Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

ORTHRUS: A Model for a Decentralized and Fair Data Marketplace Supporting Two Types of Output

1 Department of Information Security, Graduate School, Pukyong National University, Busan, 48513, Republic of Korea

2 Division of Computer Engineering and Artificial Intelligence, Pukyong National University, Busan, 48513, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Sang Uk Shin. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Cutting-Edge Security and Privacy Solutions for Next-Generation Intelligent Mobile Internet Technologies and Applications)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(2), 2787-2819. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.072602

Received 30 August 2025; Accepted 30 October 2025; Issue published 26 November 2025

Abstract

To reconstruct vehicle accidents, data from the time of the incident—such as pre-collision speed and collision point—is essential. This data is collected and generated through various sensors installed in the vehicle. However, it may contain sensitive information about the vehicle owner. Consequently, vehicle owners tend to be reluctant to provide their vehicle data due to concerns about personal information exposure. Therefore, extensive research has been conducted on secure vehicle data trading models. Existing models primarily utilize centralized approaches, leading to issues such as single points of failure, data leakage, and manipulation. To address these problems, this paper proposes ORTHRUS, a blockchain-based vehicle data trading marketplace that ensures transparency, traceability, and decentralization. The proposed model accommodates two categories of output data: the original data and the computed result from the function. Additionally, in the proposed model, data owners retain control over their data, enabling them to directly choose which types of data to provide. By employing Multi-party computation (MPC) technique, MOZAIK architecture, and the random leader selection technique, the proposed scheme, ORTHRUS, guarantees the input privacy and resistance to pre-collusion attacks. Furthermore, the proposed model promotes fairness by identifying dishonest behavior among participants by enforcing penalties and rewards through the implementation of smart contracts.Keywords

As digital technologies advance, the volume of data is experiencing exponential growth [1]. Consequently, challenges associated with data collection, storage, and management have become increasingly prominent. In response to these challenges, data sharing and trading have commenced through user interactions. This phenomenon has given rise to the concept of “data space”. A data space is defined as a distributed system that is governed by a framework ensuring trust and data sovereignty [2]. It is essential for such a system to provide a wide variety of data types and formats, along with tools for searching, querying, and managing all data contained within the data space. This paper presents a vehicle data space specifically tailored for the Internet of Vehicles (IoV) environment, with a particular focus on vehicle data. The IoV constitutes a dynamic network infrastructure that facilitates the connection of vehicles, users, and various smart devices to the internet [3]. Within the IoV ecosystem, vehicles are capable of collecting and generating diverse types of data, encompassing both vehicle-specific information and environmental data, through interactions with onboard sensors and external factors. Each entity within the IoV ecosystem engages in the sharing or trading of its collected and generated vehicle data, thereby creating new value and enhancing user services. However, current methodologies for data sharing and trading are predominantly centralized, which presents several challenges, including a single point of failure, data leakage and manipulation, as well as concerns regarding data confidentiality. To mitigate these challenges, research has been undertaken to explore data sharing and trading within a blockchain framework. Blockchain technology enables reliable data trading by providing several benefits, including transparency, traceability, decentralization, and non-repudiation [4,5]. However, security vulnerabilities in the data storage process continue to exist, resulting in challenges such as data leakage, tampering, and breaches of privacy. Furthermore, entities currently seeking to trade vehicle data rely on the data trading marketplace they participate in. This means vehicle data owners lack ownership, control, or management rights over their own data. Consequently, issues such as privacy protection, data confidentiality, and data resale arise. Additionally, relying on a data trading marketplace means adhering to the data provision methods supported by that model. This means that data owners cannot trade their data in the manner they desire. If a data owner desires to trade data in a specific manner, they must seek out a data trading marketplace that supports that method. This hinders user convenience. Furthermore, users seeking diverse data computation results must participate in multiple data trading marketplace. This necessitates providing their information to various marketplaces, thereby creating privacy-related concerns. In this paper, we introduce ORTHRUS, a blockchain-based model for vehicle data trading that prioritizes privacy protection. The proposed model accommodates two categories of output data: the original data and the computed result from the function. Scenarios that necessitate these types of output data include:

• Original data: One of the most common forms of raw vehicle data is video data. For example, video data recorded from dashcams can serve as objective evidence in legal proceedings for various cases, such as actual traffic accidents and vehicle theft. In addition, actual traffic accident videos or image data recorded by the dashcam can be used as training data for autonomous vehicle traffic accident detection models. The dashcam video data that perform these functions must not be forged, altered, or modified, and must remain original.

• The computed result from the function: The computed result from the function is a value obtained from the aggregation of multiple vehicle data points, rather than relying on data from a single vehicle. This is crucial for autonomous driving services, including motion planning, vehicle route prediction, and driver behavior prediction, among others. For instance, to enhance driving security across diverse traffic scenarios, autonomous vehicles employ predictive techniques and decision-making algorithms. To support these algorithms, it is necessary to utilize and compute a variety of vehicle data, including vehicle speed, brake pressure, and driver behavior.

The contributions in this paper are as follows:

1. Ensure fairness: The proposed model promotes fairness by identifying dishonest behavior among participants utilizing commitment and signature techniques. Additionally, it enforces penalties and rewards through the implementation of smart contracts.

2. Protecting input privacy: Input privacy refers to the concealment of transaction data supplied by the data owner from both the data requestor and the computation node responsible for executing the computational process [6]. The proposed model limits the access and acquisition of the original data by all participants, allowing only the computation result of a function to be disclosed as the final output. Futhermore, access to the original data is granted to legitimate participants only when the provision of the original data is permitted.

3. Preventing pre-collusion attacks: The proposed model mitigates the risk of pre-collusion attacks by employing random leader selection techniques to randomly designate computation nodes for participation in the computation process. Specifically, it is probably very low to predict in advance that a given node is selected as a computation node. Consequently, even if malicious nodes were to collude, the likelihood of their selection for participation in the actual computation process remains exceedingly low.

4. Ensure data sovereignty: Data sovereignty pertains to the allocation of control over personal data to the individual data owner [7]. In the proposed model, data owners retain authority over their data and possess the ability to determine the method of data delivery.

This paper is structured as follows: Section 2 presents the cryptographic techniques utilized in the proposed model, while Section 3 delineates the operational procedures of the model in a step-by-step manner. Section 4 discusses the implementation of the proposed model, along with the results and analysis derived from this implementation. Finally, Section 5 offers a conclusion to the paper.

Khan et al. [8] introduced BELIEVE, a blockchain platform based on multi-party computation (MPC) [9], which serves as a framework for efficient verification via location identification and encryption. BELIEVE employs an adaptive strategy that empowers data sources to autonomously ascertain the timing of verification and the specifics of their trajectories. Additionally, it utilizes smart contracts to facilitate the verification of mobility data. The platform also guarantees privacy through an MPC-based consensus mechanism among proximate mobile peers, thereby eliminating the need to share original data.

Li et al. [10] introduced a Blockchain-based Speed Advisory System (BSAS), which enhances the existing Consensus-based Speed Advisory System (CSAS) by integrating blockchain technology. This integration aims to establish a trustworthy framework that prioritizes user privacy. BSAS employs cryptographic primitives to safeguard the confidentiality of the

Golob et al. [6] proposed a decentralized data marketplace that prioritizes input and output privacy within a blockchain framework. This marketplace guarantees payment fairness by automatically compensating data providers with cryptocurrency tokens. Additionally, it employs two privacy techniques—secure multi-party computation (MPC) and robust differential privacy guarantees—to facilitate a privacy-centric data exchange.

Yuan et al. [11] proposed TRUCON, a blockchain-based data sharing mechanism designed to facilitate congestion control and data deduplication within Internet of Vehicles (IoV) environments. TRUCON employs the Kademlia algorithm, enabling source vehicles to restrict the number of reference vehicles involved in the transmission of traffic data. Additionally, it incorporates a Cuckoo Filter-based deduplication technique to mitigate unnecessary data sharing. This approach enhances both the integrity and reliability of data sharing, while simultaneously improving network efficiency.

Sadiq et al. [12] proposed a data trading model based on the Internet of Vehicles (IoV) that guarantees secure data storage and the privacy of vehicles within a blockchain framework. The model employs a digital signature scheme grounded in elliptic curve bilinearity to ensure the authenticity and integrity of the trading data. Additionally, it utilizes smart contracts that are autonomously executed between trading parties to address payment disputes and ensure the fulfillment of payment obligations.

This chapter provides an overview of Multi-Party Computation (MPC) [9] and the MOZAIK architecture [13] as they pertain to ORTHRUS. Additionally, it outlines the fundamental cryptographic primitives utilized in this context.

First introduced by Yao in the 1980s, secure multi-party computation (MPC) is a versatile cryptographic technique that enables multiple distributed participants to collaboratively compute arbitrary functions while maintaining the confidentiality of their private inputs and outputs [9]. This process ensures privacy, as each participant remains unaware of the input data of the other participants, and the output of the computation cannot be deduced from the input data of others. Additionally, consistency is assured in that honest participants will obtain identical computational results. The ORTHRUS employs Multi-Party Computation (MPC) grounded in the principles of Secret Sharing, facilitating participant interaction while maintaining data confidentiality. Secret Sharing is a method that protects confidential input data within various MPC frameworks, enabling the division of secret input data or multiple confidential inputs into several shares [14]. This paper adopts the SPDZ protocol as a representative technique based on Secret Sharing for the implementation of MPC.

SPDZ Protocol

In the SPDZ protocol, the values exchanged among all participants are shares produced through a secret sharing technique, which are subsequently utilized for circuit evaluation [15]. The SPDZ framework is comprised of three distinct phases: an offline phase, an online phase, and a phase dedicated to output and verification.

• Offline phase: This phase, commonly referred to as the preprocessing stage, produces a set of shared random numbers utilized for the purpose of masking confidential input data [15]. Additionally, it executes a multiplication operation to create a predominant multiplication triple

• Online phase: This phase entails the collaborative computation of arithmetic circuits utilizing secretly shared input data, which encompasses operations such as addition, multiplication, and Message Authentication Codes (MAC) [15].

1. Addition: Given secretly shared values

–

–

–

2. Multiplication: Given a value that is shared in secrecy, the objective is to compute the product of these values, which includes the multiplication of triples. We define a multiplication triple as the ordered set

– Compute

– Compute

– Finally, compute

3. MAC: The SPDZ protocol employs the Message Authentication Code (MAC) technique to protect messages from dishonest parties [15]. The MAC key is established as a global variable that remains unknown to the participants and is shared in a confidential manner. All secret data are encoded in a manner that incorporates the MAC, rendering the resultant value challenging to alter without the consensus of the other participants. Consequently, by verifying the MAC, it is possible to detect dishonest behavior and ensure the integrity of the data.

• Output and Verification phase: This phase involves the verification of all published numerical data and final output values through the use of Message Authentication Code (MAC). Verification can be conducted in batches utilizing a randomized linear combination. In the event of a discrepancy during the MAC verification phase, the protocol will be terminated.

The primary algorithms of the MOZAIK architecture are developed utilizing secret sharing techniques [13] and the AEAD (Symmetric Authenticated Encrypted with Associated Data) algorithm [16].

The secret sharing mechanism employed in the MOZAIK architecture is based on threshold-based secret sharing. This method involves partitioning a single source of data into

The AEAD [16] is a cryptographic technique that combines encryption of the original data with the generation of an authentication tag alongside the ciphertext. This authentication tag serves to verify both the integrity and confidentiality of the data. The underlying algorithm is represented by the encryption algorithm

The main algorithms of the MOZAIK architecture based on this are the key generation algorithm

•

•

•

The proposed model applies the following cryptographic primitives.

1. A cryptographically secure hash function

2. A semantically secure symmetric cipher consisting of

3. An asymmetric cipher that is semantically secure against a chosen ciphertext attack consisting of

4. An existential unforgeability under chosen message attack (EU-CMA) secure electronic signature technique consisting of a polynomial-time algorithm

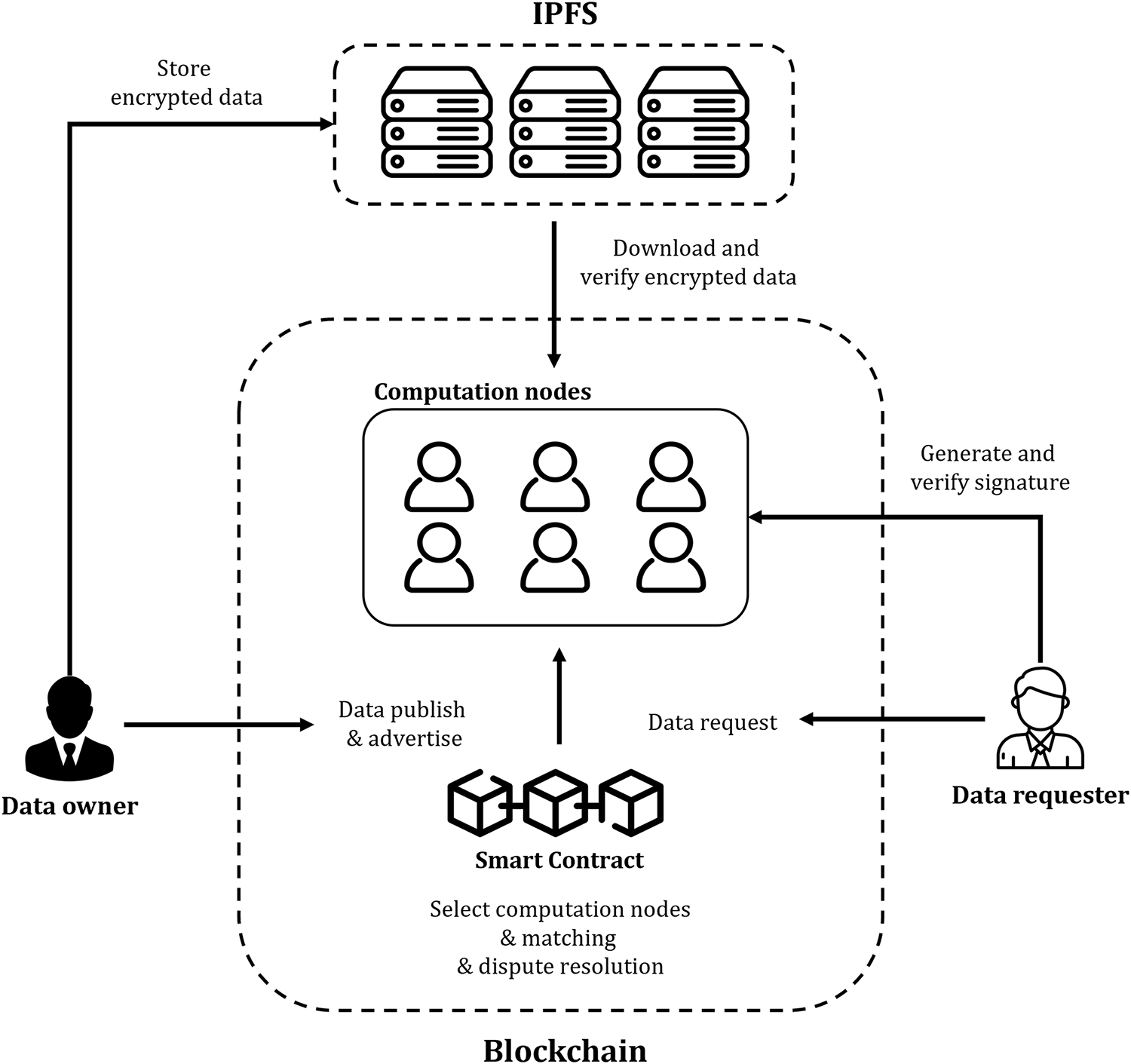

In this chapter, we introduce ORTHRUS, a model for vehicle data transactions that preserves privacy while accommodating two types of output data within a public blockchain framework. Fig. 1 shows an overview of the model proposed in this paper.

Figure 1: Overview of the proposed model

The ORTHRUS framework comprises several key components, including the Data Owner (DO), Data Requester (DR), Computation Node (CN), Smart Contract (SC) and the Interplanetary File System (IPFS). The DO is a participant who deploys the smart contracts defined in the proposed model on the blockchain and engages in trading their own data. Conversely, the DR refers to a participant who, within the blockchain peer-to-peer network, acquires data from a DO holding the required information in exchange for a fair price. The CNs are the entities actively engaged in computation, selected at random by the smart contract to participate in the computational process. These nodes serve as actual computation participants and are incentivized based on the correctness of their computations at the conclusion of the transaction. Each time a transaction is initiated, these DO, DR, and CN generate key pairs for transactions and signatures, respectively, utilizing a cryptographically secure public-key algorithm. The proposed model is designed based on a blockchain. The blockchain used here supports SC. The SC is a stateful ideal functionality, allowing all components, including attackers, to expose their internal state. Furthermore, the SC selects CN to participate in the actual computation process by employing a randomized leader selection technique, such as that used in Algorand [22]. Upon receiving a dispute resolution request from component of the proposed model, the SC initiates a dispute resolution process to identify dishonest participants, who are then subject to penalties such as deposit forfeiture and a reduction in their reputation score. The ORTHRUS uses IPFS, a scalable peer-to-peer data storage platform [8]. To mitigate storage costs, we store ciphertexts and encrypted secret key shares within IPFS and subsequently publish the addresses returned by IPFS on the blockchain [12].

3.1 Assumptions and Threat Model

The ORTHRUS is built on top of a public blockchain, thereby inheriting security properties such as integrity, tamper-resistance, and others from the underlying blockchain platform that hosts the smart contracts. The system assumes a synchronous network model with authenticated peer-to-peer channels, which limits the adversary’s ability to manipulate communication [23]. Specifically, while an adversary may delay any message passed between honest parties by a known upper bound

• The main components of ORTHRUS, DO, DR, and CN, do not trust each other and are assumed to act in their own self-interest and act rationally accordingly.

• The CN, which performs the actual computation and validation in ORTHRUS, is not a fully trusted entity.

• In order to use the randomized leader selection technique in ORTHRUS, it is assumed that the number of nodes on the blockchain network that want to participate in the computation process is sufficient, and the randomized leader selection technique is also assumed to be secure because it inherits the security of the technique used.

• We consider only static corruption [24] and standalone [25] models, where an adversary can only compromise any object before the protocol is executed, that is, an adversary can only compromise a protocol participant before the protocol is executed.

• The cryptographic techniques mentioned in Section 2 are assumed to be secure against a Probabilistic Polynomial Time (P.P.T.) attacker.

• The security of MPC technique applied to ORTHRUS is guaranteed in the presence of subthreshold adversarials by relying on admissible Threshold Adversarial Structures to ensure the security of MPC. This ensures output correctness and input privacy. Furthermore, the accuracy and verifiability of the output results depend on the applied MPC technique. In the proposed model, the threshold or the protocol’s computation process can change based on the attacker model considered by the applied SPDZ protocol.

The ORTHRUS employs a reputation mechanism to enhance fairness and prevent Byzantine behavior [26]. The following studies exist on reputation mechanisms. Zhang et al. [26] proposed a blockchain-based Cyber Threat Intelligence (CTI) model combining consortium blockchains with distributed reputation management systems. This model prevents bribery attacks and offers faster performance than existing Byzantine Fault Tolerance (BFT) models. Liu et al. [27] proposed BtRal, a blockchain and trust-based reputation evaluation incentive mechanism. It introduced a multidimensional reputation evaluation method. It prevents malicious or pre-collusive evaluation attacks using multifactor moderation. It also designed and proposed rewards and penalties through reputation-based tokens. While reputation mechanisms themselves are an important research topic actively studied in the field of data marketplaces to enhance fairness and security, this paper focuses on secure and trustworthy data trading. Existing, well-established reputation mechanisms can be utilized to implement the proposed model. However, the specific details of the reputation mechanism itself are beyond the scope of this paper.

The ORTHRUS system begins with the deployment of the DO smart contract, followed by pre-processing, matching, and the actual computation steps for data trading. Since ORTHRUS accommodates two types of output data, the internal behavior during the computation phase is contingent upon the output data type requested by the DR. In this paper, the output data type refers to the specific data type requested by the DR, which can be categorized into two types: original data

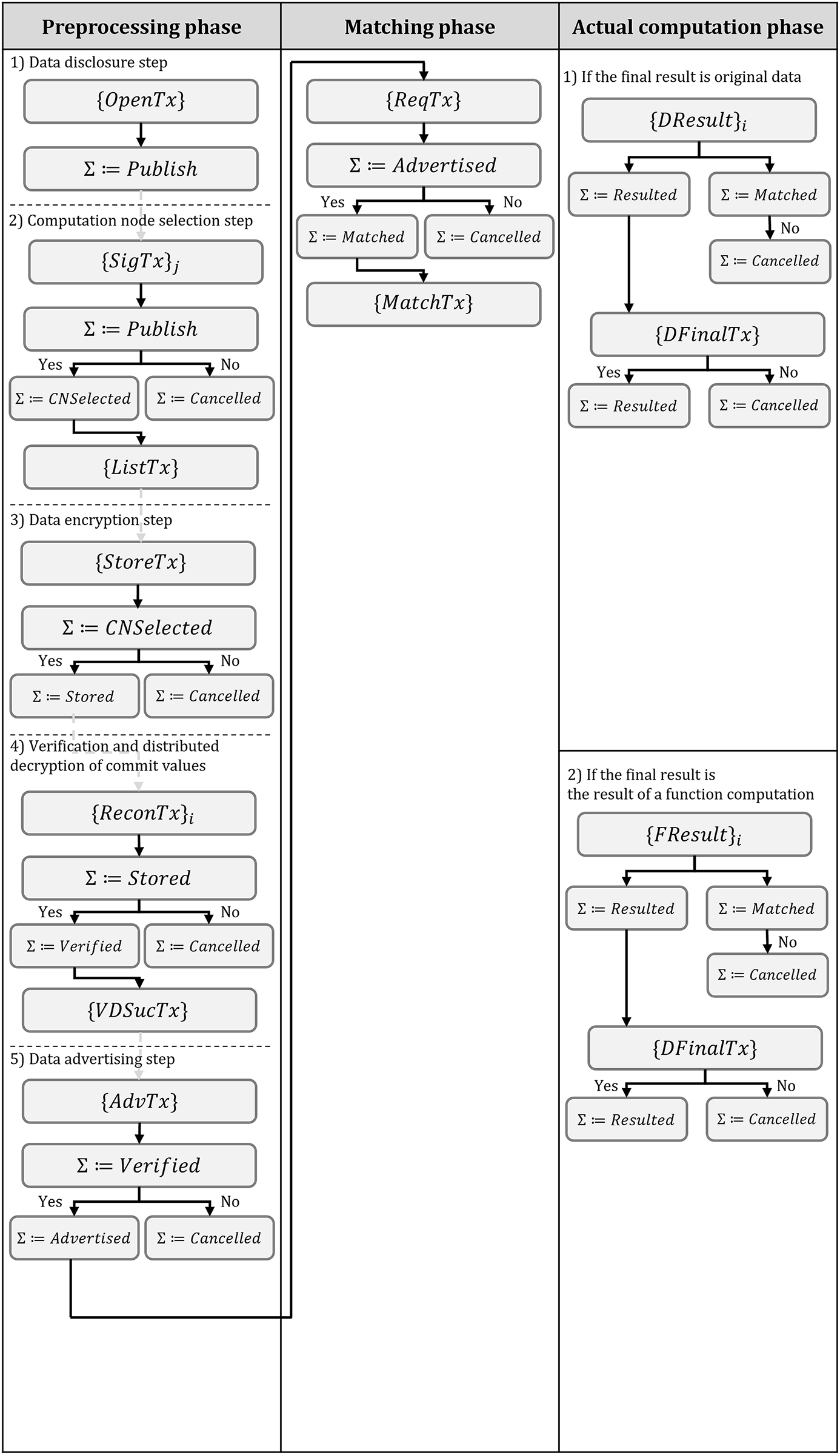

Figure 2: The processing flow of transactions and state variables handled by smart contracts in the proposed model

The preprocessing phase consists of a data disclosure step, a compute node selection step, a data encryption step, a commit value verification and distributed decryption step, and a data ad step. The detailed algorithms for each step are described in Appendix A.

• Data disclosure step:

The DO defines the data it wishes to trade as the original data D and publishes a transaction

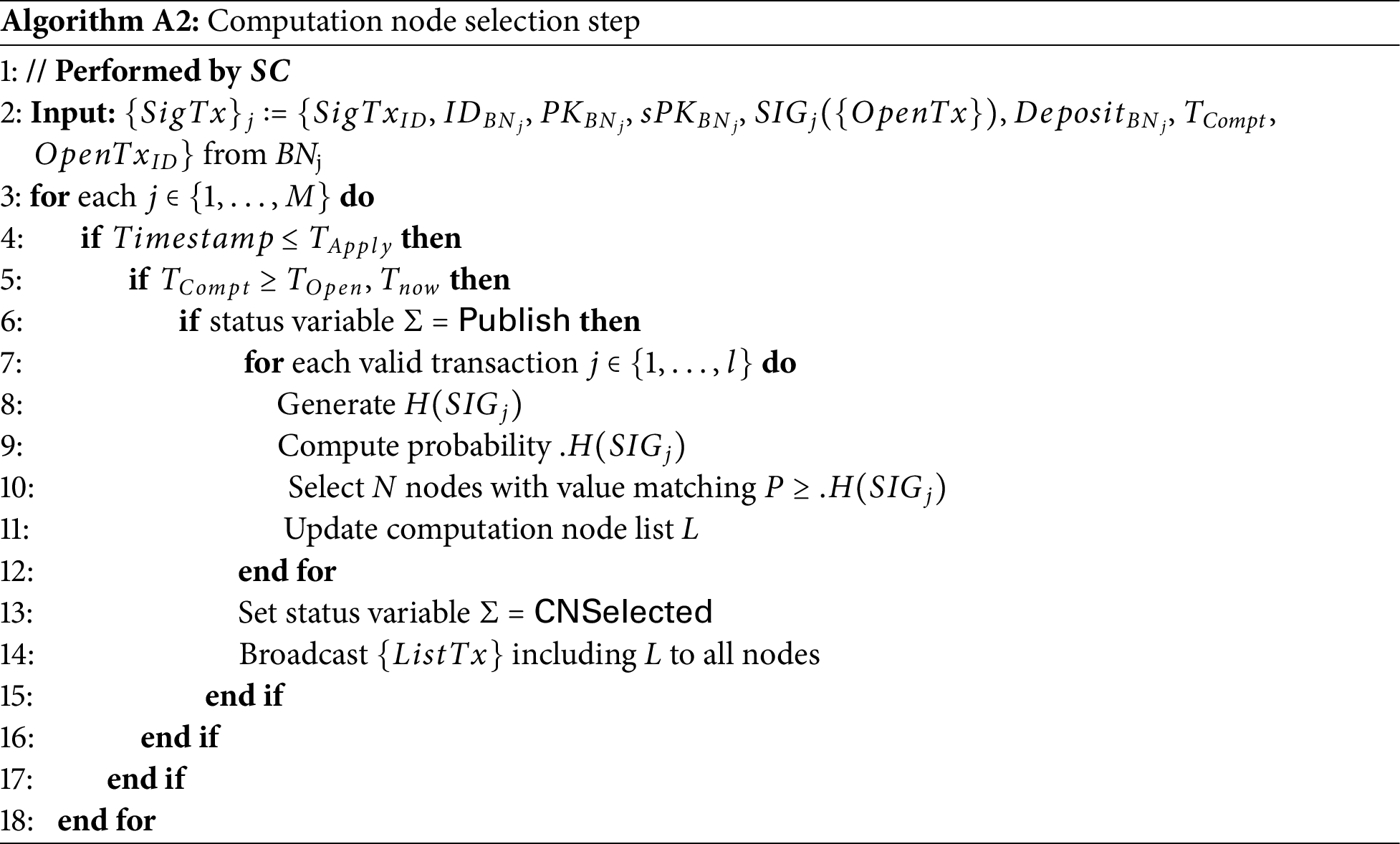

• Computation node selection step:

Among all the participating nodes

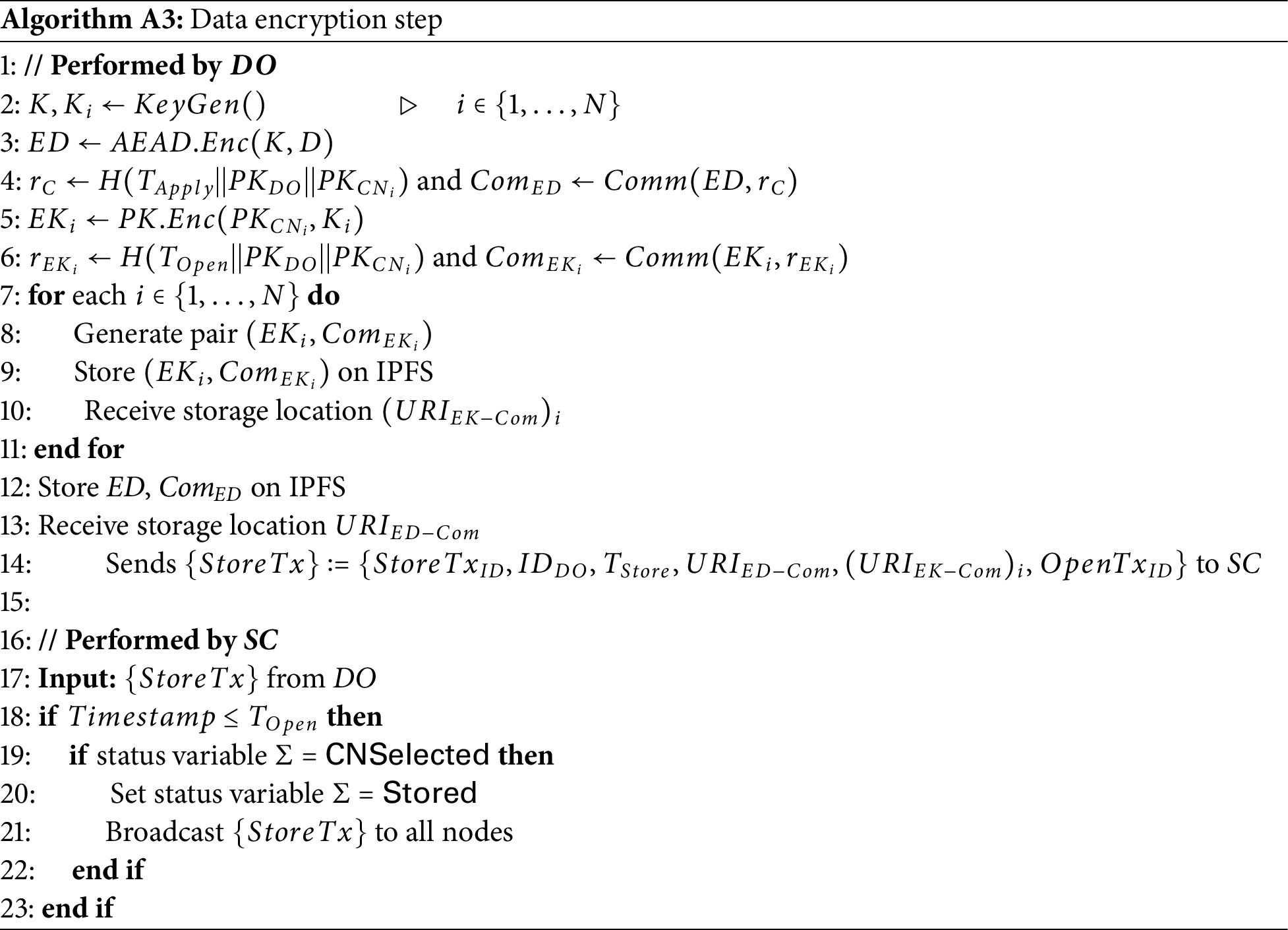

• Data encryption step:

The DO generates a secret key K using the

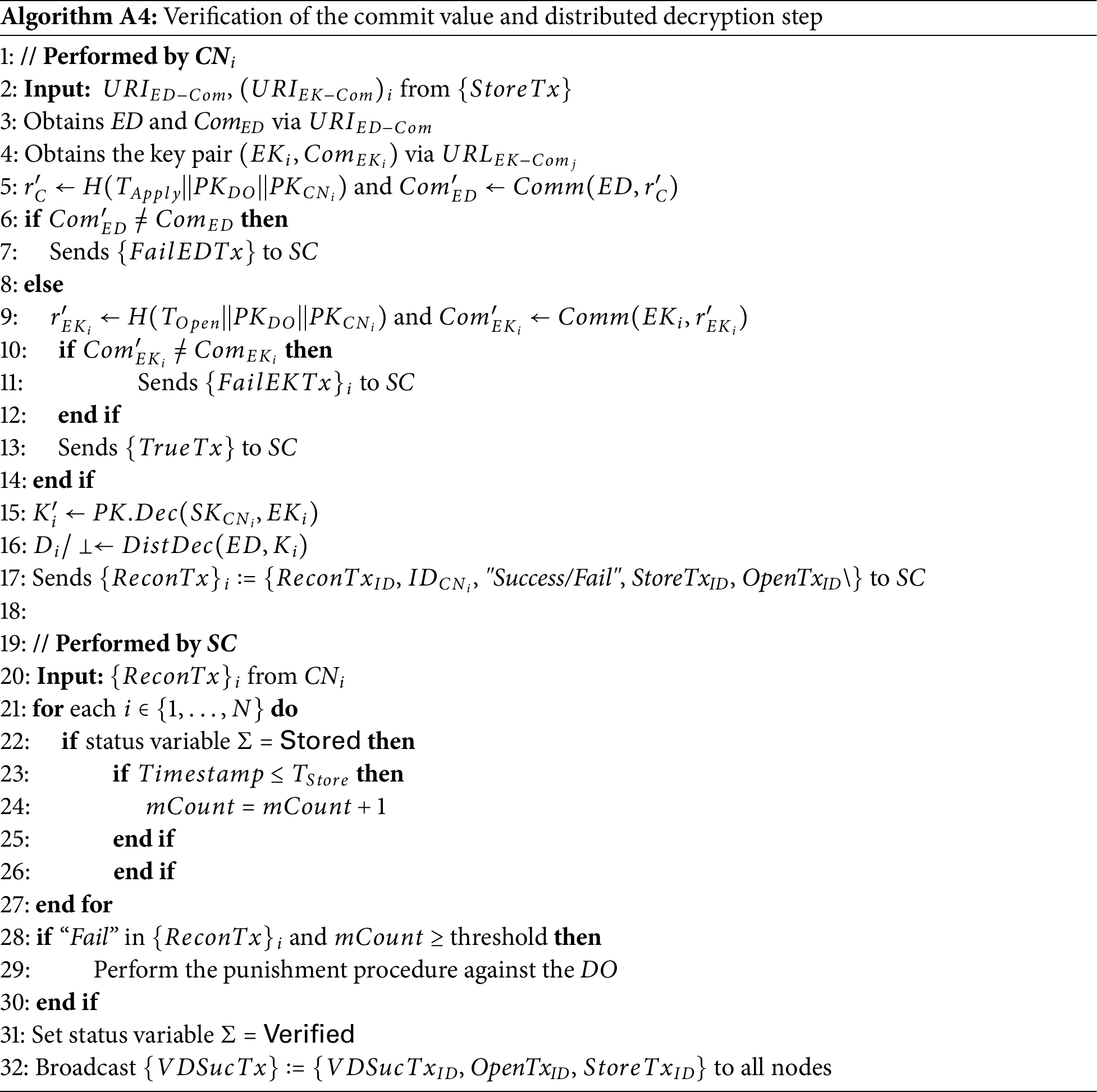

• Verification and distributed decryption of commit values:

The

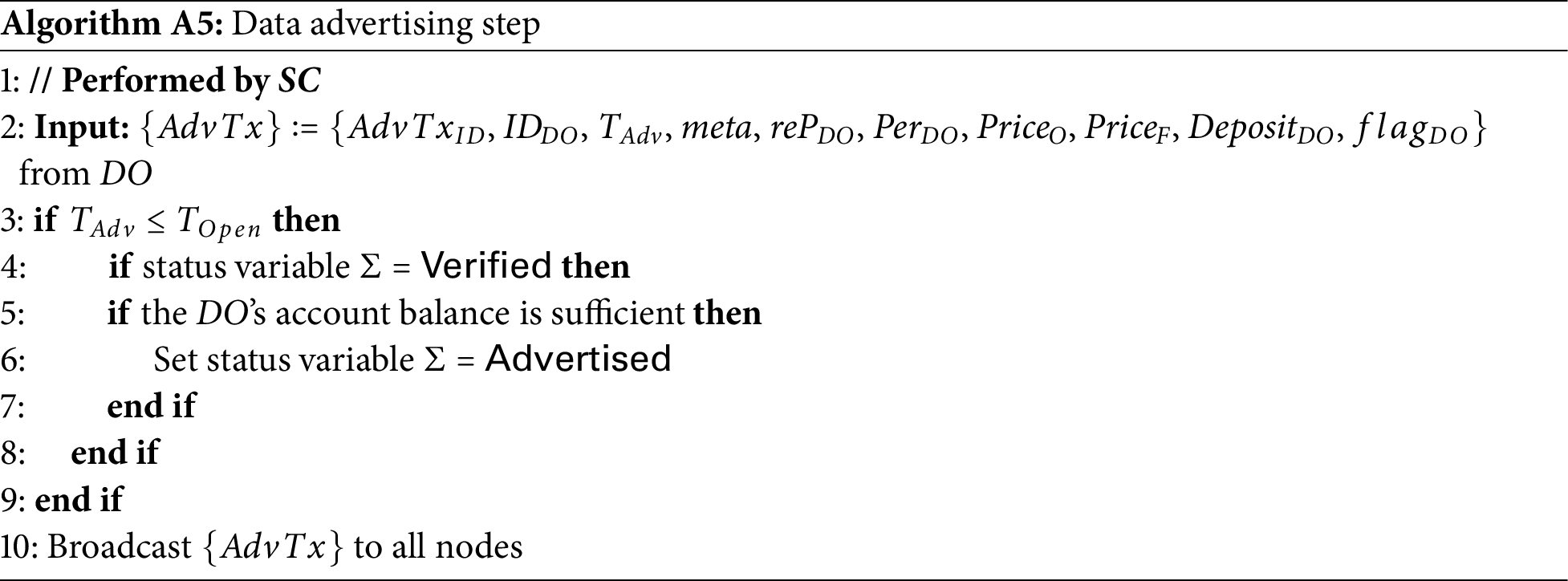

• Data advertising step:

To sell its data, the DO sends an advertising transaction

First, the DR selects a tra nsaction that contains the data it wants and how it wants the data to be provided from among the

3.2.3 Actual Computation Phase

The steps are described separately for the cases where the final result is the original data and for the cases where the final result is the result of a function computation.

1. If the final result is original data

This means that when

• Encryption and signature generation step:

• Verification step:

The DR obtains

2. If the final result is the result of a function computation

• Function computation step:

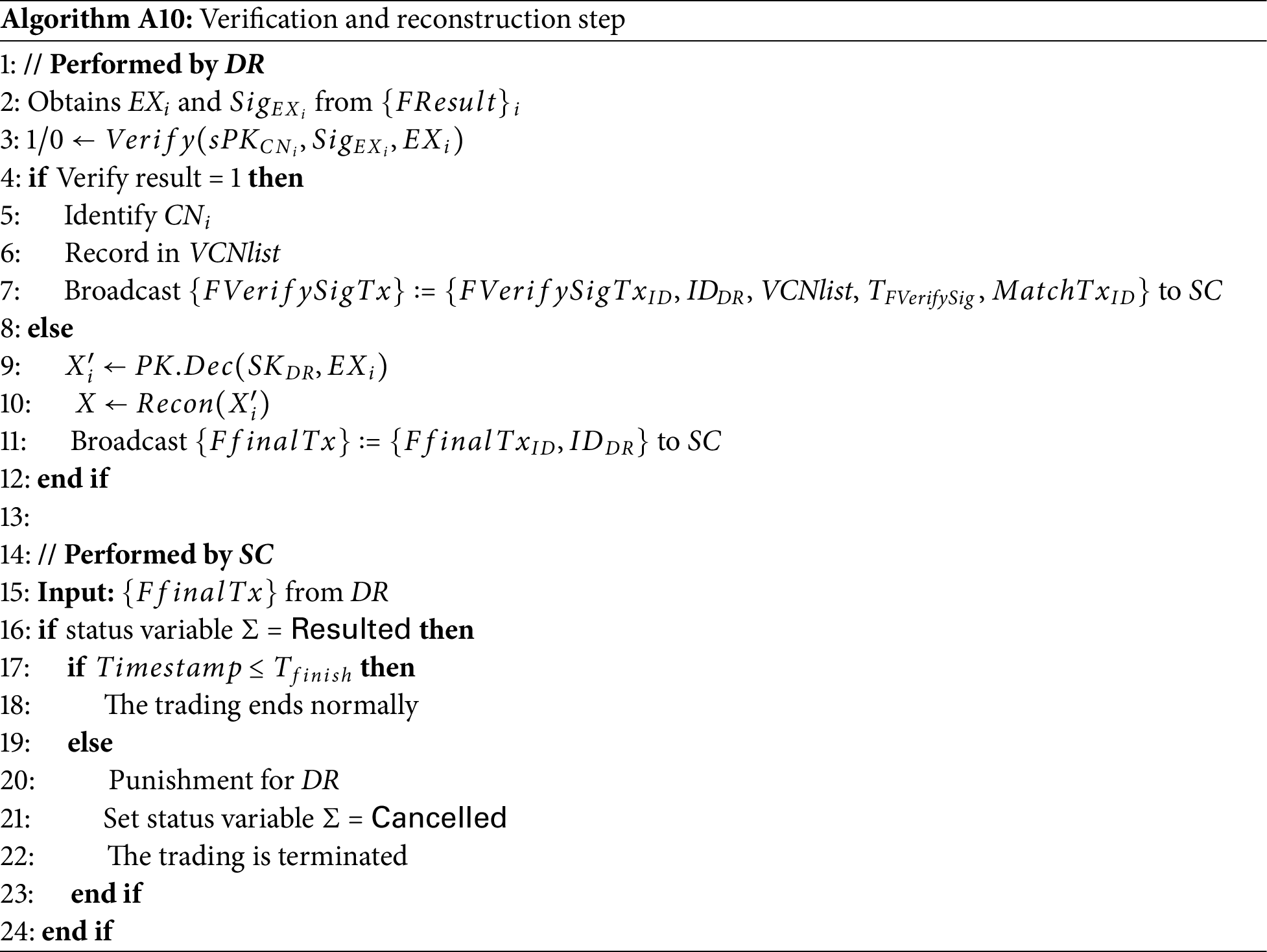

• Verification and reconstruction step:

DR obtains

3.2.4 Dispute Resolution Phase

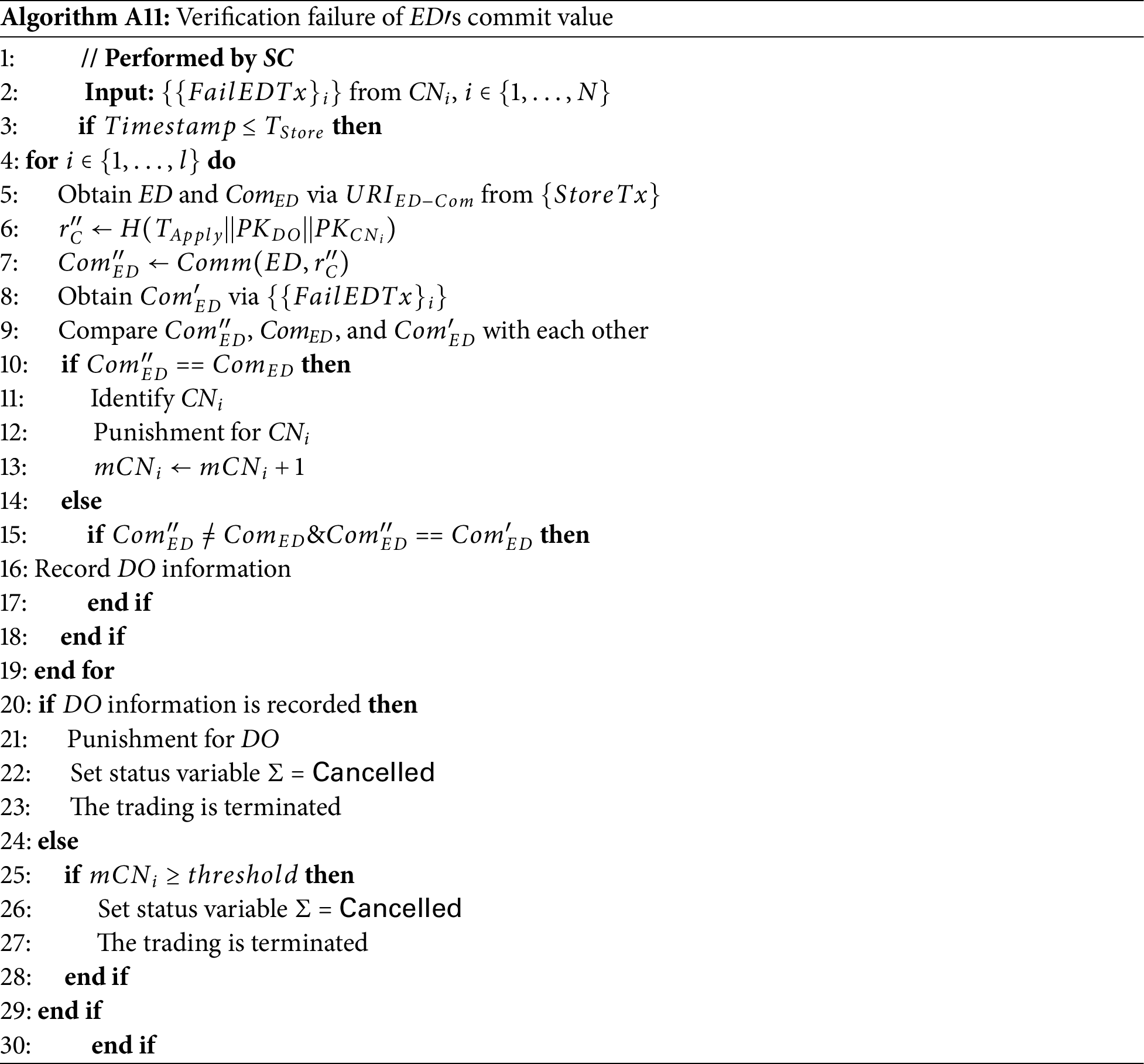

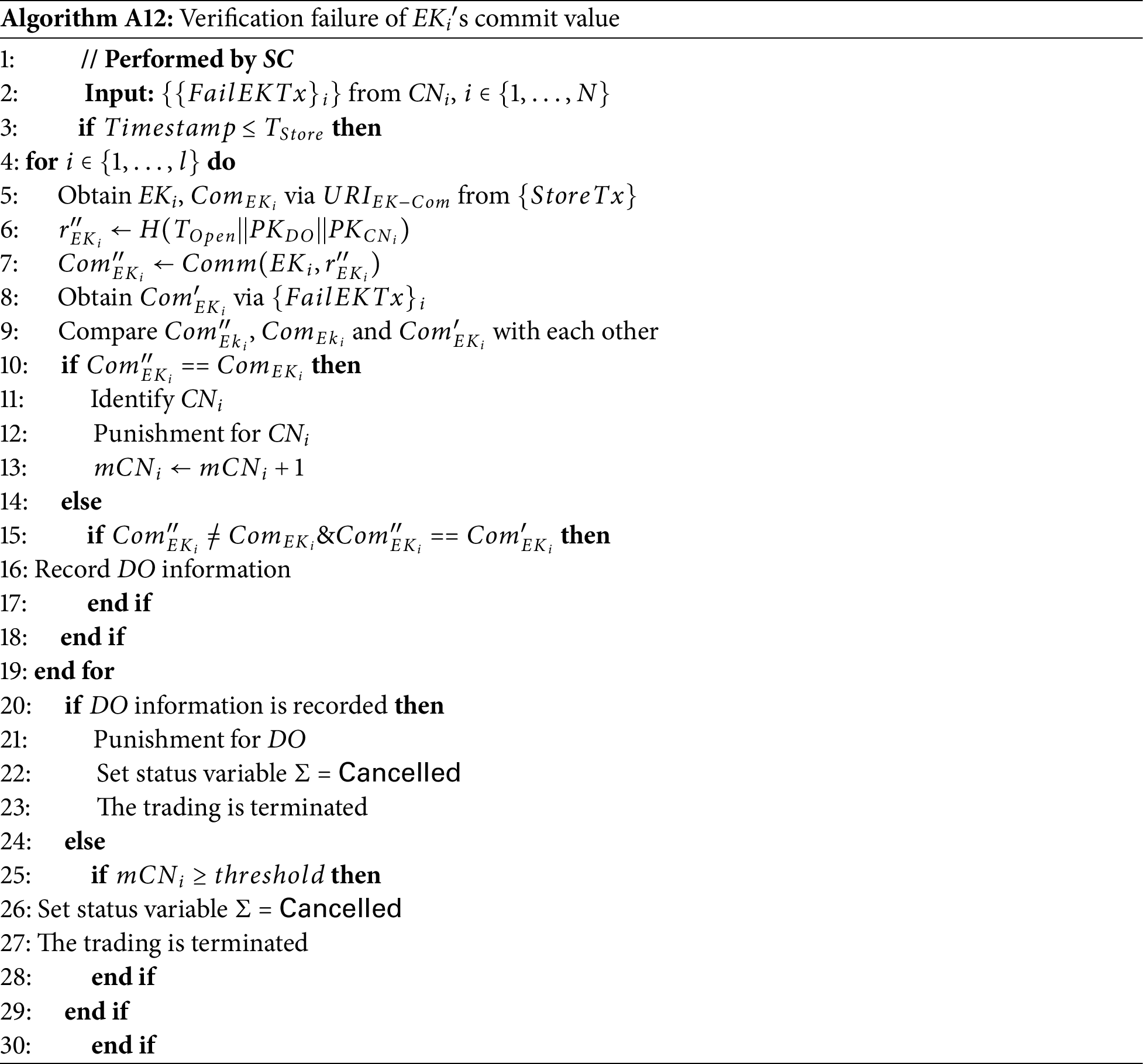

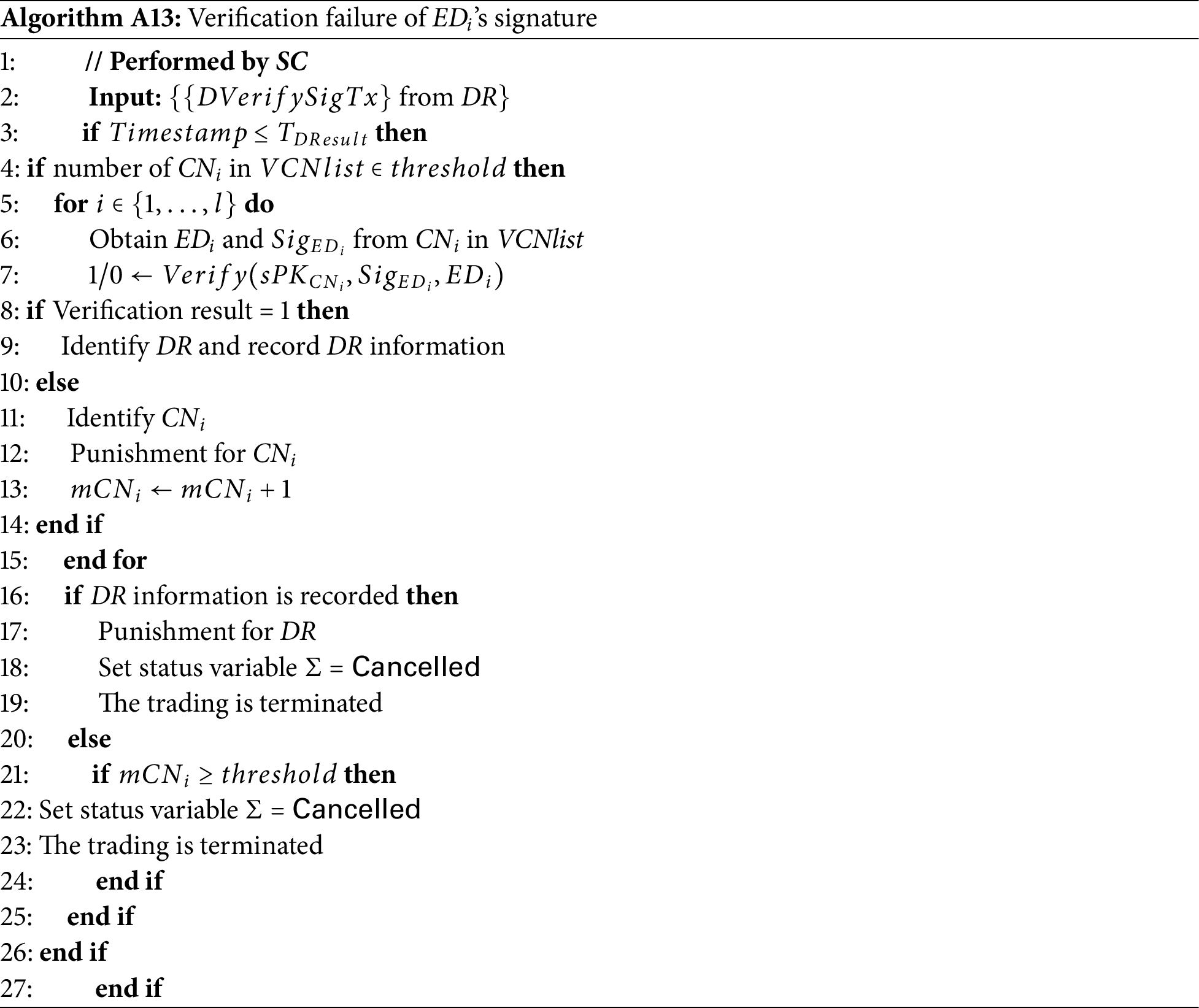

The dispute resolution phase is performed by participants requesting SC to resolve disputes in the event that (1) ED′s commit value verification fails, (2)

1. ED′s commit value verification fails

This step is the dispute resolution request phase triggered by

2.

This step is the dispute resolution request phase triggered by

3.

This step is the dispute resolution request phase triggered by DR′s signature verification failure for

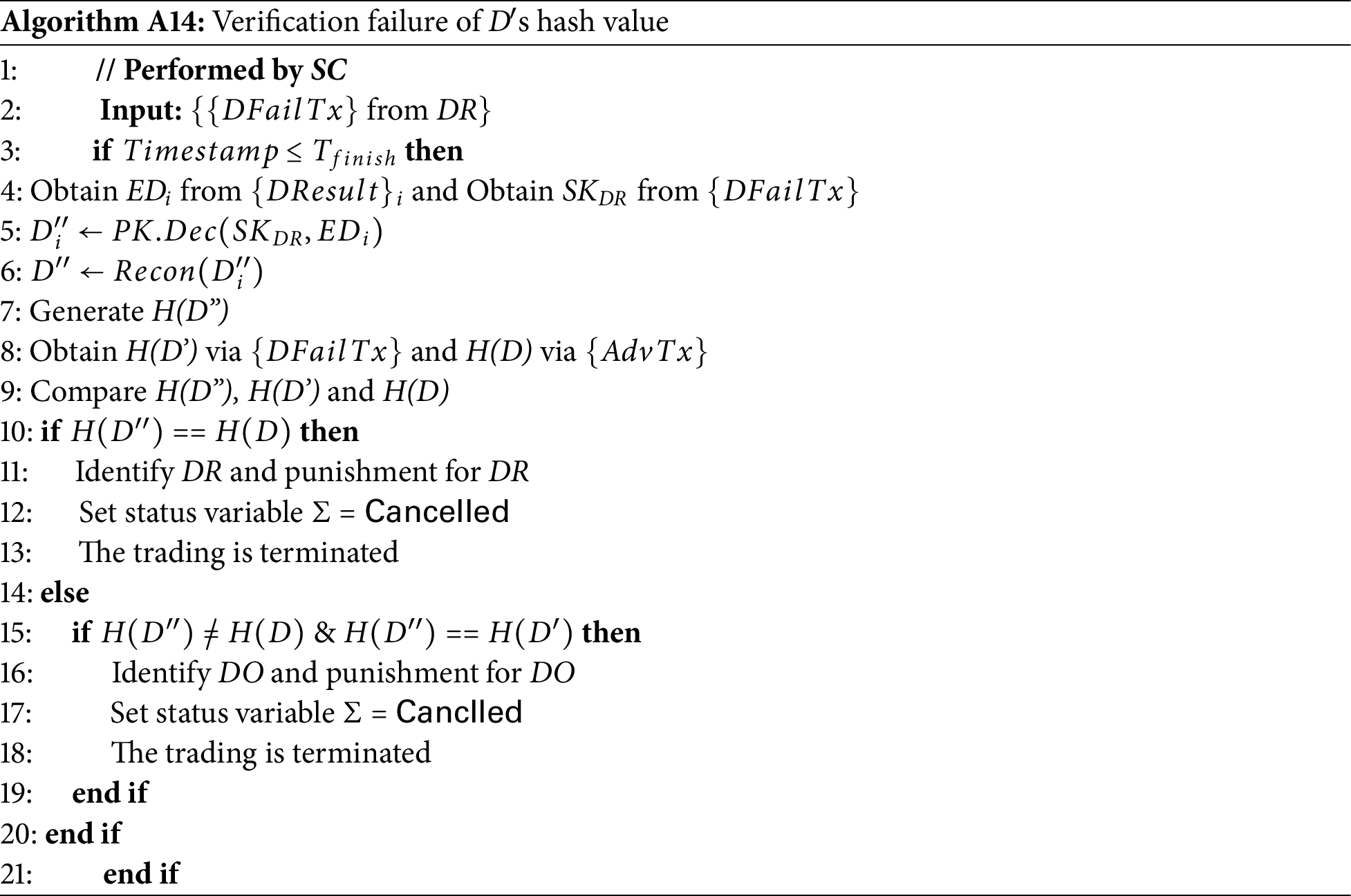

4. D′s hash value verification fails

This step is the dispute resolution request phase triggered by DR′s failure to verify D′s hash value. The DR transmits

5.

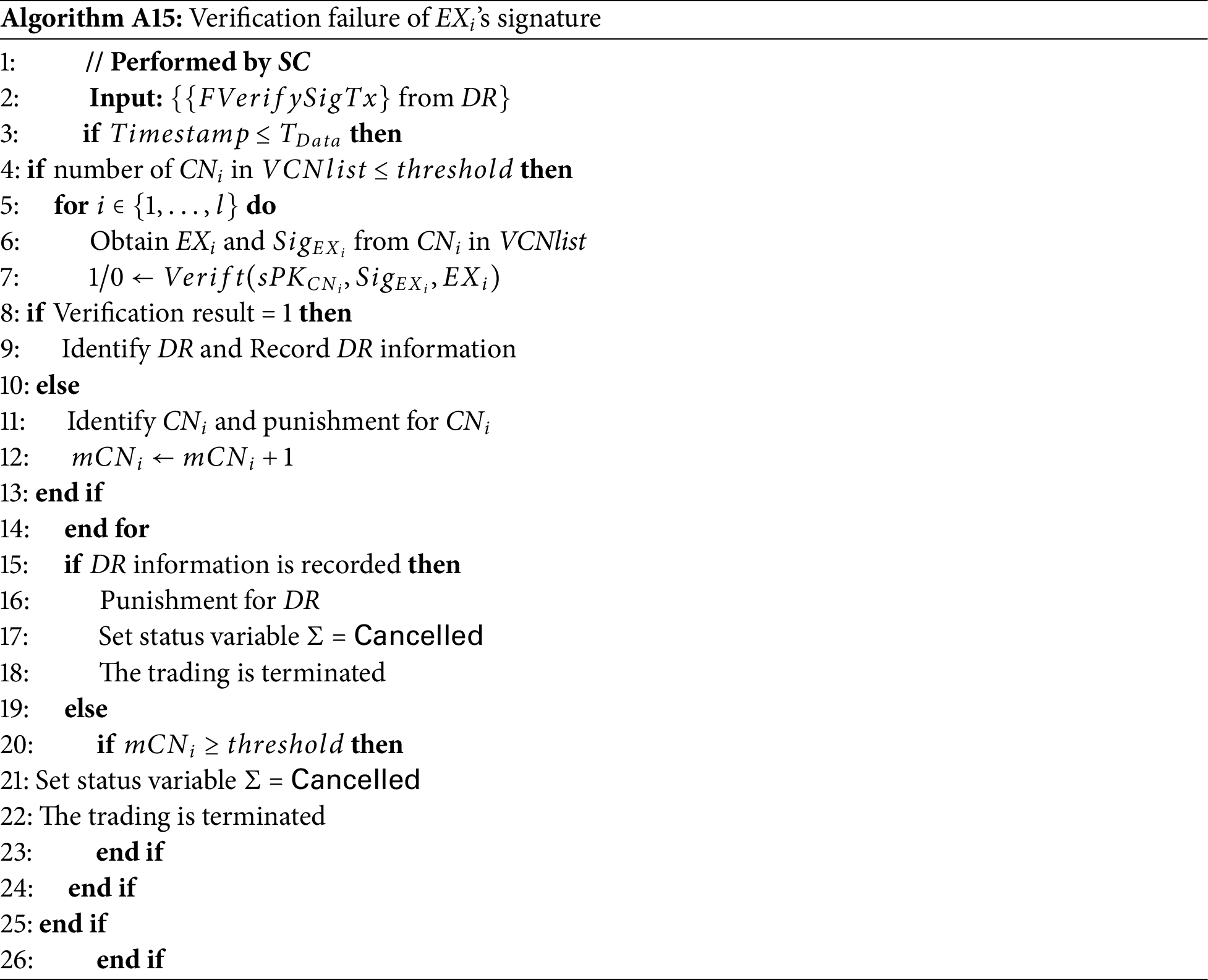

This step is the dispute resolution request phase triggered by DR′s signature verification failure for

4 Implementations and Analysis of ORTHRUS

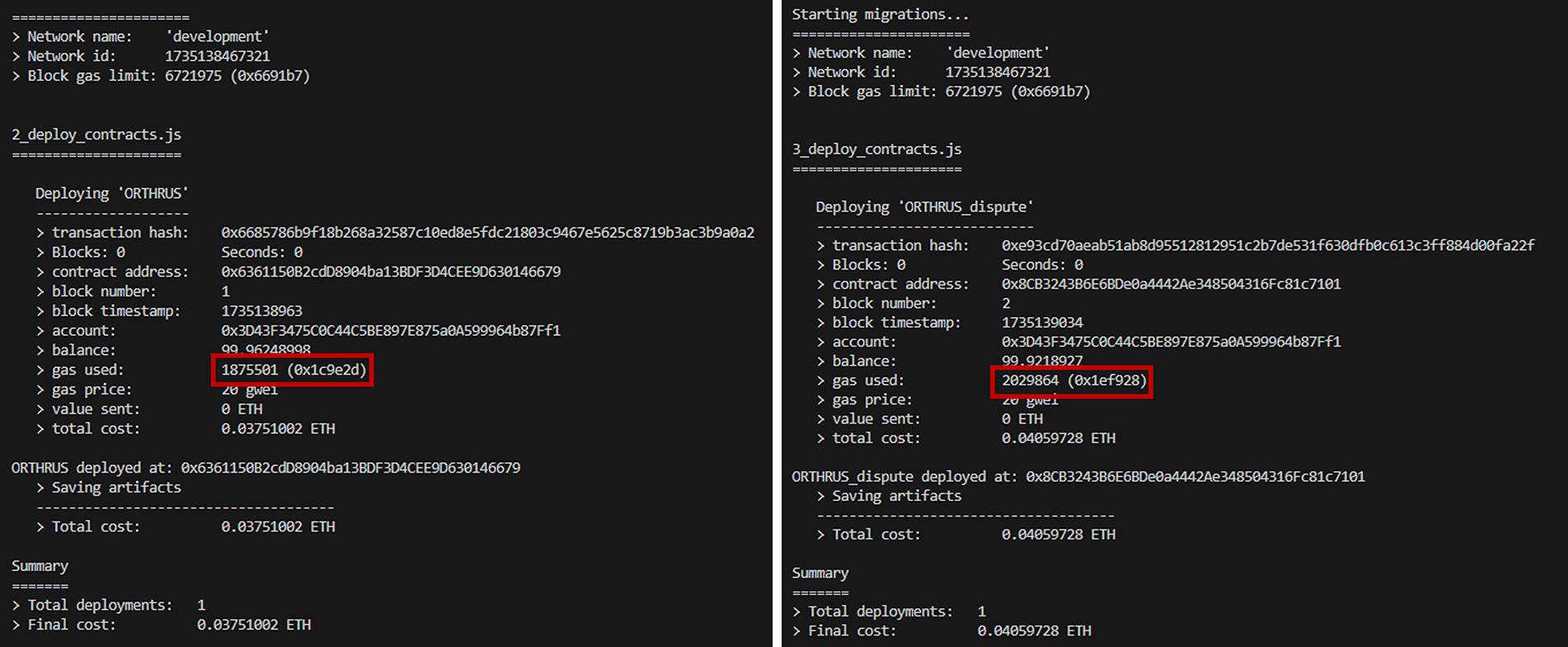

In this chapter, we design the ORTHRUS based on the Ethereum blockchain network environment to examine gas usage. We also describe security analysis, such as fairness and resistance to pre-collusion attacks.

In this paper, we designed ORTHRUS based on the Ethereum blockchain network environment with smart contracts. We utilized the Ganache test network to create accounts for participants and deploy smart contracts in ORTHRUS. In ORTHRUS, smart contracts perform transaction validation, dispute resolution steps, punishments, and rewards. We used the Solidity language to implement ORTHRUS’ smart contracts that operate in an on-chain environment, and JavaScript for the rest.

The ORTHRUS implementation consists of an off-chain part that generates signatures, a main smart contract part, and a smart contract part that performs dispute resolution steps. The smart contract part that connects to the Ganache environment and performs the main operation is deployed first, followed by the smart contract that performs the dispute resolution step. Various signature values used in the dispute resolution process are generated through the off-chain part using the Elliptic Curve Digital Signature Algorithm (ECDSA) method, and the smart contract uses them to perform verification. In addition, hash values for signatures in the main smart contract part are generated using keccask256.

4.1.1 Analysis of ORTHRUS Implementation Result

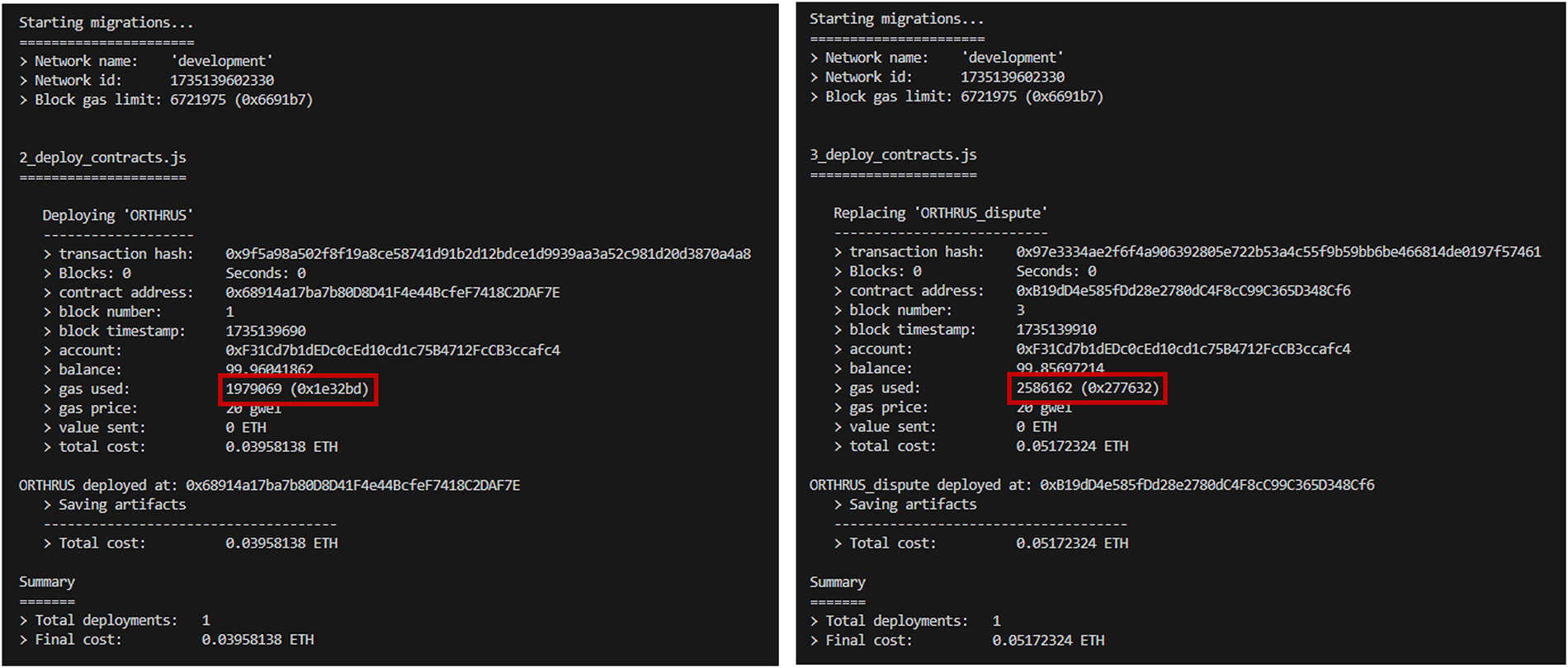

In this paper, N computational nodes are randomly selected from the nodes participating in the blockchain network, and the selected computational nodes perform cryptographic processing and computation of functions based on the MPC technique. To implement this, in the ORTHRUS implementation program, the total number of nodes participating in the blockchain network is set to 15, and the number of computing nodes to be selected, N, is set to 3 and 5 to compare the MPC computation efficiency and the smart contract gas cost, respectively. The analysis is limited to on-chain efficiency.

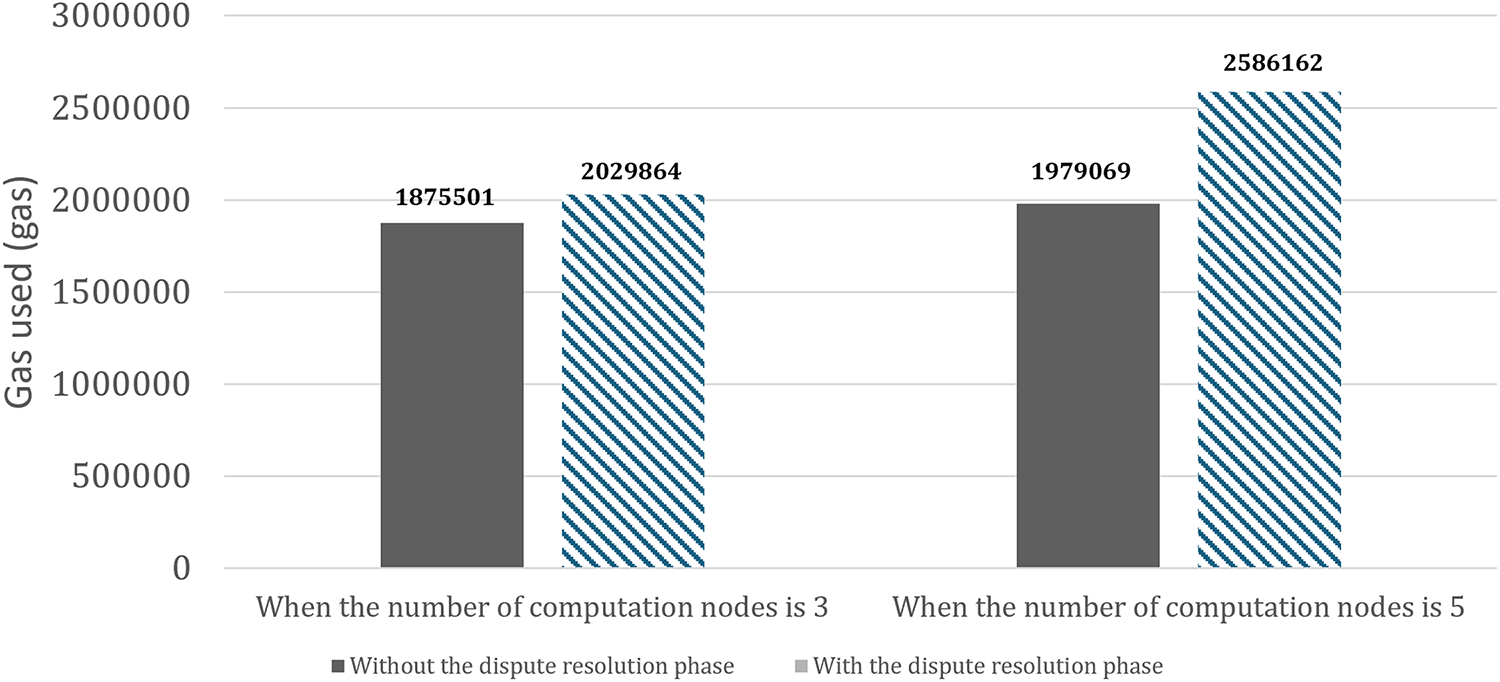

First, the gas usage in the main smart contract part is 1,875,501 when the actual number of compute nodes is 3. If we set the gas price at 20 gwei to calculate the total cost, 0.03751002 ETH is consumed. The gas usage of the smart contract that performs the dispute resolution step is 2,029,864, and if we set the gas price to the same value to calculate the total cost, 0.04059728 ETH is consumed. When the actual number of computing nodes is 5, the gas usage of the main smart contract is 1,979,069, for a total cost of 0.03958138 ETH. The gas consumption of the smart contract that performs the dispute resolution step is 2,586,162, totaling 0.05172324 ETH. From this we can see that as the number of computing nodes increases, the gas usage and cost of deploying smart contracts increases. Figs. 3 and 4 show the results of gas usage as a function of the number of compute nodes. Fig. 5 presents a quantitative comparison based on Figs. 3 and 4.

Figure 3: When the number of computation nodes is 3, gas usage

Figure 4: When the number of computation nodes is 5, gas usage

Figure 5: Comparison of gas usage based on the number of computation nodes

The main computational overhead off-chain is the distributed decryption process between peers, which involves the computation of AEAD′s

4.1.2 Anaylsis of ORTHRUS Storage Overhead

This section analyzes the storage overhead of ORTHRUS on the blockchain. The following data is stored on-chain for each phase.

1. Pre-processing phase:

• Data Publishing Step:

• Computation node selection step:

• Data Encryption Step:

• Verification and distributed decryption of commit values:

• Data advertising step:

2. Matching phase:

3. Actual computation phase:

• The output result is the original data:

• The output result is the result of a function computation:

Note that the values stored during the actual computation step are only those values that would be stored if the verification result is successful.

To compute storage complexity, we assume that the proposed protocol has key lengths of cryptographic primitives with 128-bit security; that is, we can choose bit lengths for 128-bit symmetric ciphers, 256-bit hash functions, and 256-bit elliptic curve pairings. Accordingly, in the proposed protocol PK is 512 bits long and SK is 256 bits long. The signature is generated with a length of 512 bits because it utilizes the ECDSA scheme. The ID of the participant and the ID of the transaction are assumed to be 160 bits, the

The storage overhead of the preprocessing step is 5026 bits, the matching step is 2786 bits, and the final result is 1536 bits if the final result is the original data and 1376 bits if the final result is the result of a function computation. Therefore, the on-chain storage overhead seems to be a bit high, as 9348 bits (about 1.14 KB) are required when the final result is the original data, and 9188 bits (about 1.12 KB) are required when the final result is the result of a function computation. However, storage overhead can be reduced by using off-chain storage, that is, storing the actual data in off-chain storage while keeping its metadata on-chain. For example, if the output result is the original data in the actual computation step, the storage overhead can be reduced by storing only

This section describes the security of the ORTHRUS with the following lemmas and theorem.

Lemma 1. If all participants are honest, ORTHRUS satisfies completeness based on the assumptions and threat model in Section 3.1.

Proof. The completeness of the ORTHRUS is guaranteed when DO, DR, and CN follow the protocol with honesty.

• Case 1: If DR requests the original data as the final result and all the participants are honest, DR will obtain

• Case 2: If DR requests the output of the function computation as the final output and all participants are honest, then during the verification of the actual computation step of the proposed model, DR will obtain

Lemma 2. Assuming that the random leader selection technique applied in ORTHRUS is secure, based on the assumptions in Section 3.1 and the threat model, ORTHRUS is secure against prior collusion attack between the attacker and each participant.

Proof. In a proposal model, an attacker can only compromise a participant before executing the protocol in that model. Therefore, in order to perform a pre-collusion attack, the attacker must select the blockchain nodes to perform the collusion attack before the proposal protocol is executed. Furthermore, the selected blockchain node must be selected as a CN participant in the actual computation of the proposed protocol. However, based on the unpredictability of the output of the hash function and the signature technique applied in the proposal protocol, it is computationally difficult for an attacker to predict which blockchain nodes will be selected as CNs before the proposal protocol is executed. Furthermore, the collusion attack among CNs during the execution of the proposal protocol is based on the security of Algorand [22], the random leader selection technique used for the selection of CN. In other words, if the hash function, signature technique, and Algorand [22] are secure, the probability of success of the attacker’s collusion attack with the blockchain nodes in the proposed model is negligible. ORTHRUS also allows collusion between CNs and DOs and collusion between CNs and DRs.

• Case 1.

During the validation of the commit value in the preprocessing phase, it can try to manipulate the validation results of

• Case 2.

The DR in the actual computation phase may attempt to manipulate the verification result while verifying

As such, the probability of such a pre-collusion attack succeeding against ORTHRUS is negligible if the applied hash function, signature technique, and random leader selection technique Algorand [22] are secure.

Lemma 3. ORTHRUS assumes that the cryptographic techniques underlying the proposed model are secure, given the assumptions in Section 3.1 and the threat model. Thus, ORTHRUS satisfies fairness even if DO or DR is compromised by a nonadaptive P.P.T. adversary.

Proof. Fairness satisfies both DR fairness and DO fairness.

• DR fairness: DR fairness means that even in the presence of dishonest DOs, honest DRs only pay for validly acquired data. We assume that an attacker can compromise the DOs that provide data to the honest DR and the CNs that help in the computation. The following are scenarios in which an attacker compromises DO or CN.

1. To disrupt the normal flow of the protocol, an attacker may attempt to corrupt

2. An attacker could attempt to compromise DO so that an invalid

3. An attacker could compromise DO, causing it to store an invalid

4. An attacker can compromise DO, causing DO to release an incorrect

• DO fairness: DO fairness means that DO who act honestly receives a fair amount of money for the valid data they provide to the DR. In response, an attacker can compromise the fairness of the honest DO by allowing DR and CN, who did not pay the legitimate payment, to obtain the data provided by DO in the process of trading.

1. The attacker can attempt to compromise the CN and obtain the original data D.

2. An attacker can compromise the CN and attempt to reconstruct D by gathering

3. By compromising the DR, an attacker can attempt to obtain D provided by an honest DO without paying a fair price. The DR can obtain the D provided by the honest DO through verification in the actual computation phase. The DR may attempt to avoid paying fairly by not sending a

As long as the cryptographic primitives applied in the proposed protocol, such as secure hash functions, public key ciphers, etc. cannot be compromised by an attacker, the fairness of the DO is guaranteed.

Lemma 4. ORTHRUS satisfies confidentiality for non-adaptive P.P.T. adversaries based on the assumptions and threat model in Section 3.1.

Proof. The secret key share

Lemma 5. Based on the assumptions and the threat model in Section 3.1, if the proposal protocol operates in the case where ORTHRUS output data is the result of a function computation, the original data provided by DO is not disclosed to any participants, that is, the proposal model guarantees input privacy.

Proof: In the trading process of the proposed protocol when the output data is the result of the function computation, an attacker may try to obtain D, from participants without paying the rightful price.

1. If the attacker wants to obtain D via ED and

2. DR and

3. Each

As such, if the cryptographic mechanisms and MPC techniques applied in the proposed model are secure, the likelihood of an attacker compromising input privacy is negligible.

Lemma 6. Based on the assumptions and threat model in Section 3.1, the ORTHRUS satisfies Timeliness if either DO or DR is honest and the SC is secure.

Proof: Timeliness means that an honest component can always reach a point in the protocol where it can stop in a finite amount of time with guaranteed fairness. For a proposal model with an SC and at least one honest participant, the following termination cases exist:

• No abort: The proposal model ends when

• Cancellation at the computation node selection stage: In the computation node selection stage,

• Cancel in the data storage stage: At the stage of storing encrypted values in IPFS,

• Revocation in the verification phase of

• Cancel at the data request stage: At the stage where DR publishes a data request to the blockchain network, including the data type he wants,

• Cancellation in the encryption phase of

Theorem 1: If the cryptographic primitives underlying ORTHRUS are secure and the blockchain and smart contracts are secure, then ORTHRUS satisfies completeness, resistance to pre-collusion attacks, fairness, confidentiality, input privacy, and timeliness.

Proof: Guaranteed by Lemma 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6.

The ORTHRUS is secure against second-resell attacks. A second reselling attack occurs when a malicious buyer purchases data from the blockchain and then resells the same data for their own profit. If duplicate data are found, the seller is verified to be the owner of the original data and the seller is verified to be the buyer in the previous transaction. If the current seller was the buyer in the previous transaction, the resale transaction can be invalidated. In ORTHRUS, DO′s activities are recorded on the blockchain using transactions. In addition, commitment techniques, signature techniques, hash functions, etc. are applied to verify the values shared between each participant in the ORTHRUS transaction process. Based on the techniques applied, ORTHRUS prevents secondary resale within the platform. However, it does not prevent the resale of the data in other ways or on other platforms for personal gain.

4.3 Comparative Analysis with Existing Research

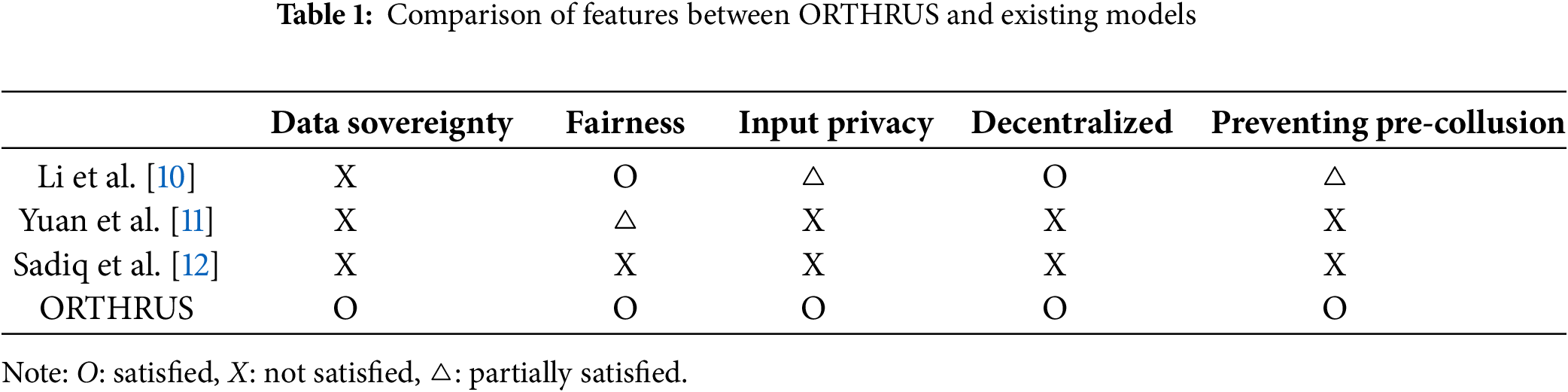

In this section, we compare three of the existing studies mentioned in Section 1 with the ORTHRUS based on the security analysis criteria.

Li et al. [10] proposed a BSAS to recommend a consensus speed for a group of vehicles based on a blockchain. The BSAS computes a polynomial to obtain the optimal rate, where each user’s secret value is unknown to the others. BSAS randomly selects operators, but it does not guarantee against collusion attacks among other users. Therefore, if collusion among users is successful, the secret value used to compute the polynomial can be known. In other words, if the trustworthiness of the polynomial or the trustworthiness of the computation participants is not guaranteed, the security of the secret value is not guaranteed. Yuan et al. [11] proposed TRUCON, a blockchain-based data sharing mechanism with congestion control in IoV environments. TRUCON has a trust factor and there is no punishment or reward process. In addition, message forwarding is done between vehicles and RSUs, but it does not consider detailed privacy issues and malicious behavior of dishonest participants. Sadiq et al. [12] proposed a vehicle data transaction model based on a consortium blockchain with trusted authorities. It stores unencrypted original data in IPFS and utilizes the same unencrypted original data for data transactions. It does not take into account the existence of dishonest participants, and there is no mechanism for punishment and reward.

In contrast, ORTHRUS is designed on a public blockchain with no trust factor, ensuring full decentralization. In addition, the nodes that participate in the actual computation process are selected using a randomized leader selection technique, making it difficult to predict the probability that a node that has colluded in malicious behavior in advance will participate in the computation process. This prevents collusion attacks. Since ORTHRUS inherits the security of the applied cryptographic techniques, if the final output is the original data, participants other than DR who have paid a reasonable amount of money are not permitted to access D. If the final result is the result of a function computation, then all participants cannot access and obtain the original data D. The ORTHRUS enforces punishments such as deposit forfeiture and reputation score reduction through smart contracts to participants who engage in malicious behavior. Conversely, if the transaction is terminated legitimately, they receive a share of the data payment and incentives, and their reputation score increases. Finally, the ORTHRUS supports both original data and function computation result as final outputs, overcoming the problem of existing vehicle data trading methods that depend on the type and delivery method of final outputs supported by the registered trading platform. The ORTHRUS allows data owners to provide their own data in the type and manner they want. At the same time, when the data transaction process begins, the rights to the data provided by the data owner are not transferred, and the data owner retains control over the original data. In other words, the data owner sets the type of data provision and the transaction method, ensuring data sovereignty. In this way, ORTHRUS, which supports two types of data as the end result and guarantees data sovereignty, presents a revolutionary way to trade vehicle data, enabling users to obtain all desired data types within a single platform, instead of using multiple platforms to obtain the desired data types. Table 1 below shows a comparison of features with existing studies.

In an IoV environment, vehicles collect and generate data through interactions with various sensors and peripherals. This data is then utilized for user convenience systems or transportation systems. However, existing vehicle data sharing and transaction models are designed in a centralized way due to the trust factor, leading to various problems such as single point of failure, data leakage, and privacy protection. To solve these problems, blockchain-based models have emerged, but vehicle owners’ sensitive information contained in vehicle data is still not protected, and data owners are not guaranteed data sovereignty due to the reliance on participatory data transaction models.

In this paper, we proposed ORTHRUS, a blockchain-based model for vehicle data trading that prioritizes privacy protection. The ORTHRUS guarantees data sovereignty by allowing data owners to trade data in the way they want. In addition, unlike previous studies, ORTHRUS supports two types of outputs: original data and function computation results. By employing MPC technique, MOZAIK architecture, and the random leader selection technique, the proposed scheme, ORTHRUS, guarantees the input privacy and resistance to pre-collusion attacks. Furthermore, the proposed model promotes fairness by identifying dishonest behavior among participants by enforcing penalties and rewards through the implementation of smart contracts. Finally, the distributed decryption performance of the proposed model depends on the performance of the applied MPC technique. Currently, one of the most important and challenging issues in MPC is performance optimization, and for MPC to be deployed in commercial services, its performance problems must be resolved. Even in existing services applying MPC techniques, the number of computational servers used ranges from a minimum of two to a maximum of five. The ORTHRUS system proposed in this paper also conducted performance analyses using only three and five computational nodes, similar to these services. Therefore, limitations exist regarding computational efficiency and service scalability. Consequently, future research will focus on optimizing MPC performance in ORTHRUS implementations involving a larger number of computational nodes. This future research is expected to further enhance the practicality of the proposed ORTHRUS model and contribute to the advancement of privacy-preserving computing technology in distributed environments.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the IITP (Institute of Information & communications Technology Planning & Evaluation)-ITRC (Information Technology Research Center) grant funded by the Korea government (Ministry of Science and ICT) (IITP-2025-RS-2020-II201797), and was supported as a ‘Technology Commercialization Collaboration Platform Construction’ project of the INNOPOLIS FOUNDATION (Project Number: 1711202494).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Su Jin Shin, Sang Uk Shin; data collection: Su Jin Shin; analysis and interpretation of results: Su Jin Shin, Sang Uk Shin; draft manuscript preparation: Su Jin Shin. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Appendix A ORTHRUS’s Pseudo-code

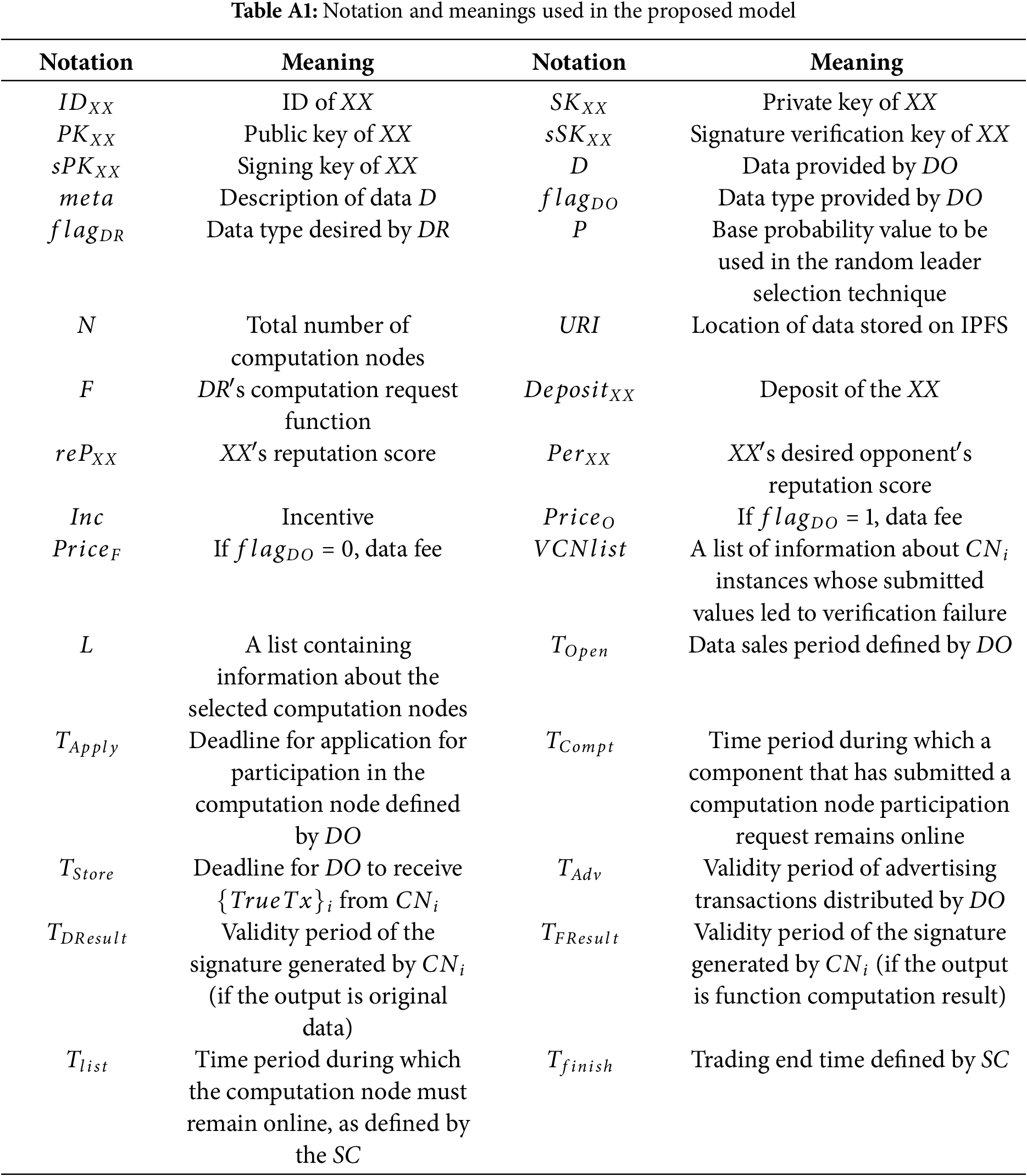

The ORTHRUS consists of a preprocessing phase, a matching phase, and an actual computation phase. Appendix A presents each stage of the ORTHRUS in pseudo-code. Additionally, Table A1 explains the symbols used in the algorithm.

Appendix A.1 Preprocessing Phase

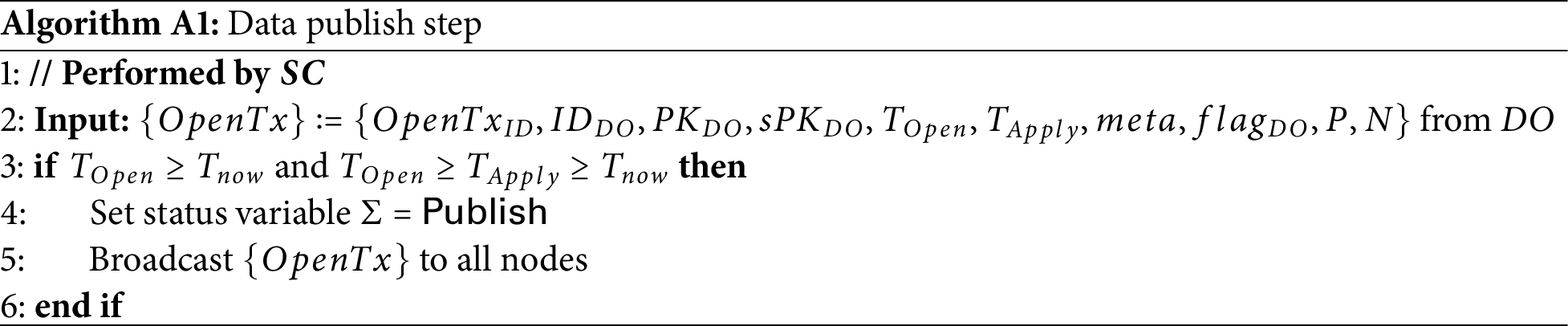

• Data publish step:

Upon receiving

• Computation node selection step:

Blockchain participating nodes generate their signatures based on

• Data encryption step:

The DO transmits

• Verification and distributed decryption of commit values:

Algorithm A4 shows the process where

• Data advertising step: Algorithm A5 is the process by which DO distributes transactions to the blockchain network for data sales.

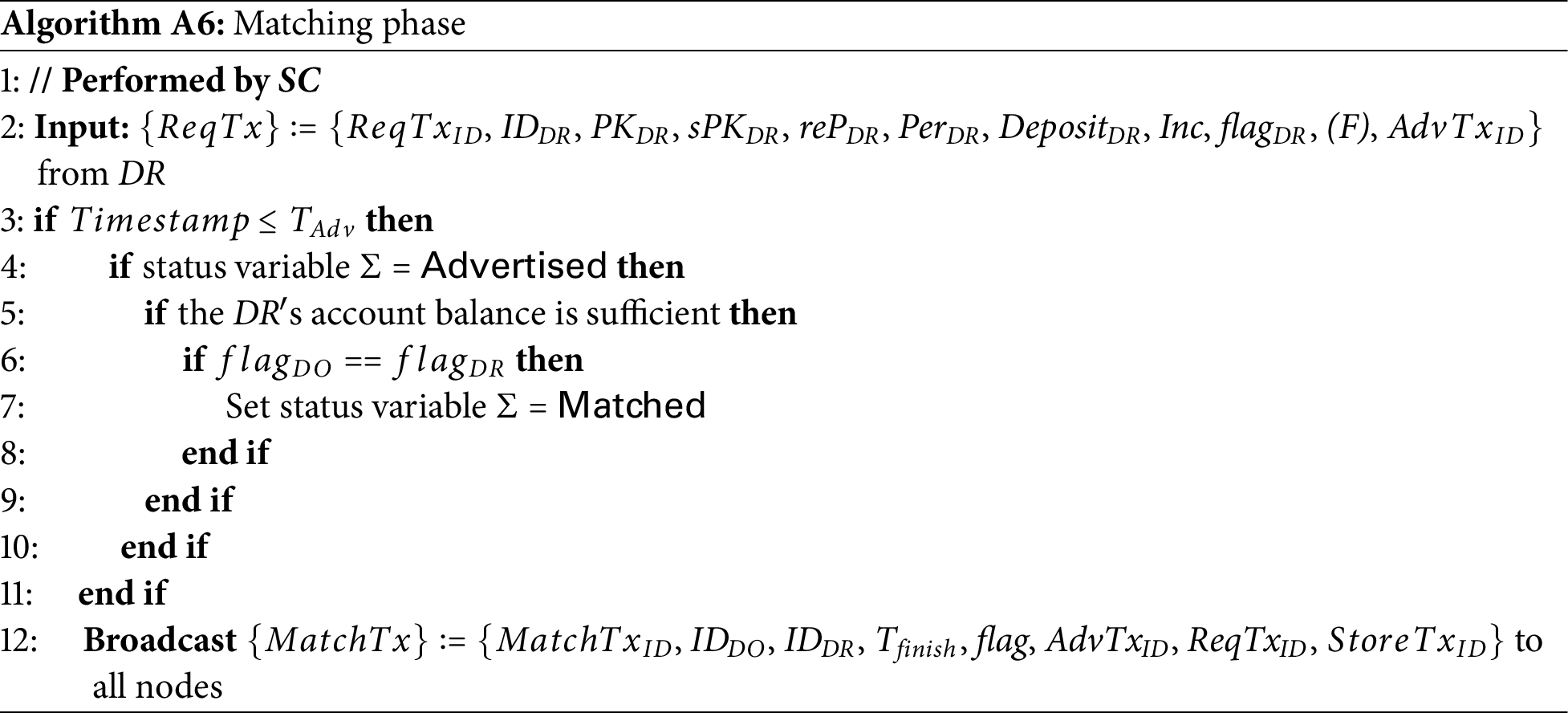

Appendix A.2 Matching Phase: Algorithm A6 shows the process where SC matches DR and DO. Here, if

Appendix A.3 Actual Computation Phase: This process executes differently depending on the

• If the final result is original data

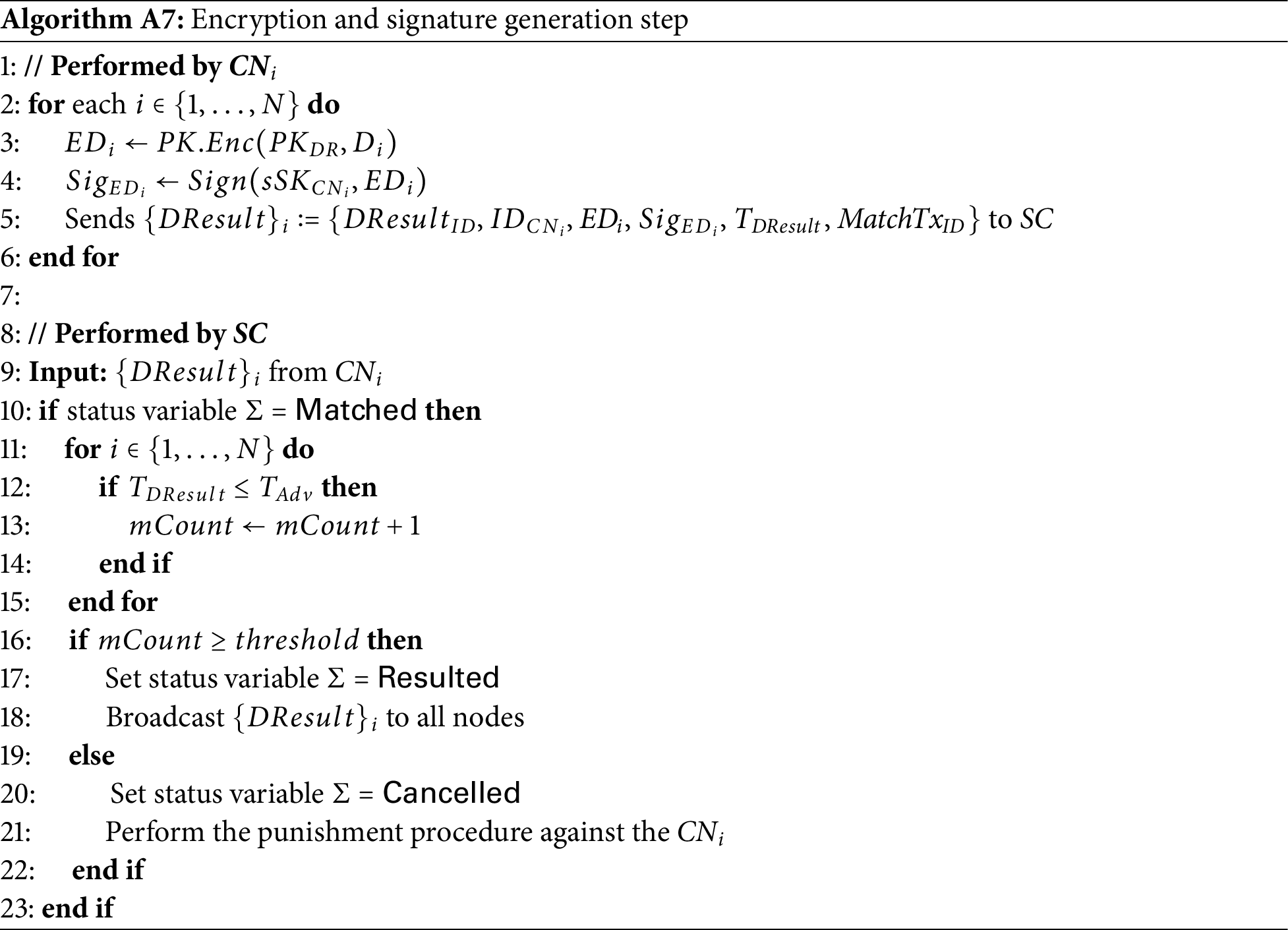

This proceeds in two stages: (1) the encryption and signature generation step and (2) the verification step.

1. The encryption and signature generation step: The

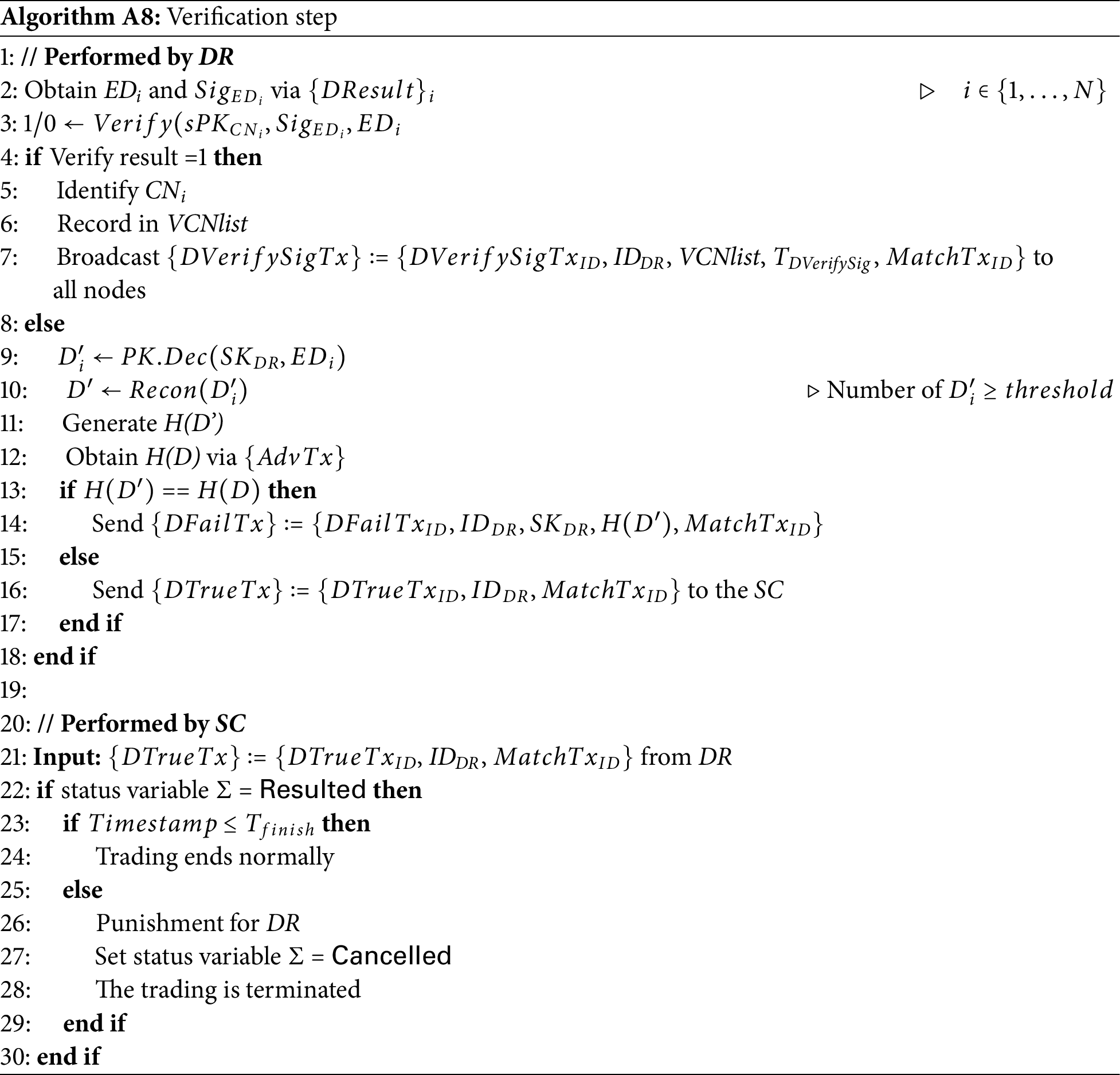

2. The verification step: The DR generates a hash value

• If the final result is the result of a function computation

This process consists of (1) the function computation step and (2) the verification and reconstruction step.

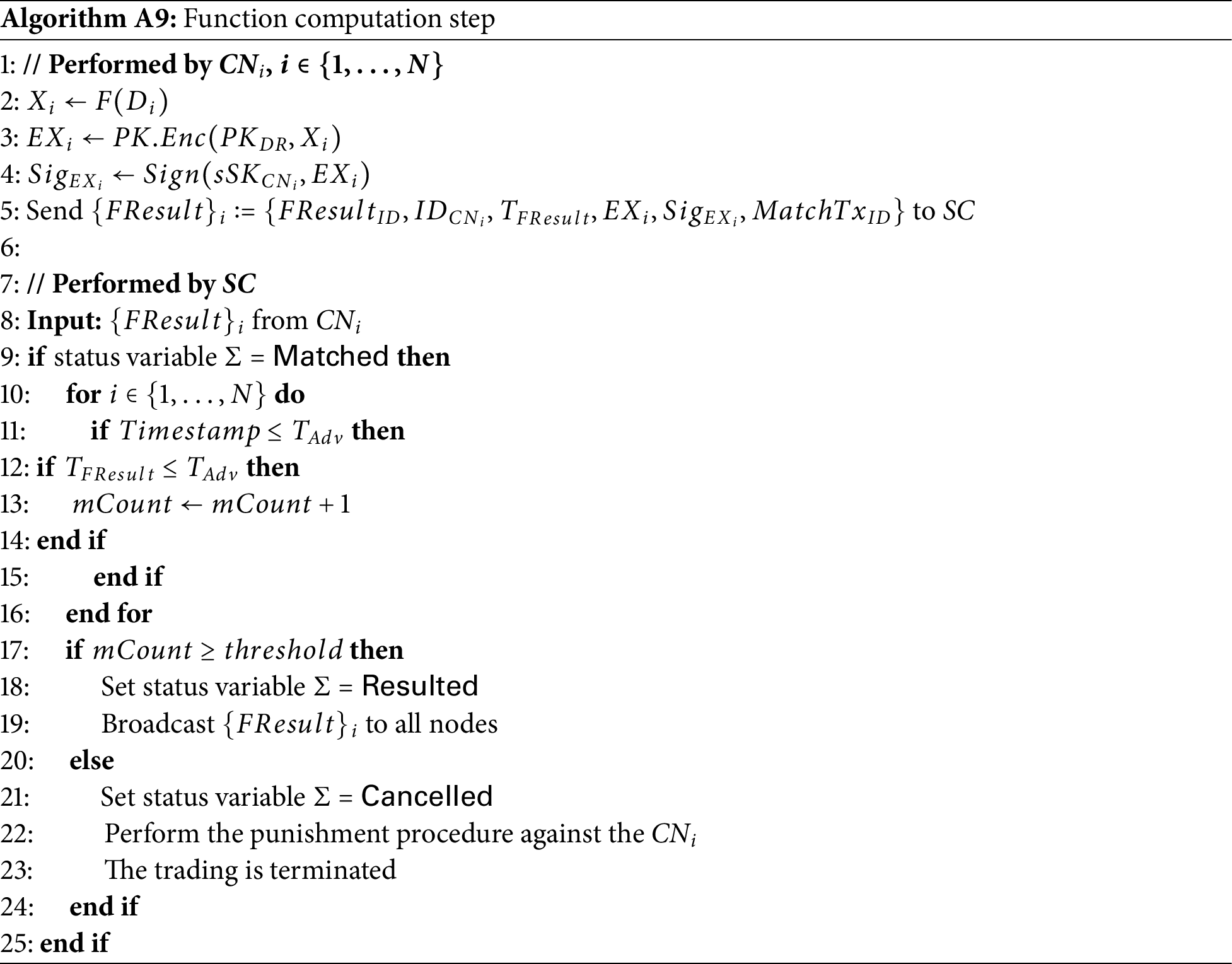

1. The function computation step: The

2. The verification and reconstruction step: The DR performs verification on

Appendix B Pseudo-Code of the Dispute Resolution Phase

The dispute resolution phase proceeds when the SC receives a dispute resolution request from other participants under the following conditions: (1) ED′s commit value verification fails, (2)

Appendix B.1 Verification Failure of ED′s Commit Value: This process occurs when

Appendix B.2 Verification Failure of

Appendix B.3 Verification Failure of

Appendix B.4 Verification Failure of D′s Hash Value: This process occurs when DR, fails to verify the hash value for D and sends

Appendix B.5 Verification Failure of

References

1. Farayola OA, Olorunfemi OL, Shoetan PO. Data privacy and security in it: a review of techniques and challenges. Comput Sci IT Res J. 2024;5(3):606–15. doi:10.51594/csitrj.v5i3.909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Fabianek C, Krenn S, Loruenser T, Siska V. Secure computation and trustless data intermediaries in data spaces. arXiv:2410.16442. 2024. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2410.16442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Karim SM, Habbal A, Chaudhry SA, Irshad A. Architecture, protocols, and security in IoV: taxonomy, analysis, challenges, and solutions. Secur Commun Netw. 2022;2022(1):1131479. doi:10.1155/2022/1131479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Luo Y, You W, Shang C, Ren X, Cao J, Li H. A cloud-fog enabled and privacy-preserving IoT data market platform based on blockchain. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2024;139(2):2237–60. doi:10.32604/cmes.2023.045679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Lan C, Li H. BC-PC-Share: blockchain-based patient-centric data sharing scheme for PHRs in cloud computing. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2023;136(3):2985–3010. doi:10.32604/cmes.2023.026321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Golob S, Pentyala S, Dowsley R, David B, Larangeira M, De Cock M, et al. A decentralized information marketplace preserving input and output privacy. In: DEC ’23: Proceedings of the Second ACM Data Economy Workshop; 2023 June 18; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

7. Gabrielli S, Krenn S, Pellegrino D, Pérez Baún JC, Pérez Berganza P, Ramacher S, et al. Kraken: a secure, trusted, regulatory-compliant, and privacy-preserving data sharing platform. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2022. p. 107–30. [Google Scholar]

8. Khan JA, Wang W, Ozbay K. BELIEVE: privacy-aware secure multi-party computation for real-time connected and autonomous vehicles and micro-mobility data validation using blockchain—a study on New York City data. Transp Res Rec. 2024;2678(3):410–21. doi:10.1177/03611981231180200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Zhao C, Zhao S, Zhao M, Chen Z, Gao CZ, Li H, et al. Secure multi-party computation: theory, practice and applications. Inf Sci. 2019;476(1):357–72. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2018.10.024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Li J, Li S, Cheng L, Liu Q, Pei J, Wang S. BSAS: a blockchain-based trustworthy and privacy-preserving speed advisory system. IEEE Trans Vehicular Technol. 2022;71(11):11421–30. doi:10.1109/TVT.2022.3189410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Yuan M, Xu Y, Zhang C, Tan Y, Wang Y, Ren J, et al. Trucon: blockchain-based trusted data sharing with congestion control in internet of vehicles. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2022;24(3):3489–500. doi:10.1109/TITS.2022.3226500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Sadiq A, Javaid N, Samuel O, Khalid A, Haider N, Imran M. Efficient data trading and storage in internet of vehicles using consortium blockchain. In: 2020 International Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing (IWCMC); 2020 Jun 15–19; Limassol, Cyprus. p. 2143–8. doi:10.1109/iwcmc48107.2020.9148188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Marquet E, Moeyersons J, Pohle E, Van Kenhove M, Abidin A, Volckaert B. Secure key management for multi-party computation in Mozaik. In: 2023 IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy Workshops (EuroS&PW); 2023 Jul 3–7; Delft, Netherlands. p. 133–40. [Google Scholar]

14. Chattopadhyay AK, Saha S, Nag A, Nandi S. Secret sharing: a comprehensive survey, taxonomy and applications. Comput Sci Rev. 2024;51(2):100608. doi:10.1016/j.cosrev.2023.100608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Damgård I, Keller M, Larraia E, Pastro V, Scholl P, Smart NP. Practical covertly secure MPC for dishonest majority-or: breaking the SPDZ limits. In: 18th European Symposium on Research in Computer Security; 2013 Sep 9–13; Egham, UK. p. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

16. Rogaway P. Authenticated-encryption with associated-data. In: Proceedings of the 9th ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security; 2002 Nov 18–22; Washington, DC, USA. p. 98–107. [Google Scholar]

17. Al-Kuwari S, Davenport JH, Bradford RJ. Cryptographic hash functions: recent design trends and security notions. In: 6th China International Conference on Information Security and Cryptology (Inscrypt 2010); 2010 Oct 20–23; Shanghai, China. p. 133–50. [Google Scholar]

18. Bellare M, Desai A, Jokipii E, Rogaway P. A concrete security treatment of symmetric encryption. In: Proceedings 38th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science; 1997 Oct 20–22; Miami Beach, FL, USA. p. 394–403. [Google Scholar]

19. Benaloh J. Dense probabilistic encryption. In: Proceedings of the Workshop on Selected Areas of Cryptography; 1994; Kingston, ON, Canada. p. 120–45. [Google Scholar]

20. Naor M, Yung M. Public-key cryptosystems provably secure against chosen ciphertext attacks. In: STOC90: 22nd Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing; 1990 May 13–17; Baltimore, MD, USA. p. 427–37. [Google Scholar]

21. Goldwasser S, Micali S, Rivest RL. A digital signature scheme secure against adaptive chosen-message attacks. SIAM J Comput. 1988;17(2):281–308. doi:10.1137/0217017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Chen J, Algorand MS. arXiv:1607.01341. 2016. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1607.01341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Kosba A, Miller A, Shi E, Wen Z, Papamanthou C. Hawk: the blockchain model of cryptography and privacy-preserving smart contracts. In: 2016 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP); 2016 May 22–26; San Francisco, CA, USA. p. 839–58. [Google Scholar]

24. Abe M, Ohkubo M. A framework for universally composable non-committing blind signatures. Int J Appl Cryptogr. 2012;2(3):229–49. doi:10.1504/IJACT.2012.045581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Lindell AY. Adaptively secure two-party computation with erasures. In: Paper Session Presented at: Cryptographers’ Track at the RSA Conference; 2009 April 20–24; San Francisco, CA, USA. p. 117–32. [Google Scholar]

26. Zhang X, Miao X, Xue M. A reputation-based approach using consortium blockchain for cyber threat intelligence sharing. Secur Commun Netw. 2022;2022(1):7760509. doi:10.1155/2022/7760509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Liu Y, Liu Z, Zhang Q, Su J, Cai Z, Li X. Blockchain and trusted reputation assessment-based incentive mechanism for healthcare services. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2024;154(3):59–71. doi:10.1016/j.future.2023.12.023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Bhati AS, Pohle R, Abidin A, Andreeva E, Preneel B. Let’s Go Eevee! A friendly and suitable family of AEAD modes for IoT-to-cloud secure computation. In: CCS ’23: ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security; 2023 Nov 26–30; Copenhagen Denmark. p. 2546–60. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools