Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

It’s in the blood: plasma as a source for biochemical identification and biological characterization of novel leukocyte chemoattractants

1

Laboratory of Molecular Immunology, Rega Institute for Medical Research, KU Leuven, Herestraat 49—Box 1042, 3000 Leuven, Belgium

2

Department of Radiology, AZ Groeninge, President Kennedylaan 4, 8500 Kortrijk

3

Laboratory of Immunobiology, Rega Institute for Medical Research, KU Leuven, Herestraat 49—Box 1044, 3000 Leuven, Belgium

* Corresponding Author: S. Struyf,

European Cytokine Network 2025, 36(1), 6-14. https://doi.org/10.1684/ecn.2025.0501

Accepted 01 February 2025;

Abstract

Since their discovery, chemotactic cytokines or chemokines have been intensively studied for about half a century. Chemokines originate from tissue cells, leukocytes, blood platelets and plasma. Here, we review a number of seminal findings on plasma chemokines within an historical and international context. These aspects include how induction and purification protocols led to the discovery of a new family of mediators, named chemokines, on the basis of protein sequencing; how molecular cloning techniques facilitated discoveries of additional family members on the basis of conserved protein structures; how blood plasma and platelets were used as a source of inducible and constitutively expressed chemokines; how various forms of proteolytic reactions may convert precursor proteins into chemokines and either potentiate or inactivate their activity; how abundancy classes and synergism should be interpreted through critically considering plasma chemokine biology; and how other blood proteins, such as serum amyloid A, interact in functional terms with CXC and CC chemokines. The gradual dissection of all these elements not only reveals the complexity of chemokine actions, but also stimulates a more comprehensive interpretation of chemokine levels in plasma and serum, with future chemokinome analyses in mind.Keywords

Plasma is an important carrier of nutrients and messenger proteins, including not only classic hormones but also cytokines as signalling molecules of the immune system. The first cytokines were discovered by consecutive protein purification steps from natural sources based on a specific biological activity, measurable in a laboratory test system, e.g. interferon activity by protection of a cell culture against viral infection. We previously described a number of important aspects on the history of cytokine discoveries since the 1960s in a recent narrative review [1]. For the enhanced production of endogenous immuno-modulators, such as cytokines, producer cells, e.g. fibroblasts or leukocytes, were induced by exogenous stimuli, such as viral double-stranded RNA (dsRNA), bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or plant mitogens. In the mid-1970s, commonly used stimuli were pragmatically borrowed or copied from natural sources, e.g. live virus vaccines, bacterial products and food products. After about half a century and fundamental research into mechanisms of action, we now understand that many of these agonists and natural products act via the Toll-like (TLRs), Rig-like (RLRs), and NOD-like receptors (NLRs) [2, 3] and by clustering of receptors via the multivalency of lectins [4]. Downstream of this innate immune receptor activation, triggered signalling events converge into intracellular changes, leading to programmed production of cytokines.

Cytokines are secreted into the conditioned media from cultured fibroblasts and leukocytes. These low-molecular-weight proteins can subsequently be isolated by chromatographic purification, based on their specific biochemical properties, such as affinity (for lectins, heparins, or antibodies), size, isoelectric point or hydrophobicity. With the use of large-scale cell cultures and semi-industrial downstream processing, cytokines could be purified to homogeneity, allowing us to determine their primary structure by amino acid sequencing. Alpha interferons were the first cytokines to be identified from leukocytes [5], whereas mouse [6] and human fibroblasts [7, 8] were used to purify beta interferons (IFN-β) based on their antiviral activity in vitro. Interleukin (IL)-1 and IL-6 were later discovered as (glyco)proteins produced by in vitro stimulated monocytes and fibroblasts, respectively, and were sequenced in similar ways after purification [9]. The success of such approaches was possibly based upon the extremely high specific activity of these cytokines, expressed in units of biological activity/mg of protein (minimal effective concentration of 10 pg/mL in biological assays).

Although plasma constitutes an easily obtainable source of extracellular fluid, the purification of cytokines from peripheral blood plasma remains a challenge, because plasma is rich in constitutive proteins circulating at high concentrations, such as albumin, fibrinogen, immunoglobulins and other globulins (large plasma proteins possessing globular structures, which often control the transport of minerals, lipids, vitamins and hormones via direct interaction). Upon infection, circulating immunoglobulins, acute phase proteins, complement factors and cytokines play important roles in the host defence. Many bulk proteins were biochemically identified by purification from fresh blood plasma. Notably, although circulating cytokine levels are drastically upregulated in vivo during inflammation, their levels remained far below the detection limits of manual or automated protein sequencing technologies. However, a number of more abundant inflammatory mediators with chemotactic activity were directly isolated and identified from blood plasma. The latter include the complement cleavage fragment C5a [10] and the acute phase protein, serum amyloid A [11] (cf. infra).

FROM CYTOKINE-INDUCED BLOOD CELL-DERIVED CHEMOATTRACTANTS TO CONSTITUTIVE PLASMA CHEMOKINES

Interleukin-8 (IL-8) is the first member of a family of chemotactic cytokines that were isolated and identified based on their chemotactic activity and shared conserved cysteine motifs [12–15]. Based on the conservation of their cysteine residues, chemokines are classified into four subfamilies: CXC, CC, C and CX3C chemokines [16–18]. Prototypic examples are: (i) the strongest human neutrophil chemoattractant, CXC chemokine ligand 8 (IL-8/CXCL8) [19], and (ii) the monocyte chemoattractant CC chemokine ligand 2/monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1/CCL2) [20]. After the identification of IL-8, the presence of additional inducible chemotactic factors was investigated in conditioned media from human cells cultured in vitro with bovine serum and stimulated with inflammatory mediators, such as IL-1 or LPS. The cell-conditioned medium was purified according to a standard chemokine purification strategy based on affinity for heparin, molecular size and isoelectric point as biochemical parameters. Pure proteins present in chromatographically obtained column fractions were identified by NH2-terminal sequencing of proteolytic fragments. In this way, a novel CC chemokine structure was completely elucidated and designated as regakine-1 [21]. Surprisingly, this chemokine turned out to be of bovine origin and was derived from the bovine serum used to grow the cells. Furthermore, regakine-1 was found to be constitutively present at high levels (ng/mL) in bovine blood circulation. However, regakine-1 showed only poor chemotactic activity for neutrophils and lymphocytes compared to human CXCL8 or other CC chemokines.

Chemokines activate leukocytes through binding to G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), designated as CXC chemokine receptors (CXCR) and CC chemokine receptors (CCR) [22]. The receptors activated on human leukocytes by regakine-1 have not yet been identified, and surprisingly, neither has a human (plasma) chemokine equivalent. In contrast to some other chemokines, which show enhanced chemotactic activity after NH2-terminal processing by proteases, e.g. NH2-terminal cleavage of CXCL8 by matrix metalloprotease-9 (MMP-9) [23], NH2-terminally truncated variants of regakine-1 did not show enhanced chemotactic potency [24]. Based on the hypothesis that regakine-1 could function as a natural chemokine antagonist, it was discovered that, instead, it synergized with chemokines in a chemotaxis assay [21]. This new phenomenon was confirmed by demonstrating synergism in chemotaxis assays between known CXC and CC chemokines (vide infra), such as the neutrophil attractant CXCL8 and the monocyte chemotactic protein-3 (MCP-3/CCL7) [25].

In conclusion, we purified a constitutive CC chemokine from bovine plasma that synergized with human chemokines in chemotaxis tests, and we named this regakine-1.

FROM INACTIVE CONSTITUTIVE BETA-THROMBOGLOBULIN TO INFLAMMATORY NEUTROPHIL-ACTIVATING PEPTIDE-2/CXCL7

Beta-thromboglobulin is a blood plasma protein secreted from alpha granules of activated platelets [26]. Although its primary structure (81 amino acids) has been known for about half a century, its true biological function has remained elusive until recently. Beta-thromboglobulin is a cleavage product of connective tissue-activating peptide III (85 residues) (cleaved by plasmin and other serine proteases, such as cathepsin G), which is itself derived from its precursor, platelet basic protein (94 residues) [27, 28]. Upon purification of heparin-binding proteins from thrombin-stimulated blood platelets, four novel NH2-terminally truncated forms of platelet basic protein were discovered [29]. The shortest form (70 residues) showed the same length as the structurally related CXCL8. It was subsequently found that this 70-residue form is a potent neutrophil-activating protein, designated NAP-2/CXCL7 [30, 31]. Although less potent than CXCL8 as a chemoattractant, CXCL7 induces neutrophil infiltration in rabbit skin upon local administration, as well as granulocytosis upon systemic application [30]. To exert these biological activities, CXCL7 binds to and signals through a receptor, shared with CXCL8 and all other CXC chemokines, containing the tripeptide motif ELR, immediately before the first conserved cysteine residues, namely CXCR2 [22]. Besides CXCR2, neutrophils also express another CXCL8 receptor, which is activated only by CXCL6, CXCL8 and NH2-terminally truncated CXCL5 [32, 33]. Thus, platelet basic protein, as an apparently inactive chemotactic precursor protein that is constitutively present in blood, can be enzymatically converted to a fully active inflammatory chemokine in the circulation after release by thrombin-activated platelets and proteolytic alterations due to concomitant serine protease activity [27]. It is relevant to note that during blood clotting, thrombin is an active serine protease, the inactive serine protease plasminogen is converted to active plasmin by plasminogen activators during fibrinolysis, and active complement serine proteases are generated by the classic, alternative and lectin pathways of the complement system. In contrast to constitutive β-thromboglobulin, CXCL8 is induced by exogenous products (e.g. bacterial LPS, viral dsRNA) or endogenous inflammatory cytokines (e.g. IL-1 and TNF). However, CXCL8 is produced in various body compartments by fibroblasts and more specialized cell types, as well as in the blood circulation by monocytes and endothelial cells [12, 34, 35].

FROM CONSTITUTIVE PLATELET FACTOR-4/CXCL4 TO PF-4VAR/CXCL4L1 AND INHIBITION OF ANGIOGENESIS

In retrospect, platelet factor-4 (PF-4/CXCL4) is the oldest reported chemokine, identified as a platelet-derived protein. This discovery was long before that of the first chemotactic cytokine, IL-8/CXCL8, and the introduction of the terminology and abbreviations of chemokines and their receptors [36]. In fact, many biological activities -different from chemotaxis- were ascribed to constitutive plasma PF-4/CXCL4, and these included angiostatic properties [37]. In addition, through cloning techniques, two groups independently identified a non-allelic gene variant of CXCL4 that they named PF-4alt or PF-4var1, which were predicted to encode a protein that differs from CXCL4 at only three amino acids [38, 39]. However, only the mRNA and gene were initially characterized, and demonstration of translation into biologically active protein was lacking. Nevertheless, we were able to isolate and identify PF-4var1, now designated CXCL4L1, as an authentic natural protein released from thrombin-stimulated platelets [40]. However, the amount of CXCL4L1 secreted by platelets is far less than that of PF-4/CXCL4. Pure natural, as well as recombinant CXCL4L1 were found to be more potent inhibitors of CXCL8-induced endothelial cell migration in vitro as well as in vivo angiogenesis compared to CXCL4. Hence, CXCL4L1 prevents angiogenesis-mediated tumour growth and metastasis in animal models more effectively than CXCL4 [40]. Furthermore, CXCL4L1 inhibits diabetes-induced blood-retinal barrier breakdown in streptozotocin-treated rats [41]. The COOH-terminal fragment, CXCL4L1(47-70), fully retains its angiostatic capacity in vitro and its potential to inhibit metastasis [42, 43]. Binding of CXCL4L1 to endothelial cells is inhibited by the CXCR3 ligand, CXCL10, indicating that both chemokines signal through the same receptors. Indeed, the anti-tumour effect of CXCL4L1 is not observed in CXCR3 knockout mice and is inhibited by antibodies against CXCR3 in wild-type mice [44]. The increased angiogenic potential of CXCL4L1, compared to CXCL4, is related to the small alterations in C-terminal amino acids, where primarily the replacement of Leu67 to His changes the orientation of the C-terminal α-helix [45]. Aside from its origin from platelets, CXCL4L1 is expressed by vascular smooth muscle cells and pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells [46, 47].

FROM PLATELET-DERIVED CXC CHEMOKINES TO PLASMA CC CHEMOKINES

Platelets were found to function not only as a rich storage site and source for specific CXC chemokines, but also for some CC chemokines. In particular, RANTES/CCL5 is immunologically detected at rather high concentrations in serum, possibly through release from thrombin-stimulated platelets [48, 49]. However, it was not picked up as a biologically active entity when purifying conditioned medium from stimulated peripheral leukocytes. This could be due to its rapid NH2-terminal processing by CD26/DPPIV into CCL5(3-68), implementing loss of CCR1 and CCR3 signalling and concomitant lack of chemotactic activity for monocytes and eosinophils, respectively [50, 51]. In contrast, CCL5(3-68) shows higher affinity for CCR5 than intact CCL5 and hence more potent lymphotactic and anti-HIV activities [50, 52, 53].

HCC-1/CCL14 has been identified as an abundant protein isolated from the hemofiltrate of patients with kidney failure. Although its protein sequence revealed a CC chemokine structure, no significant chemotactic effect could be ascribed to mature CCL14 [54]. However, upon NH2-terminal processing into CCL14(9-74) by plasmin or urokinase-type plasminogen activator, this CC chemokine becomes a strong agonist for CCR1 and CCR5, with moderate effects on CCR3. Hence, CCL14(9-74) is a potent chemoattractant for monocytes and lymphocytes [55, 56]. In addition, levels of CCL14 immunoreactivity are detectable in the blood circulation, but it is not known whether these represent inactive (intact) or active (processed) CCL14 proteoforms [57].

Pulmonary and activation-regulated chemokine (PARC)/CCL18 was discovered through data mining of expressed sequence-tagged human cDNA libraries in 1997, based on its homology to CCL3 and the positioning of its cysteine residues. Expression of recombinant CCL18 protein allowed for the detection of lymphocyte chemotactic activity [58]. Unexpectedly, high constitutive levels of CCL18 (25 ng/mL) were detected in blood plasma, contrasting with the low concentrations of most inducible chemokines such as CXCL8 (maximally 6 pg/mL) [59]. Further, enhanced CCL18 levels were observed in the blood of paediatric leukaemia patients [57] and patients with unstable angina pectoris [59].

FROM CHEMOKINE SYNERGY TO SERUM AMYLOID A AND MATRIX METALLOPROTEASE-9

Synergy between chemokines in stimulating chemotaxis can be a consequence of different molecular events. The first is heterodimerization of chemokines; as a dimer, chemokines become more potent in activating a single receptor type [60, 61]. Alternatively, two different chemokine receptors are involved, either through heterodimerization [62] or by converging signalling pathways [25, 61]. Indeed, CXCR and CCR dimerization has been reported, and we previously demonstrated that chemokine synergy to stimulate chemotaxis is blocked by specific receptor antagonists [25]. In this context, at high doses, the monocyte-attracting CC chemokine CCL2 synergizes with CXCL8 at low concentration to stimulate neutrophil chemotaxis, and vice versa for monocyte chemotaxis [25]. In vivo relevance of chemokine heteromers and the therapeutic potential of targeting chemokine heteromer formation were demonstrated by Weber et al. [63]. In the latter study, stable peptide inhibitors, designed to specifically disrupt proinflammatory CCL5-CXCL4 interactions, reduced atherosclerosis through attenuation of inflammatory monocyte recruitment.

Along with regakine-1, other synergizing chemotactic factors, such as a COOH-terminal fragment of the acute phase protein serum amyloid A (SAA), were isolated from bovine serum. The human equivalent of this SAA fragment synergized with CXCL8 to stimulate neutrophil chemotaxis [64]. Like intact SAA, which also chemoattracts monocytes [65], this COOH-terminal peptide was found to bind and signal through a GPCR, i.e. formyl peptide receptor 2 (FPR2) [64, 66]. FPR2 was demonstrated to be implicated in the synergistic interaction between SAA (fragments) and chemokines [64, 67, 68]. Interestingly, the above described COOH-terminal SAA fragments are generated through cleavage by MMP-9, and exert similar synergistic activities, whereas the NH2-terminal counterparts fail to synergize with CXCL8 [67]. SAA is reported to be a potent inducer of cytokines and chemokines via binding to Toll-like receptors (TLR) 2 and 4. However, intact recombinant SAA, or synthetic SAA fragments purified to homogeneity, do not show any inducing capacity. It was concluded that commercial preparations of SAA were contaminated with lipoproteins and lipopolysaccharides which were responsible for these TLR-mediated induction effects [69–71].

BIOLOGICAL ROLE OF PLASMA-DERIVED CHEMOKINES

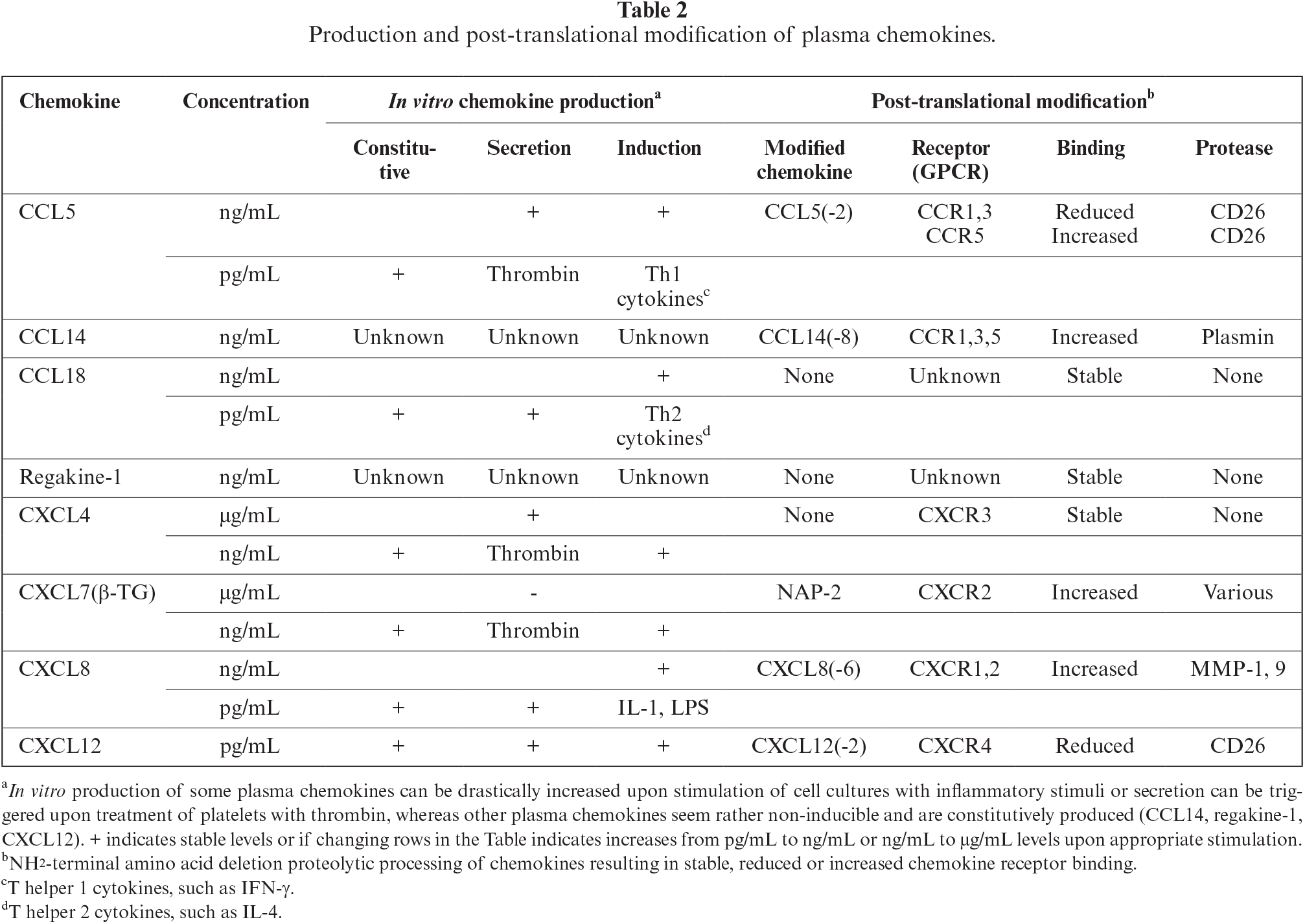

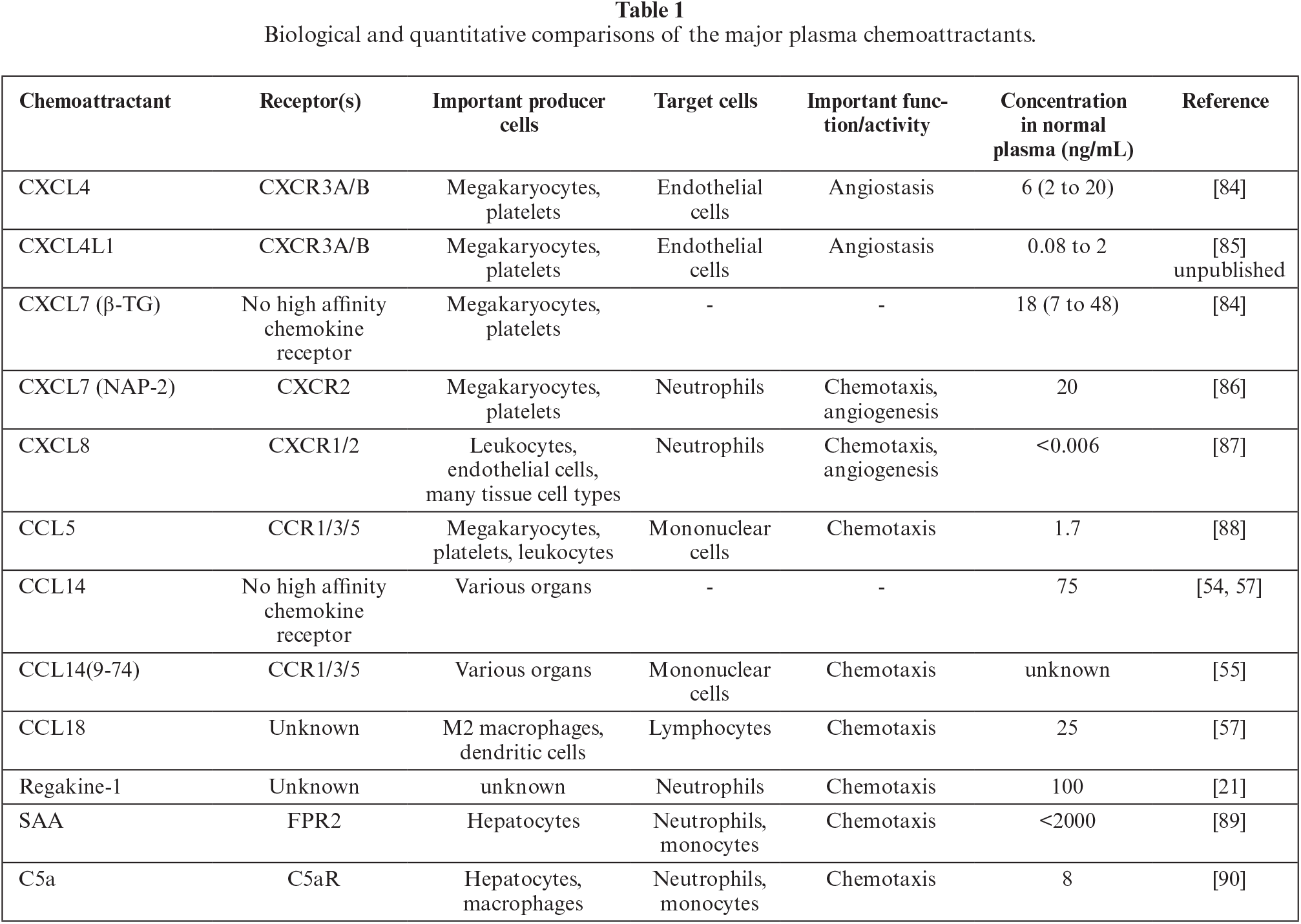

It has long been argued that chemokines are redundant in biological activity, as some receptors bind more than five chemokine ligands. However, based on detailed structural information and better and more in-depth functional investigations with highly purified chemotactic mediators, the above redundancy statement has become obsolete. Indeed, when considering multiple parameters, most chemokines are unique within the family due to distinct structural or functional characteristics. Biologically, chemokines can be subdivided into inflammatory versus homeostatic factors or inducible versus constitutive mediators. Parameters allowing to functionally distinguish between chemokines include: animal species, producer cell type, organ/tissue distribution, physiological stimulus, inflammatory inducer, kinetics of production and action, target cell types, receptor usage, proteolytic processing, and post-translational modification. The group of constitutive plasma chemokines contains both CXC and CC chemokine family members (Table 1).

Regakine-1 is a constitutive CC chemokine present at high concentrations in bovine blood, but a human homolog is lacking. Although, to date, its biological function is poorly understood, its existence allows us to speculate that, in evolutionary terms, this chemokine could be related to anatomical or physiological differences between human and bovine species. With regard to CXCL4 and CXCL7, these platelet-derived factors differ in post-translational processing. CXCL7 is generated during the inflammatory response by proteolytic NH2-terminal cleavage of its constitutive, but inactive, precursors to become chemotactically active [30]. Moreover, CXCL4 and CXCL7 function through distinct receptors, CXCR3 and CXCR2, respectively, rendering these chemokines completely different in biological terms [22, 44]. Indeed, CXCL7 promotes angiogenesis, whereas CXCL4 and CXCL4L1 are angiostatic factors [37, 40, 72]. Furthermore, despite the fact that CXCL7 and CXCL8 share CXCR2 to attract neutrophils, these chemokines differ considerably with regards to cellular source and corresponding gene regulation. In particular, CXCL7 is uniquely generated by release from thrombin-stimulated blood platelets, whereas CXCL8 is induced in multiple cell types, including fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and monocytes, in various tissues, as well as the blood stream during an inflammatory response [30, 73]. In contrast, CCL5 is produced by both blood platelets and connective tissue fibroblasts upon appropriate differential stimulation for each cell type, pointing to distinct functions of this chemokine in separate body compartments [74, 75]. Furthermore, CCL5 binds to several CC-chemokine receptor types which accounts for its broad spectrum of target cells. Minimal NH2-terminal processing by CD26/dipeptidyl peptidase IV converts this chemokine into a more potent agonist or an antagonist depending on the receptor type expressed on the target cell type [50–53].

ROLE OF CONSTITUTIVE PLASMA CHEMOKINES IN NORMAL PHYSIOLOGY AND PATHOLOGY

Infection by viral or bacterial pathogens often starts locally leading to cytokine production in the affected tissues or organ. As soon as such infection becomes systemic, inflammatory chemokine levels in the blood circulation increase drastically, as part of the so-called “cytokine storm”. For example, bacterial sepsis results in high production levels of CXCL8, which is induced in blood vessel endothelial cells and circulating monocytes by exogenous (LPS) or endogenous (IL-1) mediators [13, 34, 76]. Hence, these high CXCL8 levels provoke rapid granulocytosis by recruiting neutrophils from the marginating pool and by easier entry of neutrophils and their precursors into the blood circulation within the bone marrow. Similarly, CXCL7, secreted by thrombin-stimulated platelets and converted proteolytically into an active chemoattractant, also causes neutrophilia. These two CXCR1/2 agonists are complementary to each other in that they differ in cellular origin and how they are induced, leading to different kinetics of appearance into the circulation. Furthermore, chemokine-activated neutrophils assist in the CXCL8-induced recruitment of hematopoietic progenitor cells from the bone marrow [77]. This mobilizing effect of CXCL8 requires the involvement of MMP-9 [78], which, in addition, cleaves CXCL8 into a more potent neutrophil chemoattractant [23]. In this context, it remains unclear what could be the role of the constitutive presence of CXCL7 precursors in the blood circulation.

Early reports subdivided CXC chemokines into angiogenic and angiostatic factors depending on the presence of an ELR motif immediately before the CXC hallmark [72]. Indeed, ELR+ CXC chemokines all bind to CXCR2 on endothelial cells and mediate endothelial migration and proliferation. However, the absence of the ELR motif in CXC chemokines is not an indicator of angiostatic properties, as ELR-negative CXCL12 stimulates angiogenesis [79]. A feature of angiostatic chemokines that they have in common is that they bind to the CXCR3 receptor [80, 81], e.g. CXCL4, CXCL4L1, CXCL9, CXCL10 and CXCL11. As a consequence, the chemotactic effect of circulating ELR+ CXCL8 on endothelial cells is inhibited by platelet-derived CXCL4 and CXCL4L1, as evidenced in an in vitro migration test, as well as in the rabbit cornea assay for angiogenesis [40]. Importantly, CXCL4L1 potently inhibits tumour metastasis in murine cancer models [40]. However, CXCL4L1 produced by pancreatic tumour cells can stimulate proliferation of CXCR3-expressing tumour cells in an autocrine manner, accounting for the observed correlation between CXCL4L1 expression and worse prognosis [47].

QUANTITATIVE AND QUALITATIVE ASPECTS OF PLASMA CHEMOATTRACTANTS

Most inflammatory chemokines, such as CXCL8, are present at undetectable levels or at very low (pg/mL) concentrations in plasma from healthy donors (Table 2). However, upon infection, these chemokines are produced de novo by blood vessel endothelial cells and circulating mononuclear leukocytes through direct induction by bacterial (LPS) or viral (dsRNA) products or by indirect stimulation via inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IFN-γ). As a consequence, within a few hours, inflammatory chemokine concentrations can raise to high levels (ng to μg/mL) within the blood circulation, e.g. during septic shock. In contrast, plasma chemokines are constitutively present at significant concentrations (μg/mL) in the blood circulation. Plasma levels of some of these chemokines stored in platelet granules, such as CXCL4 and CXCL7, can be further increased within minutes after stimulation of their release with thrombin. However, CXCL7 does not become fully active as a neutrophil chemoattractant until it is NH2-terminally processed by various proteases to become a potent CXCR2 agonist. Similarly, the plasma chemokine, CCL14, must be processed by plasmin to generate a potent chemoattractant for mononuclear leukocytes via signalling through CCR1 and 5. In contrast, active CCL5 can be selectively inactivated as CCR1 and CCR3 agonists after truncation of two NH2-terminal residues by CD26, whereas its affinity for CCR5 is further increased by CD26. For other plasma chemokines, such as regakine-1, no significant effect of NH2-terminal processing has been observed in modulating their biological potency. However, inducible inflammatory chemokines can be further proteolytically processed to become either biologically more active (e.g. CXCL8 by MMP-9) or inactive (e.g. CCL5 by CD26). Finally, constitutive chemokines, such as regakine-1, at moderate concentration, can synergize with low concentrations of CXCL8 or CCL7 to stimulate neutrophil and monocyte chemotaxis, respectively. In conclusion, the biological potential of plasma chemokines is fine-tuned both quantitatively and qualitatively, contributing to the complex chemokine network in the blood circulation.

CONCLUSIONS: PLASMA CHEMOKINES, A SMURF COMMUNITY OF CHEMOATTRACTANTS IN THE BLOOD CIRCULATION

Chemokines form a large family of structurally related entities, with distinct biochemical and biological properties of each member. In this sense, chemokines form signalling molecules within a “society”, with immune cells and plasma molecules being moved passively (lymphatic system) and actively (blood circulation) through the organism to provide immune defence. As mentioned above, the study of chemokines within the immune system is quite complex and many aspects have to be considered before one may formulate a holistic summary. One way to explain such a complex “community” (and perhaps the best approach) is to dissect the complicated aspects into many simpler elements, and to refer to each element in understandable terminology and symbols, similar to comic strips designed for children. Regarding the latter, several exemplary Belgian authors and illustrators have excelled in this field: from Maurice Maeterlinck (Nobel prize in literature, 1911, and author of l’Oiseau bleu) to Hergé (creator of The Adventures of Tintin) and Peyo, the father of “ The Smurfs” [82]. Their works have been translated into the most common languages, providing messages on educational aspects of society at a truly international level. As an analogy, we consider the interactions of chemokines (and the difficulties associated with chemokine research) to be similar to the actions of many members of the family of “Smurfs”, each member with a particular appearance, with unique physiognomy and character. Chemokines often operate simultaneously in complex environments, mostly together in synergy, to combat common enemies, but sometimes antagonize each other [81]. This analogy is intended to further inspire those in the field of chemokine research with regards to enhancing knowledge, education, and discovery.

In conclusion, in the vascular system, blood plasma, together with all corpuscular elements (red blood cells, leukocytes and platelets), circulates as a unique liquefied tissue through the body by a motor-driven semi-closed system. The corpuscular elements are delivered from within the bone marrow and the immune system, whereas plasma proteins are mainly derived from specialized organs and tissues, including the liver and those of the immune system [83]. Here, we have addressed a number of important aspects of chemokine actions within the hydrodynamic constraints of a living organism, with special attention to plasma chemokines. In contrast to the open hydrological system of the earth (in which water is unidirectionally drained to the sea by means of gravity and returns from sea to land by evaporation and condensation as rain), the blood circulation system allows for uptake and distribution of exogenous substances throughout the body. Through the discovery of new chemotactic factors and the study of their regulation, we have shown that monocytes, lymphocytes and granulocytes are excellent producer and target leukocytes. In addition, tissue fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and platelets may be excellent producers of chemokines that are present in plasma and distributed throughout the organism [83]. As a surrogate for plasma, animal serum obtained from coagulated blood, commonly used to support in vitro growth of different cell types, may also be used as a source of chemokines. The function of chemokines with regards to plasma physiology and pathology should be studied considering the overall complexity of chemokine biology. We hope that the outlined examples and mechanistic studies will stimulate readers to think more critically about phenomenological chemokine investigation.

DISCLOSURE

Financial support: This research was funded by KU Leuven, the Rega Foundation, and the Fund for Scientific Research of Flanders “FWO-Vlaanderen”.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Acknowledgments: JVD and GO are currently Emeritus Professors and thank fellow researchers for their longstanding collaborations. This manuscript is written in memory of Isabelle Ronsse, René Conings, Jean-Pierre Lenaerts and Willy Put who helped to execute the experimental work leading to the discovery of many chemokines. The authors wish to thank their spouses for their tolerance and patience allowing their partners full dedication to perform scientific research. The mentorship by Paul Proost, Alfons Billiau and Piet De Somer is also very much appreciated.

REFERENCES

1. Van Damme J, Opdenakker G, Van Damme S, Struyf S. Antibodies as tools in cytokine discovery and usage for diagnosis and therapy of inflammatory diseases. Eur Cytokine Netw 2023;34:1-9. [Google Scholar]

2. Broz P, Monack DM. Newly described pattern recognition receptors team up against intracellular pathogens. Nat Rev Immunol 2013;13:551-65. [Google Scholar]

3. Kawai T, Akira S. The roles of TLRs, RLRs and NLRs in pathogen recognition. Int Immunol 2009;21:317-37. [Google Scholar]

4. De Coninck T, Van Damme EJM. The multiple roles of plant lectins. Plant Sci 2021;313 [Google Scholar]

5. Zoon KC, Smith ME, Bridgen PJ, et al. Amino terminal sequence of the major component of human lymphoblastoid interferon. Science 1980;207:527-8. [Google Scholar]

6. Taira H, Broeze RJ, Jayaram BM, et al. Mouse interferons: amino terminal amino acid sequences of various species. Science 1980;207:528-30. [Google Scholar]

7. Billiau A, Van Damme J, Van Leuven F, et al. Human fibroblast interferon for clinical trials: production, partial purification, and characterization. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1979;16:49-55. [Google Scholar]

8. Knight EJr., Hunkapiller MW, Korant BD, Hardy RW, Hood LE. Human fibroblast interferon: amino acid analysis and amino terminal amino acid sequence. Science 1980;207:525-6. [Google Scholar]

9. Van Damme J, De Ley M, Opdenakker G, et al. Homogeneous interferon-inducing 22K factor is related to endogenous pyrogen and interleukin-1. Nature 1985;314:266-8. [Google Scholar]

10. Tack BF, Morris SC, Prahl JW. Fifth component of human complement: purification from plasma and polypeptide chain structure. Biochemistry 1979;18:1490-7. [Google Scholar]

11. Dwulet FE, Wallace DK, Benson MD. Amino acid structures of multiple forms of amyloid-related serum protein SAA from a single individual. Biochemistry 1988;27(5)1677-82. [Google Scholar]

12. Schröder JM, Mrowietz U, Morita E, Christophers E. Purification and partial biochemical characterization of a human monocyte-derived, neutrophil-activating peptide that lacks interleukin 1 activity. J Immunol 1987;139:3474-83. [Google Scholar]

13. Van Damme J, Van Beeumen J, Opdenakker G, Billiau A. A novel, NH2-terminal sequence-characterized human monokine possessing neutrophil chemotactic, skin-reactive, and granulocytosis-promoting activity. J Exp Med 1988;167:1364-76. [Google Scholar]

14. Yoshimura T, Matsushima K, Tanaka S, et al. Purification of a human monocyte-derived neutrophil chemotactic factor that has peptide sequence similarity to other host defense cytokines. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1987;84:9233-7. [Google Scholar]

15. Peveri P, Walz A, Dewald B, Baggiolini M. A novel neutrophil-activating factor produced by human mononuclear phagocytes. J Exp Med 1988;167:1547-59. [Google Scholar]

16. Luster AD. Chemokines--chemotactic cytokines that mediate inflammation. N Engl J Med 1998;338:436-45. [Google Scholar]

17. Zlotnik A, Yoshie O. The chemokine superfamily revisited. Immunity 2012;36:705-16. [Google Scholar]

18. Rot A, von Andrian UH. Chemokines in innate and adaptive host defense: basic chemokinese grammar for immune cells. Annu Rev Immunol 2004;22:891-928. [Google Scholar]

19. Baggiolini M, Dewald B, Moser B. Human chemokines: an update. Annu Rev Immunol 1997;15:675-705. [Google Scholar]

20. Yoshimura T, Robinson EA, Tanaka S, et al. Purification and amino acid analysis of two human glioma-derived monocyte chemoattractants. J Exp Med 1989;169:1449-59. [Google Scholar]

21. Struyf S, Proost P, Lenaerts JP, et al. Identification of a blood-derived chemoattractant for neutrophils and lymphocytes as a novel CC chemokine, Regakine-1. Blood 2001;97:2197-204. [Google Scholar]

22. Bachelerie F, Ben-Baruch A, Burkhardt AM, et al. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. [corrected]. LXXXIX. Update on the extended family of chemokine receptors and introducing a new nomenclature for atypical chemokine receptors. Pharmacol Rev 2014;66:1-79. [Google Scholar]

23. Van den Steen PE, Proost P, Wuyts A, Van Damme J, Opdenakker G. Neutrophil gelatinase B potentiates interleukin-8 tenfold by aminoterminal processing, whereas it degrades CTAP-III, PF-4, and GRO-alpha and leaves RANTES and MCP-2 intact. Blood 2000;96:2673-81. [Google Scholar]

24. Gouwy M, Struyf S, Mahieu F, et al. The unique property of the CC chemokine regakine-1 to synergize with other plasma-derived inflammatory mediators in neutrophil chemotaxis does not reside in its NH2-terminal structure. Mol Pharmacol 2002;62:173-80. [Google Scholar]

25. Gouwy M, Struyf S, Catusse J, Proost P, Van Damme J. Synergy between proinflammatory ligands of G protein-coupled receptors in neutrophil activation and migration. J Leukoc Biol 2004;76:185-94. [Google Scholar]

26. Begg GS, Pepper DS, Chesterman CN, Morgan FJ. Complete covalent structure of human beta-thromboglobulin. Biochemistry 1978;17:1739-44. [Google Scholar]

27. Walz A, Baggiolini M. Generation of the neutrophil-activating peptide NAP-2 from platelet basic protein or connective tissue-activating peptide III through monocyte proteases. J Exp Med 1990;171:449-54. [Google Scholar]

28. Holt JC, Niewiarowski S. Conversion of low-affinity platelet factor 4 to beta-thromboglobulin by plasmin and trypsin. Biochim Biophys Acta 1980;632:284-9. [Google Scholar]

29. Van Damme J, Van Beeumen J, Conings R, Decock B, Billiau A. Purification of granulocyte chemotactic peptide/interleukin-8 reveals N-terminal sequence heterogeneity similar to that of beta-thromboglobulin. Eur J Biochem 1989;181:337-44. [Google Scholar]

30. Van Damme J, Rampart M, Conings R, et al. The neutrophil-activating proteins interleukin 8 and beta-thromboglobulin: in vitro and in vivo comparison of NH2-terminally processed forms. Eur J Immunol 1990;20:2113-8. [Google Scholar]

31. Walz A, Dewald B, von Tscharner V, Baggiolini M. Effects of the neutrophil-activating peptide NAP-2, platelet basic protein, connective tissue-activating peptide III and platelet factor 4 on human neutrophils. J Exp Med 1989;170:1745-50. [Google Scholar]

32. Wuyts A, Proost P, Lenaerts JP, et al. Differential usage of the CXC chemokine receptors 1 and 2 by interleukin-8, granulocyte chemotactic protein-2 and epithelial-cell-derived neutrophil attractant-78. Eur J Biochem 1998;255:67-73. [Google Scholar]

33. Metzemaekers M, Mortier A, Vacchini A, et al. Endogenous modification of the chemoattractant CXCL5 alters receptor usage and enhances its activity toward neutrophils and monocytes. Sci Signal 2021;14(673) [Google Scholar]

34. Strieter RM, Kunkel SL, Showell HJ, et al. Endothelial cell gene expression of a neutrophil chemotactic factor by TNF-alpha, LPS, and IL-1 beta. Science 1989;243:1467-9. [Google Scholar]

35. Van Damme J, Decock B, Conings R, et al. The chemotactic activity for granulocytes produced by virally infected fibroblasts is identical to monocyte-derived interleukin 8. Eur J Immunol 1989;19:1189-94. [Google Scholar]

36. Deuel TF, Keim PS, Farmer M, Heinrikson RL. Amino acid sequence of human platelet factor 4. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1977;74:2256-8. [Google Scholar]

37. Maione TE, Gray GS, Petro J, et al. Inhibition of angiogenesis by recombinant human platelet factor-4 and related peptides. Science 1990;247:77-9. [Google Scholar]

38. Green CJ, Charles RS, Edwards BF, Johnson PH. Identification and characterization of PF4varl, a human gene variant of platelet factor 4. Mol Cell Biol 1989;9:1445-51. [Google Scholar]

39. Eisman R, Surrey S, Ramachandran B, Schwartz E, Poncz M. Structural and functional comparison of the genes for human platelet factor 4 and PF4alt. Blood 1990;76:336-44. [Google Scholar]

40. Struyf S, Burdick MD, Proost P, Van Damme J, Strieter RM. Platelets release CXCL4L1, a nonallelic variant of the chemokine platelet factor-4/CXCL4 and potent inhibitor of angiogenesis. Circ Res 2004;95:855-7. [Google Scholar]

41. Abu El-Asrar AM, Mohammad G, Nawaz MI, et al. The Chemokine Platelet Factor-4 Variant (PF-4var)/CXCL4L1 Inhibits Diabetes-Induced Blood-Retinal Barrier Breakdown. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2015;56:1956-64. [Google Scholar]

42. Vandercappellen J, Liekens S, Bronckaers A, et al. The COOH-terminal peptide of platelet factor-4 variant (CXCL4L1/PF-4var47-70) strongly inhibits angiogenesis and suppresses B16 melanoma growth in vivo. Mol Cancer Res 2010;8:322-34. [Google Scholar]

43. Van Raemdonck K, Gouwy M, Lepers SA, Van Damme J, Struyf S. CXCL4L1 and CXCL4 signaling in human lymphatic and microvascular endothelial cells and activated lymphocytes: involvement of mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases, Src and p70S6 kinase. Angiogenesis 2014;17:631-40. [Google Scholar]

44. Struyf S, Salogni L, Burdick MD, et al. Angiostatic and chemotactic activities of the CXC chemokine CXCL4L1 (platelet factor-4 variant) are mediated by CXCR3. Blood 2011;117:480-8. [Google Scholar]

45. Kuo JH, Chen YP, Liu JS, et al. Alternative C-terminal helix orientation alters chemokine function: structure of the anti-angiogenic chemokine, CXCL4L1. J Biol Chem 2013;288:13522-33. [Google Scholar]

46. Kaczor DM, Kramann R, Hackeng TM, Schurgers LJ, Koenen RR. Differential Effects of Platelet Factor 4 (CXCL4) and Its Non-Allelic Variant (CXCL4L1) on Cultured Human Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells. Int J Mol Sci 2022;23(2) [Google Scholar]

47. Quemener C, Baud J, Boye K, et al. Dual Roles for CXCL4 Chemokines and CXCR3 in Angiogenesis and Invasion of Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer research 2016;76:6507-19. [Google Scholar]

48. Aukrust P, Müller F, Froland SS. Circulating levels of RANTES in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection: effect of potent antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis 1998;177:1091-6. [Google Scholar]

49. Kameyoshi Y, Dorschner A, Mallet AI, Christophers E, Schröder JM. Cytokine RANTES released by thrombin-stimulated platelets is a potent attractant for human eosinophils. J Exp Med 1992;176:587-92. [Google Scholar]

50. Proost P, De Meester I, Schols D, et al. Amino-terminal truncation of chemokines by CD26/dipeptidyl-peptidase IV. Conversion of RANTES into a potent inhibitor of monocyte chemotaxis and HIV-1-infection. J Biol Chem 1998;273:7222-7. [Google Scholar]

51. Struyf S, De Meester I, Scharpé S, et al. Natural truncation of RANTES abolishes signaling through the CC chemokine receptors CCR1 and CCR3, impairs its chemotactic potency and generates a CC chemokine inhibitor. Eur J Immunol 1998;28:1262-71. [Google Scholar]

52. Iwata S, Yamaguchi N, Munakata Y, et al. CD26/dipeptidyl peptidase IV differentially regulates the chemotaxis of T cells and monocytes toward RANTES: possible mechanism for the switch from innate to acquired immune response. Int Immunol 1999;11:417-26. [Google Scholar]

53. Oravecz T, Pall M, Roderiquez G, et al. Regulation of the receptor specificity and function of the chemokine RANTES (regulated on activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted) by dipeptidyl peptidase IV (CD26)-mediated cleavage. J Exp Med 1997;186:1865-72. [Google Scholar]

54. Schulz-Knappe P, Magert HJ, Dewald B, et al. HCC-1, a novel chemokine from human plasma. J Exp Med 1996;183:295-9. [Google Scholar]

55. Detheux M, Standker L, Vakili J, et al. Natural proteolytic processing of hemofiltrate CC chemokine 1 generates a potent CC chemokine receptor (CCR)1 and CCR5 agonist with anti-HIV properties. J Exp Med 2000;192:1501-8. [Google Scholar]

56. Vakili J, Ständker L, Detheux M, et al. Urokinase plasminogen activator and plasmin efficiently convert hemofiltrate CC chemokine 1 into its active [9–74] processed variant. J Immunol 2001;167:3406-13. [Google Scholar]

57. Struyf S, Schutyser E, Gouwy M, et al. PARC/CCL18 is a plasma CC chemokine with increased levels in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Am J Pathol 2003;163:2065-75. [Google Scholar]

58. Hieshima K, Imai T, Baba M, et al. A novel human CC chemokine PARC that is most homologous to macrophage-inflammatory protein-1 alpha/LD78 alpha and chemotactic for T lymphocytes, but not for monocytes. J Immunol 1997;159:1140-9. [Google Scholar]

59. Kraaijeveld AO, de Jager SC, de Jager WJ, et al. CC chemokine ligand-5 (CCL5/RANTES) and CC chemokine ligand-18 (CCL18/PARC) are specific markers of refractory unstable angina pectoris and are transiently raised during severe ischemic symptoms. Circulation 2007;116:1931-41. [Google Scholar]

60. Sebastiani S, Danelon G, Gerber B, Uguccioni M. CCL22-induced responses are powerfully enhanced by synergy inducing chemokines via CCR4: evidence for the involvement of first beta-strand of chemokine. Eur J Immunol 2005;35:746-56. [Google Scholar]

61. Gouwy M, Schiraldi M, Struyf S, Van Damme J, Uguccioni M. Possible mechanisms involved in chemokine synergy fine tuning the inflammatory response. Immunol Lett 2012;145(1-2)10-4. [Google Scholar]

62. Mellado M, Rodriguez-Frade JM, Vila-Coro AJ, et al. Chemokine receptor homo- or heterodimerization activates distinct signaling pathways. EMBO J 2001;20:2497-507. [Google Scholar]

63. Koenen RR, von Hundelshausen P, Nesmelova IV, et al. Disrupting functional interactions between platelet chemokines inhibits atherosclerosis in hyperlipidemic mice. Nat Med 2009;15:97-103. [Google Scholar]

64. De Buck M, Gouwy M, Berghmans N, et al. COOH-terminal SAA1 peptides fail to induce chemokines but synergize with CXCL8 and CCL3 to recruit leukocytes via FPR2. Blood 2018;131:439-49. [Google Scholar]

65. Badolato R, Wang JM, Murphy WJ, et al. Serum amyloid A is a chemoattractant: induction of migration, adhesion, and tissue infiltration of monocytes and polymorphonuclear leukocytes. J Exp Med 1994;180:203-9. [Google Scholar]

66. Su SB, Gong W, Gao JL, et al. A seven-transmembrane, G protein-coupled receptor, FPRL1, mediates the chemotactic activity of serum amyloid A for human phagocytic cells. J Exp Med 1999;189:395-402. [Google Scholar]

67. Gouwy M, De Buck M, Abouelasrar Salama S, et al. Matrix Metalloproteinase-9-Generated COOH-, but Not NH(2)-Terminal Fragments of Serum Amyloid A1 Retain Potentiating Activity in Neutrophil Migration to CXCL8, With Loss of Direct Chemotactic and Cytokine-Inducing Capacity. Front Immunol 2018;9:1081. [Google Scholar]

68. Abouelasrar Salama S, Gouwy M, Van Damme J, Struyf S. Acute-serum amyloid A and A-SAA-derived peptides as formyl peptide receptor (FPR) 2 ligands. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2023;14:1119227. [Google Scholar]

69. Abouelasrar Salama S, Gouwy M, Van Damme J, Struyf S. The turning away of serum amyloid A biological activities and receptor usage. Immunology 2021;163:115-27. [Google Scholar]

70. Burgess EJ, Hoyt LR, Randall MJ, et al. Bacterial Lipoproteins Constitute the TLR2-Stimulating Activity of Serum Amyloid A. J Immunol 2018;201:2377-84. [Google Scholar]

71. Abouelasrar Salama S, De Bondt M, Berghmans N, et al. Biological Characterization of Commercial Recombinantly Expressed Immunomodulating Proteins Contaminated with Bacterial Products in the Year 2020: The SAA3 Case. Mediators Inflamm 2020;2020:6087109. [Google Scholar]

72. Strieter RM, Polverini PJ, Kunkel SL, et al. The functional role of the ELR motif in CXC chemokine-mediated angiogenesis. J Biol Chem 1995;270:27348-57. [Google Scholar]

73. Brandt E, Ludwig A, Petersen F, Flad HD. Platelet-derived CXC chemokines: old players in new games. Immunol Rev 2000;177:204-16. [Google Scholar]

74. Gleissner CA, von Hundelshausen P, Ley K. Platelet chemokines in vascular disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2008;28:1920-7. [Google Scholar]

75. Schall TJ. Biology of the RANTES/SIS cytokine family. Cytokine 1991;3:165-83. [Google Scholar]

76. Hack CE, Hart M, van Schijndel RJ, et al. Interleukin-8 in sepsis: relation to shock and inflammatory mediators. Infect Immun 1992;60:2835-42. [Google Scholar]

77. Pruijt JFM, Verzaal P, van Os R, et al. Neutrophils are indispensable for hematopoietic stem cell mobilization induced by interleukin-8 in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2002;99:6228-33. [Google Scholar]

78. Pruijt JF, Fibbe WE, Laterveer L, et al. Prevention of interleukin-8-induced mobilization of hematopoietic progenitor cells in rhesus monkeys by inhibitory antibodies against the metalloproteinase gelatinase B (MMP-9). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1999;96:10863-8. [Google Scholar]

79. Salcedo R, Oppenheim JJ. Role of chemokines in angiogenesis: CXCL12/SDF-1 and CXCR4 interaction, a key regulator of endothelial cell responses. Microcirculation 2003;10(3-4)359-70. [Google Scholar]

80. Van Raemdonck K, Van den Steen PE, Liekens S, Van Damme J, Struyf S. CXCR3 ligands in disease and therapy. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2015;26:311-27. [Google Scholar]

81. Reynders N, Abboud D, Baragli A, et al. The Distinct Roles of CXCR3 Variants and Their Ligands in the Tumor Microenvironment. Cells 2019;8(6) [Google Scholar]

82. Rose C. Behind the blue: the story of Peyo. The Comics Journal 2018https://www.tcj.com/behind-the-blue-the-story-of-peyo/ [Google Scholar]

83. Opdenakker G, Fibbe WE, Van Damme J. The molecular basis of leukocytosis. Immunol Today 1998;19:182-9. [Google Scholar]

84. Kaplan KL, Owen J. Plasma levels of beta-thromboglobulin and platelet factor 4 as indices of platelet activation in vivo. Blood 1981;57:199-202. [Google Scholar]

85. Patsouras MD, Sikara MP, Grika EP, et al. Elevated expression of platelet-derived chemokines in patients with antiphospholipid syndrome. Journal of autoimmunity 2015;65:30-7. [Google Scholar]

86. Smith C, Damas JK, Otterdal K, et al. Increased levels of neutrophil-activating peptide-2 in acute coronary syndromes: possible role of platelet-mediated vascular inflammation. J Autoimmun 2006;48:1591-9. [Google Scholar]

87. Metzemaekers M, Cambier S, Blanter M, et al. Kinetics of peripheral blood neutrophils in severe coronavirus disease 2019. Clin Transl Immunology 2021;10:e1271. [Google Scholar]

88. Weiss L, Si-Mohamed A, Giral P, et al. Plasma levels of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 but not those of macrophage inhibitory protein-1alpha and RANTES correlate with virus load in human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Infect dis 1997;176:1621-4. [Google Scholar]

89. De Buck M, Gouwy M, Wang JM, et al. Structure and Expression of Different Serum Amyloid A (SAA) Variants and their Concentration-Dependent Functions During Host Insults. Cur Med Chem 2016;23:1725-55. [Google Scholar]

90. Lechner J, Chen M, Hogg RE, et al. Higher plasma levels of complement C3a, C4a and C5a increase the risk of subretinal fibrosis in neovascular age-related macular degeneration: Complement activation in AMD. Immun Ageing 2016;13:4. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools