Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Effects of Three Various Frequencies of 24-Form Tai Chi on Anxiety and Depression Symptoms in College Students

College of Sports Science, Qufu Normal University, Jining, 272000, China

* Corresponding Author: Yumeng Kong. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Enhancing Mental Health through Physical Activity: Exploring Resilience Across Populations and Life Stages)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(10), 1577-1594. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.069985

Received 04 July 2025; Accepted 30 September 2025; Issue published 31 October 2025

Abstract

Background: Anxiety and depression are prevalent among university students, calling for effective non-pharmacological interventions. Tai Chi shows potential in reducing these symptoms, but research on its effects at different frequencies in younger populations is limited. This study compared the impacts of high-(5 sessions/week), medium-(3 sessions/week), and low-frequency (2 sessions/week) 24-form Tai Chi on college students’ anxiety/depression, versus a control group. Methods: A randomized controlled trial (RCT) included 120 university students with mild-to-moderate anxiety/depression, randomly assigned to 4 groups (30 each). The 8-week intervention used the Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) and Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS) for assessments at baseline, week 4, and week 8. Analyses included paired t-tests (within-group changes), one-way ANOVA (between-group differences), repeated measures ANOVA (RM-ANOVA, temporal changes), and Mixed Model for Repeated Measures (MMRM, longitudinal changes with missing data). Results: All intervention groups had significant SAS/SDS reductions: high-frequency group (SAS: 20.4%, t = 7.21, p < 0.001; SDS: 22.1%, t = 6.92, p < 0.001) > medium-frequency group (SAS: 18.3%, t = 5.06, p < 0.001; SDS: 19.8%, t = 5.18, p < 0.001) > low-frequency group (SAS: 15.2%, t = 4.09, p < 0.001; SDS: 17.4%, t = 4.67, p < 0.001). No changes were seen in the control group. The high-frequency group outperformed the low-frequency and control groups (p < 0.05); RM-ANOVA and MMRM confirmed sustained, time-dependent effects, with the high-frequency group being optimal. Conclusion: 24-form Tai Chi effectively reduces college students’ anxiety/depression, with efficacy increasing with frequency (high > medium > low). The high-frequency protocol (5 sessions/week) is the most effective non-pharmacological intervention, and MMRM confirms its sustained efficacy.Keywords

Anxiety and depression are one of the most common mental health problems in the world, with a particularly high incidence rate among young college students [1]. Literature has confirmed that compared to the general population, college students have a significantly higher incidence of anxiety and depression symptoms [1,2]. For example, the World Health Organization’s (WHO) World Mental Health Survey shows that 20% of college students have suffered from psychological disorders in the past year, with a large portion exhibiting pre-existing symptoms before enrollment [2]. According to the statistics of the WHO, depression has become the main cause of disability among people aged 15–29, and the incidence rate of anxiety disorders is also high [2,3]. These mental health challenges not only seriously harm students’ academic performance and quality of life, but are also closely related to increased suicide risk and long-term chronic disease burden.

One of the main reasons for anxiety and depression among college students is the enormous academic pressure they face [3–5]. Due to the heavy academic burden, upcoming deadlines, and exams, college students often experience high levels of stress [6]. The requirement to maintain academic performance and expectations for future career success may lead to overwhelming feelings of inadequacy and fear of failure [7]. Research has shown that academic stress is an important predictor of anxiety and depression among college students [8]. In addition, balancing academic responsibilities with social and personal pressures further exacerbates their mental health challenges [9]. For example, students may feel stressed due to a lack of time for relaxation or exercise, or difficulty managing interpersonal relationships and maintaining mental health in academic responsibilities [10]. Given these pressure factors, college students are a key group for studying mental health intervention measures. In college life, the unique combination of academic needs, social pressure, and personal adaptation makes this group particularly susceptible to anxiety and depression [11]. In addition, addressing mental health issues at this stage can bring significant long-term benefits, including improved academic performance, reduced dropout rates, and improved quality of life [12,13].

Tai Chi has recently attracted widespread attention as an effective non-pharmacological intervention for treating anxiety and depression [8]. Numerous studies have confirmed its effectiveness in improving emotional health, especially for middle-aged and elderly people as well as chronic disease patients [14,15]. For example, systematic reviews and meta-analyses consistently report that Tai Chi significantly reduces symptoms of depression and anxiety, while improving overall mental health [14,15]. However, there is still relatively little research on the impact of Tai Chi on young people, especially college students [16]. Most existing literature focuses on the elderly and patients with chronic diseases, emphasizing the need for further investigation into the effects of Tai Chi on the mental health of young people, especially under different exercise frequencies and intensities [15]. In addition, optimizing Tai Chi intervention programs to maximize their psychological health benefits remains an important but unresolved issue [17,18].

Therefore, our study aims to evaluate the effects of three different frequency based 24 style Tai Chi interventions on anxiety and depression symptoms in college students. By comparing high-frequency, mid-frequency, and low-frequency Tai Chi interventions, this study investigated how various exercise frequencies affect mental health outcomes. These findings will provide empirical evidence to guide the development of personalized exercise recommendations for mental health interventions, particularly for populations experiencing academic stress and related mental health issues.

The primary objective of our study is to assess the impacts of three distinct 24-form Tai Chi exercise intervention protocols, namely, a high-frequency intervention group, a medium-frequency intervention group, and a low-frequency intervention group—compared with a non-intervention control group, on reducing anxiety and depressive symptoms among college students. The specific aims are as follows: (1) To explore the influence of three various intensity and frequency levels of 24-form Tai Chi exercise interventions on anxiety symptoms in college students; (2) To investigate the impacts of these three intervention protocols on depressive symptoms in college students; (3) To compare the differences between the exercise intervention groups and the control group, hence evaluating the practical efficacy of exercise intervention approaches on mental health outcomes.

The design and methodology of our study rigorously adhere to the ethical principles summarized in the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki [19]. In addition, our study protocol has been reviewed and approved by the Biomedical Ethics Committee of Qufu Normal University (Approval No.: 2025-111). Prior to participation, all subjects offered written informed consent. This randomized controlled trial (RCT) has been approved by the Thai Clinical Trial Registry (Number: TCTR20250528007, https://www.thaiclinicaltrials.org/show/TCTR20250528007, accessed on 28 May 2025).

To ensure adequate statistical power for detecting the impacts of various Tai Chi intervention protocols on anxiety and depressive symptoms among college students, an a priori sample size calculation was performed. Based on previous studies examining similar exercise interventions for mental health outcomes, we anticipated a medium effect size (Cohen’s d ≈ 0.5) for the decrease in anxiety and depression symptoms. With a significance level (α) set at 0.05 and a statistical power (1 − β) of 0.80 [20], a power analysis was conducted using G*Power 3.1.9.6 software [21]. The analysis indicated that a minimum of 28 participants per group would be required.

To account for potential attrition (estimated at approximately 10%), the target sample size was increased to 30 participants per group. Consequently, a total of 120 participants were included and randomly allocated to the four study groups using a computer-generated random number sequence via SPSS 26 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) [22], ensuring allocation concealment.

3.1.2 Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria for our study were as follows: (1) Age range: Participants were needed to be aged between 18 and 25 years, and currently enrolled as university students. (2) Anxiety and/or depressive symptoms: Participants needed to present mild to moderate anxiety and/or depressive symptoms at baseline, as measured by standardized psychological tools (Self-Rating Anxiety Scale [SAS] score > 50 or Self-Rating Depression Scale [SDS] score > 53). (3) Physical health status: Participants must be free from significant physical illnesses, musculoskeletal disorders, or cardiovascular conditions that would impair their ability to engage in the exercise intervention (e.g., no severe joint or muscle injuries). (4) Absence of concurrent psychological interventions: Participants were excluded if they were receiving other forms of psychological therapy or pharmacological treatment for mental health conditions during the study period. (5) Voluntary participation: All participants were needed to provide written informed consent, confirming their understanding of the study’s objectives, procedures, and potential risks.

Participants were excluded based on the following criteria: (1) Severe mental health conditions: Individuals diagnosed with severe anxiety, major depressive disorder, or other serious psychiatric disorders (e.g., schizophrenia, bipolar disorder). (2) Contraindications to exercise: Those with absolute contraindications to physical activity or severe medical conditions (e.g., cardiovascular diseases, uncontrolled hypertension, acute infectious diseases, unhealed fractures, or significant musculoskeletal injuries). (3) Prior Tai Chi experience: formal Tai Chi training during the last year. (4) Current psychotropic medication use: Participants taking anxiolytics, antidepressants, or other medications with documented effects on anxiety/depression symptoms at baseline or during the study period. (5) Poor intervention adherence: Failure to attend scheduled Tai Chi sessions (e.g., >3 absences) or non-compliance with the protocol. (6) Pregnancy or lactation: Female participants who were pregnant or breastfeeding. (7) Concurrent participation in other exercise programs: Engagement in structured exercise interventions (e.g., yoga, aerobics) during the study. (8) Participants who are currently undergoing or have undergone any form of psychological therapy, including relaxation techniques, mindfulness, or other similar interventions, during the study period. (9) Participants who are taking medication or have participated in other mental health interventions that might confound the results.

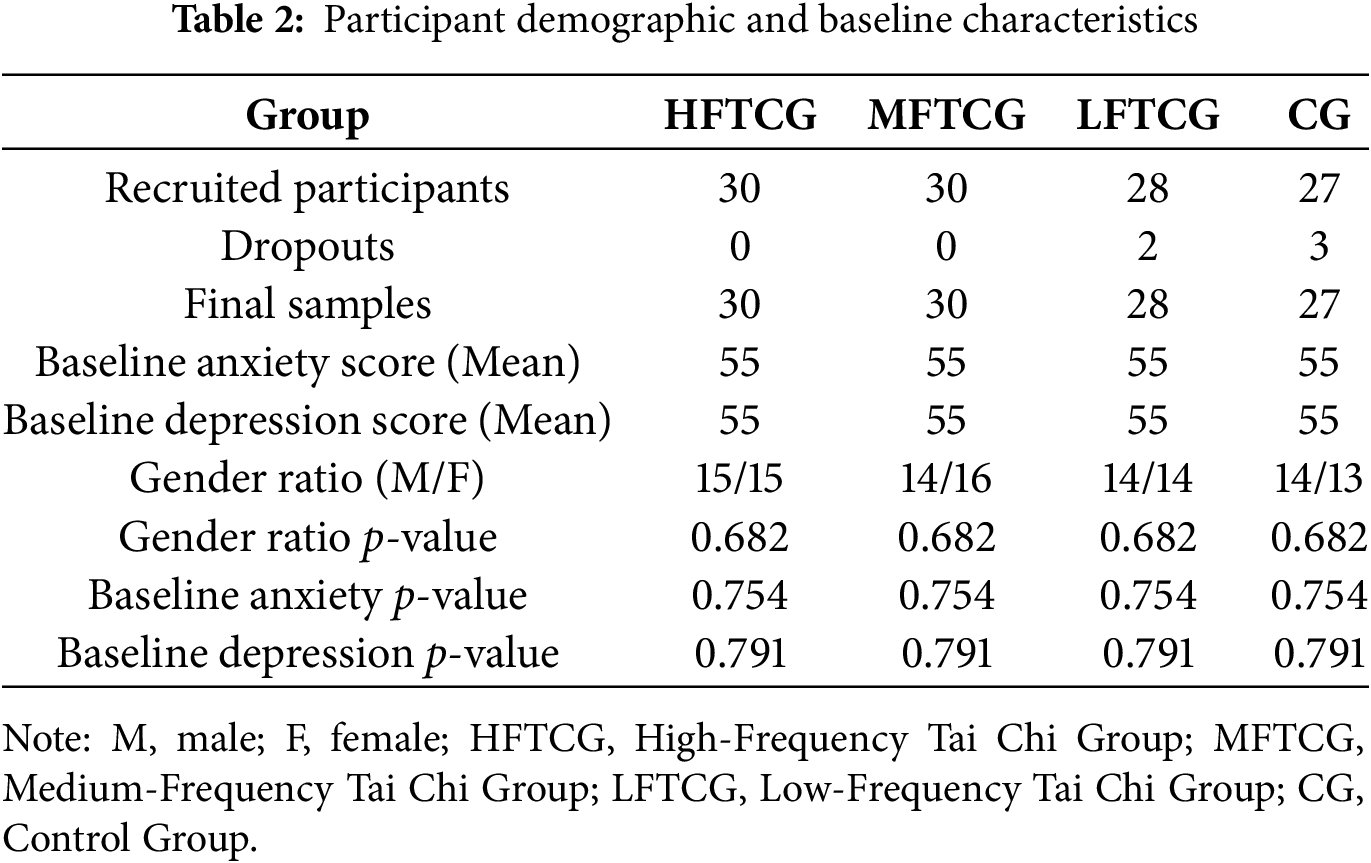

This study recruited a total of 120 university students who met the inclusion criteria and provided written informed consent. During the study period, five participants withdrew from the study due to personal reasons, resulting in a final sample of 115 participants, distributed across the four intervention groups as follows: High-Frequency Tai Chi Group (HFTCG): 30 participants (15 males, 15 females). Medium-Frequency Tai Chi Group (MFTCG): 30 participants (14 males, 16 females). Low-Frequency Tai Chi Group (LFTCG): 28 participants (14 males, 14 females). Control Group (CG): 27 participants (13 males, 14 females). Reasons for Participant Dropout: In the Control Group (CG), 3 participants dropped out for personal reasons, including academic pressure and schedule conflicts. In the LFTCG, 2 participants withdrew due to personal issues such as family matters and time constraints. No participants dropped out of the HFTCG or MFTCG during the study period. Detailed Characteristics of Each Intervention Group: HFTCG: Participants in this group were aged 18–24 years.

The baseline SAS scores ranged from 51 to 58, and the SDS scores were between 52 and 59. MFTCG: Participants were also aged 18–24 years. Baseline SAS scores ranged from 52 to 59, and SDS scores ranged from 53 to 60. LFTCG: Participants in this group were aged 18–25 years. Baseline SAS scores ranged from 53 to 60, and SDS scores ranged from 54 to 61. CG: Participants in the control group were aged 18–24 years. Baseline SAS scores ranged from 51 to 58, and SDS scores ranged from 52 to 59. No significant differences were found between the groups in terms of age, gender, or baseline anxiety and depression scores, indicating comparable characteristics at the time of enrollment.

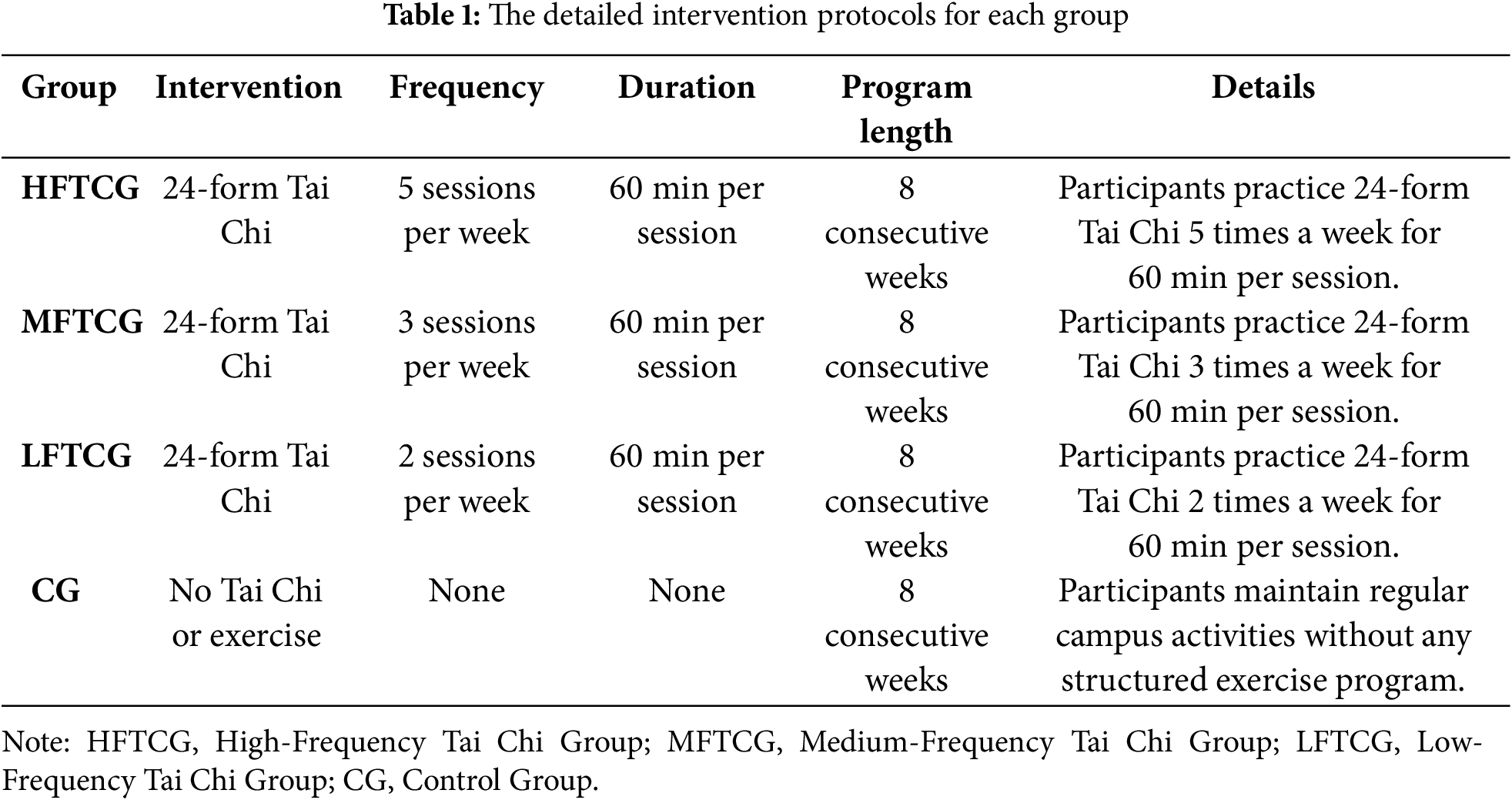

This study adopted an RCT design with four distinct intervention groups. The intervention protocols for each group were as follows: The HFTCG practiced 24-form Tai Chi 5 times per week, with each session lasting 60 min, for 8 consecutive weeks. The MFTCG practiced the same form of Tai Chi 3 times per week, also for 60 min per session, for 8 weeks. The LFTCG practiced Tai Chi 2 times per week, with each session lasting 60 min for 8 weeks. The CG did not participate in any structured exercise program and continued with their regular campus activities for the 8-week monitoring period.

Adherence to the intervention protocols was closely observed, with attendance records maintained for each participant. Those who missed more than three sessions were excluded from the analysis to ensure proper adherence. The quality of Tai Chi practice was also observed by experienced instructors, who provided corrections as needed to ensure participants performed the forms correctly. The detailed intervention protocols for each group are summarized in Table 1.

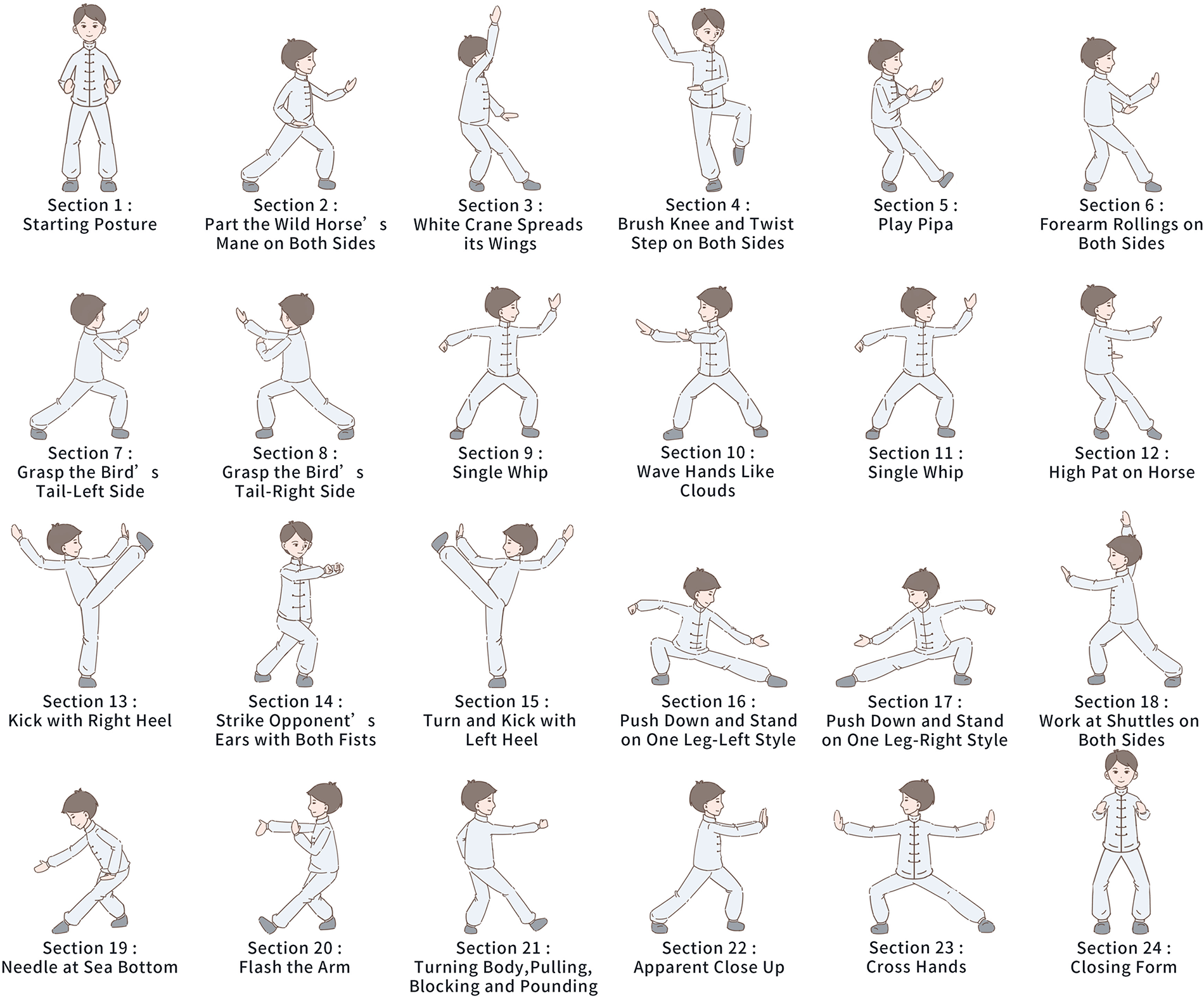

In addition, figures illustrating the study procedure and the 24-form Tai Chi movements will be included. Fig. 1 provides a visual representation of the 24-form Tai Chi movements. This design ensures consistency across groups, allowing for a comparison of the effects of various Tai Chi practice frequencies on anxiety and depression symptoms in college students.

Figure 1: The visual representation of the 24-form Tai Chi movements

The SAS is a widely used self-assessment tool designed to assess an individual’s anxiety levels. Developed by the Chinese psychologist Zung (1965) [23], the SAS comprised of 20 items, with items 17 and 19 being reverse-scored. Each item is rated on a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from “1 (none or a little of the time)” to “4 (most or all of the time)”.

3.3.2 Depression Assessment Tool

The SDS, led by Dr. William W.K. Zung in 1965 [24], is a validated psychometric instrument designed to evaluate the presence and severity of depressive symptoms. This 20-item self-report questionnaire evaluates affective, psychological, and somatic manifestations of depression, with respondents rating the frequency of each symptom on a 4-point Likert scale. Higher composite scores present greater depressive symptomatology. In the current study, the SDS will be administered at three time points: (1) Baseline assessment (pre-intervention); (2) Interim assessment (week 4 of intervention); (3) Post-intervention assessment (week 8). This longitudinal assessment protocol enables comparative analysis of depressive symptom trajectories across experimental groups while controlling for baseline measures. The standardized administration procedure ensures consistency in data collection across all time points.

This study included four groups of participants, each receiving various interventions over the 8-week period: HFTCG: Participants in this group engaged in the 24-form Tai Chi intervention five times per week, with each session lasting 60 min. MFTCG: Participants in this group practiced the 24-form Tai Chi three times per week, with each session lasting 60 min. LFTCG: Participants in this group practiced the 24-form Tai Chi two times per week, with each session lasting 60 min. CG: This group did not participate in any Tai Chi or other structured exercise programs. Participants in the control group continued their usual campus activities without any additional intervention during the 8-week period.

3.5 Implementation of the Blinding Procedure

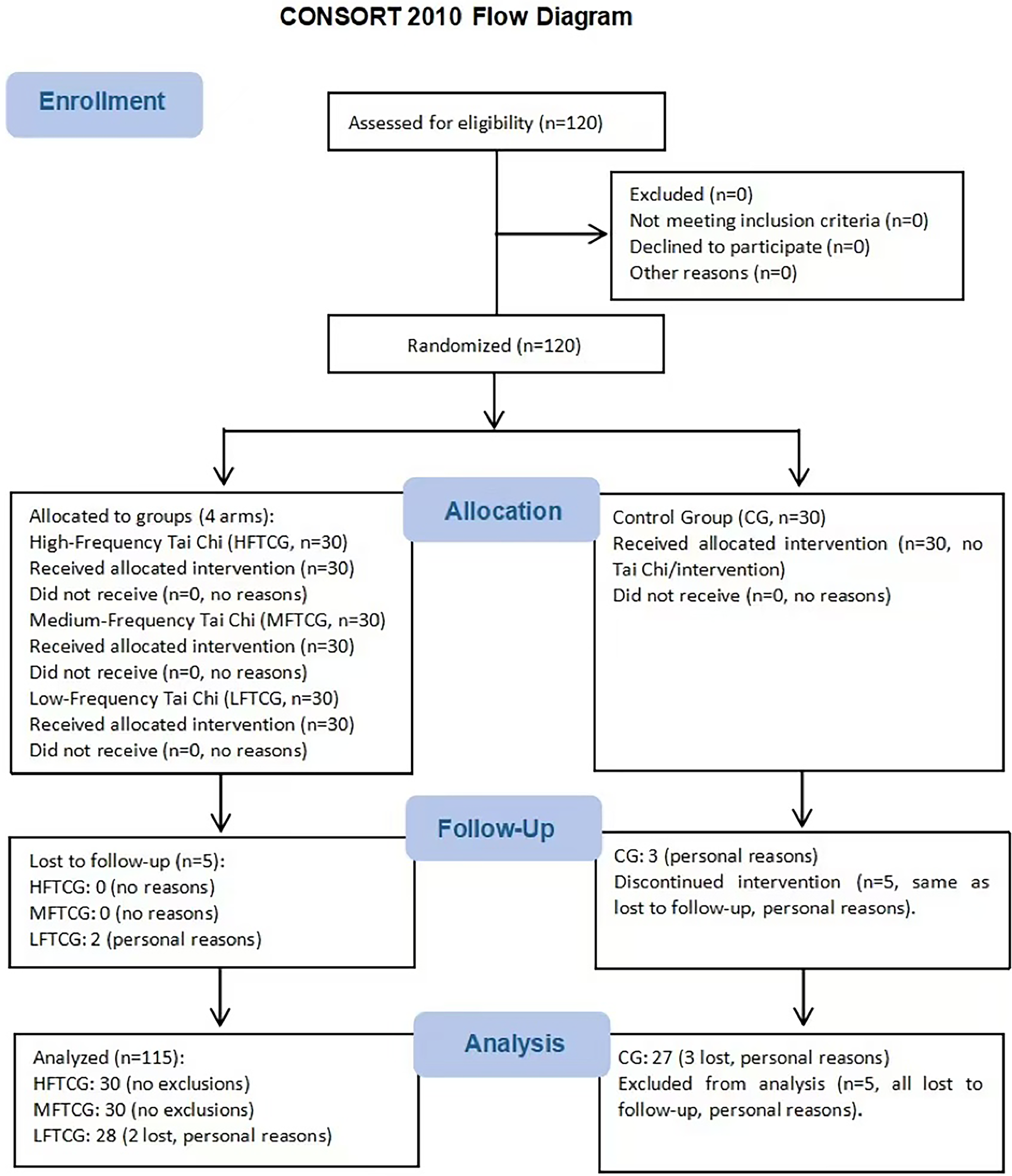

This study adopted a single-blind design to minimize potential biases and ensure the validity of findings. Participants were informed they were participating in a study examining exercise interventions for mental health, but remained unaware of their specific group allocation (HFTCG, MFTCG, LFTCG, or CG) to prevent expectancy impacts. All psychological assessments (SAS/SDS) were led at standardized timepoints (baseline, week 4, and week 8) by independent evaluators who were blinded to group assignments, hence eliminating assessor bias. While Tai Chi instructors necessarily knew group assignments to ensure proper intervention delivery, they were fully separated from the assessment process and data analysis to sustain objectivity. This design incorporated multiple safeguards, including standardized assessment environments, data anonymization, and post-study verification of blinding success, following CONSORT 2010 guidelines (Fig. 2) for non-pharmacological trials to optimize scientific rigor while sustaining practical feasibility.

Figure 2: The CONSORT 2020 flow chart of the included participants. Note: HFTCG, high-frequency Tai Chi group; MFTCG, medium-frequency Tai Chi group; LFTCG, low-frequency Tai Chi group; CG, control group

The data were processed and analyzed using SPSS 26 statistical software [22]. First, baseline differences in anxiety and depressive symptoms among the four groups were examined using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to ensure comparability at the initiation of the study. Second, paired samples t-tests were conducted to assess within-group changes in symptoms before and after the intervention, evaluating the individual effects of Tai Chi on each group. Third, for between-group comparisons, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied to analyze the influence of various intervention frequencies on outcomes; if significant differences were detected, the least significant difference (LSD) post-hoc test was used to identify specific group disparities. The LSD test was selected because our data met the assumptions of homogeneity of variance (Levene’s test, p > 0.05) and equal sample sizes across groups (n = 30 per group), conditions under which LSD maintains appropriate power to detect true differences while controlling Type I error at the nominal α level (0.05) [25]. Fourth, repeated-measures ANOVA (RM-ANOVA) was used to explore intervention effects across multiple time points, examining longitudinal changes in symptoms [26]. Fifth, to control for potential confounding factors (e.g., baseline symptom scores), analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was utilized to minimize their impact on results, enhancing the accuracy of intervention effect estimation [27]. Finally, the Mixed Model for Repeated Measures (MMRM) [28] was employed to confirm result robustness. MMRM is advantageous for handling missing data and analyzing longitudinal outcomes flexibly, accounting for correlations between repeated measures within participants, hence ensuring consistent results across time points and enhancing conclusion reliability. The significance level was set at p < 0.05 [29].

At the time of enrollment, there were no significant differences in demographic or clinical characteristics across the four groups, with the following baseline characteristics observed: Baseline Anxiety Score (Mean): All groups had a similar baseline SAS score of 55 (p > 0.05); Baseline Depression Score (Mean): The baseline SDS score was also 55 for all groups (p > 0.05); Gender Ratio: The gender distribution was relatively balanced across groups, with HFTCG having 15 males and 15 females, MFTCG having 14 males and 16 females, LFTCG having 14 males and 14 females, and CG having 14 males and 13 females, and gender ratio differences were not statistically significant (p > 0.05). Detailed demographic and clinical characteristics of the study participants are presented in Table 2, which summarizes the baseline anxiety and depression scores, as well as gender distribution for each group. Fig. 2 demonstrates the flow chart of participant enrollment, allocation, follow-up, and analysis.

4.2 Changes in Anxiety and Depression Symptoms

4.2.1 Changes in Anxiety Symptoms

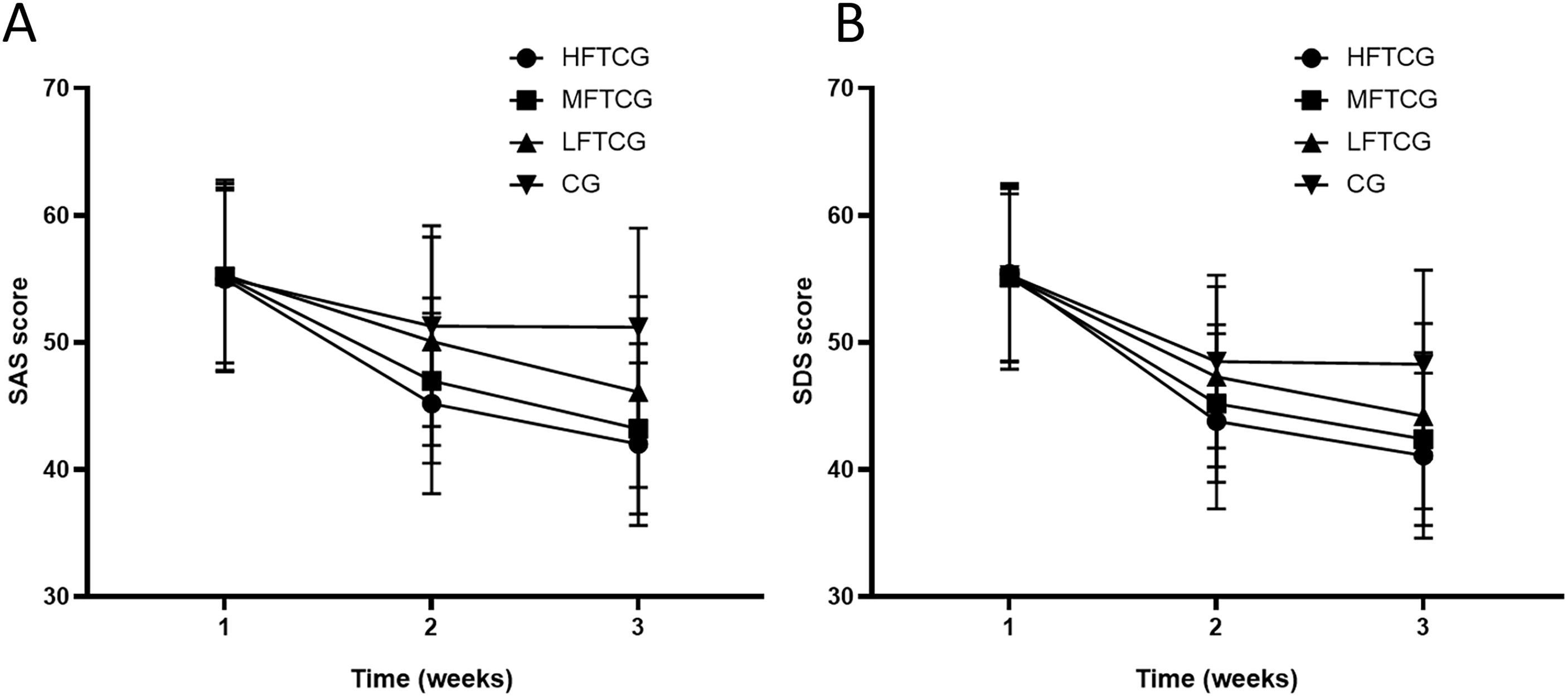

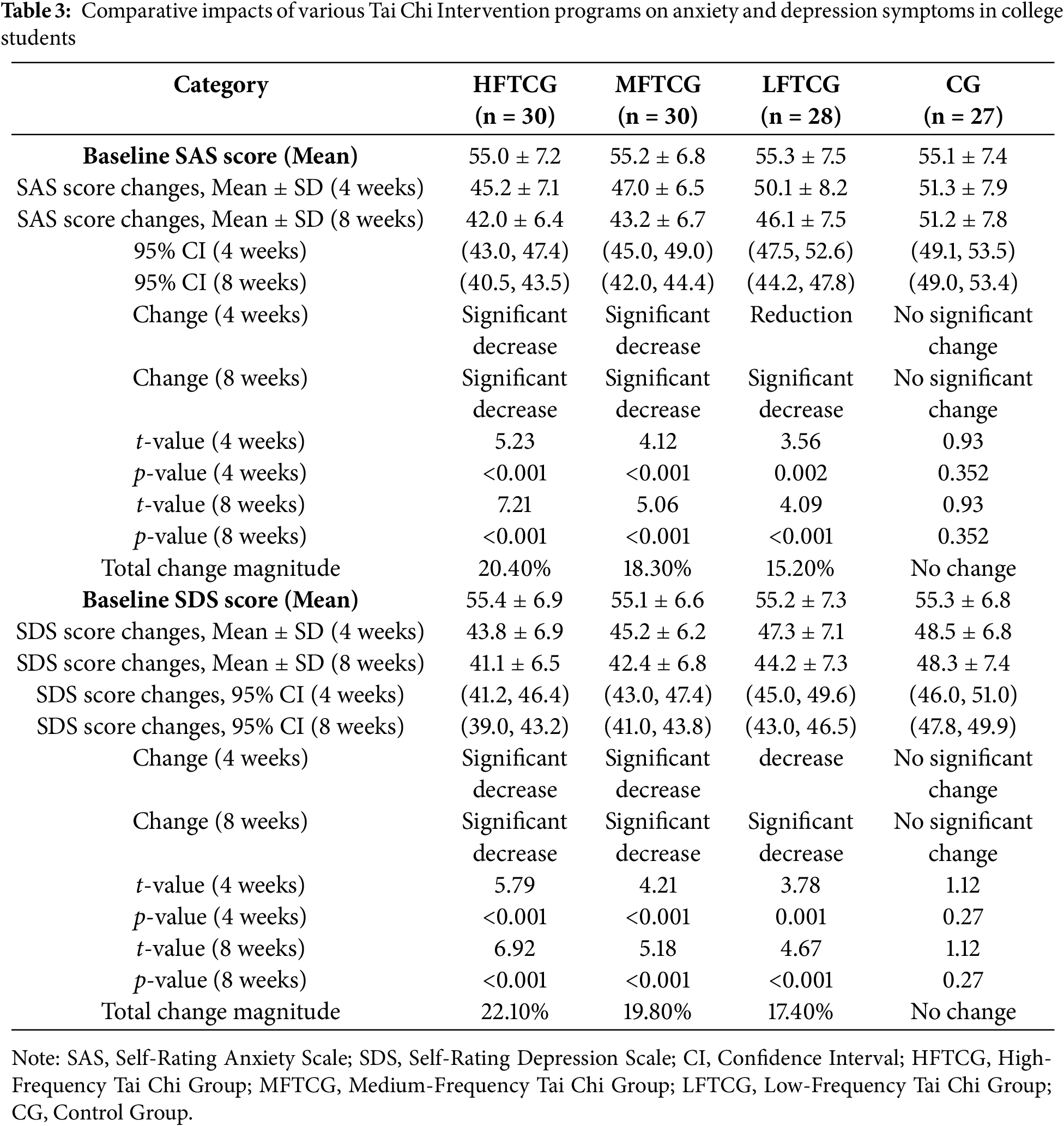

According to the SAS scores, no significant differences in anxiety levels were observed among the four groups at baseline (pre-intervention) (Table 2). Paired-sample t-tests were conducted to assess post-intervention changes across the groups, with the following findings: HFTCG: After 4 weeks of intervention, SAS scores decreased significantly (t = 5.23, p < 0.001). By the 8-week mark, a further reduction in SAS scores was presented, reaching a statistically significant difference (t = 7.21, p < 0.001). Compared with baseline, scores at 8 weeks demonstrated a 20.4% reduction. MFTCG: A significant decrease in SAS scores was witnessed after 4 weeks (t = 4.12, p < 0.001). This trend continued at 8 weeks, with an extra decrease (t = 5.06, p < 0.001). The total reduction from baseline was 18.3%. LFTCG: At 4 weeks, SAS scores showed a reduction (t = 3.56, p = 0.002). The change at 8 weeks was less pronounced, but still significant (t = 4.09, p < 0.001). The overall decrease from baseline was 15.2%. CG: Since the CG did not engage in Tai Chi practice during the 8-week period, no significant change in SAS scores was observed (t = 0.93, p = 0.352). Furthermore, Fig. 3 displays the plot trend chart of SDS and SAS scores for four groups from baseline to week 8.

Figure 3: Plot trend chart. (A) SAS and (B) SDS scores for four groups from baseline to week 8. Note: The “1” on the horizontal axis represents “Baseline”; “2” represents “4 weeks”; “3” represents “8 weeks”. SAS, self-rating anxiety scale; SDS, self-rating depression scale; HFTCG, high-frequency Tai Chi group; MFTCG, medium-frequency Tai Chi group; LFTCG, low-frequency Tai Chi group.

4.2.2 Changes in Depressive Symptoms

According to the SDS scores, no significant baseline differences were observed among the four groups prior to intervention (Table 3). Paired-sample t-tests suggested the following longitudinal changes: HFTCG: A significant reduction in SDS scores was observed at 4 weeks post-intervention (t = 5.79, p < 0.001). Scores continued to decline at 8 weeks, achieving statistical significance (t = 6.92, p < 0.001). Compared with baseline, an absolute reduction of 22.1% was recorded at 8 weeks. MFTCG: SDS scores decreased significantly after 4 weeks (t = 4.21, p < 0.001). Further reduction was noted by 8 weeks (t = 5.18, p < 0.001). The cumulative reduction from baseline reached 19.8%. LFTCG: A modest, but significant decrease in SDS scores emerged at 4 weeks (t = 3.78, p = 0.001). Progress continued at 8 weeks (t = 4.67, p < 0.001). The total reduction amounted to 17.4% vs. baseline. CG: As no intervention was administered, no significant SDS score changes were detected (t = 1.12, p = 0.270).

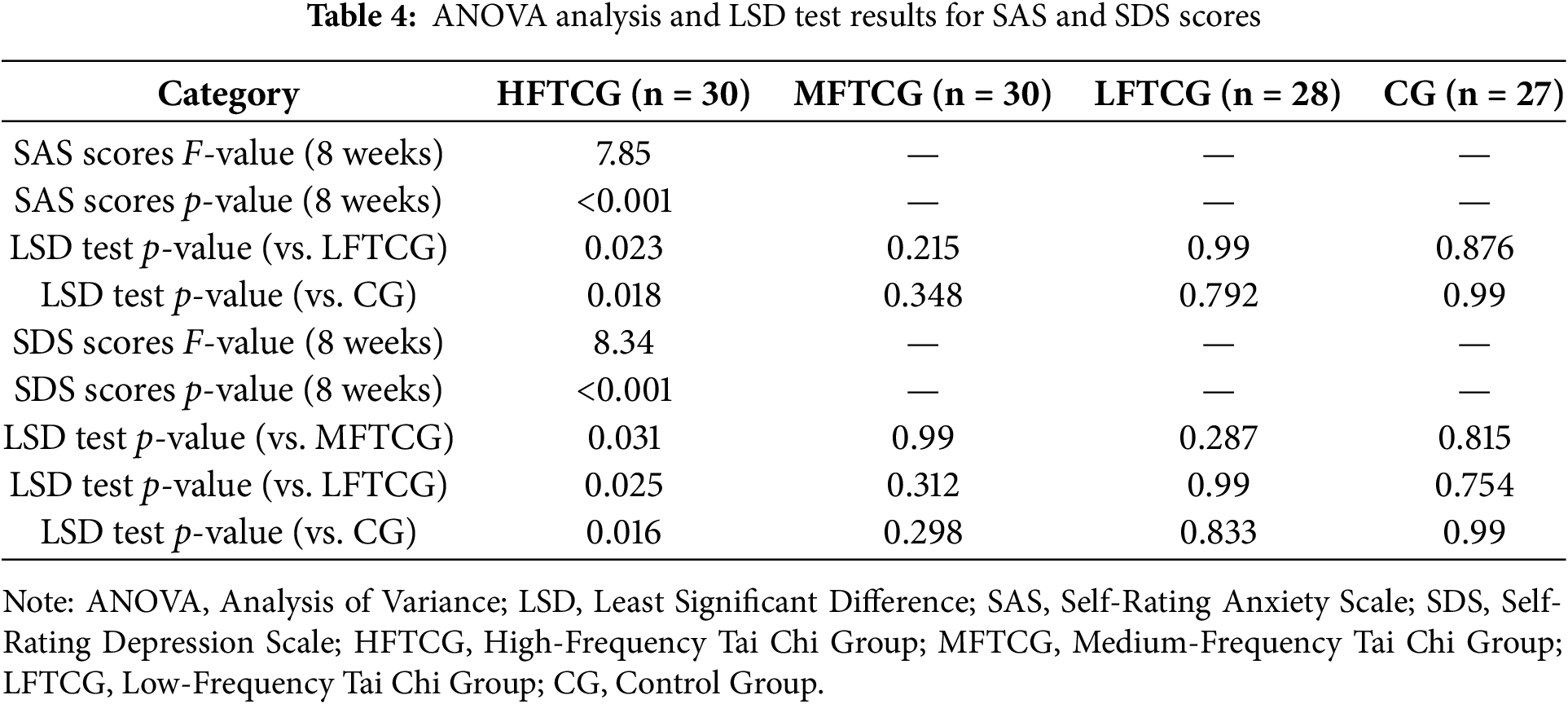

A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to compare intergroup differences in anxiety and depressive symptom changes. For anxiety symptoms (SAS scores), significant intergroup differences were observed at 8 weeks post-intervention (F(3, 111) = 7.85, p < 0.001). Post hoc LSD tests revealed that the HFTCG showed significantly greater reductions in anxiety compared to both the LFTCG and the CG (p < 0.05). However, no significant differences were found between the MFTCG and either the LFTCG or CG. For depressive symptoms (SDS scores), intergroup differences were similarly significant (F(3, 111) = 8.34, p < 0.001). Post hoc LSD tests showed that the HFTCG demonstrated superior improvement in depressive symptoms compared to the MFTCG, LFTCG, and CG (p < 0.05 for all comparisons). Detailed results from the ANOVA and LSD tests are provided in Table 4.

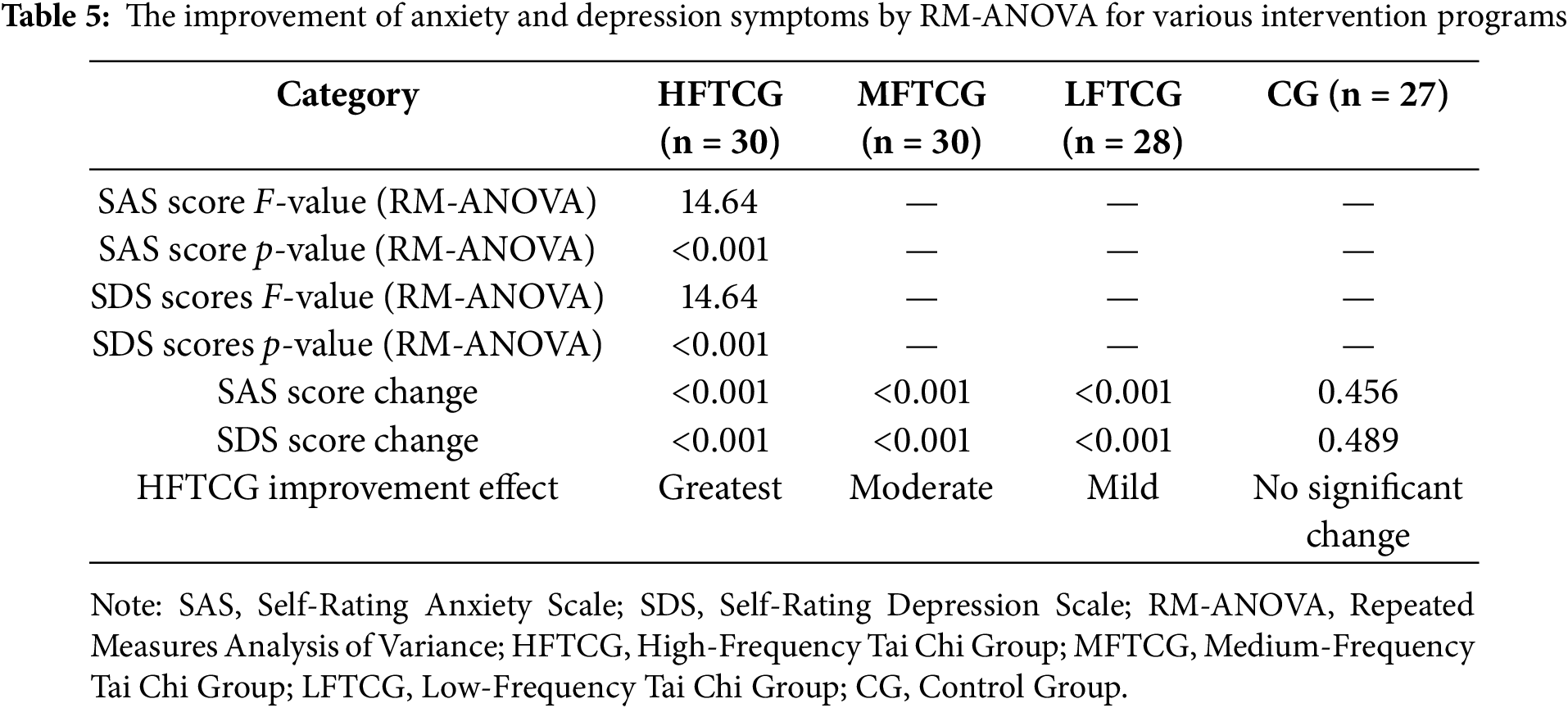

4.4 The Effect of Intervention Changes with Time

RM-ANOVA was adopted to assess temporal changes in treatment impacts across diverse assessment points. The results showcased: All intervention groups presented significant progressive improvements in both anxiety and depressive symptoms over the 8-week period (F(2, 222) = 14.64, p < 0.001). Treatment efficacy demonstrated temporal improvement, with the HFTCG showing the most substantial therapeutic gains by week 8. Detailed RM-ANOVA results for anxiety and depressive symptom improvements across intervention protocols are presented in Table 5.

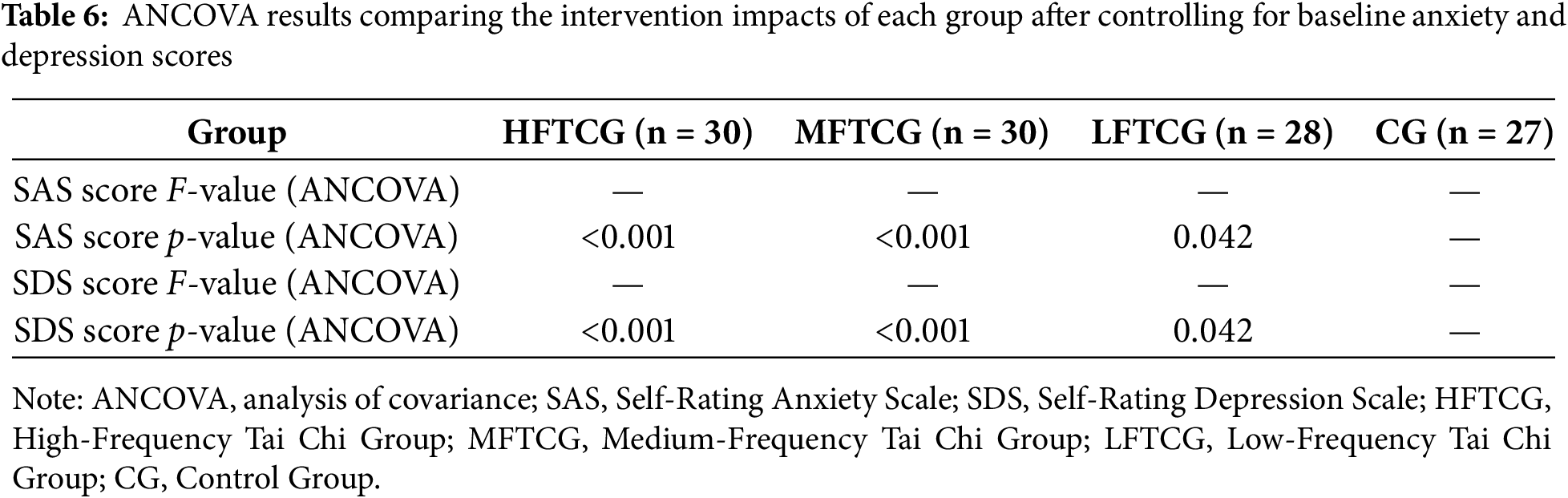

To account for the impact of baseline anxiety and depression scores on the outcomes, our study conducted an ANCOVA was performed. The results presented that, after controlling for baseline scores, both the HFTCG and MFTCG still exhibited significantly superior improvements in anxiety and depressive symptoms in contrast to the CG (p < 0.001), whereas the LFTCG showed a relatively smaller improvement effect (p = 0.042). The ANCOVA results comparing the intervention impacts across groups after adjusting for baseline anxiety and depression scores are presented in Table 6.

During the study period, no severe adverse events were reported. A subset of participants experienced mild muscle fatigue and joint discomfort. however, all symptoms were resolved spontaneously within a short duration and did not compromise the study’s progression.

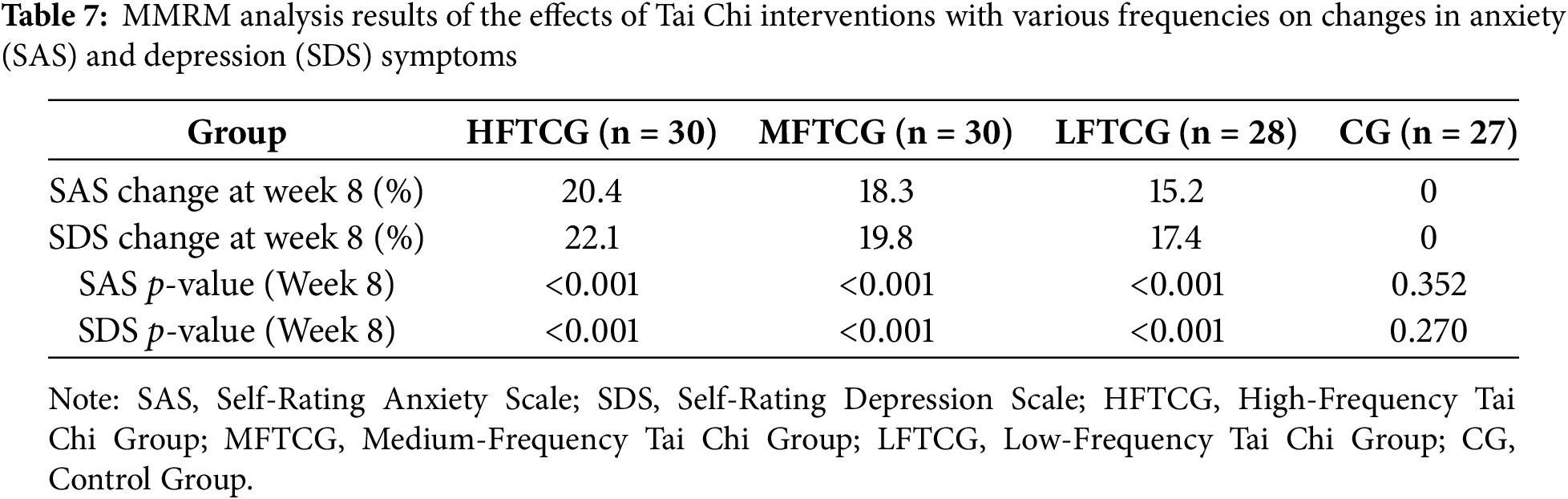

The results of the MMRM analysis confirmed the consistency of the observed outcomes across time points (baseline, week 4, and week 8). Specifically, significant reductions in both anxiety (SAS) and depression (SDS) scores were maintained throughout the 8-week intervention period for all intervention groups. The HFTCG showed the most pronounced improvements, with a significant reduction of 20.4% in SAS scores (p < 0.001) and 22.1% in SDS scores (p < 0.001) by week 8. The MFTCG exhibited a reduction of 18.3% in SAS scores (p < 0.001) and 19.8% in SDS scores (p < 0.001), while the LFTCG demonstrated a 15.2% decrease in SAS scores (p < 0.001) and 17.4% in SDS scores (p < 0.001). In contrast, the CG showed no significant changes across any of the time points (SAS: p = 0.352; SDS: p = 0.270). Table 7 illustrates MMRM analysis results of the effects of Tai Chi interventions with various frequencies on changes in anxiety (SAS) and depression (SDS) symptoms.

5.1 Significance of High-Frequency Tai Chi Intervention Effect

The HFTCG illustrated the strongest intervention effects, especially in reducing anxiety and depressive symptoms. Post-intervention, participants in the HFTCG exhibited substantial reductions in both anxiety (as measured by SAS scores) and depression (SDS scores), with significantly greater improvement magnitudes in contrast to other groups. Specifically, anxiety symptom scores reduced by 20.4% over the eight-week period, while depressive symptom scores declined by 22.1%. These findings demonstrated that high-frequency Tai Chi intervention effectively slows down anxiety and depression among college students, with its therapeutic impacts being statistically superior among the four experimental groups.

These results align with recent empirical literature. Various studies have established that higher-frequency exercise interventions may be more efficacious in mitigating mental health disorders, and particularly, anxiety and depression [30,31]. Physical exercise has been extensively recorded to confer psychological benefits through dual mechanisms: (1) physiological modulation (e.g., reduced sympathetic nervous activity and enhanced parasympathetic function) and (2) psychological improvement (e.g., strengthened self-efficacy and emotional regulation). Within the context of Tai Chi, the higher practice frequency likely expanded therapeutic outcomes through enhanced physiological adaptation and relaxation impacts attributable to more maintained movement cycles, hence producing superior anxiolytic and antidepressant impacts.

Besides, the observed symptom alleviation may be partially induced by Tai Chi’s unique integration of meditative and deep-breathing components. As a mind-body discipline, Tai Chi incorporates psychoregulatory techniques such as mindfulness and deliberate respiratory control, which become more effectively engaged with regular practice [32]. This reveals that optimal intervention efficacy requires both appropriate frequency and temporal structuring to strengthen mental health benefits.

5.2 Limitations of the Effect of Low-Frequency Tai Chi Intervention

While the LFTCG also indicated measurable improvements in anxiety and depressive symptoms, the effect sizes were significantly smaller than those uncovered in the HFTCG. Quantitatively, the LFTCG showed symptom reductions of 15.2% (anxiety) and 17.4% (depression), which were markedly lower than the HFTCG’s reductions of 20.4% and 22.1%, respectively. These findings suggest that while low-frequency Tai Chi provides some psychological benefits, its therapeutic efficacy appears substantially limited in contrast to higher-frequency interventions.

This observed disparity may be attributed to fundamental differences in intervention dosage. The lower practice frequency in LFTCG resulted in reduced cumulative exposure, potentially lowering both physiological adaptation and psychological conditioning impacts. Current evidence consistently indicates that exercise-induced mental health benefits exhibit a clear dose-response relationship, contingent upon intervention frequency, intensity, and duration [33,34]. Higher-frequency regimens promote more sustained neurobiological modulation (e.g., endorphin release, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis regulation) and confer greater psychological benefits through reinforced behavioral conditioning [35]. In contrast, the suboptimal frequency in LFTCG may have failed to reach the critical threshold needed for robust physiological and psychological changes.

Besides, the abbreviated practice schedule in LFTCG likely compromised participants’ ability to fully engage with Tai Chi’s meditative components. As a movement-based mindfulness practice, Tai Chi requires regular, maintained engagement to cultivate psychosomatic awareness and stress resilience. The intermittent practice pattern in LFTCG may have prevented the consolidation of these mind-body integration impacts, hence attenuating potential benefits for emotional regulation.

To sum up, while low-frequency Tai Chi demonstrates statistically significant impacts, its clinical meaningfulness appears constrained by insufficient intervention intensity. These findings emphasized the importance of dosage optimization in mind-body interventions, suggesting that future research should delve into threshold frequencies needed for clinically significant outcomes and explore adjunct strategies to enhance efficacy in time-constrained protocols.

5.3 Medium Effect of Medium Frequency Tai Chi

The MFTCG indicated statistically significant improvements in both anxiety and depressive symptoms, although the effect sizes were particularly smaller than those observed in the HFTCG. Quantitative analysis suggested that after 4 weeks of intervention, the MFTCG showed symptom reductions of 18.3% (anxiety) and 19.8% (depression), which continued to enhance through week 8, but failed to reach the therapeutic levels achieved by HFTCG. These findings suggest that while moderate-frequency Tai Chi intervention yields measurable mental health benefits, its efficacy may be suboptimal because of insufficient synchronization between practice frequency and the needed physiological/psychological adaptation thresholds.

It is worth noting that this observed efficacy gradient may be explained through Tai Chi’s unique dual-mechanism framework. As a mind-body integrative exercise, Tai Chi simultaneously engages both physical movement and meditative components, with participants benefiting from coordinated deep breathing and mindfulness practices that boost stress resilience and emotional regulation [30,36]. The higher practice frequency in HFTCG likely facilitates more consistent activation of these synergistic impacts through repeated neurobiological reinforcement. In contrast, the intermediate intervals in MFTCG may disrupt the cumulative benefits by exceeding the critical window for sustaining physiological and psychological adaptations.

From a neurophysiological perspective, the MFTCG’s intervention frequency might be insufficient to sustain optimal levels of endorphin release and cardiorespiratory improvement, both established mediators of exercise-induced mood improvement [37,38]. While high-frequency practice sustains assessed endorphin levels through regular stimulation, medium-frequency intervals could enable these beneficial impacts to subside between sessions. Similarly, the meditative component’s therapeutic potential for anxiety and depression [39,40] may be partially compromised in MFTCG due to reduced opportunities for mindfulness skill consolidation.

Particularly, the MFTCG still produced clinically significant improvements, demonstrating that medium-frequency protocols remain a viable alternative for populations with scheduling constraints or limited exercise capacity. This finding has vital practical implications, suggesting that individuals who cannot adhere high-frequency regimens may still achieve substantial mental health benefits from modified Tai Chi programs. Future research should delve into optimization strategies for medium-frequency interventions, potentially through amplifying session intensity, enhanced mindfulness components, or supplementary home practice modules to bridge the efficacy gap with high-frequency protocols.

5.4 No Change in the Control Group

The control group (CG) did not participate in any Tai Chi practice or alternative exercise interventions throughout the 8-week study period. As a consequence, this group presented no significant improvements in either anxiety or depressive symptoms. Statistical analysis of SAS and SDS scores suggested no meaningful changes between baseline and post-intervention measurements (t = 0.93, p = 0.352), indicating a stable, but unenhanced mental health status among university students without active intervention. These null findings offer a critical comparative baseline that substantiates the therapeutic impact observed in the intervention groups. Besides, the CG’s static symptom profile underscores two critical observations: spontaneous improvement of anxiety/depression symptoms is unlikely in the absence of targeted interventions, and routine lifestyle patterns lacking structured physical activity or psychological components may be insufficient to reduce mental health concerns in collegiate populations. This controlled comparison enhances the evidence for Tai Chi’s specific efficacy beyond natural symptom fluctuation. It is interesting that the contrast with Tai Chi intervention groups elucidates the modality’s dual-pathway mechanism: physiological modulation (e.g., autonomic nervous system regulation, endorphin release) synergistically combines with psychobehavioral components (e.g., meditative breathing, mindfulness) to produce clinically significant improvements [32]. The CG’s unchanged status thus serves as an experimental control validating that observed therapeutic impacts derive from active intervention components rather than temporal or assessment artifacts.

These findings carry significant implications for mental health promotion in academic settings. The persistent symptom levels in CG participants highlight the risks of unaddressed mental health needs in high-pressure university environments. In contrast, Tai Chi emerges as an evidence-based, scalable intervention combining several benefits: minimal risk profile, practical implementability, and simultaneous targeting of both physiological and psychological symptom maintenance factors.

While our study demonstrates the immediate effectiveness of Tai Chi intervention in alleviating anxiety and depression symptoms, it is crucial to consider whether these benefits are maintained over time. The results observed at the 8-week mark showed significant reductions in both anxiety (SAS) and depression (SDS) scores across the high-frequency, medium-frequency, and low-frequency Tai Chi groups compared to the control group. However, the study did not extend beyond 8 weeks to evaluate the long-term sustainability of these effects.

The long-term sustainability of these benefits is a key aspect for future research. Existing literature on physical activity and mental health interventions suggests that while short-term benefits are often significant, the maintenance of such improvements depends on the consistency and intensity of the intervention [41–43]. Among Tai Chi, it is plausible that continued practice, especially at higher frequencies, may help maintain or even enhance the therapeutic effects over time. However, without follow-up data extending beyond the intervention period, we cannot definitively conclude whether these improvements in anxiety and depression symptoms are maintained in the long run. Several studies have reported that while initial gains from interventions like Tai Chi are often robust, their durability can diminish without ongoing engagement [44,45]. This suggests that the participants in our study may require continued participation in Tai Chi or similar physical activities to retain the mental health benefits observed during the study period. Future research should ideally include longer follow-up periods to assess whether the positive effects of Tai Chi continue over time and to explore the need for periodic “booster” sessions to sustain these benefits.

To better understand the long-term impact, future trials could incorporate follow-up assessments at multiple points after the intervention (e.g., 6 months, 1 year), allowing researchers to evaluate whether the improvements observed during the 8 weeks remain or if further interventions are necessary.

Our study demonstrates that high-frequency 24-form Tai Chi effectively reduces anxiety and depressive symptoms among university students, with the most significant improvements observed in the high-frequency group. While moderate- and low-frequency interventions showed some benefits, they were less pronounced. These results emphasize the importance of intervention frequency in the effectiveness of Tai Chi for mental health. The findings suggest that high-frequency Tai Chi could be a valuable addition to mental health promotion programs for stress-sensitive populations, particularly university students. Future research should explore long-term adherence and the underlying mechanisms to enhance clinical applications.

Acknowledgement: We would like to express our gratitude to Dr. Jasmine Thompson, a native English speaker, for her language refinement and optimization of this manuscript.

Funding Statement: China National Social Science Fund Project, 19BTY052.

Author Contributions: Yumeng Kong: Contributed to the core research process, including study design, data collection, data analysis, and manuscript writing; participated in the review and approval of the final version of the manuscript. Xuesong Guo: Collaborated in key research links, involving study design, data collection, data analysis, and manuscript writing; joined the review and approval of the final manuscript. Yifei Wang: Engaged in essential research work, covering study design, data collection, data analysis, and manuscript writing; participated in the review and approval of the final version of the manuscript. All authors (Yumeng Kong, Xuesong Guo, Yifei Wang) jointly reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript to ensure the accuracy, integrity, and scientificity of the research content and writing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets generated or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol was approved by the Biomedical Ethics Committee of Qufu Normal University (Approval No.: 2025-111) and registered with the Thai Clinical Trial Registry (Number: TCTR20250528007), https://www.thaiclinicaltrials.org/show/TCTR20250528007 (accessed on 16 September 2025). Registration Date: 28 May 2025.

Informed Consent: All participants provided written informed consent prior to enrollment.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Li W, Zhao Z, Chen D, Peng Y, Lu Z. Prevalence and associated factors of depression and anxiety symptoms among college students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2022;63(11):1222–30. doi:10.1111/jcpp.13606. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Auerbach RP, Alonso J, Axinn WG, Cuijpers P, Ebert DD, Green JG, et al. Mental disorders among college students in the world health organization world mental health surveys. Psychol Med. 2016;46(14):2955–70. doi:10.1017/s0033291716001665. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Steare T, Gutiérrez Muñoz C, Sullivan A, Lewis G. The association between academic pressure and adolescent mental health problems: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2023;339(70):302–17. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2023.07.028. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Zhang C, Shi L, Tian T, Zhou Z, Peng X, Shen Y, et al. Associations between academic stress and depressive symptoms mediated by anxiety symptoms and hopelessness among Chinese college students. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2022;15:547–56. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S353778. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Kotyśko M, Frankowiak J. The importance of perceived social support for symptoms of depression and academic stress among university students—a latent profile analysis. PLoS One. 2025;20(5):e0324785. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0324785. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Benítez-Agudelo JC, Restrepo D, Navarro-Jimenez E, Clemente-Suárez VJ. Longitudinal effects of stress in an academic context on psychological well-being, physiological markers, health behaviors, and academic performance in university students. BMC Psychol. 2025;13(1):753. doi:10.1186/s40359-025-03041-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Wang Y, Ge Y, Chu M, Xu X. Factors influencing nursing undergraduates’ motivation for postgraduate entrance: a qualitative inquiry. BMC Nurs. 2024;23(1):728. doi:10.1186/s12912-024-02373-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Li Z, Li J, Kong J, Li Z, Wang R, Jiang F. Adolescent mental health interventions: a narrative review of the positive effects of physical activity and implementation strategies. Front Psychol. 2024;15:1433698. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1433698. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Sprung JM, Rogers A. Work-life balance as a predictor of college student anxiety and depression. J Am Coll Health. 2021;69(7):775–82. doi:10.1080/07448481.2019.1706540. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Monserrat-Hernández M, Checa-Olmos JC, Arjona-Garrido Á, López-Liria R, Rocamora-Pérez P. Academic stress in university students: the role of physical exercise and nutrition. Healthcare. 2023;11(17):2401. doi:10.3390/healthcare11172401. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Beiter R, Nash R, McCrady M, Rhoades D, Linscomb M, Clarahan M, et al. The prevalence and correlates of depression, anxiety, and stress in a sample of college students. J Affect Disord. 2015;173:90–6. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2014.10.054. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Zhang J, Peng C, Chen C. Mental health and academic performance of college students: knowledge in the field of mental health, self-control, and learning in college. Acta Psychol. 2024;248(6):104351. doi:10.1016/j.actpsy.2024.104351. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Gull M, Kaur N, Abuhasan WMF, Kandi S, Nair SM. A comprehensive review of psychosocial, academic, and psychological issues faced by university students in India. Ann Neurosci. 2025;7:124. doi:10.1177/09727531241306571. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Kuang X, Dong Y, Song L, Dong L, Chao G, Zhang X, et al. The effects of different types of Tai Chi exercise on anxiety and depression in older adults: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Front Public Health. 2024;11:1295342. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2023.1295342. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Liu F, Cui J, Liu X, Chen KW, Chen X, Li R. The effect of Tai Chi and Qigong exercise on depression and anxiety of individuals with substance use disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2020;20(1):161. doi:10.1186/s12906-020-02967-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Wang Y. Tai Chi exercise and the improvement of mental and physical health among college students. In: Tai Chi Chuan. Basel, Switzerland: kARGER; 2008. p. 135–45. doi:10.1159/000134294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Yin J, Yue C, Song Z, Sun X, Wen X. The comparative effects of Tai Chi versus non-mindful exercise on measures of anxiety, depression and general mental health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2023;337(3):202–14. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2023.05.037. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. He J, Chan SH, Lin J, Tsang HW. Integration of Tai Chi and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for sleep disturbances in older adults: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Sleep Med. 2024;122(3):35–44. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2024.07.029. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. World Medical Association. World medical association declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191–4. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.281053. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Serdar CC, Cihan M, Yücel D, Serdar MA. Sample size, power and effect size revisited: simplified and practical approaches in pre-clinical, clinical and laboratory studies. Biochem Med. 2021;31(1):010502. doi:10.11613/BM.2021.010502. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Kang H. Sample size determination and power analysis using the G*Power software. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2021;18:17. doi:10.3352/jeehp.2021.18.17. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Liang G, Fu W, Wang K. Analysis of t-test misuses and SPSS operations in medical research papers. Burns Trauma. 2019;7(1):s41038–19–0170–3. doi:10.1186/s41038-019-0170-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Zung WW. A rating instrument for anxiety disorders. Psychosom: J Consult Liaison Psychiatry. 1971;12(6):371–9. doi:10.1016/s0033-3182(71)71479-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Zung WW, Richards CB, Short MJ. Self-rating depression scale in an outpatient clinic. Further validation of the SDS. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1965;13(6):508–15. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1965.01730060026004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Zakibakhsh N, Basharpoor S, Ghalyanchi Langroodi H, Narimani M, Nitsche MA, Ali Salehinejad M. Repeated prefrontal tDCS for improving mental health and cognitive deficits in multiple sclerosis: a randomized, double-blind, parallel-group study. J Transl Med. 2024;22(1):843. doi:10.1186/s12967-024-05638-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Muhammad LN. Guidelines for repeated measures statistical analysis approaches with basic science research considerations. J Clin Invest. 2023;133(11):e171058. doi:10.1172/JCI171058. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Egger MJ, Coleman ML, Ward JR, Reading JC, Williams HJ. Uses and abuses of analysis of covariance in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1985;6(1):12–24. doi:10.1016/0197-2456(85)90093-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Bell ML, Rabe BA. The mixed model for repeated measures for cluster randomized trials: a simulation study investigating bias and type I error with missing continuous data. Trials. 2020;21(1):148. doi:10.1186/s13063-020-4114-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Bonovas S, Piovani D. On p-values and statistical significance. J Clin Med. 2023;12(3):900. doi:10.3390/jcm12030900. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Saeed SA, Cunningham K, Bloch RM. Depression and anxiety disorders: benefits of exercise, Yoga, and meditation. Am Fam Physician. 2019;99(10):620–7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

31. Zhu L, Li L, Li XZ, Wang L. Mind-body exercises for PTSD symptoms, depression, and anxiety in patients with PTSD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychol. 2022;12:738211. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.738211. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Kong J, Wilson G, Park J, Pereira K, Walpole C, Yeung A. Treating depression with Tai Chi: state of the art and future perspectives. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:237. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00237. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Wu C, Xu Y, Chen Z, Cao Y, Yu K, Huang C. The effect of intensity, frequency, duration and volume of physical activity in children and adolescents on skeletal muscle fitness: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(18):9640. doi:10.3390/ijerph18189640. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Zheng J, Su X, Xu C. Effects of exercise intervention on executive function of middle-aged and elderly people: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Front Aging Neurosci. 2022;14:960817. doi:10.3389/fnagi.2022.960817. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Wang Y, Ashokan K. Physical exercise: an overview of benefits from psychological level to genetics and beyond. Front Physiol. 2021;12:731858. doi:10.3389/fphys.2021.731858. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Sani NA, Yusoff SSM, Norhayati MN, Zainudin AM. Tai Chi exercise for mental and physical well-being in patients with depressive symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(4):2828. doi:10.3390/ijerph20042828. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Schoenfeld TJ, Swanson C. A runner’s high for new neurons? Potential role for endorphins in exercise effects on adult neurogenesis. Biomolecules. 2021;11(8):1077. doi:10.3390/biom11081077. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Nowacka-Chmielewska M, Grabowska K, Grabowski M, Meybohm P, Burek M, Małecki A. Running from stress: neurobiological mechanisms of exercise-induced stress resilience. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(21):13348. doi:10.3390/ijms232113348. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Liu X, Li R, Cui J, Liu F, Smith L, Chen X, et al. The effects of Tai Chi and Qigong exercise on psychological status in adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychol. 2021;12:746975. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.746975. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Payne P, Crane-Godreau MA. Meditative movement for depression and anxiety. Front Psychiatry. 2013;4:71. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00071. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Rebar AL, Stanton R, Geard D, Short C, Duncan MJ, Vandelanotte C. A meta-meta-analysis of the effect of physical activity on depression and anxiety in non-clinical adult populations. Health Psychol Rev. 2015;9(3):366–78. doi:10.1080/17437199.2015.1022901. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Smith PJ, Merwin RM. The role of exercise in management of mental health disorders: an integrative review. Annu Rev Med. 2021;72(1):45–62. doi:10.1146/annurev-med-060619-022943. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Freak-Poli RLA, Cumpston M, Albarqouni L, Clemes SA, Peeters A. Workplace pedometer interventions for increasing physical activity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;2020(7):CD009209. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd009209.pub2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Wang F, Lee EO, Wu T, Benson H, Fricchione G, Wang W, et al. The effects of Tai Chi on depression, anxiety, and psychological well-being: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Behav Med. 2014;21(4):605–17. doi:10.1007/s12529-013-9351-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Liu X, Vitetta L, Kostner K, Crompton D, Williams G, Brown WJ, et al. The effects of Tai Chi in centrally obese adults with depression symptoms. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2015;2015(6):879712. doi:10.1155/2015/879712. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools