Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Psychometric Properties of the Shortened Chinese Version of the Community Attitudes towards the Mentally Ill Scale

1 School of Sociology, China University of Political Science and Law, Beijing, 100088, China

2 Department of Social Work and Social Administration, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China

* Corresponding Author: Siu-Man Ng. Email:

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(10), 1471-1482. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.068702

Received 04 June 2025; Accepted 10 September 2025; Issue published 31 October 2025

Abstract

Background: Existing Chinese stigma scales focus on the perceptions of people with mental illness (PMI) without assessing the general public’s attitudes toward integrating PMI into the community. Developing a valid and reliable Chinese instrument measuring the attitude domain will be helpful to future research in this area. The current study aimed to validate a shortened Chinese version of the Community Attitudes towards the Mentally Ill Scale (C-CAMI-SF). Methods: Four hundred participants who are (1) Chinese; (2) aged 18 years and above; and (3) able to complete the Chinese questionnaire in a self-reported manner participated in the research. Principal component analysis was conducted to explore the factor structure of the scale. Internal consistency was examined using the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. Three other questionnaires: Social Distance Scale (SDS), The Attribution Questionnaires-9-Item Version (AQ-9), and the Interpersonal Support Evaluation List-12 (ISEL-12), were used to examine the convergent and divergent validity of the scale. Results: Finally, seventeen items were retained in the C-CAMI-SF with factor loadings ranging from 0.51 to 0.81. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of the scale were revealed to be 0.58, 0.57, 0.75, and 0.68 for each subscale, respectively. Although the first two values fall just short of the conventional 0.70 benchmark, this is still acceptable for a unidimensional subscale comprising only 3–4 items. Significant correlations (p < 0.05) were obtained in the expected directions between the C-CAMI-SF and the other three validity check scales. Conclusion: The 17-item C-CAMI-SF validated in the current study demonstrated good psychometric properties and conceptual coherence. It also provided implications for future stigma reduction interventions.Keywords

Previous studies suggest that public stigma toward groups with implicit marks, such as people with mental illness (PMI), is harmful [1]. For PMI, perceived public stigma may exclude them and devalue their social status and networks [2–4]. This loss may cause their normal lives to further deteriorate and make them believe that they deserve the stigma they experience. The general public may feel unsafe with community psychiatric institutions near their residence [5] and support keeping a larger social distance from PMI [6]. Even mental health staff and medical students may express relatively high levels of stigma toward PMI [7,8]. When it comes to severe mental illnesses, such as schizophrenia and bipolar disease, these negative attitudes become even worse [9]. This situation occurs in the Chinese context as well. Owing to culturally embedded notions of mental illness, PMI and their families often opt to conceal the condition, apprehensive that disclosure could precipitate social exclusion and impute diminished social and moral competence. Although individuals with frequent and sustained contact with PMI often display a more accurate understanding of the disorder, such improved knowledge is not necessarily accompanied by more favorable attitudes toward this population [10]. Consequently, these deeply entrenched stigmatizing attitudes toward PMI are likely to persist over extended periods [11].

In order to tackle the negative consequences of public stigma toward PMI in the Chinese context, developing validated measurements to examine the degree of public stigma is the first step. One locally developed scale, the Stigma Scale towards PMI [12], is the most widely used in the Chinese context. The 26-item scale is rated by five Likert points and includes three perspectives: social distance, danger, and competence. Although the whole scale has high internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.89, the sample in Zeng and colleagues’ study mainly comprised medical professionals and students, and family members of PMI. Its application to the general public has not been validated. Scales translated from the English version and adapted in a Chinese context have also been used to measure public stigma toward PMI. An official scale, Attitudes towards Mental Illness [13], measuring public stigma toward PMI, is adapted from Link and colleagues’ [14] Devalued and Discrimination Scale (DDS). The adapted version includes 12 items and has been used in several surveys in China. However, reliability and validity information were not reported publicly [15]. The Community Attitudes towards The Mentally Ill (CAMI) scale has also been validated in China [16]. The adaptive version kept three factors from the original scale, with 16 items retained. However, it was only tested by 100 medical professionals, and its reliability was not reported.

After briefly reviewing the instruments measuring public stigma toward PMI, we found that instruments applicable to Chinese stigma research are quite limited. Instead of having a concrete focus on components of public stigma, current Chinese scales only provide preliminary descriptions regarding mental illness and PMI. Especially under the promotion of the de-institutionalization of PMI, residents’ attitudes toward the reintegration of PMI into the community and society as a whole are still not accurately measured and discussed in the existing literature. In other words, whether or not the general public in Chinese society can accept rehabilitation and recovery services for PMI “in their backyards” has not been examined.

As a result, to measure community attitudes toward PMI, the CAMI scale became the first choice of this research. The scale was developed from the perspective of the general public, which satisfied our requirements in regard to measuring public stigma. Moreover, the inclusion of attitude toward community mental health services reflects the dilemma in the Chinese context in a timely manner. Participants might be able to comply with social desirability when answering emotion-related questions, but their attitudes toward community services could help unveil the participants’ underlying ideas.

However, the scale cannot be used directly in Chinese research for the following reasons. First, the 40-item scale is relatively long, as repeated measurements are required in academic research. Second, the positively and negatively worded items in the original scale might actually measure the same thing under one factor, which might have the potential to guide participants’ attitudes. Moreover, it might not be feasible to say that the denial of negatively worded items indicates the opposite meaning of the acceptance of positively worded items. For example, one of the negatively worded items in the authoritarian subscale is: “The mentally ill should not be treated as outcasts of society”. Even if participants do not accept this statement, this does not necessarily mean that they support the inclusion of the mentally ill in their community. After examining the factor loadings of the negatively worded items under each subscale in the original scale, the results showed that these items had rather low loadings, compared with the positively worded items. As a result, there is potential to further improve the validity of the scale and examine its structure by omitting the negatively worded items. Third, the content of some statements under one factor might be repeated. For example, when measuring benevolence, attitudes reflected by tax money allocation were described twice in the scale. Finally, the scale was first developed in the 1980s and so the expressions and social context need to be examined under the current context. Although the CAMI scale has been translated to different languages, including Chinese, and validated in different contexts [16–19], validation with an adequate sample size has not been recently carried out in China.

Consequently, the original 40-item CAMI scale will be translated, shortened, and validated in the current study. The main task of this research is to develop a shorter version of the CAMI scale that can be used in the Chinese context, focusing on the direct descriptions of each subscale. The new scale is named the Shortened Chinese Version of the Community Attitudes towards the Mentally Ill Scale (C-CAMI-SF).

For sample-size estimation in the present study, we integrated recommendations from existing discussion. Early conventions for exploratory factor analysis (EFA) propose that the required number of respondents equals to the number of response categories per item [20]. A minimum ratio of 10 participants per item is also widely accepted [21–23], whereas sample size exceeding 300 respondents yield more stable factor solutions [24]. Synthesizing these perspectives, we adopted the 1:10 participant-to-item ratio, thereby targeting a minimum of 400 participants to ensure robust psychometric evaluation.

Participants were recruited through a convenience-sampling strategy. Invitations were disseminated on Chinese-predominant social-media platforms such as WeChat and WhatsApp between September and October 2018. The inclusion criteria were: (1) Chinese; (2) aged 18 years and above; and (3) able to complete the Chinese questionnaire in a self-reported manner. Consent to participate in the study was obtained before the start of the online survey. Participants could quit the online survey at any time without any negative consequences. The Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Hong Kong (No. EA1807014) approved this study.

A battery of questionnaires was created on an online survey website and could be accessed by the participants through an online survey link. The main scale to be validated was the original CAMI scale. Adaptation and translation were performed in advance by linguistic and mental health professionals. Another three scales were included to test the convergent and discriminant validity of the C-CAMI-SF: the 7-item Social Distance Scale (SDS), the Attribution Questionnaires-9-Item Version (AQ-9), and the Interpersonal Support Evaluation List-12 (ISEL-12). Self-reported demographic characteristics included age, gender, education level, marital status, previous diagnosis of mental illnesses, and the mental health status of family members; these were collected before the intervention.

2.2.1 The Community Attitudes towards the Mentally Ill Scale (CAMI)

The original 40-item English version was carefully examined by the two authors and two other professionals in the mental health field, following standard procedures that ensured the content validity of the scale. Translation and back-translation were conducted by two linguistic professionals. The authors checked the translation and back-translation results with the two professionals in the mental health field to revise the expression of each item. A pilot test was conducted to guarantee the accuracy and feasibility of the content. All 40 items were retained as the item pool for selection.

The original five-point Likert scale [25] included four subscales measuring four perspectives of stigma attitudes: authoritarian (AT), benevolence (BN), social restrictiveness (SR), and community mental health ideology (CMHI). The AT and SR subscales reflect participants’ intolerant and controlling tendencies toward PMI, while the other two subscales reflect participants’ understanding and tolerance of PMI. The reliability of the CAMI scale yielded Cronbach’s alpha coefficients from 0.68 to 0.88 [25]. Higher scores on the AT and SR subscales indicate more stigmatizing attitudes, while higher scores on the BN and CMHI subscales indicate less stigmatizing attitudes.

2.2.2 Social Distance Scale (SDS)

The SDS [26] was used to examine participants’ avoidance of PMI. The four-point Likert scale includes seven items asking about participants’ willingness under different social contexts (e.g., living next door to the mentally ill). The score range of the SDS is 0 to 3. Higher scores indicate greater distance from PMI. The reliability of the SDS yielded Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of 0.75 to 0.76 [27,28].

2.2.3 The Attribution Questionnaires-9-Item Version (AQ-9)

The AQ-9 [29] includes nine stereotypes about PMI. The nine perspectives were blame, anger, pity, help, dangerousness, fear, avoidance, segregation, and coercion. The AQ-9 is the shortest version of the tool, which just involves selecting the item with the highest loading under each factor. The scale is rated on a nine-point Likert scale. The reliability of the nine factors yielded internal consistency ranging from 0.62 to 0.82 [30].

2.2.4 Interpersonal Support Evaluation List-12 (ISEL-12)

This 12-item scale measures people’s perception of social support [31]. It includes three subscales: appraisal support, belonging support, and tangible support. Each subscale comprises four items and is rated on a four-point Likert scale. The reliability of the entire scale yielded Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranging from 0.88 to 0.90 in the sample of the general public [32].

All data analyses were carried out using the statistical software SPSS 23 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Principal component analysis was conducted to explore the factor structure of the C-CAMI-SF. Factors with a criterion of an eigenvalue >1 will be retained [33]. As the four subscales of the original CAMI scale indicate four independent aspects of stigma attitudes, and the scores of the four subscales cannot be added up directly, factor analyses were conducted respectively for the four subscales. Prior to factor analysis, the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy and Bartlett’s test of sphericity were performed to assess data suitability. A KMO value > 0.50 and a Bartlett’s test significant at p < 0.05 were required to confirm that factor analysis was appropriate for the dataset [22,23]. Internal consistency was examined using the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. A value of 0.70 or above was accepted as a satisfactory level of scale reliability [34]. The convergent and discriminant validity were examined using the correlations between the C-CAMI-SF and the other three validity check scales. It was expected that the AT and SR subscales would have positive associations with the SDS and seven factors in the AQ-9, excluding the pity and help factors. Positive associations were also expected between the BN and CMHI subscales and the pity and help factors in the AQ-9. No correlation was expected between the C-CAMI-SF and the ISEL-12 scale.

The reduction of the number of items per subscale was carried out on the basis of the exploratory factor analysis. Items loaded on more than one factor were excluded. If several items expressed similar content, the one with the higher factor loading and effect size was retained. Items with corrected inter-item total correlation loadings less than 0.40 were deleted as well, as loadings of less than 0.40 are considered “weak” [35].

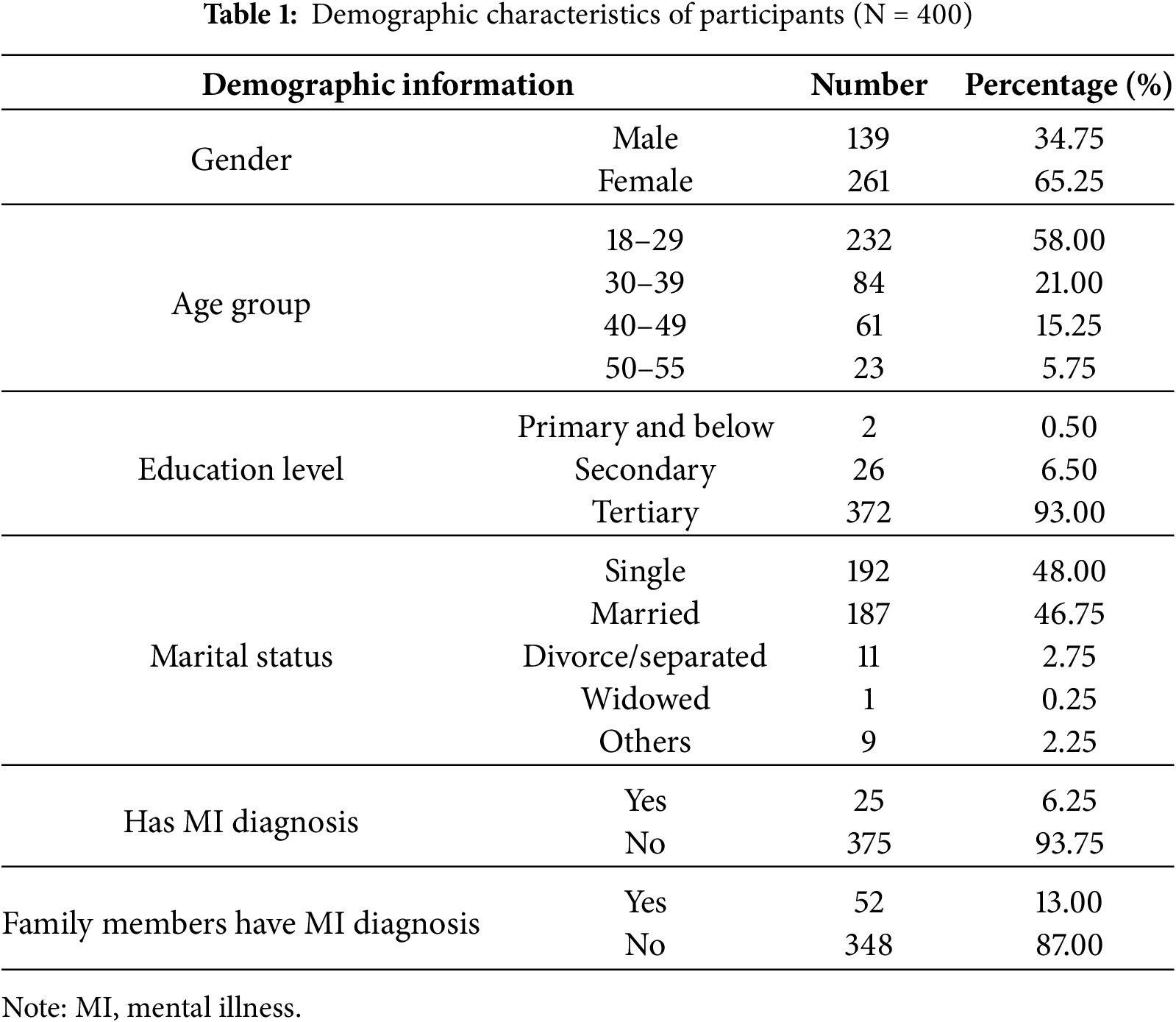

A total of 400 participants satisfied the inclusion criteria among the 455 participants who consented to participate; the responses of these 400 participants were used in the current study. The mean age was 31.40 years (SD = 8.87), and 65% of the participants were women. The majority of participants (69%) were full-time employees and had tertiary education levels (93%). Single (48%) and married (47%) participants were relatively equal. Only 25 of the 400 participants reported had previous diagnoses of mental disorders. Table 1 summarizes the demographic data of the sample.

3.2 Factor Structure and Construct Explication

Factor analyses were conducted respectively for the four subscales. All four subscales satisfied the requirements for factor analysis. The results of the KMO test of the four subscales were 0.70, 0.62, 0.75, and 0.71, respectively. And the results of the Bartlett’s test of the four subscales were all significant with p < 0.001.

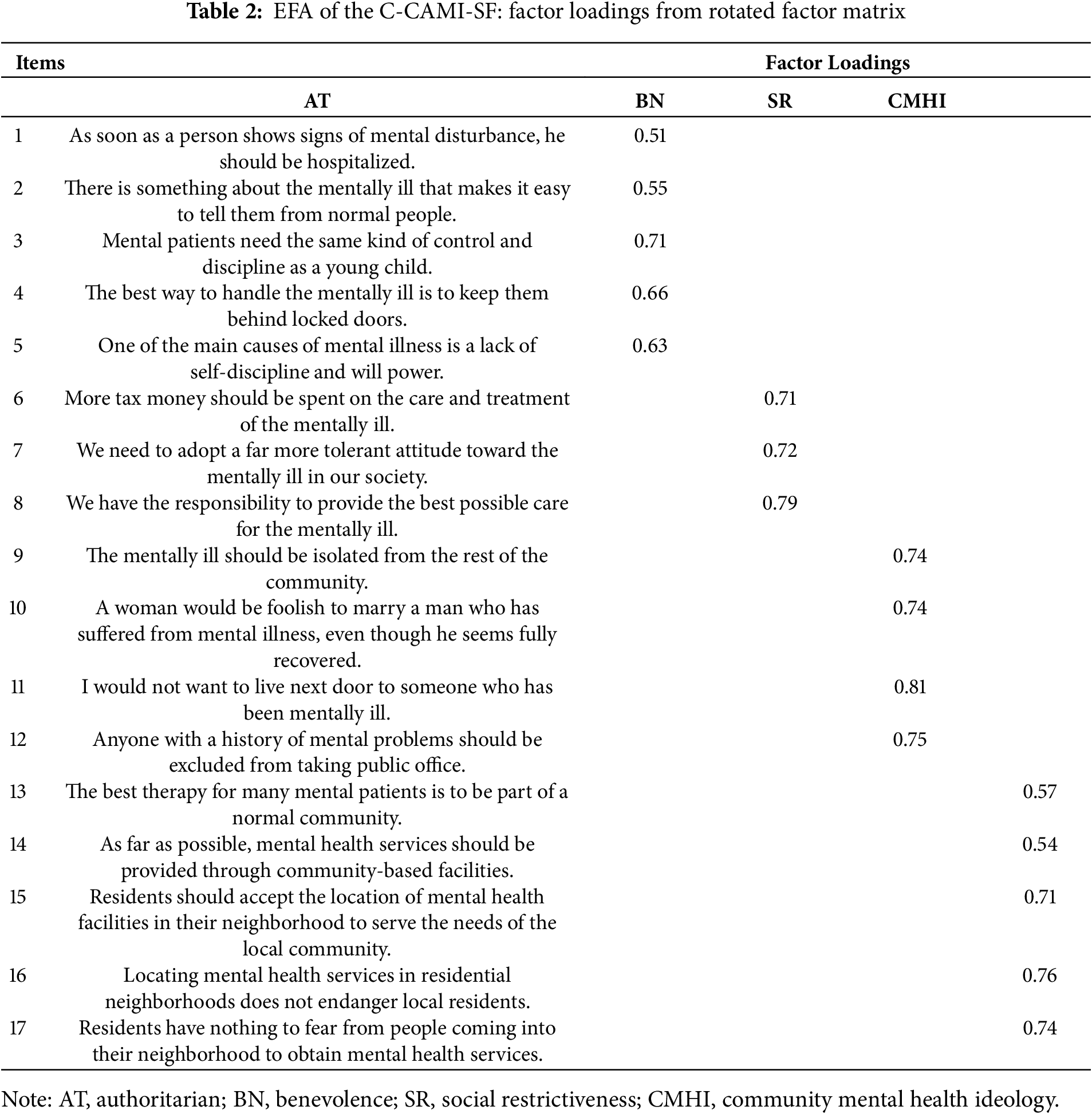

EFA focused on the positively worded items of the CAMI scale. Using principal component analysis with a criterion of an eigenvalue >1, all subscales satisfied the single-factor structure. The four-factor orthogonal solution accounted for 53.11% of the variance. Variance accounted for by items in each subscale was 38.25%, 54.83%, 57.66%, and 44.74%, respectively. Factor loadings under each subscale are listed in Table 2. With a significant loading set at 0.40, 17 items in total were retained for the Chinese CAMI-SF Scale.

The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of the four subscales were 0.58, 0.57, 0.75, and 0.68, respectively. Inter-factor correlations were lower, ranging between −0.16 and 0.52, which indicates the independence of each subscale.

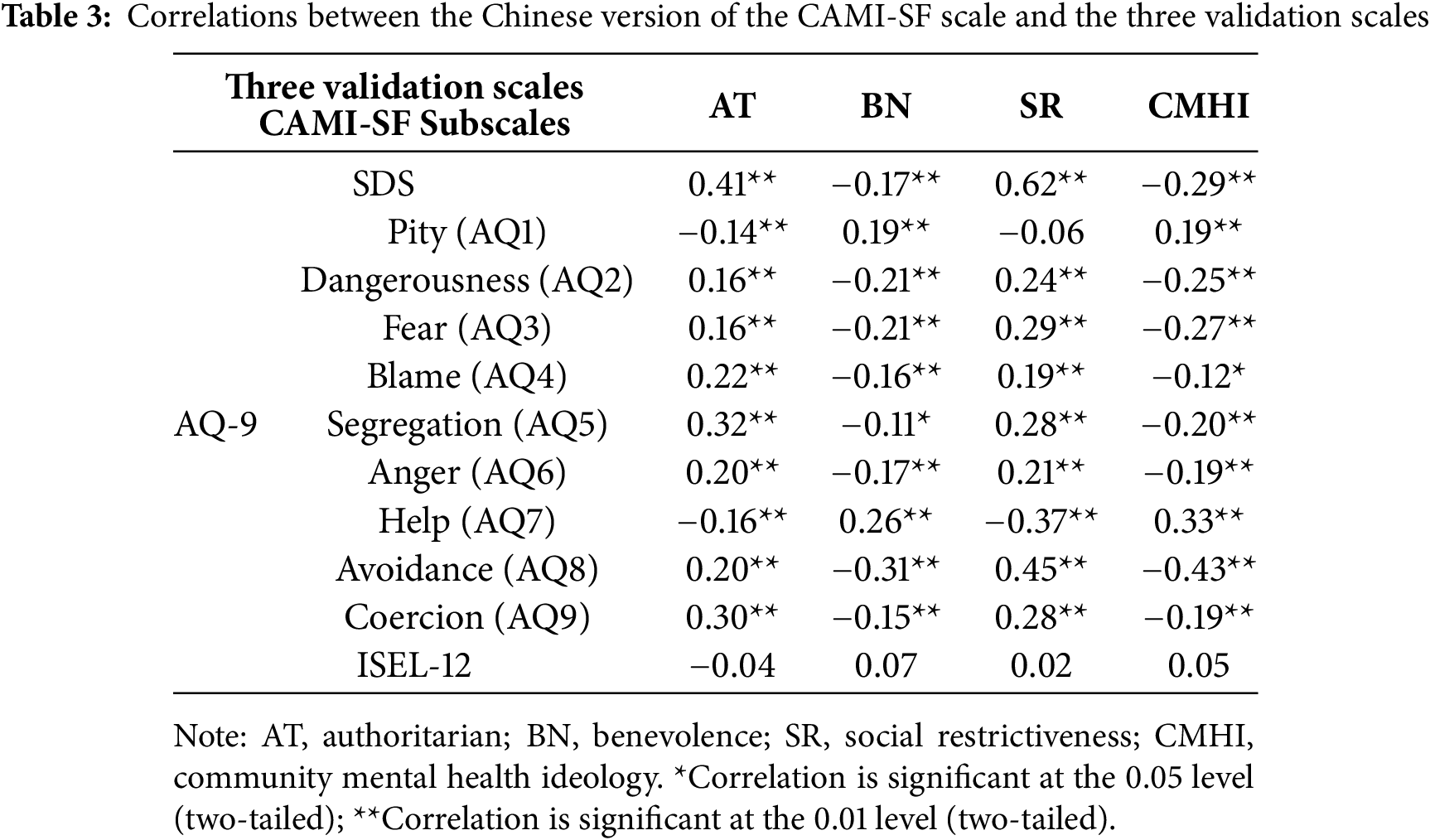

Correlations between the C-CAMI-SF and the validation scales are summarized in Table 3. All four subscales have significant correlations in the expected directions with the SDS and AQ-9. The AT and SR subscales had positive correlations with the SDS, while the BN and CMHI subscales had negative correlations with the SDS. Each item in the AQ-9 represents one aspect of emotional reactions or behaviors in the stigma process [24]. Pity (AQ1) may lead to helping (AQ7) behavior, while blame (AQ4), anger (AQ6), danger (AQ2), and fear (AQ3) may predict avoidance (AQ8), segregation (AQ5), and coercion (AQ9). As expected, the AT and SR subscales had positive correlations with negative emotional responses (AQ2, 3, 4, 6) and discriminative behaviors (AQ5, 8, 9), and negative correlations with supporting emotional responses (AQ1) and behavior (AQ7). The other two subscales, the BN and CMHI subscales, presented the opposite result. All four subscales had insignificant correlations with the ISEL-12.

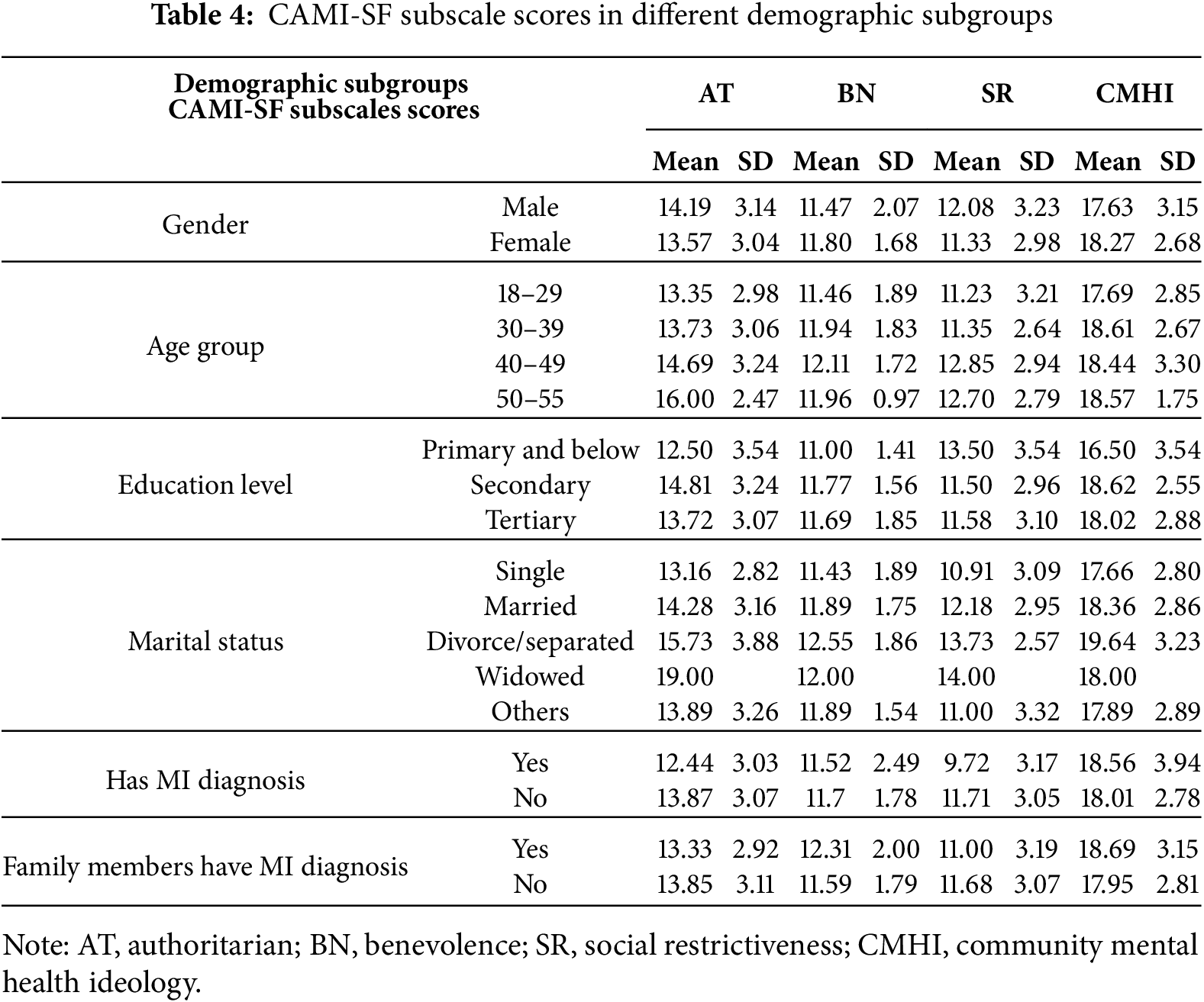

3.5 Descriptive Statistics for the C-CAMI-SF

The mean scores of the four subscales in the current sample were 13.79, 11.69, 11.59, and 18.05, respectively. The theoretical ranges of each subscale were 5–25, 5–15, 5–20, and 5–25, accordingly. The means and standard deviations of each subscale score in different strata of each demographical variable are listed in Table 4. For each variable, an ANOVA was conducted to compare the subscale scores among different strata. All factors except education level had significant influences on the subscale scores.

Female participants presented less restrictive attitudes (p = 0.02) and more welcoming attitudes in regard to integrating PMI in the community (p = 0.03) than male participants. Participants in the 18–29 age group had significantly lower AT (p = 0.013) and SR (p = 0.001) scores than those in the 40–49 age group. Their AT scores were also lower than those of participants aged over 50 (p < 0.001). The SR scores of participants in the 30–39 age group were also lower than those of participants in the 40–49 age group (p = 0.02). Participants with previous diagnoses of mental illness presented less authoritative (p = 0.02) and restrictive attitudes (p = 0.002) toward PMI than those without diagnoses. Participants with family members with mental illnesses showed more tolerant attitudes, with higher BN scores (p = 0.009), than participants without such family members.

The aim of the current study is to develop a shorter version of the CAMI scale that could be used in the Chinese context. A total of 20 negatively worded items were all removed from the scale, considering their item loadings and the content validity of the whole scale. Exploratory factor analyses for each of the four subscales produced the final 17-item, four-factor version of the current C-CAMI-SF, which presented satisfying psychometric properties and conceptual coherence. Factor loadings of all items ranged from 0.51 to 0.81, explaining most of the variance under each factor. Item loadings were higher than those in the original scale, most of which only showed loadings around 0.50 to 0.60. Regarding interval consistency, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of the C-CAMI-SF were revealed to be 0.58, 0.57, 0.75, and 0.68 for each subscale, respectively. Although only one subscale had a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient higher than 0.70, the reliability of this coefficient was acceptable for subscales with only three to five items [36]. The reliability of the subscales was examined, rather than that of the scale as a whole, because the scores of the four factors could not be added up directly. These four factors should be examined separately to measure the existence of public stigma. For the analysis of construct validity, correlation analysis of the C-CAMI-SF and the three validity scales supported the convergent and discriminant construct validity of the 17-item scale. Significant correlations were obtained in the expected directions between the C-CAMI-SF and the other three scales.

The mean scores of the four subscales in the current sample were 13.79, 11.69, 11.59, and 18.05, respectively. As the theoretical ranges of each subscale were 5–25, 5–15, 5–20, and 5–25, accordingly, the degree of authoritative and restrictive attitudes in the current sample was relatively high. In other words, stigmatizing tendencies in the current Chinese sample were comparatively severe, which is consistent with prior research findings [37–39]. In order to enhance the prevention and early intervention of mental illness, the dissemination of accurate information and the cultivation of non-prejudicial attitudes towards mental illness are of fundamental importance. Previous research conducted in China has demonstrated that the general population frequently recognizes the presence of prejudicial attitudes toward PMI, yet simultaneously disavows engaging in discriminatory behaviors [10]. Although this divergence may be attributable to advances in mental health literacy and the promotion of anti-stigma interventions, it also illuminates the persistent conceptual and empirical difficulty of distinguishing between the attitudinal and behavioral components of public stigma. In other words, the very attitudes we label as stigmatizing may already foreshadow our underlying—whether intended or enacted—discriminatory behavior. Consequently, rigorous assessment must encompass not only the subjective experiences of PMI but also the observable dynamics of interpersonal interaction and the provision of public services. Moreover, at this juncture, a more profound comprehension and precise evaluation of the stigmatization associated with mental illness within the Chinese sociocultural context are particularly crucial. An earlier study revealed that Hong Kong Chinese hold significantly more stigmatizing attitudes toward mental illness and encounter greater barriers to professional help-seeking than Chinese Americans [40]. A review of culturally specific factors shaping stigma in Chinese societies shows that the perceived loss of “face” and the familial burden imposed by mental illness intensify guilt and self-devaluation among PMI [41]. This finding again emphasizes the necessity of conducting public stigma research in regard to PMI and exploring effective projects to alleviate this situation.

From the analysis of each subscale score in different demographical domains, it could be inferred that age, gender, marital status, and participants’ and their family members’ previous diagnoses of mental illnesses had significant effects on participants’ controlling and hostile attitudes toward PMI. The differences in the Chinese context are in line with Western research, in that younger people, female respondents, and people who have personal experiences of mental illnesses were more understanding and supportive of PMI [42]. This finding suggests that future intervention studies should focus on creating change among other groups of people by, for example, including more male participants and promoting more knowledge of subjective experiences of PMI.

The present study is subject to limitations, primarily concerning the sampling methodology. Specifically, the sample was recruited through a convenience sampling approach, which may compromise the representativeness and generalizability of the findings. Future validation studies of the scale should strategically target diverse demographic groups and individuals with various types of mental illnesses to enhance the robustness and applicability of the instrument. For instance, the sample should include individuals of varying educational attainment, male participants, and more older adults. Also, in the current validation process, we retained the original structure of the CAMI scale. This decision was informed by our appreciation for the four distinct perspectives encapsulated within the scale, which effectively delineate the multifaceted manifestations of public stigma toward mental illness. The emphasis on community settings and the general public is particularly valuable for common social surveys, as it captures the prevailing attitudes within the broader societal context. Nevertheless, subsequent studies should empirically corroborate the four-factor structure of the scale through confirmatory factor analysis; such evidence would also inform the refinement of the item selection, thereby enhancing the internal consistency of both the AT and BN subscales.

In conclusion, the 17-item Shortened Chinese Version of the C-CAMI-SF validated in this study exhibited satisfactory psychometric properties. The original four-factor structure effectively presented the essential dimensions of public stigma toward mental illness. The reliability coefficients for each subscale were 0.58, 0.57, 0.75, and 0.68, respectively. Items that accounted for the most variance within each factor were retained, thereby ensuring the scale’s coherence and discriminative power. The overall scale is succinct and streamlined, making it highly suitable for use in community settings and repeated-measures contexts.

By accurately assessing the stigma situation within the Chinese context, the C-CAMI-SF facilitates enhanced awareness of mental illness and promotes early intervention among the general public. A more nuanced comprehension of public stigma toward PMI might enable future research to systematically elucidate its underlying determinants and thereby identify evidence-based targets for anti-stigma interventions. And thus, it holds significant potential for advancing mental health literacy and fostering a more inclusive social environment for all people.

Acknowledgement: We thank the efforts of all personnel involved in recruitment and data collection of the current study.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The study was designed collectively by Si-Yu Gao and Siu-Man Ng. Data collection, data analysis and manuscript writing were conducted by Si-Yu Gao. And both authors contributed intellectually to its revision and agreed with its submission. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from both authors upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Hong Kong (Reference number: EA1807014). Online informed consent form was collected from each participant prior to data collection. The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. World Health Organization. World Mental Health Report: transforming mental health for all [Internet]; 2022 [cited 2025 Aug 17]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240049338. [Google Scholar]

2. Gurung D, Poudyal A, Wang YL, Neupane M, Bhattarai K, Wahid SS, et al. Stigma against mental health disorders in Nepal conceptualised with a ‘what matters most’ framework: a scoping review. Epidemiol Psych Sci. 2022;31:e11. doi:10.1017/S2045796021000809. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Hampson ME, Watt BD, Hicks RE. Impacts of stigma and discrimination in the workplace on people living with psychosis. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):288. doi:10.1186/s12888-020-02614-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Corrigan P, Roe D, Tsang H. Challenging the stigma of mental illness. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2011. [Google Scholar]

5. Zhang Z, Sun K, Jatchavala C, Koh J, Chia Y, Bose J, et al. Overview of stigma against psychiatric illnesses and advancements of anti-stigma activities in six Asian Societies. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(1):280. doi:10.3390/ijerph17010280. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Schomerus G, Schindler S, Sander C, Baumann E, Angermeyer MC. Changes in mental illness stigma over 30 years—improvement persistence, or deterioration? Eur Psychiatry. 2022;65(1):e78. doi:10.1192/j.eurpsy.2022.2337. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Riffel T, Chen SP. Stigma in healthcare? Exploring the knowledge, attitudes, and behavioural responses of healthcare professionals and students toward individuals with mental illnesses. Psychiatr Q. 2020;91(4):1103–19. doi:10.1007/s11126-020-09809-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Lien YY, Lin HS, Lien YJ, Tsai CH, Wu TT, Li H, et al. Challenging mental illness stigma in healthcare professionals and students: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Psychol Health. 2020;36(6):669–84. doi:10.1080/08870446.2020.1828413. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Mothersill D, Loughnane G, Grasso G, Hargreaves A. Knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours towards schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and autism: a pilot study. Ir J Psychol Med. 2023;40(4):634–40. doi:10.1017/ipm.2021.81. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Gao S, Ng SM. Reducing college student’s stigma toward people with schizophrenia: a pilot trial. Res Social Work Prac. 2023;34(7):715–24. doi:10.1177/10497315231184142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Yin H, Wardenaar KJ, Xu G, Tian H, Schoevers RA. Mental health stigma and mental health knowledge in Chinese population: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):323. doi:10.1186/s12888-020-02705-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Zeng QZ, He YL, Tian H, Miu JM, Yu WL. Development of scale of stigma in people with mental illness. Chinese Mental Health J. 2009;21(4):217–20,250. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

13. National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. Circular of the General Office of the Ministry of Health on the Issuance of a Survey and Evaluation Programme for Indicators of Mental Health Performance [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jul 21]. Available from: https://www.nhc.gov.cn/wjw/gfxwj/201003/3fcd9fc884454b3ebccc2dd85067b6f4.shtml. [Google Scholar]

14. Link BG, Cullen FT, Struening E, Shrout PE, Dohrenwend BP. A modified labeling theory approach to mental disorders: an empirical assessment. Am Sociol Rev. 1989;54(3):400. (In Chinese). doi:10.2307/2095613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Pan SM, Zhou Y. Instruments for measuring public stigma towards mental illnesses. Chinese J Modern Nurs. 2013;19(21):2481–2. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1671-8348.2014.10.041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Sévigny R, Yang WY, Zhang PY, Marleau J, Yang ZY, Su L, et al. Attitudes toward the mentally ill in a sample of professionals working in a psychiatric hospital in Beijing (China). Int J Soc Psychiatry. 1999;45(1):41–55. doi:10.1177/002076409904500106. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Brockington I, Hall P, Levings J, Murphy C. The community’s tolerance of the mentally ill. Br J Psychiatry. 1993;162(1):93–9. doi:10.1192/bjp.162.1.93. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Högberg T, Magnusson A, Ewertzon M, Lützén K. Attitudes towards mental illness in Sweden: adaptation and development of the Community Attitudes towards Mental Illness questionnaire. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2008;17(5):302–10. doi:10.1111/j.1447-0349.2008.00552.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Ochoa S, Martínez-Zambrano F, Vila-Badia R, Arenas O, Casas-Anguera E, García-Morales E, et al. Spanish validation of the social stigma scale: community attitudes towards mental illness. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment. 2016;9(3):150–7. doi:10.1016/j.rpsm.2015.02.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Hair JF, Gabriel MLDS, da Silva D, Braga Junior S. Development and validation of attitudes measurement scales: fundamental and practical aspects. RAUSP Manag J. 2019;54(4):490–507. doi:10.1108/RAUSP-05-2019-0098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Clark LA, Watson D. Constructing validity: basic issues in objective scale development. Psycho Assess. 1995;7(3):309–19. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.7.3.309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Hair JF, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE. Multivariate data analysis. 8th ed. London, UK: Cengage Learning; 2019. [Google Scholar]

23. DeVellis RF. Scale development: theory and applications. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: Sage; 2003. [Google Scholar]

24. Comrey AL, Lee H. A first course in factor analysis. Hillsdale, NJ, USA: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; 1992. [Google Scholar]

25. Taylor SM, Dear MJ. Scaling community attitudes toward the mentally ill. Schizophr Bull. 1981;7(2):225–40. doi:10.1093/schbul/7.2.225. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Link BG. Understanding labeling effects in the area of mental disorders: an assessment of the effects of expectations of rejection. Am Sociol Rev. 1987;52(1):96–112. doi:10.2307/2095395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Penn DL, Guynan K, Daily T, Spaulding WD, Garbin CP, Sullivan M. Dispelling the stigma of schizophrenia: what sort of information is best? Schizophr Bull. 1994;20(3):567–78. doi:10.1093/schbul/20.3.567. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Corrigan PW, Rowan D, Green A, Ludin R, River P, Uphoff-Wasowski K, et al. Challenging two mental illness stigmas: personal responsibility and dangerousness. Schizophr Bull. 2002;28(2):293–309. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006939. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Corrigan P, Markowitz FE, Watson A, Rowan D, Kubiak M. An attribution model of public discrimination towards persons with mental illness. J Health Soc Behav. 2003;44(2):162–79. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

30. Corrigan PW, Powell KJ, Michaels PJ. Brief battery for measurement of stigmatizing versus affirming attitudes about mental illness. Psychiat Res. 2014;215(2):466–70. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2013.12.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Cohen S, Mermelstein R, Kamarck T, Hoberman HM. Measuring the functional components of social support. In: Sarason IG, Sarason BR, editors. Social support: theory, research, and applications. Vol. 24. The Hague, The Netherlands: Martinus Niijhoff; 1985. p. 73–94. doi:10.1007/978-94-009-5115-0_5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Department of Psychology, Carnegie Mellon University. Social Support [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 17]. Available from: https://www.cmu.edu/common-cold-project/measures-by-study/psychological-and-social-constructs/social-relationships-loneliness-measures/social-support.html. [Google Scholar]

33. Wold S, Esbensen K, Geladi P. Principal component analysis. Chemom Intell Lab Syst. 1987;2(1–3):37–52. doi:10.1016/0169-7439(87)80084-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Kline Peditor. A psychometrics primer. London, UK: Free Association Books; 2000. [Google Scholar]

35. Norman GR, Streiner DL. Biostatistics: the bare essentials. St Louis, MO, USA: Mosby; 1994. [Google Scholar]

36. Cortina JM. What is coefficient alpha? An examination of theory and applications. J Appl Psychol. 1993;78(1):98–104. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.78.1.98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Xu XY, Li XM, Zhang JH, Wang WQ. Mental health-related stigma in China. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2017;39(2):126–34. doi:10.1080/01612840.2017.1368749. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Li X-H, Wong Y-LI, Wu Q, Ran M-S, Zhang T-M. Chinese college students’ stigmatization towards people with mental illness: familiarity, perceived dangerousness, fear, and social distance. Healthcare. 2024;12(17):1715. doi:10.3390/healthcare12171715. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Yang F, Yang BX, Stone TE, Wang XQ, Zhou Y, Zhang J, et al. Stigma towards depression in a community-based sample in China. Compr Psychiat. 2020;97(3):152152. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2019.152152. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Chen SX, Mak WWS, Lam BCP. Is it cultural context or cultural value? Unpackaging cultural influences on stigma toward mental illness and barrier to help-seeking. Soc Psychol Pers Sci. 2020;11(7):1022–31. doi:10.1177/1948550619897482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Ran MS, Hall BJ, Su TT, Prawira B, Breth-Petersen M, Li XH, et al. Stigma of mental illness and cultural factors in Pacific Rim region: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21(8):16. doi:10.1186/s12888-020-02991-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Yang LH, Kleinman A, Link BG, Phelan JC, Lee S, Good B. Culture and stigma: adding moral experience to stigma theory. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(7):1524–35. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.11.013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools