Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Next-Generation Lightweight Explainable AI for Cybersecurity: A Review on Transparency and Real-Time Threat Mitigation

1 Department of Computer Science, College of Computer and Information Sciences, Jouf University, Sakaka, 72388, Al-Jouf, Saudi Arabia

2 College of Computer Science and Software Engineering, Shenzhen University, Shenzhen, 518060, China

3 School of Computing, Engineering and the Built Environment, University of Roehampton, London, SW155PJ, UK

4 Department of Computer Engineering and Networks, College of Computer and Information Sciences, Jouf University, Sakaka, 72388, Al-Jouf, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Authors: Khulud Salem Alshudukhi. Email: ; Mamoona Humayun. Email:

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(3), 3029-3085. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.073705

Received 24 September 2025; Accepted 30 October 2025; Issue published 23 December 2025

Abstract

Problem: The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) into cybersecurity, while enhancing threat detection, is hampered by the “black box” nature of complex models, eroding trust, accountability, and regulatory compliance. Explainable AI (XAI) aims to resolve this opacity but introduces a critical new vulnerability: the adversarial exploitation of model explanations themselves. Gap: Current research lacks a comprehensive synthesis of this dual role of XAI in cybersecurity—as both a tool for transparency and a potential attack vector. There is a pressing need to systematically analyze the trade-offs between interpretability and security, evaluate defense mechanisms, and outline a path for developing robust, next-generation XAI frameworks. Solution: This review provides a systematic examination of XAI techniques (e.g., SHAP, LIME, Grad-CAM) and their applications in intrusion detection, malware analysis, and fraud prevention. It critically evaluates the security risks posed by XAI, including model inversion and explanation-guided evasion attacks, and assesses corresponding defense strategies such as adversarially robust training, differential privacy, and secure-XAI deployment patterns. Contribution: The primary contributions of this work are: (1) a comparative analysis of XAI methods tailored for cybersecurity contexts; (2) an identification of the critical trade-off between model interpretability and security robustness; (3) a synthesis of defense mechanisms to mitigate XAI-specific vulnerabilities; and (4) a forward-looking perspective proposing future research directions, including quantum-safe XAI, hybrid neuro-symbolic models, and the integration of XAI into Zero Trust Architectures. This review serves as a foundational resource for developing transparent, trustworthy, and resilient AI-driven cybersecurity systems.Keywords

The rapid evolution of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning has revolutionized cybersecurity [1]. These technologies enable advanced threat detection, anomaly identification, and automated response mechanisms [2–6]. However, as AI systems grow increasingly complex, their decision-making processes often become opaque. This is the problem which is usually referred to as the black box problem [7,8]. This invisibility on the part of cybersecurity is very challenging in that the rationale behind AI decisions must be known to be trusted, compliant, and responsive to incidents. Explainable AI has turned out to be a critical point of concern. It will enhance the appropriateness and responsible nature of AI models without negatively affecting their performance [9–11].

Explainable AI integration in cybersecurity is an important interdependency of interpretability and security. This will make sure that the AI that is used as a security tool is not only helpful but familiar to the human operators [12]. In critical environments such as network security, fraud detection, and malware analysis, stakeholders should have the capacity to authenticate and rationalize AI decisions. Security analysts, compliance officers, and organisational leaders can be part of this group and should avoid algorithmic bias and system integrity [13,14]. AI outputs may bring about mistrust, wrong security policy, and nonconformity with regulations without clear explanations. This is particularly a critical issue in industries where data protection laws are stringent, like the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) [15], and the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) [16].

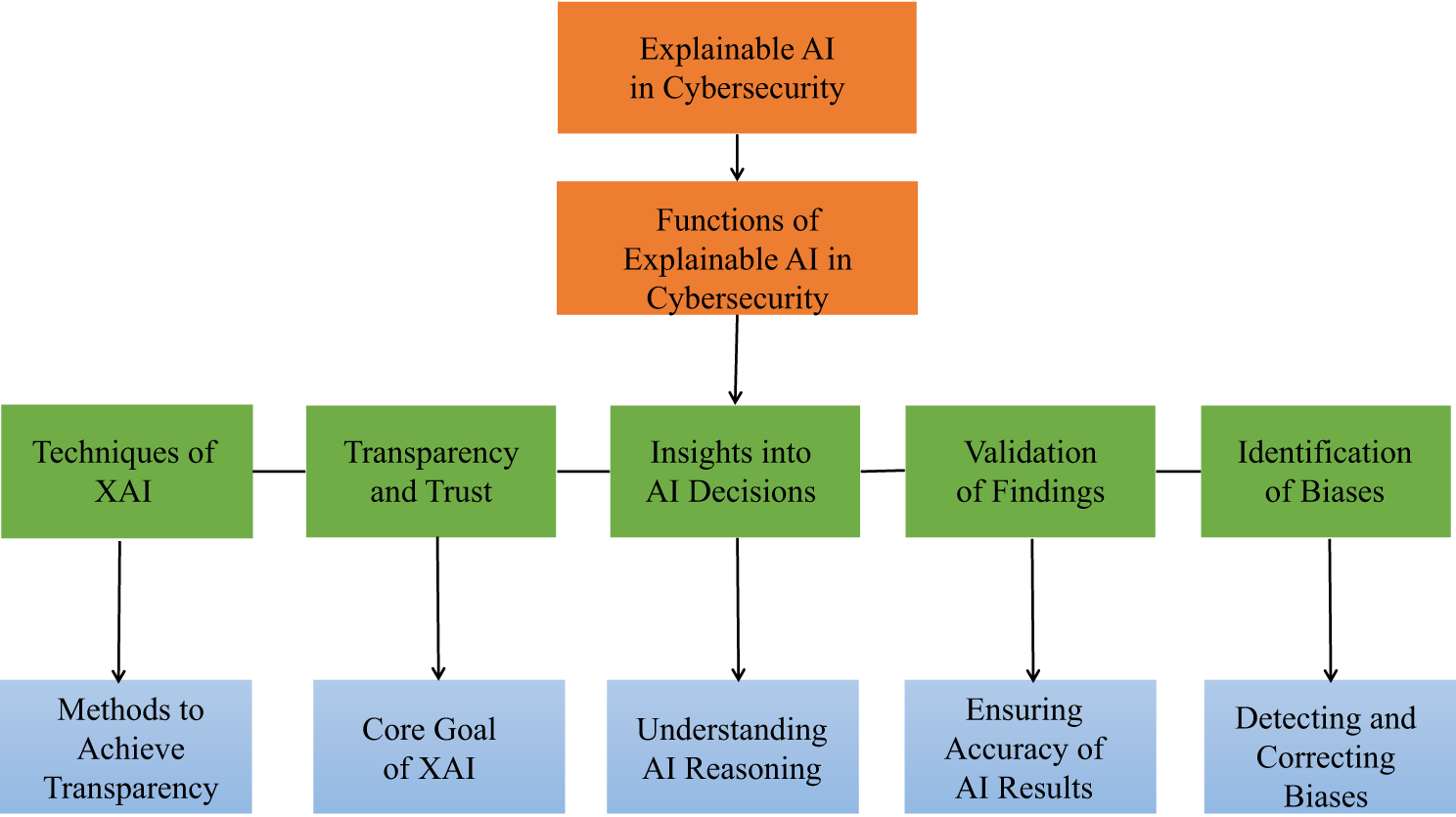

The main concept of explainable AI in cybersecurity is that the user must understand the decision made by the AI. This enhances transparency and helps to build trust. One should also know why an AI makes a certain conclusion. The users should also be in a position to substantiate the validity of the results of the AI. Moreover, it is necessary to eliminate and manage biases, which will make the results unbiased and objective. Furthermore, Fig. 1 discusses the Explainable AI (XAI) architecture of cybersecurity, its main functions, methods, and objectives. According to the diagram, XAI methods like the creation of interpretable models or saliency maps are important in such critical roles as creating transparency and trust, understanding AI decisions, justifying findings, and detecting biases. All these functions are directly related to the main objective of the XAI, that is, to maintain an understandable, precise, and unbiased AI process of reasoning, which ultimately enables human analysts to be sure and trust automated cybersecurity systems. Such a visual overview is efficient to relate practical methods of XAI to the objectives that are general in a security context.

Figure 1: Core principles of explainable AI for cybersecurity

The latest models of cybersecurity consider AI to be the one that detects threats in real-time, analyzes behavior, and predicts security [5,17–19]. Techniques like deep learning, ensemble methods, and reinforcement learning have demonstrated superior accuracy in identifying sophisticated cyber threats [20]. These include zero-day exploits, Advanced Persistent Threats, and polymorphic malware. Yet, these models often function as black boxes, providing little to no insight into their decision-making processes. For example, an AI system may erroneously flag a legitimate user’s activity as malicious without clear justification. This can lead to unnecessary access denials or operational disruptions [21,22].

Explainability in cybersecurity AI is not merely a convenience but a necessity. Security teams must be able to:

• Audit AI decisions to ensure automated threat classifications align with organizational security policies.

• Debug false positives/negatives by identifying why an AI model misclassified a benign file as malware or failed to detect a real attack.

• Comply with regulations by meeting legal and ethical standards that mandate transparency in automated decision-making.

• Enhance human-AI collaboration by allowing security analysts to refine AI models based on interpretable feedback.

The absence of explainability places organizations at risk. They may implement AI systems that are efficient on paper but unreliable in practice. This unreliability can culminate in security breaches, financial losses, and reputational damage.

Highly complex models, such as deep neural networks and ensemble methods, often achieve state-of-the-art performance but are inherently difficult to interpret. Simpler models, such as decision trees or logistic regression, are more transparent but may lack the precision required for modern cyber threats [23,24]. Striking a balance between accuracy and explainability remains a key challenge. Furthermore, cyber attackers can potentially reverse-engineer Explainable AI techniques to understand how AI-based security systems detect threats. This knowledge enables them to craft evasion strategies [25,26]. For example, if an AI model’s decision boundaries are exposed, attackers could modify malware to bypass detection while remaining undetected.

The threats in the cyber domain keep changing, and AI models must adapt continuously. Explainability methods must also evolve, ensuring interpretations remain valid with each new model version. Traditional explanation strategies like SHAP and LIME might not perform well in such dynamic settings. Moreover, many Explainable AI approaches are computationally costly, making them impractical for real-time cybersecurity where low-latency response is vital. Therefore, creating scalable interpretability that does not decrease system performance is a persistent research problem.

Methods such as Shapley Additive Explanations [27] and Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations [28] provide post-hoc explanations for any AI model by approximating its behavior. These techniques are particularly useful in cybersecurity for explaining individual predictions, such as why a specific network packet was flagged as malicious. Some AI models, such as rule-based systems [29], decision trees [30], and linear models [31], are inherently interpretable. Although they may not match the performance of complex models in all scenarios, they are increasingly used in security applications where transparency is prioritized.

A viable alternative is the combination of interpretable models and complex AI, which provides a middle ground. An example is that a deep learning model may detect an anomaly, and a rule-based system would be used to provide an explanation of it in human form. The application of AI dashboards to security operations centres is also becoming popular, and these devices enable analysts to consider AI conclusions [32]. They help fill the divide between the technicality of the explanation and practical security knowledge.

To summarise, Explainable AI is an essential innovation in the area of cybersecurity that allows AI-based protection to be both strong and transparent. Interpretability will lead to more trustworthy systems, high-quality regulatory compliance, and human-AI interaction. Nevertheless, there are still great issues in the area of accuracy, security, and scalability. Future developments of cybersecurity products will be defined by future advances in Explainable AI processes, adversarial resistance, and regulatory systems. Explainability needs to be introduced in the security systems to develop resilient and stable AI-based security systems in the face of more advanced cyber threats.

As demonstrated in this review paper, Explainable AI is highly required in the cybersecurity domain. AI-based security systems are normally used to model black-box models, and this negates trust and transparency. Such a systematic study of the XAI methods places us in a position to have the entire picture of the trade-off between interpretability and security. The ability to interpret them, security issues, and implementation are discussed. Adversarial robustness, regulatory compliance, and moral factors are some of the major challenges as reported in the research. It also talks about the novel opportunities in the field of research that involve quantum-safe XAI and the use of AI in a zero-trust architecture. This work can be used as the foundation for the creation of safe, open, and regulation-compliant AI systems to address cybersecurity. Such systems would be effective and suitable in the contemporary digital world, as they would enable us to debate the primary principles and analyse them in-depth.

The following are the main contributions of the current review study:

1. Comprehensive Analysis of XAI in Cybersecurity: Presents an exhaustive examination of Explainable AI (XAI) techniques and their potential to strengthen cybersecurity strategies and systems.

2. Comparative Evaluation of XAI Techniques: Systematically assesses various XAI methods based on interpretability, security risks, and practical applicability in cybersecurity systems.

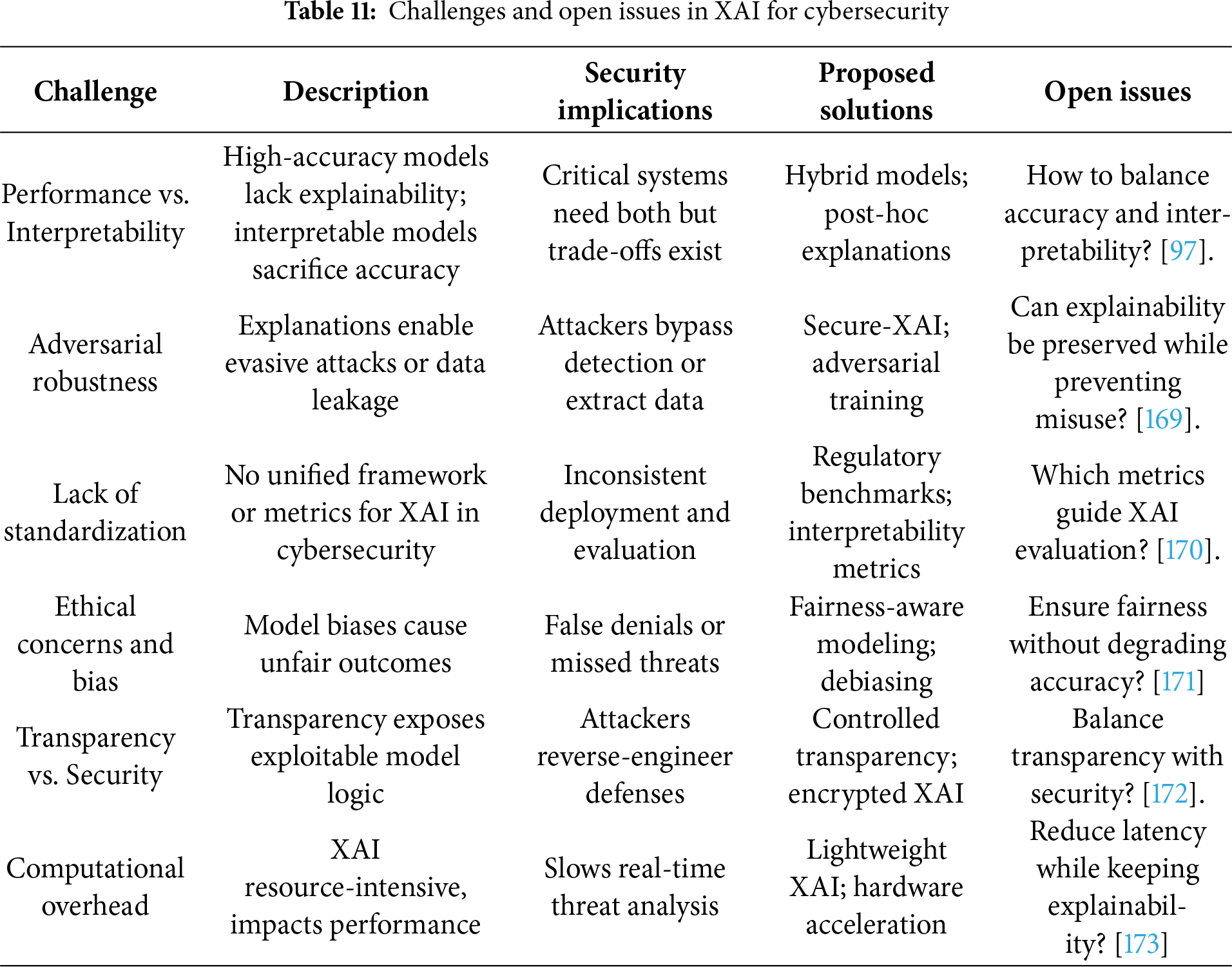

3. Identification of Critical Challenges: Highlights fundamental issues including the explainability-security trade-off, adversarial robustness, standardization gaps, and ethical concerns.

4. Regulatory and Compliance Analysis: Examines the role of explainability in major regulations (GDPR, NIST, ISO 27001) with emphasis on auditability and forensic requirements.

5. Future Research Directions: Proposes novel research avenues in XAI applications for zero-trust architectures, post-quantum cybersecurity, and hybrid models integrating symbolic reasoning with deep learning.

6. Bridging Transparency and Security: Emphasizes the development of interpretable, adversarially robust AI models that maintain cybersecurity effectiveness.

The review can be used as an advanced source of literature by researchers, policymakers, and cybersecurity professionals who are striving to create powerful, explainable AI-based systems of security.

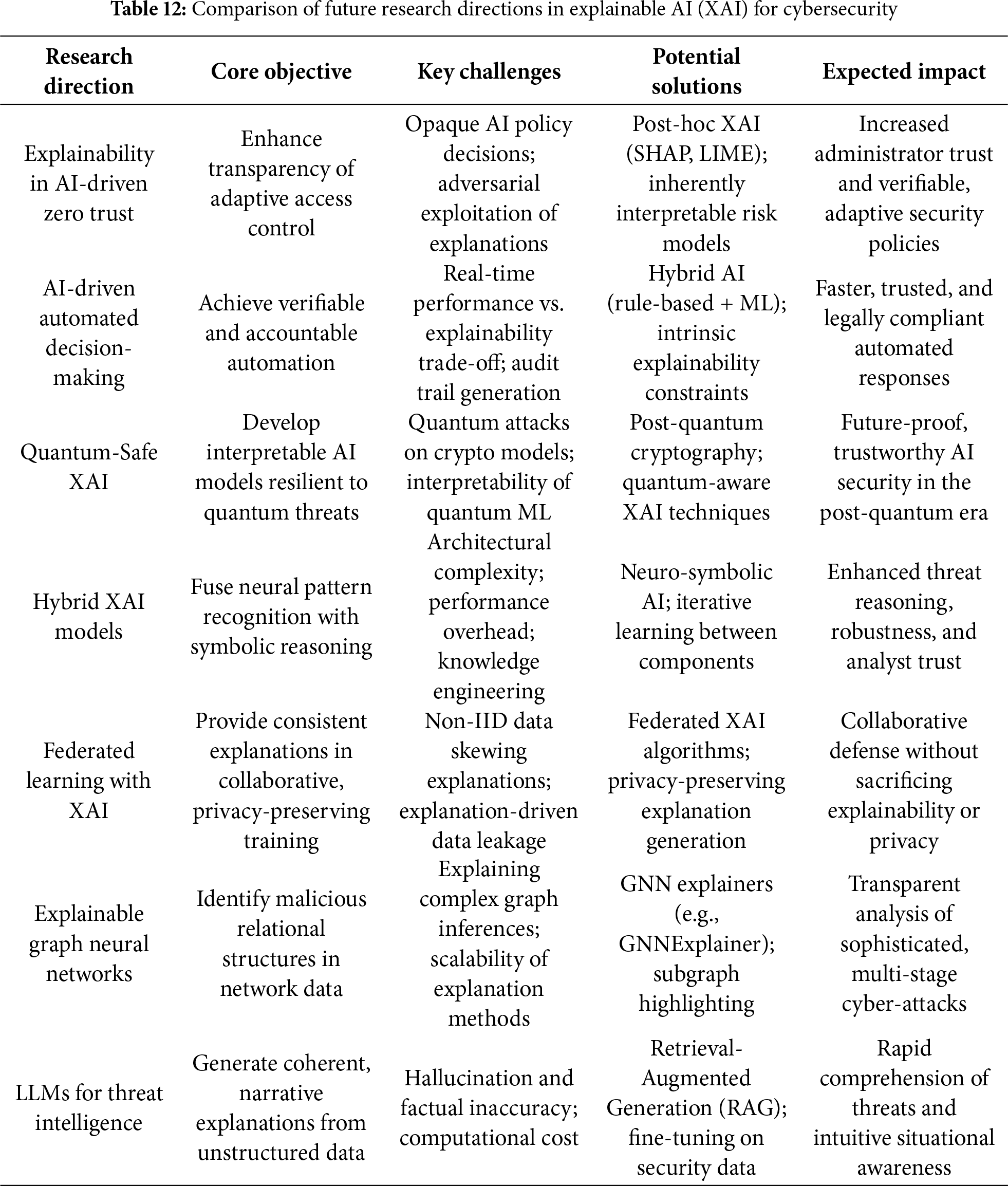

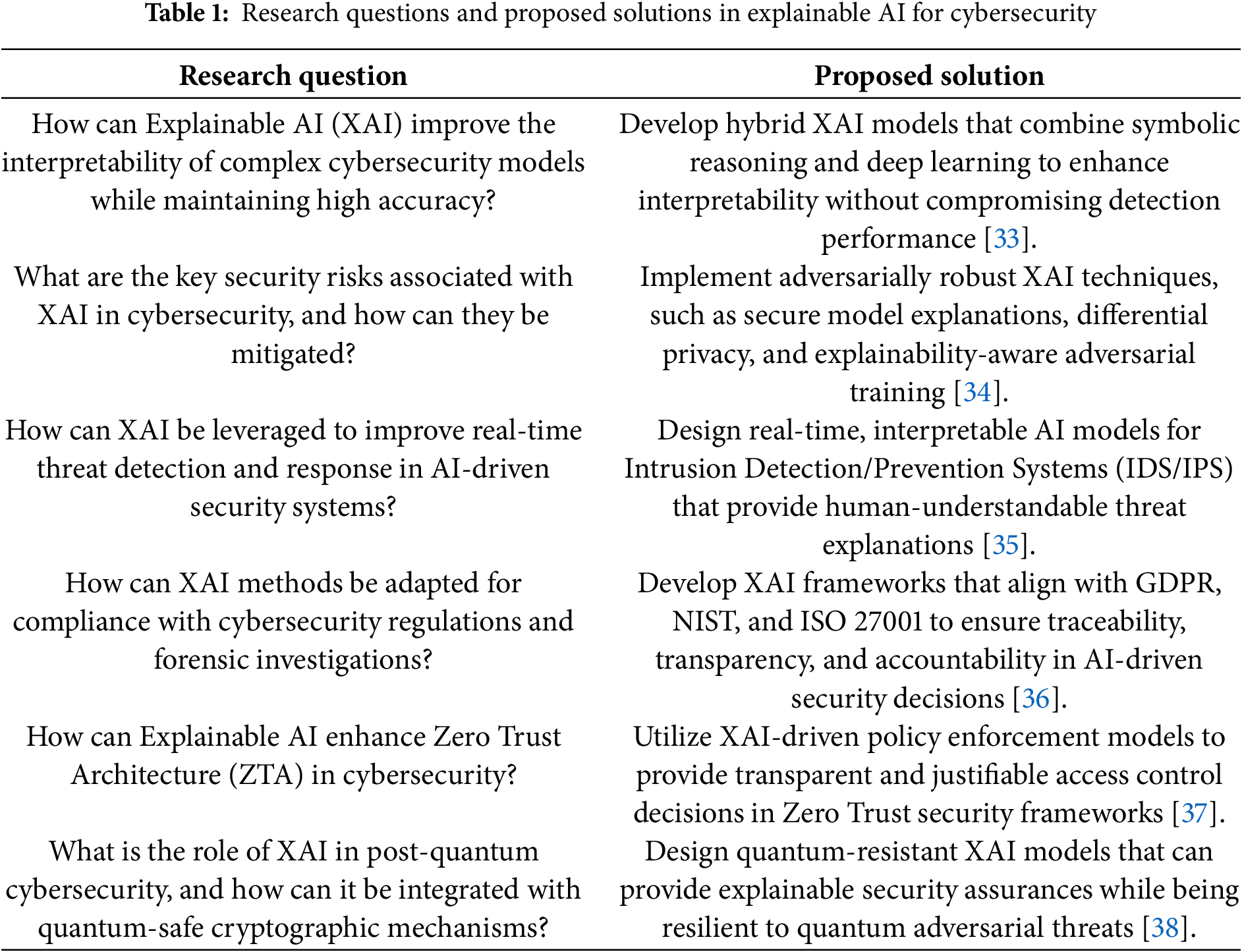

1.3 Research Questions and Proposed Solutions

This section identifies critical research questions in Explainable AI for cybersecurity and presents corresponding solutions to address these challenges, as detailed in (Table 1). The proposed solutions focus on four key objectives. The first is to enhance model interpretability without compromising security effectiveness. The second involves developing robust defenses against the adversarial exploitation of XAI systems. The third objective is to ensure compliance with evolving regulatory frameworks. Finally, the fourth aims to facilitate XAI integration into next-generation security paradigms, including zero-trust architectures and post-quantum cybersecurity. By systematically addressing these research questions, this study aims to bridge the gap between AI-powered security and operational explainability. This work ultimately advances the development of transparent, robust, and efficient cybersecurity systems.

This section introduces (Table 2), which summarizes the mathematical formulas and abbreviations used throughout this review. The table demonstrates the range of mathematical formalisms employed to describe Explainable AI concepts within cybersecurity. Each entry includes a brief description to clarify the formula’s purpose and rationale. Providing this reference allows readers to approach the technical content with greater ease and understanding. This approach bridges the gap between theoretical concepts and their practical implementation in cybersecurity contexts.

Explainable AI serves as a crucial cybersecurity tool by making AI decision-making processes transparent. This section provides precise mathematical definitions for key cybersecurity applications, which will be elaborated in subsequent sections.

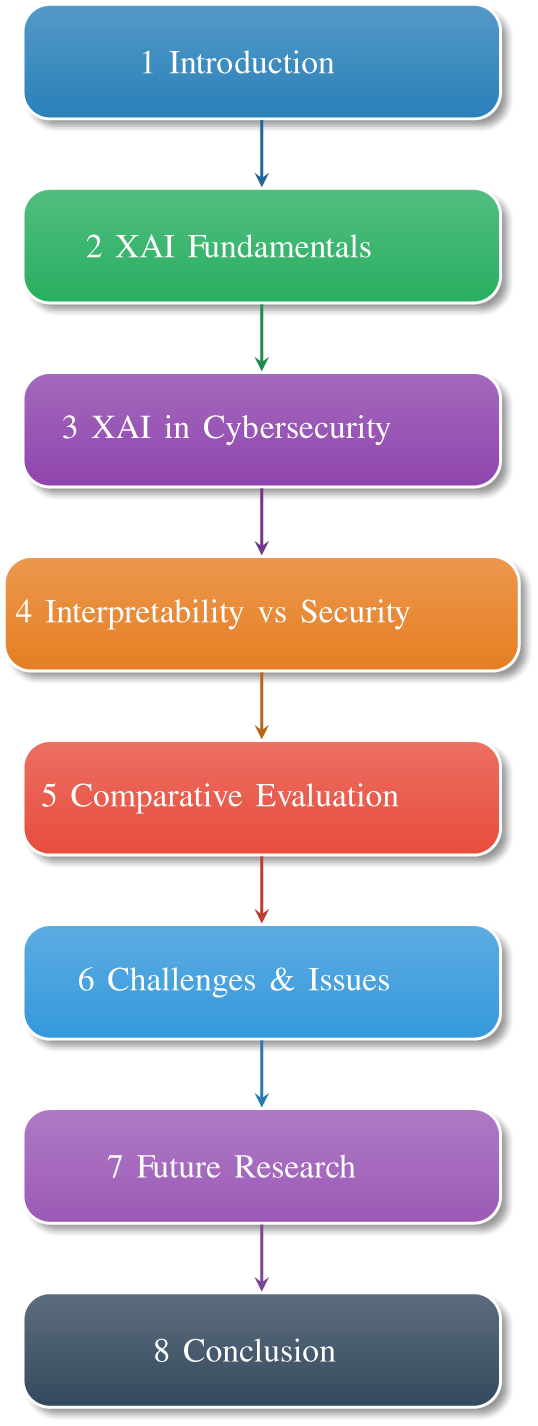

The article begins with an roadmap of (Fig. 2) with introduction highlighting the importance of XAI in addressing the “black box” problem in AI-driven cybersecurity systems, emphasizing its role in enhancing trust, compliance, and accountability. Section 2 outlines the preliminaries, including mathematical formulations used in the study. Section 3 delves into the fundamentals of XAI, covering definitions, key techniques (e.g., SHAP, LIME, Grad-CAM), and applications in cybersecurity tasks like intrusion detection, malware classification, and phishing detection. Section 4 explores the role of XAI in improving threat detection, regulatory compliance, and forensic investigations. Section 5 discusses the trade-off between interpretability and security, detailing risks such as adversarial attacks and defense mechanisms like secure-XAI models and differential privacy. Section 6 offers a comparative evaluation of XAI techniques, while Section 7 identifies challenges like performance-interpretability trade-offs and ethical concerns. Finally, Section 8 proposes future research directions, including quantum-safe XAI and hybrid models, concluding with a summary of XAI’s transformative potential and inherent risks in cybersecurity.

Figure 2: Roadmap of the review article

2 Fundamentals of Explainable AI (XAI)

The field of Explainable AI investigates the principles and practices for making AI models transparent, understandable, and trustworthy for human users. In this section, the key concepts are explained, such as model explainability, fairness, and accountability. These are the factors that provide full profiling and justification of the decision-making processes of AI systems. The most significant concepts are introduced in the following sections.

2.1 Definition and Importance of XAI

Explainable AI is defined as a set of approaches and processes that enhance the interpretability, transparency, and understandability of artificial intelligence models to human users [39,40]. Even classical AI systems, especially the deep learning models, can be black boxes in which even professionals are not aware of how they arrive at their decision-making [7,9,41]. The consequences in the high-stakes fields like cybersecurity, medicine, and finance are immense. To establish trust, accountability, and regulatory compliance, it is required to have a full-scale picture of how AI systems work internally [42–44].

The use of XAI in the world of cybersecurity is important because of various issues. First, it enhances trust in AI-based security systems by making it possible to have the rationalisation of the decisions and comes in a transparent way that enables security experts to prove the model predictions. Second, it improves incident response by displaying the logic of the actions that make the occurrences attacks or anomalies. Third, it helps to adhere to the regulatory regimes, including the General Data Protection Regulation, which entails disclosure of automated decision-making [45]. Lastly, by exposing the vulnerability of models that are potentially exploited by the adversaries, XAI enhances defensive security, thus creating more robust AI-based security systems [46].

XAI practices are designed to achieve transparent, interpretable, and trusting AI system decisions. Such approaches are especially important in industries with high responsibility, such as healthcare, finance, and security, where it is necessary to know the rationale of AI evaluations. The methods of XAI are broadly classified into two groups: intrinsic explainability, which is meant to be explainable, and post-hoc explainability, which explains decisions that have been trained in complex models.

2.2.1 Post-Hoc vs. Intrinsic Explainability

There are two major categories of XAI approaches:

Post-Hoc Explainability: These methods describe model predictions when the model has generated these predictions [47,48]. They do not change the underlying AI model, but instead offer some explanations in terms of visualizations, feature importance measurements, or surrogate models. The use of post-hoc interpretability is especially useful in the context of deep learning models, which are complex and obscure in nature.

Intrinsic Explainability: These techniques are built directly into the AI model’s architecture. Models with intrinsic explainability, such as decision trees and linear regression, offer transparent decision-making processes [49,50]. Unlike black-box models, they require no additional interpretation methods as their structure naturally supports human understanding. However, such models may sometimes sacrifice predictive performance compared to more complex deep learning approaches.

The deep learning-based intrusion detection systems are opaque and are often analysed by post-hoc methods. These techniques analyse trained neural networks to offer information on the decision-making processes, without altering the models. The use of explanation tools, including LIME, SHAP, and saliency maps, is commonly used to unveil the influence of features in predictions and, therefore, increase the trustworthiness and transparency of automatic systems. Nevertheless, post-hoc explanations can come with such problems as a lack of consistency and behavioural variance with the real model.

Contrary, explainable models such as decision trees, rule-based systems, and fuzzy logic frameworks are primarily applied in any situation where there is an anomaly detection requirement, and where it is important to provide an explicit explanation of model results. Those models are concerned with interpretability, i.e., cybersecurity experts can be capable of following the outcome of detection to rules or logical models that can be read by humans. This skill would be useful particularly during emergency life situations, which demand accountability and swiftness.

A trade-off between explainability and performance has been one of the dilemmas that have been at the centre of the field. Uncomplicated models are more transparent, and deep learning ones are more accurate. The current studies aim to fill such a gap by using hybrid methods that combine deep learning with symbolic reasoning or rule-based parts. These hybrid systems are supposed to provide high performance in detection and interpretability. Moreover, the increasing regulatory and moral demands are increasing the pace of using explainable AI in cybersecurity. Deciding on whether to interpret the post-hoc or provide intrinsic explanations is thus largely dependent on the context of the deployment, operational objectives, and tolerance to risk by the organisation.

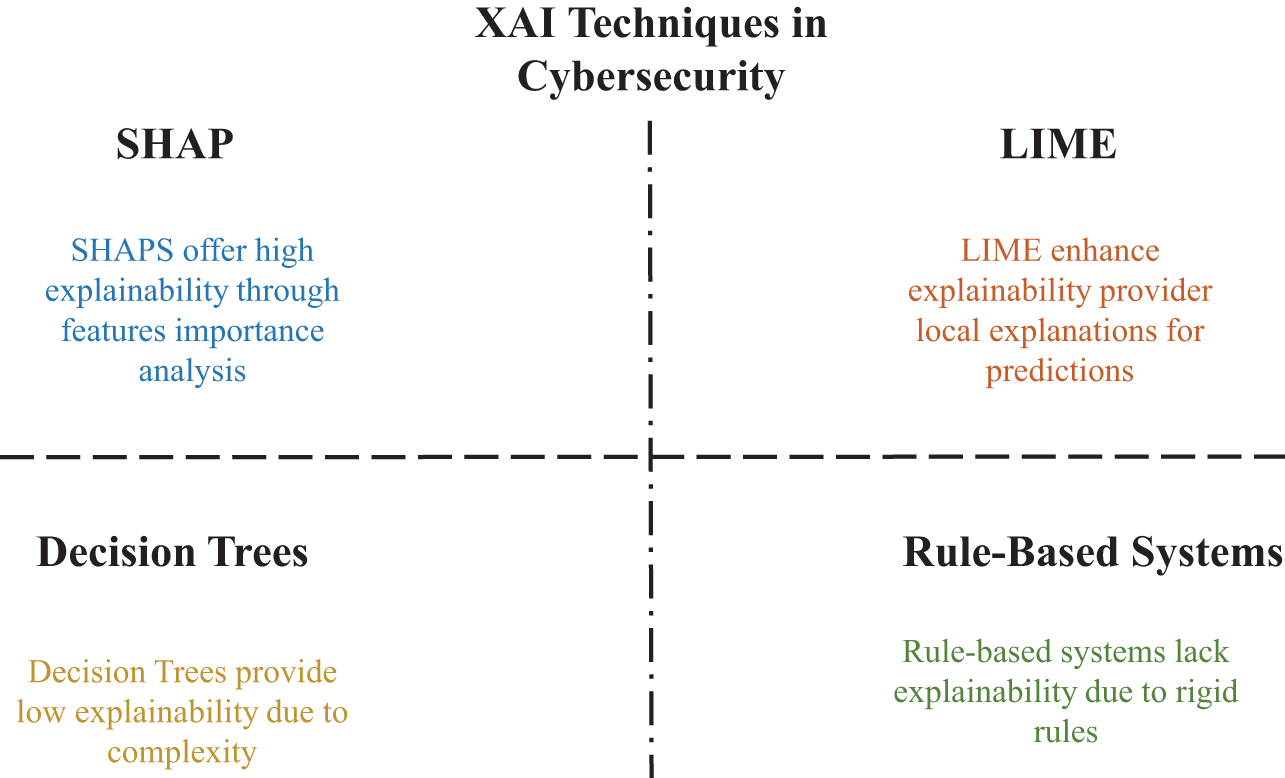

We compares various Explainable AI methods used in cybersecurity and evaluates their explanatory capabilities. SHAP provides high explainability by precisely measuring feature importance for individual predictions. LIME contributes to transparency by generating local, model-agnostic explanations for each instance. While Decision Trees are interpretable for simple models, their explainability diminishes significantly as complexity increases. Rule-based systems offer structured and transparent logic but often lack flexibility due to their reliance on predefined, rigid rules. Fig. 3 illustrates the fundamental trade-offs between interpretability and complexity in AI-driven cybersecurity solutions.

Figure 3: Comparison of XAI techniques in cybersecurity based on explainability. In a practical case study using the EMBER dataset, SHAP analysis revealed that NumberOfSections and SizeOfCode were the most impactful features for a malware classifier, aligning with expert intuition and traditional reverse engineering practices [51]

2.2.2 Model-Specific vs. Model-Agnostic Approaches

Explainable AI techniques can be further classified into model-specific and model-agnostic approaches, each offering distinct advantages for cybersecurity applications.

Model-Specific Approaches: The techniques have specific machine learning architecture dependencies and use the internal mechanisms to produce the explanations [52]. In particular, Grad-CAM is designed to work with convolutional neural networks, and it allows visualising the important areas in the image-based cybersecurity processes like malware detection [53]. Likewise, decision trees and gradient boosting models have built-in feature importance scores, which are intrinsically interpretable without the need to use additional tools to interpret the models.

Model-Agnostic Approaches: The techniques are also not architecture-specific and can be generalised to any black-box AI system [54]. Well-known ones are SHAP and LIME, which produce explanations using surrogate models or local approximations to the behaviour of the target model [55,56]. Due to this flexibility, they can be used in a wide range of cybersecurity applications, including phishing, network traffic, and others.

The explainability-performance trade-off is a trade-off that is considered carefully when choosing between model-specific or model-agnostic methods. Model-specific models are typically more precise and faithful, and only offer specific model architectures. The model-agnostic approaches are more flexible and are commonly used to analyse the complex deep learning systems within the context of cybersecurity to guarantee the required degrees of trust and transparency among the various AI implementations.

Beyond the established post-hoc and intrinsic methods, several emerging XAI paradigms offer novel avenues for transparency in cybersecurity:

• Causal Interpretability: This approach moves beyond correlational feature importance to model the cause-effect relationships within data [57]. In cybersecurity, this could help distinguish between features that are merely correlated with an attack and those that actually cause it. For example, a causal model could determine if a specific sequence of system calls genuinely leads to a privilege escalation, providing deeper, more actionable insights for root cause analysis during forensic investigations.

• Prototype-Based Explanations: Methods like ProtoPNet explain classifications by comparing inputs to prototypical examples learned during training [58]. In malware classification, a model could justify its decision by showing, “This file is malicious because it contains code segments similar to these prototypical snippets from the WannaCry family.” This provides intuitive, case-based reasoning that is natural for security analysts.

• Concept Activation Vectors (CAV): CAVs interpret internal neural network layers in terms of human-understandable concepts [59]. A network traffic analyzer could be probed to reveal that it flags traffic as anomalous because it activates neurons associated with the concepts of “covert channel” or “beaconing,” directly linking model internals to high-level threat concepts.

These emerging paradigms address limitations of traditional XAI methods by providing more intuitive, causal, and concept-based explanations that align better with human reasoning processes in security analysis. Their integration into cybersecurity workflows represents a promising direction for enhancing both transparency and actionable intelligence.

Numerous Explainable AI methods have been developed to enhance the interpretability of AI models, each offering distinct advantages for cybersecurity applications.

SHAP: Based on cooperative game theory, SHAP quantifies the contribution of individual input features to model predictions by assigning each feature an importance score. This method provides a unified approach to explain model output. It is particularly valuable in intrusion detection systems, where security analysts require objective, quantitative insights into which network attributes most strongly influenced the classification of an event as an anomaly [60].

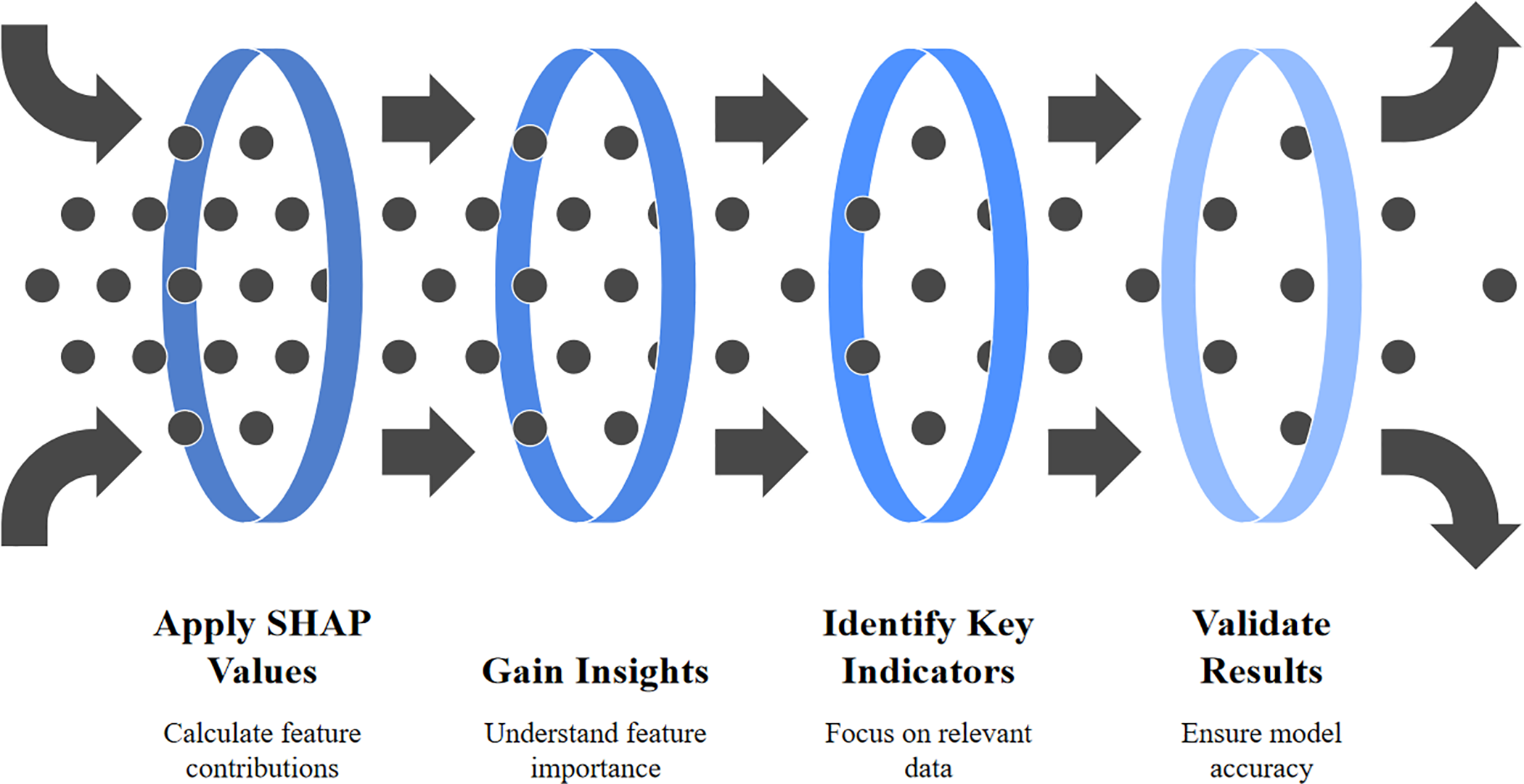

Fig. 4 outlines the application of SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) values in a machine learning workflow, illustrating a process that begins with calculating the individual contribution of each feature to a model’s prediction, which then facilitates gaining insights into overall feature importance, helps in identifying the key indicators or most influential variables, and finally supports validating the model’s results to ensure its predictions are accurate and reliable.

Figure 4: Enhancing intrusion detection with SHAP

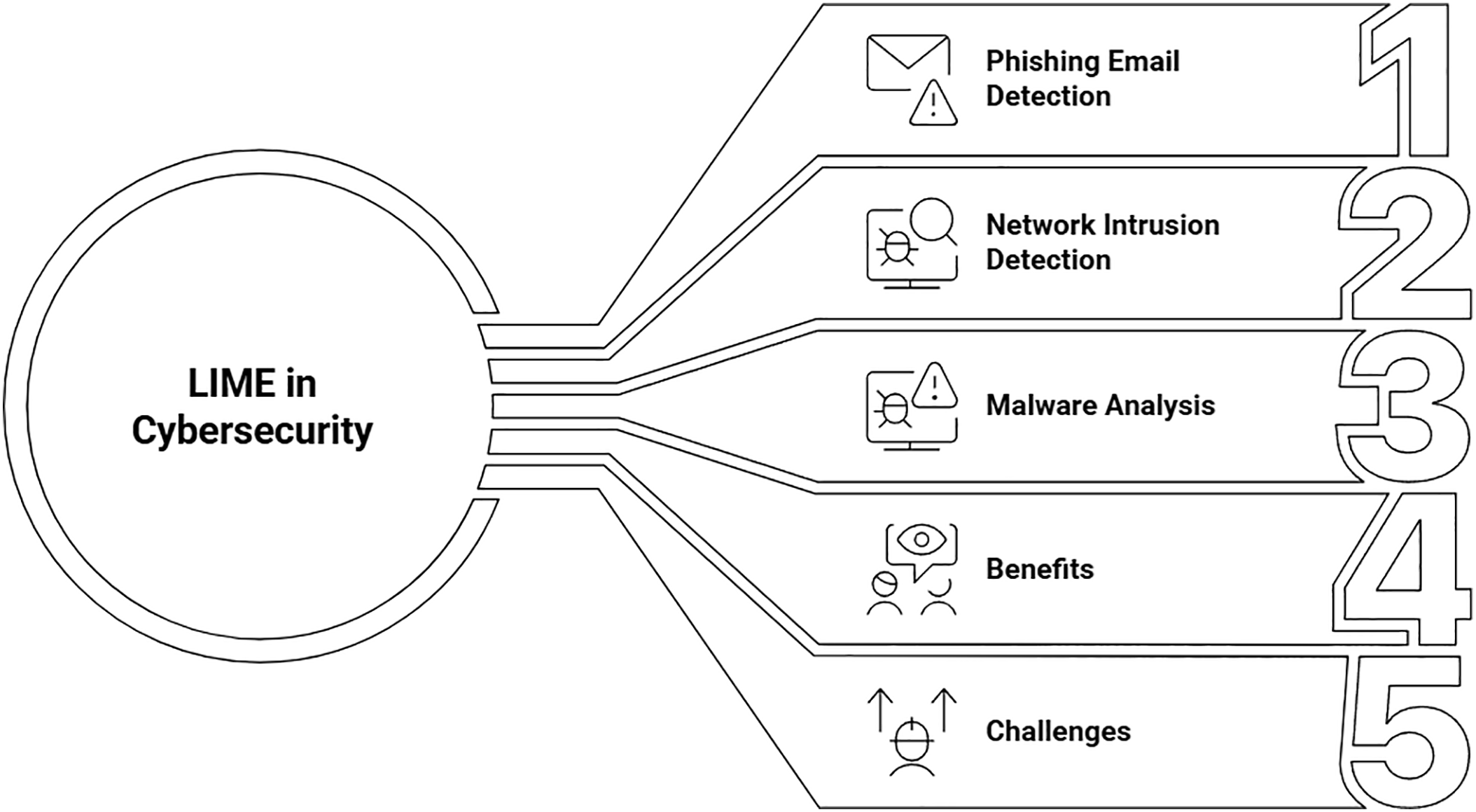

LIME: This model-agnostic method creates local, interpretable models to approximate the predictions of complex AI systems [61]. In cybersecurity applications, LIME can explain individual classifications, such as why a specific email was flagged as phishing or a network packet was deemed malicious. These explanations provide security teams with actionable insights, enabling them to respond effectively to potential threats like online fraud or unauthorized network access [62].

Fig. 5 outlines the application of the LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) method within the field of cybersecurity, positioning it as a crucial tool for interpreting complex “black-box” machine learning models. It highlights key use cases where LIME provides explainable AI (XAI) insights, such as understanding why an email is flagged as phishing, identifying the features that indicate a network intrusion, or analyzing the malicious behavior of software. The figure also acknowledges that while LIME offers significant benefits by building trust in AI systems, aiding in model debugging, and improving forensic analysis, its practical adoption faces challenges like the computational overhead required to generate explanations and ensuring the explanations themselves are robust and reliable for high-stakes security decisions.

Figure 5: LIME’s role in cybersecurity, highlighting key applications such as phishing detection and malware analysis, along with its associated benefits and challenges

Grad-CAM: This model-specific visualization technique interprets Convolutional Neural Networks by highlighting the regions of an input image that most strongly influence the model’s decisions [63]. In cybersecurity, Grad-CAM is applied to visualize binary data represented as images, aiding in the classification and analysis of malware families by revealing which patterns the model uses for identification.

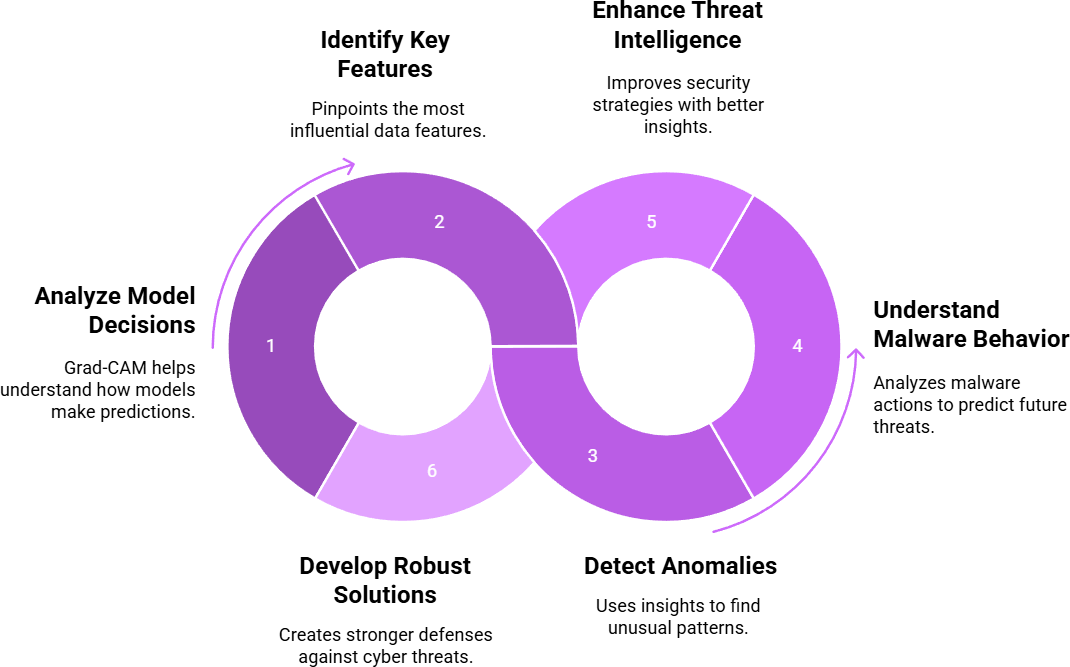

Fig. 6 illustrates the key applications of Grad-CAM (Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping) in the field of cybersecurity, demonstrating how this explainable AI technique transforms complex machine learning models from opaque “black boxes” into interpretable tools. It shows that by pinpointing the most influential features in data and analyzing how a model makes its predictions, security teams can better understand malicious software behavior, accurately detect anomalous activities, and develop more robust defensive solutions. Ultimately, these deep insights enhance overall threat intelligence, allowing for the creation of more proactive and effective security strategies to counter evolving cyber threats.

Figure 6: Key applications of grad-CAM in threat analysis

Integrated Gradients: This method quantifies feature importance by calculating the integral of gradients from a baseline input to the actual input [64]. It proves particularly effective for interpreting deep learning models applied to security logs, user behavior patterns, and network traffic anomalies.

Counterfactual Explanations: These explanations identify minimal modifications to inputs that would alter a model’s prediction [65]. This method is extremely useful in learning how the slight alterations in the network traffic patterns or software actions might modify the security classifications of AI.

Such Explainable AI techniques are strategic to the cybersecurity industry since they will assist cybersecurity experts in enhancing the transparency and responsibility of AI-based security systems. The complex models are transformed into the trusted components of the working security infrastructure by this method.

2.4 Applications of XAI in Cybersecurity

2.4.1 Intrusion Detection Systems (IDS)

Modern Intrusion Detection Systems (IDS) have evolved to leverage sophisticated machine learning models that process network traffic data [66]. This data is represented mathematically as high-dimensional vectors

A classical yet powerful statistical approach for identifying outliers in such a multivariate setting is based on the generalized Mahalanobis distance. This distance metric is superior to the Euclidean distance as it accounts for the correlations between different features and the inherent variance of the dataset. It is formally defined by the equation:

In this equation,

Here, the goal is to find the mean and covariance that minimize the determinant of the covariance matrix—a measure of the data’s volume—while constraining the solution to a subset of size

Complementing these statistical methods, deep learning architectures, particularly autoencoders, have become a cornerstone of modern anomaly detection [67]. An autoencoder is a neural network designed to learn a compressed, lower-dimensional representation of the input data. It consists of two primary components: an encoder function

The first term is the mean squared error reconstruction loss, forcing the autoencoder to learn the salient features of the normal traffic. The second term,

here,

Given the complexity and “black-box” nature of both statistical and deep learning models, explainability methods are essential for interpreting their decisions and building trust in the IDS. Among the most theoretically sound approaches are Shapley values, which originate from cooperative game theory and fairly distribute the “payout” (the model’s prediction) among the “players” (the input features). The exact computation of the Shapley value for a feature

This equation considers every possible permutation

This approximation estimates the feature importance by considering the product of the feature’s gradient (its local sensitivity) and its deviation from a baseline value, averaged over a local distribution of inputs.

Another prominent explainability technique for deep networks is Layer-wise Relevance Propagation (LRP) [68]. Instead of analyzing the input gradients, LRP operates by distributing the model’s output score backward through the network layers, from the output back to the input, assigning a relevance score

In this rule,

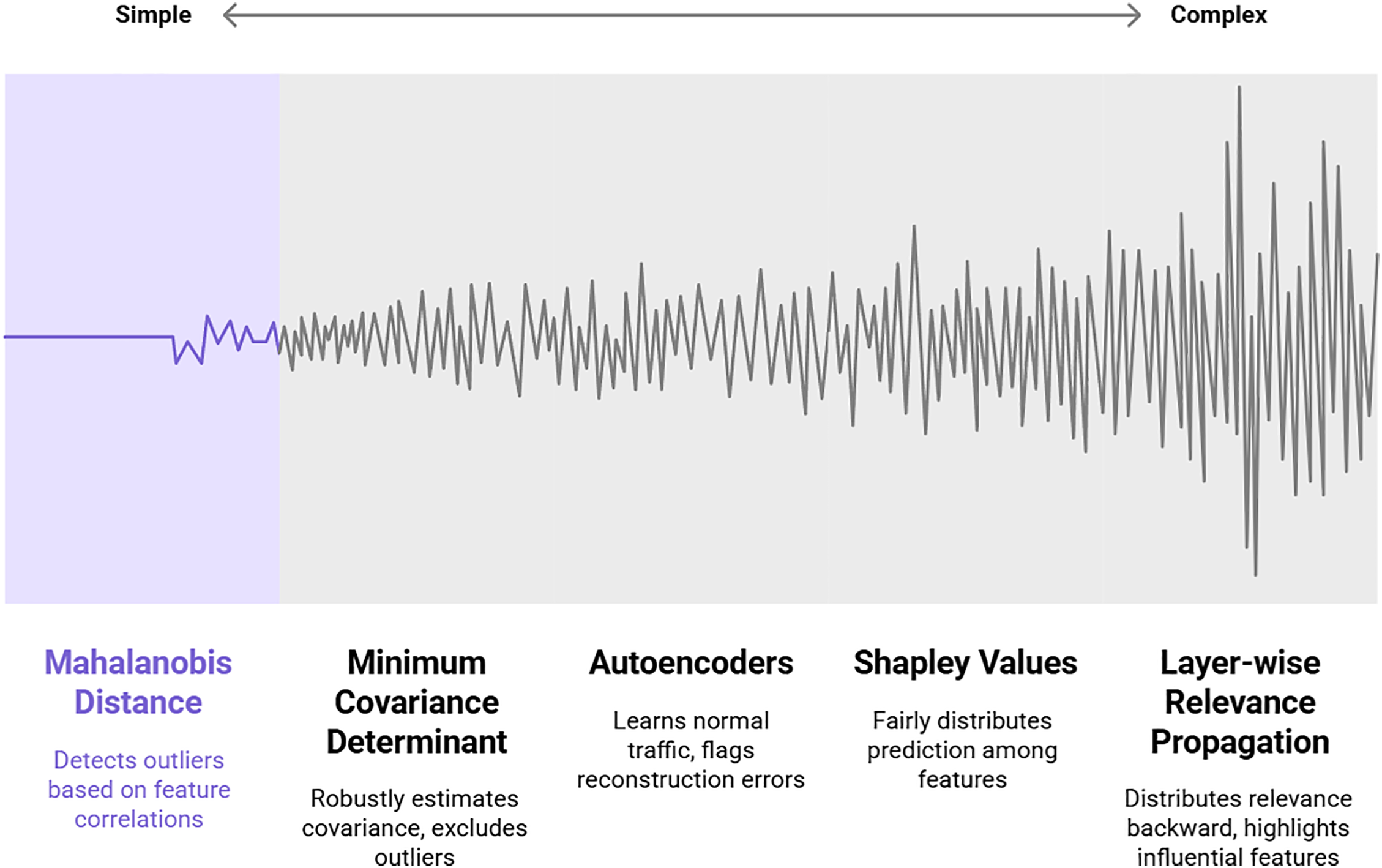

Fig. 7 presents a taxonomy of techniques used in anomaly-based intrusion detection systems, categorizing them from simple to complex. It outlines core statistical methods for identifying outliers, such as Mahalanobis Distance, which detects anomalies by considering feature correlations, and Minimum Covariance Determinant, a robust estimator that excludes outliers to define a “normal” baseline. For more complex, non-linear patterns, it highlights Autoencoders, which learn to reconstruct normal network traffic and flag instances with high reconstruction errors as potential attacks. Finally, the figure includes advanced model interpretation techniques like Shapley Values and Layer-wise Relevance Propagation, which do not detect intrusions themselves but are crucial for explaining the predictions of complex models by fairly attributing importance to the input features that influenced the alert.

Figure 7: A taxonomy of intrusion detection techniques, ranging from simple to complex

The modern paradigm of automated malware analysis hinges on the transformation of raw executable files into structured [69], numerical feature vectors

Here,

where

Once feature vectors are constructed, they are fed into classification models. A powerful and traditional model is the Support Vector Machine (SVM) with a non-linear Radial Basis Function (RBF) kernel. The SVM decision function for a new sample

In this formulation, the

where

This equation shows how the forget gate, input gate, and candidate cell state work together to selectively remember or forget information over long sequences, making it highly effective for analyzing the ordered sequence of Application Programming Interface (API) calls or instruction blocks.

Given the critical consequences of misclassifying malware, interpretability methods are not a luxury but a necessity. Integrated Gradients is a prominent method that attributes the prediction of a model

This provides a complete attribution that satisfies desirable axiomatic properties. Another powerful interpretability approach is counterfactual explanation, which answers the question: “What would need to change for this malicious sample to be classified as benign?” This is framed as an optimization problem:

The goal is to find a new sample

These mathematical formulations for feature extraction, classification, and interpretation collectively show how Explainable AI (XAI) creates the dual foundation for both high-performance detection and the crucial ability to explain seemingly obscure decision-making in cybersecurity systems, a point strongly emphasized in the contemporary literature ([23,24,71]).

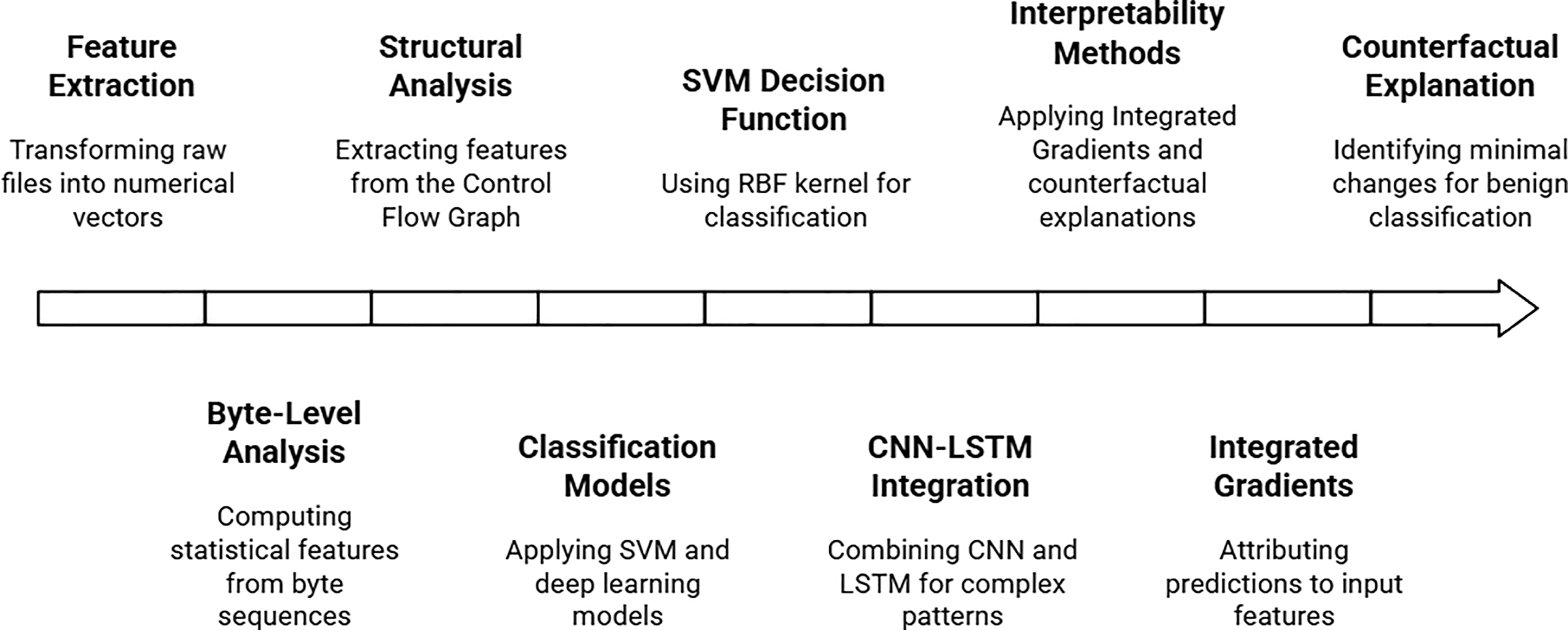

Fig. 8 outlines a comprehensive machine learning pipeline for malware detection and interpretation. The process begins with Feature Extraction, where raw malware files are transformed into numerical vectors through Structural Analysis of elements like the Control Flow Graph and Byte-Level Analysis to compute statistical features. These features are then fed into Classification Models, such as an SVM with an RBF kernel or a hybrid CNN-LSTM Integration model, to identify complex patterns and distinguish between malicious and benign software. Crucially, the pipeline emphasizes transparency by employing Interpretability Methods like Integrated Gradients, which attributes the model’s prediction to specific input features, and Counterfactual Explanations, which identify the minimal changes needed for a malicious file to be classified as benign, thereby providing actionable insights into the model’s decision-making process.

Figure 8: Architecture of an interpretable malware detection system using hybrid deep learning models

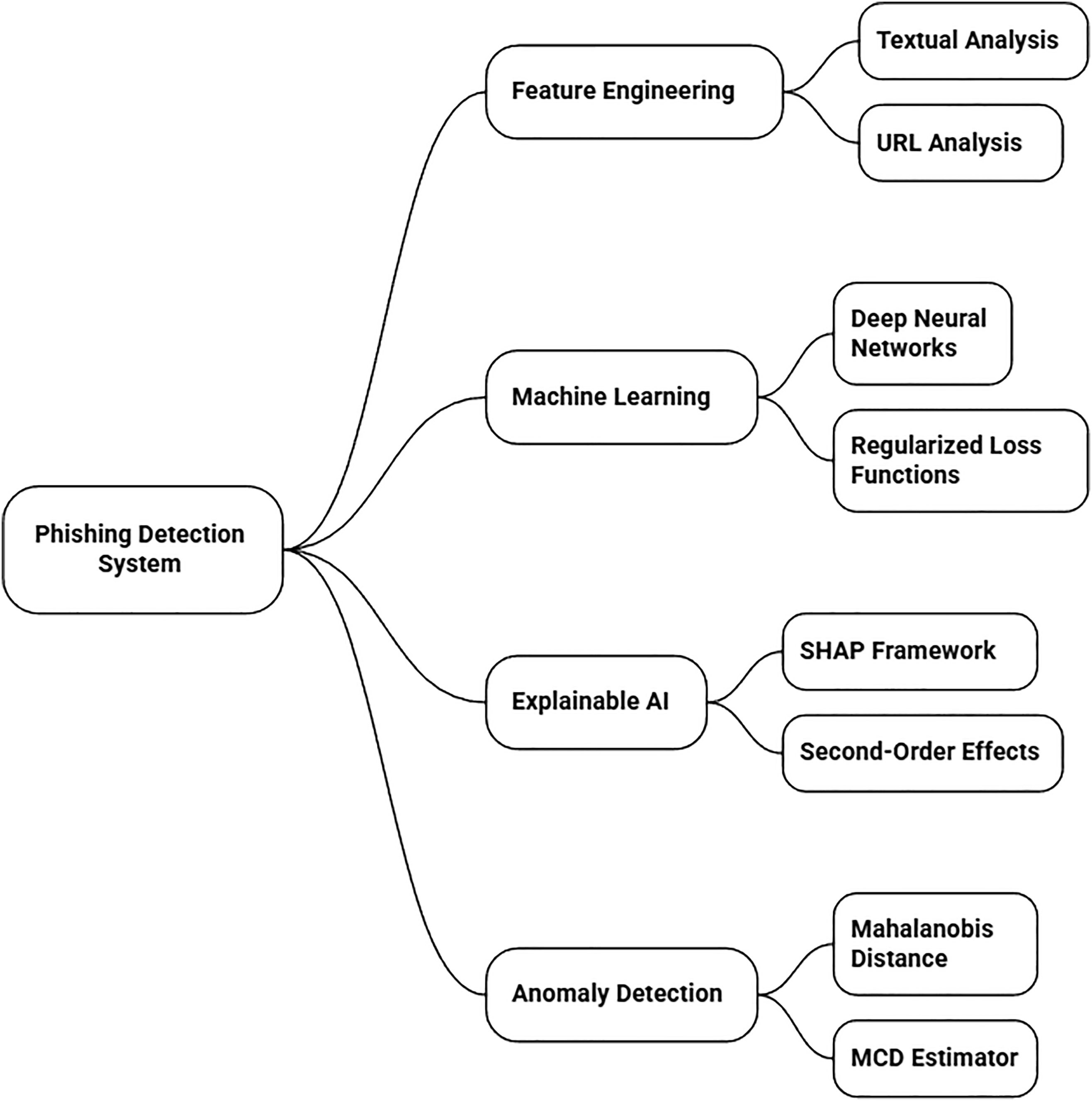

Modern phishing detection systems represent a sophisticated fusion of feature engineering, machine learning, and explainable AI (XAI) to combat evolving cyber threats, as highlighted in recent literature ([72,73]). The foundational step in this process is transforming a raw email into a numerical feature vector

Textual analysis is crucial, as phishing emails often exhibit specific linguistic patterns. A sophisticated textual feature can be derived by modeling the email’s text

Here, the first term,

URL analysis is another critical pillar of feature extraction. Phishers often use deceptive URLs that resemble legitimate ones through slight character substitutions, insertions, or deletions. The Levenshtein distance

A small Levenshtein distance to a popular brand’s domain is a strong indicator of a typosquatting attack.

Once these diverse features are assembled into a vector

This equation describes a multi-layer perceptron where the input is transformed through one or more hidden layers using a ReLU activation function

The first part of the loss is the standard cross-entropy, which measures the discrepancy between the model’s predictions and the true labels

To build trust and provide actionable insights, explainability is paramount. An extension of the SHAP framework that incorporates second-order effects provides more accurate feature attributions. The attribution for feature

This formula extends beyond the first-order approximation by adding a second-term that accounts for the curvature of the model function

Finally, for a robust defense, phishing detection systems often incorporate an anomaly detection module to flag novel attacks that do not resemble known patterns. The Mahalanobis distance is a key metric for this purpose, measuring how far a sample

To ensure that the estimates for the mean

This formulation finds the mean and covariance that minimize the determinant (a measure of volume) based on a clean subset of the data of size

Fig. 9 outlines the architecture of a modern, explainable phishing detection system that integrates multiple analytical approaches. The process begins with Feature Engineering, where both Textual Analysis (e.g., email body content) and URL Analysis (e.g., suspicious domain characteristics) are used to extract relevant signals. These features are then processed by Machine Learning models, including Deep Neural Networks optimized with Regularized Loss Functions to prevent overfitting and improve generalization. To handle novel and evolving threats, an Anomaly Detection module employs techniques like the Mahalanobis Distance with a robust MCD Estimator to identify outliers. Crucially, the entire system is made interpretable using Explainable AI (XAI) principles, specifically the SHAP framework, which helps reveal the contribution of individual features and even uncovers complex Second-Order Effects (feature interactions) behind each prediction, building trust and allowing for deeper model analysis.

Figure 9: A unified framework for phishing detection combining feature engineering, machine learning, and explainable AI

2.4.4 User Authentication and Fraud Detection

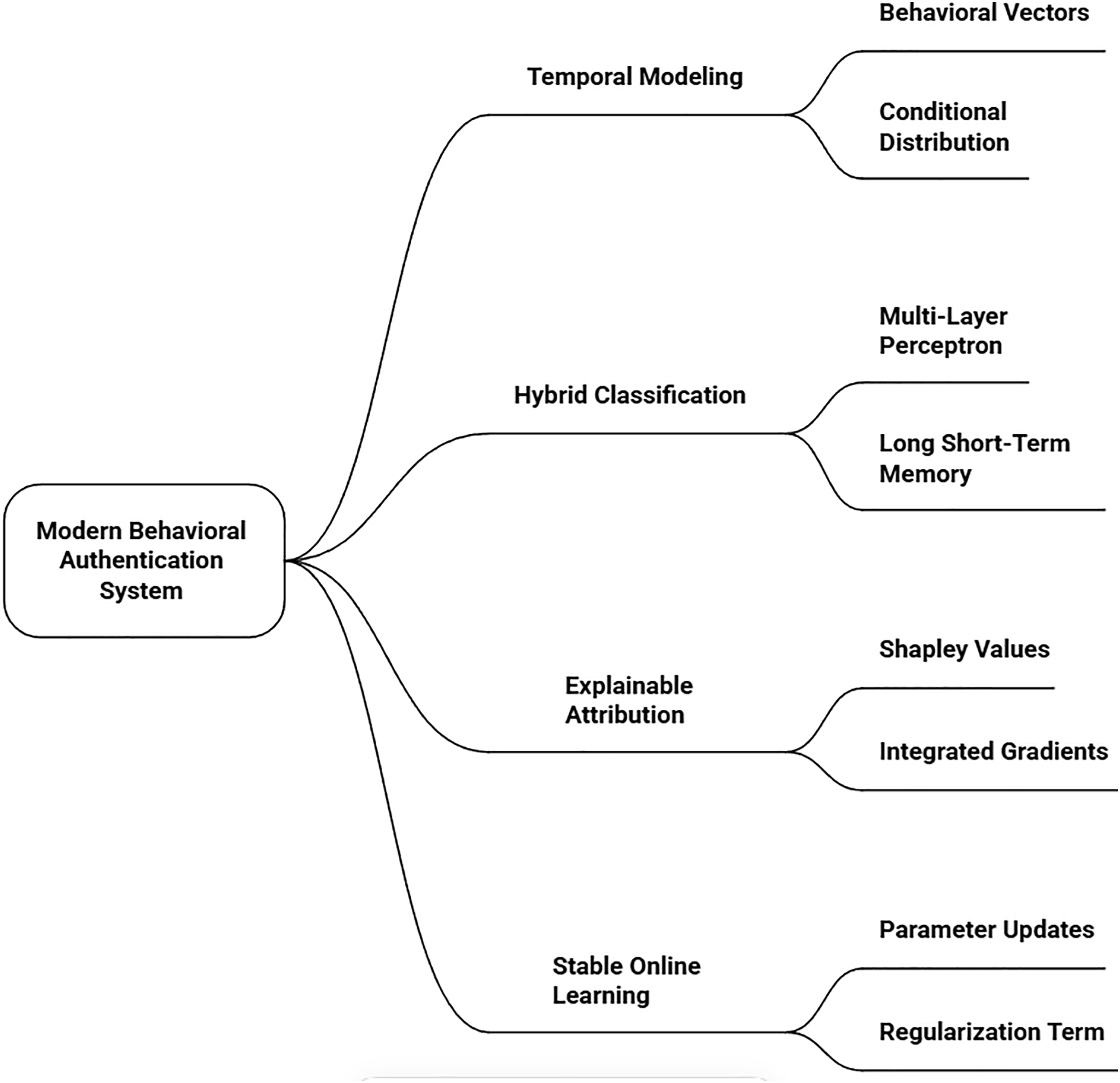

Modern behavioral authentication systems represent a paradigm shift from static credential checks to continuous, dynamic verification by modeling user behavior as a rich temporal process [74]. This process is represented as a sequence of behavioral vectors

This equation states that the behavioral vector

here,

To classify whether a sequence of behavior originates from the legitimate user or a fraudster, a sophisticated classifier is employed that synthesizes both static and dynamic information. The classifier’s architecture is defined as:

In this formulation, a Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) processes static features

here, a sample is classified as anomalous if the classifier’s output score

Given the high-stakes nature of authentication, explainability is crucial. To attribute the model’s fraud decision to specific behavioral features at specific times, Shapley values are extended to handle temporal dependencies. The Shapley value for feature

This complex-looking formula has an intuitive interpretation: it fairly distributes the classifier’s “payout” (the fraud score) among all feature-time pairs by considering every possible subsequence

This method, known as Integrated Gradients, computes the attribution for feature

Finally, to maintain accuracy in the face of evolving user behavior and novel attack vectors, the system continuously updates itself via online learning. The model parameters

This update rule states that the parameters at time

Collectively, these mathematical formulations for temporal modeling, hybrid classification, explainable attribution, and stable online learning provide the rigorous foundations necessary for building effective, transparent, and adaptive explainable AI systems for phishing detection and fraud prevention, as emphasized in contemporary security research [75,76].

Fig. 10 outlines the architecture of a modern behavioral authentication system, which verifies a user’s identity based on their unique behavioral patterns. The process begins with Behavioral Vectors, which are numerical representations of user actions like typing rhythm or mouse movements. Temporal Modeling techniques, such as Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, analyze the sequence and timing of these actions to create a dynamic user profile. To ensure transparency and trust, Explainable Attribution methods, including Shapley Values and Integrated Gradients, are used to pinpoint which specific behaviors were most influential in the authentication decision. Finally, the system employs Stable Online Learning, which allows it to securely and gradually adapt to a user’s evolving behavior over time through parameter updates and regularization, maintaining both security and performance without forgetting previous knowledge.

Figure 10: A conceptual architecture of a modern behavioral authentication system, detailing core components for temporal modeling, explainable attribution, and stable online learning

2.4.5 Adversarial Attack Mitigation

The mathematical foundation for mitigating adversarial attacks in AI systems involves a rigorous study of model vulnerabilities and the development of robust defense strategies [77]. The core threat is formalized as a constrained optimization problem, where an adversary seeks a perturbation

To detect such attacks, Explainable AI (XAI) methods are employed to analyze model internals. The Jacobian matrix

The foremost defense strategy, adversarial training, directly incorporates these threats into the learning process through a min-max optimization:

Finally, explainability is extended to the adversarial context to understand which features contribute to model robustness. This is achieved by defining Shapley values for robust performance:

2.4.6 Insider Threat Detection

The sophisticated analysis of behavioral patterns for insider threat detection relies on advanced mathematical modeling that applies statistical and machine learning techniques to temporal sequences of employee activities [80,81]. These activities are represented as a sequence of multivariate observations

where the encoder

Explainability in these temporal models is achieved through several mathematical frameworks. Shapley values are extended to attribute importance to feature-time pairs:

where

These mathematical formulations enable precise anomaly identification and interpretation through variational inference for uncertainty quantification, differential analysis of LSTM gates for temporal localization, game-theoretic attribution across time, and spectral analysis of attention weights. The explainability frameworks operate through multiple mathematical lenses, including reconstruction analysis:

The integration of these advanced techniques—including Bayesian credibility intervals for evidence quantification, temporal pattern tracing, counterfactual analysis, and reinforcement learning for alert optimization—provides a robust foundation for explainable detection systems [82,83]. This represents a significant advancement over static approaches [84], delivering auditable decision trails that are crucial for operational trust and regulatory compliance [85,86].

2.4.7 Regulatory Compliance and Risk Assessment

The mathematical formalization of regulatory compliance for AI-driven cybersecurity systems necessitates a rigorous framework that bridges legal statutes and technical implementation [87]. This framework can be defined as a tuple

Specific regulations impose distinct mathematical constraints on the model’s behavior and explanations. To satisfy GDPR’s right to explanation, the system must generate a comprehensive explanation

A comprehensive risk assessment framework is crucial for monitoring compliance, combining model uncertainty and explanation stability. The epistemic uncertainty

The complete optimization for developing a compliant AI system synthesizes these elements:

For dynamic environments, temporal compliance monitoring introduces additional complexity, modeled through a state-space formulation

This comprehensive mathematical framework bridges the gap between legal requirements and technical implementations. It enables the development of provably compliant Explainable AI systems for cybersecurity applications [91,92]. The formal guarantees provided by these methods address core challenges in trustworthy AI deployment within regulated environments, as identified by [93].

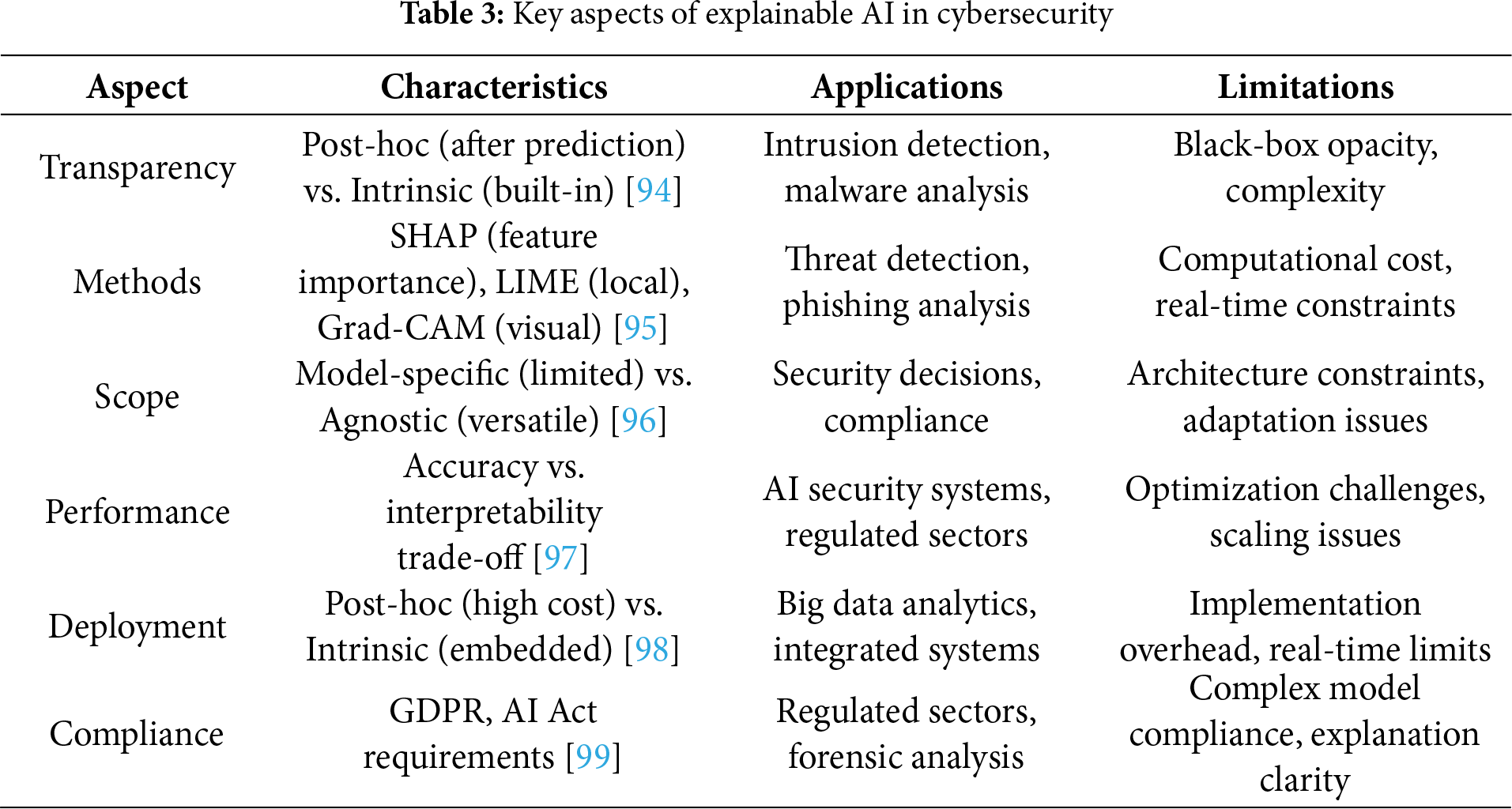

Table 3 provides a comprehensive overview of the key aspects of Explainable AI (XAI) within the cybersecurity domain, systematically comparing their characteristics, practical applications, and inherent limitations. It organizes the field into six core aspects: Transparency (contrasting post-hoc and intrinsic methods), specific XAI Methods like SHAP and LIME, the Scope of explanation techniques (model-specific vs. agnostic), the Performance trade-off between accuracy and interpretability, Deployment considerations, and Compliance with regulatory frameworks. The table effectively illustrates how these factors interplay, highlighting that while XAI is crucial for applications such as intrusion detection and regulatory adherence, it is consistently challenged by issues like computational cost, model opacity, and implementation complexity [94–99].

3 Role of Explainable AI (XAI) in Cybersecurity

The introduction of the cybersecurity frameworks into Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) has been carving out nothing less than a revolution [4], realized in the form of automated threat detection, predictive analytics, and the response to the incident on a scale and speed that human analysts could not have achieved on their own. However, this adoption has been accompanied by a significant and growing challenge: the “black box” problem. Many advanced AI models, particularly complex deep learning networks and ensemble methods, operate in ways that are opaque, making it difficult for cybersecurity professionals to understand why a particular decision was made. This is where Explainable AI (XAI) becomes not just a technical enhancement, but a foundational pillar for trustworthy and effective cybersecurity. XAI refers to a suite of techniques and methods that make the outputs of AI models understandable and interpretable to human experts. In the high-stakes domain of cybersecurity, where decisions can impact national security, corporate integrity, and individual privacy, understanding the “why” behind an alert is as critical as the alert itself [100]. It transforms AI from an inscrutable oracle into a collaborative partner, enabling a synergy between human intuition and machine precision.

3.1 Enhancing Threat Detection and Response

In the context of threat detection, AI systems are tasked with identifying malicious activity within vast oceans of network traffic, system logs, and user behaviors [101]. A traditional Security Information and Event Management (SIEM) system might flag an anomaly—for instance, a user accessing a database at an unusual hour. An XAI-augmented system, however, would go beyond the binary alert. It would provide a detailed rationale, such as: “This activity was flagged as high-risk because the user’s account (usually active 9-5 in the EST timezone) initiated a large data transfer to an external IP address in a non-whitelisted country, a combination of factors that deviates from 99.7% of their historical behavior and matches 85% of the patterns observed in previous data exfiltration attempts.” This granular explanation allows a Security Operations Center (SOC) analyst to triage the incident with profound context. They can immediately discern if this is a genuine insider threat, a compromised account, or simply an employee working late on a critical project. This drastically reduces the mean time to detect (MTTD) and, more importantly, the mean time to respond (MTTR), as analysts are not wasting precious minutes or hours deciphering the AI’s logic [102]. The explainability turns a potentially overwhelming alert into a guided investigation, streamlining the entire incident response workflow.

3.2 Building Trust and Facilitating Human-AI Collaboration

Trust is the currency of an effective security team. If analysts cannot understand the reasoning behind an AI’s recommendations, they are likely to suffer from “alert fatigue” and begin to ignore or second-guess the system, a phenomenon known as automation bias in reverse. XAI directly addresses this by building a bridge of trust between the human and the machine. When an analyst can see the specific features—such as a specific sequence of system calls, a particular registry key change, or a unique packet signature—that led a model to classify a file as malware, they are more likely to trust the verdict and act upon it. This collaborative dynamic is crucial for adaptive defense. For example, if an XAI system explains that it flagged a new piece of software as suspicious due to its attempts to disable a specific Windows Defender service, an analyst can use that human context to realize this is a legitimate action for a certain system utility [103]. They can then provide this feedback to retrain the model, creating a virtuous cycle of improvement. This human-in-the-loop feedback, powered by explanations, ensures the AI system continuously learns and adapts to the unique and evolving environment it is meant to protect, preventing the model from becoming stale and ineffective.

3.3 Proactive Defense: Improving Model Robustness and Identifying Adversarial Attacks

Cyber adversaries are increasingly sophisticated and are themselves leveraging AI to craft attacks designed to evade detection [104]. These are known as adversarial attacks, where inputs are subtly manipulated to fool AI models. For instance, an attacker might add minimal, human-imperceptible noise to a malware binary, causing the AI classifier to incorrectly label it as benign. A black-box model offers little insight into why it was fooled, leaving defenders in the dark. XAI shines a light on these vulnerabilities. By using techniques like saliency maps or feature importance analysis, security researchers can understand which parts of the input data the model is most sensitive to. If they discover that the model is overly reliant on a specific, easily manipulated file header for classification, they have identified a critical weakness. This understanding allows them to proactively retrain the model with adversarial examples, reinforce its feature set, and build a more robust and resilient defense system. In this sense, XAI moves the cybersecurity posture from a reactive one to a proactive one, enabling the hardening of AI defenses before they can be exploited in a live attack.

In conclusion, the role of Explainable AI in cybersecurity is transformative and multifaceted [12]. It is the critical link that closes the gap between raw algorithmic output and actionable human intelligence. By providing transparency, XAI empowers security analysts, accelerates investigations, builds essential trust, ensures regulatory compliance, and fortifies defenses against evolving adversarial threats. Since AI becomes more of a natural part of our digital security, the explainability of its actions will stop being a luxury and will become an unconditional prerequisite to the development of secure, responsible, and robust cyber-ecosystems.

3.4 Regulatory and Compliance Aspects

With the continued use of AI in cybersecurity, the regulatory bodies have provided clear demands that must be met in transparency and accountability. Explainable AI can assist organisations to address such needs by offering explainable systems and auditable decision-making processes that would be appropriate in investigations and compliance reporting.

3.4.1 Explainability Requirements in Cybersecurity Frameworks

General Data Protection Regulation, NIST Cybersecurity Framework, and ISO 27001 regulatory frameworks require the explanatory capabilities of AI systems [105]. GDPR will provide users with the right to be informed about the systems that are based on AI and that have an impact on their experience. As an illustration, the customers who may be victims of automated fraud detection should be provided with reasons that they understand in cases where their transactions raise an alarm. In a similar manner, NIST and ISO 27001 demand that organisations should show accountability in their AI-based cybersecurity actions. With the application of Explainable AI, companies can provide adequate explanations of AI decision-making, which will guarantee automation of security activities [106].

3.4.2 Role of XAI in Auditability and Forensic Investigations

Explainable AI systems are required to detect and trace the occurrence of cyberattacks and provide evidence during security audits and forensic investigations of such incidents [107]. The conventional AI systems do not tend to expose the factors that define the classifications of security breaches. The explainable AI systems, such as decision trees, rule-based systems, and feature attribution systems, allow an investigator to trace the logic behind the AI-generated warnings. As an example, during an investigation of a ransomware attack, an explainable model may indicate that unusual encryption patterns, unauthorised privilege escalation, and unusual access sequence of files are some of the major indicators of compromise. Such lessons allow forensic experts to build timelines of attacks, determine the weaknesses of the system, and create more effective defences. Additionally, Explainable AI facilitates cyber risk assessments by providing interpretable risk scores with step-by-step justifications, enabling organizations to prioritize security investments effectively [108].

Explainable AI has become indispensable for enhancing AI-based cybersecurity systems, ensuring regulatory compliance, and enabling forensic investigations [79]. By providing clear explanations for AI decisions, it improves the effectiveness of intrusion detection, malware analysis, fraud detection, and insider threat prevention. Furthermore, Explainable AI supports compliance with major regulatory frameworks by making AI models accountable and auditable. As cyber threats continue to evolve, the role of Explainable AI in cybersecurity will expand, fostering trust through transparency and strengthening AI-driven defense mechanisms [109].

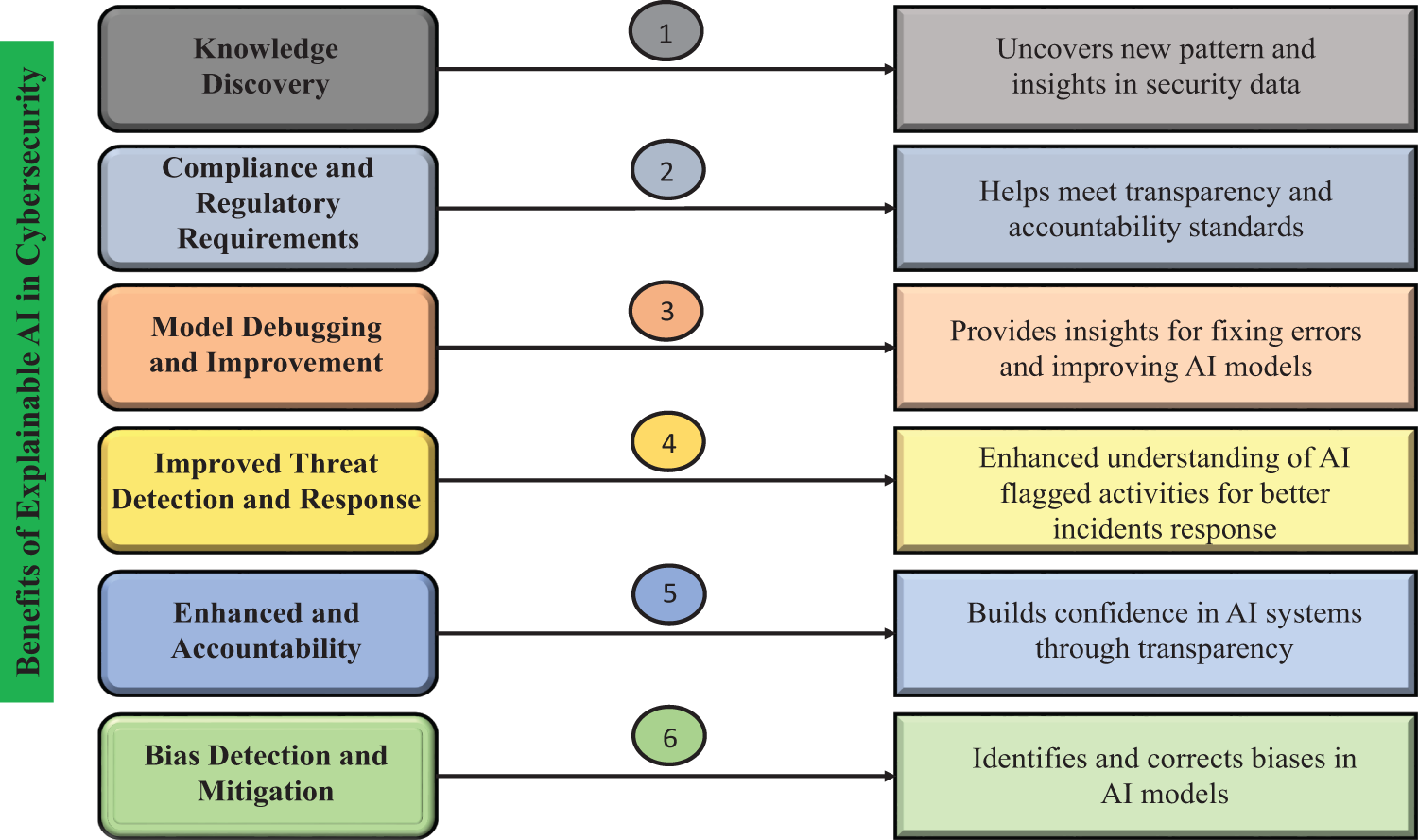

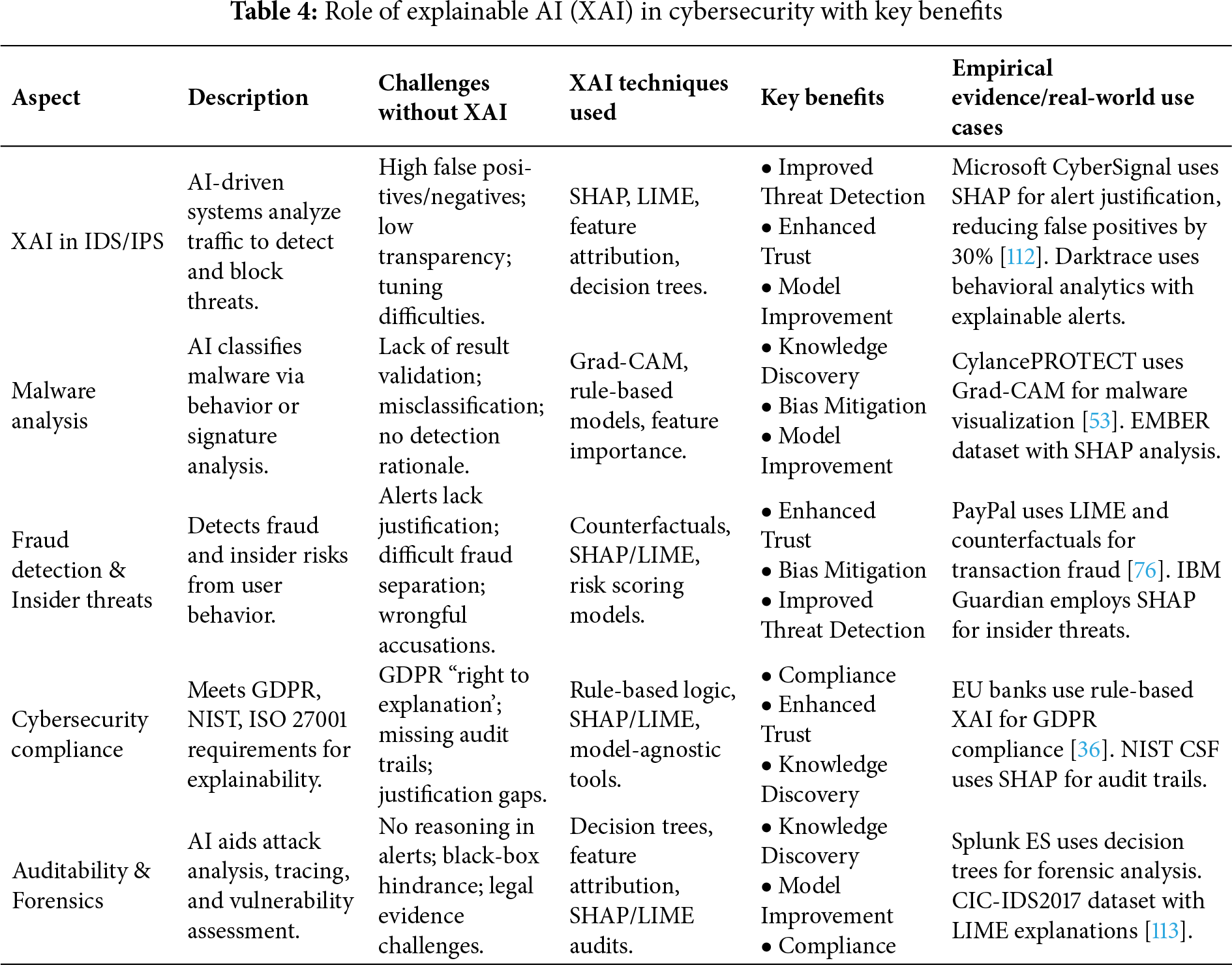

The integrated analysis from (Fig. 11), and (Table 4), comprehensively outlines the multifaceted role and benefits of Explainable AI (XAI) in cybersecurity, demonstrating how it bridges the gap between complex AI operations and human-understandable security practices. Firstly, in enhancing threat detection and response, XAI techniques like SHAP and LIME are pivotal in Intrusion Detection and Prevention Systems (IDS/IPS); for example, Microsoft’s CyberSignal uses SHAP to justify alerts, which has been shown to reduce false positives by 30%, thereby allowing security analysts to prioritize genuine threats effectively and refine detection models. Secondly, in the domain of malware analysis and classification, tools such as Grad-CAM provide visual explanations by highlighting the specific code segments or binary features that led a model to classify a file as malicious, as seen in systems like CylancePROTECT, which not only improves detection accuracy but also facilitates knowledge discovery by helping analysts understand emerging malware families. Third, to detect fraud and prevent insider threats, the XAI techniques, such as counterfactual explanations and SHAP-based risk scoring, implemented by PayPal and IBM Guardian among others, provide clear explanations of why a specific transaction or behaviour of a user is flagged, which can be useful in identifying actual fraud and processing false alarms, minimising false positives, and fostering trust in automated monitoring systems. More critically, a critical benefit is that it allows regulatory compliance and auditing, where XAI can directly respond to the requirement of the various frameworks such as GDPR, NIST, and ISO 27001 to produce traceable and justifiable audit trails, such as providing the legally mandated requirement of a right to explanation of automated decisions (EU banks use rule-based XAI logic to do this), or tools such as Splunk ES may use decision trees to perform forensic analysis and allow investigators to recreate attack timelines with clear and defensible evidence. Finally, overarching all these applications are the core benefits of bias mitigation and enhanced trust, as the transparency provided by XAI allows organizations to identify and correct for model biases that could lead to discriminatory outcomes, thereby fostering greater confidence among security teams, stakeholders, and regulators in AI-driven cybersecurity systems, ensuring they are not only effective but also fair and accountable.

Figure 11: Key benefits of explainable AI (XAI) in cybersecurity. For example, Microsoft’s CyberSignal employs SHAP to justify alerts, which has been reported to reduce false positives by 30% and significantly improve analyst trust and response times [110]. Similarly, Darktrace’s Enterprise Immune System uses behavioral analytics with explainable alerts to reduce mean time to detection by over 90% [111]

4 The Trade-Off between Interpretability and Security

Explainable AI offers significant benefits for security systems by improving trust, compliance standards, and investigative capabilities [114]. However, a primary research challenge involves addressing how interpretability can potentially work against security. The increased model transparency designed to enhance trust and accountability may simultaneously introduce security threats by exposing model vulnerabilities. This section assesses the specific vulnerabilities of Explainable AI systems and examines security measures developed to address these weaknesses.

4.1 Security Risks of XAI Models

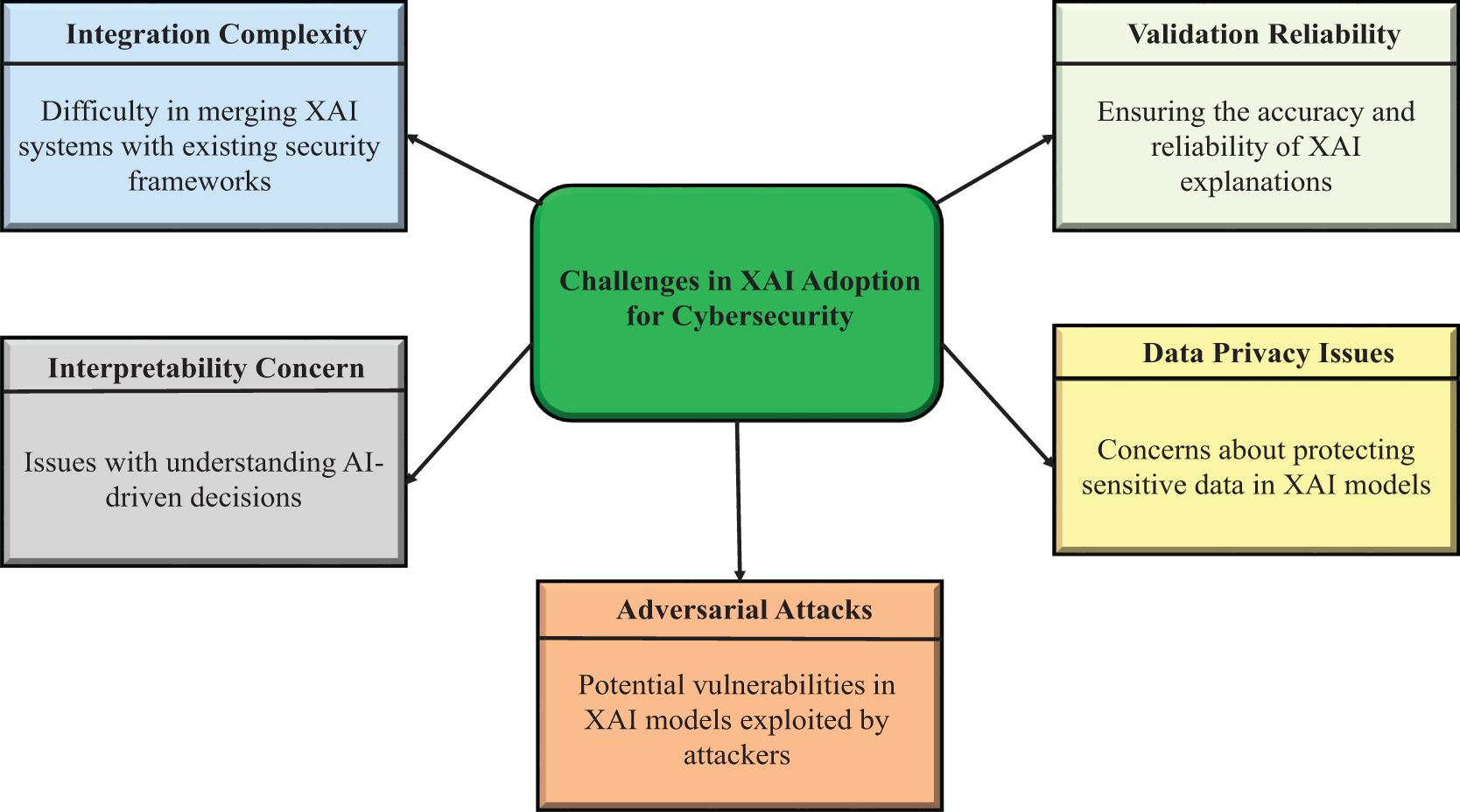

The process of making AI decisions more interpretable through XAI methods allows attackers to exploit the increased visibility of AI systems. Multiple security risks relate to XAI models engage as follows:

4.1.1 How Interpretability Can Expose Vulnerabilities (e.g., Adversarial Examples)

Explainable AI (XAI) methods like SHAP and LIME reveal the key features that influence a model’s decisions; however, this very transparency can be weaponized by attackers. By understanding which attributes are critical, for instance in an Intrusion Detection System (IDS) or malware classifier, adversaries gain strategic intelligence on how to craft inputs that bypass detection. They mathematically generate these adversarial examples by adding a small, calculated perturbation to the original input, often following the gradient of the model’s loss function as formalized by

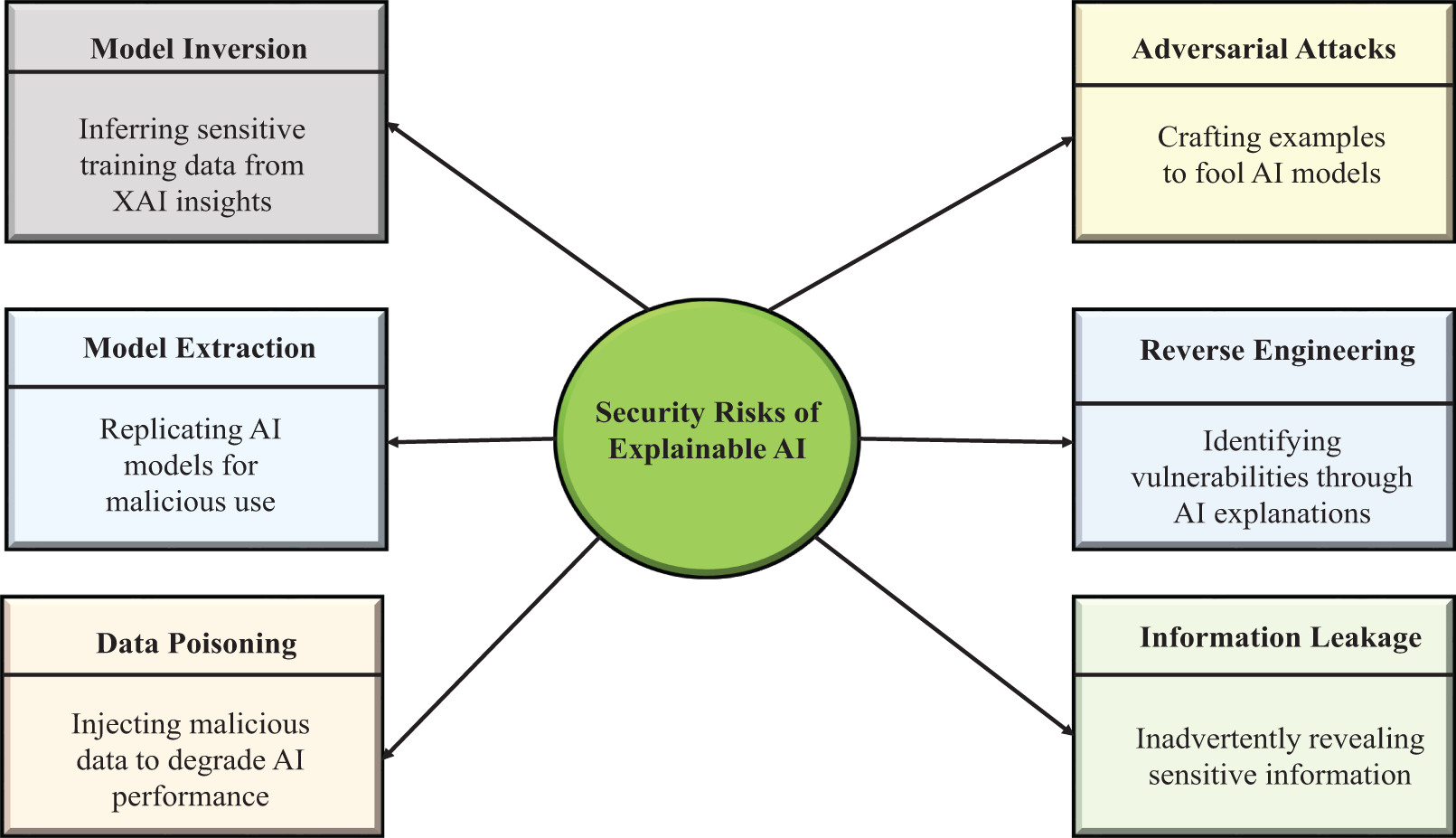

Fig. 12 illustrates the various security risks associated with Explainable AI (XAI). These risks include Model Inversion, which involves extracting sensitive data from the explanations provided by XAI; Model Extraction, where AI models are replicated for malicious purposes; Data Poisoning, the act of injecting harmful data to degrade AI performance; Adversarial Attacks, which involves crafting inputs to deceive AI models; Reverse Engineering, identifying AI vulnerabilities through its explanations; and Information Leakage, where sensitive information is inadvertently exposed. Each risk is positioned in concentric layers, highlighting the varying levels of threat.

Figure 12: Security risks of explainable AI. These risks are not merely theoretical; model inversion attacks have been demonstrated to partially reconstruct facial images from explainable facial recognition systems [116], highlighting the privacy perils of excessive transparency. In cybersecurity, adversarial examples crafted using SHAP explanations have been shown to evade malware detectors with over 80% success rate

4.1.2 Model Inversion and Membership Inference Attacks Using Explanations

Model inversion attacks are dangerous privacy threats that utilize XAI methods to reconstruct sensitive input data based on a model’s behavior, which is particularly critical when models process confidential information like biometric data or cybersecurity logs [117]. A related threat, membership inference attacks, enables an adversary to determine if a specific data point was part of the model’s training set, potentially by exploiting explanations like SHAP or Grad-CAM heatmaps to identify the presence of particular users or attack signatures in security datasets. Mathematically, these attacks exploit the difference in model confidence scores between training and non-training samples by training an attack model, often formulated as

4.1.3 Risks of Transparency in Security-Sensitive Environments

While XAI improves trust, excessive transparency can help adversaries understand the inner workings of cybersecurity models. This can be particularly dangerous in applications such as:

Anti-malware solutions: If attackers know which file features are used for malware detection, they can craft malicious software that evades detection [118,119].

Access control and authentication systems: If XAI reveals decision-making patterns in biometric authentication, adversaries can create more accurate spoofing attacks [120].

Threat detection models: If cybercriminals understand what kinds of network activity cause an alert, they will be able to adjust their attacks to bypass these defenses [121]. In this case, interpretability and security trade-offs are required, and it is necessary to control the exposure of model explanations [64].

4.2 Prescriptive Patterns for Secure XAI Deployment

The burden between model transparency and security is not a binary choice but a managed balance. Based on the principle of least-privilege explanation [122], we propose the following prescriptive patterns for deploying XAI in high-stakes cybersecurity environments. These patterns ensure that explanations are provided only when necessary, to the right entity, and in a way that minimizes the risk of adversarial exploitation.

• Role-Gated Explanations: Access to detailed explanations is restricted based on user roles and clearances within the Security Operations Center (SOC).

– Tier 1 Analyst: Receives simple, high-level reason codes (e.g., “Suspicious due to anomalous geolocation and time of access”).

– Tier 2/3 Analyst & Forensics: Gains access to full feature-attribution details (e.g., SHAP values, LIME outputs).

– External User/API: Receives only the binary decision (e.g., “Access Denied”) or a generic, non-informative message.

This prevents low-privilege users or potential attackers from gaining insights into the model’s decision logic.

• Randomized & Quantized Attributions: To protect against model inversion and extraction attacks, explanations can be deliberately obfuscated.

– Randomized Attribution: Add controlled noise to feature importance scores (e.g.,

– Quantized Attribution: Map continuous importance scores to a small set of discrete levels (e.g., Low, Medium, High). This preserves the explanatory intent while hiding the exact, potentially exploitable, decision boundaries.

• Explain-on-Deny: A critical pattern for authentication and access control systems where providing explanations for a grant can leak information.

– Upon Access Grant: Provide no explanation or a generic one (e.g., “Access Approved”).

– Upon Access Deny: Provide a detailed, actionable explanation to the legitimate user (e.g., “Access denied due to failed 2FA from a new device. Please use your registered device.”).

This pattern helps legitimate users troubleshoot issues without giving attackers a roadmap for crafting successful attacks.

• Explanation Rate-Limiting & Budgets: To prevent automated explanation harvesting attacks, treat explanation generation as a costly API.

– Enforce strict rate limits (e.g., N explanation queries per minute per user/IP).

– Implement explanation “budgets” for external API consumers.

– Log all explanation requests for audit and anomaly detection, treating a high volume of explanation requests as a potential reconnaissance attack.

• Context-Aware Explanation Fidelity: The level of detail in an explanation should adapt to the context and perceived risk.

– Low-Risk Context: From a trusted IP range, provide full explanations to aid analyst workflow.

– High-Risk Context: From an unknown IP or during an active attack, suppress or generalize explanations to prevent aiding the adversary.

These patterns can be combined to create a defense-in-depth strategy for XAI deployment. For instance, a system could employ role-gated, explain-on-deny with quantized attributions for external users, while allowing full, real-time explanations for senior analysts on the internal network. By making the transparency-security trade-off prescriptive, organizations can strategically deploy XAI to build trust and maintain compliance without unduly increasing their attack surface.

Considering these security risks of XAI, several defense mechanisms have been suggested to achieve increased robustness without sacrificing interpretability. These are detailed in a subsequent subsection below.

4.3.1 Secure-XAI Models: Balancing Interpretability and Robustness

Secure-XAI frameworks are designed to provide explanations without exposing sensitive model information. These models integrate techniques such as:

Feature obfuscation: Limiting the level of detail in explanations to prevent adversarial exploitation [123].

Selective explainability: Providing explanations only to trusted parties (e.g., security analysts) while restricting access for external queries.

Randomized feature attribution: Introducing randomness in explanation generation to make it difficult for attackers to exploit the model systematically [124].

4.3.2 Adversarial Training for Explainable AI Models

Adversarial training is a method to enhance AI model robustness by training them on adversarially perturbed inputs, thereby improving their resilience to adversarial attacks [125]. This process involves techniques that can interact with explanation methods, such as gradient masking—a regularization method where attackers can exploit explanation-based gradients—and adversarial explanation training, where the explanations themselves are structured to identify and mitigate potential vulnerabilities. Mathematically, adversarial training is formulated as a min-max optimization problem:

4.3.3 Privacy-Preserving XAI Techniques (e.g., Differential Privacy)

To mitigate inference attacks that exploit explanations to reveal confidential information, privacy-preserving XAI techniques have been introduced, which safeguard explanations from exposing sensitive data [126]. A foundational technique in this domain is Differential Privacy, which adds controlled noise to model explanations to prevent adversaries from deciphering private training information [127]; in DP-based XAI, explanations

Our analysis identifies key security threats to Explainable AI (XAI) and corresponding defensive countermeasures. Explanations generated by XAI systems introduce three primary points of vulnerability that adversarial attacks, model inversion, and membership inference can exploit to compromise security and privacy. To mitigate these risks, defense strategies such as adversarial training, differential privacy, and federated learning are employed.

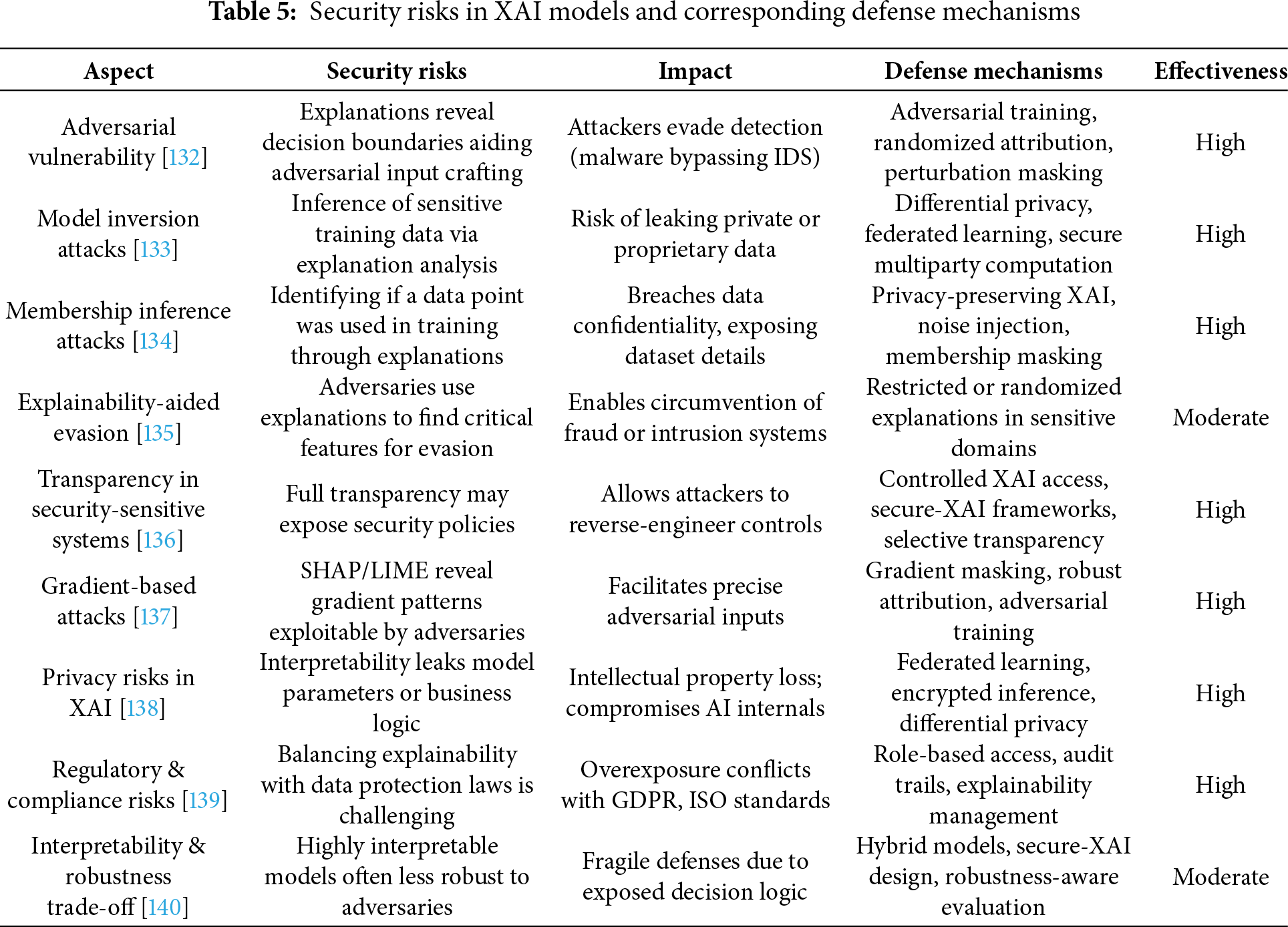

The analysis, detailed in (Table 5), evaluates two significant risks: explainability-assisted evasion attacks and gradient-based attacks. This evaluation underscores the critical need for robust feature attribution methods and carefully controlled transparency mechanisms. The document also addresses the inherent security dilemma between model performance and explainability, as increased interpretability can often lead to a less secure system.

Finally, a review assesses the applicability of explainability security measures required for compliance with standards such as GDPR, NIST, and ISO 27001, linking these to the defense fortification strategies discussed in the (Table 5).

5 Comparative Evaluation of XAI Techniques for Cybersecurity Applications

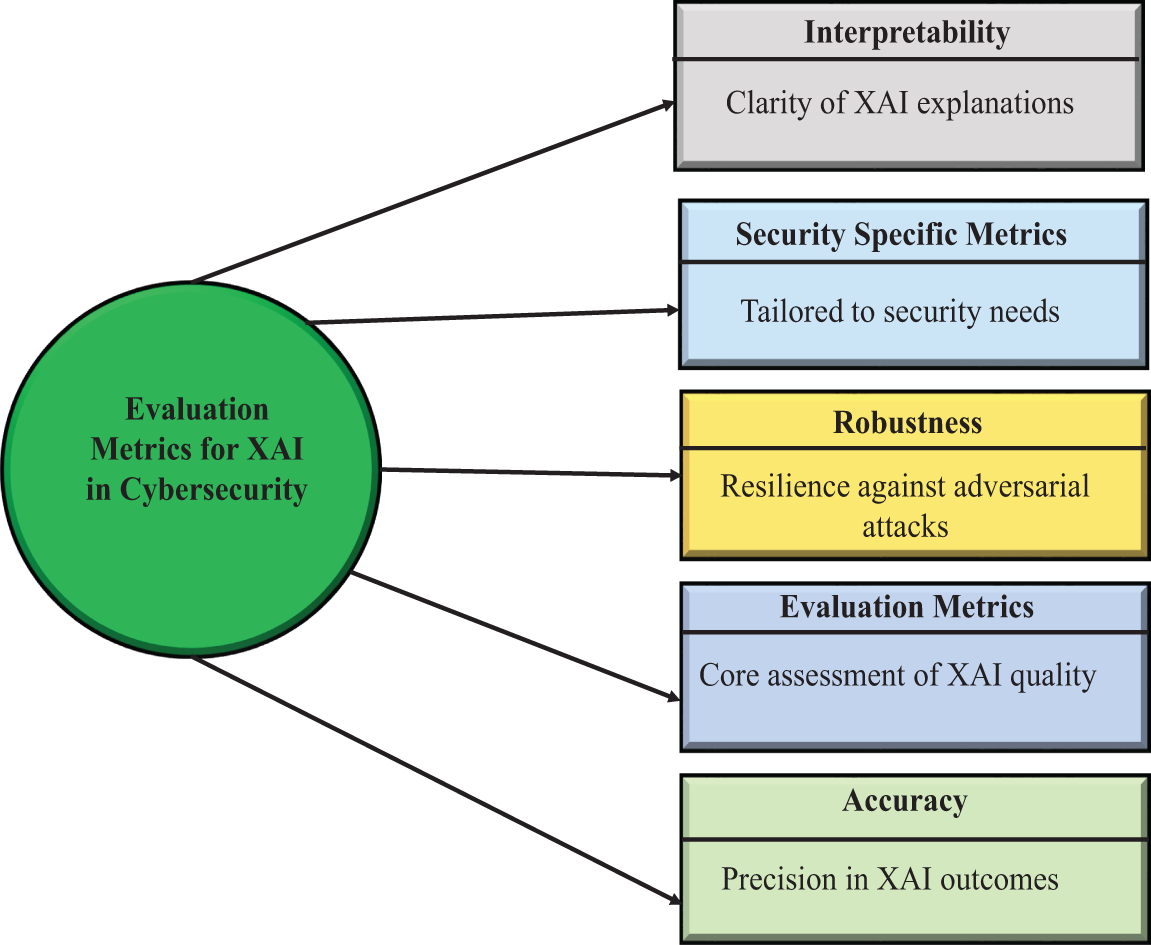

Fig. 13 illustrates the concentric evaluation metrics essential for assessing Explainable AI effectiveness in cybersecurity contexts. These metrics form a comprehensive framework for measuring multiple dimensions of XAI performance. To better understand XAI applicability, we examine each metric’s specific importance to cybersecurity with concrete examples.

Figure 13: Comprehensive evaluation metrics for assessing the quality, reliability, and security of explainable AI (XAI) systems in cybersecurity applications

Evaluation metrics are used as the basis for determining the quality of the XAI system. These metrics enable practitioners to gauge efficiency and reliability within the sector of cybersecurity endeavour. Since XAI considers transparency and explainability in an AI decision, certain measures in the field are required to measure them. Such moves render decisions of AI and justifications transparent and credible. The evaluation procedure has taken into consideration the areas of performance that are highly significant in cybersecurity interests.

One of the most significant measures to evaluate AI systems in cybersecurity is accuracy. The rightness and the accuracy of the XAI results are measured by this measure. The concept of accuracy used in cybersecurity implies that the decisions made by AI are correct to identify a threat and reduce false classification. As an example, an XAI system for identifying potential vulnerabilities or abnormal behaviour cannot work effectively unless it is very accurate. The number of false positives and negatives would be too high to render the system operable. The XAI quality lies in the accuracy, and the cybersecurity specialists are provided with trustworthy information to make decisions. False predictions of the threats can ruin the security or the unnoticed attacks, and precision is important in the XAI assessment.

The concept of robustness is the characteristic of the system to withstand adversarial attacks, whereby bad users can manipulate the input data in some subtle way to deceive the AI models. XAI vulnerabilities in cybersecurity can be used to bypass security checks or result in false positives in the detection systems. Part to assess the level of strength, they can be tested on how XAI systems will respond to these attacks and report the corresponding outputs. Such manipulations that have such XAI systems should be maintained in quality decisions and security integrity. The more advanced the adversarial methods are, the more ruggedness is a competitive advantage to adversarial methods. This measure is a capacity of systems concerning their sensitivity to the attack conditions in the real world.

The outstanding difference between XAI and traditional AI models that consider the interpretation and straightforwardness of the AI decision-making processes is interpretability. Justifications of AI should be accurate and understandable in the scenario of cybersecurity specialists who are in high-stress conditions. Interpretability will make sure that the specialists do not just know how AI systems arrive at a specific decision, such as why the network activity is suspicious or why the vulnerability is critical. Absence of interpretability may cause a lack of trust in the system to the cybersecurity team, who do not want to follow the recommendation of the system. Additionally, high interpretability can serve to satisfy the guidelines, regulations, and ethical principles of automated decision-making because it enables organisations to clarify automated decisions in a familiar and comprehensible language. The transparent and decipherable models will become invaluable during the audits or regulatory inspections.

The cybersecurity domain is expected to have special metrics of security to meet the unique needs and requirements of the domain. These measures are obtained not only by the general AI performance evaluators but also by the success of the XAI systems in terms of the desired security objectives. It is also possible to associate other measures to the ability of the system to identify threats on the fly, new threat patterns, or minimise false alarms in noisy environments. They are also used in the estimation of the performance of the systems in various cyberspace security cases, such as network security, malware, and fraud prevention. Assistance in determining the items in the XAI that would make the best impact on the practices and risk-related decisions of cybersecurity professionals can help them later. These tailor-made designs will make sure that the XAI models are formalised as high-performance, abstract, besides the real-world optimizations to certain security issues. The significance of such customised tests lies in a condition where the effects of the security breach can be extremely drastic.

Lastly, these evaluation metrics offer an overall evaluation system of the quality of the XAI system regarding cybersecurity. They are all the accuracy, robustness, interpretability, and metrics that are security-specific and guarantee the efficiency of the XAI systems in the security environment. The XAI testing on these dimensions can enable organisations to ensure that their AI models will not provide inaccurate answers, be resistant to adversarial attack, form clear judgments, and be safe regarding cybersecurity. Cyber threats are dynamic, and therefore, such holistic evaluations have gained more relevance in the design and implementation of AI that will realise the security benefits at minimum cost.

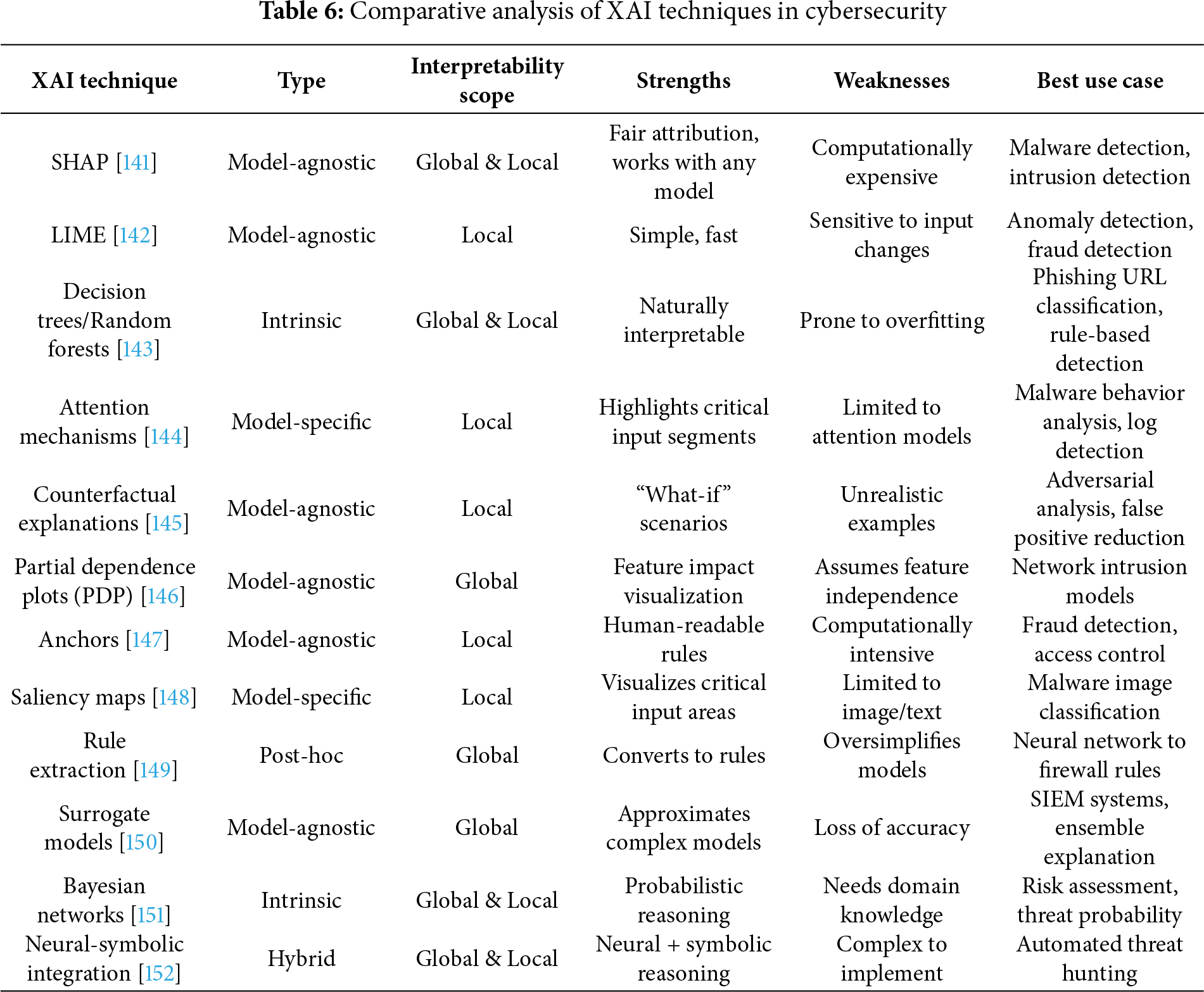

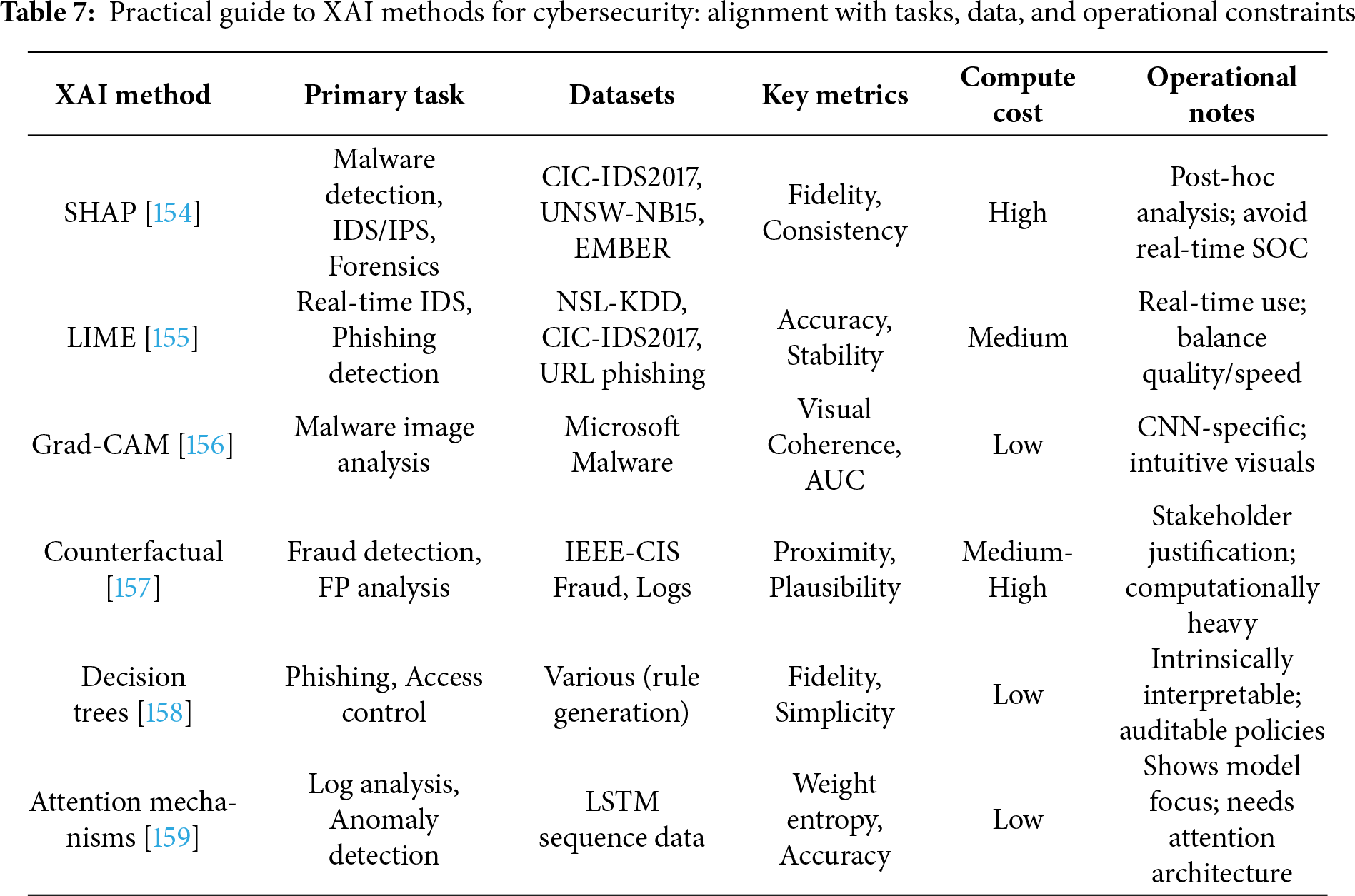

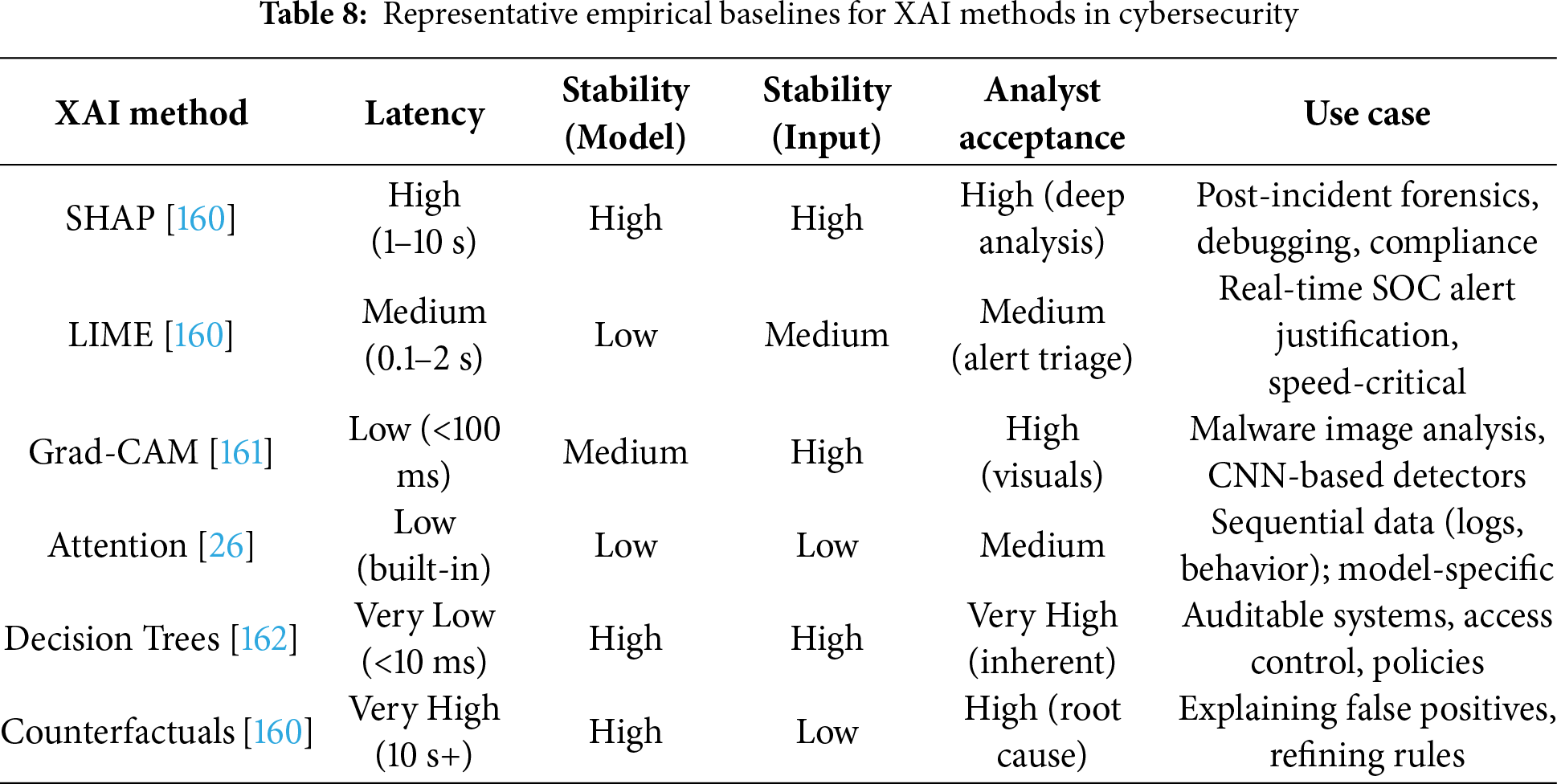

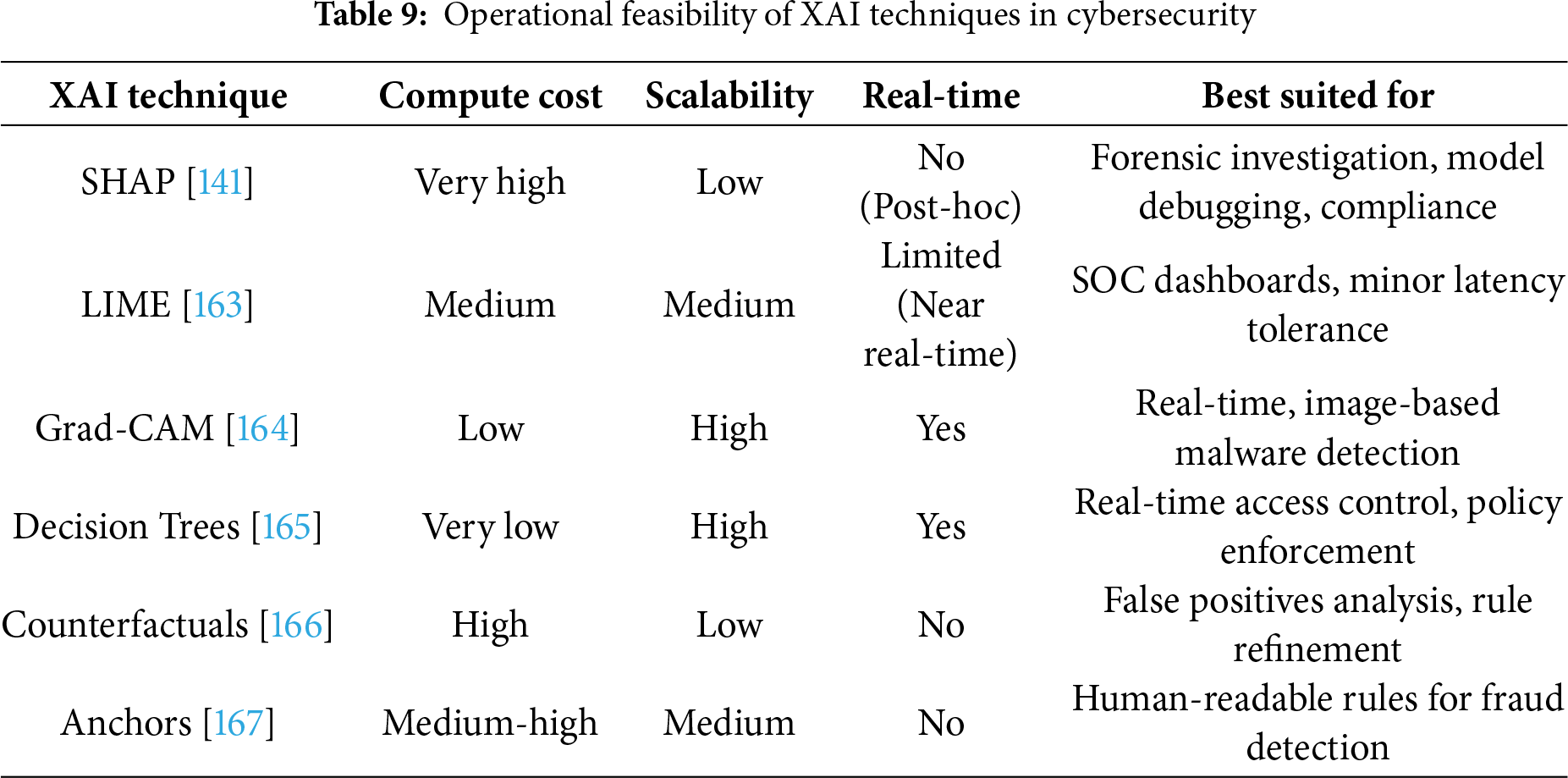

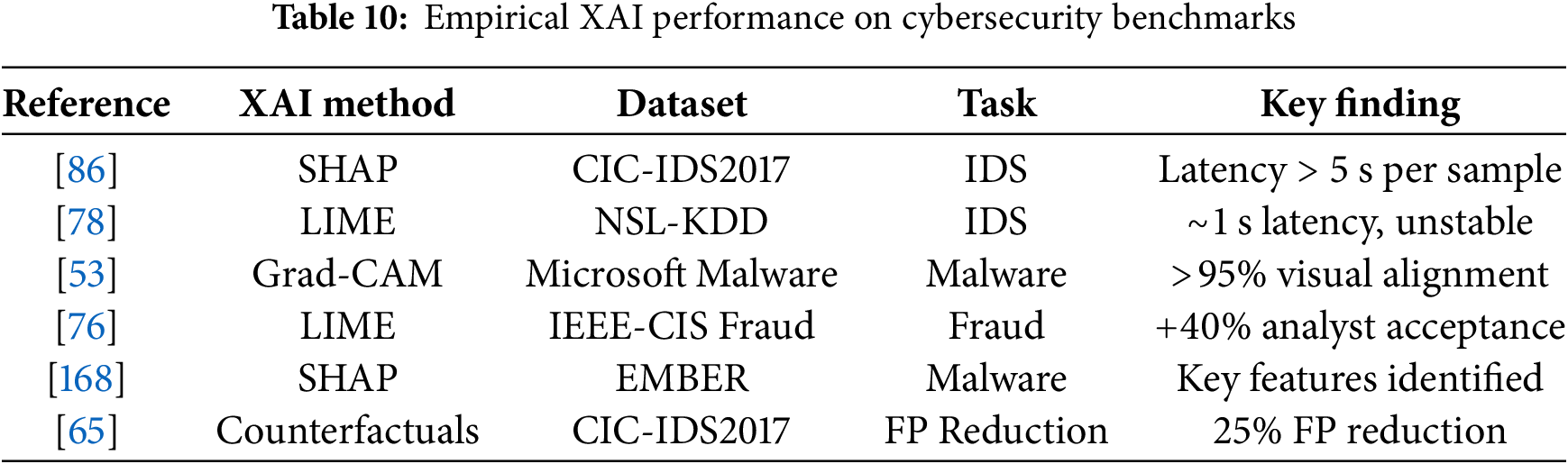

Table 6 provides a comparative analysis of prominent Explainable AI methods within cybersecurity contexts. This evaluation examines method types, interpretability levels, strengths, weaknesses, and optimal applications. The classification system is based on the model-agnostic, model-specific, or hybrid nature of methods and their specific advantages and drawbacks in terms of interpretability, computational complexity, and domain-specific utility.

SHAP is a model-agnostic technique that offers both local and global interpretability as well as fairly assigning features to prediction. Its main weakness is that it is computationally expensive, and this might not be allowed in time-sensitive applications or massive datasets. In the area of cybersecurity, SHAP provides useful information to malware detection systems, intrusion detection systems, and clarifies which characteristics or behaviours should be used to impact the model outputs.

It is a model-agnostic approach that only emphasises local interpretability, giving estimates of the black box models by using interpretable surrogacy models in single predictions. The advantages of LIM are simplicity and speed, which allow the generation of an explanation quickly. Nevertheless, this decreases resilience to more fluctuating environments because it is sensitive to changes in inputs. The main tasks of cybersecurity applications include anomaly detection and fraud analysis, in which it is worth having a rapid interpretation of crucial individual predictions [153].

These intrinsic model-specific approaches have global and local interpretability in the form of human-readable rules of decision. They are overfitted and prone to overfitting, especially in deep trees or noisy data, due to their inherent transparency. These models can be efficiently used in cybersecurity in phishing URL classification and rule-based detection situations, where transparent decision-making is required.

Attention mechanisms, as model-specific mechanisms implemented in deep learning models, are a source of local interpretability since they generate important segments of inputs. They are still only applied to neural networks that have explicit layers of attention. Cybersecurity systems comprise malware code analysis and log identification, where the recognition of critical behavioural patterns or log records is used in the process of detecting threats.

These model-agnostic techniques provide the ability to understand predictions locally with what-if scenarios that define sufficient changes to make. Being useful in the determination of the limits of decision-making, they can result in unrealistic situations within complicated models. Applications to cybersecurity are concentrating on adversarial analysis and false positive reduction, where the explanation of the boundaries and errors of decisions can increase the resilience of the model.