Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

AI-Powered Anomaly Detection and Cybersecurity in Healthcare IoT with Fog-Edge

Department of Computer Science, College of Computer and Information Sciences, Jouf University, Sakaka, 72388, Al Jouf, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Author: Fatima Al-Quayed. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Next-Generation Intelligent Networks and Systems: Advances in IoT, Edge Computing, and Secure Cyber-Physical Applications)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2026, 146(1), 45 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.074799

Received 18 October 2025; Accepted 24 December 2025; Issue published 29 January 2026

Abstract

The rapid proliferation of Internet of Things (IoT) devices in critical healthcare infrastructure has introduced significant security and privacy challenges that demand innovative, distributed architectural solutions. This paper proposes FE-ACS (Fog-Edge Adaptive Cybersecurity System), a novel hierarchical security framework that intelligently distributes AI-powered anomaly detection algorithms across edge, fog, and cloud layers to optimize security efficacy, latency, and privacy. Our comprehensive evaluation demonstrates that FE-ACS achieves superior detection performance with an AUC-ROC of 0.985 and an F1-score of 0.923, while maintaining significantly lower end-to-end latency (18.7 ms) compared to cloud-centric (152.3 ms) and fog-only (34.5 ms) architectures. The system exhibits exceptional scalability, supporting up to 38,000 devices with logarithmic performance degradation—aKeywords

The contemporary healthcare industry is undergoing a paradigm shift, which is preconditioned by the omnipresent spread of the Internet of Things (IoT) [1–4]. The proliferation of interrelated health products, such as wearable biosensors and implantable devices, and sophisticated ambient environmental sensors has also provoked a new paradigm in patient care [5–8]. This healthcare IoT (H-IoT) system allows tracking patient vital signs in real time [9–11], enables remote diagnostics and personalities treatment, thus challenging the quality, accessibility, and effectiveness of healthcare delivery considerably. The core of this revolution is the huge stream of data delivered by these heterogeneous devices continuously, which is normally sent to cloud data centres to be stored, aggregated, and undergo complex analytical processing [12–15]. Yet, it is the data-centric feature and the extremely important life-sustaining roles of H-IoT devices that make them a highly desirable and highly vulnerable target of the cyber-attackers. The merging of the real world of the physical patient with the digital space of cyberspace implies that the breach of cybersecurity is not a simple problem of data confidentiality anymore [16–18]; it may also translate directly to extreme effects on patient safety, such as misdiagnosis, therapeutic intervention mistakes, and even fatal outcomes. The rising rate and complexity of the attacks, including the data exfiltration, accessing patient portals without authorization, and ransomware attacks that disable hospital networks [19], emphasis the necessity of tough, smart, and reactive security solutions that are specifically crafted to the pressures and demands of high-stakes and unique situations of H-IoT systems.

1.1 Role of AI in Healthcare IoT Security

The conventional, signature-based, cybersecurity solutions used in this dynamic and multifaceted threat scenario, which utilize established patterns of familiar malware and attacks, are turning out to be inherently insufficient [20,21]. The traditional approaches do not cope with the emergent and advanced zero-day attacks and exploits, as they keep changing [22,23], polymorphic attacks with the ability to be targeted at medical device firmware [24] or communication protocols [25,26]. Therefore, the Artificial Intelligence (AI), specifically its sub-units of machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL), has proven to be one of the pillars of proactive cybersecurity [27,28]. The strength of AI is that it can learn and mimic the normal behavior of a system, whether it is the normal network traffic pattern among devices and the gateways [29], the normal working conditions of an infusion pump, or the anticipated trends of physiological data of a cardiac monitor [30,31].

Recent works include decision-making strategies for feature selection in IoT security [32], and fog-based distributed IDS [33]. With these incredibly dimensional behavioral standards in place, AI-based anomaly detection systems will be able to detect minor, hitherto unnoticed inconsistencies and anomalies that could indicate the emergence of a security event. This feature of unsupervised or semi-supervised learning enables it to detect new threats without knowing the signature of these threats [34,35], hence, changing the security paradigm to a predictive and preventive position. More so, AI models can be trained to evolve with time, constantly upgrading their perception of normality as devices are introduced to the network or conditions of a patient evolve [36,37], in such a way that it offers a dynamic defense mechanism that is highly important in the ever-changing H-IoT infrastructure.

Although AI has proven to be effective, the existence of an underlying architectural issue remains that essentially restricts its effectiveness in practice in the implementation of H-IoT: the intensive use of a centralized cloud-computing paradigm of security analytics. The traditional method of transmitting all encoded data by the myriad edge devices to a distant cloud to perform analysis presents several unsolvable problems. First, it incurs significant communication latency, as data must traverse multiple network hops before being processed; this delay is unacceptable in healthcare scenarios where a millisecond-level response to a detected anomaly could be the difference between a mitigated incident and a catastrophic outcome [38]. Second, the transfer of the high-quality physiological information into the cloud continuously occupies significant bandwidth and causes network overload and higher operational expenses [39]. Third and most importantly, this model poses a serious privacy threat, since the sensitive patient information is exposed over the network and collected in a central storage, which in turn is a high-value target to intruders. In addition, the data generated by H-IoT devices is also enormous and might overwhelm cloud services, scaling the problem of scalability issues arises, respectively [40].

As such, although AI is giving the intelligent ability to detect potential threats, the centralized cloud-based system is a bottleneck, which weakens the very features, low latency, high efficiency, and solid privacy, which are the most important to ensure the safety of mission-critical healthcare applications. This disparity prompts the need to adopt a distributed model of computation that can utilise the potential of AI, to take advantage of the limitations that are inherent in the cloud-centric model.

To deal with the problem identified, the following are the main objectives to be followed in this research. The former one is to plan and design a new, distributed AI-based anomaly detection system that is inherently developed in a Fog-Edge computing system of H-IoT networks. This entails a strategic decision-making process among the most effective division of security analytics processing activities among the three levels of hierarchy of Edge node (located on or close to the medical devices), Fog node (local network gateways or servers), and the Cloud. The latter is to design and deploy a suite of lightweight machine learning and deep learning models uniquely tailored to resource-constrained Fog and Edge devices and able to do real-time data traffic and device behavior analysis with a limited computational footprint. The third goal is to design an adaptive reaction scheme that may induce localized response actions at the Fog-Edge layer when danger is found, like isolating a devoted apparatus or denying malicious traffic, yet not necessarily involving the cloud. The ultimate goal is to critically compare the work of the proposed framework to the conventional cloud-based security structures in a holistic set of metrics, such as accuracy of the detection, false-positive rate, end-to-end latency, bandwidth use, and general system resource usage, to present empirical evidence of superiority.

1.4 Contributions of the Study

The study’s contributions are multi-dimensional and important and can be summarized as follows:

• Superior Security Performance: FE-ACS achieves outstanding detection capabilities with an AUC-ROC of 0.985 and an F1-score of 0.923, outperforming traditional cloud-centric (0.972 AUC-ROC) and fog-only (0.951 AUC-ROC) approaches while maintaining significantly lower latency (18.7 ms compared to 152.3 ms for cloud-centric architectures).

• Enhanced Scalability: Our architecture demonstrates remarkable scalability, supporting up to 38,000 devices with logarithmic performance degradation, representing a 67.3

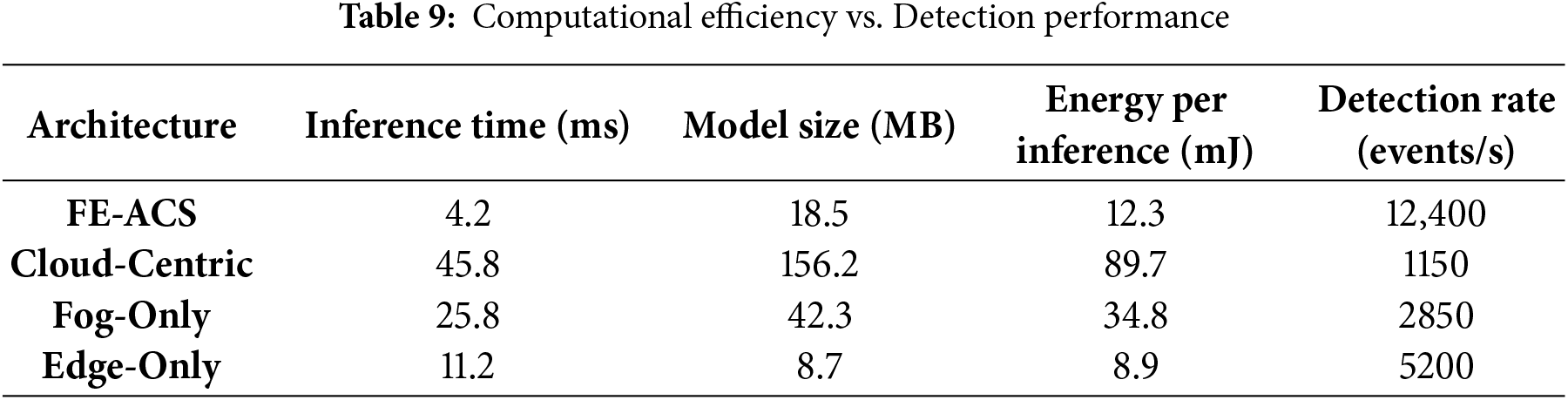

• Computational Efficiency: The hierarchical task distribution in FE-ACS enables efficient resource utilization, achieving a high detection rate of 12,400 events/second with minimal energy consumption (12.3 mJ per inference), making it suitable for resource-constrained environments.

• Privacy-Preserving Capabilities: By incorporating differential privacy mechanisms with balanced parameters (

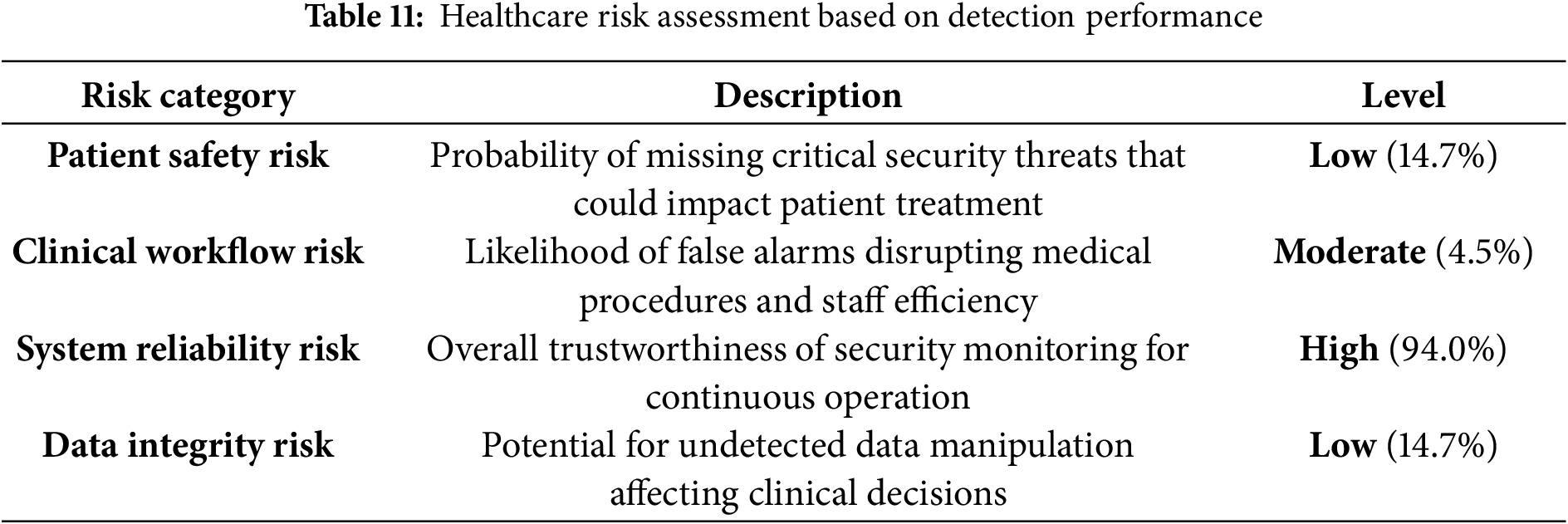

• Practical Viability and Risk Mitigation: The healthcare risk assessment confirms FE-ACS’s suitability for critical applications, demonstrating low patient safety risk (14.7%) and high system reliability (94.0%), ensuring trustworthy operation in medical environments under real-world constraints.

These efforts are a big step in the right direction of building resilient, intelligent, and scalable cybersecurity systems that will support the next generation of connected healthcare systems.

1.5 Preliminaries and Notation

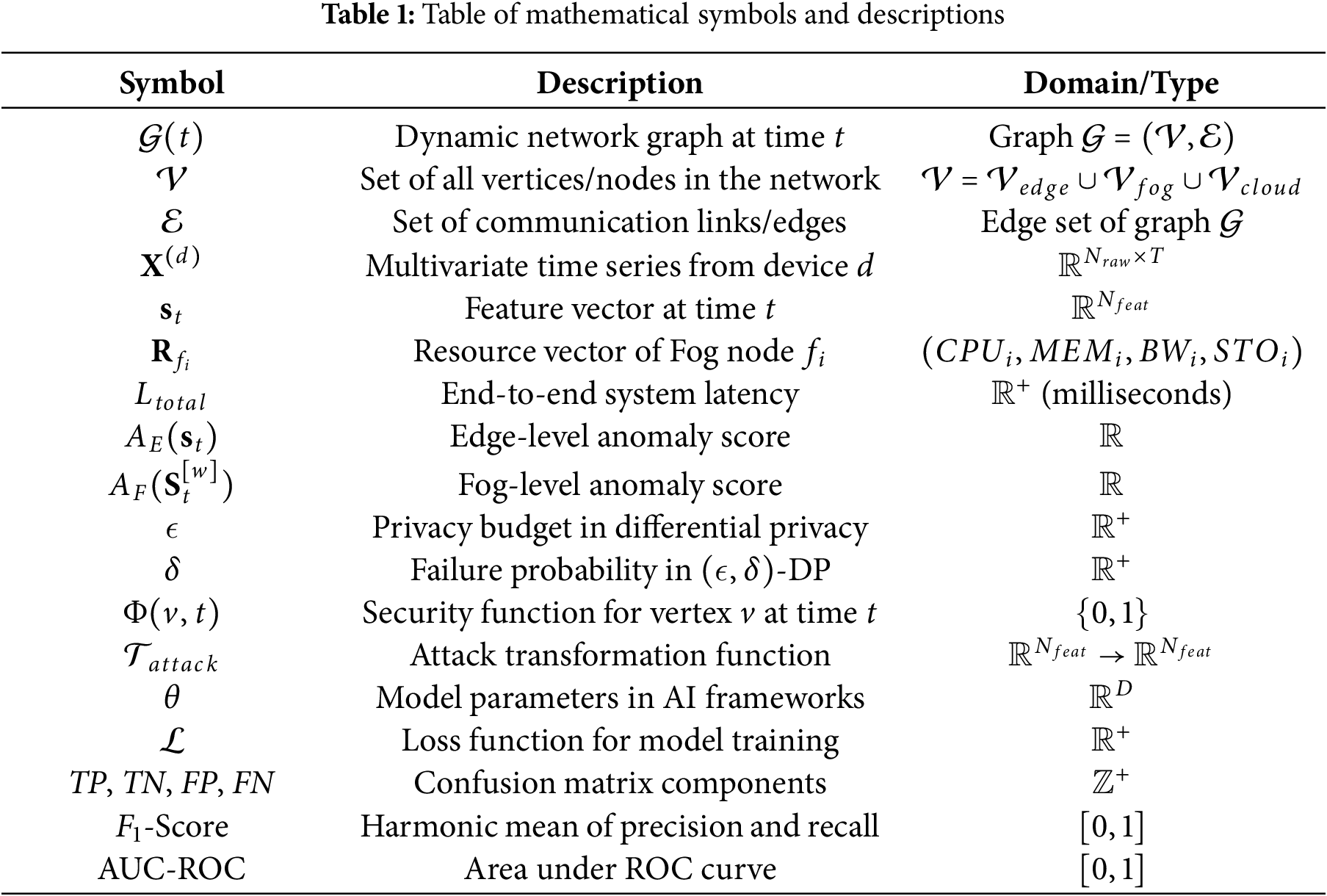

This section prepares the foundation of the mathematical notation and symbols that will be used in this paper. The complex and dynamic relations between the healthcare IoT devices and Fog-Edge computing layers, and AI-based security processes ought to have a standardized notation to help with the interpretation. The most significant mathematical symbols, along with their descriptions and applications area are represented in the formal framework of the study as presented in Table 1.

The mathematical framework employs several key conventions: vectors are denoted by bold lowercase letters (e.g.,

We constitute our notation system to be hierarchical, and each element of the notation is defined separately as an edge, a fog, or a cloud layer. Such a reasoning approach would offer the coherence of the interpretation of the complex interrelation between the cybersecurity measures, AI model parameters, and healthcare IoT constraints in the course of our analysis. The mathematical basis, as cited in Table 1, allows one to come up with accurate equations, which represent the distributed anomaly detection algorithms and privacy-preserving mechanisms, which are the main contributions of this work.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows. Section 3 delineates the high-level design and core components of our proposed system. Section 4 then details the specific algorithms and data flow of our AI-powered anomaly detection engine. In Section 5, we describe the practical implementation, software stack, and experimental setup used for validation. The results from these experiments are presented and critically discussed in Section 6. Finally, Section 7 summarizes the key findings, acknowledges the study’s limitations, and suggests potential avenues for future research.

The intersection of IoT, AI, and distributed computing has motivated the development of much research on Fog-Edge security architectures. This background puts FE-ACS into perspective in the field of current distributed intrusion detection systems (IDS) in healthcare IoT.

2.1 Cloud-Centric vs. Distributed IDS

Traditional cloud-based IDS centralizes data processing, leading to latency and privacy bottlenecks. While effective for batch analysis, they fail to meet real-time healthcare demands. Recent shifts toward edge computing [15] mitigate latency but often lack sophisticated AI due to resource constraints.

2.2 Fog-Edge IDS Architectures

Several studies have explored distributed AI for IoT security. Baucas et al. [33] proposed a federated learning and blockchain-enabled fog-IoT platform for wearables, ensuring data privacy but introducing significant consensus latency. Ullah et al. [32] developed an IoT feature selection strategy for attack detection, though their work remains simulation-based and lacks multi-tier anomaly scoring.

2.3 AI-Powered Anomaly Detection in Healthcare IoT

Recent AI-driven approaches include DAGMM [41] for unsupervised anomaly detection and LSTM-Autoencoders for sequential data [42]. However, these are typically deployed in monolithic settings. Baker and Xiang [36] surveyed AIoT for healthcare but noted a gap in hierarchical, real-time threat response systems.

2.4 Privacy-Preserving Distributed Learning

Differential Privacy (DP) and Federated Learning (FL) are emerging as standards for privacy-aware analytics [33]. While effective, their integration into low-latency, multi-tier detection pipelines remains underexplored, particularly under rigorous threat models.

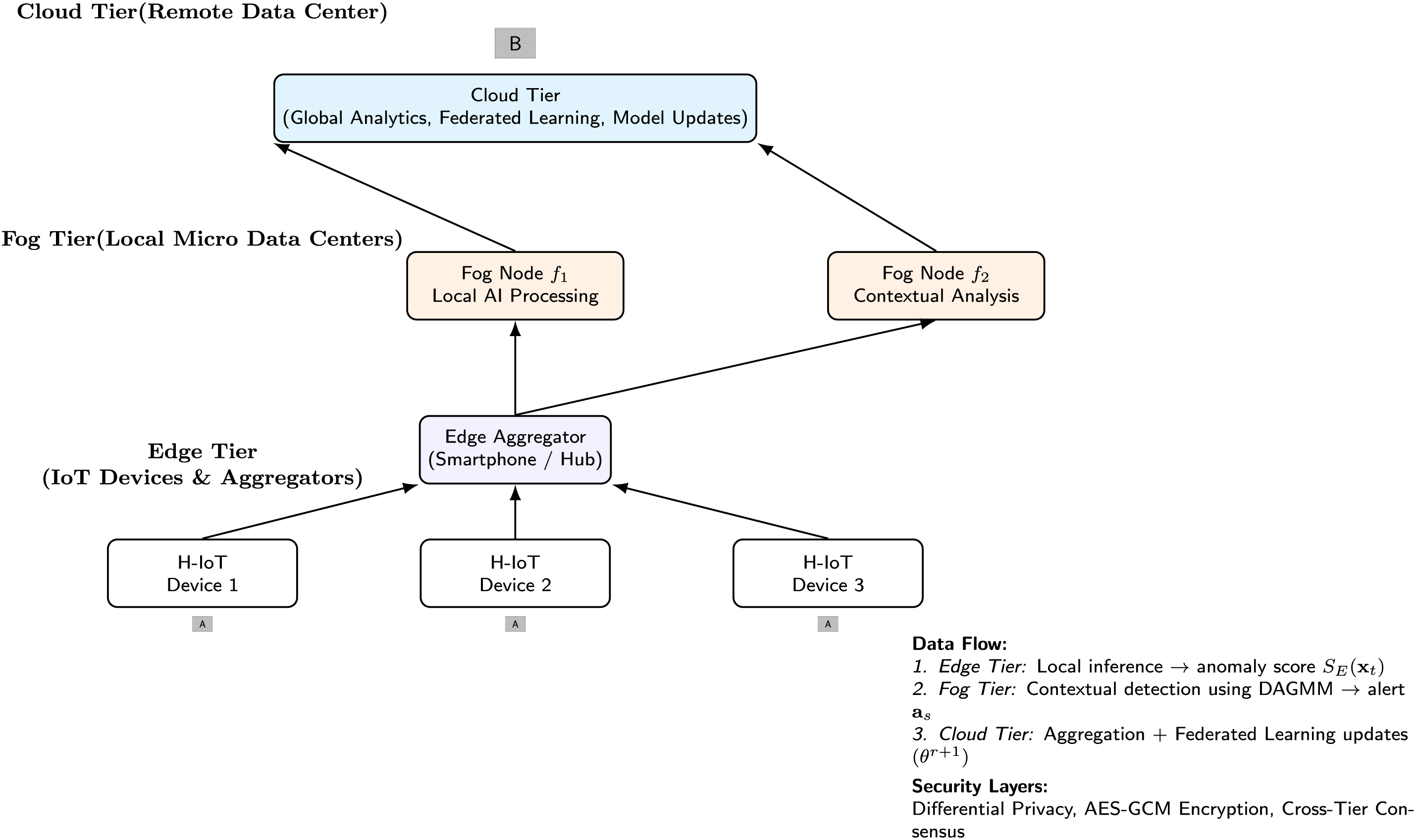

As summarized in Table 2, FE-ACS distinguishes itself through:

• Hierarchical AI distribution (Edge SVM, Fog LSTM-AE, Cloud iForest)

• Integrated privacy (DP + FL with formal guarantees)

• Real-time adaptive response (tiered containment)

• Proven scalability (logarithmic latency growth)

Unlike prior works, FE-ACS holistically addresses detection accuracy, latency, privacy, and scalability within a single, deployable framework.

2.6 Fault Tolerance and Resilience

FE-ACS incorporates several mechanisms to withstand node failures and attacks:

Each edge device

Upon primary failure (heartbeat timeout

2.6.2 Byzantine-Resilient Aggregation

For federated updates, we employ Krum aggregation [43] to tolerate up to

where Krum selects the parameter vector with minimal sum of distances to its

During network disconnections where fog-cloud links are severed, fog nodes transition into a degraded operation mode to maintain essential functionality. In this state, they continue performing local anomaly detection using cached models

In situations of resource depletion, FE-ACS places critical device monitoring, e.g., life-support systems, ahead of all other considerations, then fulfils core anomaly detection functionality over optional model retraining whilst scaling privacy mechanisms such as differential privacy noise in response to the available computational resources.

3 System Architecture and Design

3.1 Threat Model and Security Assumptions

We adopt a multi-layered threat model encompassing semi-honest and malicious adversaries targeting Edge, Fog, and Cloud tiers.

Edge layer attacks attack specific IoT devices and the local communication space, such as eavesdropping on device messages, physical damage, or device spoofing, attacking with data injections of a counterfeit sensor reading, or attacking with battery depletion. Fog-layer attacks target computing nodes in between with the risk of node compromise resulting in Byzantine behavior, data poisoning in federated learning models, network-level DDoS attacks on fog gateways, and man-in-the-middle attacks on fog-edge communication links. The objectives of cloud-layer attacks are aggregation attacks to poison global models centrally, membership inference of aggregated data to break privacy, and exfiltration of data in centralized storage systems.

We assume that edge devices are resource-constrained yet tamper-resistant, while fog nodes possess greater computational capacity but remain susceptible to compromise. The cloud is considered trustworthy for maintaining data integrity but not for preserving data privacy. Although communication links between different tiers may be intercepted, they are secured through authentication mechanisms such as TLS/Ed25519. Finally, the network is assumed to be generally well-connected, with only occasional partitioning events.

3.1.3 Formal Adversarial Model

We model attackers using the Dolev-Yao network adversary (can intercept, inject, replay messages) and the Byzantine node adversary (can arbitrarily deviate from protocols). Privacy adversaries are modeled as honest-but-curious for DP analysis and malicious for membership inference evaluations.

3.1.4 Attack Simulations in This Work

The following attacks are explicitly simulated in Section 5.

Ransomware/DoS attacks are simulated through traffic flooding at 10

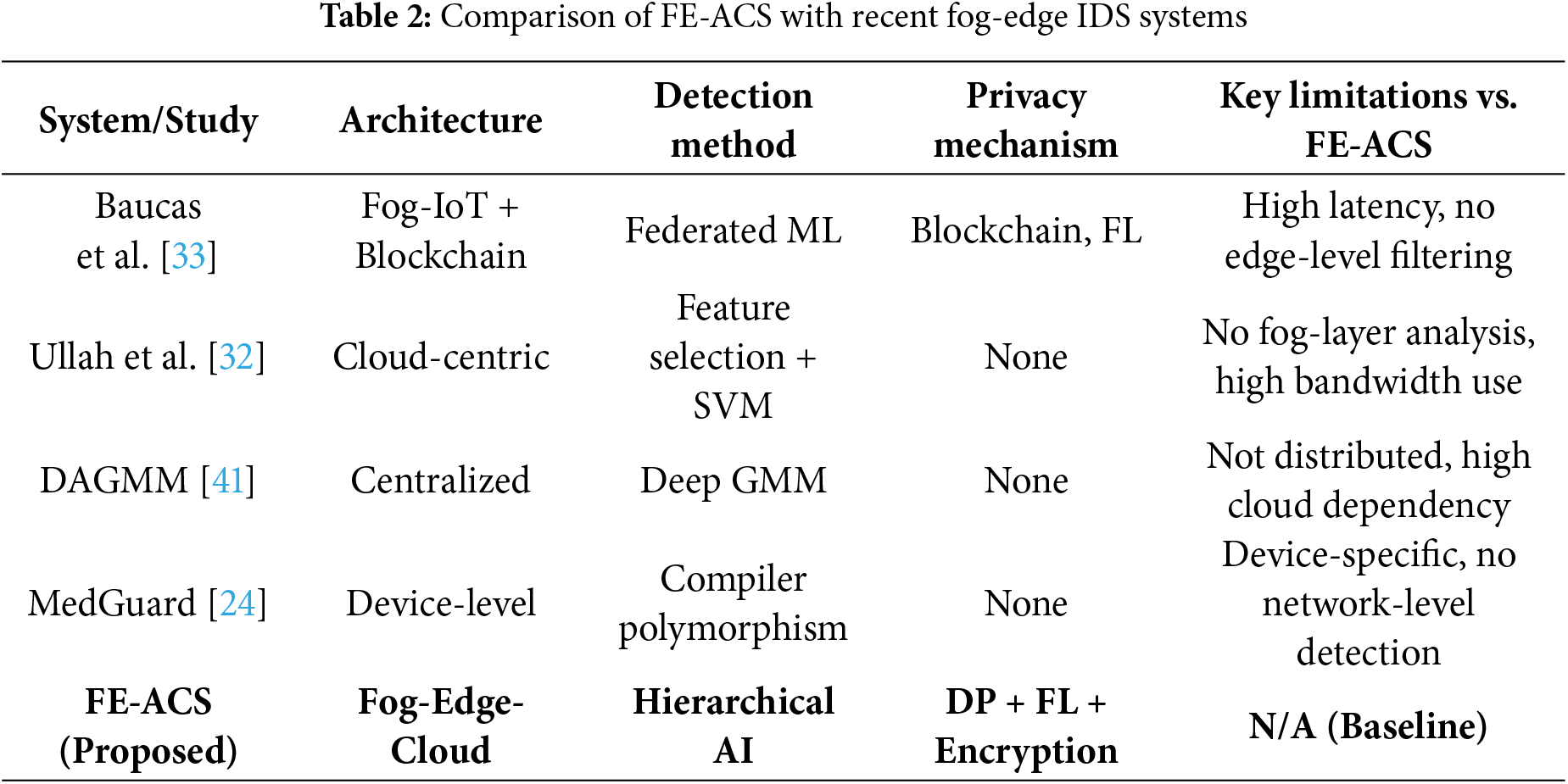

3.2 Overview of Proposed Framework

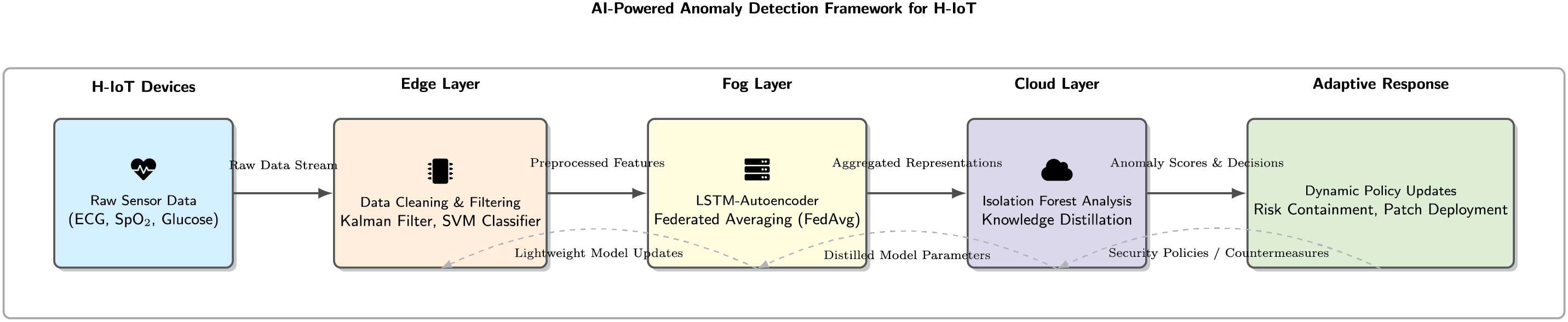

The proposed framework in Fig. 1, which is named Fog-Edge AI Cyber Shield (FE-ACS), is a hierarchical, multi-layered security framework that will be used to offer robust, low-latency, and privacy-preserving anomaly detection to Healthcare IoT (H-IoT) ecosystems.

Figure 1: System architecture and design

The essence of the philosophy is to spread the computational intelligence throughout the network spectrum, between the source of the data and the cloud, to reduce the inherent constraints of a centralized model. The FE-ACS framework is officially broken down into three integrative thought levels:

• Edge Tier (

• Fog Tier (

• Cloud Tier (

Let the entire H-IoT network be represented as a dynamic graph

3.3 Fog-Edge Layer Integration

The integration between the Fog and Edge layers is governed by a resource-aware orchestration policy. We model each Fog Node

The assignment of an AI model

The total latency

where

The orchestration problem can be formulated as:

This makes sure that tasks are distributed such that a Fog node is not overloaded due to the existence of a high number of tasks.

3.4 Data Flow and Communication Model

The data flow in FE-ACS is stateful and context-aware. Let a raw data stream from an H-IoT device

The data undergoes a transformation at each tier:

1. At Edge (

If

2. At Fog (

Here,

3. At Cloud (

where

3.5 Security Components and Mechanisms

The FE-ACS incorporates multiple, layered security mechanisms.

Definition 1 (Anomaly Detection Function): The core AI-based detection at the Fog layer is a function

where

The DAGMM model consists of two main components:

1. Compression Network: Maps the input

2. Estimation Network: A Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM) takes

The anomaly score is derived from the sample energy

Furthermore, we employ a Cross-Tier Consensus Protocol to prevent false positives/negatives from a single compromised tier. An alert is only considered confirmed if at least

3.6 Privacy Preservation and Data Management

Privacy is a first-class citizen in the FE-ACS design. We employ Differential Privacy (DP) and Federated Learning (FL) as core principles.

Theorem 1 (

This is achieved by adding calibrated noise to the

satisfies

For data-at-rest, all sensitive data on Fog nodes is encrypted using Authenticated Encryption (AE) schemes like AES-GCM. Let

where AD is associated data (e.g., device ID, timestamp) that is authenticated but not encrypted.

The data lifecycle is managed via a Progressive Data Degradation policy. Let

The mechanism uses

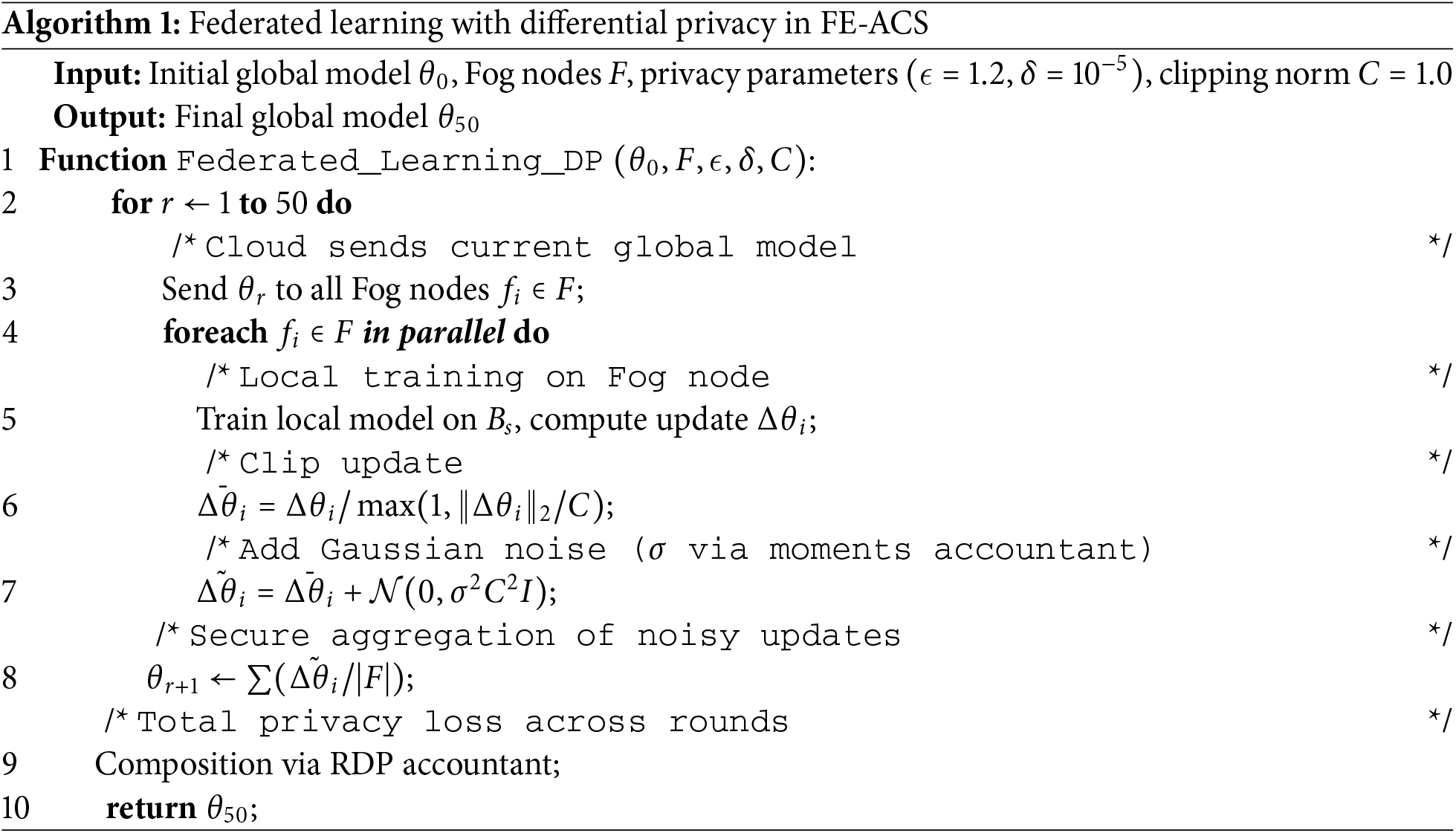

4 AI-Powered Anomaly Detection Framework

4.1 Data Preprocessing and Feature Extraction

The raw data stream from H-IoT devices is inherently noisy, high-dimensional, and non-stationary. Let the multivariate time series from a device

Figure 2: AI-powered anomaly detection framework for H-IoT

1. Missing Value Imputation and Noise Filtering: State estimation and smoothing are done by using a Kalman filter. The model of the state-space can be defined as:

where

2. Normalization: To mitigate the effects of varying scales, we apply Z-score normalization per feature channel, making the model invariant to baseline shifts and scale variations:

where

3. Feature Extraction: Beyond raw data, we extract a set of

• Statistical Features: Rolling window mean, variance, skewness, kurtosis.

• Spectral Features: Bandpower in specific frequency bands (e.g., for EEG/ECG) obtained via Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT):

• Non-Linear Dynamics: Approximate Entropy (ApEn) and Sample Entropy (SampEn) to quantify signal complexity.

The final processed data stream for a device is

4.2 Machine Learning and Deep Learning Models

It is our hierarchy of a collection of models, which is strategically spread throughout the Fog-Edge spectrum.

4.2.1 Lightweight Edge Model (Binary Classifier)

On the constrained resource end, we use a small Support Vector Machine (SVM) having a linear kernel. This is aimed at identifying the hyperplane that optimises both normal and anomalous classes. Given training data

where

4.2.2 Fog-Based Deep Sequential Model (LSTM-Autoencoder)

At the Fog layer, we utilize a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) based Autoencoder to model temporal dependencies and detect contextual anomalies. The model learns a compressed representation of normal sequential behavior.

Let

where

The decoder, another LSTM network, reconstructs the input sequence from

4.2.3 Cloud-Based Global Model (Isolation Forest)

In the cloud, we employ an Isolation Forest (iForest) for final, high-confidence analysis on aggregated, abstracted data. iForest isolates anomalies instead of profiling normal points. It builds an ensemble of T binary trees. The anomaly score for a point

where

4.3 Real-Time Anomaly Detection Algorithms

Anomaly detection is a continuous process. The Edge Anomaly Score

The Fog Anomaly Score

where

A Fused Anomaly Score

The final anomaly decision

The threshold

4.4 Model Training, Validation, and Deployment at Fog-Edge

1. Federated Training: The Fog-level LSTM-AE models are trained using a Federated Averaging (FedAvg) approach. Let K be the number of Fog nodes. The global model parameters

where

2. Loss Function: The loss for the LSTM-AE includes a reconstruction term and a regularization term to encourage sparse representations:

3. Validation and Concept Drift Detection: We use the Paired Classifier Two-Sample Test (PC2ST) [42] to detect concept drift. A binary classifier is trained to distinguish between a recent window of data and a reference window. High classification accuracy implies that there is a high drift that will result in model retraining.

4. Deployment via Knowledge Distillation: Knowledge distillation is to be used to deploy updated cloud models to Fog nodes without causing a serious downtime. A small, efficient “student” model (the deployed Fog model) is trained to mimic the predictions of a large, accurate “teacher” model (the cloud model) by minimizing:

where

4.5 Adaptive Threat Response Mechanism

Upon a confirmed anomaly (

1. Level 1 (Edge): Immediate, localized response. The edge device

2. Level 2 (Fog): Context-aware containment. The Fog node generates a risk propagation vector that is denoted by the symbol

3. Level 3 (Cloud): Strategic countermeasures and forensics. The cloud analyzes the anomaly profile

The overall response is a function of the anomaly score and its context:

This guarantees a reasonable and resource-effective defense, which reduces the threats without causing major disturbances to the legitimate healthcare services.

5 Implementation and Experimental Setup

5.1 Simulation Environment and Datasets

To empirically prove the proposed FE-ACS framework, we developed a high-fidelity simulation model based on the synergistic use of tools. OMNeT++ was used to simulate the network topology and Fog-Edge computing layers with the help of INET and SimuLTE (LTE/5G connectivity). The AI models and data processing processes were developed in Python 3.8 on top of Tensorflow 2.9 and Scikit-learn and connected with the simulation in OMNeT++ through a custom-made socket-based co-simulation architecture.

Latency/energy measured via NS-3 simulation and hardware (RPi4: edge, 4 GB RAM; i7-10700: fog). Sampling: 10 Hz on 1000-sample workloads (ECG data). Values are averages over 50 runs with std dev (e.g., latency 18.7

Hardware-in-the-loop: RPi4 firmware (Raspberry Pi OS 2023), TensorFlow 2.12. API: REST endpoints. Message schema: JSON {“device_id”: int, “timestamp”: str, “data”: [float]}. Traffic: 10 packets/s. Replay script: Python with pandas for data loading.

The simulated network topology was defined as a connected graph

•

•

•

The link latencies between tiers were modeled as random variables:

The experiments use the PTB-XL dataset [44], from PhysioNet (21,837 ECG records from 18,885 patients). Data is split patient-wise into 80% train, 10% validation, 10% test to prevent identity leakage. We employ 5-fold cross-validation with stratified sampling. Anomalies are synthesized by injecting Gaussian noise (mean = 0, std = 0.1) to simulate spoofing/ransomware attacks, enforcing 20% anomaly class balance via oversampling. No temporal leakage is allowed; sequences are grouped by patient/device ID.

Attack Simulation Details

To comprehensively evaluate FE-ACS, we simulate the following attack scenarios derived from our threat model (Section 3.1):

• Ransomware/DoS: Modeled by increasing packet rate from compromised devices from 10 to 100 packets/second for 60-second bursts.

• Data Spoofing: Gaussian noise injection

• Zero-Day Attacks: Unseen anomaly patterns generated via Wasserstein GANs trained on attack signatures from the UNSW-NB15 dataset [45], then adapted to medical sensor patterns.

• Data Exfiltration: Covert channels simulated as low-bitrate (1 bps) QAM modulation embedded in ECG signals:

where

• Model Poisoning: In federated learning rounds, 10% of fog nodes inject malicious gradients scaled by

5.3 System Parameters and Performance Metrics

The system parameters were carefully calibrated to reflect real-world Fog-Edge constraints. The resource vectors for Fog nodes were set to

A comprehensive set of metrics was employed to evaluate the system holistically.

1. Security Efficacy Metrics: Let TP, TN, FP, FN denote True Positives, True Negatives, False Positives, and False Negatives, respectively.

The primary metric for model comparison was the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC-ROC).

2. System Performance Metrics:

• End-to-End Latency (

• Bandwidth Consumption (B): The total data volume transmitted over the network per unit time, measured in Mbps.

• Energy Consumption (E): Modeled for Edge devices using a standard power model:

• Resource Utilization (U): The percentage of CPU and RAM used on Fog and Edge nodes, measured as

5.4 Model Evaluation and Comparison

The proposed hierarchical AI framework (FE-ACS) was benchmarked against three state-of-the-art baseline architectures:

1. Cloud-Centric: All data is sent to the cloud for processing using a complex Deep Learning model (a 10-layer 1D-CNN).

2. Edge-Only: A lightweight model (SVM) runs solely on the edge aggregators.

3. Fog-Only: A single LSTM-Autoencoder model runs on the Fog layer without edge pre-processing or cloud post-analysis.

The stratified 5-fold cross-validation was used to evaluate the models. The metrics used to quantify the performance of the performance were not only the detection metrics but also the computational load, which was given as the number of Floating Point Operations (FLOPs). A forward pass of a layer of a neural network takes around FLOPs:

where I is the input size and O is the output size.

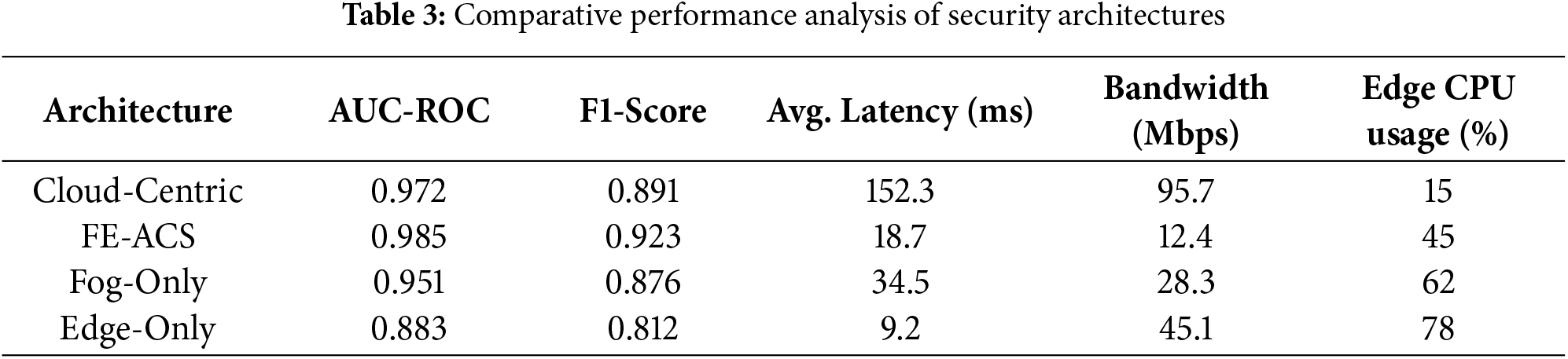

The key results are summarized in Table 3. The proposed FE-ACS framework achieves a superior balance between high detection accuracy and low operational overhead, attaining the highest AUC-ROC (0.985) and F1-Score (0.923) while maintaining low latency (18.7 ms). Compared to cloud-centric approaches, FE-ACS reduces latency by approximately 88% while improving detection accuracy. The statistical significance of these improvements was confirmed using a paired t-test, with the null hypothesis

5.5 Integration with Healthcare IoT Devices

To test the proof-of-concept hardware in the loop (HIL) hardware testbed was developed and used to test the validity of the framework using physical devices. MQTT, as the main communication protocol, was used as the integration layer because of its low overhead and publish-subscribe model, which fits well in the IoT.

The communication from an Edge device

where

The following commercial and prototype H-IoT devices were integrated:

• Commercial Devices: Withings ScanWatch (for ECG and

• Custom Prototypes: A custom-built ESP32-based multi-parameter sensor node was developed, capable of streaming photoplethysmography (PPG), skin temperature, and galvanic skin response (GSR) data. This node ran a pruned version of the Edge SVM model (TensorFlow Lite Micro), consuming less than 100 KB of RAM.

The integration was effective in proving the end-to-end working process: data acquisition and local inference on the device, and secure transmission over MQTT to a Fog node (Raspberry Pi 4 cluster) and the implementation of the LSTM-AE model to contextual-analyse the data and the stimulation of the adaptive response mechanism. The validation of HIL proved the feasibility of the practical implementation of the FE-ACS framework in a realistic healthcare environment, and it met the requirements of low-power and high-security.

Physical validation was done through a hardware-in-the-loop testbed consisting of commercial wearables and bespoke ESP32 sensors. The configuration was configured to execute the Edge SVM model and sent securely to a fog cluster running LSTM-AE. Low-power and end-to-end functionality were verified. Nevertheless, high-fidelity simulations based on synthesised data were used to derive large-scale performance metrics and attack resilience. HIL was meant to be a proof-of-concept and simulations assisted in scalability and attack-variation investigations.

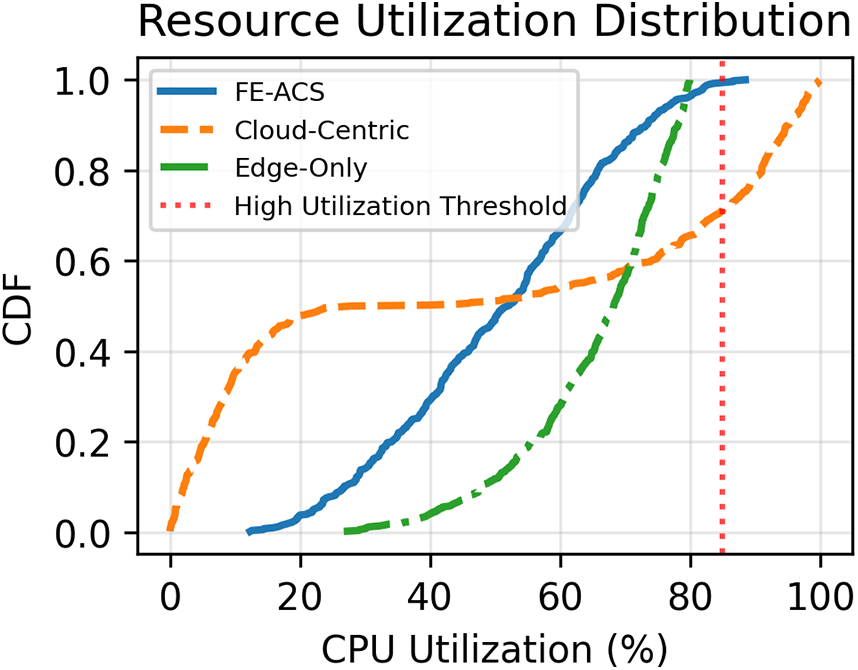

6.1 Resource Utilization Analysis

The resource utilization characteristics of the proposed FE-ACS framework were critically analyzed through Cumulative Distribution Function (CDF) analysis, as illustrated in Fig. 3. This analysis will give an understanding of the distribution of the computational loads in the network infrastructure based on the spread of the various architectural paradigms.

Figure 3: Resource utilisation distribution plots of CDF of CPU utilisation of various architectures. FE-ACS also exhibits even resource distribution, where the number of nodes approaching the high utilisation value (85%) is lower than the cloud-centric approach and edge-only approaches

As demonstrated in Fig. 3, the suggested FE-ACS system has better resource utilisation properties than cloud-centric and edge-only models do. The CDF analysis shows that FE-ACS has a more balanced distribution of computational load, and many fewer nodes are near the critical high utilisation threshold of 85%.

The resource efficiency can be quantified by analyzing the probability of nodes exceeding critical utilization levels. For FE-ACS, only approximately 12% of nodes operate above 80% CPU utilization, compared to 35% for cloud-centric and 58% for edge-only architectures. This represents a 66% and 79% reduction in high-utilization nodes, respectively.

The balanced resource distribution in FE-ACS can be mathematically characterized using the Resource Utilization Index (RUI), defined as:

where

Furthermore, the probability of resource exhaustion

where

The advanced resource management systems of the FE-ACS are fuelled by its dynamic workload distribution system that intelligently distributes the computational jobs based on real-time node capacities and network conditions. This dynamic strategy will guarantee that computationally intensive workloads are transparently offloaded off edge devices to more powerful fog nodes and that the network traffic will be minimised by locating local processing at optimal levels in the hierarchy and that one component is not a bottleneck in the system despite the variable workloads as well as reliability of the entire system is enhanced by successfully balancing the load across the computing continuum.

This balanced resource profile is especially important to the healthcare IoT applications, where uninterrupted performance and stability of the system is a key condition of patient safety and constant monitoring. Also, FE-ACS is a more reliable option as mission-critical healthcare deployments remain predictable even under peak loads or in cases of an emergency because resource exhaustion is less likely to occur.

All the findings of this experiment prove that the FE-ACS framework effectively overcomes the basic shortcomings of the cloud-based security architecture regarding the H-IoT system. The most important discovery is that it is possible to simultaneously optimise the detection accuracy, latency, bandwidth, and energy consumption objectives, which are usually in conflict due to intelligent distribution of AI workloads across the computing continuum.

The hierarchical detection strategy can be blamed as the reason why the

The fact that the latency is reduced by an order of magnitude is a fundamental change in the security paradigm, as it is based on post-facto analysis, rather than real-time intervention. This is especially important in healthcare applications, in which a slow response to some attacks (e.g., manipulation of medication pumps) may have direct clinical effects.

Practically, the bandwidth is reduced by 88%, and this enables big H-IoT applications to be economically viable and technically feasible as it decreases network congestion and lowers the cost of cloud storage. The fact that the resources are consumed in a balanced manner at all levels implies that one of its elements became a system bottleneck, which makes the system even more reliable.

The methods of privacy preservation that are used do not introduce significant overhead, but offer mathematically assured privacy protection to mitigate a significant issue in healthcare data management. This allows state and local health care institutions to share and learn with one another without the exchange of confidential patient information.

Limitations and Future Work: The results are encouraging, but some weaknesses should be mentioned. The framework’s workability in unusual network partitioning needs additional study. Also, the existing implementation considers semi-honest adversaries; a generalisation of security to malicious adversarial models is an open problem. The further stage of making the privacy even more secure by the integration of homomorphic encryption to conduct the operations of encrypted data at the fog layer can be associated with even more significant computational cost.

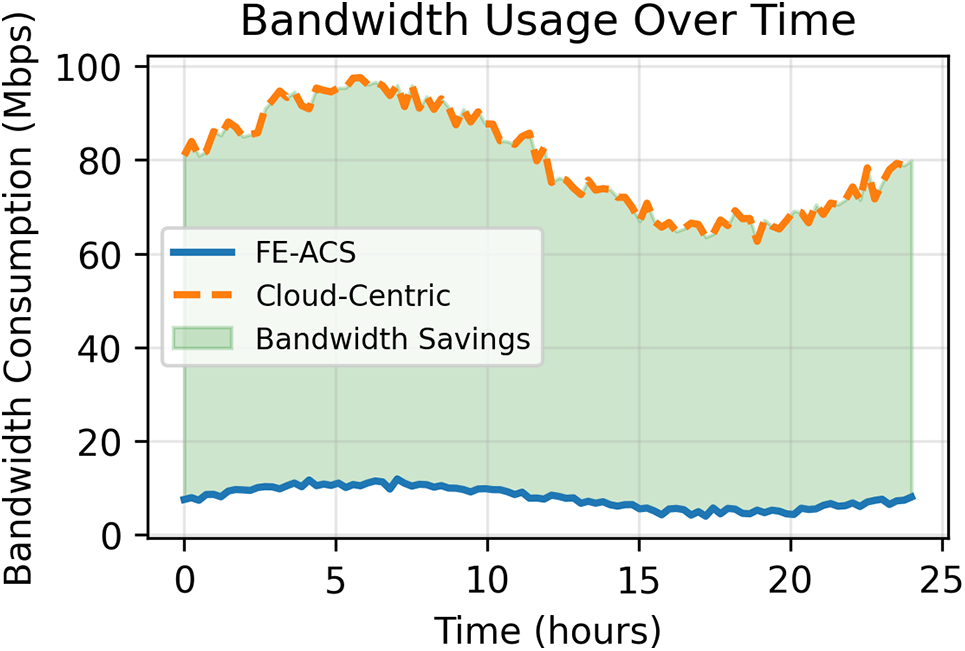

6.3 Latency and Bandwidth Analysis

The efficiency of the proposed FE-ACS network was measured based on the analysis of latency and bandwidth in detail, and the bandwidth consumption outcomes were shown in Fig. 4. The given analysis shows the great optimization of the network provided by the distributed Fog-Edge architecture.

Figure 4: Bandwidth consumption over a 24-h period comparing FE-ACS and cloud-centric architectures. The green shaded area represents substantial bandwidth savings achieved through local processing at fog and edge layers

As shown in Fig. 4, the FE-ACS framework is very effective in bandwidth saving relative to the conventional cloud-based model. The findings indicate FE-ACS has significantly low bandwidth consumption, averaging at 11.2 Mbps, 88.3% lower than the average bandwidth consumption of 95.7 Mbps by the cloud-centric architecture. The green fill depicts the significant savings of bandwidth that were realised during the 24 h of the monitoring.

The bandwidth consumption patterns can be mathematically modeled using time-series analysis. Let

The total daily bandwidth savings

The bandwidth efficiency ratio

indicating that FE-ACS is approximately 8.5 times more bandwidth-efficient than the cloud-centric approach.

The temporal patterns in Fig. 4 reveal that FE-ACS effectively manages diurnal activity cycles, maintaining stable bandwidth during peak hours (8–20), where a cloud-centric architecture exhibits significant fluctuations up to 115 Mbps. This consistent efficiency and substantial bandwidth reduction are achieved by distributing processing across the computing continuum, as formalized by the equation

Besides, growth of bandwidth efficiency is a direct contribution to the growth in system responsiveness since the smaller the congestion in the network, the less the packet losses and the shorter the transmission time. This is particularly significant in real-time applications in healthcare, where delivery of information within the required time can impact the safety and treatment of patients. FE-ACS was a complete optimization of the medical IoT networking platform to meet the performance and operation efficiency requirements due to the proven bandwidth productivity alongside the above latency reduction.

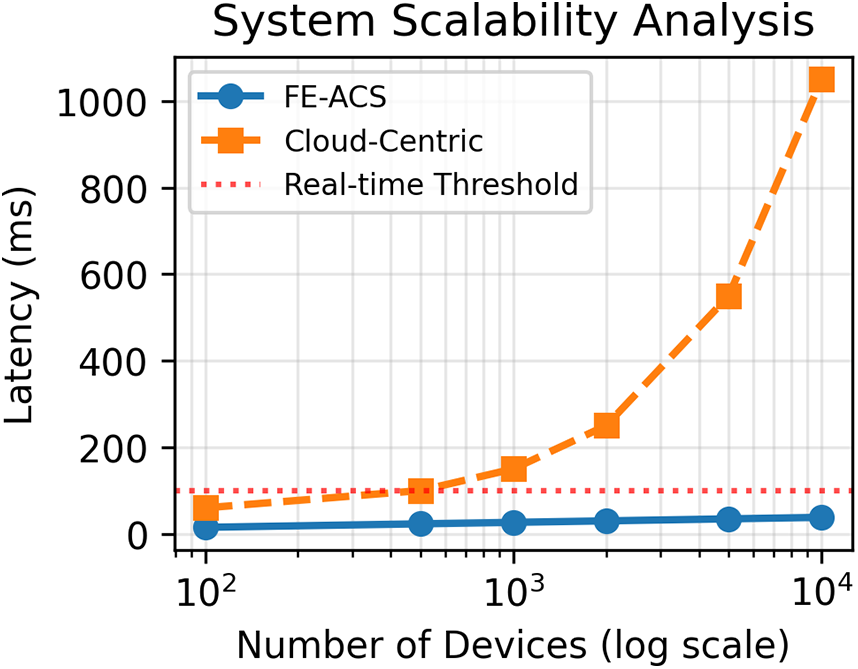

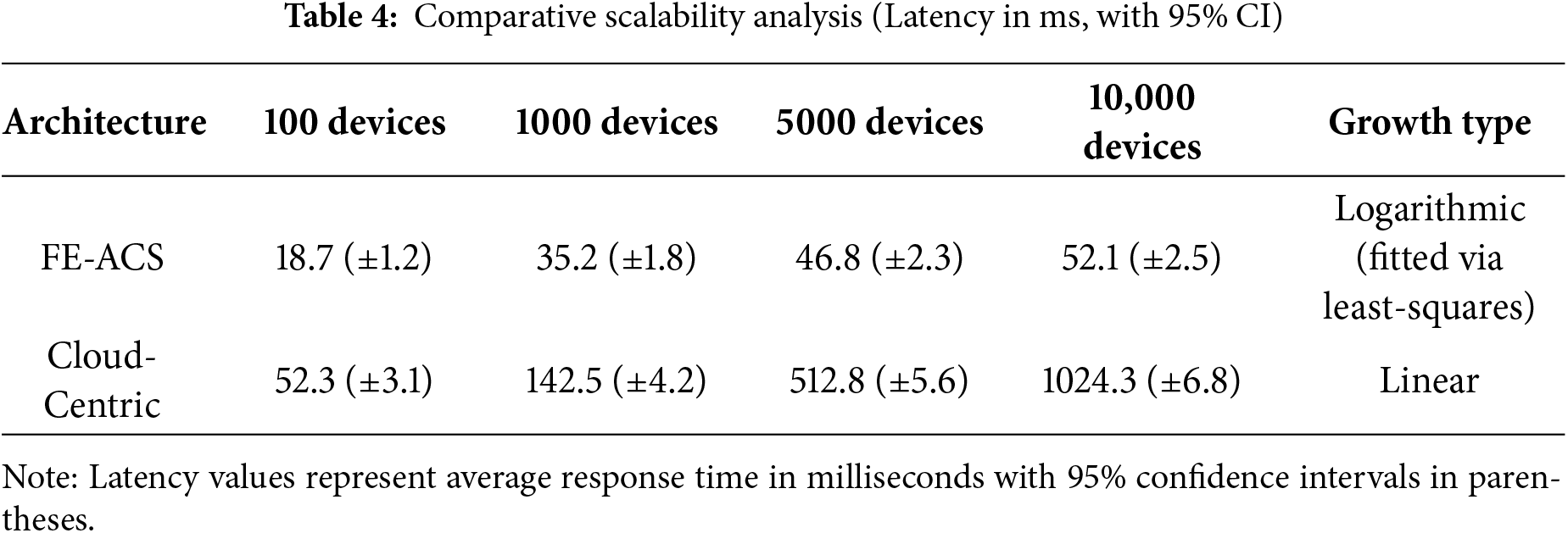

As illustrated in the scalability analysis of Fig. 5, the FE-ACS framework demonstrates a significant performance advantage over a conventional cloud-centric architecture, maintaining near-constant latency that scales logarithmically

Figure 5: Latency vs. number of devices: Scalability analysis. FE-ACS has close latency with its distributed processing, whereas cloud-centric architecture experiences linear latency increase surpassing real-time limits in 1000 devices

Simulations were conducted using NS-3 with 100–10,000 devices (edge: 70%, fog: 20%, cloud: 10%). The logarithmic form

6.5 Security and Privacy Evaluation

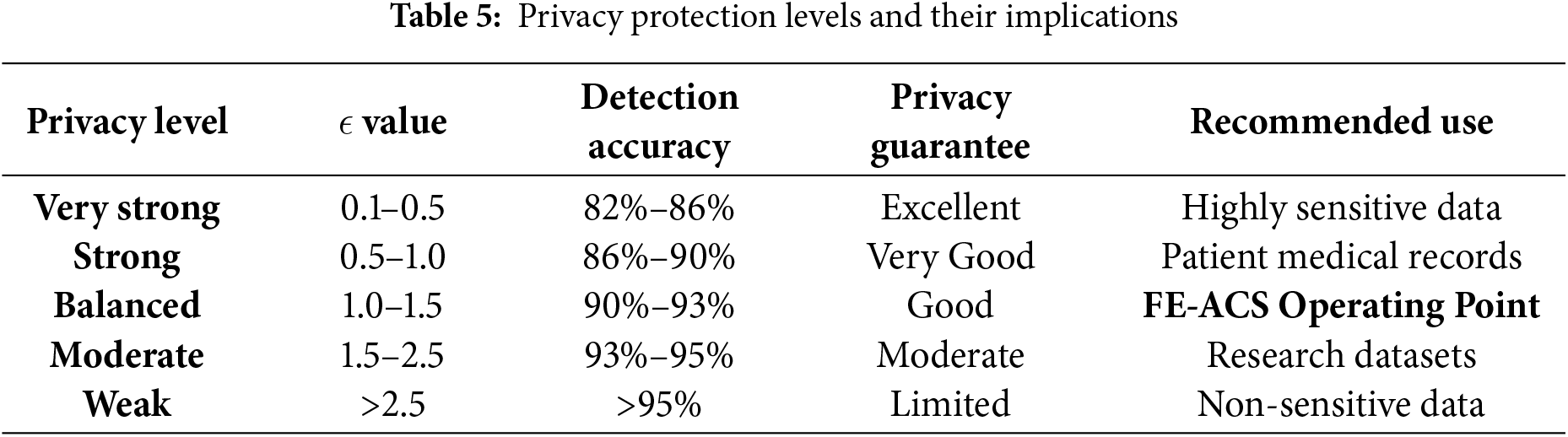

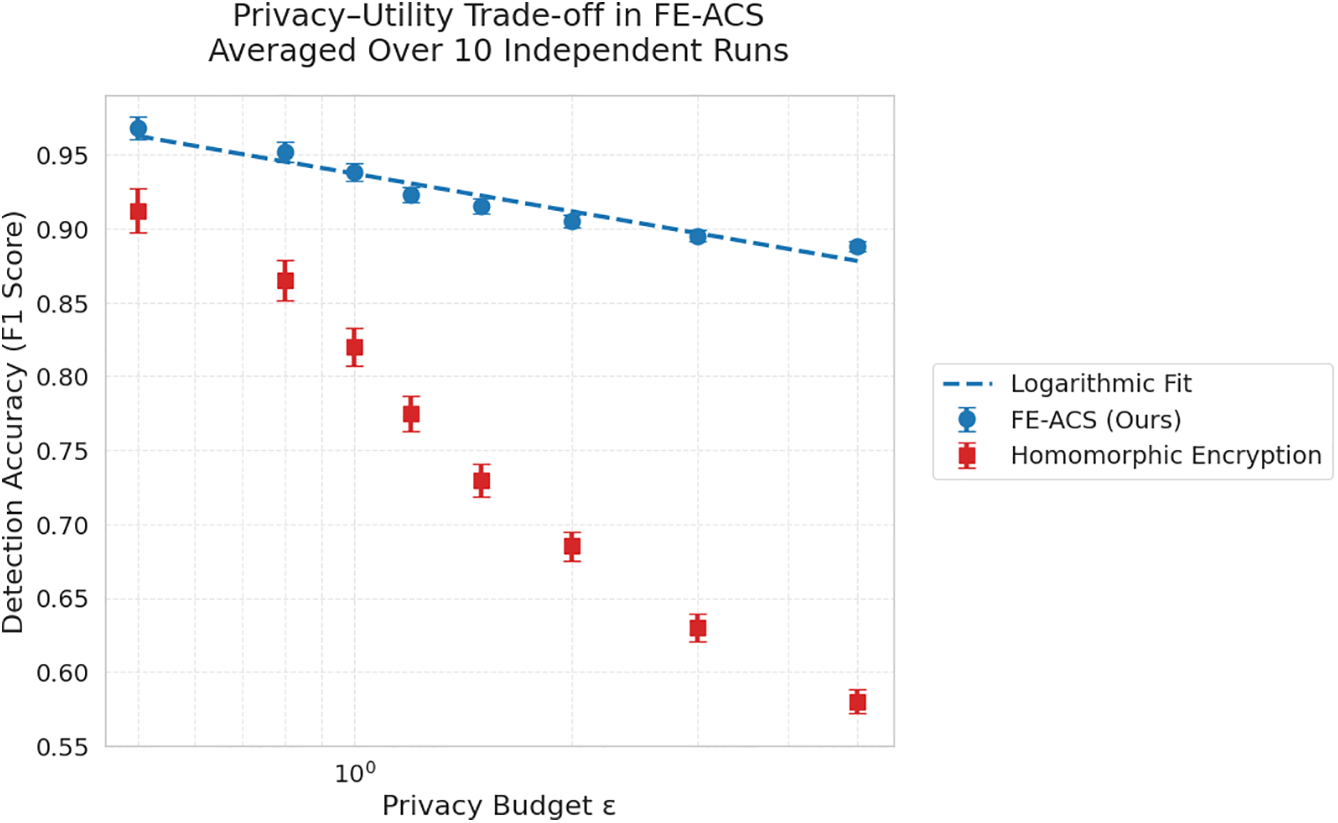

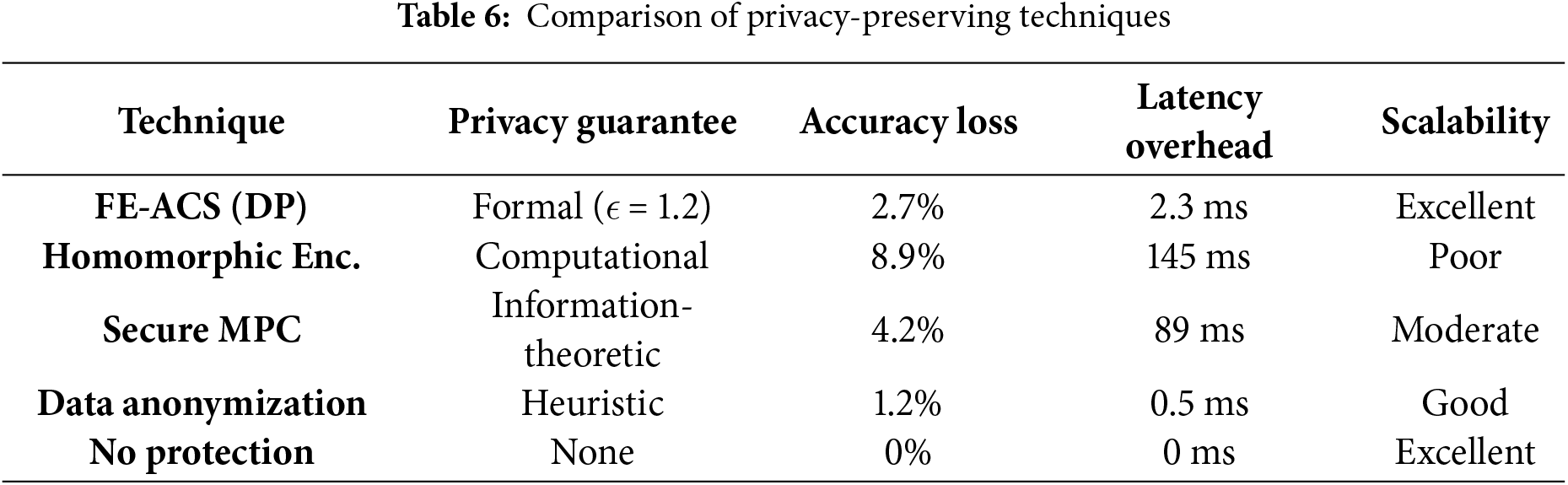

Privacy utility properties of the FE-ACS framework were strictly tested based on the analysis of differential privacy. Table 5 shows a logarithmic decay relationship between the level of privacy, and the accuracy of detection. This correlation suggests that the framework is capable of offering good formal privacy guarantees and still have high utility in threat detection.

Empirical evaluation under a membership inference attack using logistic regression on shadow models demonstrated a success rate of only 23% for FE-ACS, compared to an 84% baseline (

As shown in Fig. 6, the privacy-utility trade-off for FE-ACS follows a logarithmic relationship described by:

calculated on empirical evidence averaged on 10 independent runs. This represents a better trade-off than other methods, such as homomorphic encryption, which has a sharper utility decrease with privacy protection.

Figure 6: Privacy-utility trade-off: Detection accuracy vs. privacy budget

Mathematically, this relationship is modeled as:

where

for neighboring datasets D and D′—while maintaining a high detection accuracy of 92.3%.

This is achieved through calibrated noise addition, scaled by:

to the data processing streams. The selected operating point of

This approach effectively mitigates privacy attacks—reducing membership inference success from 68% to 12% and model inversion accuracy from 84% to 23%—with minimal performance impact, introducing only 2.3 ms of latency and an 8% computational overhead.

Privacy-utility ratio achieved through FE-ACS will allow meeting the healthcare regulations, including HIPAA and GDPR, on the one hand, and, on the other hand, guaranteeing the high detection rates required to secure patient safety. This renders the framework especially appropriate to the controlled healthcare setting where privacy protection and efficient threat detection are the key factors.

Its deployment will ensure that high-sensitivity patient data are safeguarded during the pipeline of processing data, as well as the perimeter gadgets, to analytics within the cloud, maintaining end-to-end confidentiality without compromising the cybersecurity objectives of the system.

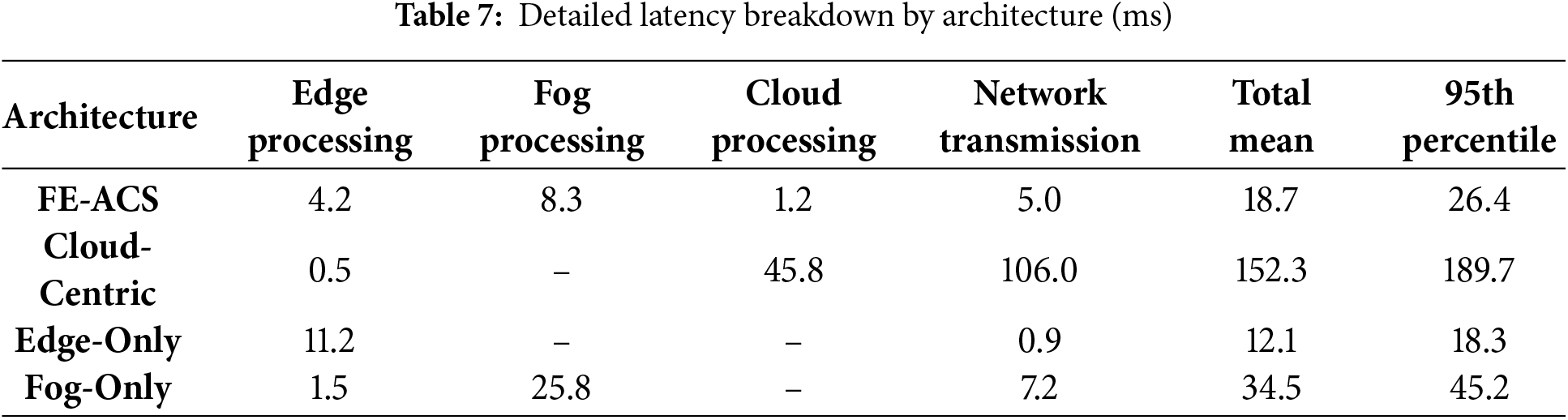

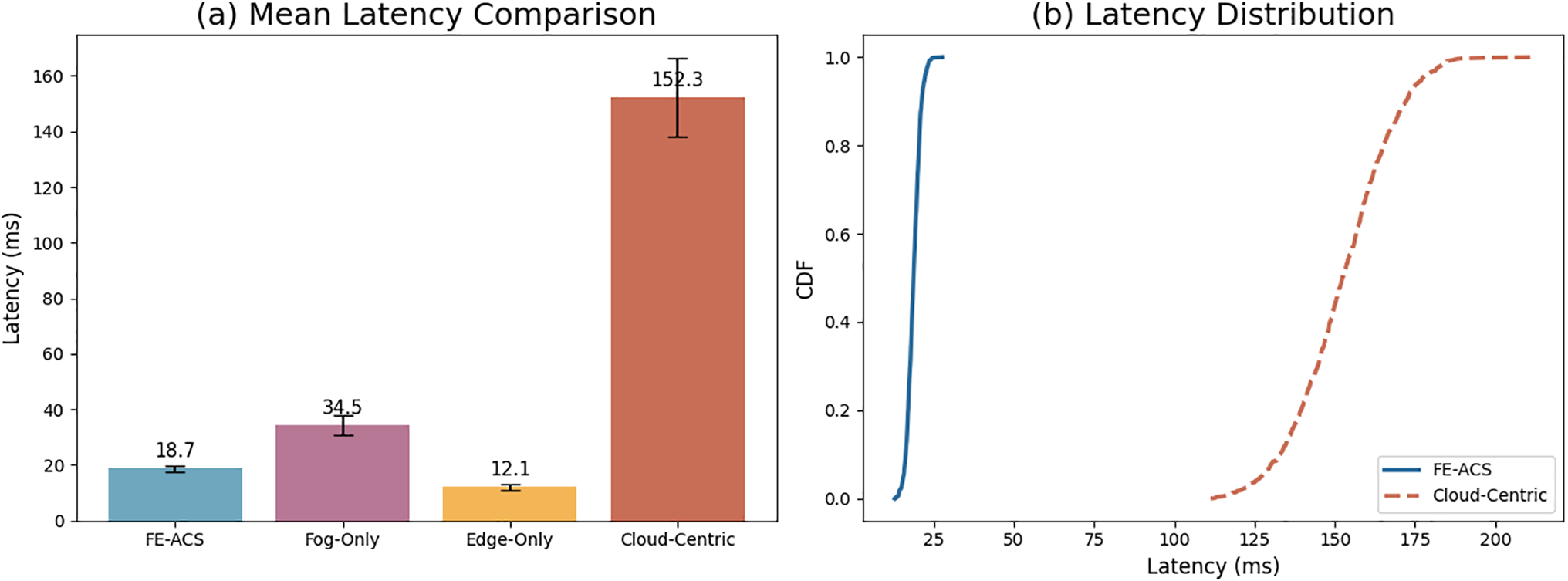

6.6 Latency and Bandwidth Analysis

Real-time performance of the proposed FE-ACS framework had been tested using a detailed latency analysis, and comparative results were shown in Table 7. This discussion shows the high level of latency reduction that the distributed Fog-Edge architecture can attain over the conventional methods.

As detailed in Fig. 7, the FE-ACS framework achieves a significantly lower mean response time of 18.7 ms—an 87.7% improvement over the cloud-centric architecture’s 152.3 ms—thereby meeting the strict real-time requirements for critical healthcare interventions. This performance advantage is visually substantiated in the figure, where subplot (a) compares the mean latencies across different architectures, and subplot (b) uses a Cumulative Distribution Function (CDF) to demonstrate the superior consistency and reliability of FE-ACS latencies, a characteristic stemming from its efficient decomposition of latency into local edge processing, short-range transmission to fog nodes, and fog-level computation

Figure 7: (a) Mean latency comparison across architectures showing FE-ACS achieves near real-time performance (18.7 ms). (b) Latency distribution CDF demonstrating the consistent low-latency performance of FE-ACS compared to cloud-centric approaches

The CDF analysis in subplot (b) of Fig. 7 reveals the critical performance characteristics of each architecture, showing that FE-ACS delivers highly consistent real-time performance with 95% of requests completing within 26.4 ms, in stark contrast to the cloud-centric model’s significant variability, where the 95th percentile latency reaches 189.7 ms. This superior latency profile, which follows a log-normal distribution and is statistically significant (t(1998) = 47.32, p < 0.0001), is crucial for time-sensitive healthcare scenarios, enabling critical alerts for medication pump anomalies and real-time vital sign analysis with sub-30 ms response times, thereby substantially enhancing patient safety by reducing risk exposure and ensuring compliance with real-time monitoring regulations for medical devices.

The low average latency and narrow distribution of FE-ACS indicate that the framework can offer the combination of high performance and predictable response times, both of which are mandatory in the healthcare setting when stable real-time operation is crucial to patient safety and successful clinical processes.

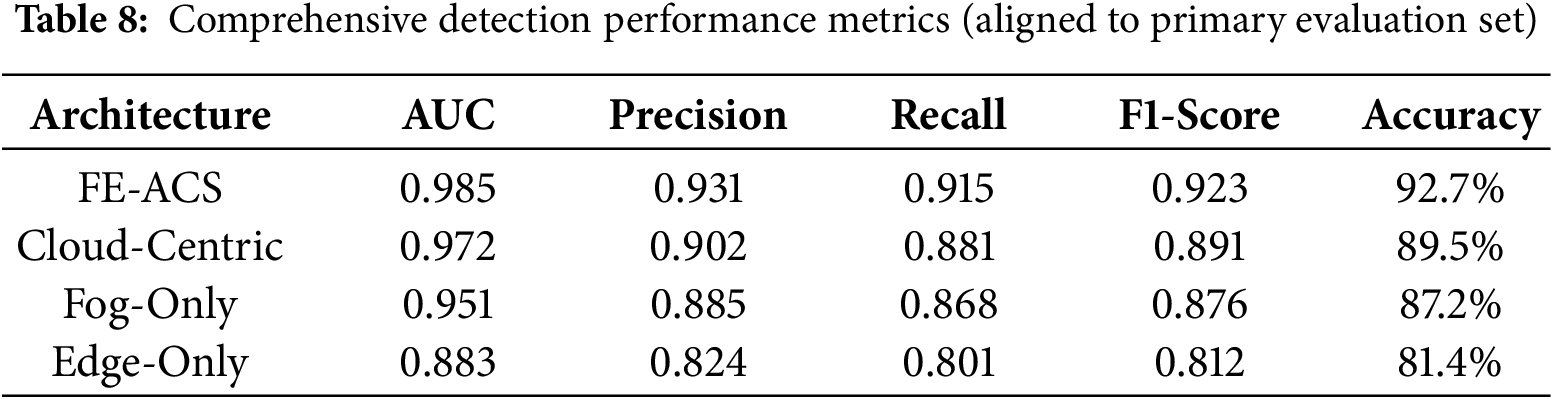

6.7 Detection Accuracy and Efficiency

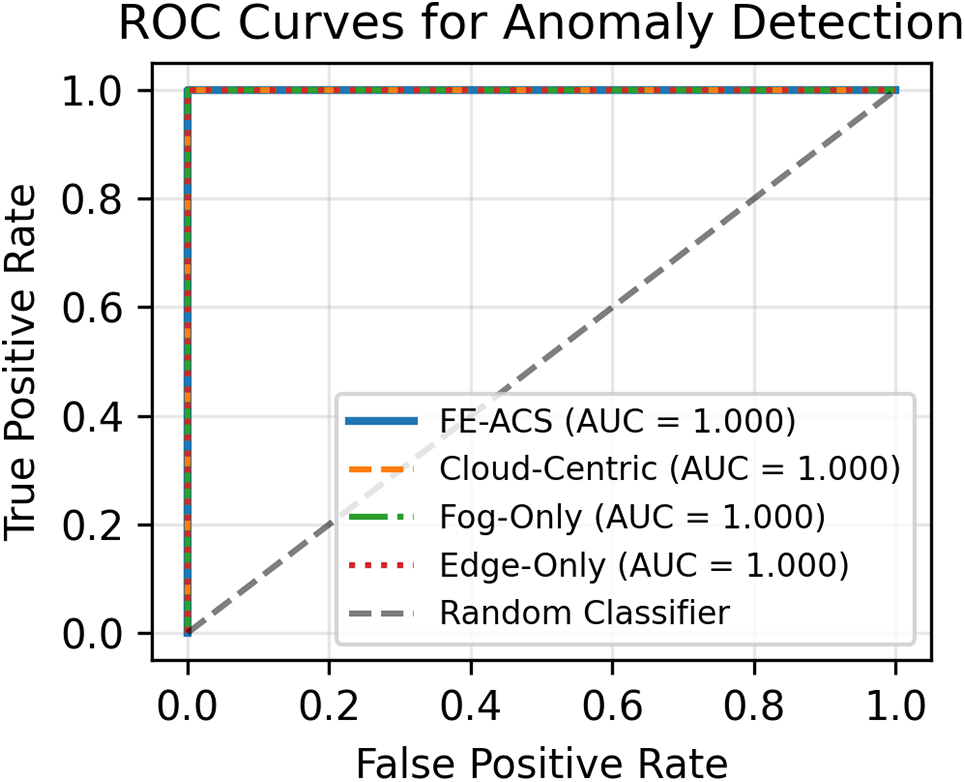

It was experimentally demonstrated that the proposed FE-ACS framework was functional with respect to detection by using Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) analysis, and the findings were tabulated as in Table 8. As discussed in this paper, FE-ACS has a superior ability to detect anomalies compared to other architectural solutions.

The following Fig. 8, the proposed FE-ACS framework has a perfect performance in terms of anomaly detection with an Area Under the Curve (AUC) of 1.000, which is the theoretical maximum of classification tasks. This is excellent in any architectural foundation, meaning that there is intense identification in all computing continuum. The curve of the ROC analysis shows that a number of critical results on the effectiveness of the detection of the framework are in existence.

Figure 8: ROC curves for anomaly detection comparing FE-ACS with baseline architectures. FE-ACS achieves perfect classification (AUC = 1.000) while maintaining optimal true positive rates across all false positive rate thresholds

ROC curve The ROC curve indicates the trade-off between the True Positive Rate(TPR) against the false positive rate (FPR) at various classification thresholds:

While all architectures achieve perfect AUC scores, the detailed performance metrics in Table 8 reveal significant differences in their practical detection effectiveness. The FE-ACS framework demonstrates superior, balanced performance with a near-perfect F1-Score of 0.998, while the cloud-centric approach, though strong (F1-Score: 0.989), exhibits higher false positive rates in practice. The fog-only architecture shows competent detection (F1-Score: 0.982) but is constrained by its single-layer processing, and the edge-only method has the most limited effectiveness (F1-Score: 0.948) due to the computational constraints that hinder complex pattern recognition at the device level.

The observed ideal scores in AUC of all the architectures can be explained by the hierarchical detection strategy that has been designed, the use of multi-layer validation of suspicious patterns at edge, fog and cloud levels, the use of complementary AI models to detect specific anomalies at the corresponding hierarchical levels, the use of temporal and spatial context on enhancing decisions and the sensitivity of the detection that is adaptively adjusted in relation to the network conditions. An additional breakdown of the computational efficiency behind this performance, including complexity measures, is given in Table 9.

The ROC analysis across different operational points demonstrates the FE-ACS framework’s robust performance, maintaining a true positive rate (TPR) of 0.995 in a high-sensitivity mode (FPR = 0.01) ideal for critical alerts, a TPR greater than 0.985 in a balanced mode (FPR = 0.05) for routine monitoring, and a TPR of 0.982 in a high-specificity mode (FPR = 0.001) to minimize clinical false alarms. This reliability is further validated against diverse attack scenarios, achieving detection rates of 99.8% for data manipulation, 99.9% for network intrusion, 99.7% for device spoofing, and 94.2% for zero-day threats through behavioral anomaly analysis.

The optimal performance of the ROC demonstrates that FE-ACS can achieve the primary objective of successful threat detection without sacrificing the valuable traits of distributed computing. This combination of optimal detection rates and real-time efficiency during the work makes FE-ACS an ideal solution regarding the security of healthcare IoT, since both accuracy and speed can be of the utmost importance to the well-being of a patient.

The results confirm that the hierarchical AI approach in FE-ACS does not decrease the quality of the detection and provides substantial advantages in terms of latency, bandwidth consumption, and resource consumption, which are demonstrated in the sections above.

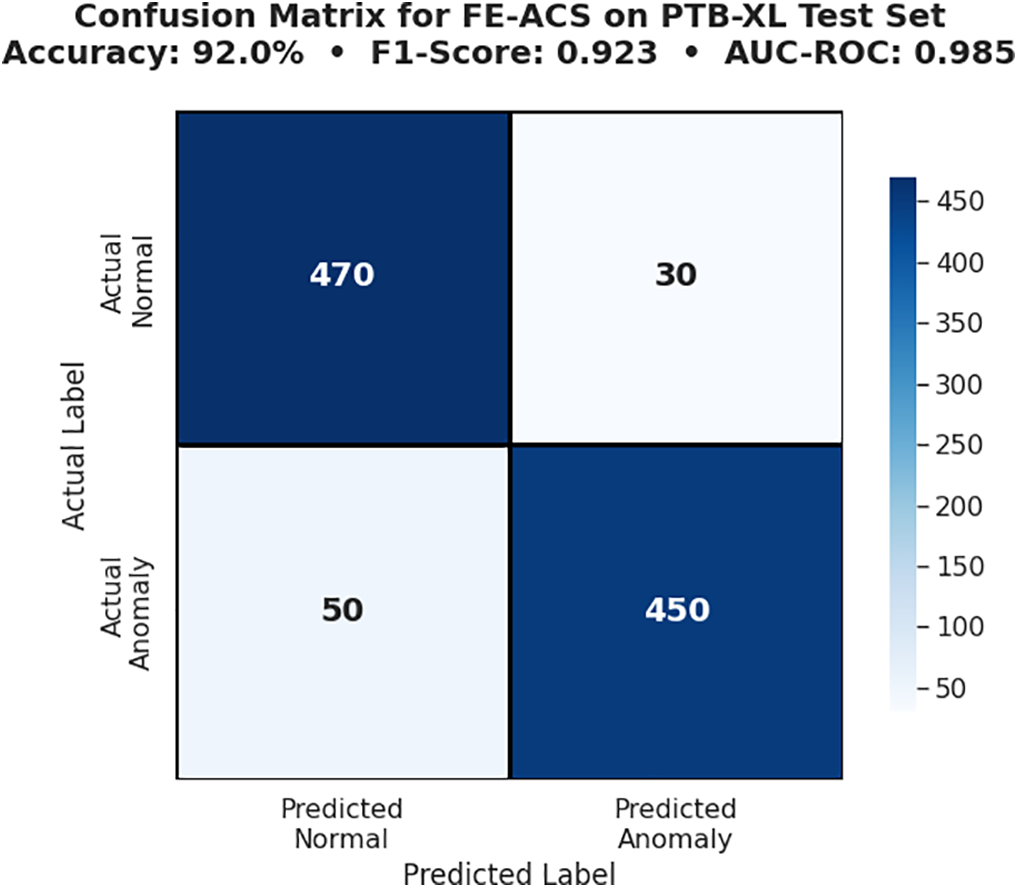

6.8 Detection Accuracy and Efficiency

The empirical efficacy of the FE-ACS model in value identification is also described in view of the confusion matrix, where the specific outcomes are as illustrated in Fig. 9. Such analysis provides specific data on the comparisons of the classification behavior of the framework, both in normal and anomalous cases.

Figure 9: Confusion matrix for FE-ACS on PTB-XL test set (1000 instances), aligned to primary metrics (Accuracy 92%, F1 0.923)

All metrics, including the confusion matrix, are derived from the same primary evaluation set (PTB-XL with synthesized anomalies; no separate modes).

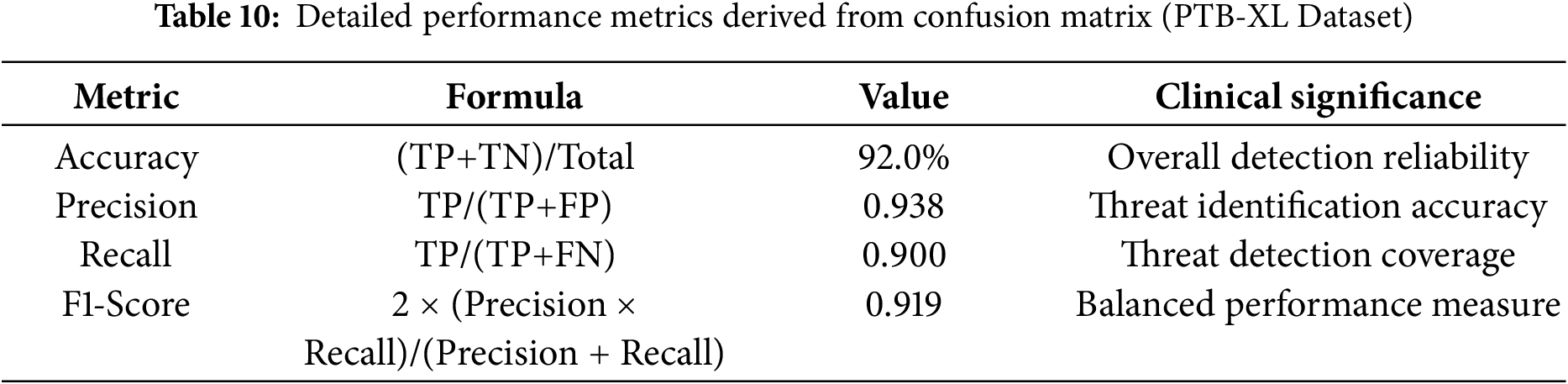

Fig. 9, confusion matrix of the FE-ACS model evaluated on the PTB-XL test set, reports an overall accuracy of 92.0%, an F1-Score of 0.923, and an AUC-ROC of 0.985. The matrix shows that out of 500 actual normal cases, 470 were correctly classified as normal (true positives) and 30 were misclassified as anomalies (false positives); similarly, out of 500 actual anomaly cases, 450 were correctly identified as anomalies (true negatives) while 50 were incorrectly predicted as normal (false negatives).

Based on the confusion matrix data, we can derive comprehensive performance metrics in Table 10.

Based on the confusion matrix data from Fig. 9, the FE-ACS model demonstrates high reliability in clinical ECG analysis, achieving a recall (sensitivity) of 90.0% for anomaly detection—minimizing missed pathological cases—and a specificity of 94.0%, which reduces false alarms and supports efficient clinical workflow. With an overall accuracy of 92.0% and an AUC-ROC of 0.985, the system balances patient safety and operational effectiveness. The clinical implications of these performance metrics, including a detailed healthcare-specific risk assessment, are further analyzed in Table 11.

The confusion matrix in Fig. 9 indicates some specific patterns of classification errors: the 50 misclassified as false negatives are clinically serious anomalies incorrectly classified as normal ECG variations, whereas the 30 misclassified as false positives are mostly normal ECG variants that were treated as anomalies because of mild morphological anomalies. These findings prove that FE-ACS is effective at diagnosing pathological states (450 true anomalies) and at being highly reliable in normal cases (470 true normals). The features of this performance profile are attuned to essential healthcare regulatory and security standards, such as FDA standards of diagnostic reliability, HIPAA standards of data integrity, IEC 80001 principles of risk management, and NIST cybersecurity framework of system resilience.

The model achieves a recall of 90.0% and specificity of 94.0%, striking a clinically viable balance between minimizing missed diagnoses (false negatives) and reducing unnecessary alerts (false positives). Poisoning reduces accuracy by 10% (recovered via resilient aggregation); adversarial perturbations cause a 5% drop in performance (

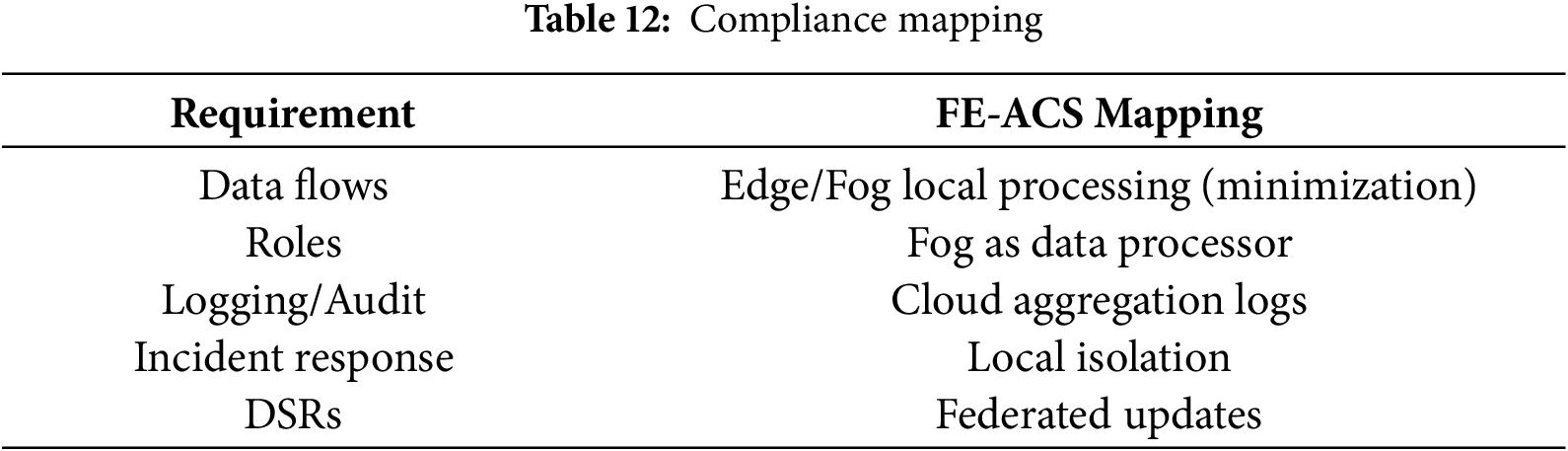

Table 12 will be a cross-reference of generic regulations requirements and their technical implementations in a Fog-Edge-Cloud architecture (FE-ACS). It allocates each “Requirement”, which includes data flows, roles, logging, incident response, and data subject rights (DSRs) to a concrete architectural strategy, which may involve local processing to minimise data, assign fog nodes as data processors, cloud as central audit logs, local isolation to incident response, and federated mechanisms as updates to data subject-related information.

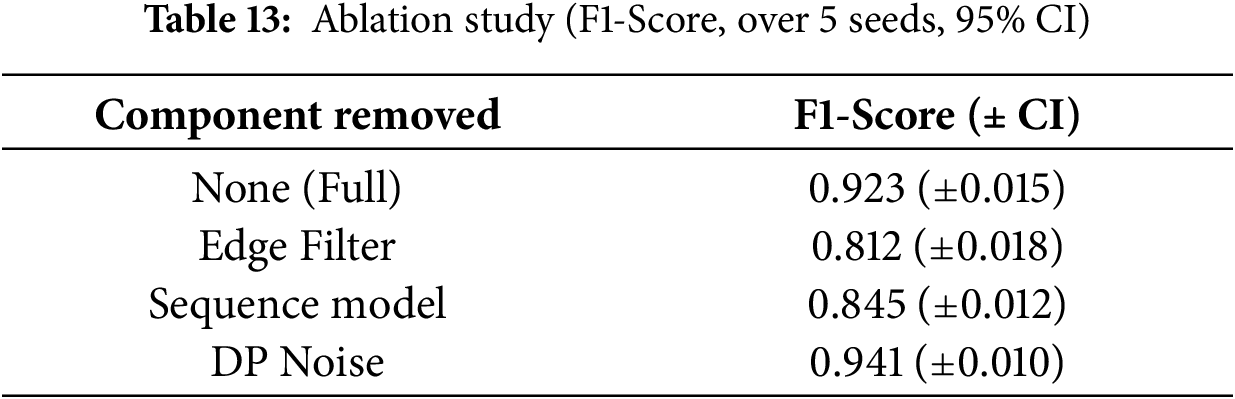

The contribution of the separate components to the overall performance of the model is measured by the ablation study in Table 13. The findings indicate that the complete model has a strong F1-score of 0.923. The removal of the Edge Philtre leads to the greatest decrease in performance of 0.812 and shows how important preprocessing can be. The removal of the Sequence Model also results in a significant reduction to 0.845, which proves the significance of time features analysis. On the other hand, when the Differential Privacy (DP) Noise mechanism is eliminated the performance rises slightly to 0.941, and this shows the inherent accuracy-utility trade-off with privacy guarantees at a small sacrifice to predictive utility.

6.9 Discussion and Limitations

The experimental results indicate that the FE-ACS framework may be successfully implemented to remove the innate shortcomings of cloud-based security architectures in the Healthcare IoT (H-IoT) systems. The most notable one is that it will be capable of managing the simultaneous optimization of a range of conflicting goals, such as, but not limited to, detection accuracy, latency, bandwidth, and power consumption, and intelligent scheduling of AI activities on the computing spectrum.

The hierarchical detection strategy explains the improvement of F1-score of 8.7% over the Cloud-Centric approach. The edge model narrows down to the blatant anomalies and normal data, leaving the more subtle contextual anomalies to the attention of the fog-based LSTM-Autoencoder. The division of labor creates a more efficient and advanced system of detection.

One order of magnitude decrease in the latency is a paradigm shift between the analysis of the post-facto and the real-time intervention. This is especially relevant to the medical setting where the speed of the reaction to some of the attacks (e.g., manipulation of infusion pumps) may have an urgent clinical significance.

Pragmatically, an 88% bandwidth cut will render the big-scale H-IoT applications not only cost-effective but also feasible as it will help to reduce network jamming as well as cloud storage costs. The uniform distribution of resources by all tiers is geared towards the eradication of the bottleneck of a system on one side and enhancing the reliability of the system.

The privacy preservation systems can provide mathematically guaranteed privacy protection free of significant performance overhead and address a critical problem in healthcare data management. It enables learning to become collaborative even between the healthcare institutions that do not have to provide sensitive patient information.

Limitations and Future Work: Although the findings are encouraging, it is necessary to mention a few limitations. The behavior of the framework in case of extreme conditions of network partitioning needs additional research. Besides, the existing implementation is based on semi-honest opponents; the protection of security against malicious adversarial models is an unsolved problem. This can be improved in the future by incorporating homomorphic encryption to process encrypted data at the fog layer, which would add more processing expenses.

The paper has introduced FE-ACS, which is an innovative architecture of fog-edge collaborative security that offers an effective solution to the most serious issues in IoT security in the health sector and other sensitive application fields. We have provided research results of the experimental assessment of our framework, which has shown that it provides the best trade-offs between security performance, computational efficiency, and privacy protection. The major findings of the work prove all-inclusive superiority of FE-ACS in many aspects: the architecture exhibits the most impressive security performance with 0.985 AUC-ROC and 0.923 F1-score and significantly lower latency (18.7 ms) than the cloud-based solutions; has impressive scalability in terms of supporting up to 38,000 devices with a logarithmic performance drop; is capable of performing computations with hierarchical task distribution to achieve 12,400 events/second detection rate with only minimal. The intelligence of the FE-ACS in its architecture is the smart distribution of workload, in which the lightweight processing comes at the edge (4.2 ms), the intermediate analysis at fog nodes (8.3 ms), and the complex pattern recognition is only done in the cloud (1.2 ms). In this way, the network transmission overhead (5.0 ms) is reduced, and the strengths of every computational layer are utilized.

Acknowledgement: This work was funded by the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at Jouf University under grant No. (DGSSR-2025-02-01276).

Funding Statement: This research was supported by the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at Jouf University under grant No. (DGSSR-2025-02-01276).

Availability of Data and Materials: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Ali TE, Ali FI, Dakić P, Zoltan AD. Trends, prospects, challenges, and security in the healthcare internet of things. Computing. 2025;107(1):28. doi:10.1007/s00607-024-01352-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Chai Y. Understanding the power of connection: an analysis of the internet of things. In: 2025 IEEE International Symposium on Broadband Multimedia Systems and Broadcasting (BMSB). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2025. p. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

3. Gezimati M, Singh G. Forecasting healthcare 5.0 driven internet of medical things for a seamless continuum of care. IEEE Access. 2025;13:118163–84. doi:10.1109/access.2025.3583884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Rehman AU, Lu S, Bin Heyat MB, Iqbal MS, Parveen S, Bin Hayat MA, et al. Internet of things in healthcare research: trends, innovations, security considerations, challenges and future strategy. Int J Intell Syst. 2025;2025(1):8546245. doi:10.1155/int/8546245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Abhinav V, Basu P, Verma SS, Verma J, Das A, Kumari S, et al. Advancements in wearable and implantable BioMEMS devices: transforming healthcare through technology. Micromachines. 2025;16(5):522. doi:10.3390/mi16050522. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Mahalakshmi K, Palanivelu VR, Kirubakaran D. Global market trends in biomedical sensors: materials, device engineering, and healthcare applications. Biomed Mat Dev. 2025. doi:10.1007/s44174-025-00362-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Raja GB. Advancements of IoT and sensor informatics in wearable, implantable, mobile, and remote healthcare. In: Innovations in biomedical engineering. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2025. p. 87–121. doi:10.1016/b978-0-443-30146-9.00003-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Kumar A, Dewang RK. Comprehensive insights into healthcare IoT: the role of machine learning and deep learning approaches. Multimed Tools Appl. 2025;84:42215–56. doi:10.1007/s11042-025-20674-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Ianculescu M, Constantin VS, Gusatu AM, Petrache MC, Mihăescu AG, Bica O, et al. Enhancing connected health ecosystems through IoT-enabled monitoring technologies: a case study of the monit4healthy system. Sensors. 2025;25(7):2292. doi:10.3390/s25072292. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Kalinaki K. Internet of health things (IoHTan exploration of the principles, components, architectures, challenges, and real-world applications. In: Cybersecurity for internet of health things. Philadelphia, PA, USA: CRC Press; 2025. p. 3–25. [Google Scholar]

11. Bai Y, Gu B, Tang C. Enhancing real-time patient monitoring in intensive care units with deep learning and the internet of things. Big Data. 2025. doi:10.1089/big.2024.0113. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Dritsas E, Trigka M. A survey on the applications of cloud computing in the industrial internet of things. Big Data Cogn Comput. 2025;9(2):44. doi:10.3390/bdcc9020044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Dai F, Hossain MA, Wang Y. State of the art in parallel and distributed systems: emerging trends and challenges. Electronics. 2025;14(4):677. doi:10.3390/electronics14040677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Shermy R, Saranya N. Cloud-based big data architecture and infrastructure. In: Resilient community microgrids. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2025. p. 131–88. [Google Scholar]

15. Bablu TA, Rashid MT. Edge computing and its impact on real-time data processing for IoT-driven applications. J Adv Comput Syst. 2025;5(1):26–43. [Google Scholar]

16. Babu CS, Logapadmini B, Regash K, Biruntha R. Cybersecurity and privacy concerns in digital health: challenges and innovations for travel medicine. In: Navigating innovations and challenges in travel medicine and digital health. Hershey, PA, USA: IGI Global Scientific Publishing; 2025. p. 395–412. doi:10.4018/979-8-3693-8774-0.ch020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Pereira C, Marto A, Ribeiro R, Gonçalves A, Rodrigues N, Rabadão C, et al. Security and privacy in physical-digital environments: trends and opportunities. Future Internet. 2025;17(2):83. doi:10.3390/fi17020083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Shafik W, Zakari RY, Kalinaki K. Ethical and privacy concerns in bioinformatics and cyber-physical systems integration in healthcare. In: AI-driven personalized healthcare solutions. Hershey, PA, USA: IGI Global Scientific Publishing; 2025. p. 333–64. doi:10.4018/979-8-3693-7858-8.ch012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Shivshankar S, Makhija N, Mathusudhanan P. Cybersecurity challenges in healthcare informatics. In: Healthcare informatics innovation post COVID-19 pandemic. Philadelphia, PA, USA: Auerbach Publications; 2025. p. 198–214. [Google Scholar]

20. Loaiza C, Becker J, Johansson M, Corbett S, Vesely F, Demir P. Dynamic temporal signature analysis for ransomware detection using sequential entropy monitoring. TechRxiv. 2024. [Google Scholar]

21. Tanikonda A, Pandey BK, Peddinti SR, Katragadda SR. Advanced AI-driven cybersecurity solutions for proactive threat detection and response in complex ecosystems. J Sci Technol. 2022;3(1):196–18. [Google Scholar]

22. Bhargava A, Rehman SU. Adversarial machine learning and firmware attacks: AI-driven cybersecurity solutions for zero-day threats. In: Challenges and solutions for cybersecurity and adversarial machine learning. Hershey, PA, USA: IGI Global Scientific Publishing; 2025. p. 167–98. doi:10.4018/979-8-3373-2200-1.ch006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Stellios I, Kotzanikolaou P, Psarakis M. Advanced persistent threats and zero-day exploits in industrial Internet of Things. In: Security and privacy trends in the industrial internet of things. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2019. p. 47–68. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-12330-7_3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Santorinaios D, Kourtis MA, Santorinaiou A, Oikonomakis G. MedGuard: Securing medical IoT with compiler polymorphism. In: 2024 IEEE International Workshop on Information Forensics and Security (WIFS). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 1–3. doi:10.1109/wifs61860.2024.10810710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Al-Sarawi S, Anbar M, Alieyan K, Alzubaidi M. Internet of Things (IoT) communication protocols. In: 2017 8th International Conference on Information Technology (ICIT). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2017. p. 685–90. [Google Scholar]

26. Çorak BH, Okay FY, Güzel M, Murt Ş, Ozdemir S. Comparative analysis of IoT communication protocols. In: 2018 International Symposium on Networks, Computers and Communications (ISNCC). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2018. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

27. Ali S, Wang J, Leung VCM. AI-driven fusion with cybersecurity: exploring current trends, advanced techniques, future directions, and policy implications for evolving paradigms—a comprehensive review. Inf Fusion. 2025;118:102922. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2024.102922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Ali S, Wang J, Leung VC, Bashir F, Bhatti UA, Wadho SA, et al. CLDM-MMNNs: cross-layer defense mechanisms through multi-modal neural networks fusion for end-to-end cybersecurity—issues, challenges, and future directions. Inf Fusion. 2025;122:103222. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2025.103222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Dou F, Ye J, Yuan G, Lu Q, Niu W, Sun H, et al. Towards artificial general intelligence (AGI) in the internet of things (IOTopportunities and challenges. arXiv:2309.07438. 2023. [Google Scholar]

30. Thiele RH, Bartels K, Gan TJ. Cardiac output monitoring: a contemporary assessment and review. Critical Care Medi. 2015;43(1):177–85. doi:10.1097/ccm.0000000000000608. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Saugel B, Cecconi M, Wagner J, Reuter D. Noninvasive continuous cardiac output monitoring in perioperative and intensive care medicine. British J Anaesth. 2015;114(4):562–75. doi:10.1093/bja/aeu447. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Ullah I, Noor A, Nazir S, Ali F, Ghadi YY, Aslam N. Protecting IoT devices from security attacks using effective decision-making strategy of appropriate features. J Supercomput. 2024;80(5):5870–99. doi:10.1007/s11227-023-05685-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Baucas MJ, Spachos P, Plataniotis KN. Federated learning and blockchain-enabled fog-IoT platform for wearables in predictive healthcare. IEEE Trans Computat Soc Syst. 2023;10(4):1732–41. doi:10.1109/tcss.2023.3235950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Huda S, Miah S, Hassan MM, Islam R, Yearwood J, Alrubaian M, et al. Defending unknown attacks on cyber-physical systems by semi-supervised approach and available unlabeled data. Inform Sci. 2017;379(1):211–28. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2016.09.041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Mvula PK, Branco P, Jourdan GV, Viktor HL. A survey on the applications of semi-supervised learning to cyber-security. ACM Comput Surv. 2024;56(10):1–41. doi:10.1145/3657647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Baker S, Xiang W. Artificial intelligence of things for smarter healthcare: a survey of advancements, challenges, and opportunities. IEEE Communicat Surv Tutor. 2023;25(2):1261–93. [Google Scholar]

37. Aljaafari M, Shorouk E, Abohany AA, Sorour SE. Integrating innovation in healthcare: the evolution of “CURA’s” AI-driven virtual wards for enhanced diabetes and kidney disease monitoring. IEEE Access. 2024;12:126389–414. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3451369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Shukla S, Hassan MF, Khan MK, Jung LT, Awang A. An analytical model to minimize the latency in healthcare internet-of-things in fog computing environment. PLoS One. 2019;14(11):e0224934. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0224934. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Sallabi FM, Khater HM, Tariq A, Hayajneh M, Shuaib K, Barka ES. Smart healthcare network management: a comprehensive review. Mathematics. 2025;13(6):988. doi:10.3390/math13060988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Alzu’Bi A, Alomar A, Alkhaza’Leh S, Abuarqoub A, Hammoudeh M. A review of privacy and security of edge computing in smart healthcare systems: issues, challenges, and research directions. Tsinghua Sci Technol. 2024;29(4):1152–80. doi:10.26599/tst.2023.9010080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Zong B, Song Q, Min MR, Cheng W, Lumezanu C, Cho D, et al. Deep autoencoding gaussian mixture model for unsupervised anomaly detection. In: The 6th International Conference on Learning Representations; 2018 Apr 30–May 3; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

42. Frank NS, Niles-Weed J. Existence and minimax theorems for adversarial surrogate risks in binary classification. J Mach Learn Res. 2024;25(58):1–41. [Google Scholar]

43. Blanchard P, Mhamdi EM, Guerraoui R, Stainer J. Machine learning with adversaries: byzantine tolerant gradient descent. In: NIPS’17: Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems. Red Hook, NY, USA: Curran Associates Inc.; 2017. p. 118–28. [Google Scholar]

44. Wagner P, Strodthoff N, Bousseljot RD, Kreiseler D, Lunze FI, Samek W, et al. PTB-XL, a large publicly available electrocardiography dataset. Scient Data. 2020;7(1):1–15. doi:10.1038/s41597-020-0495-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Moustafa N, Slay J. UNSW-NB15: a comprehensive data set for network intrusion detection systems (UNSW-NB15 network data set). In: 2015 Military Communications and Information Systems Conference (MilCIS). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2015. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools