Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

The Impact of Exercise Commitment on Flourishing via Psychological Capital (PsyCap): A Second-Order PLS-SEM Approach

1 Department of Sports Convergence Science, Graduate School, Konkuk University, Seoul, 05029, Republic of Korea

2 Department of Physical Education, College of Education, Konkuk University, Seoul, 05029, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Kyuhyun Choi. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Enhancing Mental Health through Physical Activity: Exploring Resilience Across Populations and Life Stages)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(10), 1515-1532. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.068306

Received 25 May 2025; Accepted 27 August 2025; Issue published 31 October 2025

Abstract

Objectives: For the younger generation (i.e., Millennials and Generation Z), running is not only about physical health, but also about building psychological resources and multidimensional well-being, reflecting their unique culture and lifestyle. This study aims to investigate the structural relationships among exercise commitment, psychological capital (PsyCap), and flourishing in younger adults in South Korea by integrating Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) and Broaden-and-Build Theory (BBT) using a second-order partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Methods: A total of 166 participants were recruited through convenience sampling via online survey. They were young South Korean adults (born 1983–2005) who run at least once a week and were recruited through two universities and running communities. The survey included validated scales measuring exercise commitment (cognitive and behavioral), PsyCap (hope, efficacy, resilience, and optimism), and flourishing (emotional, psychological, and social well-being). Data were analyzed using PLS-SEM with 5000 bootstrap resamples in SmartPLS 4.1.1.2. Subsequently, measurement and structural models were assessed through confirmatory composite analysis (CCA), and common method variance (CMV) was checked using Harman’s single-factor test. Results: Exercise commitment significantly predicted PsyCap (β = 0.171, p < 0.05) and PsyCap significantly predicted flourishing (β = 0.444, p < 0.001). Mediation analysis confirmed that PsyCap fully mediated the relationship between exercise commitment and flourishing (β = 0.071, p < 0.05). Although the indirect effect may appear numerically small, it translated to a 7.1% increase in flourishing scores—a practically meaningful effect in social science contexts where even modest changes yield real-world impact. The findings empirically support the integration of two frameworks, highlighting both motivational (SCT) and affective (BBT) pathways through which exercise fosters multidimensional well-being. Conclusions: Theoretically, this study advances understanding of how cognitive and behavioral commitment contribute to the development of psychological resources that collectively drive flourishing. Practically, the results suggest that running programs targeting younger adults should focus on fostering PsyCap—via goal setting, social support, and digital engagement—to maximize well-being outcomes. Moreover, the findings have the potential to inform mental health promotion strategies beyond the Korean context. This study has several limitations, including a skewed sample resulting from convenience sampling, the lack of comparative analysis across different age cohorts, and the use of second-order constructs that may obscure dimension-specific effects. Future research should address these limitations by employing stratified sampling, adopting comparative study designs, and conducting model comparisons between first- and second-order constructs to elucidate both overarching and dimension-specific pathways.Keywords

Since the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a marked increase in interest in outdoor, low-contact physical activities, including in South Korea [1,2]. Among various options, running stands out as one of the most basic and accessible forms of physical activity, easily incorporated into daily life. In the early 2000s, the number of runners in Korea was estimated at approximately two million, but as of 2025, a running boom—especially among younger adults—has led to estimates of around ten million participants [3,4]. According to the National Sports Participation Survey, 61.2% of Koreans engaged in physical activity in 2022, with walking and running accounting for the highest proportion at 48.8% [5]. Thus, running has become firmly established as a leading trend in leisure and sports among younger adults in Korea.

Running is characterized by low barriers to entry and minimal constraints, allowing participants to autonomously set and pursue their own goals [6]. In addition to its physical benefits—such as improved cardiorespiratory fitness, reduced body fat [7], enhanced mental health [8], and lower mortality rates [9]—running is especially popular among younger adults who face various constraints (e.g., distance, cost, time), as it can be enjoyed with minimal restrictions [10]. Furthermore, the characteristics of the younger generation—digital nativity, community orientation, and fear of missing out (FoMO) [11]—are closely linked to their running participation. Young people tend to join running groups that share common goals and interests without imposing strict obligations [12], and often use social media and wearable devices to record and share their exercise, goals, and achievements. For this generation, running is not only about physical health, but also about building psychological resources and multidimensional well-being.

Recent research in positive and health psychology has emphasized that the benefits of exercise engagement extend beyond physical health, contributing to the enhancement of psychological capital (PsyCap) and ultimately promoting flourishing in emotional, psychological, and social domains [13–15]. For example, Stevinson et al. [6] found that beginner running programs are closely related to sustained exercise and improvements in psychological factors, with social support in group activities fostering pride, accomplishment, and positive PsyCap. PsyCap, in turn, plays a vital role in managing stress and maintaining positive emotions [16,17]. These psychological resources can be strengthened through exercise experiences such as flow [18], which help relieve stress and enhance overall life satisfaction and positive affect [19]. Additionally, PsyCap supports psychological recovery in stressful situations [20], and components such as resilience and self-efficacy positively influence well-being and goal attainment [19,21].

The mechanisms underlying these benefits can be understood through Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) [22], and Broaden-and-Build Theory (BBT) [13,23]. Despite growing interest in the psychological benefits of exercise among younger adults, several important research gaps remain. First, although the multidimensional nature of PsyCap is well-established [24,25], studies that have modeled both exercise commitment and PsyCap as higher-order constructs in the exercise context remain limited. Most existing research treats these variables as unidimensional or examines only partial relationships [26,27], leaving a research gap in our understanding of how cognitive and behavioral dimensions of commitment jointly contribute to the development of PsyCap among younger adult runners. Second, although both SCT and BBT have been applied to explain exercise motivation and well-being, empirical integration of these frameworks within a single model is rarely addressed in existing research. Prior work has typically relied on a single theoretical lens or focused on direct effects, without testing the complementary motivational and affective pathways proposed by SCT and BBT in the context of exercise-induced flourishing [14,27]. Third, most prior studies have focused on specific subgroups without addressing the unique characteristics of younger adults [28]. There is a lack of empirical research that reflects the distinctive social and motivational context of younger adult Korean runners, particularly in the post-pandemic era.

Therefore, this study aims to empirically test the structural relationships among exercise commitment PsyCap, and flourishing in younger adult runners in South Korea, employing a second-order partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) approach. Specifically, the study investigates that (1) the effect of exercise commitment on PsyCap, (2) the effect of PsyCap on well-being, and (3) the full mediating effect of PsyCap. By integrating SCT and BBT, this research provides both theoretical and practical contributions, expanding our understanding of the interplay between exercise participation, PsyCap, and well-being, and offering actionable insights for health promotion and sports program design.

2.1 Social Cognitive Theory and Broaden-and-Build Theory

SCT is a framework that explains how human behavior is learned and regulated through the reciprocal interactions of cognitive, behavioral, and environmental factors [22]. According to SCT, individuals set exercise-related goals and achieve them through motivation, with self-efficacy and resilience playing pivotal roles in this process. Self-efficacy refers to an individual’s belief in their capability to organize and execute actions required to manage prospective situations [29]. For instance, running’s low barriers to entry allow younger adults easily set and achieve incremental goals (e.g., 5K completion). These micro-mastery experiences [6] reinforce capability beliefs, aligning with SCT’s emphasis on mastery as a source of self-efficacy [29]. Previous research suggests that psychological resources can be strengthened through exercise commitment, particularly when individuals experience a sense of flow or deep engagement in physical activity [18,30,31]. These mechanisms have been shown to positively influence well-being, or flourishing [32].

BBT posits that positive emotions broaden individuals’ momentary thought-action repertoires and, over time, help build enduring personal resources [23,33]. In the context of exercise, positive emotions experienced during activities-such as flow or deep engagement-expand cognitive and emotional capacities, thereby building resilience, enhancing optimism, and ultimately promoting well-being. Empirical studies support the idea that positive affect during exercise contributes to the development of psychological resources and flourishing [14,34]. Specifically, exercise commitment, which can be conceptualized as comprising cognitive and behavioral dimensions [31,35], serves to strengthen positive emotional experience. PsyCap has been empirically validated as a higher-order construct with substantial effects on well-being, performance, and adaptive functioning across various domains, including health and organizational settings [25,36]. Whereas SCT explains how exercise commitment enhances efficacy and resilience through behavioral mastery, BBT explains how emotionally positive exercise experiences foster hope and optimism over time. Together, these pathways culminate in the development of PsyCap, which in turn supports flourishing.

Attempts to integrate the frameworks of SCT and BBT have emerged in exercise psychology and mental health research, laying the foundation for subsequent studies. For example, Rovniak et al. [37] proposed a classification of determinants of exercise persistence into cognitive triggers and emotional amplifiers. Their findings suggested that while SCT’s cognitive mechanisms facilitate goal setting and self-regulation, BBT’s emotional dynamics enhance exercise maintenance by fostering positive affective experiences—thus providing early conceptual insights into the synergy between the two theories. Similarly, Rhodes and Kates [38], through a systematic review of affective responses to physical activity and their influence on future intentions, offered empirical support for the linkage between exercise, emotion, and behavior. These studies contributed to the foundation of the cognitive and affective mechanisms, underscoring the interactive effects of cognition and emotion in promoting sustained health behavior participation.

This integrative framework is relevant for understanding how sustained exercise behavior fosters multidimensional well-being in younger adults. In the fields of exercise psychology and mental health, it offers theoretical unification and empirical validation of the synergistic mechanisms between cognitive-behavioral and affective pathways.

2.2 The Relationship between Exercise Commitment and Psychological Capital

Exercise commitment is broadly defined as an individual’s cognitive determination and behavioral persistence to maintain regular physical activity, even in the face of obstacles [31,39]. Recent literature conceptualizes exercise commitment as a dual-dimensional construct, comprising both cognitive and behavioral components. Cognitive commitment refers to the mental resolve to prioritize exercise, including goal setting, outcome expectations, and value attribution, while behavioral commitment manifests as consistent action, habit formation, and the ability to overcome barriers [31,35]. For younger adults, particularly Millennials and Generation Z cohorts, the use of digital platforms and fitness apps has been shown to amplify both cognitive and behavioral commitment by providing real-time feedback, goal tracking, and social accountability [40].

PsyCap, is a higher-order construct encompassing four core psychological resources—hope, efficacy, resilience, and optimism—collectively referred to as the hope, self-efficacy, resilience, and optimism (HERO) framework [15]. Hope is characterized by goal-directed energy and planning pathways, efficacy by confidence in one’s abilities, resilience by the capacity to recover from setbacks, and optimism by positive expectations for the future [36,41]. Luthans et al. [24] conceptualized PsyCap as a second-order construct, arguing that the integrated construct captures synergistic effects where the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. Comparative analyses confirm its superior fit over first-order models, providing theoretical parsimony, while validating PsyCap’s hierarchical structure [42–44].

PsyCap has been empirically validated as a critical predictor of well-being, performance, and adaptability across diverse contexts, including exercise and health [28,42,45]. Physical activity provides a dynamic context for goal setting, mastery experiences, and emotional regulation, which align naturally with the development of positive psychological resources [13,14]. Research demonstrates that exercise commitment enhances PsyCap, with each dimension of commitment contributing to specific HERO components. Cognitive commitment, through intentional goal setting and value attribution, has been shown to increase hope and optimism by fostering clear pathways and positive expectations [46]. For instance, a recent study found that runners who engaged in structured goal-setting reported higher levels of hope and optimism, mediated by enhanced pathway thinking and positive outcome expectancies.

Meanwhile, behavioral commitment, reflected in consistent participation and exercise, expressions of enthusiasm, strengthens efficacy and resilience through mastery experiences and learned coping strategies [47]. Longitudinal evidence indicates that individuals with high behavioral commitment to running develop greater self-efficacy and recover more quickly from setbacks, such as injuries or motivational lapses. These findings support the view that the two dimensions of exercise commitment synergistically boost overall PsyCap: cognitive commitment primarily fosters hope and optimism, while behavioral commitment reinforces efficacy and resilience [12,35].

Based on this theoretical and empirical foundation, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 1: The second-order construct of exercise commitment will have a positive effect on the second-order construct of PsyCap.

2.3 The Relationship between Psychological Capital and Flourishing

Flourishing is widely recognized as a holistic state of optimal well-being, reflecting not only the absence of mental illness but also the presence of positive functioning across emotional, psychological, and social domains [32]. To capture this multidimensional construct, the present study employs the Mental Health Continuum-Short Form (MHC-SF), which conceptualizes well-being as a second-order factor composed of three interrelated dimensions: emotional, psychological, and social well-being. This approach is preferred in non-clinical populations due to its theoretical validity and methodological parsimony [48], as it efficiently captures the multidimensional nature of flourishing while maintaining conceptual integrity. The MHC-SF is particularly suitable for younger populations, as it reflects their complex well-being needs in contemporary society—balancing identity exploration, social connectivity, and emotional regulation [49]. Its second-order structure allows for a nuanced analysis of both global flourishing and its specific facets, aligning with current perspectives in well-being science.

In parallel, PsyCap has emerged as a critical psychological resource that contributes to flourishing. The theoretical linkage between PsyCap and flourishing is supported by multiple lines of evidence. PsyCap equips individuals with the internal psychological resources necessary to pursue meaningful goals, sustain motivation, regulate emotions, and adaptively respond to life stressors—mechanisms that are central to flourishing [33,50]. Recent research further demonstrates that higher levels of PsyCap are positively associated with all three dimensions of the MHC-SF, with particularly robust effects on psychological and social well-being [24]. For example, hope and optimism facilitate future-oriented thinking and positive expectations, efficacy contributes to emotional regulation and stress coping, and resilience supports social connectedness and recovery from interpersonal or motivational challenges [51]. Taken together, these findings underscore the value of conceptualizing both PsyCap and flourishing as second-order constructs. This approach enables a clearer understanding of how psychological resources support optimal well-being. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 2: The second-order construct of PsyCap will have a positive effect on the second-order construct of flourishing (MHC-SF).

2.4 The Mediating Role of Psychological Capital

PsyCap has emerged as a critical mediating mechanism through which exercise commitment may lead to flourishing. While exercise commitment has long been associated with various well-being outcomes, recent studies’ findings indicate that its direct effect often becomes non-significant when PsyCap is included in the model—indicating the potential for a full mediation pathway [30,52,53]. Specifically, cognitive commitment—such as setting incremental running goals—enhances hope by fostering pathway thinking, while behavioral commitment—like adhering to a training schedule—cultivates resilience through repeated mastery experiences. These psychological resources subsequently promote flourishing by sustaining goal-directed behavior, aiding in stress recovery, and fostering social connectedness [44,54].

In addition to theoretical support, empirical findings from positive psychology interventions have further validated these mechanisms. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies demonstrated that such interventions significantly enhance optimism and subjective well-being, offering a foundation for long-term flourishing [55]. Similarly, Lambert et al. [56] reported that a structured positive psychology program in a culturally diverse university context led to substantial improvements in happiness and reductions in negative affect. More recently, Arslan et al. [57] found that gains in PsyCap components such as hope and optimism, achieved through Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) based interventions, were sustained over two years and significantly predicted higher levels of mental well-being.

Among younger adult exercisers, this mediating process appears to be amplified through digital engagement. Fitness apps such as Nike Run Club transform solitary workouts into socially reinforced experiences, enhancing self-efficacy through visible progress tracking and boosting optimism via peer encouragement. The public sharing of running milestones on social media further reinforces this process: social accountability strengthens exercise commitment, while feedback in the form of likes and comments enhances perceived social support. This interaction has been referred to as “digital PsyCap scaffolding”—a socio-technical process by which digital platforms contribute to the cultivation of PsyCap [58]. The following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 3: PsyCap will fully mediate the relationship between exercise commitment and flourishing.

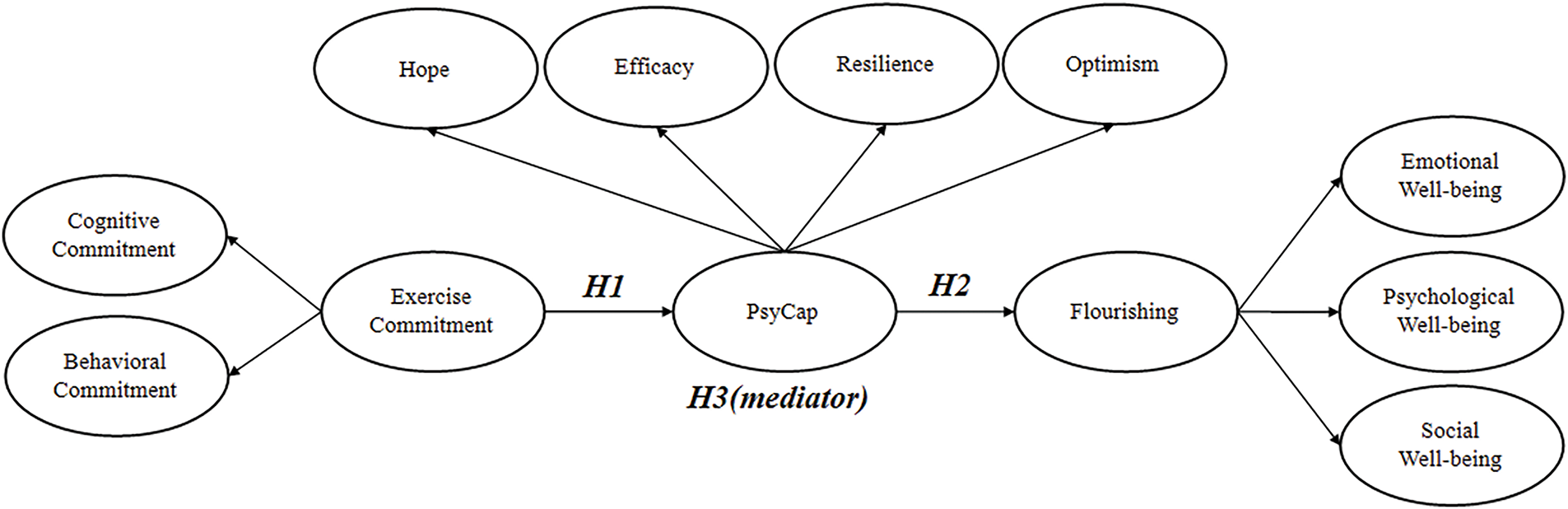

The following presents the hypotheses and the research model (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Hypothesized research model. Note: Exercise Commitment, PsyCap, and Flourishing are modeled as second-order constructs

3.1 Participants and Procedure

To test our hypotheses, we targeted South Korean younger adult runners (born between 1983 and 2005) who engage in running at least once a week. The survey was created using Google Forms and distributed online to running participants at S University and K University in Seoul, as well as to running communities in Seoul, Icheon-si, and Gwacheon-si, Gyeonggi-do (via open KakaoTalk channels). Participants were recruited through convenience sampling, based on accessibility and willingness to participate. Data were collected from 14–18 May 2025. Of the 170 initial observations, four were removed based on prescreening questions (i.e., those who reported running 0 times per week), resulting in 166 usable responses. The final sample consisted of 110 male participants (66.3%), 56 female participants (33.7%). The age distribution was as follows: participants in their 20s (n = 34, 20.5%), in their 30s (n = 124, 74.7%), and in their 40s (n = 8, 4.8%). The participants’ places of residence were as follows: 98 individuals (59.1%) lived in Seoul, 58 (34.9%) in Gyeonggi-do, and 10 (6.0%) in other regions. Regarding frequency, 100 participants (60.3%) reported running 1–2 times per week, 66 (39.8%) ran 3–4 times per week, and 8 (4.8%) ran 5 or more times per week. For running experience, 50 participants (30.1%) had been running for 0–6 months, 26 (15.7%) for 7–12 months, 20 (12.0%) for 13–18 months, 24 (14.5%) for 19–24 months, and 46 (27.7%) for more than 25 months.

We administered an online self-report survey consisting of 38 closed-ended items measuring the study constructs and six demographic questions. Except for the demographic items, the constructs were assessed using either a six-point Likert scale (flourishing: ranging from 1 = never to 6 = every day) or a seven-point Likert scale (exercise commitment and PsyCap: ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree).

Exercise Commitment (Cognitive and Behavioral): The scale for exercise commitment in this study was based on the Expansion of Sports Commitment Model (ESCM) by Scanlan et al. [39], and utilized 12 items developed and employed in previous studies by Jung [31] and Lee et al. [35]. The scale includes eight items assessing cognitive commitment (i.e., pride, determination, and desire related to exercise) and four items assessing behavioral commitment (i.e., behavioral expressions of exercise enthusiasm).

Psychological Capital (PsyCap): The Compound PsyCap Scale (CPC-12), which is useful for predicting mental health, consists of 12 items, with three items each measuring HERO. In this study, we used the scale employed in previous research by Lorenz et al. [59] and Dudasova et al. [43].

Flourishing (Emotional, Psychological, and Social): Flourishing was measured in this study using MHC-SF [32,60], which comprises emotional, psychological, and social well-being dimensions. The three emotional well-being items pertain to happiness, life satisfaction, and positive emotions. In addition, the six psychological well-being items cover aspects such as self-acceptance and environmental mastery. The five social well-being items assess social contribution, social acceptance, and social integration.

For data analysis, we utilized PLS-SEM with a second-order approach to examine the structural relationships in our research framework. The PLS-SEM is a prediction-oriented method applicable to both exploratory research with underdeveloped theories and confirmatory analysis [61]. It is particularly optimal for complex models (e.g., higher-order constructs) and small-to-moderate sample sizes, whereas covariance-based SEM is better suited for large samples and theory confirmation [62].

The analysis was conducted using Smart PLS 4.1.1.2, a widely recognized software for PLS-SEM applications. We first evaluated the measurement model by assessing the reliability and validity of both first and second-order constructs (i.e., confirmatory composite analysis). For the structural model, we analyzed path coefficients, predictive accuracy (Q2), and explanatory power (R2) to test the hypothesized relationships. To ensure robustness, we applied bootstrapping with 5000 resamples to estimate the significance of path analysis. Specifics of the measurement model (reliability and validity) and structural model (path analysis) evaluations are described as follows. To assess the presence of full mediation, we examined the direct, indirect, and total effects between exercise commitment and flourishing, following recommended procedures in mediation analysis using PLS-SEM [62]. Statistical significance was evaluated through 5000 bootstrap resamples, and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used to confirm the validity of the indirect effect. Full mediation was supported when the indirect path was significant and the direct path became non-significant, indicating that the influence of exercise commitment on flourishing was transmitted entirely through PsyCap. In addition, common method variance (CMV) was assessed through Harmen’s single-factor test.

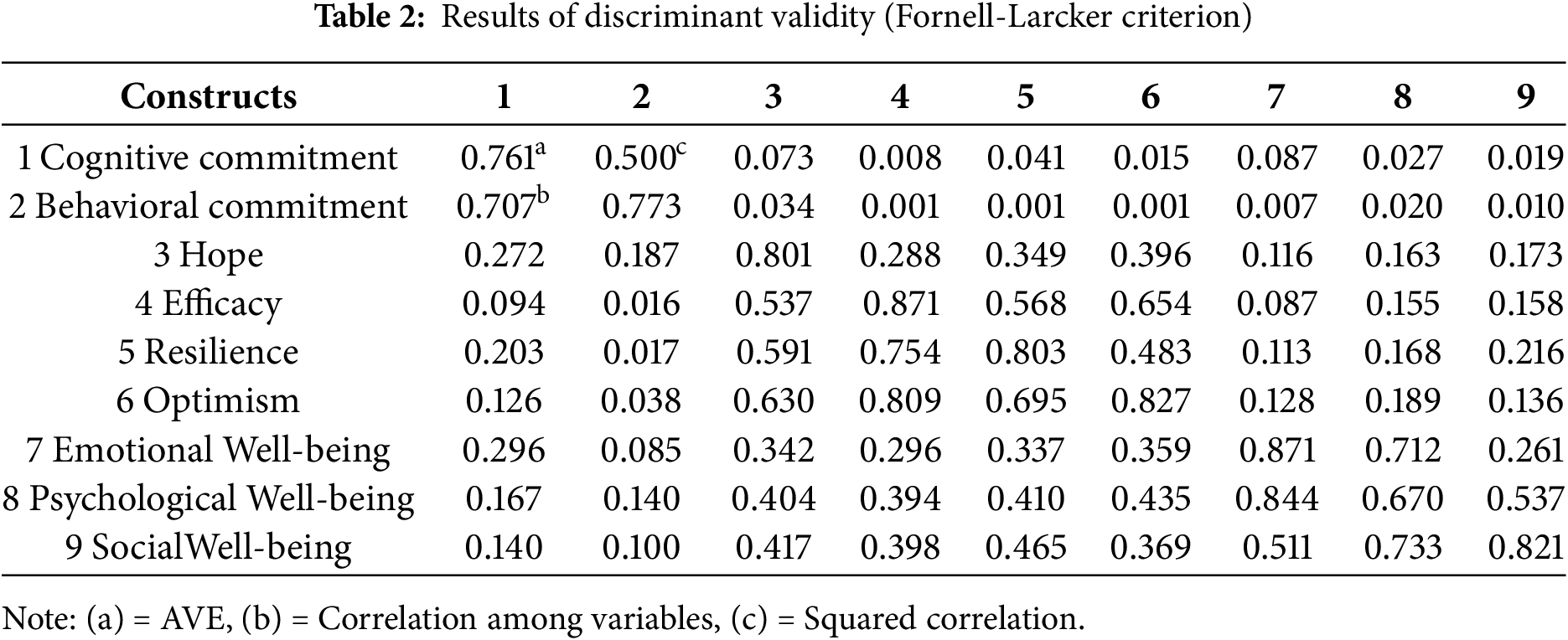

Measurement Model Analysis: To evaluate the measurement model’s psychometric properties, we assessed outer loadings, composite reliability (CR), Cronbach’s alpha, and average variance extracted (AVE). Internal consistency was deemed acceptable if both Cronbach’s alpha and CR exceeded 0.70 [62]. Convergent validity was confirmed with AVE values exceeding 0.50, indicating that each construct accounted for more than 50% of the variance in its indicators. For discriminant validity, we applied the Fornell-Larcker criterion [63], requiring the square root of each construct’s AVE to exceed its correlations with other constructs or for AVE values to surpass squared inter-construct correlations. Additionally, Harman’s single-factor test was conducted to assess potential CMV. A single factor explaining less than 50% of the total variance, indicating that CMV was not a serious concern [64].

Structural Model Analysis: To address potential multi-collinearity issues, we analyzed collinearity statistics, and the results revealed that the variance inflation factor (VIF) values for the predictor constructs were well below the threshold of 5 [65]. Model fit was assessed using the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), with values less than or equal to 0.10 indicate acceptable model fit [66]. The model’s explanatory power for the endogenous variable was assessed using the coefficient of determination (R2), which yielded a value of 0.25, 0.50, 0.75, represent explanatory power (weak, moderate, and substantial level). Predictive accuracy was assessed via the blindfolding technique [61]. Where Q2 values greater than zero confirmed the model’s predictive relevance for endogenous constructs [62]. For hypothesis testing, bootstrapping with 5000 subsamples was conducted to determine the statistical significance of path coefficients, analyzed through 95% CIs.

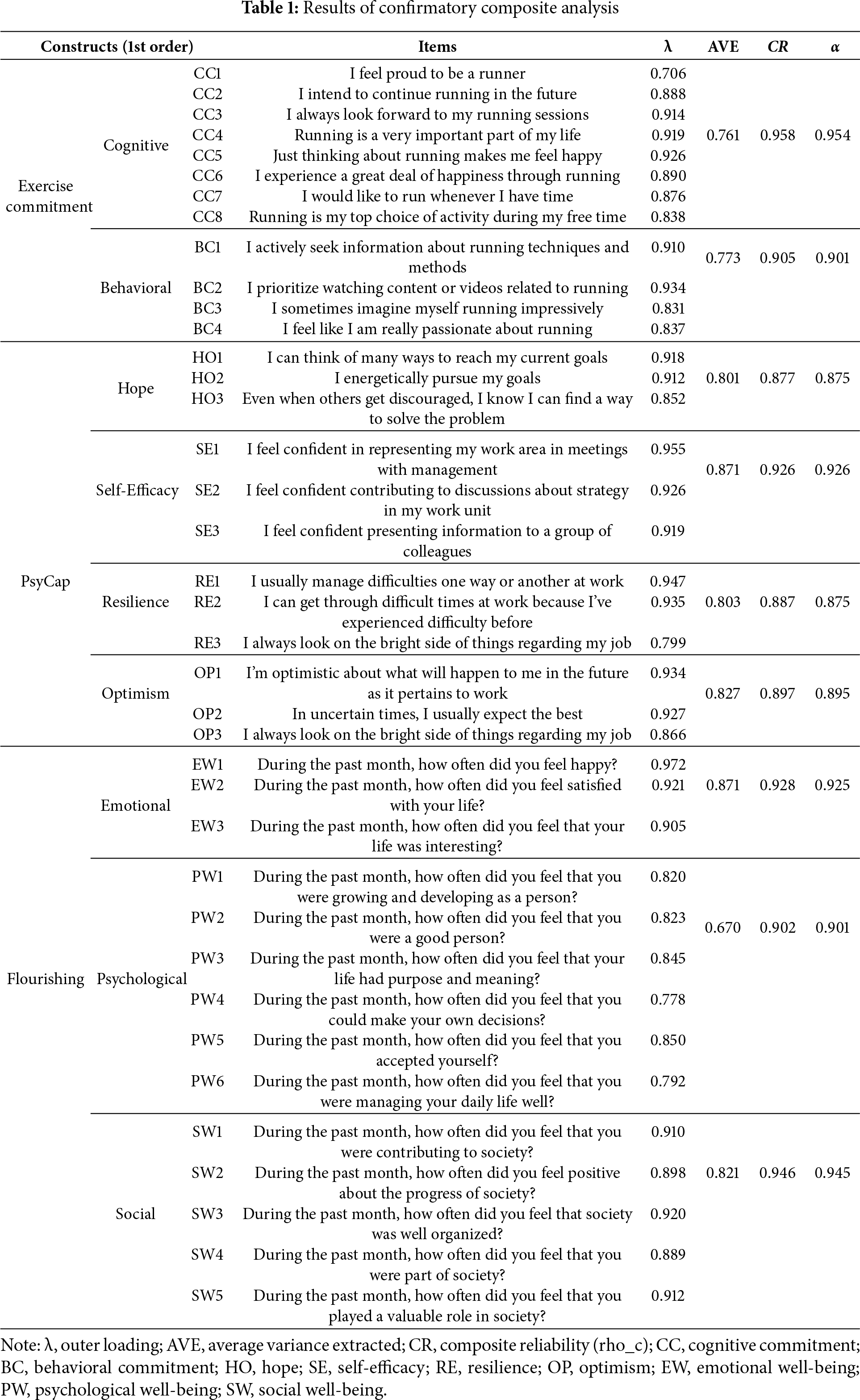

4.1 Measurement Model (Confirmatory Composite Analysis)

The measurement model was validated following established PLS-SEM protocols for second-order (reflective-reflective) constructs [62,67]. For first-order constructs, all outer loadings exceeded the 0.70 threshold (range: 0.706–0.972), demonstrating satisfactory indicator validity [68]. Convergent validity was confirmed through AVE values between 0.668 and 0.871, surpassing the 0.50 benchmark [64]. CR scores of 0.870–0.958 indicated robust internal consistency [68]. Discriminant validity was established via the Fornell-Larcker criterion, with all square roots of AVEs exceeding corresponding inter-construct correlations [63]. Additionally, Harman’s single-factor test indicated that the first factor accounted for 34.3% of the variance, which is below the 50% threshold [64]. For second-order validation, the repeated indicators approach [67] revealed outer loadings ranging from 0.599 to 0.924, meeting the 0.50 threshold for exploratory research contexts [62]. Second-order AVEs of 0.620–0.668 further confirmed higher-order convergent validity, adhering to Sarstedt et al.’s [67] recommendations. CR values ranged from 0.949 to 0.959, and Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranged from 0.944 to 0.953, indicating excellent internal consistency [62]. This hierarchical structure demonstrated psychometric adequacy across both measurement tiers. The following Tables 1 and 2 are the results of validity and reliability.

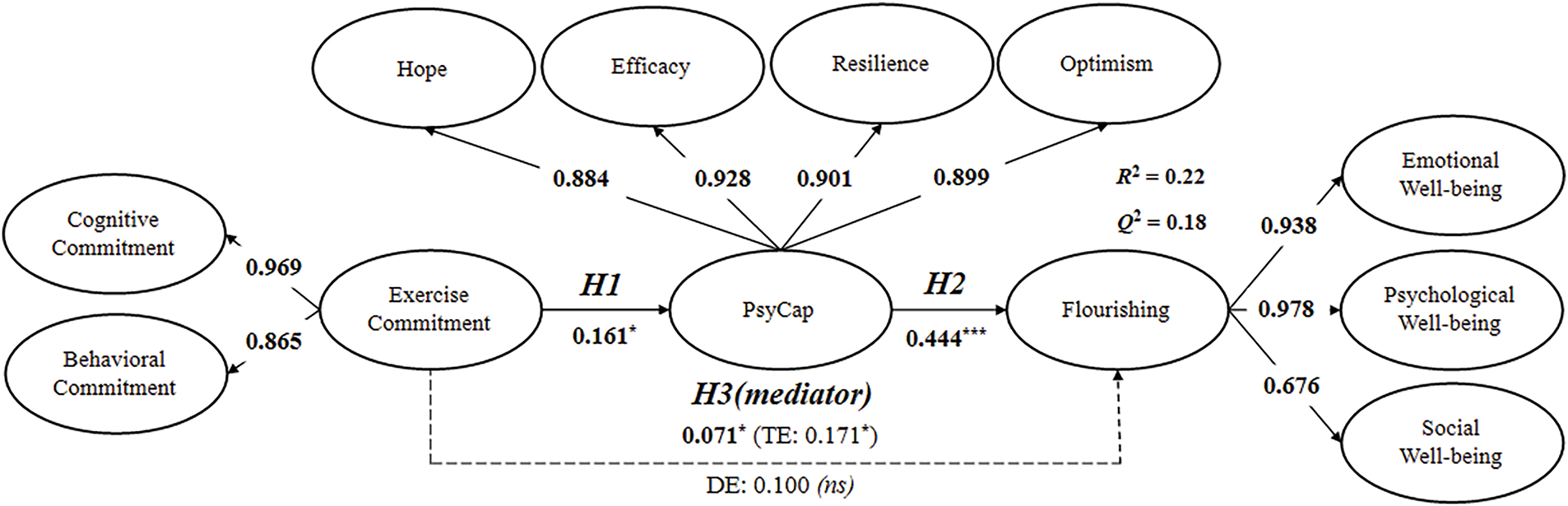

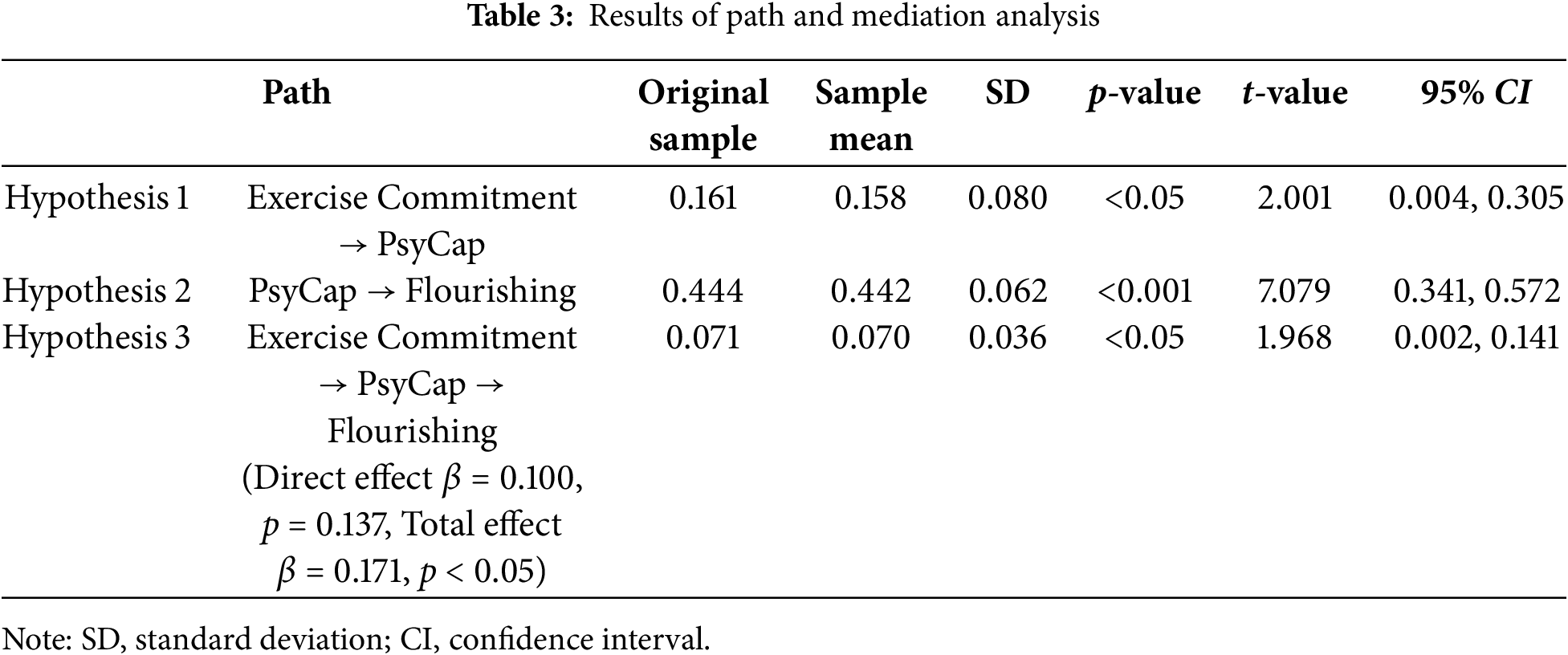

4.2 Structural Model (Path and Mediation Analysis)

To evaluate the structural model’s explanatory and predictive capabilities, the study examined R2 (coefficient of determination) and Q2 (predictive relevance) indices. The analysis revealed modest explanatory power, with an R2 value of 0.22 (22%) for the endogenous variable (flourishing), consistent with social science research where complex phenomena [65] and design constraints [66] often limit variance explanation. This aligns with evidence view that small-but-significant effects can drive meaningful real-world change in public health contexts [69]. Predictive relevance was further assessed via PLSpredict, yielding a Q² value of 0.18 for flourishing. Since this value surpassed the threshold of zero, the results suggest adequate predictive relevance of the model [62] (see Fig. 2). In addition, to assess potential multicollinearity issues, VIF were examined. Since each endogenous construct in the model was predicted by only one exogenous variable, all VIF values were 1.00. This outcome is expected, as VIF equals 1 when only a single predictor is present in a regression equation, indicating the absence of multi-collinearity. The model fit (SRMR = 0.106) slightly exceeds the ideal threshold of 0.10 but remains acceptable when theoretical support is strong [70].

Figure 2: Hypotheses testing results. Note: *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001; the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) = 0.106; ns, non-significant; TE, total effect; DE, direct effect

As shown in Table 3, the results of the path analysis indicated that exercise commitment had a significant positive effect on PsyCap (β = 0.161, t = 2.001, p < 0.05), providing support for Hypothesis 1. Secondly, PsyCap significantly influenced flourishing (β = 0.444, t = 7.097, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 2. Furthermore, the mediation analysis revealed that PsyCap fully mediated the relationship between exercise commitment and flourishing (β = 0.071, t = 1.968, p < 0.05, 95% CI [0.002,0.141]), thereby supporting Hypothesis 3 (Direct effect β = 0.100, Indirect effect β = 0.071, p < 0.05, Total effect β = 0.171, p < 0.05). Specifically, a one-unit increase in exercise commitment corresponds to a 7.1% rise in flourishing via PsyCap.

The present study tested three hypotheses concerning the relationships among exercise commitment, PsyCap, and flourishing in younger adult runners in South Korea. First, exercise commitment, conceptualized as a second-order construct encompassing both cognitive and behavioral dimensions, significantly and positively affected PsyCap. This finding aligns with previous research demonstrating that cognitive commitment (e.g., goal setting, value attribution) enhances hope and optimism. In addition, behavioral commitment (e.g., consistent participation, exercise expressions of enthusiasm) strengthens efficacy and resilience, together fostering the development of PsyCap. These findings are consistent with prior research highlighting the positive association between exercise immersion and the development of PsyCap [18,19,47,53]. For instance, significant associations have been reported between engagement in physical activity and flow states, with flow experiences being positively related to self-efficacy [18,53] and resilience [47]—core components of PsyCap. Similarly, Belcher et al. [19] reported that engagement in sport and goal-oriented commitment promote hope and optimism—core components of PsyCap—by fostering a sense of mastery and progress. The present study extends these findings by demonstrating that, when exercise commitment is conceptualized as a second-order construct encompassing both cognitive and behavioral dimensions, it significantly predicts PsyCap among younger adult runners.

Second, the demonstrated positive effect of PsyCap on flourishing aligns with previous research in both organizational and health psychology. Studies by Luthans et al. [50] and Hefferon and Mutrie [14] emphasized that individuals with higher levels of hope, efficacy, resilience, and optimism are more likely to experience emotional, psychological, and social well-being. Liu et al. [45] further validated that each PsyCap dimension contributes meaningfully to adaptive functioning and mental health, particularly among active populations. Our findings reinforce the PsyCap-well-being relationship among younger adult sports participants, demonstrating its robustness even when both constructs are modeled as second-order constructs.

Third, and most notably, mediation analysis revealed that PsyCap fully mediated the relationship between exercise commitment and flourishing. In other words, the positive impact of exercise commitment on well-being was transmitted entirely through the enhancement of psychological resources, not through a direct pathway. This full mediation effect is consistent with recent studies, which have shown that the direct effect of exercise commitment on well-being becomes non-significant when PsyCap is included as a mediator [45,53]. Although the indirect effect (β = 0.071, p < 0.05) may appear numerically small, it translates to a 7.1% increase in flourishing scores—a practically meaningful effect in social science contexts where even modest changes yield real-world impact [71]. The mediating role of PsyCap highlights the importance of fostering psychological resources in addition to promoting behavioral engagement. These insights point to the potential effectiveness of integrated interventions that simultaneously address both motivational and PsyCap pathways to maximize the impact of exercise on multidimensional well-being.

Fourth, from a methodological perspective, using a second-order PLS-SEM model highlights the advantages of hierarchical modeling. Second-order models allow researchers to measure complex constructs more systematically by capturing higher-order concepts that cannot be assessed directly with first-order indicators [72]. This approach simplifies model structure, enhances interpretability, and supports the generalization of findings across different populations and research contexts [67]. Overall, it offers a clear and efficient framework for studying complex psychological processes and lays the groundwork for future research in diverse settings.

In sum, this study demonstrates that complementary mechanisms—motivation/self-regulation (SCT) and positive affect/resource-building (BBT)—synergistically promote flourishing. Notably, for younger adults who prioritize well-being over competition, the cultivation of PsyCap emerged as the primary pathway to flourishing. These findings offer a novel contribution that extends prior research on mental health promotion. Overall, the insights underscore the importance of integrating multiple theoretical perspectives to advance in future research.

The findings of this study provide important practical implications for sports instructors, event organizers, and policymakers aiming to promote sustained sports participation and well-being among younger adults. First, sports instructors and coaches should prioritize the development of PsyCap—including hope, efficacy, resilience, and optimism—when designing running programs. By structuring training with clear, incremental goals and offering regular encouragement, instructors can help participants build confidence and overcome common barriers such as perceived difficulty, time, and cost. Fostering a supportive group environment within running clubs or teams can further enhance PsyCap and facilitate long-term engagement.

For event organizers and sports marketers, the unique characteristics of running—its low barriers to entry and adaptability to individual skill levels—can be leveraged to attract and retain participants. Offering events with various distances and difficulty levels enables individuals to participate according to their abilities and personal goals, reducing psychological and practical barriers. Emphasizing running events as opportunities for personal growth and well-being, rather than solely as competitive challenges, can resonate with younger adults who value holistic health and self-development. Public recognition of participants’ achievements, regardless of performance level, can foster a sense of accomplishment and further build psychological resources.

From a broader perspective, recent trends in South Korea demonstrate a remarkable surge in running participation, with the number of runners estimated at 10 million and post-pandemic offline events and marathons fueling this growth [4]. This widespread enthusiasm for running highlights both the demand for accessible sports and the potential for running programs to effectively enhance PsyCap and well-being among younger adults. By implementing these strategies, practitioners and policymakers can help increase sustained physical activity, foster greater satisfaction and well-being, and develop a healthier, more resilient younger generation in South Korea.

Running is not only a major trend in South Korea but also a globally accessible and inclusive activity [1]. Accordingly, the practical relevance of the findings has the potential to inform mental health promotion strategies beyond the Korean context. For successful international application, it is essential to consider sociocultural adaptation, understand individual and generational characteristics, and address the digital divide. A key consideration is bridging digital gaps that may exclude certain populations; providing digital literacy education alongside running programs can reduce digital exclusion. This approach holds significant potential for mental health promotion programs and policy development, offering scalable and sustainable value for enhancing well-being and active lifestyles across diverse populations.

5.3 Limitations and Future Direction

Our study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings, and these also inform directions for future research.

First, convenience sampling resulted in a sample skewed in terms of both geography and gender, thereby limiting the generalizability of the findings. Although the multi-group analysis (MGA) revealed no statistically significant differences in any path coefficients by gender, unmeasured regional variability in factors such as structural sports constraints (e.g., location and distance) may still influence the observed mechanisms. In addition, the use of digital recruitment platforms may have introduced further bias by concentrating the sample within specific sociocultural or technological contexts, potentially affecting the external validity of the results. Therefore, future research should consider employing stratified sampling to achieve broader geographic representation and include control variables—such as constraints or constraint negotiation—measured with validated instruments, to enhance the external validity and robustness.

Therefore, future research should employ stratified sampling to achieve broader geographic representation and include control variables such as leisure constraints or constraint negotiation, measured with validated instruments, to enhance the external validity and robustness.

Second, while the sample size (n = 166) meets PLS-SEM thresholds (10× maximum structural paths or 150 cases for complex models) [68], larger and more diverse samples would enhance statistical power and generalizability. This is particularly critical for studies employing second-order constructs and moderation analyses, where increased samples reduce estimation bias and facilitate more robust multi-group or longitudinal comparisons. Future studies should prioritize larger, more diverse samples to strengthen the validity and applicability of their findings.

Third, this study was limited to the Millennials and Generation Z cohorts, precluding examination of generational differences in proposed relationships. It remains unclear whether the observed mechanisms are unique to younger adults or generalizable to other age cohorts (e.g., Generation X or Baby Boomers). Future research should adopt comparative designs to investigate generational differences in the effects of exercise commitment on PsyCap and flourishing. Crucially, incorporating sports consumption characteristics of the younger adults—such as digital nativity, technological familiarity, or social identity [11]—as moderating variables would better reflect cohort-specific tendencies. Empirical evidence highlights stark generational contrasts: Younger adults leverage fitness apps, social media, and wearables to enhance their sports experiences and social connectivity [73], where older adults face digital literacy barriers that diminish their motivation for digitally mediated physical activities and shift focus toward health maintenance over social or competitive motives [74]. These divergences underscore the necessity for future research to explicitly examine how digital practices and running participations vary across generations through rigorous comparative frameworks.

Lastly, all latent variables were modeled as second-order (reflective-reflective) constructs. While this hierarchical modeling approach enhances theoretical parsimony and captures the integrative nature of constructs [62,67] like exercise commitment, PsyCap, and flourishing, it may mask nuanced relationships among first-order dimensions. For example, distinct effects of cognitive vs. behavioral commitment on specific PsyCap facets (e.g., hope, resilience) remain unexamined. Future research should compare second-order and first-order models to elucidate both overarching and dimension-specific pathways.

Among the various options to enhance both physical and mental well-being, running is recognized as a straightforward and accessible form of exercise that can be readily incorporated into daily life. Grounded in SCT and BBT, the current study examined the structural relationships among exercise commitment, PsyCap, and multidimensional well-being in younger adults. All proposed hypotheses were supported, with exercise commitment significantly predicting PsyCap, which in turn exerted a significant positive effect on flourishing.

In summary, this study highlights how the complementary mechanisms from two theoretical frameworks foster flourishing through PsyCap. Notably, for younger adults who prioritize well-being over competition, developing PsyCap emerged as the key pathway to flourishing. These results contribute new insights that build upon existing mental health promotion research. Specifically, the insights underscore the need for integrating multiple theoretical frameworks to further progress in future studies. Moreover, these findings provide actionable insights for sports practitioners and policymakers aiming to enhance the well-being of younger adults. The unique characteristics of running can be leveraged to attract and retain participants; thus, cultivating supportive running environments that foster PsyCap through goal-setting and social support, while reducing psychological and environmental barriers, is essential. These practical implications have the potential to inform mental health promotion strategies beyond the Korean context.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Jinwoong Choi (first author) was responsible for the study design and conceptualization. Young-lae Choi (second author) contributed to data interpretation. Kyuhyun Choi (corresponding author) was involved in data collection and analysis. The first author Jinwoong Choi and the corresponding author Kyuhyun Choi drafted the initial manuscript, which was subsequently reviewed by the second author. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Requests for access to the data and materials used in this research may be addressed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval: This study did not require ethics approval, as it involved only anonymous survey data. The researchers conducted a review using our institution’s internal self-check exemption checklist. Participation was completely voluntary, and respondents could withdraw at any time without consequences. All participants provided informed consent prior to participation. The data were collected and analyzed anonymously to ensure confidentiality and privacy.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Wunsch K, Kienberger K, Niessner C. Changes in physical activity patterns due to the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(4):2250. doi:10.3390/ijerph19042250. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Yu GB, Kim N. COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on consumers in South Korea. In: Community, economy and COVID-19: lessons from multi–country analyses of a global pandemic. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2022. p. 437–60. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-98152-5_21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Ahn J. Running again. MK News. 2024 Feb 29 [cited 2025 May 21]. (In Korean). Available from: https://www.mk.co.kr/news/culture/10954037. [Google Scholar]

4. Shin Y. Interview with Ahn Jung-eun, Korea’s Youngest Six Major Marathons Finisher, and Jessica Min, Travel Trend Expert. Seoul, Republic of Korea: Nate News; 2025 Apr 22 [cited 2025 May 21]. (In Korean). Available from: https://news.nate.com/view/20250422n38180. [Google Scholar]

5. Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism. 2022 Korea National Sports Participation Survey [Internet]. Sejong, Republic of Korea: Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism; 2023 [cited 2025 May 21]. (In Korean). Available from: https://www.mcst.go.kr/kor/s_policy/dept/deptView.jsp?pSeq=1691&pDataCD=0417000000&pType=. [Google Scholar]

6. Stevinson C, Plateau CR, Plunkett S, Fitzpatrick EJ, Ojo M, Moran M, et al. Adherence and health-related outcomes of beginner running programs: a 10-week observational study. J Phys Act Health. 2020;17(9):911–8. doi:10.1080/02701367.2020.1799916. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Oja P, Titze S, Kokko S, Kujala UM, Heinonen A, Kelly P, et al. Health benefits of different sport disciplines for adults: systematic review of observational and intervention studies with meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49(7):434–40. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2014-093885. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Chekroud SR, Gueorguieva R, Zheutlin AB, Paulus M, Krumholz HM, Krystal J, et al. Association between physical exercise and mental health in 1.2 million individuals in the USA between 2011 and 2015: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Psychiaty. 2018;5(9):739–46. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30227-X. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Lee DC, Pate RR, Lavie CJ, Sui X, Church TS, Blair SN. Leisure-time running reduces all-cause and cardiovascular mortality risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(5):472–81. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2014.04.058. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Lower-Hoppe LM, Aicher TJ, Baker BJ. Intention–behaviour relationship within community running clubs: examining the moderating influence of leisure constraints and facilitators within the environment. World Leis J. 2023;65(1):3–27. doi:10.1080/16078055.2022.2125572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Yim BH, Byon KK, Baker TA, Zhang JJ. Identifying critical factors in sport consumption decision making of millennial sport fans: mixed-methods approach. Eur Sport Manag Q. 2021;21(4):484–503. doi:10.1080/16184742.2020.1755713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Han S. Reading sports trends through running culture. Sport Sci. 2020;150:8–13. (In Korean). [Google Scholar]

13. Fredrickson BL. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am Psychol. 2001;56(3):218–26. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Hefferon K, Mutrie N. 7 Physical activity as psychology intervention. In: Acevedo EO, editor. The Oxford handbook of exercise psychology. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2012. p. 117–28. [Google Scholar]

15. Luthans F, Avolio BJ, Avey JB, Norman SM. Positive psychological capital: measurement and relationship with performance and satisfaction. Pers Psychol. 2007;60(3):541–72. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.2007.00083.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Fletcher D, Sarkar M. Psychological resilience: a review and critique of definitions, concepts and theory. Eur Psychol. 2013;18(1):12–23. doi:10.1027/1016-9040/a000124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Galli N, Gonzalez SP. Psychological resilience in sport: a review of the literature and implications for research and practice. Int J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2015;13(3):243–57. doi:10.1080/1612197X.2014.946947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Jackson SA, Kimiecik JC, Ford SK, Marsh HW. Psychological correlates of flow in sport. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2001;20(4):358–78. doi:10.1123/jsep.20.4.358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Belcher BR, Zink J, Azad A, Campbell CE, Chakravartti SP, Herting MM. The roles of physical activity, exercise, and fitness in promoting resilience during adolescence: effects on mental well-being and brain development. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging. 2021;6(2):225–37. doi:10.1016/j.bpsc.2020.08.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Yu X, Xing S, Yang Y. The relationship between psychological capital and athlete burnout: the mediating relationship of coping strategies and the moderating relationship of perceived stress. BMC Psychol. 2025;13(64):109. doi:10.1186/s40359-025-02379-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Diotaiuti P, Corrado S, Mancone S, Falese L. Resilience in the endurance runner: the role of self-regulatory modes and basic psychological needs. Front Psychol. 2021;11:558287. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.558287. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA: Prentice-Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

23. Fredrickson BL, Joiner T. Positive emotions trigger upward spirals toward emotional well-being. Psychol Sci. 2002;13(2):172–5. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.00431. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Luthans F, Youssef CM, Avolio BJ. Psychological capital: developing the human competitive edge. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

25. Siu OL, Cooper CL, Phillips DR. Intervention studies on enhancing work well-being, reducing burnout, and improving recovery experiences among Hong Kong health care workers. J Stress Manage. 2014;21(1):69–84. doi:10.1037/a0033291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Nguyen TD, Cao TH, Nguyen TM, Nguyen TT. Psychological capital: a literature review and research trends. AJEB. 2024;8(3):412–29. doi:10.1108/AJEB-08-2023-0076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Peethambaran M, Naim MF. The workplace crescendo: unveiling the positive dynamics of high-performance work systems, flourishing at work and psychological capital. Ind Commer Train. 2024;56(4):377–89. doi:10.1108/ICT-01-2024-0008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Park J, Uhm JP, Kim S, Kim M, Sato S, Lee HW. Sport community involvement and life satisfaction during COVID-19: a moderated mediation of psychological capital by distress and generation Z. Fron Psychol. 2022;13:861630. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.861630. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Bandura A. Self-efficacy: the exercise of control. New York, NY, USA: W. H. Freeman; 1997. [Google Scholar]

30. Li Y, Xu J, Zhang X, Chen G. The relationship between exercise commitment and college students’ exercise adherence: the chained mediating role of exercise atmosphere and exercise self-efficacy. Acta Psycholo. 2024;246:104253. doi:10.1016/j.actpsy.2024.104253. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Jung YG. Validity verification of sport commitment behavior. Korean J Sport Psycho. 2004;15(1):1–21. (In Korean). [Google Scholar]

32. Keyes CLM. The mental health continuum: from languishing to flourishing in life. J Health Soc Behav. 2002;43(2):207–22. doi:10.2307/3090197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Fredrickson BL. The broaden–and–build theory of positive emotions. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2004;359(1449):1367–77. doi:10.1098/rstb.2004.1512. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Cohn MA, Fredrickson BL, Brown SL, Mikels JA, Conway AM. Happiness unpacked: positive emotions increase life satisfaction by building resilience. Emotion. 2009;9(3):361–8. doi:10.1037/a0015952. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Lee YJ, Kim AR, An KO. Participation level, rating of perceived exertion, exercise commitment and exercise adherence of marathon participation. Korean J Kinesiol. 2015;17(3):7–15. (In Korean). doi:10.15758/jkak.2015.17.3.7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Newman A, Ucbasaran D, Zhu F, Hirst G. Psychological capital: a review and synthesis. J Organ Behav. 2014;35(S1):120–38. doi:10.1002/job.1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Rovniak LS, Anderson ES, Winett RA, Stephens RS. Social cognitive determinants of physical activity in young adults: a prospective structural equation analysis. Ann Behav Med. 2002;24:149–56. doi:10.1207/S15324796ABM2402_12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Rhodes RE, Kates A. Can the affective response to exercise predict future motives and physical activity behavior? a systematic review of published evidence. Ann Behavl Med. 2015;49(5):715–31. doi:10.1007/s12160-015-9704-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Scanlan TK, Carpenter PJ, Simons JP, Schmidt GW, Keeler B. The sport commitment model: measurement development for the youth-sport domain. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 1993;15(1):16–38. doi:10.1123/jsep.15.1.16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Zhang WJ, Xu M, Feng YJ, Mao ZX, Yan ZY, Fan TF. The value-added contribution of exercise commitment to college students’ exercise behavior: application of extended model of theory of planned behavior. Front Psychol. 2022;13:869997. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.869997. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Seligman MEP. Flourish: a visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. New York, NY, USA: Simon & Schuster; 2011. [Google Scholar]

42. Avey JB, Luthans F, Smith RM, Palmer NF. Impact of positive psychological capital on employee well-being over time. J Occup Health Psychol. 2010;15(1):17–28. doi:10.1037/a0016998. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Dudasova L, Prochazka J, Vaculik M, Lorenz T. Measuring psychological capital: revision of the compound psychological capital scale (CPC-12). PLoS One. 2021;16(3):e0247114. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0247114. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Dudasova L, Prochazka J, Vaculik M. Psychological capital, social support, work engagement, and life satisfaction: a longitudinal study in COVID-19 pandemic. Curr Psychol. 2024;43(24):1–15. doi:10.1007/s12144-024-05841-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Liu X, Wang Z, Zhang C, Xu J, Shen Z, Peng L, et al. Psychological capital and its factors as mediators between interpersonal sensitivity and depressive symptoms among Chinese undergraduates. Psychol Res Behav Manage. 2024;17:429–41. doi:10.2147/prbm.s452993. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Feldman DB, Dreher DE. Can hope be changed in 90 minutes? Testing the efficacy of a single-session goal-pursuit intervention for college students. J Happiness Stud. 2012;13(4):745–59. doi:10.1007/s10902-011-9292-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Li X, Wang J, Yu H, Liu Y, Xu X, Lin J, et al. How does physical activity improve adolescent resilience? Serial indirect effects via self-efficacy and basic psychological needs. PeerJ. 2024;12:e17059. doi:10.7717/peerj.17059. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Lamers SM, Westerhof GJ, Bohlmeijer ET, Ten Klooster PM, Keyes CL. Evaluating the psychometric properties of the mental health continuum-short form (MHC-SF). J Clin Psychol. 2011;67(1):99–110. doi:10.1002/jclp.20741. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Keyes H, Gradidge S, Gibson N, Harvey A, Roeloffs S, Zawisza M, et al. Attending live sporting events predicts subjective wellbeing and reduces loneliness. Front Public Health. 2023;10:989706. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.989706. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Luthans F, Youssef-Morgan CM, Avolio BJ. Psychological capital and beyond. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

51. Hefferon K, Boniwell I. Positive psychology: theory, research and applications. New York, NY, USA: McGraw-Hill Education; 2011. [Google Scholar]

52. Ho HC, Chan YC. Flourishing in the workplace: a one-year prospective study on the effects of perceived organizational support and psychological capital. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(2):922. doi:10.3390/ijerph19020922. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Zhang G, Feng W, Zhao L, Zhao X, Li T. The association between physical activity, self-efficacy, stress self-management and mental health among adolescents. Sci Rep. 2024;14:5488. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-56149-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Luthans F, Avey JB, Clapp-Smith R, Li W. More evidence on the value of Chinese workers’ psychological capital: a potentially unlimited competitive resource? Int J Hum Resour Manage. 2008;19(5):818–27. doi:10.1080/09585190801991194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Bolier L, Haverman M, Westerhof GJ, Riper H, Smit F, Bohlmeijer E. Positive psychology interventions: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:119. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-119. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Lambert L, Passmore HA, Joshanloo M. A positive psychology intervention program in a culturally-diverse university: boosting happiness and reducing fear. J Happiness Stud. 2019;20(4):1141–62. doi:10.1007/s10902-018-9993-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Arslan G, Aydoğdu U, Uzun K. Longitudinal impact of the ACT-based positive psychology intervention to improve happiness, mental health, and well-being. Psychiatr Q. 2025;84:30. doi:10.1007/s11126-025-10145-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Lomas T, Gardiner K, Ivtzan I, Hefferon K. Applied positive psychology: integrated positive practice. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: Sage Publications; 2024. [Google Scholar]

59. Lorenz T, Beer C, Pütz J, Heinitz K. Measuring psychological capital: construction and validation of the compound PsyCap scale (CPC-12). PLoS One. 2016;11(4):e0152892. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0152892. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Keyes CLM. Brief description of the mental health continuum short form (MHC-SF). Atlanta, GA, USA: Emory University; 2009 [cited 2025 May 21]. Available from: https://peplab.web.unc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/18901/2018/11/MHC-SFoverview.pdf. [Google Scholar]

61. Sarstedt M, Ringle CM, Hair JF. Treating unobserved heterogeneity in PLS-SEM: a multi-method approach. In: Latan H, Noonan R, editors. Partial least squares path modeling: basic concepts, methodological issues and applications. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2017. p. 197–217. [Google Scholar]

62. Hair JF, Hollingsworth CL, Randolph AB, Chong AYL. An updated and expanded assessment of PLS-SEM in information systems research. Ind Manage Data Syst. 2017;117(3):442–58. doi:10.1108/IMDS-04-2016-0130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Fornell C, Larcker DF. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res. 1981;18(1):39–50. doi:10.1177/002224378101800104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee JY, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88(5):879–903. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Shmueli G, Koppius OR. Predictive analytics in information systems research. MIS Q. 2011;35(3):553–72. doi:10.2307/23042796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Hair JF, Hult GTM, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M. A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2017. [Google Scholar]

67. Sarstedt M, Hair JF, Cheah JH, Becker JM, Ringle CM. How to specify, estimate, and validate higher-order constructs in PLS-SEM. Australas Mark J. 2019;27(3):197–211. doi:10.1016/j.ausmj.2019.05.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Hair JF, Risher JJ, Sarstedt M, Ringle CM. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur Bus Rev. 2019;31(1):2–24. doi:10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Greenland S, Mansournia MA, Altman DG. Sparse data bias: a problem hiding in plain sight. BMJ. 2016;352:i1981. doi:10.1136/bmj.i1981. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Henseler J, Hubona G, Ray PA. Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: updated guidelines. Ind Manage Data Syst. 2016;116(1):2–20. doi:10.1108/IMDS-09-2015-0382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Ferguson CJ. An effect size primer: a guide for clinicians and researchers. Prof Psychol: Res Pract. 2009;40(5):532–8. doi:10.1037/a0015808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Becker JM, Klein K, Wetzels M. Hierarchical latent variable models in PLS-SEM: guidelines for using reflective-formative type models. Long Range Plan. 2012;45(5–6):359–94. doi:10.1016/j.lrp.2012.10.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Dewa LH, Lavelle M, Pickles K, Kalorkoti C, Jaques J, Pappa S, et al. Young adults’ perceptions of using wearables, social media and other technologies to detect worsening mental health: a qualitative study. PLoS One. 2019;14(9):e0222655. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0222655. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Oh SS, Kim KA, Kim M, Oh J, Chu SH, Choi J. Measurement of digital literacy among older adults: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(2):e26145. doi:10.2196/26145. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools