Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Explore Advanced Hybrid Deep Learning for Enhanced Wireless Signal Detection in 5G OFDM Systems

1 Institute of Technology, Middle Technical University, Baghdad, 10074, Iraq

2 School of Computer Science and Engineering, University of Aizu, Aizuwakamatsu, 965-8580, Japan

3 Division of Artificial Intelligence Engineering, Sookmyung Women’s University, Seoul, 04310, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Authors: Jungpil Shin. Email: ; Yujin Lim. Email:

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(3), 4245-4278. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.073871

Received 27 September 2025; Accepted 18 November 2025; Issue published 23 December 2025

Abstract

Single-signal detection in orthogonal frequency-division multiplexing (OFDM) systems presents a challenge due to the time-varying nature of wireless channels. Although conventional methods have limitations, particularly in multi-input multioutput orthogonal frequency division multiplexing (MIMO-OFDM) systems, this paper addresses this problem by exploring advanced deep learning approaches for combined channel estimation and signal detection. Specifically, we propose two hybrid architectures that integrate a convolutional neural network (CNN) with a recurrent neural network (RNN), namely, CNN-long short-term memory (CNN-LSTM) and CNN-bidirectional-LSTM (CNN-Bi-LSTM), designed to enhance signal detection performance in MIMO-OFDM systems. The proposed CNN-LSTM and CNN-Bi-LSTM architectures are evaluated and compared with both traditional methods and standalone deep learning models. Training was conducted offline using a dataset generated from a 2 × 2 MIMO-OFDM system with a 3GPP 5G channel model. The trained models are evaluated using accuracy, loss, and computational time, and further analysis of signal detection performance is based on bit error rate, optimal cyclic prefix length, and optimal pilot subcarrier configurations under various noise conditions and channel uncertainty scenarios. The results demonstrate that the proposed CNN-based architectures, particularly the CNN-Bi-LSTM trained model, significantly reduce the need for pilot and cyclic prefix symbols while delivering superior performance, especially at SNRs. All the hybrid deep learning architectures (CNN-LSTM, CNN-Bi-LSTM) demonstrated greater robustness and adaptability under dynamic channel conditions, outperforming conventional methods and benchmark deep learning architectures. These results indicate the effectiveness of CNN-based feature extractors in learning generalized spatial patterns, positioning these hybrid models as highly efficient and reliable solutions for MIMO-OFDM signal detection in 5G and future wireless communication systems.Keywords

Orthogonal frequency-division multiplexing (OFDM) is a modulation method that is often used in wireless broadband systems. It effectively reduces intersymbol interference (ISI) caused by the delay spread of the channels, thereby mitigating frequency-selective fading in wireless channels. However, channel estimation remains a significant challenge in OFDM systems, as the channel response can vary rapidly over time because of the mobility of the transmitter and receiver [1].

Although many studies have considered statistical approaches for OFDM channel state estimation to accurately detect signals, most of them require prior knowledge of the channel state information (CSI) at the receiver end [2–5]. Typically, pilot symbols are inserted into the transmitted signal to enable CSI estimation before data detection. With an accurately estimated CSI, the receiver can reliably recover the transmitted symbols. The least squares (LS) technique requires partial prior statistics and is simpler to implement, whereas minimum mean-square error (MMSE) estimators are fully statistical and generally more accurate when statistical information is available. The LS estimator does not require prior knowledge of channel statistics [6], whereas the MMSE estimator provides superior detection performance when second-order channel statistics are employed [7]. Numerous researchers have conducted channel estimation and have refined analytical techniques such as MMSE estimators for various scenarios [5,8]

In recent decades, artificial neural network (ANN) and deep neural network (DNN) architectures have demonstrated high performance in diverse applications, such as CSI-based localization [9], channel equalization [10], and channel decoding [11]. With the growing availability of computational resources and large datasets, the potential for integrating the deep learning (DL) approach into communication systems continues to expand. While online training has successfully employed ANNs for channel equalization, DNNs introduce new challenges because of their larger number of parameters [12]. Recently, the DL approach has demonstrated increasing potential in communication systems, largely driven by the availability of large-scale datasets and computational resources [13–15]. In addition to these DL architectures, several recent studies have proposed hybrid DL architectures that combine convolutional and recurrent layers, which have attracted increasing attention because of their ability to capture both local and long-term dependencies in sequential data. Studies [16,17] have confirmed that convolutional neural network-long short-term memory (CNN-LSTM) and convolutional neural network-based bidirectional long short-term memory (CNN-Bi-LSTM) networks perform comparably to attention-based DL models in classification and regression tasks because of their ability to effectively capture both spatial and temporal dependencies in complex sequential data. Similarly, recent work [18] attests that CNN–Bi-LSTM architectures are highly effective for detecting signals under challenging channel conditions, further supporting the choice of enhanced hybrid DL models in this study. In the same context, lightweight convolutional neural network (Lightweight-CNN)-based architectures have demonstrated effectiveness for challenging signal detection and synchronization tasks [19], underscoring the relevance of convolutional feature extraction in modern wireless signal detection systems. In accordance with these motivated advances, this work has adopted hybrid CNN-LSTM and CNN-Bi-LSTM architectures to enhance representation learning and improve the robustness of the proposed 2 × 2 for multiple-input multiple-output orthogonal frequency division multiplexing (MIMO-OFDM) signal detection in 5G wireless receivers and evaluates their performance against conventional detection techniques.

In the current paper, various DNN architectures are studied to improve symbol detection in OFDM systems. These models typically require extensive training data and long training times. To address these issues, this paper proposes hybrid DL architectures for 2 × 2 MIMO-OFDM signal detection in 5G wireless receivers and evaluates their performance against that of conventional detection techniques. The proposed CNN-based hybrid architectures are trained offline using synthetic data generated by a simulated MIMO-OFDM system.

Once trained, the models are employed for signal detection under varying channel conditions. Simulation results demonstrate that the proposed convolutional neural network-based hybrid architectures outperform existing deep learning models such as CNN [7], LSTM, and Bi-LSTM [16,20,21], as well as conventional signal estimators such as LS and MMSE [2–4], particularly when only a limited number of subcarriers and pilot symbols are available.

The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

• This work presents an end-to-end hybrid MIMO-OFDM signal detection framework that integrates CNN-based architectures with different recurrent architectures. In particular, we develop DL-based CNN-LSTM and CNN-Bil-LSTM architectures tailored for the application of 5G and emerging 6G wireless signal detection. Unlike prior studies, the proposed framework exploits convolution layers to capture spatial-frequency correlations from subcarrier packages effectively, while the LSTM block captures temporal channel variations, enabling more robust and spectrally efficient detection under dynamic channel conditions.

• The proposed hybrid DL architectures significantly reduce the dependance on pilot symbols and cyclic prefix (CP) overhead while maintaining competitive performance.

• Beyond conventional baseline methods for channel estimation (LS and MMSE), we compare our proposed CNN-based hybrid architectures against state-of-the-art DL MIMO-OFDM signal detection (CNN, LSTM, and Bi-LSTM) and demonstrate consistent gains in BER, convergence speed, and generalization to blind channel conditions.

• We provide an in-depth analysis of the training and inference complexity of the proposed hybrid DL architectures for MIMO-OFDM signal detection, revealing that our hybrid DL architectures achieve favorable performance in terms of accuracy, complexity, and latency, which makes them candidates for real-time receivers.

• The results reveal several striking insights into the performance of the proposed hybrid DL architectures for MIMO-OFDM signal detection compared with different architectures and conventional methods in terms of the training computation, implementation complexity, and bit error rate (BER) under different channel conditions. Our results demonstrate the performance of the proposed design of CNN-based hybrid architectures CNN-LSTM and CNN-Bi-LSTM for MIMO-OFDM signal detection by learning generalized spatial patterns across subcarriers, reducing the reliance on dense pilots.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we provide background information on related work. Section 3 introduces the OFDM system architecture and the MIMO channel model. Section 4 describes channel estimation techniques and linear signal detection methods for OFDM systems. Section 5 presents the mathematical formulation and data-driven framework for channel estimation in MIMO-OFDM systems. Section 6 presents the simulation settings and results, and finally, Section 7 concludes the study.

Wireless communication channels naturally experience multipath fading degradation, which leads to critical impairments such as ISI, cross-channel mixing (XCM), Doppler shifts, and frequency-selective fading. These effects degrade signal integrity by causing time dispersion, symbol overlap, and distortion in both the time and frequency domains, posing significant challenges for reliable signal detection and decoding in modern wireless systems. To mitigate these impairments, receivers require prior knowledge of the channel impulse response, which is typically obtained through specialized channel estimation techniques. Accurate channel estimation is a crucial aspect of wireless communication, as its quality directly impacts overall system performance [22]. Two main approaches for channel estimation are widely discussed in the literature: blind estimation and pilot-based estimation [23,24]. Blind channel estimation leverages the statistical properties of received signals without the need for dedicated training symbols, thereby reducing overhead and transmission costs. However, it requires many received symbols to produce accurate estimates, which can lead to degraded performance compared with that of pilot-based approaches. In contrast, pilot-based approaches include the insertion of known data symbols (pilots) into the transmitted signal at the beginning of the transmission of a frame to initiate the estimation of channel parameter accuracy [25]. Early studies demonstrated that the LS estimator offers low-complexity estimation without requiring prior channel statistics but at the cost of reduced accuracy. On the other hand, the MMSE estimator achieves higher accuracy by utilizing second-order channel statistics, although it introduces significant computational complexity [2–4]. To address this, various methods have been proposed in the literature to reduce the computational burden associated with MMSE estimation [5]. In recent years, ANNs have become popular choices for channel estimation because of their adjustable interconnected neurons with weighted inputs, offering a simpler alternative to traditional estimation techniques [25].

Some researchers in previous studies used radial basis Function (RBF) networks for OFDM channel estimation [25,26], whereas others have utilized backpropagation neural networks (BPNNs) to estimate channel coefficients under varying fading conditions [27]. They reported that the MMSE estimator outperforms both the LS and BPNN methods in terms of accuracy; however, it has higher computational complexity. To address the performance limitations of BPNN architectures, which typically consist of three main layers, Cheng et al. [28] integrated genetic algorithms (GAs) with BPNNs and demonstrated enhanced performance compared with standard BPNN approaches. Although these earlier channel estimation approaches provided certain improvements over traditional estimation techniques, they often suffer from limitations in terms of learning complex temporal dependencies and generalizing to dynamic channel environments. These challenges have led to a growing interest in more advanced DL architectures, such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and recurrent neural networks (RNNs), which offer greater capacity to model nonlinear relationships and time-varying channel characteristics.

Recent studies indicate that DL architecture can outperform conventional estimation techniques even when insufficient pilot signals are available [16,20,21]. DL models have demonstrated effectiveness for symbol detection in OFDM and MIMO-OFDM systems by eliminating the need for heavy dependence on pilot symbol insertion, which is unlike conventional estimation techniques that rely heavily on pilot symbols [16]. Nair and Menon (2022) [20] addressed pilot overhead in MIMO-OFDM systems with a Bi-LSTM network for joint channel estimation and symbol detection, showing effective performance in complex signal scenarios, while Wang et al. (2020) [16] employed a Bi-LSTM network integrated with convolutional layers and batch normalization for signal detection in uplink OFDM systems operating over time-varying channel responses.

Hassan et al. (2024) [21] developed a deep LSTM-based channel state estimator that outperformed conventional methods and Bi-LSTM models, providing reliable performance even with fewer pilot symbols and no prior channel knowledge. In Non-orthogonal multiple access (NOMA) systems, DL methods have shown similar promise. Smirani et al. (2024) [10] proposed a layered ensemble learning model called Stacked Generalization for Channel Estimation (SGCE) for NOMA systems, which eliminates the need for pilot insertion while enhancing throughput and prediction accuracy by combining six machine learning techniques. These studies together demonstrated the potential of ensemble machine learning techniques and recurrent DL models to enhancement spectral efficiency, decrease error rates, and improve the overall reliability of wireless communication systems.

Gao et al. [29] presented DL-based architectures for channel estimation (CENet) and symbol dictations in OFDM systems. Their results demonstrated that these architectures exhibit strong resilience to variations in channel parameters, confirming the adaptability of DL approaches in dynamic wireless environments [30]. CNNs have advantages over classical neural network architectures because they effectively use the relationships between neighboring channel elements in the spatial, temporal, and frequency domains. The CNN-based signal detection technique outperforms the standard MMSE approach in terms of performance [31]. In [29,31], researchers employed an untrained CNN to reduce noise in channels affected by pilot contamination. CNNs can efficiently reconstruct a three-dimensional channel by compressing related channels from a smaller, randomly chosen input tensor. Recently, this functionality has been used in CNN-based channel estimation [16,20] and in feedback on channel state information [32].

In the present work, we demonstrate the advantages of CNN-based channel estimation with different channel conditions and investigate the use of convolutional layers for capturing spatial-frequency features from OFDM symbol sequences. In [7], Ye et al. utilized numerous concatenated DNNs consisting of five dense layers to represent the channel in an OFDM system, which involves channel noise and simple time responses. The studies in [24,33] reformulate the channel estimation problem as an image recognition task using superresolution techniques.

These works estimate the beam-space channel vector using two types of DNN structures: fully connected (dense) layers and CNNs [33]. These models capture the spatial characteristics of the channel response across the antenna array between the transmitter and receiver. Similarly, in [34], the authors treat the time-frequency response of the OFDM channel as a two-dimensional image and calculate it using a DNN at certain pilot points. The aforementioned studies provide new insights into the use of DNNs for modeling nonlinear channels. However, these investigations have focused primarily on simplified DNN models and simulated datasets. To this end, further research is needed to investigate more diverse DNN architectures, including hybrid models such as CNN–RNNs, and to validate their performance under real-world communication conditions. OFDM is a multicarrier modulation technique in which the spacing between carriers is selected to ensure orthogonality among subcarriers, thereby minimizing intercarrier interference (ICI) [6].

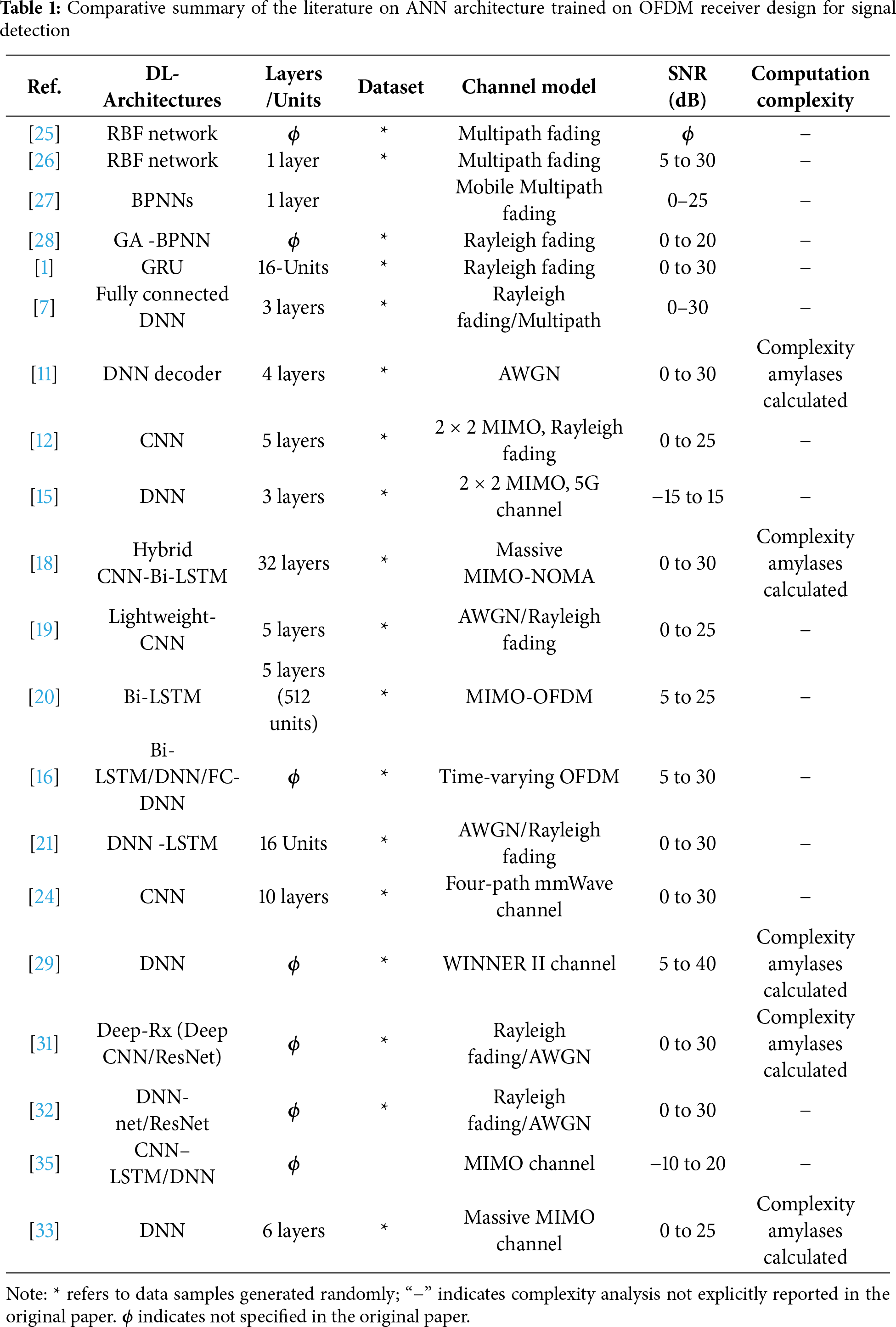

Table 1 lists a comparative overview of earlier studies that applied ANN architectures to OFDM receiver designs. The evaluations of these models demonstrate the shift in research from conventional shallow networks, such as RBFs and BPNNs, to more advanced and DL architectures. Early ANN-based architectures [25–28] provided low-complexity solutions for channel estimation under conditions of moderate fading. However, the performance of ANN-based OFDM signal detection often deteriorates in dynamic or highly dispersive environments due to constrained feature representation capabilities. With the advancement of DL, deeper architectures such as DNNs [1,11], CNNs [12,19,24], and recurrent neural networks (RNNs), including gated recurrent unit (GRU) networks [1] and LSTM variants, have been studied [30–33]. These architectures are better suited to handle nonlinearities and temporal dependencies in wireless channels.

Studies that combine CNN and Bi-LSTM, or other hybrid setups [31], especially those that mix convolutional and recurrent networks (such as CNN-LSTM and CNN-Bi-LSTM), have shown better performance in the presence of noise and multipath fading, with better estimation accuracy over a wider SNR range [32,35]. However, these gains come with an increase in computational complexity and training requirements. Furthermore, it is evident that the majority of prior studies utilized randomly generated datasets to facilitate equitable comparisons between models, owing to the arbitrary nature of the advice regarding the generalizability of the results. Additionally, studies have examined architectures using different criteria [11,18], whereas others have focused on the calculated complexity of mathematical representations [29,31,33].

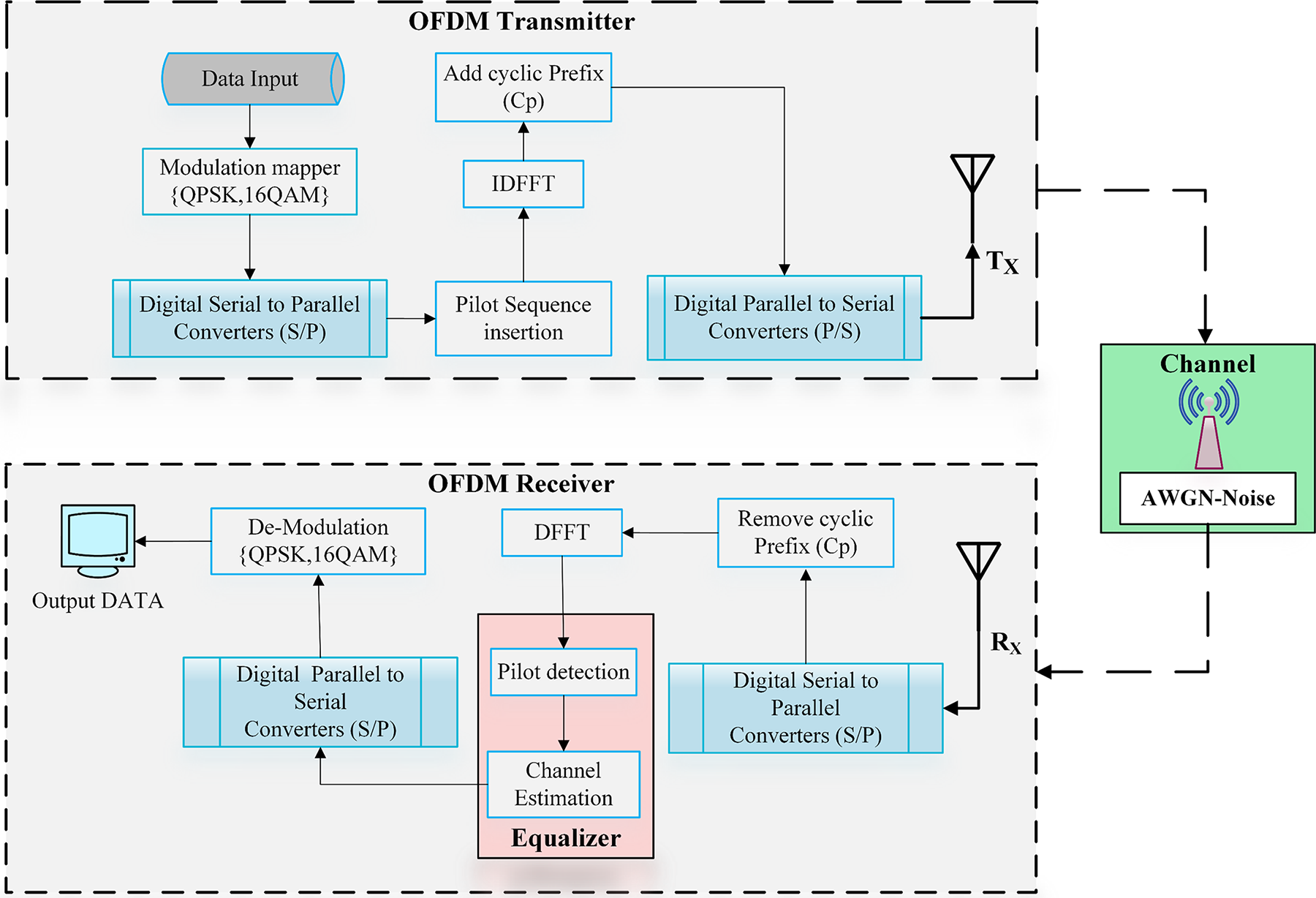

In this paper, hybrid DL architectures are adopted for enhanced MIMO-OFDM receiver performance. Compared with conventional DL models, the proposed hybrid DL architectures (CNN-LSTM and CNN-Bi-LSTM) aim to achieve a better trade-off between computational efficiency and estimation accuracy. The architecture of a typical OFDM system, consisting of both transmitter and receiver components, is shown in Fig. 1. The major functional blocks include pilot insertion, channel estimation, signal detection, and demodulation.

Figure 1: A typical block diagram of the OFDM system

According to Fig. 1, the complete OFDM system comprises transmitter and receiver structures. The transmitter performs modulation (e.g., QPSK, 16QAM), serial-to-parallel conversion, pilot insertion, inverse discrete fast Fourier transform (IDFFT) block, and CP addition before transmission over an additive white Gaussian noise (AWGN) channel. The receiver reverses these steps with CP removal, discrete fast Fourier transform (DFFT), pilot detection, channel estimation, equalization, demodulation, and data recovery [20].

3 OFDM System Architecture and Channel Model

At the transmitter, the input bitstream is first modulated using an appropriate digital modulation scheme (e.g., QPSK or QAM). The modulated symbols are then converted from a serial-to-parallel format to enable multicarrier transmission, as depicted in Fig. 1. A pilot insertion block embeds predefined pilot symbols at known positions within the data stream to help channel estimation at the receiver more accurately. The resulting sequence is then transformed from the frequency domain to the time domain using the IDFFT, which generates the OFDM signal. To combat ISI due to multipath fading, a CP is appended to each OFDM symbol before transmission over the wireless channel.

At the receiver, the reverse operations are applied. The received signal is first converted from serial to parallel, and the CP is removed to restore the original OFDM symbol structure. A DFFT is then applied to convert the signal back to the frequency domain.

In MIMO systems, multiple received signals from several antennas are processed simultaneously [36]. A linear combiner is then applied to maximize the SNR or mitigate interstream interference. Afterward, the combined signal is passed through an analogy-to-digital converter, and pilot symbols are detected to perform channel estimation. On the basis of the estimated channel information, equalization is carried out to compensate for the channel-induced distortions. Finally, the data are converted back from parallel to serial format and demodulated using the corresponding scheme, and the original transmitted bitstream is recovered [37].

3.1 Symbol Modulation and Mapping in the OFDM Transmitter

Modulation in digital communication systems refers to the process of converting a series of binary bits into complex symbols for transmission. Symbol mapping assigns bit groups to these symbols, which are then modulated using schemes such as PSK or QAM. In multicarrier transmission, it is possible to add zeros to the bits to align them with the number of subcarriers [38].

A serial-to-parallel conversion distributes symbols across carriers, and pilot symbols are embedded to aid channel estimation. Afterward, an IDFFT is conducted to obtain the OFDM time signal for each block of symbols. Next, the CP is added as guard time to avoid any interchannel interference. The channel block adds noise and interferes with the data sent by the OFDM transmitter. The channel blocks considered consist of a Rayleigh multipath, in addition to AWGN.

3.2 Mathematical Model of the 5G MIMO Channel

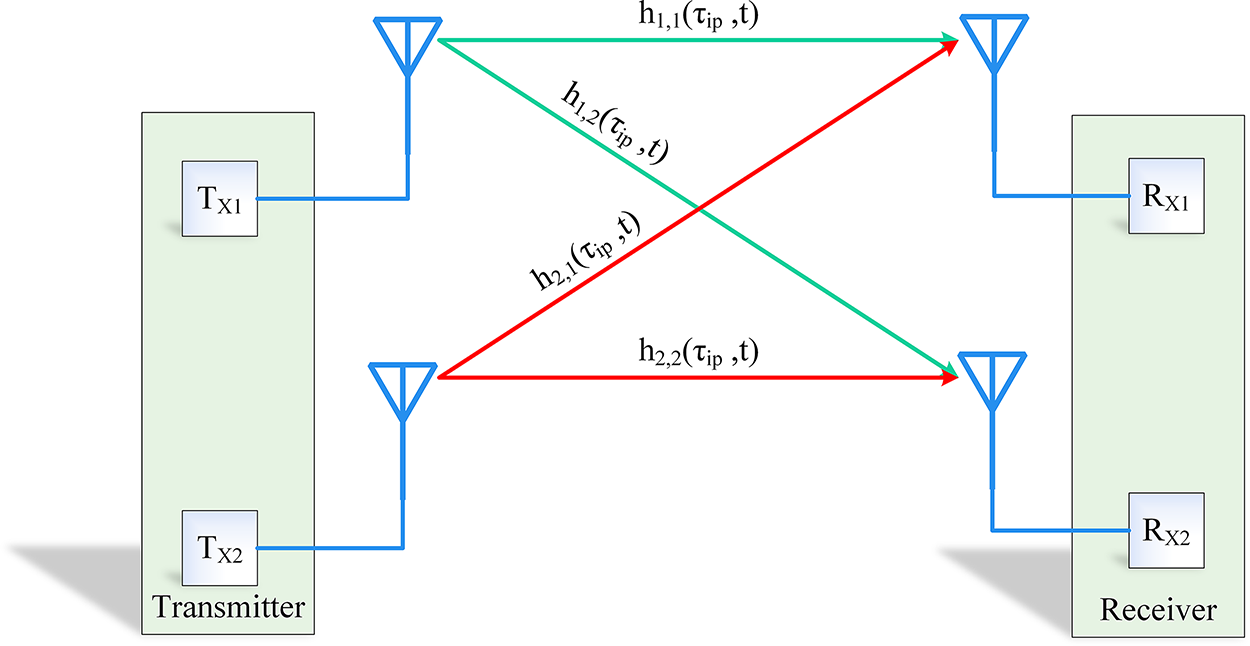

In this paper, we implement the multipath fading channel model, characterized by frequency-selective fading and time-varying behavior. The 5G MIMO channel model, which consists of two transmitting antennas and two receiving antennas, is shown in Fig. 2. The impulse response from the

where

where

Here,

Figure 2: 5G 2 × 2 MIMO channel model, where the transmit antenna indices are denoted as

3.3 Mathematical Description and Receiver Processing in OFDM Systems

The OFDM system begins by mapping the input data stream into symbols using modulation schemes such as QPSK or 16-QAM. The modulated symbols are then converted from parallel to serial format using a (P/S) converter. An IDFT block transforms the frequency-domain sequence into a time-domain signal following the insertion of pilot symbols [22].

where

where

where

where

where

• Given the presence of pilot symbols, the received signal in the frequency domain is expressed as follows:

• To obtain the estimated channel response, if

• After the transmitted signal is estimated, the next step is demodulation. The process can be outlined as follows:

1. Signal Equalization: When the estimated channel response is used, the received signal is equalized to recover the transmitted data sequence

2. Demodulation: To return to the original data stream, the estimated transmitted sequence

4 Channel Estimation and Signal Detection

Accurate channel estimation is critical for reliable detection in OFDM systems, as the performance of symbol recovery largely depends on the accuracy of the estimated channel coefficients. Numerous methods have been developed to estimate the channel by exploiting pilot symbols embedded in the transmitted signal. These methods typically minimize the estimation error by comparing the originally transmitted pilot symbols with their received counterparts. In this work, two conventional channel coefficient estimation techniques are performed using a comb-type pilot arrangement, with the LS and MMSE approaches considered representative methods [2–5].

The LS estimator is attractive because of its low complexity and ease of implementation, whereas the MMSE estimator achieves improved performance by incorporating channel statistics and noise variance at the cost of higher computational complexity. The following subsections provide a detailed discussion of conventional LS and MMSE estimators and introduce the proposed deep learning-based channel estimation method.

4.1 Conventional Channel Estimation Techniques

Even without any prior knowledge of channel statistics, the LS estimator is utilized to minimize the squared error between the received and original signals. The LS channel estimation formula for complex-valued pilot signals can be expressed as follows:

where

In addition to the LS estimation technique, other typically used techniques for channel estimation include the MMSE, the best linear unbiased estimator (BLUE), and adaptive boosting (AdaBoost) [8]. MMSE estimation extends the LS technique by combining both noise variance and channel statistics to minimize the mean squared error between the estimated and actual channel responses [5]. The formula for channel estimation using the MMSE method is as follows:

where

The LS estimator is a simple and computationally efficient method, but it has limited accuracy under high noise conditions. While the MMSE approach enhances estimation accuracy, especially under noisy conditions, it comes at the cost of higher computational complexity.

4.2 Deep Learning-Based Channel Estimation and Training Methods

CNNs are efficient DL architectures widely used in tasks such as classification and pattern recognition. Owing to their high level of efficiency, they have become popular options in DL [41]. Unlike regular DNN architectures, CNNs automatically find important details in the input data using different types of layers, such as convolutional, pooling, and fully connected layers. The backpropagation algorithm is used to train the layers of CNNs by allowing the convolutional and pooling layers to extract and map more complex features from the input data, while the fully connected layers handle the classification task [42]. In the literature, numerous CNN architectures have been presented [16,20,29,31]. However, the CNN architecture presented in this paper adopts a deeper configuration of convolutional layers (CLs) designed to strike an optimal balance between effectiveness and computational complexity.

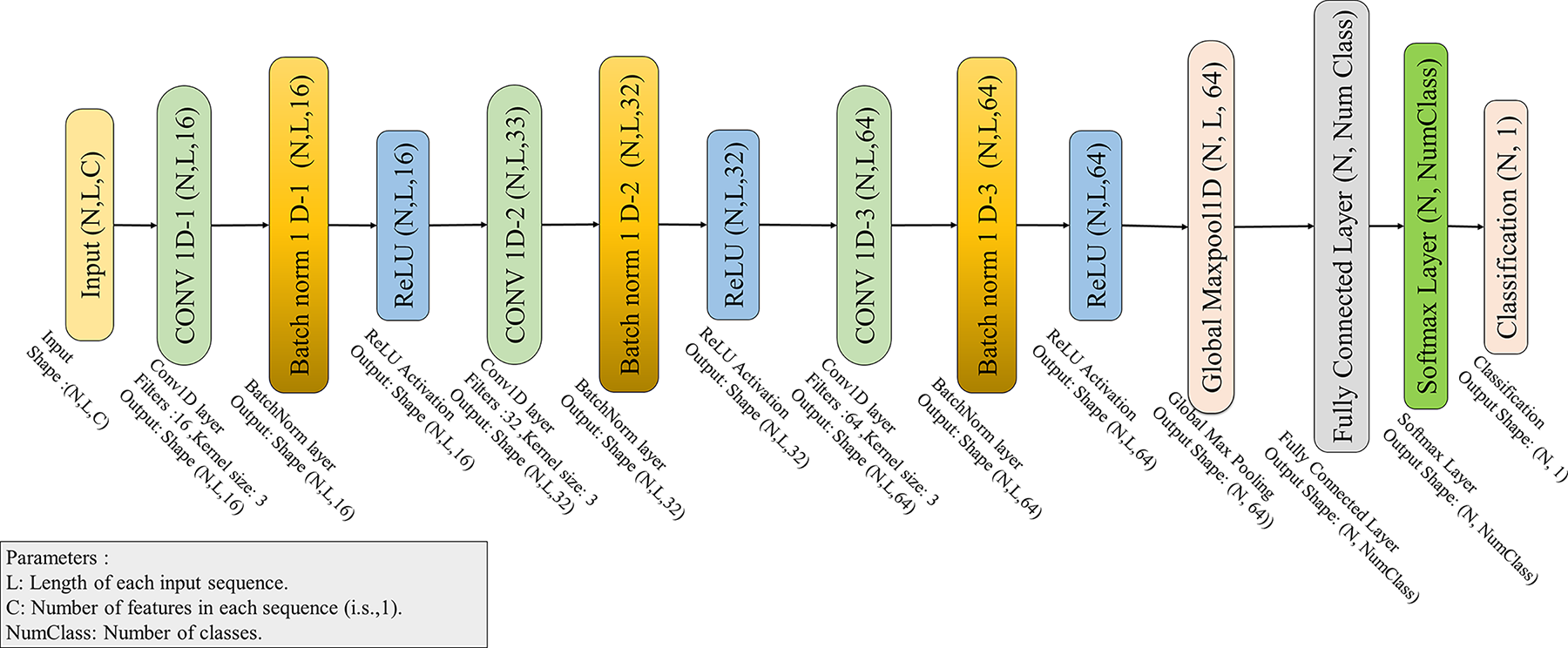

As shown in Fig. 3, the proposed multiple-layer CNN architecture comprises three CLs, each followed sequentially by batch normalization and a nonlinear activation function. Using a multiple-layer CNN architecture with three CLs provides several advantages, including enhanced model efficiency during the training process while maintaining a reasonable computation time, even on lower-specification platforms. The CL is a crucial component of a CNN that is responsible for extracting basic and complex patterns from an input sequence by using one-dimensional convolution with a specific filter size [7]. The following expression represents the convolution process in the r-th convolutional layer of a CNN:

Thus, the k-th filter in the r-th layer yields the following output:

where

Figure 3: Layer arrangement of the proposed CNN architecture

The fifth layer of the proposed multiple-layer CNN is a global max pooling layer, which reduces the dimensionality of the sequence by selecting the maximum value across all positions, which is consequential in a 64-dimensional vector for each sequence step in the batch [41]. The architecture concludes with a fully connected layer (FCL), followed by the final softmax layer, which generates the probability distribution across all possible output labels.

4.2.1 LSTM and Bi-LSTM Architectures

This section presents the architecture of the DNN employed for channel estimation in an OFDM system. A neural network with more than two layers is typically referred to as a DNN [12].

1. Long Short-Term Memory Architecture

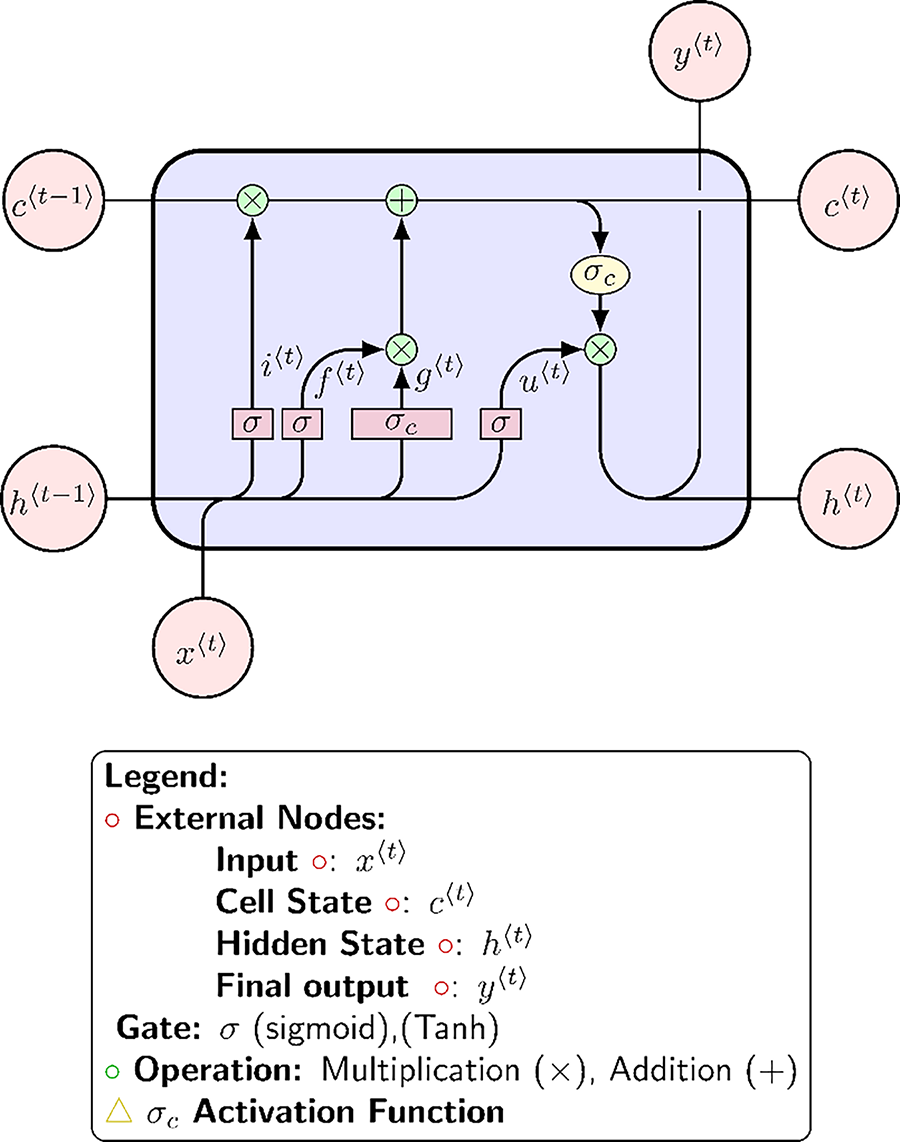

The LSTM architecture extends the abilities of conventional RNNs by consisting of input, forget, and output gates, along with a memory cell. These gates regulate the flow of information and enable the network to capture long-term temporal dependencies [43]. The structure of a single LSTM cell is shown in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: LSTM single-cell architecture. The following notation describes the components of an LSTM cell:

The forget gate enables the LSTM cell to eliminate unnecessary information from the backward step using the current input

• The input gate of the LSTM formulation is as follows:

• The forget gate of the LSTM formulation is as follows:

• The cell candidate of the LSTM formulation is as follows:

where

The cell state update and hidden state update are formulated as follows:

where

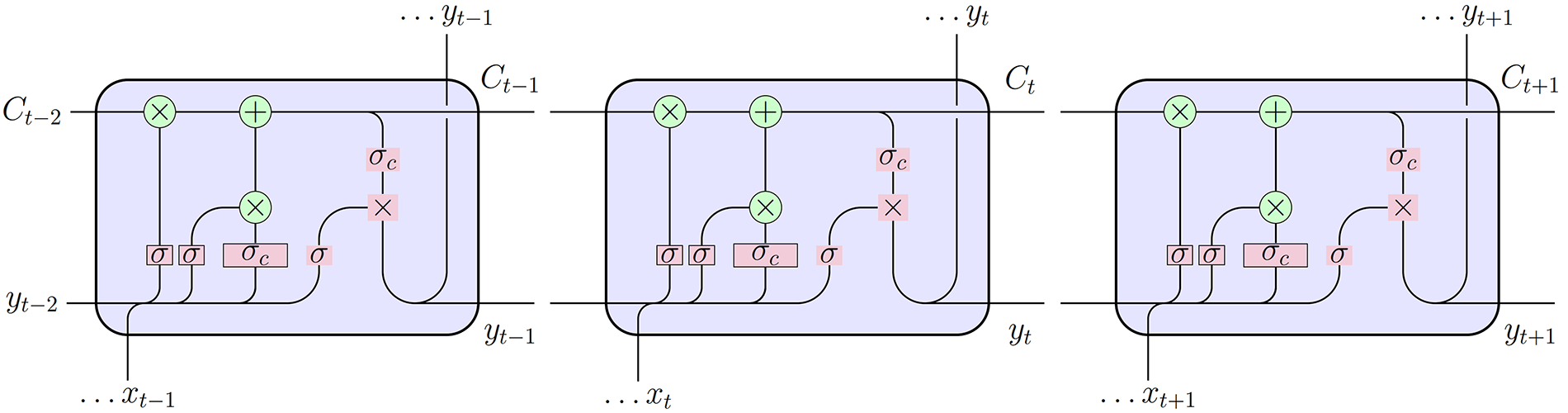

The LSTM (Eqs. (17)–(20)) use these components to regulate information retention or forgetting over time, enabling the network to efficiently handle long-term dependencies in sequential symbols. The LSTM network captures information from past inputs to make predictions or understand sequences, as shown in Fig. 5.

Figure 5: Multicell LSTM architecture

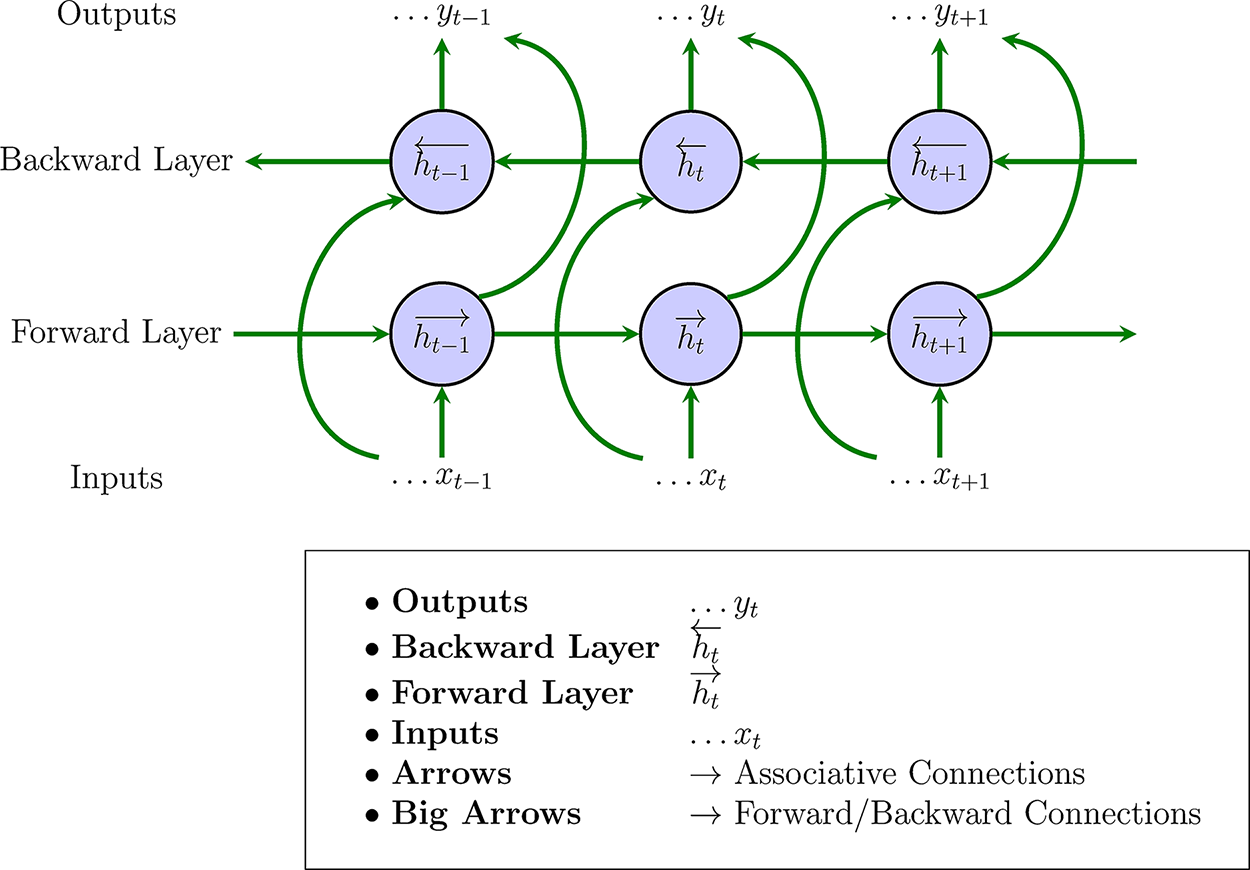

2. Bidirectional-LSTM Architecture

The Bi-LSTM architecture is an advanced version of RNNs and is specifically designed on the basis of the LSTM architecture. The Bi-LSTM layer consists of two separate LSTM cells used to capture long-term temporal pattern dependencies across data sequences in two directions: forward and backward [43,44]. The Bi-LSTM network architecture comprises five principal layers: a sequence input layer, a bidirectional LSTM layer, a fully connected layer, a softmax layer, and a layer dedicated to classification [43]. An arrangement of multiple layers in a vertical sequence of Bi-LSTM cells makes up a multilayer Bi-LSTM network, also known as a stacked Bi-LSTM [45].

The key difference between LSTM networks and Bi-LSTM networks is the approach used to process the input sequence and extract information from the data. In a Bi-LSTM, data are gathered from both past and future inputs, which provides a more complete understanding of the sequence. It processes the sequence in two directions: forward (from the first element to the last) and reverse (from the last element to the first), as shown in Fig. 6.

Figure 6: Bi-LSTM architecture

This approach allows the network to capture information from both the past and the future relative to each time step. The concurrent information from both forward and backward propagation in Bi-LSTM is conveyed to the output unit. Consequently, as illustrated in Fig. 6, storing both past and future sequences of data is possible. Both the forward and backward LSTM networks receive the input at a specific time, denoted as

where

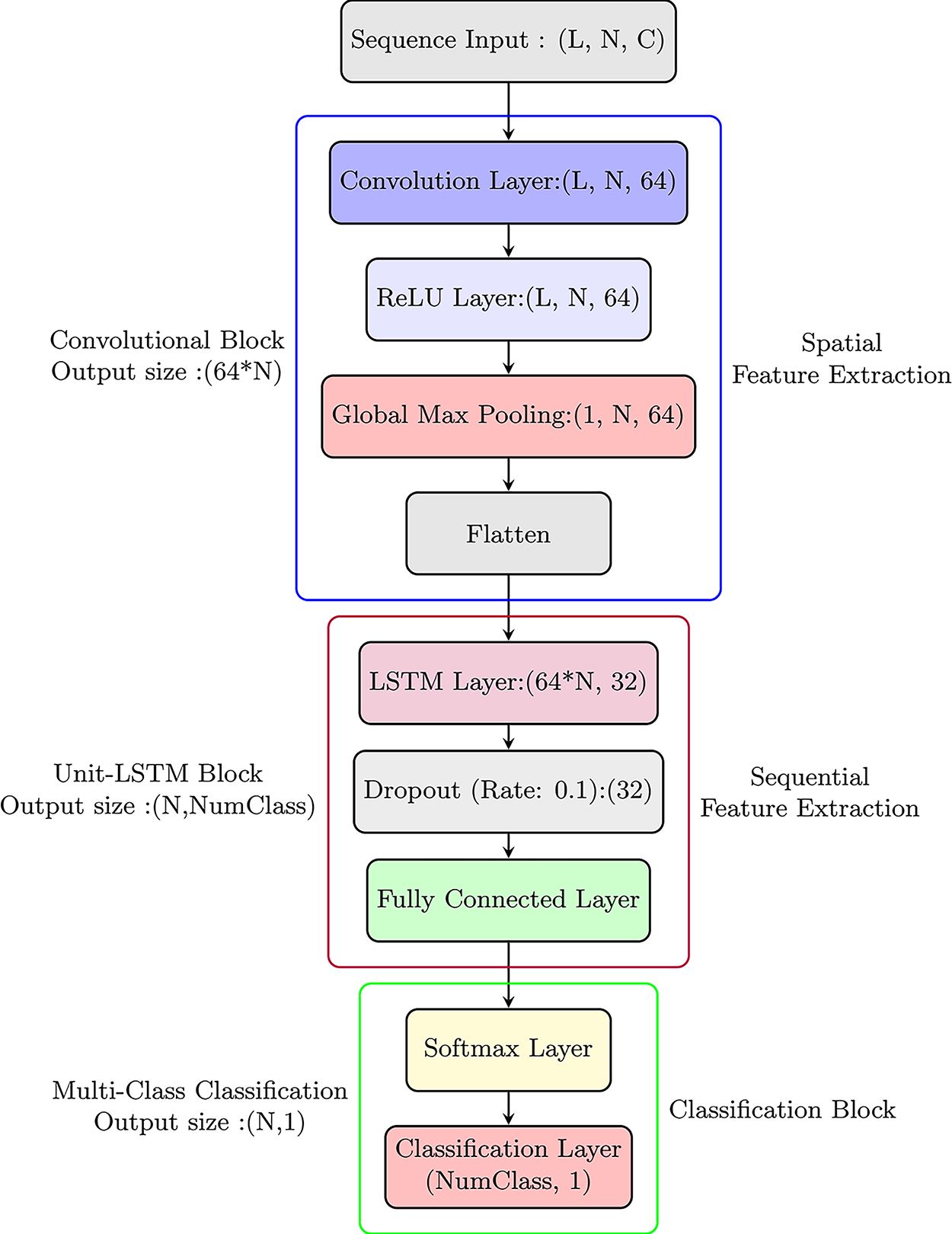

4.2.2 Hybrid DNN Architecture for Sequence Classification

This section introduces a hybrid CNN-LSTM architecture as a more effective alternative to baseline DNNs for channel estimation. This architecture combines the strengths of CNNs as spatial feature extraction layers and LSTMs as temporal dependency modeling. The proposed design of the CNN-LSTM hybrid architecture is shown in Fig. 7. Unlike conventional DNNs that consider all inputs individually by using fully connected layers, as reported in [16,20,33], the CNN-LSTM effectively captures both spatial and temporal features from input patterns, which offer unique relationships. The convolutional block accounts for spatial feature extraction, which is essential for recognizing local patterns at each time step of the sequence. By leveraging convolutional filters, the convolutional block automatically learns salient spatial features, thereby reducing the reliance on extensive manual feature engineering. Additionally, the use of shared filters across the sequence reduces the number of trainable parameters compared with conventional DNNs with FLCs [43,44], resulting in improved computational efficiency and a lower risk of overfitting. While convolutional blocks effectively capture spatial dependencies, LSTM blocks capture temporal dependencies inherent in sequential patterns, which are critical in sequential data because prior knowledge influences future results [21].

Figure 7: The layer arrangement of the proposed hybrid CNN-LSTM architecture

In the proposed hybrid architecture, the LSTM layers process the spatial features extracted by the convolutional block, enabling the identification of long-term dependencies and temporal trends. To further improve the proposed hybrid generalization capabilities, dropout regularization is applied within the LSTM block. Dropout functions by randomly deactivating a subset of neurons during training, inspiring the network to learn robust, generalized feature representations rather than memorizing specific training samples [46]. The proposed hybrid CNN-LSTM architecture leverages the complementary strengths of both components by explicitly dividing the roles of spatial and temporal feature extraction.

Compared with conventional DNN architectures with FCLs, this hybrid model provides a more effective and understandable framework for complex pattern extraction. Each block in the architecture has a distinct and effective purpose: the CNN layers focus on capturing spatial features, the LSTM layers handle temporal relationships, and the FCLs, along with softmax, execute the final classification based on the integrated spatial–temporal features. Together, the proposed combined CNN and LSTM results in a powerful DNN capable of handling complex sequential data.

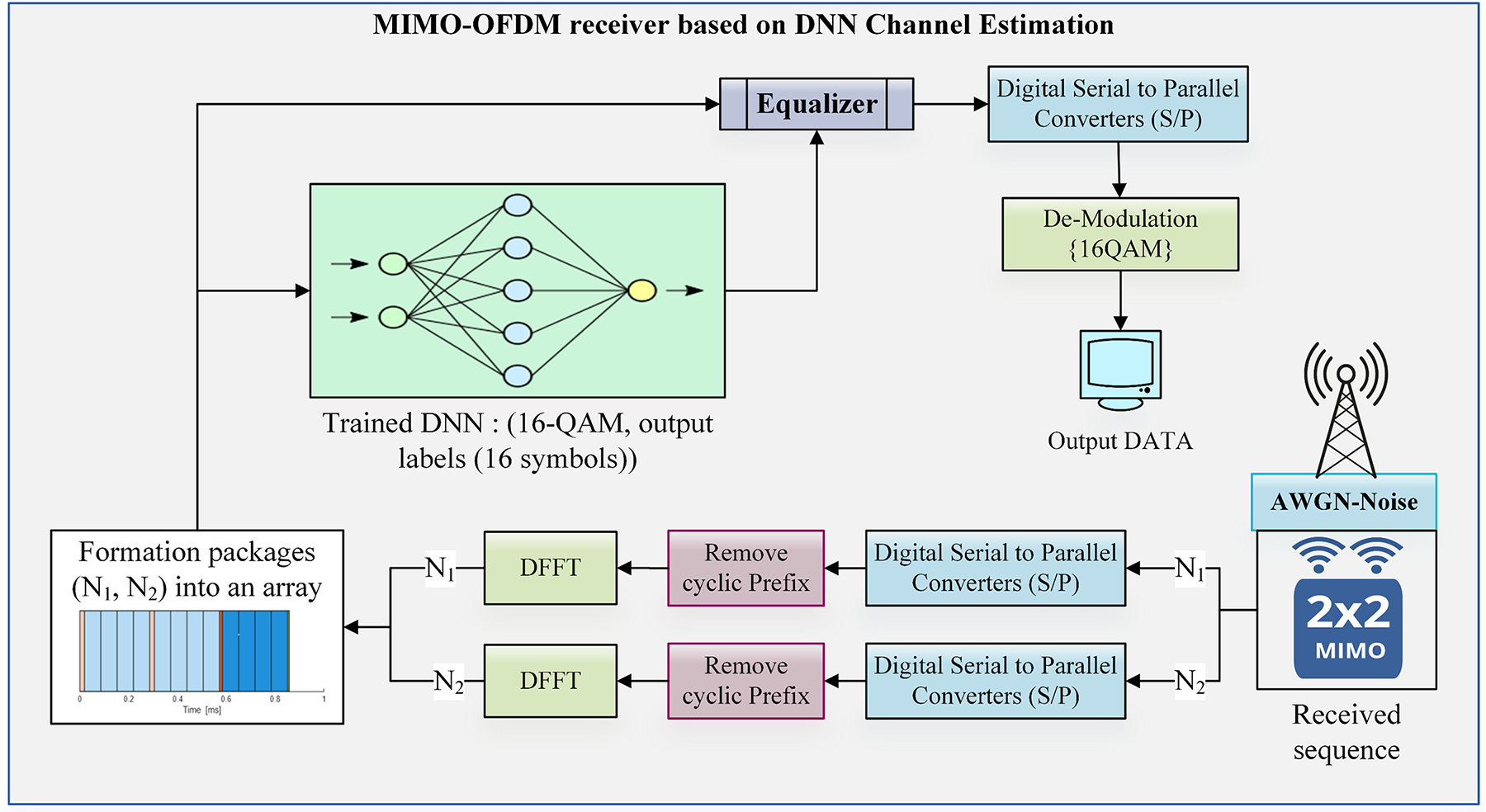

5 Mathematical Formulation of DNN-Based Channel Estimation

All the considered DNN architectures, CNN-LSTM, CNN-Bi-LSTM, and Deep-CNN, are trained offline using received OFDM data as the input and the corresponding transmitted data as the output. The schematic design of an OFDM receiver integrated with DNN-based channel estimation is shown in Fig. 8. A 2 × 2 MIMO-OFDM system was simulated with a narrowband Rayleigh fading channel model, and training datasets were generated using randomly placed pilot and data symbols. The received OFDM frame is processed and used as input to the DNN models. To minimize the error between the predicted output and the original transmitted data, the DNN architectures are trained using the adaptive moment estimation (Adam) optimization algorithm. The performance of the proposed DNN-based estimators, which include LSTM, Bi-LSTM, and CNN, is compared against that of conventional channel estimation methods [2].

Figure 8: Schematic design of an OFDM system with deep neural network architecture-based channel estimation

Adam is widely adopted in DL because of its ability to combine the strengths of both RMSprop and momentum [42]. This results in faster convergence and reduced training time. Its use of adaptive learning rates allows for more efficient parameter updates, which is particularly beneficial when training deep neural network architectures [47]. The update process is expressed as follows:

The moving average for gradients and squared gradients can be defined as follows:

Bias-corrected estimates and then moving averages of bias-corrected

where

where

Dataset Preparation

In this study, the input to the proposed hybrid models is the output signal from the MIMO-OFDM system. Since this signal undergoes QAM modulation and is transformed using the IFFT operator, the resulting data are complex-valued. However, as most DL architectures are designed to handle real-valued inputs, complex numbers are not processed directly in this work. Instead, the complex data are converted into real-valued form. The transformation of the input data follows this formulation:

where

Following this transformation, the dimensionality of the data is adjusted accordingly. Specifically, the received signal

This real-valued formation facilitates compatibility with standard DL architectures while preserving the information contained in the complex domain [35].

6 Simulation Settings and Results

Three robust DL models (CNN-LSTM, CNN-Bi-LSTM, and deep CNN) for channel estimation and signal detection were investigated by using a two-phase process. In the first phase, offline training elaborated on the OFDM samples from multiple data streams under varying channel conditions. In the second phase of the process, the trained model was evaluated to determine whether it is able to predict transmitted information without the need for an explicit channel estimate. During the training phase, a dataset was created by sending OFDM frames via a selected wireless channel model. The channel parameters and noise are impacted by both the original broadcasted symbols and the OFDM signals accepted by the receiver from the dataset. The trained model was then deployed on the testing dataset to retrieve the signals that were sent, leveraging its acquired knowledge and inherent ability to extract features. All of the experiments were simulated in a computer-based environment, and native MATLAB functions were used to implement the random raw data and channel effects.

6.1 Offline Model Training and Evaluation Metrics

This section presents a performance comparison of the proposed hybrid architectures, including CNN-LSTM, CNN-Bi-LSTM, and CNN, against statistical channel estimation techniques, including LS and MMSE [2–4].

In addition, baseline DL models such as LSTM [7] and Bi-LSTM [16,20,21] have been proposed. The evaluation is based on several metrics: the BER across varying SNRs, training time, and accuracy of transmitted bit detection during the training stage. Multiple simulation scenarios were conducted to validate the effectiveness of the proposed DL architectures in estimating the CSI and recovering transmitted symbols. To assess performance under realistic conditions, simulations were performed using three different Cp- lengths (0, 16, and 32) and pilot configuration scenarios (4, 8, and 64). The 3GPP TR 38.901 5G channel model was adopted because of its ability to realistically simulate wireless propagation environments, which can degrade channel estimation performance and overall system reliability, as highlighted in [40]. The DL models were trained offline using datasets generated specifically for this study.

These datasets were subsequently used to estimate the CSI and recover transmitted information in a 2 × 2 MIMO-OFDM wireless communication system. A total of 40,000 OFDM packets were generated for a 2 × 2 MIMO-OFDM system. Each packet consisted of one pilot symbol and one data symbol per transmit antenna. The dataset is split into 80% for training (32,000 packets) and 20% for validation (8000 packets). The dataset was created across different SNR levels to guarantee strong system performance under changing channel conditions.

While some studies have used SNR levels above 5 dB during training [7,24] and others have restricted training to 10 dB [35], this paper employs a broader range; specifically, training data were generated using SNR levels of 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35, and 40 dB. This broader range allows the proposed models to learn features resilient to noise and applicable to real-world wireless environments.

Table 2 summarizes the OFDM system configuration parameters, while Table 3 details the comprehensive parameters used in the proposed DL models. These parameters were selected through an analytical approach to maximize model performance.

The studied OFDM system transmits 10,000 data subcarriers organized across multiple OFDM symbols, each consisting of 64 subcarriers. Pilot sequences of length 4, 8, or 64 are inserted to support accurate channel estimation and reliable data recovery [5,21,35].

The adopted channel model incorporates a TDL-A profile with multipath propagation and Doppler effects at 10 and 350 Hz, simulating both low- and high-mobility conditions. The AWGN is applied with an SNR ranging from 10 to 40 dB, including a 5 dB padding margin, to better simulate realistic channel conditions.

Compared with CNN-LSTM (32), CNN-Bi-LSTM is designed with a larger hidden size (64), potentially capturing more complex features. The CNN-only model uses more convolutional layers (3 Conv1D layers) and no recurrent layers, focusing solely on spatial feature extraction with a deeper architecture (14 layers). All the models use the Adam optimizer and cross-entropy loss for multiclass classification.

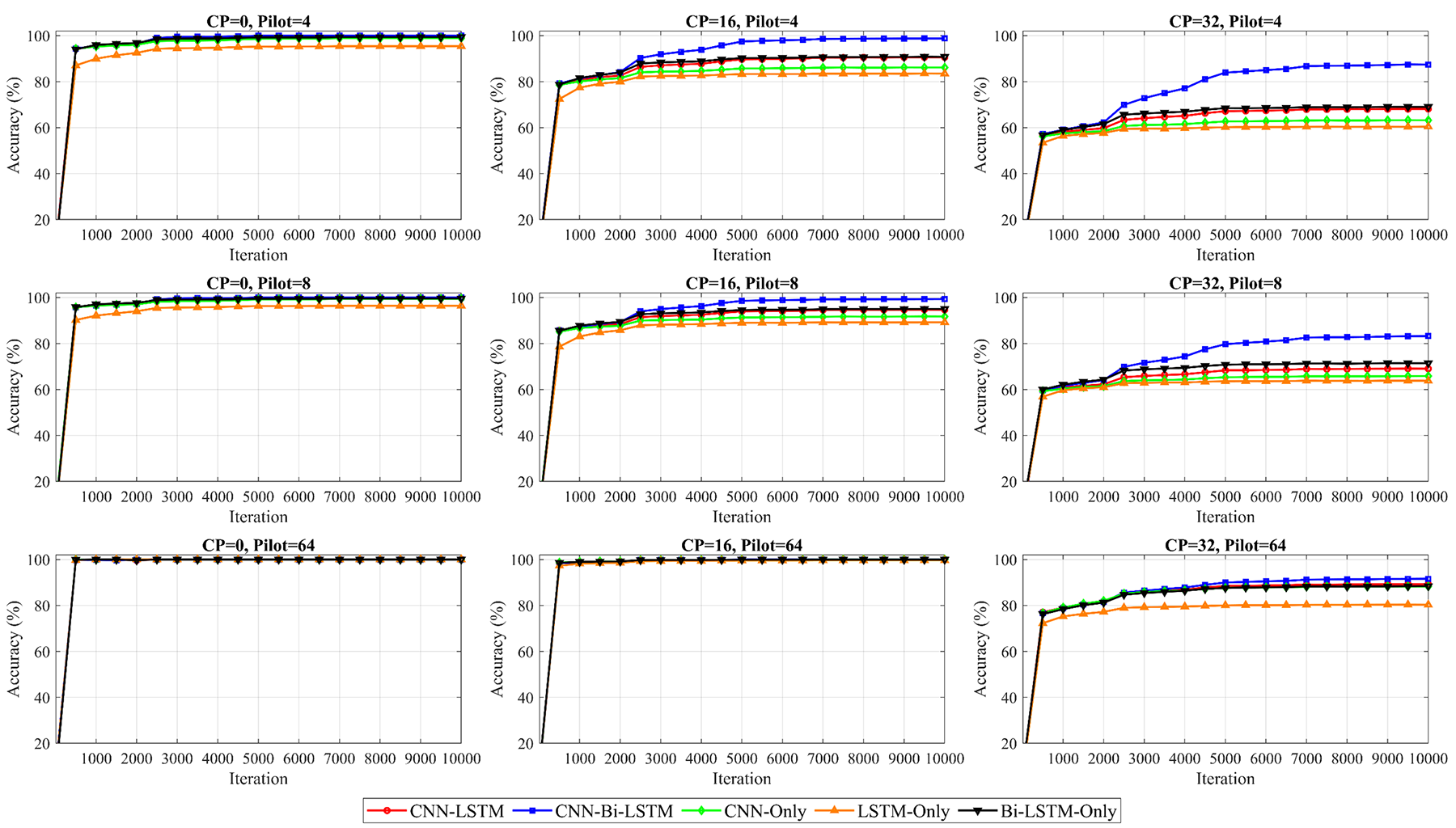

6.1.1 Training Evaluation Metrics

In this subsection, the performance of the proposed 2 × 2 MIMO-OFDM channel estimation models is evaluated during the training phase using two key metrics: cross-entropy loss and recognition accuracy. All of the studied channel estimation models were implemented on a Lenovo computer platform (Model: 21JNN0CKGR) equipped with a 13th Gen Intel® Core™ i7-13700H CPU processor (20 cores, at.40 GHz), and 16 GB of RAM and run under the (OS) Windows 11 (64-bit) operating system. To ensure robustness, the average values of multiple runs were computed for recognition accuracy across five model architectures: CNN-LSTM, CNN-Bi-LSTM, CNN-only, LSTM-only, and Bi-LSTM-only. The evaluation was conducted by using varying cyclic prefix lengths of 0, 16, and 32 and pilot configurations of 4, 8, and 64. The training was performed with a maximum of 100 epochs and a mini-batch size of 1000. The results are illustrated in Figs. 9 and 10, which illustrate the training model performance, accuracy of detection, and cross-entropy loss under various CP lengths and pilot configuration scenarios. A comparative analysis of symbol detection accuracy for the studied DL architectures is shown in Fig. 9: CNN-LSTM, CNN-Bi-LSTM, CNN, LSTM, and Bi-LSTM. Increasing the pilot size significantly improves the detection accuracy across all CP lengths, and all of the architectures achieve near-perfect symbol detection accuracy after quite a few iterations when the pilot size is set to 64. These findings indicate that a larger number of pilot symbols provides richer training data, enabling more effective channel estimation and symbol recognition.

Figure 9: Comparison of the accuracy rates for symbol detection between the proposed hybrid architectures and their existing counterparts for the model trained using the Intel Core 2.4 GHz i7-13700H CPU platform

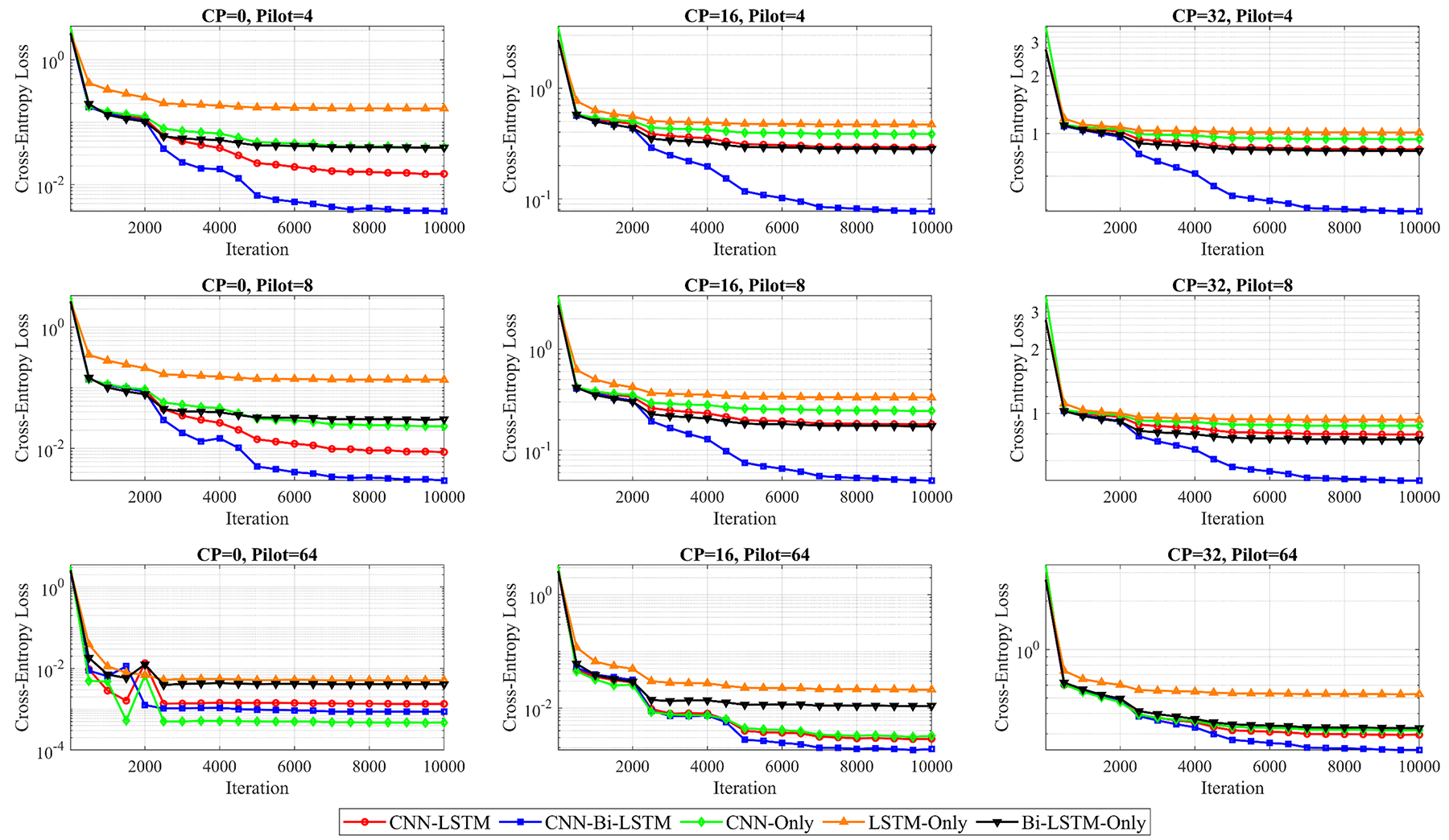

Figure 10: Loss factor–cross-entropy comparison between the proposed hybrid architectures and existing counterparts for the model trained using the Intel Core 2.4 GHz i7-13700H CPU platform

In the case of smaller pilot sizes of 4 and 8 symbols, the differences between the considered architectures become more obvious. Under these constrained conditions, compared with their standalone counterparts, both the CNN-LSTM and CNN-Bi-LSTM hybrid architectures demonstrate superior performance. The hybrid architectures benefit from the combination of spatial feature extraction through CNN layers and temporal sequence modeling through LSTM layers.

On the other hand, the performance impact of increasing the CP length is visible. With no CP, all of the models maintain high accuracy, especially when trained with larger pilot sizes. However, as the CP length increases to 16 and then 32 symbols, a reduction in accuracy is observed. This effect is most pronounced in the case of a 4-symbol pilot, when the models struggle to maintain high accuracy even after extended training.

The reduced performance with longer CP lengths can be attributed to the increased redundancy in the signal, which reduces the proportion of useful information. This redundancy makes it more challenging for the models to learn meaningful patterns. Nevertheless, the CNN-Bi-LSTM model maintains relatively strong performance, indicating its robustness in terms of handling signal distortions caused by extended CP. In the model comparison, CNN-Bi-LSTM achieves better accuracy across nearly all of the configurations. These results indicate the advantage of the bidirectional temporal layer combined with the spatial feature extraction layer. The performance of the CNN-LSTM model is similar, as it also benefits from the hybrid design. Furthermore, the CNN models generally perform better than both the LSTM and Bi-LSTM configurations do, particularly in scenarios with a long CP length and small pilot sizes, indicating that temporal layers alone are insufficient under challenging conditions.

Moreover, in the offline training phase, a comparison of the cross-entropy loss across different DL configurations is shown in Fig. 10. The models were trained using various pilot sizes and CP lengths. As the number of pilot symbols increases, all the models converge faster and achieve lower final loss values when the effect of changing the pilot size is analyzed.

When the pilot size is set to 64 symbols, most models stabilize with minimal loss after a few thousand iterations. These results confirm that larger pilot sizes provide more reliable training signals, enabling efficient learning and reducing uncertainty in symbol recognition. With a lower pilot size, especially for four symbols, the loss remains higher, and convergence slows.

Under these conditions, the performance differences among architectures become more visible. CNN-Bi-LSTM consistently converges to the lowest loss values, while CNN-LSTM also demonstrates superior learning capabilities even with limited pilot information. An increase in CP length leads to a general increase in loss values across all architectures. This effect is most noticeable in the case of 4-symbol pilots, where longer CPs result in higher and more persistent loss levels. The added redundancy from longer CPs decreases the effective data-to-noise ratio, making the learning task more difficult. Although the Cp-length affects some models, CNN-Bi-LSTM shows strong resilience, maintaining the lowest loss trajectory in nearly all the cases.

In contrast, the LSTM and Bi-LSTM architectures suffer from higher loss values, particularly when the CP is extended to 32 symbols. These results suggest that these architectures are less effective at handling temporal distortions without the support of spatial feature extraction. Among the architectures studied, CNN-Bi-LSTM achieves the best performance, with the lowest loss across almost all the configurations. CNN-LSTM closely follows, showing that combining a CNN with unidirectional LSTM is still effective. In contrast, the CNN architecture outperforms LSTM, especially in early iterations, because of its ability to capture spatial patterns effectively.

In the same context, the LSTM and Bi-LSTM architectures show slower convergence and higher final loss, particularly under low pilot size and high CP-length package settings, demonstrating their limited effectiveness in channel estimation and OFDM symbol detection tasks.

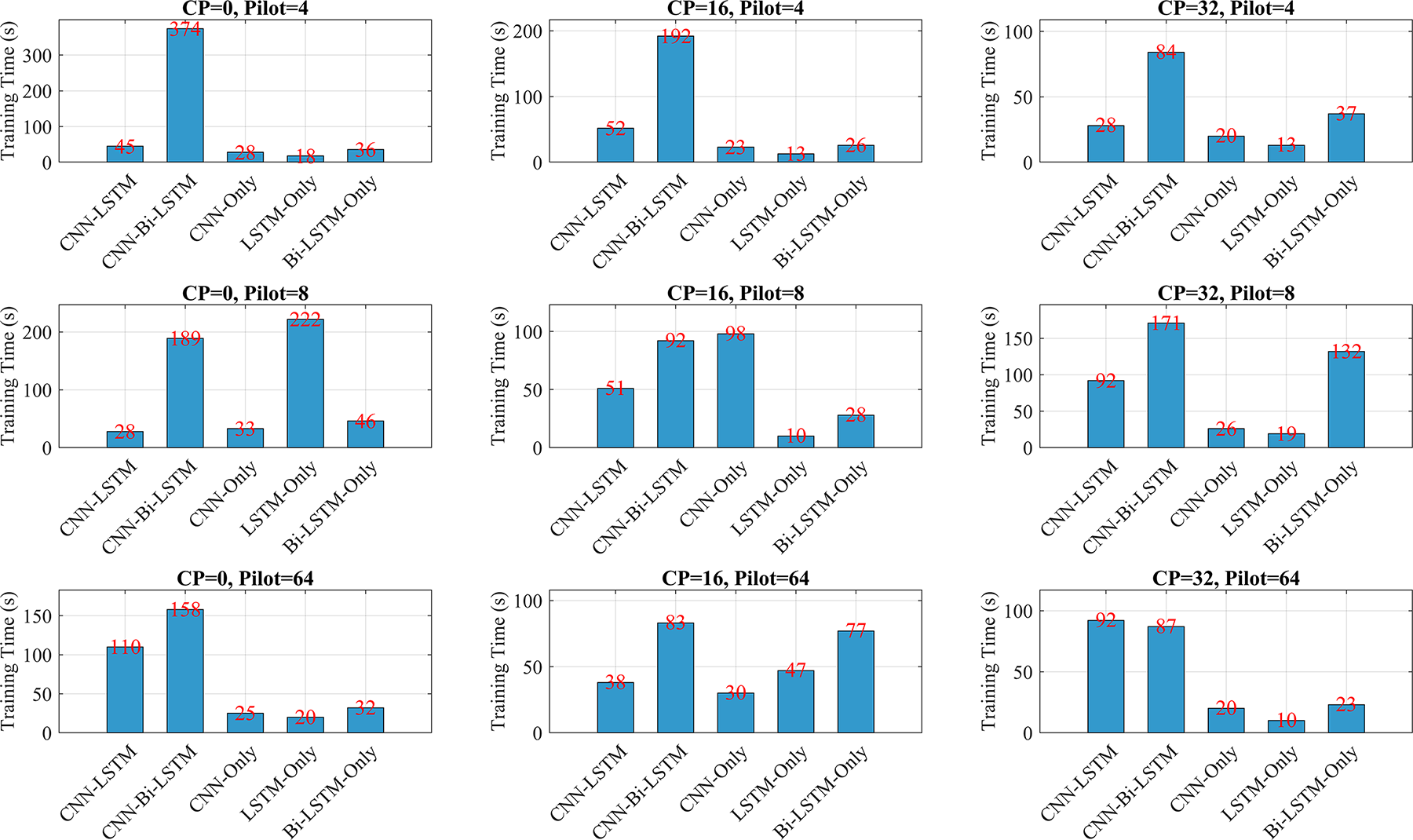

6.1.2 Comparative Analysis of Hardware Requirements for Proposed Architectures

This subsection discusses the computation time required to train interesting DL configurations using a simulation computer executor. The simulation computer executor contains a CPU at 2.40 GHz and 16 GB of RAM and runs under OS Windows 11 (64-bit). To ensure robustness, the reported training time reflects the average duration needed to process a single batch of data segments under varying CP lengths and pilot sizes. These results are shown in Fig. 11, highlighting the performance variations across different CP-lengths and pilot size scenarios. The time required for training various DL architectures under different pilot sizes (4, 8, and 64 symbols) and CP lengths (0, 16, and 32 symbols).

Figure 11: Training time comparison between the proposed hybrid architectures and existing counterparts for the model trained using the Intel Core 2.4 GHz i7-13700H CPU platform. The recorded training time corresponds to the duration required to process one batch of data segments

The CNN-Bi-LSTM model consistently requires the longest training time in nearly all the scenarios, reflecting the computational overhead introduced by bidirectional recurrence combined with convolutional layers. For instance, in the case of 4 pilot symbols and no CP, it reaches a peak time of 374 s per batch. Compared with the single-stream models, CNN-LSTM also has longer training durations, although the training duration is still significantly shorter than that of CNN-Bi-LSTM.

In contrast, the LSTM-only and CNN-only models are generally more efficient. Among them, CNN-only is particularly efficient and benefits from parallelizable convolution operations. The Bi-LSTM-only model has moderately higher time requirements because of its bidirectional structure, but it is still faster than the hybrid CNN-Bi-LSTM. Increasing the pilot size generally leads to increased training time for the hybrid models. This trend is particularly noticeable for CNN-LSTM and CNN-Bi-LSTM, which process more data through both convolutional and recurrent layers. For example, when CP = 0, increasing the pilot size from 4 to 8 significantly increases the training time for CNN-Bi-LSTM from 374 to 189 s. However, for simpler models such as the CNN and LSTM, the increase in training time with more pilot data is less dramatic. Furthermore, when the CP length increases, the training time tends to decrease slightly or remain stable.

This reduction can be attributed to increased redundancy in the input data introduced by the CP, which might reduce the effective complexity of the learning task per iteration. However, this trend is not uniform and varies across architectures and pilot sizes. For example, when there are 64 pilot symbols and the CP is increased from 0 to 32, the training time of the CNN-Bi-LSTM decreases from 168 to 87 s.

In terms of computer training time, the proposed models exhibit varying levels of computational demand. Among the proposed models, CNN-only is the most computationally efficient, as it avoids the sequential dependencies of LSTM layers and relies solely on convolutional operations, which are highly parallelizable. While CNN-Bi-LSTM offers the highest accuracy and robustness, it comes at the cost of significantly increased training time.

Therefore, for time-constrained or resource-limited environments, CNNs provide a practical trade-off between performance and computational efficiency. In practical scenarios, the channel estimation accuracy and training speed of DNN models are critical, as they reflect the algorithm’s computational complexity and efficiency. For real-time deployment, it is feasible to utilize digital signal processing (DSP) platform hardware with similar computational capabilities, as shown in Table 4.

As listed in Table 4, the comparative analysis emphasizes the focus among various machine learning (ML)-capable real-time platforms. Xilinx ZCU104 provides FPGA flexibility for custom parallel processing but has modest CPU and RAM requirements. NVIDIA Jetson Orin Nano delivers powerful GPU-accelerated ML inference with excellent power efficiency.

Xilinx ZCU104 is the best choice for faster channel estimation and symbol detection, especially in real-time DL-2 × 2 MIMO-OFDM systems, because it combines excellent ML processing, flexible signal processing, and the hardware support needed for wireless communication.

The Jetson Orin Nano is a great option for ML tasks such as CNN-LSTM architectures, especially when working with large datasets for 2 × 2 MIMO-OFDM systems. However, for real-time signal processing where fast response is needed, using Jetson Orin Nano together with an FPGA platform works better. The Jetson handles complex computations, while the FPGA manages fast, low-latency tasks. However, this setup can be pricier, use more power, and require additional design complexity, which must be carefully considered on the basis of the processing demands.

6.2 Performance Evaluation under Static and Dynamic Channel Conditions

This subsection presents the simulation-based online evaluation of the proposed DL models. Most of the literature focuses on the static channel response, and few studies have discussed dynamic values during the testing phase. In our work, the performance assessment is conducted under two distinct testing scenarios. In the first scenario, static channel response conditions, the trained DL models are tested using the same channel responses as those used during training. The second scenario involves dynamic channel conditions, which use new channel response values that were unseen during the training process of the DL models. In these scenarios, both training and testing were intentionally conducted under controlled yet diverse simulated conditions to ensure a fair and consistent comparison between the DL-based and conventional methods (LS and MMSE). In the training phase, the OFDM packet configuration described in Table 1 was utilized. During testing, variations in CP lengths and pilot subcarrier configurations, along with the models, were evaluated across SNR values ranging from −10 to 20 dB in increments of 2 dB, for a total of 16 SNR points. Each configuration underwent evaluation across 10 Monte Carlo iterations, with each iteration processing 10,000 OFDM packets to ensure statistical reliability and minimize the likelihood of overfitting to a specific channel realization.

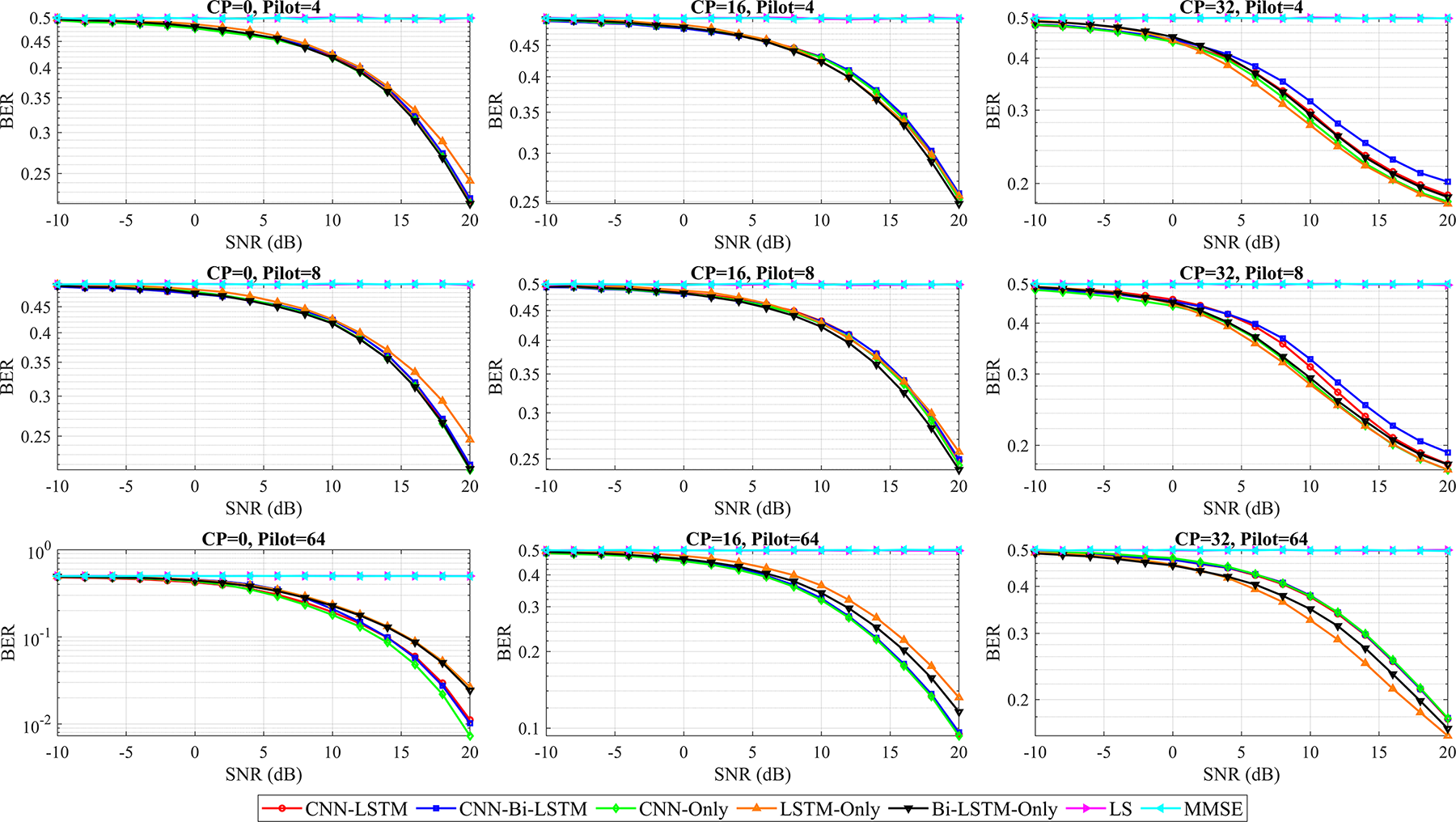

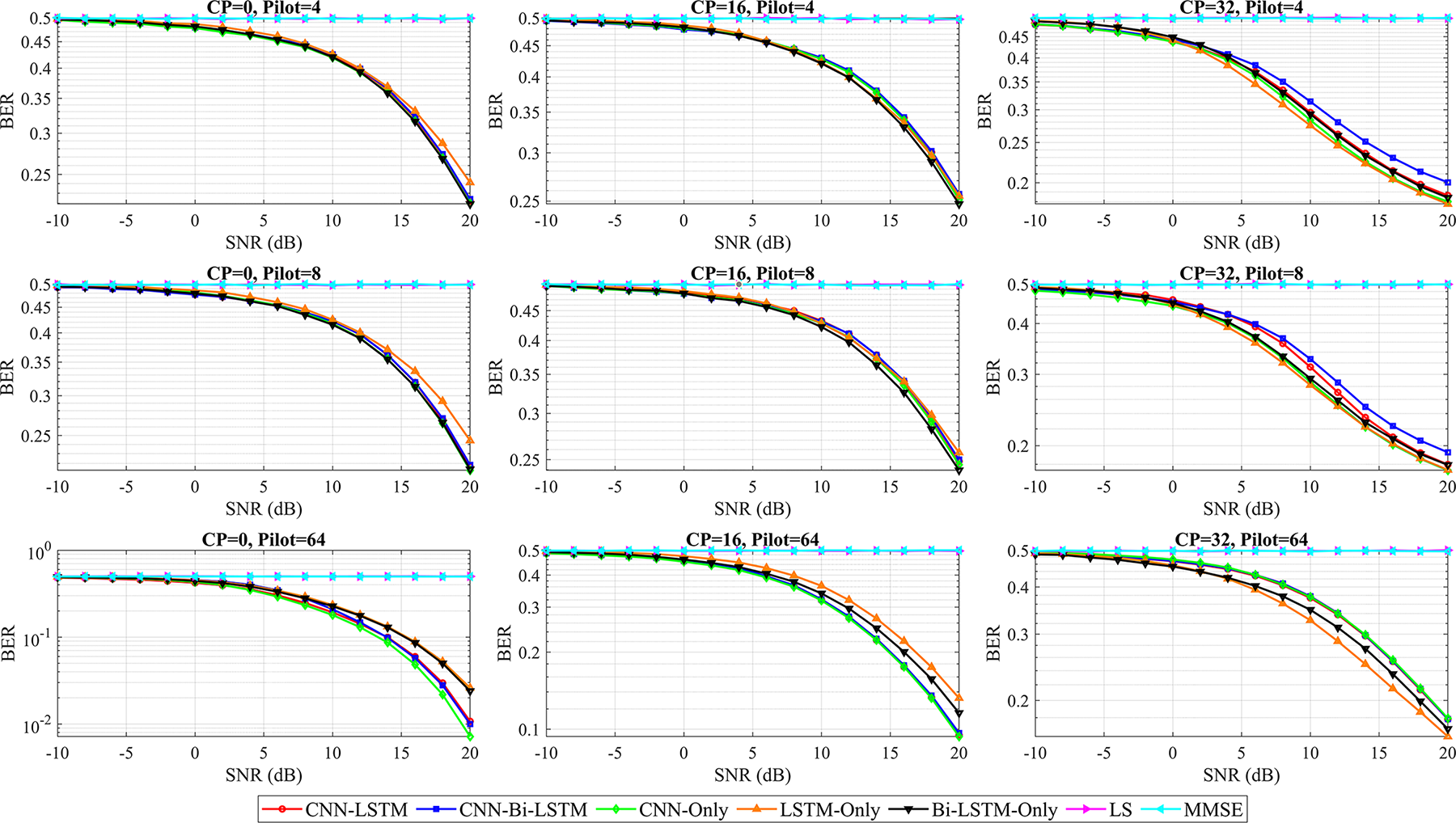

All of the simulations were performed by using a standard computing platform, and the BER was calculated to demonstrate the accuracy of the transmitted bit detection. The performance results, summarized in Figs. 12 and 13, emphasize the generalizability and dependability of each trained DL model under both static and dynamic channel conditions across varying CP lengths and pilot sizes. The BER comparison under static channel matrix conditions is shown in Fig. 12. The results show that all of the considered CNN-based architectures significantly outperform conventional estimation methods such as LS and the MMSE, especially in low-to-mid SNR regimes, which emphasizes the strong learning capabilities of the proposed hybrid architectures.

Figure 12: BER comparison of the proposed hybrid architectures and existing models trained on an Intel i7-13700H (2.4 GHz) CPU under a static channel matrix

Figure 13: BER comparison of the proposed hybrid architectures and existing models trained on an Intel i7-13700H (2.4 GHz) CPU under a dynamic channel matrix

Overall, the CNN-Bi-LSTM architecture achieves the best overall performance, mainly at low SNRs and with small pilot symbols of 4 and 8. It maintains a lower BER across CP values, showing strong resilience under static channels, which is ideal for 5G and 6G use cases such as vehicle and mobile scenarios. Similarly, CNN-only performs exceptionally well with a large pilot size of 64 and no CP, achieving a BER close to that of CNN-Bi-LSTM but with lower complexity, which makes it suitable for low-power 6G edge devices and IoT applications for which real-time processing is critical. In contrast, the LSTM-only and bi-LSTM-only architectures achieve moderate BER performance, benefiting from the temporal learning capabilities of the recurrent layers; however, they still lag behind the CNN-based models in terms of accuracy and robustness.

A BER comparison when different values of the channel matrix are used is shown in Fig. 13. It is obvious that under more challenging channel conditions, the proposed hybrid CNN-LSTM and CNN-Bi-LSTM architectures achieve an advantage in maintaining performance, consistently yielding the lowest BER compared with all the other MIMO-OFDM signal detection methods. While the overall BER is higher for all the models because of the time-varying nature of the channel, the proposed hybrid architectures demonstrate superior robustness and adaptability in tracking these changes, proving more effective for realistic wireless communication scenarios where channels fluctuate over time. On the other hand, the LSTM and Bi-LSTM architectures show a similar trend as in the static scenario does. Under more realistic channel conditions, the BER values are generally greater for a given SNR than for a static channel matrix.

The LSTM and Bi-LSTM models achieve performances that surpass those of LS and, occasionally, the MMSE, but they consistently lag behind the proposed design of CNN-only and, especially, the hybrid CNN-LSTM and CNN-bi-LSTM. The performance of both the LSTM and Bi-LSTM models is less effective in the more challenging dynamic channel matrix than in the hybrid DL models, indicating that whereas the LSTM models are designed for sequential data and can track some time variations, they struggle to capture the full complexity of dynamic channels without the combined spatial feature learning of CNNs. Bi-LSTMs offer a marginal improvement by processing sequences in both directions, but CNN integration is more critical for robust performance.

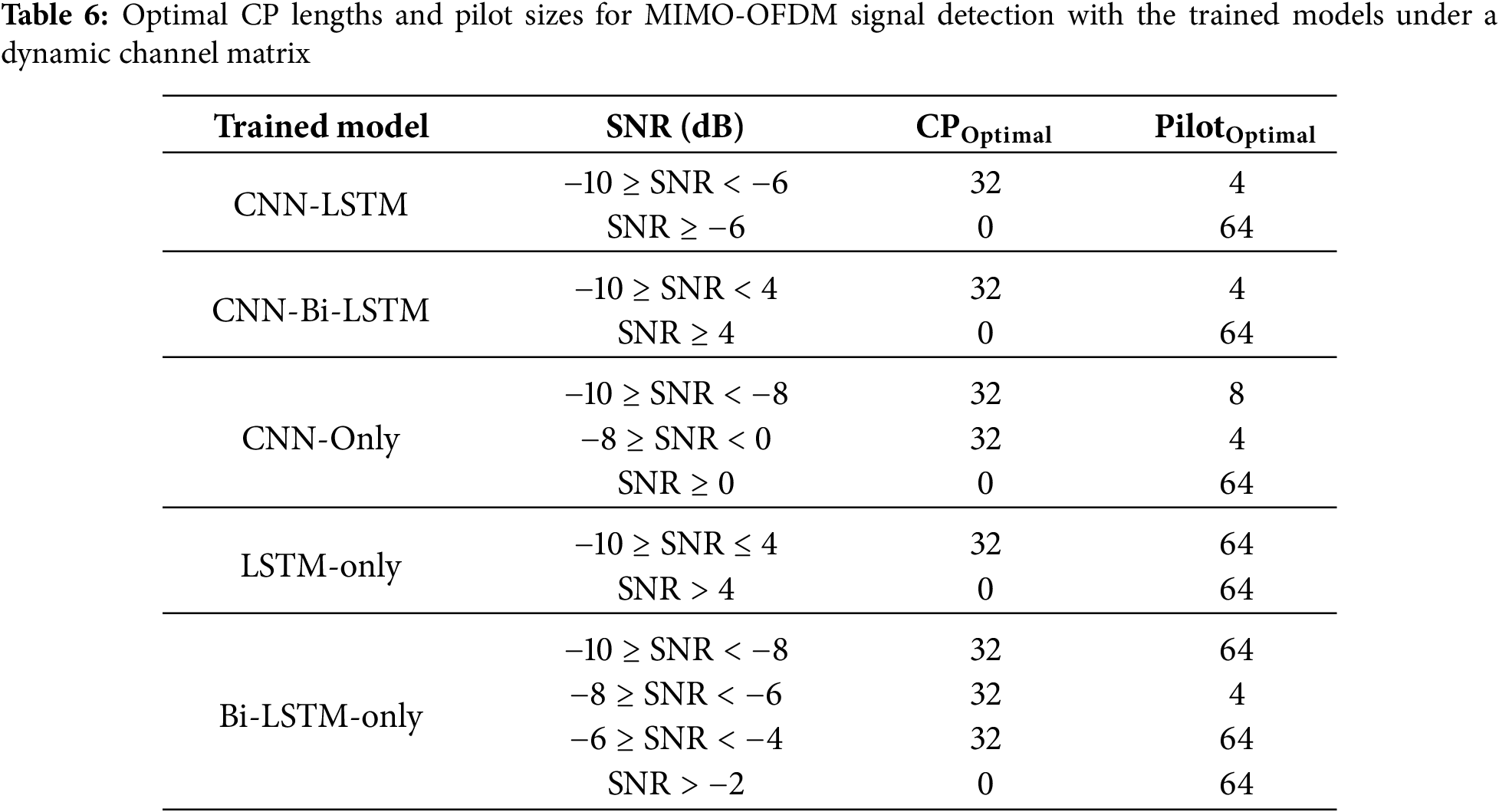

Tables 5 and 6 display the optimal CP lengths and pilot formats for MIMO-OFDM signal detection when using DL-trained models under static and dynamic channel matrix conditions, respectively. The optimization is based on identifying the CP lengths and pilot sizes that yielded the lowest BER across all evaluated SNR levels.

In Table 5, under static channel matrix conditions, CNN-LSTM indicates a distinct switching behavior at SNR = −8 dB. For SNRs below −8 dB, a CP length of 32 and a minimal pilot format of 4 are optimal, indicating the need for temporal redundancy and minimal reference symbols in low SNR ranges. At SNRs ≥ −8 dB, the CNN-LSTM shifts to a CP-free setting with a larger pilot size of 64, reflecting confidence in the detection effectiveness once the noise level becomes manageable. Likewise, the CNN-Bi-LSTM model adopts the same split but with a more extended SNR threshold up to 4 dB, indicating improved tolerance to noise due to the bidirectional processing of temporal features. While the CNN-only, slightly less flexible, still adapts effectively, switching to CP-free operation at SNRs ≥ 0 dB.

This observation indicates that convolutional features alone can yield reliable signal detection performance once the channel conditions are favorable. On the other hand, the conventional single models (LSTM-only, Bi-LSTM-only) demonstrate more frequent shifts in configuration over narrower SNR bands. For instance, Bi-LSTM-only exhibits four different configuration regimes, indicating heightened susceptibility to SNR fluctuations and a less stable operational profile. These results emphasize the ability of the proposed CNN-based hybrid models to achieve consistent performance with simple adaptive control.

As shown in Table 6, all of the models exhibit some degree of configuration adaptation to the optimal CP lengths and pilot sizes in MIMO-OFDM signal detection under dynamic channel matrix conditions, which better represent real-world scenarios with time-varying fading. The CNN-LSTM model maintains its dual-regime structure with a threshold at −6 dB, similar in pattern to the static case but adjusted to account for additional channel variability. CNN-Bi-LSTM demonstrates the highest adaptability, orienting an intermediate pilot configuration (CP = 32, Pilot = 8) for SNRs between −10 and −8 dB before reverting to its typical minimum-pilot and CP-free regime for higher SNRs. This configuration indicates superior handling of abrupt channel dynamics through enhanced temporal modeling in both directions.

The architecture that uses only the CNN produces a distinct separation at 0 dB, where it maintains low CP and pilot overhead under low-SNR conditions and shifts to CP-free operation when the conditions improve. This stable two-regime strategy is indicative of the robustness and generalizability of the CNN architecture, even without temporal recurrence. Both LSTM and Bi-LSTM continue to indicate more granular configuration shifts. For example, the Bi-LSTM-only model operates under four distinct SNR bands, which complicates real-time adaptation and indicates weaker generalization under dynamic fading.

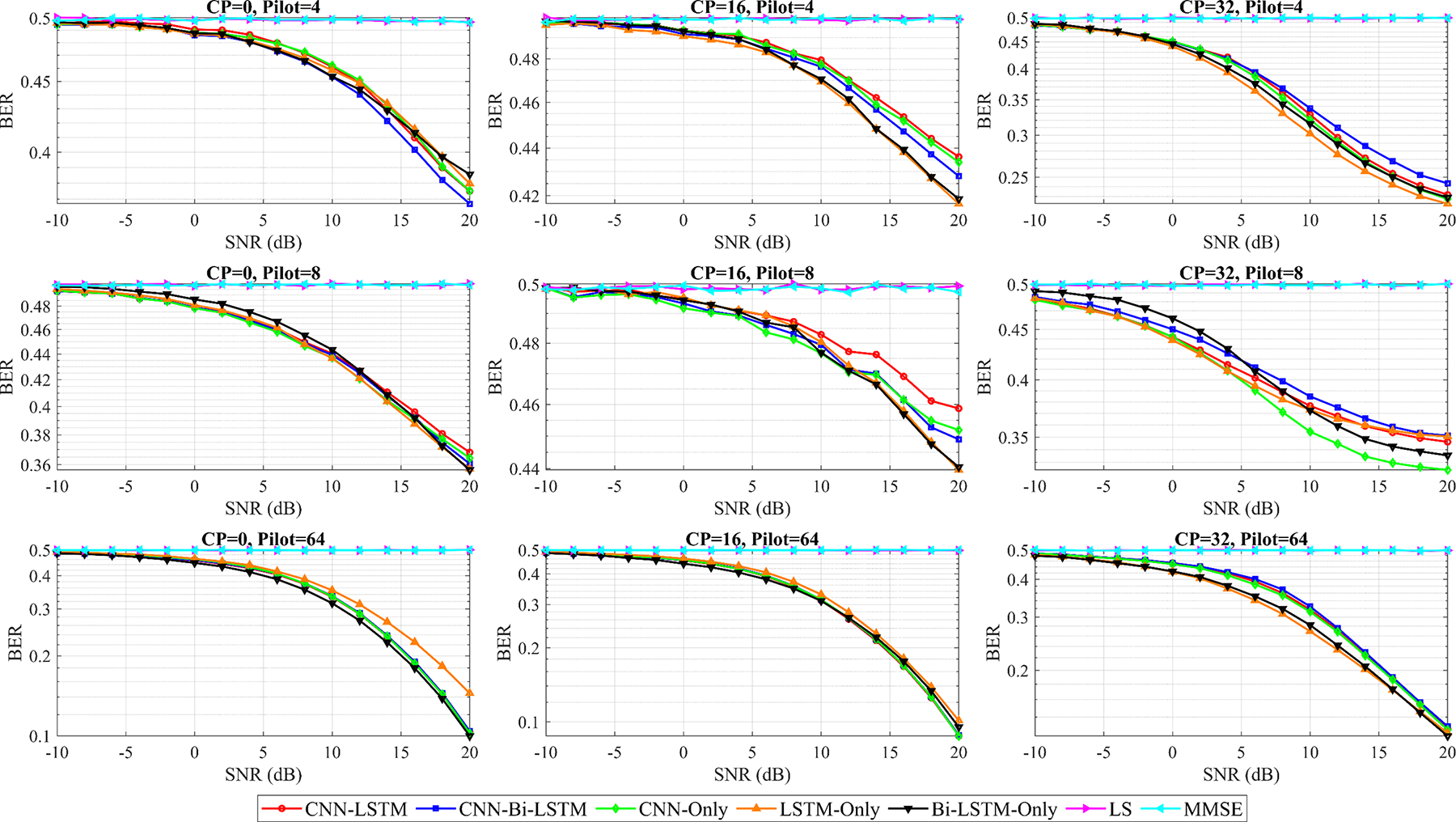

6.3 Channel Matrix Uncertainty Impact

In practical MIMO-OFDM systems, channel uncertainty significantly impacts signal detection accuracy. The complex-valued channel matrix (

where

To further evaluate model robustness, the SNR was varied from −10 to 20 dB in 2 dB increments. This range encompasses both severely degraded and high-quality signal conditions, enabling a comprehensive evaluation of model adaptability to varying noise levels. The difference in the channel matrix changes its eigenstructure and spatial correlation, which makes it more difficult to separate data streams using conventional LS and MMSE estimators.

In contrast, DL-based models learn a nonlinear mapping between received and transmitted symbols, enabling them to partially compensate for such distortions. The proposed hybrid CNN-LSTM and CNN-bi-LSTM architectures, in particular, demonstrate higher resilience to channel variations because of their combined spatial–temporal feature extraction capability. The BER performance of the proposed and benchmark models under TDL channel matrix uncertainty, where the channel coefficients vary according to randomly selected TDL profiles, is shown in Fig. 14.

Figure 14: BER performance of the MIMO-OFDM system using the proposed hybrid DLarchitectures and benchmark models trained on an Intel Core i7-13700H (2.4 GHz) CPU under TDL channel matrix uncertainty

To ensure robust model performance at the minimum BER, the optimal CP lengths and pilot subcarrier configurations are evaluated with respect to varying SNR levels. Table 7 shows the SNR-dependent selection of CP lengths and pilot subcarrier formats for each trained model under TDL channel matrix uncertainty. It appears that at low SNRs (−10 dB to less than 6 dB), longer CPs (32) and moderate pilot sizes (4–8) are required to mitigate multipath effects, whereas at higher SNRs, shorter CPs (16) combined with larger pilot sets (64) achieve improved BER performance. The results indicate that hybrid DL architectures (CNN-LSTM and CNN-Bi-LSTM) effectively adapt to channel matrix uncertainty, achieving robust detection over various SNR and TDL channel conditions, including multipath fading and delay spreads. Conventional single architectures (CNN-only, LSTM-only, and Bi-LSTM-only) follow similar directions but may demand greater pilot overhead to maintain performance at low SNRs.

These results confirm that the proposed hybrid architectures effectively mitigate the performance degradation induced by channel matrix uncertainty and SNR mismatches. The results also indicated that the proposed hybrid CNN-LSTM and CNN-Bi-LSTM architectures show adequate resilience to both channel matrix uncertainty and SNR mismatches.

These models effectively capture spatial and temporal dependency patterns, enabling more robust signal detection under various noise conditions. However, standalone models like CNN, LSTM, and Bi-LSTM exhibit lower performance, highlighting the significance of architectural diversity in generalizing to unfamiliar environments.

In this paper, we propose a new framework, a CNN-based hybrid RNN, for detecting signals in a 5G OFDM system. The CNN network was combined with RNNs and was trained offline using simulation data from a 2 × 2 MIMO-OFDM system. Two architectures, RNN, LSTM and Bi-LSTM, are designed to better handle sequential signals for the MIMO-OFDM system. Our results strongly supported the core hypothesis that compared with conventional analytical methods, DL could provide more adaptive and efficient solutions. The most striking result reveals that the proposed hybrid DL architectures CNN-Bi-LSTM and LSTM-CNN significantly reduce the overhead required for CP symbols and pilot configuration symbols without influencing performance, especially at low SNRs. Among the architectures studied, CNN-Bi-LSTM achieved superior performance, while the CNN provides a lightweight and efficient alternative with a minimum required number of pilot symbols and CP symbols. The LSTM-trained model, which uses a pilot symbol size of 64, is dependent on extensive reference symbols to compensate for weak spatial–temporal feature extraction, even for almost all the SNR values. The Bi-LSTM fluctuates across four different settings under dynamic channels, which complicates deployment in real-time systems.

The utilization of randomly generated simulated symbols and a 2 × 2 MIMO-OFDM setup provides a controlled environment for evaluating the performance of the DL architecture for MIMO-OFDM signal detection but may not fully represent the variability of real-world wireless channels. Notably, the reported BER values correspond to the uncoded outputs of the CNN-LSTM and CNN-Bi-LSTM models. In practical implementations of 2 × 2 MIMO-OFDM systems, standard error-correction schemes, such as low-density parity-check (LDPC) codes or Turbo codes, are typically employed and are expected to improve the effective BER substantially.

This improvement addresses a major limitation observed in the simple LSTM and simple Bi-LSTM networks, which demonstrated a strong dependency on extensive pilot symbols to achieve comparable performance. This fluctuation and reliance on dense reference symbols complicate their deployment in dynamic, real-time systems, reinforcing the robustness and efficiency of our CNN-based approaches. From a broader perspective, these findings suggest a paradigm shift away from traditional analytical techniques toward more data-driven, intelligent signal processing.

The adaptability and superior performance of our hybrid models, particularly at low SNR levels, make them highly promising for implementation in demanding environments where channel conditions are less predictable. Future work will include more rigorous analyses and extensive experiments to validate our results further. The focus should be on optimizing current architectures for real-time implementation and examining their performance within a complete end-to-end simulation system. Additionally, it is important to develop more lightweight CNN-based models specifically designed for detecting signals in massive MIMO-OFDM configurations (e.g., 4 × 4 and 8 × 8) to evaluate scalability and performance in more complex 5G-like environments. In the future, testing the practical applicability of the proposed architectures with different channel distributions, realistic 5G propagation scenarios, and different modulation formats will be important.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the IITP (Institute of Information & Communications Technology Planning & Evaluation)-ICAN (ICT Challenge and Advanced Network of HRD) grant funded by the Korea govern-ment (Ministry of Science and ICT) (IITP-2025-RS-2022-00156299).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: major contribution to writing of the article, model building, data extraction, overall design and execution, and visualization, Ahmed K. Ali; supervision, Jungpil Shin, Yujin Lim; project administration, Da-Hun Seong, Yujin Lim; data curation, Ahmed K. Ali, Da-Hun Seong; writing—review and editing, Ahmed K. Ali, Yujin Lim, Da-Hun Seong. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Essai Ali MH, Rabeh ML, Hekal S, Abbas AN. Deep learning gated recurrent neural network-based channel state estimator for OFDM wireless communication systems. IEEE Access. 2022;10:69312–22. doi:10.1109/access.2022.3186323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Liu K, Xing K. Research of MMSE and LS channel estimation in OFDM systems. In: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Information Science and Engineering; 2010 Dec 4–6; Hangzhou, China. New York NY, USA: IEEE; 2010. p. 2308–11. [Google Scholar]

3. Hamilton BR, Ma X, Kleider JE, Baxley RJ. OFDM pilot design for channel estimation with null edge subcarriers. IEEE Trans Wirel Commun. 2011;10(10):3145–50. doi:10.1109/twc.2011.090611.101922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Abdelgader AMS, Feng S, Wu L. On channel estimation in vehicular networks. IET Commun. 2017;11(1):142–9. [Google Scholar]

5. Razavi SM, Ratnarajah T. Adaptive LS- and MMSE-based beamformer design for multiuser MIMO interference channels. IEEE Trans Veh Technol. 2016;65(1):132–44. doi:10.1109/tvt.2015.2391195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Hwang T, Yang C, Wu G, Li S, Li GY. OFDM and its wireless applications: a survey. IEEE Trans Veh Technol. 2009;58(4):1673–94. doi:10.1109/tvt.2008.2004555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Ye H, Li GY, Juang BH. Power of deep learning for channel estimation and signal detection in OFDM systems. IEEE Wirel Commun Lett. 2018;7(1):114–7. doi:10.1109/lwc.2017.2757490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Prasad R, Murthy CR, Rao BD. Joint channel estimation and data detection in MIMO-OFDM systems: a sparse bayesian learning approach. IEEE Trans Signal Process. 2015;63(20):5369–82. doi:10.1109/tsp.2015.2451071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Wang X, Gao L, Mao S, Pandey S. CSI-based fingerprinting for indoor localization: a deep learning approach. IEEE Trans Veh Technol. 2017;66(1):763–76. doi:10.1109/tvt.2016.2545523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Smirani LK, Jamel L, Almuqren L. Improving channel estimation in a NOMA modulation environment based on ensemble learning. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2024;140(2):1315. doi:10.32604/cmes.2024.047551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Gruber T, Cammerer S, Hoydis J, Ten BS. On deep learning-based channel decoding. In: Proceedings of the 2017 51st Annual Conference on Information Sciences and Systems, CISS 2017; 2017 Mar 22–24; Baltimore, MD, USA. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

12. Klautau A, Gonzalez-Prelcic N, Mezghani A, Heath RW. Detection and channel equalization with deep learning for low resolution MIMO systems. In: Proceedings of the 2018 52nd Asilomar Conference on Signals, Systems and Computers; 2018 Oct 28–31; Pacific Grove, CA, USA. p. 1836–40. [Google Scholar]

13. Thakkar K, Goyal A, Bhattacharyya B. Deep learning and channel estimation. In: Proceedings of the 2020 6th International Conference on Advanced Computing and Communication Systems, ICACCS 2020; 2020 Mar 6–7; Coimbatore, India. p. 745–51. [Google Scholar]

14. Wallayt W, Younis MS, Imran M, Shoaib M, Guizani M. Automatic modulation classification for low SNR digital signal in frequency-selective fading environments. Wirel Pers Commun. 2015;84(3):1891–906. doi:10.1007/s11277-015-2544-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Le Ha A, Van Chien T, Nguyen TH, Choi W, Nguyen VD. Deep learning-aided 5G channel estimation. In: Proceedings of the 2021 15th International Conference on Ubiquitous Information Management and Communication, IMCOM 2021; 2021 Jan 4–6; Seoul, Republic of Korea. [Google Scholar]

16. Wang S, Yao R, Tsiftsis TA, Miridakis NI, Qi N. Signal detection in uplink time-varying OFDM systems using RNN with bidirectional LSTM. IEEE Wirel Commun Lett. 2020;9(11):1947–51. doi:10.1109/lwc.2020.3009170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Liao Y, Hua Y, Cai Y. Deep learning based channel estimation algorithm for fast time-varying MIMO-OFDM systems. IEEE Commun Lett. 2020;24(3):572–6. doi:10.1109/lcomm.2019.2960242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Abdelhamed MA, Samy M, Elnaghi BE, Magdy A. A hybrid CNN-BILSTM deep learning framework for signal detection of a massive MIMO-NOMA system. Results Eng. 2025;27:105852. doi:10.1016/j.rineng.2025.105852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Qing C, Tang S, Cai X, Wang J. Lightweight 1-D CNN-based timing synchronization for OFDM systems with CIR uncertainty. IEEE Wirel Commun Lett. 2022;11(11):2375–9. doi:10.1109/lwc.2022.3204047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Nair AK, Menon V. Joint channel estimation and symbol detection in MIMO-OFDM systems: a deep learning approach using Bi-LSTM. In: Proceedings of the 2022 14th International Conference on Communication Systems & Networks (COMSNETS); 2022 Jan 4–8; Bangalore, India. p. 406–11. [Google Scholar]

21. Hassan HA, Mohamed MA, Shaaban MN, Ali MHE, Omer OA. An efficient deep neural network channel state estimator for OFDM wireless systems. Wirel Netw. 2024;30(3):1441–51. doi:10.1007/s11276-023-03585-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Cho YS, Kim J, Yang WY. Mimo-ofdm wireless communications with matlab. Hoboken, NJ, USA: Wiley; 2010. 457 p. [Google Scholar]

23. Biguesh M, Gershman AB. Training-based MIMO channel estimation: a study of estimator tradeoffs and optimal training signals. IEEE Trans Signal Process. 2006;54(3):884–93. doi:10.1109/tsp.2005.863008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. He H, Wen CK, Jin S, Li GY. Deep learning-based channel estimation for beamspace mmWave massive MIMO systems. IEEE Wirel Commun Lett. 2018;7(5):852–5. doi:10.1109/lwc.2018.2832128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. He X, Yang R, Zhang J, Zhang Y. An OFDM channel estimation method with radial basis function neural network. Appl Mech Mater. 2013;263-266(Pt 1):1142–9. doi:10.4028/www.scientific.net/amm.263-266.1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Moffa G. OFDM channel equalization based on radial basis function networks. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Artificial Neural Networks; 2006 Sep 10–14; Athens, Greece. p. 201–10. [Google Scholar]

27. Taşpinar N, Seyman MN. Back propagation neural network approach for channel estimation in OFDM system. In: Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE International Conference on Wireless Communications, Networking and Information Security, WCNIS 2010; 2010 Jun 25–27; Beijing, China. New York NY, USA: IEEE; 2010. p. 265–8. [Google Scholar]

28. Cheng CH, Huang YH, Chen HC. Channel estimation in OFDM systems using neural network technology combined with a genetic algorithm. Soft Comput. 2016;20(10):4139–48. doi:10.1007/s00500-015-1749-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Gao X, Jin S, Wen CK, Li GY. ComNet: combination of deep learning and expert knowledge in OFDM receivers. IEEE Commun Lett. 2018;22(12):2627–30. doi:10.1109/lcomm.2018.2877965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Vilas Boas EC, Silva JDS, de Figueiredo FAP, Mendes LL, de Souza RAA. Artificial intelligence for channel estimation in multicarrier systems for B5G/6G communications: a survey. In: Eurasip Journal on wireless communications and networking. Vol. 2022. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2022. [Google Scholar]

31. Honkala M, Korpi D, Huttunen JMJ. DeepRx: fully convolutional deep learning receiver. IEEE Trans Wirel Commun. 2021;20(6):3925–40. doi:10.1109/twc.2021.3054520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Yi X, Zhong C. Deep learning for joint channel estimation and signal detection in ofdm systems. IEEE Commun Lett. 2020;24(12):2780–4. doi:10.1109/lcomm.2020.3014382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Huang H, Yang J, Huang H, Song Y, Gui G. Deep learning for super-resolution channel estimation and doa estimation based massive MIMO system. IEEE Trans Veh Technol. 2018;67(9):8549–60. doi:10.1109/tvt.2018.2851783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Soltani M, Pourahmadi V, Mirzaei A, Sheikhzadeh H. Deep learning-based channel estimation. IEEE Commun Lett. 2019;23(4):652–5. doi:10.1109/lcomm.2019.2898944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Huang X, Yuan Y, Li J. MIMO signal detection based on IM-LSTMNet model. Electronics. 2024;13(16):1–18. [Google Scholar]

36. Electron IJ, Aeü C, Meenalakshmi M, Chaturvedi S, Dwivedi VK. Enhancing channel estimation accuracy in polar-coded MIMO—OFDM systems via CNN with 5G channel models. AEUE—Int J Electron Commun. 2024;173:155016. doi:10.1016/j.aeue.2023.155016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Rappaport TS. Wireless communications: principles and practice. In: Pearson education India. Vol. 3. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA: Pearson Education India; 2010. p. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

38. Sklar B. Digital communications: fundamentals and applications. Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA: Pearson Education; 2021. [Google Scholar]

39. Gong X, Huang C, Yue X, Yang Z, Liu F. Performance analysis of RIS assisted NOMA networks over rician fading. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2023;135(3):2531–55. doi:10.32604/cmes.2023.024940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. ETSI. Study on channel model for frequencies from 0.5 to 100 GHz (3GPP TR 38.901 version 16.1.0 Release 16). In: Techincal report. Nice, France: European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI). [Google Scholar]

41. Shah MH, Dang X. Low-complexity deep learning and RBFN architectures for modulation classification of space-time block-code (STBC)-MIMO systems. Digit Signal Process. 2020;99:102656. doi:10.1016/j.dsp.2020.102656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Schmidhuber J. Deep learning in neural networks: an overview. Neural Netw. 2015;61:85–117. doi:10.1016/j.neunet.2014.09.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Hochreiter S, Schmidhuber J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 1997;9(8):1735–80. doi:10.1162/neco.1997.9.8.1735. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Luo C, Ji J, Wang Q, Chen X, Li P. Channel state information prediction for 5G wireless communications: a deep learning approach. IEEE Trans Netw Sci Eng. 2020;7(1):227–36. doi:10.1109/tnse.2018.2848960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]