Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Joint Estimation of Elevation and Azimuth Angles with Triple-Parallel ULAs Using Metaheuristic and Direct Search Methods

1 Department of Electrical Engineering, COMSATS University Islamabad, Islamabad, 45550, Pakistan

2 School of Computer Science & Engineering, Yeungnam University, Gyeongsan-si, 38541, Republic of Korea

3 Information Systems Department, College of Computer and Information Sciences, Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU), Riyadh, 11432, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Author: Abdul Khader Jilani Saudagar. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Computer Modeling for Future Communications and Networks)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(2), 2535-2550. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.072638

Received 31 August 2025; Accepted 21 October 2025; Issue published 26 November 2025

Abstract

Accurate estimation of the Direction-of-Arrival (DoA) of incident plane waves is essential for modern wireless communication, radar, sonar, and localization systems. Precise DoA information enables adaptive beamforming, spatial filtering, and interference mitigation by steering antenna array beams toward desired sources while suppressing unwanted signals. Traditional one-dimensional Uniform Linear Arrays (ULAs) are limited to elevation angle estimation due to geometric constraints, typically within the range [0, π]. To capture full spatial characteristics in environments with multipath and angular spread, joint estimation of both elevation and azimuth angles becomes necessary. However, existing 2D and 3D array geometries often entail increased hardware complexity and computational cost. This work proposes a novel and efficient framework for joint elevation and azimuth angle estimation using three spatially separated, parallel ULAs. The array configuration exploits spatial diversity and orthogonal projections to capture complete directional information with minimal structural overhead. A customized objective function based on the mean square error between measured and reconstructed array outputs is formulated to guide the estimation process. To solve the resulting non-convex optimization problem, three strategies are investigated: a global Genetic Algorithm (GA), a local Pattern Search (PS), and a hybrid GA-PS method that combines global exploration with local refinement. The proposed framework supports automatic pairing of elevation and azimuth angles, eliminating the need for manual post-processing. Extensive simulations validate the robustness, convergence, and accuracy of all three methods under varying signal-to-noise ratio conditions. Results confirm that the hybrid GA-PS approach achieves superior estimation performance and reduced computational complexity, making it well-suited for real-time and resource-constrained applications in next-generation sensing and communication systems.Keywords

The sixth generation (6G) of wireless communication systems is expected to support transformative applications such as autonomous transportation, real-time holographic interaction, ubiquitous extended reality (XR), and intelligent sensing in smart factories. These use cases demand highly accurate beam steering, user localization, and spatial awareness, all of which are critically dependent on precise DoA estimation.

DoA refers to the angular position (azimuth and elevation) from which a signal is received at an antenna array. In conventional beamforming or spatial multiplexing systems, knowledge of DoA enables the base station or radar to focus energy in desired directions while suppressing interference. As communication systems evolve toward joint sensing and communication paradigms (6G-ISAC), accurate and fast DoA estimation becomes fundamental to achieving low-latency, high-reliability, and energy-efficient operation.

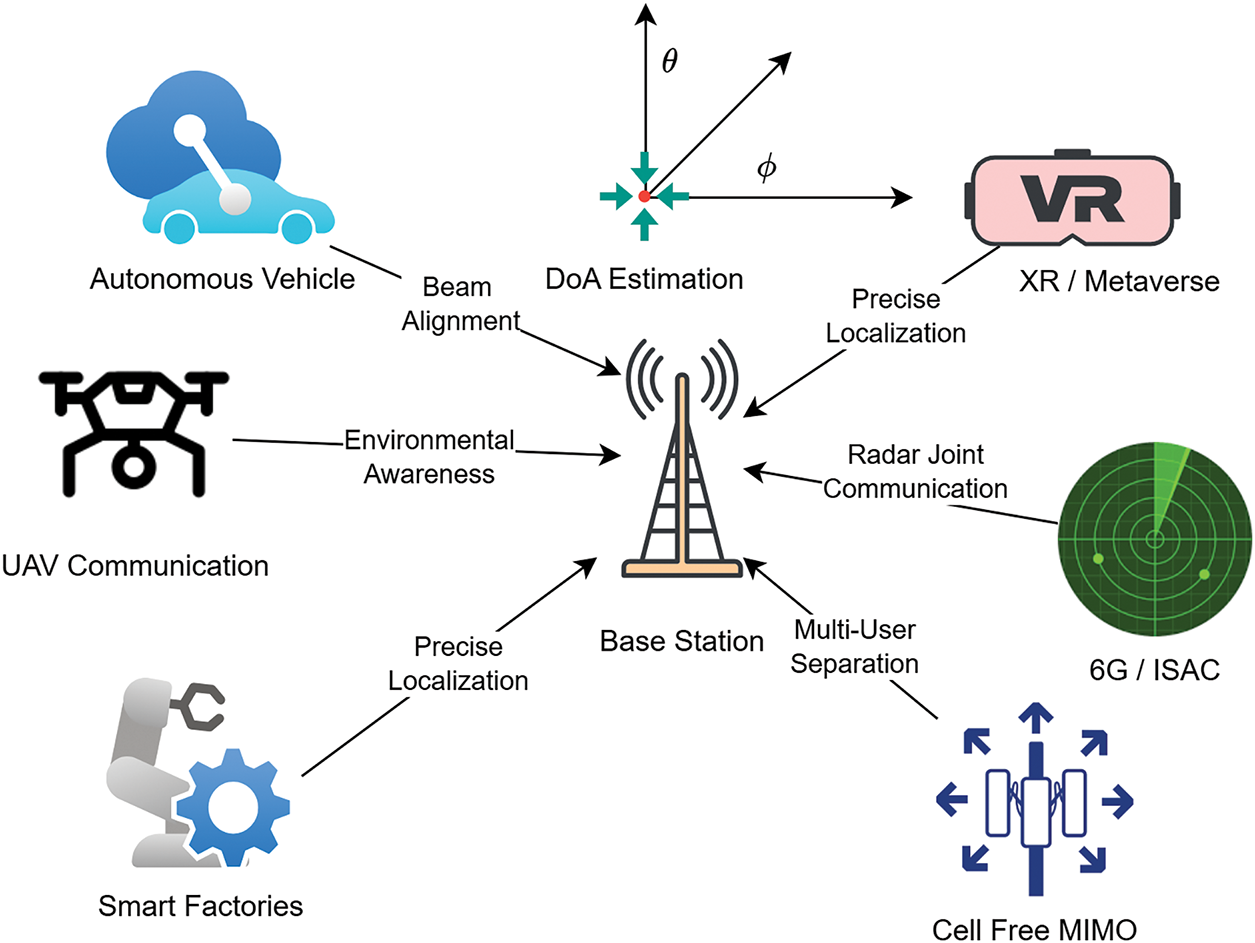

To highlight the ubiquitous deployment of DoA estimation in new technologies, Fig. 1 offers some notable application areas where precise angular estimation plays a key role. In autonomous vehicles, DoA enables Vehicle-to-Everything (V2X) communication by enabling dynamic beam following, thereby enhancing vehicular safety and low-latency connectivity. In unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) communications, such as aerial relays and swarm coordination, DoA estimation facilitates optimal path planning, collision avoidance, and mutual interference reduction. Similarly, in cell-free multiple-input multiple-output (MIMO) systems, where multiple distributed antennas cooperate to serve users in dense urban environments, accurate DoA information is necessary for user-centric beamforming and coordinated access.

Figure 1: Emerging 6G use cases where DoA estimation is a key enabling technology, including V2X, UAV tracking, ISAC, XR localization, and smart factory control

In Metaverse and extended reality (XR) applications, DoA enables seamless user interaction through accurate indoor positioning and beam steering, enabling lag-free and immersive experiences. In 6G networks with Integrated Sensing and Communication (ISAC) capabilities, real-time DoA tracking offers integrated radar-communication features such as object detection and channel-aware communication. Finally, in factory automation environments, DoA estimation enhances robot hardware localization and autonomous control, especially in multipath-prone and adverse radio frequency conditions. These multiple applications collectively point to the pivotal position of adaptive and resilient DoA estimation in characterizing the future generation of smart and interconnected systems.

Despite the long-standing research on DoA estimation, several challenges remain unresolved, particularly for joint azimuth and elevation estimation using simple array structures. Most classical methods require complex array geometries or exhibit poor performance in low-SNR or coherent-source environments. Moreover, these methods often require manual pairing of azimuth and elevation angles, a task not feasible for real-time or large-scale deployments. The key contributions of this paper are as follows:

• We propose a novel 2D DoA estimation framework employing three parallel ULAs to simultaneously estimate elevation and azimuth angles with enhanced spatial resolution.

• A hybrid optimization strategy is developed by integrating GA for global search and PS for local refinement, enabling robust and efficient convergence even in complex search spaces.

• The algorithm supports automatic angle pairing without requiring manual post-processing, thereby reducing algorithmic overhead and enhancing deployment practicality.

• The proposed method demonstrates high estimation accuracy and robustness under low SNR and varying snapshot conditions, validated through extensive Monte Carlo simulations.

• Comparative analysis with state-of-the-art DoA estimation techniques confirms the superiority of the proposed GA-PS hybrid approach in terms of angular resolution, convergence speed, and computational efficiency.

The remaining parts of this paper are organized in the following manner. Section 2 provides an extensive overview of state-of-the-art DoA estimation techniques, highlighting their limitations and advancements. Section 3 provides the system model, introducing the configuration and signal expression for the proposed three-parallel ULA structure. Section 4 provides the suggested hybrid optimization strategy. Simulation results and performance evaluation under various scenarios are reported in Section 5. Section 6 concludes the paper, and finally, potential directions for future work are outlined.

Accurate estimation of the DoA of signals remains a cornerstone for advanced communication systems, particularly as the world transitions toward 6G networks characterized by high mobility, spatial multiplexing, and integrated sensing and communication (ISAC) capabilities. The growing diversity of wireless applications, from V2X and UAV communications to massive MIMO and industrial Internet of Things (IoT), has intensified the demand for robust and scalable DoA estimation frameworks. As a result, a significant body of research has emerged, spanning from classical signal processing techniques to modern hybrid metaheuristic methods and unconventional antenna configurations. This section surveys key developments across these areas to contextualize the contributions of the current study.

2.1 Classical Methods and Their Limitations

Early research into DoA estimation has primarily focused on subspace-based techniques, such as MUSIC [1,2], and Maximum Likelihood (ML) estimators. These methods have formed the backbone of numerous applications due to their high angular resolution and ability to resolve multiple sources under ideal conditions. However, their performance degrades in low SNR, coherent source scenarios, and environments with limited snapshots [3,4]. While some extensions attempt to adapt these methods to non-uniform or planar arrays [5,6], the need for eigen-decomposition and manual angle pairing persists. For instance, Dong et al. proposed an automatic pairing scheme for L-shaped arrays using signal separation principles [7], whereas Wei et al. introduced pair-matching via covariance matrices [8] at the cost of higher complexity.

2.2 Array Geometries for 2D-DoA Estimation

Beyond classical ULAs, researchers have explored complex array topologies to enable 2D angle estimation. Circular, spherical, and conformal arrays offer full azimuth-elevation coverage but require sophisticated calibration [5,9]. Notably, Wu et al. investigated sparse L-shaped arrays with convex optimization to improve resolution under structural constraints [10]. Zhang et al. developed a rank-reduction-based algorithm for three-parallel ULAs that inspired subsequent studies in hybrid estimation [11]. Stacked metasurfaces are another innovative direction. An et al. proposed a reconfigurable metasurface array for 2D estimation in intelligent communication environments [12], while Cho et al. validated automotive radar configurations that exploit conformal array properties [13]. Although these architectures improve angular resolution and multi-target handling, they increase hardware and deployment complexity.

2.3 Metaheuristic and Hybrid Optimization Algorithms

Metaheuristic algorithms are well-suited for DoA estimation due to their ability to handle non-convex, high-dimensional search spaces. GA is widely used, offering flexible encoding and global exploration capabilities [14,15]. Their use in signal processing is growing rapidly, especially in radar and sensor array applications [16]. Other algorithms include Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) [17], Artificial Bee Colony (ABC) [18], and Cultural Algorithms [19], each with varying convergence characteristics. Pattern Search (PS), while less popular in signal processing, offers fast local convergence and is effective in derivative-free contexts [20,21]. Hybrid frameworks combining GA with local search have demonstrated excellent trade-offs between accuracy and convergence speed [22–24]. Zaman et al. employed a 2-L-shaped array optimized by a hybrid GA for joint amplitude and 2D DoA estimation [25], which reduces manual pairing efforts. Komeylian also examined hybrid antenna designs for DoA estimation using evolutionary search [26].

2.4 Emerging 6G Use Cases and Requirements

DoA estimation now underpins multiple 6G-oriented applications. In V2X, beam-switching based on DoA improves safety and reduces latency during handovers [27]. UAV swarms benefit from distributed DoA systems for target tracking and avoidance [28]. Liu et al. surveyed ISAC systems where DoA plays a role in simultaneous localization and communication [29], and Batalla et al. demonstrated its use in industrial localization under harsh environments [30]. These use cases highlight the demand for scalable and deployable DoA algorithms with minimal hardware overhead and real-time operability. Table 1 provides a structured comparison of representative 2D DoA estimation approaches, highlighting the diversity in array geometries, estimation methodologies, optimization strategies, and application domains.

Although considerable progress has been made in 2D DoA estimation through advanced geometries and optimization algorithms, a persistent challenge lies in balancing structural simplicity, computational efficiency, and angle pairing robustness. Most subspace-based and grid search methods require either large array apertures or post-estimation correction steps. Meanwhile, many metaheuristic solutions, while powerful, are constrained by slow convergence or application-specific tuning. Moreover, few works combine the benefits of both global and local search in a way that generalizes across platforms. In this context, the present work introduces a triple-parallel ULA architecture that leverages the geometric simplicity of linear arrays while enabling joint azimuth-elevation estimation. By fusing Genetic Algorithm and Pattern Search, we aim to create an adaptive, low-complexity solution capable of auto-pairing and robust estimation under practical 6G conditions such as low SNR and fast-changing environments.

3 System Model for Three Parallel Uniform Linear Arrays

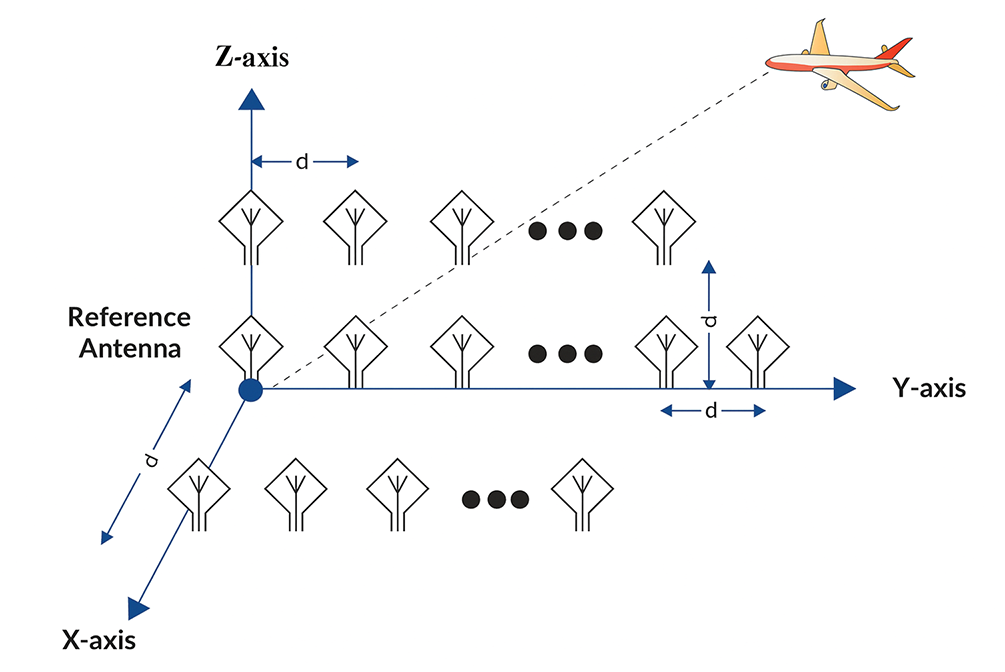

This section outlines the signal model for the proposed three-parallel ULA configuration. We consider a passive monostatic phased-array radar system in which the receiver employs three Uniform Linear Arrays (ULAs) that are spatially separated but mutually parallel. Each ULA lies along a different spatial orientation—aligned with the Y-axis, the

Figure 2: Generic diagram for 3-parallel ULA configuration

Let us assume that I narrowband, far-field sources impinge upon the array with elevation angles

Each ULA contains a different number of elements for symmetry and angular resolution: the array along the Y-axis has

The response at the

where

Define the intermediate phase parameter

Eq. (3) can be compactly represented as

where

The ULA in the

Define

Eq. (6) can be concisely expressed as

where

The array in the

Defining

Here,

The full observation model for the three-parallel ULA system is

The matrix

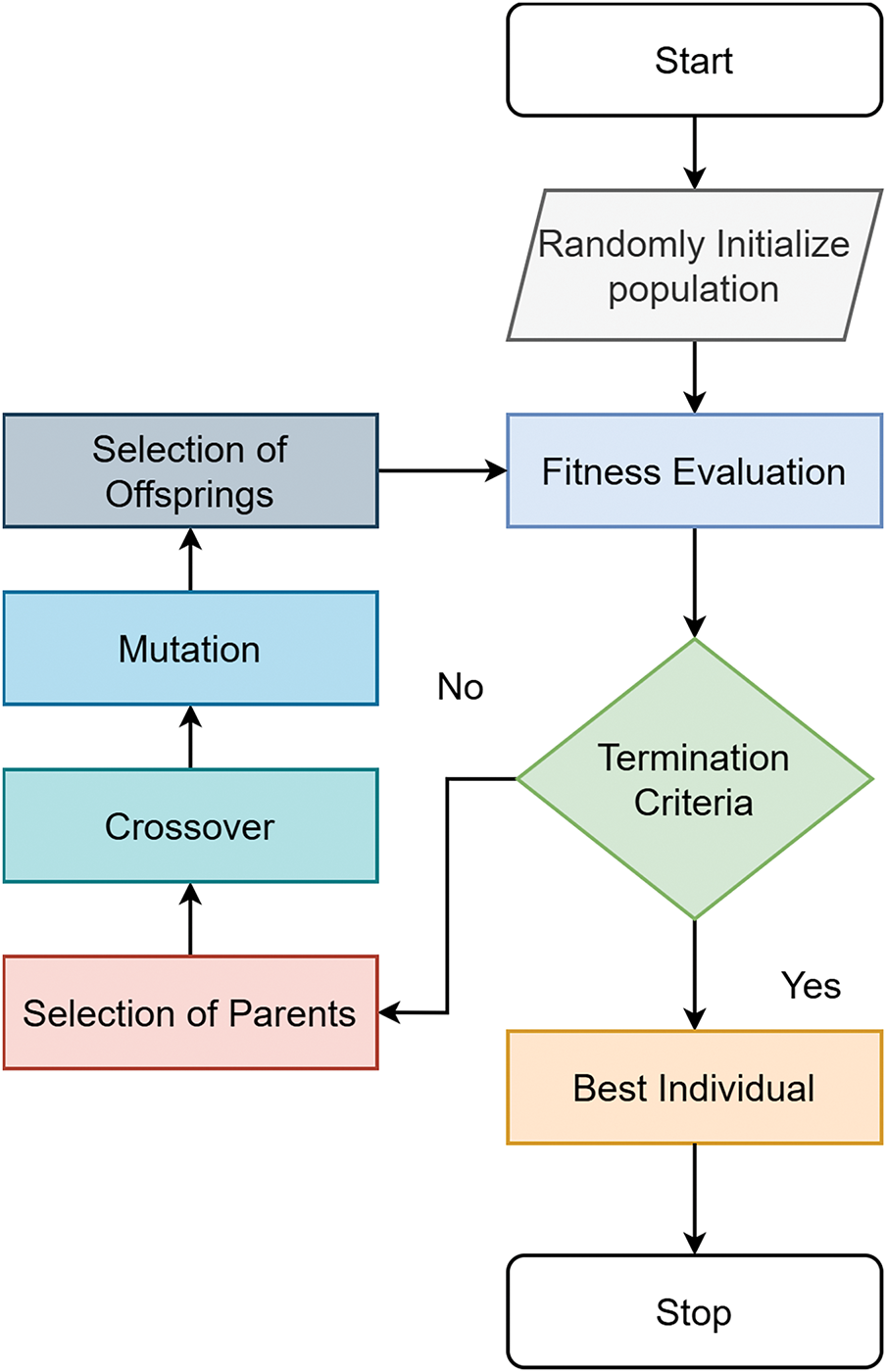

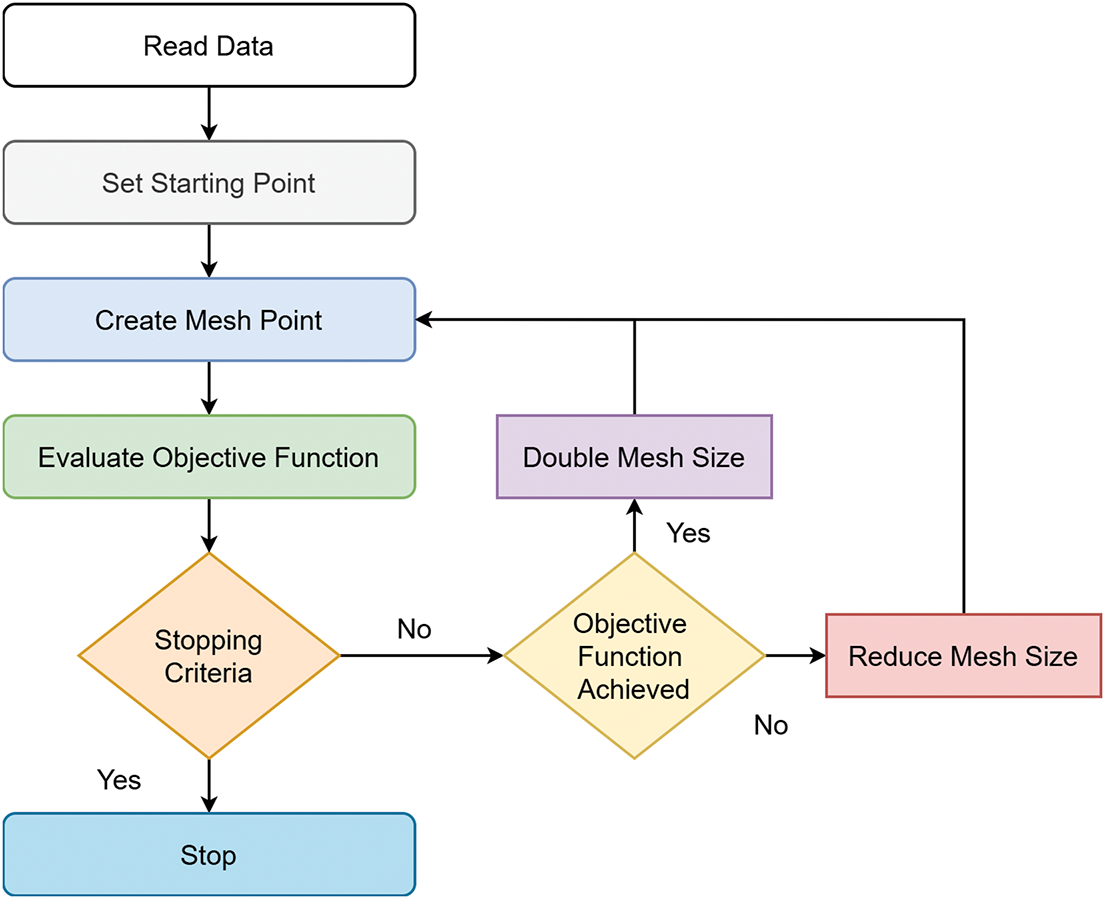

This section presents the proposed optimization framework for joint elevation and azimuth angle estimation using the three-parallel ULA configuration. The estimation process is formulated as a nonlinear optimization problem, where the objective is to minimize the error between the measured and estimated array outputs. We explore three optimization strategies: Genetic Algorithm (GA), Pattern Search (PS), and a hybrid GA-PS approach. The individual components, algorithmic flowcharts, and pseudo-code for each method are discussed in detail.

Fig. 3 illustrates the general workflow of the Genetic Algorithm, which performs global exploration across the solution space. Its output is then refined through PS, as depicted in Fig. 4, enabling localized convergence to precise angle estimates. The hybrid GA-PS algorithm leverages both the exploratory strength of GA and the exploitation ability of PS to effectively avoid local minima and accelerate convergence.

Figure 3: Generic flow diagram for genetic algorithm

Figure 4: Generic flow diagram of pattern search

The Genetic Algorithm is a metaheuristic optimization technique inspired by Darwinian evolution and natural selection. Originally introduced by J. H. Holland, GA simulates the biological processes of reproduction, mutation, and survival of the fittest to evolve solutions toward optimality over multiple generations.

In the context of DoA estimation, each candidate solution (chromosome) encodes a possible set of elevation and azimuth angles. The GA iteratively refines this population by evaluating their fitness against a defined cost function. The standard procedure for GA is summarized in the pseudo-code below, with the corresponding flowchart shown in Fig. 3.

Step I: Chromosome Initialization

The algorithm begins by randomly generating a population of S chromosomes. Each chromosome is a vector of length

where

Step II: Objective (Cost) Function Formulation

The fitness of each chromosome is evaluated using a cost function (CF), which quantifies the system-wide mean squared error (MSE) between the observed outputs and the reconstructed array outputs based on the candidate angles. Mathematically, the cost function is

We define the normalized form of the objective function for all three arrays

where

and

Step III: Termination Criteria

The GA process continues until the cost function value falls below a pre-defined threshold or the maximum number of generations is reached.

Step IV: Parent Selection

From the current generation, chromosomes with higher fitness values are selected to become parents for reproduction. Techniques such as stochastic universal sampling, tournament selection, or roulette wheel selection can be employed based on fitness proportion.

Step V: Reproduction via Crossover and Mutation

New offspring are generated by applying genetic operators, where crossover combines genes from two parents to produce new chromosomes, and mutation randomly alters gene values to introduce diversity. These operators enable the algorithm to explore a wide search space and prevent premature convergence.

Step VI: Offspring Selection and Generation Update

From the new generation, the fittest chromosomes are retained, and the rest are replaced. Methods such as elitism (retaining best chromosomes) and survival-of-the-fittest strategies ensure continuous improvement across generations.

Pattern Search is a deterministic, derivative-free local optimizer well-suited for refining candidate solutions. It systematically explores the search space by evaluating a set of candidate points around the current best solution using a mesh-based strategy.

At each iteration, PS generates a mesh around the current solution. If a better point is found, the mesh is expanded. If not, the mesh is contracted. The process repeats until convergence criteria are satisfied. Key features of PS include the fact that it does not require gradient information, uses polling directions and mesh refinements, and is effective for fine-tuning in non-smooth landscapes.

To overcome the limitations of standalone methods, we adopt a hybrid GA-PS approach. The GA first performs global exploration to identify promising candidate solutions. The best solution from GA is then refined using PS, leading to improved accuracy and faster convergence.

This hybrid strategy is especially beneficial for high-dimensional, non-convex optimization problems like 2D DoA estimation, where multiple local minima may exist. The combination ensures both exploration and exploitation, which is critical in noisy, underdetermined, or snapshot-limited environments.

4.5 Implementation and Parameter Settings

All algorithms were implemented using MATLAB’s optimization toolbox. Table 2 summarizes the parameter configurations for GA and PS. In this section, we proposed a robust hybrid optimization strategy that combines the strengths of global and local search methods for accurate and efficient estimation of elevation and azimuth angles in 3-ULA systems. The GA ensures global exploration, while PS improves convergence in the neighborhood of optimal solutions. Together, they form a scalable, reliable framework suitable for real-time and resource-constrained 6G applications.

This section presents the simulation results for the proposed optimization schemes: GA, PS, and hybrid GA-PS, for estimating the elevation and azimuth angles of multiple incident plane waves. The performance of each algorithm is evaluated under various conditions, including changes in the number of sources and SNR.

The spacing between adjacent elements in each ULA is set to

Case 1: Two Signal Sources at SNR = 15 dB

In this scenario, two narrowband sources impinge on the 3-parallel ULA system. The true direction-of-arrival angles are set to

Table 3 presents the estimated angles using each algorithm. The hybrid GA-PS approach achieves the closest estimates to the ground truth, followed by GA. PS shows larger deviations, especially in estimating elevation angles. The results confirm the effectiveness of GA in global exploration, and demonstrate that the local refinement by PS improves precision further.

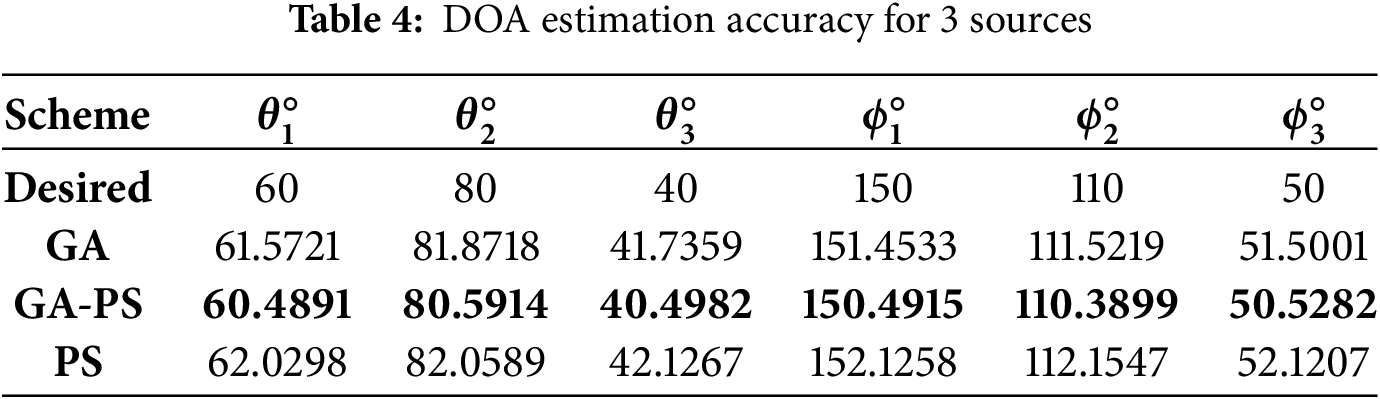

Case 2: Three Sources with Increased Angular Diversity

This experiment evaluates algorithm robustness with three signal sources. The desired elevation and azimuth angles are as follows:

The results in Table 4 show that although estimation errors increase slightly due to the growing search space, the GA-PS method remains consistently accurate. GA performs well, but PS suffers noticeably in both azimuth and elevation estimation due to local trapping.

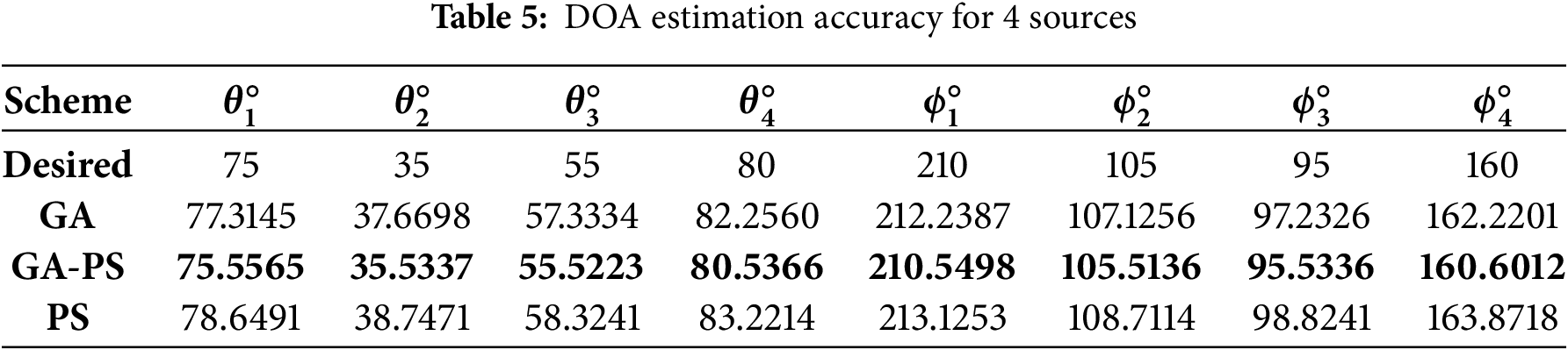

Case 3: Four Sources: High Complexity Scenario

As the number of sources increases to four, the search space becomes more complex and high-dimensional. The desired directions are

Table 5 illustrates a drop in accuracy across all algorithms due to the larger number of parameters. The hybrid GA-PS method still produces the most accurate estimates, demonstrating the benefit of combining global and local search. GA retains moderate accuracy, while PS is visibly affected by convergence limitations.

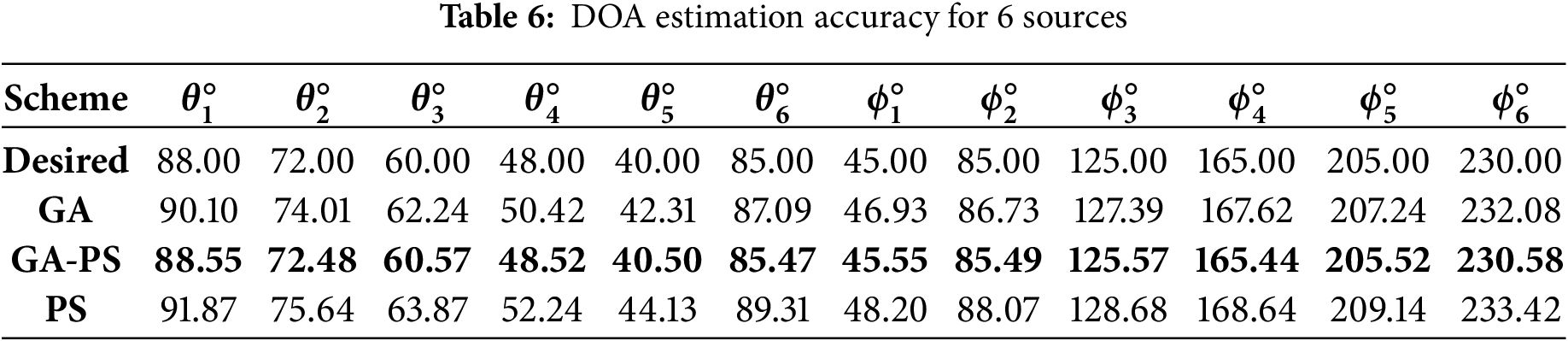

Case 4: Six Sources: High-Dimensional Scenario

To assess scalability, we consider six simultaneous narrowband sources impinging on the 3-parallel ULA system. The desired angles are

With six sources as shown in Table 6, the search space grows substantially and the cost surface becomes more multi-modal. Consistent with the earlier cases, the hybrid GA-PS approach preserves sub-degree accuracy through global exploration followed by local refinement, the plain GA retains moderate accuracy but exhibits larger bias, and PS alone shows the largest deviations due to local trapping.

Case 5: Robustness across SNR Levels (RMSE Analysis)

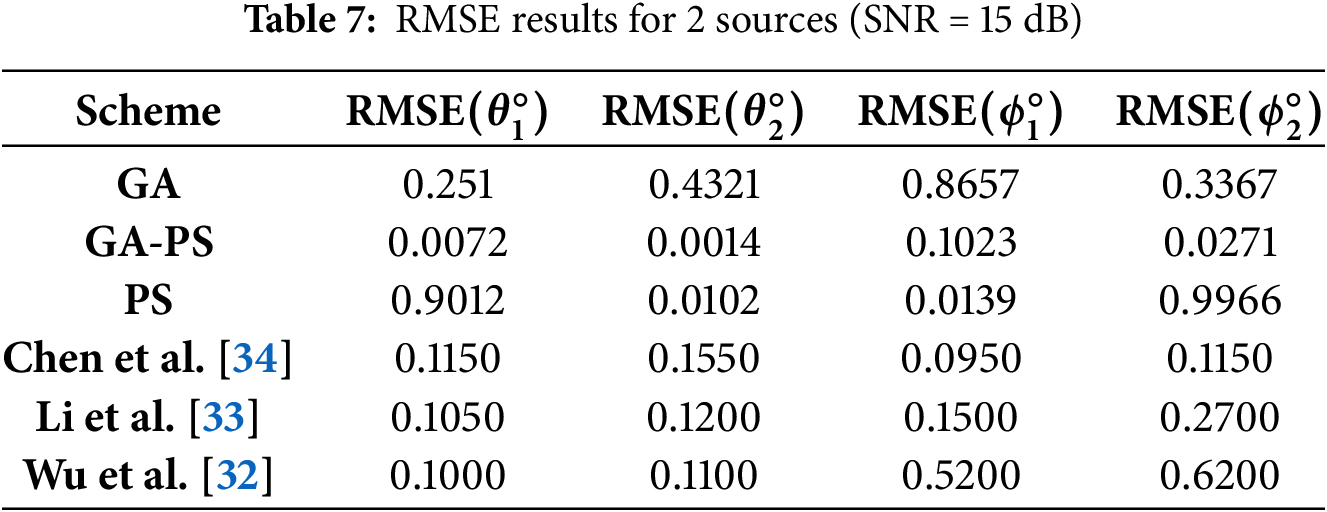

To evaluate the robustness of the algorithms, we simulate three sources under the SNR of 15 dB. The root mean square error (RMSE) is computed for each scheme and tabulated in Table 7. Several classical propagator-based algorithms have also been considered for comparison. Wu et al. [32] proposed a fast 2-D DOA estimation method using three-parallel ULAs, but their approach requires additional azimuth-elevation pair matching and often suffers performance degradation in practical mobile elevation angles between

The RMSE values reported in Table 7 highlight the superior performance of the proposed hybrid GA-PS approach. At an SNR of 15 dB, GA-PS achieves remarkably low errors across all four parameters, with azimuth errors as small as

Early stopping routinely terminates the search well before the nominal budgets. The GA scheme converges after approximately 35–60% of the 2000-generation cap, and the PS scheme after 30–40% of the 3000-iteration cap, with the exact fraction depending on the number of sources I. The runtime of the hybrid GA-PS scales nearly linearly with I, with median per-trial runtimes on a single thread of about

GA-PS significantly outperforms the Chen, Li and Wu schemes. Chen’s algorithm [34], which utilizes complete array information and automatic azimuth-elevation pairing, produces balanced results with errors in the range of

The GA-PS hybrid outperforms standalone GA and PS in both accuracy and robustness. GA performs better than PS due to its global search capability, particularly when the number of sources is small or the noise level is low. PS alone offers faster execution but is more susceptible to suboptimal convergence in high-dimensional or noisy scenarios. Furthermore, the performance gap between GA-PS and the other methods widens as the number of sources or the noise level increases, reinforcing the effectiveness of the hybrid optimization approach. The results clearly demonstrate the superiority of the proposed hybrid framework, making it a strong candidate for real-time DoA estimation in complex and noise-prone environments such as 6G, UAV, and radar applications.

This work presented evolutionary optimization methods, namely GA, PS and a hybrid GA-PS, for joint elevation/azimuth DOA estimation of multiple plane waves using a three-parallel ULA. We formulated a unified optimization framework for DOA estimation and instantiated three solvers. The hybrid GA-PS couples global exploration with local refinement, providing a practical balance between search breadth and precision.

The three methods deliver accurate DOA estimates, with the hybrid GA-PS consistently producing the smallest angle errors and the most stable convergence. Empirically, the hybrid converges faster than GA-only or PS-only and maintains computational feasibility as the number of sources increases, supported by early stopping and vectorized evaluations.

The approach is well-suited to real-time sensing and communication tasks, e.g., 6G/ISAC, UAV links, and radar tracking, where robust multi-source angle estimation is required.

Despite the promising results demonstrated by the proposed methodology, there are some limitations of our proposed method. First, the algorithm assumes that the number of antenna elements is greater than or equal to the number of signal sources. When the number of sources exceeds the number of array elements, the system becomes underdetermined, resulting in more unknown parameters than available equations. In such scenarios, accurate estimation of angles becomes infeasible due to rank deficiency in the array manifold matrix, thereby limiting the applicability of the proposed scheme. Second, the proposed model is developed under the far-field assumption. This approach does not account for near-field conditions, where the spherical nature of wavefronts introduces additional phase curvature across the sensors.

In future work, we will relax the canonical assumptions and evaluate the estimator under coherent/correlated sources, array-manifold perturbations, and colored noise, as well as extend the framework to joint arrival/departure estimation in MIMO settings and explore learning-assisted acceleration.

Acknowledgement: The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU) for funding this work through (grant number IMSIU-DDRSP2504).

Funding Statement: This work was supported and funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU) (grant number IMSIU-DDRSP2504).

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Fawad Zaman; methodology, Fawad Zaman and Adeel Iqbal; software, Bakhtiar Ali; validation, Bakhtiar Ali; formal analysis, Abdul Khader Jilani Saudagar; writing—original draft preparation, Fawad Zaman; writing—review and editing, Adeel Iqbal and Abdul Khader Jilani Saudagar; visualization, Bakhtiar Ali; supervision, Fawad Zaman. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Schmidt R. Multiple emitter location and signal parameter estimation. IEEE Trans Antennas Propag. 1986;34(3):276–80. doi:10.1109/tap.1986.1143830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Stoica P, Nehorai A. MUSIC, maximum likelihood, and Cramer-Rao bound. IEEE Trans Acoust Speech Signal Process. 2002;37(5):720–41. doi:10.1109/29.17564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Gentilho EJr, Scalassara PR, Abrão T. Direction-of-arrival estimation methods: a performance-complexity tradeoff perspective. J Signal Process Syst. 2020;92(2):239–56. doi:10.1007/s11265-019-01467-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Xu Z, Chen Y, Zhang P. A sparse uniform linear array DOA estimation algorithm for FMCW radar. IEEE Signal Process Lett. 2023;30:823–7. doi:10.1109/lsp.2023.3292739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Li Q, Su T, Wu K. Accurate DOA estimation for large-scale uniform circular array using a single snapshot. IEEE Commun Lett. 2019;23(2):302–5. doi:10.1109/lcomm.2018.2889855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Yadav SK, George NV. Underdetermined DOA estimation using arbitrary planar arrays via coarray manifold separation. IEEE Trans Veh Technol. 2022;71(11):11959–71. doi:10.1109/tvt.2022.3194409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Dong YY, Dong CX, Xu J, Zhao GQ. Computationally efficient 2-D DOA estimation for L-shaped array with automatic pairing. IEEE Antennas Wirel Propag Lett. 2016;15:1669–72. doi:10.1109/lawp.2016.2521785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Wei Y, Guo X. Pair-matching method by signal covariance matrices for 2D-DOA estimation. IEEE Antennas Wirel Propag Lett. 2014;13:1199–202. doi:10.1109/lawp.2014.2331076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Wan L, Si W, Liu L, Tian Z, Feng N. High accuracy 2D-DOA estimation for conformal array using PARAFAC. Int J Antennas Propag. 2014;2014(1):394707. doi:10.1155/2014/394707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Wu R, Zhang Z. Convex optimization-based 2-D DOA estimation with enhanced virtual aperture and virtual snapshots extension for L-shaped array. IEEE Trans Veh Technol. 2020;69(6):6473–84. doi:10.1109/tvt.2020.2988327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Zhang Y, Xu X, Sheikh YA, Ye Z. A rank-reduction based 2-D DOA estimation algorithm for three parallel uniform linear arrays. Signal Process. 2016;120(5):305–10. doi:10.1016/j.sigpro.2015.09.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. An J, Yuen C, Guan YL, Di Renzo M, Debbah M, Poor HV, et al. Two-dimensional direction-of-arrival estimation using stacked intelligent metasurfaces. IEEE J Sel Areas Commun. 2024;42(10):2786–802. [Google Scholar]

13. Cho S, Song H, You KJ, Shin HC. A new direction-of-arrival estimation method using automotive radar sensor arrays. Int J Distrib Sens Netw. 2017;13(6):1550147717713628. doi:10.1177/1550147717713628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Eiben AE, Smith JE. Introduction to evolutionary computing. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2015. [Google Scholar]

15. Gen M, Lin L. Genetic algorithms and their applications. In: Springer handbook of engineering statistics. London, UK: Springer; 2023. p. 635–74 doi:10.1007/978-1-4471-7503-2_33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Ch LDT, Puli KK. Genetic algorithm based single snapshot 1D, 2D DOA estimation at low SNR. Signal Image Video Process. 2025;19(6):445. doi:10.1007/s11760-025-04011-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Mavrovouniotis M, Li C, Yang S. A survey of swarm intelligence for dynamic optimization: algorithms and applications. Swarm Evol Comput. 2017;33(11):1–17. doi:10.1016/j.swevo.2016.12.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Kaya E, Gorkemli B, Akay B, Karaboga D. A review on the studies employing artificial bee colony algorithm to solve combinatorial optimization problems. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2022;115(3):105311. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2022.105311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Vahdatpour MS. Addressing the knapsack challenge through cultural algorithm optimization. arXiv:2401.03324. 2023. [Google Scholar]

20. Torczon V. On the convergence of pattern search algorithms. SIAM J Optim. 1997;7(1):1–25. doi:10.1137/s1052623493250780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Madic M, Radovanovic M. Optimization of machining processes using pattern search algorithm. Int J Ind Eng Comput. 2014;5(2):223. [Google Scholar]

22. Maghawry A, Hodhod R, Omar Y, Kholief M. An approach for optimizing multi-objective problems using hybrid genetic algorithms. Soft Comput. 2021;25(1):389–405. doi:10.1007/s00500-020-05149-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Rani GS, Jayan S, Alatas B. Analysis of chaotic maps for global optimization and a hybrid chaotic pattern search algorithm for optimizing the reliability of a bank. IEEE Access. 2023;11(3):24497–510. doi:10.1109/access.2023.3253512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Li Z, Huang J, Wang J, Ding M. Development and application of hybrid teaching-learning genetic algorithm in fuel reloading optimization. Prog Nucl Energy. 2021;139(10):103856. doi:10.1016/j.pnucene.2021.103856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Zaman F, Qureshi IM, Khan JA, Khan ZU. An application of artificial intelligence for the joint estimation of amplitude and two-dimensional direction of arrival of far field sources using 2-L-shape array. Int J Antennas Propag. 2013;2013(1):593247. doi:10.1155/2013/593247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Komeylian S. Optimization modeling of the hybrid antenna array for the DOA estimation. Int J Electron Commun Eng. 2021;15:72–7. [Google Scholar]

27. Va V, Shimizu T, Bansal G, Heath RW. Beam design for beam switching based millimeter wave vehicle-to-infrastructure communications. In: 2016 IEEE International Conference on Communications (ICC); 2016 May 22–27; Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

28. Zhang C, Wang W, Hong X, Zhou J. A multi-sources DOA localization method based on UAV cluster systems. IEEE Trans Veh Technol. 2024;73(6):8681–92. doi:10.1109/tvt.2023.3348507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Liu F, Masouros C, Petropulu AP, Griffiths H, Hanzo L. Joint radar and communication design: applications, state-of-the-art, and the road ahead. IEEE Trans Commun. 2020;68(6):3834–62. doi:10.1109/tcomm.2020.2973976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Batalla JM, Mavromoustakis CX, Mastorakis G, Xiong NN, Wozniak J. Adaptive positioning systems based on multiple wireless interfaces for industrial IoT in harsh manufacturing environments. IEEE J Sel Areas Commun. 2020;38(5):899–914. doi:10.1109/jsac.2020.2980800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Akbar S, Sohail M, Raja MAZ, Zaman F, Ullah R, Khan MAR, et al. Meta-heuristic computing knacks for target angle estimation in monostatic radar system with coprime arrays. Ain Shams Eng J. 2024;15(5):102689. doi:10.1016/j.asej.2024.102689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Wu Y, Liao G, So HC. A fast algorithm for 2-D direction-of-arrival estimation. Signal Process. 2003;83(8):1827–31. doi:10.1016/s0165-1684(03)00118-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Li J, Zhang X, Chen H. Improved two-dimensional DOA estimation algorithm for two-parallel uniform linear arrays using propagator method. Signal Process. 2012;92(12):3032–8. doi:10.1016/j.sigpro.2012.06.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Chen H, Hou C, Wang Q, Huang L, Yan W, Pu L. Improved Azimuth/Elevation angle estimation algorithm for three-parallel uniform linear arrays. IEEE Antennas Wirel Propag Lett. 2015;14:329–32. doi:10.1109/lawp.2014.2360419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools