Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Multi-Grid, Single-Mesh Online Learning Framework for Stress-Constrained Topology Optimization Based on Isogeometric Formulation

Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology Clear Water Bay, Kowloon, Hong Kong, 999077, China

* Corresponding Author: Wenjing Ye. Email:

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(2), 1665-1688. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.072447

Received 27 August 2025; Accepted 10 October 2025; Issue published 26 November 2025

Abstract

Recent progress in topology optimization (TO) has seen a growing integration of machine learning to accelerate computation. Among these, online learning stands out as a promising strategy for large-scale TO tasks, as it eliminates the need for pre-collected training datasets by updating surrogate models dynamically using intermediate optimization data. Stress-constrained lightweight design is an important class of problem with broad engineering relevance. Most existing frameworks use pixel or voxel-based representations and employ the finite element method (FEM) for analysis. The limited continuity across finite elements often compromises the accuracy of stress evaluation. To overcome this limitation, isogeometric analysis is employed as it enables smooth representation of structures and thus more accurate stress computation. However, the complexity of the stress-constrained design problem together with the isogeometric representation results in a large computational cost. This work proposes a multi-grid, single-mesh online learning framework for isogeometric topology optimization (ITO), leveraging the Fourier Neural Operator (FNO) as a surrogate model. Operating entirely within the isogeometric analysis setting, the framework provides smooth geometry representation and precise stress computation, without requiring traditional mesh generation. A localized training approach is employed to enhance scalability, while a multi-grid decomposition scheme incorporates global structural context into local predictions to boost FNO accuracy. By learning the mapping from spatial features to sensitivity fields, the framework enables efficient single-resolution optimization, avoiding the computational burden of two-resolution simulations. The proposed method is validated through 2D stress-constrained design examples, and the effect of key parameters is studied.Keywords

Structural topology optimization (TO) aims to find the optimal material distribution within a given design domain such that an objective function is minimized and constraints are satisfied [1]. Compared with size optimization and shape optimization, TO offers a greatly enlarged design space and consequently better design solutions. It is, however, the most challenging, as it deals with the creation of new geometries from scratch.

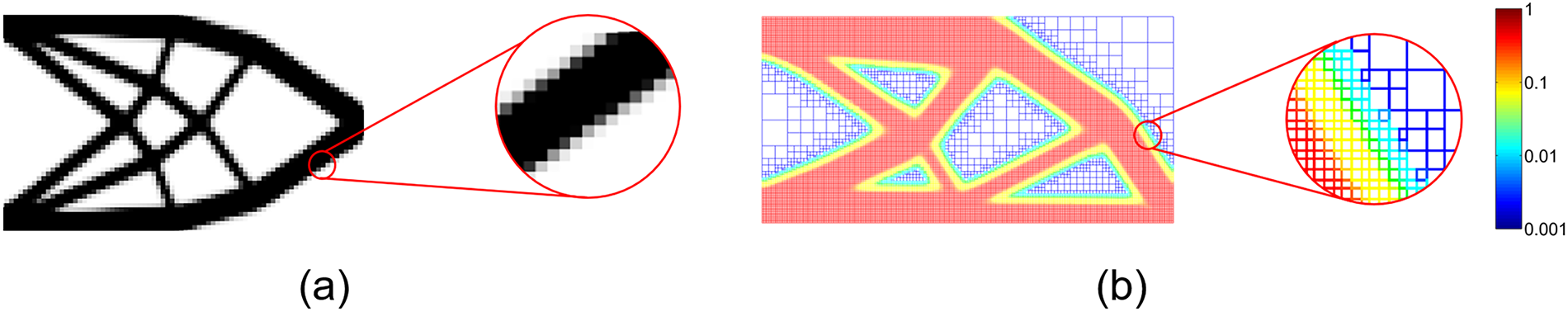

Most existing topology optimization (TO) methods implicitly represent structures using a fixed grid of pixels or voxels and employ the widespread finite element method (FEM) to evaluate objective functions and constraints. Despite their broad applicability, these grid-based, FEM-reliant approaches face certain limitations. For instance, the low-order continuity between neighboring finite elements [1]—illustrated in Fig. 1a—can significantly reduce computational accuracy, especially for stress-related metrics. This makes such methods less suitable for stress-constrained TO design. To address this, some studies have proposed using adaptive mesh refinement to improve the smoothness of structure boundaries and enhance stress calculations [2–4]. The main idea is to refine the mesh in regions where higher accuracy is needed and coarsen it elsewhere to improve computational efficiency. However, even with a refined mesh, the design is still represented as a pixel-based image with non-smooth boundaries, as shown in Fig. 1b. Beyond the issue of stress calculation, optimized designs often require additional post-processing to be compatible with computer-aided design (CAD) software for manufacturing, which can further compromise design quality.

Figure 1: Optimized structure using (a) FEM-based TO [1], (b) FEM-based TO with adaptive mesh refinement [3]

To overcome the limitations of traditional FEM, Hughes and his co-workers [5,6] introduced the isogeometric analysis (IGA) framework, which unifies CAD and computer-aided engineering (CAE) by employing the same spline basis functions for both geometry representation and numerical analysis. This seamless integration eliminates the need for mesh generation and offers higher continuity and numerical accuracy compared to conventional FEM. All these advantages make IGA particularly advantageous for TO and form a new paradigm: isogeometric topology optimization (ITO). In particular, for stress-constrained design problems, the higher-order continuity of spline basis functions significantly enhances the accuracy of both structural representation and stress evaluation.

Significant efforts have been made to extend classical TO methods by incorporating IGA [7–9]. Representative examples include its integration with level-set [10], evolution method [11], and moving morphable component [12] approaches. Moreover, IGA has been combined with the boundary element method to tackle optimization problems in acoustics [13–15]. The density-based TO methods can be integrated with IGA by assigning design variables to the control points of the Non-uniform Rational B-splines (NURBS) basis function [16–19]. Stress-related ITO problems, typically believed to be more challenging due to factors such as the non-linear behavior of stress and the localized nature of stress constraints [20], have also been studied in recent years. For example, Kazemi et al. [21] proposed an ITO method for minimizing structural weight under local stress constraints using NURBS-based IGA, with control points’ density as design variables. The optimization process utilizes direct sensitivity analysis combined with the Method of Moving Asymptotes (MMA) for iterative updates [22]. To handle stress singularities, the ε relaxation method is employed. However, the optimized structures exhibit insufficient smoothness, likely due to the limited number of NURBS patches. Additionally, the reliance on direct sensitivity analysis (without using adjoint method) reduces efficiency for large-scale problems. Jahangiry and Tavakkoli [23] developed a level-set-based ITO method. The design variables are the control points of the NURBS-based level set function, which are iteratively updated by solving the Hamilton-Jacobi equation using the forward Euler scheme. Numerical examples, including weight minimization under local stress constraints and the simultaneous minimization of weight and strain energy, demonstrate the method’s capability to achieve reasonable results with smooth boundaries. Building on Gao’s work [17], Liu et al. [24] extended the SIMP-based IGA to tackle global stress-constrained TO problems. Density values at NURBS control points are used to construct the density distribution function, with a filter applied to ensure smoothness. The optimization problem is solved using MMA, while a global p-norm stress aggregation function constrains the stress during volume minimization. Numerical examples confirm that this approach can deliver smooth geometry representations and reliable stress analysis. To improve the optimization efficiency of Liu’s SIMP-based IGA work, Zhai [25] proposed a hybrid optimizer combining the alternating direction method of multipliers (ADMM) with MMA. Different from minimizing weight, Villalba et al. [26] focused on stress-constrained compliant mechanisms, using quadratic B-splines for material layout and structural analysis. By incorporating an overweight constraint to manage stress, their method achieves a 40%–60% reduction in computational time compared to classical FEM. In the monograph of Gao et al. [27], they studied the volume-constrained stress minimization problems in the ITO framework. Two global stress aggregation formulations (p-norm and Kreisselmeier-Steinhauser) are utilized to measure stress, which effectively eliminates boundary stress concentration issues. Vo et al. [28] integrated a gradient-free proportional topology optimization scheme into the isogeometric analysis framework, where NURBS basis functions simultaneously represent geometry, displacement, and material density. The approach defines densities at integration points in proportion to compliance, derives their relation to control points, and constructs a global NURBS-based density description.

Despite the significant development of ITO, the efficiency challenge remains and in fact becomes even more critical in large-scale stress-constrained TO designs. Compared with compliance design, stress-constrained TO is significantly more complex, often requiring many more iterations and longer convergence times. To address this, we extend a previously developed multi-grid, single-mesh online learning framework [29]—originally designed for compliance-based TO—to the ITO setting. This extension leverages the ITO framework’s inherent capacity for smooth geometric representation, enabling more accurate stress calculations.

The use of artificial neural network (ANN)-based surrogate models to accelerate topology optimization (TO) is an active field of research [30–34]. While various methods have been proposed, they often require large, expensive-to-generate training datasets. For applications involving only a few large-scale design problems, generating a large training dataset certainly is not efficient and sometimes even infeasible. For such cases, online learning presents another promising approach [35]. Unlike offline methods that rely on pre-collected datasets, online learning collects training data from designs and analysis results obtained during previous TO iterations. This eliminates the need for extensive upfront data generation and allows the neural networks to adapt specifically to the problem at hand, making online learning particularly well-suited for large-scale TO problems. To ensure accuracy, ANN models are continuously updated throughout the TO process as new training data is available. This iterative refinement ensures that the surrogate models remain closely aligned with the evolving design space, improving both computational efficiency and solution quality.

Online learning framework for TO was first proposed in [35] for compliance design. The method employs a localized patch-based prediction strategy to greatly enhance the scalability of the method and training data diversity. However, it neglects the structural information outside each local region when predicting patch responses. This may lead to an undetermined mapping and suboptimal prediction accuracy. Additionally, the coarse-fine two-grid mapping technique employed introduces additional computational overhead associated with generating coarse grid solutions. To overcome these limitations, our group recently developed a multigrid, single-mesh online learning TO method [29], which has demonstrated a better performance. In the present work, we further extend this advanced framework to stress-constrained design problems and validate its efficacy through a series of illustrative examples.

NURBS are widely employed in IGA and have become the primary technology for representing complex geometries in CAD software. To define a B-spline, a knot vector must be specified as an ordered sequence of increasing parameter values, denoted as

For a given knot vector

where

where

Given two knot vectors for each parametric direction

where

B-spline cannot represent certain shapes exactly, such as circles. Consequently, NURBS has become the de facto standard in CAD for handling more complex shapes [36]. Based on B-spline, a NURBS surface can be expressed as:

where

where

2.2 Isogeometric Structural Analysis

Using NURBS basis functions

where

In this study, the same NURBS basis functions are used to represent the displacement field in structural analysis. The displacement field can be defined as:

where

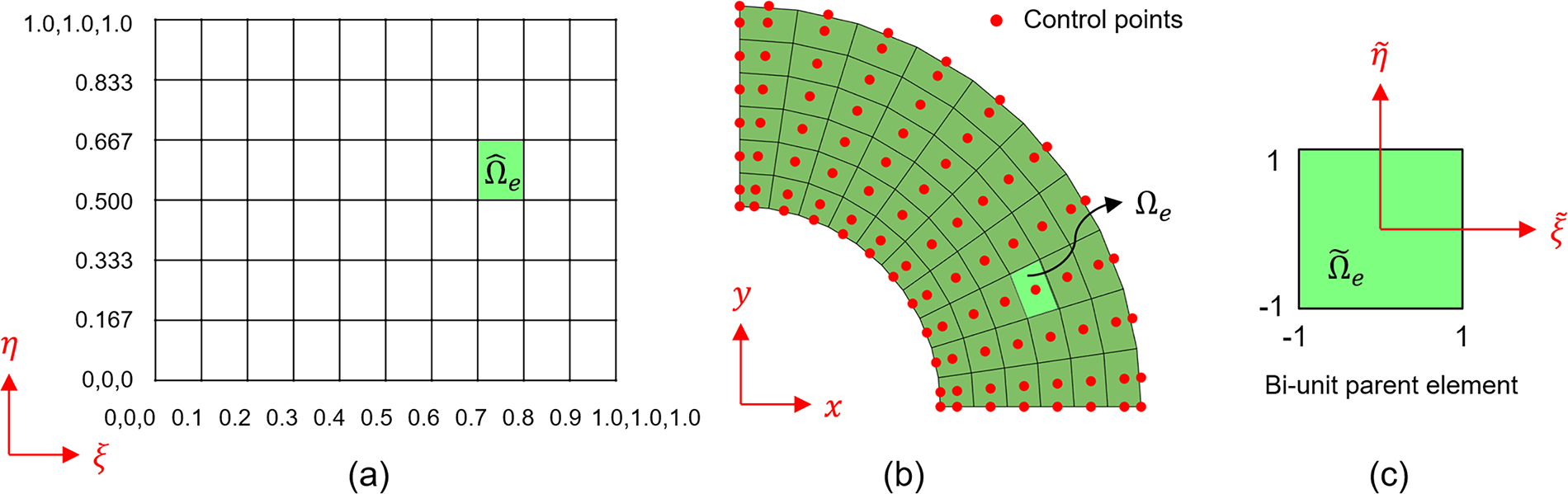

In the IGA framework, elements are defined similarly to that in the FEM, with each IGA element corresponding to a knot span, denoted

where B is the strain-displacement matrix derived from the partial derivatives of NURBS basis functions

where

Figure 2: Schematic of an 2D element,

Boundary conditions in IGA are implemented as follows [5]. Each control point is assigned to a load vector

Finally, the displacement

3 Stress-Constrained Design Problem

This section outlines the TO formulation of stress-constrained design problems based on IGA. The NURBS-based density distribution function is used to formulate the ITO approach, with IGA applied to compute structural responses. The Method of Moving Asymptotes (MMA) is employed to update design variables.

Nodal densities

where

where

where

After filtering, a projection function [38] is applied to reduce intermediate density values:

where

Based on the projection function,

In isogeometric analysis, the knot vector discretizes the design domain into IGA elements. For the stress-constrained topology optimization problem studied in this work, a constant density distribution within each IGA element is employed for problem formulation and sensitivity calculations. The density at the centroid of an IGA element is chosen as the elemental relative density,

where

where

The von Mises stress at a stress evaluation point a is expressed as:

where

To alleviate the difficulty in the optimization caused by local stress constraint, a p-norm global stress measure is employed to approximate the local maximum stress:

where

Based on the adjoint method detailed in the next subsection, the sensitivity of the objective and the constraint are obtained and summarized as:

where

The term

After obtaining the sensitivity, the MMA optimizer [22] is used to update the control density

Sensitivity Analysis

Based on the IGA discretization, the volume minimization problem with a maximum von Mises stress constraint is formulated in Eq. (18). The sensitivity of the objective function

First, the derivative of objective

Since the density at the centroid of an IGA element is chosen as the elemental relative density,

where

where

where

Next, the derivative of objective

The intermediate terms are as follows:

Since

Substituting Eqs. (32) into (29) yields:

Since external load is a constant,

Multiplying Eq. (34) by

Collecting all terms related to

Solving Eq. (36) and substituting

where

The most time-consuming step in the IGA process is the calculation of the sensitivities

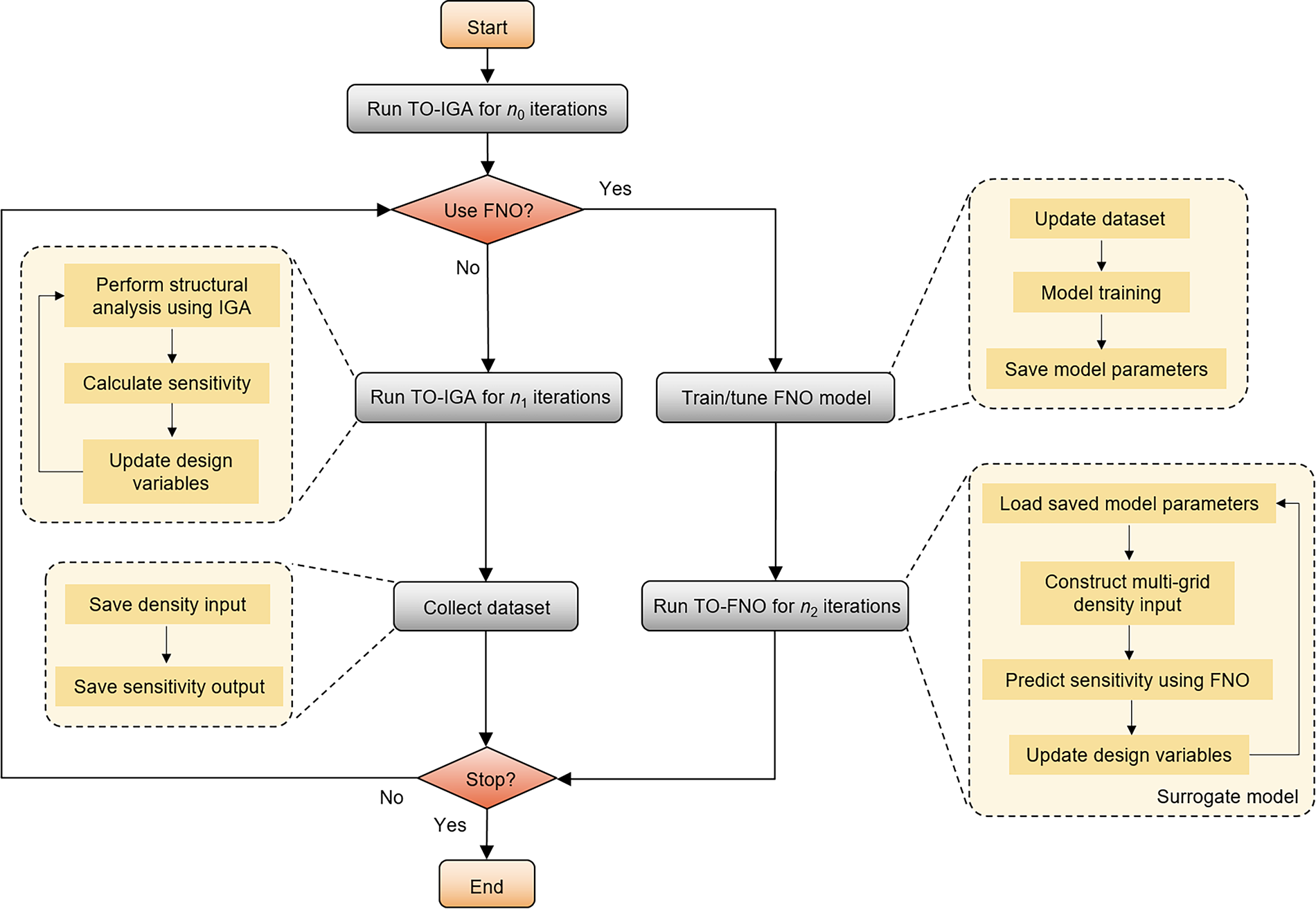

The flowchart of the online learning process is shown in Fig. 3. During the initialization phase, the traditional TO process based on isogeometric analysis (TO-IGA) is conducted for

Figure 3: The flowchart of the proposed online learning framework based on the IGA and FNO surrogate model

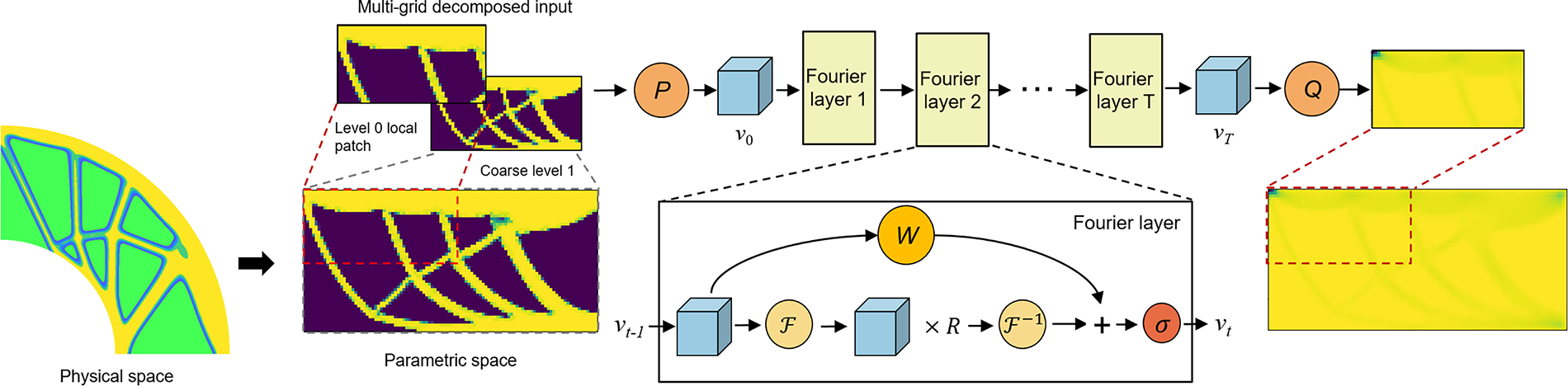

In this work, the FNO [40] is employed to construct a surrogate model that maps the control density

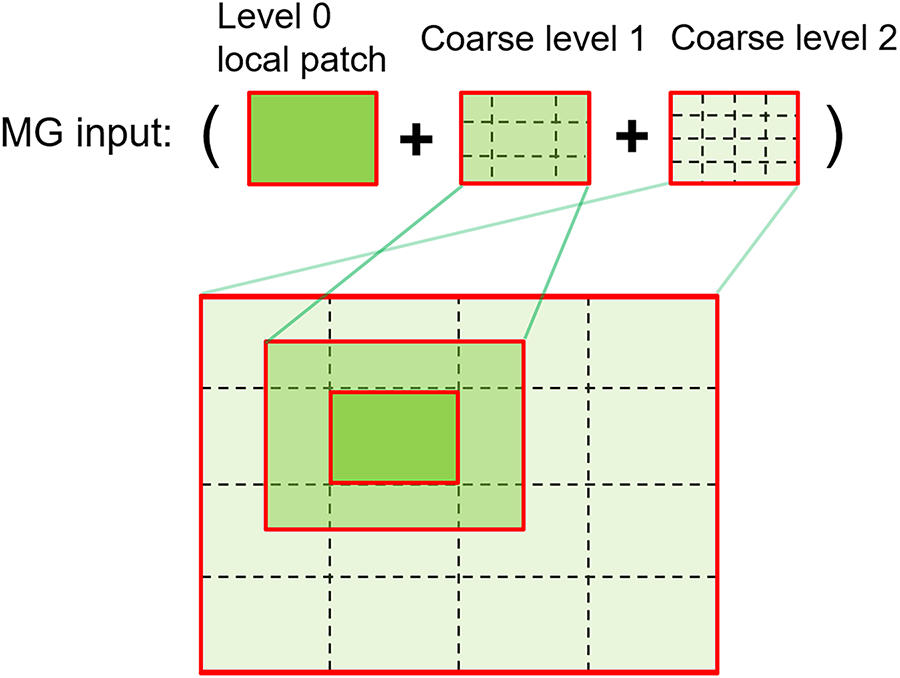

The architecture of the FNO and the multi-grid input of the density field are illustrated in Fig. 4. In this case shown in the figure, the MG level is 1, comprising two resolution levels (level 0 and level 1). The optimized structure is represented by density in physical space, however, the control density sorted in parametric space is selected as the input of FNO. The input tensor can be expressed as

Figure 4: The architecture of multi-grid FNO. Left column: multi-grid density input with MG level of 1; Middle column: the architecture of the FNO; Right column: the predicted sensitivity

The iterative updating process

The updating formula for the latent representation is illustrated in Eq. (39). The key idea in this updating formula is to add a non-local integral operation to the usual network updating procedure in each hidden layer:

where

where

The multi-grid decomposition approach adopted in this work builds upon the method presented in [42] and is designed for a domain D discretized into

• Initial configuration:

– If any domain edge is shorter than

– At a target resolution level L, the domain D is uniformly divided into

• Hierarchical context expansion (levels

– For each region

– If these expanded regions extend beyond the domain boundaries, they are truncated accordingly.

– Each region

• Final output construction:

– The downsampled patches from all levels (from 0 to L) are concatenated along the feature dimension to form a multi-grid input representation.

Fig. 5 demonstrates the hierarchical decomposition when the maximum level is set to 2. The base region at level 0 (green square) is first identified within the domain. Around this region, increasingly larger patches are defined at coarse levels 1 and 2. At each level, the corresponding patch is downsampled to match the resolution of the level-0 patch, maintaining a consistent size across all levels. The final MG input is constructed by concatenating the level 0 patch with its coarse-level counterparts, forming a multi-scale feature representation that captures both local detail and broader contextual information.

Figure 5: An illustration of the multi-grid input construction with MG level of 2

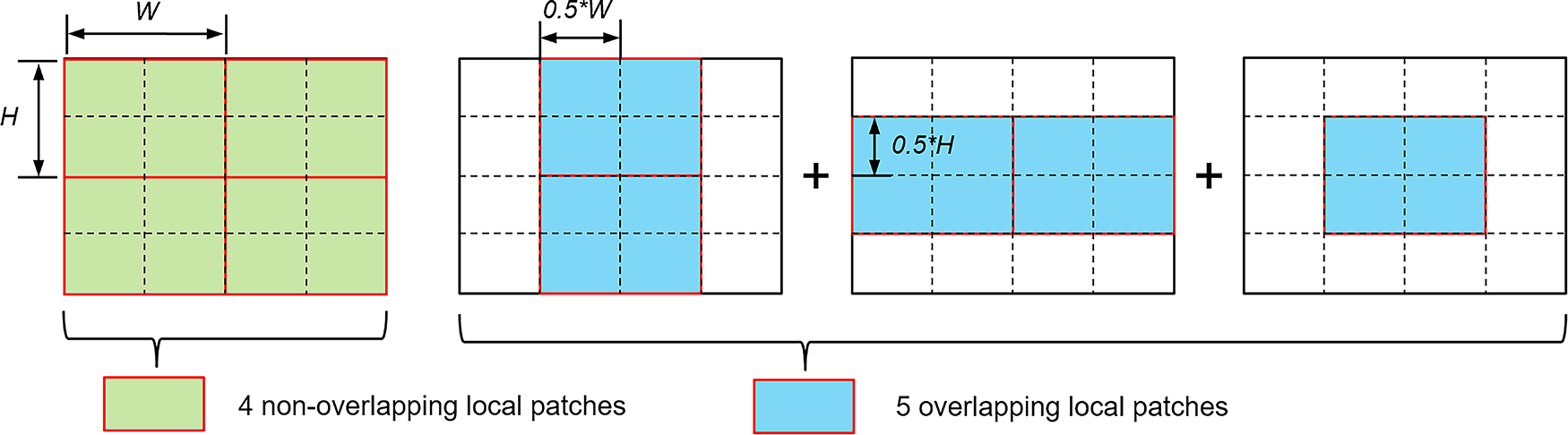

To enhance dataset richness, an overlapping scheme is applied to local regions. For each local patch of size

Figure 6: Illustration of the overlapping strategy with the overlapping ratio of 0.5 in both directions

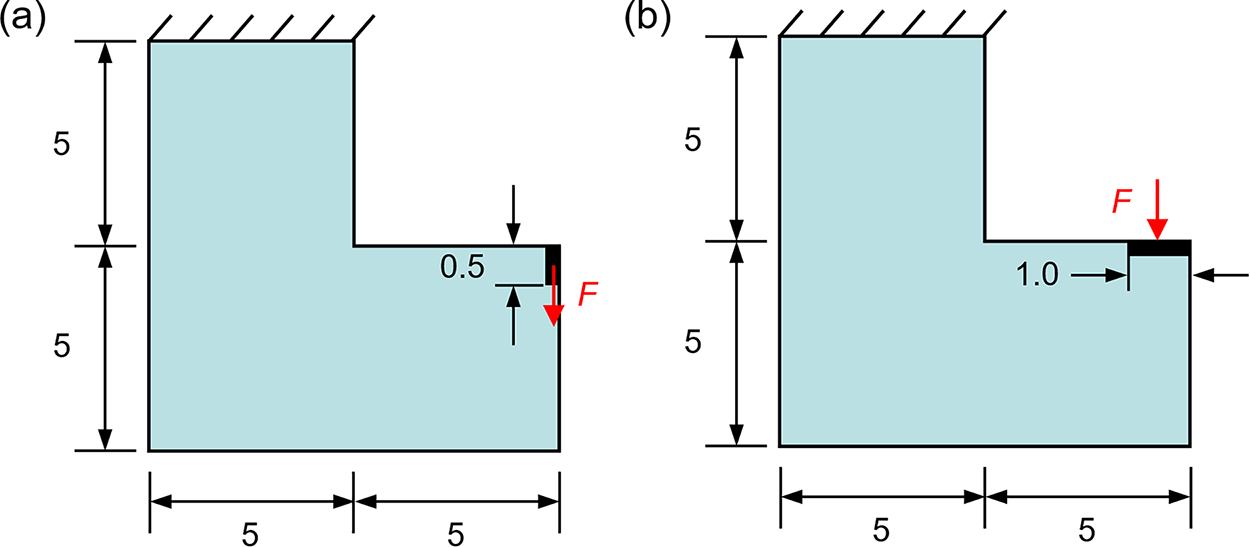

Two L-bracket design problems with different load positions, with their problem setups illustrated in Fig. 7, are used as the benchmark examples to validate the effectiveness of the online learning framework. The optimization parameters are set as follows. The filter radius is 4, which means the adjacent 4 control densities are used for smoothing. The default norm value for the p-norm is 8. In this work, a uniformly distributed load

where

Figure 7: Design domain of the L-bracket for the stress-constrained design: (a) load applied at the top, and (b) load applied on the side

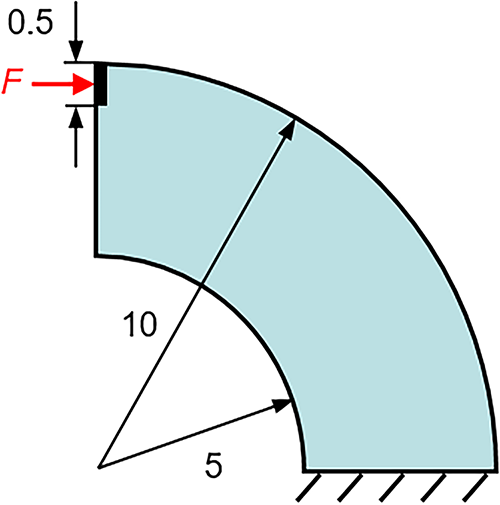

We also consider another design domain of quarter annulus, illustrated as Fig. 8. A total load of 2.0 N, and the stress constraint limit is set at 40 Pa.

Figure 8: Design domain of the quarter annulus for the stress-constrained design

All numerical experiments are conducted on a Windows 10 Pro operating system with an i7-11700 CPU, 16 GB RAM, and an NVIDIA 3060 GPU with 12 GB RAM. The implementation was done in MATLAB 2020b, with the online learning component executed using Python 3.8 and PyTorch 1.10.2 framework. In the FNO model, the number of modes kept after the Fourier transform is 12. The channel width is 64 after the lifting layer.

5.1 Stress-Constrained Design Results

During the online learning process, the

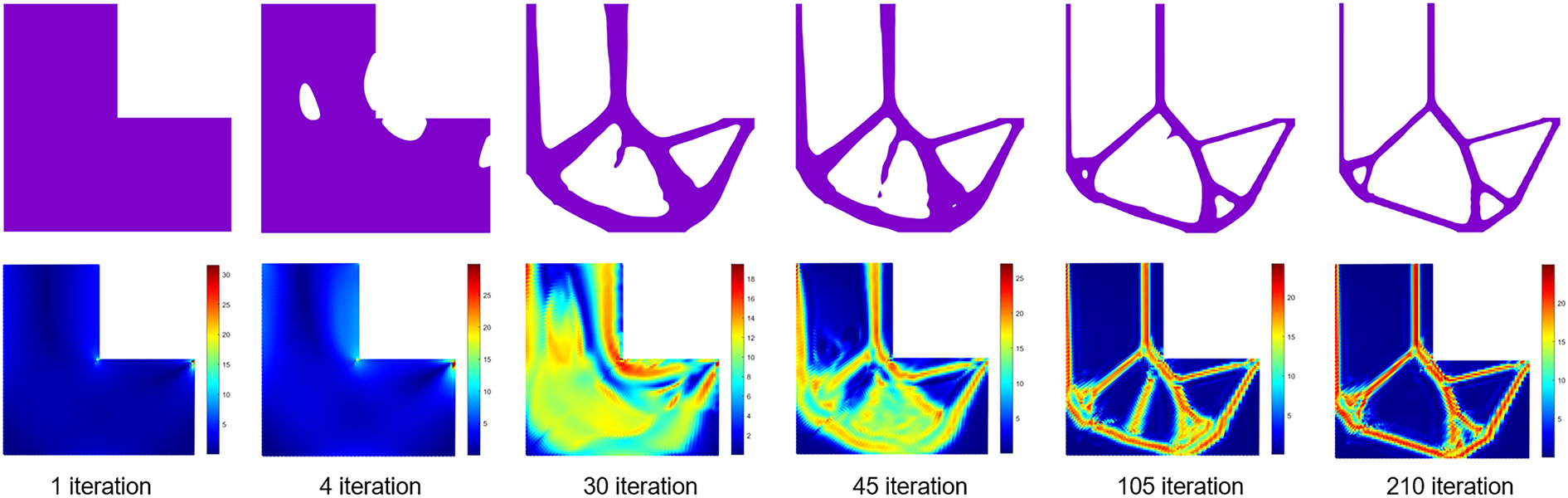

For the design problem described in Fig. 7a, based on our online learning framework, the structural evolution and the corresponding von Mises stress distributions at different iterations are shown in Fig. 9. The stress plots are generated from a point cloud. Each point corresponds to a Gauss point and is colored by its computed stress value. The results illustrate that the structure gradually converges to an optimized design.

Figure 9: Design evolution and von Mises stress distribution at different iterations for the L-bracket example illustrated in Fig. 7a

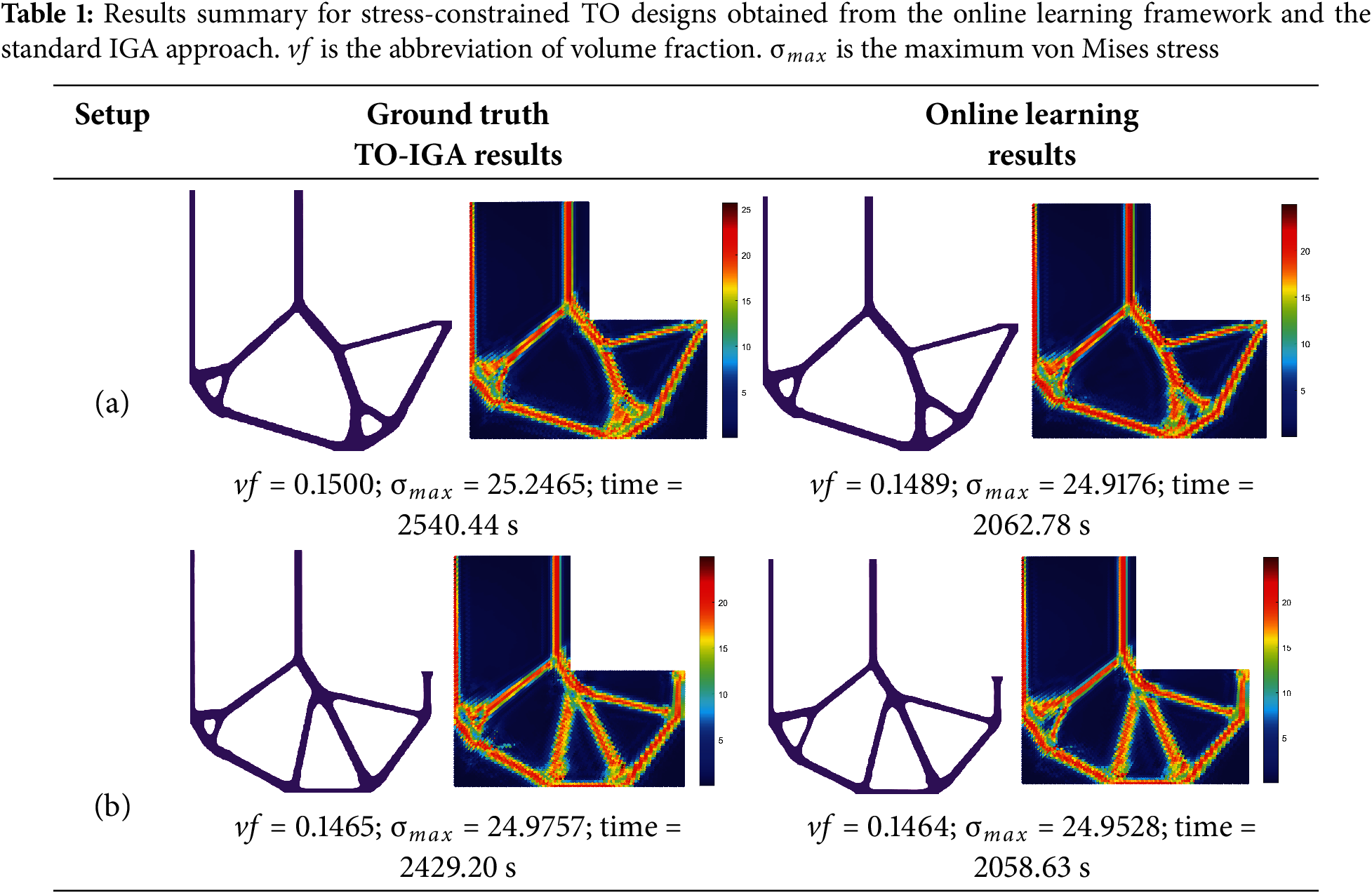

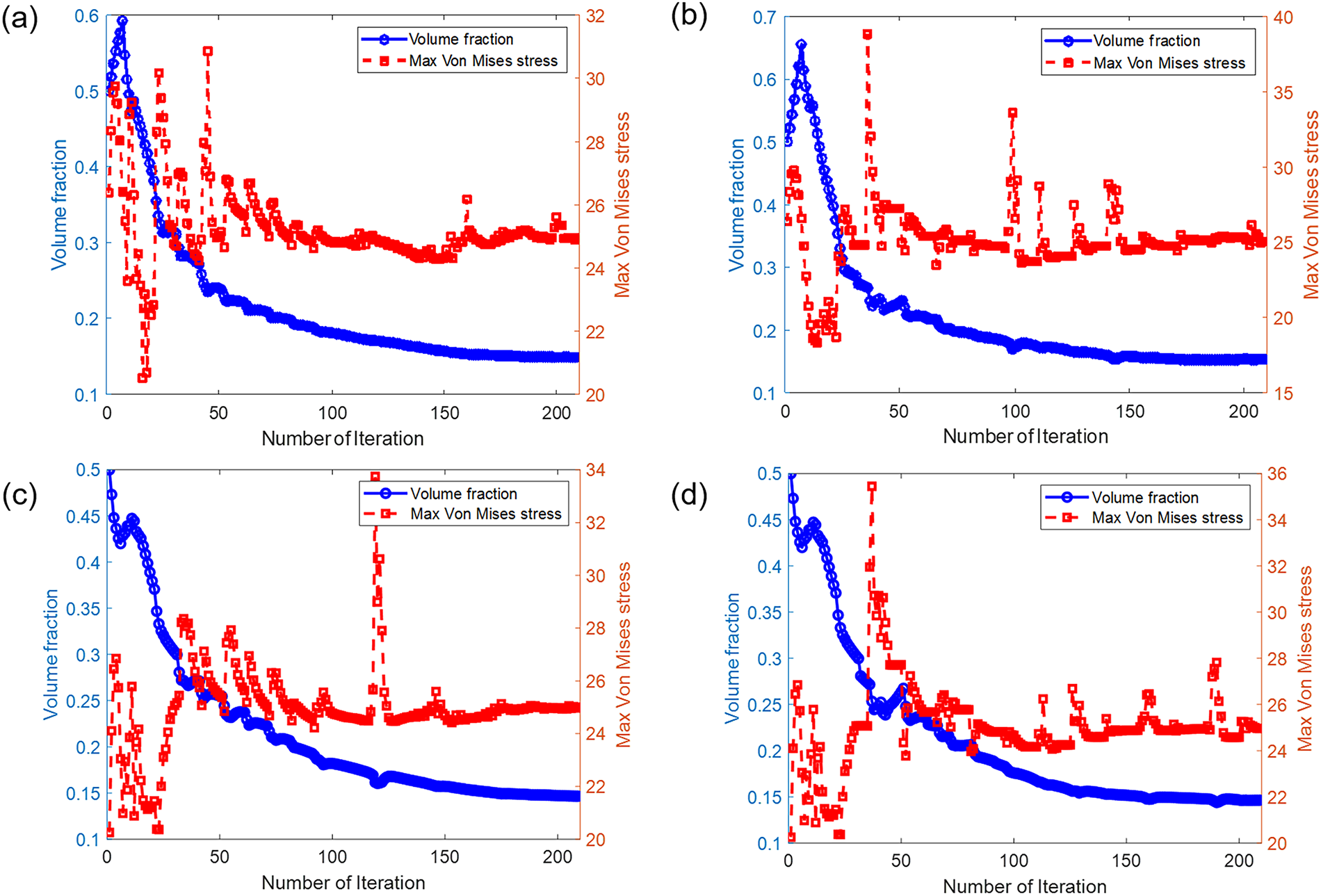

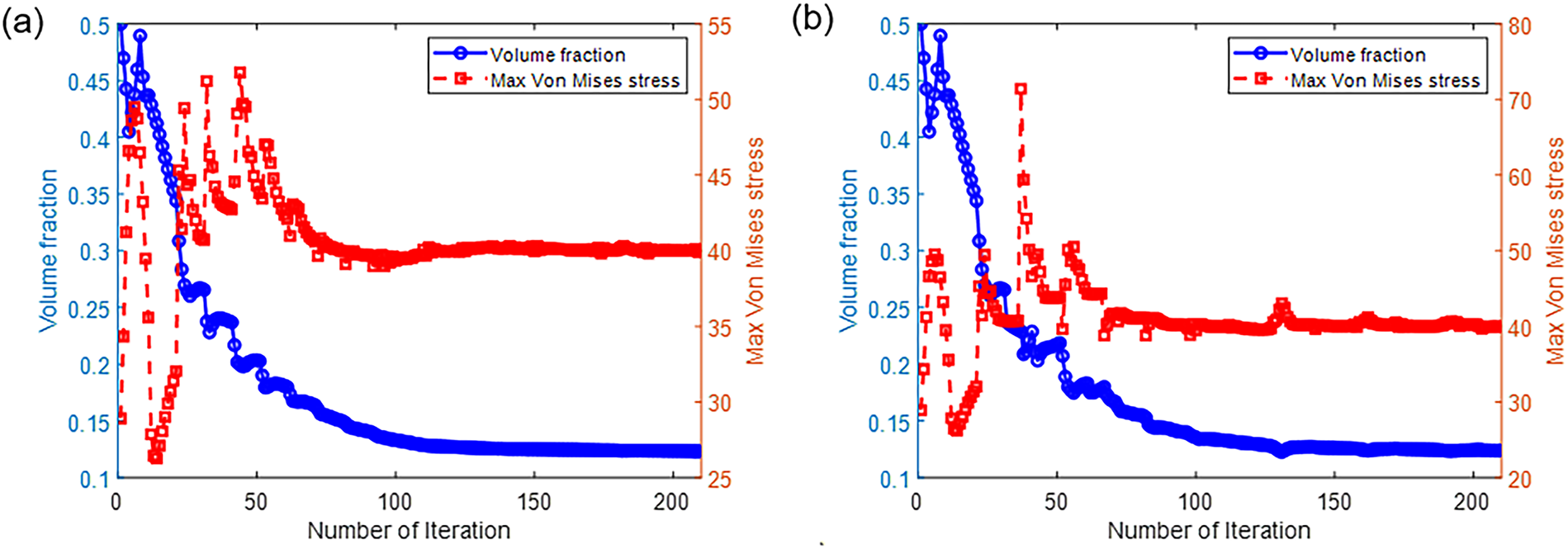

Design results for both design problems are listed in Table 1, showing that the proposed online learning framework achieves results comparable to the ground truth TO-IGA in terms of the volume fraction value and stress constraint satisfaction. The effectiveness of the framework is validated by these findings. The evolution curves of volume fraction and the maximum von Mises stress are plotted in Fig. 10, indicating that the curve of the maximum von Mises stress obtained from the online learning process is less smooth than that of the ground truth TO-IGA due to discrepancies between FNO-predicted sensitivities and actual values. These differences occasionally cause localized increases in stress, which are corrected in subsequent IGA updates. As the optimization converges, the maximum stress stabilizes and basically meets the constraints. At the same time, the online learning method can reduce the number of IGA evaluations from 210 to 150, reducing the total computational time by about 20%.

Figure 10: Volume fraction and maximum von Mises stress evolution curves of (a) ground truth result for the design problem shown in Fig. 7a, (b) online learning result for the design problem shown in Fig. 7a setup, (c) ground truth result for the design problem shown in Fig. 7b, (d) online learning result for the design problem shown in Fig. 7b

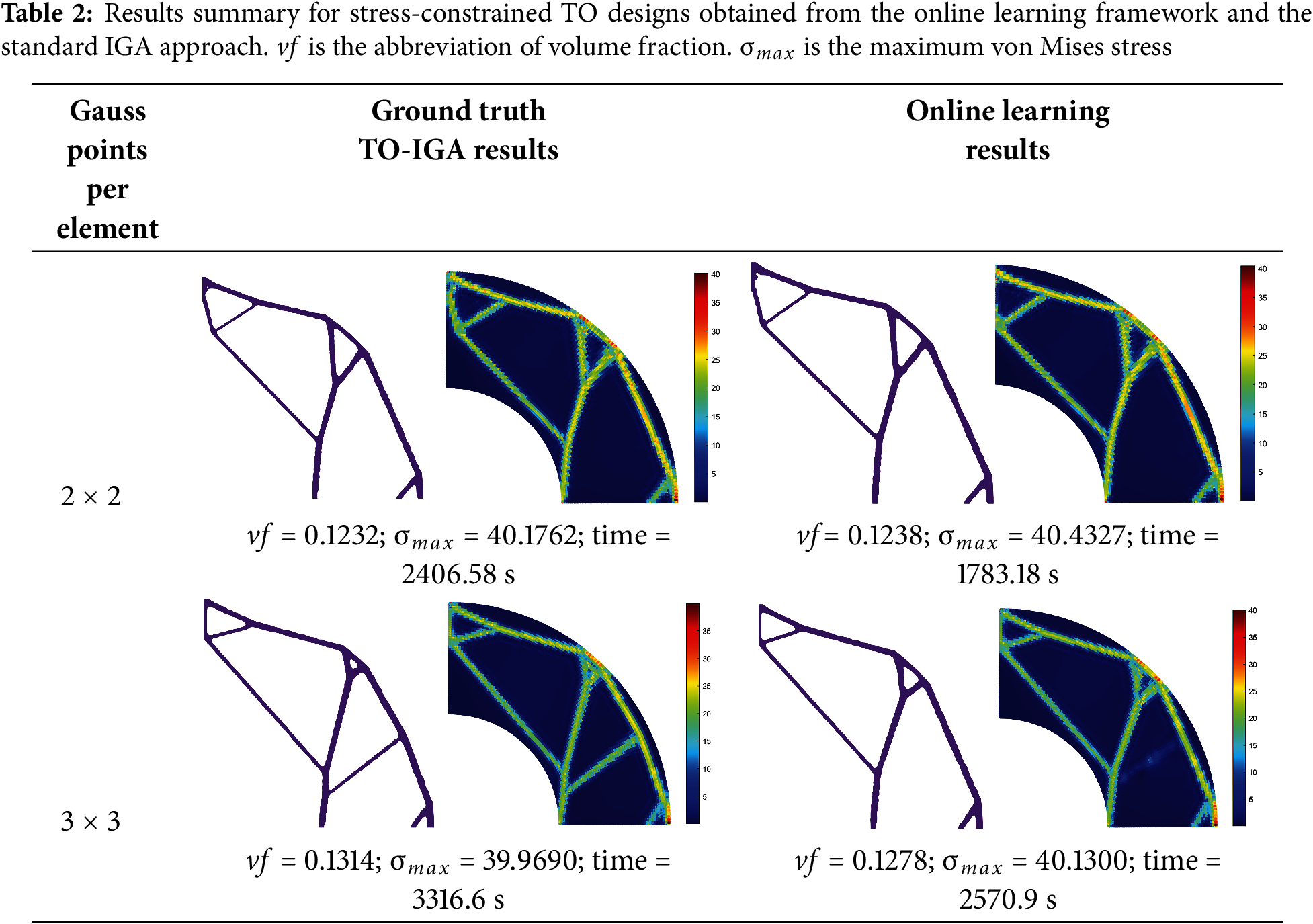

Under the same online learning parameter settings, the design results for the quarter annulus example are summarized in Table 2. We employ two different numbers of Gauss points to assess their influence. Increasing the number of Gauss points improves the accuracy of the response evaluation, leading to slight variations in the final optimized designs. Using a larger number of Gauss points also increases the total solving time. Nevertheless, under both settings, the online learning method consistently produces designs that are comparable to the ground truth, further confirming its effectiveness across different examples.

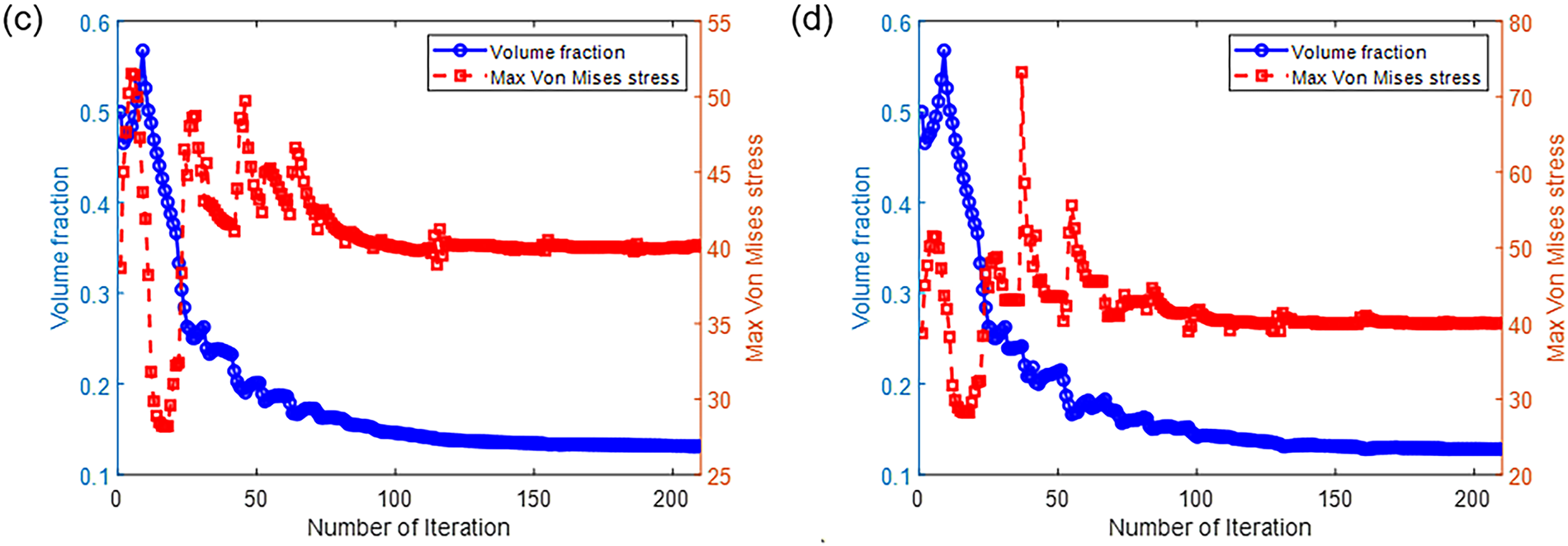

The evolution curves of volume fraction and the maximum von Mises stress using different Gauss points are plotted in Fig. 11. Convergence of the curves is observed with the increasing iteration count in the quarter-annulus example.

Figure 11: Volume fraction and maximum von Mises stress evolution curves of (a) ground truth result using 2 × 2 Gauss points for the design problem shown in Fig. 8, (b) online learning result using 2 × 2 Gauss points for the design problem shown in Fig. 8 setup. (c) ground truth result using 3 × 3 Gauss points for the design problem shown in Fig. 8, (d) online learning result using 3 × 3 Gauss points for the design problem shown in the setup of Fig. 8

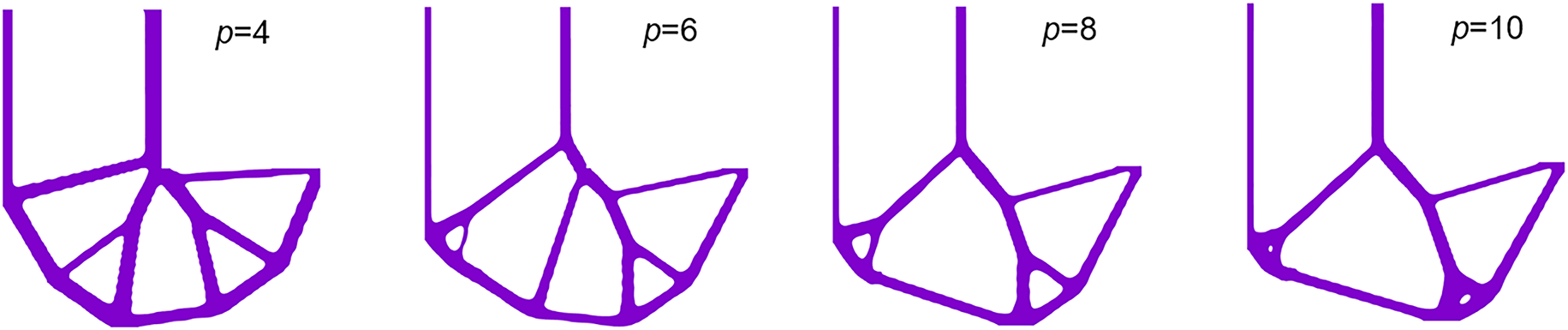

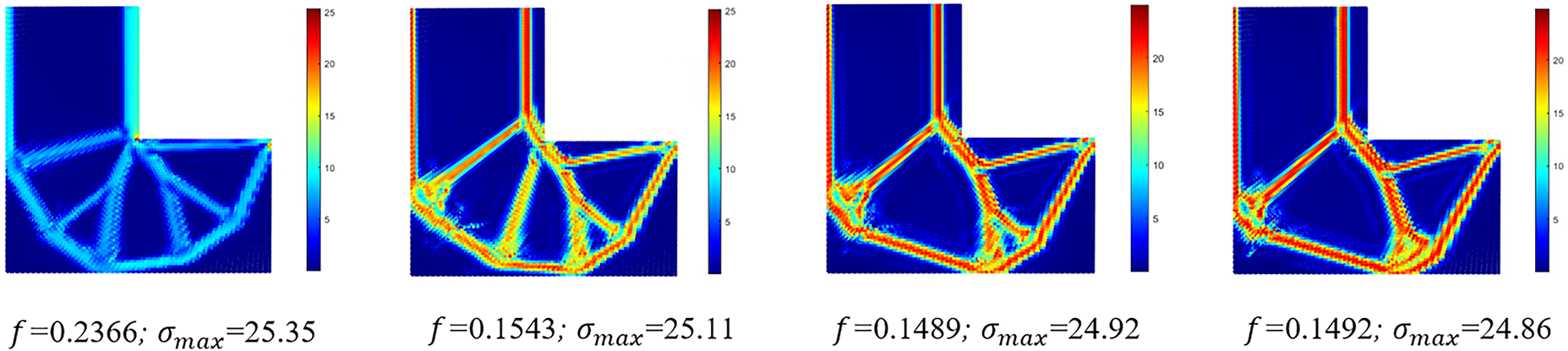

In this study, we employ p-norm stress as an approximation for maximum stress. The parameter p plays a crucial role in determining the approximation accuracy. To investigate the influence of the p-norm parameter on stress-constrained optimization, we test p-norm values of 4, 6, 8, and 10. The online learning settings are the same as those stated in Section 5.1, with results shown in Fig. 12. When p is too small, the optimized designs exhibit sharp corners. This phenomenon occurs because smaller values of p result in less accurate p-norm approximations of the maximum stress. As a result, the maximum stress of the optimized structure is slightly higher than those optimized structures obtained with a larger p value. For

Figure 12: Online learning optimization results for different p-norm values. f is the volume objective.

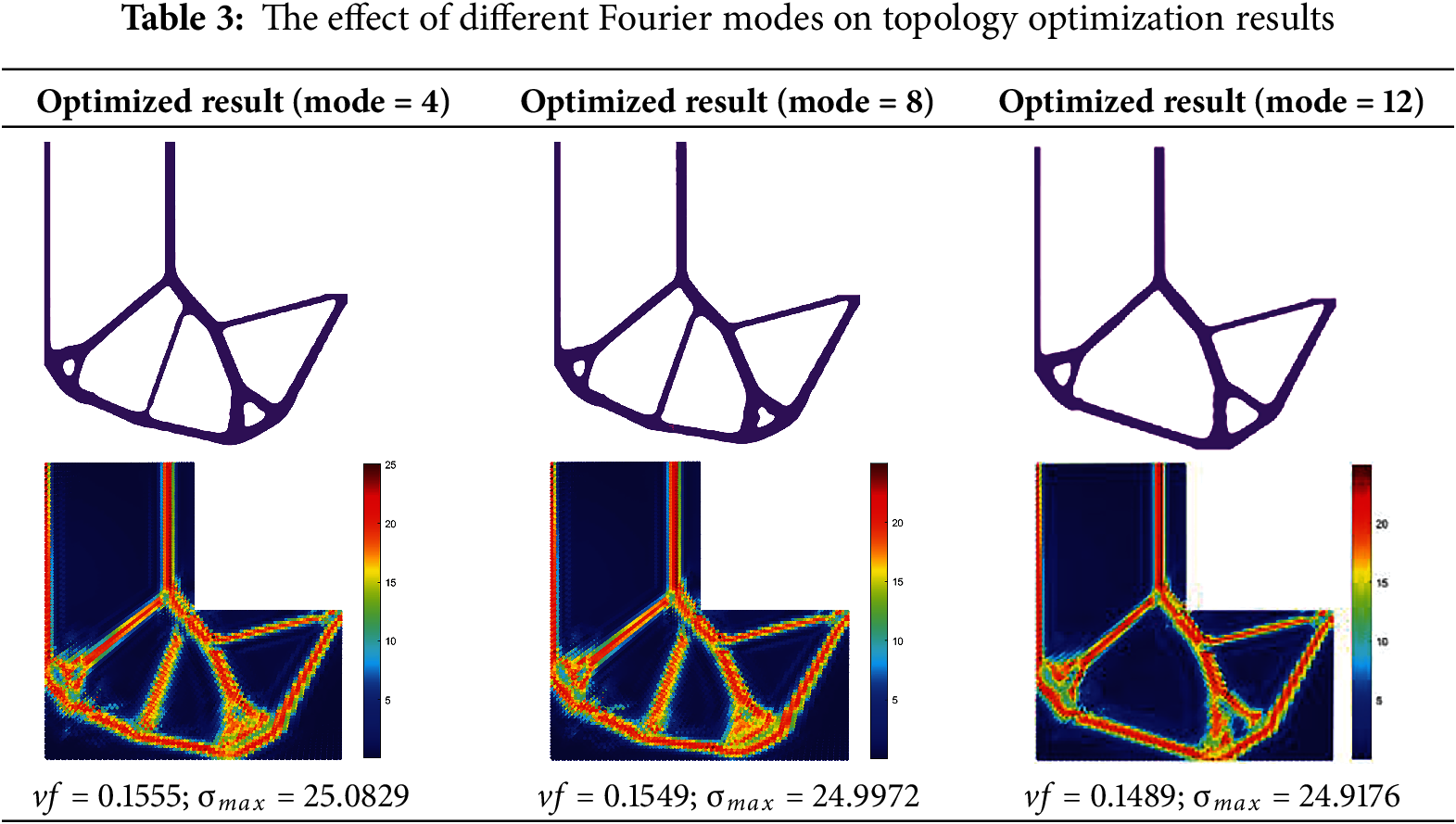

In our implementation, we chose the default value of 12 Fourier modes based on findings from our previous work [41], where we observed that using 12 modes provides a good balance between accuracy and computational cost across a range of PDE-related problems. To further investigate the sensitivity of our method to the number of Fourier modes, we conduct additional experiments based on the first case in Table 1. We compare results obtained using 4, 8, and 12 Fourier modes. The results are summarized in the following Table 3. As shown, using fewer modes (e.g., 4) slightly increases the objective value, indicating a minor degradation in performance. Increasing the number of modescan improve that.

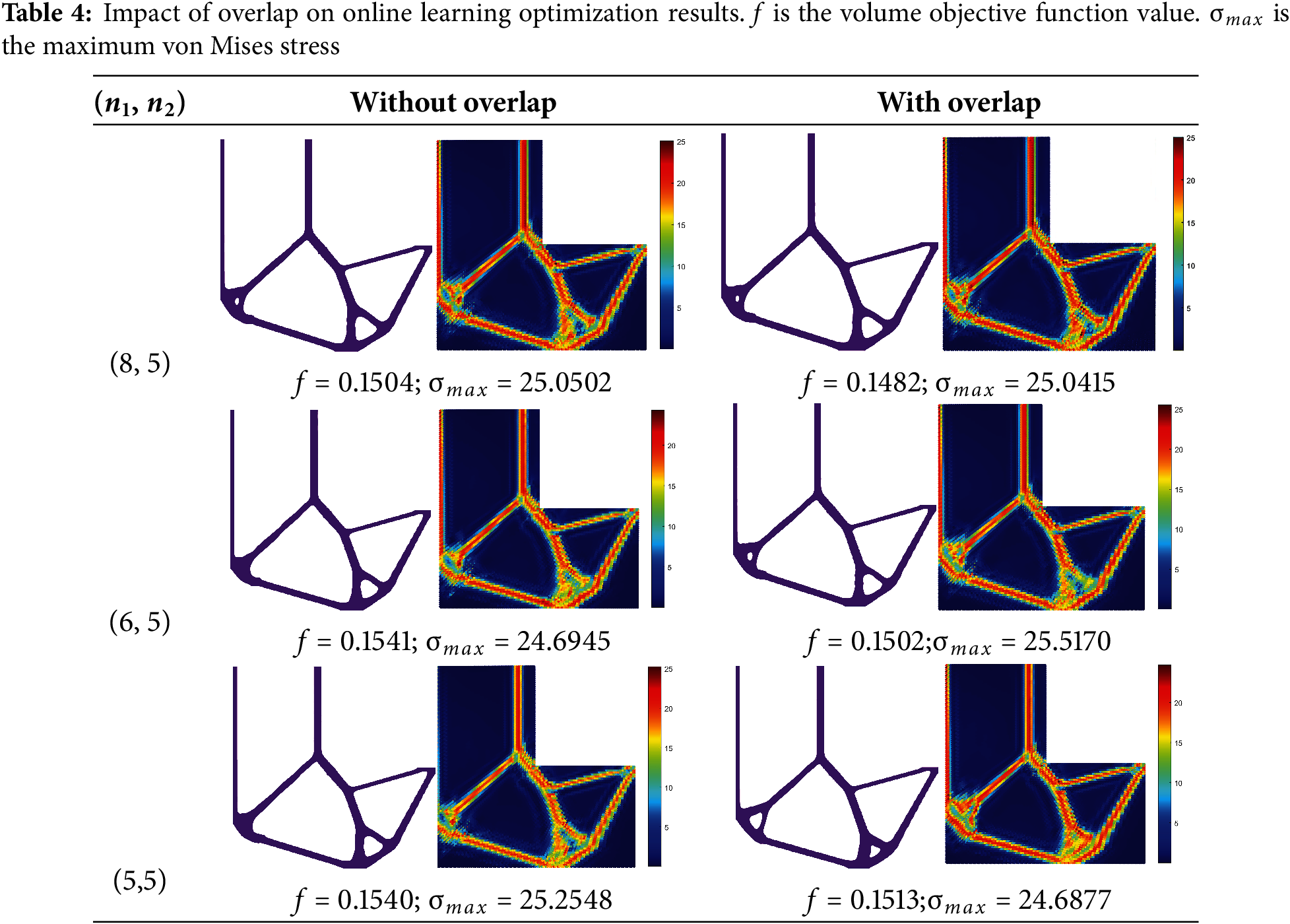

In the methodology section, we propose an overlapping strategy to increase the training data amount available for FNO training. Next, we examine the impact of this strategy on the effectiveness of the online learning approach for stress-constrained design problems. In this study, we fix

If the overlapping ratio is too small, it fails to effectively expand the dataset, whereas excessively large overlapping ratios are also not recommended. Because they will result in a higher GPU memory usage and a longer training time due to the increased number of training samples. Addition, extremely large overlapping ratios do not necessarily improve the accuracy as overfitting may occur. Therefore, a default value of 0.5 is adopted in our experiments.

As shown in Table 1, the online learning approach reduces the total amount of computational time of the two design problems. However, the reduced amount is rather small, which is less than 20%. There are two main reasons for the small improvement in efficiency. First, a relatively small

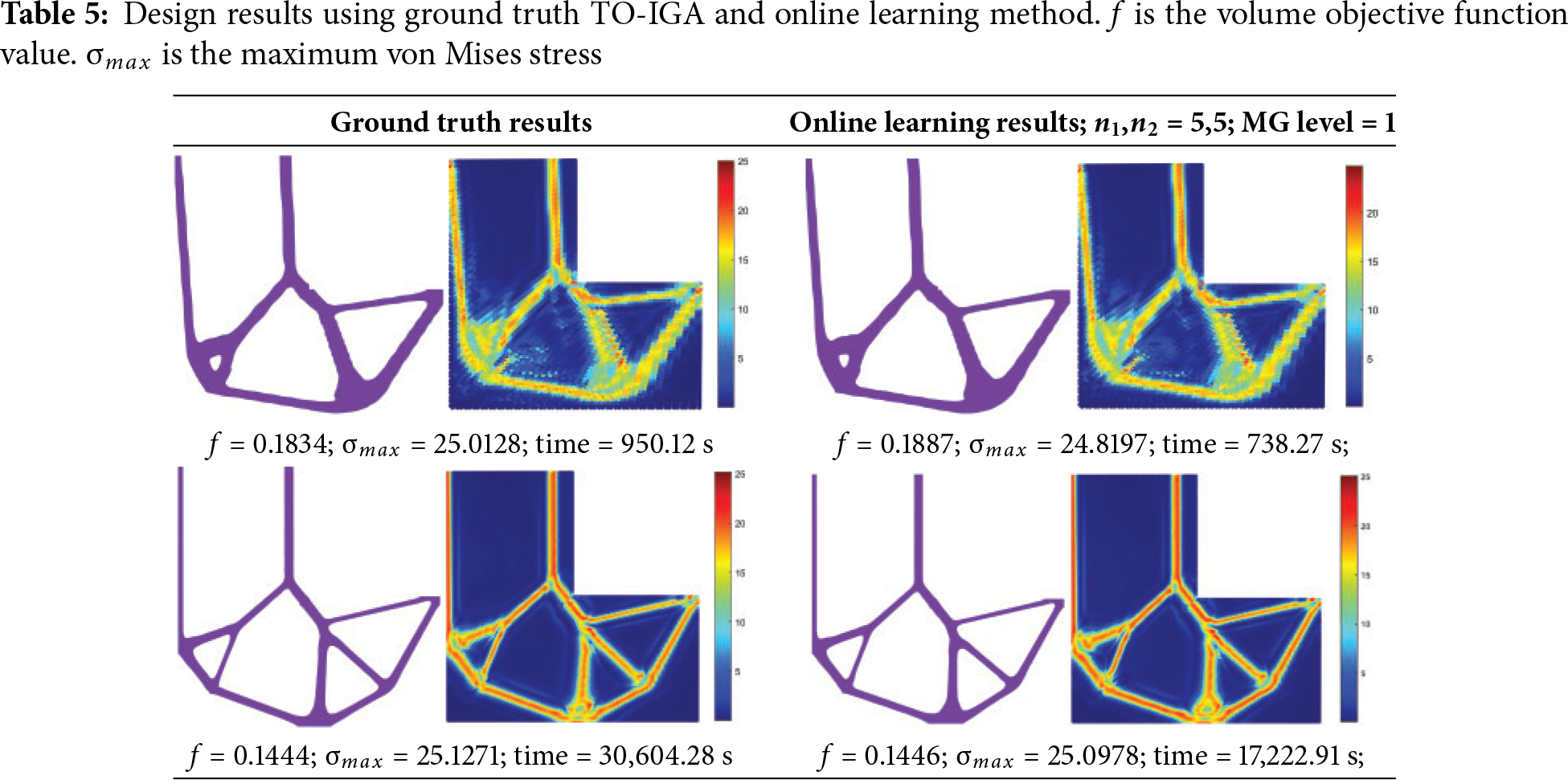

Second, the size of the two problems considered is rather small (103 × 52), it is expected a larger efficiency gain would be obtained for large-scale problems. We examine two additional design cases of different design resolutions, but with the same problem setup as shown in Fig. 7a. The control point grids are set to (a) 63 × 48 and (b) 207 × 102, respectively. After padding, the input sizes of FNO are 64 × 48 and 208 × 104, respectively. For the larger case, the filter radius is 8 and

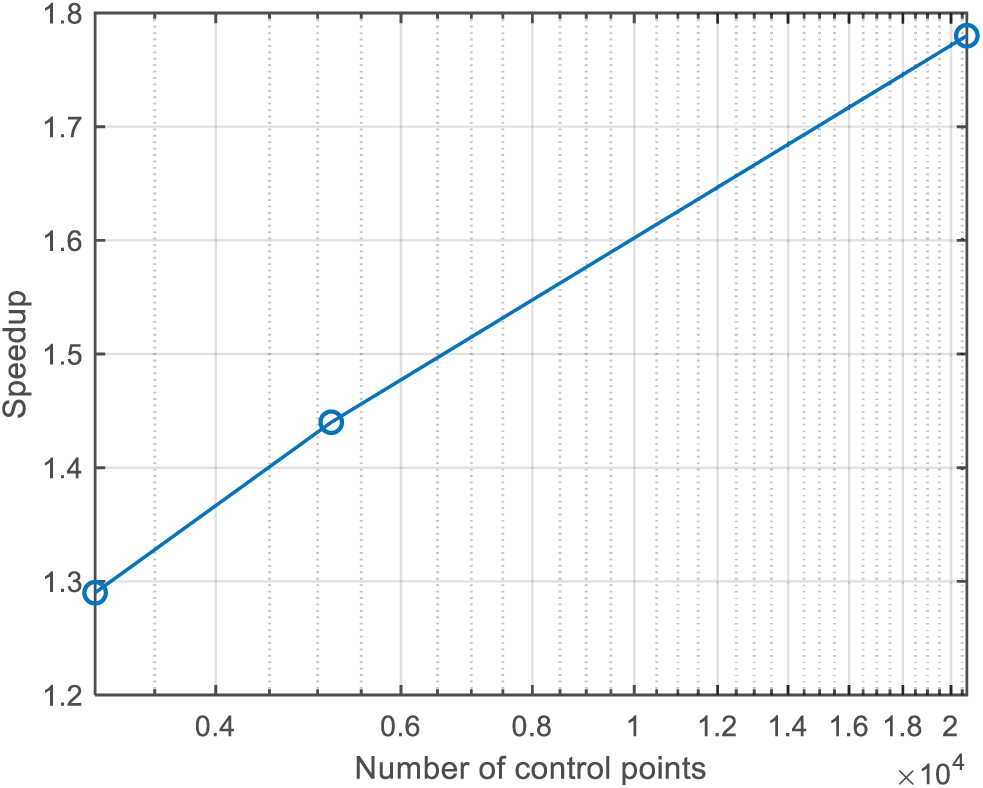

The design results of the two additional cases are provided in Table 5. As shown, compared to the case with the size of 103 × 52, the speedup drops to 1.29× in case (a), while increasing to 1.78× in case (b). Based on the results from these three experiments, we plot the relationship between speedup and the number of control points, as shown in Fig. 13. As the number of control points increases, the speedup gradually approaches the theoretical upper limit value of (

Figure 13: The relationship between speedup and the number of control points

The trade-off between efficiency and accuracy is inherent in machine learning methods and is often difficult to analyze theoretically. However, our numerical experiments (including compliance design cases) indicate that a relative error of approximately 0.1% yields satisfactory designs with performance comparable to the ground-truth solution. The training data required to achieve this error threshold depends on the problem’s complexity. The adaptive hierarchical strategy proposed in [29] can be employed to select appropriate multigrid levels and overlapping ratios based on a targeted speedup ratio.

In addition to the increased speedup achieved as the number of control points increases, the results also show that the objective function decreases from 0.1887 to 0.1446. Moreover, the optimized topology becomes more complex with refinement: the design contains four holes for the first two cases, whereas five holes appear in the finest mesh. These observations are consistent with the expectation since the design space expands as the number of control points increases.

This work presents an online learning framework to improve efficiency of isogeometric topology optimization, where the FNO surrogate is employed to predict sensitivity fields. A multi-grid decomposition strategy is employed, enabling the augmentation of training data and embedding global information across different levels in the input. This strategy enhances framework scalability and FNO prediction accuracy. The results of numerical experiments demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed framework across two stress constrained design problems. By incorporating FNO as surrogate models, the framework significantly reduces the number of IGA evaluations and sensitivity calculations, leading to substantial computational savings while maintaining results comparable to ground-truth IGA solutions in large-scale examples. Reducing the usage ratio of IGA updates can further improve efficiency; however, this also reduces the amount of available data, which may negatively impact the accuracy of FNO predictions. Therefore, there’s a tradeoff between efficiency and accuracy. Overlapping strategy can help increase the training dataset size, which can enhance the FNO’s prediction accuracy.

There remain multiple promising directions for future research. For example, future efforts could focus on dynamically adjusting the FNO usage ratio during inference, possibly guided by design change indicators. Additionally, while the framework is validated on medium-scale problems, its scalability to giga-scale and 3D stress-constrained designs remain undemonstrated. Future work will include such large-scale 3D stress-constrained design problems and extensions to other application problems, such as acoustic wave analysis.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work is supported by the Hong Kong Research Grants under Competitive Earmarked Research Grant No. 16206320.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Wenjing Ye; data collection: Kangjie Li; analysis and interpretation of results: Kangjie Li, Wenjing Ye; draft manuscript preparation: Kangjie Li. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available on request from the authors.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Bendsøe MP, Sigmund O. Material interpolation schemes in topology optimization. Arch Appl Mech. 1999;69:635–54. doi:10.1007/s004190050248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. de Troya MA S, Tortorelli DA. Adaptive mesh refinement in stress-constrained topology optimization. Struct Multidiscip Optim. 2018;58(6):2369–86. doi:10.1007/s00158-018-2084-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Wang S, de Sturler E, Paulino GH. Dynamic adaptive mesh refinement for topology optimization. arXiv:1008.3453. 2010. [Google Scholar]

4. Hoshina TY, Menezes IF, Pereira A. A simple adaptive mesh refinement scheme for topology optimization using polygonal meshes. J Braz Soc Mech Sci Eng. 2018;40(7):348. doi:10.1007/s40430-018-1267-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Hughes TJ, Cottrell JA, Bazilevs Y. Isogeometric analysis: CAD, finite elements, NURBS, exact geometry and mesh refinement. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng. 2005;194(39–41):4135–95. doi:10.1016/j.cma.2004.10.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Cottrell JA, Hughes TJ, Bazilevs Y. Isogeometric analysis: toward integration of CAD and FEA. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2009. 352 p. [Google Scholar]

7. Seo YD, Kim HJ, Youn SK. Isogeometric topology optimization using trimmed spline surfaces. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng. 2010;199(49–52):3270–96. doi:10.1016/j.cma.2010.06.033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Dedè L, Borden MJ, Hughes TJ. Isogeometric analysis for topology optimization with a phase field model. Arch Comput Methods Eng. 2012;19:427–65. doi:10.1007/s11831-012-9075-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Chen W, Su X, Liu S. Algorithms of isogeometric analysis for MIST-based structural topology optimization in MATLAB. Struct Multidiscip Optim. 2024;67(3):43. doi:10.1007/s00158-024-03764-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Wang Y, Benson DJ. Isogeometric analysis for parameterized LSM-based structural topology optimization. Comput Mech. 2016;57:19–35. doi:10.1007/s00466-015-1219-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Qiu W, Wang Q, Gao L, Xia Z. Evolutionary topology optimization for continuum structures using isogeometric analysis. Struct Multidiscip Optim. 2022;65(4):121. doi:10.1007/s00158-022-03215-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Hou W, Gai Y, Zhu X, Wang X, Zhao C, Xu L, et al. Explicit isogeometric topology optimization using moving morphable components. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng. 2017;326:694–712. doi:10.1016/j.cma.2017.08.021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Shaaban AM, Anitescu C, Atroshchenko E, Rabczuk T. 3D isogeometric boundary element analysis and structural shape optimization for Helmholtz acoustic scattering problems. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng. 2021;384:113950. doi:10.1016/j.cma.2021.113950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Shaaban AM, Anitescu C, Atroshchenko E, Rabczuk T. Isogeometric boundary element analysis and shape optimization by PSO for 3D axi-symmetric high frequency Helmholtz acoustic problems. J Sound Vib. 2020;486:115598. doi:10.1016/j.jsv.2020.115598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Wang J, Jiang F, Zhao W, Chen H. A combined shape and topology optimization based on isogeometric boundary element method for 3D acoustics. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2021;127(2):645–81. doi:10.32604/cmes.2021.015894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Hassani B, Khanzadi M, Tavakkoli SM. An isogeometrical approach to structural topology optimization by optimality criteria. Struct Multidiscip Optim. 2012;45:223–33. doi:10.1007/s00158-011-0680-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Gao J, Gao L, Luo Z, Li P. Isogeometric topology optimization for continuum structures using density distribution function. Int J Numer Methods Eng. 2019;119(10):991–1017. doi:10.1002/nme.6081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Gao J, Wang L, Luo Z, Gao L. IgaTop: an implementation of topology optimization for structures using IGA in MATLAB. Struct Multidiscip Optim. 2021;64:1669–700. doi:10.1007/s00158-021-02858-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Zhuang C, Xiong Z, Ding H. An efficient 2D/3D NURBS-based topology optimization implementation using page-wise matrix operation in MATLAB. Struct Multidiscip Optim. 2023;66(12):254. doi:10.1007/s00158-023-03701-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. da Silva GA, Aage N, Beck AT, Sigmund O. Local versus global stress constraint strategies in topology optimization: a comparative study. Int J Numer Methods Eng. 2021;122(21):6003–36. doi:10.1002/nme.6781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Kazemi HS, Tavakkoli SM, Naderi R. Isogeometric topology optimization of structures considering weight minimization and local stress constraints. Int J Optim Civ Eng. 2016;6(2):303–17. [Google Scholar]

22. Svanberg K. The method of moving asymptotes—a new method for structural optimization. Int J Numer Methods Eng. 1987;24(2):359–73. doi:10.1002/nme.1620240207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Jahangiry HA, Tavakkoli SM. An isogeometrical approach to structural level set topology optimization. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng. 2017;319:240–57. doi:10.1016/j.cma.2017.02.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Liu H, Yang D, Hao P, Zhu X. Isogeometric analysis based topology optimization design with global stress constraint. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng. 2018;342:625–52. doi:10.1016/j.cma.2018.08.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Zhai X. Alternating optimization method for isogeometric topology optimization with stress constraints. J Comput Math. 2024;42(1):134–55. doi:10.4208/jcm.2209-m2021-0358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Villalba D, Gonçalves M, Dias-de-Oliveira J, Andrade-Campos A, Valente R. IGA-based topology optimization in the design of stress-constrained compliant mechanisms. Struct Multidiscip Optim. 2023;66(12):244. doi:10.1007/s00158-023-03697-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Gao J, Gao L, Xiao M. Isogeometric topology optimization: methods, applications and implementations. Singapore: Springer; 2022. 212 p. [Google Scholar]

28. Vo D, Nguyen MN, Bui TQ, Suttakul P, Rungamornrat J. Isogeometric gradient-free proportional topology optimization (IGA-PTO) for compliance problem. Int J Numer Methods Eng. 2023;124(19):4275–310. doi:10.1002/nme.7315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Li K, Ye W. A multi-grid, single-mesh online learning framework for efficient large-scale topology optimization. Eng Comput. Forthcoming. 2025. [Google Scholar]

30. Toan ML, Elena A, Tinh QB, Jaroon R. Material and thickness optimization of microscale in-plane FG thin-walled structures using deep neural network-assisted artificial hummingbird lgorithms. Comp Struct. 2025;368:119227. doi:10.1016/j.compstruct.2025.119227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Woldseth RV, Aage N, Bærentzen JA, Sigmund O. On the use of artificial neural networks in topology optimisation. Struct Multidiscip Optim. 2022;65(10):294. doi:10.1007/s00158-022-03347-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Xiang C, Wang D, Pan Y, Chen A, Zhou X, Zhang Y. Accelerated topology optimization design of 3D structures based on deep learning. Struct Multidiscip Optim. 2022;65(3):99. doi:10.1007/s00158-022-03194-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Gao Y, Zhou S, Li M. Structural topology optimization based on deep learning. J Comput Phys. 2025;520:113506. doi:10.1016/j.jcp.2024.113506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Xue L, Liu J, Wen G, Wang H. Efficient, high-resolution topology optimization method based on convolutional neural networks. Front Mech Eng. 2021;16(1):80–96. doi:10.1007/s11465-020-0614-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Chi H, Zhang Y, Tang TLE, Mirabella L, Dalloro L, Song L, et al. Universal machine learning for topology optimization. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng. 2021;375:112739. doi:10.1016/j.cma.2019.112739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Piegl L, Tiller W. The NURBS book. 2nd ed. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 1997. 646 p. [Google Scholar]

37. Wendland H. Piecewise polynomial, positive definite and compactly supported radial functions of minimal degree. Adv Comput Math. 1995;4:389–96. doi:10.1007/bf02123482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Giraldo-Londoño O, Paulino GH. PolyStress: a Matlab implementation for local stress-constrained topology optimization using the augmented Lagrangian method. Struct Multidiscip Optim. 2021;63(4):2065–97. doi:10.1007/s00158-020-02760-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Holmberg E, Torstenfelt B, Klarbring A. Stress constrained topology optimization. Struct Multidiscip Optim. 2013;48:33–47. doi:10.1007/s00158-012-0880-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Li Z, Kovachki N, Azizzadenesheli K, Liu B, Bhattacharya K, Stuart A, et al. Fourier neural operator for parametric partial differential equations. arXiv:2010.08895. 2020. [Google Scholar]

41. Li K, Ye W. D-FNO: a decomposed Fourier neural operator for large-scale parametric partial differential equations. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng. 2025;436:117732. doi:10.1016/j.cma.2025.117732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Kossai J, Kovachki N, Azizzadenesheli K, Anandkumar A. Multi-grid tensorized Fourier neural operator for high-resolution PDEs. Trans Mach Learn Res. 2024;8:1–27. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools