Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Robust Control and Stabilization of Autonomous Vehicular Systems under Deception Attacks and Switching Signed Networks

1 Department of Mathematics, College of Sciences, Northern Border University, Arar, 91413, Saudi Arabia

2 Department of Mathematics, Faculty of Sciences, University of Mianwali, Mianwali, 42200, Punjab, Pakistan

3 Department of Mathematics and Statistics, The University of Lahore, Sargodha, 40100, Pakistan

4 Department of Mathematics, College of Sciences and Arts (Muhyil), King Khalid University, Muhyil, 61421, Saudi Arabia

5 Department of Mathematics, College of Sciences and Arts (Magardah), King Khalid University, Magardah, 61421, Saudi Arabia

6 Mathematics Department, College of Humanities and Science in Al Aflaj, Prince Sattam Bin Abdulaziz University, Al-Kharj, 11912, Saudi Arabia

7 Department of Mathematics, College of Science, University of Ha’il, Ha’il, 2440, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Author: Azmat Ullah Khan Niazi. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Computational Modeling, Simulation, and Algorithmic Methods for Dynamical Systems)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(2), 1903-1940. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.072973

Received 08 September 2025; Accepted 27 October 2025; Issue published 26 November 2025

Abstract

This paper proposes a model-based control framework for vehicle platooning systems with second-order nonlinear dynamics operating over switching signed networks, time-varying delays, and deception attacks. The study includes two configurations: a leaderless structure using Finite-Time Non-Singular Terminal Bipartite Consensus (FNTBC) and Fixed-Time Bipartite Consensus (FXTBC), and a leader—follower structure ensuring structural balance and robustness against deceptive signals. In the leaderless model, a bipartite controller based on impulsive control theory, gauge transformation, and Markovian switching Lyapunov functions ensures mean-square stability and coordination under deception attacks and communication delays. The FNTBC achieves finite-time convergence depending on initial conditions, while the FXTBC guarantees fixed-time convergence independent of them, providing adaptability to different operating states. In the leader—follower case, a discontinuous impulsive control law synchronizes all followers with the leader despite deceptive attacks and switching topologies, maintaining robust coordination through nonlinear corrective mechanisms. To validate the approach, simulations are conducted on systems of five and seventeen vehicles in both leaderless and leader—follower configurations. The results demonstrate that the proposed framework achieves rapid consensus, strong robustness, and high resistance to deception attacks, offering a secure and scalable model-based control solution for modern vehicular communication networks.Keywords

Vehicular networking has become essential in modern intelligent transportation systems, enabling efficient communication for safety and coordination among vehicles. With 5G technology offering ultra-reliable and low-latency links, such networks support advanced applications requiring real-time responsiveness [1]. Recent research in vehicular ad hoc networks (VANETs) has emphasized enhancing routing stability, communication reliability, and control robustness through predictive and trajectory-based approaches. Predictive modeling techniques forecast future vehicular states, enabling routing algorithms to sustain reliable communication links even under rapidly changing mobility conditions [2]. Similarly, bus-trajectory-based street-centric routing leverages predefined bus routes to optimize message delivery and reduce latency in dense urban environments [3]. Furthermore, recent advances in prescribed-time optimal control for switched nonlinear systems provide a powerful framework for achieving optimal-precision coordination within vehicular platoons, ensuring that stability and convergence are attained within a user-defined time despite switching network and system nonlinearities [4]. Decision-making and motion planning frameworks ensure smooth, oscillation-free movement by coordinating perception and control modules [5]. Focuses on the importance of protecting vehicle location privacy to ensure secure communication and prevent tracking in intelligent transportation systems. Emphasizes privacy preservation as a key factor for safety and trust in vehicular networks [6]. Furthermore, semi-global stabilization of parabolic systems with input saturation ensures stability under actuator constraints using Lyapunov and back-stepping-based control, enhancing robustness in distributed vehicular dynamics [7]. Recent advancements in intelligent transportation and autonomous control systems focus on adaptive and resilient designs to ensure stability, coordination, and safety in dynamic environments. Knowledge-guided self-learning control strategies enhance mixed vehicle platoon performance under communication delays, while cognitive risk prediction models utilize spatiotemporal features to assess human driving behavior and prevent potential hazards [8,9]. Coordinated tracking control of integrated wheel-end systems supports precise motion management, and advanced identification algorithms improve network stability and fault detection in complex control structures for the surveillance task schedule [10,11]. Enhanced localization techniques using Low Earth Orbit (LEO) satellite signals strengthen real-time positioning accuracy in uncertain conditions [12]. Furthermore, recurrent neural network–based sliding mode control provides robust stabilization for uncertain tilting quad rotor UAVs by handling external disturbances and modeling errors, while AI-driven perturbation defense techniques ensure accurate recognition of ultra high-speed weak targets, thereby reinforcing the reliability and intelligence of autonomous aerial and vehicular systems [13,14]. The intelligent vehicular systems highlights the integration of advanced testing, sensing, modeling, and resilient control strategies to ensure safety, autonomy, and robustness in dynamic environments. Adversarial scenario generation using hierarchical reinforcement architectures provides rigorous validation for intelligent vehicles, while high-fidelity ultrasonic radar in-the-loop testing enables realistic assessment of automatic parking systems [15,16]. Lane-changing models that incorporate human driving behavior and spatiotemporal decision features enhance motion prediction and cooperative driving accuracy [17,18].

Adaptive PI event-triggered control strategies for nonlinear systems with input delays enhance system responsiveness and robustness against time-varying uncertainties, contributing to improved stability in networked control environments [19]. The trade-off between code estimation error rate and terminal gain has been analyzed to strengthen communication reliability and resilience against adversarial disturbances in vehicle networks [20]. Furthermore, an improved social force model based on pedestrian collision avoidance behavior in counterflow conditions provides deeper insight into dynamic interactions within mixed traffic environments, improving safety and flow efficiency [21]. A hybrid framework combining neural networks with physics-based estimators enables accurate vehicle longitudinal dynamics modeling using limited driving data, bridging the gap between data-driven learning and physical interpretability [22]. Distributed safety-critical formation control using contracting bearing estimators and control barrier functions ensures reliable coordination among connected vehicles under sensing and communication limitations [23]. Finally, intelligent event-triggered lane-keeping security control mechanisms for autonomous vehicles under Denial-of-Service (DoS) attacks significantly enhance communication efficiency and cyber-resilience in connected vehicular networks [24]. Finally, stability and stabilization principles for sampled-data Lurie systems provide theoretical foundations supporting the implementation of these intelligent control strategies in discrete-time vehicular applications [25].

The intelligent autonomous systems and robust control highlights advances in perception, learning, and cooperative navigation to ensure safe and efficient decision-making in complex environments. Human interaction recognition using extended filtering improves behavior estimation and interaction awareness, while real-time contactless eye-blink detection enhances driver safety by monitoring fatigue without physical sensors [26,27]. Interaction-aware trajectory prediction based on transformer-driven transfer learning enables proactive motion planning by forecasting surrounding agents’ intentions, thus improving collision avoidance and cooperative driving efficiency [28,29]. Robust localization frameworks integrating multi-sensor fusion and synchronization algorithms ensure precise navigation performance despite urban signal interference and noise [30,31]. Additionally, noise-tolerant and predefined-time zeroing neural networks offer resilient synchronization and rapid dynamic computations for nonlinear systems, supporting stable control performance under disturbances [32,33]. Furthermore, vehicle-assisted service caching and task offloading in vehicular edge computing, when combined with Nash-equilibrium-based robust control under servo constraints, significantly enhance distributed coordination, reduce latency, and enable adaptive cooperative operation in autonomous and humanoid robotic systems [34,35].

Research on vehicular perception and control emphasizes adaptive learning and deception-resilient recognition to ensure reliability and safety in dynamic driving environments. A neural network incorporating plasticity effectively detects driver fatigue on real roads by adapting to changing behavioral and physiological patterns while resisting deceptive signal variations that may mask true driver conditions [36]. Likewise, a self-supervised evaluation method using a hyper graph neural network with dynamic feature learning accurately assesses insulation conditions in vehicle cable terminals, remaining robust against deceptive or corrupted sensor inputs that could threaten electrical stability and safety [37]. Together, these studies highlight how adaptive and self-learning neural models strengthen resilience and situational awareness in modern vehicular systems. Research on cyber–physical resilience and deception-resistant control in vehicular and transportation networks integrates detection, coordination, and adaptive learning to counter malicious interference and data manipulation. A DDoS detection framework using interquartile range and deep feature fusion convolutional networks identifies abnormal traffic behaviors in software-defined systems, serving as the first layer of defense against large-scale deception-based disruptions [38]. Complementing this, AST-based static fuzz mutation enhances software reliability by identifying concurrency vulnerabilities that attackers might exploit to inject deceptive commands or data anomalies [39]. Presents distributed robust finite-time consensus protocols designed for nonlinear multi-agent systems under uncertainties and disturbances. Emphasizes rapid convergence and resilience, ensuring system stability within a finite time through decentralized control strategies [40]. Perception task-oriented information sharing across autonomous vehicles further strengthens system awareness, enabling robust response to occlusion-based or deceptive sensory manipulation [41]. To ensure secure dynamic control, fixed-time safe tracking for uncertain nonlinear systems achieves rapid recovery and resilience against feedback distortion or deceptive control signals [42]. Finally, machine learning-driven analysis of transport infrastructure connectivity and conflict resolution enhances system resilience by detecting hidden anomalies and strategic deception within large-scale transportation data [43]. Moreover, recent robust adaptive control strategies further strengthen platoon coordination by incorporating disturbance estimation, compensation, and resilience against network disconnections and finite-time networks [44,45], ensuring reliable and secure operation across varying traffic and communication conditions in complex fractional-order networks.

Motivated by the challenges of maintaining coordination and stability in nonlinear vehicle platoons affected by time-varying delays, switching topologies, and deception attacks, this study presents a unified model-based control framework integrating both finite-time and fixed-time bipartite consensus schemes. The main contributions are as follows:

• A distributed impulsive control protocol is designed to achieve Finite-Time Non-Singular Terminal Bipartite Consensus (FNTBC) and Fixed-Time Bipartite Consensus (FXTBC) under switching signed networks, ensuring rapid convergence and resilience to communication disturbances.

• A deception-attack detection and suppression mechanism is incorporated within impulsive control events, enhancing network security and maintaining synchronization accuracy under malicious data manipulation.

• The vehicle dynamics are modeled as second-order nonlinear systems capturing both position and velocity behaviors, accurately reflecting realistic platoon interactions.

• A delay-compensated control strategy is introduced to handle time-varying communication delays, preserving coordinated motion despite asynchronous updates.

• The stability and boundedness of the proposed framework are rigorously established using Lyapunov theory, impulsive differential systems, and Markovian switching models.

• The overall framework operates using only local information, making it scalable and implementable in large-scale vehicular communication networks.

The following sections make up the rest of this paper:

1. Section 1 provides background information and research motivation, and the primary contributions of the study.

2. Section 2 provides a brief overview of graph theory basics before moving on to analyze impulsive systems under finite- and fixed-time stability conditions with their required assumptions and definitions, and problem formulation.

3. Section 3 contains the main analytical results, which include leaderless and leader-following control strategies for finite-time and fixed-time bounded consensus in networked vehicle systems, supported by four principal theorems.

4. Section 4 presents simulation results which confirm the effectiveness of the proposed control methods.

5. Section 5 of the paper presents essential findings together with recommendations for additional research.

A signed graph

A nonzero weight

The weights

A graph is considered connected if, for any pair of distinct nodes

The off-diagonal entries are

Lemma 1. [46] A signed graph G is structurally balanced if it contains a spanning tree. The Laplacian matrix

Definition 1. [46] A signed graph G is considered structurally balanced if its node set V can be divided into two disjoint subsets

The edge weights satisfy the condition

Each matrix

The following vehicle platooning provides conditions that are equivalent to the structural balance of the graph.

Lemma 2. [46] A signed graph G is said to be connected and structurally balanced if it satisfies the following conditions

• A diagonal matrix

• The associated Laplacian matrix

Lemma 3. The bipartite consensus formulation uses the gauge transformation

The mapping

Remark 1. Lemma 3 demonstrates that the gauge transformation maintains bounded vehicle states because it protects the absolute values of the states. The transformation between cooperative and competitive clusters only changes the sign of the states but keeps their magnitudes unchanged, which results in physically valid state trajectories for bipartite consensus.

Remark 2. In this work, we assume that external disturbances (such as aerodynamic drag, tire friction variation, road slope, and wind) are bounded or sufficiently small relative to the primary destabilizing effects considered. According to recent studies such as [47], network disconnections and communication delays rank among the top contributors to platoon instability, whereas external disturbances, while non-negligible, have a smaller relative impact. Under this assumption, we focus primarily on mitigating communication-based uncertainties and deception attacks.

2.2 Analysis of Impulsive Systems under Finite-Time and Fixed-Time Stability

Vehicle platooning consists of M vehicles that demonstrate nonlinear impulsive behavior. The dynamics of each vehicle are characterized by the following equations

The state vector of the

The state vector

Lemma 4. [48] Suppose

These results show that under the given conditions, the

Lemma 5. [49] Let’s analyze the nonlinear impulsive system defined by Eq. (1) and suppose there be a function

Lemma 6. [50] Consider a system characterized by a bounded impulsive interval

1. For all

2. The jump condition

• For

• For

Such that all the constants fulfill

3. The derivative of

Examine a second-order vehicle platooning consisting of M vehicles that communicate through an undirected signed graph G. The following describes the dynamics of the leader’s behavior.

where

The dynamic behavior of each vehicle is modeled as

The control input is given as

Assumption 1. The leaderless system Eq. (3) operates under the assumption that the interaction graph remains structurally balanced and connected, which enables reliable information exchange and vehicle state alignment. The leader-following framework uses systems Eqs. (3) and (4) under the assumption that the communication topology G contains a directed spanning tree with the leader positioned at the root. The network structure ensures that the leader’s information reaches all followers either directly or indirectly.

The set of nodes in the signed graph G can be divided into two disjoint subsets

Definition 2. Considering a leaderless vehicle platooning governed by system (4) is said to achieve finite-time bipartite consensus if, for some appropriate control input

where

If the

This section examines control mechanisms for both leaderless and leader-driven vehicle platooning under finite-time and fixed-time boundary consensus protocols. The mechanisms operate within an impulsive control framework to achieve coordination under specified convergence criteria.

3.1 Leaderless Finite-Time Bipartite Consensus (FNTBC) and Fixed-Time Bipartite Consensus (FXTBC) in Networked Vehicles

The concepts of Finite-Time Non-Singular Terminal Bipartite Consensus (FNTBC) and Fixed-Time Bipartite Consensus (FXTBC) play crucial roles in ensuring rapid coordination among networked vehicles. Although both aim to achieve bipartite consensus in a finite duration, their convergence characteristics differ significantly.

Specifically, FNTBC guarantees that the consensus among agents is reached within a finite time that depends on the initial conditions of the system. The convergence rate in this case varies with the magnitude of initial errors, leading to fast stabilization when initial discrepancies are small. In contrast, FXTBC achieves convergence within a fixed upper bound of time, completely independent of the initial conditions. This is realized by introducing additional nonlinear corrective terms with exponents greater than one, which strengthen the control action as the system approaches equilibrium.

From a practical perspective, FNTBC is efficient when the initial state differences among vehicles are moderate and known, while FXTBC is more suitable for scenarios where initial states are highly uncertain, such as large-scale vehicle platoons or dynamically changing environments.

3.1.1 Leaderless Finite-Time Bipartite Consensus (FNTBC)

The finite time bipartite consensus (FNTBC) criterion from Eq. (5) for the vehicle platooning dynamics modeled in Eq. (4) requires a strategically designed impulsive control scheme that uses discontinuous impulses and nonlinear consensus dynamics to achieve finite-time boundary convergence. The impulsive control protocol is extended to handle both communication delays and malicious deception attacks for more realistic vehicle platooning dynamics. The control input for the

where,

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

The uniformly spaced time sequence

The sequences

The impulsive structure enables vehicles to interact minimally yet efficiently. The proposed control protocol (7) modifies both continuous and instantaneous behavior of each vehicle to achieve finite-time convergence even with sporadic corrections.

The dynamic model for vehicle

Lemma 7. The system described by Eq. (4) with the control protocol defined in (7) operates as a vehicle platooning. The weighted average state of the system, denoted by

Remark 3. The control mechanism operates conventionally at times other than impulses. The vehicles experience major state changes during impulse moments. Dirac delta function activation causes this phenomenon, which results in an immediate and powerful state adjustment. The impulsive effects play a major role in speeding up the system’s convergence process.

The original system (4) can be compactly expressed as

where

Theorem 1. Consider a system of M vehicles described by second-order dynamics as in Eq. (4) following the impulsive control strategy, to reach finite-time bipartite consensus under deception attacks, which is defined by Eq. (7). The parameters should be chosen to meet the following conditions:

The system reaches leaderless finite time bipartite consensus (FNTBC) in finite time when the network’s interaction topology, represented as an undirected signed graph G, is structurally balanced and connected.

The settling time

while

The Laplacian matrix is denoted by

Proof: Define the transformed state as

where

The impulsive dynamics are given by Eq. (9)

We compute the derivative of

Using the continuous dynamics, we get,

Now, we use the identity for antisymmetric nonlinear functions

where we choose

where

Since

The transformation of

We get:

At impulse times

where

represents the deception attack introduced during impulsive instants.

The Lyapunov function at

Provided the gain matrices satisfy.

and the bounds,

we ensure that,

even in the presence of bounded deception attacks.

Combining the continuous-time decay and impulsive updates, we obtain,

This guarantees fixed-time convergence. The settling time

thus, the impulsive protocol ensures fixed-time non-singular terminal bipartite consensus despite the presence of bounded deception attacks.

Remark 4. The Lyapunov framework used in this study combines continuous stability analysis between impulsive events with discrete jump analysis at

Remark 5. The main distinction between FNTBC and FXTBC lies in their dependence on initial conditions. In FNTBC, the convergence time varies according to the initial state differences, whereas in FXTBC, the convergence time is fixed and predefined, regardless of the initial conditions. This fixed-time property offers stronger robustness and predictability for practical systems such as autonomous vehicle coordination, where the control objective must be achieved within a guaranteed time bound. Consequently, FXTBC enhances reliability under uncertain or rapidly changing initial states.

3.1.2 Fixed-Time Control for Leaderless Vehicle Platooning

The fixed time bipartite consensus (FXTBC) objective described in Eq. (5) for the vehicle platooning defined in Eq. (4) requires a new impulsive control protocol, which is presented below to achieve its goal.

The control parameters are defined as

Lemma 8. The control strategy defined by protocol (10) applied to the vehicle platooning modeled by Eq. (4) results in a constant average state vector throughout time

Proof: The argument validating this result aligns closely with the reasoning presented in Lemma 5 of [51]. The analytical steps are nearly identical to those in the previous result, so the detailed proof is not reproduced here for brevity.

Remark 6. The main difference between the control protocol in (7) and the one proposed in (10) is the presence of the term

where,

•

•

•

•

•

The impulsive deception attack input injected at the impulsive instants

•

• The nonlinear functions are defined elementwise as:

where

Theorem 2. Consider the dynamical system described by Eq. (4) receives impulsive control through Eq. (10) while maintaining the conditions of Assumption (1) The system contains

The impulsive interval is assumed to satisfy further conditions

Particularly

• When

• When

The auxiliary parameters are defined through the following structure

Proof: Define the transformed state as

where

Let us define the Lyapunov function candidate:

where

is the stacked state vector.

The impulsive dynamics are given by Eq. (11),

We compute the derivative of

Using the continuous dynamics, we get,

Now, we use the identity for antisymmetric nonlinear functions

where we choose

where

Since

we get

At impulse times

where,

represents the deception attack introduced during impulsive instants.

The Lyapunov function at

Provided the gain matrices satisfy,

and the bounds,

we ensure that

even in the presence of bounded deception attacks.

Combining the continuous-time decay and impulsive updates, we obtain

This guarantees fixed-time convergence. The settling time

thus, the impulsive protocol ensures fixed-time non-singular terminal bipartite consensus despite the presence of bounded deception attacks.

Remark 7. Impulsive control shows faster convergence rates than traditional continuous (non-impulsive) control strategies. The settling time

The integer

3.2 Finite-Time and Fixed-Time Leader-Following Control in Vehicle Platooning

Lemma 9. Let

3.2.1 Finite-Time Leader-Following Control in Vehicle Platooning

The leader-following control objective (6) requires the following impulsive control strategy to meet the framework of systems (3) and (4).

where constants

Remark 8. The leader’s control law is assumed to have a flexible design, constrained only by boundedness. Furthermore, the model does not include impulsive effects on the leader, which distinguishes its dynamics from that of the follower vehicles. The model assumes that the leader vehicle communicates unidirectionally by sending signals to follower vehicles without receiving feedback. The evolution of vehicle

Let us define the global state vector as

With each component defined by

The leader-follower dynamics described in Eqs. (3) and (4) can be represented in a more compact form as,

where,

And the leader dynamics are,

Stated

Assumption 2. The function

The impulsive deception attack input injected at the impulsive instants

Assumption 3. The function

where

Theorem 3. The systems (3) and (4) operate under the assumption that the communication graph is connected. Under the validity of Assumptions (1) and (3), it is guaranteed that the vehicles achieve finite-time bipartite tracking with

The maximum time required for vehicles to reach consensus, or settling time

where

Proof: The stability analysis starts with the following Lyapunov candidate,

The system dynamics for time instances excluding impulse times

By substituting

Thus,

Expanding and using properties of the Laplacian matrices and the boundedness of

where

This simplifies to

Bounding the norm

Therefore,

At each impulsive instant

because from (14),

and the matrix inequality

which holds for

and the attack input

Hence, the impulsive control law (12) achieves finite-time leader-following bipartite consensus for systems (3) and (4) by Lemma 5. By adjusting

the settling time

The impulsive control law (12) fulfills the objective of leader-following finite time bipartite consensus (FNTBC) for systems (3) and (4) according to Lemma (5). Introducing

3.2.2 Fixed-Time Leader-Following Control in Vehicle Platooning

This section presents a new impulsive control strategy to achieve the leader-following fixed time bipartite consensus (FXTBC) objective for systems (3) and (4). The control input

where constants

where

where

With

Where

Theorem 4. Consider the vehicle platooning system described by Eqs. (3) and (4), operating under the impulsive control protocol (18). Suppose that Assumptions (1) and (3) hold, and the impulsive gains satisfy

where

• If

• If

where the decay factor

and the constants are given by

Proof: Define the tracking error as,

Let the Lyapunov function candidate be,

For

Using standard inequalities and properties of the sign function,

From Lemma 8 (norm relation), we have,

Then,

where

At impulsive time

where

where

If

• For

• For

Hence, the fixed-time bounded consensus is achieved. The system described by Eqs. (3) and (4) achieves fixed-time bipartite consensus under the influence of the impulsive control protocol (18) as per Lemma 9. The system achieves consensus within a fixed time when the upper bound of

Remark 9 (Distinction between FNTBC and FXTBC in the Leader-Follower Framework). The key distinction between Finite-Time Non-Singular Terminal Bipartite Consensus (FNTBC) and Fixed-Time Bipartite Consensus (FXTBC) in the leader-follower framework lies in the dependency of the convergence time on the initial conditions. In the case of FNTBC, all followers reach the leader’s state within a finite time that depends on their initial state differences. Consequently, the settling time varies according to the initial magnitude of the tracking errors, making FNTBC more suitable when the initial conditions are known or bounded. Conversely, FXTBC guarantees convergence to the leader’s trajectory within a predefined upper time bound that is completely independent of the initial states. This independence is achieved by incorporating additional nonlinear terms and discontinuous impulsive components in the control law, which enhance the convergence rate and improve robustness. Such a design enables each follower to rapidly correct its position, velocity, and acceleration deviations, ensuring synchronization even under large initial disparities or external disturbances. Therefore, while FNTBC provides adaptive convergence efficiency, FXTBC offers stronger robustness and predictability for real-time vehicle platooning applications where time constraints and safety margins are critical.

The simulation results presented in this section validate the effectiveness of the implemented impulsive control strategies.

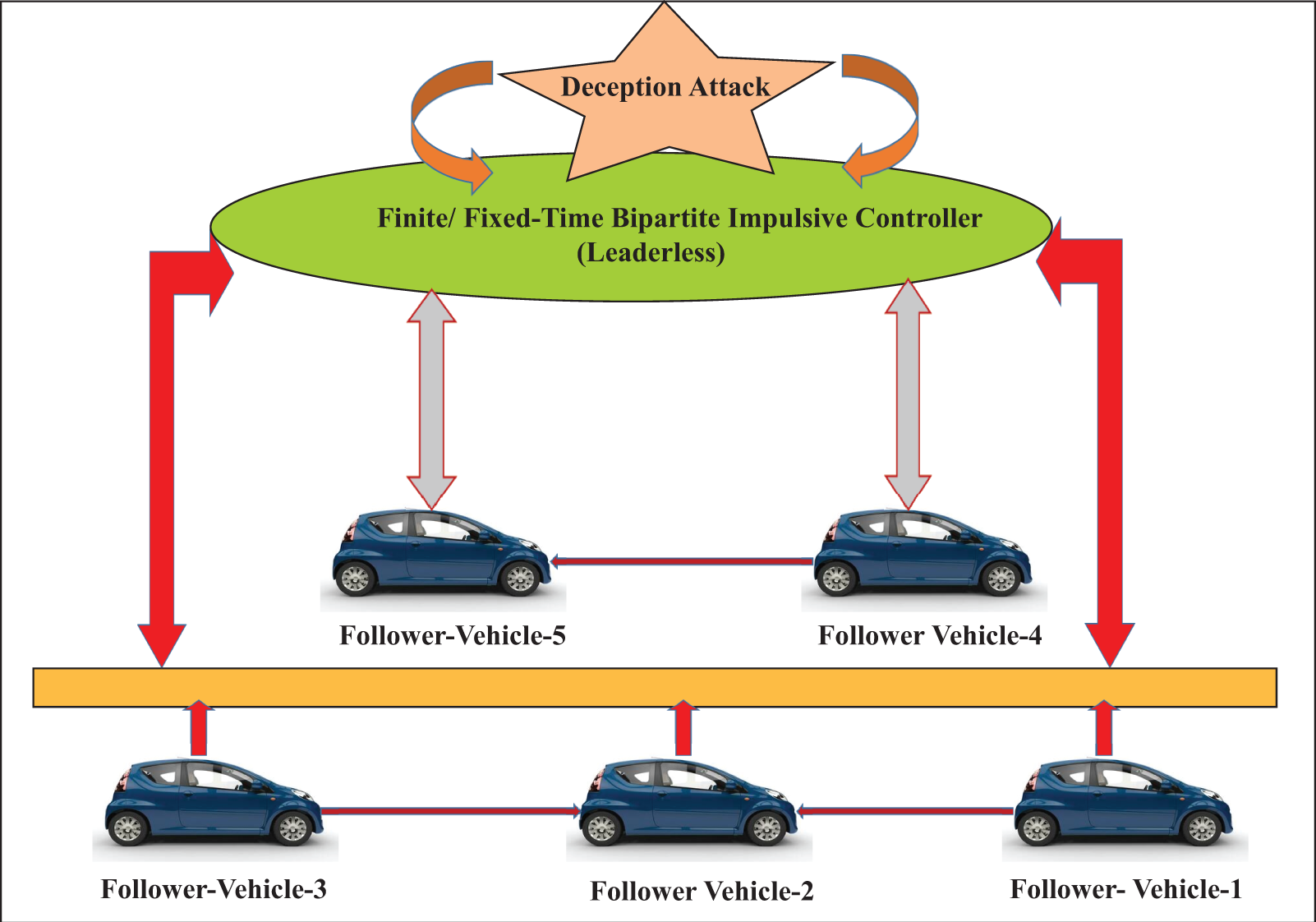

Example 1. Finite/Fixed-Time Bipartite Control in Leaderless Vehicle Platooning under Deception Attack.

The system consists of five vehicles that follow model (4) without a designated leader. The communication network G that controls this system appears in Fig. 1. The network G shows structural balance through direct observation. The system contains two groups, where vehicles 1, 2, and 3 belong to one group and vehicles 4 and 5 belong to the other group according to the diagonal matrix partitioning. Derived the Laplacian matrix from the vehicle communication topology in Fig. 1, such that,

Figure 1: Shows Finite/fixed-leaderless communication between the vehicles under the deception attack

The initial conditions for the vehicles are assigned as follows

We simulate a platoon of M = 4 vehicles l = 2 state variables per vehicle (position and velocity). The finite-/fixed-time impulsive control with deception attack is initialized as follows,

• Control gains:

• Impulse instant,

• Impulsive gains:

• Deception attack amplitudes:

• Initial condition:

• Simulation interval:

And,

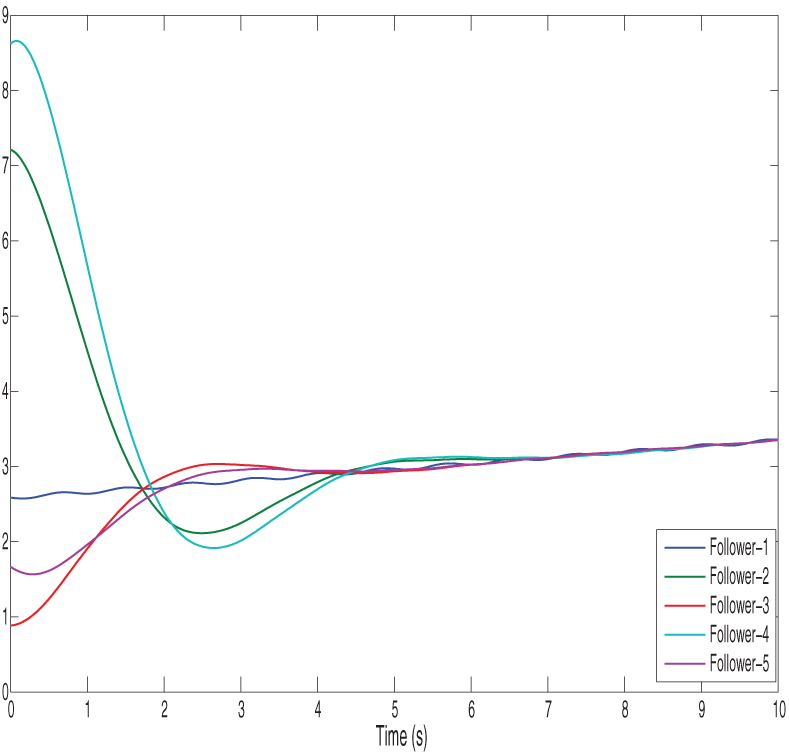

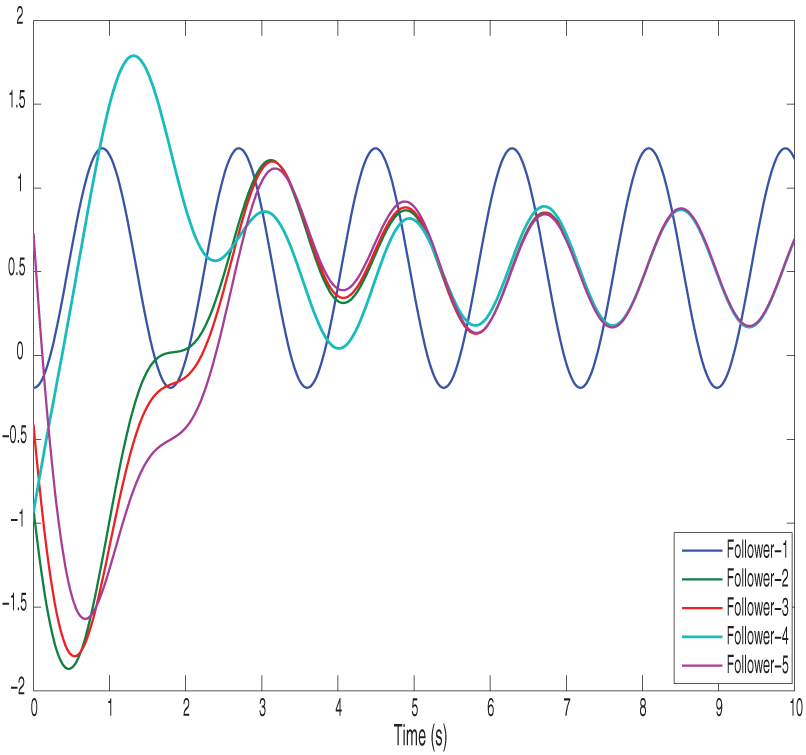

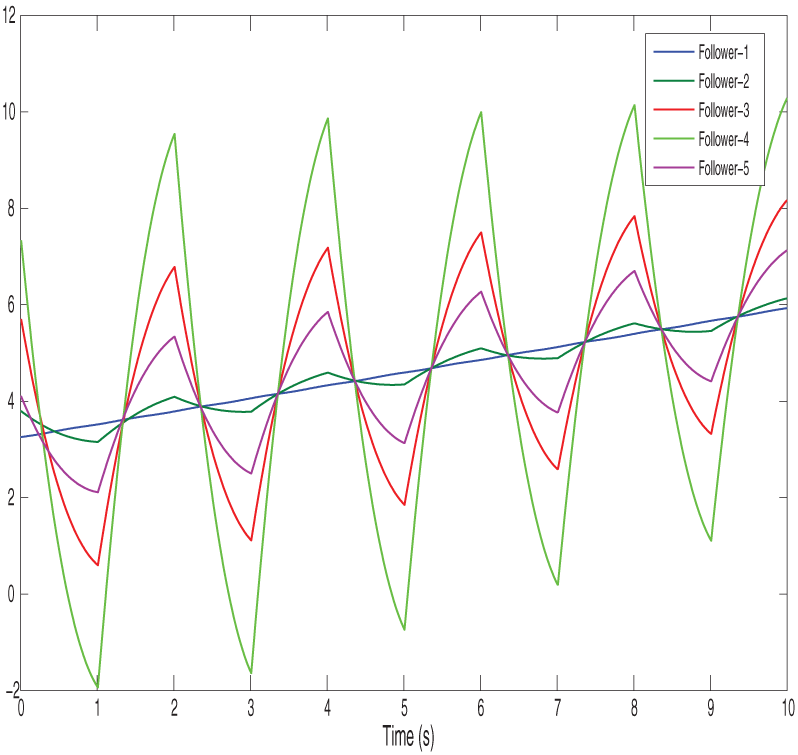

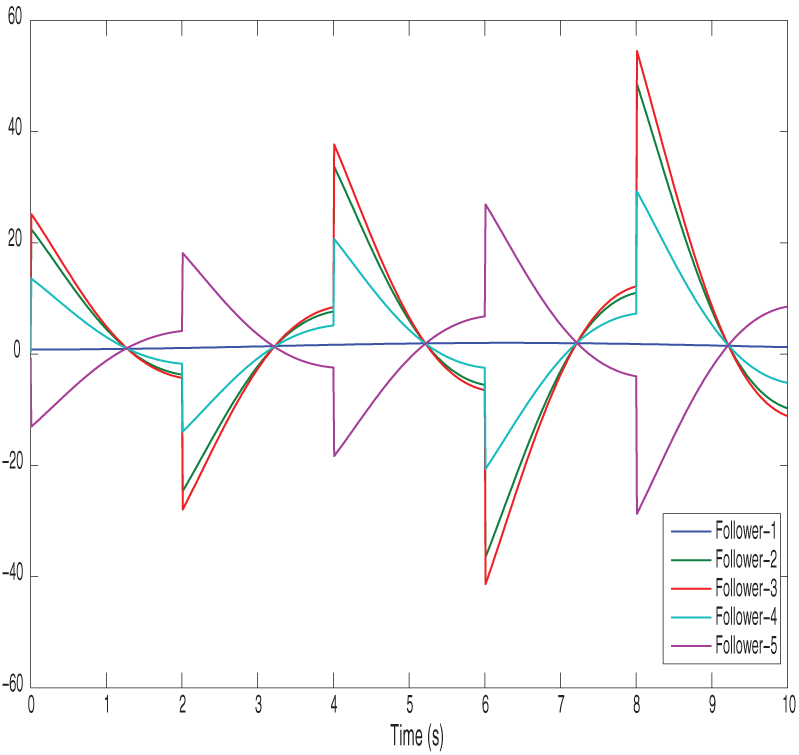

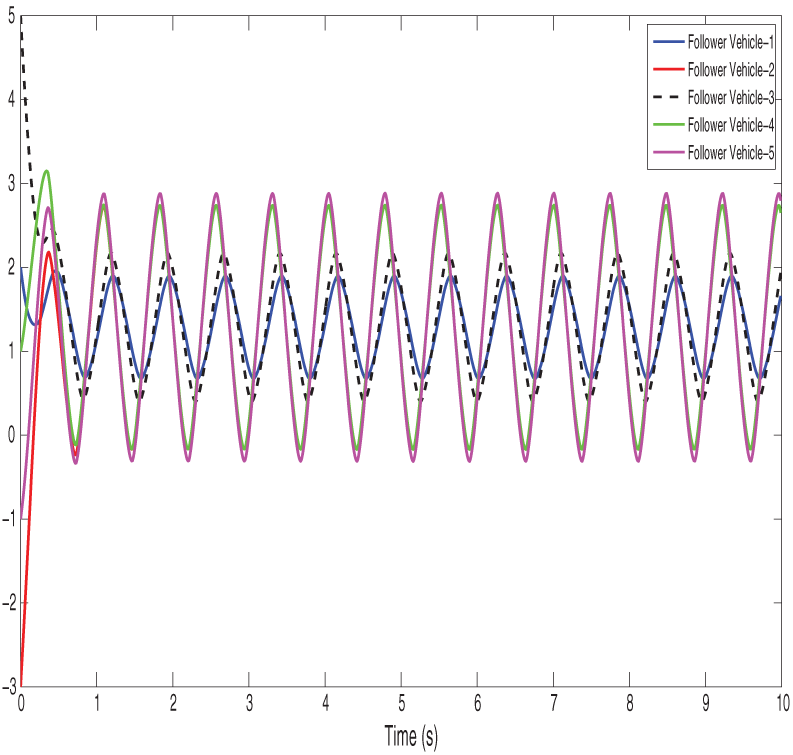

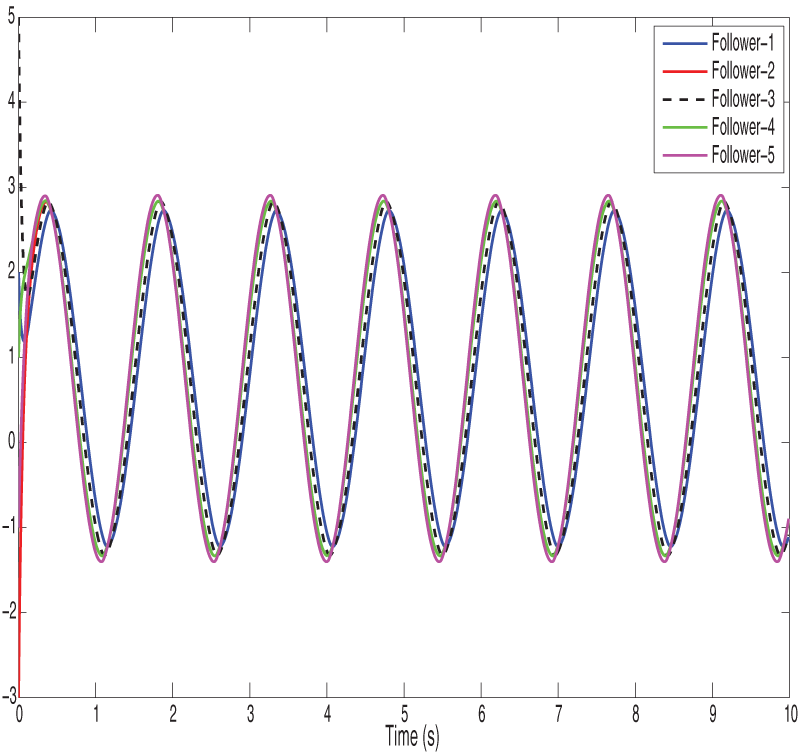

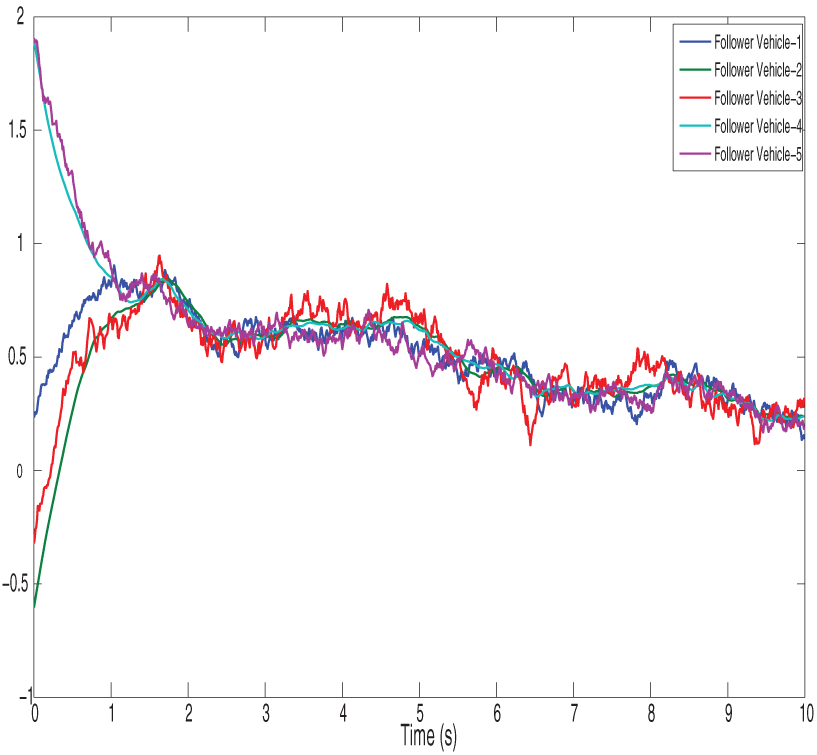

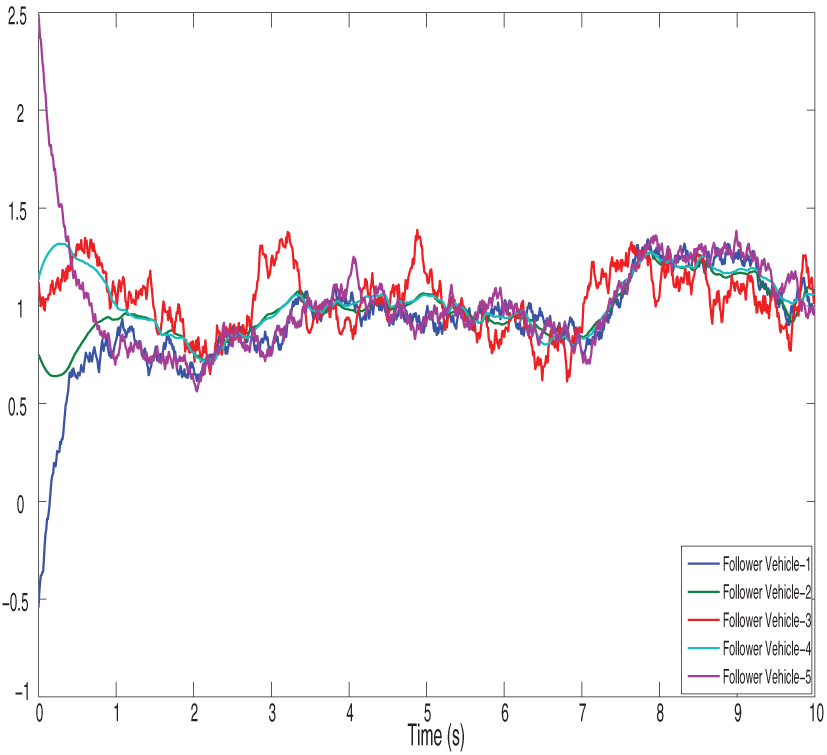

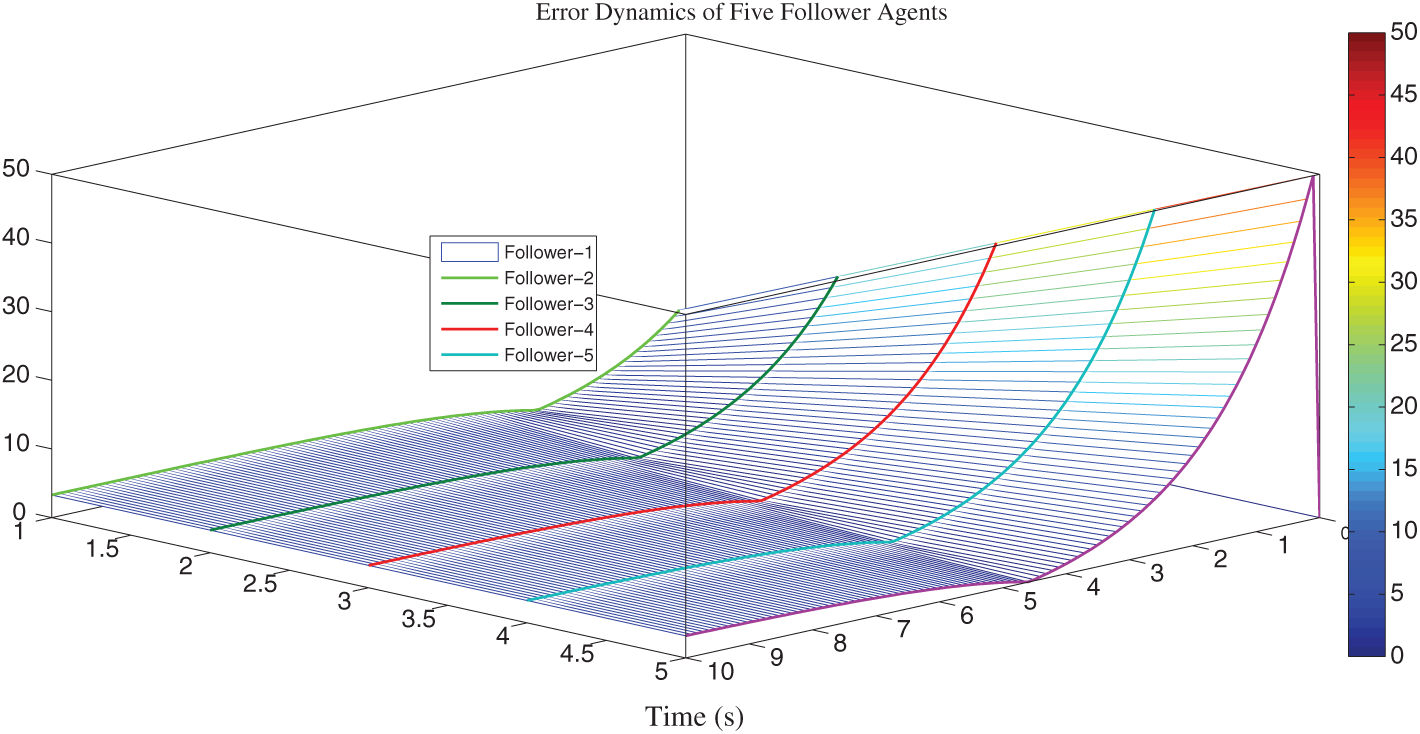

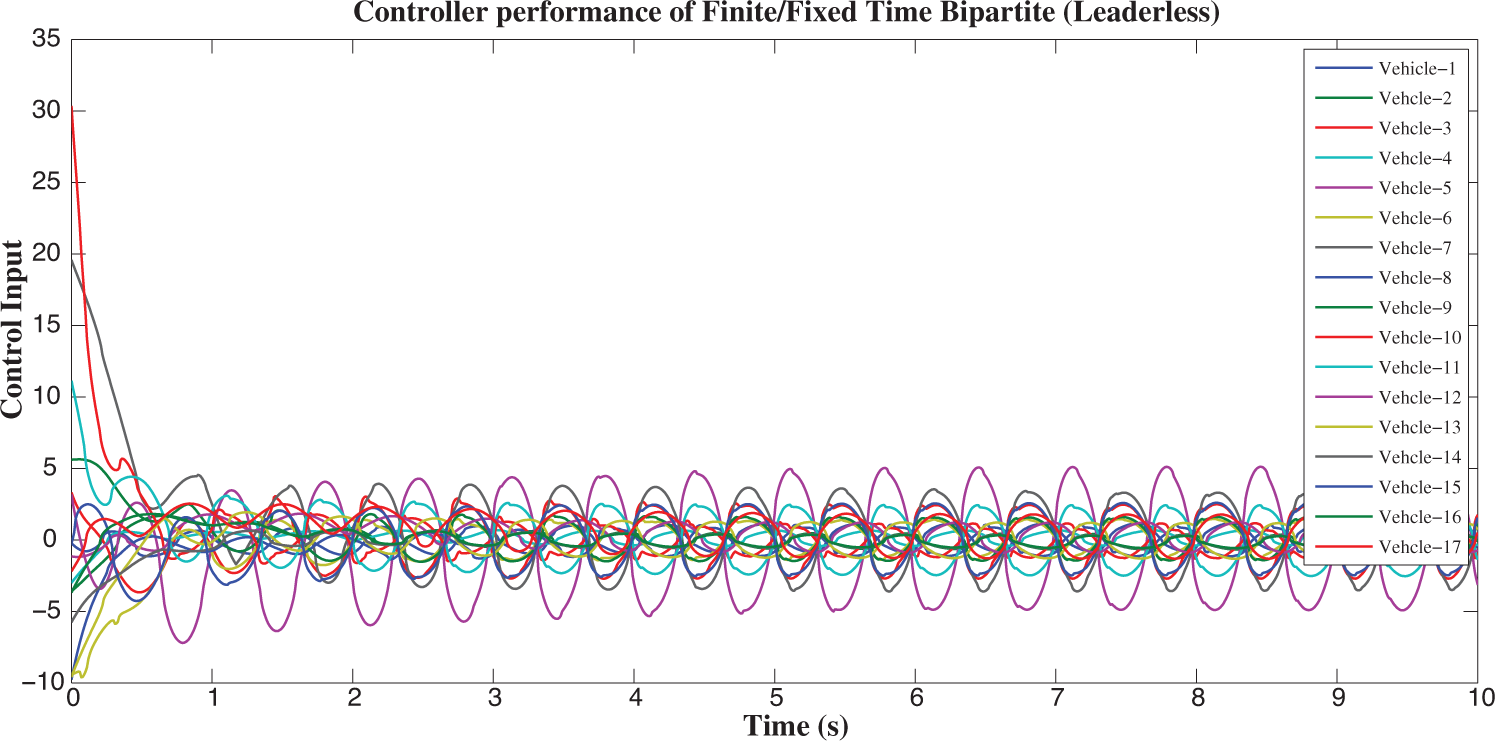

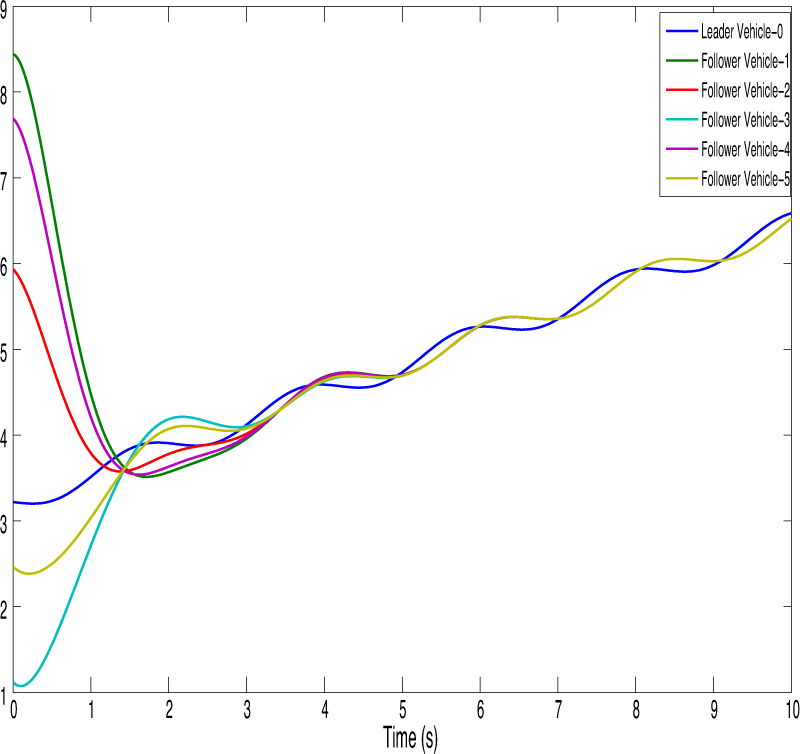

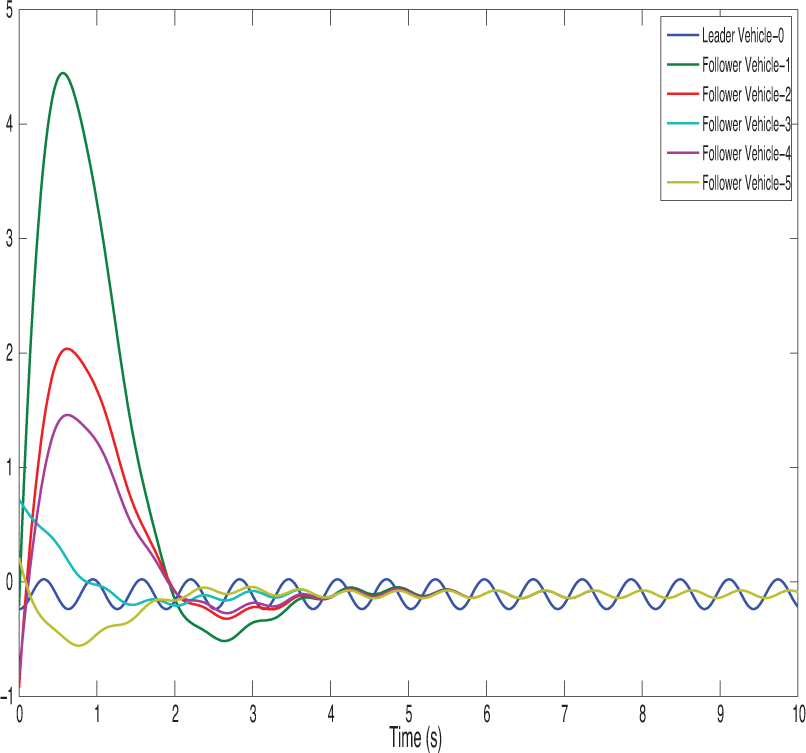

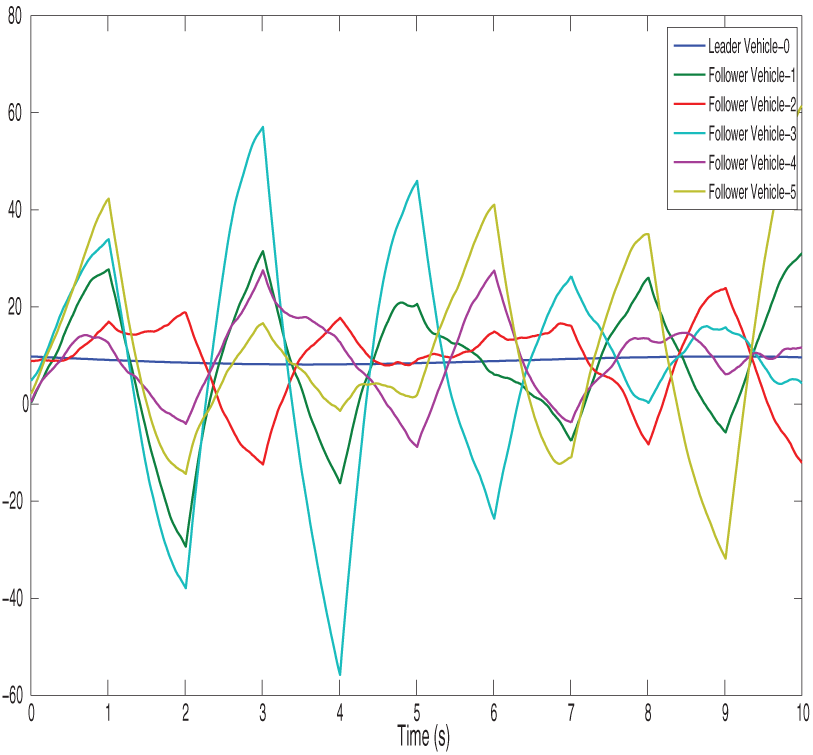

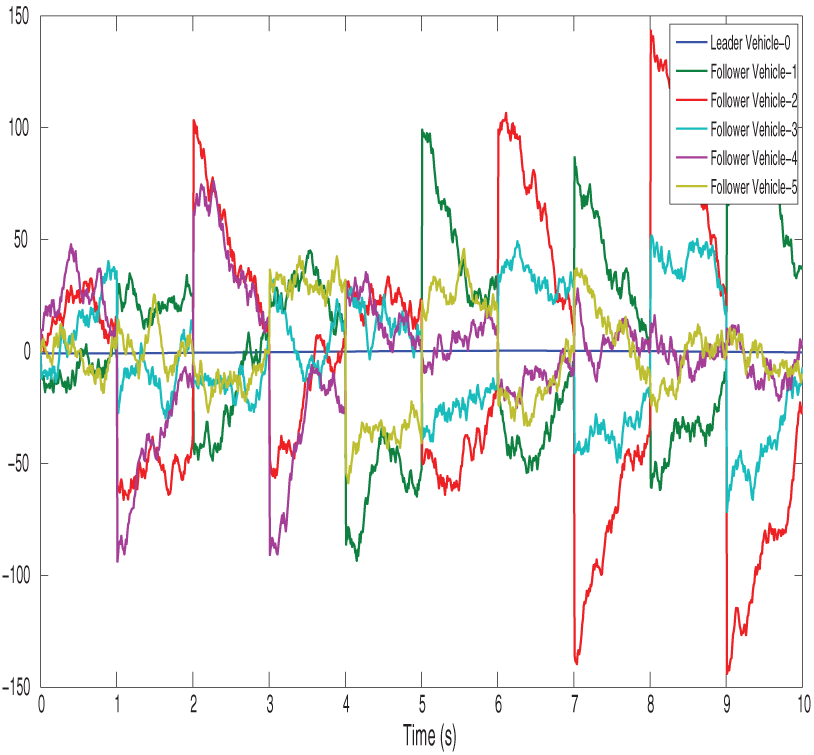

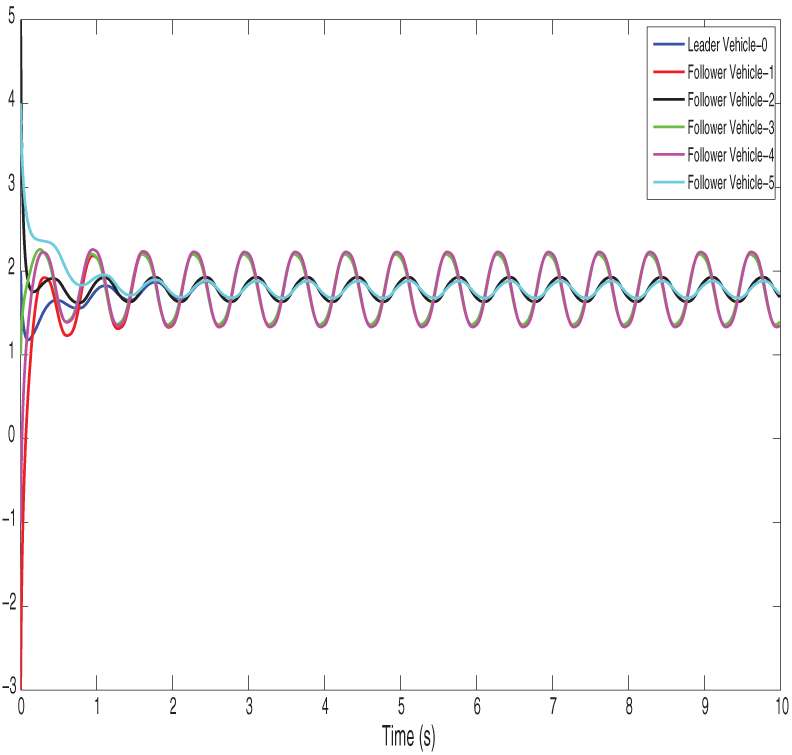

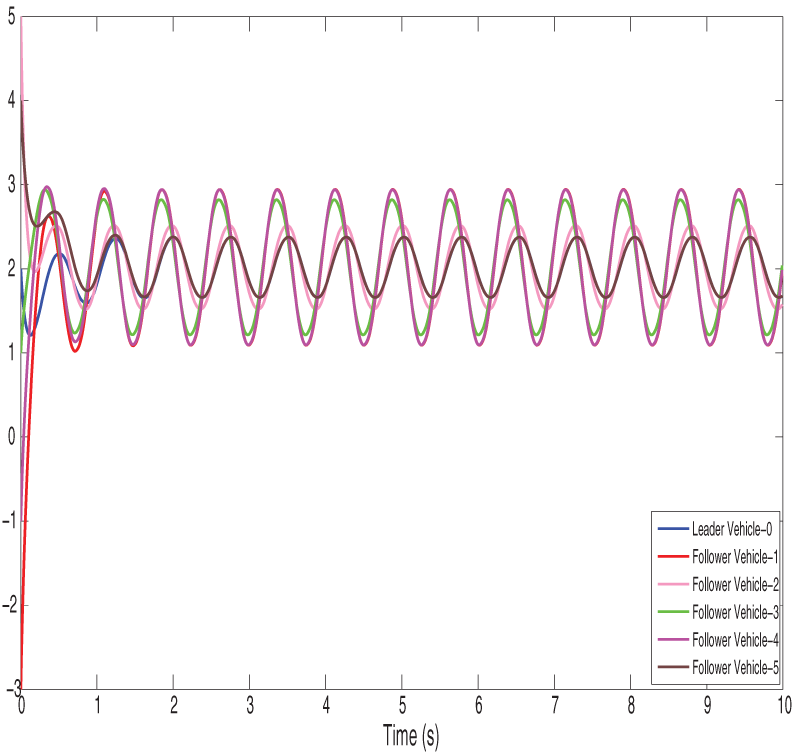

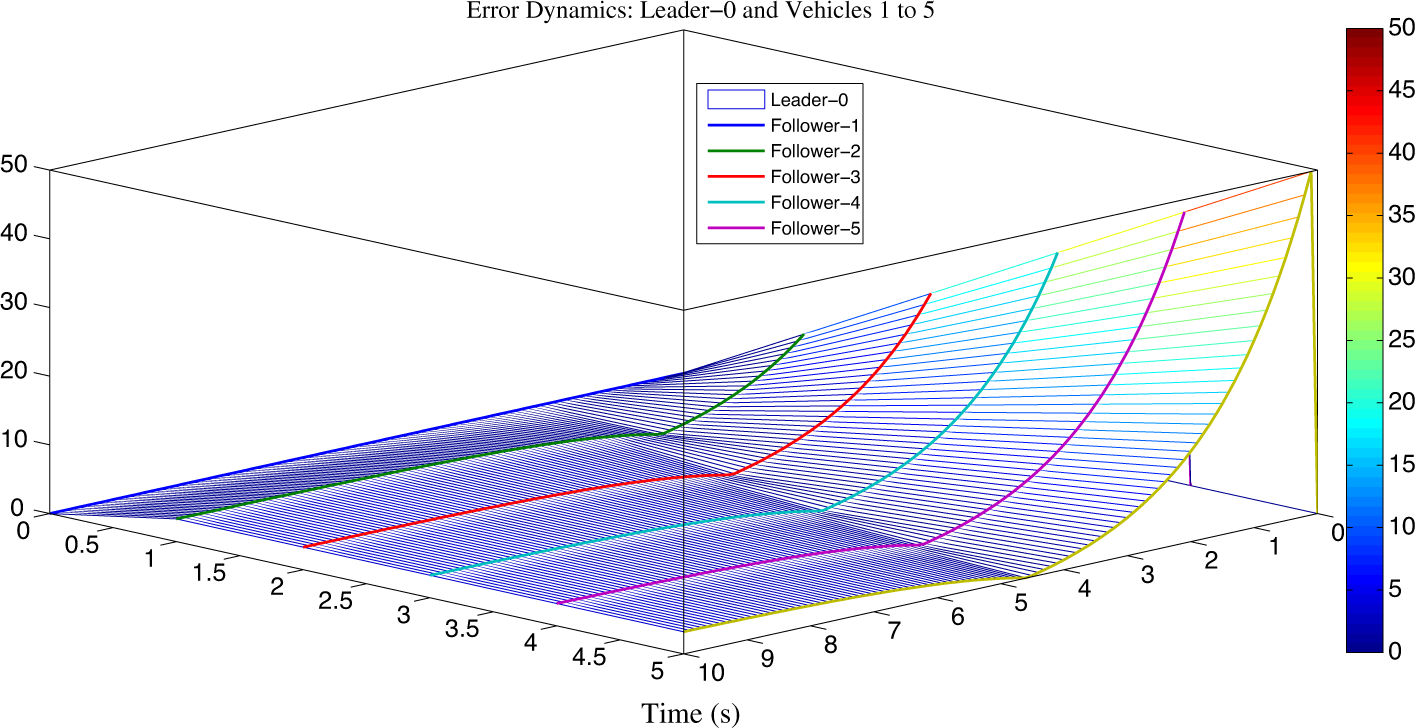

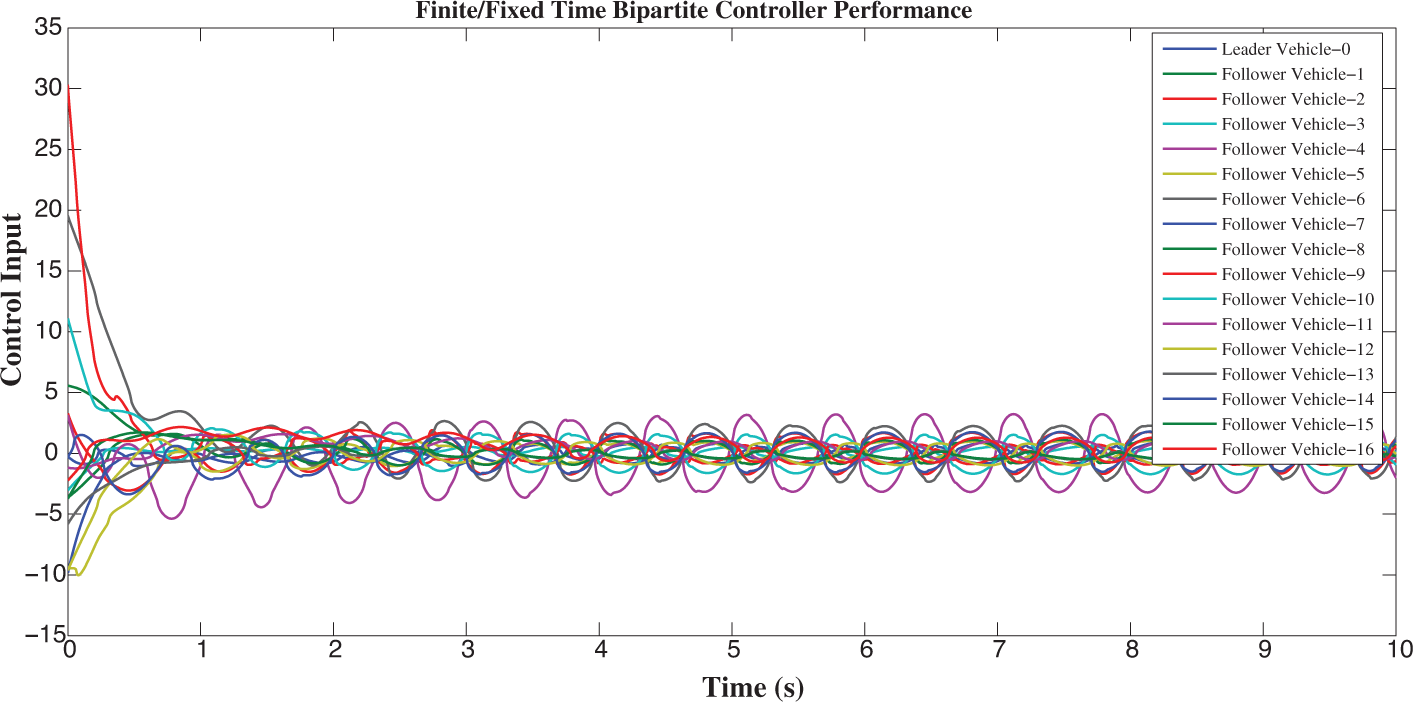

Figs. 2 and 3 show the position state trajectories and velocity state trajectories of vehicles, respectively. Figs. 4 and 5 show finite-time control trajectories and fixed-time control trajectories of vehicles, respectively. Figs. 6 and 7 show path finite-time and fixed-time control input under the deception attack of vehicles, respectively. Figs. 8 and 9 show the signal dropping under the finite-time and fixed-time bipartite impulsive controller (Leaderless). Figs. 10 and 11 show the error dynamics and performance of controller of leaderless vehicles, respectively.

Figure 2: Illustrates the position state trajectories of vehicles

Figure 3: Illustrates the velocity state trajectories of vehicles

Figure 4: Shows finite-time control trajectories

Figure 5: Shows fixed-time control trajectories

Figure 6: Shows path finite-time control input under the deception attack of vehicles

Figure 7: Shows path fixed-time control input under the deception attack of vehicles

Figure 8: Shows the signal dropping under the finite-time bipartite impulsive controller (Leaderless)

Figure 9: Shows the signal dropping under the fixed-time bipartite impulsive controller (Leaderless)

Figure 10: Shows the error dynamics of leaderless vehicles

Figure 11: Shows the performance of controller of 17 vehicles

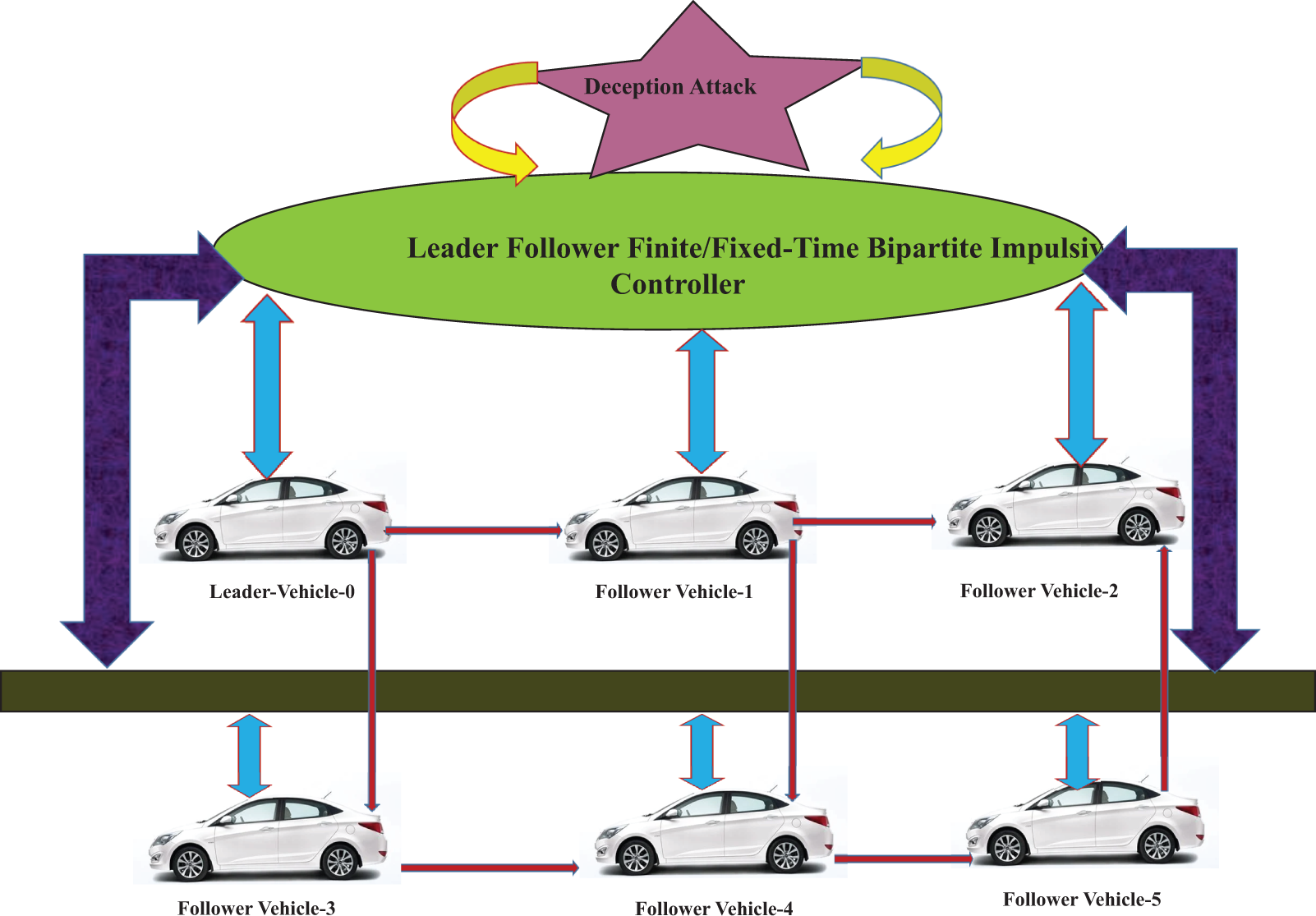

Example 2. The system consists of one leader (vehicle 0) and five followers, as shown in Fig. 12. The vehicles behavior follows models (3) and (4). Vehicle 0 functions as the leader to transmit information to vehicles 1 and 3, which results in the adjacency matrix.

Figure 12: Shows the Finite/fixed leader-follower communication topology under the deception attack

The Laplacian matrix is derived from the communication topology shown in Fig. 12. The Laplacian matrix derived from Fig. 12,

The control input for the leader is defined as

The initial states of the followers are assigned as,

The impulsive interval

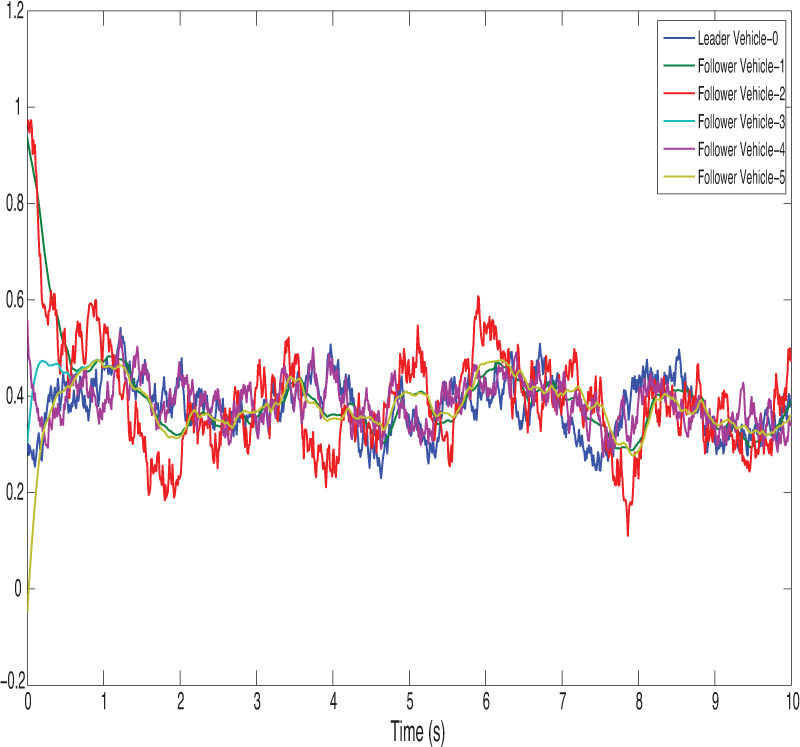

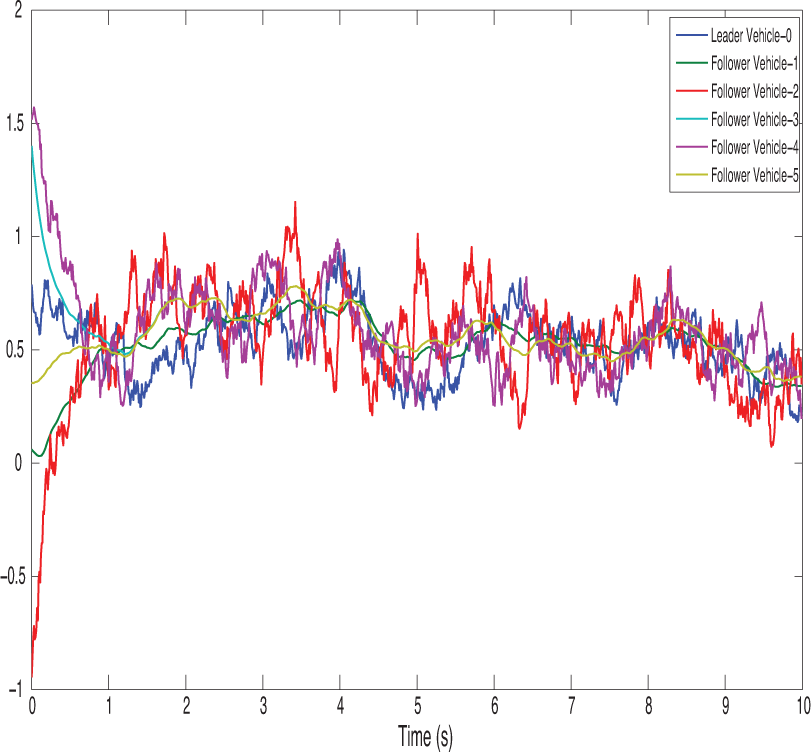

Figs. 13 and 14 show the position state trajectories and velocity state trajectories of vehicles, respectively. Figs. 15 and 16 show finite-time control trajectories and fixed-time control trajectories of vehicles, respectively. Figs. 17 and 18 show the path finite-time and fixed-time control input under the deception attack of vehicles, respectively. Figs. 19 and 20 show the signal dropping under the finite-time and fixed-time bipartite impulsive controller (Leader-Following). Figs. 21 and 22 show the error dynamics of leader-following vehicles and the performance of controller with 1 leader and 16 followers vehicles, respectively.

Figure 13: Represents the position state trajectories of vehicles

Figure 14: Represents the velocity state trajectories of vehicles

Figure 15: shows finite-time control trajectories of vehicles

Figure 16: Shows finite-time control trajectories of vehicles

Figure 17: Shows the path finite-time control input under the deception attack of vehicles

Figure 18: Shows the path fixed-time control input under the deception attack of vehicles

Figure 19: Shows the signal dropping under the finite-time bipartite impulsive controller (Leader-Following)

Figure 20: Shows the signal dropping under the fixed-time bipartite impulsive controller (Leader-Following)

Figure 21: Shows the error dynamics of leader-following vehicles

Figure 22: Shows the performance of the controller with 1 leader and 16 follower vehicles

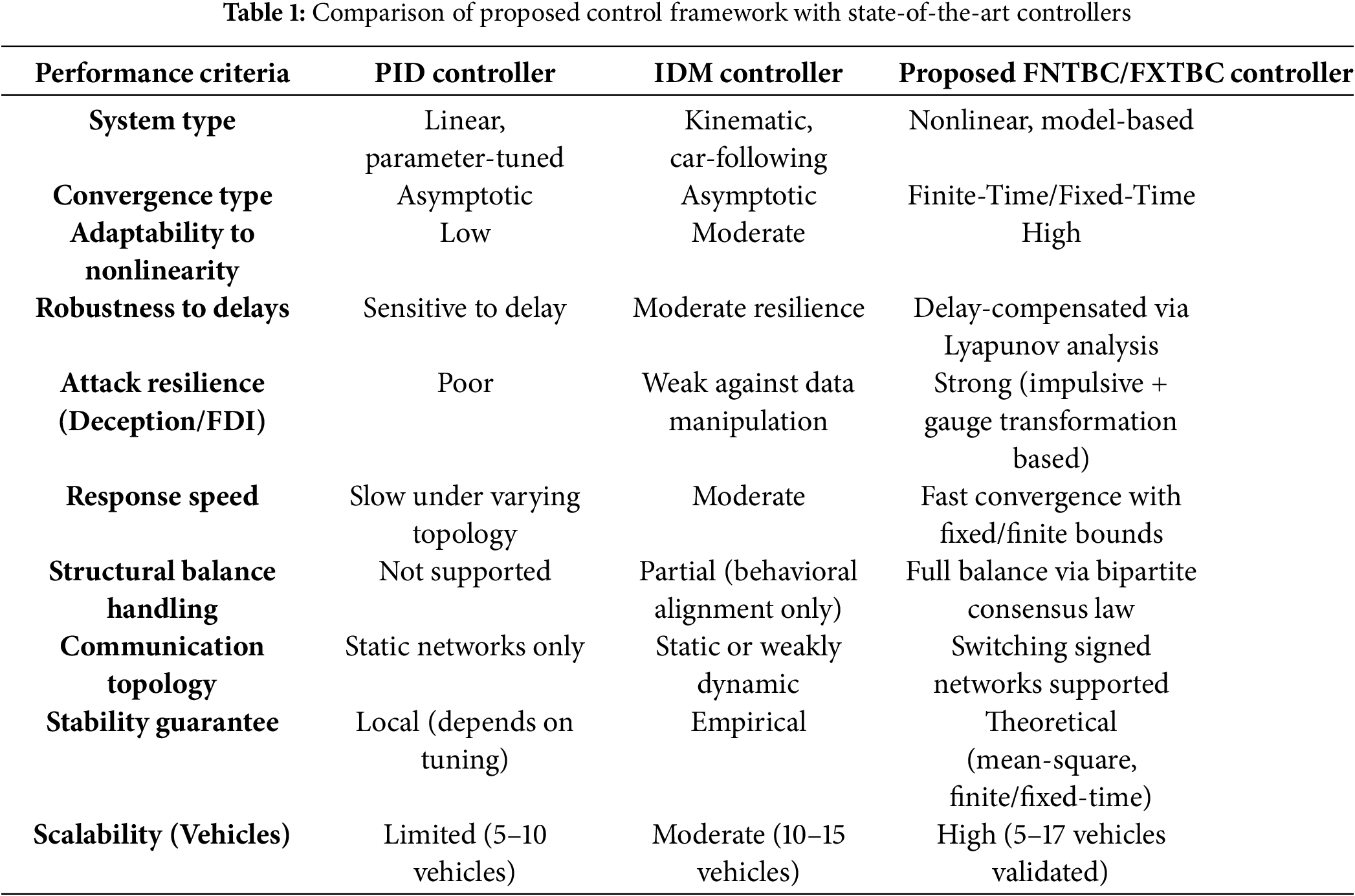

In Table 1, the performance of the proposed controller is compared with classical PID and IDM strategies across multiple criteria.

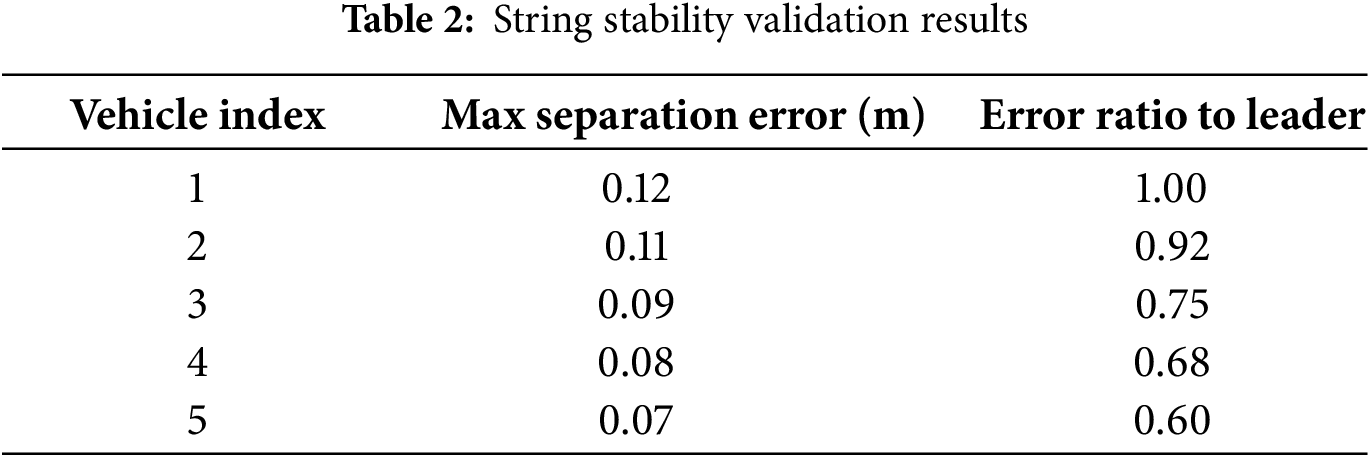

The condition of string stability requires that spacing errors between vehicles do not grow when moving through the platoon. The Lyapunov-based analysis in Theorem 3 shows that spacing errors stay within limits for all vehicles in the platoon. The proposed method demonstrates string stability through Table 2, which shows the maximum steady-state separation errors for each vehicle.

This paper developed a unified model-based impulsive control framework to achieve finite-time and fixed-time bipartite consensus in second-order nonlinear vehicle platooning systems operating under switching signed interaction networks, communication delays, and deception attacks. By integrating Lyapunov stability theory and impulsive system dynamics, the proposed strategy guarantees bounded inter-vehicle separation and string stability in both leaderless and leader–follower structures. Simulation studies on five- and seventeen-vehicle formations validate the effectiveness of the approach, achieving convergence within approximately

Acknowledgement: The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Research and Graduate Studies at King Khalid University for funding this work through Large Research Project under grant number RGP. 2/103/46”, the authors also express their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at Northern Border University, Arar, Saudi Arabia for funding this research work through project number “NBU-FFR-2025-871-15” and this study is supported via funding from Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University project number (PSAU/2025/R/1447).

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Muflih Alhazmi; Software, Nafisa A. Albasheir; Validation, Ameni Gargouri; Formal analysis, Muflih Alhazmi; Resources, Naveed Iqbal; Writing—original draft, Waqar Ul Hassan and Saba Shaheen; Writing—review & editing, Waqar Ul Hassan and Azmat Ullah Khan Niazi; Supervision, Azmat Ullah Khan Niazi and Muflih Alhazmi; Project administration, Muflih Alhazmi and Mohammed M. A. Almazah. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The code is considered an intellectual property of the Northern Border University project, and therefore not publicly available. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Azmat Ullah Khan Niazi, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Sun G, Sheng L, Luo L, Yu H. Game theoretic approach for multipriority data transmission in 5G vehicular networks. IEEE Transact Intell Transport Syst. 2022;23(12):24672–85. doi:10.1109/TITS.2022.3198046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Sun G, Song L, Yu H, Chang V, Du X, Guizani M. V2V routing in a VANET based on the autoregressive integrated moving average model. IEEE Transact Vehic Technol. 2019;68(1):908–22. doi:10.1109/TVT.2018.2884525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Sun G, Zhang Y, Liao D, Yu H, Du X, Guizani M. Bus-trajectory-based street-centric routing for message delivery in urban vehicular ad hoc networks. IEEE Transact Vehic Technol. 2018;67(8):7550–63. doi:10.1109/TVT.2018.2828651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Zhang Y, Xiang Z. Prescribed-time optimal control for a class of switched nonlinear systems. IEEE Trans Autom Sci Eng. 2024;22:3033–43. doi:10.1109/TASE.2024.3388456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Li Z, Hu J, Leng B, Xiong L, Fu Z. An integrated of decision-making and motion planning framework for enhanced oscillation-free capability. IEEE Transact Intell Transport Syst. 2024;25(6):5718–32. doi:10.1109/TITS.2023.3332655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Benarous L, Zeadally S, Boudjit S, Mellouk A. A review of pseudonym change strategies for location privacy preservation schemes in vehicular networks. ACM Comput Surv. 2025;57(8):1–37. doi:10.1145/0000000.0000000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Xu X, Li B. Semi-global stabilization of parabolic PDE-ODE systems with input saturation. Automatica. 2025;171(3):111931. doi:10.1016/j.automatica.2024.111931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Wang J, Wang H, Song J, Chen X, Guo J, Li K, et al. Knowledge-guided self-learning control strategy for mixed vehicle platoons with delays. Nature Communicat. 2025;16(1):7705. doi:10.1038/s41467-025-62597-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Song D, Zhao J, Zhu B, Han J, Jia S. Subjective driving risk prediction based on spatiotemporal distribution features of human driver’s cognitive risk. IEEE Transact Intell Transport Syst. 2024;25(11):16687–703. doi:10.1109/TITS.2024.3409874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Luan Z, Zhao W, Wang C. Coordinated tracking control of the integrated wheel-end system based on generalized instantaneous steering center constraint. IEEE Transact Transport Electrif. 2025;11(3):8271–81. doi:10.1109/TTE.2025.3538892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Long X, Cai W, Yang L, Huang H. Improved particle swarm optimization with reverse learning and neighbor adjustment for space surveillance network task scheduling. Swarm Evolution Comput. 2024;85(8):101482. doi:10.1016/j.swevo.2024.101482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Sun Q, Jian X, Han C, Li Y. An improved opportunistic localization algorithm using LEO signals based on PSODC. IEEE Transact Instrument Measur. 2025;74(2):1–10. doi:10.1109/TIM.2025.3593550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Xiong J, Wang X, Li C. Recurrent neural network based sliding mode control for an uncertain tilting quadrotor UAV. Int J Robust Nonlinear Cont. 2025;161(14):12253. doi:10.1002/rnc.70108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Xue B, Zheng Q, Li Z, Wang J, Mu C, Yang J, et al. Perturbation defense ultra high-speed weak target recognition. Eng Applicat Artif Intell. 2024;138(1):109420. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2024.109420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Zhu B, Tang R, Zhao J, Zhang P, Li W, Cao X, et al. Critical scenarios adversarial generation method for intelligent vehicles testing based on hierarchical reinforcement architecture. Accid Anal Prevent. 2025;215(4):108013. doi:10.1016/j.aap.2025.108013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Zhu B, Cao X, Zhang P, Zhao J, Han J, Tang R. High-fidelity ultrasonic radar in-the-loop accelerated test for automatic parking systems. IEEE Transact Intell Transport Syst. 2025;26(10):17055–67. doi:10.1109/TITS.2025.3574505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Song D, Zhu B, Zhao J, Han J. Modeling lane-changing spatiotemporal features based on the driving behavior generation mechanism of human drivers. Expert Syst with Applicat. 2025;284(10):127974. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2025.127974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Zhang H, Xu Y, Luo R, Mao Y. Fast GNSS acquisition algorithm based on SFFT with high noise immunity. China Communicat. 2023;20(5):70–83. doi:10.23919/JCC.2023.00.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Wang J, Wu Y, Chen CLP, Liu Z, Wu W. Adaptive PI event-triggered control for nonlinear systems with input delay. Inform Sci. 2024;677(24):120817. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2024.120817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Li X, Lu Z, Yuan M, Liu W, Wang F, Yu Y, et al. Tradeoff of code estimation error rate and terminal gain in SCER attack. IEEE Transact Instrument Measur. 2024;73(7):1–12. doi:10.1109/TIM.2024.3406807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Yang J, Zang X, Chen W, Luo Q, Wang R, Liu Y. Improved social force model based on pedestrian collision avoidance behavior in counterflow. Phys A Statist Mech Applicat. 2024;642(17):129762. doi:10.1016/j.physa.2024.129762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Zhou Z, Wang Y, Liu X, Li Z, Wu M, Zhou G. Hybrid of neural network and physics-based estimator for vehicle longitudinal dynamics modeling using limited driving data. IEEE Transact Intell Transport Syst. 2025;26(10):16735–46. doi:10.1109/TITS.2025.3585346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Chen J, Li M, Marcantoni M, Jayawardhana B, Wang Y. Range-only distributed safety-critical formation control based on contracting bearing estimators and control barrier functions. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025;12(19):40968–79. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2025.3590774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Ding F, Liu Z, Wang Y, Liu J, Wei C, Nguyen A, et al. Intelligent event triggered lane keeping security control for autonomous vehicle under DoS attacks. IEEE Transact Fuzzy Syst. 2025;33(10):3595–608. doi:10.1109/TFUZZ.2025.3597276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Wang W, Liang J, Zeng H. Sampled-data-based stability and stabilization of Lurie systems. Appl Mathem Comput. 2025;501(10):129455. doi:10.1016/j.amc.2025.129455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Bukht TFN, Alazeb A, Mudawi NA, Alabdullah B, Alnowaiser K, Jalal A, et al. Robust human interaction recognition using extended kalman filter. Comput Mater Contin. 2024;81(2):2987–3002. doi:10.32604/cmc.2024.053547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Hu J, Jiang H, Liu D, Xiao Z, Zhang Q, Min G, et al. Real-time contactless eye blink detection using radar. IEEE Transact Mobile Comput. 2024;23(6):6606–19. doi:10.1109/TMC.2023.3323280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Liang J, Tan C, Yan L, Zhou J, Yin G, Yang K. Interaction-aware trajectory prediction for safe motion planning in autonomous driving: a transformer-transfer learning approach. IEEE Transact Intell Transport Syst. 2025;26(10):17080–95. doi:10.1109/TITS.2025.3588228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Ren Y, Chang Y, Cui Z, Chang X, Yu H, Li X, et al. Is cooperative always better? Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning with explicit neighborhood backtracking for network-wide traffic signal control. Transport Res Part C Emerg Technol. 2025;179(3):105265. doi:10.1016/j.trc.2025.105265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Wang Y, Sun R, Jiang L, Chen H, Mao Y, Yotto Ochieng W. Multipath inflation factor for robust fusion-based navigation in urban areas. IEEE Inter Things J. 2025;12(11):16256–65. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2025.3535819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Li J, Sun R, Wang Y, Ochieng WY. A robust time synchronization algorithm for integrated navigation in urban environments. Measur Sci Technol. 2025;36(3):036302. doi:10.1088/1361-6501/ada9a2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Liu X, Zhao L, Jin J. A noise-tolerant fuzzy-type zeroing neural network for robust synchronization of chaotic systems. Concurr Comput Pract Exper. 2024;36(22):e8218. doi:10.1002/cpe.8218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Jin J, Zhu J, Zhao L, Chen L, Gong J. A robust predefined-time convergence zeroing neural network for dynamic matrix inversion. IEEE Transact Cybernet. 2023;53(6):3887–900. doi:10.1109/TCYB.2022.3179312. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Jiang H, Cai J, Xiao Z, Yang K, Chen H, Liu J. Vehicle-assisted service caching for task offloading in vehicular edge computing. IEEE Transact Mobile Comput. 2025;24(7):6688–700. doi:10.1109/TMC.2025.3545444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Liu X, Wu C, Zhen S, Sun H, Sun C, Chen Y. Robust control under servo constraint following via nash equilibrium theory for bimanual humanoid manipulation. IEEE Transact Fuzzy Syst. 2025;33(11):4069–82. doi:10.1109/TFUZZ.2025.3609828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Li Z, Cai J, Chen Q, Chen L, Qing M, Yang SX. A network with neural plasticity for driver fatigue recognition on real roads. IEEE Transact Indust Elect. 2025. doi:10.1109/TIE.2025.3585046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Cao B, Liu K, Wu G, He Z, Xin D, Chen K, et al. A self-supervised evaluation approach of insulation condition for vehicle cable terminals using hypergraph neural network with dynamic features. IEEE Transact Indust Inform. 2025;21(12):9330–40. doi:10.1109/TII.2025.3598442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Yue M, Yan H, Han R, Wu Z. A DDoS attack detection method based on IQR and DFFCNN in SDN. J Netw Comput Applicat. 2025;240(24):104203. doi:10.1016/j.jnca.2025.104203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Zheng W, Liu C, Deng P, Chen X, Wu X. Enhancing concurrency vulnerability detection through AST-based static fuzz mutation. J Syst Softw. 2025;222:112352. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2025.112352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Zuo Z, Tie L. Distributed robust finite-time nonlinear consensus protocols for multi-agent systems. Int J Syst Sci. 2016;47(6):1366–75. doi:10.1080/00207721.2014.925608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Xiao Z, Shu J, Jiang H, Min G, Chen H, Han Z. Overcoming occlusions: perception task-oriented information sharing in connected and autonomous vehicles. IEEE Netw. 2023;37(4):224–9. doi:10.1109/MNET.018.2300125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Guo C, Hu J, Hao J, Celikovský S, Hu X. Fixed-time safe tracking control of uncertain high-order nonlinear pure-feedback systems via unified transformation functions. Kybernetika. 2023;59(3):342–64. doi:10.14736/kyb-2023-3-0342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Luo J, Wang G, Li G, Pesce G. Transport infrastructure connectivity and conflict resolution: a machine learning analysis. Neural Comput Applicat. 2022;34(9):6585–601. doi:10.1007/s00521-021-06015-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Viadero-Monasterio F, Meléndez-Useros M, Jiménez-Salas M, Boada BL. Robust adaptive heterogeneous vehicle platoon control based on disturbances estimation and compensation. IEEE Access. 2024;12(7):96924–35. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3428341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Zhang L, Zhong J, Lu J. Intermittent control for finite-time synchronization of fractional-order complex networks. Neural Netw. 2021;144(12):11–20. doi:10.1016/j.neunet.2021.08.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Zhai X, Wen G, Peng Z, Zhang X. Leaderless and leader-following fixed-time consensus for multiagent systems via impulsive control. Int J Robust Nonlin Cont. 2020;30(13):5253–66. doi:10.1002/rnc.5059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Viadero Monasterio F, Meléndez Useros M, Jiménez Salas M, López Boada B, López Boada MJ. What are the most influential factors in a vehicle platoon? In: 2024 IEEE EAIS: Emerging Applications of Artificial Intelligence Systems; 2024 May 23–24; Madrid, Spain. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE. p. 1–7. doi:10.1109/EAIS58494.2024.10569102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Altafini C. Consensus problems on networks with antagonistic interactions. IEEE Trans Automat Contr. 2012;58(4):935–46. doi:10.1109/TAC.2012.2224251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Chang Y, Ren Y, Jiang H, Fu D, Cai P, Cui Z, et al. Hierarchical adaptive cross-coupled control of traffic signals and vehicle routes in large-scale road network. Comput-Aided Civil Infrastruct Eng. 2025;85(8):64. doi:10.1111/mice.13508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Khan A, Javeed MA, Hassan WU, Zhong Y, Ahmed S, Niazi AUK. Event-triggered consensus control with dynamic agents and communication delays in heterogeneous multi-agent systems. Alex Eng J. 2025;128:1–11. doi:10.1016/j.aej.2025.04.100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Viadero-Monasterio F, Meléndez-Useros M, Jiménez-Salas M, Boada BL. Robust adaptive control of heterogeneous vehicle platoons in the presence of network disconnections with a novel string stability guarantee. IEEE Transact Intell Vehic. 2025. doi:10.1109/TIV.2025.3578936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools