Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Enhancing Roaming Security in Cloud-Native 5G Core Network through Deep Learning-Based Intrusion Detection System

1 Department of Electrical Engineering, Udayana University, Badung, 80361, Indonesia

2 Department of Cyber Security, Kookmin University, Seoul, 02707, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Ilsun You. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Cutting-Edge Security and Privacy Solutions for Next-Generation Intelligent Mobile Internet Technologies and Applications)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(2), 2733-2760. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.072611

Received 30 August 2025; Accepted 10 October 2025; Issue published 26 November 2025

Abstract

Roaming in 5G networks enables seamless global mobility but also introduces significant security risks due to legacy protocol dependencies, uneven Security Edge Protection Proxy (SEPP) deployment, and the dynamic nature of inter-Public Land Mobile Network (inter-PLMN) signaling. Traditional rule-based defenses are inadequate for protecting cloud-native 5G core networks, particularly as roaming expands into enterprise and Internet of Things (IoT) domains. This work addresses these challenges by designing a scalable 5G Standalone testbed, generating the first intrusion detection dataset specifically tailored to roaming threats, and proposing a deep learning based intrusion detection framework for cloud-native environments. Six deep learning models including Multilayer Perceptron (MLP), one-dimensional Convolutional Neural Network (1D CNN), Autoencoder (AE), Recurrent Neural Network (RNN), Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU), and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) were evaluated on the dataset using both weighted and balanced metrics to account for strong class imbalance. While all models achieved over 99% accuracy, recurrent architectures such as GRU and LSTM outperformed others in balanced accuracy and macro-level evaluation, demonstrating superior effectiveness in detecting rare but high-impact attacks. These results confirm the importance of sequence-aware Artificial Intelligence (AI) models for securing roaming scenarios, where transient and context-dependent threats are common. The proposed framework provides a foundation for intelligent, adaptive intrusion detection in 5G and offers a path toward resilient security in Beyond 5G and 6G networks.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Global roaming enables mobile users to access voice, messaging, and data services outside their home networks by connecting to international partner networks. It relies on standardized signaling protocols and inter-operator agreements to ensure interoperability across diverse infrastructures. While traditionally essential for international travelers, roaming is increasingly important for enterprise applications, such as IoT and private networks. Although only 34% of enterprises currently require international IoT connectivity [1], use cases like asset tracking demand seamless transitions between private and public networks and compatibility with legacy systems [2]. As roaming expands into these new domains, the protection of signaling information becomes a critical concern, particularly due to the sensitive data exchanged across networks with varying security standards.

However, the roaming ecosystem has long faced significant security challenges, many of which stem from the use of legacy signaling protocols. In 2G and 3G networks, the SS7 protocol lacked encryption and authentication, enabling attackers to eavesdrop on communications, track subscriber locations, and conduct denial-of-service or call interception attacks [3–5]. Although the introduction of Diameter in 4G introduced improvements, many networks maintained backward compatibility with SS7, and insecure interconnection practices via IPX providers remained prevalent. These hybrid deployments left mobile core networks vulnerable to cross-domain attacks. The Syniverse breach, for example, demonstrated how attackers could maintain persistent, unauthorized access to signaling infrastructure over several years, affecting hundreds of operators and millions of subscribers [6].

The emergence of 5G Standalone (SA) architecture introduced major enhancements to roaming security through Service-Based Architecture (SBA) and the Security Edge Protection Proxy (SEPP) [7–9]. SBA modularizes core network functions as stateless microservices that communicate over APIs, increasing flexibility and scalability. SEPP, mandated for inter-PLMN signaling, aims to secure the N32 interface using TLS and mutual authentication, preventing unauthorized access and eavesdropping on cross-border signaling. However, deployment remains uneven. According to 2025 reports [10], only 73 of the 163 operators investing in 5G SA had launched fully standalone services. Many continue to rely on Non-Standalone (NSA) or hybrid architectures, which either bypass SEPP or operate in insecure transitional modes. Additionally, core interfaces such as N32-c (for control signaling) and N32-f (for service discovery) are underexplored, despite their growing importance and susceptibility to abuse in inter-operator roaming.

This uneven rollout of 5G SA highlights broader security challenges as networks shift toward cloud-native architectures, large-scale data exchange, and massive IoT connectivity. While these changes enable flexibility and innovation, they also expand the attack surface [11–15], particularly in roaming scenarios that span multiple administrative domains. The adoption of SBA and containerized functions across cloud environments introduces vulnerabilities beyond the reach of legacy telecom defenses. Threats like signaling overload, probing, and TLS attacks on SEPPs are increasingly feasible in this fragmented landscape. As noted by [16], 32% of operators are concerned about the broader attack surface in 5G, with 29% citing roaming as a key risk. Securing these evolving infrastructures is critical to maintaining trust in global mobile networks.

Traditional rule-based security tools are inadequate for addressing the scale, complexity, and dynamism of cloud-native 5G roaming systems. To this end, AI offer a promising alternative by enabling systems to learn behavioral baselines and detect anomalous activities in real time [17–21]. AI-based detection systems can model interactions among distributed network functions, monitor deviations in control-plane signaling, and identify patterns indicative of SEPP misuse or cross-domain signaling abuse. Despite growing interest in AI for telecom security, little attention has been given to SBA-specific inter-PLMN interactions, especially those involving N32-c and N32-f signaling. These interfaces represent blind spots in both standardization and practical defense mechanisms. Intelligent, context-aware monitoring of these components is essential for enabling real-time, adaptive protection in roaming environments that lack centralized visibility or trust enforcement.

This work addresses these emerging challenges and fills key research gaps through the following contributions:

• Design and implement a cloud-native 5G Core Network testbed that emulates realistic roaming scenarios within a scalable, containerized environment.

• Introduce the 5G Core Network Roaming Intrusion Detection Dataset, the first of its kind tailored specifically for roaming-related threats in a 5G cloud-native environment.

• Propose an intrusion detection framework that operates natively within the cloud infrastructure, enabling efficient detection of roaming attacks.

• Evaluate a range of deep learning algorithms within this framework to assess their effectiveness in identifying roaming intrusions, offering valuable insights into the viability of AI-based defense mechanisms in B5G and 6G.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews existing research on roaming security, SEPP deployments, and AI-based intrusion detection systems in 5G networks. Section 3 details the methodology, including the design of our cloud-native 5G SA testbed, the generation of roaming threat scenarios, and the architecture of the proposed AI-based detection framework. Section 4 presents the experimental setup, including dataset collection, feature engineering, and model implementation. Section 5 discusses the evaluation results of multiple deep learning algorithms and provides analysis on their performance in detecting roaming-specific threats. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper and outlines future research directions to advance secure and intelligent roaming in Beyond 5G and 6G networks.

Roaming remains a critical component of mobile communication systems, yet it introduces significant security vulnerabilities that persist across generations of network technologies. The study [22] demonstrates how attackers with access to roaming agreements can exploit authentication mechanisms to deploy stealthy Rogue Base Stations (RBSes), enabling undetected traffic interception and manipulation even under updated 5G procedures. Similarly, the work [23] analyzes signaling-based denial-of-service (DoS) attacks in 5G roaming environments, showing that such attacks can amplify their impact on Public Land Mobile Networks (PLMNs) by up to 2.69

As 5G networks evolve, the security of the 5G Core Network (5GCN) has become a critical concern due to its software-defined, service-based, and virtualized architecture. Broader threats such as Distributed Denial-of-Service (DDoS) attacks have gained prominence, exploiting the increased complexity and openness of 5G infrastructures. The studies [25,26] demonstrate how deep learning, specifically CNN, can detect botnet-driven DDoS attacks targeting core components. To address such threats proactively, the work [27] proposes a neural network-based framework that identifies and blocks malicious traffic before it infiltrates the core network. Likewise, the study [28] stresses the importance of resource isolation to contain the impact of DDoS attacks, particularly in multi-tenant, virtualized environments. Further advancing detection capabilities, the research [29] explores deep learning-based intrusion detection in cyber–physical systems over 5G, proposing transfer learning as a solution to the scarcity of labeled training data in operational settings. In addition to DDoS threats, anomaly detection in the control plane is essential for safeguarding network function (NF) interactions.

Several recent studies highlight the effectiveness of RNN-based architectures in modeling sequential patterns for intrusion detection. ADSeq-5GCN [30] employs a BiLSTM-based framework to capture NF-to-NF communication sequences, enabling the detection of subtle control-plane anomalies. Similarly, DeepSecure [31] utilizes LSTM models to identify DDoS attacks in 5G environments without relying on manual thresholds or handcrafted features. A federated RNN-based IDS [32] has also been proposed for IoT environments, demonstrating how sequential modeling can be leveraged in distributed settings while preserving data locality. These approaches underscore the importance of modeling temporal behaviors in complex network environments, where attacks often manifest as subtle, time-dependent deviations. In this context, LSTM networks are particularly effective in learning long-range dependencies in signaling sequences, making them well-suited for detecting anomalies in dynamic 5G core network traffic.

Targeting signaling-level threats, the study [33] demonstrates how entropy and statistics-based preprocessing combined with classical ML classifiers can effectively identify high-volume signaling attacks, with Random Forest achieving 98.7% accuracy. Secure5G [27] further extends IDS functionality by integrating proactive threat isolation into a deep learning-based slicing model, enabling secure, end-to-end network slicing services. Additionally, the study [34] highlights how efficient feature selection can maintain high detection performance while significantly improving the computational efficiency of ML-based detection systems in real-time 5G CN environments.

Recent advances in AI have significantly enhanced the capabilities of IDS, especially in addressing the challenges posed by high-throughput, cloud-native, and big data-driven environments. Traditional machine learning-based IDS approaches often fall short in scalability and adaptability, prompting the emergence of more dynamic and intelligent models. The works [35–37] introduce a deep autoencoder-based method that reconstructs complete event sequences for anomaly detection, effectively capturing structural dependencies to reduce false positives and improve detection accuracy. To address the complexities of large-scale distributed networks, the studies [38,39] propose a Reinforcement Learning framework that leverages cloud computing and big data streaming techniques to enable real-time, cooperative intrusion detection with minimal latency and high accuracy. The researches [40,41] offer a comprehensive review and taxonomy of deep learning-based IDS techniques, including autoencoders, deep belief networks, restricted Boltzmann machines, and recurrent neural networks, emphasizing their role in detecting sophisticated and evolving threats. In the context of 5G and virtualized infrastructures, the study [42] presents a multi-layered intrusion detection and prevention system that combines SDN/NFV technologies with AI-based mechanisms, such as entropy-based classification, deep reinforcement learning, and game-theoretic models, to mitigate attacks like DDoS and flow table overloading effectively. Focusing on adaptability within cloud environments, the work [43] develops an intrusion detection system based on Double Deep Q-Networks (DDQN) and prioritized experience replay, which can detect novel and adversarial attacks while maintaining computational efficiency. Complementing these approaches, the study [44] introduces a hypervisor-based IDS that utilizes online multivariate statistical change tracking and an instance-oriented feature model to detect anomalies at the virtualization layer.

A recent contribution in the domain of 5G security datasets is 5G-NIDD [45], which introduces a fully labeled dataset collected from a functional 5G testbed. It captures a range of application-layer traffic such as HTTP, HTTPS, SSH, and SFTP, providing a valuable resource for developing and benchmarking AI/ML-based intrusion detection systems. The dataset has been used to evaluate classical machine learning models, offering insights into their performance in realistic 5G environments. However, its focus remains on general network activity rather than signaling-specific threats. As such, while 5G-NIDD is useful for broad IDS evaluation, it does not include inter-PLMN signaling anomalies over the SEPP interface.

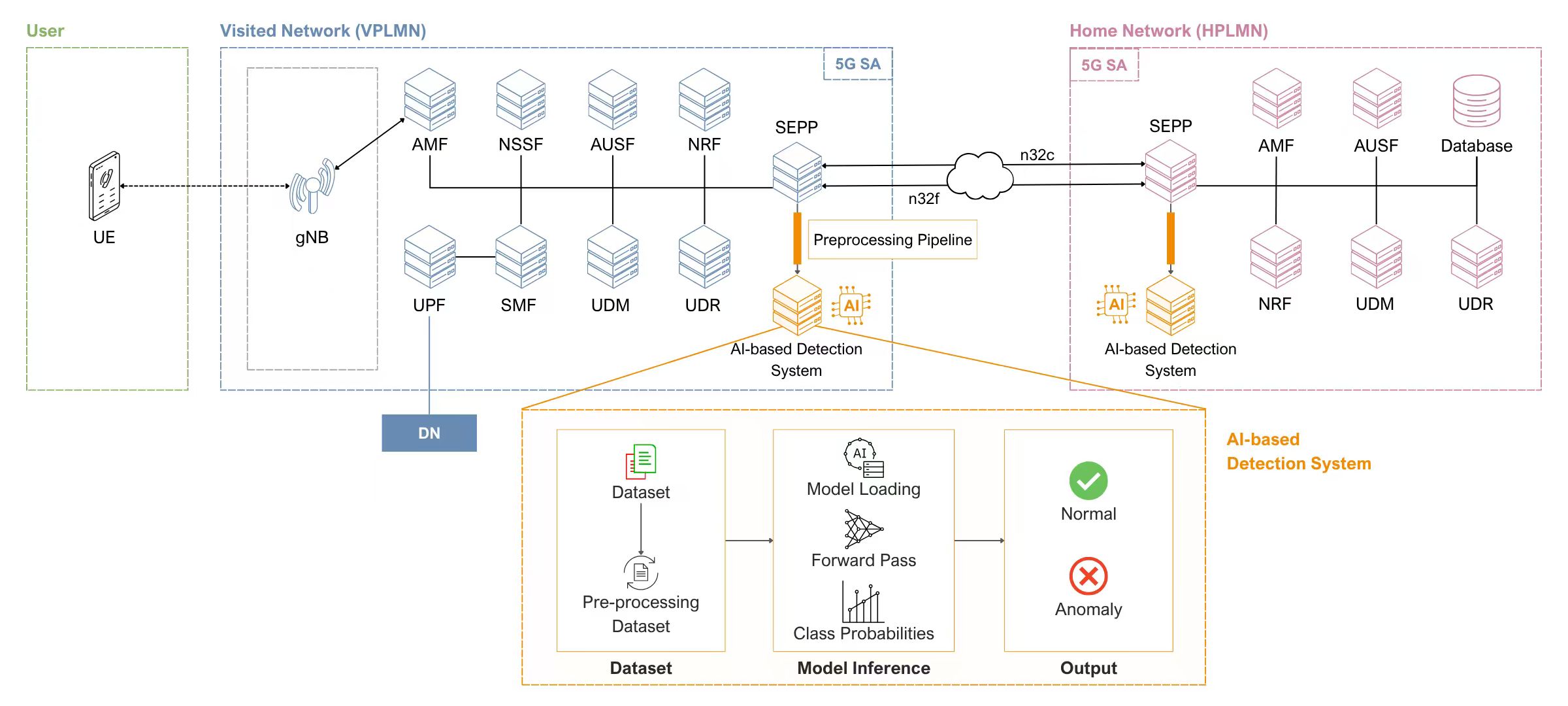

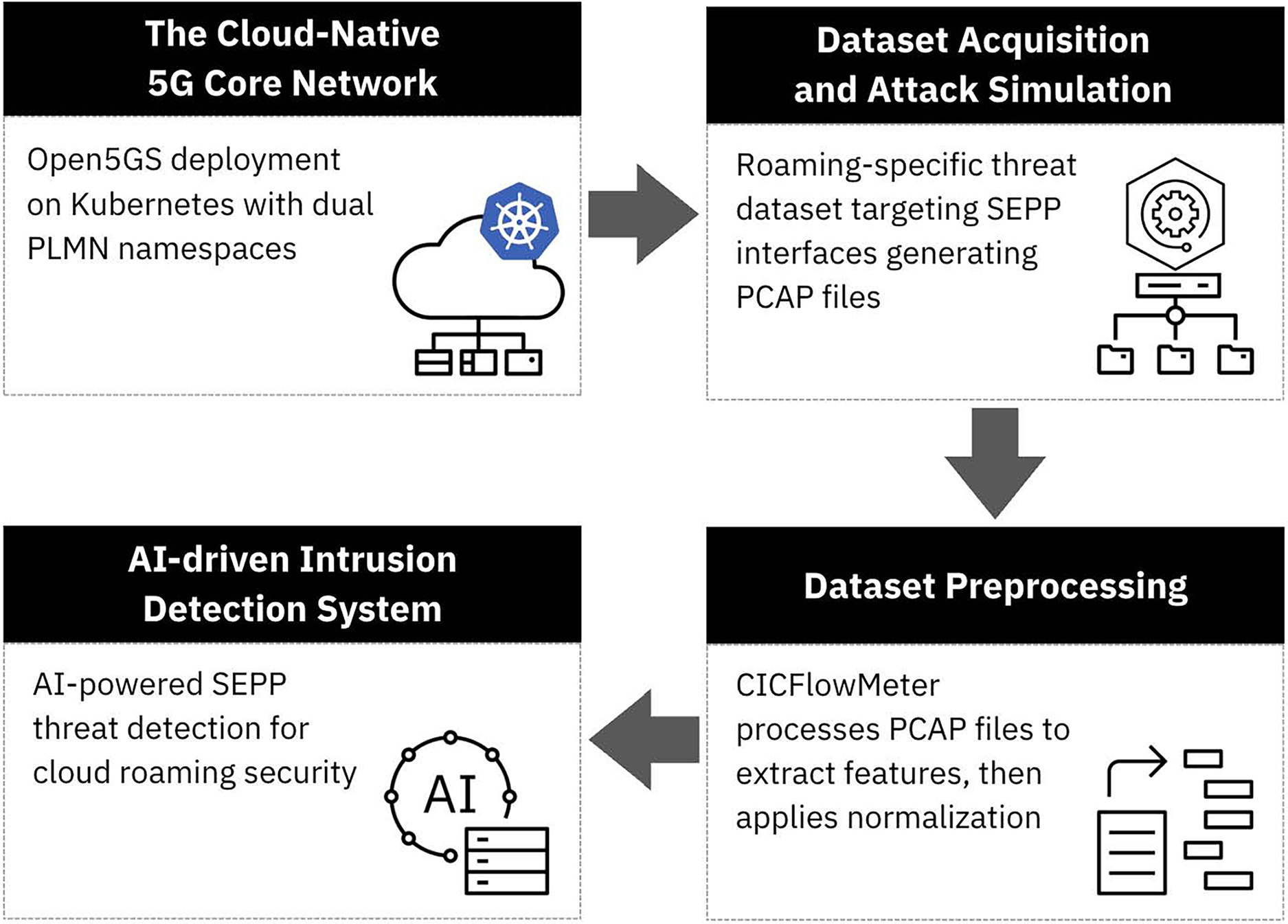

In this research, we present our cloud-based testbed setup for the global roaming environment, as well as our methods in generating the normal and attacked datasets. The overall methodology is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: AI-driven intrusion detection framework for cloud-native 5G networks using SEPP interface analysis

3.1 The Cloud-Native 5G Core Network

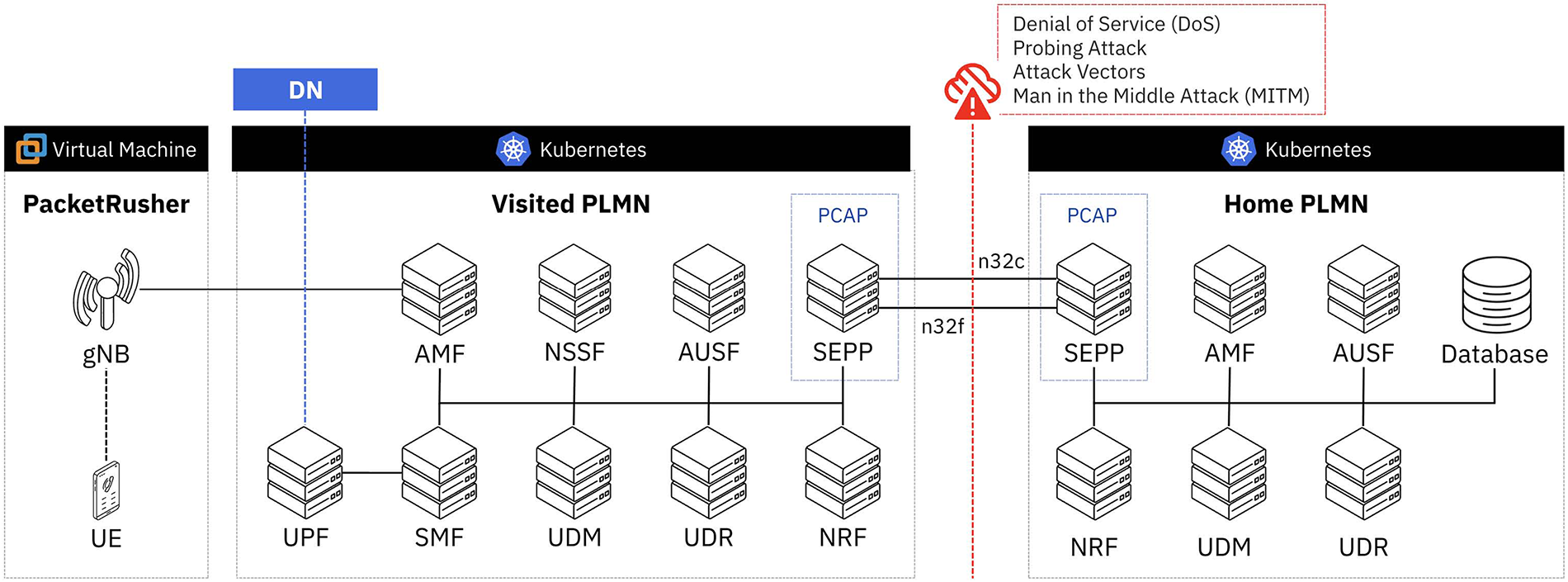

The experimental environment employs a cloud-native 5G core network architecture implemented using Open5GS [46] deployed on a Kubernetes cluster [47] to simulate realistic global roaming scenarios as shown in Fig. 2. Open5GS provides a complete implementation of 3GPP Release-17 specifications, including all necessary Network Functions for 5G Service-Based Architecture (SBA) operations. The containerized deployment ensures scalability and isolation while maintaining the flexibility required for comprehensive security testing across geographically distributed network components.

Figure 2: 5G testbed architecture with inter-PLMN SEPP communication and attack vector simulation environment

The Kubernetes deployment is organized into two distinct namespaces representing geographically separated PLMN. The HPLMN namespace hosts the home network infrastructure, containing core network functions including Authentication Server Function (AUSF), Unified Data Management (UDM), Access and Mobility Management Function (AMF), and Session Management Function (SMF). The VPLMN namespace mirrors this architecture to represent the visited network, enabling complete inter-PLMN roaming scenarios with realistic network function interactions. SEPP instances are deployed in both namespaces to handle inter-PLMN communications through standardized N32 interfaces, with N32c managing control plane operations including TLS 1.3 handshake procedures and N32f handling forwarding plane operations, both implementing TLS 1.3 encryption for secure inter-PLMN communications.

The subscriber database consists of 100,000 entries stored in MongoDB collections, with International Mobile Subscriber Identities (IMSIs) ranging from 0000000001 to 0000100000, each containing complete authentication credentials including permanent keys (K), operator variant algorithm configuration (OPc), and AMF values. PacketRusher [48] is employed to simulate both User Equipment (UE) and gNodeB functionalities, generating realistic 5G registration procedures and mobility management scenarios. The PacketRusher implementation follows 3GPP procedures for initial registration, authentication, and session establishment, providing a comprehensive simulation environment for both normal roaming operations and attack scenario evaluation.

3.2 Dataset Acquisition and Attack Simulation

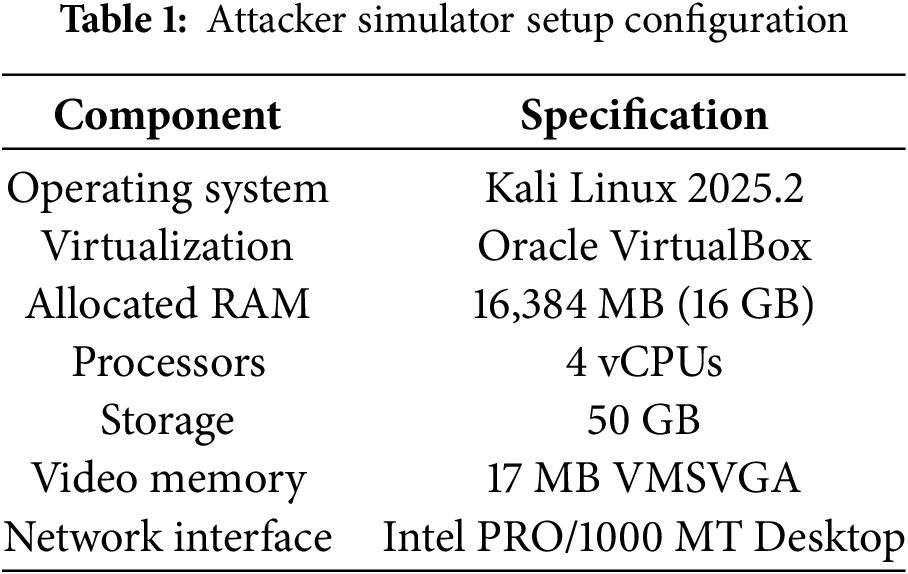

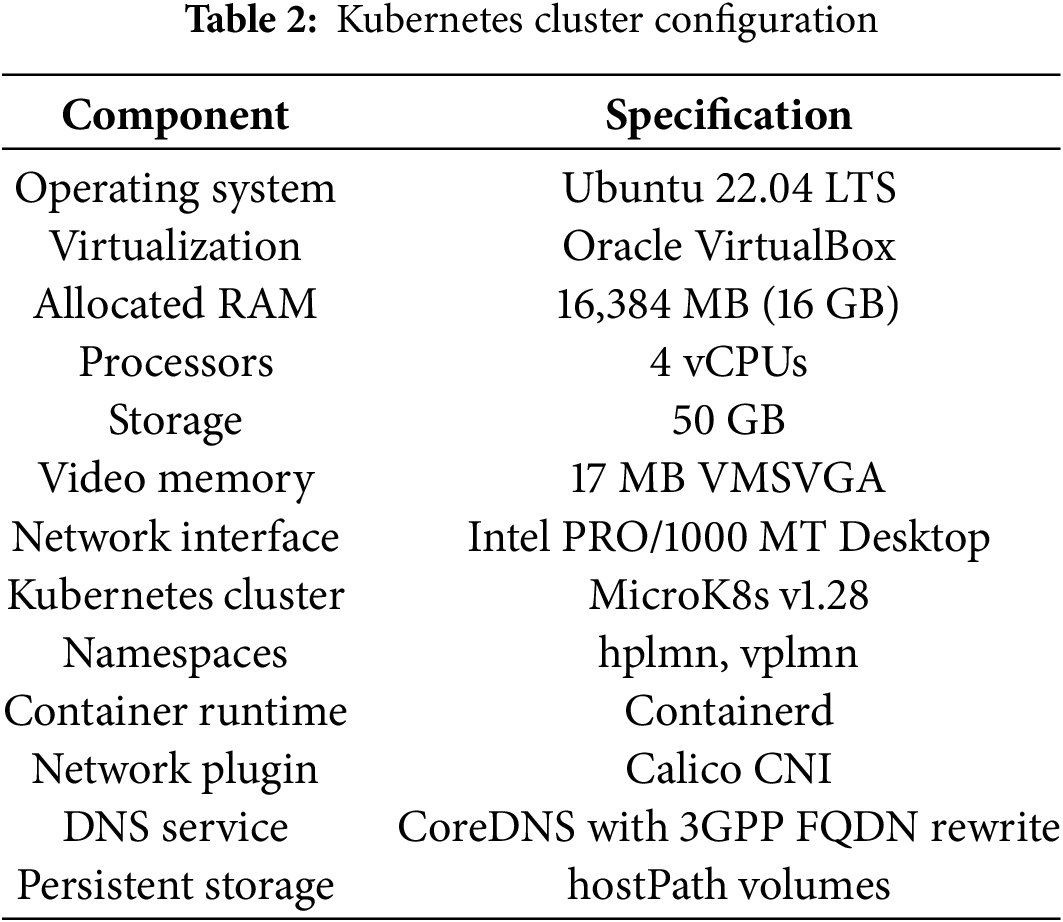

The dataset generation process represents the first comprehensive approach to simulating roaming-specific threats targeting SEPP network functions within a cloud-native 5G environment. Unlike existing datasets that focus on traditional network attacks or general 5G core network threats, our approach specifically targets the unique vulnerabilities and attack vectors present in inter-PLMN roaming scenarios through SEPP interfaces. The attack simulation incorporates proven attack methodologies from established research [49] while adapting them to the unique characteristics of cloud-native 5G roaming environments. Tables 1 and 2 summarize the general setup within the controlled environment.

3.2.1 Normal Traffic Dataset Generation

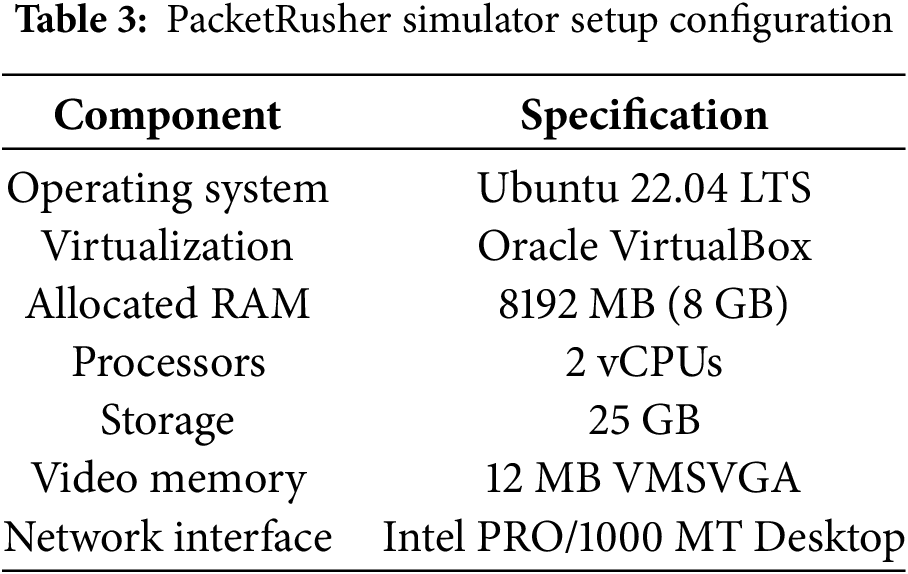

Normal network behavior data is generated using PacketRusher, an open-source gNB and UE simulator that interfaces directly with the deployed 5G core network. The PacketRusher simulator configuration is detailed in Table 3. The simulator orchestrates realistic roaming scenarios where UEs execute periodic registrations every 1 s, generating 100,000 registration procedures, resulting in a dataset totaling 9.41 GB. Each registration follows the complete 5G Authentication and Key Agreement (5G-AKA) protocol flow, including SEPP establishment for secure inter-operator communication.

The key novelty lies in capturing authentic SEPP-mediated inter-PLMN signaling patterns. PacketRusher’s configuration enables authentic roaming signaling patterns where simulated UEs register to the VPLMN infrastructure while authentication credentials are validated against the HPLMN subscriber database through N32-c and N32-f interfaces. The simulator captures comprehensive protocol message exchanges that include:

• N32-c Control Signaling: TLS 1.3 handshake procedures, certificate exchanges, and control plane message routing between SEPP instances

• N32-f Forwarding Operations: Service discovery messages and forwarding plane communications

• Inter-PLMN Authentication Flows: Complete 5G-AKA procedures spanning multiple administrative domains

• Service-Based Architecture Communications: HTTP/2 REST API interactions between distributed network functions

3.2.2 Attack Framework and Taxonomy

Our attack simulation employs a hybrid taxonomy combining MITRE ATT&CK techniques with 3GPP TS 33.501 security threat specifications to comprehensively categorize 5G network attacks, building upon established methodologies from existing research [25,33]. The framework maps network reconnaissance activities to technique MITRE-T1595 (Active Scanning), encompassing port scanning, service enumeration, and 5G network function discovery. Availability attacks leverage MITRE-T1498 (Network Denial of Service) and MITRE-T1499 (Endpoint Denial of Service) taxonomies, covering protocol-specific resource exhaustion targeting 5G core network functions like the SEPP.

TLS vulnerability exploitation maps to MITRE-T1040 (Network Sniffing) and MITRE-T1557.002, encompassing downgrade attacks, certificate validation bypass, and cipher suite manipulation targeting the 5G SBA interfaces. This hybrid approach ensures comprehensive coverage of both traditional network attacks and 5G-specific threat vectors, enabling systematic attack scenario development and accurate ground truth labeling for deep learning model training.

3.2.3 Attack Dataset Generation

Attack traffic datasets were systematically generated using established methodologies adapted from recent cloud-based intrusion detection research [49]. The simulations were conducted on a Kali Linux virtual machine (VM) configured within the same local area network, simulating an adversary targeting the SEPP communication channel. This setup mimics realistic attack scenarios in the context of inter-PLMN 5G roaming traffic, as described in Table 1.

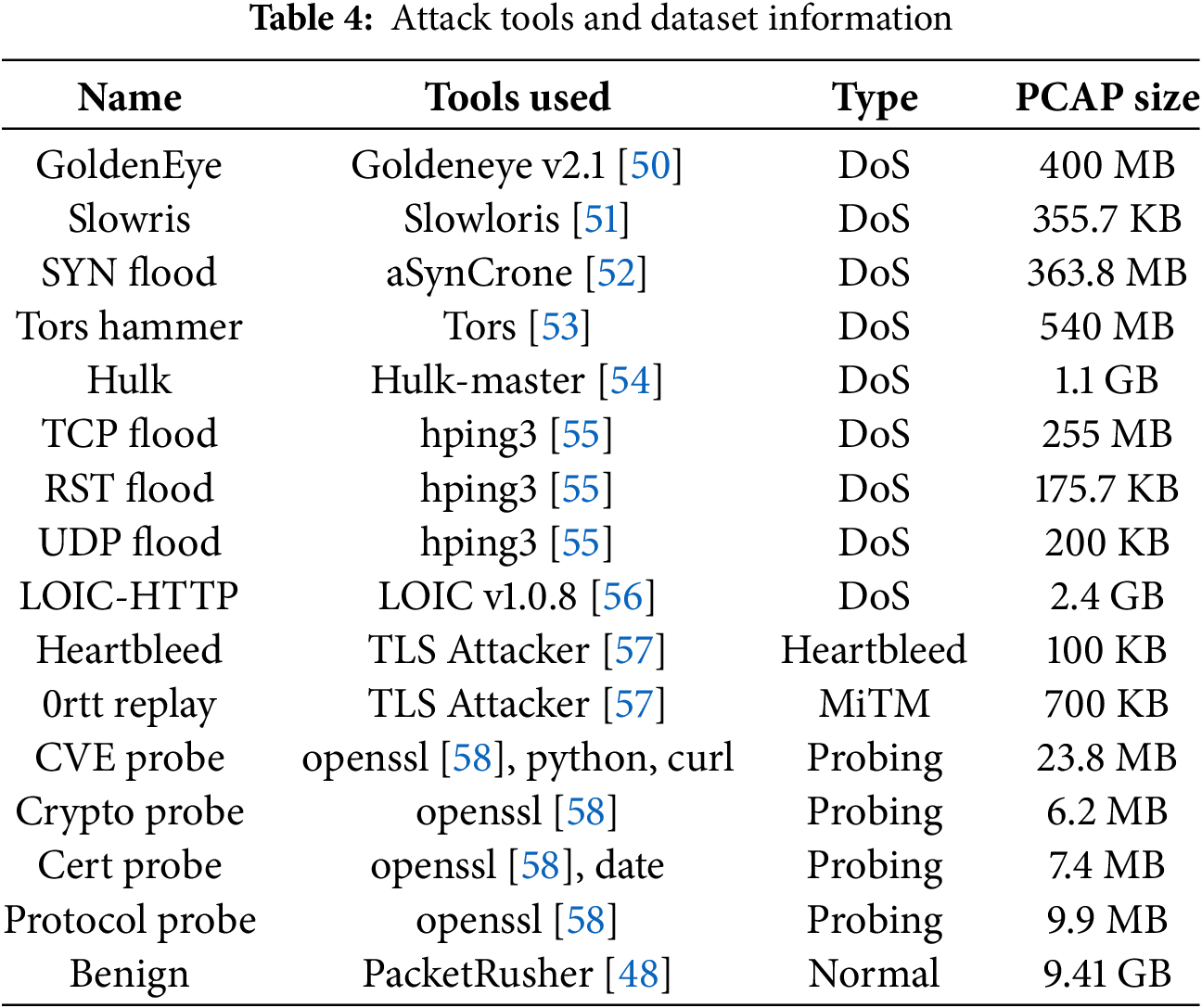

Each attack category was executed using specialized tools designed to exploit specific vulnerabilities in cloud-native 5G infrastructure. These include a range of DoS techniques, probing activities, and TLS exploitation (such as Heartbleed and 0-RTT replay). A detailed list of the attack types, tools used, and corresponding PCAP sizes is provided in Table 4, which serves as the basis for the construction of the labeled attack dataset.

Denial of Service Attacks

The Denial of Service (DoS) dataset encompasses multiple attack variants targeting different layers of the SEPP infrastructure. Following methodologies established in [49] for network attacks, we implement diverse DoS techniques: high-intensity application-layer attacks using GoldenEye and Slowloris with controlled load testing and gradual ramp-up patterns to evade detection mechanisms. Transport-layer attacks include SYN flooding using aSynCrone, TCP flooding via hping3, and RST flooding. Distributed attack scenarios leverage Hulk-master and LOIC HTTP to simulate coordinated multi-source attacks, while Tors Hammer represents anonymized attack vectors through Tor networks.

TLS Exploitation and Probing Attacks

Comprehensive probing and Transport Layer Security (TLS) exploitation campaigns target the N32 interface between SEPP nodes, adapting techniques from established TLS vulnerability research. These attacks systematically discover security properties of the inter-operator communication channel while attempting to exploit known Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVEs) affecting TLS implementations. The Heartbleed and 0rtt Replay attacks employ TLS Attacker tools to exploit OpenSSL implementations. CVE reconnaissance utilizes a multi-tool approach with openssl, python, and curl for comprehensive vulnerability discovery. Cryptographic analysis leverages openssl for cipher suite enumeration and weakness identification, while certificate validation attacks employ openssl and date utilities for certificate chain manipulation and validation bypass attempts. Protocol-level attacks target TLS version negotiation vulnerabilities in SEPP N32 interfaces.

3.2.4 Attack Execution and Data Collection Methodology

Attack execution leverages a combination of specialized tools and custom scripts to simulate diverse threat scenarios against the 5G roaming infrastructure, following established penetration testing methodologies adapted for cloud-native environments. Network reconnaissance employs nmap with SSL-specific NSE scripts for service enumeration and TLS configuration analysis, while OpenSSL utilities (s_client, x509, ciphers, version) conduct comprehensive cryptographic vulnerability assessments including cipher suite downgrade attacks and certificate validation bypasses.

Data collection employs tcpdump for comprehensive packet capture across multiple network interfaces, capturing both attack traffic and normal operational flows simultaneously. Each attack execution generates labeled datasets with precise temporal correlation between attack initiation timestamps and observed network behaviors. The collection framework preserves complete protocol stacks from physical layer radio frequency patterns to application layer HTTP/2 service communications, enabling multi-granular analysis of attack signatures and their propagation through the 5G network stack, ensuring the normal traffic dataset reflects genuine 5G roaming operational characteristics and timing patterns essential for establishing baseline network behavior.

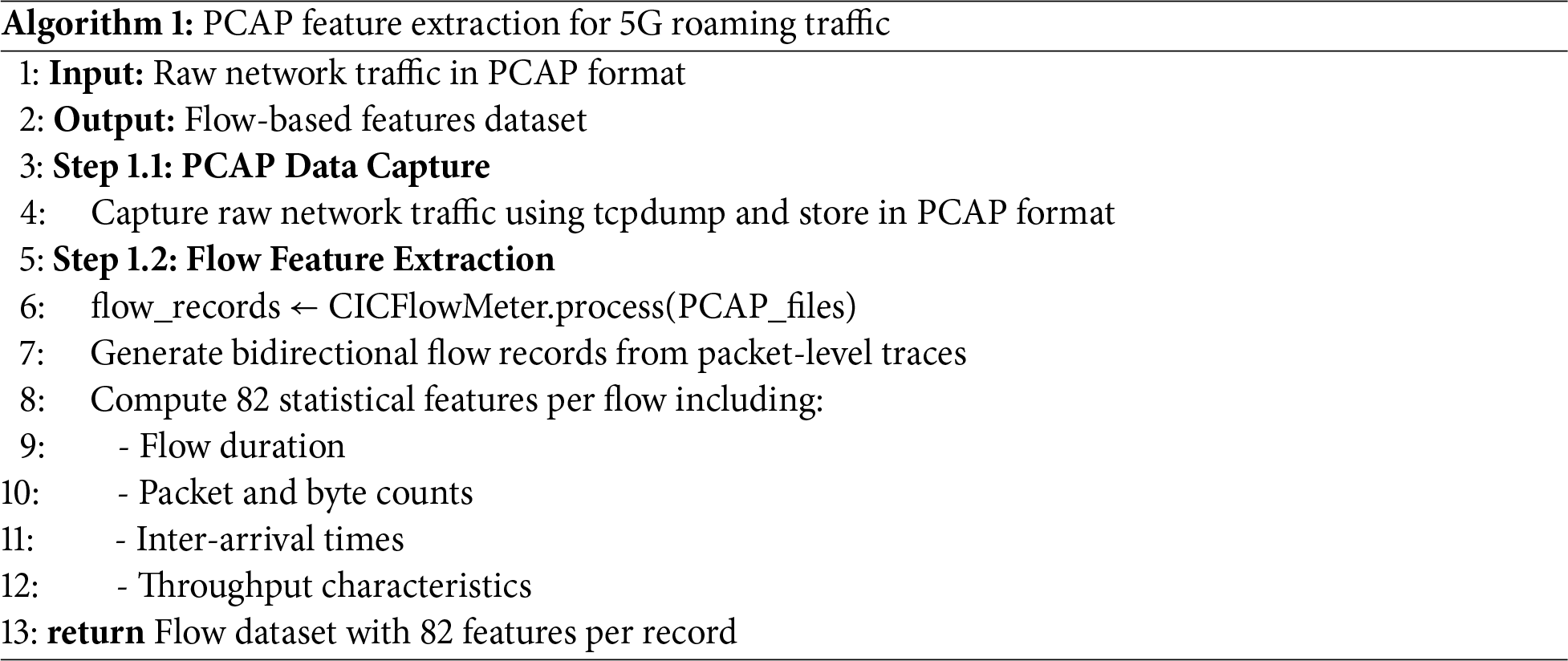

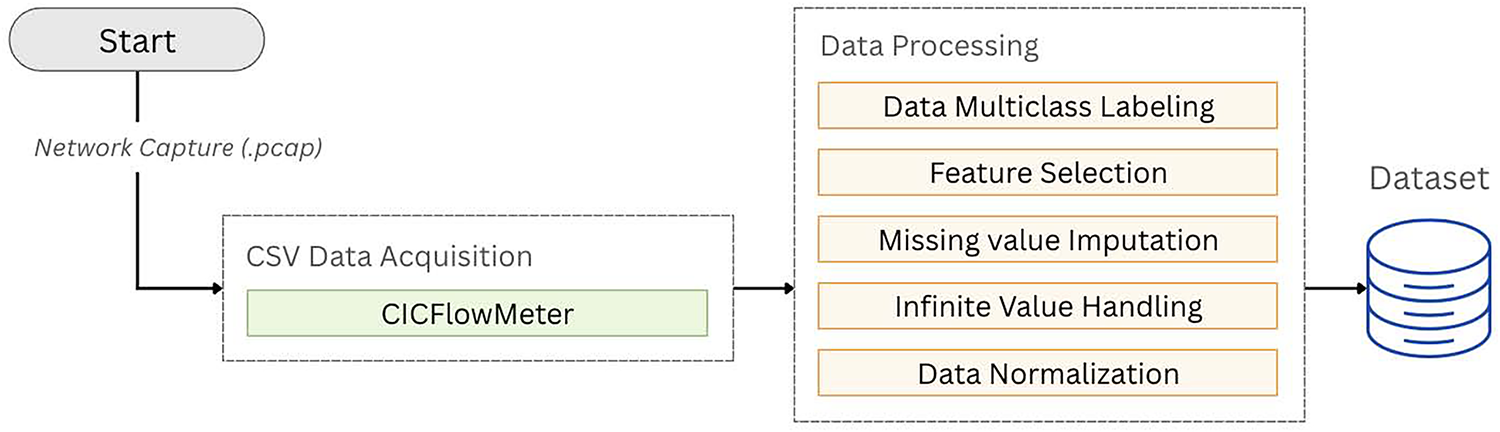

The preprocessing of the dataset begins with the capture of raw network traffic using tcpdump, a tool that extracts flow-based features from packet-level traces. CICFlowMeter [59] generates bidirectional flow records and computes 82 statistical features per flow, including metrics such as flow duration, packet and byte counts, inter-arrival times, and throughput characteristics. The complete feature extraction is formalized in Algorithm 1.

After the flow features are extracted, the data is labeled for multiclass classification, assigning each flow to its respective category for supervised learning tasks. Following labeling, a feature selection process is applied to reduce redundancy and enhance model performance. The Time column is removed first, as it provides little value for behavioral analysis. Features exhibiting no variance across all records are discarded since they do not contribute useful information for classification. In addition, identifier-related fields such as source and destination IP addresses, source and destination ports, and the protocol field are excluded to prevent data leakage and ensure the model focuses on behavioral aspects rather than static network identifiers. These steps reduce the original 82 features down to a more focused set of 76.

To improve the dataset’s quality and robustness, further data cleansing is performed. Records containing infinite values, which can result from measurement anomalies or division-by-zero errors, are removed. Rows with negative values are also excluded, as network flow features like durations and byte counts are expected to be non-negative. Once cleansing is complete, the dataset undergoes normalization. All numerical features are standardized using z-score normalization via StandardScaler, transforming them to have a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one. This normalization step ensures consistent feature scaling and contributes to more stable and accurate model training during classification. An overview of this end-to-end dataset generation and preprocessing workflow is illustrated in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Dataset generation and preprocessing diagram

3.4 Proposed Intrusion Detection Framework

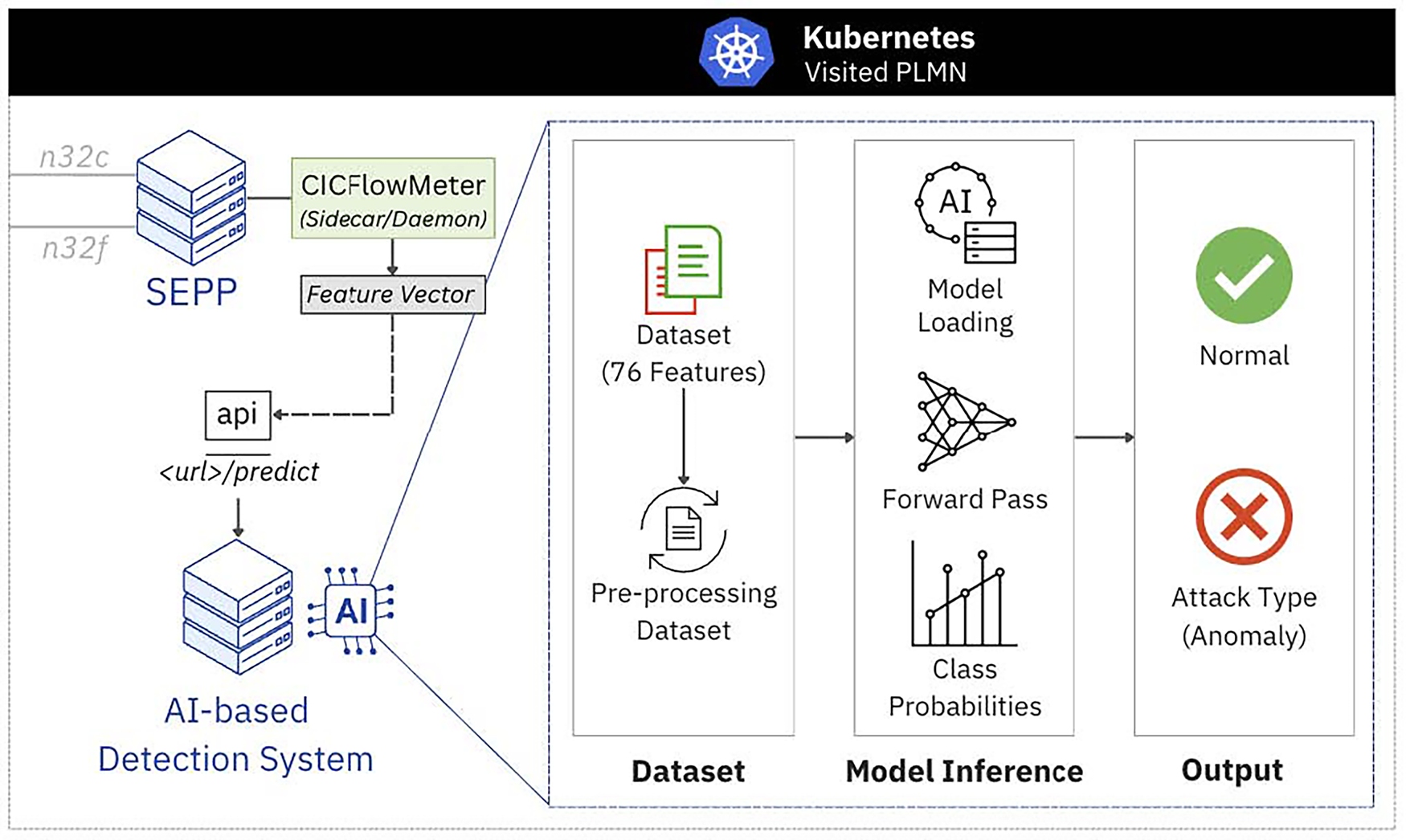

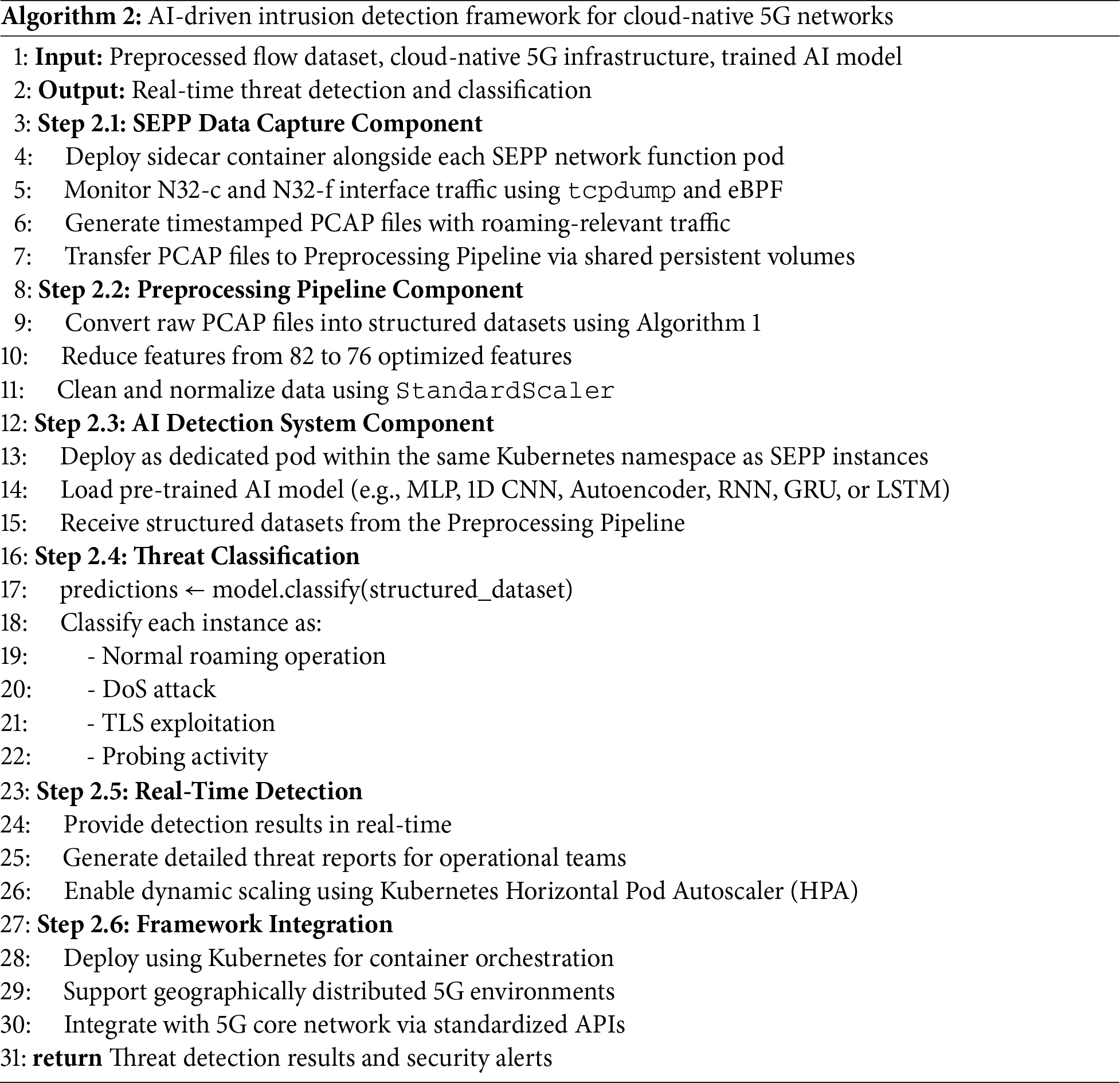

This section presents a cloud-native intrusion detection framework specifically designed to detect roaming-related threats within 5G SBA environments. Traditional rule-based security tools are insufficient to address the complexity, scalability, and dynamic nature of modern 5G roaming systems, particularly in inter-PLMN communications. To overcome these limitations, the proposed AI-driven framework leverages Kubernetes-native deployment and operates through containerized microservices, enabling real-time threat detection within SEPP-mediated roaming traffic. The framework includes dedicated components for data capture, preprocessing, and AI-based classification, ensuring efficient and scalable operation in distributed environments. The overall architecture and process flow of the system are illustrated in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: AI framework and process flow on cloud-native environment

The proposed framework adopts a distributed microservices architecture deployed on Kubernetes for scalable and efficient operation. The system comprises three primary components: SEPP Data Capture, Preprocessing Pipeline, and AI Detection System. Each component operates as an independent containerized service within the Kubernetes cluster, ensuring scalability and seamless integration with existing 5G core network functions. The complete algorithmic implementation of this cloud-native intrusion detection framework is detailed in Algorithm 2, which demonstrates the systematic data flow from SEPP network function packet capture through comprehensive preprocessing stages to AI-based analysis utilizing the deep learning algorithms evaluated in Section 5. The design ensures minimal latency between threat detection and response while maintaining the performance characteristics required for production 5G roaming operations.

3.4.1 SEPP Data Capture Component

The SEPP Data Capture component operates as a sidecar container alongside each SEPP network function pod within the Kubernetes cluster, monitoring N32-c and N32-f interface traffic through tcpdump and eBPF-based mechanisms. The component generates timestamped PCAP files with intelligent filtering for roaming-relevant traffic patterns and transfers them to the Preprocessing Pipeline through shared persistent volumes within the Kubernetes environment.

3.4.2 Preprocessing Pipeline Component

The Preprocessing Pipeline transforms raw PCAP files into structured datasets suitable for deep learning analysis. The pipeline implements the comprehensive methodology detailed in Section 3.3, including CICFlowMeter feature extraction reducing the original 82 features to 76 optimized features, data labeling for multiclass classification, cleansing procedures to eliminate infinite values and negative measurements, normalization using StandardScaler, and dataset generation optimized for the deep learning architectures evaluated in this work.

3.4.3 AI Detection System Component

The AI Detection System is deployed as a dedicated pod within the same Kubernetes namespace as the monitored SEPP instances, ensuring low-latency data access and efficient resource utilization. It receives structured datasets from the Preprocessing Pipeline and utilizes a selected pre-trained deep learning model for intrusion detection. The supported models include MLP, 1D-CNN, Autoencoder, RNN, GRU, and LSTM.

The system does not rely on a multi-model ensemble; instead, it utilizes a single pre-trained model selected based on deployment needs or prior evaluation results to perform multi-class classification. This model is responsible for distinguishing between normal roaming operations and various attack categories, including DoS attacks, TLS exploitation, and probing activities. The system supports real-time detection by generating predictions with associated confidence scores and provides detailed threat analysis to assist operational security teams. Its containerized design enables dynamic resource scaling through Kubernetes, ensuring consistent detection performance under varying network traffic conditions.

3.4.4 Framework Deployment and Integration

The framework is deployed using Kubernetes for enterprise-grade container orchestration, providing fault tolerance, high availability, and scalability. Horizontal scaling is achieved through integration with the Kubernetes Horizontal Pod Autoscaler (HPA), allowing automatic adjustment of detection system replicas based on CPU utilization or traffic volume.

This architecture supports deployment across geographically distributed 5G environments, enabling localized threat detection with centralized oversight. Integration with the existing 5G core network infrastructure is facilitated through standardized APIs, ensuring seamless compatibility with operational workflows, network management systems, and security platforms.

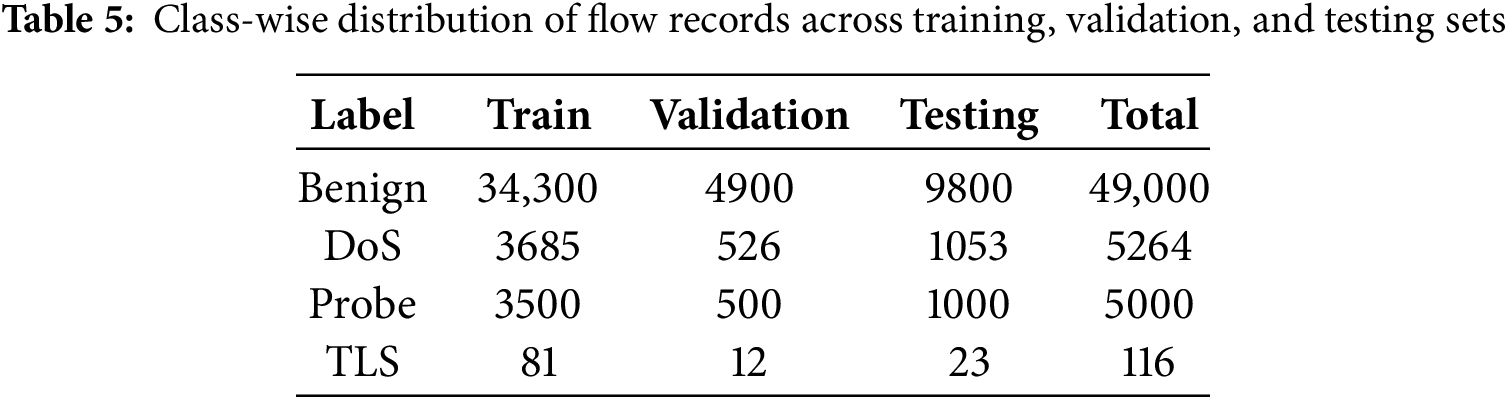

The dataset used in this study was specifically constructed to evaluate deep learning models for intrusion detection in a roaming network scenario. The traffic samples were derived from a collection of pre-processed CSV files, each representing either benign traffic or a specific network attack type. The benign category, labeled normal, was sourced from normal scenario, while malicious traffic was organized into three major categories: TLS-based attacks, Probe attacks, and DoS attacks.

The TLS attack category included the 0-RTT and Heartbleed attack datasets in their entirety. The Probe category comprised four subtypes: certificate probe, cryptographic probe, CVE-based probe, and protocol probe. For this category, stratified sampling was applied to ensure balanced representation across subtypes, with 1000 samples each from certificate, cryptographic, and protocol probes, and 2000 samples from CVE-based probes. The DoS category was formed by combining eight attack subtypes: GoldenEye, HULK, RST flood, Slowloris, SYN flood, TCP ACK flood, Tors, and UDP flood. Each subtype was randomly sampled with a fixed number of instances where applicable, while others were included in full to preserve variability.

To prevent class imbalance from skewing model performance, the benign traffic class was randomly downsampled to 49,000 records while preserving statistical representativeness. The final dataset also included 5264 samples labeled as DoS, 5000 as Probe, and 116 as TLS attack. This resulted in a balanced and manageable dataset comprising 59,380 flow records, each containing 76 behavioral features. The dataset was subsequently divided into training, validation, and testing subsets using a 70:10:20 split, ensuring that the class distribution remained consistent across all subsets. A detailed breakdown of class-wise sample allocation is presented in Table 5.

The experiments were conducted out on a computer with an Intel Core i7-13700K CPU (3.40 GHz), 64 GB of RAM, and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4080 GPU (16 GB), running on a 64-bit Ubuntu 24.01.1 LTS operating system. The experiment was implemented using PyTorch version 2.4.1 as the deep learning framework.

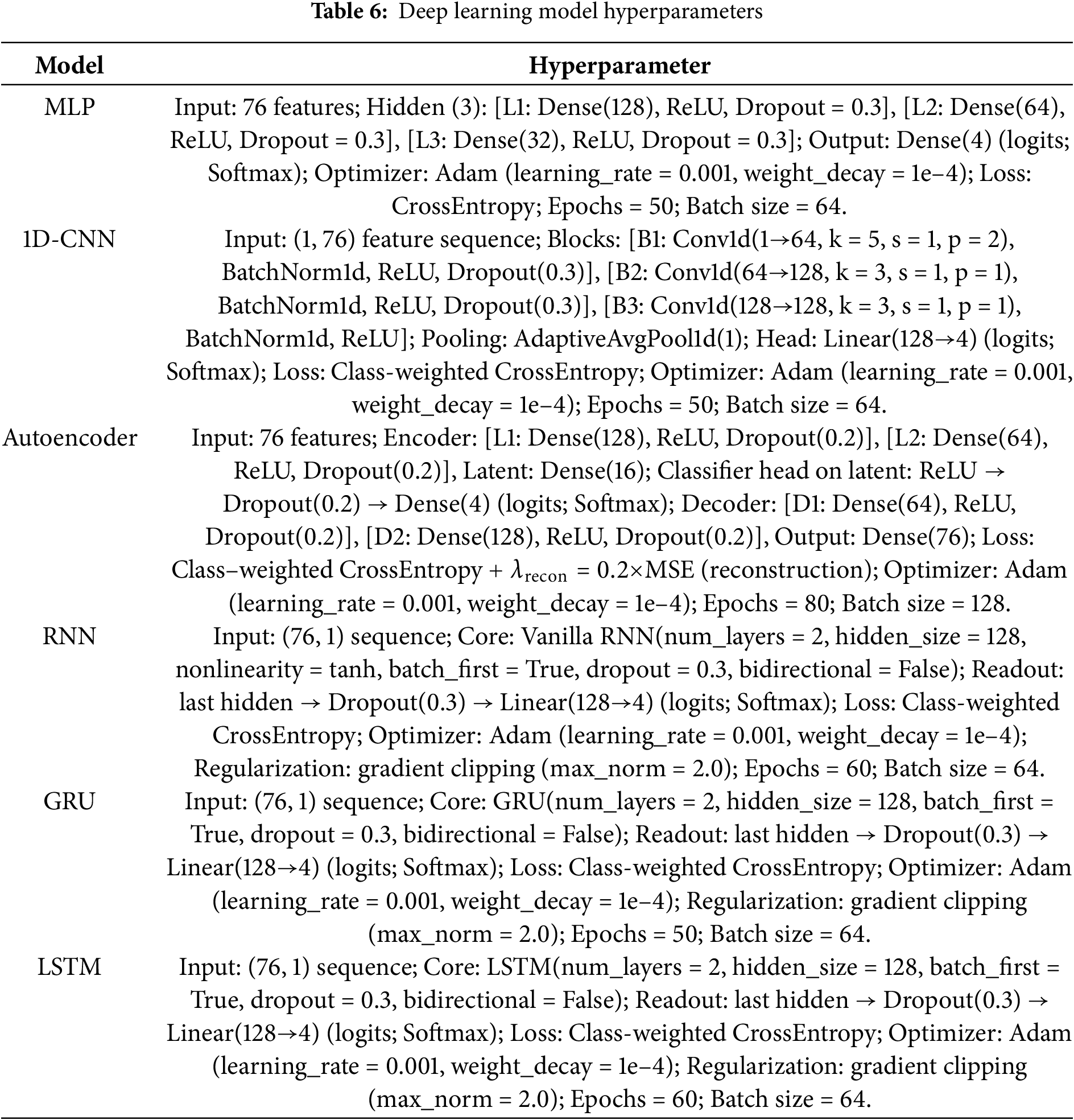

To evaluate the effectiveness of deep learning in intrusion detection for roaming network environments, we trained and compared multiple architectures, including a MLP, 1D-CNN, Autoencoder, RNN, GRU, and LSTM. These models were selected to capture different representational capabilities.

Each model was trained using the same intrusion detection dataset, which is characterized by a highly imbalanced distribution of classes. To ensure fair comparison, consistent preprocessing steps and training protocols were applied across all models. Hyperparameters such as learning rate, number of hidden layers, activation functions, and optimization strategies were carefully tuned for each architecture are describe in Table 6.

By evaluating models with both accuracy-based and imbalance-aware metrics, we aim to capture not only their overall classification ability but also their effectiveness in detecting rare and transient attack types that are particularly critical in roaming environments.

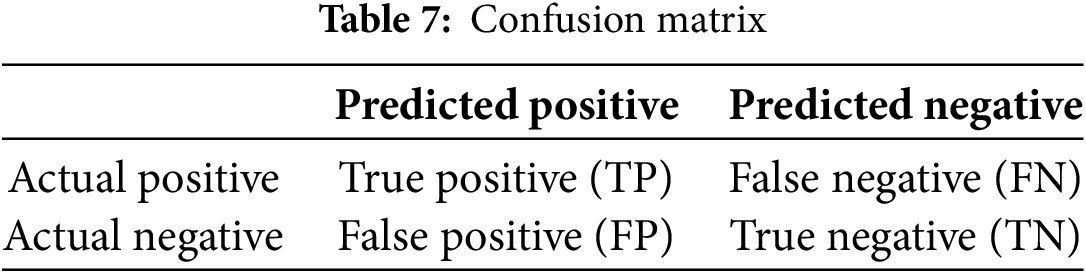

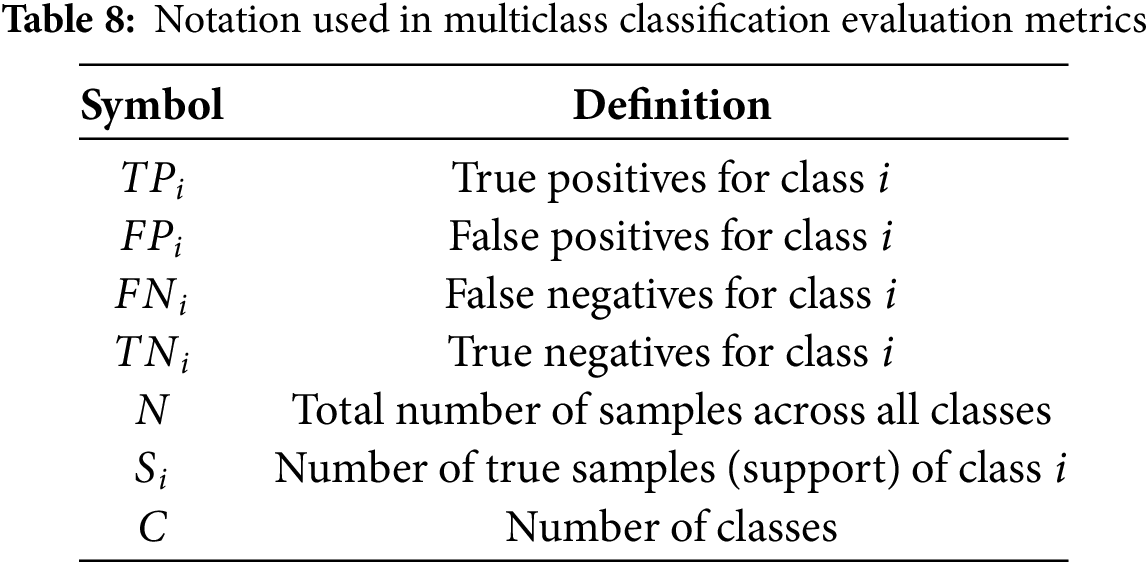

To evaluate the performance of classification models, we adopt a range of metrics derived from the confusion matrix. This matrix provides a summary of prediction outcomes by comparing actual class labels with those predicted by the model, as illustrated in Table 7. In the context of binary classification, the four primary outcomes are: True Positives (TP), where positive instances are correctly classified; False Positives (FP), where negative instances are incorrectly predicted as positive (Type I error); True Negatives (TN), where negative instances are correctly identified; and False Negatives (FN), where positive instances are mistakenly classified as negative (Type II error).

From the confusion matrix, various evaluation metrics can be derived to assess classification performance. In multiclass settings, these metrics are extended using macro-averaging, which treats each class equally, and weighted-averaging, which accounts for class imbalance by assigning weights based on class frequency. The notations used in the following definitions are summarized in Table 8.

• Accuracy (ACC) is the ratio of correctly predicted instances to the total number of predictions

• Balanced Accuracy (BACC) is the average of recall scores across all classes, offering a more robust evaluation under class imbalance

• Macro Precision (MP) Arithmetic mean of per-class precision:

• Macro Recall (MR) Arithmetic mean of per-class recall:

• Macro F1-Score (MF1) Arithmetic mean of per-class F1-scores, where

• Weighted Precision (wP) The weighted average of per-class precision, weighted by the number of true instances in each class.

• Weighted Recall (wR) The weighted average of per-class recall.

• Weighted F1-Score (wF1) The weighted average of per-class F1 scores.

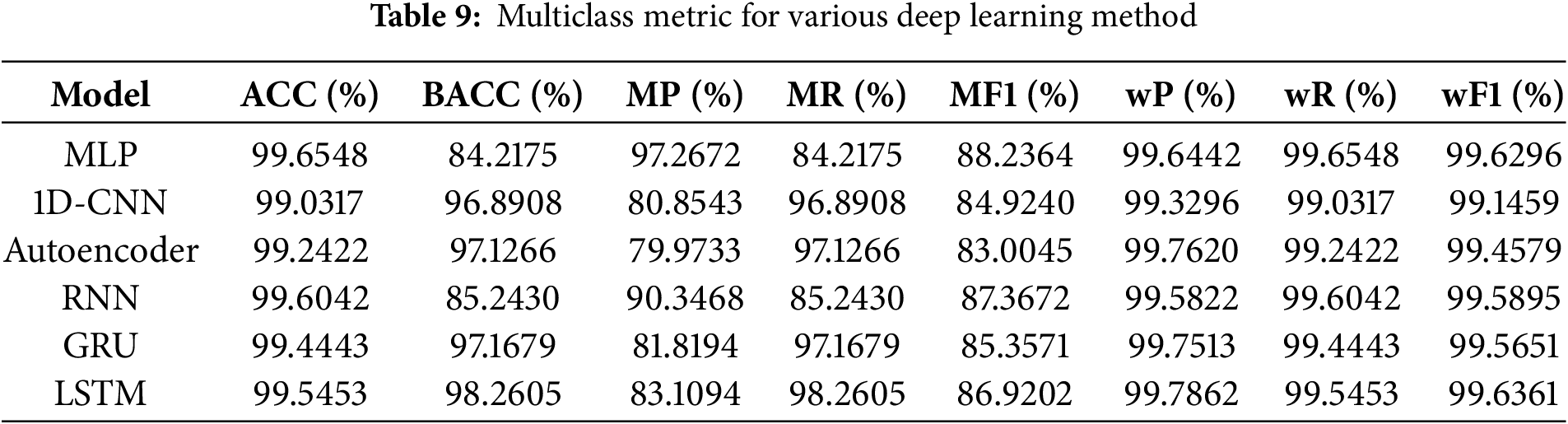

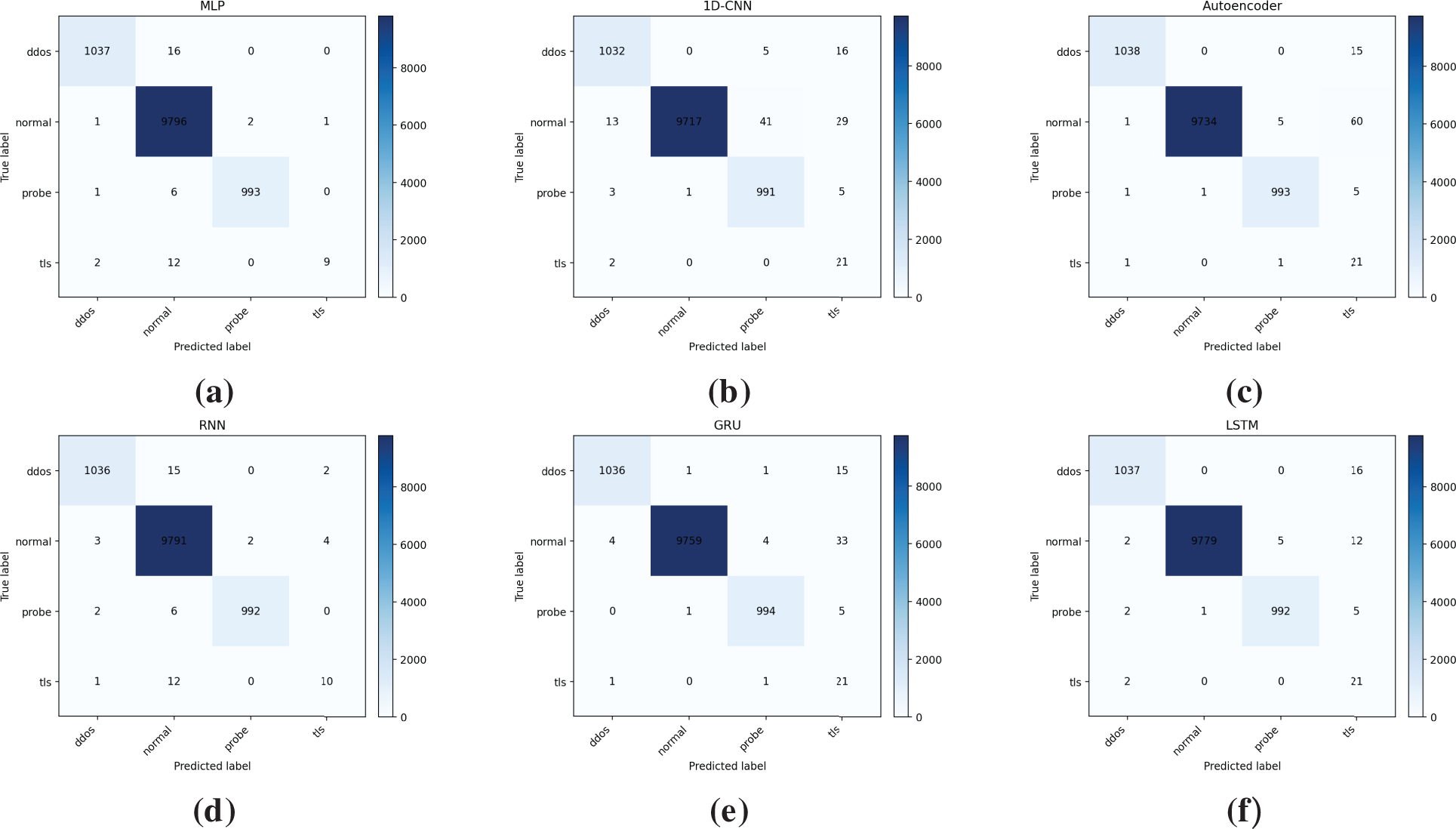

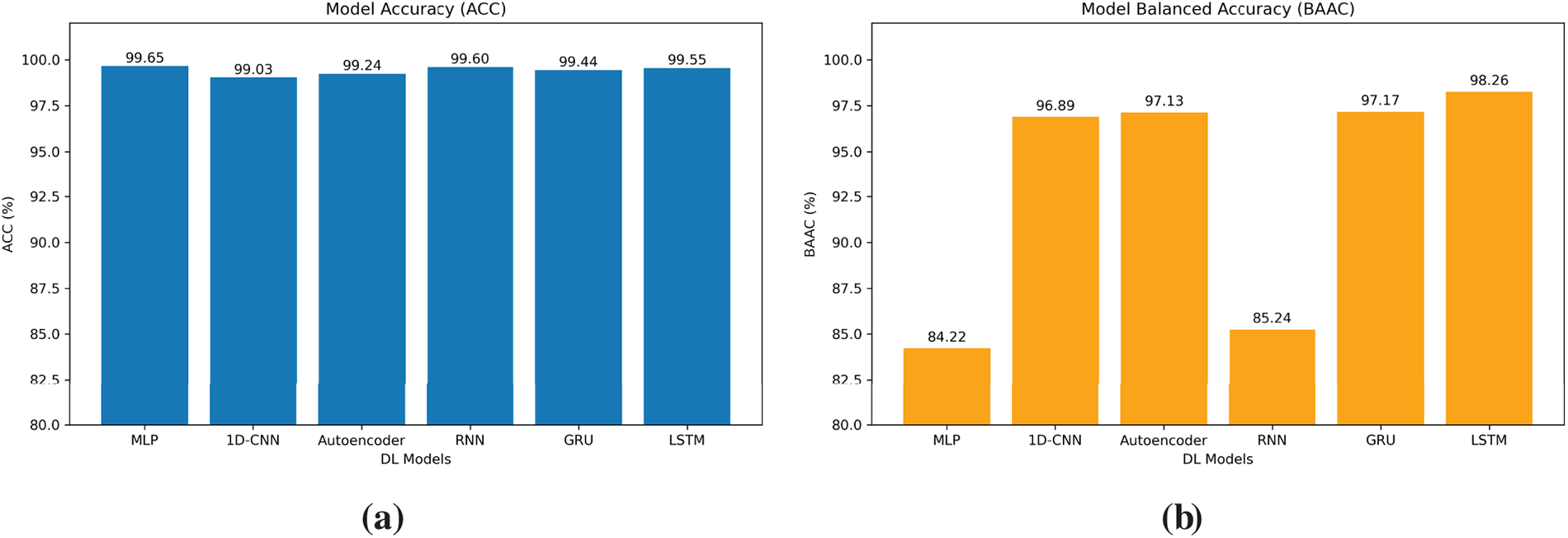

Table 9 presents the comparative performance of six deep learning models, namely MLP, 1D-CNN, Autoencoder, RNN, GRU, and LSTM, across multiple evaluation metrics on the proposed multiclass intrusion detection dataset for roaming scenarios. All models achieved very high overall accuracy, exceeding 99%, with MLP attaining the highest at 99.65%. However, in the context of a highly imbalanced dataset dominated by normal traffic (82.5% of samples), overall accuracy does not provide a reliable indication of intrusion detection performance. This limitation is evident in MLP’s case: despite achieving the highest accuracy, its BACC dropped to only 84.21%, reflecting weak detection of minority attack classes such as TLS intrusions, which accounted for only 0.2% of the dataset. As shown in Fig. 5, MLP’s confusion matrix further highlights this issue, with most misclassifications concentrated in the minority attack categories.

Figure 5: Confusion matrices of deep learning models for multi-class classification. (a) MLP (b) 1D-CNN (c) Autoencoder (d) RNN (e) GRU (f) LSTM

In contrast, models capable of learning temporal and sequential features exhibited stronger generalization across all classes. LSTM achieved the best BACC at 98.26%, closely followed by GRU (97.17%) and Autoencoder (97.13%). These models also recorded superior macro-level performance, with LSTM obtaining the highest macro F1 score of 88.19%, followed by MLP at 88.23% and GRU at 85.36%. The performance trade-offs between precision and recall are noteworthy: MLP achieved the highest macro precision at 97.27%, but its macro recall was significantly lower at 84.21%, indicating a tendency to minimize false positives at the expense of missing minority-class attacks. Conversely, GRU and LSTM demonstrated high macro recall (97.17% and 97.19%, respectively), making them more reliable in detecting rare and transient intrusions, as also evident in their confusion matrices in Fig. 5.

The Autoencoder exhibited an interesting performance profile. While its weighted F1 score reached 99.46%, indicating excellent overall performance when majority-class dominance was considered, its macro F1 dropped to 83.00%, revealing difficulties in handling underrepresented classes. The RNN provided intermediate results, with a BACC of 85.24% and macro F1 of 87.37%, outperforming MLP in recall but failing to match the advanced gated recurrent architectures. Collectively, these findings suggest that recurrent models such as GRU and LSTM are better suited to roaming intrusion detection, as their ability to capture sequential dependencies enables them to differentiate anomalous patterns from normal roaming fluctuations more effectively than feedforward or convolutional networks.

Fig. 6 further illustrates these performance differences. As shown in Fig. 6a, overall accuracy remains high and comparable across all models. However, Fig. 6b reveals substantial variation in balanced accuracy. LSTM and GRU clearly outperform MLP in this regard, emphasizing the importance of using evaluation metrics that reflect class imbalance.

Figure 6: Comparison of deep learning models in terms of classification performance. (a) Accuracy comparison. (b) Balanced Accuracy comparison

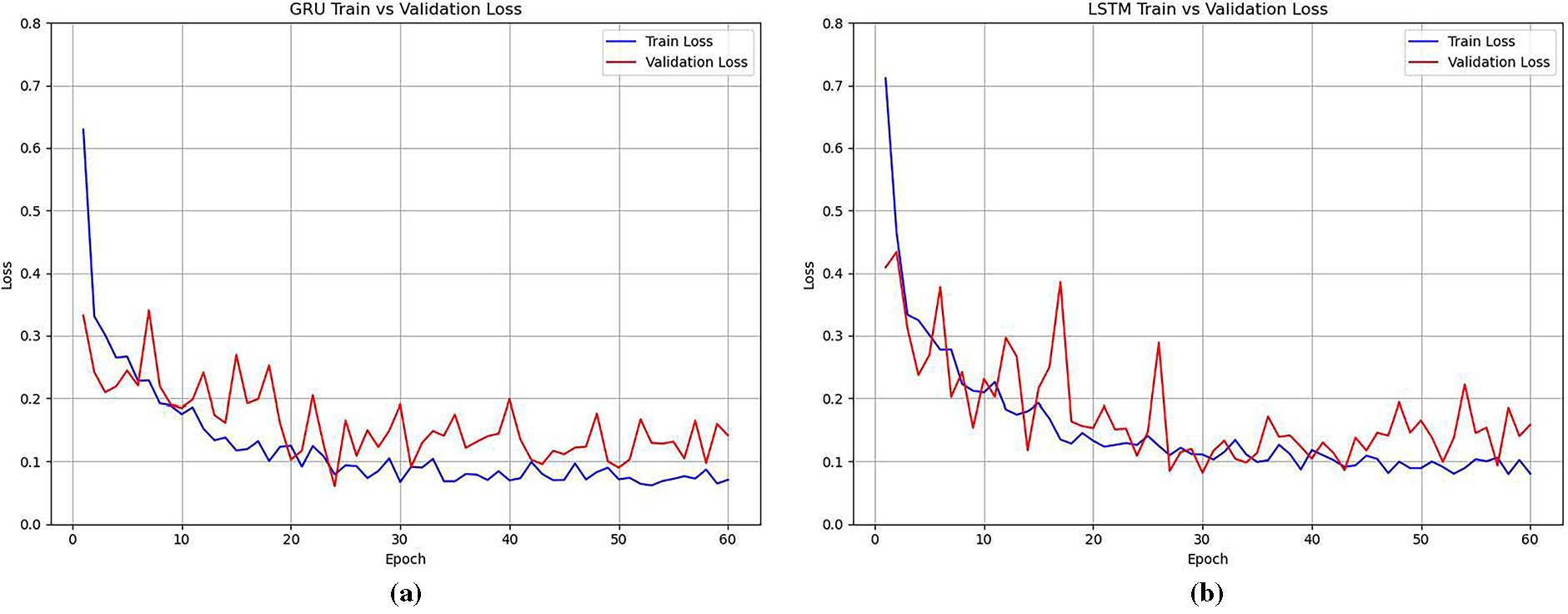

Training and validation behaviors of GRU and LSTM are depicted in Fig. 7. For GRU, both training and validation loss steadily decreased during the first 25 epochs. Balanced accuracy improved from 76.5% in the first epoch to over 97% by epoch 25, after which it remained consistently high. This trend indicates effective generalization to minority classes and stable performance throughout the remaining epochs, with validation accuracy maintained above 99.5% and balanced accuracy ranging from 95 to 97%.

Figure 7: Training and Validation loss. (a) GRU. (b) LSTM

LSTM showed a similar pattern, with some variability early in training. Nevertheless, the model gradually converged. By epoch 30, validation accuracy consistently exceeded 99%, and validation loss stabilized between 0.08 and 0.15. These trends are consistent with LSTM’s strong final performance metrics, particularly its BACC and macro F1 score. While LSTM took longer to converge compared to GRU, it ultimately demonstrated superior capability in learning sequential dependencies critical for detecting rare intrusions.

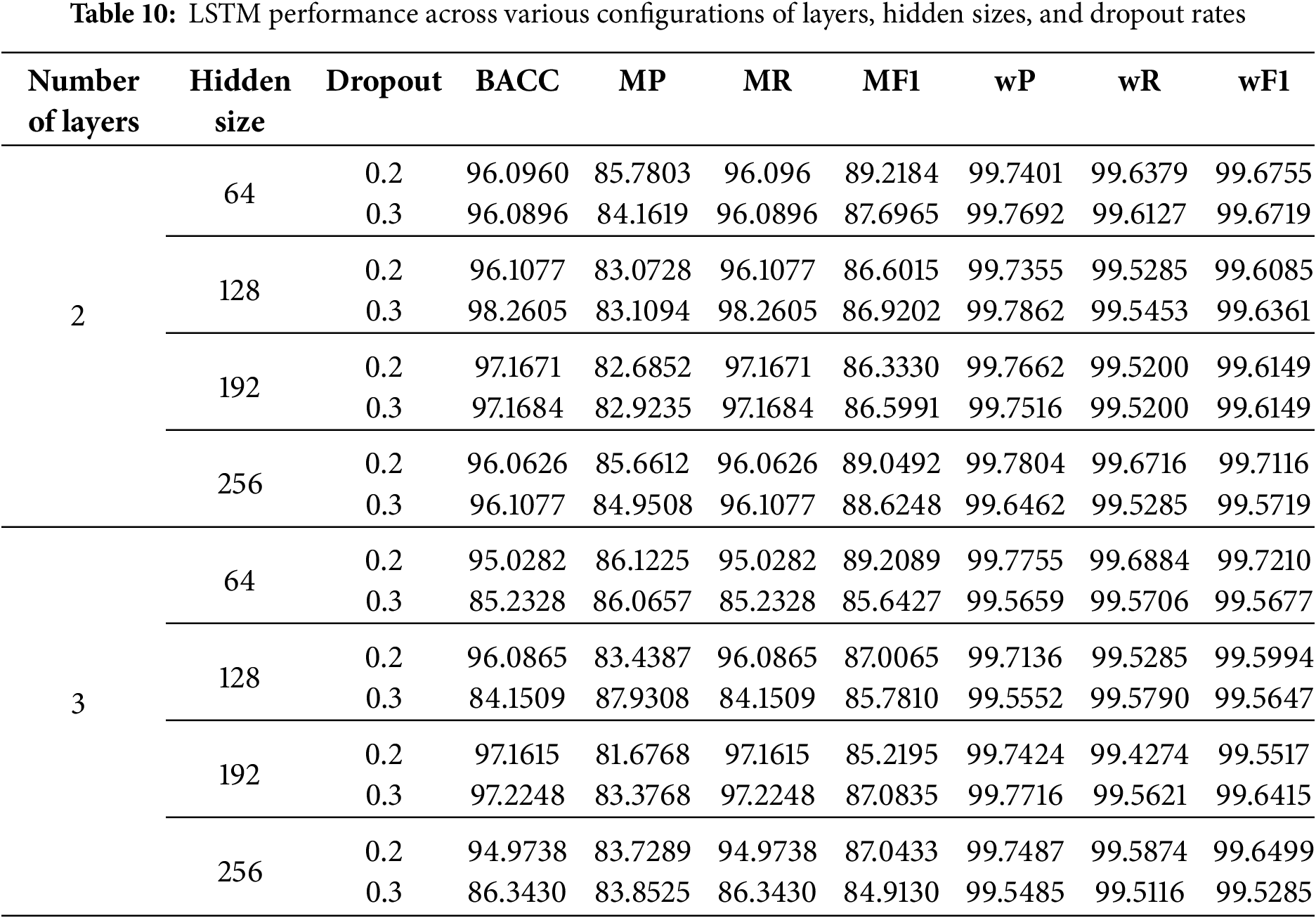

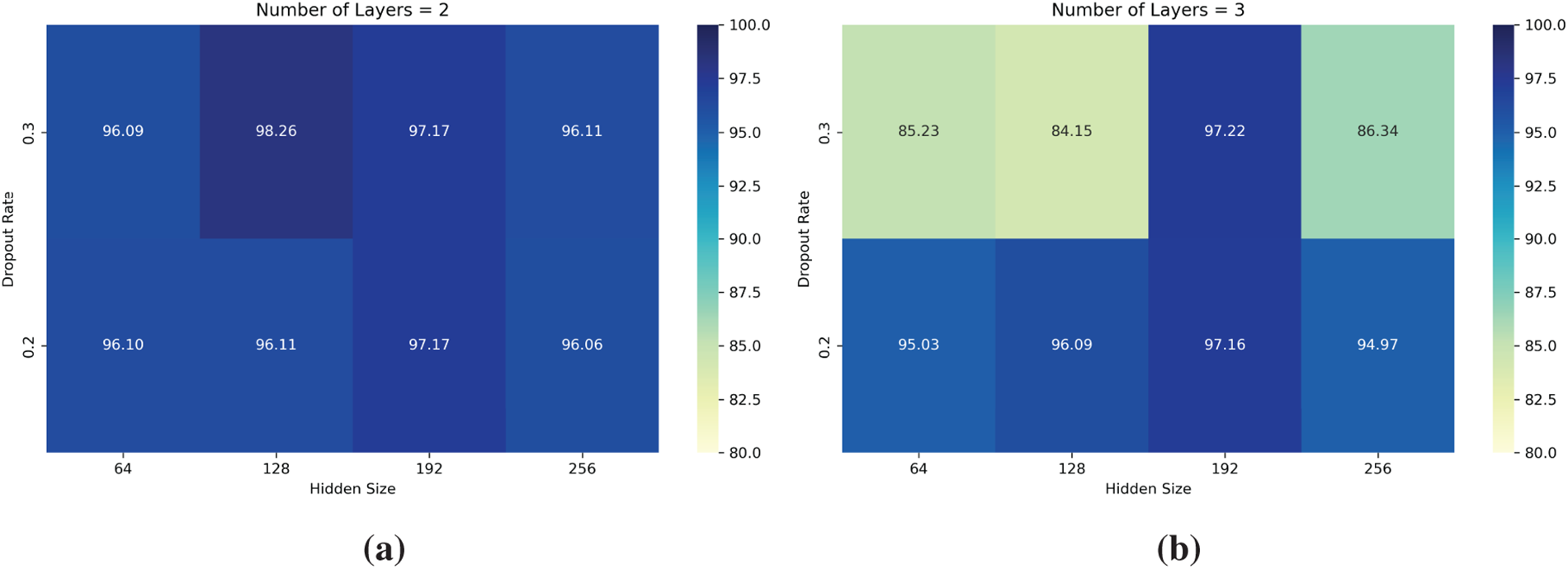

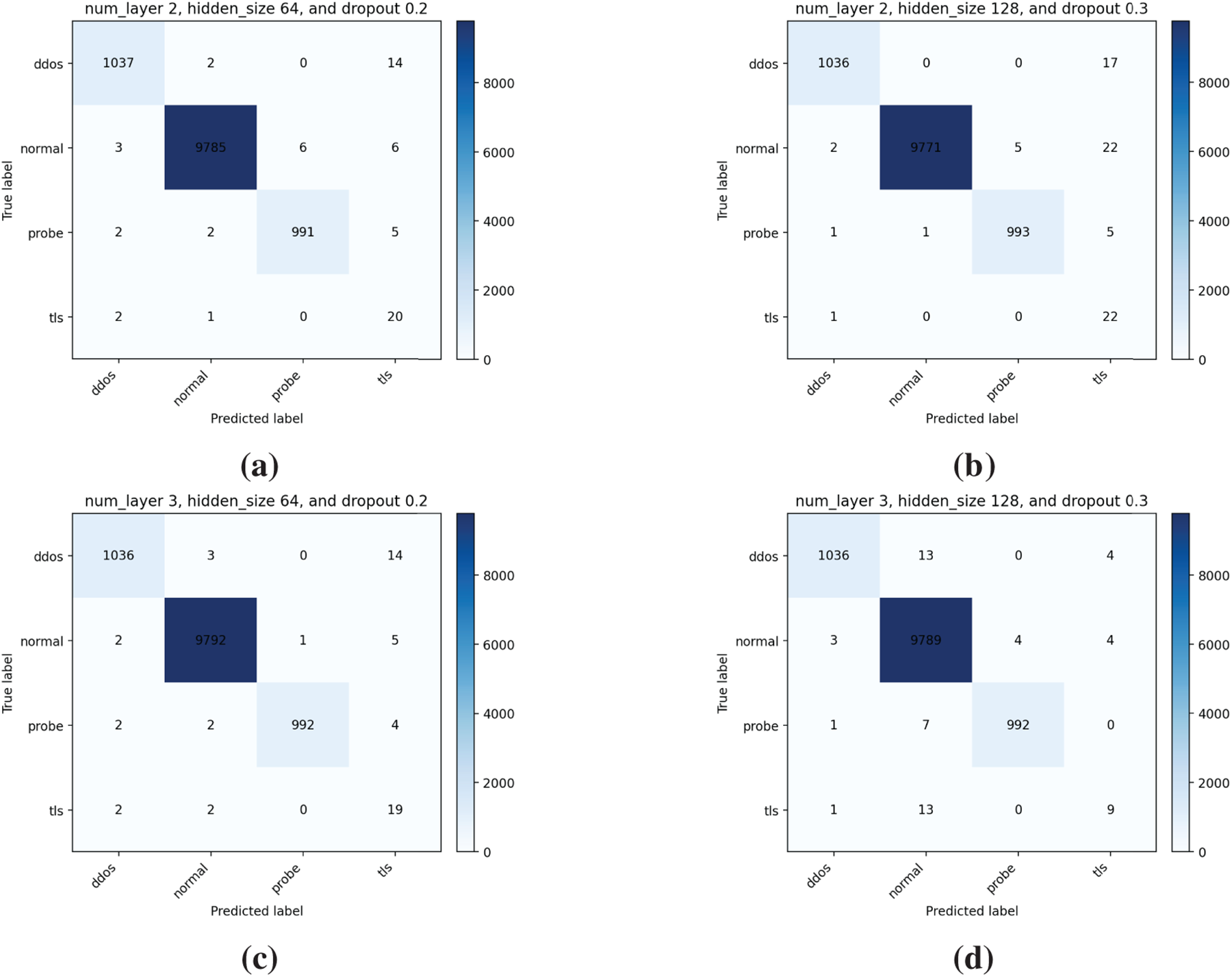

To further optimize the performance of the LSTM model, an extensive hyperparameter tuning experiment was conducted by varying the number of layers (2 or 3), hidden sizes (64, 128, 192, and 256), and dropout rates (0.2 and 0.3). Table 10 summarizes the results across multiple metrics, while Fig. 8 provides a visual overview of BACC across the various configurations. The heatmaps clearly illustrate how different combinations of hidden size and dropout affect performance for both 2-layer and 3-layer LSTM models, helping to identify the most effective architectural choices.

Figure 8: Heatmaps of BACC across different LSTM configurations. (a) 2 Layers. (b) 3 Layers

Among all tested configurations, the LSTM model with 2 layers, a hidden size of 64, and a dropout rate of 0.2 achieved the highest macro F1-score of 89.22%, while maintaining a strong BACC of 96.10%. As shown in the confusion matrix in Fig. 9a, this model demonstrates balanced classification performance across both majority and minority classes. The matrix reveals clear separability even for infrequent attacks, indicating robust generalization without overfitting.

Figure 9: Confusion matrices of LSTM models for various configuration. (a) num_layer 2, hidden_size 64 and dropout 0.2 (b) num_layer 2, hidden_size 128 and dropout 0.3 (c) num_layer 3, hidden_size 64 and dropout 0.2 (d) num_layer 3, hidden_size 128 and dropout 0.3

The highest Balanced Accuracy (98.26%) was achieved by the configuration with 2 layers, a hidden size of 128, and dropout 0.3. This model also attained the best macro Recall (98.26%) and the highest weighted Precision (99.79%), reflecting strong performance in detecting rare attack classes while maintaining low false positive rates. The corresponding confusion matrix in Fig. 9b shows notably high true positive rates across all attack categories, including the rare TLS class, making this configuration the most suitable for sensitive environments where minority detection is critical.

The model using 3 layers, a hidden size of 64, and a dropout rate of 0.2 demonstrated the best weighted Recall (99.69%) and weighted F1-score (99.72%), as seen in Fig. 9c. While its BACC was slightly lower (95.03%), this configuration maintained high performance across all samples, particularly in the dominant normal class, and showed fewer misclassifications overall. This makes it a strong candidate for deployment in scenarios where consistent performance across all traffic is prioritized.

Interestingly, the configuration with 3 layers, hidden size of 128, and dropout 0.3 produced the highest macro Precision (87.93%), highlighting its tendency to minimize false positives. However, its overall BACC and F1 were lower, as seen in Fig. 9d, where the confusion matrix shows more frequent misclassifications of rare attack classes. This model may be more appropriate in operational settings where precision is prioritized over recall, such as minimizing false alarms in real-time intrusion detection systems.

The performance evaluation was conducted within a cloud-native Kubernetes environment, as detailed in Table 2. The deployment utilized MicroK8s v1.28 with containerd runtime and Calico CNI for container orchestration and networking, with dedicated namespaces (hplmn, vplmn) for home and visited public land mobile networks. Each AI detection model was deployed as a containerized microservice with resource limits of 2 CPU cores and 2 GB RAM, and reservations of 1 CPU core and 128 MB RAM, representing a realistic cloud-native intrusion detection setup for 5G core network security monitoring in roaming scenarios.

This evaluation framework ensures that performance metrics reflect the resource constraints of the cloud-native deployment environment used for the experiments.

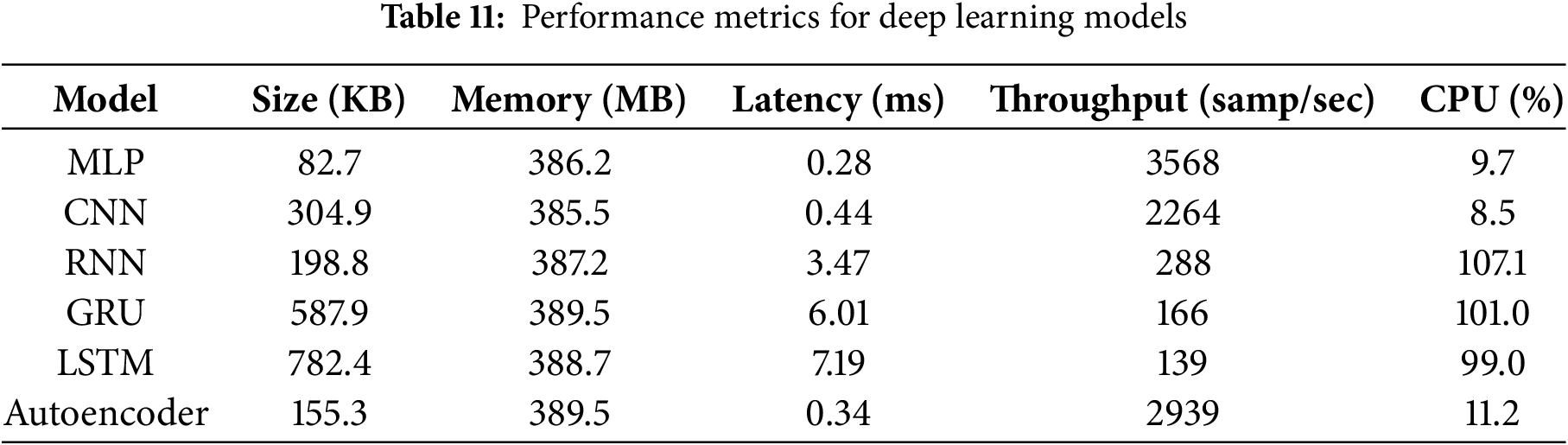

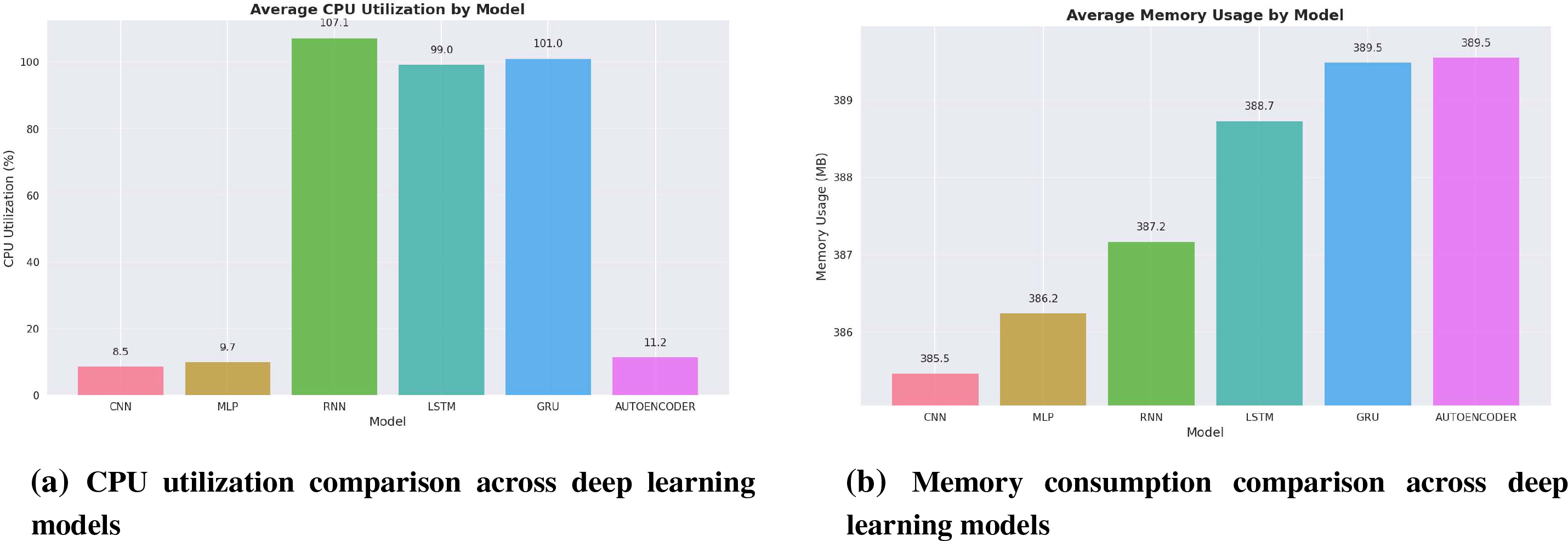

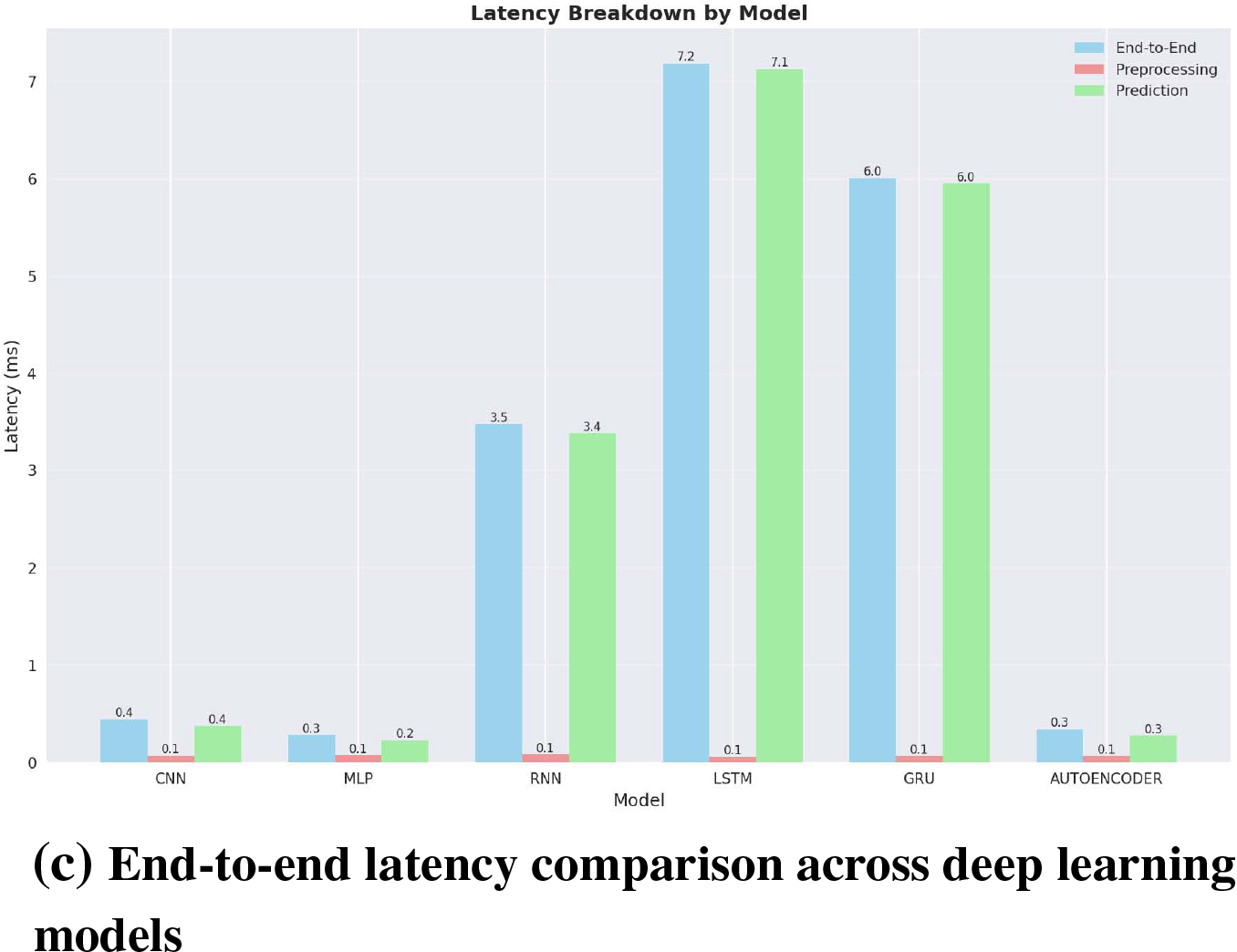

Table 11 presents the measured performance metrics for each deep learning model when deployed as containerized microservices with resource limits of 2 CPU cores and 2 GB RAM. The evaluation was conducted using the same resource constraints across all models to ensure fair comparison.

The metrics include model size, which represents the memory footprint of the trained model in kilobytes and affects storage requirements and loading times; memory consumption, which indicates the runtime RAM usage during inference in megabytes and determines resource allocation needs; latency, which measures the end-to-end processing time per network flow in milliseconds and indicates real-time processing capability; throughput, which quantifies the number of network flows processed per second and shows processing capacity; and CPU utilization, which reflects the percentage of allocated CPU resources used during processing and indicates computational intensity.

All models operated within the 2 GB RAM limit specified for the containerized deployment. CPU utilization varied significantly across architectures, ranging from 8.5% for CNN to 107.1% for RNN, indicating different computational intensities required for inference operations.

5.2.2 Performance Characteristics

The performance results show clear differences between model architectures in terms of computational requirements and processing capabilities. These differences have direct implications for the deployment of intrusion detection systems in varying network traffic conditions.

Feedforward models (MLP, Autoencoder) achieved the highest throughput rates of 2939–3568 samples per second with correspondingly low latency values of 0.28–0.34 ms. These models maintained moderate memory consumption between 386.2–389.5 MB and operated at relatively low CPU utilization levels of 9.7%–11.2%. The high throughput and low latency characteristics indicate capability for processing high-volume network traffic with minimal processing delay.

Convolutional networks (CNN) provided intermediate performance levels with 2264 samples per second throughput and 0.44 ms latency. Memory consumption was measured at 385.5 MB with CPU utilization at 8.5%, indicating efficient resource usage for the processing capability achieved.

Recurrent models (RNN, GRU, LSTM) showed significantly lower throughput rates ranging from 139–288 samples per second, with correspondingly higher latency values of 3.47–7.19 ms. These models consumed 387.2–389.5 MB of memory while operating at high CPU utilization levels between 99.0%–107.1%. The lower throughput and higher latency reflect the increased computational complexity required for processing sequential dependencies in network traffic patterns.

All models operated within the 2 GB RAM limit specified for the containerized deployment environment. The variation in CPU utilization across architectures, with recurrent models showing near-full utilization of allocated resources, indicates fundamental differences in computational complexity between feedforward and sequential processing approaches. Fig. 10 illustrates these performance differences across the different architectures, highlighting the trade-offs between processing speed, computational resource requirements, and memory usage.

Figure 10: Performance comparison across deep learning models for intrusion detection: (a) CPU utilization, (b) memory consumption, and (c) end-to-end latency

The performance results, combined with the detection accuracy metrics from Table 9, reveal trade-offs between computational efficiency and detection capability across the evaluated architectures. While all models achieved high overall accuracy rates above 99%, the performance characteristics varied significantly depending on the architectural approach used.

Feedforward models (MLP, Autoencoder) achieved the highest throughput rates of 2939–3568 samples per second with low latency values of 0.28–0.34 ms. Convolutional networks (CNN) provided intermediate performance levels with 2264 samples per second throughput and 0.44 ms latency. Recurrent models (RNN, GRU, LSTM) showed lower throughput rates ranging from 139–288 samples per second with correspondingly higher latency values of 3.47–7.19 ms, reflecting the additional computational requirements for processing sequential patterns in network traffic data.

These performance differences, when considered alongside the detection accuracy results, illustrate the trade-offs between computational efficiency and detection capability across the different architectural approaches evaluated in this study.

The experimental results underscore several critical insights for intrusion detection in cloud-native 5G roaming environments. First, the findings demonstrate the inadequacy of accuracy as a primary evaluation metric in highly imbalanced datasets. Although all models achieved greater than 99% accuracy, this metric masked important weaknesses in detecting minority-class intrusions. In roaming scenarios, overlooking a single TLS or signaling attack may lead to cross-network propagation, making Balanced Accuracy and macro-level metrics far more reliable indicators of operational effectiveness.

Second, the superior performance of sequential deep learning models such as GRU and LSTM highlights the importance of temporal feature learning in roaming security. Roaming traffic is inherently dynamic, characterized by frequent re-attachments, abrupt signaling transitions, and protocol variability. Gated recurrent models, with their ability to retain relevant context and filter transient noise, achieved higher BACC and macro recall compared to static architectures such as MLP and CNN. This capability allowed them to identify short-lived or subtle anomalies that could otherwise be overlooked in the variability of roaming traffic. Among all models, LSTM emerged as the most balanced approach, delivering the best macro F1 and BACC scores, while GRU offered a competitive alternative with reduced computational complexity. However, this detection capability comes with trade-offs in computational performance, with recurrent models showing lower throughput (139–288 samples/second) and higher latency (3.47–7.19 ms) compared to feedforward models (2939–3568 samples/second throughput and 0.28–0.34 ms latency).

Third, the comparative results highlight trade-offs between false positives and false negatives in intrusion detection, as well as between detection accuracy and computational requirements. MLP’s bias toward precision suggests that it may be more suitable in environments where false alarms must be minimized, though this comes at the cost of failing to detect rare but critical attacks. The Autoencoder, despite excelling in modeling majority-class behavior, demonstrated limited effectiveness in detecting minority-class anomalies, underscoring the need for complementary techniques such as oversampling, synthetic attack generation, or ensemble learning to mitigate class imbalance. Recurrent models (RNN, GRU, LSTM) exhibited higher CPU utilization (99.0%–107.1%) compared to feedforward models (8.5%–11.2%), reflecting their increased computational demands for sequential processing.

Despite the comprehensive analysis of classical and deep learning techniques, reinforcement learning (RL) presents a promising yet underexplored direction for intrusion detection in cloud-native 5G environments. Unlike traditional supervised models, RL enables agents to learn adaptive detection strategies through continuous interaction with dynamic environments, making it well-suited for decentralized and evolving architectures such as inter-PLMN roaming. As highlighted in the work [60], RL techniques offer significant advantages in modeling long-term dependencies, adapting to changing threat patterns, and reducing the reliance on static labeled data. In the context of cloud-based IDS, RL can support real-time adaptation and optimization of detection policies across distributed network functions. Additionally, combining RL with temporal deep learning models like LSTM or GRU could further enhance the system’s ability to capture complex sequential behaviors while continuously refining its decision-making capabilities in response to new or evolving attacks.

Finally, the implications for practical deployment are significant. The results suggest that intrusion detection systems for cloud-native 5G roaming should prioritize models that are sensitive to minority-class threats, as these represent the most consequential risks in inter-PLMN signaling. Sequential deep learning architectures are particularly well suited for monitoring critical interfaces such as N32-c and N32-f, where subtle deviations in signaling sequences may indicate early stages of attacks. Future research should explore hybrid ensemble approaches that combine the precision of feedforward and convolutional models with the recall advantages of gated recurrent architectures. In addition, data augmentation strategies could improve minority-class representation, while explainability mechanisms would enhance trust and facilitate faster operator response in complex multi-domain roaming environments.

This work addressed the emerging security challenges of roaming in cloud-native 5G core networks by proposing and evaluating an intrusion detection framework based on deep learning. We designed a testbed that emulates realistic roaming scenarios and introduced the first roaming-specific intrusion detection dataset for 5G, enabling the systematic study of rare and complex attack patterns. Six deep learning models, including feedforward, convolutional, and recurrent architectures, were assessed on this dataset to examine their suitability for detecting roaming-specific intrusions in highly imbalanced traffic environments.

The experimental results demonstrated that while all models achieved accuracies above 99%, overall accuracy was not a reliable indicator of performance in the presence of class imbalance. Balanced accuracy and macro-averaged metrics provided more meaningful insights into model effectiveness, particularly for minority-class intrusions such as TLS-based attacks. Sequential models, especially LSTM and GRU, consistently outperformed others by achieving higher macro recall and balanced accuracy, reflecting their ability to capture temporal dependencies and adapt to dynamic roaming traffic patterns. However, this superior detection capability comes with trade-offs in computational performance, with recurrent models showing lower throughput (139–288 samples/second) and higher latency (3.47–7.19 ms) compared to feedforward models (2939–3568 samples/second throughput and 0.28–0.34 ms latency). These findings highlight the importance of prioritizing sequential architectures for roaming intrusion detection in cloud-native deployments, where short-lived or subtle anomalies may otherwise remain undetected, while considering the computational requirements for practical implementation.

The results further emphasize the necessity of reevaluating evaluation metrics and model design for roaming security. Models such as MLP and Autoencoder excelled in precision and majority-class detection but struggled to identify rare intrusions, demonstrating that traditional approaches optimized for overall accuracy are insufficient in this domain. Recurrent architectures offered a more balanced trade-off between detection accuracy and computational requirements, making them particularly well suited for monitoring critical inter-PLMN signaling interfaces such as N32-c and N32-f, despite their higher resource demands (99.0%–107.1% CPU utilization vs. 8.5%–11.2% for feedforward models).

Future advancements in roaming intrusion detection for next-generation networks must address several critical and emerging challenges. A promising direction involves utilizing data augmentation strategies, including synthetic oversampling and generative modeling, to address class imbalance and enhance the representation of rare attack types in training datasets. Federated learning also offers a valuable approach for enabling collaborative intrusion detection across mobile network operators while maintaining data privacy, which is essential in distributed B5G and future 6G environments. In parallel, enhancing the interpretability and transparency of deep learning-based detectors through explainable AI (XAI) techniques will be critical for improving operator trust and facilitating faster, more informed responses to detected threats. As part of our future work, we plan to expand our dataset to include more diverse and complex attack scenarios within multi-PLMN environments, particularly those involving IPX (roaming hub) interconnections and signaling flows using protocols such as PRINS. These scenarios introduce additional security challenges due to indirect trust relationships, longer signaling paths, and varying SEPP deployments across networks. Together, these research directions and planned extensions will contribute to the development of more robust, scalable, and trustworthy roaming-aware intrusion detection systems for future mobile networks.

Acknowledgement: This work was supported by Institute of Information & Communications Technology Planning & Evaluation (IITP) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT).

Funding Statement: This work was supported by Institute of Information & communications Technology Planning & Evaluation (IITP) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (RS-2024-00441484, Development of Open Roaming Technology for Private 5G Network).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, I Wayan Adi Juliawan Pawana and Ilsun You; methodology, I Wayan Adi Juliawan Pawana; validation, I Wayan Adi Juliawan Pawana and Yongho Ko; formal analysis, I Wayan Adi Juliawan Pawana; investigation, I Wayan Adi Juliawan Pawana and Vincent Abella; data curation, Vincent Abella and Jhury Kevin Lastre; writing—original draft preparation, I Wayan Adi Juliawan Pawana; writing—review and editing, Vincent Abella, Jhury Kevin Lastre, Yongho Ko, and Ilsun You; visualization, Vincent Abella and Jhury Kevin Lastre; supervision, Ilsun You; project administration, Ilsun You; funding acquisition, Ilsun You. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Author, [I Wayan Adi Juliawan Pawana], upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. GSMA Intelligence. Radar: roaming in a post-covid world | GSMA Intelligence. [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2025 Aug 6]. Available from: https://www.gsmaintelligence.com/research/radar-roaming-in-a-post-covid-world. [Google Scholar]

2. GSMA Intelligence. Private 5G Networks: time to scale up. [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Aug 6]. Available from: https://www.gsmaintelligence.com/research/private-5g-networks-time-to-scale-up. [Google Scholar]

3. Rao SP, Oliver I, Holtmanns S, Aura T. We know where you are! In: 2016 8th International Conference on Cyber Conflict (CyCon); 2016 Oct 21–23; Washington, DC, USA. p. 277–93. doi:10.1109/CYCON.2016.7529440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Kirchgaessner S, Sabbagh D, Black C. Israeli spy firm suspected of accessing global telecoms via channel Islands. [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2025 Aug 6]. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/dec/16/israeli-spy-firm-suspected-accessing-global-telecoms-channel-islands. [Google Scholar]

5. Ullah K, Rashid I, Afzal H, Iqbal MMW, Bangash YA, Abbas H. SS7 vulnerabilities—a survey and implementation of machine learning vs rule based filtering for detection of SS7 network attacks. IEEE Commun Surv Tutor. 2020;22(2):1337–71. doi:10.1109/COMST.2020.2971757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Network F. Syniverse quietly reveals 5-year data breach [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2025 Aug 6]. Available from: https://www.fierce-network.com/wireless/syniverse-quietly-reveals-hackers-had-access-to-database-over-5-years. [Google Scholar]

7. 3GPP. TS 33.501 Security architecture and procedures for 5G System [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Aug 6]. Available from: https://www.3gpp.org/dynareport/33501.htm. [Google Scholar]

8. 3GPP. 5G roaming security [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Aug 6]. Available from: https://www.3gpp.org/technologies/roaming-security-sa3. [Google Scholar]

9. GSMA. 5GS Roaming guidelines Version 12.0 [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Aug 6]. Available from: https://www.gsma.com/newsroom/wp-content/uploads/NG.113-v12.0.pdf. [Google Scholar]

10. GSMA. 5G-Standalone April 2025 [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Aug 6]. Available from: https://gsacom.com/paper/5g-standalone-april-2025/. [Google Scholar]

11. Shin D, Kim J, Pawana IWAJ, You I. Enhancing cloud-native DevSecOps: a zero trust approach for the financial sector. Comput Standards Interfaces. 2025;93:103975. doi:10.1016/j.csi.2025.103975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Kumar S, Dwivedi M, Kumar M, Gill SS. A comprehensive review of vulnerabilities and AI-enabled defense against DDoS attacks for securing cloud services. Comput Sci Rev. 2024;53:100661. doi:10.1016/j.cosrev.2024.100661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Uddin R, Kumar SAP, Chamola V. Denial of service attacks in edge computing layers: taxonomy, vulnerabilities, threats and solutions. Ad Hoc Netw. 2024;152:103322. doi:10.1016/j.adhoc.2023.103322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Aslan Ö, Aktuğ SS, Ozkan-Okay M, Yilmaz AA, Akin E. A comprehensive review of cyber security vulnerabilities, threats, attacks, and solutions. Electronics. 2023;12(6):1333. doi:10.3390/electronics12061333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Arisdakessian S, Wahab OA, Mourad A, Otrok H, Guizani M. A survey on IoT intrusion detection: federated learning, game theory, social psychology, and explainable AI as future directions. IEEE Internet of Things J. 2023;10(5):4059–92. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2022.3203249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. GSMA Intelligence. Securing private networks in the 5G Era [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2025 Aug 6]. Available from: https://www.gsmaintelligence.com/research/securing-private-networks-in-the-5g-era. [Google Scholar]

17. Sajid M, Malik KR, Almogren A, Malik TS, Khan AH, Tanveer J, et al. Enhancing intrusion detection: a hybrid machine and deep learning approach. J Cloud Comput. 2024;13(1):123. doi:10.1186/s13677-024-00685-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Pawana IWAJ, Astillo PV, You I. Lightweight LLM-based anomaly detection framework for securing IoTMD enabled diabetes management control systems. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. 2025. doi:10.1109/JBHI.2025.3577604. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Altunay HC, Albayrak Z. A Hybrid CNN+LSTM-based intrusion detection system for industrial IoT networks. Eng Sci Technol. 2023;38:101322. doi:10.1016/j.jestch.2022.101322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Kasongo SM. A deep learning technique for intrusion detection system using a recurrent neural networks based framework. Comput Commun. 2023;199:113–25. doi:10.1016/j.comcom.2022.12.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Hermosilla A, Gallego-Madrid J, Martinez-Julia P, Ortiz J, Kafle V, Skarmeta A. Advancing 5G Network applications lifecycle security: an ML-driven approach. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2024;141(2):1447–71. doi:10.32604/cmes.2024.053379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Lange S, Gringoli F, Hollick M, Classen J. Wherever i may roam: stealthy interception and injection attacks through roaming agreements. In: Computer security–ESORICS 2024. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature; 2024. Vol. 14985. p. 208–28. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-70903-6_11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Chang CH, Chang RL, Chen HY, Lin TN. 6G security: the vulnerability of roaming technology via DoS exploit of signaling control plane. In: 2024 IEEE International Conference on Communications Workshops (ICC Workshops); 2024 Jun 9–13; Denver, CO, USA. p. 1413–8. doi:10.1109/ICCWorkshops59551.2024.10615651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Guo Y, Ermis O, Tang Q, Trang H, De Oliveira A. An empirical study of deep learning-based SS7 attack detection. Information. 2023;14(9):509. doi:10.3390/info14090509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Hussain B, Du Q, Sun B, Han Z. Deep learning-based DDoS-attack detection for cyber-physical system over 5G network. IEEE Trans Ind Inform. 2021;17(2):860–70. doi:10.1109/TII.2020.2974520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Alsoufi M, Siraj M, Ghaleb F, Al-Razgan M, Al-Asaly M, Alfakih T, et al. Anomaly-based intrusion detection model using deep learning for IoT networks. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2024;141(1):823–45. doi:10.32604/cmes.2024.052112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Thantharate A, Paropkari R, Walunj V, Beard C, Kankariya P. Secure5G: a deep learning framework towards a secure network slicing in 5G and beyond. In: 2020 10th Annual Computing and Communication Workshop and Conference (CCWC); 2020 Jan 6–8; Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 0852–7. doi:10.1109/CCWC47524.2020.9031158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Sattar D, Matrawy A. Towards secure slicing: using slice isolation to mitigate DDoS attacks on 5G core network slices. In: 2019 IEEE Conference on Communications and Network Security (CNS); 2019 Jun 10–12; Washington, DC, USA. p. 82–90. doi:10.1109/CNS.2019.8802852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Farzaneh B, Shahriar N, Muktadir AHA, Towhid MS, Khosravani MS. DTL-5G: deep transfer learning-based DDoS attack detection in 5G and beyond networks. Comput Commun. 2024;228:107927. doi:10.1016/j.comcom.2024.107927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Tian Z, Patil R, Gurusamy M, McCloud J. ADSeq-5GCN: anomaly detection from network traffic sequences in 5G core network control plane. In: 2023 IEEE 24th International Conference on High Performance Switching and Routing (HPSR); 2023 Jun 5–7; Albuquerque, NM, USA. p. 75–82. doi:10.1109/HPSR57248.2023.10147931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Kuadey NAE, Maale GT, Kwantwi T, Sun G, Liu G. DeepSecure: detection of distributed denial of service attacks on 5G network slicing—deep learning approach. IEEE Wireless Commun Lett. 2022;11(3):488–92. doi:10.1109/LWC.2021.3133479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Rezaei H, Taheri R, Jordanov I, Shojafar M. Federated RNN for intrusion detection system in IoT environment under adversarial attack. J Netw Syst Manage. 2025;33(4):82. doi:10.1007/s10922-025-09963-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Park S, Cho B, Kim D, You I. Machine learning based signaling DDoS detection system for 5G stand alone core network. Appl Sci. 2022;12(23):12456. doi:10.3390/app122312456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Kim YE, Kim YS, Kim H. Effective feature selection methods to detect IoT DDoS attack in 5G core network. Sensors. 2022;22(10):3819. doi:10.3390/s22103819. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Yuan LP, Liu P, Zhu S. Recompose event sequences vs. predict next events: a novel anomaly detection approach for discrete event logs. In: Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Asia Conference on Computer and Communications Security. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2021. p. 336–48. doi:10.1145/3433210.3453098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Mrabah N, Khan NM, Ksantini R, Lachiri Z. Deep clustering with a dynamic autoencoder: from reconstruction towards centroids construction. Neural Netw. 2020;130:206–28. doi:10.1016/j.neunet.2020.07.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Guo X, Gao L, Liu X, Yin J. Improved deep embedded clustering with local structure preservation. In: Proceedings of the 26th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, IJCAI’17. Washington, DC, USA: AAAI Press; 2017. p. 1753–9. doi:10.5555/3172077.3172131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Louati F, Ktata FB, Amous I. Big-IDS: a decentralized multi agent reinforcement learning approach for distributed intrusion detection in big data networks. Cluster Comput. 2024;27(5):6823–41. doi:10.1007/s10586-024-04306-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Hossain MA. Deep Q-learning Intrusion Detection System (DQ-IDSa novel reinforcement learning approach for adaptive and self-learning cybersecurity. ICT Express. 2025;11:875–80. doi:10.1016/j.icte.2025.05.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Lansky J, Ali S, Mohammadi M, Majeed MK, Karim SHT, Rashidi S, et al. Deep learning-based intrusion detection systems: a systematic review. IEEE Access. 2021;9:101574–99. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3097247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Chinnasamy R, Subramanian M, Easwaramoorthy SV, Cho J. Deep learning-driven methods for network-based intrusion detection systems: a systematic review. ICT Express. 2025;11(1):181–215. doi:10.1016/j.icte.2025.01.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Abdulqadder IH, Zhou S, Zou D, Aziz IT, Akber SMA. Multi-layered intrusion detection and prevention in the SDN/NFV enabled cloud of 5G networks using AI-based defense mechanisms. Comput Netw. 2020;179:107364. doi:10.1016/j.comnet.2020.107364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Sethi K, Kumar R, Mohanty D, Bera P. Robust adaptive cloud intrusion detection system using advanced deep reinforcement learning. In: Security, privacy, and applied cryptography engineering. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2020. p. 66–85. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-66626-2_4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Aldribi A, Traoré I, Moa B, Nwamuo O. Hypervisor-based cloud intrusion detection through online multivariate statistical change tracking. Comput Secur. 2020;88:101646. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2019.101646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Samarakoon S, Siriwardhana Y, Porambage P, Liyanage M, Chang SY, Kim J, et al. 5G-NIDD: a comprehensive network intrusion detection dataset generated over 5G Wireless Network. arXiv:2212.01298. 2022. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2212.01298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Lee S. Open5gs/Open5gs: Open5GS is a C-language Open Source implementation for 5G Core and EPC, i.e. the core network of LTE/NR network (Release-17) [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Aug 6]. Available from: https://github.com/open5gs/open5gs. [Google Scholar]

47. The Kubernetes Authors. Kubernetes: production-grade container orchestration [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Aug 1]. Available from: https://kubernetes.io. [Google Scholar]

48. D’Emmanuele V, Raguideau A. PacketRusher: high performance 5G UE/gNB simulator and CP/UP load tester [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 Aug 6]. Available from: https://github.com/HewlettPackard/PacketRusher. [Google Scholar]

49. Vashishtha LK, Chatterjee K. Strengthening cybersecurity: testCloudIDS dataset and SparkShield algorithm for robust threat detection. Comput Secur. 2025;151:104308. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2024.104308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Kali Linux. Goldeneye | Kali Linux Tools [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Aug 6]. Available from: https://www.kali.org/tools/goldeneye/. [Google Scholar]

51. Andre. YoloFTW/PyLoris [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2025 Aug 6]. Available from: https://github.com/YoloFTW/PyLoris.git. [Google Scholar]

52. Övünç E. EmreOvunc/Python-SYN-Flood-Attack-Tool [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Aug 6]. Available from: https://github.com/EmreOvunc/Python-SYN-Flood-Attack-Tool.git. [Google Scholar]

53. Karl. Karlheinzniebuhr/Torshammer [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Aug 6]. Available from: https://github.com/Karlheinzniebuhr/torshammer.git. [Google Scholar]

54. Grafov IA. Grafov/Hulk [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Aug 6]. Available from: https://github.com/grafov/hulk.git. [Google Scholar]

55. Kali Linux. Hping3 | Kali Linux Tools [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Aug 6]. Available from: https://www.kali.org/tools/hping3/. [Google Scholar]

56. Oliveira J. NewEraCracker/LOIC [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Aug 6]. Available from: https://github.com/NewEraCracker/LOIC.git. [Google Scholar]

57. Somorovsky J. Systematic fuzzing and testing of TLS libraries. In: Proceedings of the 2016 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security. CCS ’16. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; 2016. p. 1492–1504. doi:10.1145/2976749.2978411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. The OpenSSL Project. Openssl/Openssl [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Aug 6]. Available from: https://github.com/openssl/openssl. [Google Scholar]

59. Hieu L. CICFlowmeter [Internet]. [cited 2025 May 9]. Available from: https://github.com/hieulw/cicflowmeter. [Google Scholar]

60. Kheddar H, Dawoud DW, Awad AI, Himeur Y, Khan MK. Reinforcement-learning-based intrusion detection in communication networks: a review. IEEE Commun Surv Tutor. 2025;27(4):2420–69. doi:10.1109/COMST.2024.3484491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools