Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Exploring the Experiences of Personal Recovery among Mental Health Consumers and Their Caregivers Receiving Strength-Based Family Interventions

1 Graduate Institute of Social Work, Taipei City, 11605, Taiwan

2 Department of Community Psychiatry, Kaohsiung Municipal Kai-Syuan Psychiatric Hospital, Kaohsiung City, 802511, Taiwan

* Corresponding Author: Li-yu Song. Email:

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2023, 25(8), 915-925. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2023.019349

Received 18 September 2021; Accepted 27 September 2022; Issue published 06 July 2023

Abstract

Background: This study explored the personal recovery of consumers and their caregivers receiving the strength-based family intervention. Method: A three-year project was implemented with 43 dyads from 5 community psychiatric rehabilitation agencies in northern, central, and Southern Taiwan. This paper presents qualitative analysis with a focus on describing the experiences of personal recovery. To gain a deeper understanding of the participants’ personal experiences and perspectives, semi-structured in-depth interviews were conducted on three occasions (six months after the inception of the experiment, 18 months after, and when the participants left the services of this study). Over the three occasions, a total of 27 consumers and 28 caregivers were interviewed. Data analysis was conducted based on grounded theory. Results: Consumers expressed positive experiences in the domain of the recovery process (positive sense of self, taking responsibility, and better coping) and on the objective indicators of recovery (functioning, interpersonal interaction, and family relationship). Caregivers experienced lessened psychological burdens. They also revealed improvements to their sense of self (recovery process) and subjective indicators of recovery outcomes, including feeling empowered and having a better quality of life. Moreover, they had better interaction with consumers (objective domain of recovery). Conclusion: These findings suggest that the strength-based perspective is an acceptable, culturally-compatible approach among Chinese mental health consumers and their caregivers. The investigators suggest that additional resources would be necessary to support a change in the service system in Taiwan so that family-based services can be provided to promote the recovery of mental health consumers and their family caregivers.Keywords

Mental illness could cause profound and long-term impacts on persons with the illness (hereinafter called the consumer) and their family caregivers. Consumers might suffer from damage in terms of functioning, a disability to role performance, and disadvantages in social participation [1]. Family caregivers shoulder the responsibility of helping consumers take medication, daily living activities, financial assistance, etc., which may create a sense of objective burden. Additionally, they may experience subjective burdens, including social stigma, family strain, consumer dependency, and guilt [2–4]. Family caregivers need to cope with the consumer’s behavior and their own reactions. They have expressed multiple needs, including knowing what the appropriate expectations are, learning how to motivate consumers, understanding the consumers’ disorder, learning coping skills, and having social support for themselves [2]. It seems inevitable that mental health professionals need to work with caregivers and provide support for them to perform their duties. The World Health Organization [5] calls for effective collaboration between formal and informal care providers. Furthermore, the global trend of mental health services suggests involving consumers and families fully in orienting mental health systems towards recovery [6,7].

Ever since the 1990s, recovery has been the guiding vision of mental health services [1]. Recovery has been defined by the President’s New Freedom Commission on Mental Health as “the process by which people are able to live, work, learn, and participate fully in their communities [6]. For some individuals, recovery is the ability to live a fulfilling and productive life despite a disability. For others, recovery implies the reduction or complete remission of symptoms”. In this definition, the first view refers to personal recovery with a focus on process, and the second refers to clinical or functional recovery with a focus on outcome [7–9]. Despite the diversity in the definition of recovery, Tse et al. [10] maintained that they are actually complementary to each other. Law et al. [11] studied how consumers defined recovery and found that the concepts of rebuilding their lives, their self-image, and hope were essential in defining recovery. Thus, from a consumer perspective, recovery usually refers to personal recovery.

Family plays an important role in a consumer’s journey toward recovery. Reupert et al. [12] reviewed 31 studies from 1980 to 2013 and found that family caregivers provide hope, encouragement, opportunities, emotional support, and instrumental support for the consumer. On the other hand, family caregivers may also bring a negative impact on the consumer. The intensive interactions between consumers and family caregivers might create conflicts. Some family caregivers may not be adaptable enough or even be overprotective, which could hinder a consumer’s autonomy over the course of their recovery. Family conflict may affect a consumer’s family dynamic and their recovery [13]. Lim et al. [14] found that more positive family relationships could predict consumer recovery for 6-month period after controlling for initial functional capacity. Reupert et al. [12] suggested in their findings that consumers and family caregivers maintain a balance between being apart and being connected so that the autonomy of each could be sustained with reciprocity and cohesion enhanced. Family caregivers and consumers could build a partnership and collaborative relationship instead of a division between caregiver and caretaker [15].

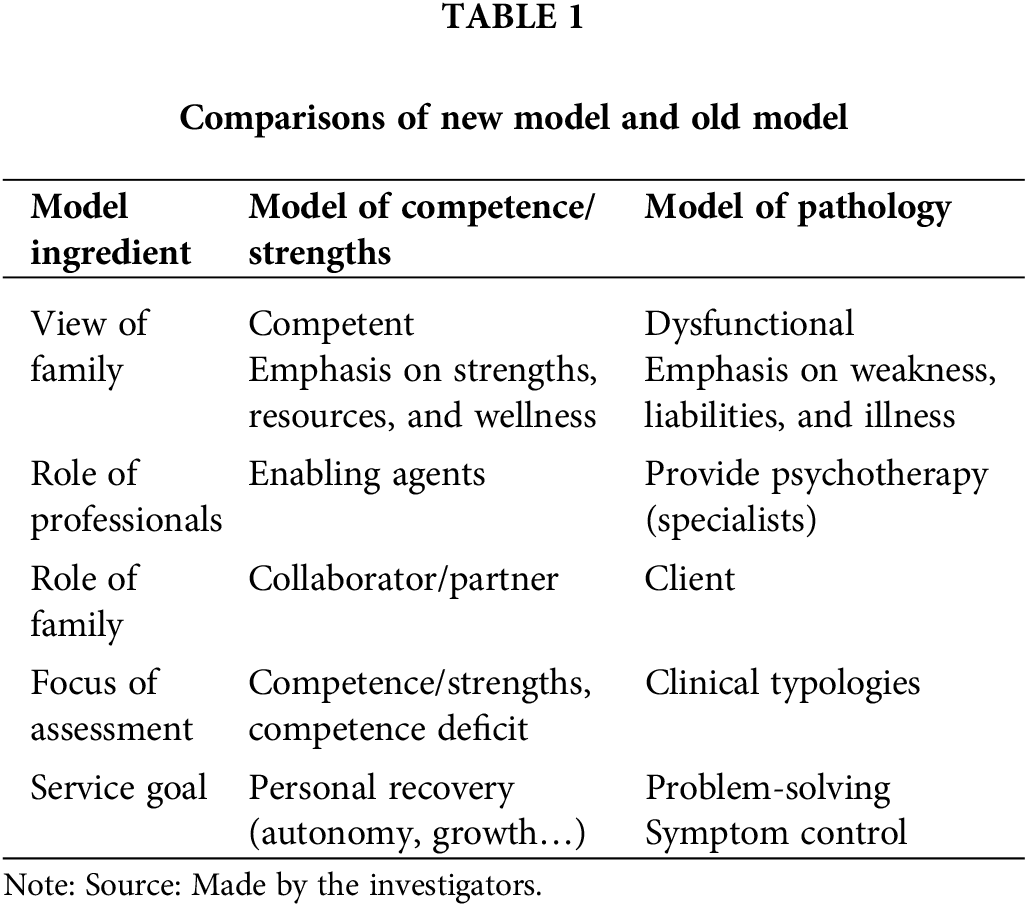

As for the models of family intervention, over the past six decades, multiple approaches have coexisted [16]. Those models vary in terms of their view of the family, treatment goals, professional roles, familial roles, and the focus of an assessment. Since the late 20th, there has been a pronounced paradigm shift in professional practice with families, from a model of pathology to one of competence. Professionals’ view of families has shifted from seeing families as pathogenic or dysfunctional to viewing families as basically or potentially competent, from emphasizing weakness, liabilities, and illness to one of strengths, resources, and wellness. The role of professionals has been changed from one of the practitioners who provide psychotherapy to one of enabling agents who facilitate families to reach their goals. The family’s role has shifted from a client to a collaborator. The focus of assessment has changed from clinical typologies to competencies and competence deficits [4]. As Wise [17] claimed that the service approach has been redirected towards a “growth-development model”; i.e., it intensifies the strengths and resources of a family. Moreover, the recovery movement emphasizes that a consumer assumes greater responsibility for directing their own path to improvement, and with the comprehensive consumer- and family-centered services as integral components of psychiatric services [7]. Glynn et al. [7] argued that “the last 35 years have witnessed a proliferation of psychoeducational family interventions for schizophrenia that have been associated with reductions in relapse and readmission… Nevertheless, most of the validated family interventions would benefit from further refinement to be totally consistent with recovery values. Modifications in language, content, and outcomes of concern are necessary to reflect fully a recovery orientation” (pp. 451–452).

Recently, recovery-oriented family interventions have been advocated and developed, such as the family-inclusive approaches towards reablement [18] and mindfulness interventions for family caregivers [19]. Tew et al. [18] found that the key to success in reablement (focusing on capability, personal agency, and quality of life) rested upon the family relationship issues being resolved and family caregivers could encourage the establishment of connections with the community while using the family as a safe base. Mindfulness interventions could help caregivers realize the importance of themselves, develop new perspectives on their circumstances, and have decreased self-judgment [19]. Martin et al. [20] also pointed out that meaningful family inclusion rests on a partnership approach that values the input of families and consumers.

For the caregiver to be a full partner in the services, a caregiver’s own recovery has gained attention as well. Dixon et al. [21] called for professional attention to caregivers’ own needs. For example, they need to resolve their own emotional burdens, preserve the integrity of their own lives, and fulfill their hopes and dreams. Wyder et al. [15] proposed the central elements of a caregiver’s own recovery: establishing connections with others, maintaining hope and aspiration for themselves, redefining their identity, creating new meaning in life, and feeling empowered to change their and their loved one’s situation.

In summary, the above literature reviewed called for a strength-based, recovery-oriented, and collaborative approach to family intervention. Table 1 presents the comparisons between the pathological model and strength model on five ingredients. The strength model views families as competent with strengths, and a collaborator/partner. The role of professionals is an enabling agent, the focus of assessment is on both competence and competence deficit. The goal of services is to facilitate recovery (Table 1). A family caregiver’s own needs are also recognized and need help to work towards their own recovery. The elements proposed by Wyder et al. [15] require that professionals treat caregivers as an individual client; thus, it is desirable that professionals take a dual-focus case management approach to facilitate the personal recovery of consumers and caregivers, as the services usually involve multiple aspects of human life. To date, there is a lack of family intervention that has adopted such an approach. To fill the gap, this study aimed to provide a dual-focus case management based on the strength-based model and examine the recovery experiences of the service recipients.

The strength-based model developed by Saleebey [22], Rapp et al. [23], and their colleagues at the University of Kansas have been applied to psychiatric rehabilitation for almost 40 years. The strength-based model assumes that every individual has strengths and has the potential to learn, grow, and change. It focuses on the consumer’s wants and autonomy and mobilizes their strengths to facilitate recovery. This model emphasizes collaboration and partnership between professionals and consumers, which aligns with the value base of recovery-oriented services: person orientation, person involvement, self-determination/choice, and growth potential [24]. The strength-based model of case management offers a set of working principles, tools, and methods that are designed to help consumers to recover through the attainment of the goals they set for themselves and by acquiring personal and environmental resources identified [23,25]. The existing literature has shown that this model applied to psychiatric rehabilitation has yielded positive results in terms of decreased re-hospitalization, decreased symptoms, enhanced satisfaction with service, quality of life, vocational functioning, social functioning, social contacts, and social support [26,27]. However, these studies have primarily focused on consumers. To date, the effect of the strength-based family intervention has not yet been systematically examined. Thus, this study implements a strength-based family intervention and explored the experiences on personal recovery among consumers and caregivers.

In Taiwan, most people (71%) with psychiatric disabilities in the community are living with their families [28]. Thus, family caregivers shoulder tremendous responsibilities in supporting the consumers. The existing services for caregivers are usually short-term psycho-education or respite care, and other supportive services [29]. To our knowledge, only a few have received those services in Taiwan. Additionally, from the observations of our previous study [30], caregivers may be facilitators; yet they may become obstacles to the recovery of consumers as well. The obstacles are such that caregivers often hold a negative view of the consumer, have insufficient concerns and support, have poor communication, are overprotective, and have family conflicts. Due to the trend of family inclusiveness and recovery orientation in mental health services [7,15,17–21] and the lack of individualized services for caregivers in Taiwan, the investigators intended to implement strength-based case management [22,23] into family interventions to facilitate positive perceptions and interactions among family members, and then to enhance the personal recovery of consumers and caregivers.

As mentioned above, recovery is a holistic concept, including processes and outcomes. Song et al. [31] constructed the unity model of recovery and with this model the recovery process has three components: (1) Sense of self; (2) management of disability; and (3) hope, willingness, and action. The recovery outcomes included objective domains (intimate family relationship, reciprocal friendship, attainment of interpersonal and occupational skills, involvement in social activities, and achievement of social roles) and subjective domains (self-efficacy, enhanced quality of life, and enjoying life satisfaction). Further, Song et al. [32] revealed five categories for the recovery process: (1) connectedness, (2) hope, optimism about the future, (3) identity, (4) meaning in life, and (5) empowerment, otherwise known as CHIME. In this study, a qualitative approach was utilized to answer the following research questions: What are the aspects of recovery experienced by consumers and their caregivers after receiving the strength-based family intervention?

A three-year family intervention applying the strength-based model was implemented in Taiwan from July 2012 to June 2015, including a preparation stage (3 months), an intervention stage (2.5 years), and data analysis stage (3 months). A mixed-method approach was adopted [33] by using qualitative and quantitative data collection methods to capture the width and depth of the recovery experiences of the participants. The quantitative part aimed at examining the changes over time on recovery related measures. Whereas, a qualitative research approach was adopted since this study was exploratory in nature and focused on mental process and the construction of participants’ experiences [34,35]. The investigators intended to gain a deeper understanding of the participants’ experiences of personal recovery. This paper presents the qualitative part of the study.

Five community psychiatric rehabilitation agencies in northern, central, and southern Taiwan were contacted and informed of details about this study. The agencies were included based on the following inclusion criteria: (1) the investigators have an established relationship with the leader of the agency; and (2) based on our observations, the leader is devoted to psychiatric rehabilitation and is motivated to improve their services. A total of 26 case managers provided strength-based family interventions to the participants. The discipline background of the case managers was mainly social work (33.3%) followed by sociology (16.7%), occupational therapy (16.7%), psychology (11.1%), nursing (11.1%), and other (11.1%). Semi-structured in-depth interviews were conducted to capture the changing processes and domains of personal recovery.

Criteria for the inclusion of participants were: (1) consumers must have a severe mental illness other than substance abuse, a personality disorder, or dementia due to any cause; (2) family caregivers who have lived with a consumer for at least 6 months within the past year and were identified by the consumer as their key caregiver; and (3) they agreed to participate in this study. Due to heavy workload, each case manager applied the strength-based model on 2 dyads at a time in addition to their usual work with consumers.

A total of 43 dyads (consumers and caregivers) agreed to participate in this study. The characteristics of the participants at the beginning of the intervention were as follows.

The mean age of consumers was 34.09 (Sd = 9.88, range = 19–61). About two-thirds of the consumers were male (67.4%). Most were not married (90.7%). Almost half (46.5%) had a high school diploma, and 34.5% had a college degree or above. Almost all (97.7%) were living with family members, and only one lived alone. The majority (76.7%) had a diagnosis of schizophrenia and 18.6% had an affective disorder. The mean number of prior hospitalizations was 3.43 times. All of them were on psychiatric medication.

The mean age of caregivers was 57.60 (Sd = 10.77, range = 23–84). The majority of caregivers were female (74.4%). Two-thirds (67.2) were the mother of the consumer, and 21% were the father. Most of them were married (67.4%). About one-third (32.6%) had a high school diploma, and 23.3% had a college degree or above. A total of 60.5% were not employed. Slightly over half (52.4%) had other similar responsibilities with other consumers.

Semi-structured in-depth interviews were conducted on three occasions: six months after the inception of the experiment, 18 months after, and when the case was closed. The selection of interviewees was based on the consideration of willingness, diversity, and conceptual saturation, meaning that the data could reflect the comprehensive experiences of the consumers’ recovery experiences. On the first two occasions, 10 consumers and 9 caregivers were interviewed, respectively. Each agency was asked to select one dyad that had made some progress and one dyad that had less progress at that time. Through this selection strategy, the investigators intended to increase the breadth of circumstances of the interviewees, the information was not used in further analyses. Moreover, among the 10 dyads that terminated their participation in this study with positive results, seven consumers and 10 caregivers were interviewed. Over the three occasions, a total of 27 consumers and 28 caregivers were interviewed.

The family intervention based upon the strength-based model

In this study, strength-based case management family interventions were provided to consumers and a primary caregiver. The service for caregivers was added on top of the existing services for consumers. Moreover, the service modal shifted from a conventional problem-solving and deficit model to a strength-based model.

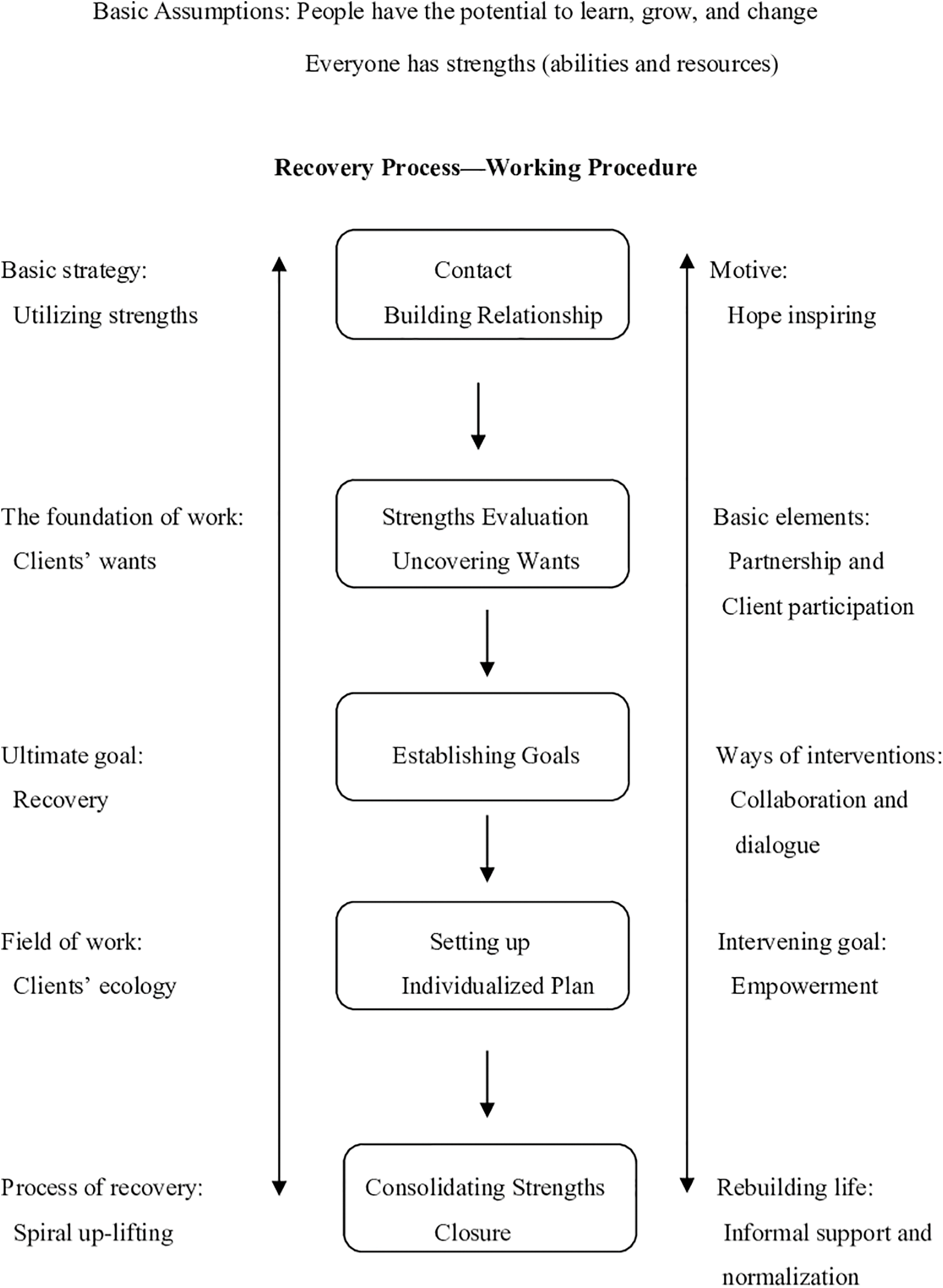

The intervention followed the paradigm of a strength-based perspective (Fig. 1), which was synthesized by Lincoln et al. [36] from Saleebey [22] and Rapp et al. [23]. Recovery is treated as the ultimate goal and strength is used as a strategy to empower the participants and to facilitate the process of achieving goals.

Figure 1: Paradigm of strengths perspective sources: Song & Shih (2009b, p. 65) [36].

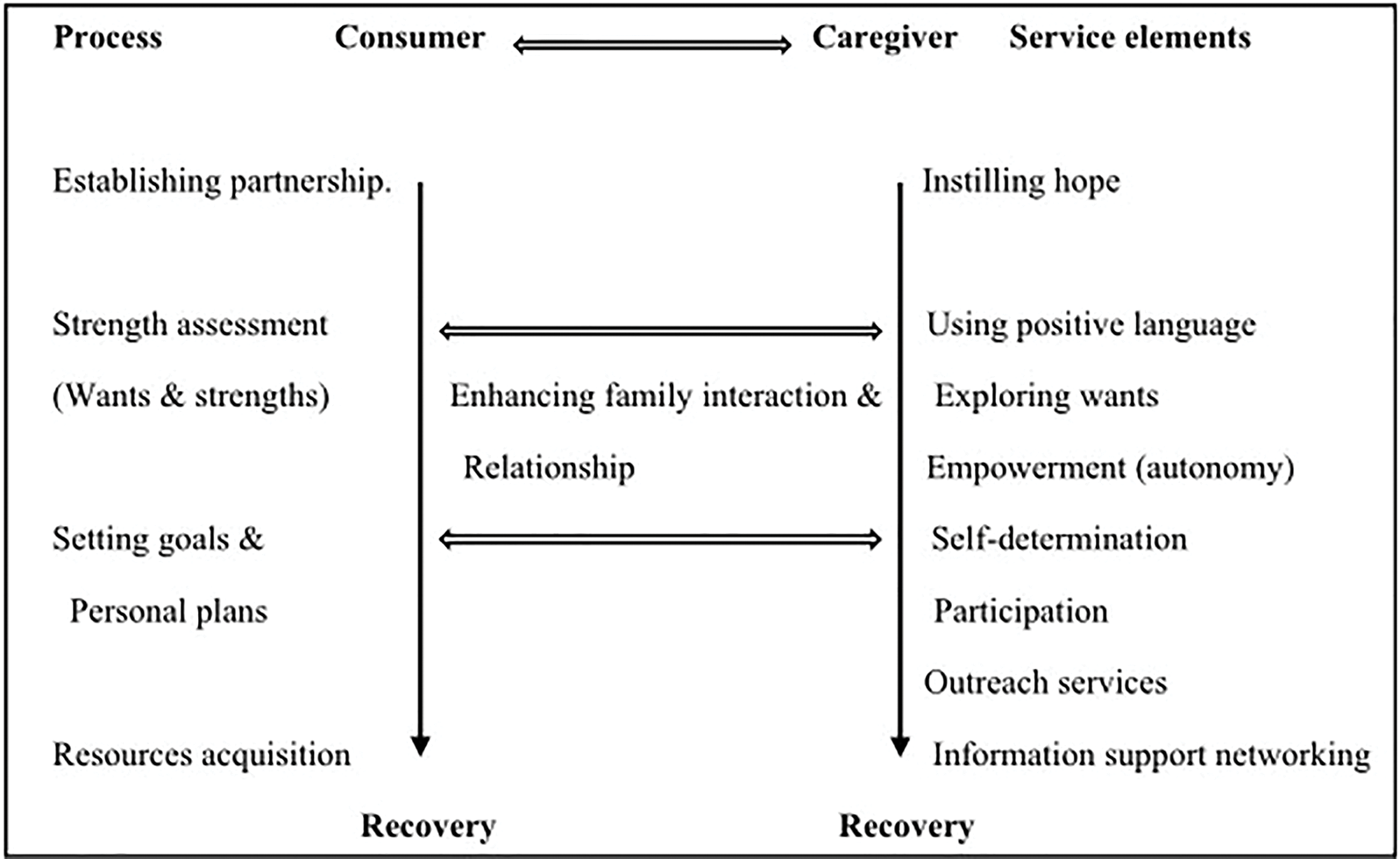

There are six working principles within this model [22,23]. The first two are concerned with ontological assumptions about human beings. The remaining four are related to the methods of the model. First, every living human being has strengths. Professionals help both consumers and caregivers (participants) to recognize their strengths and use them to empower the participants and facilitate them towards their goals. Second, the participants have the potential to learn, grow, and change. This belief can affect professional attitudes towards participants, and with this belief, professionals can instill hope and have the strength to work with the participants, especially when facing setbacks. The third principle is self-determination. This perspective assumes that the participants are an expert in their life situations. Moreover, the foundation of collaborative work is based on the participants’ wants. The fourth principle emphasized professional relationships with the participants. This model stressed collaboration and partnership through dialogue. The fifth principle concerns outreach to the participants in their living environment. Therefore, professionals would know the context of their behaviors better and then, from this, the potential resources that could be used. The sixth principle holds that the community is an oasis of resources. This model further emphasizes the exploration of informal resources prior to any formal resources being used, which allows professionals to help consumers to establish a natural support system within their community. The strength-based family intervention model is presented in Fig. 2. The project goal is to facilitate the recovery of consumers and caregivers, respectively. The working process followed the protocol of the strength-based case management on the left-hand side and the service elements on the right.

Figure 2: Strength-based family intervention model.

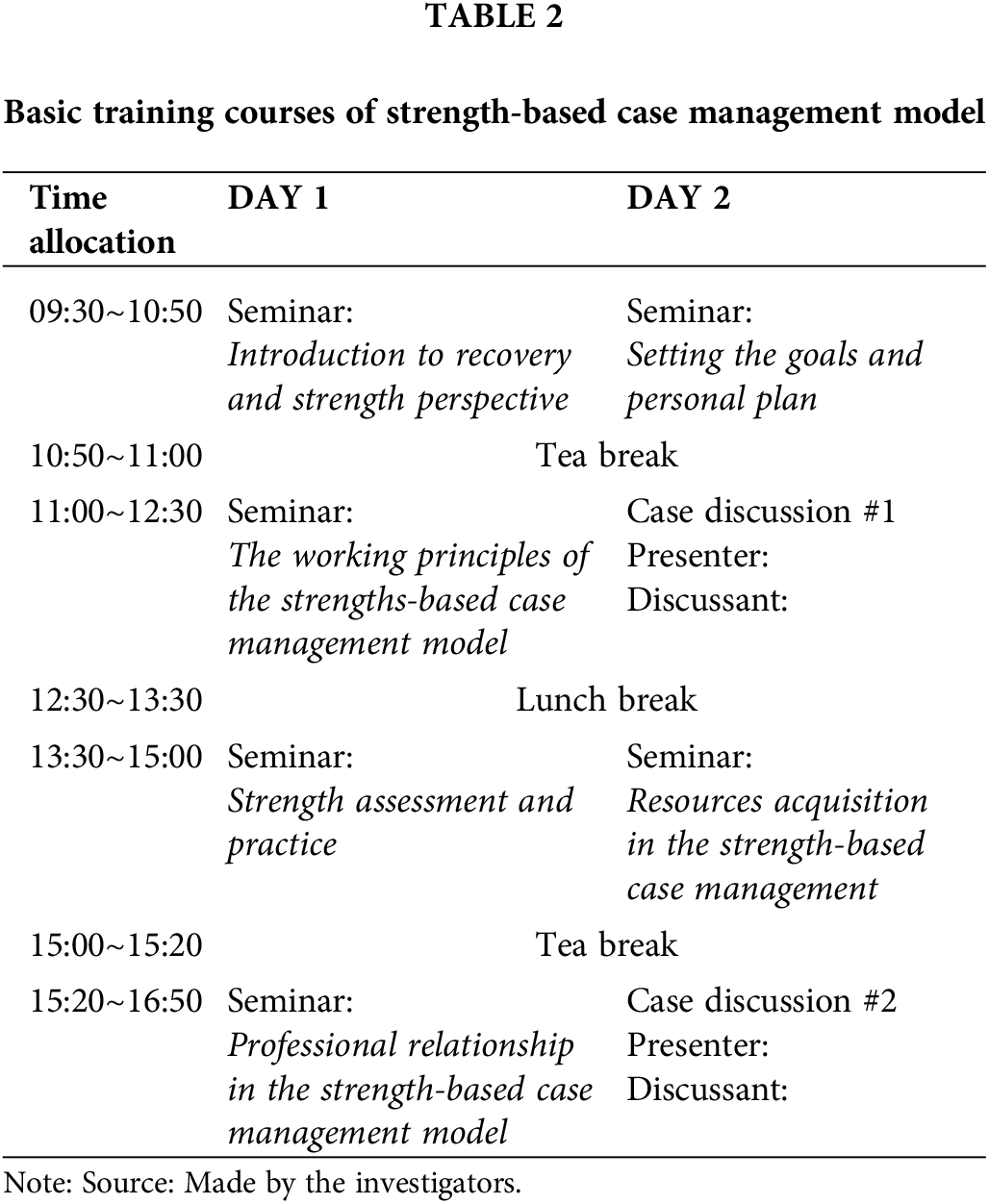

The intervention followed a program protocol that included training, implementation, supervision, and evaluation. First, case managers received a two-day basic training of the strength-based model in 6 sessions. The course content is presented in Table 2. The trainers were the first author and other colleagues assisted with teaching and supervision experiences on the strength-based model. Second, the research team discussed the implementation steps and related issues with the professionals at each agency. Third, case managers started the selection and invitation process for the dyads. Afterward, consumers and family caregivers signed an informed consent agreement. Fourth, the investigators provided monthly external supervision for each agency to help case managers transform the six principles of the strength-based perspective into daily practice. Fifth, the implementation issues were also discussed in monthly internal supervision meetings at each agency. Six, the research team conducted data collection in accordance with our data collection plan. Two major tools, strengths assessment, and personal planning, developed by Rapp et al. [23], were used in this study. Individualized services were provided to the dyads, respectively. There was no required intensity of services in the intervention since that depends on each client’s situation and needs, and on each case manager’s caseload. However, to establish a trusting relationship, intensive contacts and services were expected, especially in the beginning stage of the intervention.

To observe the process and ensure the fidelity of programs implementation, a check-in form was designed to log the contacts made between case managers and consumers, including the purpose of the contact, frequency of contact, the location of the meeting, the principles utilized, and the level of accomplishment towards the service goals. This logging system has been used in another study [37]. All implementation issues were discussed in regular supervision meetings to improve the fidelity of the study, including the relationship between the case managers and consumers, the strengths assessment, the strategies to motivate the participants, and the strategies to improve the dyads’ relationship and to help them fulfill their goals, etc.

Face to face interviews were conducted at each participants’ home by four research assistants. The participant’s case managers introduced the research assistants to the participants to help establish trust with them, thus might help increase the trustworthiness of the data. The assistants all had been equipped with the knowledge on the qualitative research approach, the strength-based model through the courses at the university, the training sessions, and attending the supervision meetings. Prior to the interviews, a training session was conducted by the first investigator to familiarize the assistants with the interview guide. Each interview lasted from 45–90 min and was audio-recorded. Each participant was given a voucher (worth $16.67 USD) for a convenience store as payment for participation.

A semi-structured interview guide was designed by the first author. It was finalized through a test interview and discussions with colleagues and the participating agencies. The participants were asked the following questions: 1. How do you think about your future?; 2. How do you feel or think about yourself right now?; 3. Looking back when you just joined the project, in what ways are you different from then?; 4. Please describe the changing process. 5. If you have experienced changes, what made you change?; 6. Do you think that the change could last in the future?; 7. What influence do the services have on you?; 8. What do you think of the strength assessment and personal planning?; 9. Do you think that your caregiver/the consumer has changed in any way?; and 10. Looking back when you just joined the project, do you think that your relationship with your caregiver/the consumer has changed in any way? The interviews did not necessarily follow the sequence of the questions. Instead, it depended on the flow of the conversation and the interviewers probed further to attain as rich information as they could.

The script of each interview was transcribed verbatim into dialogic text. The procedure of data analysis began with open coding and conceptual labeling based on the Grounded theory [38]. The initial open coding was performed by research assistants and then further reviewed by the first author to ensure inter-rater reliability. The open coding then was compared across participants to extract similar and different properties and themes. The analyses were conducted manually without using any software. Each interviewee was assigned a code. For example, A57c means agency A, dyad number 57, and a consumer (c). Also, the consumer’s caregiver was assigned a code as A57f.

Compliance with ethical standards

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest: None.

Research involving Human Participants and/or Animals

A total of 43 dyads (consumers and caregivers) participated in this study.

This study has been approved by the Chang Gung Medical Foundation Institutional Review Board in Taiwan for quality and research ethics. Each participant signed a copy of informed consent after they agreed to participate in this study. The informed consent document included the following information: a brief introduction of this study, the sponsor and project number of this study, the purpose of this study, the study methods and processes, the potential risks and coping methods, the anticipated study benefits, the management in case of emergency, payments for participation, an assurance of anonymity, the protection of service rights in case of drop out, the rights of the participant, and the ownership of the study product.

The results have been published in the book written by the investigators in Chinese [38]. In this paper, we extract and summarize the findings to share with the readers in the West. Consumers and caregivers revealed rich and positive changes in the domains of recovery. The details are as follows. Due to limited space, only one or two personal accounts were presented for each domain.

Consumers made progress on domains in the recovery process, such as positive beliefs and attitudes (sense of self), took responsibility, and demonstrated better coping. Additionally, they expressed changes on objective domains of recovery, including functional improvements, interpersonal interactions enhanced, and family relationships improved.

One critical element of recovery was the sense of self. Eight consumers (A05c, A57c, B48c, E34c, E36c, E43c, C13c, and D19c) experienced a better sense of self, including self-acceptance, self-awareness, and a sense of hope. For example, B48c and E36c accepted their mental illness and tried to do better so they would not be looked down upon. E36 said: ‘My parent won’t stop loving me, but I cannot depend on them forever. I tried to change myself as much as I can, so people won’t look down on me’ (E36c-10). A57c felt good about herself because she had learned how to cook and make tea, which brought about positive comments from others. E43c was aware that her gaining weight might be due to a sense of emptiness.

Three consumers (E42c, E43c, and E61c) began to take responsibility to learn, change, and grow. For example, E61c could perform his duty and try his best to do a good job. E43c started to record the progress in her daily life. She realized that she needed to make an effort and change, so others would accept her as an unemployed person. One thing she did was to help take care of her niece.

‘I used to feel annoyed when I was asked to do things. Then I thought that if I don’t do these things now, no one will do these with me. So I should act first, let them know that I am making changes, then they will gradually accept me as an unemployed person’ (E43c-11).

Over time, three consumers had learned a more effective way to cope with symptoms and disability. A03c did not hide at home anymore. She participated in rehabilitation frequently and her emotional state was lifted. B46c and C12c reminded themselves to try their best but not to push too hard.

Consumer functional improvements refer to their health, financial, and employment statuses. Some consumers showed improvement in taking medication (E36c, E42c), improved health status (E42c, E38c), and reduced medication dose (E61c). Also, some consumers could manage their finances better. E42c paid her phone bill. E43c knew that she should control her spending based on what she had. E61c had a job; therefore, he was financially independent. Concerning employment, B48c went for a job interview as a test for himself. E42c had increased her work efficiency at the shelter. E61c had a part-time job and was about to increase his working hours so he could earn more money.

Interpersonal interaction enhanced

One of the focuses of the model was to facilitate consumers establishing informal social networks and mutual help. Social skills are a key ability for social networking. Ten consumers (A03c, A04c, B48c, C54c, D19c, E34c, E36c, E42c, E43c, and E61c) revealed improvements in the frequency of interactions and social skills, including being more understanding, expressing themselves, being empathetic, accepting suggestions, and helping others. For example, B48c mentioned that the service helped him understand human perception and psychological states to become more empathetic. He said: ‘I think that we should communicate our feelings, especially the suppressed thoughts. According to my observation, one of the side effects of having a mental illness is a sense of insecurity and hopelessness for the future.’ (B48c-14) E61c found a job as a security guard. He was willing to help others. One day he helped a lady find her purse and received great appreciation from her, which made him feel good about himself.

Six consumers (A03c, B48c, E36c, E42c, E43c, and E52c) expressed improvement in family interactions and relationships. B48c could communicate with his parents about medication and regain autonomy and trust from his parents. He said: ‘My parents would ask my opinions now. This is good! Besides, my mother doesn’t mind my business as often as before. She can trust me in some ways.’ (B48c-17) C11c and C12c could appreciate their parental support. E36c and his mother had a close but conflicted relationship. After the intervention, E36c got a job and moved out; now they could communicate better when they were communicating. E36c commented that ‘my mother is more amiable now.’ (E36c-9) E42c’s father could not accept her disability. She had learned how to hide when he was angry. She also traveled with her parents sometimes. E43c had increased her functionality at home as a caretaker of her older sister and niece. She was able to express her opinions and had more personal interactions with her siblings. She said: ‘my brother and sisters would invite me out if they saw me staying at home all day long.’ (E43p-14)

Caregiver recovery experiences

Caregivers experienced decreased psychological burdens. They also revealed transcendence of and moving towards a more positive attitude about themselves. Major changes occurred on the subjective domains of recovery outcome, including felt empowered and had a better quality of life. Moreover, they had better interaction with consumers (objective domain of recovery).

Decreased psychological burdens

Psychological burdens are a common phenomenon among caregivers. As the consumers made some progress and became stable, four caregivers (B48f, B55f, E36f, and E61f) mentioned that they felt more relaxed, less worried, and happier. The decreased burden arose because the caregiver had learned to look at situations from different perspectives (A03f and B55f). B55f said, ‘I used to think that I might cause his illness. I feel less this way now.’ (B55f-3)

Transcendence toward a more positive attitude

Taking a positive perspective is critical to happiness. Through dialogues, the services could help some caregivers (B48f, B55f, E38f, E42f, and E43f) reflect on their suffering, become more empathetic for those who are in the same situation, be more accepting of frustration, let go of some of their responsibilities, and holding more positive views towards themselves. C12f and E41f could recognize their vocational strengths, e.g., having a license or being good at sewing, which was helpful for employment. B48f expressed a transcendental view of her son’s illness:

‘I think that this (my son’s illness) is the lesson that God gives me, so, I would not become too complacent. I can treasure what I have and become more understanding now.’ (B48f-11, 12)

Two caregivers mentioned that through the service she felt empowered. B55f could share her positive coping methods with other caregivers and felt positive about herself. E61f had learned to use social resources and to cope with his son’s symptoms with a steadfast attitude. She said:

‘I was beaten by him twice or three times and needed to call an ambulance. Two doors were broken by him. You could see how serious it was. But, I could stay calm and watch what happened. I used to cry and feel afraid. Now I can face him and see how serious it can get.’ (E61f-11)

Despite the heavy care responsibility, some caregivers were able to shift focus to themselves and expand their life domains. Sixteen caregivers (A03f, A5f, A09f, A57f, B44f, B48f, B55f, C12f, C54f, E34f, E36f, E41f, E42f, E43f, E61f, and E64f) experienced a better quality of life in some life domains, including work, health, interests and hobbies, and having a life for themselves. For example, E43f changed her view of work, became less focused on achievement in her work; E42f expressed that her health had improved; E34f was knowledgeable about goods and was willing to share with others; A03f, B48f, E36f, and E61f started to visit friends or relatives and gained pleasure from doing so. Due to past negative experiences stemming from illness, disability, and social stigma, the worries were constantly lingering in the minds of caregivers. In addition, their personal lives were disrupted because of the caring responsibility. As consumers regained stability, autonomy, and a social role, some caregivers were able to pursue their own interests.

‘He didn’t go out at all before. I was worried about him and my life centered around him, which made me feel distressed. He has his own life now since he received your service. I am happy for him. I start to plan my own life, learn things, get a job, and find the center of my life.’ (E61f-8)

Better interaction with consumers

Eleven caregivers (A03f, B448f, B53f, B55f, C13f, C54f, E36f, E41f, E43f, E62f, and E64f) expressed improvements in their interactions with consumers. Caregivers used to convey their goodwill and expectations by nagging and pushing consumers, which caused familial tensions. In this study, case managers fostered caregivers to see a consumer’s strengths and positive side to facilitate constructive interactions between the dyads. Thus, they learned more positive ways to react to consumer behaviors, encourage consumers, communicate with them, and respect their autonomy. Moreover, positive changes from consumers, in turn, contributed to the happiness and relaxation of caregivers; thus, they were able to let go of some of their worries sometimes.

‘I became mature now (Ha! Ha! Ha!). I used to be hard on him and try to refute him, not listening to him. I would say: “you should not think that way”... But, now I would listen to him patiently, let him finish what he wanted to say.’ (B48f-8)

The qualitative data reflected the rich and diversified personal recovery that the participants had experienced. Those experiences were what the strength-based family intervention intended to achieve. The participants experienced changes in the domains of recovery, including processes and outcomes. One of the focuses of the intervention was to improve the relationship among the dyads. Some participants did mention that they had better interactions with caregivers/consumers or that their family relationships had improved. Through the individualized intervention of strength-based case management, some caregivers were able to set up and work on their own goals. They felt empowered, which enhanced their quality of life. The findings revealed that the strength-based family intervention is aligned with the recovery-oriented family intervention as Wyder et al. [15] proposed. Previous studies showed that psychoeducation, as an evidence-based practice, could be conducive to preventing relapse and rehospitalization, medication compliance, social functioning improvement, decreased expressing emotions, or caregiver burden [7,21,39]. This study demonstrated that the strength-based family intervention appeared to bring positive experiences in recovery-related domains that were not captured before, such as holding positive beliefs and attitudes toward oneself, taking responsibility, transcendence over adversity, feeling empowered, and improvement on family interactions and relationships. These impacts are what strength-based family intervention is intended to attain, for example, the program objectives of the family-inclusive approach [15] and the mindfulness intervention for families living with mental health problems [19], Furthermore, compared to applying the strengths-based case management model only on consumers [26,27], the dual-focused approach seems to be conducive in facilitating consumers’ positive belief and attitude, taking responsibility, better coping, and family relationship in addition to functional improvements, social contacts, and social support mentioned in the previous literature [26,27].

This study intended to facilitate caregiver recovery, i.e., to spend some time on personal development, fulfilling their dreams and wants, as well as enhancing their quality of life as well. Despite the difficulties that Chinese caregivers were required to shift focus on themselves, the personal accounts in this study did show some improvements in holding more positive views of the self and feeling empowered. Moreover, sixteen caregivers revealed an improvement in their quality of life.

Despite the positive changes, some consumers and caregivers in this study faced some challenges that prevented them from pursuing their goals. The challenges stemmed from the inner state and the environment of the participants. For example, consumer physical health problems, low stamina, lack of confidence, family negative influence, social stigma, etc.

As for the caregivers, one major challenge was that some could not shift their focus from the consumer to themselves. In the worldview of Chinese culture, the relationships among family members is eternal. Thus, individuals are constrained by familial relationships, and interdependency is emphasized since family members are bound together by the idea that they have responsibilities to each other [40,41]. Parents are expected to not leave their children uncared for no matter what circumstances they are facing. Therefore, their goals were mainly centered on consumer treatments and rehabilitation. They usually did not think or talk about their wants during the early part of the intervention. Nevertheless, the strength-based model, which emphasizes establishing a genuine and collaborative relationship with consumers, fits the relationship-oriented Chinese culture [41,42]. For the Chinese, the code of interaction is determined by the type of relationship among people. For family members, responsibility regulates the choices of interaction patterns; for acquaintances, affection influences the course of action; for strangers, interest determines the decision of action [41]. The strength-based model helped the professionals turn the relationship with the consumers from strangers to being more friend-like. There is the transaction of warmth, mutual understanding, informality, at ease, common interest, affection, etc. among them. Professionals have discussed caregivers’ ideas with them and invited them to participate in social activities. Sometimes caregivers accepted the invitation because they had established a friend-like relationship with the professionals; thus, they did not want to make professionals lose face [43]. Through the relationship, some professionals could gradually facilitate caregivers to find a balance between caring as well as self-development and recovery. Such a balance between the opposite sites is the essence of Chinese philosophy, The Golden Mean (中庸之道) [40]. For which the point of balance is unique for each person; professionals help the caregivers find the point that fits their circumstances.

Another major challenge was that few caregivers did not want to disclose their deep and inner feelings; thus, they did not ask for help on emotional issues. Dixon et al. [21] also revealed similar barriers for caregivers to use family services, such as time and energy constraints, and social stigma.

To overcome the above-mentioned challenges, changes in service delivery are needed. Case managers would need to put more effort into finding effective strategies and skills to facilitate goal setting and actions. For some families, it might take a longer time for them to change from the status quo. However, the case managers in this project could not spend more time with caregivers to work on their goals due to time constraints. Their job responsibility focused mainly on consumers and as mentioned by Dixon et al. [21], the services for caregivers were usually not paid and not emphasized by the system. These findings suggested that if more resources are allocated to strength-based family intervention for this population with a dual-focused approach, then it might help facilitate the participants’ empowerment and recovery.

This study revealed preliminary results on utilizing the strength-based model in family interventions. It was the first study that applied strength-based case management to both consumers and caregivers in Taiwan, the data was rich and diversified. The findings showed the helpfulness of the strength-based model. However, the study had some limitations. First, given the small number of dyads and the exploratory nature of this study, the findings do not imply a causal relationship between the strengths-based family intervention and the positive recovery experiences. Second, other life events might have exerted a certain influence on the participants’ recovery experiences. Third, the unique characteristics of the participants might compromise the transferability of the findings, which is a universal limitation for qualitative data. Fourth, the positive experiences we observed might be influenced by maturation effects among the dyads in addition to the intervention. Fifth, social desirability might somewhat undermine the trustworthiness of the data. Finally, in this study, case managers provided extra services for caregivers given their usual services to consumers. Thus, the time spent with caregivers was much less than with consumers. Nevertheless, despite this constraint, caregivers in this study still showed some progress. Future studies are needed to further examine the impact of the model by securing extra funding to support professional work with caregivers.

The strength-based perspective appear to be conducive to the personal recovery of some consumers and caregivers. The dual-focused approach in family treatment could fit the relationship-oriented culture among Chinese. However, it also places new challenges in facilitating caregivers to work on their goals for themselves. Such a challenge could be overcome by establishing a genuine and trusting relationship with caregivers. Further, by allocating more manpower to provide family-based and strength-based interventions might facilitate the implementation of a dual-focused approach.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank the Ministry of Science and Technology in Taiwan for providing the funding for this study. The unfailing participation of the agencies, case managers, consumers, and caregivers is also greatly appreciated.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Anthony W, Cohen M, Farkas M, Gagne C. Psychiatric rehabilitation [Internet]. Boston, MA: Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation, Boston University; 2002. [Google Scholar]

2. Corrigan PW. Principles and practice of psychiatric rehabilitation: an empirical approach [Internet]. New York, NY: The Guildford Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

3. Gatsou L, Yates S, Goodrich N, Pearson D. The challenges presented by parental mental illness and the potential of a whole-family intervention to improve outcomes for families. Child Fam Soc Work [Internet]. 2017;22(1):388–97. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Lefley HP. Family caregiving in mental illness [Internet]. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1996. [Google Scholar]

5. World Health Organization. Mental health action plan 2013–2020. http://www.who.int/mental_health/publications/action_plan/en/index.html. [Accessed 2013]. [Google Scholar]

6. President’s New Freedom Commission on Mental Health. Achieving the promise: transforming mental health care in America. Final report. Available from: https://govinfo.library.unt.edu/mentalhealthcommission/reports/FinalReport/FullReport-1.htm. [Accessed 2003]. [Google Scholar]

7. Glynn SM, Cohen AN, Dixon LB, Niv N. The potential impact of the recovery movement on family interventions for schizophrenia: opportunity and obstacles. Schizophr Bull [Internet]. 2006;32(3):451–63. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbj066. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Liberman RP, Kopelowicz A. Recovery from schizophrenia: a challenge for the 21st century. Int Rev Psychiatr [Internet]. 2002;14(4):245–55. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0954026021000016897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Slade M. Personal recovery and mental illness [Internet]. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

10. Tse S, Davidson L, Chung KF, Ng KL, Yu CH. Differences and similarities between functional and personal recovery in an Asian population: a cluster analytic approach. Psychiatry-Interpers Biol Process [Internet]. 2014;77(1):41–56. doi:https://doi.org/10.1521/psyc.2014.77.1.41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Law H, Morrison AP. Recovery in psychosis: a delphi study with experts by experience. Schizophr Bull [Internet]. 2014;40(6):1347–55. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbu047. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Reupert A, Maybery D, Cox M, Stokes ES. Place of family in recovery models for those with a mental illness. Int J Ment Health Nu [Internet]. 2015;24(6):495–506. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12146. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Chan CKP, Ho RTH. Discrepancy in spirituality among patients with schizophrenia and family care-givers and its impacts on illness recovery: a dyadic investigation. Br J Soc Work [Internet]. 2017;47(1):28–47. [Google Scholar]

14. Lim C, Barrio C, Hernandez M, Barragán A, Brekke JS. Recovery from schizophrenia in community-based psychosocial rehabilitation settings: rates and predictors. Res Social Work Prac [Internet]. 2017;27(5):538–51. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731515588597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Wyder M, Bland R. The recovery framework as a way of understanding families’ responses to mental illness: balancing different needs and recovery Journeys. Aust Soc Work [Internet]. 2014;67(2):179–96. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2013.875580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Nichols MP. Family therapy: concepts and methods [Internet]. New York, NY: Pearson Education, Inc.; 2008. [Google Scholar]

17. Wise JB. Empowerment practice with families in distress [Internet]. New York, NY: Columbia University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

18. Tew J, Nicholls V, Plumridge G, Clarke H. Family-inclusive approaches to reablement in mental health: models, mechanisms and outcomes. Brit J Soc Work [Internet]. 2016;47(3):864–84. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcw106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Stjernswärd S, Hansson L. User value and usability of a web-based mindfulness intervention for families living with mental health problems. Health Soc Care Comm [Internet]. 2016;25(2):700–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12360. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Martin RM, Ridley SC, Gillieatt SJ. Family inclusion in mental health services: reality or rhetoric? Int J Soc Psychiatr [Internet]. 2017;63(6):480–7. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764017716695. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Dixon L, McFarlane WR, Lefley H, Lucksted A, Cohen M, Falloon I, et al. Evidence-based practices for services to families of people with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiat Serv [Internet]. 2001;52(7):903–10. doi:https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.52.7.903. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Saleebey D. The strengths perspective in social work practice [Internet]. 5th ed. New York, NY: Pearson Education, Inc.; 2009. [Google Scholar]

23. Rapp C, Goscha RJ. The strengths model: case management with people suffering from severe and persistent mental illness [Internet]. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

24. Farkas M, Gagne C, Anthony W, Chamberlin J. Implementing recovery-oriented evidence based programs: identifying the critical dimensions. Community Ment Hlt J [Internet]. 2005;41(2):141–58. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-005-2649-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Francis A. Strengths-based assessments and recovery in mental health: reflections from practice. Int J Soc Work Hum Serv [Internet]. 2014;2(6):264–71. doi:https://doi.org/10.13189/ijrh.2014.020610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Marty D, Rapp C, Carlson L. The experts speak: the critical ingredients of strengths model case management. Psychiatr Rehabil J [Internet]. 2001;24(3):214–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/h0095090. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Rapp C, Goscha RJ. The principles of effective case management of mental health services. Psychiatr Rehabil J [Internet]. 2004;27(4):319–33. doi:https://doi.org/10.2975/27.2004.319.333. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Song L. Predictors of personal recovery for persons with psychiatric disabilities: an examination of the Unity Model of Recovery. Psychiat Res [Internet]. 2017;250(1):185–92. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.01.088. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Law & Regulations Database of the Republic of China. Physical and psychiatric disability family caregiver service act. Available from: https://law.moj.gov.tw/LawClass/LawAll.aspx?pcode=D0050186. [Accessed 2019]. [Google Scholar]

30. Song L, Shih C, Hsu S. Strengths perspective and the recovery of persons with psychiatric disability (in Chinese) [Internet]. Taipei City, Taiwan: Hung Yeh publications; 2015. [Google Scholar]

31. Song L, Shih C. Factors, process, and outcomes of recovery from psychiatric disability—The unity model. Int J Soc Psychiatr [Internet]. 2009a;55(4):348–60. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764008093805. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Leamy M, Bird V, Boutillier CL, Williams J, Slade M. Conceptual framework for personal recovery in mental health: systematic review and narrative synthesis. Br J Psychiatry [Internet]. 2011;199(6):445–52. doi:https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.110.083733. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Aarons GA, Fettes DL, Sommerfeld DH, Palinkas LA. Mixed methods for implementation research: application to evidence-based practice implementation and staff turnover in community-based organizations providing child welfare services. Child Maltreat [Internet]. 2012;17(1):67–79. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559511426908. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. GrinnellJr R. Social work research and evaluation [Internet]. 4th ed. Itasca, IL: F.E. Peacock Publishers, Inc.; 1993. [Google Scholar]

35. Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry [Internet]. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1985. [Google Scholar]

36. Song L, Shih C. Strengths perspective: social work theory and practice (in Chinese) [Internet]. Taipei City, Taiwan: Hung Yeh Publications; 2009b. [Google Scholar]

37. Song L, Shih C. Recovery from partner abuse: the application of the strengths perspective. Int J Soc Welf [Internet]. 2010;19(1):23–32. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2397.2008.00632.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: grounded theory procedures and techniques [Internet]. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1990. [Google Scholar]

39. Pharoah F, Mari J, Rathbone J, Wong W. Family intervention for schizophrenia (review). The cochrane collaboration [Internet]. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.; 2010. [Google Scholar]

40. Yang CF. How to understand the Chinese [Internet]. Taipei: Yuan Liou Publishing; 2001. [Google Scholar]

41. Yang KS. The theoretical analysis of Chinese social orientation. In: Yang KS, Hwang KK, Yang CF, editors. Chinese indigenous psychology [Internet]. Taipei: Yuan Liou Publishing; 2005. p. 173–214. [Google Scholar]

42. Hwang KK. The theoretical construction of the relationalism among Chinese. In: Yang KS, Hwang KK, Yang CF, editors. Chinese indigenous psychology [Internet]. Taipei: Yuan Liou Publishing; 2005a. p. 215–48. [Google Scholar]

43. Hwang KK. The perspective of face and mientze (面子) in Chinese society. In: Yang KS, Hwang KK, Yang CF, editors. Chinese indigenous psychology [Internet]. Taipei: Yuan Liou Publishing; 2005b. p. 365–406. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools