Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Encoder-Guided Latent Space Search Based on Generative Networks for Stereo Disparity Estimation in Surgical Imaging

1 School of Automation, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, Chengdu, 611731, China

2 School of the Environment, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD 4072, Australia

3 Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843, USA

4 Department of Geography, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843, USA

5 School of Artificial Intelligence, Guangzhou Huashang university, Guangzhou, 511300, China

* Corresponding Authors: Siyu Lu. Email: ; Wenfeng Zheng. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Recent Advances in Signal Processing and Computer Vision)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(3), 4037-4053. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.074901

Received 21 October 2025; Accepted 01 December 2025; Issue published 23 December 2025

Abstract

Robust stereo disparity estimation plays a critical role in minimally invasive surgery, where dynamic soft tissues, specular reflections, and data scarcity pose major challenges to traditional end-to-end deep learning and deformable model-based methods. In this paper, we propose a novel disparity estimation framework that leverages a pretrained StyleGAN generator to represent the disparity manifold of Minimally Invasive Surgery (MIS) scenes and reformulates the stereo matching task as a latent-space optimization problem. Specifically, given a stereo pair, we search for the optimal latent vector in the intermediate latent space of StyleGAN, such that the photometric reconstruction loss between the stereo images is minimized while regularizing the latent code to remain within the generator’s high-confidence region. Unlike existing encoder-based embedding methods, our approach directly exploits the geometry of the learned latent space and enforces both photometric consistency and manifold prior during inference, without the need for additional training or supervision. Extensive experiments on stereo-endoscopic videos demonstrate that our method achieves high-fidelity and robust disparity estimation across varying lighting, occlusion, and tissue dynamics, outperforming Thin Plate Spline (TPS)-based and linear representation baselines. This work bridges generative modeling and 3D perception by enabling efficient, training-free disparity recovery from pre-trained generative models with reduced inference latency.Keywords

Stereo disparity estimation is a fundamental step in 3D perception and reconstruction, with wide applications in autonomous systems, medical imaging, and robotic surgery [1–3]. In robot-assisted minimally invasive surgery (MIS), accurate 3D reconstruction of soft tissue surfaces from stereo-endoscopic video is critical for enabling safe and precise robotic navigation [4,5]. However, the stereo matching task in MIS faces several unique challenges: dynamic tissue motion, frequent occlusions, specular reflections, and limited labeled training data. These factors significantly degrade the performance of both traditional model-based approaches and data-driven deep learning methods [6,7].

Classical deformable models such as thin-plate splines (TPS) [8], B-spline surfaces [9], and triangle meshes [10] have been widely used to impose shape priorities on the disparity map, converting stereo matching into an optimization problem over a low-dimensional parameter space. However, these models are typically linear and scene-independent, making them insufficient to capture the complex, nonlinear geometric variations of soft tissues during surgery. Additionally, their performance is highly sensitive to initialization and prone to convergence failures in the presence of noise or motion blur [11,12].

Recent advances in deep learning have enabled powerful end-to-end disparity estimation networks such as GC-Net [13], PSMNet [14], and GwcNet [15]. These models learn to regress disparity directly from image pairs using large-scale annotated datasets. Nevertheless, their reliance on extensive supervision and scene-specific training limits their applicability in real-world MIS environments, where data collection and labeling are both labor-intensive and often infeasible. Moreover, these models tend to memorize training distributions and lack the ability to adapt to out-of-distribution scenes, leading to unreliable predictions in dynamic surgical contexts [16,17].

To overcome these limitations, recent studies have explored generative models, especially generative adversarial network (GAN) as tools to represent prior distributions over high-dimensional data [18]. Among them, StyleGAN [19] stands out for its ability to generate diverse, high-resolution images by mapping a latent vector from a lower-dimensional space into a richly structured output domain. Building on this, the Image2StyleGAN framework [20] introduced a method for embedding real images into the latent space of a pretrained StyleGAN through optimization, enabling precise semantic control over image attributes.

In prior work, Yang et al. [21] adapted this idea to 3D reconstruction, by training a StyleGAN generator to learn the manifold of disparity maps computed from historical MIS scenes using TPS. In that work, the generator is integrated into a classical stereo framework, and disparity estimation is performed via optimization in the generator’s latent space. However, the method only briefly outlined the latent optimization process, and did not address the mathematical properties of the latent space, regularization strategies, or its impact on reconstruction robustness.

To further advance the practical utility of generative disparity modeling in MIS, this paper investigates whether the latent space of a pretrained StyleGAN generator can support direct, encoder-guided embedding for disparity estimation. Building upon the observation that disparity maps corresponding to dynamic soft tissues form a structured and learnable manifold, we propose an encoder-assisted framework that estimates latent codes based on the relationship between left-right stereo views and an initial disparity hypothesis. Unlike prior optimization-based approaches that require iterative gradient descent during inference, our method leverages an encoder to rapidly infer latent vectors, enabling lower latency inference while maintaining the generative prior constraints.

This design is motivated by the hypothesis that the encoder can implicitly learn to adjust the latent representation in a direction that improves the photometric consistency between reconstructed and observed images. We validate this hypothesis through extensive experiments across surgical video sequences, demonstrating not only improved inference speed but also higher accuracy and robustness compared to traditional linear models and optimization-based embedding schemes. The results confirm both the expressive capacity and the embedding feasibility of the StyleGAN latent space for stereo disparity tasks, offering a promising solution to low-latency, label-efficient 3D reconstruction in dynamic clinical environments.

Previous work [20] has demonstrated the feasibility of StyleGAN latent space embedding by searching for optimal latent vectors through inversion. These efforts established the embeddability of the intermediate latent space

Given the partial invertibility of the StyleGAN generator, learning a reverse mapping from the image space back to the latent space via an encoder becomes a practical solution. Moreover, stereo image pairs and disparity maps inherently share strong structural correlations. Thus, by leveraging the VGG network’s ability to extract high-level image features, it is feasible to learn latent representations of disparity maps directly from stereo images.

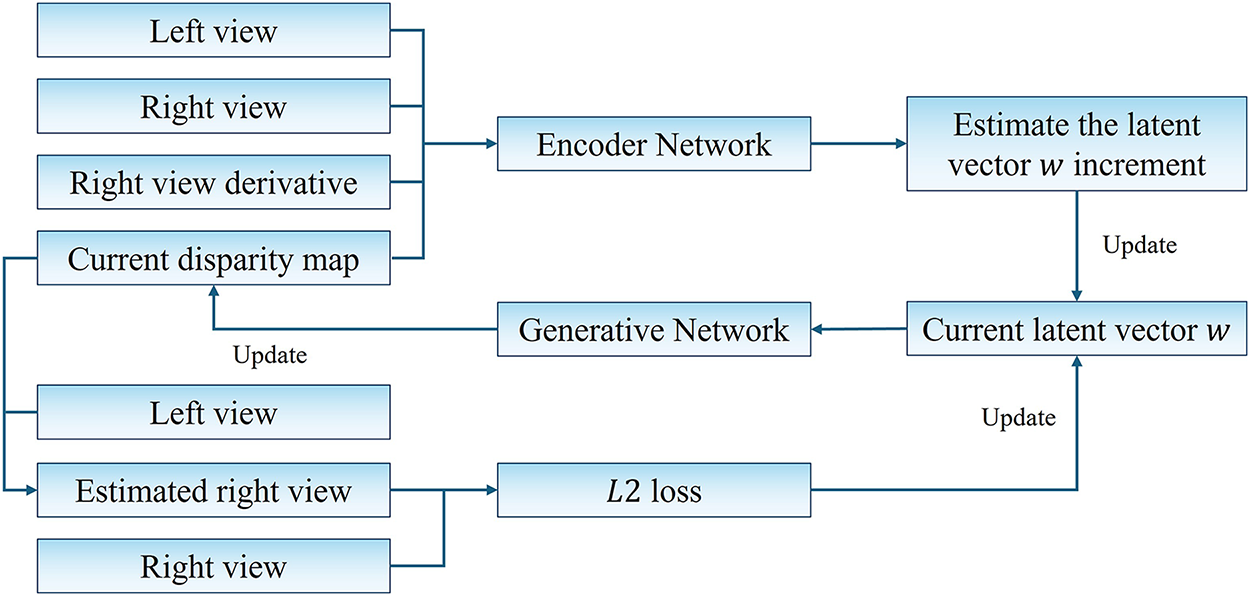

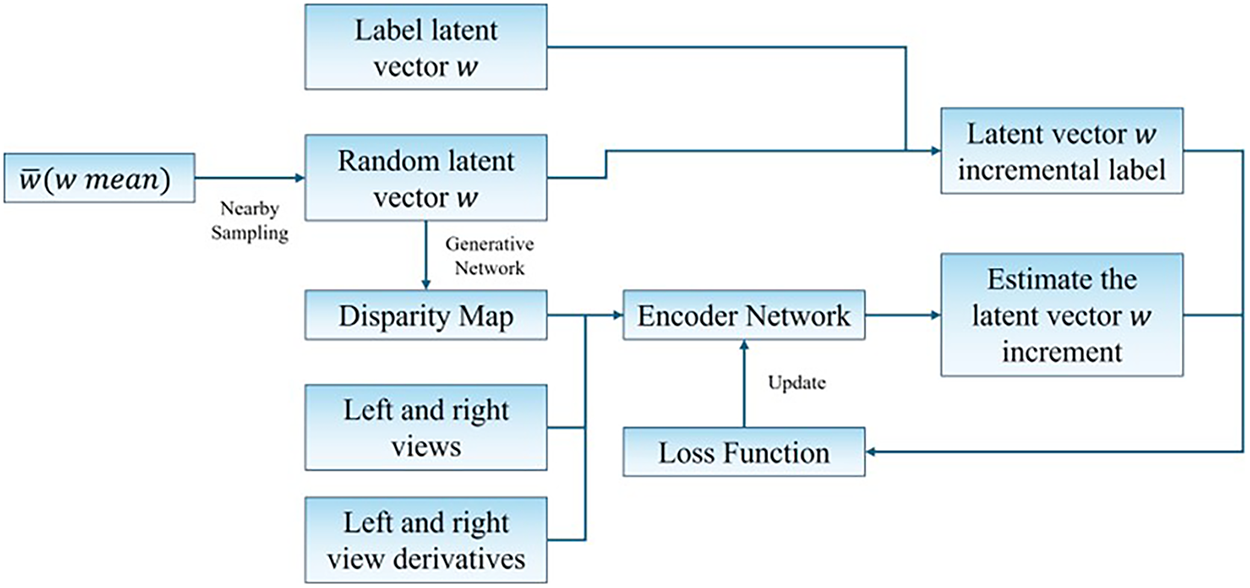

In this work, we propose an encoder-assisted latent vector prediction framework that exploits stereo image features to estimate the disparity map indirectly via latent space manipulation. The overall pipeline is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Framework of the proposed encoder-assisted StyleGAN inversion method

Specifically, the encoder is designed to extract disparity-relevant information from left–right image pairs and predict the increment to the current latent code, rather than directly regressing the entire code. This choice is motivated by the intuition that the encoder, having access to both the current disparity and the stereo context, can better estimate a residual correction that drives the latent code closer to the ground truth. The encoder extracts disparity-relevant features from stereo pairs and predicts a latent vector update, which is further refined via photometric reconstruction loss.

To compensate for the encoder’s lower precision compared to optimization-based embedding strategies, we incorporate the unsupervised photometric loss introduced in [21]. This method employs a two-stage optimization strategy. In the initial stage, the encoder-predicted latent vector increment

2.2 Structure and Training of Encoder Network

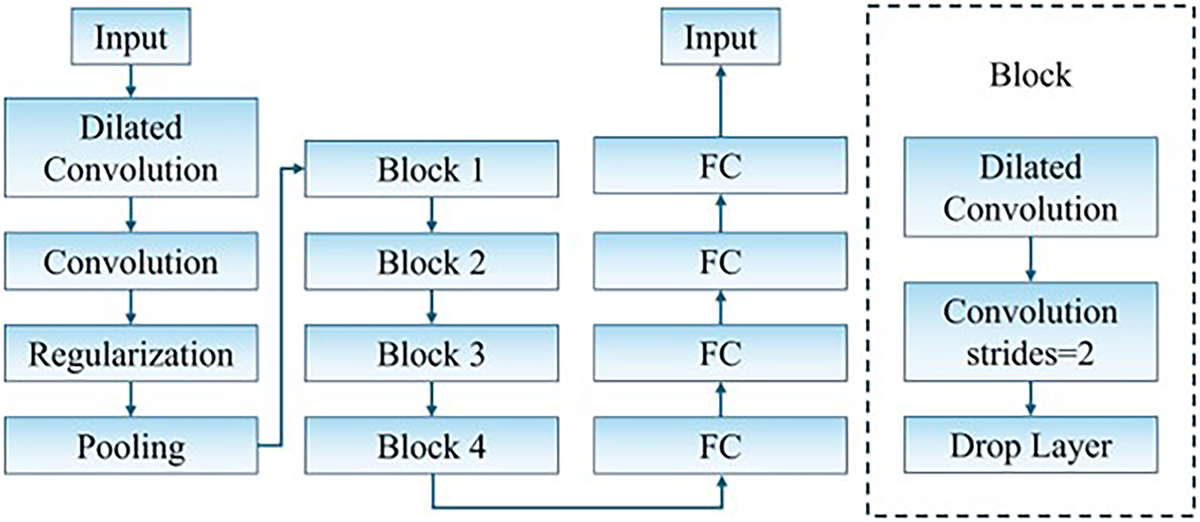

To efficiently predict latent vector increments for disparity estimation, we propose a modified VGG-based encoder architecture tailored to the characteristics of stereo endoscopic images and the StyleGAN latent space. The encoder comprises two main stages:

Stage 1 primarily handles view synthesis and error embedding. In this step, the left view and the current disparity map are linearly combined to synthesize an estimated right view. The photometric difference between this synthesized image and the true right view serves as an indicator of disparity correctness.

Stage 2 is responsible for feature encoding of the latent correction. In this stage, the estimated right view, the current disparity map, and the true right view are concatenated as input to the encoder. Through a series of convolution and downsampling operations, the encoder predicts a latent space

Figure 2: Encoder network architecture

Unlike conventional architectures that rely on max pooling, we employ stride-based downsampling to preserve the sign distribution of features. This design choice is crucial, as a portion of the StyleGAN latent vector components are negative. Max pooling tends to distort this balance by clipping negative activations, which degrades training stability and expressiveness. While stride-based downsampling may overlook some local pixel details, this loss is tolerable in our setting due to the prevalence of low-texture regions on soft tissue surfaces.

To enhance the receptive field and capture contextual information critically for smooth surface geometry, dilated convolutions are introduced in every encoding block. This allows the network to aggregate features over a broader area without increasing the number of parameters. Each dilated convolution is followed by a standard convolution layer to fuse local and global features. Given the relatively small input resolution in our dataset, the dilation rates were empirically set to

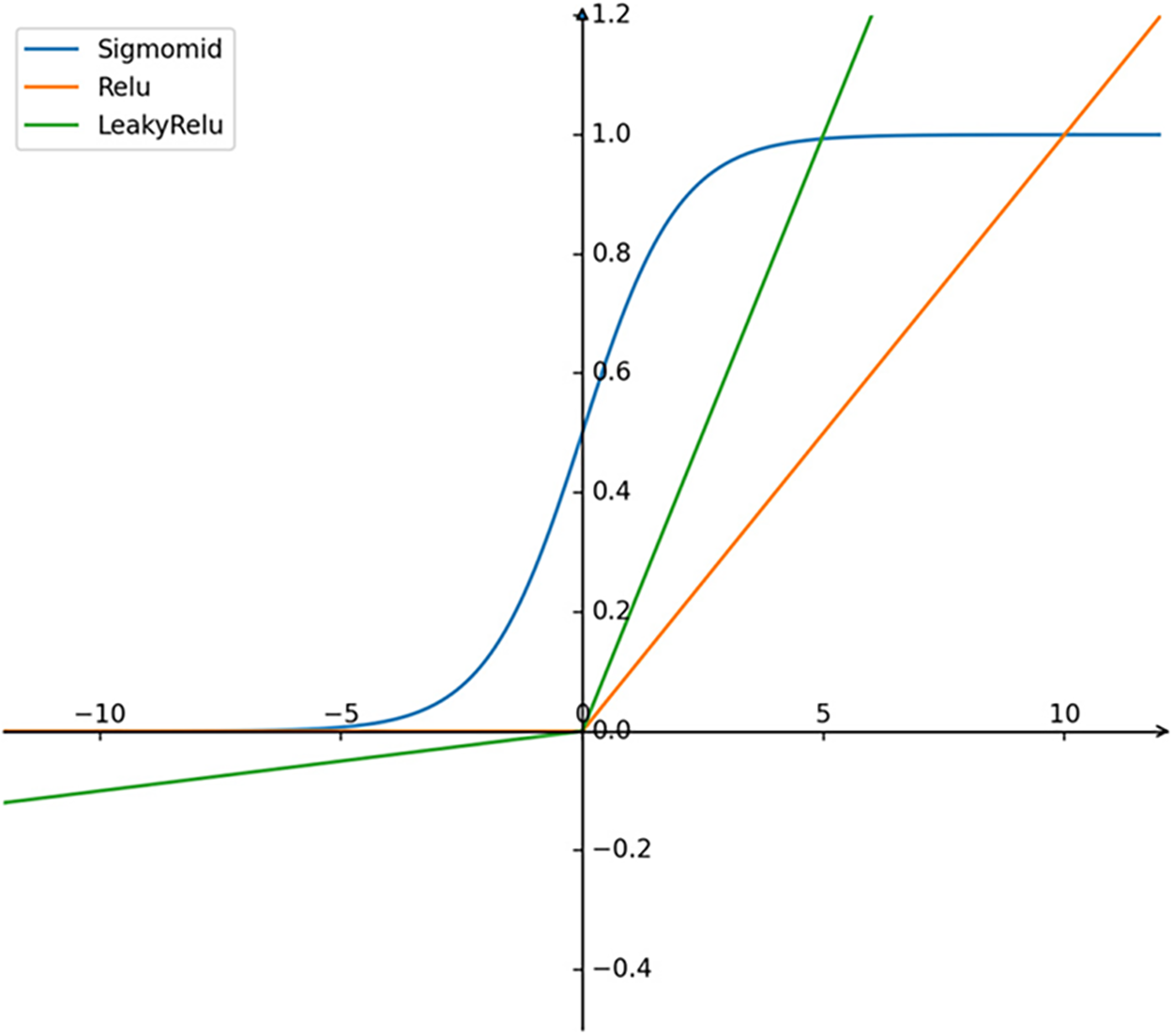

A key design consideration is the compatibility between encoder outputs and the StyleGAN latent space

Figure 3: Sigmoid, Relu and LeakyRelu activation functions

To address this, we adopt LeakyReLU as the activation function in all convolutional and intermediate fully connected layers. This choice retains negative feature values, preserving latent expressiveness. Furthermore, the final two fully connected layers of the encoder are left without any activation function, ensuring that each output dimension can represent both positive and negative values with equal probability, consistent with the latent space distribution.

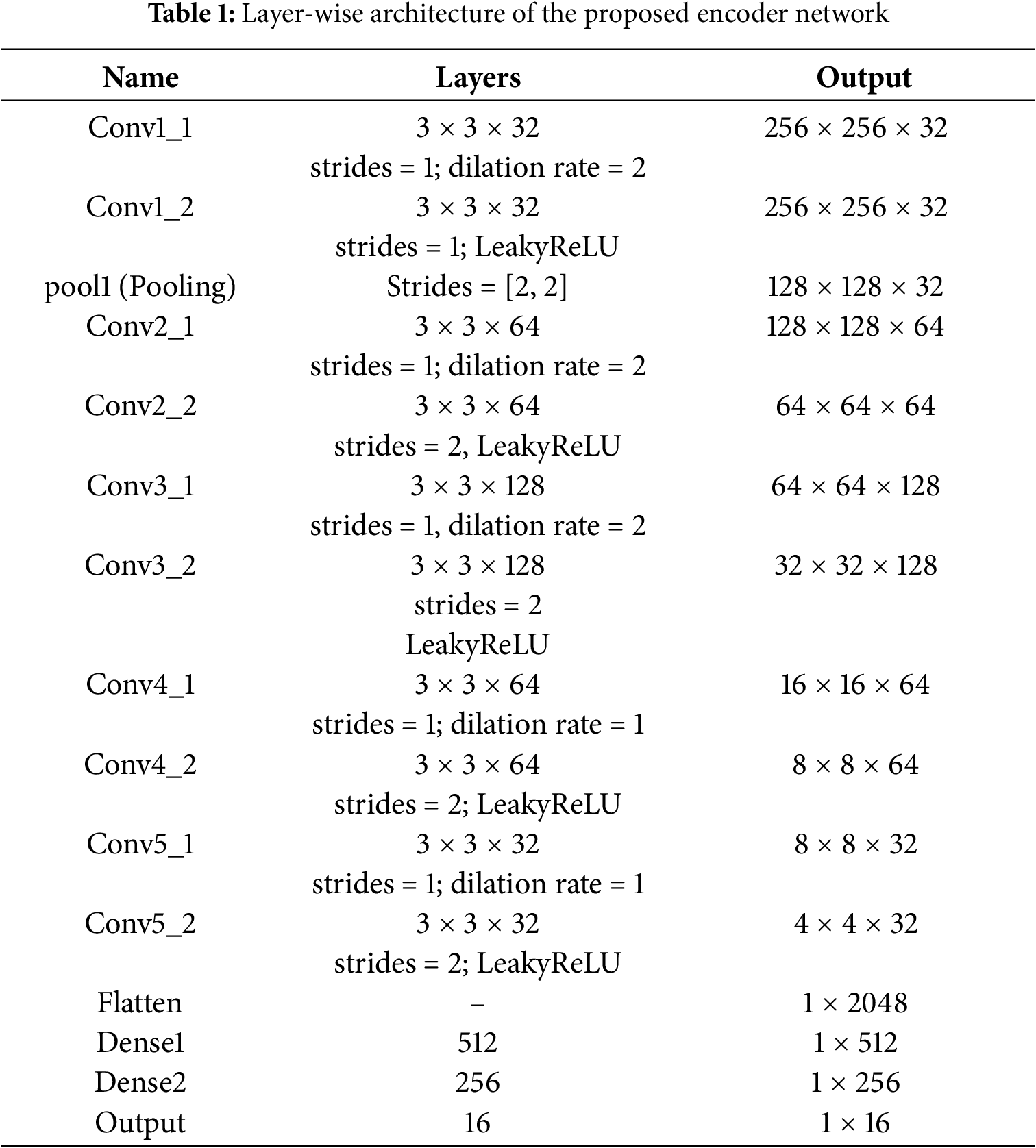

The complete encoder structure and layer specifications are provided in Table 1.

Since the encoder in this paper maps from the StyleGAN image space to the latent space

First, a reconstruction method is applied to obtain the estimated disparity maps of the 600 training frames and their corresponding latent vectors

The initialization proceeds by randomly sampling

Taking these

Figure 4: Encoder network training process

To estimate the error between the latent vector w delta label and the estimated latent vector w delta, the mean squared error is used as the loss function of the encoder network in this paper. The mathematical expression is as Eq. (2):

where N is the dimension of the latent vector, N = 16.

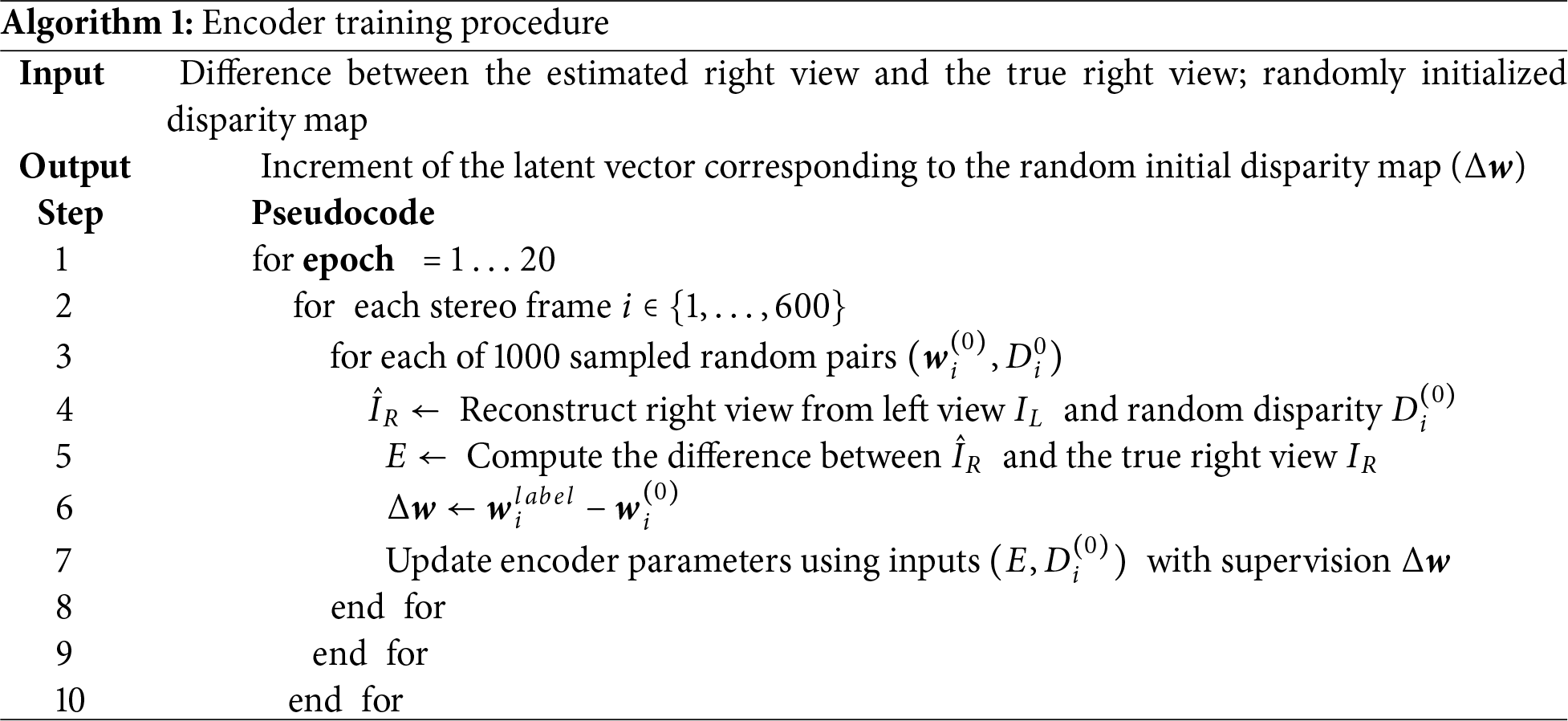

Considering that, for each frame, the latent vector label w is surrounded in the latent space by many possible random latent vectors, we train the encoder frame by frame. For every frame, we perform one complete pass over the dataset of 1000 randomly sampled latent vectors w around its label and then move to the next frame to train on its 1000 samples. We conduct 20 training rounds in total. The pseudocode of the encoder training is given below as Algorithm 1.

Where,

To verify the effectiveness and accuracy of the proposed algorithm, the following experiments were conducted:

(1) Comparison of reconstruction accuracy and convergence speed between the encoder-based StyleGAN training and reconstruction model and the trained-and-reconstructed StyleGAN model.

(2) Comparison of robustness between the encoder-based StyleGAN training and reconstruction model and the trained-and-reconstructed StyleGAN model.

These experiments primarily validated the reversibility of the StyleGAN generative network and the effectiveness of the proposed model.

We validated the proposed method on two stereoscopic endoscopic videos acquired with a da Vinci® surgical robot: (1) a silicone heart driven by a pneumatic pump [23], and (2) a real beating heart from a CABG procedure [24]. Each video contains 700 rectified stereo frames with a per-view spatial resolution of 288 × 360 pixels. The original videos can be obtained from the Hamlyn Centre website: https://hamlyn.doc.ic.ac.uk/vision/ (accessed on 10 November 2025).

For both videos, the region of interest (ROI) is the central 256 × 256 patch of the right view. Stereo pairs were rectified prior to ROI extraction. For each video, the first 600 frames are used as “historical” images to train the encoder network. The remaining 100 frames serve as the test set to evaluate the reconstruction performance of the StyleGAN-based model refined by the encoder.

The experiments were implemented in TensorFlow 1.8 and executed on a workstation with the hardware and software listed in Table 2.

Table 3 shows the hyperparameter settings of the model during training.

We used a pretrained 16-StyleGAN generator identical to the model reported in [21], which was trained on the in vivo real-heart dataset. This generator served to synthesize disparity maps and their latent codes for encoder training. For performance evaluation, results from our improved 16-StyleGAN are compared directly with this baseline trained on in vivo.

To approximate the center of the latent

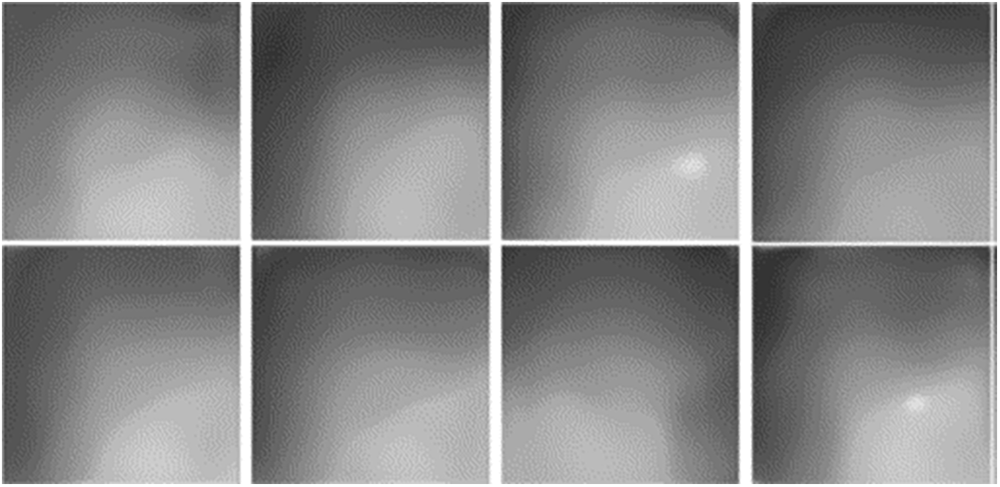

Qualitatively, the synthesized disparity maps exhibit smooth and plausible cardiac shapes, indicating that the generator has learned meaningful structural priorities (see Fig. 5). Typical artifacts are also observed. Small white speckles occasionally appear when sampled latent vectors lie far from the distribution center, leading to departures from the normal disparity range. Texture banding is visible in some images due to excessive texture content. In a few cases, mirror-symmetric disparity maps arise, reflecting the flip and mirror augmentations used during StyleGAN training. These synthesized disparity maps, together with their latent vectors, form part of the encoder inputs to learn the inverse mapping from disparity to the latent code.

Figure 5: Randomly generated disparity maps

3.3 Performance Test of the Encoder-Improved StyleGAN Model

3.3.1 Test-Set Reconstruction Loss: Convergence Speed Comparison

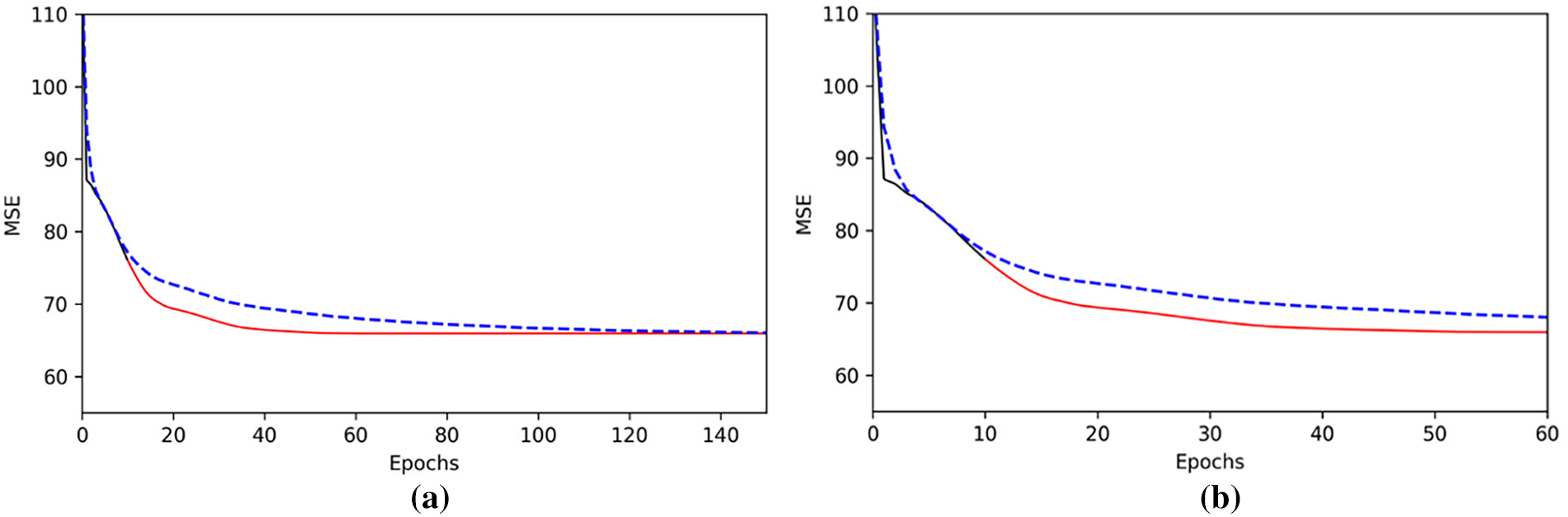

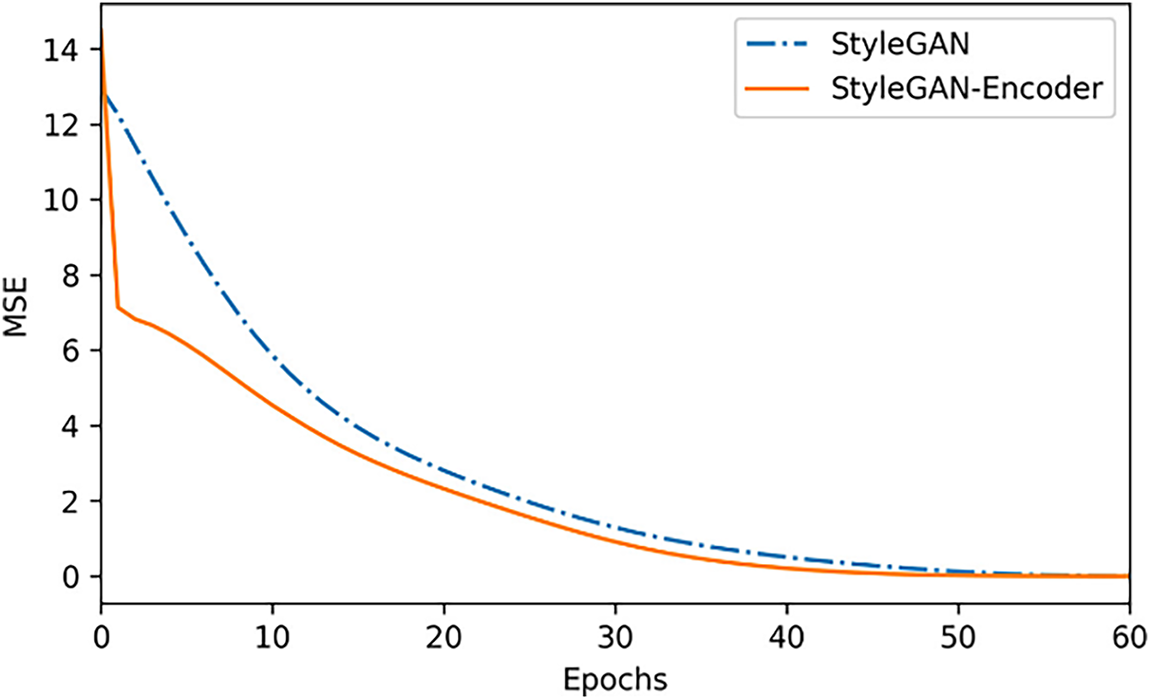

On about 100 views in the test set, with w center as the initialization, under the same StyleGAN model, the average speed of error convergence with and without adding encoders is compared. As shown in Fig. 6:

Figure 6: Average loss curves of StyleGAN and StyleGAN-Encoder on the test set images (The dotted line represents the StyleGAN model, and the solid line represents the StyleGAN model improved by the encoder): (a) Loss curves of the two methods after 150 rounds of optimization; (b) Loss curves of the two methods after the first 60 rounds of optimization

Fig. 6a shows the results after 150 reconstruction rounds for both methods. Both methods ultimately converged to the same optimal quality. It can be seen that the algorithm proposed in this study converged to the optimal value in about 40 rounds, while the StyleGAN reconstruction system in [21] required about 140 rounds to reach the optimal value. Fig. 6b is a zoomed-in view of the first 60 rounds of reconstruction, which can more closely illustrate the advantages of this solution. Here, the two methods used the same learning rate to ensure comparability of the results.

3.3.2 Test-Set Reconstruction Loss: Convergence Distance Comparison

When reconstructing, the two methods above use the optimal latent vector converged to by the two methods as a reference to calculate the distance between the current latent vector and the optimal latent code after each round of optimization. As shown in Eq. (3):

The comparison results of the StyleGAN model and the improved StyleGAN model based on the encoder network are shown in Fig. 7:

Figure 7: The distance curve from the optimal latent vector during the optimization process

On average, the StyleGAN reconstruction with the encoder converges to the optimal latent vector faster, and there is a significant drop in the area where the curve begins, which proves the effectiveness of the algorithm in this paper.

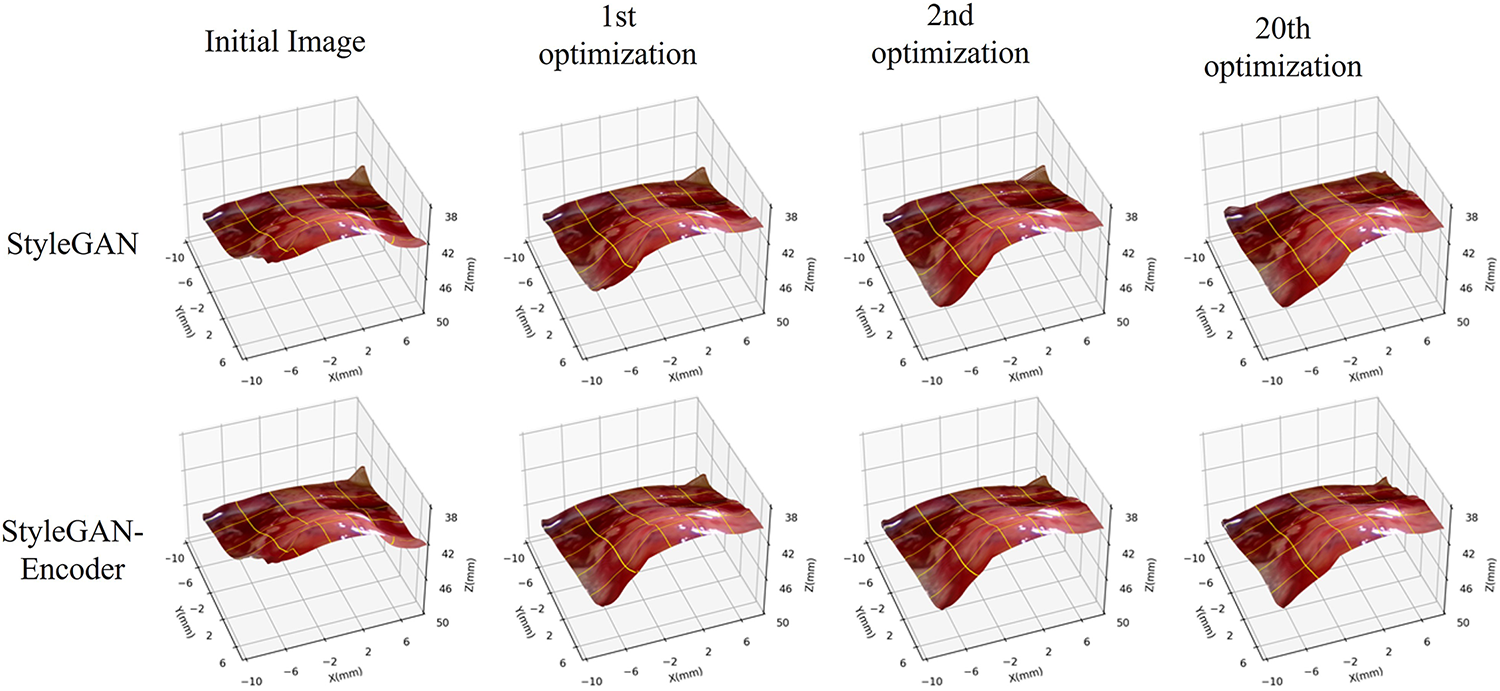

3.3.3 Qualitative Optimization

To qualitatively assess the effectiveness of the proposed method, we select the first frame of the test set and initialize the optimization at the center of the W space. We then track the reconstruction over iterations to examine the benefit of introducing the encoder. Results are shown in Fig. 8. The top row presents surfaces reconstructed by StyleGAN without the encoder, and the bottom row shows results with the encoder. The first column corresponds to the initial state (same generator and the same W-space initialization for both methods), while the subsequent columns depict the 1st, 2nd, and 20th optimization steps. Runtime evaluation indicates that the original StyleGAN optimization requires 0.65 s per frame, while the encoder-guided StyleGAN achieves 0.43 s per frame on dual RTX 2080 Ti GPUs, yielding a 34% speedup. The encoder initialization improves computational efficiency by reducing latent-space iterations.

Figure 8: Example of the optimization process on the vector dataset

Without the encoder, the prominent bulged region of the heart exhibits noticeable wrinkles and grooves at early iterations and only becomes smoother by the 20th step. In contrast, with the encoder, the surface becomes relatively smooth after just one iteration and conforms more naturally to the expected shape. Qualitatively, these observations indicate that the encoder guides the search toward a suitable latent vector much faster.

3.4 StyleGAN-Encoder Model Robustness Experiment

Beyond accuracy and convergence speed, we further examine the robustness of the encoder-augmented 16-StyleGAN. Intuitively, given the left/right views and the current disparity as inputs, the encoder should guide the generator toward a stable latent vector, enabling more reliable reconstructions under perturbations. We evaluate robustness along two axes: resistance to occlusions and resistance to motion blur. This subsection reports the occlusion study.

3.4.1 Occlusion Robustness Test

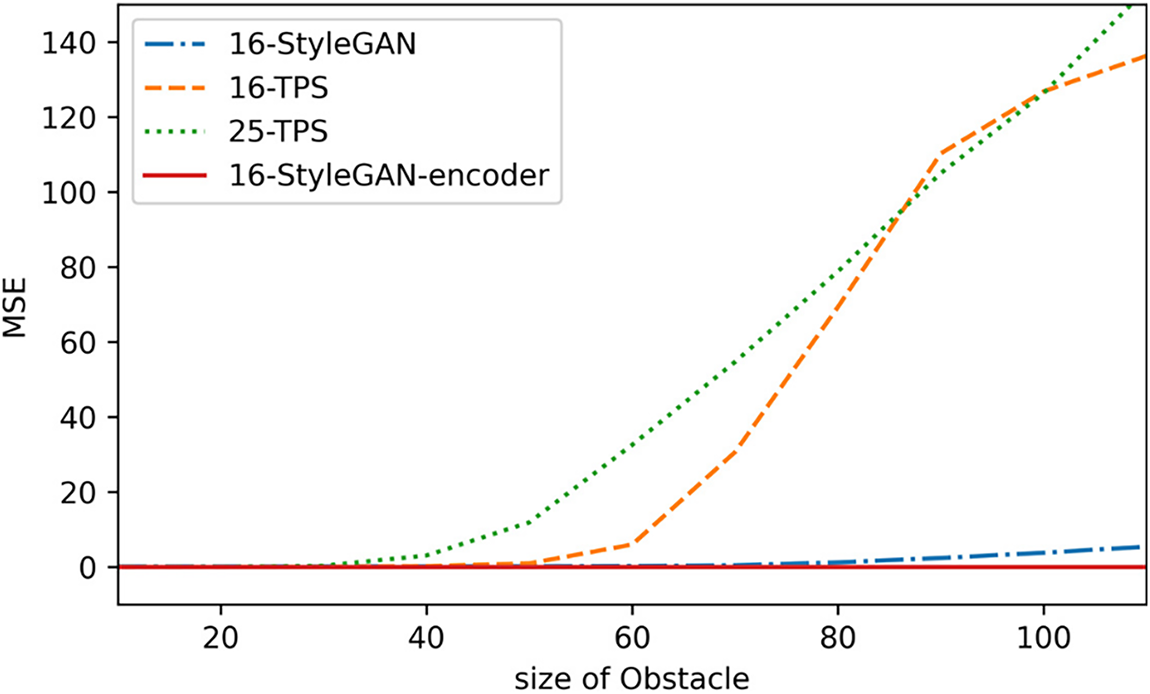

We assess robustness on the in vivo dataset [21] by injecting synthetic occluders into the right view of each test image. Specifically, square masks with edge lengths of 10, 20, …, 120 pixels are overlaid to simulate left–right inconsistency caused by occluded regions. For each occluder size, we compute the mean-squared error (MSE) between the predicted disparity map and the model’s prediction on the same image without occlusion. We evaluate four models on 100 test frames: 16-TPS, 25-TPS, 16-StyleGAN, and 16-StyleGAN-Encoder.

As shown in Fig. 9, the disparity errors of the generic TPS models rise sharply as the occluder grows. Owing to its higher degrees of deformation freedom, 25-TPS is more sensitive and already exhibits noticeable deviations under small occlusions. 16-StyleGAN is substantially more robust than TPS, keeping the error at a relatively low level. The proposed 16-StyleGAN-Encoder is the most robust: even when the occluder size reaches the point where 16-StyleGAN begins to degrade, the encoder-guided model maintains stable disparity predictions that remain close to the unoccluded results.

Figure 9: Comparison of occlusion robustness among four methods on the test set

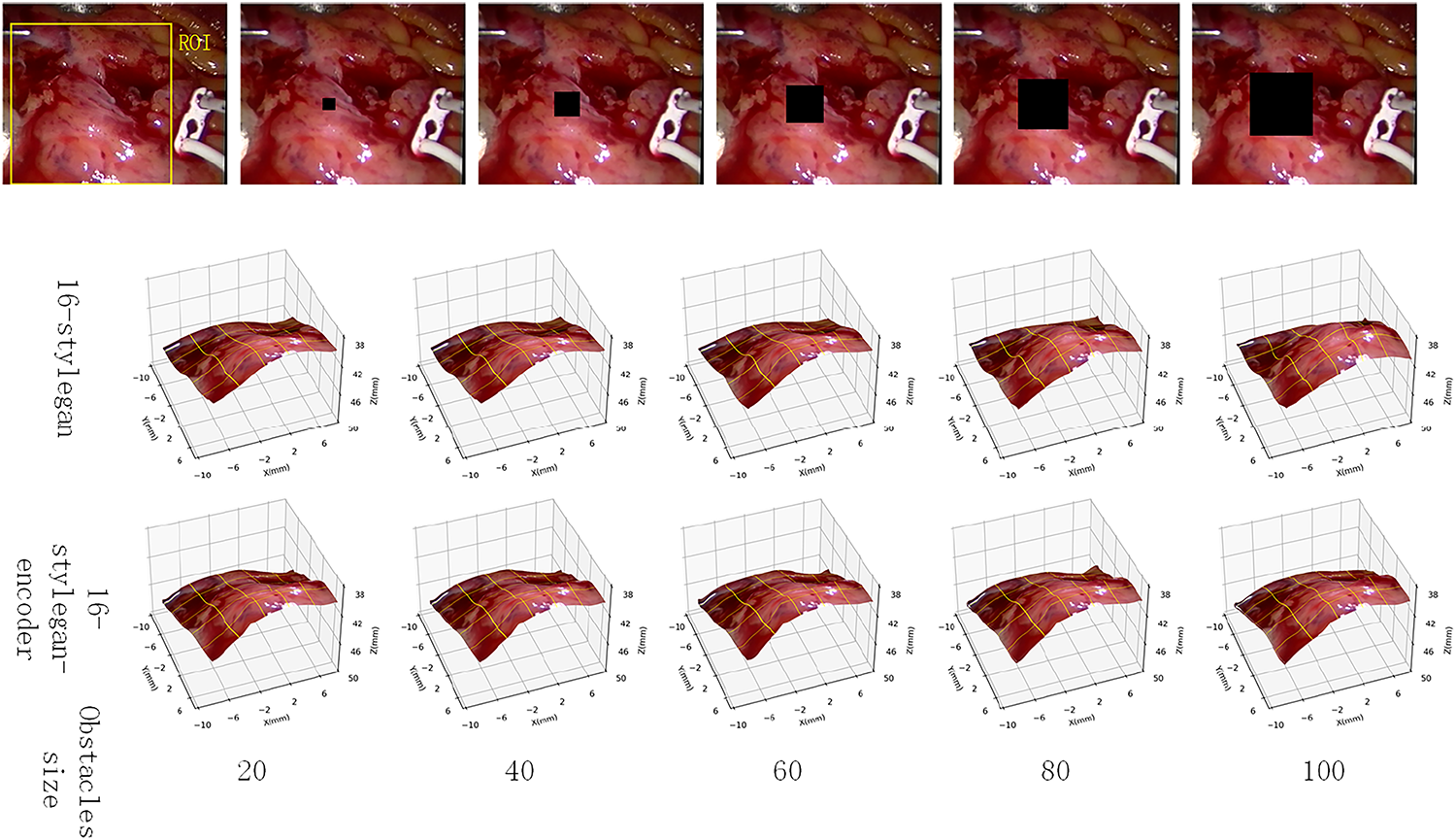

To visually illustrate the difference between the StyleGAN model and the encoder-modified StyleGAN model, this article selects a single image and presents the output of the StyleGAN model and the StyleGAN-encoder model under different obstacles. The first row of Fig. 10 shows the right view of frame 85 of the test set. The first row shows the image after adding a black occluder, with the occluder size set to 20, 40, 60, 80, and 100. The second and third rows show the 3D reconstructions of the StyleGAN model and the StyleGAN-encoder model, respectively.

Figure 10: Comparison of anti-occlusion capabilities

As can be seen, when the occluder side lengths are 20, 40, 60, and 80, the reconstruction results are similar between the two models. However, when the occluder size is increased to 100 × 100, the StyleGAN model’s heart surface exhibits a noticeable bulge, while the encoder-modified StyleGAN maintains a natural appearance.

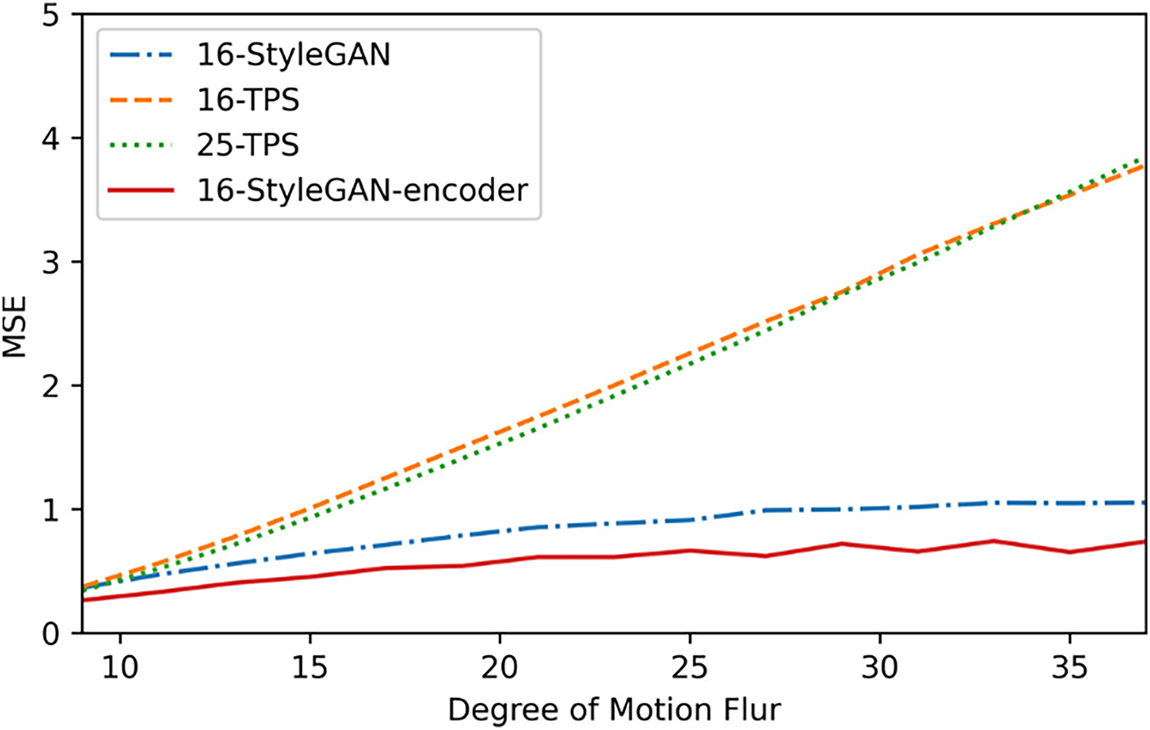

In this experiment, a 100 × 100-pixel region within the ROI of the left and right images was blurred using a 1D row-wise mean filter to stress-test the model against motion blur. Fig. 11 shows the average pixel-wise mean square error (MSE) curves of the output disparity maps of the three models for 100 test frames at different blur levels (filter lengths ranging from 9 to 37) relative to the original disparity maps.

Figure 11: Comparison of Motion Blur Stress robustness among four methods on the test set

The figure shows that the 16-StyleGAN model exhibits strong motion blur resistance, with an MSE curve significantly lower than that of the two conventional TPS models. The encoder-based StyleGAN model exhibits the best robustness, consistently maintaining the lowest loss. This demonstrates that the encoder-based improvements further enhance the robustness of the StyleGAN network.

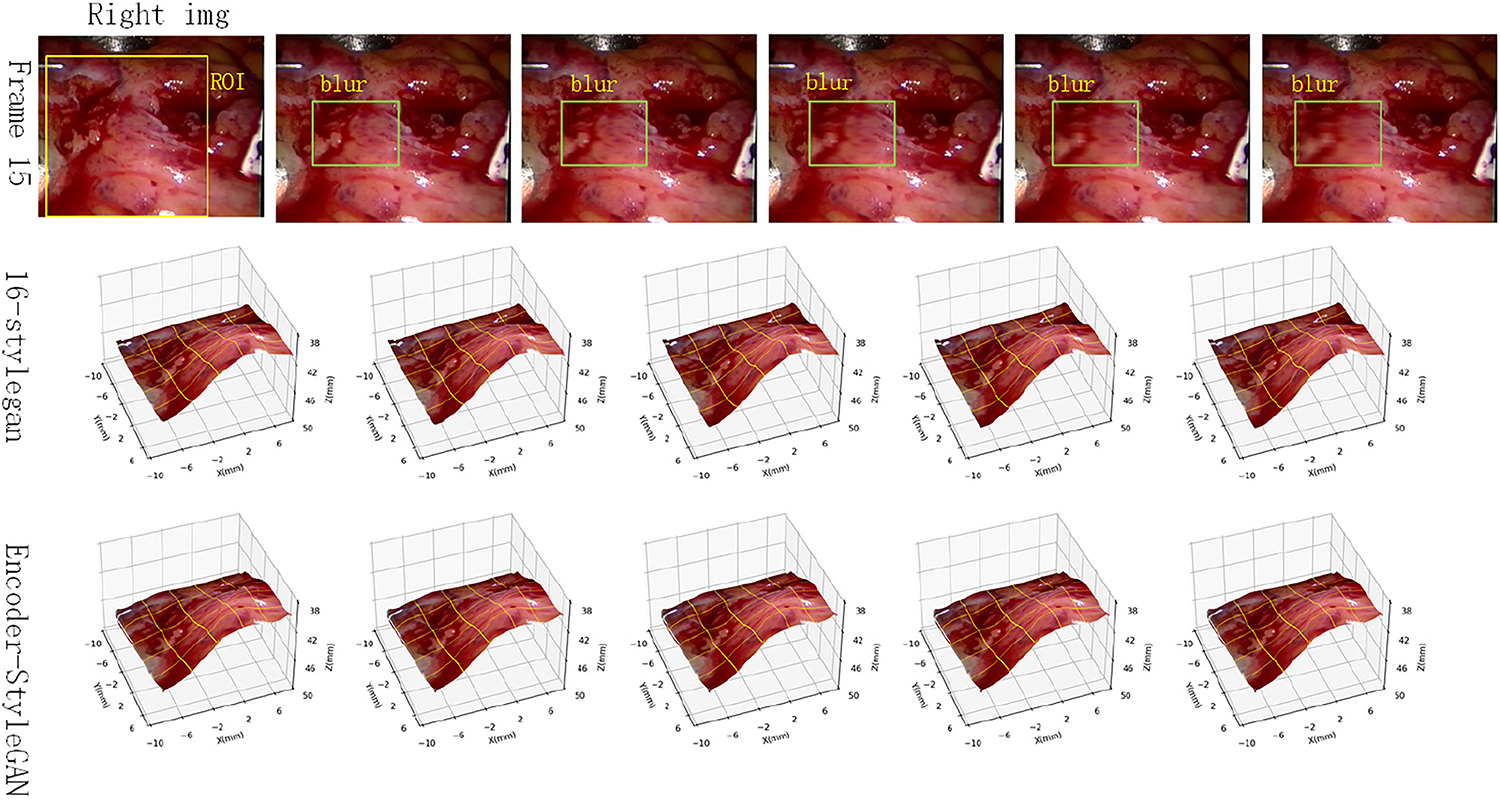

Furthermore, we selected frame 15 of the test set as a test image and compared the reconstruction results of the StyleGAN model and the encoder-modified StyleGAN model under different degrees of motion blur. The results are shown in Fig. 12.

Figure 12: Comparison of anti-motion blur capabilities

As can be seen, the StyleGAN model still produces some unnatural artifacts in some image details, such as the upper left corner of some images (the fourth and fourth images in the second row). However, the StyleGAN-encoder outputs more natural results in these images, achieving a certain degree of improvement in detail.

In summary, the StyleGAN-encoder model exhibits greater robustness and adaptability to a wider range of harsh human environments. It can also perform stable 3D reconstruction despite occlusions and motion blur artifacts. This is because the encoder receives both left and right views simultaneously, integrating more information and, to a certain extent, reducing the impact of occlusions and motion blur on reconstruction.

This study presents a disparity estimation framework that integrates a pretrained StyleGAN generator with an encoder-assisted inference scheme, aiming to address the unique challenges of stereo matching in minimally invasive surgery (MIS), such as tissue dynamics, occlusions, and imaging artifacts. Experimental results demonstrate that this approach effectively accelerates convergence during latent space optimization while preserving or even enhancing reconstruction accuracy. Unlike conventional TPS-based or linear geometric models, which struggle to represent the nonlinear deformations of soft tissue, the generative prior imposed by StyleGAN provides a flexible, data-driven representation of the disparity manifold. This representation proves particularly advantageous in modeling the complex, non-rigid geometries encountered in real-world surgical scenes.

A key insight from our experiments is that the encoder enhances robustness to occlusions, motion blur, and tissue dynamics in MIS scenes through task-specific integration of multi-source stereo data and latent space refinement. Unlike unguided iterative gradient descent in [21] or linear TPS models, our encoder incorporates left-right stereo pairs, initial disparity maps, and photometric residuals, enabling compensation for degraded regions using intact cues from the other view. This multi-modal input design, combined with latent vector increments rather than full codes, constrains updates within the StyleGAN latent space’s high-confidence region, reducing drift into invalid domains and preventing unrealistic disparities. As shown in Section 3.4, this design results in significant robustness gains. This is critical for MIS, where visual distortions are common.

However, the framework’s performance is sensitive to latent space stability. Uncertainty stemming from the limited expressiveness of the 16-dimensional latent space and deviations from the learned disparity manifold directly affects disparity quality, with out-of-distribution test cases causing artifacts like white speckles in synthesized maps. Such uncertainty can lead to misalignments or catastrophic errors, which are particularly problematic for robotic surgery. To address this issue, future research may explore integrating uncertainty estimation techniques (e.g., Monte Carlo dropout or latent-space variance metrics) to quantify and reduce ambiguity in disparity predictions.

The key innovation of this work lies in combining generative priors with explicit latent vector refinement. The encoder leverages both the stereo context and photometric residuals to guide the initial latent vector closer to the optimal solution, substantially reducing the number of optimization iterations required during inference. This design allows the method to maintain applicability without compromising accuracy. The results on test sequences, including both synthetic and real cardiac scenes, reveal that the encoder-guided approach not only reduces computational overhead but also enhances robustness to occlusions and motion blur—two common challenges in endoscopic video analysis. These robustness gains are attributed to the encoder’s ability to integrate information from both left and right views, effectively compensating for partial visual degradation.

The quantitative evaluation in this study is based on the average pixel-wise mean square error (MSE) between the reconstructed projection and the corresponding original view. Since the dataset is derived from monocular endoscopic video frames and lacks ground-truth depth or disparity labels, standard stereo metrics such as End-Point Error (EPE) and Bad Pixel Rate (BPR) cannot be applied. MSE serves as a consistent full-reference measure of image reconstruction fidelity, while qualitative visualizations further demonstrate perceptual quality. Although Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) is sometimes reported, it is mathematically equivalent to MSE and thus omitted here to avoid redundancy. The adopted metric system is therefore aligned with the data characteristics and the reconstruction objectives of this study.

A notable limitation of this work lies in the restricted diversity of publicly available stereo or monocular endoscopic datasets. The Hamlyn sequences used here represent one of the few open-access datasets with sufficiently rectified stereo pairs suitable for disparity reconstruction. Consequently, this study focuses on demonstrating methodological feasibility and robustness, rather than exhaustive generalization. The consistent reconstruction performance across different sequences suggests reliable model behavior under varying surgical conditions. Nevertheless, future research will aim to extend validation to additional domains, including thoracoscopic and laparoscopic procedures, and to incorporate domain adaptation methods for improved cross-scene generalization.

In terms of computational performance, the proposed encoder-guided StyleGAN achieves an inference time of 0.43 s per frame, compared to 0.65 s for the original StyleGAN-based latent optimization, representing a 34% speedup. This improvement results from the encoder’s ability to provide an informed initialization of the latent code, which significantly reduces the number of optimization iterations required during inference. Although the current implementation (~2.3 FPS) does not yet meet the threshold of real-time operation, the achieved 34% efficiency gain demonstrates strong potential for low-latency inference, especially when deployed on more advanced hardware or optimized GPU pipelines.

Overall, the present framework establishes a feasible and efficient pipeline for disparity estimation in minimally invasive surgery, offering both robustness and scalability for future integration into clinical and robotic applications.

In this paper, we introduced an encoder-guided latent space optimization framework for disparity estimation in minimally invasive surgical scenes. By embedding the disparity estimation task into the latent space of a pretrained StyleGAN generator, and further accelerating convergence through encoder-predicted latent vector corrections, the proposed approach achieves efficient, robust, and high-fidelity 3D reconstruction from stereo-endoscopic images. Extensive evaluations on challenging surgical videos demonstrated that our method significantly outperforms TPS-based and optimization-only approaches in terms of convergence speed, reconstruction quality, and robustness to visual degradation. These findings highlight the effectiveness of incorporating generative priors and latent space geometry into the stereo matching pipeline, particularly in scenarios where training data is limited and inference speed is critical. The framework presented in this study bridges the gap between deep generative modeling and stereo geometry, paving the way for future real-time 3D perception systems in surgical robotics.

Despite the advantages demonstrated, several limitations remain. The framework is reliant on the representational capacity of the pretrained StyleGAN generator, which in turn depends on the diversity and quality of the training dataset. Consequently, failure cases may occur when the disparity in a test frame lies far from the learned manifold, especially in cases involving novel anatomical configurations or lighting conditions. Moreover, the use of a relatively low-dimensional latent space (16D) may constrain the model’s expressiveness in capturing fine-grained disparity variations. Another limitation is that the encoder and generator are trained in isolation; end-to-end joint training may further improve compatibility between latent predictions and disparity generation.

Looking forward, several directions warrant further exploration. Future work could consider integrating higher-dimensional or hierarchical latent spaces to improve reconstruction fidelity. Additionally, incorporating domain adaptation techniques or contrastive learning objectives may enhance the generalizability of the encoder across different surgical domains. Finally, replacing StyleGAN with more recent generative architectures such as diffusion models or autoregressive transformers may yield even stronger priors for disparity representation. Overall, this work offers a promising foundation for bridging generative modeling and 3D geometry in the context of data-efficient stereo reconstruction in clinical environments.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: Support by Sichuan Science and Technology Program [2023YFSY0026, 2023YFH0004] and Guangzhou Huashang University [2024HSZD01].

Author Contributions: Conceptualization: Bo Yang and Wenfeng Zheng; methodology: Siyu Lu and Siyuan Xu; software: Siyuan Xu and Siyu Lu; validation: Guangyu Xu and Yuxin Liu; formal analysis: Siyu Lu and Junmin Lyu; investigation: Guangyu Xu and Junmin Lyu; resources: Wenfeng Zheng and Bo Yang; data curation: Siyuan Xu and Yuxin Liu; writing—original draft preparation: Guangyu Xu, Wenfeng Zheng and Siyu Lu; writing—review and editing: Guangyu Xu, Wenfeng Zheng and Siyu Lu; visualization: Siyuan Xu, Guangyu Xu and Junmin Lyu; supervision: Bo Yang; project administration: Wenfeng Zheng; funding acquisition: Wenfeng Zheng. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: We used 2 datasets, one is a silicone heart driven by a pneumatic pump from reference [23], and one is a real beating heart from a CABG procedure in reference [24].

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Wang C, Cui X, Zhao S, Guo K, Wang Y, Song Y. The application of deep learning in stereo matching and disparity estimation: a bibliometric review. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;238:122006. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2023.122006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Psychogyios D, Mazomenos E, Vasconcelos F, Stoyanov D. MSDESIS: multitask stereo disparity estimation and surgical instrument segmentation. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2022;41(11):3218–30. doi:10.1109/TMI.2022.3181229. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Luo H, Wang C, Duan X, Liu H, Wang P, Hu Q, et al. Unsupervised learning of depth estimation from imperfect rectified stereo laparoscopic images. Comput Biol Med. 2022;140:105109. doi:10.1016/j.compbiomed.2021.105109. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Tian J, Zhou Y, Chen X, AlQahtani SA, Zheng W, Chen H, et al. A novel self-supervised learning network for binocular disparity estimation. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2025;142(1):209–29. doi:10.32604/cmes.2024.057032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Tian J, Ma B, Lu S, Yang B, Liu S, Yin Z. Three-dimensional point cloud reconstruction method of cardiac soft tissue based on binocular endoscopic images. Electronics. 2023;12(18):3799. doi:10.3390/electronics12183799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Wu R, Liang P, Liu Y, Huang Y, Li W, Chang Q. Laparoscopic stereo matching using 3-Dimensional Fourier transform with full multi-scale features. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2025;139:109654. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2024.109654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Zampokas G, Peleka G, Tsiolis K, Topalidou-Kyniazopoulou A, Mariolis I, Tzovaras D. Real-time stereo reconstruction of intraoperative scene and registration to preoperative 3D models for augmenting surgeons' view during RAMIS. Med Phys. 2022;49(10):6517–26. doi:10.1002/mp.15830. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Yang B, Xu S, Chen H, Zheng W, Liu C. Reconstruct dynamic soft-tissue with stereo endoscope based on a single-layer network. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2022;31:5828–40. doi:10.1109/tip.2022.3202367. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Huang Y, Da FP. Three-dimensional face point cloud hole-filling algorithm based on binocular stereo matching and a B-spline. Front Inf Technol Electron Eng. 2022;23(3):398–409. doi:10.1631/fitee.2000508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Liu J, Pu M, Wang G, Chen D, Jia T. Binocular active stereo matching based on multi-scale random forest. In: Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 13th International Conference on CYBER Technology in Automation, Control, and Intelligent Systems (CYBER); 2023 Jul 11–14; Qinhuangdao, China. p. 1155–60. doi:10.1109/cyber59472.2023.10256508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Scheikl PM, Tagliabue E, Gyenes B, Wagner M, Dall’Alba D, Fiorini P, et al. Sim-to-real transfer for visual reinforcement learning of deformable object manipulation for robot-assisted surgery. IEEE Robot Autom Lett. 2023;8(2):560–7. doi:10.1109/lra.2022.3227873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Wang Y, Long Y, Fan SH, Dou Q. Neural rendering for stereo 3D reconstruction of deformable tissues in robotic surgery. In: Medical image computing and computer assisted intervention—MICCAI 2022. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature; 2022. p. 431–41. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-16449-1_41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Kendall A, Martirosyan H, Dasgupta S, Henry P, Kennedy R, Bachrach A, et al. End-to-end learning of geometry and context for deep stereo regression. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2017 Oct 22–29; Venice, Italy. p. 66–75. doi:10.1109/ICCV.2017.17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Chang JR, Chen YS. Pyramid stereo matching network. In: Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2018 Jun 18–23; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. p. 5410–8. doi:10.1109/cvpr.2018.00567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Guo X, Yang K, Yang W, Wang X, Li H. Group-wise correlation stereo network. In: Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2019 Jun 15–20; Long Beach, CA, USA. p. 3268–77. doi:10.1109/cvpr.2019.00339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Rivas-Blanco I, Perez-Del-Pulgar CJ, Garcia-Morales I, Munoz VF. A review on deep learning in minimally invasive surgery. IEEE Access. 2021;9:48658–78. doi:10.1109/access.2021.3068852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Caballero D, Sánchez-Margallo JA, Pérez-Salazar MJ, Sánchez-Margallo FM. Applications of artificial intelligence in minimally invasive surgery training: a scoping review. Surgeries. 2025;6(1):7. doi:10.3390/surgeries6010007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Goodfellow I, Pouget-Abadie J, Mirza M, Xu B, Warde-Farley D, Ozair S, et al. Generative adversarial networks. Commun ACM. 2020;63(11):139–44. doi:10.1145/3422622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Bermano AH, Gal R, Alaluf Y, Mokady R, Nitzan Y, Tov O, et al. State-of-the-art in the architecture, methods and applications of StyleGAN. Comput Graph Forum. 2022;41(2):591–611. doi:10.1111/cgf.14503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Abdal R, Qin Y, Wonka P. Image2StyleGAN: how to embed images into the StyleGAN latent space?. In: Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2019 Oct 27–Nov 2; Seoul, Republic of Korea. p. 4431–40. doi:10.1109/iccv.2019.00453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Yang B, Xu S, Yin L, Liu C, Zheng W. Disparity estimation of stereo-endoscopic images using deep generative network. ICT Express. 2025;11(1):74–9. doi:10.1016/j.icte.2024.09.017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Gatys LA, Ecker AS, Bethge M. Texture synthesis using convolutional neural networks. In: Proceedings of the 29th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems; 2015 Dec 7–12; Montreal, QC, Canada. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press. p. 262–70. [Google Scholar]

23. Stoyanov D, Scarzanella MV, Pratt P, Yang GZ. Real-time stereo reconstruction in robotically assisted minimally invasive surgery. In: Medical image computing and computer-assisted intervention—MICCAI 2010. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2010. p. 275–82. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-15705-9_34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Stoyanov D, Mylonas GP, Deligianni F, Darzi A, Yang GZ. Soft-tissue motion tracking and structure estimation for robotic assisted MIS procedures. In: Medical image computing and computer-assisted intervention—MICCAI 2005. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2005. p. 139–46. doi:10.1007/11566489_18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools