Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Framework for the Structural Analysis of Fractional Differential Equations via Optimized Model Reduction

1 Mathematical Modelling Department, Faculty of Fundamental Sciences, Vilnius Gediminas Technical University, Saulėtekio al. 11, Vilnius, LT-10223, Lithuania

2 Department of Mathematical Modelling, Kaunas University of Technology, Studentu 50-147, Kaunas, LT-51368, Lithuania

3 Department of Software Engineering, Kaunas University of Technology, Studentu 50-415, Kaunas, LT-51368, Lithuania

* Corresponding Author: Minvydas Ragulskis. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Analytical and Numerical Solution of the Fractional Differential Equation)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(2), 2131-2156. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.072938

Received 07 September 2025; Accepted 20 October 2025; Issue published 26 November 2025

Abstract

Fractional differential equations (FDEs) provide a powerful tool for modeling systems with memory and non-local effects, but understanding their underlying structure remains a significant challenge. While numerous numerical and semi-analytical methods exist to find solutions, new approaches are needed to analyze the intrinsic properties of the FDEs themselves. This paper introduces a novel computational framework for the structural analysis of FDEs involving iterated Caputo derivatives. The methodology is based on a transformation that recasts the original FDE into an equivalent higher-order form, represented as the sum of a closed-form, integer-order component G(y) and a residual fractional power series Ψ(x). This transformed FDE is subsequently reduced to a first-order ordinary differential equation (ODE). The primary novelty of the proposed methodology lies in treating the structure of the integer-order component G(y) not as fixed, but as a parameterizable polynomial whose coefficients can be determined via global optimization. Using particle swarm optimization, the framework identifies an optimal ODE architecture by minimizing a dual objective that balances solution accuracy against a high-fidelity reference and the magnitude of the truncated residual series. The effectiveness of the approach is demonstrated on both a linear FDE and a nonlinear fractional Riccati equation. Results demonstrate that the framework successfully identifies an optimal, low-degree polynomial ODE architecture that is not necessarily identical to the forcing function of the original FDE. This work provides a new tool for analyzing the underlying structure of FDEs and gaining deeper insights into the interplay between local and non-local dynamics in fractional systems.Keywords

Fractional differential equations (FDEs) have emerged as indispensable tools in mathematical modeling, extending the classical concepts of differentiation and integration to non-integer orders [1]. This generalization allows FDEs to capture complex phenomena exhibiting memory effects and non-local dynamics, which are often inadequately described by traditional integer-order models. The inherent ability of fractional operators, such as the widely used Caputo derivative [1], to incorporate system history makes FDEs particularly suitable for applications across diverse fields, including viscoelasticity [2,3], finance [4,5], biology [6,7], health sciences [8,9], control theory [10,11], signal processing [12,13] and others.

Despite their descriptive power, finding and analyzing solutions to FDEs poses significant challenges. While analytical solutions exist only for specific classes of FDEs [14,15], a broad landscape of methodologies has been developed to address various scientific objectives within the field of fractional calculus. A large portion of research includes numerical solvers, which aim to compute high-fidelity approximations of the solution with a focus on accuracy and stability [16,17]. Such methods are essential for simulating complex physical systems, for example in studies on the phase dynamics of Josephson junctions [18] or the analysis of heat transport in porous media [19], where a precise numerical result is the primary goal. Alongside these are semi-analytical methods, which often aim to bridge the gap between exact solutions and purely numerical approximations, offering computational efficiency while retaining a degree of analytical insight [20,21].

Other research directions have also been pursued. Model order reduction techniques, such as proper orthogonal decomposition [22], are data-driven methods designed to replace high-dimensional, computationally expensive mathematical models with more efficient low-dimensional surrogate models. The fundamental idea of such techniques is that the dynamics of many complex systems with large degrees of freedom often evolve on a much lower-dimensional manifold, which these methods aim to identify. The primary motivation is efficiency, particularly in multi-query or real-time applications, where repeated evaluation of the full-order model is prohibitive. Another class of methods that address a similar problem involves computational transformations, such as the use of rational approximations [23] to replace the fractional operator with a system of ODEs for the purpose of accelerating the numerical solution process. In contrast, system identification methods address an inverse problem, where the goal is to discover the governing equations of a system from measurement data. A prominent example is the sparse identification of nonlinear dynamics (SINDy) framework [24], which offers a systematic way to identify parsimonious and interpretable models from time-series data. The objective of the present work is distinct from these approaches. It is not intended to compete with numerical solvers on precision, nor with data-driven methods on model discovery. Instead, it introduces a framework for the structural analysis of a known FDE, with the goal of gaining a deeper understanding of its mathematical properties.

Among existing semi-analytical approaches, methods based on fractional power series (FPS) expansions have proven effective [25,26]. Previous research demonstrated that certain types of FDEs can be effectively analyzed using FPS expansions combined with operator calculus. Previous work [26] has shown that an FDE involving a single Caputo derivative of order

can be transformed into an equivalent FDE involving the

where functions

These derivations recast the fractional problem into the domain of ODEs, allowing the application of well-established analytical or numerical techniques for ODEs. It should be noted that these transformations, while powerful, involve the emergence of auxiliary functions in the form of infinite series that require truncation for practical computation, influencing the accuracy of the resulting ODE approximation [26].

The work presented in [26] established this transformation as a deterministic, analytical procedure for deriving a single, fixed higher-order representation to facilitate a solution. The primary contribution of the present study is a conceptual extension of that work. It is important to note that the separation of the system’s dynamics into an integer-order component

The original FDE (4) can be transformed, similarly to the derivations presented in [26], into a higher-order FDE (2), represented as the sum of a closed-form, integer-order dynamic component, denoted

The central hypothesis of this paper is that by treating the structure of

This paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the preliminaries, including definitions of fractional power series and the transformation framework that reduces an FDE to an ODE. Section 3 details the proposed methodology, outlining the parameterization of the integer-order component and the formulation of the optimization problem. Section 4 presents the results of numerical experiments on both linear and nonlinear FDEs, including detailed parameter and sensitivity analyses. Finally, Sections 5 and 6 provide concluding remarks, summarize the findings, and discuss the implications for the structural analysis of fractional systems.

This section establishes the mathematical foundation necessary for the subsequent analysis. Key definitions related to fractional calculus, FPS, and the specific type of FDEs under investigation are presented.

2.1 Fractional Power Series Algebra

FPS provide a convenient framework to analyze the solutions of the FDEs considered in this paper [25]. Solutions

A FPS centered at

This series is assumed to converge for

The coefficients are related by

2.1.2 Fractional Power Series Operations

Addition of two FPS as well as multiplication of FPS by a scalar is defined in a standard way, while multiplication of two FPS

using the property

The binomial coefficient of non-integer arguments

A Caputo differentiation operator of order

Thus, the iterated application of the Caputo derivative of order

This property simplifies the application of fractional operators to series solutions.

2.2 Transformation of the FDE and Reduction to the ODE

2.2.1 Transformation Methodology

Previous work demonstrated a methodology for transforming FDEs involving the operator

subject to

This transformation utilizes the properties of FPS and introduces auxiliary relations to manage the fractional differentiation of nonlinear functions of

where

Here,

For a general analytic nonlinearity

2.2.2 Reduction to a First-Order ODE

Subsequently, the resulting

Letting

with

For computation, the infinite series

which introduces an approximation error, the magnitude of which depends on the truncation order M and the convergence properties of

Building upon the established concepts, this section outlines the methodology for analyzing the more general

Consider the FDE involving the

subject to initial conditions

for

This equation can be transformed into the

Performing this transformation leads to an equation structure:

This transformation process, however, reveals an ambiguity. The separation of the system’s dynamics into a closed-form, integer-order component

Previous work in this area has focused on deriving a single, valid transformation to facilitate a solution, without exploring the implications of this non-uniqueness. For instance, the methodology presented in [26] was fundamentally analytical and relied on deriving specific auxiliary relations to establish a deterministic, step-by-step procedure for converting an FDE into a higher-order form. The primary objective of that approach was to prove the transformation’s viability for the construction of the solution. Consequently, the resulting integer-order component

This paper shifts that perspective by exploiting the aforementioned ambiguity. Instead of manually deriving one possible architecture based on preselected analytical relations, this work treats the structure of

3.2 Reduction to ODE and Truncation

Regardless of the specific choice of

The initial conditions

For computation, the infinite series

leading to the approximate ODE:

where

This truncation is a primary source of approximation error. The core idea is that by optimizing the structure of

The choice of the truncation order M used in this study is based on both the theoretical properties of the residual series and practical considerations of convergence. Theoretically, the coefficients

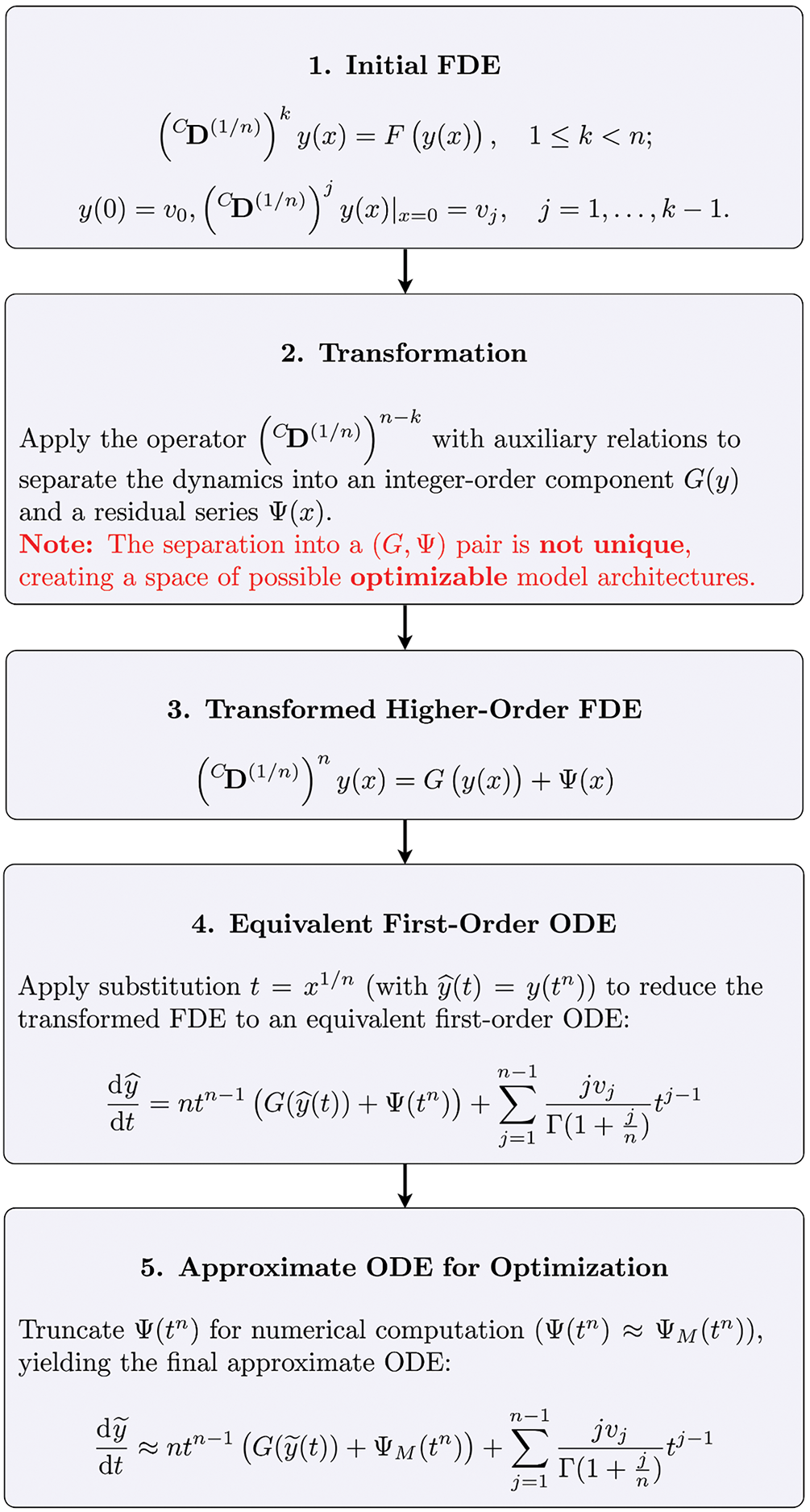

The step-by-step process described in this section is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: The step-by-step process described in Section 3.2 which is used in obtaining an approximate ODE for a given FDE

To explore the range of possible architectures and find an optimal one, the function

where

The overall optimization procedure is structured as follows:

1. Define the search space: For a given polynomial degree

The coefficients

and

then

2. Compute quality metrics: The goal is to find a parameter vector

• The solution accuracy, quantified by the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) between the approximate solution

where the error is evaluated over a discrete set of P points,

• The model’s structural simplicity, quantified by the magnitude of the truncated residual series, measured by its

where

3. Establish a baseline for normalization: To create a balanced optimization problem from these two potentially different-scaled objectives, a dynamic normalization strategy is employed. First, a baseline parameter vector,

For example, given a linear forcing function of the form

4. Define the final objective function: The final, normalized scalar objective function

In this study, balanced weights

5. Perform global optimization: A global optimization algorithm, Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) [27], is used to find the optimal parameter vector

While other algorithms like genetic algorithms or simulated annealing could also be applied, a comparative study of different optimizers was considered beyond the scope of this work, which aims to demonstrate the feasibility of the overall framework. It is important to note that the normalized objective function

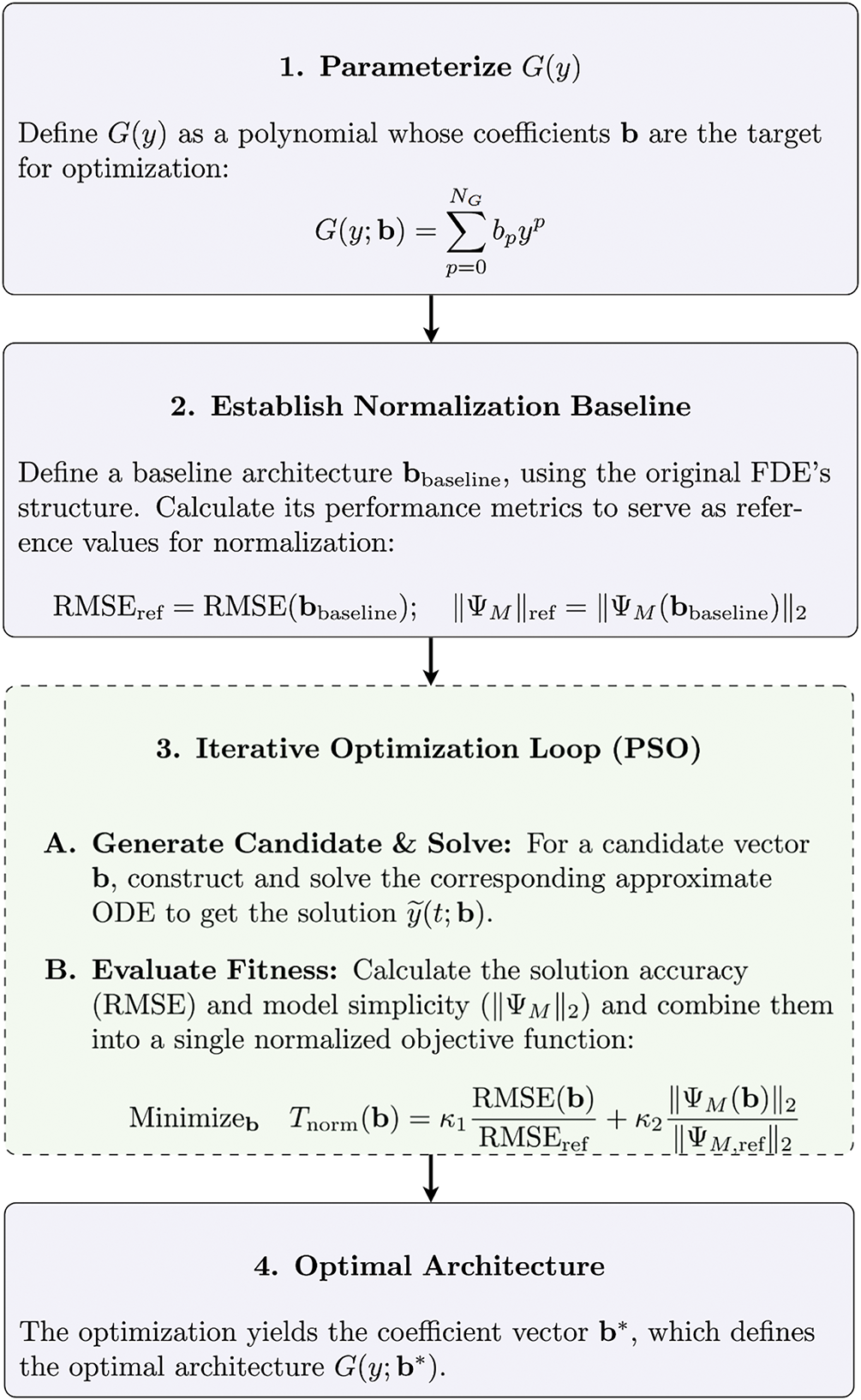

To summarize the procedure presented in section succinctly, see the steps outlined in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: The step-by-step process described in Section 3.3, outlining the procedure for determining optimal

The computational complexity of the proposed framework is primarily determined by the global optimization process, as the initial FDE-to-ODE transformation is performed only once. The dominant source of computational cost is the iterative evaluation of the objective function

The complexity of a single evaluation for a candidate parameter vector

It is important to contextualize this computational cost. The optimization procedure is a computationally intensive, offline analysis performed once for a given FDE structure. The objective of this one-time investment is not to produce a single numerical solution more efficiently, but rather to obtain a simplified, integer-order ODE architecture that reveals fundamental properties of the FDE’s dynamics. The analytical advantage gained from this process—a deeper insight into the interplay between local and non-local behaviors—is the primary justification for the proposed computational framework.

This section presents numerical experiments designed to illustrate the proposed methodology for finding optimal ODE architectures. The approach is applied to two distinct cases: a linear FDE with a known exact solution and a nonlinear (quadratic) FDE where a high-fidelity numerical solution serves as the reference. The primary goal is to demonstrate the optimization process and analyze the resulting ODE structures, particularly the optimized polynomial

First, a linear FDE, involving the iterated Caputo derivative

subject to initial conditions

This FDE possesses an exact analytical solution expressed using the Mittag-Leffler functions [29]:

This exact solution serves as the high-fidelity reference

The methodology transforms the FDE (33) into the

which is then reduced to the approximate ODE (23) using the parameterized polynomial

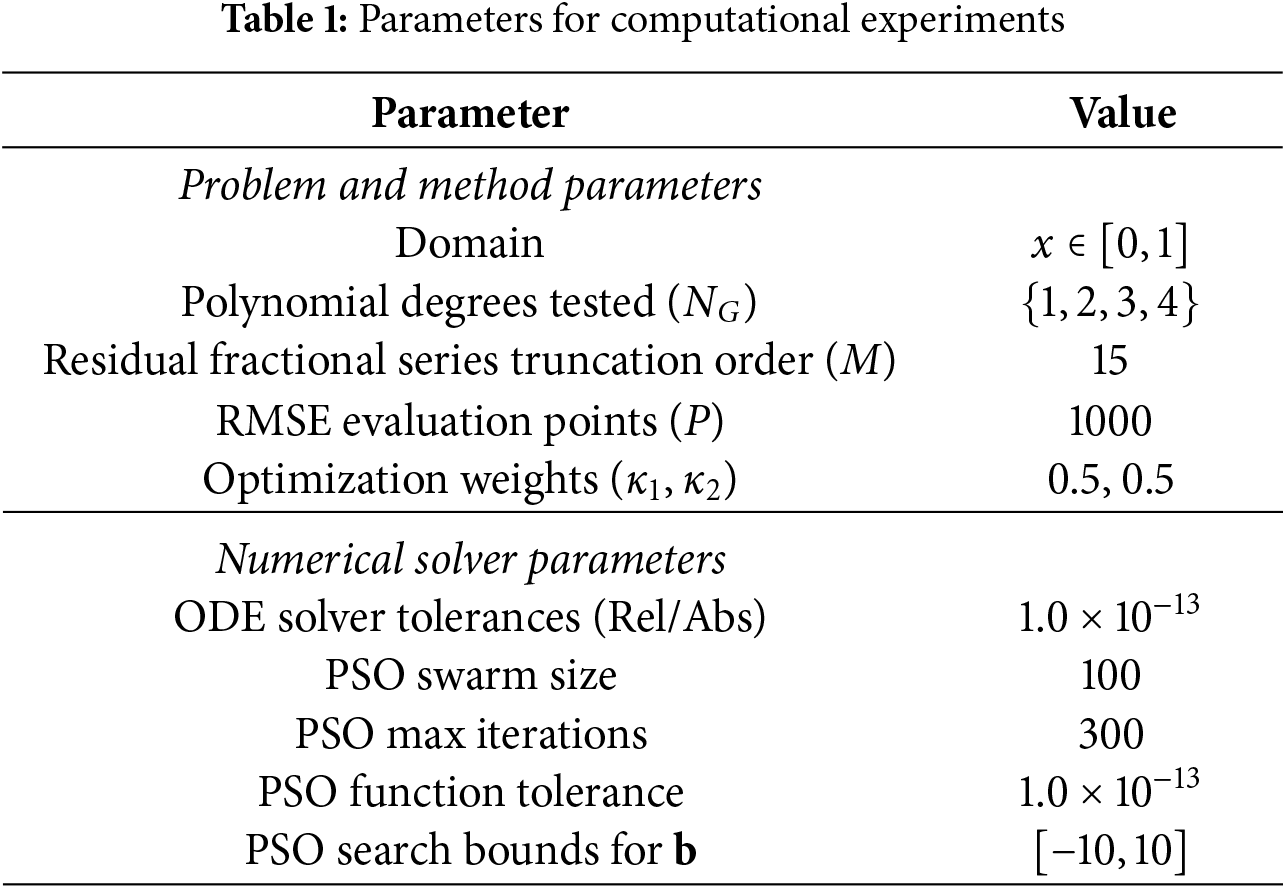

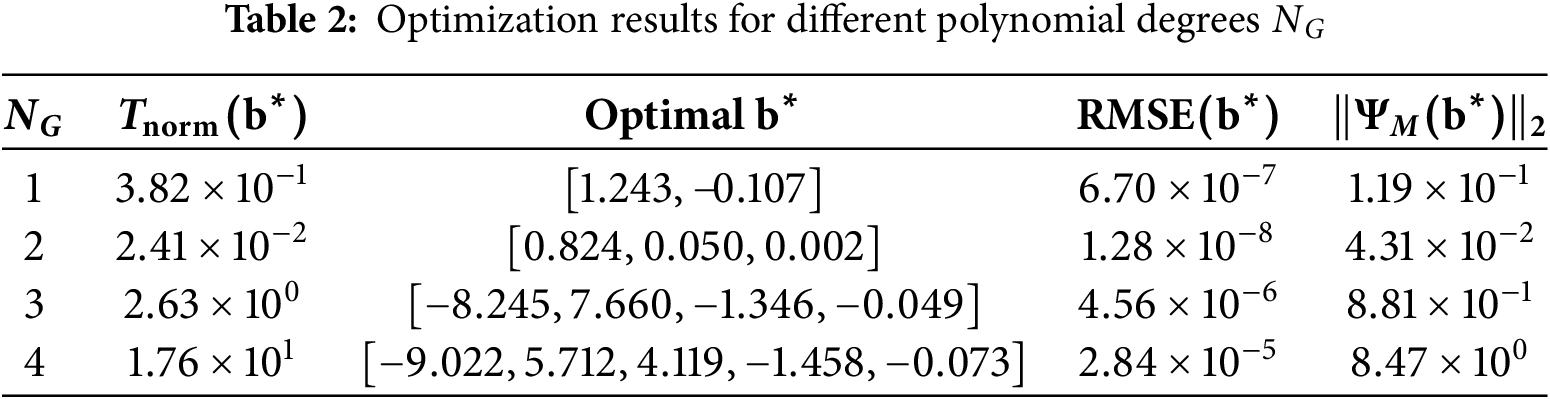

First, the case

is analyzed. The results, summarized in Table 2, show that the case of

Conversely, increasing the complexity further to

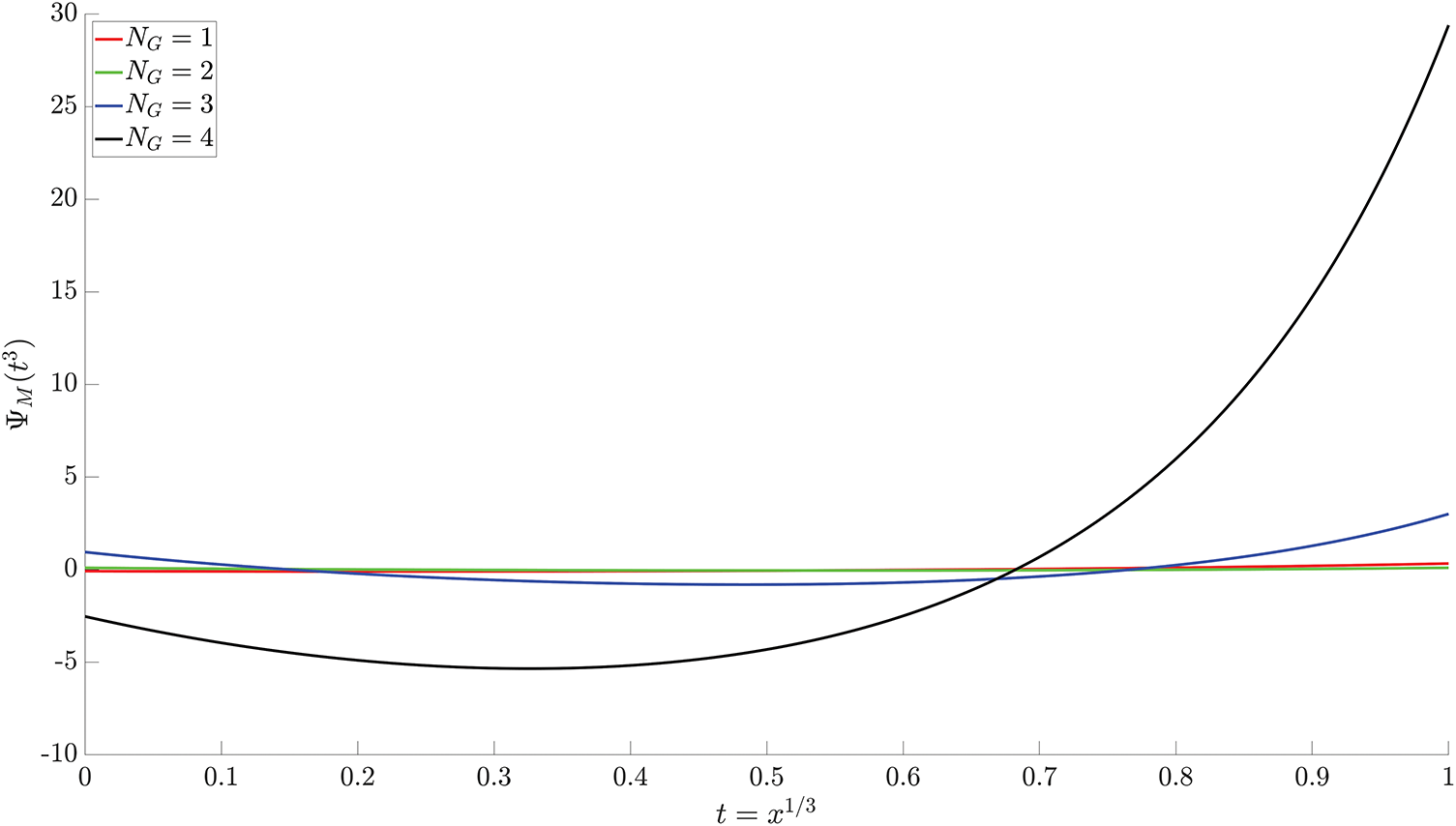

Moreover, Fig. 3 provides a visual representation of the optimized residual fractional series, which corroborates the numerical results in Table 2. The plot clearly shows that the residual fractional series for the

Figure 3: Optimized residual fractional series

These findings are significant, as they demonstrate the framework’s capacity to identify an optimal level of complexity, beyond which adding more parameters is detrimental. The analysis reveals that the underlying integer-order dynamics of this specific fractional system are most effectively represented not by a simple linear model, but by a quadratic one.

4.1.1 Parameter Space Analysis of Optimal Model Complexity

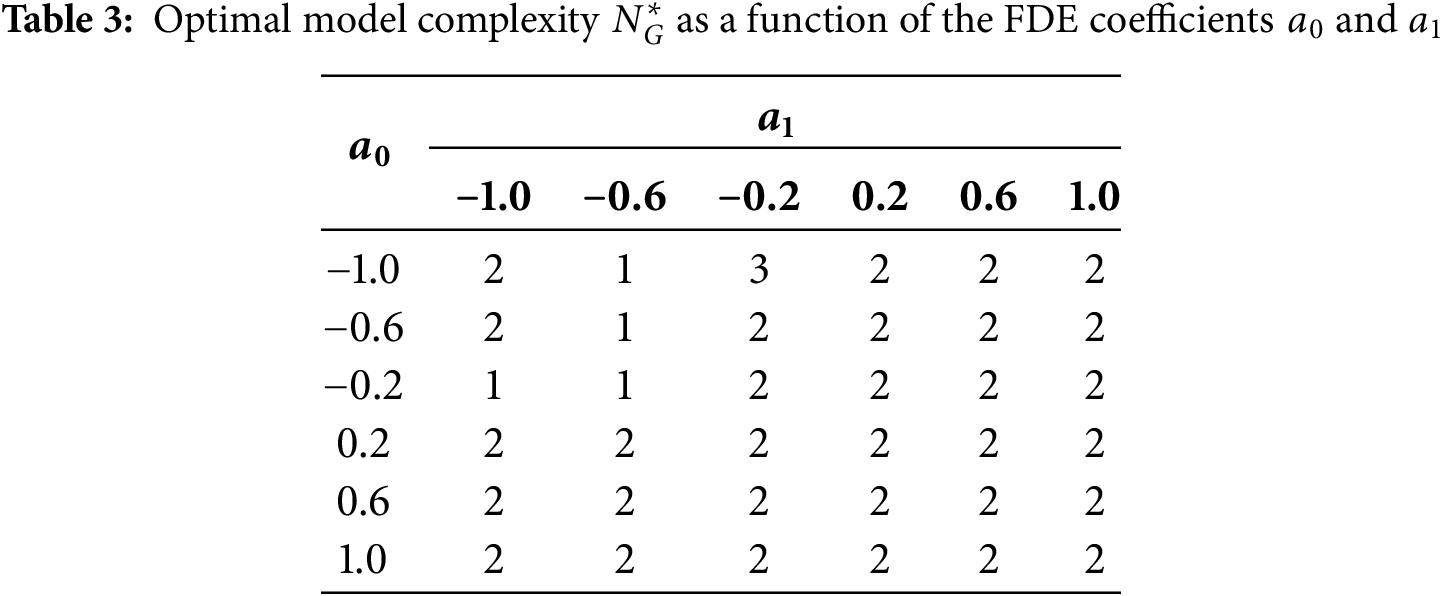

To further investigate the robustness of the optimal model architecture, a parameter space analysis is conducted. The optimization procedure is systematically applied across a grid of FDE coefficients, with

The results of this meta-analysis are summarized in Table 3, which presents a map of the optimal polynomial degree,

A closer examination of the cases where

The single instance where

Collectively, these findings strongly support the conclusion that a quadratic ODE architecture provides a robust and broadly applicable representation for the linear fractional differential equation under study. The stability of this result across a wide range of system parameters suggests that the method is not merely finding isolated numerical artifacts but is successfully identifying a fundamental, underlying integer-order structure inherent to the fractional system.

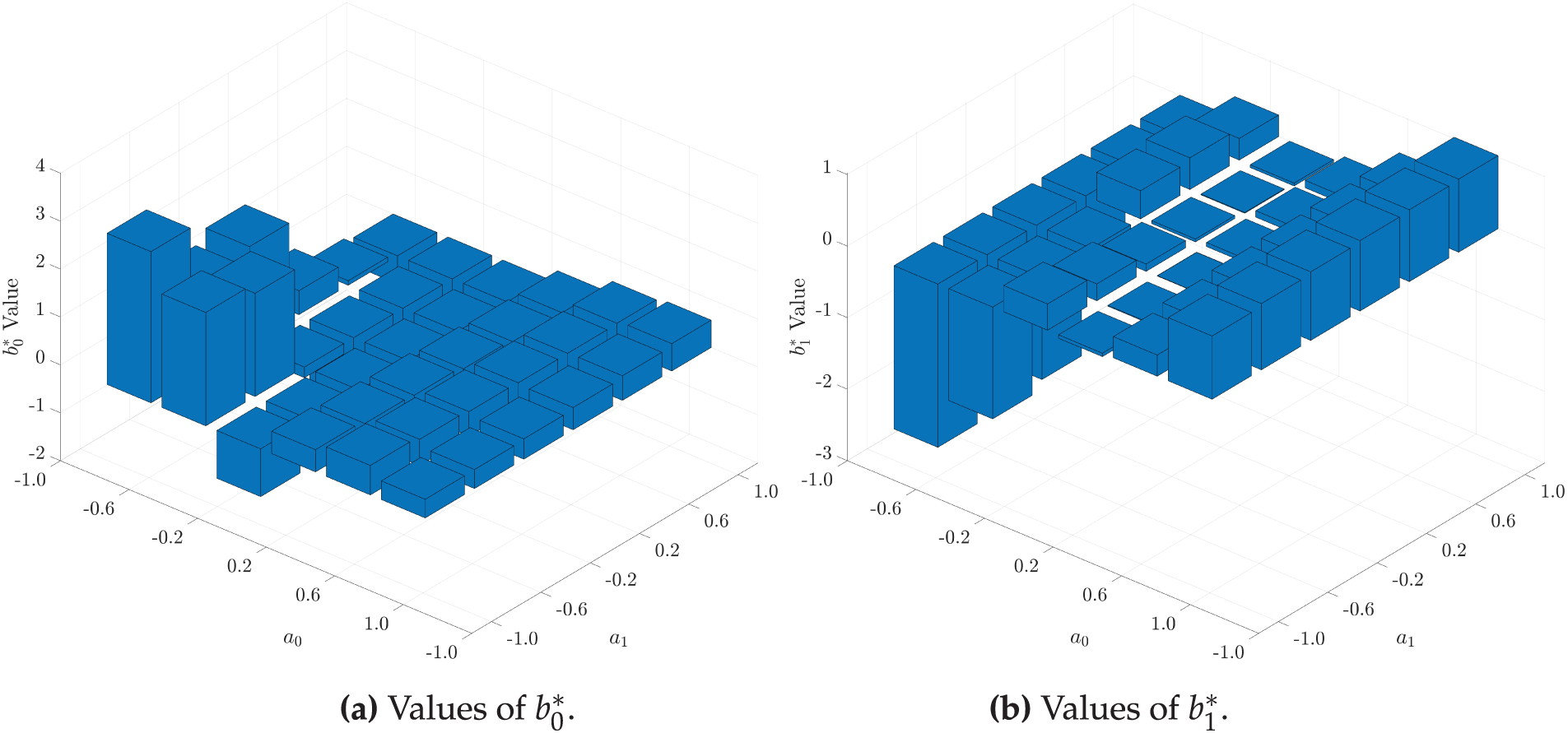

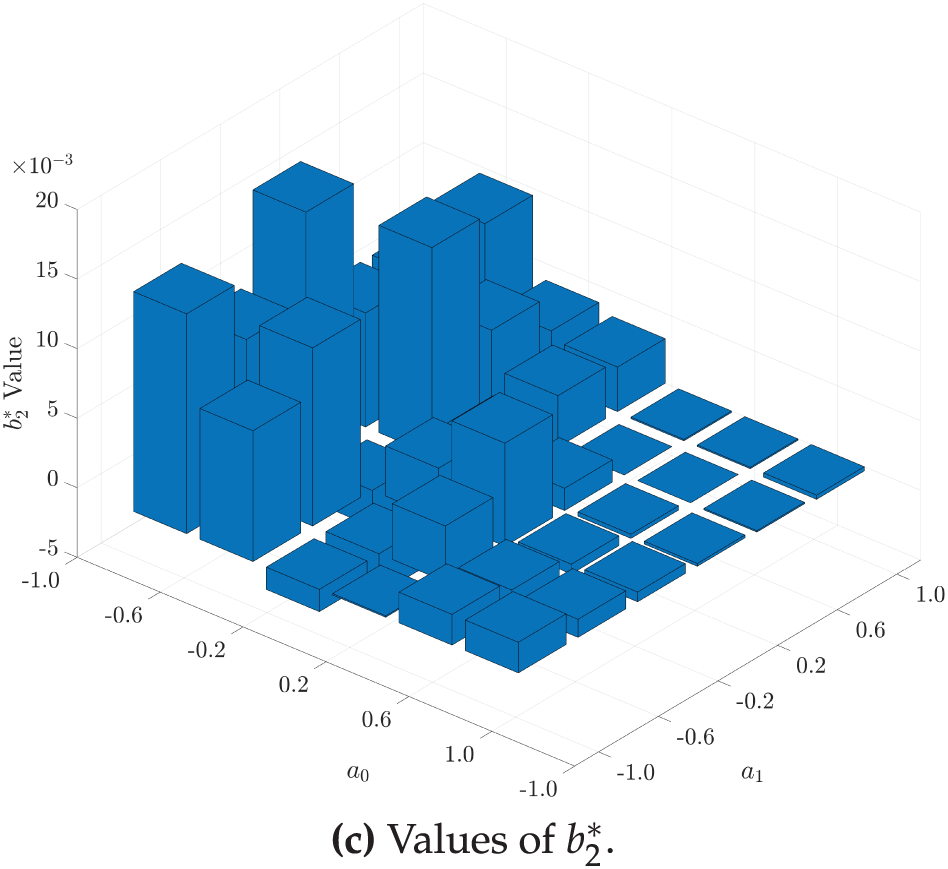

To better understand the structure of the quadratic architecture (

Figure 4: The optimal coefficients

4.1.2 Effects of Initial Condition on the Complexity of the Model

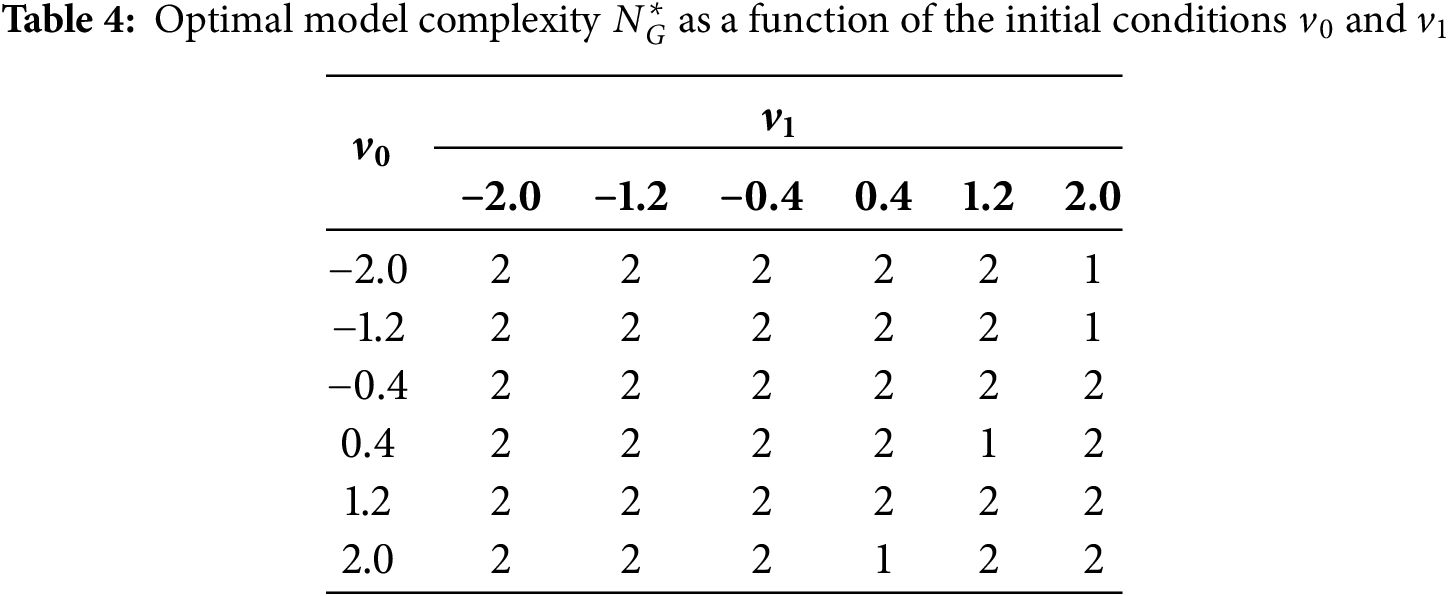

To assess whether the optimal ODE architecture is an intrinsic property of the FDE or is dependent on the specific solution trajectory, a second meta-analysis has been performed. In this set of experiments, the FDE coefficients are held constant at

The results, presented in Table 4, demonstrate a high degree of stability in the optimal model architecture. Across the 36 different initial conditions tested, the quadratic model (

Notably, the few instances where

The combined results from the parameter space analyses of both the FDE coefficients and the initial conditions provide strong evidence for the central hypothesis. The methodology consistently identifies a quadratic ODE as the most suitable integer-order representation for the given linear FDE. This stability across different system parameters and solution trajectories indicates that the optimization framework is successfully uncovering a fundamental, intrinsic property of the fractional system’s dynamics, rather than artifacts of a specific configuration.

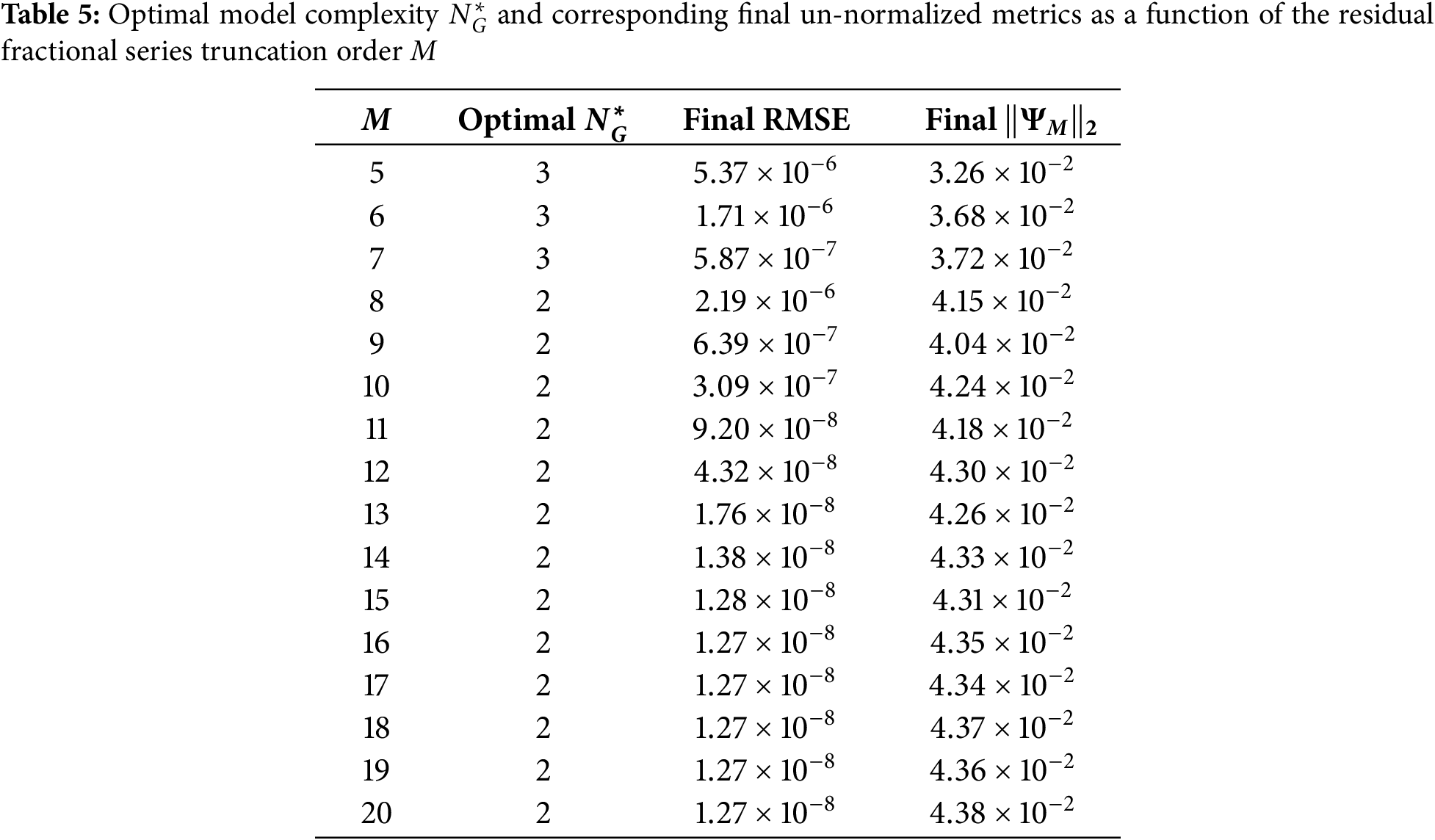

4.1.3 Sensitivity Analysis on the Truncation Order of the Residual of the Fractional Series

A sensitivity analysis has been conducted to evaluate the influence of the residual fractional series truncation order, M, on the performance of the optimization framework. For this study, the FDE coefficients and initial conditions are held constant at the values used in the first example (

The results, summarized in Table 5, reveal a distinct trend. For lower values of M (specifically,

This transition in the optimal model complexity is a significant finding. It suggests that when the residual fractional series

Furthermore, an examination of the final un-normalized metrics reveals the practical limits of increasing the residual series order. While the final RMSE of the optimal solution improves substantially as M increases from 8 to 15, it converges to approximately

In conclusion, this sensitivity analysis demonstrates the robustness of the proposed methodology. It shows that provided the residual fractional series is approximated with a sufficient number of terms, the optimization consistently converges to the same optimal ODE architecture. This reinforces the conclusion that the framework is successfully identifying an intrinsic and stable integer-order representation of the fractional system.

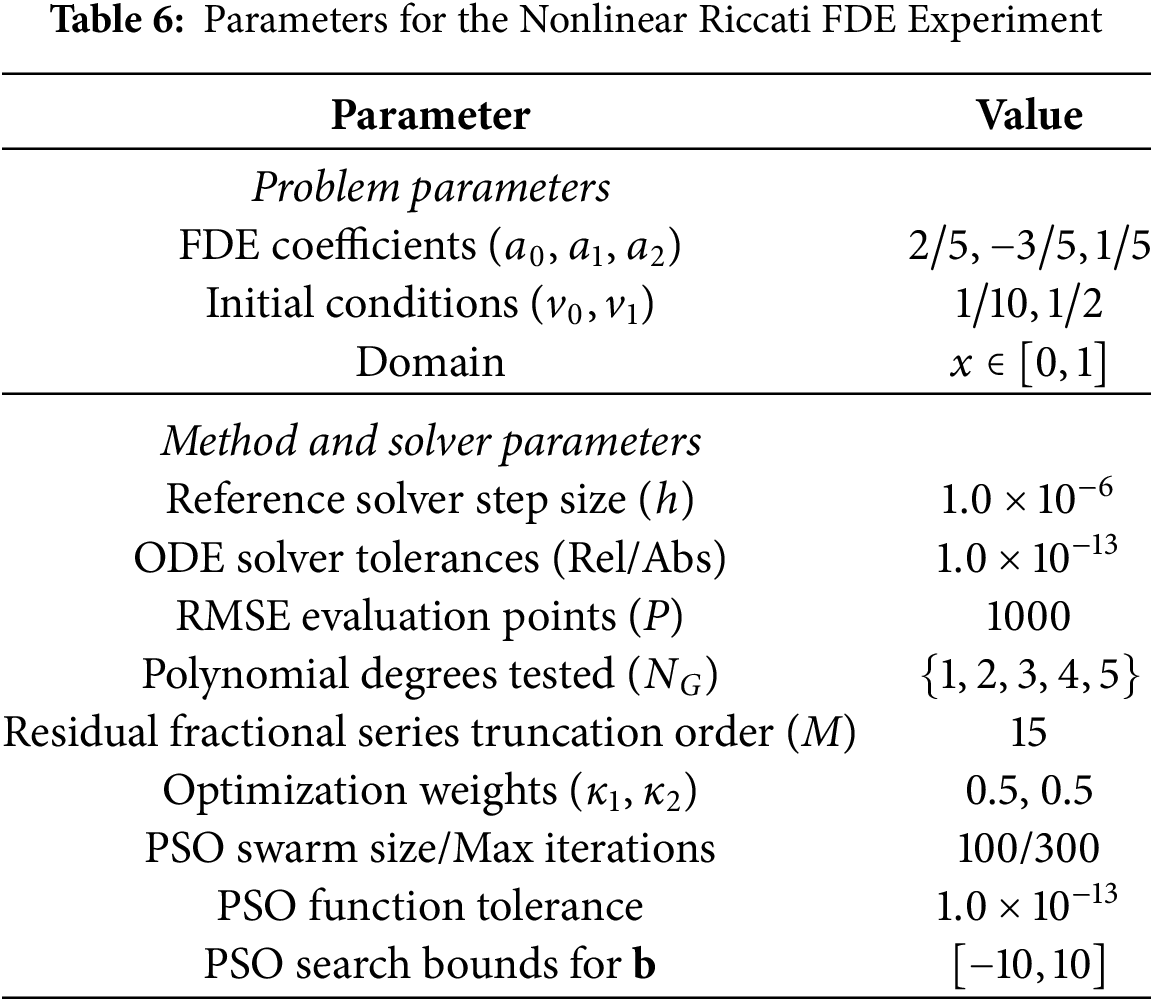

4.2 Case 2: Nonlinear Riccati FDE

To demonstrate the methodology’s applicability to nonlinear problems without known analytical solutions, the framework is applied to a fractional Riccati FDE. The equation, corresponding to

subject to initial conditions

The same optimization framework as in the linear case is used. The specific FDE parameters and computational settings for this experiment are detailed in Table 6.

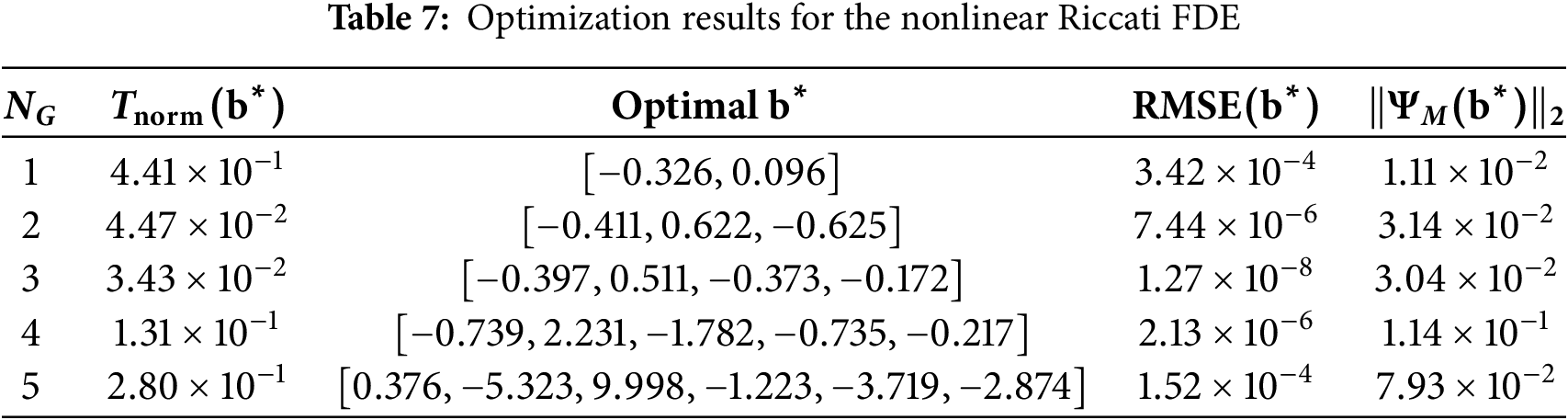

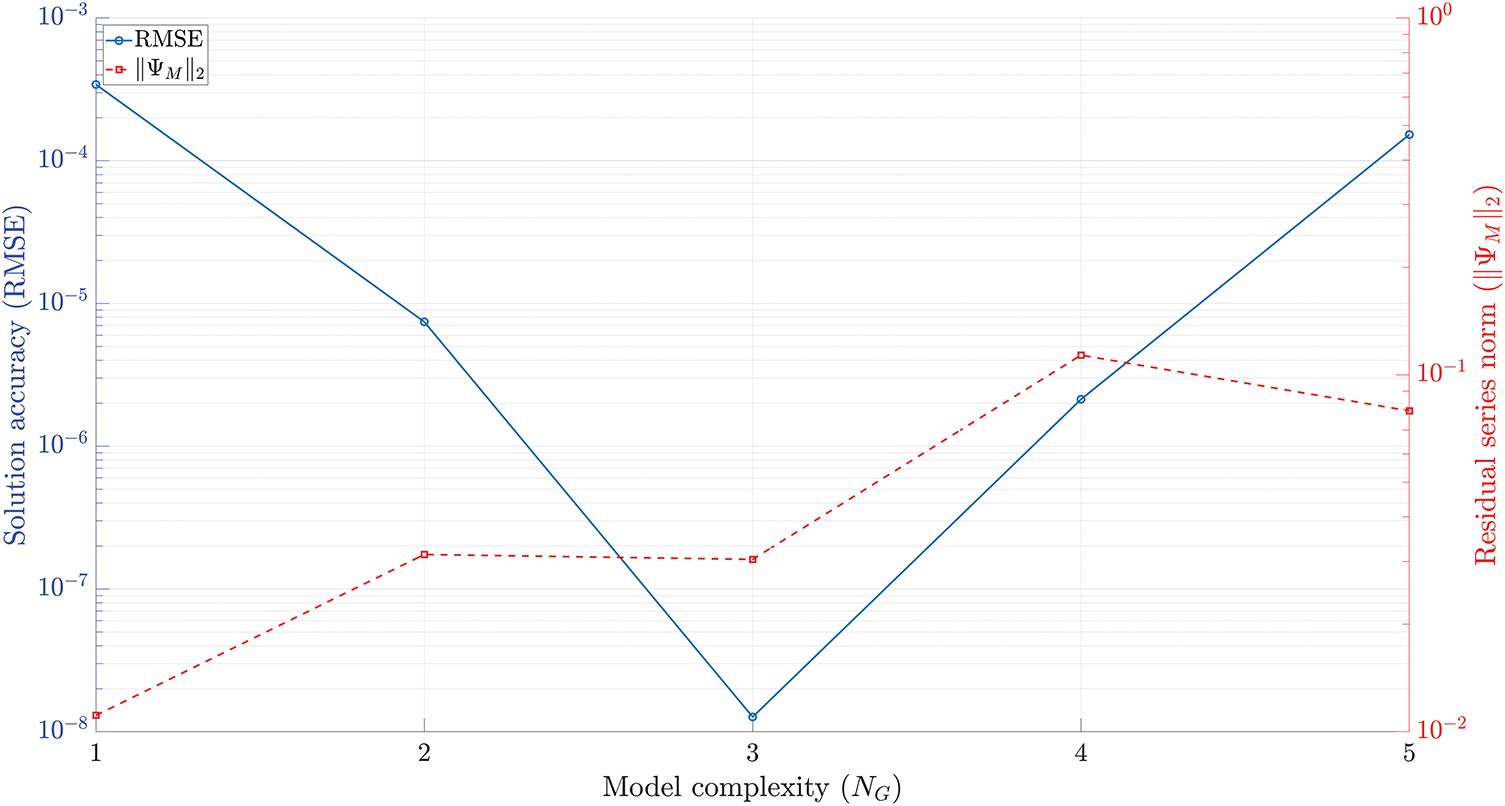

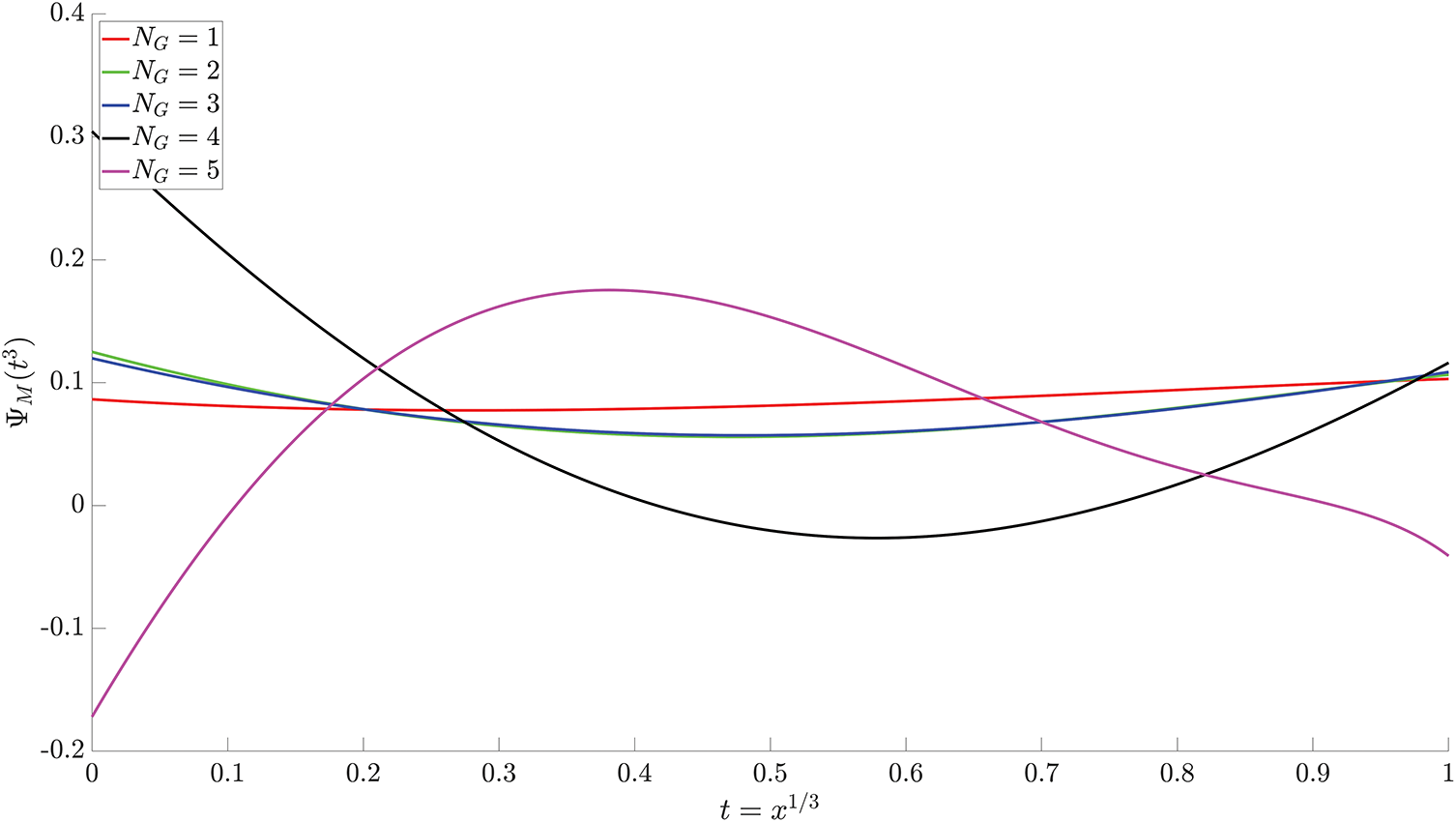

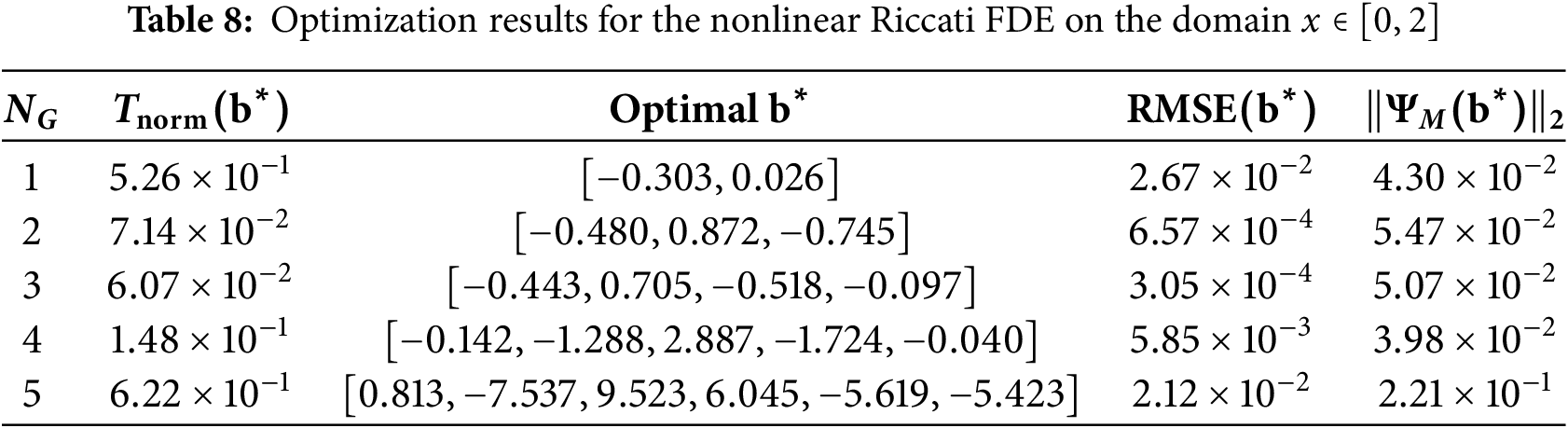

The optimization results for polynomial degrees

Figure 5: The complexity-accuracy trade-off curve for the nonlinear Riccati FDE. The plot shows the final solution accuracy (RMSE, left axis) and the norm of the residual series (

The emergence of an optimal architecture that is of a higher polynomial degree than the original FDE’s nonlinearity is a significant finding. This suggests that the transformation from the FDE to the ODE, which involves the action of a fractional operator on the nonlinear term, generates a richer set of dynamics. The optimization framework discovers that it is more effective to capture the dominant part of these emergent dynamics within the integer-order component

A trade-off between solution accuracy and the magnitude of the residual fractional series is also observed. While the linear model (

Figure 6: Optimized residual fractional series

Consistent with the findings from the linear analysis, increasing the model complexity beyond an optimal point (

4.2.1 Effect of the Integration Horizon

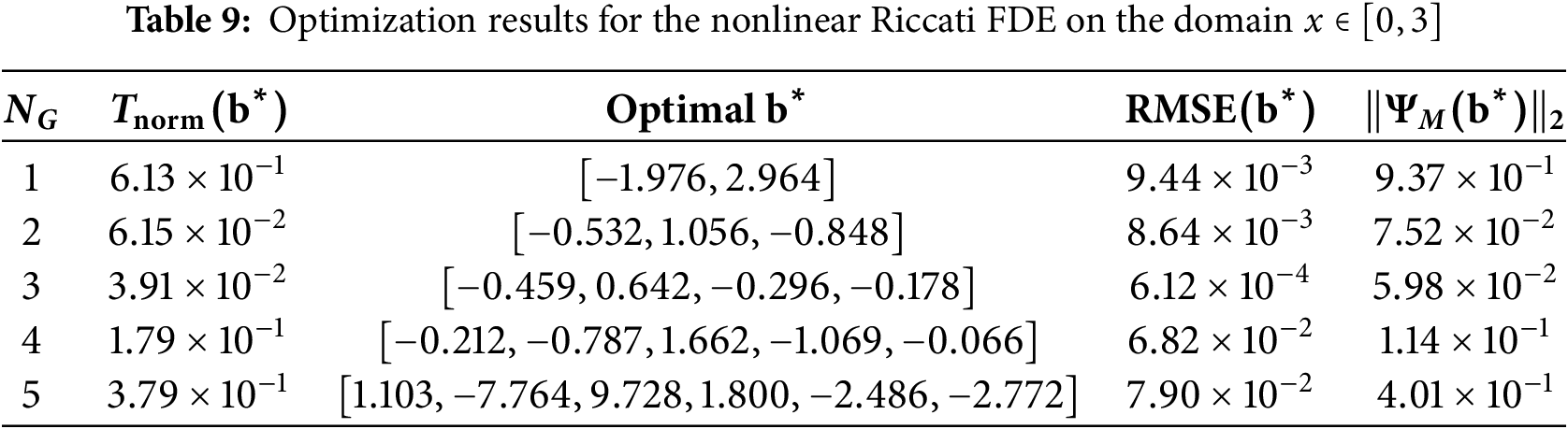

To verify the effectiveness and generality of the proposed framework over different integration intervals, the experiment on the nonlinear Riccati FDE was repeated for two longer domains:

The optimization results for the extended domains are presented in Tables 8 and 9. The analysis reveals a consistency in the optimal architecture. For both the

4.2.2 Comparison with an Alternative Optimization Algorithm

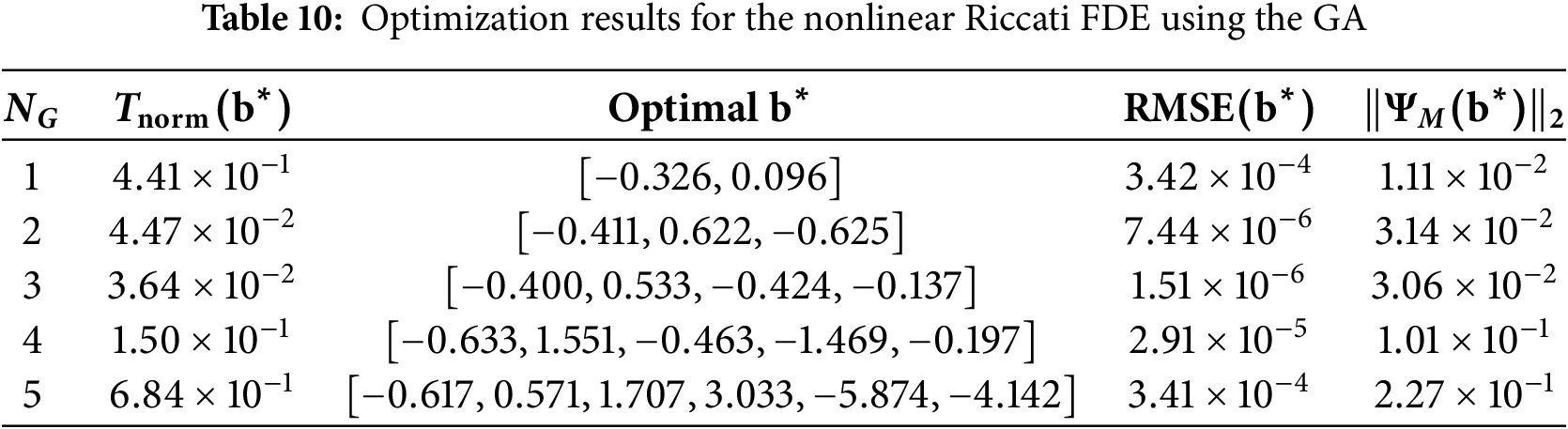

To ensure that the findings of this study are not specific to the choice of the optimization algorithm, the experiment on the nonlinear Riccati FDE presented at the beginning of this section (with the integration interval

The optimization results obtained using the GA are presented in Table 10 and are consistent with the PSO results from Table 7. GA also unambiguously identifies the cubic model (

4.2.3 Sensitivity Analysis of the Optimal Solution

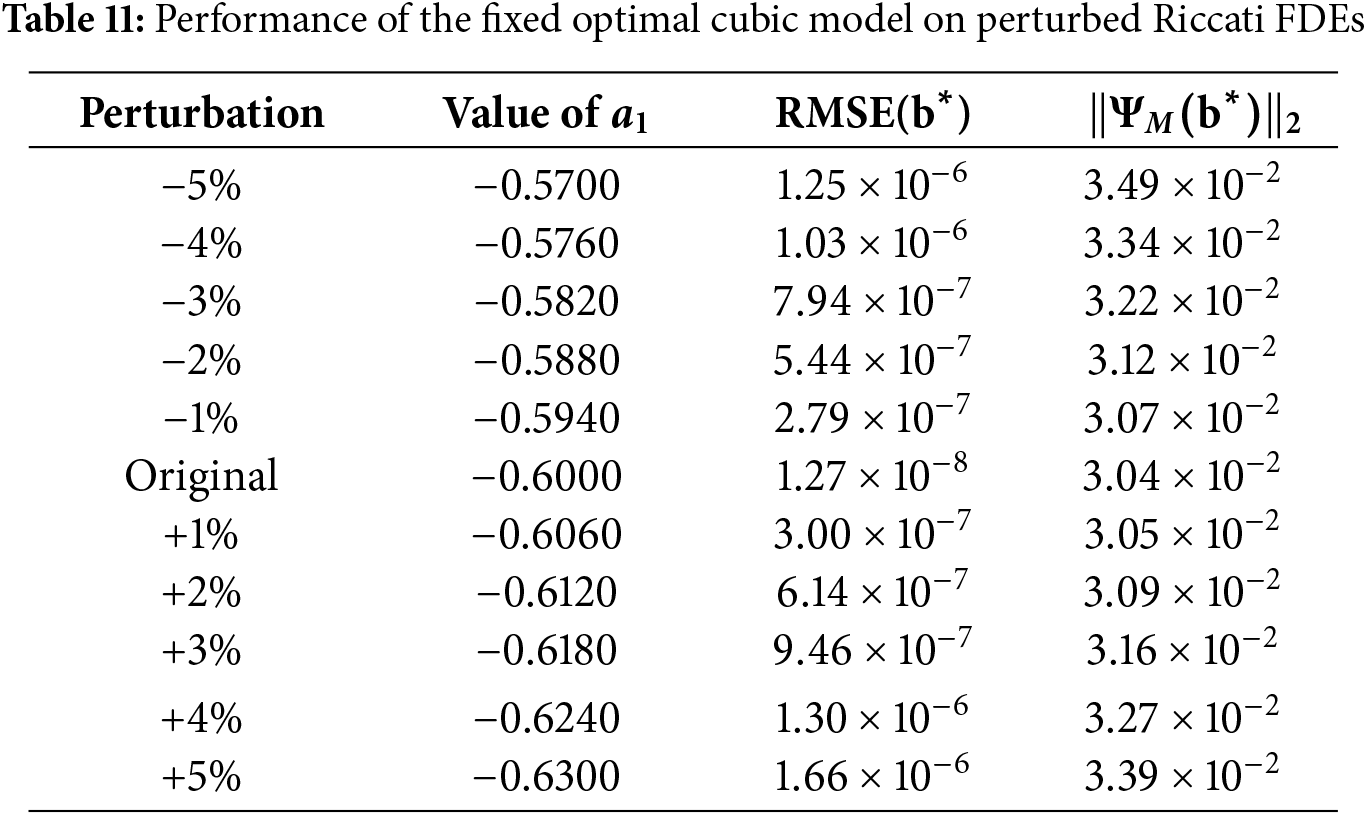

To assess the robustness of the optimization outcomes, a sensitivity analysis was performed on the optimal solution found by the PSO algorithm for the nonlinear Riccati FDE (see Table 7). The objective of this analysis is to determine if the identified optimal architecture is stable with respect to small variations in the FDE’s parameters. For this study, the optimal cubic architecture (

The results of this analysis are presented in Table 11. The results show that the optimal solution exhibits structural stability, with performance metrics degrading continuously with respect to parameter perturbations. Both the final RMSE and the norm of the residual series are minimized for the unperturbed, original problem and increase monotonously and symmetrically as the perturbation magnitude grows. This demonstrates that the optimal solution represents a stable optimum within a local neighborhood of the parameter space, confirming the robustness of the optimization outcome.

The effectiveness of the presented approach was demonstrated on both a linear FDE and a nonlinear fractional Riccati equation. These cases were selected as representative examples to establish the feasibility of the proposed structural analysis on both a linear problem with a known analytical solution and a nonlinear problem requiring a numerical reference solution. The fractional Riccati equation, in particular, serves as a relevant nonlinear model due to its importance in applied mathematics for modeling real-world phenomena, including population dynamics and tumor growth [31], where the inclusion of memory effects via fractional operators is an active area of research to improve model realism [32]. The numerical results consistently show that the method can identify an optimal, low-degree polynomial ODE that accurately captures the dynamics of the fractional system. For the linear FDE, a quadratic architecture has been found to be robustly optimal across a wide range of system parameters and initial conditions, revealing an underlying structure more complex than the original linear forcing term. For the nonlinear Riccati FDE, a cubic architecture has been identified as optimal.

Notably, the results often indicate a significant decline in performance when the model complexity is increased beyond the optimal degree which could indicate the model’s sensitivity to over-parameterization. The primary goal of this work is to introduce the novel concept of structural optimization for FDEs and demonstrate its feasibility on representative examples. Thus, in this foundational study, objective function is designed to measure only the core metrics of interest: solution accuracy and the magnitude of the residual series. It does not contain an explicit regularization term that would penalize model complexity. However, while the framework minimizes the error against the reference, the dual nature of the objective function, which also penalizes

A crucial distinction must be drawn between the proposed framework and other established methodologies. While high-fidelity numerical methods provide accurate solutions, they yield a numerical result without offering deeper insight into the underlying structure of the FDE. It is not the goal of this study to compete with these methods in terms of raw numerical precision, but to introduce a novel tool for structural analysis. By identifying an optimal, low-degree integer-order ODE, our framework provides a simplified yet powerful lens through which to understand the intrinsic dynamics of the fractional system. It emphasizes the interplay between local, integer-order behavior (captured by

This paper introduces a novel computational framework for identifying optimal integer-order ODE representations for FDEs containing iterated Caputo derivatives. The methodology utilizes a transformation that recasts the FDE into a higher-order form composed of an integer-order dynamic component

In summary, this work provides a new tool for analyzing the underlying structure of FDEs and gaining deeper insights into the interplay between local and non-local dynamics. The primary limitations of this foundational study are its focus on a specific class of FDEs with iterated Caputo derivatives and the use of a polynomial basis for parameterization, which may not be optimal for all systems.

Future research could extend this framework to broader classes of FDEs, including its scalability to high-dimensional and coupled systems of equations or those involving other fractional operators (such as the Atangana-Baleanu or Riemann-Liouville operators, etc.). Furthermore, exploring alternative parameterizations for the integer-order component, such as rational functions, may reveal even richer structural properties of fractional systems.

Acknowledgement: This research was funded by the Research Council of Lithuania.

Funding Statement: This project has received funding from the Research Council of Lithuania (LMTLT), agreement No. S-PD-24-120.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Tadas Telksnys, Inga Telksniene, Minvydas Ragulskis and Raimondas Čiegis; methodology, Tadas Telksnys, Inga Telksniene, Minvydas Ragulskis and Romas Marcinkevičius; software, Inga Telksniene and Romas Marcinkevičius; validation, Inga Telksniene, Tadas Telksnys and Romas Marcinkevičius; formal analysis, Minvydas Ragulskis, Zenonas Navickas, Tadas Telksnys, Inga Telksniene and Raimondas Čiegis; investigation, Inga Telksniene, Tadas Telksnys, Romas Marcinkevičius, Zenonas Navickas, Minvydas Ragulskis and Raimondas Čiegis; writing—original draft preparation, Inga Telksniene, Tadas Telksnys and Minvydas Ragulskis; writing—review and editing, Inga Telksniene, Tadas Telksnys, Romas Marcinkevičius, Zenonas Navickas, Minvydas Ragulskis and Raimondas Čiegis; supervision, Minvydas Ragulskis and Raimondas Čiegis; funding acquisition, Inga Telksniene and Raimondas Čiegis. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| FDE | Fractional Differential Equation |

| ODE | Ordinary Differential Equation |

| FPS | Fractional Power Series |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| PSO | Particle Swarm Optimization |

| GA | Genetic Algorithm |

References

1. Podlubny I. Fractional differential equations: an introduction to fractional derivatives, fractional differential equations, to methods of their solution and some of their applications. San Diego, CA, USA: Academic Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

2. Suzuki JL, Kharazmi E, Varghaei P, Naghibolhosseini M, Zayernouri M. Anomalous nonlinear dynamics behavior of fractional viscoelastic beams. J Comput Nonlinear Dyn. 2021;16(11):111005. doi:10.1115/1.4052286. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Loghman E, Bakhtiari-Nejad F, Kamali A, Abbaszadeh M, Amabili M. Nonlinear vibration of fractional viscoelastic micro-beams. Int J Non Linear Mech. 2021;137(1–4):103811. doi:10.1016/j.ijnonlinmec.2021.103811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Ali I, Khan SU. A dynamic competition analysis of stochastic fractional differential equation arising in finance via pseudospectral method. Mathematics. 2023;11(6):1328. doi:10.3390/math11061328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Li B, Zhang T, Zhang C. Investigation of financial bubble mathematical model under fractal-fractional Caputo derivative. Fractals. 2023;31(05):2350050. doi:10.1142/s0218348x23500500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Abdeljawad T, Sher M, Shah K, Sarwar M, Amacha I, Alqudah M, et al. Analysis of a class of fractal hybrid fractional differential equation with application to a biological model. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):18937. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-67158-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Singh J, Ganbari B, Kumar D, Baleanu D. Analysis of fractional model of guava for biological pest control with memory effect. J Adv Res. 2021;32(1):99–108. doi:10.1016/j.jare.2020.12.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Chatterjee AN, Ahmad B. A fractional-order differential equation model of COVID-19 infection of epithelial cells. Chaos Solitons Fract. 2021;147:110952. [Google Scholar]

9. Srivastava H, Jan R, Jan A, Deebani W, Shutaywi M. Fractional-calculus analysis of the transmission dynamics of the dengue infection. Chaos. 2021;31(5):053130. doi:10.1063/5.0050452. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Baleanu D, Sajjadi SS, Jajarmi A, Defterli Ö. On a nonlinear dynamical system with both chaotic and nonchaotic behaviors: a new fractional analysis and control. Adv Differ Equ. 2021;2021(1):234. doi:10.1186/s13662-021-03393-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Jajarmi A, Baleanu D. On the fractional optimal control problems with a general derivative operator. Asian J Control. 2021;23(2):1062–71. doi:10.1002/asjc.2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Zhang X, Ding F. Optimal adaptive filtering algorithm by using the fractional-order derivative. IEEE Signal Process Lett. 2021;29(1):399–403. doi:10.1109/lsp.2021.3136504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Jackson J, Perumal R. A robust image encryption technique based on an improved fractional order chaotic map. Nonlinear Dyn. 2025;113(7):7277–96. doi:10.1007/s11071-024-10480-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Ebaid A, Cattani C, Al Juhani AS, El-Zahar ER. A novel exact solution for the fractional Ambartsumian equation. Adv Differ Equ. 2021;2021(1):88. doi:10.1186/s13662-021-03235-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Sene N. Analytical solutions of a class of fluids models with the Caputo fractional derivative. Fractal Fract. 2022;6(1):35. doi:10.3390/fractalfract6010035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Zabidi NA, Majid ZA, Kilicman A, Ibrahim ZB. Numerical solution of fractional differential equations with Caputo derivative by using numerical fractional predict-correct technique. Adv Cont Disc Mod. 2022;2022(1):26. doi:10.1186/s13662-022-03697-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Dimitrov Y, Georgiev S, Todorov V. Approximation of Caputo fractional derivative and numerical solutions of fractional differential equations. Fractal Fract. 2023;7(10):750. doi:10.3390/fractalfract7100750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Ali I, Rasheed A, Anwar MS, Irfan M, Hussain Z. Fractional calculus approach for the phase dynamics of Josephson junction. Chaos Solitons Fract. 2021;143:110572. [Google Scholar]

19. Khan M, Rasheed A, Anwar MS. Numerical analysis of nonlinear time-fractional fluid models for simulating heat transport processes in porous medium. ZAMM-J Appl Math Mech/Zeitschrift Für Angewandte Mathematik Und Mechanik. 2023;103(9):e202200544. doi:10.1002/zamm.202200544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Alsulami M, Alyami M, Al-Mazmumy M, Alsulami A. Semi-analytical investigation for the ψ-Caputo fractional relaxation-oscillation equation using the decomposition method. Eur J Pure Appl Math. 2024;17(3):2311–98. [Google Scholar]

21. Iqbal N, Chughtai MT, Ullah R. Fractional study of the non-linear Burgers’ equations via a semi-analytical technique. Fractal Fract. 2023;7(2):103. doi:10.3390/fractalfract7020103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Jin B, Zhou Z. An analysis of Galerkin proper orthogonal decomposition for subdiffusion. ESAIM Math Model Numer Anal. 2017;51(1):89–113. doi:10.1051/m2an/2016017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Khristenko U, Wohlmuth B. Solving time-fractional differential equations via rational approximation. IMA J Numer Anal. 2023;43(3):1263–90. doi:10.1093/imanum/drac022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Brunton SL, Proctor JL, Kutz JN. Discovering governing equations from data by sparse identification of nonlinear dynamical systems. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 2016;113(15):3932–7. doi:10.1073/pnas.1517384113. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Navickas Z, Telksnys T, Telksniene I, Marcinkevicius R, Ragulskis M. The fractal structure of analytical solutions to fractional Riccati equation. Fractals. 2024;32(04):2340130. doi:10.1142/s0218348x23401308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Marcinkevicius R, Telksniene I, Telksnys T, Navickas Z, Ragulskis M. The construction of solutions to

27. Kennedy J, Eberhart R. Particle swarm optimization. In: Proceedings of ICNN’95-International Conference on Neural Networks; 1995 Nov 27–Dec 1; Perth, WA, Australia. p. 1942–8. [Google Scholar]

28. Wang D, Tan D, Liu L. Particle swarm optimization algorithm: an overview. Soft Comput. 2018;22(2):387–408. doi:10.1007/s00500-016-2474-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Duan J. A generalization of the Mittag–Leffler function and solution of system of fractional differential equations. Adv Differ Equ. 2018;2018(1):239. doi:10.1186/s13662-018-1693-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Garrappa R. Numerical solution of fractional differential equations: a survey and a software tutorial. Mathematics. 2018;6(2):16. doi:10.3390/math6020016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Timofejeva I, Telksnys T, Navickas Z, Marcinkevicius R, Mickevicius R, Ragulskis M. Solitary solutions to a metastasis model represented by two systems of coupled Riccati equations. J King Saud Univ-Sci. 2023;35(5):102682. doi:10.1016/j.jksus.2023.102682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Arshad S, Baleanu D, Tang Y. Fractional differential equations with bio-medical applications. In: Applications in engineering, life and social sciences, part A. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter; 2019. p. 1–20. doi:10.1515/9783110571905-001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools