Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

DeepNeck: Bottleneck Assisted Customized Deep Convolutional Neural Networks for Diagnosing Gastrointestinal Tract Disease

1 Department of Computer Science, COMSATS University Islamabad, Vehari Campus, Vehari, 61100, Pakistan

2 Department of Information Systems, College of Computer and Information Sciences, Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, P.O. Box 84428, Riyadh, 11671, Saudi Arabia

3 Department of Electrical Engineering and Information Technology (DIETI), University of Naples “Federico II”, Naples, 80138, Italy

4 Department of Computer Science, University of Gujrat, Gujrat, 50700, Pakistan

* Corresponding Author: Rashid Jahangir. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Artificial Intelligence Models in Healthcare: Challenges, Methods, and Applications)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(2), 2481-2501. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.072575

Received 29 August 2025; Accepted 15 October 2025; Issue published 26 November 2025

Abstract

Diagnosing gastrointestinal tract diseases is a critical task requiring accurate and efficient methodologies. While deep learning models have significantly advanced medical image analysis, challenges such as imbalanced datasets and redundant features persist. This study proposes a novel framework that customizes two deep learning models, NasNetMobile and ResNet50, by incorporating bottleneck architectures, named as NasNeck and ResNeck, to enhance feature extraction. The feature vectors are fused into a combined vector, which is further optimized using an improved Whale Optimization Algorithm to minimize redundancy and improve discriminative power. The optimized feature vector is then classified using artificial neural network classifiers, effectively addressing the limitations of traditional methods. Data augmentation techniques are employed to tackle class imbalance, improving model learning and generalization. The proposed framework was evaluated on two publicly available datasets: Hyper-Kvasir and Kvasir v2. The Hyper-Kvasir dataset, comprising 23 gastrointestinal disease classes, yielded an impressive 96.0% accuracy. On the Kvasir v2 dataset, which contains 8 distinct classes, the framework achieved a remarkable 98.9% accuracy, further demonstrating its robustness and superior classification performance across different gastrointestinal datasets. The results demonstrate the effectiveness of customizing deep models with bottleneck architectures, feature fusion, and optimization techniques in enhancing classification accuracy while reducing computational complexity.Keywords

The gastrointestinal (GI) tract is a critical component of the digestive system responsible for the ingestion, breakdown, absorption of nutrients, and elimination of waste [1]. Disorders of the GI tract are increasingly prevalent and, if undetected in their early stages, may progress into malignancies. Gastrointestinal cancer refers to a group of cancers affecting organs such as the pancreas, gallbladder, colon, esophagus, liver, small intestine, rectum, and stomach [2,3]. Depending on the cancer type and progression stage, symptoms can include vomiting, nausea, weight loss, bowel irregularities, fatigue, and abdominal pain [4,5]. Although extensive research and molecular profiling of GI cancers have been conducted over the past two decades, early detection remains a persistent challenge. Key risk factors include dietary habits, smoking, alcohol consumption, obesity, and microbial infections. Recent advances in medical image segmentation techniques, such as U-Net architectures and optimized clustering approaches, have shown promise in improving early and accurate detection of GI abnormalities [6]. Despite advancements in diagnostic methods, GI cancers continue to rank among the leading causes of global cancer-related mortality, largely due to late-stage diagnoses [7].

Recent statistics underscore the urgency of addressing GI cancers. For instance, approximately 28,600 new cases are reported annually in Australia, with an average of 39 daily fatalities. On a global scale, diseases of the stomach, esophagus, and colon accounted for 2.8 million new cases in a recent year [1,8]. In 2018, there were an estimated 4.8 million diagnosed cases and 3.4 million deaths attributed to GI cancers. In the United States alone, 27,510 cases were recorded as of 2019, with 62.63% of patients being male. Mortality rates were similarly gender-skewed, with 40.49% male and 39.1% female fatalities [1]. However, these figures are often presented without standardized population baselines, limiting cross-comparability and regional relevance.

One of the major tools for non-invasive visualization of GI abnormalities is Wireless Capsule Endoscopy (WCE), which captures images of the GI tract using a swallowable device approximately 11 by 30 mm in size. These images are transmitted via radio-telemetry to an external recording device [9]. Unlike conventional endoscopic procedures that require insertion of wired instruments and are often uncomfortable for patients [10], WCE offers a more patient-centric and minimally invasive alternative [11,12]. Despite these advantages, WCE introduces significant computational challenges due to the high volume, redundancy, and variability in image data. These factors complicate the task of automated detection and classification of GI diseases and demand efficient and scalable machine learning solutions.

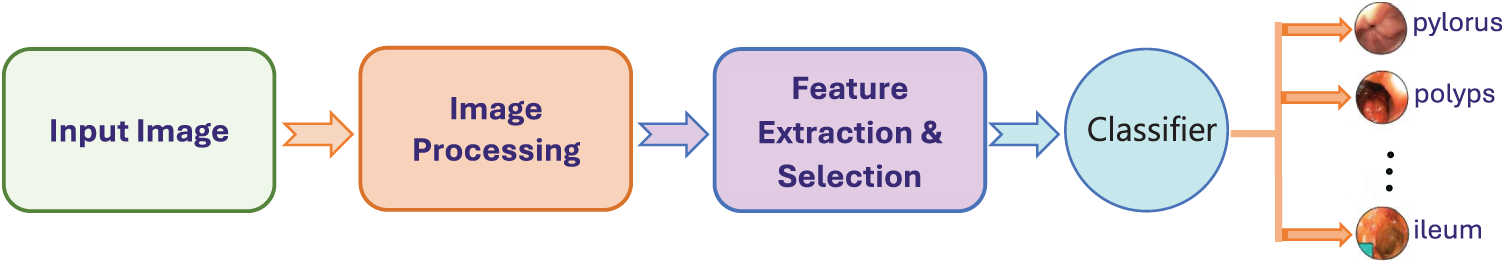

To address these challenges, computer-aided diagnosis (CAD) systems have been developed to support clinical decision-making [13]. Fig. 1 illustrates a typical CAD pipeline used in gastrointestinal image analysis. Most existing systems rely on supervised learning methods to extract discriminative features from WCE images [14,15]. Early approaches focused on handcrafted features, including shape, texture, and color descriptors [16,17]. While informative, such features often lack generalization capabilities across diverse datasets.

Figure 1: General computer-aided diagnosis system for gastrointestinal tract cancer classification

Recent advances in deep learning, particularly Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), have shown considerable promise in automatically learning hierarchical feature representations from raw image data [18,19]. Architectures such as ResNet50 [20], NasNetMobile [5], AlexNet [21], and VGG16 [22] have been widely adopted for feature extraction in GI image analysis. However, the high-dimensional nature of features produced by deep networks can include redundant or irrelevant information. Effective feature selection techniques are thus required to reduce dimensionality while preserving classification performance [23,24]. Metaheuristic optimization algorithms such as Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA) [25], Genetic Algorithm (GA) [26], Entropy Selection, Particle Optimization [18], and Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) [27,28] have been explored for this purpose.

Finally, selected features are passed to classifiers for disease categorization. Various classifiers have been employed, including Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA), K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN), AdaBoost, Multiclass Support Vector Machines (M-SVM) [29], and neural network variants such as Complex Tree (CT), Narrow Neural Network (N-NN), Wide Neural Network (W-NN), Bilayered (Bi-NN), Trilayered (Tri-NN), and Medium Neural Network (MNN) [30]. However, challenges such as class imbalance, interpretability, and domain adaptation still limit the robustness and generalizability of these systems. This paper aims to address these issues by proposing a novel feature selection and classification framework tailored for GI disease detection using WCE images.

The paper is arranged as follows: Section 2 reports the existing studies of DL for gastrointestinal tract diseases. Section 3 presents an in-depth explanation of the networks for feature extraction and fusion process, and the classification employed. Section 4 provides the results and discussion derived from numerous experiments. Lastly, the Section 6 reports the conclusion of this paper.

This section reviews prior work on gastrointestinal (GIT) disease classification, with a focus on deep learning, hybrid architectures, and feature optimization strategies. Over the past decade, the use of convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and related machine learning techniques has gained significant traction in GIT image analysis [31]. A major contribution to the field is the Hyper-Kvasir dataset introduced by Borgli et al. [32], comprising labeled endoscopic images for 23 GIT conditions. This dataset enabled training of standard CNN architectures such as ResNet and DenseNet for multi-class disease classification, demonstrating its value as a benchmarking resource.

Several studies have adopted transfer learning to improve performance. Gómez-Zuleta [22] evaluated VGG-16, ResNet-50, and Inception-v3 for automatic polyp detection across five datasets. VGG-16 outperformed others with 81% accuracy, yet overall performance remained constrained by limited feature discrimination in subtle lesion types. Likewise, Hmoud Al-Adhaileh et al. [8] applied transfer learning and augmentation on the Kvasir dataset, achieving high accuracies with AlexNet, ResNet50, and GoogLeNet. However, the study lacked efficient feature selection mechanisms, which introduced redundant information and increased computational cost. To address this, reference [18] proposed the GestroNet framework, integrating handcrafted texture descriptors with deep features extracted from VGG-16, ResNet50, and InceptionNet. Feature optimization techniques such as entropy, principal component analysis (PCA), and mRMR were used before classification. This hybrid fusion approach improved diagnostic performance (95.02%), but challenges persisted in capturing fine-grained variations, particularly in stomach cancer classes. Optimization-based feature selection has also been explored. For example, deep saliency and Bayesian-optimized MobileNet-V2 was tested on Kvasir1, and Kvasir2 datasets, achieving up to 99.61% accuracy [18]. Another study combined auto-encoders with residual blocks and used hybrid Marine Predator and Slime Mould algorithms for selecting fused features, which were classified via neural networks to attain 93.8% accuracy [5]. Yet, the lack of attention mechanisms limited the refinement of critical regions in endoscopic frames. Reference [31] addressed this by proposing GastroNet, an attention-driven deep framework enhanced by cosine similarity optimization. ResNet-152, ResNet-50, and Mask R-CNN were used for extracting localized features, refined through Improved Ant Colony Optimization (ACO). This system achieved 96.43% accuracy, but was dependent on large training samples and struggled with generalization to underrepresented classes. Reference [33] proposed a Siamese Neural Network (SNN) framework for the early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) using MRI images from the Kaggle Alzheimer dataset. The approach focused on learning inter-class similarity between Very Mild Dementia (VMD) and Non-Dementia (ND) categories, aided by Gaussian and Median filter-based enhancements. The model achieved 99.62% training accuracy and 97.67% validation accuracy, demonstrating the effectiveness of similarity-based learning for early-stage AD classification.

EfficientNet-based models have also shown promise. Reference [34] developed a hybrid deep learning model for the multi-class classification of Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) stages using MRI images from the Kaggle dataset, encompassing non-demented, very mild dementia, mild dementia, and moderate dementia categories. The images underwent background removal and k-means clustering-based segmentation, followed by feature extraction using EfficientNet B3 and gray-level co-occurrence matrix (GLCM). The proposed model achieved an average training accuracy of 99.99% and testing accuracy of 99.67%, demonstrating strong discriminative capability across disease stages. In [35], EfficientNet-NSGA-II framework achieved 99.97% accuracy. However, trade-offs between performance and inference speed were not addressed. Another study [36] using ResNet50 on the Kvasir dataset reported 99.8% training accuracy and high precision-recall scores, yet variability in image quality remained a barrier to clinical deployment. Lightweight architectures like Xception and DenseNet121 were explored in [37], achieving up to 92.58% accuracy, while reference [38] used feature concatenation from visual geometry group (VGG) and InceptionNet with SVM, reporting 98% accuracy. However, most of these models focused on classification metrics without assessing robustness to imbalanced datasets or deployment constraints. Beyond supervised methods, self-supervised learning and data-efficient augmentation techniques have emerged. In [39], a hybrid sampling strategy improved classification with only 10% labeled data, highlighting the potential for reducing annotation effort. In [40], the DEA method used Grad-CAM for feature refinement, improving segmentation scores on Hyper-Kvasir and ISIC datasets. Furthermore, reference [35] combined EfficientNet with NSGA-II for colon cancer diagnosis, achieving 99.97% accuracy, though computational complexity remained high. Reference [41] introduced a specialized multi-route deep convolutional neural network (DCNN) designed for automated identification of gastrointestinal abnormalities from endoscopic images. The model, evaluated on Kvasir and Kvasir-Capsule datasets, achieved superior performance (MCC = 0.9743) with strong generalization under class imbalance. Their approach effectively reduced diagnostic variability and demonstrated the potential of DCNNs to support clinical decision-making in gastrointestinal disease classification. Reference [42] proposed an advanced deep convolutional neural network (DCNN) for automated multi-class classification of skin lesions using dermoscopic images from ISIC-17, ISIC-18, and ISIC-19 datasets. The model, designed with multiple convolutional layers and optimized filter configurations, achieved 94% precision, 93% sensitivity, and 91% specificity, outperforming existing methods with an AUROC of 0.964 on ISIC-17. Their study highlights the clinical potential of deep learning for reliable and efficient skin lesion classification, offering valuable insights transferable to other medical imaging domains such as gastrointestinal disease detection.

In summary, existing studies have demonstrated strong performance in GI disease classification using CNNs, transfer learning, and feature optimization. However, gaps remain in several areas: (1) limited focus on interpretability and attention mechanisms for region-specific learning, (2) weak generalization across varying imaging devices and clinical settings, (3) insufficient handling of rare class samples and imbalanced datasets, and (4) challenges in balancing model accuracy with computational efficiency for real-time applications. Our proposed work addresses these challenges by developing an deep learning framework with feature optimization, tailored for robust classification of GIT disorders from WCE images.

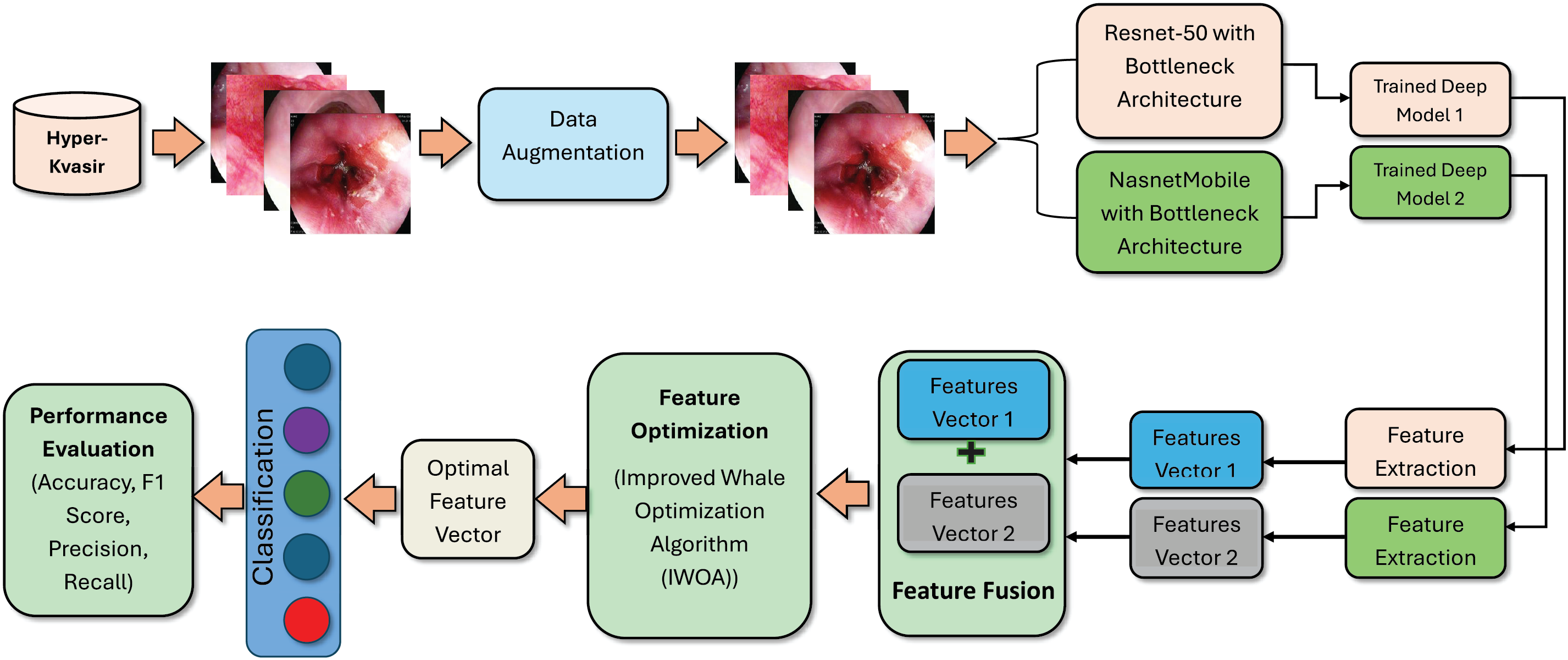

The dataset used in this manuscript is highly imbalanced, with some classes containing only a few images. To address this issue, data augmentation techniques are employed. Features are first extracted using NasnetMobile and ResNet50, both with bottleneck architectures. The extracted feature vectors, denoted as

Figure 2: Proposed methodology of GIT diseases classification

Two publicly available datasets: Kvasir v2 and Hyper-Kvasir are used in this work. The Kvasir-V2 dataset is an extensive compilation of high-resolution gastrointestinal endoscopic images, meticulously assembled for research and development objectives [43]. The dataset is balanced, with 8 classes and 8000 images. The three categories of dataset comprise anatomical markers like the Z-line, pylorus, and cecum. The precise classification of these three categories is essential for enabling efficient navigation inside the gastrointestinal tract. Three categories are designated as oesophagitis, polyps, and ulcerative colitis, which provide images corresponding to pathological findings, while two categories pertain to the endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) technique described as “dyed and lifted polyps” and “dyed resection margins”. The Hyper-Kvasir dataset was gathered from Norway’s Baerum Hospital and is available to the public. 10,662 gastrointestinal endoscopic images divided into 23 categories are included in the collection [32]. Sixteen are associated with the lower gastrointestinal tract, and seven with the upper gastrointestinal tract. The dataset has an imbalance issue, where certain classes have a very limited number of images. To address this problem, data augmentation techniques are implemented. In our experiments, we employed standard image augmentation techniques including random horizontal and vertical flips, rotations with 90, 180 and 270 degrees. This augmentation is applied on imbalace classes.

3.2 Proposed Contrast Enhancement

The Hyper-Kvasir dataset exhibits significant variations in lighting and contrast, which can hinder the performance of deep learning models for GIT disease classification. To address this, we integrate two histogram-based enhancement techniques—Brightness Preserving Histogram Equalization (BPHE) [44] and Dualistic Sub-Image Histogram Equalization (DSIHE) [45]—in the preprocessing pipeline. These methods aim to enhance visual quality while retaining structural and brightness information, which is essential for accurate region-focused learning in CNN-based classifiers.

BPHE modifies the intensity distribution to produce a more uniform histogram while preserving brightness. It enhances both dark and bright regions independently, which is particularly beneficial for medical imaging tasks where visibility of subtle tissue boundaries is critical. The method first partitions the input image into low-contrast and high-contrast regions based on mean intensity.

Complementing BPHE, DSIHE enhances contrast by dividing the image based on a grey-level threshold and applying histogram equalization separately. This strategy helps mitigate over-enhancement in brighter areas and under-enhancement in darker regions, ensuring balanced contrast suitable for complex endoscopic visuals. In our pipeline, contrast enhancement is applied to the entire dataset after augmentation. These steps improve visibility of local structures, helping the model learn more discriminative features during training. The inclusion of BPHE and DSIHE significantly boosts classification accuracy, especially for visually subtle disease categories.

3.3.1 NasnetMobile with Bottleneck Architecture (NasNeck)

To enhance GI image classification, we modified the NasnetMobile model by appending a residual bottleneck block to improve feature refinement. While bottleneck modules are standard in literature, their integration here is motivated by the need to improve representation of subtle textures and low-contrast features typical in gastrointestinal images.

NasnetMobile, based on Neural Architecture Search (NAS), processes input images resized to 224

The output is then passed through a Global Average Pooling (GAP) layer and a fully connected layer, followed by a SoftMax activation to produce class probabilities. The ‘global_average_pooling2d_1’ layer was selected for feature extraction because the final layer produced too few features to be informative. This layer provided a better balance between spatial abstraction and representational richness, improving downstream classification performance.

NasNeck Features: A feature vector of size

3.3.2 ResNet50 with Bottleneck Architecture (ResNeck)

We also modified the ResNet50 model by appending a residual bottleneck block after its base feature extraction layers. ResNet50’s deep residual structure is well-suited for training with stability, and the added bottleneck block helps refine localized spatial patterns that are crucial in GI disease classification.

The bottleneck follows the same structure as in NasNeck: a 1

For feature extraction, the ‘avg_pool’ layer was chosen. Similar to NasNeck, deeper layers produced limited features that lacked sufficient information for robust classification. The selected layer provided a good compromise between dimensionality and discriminative power.

ResNeck Features: A feature vector of size

Feature fusion aims to combine complementary information from multiple feature spaces to enhance classification performance. In this study, we propose a refined fusion strategy based on correlation analysis, termed the Modified Correlation-Extended Serial Technique. This method is designed to minimize redundancy and emphasize synergistic features extracted from two deep CNN models.

Let

Features with strong positive correlation (correlation value > 0) are retained in a new vector

The final fused feature vector is obtained by concatenating

The resulting vector has a dimension of

3.5.1 Improved Whale Optimization Algorithm (IWOA)

The Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA), introduced by Mirjalili in 2016 [25], is a metaheuristic algorithm inspired by the bubble-net hunting strategy of humpback whales. It includes three core mechanisms: encircling prey, spiral position updating, and random search for prey.

Encircling Prey:

Once a target (prey) is identified, the whale encircles it. This is mathematically modeled as:

where

Here,

Spiral Position Update:

Whales swim along a spiral path to simulate the bubble-net behavior:

where

The whale’s behavior alternates probabilistically between encircling and spiral swimming:

Random Search for Prey:

For global exploration, whales randomly update positions:

where

3.5.2 Modifications to Classical WOA

To improve performance, we modify WOA by introducing dynamic control of D, adaptive probability updates, and jump behavior.

Adaptive Probabilities:

To balance exploration and exploitation dynamically:

Dynamic Coefficient:

where

Jump Behavior:

To avoid local optima and enhance diversity, a jump mechanism is defined:

where

Improved whale optimization algorithm (IWOA) hyperparameters: Population size 30, iterations 100, jump coefficient 0.05, initial probability 0.90, minimum probability 0.10, decay S 2. Random seeds used 42, 77, 123, 321, 777.

Fitness Function: Although classification tasks typically use cross-entropy or accuracy as evaluation metrics, this study employed Mean Square Error (MSE) as the fitness function to measure the squared difference between predicted class probabilities and one-hot encoded ground truth vectors. This allowed the optimization process to assess how effectively a candidate feature subset enables the model to approximate class distributions. The choice of MSE is motivated by its simplicity, differentiability, and computational efficiency which makes it suitable for iterative evaluation in the metaheuristic loop.

After optimization, the fused feature vector (

The Hyper-Kvasir and Kvasir V2 datasets are serves as a resource for results and analysis. The Hyper Kvasir dataset comprises 10,662 images, which are organized into twenty-three distinct classes. To mitigate this issue, data augmentation (horizontal and vertical flips, and rotations of 90∘, 180∘, and 270∘) was applied across the entire dataset, followed by contrast enhancement using Brightness Preserving Histogram Equalization (BPHE) and Dualistic Sub-Image Histogram Equalization (DSIHE). These preprocessing steps improved image quality and ensured consistent brightness and contrast across all samples. After preprocessing, the dataset was split into 80% training and 20% testing using stratified sampling. The CNN-based feature extraction models (NasNeck and ResNeck) were trained on the training set using a batch size of 32, initial learning rate of 0.0001, and the Stochastic Gradient Descent with Momentum (SGDM) optimizer for 50 epochs to ensure stable convergence. Following feature extraction, 10-fold cross-validation was employed for the neural network classifiers, Narrow Neural Network (NNN), Medium Neural Network (MNN), Wide Neural Network (WNN), Bi-Layered (Bi-NN), and Tri-Layered (Tri-NN) to ensure robust performance estimation and minimize variance. Within each fold, feature fusion and IWOA-based feature selection were performed on the training subset only, and the resulting optimized features were evaluated on the corresponding validation subset. The classifiers were trained using the Adam optimizer with early stopping to enhance generalization. All experiments were conducted with a fixed random seed (42) and stratified partitions for reproducibility.

The system implementation utilizes a core i7 Quad-core processor, accompanied by 16 GB of RAM. The system is equipped with a graphics card that has 4 GB of VRAM. The results are achieved using MATLAB R2023a.

4.1 Experiments on Hyper Kvasir Dataset

In this section, we evaluate our method on Hyper Kvasir dataset.

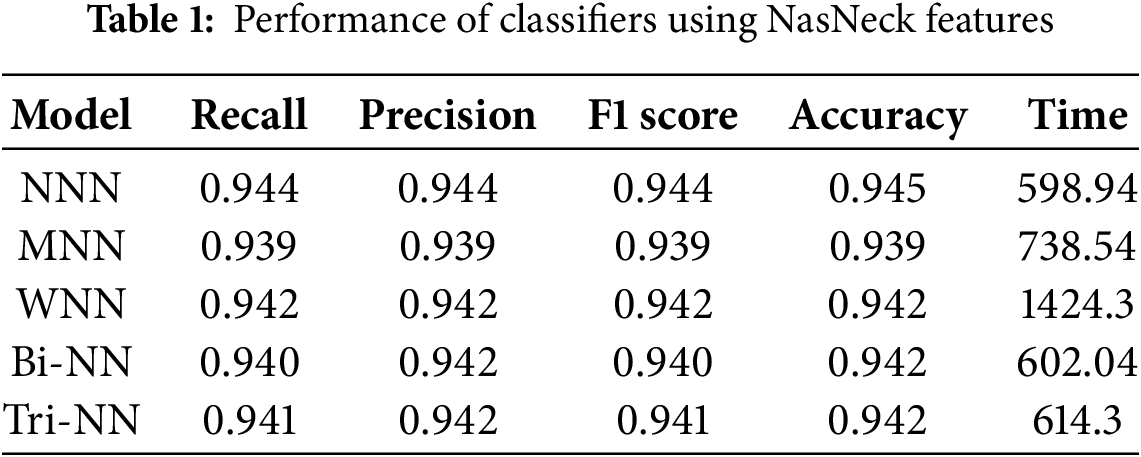

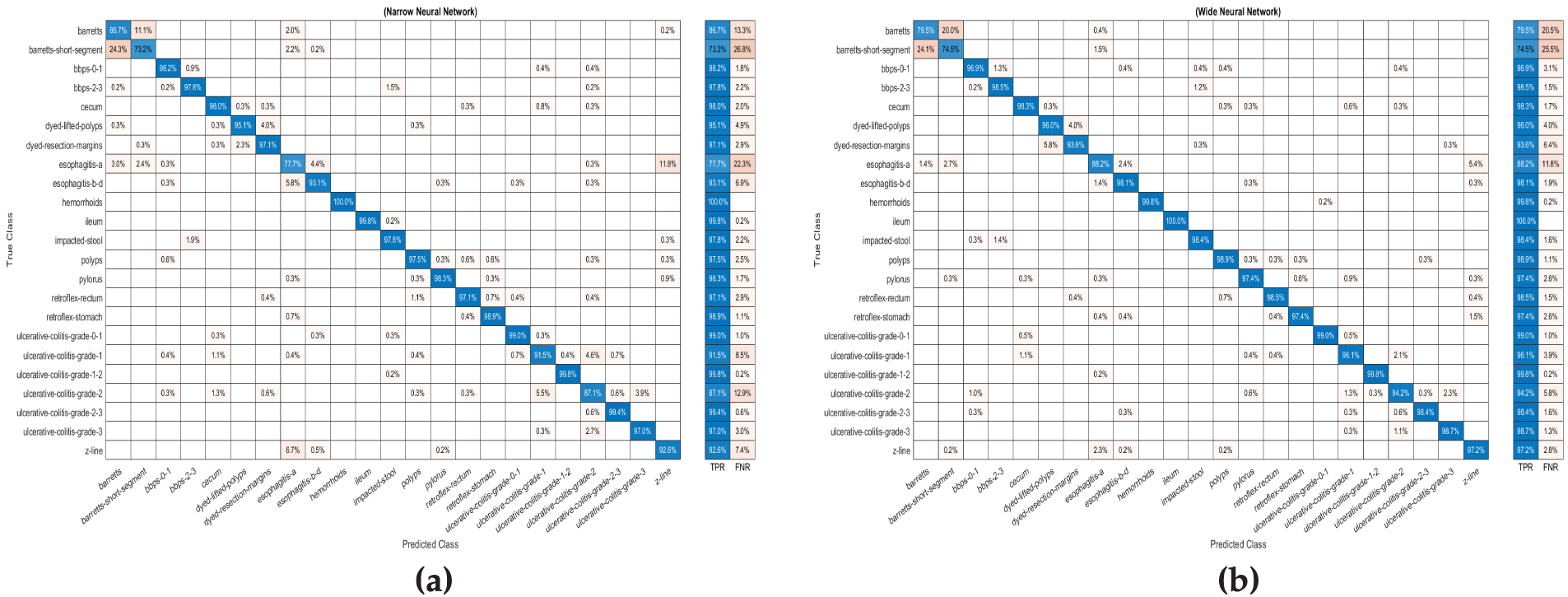

Results are presented in both tabular and graphical formats. Table 1 illustrates the results of the features extracted by NasNeck, provided as input to the neural network classifiers. Five neural network classifiers were used to evaluate the selected feature subsets: Narrow Neural Network (NNN), Medium Neural Network (MNN), Wide Neural Network (WNN), Bi-Layered (Bi-NN), and Tri-Layered (Tri-NN). The narrow, medium, and wide models consisted of a single hidden layer with 32, 64, and 128 neurons, respectively, using ReLU activation and dropout (0.4–0.5). The bi-layered model used two hidden layers (128

The investigation indicates that the NNN achieved the highest overall accuracy of 0.95, outperforming other architectures in precision, recall, and F1 score. Specifically, the NNN demonstrated a precision of 0.944, a recall of 0.944, and an F1 score of 0.944, highlighting its ability to balance sensitivity and specificity effectively. The Medium Neural Network (MNN) recorded the lowest accuracy at 0.94, while the WNN, Bi-NN, and Tri-TNN achieved an accuracy of 0.94. Among all classifiers, the WNN required the longest training time of 1424.3 s, whereas the NNN exhibited the shortest training time at 598.94 s, demonstrating its computational efficiency without compromising performance. These results emphasize the robustness and efficiency of the NNN as the most reliable classifier in the study. Fig. 3a illustrates the confusion matrix for the (NNN).

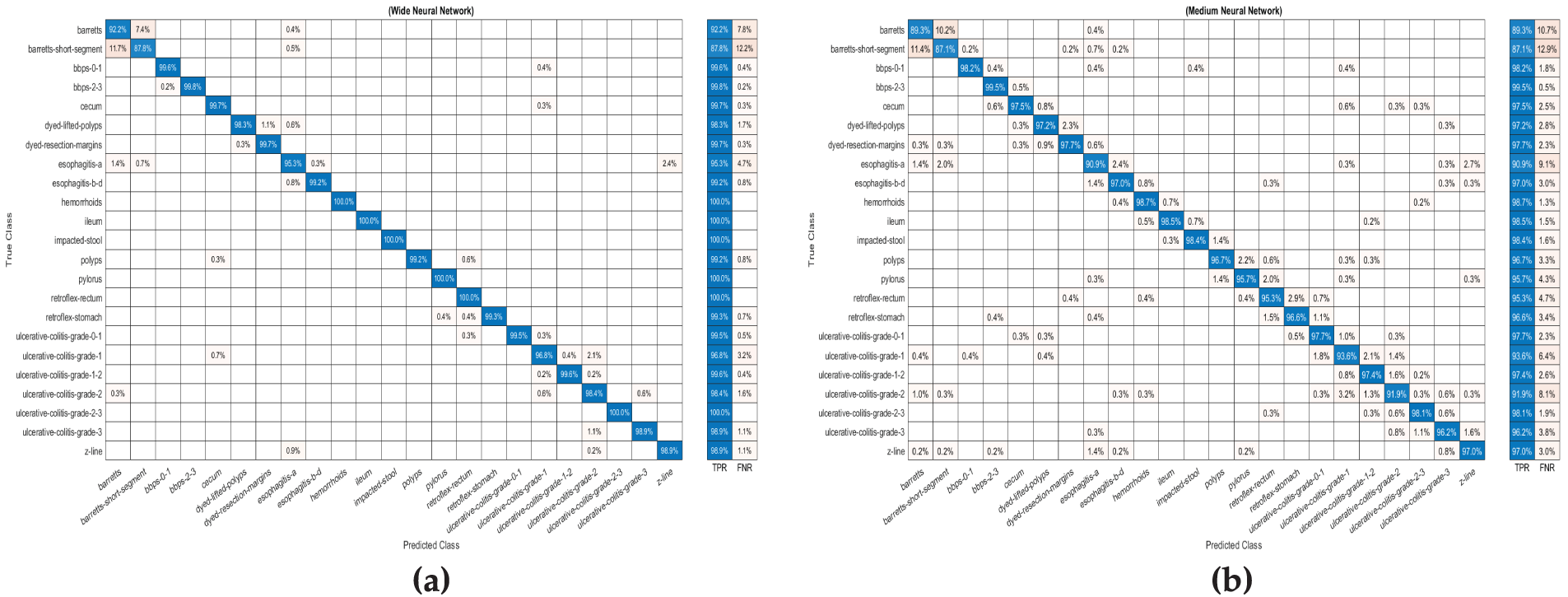

Figure 3: The confusion matrix for (a) Narrow Neural Network (b) (Wide Neural Network) via features extracted by ResNet-50 with a bottleneck architecture

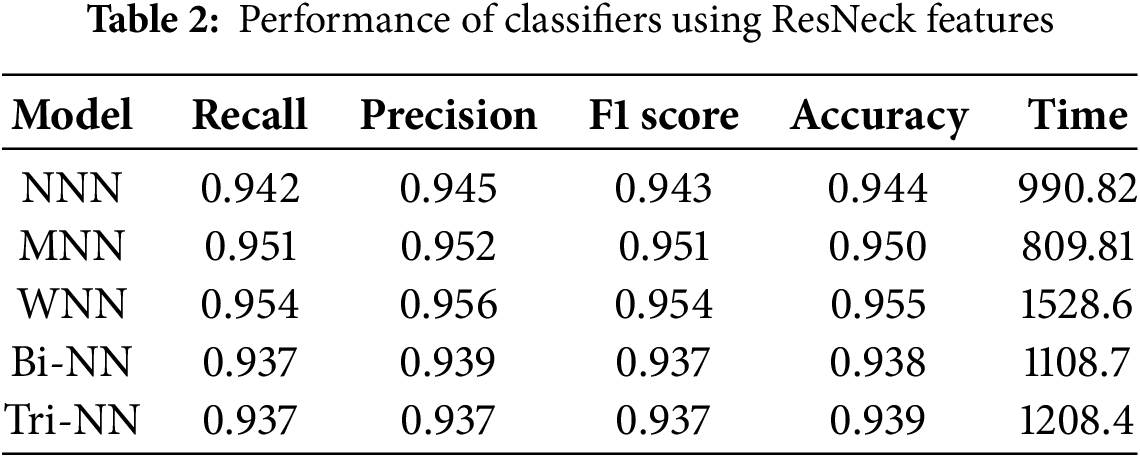

Table 2 illustrates the results of the features extracted by ResNet-50 with a bottleneck architecture, provided as input to the neural network classifiers. The investigation indicates that the WNN achieved the highest overall accuracy of 95.5%, outperforming other architectures in precision, recall, and F1 score. Specifically, the WNN demonstrated a precision of 0.956, a recall of 0.954, and an F1 score of 0.954, showcasing its superior performance across evaluation metrics. The MNN recorded the second-highest accuracy at 95.0%, with corresponding metrics of precision (0.952), recall (0.951), and F1 score (0.951). In contrast, the Bi-NN and Tri-NN recorded the lowest accuracy at 93.8% and 93.9%, respectively. Among all classifiers, the WNN required the longest training time of 1528.6 s, while the MNN exhibited the shortest training time at 809.81 s, demonstrating its computational efficiency. These results highlight the effectiveness of the WNN in delivering high accuracy, albeit at the cost of increased computational time. Fig. 3b illustrates the confusion matrix for the (WNN).

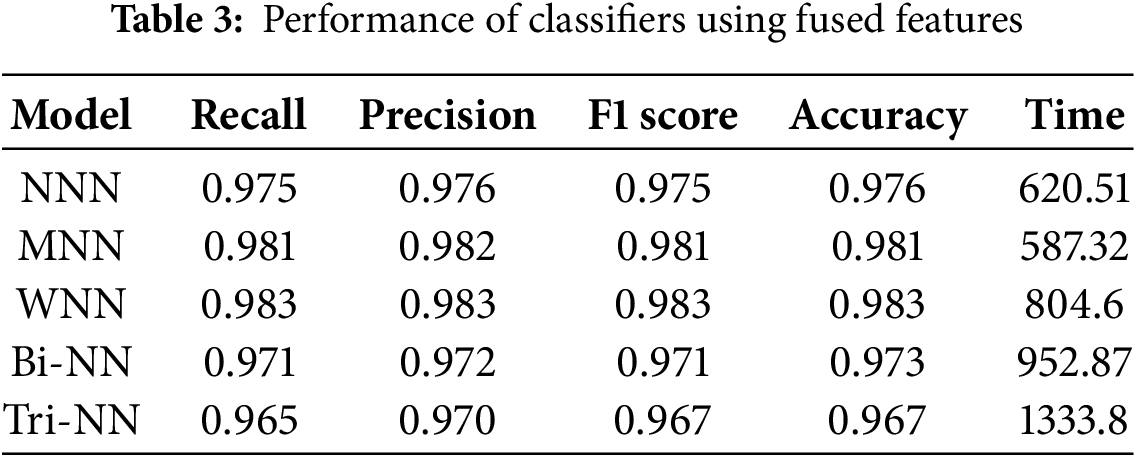

Table 3 illustrates the results of the fused features extracted by combining NasNeck and ResNeck, provided as input to the neural network classifiers. The investigation indicates that the WNN achieved the highest overall accuracy of 98.3%, demonstrating superior performance across evaluation metrics, with a precision of 0.983, recall of 0.983, and F1 score of 0.983. The MNN followed closely, achieving an accuracy of 98.1%, with corresponding metrics of precision (0.982), recall (0.981), and F1 score (0.981). The Bi-BNN and Tri-NN recorded the lowest accuracy of 97.3% and 96.7%, respectively. Among all classifiers, the MNN exhibited the shortest training time at 587.32 s, making it computationally efficient, while the Tri-NN required the longest training time at 1333.8 s. Fig. 4a illustrates the confusion matrix for the (WNN).

Figure 4: The confusion matrix for Wide Neural Network using (WNN) (a) fused features extracted by NasNeck and ResNeck. (b) and confusion matrix for Medium Neural Network (MNN) on optimized features

The impact of fusion is evident in the significant improvement in performance metrics across all classifiers compared to results achieved using single architectures. The fused features leverage the strengths of both NasNeck and ResNeck, resulting in enhanced accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 scores. This approach not only improves classification performance but also maintains a balanced trade-off between accuracy and computational efficiency, as seen in the superior performance of the WNN and MNN. Fusion effectively combines complementary information from both architectures, leading to a more robust and reliable system for classification tasks.

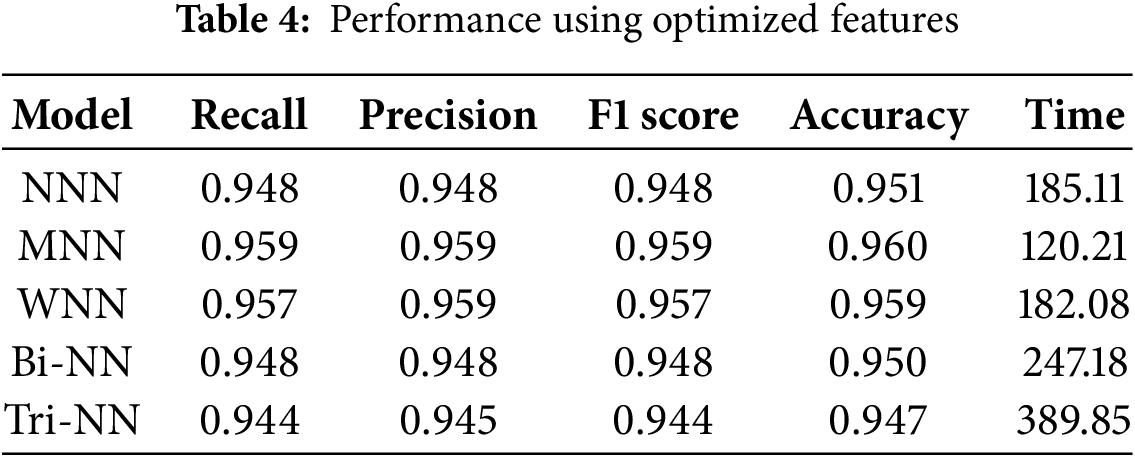

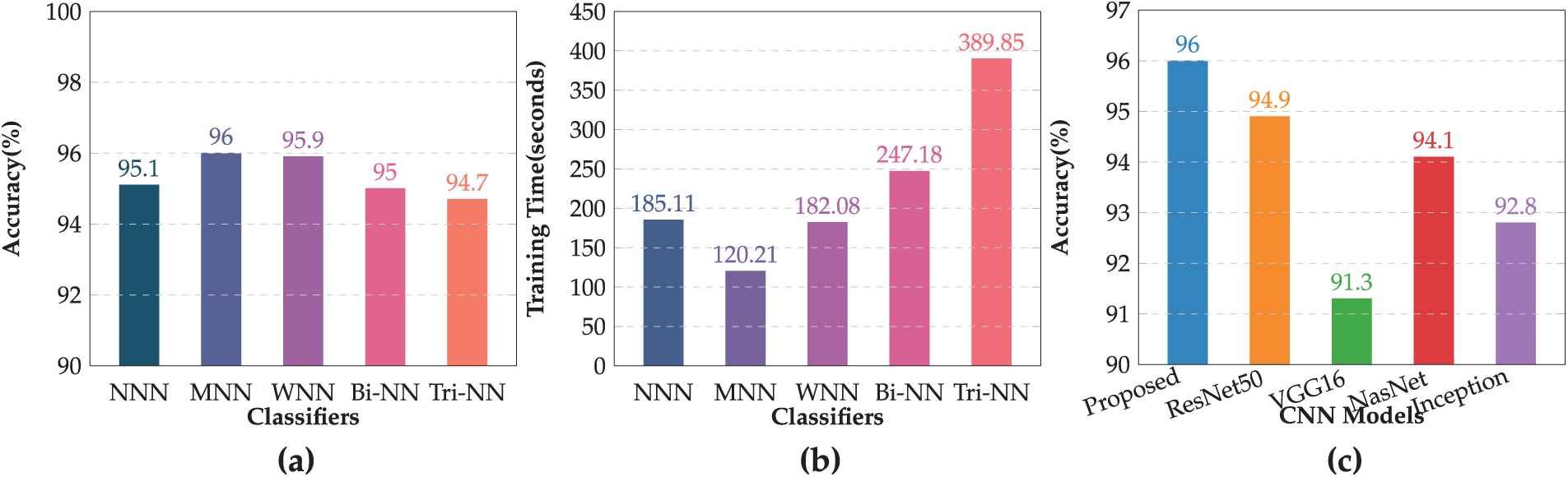

Table 4 illustrates the results of the fused features, optimized using IWOA, which were provided as input to the neural network classifiers. The investigation shows that the MNN achieved the highest overall accuracy of 96.0%, with precision, recall, and F1 score values of 0.959, demonstrating its superior performance among all classifiers. The WNN followed closely, achieving an accuracy of 95.9%, with corresponding metrics of precision (0.959), recall (0.957), and F1 score (0.957). The NNN achieved a moderate accuracy of 95.1%, while the Bi-NN and Tri-NN recorded accuracy of 95.0% and 94.7%, respectively. Fig. 4b illustrates the confusion matrix for the (MNN). To overcome overfitting, the IWOA was utilized to select the best features and to effectively reduce the redundancy and irrelevant information in the feature set. This approach ensured that the models were trained on the most relevant features and improved generalization. Furthermore, the optimization significantly reduced training time, with the MNN requiring the shortest training time of 120.21 s, followed closely by the WNN at 182.08 s. This demonstrates both computational efficiency and robust performance. These results underscore the effectiveness of feature optimization in improving classification performance while maintaining computational efficiency.

Models Comparison

This section presents the graphical representation of the results. Fig. 5a illustrates the bar chart depicting the accuracies of all classifiers in the evaluation of proposed methodology. Each classifier’s accuracy is represented with distinct colors. The MNN achieved the highest accuracy of 96.0%, demonstrating superior performance compared to other classifiers. WNN followed closely with an accuracy of 95.9%, while Tri-NN showed the lowest accuracy of 94.7%. Fig. 5b displays the bar chart for the training time required by each classifier under the proposed approach. Tri-NN consumed the highest time of 389.85 s, indicating greater computational complexity, whereas the MNN exhibited the least time cost of 120.21 s, showcasing its efficiency in training compared to other classifiers. Fig. 5b provides a clear comparison of both the accuracy and time efficiency for all classifiers, highlighting the trade-offs between accuracy and computational cost.

Figure 5: Performance of the proposed model: (a) Accuracy of all classifiers, (b) Training time comparison of classifiers, (c) Accuracy comparison of proposed model with pre-trained CNNs models

Fig. 5c presents the comparison of the accuracy achieved by the proposed model with several pre-trained CNN models. The evaluation included widely used architectures such as ResNet50, VGG16, NasnetMobile, and Inception V3. The results demonstrate that the proposed model outperformed all the pre-trained models and achieved the highest accuracy of 96.0%. Among the existing models, ResNet50 came closest with an accuracy of 94.9%, followed by NasnetMobile at 94.1%, and Inception V3 at 92.8%. VGG16, while effective, yielded the lowest accuracy at 91.3%. These findings highlight the effectiveness of the proposed methodology in achieving superior classification performance compared to conventional pre-trained CNN architectures. The proposed model not only delivers enhanced accuracy but also establishes its robustness and suitability for GI classification tasks.

4.2 Experiments on Kvasir V2 Dataset

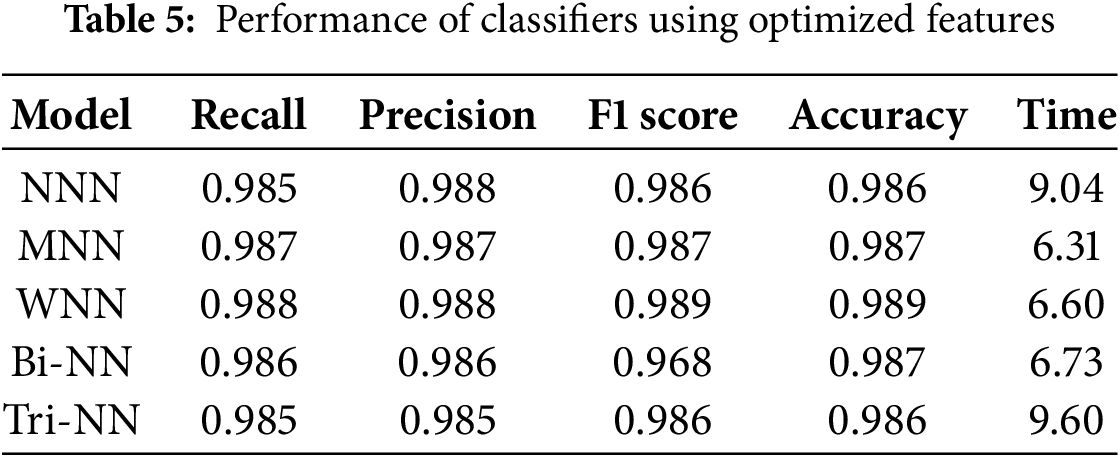

In this section, we evaluate our method on Kvasir V2 dataset. The results of the fused features, optimized using IWOA, which were provided as input to the neural network classifiers, are presented in Table 5. The investigation shows that the Wide Neural Network (WNN) achieved the highest overall accuracy of 98.9%, with precision, recall, and F1 score values of 0.988, 0.988, and 0.989, respectively, demonstrating its superior performance among all classifiers. The Medium Neural Network (MNN) followed closely, achieving an accuracy of 98.7%, with corresponding metrics of precision (0.987), recall (0.987), and F1 score (0.987). The Narrow Neural Network (NNN) and Tri-layered Neural Network (TNN) each recorded an accuracy of 98.6%, while the Bi-layered Neural Network (BNN) also matched the MNN with an accuracy of 98.7%.

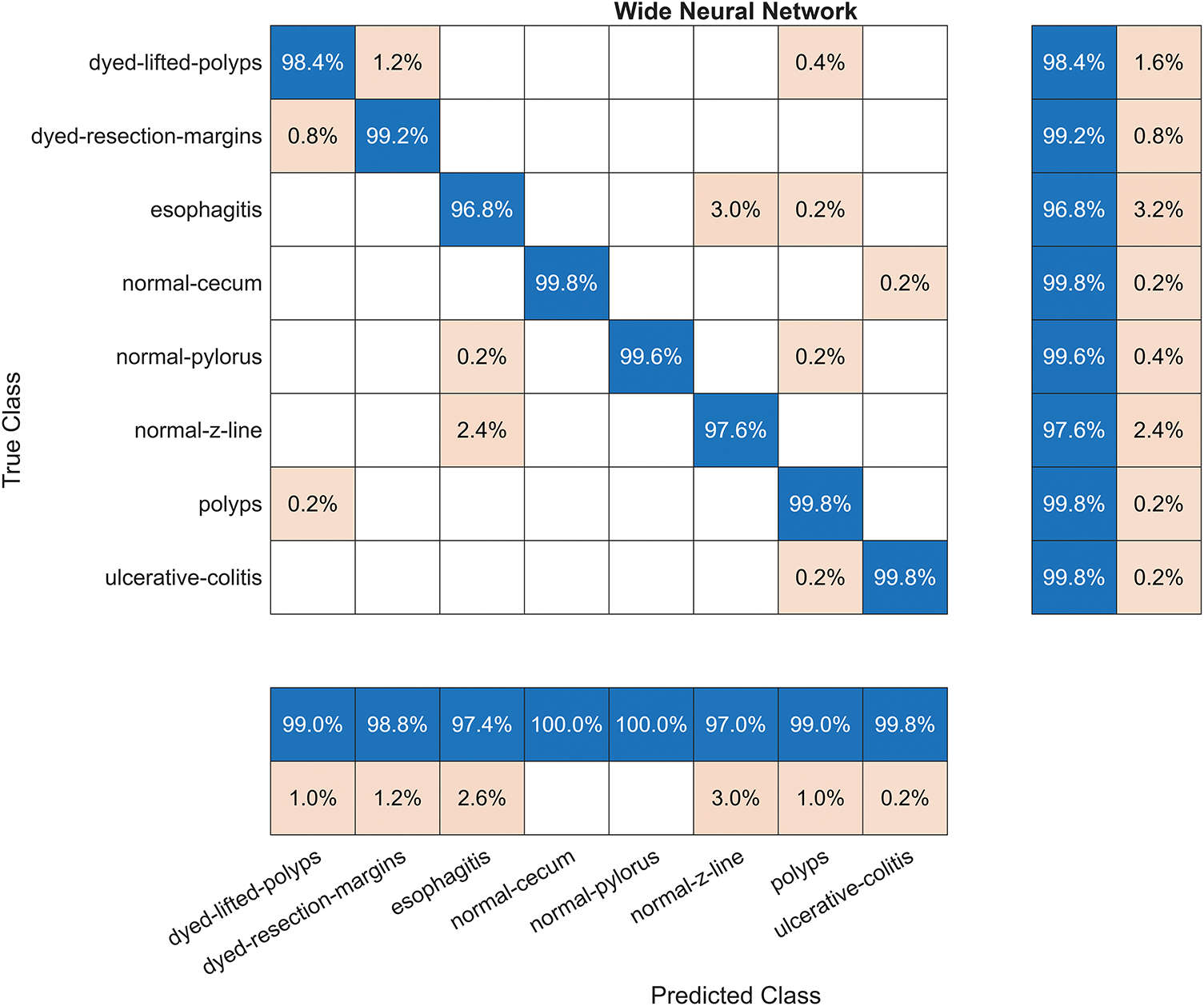

Fig. 6 illustrates the confusion matrix for the WNN.

Figure 6: The confusion matrix for the Wide Neural Network (WNN) using optimized features

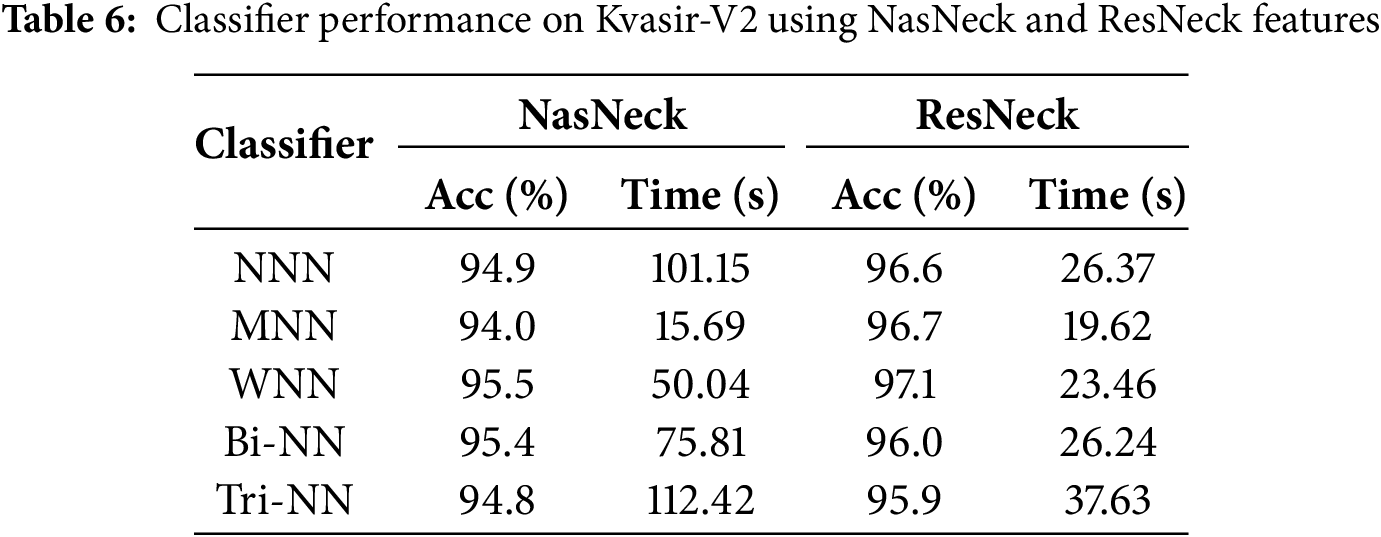

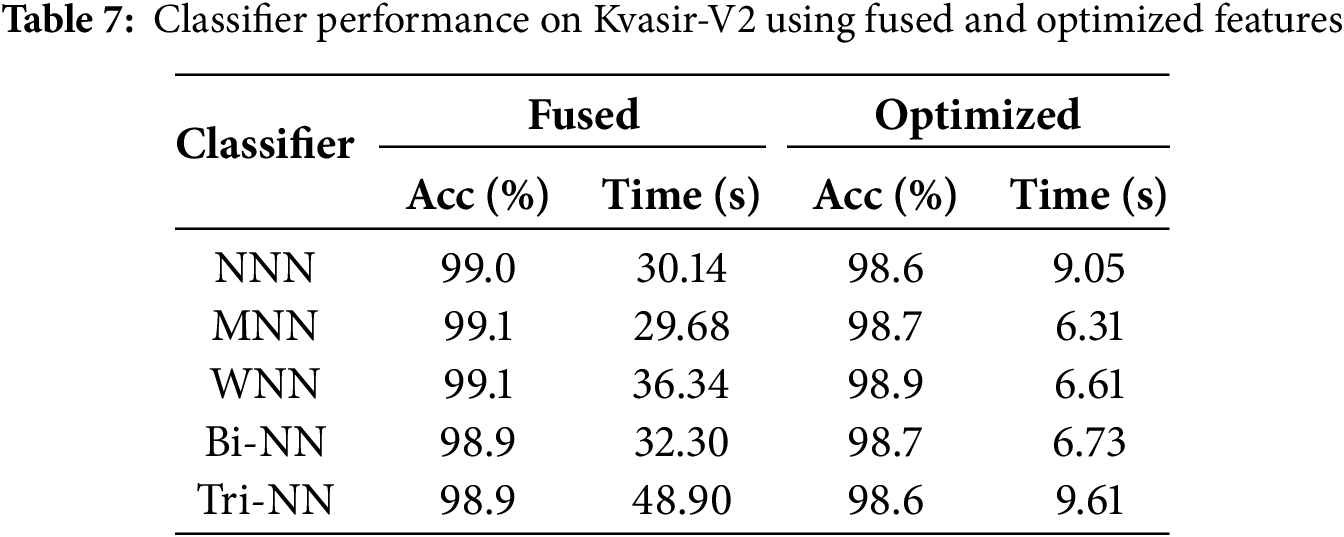

The results presented in Tables 6 and 7 represent intermediate steps in the evaluation process of the proposed framework on the Kvasir-V2 dataset. Table 6 outlines the performance of classifiers using features extracted individually by NasNeck and ResNeck, where the WNN achieved the highest accuracy of 97.1% with ResNeck. In contrast, Table 7 demonstrates the impact of feature fusion and IWOA-based optimization. The fused features resulted in a notable performance boost, with MNN and WNN both achieving a peak accuracy of 99.1%. Additionally, the proposed optimization method significantly reduced training time while preserving high classification accuracy. Overall, the MNN and WNN classifiers consistently offered the most effective balance between performance and efficiency across all configurations.

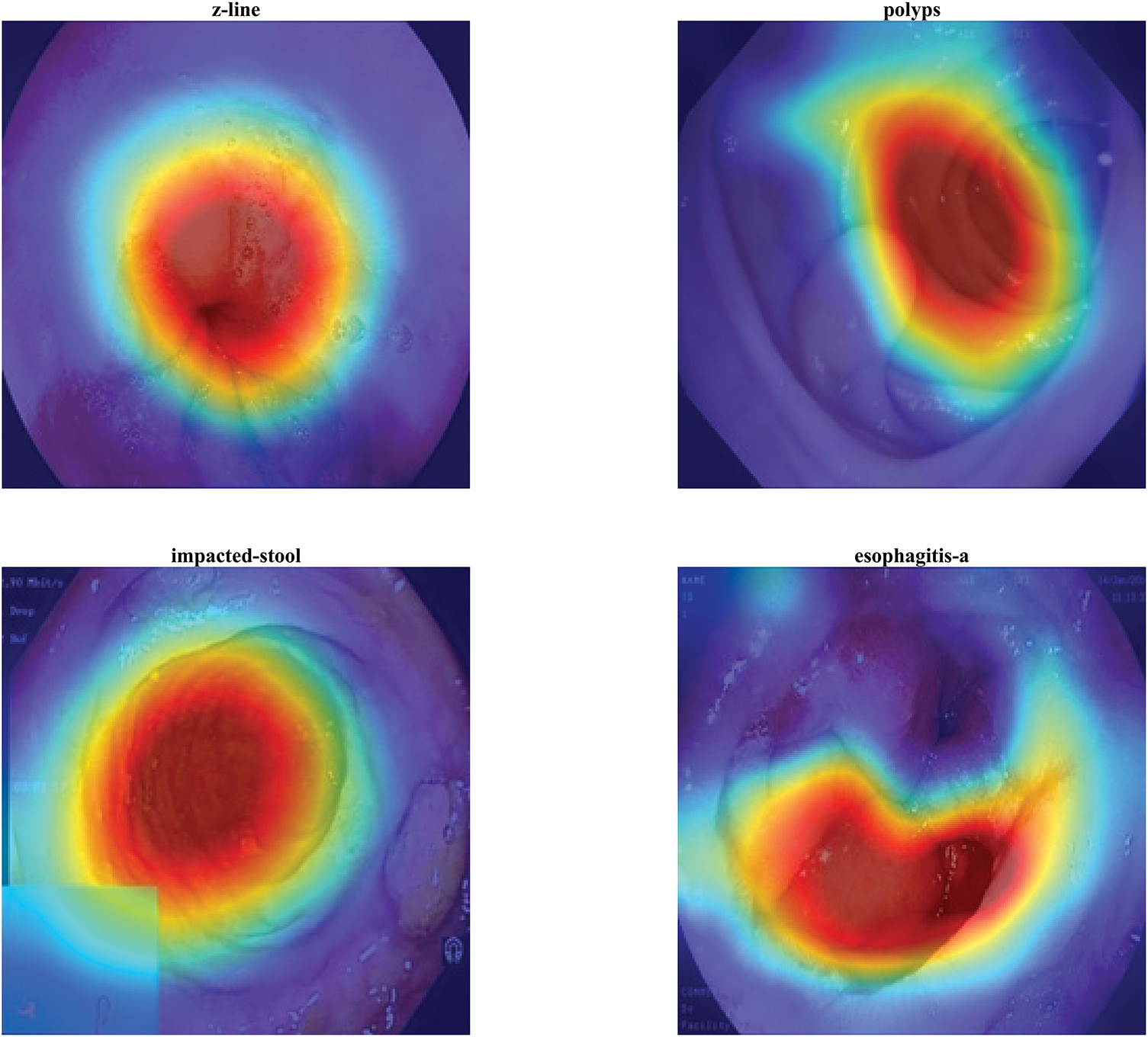

Explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) techniques, such as Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM), are employed to highlight the discriminative regions of medical images that contribute most to the model’s prediction, thereby enhancing interpretability and clinical trust. Fig. 7 illustrates Grad-CAM overlays for four representative gastrointestinal images, namely z-line, polyps, impacted-stool, and esophagitis-a. The heatmaps highlight the regions that the deep learning model considers most discriminative for classification, superimposed directly on the original endoscopic views. In the z-line image, strong activation is observed around the mucosal boundary, reflecting the clinical relevance of this region where pathological changes often arise. For the polyps sample, the highlighted red zone precisely corresponds to the polyp structure, confirming the model’s ability to localize small but clinically significant anomalies. The impacted-stool image shows consistent activation within the obstructed lumen area, which aligns with the irregular texture and density features. In the case of esophagitis-a, the overlay highlights the inflamed mucosal folds, which are characteristic of esophageal inflammation. These overlays provide an interpretable link between the model’s decision and the visible pathology, enhancing clinical trust and transparency in the diagnostic process.

Figure 7: 2D Grad-CAM overlays highlighting discriminative regions in z-line, polyps, impacted-stool, and esophagitis-a images

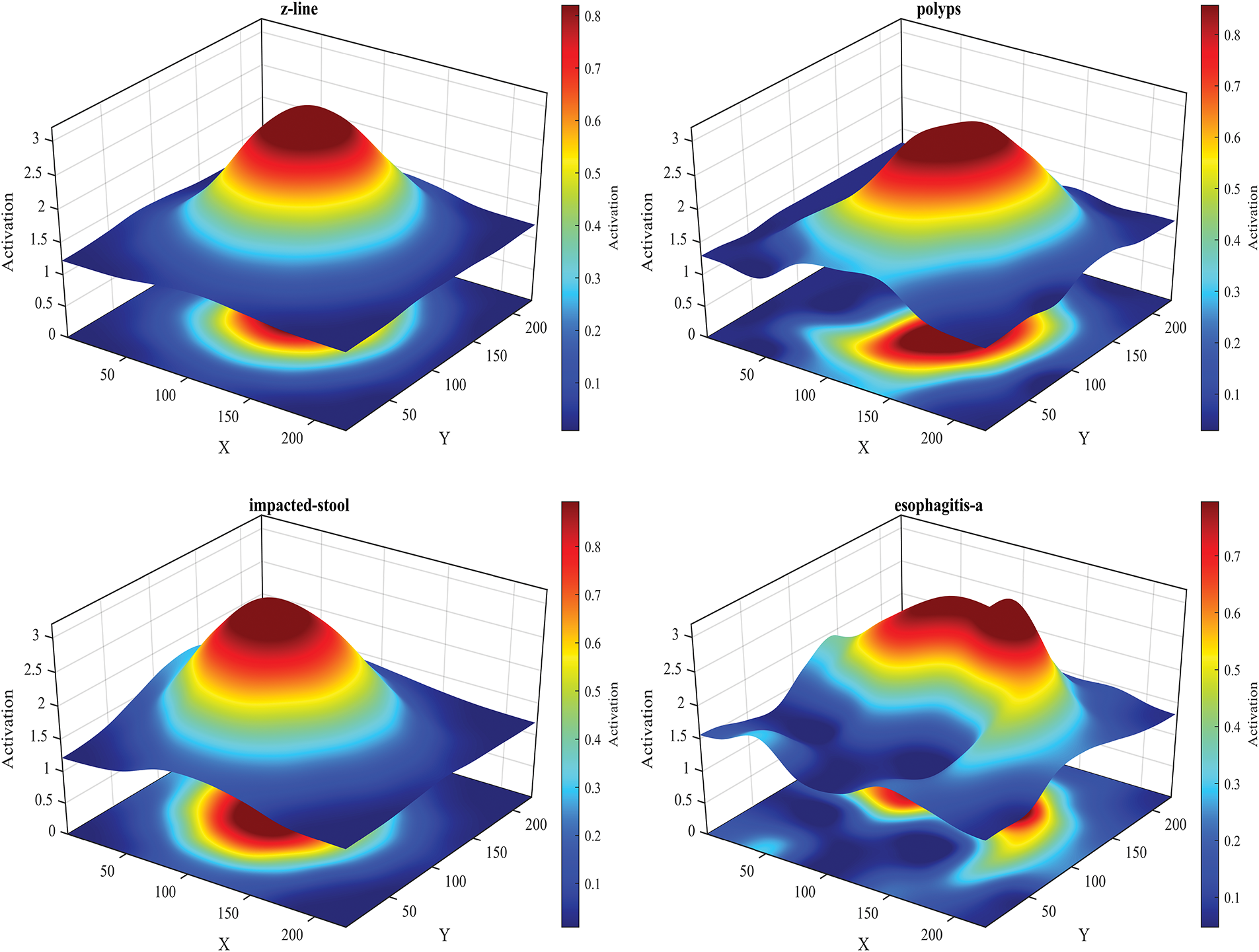

Fig. 8 presents 3D floating surface visualizations of Grad-CAM activations for the same four gastrointestinal classes: z-line, polyps, impacted-stool, and esophagitis-a. The addition of a lifted surface above the base heatmap allows both the intensity and the spatial distribution of network activations to be examined simultaneously. In the z-line case, a single prominent peak emerges at the mucosal boundary, reinforcing the clinical relevance of this region. For the polyps sample, the surface rises sharply over the polyp location, illustrating the model’s strong confidence and localized attention. The impacted-stool visualization shows a dense, rounded peak over the obstructed lumen, capturing the irregular blockage pattern with high activation strength. In contrast, esophagitis-a demonstrates a broader and less uniform elevation, consistent with the diffuse and patchy nature of esophageal inflammation. Compared to 2D overlays, this 3D representation provides a more quantitative view of feature importance, highlighting the magnitude of activations alongside their spatial distribution, which is particularly valuable for in-depth interpretability and model validation.

Figure 8: 3D Grad-CAM surface plots showing activation intensity and spatial distribution for z-line, polyps, impacted-stool, and esophagitis-a

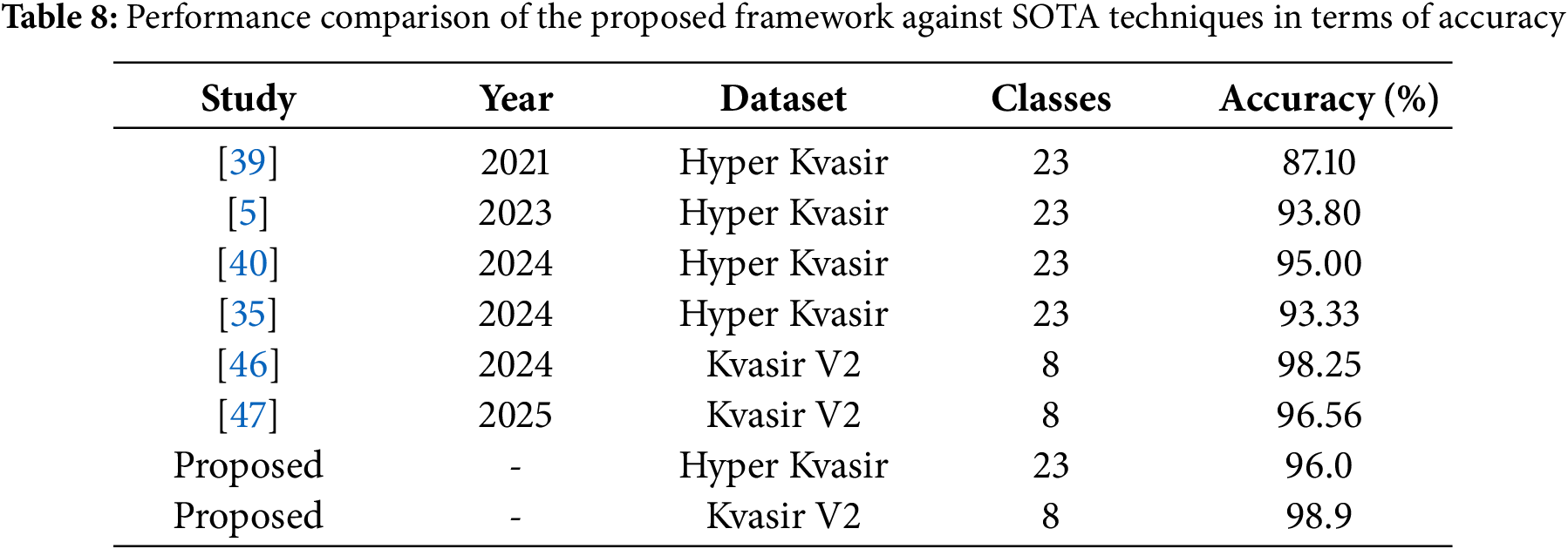

Lastly, Table 8 compares the results achieved in this study with recent state-of-the-art works. Reference [39] classified the Hyper-Kvasir dataset using 23 classes and achieved an accuracy of 87.10%. Similarly, reference [5] utilized the same dataset and number of classes, reporting an accuracy of 93.80%. Reference [40] achieved 95.00% accuracy with 23 classes, while reference [35] attained an accuracy of 93.33%. Reference [46] classified the Kvasir V2 dataset using 8 classes and achieved an accuracy of 98.25%. Similarly, reference [47] utilized the Kvasir v2 dataset reporting an accuracy of 96.56%. It is evident that the proposed framework outperforms all recent state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods, achieving the highest accuracy of 96.00% on the Hyper-Kvasir dataset with 23 classes and 98.90% on Kvasir V2 dataset.

To further strengthen the clinical relevance and robustness of the proposed DeepNeck framework, several aspects that can be improved in future research. Specifically, the importance of incorporating rigorous statistical validation to substantiate the superiority of this method. Moreover, the proposed framework can be evaluated on larger, more diverse, and clinically heterogeneous datasets, including cases from different imaging devices, clinical centers, and rare disease classes. This will allow to validate the adaptability of DeepNeck to real-world conditions. In addition, computational efficiency will be systematically examined in future work by reporting GPU latency, inference speed, training time, and memory consumption to ensure practical feasibility for integration into real-time clinical applications.

Accurate diagnosis of gastrointestinal (GI) tract diseases is vital for effective treatment. In this study, we proposed a deep learning framework that addresses key challenges in medical image classification, particularly class imbalance, feature redundancy, and multi-class discrimination. The proposed method integrates feature extraction using two convolutional neural networks—NasNeck and ResNeck—followed by feature fusion through a correlation-based strategy and dimensionality reduction using an Improved Whale Optimization Algorithm (IWOA). The optimized feature vector is then used for classification via neural networks, achieving classification accuracies of 96.0% on the Hyper-Kvasir dataset and 98.9% on the Kvasir V2 dataset. The framework demonstrated the following core strengths: (1) Data augmentation contributed to mitigate class imbalance and enhanced generalization, (2) Feature fusion from NasNeck and ResNeck networks yielded a more diverse and representative feature space, (3) The IWOA-based feature selection reduced the original fused feature dimension (from 3104 to 706) and improved both accuracy and efficiency, (4) Neural network classifiers trained on the optimized features outperformed comparable models in benchmark comparisons. Although this study proposed the modular pipeline design to enable flexible deployment—such as the use of pre-trained features with or without further optimization—no formal ablation studies were conducted to isolate the contributions of individual components. This gap remains a priority for future work to substantiate the modularity claim. Likewise, the assertion of computational efficiency on GPUs or edge devices is not supported by detailed latency and memory profiles. A comprehensive benchmark of inference time, GPU utilization, and memory footprint is essential to rigorously evaluate the feasibility of real-time deployment.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work is supported by Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia through the Researchers Supporting Project PNURSP2025R333.

Author Contributions: Formal analysis, Methodology, and Writing—original draft of the article: Sidra Naseem; Methodology, Supervision, and Writing—original draft of the article: Rashid Jahangir; Conceptualization, Funding, and Visualization: Nazik Alturki; Validation, Visualization, Review the article: Faheem Shehzad; Conceptualization, Visualization, Review the article: Muhammad Sami Ullah. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in [OSF] at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/MH9SJ (accessed on 13 November 2024) and in [ACM] at https://dl.acm.org/do/10.1145/3193289/full/ (accessed on 13 November 2024).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Sharma N, Sharma A, Gupta S. A comprehensive review for classification and segmentation of gastro intestine tract. In: 2022 6th International Conference on Electronics, Communication and Aerospace Technology; 2022 Dec 1–3; Coimbatore, India. p. 1493–9. [Google Scholar]

2. Sharmila Joseph J, Vidyarthi A. Multiclass gastrointestinal diseases classification based on hybrid features and duo feature selection. J Biomed Nanotechnol. 2023;19(2):288–98. doi:10.1166/jbn.2023.3533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Ayyaz MS, Lali MIU, Hussain M, Rauf HT, Alouffi B, Alyami H, et al. Hybrid deep learning model for endoscopic lesion detection and classification using endoscopy videos. Diagnostics. 2021;12(1):43. doi:10.3390/diagnostics12010043. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Mohapatra S, Pati GK, Mishra M, Swarnkar T. Gastrointestinal abnormality detection and classification using empirical wavelet transform and deep convolutional neural network from endoscopic images. Ain Shams Eng J. 2023;14(4):101942. doi:10.1016/j.asej.2022.101942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Haseeb A, Khan MA, Alhaisoni M, Aldehim G, Jamel L, Tariq U, et al. A fusion of residual blocks and stack auto encoder features for stomach cancer classification. Comput Mater Contin. 2023;77(3):3895–920. doi:10.32604/cmc.2023.045244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Shao J, Chen S, Zhou J, Zhu H, Wang Z, Brown M. Application of U-Net and optimized clustering in medical image segmentation: a review. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2023;136(3):2173–219. doi:10.32604/cmes.2023.025499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Arnold M, Abnet CC, Neale RE, Vignat J, Giovannucci EL, McGlynn KA, et al. Global burden of 5 major types of gastrointestinal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2020;159(1):335–49. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.068. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Hmoud Al-Adhaileh M, Mohammed Senan E, Alsaade FW, Aldhyani THH, Alsharif N, Abdullah Alqarni A, et al. Deep learning algorithms for detection and classification of gastrointestinal diseases. Complexity. 2021;2021(1):6170416. doi:10.1155/2021/6170416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Iddan G, Meron G, Glukhovsky A, Swain P. Wireless capsule endoscopy. Nature. 2000;405(6785):417–7. doi:10.1038/35013140. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Alsunaydih FN, Redouté JM, Yuce MR. A locomotion control platform with dynamic electromagnetic field for active capsule endoscopy. IEEE J Transl Eng Health Med. 2018;6:1–10. doi:10.1109/jtehm.2018.2837895. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Cao Q, Deng R, Pan Y, Liu R, Chen Y, Gong G, et al. Robotic wireless capsule endoscopy: recent advances and upcoming technologies. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):4597. doi:10.1038/s41467-024-49019-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Alam MW, Hasan MM, Mohammed SK, Deeba F, Wahid KA. Are current advances of compression algorithms for capsule endoscopy enough? A technical review. IEEE Rev Biomed Eng. 2017;10:26–43. doi:10.1109/rbme.2017.2757013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Saba T, Khan MA, Rehman A, Marie-Sainte SL. Region extraction and classification of skin cancer: a heterogeneous framework of deep CNN features fusion and reduction. J Med Syst. 2019;43(9):289. doi:10.1007/s10916-019-1413-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Iakovidis DK, Georgakopoulos SV, Vasilakakis M, Koulaouzidis A, Plagianakos VP. Detecting and locating gastrointestinal anomalies using deep learning and iterative cluster unification. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2018;37(10):2196–210. doi:10.1109/tmi.2018.2837002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Ghatwary N, Ye X, Zolgharni M. Esophageal abnormality detection using densenet based faster r-cnn with gabor features. IEEE Access. 2019;7:84374–85. doi:10.1109/access.2019.2925585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Münzer B, Schoeffmann K, Böszörmenyi L. Content-based processing and analysis of endoscopic images and videos: a survey. Multimed Tools Appl. 2018;77(1):1323–62. doi:10.1007/s11042-016-4219-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Li B, Meng MQH. Computer-based detection of bleeding and ulcer in wireless capsule endoscopy images by chromaticity moments. Comput Biol Med. 2009;39(2):141–7. doi:10.1016/j.compbiomed.2008.11.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Khan MA, Sahar N, Khan WZ, Alhaisoni M, Tariq U, Zayyan MH, et al. GestroNet: a framework of saliency estimation and optimal deep learning features based gastrointestinal diseases detection and classification. Diagnostics. 2022;12(11):2718. doi:10.3390/diagnostics12112718. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Khan MA, Javed MY, Sharif M, Saba T, Rehman A. Multi-model deep neural network based features extraction and optimal selection approach for skin lesion classification. In: 2019 International Conference on Computer and Information Sciences (ICCIS); 2019 Apr 3–4; Sakaka, Saudi Arabia. [Google Scholar]

20. Szegedy C, Ioffe S, Vanhoucke V, Alemi A. Inception-v4, inception-resnet and the impact of residual connections on learning. In: Proceedings of the 31th AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2017 Feb 4–9; San Francisco, CA, USA. p. 4278–84. [Google Scholar]

21. Krizhevsky A, Sutskever I, Hinton GE. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. In: Advances in neural information processing systems. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press; 2012. doi:10.1145/3065386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Gómez-Zuleta MA, Cano-Rosales DF, Bravo-Higuera DF, Ruano-Balseca JA, Romero-Castro E. Artificial intelligence techniques for the automatic detection of colorectal polyps. Revista Colombiana de Gastroenterología. 2021;36(1):7–16. [Google Scholar]

23. Pontabry J, Rousseau F, Studholme C, Koob M, Dietemann JL. A discriminative feature selection approach for shape analysis: application to fetal brain cortical folding. Med Image Anal. 2017;35(12):313–26. doi:10.1016/j.media.2016.07.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Kishore MR. An effective and efficient feature selection method for lung cancer detection. Int J Comput Sci Inf Technol (IJCSIT). 2015;7(4):135–41. [Google Scholar]

25. Mirjalili S, Lewis A. The whale optimization algorithm. Adv Eng Softw. 2016;95(12):51–67. doi:10.1016/j.advengsoft.2016.01.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Sivanandam S, Deepa S, Sivanandam S, Deepa S. Genetic algorithm optimization problems. In: Introduction to genetic algorithms. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2008. p. 165–209. [Google Scholar]

27. Sharif M, Amin J, Raza M, Yasmin M, Satapathy SC. An integrated design of particle swarm optimization (PSO) with fusion of features for detection of brain tumor. Pattern Recognit Lett. 2020;129:150–7. doi:10.1016/j.patrec.2019.11.017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Nagra AA, Khan AH, Abubakar M, Faheem M, Rasool A, Masood K, et al. A gene selection algorithm for microarray cancer classification using an improved particle swarm optimization. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):19613. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-68744-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Khan MA, Alhaisoni M, Tariq U, Hussain N, Majid A, Damaševičius R, et al. COVID-19 case recognition from chest CT images by deep learning, entropy-controlled firefly optimization, and parallel feature fusion. Sensors. 2021;21(21):7286. doi:10.3390/s21217286. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Khan MU, Samer S, Alshehri MD, Baloch NK, Khan H, Hussain F, et al. Artificial neural network-based cardiovascular disease prediction using spectral features. Comput Electr Eng. 2022;101:108094. doi:10.1016/j.compeleceng.2022.108094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Noor MN, Nazir M, Ashraf I, Almujally NA, Aslam M, Fizzah Jilani S. GastroNet: a robust attention-based deep learning and cosine similarity feature selection framework for gastrointestinal disease classification from endoscopic images. CAAI Trans Intell Technol. 2023. doi:10.1049/cit2.12231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Borgli H, Thambawita V, Smedsrud PH, Hicks S, Jha D, Eskeland SL, et al. HyperKvasir, a comprehensive multi-class image and video dataset for gastrointestinal endoscopy. Sci Data. 2020;7(1):283. doi:10.1038/s41597-020-00622-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Tekin R, Onur TÖ. Binary classification of Alzheimer’s disease using siamese neural network for early stage diagnosis. Celal Bayar University J Sci. 2025;21(2):152–8. [Google Scholar]

34. Tekin R, Onur TÖ. Classification of Alzheimer’s disease with efficientNet B3. Bozok J Eng Archit. 2024;3(2):68–77. [Google Scholar]

35. Saba N, Zafar A, Suleman M, Zafar K, Zafar S, Saleem AA, et al. A synergistic approach to colon cancer detection: leveraging efficientNet and NSGA-II for enhanced diagnostic performance. IEEE Access. 2024;12:192264–78. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3519216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Rubab S, Jamshed M, Khan MA, Almujally NA, Damaševičius R, Hussain A, et al. Gastrointestinal tract disease classification from wireless capsule endoscopy images based on deep learning information fusion and Newton Raphson controlled marine predator algorithm. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):32180. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-17204-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Patel V, Patel K, Goel P, Shah M. Classification of gastrointestinal diseases from endoscopic images using convolutional neural network with transfer learning. In: 5th International Conference on Intelligent Communication Technologies and Virtual Mobile Networks (ICICV); 2024 Mar 11–12; Tirunelveli, India. p. 504–8. [Google Scholar]

38. Haile MB, Salau AO, Enyew B, Belay AJ. Detection and classification of gastrointestinal disease using convolutional neural network and SVM. Cogent Eng. 2022;9(1):2084878. doi:10.1080/23311916.2022.2084878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Wu X, Chen C, Zhong M, Wang J. HAL: hybrid active learning for efficient labeling in medical domain. Neurocomputing. 2021;456(5):563–72. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2020.10.115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Wu X, Li Z, Tao C, Han X, Chen YW, Yao J, et al. DEA: data-efficient augmentation for interpretable medical image segmentation. Biomed Signal Process Control. 2024;89(8):105748. doi:10.1016/j.bspc.2023.105748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Iqbal I, Walayat K, Kakar MU, Ma J. Automated identification of human gastrointestinal tract abnormalities based on deep convolutional neural network with endoscopic images. Intell Syst Appl. 2022;16(4):200149. doi:10.1016/j.iswa.2022.200149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Iqbal I, Younus M, Walayat K, Kakar MU, Ma J. Automated multi-class classification of skin lesions through deep convolutional neural network with dermoscopic images. Comput Med Imaging Graph. 2021;88:101843. doi:10.1016/j.compmedimag.2020.101843. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Pogorelov K, Randel KR, Griwodz C, Eskeland SL, de Lange T, Johansen D, et al. Kvasir: a multi-class image dataset for computer aided gastrointestinal disease detection. In: Proceedings of the 8th ACM on Multimedia Systems Conference; 2017 Jun 20–23; Taipei, Taiwan. p. 164–9. [Google Scholar]

44. Kim YT. Contrast enhancement using brightness preserving bi-histogram equalization. IEEE Trans Consum Electr. 1997;43(1):1–8. doi:10.1109/30.580378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Mohan KR, Thirugnanam G. A dualistic sub-image histogram equalization based enhancement and segmentation techniques for medical images. In: 2013 IEEE Second International Conference on Image Information Processing (ICIIP-2013); 2013 Dec 9–11; Shimla, India. p. 566–9. [Google Scholar]

46. Khan ZF, Ramzan M, Raza M, Khan MA, Iqbal K, Kim T, et al. Deep convolutional neural networks for accurate classification of gastrointestinal tract syndromes. Comput Mater Contin. 2024;78(1):1207–25. doi:10.32604/cmc.2023.045491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Raju ASN, Venkatesh K, Gatla RK, Hussain SJ, Polamuri SR. Medivision: empowering colorectal cancer diagnosis and tumor localization through supervised learning classifications and grad-CAM visualization of medical colonoscopy images. Cogn Comput. 2025;17(2):1–39. doi:10.1007/s12559-025-10433-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools