Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Cognitive NFIDC-FRBFNN Control Architecture for Robust Path Tracking of Mobile Service Robots in Hospital Settings

1 School of Electrical and Electronic Engineering, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Nibong Tebal, 14300, Penang, Malaysia

2 Biomedical Engineering Department, University of Technology, Baghdad, 10066, Iraq

3 Control and Systems Engineering Department, University of Technology, Baghdad, 10066, Iraq

* Corresponding Author: Nur Syazreen Ahmad. Email:

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2026, 146(1), 32 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.071837

Received 13 August 2025; Accepted 10 November 2025; Issue published 29 January 2026

Abstract

Mobile service robots (MSRs) in hospital environments require precise and robust trajectory tracking to ensure reliable operation under dynamic conditions, including model uncertainties and external disturbances. This study presents a cognitive control strategy that integrates a Numerical Feedforward Inverse Dynamic Controller (NFIDC) with a Feedback Radial Basis Function Neural Network (FRBFNN). The robot’s mechanical structure was designed in SolidWorks 2022 SP2.0 and validated under operational loads using finite element analysis in ANSYS 2022 R1. The NFIDC-FRBFNN framework merges proactive inverse dynamic compensation with adaptive neural learning to achieve smooth torque responses and accurate motion control. A two-stage simulation evaluation was conducted. In the first stage, the controller was tested in a simulated hospital environment under both ideal and non-ideal conditions. In the second, it was benchmarked against four established controllers - Neural Network Model Reference Adaptive (NNMRA), Z-number Fuzzy Logic (Z-FL), Adaptive Dynamic Controller (ADC), and Fuzzy Logic-PID (FL-PID)—using circular and lemniscate trajectories. Across ten runs, the proposed controller achieved the lowest tracking errors under all conditions. Under ideal conditions, it achieved average improvements of 55.24%, 75.75%, and 55.20% in integral absolute error (IAE), integral squared error (ISE), and mean absolute error (MAE), respectively, with coefficient of variation (CV) reductions above 55%. Under non-ideal conditions, average improvements exceeded 64% in IAE, 77% in ISE, and 66% in MAE, while maintaining CV reductions above 57%. These results confirm that the NFIDC-FRBFNN controller offers superior accuracy, robustness, and consistency for real-time path tracking in healthcare robotics.Keywords

Mobile Service Robots (MSRs) are autonomous systems designed to perform diverse tasks and navigate complex environments with minimal human intervention. MSRs have gained significant attention due to their broad applicability in various domains, including healthcare, environmental monitoring, virtual environments, and search-and-rescue operations [1,2]. They offer significant advantages in performing repetitive tasks, operating in hazardous conditions, and providing continuous service without fatigue, making them highly suitable for dynamic environments such as hospitals [3].

In hospital settings, trajectory tracking accuracy of MSRs is particularly critical, as navigation errors can lead to operational inefficiencies or even pose safety risks [4]. Reliable trajectory tracking is challenging due to inherent model uncertainties, such as variations in robot payload, sensor inaccuracies, and unpredictable external disturbances encountered in real-world scenarios [5,6]. Therefore, developing robust control systems that ensure precise path-following performance despite these uncertainties is a central research goal.

Over the past decades, a variety of control strategies have been developed to address the trajectory tracking problem of nonholonomic mobile robots operating under diverse and uncertain conditions. These include model predictive control [7], sliding mode control [8], and backstepping control [9]. For differential-wheeled mobile robots, Adaptive Dynamic Controllers (ADCs) have been proposed to achieve online parameter adaptation using Lyapunov-based stability analysis combined with

Further research has explored neural network-based control strategies due to their adaptive and data-driven capabilities [13,14]. For example, neural-backstepping adaptive controllers can dynamically respond to real-time variations, enhancing tracking performance in uncertain environments [15]. However, such controllers typically demand high computational power and significant training data, restricting their real-time applicability. Hybrid techniques, combining fuzzy logic with traditional PID controllers, have also been explored [16,17]. While offering adaptive gains and flexibility, these approaches suffer from empirical tuning difficulties and stability concerns under nonlinear dynamics and variable operating conditions.

Recent efforts, such as the Z-Number Fuzzy Logic (Z-FL) controller [18], Back-Stepping Fuzzy Sliding Mode Control (BFSMC) [19], and fractional-order PID controllers optimized using metaheuristic algorithms [20], have attempted to improve tracking accuracy and adaptability under nonlinear and uncertain conditions. While these approaches offer flexibility and enhanced performance in structured settings, they also introduce notable drawbacks. Metaheuristic-based optimization, for instance, often involves high computational complexity and extended tuning time, especially when searching large parameter spaces. More critically, most of these optimization techniques are performed offline, resulting in fixed controller parameters during runtime [21]. This limits the controller’s adaptability to sudden model changes, payload variations, or external disturbances-conditions that are common in real-world environments such as hospitals. Consequently, although the initial tuning may produce favorable results under nominal conditions, the inability to adjust dynamically reduces robustness and may lead to degraded performance in uncertain or dynamic scenarios. Furthermore, the success of metaheuristic approaches heavily depends on the quality of the fitness function and parameter initialization, making them less reliable without extensive empirical tuning and expert intervention [22].

The study in [23] proposes a learning-based control framework for autonomous vehicles that integrates an adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System with a Linear Matrix Inequality approach. However, the method shows limited flexibility and dynamic handling capability. In [24], a hybrid predictive control strategy combining a non-singleton type-3 fuzzy system with a Boltzmann model predictive controller is developed to enhance trajectory tracking along chaotic reference paths. Nevertheless, the approach relies on over-idealized assumptions, involves high computational complexity, and depends on manually selected parameters, which restrict its scalability and compromise stability.

To overcome these issues, the present study introduces an innovative cognitive control architecture combining Numerical Feedforward Inverse Dynamic Control (NFIDC) and Feedback Radial Basis Function Neural Networks (FRBFNN). FRBFNNs have been adopted in this work to provide smooth and optimal control action values to the two wheels of the MSR. They are particularly well-suited for trajectory tracking and control applications due to their simplified structure comprising an input layer, a single hidden layer with Gaussian radial basis functions, and an output layer. This configuration allows FRBFNNs to model localized input-output relationships effectively while remaining computationally efficient and interpretable, in contrast to the opaque nature of deep multilayer neural networks [25,26]. Their fast response time and high accuracy make them ideal for real-time applications in dynamic environments [27,28].

While standalone FRBFNN have demonstrated effective approximation and adaptive learning for nonlinear systems, they often fall short in capturing full system dynamics under real-time constraints. Therefore, in this work, the FRBFNN is integrated with the NFIDC to form a hybrid control system. The NFIDC provides proactive control by computing inverse dynamics through numerical methods, ensuring that the control inputs directly account for the system’s physical dynamics. This integration enables the controller to achieve higher accuracy and responsiveness in trajectory tracking, even in the presence of modeling uncertainties and external disturbances. The novelty of the proposed NFIDC-FRBFNN hybrid lies in its complementary design: NFIDC generates accurate feedforward torque to improve transient response and minimize steady-state error, while FRBFNN adaptively compensates for unmodeled dynamics and uncertainties with low computational cost. Unlike fuzzy-PID and other rule-based hybrids that depend on static parameters and lack self-learning capabilities, this framework achieves a unique balance of precision, adaptability, and efficiency, which underpins its superior performance in energy-efficient trajectory tracking.

The proposed NFIDC-FRBFNN controller is developed with the practical motivation of enhancing the trajectory tracking performance of MSRs in hospital environments. While applicable to general settings, the hospital context highlights unique challenges such as fluctuating payloads from transporting medical supplies, equipment, or patient-related items, as well as frequent external disturbances that can affect robot stability and accuracy. The NFIDC-FRBFNN framework is designed to minimize positional and orientation errors while adapting robustly to these variations and uncertainties. To thoroughly validate its effectiveness, a two-stage simulation experiment is conducted. In the first stage, the controller’s performance is assessed within a simulated hospital ward under both ideal and non-ideal conditions, explicitly modeling uncertainties (e.g., dynamic variations in the robot’s mass parameter) and external disturbances. In the second stage, the controller is benchmarked against established methods from the literature, namely NNMRA, Z-FL, ADC, and Fuzzy Logic-PID (FL-PID), using circular and lemniscate reference trajectories [10–12,18]. This work differs from the aforementioned methods as follows:

• ADC: While ADC ensures stability through Lyapunov-based adaptation, it incurs higher computational cost per update. The proposed NFIDC-FRBFNN achieves comparable stability guarantees with significantly lower adaptation overhead.

• FL-PID: Fuzzy-PID tuning enhances flexibility compared to fixed PID by adjusting

• Z-FL: The Z-FL controller employs fixed membership functions and a predefined rule base, resulting in deterministic yet non-adaptive behavior. While effective under ideal conditions, its performance deteriorates under uncertainties. The proposed hybrid introduces adaptive nonlinear approximation that sustains accurate tracking even in uncertain and disturbed environments.

• NNMRA: Neural MRAC schemes require extensive training and careful model tuning, which increase complexity and risk of overfitting. The NFIDC-FRBFNN eliminates such dependencies through fast adaptive learning and reduced computational demand.

The results, averaged across 10 runs, show that the proposed controller consistently achieved the lowest tracking errors under all conditions. Under ideal conditions, it achieved average improvements of 55.24%, 75.75%, and 55.20% in integral absolute error (IAE), integral squared error (ISE), and mean absolute error (MAE), respectively, with corresponding coefficient of variation (CV) reductions of 64.01%, 61.58%, and 55.63%. Under non-ideal conditions, which included both model uncertainty and external disturbances, comparable improvements were maintained—exceeding 64% in IAE, 77% in ISE, and 66% in MAE, while sustaining average CV reductions above 58%. These results confirm that the NFIDC–FRBFNN controller provides superior tracking accuracy, robustness, and consistency compared to conventional adaptive and fuzzy-based approaches, demonstrating its strong potential for precise and reliable real-time path tracking in healthcare robotics applications.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents the design of the MSR using SolidWorks, the system modeling, and the proposed cognitive control strategy; Section 3 presents and discusses the simulation results; and Section 4 concludes the paper with a summary of key findings.

2.1.1 Base Structure of the MSR

Non-holonomic wheeled mobile robots have fewer controllable degrees of freedom (DoF) than their total DoF, limiting motion but providing advantages in structured environments such as hospitals. This configuration ensures stable, predictable movement suitable for navigating narrow corridors, avoiding obstacles, and following predefined paths with high precision.

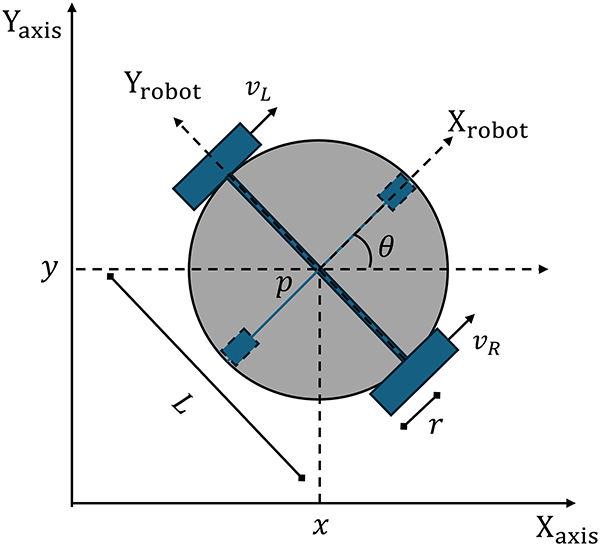

The MSR developed in this work adopts a non-holonomic differential drive design, as shown in Fig. 1, with parameters listed in Table 1. The drive system consists of two large wheels on either side of the base, each powered by an independent analog direct current (DC) motor for propulsion and steering. Two smaller caster wheels at the front and rear provide passive stability and allow free rotation during turns without contributing to motion. The robot’s center of mass is located at point

Figure 1: Schematic of the non-holonomic MSR

2.1.2 MSR Design Using SolidWorks

Design and Modeling Using SolidWorks

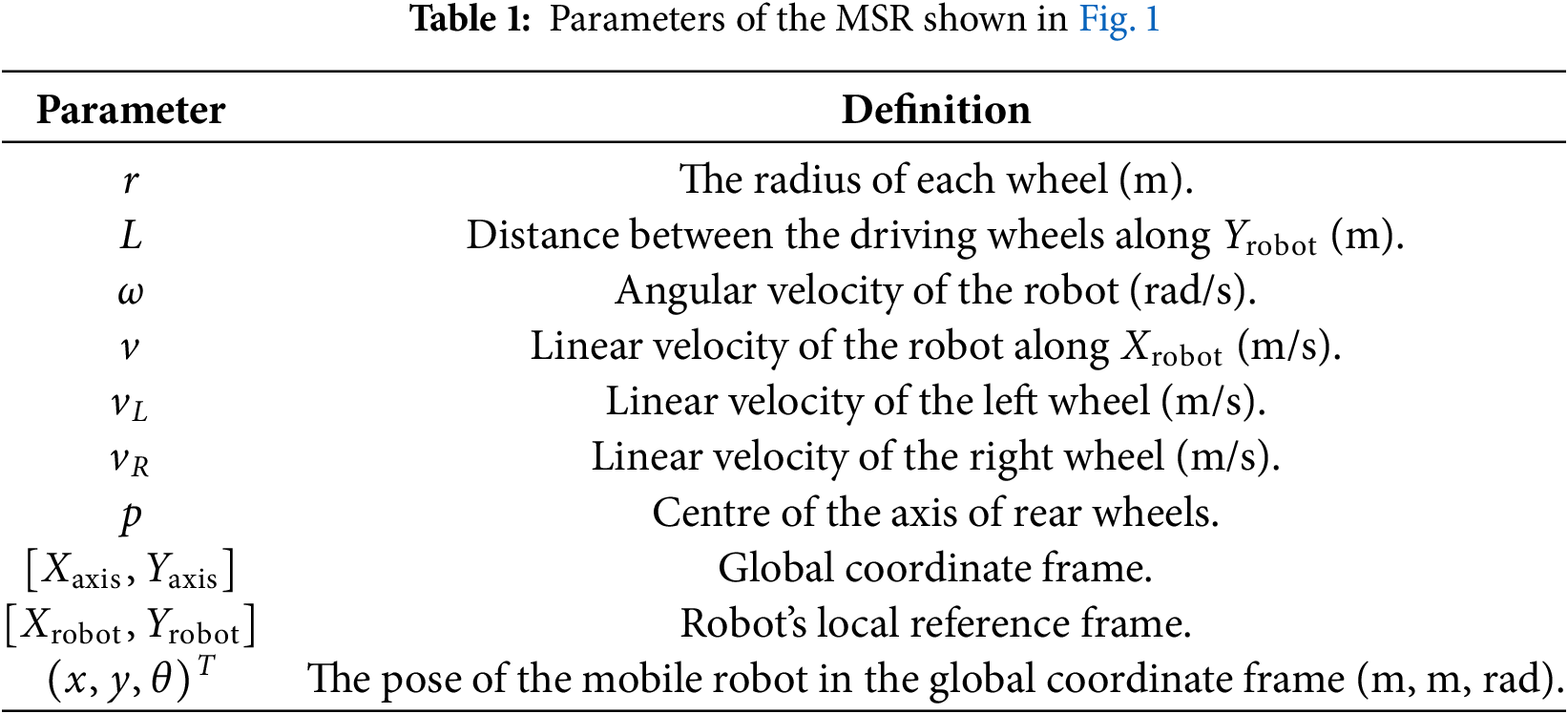

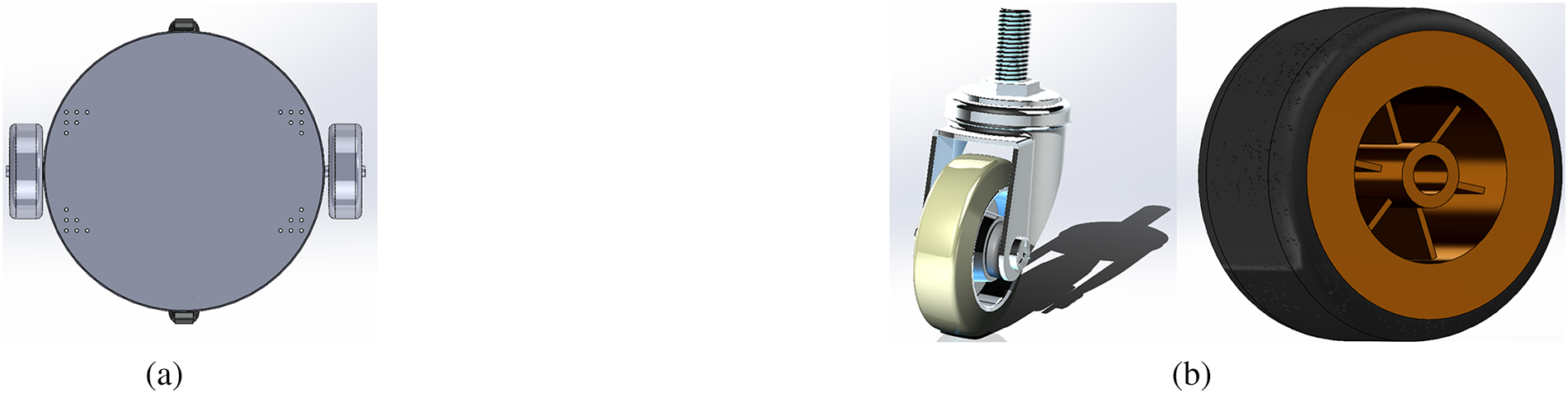

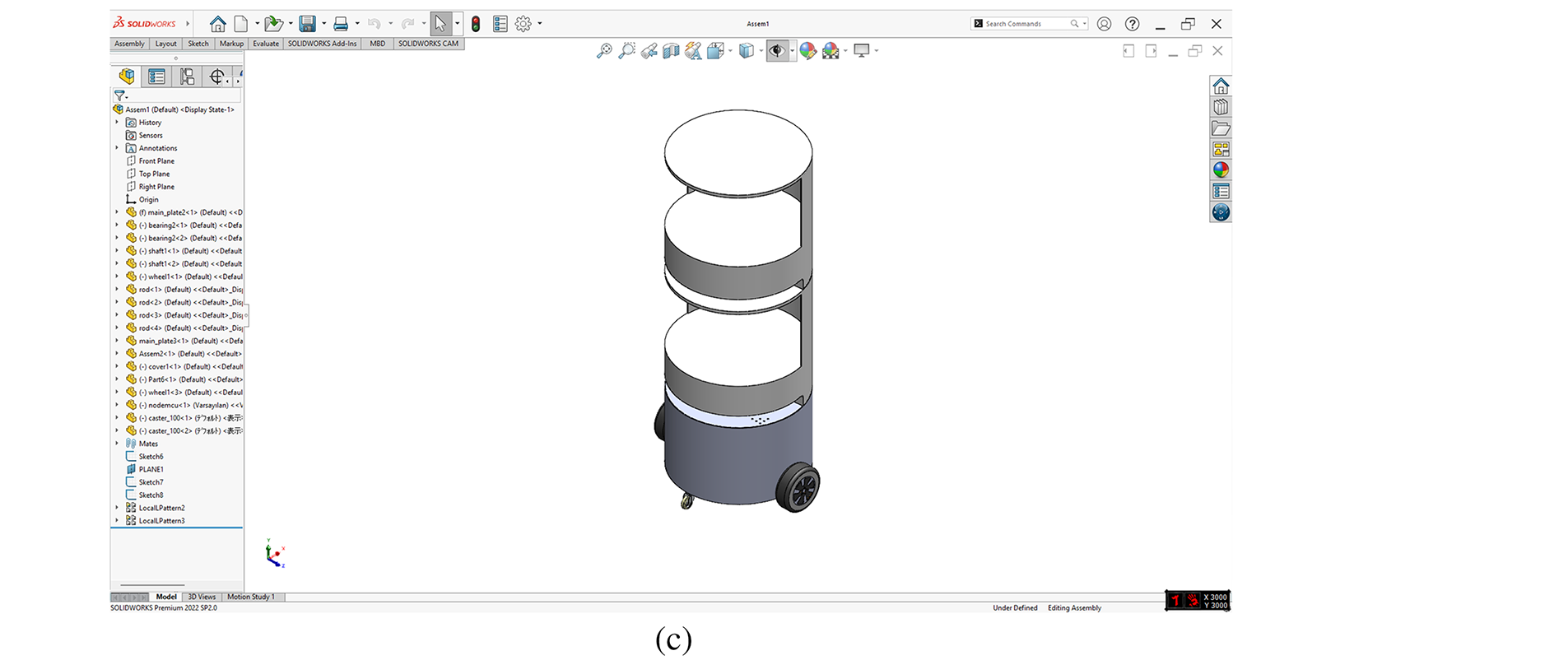

The MSR in this work is designed with a compact, modular chassis suited for indoor environments such as hospital rooms. As shown in Fig. 2, the robot features a differential drive system with two large driving wheels mounted symmetrically on either side of the base, supported by two caster wheels located at the front and rear for enhanced stability and maneuverability. The 3D model was developed in SolidWorks to ensure precise component integration and mechanical robustness. The stacked cylindrical structure in the full assembly (Fig. 2c) provides a dedicated space for mounting electronic components, sensors, and payload, while maintaining balance and ease of access for maintenance and upgrades.

Figure 2: SolidWorks-based design of the Mobile Service Robot (MSR): (a) top view of the MSR base showing wheel placement, (b) individual wheel components—main driving wheel (right) and caster wheel (left), and (c) complete 3D assembly of the MSR chassis

Structural Analysis Using ANSYS

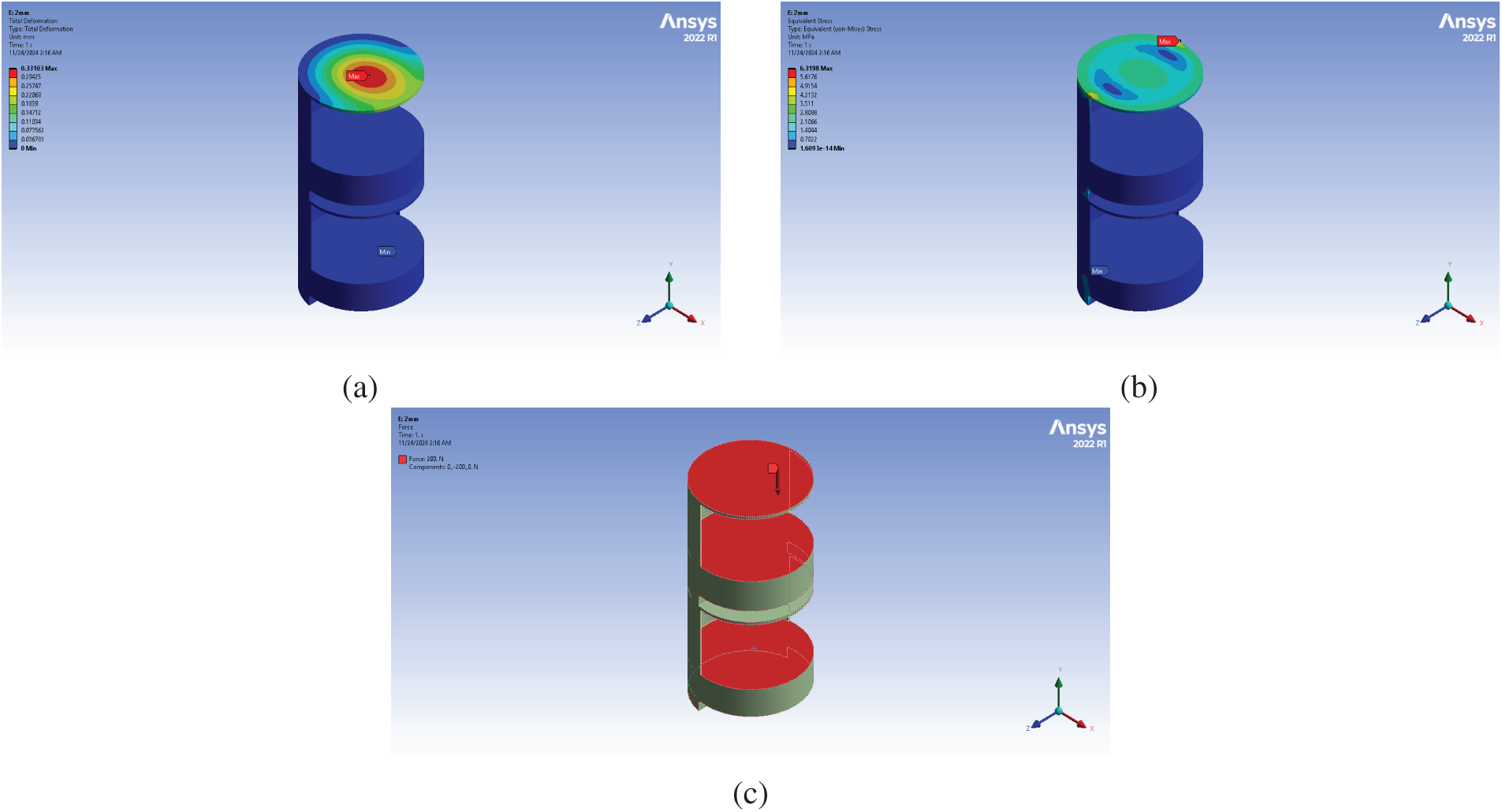

The SolidWorks Computer-Aided Design (CAD) model was imported into ANSYS 2022 R1 for finite element analysis (FEA) to evaluate the MSR’s structural integrity under operational loads. A static structural simulation was conducted using an optimized mesh and realistic boundary conditions. A vertical force of 200 N was applied to the top platform to represent the expected payload, while fixed supports at the base replicated ground constraints.

The analysis provided valuable insights into the robot’s deformation characteristics, stress concentration zones, and overall structural resilience. As illustrated in Fig. 3, the results are presented in three parts: (a) total deformation indicating displacement patterns across the chassis, (b) equivalent Von Mises stress distribution highlighting areas of mechanical stress, and (c) the defined boundary conditions applied during the simulation.

Figure 3: Structural analysis results of the MSR using ANSYS 2022 R1: (a) total deformation under applied load, (b) equivalent (Von Mises) stress distribution, and (c) applied boundary conditions including fixed supports and loading scenario

Finite Element Method (FEM) was conducted using fixed supports and a 200 N load, yielding the following quantitative results. The numerical results of the simulation are summarized as follows:

• Max von Mises stress (

• Maximum deflection (

• Safety factor (SF): 15

Mesh details: The mesh type is a tetrahedron type with element sizes of 4 mm and a total of 1,643,099. The mesh with 1,643,099 nodes is chosen to balance accuracy and computation time.

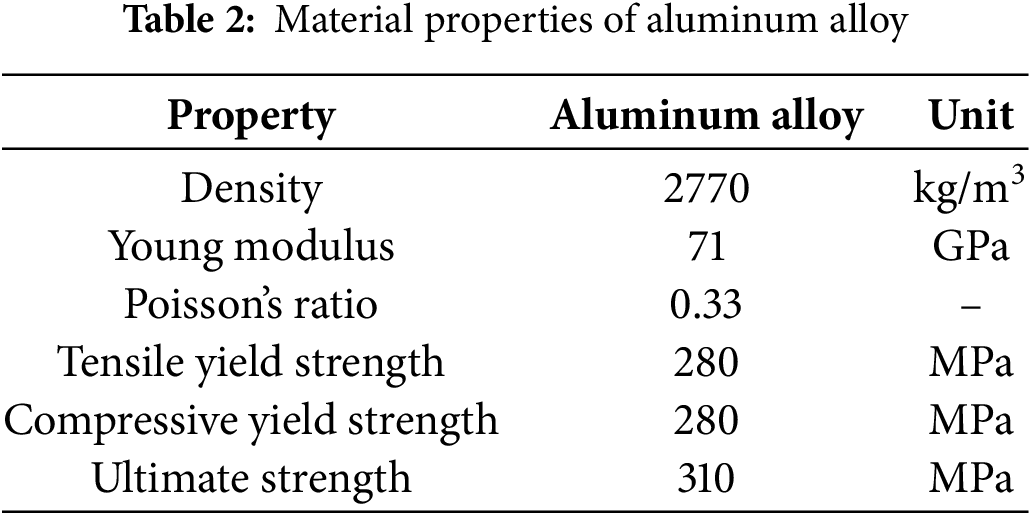

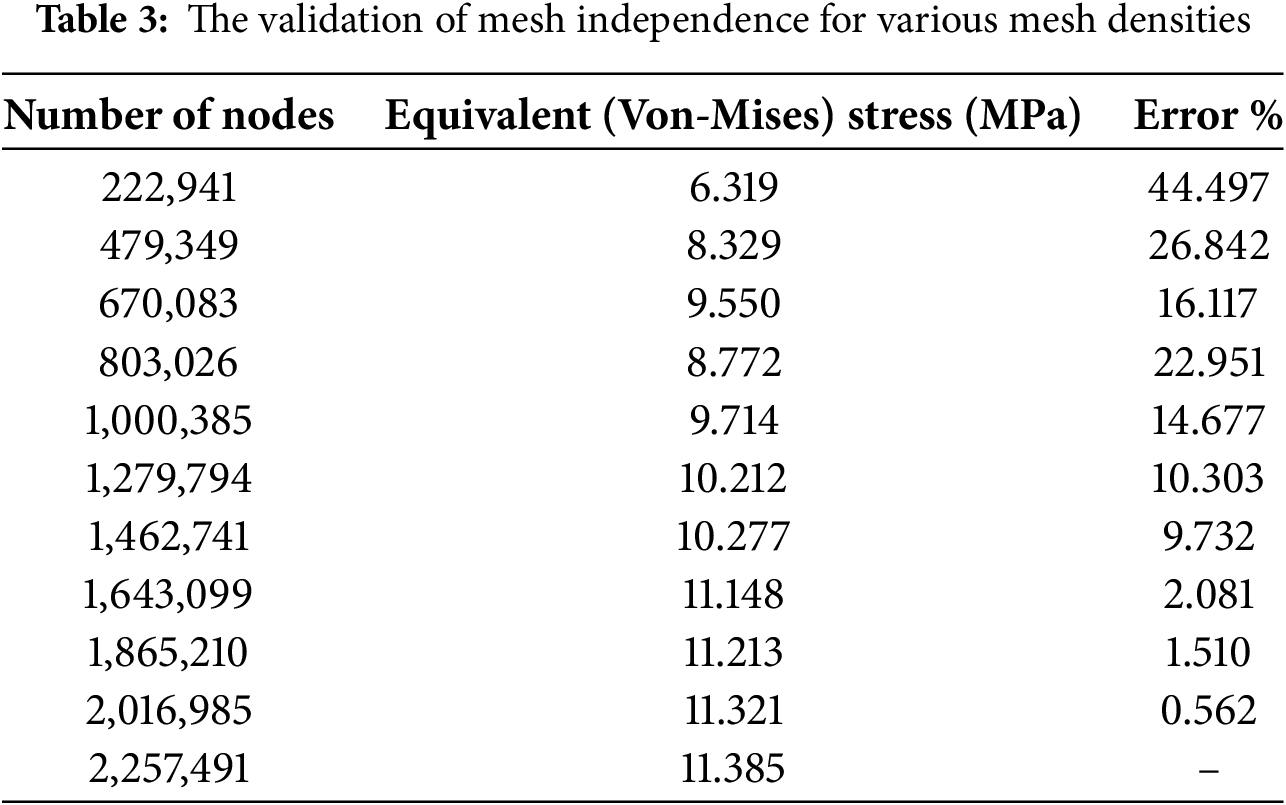

Material properties: Aluminum alloy is the material used in the chassis design. The selected aluminum alloy has detailed mechanical properties that are presented in Table 2:

Independence check: Mesh independence validation is presented in Table 3.

A 200 N force was applied to represent the worst-case payload, accounting for the robot’s weight, onboard equipment, and maximum medical load. This ensures structural validation under demanding operational conditions. The FEA results thus reflect a realistic and conservative scenario. The wheel’s bottom surface was fixed to simulate ground contact, while external forces were applied to the upper layers to model payload transfer. As shown in Fig. 3, the boundary setup includes fixed supports at the wheelbase and loading on the upper platform, accurately representing the load path and enabling reliable stress and deformation analysis.

Accurate understanding of a MSR’s mechanical behavior is fundamental to developing effective control strategies. The kinematic model describes the geometric relationship between wheel velocities and the robot’s motion in the inertial frame, without accounting for external forces [29,30]. As illustrated in Fig. 1, the robot’s global pose is defined in the inertial reference frame

where

This leads to the velocity transformation:

where R is the instantaneous curvature radius of the trajectory. Due to its non-holonomic nature, the MSR is subject to kinematic constraints that restrict lateral wheel motion. These are expressed as:

The linear and angular velocities of the MSR are derived from the left and right wheel velocities,

The discrete-time kinematic model of the MSR is then described by:

where

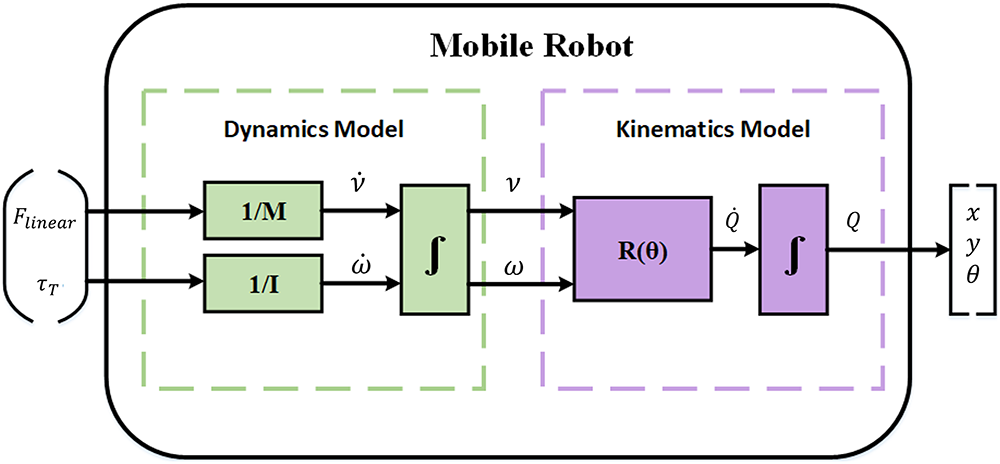

The dynamic behavior of the MSR can be described using Newtonian mechanics. The total tangential force and torque generated by the two actuators (right and left wheels) are given by:

where

Applying Newton’s second law, the linear and angular accelerations of the robot can be expressed as:

where M and I denote the mass and moment of inertia of the MSR, respectively. Substituting (10) and (11) into (12) and (13), the dynamic model can be compactly represented as:

Fig. 4 illustrates the integrated kinematic and dynamic model of the MSR system.

Figure 4: The kinematic and dynamic models of the MSR

2.2 Cognitive Control Strategy

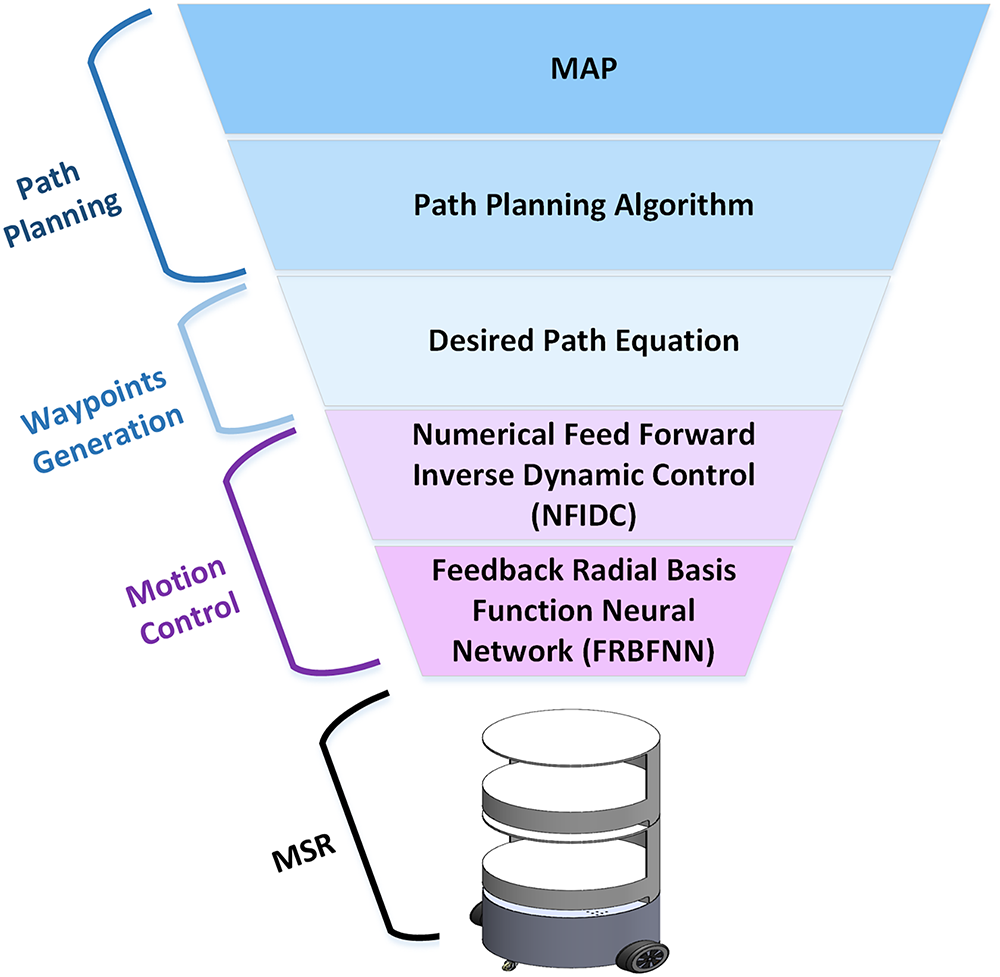

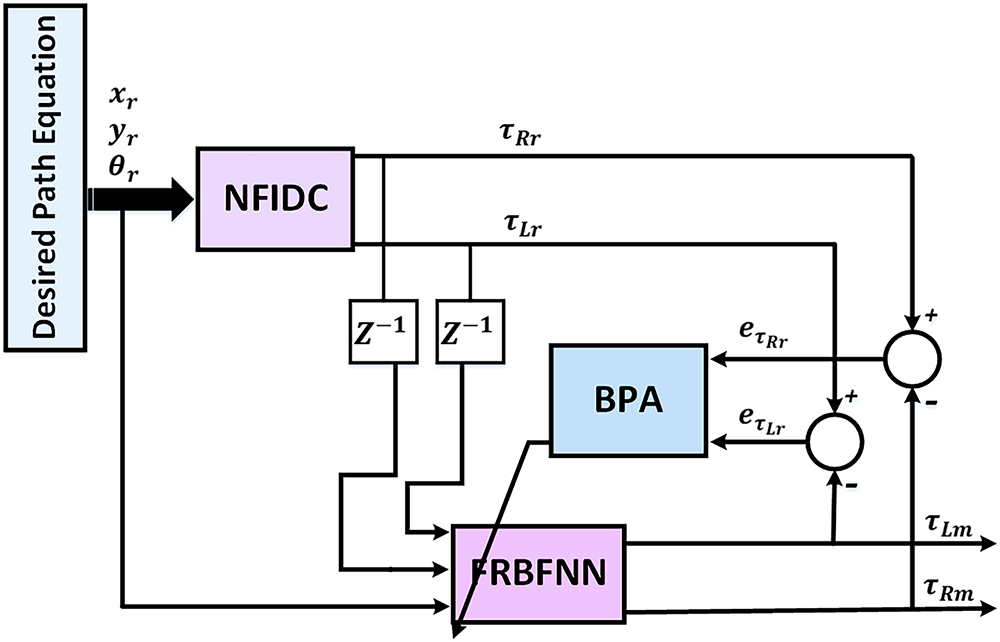

This study proposes a cognitive control strategy for trajectory tracking of a MSR in a hospital environment. The strategy integrates hierarchical layers of intelligence, starting from spatial representation and route generation to advanced motion control. The core contribution lies in the design of a hybrid motion controller that combines NFIDC and a FRBFNN. The overall framework is illustrated in Fig. 5. The strategy consists of the following layers:

Figure 5: Hierarchical structure of the proposed cognitive control strategy for the MSR

• Map: A realistic hospital room layout is constructed to emulate a clinical environment. The map includes essential infrastructure such as patient beds, IV stands, a medication station, chairs, and a monitoring desk. This layout defines the physical boundaries and constraints for path planning.

• Path Planning Algorithm: Based on the map, an optimal trajectory is generated using the Hybrid Whale Particle Swarm Optimization (HWPSO) technique, as detailed in our previous work [32]. This algorithm computes an efficient route from the initial to the target position while avoiding obstacles.

• Desired Path Equation: The waypoints from the planned trajectory are mathematically converted into a continuous path equation. This path defines the reference inputs for the control system.

• NFIDC: The NFIDC utilizes the inverse dynamics of the MSR to compute initial torque commands for the left and right wheels. This stage ensures that the MSR follows the desired path under ideal conditions without considering real-time disturbances.

• FRBFNN: To enhance robustness and adaptability, the FRBFNN controller provides real-time correction of the feed-forward torques by learning from tracking errors. This component ensures the MSR maintains accurate trajectory tracking even under external perturbations.

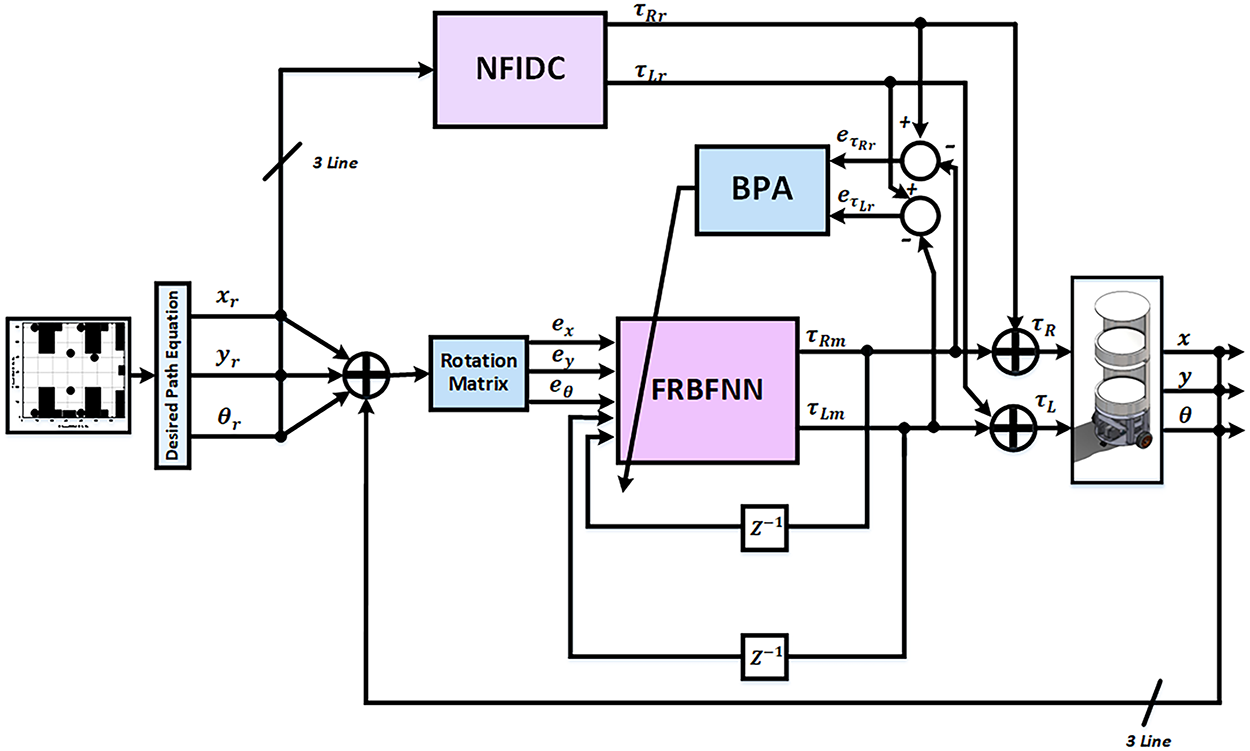

This hierarchical design integrates global optimization with adaptive feedback learning, forming a robust and intelligent motion control framework well-suited for complex indoor environments such as hospitals. Fig. 6 illustrates the complete structure of the motion control strategy, which effectively bridges the gap between high-level path planning and low-level dynamic execution on the MSR platform. The proposed NFIDC and FRBFNN controllers are described in detail in the subsequent subsections.

Figure 6: Motion control strategy design for the MSR model

2.2.1 Numerical Feed-Forward Inverse Dynamic Controller (NFIDC)

The NFIDC is employed to generate the reference torque control action for the MSR at each point when it moves in steady-state. The inverse dynamic model of the nonlinear MSR is used to propose the control law. Let

Since the angular velocity is related to curvature by

we obtain

where a sufficiently small

2.2.2 Feedback Radial Basis Function Neural Network (FRBFNN) Controller

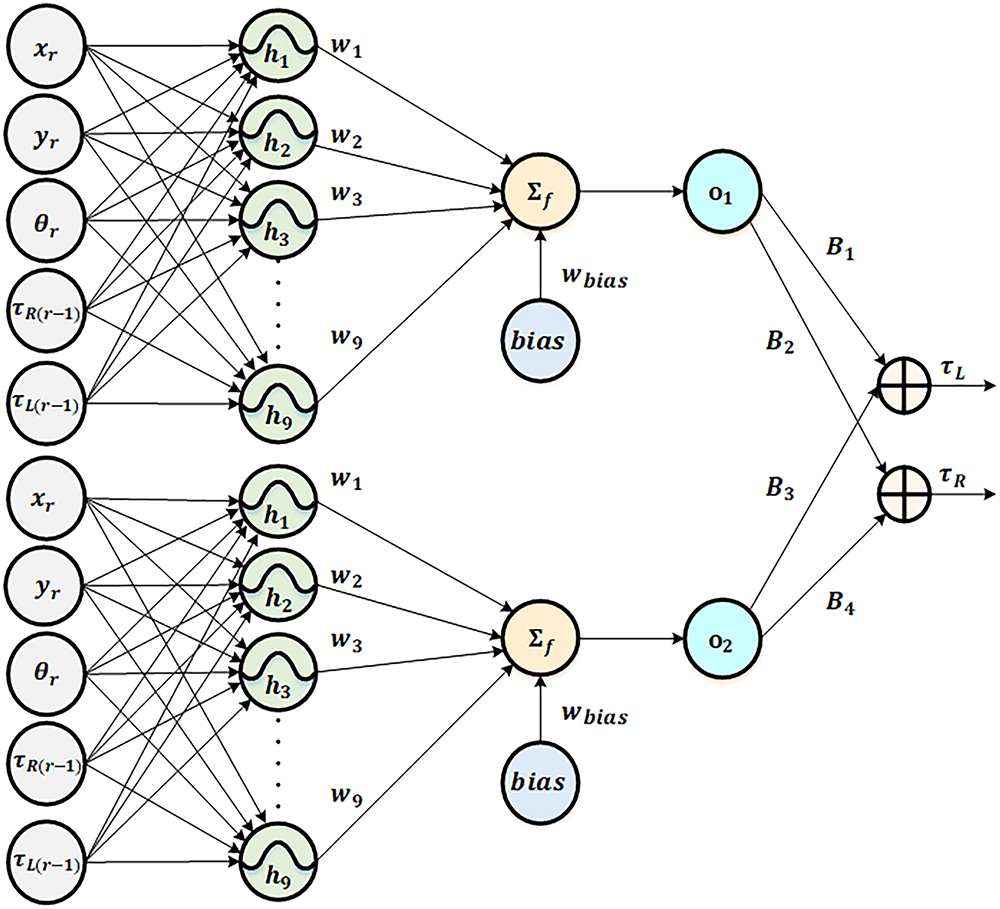

The FRBFNN controller provides adaptive feedback torque control during transient states, helping the MSR maintain its desired trajectory and minimize tracking errors in position and orientation. This controller is based on the Radial Basis Function Neural Network (RBFNN), which is widely used in nonlinear control due to its simplicity, strong approximation capability, and robust theoretical foundation [33]. The general structure of the RBFNN, shown in Fig. 7, comprises three layers:

Figure 7: Structure of the proposed FRBFNN controller

Input Layer:

•

•

Hidden Layer:

• Comprises neurons

Output Layer:

• Produces torque corrections for the left (

• Includes a bias term to enhance flexibility and learning performance.

Weight Connections:

•

•

The network structure uses two identical RBFNNs—

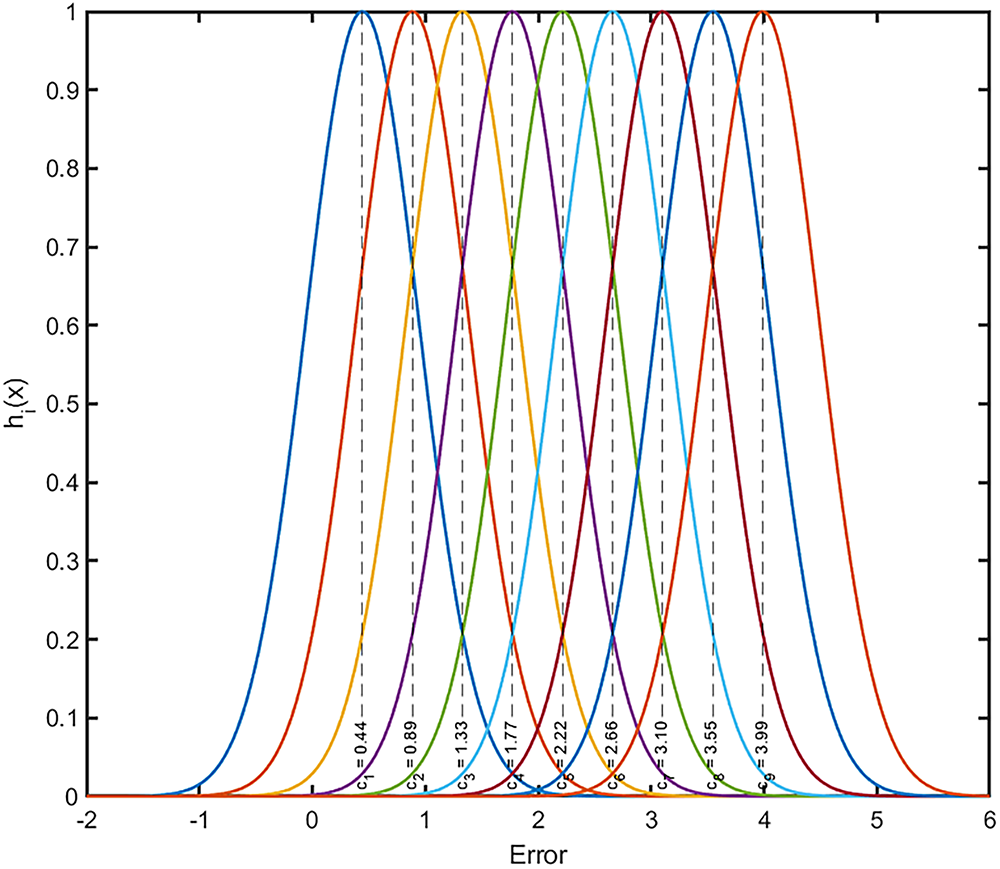

All inputs and outputs were symmetrically normalized in the range

where

where

Figure 8: Illustration on the Gaussian basis functions utilized in the proposed FRBFNN controller

The output layer employs a sigmoidal function:

The final control torques from the FRBFNN are given by:

The proposed FRBFNN feedback controller was trained offline using a dataset divided equally into 50% for training and 50% for testing. The training data were generated from the inverse dynamic model of the mobile robot (NFIDC). During real-time operation, the network weights were further refined online using a backpropagation algorithm. While no universally optimal ratio exists, this choice was made to strike a balance between providing sufficient data for effective network training and retaining a large portion for independent validation. This strategy helps mitigate overfitting while ensuring that the controller’s generalization capability is properly assessed under unseen conditions:

which measures the discrepancy between the reference torques (

The dual-output FRBFNN architecture offers key benefits. It enables shared learning between outputs, improving control accuracy through coordinated signal correction. Dynamic coupling allows the network to capture wheel interactions for smooth, synchronized motion. Moreover, continuous real-time adjustment of control signals enhances error compensation, ensuring precise trajectory tracking and robustness under varying conditions.

2.2.3 Online Neural Network Training

The weights of the FRBFNN controller are trained using the back-propagation algorithm (BPA) [34], as illustrated in Fig. 9. This supervised learning approach minimizes the control error by iteratively adjusting the network weights based on the gradient of a predefined cost function.The weight update rule for neuron

where

Figure 9: Learning structure of the FRBFNN controller

After training, the final control law for the proposed motion controller combines the reference torque generated by the NFIDC with the corrective torque from the FRBFNN:

This hybrid control output ensures that the MSR can dynamically compensate for modeling errors, external disturbances, and time-varying uncertainties, thereby maintaining smooth and accurate trajectory tracking performance.

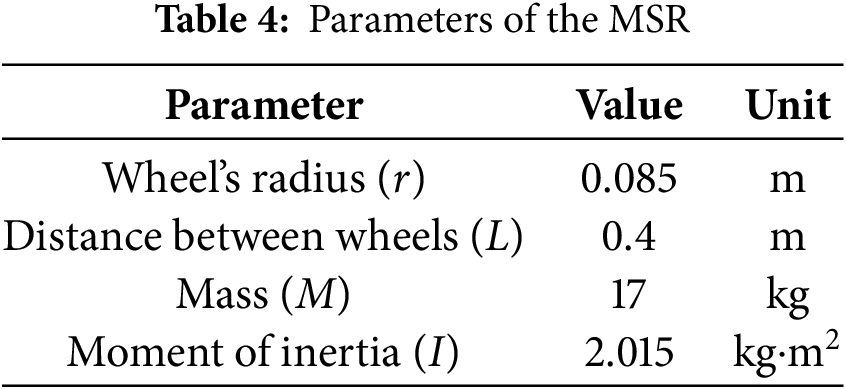

The MSR developed in this study adheres to the specifications summarized in Table 4. To evaluate the trajectory tracking performance of the proposed NFIDC-FRBFNN controller, a two-stage simulation experiment is conducted in MATLAB.

In the first stage, the HWPSO algorithm [32] is employed to compute the optimal path within a simulated hospital ward, as illustrated in Fig. 10. The environment realistically replicates a clinical setting, incorporating four patient beds, a medication trolley, IV stands, a pair of chairs, and a monitoring station representing critical elements of a typical hospital room. The MSR is tasked with navigating from the initial position at

Figure 10: The workspace used for the MSR performance evaluations where (a) shows the entire hospital ward, and (b) shows side view of the room

In addition, external disturbances, denoted by

The disturbance terms simulate real-world interaction effects such as uneven floor surfaces, contact with hospital equipment, or minor collisions with environmental objects, all of which can disrupt the robot’s movement and torque balance. By incorporating both mass variation and asymmetric external disturbances into the simulation, the controller’s ability to maintain stable and accurate tracking under dynamic and unpredictable conditions is rigorously evaluated.

In the second stage of the performance evaluation, the proposed NFIDC-FRBFNN controller is benchmarked against several established controllers from the literature: ADC, FL-PID, NMRA and Z-FL [10–12,18]. The evaluation is performed on two representative reference trajectories: a circular path and a lemniscate path, defined respectively as follows:

This comparative study aims to further validate the robustness and generalization capability of the proposed control strategy by determining which controller achieves the lowest tracking errors in terms of the robot’s position along the X-axis and Y-axis, as well as its linear velocity.

To assess the tracking accuracy and robustness of each controller, the mean

where

The percentage improvement of the proposed controller over a baseline was calculated based on the mean values as:

where

To evaluate consistency, the CV was computed for each controller as:

and the percentage reduction in CV was obtained as:

Accordingly, the results are reported in the form of

3.1 Evaluation in a Simulated Hospital Environment

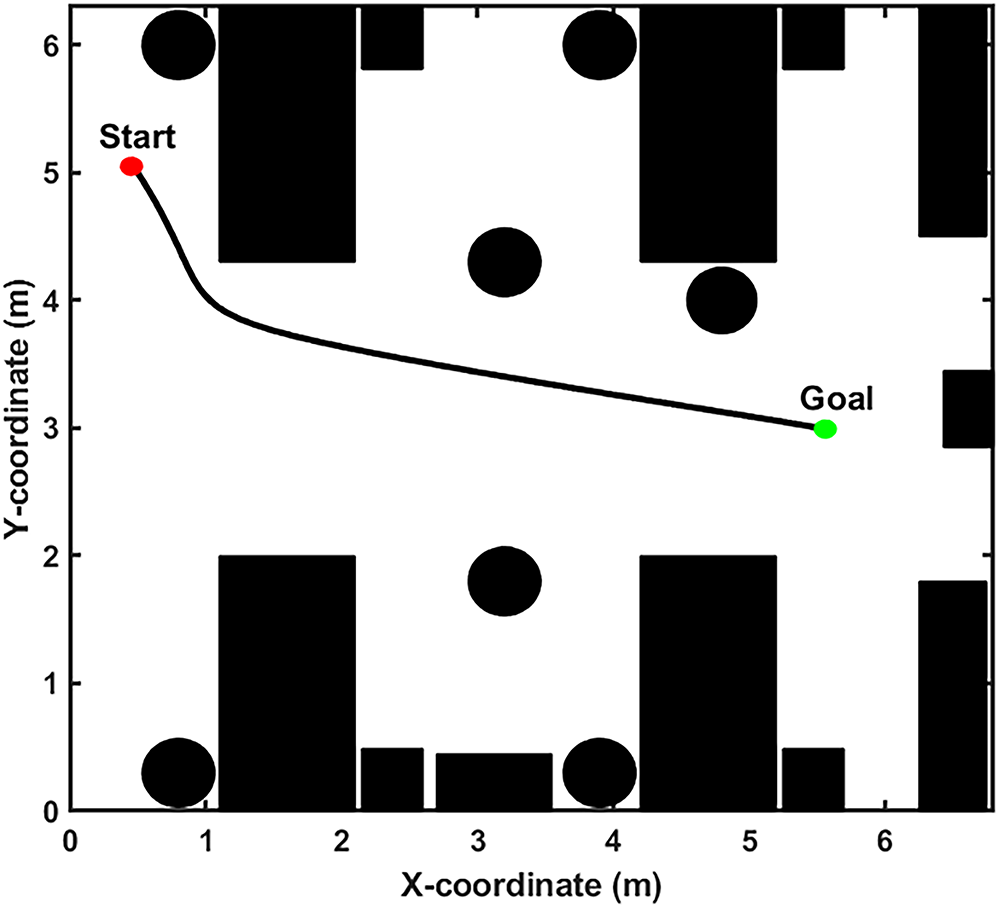

The simulation results of the optimized path are illustrated in Fig. 11. The corresponding reference path was mathematically formulated using polynomial fitting, as shown in (37):

Figure 11: Optimized reference trajectory path obtained by utilizing HWPSO algorithm for FRBFNN training and testing

This equation was used to generate input samples for training and testing the FRBFNN controller.

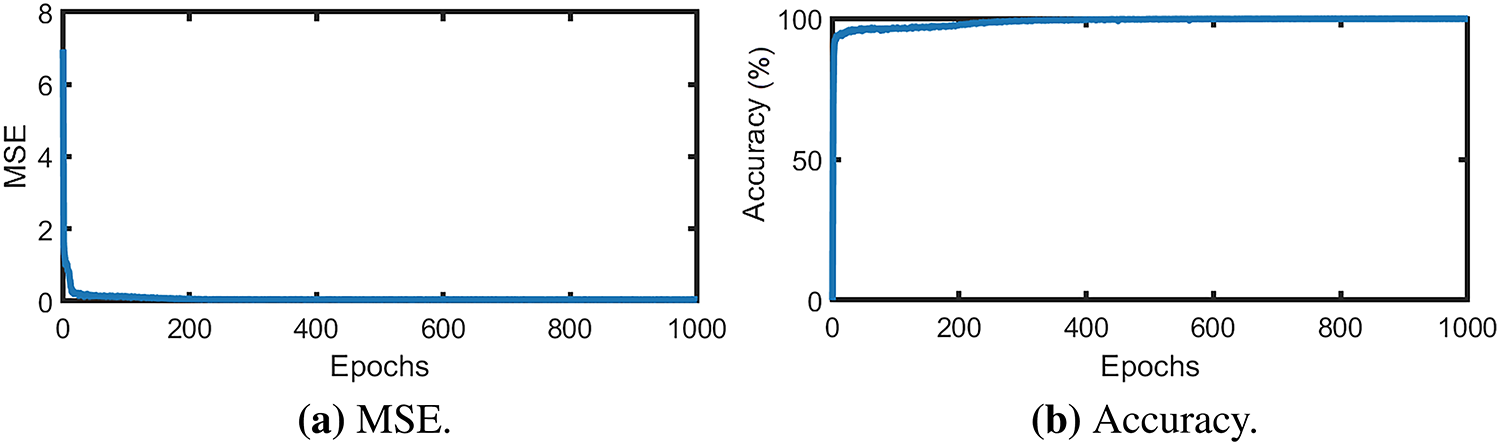

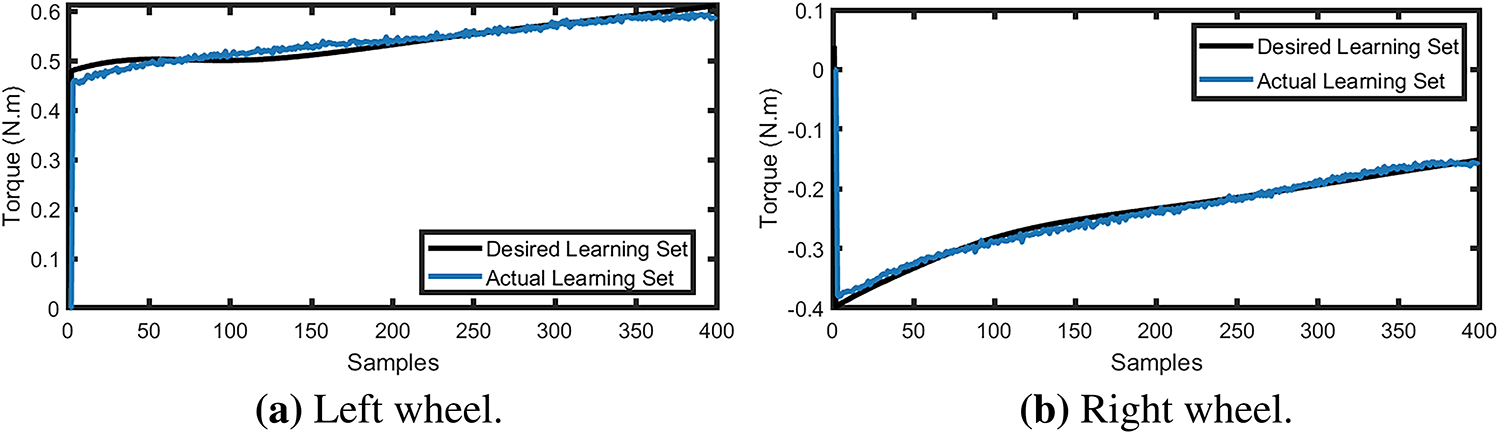

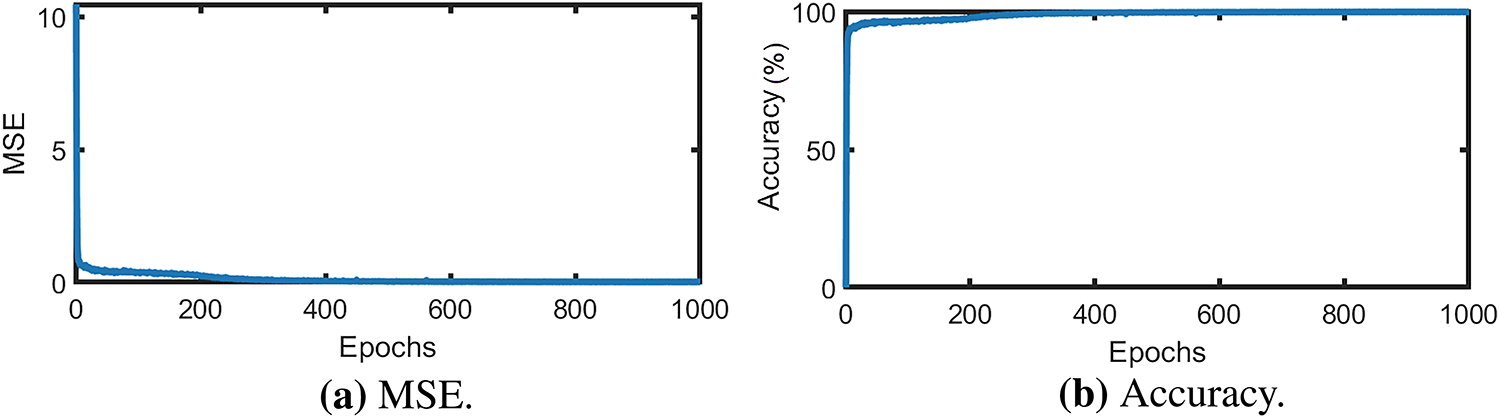

To perform offline training of the controller, the trajectory-tracking dataset was split into learning and testing sets, with a total of 499 samples per path. The learning performance of the FRBFNN controller over 1000 epochs is depicted in Fig. 12. As shown in Fig. 12a, the MSE converged to below 0.0421, indicating stable learning without issues such as overfitting or divergence. Fig. 12b demonstrates that the learning accuracy reached 99.416%, confirming effective convergence. Fig. 13 shows the resulting torque control signals for both wheels, where the actual outputs closely match the desired references.

Figure 12: Convergence performance of the FRBFNN during the training phase, illustrating (a) the rapid reduction of MSE and (b) the corresponding increase in learning accuracy over 1000 epochs

Figure 13: Torque learning performance of the FRBFNN showing close agreement between the desired and actual learning sets for (a) the left wheel and (b) the right wheel, indicating accurate nonlinear mapping and effective adaptive learning

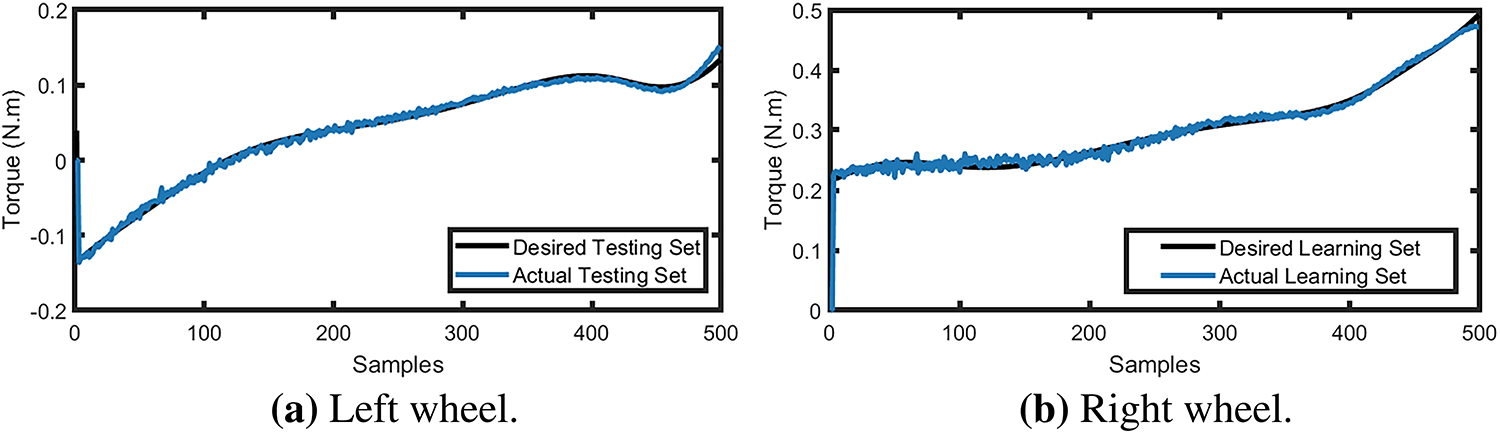

In the testing phase, the trained controller was evaluated using an independent test set. As illustrated in Fig. 14a, the MSE remained below 0.024, verifying that the model generalizes well without over-learning. The testing accuracy, shown in Fig. 14b, exceeded 99.846% after 1000 epochs. The torque profiles generated during the testing phase for the left and right wheels are plotted in Fig. 15, showing consistent tracking of the reference torques. These results confirm that the proposed NFIDC-FRBFNN controller maintains high learning fidelity and robustness across both training and testing phases.

Figure 14: Convergence performance of the FRBFNN during the testing phase, showing (a) MSE reduction and (b) corresponding accuracy across 1000 epochs

Figure 15: Torque testing performance of the FRBFNN, illustrating the close correspondence between desired and actual torque outputs for (a) the left and (b) the right wheel, confirming effective generalization of the learned model

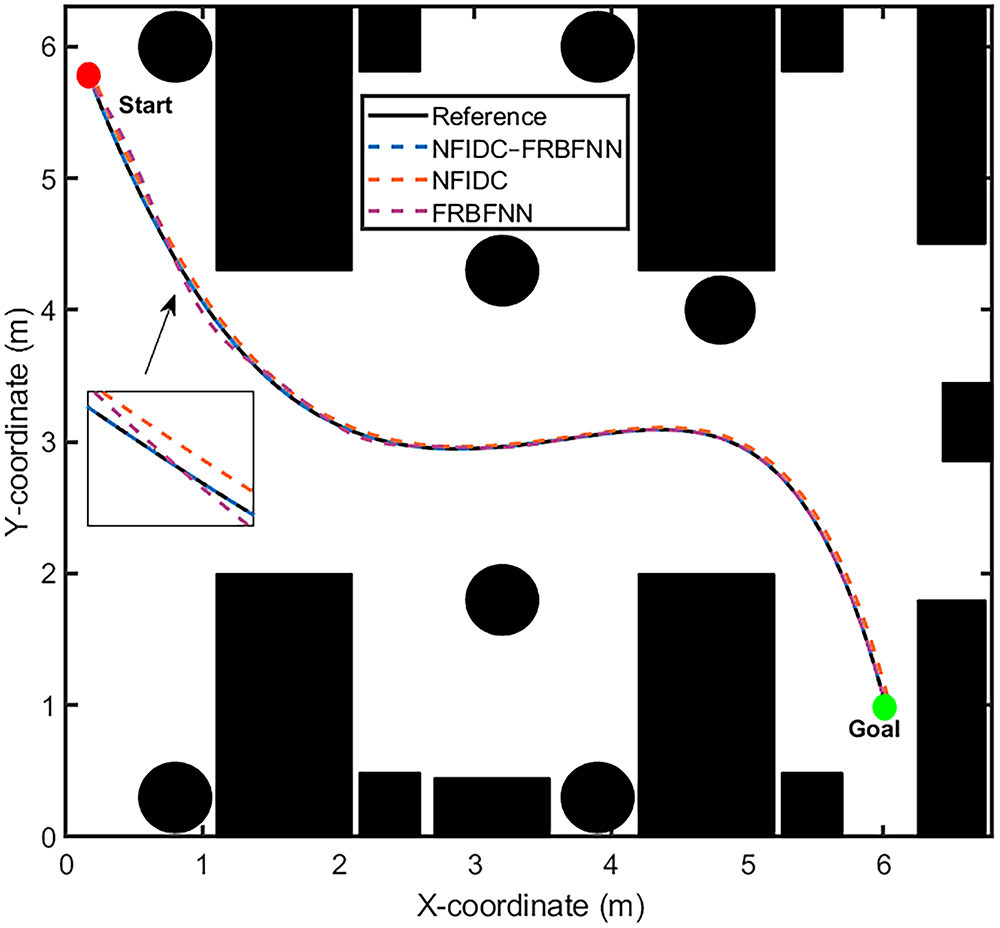

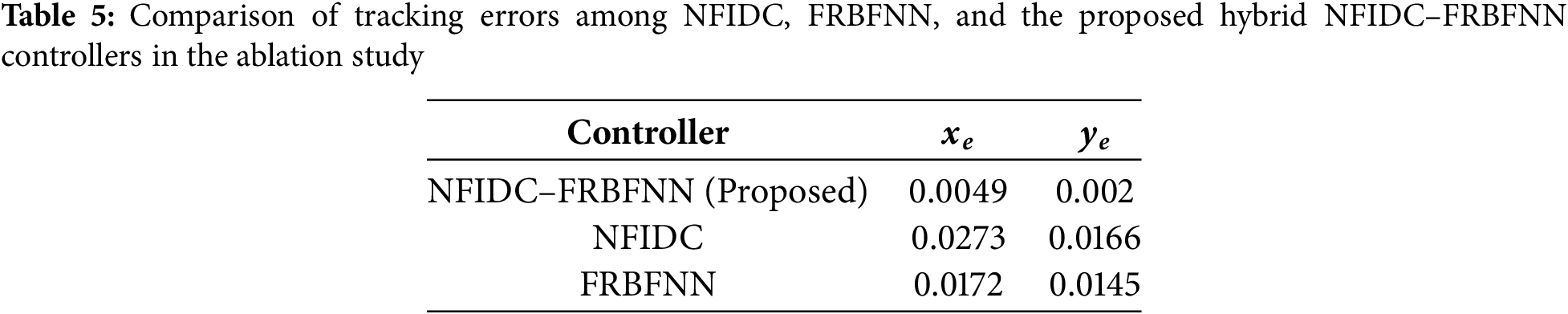

An ablation study was conducted in the simulated hospital environment to evaluate the contribution of each component. As shown in Fig. 16, both NFIDC and FRBFNN controllers could track the desired trajectory but with noticeable deviations. The NFIDC controller maintained acceptable tracking yet lacked adaptability in high-curvature regions, while the FRBFNN offered smoother motion but exhibited slight overshoot. In contrast, the hybrid NFIDC–FRBFNN achieved the most stable and accurate tracking, closely following the reference path under all conditions. The terminal errors

Figure 16: Comparison of trajectory tracking performance between NFIDC, FRBFNN, and the proposed NFIDC–FRBFNN

The NFIDC component primarily enhances the baseline model’s compensation and tracking accuracy, whereas the FRBFNN corrects and provides robustness against high-curvature or uncertain regions. The proposed model combines model-based accuracy with learning in a complementary and synergistic manner, resulting in overall performance improvement, as demonstrated in the ablation study.

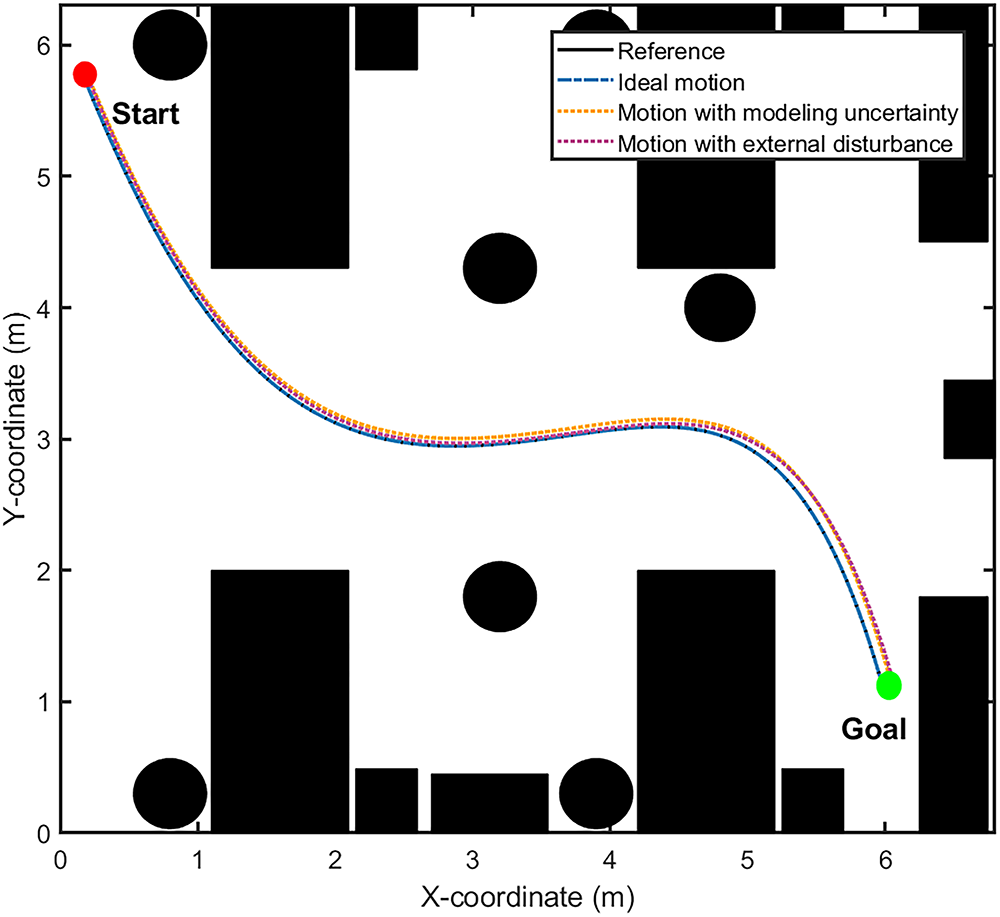

Fig. 17 presents the MSR’s trajectory tracking performance under three distinct conditions: ideal motion, motion with model uncertainty, and motion under external disturbances, evaluated for a different start-to-goal configuration within the same hospital environment. Despite these variations, the MSR effectively follows the reference path, demonstrating the robustness of the proposed control approach. The corresponding polynomial expression for the reference trajectory is given in (38):

Figure 17: The trajectory tracking performance of the NFIDC-FRBFNN-controlled MSR evaluated under three situations: ideal motion, motion with model uncertainty, and motion with external disturbance

This reference trajectory was used as the basis for evaluating the controller’s tracking accuracy and robustness in the presence of uncertainty and external disturbance.

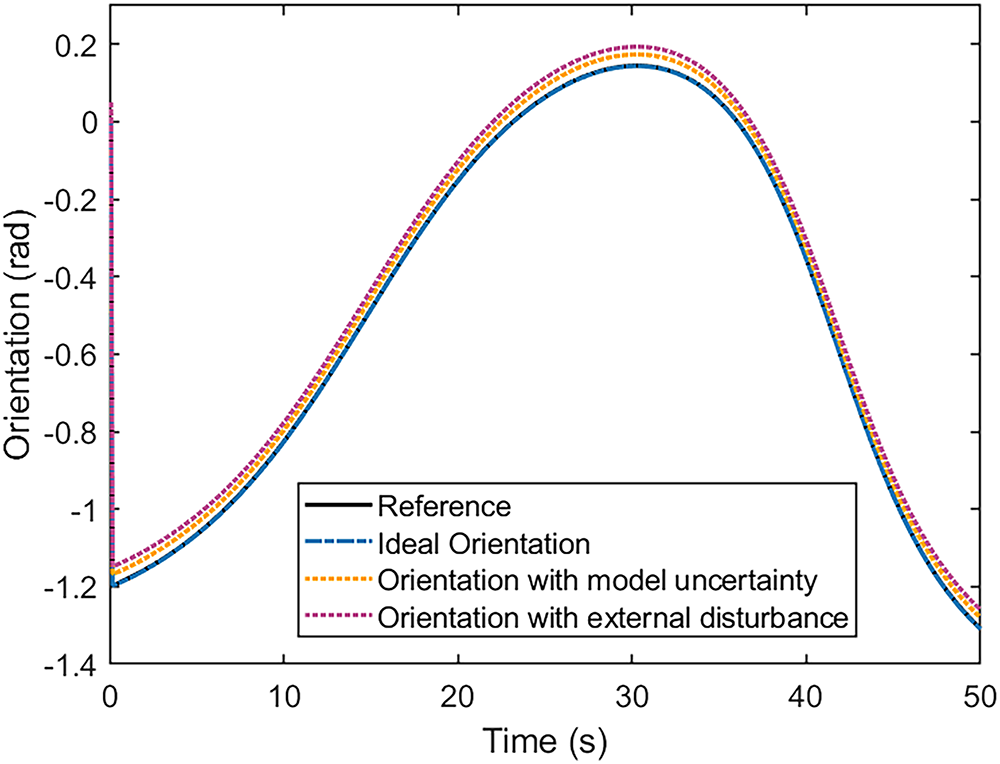

Fig. 18 presents the comparison between the desired and actual orientation trajectories of the MSR. Under ideal conditions, the MSR closely follows the reference orientation curve. When model uncertainty is introduced simulated by dynamically altering the MSR’s mass to represent payload variability the orientation tracking remains relatively stable, though with slightly increased deviation. In the presence of external disturbances, more notable deviations are observed. However, the controller still maintains a consistent response and rapidly re-aligns with the desired orientation, validating its robustness against time-varying perturbations.

Figure 18: The desired and actual orientations of the NFIDC-FRBFNN-controlled MSR in the hospital environment under ideal and non-ideal (uncertainty and disturbance) conditions

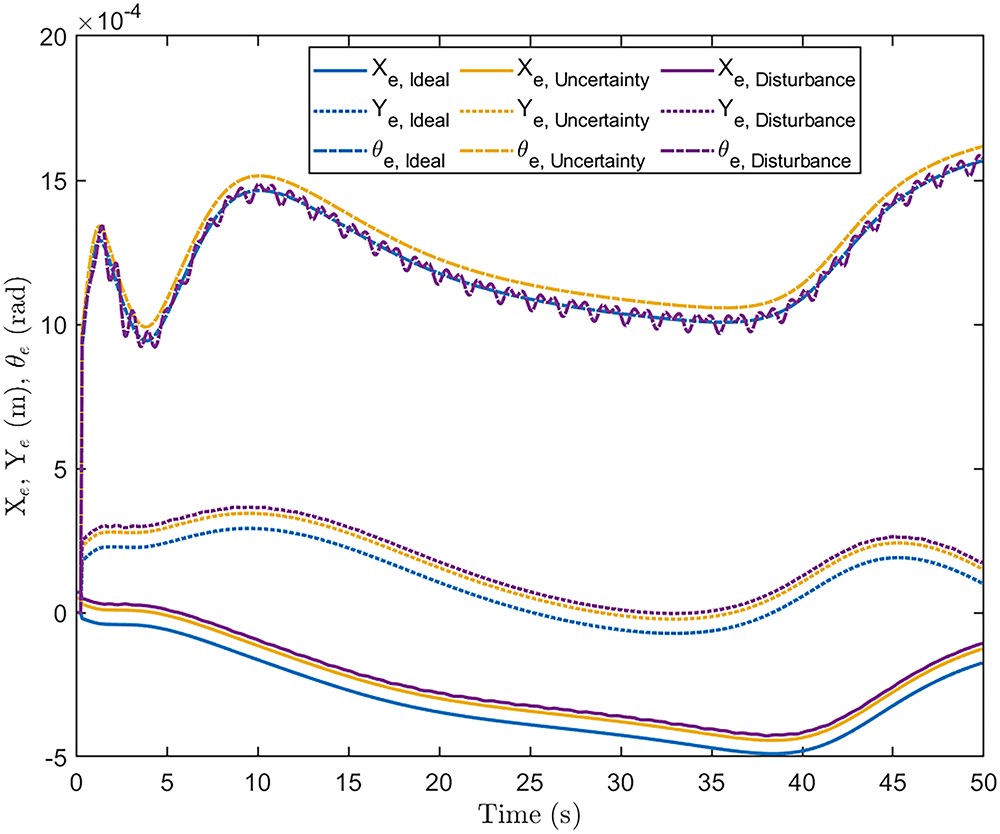

To quantify the controller’s trajectory-following precision, the tracking errors for position (

Figure 19: Position and orientation tracking errors of the NFIDC-FRBFNN-controlled MSR operating in the hospital environment under ideal and non-ideal (uncertainty and disturbance) conditions. The low error profiles confirm that the controller can mitigate deviations effectively without compromising path-following accuracy

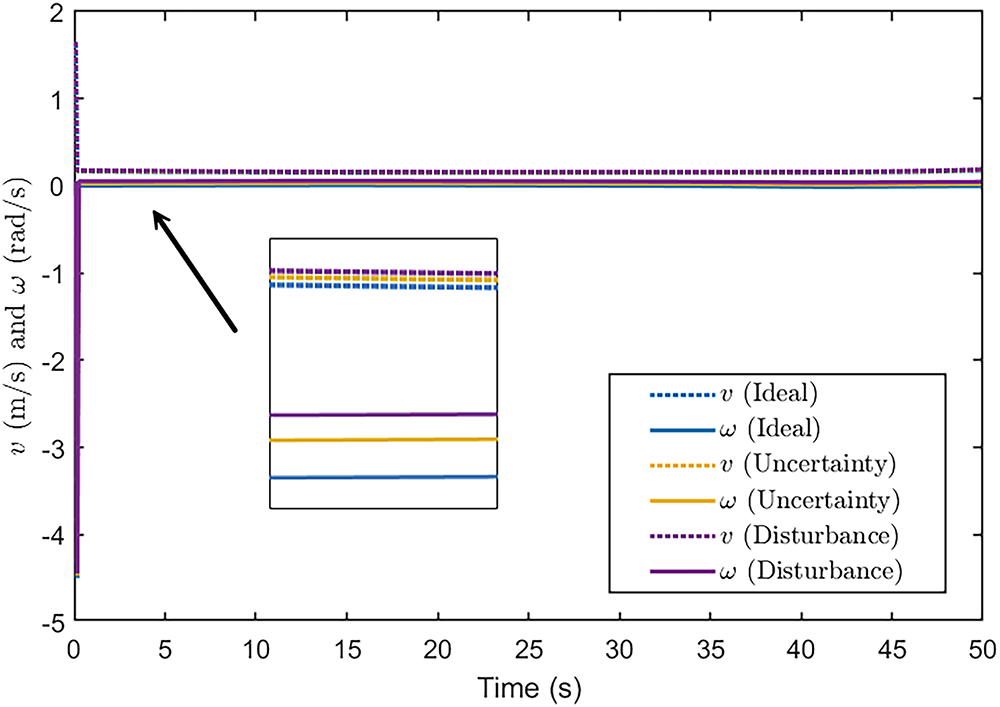

Complementing the error analysis, Fig. 20 depicts the linear and angular velocity profiles of the MSR. Under ideal conditions, both velocity components are smooth and stable. The presence of uncertainty and disturbances introduces minor fluctuations, particularly in the angular velocity response. Nevertheless, the NFIDC-FRBFNN controller successfully suppresses oscillations and quickly restores the desired velocities. This indicates the controller’s ability to produce consistent, safe, and smooth navigation—critical in structured environments like hospital corridors.

Figure 20: Angular and linear velocity responses of the NFIDC-FRBFNN-controlled MSR in the simulated hospital environment. Results are shown for both ideal and non-ideal conditions, illustrating the controller’s ability to maintain smooth and stable motion despite environmental perturbations

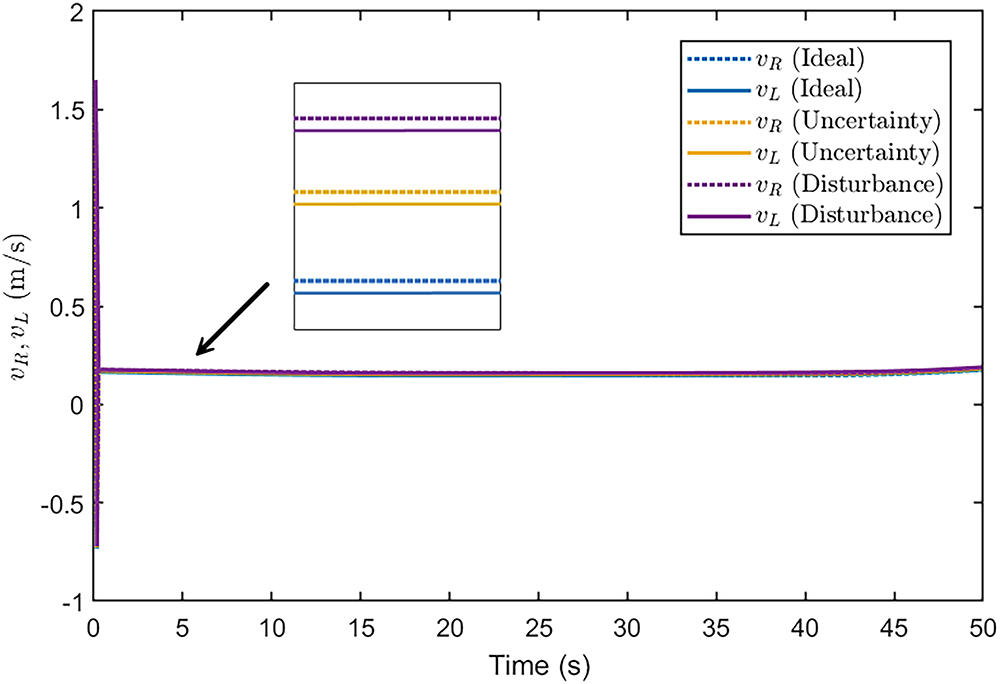

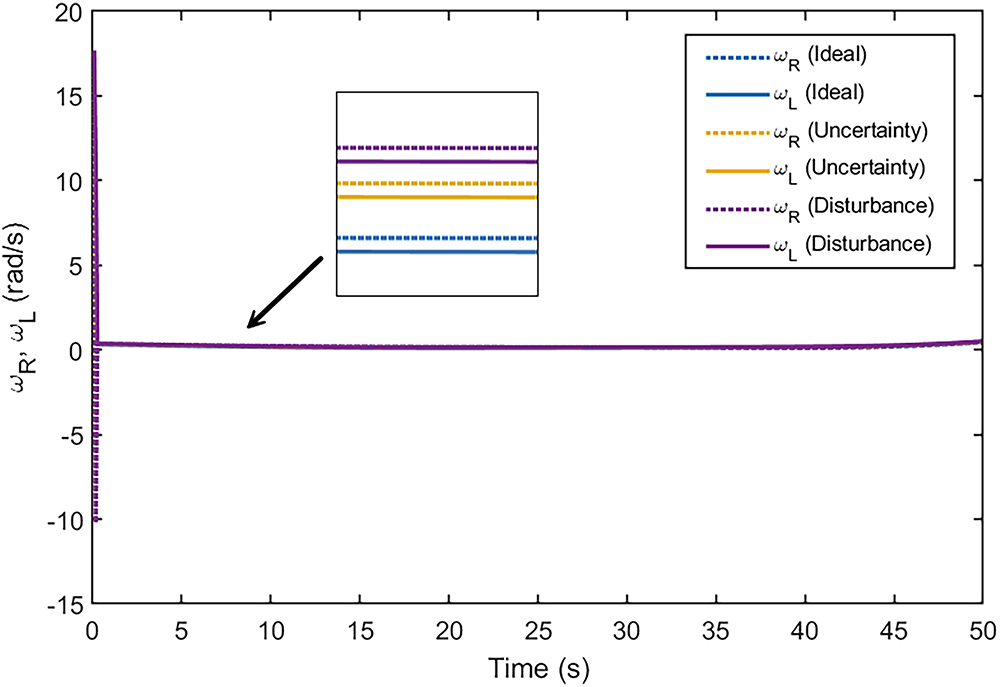

Figs. 21 and 22 examine the individual responses of the MSR’s left and right wheels. Under ideal conditions, the linear and angular velocities of both wheels are well synchronized, resulting in stable locomotion. Under uncertainty, asymmetric fluctuations appear due to unbalanced mass or load. Similarly, external disturbances create small mismatches in wheel dynamics. Despite these disturbances, the controller manages to keep the deviations within acceptable bounds, ensuring effective differential drive operation and coordinated wheel control.

Figure 21: Linear velocities of the MSR’s left and right wheels (

Figure 22: Angular velocities of the MSR’s left and right wheels (

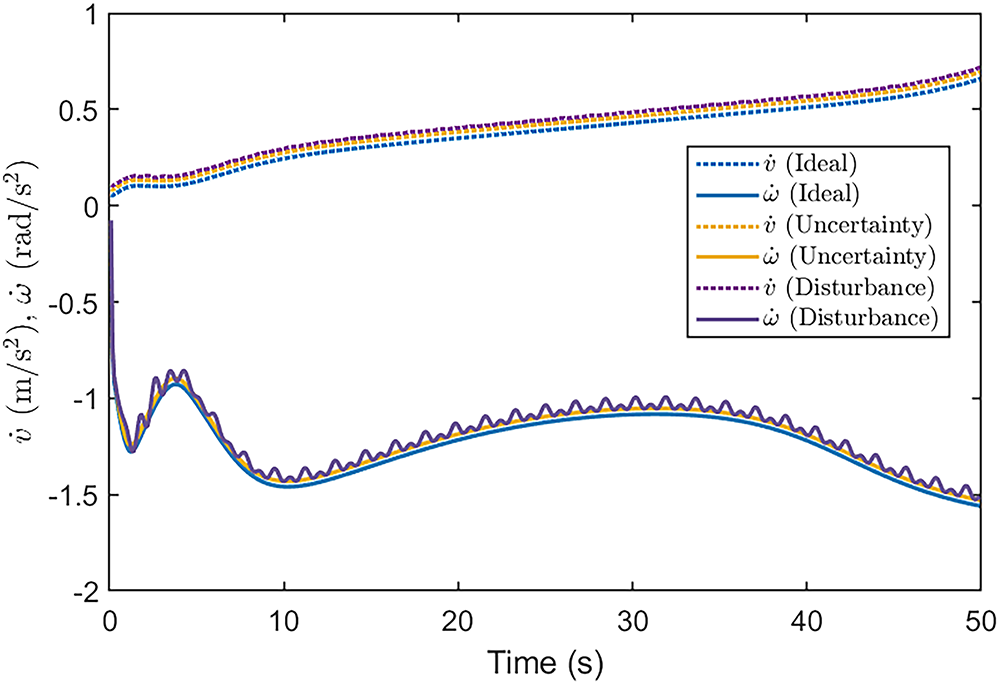

Lastly, Fig. 23 provides insights into the linear and angular acceleration profiles of the MSR. Acceleration data are crucial for analyzing how the controller reacts to sudden changes and maintains dynamic stability. Under ideal conditions, both accelerations remain smooth. When exposed to uncertainty and disturbances, transient fluctuations appear, particularly in angular acceleration. Still, the controller effectively regulates these spikes and maintains overall control quality. The consistency in acceleration response across conditions underscores the controller’s capacity to deliver robust and adaptive performance without inducing instability or abrupt motion.

Figure 23: Linear and angular acceleration profiles of the NFIDC-FRBFNN-controlled MSR in the hospital environment during trajectory tracking under ideal and non-ideal (uncertainty and disturbance) conditions. The results illustrate that under ideal conditions, both

In summary, the results in Figs. 17–23 collectively demonstrate the proposed NFIDC-FRBFNN controller’s superior path-tracking accuracy, orientation stability, and dynamic responsiveness. Even in the presence of modeling uncertainties and external disturbances, the controller sustains high performance and adaptability, making it a suitable candidate for MSR deployment in hospital settings.

3.2 Comparative Benchmarking on Standard Reference Trajectories

To further evaluate the generalization and robustness of the proposed NFIDC-FRBFNN controller, benchmarking experiments were conducted using two standard reference trajectories: circular and lemniscate paths. These trajectories present notable challenges for mobile robot control, particularly due to their curvature and the inherent non-holonomic constraints of differential-drive systems. The evaluation compares the proposed controller with four well-established control methods from the literature—ADC, FL-PID, NNMRA, and Z-FL [10–12,18], to assess tracking performance in terms of trajectory accuracy, velocity regulation, and error minimization.

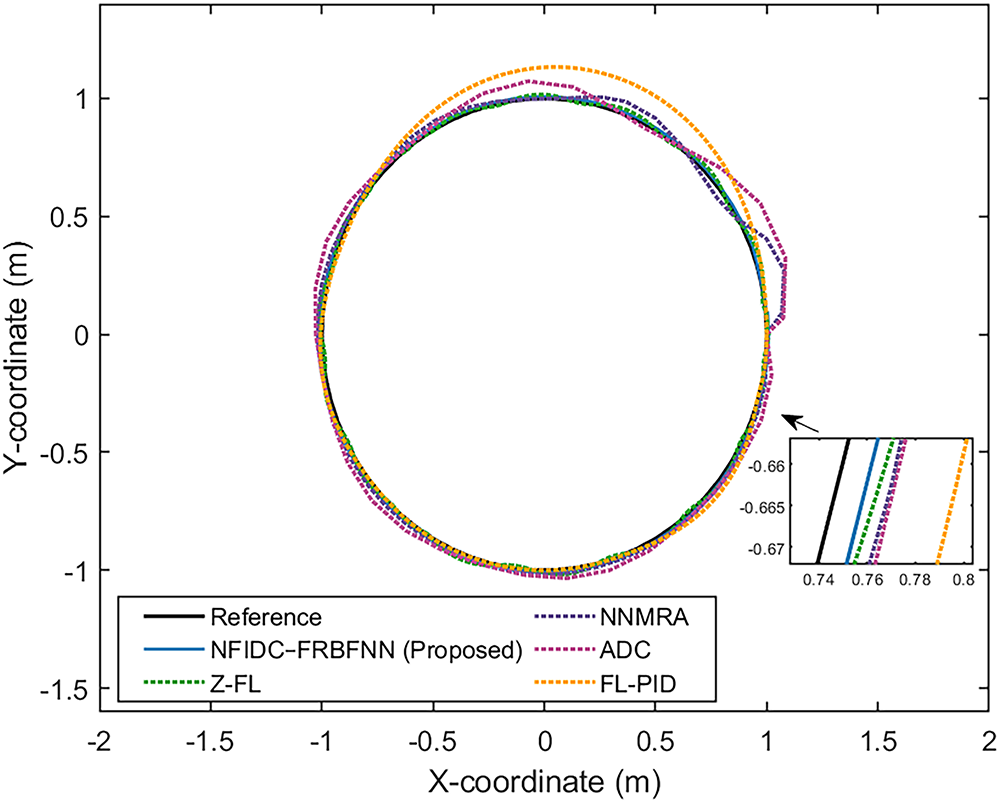

Fig. 24 illustrates the robot trajectories along a circular reference path. The NFIDC-FRBFNN controller closely follows the reference curve, with minimal deviation, in contrast to the larger offsets observed in FL-PID and ADC controllers. The proposed controller maintains tighter adherence throughout the loop, particularly near the sharp curvatures, as highlighted in the magnified segment.

Figure 24: Simulation results for the circular path tracking under ideal condition

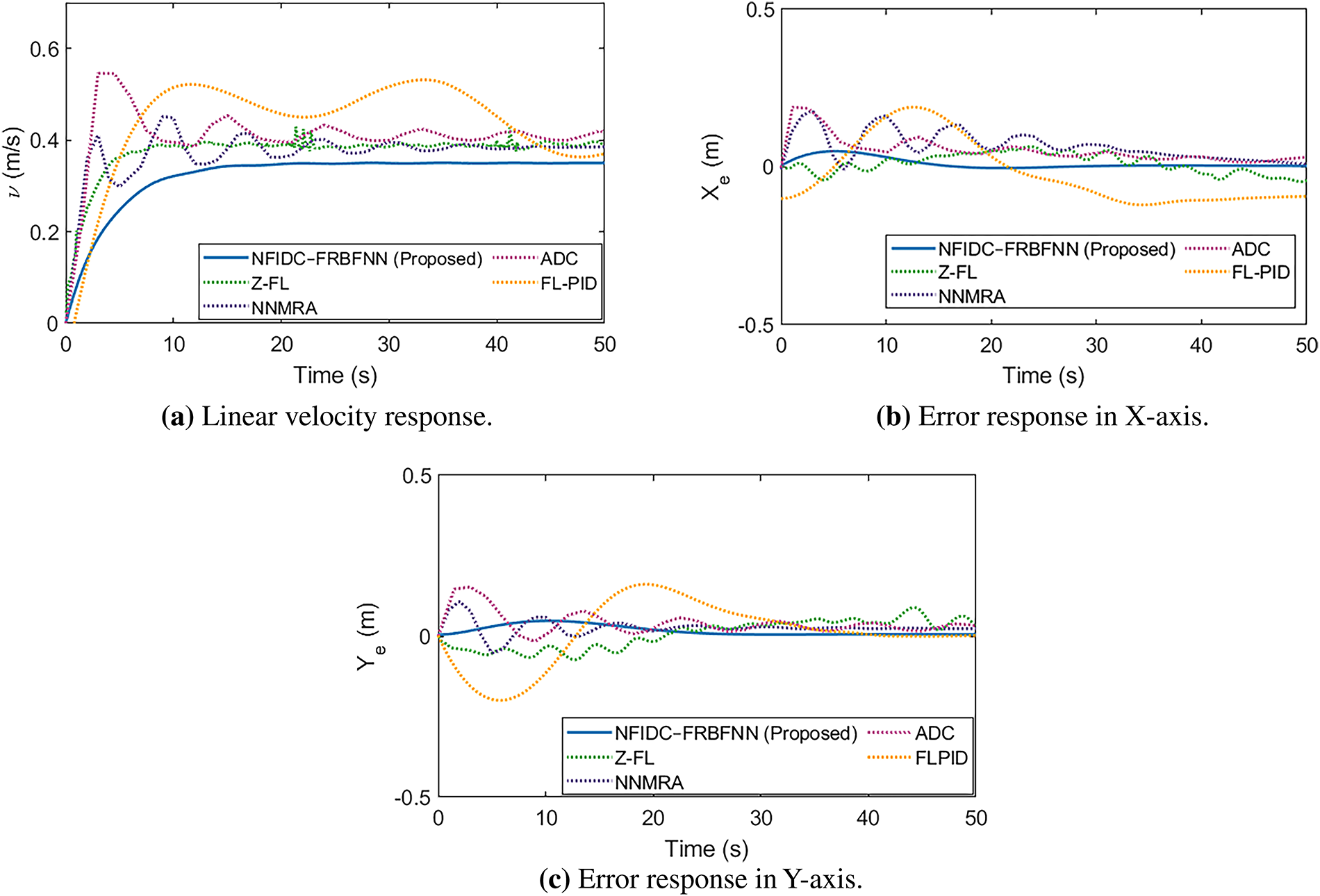

The corresponding linear velocity and position tracking errors along the X- and Y-axes are shown in Fig. 25. Fig. 25a demonstrates that the NFIDC-FRBFNN controller achieves the fastest convergence to the desired velocity with negligible overshoot. Meanwhile, other methods such as FL-PID and ADC suffer from more pronounced oscillations and slower stabilization. Error responses in Fig. 25b,c confirm that the proposed method consistently maintains lower deviations across both axes. These results underscore its superior disturbance rejection and steady-state precision.

Figure 25: Simulation results in terms of (a) linear velocity response, (b) error response in X-axis, and (c) error response in Y-axis for the circular path in Fig. 24

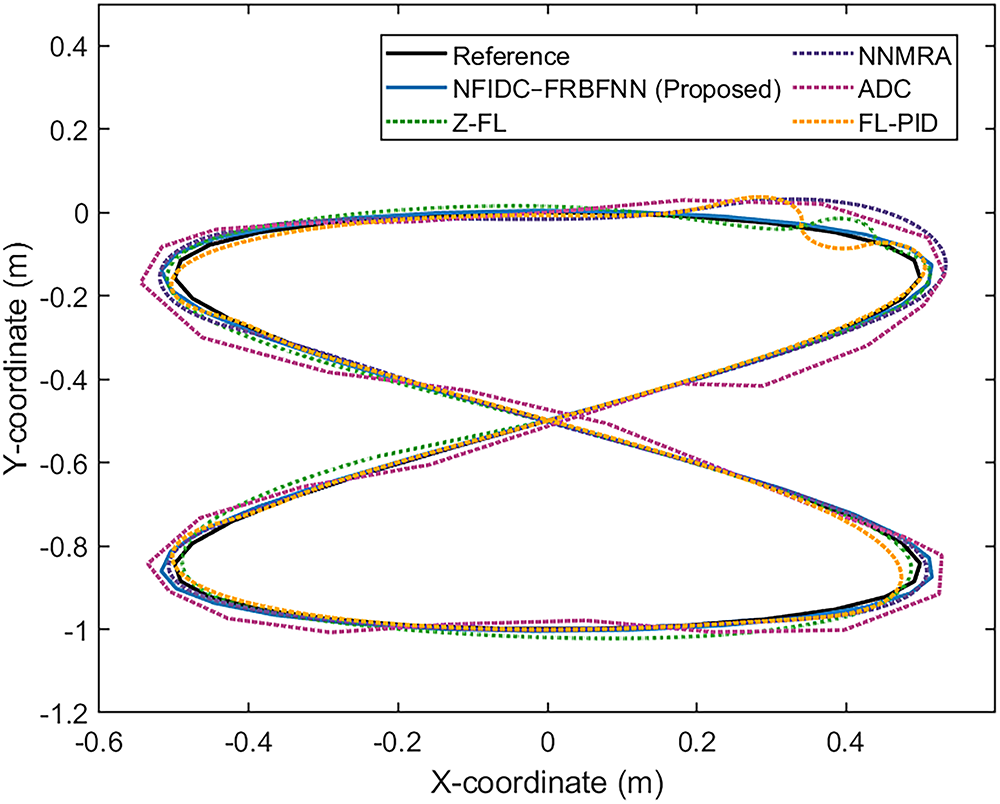

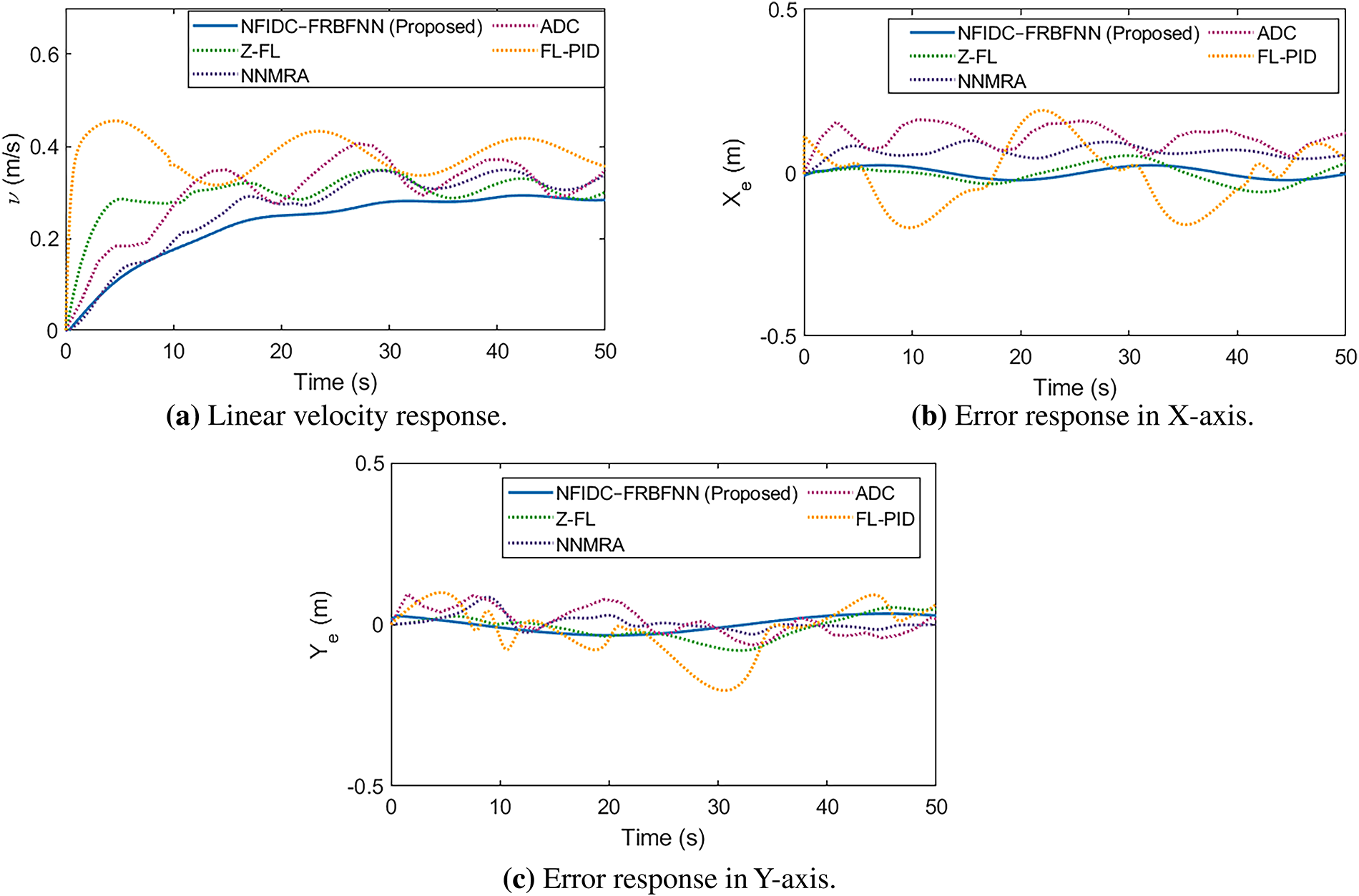

Fig. 26 shows the robot’s response to a lemniscate reference trajectory. This path imposes more dynamic directional changes than the circular trajectory, thereby challenging the controller’s adaptability. The proposed controller again demonstrates robust path-following behavior with minimal divergence, whereas other methods exhibit larger discrepancies, particularly during curve transitions. As illustrated in Fig. 27, the NFIDC-FRBFNN controller not only delivers smooth linear velocity tracking (Fig. 27a) but also sustains the lowest positional errors in both the X- and Y-axes (Fig. 27b,c). The FL-PID and ADC controllers are seen to struggle with larger amplitude oscillations and delayed convergence.

Figure 26: Simulation results for the lemniscate path tracking under ideal condition

Figure 27: Simulation results in terms of (a) linear velocity response, (b) error response in X-axis, and (c) error response in Y-axis for the lemniscate path in Fig. 26

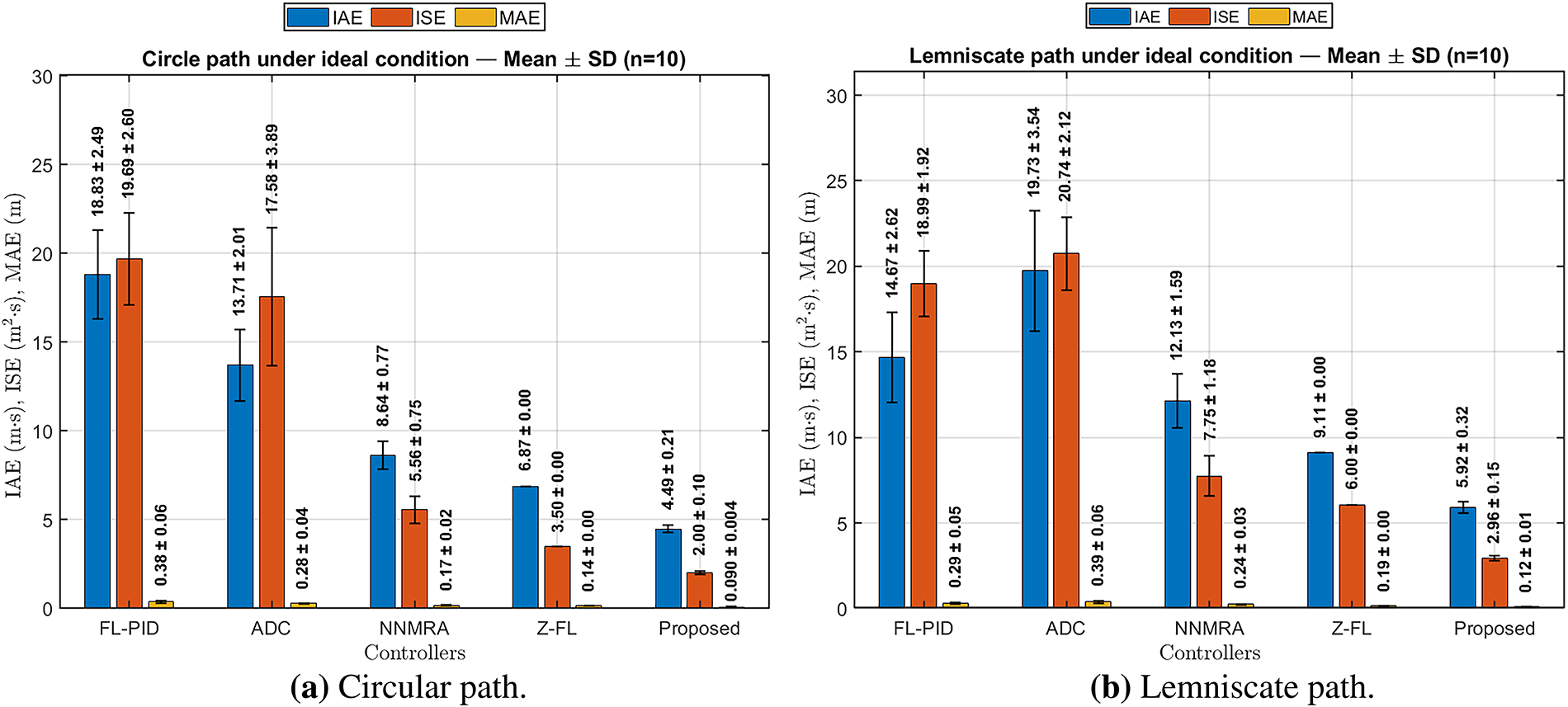

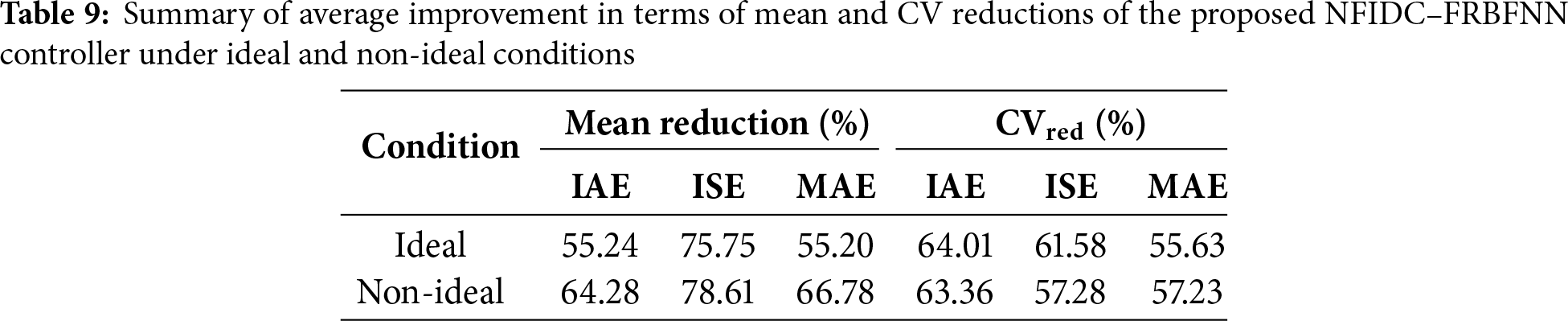

Fig. 28 quantitatively compares the tracking performance of all controllers using the IAE, ISE, and MAE metrics. The bar plots represent the mean values, while the annotations indicate the mean

Figure 28: Tracking error comparison between the proposed NFIDC–FRBFNN controller and existing methods (Z-FL, NNMRA, ADC, and FL-PID) under ideal conditions. Subfigure (a) shows the tracking errors for a circular path, while subfigure (b) presents the results for a lemniscate path. The bars represent the mean

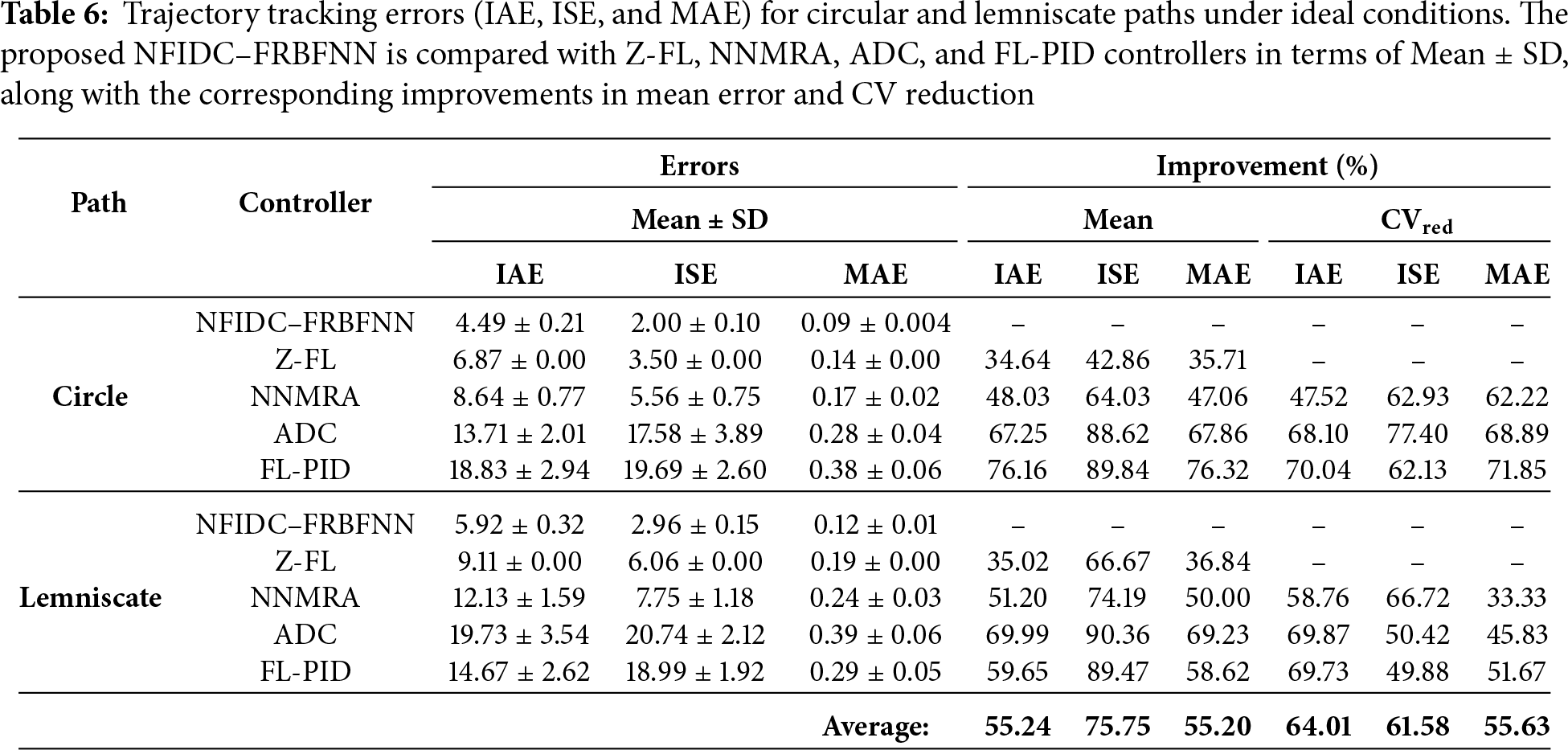

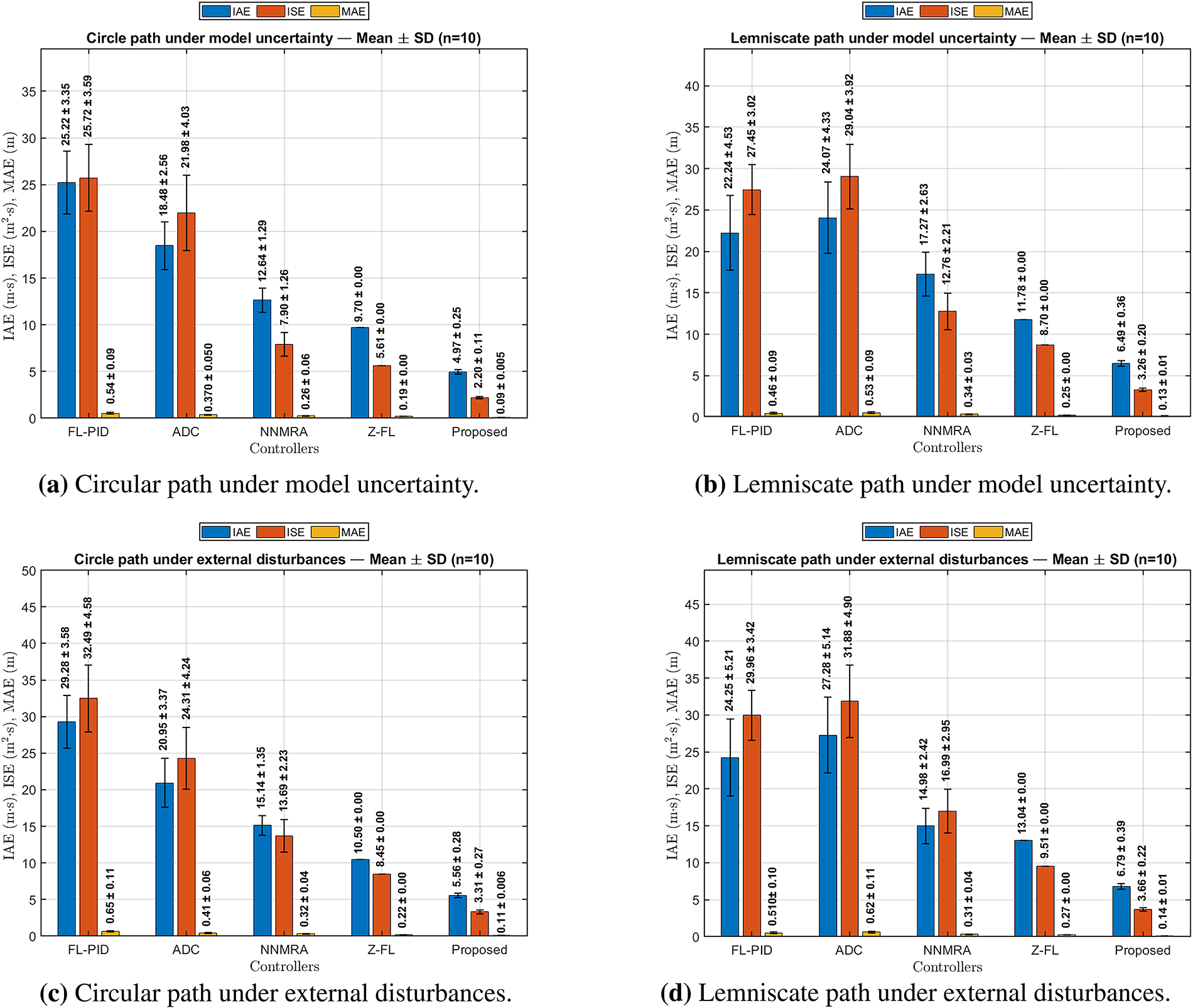

Table 6 summarizes the trajectory tracking performance and percentage improvements achieved by the proposed NFIDC–FRBFNN controller under ideal conditions. The results show that the proposed method consistently outperforms all benchmark controllers (Z-FL, NNMRA, ADC, and FL-PID) across both trajectory types and all error indices (IAE, ISE, and MAE). It is worth noting that the Z-FL controller is deterministic, as it uses two fixed inputs—distance and orientation errors [18]—along with a predefined fuzzy rule base and membership functions that remain unchanged during operation. The inference and defuzzification processes are performed using standard centroid formulations, leading to identical outputs for repeated inputs and, consequently, no statistical variation across runs. In contrast, the other controllers exhibit variability due to their adaptive nature: (i) NNMRA employs MRAC and Lyapunov-based adaptation with neural networks, leading to run-to-run differences in IAE, ISE, and MSE; (ii) ADC applies a direct adaptive dynamic scheme with

Beyond accuracy improvement, the CV analysis further highlights the consistency and robustness of the proposed controller. The NFIDC–FRBFNN not only achieves significant reductions in mean tracking errors but also demonstrates improved stability across multiple runs. Specifically, the controller attained average CV reductions of 64.01% (IAE), 61.58% (ISE), and 55.63% (MAE), indicating more consistent performance compared to all benchmarks. In terms of average mean improvement, the proposed NFIDC–FRBFNN achieved 55.24%, 75.75%, and 55.20% improvement in IAE, ISE, and MAE, respectively. These results collectively confirm the controller’s superior trajectory tracking precision, robustness, and consistency under ideal conditions.

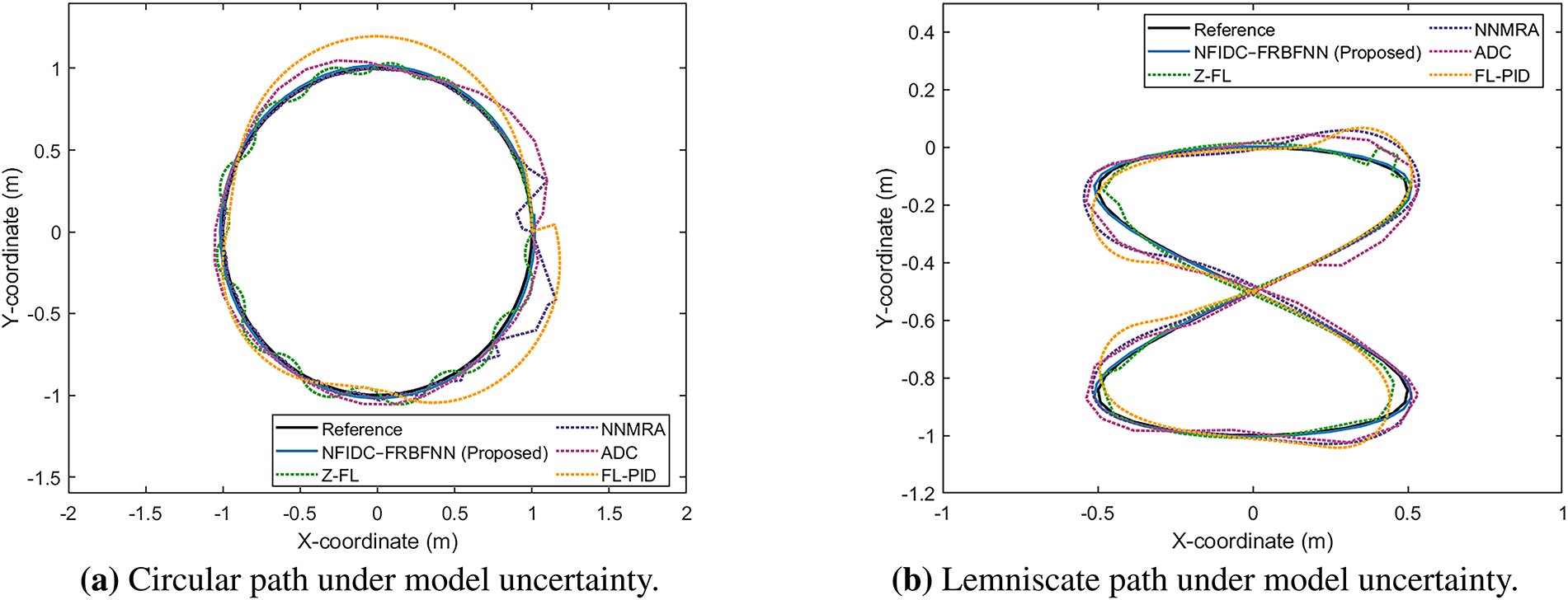

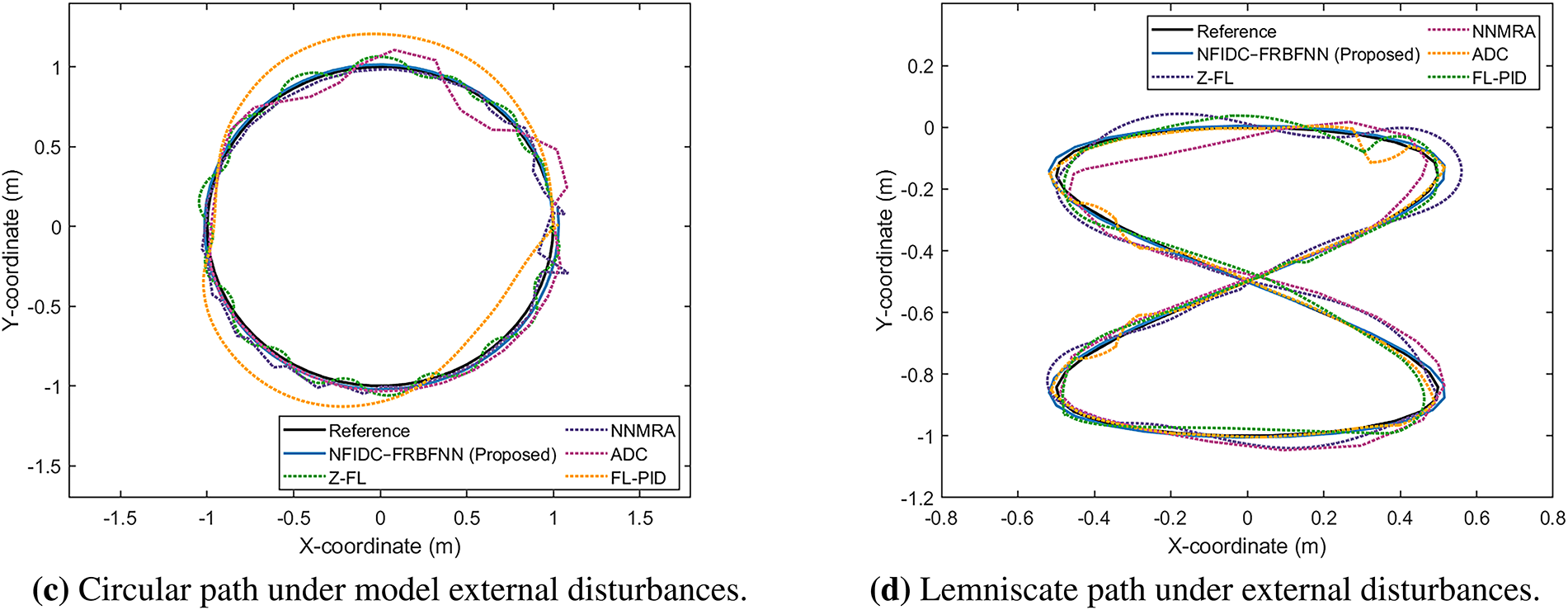

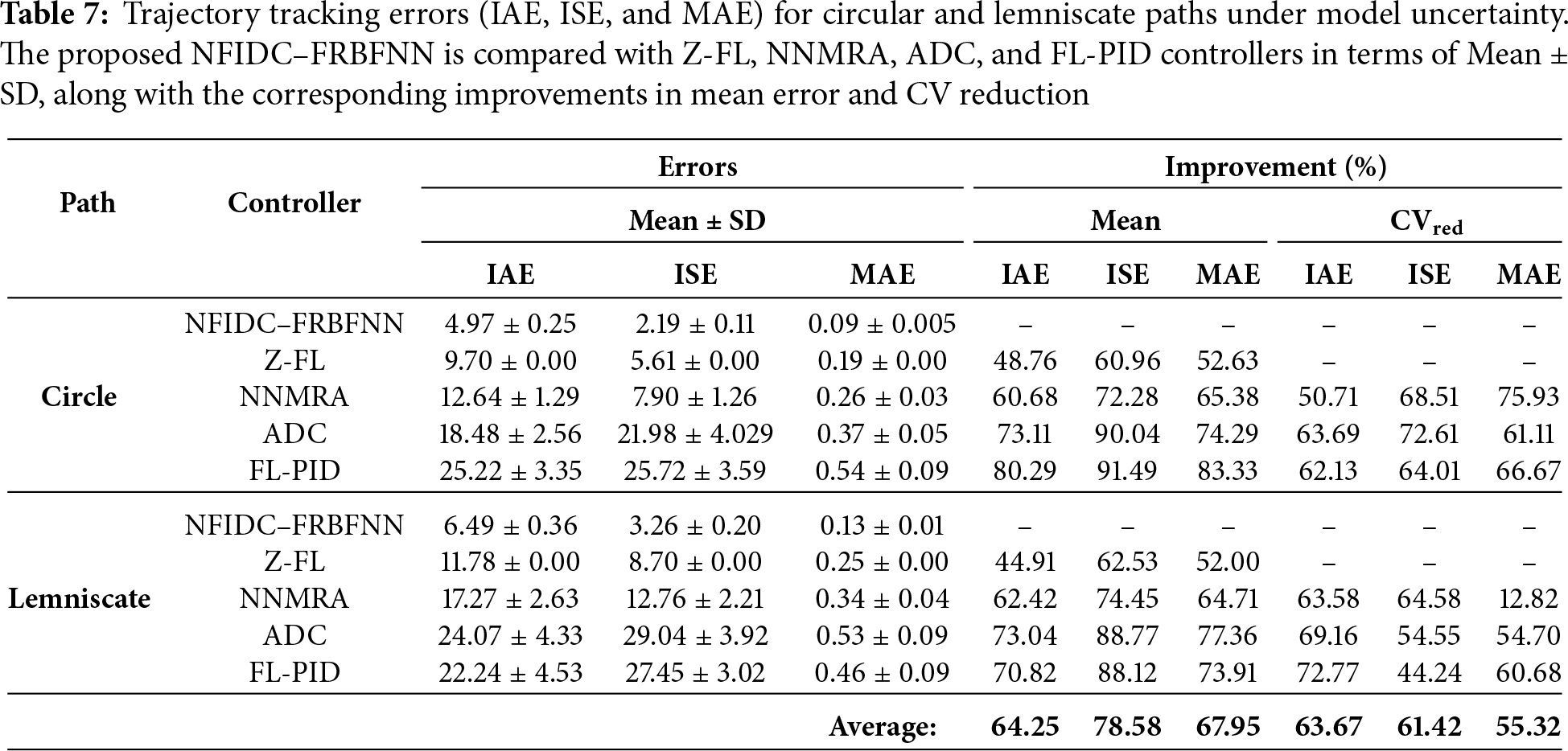

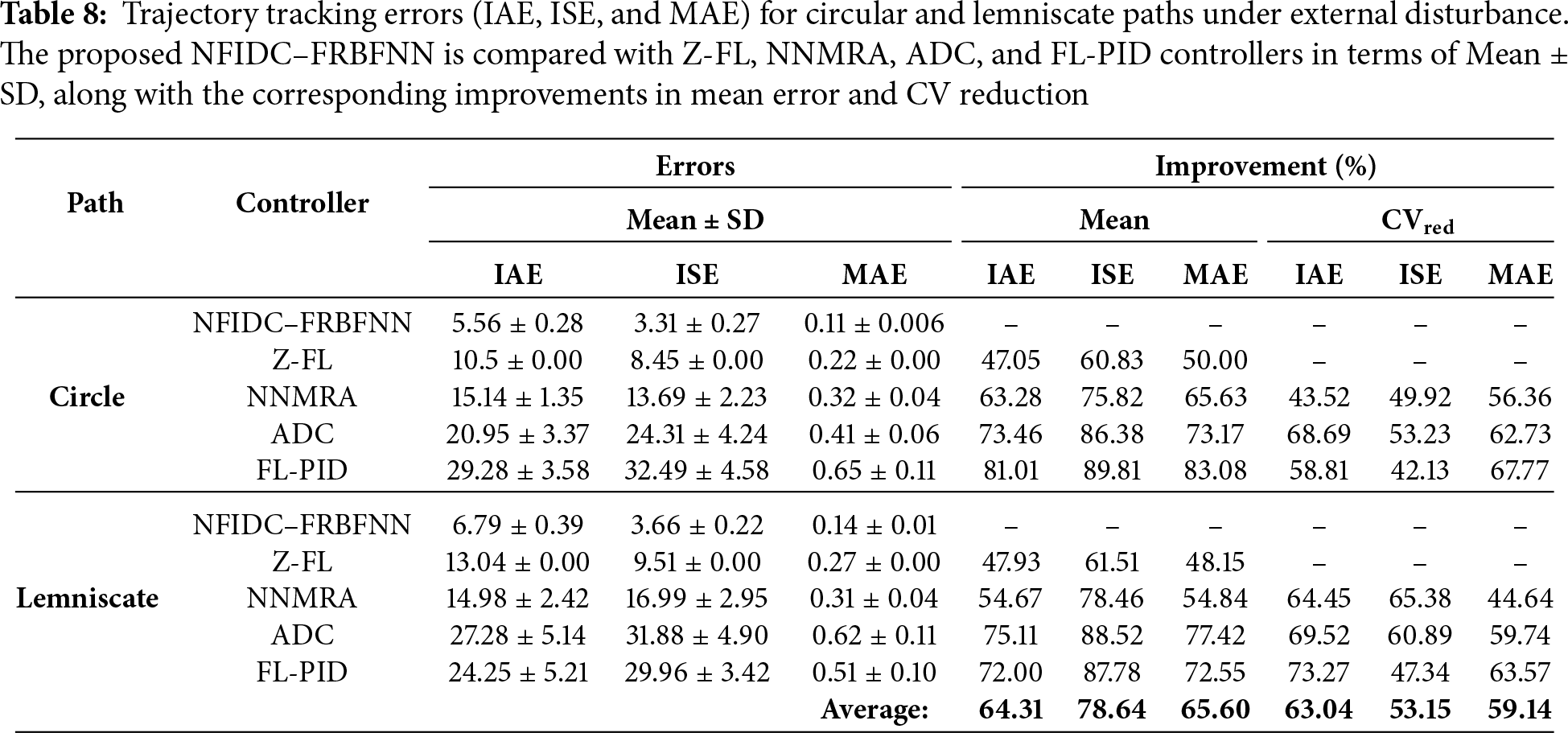

The trajectory profiles of the NFIDC–FRBFNN controller under non-ideal conditions specifically model uncertainty and external disturbances are illustrated in Fig. 29, while the quantitative results across 10 simulation runs are summarized in Tables 7 and 8, with their statistical distributions illustrated in Fig. 30. As seen in Fig. 29a,b, all controllers generally maintain acceptable tracking accuracy under model uncertainty. However, the proposed NFIDC–FRBFNN exhibits the closest adherence to the reference paths for both circular and lemniscate trajectories, demonstrating superior adaptation to the varying system dynamics. The ADC and FL-PID controllers show larger trajectory deviations and curvature overshoots, while the Z-FL and NNMRA controllers experience mild oscillations due to their fixed rule base and slower parameter convergence, respectively. Quantitatively, Table 7 indicates that the proposed controller achieves the lowest mean errors across all indices, with average improvements of 64.25% (IAE), 78.58% (ISE), and 67.95% (MAE). In addition, the CV reductions of 63.67% (IAE), 61.42% (ISE), and 55.32% (MAE) confirm that the NFIDC–FRBFNN maintains consistent performance even with parameter uncertainties.

Figure 29: Trajectory tracking comparison of the proposed NFIDC–FRBFNN controller with existing methods (Z-FL, NNMRA, ADC, FL-PID) under non-ideal conditions. Subfigures (a) and (b) illustrate the tracking performance under model uncertainty for circular and lemniscate paths, respectively, while subfigures (c) and (d) depict the results under external disturbances. The reference trajectory represents the desired path, and the plotted curves show the actual trajectories obtained using different controllers

Figure 30: Tracking error comparison of the proposed NFIDC–FRBFNN controller with existing methods (Z-FL, NNMRA, ADC, FL-PID) under non-ideal conditions. Subfigures (a,b) present the tracking errors for circular and lemniscate paths under model uncertainty, respectively, while subfigures (c,d) show the results under external disturbances. The bars represent the mean

Under external disturbances (Fig. 29c,d), the NFIDC–FRBFNN controller continues to demonstrate strong robustness, maintaining close adherence to the desired trajectories with minimal deviation. As summarized in Table 8, the proposed controller records average improvements of 64.31% (IAE), 78.64% (ISE), and 65.60% (MAE), alongside notable CV reductions between 53.15% and 63.04%, indicating strong disturbance rejection and stable adaptation. Consistent with the results under model uncertainty, the most substantial gains are observed in ISE, underscoring the controller’s effectiveness in minimizing cumulative tracking errors an essential capability for managing dynamic behaviors along complex paths like the lemniscate.

The bar charts in Fig. 30 further visualize these statistical results, where the NFIDC–FRBFNN consistently yields the lowest mean and SD values across all performance indices. The narrow error bars emphasize its robustness and repeatability under model uncertainties and external disturbances, validating the hybrid design’s effectiveness in maintaining both tracking accuracy and control stability. Overall, these findings confirm that the proposed NFIDC–FRBFNN controller achieves superior precision, smoothness, and robustness across both ideal and non-ideal conditions, significantly outperforming all comparative benchmark methods.

Table 9 summarizes the overall trajectory tracking improvements achieved by the proposed NFIDC–FRBFNN controller under both ideal and non-ideal conditions. Under ideal conditions, the controller attained average improvements of 55.24%, 75.75%, and 55.20% in IAE, ISE, and MAE, respectively, with corresponding CV reductions of 64.01%, 61.58%, and 55.63%. When subjected to non-ideal conditions involving model uncertainties and disturbances, both mean improvements and CV reductions remained consistently high—64.28%, 78.61%, and 66.78% for IAE, ISE, and MAE, respectively—while maintaining stability with CV reductions above 55%. The most prominent enhancement is observed in the

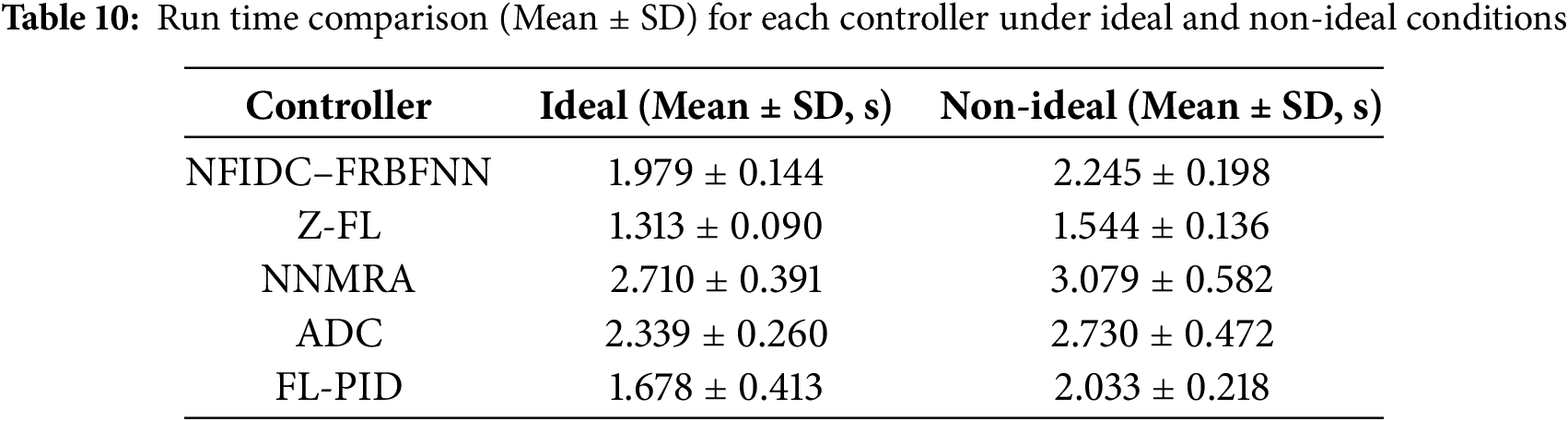

Table 10 presents the run-time comparison between the proposed and benchmark controllers under both ideal and non-ideal conditions. While the NFIDC–FRBFNN requires slightly longer computation time (1.979 s under ideal and 2.245 s under non-ideal conditions) compared to the simpler Z-FL and FL-PID controllers, its run time remains well within real-time operational limits for mobile robots. This marginal increase in computation cost is justified by its superior tracking precision, lower error variability, and enhanced robustness.

To further assess computational feasibility, the mean inference time per control cycle was evaluated in simulation for all controllers under both ideal and non-ideal conditions. The proposed NFIDC-FRBFNN achieved satisfactory computational efficiency, recording an average inference time of 39.58 ms (ideal) and 44.9 ms (non-ideal). In contrast, NNMRA (54.2 ms ideal, 61.58 ms non-ideal) and ADC (46.78 ms ideal, 54.6 ms non-ideal) exhibited higher inference delays due to their complex adaptive mechanisms. Meanwhile, the rule-based Z-FL (26.26 ms ideal, 30.88 ms non-ideal) and FL-PID (33.56 ms ideal, 40.66 ms non-ideal) produced faster responses but at the cost of reduced adaptability. Overall, the proposed controller demonstrates an effective balance among accuracy and computational efficiency, making it well-suited for real-time mobile robot trajectory tracking applications.

This paper presented a cognitive control strategy for MSRs operating in hospital environments by integrating NFIDC with a FRBFNN. The proposed NFIDC-FRBFNN architecture was designed to generate smooth and optimal torque control actions, enabling the MSR to follow desired trajectories with high precision, stability, and robustness under model uncertainties and external disturbances. A two-stage simulation-based evaluation validated the controller’s performance. In the first stage, the controller was tested in a realistic hospital environment under both ideal and non-ideal conditions. In the second stage, it was benchmarked against four established controllers—NNMRA, Z-FL, ADC, and FL-PID—using circular and lemniscate trajectories. The proposed controller consistently achieved the lowest tracking errors across all evaluated conditions.

Although the NFIDC-FRBFNN controller demonstrated promising results in simulation, several aspects remain to be addressed. The present study is limited to simulation, without formal closed-loop stability proofs or consideration of hardware-induced delays. Future work will therefore focus on (i) hardware-in-the-loop validation to capture actuator and sensor dynamics, (ii) deployment on a ROS2-based hospital mock-up for realistic testing, and (iii) pilot studies with quantitative benchmarks, such as maintaining a maximum lateral error below 5 cm at velocities of 0.6–0.8 m/s. In addition, a formal Lyapunov-based stability analysis will be developed by defining an appropriate tracking-error signal, constructing a mechanical-energy-type Lyapunov candidate function consistent with the robot’s nonlinear dynamics, and proving that its time derivative is negative semi-definite along system trajectories. Assuming the learning compensator yields a bounded approximation residual, convergence to a small invariant set, implying practical tracking with guaranteed closed-loop stability can be established using LaSalle’s invariance principle.

Future extensions will focus on multi-robot and real-world implementations. The NFIDC-FRBFNN framework will be adapted for collaborative MSR tasks involving trajectory overlap, coordination, and communication delays. Experimental validation on an actual MSR hardware platform will be conducted to evaluate robustness under dynamic obstacles, sensor noise, and system uncertainties. Energy efficiency will also be investigated to determine whether the hybrid controller’s performance gains introduce additional energy costs and how such effects can be mitigated through optimization. From an ethical and operational perspective, patient safety will remain paramount. Future implementations will also integrate higher-level safety mechanisms, including obstacle avoidance, collision prevention, and emergency stop protocols, while ensuring smooth human–robot interaction within clinical workflows.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank Al-Wasity Teaching Hospital, Baghdad, Iraq, for providing the facilities necessary for this study. They also wish to acknowledge the Ministry of Higher Education, Malaysia, and Universiti Sains Malaysia for their financial support of this project.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the Malaysia Ministry of Higher Education under Fundamental Research Grant Scheme with Project Code: FRGS/1/2024/TK07/USM/02/3.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization: Huda Talib Najm; Methodology: Huda Talib Najm; Formal analysis: Huda Talib Najm; Investigation: Huda Talib Najm, Nur Syazreen Ahmad; Project administration: Nur Syazreen Ahmad; Supervision: Ahmed Sabah Al-Araji, Nur Syazreen Ahmad; Funding acquisition: Huda Talib Najm, Nur Syazreen Ahmad; Writing—original draft: Huda Talib Najm; Writing—review & editing: Nur Syazreen Ahmad. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Rubio F, Valero F, Llopis-Albert C. A review of mobile robots: concepts, methods, theoretical framework, and applications. Int J Adv Robot Syst. 2019;16(2):1–22. doi:10.1177/1729881419839596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Lim WM, Jasim KM, Malathi A. Service robots in healthcare: toward a healthcare service robot acceptance model (SRAM). Technol Soc. 2025;82(8):102923. doi:10.1016/j.techsoc.2025.102932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Leong PY, Ahmad NS. Exploring autonomous load-carrying mobile robots in indoor settings: a comprehensive review. IEEE Access. 2024;12(1):131395–417. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3435689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Holland J, Kingston L, McCarthy C, Armstrong E, O’Dwyer P, Merz F, et al. Service robots in the healthcare sector. Robotics. 2021;10(1):47. doi:10.3390/robotics10010047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Medina L, Guerra G, Herrera M, Guevara L, Camacho O. Trajectory tracking for non-holonomic mobile robots: a comparison of sliding mode control approaches. Results Eng. 2024;22(2):102105. doi:10.1016/j.rineng.2024.102105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Wang X, Dou G, Chen T, Lu J. Improved robust model predictive trajectory tracking control for intelligent vehicles based on multi-cell hyperbody vertex modeling and double-layer optimization. Sensors. 2025;25(21):6537. doi:10.3390/s25216537. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Zhang JJ, Fang ZL, Zhang ZQ, Gao RZ, Zhang SB. Trajectory tracking control of nonholonomic wheeled mobile robots using model predictive control subjected to Lyapunov-based input constraints. Int J Control Autom Syst. 2022;20(5):1640–51. doi:10.1007/s12555-019-0814-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Jokar H, Serajgah SA. A nonsingular fast terminal sliding mode control scheme for robust trajectory tracking of the underactuated EvoBot modular mobile robot in the vertical plane. ISA Trans. 2025;165:83–97. doi:10.1016/j.isatra.2025.06.013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Qiang L, Tang HH, Ahmad NS. Improving trajectory tracking of differential wheeled mobile robots with enhanced GWO-optimized back-stepping and FOPID controllers. IEEE Access. 2025;13:48872–87. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2025.3552312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Martins FN, Celeste WC, Carelli R, Sarcinelli-Filho M, Bastos-Filho TF. An adaptive dynamic controller for autonomous mobile robot trajectory tracking. Control Eng Pract. 2008;16(11):1354–63. doi:10.1016/j.conengprac.2008.03.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Martins FN, Sarcinelli-Filho M, Carelli R. A velocity-based dynamic model and its properties for differential drive mobile robots. J Intell Robot Syst. 2017;85(2):277–92. doi:10.1007/s10846-016-0381-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Hassan N, Saleem A. Neural network-based adaptive controller for trajectory tracking of wheeled mobile robots. IEEE Access. 2022;10:13582–97. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3146970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Chen Y, Cheng C, Zhang Y, Li X, Sun L. A neural network-based navigation approach for autonomous mobile robot systems. Appl Sci. 2022;12(15):7796. doi:10.3390/app12157796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Wang G, Liu X, Zhao Y. Neural network-based adaptive motion control for a mobile robot with unknown longitudinal slipping. Chin J Mech Eng. 2019;32(1):61. doi:10.1186/s10033-019-0373-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Ha VT, Thuong TT. Neural-backstepping adaptive control for nonlinear motion of sliding mobile robots. Int J Mech Eng Robot Res. 2025;14(3):323–39. doi:10.18178/ijmerr.14.3.323-339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Tiep DK, Lee K, Im DY, Kwak B, Ryoo YJ. Design of fuzzy-PID controller for path tracking of mobile robot with differential drive. IJFIS. 2018;18(3):220–8. doi:10.5391/IJFIS.2018.18.3.220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Xu Q, Kan J, Chen S, Yan S. Fuzzy PID based trajectory tracking control of mobile robot and its simulation in simulink. Int J Control Autom Syst. 2014;7(8):233–44. doi:10.14257/ijca.2014.7.8.20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Abdelwahab M, Parque V, Elbab AMRF, Abouelsoud AA, Sugano S. Trajectory tracking of wheeled mobile robots using Z-number based fuzzy logic. IEEE Access. 2020;8:18426–41. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2968421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Wu X, Jin P, Zou T, Qi Z, Xiao H, Lou P. Backstepping trajectory tracking based on fuzzy sliding mode control for differential mobile robots. J Intell Robot Syst. 2019;96(1):109–21. doi:10.1007/s10846-019-00980-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Xu L, Du J, Song B, Cao M. A combined backstepping and fractional-order PID controller to trajectory tracking of mobile robots. Syst Sci Control Eng. 2022;10(1):134–41. doi:10.1080/21642583.2022.2047125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Tang HH, Ahmad NS. Enhanced fuzzy logic control for active suspension systems via hybrid water wave and particle swarm optimization. Int J Control Autom Syst. 2025;23(2):560–71. doi:10.1007/s12555-024-0513-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Rajwar K, Deep K, Das S. An exhaustive review of the metaheuristic algorithms for search and optimization: taxonomy, applications, and open challenges. Artif Intell Rev. 2023;56(11):13187–257. doi:10.1007/s10462-023-10470-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Sheikhsamad M, Puig V. Learning-based control of autonomous vehicles using an adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system and the linear matrix inequality approach. Sensors. 2024;24(8):2551. doi:10.3390/s24082551. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Alkabaa AS, Taylan O, Balubaid M, Zhang C, Mohammadzadeh A. A practical type-3 Fuzzy control for mobile robots: predictive and Boltzmann-based learning. Complex Intell Syst. 2023;9(6):6509–22. doi:10.1007/s40747-023-01086-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. de Jesús Rubio J, Garcia D, Sossa H, Garcia I, Zacarias A, Mujica-Vargas D. Energy processes prediction by a convolutional radial basis function network. Energy. 2023;284(1):128470. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2023.128470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Amirian M, Schwenker F. Radial basis function networks for convolutional neural networks to learn similarity distance metric and improve interpretability. IEEE Access. 2020;8:123087–97. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3007337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Mane DT, Kulkarni A, Pradhan B, Bade S, Gite S, Bidwe RV, et al. A novel fuzzy hypersphere neural network classifier using class specific clustering for robust pattern classification. IEEE Access. 2024;12(3):124209–19. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3454296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Sun L, Li S, Liu H, Sun C, Qi L, Su Z, et al. A brand-new simple, fast, and effective residual-based method for radial basis function neural networks training. IEEE Access. 2023;11:28977–91. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3260251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Tagliavini L, Colucci G, Botta A, Cavallone P, Baglieri L, Quaglia G. Wheeled mobile robots: state of the art overview and kinematic comparison among three omnidirectional locomotion strategies. J Intell Robot Syst. 2022;106(3):57. doi:10.1007/s10846-022-01745-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Savaee E, Hanzaki AR, Anabestani Y. Kinematic analysis and odometry-based navigation of an omnidirectional wheeled mobile robot on uneven surfaces. J Intell Robot Syst. 2023;108(2):13. doi:10.1007/s10846-023-01876-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Gao X, Zhang Y, Liu J, Li Z. Robust model predictive tracking control for the wheeled mobile robot with boundary uncertain based on linear matrix inequalities. IET Cyber-Syst Robot. 2023;5(1):12086. doi:10.1049/csy2.12086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Najm HT, Ahmad NS, Al-Araji AS. Enhanced path planning algorithm via hybrid WOA-PSO for differential wheeled mobile robots. Syst Sci Control Eng. 2024;12(1):2334301. doi:10.1080/21642583.2024.2334301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Yang Y, Wang P, Gao X. A novel radial basis function neural network with high generalization performance for nonlinear process modelling. Processes. 2022;10(1):140. doi:10.3390/pr10010140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Wurzberger F, Schwenker F. Learning in deep radial basis function networks. Entropy. 2024;26(5):368. doi:10.3390/e26050368. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools