Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Hybrid Split-Attention and Transformer Architecture for High-Performance Network Intrusion Detection

1 School of Software, Yunnan University, Kunming, 650504, China

2 Yunnan Key Laboratory of Smart City in Cyberspace Security, Yuxi Normal University, Yuxi, 653100, China

3 School of Information Science and Technology, Yunnan Normal University, Kunming, 650500, China

* Corresponding Author: Yongtao Yu. Email:

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(3), 4317-4348. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.074349

Received 09 October 2025; Accepted 24 November 2025; Issue published 23 December 2025

Abstract

Existing deep learning Network Intrusion Detection Systems (NIDS) struggle to simultaneously capture fine-grained, multi-scale features and long-range temporal dependencies. To address this gap, this paper introduces TransNeSt, a hybrid architecture integrating a ResNeSt block (using split-attention for multi-scale feature representation) with a Transformer encoder (using self-attention for global temporal modeling). This integration of multi-scale and temporal attention was validated on four benchmarks: NSL-KDD, UNSW-NB15, CIC-IDS2017, and CICIOT2023. TransNeSt consistently outperformed its individual components and several state-of-the-art models, demonstrating significant quantitative gains. The model achieved high efficacy across all datasets, with F1-Scores of 99.04% (NSL-KDD), 91.92% (UNSW-NB15), 99.18% (CIC-IDS2017), and 97.85% (CICIOT2023), confirming its robustness.Keywords

The expansion of the digital attack surface, driven by complex and distributed network architectures, has led to more sophisticated and rapid cyber intrusions. This evolving threat landscape erodes the efficacy of conventional defenses, such as signature-based intrusion detection systems (IDS). This reality demands a new generation of Network Intrusion Detection Systems (NIDS) with adaptive and predictive capabilities to discern both known and emergent (zero-day) threats in high-velocity data streams. Consequently, research has pivoted towards deep learning (DL), valued for its ability to autonomously extract salient feature hierarchies from high-dimensional network traffic [1].

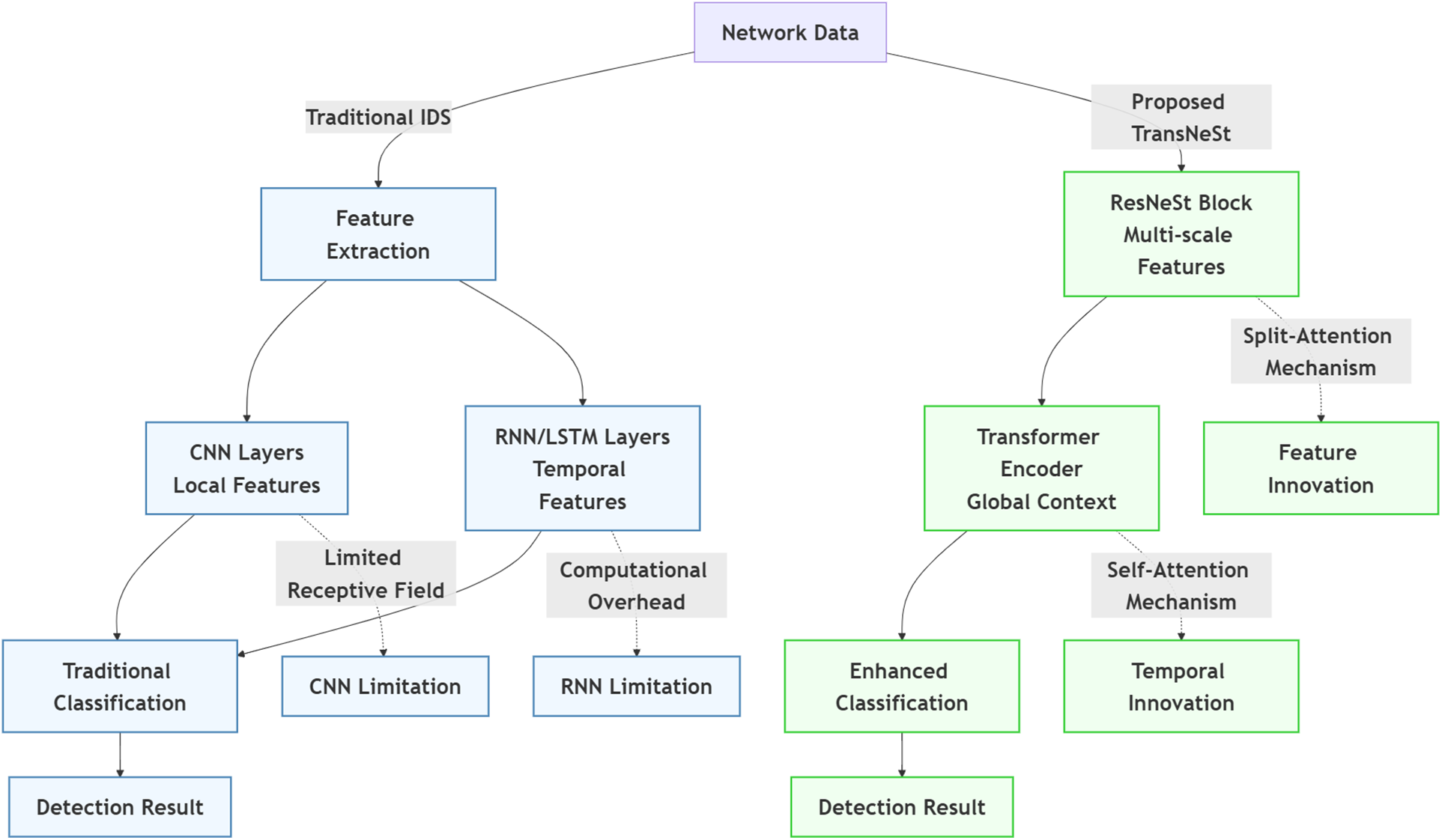

Early DL-based NIDS highlighted a key trade-off. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) identified localized patterns, but their limited receptive field struggled with long-range temporal dependencies [2]. Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) models were designed for sequential analysis, but faced high computational overhead and gradient issues [3]. To address these limitations, the field has advanced significantly. One line of research involves sophisticated hybrid recurrent models, such as BiGRU (Bidirectional Gated Recurrent Unit)-LSTM with attention, which have proven robust for capturing complex temporal patterns [4]. A second, highly influential line of research adopted the Transformer architecture [5], leveraging its powerful self-attention mechanism to model global dependencies. As recent surveys confirm, Transformers and even Large Language Models (LLMs) are now a central focus for efficient intrusion detection [6].

However, while these approaches excel at modeling temporal and global relationships, the direct application of standard Transformers, for example, is not optimized for extracting the granular, multi-scale feature hierarchies embedded within individual network flows. This creates an opportunity for an architecture that synergistically unifies the global contextual modeling of Transformers with the multi-scale feature extraction capabilities of advanced convolutional networks [7]. To resolve this specific trade-off, we designed TransNeSt, a hybrid architecture that integrates a ResNeSt (ResNet with Split-Attention) backbone [8] with a Transformer encoder. The core of our contribution is the novel adaptation of the Split-Attention mechanism, originally conceived for computer vision, to the one-dimensional structure of network traffic data. The ResNeSt backbone functions as a potent feature generator, employing its multi-path structure and cross-channel attention to produce a sequence of rich, cardinal-group feature representations from the raw traffic. This output sequence then serves as the input for the Transformer encoder, which leverages self-attention to explicitly model the global contextual relationships between these high-level feature sets.

We validated TransNeSt’s performance and generalization capabilities through rigorous experimentation on four standard benchmarks: NSL-KDD, UNSW-NB15, CICIDS-2017 and CICIOT2023. These datasets were selected to ensure a comprehensive evaluation against a spectrum of threats, from legacy attack vectors to complex, modern intrusions. Across all four benchmarks, TransNeSt consistently achieved higher performance metrics than the other models tested, indicating its effectiveness for deep learning-based intrusion detection. A comparison of our proposed pipeline against traditional approaches is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Comparison of the Traditional IDS pipeline (left) and the proposed TransNeSt architecture (right)

The research presented herein offers several significant contributions:

1. This paper proposes TransNeSt, a novel hybrid deep learning architecture designed to leverage ResNeSt for its multi-scale feature extraction prowess while employing the Transformer to capture global contextual relationships in network intrusion detection.

2. We have successfully adapted the Split-Attention mechanism, initially conceived for two-dimensional image analysis, for application to one-dimensional network traffic data, thereby demonstrating its considerable versatility and significant potential beyond the domain of computer vision.

3. We performed a comprehensive and rigorous evaluation using a diverse set of datasets. Our results demonstrate the detection efficacy and generalizability of our approach and provide strong performance results on these benchmarks.

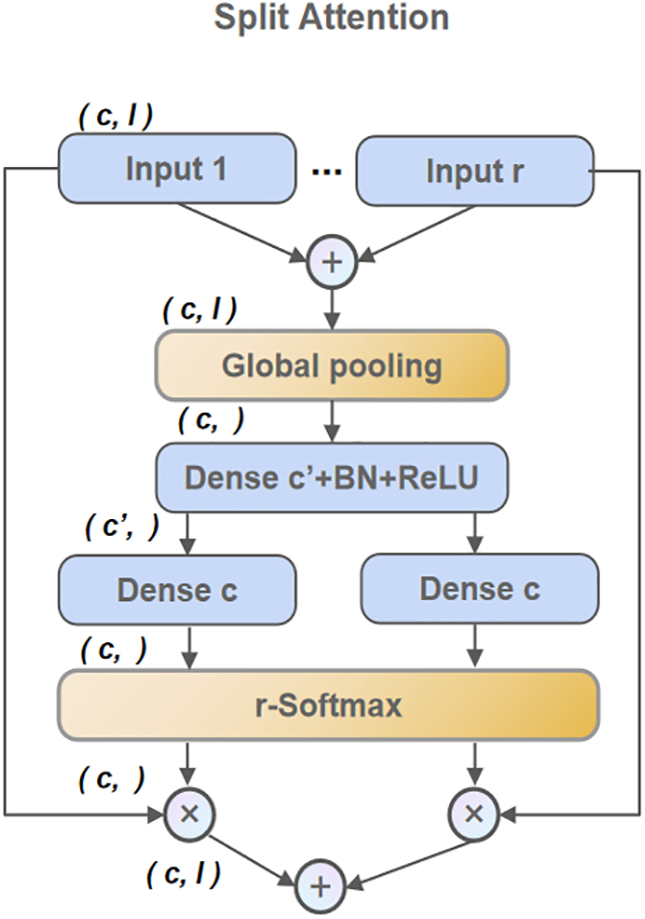

2.1 Machine Learning and Optimization Approaches

The landscape of network intrusion detection continues to be substantively shaped by advancements in both classical and contemporary computational intelligence paradigms. Research has focused on optimizing classical models and addressing specific data challenges. For parameter refinement, Kolukisa et al. [9] synergized logistic regression with a parallelized artificial bee colony (ABC) algorithm, achieving commendable detection performance. To confront high-dimensional feature spaces, Turukmane et al. [10] integrated multi-layer Support Vector Machines (SVMs) with singular value decomposition. For the complexities of mixed-traffic environments, Rustam et al. [11] introduced the Fully Automated Malicious Traffic Detection System (FAMTDS) framework, using a Moth Flame Optimizer (MFO) for automation. Addressing the critical problem of data imbalance, Hooshmand et al. [12] developed a multi-stage model (K-means (SKM) hybrid, Denoising Autoencoder (DAE), and XGBoost classifier), achieving binary/multiclass accuracies up to 99.57% on NSL-KDD. Finally, for scalable stream processing, He et al. [13] proposed a Bayesian gamma mixture model (GaMM) employing extended stochastic variational inference (ESVI).

2.2 Deep Learning Architectures for NIDS

The utility of deep learning in modern intrusion detection stems from its capacity for automated hierarchical feature extraction. Research has explored several integration strategies. For instance, novel architectures are being developed to work with limited labeled data; Xu et al. [14] proposed the Time-Space Separable Attention Network (TSSAN), which utilizes depth-wise separable convolution and a time-space self-attention mechanism to extract features in an unsupervised or semi-supervised context. Architectural synergy has also been exploited to model both spatial and temporal dependencies; Liu et al. [15] proposed the Residual Memory Convolutional Neural Network (RMCNN), a hybrid model that first extracts spatial features with CNN layers, then captures temporal dynamics using a Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU), and reinforces critical features with a multi-head attention mechanism. To address the challenge of novel, unseen attacks in few-shot scenarios, meta-learning frameworks have been introduced. Xu et al. [16] proposed Marrying Attention and Convolution-based Meta-learning (MACML), an optimization-based meta-learning method that “marries” a self-attention mechanism (for global dependencies) with a CNN (for local features), enabling rapid adaptation to new attack types with minimal samples. Hybrid dimensionality reduction has also been proposed for LSTM-based models, as seen in the two-stage fusion strategy by Thakkar et al. [17]. Their method, fusing a non-linear Autoencoder (AE) with linear Principal Component Analysis (PCA), yielded a performance gain of up to 3% over a standard AE+LSTM baseline. Similarly, Alsoufi et al. [18] addressed high-dimensional IoT data by employing a Sparse Autoencoder (SAE) for feature dimensionality reduction coupled with a CNN for classification, demonstrating significant accuracy improvements in IoT environments

2.3 Hybrid and Ensemble Frameworks

A prominent research strategy is to couple DL feature engineering with classical classifiers or other learning paradigms. Chen et al. [19], for example, introduced Metric Learning Framework with Dual One-Class Units (MLF-DOU), which uses one-class classifiers and a triplet network-based metric learning stage to maximize inter-class separability, demonstrating superior accuracy and F1-score on UNSW-NB15. Hierarchical designs represent another approach to tackle specific challenges, such as identifying rare attack classes (a form of data imbalance). Wang et al. [20] devised a two-layer model where a CNN-BiLSTM layer (addressing temporal dependencies) performs coarse-grained classification, followed by a Stacking ensemble learner for fine-grained analysis of minority classes, which demonstrated superior recall. Reinforcement learning offers a third path; Hossain [21] ventured into this with their Deep Q-Learning Intrusion Detection System (DQ-IDS). This Deep Q-Network (DQN) autonomously learns classification policies using experience replay and adaptive exploration, achieving a notable 97.18% accuracy and 98.52% F1-score on the real-world CICIoT2023 dataset. Finally, to handle the dynamic nature of threats and avoid “catastrophic forgetting,” Wang et al. [22] introduced CTWA, an incremental learning method that uses a Convolutional Autoencoder (CAE) and Temporal Convolutional Network (TCN) to extract features. This framework applies Weight Alignment (WA) techniques, enabling the model to learn new attack classes without losing knowledge of old ones.

2.4 Strategies for Data Imbalance

Persistent data imbalance remains a critical challenge. One solution is generative data enrichment; Arafah et al. [23] confronted this with the Autoencoder-Wasserstein Generative Adversarial Network (AE-WGAN), where a Wasserstein Generative Adversarial Network synthesizes high-fidelity minority attack samples, yielding substantial performance gains. An alternative strategy integrates imbalance correction directly into the classification pipeline. The Network Intrusion Detection System-Convolutional Neural Network Random Forest (NIDS-CNNRF) model, proposed by Yang et al. [24], exemplifies this by coupling a standard CNN extractor with a Random Forest (RF) classifier, but first applying PCA and the Adaptive Synthetic Sampling (ADASYN) algorithm to resample the data, which was validated across several benchmarks.

2.5 Key Challenges and Research Gaps

The literature reveals a clear trajectory towards hybrid models, but a persistent limitation is this reliance on standard CNNs for feature extraction. This highlights a key research gap: the need for models that integrate feature extractors capable of capturing more complex, multi-scale hierarchies. The proposed TransNeSt architecture is designed to fill this gap. To our knowledge, no existing NIDS research has adapted split-attention mechanisms (ResNeSt), originally designed for 2D computer vision, for 1D network traffic analysis. TransNeSt directly addresses the multi-scale feature challenge by integrating a state-of-the-art ResNeSt block and couples it with a Transformer encoder to effectively model long-term temporal dependencies, creating a more profound synergy between feature representation and temporal analysis.

This review of the literature, for which a detailed summary is presented in Table 1, highlights three persistent challenges that motivate our work. First, data imbalance is a critical and prevalent challenge, as rare but dangerous attack classes like Remote-to-Local (R2L) and User-to-Root (U2R) are vastly underrepresented, causing models to develop a bias toward majority (benign) traffic. Second, effectively modeling complex temporal dependencies remains an open problem; while LSTMs were an improvement over CNNs, they suffer from computational overhead, and attacks are often sophisticated, multi-stage sequences that are difficult to model. Third, discerning subtle attacks requires capturing a multi-scale feature hierarchy, but the standard CNNs used in many hybrid models fail to capture the granular, hierarchical feature relationships embedded within network traffic.

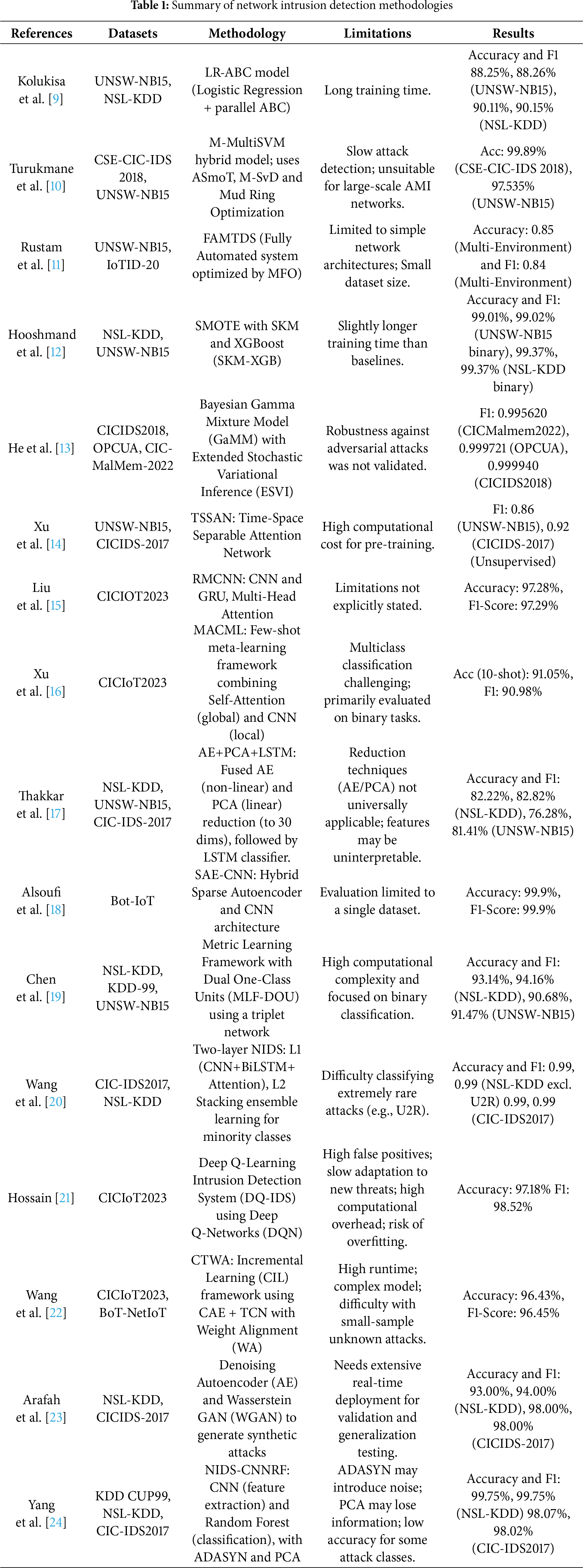

To address the challenge of capturing both fine-grained spatial patterns and complex temporal dependencies in network traffic data, this paper introduces an innovative hybrid deep learning architecture for Network Intrusion Detection, a framework we have termed TransNeSt. The architecture of this model, illustrated in Fig. 2, is expressly designed to create a powerful synergy between high-resolution convolutional feature extraction and global, attention-based temporal analysis. The model’s workflow is structured into two sequential stages. Initially, a ResNeSt Block functions as an advanced feature extractor, meticulously analyzing input network flows to capture fine-grained, multi-scale spatial patterns. Subsequently, the sequence of feature representations generated by this block is then passed to a Transformer Block, which captures the long-range temporal dependencies across the entire sequence. This integrated architecture facilitates a comprehensive understanding of network traffic, which is paramount for the robust detection of both simple and sophisticated, multi-stage cyber-attacks.

Figure 2: TransNeSt architecture

The overall architecture of TransNeSt follows a two-stage sequential workflow. First, a ResNeSt Block functions as an advanced feature extractor, processing the input sequence to capture fine-grained, feature-based spatial patterns. Subsequently, the sequence of enriched feature representations generated by this block is passed to a Transformer Block, which models the long-range temporal dependencies across the entire sequence.

Formally, the input to our model is a sequence of pre-processed network traffic data, denoted as

The ResNeSt block, originally designed for 2D image analysis, is a core component of our model. A key innovation of our work is the adaptation of its architecture to effectively process 1D sequential network traffic data by replacing 2D convolutions with their 1D counterparts (e.g.,

The process within a ResNeSt block begins with an input feature map of dimensions

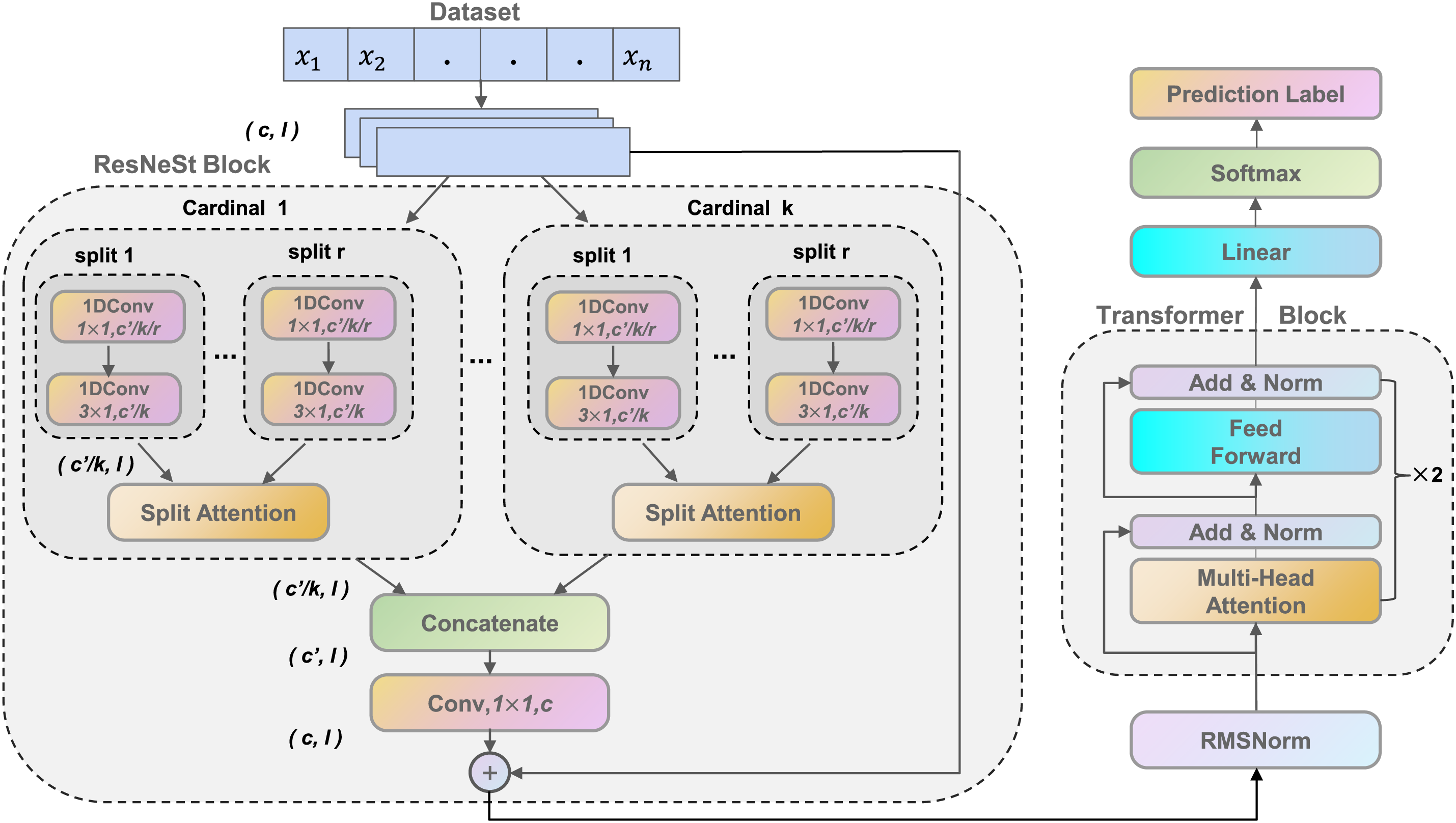

The Split Attention mechanism, explicitly diagrammed in Fig. 3, directs the flow of information and adaptively recalibrates feature responses within each cardinal group. The mechanism unfolds as follows:

Figure 3: A detailed view of the Split Attention mechanism

First, the transformed feature maps from the

To generate a channel-wise summary of contextual information, global average pooling (

This vector

where

These scores are normalized across the radix dimension for each channel using an r-Softmax function. The attention weight

This ensures that for any channel

where

Subsequent to the extraction of localized feature hierarchies by the ResNeSt block, the modeling of temporal dynamics across the sequence of network events is entrusted to a bespoke Transformer Block [5]. A pivotal architectural decision within this block is the normalization strategy. In a departure from the canonical Transformer, we substitute the conventional Layer Normalization with Root Mean Square Normalization (RMSNorm) [26]. This modification is deliberately implemented to enhance computational throughput and training efficiency. As demonstrated in [26], RMSNorm achieves comparable performance to LayerNorm but with significantly reduced computational overhead, observing speedups from 7% to 64% across different models. This efficiency gain comes from simplifying the operation: RMSNorm preserves the essential re-scaling invariance of LayerNorm but eschews the mean-centering operation, which contributes less to training stability while incurring computational costs. RMSNorm thus provides a more efficient drop-in replacement. For an input feature vector

where

Each Transformer block comprises two main sub-layers: a Multi-Head Attention (MHA) mechanism and a position-wise Feed-Forward Network (FFN).

In the MHA sub-layer, the input tensor

where

The output of the MHA sub-layer is subsequently processed by the FFN, which consists of two linear transformations with a ReLU activation:

Each of these sub-layers is encapsulated with a residual connection and an RMSNorm layer. To build a deeper representation, this entire four-sub-layer block is stacked for two iterations.

3.4 Output and Classification Layer

The architectural design of the TransNeSt model culminates in a dedicated classification head, which performs the final, decisive conversion of the deeply learned feature vectors into a final probability distribution over the class labels. Adhering to the established paradigm for Transformer-based classification, the predictive inference is predicated on the terminal hidden state vector corresponding to a special classification token [CLS]. This vector, denoted as

To transform these raw logits into a valid posterior probability distribution, the Softmax activation function is employed to yield the probability

The model’s final prediction,

The model is trained to perform multi-class classification, as all datasets used in this study involve multiple classes of network activity (e.g., Normal and various attack types). To optimize the model’s parameters, we employ the Categorical Cross-Entropy (CCE) loss function. This loss function is standard for multi-class problems and measures the dissimilarity between the model’s predicted probability distribution P and the true one-hot encoded label vector

where K is the total number of classes,

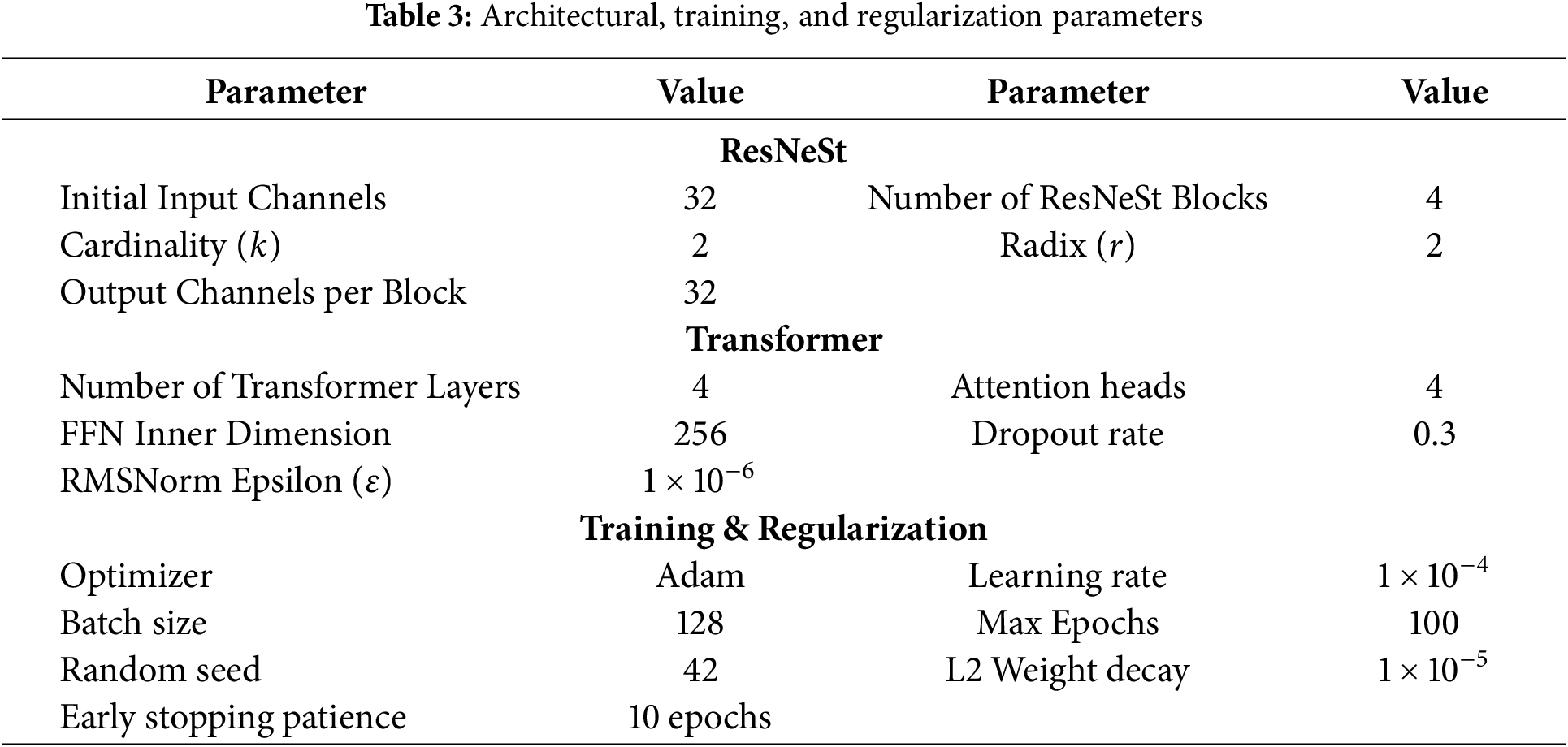

The feature extraction backbone, a stack of ResNeSt modules, was configured to create a robust and hierarchical feature representation. We selected four sequential blocks to ensure sufficient depth for learning complex feature representations from the input data. Within each block, we further optimized the split-attention mechanism to enhance representational power. Within each block, the split-attention mechanism was configured with a cardinality (

In the temporal modeling stage, the Transformer Encoder was designed to effectively capture long-range dependencies. The encoder uses a 4-layer configuration, where each layer contains a Multi-Head Attention mechanism with 4 parallel heads and a Feed-Forward Network with an inner dimension of 256. To enhance regularization, a dropout rate of 0.3 was applied within the Transformer’s sub-layers. As previously justified, standard LayerNorm was replaced with the more parameter-efficient RMSNorm, configured with a numerical stability term

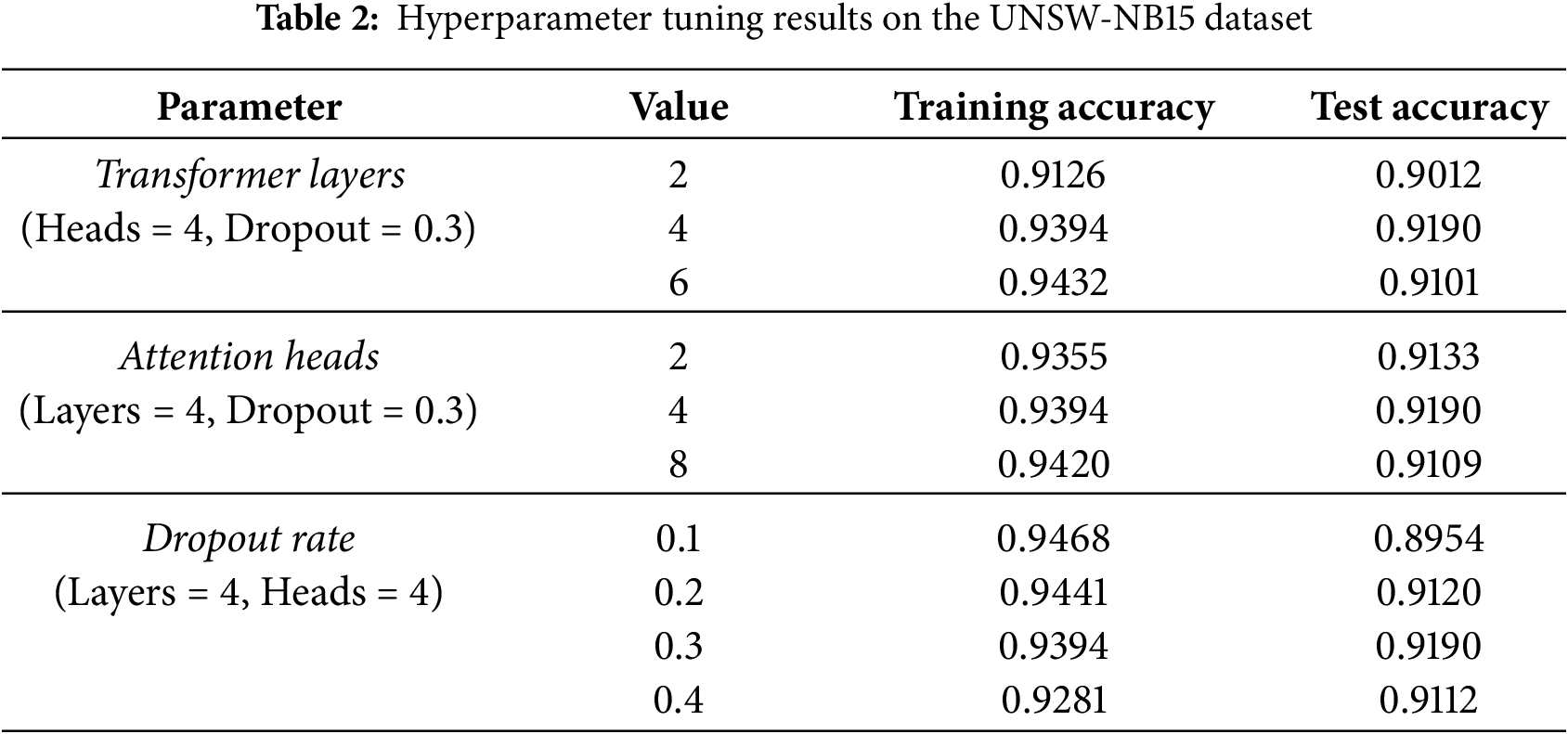

To ensure consistent experimental outcomes and effectively manage the model’s complexity, we actively prevented overfitting through a combination of architectural, data, and training-level regularization. This included applying Dropout, controlling the model’s depth, employing the Adaptive Moment Estimation (Adam) optimizer with L2 Regularization (Weight Decay), and data augmentation. Furthermore, an Early Stopping was used to halt training at the point of peak generalization. The choice of key hyperparameters was determined through an empirical tuning process on the UNSW-NB15, with results summarized in Table 2. This configuration was found to provide the best balance between model capacity and generalization, avoiding the underfitting of simpler models (e.g., 2 layers) and the diminishing returns or overfitting of more complex ones (e.g., 0.1 dropout). To ensure consistent experimental outcomes and effectively manage this final model’s complexity, we incorporated several key training procedures.

The final architectural parameters derived from this selection process are summarized in Table 3.

To establish the empirical validity and generalization capabilities of the proposed model, our investigation was performed on a curated selection of four canonical benchmark datasets: NSL-KDD, UNSW-NB15, CIC-IDS2017, and the contemporary CICIoT2023. This collection ensures a rigorous evaluation across diverse network topologies, traffic profiles, and adversarial tactics. To ensure a consistent and unbiased evaluation, each dataset was partitioned into a training set (80%) and a testing set (20%) using a stratified sampling approach, thereby preserving the original class distribution in both subsets.

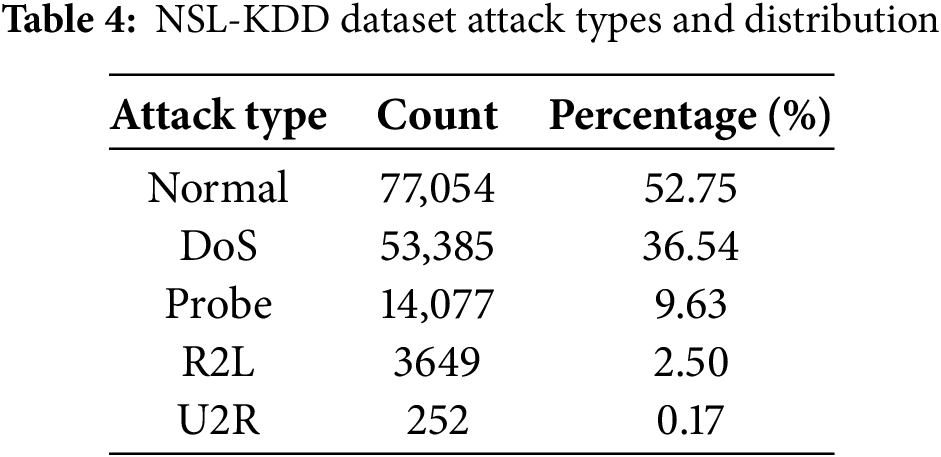

We first utilized the NSL-KDD dataset [27], a foundational benchmark for comparative analysis comprising a 41-feature vector. As detailed in Table 4, the dataset exhibits severe class imbalance, with critical minority attack classes like U2R (0.17%) and R2L (2.50%) being heavily underrepresented.

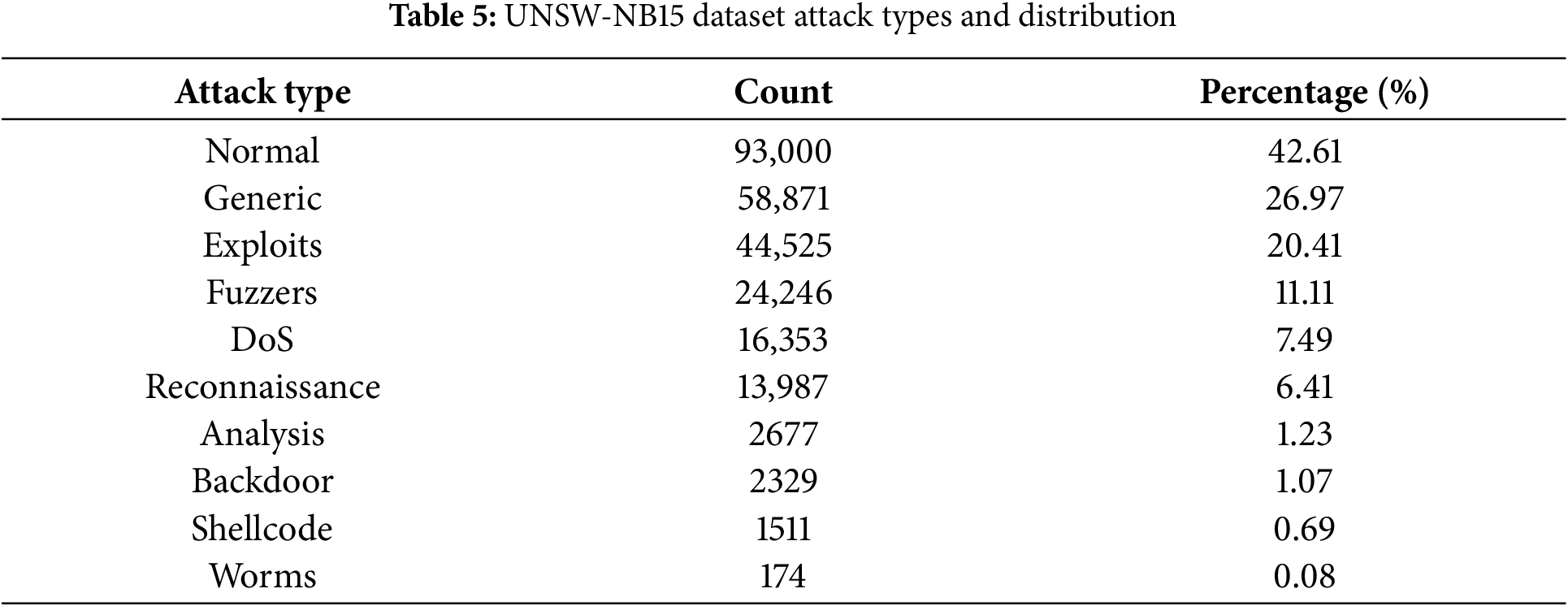

To assess performance against modern threats, we incorporate the UNSW-NB15 dataset [28], which provides 42 features per record. Its class distribution, shown in Table 5, presents a significant imbalance challenge, with minority classes such as Worms (0.08%) and Shellcode (0.69%) being exceptionally rare.

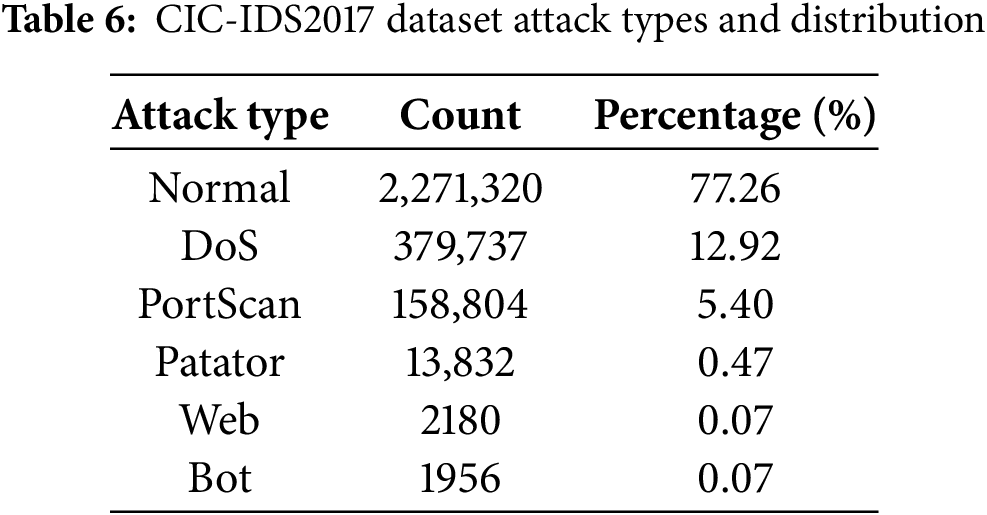

For a test of real-world applicability, we employed the CIC-IDS2017 dataset [29], noted for its high-dimensional (80+ features) space. As shown in Table 6, this dataset is heavily skewed, posing a challenge in detecting scarce minority attacks like Web and Bot, each representing only 0.07% of the data.

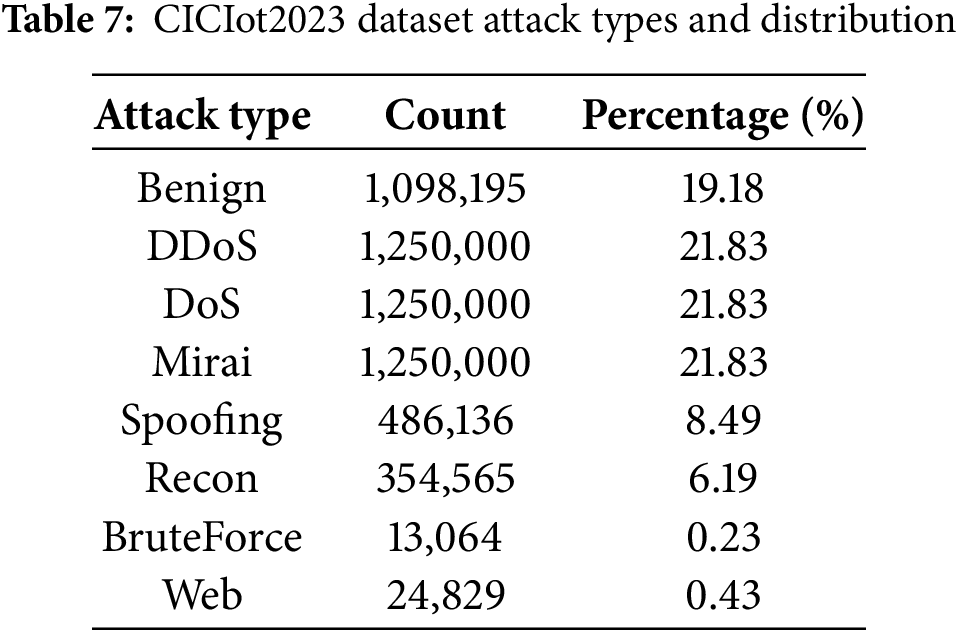

Finally, to evaluate scalability on large-scale IoT traffic, we incorporate the CICIoT2023 dataset [30]. This benchmark consists of 46 features per record. It presents a unique imbalance structure, as shown in Table 7, coexisting dominant attack classes with severe minority classes like BruteForce (0.23%) and Web (0.43%).

We implemented a multi-stage data preprocessing pipeline involving feature selection, categorical encoding, and feature scaling. We performed feature selection to remove non-informative attributes. For NSL-KDD, all 41 original features were used. For UNSW-NB15, the id and attack_cat features were removed, retaining 42 features. For CIC-IDS2017, we removed 6 metadata features (Flow ID, Source IP, Source Port, Destination IP, Protocol, Timestamp), resulting in a 78-feature set. For CICIoT2023, all 46 features were utilized. Subsequently, categorical attributes were transformed using one-hot encoding. This step expanded the NSL-KDD dataset from 41 to 122 dimensions and the UNSW-NB15 dataset from 42 to 196 dimensions. The remaining 78 features of CIC-IDS2017 and all 46 features of CICIoT2023 are numerical and did not require this encoding step.

Data quality was addressed by imputing any missing or non-finite feature values with zero. To mitigate the biasing effects of disparate feature scales, all numerical data were standardized using Min–Max normalization. This transformation was applied per-feature (i.e., column-wise), re-scaling each feature element

where

We evaluate model performance based on the standard confusion matrix outcomes: True Positives (TP), True Negatives (TN), False Positives (FP, or Type I errors), and False Negatives (FN, or Type II errors), which are considered on a per-class basis for our multi-class task. While we report overall Accuracy, its utility is limited in imbalanced datasets where a high score may simply reflect strong performance on the dominant (benign) class.

Therefore, our primary evaluation focuses on Precision and Recall. Precision measures the fidelity of alerts, quantifying the proportion of predicted attacks that are genuinely malicious; this is critical for minimizing the operational cost of investigating false alarms.

Recall (or Sensitivity) measures detection completeness, indicating the proportion of actual attacks the model successfully identifies; this is essential for ensuring threats are not missed.

To account for the inherent trade-off between Precision and Recall, we employ the F1-Score. As the harmonic mean of Precision and Recall, the F1-Score provides a single, balanced measure of performance. This metric is particularly well-suited for imbalanced classification tasks (as opposed to Accuracy) because it does not depend on True Negatives, thus focusing evaluation on the positive (minority) classes.

To visualize model performance independent of a specific classification threshold, we employ the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve. The ROC curve is a graphical plot illustrating the trade-off between two key metrics—the True Positive Rate (TPR) and the False Positive Rate (FPR)—calculated across a range of decision thresholds. The TPR, which is mathematically equivalent to Recall, measures the proportion of actual attacks (positives) that are correctly identified.

Conversely, the FPR measures the proportion of benign instances (negatives) that are incorrectly classified as attacks.

A critical and prevalent challenge in network intrusion detection is the severe class imbalance inherent in realistic datasets, a characteristic clearly delineated in our datasets. On benchmark datasets, minority attack classes like R2L, U2R, and Worms are vastly underrepresented compared to normal traffic and common attacks. This imbalance can bias the model during training, leading to high accuracy on majority classes but dangerously poor recall on rare, yet often critical, threats [31].

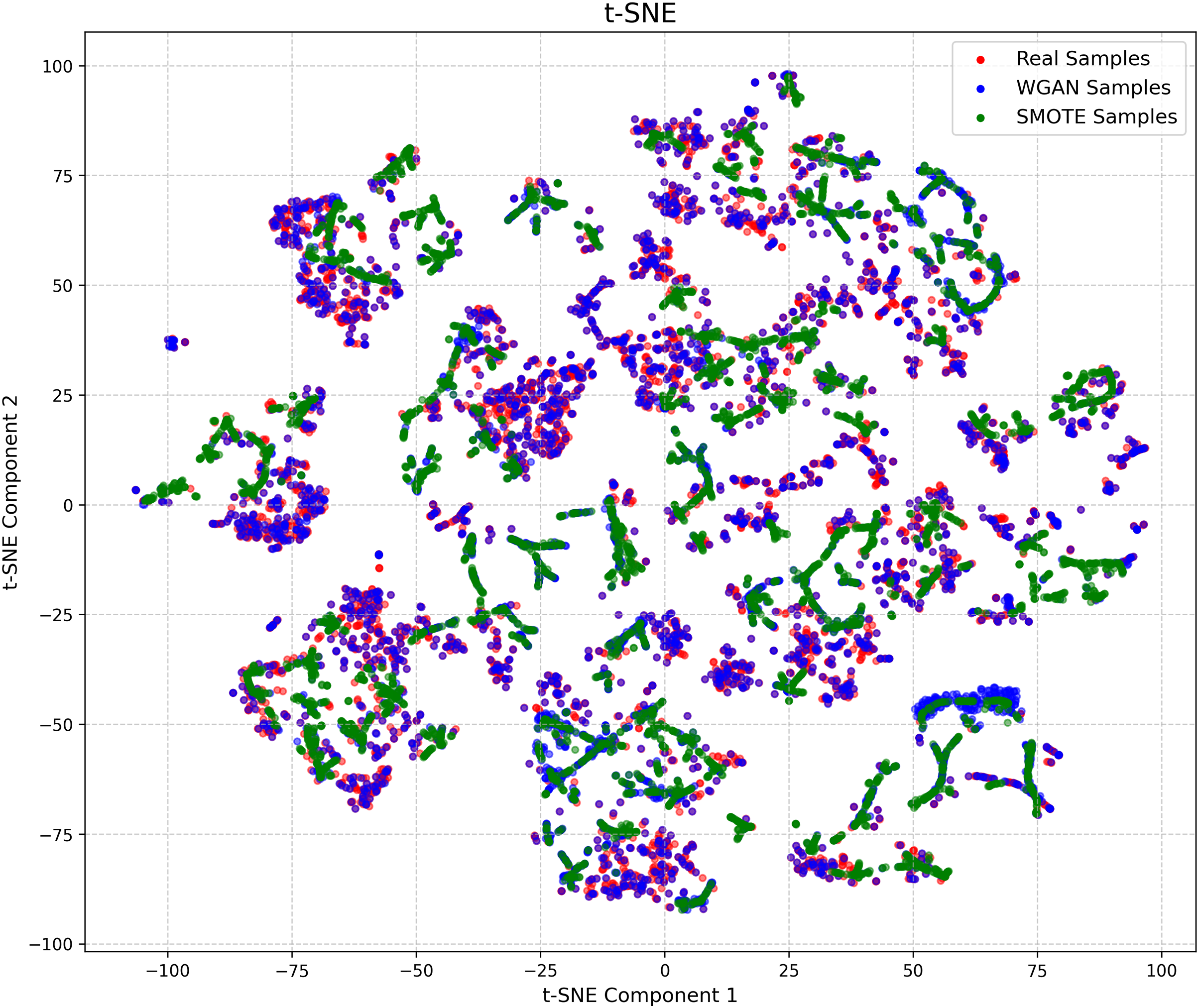

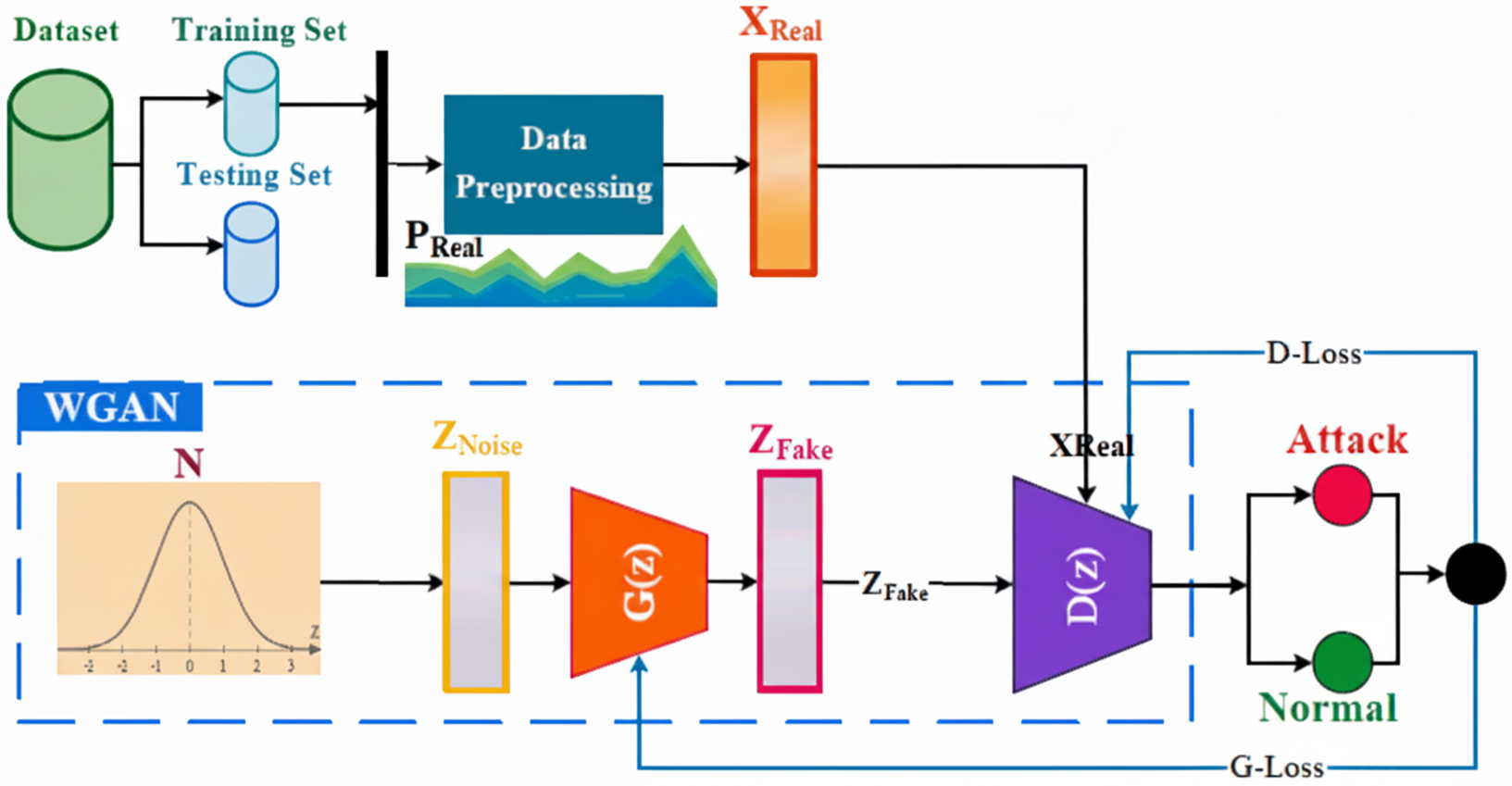

To mitigate this issue, we moved beyond conventional oversampling techniques like Synthetic Minority Over-sampling TEchnique (SMOTE) [32] or ADASYN [33], which generate synthetic samples through linear interpolation and may not fully capture the complex, non-linear distribution of attack data. Instead, we employed a sophisticated data augmentation strategy based on a Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) [34], specifically a variant of the Wasserstein GAN (WGAN). This approach is inspired by recent advancements that have successfully used generative models to create high-fidelity synthetic attack data for NIDS [23]. The WGAN architecture was chosen for its training stability and its ability to overcome the mode collapse problem common in standard GANs, thereby ensuring the generation of diverse and realistic minority samples [35].

This process is visualized on a 2D plane, using the Web minority class from the CIC-IOT2023 dataset as a case study. As illustrated in Fig. 4, the visualization provides strong support for our methodological choice. The WGAN-generated samples (blue dots) demonstrate a distribution that closely mirrors the original ‘Real Samples’ (red dots), clustering in similar regions and respecting the underlying data manifold. The SMOTE-generated samples (green dots), while also providing augmentation, show a distribution that does not align as closely with the true data structure compared to the WGAN samples.

Figure 4: t-SNE (t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding) visualization comparing Real Samples (red), WGAN-generated Samples (blue), and SMOTE-generated Samples (green) for the ‘Web’ attack class from the CIC-IOT2023 dataset

The WGAN framework replaces the Jensen-Shannon divergence with the Wasserstein-1 distance (

where

Figure 5: WGAN architecture

Our process involved training a dedicated WGAN model for each minority attack class. The training follows an adversarial process governed by two distinct loss functions. The critic is trained to maximize the objective in Eq. (19), which corresponds to minimizing the following loss:

Conversely, the generator is trained to produce samples that are indistinguishable from real data, which corresponds to minimizing its loss function:

Training for each per-class WGAN was continued until the Wasserstein distance estimate converged. The trained generator was then used to synthesize the new samples to create a more balanced class distribution for training. This targeted augmentation ensures that our TransNeSt model is exposed to a richer and more varied representation of rare attack patterns, enhancing its ability to learn their distinguishing features.

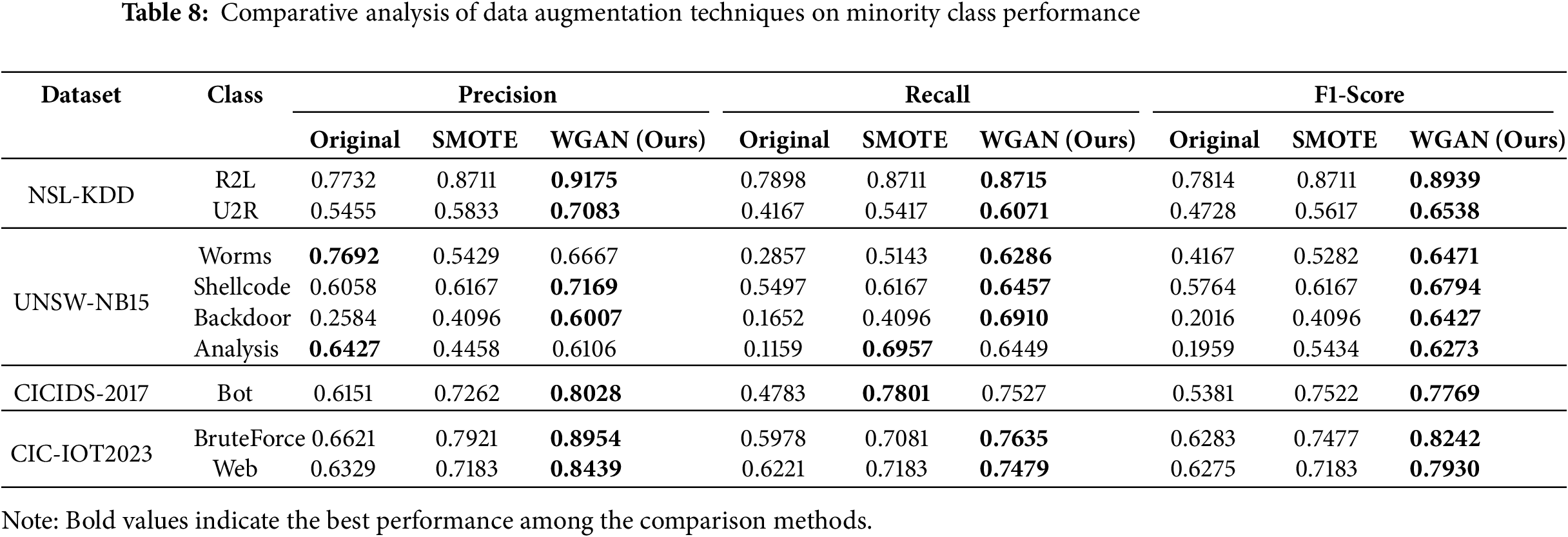

To experimentally quantify the impact of our WGAN-based augmentation. We evaluated the performance of our TransNeSt model on the minority attack classes across all four datasets under these three augmentation strategies. The results of this comparison are detailed in Table 8.

The data clearly demonstrate the superiority of the WGAN (Ours) approach. Across the vast majority of minority classes, our WGAN-augmented model achieves the highest scores in Precision, Recall, and F1-Score. By addressing the data imbalance at its source, we aim to significantly improve the model’s recall on minority classes without compromising precision, ultimately fostering a more robust and reliable detection system.

5 Experiment and Result Analysis

To rigorously evaluate the proposed TransNeSt architecture, our experimental design incorporates a controlled ablation study. We benchmarked TransNeSt against its core constituent components—a standalone ResNeSt and a standalone Transformer—to empirically validate that the hybrid design offers a synergistic improvement over its individual parts. Furthermore, to demonstrate that our specific fusion strategy is superior to conventional methods, we included a generic ResNet-Transformer hybrid as an additional challenging baseline. This comparative analysis was performed on four standard network intrusion detection datasets (NSL-KDD, UNSW-NB15, CICIDS-2017 and CICIOT2023), with model efficacy quantified by Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1-Score. It is critical to note that to ensure a fair comparison, all models discussed in this section were trained and evaluated on the same WGAN-augmented datasets.

All experiments were conducted on a server running Ubuntu 22.04. The software environment was built upon Python 3.10, PyTorch 2.1.2, and CUDA 11.8. The hardware platform consisted of a 12-core Intel(R) Xeon(R) Silver 4214R CPU @ 2.40 GHz and a single NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3080 Ti GPU with 12 GB of VRAM.

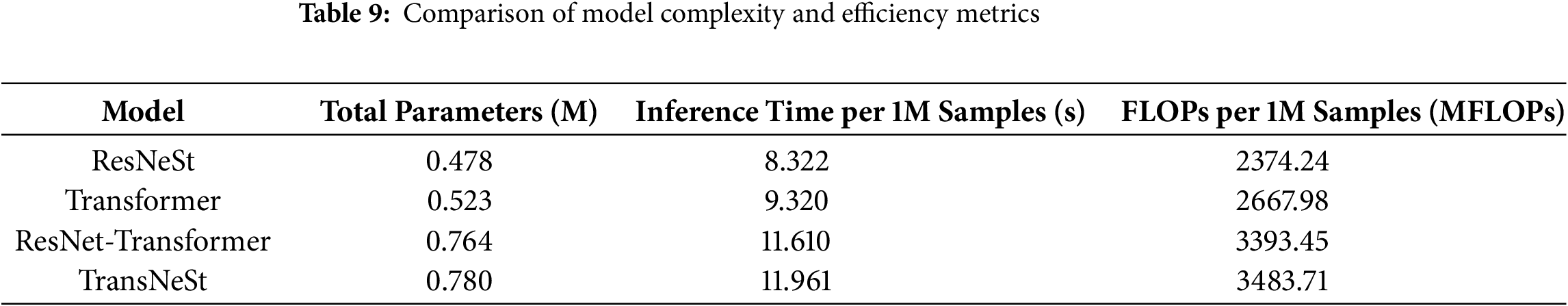

Before presenting the detection performance results, we first provide a quantitative analysis of each model’s computational complexity and efficiency, including its total parameters and Floating Point Operations (FLOPs). The key metrics for this benchmark are summarized in Table 9.

The data in Table 9 establishes the computational cost for each architecture. As observed, our proposed TransNeSt model maintains a complexity profile comparable to the standard ResNet-Transformer hybrid.

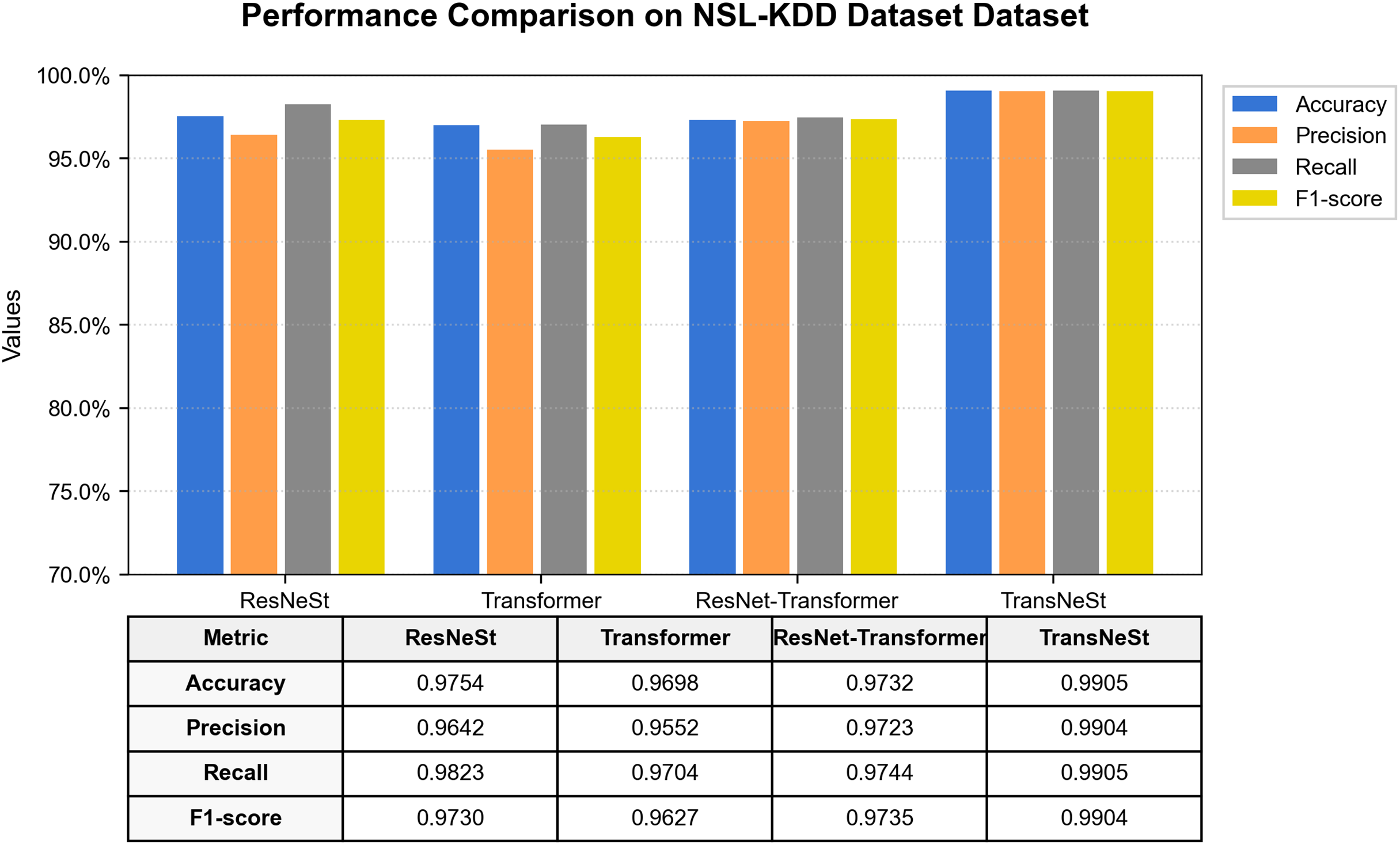

5.1 Evaluation Using the NSL-KDD Dataset

We initiated our empirical evaluation on the foundational NSL-KDD benchmark. The comprehensive performance comparison, illustrated in Fig. 6, clearly establishes the superiority of the proposed TransNeSt architecture. Our model achieved the highest performance across all metrics, attaining an F1-Score of 99.04% and an accuracy of 99.05%.

Figure 6: Performance comparison of all models on the NSL-KDD dataset

The results also serve as a compelling ablation study, isolating the contributions of our model’s core components. The standalone ResNeSt model, acting as a powerful feature extraction baseline, achieved a remarkable F1-score of 97.30%, demonstrating the inherent effectiveness of the split-attention mechanism in capturing salient traffic features. The standalone Transformer, while also performing well, was surpassed by the ResNeSt, underscoring the importance of robust initial feature representation. Crucially, our integrated TransNeSt model outperformed both individual components, validating the synergistic benefit of combining ResNeSt’s fine-grained feature extraction with the Transformer’s sequential modeling capabilities.

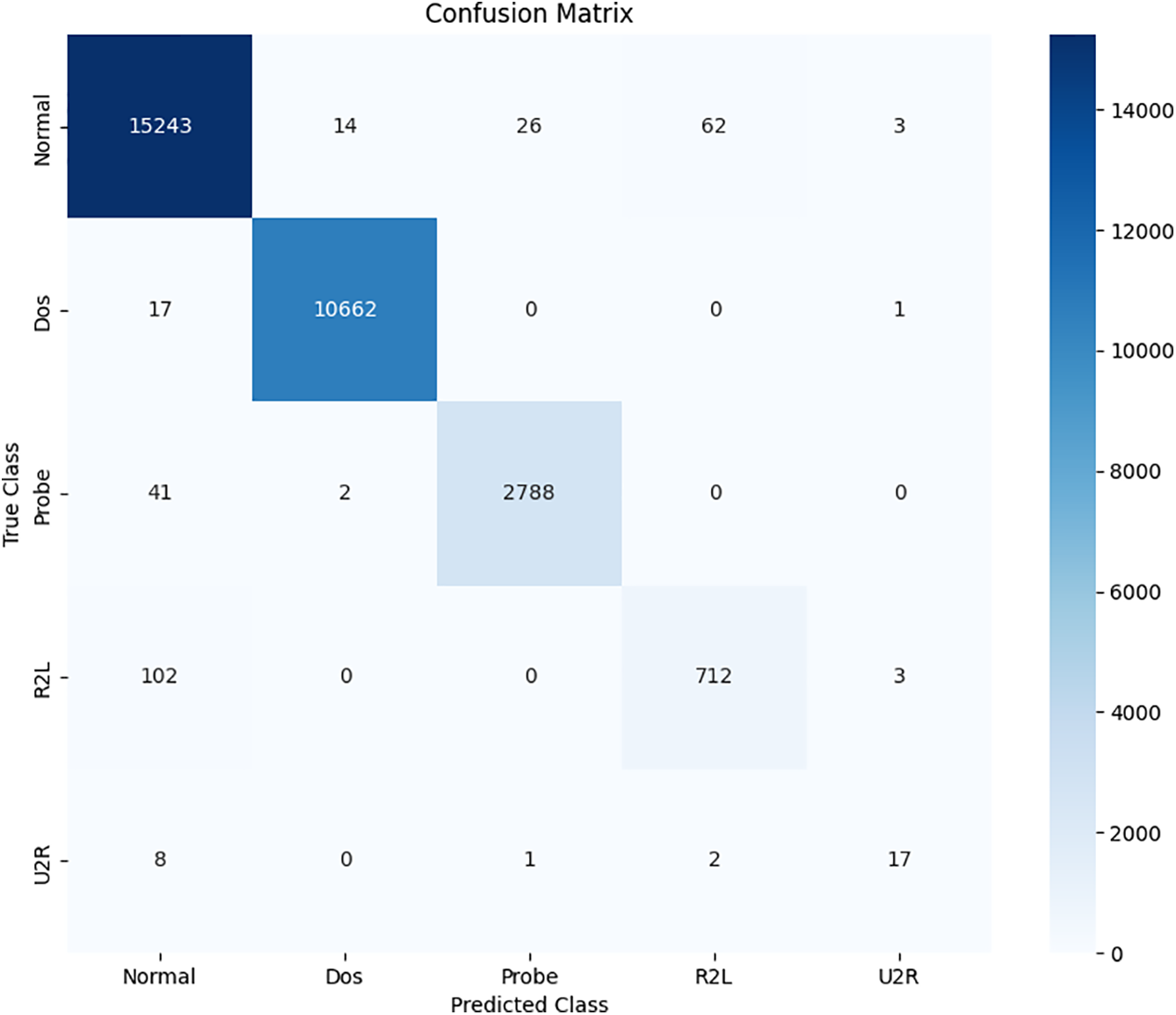

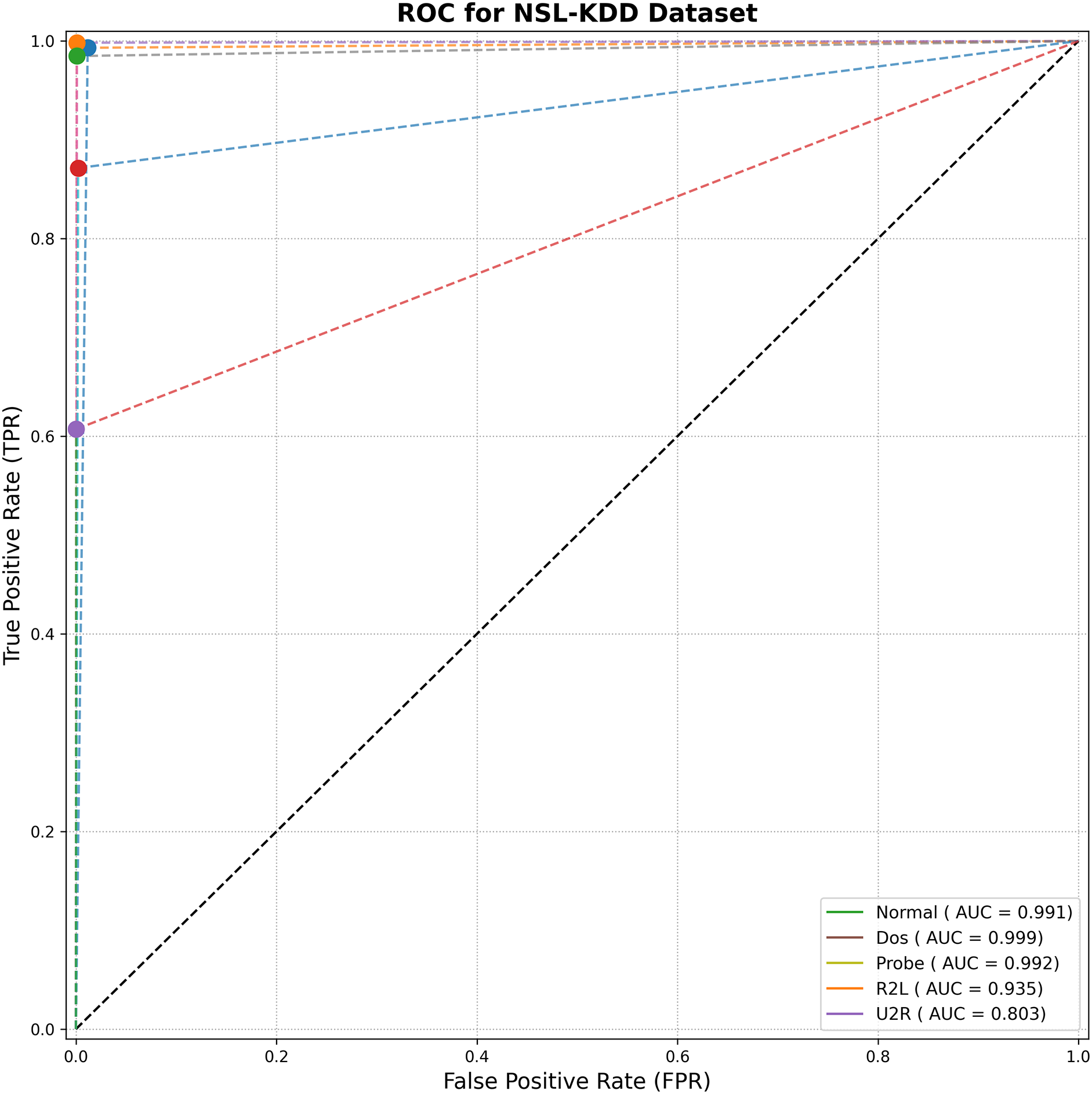

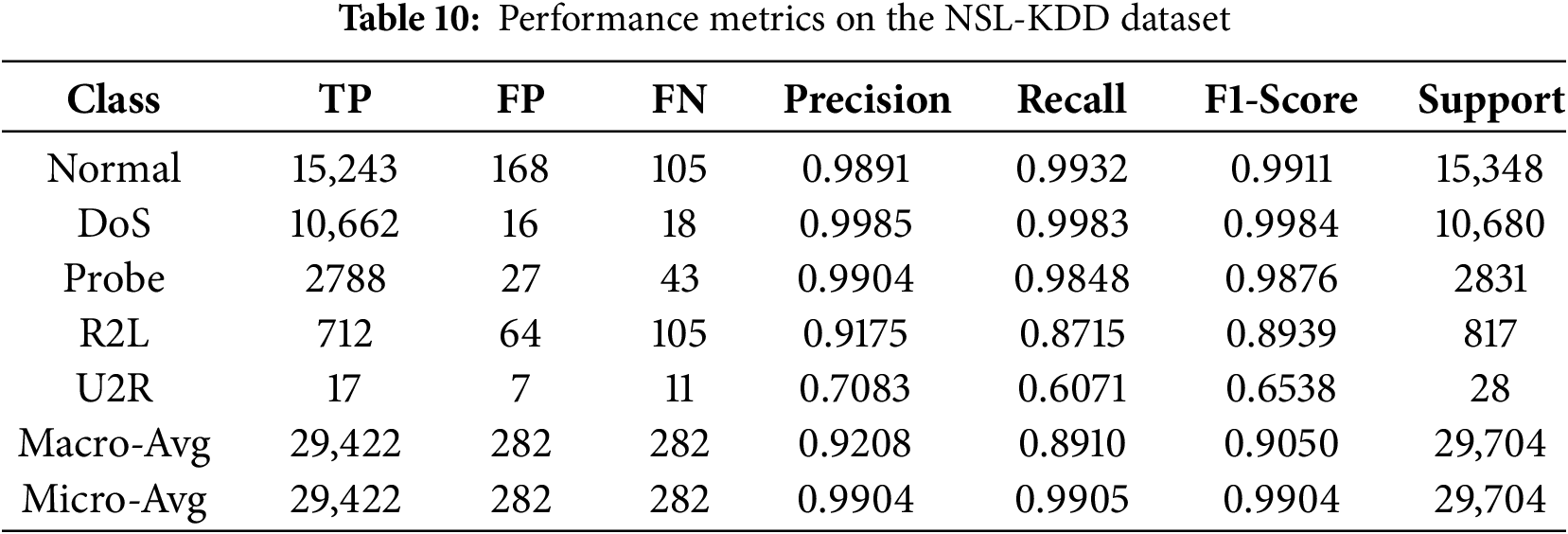

A deeper analysis of per-class performance, detailed in the confusion matrix (Fig. 7), ROC curves (Fig. 8), and performance metrics (Table 10), highlights the model’s robust performance. TransNeSt achieves outstanding F1-scores on majority classes like ‘DoS’ (99.84%) and ‘Normal’ (99.11%). More critically, this strength extends to the challenging minority attack classes, a success largely attributable to our augmentation strategy. As the comparative analysis in Table 8 empirically demonstrates, our WGAN-based approach yields performance gains over both the baseline and traditional SMOTE. For the extremely rare U2R class, WGAN elevates the F1-Score to 0.6538, surpassing the baseline’s 0.4728 and SMOTE’s 0.5617, thereby validating its efficacy in generating high-fidelity synthetic data.

Figure 7: Confusion matrix for TransNeSt on the NSL-KDD dataset

Figure 8: ROC curve analysis for TransNeSt on the NSL-KDD dataset

Performance on R2L (89.39% F1) and U2R (65.38% F1) remain comparatively lower than that of the high-support classes. This challenge is attributed to the extreme data scarcity and low feature diversity of these attack instances. It suggests that while WGAN provides a critical performance boost, fully modeling the feature boundaries of these subtle attacks remains the primary difficulty and a key focus for subsequent research.

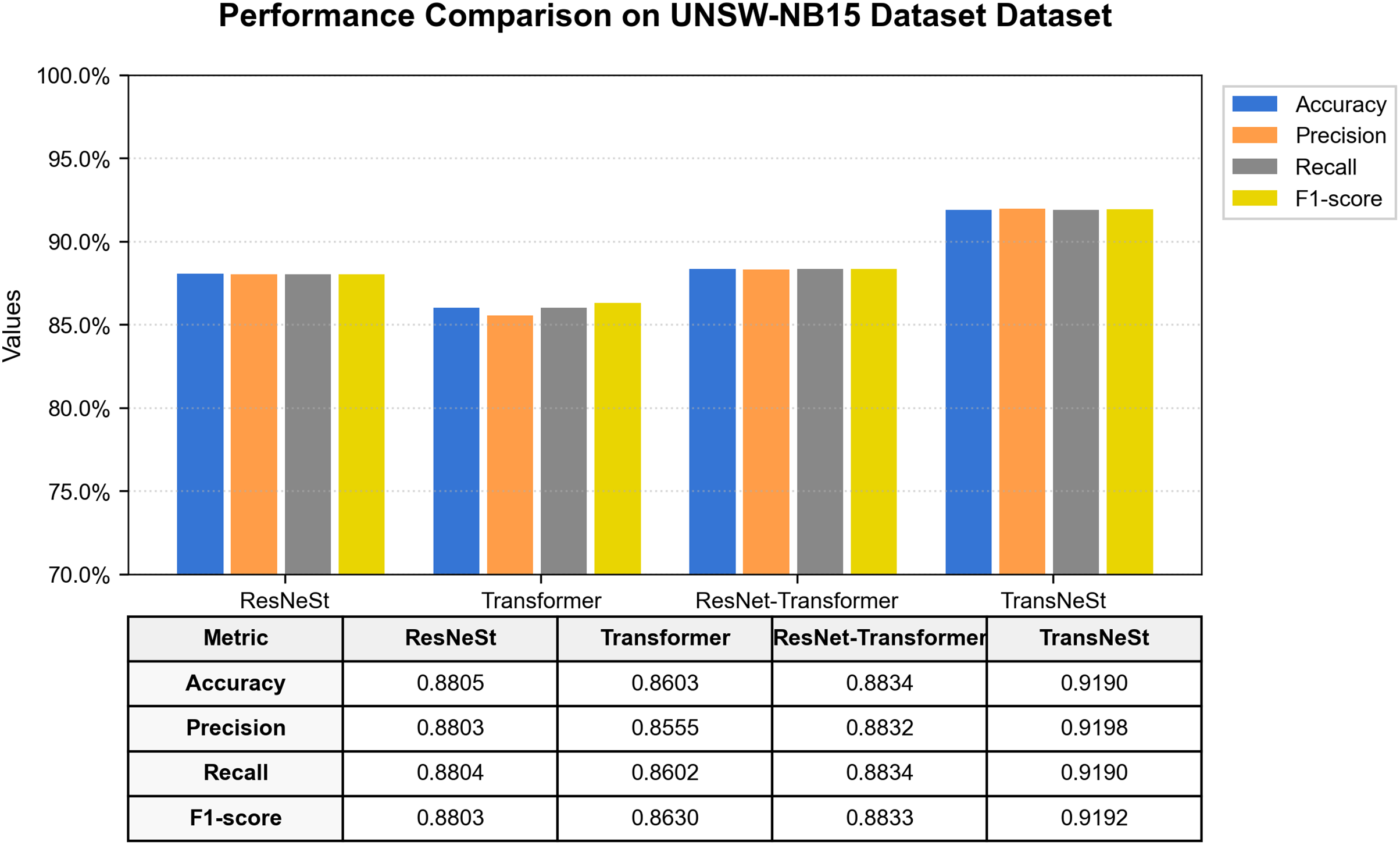

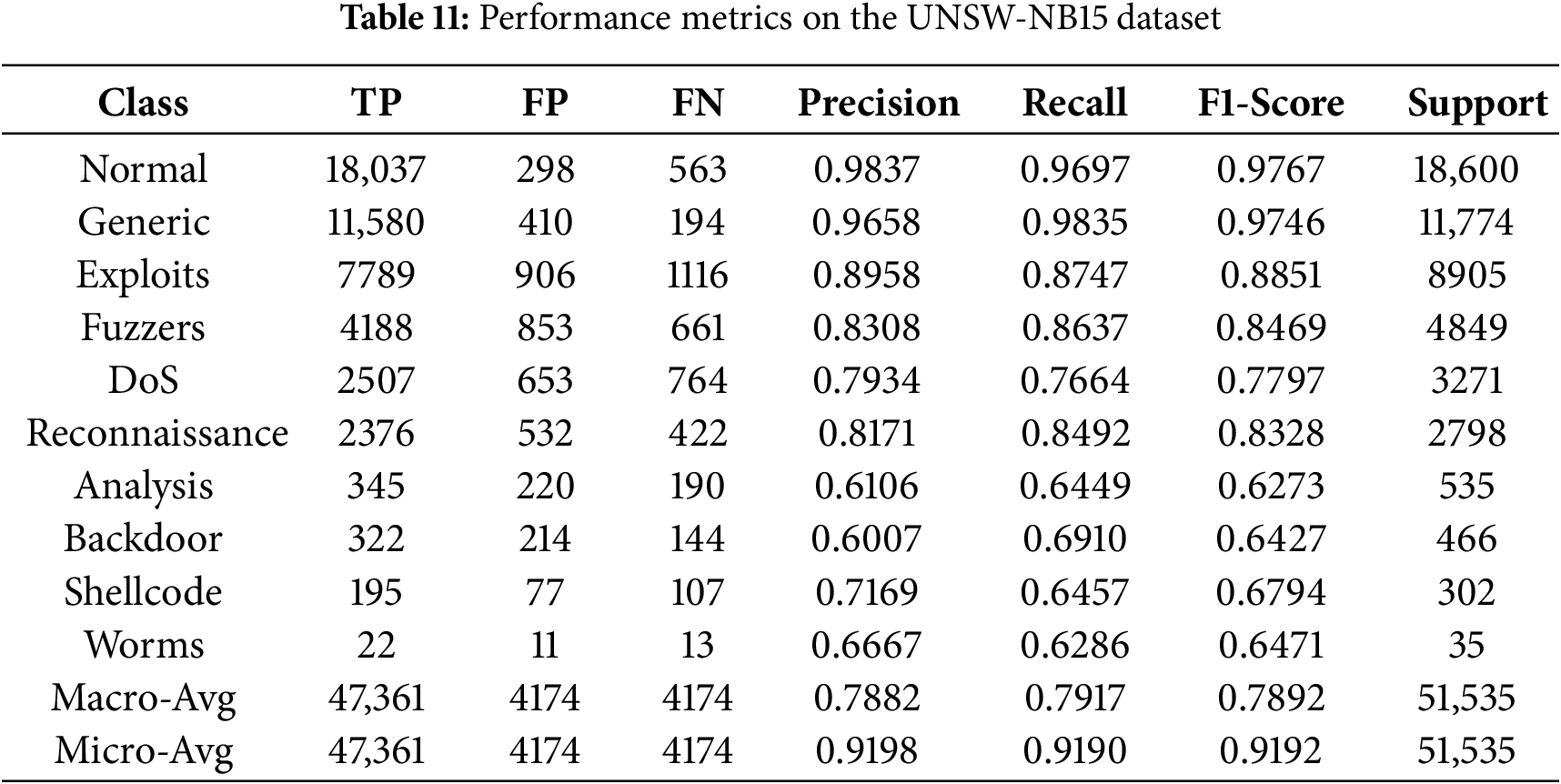

5.2 Evaluation Using the UNSW-NB15 Dataset

To assess the model’s efficacy against more contemporary and diverse threats, we conducted evaluations on the UNSW-NB15 dataset. As shown in Fig. 9, TransNeSt once again significantly outperformed all baseline models, achieving a top-tier F1-Score of 91.92% and an accuracy of 91.90%. This F1-Score, while lower than the 99.04% achieved on NSL-KDD, reflects the distinctly higher complexity, greater class imbalance, and more subtle feature patterns inherent in this modern and more challenging dataset.

Figure 9: Performance comparison of all models on the UNSW-NB15 dataset

This dataset provides further evidence of our architecture’s successful design. The standalone ResNeSt again proved to be a potent feature extractor with an F1-score of 88.03%, reinforcing the value of its multi-path, channel-aware attention structure for discerning modern attack patterns. The subsequent integration with the Transformer block in TransNeSt yielded a substantial performance gain of nearly 4 percentage points in F1-score. This improvement highlights the critical role of the Transformer in modeling the temporal relationships between the rich feature sets generated by ResNeSt, a synergy that is essential for handling the complexity of the UNSW-NB15 dataset.

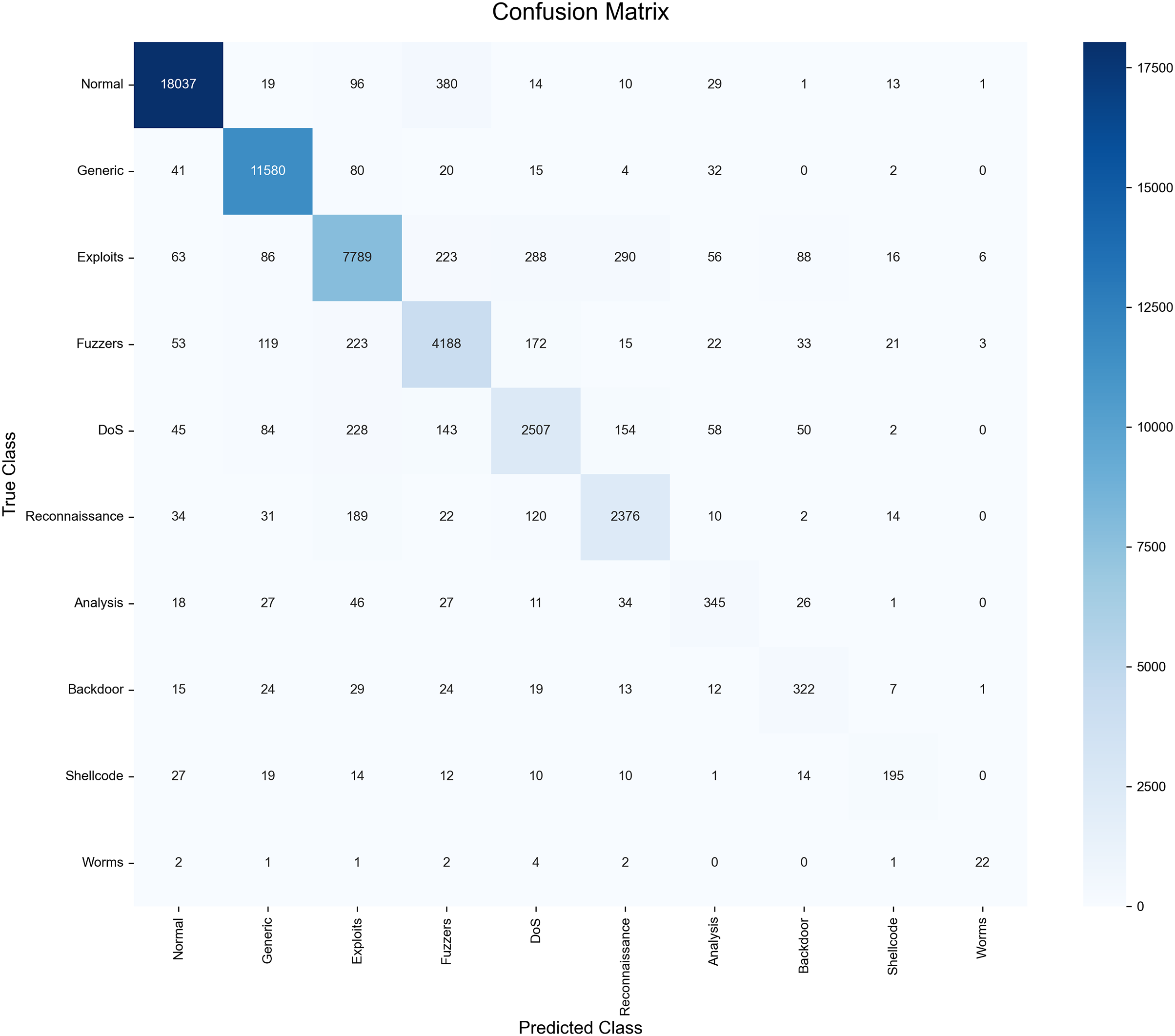

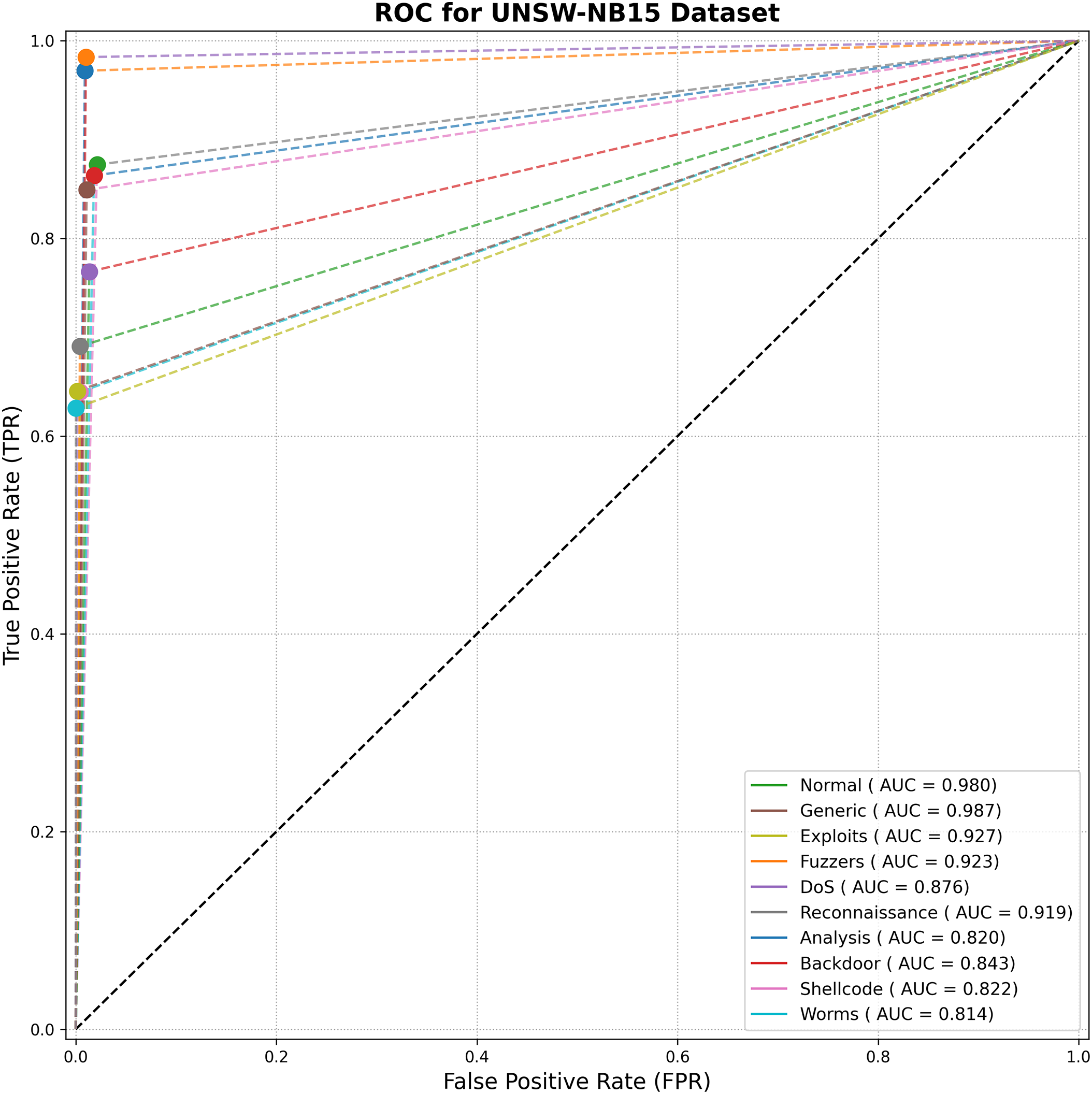

The detailed per-class metrics are presented in Table 11, with corresponding confusion matrix in Fig. 10 and the ROC curves in Fig. 11. The model demonstrates high F1-scores on prevalent classes like ‘Normal’ (97.67%) and ‘Generic’ (97.46%). For the challenging low-support classes, the WGAN-based augmentation provides a clear advantage, as detailed in Table 8. WGAN, for example, raised the F1-Score for ‘Backdoor’ to 0.6427 (from 0.2016 baseline) and ‘Shellcode’ to 0.6794 (from 0.5764 baseline). Despite this improvement, these minority classes (e.g., ‘Analysis’, ‘Backdoor’, ‘Shellcode’, ‘Worms’) still yield the lowest F1-scores (62%–68% range). This indicates that while WGAN provides a critical boost, the low instance count and feature overlap remain the primary challenge for model refinement on this dataset.

Figure 10: Confusion matrix for TransNeSt on the UNSW-NB15 dataset

Figure 11: ROC curve analysis for TransNeSt on the UNSW-NB15 dataset

5.3 Evaluation Using the CIC-IDS2017 Dataset

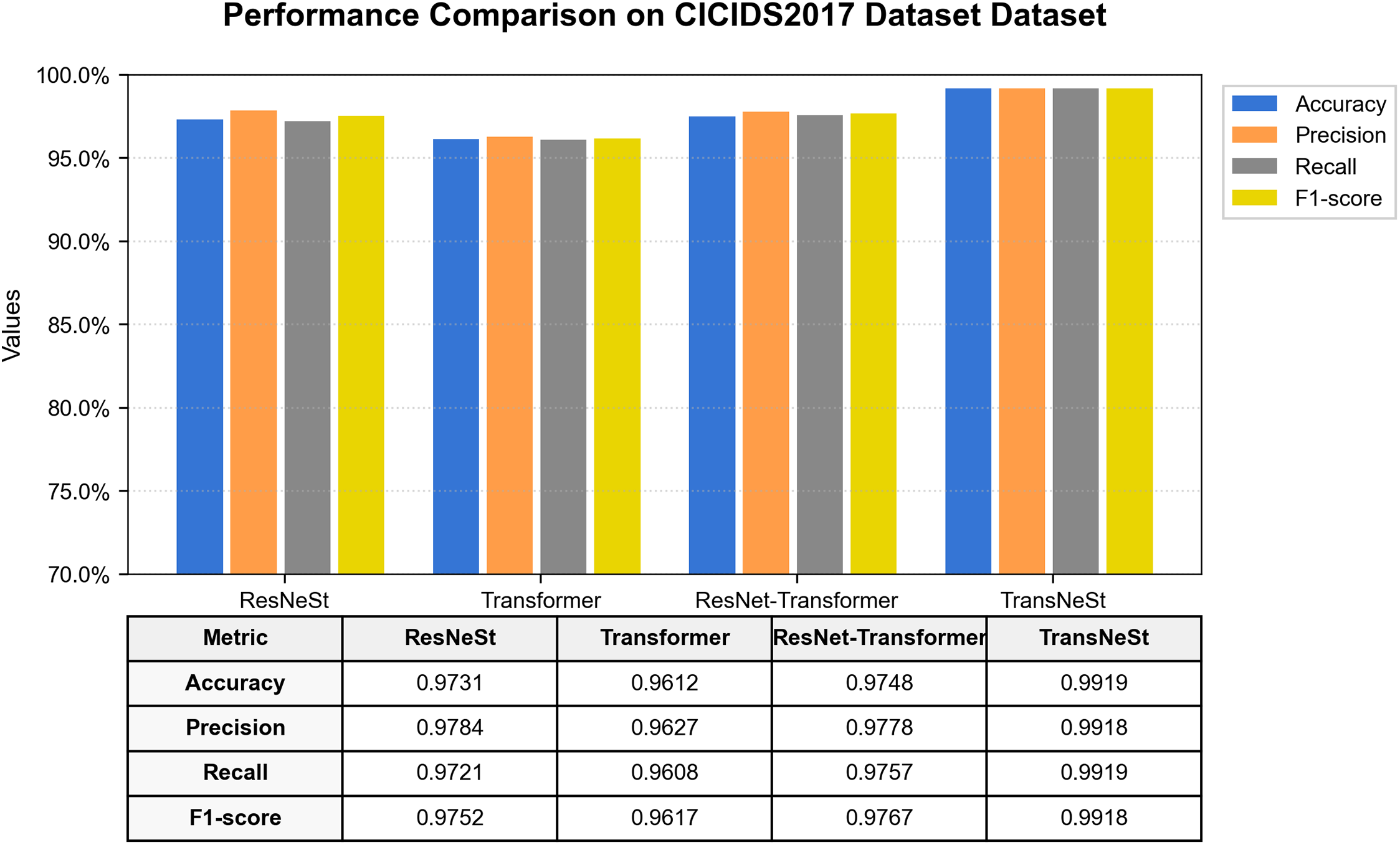

A rigorous evaluation was performed on the large-scale and highly realistic CIC-IDS2017 dataset. The results, illustrated in Fig. 12, demonstrate the model’s high performance. TransNeSt achieved an F1-Score of 99.18% and an accuracy of 99.19%, outperforming the other tested models. The ablation analysis on this dataset further solidifies our central thesis. The ResNeSt component, with an F1-score of 97.52%, proves itself to be a highly effective feature extractor even on high-volume, complex traffic. The Transformer component also performs well, but the fusion in TransNeSt again elevates the performance to a new level, surpassing the next-best model (ResNet-Transformer) by over 1.5 percentage points. This margin is significant at such high performance levels and underscores the superiority of our specific architectural combination.

Figure 12: Performance comparison of all models on the CIC-IDS2017 dataset

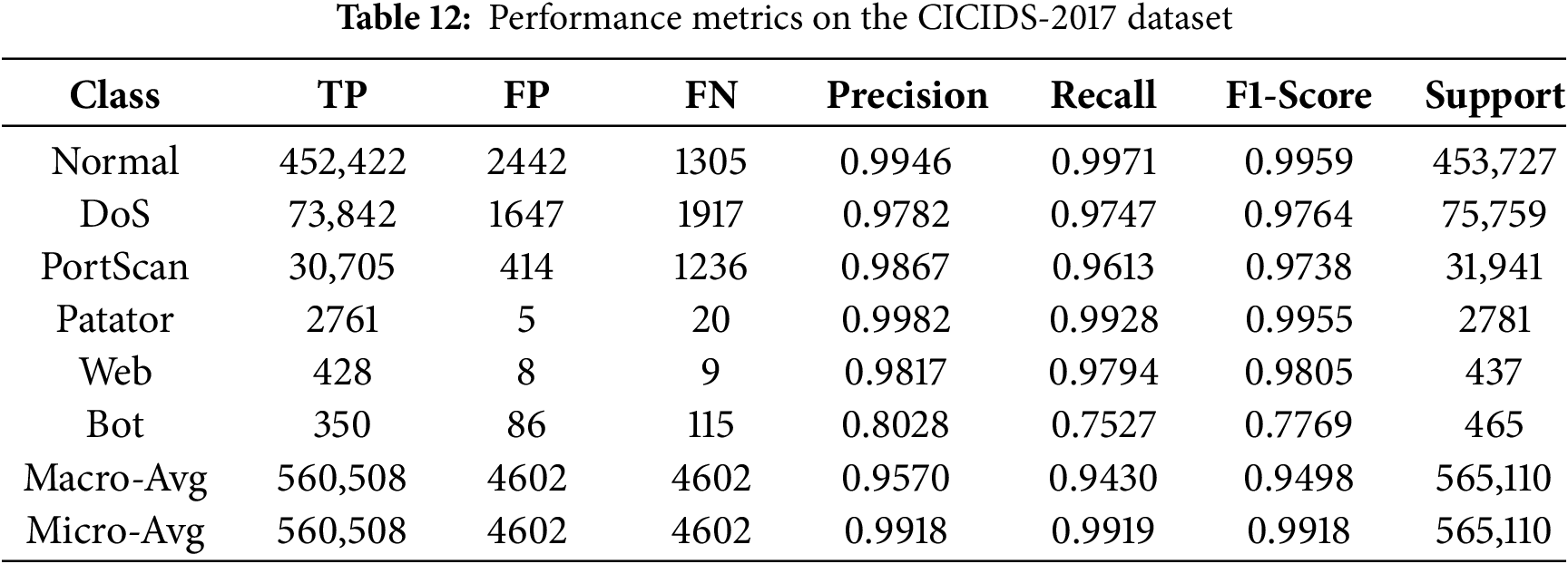

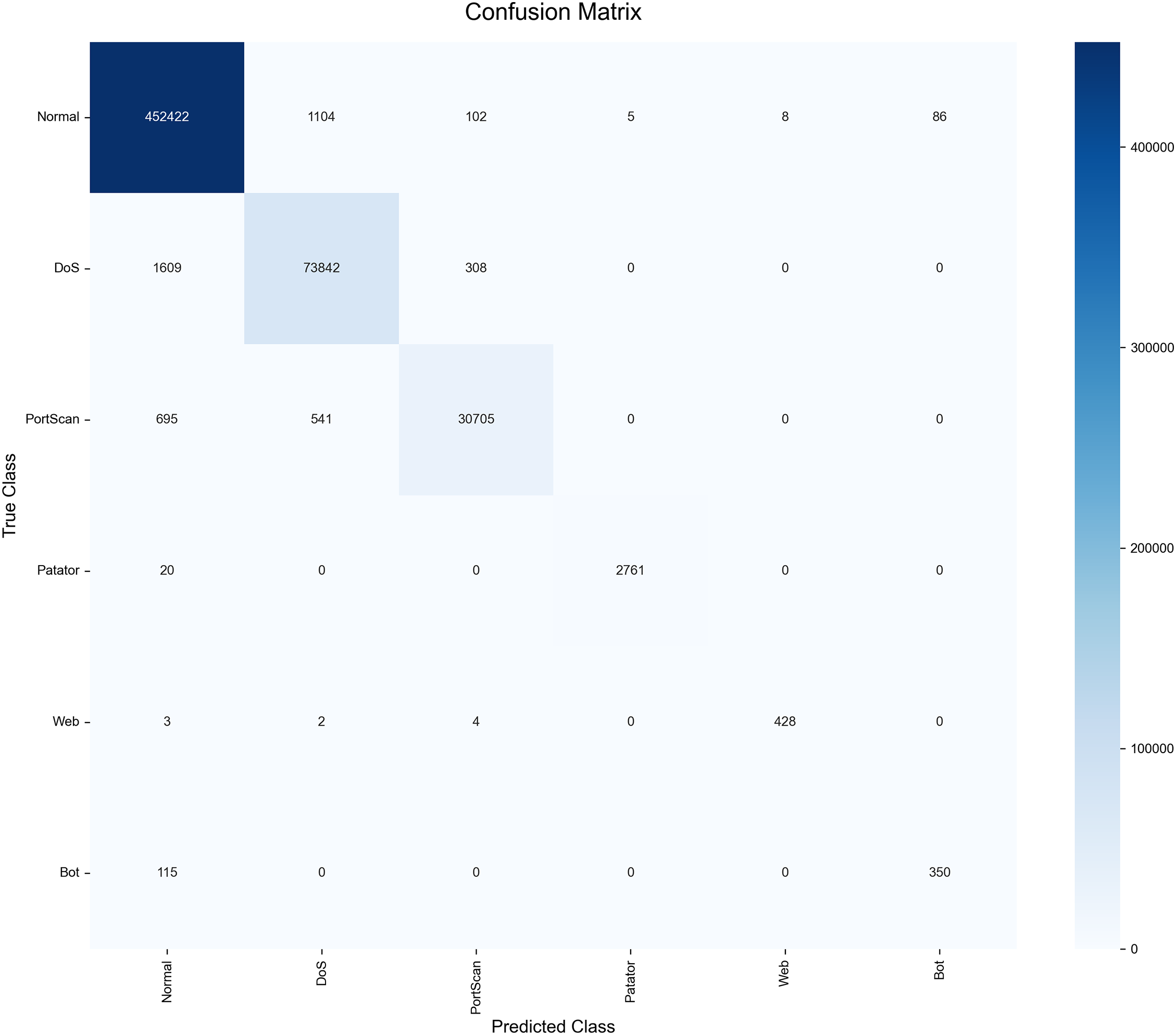

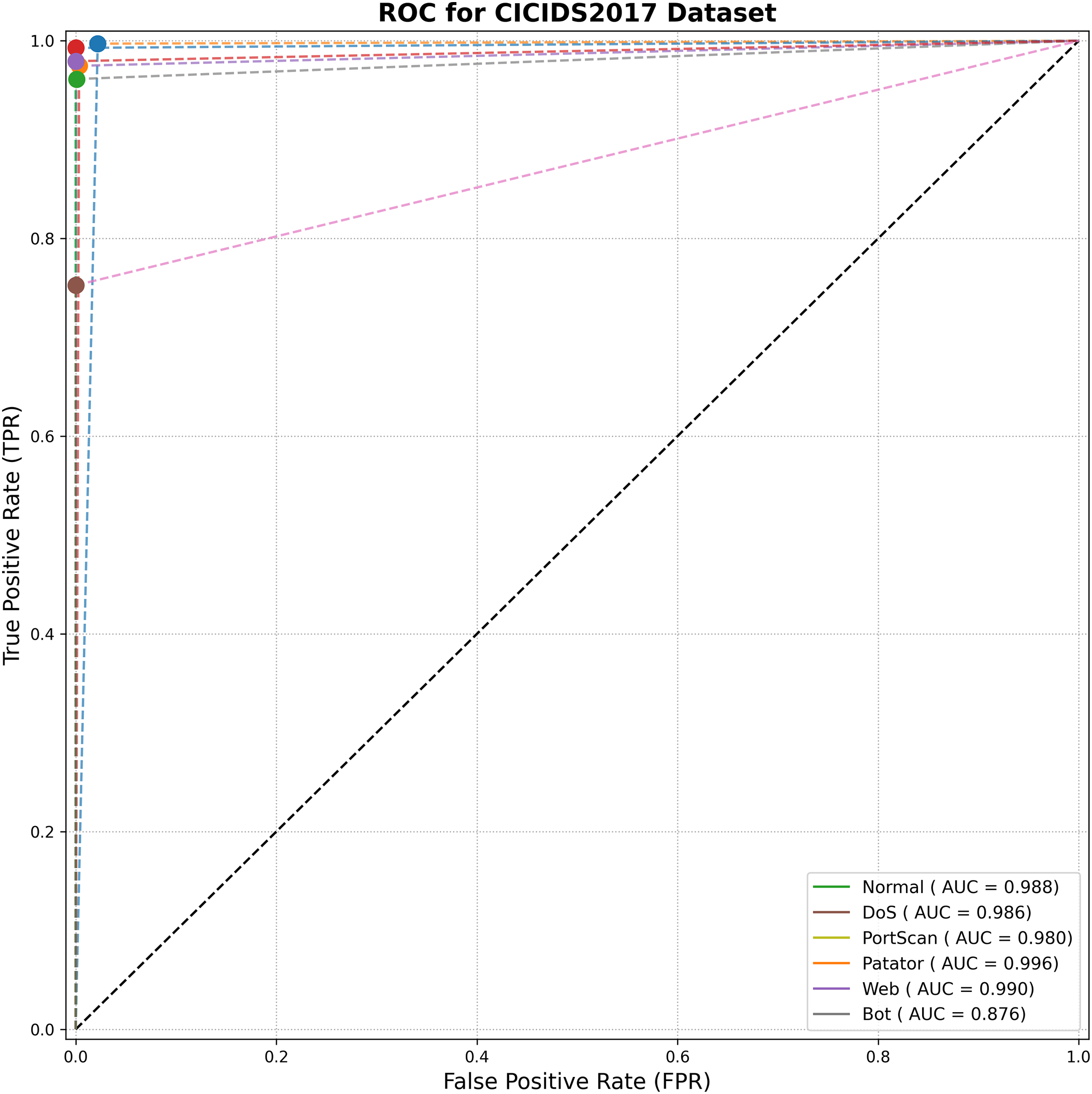

Given the severe class imbalance of this dataset, a detailed per-class analysis is crucial (Table 12, Figs. 13, and 14). TransNeSt exhibits near-perfect detection on dominant classes like ‘Normal’ (99.59% F1) and ‘DoS’ (97.64% F1). Critically, it also shows strong performance on less frequent attack types, such as the 98.05% F1-score on ‘Web’. For the ‘Bot’ class (less than 0.07% of data), the WGAN augmentation strategy proved essential. As shown in Table 8, WGAN raised the ‘Bot’ F1-Score to 0.7769, outperforming both the baseline (0.5381) and SMOTE (0.7522).

Figure 13: Confusion matrix for TransNeSt on the CICIDS-2017 dataset

Figure 14: ROC curve analysis for TransNeSt on the CIC-IDS2017 dataset

The ‘Bot’ class performance, while superior to other augmentation methods, remains the primary area for refinement. The 115 False Negatives identified for this class in (Fig. 13) are a key indicator. These are primarily misclassifications against the high-volume ‘Normal’ class. This highlights the persistent difficulty of distinguishing extremely low-support malicious flows from benign traffic, a challenge that persists even with effective data augmentation.

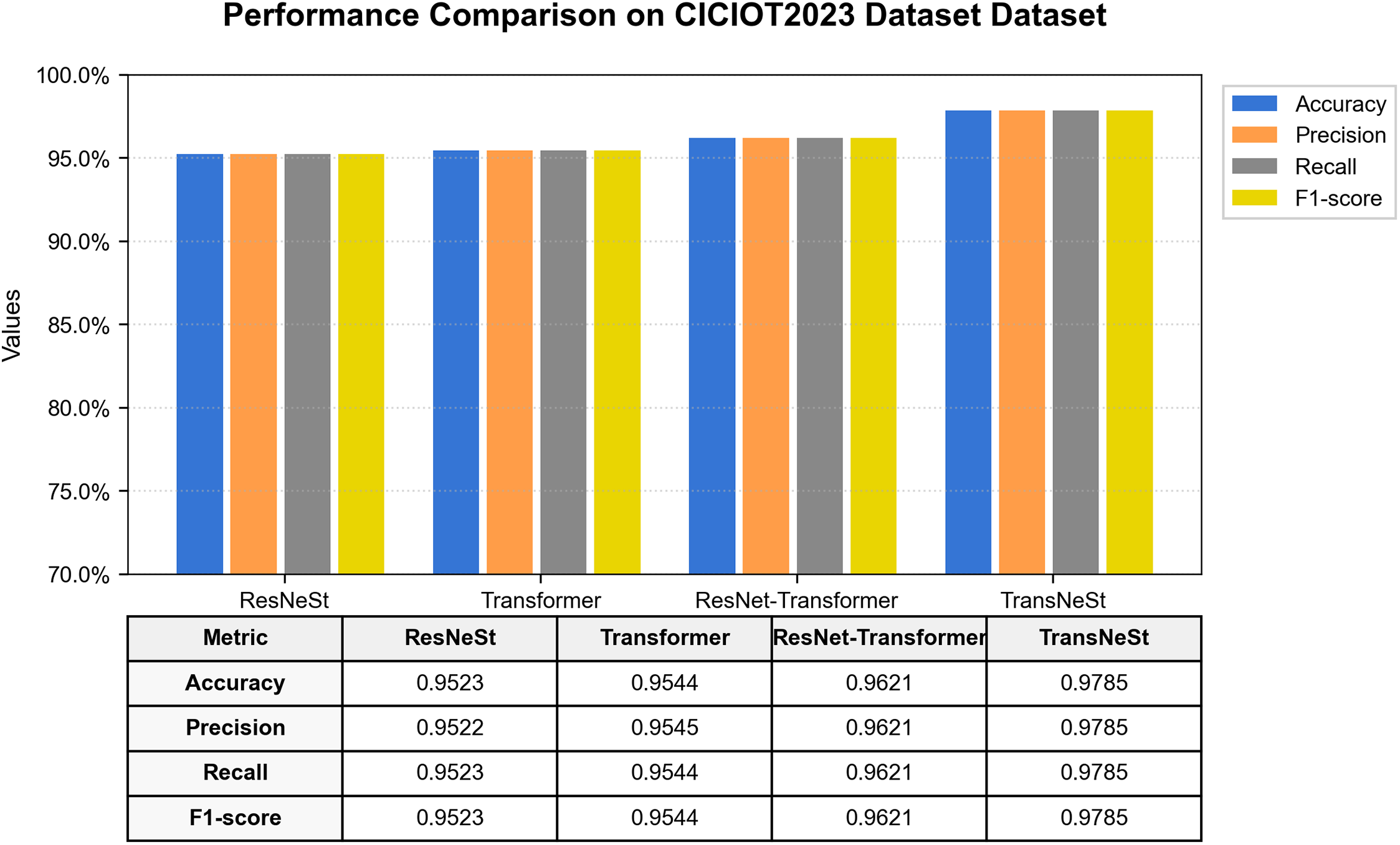

5.4 Evaluation Using the CICIoT2023 Dataset

To validate our model’s scalability and performance on a very recent, large-scale IoT benchmark, we performed a final evaluation on the CICIoT2023 dataset. The comprehensive performance comparison, illustrated in Fig. 15, confirms the superiority of our proposed architecture. TransNeSt achieved the highest F1-Score of 97.85% and an accuracy of 97.85%, again clearly outperforming the other models. This dataset’s ablation results further reinforce our design. The standalone ResNeSt (95.23% F1) and Transformer (95.44% F1) components performed well. However, their fusion in TransNeSt (97.85% F1) yielded a performance gain of over 1.6 percentage points compared to the next-best ResNet-Transformer (96.21% F1), underscoring the synergistic benefit of combining ResNeSt’s fine-grained feature extraction with the Transformer’s sequential modeling.

Figure 15: Performance comparison of all models on the CICIOT2023 dataset

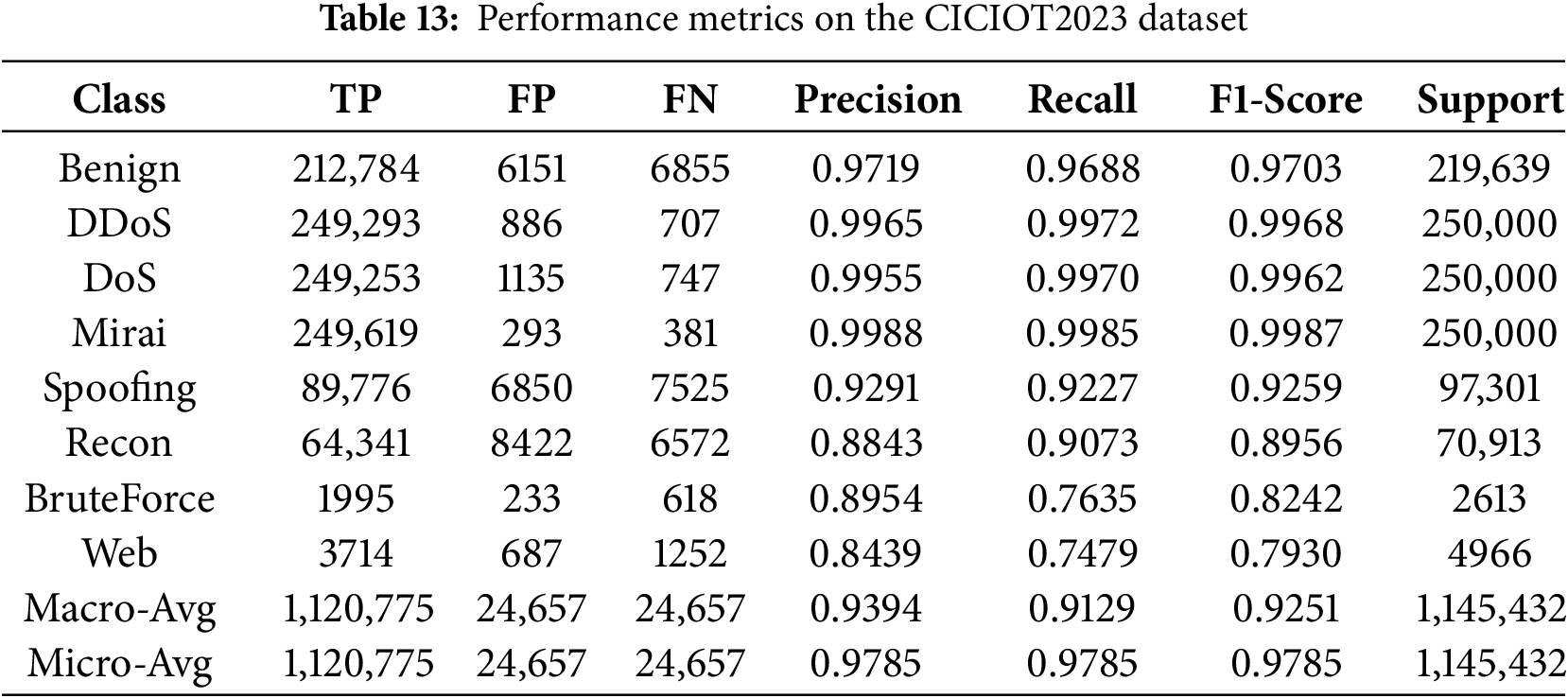

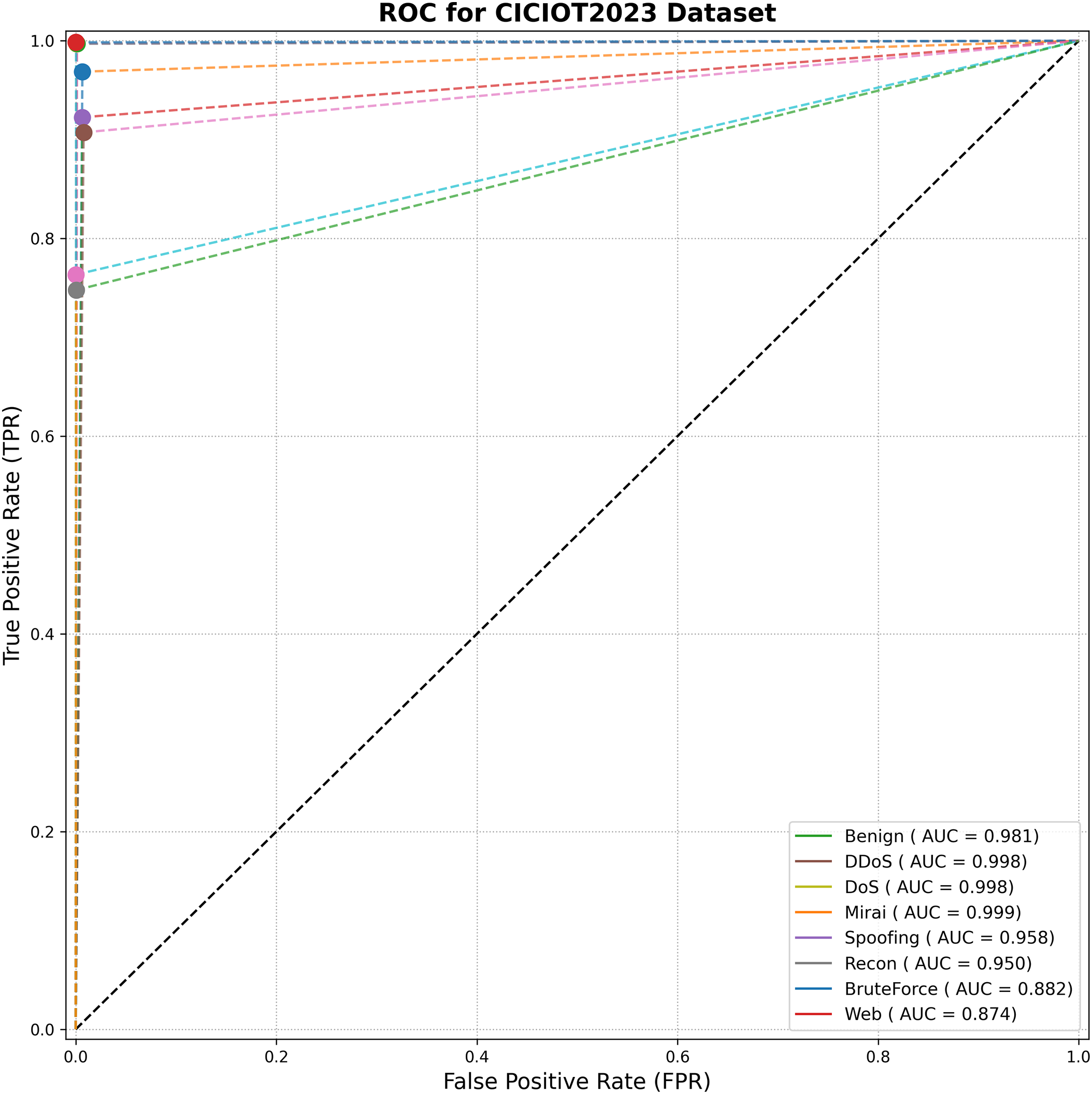

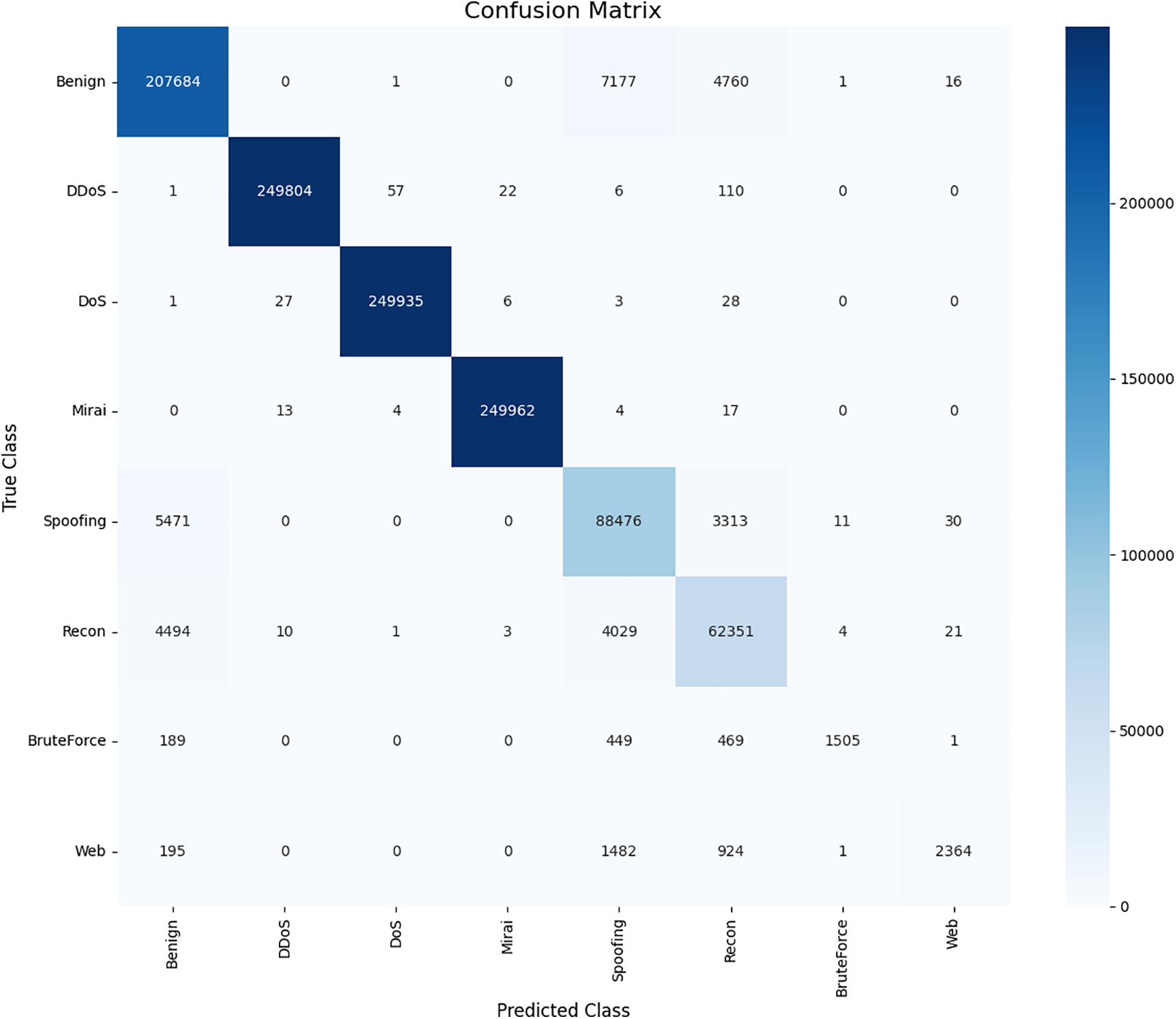

A detailed per-class analysis is crucial for this highly imbalanced dataset (Table 13, Figs. 16 and 17). The model demonstrates exceptional performance on high-volume attack classes, achieving F1-scores of 99.68% (DDoS), 99.62% (DoS), and 99.87% (Mirai). For the challenging minority classes, ‘BruteForce’ and ‘Web’, the WGAN-based augmentation strategy was essential. As quantified in Table 8, WGAN elevated the F1-Score for ‘BruteForce’ to 0.8242 (from a 0.6283 baseline) and ‘Web’ to 0.7930 (from a 0.6275 baseline), validating its efficacy. While WGAN provides a clear boost, these minority classes remain the primary area for refinement. The metrics in Table 13 identify 618 False Negatives for ‘BruteForce’ and 1252 for ‘Web’. A corresponding analysis of the confusion matrix (Fig. 17) reveals that these misclassifications are not random; they are primarily confused with ‘Spoofing’ and ‘Recon’. This indicates a high degree of feature overlap between these specific IoT attack types, posing a persistent challenge even with effective data augmentation.

Figure 16: ROC curve analysis for TransNeSt on the CICIOT2023 dataset

Figure 17: Confusion matrix for TransNeSt on the CICIOT2023 dataset

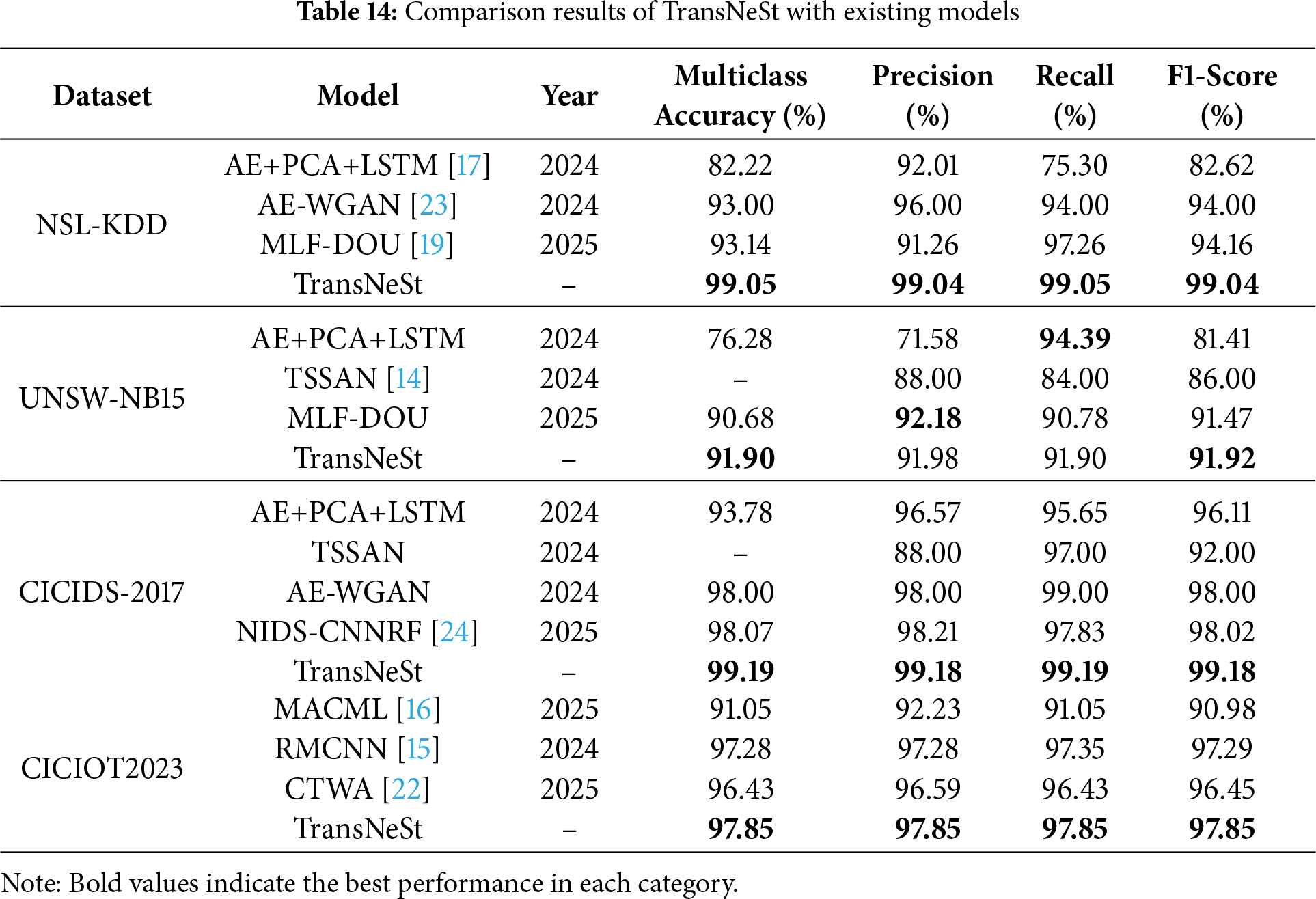

5.5 Comparison with Existing Models

To contextualize the advancement offered by our proposed model, we compare its performance against several recent NIDS models on the same four benchmark datasets. This comparison serves to contextualize the performance of the TransNeSt architecture relative to other contemporary approaches. The comprehensive results of this comparative analysis are summarized in Table 14.

On the foundational NSL-KDD benchmark, TransNeSt achieves the highest F1-Score (99.04%), demonstrating a superior balance of precision and recall compared to models like MLF-DOU [19]. This robust management of the precision-recall trade-off is also evident on the more complex UNSW-NB15 dataset, where TransNeSt again secures the top F1-Score (91.92%), surpassing other specialized models [14,19].

The model’s advantage is particularly pronounced on large-scale, modern datasets. On CICIDS-2017, TransNeSt (99.18% F1) establishes a clear margin of over 1.1 percentage points against the next-strongest competitor, NIDS-CNNRF [24]. This robust performance is confirmed on the recent CICIOT2023 IoT dataset, where our model (97.85% F1) again outperforms all contemporary methods, including the recent RMCNN [15] (97.29%) and CTWA [22] (96.45%).

In summary, the consistent outperformance of TransNeSt across these four diverse datasets against strong, contemporary models validates its innovative architectural design. The synergy between the powerful multi-scale feature representation from the ResNeSt module and the global contextual understanding from the Transformer allows our model to set a new standard for performance in intrusion detection.

This work confirms that the integration of 1D split-attention mechanisms with Transformer encoders presents a highly effective architecture for NIDS. Our key insight is that the ResNeSt block’s fine-grained feature representation serves as a more potent input for a Transformer’s global temporal analysis, directly addressing the common trade-off between multi-scale and temporal modeling.

Empirically, TransNeSt demonstrated highly effective and robust detection capabilities, achieving strong F1-Scores of 99.04% on NSL-KDD, 91.92% on UNSW-NB15, 99.18% on CIC-IDS2017, and 97.85% on CICIOT2023. These results were consistently favorable when compared to both its constituent components and existing state-of-the-art methods across all four datasets. This analysis presents an actionable takeaway: while our analysis identified TransNeSt as the most computationally intensive model tested. Its complexity remains comparable to standard hybrid architectures. This finding suggests the computational cost is a justified trade-off for achieving this high level of detection performance.

Despite these promising results, this study has limitations. The primary limitation concerns the high computational complexity of the split-attention mechanism, which may pose challenges for real-time deployment on resource-constrained edge devices. Additionally, as a deep learning-based approach, the model currently operates as a ‘black box,’ lacking intrinsic interpretability to explain the rationale behind specific classification decisions. Looking forward, we identify several key directions. The primary limitation is computational cost, which motivates model optimization. Future work will investigate advanced compression techniques, including network pruning, quantization, and knowledge distillation, to create a lightweight, deployment-ready version for resource-constrained IoT networks. A second direction is to enhance model interpretability by integrating Explainable AI (XAI) techniques, specifically SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) or Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations (LIME), to demystify its decision-making process. Finally, we will investigate the adaptation of TransNeSt for federated learning (FL), enabling collaborative, privacy-preserving training across distributed networks.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to acknowledge that this work was sponsored by the Opening Foundation of Yunnan Key Laboratory of Smart City in Cyberspace Security.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the Opening Foundation of Yunnan Key Laboratory of Smart City in Cyberspace Security (No. 202105AG070010).

Author Contributions: Study conception and design: Gan Zhu, Yongtao Yu; data collection: Gan Zhu, Xiaofan Deng, Yuanchen Dai, Zhenyuan Li; analysis and interpretation of results: Gan Zhu, Yongtao Yu; draft manuscript preparation: Gan Zhu, Xiaofan Deng,Yuanchen Dai, Zhenyuan Li. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Study data can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Aldweesh A, Derhab A, Emam AZ. Deep learning approaches for anomaly-based intrusion detection systems: a survey, taxonomy, and open issues. Knowl Based Syst. 2020;189:105124. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2019.105124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Yin C, Zhu Y, Fei J, He X. A deep learning approach for intrusion detection using recurrent neural networks. IEEE Access. 2017;5:21954–61. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2017.2762418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Roy B, Cheung H. A deep learning approach for intrusion detection in internet of things using bi-directional long short-term memory recurrent neural network. In: 2018 28th International Telecommunication Networks and Applications Conference (ITNAC). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2018. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/ATNAC.2018.8615294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Gueriani A, Kheddar H, Mazari AC, Ghanem MC. A robust cross-domain IDS using BiGRU-LSTM-attention for medical and industrial IoT security. ICT Express. 2025;8(11):8707. doi:10.1016/j.icte.2025.08.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Vaswani A, Shazeer N, Parmar N, Uszkoreit J, Jones L, Gomez AN, et al. Attention is all you need. In: Advances in neural information processing systems. Red Hook, NY, USA: Curran Associates, Inc.; 2017. 30 p. [Google Scholar]

6. Kheddar H. Transformers and large language models for efficient intrusion detection systems: a comprehensive survey. Inf Fusion. 2025;124:103347. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2025.103347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Xi C, Wang H, Wang X. A novel multi-scale network intrusion detection model with transformer. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):23239. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-74214-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Zhang H, Wu C, Zhang Z, Zhu Y, Lin H, Zhang Z, et al. Split-attention networks. In: Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2022. p. 2736–46. doi:10.1109/CVPRW56347.2022.00309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Kolukisa B, Dedeturk BK, Hacilar H, Gungor VC. An efficient network intrusion detection approach based on logistic regression model and parallel artificial bee colony algorithm. Comput Standards Interfaces. 2024;89:103808. doi:10.1016/j.csi.2023.103808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Turukmane AV, Devendiran R. M-MultiSVM: an efficient feature selection assisted network intrusion detection system using machine learning. Comput Secur. 2024;137:103587. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2023.103587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Rustam F, Aljedaani W, Elsayed MS, Jurcut AD. FAMTDS: a novel MFO-based fully automated malicious traffic detection system for multi-environment networks. Comput Netw. 2024;251:110603. doi:10.1016/j.comnet.2024.110603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Hooshmand MK, Huchaiah MD, Alzighaibi AR, Hashim H, Atlam ES, Gad I. Robust network anomaly detection using ensemble learning approach and explainable artificial intelligence (XAI). Alexandria Eng J. 2024;94:120–30. doi:10.1016/j.aej.2024.03.041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. He W, Cai X, Lai Y, Yuan X. ESVI-GaMM: a fast network intrusion detection approach based on the Bayesian gamma mixture model. Inf Sci. 2024;678:121001. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2024.121001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Xu R, Zhang Q, Zhang Y. TSSAN: time-space separable attention network for intrusion detection. IEEE Access. 2024;12:98734–49. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3429420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Liu Y, Guo F, Zhao Q, Wu C. An intrusion detection model based on a residual memory convolutional neural network with attention mechanism. J Phys Conf Series. 2024;2833(1):012009. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/2833/1/012009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Xu C, Yang J, Li P. MACML: marrying attention and convolution-based meta-learning method for few-shot IoT intrusion detection. PLoS One. 2025;20(8):e0331065. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0331065. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Thakkar A, Kikani N, Geddam R. Fusion of linear and non-linear dimensionality reduction techniques for feature reduction in LSTM-based Intrusion Detection System. Appl Soft Comput. 2024;154:111378. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2024.111378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Alsoufi MA, Siraj MM, Ghaleb FA, Al-Razgan M, Al-Asaly MS, Alfakih T, et al. Anomaly-based intrusion detection model using deep learning for IoT networks. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2024;141(1):823–45. doi:10.32604/cmes.2024.052112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Chen L, Li H, Wu P, Hu L, Chen T, Zeng N. MLF-DOU: a metric learning framework with dual one-class units for network intrusion detection. Neurocomputing. 2025;649:130754. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2025.130754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Wang J, Ge C, Li Y, Zhao H, Fu Q, Cao K, et al. A two-layer network intrusion detection method incorporating LSTM and stacking ensemble learning. Comput Mater Contin. 2025;83(3):5129–53. doi:10.32604/cmc.2025.062094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Hossain MA. Deep Q-learning intrusion detection system (DQ-IDSa novel reinforcement learning approach for adaptive and self-learning cybersecurity. ICT Express. 2025;11(5):875–80. doi:10.1016/j.icte.2025.05.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Wang H, Yang Y, Tan P. CTWA: a novel incremental deep learning-based intrusion detection method for the Internet of Things. Artif Intell Rev. 2025;58(12):1–24. doi:10.1007/s10462-025-11358-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Arafah M, Phillips I, Adnane A, Hadi W, Alauthman M, Al-Banna AK. Anomaly-based network intrusion detection using denoising autoencoder and Wasserstein GAN synthetic attacks. Appl Soft Comput. 2025;168:112455. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2024.112455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Yang K, Wang J, Zhao G, Wang X, Cong W, Yuan M, et al. NIDS-CNNRF integrating CNN and random forest for efficient network intrusion detection model. Internet of Things. 2025;32:101607. doi:10.1016/j.iot.2025.101607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. He K, Zhang X, Ren S, Sun J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In: Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2016. p. 770–778. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2016.90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Zhang B, Sennrich R. Root mean square layer normalization. In: Advances in neural information processing systems. Red Hook, NY, USA: Curran Associates, Inc.; 2019. 32 p. [Google Scholar]

27. Tavallaee M, Bagheri E, Lu W, Ghorbani AA. A detailed analysis of the KDD CUP 99 data set. In: 2009 IEEE Symposium on Computational Intelligence for Security and Defense Applications. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2009. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/CISDA.2009.5356528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Moustafa N, Slay J. UNSW-NB15: a comprehensive data set for network intrusion detection systems (UNSW-NB15 network data set). In: 2015 Military Communications and Information Systems Conference (MilCIS) 2015. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/MilCIS.2015.7348942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Panigrahi R, Borah S. A detailed analysis of CICIDS2017 dataset for designing intrusion detection systems. Int J Eng Technol. 2018;7(3.24):479–82. doi:10.14419/ijet.v7i3.24.227971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Neto EC, Dadkhah S, Ferreira R, Zohourian A, Lu R, Ghorbani AA. CICIoT2023: a real-time dataset and benchmark for large-scale attacks in IoT environment. Sensors. 2023;23(13):5941. doi:10.3390/s23135941. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Al-Qarni EA, Al-Asmari GA. Addressing imbalanced data in network intrusion detection: a review and survey. Int J Adv Comput Sci Appl. 2024;15(2):136–43. doi:10.14569/IJACSA.2024.0150215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Chawla NV, Bowyer KW, Hall LO, Kegelmeyer WP. SMOTE: synthetic minority over-sampling technique. J Artif Intell Res. 2002;16:321–57. doi:10.1613/jair.953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. He H, Bai Y, Garcia EA, Li S. ADASYN: adaptive synthetic sampling approach for imbalanced learning. In: 2008 IEEE International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IEEE World Congress on Computational Intelligence) 2008. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE. p. 1322–8. doi:10.1109/IJCNN.2008.4633969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Goodfellow IJ, Pouget-Abadie J, Mirza M, Xu B, Warde-Farley D, Ozair S, et al. Generative adversarial nets. In: Advances in neural information processing systems. arXiv:1406.2661. 2014. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1406.2661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Arjovsky M, Chintala S, Bottou L. Wasserstein generative adversarial networks. arXiv:1701.07875. 2017. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1701.07875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools