Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Validation of the Chinese Version of the Affective Exercise Experiences Questionnaire (AFFEXX-C)

1 Body-Brain-Mind Laboratory, School of Psychology, Shenzhen University, Shenzhen, 518060, China

2 Swiss Center for Affective Sciences, University of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland

3 Department of Psychology, Laboratory for the Study of Emotion Elicitation and Expression (E3Lab), University of Geneva,

Geneva, Switzerland

4 University Grenoble Alpes, SENS, Grenoble, F-38000, France

5 Department of Kinesiology, California State University Bakersfield, Bakersfield, CA, USA

6 Research Group Degenerative and Chronic Diseases, Movement, Faculty of Health Sciences Brandenburg, University of

Potsdam, Potsdam, Germany

7 Department of Sport, Exercise & Health, University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland

8 Department of Kinesiology and Community Health, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, IL, 61801, USA

* Corresponding Author: Liye Zou. Email:

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2023, 25(7), 799-812. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2023.028324

Received 24 October 2022; Accepted 15 December 2022; Issue published 01 June 2023

Abstract

Despite the well-established benefits of regular physical activity (PA) on health, a large proportion of the world population does not achieve the recommended level of regular PA. Although affective experiences toward PA may play a key role to foster a sustained engagement in PA, they have been largely overlooked and crudely measured in the existing studies. To address this shortcoming, the Affective Exercise Experiences (AFFEXX) questionnaire has been developed to measure such experiences. Specifically, this questionnaire was developped to assess the following three domains: antecedent appraisals (e.g., liking vs. disliking exercise in groups), core affective exercise experiences (i.e., pleasure vs. displeasure, energy vs. tiredness, and calmness vs. tension), and exercise motivation (i.e., attraction vs. antipathy toward exercise). The current study aimed to validate a Chinese version of the AFFEXX questionnaire (AFFEXX-C). In study 1, 722 Chinese college students provided data for analyses of factorial, convergent, discriminant, criterion validity, and testretest reliability of the AFFEXX-C. In addition, 1,300 college students were recruited in study 2 to further validate its structural model. Results showed that the AFFEXX-C demonstrates a good fit and reliability. Additionally, results further supported the hypothesized model based on previous research: antecedent appraisals predicted core affective exercise experiences, which in turn predicted attraction-antipathy toward physical exercise. The AFFEXX-C was found to be a reliable and valid measure of affective exercise experiences in a population of Chinese college students.Keywords

The World Health Organization (WHO) has recommended that adults should perform at least 150 min/week of moderate-intensity physical activity (PA) or 75 min/week of vigorous-intensity PA—at best accompanied by at least two sessions of strength training per week—to maintain and promote general health [1,2]. However, the proportion of adults who fail to meet these PA guidelines remains relatively high. For example, recent estimates suggest that nearly 80% of people fail to achieve the aerobic and muscle-strengthening guidelines [3]. Among the populations at particular risk for physical inactivity are college students. For example, 41.4% of college students can be classified as physically inactive, ranging from 21.9 % in Kyrgyzstan to 80.6% in Pakistan [4,5]. This high prevalence of physical inactivity has severe consequences as it contributes to the increased risk of premature mortality [6,7] and a variety of chronic diseases [8,9], including hypertension, coronary heart disease, cognitive decline [10–12], depressive symptoms [13], type II diabetes mellitus, and cancers [14]. Moreover, the economic burden due to physical inactivity is substantial. Latest data from WHO suggests that health consequences related to physical inactivity cause healthcare costs of nearly 520 billion USD by 2030 worldwide, while physical inactivity-related productivity loss reaches 47.6 billion USD per year [15]. Against this background, global efforts to promote regular PA (e.g., in structured and planned forms also referred to as physical exercises) are urgently required.

Although numerous efforts have been made to better understand why many individuals intending to be physically active fail to turn these intentions into action, our ability to understand this so-called intention-behavior gap is, so far, relatively limited. Recently, affective mechanisms have taken a prominent place in recent theories aiming to explain individuals’ engagement in PA [16–18], to the point that these mechanisms could be considered as pivotal constructs to explain the gap between intention and action. Experimental studies in line with these theories have shown that experiencing a positive affective response during physical activity increases the probability of re-engaging in this behavior in the future [19–22]. Despite these promising results, studies investigating the role of affective mechanisms are still relatively limited due to at least one main reason: the lack of validated scales to accurately measure the affective constructs and mechanisms.

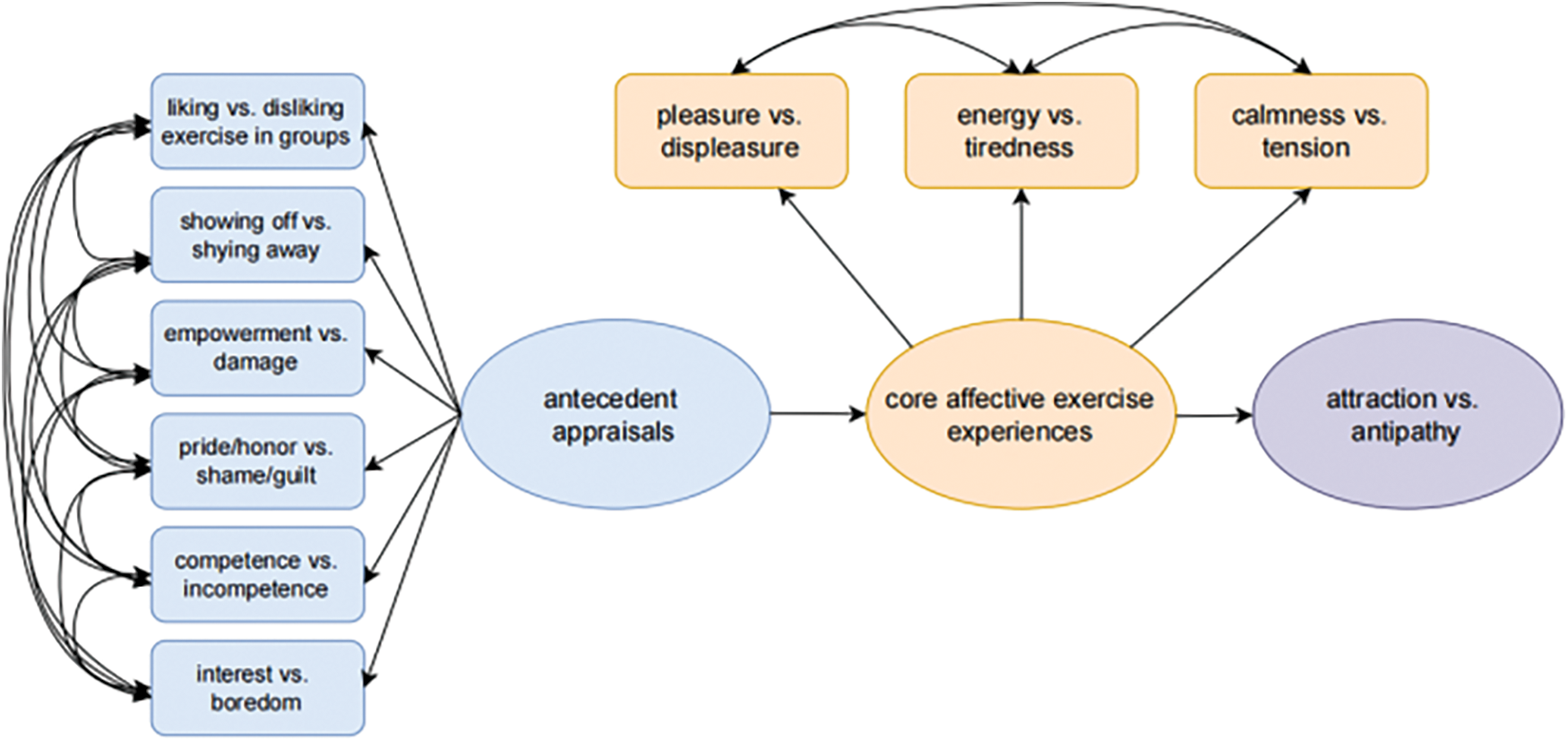

To fill this gap, Ekkekakis and colleagues proposed a construct, namely affective exercise experiences, which was defined as a “summary valanced designation, ranging from pleasant to unpleasant, that reflects the history of associations between exercise over the life course of an individual and the attendant affective responses” [23]. Anchored within the affective-reflective theory [24], Ekkekakis et al. have developed a new questionnaire to assess such affective exercise experiences, namely the Affective Exercise Experiences (AFFEXX) questionnaire. The authors proposed a conceptual model of the AFFEXX questionnaire (see Fig. 1), which relied on a three-tiered causal chain—antecedent appraisals influencing core affective experiences, which in turn influence attraction-antipathy toward exercise [23]. In a validation study, the AFFEXX questionnaire showed good reliability and validity to assess the impact of affective constructs on exercise motivation in a sample of US college students [23].

Figure 1: Illustration of the structural model of the AFFEXX questionnaire (36 items).

Despite the importance of the affective mechanisms to foster engagement in PA, a validated Chinese version of the scale is lacking at the time of writing. The first aim of the study was thus to validate a Chinese version of the AFFEXX questionnaire (AFFEXX-C). Moreover, evidence suggests that affect-related processes are culturally patterned [25]. Accordingly, the structure of the AFFEXX questionnaire could differ between different cultures, especially between western, individualism relative to eastern, collectivist countries [26]. The second aim of the study was therefore to examine the cross-cultural validity of the AFFEXX-C in a Chinese sample to assess to which extent the hypothesized model proposed in previous western research is maintained or differed in an eastern country. Moreover, at the conceptual level, it is essential to test the hypothesized model proposed in previous research [23] (i.e., antecedent appraisals → core affective exercise experiences → attraction-antipathy toward exercise) to further verify the role of the first two structures in exercise motivation.

In this research, college students were invited to complete a questionnaire on the online Questionnaire-Star platform. Specifically, a scan code was sent to colleagues of the leading author across China. Those colleagues agreed to help distribute the code to their students via WeChat. Only students who were willing to participate in this study got access to the questionnaire. In study 1, the survey included the AFFEXX-C and other instruments designed to assess the convergent validity (i.e., affective attitudes), discriminant validity (i.e., instrumental attitudes, behavioral intention, exercise self-efficacy and situated decisions to exercise), and criterion validity (self-reported PA behaviors). Reliability assessment was also conducted in the first survey and test-retest analysis was additionally performed on participants (referring to a portion of the sample size in study 1) who responded to the same survey about three weeks later. In study 2, another independent sample of college students was recruited with the same procedure described above to validate the conceptual model of the AFFEXX-C (see Fig. 1). This protocol was approved by the ethics committee of Shenzhen University (PN-202200026) and all study procedures were in accordance with the latest version of the Declaration of Helsinki. All individuals who were interested in participating in this study provided informed consent before any data collection.

AFFEXX questionnaire and scale translation

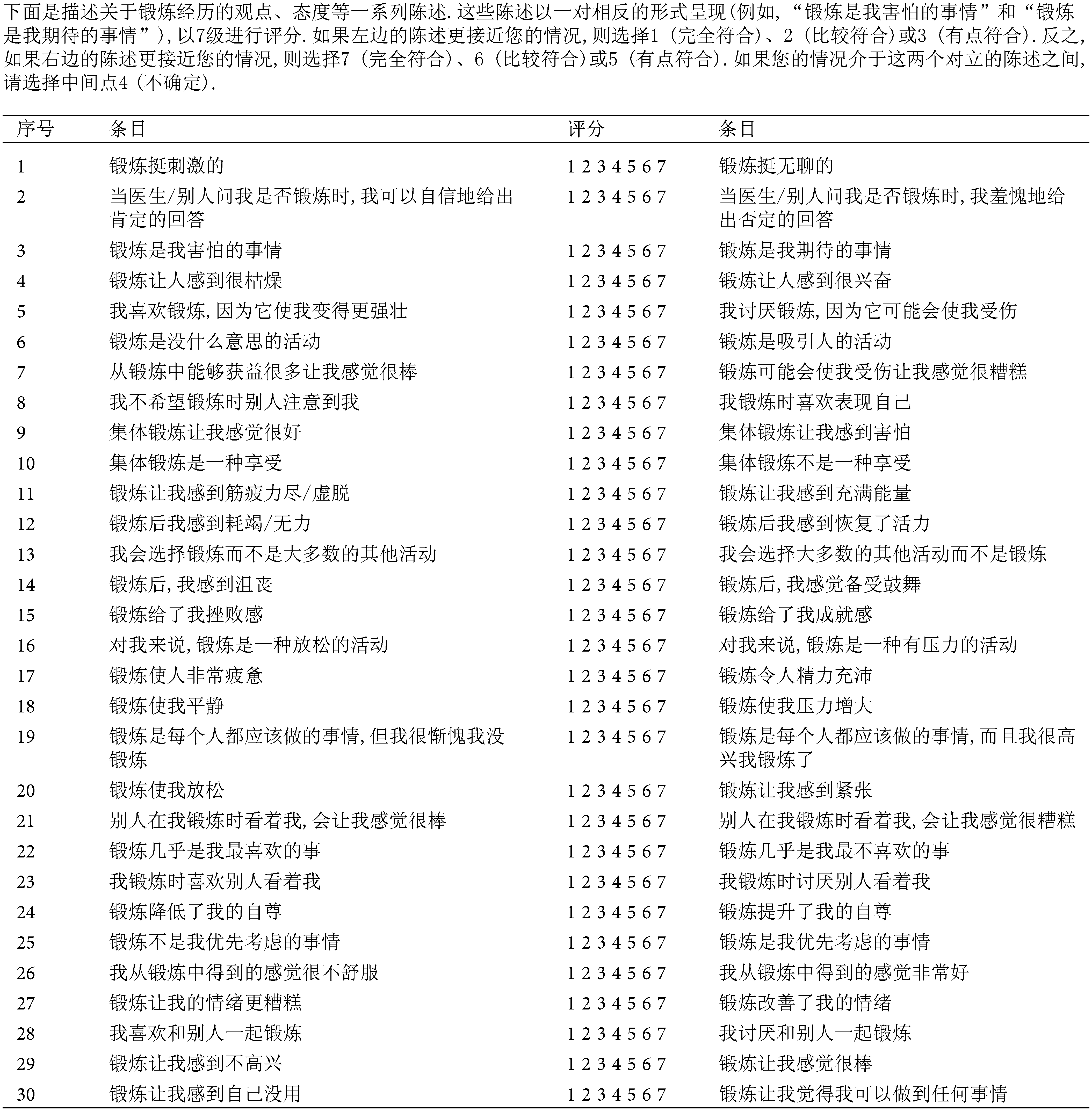

The AFFEXX questionnaire was originally developed by Ekkekakis and colleagues [23] and consists of 36 items and 10 factors assessing three structures (i.e., antecedent appraisals, core affective exercise experiences, and attraction-antipathy; more details can be found in Supplementary data). Each response was made on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“if the statement on the left perfectly matches what you would say”) to 7 (“if the statement on the right perfectly matches what you would say”). A higher mean score of each factor (i.e., the average scores of the entries items of each factor) indicates a more positive level of antecedent appraisals, core affective exercise experiences, or greater attraction (vs. antipathy) towards physical exercise. Previous research reported good validity and reliability in an English-speaking US sample, with all Cronbach’s coefficients being higher than 0.80 [23]. A Chinese-language version of the AFFEXX questionnaire (AFFEXX-C) was developed to capture the above three structures.

Researchers from the Body-Brain-Mind Laboratory contacted the authors who developed the original AFFEXX questionnaire and communicated with them for the project about translating and validating this instrument among the Chinese population. Two English-Chinese bilingual researchers who specialized in psychology translated the original questionnaire into Chinese. Subsequently, the translated version was sent to four Chinese exercise psychologists with good bilingual skills (Chinese and English) who reviewed and provided feedback on this version. Based on their feedback, this newly translated version was revised and then sent to two individuals fluent in English and Chinese and invited to independently perform back-translation. Meanwhile, a discussion meeting was scheduled with one of the original authors of the AFFEXX questionnaire to confirm whether the translations adequately captured the original three structures. As a result, the 36-item AFFEXX-C was built.

We recruited Chinese-speaking college students for the current study who met the following inclusion criteria: (i) healthy, without any self-reported psychiatric or neurological disorders, other chronic diseases, or contraindications to PA, and (ii) aged between 17 and 29 years. In addition, we excluded participants who responded with an unreasonable duration to complete the questionnaires (i.e., less than 3 minutes, as determined as minimum duration by the researcher team during a pilot testing), participants with implausible responses (e.g., time spent on exercise participation of >16 h), or those who failed to pass the polygraph questions (i.e., Please select “I’m sure I can do it” for this question). In total, 722 eligible participants (excluding 86 participants) were included for the final data analysis in study 1 (408 female, 314 male, age = 19.92 ± 1.45 years, Body Mass Index = 21.13 ± 4.54 kg/m2), with 197 who completed the questionnaire a second time 3 weeks later for test-retest reliability. In study 2, 1,300 college students (700 female, 600 male, age = 19.84 ± 1.45 years, Body Mass Index = 20.55 ± 2.82 kg/m2) were included according to the same criteria mentioned above, after excluding 53 participants with implausible responses.

To examine convergent and discriminant validity, three constructs from the theory of planned behavior (TPB) were assessed [27]. Specifically, instrumental attitudes (including five items following the stem “For me, exercising on at least 5 of the next 7 days for recreation, leisure, exercise or sport would”, e.g., “be useless” or “be useful”), affective attitudes (including six items following the same stem, e.g., “feel satisfying” or “feel unsatisfying”) and behavioral intention (including three items, e.g., “I plan on exercising on at least 5 of the next 7 days for recreation, leisure, exercise, or sport”, responded by “definitely no” or “definitely yes”) were measured using a 7-point bipolar scale, ranging from 1 (“if the statement on the left perfectly matches what you would say”) to 7 (“if the statement on the right perfectly matches what you would say”), with higher scores representing more positive attitudes and stronger behavioral intention. In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha of the three constructs of the TPB were 0.86, 0.94, and 0.90, respectively. As in the original study [23], affective attitudes were used to assess convergent validity, and instrumental attitudes and behavioral intentions were measured to determine discriminant validity.

The Exercise Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (ESE), developed by Wu et al. [28], was used to measure participants’ beliefs in their ability to perform physical exercises. This single-dimension questionnaire contained 12 items in total and each item was scored on a 3-point rating scale ranging from 1 (I can't do it) to 3 (I'm sure I can do it), with a higher score representing a greater exercise self-efficacy. In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha of this construct was 0.91. The ESE served as another indicator for testing the discriminant-validation criterion.

The Situated Decisions to Exercise Questionnaire (SDEQ) was used to assess individual tendencies to decide whether to exercise or not in situations in which individuals are faced with behavioral alternatives [29]. This questionnaire includes eight items describing eight prototypical situations (e.g., “You’re finishing your classes and you are just about to go to the gym. Now you hear that your classmates plan to go for a drink. They invite you”). In each situation, participants were asked to indicate whether they would likely exercise now or refrain from it. Answers ranged from 1 (definitely yes) to 5 (absolutely no). The lower the mean score of the eight items, the more likely individuals would decide to exercise when faced with other choices. The English version of this questionnaire has a good internal consistency indicated by a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.79 [29], which is supported by the present study, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.81. The SDEQ served as another indicator for testing the discriminant-validation criterion.

To evaluate predictive validity, the level of usual PA was assessed by the International Physical Activity Questionnaire-Short Form (IPAQ-SF). Participants were asked to reflect on how many days, and how many minutes they engaged in PA in the last seven days, namely vigorous PA (VPA), moderate PA (MPA), and walking leisure (i.e., not used for transportation). The level of regular PA was quantified by weighting each type of activity following the energy requirements defined in METs (referred to as metabolic equivalent) and expressed as MET-min per week (MET level*minutes of activity*events per week) [30]. The total level of PA (expressed in MET-min/week) was the sum of the three kinds of PA levels. Additionally, the level of moderate-to-vigorous PA (MVPA, calculated by the sum of the VPA and MPA) was also used as an indicator of the overall level of PA. A study on the Chinese version of IPAQ-SF reported good test-retest reliability with coefficients of 0.75 to 0.93 for the different levels of PA [31].

Data analyses were carried out in IBM SPSS 24.0 (Armonk, NY, USA) and Mplus 8 (Los Angeles, CA, USA). In study 1, demographic information (e.g., age and sex) was first visually inspected, and means (M) and standard deviations (SD) for continuous variables and numbers and percentage for categorical variables were calculated. Secondly, 722 college students were randomly divided into two samples (sample 1 and sample 2). Based on sample 1 (n = 339), i) Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett’s test were conducted as exploratory factor analysis (EFA). We used the principal axis method of factor extraction followed by oblimin rotations to account for the assumption of intercorrelations between the factors of the AFFEXX-C. According to the guidelines [32–34], items with factor loadings ≥ 0.50 and cross-loadings ≤ 0.25 were included. Based on sample 2 (n = 383), ii) internal consistency was tested with Cronbach’s alpha, and iii) three confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs) of antecedent appraisals, core affective exercise experiences, and attraction-antipathy were conducted. To measure the fit of these models, the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) and other parameters were considered, including the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), with a 90% Confidence Interval (CI). According to Hu and Bentler [35], the recommended acceptable values for these indices were as followed: CFI and TLI ≥ 0.95; SRMR and RMSEA ≤ 0.06. Finally, iv) to test convergent, discriminant, and predictive validity, the relationships between the factors of the AFFEXX-C and other variables (e.g., level of regular PA and exercise self-efficacy) were tested by partial correlation analyses in the total sample (N = 722). The correlation coefficient was rated as follows: <0.19; low correlation: 0.20 to 0.39; moderate correlation: 0.40 to 0.59; moderately high correlation: 0.60 to 0.79; high correlation: ≥0.80 [36]. Additionally, a total of 197 participants volunteered to carry out the re-test three weeks later and their data was used to determine the test-retest reliability. ICC values were rated by the following criterion [37]: <0.40 as poor, from 0.40 to 0.59 as fair, from 0.60 to 0.74 as good, and ≥0.75 as excellent. Finally, to confirm the validity of the conceptual model of the AFFEXX-C, structural modeling analyses were carried out in study 2 (N = 1,300). A p-value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all two-tailed tests.

Descriptive statistics in study 1

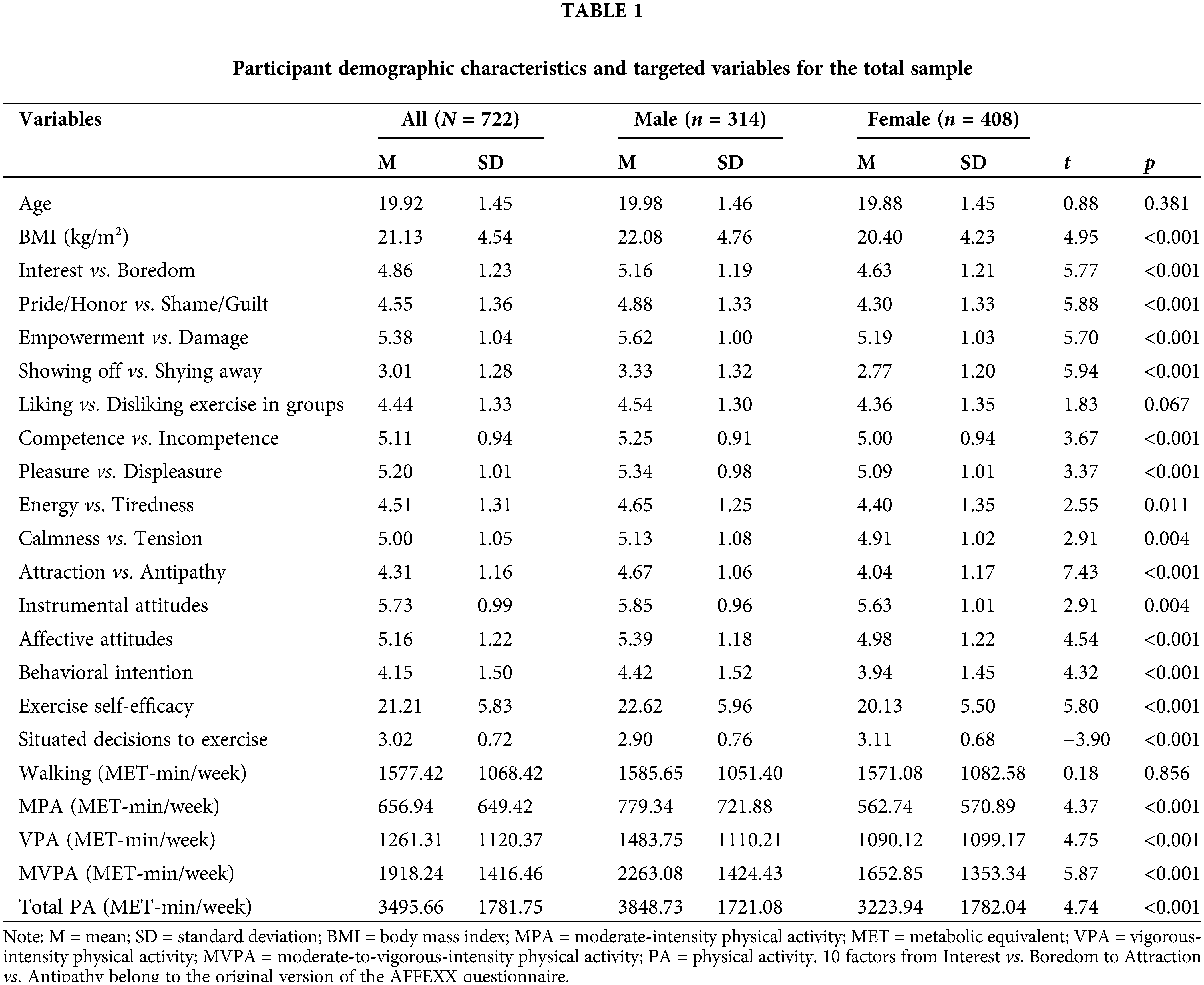

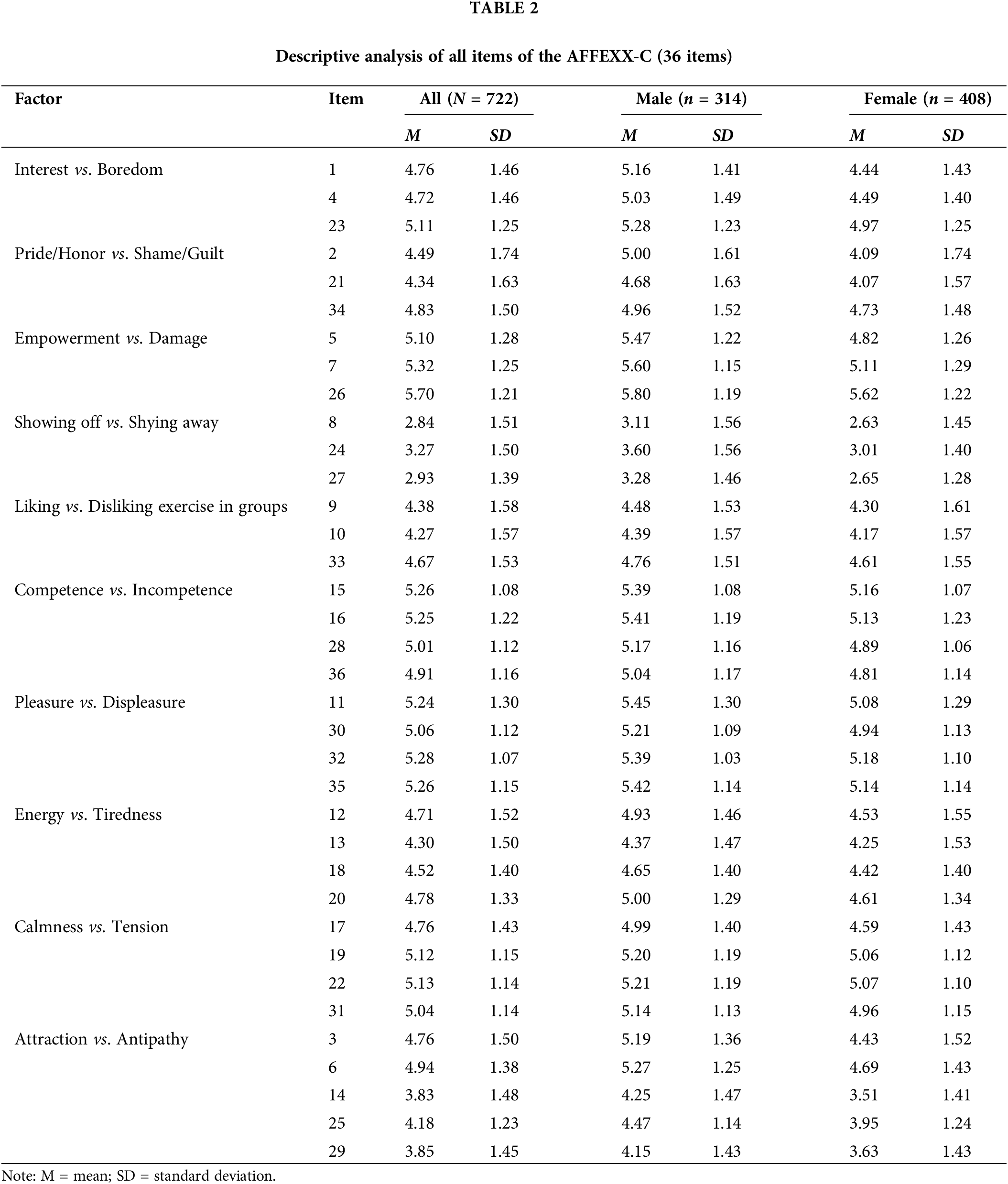

Descriptive statistics for the total sample in study 1 (N = 722) are presented in Table 1. The means and standard deviations of the AFFEXX-C are shown on all items in Table 2.

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA)

The EFA of the items developed to represent antecedent appraisals, core affective exercise experiences, and attraction vs. antipathy (KMO = 0.891 > 0.80, p < 0.001; KMO = 0.930 > 0.90, p < 0.001; KMO = 0.854 > 0.80, p < 0.001) were computed in sample 1 (n = 339). According to the criterion [32–34], six items (11, 20, 23, 26, 31, 34) were removed in EFA. The modified model with 30 items tapping into three different domains is shown in Table 3 and was used for subsequent analyses.

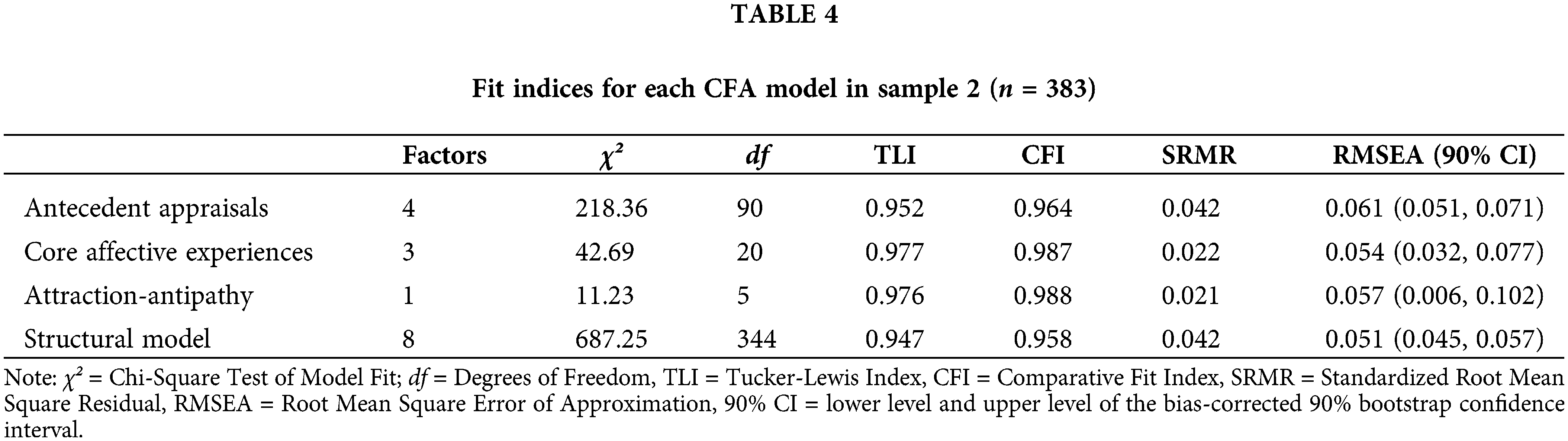

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA)

Fit statistics of the CFA from sample 2 are presented in Table 4. Good model fit indices were indicated in the analysis of antecedent appraisals (χ² = 218.36, df = 90, TLI = 0.95, CFI = 0.96, RMSEA = 0.06 [0.05, 0.07], SRMR = 0.04), core affective exercise experiences (χ² = 42.69, df = 20, TLI = 0.98, CFI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.05 [0.03, 0.08], SRMR = 0.02), and attraction-antipathy (χ² = 11.23, df = 5, TLI = 0.98, CFI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.06 [0.01, 0.10], SRMR = 0.02). The test of all eight factors in this 30-item framework also indicated a reasonable fit to the data (χ² = 687.25, df = 344, TLI = 0.95, CFI = 0.96, RMSEA = 0.05 [0.05, 0.06], SRMR = 0.02). Thus, a 30-item AFFEXX-C was established.

Internal consistency and inter-correlations among the factors of the AFFEXX-C

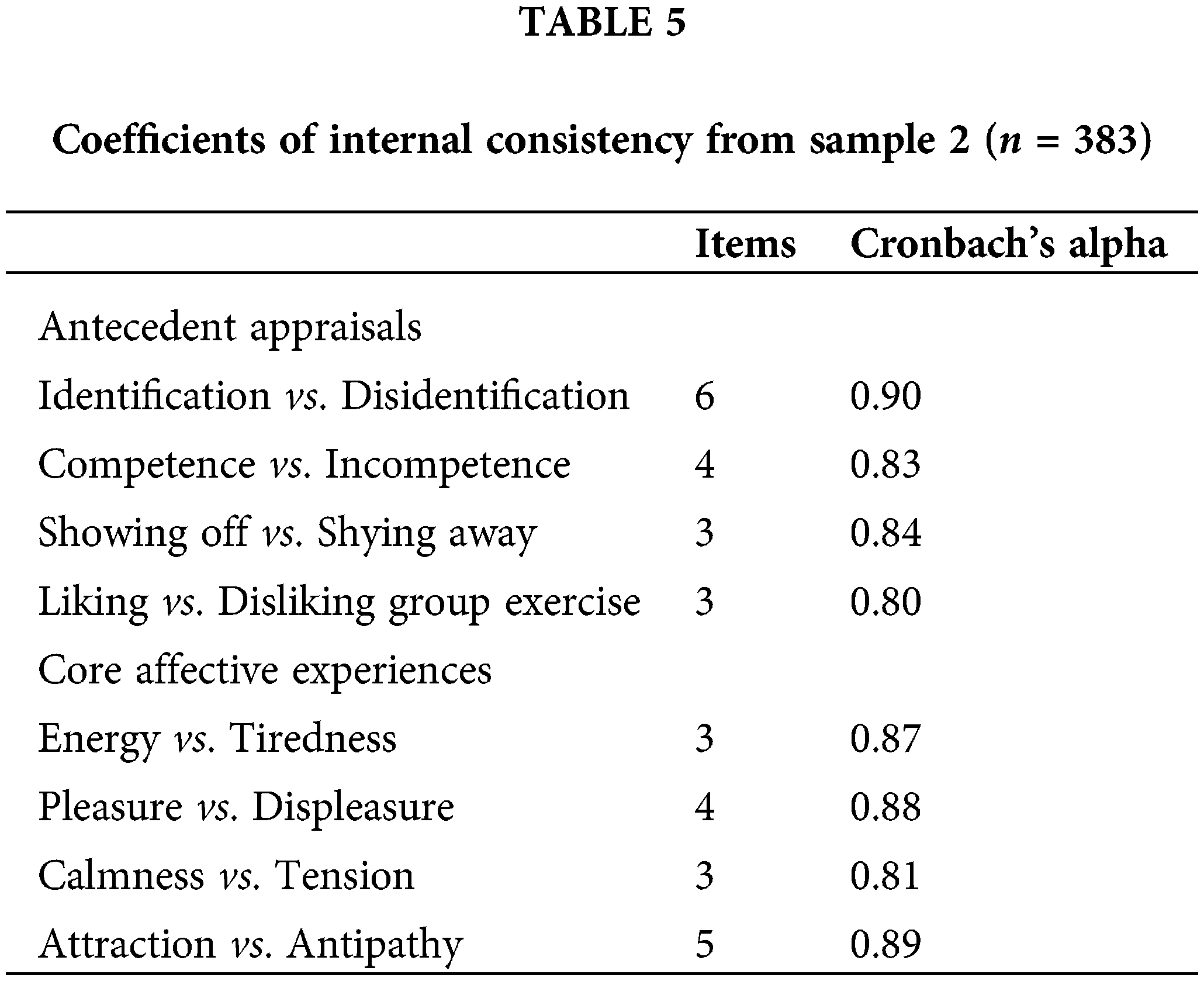

As shown in Table 5, in sample 2 (n = 383), Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranged from 0.80 to 0.90, which indicates a good internal consistency of the AFFEXX-C among Chinese college students.

Convergent and discriminant validity

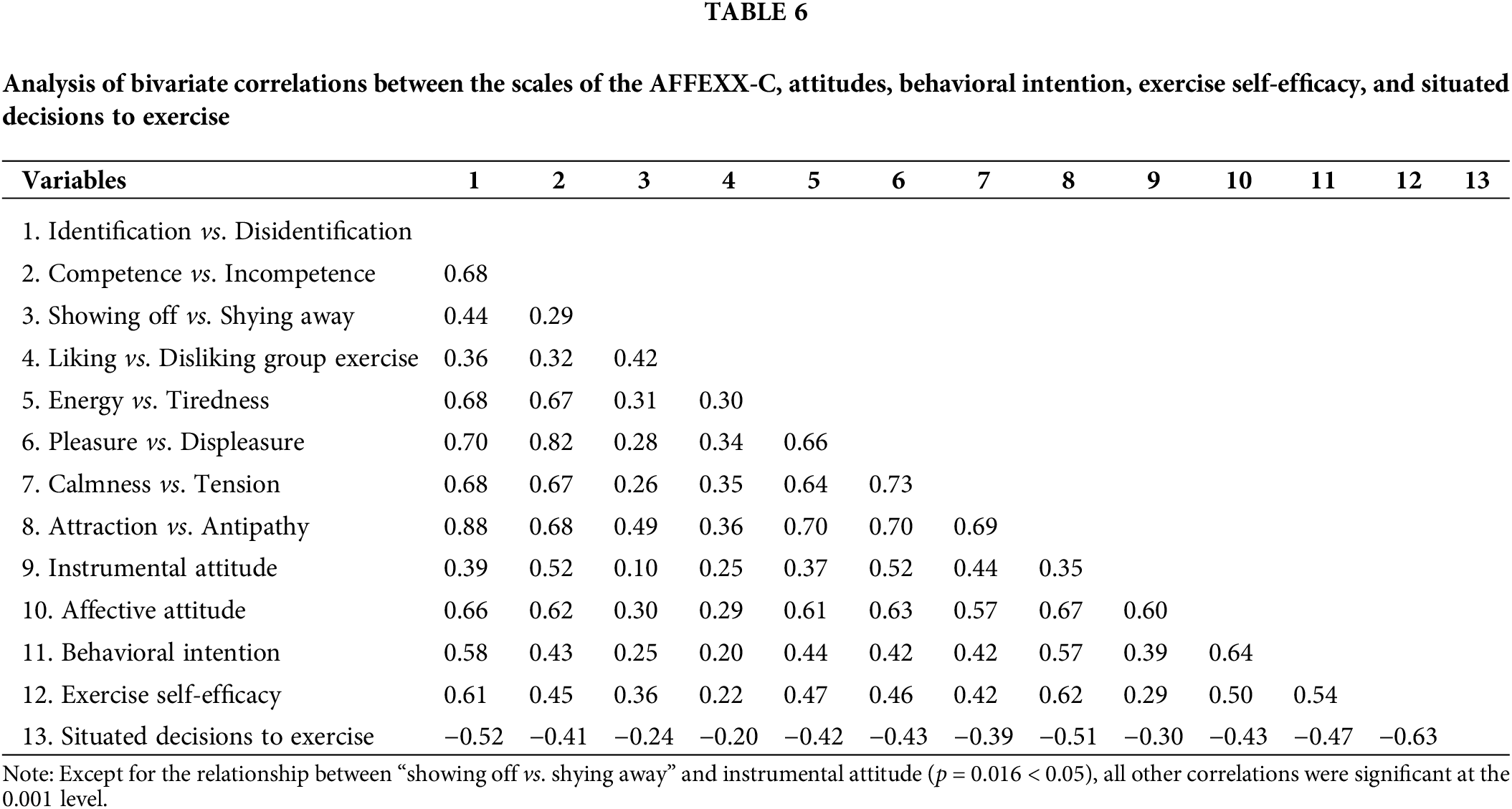

The relationships between the scales of the AFFEXX-C, instrumental attitudes, affective attitudes, behavioral intention, exercise self-efficacy, and situated decisions to exercise are presented in Table 6 for the total sample (N = 722). All variables were significantly correlated with each other (p < 0.05) in Pearson correlation analyses. For further analyses, we used cocor R package documentation to conduct statistical comparisons between these correlations [38]. In terms of convergent validity, the relationships between affective attitudes and core affective exercise experiences were observed. Specifically, scores on core affective exercise experiences (i.e., pleasure-displeasure, energy-tiredness, and calmness-tension) exhibited slightly and descriptively higher correlations with affective attitudes (r = 0.61, 0.63, and 0.57, respectively) than with instrumental attitudes (r = 0.37, 0.52 and 0.44, respectively), which was supported by the comparison of these correlations (all p < 0.001, for more details please see Appendix A). Attraction-antipathy was moderately to strongly correlated with affective attitudes (r = 0.67, p < 0.001), and mostly moderately with behavioral intention (r = 0.57, p < 0.001), exercise self-efficacy (r = 0.62, p < 0.001) and situated decisions to exercise (r = −0.51, p < 0.001). Most of the variance between attraction-antipathy and exercise self-efficacy and situated decisions to exercise was not shared (i.e., 64%–77% unique variance).

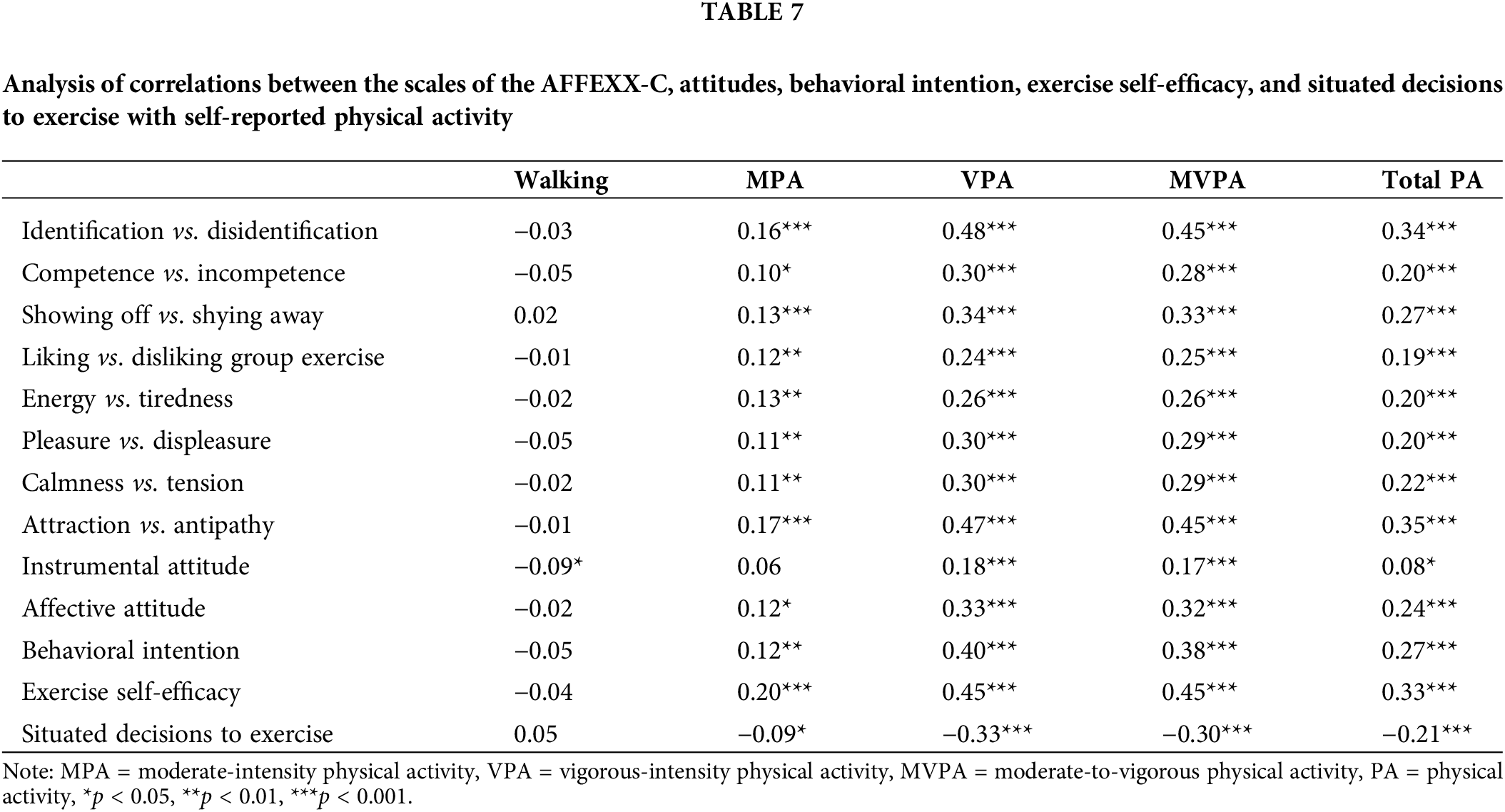

To examine criterion validity, correlations between the three structures of the AFFEXX-C and the self-reported habitual level of PA were conducted. As shown in Table 7, our results indicated that the correlations of all AFFEXX-C constructs were non-significant and near-zero with walking. MPA was weakly related to most variables (e.g., r = 0.10 to 0.16 for antecedent appraisal, r = 0.11 to 0.13 for core affective experiences, r = 0.17 for attraction-antipathy). VPA and MVPA were significantly correlated with attraction-antipathy, with correlations ranging between 0.47 and 0.45 (p < 0.001).

Test-retest reliability of the AFFEXX-C was evaluated using intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC). In the current study, we observed ICC ranging from good (r = 0.69, p < 0.001) for the liking-disliking group exercise to excellent (r = 0.87, p < 0.001) for identification-disidentification (for more details please see Appendix A).

Validation of the structural model in study 2

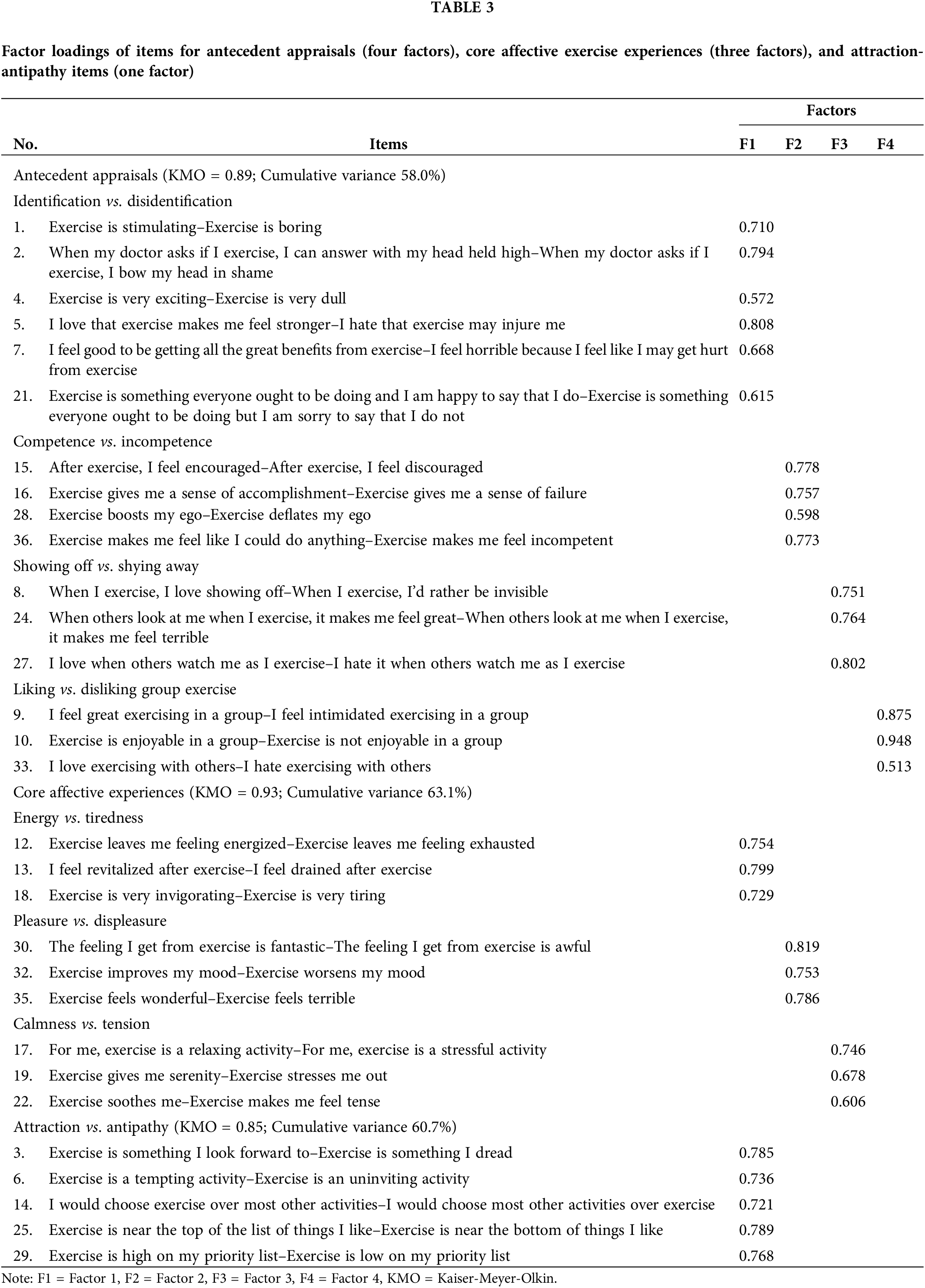

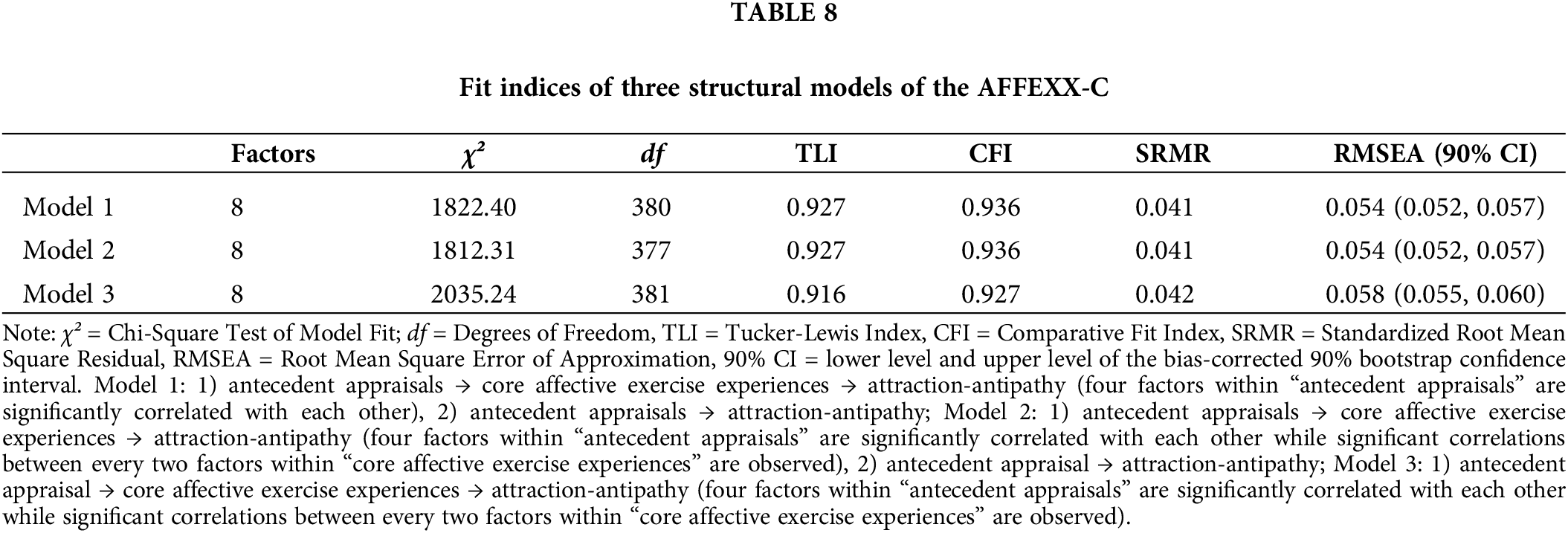

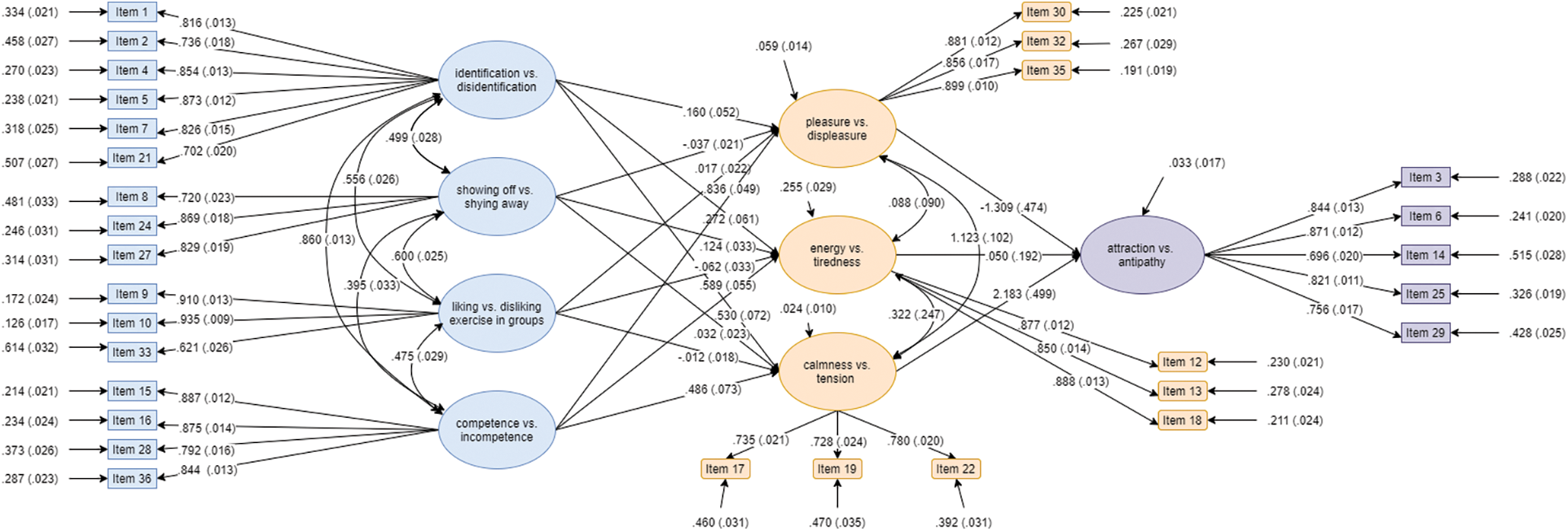

In study 2 (N = 1,300), the internal consistency of the AFFEXX-C was good, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranging from 0.85 to 0.91 (more details can be found in Appendix A). Three different structural models were tested based on the hypothesized conceptual model (see Fig. 1). According to fit indices [35], results indicated acceptable fits of the three different structural models (shown in Table 8), of which model 3 had the best fit and was the most theoretically relevant (Fig. 2). In this model, both direct effect (antecedent appraisal - > attraction-antipathy) and indirect effect (antecedent appraisal - > core affective experiences - > attraction-antipathy) are significant. Furthermore, the four factors within “antecedent appraisals” were correlated with each other while correlations between every two factors within “core affective exercise experiences” were also observed.

Figure 2: Statistical diagram of the structural model of the AFFEXX-C (Model 3). Note: Standardized path coefficients were presented in this model.

Based on two independent studies conducted in a large sample of Chinese college students, we developed and validated a Chinese version of the AFFEXX questionnaire (AFFEXX-C) to assess the key affective mechanisms involved in the regulation of PA, namely antecedent appraisals, core affective exercise experiences, and exercise motivation. Our results showed that the AFFEXX-C was valid for measuring the affective experiences toward PA in Chinese college students. Concerning the reliability of the instruments, analogous factor structures were obtained with the Chinese version of the scale relative to the original, English version of the scale. Furthermore, Cronbach’s alpha of the AFFEXX-C was good and almost identical to that in the original version (0.81 to 0.92 in the English vs. 0.80 to 0.90 in the Chinese version). Finally, the hypothesized model found in the western sample (i.e., US adults), was also partially observed in our eastern sample. Hence, in sum, our study provides evidence of the reliability and (partial) cross-cultural validity of the AFFEXX-C.

Different from the original scale of the AFFEXX questionnaire, the Chinese version involves a 30-item structure (vs. 36-item in the original version). Specifically, six items (11, 20, 23, 26, 31, 34 of the original scale) were removed due to insufficient factor loadings (<0.50) and high cross-loadings (>0.25) in the EFA. Based on these results, the dimensions of antecedent appraisals decreased from 6 to 3. Specifically, three domains (i.e., physical empowerment vs. bodily damage, pride/honor vs. shame/guilt, and interest vs. boredom) were removed. Cultural differences may explain why it makes sense to remove these three domains in a Chinese sample. For instance, Chinese college students perceive physical exercise as a part of a healthy lifestyle rather than something to be proud of, and the idea of “exercise is glorious” is not very popular among this population [39,40]. In addition, whether physical exercise is interesting or boring and physically healthy or harmful maybe not as important for Chinese as for Western individuals. Instead, most of them would not place physical exercise as a higher priority and tend to choose other activities in time conflicts and are likely to attribute it to lack of time for physical exercise [41].

The remaining items (1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 21 of the original scale) of the above domains were gathered to create a new dimension, named “identification vs. disidentification”. For example, item 21 (i.e., “Exercise is something everyone ought to be doing and I am happy to say that I do” vs. “Exercise is something everyone ought to be doing but I am sorry to say that I do not”) reflects that physical exercise corresponds to something that individuals are supposed to do, which may result from a consensus among the society on the necessity of physical exercise. In contrast to item 1 (i.e., “Exercise is stimulating” vs. “Exercise is boring”) and 4 (i.e., “Exercise is very exciting” vs. “Exercise is very dull”), this dimension relates to a conception about physical exercise that is influenced by a popular belief in Chinese culture, rather than to sheer personal attitudes. This new dimension may thus reflect the impact of social desirability or shared social-cultural attitudes on an individual’s affective exercise experiences. In other words, cultural differences may directly influence individuals’ antecedent appraisals to exercise to have an indirect impact on affective exercise experiences.

Despite these cross-cultural differences, the AFFEXX-C maintains a degree of consistency with the original version [23]. To be specific, three dimensions of the core affective experiences (i.e., pleasure-displeasure, energy-tiredness, calmness-tension), and attraction-antipathy were retained. Of them, this three-dimension structure (i.e., core affective experiences) aligns with the conceptualization of core affects suggested by Ekkekakis and colleagues investigating core affective responses to physical exercise from a dimensional perspective [42]. It is worth noting that core affective responses emphasize a core affect emanating directly from somatic sensations, whereas core affective exercise experiences are impacted by an antecedent cognitive appraisal. In other words, the affective responses to physical exercise are expanded from the core affective responses of somatic sensation (e.g., physical pain or excitement) to the complex emotions under the cultural framework (e.g., chasing or pursuit of physical exercise) [23], which implied that the affective mechanisms towards PA should not be discussed in isolation from cultural influences. Despite cultural differences between the original version and the AFFEXX-C, the similarity of core affective exercise experiences may be rooted in the general understanding of this structure. These findings might be explained by the fact that affective associations of feeling energized, pleasant, and calm might be more culturally universal than affective associations that are influenced to a greater extent by specific cognitive appraisals (i.e., antecedent appraisals) [43]. Uncertainly, whether cultural differences change the structure of the core affective exercise experiences is still up for discussion. The lack of the score of the three dimensions of this structure in the original version may impede the cross-cultural comparison. In general, as affective exercise experiences have so far been measured in only two versions, whether there is cross-cultural consistency needs to be further verified in other cultures. Future studies should provide more empirical evidence to further explore them in cross-cultural studies.

In addition, attraction-antipathy is also retained and highly related to factors of the other two structures, which is similar to the original version (0.43 to 0.82 in the English version vs. 0.36 to 0.88 in the Chinese version) [23]. This indicates that pleasant exercise experiences or positive cognitive appraisals may not alone determine an individual’s tendency to feel the attraction of exercise and trigger the desire to exercise. Consistently, researchers also assumed that combining either hedonic or reflective motivation to reflect individuals’ motivation towards physical exercise is reasonable [17]. Indeed, individuals’ responses to “attraction-antipathy” toward exercise may reflect whether an individual wants to perform physical exercise based on a combination of both reflective and automatically activated processes [23].

With respect to validity, the significant correlations that we observed between the AFFEXX-C and other variables mirror previous findings [23]. Regarding convergent validity, positive affective exercise experiences were associated with positive affective attitudes. Similar to affective attitude, a cognitive construct with the affective label, affective exercise experiences are also strongly associated with PA behavior but emphasize the individuals’ history of association with exercise. This supports the inter-individual differences in affective exercise experiences. With respect to discriminant validity, compared with affective attitudes (r = 0.57 to 0.61), affective exercise experiences were less relevant to other variables (e.g., instrumental attitudes and situated decisions to exercise). Then, the results of the criterion validity indicated that the associations between the core affective experience of the AFFEXX-C and the level of VPA and MVPA (r = 0.26 to 0.30) were almost as strong as the relationships between the latter and affective attitudes (r = 0.32 to 0.33). Additionally, we observed that the attraction-antipathy variable (as a proxy for exercise motivation) was significantly related to MVPA and VPA (r = 0.45 to 0.47), which exhibited descriptively higher correlations than these of behavioral intention (r = 0.38 to 0.40) and situated decisions to exercise (r = 0.30 to 0.33). Actually, these findings to some extent illustrate the vital role of attraction-antipathy in this complex model of decision-making to PA behavior. Overall, in line with the original version, these findings supported the good convergent, discriminant, and criterion validity of the AFFEXX-C.

Finally, the current study tested and refined the conceptual model proposed by previous research in a large sample [23]. Specifically, our findings supported the following model: antecedent appraisal → core affective exercise experiences → attraction-antipathy. In this mediating model, 4 factors of antecedent appraisals and 3 factors of core affective exercise experiences are intra-correlated with each other. Given that the original version of the AFFEXX-C only proposed a conceptual model without validation, we verified this model in the context of Chinese culture and reported the applicability of the model, which has a reduction in factors of antecedent appraisal and core affective exercise experiences compared with the hypothesis model. Our findings indicated that model 3 with an acceptable fit index was in line with the hypothesized model, which emphasized core affective exercise experiences as the central construct within a three-tiered system. Based on the conceptualization combining the level of activation and pleasure [42], this core structure forms three bipolar dimensions, namely (a) pleasure vs. displeasure associated with a moderate level of perceived activation, (b) high-activation pleasure vs. low-activation displeasure (i.e., energy vs. tiredness), and (c) low-activation pleasure vs. high-activation displeasure (i.e., calmness vs. tension). Upstream, these core affective exercise experiences are expected to be predicted by relevant cognitive appraisals of exercise, including (i) evaluating oneself whether to identify/recognize exercise, (ii) judging oneself as competent or incompetent, (iii) perceiving for oneself whether like exercising in groups, and (iv) noticing oneself tends to show off or shy away. Ultimately, affective exercise experiences shape the motivational tendency to be attracted to or feel antipathy towards physical exercise. Accordingly, this three-structure and eight-factor hypothesis model was validated, for the first time, within the Chinese cultural background.

In the current study, we adopted a multi-stage design to develop and validate the AFFEXX-C in two independent and large samples of Chinese students, which is, in its final format, slightly different from the original version of the questionnaire [23]. In addition, the hypothesis model proposed by Ekkekakis and colleagues was verified in the present study, thereby confirming its cross-cultural validity. Nevertheless, some limitations have to be acknowledged. First, the sample selection is based on convenience sampling which is less representative than random sampling and therefore limits the generalization of the current results to healthy college students. Thus, further studies in other populations are necessary to test the generalizability of our findings (e.g., non-college student emerging adults [44,45] and in older adults). Thirdly, self-reported measurement of PA was used in the current research, which is subject to social desirability bias (e.g., overestimation of PA levels). Therefore, future research could incorporate device-based measures of PA (e.g., accelerometer) to further strengthen the predictive validity of the AFFEXX-C in the Chinese population.

The modified 30-item AFFEXX-C has sound psychometric properties and thus is well-suited to assess affective exercise experiences in samples of college students. By translating and validating the AFFEXX-C, our study paves the way for future research aiming to examine the role of affective mechanisms in the regulation of PA behaviors in Chinese-speaking samples.

Funding Statement: This study was supported by the Start-Up Research Grant of Shenzhen University [20200807163056003]; the Start-Up Research Grant [Peacock Plan: 20191105534C].

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Ting Wang, Conceptualization, Methodology, Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Writing-Original Draft, Writing-Review & Editing, Visualization; Boris Cheval, Writing-Review & Editing, Formal Analysis; Silvio Maltagliati, Writing-Review & Editing; Zachary Zenko, Methodology, Writing-Original Draft, Writing-Review & Editing, Visualization; Fabian Herold, Formal Analysis, Writing-Review & Editing; Sebatian Ludyga, Formal Analysis; Markus Gerber, Writing-Review & Editing; Yan Luo, Methodology, Formal Analysis; Layan Fessler, Writing-Review & Editing, Formal Analysis; Notger G. Müller, Writing-Review & Editing; Liye Zou, Conceptualization, Methodology, Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Writing-Original Draft, Writing-Review & Editing, Visualization, Supervision, Project Administration, Funding Acquisition. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Rollo S, Antsygina O, Tremblay MS. The whole day matters: Understanding 24-hour movement guideline adherence and relationships with health indicators across the lifespan. J Sport Health Sci [Internet]. 2020;9(6):493–510. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2020.07.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Bull FC, Al-Ansari SS, Biddle S, Borodulin K, Buman MP, et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br J Sports Med [Internet]. 2020;54(24):1451–62. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2020-102955. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Bennie JA, de Cocker K, Teychenne MJ, Brown WJ, Biddle SJH. The epidemiology of aerobic physical activity and muscle-strengthening activity guideline adherence among 383,928 U.S. adults. Int J Behav Nutr Phy [Internet]. 2019;16(1):34. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-019-0797-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Pengpid S, Peltzer K, Kassean HK, Tsala Tsala JP, Sychareun V, et al. Physical inactivity and associated factors among university students in 23 low-, middle- and high-income countries. Int J Public Health [Internet]. 2015;60(5):539–49. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-015-0680-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Keating XD, Guan J, Piñero JC, Bridges DM. A meta-analysis of college students’ physical activity behaviors. J Am Coll Health [Internet]. 2005;54(2):116–25. doi:https://doi.org/10.3200/JACH.54.2.116-126. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Kohl HW, Craig CL, Lambert EV, Inoue S, Alkandari JR, et al. The pandemic of physical inactivity: Global action for public health. The Lancet [Internet]. 2012;380(9838):294–305. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60898-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Liu W, Leong DP, Hu B, AhTse L, Rangarajan S, et al. The association of grip strength with cardiovascular diseases and all-cause mortality in people with hypertension: Findings from the Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology China Study. J Sport Health Sci [Internet]. 2021;10(6):629–36. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2020.10.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Ezzatvar Y, Izquierdo M, Núñez J, Calatayud J, Ramírez-Vélez R, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness measured with cardiopulmonary exercise testing and mortality in patients with cardiovascular disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sport Health Sci [Internet]. 2021;10(6):609–19. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2021.06.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Sheng M, Yang J, Bao M, Chen T, Cai R, et al. The relationships between step count and all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events: A dose-response meta-analysis. J Sport Health Sci [Internet]. 2021;10(6):620–28. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2021.09.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Yu Q, Herold F, Ludyga S, Cheval B, Zhang Z, et al. Neurobehavioral mechanisms underlying the effects of physical exercise break on episodic memory during prolonged sitting. Complement Ther Clin [Internet]. 2022;48(1):101553. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctcp.2022.101553. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Li J, Herold F, Ludyga S, Yu Q, Zhang X, et al. The acute effects of physical exercise breaks on cognitive function during prolonged sitting: The first quantitative evidence. Complement Ther Clin [Internet]. 2022;48(2):101594. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctcp.2022.101594. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Jung M, Zou L, Yu JJ, Ryu S, Kong Z, et al. Does exercise have a protective effect on cognitive function under hypoxia? A systematic review with meta-analysis. J Sport Health Sci [Internet]. 2020;9(6):562–77. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2020.04.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Rodriguez-Ayllon M, Acosta-Manzano P, Coll-Risco I, Romero-Gallardo L, Borges-Cosic M, et al. Associations of physical activity, sedentary time, and physical fitness with mental health during pregnancy: The GESTAFIT project. J Sport Health Sci [Internet]. 2021;10(3):379–86. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2019.04.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Lee IM, Shiroma EJ, Lobelo F, Puska P, Blair SN, et al. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: An analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. The Lancet [Internet]. 2012;380(9838):219–29. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61031-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Costa Santos A, Juana, Meheus F, Ilbaw A, Bull FC. The cost of inaction on physical onactivity to healthcare systems [Internet]. 2022. [Google Scholar]

16. Conroy DE, Berry TR. Automatic affective evaluations of physical activity. Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews [Internet]. 2017;45(4):230–37. doi:https://doi.org/10.1249/JES.0000000000000120. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Williams DM, Bohlen LC. Motivation for exercise: Reflective desire versus hedonic dread. APA handbook of sport and exercise psychology. In: Exercise psychology, APA handbooks in psychology series [Internet]. Washington DC, US: American Psychological Association; 2019. p. 363–85. [Google Scholar]

18. Cheval B, Boisgontier MP. The theory of effort minimization in physical activity. Exerc Sport Sci Rev [Internet]. 2021;49(3):168–78. doi:https://doi.org/10.1249/JES.0000000000000252. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Kwan BM, Bryan A. In-task and post-task affective response to exercise: Translating exercise intentions into behaviour. Br J Health Psychol [Internet]. 2010;15: 115–31. doi:https://doi.org/10.1348/135910709X433267. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Rhodes RE, Kates A. Can the affective response to exercise predict future motives and physical activity behavior? A systematic review of published evidence. Ann Behav Med [Internet]. 2015;49(5):715–31. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-015-9704-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Schneider M, Dunn A, Cooper D. Affect, exercise, and physical activity among healthy adolescents. J Sport Exerc Psychol [Internet]. 2009;31(6):706–23. doi:https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.31.6.706. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Williams DM, Dunsiger S, Jennings EG, Marcus BH. Does affective valence during and immediately following a 10-min walk predict concurrent and future physical activity? Ann Behav Med [Internet]. 2012;44(1):43–51. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-012-9362-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Ekkekakis P, Zenko Z, Vazou S. Do you find exercise pleasant or unpleasant? The affective exercise experiences (AFFEXX) questionnaire. Psychol Sport Exerc [Internet]. 2021;55(10):101930. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2021.101930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Brand R, Ekkekakis P. Affective-Reflective Theory of physical inactivity and exercise. Ger J Exerc Sport Res [Internet]. 2017;48(1):48–58. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12662-017-0477-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Lindquist KA, Jackson JC, Leshin J, Satpute AB, Gendron M. The cultural evolution of emotion. Nat Rev Psychol [Internet]. 2022; 1: 669–681. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s44159-022-00105-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Huang WY, Wong SH. Cross-cultural validation. In: Michalos AC, Encyclopedia of quality of life and well-being research [Internet]. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands; 2014. p. 1369–71. [Google Scholar]

27. Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process [Internet]. 1991;50(2):179–211. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Wu TY, Ronis DL, Pender N, Jwo JL. Development of questionnaires to measure physical activity cognitions among taiwanese adolescents. Preventive Medicine [Internet]. 2002;35(1):54–64. doi:https://doi.org/10.1006/pmed.2002.1049. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Brand R, Schweizer G. Going to the gym or to the movies?: Situated decisions as a functional link connecting automatic and reflective evaluations of exercise with exercising behavior. J Sport Exerc Psychol [Internet]. 2015;37(1):63–73. doi:https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.2014-0018. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Sjostrom M, Ainsworth BE, Bauman A, Bull FC, Hamilton-Craig CR. Guidelines for data processing analysis of the international physical activity questionnaire (IPAQ)-short and long forms [Internet]. IPAQ Research Committee; 2015. [Google Scholar]

31. Macfarlane DJ, Lee CCY, Ho EYK, Chan KL, Chan DTS. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of IPAQ (short, last 7 days). J Sci Med Sport [Internet]. 2007;10(1):45–51. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2006.05.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Tabachnick B, Fidell L. Using mulivariate statistics [Internet]. 2012. [Google Scholar]

33. Mertler C, Reinhart R. Advanced and multivariate statistical methods: Practical application and interpretation [Internet]. 6th edition. 2016. p. 1–374. [Google Scholar]

34. Kahn JH. Factor analysis in counseling psychology research, training, and practice. Couns Psychol [Internet]. 2006;34(5):684–718. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000006286347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Lt Hu, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling: Multidiscip J [Internet]. 1999;6(1):1–55. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. [Internet]. 1988. [Google Scholar]

37. Guidelines Cicchetti D. Criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instrument in psychology. Psychol Assess [Internet]. 1994;6(4):284–90. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.6.4.284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Diedenhofen B, Musch J. cocor: A comprehensive solution for the statistical comparison of correlations. PLoS One [Internet]. 2015;10(3):e0121945. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0121945. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Wang D, Ou CQ, Chen MY, Duan N. Health-promoting lifestyles of university students in Mainland China. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2009;9(1):379. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-9-379. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Wang D, Xing XH, Wu XB. Healthy lifestyles of university students in China and influential factors. Sci World J [Internet]. 2013(6):412950–10. doi:https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/412950. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Survey on fitness beliefs and exercise habits in China. https://daxueconsulting.com/exercise-habits-in-china/. [Accessed 2021]. [Google Scholar]

42. Ekkekakis P, Zenko Z. 12-measurement of affective responses to exercise: From affectless arousal to the most well-characterized relationship between the body and affect. In: Meiselman HL, editor. Emotion measurement [Internet]. Woodhead Publishing; 2016. p. 299–321. [Google Scholar]

43. Jamieson JP, Hangen EJ, Lee HY, Yeager DS. Capitalizing on appraisal processes to improve affective responses to social stress. Emot Rev [Internet]. 2018;10(1):30–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073917693085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Kuang J, Zhong J, Yang P, Bai X, Liang Y, et al. Psychometric evaluation of the inventory of dimensions of emerging adulthood (IDEA) in China. Int J Clin Hlth Psyc [Internet]. 2023;23(1):100331. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijchp.2022.100331. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Kuang J, Zhong J, Arnett JJ, Hall DL, Chen E, et al. Conceptions of adulthood among Chinese emerging adults. J Adult Dev [Internet]. 2022. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-023-09449-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

The Chinese version of the AFFEXX questionnaire (AFFEXX-C)

中文版情感锻炼经验问卷AFFEXX-C-30

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools