Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Superpixel-Aware Transformer with Attention-Guided Boundary Refinement for Salient Object Detection

1 Department of Electrical and Electronics Engineering, Sakarya University, Sakarya, 54050, Türkiye

2 Department of Computer Engineering, Sakarya University, Sakarya, 54050, Türkiye

3 Department of Information Systems Engineering, Sakarya University, Sakarya, 54050, Türkiye

* Corresponding Author: Burhan Baraklı. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advanced Image Segmentation and Object Detection: Innovations, Challenges, and Applications)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2026, 146(1), 36 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.074292

Received 08 October 2025; Accepted 10 December 2025; Issue published 29 January 2026

Abstract

Salient object detection (SOD) models struggle to simultaneously preserve global structure, maintain sharp object boundaries, and sustain computational efficiency in complex scenes. In this study, we propose SPSALNet, a task-driven two-stage (macro–micro) architecture that restructures the SOD process around superpixel representations. In the proposed approach, a “split-and-enhance” principle, introduced to our knowledge for the first time in the SOD literature, hierarchically classifies superpixels and then applies targeted refinement only to ambiguous or error-prone regions. At the macro stage, the image is partitioned into content-adaptive superpixel regions, and each superpixel is represented by a high-dimensional region-level feature vector. These representations define a regional decomposition problem in which superpixels are assigned to three classes: background, object interior, and transition regions. Superpixel tokens interact with a global feature vector from a deep network backbone through a cross-attention module and are projected into an enriched embedding space that jointly encodes local topology and global context. At the micro stage, the model employs a U-Net-based refinement process that allocates computational resources only to ambiguous transition regions. The image and distance–similarity maps derived from superpixels are processed through a dual-encoder pathway. Subsequently, channel-aware fusion blocks adaptively combine information from these two sources, producing sharper and more stable object boundaries. Experimental results show that SPSALNet achieves high accuracy with lower computational cost compared to recent competing methods. On the PASCAL-S and DUT-OMRON datasets, SPSALNet exhibits a clear performance advantage across all key metrics, and it ranks first on accuracy-oriented measures on HKU-IS. On the challenging DUT-OMRON benchmark, SPSALNet reaches a MAE of 0.034. Across all datasets, it preserves object boundaries and regional structure in a stable and competitive manner.Keywords

Identifying the most salient objects in an image is called Salient Object Detection (SOD) [1,2]. Methods developed for this purpose aim to separate the background region of an image from the foreground object using a saliency map. This map typically highlights visually important regions and is often used for masking operations in various visual data processing tasks. It has also been widely applied in tasks such as object recognition [3,4], segmentation [5], compression [6], classification [7], object tracking [8], content cropping [9], resizing [10], and object detection [11,12].

SOD methods play significant roles in many areas beyond traditional computer vision tasks. For example, in underwater imaging and autonomous underwater robotics, highlighting meaningful regions under low contrast and spectral distortion enhances object detection, navigation, and mapping processes [13]. Saliency-guided feature extraction is important in remote sensing applications, as it reduces shadow-induced false positives and improves change detection accuracy by highlighting critical change regions in difference maps [14]. The importance and use of saliency analysis in medical imaging applications is steadily increasing. Developed approaches aim to make ambiguous tissue boundaries more distinct and highlight small structures and lesions. Additionally, the goal is to preserve the structural integrity of the image and significantly improve segmentation accuracy [15,16]. In visible-infrared transmission line inspection, saliency-based attention mechanisms that highlight thin and low-contrast structures facilitate the detection of fault areas [17]. In intelligent transportation and autonomous driving, SOD enhances the reliability of perception modules by prioritizing vulnerable road users even under low visibility conditions [18]. Furthermore, in road defect detection studies (such as potholes and cracks), saliency models serve as a critical pre-attention component in highlighting both linear, delicate structures and multi-scale deformations [19]. These applications demonstrate that SOD is an effective and general-purpose tool for identifying structurally and semantically important regions across multiple modalities.

Existing SOD methods can be divided into two main groups: traditional and deep learning-based approaches. Heuristic and statistical approaches extracting low-level features such as color, intensity, contrast, texture, and location from visual data are examples of traditional methods [20–24]. These methods have a low computational cost. However, they are outdated and often provide inadequate performance [1,2,25]. Deep learning-based methods that overcome the weaknesses of traditional methods have been developed in four main categories: fully supervised [26–30], weakly supervised [31,32], unsupervised [33,34] and adversarial [35,36].

Recent advances in deep learning-based SOD models have greatly improved performance. However, several key limitations still affect the accuracy and practicality of saliency maps. In particular, the inability to preserve high-level semantic information, insufficient integration of contextual relationships across layers, difficulties in simultaneously detecting objects of varying scales, lack of saturation at object edges, and the generation of blurry contours remain unresolved in existing models. The challenge of accurately detecting thin and detailed edge regions, the limitations of attention mechanisms in ambiguous transition areas, and the high computational load (especially problematic for mobile or real-time applications) are other issues requiring attention. Moreover, Convolutional Neural Network (CNN)- and Transformer-based methods still operate either on pixel grids or regular patch sequences, lacking explicit modeling of region topology. When superpixels are used, they typically serve only as auxiliary masks rather than as primary representational units. As a result, long-range dependencies are learned without awareness of object boundaries, and transition regions are handled only implicitly, which leads to inconsistent contour modeling and ambiguous boundary responses. Studies addressing these challenges are summarized below.

In early studies, multi-context Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) that evaluate global and local context were used and effective results were obtained [37]. However, CNN-based models cannot fully extract global contextual information due to their limited receptive fields [1]. For example, while Fully Convolutional Network (FCN)-based methods such as PiCANet [38] and BASNet [29] provide strong local feature extraction, they are insufficient in modeling long-range dependencies and can produce incorrect saliency maps in complex images. In recent studies, various methods have been developed to use global context information more effectively. For example, large receptive-field modules have been designed in ICON [39] and BBRF [40]. In addition, CGDINet [41] and CFFNet [42], hybrid networks combining CNN and Transformer architectures, have effectively performed wide-area perspective modeling.

The ability of a model to integrate contextual relationships across different layers while preserving high-level semantic information contributes to accurate object discrimination in complex scenes [1]. To achieve this, Feature Pyramid Network (FPN)-based structures [43] and attention modules (such as CBAM and SENet) have been widely adopted to combine multi-level features and enrich context [38,44]. However, these methods often compromise semantic integrity due to direct feature aggregation, which can weaken high-level representations. Approaches that maintain channel-level coherence and guide information flows more effectively across layers further enhance semantic consistency [39,42].

One challenge in SOD is the simultaneous and accurate detection of objects at varying scales. Transformer-based methods effectively capture global context and long-range dependencies but often struggle to detect small objects. In contrast, CNN-based models generally perform better in detecting small objects [45,46]. In order to benefit from the advantages of these approaches, CGDINet [41] proposed the Depth Auxiliary Module (DAM) structure that aims to represent details better at different scales by using depth information and multi-channel images. Similarly, BBRF [40] provided a balanced representation by processing deep semantic and high-resolution detail information over separate branches. MENet [47], which uses the iterative feature enhancement strategy, reduced the performance imbalances in multi-scale object segmentation.

The lack of saturation and blurry borders that occur at object edges are the most important problems in the SOD field [48–50]. Edge-supervised methods such as SCRN [51] and EGNet [52] have limited edge information learning as they only rely on pre-generated fine edge labels in model training. ICON [39] has developed a learning approach to preserve edge sharpness and internal structural integrity in saliency maps. Transformer-based UGRAN [53] finds regions of low model confidence using uncertainty maps and implements adaptive refinement especially in edge areas. DC-Net [54] reduces blurry contours by learning edge and object regions with two separate encoders and combining them in a fuse-decoder structure. PiNet [55] processes multi-level features in separate branches reducing the erroneous highlighting of unremarkable regions and loss of internal details. OLER [56] enriches boundary representation and increases edge sensitivity using thin and thick edge maps.

The growing use of mobile and embedded systems has driven the need for lightweight and efficient SOD models. ICON [39] and BBRF [40] models are unsuitable for practical applications due to their high computational costs. ICON incorporates complex mechanisms such as multi-layer attention calculations and directed information flow to preserve overall structural integrity and fine details. BBRF uses a dual-branch encoder structure that includes iterative decision paths. Such complex structures in both methods incur additional costs in terms of memory usage, limiting their usability in resource-constrained applications. Lightweight convolutional structures reducing computational load cause performance losses due to their limited representation capacity [57]. With 0.84 million parameters, ADMNet [58] offers an architecture that integrates multi-scale contextual features with densely connected modules and includes two-stage attention mechanisms, providing real-time processing capabilities while maintaining high accuracy. However, performance degradation in terms of structural consistency is observed, particularly when it is applied to images containing multiple objects or low contrast scenes. A complementary lightweight adversarial model [59] further enhances spatial consistency by combining adversarial refinement with a multi-scale contrast module, achieving competitive accuracy with significantly reduced computational overhead.

To address the limitations outlined above, a holistic macro- and micro-level salient object detection framework is proposed that explicitly exploits superpixel (SP) structure. The overall design aims to preserve global scene information while performing detail-oriented boundary refinement. At the macro stage, a Transformer-based SP classification module processes content-adaptive SP representations and partitions the image into background, salient object, and boundary regions. At the micro stage, a lightweight U-Net-like refinement module focuses solely on uncertain edge areas, thereby concentrating computational resources on the most ambiguous regions and improving the efficiency of the learning process.

With the emergence of deep learning, the use of traditional SOD approaches based solely on handcrafted features has declined significantly. Nevertheless, the explainability, computational efficiency, and semantically meaningful separation capabilities of such features still hold significant potential. Hybrid strategies that combine classical feature-based analysis and deep representations are particularly effective in exploiting this potential [57]. In the proposed framework, various statistical, structural, and color-based descriptors computed over SP regions are first aggregated into compact feature vectors. These vectors are then projected into a deep embedding space and used as SP tokens, preserving the interpretability of traditional features while providing information-rich yet compact representations that strengthen regional discrimination. The resulting tokens guide the Transformer-based SP classifier, especially in contour-intensive areas, encouraging attention mechanisms to focus on perceptually meaningful regions and facilitating more effective learning of long-range correlations.

At the macro level, images are divided into content-consistent SP regions that are subsequently classified into three categories: background, salient object, and boundary. Each region is described by semantic feature vectors, including color distributions, edge densities, frequency components, geometric structures, and neighborhood contrasts. These representations are used directly as tokens in the Transformer encoder and offer advantages in terms of computational efficiency and regional consistency compared to grid-based patch segmentations commonly used in the literature. In parallel, a ResNet-18 backbone extracts deep convolutional features, which are queried by the SP tokens through an SP–CNN cross-attention module so that each SP selectively aggregates fine-grained semantic cues from the feature map. The refined SP tokens are combined with a global context token obtained by pooling CNN features and fed into a graph-aware Transformer encoder, where adjacency relationships and pairwise spatial distances between SPs are injected into the attention logits via a learnable bias term. By taking the SP topology into account, the model reduces information loss and scale mismatch, allowing the attention module to utilize local SP features, CNN features, and global context jointly and more effectively.

Following the macro level, a micro model comes into play that focuses only on the SPs at the edge contours of the salient object. This model performs a focused refinement process that responds only to specific regions by processing the input image and SP-based contextual distance maps in two separate encoder branches. The micro model utilizes a U-Net-like architecture, facilitating the hierarchical extraction and reconstruction of features across multiple levels.

Each encoder uses the attention-based Squeeze-and-Excitation-Fusion (SEFuse) mechanism, which combines image features and SP information streams meaningfully by weighting different feature maps at the channel level. During the compression step, the statistical summary of each channel is extracted while the excitation step learns the inter-channel contextual relationships to highlight prominent information. This enables the relative importance of information from different sources to be learned at each encoder stage, resulting in more consistent and semantically rich representations. This provides a holistic learning process supporting detail accuracy and semantic continuity. Additionally, by focusing only on transition areas based on edge SP regions, the model’s sensitivity to unnecessary areas is reduced.

As a result, the proposed system not only integrates global and local contexts successfully but also offers a clear architecture that processes visual and structural information at every level, carefully executes boundary-focused detail enhancements, and maintains parameter efficiency.

This study offers the following original contributions:

• It is the first SOD framework that treats SPs as the primary representational units by encoding each SP into a multi-dimensional feature vector and using these vectors directly as tokens in a Transformer encoder.

• A dedicated SP–CNN cross-attention module is introduced, enabling each SP token to selectively aggregate fine-grained semantic cues from CNN features and improving macro-level semantic consistency.

• A graph-aware Transformer encoder is proposed, where SP adjacency and spatial distances are encoded as a learnable bias added to the attention logits, enforcing boundary continuity and structure-aware information propagation.

• A boundary-focused micro refinement stage is developed using a dual-branch U-Net that processes both raw image content and SP-based contextual distance maps. The proposed SEFuse module adaptively combines these streams at each level.

• An SP-aware edge loss is designed by computing the loss only over SPs located in salient-region boundaries, reducing unnecessary gradient propagation and improving training efficiency.

• The architecture is modular and flexible: the macro SPSeg stage can operate independently for fast inference, while the full macro–micro pipeline achieves superior accuracy–complexity balance suitable for practical applications.

• Extensive experiments on five public SOD benchmarks demonstrate that the proposed method achieves state-of-the-art or superior performance compared to recent Transformer- and CNN-based models, while maintaining a favorable balance between accuracy, parameter count, and computational cost.

The study is organized as follows. Section 2 comprehensively discusses existing SOD approaches. Section 3 explains the proposed method in detail. In Section 4, the effectiveness and performance of the proposed model are demonstrated through experimental analyses conducted on various data sets, comparisons with existing methods, and numerous ablation studies.

In recent years, numerous methods for SOD have been developed, yielding effective results across various datasets. Most contemporary SOD approaches follow a two-stage processing architecture: the first stage captures the global context while the second stage focuses on making detailed refinements in local regions.

Integrating SP representations with deep learning-based methods is an effective strategy for improving semantic consistency and structural accuracy. Approaches that evaluate features extracted by deep learning at the SP level offer advantages in learning with limited data, edge sensitivity, and explainability. For example, in the SuperCNN [60] method, each SP is normalized along with its contextual environment and fed into the CNN as input, directly estimating saliency probabilities at the SP level. In another study, a coarse saliency map of the scene is first extracted using a VGG16-based FCN, and then the map is aligned with SLIC SP regions and refined in detail using local CNN modules [61]. Additionally, it was proposed to model foreground and background probabilities at the SP level by fusing semantic features with classical visual features such as color, texture, and intensity [57].

In new approaches based on Transformer architectures using SPs, SP regions have been introduced to interact with attention mechanisms. A local–global token interaction strategy has been proposed to improve regional consistency and enhance long-range modeling [62]. In multimodal settings, SP representations have also been employed in visual–language alignment to provide semantically coherent region-level cues for pre-trained models [63]. More recently, CCTNet [64] utilized SP maps to guide attention toward delicate structures, where SPs act as auxiliary masks that modulate feature dependencies. Unlike these attention-guided formulations, our method treats SPs as the fundamental token units of the Transformer: each SP is encoded as a semantic region-level feature vector and fed directly into the Transformer encoder, effectively replacing the conventional grid-based patch embedding with a content-adaptive tokenization strategy.

SPs are used in collaboration with traditional methods to model low-contrast images. Multi-scale SP segmentation allows regional contrast, center priors, and integrity criteria to be extracted at every scale. The criteria obtained are probabilistically combined to calculate the saliency probability of each region [65]. Supporting these structures with attention maps has provided balanced results especially in regions with weak contrast and scattered objects [66]. In the SPCont [67] method, high-edge-sensitivity maps are produced by evaluating the contrast relationship between each SP’s local neighbors and the scene-wide context. In another study, SP scales are also modeled as graph layers. In each layer, the saliency of the foreground and background are calculated separately using manifold ranking, and the global context is utilized in an integrated manner through inter-layer information flow [68].

SP-based traditional learning approaches offer advantages, particularly in terms of explainability and low data requirements. For example, an adaptive metric learning-based method can semantically distinguish between foreground and background regions by learning the distance relationship between SP pairs [69]. The HDHF (Hybrid Deep and Handcrafted Features) method [70] combines multi-scale CNN features with classical features to create hybrid SP representations, which are then classified using the random forest method and converted into saliency maps.

2.2 Deep Learning-Based Methods

In deep learning-based SOD methods, in addition to high prediction accuracy, contextual information modeling, structural consistency, and uncertainty management are also targeted. Current methods use different design strategies to extract semantic integrity and structural details in the saliency map. These methods are commonly grouped into three main categories: multi-scale approaches that integrate hierarchical features, boundary-focused methods that preserve object contours and structural consistency, and uncertainty-guided strategies that refine ambiguous regions. Beyond RGB-only formulations, a growing body of work investigates multimodal SOD by incorporating auxiliary modalities such as depth or thermal infrared. These multimodal approaches aim to improve robustness under low illumination, cluttered backgrounds, or weak texture conditions by leveraging cross-modal complementarity. The following subsections summarize these existing methods in detail.

2.2.1 Multi-Scale & Feature-Level Methods

This group of methods aims to produce powerful saliency representations by effectively integrating multi-level and multi-scale features obtained from different layers. For example, in PoolNet [71], context information is condensed through pooling, while edge details are enhanced in auxiliary branches. Similarly, in the MiNet [72] model, features at different scales are combined through mutual interaction modules to reduce regional inconsistencies.

In recent years, several transformer-based methods have emerged that effectively highlight global context. One noteworthy example is the GateNet-RGB model [73], which enhances context correction in low-confidence areas by incorporating supervised side branches into the Transformer’s encoder architecture. Similarly, another approach detailed in [74] combines the local detail-capturing capabilities of CNNs with the global context extraction strengths of transformers. More recently, GLSTR [75] adopts a pure transformer encoder with a densely connected decoder, enabling joint global–local representation learning across layers while reducing redundancy and improving spatial precision.

Focusing on the comprehensive integration of multi-level features, the new generation model Multi-scale Feature Enhancement [76] processes local and global contexts together with inter-layer interactions based on VGG16. FLICSP [77] aims to separate ambiguous features in complex content using deep CNNs and multi-feature fusion. MDFANet [78] enhances sensitivity in small objects by emphasizing salient regions with contextual attention mechanisms and edge-based structural discrimination. DC-Net [54] achieves wider receptive fields more efficiently with a two-level parallel encoder structure.

In recent studies, multi-scale modeling has been further strengthened through more adaptive and structurally flexible feature integration strategies. GPONet [79] enhances multi-level fusion with gated units that selectively transmit informative features while suppressing noise, improving stability in scenes requiring a balance between fine details and global semantics. NASAL [80] approaches the problem from an architectural perspective by introducing a U-shaped neural architecture search space that automatically discovers scale-aware encoder–decoder designs, demonstrating that multi-scale integration can also be optimized through automated search. Decoder-side refinements have also gained attention. SalFAU-Net [81] strengthens cross-scale coherence by combining intermediate saliency predictions through dedicated fusion modules within each decoder stage. Meanwhile, SODAWideNet++ [82] expands receptive fields using a hybrid design that couples dilated convolutions with attention-based long-range feature extraction, enabling effective global–local representation learning without relying on classification backbones.

2.2.2 Boundary & Structural Integrity Methods

The methods in this category focus on preserving object boundaries and ensuring internal structural integrity. BASNet [29], which increases detail quality using residual feature transfer and hybrid losses, is the first method in this class. Later, PiCANet [38] produced more accurate boundaries using attention structures that account for local and global contexts at the pixel level. In addition, R3Net [83], which reduces the difference between predictions and labels with iterative learning, was developed.

Part-whole relationships are modeled in TSPOANet [84] to ensure structural integrity. Building on this idea, TCGNet [85] integrates contrast cues from CNNs with part–whole relational semantics from Capsule Networks, using correlation matrices to guide their interaction and enhance object completeness in structurally complex regions. GCPANet [86] was developed to integrate semantic, detailed, and contextual information with roaming module structures and to increase consistency in multi-object scenes. The F3Net [50] method utilizes feature fusion and a feedback decoder structure. In addition, object boundaries are improved by using loss functions sensitive to pixel positions. SCRN [51] improves the boundaries with cross-task learning, and LDF [87] reduces the blurring in the boundary regions with label decomposition. Recent studies have also revisited boundary refinement under challenging conditions. DASOD [88] addresses low-contrast, cluttered, and partially occluded regions by generating coarse body masks and refining them with detail cues, resulting in more reliable boundary preservation in structurally ambiguous areas.

2.2.3 Uncertainty-Guided Learning Methods

The methods in this category have been developed to prevent overconfident estimations in salient object detection. The learning process is guided by identifying regions where the model is uncertain. UGRAN [53] improved uncertain areas using adaptive segmentation mechanisms and multi-level attention modules. Similarly, UDNet [89] reduced boundary ambiguities by modeling internal and external contour information in separate layers. RCSBNet [90] is one of the most remarkable methods in this class. It improves structural consistency in uncertain regions and accuracy in low-confidence regions with its recursive CNN architecture and contour-saliency blending module.

2.2.4 Multimodal SOD Methods (RGB-D/RGB-T)

Multimodal SOD extends RGB-based detection by incorporating depth (RGB-D) or thermal infrared (RGB-T) cues to improve robustness under low illumination, cluttered backgrounds, and regions with weak texture. In RGB-D studies, cross-modal and cross-level fusion is commonly employed to combine geometric depth structure with RGB appearance features [91]. At the same time, hybrid Transformer–CNN designs further strengthen multi-scale correspondence and structural reasoning [92]. Representative examples such as CCAFNet [93], which integrates crossflow and scale-adaptive fusion, demonstrate the effectiveness of depth-guided refinement in improving localization and boundary completeness. RGB-T methods, reviewed comprehensively in recent surveys [94], focus on leveraging the complementary behavior of visible and thermal signals through correlation learning, modality-consistent fusion, and illumination-invariant feature extraction. The alignment-free progressive correlation network [95] avoids pixel-level registration by modeling cross-modal relations directly, while ECFFNet [96] and WaveNet [97] enhance thermal–visible integration using consistency-driven fusion blocks and wavelet-domain knowledge distillation.

3 The Proposed Algorithm—SPSALNet

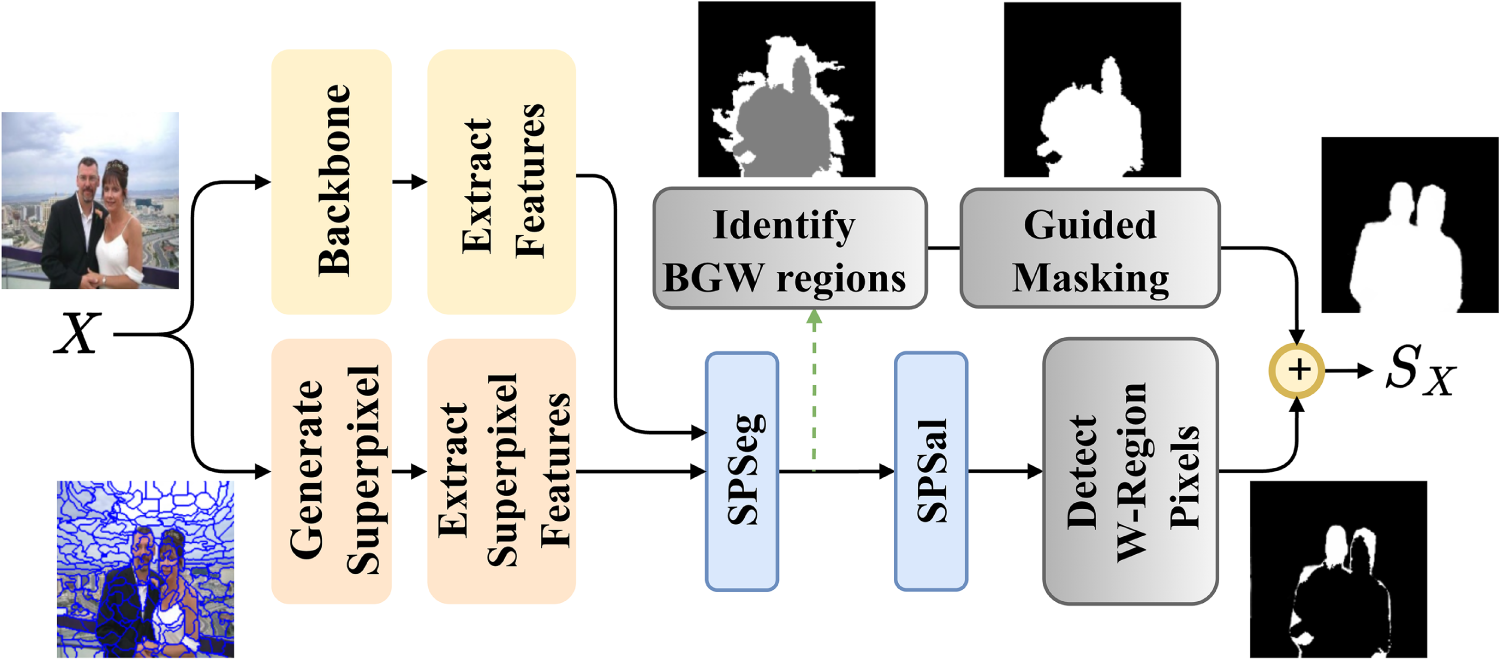

The proposed method whose block diagram is shown in Fig. 1 comprises two models. The first model called Superpixel Segmentation (SPSeg) performs SP classification. It uses a transformer-based approach that incorporates general image features, SP-level features, and the contextual relationships among SP to separate them into three groups: background, salient region, and salient object boundary region. The second model named SP-based Saliency Detection (SPSal) focuses on the pixels of the SP in the salient object boundary region identified in the SPSeg step. Its primary goal is to determine the local saliency status of these pixels using a U-Net-based approach with the attention mechanisms.

Figure 1: Block diagram for SPSALNet. X is the input image. Black (B), White (W), and Gray (G) regions are assumed to have labels

The background and salient region information provided by SPSeg is combined with the pixel-level salient object boundary information produced by SPSal to achieve clear separation between the salient object and the background. Each model uses different features to represent a SP.

3.1 SPSeg: Superpixel Segmentation & Classification

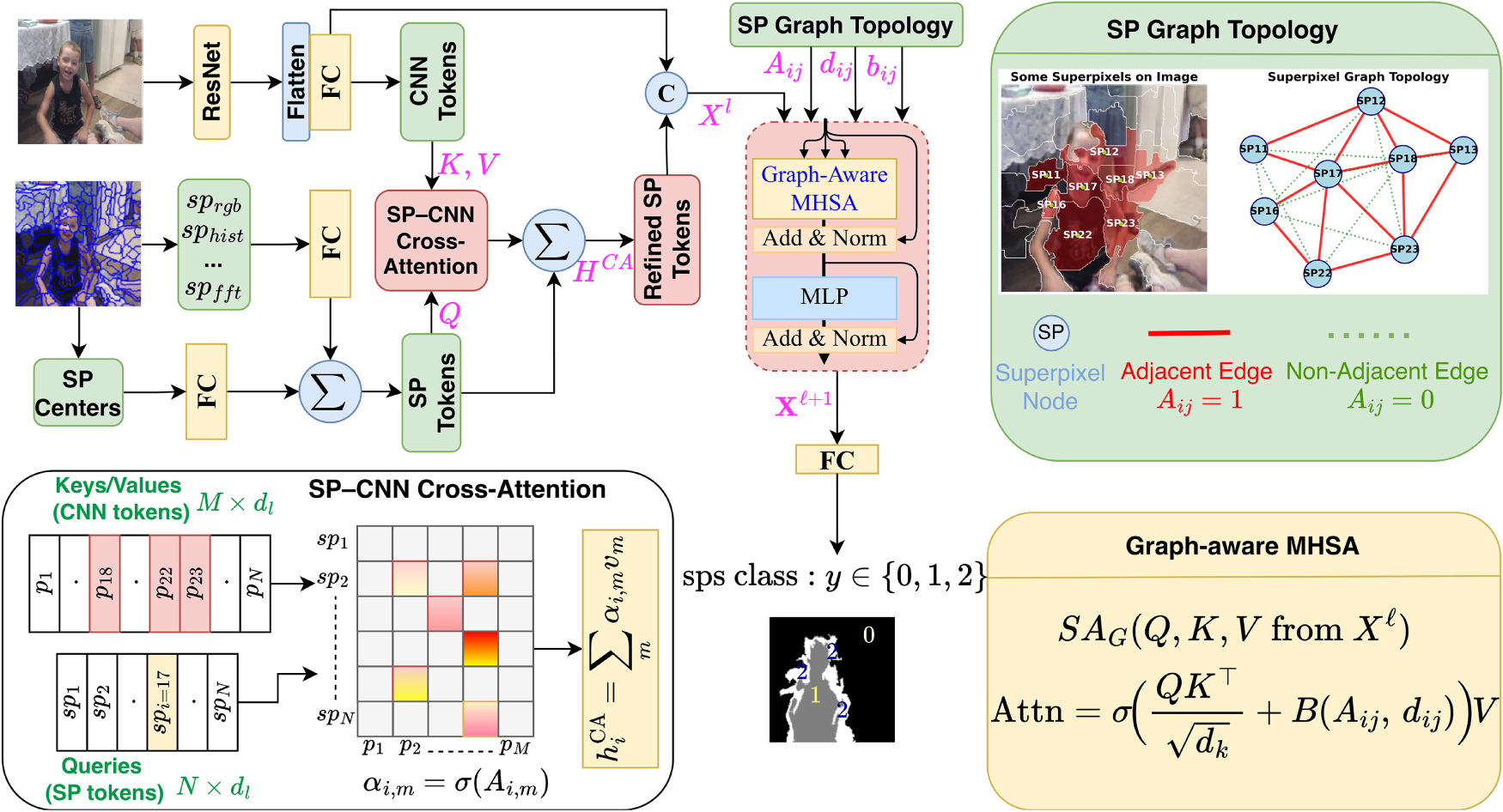

As illustrated in Fig. 2, the proposed SPSeg architecture introduces a novel SP-based transformer framework that synergistically fuses deep semantic features with hand-crafted structural representations. The workflow processes the input image through two parallel streams: a ResNet backbone extracting high-level CNN tokens and a SP generation module deriving feature-rich SP tokens. To bridge the semantic gap between these representations, we introduce a SP-CNN Cross-Attention mechanism, allowing SP nodes to selectively attend to fine-grained CNN details. Subsequently, a Graph-Aware Transformer Encoder processes the refined representations by explicitly incorporating the spatial topology—defined by adjacency

Figure 2: Detailed illustration of the SPSeg architecture. CNN-derived pixel tokens and SP-derived feature tokens are projected into a shared embedding space and fused through the proposed SP–CNN cross-attention mechanism. This module enables each SP token to selectively attend to the most informative CNN tokens, forming refined representations

Let

The transformer model

where the set of SPs whose predicted class is

In Fig. 2, SP sets

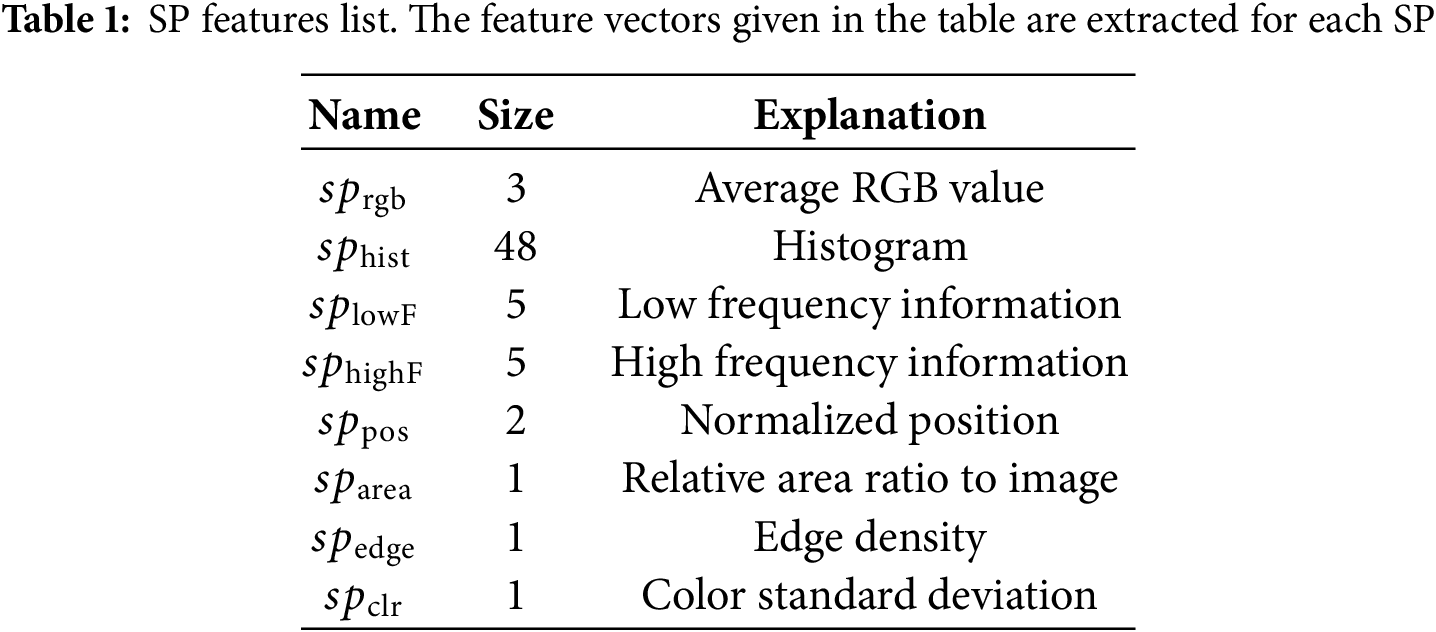

In the SPSeg model, both SP features and image features are jointly used. Each SP has an F-dimensional feature vector defined by Eq. (2) (see also Table 1).

The feature vector

The

To capture both global context and fine-grained visual cues, the input image

where

A global feature vector

In traditional transformer architectures, processing sequential information requires encoding the position of each element explicitly. In the proposed model, a learnable positional encoding mechanism is used to preserve the positional relationships of SP tokens. The 2-D center coordinates (

SP–CNN cross-attention: The SP tokens

Given

where

The cross-attention response of the

where the similarity matrix

After concatenating all heads and applying the output projection, we obtain the cross-attention output

Graph-aware transformer encoder:

The sequence

To explicitly model the SP graph, we incorporate an attention bias that depends on the adjacency and spatial distance between SPs. Let

The bias term

The outputs of the

Thus, the proposed graph-aware encoder preserves the standard transformer structure, but the SA operation is explicitly biased according to the SP graph topology. This design enables information propagation predominantly along meaningful SP neighborhoods and improves boundary consistency and structure-aware aggregation in the SPSeg stage.

Let

where

Following classification, the SP sets (

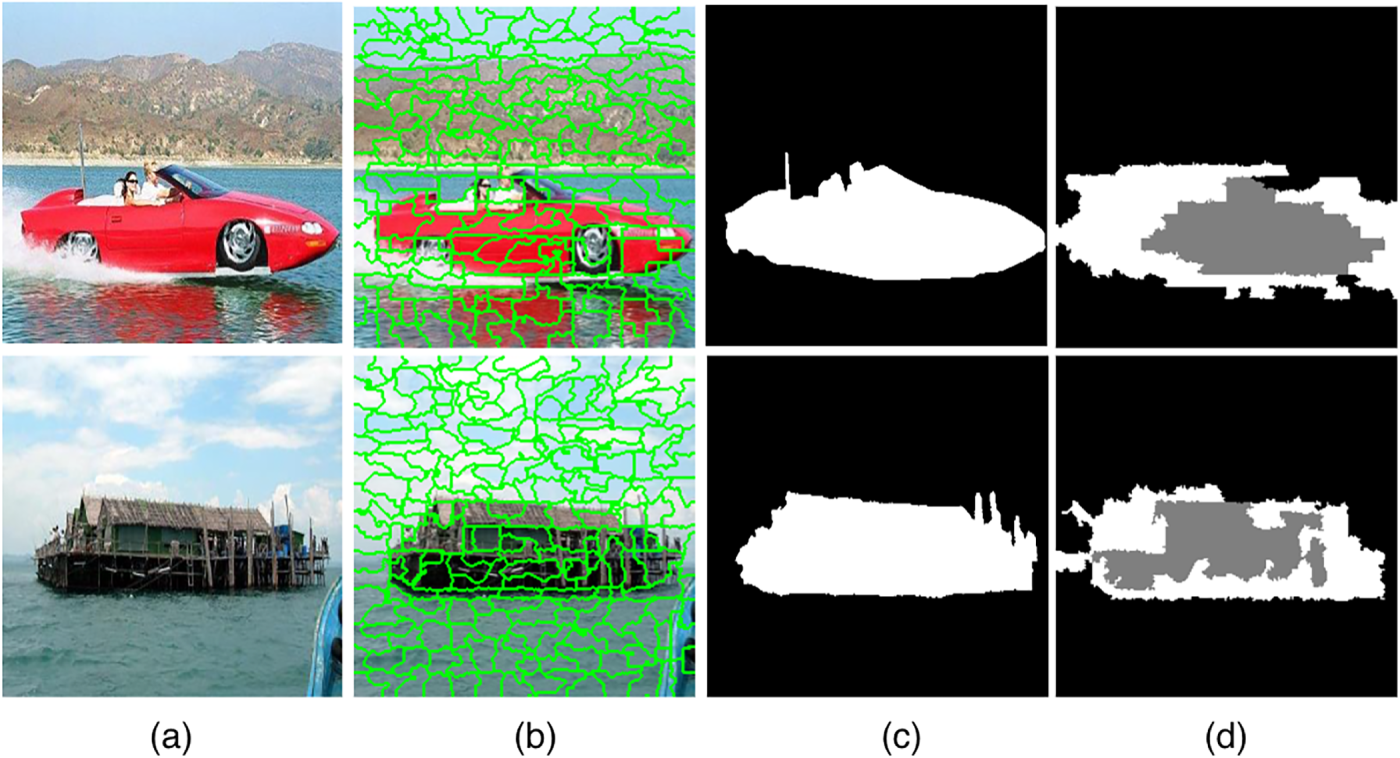

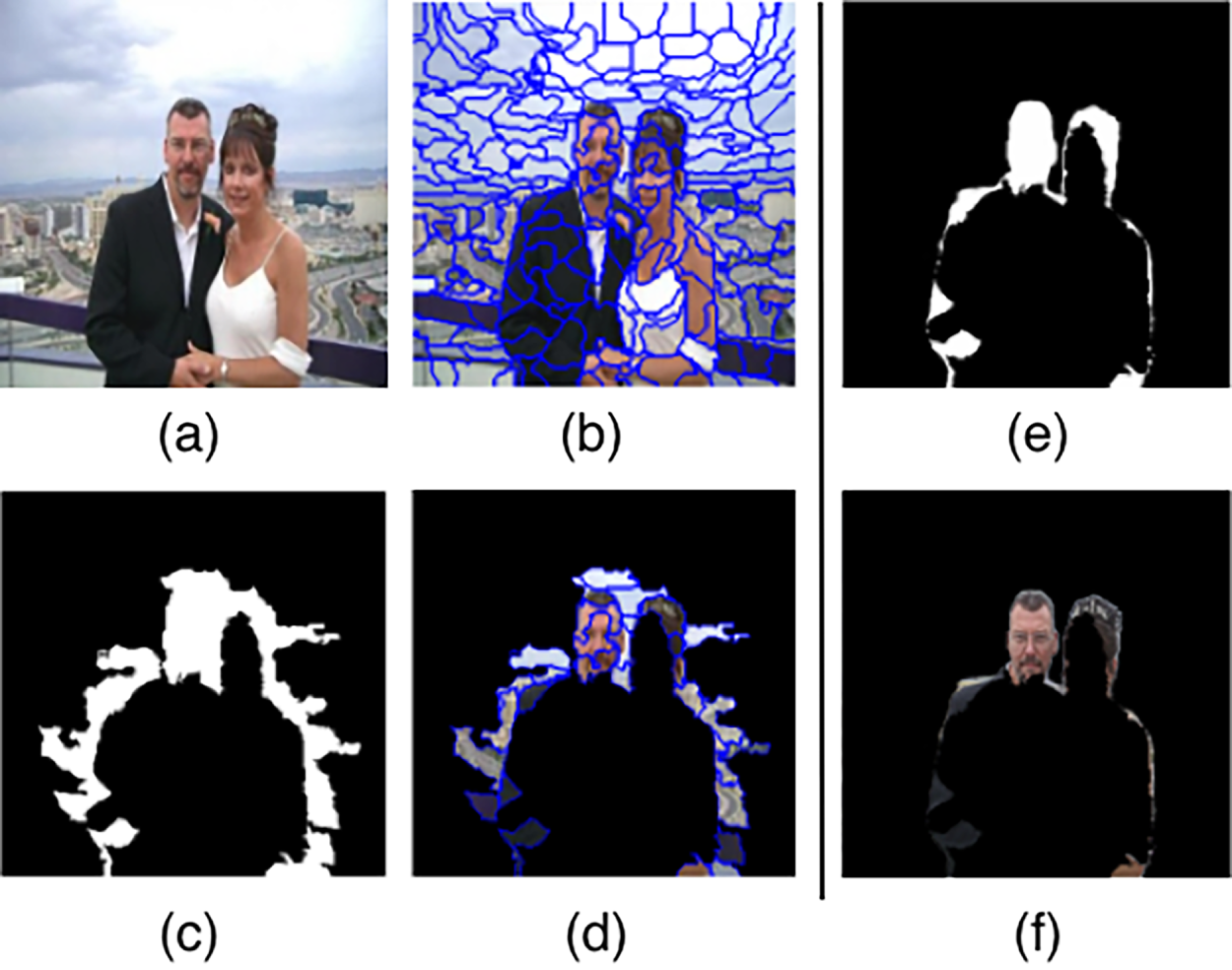

Figure 3: Classification results for the SPSeg structure. (a) Original image, (b) SP boundaries, (c) ground truth mask, and (d) representation of the region formed by the SP sets (

In summary, the estimated

3.2 SPSal (Superpixel-Based Salient Detection)

In the SPSeg stage, a coarse saliency map is generated at the SP level. The accuracy of this map improves as the number of SPs increases. However, a higher number of SPs makes region selection more challenging for the SP algorithms and increases the model’s processing load. In addition, boundary areas must be assessed separately in all cases. To handle this, the SPSal model (

Each pixel

The SPSal model is based on a U-Net architecture enhanced with SA modules, as illustrated in Fig. 4. Similar to SPSeg, it adopts a dual-input design that utilizes both masked images and SP features. However, unlike SPSeg, only spatial and color features are utilized in this stage. Spatial features are extracted at the pixel level, while color features are aggregated at the SP level.

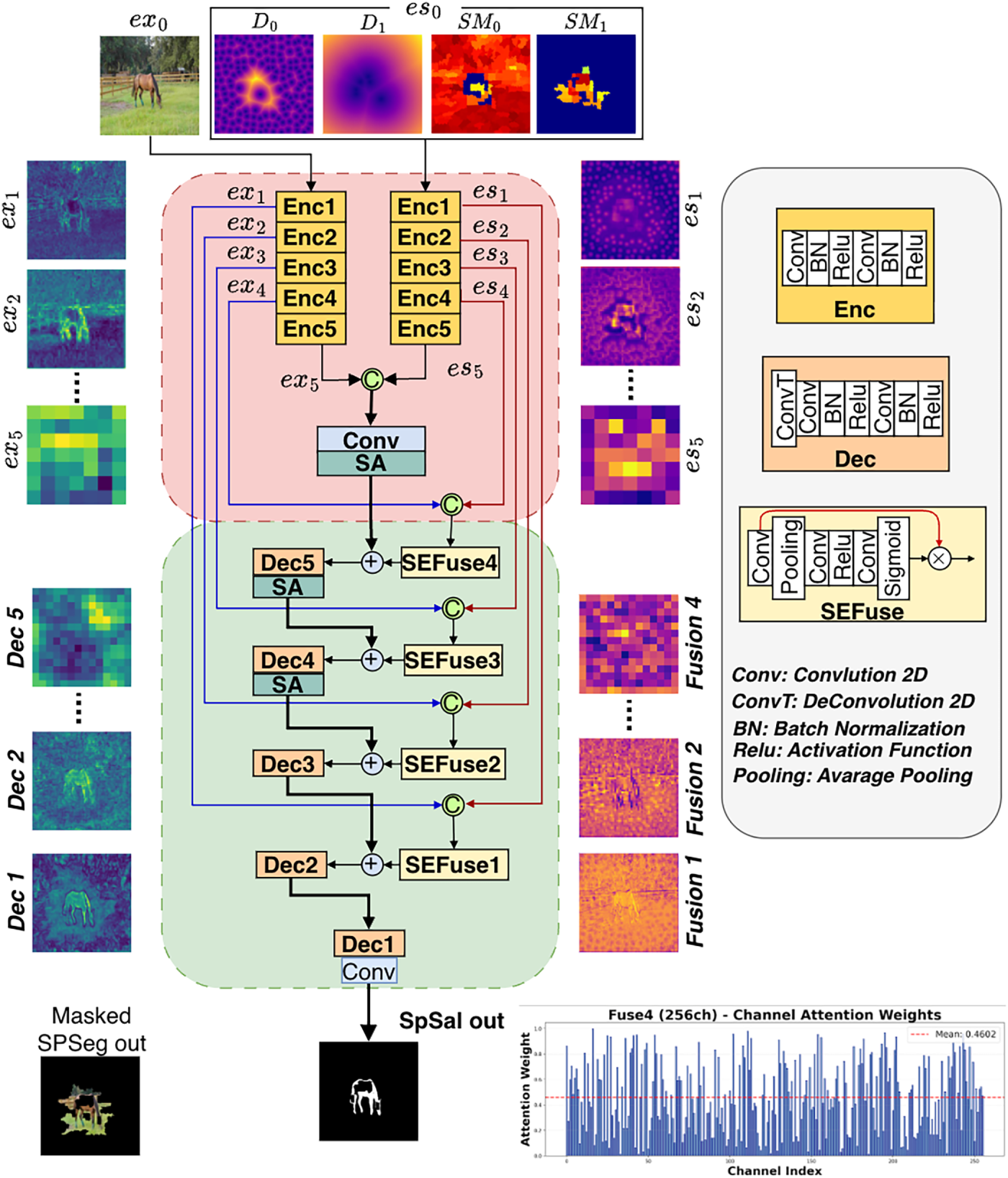

Figure 4: Block diagram of the SPSal architecture. The masked boundary image

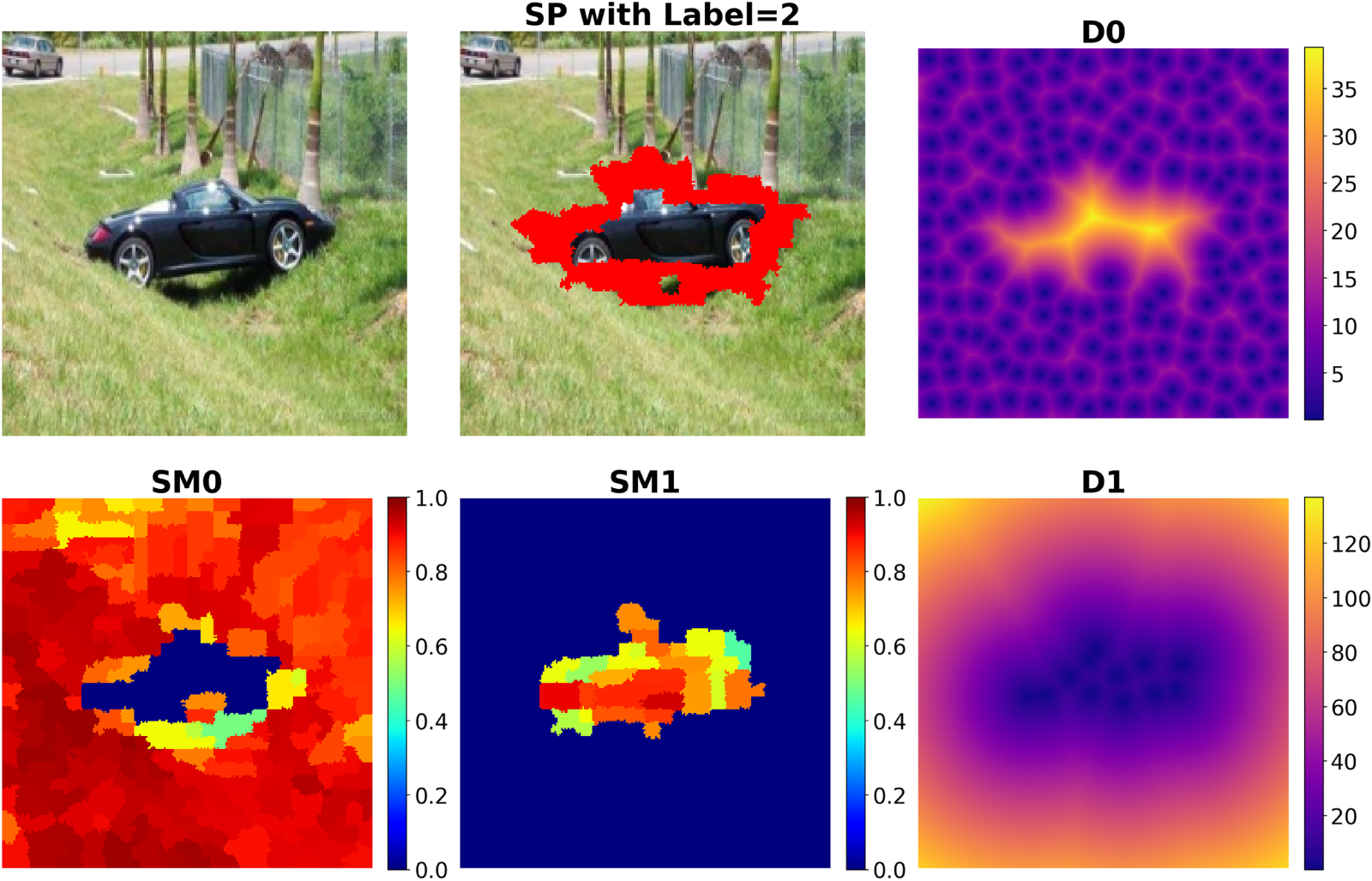

The center coordinates of

For each pixel

Figure 5: Visualization of the spatial–appearance priors used in SPSal. The top row shows the input image, the SP regions predicted as boundary class

The visual similarity of each SP in region

A class-based similarity score

Continuous similarity maps at the pixel level

These features enable the model to better evaluate SP class similarity at both semantic and visual levels, enhancing location-aware contextual attention learning, especially in boundary regions and mixed-class areas. As a result, the model generates more stable and detail-sensitive predictions in the class transition regions. The calculated features are combined and denoted as

The masked image

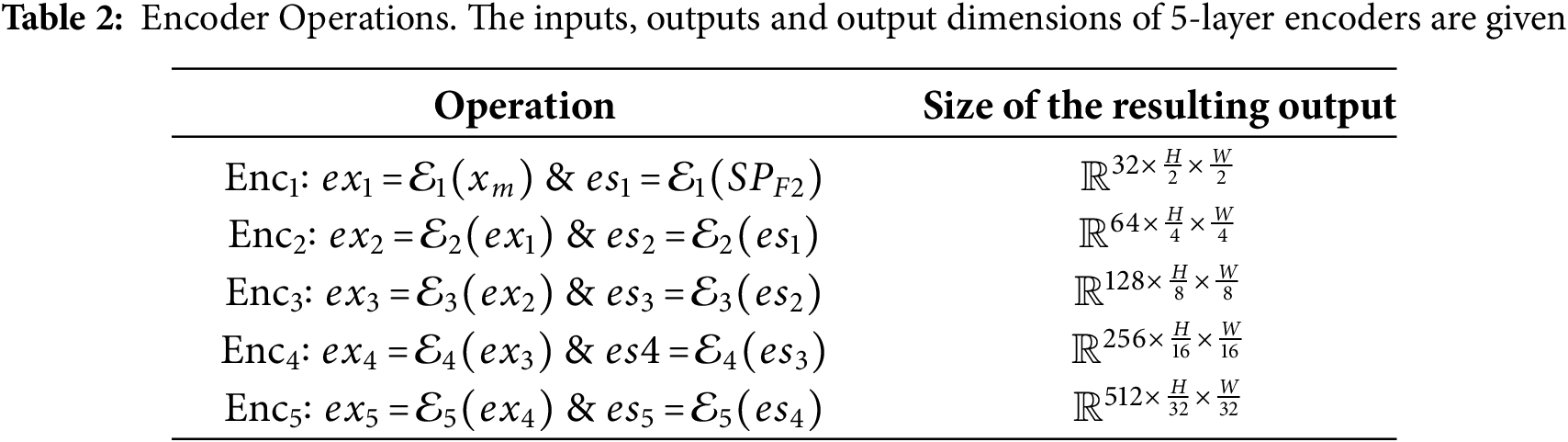

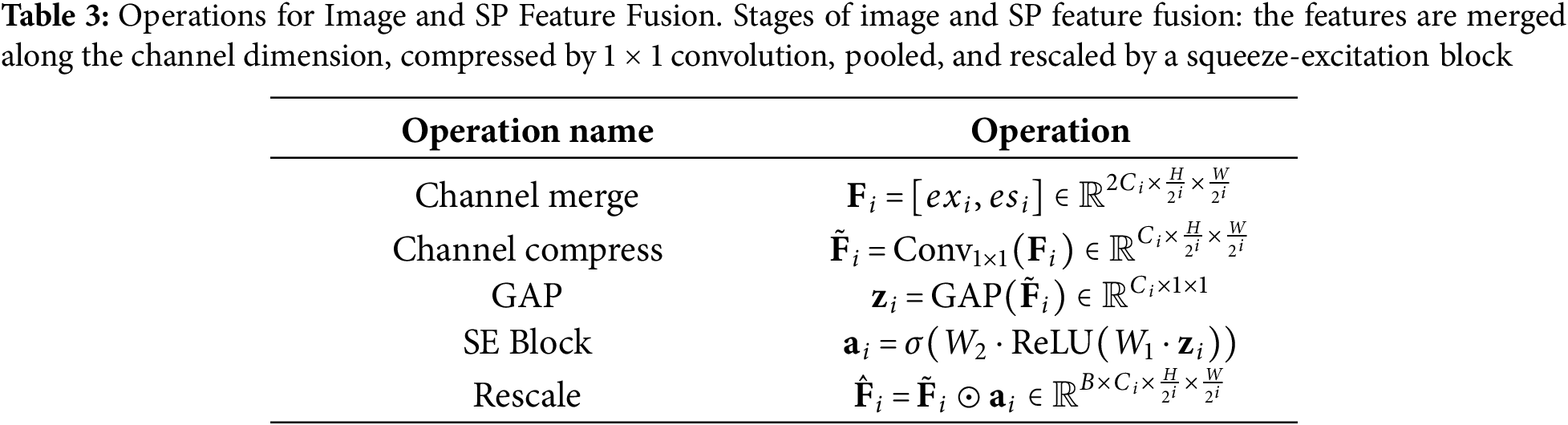

The encoder structure applied for both inputs is given in Table 2. The feature maps obtained in the deepest layers of the image and SP branches are combined at the channel level as

The

Fig. 4 shows the layer where features from the encoder layers are combined, represented by SEFuse blocks. Each SEFuse block combines image and SP features from the corresponding encoder level using the steps in Table 3 (

The input of the first decoder is formed as

In the final stage, SM for the

Fig. 6 shows the performance of the decoder output. In Fig. 6b, the SP properties input is calculated with

Figure 6: Results of salient detection for the SPSal structure. (a) Original image, (b) SEEDS SP boundaries, (c)

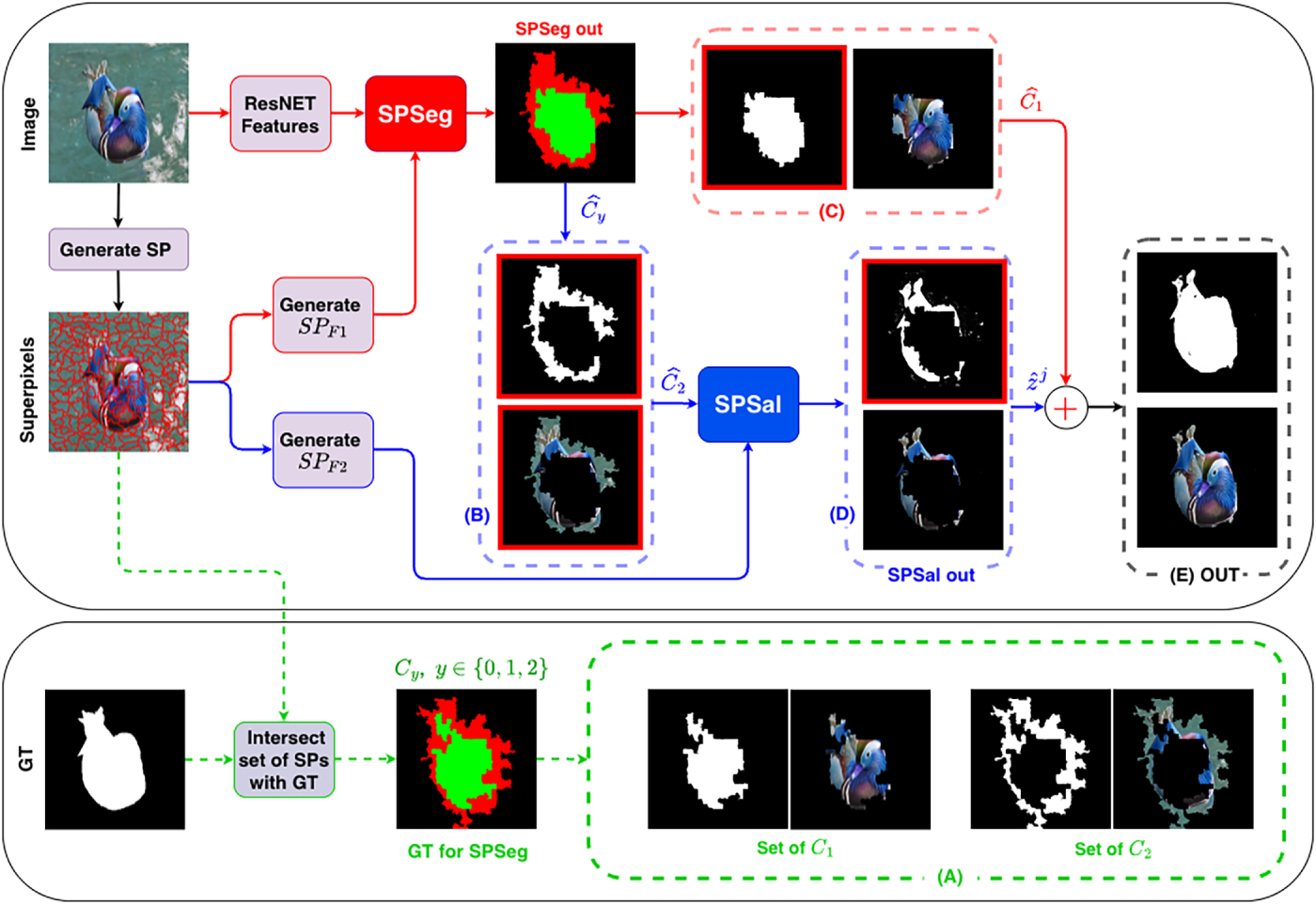

The flow diagram in Fig. 7 provides detailed visualizations of the proposed method. The ground-truth set

Figure 7: Overall workflow of the proposed SPSALNet. In the diagram above, the red line represents the SPSeg flow and the blue line represents the SPSal flow. The diagram below is provided for verification. The input image is first segmented into SPs and fed into the SPSeg module together with global features extracted by ResNet-18. The SPSeg module classifies SPs into three sets: background

The ground-truth map

The class assignment rule in Eq. (22) is a parameter-free decision mechanism determined directly by the pixel composition of each SP. SPs that contain only background or only object pixels are assigned to definitive interior classes, whereas those containing a mixture of both labels naturally correspond to ambiguous transition regions. As a result, interior regions are cleanly separated into two stable classes, while high-frequency contour transitions are modeled as a dedicated category that is later re-evaluated by the SPSal module. The three-class formulation enhances training stability and enables more precise recovery of fine-grained boundary details in the final saliency estimation.

The target ground truth image for the SPSal model is obtained using

The SPSeg model uses the cross-entropy loss function given by Eq. (24) to predict SP labels, where

The loss function used for pixel-level predicted saliency maps consists of a combination of the binary cross-entropy (BCE) loss and the Dice loss, which are defined in Eqs. (26) and (25), where M denotes the total number of pixels.

By combining the loss functions in a balanced manner as in Eq. (27) and using the

The optimal values of the model parameters

The proposed model SPSALNet is trained on the DUTS-TR dataset [31], which is the largest and most diverse training set in the SOD literature. Its wide range of object categories, background clutter, and scale variations provides sufficient variability to stabilize the learning of SP–semantic relations during the SPSeg stage. The performance of the model is evaluated on the pixel-wise annotated ECSSD [101], HKU-IS [102], DUT-OMRON [103], PASCAL-S [104], and DUTS-TE [31] benchmark datasets. These datasets collectively cover a broad spectrum of visual challenges and therefore allow a comprehensive assessment of both the macro-level SP classification module and the micro-level boundary refinement component of SPSALNet.

ECSSD contains 1000 semantically meaningful images with complex structural patterns. HKU-IS consists of 4447 images that frequently include multiple disconnected salient regions and boundary-touching objects. DUT-OMRON includes 5168 images characterized by highly cluttered backgrounds and multiple object instances, providing a challenging setting for evaluating the robustness of SP grouping. PASCAL-S provides 850 images with cognitively grounded saliency annotations and diverse object layouts. The DUTS dataset includes two subsets: DUTS-TR with 10,553 images used for training, and DUTS-TE with 5019 images used for testing; both subsets exhibit substantial variability in object scale, illumination, and background complexity. This combination of datasets forms a well-established evaluation protocol in SOD research and enables reliable testing of the proposed architecture under diverse structural, contextual, and scale-related conditions.

4.2 Model Implementation Details

All experiments were performed on an Ubuntu workstation with an NVIDIA RTX 3090 GPU. Images and masks were resized to 352

In SPSeg, a ResNet-18 model pretrained on ImageNet is used for global context inference and produces feature maps with 512 channels. These feature maps are reduced to 128 channels through adaptive average pooling followed by a linear transformation. Only the final layers of ResNet-18 were included in the training.

A fixed number (

The SP–CNN cross-attention module in SPSeg uses

The SPSal module generates edge-sensitive saliency maps using a dual-encoder, attention-enhanced encoder–decoder architecture. The RGB encoder extracts image features, while the SP encoder processes the SP-derived inputs; both encoders follow the same progression of channel dimensions: 32, 64, 128, 256, and 512. Each encoder block consists of convolution, batch normalization, and ReLU operations, with two consecutive

Features from the final encoder layers are concatenated into a

The graph-aware attention mechanism incorporates structural priors using a learnable bias function

The decoder consists of five sequential stages and uses transposed convolutions for learnable upsampling. The channel widths of these stages are 512, 256, 128, 64, and 32, with a final refinement stage also operating at 32 channels. The first two decoder stages incorporate spatial attention blocks to preserve long-range dependencies. At each stage, additional 3

The model was trained for 100 epochs with a batch size of 16. A linear warm-up was applied for the first five epochs at a learning rate of

We evaluate the proposed model using four widely used metrics in salient object detection: S-measure (

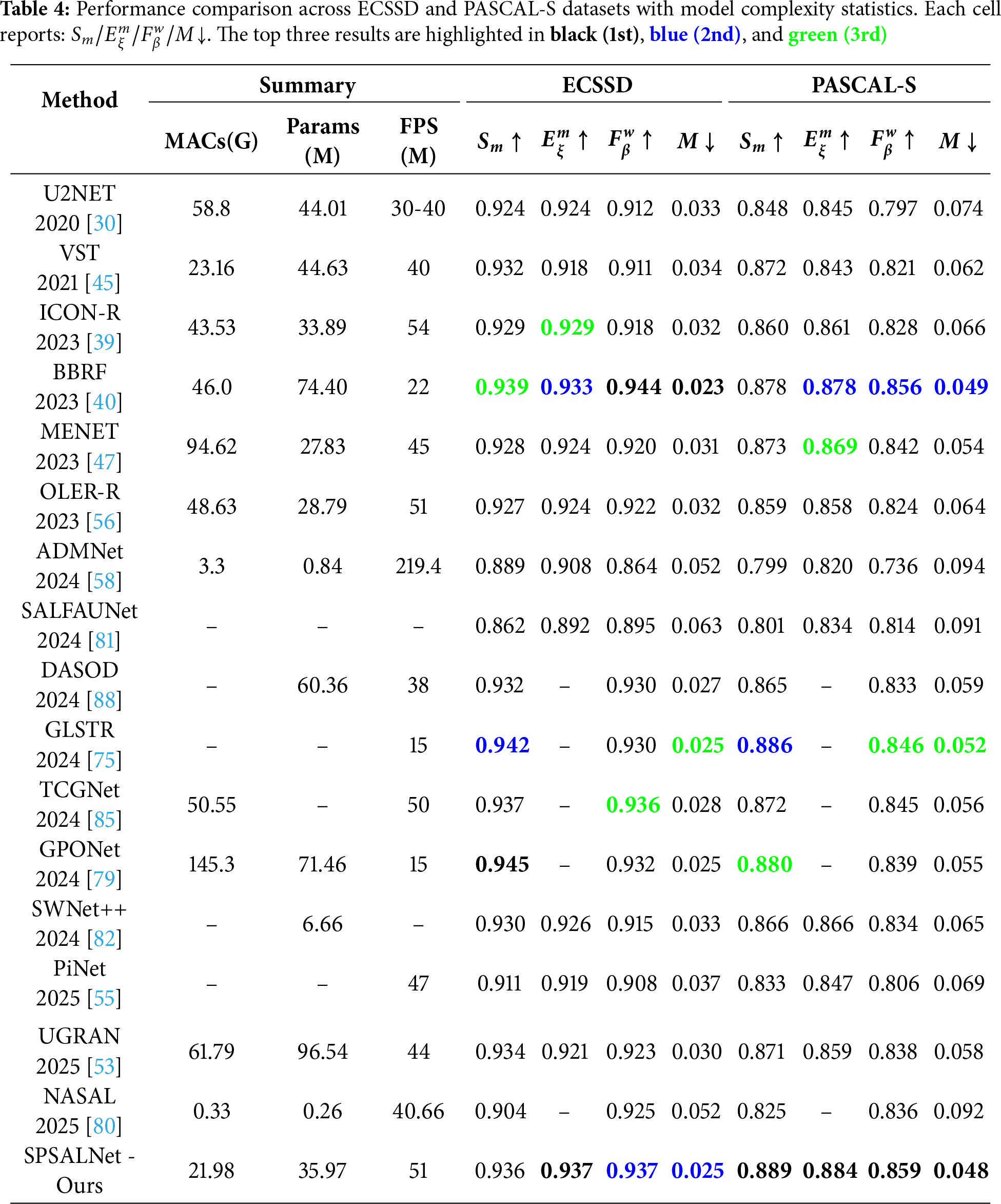

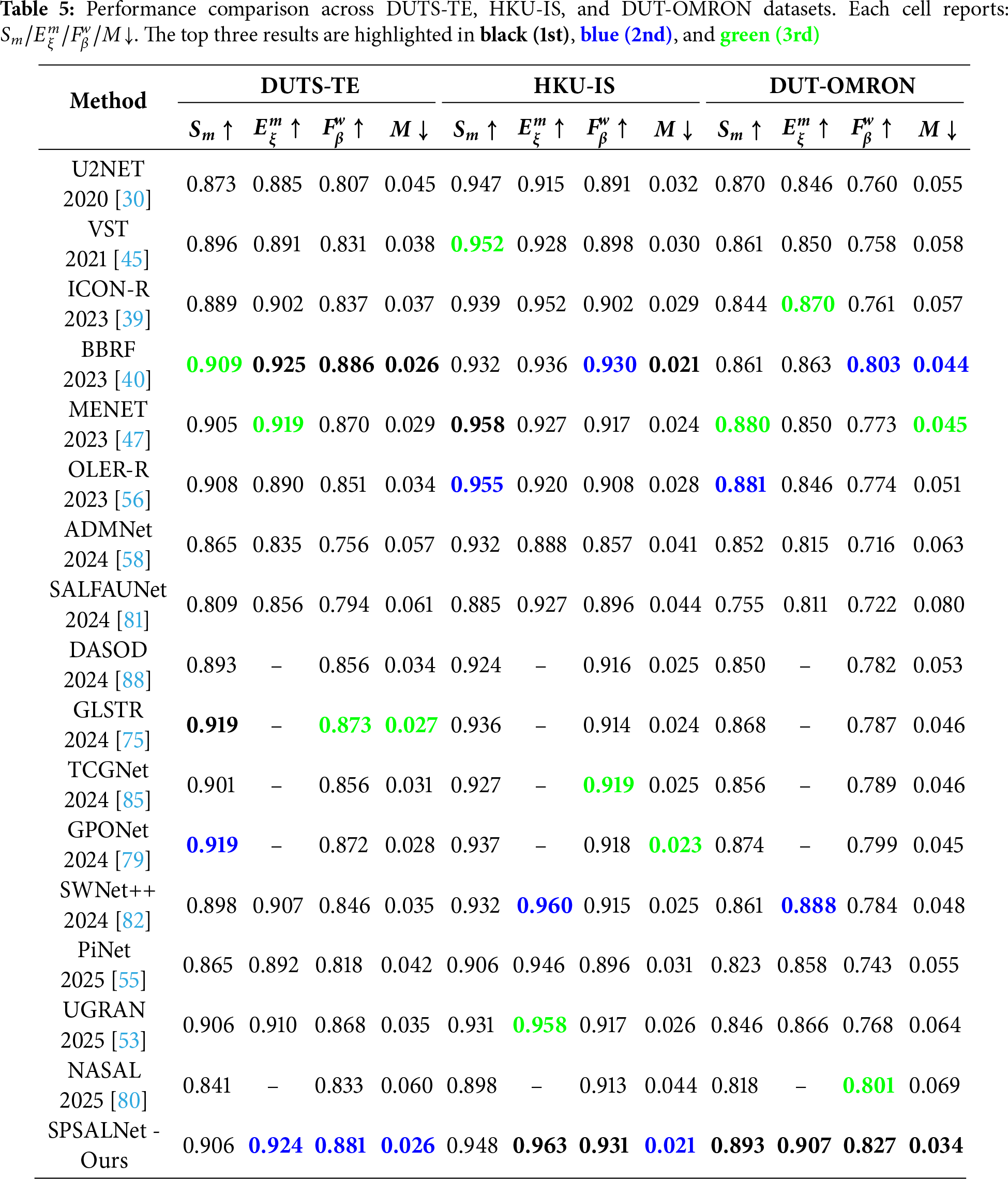

4.4 Comparison with State-of-the-Art Methods

We compare our model against recent state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods, including NASAL [80], UGRAN [53], SODAWideNet++ [82], PiNet [55], SALFAUNet [81], DASOD [88], GLSTR [75], TCGNet [85], GPONet [79], ADMNet [58], OLER-R [56], MENET [47], BBRF [40], ICON-R [39], VST [45], and U2Net [30]. Outdated or underperforming studies are not included in the comparison. Therefore, the comparison is restricted to only those studies that satisfy the criteria of high accuracy, widespread usage, and architectural diversity.

1) Performance and Efficiency Evaluation

As summarized in Table 4 (ECSSD and PASCAL-S) and Table 5 (DUTS-TE, HKU-IS, and DUT-OMRON), SPSALNet performs competitively against recent methods in terms of the computational cost–accuracy trade-off on five benchmark datasets. The observed cost–accuracy behavior is supported both by the overall architectural design (see the MACs and parameter counts reported in Table 4) and by the rich set of attributes computed for each SP. The multi-level integration of SP priors and image features enables attentive processing that preserves local details while enhancing global context awareness.

On ECSSD, SPSALNet achieves the best alignment score with

On DUTS-TE, SPSALNet ranks within the top two methods across all metrics

On HKU-IS, the model delivers the best alignment and F-measure scores

On DUT-OMRON, SPSALNet clearly outperforms existing methods, achieving the best scores in all metrics with

The achieved accuracy levels are directly attributable to the modular attention mechanisms and multi-feature fusion embedded in the SPSALNet architecture. While SP-level features are learned through categorical grouping and semantic coverage, spatial relationships and appearance similarity are modeled jointly via global context integration. The SEFuse blocks enable seamless blending of SP-based and image-based encoder outputs within the SPSal stage without losing fine structural cues, resulting in sharper boundaries and more reliable predictions in mixed-class and transition regions.

In terms of efficiency, SPSALNet operates with only

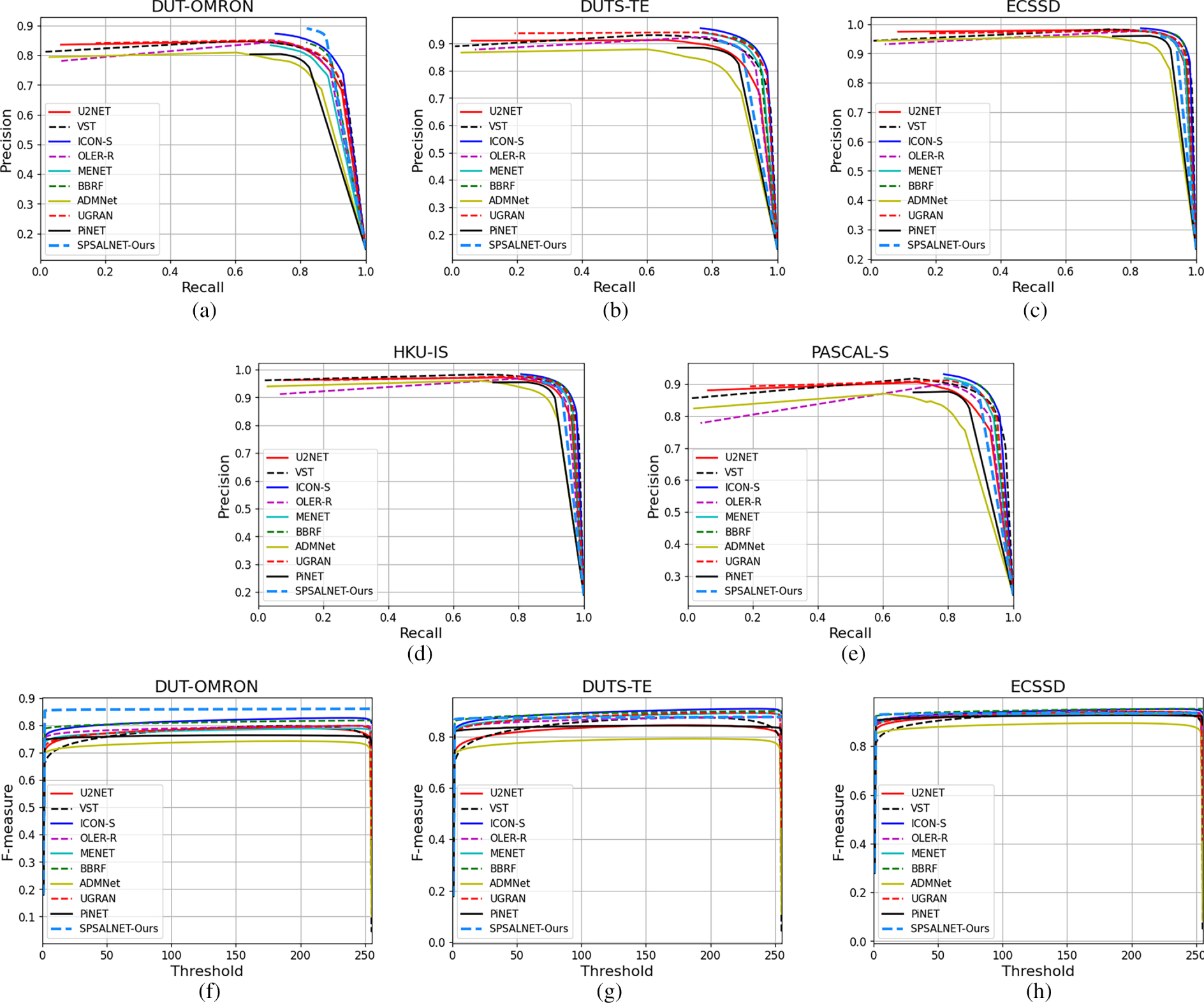

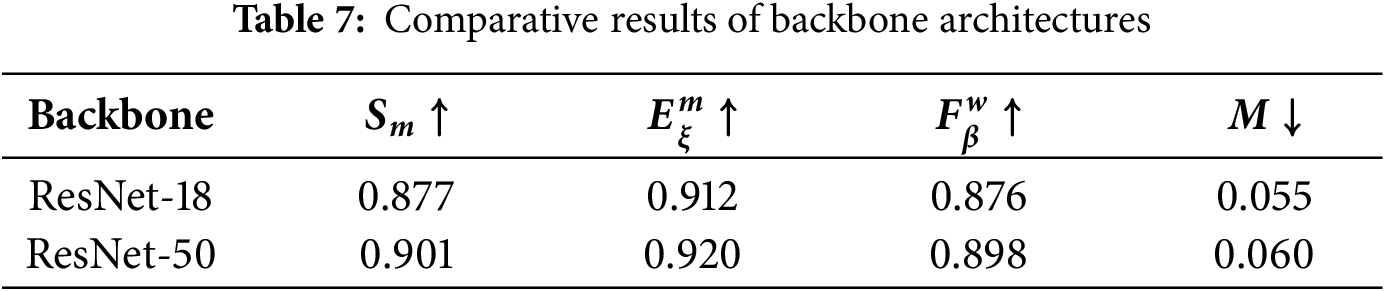

The curves in Fig. 8 further demonstrate that SPSALNet consistently produces high-quality saliency maps and achieves a favorable precision–recall trade-off with low false-positive rates. In particular, the method yields the most favorable PR and F-measure profiles on the DUT-OMRON dataset and remains highly competitive on ECSSD, HKU-IS, and DUTS-TE, often matching or surpassing high-performance architectures such as BBRF, GLSTR, and GPONet in the medium and high recall ranges. The fact that the PR curves for some datasets begin only at high recall values (

Figure 8: Comparison of Precision–Recall (PR) and F-measure curves for SPSALNet against state-of-the-art methods. (a–c) PR curves on DUT-OMRON, DUTS-TE, and ECSSD; (d,e) PR curves on HKU-IS and PASCAL-S; (f–h) F-measure curves on DUT-OMRON, DUTS-TE, and ECSSD; and (i,j) F-measure curves on HKU-IS and PASCAL-S

Threshold-based F-measure analyses in Fig. 8 support these observations. SPSALNet attains the highest or near-highest

Overall, SPSALNet is a highly efficient SOTA candidate that achieves

2) Visual Comparison

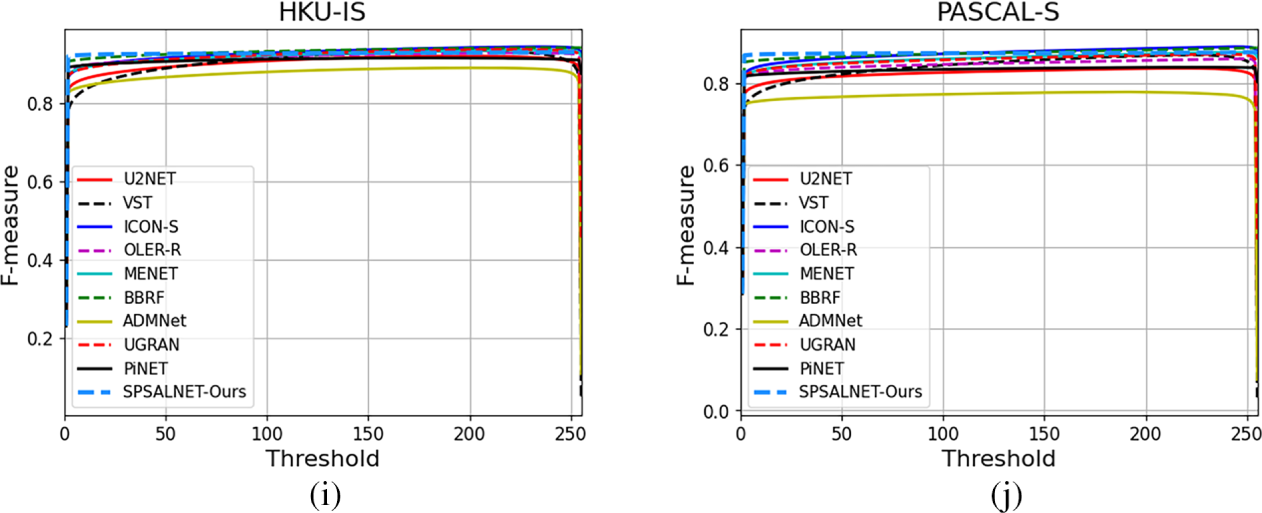

Table 6 shows the visual performance of the proposed method compared to existing methods. To assess performance across varied scenarios, we group the images into five categories: small, medium, and large objects, multiple-object scenes, and challenging cases.

Due to limited pixel area and low contrast, segmentation of small objects is quite difficult. However, the proposed model can detect these objects accurately. Thanks to the globally narrowed search regions with the SPSeg model and the local enhancement made by the SPSal model, enabling precise detection of fine salient details.

Our model competes with effective methods such as ICON-S and BBRF, especially for medium and large objects. Thanks to SEFuse blocks, low-level structural details and high-level semantic representations are balanced and integrated. This reduces detail loss in large object segmentation while increasing contour accuracy in medium-sized objects.

In scenes with multiple salient objects, the proposed model successfully detects discrete regions. Object co-occurrence, background blending, or missing object problems observed in other methods have been minimized in SPSALNet. The main reason for this is that global context learning based on SP neighborhood relationships can clearly distinguish visual regions in the scene.

The proposed model provides high accuracy in challenging cases (e.g., low contrast, fine details, noisy scenes). In regions with complex edge structures and texture clutter, sharp contours are obtained and segmentation integrity is preserved. Three main technical approaches are behind this success: First, edge-aware SP encoding preserves contour continuity at the representation level. Second, SEFuse blocks suppress low-confidence responses and emphasize boundary regions. Third, an attention-guided decoder structure prevents detail loss and preserves region homogeneity.

Overall, SPSALNet not only detects salient objects accurately in images of varying complexity but also produces sharper, more homogeneous, and cleaner segmentation. These findings confirm that SPSALNet effectively balances accuracy and robustness, providing reliable results even in challenging visual conditions.

Comprehensive ablation studies were conducted to analyze the contributions of the components of SPSALNet. The effectiveness of different structures and design choices in the model architecture was systematically evaluated. All ablation experiments were performed on the ECSSD dataset, with 880 randomly selected samples used for training and the rest for testing.

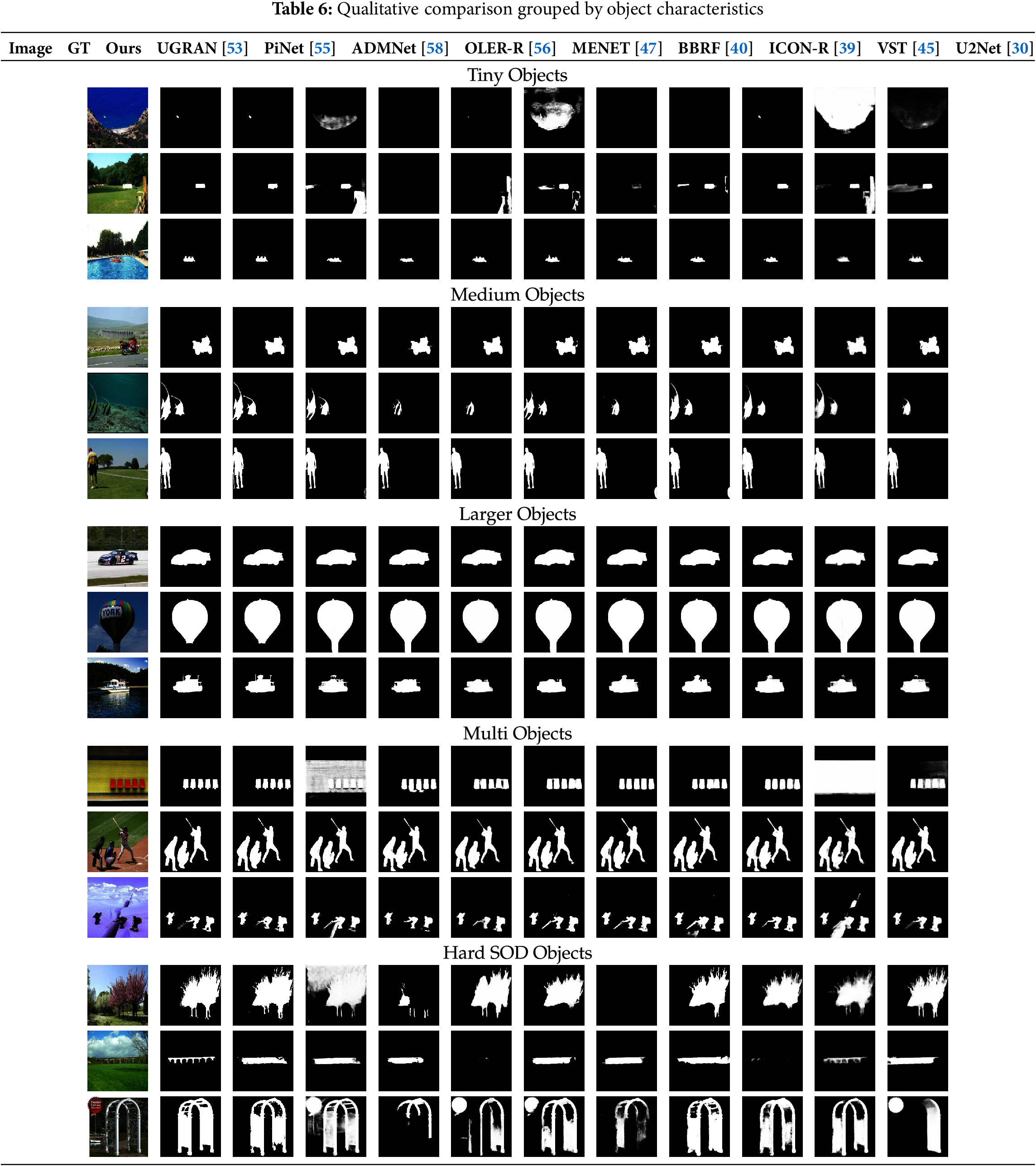

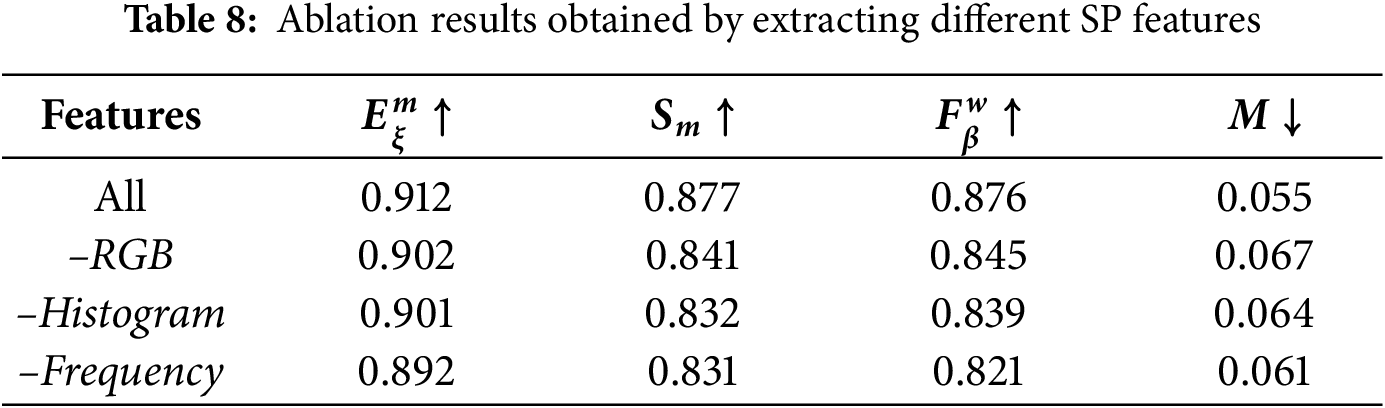

First, ResNet-18 and ResNet-50 networks were compared to evaluate the effect of the deep network used in global feature extraction. Then, the features calculated at the SP level were divided into three categories, and each of the RGB, histogram, and frequency feature groups was used alone in the model, and the relative contribution of each group was examined.

In addition, cases where the model used only image-based features or only SP features were tested separately, allowing us to investigate how effective each source of information is on its own. Furthermore, the SEFuse blocks were removed to examine how the model performs when feature fusion is disabled.

Finally, experiments were conducted with different SP counts (

These ablation studies quantitatively demonstrate how much each model component contributes, clarifying why the proposed integrated structure achieves high accuracy and precise edge sensitivity.

The proposed model employs ResNet-18 for global context extraction. This backbone’s low parameter count and fast inference make it well suited for real-time applications. Replacing ResNet-18 with a ResNet-50 based extractor revealed how a larger feature extractor affects overall performance.

ResNet-50 delivers richer contextual information through its deeper architecture and higher-dimensional feature representations. Experiments on the ECSSD dataset, however, indicate that the resulting performance gains are modest. Table 7 presents a comparison of the two backbone architectures.

With other components kept unchanged, these experiments confirm that the more compact ResNet-18 backbone provides an effective balance of accuracy and efficiency. The model’s main results were obtained using ResNet-18 on the DUTS-TR training set.

In order to analyze the contribution of SP features to model performance, ablation experiments were carried out for each feature category.

The contribution of each feature is shown in Table 8. Using the full feature set yielded the best overall results. When the RGB-based statistics were removed, the F-measure dropped and the MAE increased. Omitting the histogram and frequency features likewise caused a noticeable drop in accuracy, highlighting their contribution to the model’s contextual and structural sensitivity.

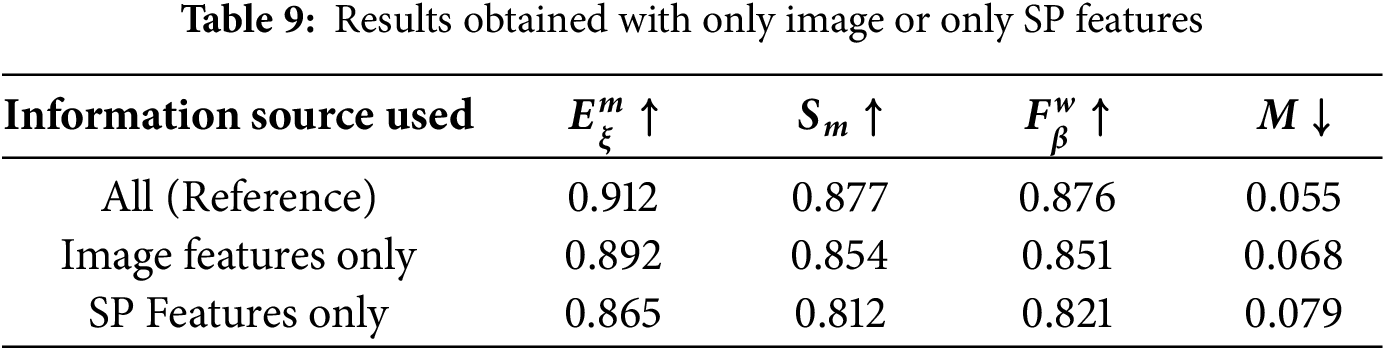

4.5.3 Relative Contribution of Image and SP Information

In order to analyze how effectively the model uses image- and SP-based information sources, two basic ablation experiments were performed, testing each component separately, as shown in Table 9.

In the first scenario, SP features were excluded, and the saliency map was estimated solely based on contextual features extracted by the ResNet backbone. This led to slight decreases in the F-measure and E-measure and a small rise in MAE, highlighting the contribution of SP representations to better accuracy and edge precision.

In the second scenario, only SP features were used and global context extraction from the image was disabled. This led to a noticeable drop in the F-measure and S-measure scores and a slight increase in MAE, indicating that the absence of image-based context reduced visual integrity and boundary sensitivity.

These two experiments show that SP- and image-based information sources are complementary; the highest performance is achieved with the full structure where both sources are used together.

SEFuse blocks used in the decoder stage of the model are designed to perform channel-level adaptive feature fusion between image and SP encoder outputs. After combining different information sources on the channel axis, these blocks re-weight them with a squeeze–excitation mechanism, thus providing channel-wise content adaptivity.

To analyze the contribution of these structures, SEFuse blocks were completely removed from the model and only direct feature fusion was performed on the relevant layers. After this change, the model’s F-measure dropped by 2.9 pp, while the S-measure and E-measure decreased by around 3.8 pp each.

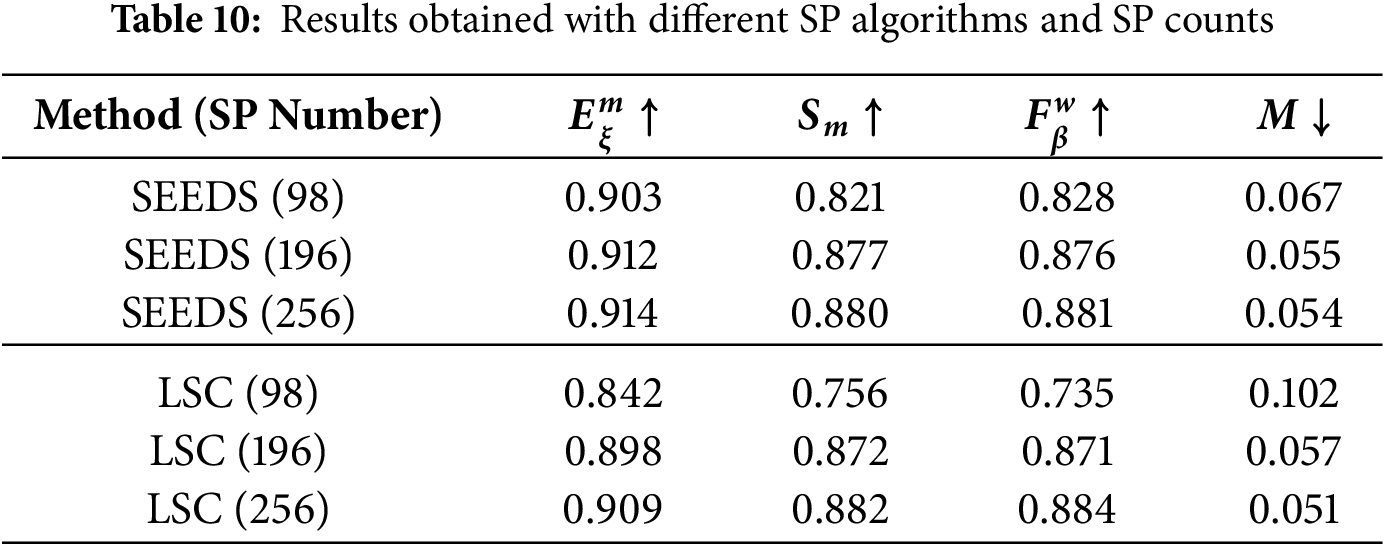

4.5.5 The Effect of SP Count and SP Segmentation Algorithms on Performance

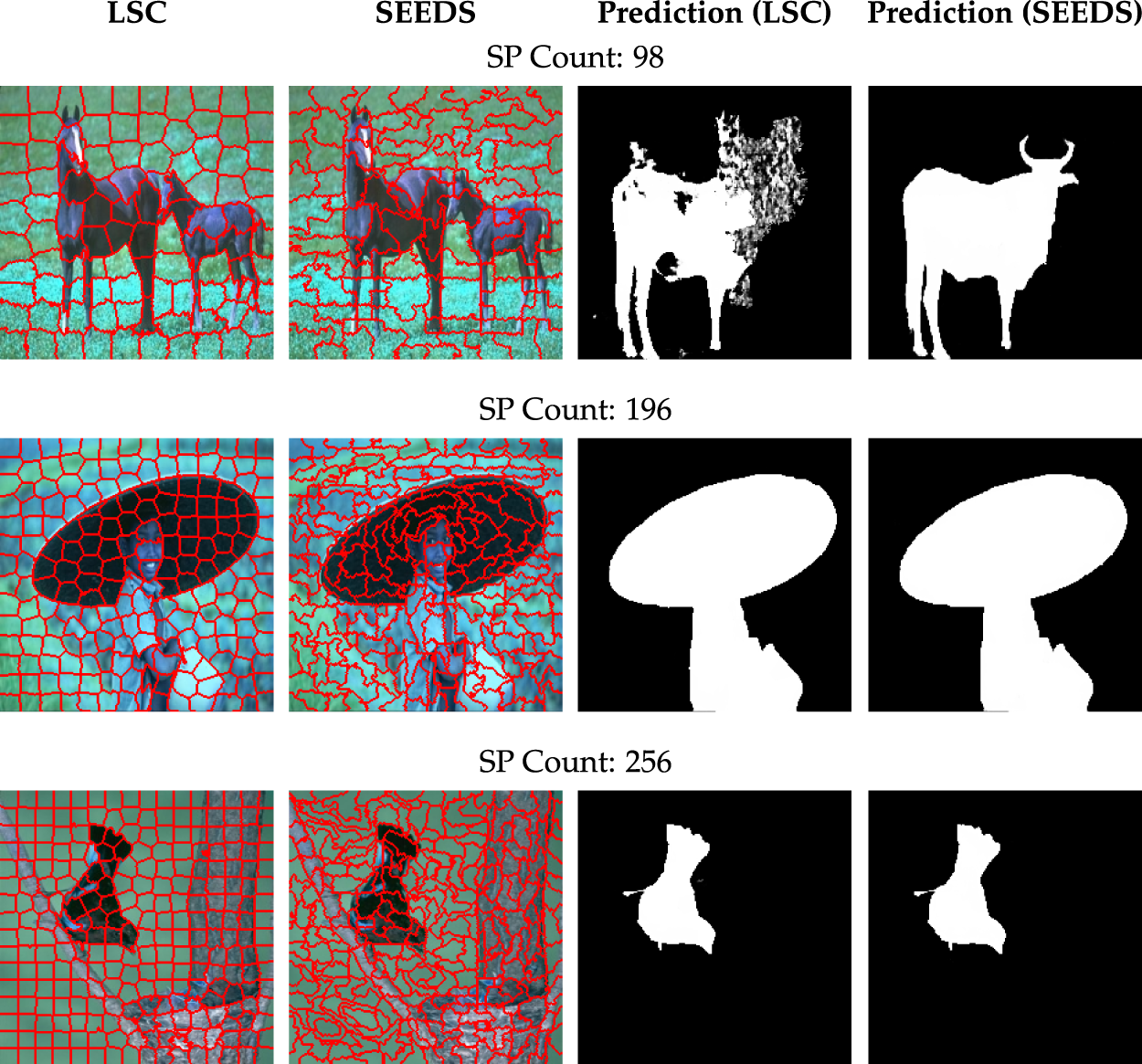

To analyze the effects of different SP segmentation algorithms and SP counts on model performance, systematic ablation experiments were conducted using both the SEEDS [98] and LSC [99] algorithms. SP counts of 98, 196, and 256 were tested for both algorithms, while keeping all other model components unchanged. The numerical results are provided in Table 10, and the visual examples can be seen in Fig. 9.

Figure 9: Comparison of superpixel segmentations obtained at different superpixel levels (

The results for the SEEDS algorithm show a slight but consistent improvement in model accuracy as the number of SPs increases. Notably, the highest S-measure and F-measure values were obtained when

In experiments performed with the LSC algorithm, the effect of the number of SP on performance was much more noticeable. Especially with a low number of SPs, there was a significant decrease in the performance of the model, and performance seriously decreased in the F-measure and MAE criteria. However, as the number of SPs increased, especially at the

In the comparison carried out for

SPSALNet employs a two-level SP-based segmentation strategy; however, the architectural design introduces specific limitations. The method relies on the hierarchical clustering of SPs, the stability of their semantic composition across the image space, and the consistency of the transition regions formed by SPs. In complex scenes, the interaction among these factors reveals practical constraints inherent to the approach. Fig. 10 shows several representative cases where the performance of SP classification, granularity, and localized refinement is suboptimal.

Figure 10: Representative failure cases. Each column corresponds to one image example, showing the original image (top), ground truth (middle), and the SPSALNet prediction (bottom)

A recurring limitation arises in scenes containing multiple objects with highly similar shapes and appearances, for example, airplanes in aerial imagery (Fig. 10, row 4). The SPSeg module relies on SP tokens whose class assignments are determined according to Eq. (22), which assumes that each SP exhibits a dominant semantic identity. When several visually similar objects lie in close proximity, the Transformer encoder in SPSeg tends to pull neighboring SP tokens toward the same class cluster due to strong feature homogeneity. As a result, the separation between

When SPs become very small, their semantic composition becomes unstable because even minor pixel-level fluctuations can shift a region from predominantly foreground to predominantly background, or vice versa. In scenes such as Fig. 10 (row 4), boundary-aligned SPs may contain nearly equal amounts of object and background pixels, making their class assignment highly ambiguous. Such SPs are frequently pushed into the

Another category of failures arises when thin structural details or closely adjacent object parts are present (Fig. 10, row 3). The SPSeg module often merges SPs across narrow gaps because such regions lack a clear dominant label under Eq. (7). As a result, boundary SPs in

Similar limitations appear in multi-scale scenarios where small objects are represented by only a few SPs (Fig. 10, row 2). Their

Lastly, elongated or filament-like structures present a persistent challenge (Fig. 10, row 1). Along such shapes, SP decomposition often becomes fragmented or low-contrast, increasing classification ambiguity within the

Overall, the failure cases indicate that SPSALNet tends to be mainly challenged by similarity-induced token fusion, adjacency-driven merging, scale imbalance, and structural thinness. These shortcomings arise from fundamental architectural trade-offs: (i) SP-based macro grouping vs. semantic purity, (ii) lightweight local refinement vs. global context modeling, and (iii) transition-focused optimization vs. holistic saliency preservation.

In this paper, we propose SPSALNet, a two-stage salient object detection framework that simultaneously prioritizes structural preservation and computational efficiency. The proposed model performs global-level segmentation using a superpixel-based Transformer classifier, while refining details through a U-Net architecture that focuses on uncertain and transition regions at the local level. In the macro stage, superpixel features and global contextual cues are jointly processed through an SP–CNN cross-attention block and a graph-aware Transformer encoder, which together enhance semantic coherence and boundary awareness. In the micro stage, the SPSal module refines only the boundary band using dual encoders and SEFuse-based feature fusion, allowing the network to allocate most of its capacity to structurally ambiguous regions.

Comprehensive experimental analyses on five public SOD benchmarks have shown that SPSALNet can provide satisfactory results in terms of both structural and content accuracy with a low computational load, achieving state-of-the-art or highly competitive performance while maintaining a favorable accuracy–efficiency trade-off. Therefore, the model is considered suitable for use in real-time or resource-constrained applications. Nevertheless, SPSALNet still exhibits limitations in scenes where salient objects are extremely small, filament-like, or represented by very few or unstable superpixels, and in cases where the initial SP segmentation quality is poor. In such settings, the fixed SP granularity and the reliance on a predefined SP decomposition may enlarge the ambiguous boundary band and reduce the effectiveness of the refinement stage.

Possible future research directions include making the superpixel segmentation stage more flexible (e.g., adaptively choosing the SP granularity or jointly learning SP partitions with the backbone), integrating uncertainty-focused learning strategies more deeply into both SPSeg and SPSal, and evaluating the applicability of the proposed architecture to different input modalities and tasks (such as RGB-D, RGB-T, or medical image segmentation). These extensions would further strengthen the robustness of SPSALNet and help mitigate the observed failure cases in highly complex or structurally extreme scenes.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank Professor Cabir Vural for his valuable feedback and guidance during the development of this work, which helped improve the quality of this manuscript.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Methodology and Software, Burhan Baraklı and Can Yüzkollar; Validation and Software, Tuğrul Taşçı; Writing—original draft preparation and Ablation studies, İbrahim Yıldırım. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The source code and the masks generated in this study will be publicly available at https://github.com/burhanbarakli/SPSALNet. All other datasets used in the experiments are publicly available and have been referenced in Section 4 of the manuscript.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable. This study did not involve human participants or animals, and no ethical approval was required.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

1GMACs are computed using only forward convolution and linear layer MAC operations for a single input; activation and batch normalization are excluded.

References

1. Wang X, Yu S, Lim EG, Wong MLD. Salient object detection: a mini review. Front Signal Process. 2024;4:1356793. doi:10.3389/frsip.2024.1356793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Ullah I, Jian M, Hussain S, Guo J, Yu H, Wang X, et al. A brief survey of visual saliency detection. Multimed Tools Appl. 2020;79(45–46):34605–45. doi:10.1007/s11042-020-08849-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Ren Z, Gao S, Chia LT, Tsang IWH. Region-based saliency detection and its application in object recognition. IEEE Trans Circ Syst Video Technol. 2014;24(5):769–79. doi:10.1109/tcsvt.2013.2280096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Hussain N, Khan MA, Sharif M, Khan SA, Albesher AA, Saba T, et al. A deep neural network and classical features based scheme for objects recognition: an application for machine inspection. Multimed Tools Appl. 2020;83(5):14935–57. doi:10.1007/s11042-020-08852-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Shelhamer E, Long J, Darrell T. Fully convolutional networks for semantic segmentation. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2017;39(4):640–51. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2016.2572683. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Itti L. Automatic foveation for video compression using a neurobiological model of visual attention. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2004;13(10):1304–18. doi:10.1109/TIP.2004.834657. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Ma S, Yang JJ. Image-based vehicle classification by synergizing features from supervised and self-supervised learning paradigms. Eng. 2023;4(1):444–56. doi:10.3390/eng4010027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Chen B, Li P, Sun C, Wang D, Yang G, Lu H. Multi attention module for visual tracking. Pattern Recognit. 2019;87:80–93. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2018.10.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Wang W, Shen J, Ling H. A deep network solution for attention and aesthetics aware photo cropping. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2019;41(7):1531–44. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2018.2840724. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Achanta R, Süsstrunk S. Saliency detection for content-aware image resizing. In: 2009 16th IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2009. p. 1005–8. doi:10.1109/ICIP.2009.5413815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Hussain T, Anwar S, Ullah A, Muhammad K, Baik SW. Densely deformable efficient salient object detection network. arXiv:2102.06407. 2021. [Google Scholar]

12. Zhang D, Tian H, Han J. Few-cost salient object detection with adversarial-paced learning. arXiv:2104.01928. 2021. [Google Scholar]

13. Elmezain M, Saad Saoud L, Sultan A, Heshmat M, Seneviratne L, Hussain I. Advancing underwater vision: a survey of deep learning models for underwater object recognition and tracking. IEEE Access. 2025;13:17830–67. doi:10.1109/access.2025.3534098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Zhang H, Wang S, Liu T. Remote sensing image change detection combined with saliency. IEEE Sens J. 2024;24(11):18108–21. doi:10.1109/jsen.2024.3390674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Joshi A, Saquib Khan M, Choi KN. Medical image segmentation using combined level set and saliency analysis. IEEE Access. 2024;12:102016–26. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3431995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Bougourzi F, Hadid A. Recent advances in medical imaging segmentation: a survey. arXiv:2505.09274. 2025. [Google Scholar]

17. Zhou W, Wang Y, Qian X. Knowledge distillation and contrastive learning for detecting visible-infrared transmission lines using separated stagger registration network. IEEE Trans Circ Syst I Regul Pap. 2025;72(8):4140–52. doi:10.1109/tcsi.2024.3521933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Arvanitis G, Stagakis N, Zacharaki EI, Moustakas K. Cooperative saliency-based pothole detection and AR rendering for increased situational awareness. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2024;25(5):3588–604. doi:10.1109/tits.2023.3327494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Zhou W, Ju Z, Cong R, Yan W. RCNet: dual-network resonance collaboration via mutual learning for RGB-D road defect detection. IEEE Trans Circ Syst Video Technol. 2025:1. doi:10.1109/tcsvt.2025.3617769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Li X, Li Y, Shen C, Dick A, Van Den Hengel A. Contextual hypergraph modeling for salient object detection. In: 2013 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2013. p. 3328–35. doi:10.1109/iccv.2013.413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Filali I, Allili MS, Benblidia N. Multi-scale salient object detection using graph ranking global-local saliency refinement. Signal Process Image Commun. 2016;47:380–401. doi:10.1016/j.image.2016.07.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Wang X, Ma H, Chen X. Geodesic weighted Bayesian model for saliency optimization. Pattern Recognit Lett. 2016;75:1–8. doi:10.1016/j.patrec.2016.02.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Li H, Lu H, Lin Z, Shen X, Price B. Inner and inter label propagation: salient object detection in the wild. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2015;24(10):3176–86. doi:10.1109/TIP.2015.2440174. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Yang J, Yang MH. Top-down visual saliency via joint CRF and dictionary learning. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2017;39(3):576–88. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2016.2547384. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Wang L, Chen R, Zhu L, Xie H, Li X. Deep sub-region network for salient object detection. IEEE Trans Circ Syst Video Technol. 2021;31(2):728–41. doi:10.1109/TCSVT.2020.2988768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Zhang J, Sclaroff S, Lin Z, Shen X, Price B, Mech R. Unconstrained salient object detection via proposal subset optimization. In: 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2016. p. 5733–42. doi:10.1109/cvpr.2016.618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Su J, Li J, Zhang Y, Xia C, Tian Y. Selectivity or invariance: boundary-aware salient object detection. In: 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2019. p. 3798–807. doi:10.1109/ICCV.2019.00390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. He S, Jiao J, Zhang X, Han G, Lau RWH. Delving into salient object subitizing and detection. In: 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2017. p. 1059–67. doi:10.1109/ICCV.2017.120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Qin X, Zhang Z, Huang C, Gao C, Dehghan M, Jagersand M. BASNet: boundary-aware salient object detection. In: 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2019. p. 7471–81. [Google Scholar]

30. Qin X, Zhang Z, Huang C, Dehghan M, Zaiane OR, Jagersand M. U2-Net: going deeper with nested U-structure for salient object detection. Pattern Recognit. 2020;106:107404. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2020.107404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Wang L, Lu H, Wang Y, Feng M, Wang D, Yin B, et al. Learning to detect salient objects with image-level supervision. In: 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2017. p. 3796–805. doi:10.1109/cvpr.2017.404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Zhang J, Yu X, Li A, Song P, Liu B, Dai Y. Weakly-supervised salient object detection via scribble annotations. In: 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2020. p. 12543–52. doi:10.1109/cvpr42600.2020.01256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Nguyen DT, Dax M, Mummadi CK, Ngo TPN, Nguyen THP, Lou Z, et al. DeepUSPS: deep robust unsupervised saliency prediction with self-supervision. In: 33rd Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2019); 2019 Dec 8–14; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

34. Zhou H, Chen P, Yang L, Lai J, Xie X. Activation to saliency: forming high-quality labels for completely unsupervised salient object detection. IEEE Trans Circ Syst Video Technol. 2023;33(2):743–55. doi:10.1109/tcsvt.2022.3203595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Tang Y, Wu X. Salient object detection using cascaded convolutional neural networks and adversarial learning. IEEE Trans Multimed. 2019;21(9):2237–47. doi:10.1109/TMM.2019.2900908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Cai Y, Dai L, Wang H, Chen L, Li Y. A novel saliency detection algorithm based on adversarial learning model. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2020;29:4489–504. doi:10.1109/TIP.2020.2972692. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Zhao R, Ouyang W, Li H, Wang X. Saliency detection by multi-context deep learning. In: 2015 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2015. p. 1265–74. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2015.7298731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Liu N, Han J, Yang MH. PiCANet pixel-wise contextual attention learning for accurate saliency detection. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2020;29:6438–51. doi:10.1109/TIP.2020.2988568. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Zhuge M, Fan DP, Liu N, Zhang D, Xu D, Shao L. Salient object detection via integrity learning. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2023;45(3):3738–52. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2022.3179526. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Ma M, Xia C, Xie C, Chen X, Li J. Boosting broader receptive fields for salient object detection. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2023;32:1026–38. doi:10.1109/TIP.2022.3232209. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Hu C, Guo J, Xie H, Zhu Q, Yuan B, Gao Y, et al. CGDINet: a deep learning-based salient object detection algorithm. IEEE Access. 2025;13:4697–723. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3525303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Xia X, Ma Y. Cross-stage feature fusion and efficient self-attention for salient object detection. J Vis Commun Image Rep. 2024;104(104271):104271. doi:10.1016/j.jvcir.2024.104271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Zhao T, Wu X. Pyramid feature attention network for saliency detection. In: 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2019. p. 3080–9. [Google Scholar]

44. Hussain T, Anwar A, Anwar S, Petersson L, Wook Baik S. Pyramidal attention for saliency detection. In: 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2022. p. 2877–87. [Google Scholar]

45. Liu N, Zhang N, Wan K, Shao L, Han J. Visual saliency transformer. In: 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2021. p. 4702–12. [Google Scholar]

46. Liu N, Luo Z, Zhang N, Han J. VST++: efficient and stronger visual saliency transformer. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2024;46(11):7300–16. doi:10.1109/tpami.2024.3388153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Wang Y, Wang R, Fan X, Wang T, He X. Pixels, regions, and objects: multiple enhancement for salient object detection. In: 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2023. p. 10031–40. [Google Scholar]

48. Hou Q, Cheng MM, Hu X, Borji A, Tu Z, Torr PHS. Deeply supervised salient object detection with short connections. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2019;41(4):815–28. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2018.2815688. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Luo Z, Mishra A, Achkar A, Eichel J, Li S, Jodoin PM. Non-local deep features for salient object detection. In: 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2017. p. 6593–601. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2017.698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Wei J, Wang S, Huang Q. F3Net: fusion, feedback and focus for salient object detection. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2020;34(7):12321–8. doi:10.1609/aaai.v34i07.6916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Wu Z, Su L, Huang Q. Stacked cross refinement network for edge-aware salient object detection. In: 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2019. p. 7263–72. [Google Scholar]

52. Zhao J, Liu JJ, Fan DP, Cao Y, Yang J, Cheng MM. EGNet: edge guidance network for salient object detection. In: 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2019. p. 8778–87. doi:10.1109/ICCV.2019.00887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Yuan Y, Gao P, Dai Q, Qin J, Xiang W. Uncertainty-guided refinement for fine-grained salient object detection. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2025;34:2301–14. doi:10.1109/TIP.2025.3557562. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Zhu J, Qin X, Elsaddik A. DC-Net: divide-and-conquer for salient object detection. Pattern Recognit. 2025;157:110903. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2024.110903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Wang X, Liu Z, Liesaputra V, Huang Z. Feature specific progressive improvement for salient object detection. Pattern Recognit. 2024;147:110085. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2023.110085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Yao Z, Wang L. Object localization and edge refinement network for salient object detection. Expert Syst Appl. 2023;213(B):118973. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2022.118973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Chi J, Wu C, Yu X, Chu H, Ji P. Saliency detection via integrating deep learning architecture and low-level features. Neurocomputing. 2019;352:75–92. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2019.03.070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Zhou X, Shen K, Liu Z. ADMNet: attention-guided densely multi-scale network for lightweight salient object detection. IEEE Trans Multimed. 2024;26:10828–41. doi:10.1109/TMM.2024.3413529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Huang L, Li G, Li Y, Lin L. Lightweight adversarial network for salient object detection. Neurocomputing. 2020;381:130–40. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2019.09.100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. He S, Lau RWH, Liu W, Huang Z, Yang Q. SuperCNN: a superpixelwise convolutional neural network for salient object detection. Int J Comput Vis. 2015;115(3):330–44. doi:10.1007/s11263-015-0822-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Li Y, Cui F, Xue X, Cheung-Wai CJ. Coarse-to-fine salient object detection based on deep convolutional neural networks. Signal Process Image Commun. 2018;64:21–32. doi:10.1016/j.image.2018.01.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Zhang A, Ren W, Liu Y, Cao X. Lightweight image super-resolution with superpixel token interaction. In: 2023 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2023. p. 12682–91. [Google Scholar]

63. Zhang S, Chen Y, Sun Y, Wang F, Yang J, Bai L, et al. Superpixel semantics representation and pre-training for vision-language tasks. Neurocomputing. 2025;615:128895. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2024.128895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Chen J, Zhang H, Gong M, Gao Z. Collaborative compensative transformer network for salient object detection. Pattern Recognit. 2024;154:110600. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2024.110600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Tong N, Lu H, Zhang L, Ruan X. Saliency detection with multi-scale superpixels. IEEE Signal Process Lett. 2014;21(9):1035–9. doi:10.1109/LSP.2014.2323407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Zhang M, Wu Y, Du Y, Fang L, Pang Y. Saliency detection integrating global and local information. J Vis Commun Image Rep. 2018;53:215–23. doi:10.1016/j.jvcir.2018.03.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Qiu Y, Mei J, Xu J. Superpixel-wise contrast exploration for salient object detection. Knowl Based Syst. 2024;292:111617. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2024.111617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Wang S, Ning Y, Li XM, Zhang C. Saliency detection via manifold ranking on multi-layer graph. IEEE Access. 2024;12:6615–27. doi:10.1109/access.2023.3347812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Li S, Lu H, Lin Z, Shen X, Price B. Adaptive metric learning for saliency detection. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2015;24(11):3321–31. doi:10.1109/TIP.2015.2440755. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Li G, Yu Y. Visual saliency detection based on multiscale deep CNN features. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2016;25(11):5012–24. doi:10.1109/TIP.2016.2602079. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Liu JJ, Hou Q, Cheng MM, Feng J, Jiang J. A simple pooling-based design for real-time salient object detection. In: 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2019. p. 3912–21. doi:10.1109/cvpr.2019.00404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Pang Y, Zhao X, Zhang L, Lu H. Multi-scale interactive network for salient object detection. In: 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2020. p. 9410–9. [Google Scholar]

73. Zhao X, Pang Y, Zhang L, Lu H, Zhang L. Suppress and balance: a simple gated network for salient object detection. In: Computer Vision—ECCV 2020. Vol. 12347. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2020. p. 35–51. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-58536-5_3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Peng Z, Guo Z, Huang W, Wang Y, Xie L, Jiao J, et al. Conformer: local features coupling global representations for recognition and detection. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2023;45(8):9454–68. doi:10.1109/tpami.2023.3243048. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Ren S, Zhao N, Wen Q, Han G, He S. Unifying global-local representations in salient object detection with transformers. IEEE Trans Emerg Topics Comput Intell. 2024;8(4):2870–9. doi:10.1109/tetci.2024.3380442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

76. Li S, Wang R, Zhou F, Wang Y, Guo N. Multi-scale feature enhancement for saliency object detection algorithm. IEEE Access. 2023;11:103511–20. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3317901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

77. Li Z, Wu J, Wang G. The application of FLICSP algorithm based on multi-feature fusion in image saliency detection. IEEE Access. 2024;12:2100–12. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3347583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

78. Yang Q, Zheng J, Chen J. Multilevel diverse feature aggregation network for salient object detection. Neurocomputing. 2025;628:129648. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2025.129648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

79. Yi Y, Zhang N, Zhou W, Shi Y, Xie G, Wang J. GPONet: a two-stream gated progressive optimization network for salient object detection. Pattern Recognit. 2024;150:110330. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2024.110330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

80. Liu ZA, Liu JJ. Towards efficient salient object detection via U-shape architecture search. Knowl Based Syst. 2025;318:113515. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2025.113515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

81. Mulat KA, Feng Z, Eshetie TS, Hasen AE. SalFAU-Net: saliency fusion attention U-Net for salient object detection. arXiv:2405.02906. 2024. [Google Scholar]

82. Dulam RVS, Kambhamettu C. SODAWideNet++: combining attention and convolutions for salient object detection. In: Antonacopoulos A, Chaudhuri S, Chellappa R, Liu CL, Bhattacharya S, Pal U, editors. Pattern recognition. Vol. 15310. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature; 2025. p. 210–26. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-78192-6_14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

83. Deng Z, Hu X, Zhu L, Xu X, Qin J, Han G, et al. R’Net: recurrent residual refinement network for saliency detection. In: IJCAI’18: Proceedings of the 27th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence. Palo Alto, CA, USA: AAAI Press; 2018. p. 684–90. doi:10.24963/ijcai.2018/95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

84. Liu Y, Zhang Q, Zhang D, Han J. Employing deep part-object relationships for salient object detection. In: 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2019 Oct 27–Nov 2; Seoul, Republic of Korea. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2019. p. 1232–41. [Google Scholar]

85. Liu Y, Zhou L, Wu G, Xu S, Han J. TCGNet: type-correlation guidance for salient object detection. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2024;25(7):6633–44. doi:10.1109/tits.2023.3342811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

86. Chen Z, Xu Q, Cong R, Huang Q. Global context-aware progressive aggregation network for salient object detection. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2020;34(7):10599–606. doi:10.1609/aaai.v34i07.6633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]