Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Reducing Stigma and Promoting Empowerment: A Pre-Post Evaluation of ACE-LYNX Intervention on the Mental Health Literacy of University Providers

1 Department of Social Work, School of Philosophy and Social Development, Shandong University, Jinan, 250100, China

2 Department of Epidemiology, School of Public Health, Cheeloo College of Medicine, Shandong University, Jinan, 250012, China

3 Department of Psychiatry, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON M5S 1A1, Canada

4 Daphne Cockwell School of Nursing, Toronto Metropolitan University, Toronto, ON M5B 2K3, Canada

* Corresponding Author: Jianguo Gao. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Mental Health Promotion in Higher Education: Interventions and Strategies for the Psychological Well-being of Teachers and Students)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(10), 1497-1514. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.069458

Received 24 June 2025; Accepted 22 September 2025; Issue published 31 October 2025

Abstract

Background: Limited mental health literacy (MHL) among university service providers is a significant obstacle to effective psychological support. Developing and systematically assessing evidence-based interventions is an urgent priority, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). This study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of the Acceptance & Commitment to Empowerment: Linking Youths AND ‘Xin’ (Hearts) (ACE-LYNX) intervention in reducing stigma, improving psychological well-being, and enhancing the MHL and empowerment practices of university mental health providers in China. Methods: A total of 124 trained providers participated in this longitudinal study. Quantitative data were collected at baseline, immediately post-intervention, and three-month follow-up using the validated scale (CAMI, DASS-21) and weekly activity logs recording empowerment practices. Generalized estimating equations (GEEs) and qualitative content analysis were used for data analysis. Results: Quantitative analysis showed a significant reduction in stigma immediately postintervention, particularly in the Social Restriction subscale (β = 1.35, p < 0.001), though this effect diminished by the 3-month follow-up (β = 1.80, p = 0.001). Notably, a lasting reduction in the providers’ stress levels was maintained. Activity logs showed the highest level of engagement at the individual level (51.4%), followed by group level (32.0%), organizational level (10.5%), and community level (6.1%). Qualitative analysis revealed three themes: Skill-based empowerment enhances professional efficacy, embedded interventions expand service boundaries, and organizational empowerment fosters sustainability. Conclusions: This dual-focus ACE-LYNX intervention effectively improved MHL and both attitudinal and functional competencies among providers. It provides a scalable framework for fostering sustainable and inclusive campus mental health ecosystems, with significant implication for enhance psychological services in resource-constrained educational settings.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileDespite competing academic demands and priorities within higher education, addressing the mental health (MH) of university students remains a vital mission, especially in light of the escalating psychological challenges reported worldwide in the post-COVID-19 era [1]. Higher education institutions are increasingly investing in campus-based MH services, with on-campus providers serving as pivotal first-line responders in identifying psychological distress, providing counseling, and facilitating referrals [2,3]. However, systemic challenges, such as workforce shortages and inconsistent service quality, continue to hinder access to care, paradoxically discouraging students from seeking support. Empirical evidence suggests that long wait times, perception of provider incompetence, and confidentiality concerns contribute to students’ reluctance to utilize campus services, even in the presence of significant MH needs [4,5]. These barriers underscore the urgent need for innovative strategies to enhance the accessibility and effectiveness of university MH ecosystems.

Scholars have increasingly advocated for expanding the MH workforce through task-shifting strategies endorsed by the World Health Organization to address workforce shortages [6]. This approach involves engaging non-specialist campus personnel, such as academic advisors, faculty members, resident assistants, and peer supporters, to provide frontline MH support within their existing roles [7]. In China, this model aligns with the nationwide rollout of a four-tier MH service network, which incorporates ideological-political counselors and student MH liaisons into early identification and psychoeducation efforts [8]. However, these non-professional providers often contend with stigma, limited mental health literacy (MHL), and inadequate intervention skills, which can compromise service quality and perpetuate negative help-seeking experiences [9]. Consequently, structured training programs and ongoing supervision are essential to equip these personnel with evidence-based competencies, ensuring ethical and effective service delivery [10,11]. The effectiveness of MH service providers fundamentally depends on their MHL level. As expanded by Jorm et al. [12], MHL encompasses essential competencies in reducing stigma and promoting proactive MH behaviors [13,14]. Destigmatization training increases providers’ willingness to engage in MH dialogs [15,16], while interdisciplinary mental health promotion (MHP) activities can foster cross-sector collaboration and help connect students to appropriate resources [17].

Prevailing training models for providers primarily focus on mental health stigma reduction such as Virtual Implicit Bias Reduction and Neutralization Training (VIBRANT) for school-based MH clinicians, and other contact-based interventions [18,19]. They lack an integration of psychological empowerment and the necessary capacity building for systemic advocacy. This oversight risks perpetuating implementation gaps, leaving providers without the self-efficacy to translate theoretical knowledge into effective practice. Global initiatives to improve non-specialists’ MHL have produced diverse models, such as the Mental Health First Aid program in Australia [20], the Staff Training on Anxiety and Resilience in Students (STARS) initiative in the United Kingdom [21], and peer support networks in Canadian universities [22]. Despite these advances, notable research gaps remain. First, limited empirical attention has been devoted to interventions for university-based providers in China, where MHL research has largely centered on cross-sectional surveys rather than implementation science. Second, most programs fail to systematically integrate the dual pathways of stigma reduction and capacity building, potentially disconnecting attitudinal changes from sustainable behavioral outcomes, even though anti-stigma intervention research has emphasized the importance of measuring behavioral outcomes [23,24]. Third, insufficient cultural adaptation of interventions, particularly those in addressing collectivist norms and academic pressures prevalent in Chinese educational contexts, may limit their local relevance and effectiveness. Furthermore, the widespread neglect of providers’ own MH needs, including chronic workplace stress and burnout, threatens to undermine the effectiveness of interventions by reducing provider engagement [25,26].

An interdisciplinary team of Chinese and Canadian researchers developed the Linking Hearts Project to address these gaps [27]. The Acceptance and Commitment to Empowerment—Linking Youth and ‘Xin’ (Hearts) (ACE-LYNX), the intervention evaluated by the Linking Hearts implementation science research project, is an innovative initiative to strengthen MH care systems in Chinese universities. This novel program integrates psychological flexibility strategies and empowerment education. The team conducted a contextual assessment to guide the cultural adaptation of ACE-LYNX before implementation. Cultural adaptations involved localizing materials through certified translation and practitioner validation, co-designing an MH101 curriculum with local experts using Chinese case vignettes and data, and adapting terminology and content for cultural relevance. The project’s objectives were to reduce stigma, enhance MHL among students and university MH professionals, foster interdisciplinary collaboration, and advance culturally responsive training frameworks, ultimately supporting the development of sustainable campus MH ecosystems.

In this study, we aimed to longitudinal evaluate the effectiveness of ACE-LYNX intervention on university mental health providers. Specifically, our primary objectives were to: (1) assess the impact of the intervention on participants’ stigmatizing attitudes toward mental illness; (2) examine changes in their psychological well-being; and (3) document their engagement in empowerment-based MHP practices following the training.

The ACE-LYNX intervention combines two evidence-based approaches: Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) and Group Empowerment Psychoeducation (GEP). Originally developed in Canadian community settings to reduce stigma and enhance empowerment among marginalized populations [28], the intervention was culturally adapted and scaled through the Linking Hearts project for implementation in Chinese universities. A detailed protocol for the project implementation has been published [27]. The ACE-LYNX intervention comprises two core components: (1) Mental Health 101 Online Education: A locally tailored e-learning curriculum delivered through four video modules totaling 10 h and recorded by certified Chinese MH professionals, which covers the fundamentals of MHL. (2) A five-day intensive group training: Structured experiential learning sessions integrating the theoretical foundations of ACT and empowerment frameworks, 13 experiential activities (e.g., paired singing, stigma rules and stories, exclusion circles) (Supplementary Table S1) [29], role-playing simulations, guided group debriefings, and individualized action planning. Trainees were provided with an ACE-LYNX implementation toolkit, which included intervention manuals, activity protocols, and fidelity checklists to support standardized delivery.

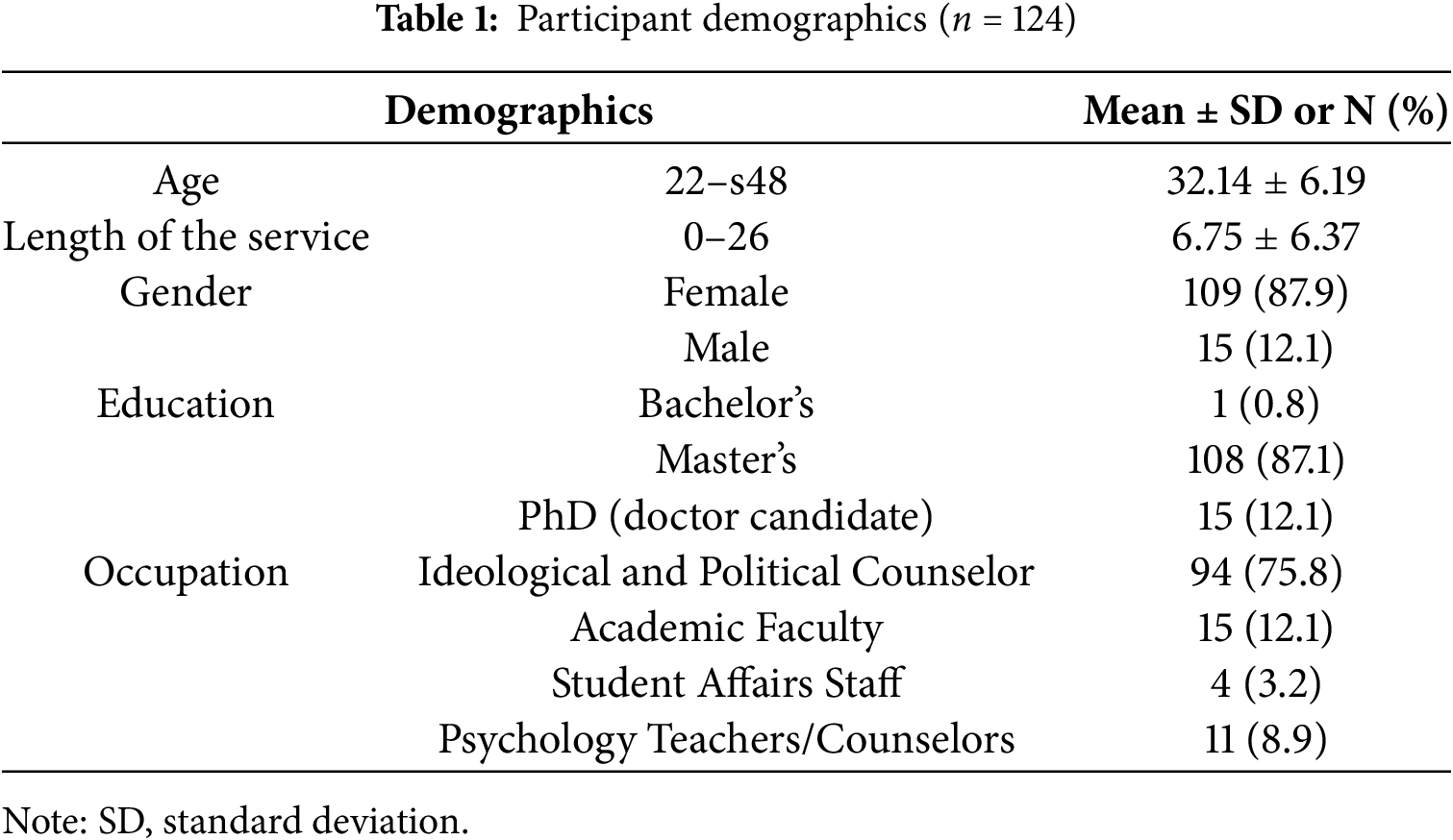

Participants were recruited from six universities in Jinan, China. Four universities implemented the intervention between December 2020 and January 2021. The remaining two universities implemented the intervention in April and June 2021. A total of 124 MH service providers completed the ACE-LYNX intervention training, preparing to serve as MH champions through peer-led workshops and overseeing student volunteer initiatives. Recruitment was conducted through institutional announcements and peer referrals, yielding 20–27 providers per university. As shown in Table 1, the sample included 109 females (87.9%) and 15 males, ranging in age from 22 to 48 years (Mean = 32, SD = 6.19). Of these participants, 11 (8.9%) were professional counselors at the Student Psychological Service Center, and 113 (91.1%) were non-specialist providers, including ideological and political counselors, faculty members, and student affairs staff. Nearly all participants (n = 123, 99.2%) held at least one master’s degree with an average of 6.8 years of service in their current positions (SD = 6.37, range: 0–26) (see Table 1).

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the ethics committee of Shandong University (Approval No. 20180123), University of Jinan, Shandong Jianzhu University, Shandong Normal University, Shandong Women’s University, and Shandong Youth University of Political Science. Written consent was obtained from each participant prior to the study.

The Community Attitudes Toward Mental Illness (CAMI) scale and the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale 21 (DASS-21) were used to assess stigmatizing attitudes and psychological distress, respectively. Quantitative data were collected at three time points: pre-intervention (T0), immediately post-intervention (T1), and 3 months post-intervention (T2). T1 data collection occurred on the final day of the 5-day training or the day after its conclusion. In addition, the participants completed weekly activity logs for 3 months following the intervention. These logs documented how participants applied ACE strategies to promote MH at the personal, interpersonal, organizational, and community levels. We collected data electronically using Wenjuanxing, a Chinese online survey platform.

The CAMI scale was originally developed by Taylor and Dear [30] to assess the public perceptions of individuals with mental disorders. This study was translated into simplified Chinese by a panel of bilingual experts. This 40-item instrument uses a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree) across four subscales: authoritarianism (beliefs supporting coercive control of individuals with mental illness), benevolence (humanitarian attitudes emphasizing societal responsibility for care), social restrictiveness (perceiving mental illness as a social threat warranting distancing), and community MH ideology (favoring community-based treatment over institutionalization). Each subscale includes five positively and five negatively worded items, with reverse-scored items aggregated to produce subscale scores ranging from 10 to 50. Higher scores for authoritarianism and social restrictiveness, along with lower scores in benevolence and community MH ideology, indicate greater stigma. The scale is widely used to assess MH attitudes among the general population and medical professionals and has been translated and applied across diverse cultural contexts [31]. The scale has shown strong reliability and validity in previous studies [32]. In our sample, the CAMI demonstrated a baseline Cronbach’s α of 0.653.

The DASS-21 was developed to align with the tripartite model, distinguishing the unique features of depression, anxiety, and stress [33]. The scale demonstrates good internal consistency and sensitivity to changes after treatment [34]. The DASS-21 is widely used to assess MH symptomatology in both healthy and vulnerable populations [35]. The 21-item Chinese version measures three domains—seven items per subscale—using a 4-point severity scale (0 = did not apply to me, to 3 = applied to me very much). Subscale scores are obtained by summing the item responses and multiplying them by two, with higher scores indicating greater symptom severity. In our sample, the baseline Cronbach’s α for the DASS-21 was 0.882.

Weekly activity logs were used to monitor the engagement of service providers in MHP during the three months following the intervention. The participants were instructed to submit one log each week, resulting in a total of 12–13 logs per person. Participants recorded their application of ACE strategies across individual, familial, and campus/community domains. To guide their entries, participants were given examples for each domain—for instance, at the campus/community level: “I organized a webinar on when to seek counseling for stress.” Following the training, the research team members shared the weekly log link in the participants’ WeChat group, accompanied by written instructions for completion and reminders about the types and scope of activities to record. This process helped ensure that the participants understood the task and recorded their activities consistently. While participants recorded activities demonstrating how they applied ACE learning in their personal and professional lives, this paper focuses on the multi-level ACE applications implemented on campus and in the community. The log contents were categorized thematically to quantify the implementation frequency and intervention reach.

Data analysis was guided by the conceptual framework of empowerment of the ACE model. The ACE-LYNX intervention conceptualizes empowerment as a social action process that fosters the participation of individuals, organizations, and communities [29]. Moreover, the literature consistently frames empowerment as a dynamic continuum, encompassing individual empowerment, mutual aid group formation, partnerships, community organizing, and broader social change [36–38]. Therefore, measuring empowerment as a process entails “monitoring the interactions between individual and organizational-level capacities, skills, and resources, as well as changes in community-level health conditions, policies, and interpersonal relationship structures within the planned timeframe.” [39]. Accordingly, this study evaluated the impact of the intervention on the empowerment practices of university MH service providers across this defined continuum. Individual empowerment often entails psychological empowerment, measured through changes in psychological distress and stigmatizing attitudes, while organizational- and community-level empowerment—such as capacity development, resource mobilization, service engagement, and community advocacy—was identified through the MHP activities documented in the activity logs.

The quantitative data from the CAMI and DASS-21 across the three time points were analyzed using SPSS 24.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Owing to the non-normal distribution of scale scores and participant attrition, generalized estimating equations (GEEs) were used to assess the effects of the intervention on stigmatizing attitudes and psychological distress over time. An exchangeable working correlation matrix was specified to account for within-subject correlations, and a linear link function was applied. The GEE approach yields population-averaged estimates and robust standard errors, ensuring consistency even in the presence of potential misspecification. The model equation was specified as follows:

where Yit is the outcome for individual i at time t. The covariance structure was specified as exchangeable, assuming approximately equal correlations between repeated measurements within individuals. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05 (two-tailed). To address missing data due to attrition, we compared the baseline characteristics (age, sex, and baseline outcome scores) of participants who completed both the T1 and T2 assessments with those who did not complete the T2 assessments. Independent samples t-tests and chi-square tests were used as appropriate. In the absence of statistically significant differences, analyses were conducted without imputation using the available data.

A total of 1558 weekly logs were submitted, with individual submissions ranging from 4 to 16 (mean = 12.7). Each log entry was given equal weight in the analysis, regardless of how many logs an individual participant submitted. No weighting was applied to adjust for variations in the number of logs submitted per participant. A qualitative analysis of weekly activity logs was conducted in NVivo 12 (Lumivero, Denver, CO, USA), using an approach that combined conventional and directed content analysis methods [40]. Conventional content analysis was used to categorize activity types and frequencies through inductive coding, whereas directed content analysis applied an a priori framework based on empowerment theory to assess efficacy narratives within practice reflections of providers [41]. Three coders independently reviewed each activity log entry to identify potential codes, then met to discuss their findings and develop an initial codebook capturing the identified activity types and descriptions of effectiveness. Three coders independently applied the established codebook to a random subsample comprising 20% of the activity logs for quality assurance. Intercoder agreement was calculated at 82.6%, with discrepancies resolved through group discussion until a consensus was reached. A single coder applied the finalized codebook to the remaining data, with regular team meetings held to resolve any ambiguities and maintain consistency. This consensus-based process minimizes researcher bias while capturing the complexity of data.

3.1 Effects on Stigmatizing Attitudes and Psychological Well-Being

Of the 124 participants at baseline, 122 completed the T1 assessment and 120 completed the T2 assessment. To assess the impact of attrition, the baseline characteristics of completers (n = 120) were compared with those of non-completers (n = 4). No significant differences were found in age, sex distribution, or baseline scores on key measures (all p > 0.05), supporting the assumption that data were missing completely at random (MCAR) (Supplementary Table S2).

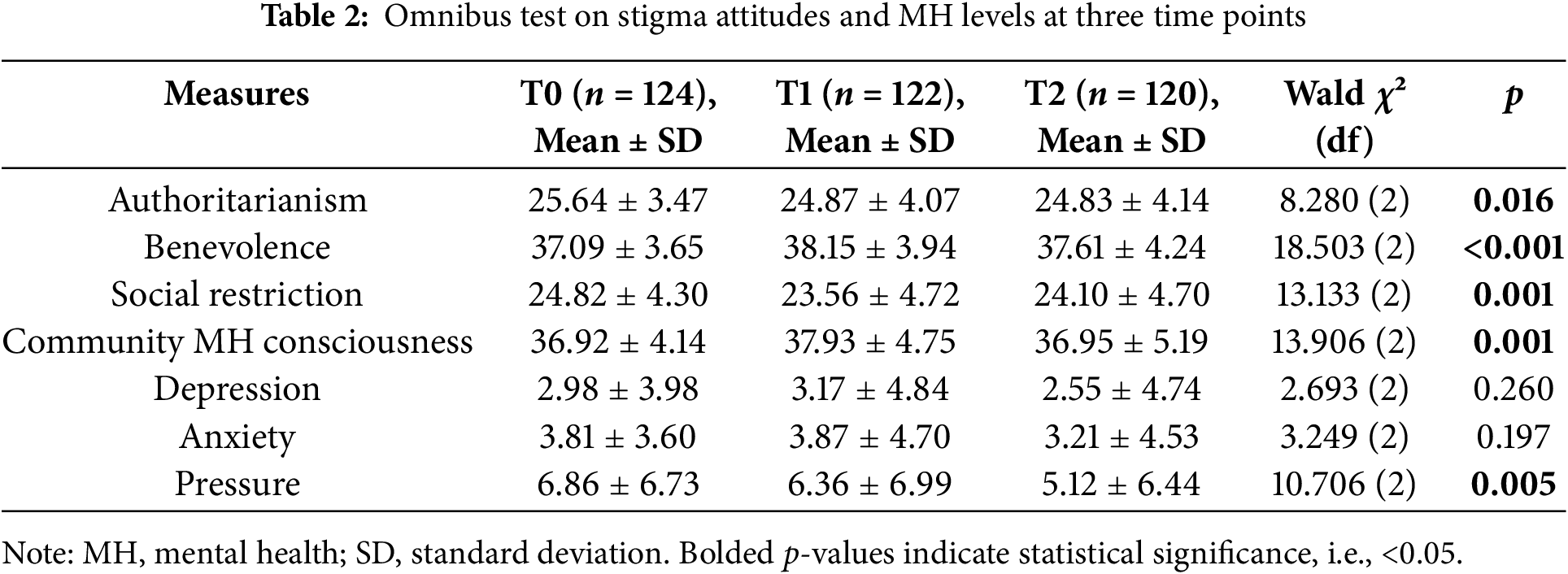

As shown in Table 2, university MH service providers demonstrated significant post-intervention improvements across all four dimensions of CAMI (p < 0.05). Specifically, scores on the prosocial subscales—Benevolence and Community Mental Health Ideology—increased, while those on the stigmatizing subscales—Authoritarianism and Social Restrictiveness—decreased, collectively indicating a reduction in MH stigma. Regarding psychological well-being, only stress levels showed a significant post-intervention decrease (Wald χ² = 10.706, df = 2, p = 0.005), whereas changes in depression and anxiety scores were not statistically significant. At baseline, the mean depression score was 2.98 (SD = 3.98), falling below the clinical cut-off of 9 [42]. Similarly, the mean anxiety score (Mean = 3.81) was below the corresponding clinical thresholds (cut-off = 7).

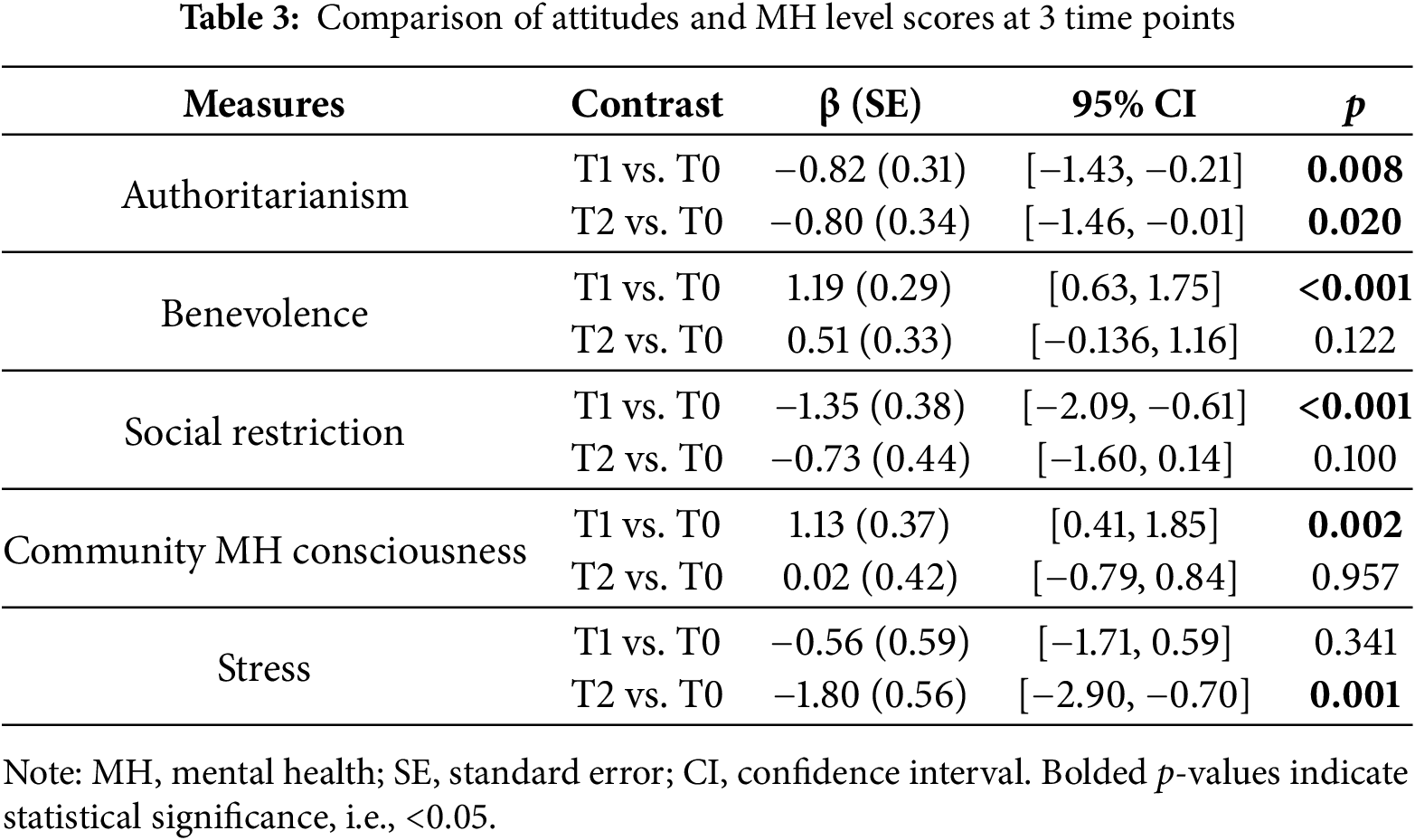

Parameter estimates (Table 3) indicated sustained reductions in authoritarianism at both post-intervention (β = −0.82, p = 0.008) and 3-month follow-up (β = −0.80, p = 0.020). In contrast, improvements in Benevolence, Social Restrictiveness, and Community MH Ideology were not sustained, returning to baseline levels by the 3-month follow-up. Participants’ stress levels showed a delayed improvement, reaching statistical significance only at the 3-month follow-up (β = −1.80, p = 0.001). These findings indicate that the intervention produced modest but meaningful shifts in attitudes and functional outcomes among providers.

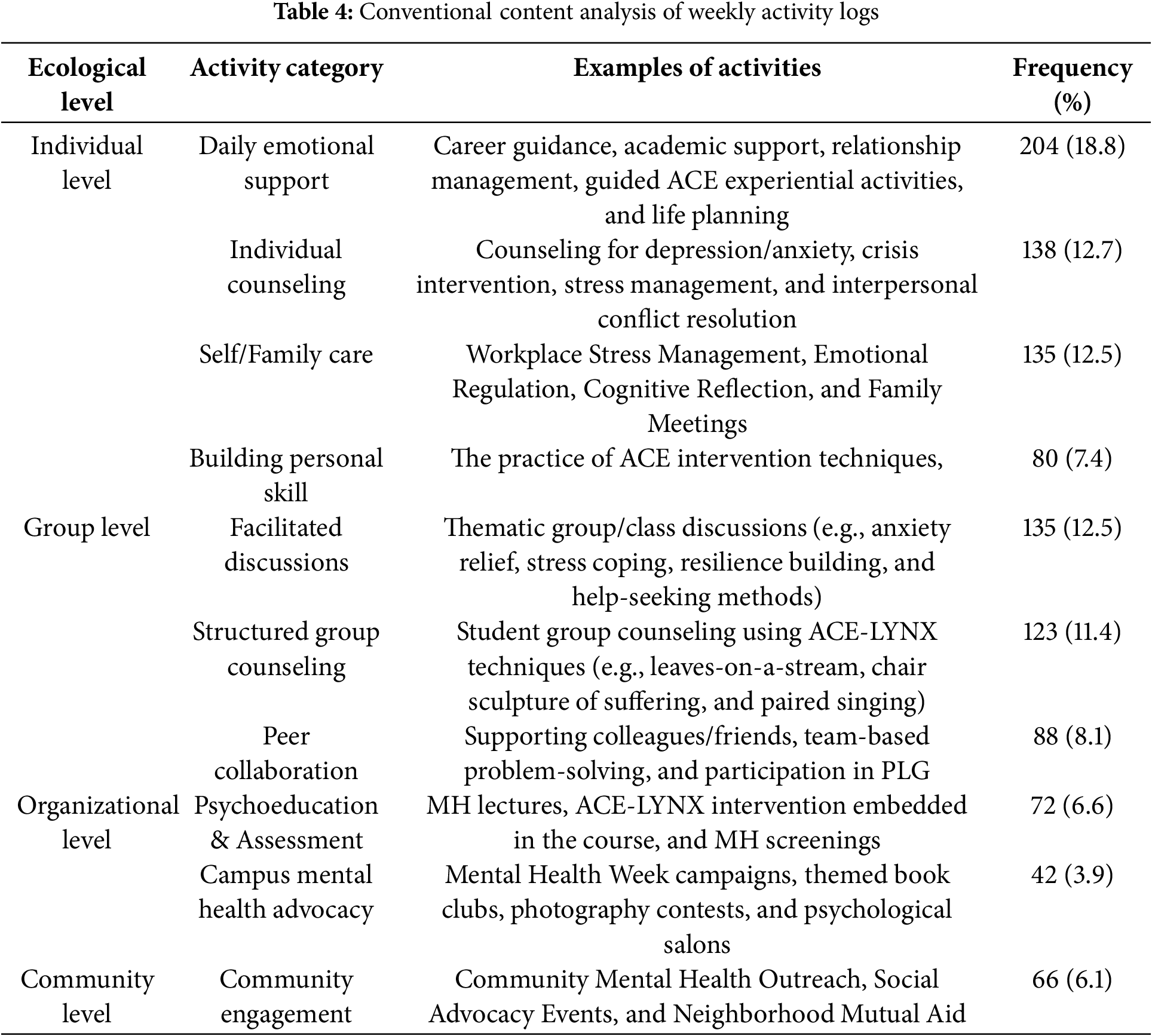

A systematic review of weekly activity logs resulted in the exclusion of 475 entries lacking substantive content (e.g., incomplete descriptions or explicit “no activity” reports), resulting in 1083 valid entries for analysis. These activities were classified into 10 categories according to their implementation context (e.g., school services, peer networks), format, objectives, and formality level. Guided by the empowerment framework, participant-reported activities were classified into four ecological levels—individual, group, organizational, and community—based on their context and intended target. For example, self-care activities were classified at the individual level; peer support and group counseling at the group level; campus-wide psychoeducation sessions at the organizational level; and advocacy or outreach initiatives at the community level (Table 4).

The analysis showed that individual-level activities were the most common, accounting for 557 entries (51.4%). Student-focused case services were the most frequent activity type (n = 342, 31.6%), comprising both informal daily emotional support (n = 204, 18.8%; e.g., “assisting students in managing anxiety about being unable to return home” or “helping students adapt to campus life post-pandemic”) and formal individual counseling (n = 138, 12.7%; e.g., “providing structured counseling sessions on stress management” or “applying psychotherapeutic techniques to address interpersonal conflicts”). The remaining individual-level empowerment activities included self- and family care (n = 135, 12.5%) and personal skill-building (n = 80, 7.4%). Group-level activities ranked second in frequency (n = 346, 32.0%) and encompassed: (1) structured group counseling using ACE techniques (e.g., experiential workshops for students and peer MH liaisons), (2) thematic focus group discussions on MH needs (e.g., peer-led dialogues on help-seeking behaviors and resilience strategies), and (3) peer collaboration, such as providing support to colleagues, participating in problem-solving groups and engaging in peer learning groups. At the organizational level, the participants undertook psychoeducational initiatives and advocacy efforts (n = 114, 10.5%), incorporating ACE principles into MH curricula and coordinating multimodal campaigns, such as MH awareness week events, book clubs, and art exhibitions. Notably, community-level initiatives were limited (n = 66, 6.1%) and primarily consisted of ACE-based experiential workshops aimed at fostering MHL among neighborhood residents.

3.3 Characteristics of Empowerment Practices and Service Efficacy

Directed content analysis of weekly activity logs identified the following three overarching themes in providers’ empowerment practices:

3.3.1 Skill-Based Empowerment Drives Service Efficacy

Providers consistently applied ACE-LYNX’s practical techniques, such as mindfulness exercises, cognitive defusion, and value clarification, to enhance the psychological support they offered to students, peers, and family members. This proactive use of skills reflects a heightened service agency, aligning with the emphasis of empowerment theory on strengthening individuals’ capacity to create meaningful change within their environments. For instance, counselor No. 1123 noted, “By incorporating defusion and mindfulness strategies, I supported a student in distinguishing between external stressors and their core values. Encouraging him to pursue his goal of obtaining a driver’s license with self-compassion ultimately contributed to his successful exam completion.” In another example, counselor No. 1118 documented for 10 consecutive weeks that she systematically incorporated ACE-LYNX techniques into her counseling practice. Such accounts underscore how skill acquisition not only enhances service delivery but also fosters a sense of agency and self-efficacy among service providers.

Similarly, the frequent integration of ACE-LYNX methods in psychological counseling, psychoeducation, group therapy, and academic or career guidance to support emotional regulation and stress reduction—confirmed by keyword frequency analysis—illustrates empowerment’s practical enactment. Providers also reported sustained engagement in peer supervision and scenario-based drills to continuously refine their competencies as they engaged in ongoing peer supervision and scenario-based drills to refine and strengthen their competencies. One provider (No. 4102) noted, “Through the ‘Leaves-on-a-stream’ activity, I guided students to visualize their anxieties floating away with the drifting leaves. After several sessions, the participants reported significant improvements in sleep quality.”

Another provider (No. 4121) also described, “A student sought counseling regarding recent distress. I facilitated the ‘Chair Sculpture of Suffering’ to encourage him to share his story and face pressure. Through the conversations, I helped him resolve his confusion and worked out a plan for his future efforts.” These cases demonstrate the tangible impact of such interventions on the well-being of students. Providers actively embody the principles of empowerment at both personal and interpersonal levels by adopting new techniques and honing them through ongoing practice and feedback.

3.3.2 Embedded Interventions Expand Service Boundaries

Service providers have strategically integrated ACE-LYNX interventions into students’ daily lives, extending beyond traditional counseling settings to achieve a “last-mile delivery” of MH support. This approach not only empowers students but also broadens the reach of MH services, enabling providers to offer support in natural student environments, such as classrooms, dormitories, and online communication platforms. In weekly activity logs, counselors consistently reported interacting with students during class meetings. These actions put core elements of empowerment theory into practice—specifically, enhancing accessibility and fostering autonomy within individuals’ daily environments. For instance, counselors noted that informal counseling methods such as ‘heart-to-heart’ conversations helped create safe and supportive spaces where students could share concerns and receive timely guidance. Provider No. 1120 noted, “After the students returned to school (after the pandemic), I went to the dormitory to talk to them. I used mindfulness to encourage them to focus on this moment, discover their values, and act on them.” Such practices not only strengthen the psychological skills of students but also actively nurture their sense of agency, a fundamental pillar of empowerment.

Furthermore, integrating support into shared daily routines fostered peer-to-peer mutual aid and strengthened collective resilience. For instance, provider No. 1123 recounted, “I organized a collaborative initiative for on-campus students during the pandemic-affected winter break, facilitating mutual adaptation to the extended stay. Through dedicated WeChat groups, we shared evidence-based strategies to alleviate common pre-graduation anxieties and implemented daily attendance to ensure adherence to healthy schedules.” This illustrates the ecological breadth of empowerment-focused interventions, where accessible support networks were intentionally cultivated within the everyday environments of student communities. Group-based seminars on psychosocial topics further promoted empowerment by fostering students’ understanding of both their own experiences and those of others. For instance, one provider (No. 2103) reported, “I conducted a seminar on interpersonal anxiety and stress in dormitories, guiding members of the same dormitory to better understand each other’s thinking patterns and living habits, because more understanding leads to more acceptance and mutual tolerance.” Through these activities, students became not only recipients of support but also active contributors in co-creating a supportive social environment.

Providers reported applying ACE-LYNX principles with flexibility to meet a diverse range of student needs. For instance, providers utilized the ‘Bulls Eye’ exercise to strengthen students’ commitment to academic and career goals, applied the Defusion technique to alleviate test anxiety, and incorporated empathy-building practices to help mediate conflict and improve interpersonal relationships among students. These contextual empowerment practices not only facilitated prompt responses to students’ psychological needs but also expanded service accessibility, reaching previously underserved areas of student life. These embedded practices exemplify empowerment at both the individual and community levels, amplifying both the reach and real-world impact of MHS.

3.3.3 Organizational Empowerment Promotes Sustainability

Service providers enhanced MH support continuity by mobilizing resources and engaging in collaborative decision-making, thereby broadening their professional networks. Activity logs indicated the consistent use of ACE-LYNX tools (e.g., technical protocols, guideline manuals) alongside capacity-building collaborations with student MH liaisons and class representatives. These efforts reinforced a three-tiered support system—professionals, paraprofessionals, and student peers—to enhance early identification and referral pathways. For example, provider No. 2102 shared, “To lead the students of the College’s Mental Services Club in activities such as leaves on the stream, mindfulness, and exclusion circles and to have them pass the activities on as they continue down the line, aiming to reach the entire student body.” This initiative illustrates organizational empowerment by fostering shared responsibility and promoting the dissemination of knowledge—both critical for ensuring long-term sustainability.

Sustained adoption was evident in the incorporation of ACE-LYNX techniques into MH curricula, as intervention elements were adapted into course structures. Additionally, frequent group discussions (n = 135, Table 4) addressed topics such as anxiety reduction, stress management, help-seeking strategies, and self-care, thereby fostering collective critical reflection and collaborative decision-making. As provider No. 5115 stated, “I organized a seminar on competency enhancement for psychological support members (peer leaders) to help improve their ability to identify psychological problems and better help their fellow students.” Symposiums focusing on MH and personal development have also emerged as additional venues for delivering ACE-LYNX interventions. These gatherings empower students to share their stories, normalizing conversations about MH. Such practices foster sustained engagement by integrating MH awareness into the rhythms of daily academic life.

In addition, participants reported engaging in activities that promoted MH within their broader communities. For example, provider No. 3113 documented delivering services through the ACE-LYNX intervention and reflected on its suitability for community settings. Counselor No. 5123 described the sharing of ACE-LYNX knowledge and activities with neighbors. Specific activities included discussing “ideas related to mental health work with community workers and disseminating mental health knowledge” (No. 5109), and sharing “the purpose and process of the Le’Go exercise with neighborhood friends. They showed real interest (in the Le’Go exercise). Hearing their reactions made me realize that everyone carries things they’d rather forget. I hope that the Le’Go exercise can help them let go of the past.” (No. 4102) This illustrates how organizational empowerment strategies can extend their transformative potential beyond institutional boundaries, enriching broader social contexts.

Although engagement at the community level was limited, the findings highlight emerging efforts to extend empowerment into broader social contexts. In sum, these organizational efforts embody a central tenet of empowerment theory—enhancing sustainability through structured, collaborative networks that move beyond individual engagement to generate broader societal impact.

This study underscores the transformative potential of the “destigmatization-empowerment” two-pronged intervention, implemented via ACE-LYNX protocols, in strengthening MHL among service providers. This approach reduces stigmatizing attitudes toward mental disorders by embedding structured, empowerment-oriented practices within education-based MH services. The integration of quantitative and qualitative findings revealed a synergistic relationship between stigma reduction, stress relief, and empowerment practices. The quantitative results demonstrated a significant reduction in the stigmatizing attitudes and perceived stress of the participants, while the qualitative analysis illuminated the mechanism underlying these changes: many service providers reported that the sense of efficacy gained through empowerment training helped alleviate stress and that cultivating a nonjudgmental attitude motivated them to engage more actively in student-centered initiatives. These findings suggest a positive feedback loop in which individual well-being improvements reinforce collective engagement, which in turn fosters further personal growth and resilience. These findings are highly significant given the central role of service providers in school-based MHP. Although existing literature shows growing evidence for stigma reduction in low- and middle-income countries, substantial gaps in both implementation and sustainability remain [43,44]. Our study directly addresses this critical research gap by implementing and evaluating an integrated intervention in Chinese universities aimed at enhancing MH practitioners’ efficacy while reducing stigma. The findings can inform policy decisions on workforce development strategies and demonstrate how empowerment-focused models can be leveraged to strengthen and optimize existing MH infrastructures. ACE-LYNX offers a transferable framework for LMICs to implement task-shifting principles within education systems, thereby promoting equitable access to MH support in resource-limited settings. Furthermore, this study examines the effects of interventions on stigmatizing attitudes and helping efficacy within the framework of the expanded concept of MHL, a research approach advocated by Chinese academics [45]. Thus, its findings are more likely to be generalizable to other Chinese universities and communities.

The marked post-intervention decline in stigmatizing attitudes of providers affirms the effectiveness of ACE-LYNX as a stigma reduction tool, aligning with global evidence that targeted education can shift attitudes [46]. However, the decline in effects across three attitude dimensions—benevolence, community MH ideology, and social restrictiveness—at follow-up reflects the “rebound phenomenon” reported in school-based MH interventions [23,47], in which initial improvements wane over time without ongoing reinforcement [48]. The high baseline scores for benevolence and community MH ideology may have produced a ceiling effect, thereby constraining the potential for observable improvement after intervention. Conversely, the V-shaped trajectory of social restrictiveness scores likely reflects deeply rooted structural stigma embedded in sociocultural norms—a systemic challenge that demands multi-level interventions extending beyond individual-level training [49,50]. The sustained reduction in authoritarianism underscores the intervention’s capacity to produce lasting changes in exclusionary attitudes at the personal level. This finding aligns with evidence from studies on healthcare providers demonstrating that targeted training can produce persistent shifts in attitudes post-intervention [51,52]. This attitudinal shift appears to stem from both ACT and GEP components, as focus group participants linked changes in their mental illness perspectives to ACT mechanisms (e.g., acceptance, values clarification) and enhanced empathy to GEP elements (e.g., recognition of interdependence) [53]. Collectively, these findings indicate that brief educational interventions can produce consistent but modest improvements in attitudes, and that sustained progress likely requires periodic booster sessions and supportive environmental conditions.

The intervention produced a marked reduction in stress among providers—a particularly noteworthy outcome given the heightened work demands during the intensive campus pandemic containment period (December 2020–June 2021, when the ACE-LYNX program was implemented). The absence of substantial improvements in depressive or anxiety symptoms likely reflects contextual constraints: this intervention period coincided with China’s dynamic zero-COVID-19 policy enforcement, during which university counselors—as frontline practitioners—were tasked with managing closed-campus systems and strict health surveillance while being persistently exposed to pandemic-related distress. Such operational burdens are well-documented risk factors for anxiety and depression [54], making the observed stress reduction particularly meaningful. This outcome can be partly attributed to the role of ACT, as previous research in China has demonstrated the effectiveness of ACT in reducing stress and enhancing psychological resilience across diverse populations [55,56]. This positive effect enhances the psychological competence and capital of service providers [57], as better immediate MH may internally equip them to manage complex, demanding work and service responsibilities as well as to navigate future challenges more effectively [58]. This directly addresses the dilemmas faced by counselors in Chinese universities arising from multiple role conflicts [9].

This study evaluated the impact of the intervention on empowerment practices by tracing the MHP activities of participants over 3 months, aligning with the broader view that empowerment entails enabling communities and practitioners to actively engage in health promotion [59]. Results of the quantitative content analysis indicated that following the intervention, service providers were willing to engage in MHP activities, with empowerment practices spanning multiple dimensions: individual, group, organizational, and community. This underscores the efficacy of group empowerment psychoeducation within the ACE intervention model, aligning with the findings of Li et al. [60]. Our qualitative content analysis of service efficacy identified a ‘skill-scenario-organization’ pathway for the development of empowering practice, illustrating the continuum of empowerment and aligning with our previous research on program empowerment effectiveness [53]. Skill empowerment refers to interventions that equip providers with accessible and adaptable techniques, thereby developing their agency by addressing multiple skill-level capability dimensions [61]. Such empowerment is essential for enhancing the effectiveness of practitioners in delivering MH support [62]. Scenario empowerment refers to interventions that embed empowerment principles in the roles of service providers, a practice recognized as highly effective for stigma reduction [46]. The expansion of service boundaries underscores the strong acceptance of the intervention by providers, signaling a positive uptake that paves the way for its integration across multiple domains within the school context. Consistent with Kruahong et al. [63], this finding underscores the active involvement of empowerment-oriented practitioners in implementing health promotion strategies. Finally, organizational empowerment encompasses the development of partnerships and service networks—strategies widely recognized for facilitating collective empowerment actions [64] and enhancing the intervention’s sustainability, replication, and scalability. The results further affirm the value and objectives of this project as an implementation study—part of a broader effort to scale up new interventions in real-world settings—and underscore the importance of closely examining the implementation process [65]. Our preliminary analysis suggests that the ACT component plays a substantial role in stress reduction, whereas the GEP component primarily enhances engagement in MHP activities. Future research will employ mediation analyses to further clarify and quantify these relationships.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the representativeness of the sample may be limited, as participation was voluntary and likely attracted individuals with a preexisting interest or motivation in school-based MH, potentially restricting the generalizability of findings to the broader provider population. Second, the absence of a control or comparison group—due to the study’s design as an implementation study of an evidence-based intervention—limits the ability to attribute observed changes solely to the ACE-LYNX program. However, because the study was conducted during the unanticipated COVID-19 pandemic, the absence of a control or comparison group further constrains causal inferences regarding the effects of the ACE-LYNX intervention. Without a waitlist or alternative training group, it is difficult to determine whether the observed changes were a direct result of the intervention or instead reflected other influences, such as maturation effects, regression to the mean, or natural recovery processes following the pandemic. The primary aim of study was to capture how the intervention functions in “real-world” conditions, consistent with the goals of implementation science. Nonetheless, we acknowledge that future research should, where feasible, incorporate a control or comparison arm to strengthen causal inference and more rigorously evaluate the intervention’s effects.

Third, the reliance on predominantly self-reported data may introduce social desirability bias. Additionally, the 30% attrition rate in weekly activity log submissions may affect the replicability and robustness of our findings. Future research would benefit from more rigorous data monitoring procedures and enhanced guidance or support for participants to improve log completion rates. Fourth, pandemic-related confounders during the intervention period (December 2020–June 2021) complicate attribution of outcomes, as concurrent stressors, policy changes, and shifts in campus life may have independently influenced both provider well-being and empowerment practices. Distinguishing the specific impacts of COVID-19 from those of the intervention on provider efficiency remains methodologically complex. Nonetheless, the mixed-methods approach allowed for methodological triangulation, producing convergent findings that, while not eliminating these limitations, offered valuable contextual insights.

The integrated ACE intervention demonstrably enhanced the MHL of school-based psychological service providers, yielding positive outcomes in stigma reduction, MH improvement, and the adoption of empowerment practices. The capacity-building initiatives within the intervention evolved into empowerment tools equipping practitioners with the skills necessary to facilitate constructive dialogue for MH behavior change. Anti-stigma initiatives should equip practitioners with a toolkit of interventions, as well as considering the use of regular reinforcement workshops or customized digital review courses to sustain attitudinal and behavioral change and prevent the erosion of outcomes over time. Future research should focus on both the fidelity of implementing the intervention’s core components in local settings and the process of cultural adaptation to increase validity of the intervention. In particular, employing observational fidelity checklists alongside structured interviews or focus groups with program implementers and participants can systematically capture both quantitative measures and qualitative insights into program delivery and contextual adaptation.

Acknowledgement: The authors gratefully acknowledge all the university mental health service providers who participated in the training and generously shared their experiences, making this study possible.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC, grant 81761128033) and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR, FRN 154986) through the Collaborative Health Program of the Global Alliance for Chronic Disease (GACD).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm the contributions to the paper as follows: Conceptualization—Kenneth Po-Lun Fung, Josephine Pui-Hing Wong, Jianguo Gao and Fenghua Wang; methodology—Kenneth Po-Lun Fung, Josephine Pui-Hing Wong, Jianguo Gao and Fenghua Wang; software—Jianguo Gao and Fenghua Wang; validation—Cun-Xian Jia, Sheng-Li Cheng and Zhi-Ying Yao; formal analysis—Fenghua Wang, Jianguo Gao and Zhi-Ying Yao; investigation—Zhi-Ying Yao; resources—Kenneth Po-Lun Fung, Josephine Pui-Hing Wong, Cun-Xian Jia and Sheng-Li Cheng; data curation—Fenghua Wang and Zhi-Ying Yao; writing—original draft preparation—Fenghua Wang and Jianguo Gao; writing—review and editing—Po-Lun Fung, Josephine Pui-Hing Wong, Jianguo Gao, Fenghua Wang, Cun-Xian Jia, Sheng-Li Cheng and Zhi-Ying Yao; visualization—Fenghua Wang; supervision—Jianguo Gao, Po-Lun Fung and Josephine Pui-Hing Wong; project administration—Cun-Xian Jia and Sheng-Li Cheng; funding acquisition—Cun-Xian Jia, Kenneth Po-Lun Fung and Josephine Pui-Hing Wong. All the authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Due to the nature of this research, the participants of this study did not agree that their data would be shared publicly, so supporting data are not available.

Ethics Approval: The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Shandong University (Approval No. 20180123), University of Jinan, Shandong Jianzhu University, Shandong Normal University, Shandong Women’s University, and Shandong Youth University of Political Science. Written consent was obtained from each participant prior to the study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.069458/s1.

Abbreviations

| MH | Mental health |

| MHL | Mental health literacy |

| ACE | Acceptance Commitment to Empowerment |

| ACE-LYNX | Acceptance Commitment to Empowerment-Linking Youth Heart and “Xin”(Heart) |

References

1. Harris BR, Maher BM, Wentworth L. Optimizing efforts to promote mental health on college and university campuses: recommendations to facilitate usage of services, resources, and supports. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2022;49(2):252–8. doi:10.1007/s11414-021-09780-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Harris MPJ, Palmedo PC, Fleary SA. What gets people in the door: an integrative model of student veteran mental health service use and opportunities for communication. J Am Coll Health. 2024;72(8):2764–74. doi:10.1080/07448481.2022.2129977. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Yang L. The dilemmas and countermeasures of college counselors in carrying out student mental health work. Adv Soc Sci. 2024;13:77–81. [Google Scholar]

4. Ning X, Wong JPH, Huang S, Fu Y, Gong X, Zhang L, et al. Chinese university students’ perspectives on help-seeking and mental health counseling. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(14):8259. doi:10.3390/ijerph19148259. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Yu M, Cheng S, Fung KP, Wong JP, Jia C. More than mental illness: experiences of associating with stigma of mental illness for Chinese college students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(2):864. doi:10.3390/ijerph19020864. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. World Health Organization, PEPFAR, UNAIDS. Task shifting: rational redistribution of tasks among health workforce teams: global recommendations and guidelines. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2007. 88 p. [Google Scholar]

7. Brown AD, Ross N, Sangraula M, Laing A, Kohrt BA. Transforming mental healthcare in higher education through scalable mental health interventions. Camb Prism Glob Ment Health. 2023;10:e33. doi:10.1017/gmh.2023.29. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China. Mental health education for students in general colleges and universities basic construction standard [Internet]. Beijing, China: Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China; 2011 [cited 2025 May 7]. Available from: http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/A12/moe_1407/s3020/201102/t20110223_115721.html. [Google Scholar]

9. Hou R, Huang S, Fung KPL, Li A, Jia C, Cheng S, et al. Who is helping students? A qualitative analysis of task-shifting and on-campus mental health services in China’s university settings. Soc Sci Med. 2024;363(1):117527. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2024.117527. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Abi Hana R, Arnous M, Heim E, Aeschlimann A, Koschorke M, Hamadeh RS, et al. Mental health stigma at primary health care centres in Lebanon: qualitative study. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2022;16(1):23. doi:10.1186/s13033-022-00533-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Goh CMJ, Shahwan S, Lau JH, Ong WJ, Tan GTH, Samari E, et al. Advancing research to eliminate mental illness stigma: an interventional study to improve community attitudes towards depression among university students in Singapore. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21(1):108. doi:10.1186/s12888-021-03106-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Jorm AF, Korten AE, Jacomb PA, Christensen H, Rodgers B, Pollitt P. “Mental health literacy”: a survey of the public’s ability to recognise mental disorders and their beliefs about the effectiveness of treatment. Med J Aust. 1997;166(4):182–6. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.1997.tb140071.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Soria-Martínez M, Navarro-Pérez CF, Pérez-Ardanaz B, Martí-García C. Conceptual framework of mental health literacy: results from a scoping review and a Delphi survey. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2024;33(2):281–96. doi:10.1111/inm.13249. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Fernandez CSP. The MHISTREET: barbershop embedded education initiative. In: Fernandez CSP, Corbie-Smith G, editors. Leading community based changes in the culture of health in the US—experiences in developing the team and impacting the community. Rijeka, Croatia: IntechOpen; 2021. doi:10.5772/intechopen.98461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Chen M, Lin GR, Wang GY, Yang L, Lyu N, Qian C, et al. Stigma toward mental disorders and associated factors among community mental health workers in Wuhan, China. Asia-Pac Psychia. 2023;15:e12542. doi:10.1111/appy.12542. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Sim A, Ahmad A, Hammad L, Shalaby Y, Georgiades K. Reimagining mental health care for newcomer children and families: a qualitative framework analysis of service provider perspectives. BMC Health Serv Res. 2023;23(1):699. doi:10.1186/s12913-023-09682-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Metzger IW, Turner ER, Erlanger A, Jernigan-Noesi MM, Fisher S, Nguyen JK, et al. Conceptualizing community mental health service utilization for BIPOC youth. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2023;52:328–42. doi:10.1080/15374416.2023.2202236. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Bhardwaj A, Gurung D, Rai S, Kaiser BN, Cafaro CL, Sikkema KJ, et al. Treatment preferences for pharmacological versus psychological interventions among primary care providers in Nepal: mixed methods analysis of a pilot cluster randomized controlled trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(4):2149. doi:10.3390/ijerph19042149. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Liu FF, Coifman J, McRee E, Stone J, Law A, Gaias L, et al. A brief online implicit bias intervention for school mental health clinicians. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(1):1. doi:10.3390/ijerph19010001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Mei C, McGorry PD. Mental health first aid: strengthening its impact for aid recipients. Evid Based Ment Health. 2020;23(4):133–4. doi:10.1136/ebmental-2020-300154. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Hallos D. STAR: Students, Trauma, and Resiliency an Overview. [cited 2025 Sep 21]. Available from: https://www.tribalyouth.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/STAR-OLE-Final-7.31.24.pdf. [Google Scholar]

22. Capponi D, Claxton T, Downton D, Eaton B, LeBlanc E, Muise R, et al. Guidelines for the practice and training of peer support [Internet]. Ottawa, ON, Canada: Mental Health Commission of Canada; 2010 [cited 2025 Sep 24]. Available from: https://mentalhealthcommission.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Guidelines-for-the-Practice-and-Training-of-Peer-Support.pdf. [Google Scholar]

23. Thornicroft G, Mehta N, Clement S, Evans-Lacko S, Doherty M, Rose D, et al. Evidence for effective interventions to reduce mental-health-related stigma and discrimination. Lancet. 2016;387:1123–32. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(15)00298-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Mehta N, Clement S, Marcus E, Stona AC, Bezborodovs N, Evans-Lacko S, et al. Evidence for effective interventions to reduce mental health-related stigma and discrimination in the medium and long term: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry. 2015;207(5):377–84. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.114.151944. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Agarwal AK, Gonzales RE, Southwick L, Schroeder D, Sharma M, Bellini L, et al. Understanding health care workers’ mental health needs: insights from a qualitative study on digital interventions. BMC Health Serv Res. 2025;25(1):654. doi:10.1186/s12913-025-12678-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Razai MS, Kooner P, Majeed A. Strategies and interventions to improve healthcare professionals’ well-being and reduce burnout. J Prim Care Community Health. 2023;14:21501319231178641. doi:10.1177/21501319231178641. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Fung K, Cheng SL, Ning X, Li ATW, Zhang J, Liu JJW, et al. Mental health promotion and stigma reduction among university students using the Reach, Efficacy, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance (RE-AIM) framework: protocol for a mixed methods study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2021;10(8):e25592. doi:10.2196/25592. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Wong JPH, Fung KPL, Li ATW. Integrative strategies to address complex HIV and mental health syndemic challenges in racialized communities: insights from the CHAMP project. Can J Community Ment Health. 2017;36(3):65–70. doi:10.7870/cjcmh-2017-027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Fung KPL, Wong JPH, Li ATW. Linking hearts, building resilience [Internet]. [cited 2023 Dec 20]. Available from: https://pressbooks.library.torontomu.ca/empowerment/. [Google Scholar]

30. Taylor SM, Dear MJ. Scaling community attitudes toward the mentally ill. Schizophr Bull. 1981;7(2):225–40. doi:10.1093/schbul/7.2.225. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Huff NR, Arnold DH, Isbell LM. The community attitudes towards mental illness (CAMI) scale 40 years later: an investigation using confirmatory factor analysis and free-response data. J Community Psychol. 2025;53(2):e70005. doi:10.1002/jcop.70005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Fung KPL, Liu JJW, Sin R, Bender A, Shakya Y, Butt N, et al. Exploring mental illness stigma among Asian men mobilized to become community mental health ambassadors in Toronto Canada. Ethn Health. 2022;27(1):100–18. doi:10.1080/13557858.2019.1640350. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Ali AM, Green J. Factor structure of the depression anxiety stress Scale-21 (DASS-21unidimensionality of the Arabic version among Egyptian drug users. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2019;14(1):40. doi:10.1186/s13011-019-0226-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Cowles B, Medvedev ON. Depression, anxiety and stress scales (DASS). In: Medvedev ON, Krägeloh CU, Siegert RJ, Singh NN, editors. Handbook of assessment in mindfulness research. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2022. p. 1–15. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-77644-2_64-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Ali AM, Alkhamees AA, Hori H, Kim Y, Kunugi H. The Depression Anxiety Stress Scale 21: development and validation of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale 8-Item in psychiatric patients and the general public for easier mental health measurement in a post COVID-19 world. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(19):10142. doi:10.3390/ijerph181910142. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Zimmerman MA. Empowerment theory: psychological, organizational, and community levels of analysis. In: Handbook of community psychology. Boston, MA, USA: Springer; 2000. p. 43–63. doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-4193-6_2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Labonte R. Health promotion and empowerment: reflections on professional practice. Health Educ Q. 1994;21(2):253–68. doi:10.1177/109019819402100209. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Rissel C. Empowerment: the holy grail of health promotion? Health Promot Int. 1994;9(1):39–47. doi:10.1093/heapro/9.1.39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Laverack G, Wallerstein N. Measuring community empowerment: a fresh look at organizational domains. Health Promot Int. 2001;16(2):179–85. doi:10.1093/heapro/16.2.179. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–88. doi:10.1177/1049732305276687. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Assarroudi A, Heshmati Nabavi F, Armat MR, Ebadi A, Vaismoradi M. Directed qualitative content analysis: the description and elaboration of its underpinning methods and data analysis process. J Res Nurs. 2018;23(1):42–55. doi:10.1177/1744987117741667. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Lee D. The convergent, discriminant, and nomological validity of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales-21 (DASS-21). J Affect Disord. 2019;259(3):136–42. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2019.06.036. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Clay J, Eaton J, Gronholm PC, Semrau M, Votruba N. Core components of mental health stigma reduction interventions in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2020;29:e164. doi:10.1017/s2045796020000797. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. The Lancet. The health crisis of mental health stigma. Lancet. 2016;387:1027. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)00687-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Jiang G, Zhao C, Wei H, Yu L, Li D, Lin X, et al. Mental health literacy: connotation, measurement and new framework. J Psychol Sci. 2020;43:232–8. [Google Scholar]

46. Guerrero Z, Iruretagoyena B, Parry S, Henderson C. Anti-stigma advocacy for health professionals: a systematic review. J Ment Health. 2024;33(3):394–414. doi:10.1080/09638237.2023.2182421. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Eiroa-Orosa FJ, Lomascolo M, Tosas-Fernández A. Efficacy of an intervention to reduce stigma beliefs and attitudes among primary care and mental health professionals: two cluster randomised-controlled trials. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(3):1214. doi:10.3390/ijerph18031214. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Petersen I, Evans-Lacko S, Semrau M, Barry MM, Chisholm D, Gronholm P, et al. Promotion, prevention and protection: interventions at the population- and community-levels for mental, neurological and substance use disorders in low- and middle-income countries. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2016;10(1):30. doi:10.1186/s13033-016-0060-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Rao D, Elshafei A, Nguyen M, Hatzenbuehler ML, Frey S, Go VF. A systematic review of multi-level stigma interventions: state of the science and future directions. BMC Med. 2019;17(1):41. doi:10.1186/s12916-018-1244-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Gronholm PC, Bakolis I, Cherian AV, Davies K, Evans-Lacko S, Girma E, et al. Toward a multi-level strategy to reduce stigma in global mental health: overview protocol of the Indigo Partnership to develop and test interventions in low- and middle-income countries. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2023;17:2. doi:10.1186/s13033-022-00564-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Smith KA, Bishop FL, Dambha-Miller H, Ratnapalan M, Lyness E, Vennik J, et al. Improving empathy in healthcare consultations—a secondary analysis of interventions. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35:3007–14. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-05994-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Vela MB, Erondu AI, Smith NA, Peek ME, Woodruff JN, Chin MH. Eliminating explicit and implicit biases in health care: evidence and research needs. Annu Rev Public Health. 2022;43(1):477–501. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-052620-103528. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Wang F, Gao J, Hao S, Tsang KT, Wong JPH, Fung K, et al. Empowering Chinese university health service providers to become mental health champions: insights from the ACE-LYNX intervention. Front Psychiatry. 2024;15:1349476. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1349476. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Fu M, Han D, Xu M, Mao C, Wang D. The psychological impact of anxiety and depression on Chinese medical staff during the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. Ann Palliat Med. 2021;10(7):7759–74. doi:10.21037/apm-21-1261. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Chen Y, Hu M, He H, Lai X, Zhou H. Intervention effect of acceptance and commitment therapy group counseling on sleep quality of female students in vocational colleges. China J Health Psychol. 2022;30:586–91. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

56. Yu F, Liu H, Li X, Huang J. Effect of group acceptance commitment therapy on quality of life of convalescent patients with schizophrenia. Psychol Mon Mag. 2021;16:51–2. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

57. Wang J, Chen Z, Wang Q, Wang Y. Effect of competence of class psychological commissioners on psychological health: the chain mediating role of perceived social support and resilience. Psychol Explor. 2021;41:176–85. [Google Scholar]

58. Ho HCY, Chan YC. The impact of psychological capital on well-being of social workers: a mixed-methods investigation. Soc Work. 2022;67(3):228–38. doi:10.1093/sw/swac020. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Avery H, Sjögren Forss K, Rämgård M. Empowering communities with health promotion labs: result from a CBPR programme in Malmö. Sweden Health Promot Int. 2022;37(1):daab069. doi:10.1093/heapro/daab069. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Li ATW, Fung KPL, Maticka-Tyndale E, Wong JPH. Effects of HIV stigma reduction interventions in diasporic communities: insights from the CHAMP study. AIDS Care. 2018;30:739–45. doi:10.1080/09540121.2017.1391982. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Ozdemir Koyu H, Kilicarslan E. Effect of technology-based psychological empowerment interventions on psychological well-being of parents of pediatric cancer patients: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psycho-Oncology. 2025;34:e70097. doi:10.1002/pon.70097. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Bull ER, Dale H. Improving community health and social care practitioners’ confidence, perceived competence and intention to use behaviour change techniques in health behaviour change conversations. Health Soc Care Community. 2021;29:270–83. doi:10.1111/hsc.13090. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Kruahong S, Tankumpuan T, Kelly K, Davidson PM, Kuntajak P. Community empowerment: a concept analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2023;79:2845–59. doi:10.1111/jan.15613. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Sjöberg S, Rambaree K, Jojo B. Collective empowerment: a comparative study of community work in Mumbai and Stockholm. Int J Soc Welfare. 2015;24:364–75. doi:10.1111/ijsw.12137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Harte P, Barry MM. A scoping review of the implementation and cultural adaptation of school-based mental health promotion and prevention interventions in low-and middle-income countries. Camb Prism Glob Ment Health. 2024;11:e55. doi:10.1017/gmh.2024.48. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools