Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Cultural Adaptation of the Mental Health Literacy Scale

1 Department of Community Mental Health, University of Haifa, Haifa, 2510500, Israel

2 School of Social Work, Zefat Academic College, Zefat, 1310401, Israel

3 Behavioral Science, Netanya Academic College, Netanya, 4223587, Israel

* Corresponding Author: Anwar Khatib. Email:

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(1), 19-28. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2024.057925

Received 31 August 2024; Accepted 06 November 2024; Issue published 31 January 2025

Abstract

Background: Mental health literacy (MHL) refers to one’s knowledge and understanding of mental health disorders and their treatments. This literacy may be influenced by cultural norms and values that shape individuals’ experiences, beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors regarding mental health. This study focuses on adapting the Mental health literacy scale (MHLS) for use in the multicultural context of Israel. Objectives include validating its construct, assessing its accuracy in measuring MHL in this diverse setting and examining and comparing levels of MHL across different cultural groups. Methods: The data collection included 1057 participants, representing all the ethnic groups of the Israeli population aged 18 and over. The tools included the MHLS and a demographic questionnaire. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was employed to assess the original structure of the MHLS. Results: The results revealed that after evaluating the original MHLS, five items were excluded, leading to the validation of a modified version—Israeli mental health scale (IMHLS) with four factors and 25 items. CFA and reliability analyses supported an established and robust four-factor model. Significant ethnic differences in MHLS scores were identified, with Muslim participants showing the highest familiarity with mental disorders, followed by Druze and Christian participants, while Jewish participants had the lowest familiarity. Conclusion: The study concluded that the IMHLS is a valid and reliable tool for assessing MHL in Israel’s diverse and multicultural population. The revised scale better reflects the cultural nuances of the Israeli context. The significant ethnic differences that the study revealed in IMHLS emphasize the importance of culturally sensitive mental health interventions tailored to different ethnic groups in Israel.Keywords

Mental disorders are a significant public health issue. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), approximately 1 in 8 people worldwide will experience a mental health problem at some point in their lives [1]. An assessment conducted in 2020, in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, revealed a 28% increase in the incidence of anxiety and major depression [2,3].

The increasing prevalence of mental problems worldwide indicates the need to take measures to prevent the development of mental disorders. Furthermore, the WHO has called for increased investment in mental health care to reduce the global burden of mental illness [1]. Indeed, early detection of disorders leads to early interventions and increases the probability of successful treatment outcomes [4,5].

One of the relevant resources for the prevention of mental health problems is mental health literacy (MHL). The term “mental health literacy” refers to the knowledge and understanding that individuals have about mental health issues, which can include recognizing signs and symptoms of mental health disorders, knowing how to seek help and support, and understanding the available treatment options. It is an important aspect of overall health literacy, as mental health plays a significant role in overall well-being [6,7].

The most widespread tool for assessing MHL is the Mental Health Literacy Scale (MHLS), developed by researchers in Australia [8]. The measure was built based on the most comprehensive and popular conceptual framework of MHL [8]. This self-report measure includes 35 items across six dimensions, namely ‘The ability to identify mental disorders’; ‘The knowledge of the risk factors and aspects related to the development of mental disorders’; ‘Knowledge of self-care’; ‘Knowledge regarding available professional help’; ‘Knowing where to look for information’; and ‘Attitudes that promote recognition or appropriate behavior for asking for help’. The psychometric properties of this instrument have shown adequate levels of validity and internal consistency [8].

Like all self-report psychometric tools, especially in the domain of mental health, it has also been found that these dimensions may be affected by cultural factors [9]. Indeed, cultural norms and values can shape people’s experiences and influence beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors regarding mental health problems [9]. The intercultural variation in values and norms about the phenomenon of mental health problems creates variations in the understanding of the phenomenon, the level of stigma associated with mental illness, the factors attributed to the development of the disorders, and the ways of treating them [7].

Different cultural norms may prescribe different behaviors in the dimensions of the MHLS. For example, in the dimensions of the ability to identify mental disorders and knowledge of the risk factors and factors related to the development of mental disorders, Western cultures can identify disorders based on the scientific medical body of knowledge [10], and they treat mental disorders as they would physical illnesses. However, in traditional religious cultures, it can be difficult to recognize mental disorders as a disease, and they may be treated as supernatural phenomena or attributed to demons, spirits, weakness, or a lack of belief in God [11].

The dimension of self-care knowledge and support provided by the family may also differ across cultures [10]. Furthermore, in Western cultures, knowledge about available professional help and where to seek information is more accessible, whereas traditional and less developed cultures often lack services or have limited access to them [12]. In Western cultures, mental help is sought from conventional therapists, while traditional cultures may seek help from religious figures or traditional healers who use alternative treatments [9]. In terms of attitudes that promote recognition and appropriate behavior in seeking help, liberal cultures tend to have fewer stigmatizing attitudes towards mental illness, which facilitates better recognition and easier access to professional help. In contrast, cultures with more stigmatizing attitudes may face challenges in recognizing mental health issues and seeking professional help [11,9]. Due to the differences in intercultural values and norms, assessing MHL in different cultures requires culturally sensitive and adapted measurement tools.

Israel is a multicultural and pluralistic society composed of two ethnic national groups: Jews and Arabs. Arabs constitute about 21% of Israel’s population [13]. Compared to Jewish society, which is considered Western, liberal, and individualistic, Arab society is regarded as more traditional, collectivist, and conservative [14,15]. Additionally, within the Arab minority, there are different groups, such as Muslims, Christians, and Druze which have different histories, cultures, and religions as well as relation to the majority Jewish group. This population tends to utilize mental health services less than Jews [16], despite showing a higher prevalence of mental health problems [17]. The reasons behind these higher rates are not always clear, but they may be attributed to cultural factors, lack of self-care knowledge [15], limited availability of services [17], attitudes that discourage recognition and help-seeking behavior [18,19], or underutilization and under availability of services [19]. Other general cultural factors may also contribute [20].

Given these cultural differences within Israeli society regarding mental health, mental illnesses, and treatment methods, it is necessary to evaluate and adapt the MHLS within a multicultural context. Therefore, the aim of the current study is to assess the validity, internal consistency and factorial structure of the original MHLS within the Israeli population. We shall also present an adapted version of the scale IMHLS reflecting the new factorial structure within the Israeli context. Additionally, the study aims to examine potential differences between Jews and Arabs-including its subcultures, in terms of scale indicators, providing a more comprehensive understanding of MHL differences between these ethnic groups.

This cross-sectional study was conducted in 2022 with 1057 individuals from the general population. This study received approval from the Ethics Committee of Zefat Academic College (IRB number: 8-2022). Written consent was acquired from the participants. The inclusion criteria for the study were as follows: (a) being over the age of 18, (b) holding Israeli citizenship, and (c) not having a diagnosed mental disorder. An information sheet was distributed through social networks such as WhatsApp, Facebook, and Instagram describing the objectives and scope of the study and inviting individuals to participate. Participants who agreed to participate were provided with a web link to access the questionnaires. The online survey (Using the Qualtrics platform) began with a description of the study’s purpose and the contact details of the researchers. The online questionnaires were pretested with 20 participants. It took approximately 30 min to complete, and minor revisions were made based on the pretest participant’s feedback. Between January 2022 and July 2022, a total of 1057 adult Israeli citizens agreed to participate in the study and completed all the questionnaires.

The data collection tools included a demographic section and the original MHLS. The questionnaire was administered in Hebrew or Arabic, based on participants’ choice. As the main language in Israel is Hebrew’ most Arab citizens learn and speak/read Hebrew from very early on. The vast majority of the participants in this study chose the Hebrew version of the questionnaire. Those who chose the Arabic version were not identified.

This questionnaire included questions regarding age, gender, marital status, whether the participant has minor children (yes/no), ethnicity (Jewish, Muslim, Christian, and Druze), level of religiosity (religious, partly religious, and secular), years of education, employment status (yes/no), type of residence (urban, rural).

The MHLS assesses all the attributes of MHL. The MHLS was constructed over three key stages, using a comprehensive methodological approach including measure development, pilot testing, and assessment of psychometrics and methodological quality. It is a 35-item organized into six dimensions that is easily administered and scored. All 35 items were rated on a Likert scale [8]. The original six dimensions of the MHLS are as follows:

1. Recognition of Mental Disorders: An inquiry could be, “To what degree do you believe personality disorders should be classified as a type of mental illness?” (eight items).

2. Understanding of Risk Factors and Causes: For instance, “To what extent do you believe that, in general, women in Israel are more susceptible to experiencing mental illnesses than men?” (two items).

3. Awareness of Self-Management Strategies: An example might be, “How beneficial do you think improving sleep quality could be for someone struggling to manage their emotions?” (two items).

4. Familiarity with Available Professional Treatments: A question could be, “To what degree do you think cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) focuses on challenging negative thoughts and promoting positive behaviors?” (three items).

5. Knowledge of Information Resources: For example, “I feel confident in my ability to identify reliable sources of information regarding mental health issues.” (four items).

6. Attitudes Supporting Help-Seeking Behavior: An example statement could be, “Visiting a mental health professional signifies a lack of strength in handling personal challenges.” (16 items-reverse scored).

All items were rated on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (very unlikely) to 5 (very likely), 1 (very unhelpful) to 5 (very helpful), or 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The items in each factor are summed, and there is also a total score, with a higher score representing a higher level of MHL. The scale was translated from English into Hebrew and Arabic using a back-and-forth translation process.

The original MHLS structure and the modified Israeli version (IMHLS) were subjected to data analysis. SPSS and AMOS, version 29.0, were used for the analysis. A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted with maximum likelihood estimation, for the original scale structure using structural equation modeling (SEM). The fit measures considered were the normed fit index (NFI), non-normed fit index (NNFI), comparative fit index (CFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). Based on the results obtained for the original MHLS, the CFA was then recalculated for a revised version of the scale (IMHLS). Due to the use of the forced-choice option, no missing values were obtained. Internal consistency was assessed using Cronbach’s α and McDonald’s omega (ω) [21]. Descriptive statistics were calculated for the IMHLS scales. To examine differences by ethnicity which was determined by the participant himself in the demographic questionnaire (Jewish, Muslim, Christian, Druze), a multivariate analysis of covariance was performed. Post hoc tests utilized estimated marginal means, with the Bonferroni adjustment applied for multiple comparisons. Considering the large sample size, the significance level (α) was set at a minimum of 0.001 to avoid inflation. Moreover, minimal effect sizes were defined to identify meaningful differences and relationships: η2 ≥ 0.02 and Pearson’s r ≥ 0.15 (or ≤−0.15). This definition of minimal effect sizes aligns with the work of Cohen [22], Hattie [23], and Lenhard et al. [24]. No missing values were found.

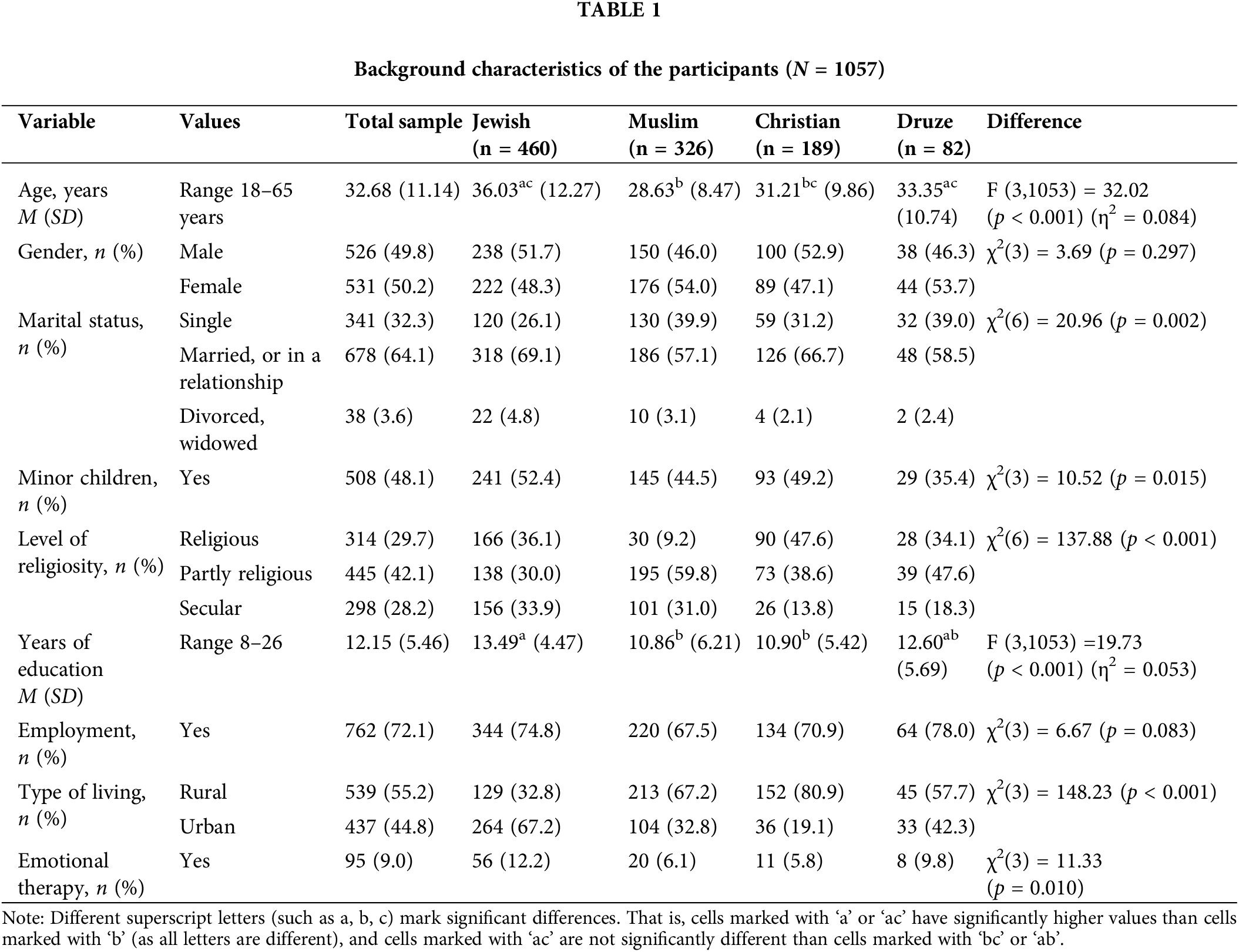

The participants consisted of approximately equal numbers of males and females, with an average age of 33, and average of 12.15 years of education, 55.2% (762) live in a rural area and 44.8% (437) live in an urban area. The religious affiliations were 43% Jewish (n = 460), 31% Muslim (n = 326), 18% Christian (n = 189), and 8% Druze (n = 82). The demographic characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1.

CFA for MHLS and the modified IMHLS

The CFA was conducted to assess the construct validity of the MHLS and the Modified MHLS (Israeli) version. The CFA for the original scale, consisting of six factors, resulted in an inadequate fit (NFI = 0.760, NNFI = 0.765, RMSEA = 0.073, CFI = 0.787). Analysis of the item loadings revealed that the reversed item 10 (“To what extent do you think it is likely that in general, men are more likely to experience an anxiety disorder compared to women”) had a negative loading on the ‘Knowledge of risk factors and causes’ factor. Similarly, the reversed item 12 (“To what extent do you think it would be helpful for someone to avoid all activities or situations that made them feel anxious if they were having difficulties managing their emotions”) loaded negatively on the ‘Knowledge of self-treatment’ factor. Additionally, the reversed item 15 (“Mental health professionals are bound by confidentiality; however, there are certain conditions under which this does not apply. To what extent do you think it is likely that the following is a condition that would allow a mental health professional to break confidentiality: if your problem is not life-threatening and they want to assist others to better support you”) had a negative loading on the ‘Knowledge of professional help available’ factor. Moreover, the reversed item 20 (“People with a mental illness could snap out of it if they wanted”) had a loading of 0.03 on the ‘Attitudes that promote recognition or appropriate help-seeking behavior’ factor. These four items were subsequently removed from the analysis.

Furthermore, as items 9 and 11 remained in their respective factors and exhibited a high correlation (r = 0.80) with the ‘Ability to recognize disorders’ factor, they were incorporated into it. The revised model consisted of four factors, totaling 31 items, and the CFA was rerun. However, the model still demonstrated an insufficient fit: NFI = 0.773, NNFI = 0.776, RMSEA = 0.078, CFI = 0.797. Upon further examination, it was observed that the ‘Knowledge of professional help available’ factor (items 13 and 14) had a high correlation (r = 0.88) with the ‘Ability to recognize disorders’ factor. Consequently, these two items were included in the latter factor. Additionally, the reversed items 21 to 28, originally part of the ‘Attitudes that promote recognition or appropriate help-seeking behavior’ factor, exhibited low loadings (0.11 to 0.35) on the latent factor, while the items pertaining to Social Openness to mental illness (29 to 35) demonstrated high loadings (0.58 to 0.85) on that factor. Consequently, these two sets of items were separated into two latent factors: attitudes and Social Openness to mental illness. The resulting model had a fit of: NFI = 0.862, NNFI = 0.880, RMSEA = 0.057, CFI = 0.889, SRMR = 0.064, with the latent factors correlating at r = 0.03 to r = 0.28).

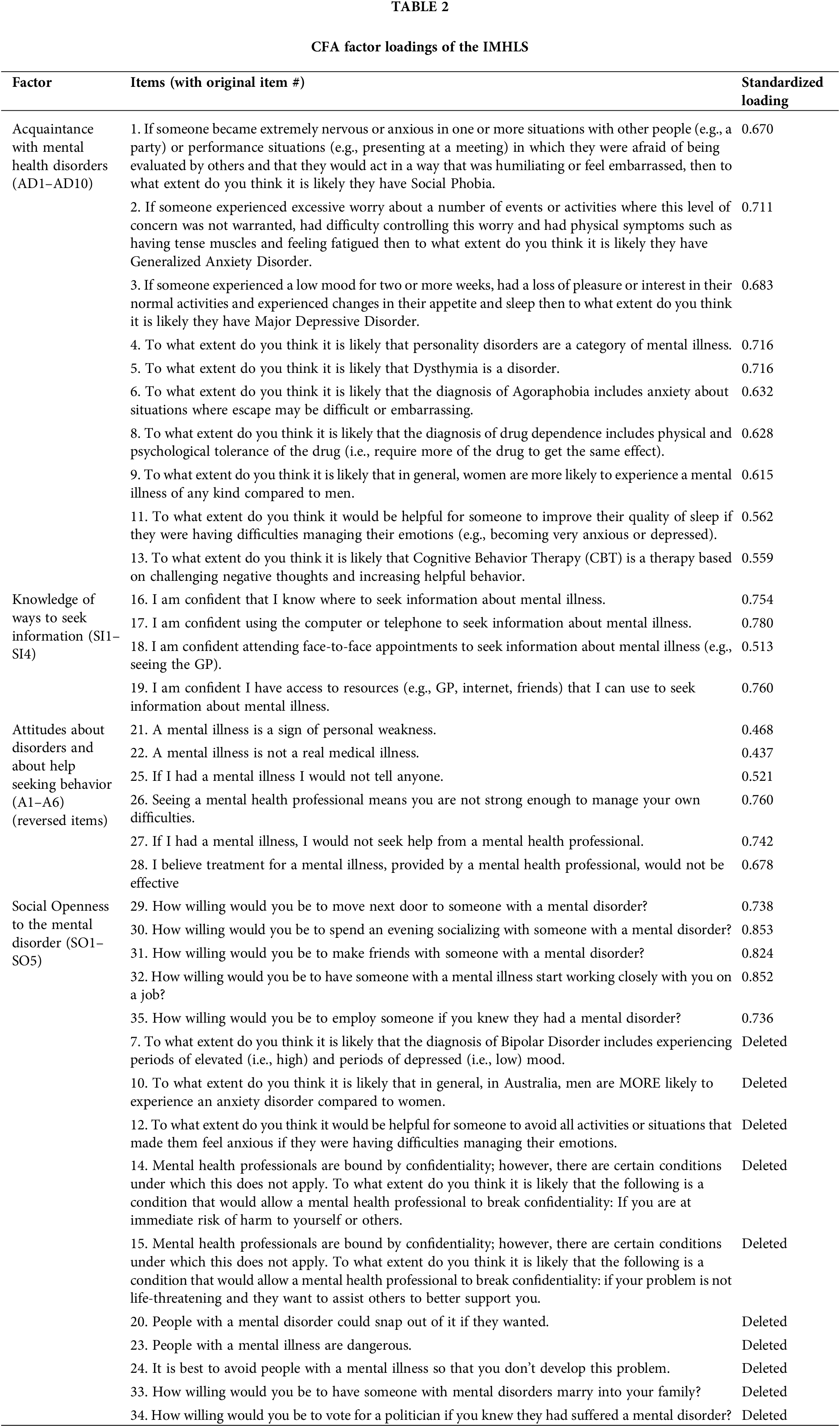

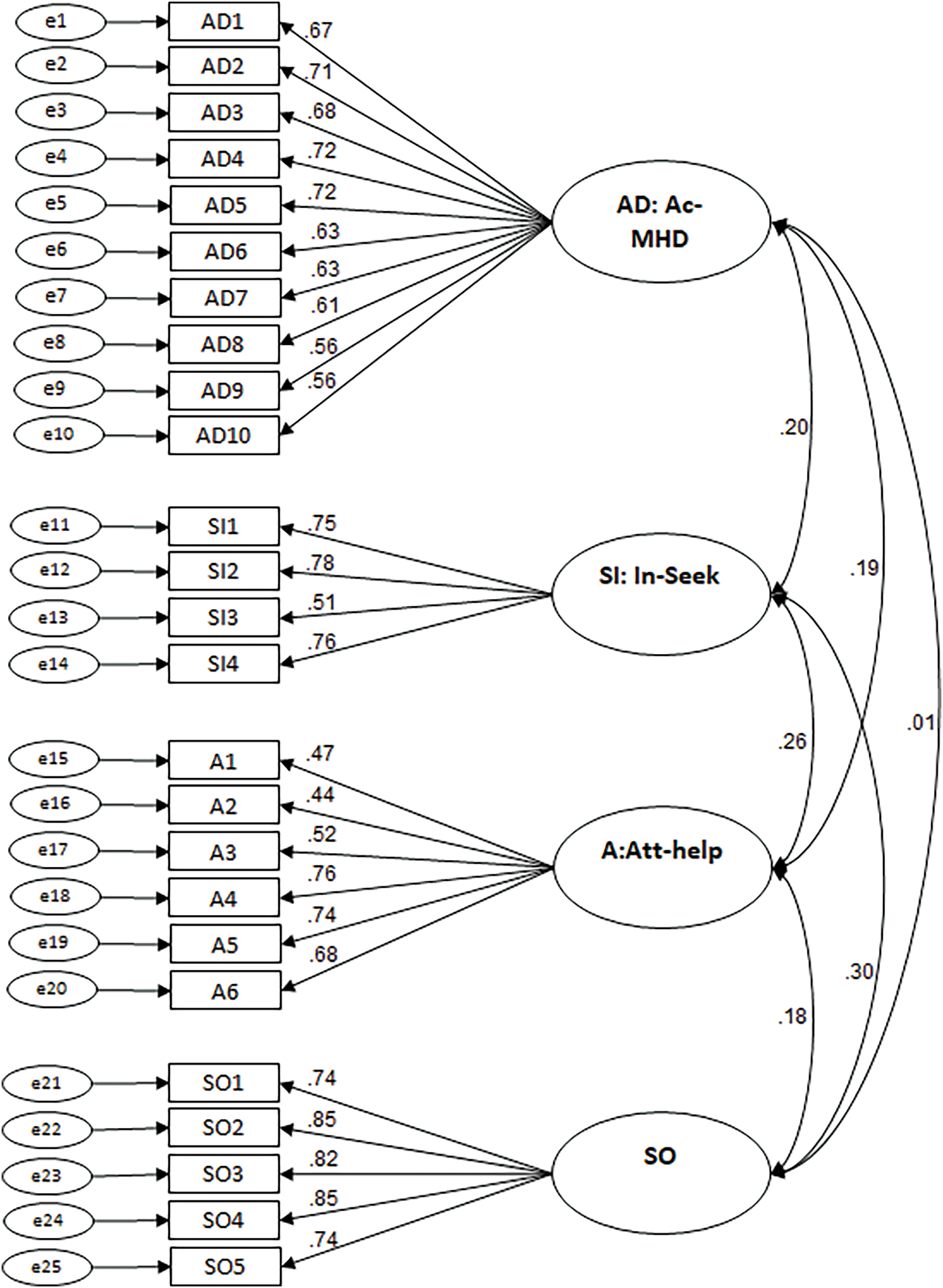

Next, the standardized residual covariances were examined. As the standard threshold value is ±3 [25], several items were found to have irregular values. Items 7, 14, 23, 24, 33, and 34 had higher values, ranging between −5.60 to 6.84 (grand absolute value mean = 2.38). Upon their removal the final MHLS (Israeli) model, consisting of 25 items, demonstrated acceptable fit indices: NFI = 0.913, NNFI = 0.929, RMSEA = 0.048, CFI = 0.937, SRMR = 0.048. CFA factor (Table 2) and Fig. 1 depict the resulting model and the final item loadings.

Figure 1: Standardized parameter estimates for the factor structure of the modified IMHLS.

Note: AD—Acquaintance with mental health disorders; SI—Knowledge of ways to seek information; A—Attitudes about disorders and help-seeking behavior; SO-MD—Social Openness to mental disorder.

Four factors were identified for the modified IMHLS. The first factor, ‘Acquaintance with mental health disorders’ (10 items), mainly consists of the original seven items from the factor ‘Ability to recognize disorders,’ with the addition of one item from each of the original factors: ‘Knowledge of risk factors and causes,’ ‘Knowledge of self-treatment,’ and ‘Knowledge of professional help available.’ The second factor corresponds to the original ‘Knowledge of ways to seek information’ (4 items) factor. The third factor, ‘Attitudes about disorders and help-seeking behavior’ (6 items), includes the first set of items from the original factor ‘Attitudes that promote recognition or appropriate help-seeking behavior,’ excluding three items. The fourth factor, ‘Social Openness to mental disorder’ (5 items), comprises the second set of items from the original factor ‘Attitudes that promote recognition or appropriate help-seeking behavior’, excluding two items.

Scale description and internal consistency

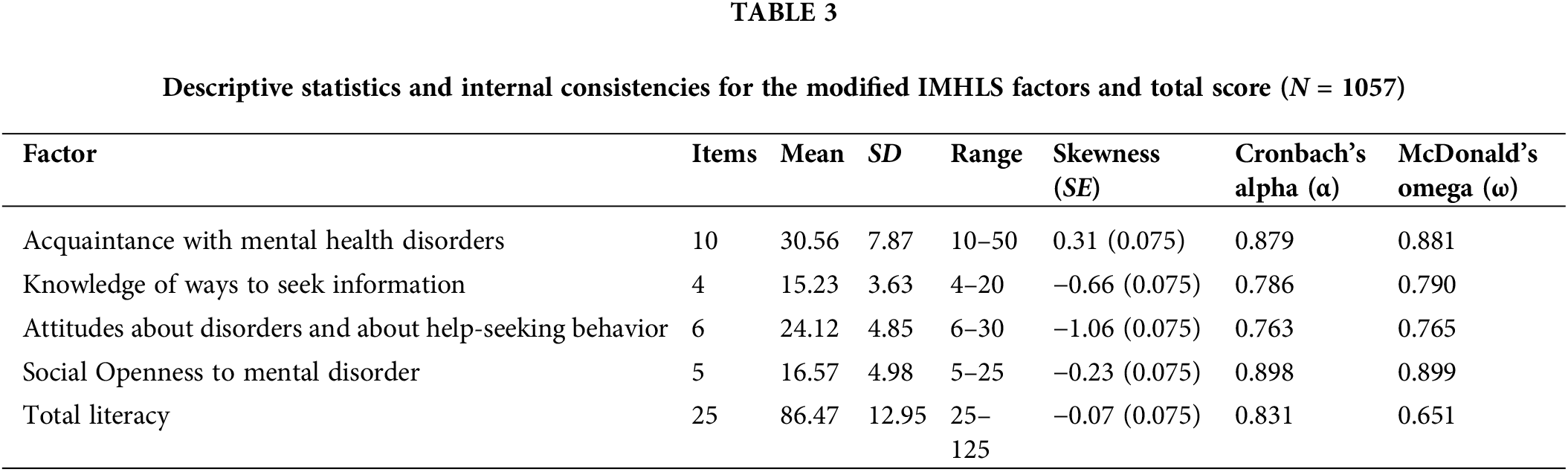

Table 3 presents descriptive statistics and internal consistencies for the modified IMHLS factors. It shows acceptable to good internal consistencies, both in terms of Cronbach’s α (0.763 to 0.898) and McDonald’s ω (omega: 0.651 to 0.899). The factor means and the total scale mean do not appear to deviate from a normal distribution.

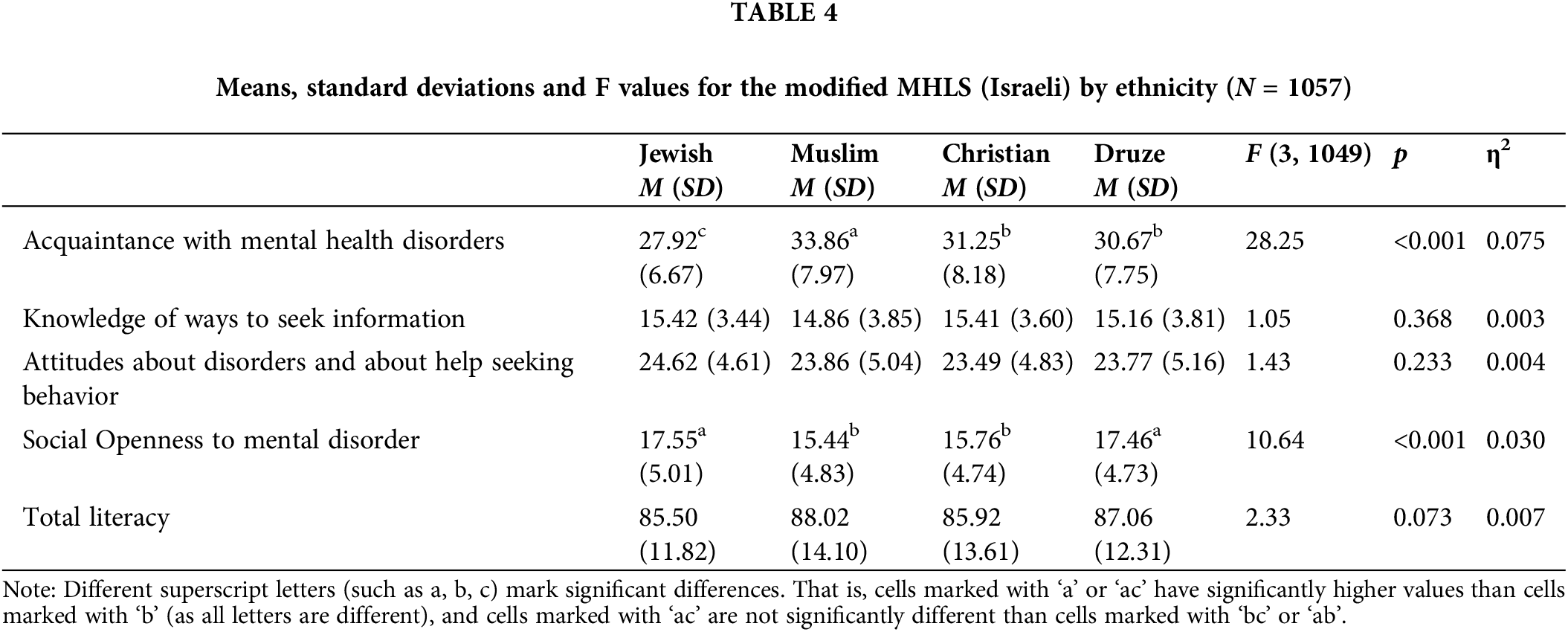

Ethnic differences in the MHLS-Israel variables were examined (Table 4). Two significant differences were found: ‘acquaintance with mental disorders’ and ‘Social Openness to mental disorders’. Muslim participants had the highest acquaintance with mental disorders (Mean = 33.86, SD = 7.97), followed by Druze participants (Mean = 30.67, SD = 7.75) and Christian participants (Mean = 31.25, SD = 8.18), while Jewish participants had the lowest acquaintance (Mean = 27.92, SD = 6.67), (F (3, 1049) = 28.25, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.075).

Regarding ‘openness to mental disorders,’ significant differences were observed in favor of Jewish participants (Mean = 17.55, SD = 5.01) and Druze participants (Mean = 17.46, SD = 4.73), (F (3, 1049) = 10.64, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.030).

This study aimed to evaluate the MHLS for a multicultural population in Israel and compare levels among different ethnicities. After evaluating the original MHLS [8], five items were dropped, and a modified version (IMHLS) with four factors and 25 items was approved. CFA and reliability analyses showed a well-established and robust four-factor model. The current analyses demonstrated a better fit and higher reliability coefficient than other published studies [8,24]. Additionally, both Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (0.763 to 0.898) and McDonald’s omega coefficient (omega: 0.651 to 0.899) were found to be acceptable.

The CFA of the IMHLS includes four factors: “Ability to recognize mental disorders” (10 items), “Knowing where to look for information” (4 items), “Attitudes about disorders and help-seeking behavior” (6 items), and “Social Openness regarding mental disorders” (5 items).

The first factor of the new scale is the ability to identify mental disorders, which includes acquaintance with mental disorders, knowledge of risk factors and causes, knowledge of self-care, and knowledge of available professional help. These skills for diagnosing mental disorders, including risk factors and seeking professional help, are extremely important in preventing and treating mental disorders. Previous studies have shown that individuals with a better ability to identify disorders such as depression or schizophrenia were more likely to receive better-adapted therapeutic interventions from mental health professionals [6]. Knowledge about risk factors is also important as it leads to better preventive behavior in coping with mental health disorders [26].

The second factor of the new scale is “knowing where to look for information.” Having a good level of knowledge about potential sources of relevant information for therapeutic help is crucial beyond individuals’ intentions to contact mental health services. Previous research has shown that improvements in knowledge about psychiatric disorders and addresses for receiving help and treatment led to a significant improvement in mental health outcomes [27–29]. Lack of knowledge about the availability of mental health treatments is a significant barrier to seeking help [30].

The third factor of the modified scale refers to “attitudes regarding the nature of mental disorders and their treatment.” Understanding people’s attitudes towards mental disorders and help-seeking behavior is essential to prevent labeling and reduce stigma. The scale items that examine people’s attitudes can effectively prevent and treat mental disorders. Previous research has shown that individuals with more positive attitudes toward mental disorders and seeking help experience less self-stigma and fewer psychological problems [31].

The fourth factor of the scale is “Social Openness to mental disorder” represents attitudes that promote social closeness and reduce stigma. This openness is essential as it promotes the recognition of mental disorders and appropriate help-seeking behavior. Previous studies have demonstrated the importance and benefits of reducing social distance from people suffering from mental disorders [32,33].

Differences in MHL between ethnic groups underscore the importance of culturally sensitive approaches to mental health care. Israel, a multicultural society with significant ethnic diversity, provides a unique context for exploring these disparities. The study of MHL among different ethnic groups—Jews, Muslims, Christians, and Druze—reveals notable differences in their familiarity with mental disorders, openness to mental health treatment, and attitudes toward help-seeking behavior.

In examining ethnic group differences, the research highlights substantial disparities in acquaintance with mental health disorders. Muslim participants demonstrated the highest acquaintance with mental disorders, followed by Druze and Christian participants, while Jewish participants scored the lowest. The greater acquaintance among Muslims may be attributed to their higher tendency to report mental health problems [34,35], which aligns with previous studies showing that Arab Muslims in Israel report more mental health issues than other groups [17]. These findings suggest that acquaintance with mental health issues does not necessarily translate into access to or utilization of mental health services. Despite higher awareness, Arab Muslims often face cultural and social barriers that prevent them from seeking professional mental health care [36]. Many prefer to attribute psychological symptoms to physical or spiritual causes [20], seeking traditional or religious remedies instead of psychiatric intervention.

Regarding the observed differences in Social Openness towards individuals with mental disorders, Druze participants surprisingly exhibited a high level of transparency, similar to Jewish participants, despite belonging to traditional Arab culture. This difference may be explained by the Druze community’s exposure to more liberal, Western values through mandatory military service in Israel, which may foster greater openness towards mental health issues, akin to the Western and liberal Jewish culture. These findings are consistent with the “treatment gap” discussed in previous research [18], which highlights factors such as limited access to mental health services, stigma, and the lack of culturally sensitive mental health services for Muslim communities, including Arabic-speaking therapists [16,17]. Not only do cultural barriers like stigma affect mental health openness, but cultural adaptation also plays a role in shaping attitudes towards mental illness. Achieving a higher level of openness requires a process of cultural transformation, which is complex and time-consuming [36].

The lower openness observed among Muslims can be attributed to the cultural stigma surrounding mental illness, which is more prevalent in traditional societies [20,36]. In these communities, mental health issues are often associated with personal weakness, leading to social rejection or isolation. This stigma not only hinders help-seeking behavior but also contributes to social reluctance to integrate individuals with mental disorders into everyday social and professional environments [19].

A crucial factor in the cultural and ethnic context is attitudes towards help-seeking behavior. Although no significant differences were found between the groups regarding mental health and help-seeking attitudes, it is evident that cultural attitudes play a key role in determining whether individuals seek professional help. Arab minorities, in particular, face a “treatment gap” where, despite experiencing higher rates of mental health problems, they are less likely to utilize mental health services compared to their Jewish counterparts [18,36]. This gap is often rooted in cultural factors, such as a strong reliance on family support, the use of traditional healers, and the perception that seeking psychiatric help is stigmatized or inappropriate [35].

Implications for clinical practice

The study highlights the need for culturally adapted MHL tools, as demonstrated by the validity of the IMHLS in assessing MHL within Israel’s diverse population. Culturally sensitive approaches are essential to address disparities, including multilingual services, partnerships with community leaders to reduce stigma, and tailored public awareness campaigns. Training healthcare providers in cultural competence and expanding services to underserved areas are also recommended. The adapted scale can be applied in future research, education, and public health efforts to improve MHL, guide interventions, and reduce mental health stigma.

Limitations and scope for future directions

The present study has several limitations. Even though a relatively large sample was obtained from all parts of the country the sample wasn’t random. The second limitation is that the health literacy assessments were based on respondents’ subjective reports and perceptions, which may introduce reporting bias. Third, the questionnaire was offered in Hebrew and Arabic, and as Hebrew is the primary language in Israel, most participants chose the Hebrew version. The few who chose to fill it in Arabic were not identified. Future research directions could include cross-cultural comparisons of MHL, longitudinal studies to track changes in MHL over time, and validation of the Arabic and Hebrew versions of the MHL scale. Further studies could explore stigma reduction interventions in traditional communities and investigate barriers to mental health service utilization, especially among minority groups. Research on the effectiveness of targeted digital campaigns and the role of socioeconomic factors in shaping MHL would also be valuable.

In conclusion, based on the results of this study and the lack of a culturally adapted MHL assessment questionnaire for the unique characteristics of the population in Israel, the modified MHLS-Israel with 30 items and four factors seems to be a suitable instrument. Due to its brevity and ease of use, this instrument can be employed to measure the level of MHL in a multicultural and pluralistic society like Israel and identify individuals with low MHL. Identifying MHL in ethnic groups can enable mental health services to design and implement appropriate community mental health intervention programs and possibly reduce the prevalence of mental disorders and provide better and more integrated services in the community.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank all the participants in this study.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Anwar Khatib and Marc Gelkopf were responsible for the initial writing of the draft and data analysis. Avital Laufer and Michal Finkelstein provided guidance on data processing and suggested revisions to the article. Anwar Khatib and Marc Gelkopf managed data processing and corrections of the article. Michal Finkelstein and Avital Laufer provided suggestions for revision and approved the final version. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data will be provided upon request to the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval: This study received approval from the Ethics Committee of Zefat Academic College (IRB number: 8-2022). Written consent was acquired from the participants.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. World Health Organization. Mental Health and COVID-19: early evidence of the pandemic’s impact. 2022. Geneva. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Sci_Brief-Mental_health-2022.1. [Accessed 2024]. [Google Scholar]

2. Alzueta E, Perrin P, Baker FC, Caffarra S, Ramos-Usuga D, Yuksel D, et al. How the COVID-19 pandemic has changed our lives: a study of psychological correlates across 59 countries. J Clin Psychol. 2020;77:556–70. doi:10.1002/jclp.23082. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Nochaiwong S, Ruengorn C, Thavorn K, Hutton B, Awiphan R, Phosuya C, et al. Global prevalence of mental health issues among the general population during the coronavirus disease-2019 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):10173. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-89700-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Galea S, Merchant RM, Lurie N. The mental health consequences of COVID-19 and physical distancing: the need for prevention and early intervention. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(6):817–8. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.1562. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Knipe D, Evans H, Ferguson D. Implementing mental health literacy in school-based settings: evidence from the ‘Healthy Mind, Healthy School’ program in Canada. Can J School Psycho. 2022;37(3):257–69. doi:10.1177/08295735211036020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Saggese E, Kelly B, Vassallo T. Public mental health literacy: contemporary perspectives on awareness and treatment-seeking. British J Psych. 2021;219(5):400–11. doi:10.1192/bjp.2021.103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Khatib A, Ben-David V, Abo-Rass F, Gelkopf M, David R. Mental health literacy among general practitioners in Israel: a qualitative study. Fam Soc. 2022;104(1):34–41. doi:10.1177/10443894221121764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. O’Connor M, Casey L. The Mental Health Literacy Scale (MHLSa new scale-based measure of mental health literacy. Psychiat Res. 2015;229(1–2):511–6. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2015.05.064. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Bhugra D. Cultural psychiatry. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2019. [Google Scholar]

10. Park H, Reupert A, McDermott B. Cross-cultural views on mental health literacy: comparative studies of depression and anxiety awareness. Int J Cross-Cult. 2022;63(2):95–107. doi:10.1177/00220221221018632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Subu MA, Holmes D, Arumugam A, Al-Yateem N, Maria Dias J, Rahman SA, et al. Traditional, religious, and cultural perspectives on mental illness: a qualitative study on causal beliefs and treatment use. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-Being. 2022;17(1):2123090. doi:10.1080/17482631.2022.2123090. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Williams T, Chen J. Cultural influences on mental health attitudes and help-seeking behavior across the United States and East Asia. Soc Psych Psych Epid. 2020;55(7):313–20. doi:10.1007/s00127-020-01892-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Central Bureau of Statistics of Israel (CBS). 2020. No. 65 Jerusalem. https://www.gov.il/en/departments/central_bureau_of_statistics/govil-landing-page; www.cbs.gov.il. [Accessed 2024]. [Google Scholar]

14. Roe D, Garber-Epstein P, Khatib A. Psychiatric rehabilitation in the context of palestinian citizens in Israel. In: Haj Yahia M, Nakash O, Levav I, editors. Mental health themes among palestinian citizens in Israel. Bloomington, IN, USA: Indiana University Press; 2019. p. 380–90. [Google Scholar]

15. Al-Hawamdeh A, Rayan A. Traditional beliefs vs. modern mental health practices in Arab societies: a case study of Israeli Arab communities. Soc Welfare: Soc Work Q. 2020;42(3):158–71. [Google Scholar]

16. Elroy I, Rosen B, Elmakias I, Samuel H. Mental health services in Israel: needs, patterns of utilization and barriers. Survey of the general adult population. Myers-JDC-Brookdale Institute. 2017. Available from: brookdaleweb.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/2017/09/Hebrew_report_749-17.17. [Accessed 2024]. [Google Scholar]

17. Daoud N, Abu-Ras W. Ethnic and cultural disparities in mental health symptoms in Israel: an analysis of the Israeli Arab and Jewish populations. Isr J Psychiat. 2021;56(1):45–53. [Google Scholar]

18. Daeem R, Mansbach-Kleinfeld I, Farbstein I, Apter A, Elias R, Ifrah A, et al. Barriers to help-seeking in Israeli Arab minority adolescents. Isr J Health Policy Res. 2019;8:45. doi:10.1186/s13584-019-0315-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Al-Krenawi A. Mental health service utilization among the Arabs in Israel. Soc Work Health Care. 2019;35(1–2):577–89. doi:10.1300/J010v35n01_12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Khatib A, Abu-Rass F. Mental health literacy among Arab university students in Israel: a qualitative study. Int J Soc Psychiat. 2022;68(7):1486–93. doi:10.1177/00207640221105063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Hayes AF, Coutts JJ. Use omega rather than Cronbach’s alpha for estimating reliability. But.. Commun Methods Meas. 2020;14(1):1–24. doi:10.1080/19312458.2020.1718629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ, USA: Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

23. Hattie J. Visible learning. London, UK: Routledge; 2009. [Google Scholar]

24. Lenhard W, Lenhard A. Calculation of effect sizes. Psychometrica. 2016. doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.17823.92329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Lee J, Kim T. Practical applications of structural equation modeling for health research. Adv Stat Appl. 2021;34(2):80–93. [Google Scholar]

26. Hamadani J, Rahman M. Mental health literacy as a pathway to health-promoting behaviors: a mediation analysis. Iran J Psychiat. 2022;13(4):e12612. [Google Scholar]

27. Stewart M, Perry C. Research on mental health literacy in diverse populations: advances and future directions. Aust N Z J Psychiat. 2022;45(3):101–9. doi:10.1080/j.1440-1614.2022.01734.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Dev A, Gupta S, Sharma KK, Chadda RK. Awareness of mental disorders among youth in Delhi. Curr Med Res Pract. 2017;7(3):84–9. doi:10.1016/j.cmrp.2017.05.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Wang Y, Lee S. Reducing stigma in mental health: strategies and implications for public health. Am J Public. 2022;112(3):70–5. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2021.301098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Martensen L, Perry B. Measuring mental health literacy: recent advances in tools and methodologies. BMC Psychiat. 2022;21:343. doi:10.1186/s12888-021-03019-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Li F, Zhang Y. Mental health help-seeking among rural populations in China: preferences and obstacles. PLoS One. 2020;15(5):e0233349. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0233349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Patel A, Gomez F. Help-seeking delays and mental health service accessibility in Australia. Soc Psych Psych Epid. 2021;54(9):893–9. doi:10.1007/s00127-021-02021-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Roberts T, Smith K. Help-seeking behavior and stigma in low vs. high suicide rate areas: a comparative study. Soc Psych Psych Epid. 2021;56(4):415–23. doi:10.1007/s00127-021-02134-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Hinz M, Müller R. Public attitudes toward mental health: changes over the last decade in Germany. Eur Psychiat. 2020;28(1):102–9. [Google Scholar]

35. Tan C, Wong J. Stigma and mental illness: insights from Singapore’s multicultural society. Epidemiol Psychiat Sci. 2020;29(5):e120. doi:10.1017/S2045796020000135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Khatib A, Abu-Rass F, Khatib A. Barriers to mental health service utilization among Arab society in Israel: perspectives from service providers. Arch Psychiat Nurs. 2024;51:127–32. doi:10.1016/j.apnu.2024.06.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools