Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Strengths in Struggle: Character Strengths Use and Psychological Well-Being in the Slums of the Philippines

Department of Psychology, University of the Philippines Diliman, Quezon City, 1101, Philippines

* Corresponding Author: Shinichiro Matsuguma. Email:

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(10), 1595-1609. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.068556

Received 31 May 2025; Accepted 15 September 2025; Issue published 31 October 2025

Abstract

Objectives: Character strengths use has been studied in WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic) societies, where it is related to happiness, resilience, and reduced distress. However, this relationship in harsh living conditions remains unstudied. This study aims to examine the relationship between character strengths use and psychological well-being among slum dwellers in the Philippines, where harsh living conditions can create severe psychological challenges. Methods: A correlational analysis was conducted in a slum community in Cavite City, Philippines, with 120 participants completing self-report questionnaires, including the Strengths Use Scale (SUS), Flourishing Scale (FS), and Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10). Correlation and regression analyses examined whether strengths use predicts psychological well-being while controlling for psychological distress and demographic factors such as family monthly income. Results: A significant positive correlation was found between strengths use and psychological well-being (r = 0.39, p < 0.01), and hierarchical linear regression analysis confirmed that SUS significantly predicted FS (β = 0.37, 95% CI = [0.08, 0.22]). Despite experiencing high levels of psychological distress (Mean = 27.22, SD = 6.78), participants demonstrated relatively higher FS scores compared to more privileged Filipino student samples. These findings suggest that character strengths use act as psychological resources even in challenging environments. Conclusions: The study supports the Dual-Factor Model of Mental Health, showing that well-being and ill-being can coexist. Strengths use may help slum dwellers cope with ongoing challenges, highlighting the potential of strengths-based interventions to foster resilience and well-being in high-adversity urban slum settings. Future research should explore how family and cultural values support well-being in difficult environments.Keywords

Character strengths, a key component of positive psychology, have been extensively studied in WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic) societies, where they have been linked to greater happiness, life satisfaction, and reduced depressive symptoms [1–5]. Character strengths also serve as protective factors against psychological distress, fostering resilience and coping mechanisms [6–8]. However, the applicability of these findings in non-WEIRD contexts, particularly in low-income settings with high adversity, remains unclear [9]. This research gap raises critical questions about whether the benefits of character strengths extend beyond affluent and well-resourced environments.

Existing studies on psychological well-being in low-income settings have produced paradoxical findings. While economic hardship is often associated with heightened psychological distress [10], some studies suggest that well-being levels among impoverished populations may be higher than expected [11–13]. This paradox underscores the importance of identifying psychological assets, such as character strengths, that may mitigate the adverse effects of poverty. Despite the apparent relevance of character strengths in such contexts, research in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) remains scarce. A systematic review by Jeffery-Schwikkard et al. found that only 18 out of 164 studies examined the effects of character strengths on mental health in LMICs [14]. Similarly, Leventhal et al. analyzed strengths-based resiliency programs for adolescent girls’ emotional, social, physical, and educational well-being in one of the poorest cities in India [15], yet broader investigations into character strengths use within impoverished urban communities remain limited.

The Philippines presents a compelling setting for studying character strengths use in adversity due to its significant urban population, with a substantial proportion residing in informal settlements. As of 2020, approximately 54% of the population lived in urban areas, and an estimated 43% of urban residents resided in slums [16,17]. According to UN-Habitat, slum households are defined by the absence of one or more essential living conditions: durable housing, access to clean water and sanitation, sufficient living space, and secure tenure [18]. These conditions contribute to chronic psychological distress, including depression and anxiety [19]. Given this context, understanding the role of character strengths in promoting well-being among slum residents is of significant theoretical and practical importance.

Several theoretical frameworks support the relevance of character strengths in high-adversity contexts. The capability approach defines well-being as the freedom to achieve valued forms of living [20,21]; in this view, character strengths can be seen as internal capabilities that enable meaningful action despite external constraints. Similarly, resilience theory emphasizes the importance of psychological assets in navigating chronic adversity [22]. Socioecological models also highlight the interaction between individual traits and broader systems such as family, community, and culture that influence how strengths are expressed and supported [23]. Together, these theories can justify a deeper examination of psychological strengths in marginalized urban settings.

Therefore, this study investigates the relationship between character strengths use and psychological well-being among slum dwellers in the Philippines. Building on findings from WEIRD societies, the study tests the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Character strengths use will be positively associated with psychological well-being among slum residents.

Hypothesis 2: Character strengths use will remain a significant predictor of psychological well-being, even after controlling for demographic variables and psychological distress.

Hypothesis 3 (Exploratory): Psychological distress may moderate the relationship between strengths use and well-being, such that the positive association between strengths use and well-being may weaken at higher levels of distress.

By testing these hypotheses, this study aims to inform the development of cost-effective, strengths-based mental health strategies tailored to residents of high-adversity urban environments.

2.1 Design, Setting, and Participants

A prospective, correlational research design was utilized since the purpose of the research is to explore the relationship between strengths use and their psychological well-being among the slum dwellers. Participants were recruited from a slum area adjacent to a public cemetery in Cavite City, Philippines. This community consists of approximately 962 households and over 8000 residents. Nestled between the cemetery and a dumpsite, many residents make a living as garbage collectors, while others work as fishermen, construction workers, or vendors. The settlement is on government land, making residency technically illegal. Residents construct makeshift homes from scrap materials, including plywood, tarps, sacks, and rusted galvanized iron sheets. Roofs, often full of holes, are secured with rocks, ropes, and tires to withstand strong winds. Houses are small, with just enough height to stand, and furnished with discarded items such as tables, chairs, electric fans, and televisions salvaged from the dumpsite. Many households lack legal electricity access and resort to unauthorized connections. Families typically consist of four to five members, and food insecurity is prevalent.

The recruitment was conducted between July and September 2023. We visited the site and distributed the following self-report questionnaires and pens to the participants. Data collection was conducted in a group-administrative manner, with five participants completing the questionnaires individually at a time. A translator provided assistance as needed in a private residence near the barangay hall—the administrative center of the barangay, the smallest local government unit in the Philippines. This setting was chosen to ensure participant privacy and a comfortable environment for data collection. The surveys were completed on paper and later digitized for analysis. Participants were excluded if they were aged less than 18 years and could not understand and answer the questionnaires in either Filipino or English. The College of Social Sciences and Philosophy Ethics Review Board of the University of the Philippines Diliman approved the research protocol (CSSP-ERB Code: CSSPERB-2023-010), which followed the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all participants by reading the informed consent, which informed them that their participation was voluntary.

A target sample size of 120 participants was determined based on a power analysis using G*Power 3.1.9.7 [24,25] for hierarchical linear regression analysis, with psychological well-being as the dependent variable and eight independent variables. Assuming a medium effect size (f2 = 0.15), a target power of 0.80, and an alpha level of 0.05, the analysis indicated that 107 participants would be needed. To account for potential attrition and ensure robustness, a final sample size of 120 was selected. The questionnaires were as follows.

2.2.1 Strengths Use Scale (SUS)

Strengths use was assessed by the Strengths Use Scale (SUS); the 14 SUS items were evaluated on a five-point Likert scale (ranging from 1–5, total range 14–70), with higher values corresponding to more frequent strengths use [26]. This scale demonstrates good internal consistency (α = 0.94) and satisfactory test–retest reliability (r = 0.67) over four weeks.

Before completing the SUS, participants were asked to read a list of 24 VIA character strengths and identify five that they believed best represented their core personality. These five self-identified character strengths, referred to as signature strengths, are those that are essential to an individual’s core identity, energizing in that expressing them uplifts the person and increases their energy levels, and effortless in that their expression comes naturally and with ease [27]. Participants then completed the SUS items specifically with these signature strengths in mind. This adaptation was intended to focus on their personally meaningful traits, although it shifts the construct being measured from general strengths use to “use of one’s five self-identified character strengths.” As such, caution is warranted in comparing these scores with studies using the original, unmodified SUS scale.

Psychological well-being was evaluated by the Flourishing Scale (FS), a measure of psychosocial flourishing based on recent theories of psychological and social well-being [28]. This social-psychological prosperity includes purpose and meaning, supportive relationships, engagement, contribution to others, competence, optimism, being respected, and being a good person. The eight items are evaluated on a seven-point Likert scale (ranging from 1–7, total range 7–56), with higher values reflecting higher psychological well-being. The scale had high Cronbach’s alpha coefficients (0.95) of internal consistency reliability. The Filipino version of FS was used for this study. The Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient of the scale was 0.87 [29].

2.2.3 Kessler Psychological Distress Scale-10 (K10)

Psychological distress was assessed by the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10) [30]. The K10 scale consists of 10 questions about emotional states, each with a five-level response scale. The measure can be used as a brief screen to identify levels of distress. The K10 scale had a high Cronbach’s alpha (0.88) of internal consistency reliability [31].

Since validated Filipino versions of the SUS and K10 were unavailable, the author translated these instruments specifically for this study. A forward–backward translation method was used: a professional bilingual freelance translator first translated the scales into Filipino, and then an independent bilingual colleague, unfamiliar with the original versions, conducted the back-translation into English. The author compared both English versions and resolved any discrepancies by focusing on semantic accuracy and cultural relevance. The translated scales were piloted with 10 residents from the target community to ensure clarity and cultural fit. No significant issues were reported.

2.2.4 Satisfaction with 12 Life Domains

Participants were asked to rate their satisfaction with twelve different domains of their lives on a scale that went from 1, “extremely dissatisfied”, to 7, “extremely satisfied.” The twelve domains were: material resources, friendship, morality, intelligence, food, romantic relationship, family, physical appearance, self, income, housing, and social life. These domains can be categorized as broad (self, material resources, and social life) and specific (morality, physical appearance, intelligence, housing, food, income, friends, family, and romantic relationships). This scale was accompanied by the same series of response faces as the Satisfaction with Life Scale [32], and was used in the study of subjective well-being among the slum dwellers [33]. These 12 domain satisfaction ratings were collected primarily for descriptive purposes, to contextualize participants’ overall quality of life across multiple life areas. They were not included in the main predictive analyses, as they fell outside the study’s primary scope, which focused on character strengths use and psychological well-being.

General demographic information was examined, including age, gender, education, employment status, housing situation, and monthly family incomes, in order to identify cofounding factors. Participants were also asked about their meaning in life in order to understand their life purpose if they possessed. Their responses to the open-ended question on meaning in life were coded using an inductive content analysis approach. All responses were reviewed and categorized into eight conceptual themes based on recurring patterns: (1) children’s education, (2) better life for family, (3) personal growth and success, (4) health and safety, (5) basic needs fulfillment, (6) helping others, (7) moving abroad for better opportunities and (8) relationship. As a sole researcher, the author conducted all coding independently, reviewing responses multiple times to ensure consistency. While no inter-coder reliability statistics were calculated, care was taken to define categories clearly and apply them uniformly.

Data obtained from the participants’ questionnaires were statistically analyzed. First, a descriptive analysis was performed to illustrate the sociodemographic characteristics of the participants, their meaning in life, and their satisfaction with 12 life domains. Then, Pearson’s correlation was conducted to examine the relationship between SUS and FS, as the normality of the variables was confirmed. After verifying the assumptions of normality and linearity, a hierarchical linear regression analysis was performed to examine the relationship between character strengths use (SUS) and psychological well-being (FS) while controlling for potential confounding variables, including age, gender, education, employment, family monthly income, housing conditions, and psychological distress (K10). To confirm this relationship between SUS and FS, a partial correlation analysis was also conducted, controlling for the same confounding variables. The significance level was set at p < 0.05 for all inferential statistical tests (Pearson’s correlation, hierarchical regression, and partial correlation analyses). All analyses were performed using SPSS version 29 for Windows (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA).

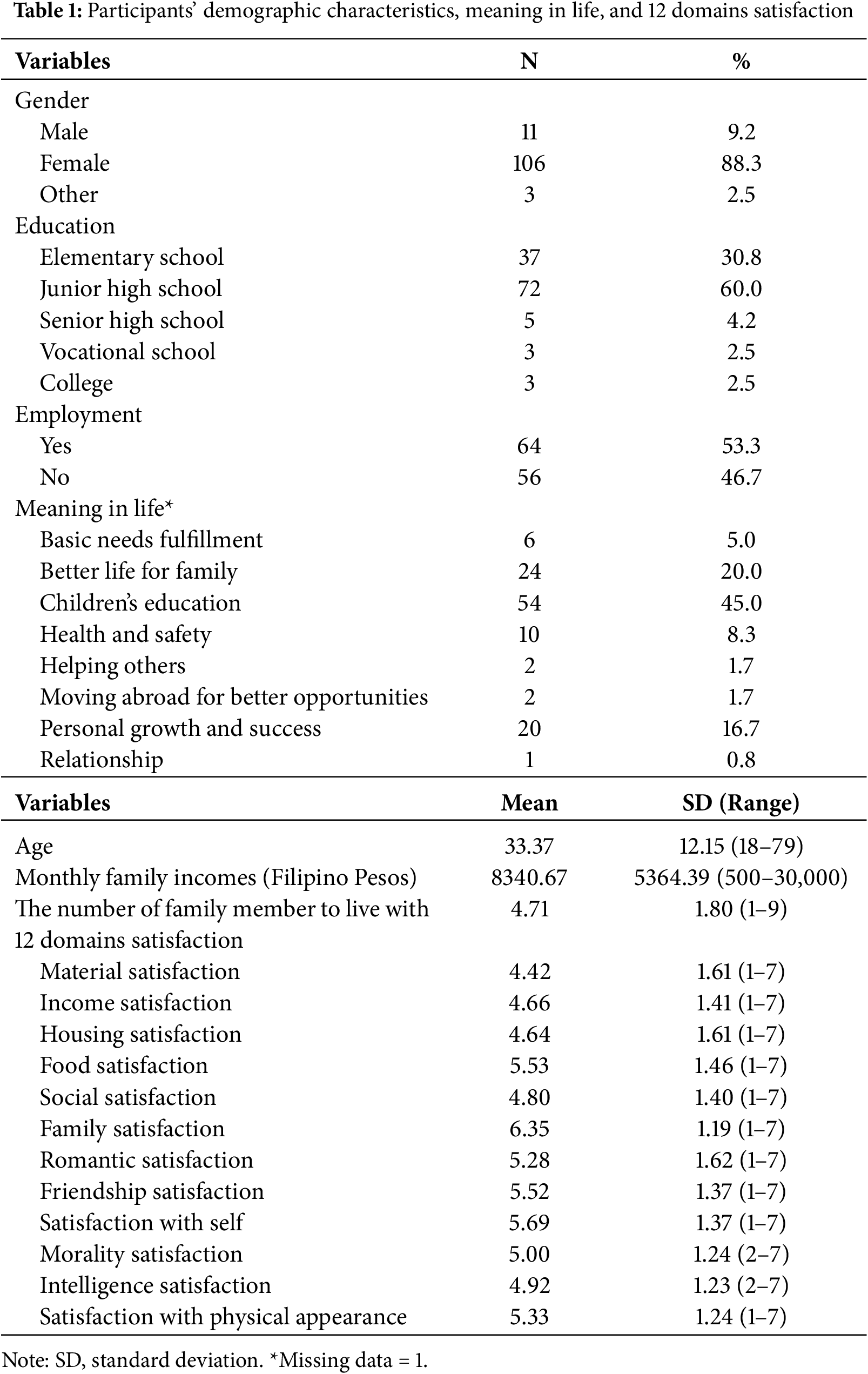

A total of 120 slum dwellers participated in the study. The mean age was 33.37 years (SD = 12.15, range = 18–79). The majority of participants were female (88.3%, n = 106), with 9.2% (n = 11) identifying as male and 2.5% (n = 3) identifying as other genders. Additional demographic characteristics, satisfaction with 12 life domains, and meaning in life are summarized in Table 1.

Among the 12 life domains assessed, participants reported the highest levels of satisfaction in family (Mean = 6.35, SD = 1.19), followed by self-satisfaction (Mean = 5.69, SD = 1.37) and food satisfaction (Mean = 5.53, SD = 1.46). Regarding meaning in life, the most frequently cited sources were children’s education (45.0%) and providing a better life for their family (20.0%), underscoring the central role of family in participants’ sense of purpose.

3.1 Strengths Use, Flourishing, and Psychological Distress

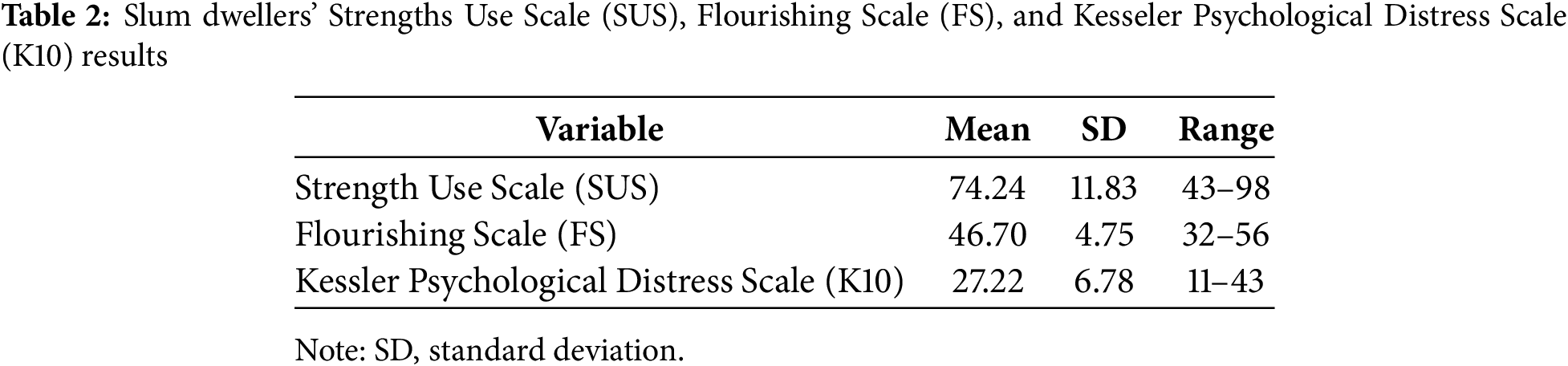

Participants’ SUS, FS, and K10 scores are presented in Table 2. The mean FS score was 46.70 (SD = 4.75). The mean K10 score was 27.22 (SD = 6.78), which falls within the “high distress” range (22–29), based on international cutoffs [34,35].

3.2 Associations between Strengths Use Scale (SUS) and Flourishing Scale (FS)

3.2.1 Pearson’s Correlation Analysis

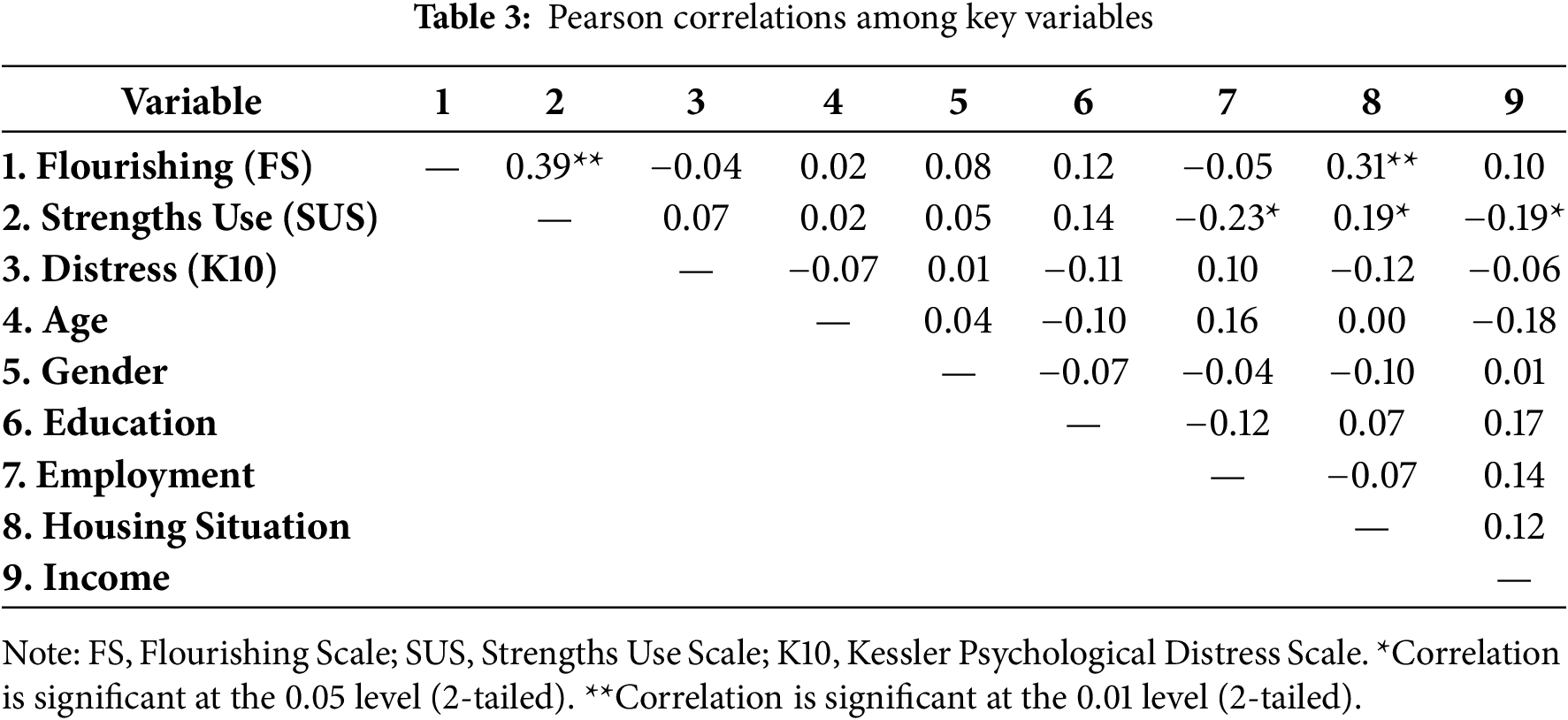

A Pearson correlation analysis was conducted to examine the association between character strengths use (SUS) and psychological well-being (FS). The results indicated a significant positive correlation, suggesting that higher strengths use is associated with greater psychological well-being. Table 3 presents the Pearson correlations among the main study variables. Strengths use (SUS) was positively correlated with flourishing (r = 0.39, p < 0.01) and housing situation (r = 0.19, p < 0.05), and negatively with employment (r = −0.023, p < 0.05) and income (r = −0.19, p < 0.05). Psychological distress (K10) was not significantly associated with flourishing or SUS. No multicollinearity concerns were evident, as none of the correlations exceeded 0.70.

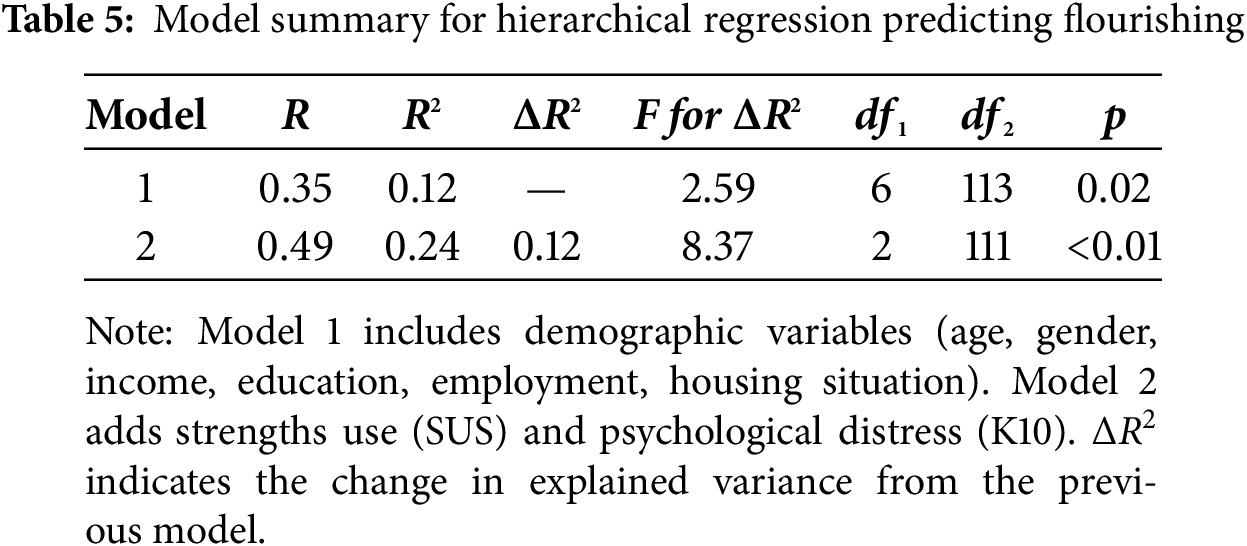

3.2.2 Hierarchical Linear Regression Analysis

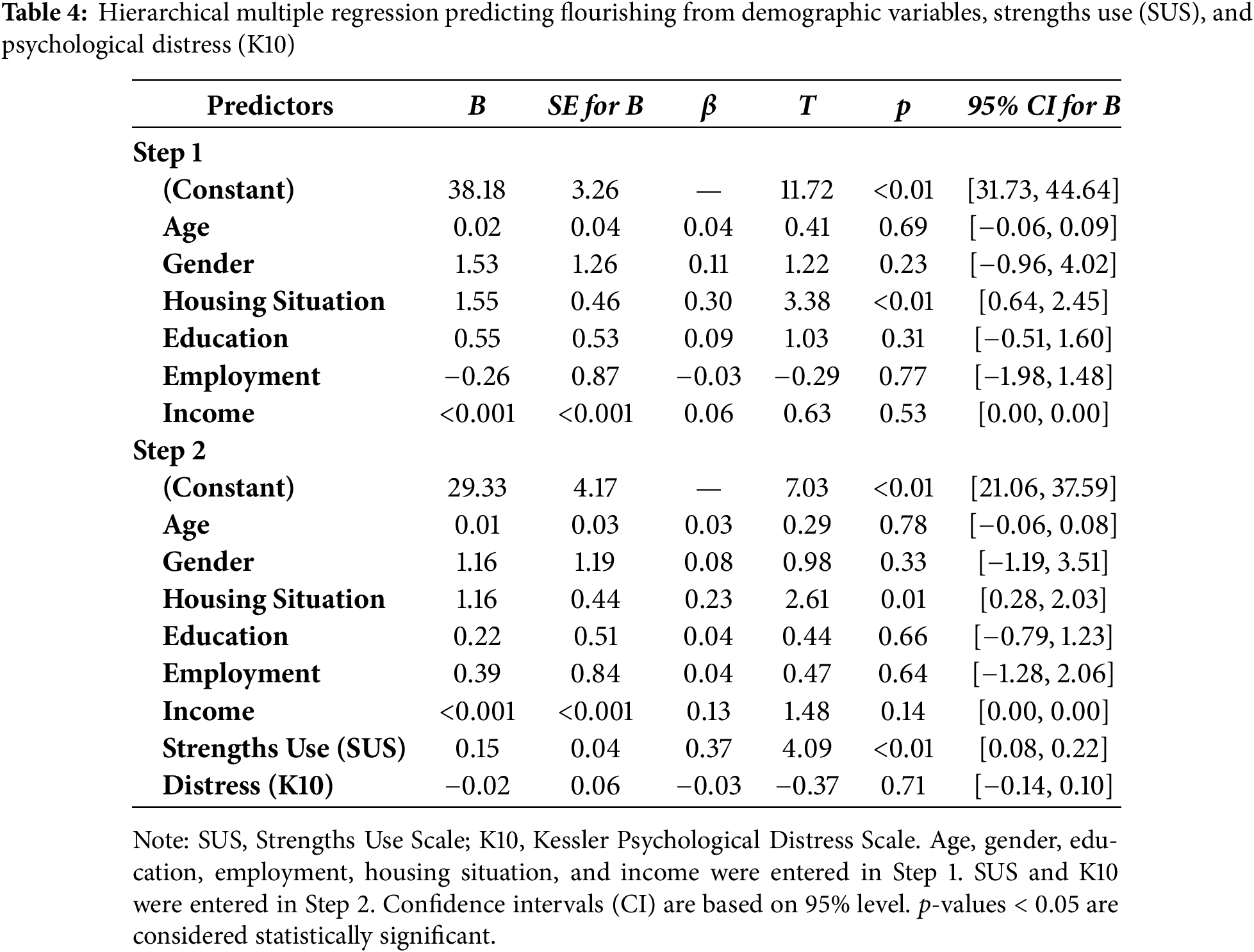

A hierarchical linear regression was conducted to examine whether strengths use (SUS) and psychological distress (K10) explained additional variance in flourishing beyond demographic variables. The results are summarized in Table 4.

In Step 1, demographic predictors (age, gender, housing situation, education, employment, and income) accounted for a significant proportion of the variance in flourishing, R2 = 0.12, F (6, 113) = 2.59, p = 0.02. In Step 2, the inclusion of SUS and K10 significantly improved the model, ΔR2 = 0.12, F (2, 111) = 8.37, p < 0.01, resulting in a total R2 = 0.24 (see Table 5).

Among all predictors, character strengths use was a significant positive predictor of flourishing (β = 0.37, 95% CI = [0.08, 0.22]), indicating a moderate effect size. In contrast, psychological distress was not significantly associated with flourishing (β = −0.03, 95% CI = [−0.14, 0.10]), as the confidence interval included zero, suggesting no meaningful effect in this sample (see Table 4).

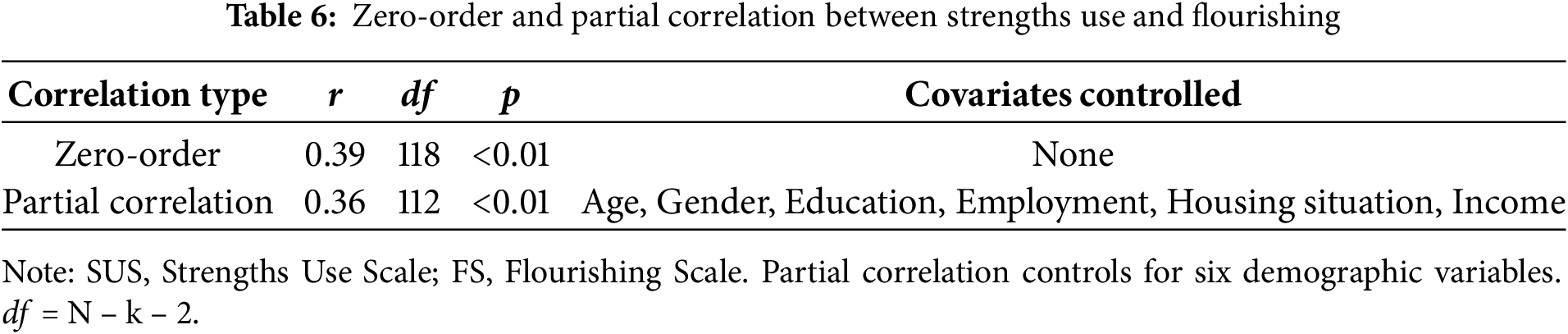

3.2.3 Partial Correlation Analysis

A partial correlation analysis was conducted to examine the association between strengths use (SUS) and flourishing (FS), controlling for six demographic covariates (age, gender, income, education, employment, and housing situation). The zero-order correlation was significant (r = 0.39, p < 0.01), and the partial correlation remained significant (r = 0.36, p < 0.01, df = 11), indicating a robust relationship even after accounting for potential confounding factors (see Table 6).

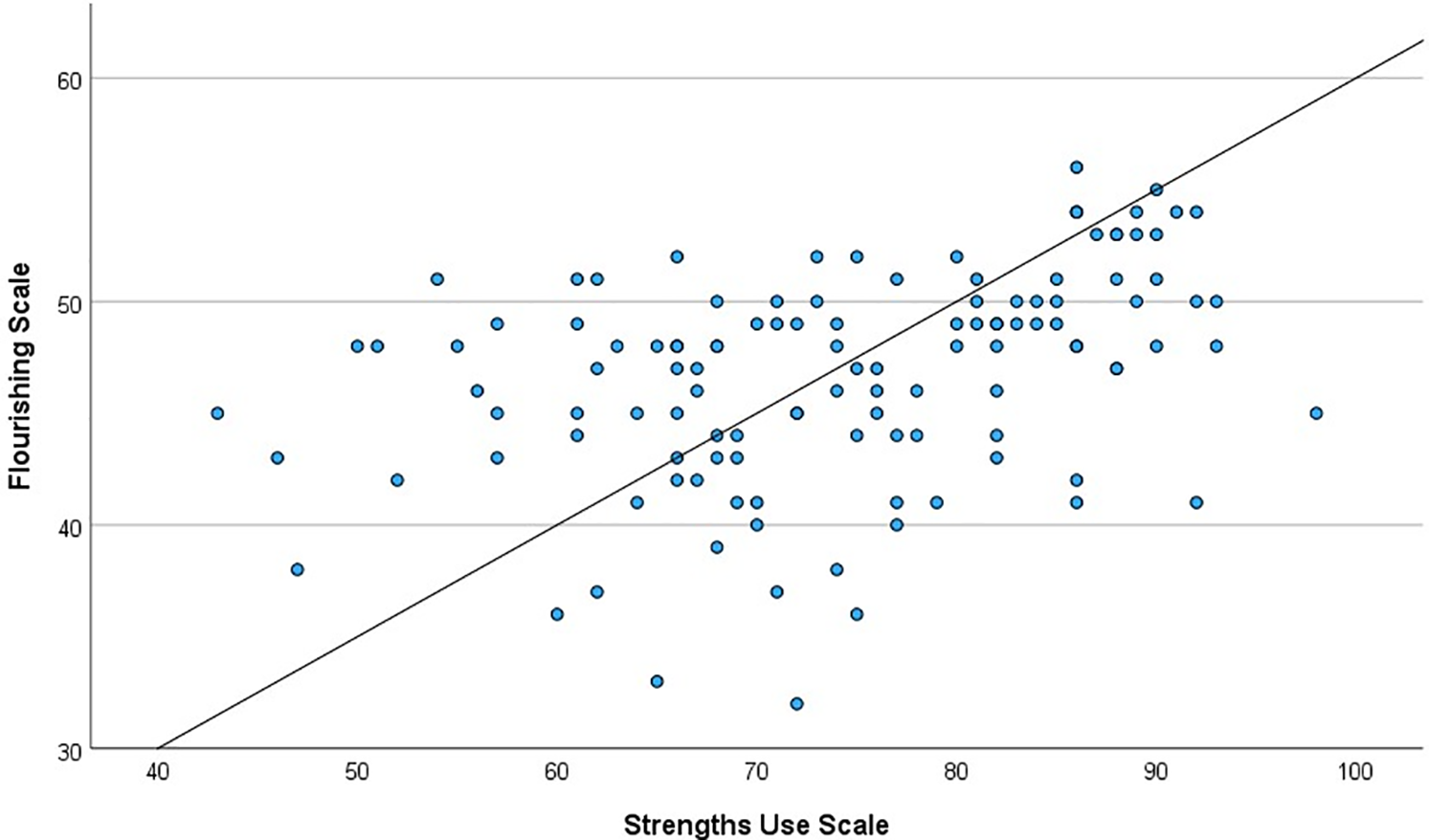

The relationship between character strengths (SUS) and psychological well-being (FS) is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: The correlation between the Strengths Use Scale (SUS) and the Flourishing Scale (FS)

This study aimed to examine the relationship between character strengths use and psychological well-being among slum dwellers in the Philippines, while also considering the impact of psychological distress in slum environments. Consistent with Hypothesis 1, greater use of character strengths was positively associated with psychological well-being. Hypothesis 2 was also supported, as this association remained significant even after controlling for demographic factors and psychological distress. By contrast, the exploratory Hypothesis 3 was not supported; instead, the positive association between strengths use and well-being remained consistent across different levels of distress. Taken together, these results indicate a stable link between character strengths use and psychological well-being in this high-adversity context, paralleling findings from WEIRD societies and challenging the assumption that living in slums necessarily correlates with lower mental health [36].

One explanation for these findings is the universal role of character strengths in fostering well-being. As internal psychological assets, character strengths remain accessible regardless of living conditions. Previous research has demonstrated that strengths use is linked to well-being among individuals facing diverse adversities, such as chronic illness [37], homelessness [38], visual impairments [39], and autism [40]. Studies across different cultural settings have also shown that strengths use contributes to both subjective and psychological well-being [41–43]. By extending these findings to slum communities, this study reinforces the notion that character strengths serve as fundamental psychological resources for well-being across diverse socioeconomic settings.

Beyond promoting well-being, character strengths may act as a psychological buffer against adversity. Research has consistently demonstrated that character strengths function as a protective factor against stress, buffering individuals from its negative psychological effects and promoting resilience [44–48]. Given these findings, it is reasonable to hypothesize that character strengths would similarly serve as a protective factor in high-stress environments, such as urban slums, where chronic adversity and socio-economic challenges place residents at elevated risk for mental health difficulties. Additionally, Niemiec emphasizes that character strengths play a dual role in mental health by both fostering well-being and mitigating suffering, reinforcing the idea that strengths use is not merely beneficial but essential in high-adversity urban settings [49].

These findings are also consistent with the Dual-Factor Model of Mental Health, which posits that psychological well-being and distress are not mutually exclusive but can coexist [50–52]. Traditional models often view well-being and distress as opposite ends of a continuum, implying that higher distress necessarily corresponds to lower well-being. However, the dual-factor perspective suggests that individuals can experience both flourishing and psychological distress simultaneously. In the context of slum communities, ongoing structural challenges—such as unstable housing, high crime rates, and economic precarity—create persistent psychological stress, as reflected in the high levels of distress reported by participants. However, their ability to utilize character strengths may have contributed to their well-being, demonstrating that flourishing is possible even in extreme hardship.

This interpretation is further supported by exploratory comparisons with previous studies. Notably, despite experiencing severe adversity, participants’ flourishing scores appeared comparable to or even slightly higher than those of Filipino students from affluent private institutions [29]. Specifically, the current sample (Mean = 46.70, SD = 4.75) reported higher flourishing than Filipino high school students (Mean = 43.92, SD = 7.10; Cohen’s d ≈ 0.46) and undergraduate students (Mean = 44.97, SD = 6.32; Cohen’s d ≈ 0.31). These small-to-moderate effect sizes highlight that high levels of psychological well-being can emerge even in contexts of significant adversity, further reinforcing the dual-factor model’s assertion that well-being and distress can coexist.

These insights offer valuable implications for interventions aimed at enhancing psychological well-being in slum communities. Strengths-based programs provide a cost-effective and sustainable approach, as character strengths are internal assets that require no financial investment, making them particularly valuable in resource-limited settings. Given their demonstrated buffering effects, interventions should prioritize strengths identification and development to foster resilience. Additionally, a dual-factor approach should be integrated into mental health initiatives, addressing both distress reduction and well-being promotion to create more comprehensive support systems.

Beyond individual strengths use, this study found that family played a central role in participants’ well-being. Family satisfaction was the highest among all life domains, and the primary sources of meaning centered on children’s education and providing a better future for loved ones. These findings align with the cultural value of kapwa (shared identity) and utang na loob (reciprocal gratitude and obligation) in Filipino society [53,54]. Although this study did not statistically analyze the relationship between family relationships and strengths use, descriptive findings such as high levels of family satisfaction and the prominence of family-related meaning underscore the cultural centrality of familial bonds in participants’ lives. This culturally salient pattern can be contextualized through broader psychological frameworks. For example, Relational-cultural theory emphasizes that growth-fostering relationships are crucial for resilience and well-being, particularly among marginalized populations [55]. In collectivist cultures such as those in East and Southeast Asia, family-oriented coping is commonly used and culturally meaningful in the face of adversity [56]. While speculative, these perspectives suggest that family support and character strengths may interact synergistically to foster well-being in high-adversity environments. By considering cultural contexts, strength-based interventions can become more meaningful in non-WEIRD cultural contexts. Moreover, this approach aligns with the third wave of positive psychology, which emphasizes the importance of incorporating cultural perspectives beyond WEIRD societies [57].

While this study provides valuable insights into character strengths use and psychological well-being among slum dwellers, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the cross-sectional design limits the ability to draw causal conclusions, underscoring the need for longitudinal studies to examine how strengths use may influence well-being over time. Second, the exclusive use of self-report measures may introduce biases such as social desirability and recall errors; future research should consider incorporating behavioral assessments or informant reports to enhance validity.

Third, although this study highlights the significance of character strengths use, its focus specifically on character strengths rather than general strengths use marks a conceptual shift, potentially limiting comparability with studies employing the standard SUS. Additionally, variation in the specific strengths selected by participants may have introduced uncontrolled variability, as certain strengths, such as Hope and Gratitude, are more strongly associated with well-being. Reflecting on one’s signature strengths may also temporarily enhance self-esteem or positive affect, potentially inflating associations with flourishing. Future studies should explore methods that balance cultural and personal relevance with methodological consistency.

Moreover, beyond character strengths, other psychological and social factors likely contribute to well-being in slum communities. Future research should investigate mechanisms such as social support, spirituality, and meaning-making, which may interact with strengths use to foster resilience. Examining whether family support moderates the impact of character strengths on well-being could offer deeper insights, particularly in collectivist cultures like the Philippines, where familial bonds are central to coping with adversity.

Another limitation lies in the qualitative analysis of meaning in life, which was coded by a single researcher without inter-coder reliability checks. Although consistency was sought through repeated reviews, future research would benefit from involving multiple coders to enhance the reliability of thematic classifications.

Finally, although the 12 domain satisfaction data were not subjected to inferential analysis, they may provide valuable insights into subjective well-being in high-adversity contexts. Future studies could explore how satisfaction across material, relational, and identity domains interacts with strengths use and overall psychological well-being.

This study highlights the significant role of character strengths in promoting psychological well-being among an underrepresented population—slum dwellers in the Philippines. The findings suggest that despite economic hardship and high levels of psychological distress, individuals can experience psychological flourishing, particularly when they actively utilize their strengths. These results expand the application of positive psychology to non-WEIRD and high-adversity environments, demonstrating that psychological resources play a crucial role in resilience beyond economically privileged settings. Furthermore, this study underscores the need for strengths-based interventions tailored specifically for slum communities. Future research should further explore the mechanisms through which strengths use fosters well-being in adversity and design culturally responsive interventions that harness these psychological assets to enhance resilience and quality of life in slum communities.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The author received no specific funding for this study.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: This study was approved by the College of Social Sciences and Philosophy Ethics Review Board of the University of the Philippines Diliman (CSSP-ERB Code: CSSPERB-2023-010).

Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from all participants by reading the informed consent, which informed them that their participation was voluntary.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Azañedo CM, Artola T, Sastre S, Alvarado JM. Character strengths predict subjective well-being, psychological well-being, and psychopathological symptoms, over and above functional social support. Front Psychol. 2021;12:661278. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.661278. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Ghielen STS, van Woerkom M, Meyers MC. Promoting positive outcomes through strengths interventions: a literature review. J Posit Psychol. 2018;13(6):573–85. doi:10.1080/17439760.2017.1365164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Miglianico M, Dubreuil P, Miquelon P, Bakker AB, Martin-Krumm C. Strength use in the workplace: a literature review. J Happiness Stud. 2020;21(2):737–64. doi:10.1007/s10902-019-00095-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Niemiec RM. VIA character strengths: research and practice (the first 10 years). In: Knoop HH, Delle Fave A, editors. Well-being and cultures: perspectives from positive psychology. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer; 2013. p. 11–29. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-4611-4_2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Schutte NS, Malouff JM. The impact of signature character strengths interventions: a meta-analysis. J Happiness Stud. 2019;20(4):1179–96. doi:10.1007/s10902-018-9990-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Harzer C, Ruch W. The relationships of character strengths with coping, work-related stress, and job satisfaction. Front Psychol. 2015;6(4):165. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00165. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Martínez-Martí ML, Ruch W. Character strengths predict resilience over and above positive affect, self-efficacy, optimism, social support, self-esteem, and life satisfaction. J Posit Psychol. 2017;12(2):110–9. doi:10.1080/17439760.2016.1163403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Niemiec RM. Six functions of character strengths for thriving at times of adversity and opportunity: a theoretical perspective. Appl Res Qual Life. 2020;15(2):551–72. doi:10.1007/s11482-018-9692-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Datu JAD, Bernardo ABI. The blessings of social-oriented virtues: interpersonal character strengths are linked to increased life satisfaction and academic success among Filipino high school students. Soc Psychol Pers Sci. 2020;11(7):983–90. doi:10.1177/1948550620906294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. World Health Organization. Depression and other common mental disorders: global health estimates [Internet]. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2017 [cited 2024 Jan 1]. Available from: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/254610/WHO-MSD-MER-2017.2-eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

11. Azam U, Jamal R. Subjective well-being of slum dwelling adolescents: validation and findings from India. Vulner Child Youth Stud. 2024;19(2):390–401. doi:10.1080/17450128.2024.2326730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Biswas-Diener R, Diener E. Making the best of a bad situation: satisfaction in the slums of Calcutta. Soc Indic Res. 2001;55(3):329–52. doi:10.1023/A:1010905029386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Sulkers E, Loos J. Life satisfaction among the poorest of the poor: a study in urban slum communities in India. Psychol Stud. 2022;67(3):281–93. doi:10.1007/s12646-022-00657-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Jeffery-Schwikkard D, Li J, Nagpal P, Lomas T. Systematic review of character development in low- and middle-income countries. J Posit Psychol. 2025;20(1):169–91. doi:10.1080/17439760.2024.2322464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Leventhal KS, Gillham J, DeMaria L, Andrew G, Peabody J, Leventhal S. Building psychosocial assets and wellbeing among adolescent girls: a randomized controlled trial. J Adolesc. 2015;45(1):284–95. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.09.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Philippine Statistics Authority. Urban population of the Philippines (2020 census of population and housing) [Internet]. Quezon City, Philippines: Philippine Statistics Authority; 2020 [cited 2024 Jan 1]. Available from: https://psa.gov.ph/content/urban-population-philippines-2020-census-population-and-housing. [Google Scholar]

17. Statista. Share of urban population living in slums in the Philippines in 2005 to 2018 [Internet]. New York, NY, USA: Statista; 2018 [cited 2024 Jan 1]. Available from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/691995/philippines-share-of-urban-population-living-in-slums/. [Google Scholar]

18. UN-Habitat. The challenge of slums: global report on human settlements 2003 [Internet]. Nairobi, Kenya: UN-Habitat; 2003 [cited 2024 Jan 1]. Available from: https://unhabitat.org/the-challenge-of-slums-global-report-on-human-settlements-2003. [Google Scholar]

19. Subbaraman R, Nolan L, Shitole T, Sawant K, Shitole S, Sood K, et al. The psychological toll of slum living in Mumbai, India: a mixed methods study. Soc Sci Med. 2014;119(2):155–69. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.08.021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Sen A. Development as freedom. New York, NY, USA: Oxford University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

21. Nussbaum M. Creating capabilities: the human development approach. Cambridge, MA, USA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

22. Masten AS. Ordinary magic: resilience processes in development. Am Psychol. 2001;56(3):227–38. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.227. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development: experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA, USA: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

24. Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007;39(2):175–91. doi:10.3758/BF03193146. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang AG. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav Res Methods. 2009;41(4):1149–60. doi:10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Govindji R, Linley PA. Strengths use, self-concordance and well-being: implications for strengths coaching and coaching psychologists. Int Coach Psychol Rev. 2007;2(2):143–53. doi:10.53841/bpsicpr.2007.2.2.143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Niemiec RM, McGrath RE. The power of character strengths: appreciate and ignite your positive personality. Cincinnati, OH, USA: VIA Institute on Character; 2019. [Google Scholar]

28. Diener E, Wirtz D, Tov W, Kim-Prieto C, Choi D-W, Oishi S, et al. New well-being measures: short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Soc Indic Res. 2010;97(2):143–56. doi:10.1007/s11205-009-9493-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Datu JAD. Flourishing is associated with higher academic achievement and engagement in Filipino undergraduate and high school students. J Happiness Stud. 2018;19(1):27–39. doi:10.1007/s10902-016-9805-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, Epstein JF, Gfroerer JC, Hiripi E, et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(2):184–9. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.60.2.184. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Sampasa-Kanyinga H, Zamorski MA, Colman I. The psychometric properties of the 10-item kessler psychological distress scale (K10) in Canadian military personnel. PLoS One. 2018;13(4):e0196562. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0196562. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The satisfaction with life scale. J Pers Assess. 1985;49(1):71–5. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Biswas-Diener R. From the equator to the north pole: a study of character strengths. J Happiness Stud. 2006;7(3):293–310. doi:10.1007/s10902-005-3646-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, Hiripi E, Mroczek DK, Normand SLT, et al. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol Med. 2002;32(6):959–76. doi:10.1017/S0033291702006074. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Andrews G, Slade T. Interpreting scores on the Kessler psychological distress scale (K10). Aust New Zealand J Public Health. 2001;25(6):494–7. doi:10.1111/j.1467-842X.2001.tb00310.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Lund C, Breen A, Flisher AJ, Kakuma R, Corrigall J, Joska JA, et al. Poverty and common mental disorders in low and middle income countries: a systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(3):517–28. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.04.027. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Yan T, Chan CW, Chow KM, Zheng W, Sun M. A systematic review of the effects of character strengths-based intervention on the psychological well-being of patients suffering from chronic illnesses. J Adv Nurs. 2020;76(7):1567–80. doi:10.1111/jan.14356. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Tweed RG, Biswas-Diener R, Lehman DR. Self-perceived strengths among people who are homeless. J Posit Psychol. 2012;7(6):481–92. doi:10.1080/17439760.2012.719923. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Matsuguma S, Kawashima M, Negishi K, Sano F, Mimura M, Tsubota K. Strengths use as a secret of happiness: another dimension of visually impaired individuals’ psychological state. PLoS One. 2018;13(2):e0192323. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0192323. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Taylor EC, Livingston LA, Clutterbuck RA, Callan MJ, Shah P. Psychological strengths and well-being: strengths use predicts quality of life, well-being and mental health in autism. Autism. 2023;27(6):1826–39. doi:10.1177/13623613221146440. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Green ZA. Character strengths intervention for nurturing well-being among Pakistan’s university students: a mixed-method study. Appl Psychol Health Well-Being. 2022;14(1):252–77. doi:10.1111/aphw.12301. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Kumar R, Bakhshi A, Singh D. Exploring the role of character strengths in positive mental health of college students. Stud Indian Place Names. 2020;40(3):2522–33. [Google Scholar]

43. Petkari E, Ortiz-Tallo M. Towards youth happiness and mental health in the United Arab Emirates: the path of character strengths in a multicultural population. J Happiness Stud. 2018;19(2):333–50. doi:10.1007/s10902-016-9820-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Liu Q, Wang Z. Perceived stress of the COVID-19 pandemic and adolescents’ depression symptoms: the moderating role of character strengths. Personal Individ Differ. 2021;182(2):111062. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2021.111062. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Waters L, Algoe SB, Dutton J, Emmons R, Fredrickson BL, Heaphy E, et al. Positive psychology in a pandemic: buffering, bolstering, and building mental health. J Posit Psychol. 2021;17(3):303–23. doi:10.1080/17439760.2021.1871945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Sivaratnam J, Cabano EMP, Erickson TM. Character virtues prospectively predict responses to situational stressors in daily life in clinical and subclinical samples. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2022;35(4):458–73. doi:10.1080/10615806.2021.1967333. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Seijts GH, Monzani L, Woodley HJR, Mohan G. The effects of character on the perceived stressfulness of life events and subjective well-being of undergraduate business students. J Manag Educ. 2022;46(1):106–39. doi:10.1177/1052562920980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Lee B, Kaya C, Chen X, Wu J-R, Iwanaga K, Umucu E, et al. The buffering effect of character strengths on depression: the intermediary role of perceived stress and negative attributional style. Eur J Health Psychol. 2019;26(3):101–9. doi:10.1027/2512-8442/a000036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Niemiec RM. Mental health and character strengths: the dual role of boosting well-being and reducing suffering. Ment Health Soc Incl. 2023;27(4):294–316. doi:10.1108/MHSI-01-2023-0012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Iasiello M, van Agteren J, Ali K, Fassnacht DB. Positive psychology is better served by a bivariate rather than bipolar conceptualization of mental health and mental illness: a commentary on Zhao & Tay (2022). J Posit Psychol. 2024;19(2):337–41. doi:10.1080/17439760.2023.2179935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Keyes CL. The mental health continuum: from languishing to flourishing in life. J Health Soc Behav. 2002;43(2):207–22. doi:10.2307/3090197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Keyes CL. Mental illness and/or mental health? Investigating axioms of the complete state model of health. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73(3):539–48. doi:10.1111/1467-839X.00054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Pe-Pua R, Protacio-Marcelino EA. Sikolohiyang Pilipino (Filipino psychologya legacy of Virgilio G. Enriquez. Asian J Soc Psychol. 2000;3(1):49–71. doi:10.1111/1467-839Xz.00054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Reyes MM. Loób and kapwa: an introduction to a Filipino virtue ethics. Asian Philos. 2015;25(2):148–71. doi:10.1080/09552367.2015.1043173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Jordan JV. Recent developments in relational-cultural theory. Women Ther. 2008;31(2–4):1–4. doi:10.1080/02703140802145540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Heppner PP, Heppner MJ, Lee DG, Wang YW, Park HJ, Wang LF. Development and validation of a collectivist coping styles inventory. J Couns Psychol. 2006;53(1):107–25. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.53.1.107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Lomas T, Waters L, Williams P, Oades LG, Kern ML. Third wave positive psychology: broadening towards complexity. J Posit Psychol. 2020;16(5):660–74. doi:10.1080/17439760.2020.1805501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools