Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Mindfulness and Mental Health of College Athletes: The Role of Stress Coping and Burnout

1 Department of Sport & Leisure Studies, Hoseo University, Asan-si, 31499, Republic of Korea

2 School of Physical Education, Hunan University of Science and Technology, Taoyuan Road, Xiangtan, 411201, China

* Corresponding Authors: Kyungsik Kim. Email: ; Sihong Sui. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Enhancing Mental Health through Physical Activity: Exploring Resilience Across Populations and Life Stages)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(10), 1553-1575. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.068523

Received 30 May 2025; Accepted 22 August 2025; Issue published 31 October 2025

Abstract

Background: Psychological stress from academic and athletic demands adversely affects college athletes’ mental health, the underlying mechanisms of this relationship remain insufficiently understood. Therefore, this study focuses on the Chinese college athletes and explores the relationship among mindfulness, stress coping, burnout, and mental health. Methods: The study used a sample of 500 student athletes from five higher sports colleges in China, collected data on various variables using standardized psychometric instruments, and analyzed the path relationships and mediating effects among the variables using structural equation modeling (SEM) and bootstrap methods. Results: Mindfulness significantly improved stress coping ability (β = 0.721, p < 0.001), and stress coping significantly improved mental health (β = 0.606, p = 0.027) and reduced burnout levels (β = −0.225, p < 0.001). Burnout had a significant negative impact on mental health (β = −0.113, p = 0.015). Mediation effect analysis revealed that stress coping played a mediating role between mindfulness and mental health (β = 0.797, p < 0.001), while the mediating effect of burnout was not statistically significant. When stress coping and burnout were considered simultaneously, they mediated the relationship between mindfulness and mental health (β = 0.033, 95% CI: [0.004, 0.104], p = 0.026). Conclusions: Mindfulness indirectly affects the mental health of college athletes by enhancing stress coping ability. The findings highlight the importance of integrating mindfulness training and stress coping strategies in sports training. Future studies should consider differences among sports to clarify the relationships between mindfulness, stress coping, burnout, and mental health.Keywords

College athletes must continually navigate their athletic responsibilities and academic demands. The dual roles they assume frequently result in high levels of stress. Scholars have demonstrated that the cumulative effect of athletic and academic obligations exacerbates psychological strain [1,2].

In China, college students experience serious mental health problems such as chronic stress, anxiety, and depression. These problems are often exacerbated by academic and career preparation and are especially evident among college athletes, who pursue a combination of academic and athletic goals. College athletes, who are required to perform well in competitions, undergo high-intensity training, face fierce competitive pressure, deal with uncertainty regarding their future career paths, and experience significant physical and psychological burdens [3].

Recently, scholars have characterized mindfulness as having a non-judgmental attitude toward and open acceptance of one’s situation [4]. Previous findings show that mindfulness is an effective coping strategy that positively relates to mental health, not merely representing a state of consciousness [5], and that it enhances happiness and self-worth [4,6]. The research team led by Norouzi et al. [7] concluded that the combination of mindfulness-based stress reduction and physical activity interventions has a significant positive effect on patients with Major Depressive Disorder (MDD). This indicates that such an integrated intervention approach can serve as an adjunct to depression treatment, aiding in the alleviation of patients’ symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress, while also improving their sleep quality.

In students, mindfulness practice can promote mental health and overall well-being by reducing anxiety, stress, and fatigue in daily life [8,9]. Research on college athletes remains limited, highlighting the need to explore the relationship between mindfulness and their mental health. In addition to promoting mental health, mindfulness negatively relates to burnout [10] and positively relates to stress coping [11]. Through in-depth research and the practical application of mindfulness theories and techniques, we can provide more comprehensive and effective mental health support for college athletes, helping them achieve better outcomes in academics, training, and life.

Conservation of Resources Theory (COR) can help explain stress and burnout [12]. The central concept of COR is the loss and acquisition of resources, which include personal characteristics, states and conditions, energy, and social support. Continual loss can lead to burnout, but with sufficient resources, an individual is less likely to experience stress [13]. Therefore, people try to conserve and build resources to prevent expected losses [12]. COR, a major theory in psychology, explains that mindfulness is an important resource for coping with stress and burnout and maintaining psychological well-being. Mindfulness could benefit college athletes, a population that tends to experience high stress due to the combined demands of academics and sports. Previous findings show that mindfulness strategies are effective tools for alleviating stress and preventing burnout in populations that experience high levels of stress [14,15].

According to COR, people feel stress and burnout when they experience imbalances between resource gain and resource loss [16]. This theory is useful in explaining the mental health of college athletes, who perform multiple roles as athletes and students. Strategies such as mindfulness relate to lower burnout and better mental health by restoring psychological resources and enhancing stress coping [17]. Understanding COR can help experts plan effective mindfulness intervention strategies to manage mental health resources in college athletes.

We applied the theory of Conservation of Resources (COR) rather than Self-Determination Theory (SDT) to analyze the mechanism through which mindfulness influences mental health in college athletes. Unlike SDT, which emphasizes optimizing and compensating resource allocation through psychological strategies such as mindfulness, COR theory focuses more on the protection and accumulation of resources, yielding a more precise picture of the characteristics of dynamic resource changes experienced by collegiate athletes under multiple pressures [18]. The resource loss experienced by college athletes primarily consists of time and energy consumed by academic work, competitive failures, and sports injuries; conversely, resource gains made possible by mindfulness training include psychological resilience and stress coping. The dynamic changes in these resources have a direct impact on mental health and competitive performance. COR offers greater specificity in examining stress coping and burnout prevention, allowing for a clearer picture of how mindfulness influences mental health through resource regulation and providing more practical guidance for psychological interventions targeting this specific population [18].

Stress can have a significant impact on the mental health of young students (e.g., college athletes), particularly those who are vulnerable to negative life events. Stress coping strategies serve as a buffer against stress by restoring the balance of psychological resources. Secades et al. [19] demonstrated that resilience helps sport performers withstand the pressure they experience. In competitive sports, athletes with high resilience tend to employ more adaptive coping strategies (e.g., task-oriented coping), helping them manage stress and maintain performance. According to COR, stress coping strategies help replenish depleted resources, thereby strengthening resilience [16] and overall mental health [20]. While stress coping strategies help the general population, they are particularly critical for college athletes, who face the dual demands of academic achievement and athletic performance. The effectiveness of their coping mechanisms significantly influences their susceptibility to burnout and their overall mental health outcomes. Ineffective strategies (e.g., avoidance or overwork) can increase mental strain and accelerate burnout [21].

Burnout is a state of physical and mental exhaustion characterized by negative shifts in attitude, emotions, and behavior, typically resulting from prolonged exposure to occupational stress [22]. Research on NCAA (National Collegiate Athletic Association) athletes has revealed that female athletes, senior athletes, and those with a history of sports injuries are more prone to burnout [23]. Athlete burnout not only positively correlates with depression but also induces a series of mental health problems [24]. Although many scholars have explored the relationship between mindfulness and mental health, stress coping and mental health, and burnout and mental health, they have often overlooked the interconnected effects of these factors.

Multiple studies have consistently shown that stress coping and burnout play a mediating role in the psychological mechanisms through which mindfulness influences mental health [25–27]. However, the interplay among mindfulness, stress coping, burnout, and mental health in college athletes remains underexplored, and prior research has often examined these variables in isolation. Therefore, this study is both necessary and meaningful for clarifying these understudied relationships and offering practical strategies to support the mental health of college athletes.

Specifically, it aimed to investigate the effects of mindfulness on stress coping, burnout, and mental health, and to clarify the mediating roles of stress coping and burnout in this relationship. By identifying the key mediating roles of stress coping and burnout in the link between mindfulness and mental health, this study expands the theoretical understanding of mindfulness interventions and provides practical implications for enhancing mental health among college athletes.

Mindfulness is a psychological state characterized by heightened focus on present experiences, conscious awareness, and acceptance of bodily sensations, thoughts, and emotions [28]. Recent findings show that people who practice mindfulness have higher levels of attention, higher self-awareness, and better emotional regulation [29].

Scholars have reported a significant positive correlation between mindfulness and mental health. Mindfulness in sports provides various benefits to athletes [30]. First, athletes who practice mindfulness can reduce fatigue and injury risk and improve performance. Second, they can appropriately cope with the stress and pressure they face in training and competitive situations. Third, they can improve psychological well-being and mental health. Coffey et al. [31] explained the mechanism through which mindfulness improves negative emotion management and contributes to mental health. Mindfulness helps individuals recognize and manage stress responses (e.g., anxiety, fear, and anger) by improving emotional awareness [32].

Additionally, Hut et al. [33] found that mindfulness training reduced stress reduction, increased happiness, and strengthened a sense of self-identity in female student-athletes. Other findings highlight the importance of mindfulness in enhancing stress coping in athletes. Vidic et al. [34] reported that a mindfulness-based intervention significantly reduced stress and improved coping skills in U.S. women’s NCAA teams.

In addition, Chua et al. [35] found, based on diary studies in the United States and Singapore, that trait mindfulness can directly improve daily positive emotions and cognitive functions and is independent of daily stressors. Similarly, Keng et al. [36] found that mindfulness related to happiness, self-esteem, and emotional regulation, relationships that were not entirely dependent on stress coping. These findings show that mindfulness, as a stable personality trait, can directly promote mental health.

Mindfulness can prevent burnout, which includes emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and decreased personal accomplishment [22]. Previous findings show a negative correlation between mindfulness and burnout. In other words, practicing mindfulness can prevent mental problems such as the progression of burnout [37]. Sauvain-Sabé et al. [38] found that mindfulness significantly reduced emotional exhaustion and depersonalization after controlling for coping strategies and emotional variables. Gronimus [39] found that trait mindfulness negatively related to burnout in German workplace populations, both directly and through reflection and acceptance. In sports, mindfulness training can help athletes regulate emotions and cope with stress, thereby reducing the possibility of burnout and further improving mental health, sleep quality, and athletic performance [40]. Based on previous findings, we proposed the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Mindfulness will affect mental health in athletes.

Hypothesis 2: Mindfulness will affect stress coping in athletes.

Hypothesis 3: Mindfulness will affect burnout in athletes.

Stress coping refers to the cognitive and behavioral responses individuals adopt when facing various pressures and challenges [41]. Stress coping typically involves cognitive evaluation of stressors, regulation of emotional responses, and the selection and execution of coping behaviors [42]. Scholars have roughly categorized coping strategies into three types: avoidance coping, emotional coping, and problem-focused coping [43].

Previous findings show that coping ability is related to mental health. According to the stress-response model proposed by Lazarus and Folkman [44], an individual’s cognitive appraisal of stressful situations, along with selected coping strategies, directly determines psychological adaptation. Positive coping mechanisms relate to emotional regulation and problem solving, whereas maladaptive strategies (e.g., avoidance or emotional suppression) are more likely to result in psychological disturbance, including anxiety and depression [45].

When college athletes face dual pressures from academics and competition, adopting favorable coping methods can significantly improve mental health and self-efficacy [46]; conversely, adopting unfavorable coping methods (e.g., avoidance and denial) can lead to the accumulation of psychological stress, severely undermining mental health [47]. McLoughlin et al. [48] reported that lifetime cumulative stress exposure in elite athletes deteriorates mental health and well-being by promoting maladaptive long-term coping strategies and increasing vulnerability to future stress. These findings suggest that college athletes can improve their mental health by improving how they cope with stress.

The relationship between stress coping and burnout is likewise critical. Adaptive coping strategies can reduce levels of burnout [13]. In contrast, maladaptive approaches (e.g., avoidance and denial) lead to the accumulation of stress and a heightened risk of burnout [49]. Previous findings show that enhanced self-regulation reduces burnout among athletes while also improving overall well-being and psychological adjustment, helping them maintain good mental states and competitive performance in high-pressure environments [50]. In contrast, maladaptive coping strategies often prove ineffective in alleviating stress and might exacerbate psychological strain, thereby increasing the risk of burnout [51].

Previous findings suggest that targeted interventions are related to better stress coping, prevention of burnout through enhanced psychological resilience, and improved mental health. We proposed the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 4: Stress coping will affect mental health in athletes.

Hypothesis 5: Stress coping will affect burnout in athletes.

Burnout is a psychological condition that gradually emerges because of prolonged occupational stress and sustained interpersonal tension [52]. Maslach and Jackson [22] developed the Three-Dimensional Model of burnout, identifying its core components as emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment. Emotional exhaustion refers to a state of extreme fatigue and psychological depletion resulting from the continuous drain of emotional resources.

Burnout manifests through a range of symptoms, which can have emotional, behavioral, cognitive, affective, and physical characteristics [53]. Within the domain of sport psychology, burnout is a major risk factor that negatively influences mental health and competitive performance [54]. In highly competitive settings, the cumulative effects of prolonged, high-intensity training, combined with external performance pressures, often lead to emotional exhaustion, diminished motivation, and, in some cases, premature retirement from sport [55].

Burnout closely relates to various mental health outcomes. Prolonged emotional exhaustion and a diminished sense of personal accomplishment significantly affect overall psychological well-being, lowering life satisfaction and decreasing work performance [56]. The negative effects of burnout on mental health are often enduring [57], particularly in sustained high-pressure environments, where emotional regulation tends to deteriorate, increasing vulnerability to chronic anxiety and sleep disturbance [58].

Burnout is a critical mental health risk factor among athletes [59]. It not only impairs athletic performance but might also contribute to depression, anxiety, and a decline in subjective well-being [60]. Accordingly, the implementation of psychological support mechanisms, the enhancement of self-regulation skills, and the establishment of robust social support systems within high-performance sports environments are essential for preventing and mitigating burnout. We propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 6: Burnout will affect mental health in athletes.

WHO [61] defined mental health as a state of well-being in which an individual realizes his or her own abilities, can cope with the common stresses of daily life, can work productively and effectively, and can contribute to his or her community.

Jahoda [62] was among the first to propose positive indicators of mental health, identifying components such as self-awareness, growth potential, and the pursuit of meaningful life goals. Building on this foundation, Keyes [63] introduced the mental health continuum theory, which categorizes psychological states along a spectrum from languishing to flourishing. This model includes four primary dimensions: emotional health, cognitive health, social functioning, and psychological resilience.

Athletes face a variety of unique stressors, including physical and competitive stress, interactions between athletes, and the possibility of early career termination due to injury [64]. The way athletes cope with these stressors is a critical factor in their mental health and athletic success [65]. In this regard, our study of the mechanism through which mindfulness affects mental health through stress coping and burnout will complement previous studies and provide important insights to the field.

2.5 Mediating Role of Stress Coping and Burnout

In recent years, scholars have paid more and more attention to the relationship between mindfulness and mental health, and stress coping has emerged as a key intermediary mechanism [66]. Mindfulness is an individual’s perception of the present without judgment. Previous findings show that mindfulness has a positive impact on the mental health of various groups of people [67,68].

Individuals with higher levels of mindfulness and stress coping ability usually feel less stress and have a stronger ability to perceive the present. Both are very important to overall mental health [66,69]. In addition, a structured mindfulness intervention plan can improve mental health outcomes by optimizing stress coping mechanisms and reducing stress responsiveness [70,71]. Findings further show that positive coping strategies play an important mediating role in the relationships among stress mentality, challenge assessment, and mental health. We proposed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 7: Stress coping will mediate the relationship between mental health and mindfulness in athletes.

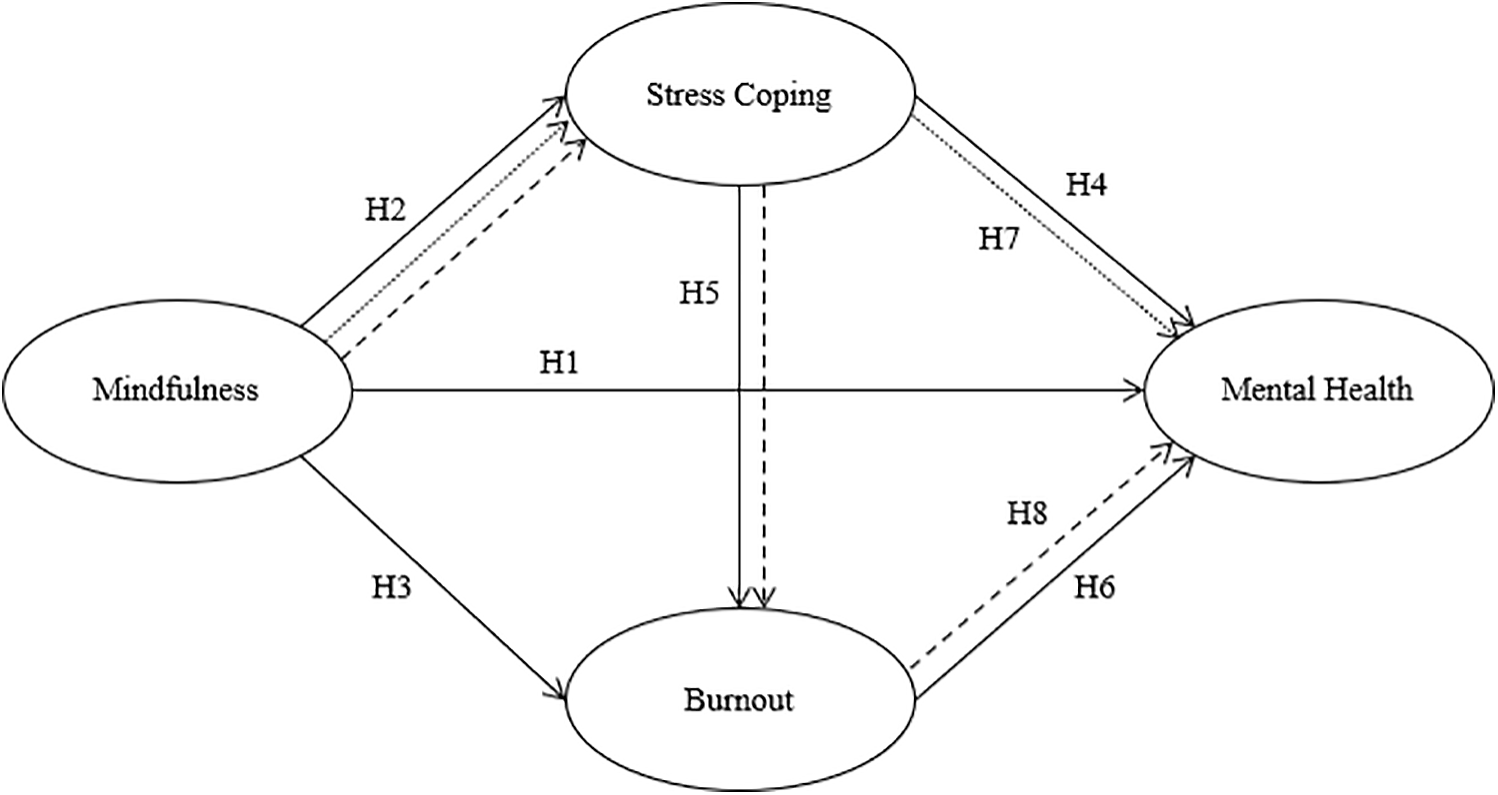

We also examined whether mindfulness affects mental health through a chain mediating process that alleviates burnout through stress coping. To date, scholars have not identified this mechanism, which has important theoretical and practical implications. Therefore, we integrated four core variables—mindfulness, stress coping, burnout, and mental health—into one model to explore how mindfulness affects the mental health of college athletes through a synergistic mediating effect of stress coping and burnout (see Fig. 1 for the overall research model). We proposed the following hypotheses.

Figure 1: Research model. Note: H, Hypothesis

Hypothesis 8: Stress coping and burnout will, in tandem, mediate the relationship between mindfulness and mental health in athletes.

We used a purposive sampling method to select 100 student-athletes from each of five Chinese universities specializing in sports: Shanghai University of Sport, Chengdu Sport University, Capital University of Physical Education and Sports, Hebei Sport University, and Guangzhou Sport University. Overall, China has 15 sport universities dedicated to training elite athletes.

We worked with sports officials at each university to obtain a list of eligible athletes, confirming their voluntary participation in accordance with the Institutional Review Board (IRB) guidelines and securing their informed consent before administering the survey. To enhance the representativeness of the sample, we made efforts to preserve the diversity of sport disciplines at each institution.

This study received IRB approval from Research Ethics Committee at Hunan University of Science and Technology (IRB number: HT2024031, approved on 30 June 2023), and all survey procedures adhered to ethical guidelines. Data collection was conducted via an online survey platform, enabling participants to complete the survey efficiently without time or location constraints.

All participants were college athletes in training who held national registered athlete certificates. A total of 600 questionnaires were distributed, and 447 valid questionnaires were collected, with an effective response rate of 74.5%. Inclusion criteria included being a student-athlete enrolled in a university, and exclusion criteria included incomplete or missing responses.

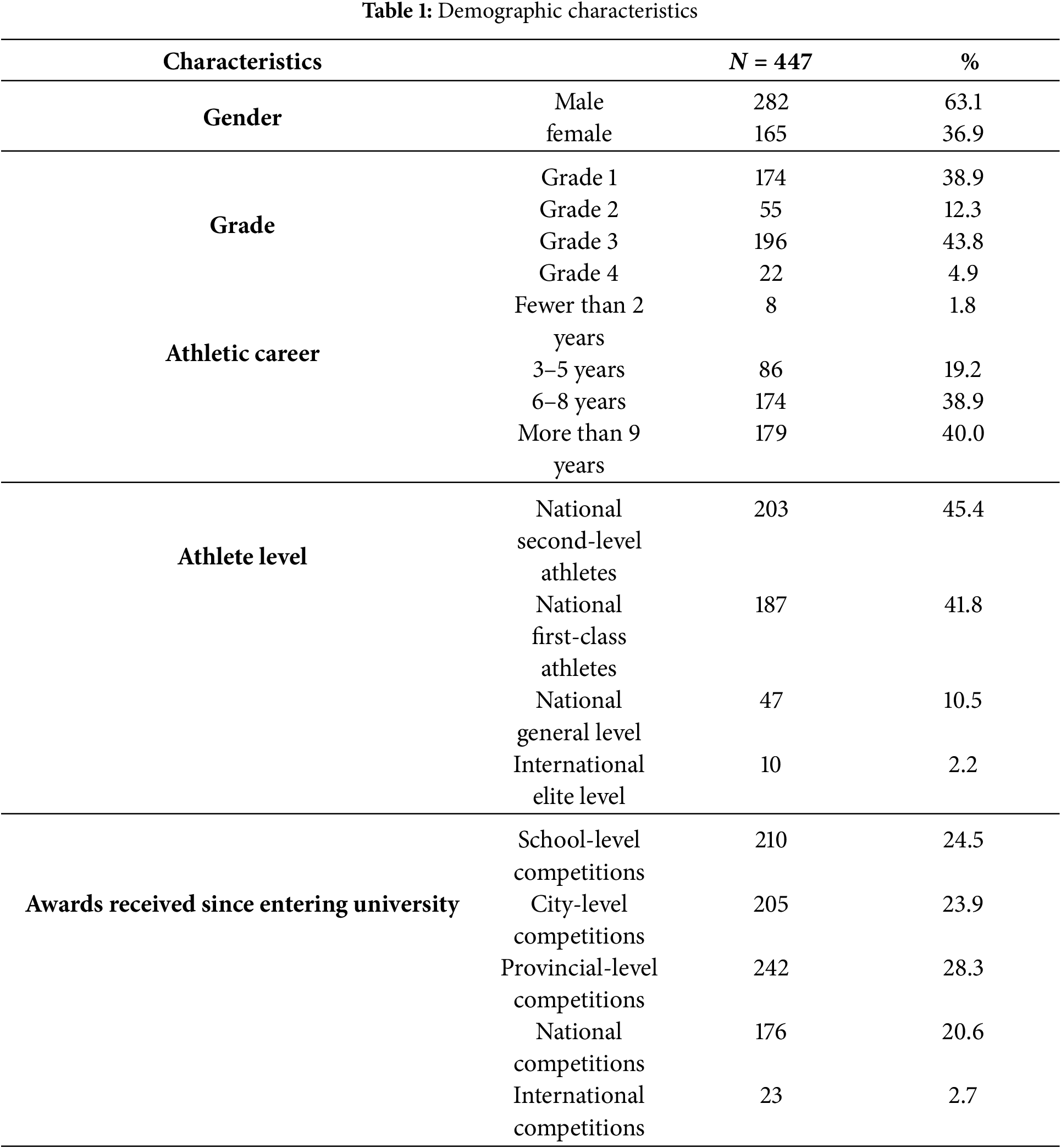

The instrument for this study was a self-report questionnaire assessing the personal characteristics, mindfulness, stress coping, burnout, and mental health of college athletes. Personal characteristics were assessed through five items: gender, grade, athletic career, athletic level, and awards received since entering university (see Table 1).

Mindfulness was measured using the Mindfulness Inventory for Sport (MIS) scale developed by Thienot et al. [72]. This instrument consists of five items on awareness, five items on non-judgmental attitude, and five items on refocusing. Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much), with higher scores indicating greater levels of mindfulness. Some items in this instrument contain negative expressions, and scores were reverse-transformed for analysis. The validity of the instrument was verified by CFA in Thienot et al., with comparative fit index (CFI) and Tucker Lewis index (TLI) indices above 0.9. Cronbach’s α was above 0.77.

The Coping Strategies in Sport Competition Inventory (ISCCS) developed by Gaudreau and Blondin [73] was used to measure stress coping. This instrument consists of 26 items: 3 items on thought control, 4 items on mental imagery, 4 items on relaxation, 3 items on effort expenditure, 4 items on logical analysis, 4 items on seeking support, and 4 items on venting of unpleasant emotions. Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much), with higher scores indicating better stress coping. The validity of the instrument was confirmed by CFA in Gaudreau and Blondin [73] at the time of development, with CFI and TLI values over 0.90. Cronbach’s α above 0.67.

The burnout measurement tool used was the Athlete Burnout Questionnaire (ABQ), developed by Raedeke and Smith [74] and used by Gerber et al. [75]. This instrument consists of 13 items: 5 items on emotional/physical exhaustion, 5 items on sport devaluation, and 3 items on reduced sense of accomplishment. Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much), with higher scores indicating greater burnout. The reduced sense of accomplishment factor includes negative items, and scores were reverse-transformed for analysis. The validity of the instrument was confirmed by CFA in Gerber et al. [75], with CFI and TLI values exceeding 0.97. Retest reliability ranged from 0.57 to 0.65.

The Mental Health Continuum-Short Form (MHC-S), developed by Keyes [76] and used by de Lara Machado and Bandeira [77], was the measure for mental health. This instrument consists of three items on emotional well-being, five items on social well-being, and six items on psychological well-being. Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much), with a higher score indicating better mental health. The CFI and TLI indices for the questionnaire were 0.90 or higher in de Lara Machado and Bandeira [77], and Cronbach’s α was 0.99.

We used a two-step approach, first confirming the validity of the measurement model through CFA and then verifying the structural model. Validity and reliability of the measurement model were verified using Average Variance Extracted (AVE), composite reliability (CR), and Cronbach’s Alpha. Convergent validity and reliability were verified using CFA, as proposed by Fornell and Larcker [78]. AVE and CR were used to verify convergent validity. Generally, AVE should be 0.5 or higher, and CR should be 0.7 or higher [78]. Cronbach’s alpha should be at least 0.60. In addition, the standardized factor coefficient (λ) between the latent variable and the observed variable should be 0.4 or higher.

The factor coefficients (λ) of the measured variables were 0.543 to 0.875 for mindfulness, 0.491 to 0.928 for stress coping, 0.730 to 0.887 for burnout, and 0.568 to 0.821 for mental health. CR values were 0.853 to 0.907 for mindfulness, 0.808 to 0.939 for stress coping, 0.830 to 0.938 for burnout, and 0.500 to 0.903 for mental health. AVE values were 0.541 to 0.665 for mindfulness, 0.582 to 0.838 for stress coping, 0.619 to 0.750 for burnout, and 0.585 to 0.902 for mental health. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.706 to 0.927. These findings show that the factor coefficients, CR, AVE, and Cronbach’s alpha of the measurement variables met the standard values and that the validity and reliability of the measurement model were excellent (see Table 2).

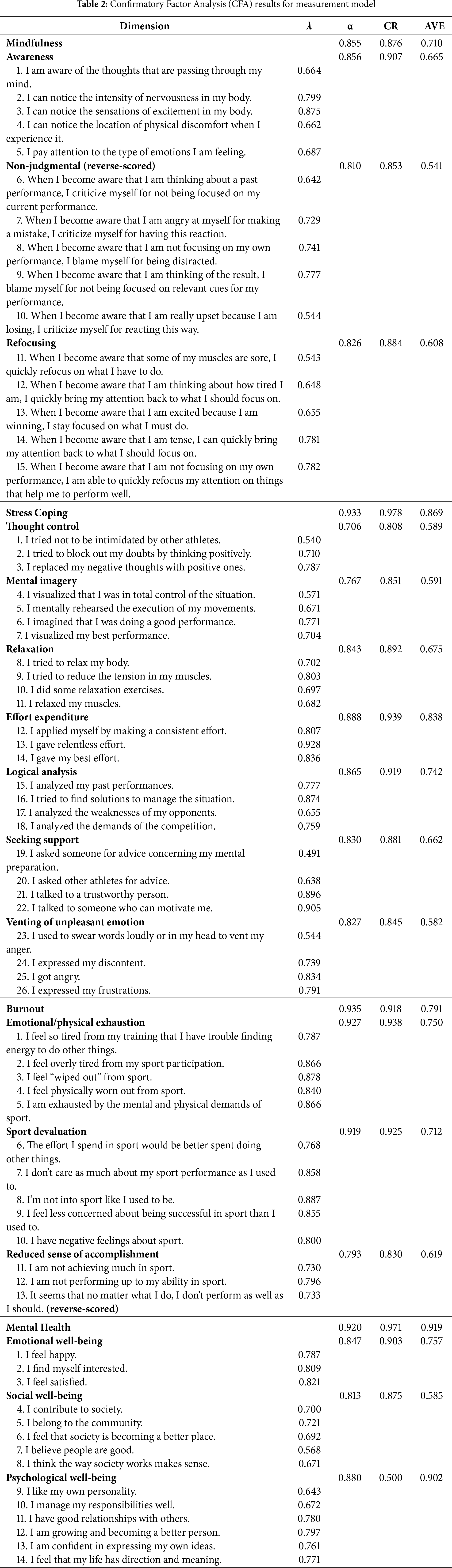

4.1 Demographic Characteristics

Among the 447 participants, 63.1% were male, and 36.9% were female. The majority were Grade 3 (43.8%), followed by Grade 1 (38.9%). Most participants had over 9 years of athletic experience (40%). Athlete levels included mainly national second-level (45.4%) and first-class athletes (41.8%). Most participants had received awards in provincial-level competitions (28.3%).

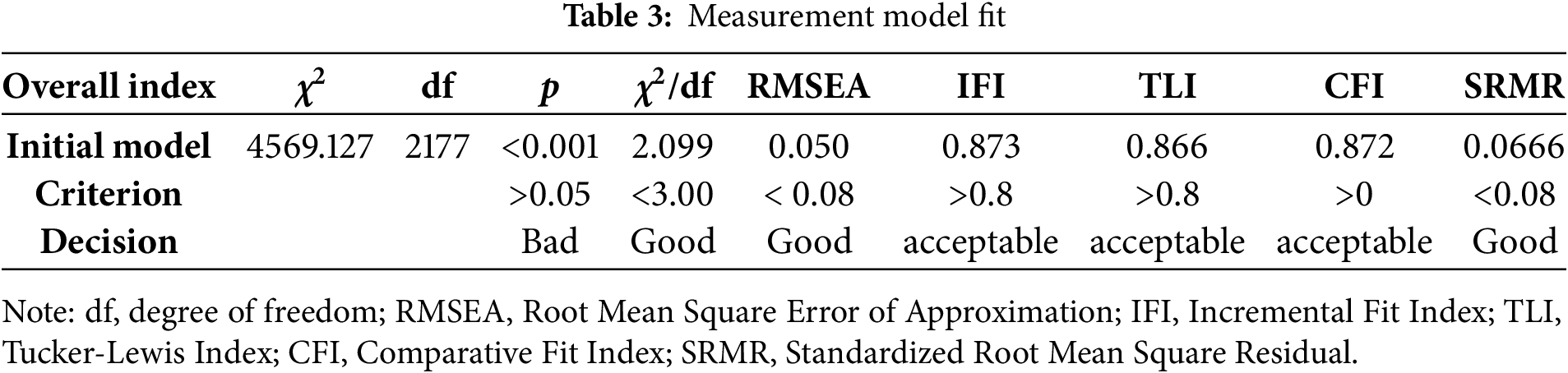

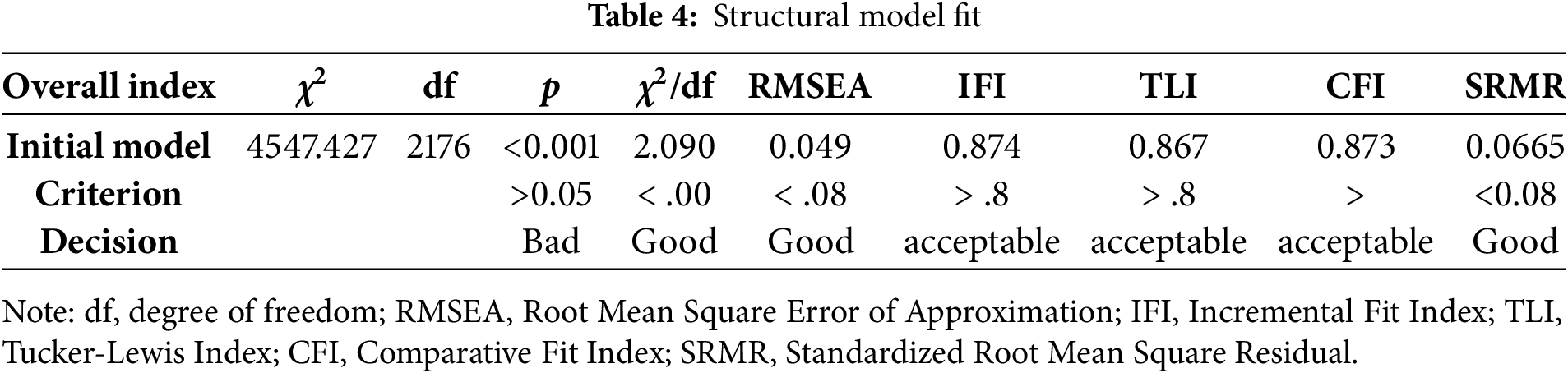

To assess model fit, we examined several indicators: chi-squared freedom ratio (χ²/df), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), standardized goodness of fit index (NFI), TLI, and CFI. Based on the criteria outlined by Lu et al. [79], the recommended thresholds are as follows: χ²/df should be less than 3.00, RMSEA should be below 0.08, IFI should exceed 0.80, TLI should be greater than 0.80, and CFI should also be greater than 0.80 [80].

Results revealed that χ²/df = 2.099, RMSEA = 0.050, IFI = 0.873, TLI = 0.866, and CFI = 0.872, indicating acceptable model fit (see Table 3). Although the main indices of the measurement model, CFI and TLI, were lower than 0.90, they were close to this threshold, so model fit was arguably acceptable.

We examined the goodness-of-fit of the relationships among mindfulness, stress coping, burnout, and mental health in college athletes and then analyzed the relationships among the variables included in the model. For this purpose, the standardized chi-square (χ²/df), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), incremental fit index (IFI), TLI, and CFI were used. All fit indices were acceptable: χ²/df = 2.090, RMSEA = 0.049, IFI = 0.874, TLI = 0.867, and CFI = 0.873 (see Table 4).

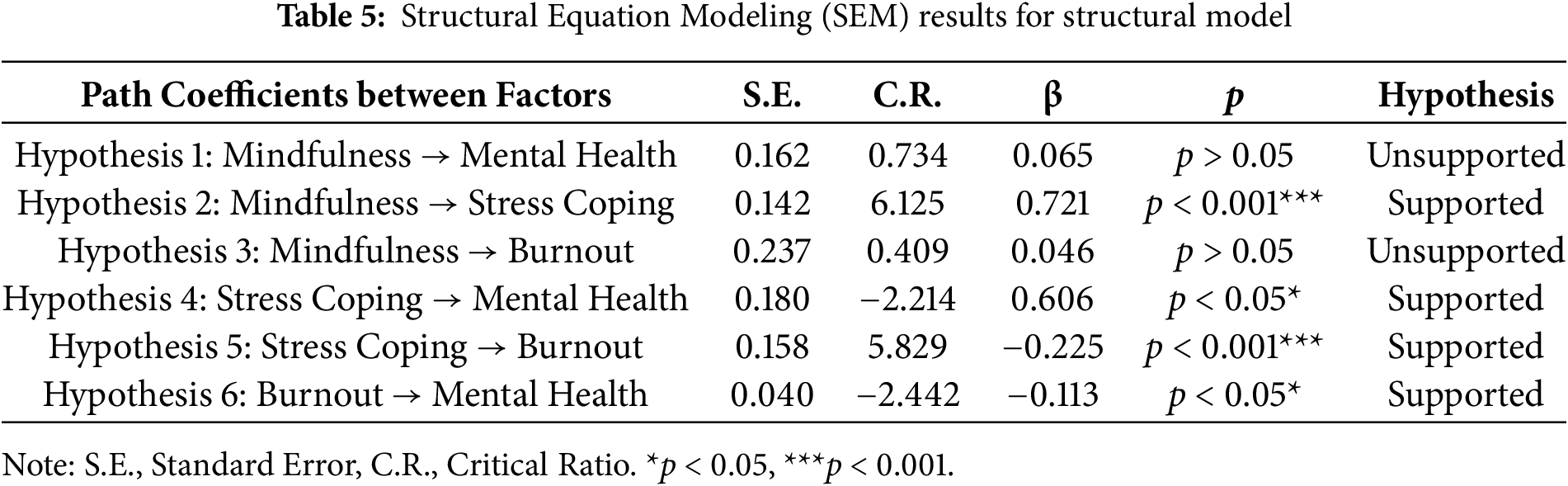

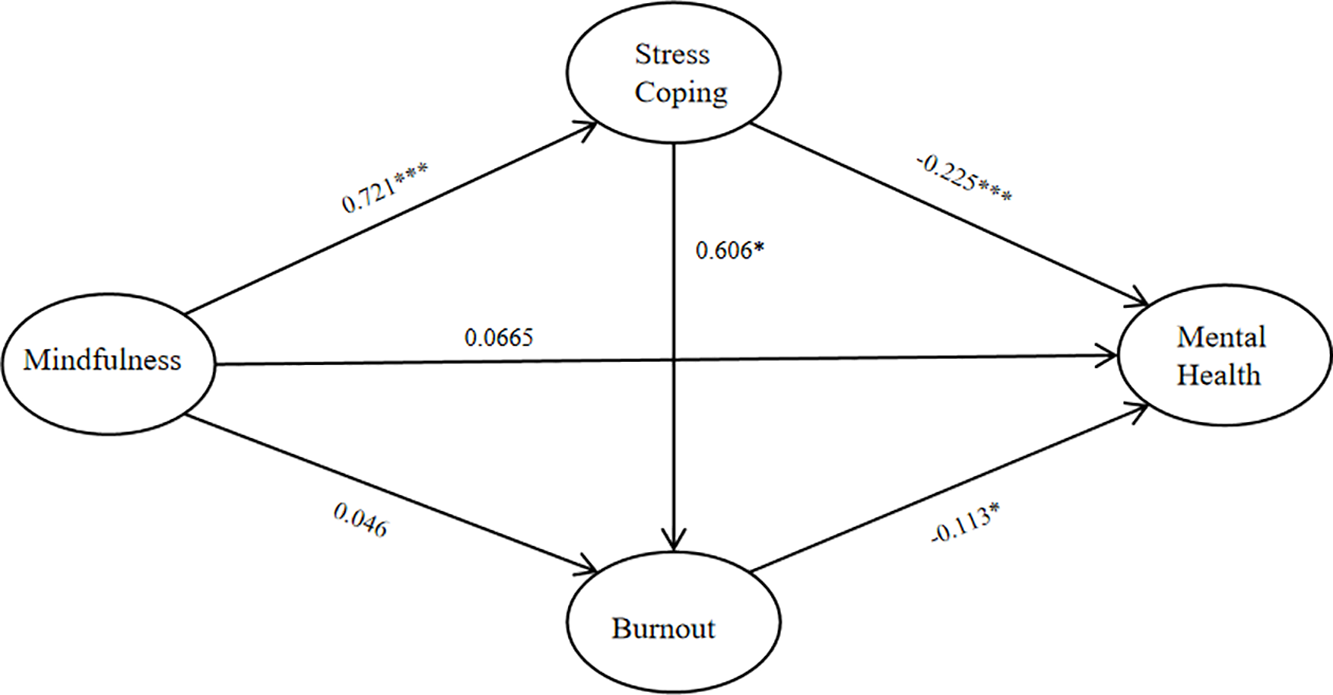

The results of hypothesis testing show that mindfulness in college athletes did not significantly affect burnout (β = 0.046, p > 0.05) or mental health (β = 0.065, p > 0.05) but had a highly significant positive effect on stress coping (β = 0.721, p < 0.001). College athletes’ stress coping had a highly significant negative effect on burnout (β = −0.225, p < 0.001) but a highly significant positive effect on mental health (β = 0.606, p < 0.05). In addition, burnout had a significantly negative effect on mental health (β = −0.113, p < 0.05). Therefore, Hypotheses 2, 4, 5, and 6 were supported, while Hypotheses 1 and 3 were not supported (see Table 5).

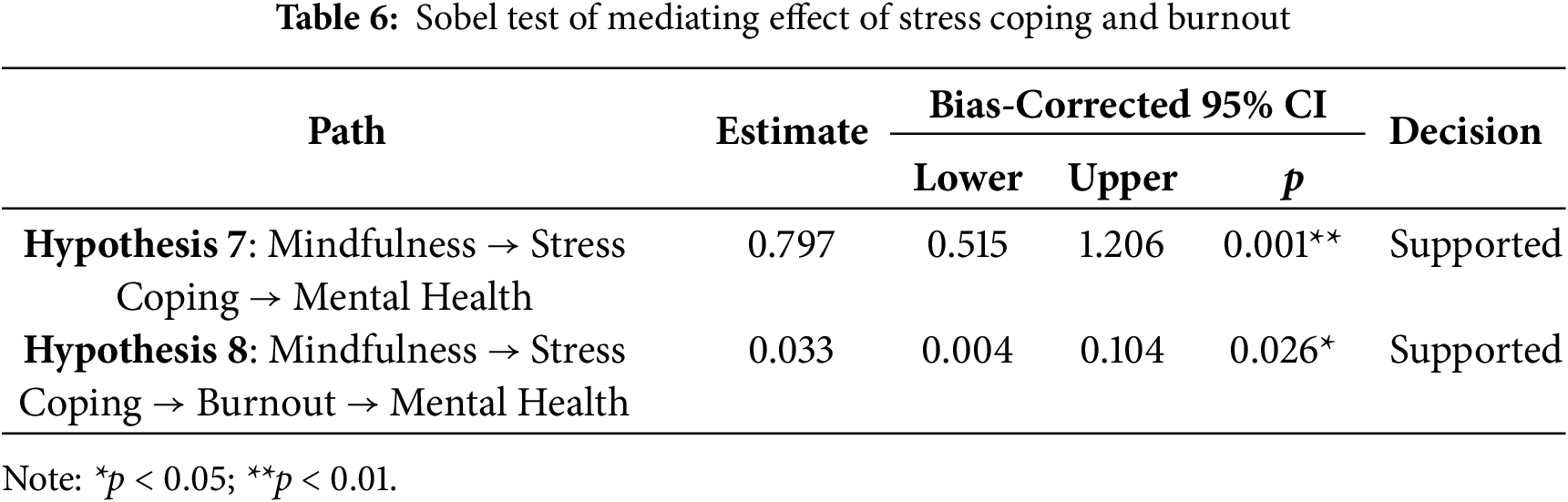

This study conducted bootstrapping, resampling 2500 samples, to examine the mediating role of stress coping and burnout on the relationship between mindfulness and mental health in college athletes. Furthermore, 95% confidence intervals were calculated and the significance of the mediation effect was tested [81]. If the 95% confidence interval includes zero, the mediation effect is insignificant; if it does not include zero, the mediation effect is considered significant.

The results showed that mindfulness significantly influenced mental health through stress coping, and the 95% confidence interval did not include zero (0.515–1.206, p = 0.001). Furthermore, mindfulness influenced stress coping, which in turn influenced burnout, and ultimately, burnout influenced mental health. In other words, stress coping and burnout played a significant mediating role between mindfulness and mental health. The 95% confidence interval did not include zero (β = 0.033, 95% CI: 0.004–0.104, p = 0.026; see Table 6 and Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Structural model. Note: *p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001

Chinese college athletes experience significant stress due to the multiple roles they undertake, including regular training, academic responsibilities, and career development, the stress of which can negatively impact mental health. Mindfulness has garnered increasing attention as helping with stress regulation and psychological stability; however, scholars have not sufficiently examined the underlying mechanisms of these relationships. Stress coping and burnout might serve as mediating variables in the relationship between mindfulness and mental health. Therefore, we investigated the direct and indirect causal relationships among mindfulness, stress coping, burnout, and mental health in college athletes.

We found that mindfulness did not have a significant effect on mental health, leaving Hypothesis 1 unsupported. The differences between previous studies and the findings of this study emphasize the importance of further investigating potential mediating variables that may influence the relationship between mindfulness and mental health. For college athletes, mindfulness may not be a key factor in directly improving mental health. Instead, it may exert its effects indirectly through other pathways. Previous studies have confirmed that mindfulness can enhance self-compassion, reduce cognitive fusion, and strengthen psychological resilience, thereby improving mental health [82]. This indirect influence provides a more complex perspective on understanding the actual efficacy of mindfulness. It is worth noting that college athletes face unique sources of stress. They need to balance high-intensity training and heavy academic workload while coping with the psychological burdens of competition. These stresses differ from those of the general population, thereby imposing higher demands on intervention strategies [83]. Based on this background, mindfulness intervention measures should be adjusted according to the characteristics of different sports. In summary, future research should further explore the mechanisms of mindfulness in different types of athletes, at different competitive levels, and under varying stress intensities, clarify the boundary conditions for its direct effects, and thereby more scientifically evaluate the actual effectiveness of mindfulness in promoting the mental health of college athletes.

The results indicate that mindfulness significantly influences stress coping. Therefore, Hypothesis 2 is supported. Mindfulness helps athletes reduce automated stress responses in tense environments and instead adopt adaptive strategies such as problem-solving and seeking support. Individuals with high levels of mindfulness are more likely to adopt problem-oriented coping strategies rather than avoiding or suppressing emotions [84]. Among college athletes, mindfulness can help them cope more effectively with stress during training and competitions by enhancing emotional regulation and cognitive flexibility [85]. Mindfulness can also indirectly promote positive stress coping behaviors by reducing negative evaluations of stress and decreasing stress perception [86]. Positive stress coping strategies can mitigate the adverse effects of long-term stress [87]. Therefore, these findings highlight the key role of mindfulness in stress management and provide theoretical support for promoting mindfulness training among college athletes.

This study found that mindfulness had no statistically significant effect on burnout. Therefore, Hypothesis 3 was rejected. mindfulness may not act directly on burnout but rather have indirect effects through other mediating variables. Burnout in college athletes may be influenced more by external factors, such as training intensity, coaching expectations, and competition performance requirements, than by psychological traits within the individual [88]. Therefore, before determining that intrinsic factors such as mindfulness do not directly contribute to burnout, it is necessary to delve deeper into the possibility that these intrinsic factors interact with external stressors [89]. The present study revealed that college athletes’ burnout was influenced by external stressors (e.g., coaching expectations, pressure to perform) as well as coping strategies. Furthermore, burnout formation is a cumulative process and short-term mindfulness interventions may not significantly change burnout patterns that develop over time. This result suggests that future research should delve deeper into the complex relationship between mindfulness and burnout, especially considering the effects of mediating and moderating variables.

Research findings have shown that stress coping significantly affects mental health. Therefore, Hypothesis 4 is supported. Appropriate methods of stress coping can help reduce levels of cortisol (the stress hormone) [90]. Positive coping strategies (e.g., cognitive restructuring, planned action) can reduce the damage of stress on mental health [91]. These findings are consistent with Lazarus and Folkman [44] stress-coping theory that stress coping is a key predictor of mental health, and that positive coping strategies (e.g., problem solving and seeking social support) significantly reduce psychological distress, whereas negative coping strategies (e.g., avoidance and emotional suppression) may exacerbate psychological problems. The ability to stress coping is especially important for college athletes. They are often exposed to intense training and competition pressures, and effective stress coping strategies can help them relieve stress [92], enhance mental toughness [93], thereby enhancing mental health. This result highlights the importance of developing positive stress coping skills among college athletes.

Findings show that stress coping significantly affects burnout. Therefore, Hypothesis 5 is supported. Stress coping affects burnout by reducing the accumulation of chronic stress, optimizing emotion regulation, reducing avoidant coping, enhancing recovery of psychological resources, adjusting perceptions of stress, and enhancing social support. Positive stress coping styles likely relate to the prevention and alleviation of burnout because lighting the negative impact of stress on the mind and body can reduce emotional fatigue and improve psychological resilience [94]. Conversely, negative coping styles (e.g., avoidance or self-blame) may exacerbate burnout, causing individuals to fall into deeper feelings of exhaustion and helplessness [95]. Therefore, positive and effective stress coping strategies are not only a keyway to mitigate burnout, but also help individuals manage stress more effectively, thereby reducing the risk of burnout [96]. Our findings further highlight stress coping as a critical intervention target for burnout prevention.

We found that burnout had a significant impact on mental health, supporting Hypothesis 6. Burnout has a detrimental impact on mental health by increasing the risk of depression and anxiety, exacerbating physiological stress responses, impairing cognitive functioning, damaging interpersonal relationships, and reinforcing maladaptive coping mechanisms [97]. Prolonged exposure to chronic stress can result in autonomic nervous system dysfunction, thereby disrupting sleep quality and compromising immune function [98]. Consequently, burnout relates to various psychological issues, including depression, anxiety, and mood disorders, particularly among college athletes [99]. These findings align with the model of athlete burnout proposed by Smith [100], who posited that burnout adversely affects mental health through mechanisms such as diminished self-efficacy and social withdrawal. The impact of burnout is particularly pronounced among college athletes, who frequently endure intense training regimens and competition pressures [83]. These findings underscore the critical importance of burnout prevention and intervention strategies for college athletes.

We found that stress coping mediated the relationship between mindfulness and mental health, supporting Hypothesis 7. Stress coping functions as a critical mechanism in the relationship between mindfulness and mental health by enhancing stress awareness, facilitating emotional regulation, reducing reliance on avoidance coping, reshaping perceptions of stress, and reinforcing social support networks [101]. Mindfulness training not only exerts a direct positive effect on mental health but also enhances cognitive stress coping, thereby reducing anxiety and depression and promoting overall psychological well-being [102]. This pathway is consistent with the sequential process of “mindfulness → adaptive coping → mental health improvement,” wherein mindfulness reduces negative stress appraisals, subsequently lowering perceived stress and fostering positive coping behaviors [103]. Our finding underscores the pivotal role of stress coping as a mediating mechanism in the relationship between mindfulness and mental health. The societal relevance of these findings might increase with evidence-based recommendations for mindfulness training programs and coping strategies specifically tailored to college athletes and individuals operating in high-stress environments.

We found that mindfulness positively influenced mental health through the mediating factors of stress coping and burnout, supporting Hypothesis 8. Specifically, mindfulness indirectly enhances mental health by enhancing emotional regulation and cognitive flexibility, as well as promoting stress coping [104]. However, the direct effect of mindfulness on burnout was not statistically significant, possibly because burnout functions as a more distal outcome [105] or plays a relatively minor role in the mindfulness-mental health relationship [106]. Nevertheless, this finding highlights the predominance of the “mindfulness-coping-adaptation” pathway. Scholars should investigate the complex interrelationships among mindfulness, stress coping, and burnout. Achieving a comprehensive understanding of these dynamics necessitates further examination of potential mediating and moderating variables. Moreover, additional study could elucidate the specific psychological mechanisms through which mindfulness helps alleviate burnout.

Several limitations warrant consideration. This study did not control the effects of sport type (combat sport, contact sport), athlete type (amateur vs. professional), athlete career, and performance level on stress coping, burnout, and mental health. Scholars should explore these sport-specific differences to develop a more nuanced and comprehensive understanding of the psychological mechanisms linking mindfulness, stress coping, burnout, and mental health within diverse athletic environments. Furthermore, this study examined the effects of mindfulness through a cross-sectional design. Future research should utilize a longitudinal experimental design to more clearly examine changes in stress coping, burnout, and mental health following the pre- and post-implementation mindfulness program.

6 Conclusions and Implications

We validated the complex relationship between mindfulness, stress coping, burnout, and mental health. Based on the COR framework, we posited that mindfulness, conceptualized as a psychological resource, would exert an indirect influence on mental health through the mediating effects of stress coping and burnout.

The findings show that mindfulness significantly enhanced mental health by promoting the use of adaptive stress coping strategies (e.g., logical analysis and relaxation techniques), although its direct effects on both burnout and mental health were not significant. In contrast, stress coping not only directly reduced the risk of burnout but also mediated the relationship between mindfulness and mental health.

These results suggest that the mechanism through which mindfulness contributes to improved mental health is not via direct emotional regulation but through the transformation and optimization of coping resources, thereby offering empirical support for the central propositions of COR.

This study identified meaningful relationships among mindfulness, stress coping, burnout, and mental health in college athletes. Nevertheless, this study did not control the effects of sport type (combat sport, contact sport), athlete type (amateur vs. professional), athlete career, and performance level on stress coping, burnout, and mental health. Scholars should explore these sport-specific differences to develop a more nuanced and comprehensive understanding of the psychological mechanisms linking mindfulness, stress coping, burnout, and mental health within diverse athletic environments.

We suggest that college athletic programs should incorporate comprehensive indicators, including mental health metrics, alongside athletic performance, to establish more holistic and sustainable athlete management.

The findings extend the application of COR to the domain of sports psychology due to its theoretical relevance to athlete stress management, the cultivation of psychological resilience, and athletic career development. COR incorporates strategies such as mindfulness and stress coping as psychological resources that enable athletes to mitigate resource depletion, safeguard mental health, and enhance long-term competitive performance. In this regard, the findings support the core tenets of COR by demonstrating that mindfulness, when conceptualized as a psychological resource, contributes to mental health through the facilitation of stress coping, thereby reinforcing COR’s emphasis on resource accumulation and stress regulation. Additionally, by broadening the theoretical linkage between burnout and mental health, our findings establish a new analytical framework for future research and expand the scope of inquiry within the field.

Our findings offer practical implications for the management and promotion of mental health in college athletes. The results indicate that mindfulness exerted an indirect yet beneficial influence on mental health. Accordingly, college athletes might derive significant psychological benefits from engaging in regular mindfulness practices, such as meditation and controlled breathing exercises, which have been shown to improve emotional regulation and attenuate the negative effects of stress. This effect might be particularly salient for athletes who train and compete in high-intensity environments. Considering these findings, we recommend that standardized mindfulness training programs be developed, disseminated, and systematically integrated into the daily training routines of college athletes.

Given that stress coping emerged as a pivotal factor influencing mental health, universities and athletic departments should implement structured stress management interventions. Additionally, the introduction of social support skill training (e.g., team-building exercises) can facilitate the development of interpersonal trust, foster mutual support networks, and reduce feelings of isolation, thereby improving psychological adaptability and resilience in the face of stressors.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: Junhe Cui contributed to writing the original draft, project management, writing review and editing, methodology, and conceptualization. Zixiang Zhou was involved in writing review and editing, supervision, and resource management. Gong Cheng conducted investigations, managed resources, and handled data management. Sihong Sui managed data, performed formal analysis, conducted investigations, and validated findings. Kyungsik Kim conceptualized the study, conducted formal analysis, managed methodology and project administration, supervised the project, and contributed to writing review and editing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval: This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee at Hunan University of Science and Technology (IRB number: HT2024031, approved on 30 June 2023). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, and they were assured of their right to withdraw from the study at any stage.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Storey QK, Hewitt PL, Ogrodniczuk JS. Managing daily responsibilities among collegiate student-athletes: examining the roles of stress, sleep, and sense of belonging. J Am Coll Health. 2024;72(6):1834–40. doi:10.1080/07448481.2022.2093610. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Choi J, Kim H, Smith A. Collegiate athletes’ challenge, stress, and motivation on dual role. J Health Phys Kinesiol. 2021;2(2):28–30. doi:10.47544/johsk.2021.2.2.28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Daumiller M, Rinas R, Breithecker J. Elite athletes’ achievement goals, burnout levels, psychosomatic stress symptoms, and coping strategies. Int J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2022;20(2):416–35. doi:10.1080/1612197x.2021.1877326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Tanhan A, Young JS. Muslims and mental health services: a concept map and a theoretical framework. J Relig Health. 2022;61(1):23–63. doi:10.1007/s10943-021-01324-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Heppner WL, Kernis MH, Lakey CE, Campbell WK, Goldman BM, Davis PJ, et al. Mindfulness as a means of reducing aggressive behavior: dispositional and situational evidence. Aggress Behav. 2008;34(5):486–96. doi:10.1002/ab.20258. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Gaur V, Salvi D, Tambi A, Tambi T. Happiness and its association with mindfulness: a non-systematic review. J Mahatma Gandhi Univ Med Sci Technol. 2021;6(1):25–8. doi:10.5005/jp-journals-10057-0144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Norouzi E, Naseri A, Rezaie L, Bender AM, Salari N, Khazaie H. Combined mindfulness-based stress reduction and physical activity improved psychological factors and sleep quality in patients with MDD: a randomized controlled trial study. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2024;53(5):215–23. doi:10.1016/j.apnu.2024.10.020. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Gallego J, Aguilar-Parra JM, Cangas AJ, Langer ÁI, Mañas I. Effect of a mindfulness program on stress, anxiety and depression in university students. Span J Psychol. 2015;17:E109. doi:10.1017/sjp.2014.102. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Kathayat CB. Mindfulness meditation for enhanced mental health and academic performance: a review. SSRN J. 2024;57(6):950. doi:10.2139/ssrn.4807443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Li C, Zhu Y, Zhang M, Gustafsson H, Chen T. Mindfulness and athlete burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(3):449. doi:10.3390/ijerph16030449. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Petterson H, Olson BL. Effects of mindfulness-based interventions in high school and college athletes for reducing stress and injury, and improving quality of life. J Sport Rehabil. 2017;26(6):578–87. doi:10.1123/jsr.2016-0047. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Hobfoll SE. Conservation of resources. A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am Psychol. 1989;44(3):513–24. doi:10.1037//0003-066x.44.3.513. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Almén N. A cognitive behavioral model proposing that clinical burnout may maintain itself. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(7):3446. doi:10.3390/ijerph18073446. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Glass CR, Spears CA, Perskaudas R, Kaufman KA. Mindful sport performance enhancement: randomized controlled trial of a mental training program with collegiate athletes. J Clin Sport Psychol. 2019;13(4):609–28. doi:10.1123/jcsp.2017-0044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Gustafsson H, Skoog T, Davis P, Kenttä G, Haberl P. Mindfulness and its relationship with perceived stress, affect, and burnout in elite junior athletes. J Clin Sport Psychol. 2015;9(3):263–81. doi:10.1123/jcsp.2014-0051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Hobfoll SE, Lilly RS. Resource conservation as a strategy for community psychology. J Community Psychol. 1993;21(2):128–48. doi:10.1002/1520-6629(199304)21:2128::AID-JCOP2290210206>3.0.CO;2-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Wendling E, Kellison TB, Sagas M. A conceptual examination of college athletes’ role conflict through the lens of conservation of resources theory. Quest. 2018;70(1):28–47. doi:10.1080/00336297.2017.1333437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Hobfoll SE, Halbesleben J, Neveu JP, Westman M. Conservation of resources in the organizational context: the reality of resources and their consequences. Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav. 2018;5(1):103–28. doi:10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Secades XG, Molinero O, Salguero A, Barquín RR, de la Vega R, Márquez S. Relationship between resilience and coping strategies in competitive sport. Percept Mot Skills. 2016;122(1):336–49. doi:10.1177/0031512516631056. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Chen S, Westman M, Hobfoll SE. The commerce and crossover of resources: resource conservation in the service of resilience. Stress Health. 2015;31(2):95–105. doi:10.1002/smi.2574. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Hobfoll SE, Freedy J. Conservation of resources: a general stress theory applied to burnout. In: Professional Burnout. London: Routledge; 2017. p. 115–29. doi:10.4324/9781315227979-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Maslach C, Jackson SE. The measurement of experienced burnout. J Organ Behavior. 1981;2(2):99–113. doi:10.1002/job.4030020205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Giusti NE, Carder SL, Wolf M, Vopat L, Baker J, Tarakemeh A, et al. A measure of burnout in current NCAA student-athletes. Kans J Med. 2022;15(3):325–30. doi:10.17161/kjm.vol15.17784. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Martignetti A, Arthur-Cameselle J, Keeler L, Chalmers G. The relationship between burnout and depression in intercollegiate athletes: an examination of gender and sport-type. J Study Phys Athletes Educ. 2020;14(2):100–22. doi:10.1080/19357397.2020.1768036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Kaiseler M, Poolton JM, Backhouse SH, Stanger N. The relationship between mindfulness and life stress in student-athletes: the mediating role of coping effectiveness and decision rumination. Sport Psychol. 2017;31(3):288–98. doi:10.1123/tsp.2016-0083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Ozcan V. Perfectionism and well-being among student athletes: the mediating role of athletic coping. Afr Educ Res J. 2021;9(2):489–97. doi:10.30918/aerj.92.21.066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Tang Y, Liu Y, Jing L, Wang H, Yang J. Mindfulness and regulatory emotional self-efficacy of injured athletes returning to sports: the mediating role of competitive state anxiety and athlete burnout. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(18):11702. doi:10.3390/ijerph191811702. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Brown KW, Ryan RM. The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;84(4):822–48. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Liang P, Jiang H, Wang H, Tang J. Mindfulness and impulsive behavior: exploring the mediating roles of self-reflection and coping effectiveness among high-level athletes in Central China. Front Psychol. 2024;15:1304901. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1304901. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Haraldsdottir K, Sanfilippo J, Anderson S, Steiner Q, McGehee C, Schultz K, et al. Mindfulness practice is associated with improved well-being and reduced injury risk in female NCAA division I athletes. Sports Health. 2024;16(2):295–9. doi:10.1177/19417381241227447. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Coffey KA, Hartman M, Fredrickson BL. Deconstructing mindfulness and constructing mental health: understanding mindfulness and its mechanisms of action. Mindfulness. 2010;1(4):235–53. doi:10.1007/s12671-010-0033-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Ardi Z, Golland Y, Shafir R, Sheppes G, Levit-Binnun N. The effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on the association between autonomic interoceptive signals and emotion regulation selection. Psychosom Med. 2021;83(8):852–62. doi:10.1097/PSY.0000000000000994. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Hut M, Glass CR, Degnan KA, Minkler TO. The effects of mindfulness training on mindfulness, anxiety, emotion dysregulation, and performance satisfaction among female student-athletes: the moderating role of age. Asian J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2021;1(2–3):75–82. doi:10.1016/j.ajsep.2021.06.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Vidic Z, St Martin M, Oxhandler R. Mindfulness intervention with a U.S. women’s NCAA division I basketball team: impact on stress, athletic coping skills and perceptions of intervention. Sport Psychol. 2017;31(2):147–59. doi:10.1123/tsp.2016-0077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Chua YJ, Hartanto A, Majeed NM. Trait mindfulness is associated with enhanced daily affectivity and cognition independent of daily stressors exposure: insights from large-scale daily diary studies in the US and Singapore. Pers Individ Differ. 2025;237(6):113044. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2025.113044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Keng SL, Smoski MJ, Robins CJ. Effects of mindfulness on psychological health: a review of empirical studies. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011;31(6):1041–56. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2011.04.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Metin SN, Uzgur K, Akkoyunlu Y, Konar N. The relationship between burnout levels and mindfulness of university students-athletes. Phys Educ Stud. 2023;27(3):97–103. doi:10.15561/20755279.2023.0301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Sauvain-Sabé M, Congard A, Kop JL, Weismann-Arcache C, Villieux A. The mediating roles of affect and coping strategy in the relationship between trait mindfulness and burnout among French healthcare professionals. Can J Behav Sci/Rev Can Des Sci Du Comport. 2023;55(1):34–45. doi:10.1037/cbs0000312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Gronimus J. Accept the stress? Examining the role of emotion regulation strategies to explain the relationship between mindfulness and burnout. J Eur Psychol Students. 2025;15(1):1–14. doi:10.59477/jeps.605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Jones BJ, Kaur S, Miller M, Spencer RMC. Mindfulness-based stress reduction benefits psychological well-being, sleep quality, and athletic performance in female collegiate rowers. Front Psychol. 2020;11:572980. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.572980. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Wendorf RA, Brouwer MA. Psychology of Stress and Coping [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 1]. Available from: https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/display/document/obo-9780199828340/obo-9780199828340-0203.xml. [Google Scholar]

42. Carver CS, Scheier MF, Weintraub JK. Assessing coping strategies: a theoretically based approach. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1989;56(2):267–83. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.56.2.267. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Amirkhan JH. A factor analytically derived measure of coping: the Coping Strategy Indicator. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1990;59(5):1066–74. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.59.5.1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Publishing Company; 1984. [Google Scholar]

45. Bondarchuk OI, Balakhtar VV, Pinchuk N, Pustovalov I, Pavlenok KS. Adaptation of coping strategies to reduce the impact of stress and lonelines on the psychological well-being of adults. J Law Sustain Dev. 2023;11(10):e1852. doi:10.55908/sdgs.v11i10.1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Nuetzel B. Coping strategies for handling stress and providing mental health in elite athletes: a systematic review. Front Sports Act Living. 2023;5:1265783. doi:10.3389/fspor.2023.1265783. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Chyi T, Lu FJ, Wang ETW, Hsu YW, Chang KH. Prediction of life stress on athletes’ burnout: the dual role of perceived stress. PeerJ. 2018;6(2):e4213. doi:10.7717/peerj.4213. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. McLoughlin E, Fletcher D, Slavich GM, Arnold R, Moore LJ. Cumulative lifetime stress exposure, depression, anxiety, and well-being in elite athletes: a mixed-method study. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2021;52(3):101823. doi:10.1016/j.psychsport.2020.101823. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Smout MF, Simpson SG, Stacey F, Reid C. The influence of maladaptive coping modes, resilience, and job demands on emotional exhaustion in psychologists. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2022;29(1):260–73. doi:10.1002/cpp.2631. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Dubuc-Charbonneau N, Durand-Bush N. Moving to action: the effects of a self-regulation intervention on the stress, burnout, well-being, and self-regulation capacity levels of university student-athletes. J Clin Sport Psychol. 2015;9(2):173–92. doi:10.1123/jcsp.2014-0036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Turgoose D, Glover N, Maddox L. Burnout and the psychological impact of policing: trends and coping strategies. In: Police psychology. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2022. p. 63–86. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-816544-7.00004-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Channawar S. A study on the cause and effect of burnout. History Res J. 2023;29(6):75–9. [Google Scholar]

53. Dale J, Weinberg R. Burnout in sport: a review and critique. J Appl Sport Psychol. 1990;2(1):67–83. doi:10.1080/10413209008406421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Kuettel A, Larsen CH. Risk and protective factors for mental health in elite athletes: a scoping review. Int Rev Sport Exerc Psychol. 2020;13(1):231–65. doi:10.1080/1750984x.2019.1689574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Rajaram R. The psychosocial factors associated with athletic retirement in elite and competitive athletes [master’s thesis]. Waterloo, ON, Canada: Wilfrid Laurier University; 2021. [Google Scholar]

56. Woods S, Dunne S, Gallagher P, McNicholl A. A systematic review of the factors associated with athlete burnout in team sports. Int Rev Sport Exerc Psychol. 2025;18(1):70–110. doi:10.1080/1750984x.2022.2148225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Maddock A. The relationships between stress, burnout, mental health and well-being in social workers. Br J Soc Work. 2024;54(2):668–86. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcad232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Chib S, Mehta AK, Selvakumar P, Saravanan A, Mishra BR, Manjunath TC. Mental health challenges and solutions in high-pressure work environments. In: Innovative approaches to managing conflict and change in diverse work environments. Hershey, PA, USA: IGI Global Scientific Publishing; 2025. p. 247–72 doi:10.4018/979-8-3693-9556-1.ch011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Moseid NFH, Lemyre N, Roberts GC, Fagerland MW, Moseid CH, Bahr R. Associations between health problems and athlete burnout: a cohort study in 210 adolescent elite athletes. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2023;9(1):e001514. doi:10.1136/bmjsem-2022-001514. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Giles S, Fletcher D, Arnold R, Ashfield A, Harrison J. Measuring well-being in sport performers: where are we now and how do we progress? Sports Med. 2020;50(7):1255–70. doi:10.1007/s40279-020-01274-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. World Health Organization. The world health report 2001—mental health: new understanding, new hope. Washington, DC, USA: World Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]

62. Jahoda M. Environment and mental health. Int Soc Sci J. 1959;11(1). [Google Scholar]

63. Keyes CLM. The mental health continuum: from languishing to flourishing in life. J Health Soc Behav. 2002;43(2):207. doi:10.2307/3090197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Bruner MW, Munroe-Chandler KJ, Spink KS. Entry into elite sport: a preliminary investigation into the transition experiences of rookie athletes. J Appl Sport Psychol. 2008;20(2):236–52. doi:10.1080/10413200701867745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Lazarus RS. How emotions influence performance in competitive sports. Sport Psychol. 2000;14(3):229–52. doi:10.1123/tsp.14.3.229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Valikhani A, Kashani VO, Rahmanian M, Sattarian R, Kankat LR, Mills PJ. Examining the mediating role of perceived stress in the relationship between mindfulness and quality of life and mental health: testing the mindfulness stress buffering model. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2020;33(3):311–25. doi:10.1080/10615806.2020.1723006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Erpiana A, Fourianalistyawati E. Peran trait mindfulness terhadap psychological well-being pada dewasa awal. Psympathic J Ilm Psikol. 2018;5(1):67–82. doi:10.15575/psy.v5i1.1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Savitri WC, Listiyandini RA. Mindfulness Dan kesejahteraan psikologis pada remaja. Psikohumaniora J Penelitian Psikologi. 2017;2(1):43. doi:10.21580/pjpp.v2i1.1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Yuan J, Sun F, Zhao X, Liu Z, Liang Q. The relationship between mindfulness and mental health among Chinese college students during the closed-loop management of the COVID-19 pandemic: a moderated mediation model. J Affect Disord. 2023;327(3):137–44. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2023.02.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Josefsson T, Ivarsson A, Lindwall M, Gustafsson H, Stenling A, Böröy J, et al. Mindfulness mechanisms in sports: mediating effects of rumination and emotion regulation on sport-specific coping. Mindfulness. 2017;8(5):1354–63. doi:10.1007/s12671-017-0711-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Tang Y, Jing L, Liu Y, Wang H. Association of mindfulness on state-trait anxiety in choking-susceptible athletes: mediating roles of resilience and perceived stress. Front Psychol. 2023;14:1232929. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1232929. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Thienot E, Jackson B, Dimmock J, Grove JR, Bernier M, Fournier JF. Development and preliminary validation of the mindfulness inventory for sport. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2014;15(1):72–80. doi:10.1016/j.psychsport.2013.10.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Gaudreau P, Blondin JP. Development of a questionnaire for the assessment of coping strategies employed by athletes in competitive sport settings. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2002;3(1):1–34. doi:10.1016/s1469-0292(01)00017-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Raedeke TD, Smith AL. Development and preliminary validation of an athlete burnout measure. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2001;23(4):281–306. doi:10.1123/jsep.23.4.281. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Gerber M, Gustafsson H, Seelig H, Kellmann M, Ludyga S, Colledge F, et al. Usefulness of the Athlete Burnout Questionnaire (ABQ) as a screening tool for the detection of clinically relevant burnout symptoms among young elite athletes. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2018;39:104–13. doi:10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.08.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

76. Keyes CLM. Mental illness and/or mental health? Investigating axioms of the complete state model of health. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73(3):539–48. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.539. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. de Lara Machado W, Bandeira DR. Positive mental health scale: validation of the mental health continuum—short form. Psico USF. 2015;20(2):259–74. doi:10.1590/1413-82712015200207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

78. Fornell C, Larcker DF. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res. 1981;18(1):39–50. doi:10.1177/002224378101800104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

79. Lu L, Wang L, Yang X, Feng Q. Zarit Caregiver Burden Interview: development, reliability and validity of the Chinese version. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2009;63(6):730–4. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1819.2009.02019.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Xu R, Wang J. A study of tourist loyalty driving factors from employee satisfaction perspective. Am J Ind Bus Manag. 2016;6(12):1122–32. doi:10.4236/ajibm.2016.612105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

81. Byrne BM. Structural equation modeling with EQS: basic concepts, applications, and programming. Oxfordshire, UK: Routledge; 2013. [Google Scholar]

82. González-Martín AM, Aibar-Almazán A, Rivas-Campo Y, Castellote-Caballero Y, Del Carmen Carcelén-Fraile M. Mindfulness to improve the mental health of university students. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1284632. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2023.1284632. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. Yang L, Zhang Z, Zhang J, Veloo A. The relationship between competitive anxiety and athlete burnout in college athlete: the mediating roles of competence and autonomy. BMC Psychol. 2024;12(1):396. doi:10.1186/s40359-024-01888-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

84. Chauhan R, Kumari K, Kumari S. Anxiety, proactive coping and well-being among student-athletes. Indian J Posit Psychol. 2024;15(4):436–42. [Google Scholar]

85. Josefsson T, Ivarsson A, Gustafsson H, Stenling A, Lindwall M, Tornberg R, et al. Effects of mindfulness-acceptance-commitment (MAC) on sport-specific dispositional mindfulness, emotion regulation, and self-rated athletic performance in a multiple-sport population: an RCT study. Mindfulness. 2019;10(8):1518–29. doi:10.1007/s12671-019-01098-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

86. Pačić-Turk L, Pavlović D. Perceived stress, coping styles and mindfulness as predictors of students’ self-reported health behaviors. Arch Psychiatry Res. 2020;56(2):109–28. doi:10.20471/dec.2020.56.02.01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

87. Chen C, Shen Y, Zhu Y, Xiao F, Zhang J, Ni J. The effect of academic adaptability on learning burnout among college students: the mediating effect of self-esteem and the moderating effect of self-efficacy. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2023;16:1615–29. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S408591. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

88. Nixdorf I, Beckmann J, Nixdorf R. Psychological predictors for depression and burnout among German junior elite athletes. Front Psychol. 2020;11:601. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00601. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

89. Edú-Valsania S, Laguía A, Moriano JA. Burnout: a review of theory and measurement. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(3):1780. doi:10.3390/ijerph19031780. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

90. Putman P, Roelofs K. Effects of single Cortisol administrations on human affect reviewed: coping with stress through adaptive regulation of automatic cognitive processing. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2011;36(4):439–48. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.12.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

91. Theodoratou M, Argyrides M. Neuropsychological insights into coping strategies: integrating theory and practice in clinical and therapeutic contexts. Psychiatry Int. 2024;5(1):53–73. doi:10.3390/psychiatryint5010005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

92. Brett CE, Mathieson ML, Rowley AM. Determinants of wellbeing in university students: the role of residential status, stress, loneliness, resilience, and sense of coherence. Curr Psychol. 2023;42(23):19699–708. doi:10.1007/s12144-022-03125-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

93. Wu CH, Nien JT, Lin CY, Nien YH, Kuan G, Wu TY, et al. Relationship between mindfulness, psychological skills, and mental toughness in college athletes. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(13):6802. doi:10.3390/ijerph18136802. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

94. Graves BS, Hall ME, Dias-Karch C, Haischer MH, Apter C. Gender differences in perceived stress and coping among college students. PLoS One. 2021;16(8):e0255634. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0255634. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

95. Giurgiu LR, Damian C, Sabău AM, Caciora T, Călin FM. Depression related to COVID-19, coping, and hopelessness in sports students. Brain Sci. 2024;14(6):563. doi:10.3390/brainsci14060563. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

96. Agyapong B, Brett-MacLean P, Burback L, Agyapong VIO, Wei Y. Interventions to reduce stress and burnout among teachers: a scoping review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(9):5625. doi:10.3390/ijerph20095625. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

97. Ovsiannikova Y, Pokhilko D, Kerdyvar V, Krasnokutsky M, Kosolapov O. Peculiarities of the impact of stress on physical and psychological health. Multidiscip Sci J. 2021. doi:10.31893/multiscience.2024ss0711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

98. Zefferino R, Di Gioia S, Conese M. Molecular links between endocrine, nervous and immune system during chronic stress. Brain Behav. 2021;11(2):e01960. doi:10.1002/brb3.1960. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

99. Tamminen KA, Bonk D, Milne MJ, Watson JC. Emotion dysregulation, performance concerns, and mental health among Canadian athletes. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):2962. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-86195-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

100. Smith RE. Athletic stress and burnout: conceptual models and intervention strategies. In: Anxiety in sports. Abingdon, UK: Talylor Francis Group; 2021. p. 183–201. doi:10.4324/9781315781594-15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

101. Al-Ghabeesh SH. Coping strategies, social support, and mindfulness improve the psychological well-being of Jordanian burn survivors: a descriptive correlational study. Burns. 2022;48(1):236–43. doi:10.1016/j.burns.2021.04.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

102. Bice MR, Ball J, Ramsey AT. Relations between mindfulness and mental health outcomes: need fulfillment as a mediator. Int J Ment Health Promot. 2014;16(3):191–201. doi:10.1080/14623730.2014.931066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

103. Creswell JD, Lindsay EK. How does mindfulness training affect health? A mindfulness stress buffering account. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2014;23(6):401–7. doi:10.1177/0963721414547415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

104. Afrashteh MY, Hasani F. Mindfulness and psychological well-being in adolescents: the mediating role of self-compassion, emotional dysregulation and cognitive flexibility. Borderline Personal Disord Emot Dysregul. 2022;9(1):22. doi:10.1186/s40479-022-00192-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

105. Xie C, Li X, Zeng Y, Hu X. Mindfulness, emotional intelligence and occupational burnout in intensive care nurses: a mediating effect model. J Nurs Manag. 2021;29(3):535–42. doi:10.1111/jonm.13193. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

106. Sauder T, Keune PM, Müller R, Schenk T, Oschmann P, Hansen S. Trait mindfulness is primarily associated with depression and not with fatigue in multiple sclerosis (MSimplications for mindfulness-based interventions. BMC Neurol. 2021;21(1):115. doi:10.1186/s12883-021-02120-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools