and reducing artifacts, making it a more effective choice for achieving high-quality super-resolution images.

Figure 15: Reconstructed images of different SR methods with scale factor 4

The aforementioned analysis focuses on the localized display effects within an image. To more comprehensively demonstrate the visual enhancements facilitated by the DDNet algorithm, we first downsample the original image by a factor of 4. Subsequently, the DDNet algorithm is applied to upscale the image, achieving a full-scale enhancement. Presenting the entire SR image allows for a more detailed observation of the SR performance across different regions of the image.

Fig. 16 shows global reconstruction images of different SR methods with a scale factor. Fig. 16 shows that the reconstructed image by bicubic interpolation is very blurred and lacks details in the marked area, while the SR algorithms show much better sharpness. From the marked area, we can obviously see that although ArbRCAN recovers its basic shape, the details are still missing, and the edges are blurred, while DDNet produces clearer and more natural edges.

Figure 16: Global reconstruction images of different SR methods with scale factor 4

Although we demonstrate the high quality of the reconstructed images of DDNet and DDNetGAN by the above case study, the single-image super-resolution technique based on deep learning remains an area with enormous potential for further research and exploration. Current SR techniques predominantly address enhancements up to 8x magnification, with advancements beyond this threshold remaining relatively unexplored. This paper successfully implements an SR algorithm capable of handling arbitrary scales, yet its efficacy is assured only up to 4x. How to achieve super-resolution at higher scales or even truly arbitrary multiples is of great research significance and worthy of further exploration and research.

In this paper, we proposed DDNet and its adversarial variant DDNetGAN, two lightweight and dynamic architectures for arbitrary-scale image super-resolution. The proposed AFB module introduces adaptive feature fusion guided by pixel-level attention and gate mechanisms, allowing the network to flexibly adapt to varying input conditions. Extensive experiments on standard datasets demonstrate that our method achieves competitive performance while maintaining a compact model size.

However, there are still limitations to our current approach. First, although our method supports arbitrary scaling factors, it still relies on interpolation-based scale handling, which may introduce artifacts in extreme scaling scenarios. Second, while we validated our method on widely-used benchmark datasets, real-world deployment may require robustness to noise, blur, and compression artifacts not present in curated datasets. Moreover, the GAN-based variant (DDNetGAN) improves texture quality but introduces instability during training.

In future work, we plan to further optimize our model structure by incorporating implicit neural representations or coordinate-based encoding strategies to improve scalability without interpolation. We also intend to explore unified frameworks for blind super-resolution and real-world degradations, as well as training-stable adversarial schemes. In addition to the directions already mentioned, several emerging trends in artificial intelligence could inspire future extensions of this work. The rapid adoption of transformer-based architectures in both low-level vision and high-level recognition tasks suggests that incorporating global self-attention or hierarchical transformer blocks into our framework could further enhance feature representation across scales. Such integration may improve the trade-off between efficiency and reconstruction fidelity, particularly in large-scale or real-world image super-resolution tasks. Advances in quantum computing and quantum-inspired algorithms may open new opportunities for accelerating optimization in super-resolution and object detection. Quantum-based models could potentially handle high-dimensional feature interactions more efficiently than classical methods, offering a promising avenue for scaling lightweight architectures to even more complex vision tasks. Exploring these directions would allow our proposed framework to stay aligned with the broader evolution of AI-driven image analysis, extending its applicability beyond super-resolution into tasks such as object detection and recognition in resource-constrained environments.

Acknowledgement: The authors express their sincere appreciation and profound gratitude to research assistants Haitao Ren and Jiawei Tian for their help and support in collecting and sorting the data.

Funding Statement: This study is supported by Sichuan Science and Technology Program [2023YFSY0026, 2023YFH0004].

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Wenfeng Zheng, Lirong Yin; data collection: Guangyu Xu; analysis and interpretation of results: Chunlai Wu, Siyu Lu, Yiqiao Gong; draft manuscript preparation: Yiqiao Gong, Chunlai Wu; edit and review: Lirong Yin, Wenfeng Zheng; supervision: Lijuan Zhang, Wenfeng Zheng. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets are available at https://data.vision.ee.ethz.ch/cvl/DIV2K/ (DIV2K), https://github.com/LimBee/NTIRE2017 (Flickr2K) (accessed on 31 August 2024), https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1pRmhEmmY-tPF7uH8DuVthfHoApZWJ1QU (Set5 & Set14) (accessed on 31 August 2024), https://opendatalab.com/OpenDataLab/Urban100 (Urban 100) (accessed on 31 August 2024), https://www2.eecs.berkeley.edu/Research/Projects/CS/vision/bsds/ (BSDS100) (accessed on 31 August 2024), http://www.manga109.org/en/ (Manga109) (accessed on 31 August 2024). The code for DDNet is available upon request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Chen H, He X, Qing L, Wu Y, Ren C, Sheriff RE, et al. Real-world single image super-resolution: a brief review. Inf Fusion. 2022;79:124–45. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2021.09.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Li Z, Liu Y, Chen X, Cai H, Gu J, Qiao Y, et al. Blueprint separable residual network for efficient image super-resolution. In: Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW); 2022 Jun 19–20; New Orleans, LA, USA. p. 832–42. doi:10.1109/CVPRW56347.2022.00099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Wang P, Bayram B, Sertel E. A comprehensive review on deep learning based remote sensing image super-resolution methods. Earth Sci Rev. 2022;232:104110. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2022.104110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. He Z, Chen D, Cao Y, Yang J, Cao Y, Li X, et al. Single image super-resolution based on progressive fusion of orientation-aware features. Pattern Recognit. 2023;133:109038. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2022.109038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Dong C, Loy CC, He K, Tang X. Learning a deep convolutional network for image super-resolution. In: Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2014: 13th European Conference; 2014 Sep 6–12; Zurich, Switzerland. p. 184–99. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-10593-2_13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Tai Y, Yang J, Liu X. Image super-resolution via deep recursive residual network. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 2790–8. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2017.298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Lv X, Wang C, Fan X, Leng Q, Jiang X. A novel image super-resolution algorithm based on multi-scale dense recursive fusion network. Neurocomputing. 2022;489(2):98–111. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2022.02.042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Lai WS, Huang JB, Ahuja N, Yang MH. Deep Laplacian pyramid networks for fast and accurate super-resolution. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 5835–43. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2017.618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Yin L, Wang L, Lu S, Wang R, Ren H, AlSanad A, et al. AFBNet: a lightweight adaptive feature fusion module for super-resolution algorithms. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2024;140(3):2315–47. doi:10.32604/cmes.2024.050853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Goodfellow IJ, Pouget-Abadie J, Mirza M, Xu B, Warde-Farley D, Ozair S, et al. Generative adversarial nets. In: Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 27; 2014 Dec 8–13; Montreal, QC, Canada. p. 2672–80. [Google Scholar]

11. Kammoun A, Slama R, Tabia H, Ouni T, Abid M. Generative adversarial networks for face generation: a survey. ACM Comput Surv. 2023;55(5):1–37. doi:10.1145/3527850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Zhou G, Song B, Liang P, Xu J, Yue T. Voids filling of DEM with multiattention generative adversarial network model. Remote Sens. 2022;14(5):1206. doi:10.3390/rs14051206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Ko K, Yeom T, Lee M. SuperstarGAN: generative adversarial networks for image-to-image translation in large-scale domains. Neural Netw. 2023;162:330–9. doi:10.1016/j.neunet.2023.02.042. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Xu Y, Luo W, Hu A, Xie Z, Xie X, Tao L. TE-SAGAN: an improved generative adversarial network for remote sensing super-resolution images. Remote Sens. 2022;14(10):2425. doi:10.3390/rs14102425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Brophy E, Wang Z, She Q, Ward T. Generative adversarial networks in time series: a systematic literature review. ACM Comput Surv. 2023;55(10):1–31. doi:10.1145/3559540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Zhao J, Ma Y, Chen F, Shang E, Yao W, Zhang S, et al. SA-GAN: a second order attention generator adversarial network with region aware strategy for real satellite images super resolution reconstruction. Remote Sens. 2023;15(5):1391. doi:10.3390/rs15051391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Zhang C, Zhang Z, Deng Y, Zhang Y, Chong M, Tan Y, et al. Blind super-resolution for SAR images with speckle noise based on deep learning probabilistic degradation model and SAR priors. Remote Sens. 2023;15(2):330. doi:10.3390/rs15020330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Ledig C, Theis L, Huszár F, Caballero J, Cunningham A, Acosta A, et al. Photo-realistic single image super-resolution using a generative adversarial network. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 105–14. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2017.19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Wang X, Yu K, Wu S, Gu J, Liu Y, Dong C, et al. Esrgan: enhanced super-resolution generative adversarial networks. In: Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2018 Workshops; 2018 Sep 8–14; Munich, Germany. p. 63–79. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-11021-5_5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Wang X, Xie L, Dong C, Shan Y. Real-ESRGAN: training real-world blind super-resolution with pure synthetic data. In: Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops (ICCVW); 2021 Oct 11–17; Montreal, BC, Canada. p. 1905–14. doi:10.1109/iccvw54120.2021.00217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Gendy G, Sabor N, He G. Lightweight image super-resolution network based on extended convolution mixer. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2024;133(1):108069. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2024.108069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Fang J, Lin H, Chen X, Zeng K. A hybrid network of CNN and transformer for lightweight image super-resolution. In: Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW); 2022 Jun 19–20; New Orleans, LA, USA. p. 1103–12. doi:10.1109/CVPRW56347.2022.00119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Gendy G, Sabor N, Hou J, He G. A simple transformer-style network for lightweight image super-resolution. In: Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW); 2023 Jun 17–24; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 1484–94. doi:10.1109/CVPRW59228.2023.00153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Lu X, Xie X, Ye C, Xing H, Liu Z, Cai C. A lightweight generative adversarial network for single image super-resolution. Vis Comput. 2024;40(1):41–52. doi:10.1007/s00371-022-02764-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Guo Y, Tan M, Deng Z, Wang J, Chen Q, Cao J, et al. Towards lightweight super-resolution with dual regression learning. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2024;46(12):8365–79. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2024.3406556. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Mardieva S, Ahmad S, Umirzakova S, Aashik Rasool MJ, Whangbo TK. Lightweight image super-resolution for IoT devices using deep residual feature distillation network. Knowl Based Syst. 2024;285:111343. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2023.111343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Umirzakova S, Mardieva S, Muksimova S, Ahmad S, Whangbo T. Enhancing the super-resolution of medical images: introducing the deep residual feature distillation channel attention network for optimized performance and efficiency. Bioengineering. 2023;10(11):1332. doi:10.3390/bioengineering10111332. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Hu X, Mu H, Zhang X, Wang Z, Tan T, Sun J. Meta-SR: a magnification-arbitrary network for super-resolution. In: Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2019 Jun 15–20; Beach, CA, USA. p. 1575–84. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2019.00167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Wang L, Wang Y, Lin Z, Yang J, An W, Guo Y. Learning a single network for scale-arbitrary super-resolution. In: Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2021 Oct 10–17; Montreal, QC, Canada. p. 4781–90. doi:10.1109/ICCV48922.2021.00476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Zong Z, Zha L, Jiang J, Liu X. Asymmetric information distillation network for lightweight super resolution. In: 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW); 2022 Jun 19–20; New Orleans, LA, USA. p. 1248–57. doi:10.1109/CVPRW56347.2022.00131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Bevilacqua M, Roumy A, Guillemot C, Morel MA. Low-complexity single-image super-resolution based on nonnegative neighbor embedding. In: Proceedings of the British Machine Vision Conference 2012. Surrey, British Machine Vision Association; 2012 Sep 3–7; Surrey, UK. p. 135.1–10. doi:10.5244/c.26.135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Zeyde R, Elad M, Protter M. On single image scale-up using sparse-representations. In: Proceedings of the 7th Curves and Surfaces; 2010 Jun 24–30; Avignon, France. p. 711–30. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-27413-8_47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Huang JB, Singh A, Ahuja N. Single image super-resolution from transformed self-exemplars. In: Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2015 Jun 7–12; Boston, MA, USA. p. 5197–206. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2015.7299156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Nie W. BSD100, Set5, Set14, Urban100 [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2025 Aug 1]. Available from: https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/BSD100_Set5_Set14_Urban100/21586188/1. [Google Scholar]

35. Fujimoto A, Ogawa T, Yamamoto K, Matsui Y, Yamasaki T, Aizawa K. Manga109 dataset and creation of metadata. In: Proceedings of the 1st International Workshop on coMics ANalysis, Processing and Understanding; 2016 Dec 4; Cancun, Mexico. p. 1–5. doi:10.1145/3011549.3011551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Wen R, Yang Z, Chen T, Li H, Li K. Progressive representation recalibration for lightweight super-resolution. Neurocomputing. 2022;504:240–50. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2022.07.050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Lee J, Hwan J. Local texture estimator for implicit representation function. In: Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2022 Jun 18–24; New Orleans, LA, USA. p. 1919–28. doi:10.1109/CVPR52688.2022.00197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Gendy G, He G, Sabor N. Lightweight image super-resolution based on deep learning: state-of-the-art and future directions. Inf Fusion. 2023;94:284–310. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2023.01.024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Yang L, Zhang H, Luo T, Qu C, Aung MTL, Cui Y, et al. Coreset: hierarchical neuromorphic computing supporting large-scale neural networks with improved resource efficiency. Neurocomputing. 2022;474:128–40. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2021.12.021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Dong C, Loy CC, Tang X. Accelerating the super-resolution convolutional neural network. In: Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2016; 2016 Oct 11–14; Amsterdam, The Netherlands. p. 391–407. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-46475-6_25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Kim J, Lee JK, Lee KM. Accurate image super-resolution using very deep convolutional networks. In: Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 1646–54. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2016.182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Hui Z, Gao X, Yang Y, Wang X. Lightweight image super-resolution with information multi-distillation network. In: Proceedings of the 27th ACM International Conference on Multimedia; 2019 Oct 21–25; Nice, France. p. 2024–32. doi:10.1145/3343031.3351084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Bansal T, Juan DC, Ravi S, McCallum A. A2N: attending to neighbors for knowledge graph inference. In: Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; 2019 Jul 28–Aug 2; Florence, Italy. p. 4387–92. doi:10.18653/v1/p19-1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Lim B, Son S, Kim H, Nah S, Lee KM. Enhanced deep residual networks for single image super-resolution. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW); 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 1132–40. doi:10.1109/CVPRW.2017.151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Zhang Y, Tian Y, Kong Y, Zhong B, Fu Y. Residual dense network for image super-resolution. In: Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2018 Jun 18–23; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. p. 2472–81. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2018.00262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Zhang Y, Li K, Li K, Wang L, Zhong B, Fu Y. Image super-resolution using very deep residual channel attention networks. In: Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2018; 2018 Sep 8–14; Munich, Germany. p. 294–310. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-01234-2_18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools