Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Keyword-Guided Training Approach to Large Language Models for Judicial Document Generation

1 Department of Computer Science and Information Engineering, Fu Jen Catholic University, New Taipei, 242062, Taiwan

2 Department of Electrical Engineering, National Taiwan University, Taipei, 106319, Taiwan

* Corresponding Author: Yi-Ting Peng. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Emerging Artificial Intelligence Technologies and Applications-II)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(3), 3969-3992. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.073258

Received 14 September 2025; Accepted 30 October 2025; Issue published 23 December 2025

Abstract

The rapid advancement of Large Language Models (LLMs) has enabled their application in diverse professional domains, including law. However, research on automatic judicial document generation remains limited, particularly for Taiwanese courts. This study proposes a keyword-guided training framework that enhances LLMs’ ability to generate structured and semantically coherent judicial decisions in Chinese. The proposed method first employs LLMs to extract representative legal keywords from absolute court judgments. Then it integrates these keywords into Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT) and Reinforcement Learning with Human Feedback using Proximal Policy Optimization (RLHF-PPO). Experimental evaluations using models such as Chinese Alpaca 7B and TAIDE-LX-7B demonstrate that keyword-guided training significantly improves generation quality, achieving ROUGE-1, ROUGE-2, and ROUGE-L score gains of up to 17%, 16%, and 20%, respectively. The results confirm that the proposed framework effectively aligns generated judgments with human-written legal logic and structural conventions. This research advances domain-adaptive LLM fine-tuning strategies and establishes a technical foundation for AI-assisted judicial document generation in the Taiwanese legal context. This research provides empirical evidence that domain-adaptive LLM fine-tuning strategies can significantly improve performance in complex, structured legal text generation.Keywords

The rapid advancement of big data and computing capability has propelled the development of artificial intelligence. Since the emergence of Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), and Transformers, along with the continuous advancements in hardware computing speeds, various Large Language Models (LLMs) have been progressively developed. For example, OpenAI’s ChatGPT, Meta’s Llama, Taiwan National Science and Technology Council’s TAIDE, and Anthropic’s Claude.

In addition to standard applications such as customer service dialogues and foreign language translation, LLMs have gradually been introduced into specialized domains, including healthcare, tourism, and law [1–4]. However, research on legal text generation in Taiwan remains limited. Most existing studies focus on English corpora, while Chinese legal documents are comparatively underexplored. Moreover, the absence of a comprehensive Chinese legal corpus makes it difficult for general-purpose language models to capture the semantic and structural features of legal texts. Therefore, a keyword-guided training approach is necessary to enhance the quality of text generation. Given these challenges, this study aims to bridge the gap by adapting large language models to the Taiwanese legal context. Specifically, a keyword-guided training approach is proposed to enhance the quality of text generation.

The advent of LLMs has significantly transformed workflows in many industries, including law. However, existing LLMs cannot be directly applied in specialized fields due to their lack of domain-specific knowledge. Moreover, most research focuses on English legal texts, leaving a gap for Chinese-language judicial documents. This study addresses this gap by introducing a keyword-guided training framework for generating Taiwanese court judgments. The research fine-tuned LLMs and employed the case fact descriptions to generate judgments automatically.

Research indicates that Taiwan District Court judges close between 56 and 80 cases monthly. The data reveals the substantial caseload shouldered by Taiwanese judges, who handle more than three cases daily. Tasks such as case adjudication and judgment drafting significantly burden judicial personnel.1

However, legal documents such as judicial judgments present challenges, including their extensive length, abundance of specialized legal terminology, and high standards for accuracy. When traditional Sequence-to-Sequence generation methods use lengthy case descriptions as direct input, the model can easily overlook crucial details, focus excessively on repetitive sentences, leading to factual deviations, or even have errors in legal understanding.

Therefore, this study proposes a “keyword-guided training framework” to generate Chinese legal judgments. Before text generation, we first utilize LLMs to extract the key legal points of a case as keywords. This approach offers two main advantages: First, they serve as semantic guides, compelling the model to structure the generated content around the most critical persons, places, events, and legal concepts. This ensures the relevance of the content and its factual basis. Second, it deconstructs the complex task of “long-text generation” into a more controllable “Concept-to-Text” task, effectively mitigating the risk of the model producing factual hallucinations. This framework is designed to guide the model to not only learn the superficial forms of language but also to master the inherent structure and logic of legal documents, thereby enhancing the quality and practical utility of the generated draft judgments.

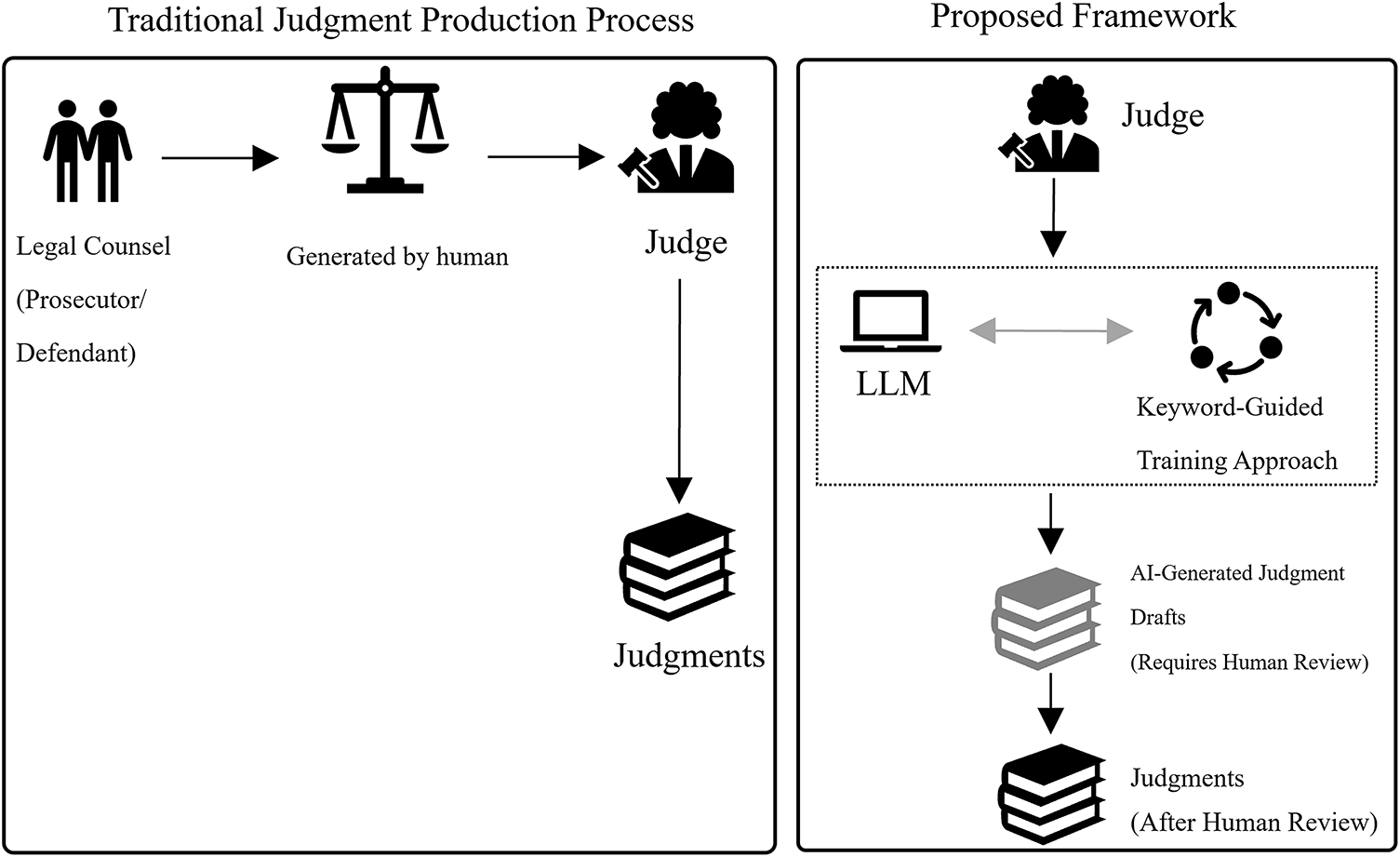

This research focuses on criminal court judgments from Taiwan and validates the approach’s technical feasibility, and offers a practical method to alleviate judicial workloads through AI-assisted document generation. As shown in Fig. 1, a comparison is made between the traditional judgment production process and the proposed framework. Furthermore, given the high societal impact of judicial decisions, this study acknowledges and discusses ethical considerations such as fairness, accountability, and transparency. Therefore, this work contributes to the technical advancement of legal Natural Language Processing (NLP) and the broader discourse on the responsible deployment of artificial intelligence in sensitive domains.

Figure 1: The concept of the proposed method

In this section, we introduce two parts of the literature review relevant to our proposed method: the technologies and applications of LLMs, particularly their applications in the legal domain, and research related to document drafting, explicitly focusing on their applications in the legal domain. As discussed in the previous section, the generation of judicial documents poses unique challenges for LLMs due to linguistic complexity and domain-specific semantics. To situate our proposed approach within the existing research landscape, this section reviews two major lines of related work: (1) applications of LLMs in the legal domain, and (2) prior studies on legal document drafting.

Applying AI to the legal domain is inherently complex due to the field’s technical nature and jurisdictional variations. Research into utilizing AI in this field has become a popular topic in many countries. Examples include employing BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) on Taiwanese court rulings for Legal Judgment Prediction (LJP) [5], developing a Virtual Legal Assistant (VLA) based on Indian law [6], using Pre-trained Language Models for Chinese legal document classification [7], and focusing on EU legislation through the Artificial Intelligence Act (AIA) to address challenges posed by Generative AI [8]. Since the introduction of LLMs, the growth of AI in the legal domain has accelerated even further. Before delving into LLMs, it is essential to understand that the architecture of recent LLMs is typically based on the Transformer architecture. The Transformer was introduced by Google in 2017 [9].

Currently, LLMs are being applied in various professional fields more frequently. For example, Rasmy et al. pre-trained a BERT model using health records and applied it to disease prediction [10]. Peng et al. introduced LLMs into the healthcare domain and proposed GatorTronGPT, which uses a GPT-3 architecture for biomedical natural language processing (NLP) and text generation in healthcare [11]. Savelka et al. applied GPT-4 to analyzing textual data in a task focused on interpreting legal concepts [12]. Wu et al. used existing LLM in the finance domain and proposed an LLM model named BloombergGPT [13]. Each LLM has different training parameters and data sources [14]. Ashish Chouhan and Michael Gertz proposed a “LexDrafter” framework that uses RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation) and LLMs to define terminology in these legal documents [15].

LLMs may produce answers that are not applicable due to differences in the training data of the original LLMs, especially in the legal domain, where laws vary by country. For example, legal professionals in the United Kingdom using ChatGPT may find that ChatGPT responses are primarily based on US law rather than UK law [16]. Therefore, existing generative LLMs cannot be directly applied in the legal domain; they must be supplemented with legal data and undergo SFT to be applicable in different countries. El Hamdani et al. added legal data to multiple LLMs and trained multiple LLMs, and the experimental results demonstrated improved performance [17].

In 2019, Ziegler et al. proposed Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF) [18]. Training LLMs typically involve three stages: Pre-training Language Model, Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT), and RLHF (Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback).

RLHF (Reinforcement Learning with Human Feedback) was used in this experiment, and the model was optimized using PPO (Proximal Policy Optimization) [18–21]. Zheng et al. pointed out that under the RLHF framework, implementing policy constraints through the PPO algorithm can improve the effectiveness of PPO’s results [22]. The study by Rahmani et al. shows that the judgments generated by fine-tuned LLMs have the highest correlation with human judgments. Therefore, this study also uses LLM-generated judgments for PPO training, enabling the LLM’s outputs to become increasingly closer to human-written judgments [23].

Adopting the Reinforcement Learning with Human Feedback using Proximal Policy Optimization (RLHF-PPO) strategy. RLHF can be divided into three phases: pre-training and a language model. Training a reward model and fine-tuning the LM with reinforcement learning. While the aforementioned studies focus on adapting LLM architectures and training methods for legal understanding, fewer works have explored how these models can be applied to the actual drafting of legal documents. Therefore, the following subsection reviews research addressing document generation and drafting within the legal domain.

2.2 Document Drafting in the Legal Domain

In the 1990s, the main difficulty of drafting documents in the legal domain is that the intended objectives and the stylistic guidelines are often unclear [24]. However, with the advancement of AI and computing resources in recent years, legal syntax and sentence structure issues that were once difficult to handle can now be addressed by incorporating LLMs. Therefore, document drafting is one of the legal applications of LLMs. Here, document drafting differs from traditional legal drafting. Butt define legal drafting as the written form of legal rights, privileges, functions, obligations, or statuses [25]. Savelka utilized GPT to extract legal text and semantic annotation of legal documents. Experimental results demonstrated that this approach is highly effective [26]. Deroy et al. believe that generative LLMs generally outperform extractive methods. However, experiments and analyses conducted on legal documents from the United States, the United Kingdom, and India have revealed inconsistencies and hallucinations in the outputs of these generative LLMs [27].

Furthermore, studies have indicated that LLMs significantly improve their performance on legal issues after training. However, they still face challenges with specific and detailed tasks, such as legal document drafting. Generating legal documents must create a reasoning tree, which adds complexity. Branting et al. utilized domain and discourse knowledge to establish a document design model [28]. Marković and Gostoji propose the LEDAS (LEgal Document Assembly System) for the interactive assembly of legal documents [29]. Narendra et al. proposed a large language model (LLM) based approach for comparing legal contracts [30]. Westermann creates a framework to establish semistructured legal reasoning and drafting [31]. Castano et al. proposed e a knowledge-based service architecture for legal document building based on Natural Language Processing and learning techniques, to semantically analyze a database of ingested legal documents and propose the most prominent and pertinent textual suggestions for new document composition [32]. Liu et al. proposed a method that can generate high-quality summaries of court judgment documents [33].

However, these works primarily focus on information extraction or summarization, rather than direct generation of full judgments. Moreover, most research has concentrated on English-language corpora, while Chinese legal documents—which exhibit distinct linguistic and structural characteristics—remain underexplored. Existing approaches also tend to apply generic pre-trained models directly, lacking mechanisms for domain-specific semantic adaptation. Consequently, generated texts often suffer from factual inconsistencies and poor logical coherence. This study introduces a keyword-guided fine-tuning framework that explicitly incorporates key legal terms into the LLM training process to address these gaps. By aligning the model’s generation with Taiwanese judicial judgments’ semantic and structural conventions, the proposed method seeks to improve the factual accuracy and discourse consistency of automatically generated legal documents. Building upon the limitations identified in the previous section, this study designs a keyword-guided fine-tuning framework that integrates keyword extraction, supervised fine-tuning (SFT), and reinforcement learning with human feedback (RLHF-PPO) to improve judgment generation quality.

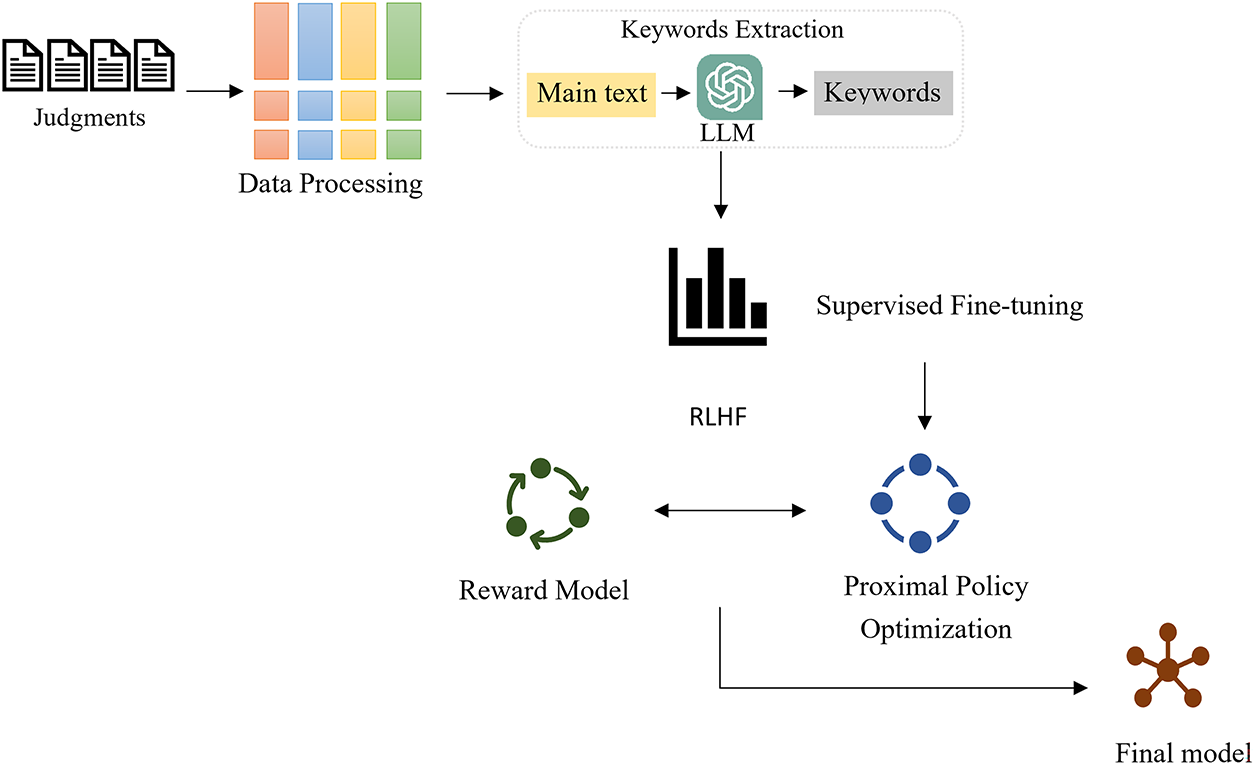

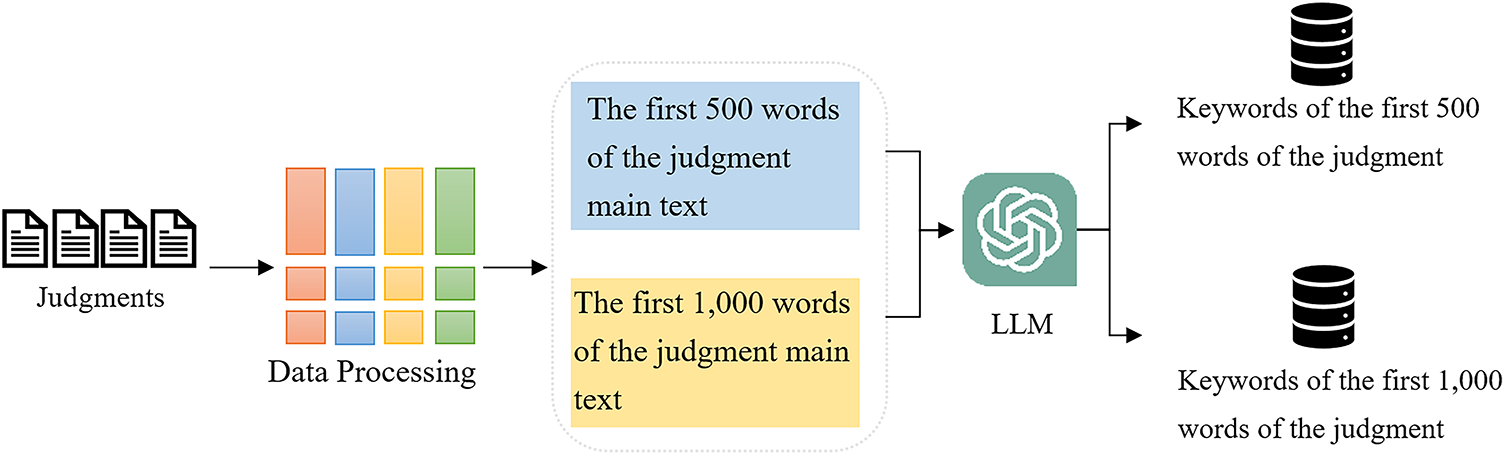

The data used in this study includes judgments from the Judicial Yuan and the criminal law code. This study uses the injury judgments as the experimental dataset. This dataset is a judgments dataset collected and compiled in a previous study [5]. The injury dataset comprises 9103 records. Considering computational resources, we trained the model using the first 500 and 1000 words of the judgments in our dataset. Since extracting keywords from Taiwanese court judgments requires language models that align with linguistic characteristics, language model choice is crucial. Therefore, this study uses the Taiwan official trained TAIDELX-7B as the LLM for keyword extraction, with the process outlined in Fig. 2. After the keyword extraction step, data cleaning is conducted using the LLM. This involves removing records where keyword extraction with TAIDELX-7B failed. Such failures include generating blank keywords or duplicating the original main text of the judgment, both of which are categorized as unsuccessful data entries. After the data processing stage, 7607 complete records were obtained and used to train the Reward Model. Additionally, to evaluate the accuracy of our method, we compare the generation performance of different Generative Large Language Models (Generative LLMs). The experimental results are measured using ROUGE-1, ROUGE-2, and ROUGE-L as evaluation metrics.

Figure 2: The concept diagram for the judgments issue of the generative language model research

The main text of the original injury judgments is referred to as the ‘main text’. This study employs LLMs to extract keywords from the main text, referred to as ‘Key words’. Subsequently, this study utilizes LLMs to automatically generate judicial judgments, referred to as ‘Generative judgment’, and compares the performance of multiple different LLMs in generating judgments.

The data used in this study primarily consists of judgments from the Judicial Yuan, with injury case judgments serving as the experimental dataset. This dataset, a collection of judgments compiled in a previous study, comprises 9103 records. Considering computational resource constraints and to establish a foundational proof-of-concept, this study focuses on generating the initial and most critical parts of the judgments; hence, length limits of 500 and 1000 words were set for model training.

This study uses generative language models to support legal judgment generation. Specifically, Meta’s LLM Llama [34] and TAIDE-LX-7B [35] are adopted for comparative experiments. These models automatically generate judgments based on objective trial conditions, existing judgments, and legal texts. In general content-generation tasks, the primary approach involves using pre-trained LLMs to produce text. However, many large language models are designed with AGI-oriented objectives and lack sufficient datasets of Taiwanese judgments written in Chinese. We propose a keyword-based training method combining SFT and RLHF-PPO to address this limitation and enhance model performance.

The methodological workflow is illustrated in Fig. 2. After collecting the judgments and processing them in the data processing stage, keywords are extracted using LLMs. Subsequently, these extracted judgment keywords are used to generate judgments. The generated judgments and original judgments are then used to train a reward model. This reward model is utilized for PPO training, ultimately resulting in the RLHF-PPO model. The experiment result will show the ROUGE scores of each LLM after SFT and the ROUGE scores of the RLHF-PPO model. The calculation max reward of RLHF is shown in Eq. (1) [19].

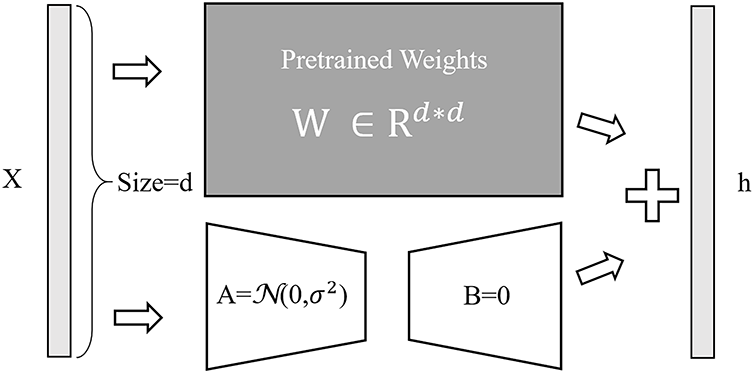

3.2.1 Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning (PEFT) and Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA)

Fine-tuning large pre-trained models is often prohibitively costly due to their scale. Hence, reducing pre-training LLMs’ parameters is becoming increasingly important. Lin et al. use the residual adapter layers to apply LLM in some task-specific [36]. Parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT) methods enable the efficient adaptation of large pre-trained models to various downstream applications by only fine-tuning a small number of (extra) model parameters instead of all the model’s parameters [37,38]. LoRA primarily reduces the number of parameters that need to be trained, making it possible to achieve LLM training objectives within limited resources. As shown in Fig. 3, by keeping the original weight matrix W unchanged and only adding an AB matrix, the training parameters are significantly reduced, thereby achieving the training goals [39]. In this study, the Chinese alpaca 7B and Chinese alpaca 13B are models trained from Llama 2 7B and Llama 2 13B using Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning (PEFT) and Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA).

Figure 3: LoRA training parameter structure

3.2.2 Process of Extracting Keywords

In this study, the collected judgments cannot be directly subjected to the keyword extraction phase because the original judgment documents require noise reduction. For example, the raw judgment data may contain irrelevant fields. These irrelevant fields must first be processed during the data processing stage to extract the necessary judgment text before proceeding to the keyword extraction module. The model was then prompted with the following instruction: ‘Extract 10 important keywords, each not exceeding 10 words.’

Fig. 4 illustrates the keyword extraction process used in this study, which primarily involves extracting the first 500 words and the first 1000 words of the main text for experiments. Given the judgment text

where

where

Figure 4: The flowchart of keyword extraction

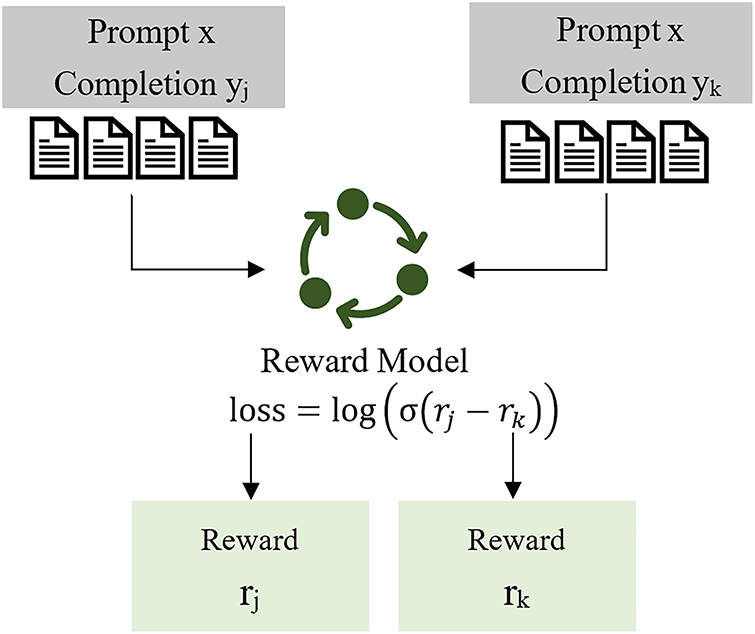

In the Reward Model phase, two types of outputs are required, and it is necessary to label which output is better or worse. The main text of the original judgment produced by the court is extracted and named ‘Completion yj’. Then, a judgment is generated using TAIDE-LX-7B and the keywords generated in the previous stage as prompts. The judgment obtained at this stage is named ‘Completion yk’. The original judgment is labeled as the higher-quality judgment (Completion yj), while the judgment generated using TAIDE-LX-7B is labeled as the lower-quality judgment (Completion yk) to train the Reward Model. The loss value is calculated as shown in Eq. (4) [40].

This experiment uses the BERT model as the base model to train the reward model [41]. The completions yj and yk are separately input into the BERT model to calculate the loss values. The process is shown in Fig. 5.

Figure 5: The flowchart of reward model

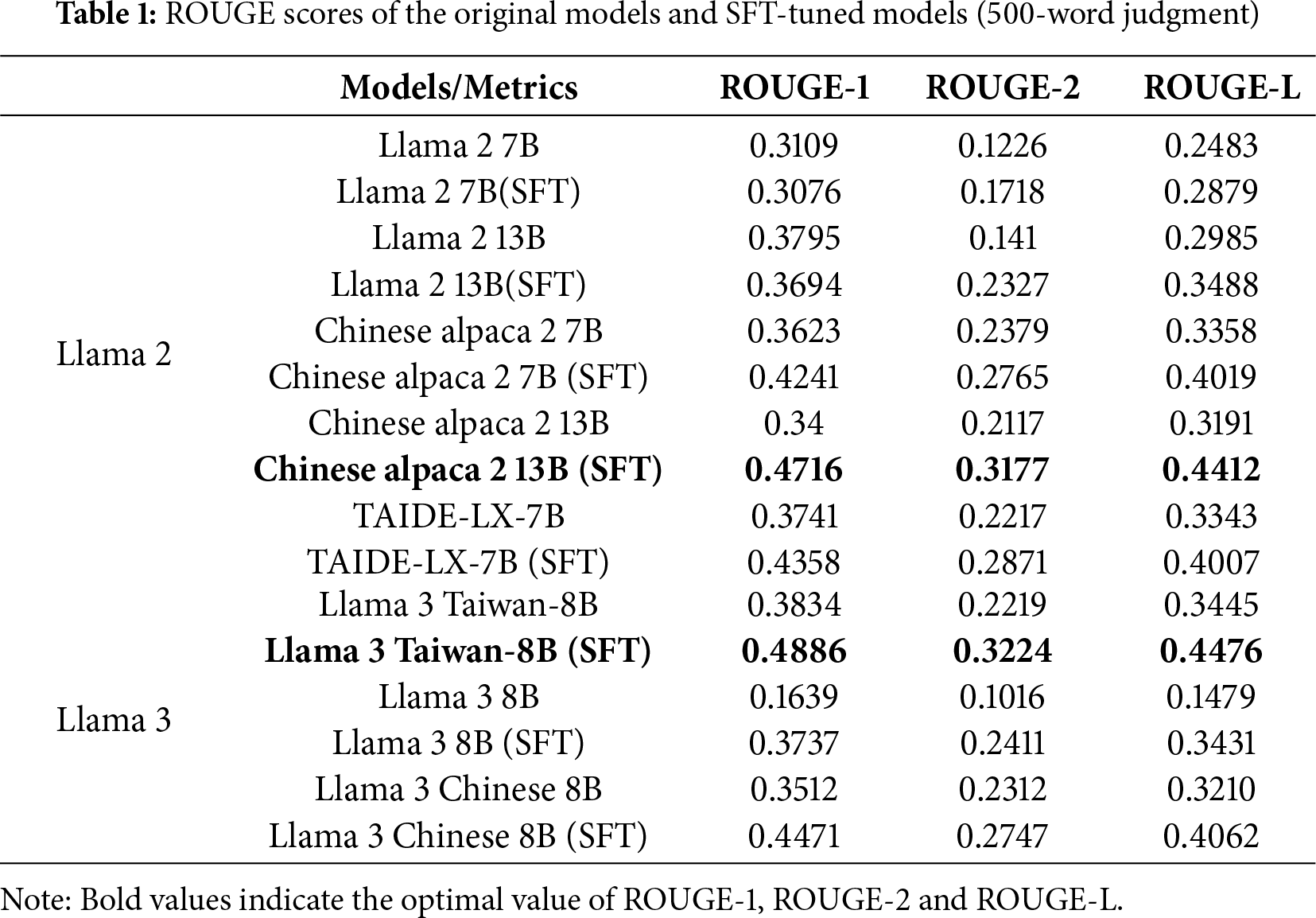

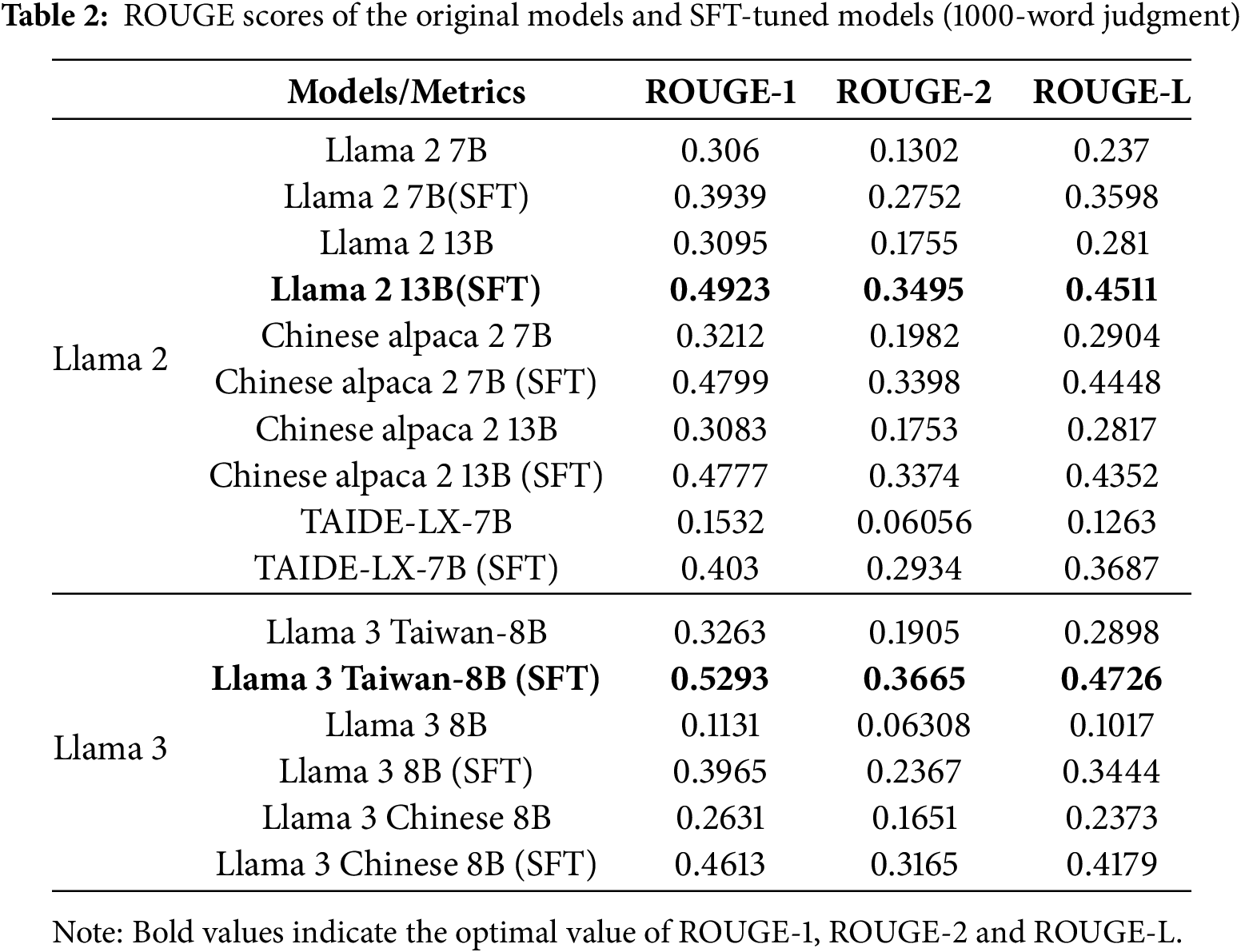

This study aims to evaluate the effectiveness of a keyword-guided training approach for generating Taiwanese legal judgments. This section will present the experimental results and provide a discussion from multiple perspectives, including model performance, the effectiveness of the training methods, and qualitative analysis. Considering computational costs and the openness of LLMs’ source code, this experiment compares eight LLMs: Llama 2 7B, Llama 2 13B, Chinese alpaca 2 7B, Chinese alpaca 2 13B, TAIDE-LX-7B, Llama 3 Taiwan-8B, Llama 3 8B, and Llama 3 Chinese 8B. The experimental results indicate that when using Llama 3 Taiwan-8B, the ROUGE-1, ROUGE-2, and ROUGE-L scores are the highest. We believe this is related to the original training process of Llama 3 Taiwan-8B, which included a large amount of data from the Taiwanese government and judicial departments. The experimental results, summarized in Tables 1 and 2, compare the generation performance of different LLMs.

This study uses ROUGE (Recall-Oriented Understudy for Gisting Evaluation) as our metric for evaluating LLM models. This section primarily uses ROUGE-N and ROUGE-L, where N denotes the n-gram length. Countmatch(gramn_nn) represents the maximum number of n-gram overlaps between the candidate summary and the set of reference summaries. When N = 1, the metric is ROUGE-1, and so forth. We employ ROUGE-1, ROUGE-2, and ROUGE-L, with their formulas presented in Eqs. (5)–(7).

ROUGE-L, which stands for Longest Common Subsequence, is primarily used to measure the degree of match between the longest common subsequences of the automatically generated summary and those of the reference summary. ROUGE-L can assess the relationships between sentences. In the Eqs. (8)–(10), the Rlcs is recall and Plcs is accuracy and Flcs is ROUGE-L.

4.2 General Efficacy of Keyword-Guided Fine-Tuning

The experimental results clearly show that for models based on the Llama 2 and Llama 3 frameworks, performance on the judgment generation task improved significantly after keyword-guided Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT). As seen in Tables 1 and 2, the SFT-tuned models show substantial increases across the ROUGE-1, ROUGE-2, and ROUGE-L metrics compared to the original base models.

A case in point is the Llama 3 8B model. Its original version, primarily trained on English corpora, performed poorly on the Chinese legal text generation task, with a ROUGE-1 score of only 0.1639. After this study’s SFT process, its ROUGE-1 score surged to 0.3737, reaching a level comparable to that of native Chinese models.

This demonstrates that the SFT framework can effectively guide and adapt a general-purpose model’s linguistic capabilities to the highly specialized domain of Taiwanese law, enabling it to master specific vocabulary, syntax, and document structures.

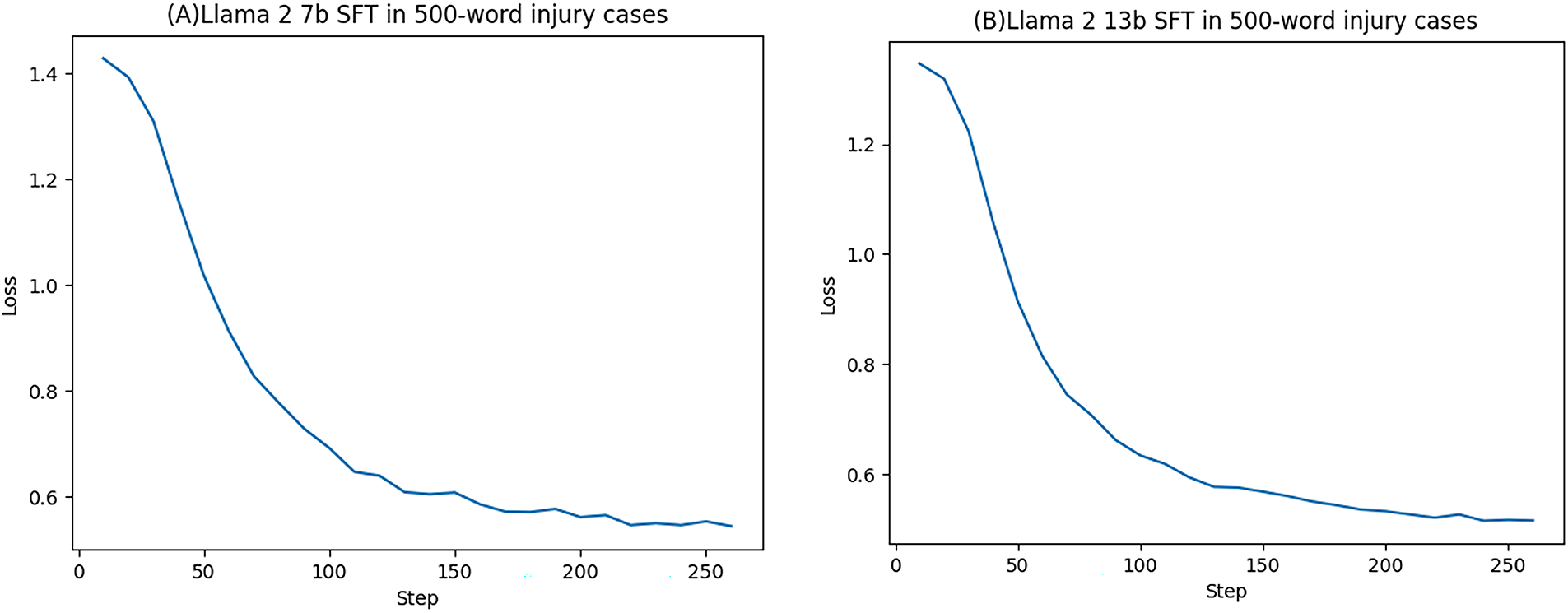

Firstly, we conducted Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT) over five epochs, training for 300 steps using Llama 2 7B and Llama 2 13B. As shown in the loss curves in Fig. 6, both LLMs exhibited a clear downward trend in loss values during the training process, with the loss values stabilizing between approximately 240 and 260 steps.

Figure 6: (A) Llama 2 7B and (B) Llama 2 13B curves of loss value in 500-word judgments

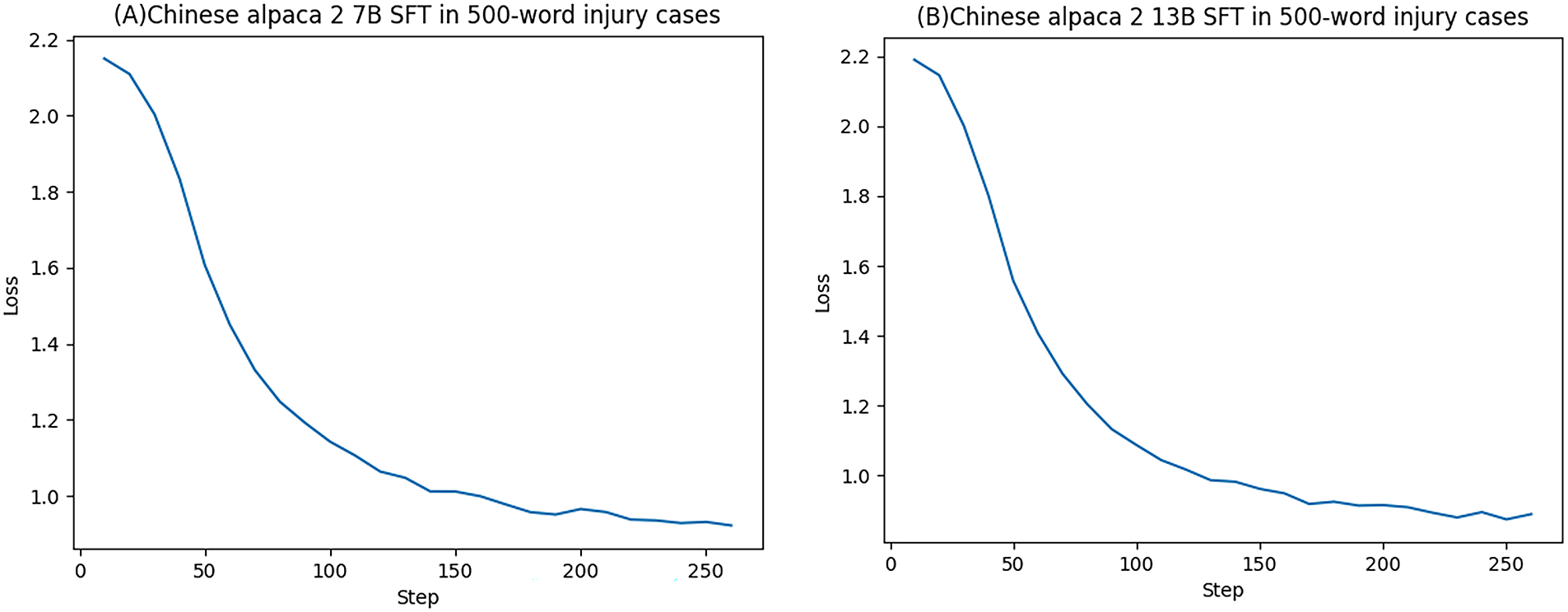

Since Llama 2 7B is primarily trained on English datasets, we performed Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT) using the Chinese version of Llama 2 7B, namely Chinese alpaca 2 7B. As shown in Fig. 7, the loss values also exhibited a consistently downward trend.

Figure 7: (A) Chinese alpaca 2 7B and (B) Chinese alpaca 2 13B curves of loss value in 500-word judgments

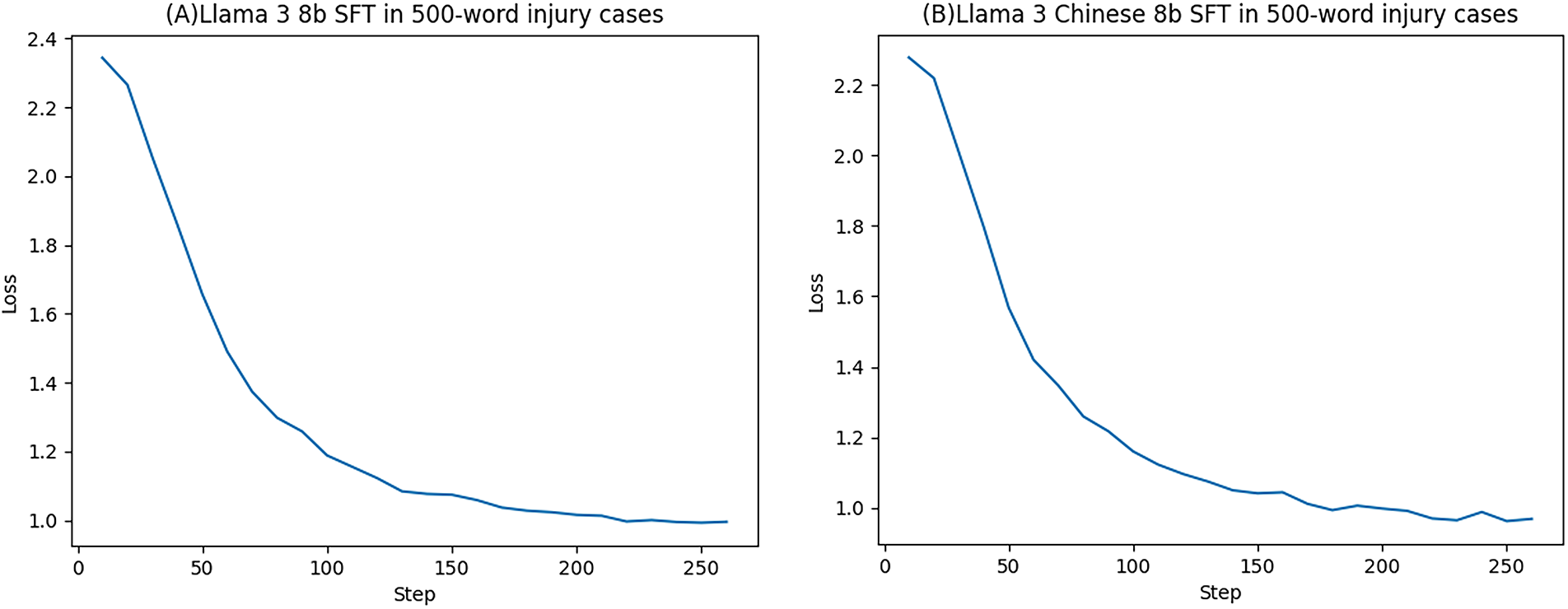

Fig. 8 shows the loss values obtained from experiments conducted with Llama 3 8B and Llama 3 Chinese 8B. It can be observed that during the Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT) of these LLMs, the loss values exhibit similar trends, stabilizing between 240 and 260 steps without significant further decreases. Therefore, this experiment’s maximum number of training steps is 260.

Figure 8: (A) Llama 3 8B and (B) Llama 3 Chinese 8B curves of loss value in 500-word judgments

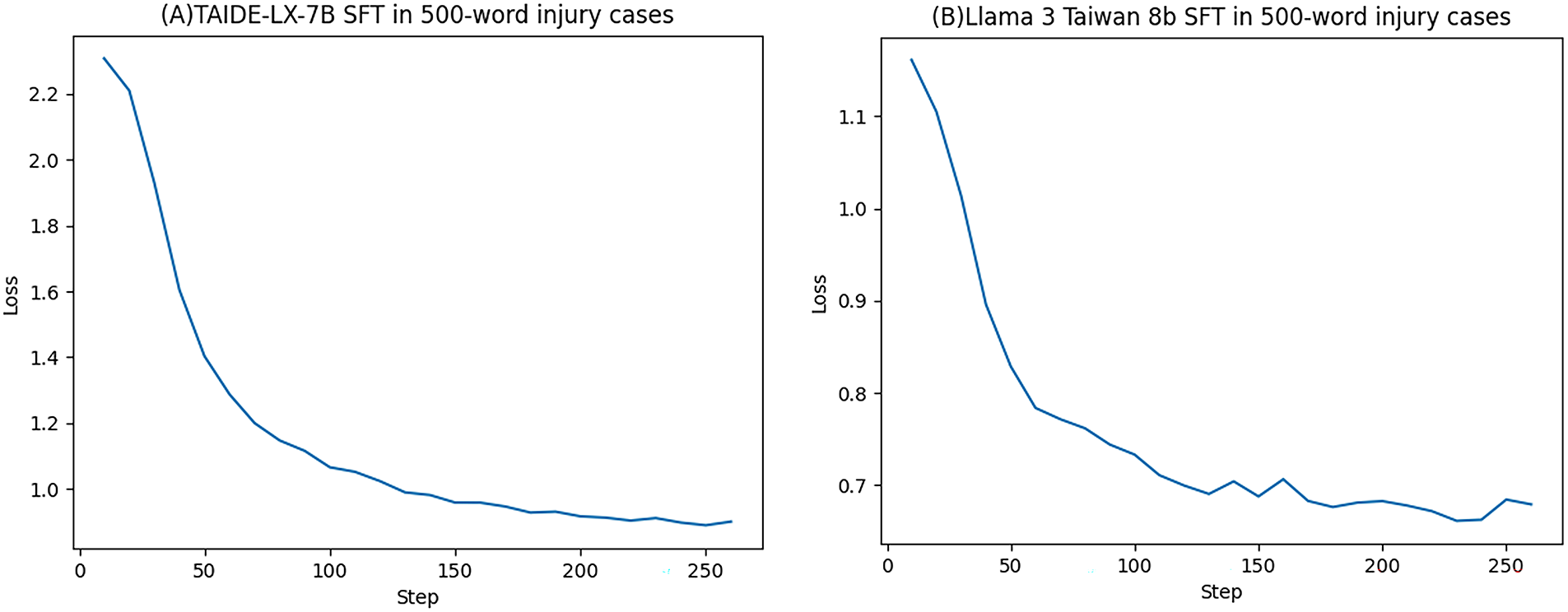

Fig. 9 shows the loss values obtained from experiments conducted with TAIDE-LX-7B and Llama-3-Taiwan-8B. It can be observed that during the Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT) of these LLMs, the loss values exhibit similar trends, stabilizing between 200 and 260 steps without significant further decreases. Therefore, this experiment’s maximum number of training steps is 260.

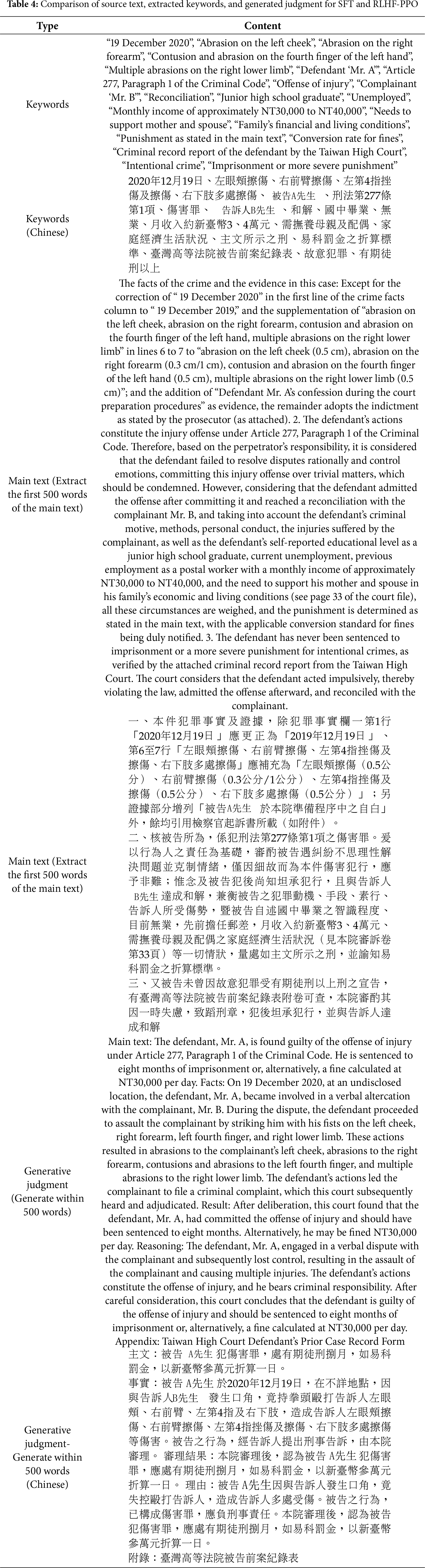

Figure 9: (A) TAIDE-LX-7B and (B) Llama-3-Taiwan-8B curves of loss value in 500-word judgments

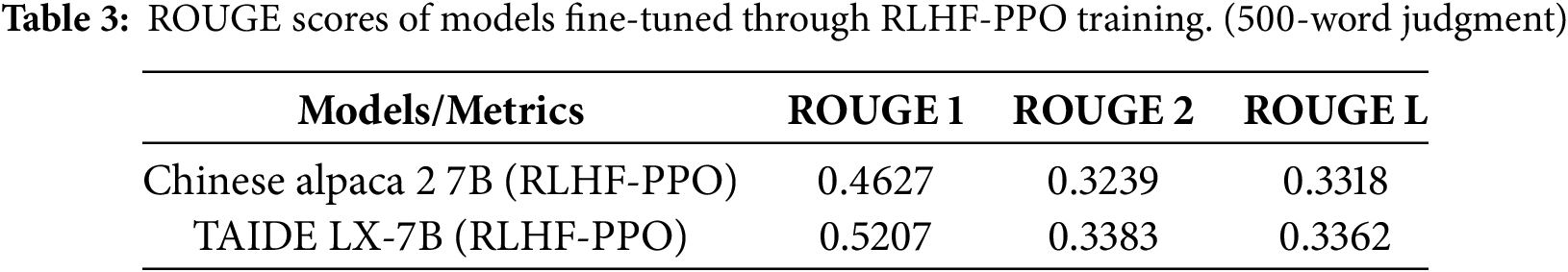

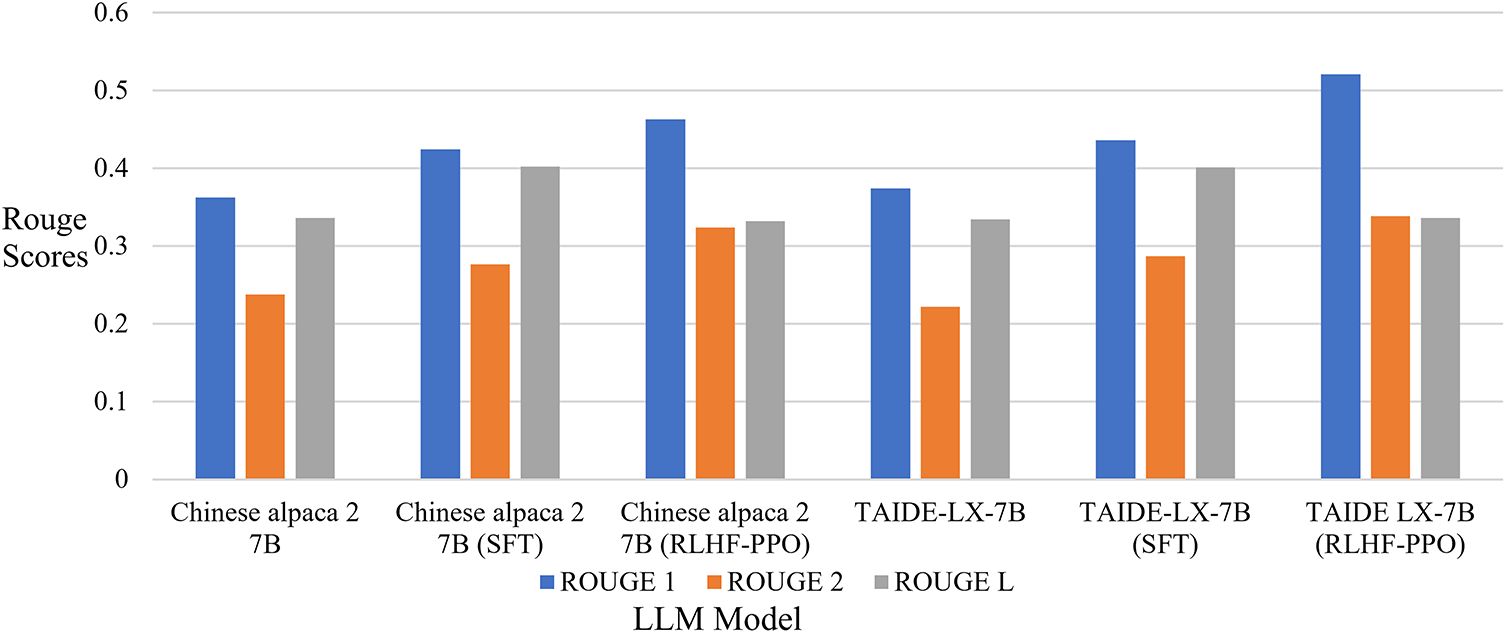

Considering computational resources, we take Chinese alpaca 7B and TAIDE LX-7B, trained in Chinese and based on Llama 2 7B, as examples. Using the generation of 500-word judgments for the experiment and employing RLHF-PPO training, the ROUGE-1, ROUGE-2, and ROUGE-L scores of both models are listed in Table 3. We believe that TAIDE LX-7B’s inclusion of Taiwanese training data results in slightly better performance than that of Chinese alpaca 7B. Fig. 10 compares the ROUGE-1, ROUGE-2, and ROUGE-L scores of the original Chinese alpaca 7B and TAIDE LX-7B models shown in Table 1, with those obtained after SFT and RLHF-PPO training, as presented in Table 3, Table 1 presents examples of the datasets used and generated during this study’s SFT. The ’main text’ consists of the first 500 words of the judgment’s main text, and the ’generative judgment’ is generated as an example within 500 words. From Table 1, after SFT, Llama 3 Taiwan-8B achieves the highest ROUGE-1, ROUGE-2, and ROUGE-L scores. The Llama 3 Taiwan-8B model primarily focuses on Taiwanese data. Similarly, among models in the Chinese language family, Chinese alpaca 2 13B outperforms Llama 3 Chinese 8B, as Chinese alpaca 2 13B is trained from the Alpaca 13B model. The results show that Chinese alpaca 2 13B slightly outperforms Llama 3 Chinese 8B in terms of performance.

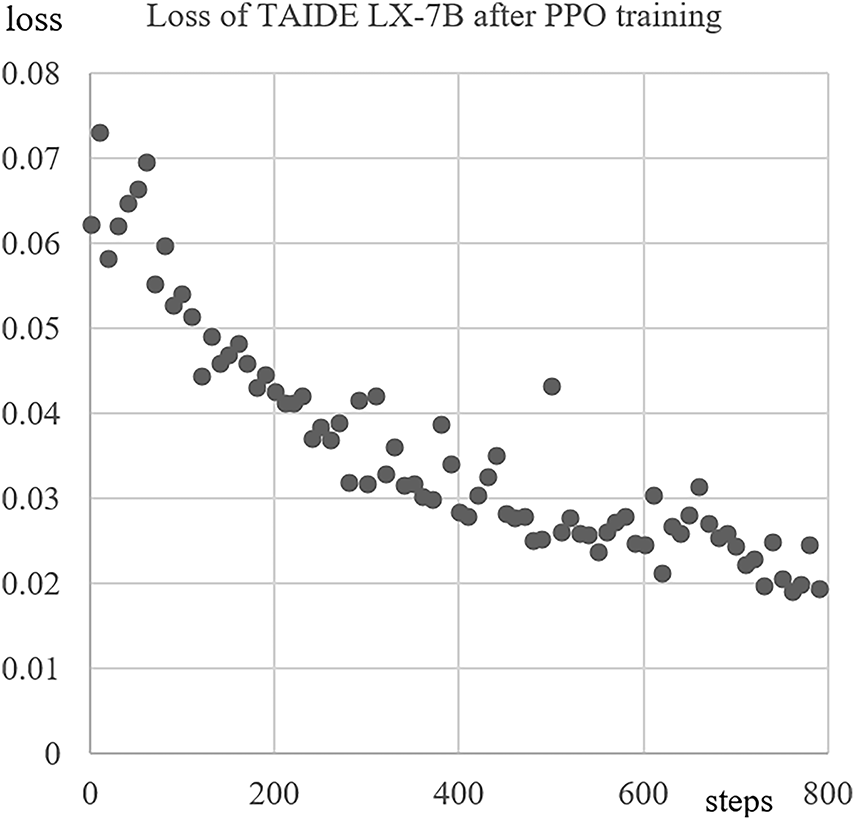

Figure 10: Loss value curve of TAIDE LX-7B after RLHF-PPO

4.3 Domain-Adapted Base Models

This study’s findings demonstrate that including important public data from Taiwanese government and judicial resources during the pre-training stage plays a vital role. This highlights an important insight: the performance of LLMs in domain-specific applications depends not only on fine-tuning strategies but is also profoundly influenced by the knowledge base established during pre-training and through a “localized” pre-training process. Llama 3 Taiwan-8B acquired a preliminary understanding of Taiwanese legal terminology, document rituals, and contextual patterns even before fine-tuning. As a result, it could absorb new knowledge more effectively than general-purpose Chinese models (e.g., Chinese Alpaca 2) or English-based models (e.g., Llama 3 8B), thereby achieving a higher performance ceiling after fine-tuning. This result reaffirms that, in specialized domains, selecting a base model with a pre-training data distribution highly relevant to the target domain is one of the key determinants of achieving optimal performance.

4.4 Further Refinement of Generation Quality with RLHF-PPO

In the experiments of this section, the study employs TAIDE-LX-7B and Chinese Llama 2 7B as examples, employing a dataset of 1000 samples to perform Reinforcement Learning with Human Feedback using Proximal Policy Optimization (RLHF-PPO). The loss values of RLHF-PPO are shown in Fig. 10.

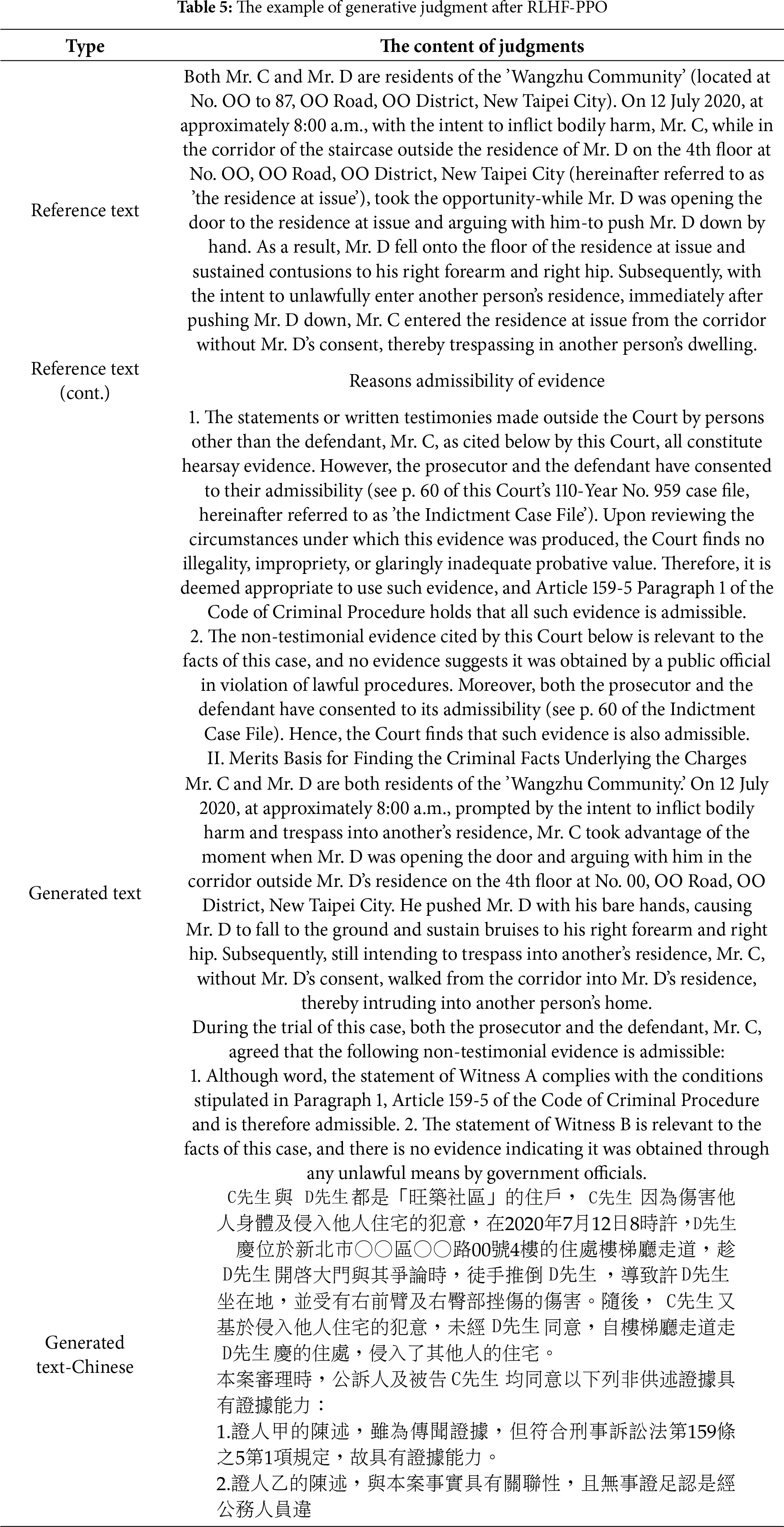

In Table 4, we provide examples of judgments generated by Chinese Llama 2 7B after RLHF-PPO training. Using approximately 500 Chinese words as a reference, it can be observed that the structure of the generated judgments is nearly complete. The plaintiff, defendant, criminal facts, and the stated charges exhibit coherent continuity.

After SFT and RLHF-PPO, Chinese alpaca 2 7B saw its ROUGE-1 score increase from 0.3623 to 0.4627 and its ROUGE-2 score from 0.2379 to 0.3239, while the ROUGE-L score showed no significant change. Similarly, TAIDE-LX-7B experienced an increase in ROUGE-1 from 0.3741 to 0.5207 and ROUGE-2 from 0.2217 to 0.3383 after SFT and RLHF-PPO, but ROUGE-L did not show a significant increase. Fig. 11 shows a comparison of the ROUGE scores for Chinese alpaca 2 7B.

Figure 11: A comparison of the ROUGE scores for Chinese alpaca 2 7B and TAIDE-LX-7B in the original models, SFT, and RLHF-PPO

To align the model’s generated output more closely with judgments written by human judges, we introduced Reinforcement Learning with Human Feedback using Proximal Policy Optimization (RLHF-PPO) training. As shown in Table 3, compared to using only SFT, the Chinese Alpaca 2 7B and TAIDE-LX-7B models improved further in their ROUGE-1 and ROUGE-2 scores after RLHF-PPO training. An impressive phenomenon worthy of in-depth discussion is that while RLHF-PPO significantly boosted ROUGE-1 and ROUGE-2 scores, its impact on the ROUGE-L score was minimal. The reasoning is as follows:

• Improvement in ROUGE-1/2: This reflects the model’s increased accuracy in generating key terms and phrases (e.g., charges, legal articles, names). The RLHF phase treats the original judgment as the ”preferred” output, rewarding the model for generating content with similar wording. This leads to better performance in unigram and bigram overlap.

• Stagnation in ROUGE-L: ROUGE-L measures the longest common subsequence and focuses more on sentence structure and overall flow. The RLHF aims to make the generated text more ”human-like” and natural. This may lead the model to learn to express the same legal meaning using different sentence structures rather than strictly replicating the original judgment. Therefore, although the qualitative merit of the generated text might be higher, the similarity of its sentence-level structure to the reference text does not increase, resulting in no significant improvement in the ROUGE-L score. This suggests that RLHF may be optimizing for text “readability” and “naturalness,” qualitative improvements that are difficult to measure with the ROUGE-L metric.

4.5 Qualitative Analysis: From Lexical Overlap to Legal Meaning

This section provides a qualitative analysis of the generated samples. As a case study, we examine the Chinese Llama 2 7B output after RLHF-PPO training.

• Structural Learning: The generated judgment draft (e.g., Table 5) is structurally complete, correctly distinguishing between sections like “Facts” and “Reasons”. It successfully extracts key elements, such as the defendant “Mr. C,” the victim “Mr. D,” and key actions like “pushed down by hand” and “trespassing” organizing them into coherent paragraphs. This indicates that the model has learned not only to generate words but also to handle the discourse patterns of legal judgments.

• The Risk of “Hallucination”: A closer look at the generated text reveals potential risks. For instance, in the case from Table 4, the model’s generated judgment states, “He is sentenced to eight months of imprisonment or a fine calculated at NT30,000 per day”. However, the original input text (the first 500 words) only mentions that “the punishment is determined as stated in the main text,” without specifying the exact sentence. This is a classic example of hallucination, where the model “invents” a plausible but factually non-existent judgment.

This case study powerfully highlights the danger of relying solely on ROUGE scores. The generated text might achieve a high ROUGE score because it contains many correct keywords, yet its core legal outcome is incorrect. This not only validates the necessity of human review by legal professionals but also points to a future research direction: what is needed are not just models that achieve high textual similarity, but models equipped with

5 Ethical and Legal Implications

While the proposed keyword-guided training approach offers significant advancements in the automation of judicial document generation, its application in sensitive legal contexts necessitates a thorough examination of the associated ethical and legal implications. The deployment of Large Language Models (LLMs) in the judicial process is not merely a technical challenge but also raises fundamental questions regarding fairness, accountability, transparency, and the potential for legal error.

Bias and Fairness Inherent biases present in this study’s training data could be perpetuated and even amplified by the LLM. The model is trained based on historical judgment data from Taiwan’s Judicial Yuan, which may reflect pre-existing biases. If not carefully addressed, the model might generate disadvantageous judgment drafts to specific groups, thereby undermining judicial fairness and trust.

Accountability and Transparency Due to LLMs’ “black box” nature, their transparency is subject to significant questioning. The reasoning process behind the legal text generated by the AI model used in this study is often opaque. If the AI-generated drafts contain misinterpreted evidence or suggest incorrect conclusions, the attribution of responsibility becomes more complex. Therefore, whether the responsibility lies with the presiding judge who uses the tool, the developers of the model, or the institution that deploys the system is an issue worthy of discussion.

Legal Risk and Accuracy As with any generative AI, the model produced in this study carries a risk of “hallucination”—generating factually incorrect or nonsensical content, which could cause the resulting judgment to deviate significantly from the judge’s original intent. In generating a judgment, this could manifest as citing non-existent legal precedents, misstating case facts, or incorrectly applying legal statutes. Such inaccuracies could have severe consequences, potentially leading to wrongful convictions or unjust rulings. As noted in this study, AI-generated judgments still require manual revision to correct for such errors and ensure their legal validity.

Mitigation Strategies Addressing these challenges requires a multifaceted approach. A crucial step is implementing a “human-in-the-loop” framework, where the AI is an assistive tool to generate initial drafts. However, the final legal reasoning, verification, and judgment remain firmly in the hands of qualified judicial personnel. Furthermore, future research can also develop Explainable AI (XAI) techniques tailored for the legal domain, which would help illuminate the model’s decision-making process. Before integrating such technologies into the judicial workflow, continuous auditing of training data for biases and rigorous, context-aware performance evaluations are also essential.

The emergence of LLMs has encouraged many researchers to explore their applications and conduct studies. However, due to the specialization and complexity of the legal domain, research on applying LLMs in law still needs to be completed. Harasta et al. analyzed generative AI, and the results indicate that legal documents written by humans generally outperform those generated by AI. [42] Currently, AI cannot fully generate legal documents. In addition to AI, hallucinations, syntax, and awkward phrasing frequently occur. Legal documents generated by AI still require manual revisions.

This study emphasizes the importance of cultural and legal context in judicial text generation. Taiwan’s judicial system is rooted in the custom of civil law, and its judgments feature a standardized format that differs from judgments in mainland China and common law opinions. By using a keyword-guided training framework and leveraging models pre-trained on Taiwanese data, we can ensure that the generated text aligns more closely with local linguistic conventions and legal reasoning patterns. This is instrumental in improving the credibility and relevance of AI-assisted judgment drafting in real-world judicial practice.

This study conducted experiments with a small-scale dataset, and there are several research limitations:

• This study is limited to legal judgments of injury cases with lengths of 500 and 1000 words. Expanding the model’s ability to handle longer documents will be an important direction for future research.

• The content generated by LLMs still carries the risk of hallucination, which may lead to legal inaccuracies. Therefore, outputs produced by LLMs must be reviewed by legal professionals and should only serve as an auxiliary tool.

• Due to computational resource constraints, the RLHF-PPO stage was validated only on two small-scale models. Future work should extend this approach to larger models (e.g., 13B or 70B parameters) to evaluate their generalization ability and scalability.

• The current evaluation relies on ROUGE scores, which cannot assess the correctness of legal reasoning. Future research should incorporate human evaluation conducted by legal experts to validate the value of generated content more comprehensively.

Therefore, this study uses LLMs to generate judicial decisions. Considering the constraints of computational resources and the judicial crew, this research uses training LLMs to generate judgments. The research introduces LLMs to decompose judgments into keywords and subsequently uses these keywords to train LLMs to generate judgments. The experimental results demonstrate that the method proposed in this study enhances the performance of judgment generation, including metrics such as judgment generation success rate, ROUGE-1, ROUGE-2, and ROUGE-L scores. In the first phase of this study, we trained the judgment generation capability using Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT) with commonly used LLMs within the Llama framework. As summarized in Tables 1 and 2, we found that the performance of each LLM improved after SFT, thereby providing preliminary evidence of the feasibility of this study. In the Llama 2 series of models, the best generation results for 500 words and 1000 words were produced by Chinese alpaca 2 13B and Chinese alpaca 2 7B, respectively. In the Llama 3 series of models, for both the 500-word and 1000-word outputs, Llama 3 Taiwan-8B performed the best.

Furthermore, after performing Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT) on the LLMs, they were further trained using RLHF-PPO to develop new LLMs. Small-scale data experiments demonstrated the feasibility of using RLHF-PPO. By comparing ROUGE scores, it was found that using RLHF-PPO could further enhance performance compared to using SFT alone. Therefore, the model underwent additional training through RLHF-PPO to align its outputs with human feedback.

This study has experimentally demonstrated that training an LLM to generate judicial decisions using a keyword-based approach involves obtaining keyword combinations from judicial decisions through the use of LLMs. Subsequently, the LLM is trained using SFT and RLHF-PPO, ultimately improving ROUGE scores.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Study conception and design: Yi-Ting Peng, Chin-Laung Lei; Literature review and data collection: Yi-Ting Peng; Analysis and interpretation of literature: Yi-Ting Peng; Visualization and graphical representation: Yi-Ting Peng; Draft manuscript preparation: Yi-Ting Peng. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data for this study is sourced from https://opendata.judicial.gov.tw/ (accessed on 20 March 2023).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

1Hoyle & Chuan-Fen, 2019, The Death Penalty Project (policy report).

References

1. Singhal K, Azizi S, Tu T, Mahdavi SS, Wei J, Chung HW, et al. Large language models encode clinical knowledge. Nature. 2023;620(7972):172–80. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-06291-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Hsu CHC, Tan G, Stantic B. A fine-tuned tourism-specific generative AI concept. Ann Tour Res. 2024;104:103723. doi:10.1016/j.annals.2023.103723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Wan Z, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Cheng F, Kurohashi S. Reformulating domain adaptation of large language models as adapt-retrieve-revise: a case study on Chinese legal domain. In: Ku LW, Martins A, Srikumar V, editors. Findings of the association for computational linguistics: ACL 2024. Bangkok, Thailand: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2024. p. 5030–41. [Google Scholar]

4. Li D, Jiang B, Huang L, Beigi A, Zhao C, Tan Z, et al. From generation to judgment: opportunities and challenges of LLM-as-a-judge. arXiv:2411.16594. 2024. [Google Scholar]

5. Peng Y, Lei C. Using bidirectional encoder representations from transformers (BERT) to predict criminal charges and sentences from Taiwanese court judgments. PeerJ Comput Sci. 2024;10:e1841. doi:10.7717/peerj-cs.1841. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Jain N, Goel G. An approach to get legal assistance using artificial intelligence. In: 2020 8th International Conference on Reliability, Infocom Technologies and Optimization (Trends and Future Directions) (ICRITO); 2020 Jun 4–5; Noida, India. p. 768–71. [Google Scholar]

7. Qin R, Huang M, Luo Y. A comparison study of pre-trained language models for chinese legal document classification. In: 2022 5th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Big Data (ICAIBD); 2022 May 27–30; Chengdu, China. p. 444–9. [Google Scholar]

8. Novelli C, Casolari F, Hacker P, Spedicato G, Floridi L. Generative AI in EU law: liability, privacy, intellectual property, and cybersecurity. Comput Law Secur Rev. 2024;55:106066. doi:10.1016/j.clsr.2024.106066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Vaswani A, Shazeer N, Parmar N, Uszkoreit J, Jones L, Gomez AN, et al. Attention is all you need. In: NIPS’17: Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems; 2017 Dec 4–9; Long Beach, CA, USA. p. 6000–10. [Google Scholar]

10. Rasmy L, Xiang Y, Xie Z, Tao C, Zhi D. Med-BERT: pretrained contextualized embeddings on large-scale structured electronic health records for disease prediction. npj Digital Med. 2021;4(1):86. doi:10.1038/s41746-021-00455-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Peng C, Yang X, Chen A, Smith KE, PourNejatian N, Costa AB, et al. A study of generative large language model for medical research and healthcare. npj Digit Med. 2023;6(1):210. doi:10.1038/s41746-023-00958-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Savelka J, Agarwal A, Bogart C, Song Y, Sakr M. Can generative pre-trained transformers GPT pass assessments in higher education programming courses? In: Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Innovation and Technology in Computer Science Education V. 1; 2023 Jul 7–12; Turku, Finland. p. 117–23. doi:10.1145/3587102.3588792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Wu S, Irsoy O, Lu S, Dabravolski V, Dredze M, Gehrmann S, et al. BloombergGPT: a large language model for finance. arXiv:2303.17564. 2023. [Google Scholar]

14. Ray PP. ChatGPT: a comprehensive review on background, applications, key challenges, bias, ethics, limitations and future scope. Internet of Things Cyber-Phys Syst. 2023;3:121–54. doi:10.1016/j.iotcps.2023.04.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Chouhan A, Gertz M. LexDrafter: terminology drafting for legislative documents using retrieval augmented generation. In: Proceedings of the LREC-COLING 2024. European Language Resources Association (ELRA); 2024 May 20–25; Torino, Italia. p. 10448–58. [Google Scholar]

16. Contini F. Unboxing generative AI for the legal professions: functions, impacts and governance. Int J Court Adm. 2024;15(2):1. [Google Scholar]

17. El Hamdani R, Bonald T, Malliaros FD, Holzenberger N, Suchanek F. The factuality of large language models in the legal domain. In: Proceedings of the 33rd ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management. CIKM ’24; 2024 Oct 21–25; Boise, ID, USA. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; 2024. p. 3741–6. doi:10.1145/3627673.3679961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Ziegler DM, Stiennon N, Wu J, Brown TB, Radford A, Amodei D, et al. Fine-tuning language models from human preferences. arXiv:1909.08593. 2020. [Google Scholar]

19. Schulman J, Wolski F, Dhariwal P, Radford A, Klimov O. Proximal policy optimization algorithms. arXiv:1707.06347. 2027. [Google Scholar]

20. Ouyang L, Wu J, Jiang X, Almeida D, Wainwright C, Mishkin P, et al. Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback. In: NIPS’22: Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems; 2022 Nov 28–Dec 9; New Orleans, LA, USA. p. 27730–4. [Google Scholar]

21. Rafailov R, Sharma A, Mitchell E, Manning CD, Ermon S, Finn C. Direct preference optimization: your language model is secretly a reward model. In: NIPS ’23: Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems; 2023 Dec 10–16; New Orleans, LA, USA. p. 53728–41. [Google Scholar]

22. Zheng R, Dou S, Gao S, Hua Y, Shen W, Wang B, et al. Secrets of RLHF in large language models Part I: PPO. arXiv:2307.04964. 2023. [Google Scholar]

23. Rahmani HA, Siro C, Aliannejadi M, Craswell N, Clarke CLA, Faggioli G, et al. Judging the judges: a collection of LLM-Generated relevance judgements. arXiv:2502.13908. 2025. [Google Scholar]

24. Branting LK, Lester JC, Callaway CB. Automating judicial document drafting: a discourse-based approach. In: Sartor G, Branting K, editors. Judicial Applications of Artificial Intelligence. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer; 1998. doi:10.1007/978-94-015-9010-5_2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Butt P. Modern legal drafting: a guide to using clearer language. 3rd ed. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

26. Savelka J. Unlocking practical applications in legal domain: evaluation of GPT for zero-shot semantic annotation of legal texts. In: Proceedings of the Nineteenth International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Law. ICAIL ’23; 2023 Jun 19–23; Braga, Portugal. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; 2023. p. 447–51. doi:10.1145/3594536.3595161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Deroy A, Ghosh K, Ghosh S. Applicability of large language models and generative models for legal case judgement summarization. Artif Intell Law. 2024 Jul;32:231. doi:10.1007/s10506-024-09411-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Branting LK, Callaway CB, Mott BW, Lester JC. Integrating discourse and domain knowledge for document drafting. In: Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Law. ICAIL ’99; 1999 Jun 14–17; Oslo, Norway. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; 1999. p. 214–20. doi:10.1145/323706.323800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Markovi M, Gostoji S. Legal document assembly system for introducing law students with legal drafting. Artif Intell Law. 2023 Dec;31(4):829–63. doi:10.1007/s10506-022-09339-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Narendra S, Shetty K, Ratnaparkhi A. Enhancing contract negotiations with LLM-based legal document comparison. In: Proceedings of the Natural Legal Language Processing Workshop 2024. Miami, FL, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2024. p. 143–53. [Google Scholar]

31. Westermann H. Dallma: semi-structured legal reasoning and drafting with large language models. In: Proceedings of the 2nd Workshop on Generative AI and Law, Co-Located with the International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML). Vienna, Austria; 2024. [Google Scholar]

32. Castano S, Ferrara A, Montanelli S, Picascia S, Riva D. A knowledge-based service architecture for legal document building. In: 2nd Workshop on Knowledge Management and Process Mining for Law, Co-Located with FOIS 2023; 2023 Jul 19–20; Sherbrooke, QC, Canada: CEUR Workshop Proceedings; 2023. [Google Scholar]

33. Liu S, Cao J, Li Y, Yang R, Wen Z. Low-resource court judgment summarization for common law systems. Inform Process Manage. 2024;61(5):103796. doi:10.1016/j.ipm.2024.103796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Touvron H, Lavril T, Izacard G, Martinet X, Lachaux MA, Lacroix T, et al. LLaMA: open and efficient foundation language models. arXiv:2302.13971. 2023. [Google Scholar]

35. TAIDE. TAIDE-LX-7B: a large language model. 2024 [cited 2024 Jun 9]. Available from: https://huggingface.co/taide/TAIDE-LX-7B. [Google Scholar]

36. Lin Z, Madotto A, Fung P. Exploring versatile generative language model via parameter-efficient transfer learning. In: Findings of the association for computational linguistics: EMNLP 2020; 2020 Nov 16–20; Online. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2020. p. 441–59. [Google Scholar]

37. Xu L, Xie H, Qin SZJ, Tao X, Wang FL. Parameter-efficient fine-tuning methods for pretrained language models: a critical review and assessment. arXiv:2312.12148. 2023. [Google Scholar]

38. Han Z, Gao C, Liu J, Zhang J, Zhang SQ. Parameter-efficient fine-tuning for large models: a comprehensive survey. arXiv:2403.14608. 2024. [Google Scholar]

39. Hu EJ, Shen Y, Wallis P, Allen-Zhu Z, Li Y, Wang S, et al. LoRA: low-rank adaptation of large language models. arXiv:2106.09685. 2021. [Google Scholar]

40. Stiennon N, Ouyang L, Wu J, Ziegler D, Lowe R, Voss C, et al. Learning to summarize with human feedback. In: NIPS’20: Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems; 2020 Dec 6–12; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 3008–21. [Google Scholar]

41. Devlin J, Chang MW, Lee K, Toutanova K. BERT: pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In: Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies; 2019 Jun 2–7; Minneapolis, MN, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2019. p. 4171–86. [Google Scholar]

42. Harasta J, Novotná T, Savelka J. It cannot be right if it was written by AI: on lawyers’ preferences of documents perceived as authored by an LLM vs a human. Artif Intell Law. 2024 Dec;25:1087. doi:10.1007/s10506-024-09422-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools