Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

GNN: Core Branches, Integration Strategies and Applications

1 School of Automation, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, Chengdu, 611731, China

2 School of the Environment, The University of Queensland, Brisbane St Lucia, QLD 4072, Australia

3 Department of Geography, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843, USA

4 School of Artificial Intelligence, Guangzhou Huashang University, Guangzhou, 511300, China

5 School of Biological and Environmental Engineering, Xi’an University, Xi’an, 710065, China

6 Department of Hydrology and Atmospheric Sciences, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721, USA

* Corresponding Authors: Feng Bao. Email: ; Lirong Yin. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: The Collection of the Latest Reviews on Advances and Challenges in AI)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2026, 146(1), 5 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.075741

Received 07 November 2025; Accepted 15 December 2025; Issue published 29 January 2026

Abstract

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), as a deep learning framework specifically designed for graph-structured data, have achieved deep representation learning of graph data through message passing mechanisms and have become a core technology in the field of graph analysis. However, current reviews on GNN models are mainly focused on smaller domains, and there is a lack of systematic reviews on the classification and applications of GNN models. This review systematically synthesizes the three canonical branches of GNN, Graph Convolutional Network (GCN), Graph Attention Network (GAT), and Graph Sampling Aggregation Network (GraphSAGE), and analyzes their integration pathways from both structural and feature perspectives. Drawing on representative studies, we identify three major integration patterns: cascaded fusion, where heterogeneous modules such as Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM), and GraphSAGE are sequentially combined for hierarchical feature learning; parallel fusion, where multi-branch architectures jointly encode complementary graph features; and feature-level fusion, which employs concatenation, weighted summation, or attention-based gating to adaptively merge multi-source embeddings. Through these patterns, integrated GNNs achieve enhanced expressiveness, robustness, and scalability across domains including transportation, biomedicine, and cybersecurity.Keywords

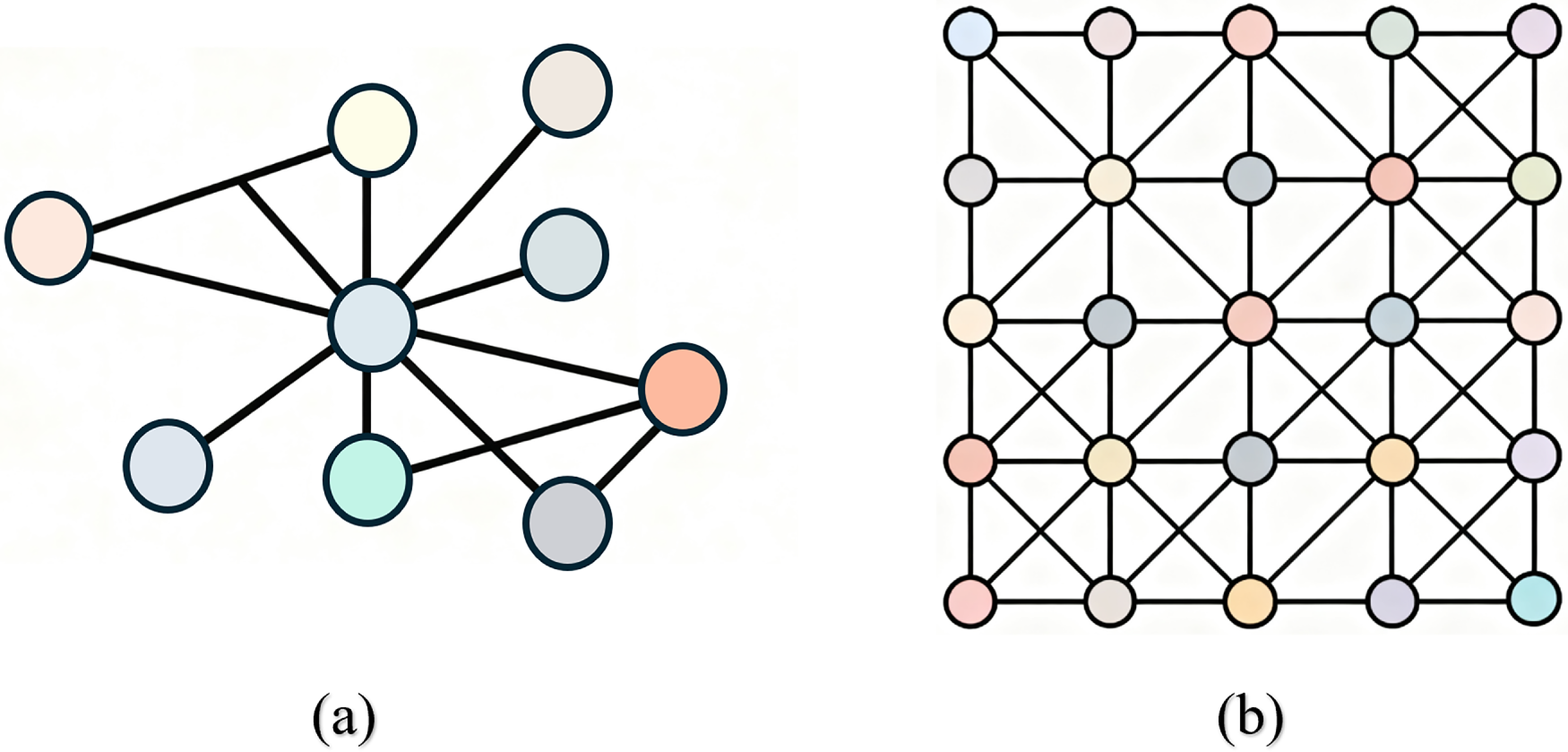

With the explosive growth of relational data in the digital era, the graph, a non-Euclidean data structure, has emerged as the predominant model for characterizing relational data in complex systems [1–4]. It can characterize the interaction information between entities in complex systems such as social networks, biomolecular structures, transportation networks, and knowledge graphs [5–8]. For example, the relationship of mutual following in social networks forms a heterogeneous graph [9,10]; protein interaction networks encode molecular functions through graphs [11,12]; urban traffic flow dynamics are represented as spatiotemporal graphs [13,14]; and knowledge process structures are depicted as tabular graphs [15–19]. The essential characteristic of this type of data nodes is the deep integration of its topological structure and semantic information, meaning that node attributes in the graph depend not only on their own features but also on their relationships with neighboring nodes [2]. The non-Euclidean space image is shown in Fig. 1a.

Figure 1: (a) Non-Euclidean Space Node feature map and (b) Euclidean spatial node feature map

However, traditional machine learning methods face significant limitations when handling non-Euclidean data. First, they heavily rely on the Euclidean space assumption. Models such as support vector machines and random forests can only effectively process regular structured data and cannot adapt to the irregular topological structure of graphs [20,21]. Moreover, models based on Euclidean space, such as Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) and Recurrent Neural Network (RNN), rely on fixed grid sequence structures and cannot process or model irregular, non-uniform points on graphs [22]. The feature map of Euclidean spatial nodes is shown in Fig. 1b. Finally, manually designed diagrams are inefficient and struggle to capture high-level semantic relationships, resulting in limited model generalization capabilities [3,23].

To address these challenges, graph neural networks (GNNs) have emerged as a specialized deep learning (DL) framework for graph-structured data [24,25]. GNNs achieve deep representation learning of graph-structured information through a “message passing” mechanism, serving as the essential bridge connecting graph analysis and machine learning [26–28]. The core idea of GNNs is to iteratively aggregate information from neighboring nodes, allowing each node to progressively fuse local structural features with global contextual information. For example, early research combined graph signal processing with deep learning through graph convolutions [29]. Recent work, such as Graph Convolutional Networks (GCN) [3,23,30], Graph Attention Networks (GAT) [15], and GraphSAGE [31], has significantly enhanced model expressiveness through spatial convolutions and attention mechanisms.

It is worth noting that graph representation learning, as the theoretical foundation of GNNs, aims to map graph structures into low-dimensional dense vector spaces while preserving both topological and semantic information [32]. For example, DeepWalk [33] and node2vec [34] generate node sequences through random walks, inspiring subsequent GNN designs to develop more efficient neighborhood sampling strategies [23].

While numerous advanced architectures have emerged in recent years, such as Graph Transformer [35], Hypergraph Neural Network [36], Temporal or Dynamic GNN [37], and Heterogeneous Graph Neural Network [38], these models can largely be viewed as extensions or specializations derived from the core message-passing paradigms of GCN, GAT, and GraphSAGE. Accordingly, this review deliberately focuses on these three canonical branches of GNN, which form the conceptual and algorithmic foundation upon which later architectures are built. This scoped focus enables a systematic synthesis of their integration strategies and comparative mechanisms, providing a coherent analytical framework that remains relevant for understanding both classical and modern GNN variants.

Despite the rapid development of GNN research, existing reviews often either focus on single-model introductions or lack in-depth analysis of integration strategies, failing to fully capture the latest progress in core technologies and fusion innovations. To address this gap, the present review concentrates on the recent development of the representative GNN branches and their integration. Specifically, this paper systematically synthesizes the three core branches of GNN (GCN, GAT, and GraphSAGE) emphasizing their technical principles, structural characteristics, and applicable scenarios. Moreover, it explores the potential integration among these core branches. With the increasing complexity of real-world graph data, single GNN models often struggle to balance performance and efficiency; therefore, we analyze integration strategies from both structural and feature levels, such as combining GraphSAGE’s sampling mechanism with GAT’s attention mechanism to improve scalability, and fusing GCN’s local structure modeling with graph embedding’s global topological capture to enhance representation power. Finally, this review summarizes the key challenges currently faced by GNNs and outlines future research directions, aiming to provide a comprehensive reference for researchers to understand the core technologies of GNNs and to inspire innovations in integration methods.

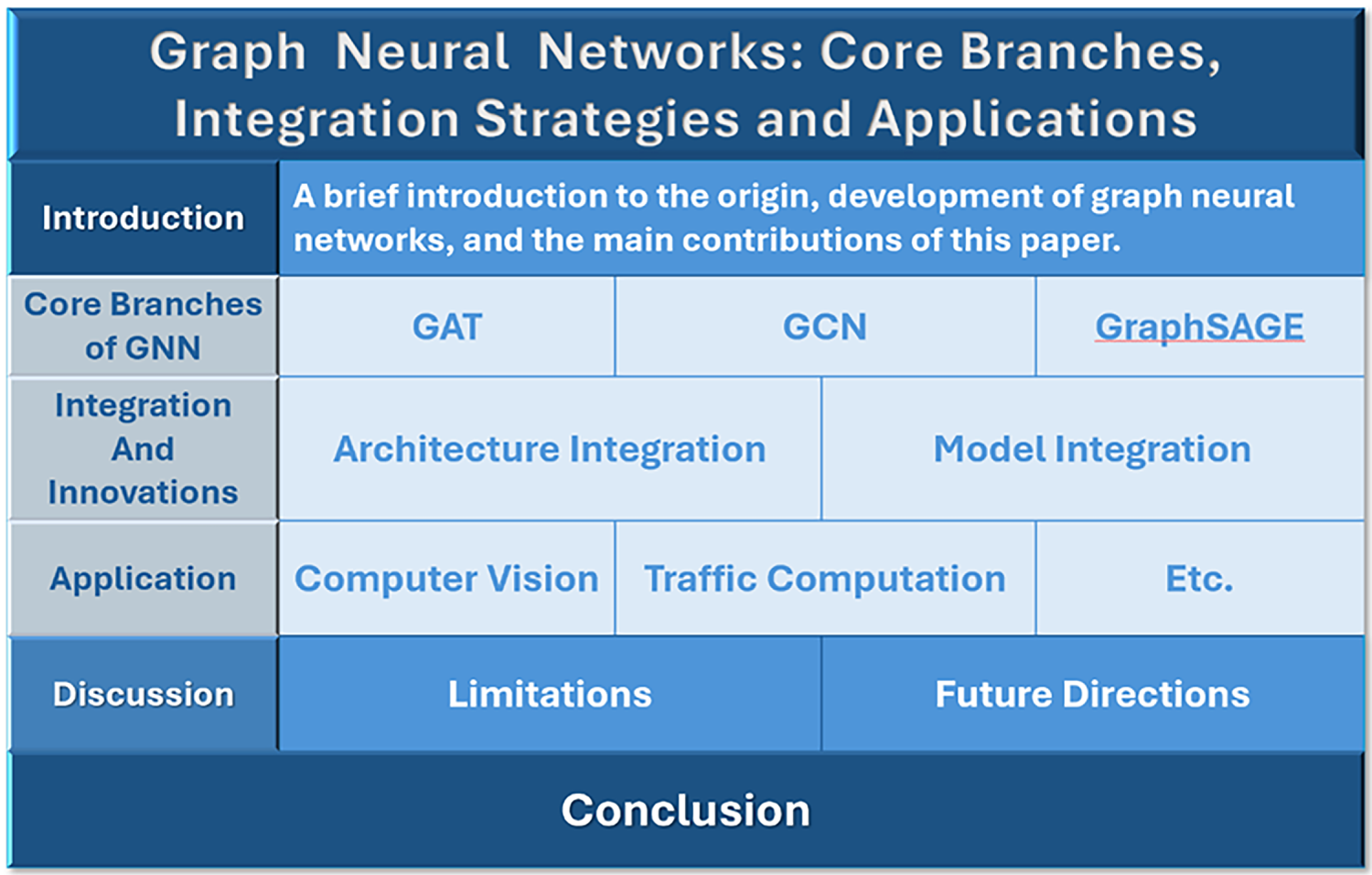

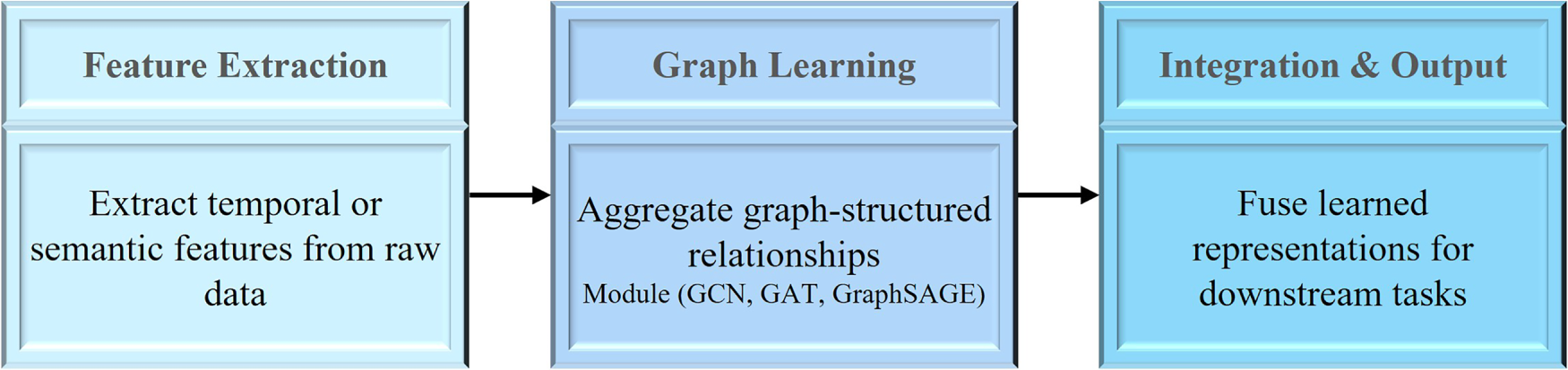

The overall organization of this paper is as follows, as illustrated in Fig. 2. We first discuss the non-Euclidean characteristics of graph data and their widespread presence in domains such as social networks and molecular structures, analyze the limitations of traditional machine learning methods in handling such data, and then define the core concepts of GNNs and graph representation learning (GRL). The subsequent section presents the fundamental theories of GNNs, including the mathematical formulation and classification of graph data as well as the core message-passing mechanisms—message generation, neighborhood aggregation, and node update. Following this theoretical foundation, the section on core technological branches elaborates on the three major mainstream GNNs. The chapter on integrated innovation serves as the central focus of this review, clarifying the logic of integration and providing a systematic analysis of integration strategies at both the structure level and the feature level.

Figure 2: Review framework

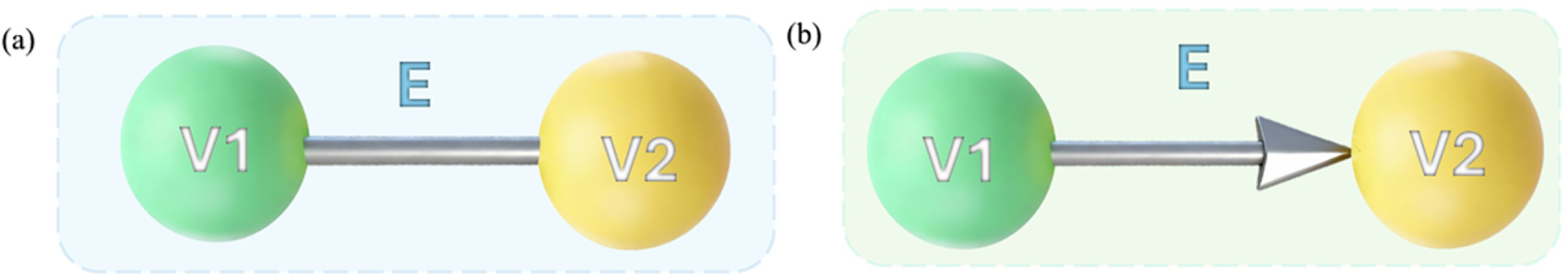

The structure of a graph consists of nodes and edges. The graph is defined as

Figure 3: Undirected graphs (a) and directed graphs (b)

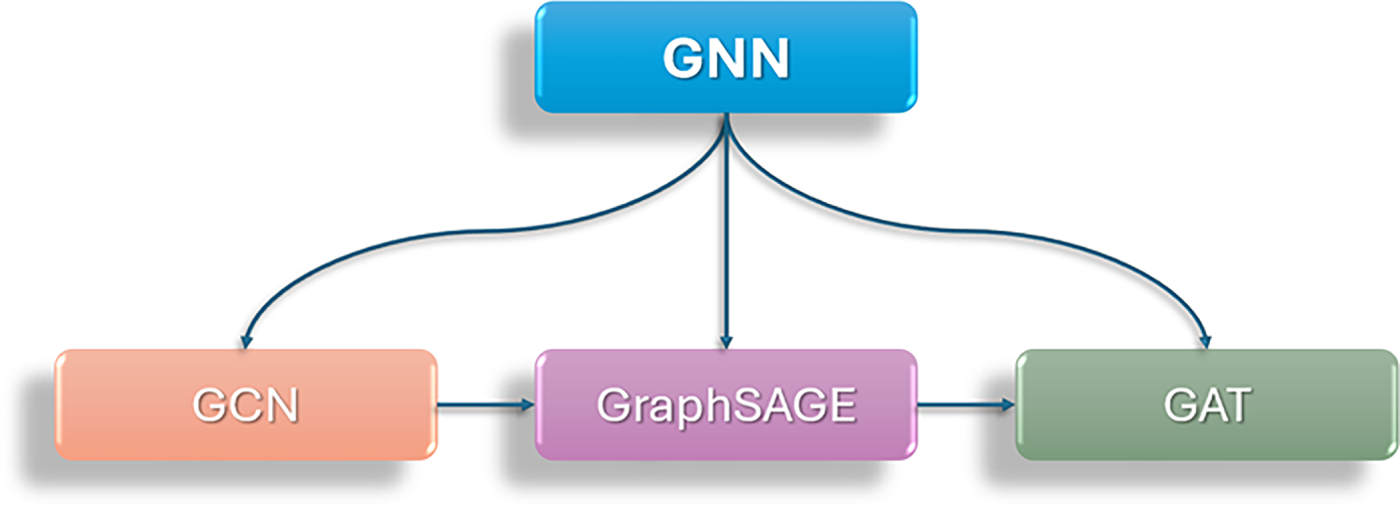

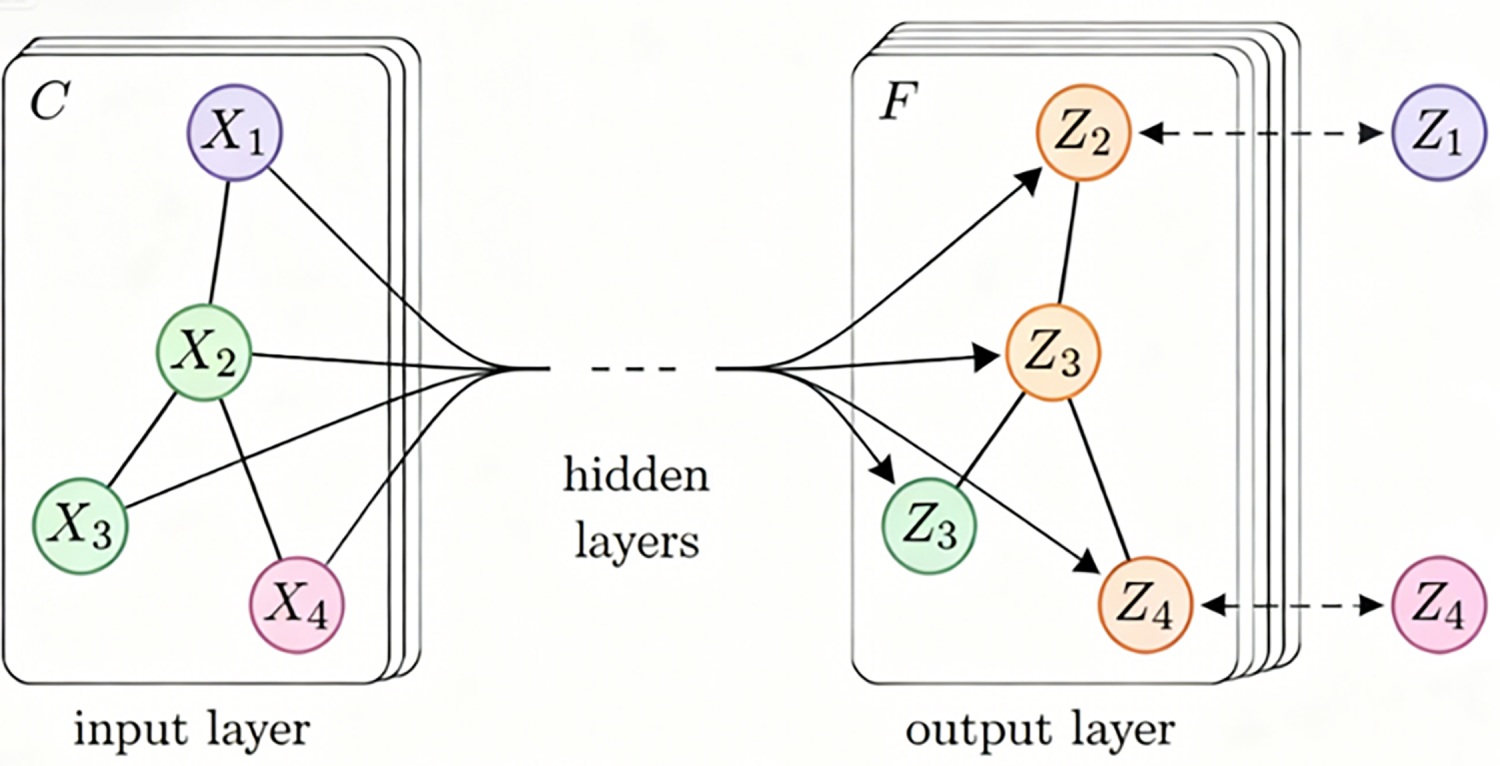

These foundational frameworks form the prerequisite for subsequent GNN model designs—such as convolutional, attention-based, and sampling approaches—and constitute the basis for applying graph data to tasks including node classification, link prediction, and graph generation. The three most core and widely applied branches of GNN are GCN and GAT (Graph Attention Network) respectively. Graph Attention Network (Graph Sample and Aggregate), GraphSAGE (Graph Sample and Aggregate), as shown in Fig. 4. Next, we will introduce these core branches in detail.

Figure 4: Structure of GNN

2.1 GCN: Neighborhood Information Based on Graph Convolution

GCN is structured into layers of input layer, hidden layer and output layer, demonstrating the processing flow of graph data by GCN, as shown in Fig. 5 [41–44]. This subsection provides a concise overview of the basic mechanism of GCN as a conceptual foundation for subsequent comparisons and integration analysis, rather than a detailed algorithmic exposition already covered in existing surveys [45,46].

Figure 5: Working of GCN

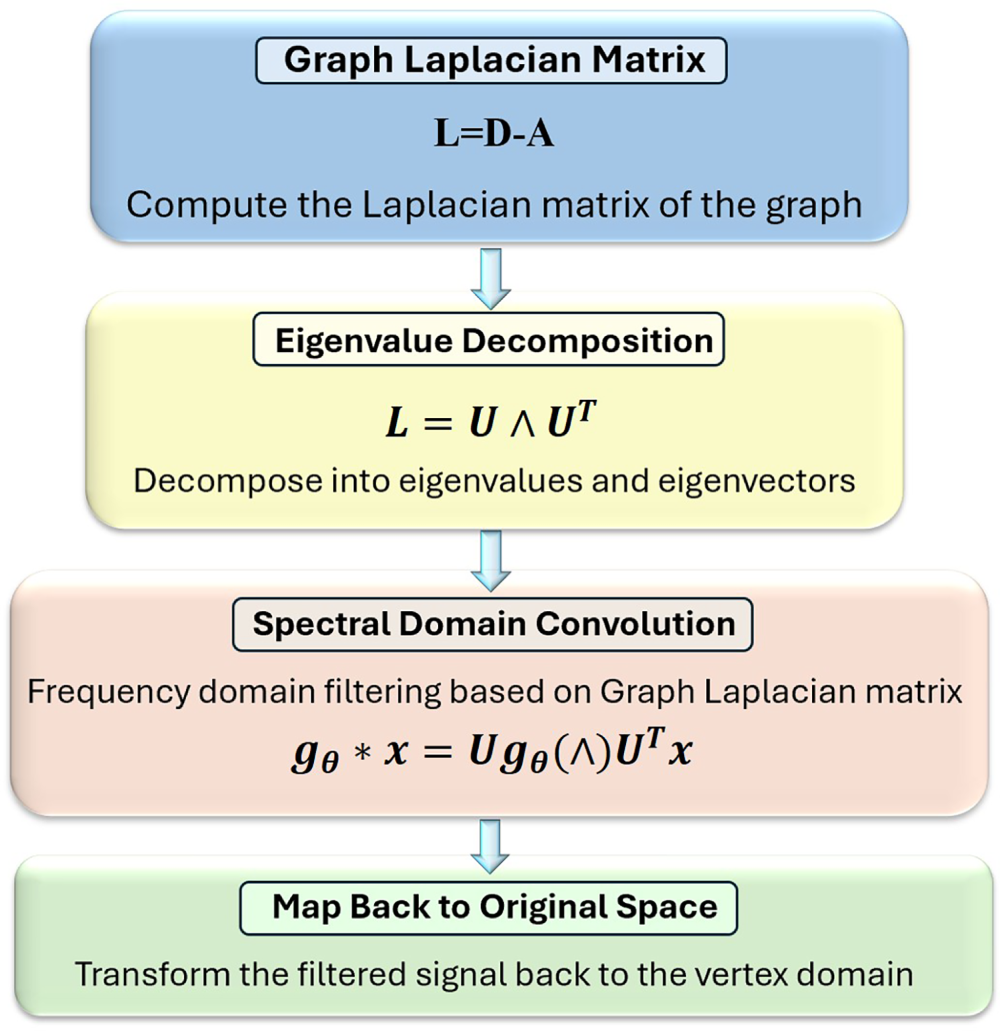

GCN represents the most prominent branch within graph deep learning models. GCN can be categorized into spectral domain methods and spatial domain methods: spectral domain methods achieve convolution through the eigen decomposition of the graph Laplacian matrix; spatial domain methods directly aggregate node neighborhood features, representing the current mainstream approach [47–50].

For semi-supervised learning in spectral domains, the semi-supervised GCN proposed by Kipf and Welling further simplifies computations, its equation as Eq. (1):

where,

Spatial domain convolutions define the convolution operation directly within the node space of the graph, The flowchart of the spectral domain method is shown in Fig. 6. By aggregating features from neighboring nodes, they update the representation of the central node, thereby more intuitively reflecting the graph’s local structural information. The general framework for GNNs in the spatial domain is the message-passing neural network (MPNN), whose message-passing and node-updating process can be expressed as Eq. (2):

where,

Figure 6: The flowchart of the spectral domain

The spatial domain convolution kernel is based on node neighborhood relationships [51–53]. By designing an appropriate aggregation function, it fuses the features of the central node and its neighboring nodes to obtain updated central node features. The flowchart of the spatial domain method is shown in Fig. 7.

Figure 7: The flowchart of the spacial domain

Past research on GCNs has exhibited certain limitations. On the one hand, most existing GCN models feature shallow structures, typically not exceeding three to four layers in depth, which significantly constrains their ability to extract high-level node features [54,55]. To overcome the shallow-layer limitation of traditional GCNs, researchers have proposed various deep GCN architectures. For instance, the introduction of the Non-local Message Passing (NLMP) framework has enabled the design of exceptionally deep graph convolutional networks while effectively mitigating over-smoothing [56]. Within this framework, novel spatial graph convolutional layers were devised to extract multi-scale, high-level node features. Concurrently, the end-to-end Deep Graph Convolutional Neural Network II (DGCNNII) model was developed, achieving a depth of up to 32 layers [55]. Through quantifying the graph smoothness at each layer and conducting ablation studies, the DGCNNII model was demonstrated to outperform numerous shallow graph neural network baseline methods. This innovation in deep architecture enables GCNs to delve deeper into hierarchical information within graph data, extracting more representative high-level node features and providing enhanced capabilities for processing complex graph structural data.

Previously, GCNs primarily focused on aggregating node features while overlooking the importance of other modal information such as edge features [57–59]. To address this, Yue et al. proposed two approaches: the Feature Embedding Adjacent Matrix and the Reverse Graph [49]. The Feature embedding adjacent matrix approach synthesizes edge features into node features, propagating them to neighboring nodes during the propagation process. The Reverse graph method constructs a special auxiliary graph to propagate edge features to neighboring edges, thereby building a comprehensive representation incorporating both edge and node features. These novel methods enhance the accuracy of graph classification, particularly on datasets where basic GCNs exhibit lower accuracy. Furthermore, Wang et al. combined hypergraph convolutional networks (HCN) with GCN to propose parallel hypergraph convolutional neural networks (PHCN) for semi-supervised automatic image labelling [60]. By connecting label graphs and sample hypergraphs, this approach considers the distribution of labels and features while performing feature aggregation, thereby enhancing labelling performance. These multimodal information fusion approaches enrich the content of GCN neighborhood information aggregation, enabling GCNs to utilize more diverse types of information for node representation updates and thereby enhancing model performance across various tasks.

Research on GCNs concerning connectivity patterns remains inadequate. For such specialized graph data structures, integrated enhancements to the GCN domain are required. For instance, in higher-order systems, studies have demonstrated that simplices can encode higher-order interactions between nodes, leading to the design of Simplex Convolutional Neural Networks (SCNN) and Deep Simplex Convolutional Neural Networks (DeepSCNN) [61]. Additionally, for scale-free graphs, Hyperbolic Deep Graph Convolutional Neural Network (HDGCNN) maps graphs from Euclidean space to hyperbolic space, defining fundamental operations for deep graph convolutional neural networks within this hyperbolic domain [56]. This approach incorporates hyperbolic feature transformation based on identity mappings, dense connection schemes utilizing novel non-local message passing frameworks, and neighborhood aggregation methods combining initial structural features with hyperbolic attention coefficients. These techniques effectively harness both the structural characteristics of graph data and node-specific features, enhancing the exploration of non-local structural features and finer granularity node characteristics within scale-free or hierarchical graphs. These neighborhood aggregation enhancements tailored for specific graph structures enable GCNs to better process diverse graph data types, thereby improving model adaptability and performance within complex graph architectures.

In summary, the neighborhood information aggregation paradigm based on graph convolutions in GCNs continues to evolve and innovate. From the fundamental mechanisms of traditional GCNs to breakthroughs in deep architectures, from multimodal information fusion to handling specialized graph structures, and from dynamic adaptive aggregation to hardware acceleration optimization, these studies have refined and enhanced GCN neighborhood information aggregation from diverse perspectives. Consequently, GCNs now better process complex graph-structured data, demonstrating greater application potential across various domains.

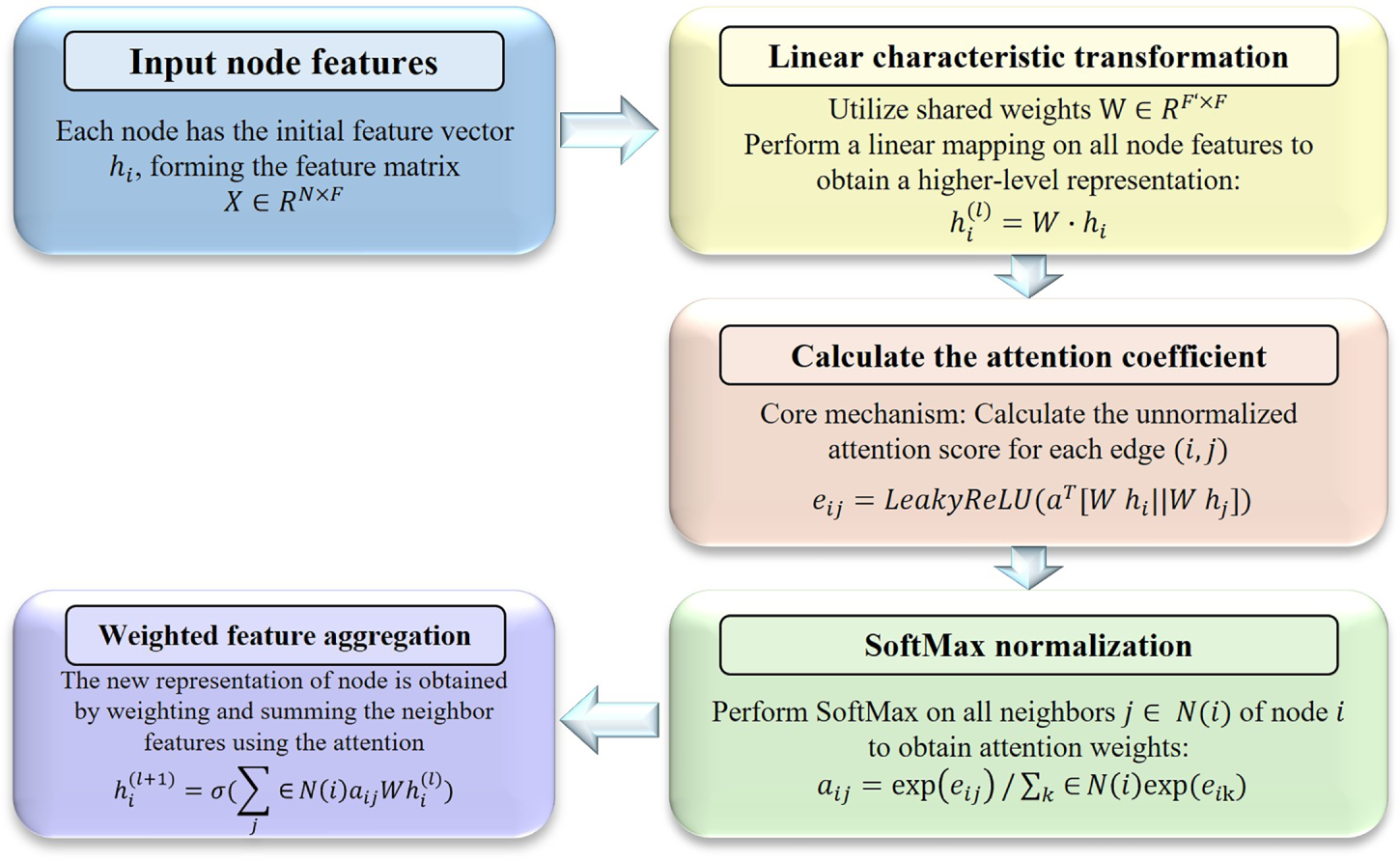

2.2 GAT: Introduce the Attention Mechanism to Represent Learning

GAT, as a breakthrough advancement in the field of graph neural networks, fundamentally integrates the attention mechanism into node representation learning. The basic GAT model computes unnormalized attention coefficients for each node pair through a self-attention mechanism, where the coefficients represent the relational strength between the target node and its neighboring nodes. Subsequently, the attention coefficients are normalized using the SoftMax function, and the normalized coefficients are employed to perform a weighted sum of the neighbors’ features, thereby generating a new representation for the target node. To stabilize the learning process and enhance model capacity, GAT typically adopts multi-head attention, concatenating or averaging the representations computed by multiple attention heads [62]. The flowchart of the core mechanism of GAT is in Fig. 8.

Figure 8: The flowchart of the core mechanism of GAT

Since the original GAT model was proposed, researchers have extensively expanded and innovated upon it from multiple dimensions. One significant direction involves the refinement and structuring of the attention mechanism. For instance, Graph Oriented Attention Networks (GOAT) introduced a target-specific attention computation method, explicitly focusing attention on a designated destination node during each iteration, thereby enhancing the interpretability of specific node influence within the graph [63]. Full-graph Attention Neural Networks (FGANN) go beyond the constraints of local neighborhoods by incorporating the influence of all nodes in the graph during self-attention computation, implicitly assigning different weights to different nodes through masked attention, thus capturing more global dependencies [64]. The Structural Attention Network (SAN) distinguishes structural differences between nodes by introducing a transition matrix and concatenates multi-hop features, enabling the model to attend to the topological structure of the graph [65].

When handling heterogeneous and multi-relational graph data, especially in knowledge graphs, variants of GAT have demonstrated strong capabilities. The Multi-Relational Graph Attention Network (MRGAT) addresses the challenge of complex multi-relational interactions in knowledge graphs by designing a self-attention layer to compute the importance of different neighboring nodes, thereby optimizing the network architecture [8]. Similarly, Heterogeneous Relation Attention Networks propose an attention-based heterogeneous GNN framework that first aggregates entity features within each relational path and then learns the importance of different relational paths to selectively aggregate information [66]. Another study presents a heterogeneous graph neural network framework based on a hierarchical attention mechanism—encompassing entity-level, relation-level, and self-level attention—to fully address the heterogeneity of knowledge graphs [8]. Additionally, the Dynamic Graph Attention Network with Contrastive Learning (DGATCL) introduces a dynamic sampling strategy to adaptively select relevant neighbors and designs a dual-branch attention mechanism to jointly capture edge importance in a relation-aware manner and the contribution of neighbors at the node level [6].

To address real-world scenarios involving dynamic graph structures or noise, researchers have proposed various methods to enhance robustness. Sparse Graph Attention Networks (SGATs) learn sparse attention coefficients under L0-norm regularization, effectively identifying and filtering out noisy or task-irrelevant edges in the graph, demonstrating particularly strong performance on disassortative graphs [67]. The Heterophily-aware Graph Attention Network (HA-GAT) explicitly models the heterophily of each edge, leveraging local distribution patterns as latent heterophily signals to enable nodes to appropriately aggregate information from dissimilar neighbors [68]. For dynamic graphs, the DyAtGNN framework innovatively integrates a temporal dynamics learning module with an adaptive structure learning module, using RNN to jointly learn model parameters and identify influential nodes, thereby effectively adapting to environments with frequent node-level changes [69].

The powerful representation learning capability of the GAT model has led to outstanding performance across numerous cross-domain applications. In computer vision, the Attention-Driven Graph Neural Network (AD-GNN) leverages dynamic graph convolution through Cross-scale Dynamic Graph (CDG) blocks and Channel Attention Spatial Dynamic Graph (CASDG) blocks to explore spatial non-local self-similarity information, effectively reconstructing fine details in face images [70]. The Group and Graph Attention Network (GGANet) jointly suppresses background noise via the Group Channel Attention (GCA) module and the Learnable Graph Attention (LGA) module, enhancing performance in dense object counting [71]. For time series forecasting, the Multiscale Pooling Attention-based Graph Attention Network (MSPA-GAT) employs a multi-GATv2 architecture to model spatial dependencies and introduces a Multiscale Pooling Attention (MSPA) mechanism to capture multi-level information, enabling accurate prediction of equipment remaining useful life (RUL) [72]. In cybersecurity, Darknet Graph Neural Networks (DGNN) utilize graph neural networks combined with attention mechanisms on Darknet Traffic Graphs (DTG) to fully exploit traffic features, achieving high-precision classification of darknet applications [73].

While GAT introduces adaptive attention weighting that improves interpretability and local sensitivity, it remains computationally expensive for dense graphs and may suffer from attention saturation. These limitations motivate integration approaches that combine attention mechanisms with sampling-based scalability. In summary, GAT and its numerous innovative variants have significantly enriched the technical pathways of graph node representation learning by introducing and continuously advancing the attention mechanism. These methods have not only optimized model theory to address key challenges such as heterogeneity, dynamics, and noise robustness, but have also demonstrated strong practical value and effectiveness across a wide range of cross-domain applications, including computer vision, temporal forecasting, and cybersecurity.

2.3 GraphSAGE: Sampling Aggregation Graph Learning Framework

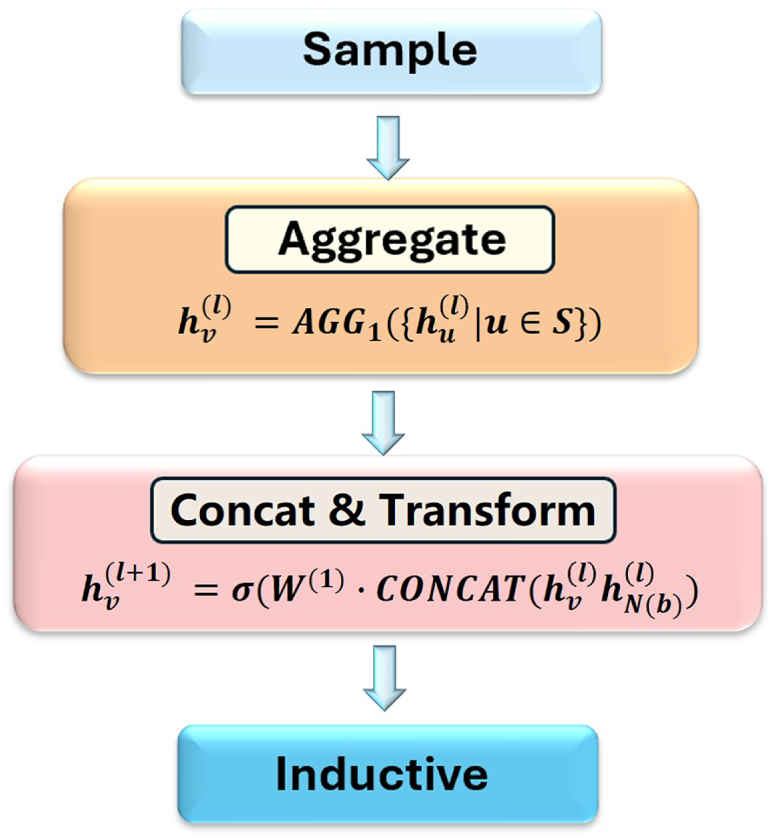

Faced with large-scale graph data, the transductive learning paradigm relied upon by traditional graph neural networks reveals its limitations, struggling to efficiently handle unseen nodes or dynamically growing graph structures. To address this issue, GraphSAGE proposes an inductive learning framework whose core idea lies in generating node embeddings by sampling and aggregating information from a node’s local neighborhood, rather than training independent embedding vectors for each node [74]. This approach not only significantly enhances model scalability, enabling generalization to new nodes unseen during training, but has also become one of the key techniques for processing large-scale graph data.

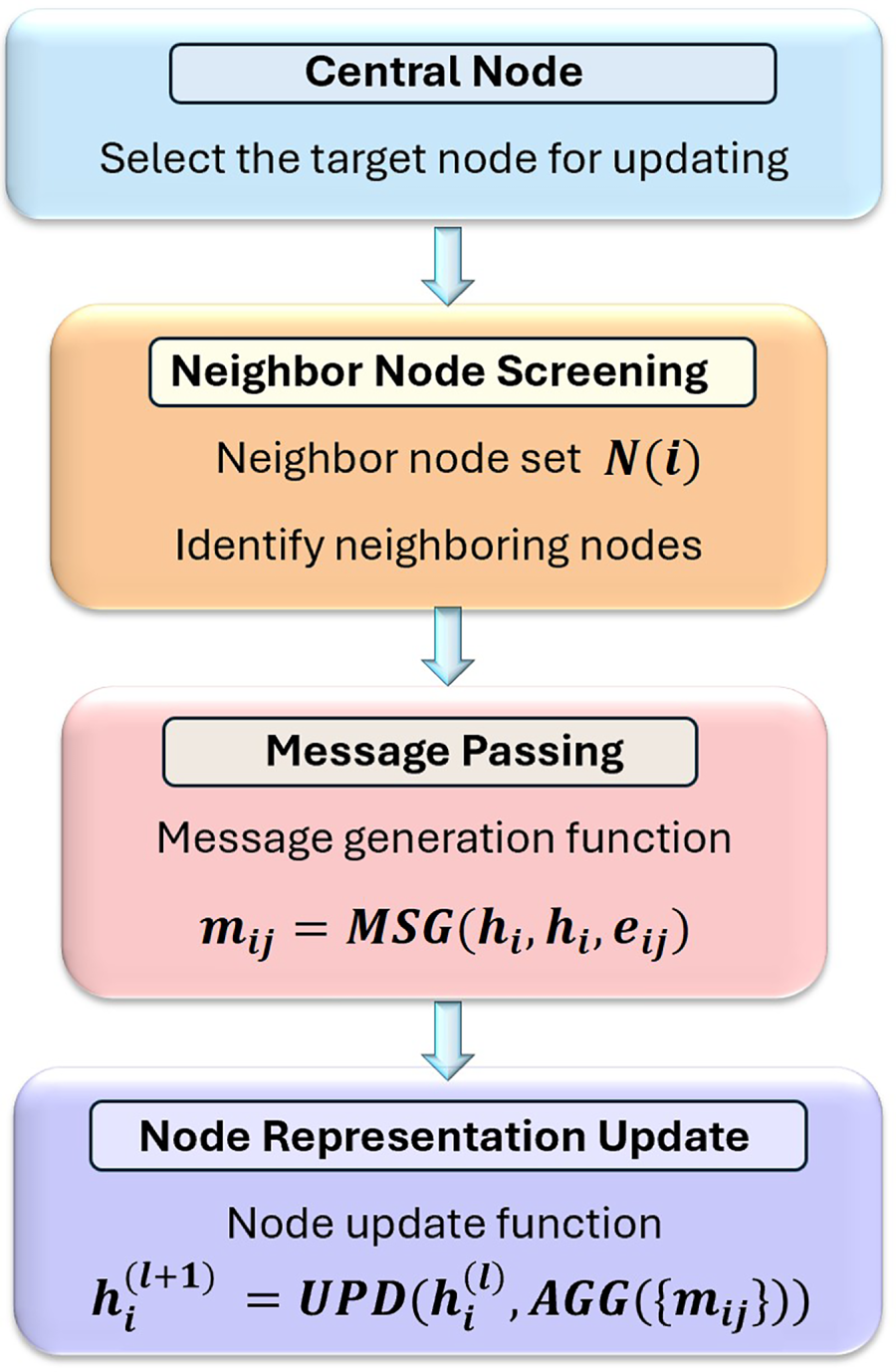

The core of GraphSAGE lies in its “sample-and-aggregate” mechanism. For each node in the graph, the algorithm first randomly samples a fixed number of neighbors from its multi-hop neighborhoods to construct a computation graph. Subsequently, it employs a learnable aggregation function—such as a mean aggregator, LSTM aggregator, or pooling aggregator—to iteratively aggregate the feature information of these sampled neighbors, ultimately generating high-order representations for the target node. This design enables GraphSAGE to efficiently process large-scale graphs with millions or even billions of nodes and edges, while avoiding dependence on the entire graph [53]. The flowchart of the core mechanism of GraphSAGE is in Fig. 9.

Figure 9: The flowchart of the core mechanism of GraphSAGE

Despite its strong adaptability and scalability, GraphSAGE also faces several inherent challenges that have become focal points in recent research. First, the neighbor explosion problem occurs as the number of sampled nodes grows exponentially with network depth, leading to high computational and memory overhead. Although sampling mitigates full-graph dependency, it does not fully resolve scalability for large-scale or high-degree graphs. Second, similar to other message-passing GNNs, GraphSAGE suffers from over-smoothing when multiple aggregation layers are stacked, causing node representations to converge and lose discriminative power. Third, from a theoretical perspective, the expressive power of GraphSAGE is still bounded by the 1-Weisfeiler–Lehman (1-WL) test, limiting its ability to distinguish certain graph structures. Finally, the sampling-aggregation trade-off introduces computational inefficiencies and instability in mini-batch training, especially for dynamic graphs.

Since the proposal of the GraphSAGE framework, researchers have extensively extended and optimized it from multiple dimensions. A key direction involves enhancing the expressive power and robustness of the aggregation function. For instance, Gated Recursion-Based GNN (GR-GNN) integrates GRU neural network units into graph learning for deep dependency-aware feature extraction at nodes, demonstrating superior accuracy and faster convergence compared to GraphSAGE and other baseline models in node classification tasks [75]. To address the challenge of class imbalance, the E-ResSAGE algorithm introduces residual learning into GraphSAGE, improving classification performance for minority classes by preserving original information, and has achieved outstanding results in applications such as intrusion detection [76]. Similarly, the E-GRACL model comprehensively enhances GraphSAGE’s capabilities in edge-level feature extraction and topological information captured by incorporating global attention mechanisms, local gated mechanisms, and contrastive learning, thereby improving the performance of Internet of Things (IoT) intrusion detection systems [77]. The Sparse Subgraph Prediction Based on Adaptive Attention (SSP-AA) method dynamically assigns weights to neighboring nodes by integrating adaptive attention mechanisms and introduces a Jumping Knowledge module to mitigate over-smoothing, further refining the quality of node representations [78]. Additionally, Centrality based GraphSAGE (CB-SAGE) innovatively incorporates graph structural properties such as betweenness centrality as additional features during the aggregation process, enabling it to better capture network structural characteristics in tasks like planar graph classification [79]. Weighted GraphSAGE (WGraphSAGE) designs weighted neighbor sampling and weighted aggregation algorithms, allowing it to automatically model and reason about both the existence and strength of relationships among nodes during graph learning, thus enabling automatic context-awareness in large-scale data access control [80].

Another key optimization direction is improving the computational and hardware execution efficiency of models. To address the computational irregularity and memory access bottlenecks present in GNN inference, specialized hardware accelerator architectures have been proposed. The GRIP architecture decomposes GNN inference into two execution phases—edge-centric and vertex-centric—and employs dedicated hardware units to process them, achieving low-latency inference and delivering significant speedups for various GNN models, including GraphSAGE [81]. Similarly, GraphAGILE, an FPGA-based overlay accelerator, efficiently executes models such as GraphSAGE through its innovative adaptive computing kernels and compiler optimizations, eliminating the need for FPGA reconfiguration and substantially reducing end-to-end inference latency [82]. The GNNIE accelerator effectively tackles workload imbalance caused by sparsity and power-law distributions by employing tiling operations, computation reordering, and a graph-aware, degree-aware caching strategy, resulting in substantial performance gains for GNN models like GraphSAGE [83].

GraphSAGE’s powerful inductive learning capability has established it as a key technology across diverse domains. In cybersecurity and intrusion detection, its applications are particularly prominent—enhancing IoT intrusion detection by incorporating edge features into GraphSAGE has significantly improved F1 scores [84]; integrating feature selection via generative adversarial networks with GraphSAGE’s topology modeling enables high-precision detection of advanced persistent threats in smart grids [85]. In traffic prediction, dynamic spatiotemporal graph convolutional networks based on GraphSAGE substantially enhance forecasting accuracy by capturing both spatial and temporal dependencies simultaneously; spatiotemporal synchronized GraphSAGE further introduces attention mechanisms, strengthening the aggregation of spatiotemporal features [86]. In recommender systems, deep GraphSAGE with jump knowledge connections effectively mitigates over-smoothing, improving recommendation quality [87]; GraphSAGE-based link prediction models with refined aggregation functions and clustering techniques also demonstrate superior performance [88]; additionally, graph models incorporating causal discovery combined with GraphSAGE representations further optimize accuracy and generalization in click-through rate prediction [89].

In other diverse applications, GraphSAGE has also demonstrated broad applicability. In bioinformatics, a heterogeneous graph learning framework integrating GAT provides a scalable tool for early lung cancer detection [90]; in power systems, a GraphSAGE-based fault diagnosis method achieves precise localization of fault points [91]; in wireless communications, GraphSAGE is utilized for path performance learning to optimize network routing selection [92]; in static signature authentication, a GraphSAGE model based on region adjacency graphs enables high-precision forgery detection [74]. Moreover, an enhanced graph network incorporating spatial-frequency domain convolution outperforms traditional GraphSAGE in node classification tasks [93], and a boosting ensemble framework using GraphSAGE as the base classifier effectively improves classification performance on imbalanced graph data [93].

Clearly, GraphSAGE successfully addresses the scalability challenges of large-scale graph learning through its innovative “sampling-aggregation” inductive learning framework. Building upon its core architecture, a series of studies have continuously enhanced its representation power and robustness by incorporating attention mechanisms, residual connections, gating functions, and structural properties into the aggregation process; meanwhile, the design of specialized hardware accelerators has significantly improved its computational efficiency. These technological advancements collectively establish GraphSAGE as a foundational model in critical domains such as cybersecurity, traffic prediction, recommendation systems, and bioinformatics, demonstrating its strong vitality and broad applicability as a cornerstone technique for scalable graph learning.

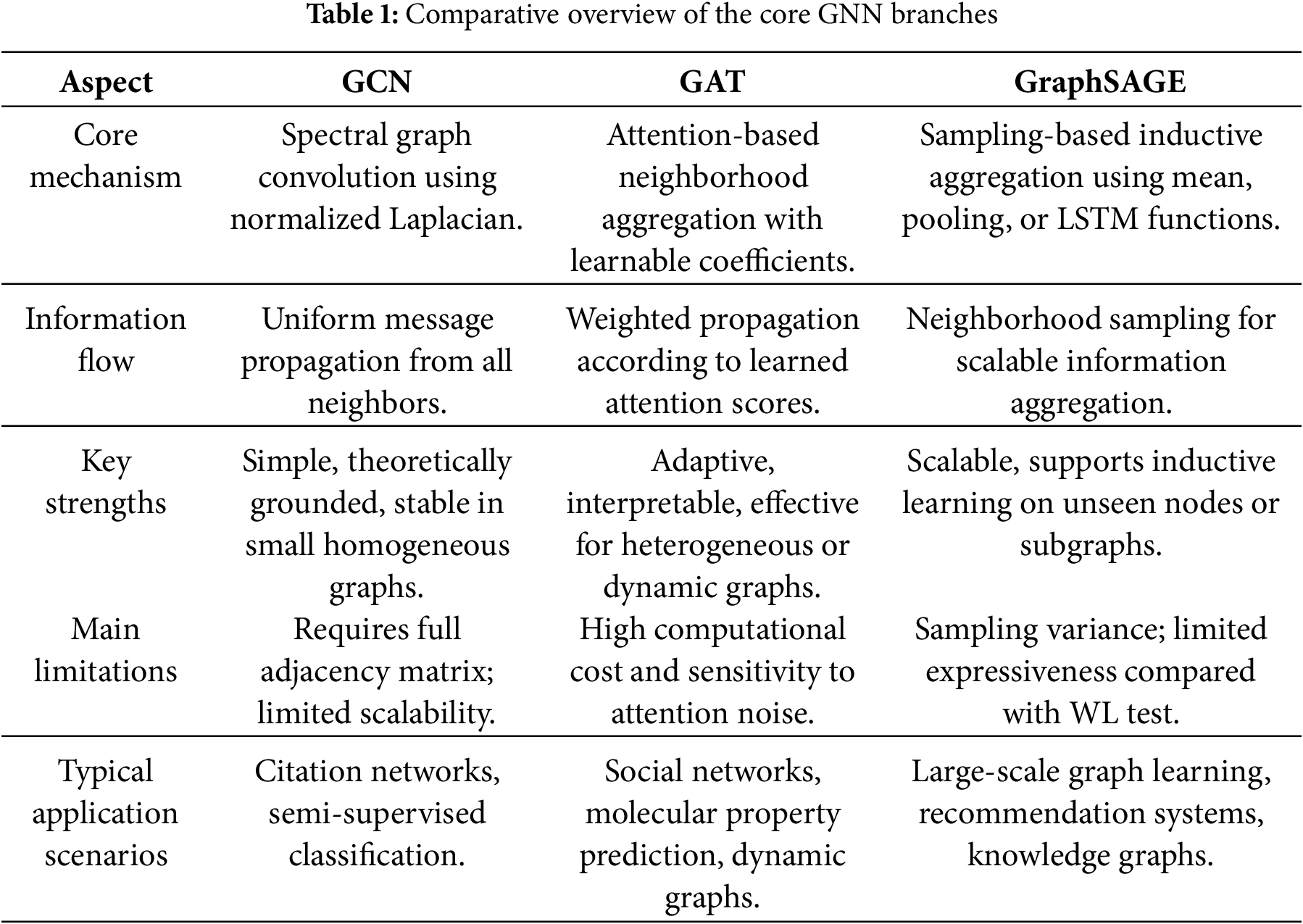

2.4 Comparative Overview of Core GNN Branches

To provide a clear comparative perspective, this subsection summarizes the key characteristics, advantages, and limitations of the three representative GNN branches discussed GCN, GAT, and GraphSAGE. While these models share the common foundation of message passing, they differ substantially in aggregation mechanisms, scalability, and inductive generalization capability. Table 1 presents a systematic comparison that highlights their technical distinctions and practical applicability across various domains.

From the comparative results in Table 1, we can see that GCN remains efficient for small, static graphs but scales poorly to large heterogeneous networks. GraphSAGE mitigates this through neighborhood sampling, while GAT enhances flexibility via attention mechanisms at the cost of higher complexity. GAT’s attention weighting allows adaptive message importance, in contrast to GCN’s uniform propagation. GraphSAGE achieves adaptivity through learnable aggregation functions. GraphSAGE is inductive and capable of handling unseen nodes, whereas GCN and GAT are primarily transductive. Each branch contributes complementary advantages: GCN’s stable topology encoding, GAT’s adaptive attention, and GraphSAGE’s scalability.

With the increasing diversity and complexity of graph-structured data, single-branch GNN architectures such as GCN, GAT, and GraphSAGE often struggle to simultaneously capture multi-scale dependencies, heterogeneous relationships, and dynamic patterns. To address these challenges, researchers have begun to explore integration-oriented GNN designs, in which multiple model branches or functional modules are combined to enhance representation capacity and adaptivity. These integrated architectures extend the basic message-passing paradigm by incorporating complementary learning mechanisms—such as convolutional, attention-based, and sampling-based operations—within a unified computational framework.

According to the architectural logic and information-fusion mechanism, existing integrated GNNs can be broadly categorized into three patterns: (1) Cascaded Fusion, where heterogeneous modules are connected sequentially so that the output of one model serves as the input to another, enabling hierarchical abstraction of spatial, temporal, or semantic features; (2) Parallel Fusion, where multiple GNN branches operate concurrently on the same graph to extract complementary structural cues, followed by a fusion layer that aggregates their embeddings through concatenation, weighting, or attention mechanisms; and (3) Feature-Level Fusion, where the learned representations from distinct branches are adaptively integrated via gating or attention functions at the feature level. These three integration patterns collectively define the structural and feature-level fusion landscape of current GNN research and provide a coherent framework for analyzing representative models reviewed in this section.

3.1.1 Cascading Architecture: Serialized Model Transfer

The cascaded architecture progressively transforms and refines node or graph representations through a layered sequence of functional modules, enabling hierarchical features learning from raw inputs to abstract graph embeddings, as shown in Fig. 10. In this paradigm, upstream modules are typically responsible for extracting temporal, spatial, or semantic features, such as those obtained by convolutional or recurrent encoders, while downstream GNN modules perform structural aggregation and contextual reasoning on the resulting graph representations. This sequential design allows information to flow from low-level feature spaces to higher-order graph abstractions, facilitating comprehensive representation learning across multiple dimensions of graph data.

Figure 10: Abstract framework of cascaded integration in graph neural networks

A cascaded architecture decomposes the feature extraction process into multiple stages, with each stage focusing on information at a specific granularity. In the context of lithium-ion battery state-of-health (SOH) prediction, Yao et al. proposed the CLGraphSAGE framework, which first extracts temporal features using CNN and LSTM, then aggregates spatial features via GraphSAGE, achieving an SOH prediction error as low as 0.2% [94]. In another case, Liu et al. introduced the DST-GraphSAGE model, cascading GraphSAGE with spatiotemporal convolution to dynamically capture long-term dependencies in traffic networks [95]. Meanwhile, this cascaded architecture has been widely adopted in bioinformatics, network fault diagnosis, and image classification [96–98]; for example, Koca et al. [12] applied it to virus–human protein interaction prediction by first extracting sequence features with Doc2Vec and then enhancing topological representations through an improved GraphSAGE.

The advantage of cascaded architecture lies in its clear structure, ease of understanding and implementation, making it particularly suitable for application scenarios where the feature extraction process exhibits clearly hierarchical characteristics. However, this architecture also faces challenges in gradient propagation and training stability, requiring careful design of interfaces between modules and optimization strategies.

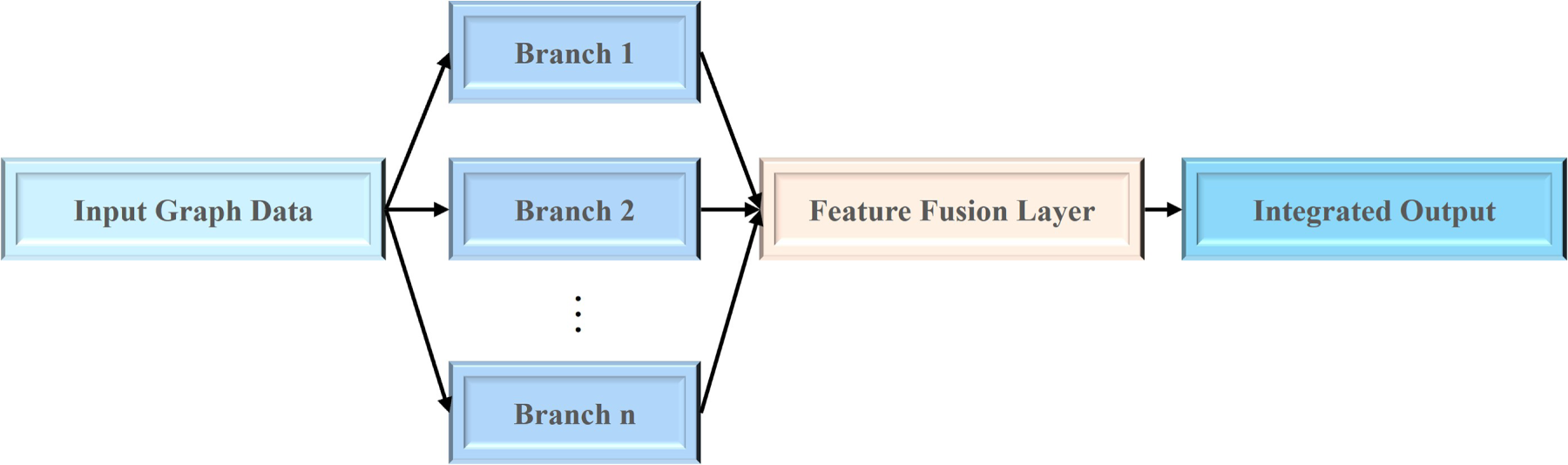

3.1.2 Parallel Architecture: Multi-Model Aggregation

Unlike the sequential information flow in cascaded architectures, parallel architectures adopt a multi-branch concurrent processing strategy, where multiple GNN modules operate simultaneously to capture complementary aspects of graph-structured data. Each branch focuses on distinct structural or semantic characteristics. The outputs from these parallel branches are then integrated through a fusion layer, which combines their learned representations via concatenation, weighted summation, or attention-based mechanisms. This parallel integration paradigm fully exploits the individual strengths of different GNN models, improving the robustness, scalability, and comprehensiveness of feature representation. The overall conceptual framework of this design is illustrated in Fig. 11, which depicts how diverse GNN branches operate in parallel and converge through a unified fusion mechanism to produce the final integrated output.

Figure 11: Abstract framework of parallel integration in GNN

The core of parallel architecture lies in constructing multiple independent feature extraction branches, each focusing on a specific type of feature or dependency relationship. For instance, the GCN branch excels at capturing global topological structures, the GAT branch leverages an attention mechanism to focus on crucial local node interactions, and the GraphSAGE branch is well-suited for inductive learning scenarios. The outputs from these branches are fused via concatenation, weighted summation, or more sophisticated attention mechanisms to form a comprehensive graph representation. In cross-domain applications, parallel architectures have been extensively validated across multiple fields. In cybersecurity, the hybrid GCN-GAT model proposed by Yilmaz and Das demonstrates the strong potential of parallel architecture [99]. In intelligent transportation systems, the STS-GraphSAGE model proposed by Yu et al. achieves accurate traffic flow prediction by parallel processing of spatial and temporal dependencies [86]. In cheminformatics, Rajalakshmi et al. compared the performance of various GNN architectures in predicting yields of cross-coupling reactions, finding that parallel fusion architectures combining different models effectively handle the heterogeneous nature of chemical reactions [100]. In infrastructure modeling, the Regional Spatial Graph Convolutional Network (RSGCN) proposed by Fan and Hackl learns multimodal spatial features of nodes in parallel, outperforming individual GraphSAGE or GCN models in both highway network and power grid reconstruction tasks [101].

The advantage of parallel architecture lies in its ability to simultaneously capture different types of relationships and features within graph data, avoiding the limitations of a single perspective. However, this architecture also faces challenges such as increased computational complexity and the design of effective fusion strategies, necessitating a careful balance between model performance and efficiency.

3.2 Model Integration: Fusion Strategy

While structural-level integration focuses on architectural composition, either through cascading or parallel connections, feature-level fusion aims to unify the learned representations from multiple GNN modules into a single embedding space. This process enables the model to capture complementary semantics across different feature hierarchies while maintaining computational flexibility. Feature-level fusion can be generally expressed as a mapping function

Depending on how

3.2.1 Basic Fusion: Feature Integration through Concatenation and Weighting

As a mainstream technique in the early development stage of graph neural networks, basic fusion mechanisms have been widely applied across various application scenarios due to their simplicity and efficiency. Despite their straightforward architecture, these methods can effectively integrate multi-source features in suitable contexts, providing foundational support for the construction of more complex models.

Basic fusion adopts static and straightforward operations to merge the outputs of different GNN branches. The most common approaches include feature concatenation, weighted summation, and linear transformation. These methods do not introduce additional learnable parameters for fusion but rely on the diversity of individual branch representations to enhance model expressiveness. A general formulation of basic fusion can be written as Eq. (4):

Here,

Alternatively, concatenation-based fusion can be represented as Eq. (5):

where

These approaches are efficient and interpretable, suitable for scenarios where model simplicity and computational efficiency are prioritized over adaptivity. For instance, Zheng et al. [102] concatenate spatiotemporal features extracted by GCN, GAT, and GraphSAGE in lithium-ion battery capacity prediction, constructing a holistic battery state representation. Weighted summation, on the other hand, achieves balanced feature integration by linearly combining feature vectors using predefined or learned weight coefficients. Wang et al. apply learnable weighting parameters to fuse features extracted by CNN and Transformer in modulation classification tasks, effectively improving signal recognition accuracy [103]. Feature concatenation introduces no additional learnable parameters and entails minimal computational overhead, making it particularly suitable for resource-constrained applications. Weighted summation enables feature integration through a simple linear transformation, offering stable training and fast convergence. However, feature concatenation may lead to the curse of dimensionality and feature redundancy, especially when fusing multiple high-dimensional features; weighted summation lacks the ability to model complex nonlinear relationships among features and struggles to adapt to dynamically changing graph structures [104,105].

In early GNN integration, basic fusion has been widely used for multimodal data and spatiotemporal feature combination [104,106,107]. For example, Cui et al. [108] in hyperspectral image classification combined pixel-level features extracted by CNN with graph features generated by GraphSAGE, thereby improving classification accuracy.

As a foundational element in the development of graph neural networks, the basic fusion mechanism provides crucial technical accumulation and practical validation for more sophisticated fusion strategies. In current research, these methods often serve as components of complex fusion systems, working in concert with other advanced techniques.

3.2.2 Advanced Interaction: Door Dynamic Information Interaction

As the application scenarios of GNN become increasingly complex, basic fusion mechanisms gradually struggle to meet the demand for fine-grained control over feature interaction. In contrast, advanced fusion introduces adaptive mechanisms that dynamically adjust the importance of each branch’s representation during training. Such strategies commonly utilize attention, gating, or meta-weighting to learn data-dependent fusion coefficients, thereby enabling more fine-grained control over information flow between modules. A representative formulation is given by Eq. (6):

where

This mechanism allows the model to adaptively emphasize more informative branches depending on the graph’s structural or semantic context. Another variant employs a gating function to regulate information passage, as shown in Eq. (7):

where

The advanced fusion mechanism is built upon information bottleneck theory and attention economics, with its core idea being the selective enhancement and suppression of features through dynamic weight allocation. The gating mechanism draws inspiration from the design principles of Gated Recurrent Units (GRU) and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks in recurrent neural networks, controlling the retention and forgetting of information via activation functions such as sigmoid and tanh, effectively mitigating the vanishing gradient problem in deep networks [109]. The attention mechanism, on the other hand, computes similarity-based weights among features to automatically focus on critical information while weakening redundant inputs [99,110].

Advanced fusion mechanisms represent the cutting edge of graph neural network development, offering powerful technical support for handling complex and dynamic graph-structured data through their dynamic and adaptive characteristics. As research progresses, these mechanisms will continue to drive the application and advancement of graph neural networks across broader domains.

GNN, with its unique ability to handle non-Euclidean data, has demonstrated great application potential in numerous fields. With the continuous development of technology, the application scope of GNN has expanded from traditional fields such as social network analysis and recommendation systems in the early days to cutting-edge fields like intelligent transportation, computer vision, biomedicine, and cross-modal learning. This section will systematically review the practical application cases of GNN in various fields, and through comprehensive table comparison and analysis of representative works in various application scenarios, fully demonstrate the breadth and depth of GNN technology application.

4.1 Intelligent Transportation System

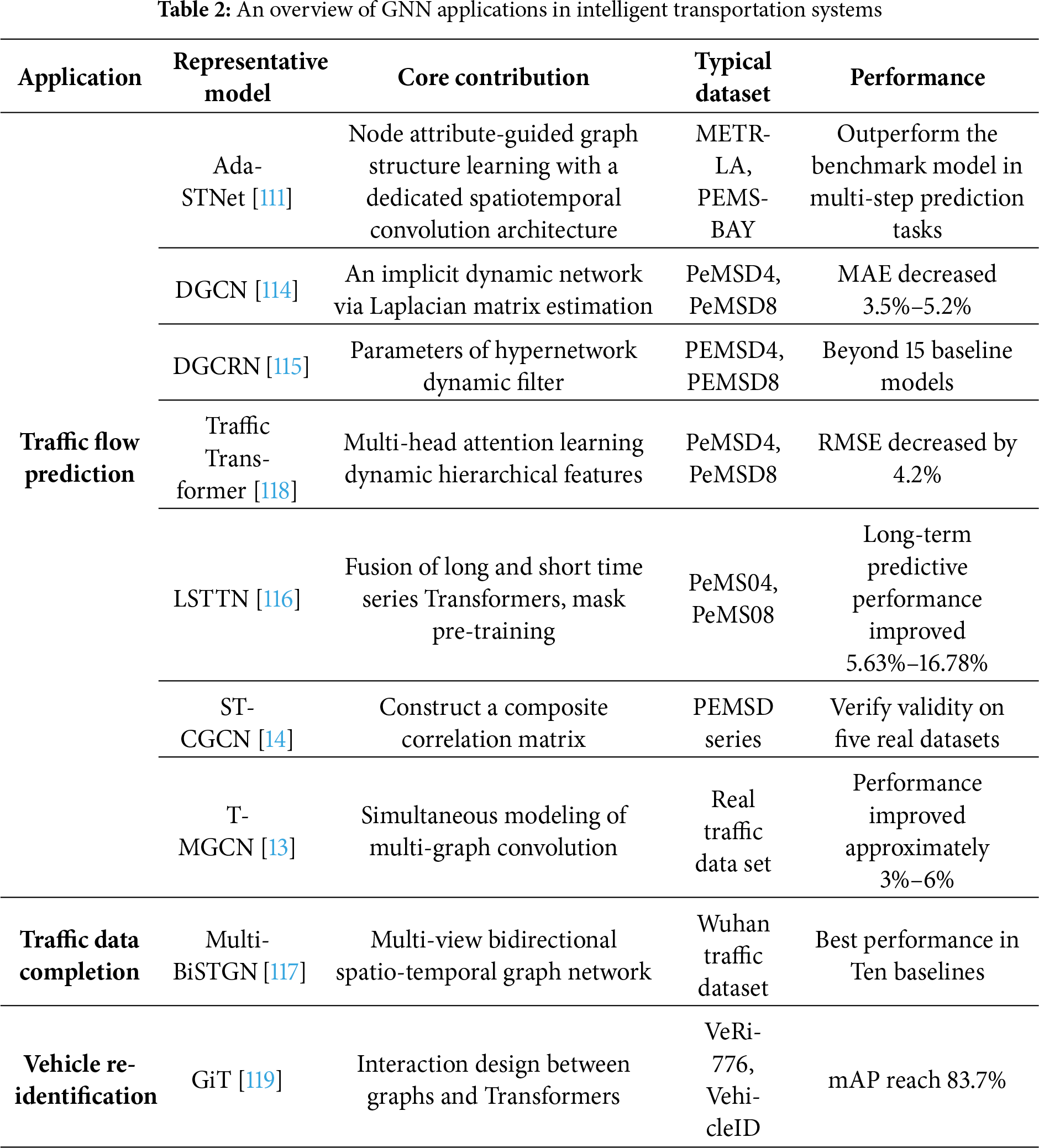

As one of the earliest real-world domains to adopt graph representation learning, intelligent transportation systems (ITS) exemplify how GNN can model spatial–temporal dependencies in dynamic networks. In ITS, GNN models the road network structure as graph data, effectively capturing the spatial topological relationship between intersections and road sections. At the same time, by combining time series modeling technology, it characterizes the dynamic laws of traffic flow evolution over time, thereby significantly enhancing the intelligent level of traffic state perception and management [111,112]. Traffic flow prediction is the most mature application direction of GNN in the field of intelligent transportation. The Ada-STNet proposed by Ta et al. [113] performs well in multi-step traffic prediction through graph structure learning guided by node attributes and a dedicated spatio-temporal convolution architecture. To address the dynamic characteristics of traffic data, Guo et al. [114] and Li et al. [115] respectively proposed dynamic graph convolutional networks and dynamic graph convolutional recurrent networks (DGCRN) based on Laplacian matrix estimation, which can adaptively learn the structure of dynamic graphs. Yan et al. combined Transformer with GNN and proposed Traffic Transformer, which achieved the best performance at that time on multiple datasets by learning dynamically hierarchical traffic flow features [57].

In terms of model architecture innovation, Luo et al. proposed the LSTTN framework, which comprehensively considers the long-term and short-term characteristics of historical traffic flow and uses a mask subsequence Transformer for pre-training [116]. In the 60-min long-term prediction, it achieved a performance improvement of 5.63% to 16.78% compared to the baseline model. Huo et al. designed a hierarchical spatio-temporal graph convolutional network that effectively alleviates the over-smoothing problem of GCN by fusing long-term and short-term Transformer networks [41]. Bao et al. proposed ST-CGCN, which constructed a composite correlation matrix integrating distance, data correlation and comfort measurement, enhancing the joint modeling ability of spatio-temporal features and external factors [14].

Traffic data completion is another important research direction. The Multi-BiSTGN proposed by Wang et al. can achieve accurate data completion in complex missing patterns (random missing, block missing, and mixed missing) by constructing a multi-view bidirectional spatiotemporal graph network [117]. Chen et al. [118] designed TFM-GCAM based on traffic flow theory to design a congestion index and a traffic flow matrix, and better capture the dynamic characteristics of nodes through the fusion of an attention mechanism.

In the vehicle re-identification task, the Graph Interaction Transformer (GiT) designed by Shen et al. simultaneously acquires robust global features and discriminative local features through the interaction between graphs and Transformers, achieving leading performance on multiple large-scale datasets [119].

At present, traffic analysis based on GNN has formed a complete technical system, covering multi-level tasks from macro to micro: At the macro level, GNN is widely applied in regional traffic flow prediction, road network congestion propagation analysis, etc. At the micro level, it supports refined tasks such as intersection signal optimization control, vehicle trajectory tracking, and vehicle re-identification. This technical system not only enhances the predictability and accuracy of dynamic regulation in the transportation system but also provides core support for building an efficient and reliable urban intelligent transportation management system, as shown in Table 2.

Despite remarkable progress, GNN applications in ITS still face significant challenges. Scalability remains a major concern as traffic graphs grow rapidly with network size; temporal heterogeneity and data sparsity hinder stable learning; and model interpretability is critical for safety-related decision-making. Integration of GNNs with temporal attention or hybrid feature-fusion frameworks offers promising directions to address these issues.

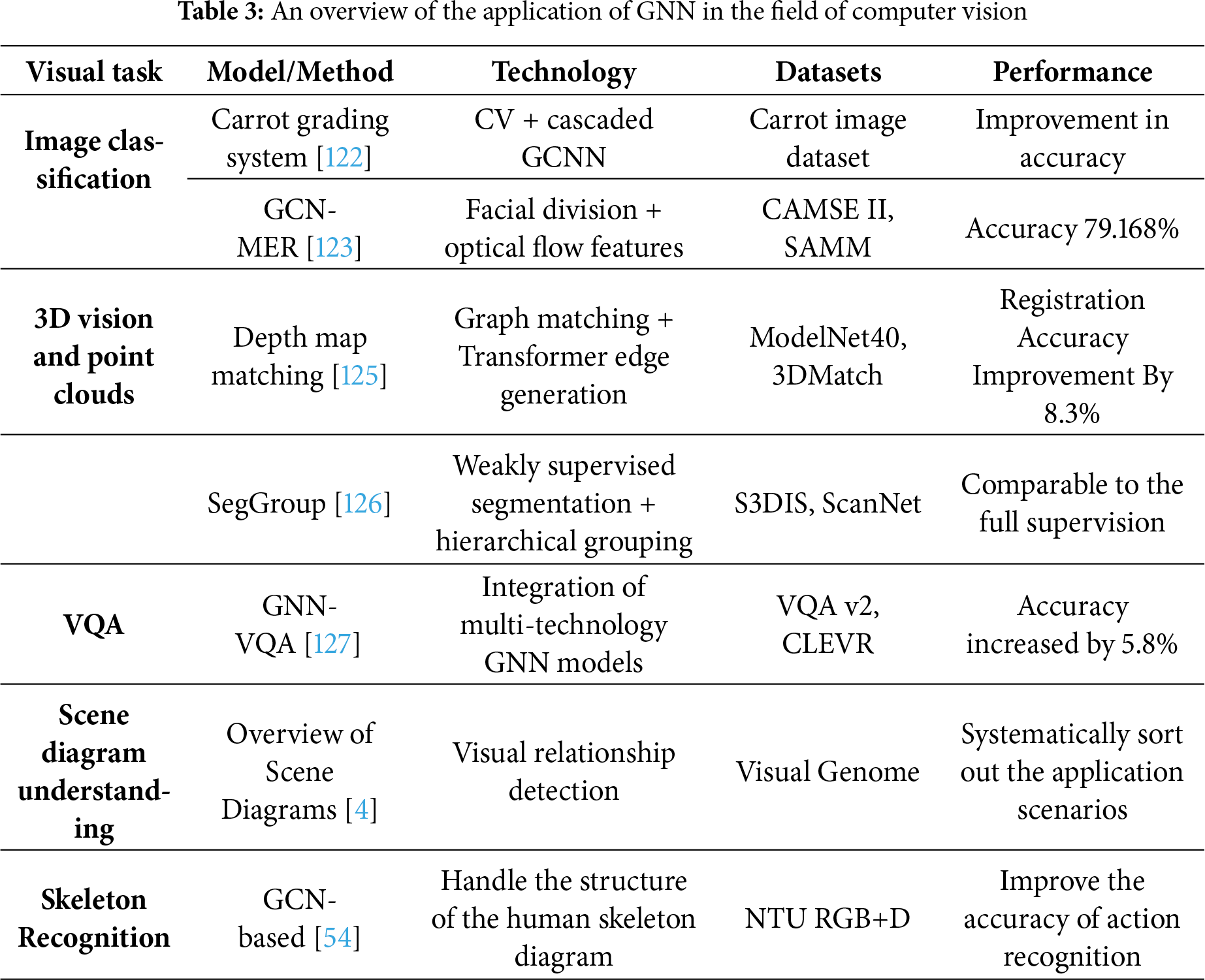

The application of GNN in computer vision extends their capabilities from structured relational reasoning to geometric and semantic understanding. Following the spatial modeling paradigm, GNNs have been used to represent scene graphs, 3D point clouds, and visual question-answering tasks, bridging perception and reasoning [120,121]. By modeling the relationships among image regions, object components or point clouds, GNNS have effectively enhanced the representation ability of visual features and achieved breakthroughs in multiple subfields. In terms of image understanding and classification, Bukumira et al. applied GNN to the carrot grading system and achieved automated quality inspection of agricultural products through cascaded graph convolutional networks and Bayesian optimization [122]. Yang et al. proposed a graph convolutional network for micro-expression recognition [123]. By extracting optical flow features from facial action units, an accuracy rate of 79.168% was achieved on the CAMSE II dataset. Li et al. [124] systematically reviewed the application of deep metric learning in few-shot image classification and pointed out that learning similarity through graph neural networks has become an important trend at present.

3D vision and point cloud processing are advantageous fields of GNN. The point cloud registration framework based on depth map matching developed by Fu et al. takes into account both local geometric features and broader structural topological relationships, achieving optimal performance on multiple benchmark datasets [125]. Tao et al. proposed SegGroup, which explores weakly supervised learning for point cloud segmentation. By hierarchically grouping and labeling only one point for each instance, it can achieve segmentation effects comparable to fully supervised methods [126].

In the visual Question answering (VQA) task, Yusuf et al. systematically reviewed the application of GNN in VQA, identified 45 different models, and classified them into four major technical routes: GCN, GAT, GIN, and GNN [127]. Chang et al. comprehensively reviewed the application of scene graphs in tasks such as visual relationship detection, image description generation, and visual question answering, providing an important tool for cross-modal understanding of vision and language [128].

By modeling the relationships among image regions, object components or point clouds, GNNS have effectively enhanced the representation ability of visual features and achieved breakthroughs in multiple subfields. Table 3 shows some cutting-edge research on GNNs in the field of computer vision.

In the field of Computer Vision, the key difficulties persist in balancing computational complexity with fine-grained relational modeling. Over-smoothing can degrade high-frequency visual cues, and large-scale visual graphs demand efficient sampling strategies. Future research should focus on adaptive graph construction and integration with convolutional backbones to enhance robustness and generalization.

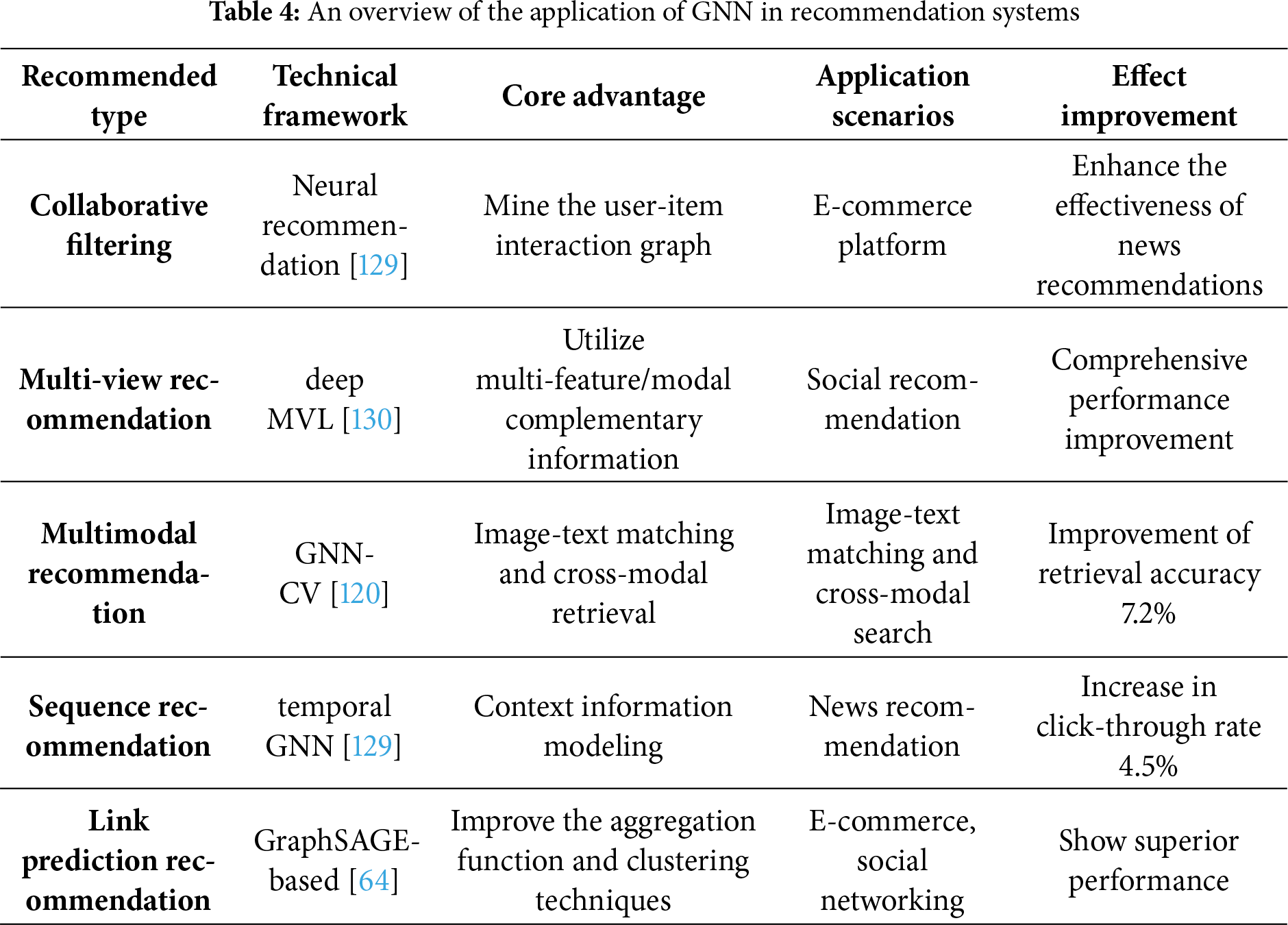

Recommender systems provide another representative scenario where GNNs leverage graph connectivity to model user–item interactions. Building on message-passing principles, GNN integrates multi-modal and contextual signals, effectively capturing collaborative behaviors and implicit relationships. Table 4 shows some cutting-edge research on GNNs in the field of Recommendation Systems.

Wu et al. systematically summarized the evolution process from collaborative filtering to information-rich recommendation, and pointed out that GNN has surpassed traditional recommendation models due to its powerful representation learning ability [129]. Yan et al. reviewed deep multi-view learning methods, covering the application of multi-view autoencoders, convolutional neural networks, and deep belief networks in recommendation systems, providing theoretical guidance for processing multi-source user behavior data [130].

At the model level, El Alaoui et al. proposed a recommendation system based on deep GraphSAGE, which alleviated the over-smoothing problem by skipping knowledge connections and significantly improved the recommendation quality [87]. Afoudi et al. demonstrated superior performance in the link prediction task of recommendation systems based on the GraphSAGE link prediction model by improving the aggregation function and clustering techniques [88]. Zhai et al. combined causal discovery with GraphSAGE representation, further optimizing the accuracy and generalization ability of click-through rate prediction [89].

Multimodal recommendation is a current research hotspot. Jia et al. explored the potential of GNN in multimodal recommendation tasks (such as image-text matching and cross-modal retrieval), enhancing the expressive power of recommendation systems by integrating visual and text features [120]. Nevertheless, data sparsity and cold-start problems remain persistent obstacles. Large-scale user–item graphs also introduce computational overhead, and personalized attention mechanisms may lead to instability. Combining sampling-based scalability from GraphSAGE with attention mechanisms from GAT can help balance efficiency and personalization

4.4 Applications in Other Fields

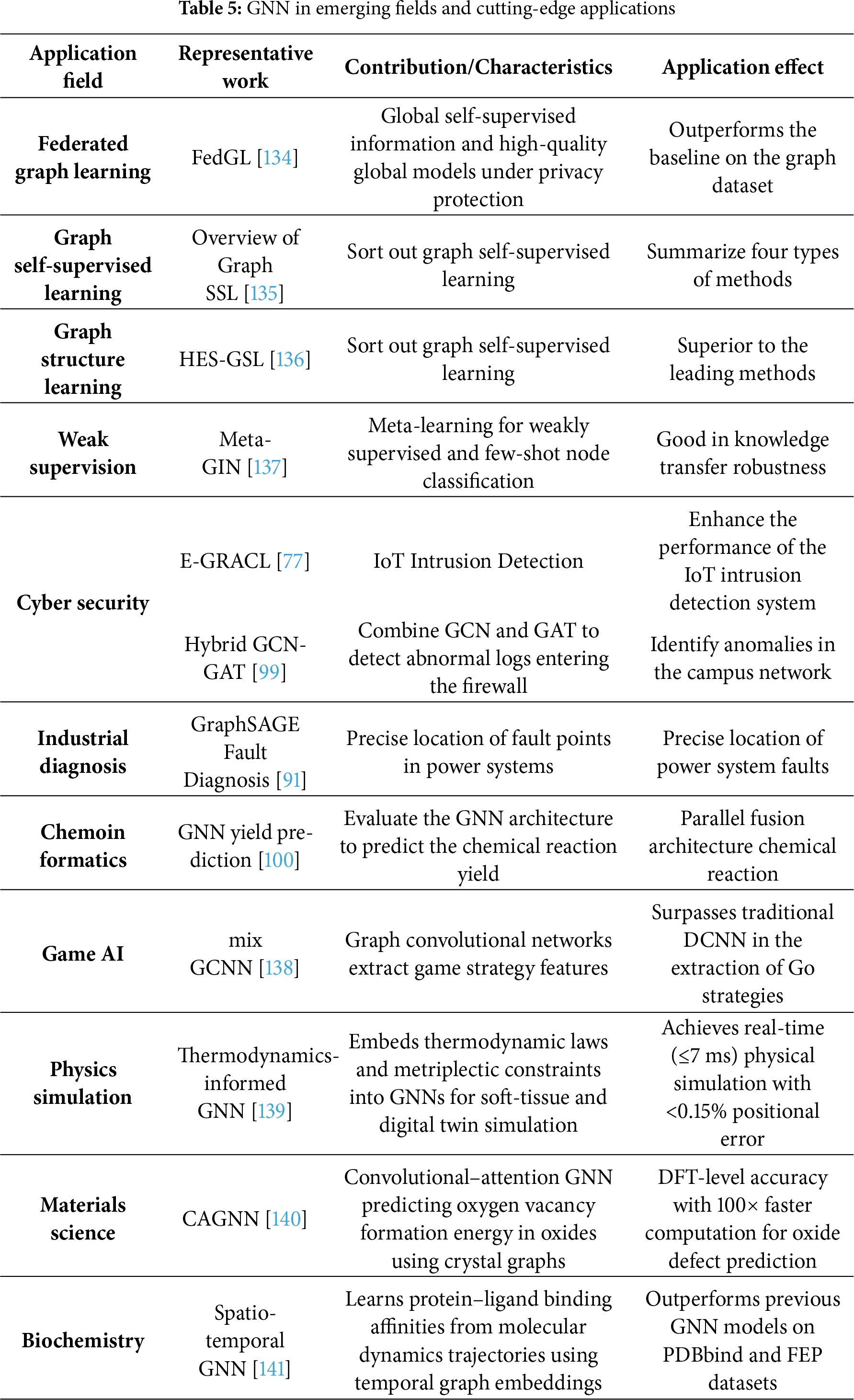

GNN has made remarkable progress in biomedical fields such as drug discovery, disease diagnosis and protein analysis, providing a powerful new tool for life science research. This subsection aims to summarize representative research directions and identify common challenges, such as model scalability, domain-specific feature construction, and cross-domain generalization, shown in Table 5. Within each area, GNNs have shown unique advantages in capturing relational dependencies and structural correlations that are difficult to model using traditional domain-specific techniques.

In the field of disease diagnosis and biomedical networks, the Hybrid Graph Contrast Network (MGCN) proposed by Yang et al. enhanced the discriminative ability of node classification on six datasets through interpolation enhancement strategies and correlation reduction mechanisms [131]. The M-GNN framework proposed by Vaida et al. integrates GCN, GraphSAGE, and GAT to process graph-level, node-level, and edge-level information, providing an extensible tool for lung cancer detection through heterogeneous graph modeling [90].

Besides, cross-modal learning requires models to understand and correlate information from different modalities (such as images and text), and it is another rapidly developing application direction of GNN.

Zhang et al. proposed a Graph Semantic Model (GSM), which utilized graph learning and semantic information to improve self-supervised monocular depth estimation, and performed excellently in weak texture and boundary regions on the KITTI dataset [132]. Su et al. proposed the SKEA framework, which utilizes cross-modal supervised information for neural entity alignment, effectively alleviating the problem of insufficient structural information in knowledge graphs and achieving a 5.24% performance improvement on sparse knowledge graphs [133].

Scene graphs, as an important bridge connecting vision and semantics, play a key role in cross-modal understanding. Chang et al. comprehensively reviewed the application of scene graphs in tasks such as visual relationship detection, image description generation, visual question answering, image editing and retrieval, and systematically sorted out this cross-modal, complex and rapidly developing research field [128].

With the development of GNN technology, a series of new learning paradigms and specialized application scenarios have emerged continuously, further expanding the application boundaries of GNN.

Federated graph learning offers a new approach to addressing the challenges of data silos and privacy protection. The FedGL framework proposed by Chen et al. discovers global self-supervised information during the federated training process, obtaining a high-quality global graph model while protecting data privacy [134]. It significantly outperforms the baseline method on four commonly used graph datasets.

Self-supervised and weakly supervised learning have become key techniques for reducing annotation dependence. Liu et al. conducted a comprehensive investigation into graph self-supervised learning and classified existing methods into four categories: generative, auxiliary attribute-based, contrastive, and hybrid methods [135]. Wu et al. proposed a self-supervised graph structure learning method with enhanced homogeneity (HES-GSL), providing an effective solution for the joint learning of graph structure and GNN parameters in the case of extremely limited label data [136]. The Meta-GIN framework proposed by Ding et al. is designed for weakly supervised few-shot node classification problems, extracting transferable meta-knowledge by interpolating node representations through meta-learning [137].

Network security is an important application field of GNN. Lin et al. proposed the E-GRACL model, which comprehensively enhanced GraphSAGE’s capabilities in edge-level feature extraction and topological information capture by integrating the global attention mechanism, local partial control mechanism, and contrastive learning [77]. Yilmaz and Das combined GCN and GAT for firewall log anomaly detection, demonstrating the potential of a hybrid architecture in network security [99].

Industrial and other applications have also widely benefited from GNN technology. Wang et al. proposed a method for fault diagnosis and precise location of power systems based on the GraphSAGE algorithm [91]. Rajalakshmi et al. compared the performance of multiple GNN architectures in predicting the yield of cross-coupling reactions [100]. Xu et al. applied a hybrid graph convolutional neural network to Go strategies and demonstrated performance surpassing traditional DCNN models on the KGS Go dataset [138].

In addition to industrial diagnosis and federated learning, GNNs have recently shown remarkable potential in scientific modeling across physics, materials science, and biochemistry. In physics, Tesán et al. [139] developed a thermodynamics-informed graph neural network for real-time simulation of digital human twins, embedding physical conservation laws directly into the GNN message-passing process to simulate soft-tissue dynamics with high fidelity and millisecond-level inference time. In materials science, Zhao et al. [140] introduced a convolutional and attentional graph neural network (CAGNN) to predict oxygen vacancy formation energies in oxide crystals, achieving density functional theory (DFT)-level accuracy while reducing computational cost by orders of magnitude. In biochemistry, Libouban et al. [141] proposed a spatio-temporal GNN framework that integrates molecular dynamics (MD) simulations with neural architectures to predict protein–ligand binding affinities. Their model learns from over 63,000 MD trajectories, capturing time-dependent molecular interactions and achieving state-of-the-art performance on PDBbind and FEP (Free Energy Perturbation) benchmark datasets. These studies collectively highlight the expanding scientific role of GNN, from data-driven discovery to physics-grounded modeling, illustrating their growing capacity to unify representation learning with physical and chemical interpretability.

Despite their versatility, cross-domain applications face obstacles such as domain-specific graph construction, lack of standardized benchmarks, and limited interpretability of learned representations. Additionally, integrating physical constraints or domain knowledge into message-passing frameworks remains an open problem requiring interdisciplinary collaboration.

4.5 Technological Evolution and System Optimization

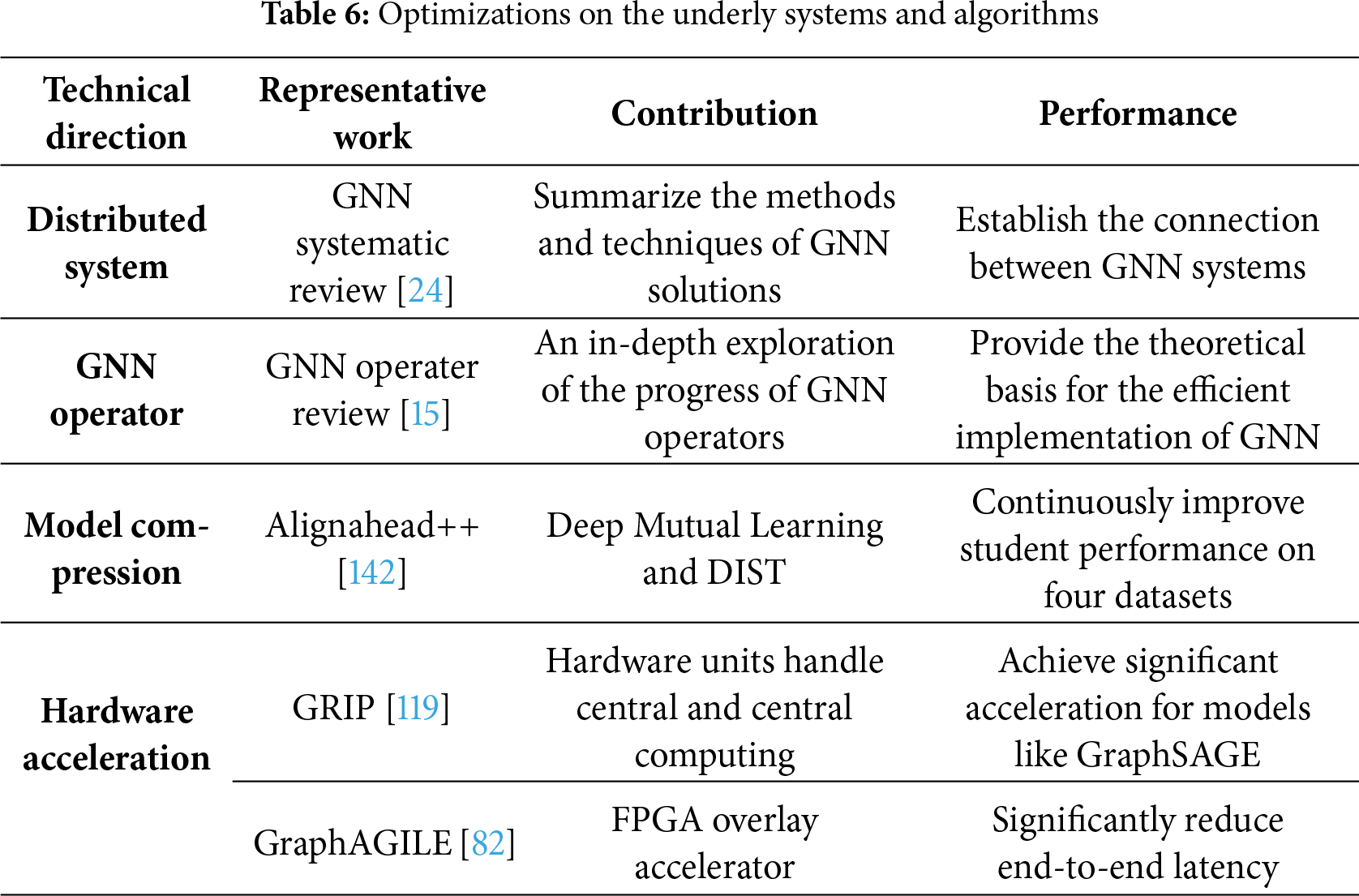

Section 4.5 synthesizes the technological progression of GNNs from model-level improvements to system-level optimization (Table 6). This evolution highlights how architectural integration and computational refinements jointly drive GNN performance in real-world deployment. The rapid development of GNN technology is inseparable from the continuous optimization of the underlying systems and algorithms. Vatter et al. systematically reviewed the evolution process of distributed GNN systems and their origins in graph processing and deep learning, and established the connections among GNN systems, graph processing systems, and deep learning systems [24]. Sharma et al. delved deeply into the mathematical essence and the latest progress of GNN operators, providing a theoretical basis for the efficient implementation of GNN models [15].

In terms of model compression and acceleration, the Alignhead++ online knowledge distillation framework proposed by Guo et al. transfers structural and feature information between student layers through an alternating training process, continuously improving student performance without the need for pre-training teacher models [142]. The GRIP architecture designed by Kiningham et al. decomposes GNN inference into two execution phases, one centered on the edge and the other centered on the vertex, achieving low-latency inference [81]. Specialized hardware accelerators such as GraphAGILE by Zhang et al. [82] and GNNIE by Mondal et al. [83] have further enhanced the computational efficiency of GNNS on large graph data.

GNN has demonstrated powerful value and flexibility in solving practical problems. From basic urban traffic management to cutting-edge drug development, from single image recognition to complex cross-modal understanding, GNNS are constantly expanding their application boundaries. These achievements fully demonstrate the value and flexibility of GNN in handling complex real-world problems. In the future, with the improvement of theoretical frameworks and the enhancement of computational efficiency, GNNS are expected to play a more crucial role in scenarios that require complex relational reasoning and cross-modal understanding.

GNNs have rapidly evolved from early convolution-based formulations into a rich family of architectures emphasizing diverse message-passing and representation strategies. While numerous existing surveys have reviewed specific branches or individual variants in detail, they generally lack a unified analytical perspective that connects structural architecture and feature-level integration mechanisms. The primary intent of this review is therefore not to reiterate model-specific derivations, but to establish a coherent framework that links different categories of GNNs through their shared integration logic and design paradigms.

As summarized in Section 3, we proposed a systematic taxonomy of GNN integration paradigms, encompassing cascaded, parallel, and feature-level fusion frameworks. The corresponding conceptual diagrams and mathematical formulations clarify the internal mechanisms through which multiple GNN branches cooperate to enhance representation learning. Cascaded architectures promote hierarchical feature abstraction by sequentially connecting heterogeneous modules; parallel architectures extract complementary topological cues through concurrent multi-branch processing; and feature-level fusion provides a unifying mechanism that mathematically integrates the outputs of various branches via concatenation, weighted combination, or attention-based operations. Together, these paradigms form an analytical foundation for understanding how integrated GNN models achieve higher adaptability and expressiveness across domains.

In comparison with prior surveys, which primarily concentrated on single-model formulations, this work contributes by synthesizing integration-oriented perspectives that bridge these core branches. By linking the structural-level taxonomy with feature-level fusion principles, our review highlights the progression from isolated model development to holistic architectural composition. This approach enables the identification of cross-cutting patterns—such as hierarchical abstraction, adaptive attention, and sampling–aggregation synergy—that recur in recent integration-oriented designs.

From a practical standpoint, the proposed taxonomy also offers indicative guidance for selecting or combining GNN architectures according to task characteristics. Applications emphasizing localized relational structures may benefit from cascaded or GCN-centric designs, whereas those requiring inductive generalization or multi-scale reasoning can exploit parallel or attention-based integrations using GraphSAGE and GAT modules. For data environments with heterogeneous or temporal dependencies, hybrid frameworks combining structure-level and feature-level fusion can provide additional flexibility.

Despite these insights, several challenges remain open. Integrated GNNs still face scalability constraints when applied to very large or dynamic graphs, and over-smoothing can emerge in deep multi-branch configurations. Moreover, the lack of standardized benchmarks makes it difficult to quantitatively evaluate and compare integration strategies. Addressing these issues will require future work on theoretical expressiveness analysis, efficient graph sampling, and domain-specific evaluation protocols.

In summary, this review contributes a structured analytical perspective on GNN integration and innovation. It bridges the conceptual gap between foundational model families and emerging hybrid frameworks, offering both a theoretical taxonomy and a practical reference for researchers seeking to design, combine, or evaluate integrated GNN architectures.

Although graph neural networks (GNNS) have demonstrated strong potential in multiple fields, their current development is still constrained by multiple bottlenecks. At the network structure level, most GCNS are limited to shallow design, while deep GNNS are prone to over-smoothing problems, resulting in the convergence of node features and the loss of discriminative properties. In terms of data adaptation, the existing models are mostly targeted at static graphs and lack the ability to model the dynamic changes of nodes, edges or structures. When dealing with large-scale graph data, training and inference will encounter computational and memory efficiency bottlenecks, especially in the graph sampling and attention mechanism stages. Meanwhile, the modeling of complex semantic relations in heterogeneous graphs is insufficient, and the interpretability of model decisions and their robustness under adversarial attacks also need to be improved urgently.

To break through the above limitations, future GNN research can start from cross-paradigm fusion and structural optimization. On the one hand, promote the deep integration of GNN with cross-paradigm models such as Transformer and reinforcement learning, leverage the self-attention mechanism of Transformer to enhance global dependency modeling, and combine reinforcement learning to optimize the processing path of graph data; On the other hand, deep GNNS resistant to over-smoothing are designed through residual connections, skip connection mechanisms, etc. At the same time, dynamic graph-specific models combined with temporal attention mechanisms are developed to accurately capture the temporal evolution characteristics of graph structures, making up for the existing shortcomings in the aspects of technology integration and architectural design.

In addition, future research should also focus on reliability improvement, breakthroughs in engineering bottlenecks, and the construction of multimodal frameworks. In terms of reliability, attention visualization and causal reasoning techniques are introduced to construct interpretable GNNS, and the robustness of the model is enhanced through adversarial training and other methods. In terms of engineering efficiency, by developing dedicated hardware accelerators and optimizing graph partitioning and sampling strategies, the computational bottlenecks of large-scale graph learning have been broken through. At the same time, promote the integration of GNN and multimodal data processing models, build a unified multimodal representation learning framework, and further expand the application boundaries of GNN.

Graph neural networks, as the core tool for processing non-Euclidean data, have made remarkable progress in both theoretical methods and practical applications. This paper systematically reviews the technical characteristics of the three core branches of GCN, GAT, and GraphSAGE, and focuses on elaborating their innovative paths in enhancing the model’s expressive power and generalization performance through structure-level and feature-level integration. Cross-domain applications have demonstrated that integrated strategies hold significant value in complex scenarios such as traffic prediction, drug discovery, and recommendation systems. Although GNNS still face challenges in deep modeling, dynamic adaptation, and computational efficiency at present, through continuous exploration in areas such as cross-paradigm architecture integration, anti-over-smoothing design, and system engineering optimization in the future, GNNS are expected to achieve a better balance among “performance–efficiency–interpretability”, further promoting their wide application in scientific computing and industrial applications.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by Guangzhou Huashang University (2024HSZD01, HS2023JYSZH01).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Wenfeng Zheng, Lirong Yin and Junmin Lyu; data processing: Guangyu Xu, Siyu Lu and Lirong Yin; analysis and interpretation of results: Guangyu Xu, Siyu Lu, and Feng Bao; draft manuscript preparation: Guangyu Xu and Wenfeng Zheng; review and editing: Feng Bao, Lirong Yin and Junmin Lyu; funding acquisition: Junmin Lyu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Zaripova K, Cosmo L, Kazi A, Ahmadi SA, Bronstein MM, Navab N. Graph-in-Graph (GiGlearning interpretable latent graphs in non-Euclidean domain for biological and healthcare applications. Med Image Anal. 2023;88:13. doi:10.1016/j.media.2023.102839. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Asif NA, Sarker Y, Chakrabortty RK, Ryan MJ, Ahamed MH, Saha DK, et al. Graph Neural Network: a comprehensive review on non-euclidean space. IEEE Access. 2021;9:60588–606. doi:10.1109/access.2021.3071274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Bhatti UA, Tang H, Wu GL, Marjan S, Hussain A. Deep learning with graph convolutional networks: an overview and latest applications in computational intelligence. Int J Intell Syst. 2023;2023(1):28. doi:10.1155/2023/8342104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Cao WM, Zheng CT, Yan ZY, He ZH, Xie WX. Geometric machine learning: research and applications. Multimed Tools Appl. 2022;81(21):30545–97. doi:10.1007/s11042-022-12683-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Li X, Zang HY, Yu XY, Wu H, Zhang ZJ, Liu JM, et al. On improving knowledge graph facilitated simple question answering system. Neural Comput Appl. 2021;33(16):10587–96. doi:10.1007/s00521-021-05762-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Li XJ, Hu J, Wang JL, Li TR. A dynamic graph attention network with contrastive learning for knowledge graph completion. World Wide Web. 2025;28(4):39. doi:10.1007/s11280-025-01352-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Weller T, Paulheim H. Acm. Evidential relational-graph convolutional networks for entity classification in knowledge graphs. In: Proceedings of the CIKM ’21: 30th ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management; 2021 Nov 1–5; Virtual Event, Australia. p. 3533–7. [Google Scholar]

8. Li ZF, Zhao Y, Zhang Y, Zhang ZL. Multi-relational graph attention networks for knowledge graph completion. Knowledge-Based Syst. 2022;251:109262. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2022.109262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Hu Q, Lin WP, Tang ML, Jiang JT. MBHAN: motif-based heterogeneous graph attention network. Appl Sci. 2022;12(12):19. doi:10.3390/app12125931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Bing R, Yuan G, Zhu M, Meng FR, Ma HF, Qiao SJ. Heterogeneous graph neural networks analysis: a survey of techniques, evaluations and applications. Artif Intell Rev. 2023;56(8):8003–42. doi:10.1007/s10462-022-10375-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Lee Y, Kim E, Choi J, Lee C. SICGNN: structurally informed convolutional graph neural networks for protein classification. Mach Learn-Sci Technol. 2024;5(4):21. doi:10.1088/2632-2153/ad979b. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Koca MB, Nourani E, Abbasoglu F, Karadeniz I, Sevilgen FE. Graph convolutional network based virus-human protein-protein interaction prediction for novel viruses. Comput Biol Chem. 2022;101:14. doi:10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2022.107755. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Lv MQ, Hong ZX, Chen L, Chen TM, Zhu TT, Ji SL. Temporal multi-graph convolutional network for traffic flow prediction. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2021;22(6):3337–48. doi:10.1109/tits.2020.2983763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Bao YX, Huang JS, Shen QQ, Cao Y, Ding WP, Shi ZQ, et al. Spatial-temporal complex graph convolution network for traffic flow prediction. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2023;121:16. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2023.106044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Sharma A, Singh S, Ratna S. Graph Neural Network operators: a review. Multimed Tools Appl. 2023;24:23413–36. doi:10.1007/s11042-023-16440-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Li J, Ji YX, Zhang Y, Ding J, Li C, Li X. Graph neural networks for network science: a mini review. Epl. 2025;150(2):8. doi:10.1209/0295-5075/adc767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Zhao JH, Wang Y, Dou XT, Wang X, Guo M, Zhang RJ, et al. Advances in spatiotemporal graph neural network prediction research. Int J Digit Earth. 2023;16(1):2034–66. [Google Scholar]

18. Pan S, Luo L, Wang Y, Chen C, Wang J, Wu X. Unifying large language models and knowledge graphs: a roadmap. IEEE Trans Knowl Data Eng. 2024;36(7):3580–99. doi:10.1109/tkde.2024.3352100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Ye Z, Kumar YJ, Sing GO, Song FY, Wang JS. A comprehensive survey of graph neural networks for knowledge graphs. IEEE Access. 2022;10:75729–41. doi:10.1109/access.2022.3191784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Dou BZ, Zhu ZL, Merkurjev E, Ke L, Chen L, Jiang J, et al. Machine learning methods for small data challenges in molecular science. Chem Rev. 2023;123(13):8736–80. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

21. Xu HZ, Pang GS, Wang YJ, Wang YJ. Deep isolation forest for anomaly detection. IEEE Trans Knowl Data Eng. 2023;35(12):12591–604. doi:10.1109/TKDE.2023.3270293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Ju W, Fang Z, Gu YY, Liu ZQ, Long QQ, Qiao ZY, et al. A comprehensive survey on deep graph representation learning. Neural Netw. 2024;173:50. [Google Scholar]

23. Sadasivan A, Gananathan K, Mary J, Balasubramanian S. A systematic survey of graph convolutional networks for artificial intelligence applications. Wiley Interdiscip Rev-Data Mining Knowl Discov. 2025;15(2):48. doi:10.1002/widm.70012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Vatter J, Mayer R, Jacobsen HA. The evolution of distributed systems for graph neural networks and their origin in graph processing and deep learning: a survey. ACM Comput Surv. 2024;56(1):37. doi:10.1145/3597428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Ahmed MJ, Mozo A, Karamchandani A. A survey on graph neural networks, machine learning and deep learning techniques for time series applications in industry. PeerJ Comput Sci. 2025;11:52. doi:10.7717/peerj-cs.3097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Rassil A, Chougrad H, Zouaki H. Augmented Graph Neural Network with hierarchical global-based residual connections. Neural Netw. 2022;150:149–66. doi:10.1016/j.neunet.2022.03.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Bi X, Jiang QL, Liu ZX, Yao X, Nie HJ, Yuan GY, et al. Structure-adaptive graph neural network with temporal representation and residual connections. World Wide Web. 2023;26(5):3389–408. doi:10.1007/s11280-023-01179-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]