Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Relationship between Chinese Medical Students’ Perceived Stress and Short-Form Video Addiction: A Perspective Based on the Multiple Theoretical Frameworks

1 Personnel Department, Jiangxi University of Chinese Medicine, Nanchang, 330103, China

2 School of Economics and Management, Jiangxi University of Chinese Medicine, Nanchang, 330103, China

3 Graduate School, Jiangxi University of Chinese Medicine, Nanchang, 330103, China

4 School of Education, Guangxi University of Foreign Languages, Nanning, 530222, China

* Corresponding Authors: Zhi-Yun Zhang. Email: ; Weiguaju Nong. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Causes, Consequences and Interventions for Emerging Social Media Addiction)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(10), 1533-1551. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.070883

Received 26 July 2025; Accepted 24 September 2025; Issue published 31 October 2025

Abstract

Objectives: Medical students often rely on recreational internet media to relieve the stress caused by immense academic and life pressures, and among these media, short-form videos, which are an emerging digital medium, have gradually become the mainstream choice of students to relieve their stress. However, the addiction caused by their usage has attracted the widespread attention of both academia and society, which is why the purpose of this study is to systematically explore the underlying mechanisms that link perceived stress, entertainment gratification, emotional gratification, short-form video usage intensity, and short-form video addiction based on multiple theoretical frameworks including the Compensatory Internet Use Model (CIU), the Interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution Model (I-PACE), and the Use and Gratification Theory (UGT). Methods: A hypothetical model with 9 research hypotheses was constructed. Taking medical students from Chinese universities as the research subjects, 1057 valid responses were collected through an online questionnaire survey, including 358 males and 658 females. Structural equation modelling (SEM) was performed using the AMOS software to test the research hypotheses. Results: (1) Perceived stress positively predicted entertainment gratification and emotional gratification (β = 0.72, p < 0.001; β = 0.61, p < 0.001); (2) Entertainment gratification and emotional gratification positively influenced short-form video usage intensity (β = 0.35, p < 0.001; β = 0.19, p < 0.001); (3) Entertainment gratification and emotional gratification positively predicted short-form video addiction (β = 0.40, p < 0.001; β = 0.17, p < 0.001); (4) Short-form video usage intensity positively influenced short-form video addiction (β = 0.36, p < 0.001); and (5) Perceived stress exerted an indirect but positive effect on both short-form video usage intensity and short-form video addiction, mediated by entertainment and emotional gratification (β = 0.37, p < 0.001; β = 0.52, p < 0.001). Conclusion: The mechanisms that underlie medical students’ short-form video addiction in stressful situations were revealed in this study. It was found that stress enhances medical students’ need for entertainment and emotional online compensation, prompting more frequent short-form video usage and ultimately leading to addiction. These results underscore the need to address the stressors faced by medical students. Effective interventions should prioritise stress management strategies and promote healthier alternative coping mechanisms to mitigate the risk of addiction.Keywords

Short-video applications have experienced a surge in popularity in recent years, emerging as the primary means for the public to access entertainment and information [1]. According to a report by the China Internet Network Information Center [2], the number of internet users in China was approximately 1.15 billion in June 2025, with short-video users accounting for 95.1% of the total internet user base. Short videos typically refer to video content that lasts 1 to 5 min, with a maximum duration of 15 min [3], covering diverse thematic domains such as entertainment, emotions, education, daily life, and technology. Short-video platforms not only support video browsing but also integrate functional modules, including likes, comments, sharing, live-streaming interactions, shopping, and group discussions, forming a comprehensive user interaction ecosystem that meets the diverse needs of various user groups [4]. Furthermore, these platforms provide user-friendly video editing tools and visually appealing filters [5], thereby enhancing users’ stickiness and prolonging their in-app engagement time [6]. As a result, short videos may appeal more to users than other social media platforms and are more likely to lead to short-form video addiction.

Internet addiction, also known as problematic internet use or compulsive internet use, is a behavioural disorder characterised by excessive and compulsive internet use, often leading to various adverse effects [7]. Among the many types of internet addiction, video-based social media addiction has emerged as the most prominent in recent years. Due to their high-frequency usage habits and the uniqueness of their developmental stage, adolescents have become a high-risk group for social media addiction, and related issues have become a pressing public mental health concern [8]. The phenomenon of students’ addiction to short-video platforms such as Douyin has shown a rapid spreading trend, with increasingly noticeable impacts [9]. Short-form video addiction refers to users’ obsession with repeatedly viewing short videos. This obsession is accompanied by cravings and a sense of dependency, leading to the excessive consumption of an inordinate amount of time and effort on short-video platforms [10]. This addiction is closely linked to users’ intensive usage, which is frequently manifested as the inability to control their behaviour in terms of the duration of short-form video usage. Therefore, excessive engagement with short videos may result in addiction [11]. The time users spend on short videos is continuing to grow. Based on the 2025 China Online Audio-Visual Development Research Report [12], the average daily time Chinese users spend watching short videos has reached 156 min (2.6 h), which further emphasises the high risk of addiction associated with this medium.

Several researchers have highlighted the relationship between short-form video addiction and various physical and mental health issues, particularly the negative effects of addiction, such as heightened anxiety, depression, and stress [13,14]. Although this issue has garnered attention, further research is necessary to explore the mechanisms that underlie the formation of short-form video addiction, especially to understand how short-form videos contribute to the development of student users’ addictive behaviour [15]. Previous studies have indicated a potential association between stress and internet addiction [16]. Medical students are a distinctive group within the university population, facing immense academic pressure that includes longer study hours, frequent examinations, a heavy workload of specialised courses, and demanding tasks in relation to clinical practice [17,18]. In addition to these academic challenges, these students also experience psychosocial pressures, such as high parental expectations and anxiety about their future career [19]. They may turn to short-form videos as a coping mechanism for these stressors, which could lead to addiction [20]. This indicates that medical students under high levels of stress may find short-form videos more appealing than other kinds of media, rendering them more vulnerable to addiction. However, existing studies of medical students’ addiction in the current literature are primarily focused on internet addiction and smartphone addiction [21,22], while discussions that specifically concern addiction to short-form videos remain relatively scarce. Hence, the purpose of this study was to investigate the mechanisms that underlie medical students’ addiction to short-form videos, thereby increasing the understanding of this specific population’s short-form video addiction.

Kardefelt-Winther [23] introduced the Compensatory Internet Use (CIU) model, which posits that individuals who are suffering from stress may turn to short-video applications as a compensatory mechanism to alleviate their suffering. Their motivations may be positive, but excessive, repetitive, and maladaptive usage can eventually lead to addiction. This also explains why individuals persist in devoting a substantial amount of time to watching short videos, even after acknowledging the negative risk of addiction. Overall, the CIU model offers a valuable framework for examining the mechanisms that link stress and addiction [24]. Therefore, using the CIU model in this study will provide insights into the mechanisms that underlie the relationship between perceived stress and addiction. Stress has been identified in existing research as a pivotal predictor of addictive behaviour [25]. To manage stress and its accompanying psychological responses, individuals often seek various coping strategies [24]. From the CIU model’s perspective, when individuals fail to effectively release their negative emotions, they may resort to online behaviour in search of compensatory gratification. This represents a coping strategy that is driven by understandable motives [23].

Furthermore, the Interaction of the Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution model (I-PACE) serves as a theoretical framework for understanding internet addiction through three dimensions: individual characteristics, subjective perception of situations, and emotional responses [26]. This model explains how psychological distress (e.g., stress) triggers problematic social media use [27]. On the other hand, the Use and Gratification Theory (UGT) posits that people use social media to satisfy their needs and obtain gratification, and behavioural addiction may be a response to stress [28]. These theories all provide important theoretical perspectives for exploring the mechanisms by which stress leads to short-form video addiction.

Short-form videos provide users with a strong sense of gratification by enabling them to engage with them during fragmented moments of their day and receive information within a very short period of time. This behaviour of fulfilling a need has become increasingly prevalent among short-form video users [29]. Entertainment and the gratification of an emotional need are the primary factors that drive adolescents to watch short-form videos [30]. The instant feedback from social media can promptly provide virtual emotional support. Due to stress, adolescents may seek emotional support and gratification on social media, engaging in video entertainment and emotional release, which leads them to spend increasing amounts of time on social media [31]. Particularly among medical students, they can obtain emotional support through social media [32], which may increase their time spent on short-form videos. Meanwhile, when student users access the internet for entertainment purposes, they are also more likely to develop online behavioural addiction [33]. Consequently, medical students’ seeking of entertainment and their affective needs gratification are likely to lead to addiction problems. Previous researchers have not examined the relevance of emotional need gratification and its role in the relationship between perceived stress and short-form video addiction, despite the fact that exploring this issue could lead to a better understanding of the internal mechanisms by which stress triggers addiction to these particular videos. Therefore, the gratification of need is explored in this study from two dimensions, namely entertainment gratification and emotional need gratification, in the context of medical students’ excessive use of short-form videos.

Most of the existing research has been focused on the harm of short-form video addiction, highlighting the need to deepen the understanding of its formation mechanisms [10]. Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the underlying mechanisms of short-form video addiction. In summary, the purpose of this research was to explore the relationship among medical students’ perceived stress, entertainment gratification, emotional need gratification, time spent on short-form videos, and short-form video addiction by extending the application of the CIU model. The findings are anticipated to assist parents and educators in developing effective intervention strategies to address this increasingly severe social issue.

2.1 Relationship between Perceived Stress and Two Types of Usage Gratification

Stress can be defined as a negative emotional experience, state, or feeling that arises when individuals perceive external demands that exceed their available resources [34]. Researchers have demonstrated that stress is closely related to short-form video addiction [35] and, from the perspective of the CIU model, the compensatory use of short-form videos serves as a strategy to cope with negative life situations (sources of stress). Prolonged stress can lead to sustained compensatory behaviour as a means of regulating negative emotions [23]. While academic and life-related challenges can cause medical students to experience high levels of stress [36], they frequently lack sufficient resources to cope with them. Therefore, short-form videos that can effectively alleviate stress [37] are particularly appealing to this population. According to the CIU model, in these circumstances, students may develop self-compensatory motivations that are rooted in avoidant coping [23]. The effectiveness of stress relief may transform into a reward mechanism, further reinforcing their behaviour of short-form video use. As a result, stress may lead to excessive short-form video use among medical students.

Students who perceive stress tend to watch short-form videos in an effort to gratify their unmet needs [38]. Moreover, the effect of stress on their cognitive mechanisms makes them inclined to prioritise short-term rewards [39], which suggests that medical students are likely to use short-form video applications as a mechanism to gratify their needs. The importance of need gratification is emphasised in the UGT and the I-PACE, which highlights its critical role in internet addiction [40,41]. Hence, it can be inferred that the compensatory use of short-form videos driven by stress stems from unmet needs.

Internet users are driven by multifaceted needs, which not only encompass entertainment but also involve complex social and cognitive factors such as emotional resonance and the pursuit of meaning [42]. Individuals are more likely to pursue need gratification if they are under stress [40], often by seeking a hedonic experience by watching short-form videos [43]. Therefore, one of the primary reasons why students watch short-form videos [38,44] is to experience entertainment and emotional gratification based on their different stress levels and individual characteristics. Hence, entertainment gratification and emotional gratification are the focus of this study, as the two key aspects of medical students’ need gratification in the context of short-form video use. It is hypothesised that, when medical students perceive stress, they will seek gratification of their entertainment and emotional needs by watching short-form videos. On this basis, the following hypotheses were proposed:

Hypothesis 1 (H1): Perceived stress is positively correlated with entertainment gratification.

Hypothesis 2 (H2): Perceived stress is positively correlated with emotional gratification.

2.2 Relationship between Two Types of Usage Gratification and Short-Video Usage Intensity

Short-form videos provide rapid visual and auditory stimulation that frequently stimulates the release of dopamine in the brain. This pleasurable experience encourages users to engage more frequently with short-form video content [35]. Moreover, users tend to develop a positive attitude toward short-form videos when they derive gratification from them, and this shapes their subsequent behaviour, such as the continued usage of these videos [45]. It has been shown in previous studies that the intensity of short-form video usage is influenced by factors such as emotional regulation (e.g., passing time, self-comfort, or motivation), boredom, and the need for relaxation [5]. Consequently, entertainment and emotional needs are likely to contribute to the intensity of short-form video usage. However, scholarly inquiries into the influence of need gratification on addiction, particularly through the dual lenses of emotional and entertainment dimensions, remain conspicuously underrepresented in the existing literature. On this basis, the following hypotheses were proposed:

Hypothesis 3 (H3): Entertainment gratification is positively correlated with the intensity of short-form video usage.

Hypothesis 4 (H4): Emotional gratification is positively correlated with the intensity of short-form video usage.

2.3 Relationship between Two Types of Usage Gratification and Short-Video Addiction

The essence of addictive behaviour lies in the interplay between the pursuit of need gratification and the depletion of self-control. The finite capacity of human self-control means that individuals often rationalise their need-satisfying behaviour by developing compensatory beliefs [43]. There are multifaceted motives for engaging with short-form video applications, but entertainment and emotional needs emerge as the primary drivers [46], dimensions that also constitute critical facets of perceived value in the context of social media. As a result, the quest for entertainment and emotional gratification may serve as a pivotal antecedent to short-form video addiction.

Short-form videos have a strong capability to gratify users’ needs across multiple domains, including escapism, entertainment, leisure, and self-expression [47]. When individuals derive gratification from these platforms, they are inclined to sustain their usage to perpetuate this positive affective state [48]. For instance, when experiencing entertainment and relaxation via short-form videos, users foster a favourable attitude toward their usage behaviour, which, in turn, precipitates more active and frequent engagement with these applications [24]. Notably, university students, who are frequently burdened by academic and life stressors, are particularly susceptible to short-form video addiction as a means of fulfilling their psychological needs [38]. This suggests that motivations rooted in the pursuit of entertainment and emotional gratification may elevate users’ risk of developing short-form video addiction. On this basis, the following hypotheses were proposed:

Hypothesis 5 (H5): Entertainment gratification is positively correlated with short-form video addiction.

Hypothesis 6 (H6): Emotional gratification is positively correlated with short-form video addiction.

2.4 Relationship between Short-Video Usage Intensity and Short-Video Addiction

It has been indicated in previous studies that prolonged usage duration is a manifestation of internet overuse, which may lead to addiction [49]. Short-form video applications continue to deliver videos that are aligned with users’ interests, and these videos autoplay indefinitely unless they are manually stopped, which undoubtedly increases their usage intensity [29]. Hence, an uncontrollable usage desire is an inherent characteristic of short-form video addiction, while usage intensity or frequency serves as a direct indicator of this addiction [10]. Therefore, the prolonged usage of short-form videos may contribute to short-form video addiction, and on this basis, the following hypothesis was proposed:

Hypothesis 7 (H7): Short-form video usage intensity is positively correlated with short-form video addiction.

2.5 Relationship between Perceived Stress, Short-Video Usage Intensity, and Short-Video Addiction

Empirical evidence of the association between stress and the behaviour of short-form video usage has been provided in some existing studies. It has been suggested in recent research that short-form videos have become a coping mechanism for students to escape from real-life pressures, leading to prolonged usage [50]. Moreover, stress may serve as a core motivation for individuals to choose short-form videos [24]. As their stress levels increase, the likelihood of excessive short-form video usage rises, as well as the resulting addiction [11]. A significant association between academic stress and the risk of excessive usage and addiction to short-form videos among students has been found in studies focused on adolescents [51]. This may be because short-form video applications have become an important regulatory tool for students to cope with real-life stress [50]. Notably, short-form videos can help adolescents temporarily escape from real-life pressures and negative emotions [52] with their reinforcement mechanism of instant gratification [53]; however, this may, in turn, exacerbate their usage of short-form videos, thereby increasing the risk of addiction. It has been demonstrated in other studies that healthcare professionals in highly stressful occupational settings also tend to use short-form videos to relieve their stress [54]. Based on the aforementioned theoretical and empirical findings, the following hypotheses were proposed:

Hypothesis 8 (H8): Perceived stress is indirectly and positively correlated with short-form video usage intensity.

Hypothesis 9 (H9): Perceived stress is indirectly and positively correlated with short-form video addiction.

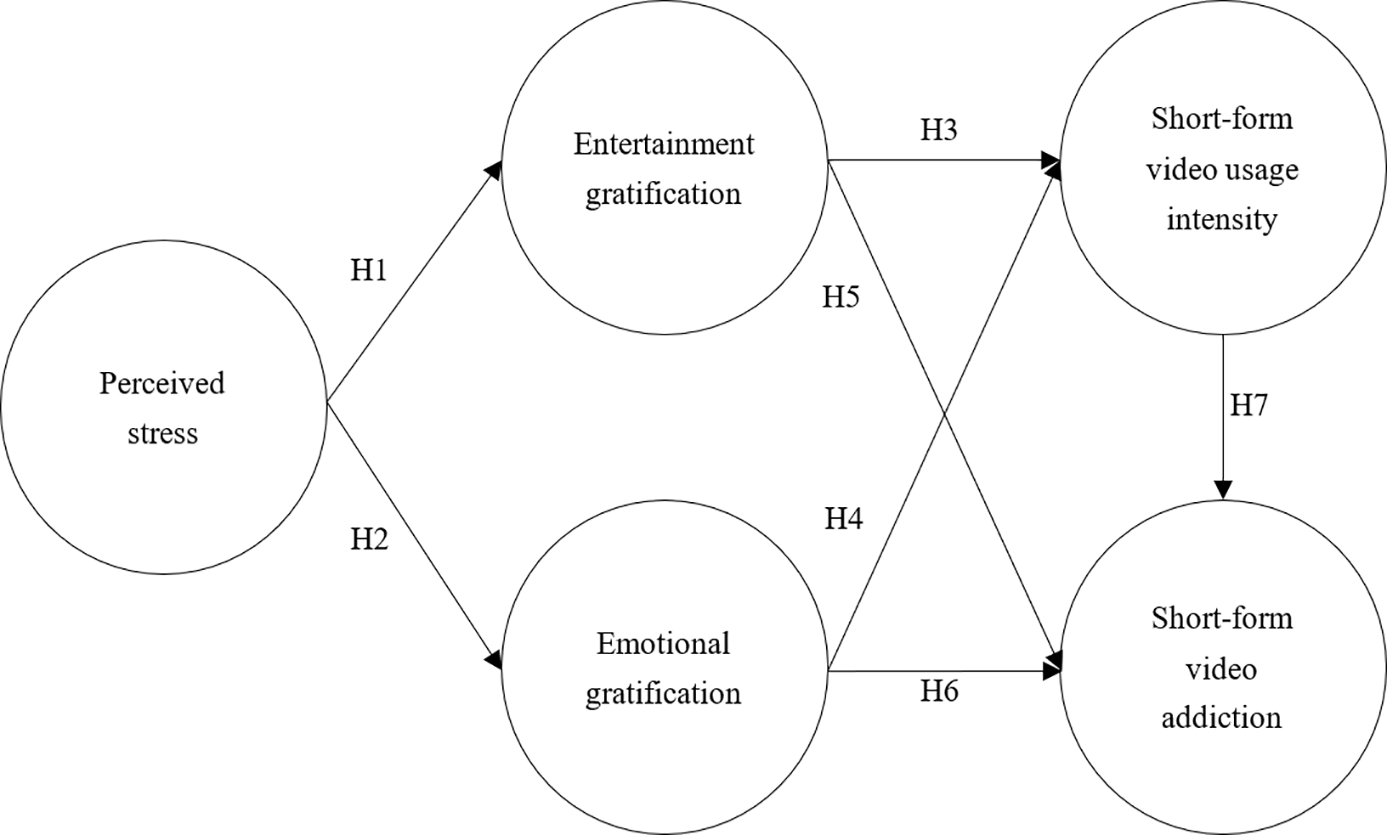

From a CIU perspective, Kardefelt-Winther [23] proposed that internet addiction can be regarded as a coping strategy that is not necessarily entirely healthy, rather than an inherently compulsive or pathological behaviour. Furthermore, the I-PACE model and UGT suggest that problematic social media use is essentially a desire to obtain gratification through social media use, serving as a coping response to stress [45,55]. Building on this, Hu and Huang [24] identified emotional responses as occupying a mediating role in the mechanism between stress and addiction in that users develop positive feedback toward the experience after achieving emotional gratification. This finding provides a more theoretical pathway to explain short-form video addiction, but a more realistic explanatory framework for internet addiction behaviour can be constructed by exploring the interplay among motivation, excessive usage, and negative outcomes [23]. In other words, medical students may develop motivations to use short-form videos as a compensatory mechanism to meet their entertainment and emotional gratification needs due to academic and life stress, thereby enabling them to cope with external pressures. Given the persistent nature of academic and life stress, this compensatory usage behaviour often exhibits a long-term trend that has the potential to evolve into short-form video addiction. On this basis, the hypothetical model of this study is presented in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Hypothetical model

This study was approved by the Academic Committee of the School of Education at Guangxi University of Foreign Languages (Approval Number: GXUFL-SE-25012). After obtaining approval, an online cross-sectional survey was conducted via the Wenjuanxing platform (https://www.wjx.cn/) from 3rd to 20th June, 2025. The questionnaires were distributed to counsellors of medical programmes at universities located in the East China region using the snowball sampling method, and they assisted in forwarding the questionnaire to students and inviting them to participate by completing the survey. After excluding questionnaires with excessively short response times, overly consistent answers, and outliers, a total of 1057 valid questionnaires were collected in this study, with an effective recovery rate of 91.91%. An informed consent statement was provided at the beginning of the electronic questionnaire, in which the purpose, background, and objectives of the study were systematically outlined, together with details of the data collection and usage methods. The measures taken to ensure the participants’ anonymity and data privacy protection were also specified, and the contact information of the principal investigators was clearly listed. Each participant was deemed to have fully read and voluntarily agreed to the informed consent statement upon completing and submitting the questionnaire.

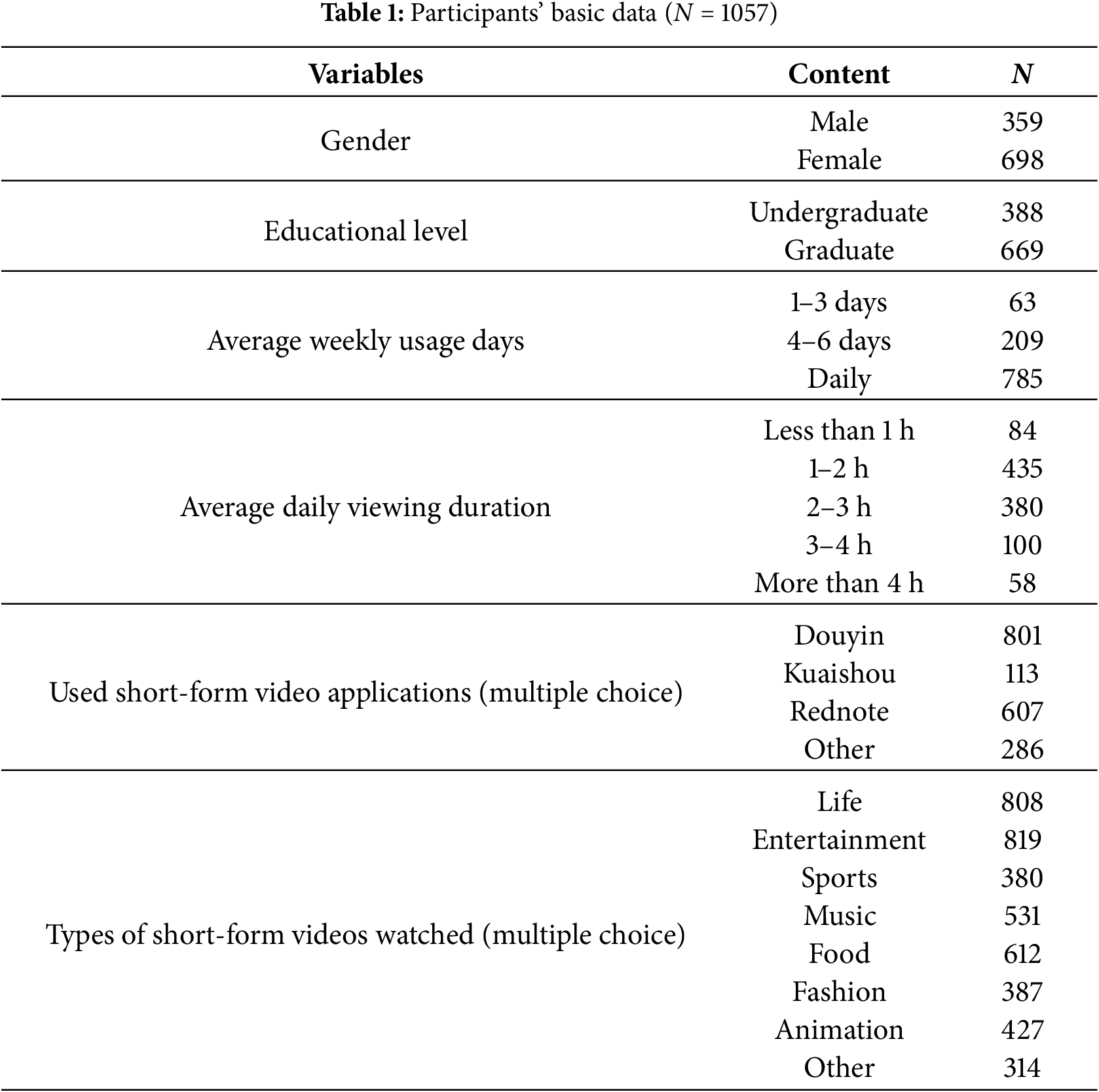

The participants of this study were medical university students aged 18 or above with a habit of using short-form video applications. Their descriptive information, including gender, educational level, average weekly usage days, average daily usage duration, types of short-form video applications used, and categories of videos watched, is presented in Table 1.

This study is based on a quantitative research design, with a questionnaire serving as the data collection tool. The questionnaire content, which was adapted from existing research instruments and relevant theoretical frameworks, was first translated into Chinese by Chinese experts with proficient English skills. Subsequently, the wording was revised by the researchers for linguistic fluency and comprehensibility so that it matched the contextual characteristics of Chinese university students. Three experts in educational psychology were invited to conduct a three-round review to ensure the validity of the questionnaire content. The first round focused on the alignment of items and research variables, the completeness of the item content, and the readability of the phrasing. The second round concentrated on the appropriateness of the revised scale content, with a further verification of the item completeness and readability. The third round consisted of a systematic review of the final revised scale to ensure its compliance with the requirements of the research design.

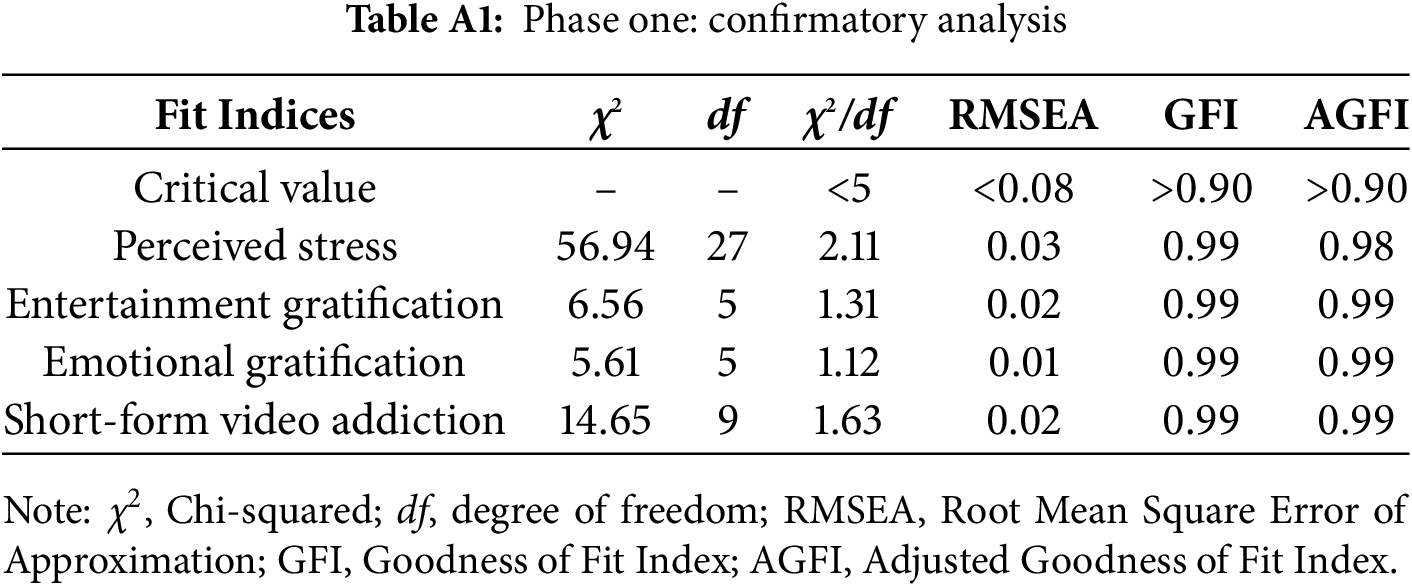

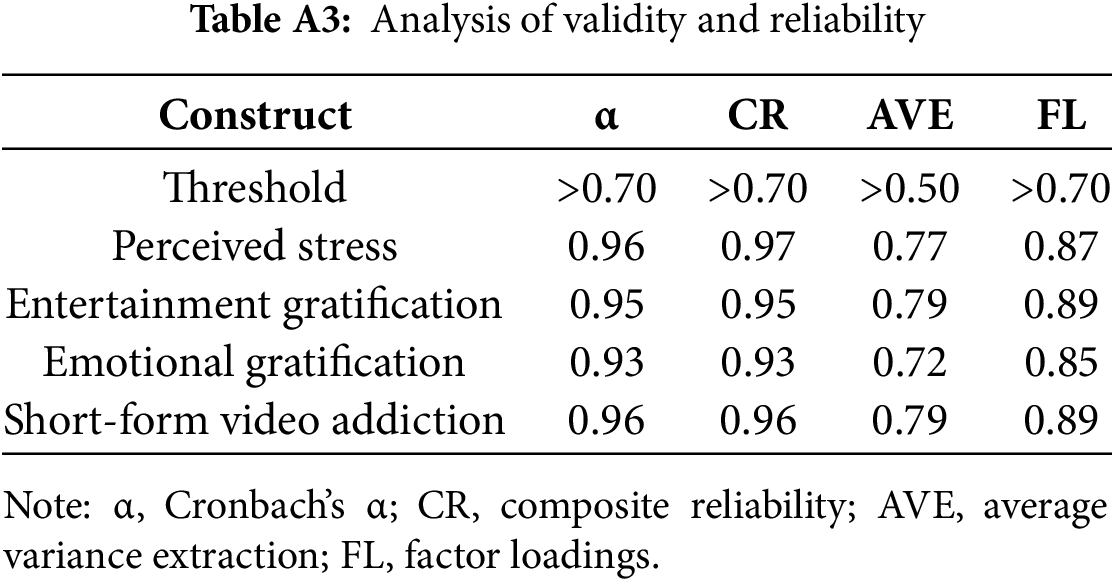

Perceived Stress refers to university students’ subjective perception of pressure caused by daily academic and life activities, as well as their perceived ability to cope with it, and, in this study, it was examined based on an adaptation of the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) developed by Cohen et al. [56], which comprises 10 items. A 5-point Likert scale (1 = never, 5 = very frequently) was used, and the higher scores indicated greater perceived stress. Sample items include: “I feel upset due to unexpected events” and “I feel unable to control important aspects of my life.” The α coefficient of the original scale was 0.78, and the α coefficient reassessed in this study was 0.96. Other reliability and validity analysis results are shown in Appendix A Tables A1–A3.

For the purposes of this study, gratification encompasses two dimensions: Entertainment Gratification and Emotional Gratification. The former reflects university students’ motivational level in seeking entertainment gratification from short-form video apps, including relaxation, enjoyment, pleasure, and killing time when bored. Khan’s [57] Relaxing Entertainment Scale, which was originally designed to measure entertainment gratification in the context of YouTube, was adapted for use in this study by replacing “YouTube” with “short-form videos” and inserting six items rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). Sample items include: “I watch short-form videos to entertain myself” and “I watch short-form videos to kill time when bored.” The α coefficient of the original scale was 0.84, and the α coefficient reassessed in this study was 0.95. Other reliability and validity analysis results are shown in Appendix A Tables A1–A3.

Emotional Gratification refers to users’ level of motivation in seeking emotional gratification by watching short-form videos, including self-expression, emotional identification, and emotional support. The Emotional Gratification Scale for Douyin Users, developed by Zhou et al. [46], was modified for use in this study to consist of six items. A 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) was also used. Sample items include: “I can express myself and gain others’ recognition on short-form video platforms” and “I can emotionally resonate with some content while watching short-form videos.” The α coefficient of the original scale was 0.89, and the α coefficient reassessed in this study was 0.93. Other reliability and validity analysis results are shown in Appendix A Tables A1–A3.

Usage Intensity is defined as the average daily time users spend on short-form video applications. It was measured using a single item on a 5-point scale with the following response options: (1) less than 1 h, (2) 1–2 h, (3) 2–3 h, (4) 3–4 h, and (5) more than 4 h.

Short-Form Video Addiction refers to users’ inability to control their behaviour when using short-form video applications. This study adopted the Short-Form Video Addiction Scale developed by Ye et al. [3], which consists of 10 items measuring participants’ perceived level of short-form video addiction. Using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree), example items include: “The time I spend watching short-form videos often exceeds my original plan” and “I neglect tasks or responsibilities because I spend time watching short-form videos.” The α coefficient of the original scale was 0.93, and the α coefficient reassessed in this study was 0.96. Other reliability and validity analysis results are shown in Appendix A Tables A1–A3.

This study employed SPSS 26.0 and AMOS 26.0 software for data processing and statistical analysis, with the specific steps as follows: First, a common method bias test was conducted using SPSS 26.0 to ensure the robustness of the research results. Next, reliability and validity analyses were performed, followed by the calculation of descriptive statistics for key variables (including means and standard deviations), and Pearson product-moment correlation analysis was used to examine the correlations among variables. Subsequently, AMOS 26.0 was utilized to conduct Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) to systematically assess the goodness-of-fit of the measurement model and the overall model, ensuring the quality of the measurement tools met acceptable standards. Finally, Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) was employed to perform confirmatory analysis on the theoretical hypothetical model to test the nine proposed research hypotheses.

4.1 Descriptive Statistical Analysis

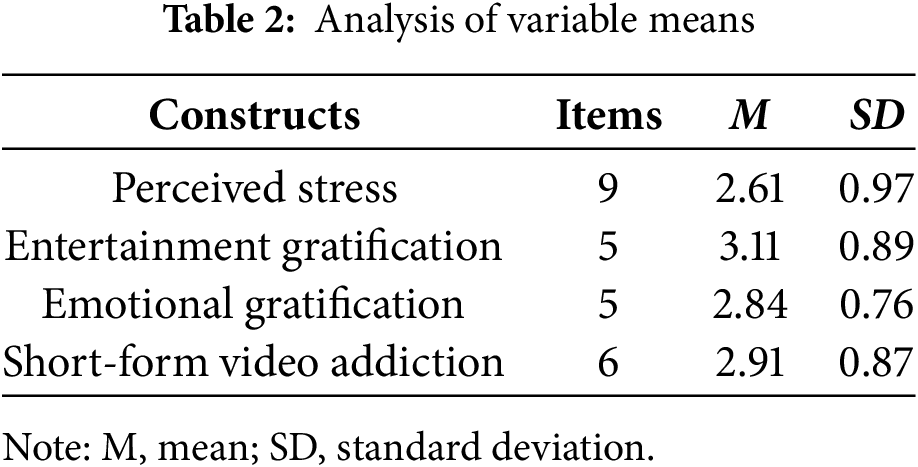

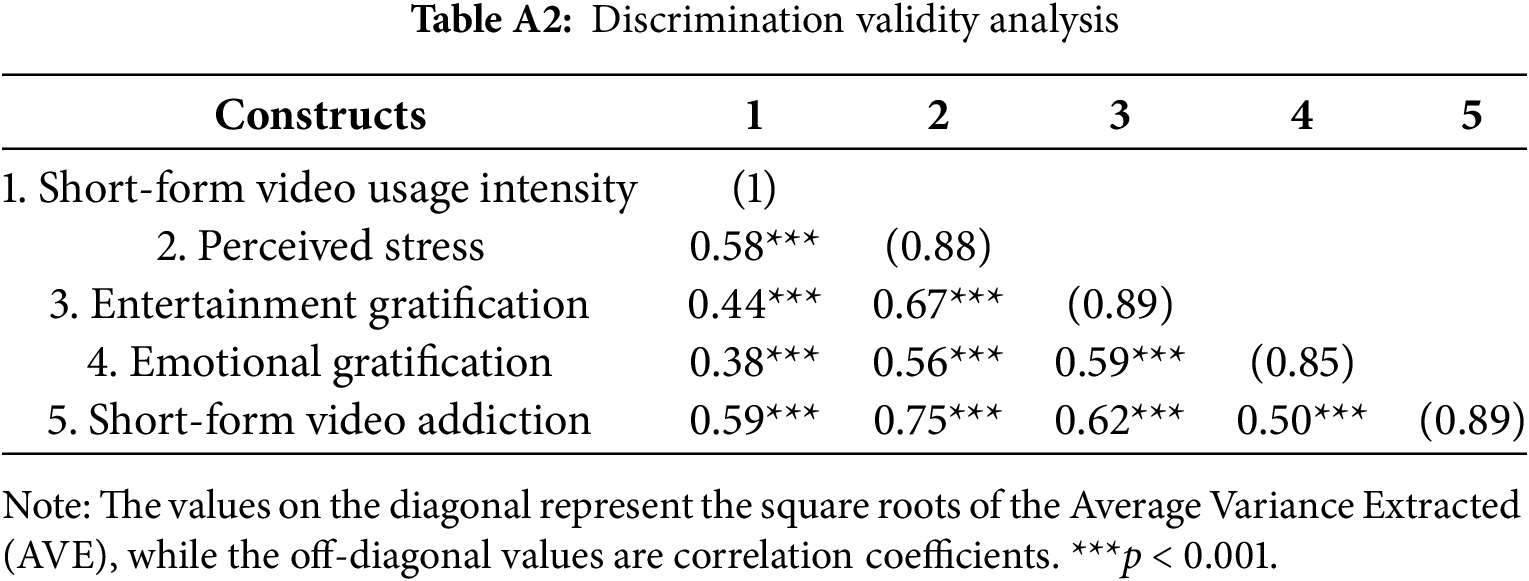

As for the means of each variable, Perceived Stress had a mean score of 2.61 (standard deviation [SD] = 0.97); Entertainment Gratification had a mean score of 3.11 (SD = 0.89); Emotional Gratification had a mean score of 2.84 (SD = 0.76); and Short-Form Video Addiction had a mean score of 2.91 (SD = 0.87), as presented in Table 2.

Before validating the research model, its fit was evaluated using the measurement model fit indices. The fit indices for this study were as follows: χ2 = 1183.41, degrees of freedom (df) = 293, χ2/df = 4.04, RMSEA = 0.05, GFI = 0.92, AGFI = 0.90, NFI = 0.96, NNFI = 0.97, CFI = 0.97, IFI = 0.97, RFI = 0.96, PNFI = 0.87, PGFI = 0.77, which meet the general criteria for structural equation modelling studies.

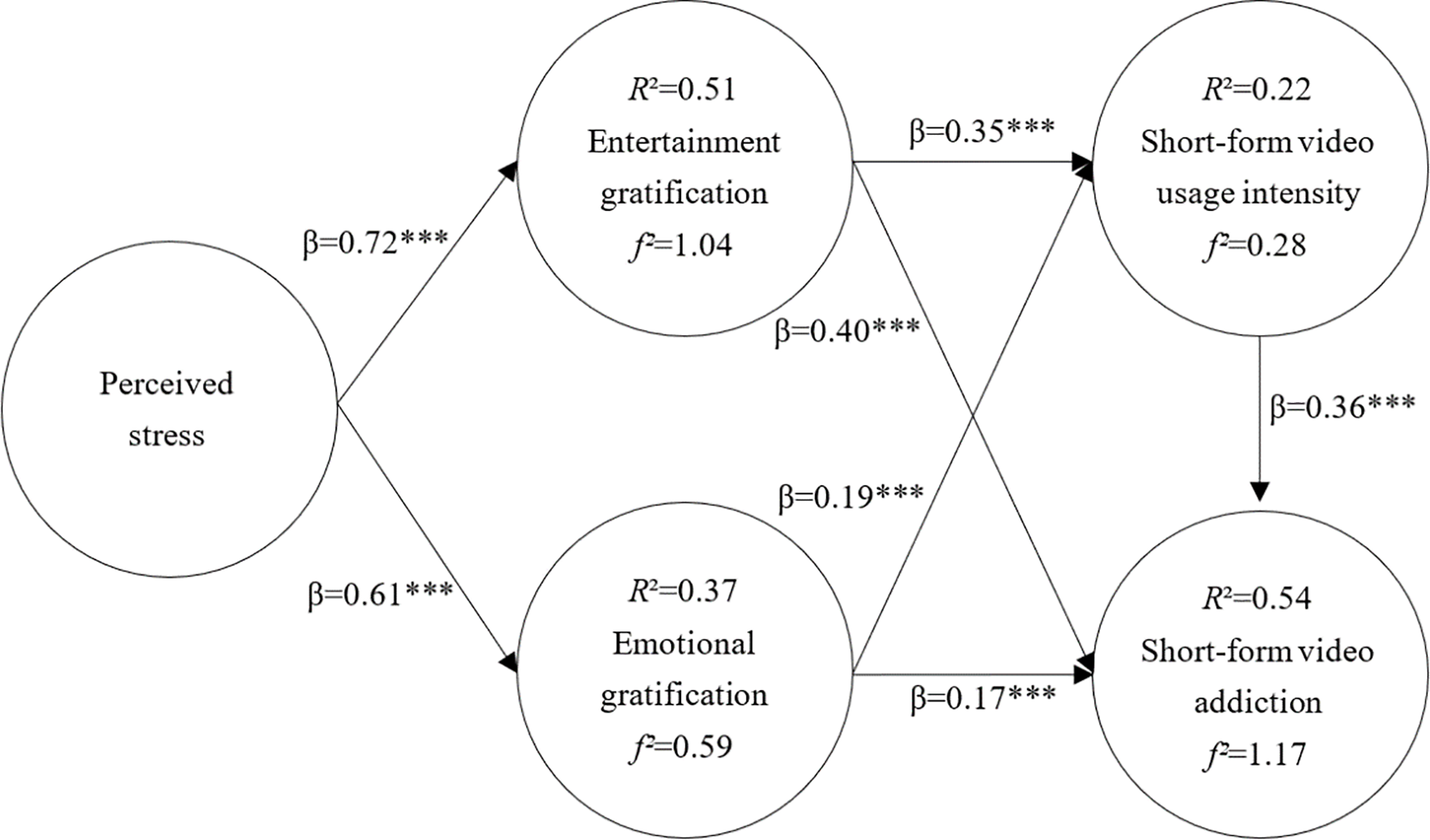

The analytical results as shown in Fig. 2 indicated that Perceived Stress was positively correlated with Entertainment Gratification (β = 0.72, p < 0.001) and Emotional Gratification (β = 0.61, p < 0.001); Entertainment Gratification was positively correlated with Usage Intensity (β = 0.35, p < 0.001) and Short-Form Video Addiction (β = 0.40, p < 0.001); Emotional Gratification was positively correlated with Usage Intensity (β = 0.19, p < 0.001) and Short-Form Video Addiction (β = 0.17, p < 0.001); and Usage Intensity was positively correlated with Short-Form Video Addiction (β = 0.36, p < 0.001). Besides, Perceived Stress explained 51% of the variance in Entertainment Gratification (f2 = 1.04) and 37% of the variance in Emotional Gratification (f2 = 0.59). Entertainment Gratification and Emotional Gratification together explained 22% of the variance in Usage Intensity (f2 = 0.28), and finally, Entertainment Gratification, Emotional Gratification, and Usage Intensity collectively explained 54% of the variance in Short-Form Video Addiction (f2 = 1.17).

Figure 2: Results model. ***p < 0.001

This study employed Bootstrapping to estimate confidence intervals for indirect effects, and used 5000 resamples to test hypotheses regarding mediation effects. Results of the indirect effect analysis showed that perceived stress had indirect positive effects on both short-video usage intensity (β = 0.37***) and short-video addiction (β = 0.52***); additionally, emotional gratification and entertainment gratification both exerted indirect positive effects on short-video addiction (β = 0.07***; β = 0.13***).

During the indirect effect analysis, it was further found that the original direct effect of perceived stress on short-video usage intensity became non-significant, indicating that entertainment gratification and emotional gratification exerted a full mediation effect in this pathway. The direct effect of perceived stress on short-video addiction remained significant, suggesting that entertainment gratification, emotional gratification, and short-video usage intensity functioned as partial mediators in this pathway. Furthermore, the direct effect of entertainment gratification on short-video addiction remained significant, indicating that short-video usage intensity served as a partial mediator in this pathway. In contrast, the direct effect of emotional gratification on short-video addiction became non-significant, suggesting that short-video usage intensity exerted a full mediation effect in this pathway.

Based on multiple theoretical frameworks including CIU, I-PACE, and UGT, this study systematically examined the formation mechanisms of short-form video addiction among Chinese medical students. Using cross-sectional data from 1057 valid respondents, path analysis was conducted, and the results supported the nine research hypotheses proposed in this study.

5.1.1 Positive Correlation between Perceived Stress and Entertainment Gratification and Emotional Gratification

Based on the findings of this study, perceived stress has a positive effect on entertainment gratification and emotional gratification, supporting research hypotheses H1 and H2. Specifically, medical students with higher levels of perceived stress are more likely to watch short-form videos for entertainment purposes and emotional gratification. The UGT posits that individuals actively choose to use short-form videos based on specific psychological needs (e.g., stress relief) and gain need gratification through media usage [45]. Consequently, stressed medical students may select short-form videos to relieve stress and seek gratification. These findings are consistent with those of previous researchers. For instance, Wegmann et al. [58] found that individuals under stress actively choose entertaining media as a coping strategy to relieve their negative emotions and to compensate for unmet psychological needs. Similarly, Xu et al. [37] suggested that short-form videos have been identified as a mechanism to cope with stress. Besides, Hu et al. [24] explained that perceived stress directly influences short-form video usage behaviour, and the need for gratification amplifies this behaviour. In summary, when medical students are stressed, they are inclined to fulfil their entertainment and emotional needs by viewing short-form videos as a way to cope with the stress.

5.1.2 Positive Correlation between Entertainment Gratification, Emotional Gratification, and Short-Form Video Usage Intensity

It is indicated by the findings of this study that entertainment gratification and emotional gratification have a positive impact on usage intensity, supporting research hypotheses H3 and H4. Specifically, the higher entertainment and emotional gratification medical students derive from short-form videos, the greater is their usage intensity because, once they experience gratification from short-form video usage, they find it increasingly difficult to control their behaviour. This finding is consistent with that of prior researchers. For instance, Jiang et al. [45] suggested that the ability of short-form videos to instantly provide information significantly increases users’ usage duration if it effectively meets their needs. Similarly, Yan et al. [6] demonstrated that short-form video platforms utilise AI algorithms to quickly assess and satisfy users’ intrinsic needs, thereby extending their usage time. Zhu et al. [44] further noted that when students achieve gratification through short-form video applications, it triggers their motivation to continue using the platform to seek potential pleasure. The I-PACE model explains this phenomenon from a psychological mechanism: the gratification obtained from using short-form videos diminishes over time, and individuals compensate for this loss of gratification by increasing their usage duration [44]. In other words, the gratification of entertainment and emotional needs significantly influences medical students’ short-form video usage behaviour; particularly, after achieving need gratification through short-form videos, they desire continuous gratification, which further strengthens their platform stickiness, which is manifested by prolonged usage time and increased usage intensity.

5.1.3 Positive Correlation between Entertainment Gratification, Emotional Gratification, and Short-Form Video Addiction

It was revealed in this study that entertainment gratification and emotional gratification have a positive impact on short-form video addiction, supporting research hypotheses H5 and H6. This finding suggests that the higher the levels of entertainment and emotional gratification medical students obtain from watching short-form videos, the greater is their short-form video addiction. In other words, medical students’ risk of developing short-form video addiction increases significantly when they experience entertainment or emotional gratification from short-form video usage. This finding is consistent with that of previous researchers. For example, Bucknell Bossen and Kottasz [30] found that seeking entertainment and emotional gratification is the primary driver of adolescents’ short-form video usage. Similarly, Zhu et al. [44] reported that gratification obtained from viewing short-form videos increases the risk of addiction among students. Wegmann et al. [58] further noted that the experience of gratification is a core feature of behavioural reinforcement mechanisms in the addiction process. In summary, if medical students achieve entertainment and emotional gratification from viewing short-form videos, their usage behaviour is reinforced, which gradually leads to them developing short-form video addiction.

5.1.4 Positive Correlation between Short-Form Video Usage Intensity and Short-Form Video Addiction

It was found from the results of this study that medical students’ short-form video usage intensity has a positive impact on their short-form video addiction, supporting research hypothesis H7. Specifically, increased usage time notably raises the risk of addiction, as excessive usage is likely to trigger addictive behaviour. This result is aligned with the perspective of Huang et al. [11], who argued that usage intensity is an essential predictor of short-form video addiction, and that addiction can be viewed essentially as the developmental outcome of excessive usage. Similarly, Ye et al. [29] highlighted the fact that university students are more susceptible to excessive short-form video usage due to their more disposable time and relatively weaker self-control, which, in turn, raises the risk of addiction. Yan et al. [59] further explained this phenomenon by noting that excessive use of short-form videos can cause students to lose interest in other offline activities, thereby trapping them in a vicious cycle of short-form video usage. In summary, medical students’ overuse of short-form videos can repeatedly reinforce this usage behaviour, ultimately causing them to develop short-form video addiction.

5.1.5 Indirect Positive Correlation between Perceived Stress and Short-Form Video Usage Intensity

The findings of this study revealed that perceived stress has an indirect positive impact on short-form video usage intensity, thereby indicating that individuals’ motivation to watch short-form videos as a means of seeking gratification is enhanced by perceived stress, which, in turn, increases their usage intensity, supporting research hypothesis H8. This result is aligned with that of previous researchers. For example, Huang et al. [11] identified perceived stress as a significant predictor of short-form video usage intensity, suggesting that stress-driven compensatory usage behaviour may further lead to excessive usage problems. As the I-PACE model points out, individuals cope with stress through problematic social media use [27]. Wegmann et al. [58] further elaborated on this phenomenon, noting that, while short-form videos can effectively alleviate stress-induced negative emotions, persistent and habitual use may gradually evolve into adverse outcomes. Similarly, Wolfers and Utz [34] provided additional insights from a motivational perspective when they argued that stress drives individuals to use the entertainment content and emotional support of short-form videos to escape real-world pressures. However, this behaviour may cause the formation of a vicious circle, resulting in increased time spent watching short-form videos. In summary, medical students are more likely to adopt short-form video use as a positive mechanism to cope with stress by obtaining entertainment and emotional gratification. However, this behaviour may be reinforced into a conditioned reflex, which ultimately leads to uncontrollable increases in usage frequency and duration.

5.1.6 Indirect Positive Correlation between Perceived Stress and Short-Form Video Addiction

The findings of this study revealed that perceived stress has an indirect positive effect on short-form video addiction, supporting research hypothesis H9. This means that individuals with higher levels of perceived stress are inclined to watch short-form videos to seek gratification, which leads to excessive usage and ultimately, the development of short-form video addiction. This result is aligned with that of previous researchers. For instance, Huang et al. [11] found that excessive stress may weaken individuals’ ability of self-control and reduce their behavioural inhibition regarding the usage of short-form videos, thereby exacerbating the risks of overuse and addiction. Chiu [60] proposed that behavioural addiction has become a mechanism to cope with stress, providing a deeper explanatory framework for the association between stress and addiction in Compulsive Internet Use. Specifically, short-form videos function as a transient, escapist pleasure mechanism that delivers a gratifying experience to users; however, this experience encourages the increased consumption of short-form videos, resulting in excessive usage [39]. In other words, highly stressed medical students are more motivated to use short-form videos to seek entertainment and emotional gratification. They turn to short-form videos to cope with life stressors, but these videos only provide temporary gratification without addressing the underlying causes of the stress. As a result, the need for compensatory usage is repeatedly activated when stress persists, ultimately leading to the development of short-form video addiction.

This study explored the antecedent variables of short-form video addiction and systematically expanded the explanatory boundaries of its antecedents. It examined the mechanism by which stress-driven need gratification ultimately triggers addiction through behavioural reinforcement. The findings provide new evidence for the application of multiple theories including CIU, I-PACE, and UGT in the field of short-form video addiction behaviour. Furthermore, by distinguishing between two types of need gratification (entertainment gratification and emotional gratification), this study verifies the differential positive predictive effects of perceived stress on distinct need gratifications in the context of short-form video use. This breaks through the single-dimensional assumption of need gratification in addiction research, revealing the dual compensatory logic of individuals simultaneously seeking entertainment and emotional gratification through short-form videos under stress. It thus offers a theoretical framework and empirical basis for understanding the dynamic relationships among usage behaviour, need gratification, and compensatory mechanisms, as well as their driving effects on addictive behaviour.

It is indicated by the findings of the study that perceived stress is a key predictor of short-form video addiction. Medical students are more susceptible to addiction when they are under stress, particularly when their psychological needs are unmet in real-world settings, and this leads them to seek entertainment and emotional connections from virtual (short-form video) content. This compensatory usage behaviour further reinforces the intensity of their short-form video usage, increasing the likelihood of addiction. The following practical implications can be proposed based on these findings: First, universities should pay attention to the academic and life stress levels of medical students. They can organise group social activities and physical exercise activities to help students alleviate their stress through healthier offline engagement. Additionally, external resource support such as study mutual-aid groups can be provided to enhance medical students’ stress-coping abilities.

Second, previous studies have indicated that effective emotional support can reduce the risk of social media addiction among medical students. Therefore, parents should strengthen emotional support mechanisms by fostering closer parent-child interaction patterns to reduce their children’s stress levels. Finally, short-form video platforms should fulfil corporate responsibility and enhance monitoring mechanisms for users’ viewing behaviour, such as implementing tiered time limits on usage duration or providing reminders about their short-form video usage time. Simultaneously, they need to optimise personalised algorithms: tailored to user groups’ backgrounds, platforms should deliver more professional and educational video content or other health-promoting recreational content, thereby reducing highly addictive entertainment use at the source.

5.4 Research Limitations and Future Directions

Although valuable empirical insights have been provided in this study into the formation mechanism of medical students’ short-form video addiction and the extension of multiple theories (including CIU, I-PACE, and UGT), it has several limitations. First, cross-sectional data were used to analyze the correlation between the variables, but it was not possible to definitively establish causal or temporal relationships. Therefore, it is recommended that future researchers adopt a longitudinal tracking design, which can capture the dynamic evolution of the variables, or employ experimental intervention methods, such as intervening in key variables like perceived stress, compensatory needs or usage intensity, while observing dynamic changes in addiction. This would provide a practical basis for intervention strategies that target short-form video addiction in student populations.

Second, although this study preliminarily distinguishes between two types of need gratification (entertainment gratification and emotional gratification), the measurement dimensions of need gratification require further deepening. Future research could use qualitative methods to explore diverse types of need gratification among short-form video users, develop multi-dimensional measurement scales, and systematically verify the differential impacts of satisfying various needs on usage intensity and addictive behaviour.

Third, this study was focused on the Chinese medical student population, who possess highly specific characteristics (e.g., academic pressure and time allocation patterns under the 5-year undergraduate training system and standardised residency training). While the applicability of CIU, I-PACE, and UGT to this particular group was verified, whether the conclusions extend to students of other high-stress or low-stress majors, or to medical students at different stages of career development, requires further validation in future studies based on expanded sample diversity and stratified analyses.

Finally, although the phenomenon of short-form video addiction has become increasingly prominent and requires more scholarly attention, other types of internet addiction should not be overlooked. It is recommended that future research expand to perspectives related to gaming disorder, nomophobia, and specific internet disorder.

This study aims to systematically explore the formation mechanisms of short-form video addiction based on multiple theoretical frameworks, including CIU, I-PACE, and UGT, with a specific focus on the examination of the intrinsic relationships among perceived stress, entertainment gratification, emotional gratification, short-form video usage intensity, and short-form video addiction. The results indicate that: (1) Perceived stress positively predicts both entertainment gratification and emotional gratification; (2) Entertainment gratification and emotional gratification exert a positive influence on short-form video usage intensity; (3) Entertainment gratification and emotional gratification have a positive predictive effect on short-form video addiction; (4) Short-form video usage intensity directly and positively impacts short-form video addiction; (5) Perceived stress indirectly and positively affects short-form video usage intensity through the mediating pathways of entertainment gratification and emotional gratification; and (6) Perceived stress indirectly and positively influences short-form video addiction through the aforementioned multiple mediational pathways. These findings reveal that stress levels among medical students drive their pursuit of entertainment and the gratification of their emotional needs, thereby significantly intensifying their short-form video usage behaviour and ultimately inducing a negative outcome of addiction.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Zhi-Yun Zhang: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing—original draft, Project administration. Weiguaju Nong: Conceptualization, Investigation, Validation, Writing—review & editing. Yaqiong Wu: Data curation, Investigation, Writing—review & editing, Validation. Chenshi Deng: Project administration, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology. Peng Wang: Methodology, Writing—review & editing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data in the article are available with the first author’s consent.

Ethics Approval: This study was approved by the Academic Committee of the School of Education at Guangxi University of Foreign Languages (Approval No.: GXUFL-SE-25012). Prior to completing the questionnaire, all the participants were assured of their anonymity and informed that their participation in the study was voluntary and they could withdraw at any time. Therefore, all students voluntarily participated in the survey.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Ding J, Hu Z, Zuo Y, Xv Y. The relationships between short video addiction, subjective well-being, social support, personality, and core self-evaluation: a latent profile analysis. BMC Public Health. 2024;24(1):3459. doi:10.1186/s12889-024-20994-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. CNNIC. The 56th statistical report on China’s internet development 2025 [Internet]. Beijing, China: China Internet Network Information Center. [cited 2025 Sep 23]. Available from: https://www.cnnic.net.cn/n4/2025/0721/c88-11328.html. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

3. Ye J-H, Wu Y-T, Wu Y-F, Chen M-Y, Ye J-N. Effects of short video addiction on the motivation and well-being of Chinese vocational college students. Front Public Health. 2022;10:847672. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.847672. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Zhang X, Wu Y, Liu S. Exploring short-form video application addiction: socio-technical and attachment perspectives. Telemat Inform. 2019;42(6):101243. doi:10.1016/j.tele.2019.101243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Caponnetto P, Lanzafame I, Prezzavento GC, Fakhrou A, Lenzo V, Sardella A, et al. Does TikTok addiction exist? A qualitative study. Health Psychol Res. 2025;13(3):127796. doi:10.52965/001c.127796. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Yan Y, He Y, Li L. Why time flies? The role of immersion in short video usage behavior. Front Psychol. 2023;14:1127210. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1127210. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Nwufo IJ, Ike OO. Personality traits and internet addiction among adolescent students: the moderating role of family functioning. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2024;21(5):520. doi:10.3390/ijerph21050520. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Ahorsu DK. Pathways to social media addiction: examining its prevalence, and predictive factors among Ghanaian youths. J Soc Media Res. 2024;1(1):47–59. doi:10.29329/jsomer.9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Ye J-H, Wang Y, Nong W, Ye J-N, Cui Y. The relationship between TikTok (Douyin) addiction and social and emotional learning: evidence from a survey of chinese vocational college students. Int J Ment Health Promot. 2025;27(7):995–1012. doi:10.32604/ijmhp.2025.066326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Liao M. Analysis of the causes, psychological mechanisms, and coping strategies of short video addiction in China. Front Psychol. 2024;15:1391204. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1391204. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Huang Q, Hu M, Chen H. Exploring stress and problematic use of short-form video applications among middle-aged chinese adults: the mediating roles of duration of use and flow experience. Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(1):132. doi:10.3390/ijerph19010132. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. CNSA. China online audio-visual development research report; 2025 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 23]. Available from: https://www.vidchina.cn/outcome/46. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

13. Jiang L, Yoo Y. Adolescents’ short-form video addiction and sleep quality: the mediating role of social anxiety. BMC Psychol. 2024;12(1):369. doi:10.1186/s40359-024-01865-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Li G, Geng Y, Wu T. Effects of short-form video app addiction on academic anxiety and academic engagement: the mediating role of mindfulness. Front Psychol. 2024;15:1428813. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1428813. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Ye J-H, Chen M-Y, Wu Y-F. The causes, counseling, and prevention strategies for maladaptive and deviant behaviors in schools. Behav Sci. 2024;14(2):118. doi:10.3390/bs14020118. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Chew PKH, Naidu KNC, Shi J, Zhang MWB. Validation of the internet gaming disorder scale-short-form and the gaming disorder test in Singapore. Asian J Soc Health Behav. 2025;8(3):125–32. doi:10.4103/shb.shb_327_24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Mao Y, Zhang N, Liu J, Zhu B, He R, Wang X. A systematic review of depression and anxiety in medical students in China. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):327. doi:10.1186/s12909-019-1744-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Gazzaz ZJ, Baig M, Al Alhendi BSM, Al Suliman MMO, Al Alhendi AS, Al-Grad MSH, et al. Perceived stress, reasons for and sources of stress among medical students at Rabigh Medical College, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):29. doi:10.1186/s12909-018-1133-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Bedewy D, Gabriel A. Examining perceptions of academic stress and its sources among university students: the perception of academic stress scale. Health Psychol Open. 2015;2(2):2055102915596714. doi:10.1177/2055102915596714. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Sun R, Zhang MX, Yeh C, Ung COL, Wu AMS. The metacognitive-motivational links between stress and short-form video addiction. Technol Soc. 2024;77(14):102548. doi:10.1016/j.techsoc.2024.102548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Lei LYC, Chen YY, Chai CS, Chew KS. Assessing the effectiveness of group motivational interviewing in raising awareness of mobile gaming addiction among medical students: a pilot study. BMC Res Notes. 2025;18(1):178. doi:10.1186/s13104-025-07250-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Mohamed EF, Mohamed AE, Youssef AM, Sehlo MG, Soliman ESA, Ibrahim AS. Facebook addiction among medical students: prevalence and consequences. Middle East Curr Psychiatry. 2025;32(1):7. doi:10.1186/s43045-025-00501-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Kardefelt-Winther D. A conceptual and methodological critique of internet addiction research: towards a model of compensatory internet use. Comput Hum Behav. 2014;31(1):351–4. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2013.10.059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Hu H, Huang M. How stress influences short video addiction in China: an extended compensatory internet use model. Front Psychol. 2024;15:1470111. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1470111. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Mu H, Jiang Q, Xu J, Chen S. Drivers and consequences of short-form video (SFV) addiction amongst adolescents in China: stress-coping theory perspective. Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(21):14173. doi:10.3390/ijerph192114173. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Brand M, Wegmann E, Stark R, Müller A, Wölfling K, Robbins TW, et al. The Interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution (I-PACE) model for addictive behaviors: update, generalization to addictive behaviors beyond internet-use disorders, and specification of the process character of addictive behaviors. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2019;104(4):10. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.06.032. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Gan W-Y, Chin W-L, Huang S-W, Tung S-E-H, Lee L-J, Poon W-C, et al. Association between mental distress and weight-related self-stigma via problematic social media and smartphone use among malaysian university students: an application of the Interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution (I-PACE) model. Int J Ment Health Promot. 2025;27(3):319–31. doi:10.32604/ijmhp.2025.060049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Katz E, Blumler JG, Gurevitch M. Uses and gratifications research. Public Opin Q. 1973;37(4):509–23. doi:10.1086/268109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Ye J-H, Zheng J, Nong W, Yang X. Potential effect of short video usage intensity on short video addiction, perceived mood enhancement (‘TikTok Brain’and attention control among Chinese adolescents. Int J Ment Health Promot. 2025;27(3):271–86. doi:10.32604/ijmhp.2025.059929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Bucknell Bossen C, Kottasz R. Uses and gratifications sought by pre-adolescent and adolescent TikTok consumers. Young Consum. 2020;21(4):463–78. doi:10.1108/YC-07-2020-1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Xiong S, Xu Y, Chen Y, Zhang B. Developmental trajectories of problematic social media use among adolescents: associations with multiple interpersonal factors. J Behav Addict. 2025;14(2):889–902. doi:10.1556/2006.2025.00032. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Wu M, Yan J, Qiao C, Yan C. Impact of concurrent media exposure on professional identity: cross-sectional study of 1087 medical students during long COVID. J Med Internet Res. 2024;26(1):e50057. doi:10.2196/50057. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Guo C, Chen M, Ji X, Li J, Ma Y, Zang S. Association between internet addiction and sleep quality in medical students: a longitudinal study. Front Psychol. 2025;16:1517590. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1517590. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Wolfers LN, Utz S. Social media use, stress, and coping. Curr Opin Psychol. 2022;45:101305. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101305. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Li S, Zhao T, Feng N, Chen R, Cui L. Why we cannot stop watching: tension and subjective anxious affect as central emotional predictors of short-form video addiction. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2025:1–15. doi:10.1007/s11469-025-01486-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Shaw J, Lai A, Singh S, Yoo SR, Fathali M, Stuck L, et al. How medical students manage depression, anxiety, and stress: a cross-sectional study. JMIR Form Res. 2025;9:e74218. doi:10.2196/74218. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Xu Y, Wang J, Ma M. Adapting to lockdown: exploring stress coping strategies on short video social media during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2023;16:5273–87. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S441744. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Guo J, Chai R. Adolescent short video addiction in China: unveiling key growth stages and driving factors behind behavioral patterns. Front Psychol. 2024;15:1509636. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1509636. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Liu Y, Ni X, Niu G. Perceived stress and short-form video application addiction: a moderated mediation model. Front Psychol. 2021;12:747656. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.747656. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Brand M, Young KS, Laier C, Wölfling K, Potenza MN. Integrating psychological and neurobiological considerations regarding the development and maintenance of specific Internet-use disorders: an Interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution (I-PACE) model. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016;71:252–66. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.08.033. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Katz E, Haas H, Gurevitch M. On the use of the mass media for important things. Am Sociol Rev. 1973;38(2):164–81. doi:10.2307/2094393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Bartsch A, Viehoff R. The use of media entertainment and emotional gratification. Procedia—Soc Behav Sci. 2010;5:2247–55. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.07.444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Yin B, Shen Y. Development and validation of the compensatory belief scale for the internet instant gratification behavior. Heliyon. 2024;10(1):23972. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e23972. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Zhu C, Jiang Y, Lei H, Wang H, Zhang C. The relationship between short-form video use and depression among Chinese adolescents: examining the mediating roles of need gratification and short-form video addiction. Heliyon. 2024;10(9):30346. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e30346. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Jiang W, Chen H-L. Can short videos work? The effects of use and gratification and social presence on purchase intention: examining the mediating role of digital dependency. Theor Appl Electron Commer Res. 2025;20(1):5. doi:10.3390/jtaer20010005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Zhou Y, Lee J-Y, Liu S. Research on the uses and gratifications of Tiktok (Douyin short video). Int J Contents. 2021;17(1):37–53. doi:10.5392/IJOC.2021.17.1.037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Miranda S, Trigo I, Rodrigues R, Duarte M. Addiction to social networking sites: motivations, flow, and sense of belonging at the root of addiction. Technol Forecast Soc Change. 2023;188:122280. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2022.122280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Tian X, Bi X, Chen H. How short-form video features influence addiction behavior? Empirical research from the opponent process theory perspective. Inf Technol People. 2023;36(1):387–408. doi:10.1108/ITP-04-2020-0186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Chou C. Internet heavy use and addiction among Taiwanese college students: an online interview study. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2001;4(5):573–85. doi:10.1089/109493101753235160. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Feng T, Wang B, Mi M, Ren L, Wu L, Wang H, et al. The relationships between mental health and social media addiction, and between academic burnout and social media addiction among Chinese college students: a network analysis. Heliyon. 2025;11(3):41869. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2025.e41869. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Ye J, Wang W, Huang D, Ma S, Chen S, Dong W, et al. Short video addiction scale for middle school students: development and initial validation. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):9903. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-92138-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Peng C, Lee J-Y, Liu S. Psychological phenomenon analysis of short video users’ anxiety, addiction and subjective well-being. Int J Contents. 2022;18(1):27–39. doi:10.5392/IJOC.2022.18.1.027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Wang Q, Guo Y, Lan Z, Liu H. The fog of short videos among adolescents: the interwoven influence of family environment, psychological capital, and self-control. Humanit Soc Sci Commun. 2025;12(1):22. doi:10.1057/s41599-024-04292-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Chung D, Meng Y, Wang J. The role of short-form video apps in mitigating occupational burnout and enhancing life satisfaction among healthcare workers: a serial multiple mediation model. Healthcare. 2025;13(4):355. doi:10.3390/healthcare13040355. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Wang D, Zhou M, Hu Y. The relationship between harsh parenting and smartphone addiction among adolescents: serial mediating role of depression and social pain. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2024;17:735–52. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S438014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385–96. doi:10.2307/2136404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Khan ML. Social media engagement: what motivates user participation and consumption on YouTube? Comput Hum Behav. 2017;66:236–47. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2016.09.024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Wegmann E, Antons S, Brand M. The experience of gratification and compensation in addictive behaviors: how can these experiences be measured systematically within and across disorders due to addictive behaviors? Compr Psychiatry. 2022;117:152336. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2022.152336. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Yan Z, Yang Z, Xu X, Zhou C, Sang Q. Problematic online video watching, boredom proneness and loneliness among first-year chinese undergraduates: a two-wave longitudinal study. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2025;18:241–53. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S498142. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Chiu S-I. The relationship between life stress and smartphone addiction on taiwanese university student: a mediation model of learning self-efficacy and social self-efficacy. Comput Hum Behav. 2014;34:49–57. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2014.01.024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools