Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

The Relationship between Parent-Child Conflict and Non-Suicidal Self-Injury: A Moderated Mediating Model

School of Teacher Education, Shangqiu Normal University, Shangqiu, 476000, China

* Corresponding Author: Min Li. Email:

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(1), 89-95. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2024.057223

Received 11 August 2024; Accepted 09 December 2024; Issue published 31 January 2025

Abstract

Objectives: To explore the approaches for reducing non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) behaviors in Chinese adolescents, the present study investigated the association between parent-child conflict and NSSI in adolescents, while also examining the mediating role of depression and the moderating role of rumination thinking. Methods: A cluster sampling method was employed to select 1227 Chinese adolescents aged 12 to 18 as participants, who completed measures including the Parent-Child conflict, Depression, Rumination Thinking, and Non-Suicidal Self-Injury questionnaires. The present study used SPSS 26.0 to conduct the Descriptive statistics, correlation analysis, and reliability tests, and PROCESS 3.3 to test the hypothesis model. Results: (1) There is a positive correlation between parent-child conflict and NSSI in adolescents; (2) Depression mediates the relationship between parent-child conflict and NSSI in adolescents; (3) Rumination thinking acts as a moderator in the association between parent-child conflict and depression. This study finds the indirect effect of depression on NSSI behaviors among Chinese adolescents. Furthermore, the study also finds protective factors by examining the role of reducing individual rumination thinking in mitigating negative emotions following adverse experiences. In conclusion, this research provides a pathway and foundation for enhancing interventions targeting NSSI behaviors among Chinese adolescents. Conclusion: The relationship between parent-child conflict and NSSI in adolescents is positively correlated. Depression acts as a mediator in the association between parent-child conflict and NSSI in adolescents. The effect of parent-child conflict on NSSI is positively moderated by rumination thinking. Specifically, low-level rumination thinking may mitigate the negative impact of parent-child conflict on depression.Keywords

Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) refers to the intentional, self-inflicted damage to body tissue that is not culturally sanctioned and lacks suicidal intent [1]. The prevalence of NSSI among general adolescents abroad ranges from 7.5% to 37.5% [2], and 21.9% in Chinses adolescents [3]. Numerous studies found that compared with adolescents without NSSI, adolescents with NSSI are more likely to commit suicide [1,4,5]. Meanwhile, NSSI can also cause an increase in individual depression and other psychological comorbidities or psychiatric disorders [6]. Therefore, given the adverse consequences of NSSI on Chinese adolescents, it is imperative to investigate ways to reduce NSSI behavior. As a familial factor, parent-child conflict exerts a significant impact on adolescents’ NSSI. Meanwhile, researchers must direct their attention toward investigating the impact of emotional difficulties (such as depression) resulting from parent-child conflict on NSSI. Furthermore, there is a need for comprehensive exploration into the role of rumination thinking about both parent-child conflicts and depression to identify effective intervention programs aimed at mitigating NSSI among adolescents.

Parent-child conflict refers to the state of confrontation in which parents and their children internalize or externalize behaviors due to their cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and attitudinal incompatibilities, such as quarrels, disagreements, and physical conflicts between parents and children [7]. According to Masten and Garmezy, the parent-child relationship emerges as the primary influential factor contributing to children’s developmental challenges and psychopathological issues [8]. Considering that, there may be a significant impact of the parent-child relationship on NSSI. Parent-child conflict also has been confirmed to worsen levels of adolescent depression [9]. Meanwhile, Existing research has found that depression significantly increases the likelihood of NSSI [10]. Therefore, the current study aims to investigate the mediating role of depression between parent-child conflict and non-suicidal self-injury in adolescents.

Rumination thinking refers to a series of spontaneous and repetitive cognitive processes concerning negative events and emotions following exposure to adverse stressors [11]. When adolescents perceive parent-child conflict as a detrimental life event, individuals exhibiting high levels of rumination tend to engage in persistent and uncontrollable ruminative thinking regarding the parent-child conflict [12], thereby exacerbating the likelihood of experiencing negative affective states and increasing susceptibility to depression. Consequently, this study also aims to explore the moderating effect of rumination on the relationship between parent-child conflict and depression among adolescents.

The effect of parent-child conflict on NSSI in adolescents

Relevant studies have shown that parent-child conflict has an important impact on children’s social adaptation [13]. According to attachment theory, the absence of a strong parent-child relationship during early life can have long-term implications on an individual’s developmental trajectory [7]. Considering that family factors may be an important impactor on NSSI in adolescents [14]. According to self-reports from adolescents, parent-child conflict emerges as one of the most prevalent triggers for NSSI [15]. Researchers found that intense parent-child conflict leads to emotional depletion and impaired self-control resources in adolescents, thus making adolescents who are already low in self-control prone to impulsive choices of NSSI to cope with stress [16]. High levels of parent-child conflict may result in unmet relational needs among adolescents, thereby eliciting negative emotions and prompting the adoption of maladaptive patterns that contribute to NSSI [15]. Additionally, according to the four-function model of NSSI, NSSI is a means of regulating emotions, cognitive experiences, communicating with or influencing others, and the presence of distal risk factors (e.g., child maltreatment) that lead to problems with emotion regulation and interpersonal communication increases the likelihood of NSSI occurrence [17]. In summary, this study puts forward the following hypothesis 1: Parent-child conflict exerts positive influences on NSSI in adolescents.

The mediating effect of depression

Depression has become one of the emotional problems that threaten the emotions and the development of sociality of adolescents [18]. The researchers believe that abnormal family relationships (such as abuse or neglect) are important factors for producing depression [19]. Previous studies have demonstrated a positive association between parent-child conflict and the development of depression in offspring [20]. A longitudinal study with a 15-year follow-up period revealed that parent-child conflict significantly increased the risk of adult offspring experiencing depression [21].

Moreover, studies have shown depression has a positive relationship with NSSI in adolescents [10] and that is an important predictive and dangerous factor for self-injury [22]. The risk of adolescent self-injury increases with anxiety and depression issues [10]. In addition, the four-function model of NSSI indicated that four processes maintain NSSI (i.e., NSSI may reduce or divert attention from unpleasant thoughts or sensations; NSSI may generate desired feelings or stimuli; NSSI may provide relief from an undesirable social situation; NSSI may encourage seeking help) [17]. Therefore, to alleviate depression, individuals might engage in self-injurious behaviors. In addition, previous studies also have shown that a poor family environment can increase adolescents’ NSSI behavior by increasing their depression [10]. In summary, we propose the following hypothesis 2: Depression may play a mediating role in the relationship between parent-child conflict and NSSI.

The moderating effect of rumination thinking

Based on the response styles theory, when individuals face stressors, there mainly are three coping styles: problem-solving, attentional shifting, and rumination [11]. Rumination thinking is associated with worse problem-solving abilities in individuals [23,24], which is a maladaptive response style and a habitual tendency and response to depressive emotions, involving repetitive and passive self-focus rather than thinking about how to solve problems [25]. Related studies have shown that adolescents who experience negative events in childhood are more inclined to use repeated negative coping styles to deal with negative emotions [26].

Meanwhile, rumination thinking, as a negative response style that makes the attention of individuals passively focused on adverse events, is associated with individual maladjustment [23]. Individuals exhibiting rumination thinking are prone to form negative cognitive patterns and continue to process information negatively about themselves and the outside world when facing negative events, which will increase the risk of depression [27]. Considering that individuals exhibiting elevated levels of rumination after parent-child conflicts display compromised problem-solving abilities. In the process, sadness, anger, and other experiences are constantly aggravated, and they are immersed in it for a long time and unable to take effective action [28], thereby increasing the likelihood of depression. In summary, the following hypothesis 3 is proposed: Rumination thinking plays a moderating role in the effect of parent-child conflict on adolescents’ depression.

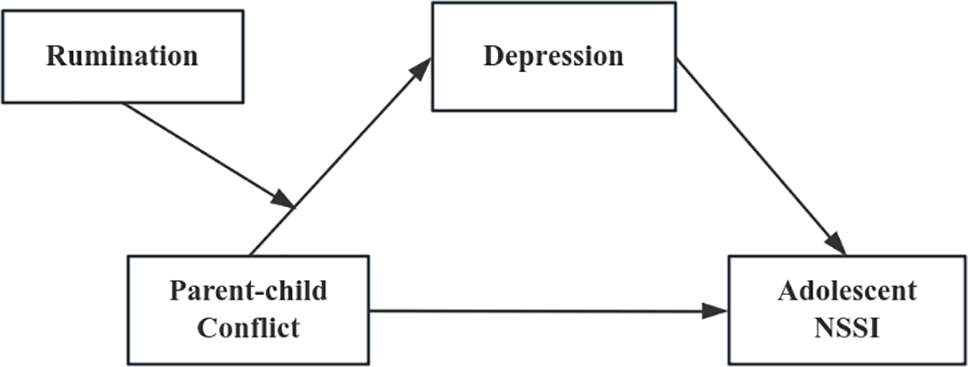

In summary, based on the four-function model of NSSI and response style theory, this study explored the effects of parent-child conflict on adolescent NSSI and its mediating (depression) and moderating (rumination thinking) mechanisms. These findings are intended to provide theoretical support and practical guidance for future research on reducing NSSI among adolescents. The hypothesis model diagram is shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Hypothesis model diagram.

The sample size was predetermined using Monte Carlo power analysis for indirect effects with a desired statistical power of 0.80 and a significance level of α = 0.05 [29]. Effect sizes derived from prior research were integrated to estimate the relationships between parent-child conflicts and NSSI (r = 0.28) [15], parent-child conflicts and depression (r = 0.39) [30], parent-child conflicts and rumination thinking (smallest effect size of r = 0.15), depression and NSSI (r = 0.40) [31], as well as rumination thinking and NSSI (r = 0.23) [32]. The results indicated that a total of 723 participants were required to adequately test the proposed model in this study, which employed a cluster sampling method. This study used a cluster sampling method, and 1240 adolescents were selected from four primary and secondary schools from Shandong Province, China as participants, and 13 of them were excluded for reasons such as not answering carefully. 1227 questionnaires were effectively recovered, and the recovery rate was 98.95% (male: 735, 59.90%; female: 492, 40.10%), the age distribution of the participants was 12–18 years old (13.11 ± 1.22).

Parent-adolescent conflicts were measured by the Family Environment Scale developed by Moos et al. [33], and Fang et al. revised the Chinese version [34]. The scale includes two dimensions of conflict intensity and frequency, a total of 16 items, such as, “In your academic aspects, such as homework score.” The scale was scored by Likert 5 points (frequency dimension: 1 = never happened, 5 = several times a day; intensity dimension: 1 = never happened, 5 = very intense), the higher the total score, the greater the parent-adolescent conflicts. In this study, Cronbach’s α of this scale was 0.880.

This study adopted the NSSI Scale developed by Feng [35]. The questionnaire consisted of 18 multiple-choice questions and 1 open question, such as, “Intentionally cut my skin with a glass, knife, etc.” The number of NSSI was scored by 3 points (0 = 0 times, 3 = 5 times or more), and the average injury degree to the body was scored by 5 points (0 = extremely light, 5 = extremely severe). The greater the cumulative score, the more severe the NSSI behavior. In this study, the Cronbach’s α of this scale was 0.962.

Ruminative responses were assessed using the Ruminative Responses Scale, originally developed by Nolen-Hoeksema et al. [36], and subsequently revised by Han et al. [37]. The scale comprises 22 items, such as “I frequently contemplate my feelings of fatigue and pain.” Ratings on the scale ranged from 1 (never) to 5 (always), with higher total scores indicating greater levels of ruminative responses. In this study, Cronbach’s α of this scale was 0.938.

The Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS-21), developed by Lovibond PF and Lovibond SH [38], was utilized in this study, with the Chinese version of DASS-21 being revised by Gong et al. [39]. The scale consists of 7 items, such as “I experience a lack of pleasure and comfort.” Responses were scored on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), where higher total scores indicate greater severity of depression. In this study, Cronbach’s α of this scale was 0.865.

The questionnaire method was employed in this study to collect scores on harsh parenting, depression, rumination thinking, and non-suicidal self-injury from participants on the SoJump platform. In addition, the procedures involving participants in this study were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards set by the Ethics Review Committee of Shangqiu Normal University and the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki [Ethics Approval Number: SQNU2005]. After obtaining informed consent from both participants and guardians, online questionnaire links were then sent to psychology staff who had received professional training for uniform distribution among students. Descriptive statistics (including the Mean and Standard Deviation), correlation analysis (the correlation relationship among variables), and reliability tests (Cronbach’s α of research instruments) were conducted using SPSS 26.0. Additionally, a moderated mediation model test (including path coefficient and the direct effect and indirect effect) was performed using PROCESS 3.3.

Control and test of common method biases

In this study, some items were expressed in reverse, and all questionnaires were filled in anonymously to control the possible common method bias in the test procedure. Moreover, the Harman single-factor test was employed to statistically examine the presence of common method biases [40]. The findings revealed that this study elucidated 14 factors with eigenvalues exceeding 1, accounting for a total variance interpretation of 68.248%. Notably, the first factor explained only 30.003% of the variance, which falls below the threshold of 40%. Consequently, it can be concluded that there is no significant evidence of common method biases in this study.

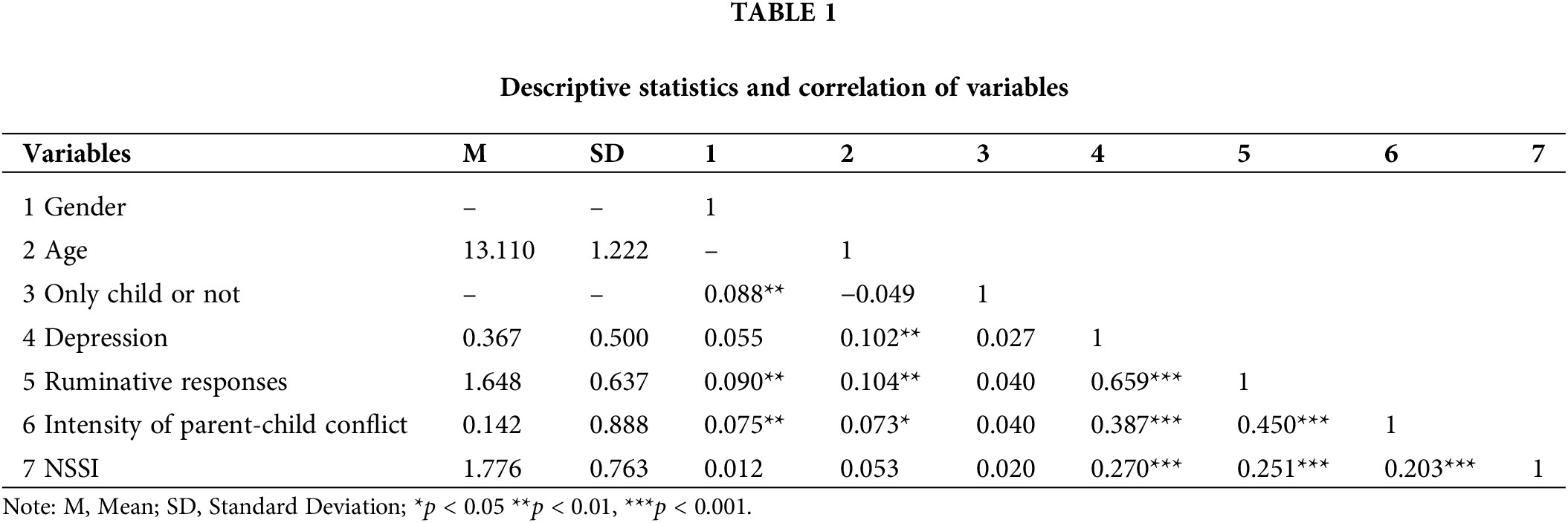

Descriptive statistics and correlation of variables

The results of correlation analysis showed that the intensity of parent-adolescent conflicts was significantly positively correlated with depression (r = 0.387, p < 0.001) and NSSI (r = 0.203, p < 0.001). And depression positively relates to the NSSI (r = 0.270, p < 0.001). The results are shown in Table 1.

Moderated mediation model testing

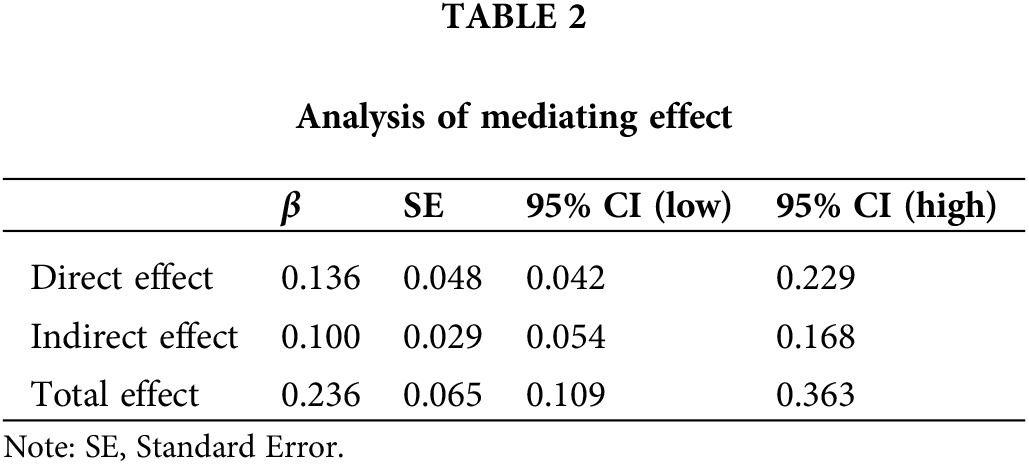

The current study used the PROCESS model 7 to test the moderated mediation model, and the results showed that parent-child conflicts significantly impacted NSSI (β = 0.117, t = 2.845, p < 0.001), and depression (β = 0.382, t = 10.296, p < 0.001), depression significantly affected NSSI (β = 0.225, t = 4.321, p < 0.01). In addition, the direct effect of parent-adolescent conflicts on NSSI was 0.136, and the bootstrap 95% CI was [0.042, 0.229]; the indirect effect of depression on parent-adolescent conflicts and NSSI was 0.1, and the bootstrap 95% CI was [0.054, 0.168]. It is suggested that depression was a mediating mechanism of parent-child conflict and adolescents’ NSSI (see Table 2).

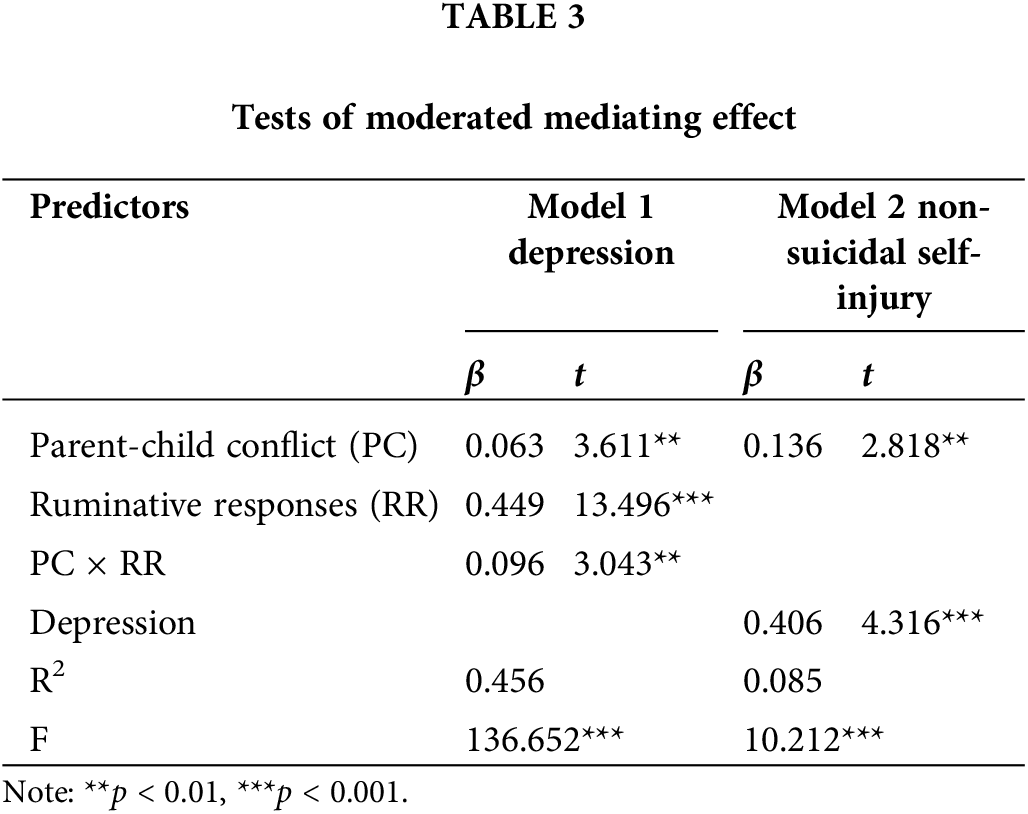

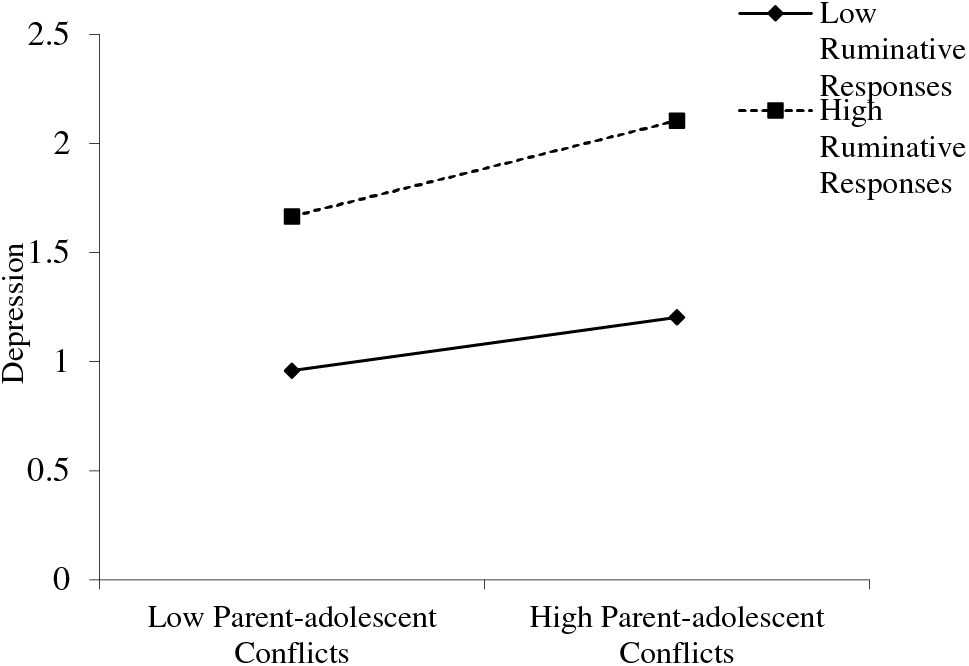

In addition, ruminative responses significantly impacted depression (β = 0.449, p < 0.001), and the interaction between parent-child conflict and ruminative responses significantly impacted depression (β = 0.096, p < 0.01). Ruminative responses may as a moderating mechanism of parent-adolescent conflicts on depression (see Table 3). Further simple slope analysis revealed a significant positive effect of parent-child conflict on depression among individuals with high rumination responses, simple slope = 0.289, t = 2.467, p = 0.014; for participants with low ruminative responses, the effect of parent-adolescent conflicts on depression was not significant, simple slope = 0.161, t = 1.617, p = 0.106, which indicated that with the improvement of individual ruminative responses, the influence of parent-child conflict on depression showed a gradually increasing trend (see Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Simple slope analysis.

The findings of the present study indicated that parent-child conflict had a positive effect on adolescents’ NSSI, which supports hypothesis 1. To a certain extent, this supports previous speculations about the influence of parent-child relationships on NSSI in adolescents, suggesting that the parent-child relationship is one of the most important interpersonal relationships for adolescents and that negative parent-child relationships increase the likelihood of NSSI [15]. The findings also further refine the four-function model of NSSI, which posits that NSSI serves as a mechanism for emotion regulation, cognitive processing, and interpersonal communication or influence [17]. Adolescents with negative parent-child relationships may harbor negative beliefs or maladaptive schemas, thereby placing them at an elevated risk of engaging in NSSI [15]. Furthermore, the act of participating in NSSI could serve as a coping mechanism for adolescents seeking to escape from oppressive, conflicting, or abusive circumstances [17]. Consequently, it is more probable for adolescents to resort to NSSI following experiences of parent-child conflict.

Meanwhile, the study revealed that depression serves as a mediating factor between parent-child conflict and NSSI in adolescents, thereby supporting hypothesis 2. Specifically, it was found that a negative family environment significantly predicts NSSI through the intermediary influence of depressive symptoms [22]. Previous studies have found that poor quality of attachment to parents, harsh punishment from parents, and low perception of social support are strongly associated with depression and other internalizing problems that predict self-injury behavior [41]. Additionally, existing research also found that family-relevant factors could increase adolescents’ NSSI by triggering their depression [30]. Adolescents growing up in dysfunctional or adverse family environments characterized by frequent parental conflicts are more prone to experiencing depression. This can lead to the adoption of maladaptive coping strategies due to a perceived lack of familial support, ultimately resulting in NSSI [42].

In addition, the study has also revealed that rumination thinking moderates the relationship between parent-child conflict and adolescents’ depression, thereby supporting hypothesis 3. This finding further substantiates the notion that rumination thinking could increase the possibility of experiencing depression after going through a negative event [43]. Previous research has demonstrated that rumination thinking moderates the process of depression induced by negative factors. For example, it can moderate the association between the excessive utilization of mobile phones/social networks and depression [44]. Moreover, these findings provide additional evidence to support the reactive style theory, suggesting that rumination serves as a pivotal vulnerability factor in the process of worsening depression [27], amplifying negative thinking patterns while impeding problem-solving abilities and eroding social support networks. Consequently, this may lead to greater maladjustment and exacerbate the likelihood of experiencing depressive symptoms [25]. Therefore, in the current study, parent-child conflict as a negative event for adolescents experiencing, individuals with high rumination thinking living in the environment of parent-child conflict, may have a higher likelihood of manifesting symptoms indicative of depression because the repeated negative thinking about the scenario of conflicts occurred between parents and themselves [12].

Firstly, the findings of various studies indicate that there is a positive correlation between parent-child conflict and the occurrence of NSSI behaviors among adolescents. This indicates that negative family relationships or family atmospheres have a detrimental impact on adolescent development. The family is the first place of individual socialization, parents are the initial and most important agents of socialization of children [45]. The family environment and the way parents treat their children can have a profound and lasting effect on adolescents. Therefore, parents need to tailor their parenting to their children’s needs, use more moderate intervention strategies, give their children a degree of autonomy, reduce the chances of parent-child conflict erupting, and create a positive family atmosphere [46], and reduce the likelihood of adolescents engaging in NSSI.

Furthermore, this study unveiled the mediating role of depression in the association between parent-child conflict and adolescent NSSI. Therefore, schools should prioritize students experiencing parent-child conflict or strained family relationships, create a conducive classroom environment, enhance support and care from teachers and peers for depressed students, and maintain frequent communication with students. These measures effectively reduce depression levels and prevent the development of NSSI in individuals facing parent-child conflict. In addition, schools should also consciously cultivate students’ psychological resilience, carry out group counseling, and educate students to vent their emotions reasonably to improve their mental health.

Finally, the present study further elucidated the moderating role of rumination thinking in the association between parent-child conflict and depression. The susceptibility of students to the influence of parent-child conflict, resulting in higher levels of depression, is particularly pronounced among those with elevated levels of rumination thinking. Therefore, schools should promptly screen students with high levels of rumination thinking, provide timely and positive psychological guidance or counseling, and offer better strategies for dealing with negative events. This will help prevent individuals with high levels of rumination thinking from increasing their levels of depression due to their inability to positively resolve the negative emotions caused by parent-child conflict.

Limitations and Future Prospects

Firstly, in terms of data collection methods, the study used a self-report method to collect all variables, which may be affected by social approval effects, etc. It is necessary to consider collecting data from different subjects simultaneously in the future, such as parental self-report data.

Secondly, the study design employed a cross-sectional approach, which limited the ability to establish a causal relationship between parent-child conflict and NSSI among adolescents. Therefore, trying to use longitudinal study design or situational experiment-induced methods in the future can better reflect the causal relationship between the two.

Finally, in terms of research content, this study explored the mediating mechanism of depression, which is a negative factor. However, we can lower the incidence of NSSI by alleviating the level of depression. Depression occurs in students and still has an impact on teenagers’ NSSI. Future research should therefore investigate positive mediating mechanisms or protective factors, such as the meaning of life, to offer additional strategies for preventing or mitigating NSSI among adolescents.

The relationship between parent-child conflict and NSSI in adolescents is positively correlated. Depression acts as a mediator in the association between parent-child conflict and NSSI in adolescents. The mediating effect of parent-child conflict on NSSI through depression is positively moderated by rumination thinking. Additionally, low-level rumination thinking may mitigate the negative impact of parent-child conflict on depression.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: The author received no specific funding for this study.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: The procedures involving participants in this study were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards set by the Ethics Review Committee of Shangqiu Normal University and the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki (Ethics Approval Number: SQNU2005).

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Syed S, Kingsbury M, Bennett K, Manion I, Colman I. Adolescents’ knowledge of a peer’s non-suicidal self-injury and own non-suicidal self-injury and suicidality. Acta Psychiat Scand. 2020;142(5):366–73. doi:10.1111/acps.v142.5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Muehlenkamp JJ, Claes L, Havertape L, Plener PL. International prevalence of adolescent non-suicidal self-injury and deliberate self-harm. Child Adolesc Psychiat Ment Health. 2012;6:10. doi:10.1186/1753-2000-6-10. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Misiak B, Szewczuk-Bogusławska M, Samochowiec J, Moustafa AA, Gawęda Ł. Unraveling the complexity of associations between a history of childhood trauma, psychotic-like experiences, depression and non-suicidal self-injury: a network analysis. J Affect Disord. 2023;337:11–7. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2023.05.044. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Georgiades K, Boylan K, Duncan L, Wang L, Colman I, Rhodes AE, et al. Prevalence and correlates of youth suicidal ideation and attempts: evidence from the 2014 Ontario Child Health Study. Can J Psychiat. 2019;64(4):265–74. doi:10.1177/0706743719830031. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Herzog S, Choo TH, Galfalvy H, Mann JJ, Stanley BH. Effect of non-suicidal self-injury on suicidal ideation: real-time monitoring study. Br J Psychiat. 2022;221(2):485–7. doi:10.1192/bjp.2021.225. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Wang L, Liu J, Yang Y, Zou H. Prevalence and risk factors for non-suicidal self-injury among patients with depression or bipolar disorder in China. BMC Psychiat. 2021;21:389. doi:10.1186/s12888-021-03392-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Kindsvatter A, Desmond KJ. Addressing parent-child conflict: attachment-based interventions with parents. J Counsel Develop. 2013;91(1):105–12. doi:10.1002/jcad.2013.91.issue-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Masten AS, Garmezy N. Risk, vulnerability, and protective factors in developmental psychopathology. In: Advances in clinical child psychology. Boston, MA, USA: Springer US; 1985. p. 1–52. [Google Scholar]

9. Low YTA. Family conflicts, anxiety and depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation of Chinese adolescents in Hong Kong. Appl Res Qual Life. 2021;16(6):2457–73. doi:10.1007/s11482-021-09925-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Gao YH, Wang YC, Wang ZP, Ma MZ, Li HJ, Wang JH, et al. Family intimacy and adaptability and non-suicidal self-injury: a mediation analysis. BMC Psychiat. 2024;24:210. doi:10.1186/s12888-024-05642-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Nolen-Hoeksema S. Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of depressive episodes. J Abnorm Psychol. 1991;100(4):569–82. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.100.4.569. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Baumeister RF, Vohs KD, Nathan DeWall C, Zhang L. How emotion shapes behavior: feedback, anticipation, and reflection, rather than direct causation. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2007;11(2):167–203. doi:10.1177/1088868307301033. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Lee JK, Marshall AD, Feinberg ME. Parent-to-child aggression, intimate partner aggression, conflict resolution, and children’s social-emotional competence in early childhood. Fam Process. 2022;61:823–40. doi:10.1111/famp.v61.2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Zhou S, Zhou Z, Tang Q, Yu P, Zou HJ, Liu Q, et al. Prediction of non-suicidal self-injury in adolescents at the family level using regression methods and machine learning. J Affect Disord. 2024;352:67–75. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2024.02.039. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Zou HY, Chen ZY, Huo LJ, Kong XH, Ling CY, Wu WC, et al. The effects of different types of parent-child conflict on non-suicidal self-injury among adolescents: the role of self-criticism and sensation seeking. Curr Psychol. 2024;43:21019–31. doi:10.1007/s12144-024-05869-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Tarantino N, Lamis DA, Ballard ED, Masuda A, Dvorak RD. Parent-child conflict and drug use in college women: a moderated mediation model of self-control and mindfulness. J Couns Psychol. 2015;62(2):3030–313. [Google Scholar]

17. Nock MK. Why do people hurt themselves? New insights into the nature and functions of self-injury. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2009;18(2):78–83. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01613.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Park S, Kim BN, Park MH. The relationship between parenting attitudes, negative cognition, and the depressive symptoms according to gender in Korean adolescents. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2016;10(1):35. doi:10.1186/s13033-016-0069-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Liu Y, Merritt DH. Examining the association between parenting and childhood depression among Chinese children and adolescents: a systematic literature review. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2018;88:316–32. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.03.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Jiang S, Du RY, Jiang CX, Tan SL, Dong ZY. Family conflict and adolescent depression: examining the roles of sense of security and stress mindset. Child & Family Social Work. 2024;52(10):717. doi:10.1111/cfs.13170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Alaie I, Låftman SB, Jonsson U, Bohman H. Parent-youth conflict as a predictor of depression in adulthood: a 15-year follow-up of a community-based cohort. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiat. 2020;29:527–36. doi:10.1007/s00787-019-01368-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Jacobson CM, Hill RM, Pettit JW, Grozeva D. The association of interpersonal and intrapersonal emotional experiences with non-suicidal self-injury in young adults. Arch Suicide Res. 2015;19(4):401–13. doi:10.1080/13811118.2015.1004492. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Park H, Kuplicki R, Martin P, Paulus MP, Guinjoan SM. Rumination and overrecruitment of cognitive control circuits in depression. Biol Psychiat Cogn Neurosci Neuroimag. 2024;9(8):800–8. [Google Scholar]

24. Yu TX, Hu JS, Zhao JY. Childhood emotional abuse and depression symptoms among Chinese adolescents: the sequential masking effect of ruminative thinking and deliberate rumination. Child Abuse Negl. 2024;154:106854. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2024.106854. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Nolen-Hoeksema S, Wisco BE, Lyubomirsky S. Rethinking rumination. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2008;3(5):400–24. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00088.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Sarin S, Nolen-Hoeksema S. The dangers of dwelling: an examination of the relationship between rumination and consumptive coping in survivors of childhood sexual abuse. Cogn Emot. 2010;24(1):71–85. doi:10.1080/02699930802563668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Beck AT. The evolution of the cognitive model of depression and its neurobiological correlates. Am J Psychiat. 2008;165(8):969–77. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08050721. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Lyubomirsky S, Tkach C. The consequences of dysphoric rumination. In: Papageorgiou C, Wells A, editors. Depressive rumination: nature, theory and treatment. UK: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.; 2003. p. 21–41. [Google Scholar]

29. Schoemann AM, Boulton AJ, Short SD. Determining Power and sample size for simple and complex mediation models. Soc Psychol Personal Sci. 2017;8(4):379–86. doi:10.1177/1948550617715068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Liu JM, Liu X, Wang H, Gao YM. Harsh parenting and non-suicidal self-injury in adolescence: the mediating effect of depressive symptoms and the moderating effect of the COMT Val158Met polymorphism. Child Adolesc Psychiat Ment Health. 2021;15(1):70. doi:10.1186/s13034-021-00423-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Liu SJ, Qi Q, Zeng ZH, Hu YQ. Cumulative ecological risk and nonsuicidal self-injury in adolescents: the mediation of depression and the moderation of impulsiveness. Child Care Health Dev. 2024;50(1):e13211. doi:10.1111/cch.v50.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Cheung JC, Sorgi-Wilson KM, Ciesinski NK, McCloskey MS. Examining the relationship between subtypes of rumination and non-suicidal self-injury: a meta-analytic review. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2024;54(3):528–55. doi:10.1111/sltb.v54.3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Moos R, Moos B. A typology of family social environment. Fam Process. 1976;15:357–71. doi:10.1111/famp.1976.15.issue-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Fang XY, Zhang JT, Liu Z. Parent-adolescent conflicts. Psychol Dev Educ. 2003;19(3):46–52 (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

35. Feng Y. The relationship between adolescent self-harm behavior and emotional factors and family environment factors (Ph.D. Thesis). Central China Normal University: China; 2008 (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

36. Nolen-Hoeksema S, Morrow J. A prospective study of depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms after a natural disaster: the 1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1991;61(1):115. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.61.1.115. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Han X, Yang HF. Chinese version of nolen-hoeksema ruminative responses scale (RRS) used in 912 college students: reliability and validity. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2009;17(5):550–1+49 (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

38. Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH. The structure of negative emotional states: comparison of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) with the beck depression and anxiety inventories. Behav Res Ther. 1995;33(3):335–43. doi:10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-U. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Gong X, Xie Y, Xu R, Luo Y. Psychometric properties of the Chinese versions of DASS-21 in Chinese college students. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2010;18(4):443–6 (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

40. Zhou H, Long L. Statistical remedies for common method biases. Adv Psychol Sci. 2004;12(6):942–50 (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

41. Wang DW, Zhou MM, Hu YX. The relationship between harsh parenting and smartphone addiction among adolescents: serial mediating role of depression and social pain. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2024;17:735–52. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S438014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Bronfenbrenner U. Ecology of the family as a context for human development: research perspectives. Dev Psychol. 1986;22(6):723–42. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.22.6.723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Nolen-Hoeksema S, Stice E, Wade E, Bohon C. Reciprocal relations between rumination and bulimic, substance abuse, and depressive symptoms in female adolescents. J Abnorm Psychol. 2007;116(1):198–207. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.198. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Elhai JD, Tiamiyu M, Weeks J. Depression and social anxiety in relation to problematic smartphone use: the prominent role of rumination. Internet Res. 2018;28(2):315–32. doi:10.1108/IntR-01-2017-0019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Bureau JF, Martin J, Freynet N, Poirier AA, Lafontaine MF, Cloutier P. Perceived dimensions of parenting and non-suicidal self-injury in young adults. J Youth Adolesc. 2010;39:484–94. doi:10.1007/s10964-009-9470-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Vasquez AC, Patall EA, Fong CJ, Corrigan AS, Pine L. Parent autonomy support, academic achievement, and psychosocial functioning: a meta-analysis of research. Educ Psychol Rev. 2016;28:605–44. doi:10.1007/s10648-015-9329-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools