Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

The Relationship between Emotional Labor Strategies and Job Performance of Rotating Teachers: A Latent Profile Analysis

1 College of Teacher Education, Zhejiang Normal University, Jinhua, 321004, China

2 College of Early-Childhood Education, Nanjing Xiaozhuang University, Nanjing, 211171, China

3 Normal School, Jinhua University of Vocational Technology, Jinhua, 321007, China

4 College of Psychology, Zhejiang Normal University, Jinhua, 321004, China

* Corresponding Author: Huanfang Wang. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Latent Profile Analysis in Mental Health Research: Exploring Heterogeneity through Person Centric Approach)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(11), 1813-1827. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.069623

Received 27 June 2025; Accepted 21 October 2025; Issue published 28 November 2025

Abstract

Background: In China, the policy of rotating teachers between urban and rural schools has been implemented to reduce educational disparities and ensure equitable access to quality education. These teachers face unique professional and emotional challenges during the rotation process, making their emotional labor a critical factor influencing their job performance. This study aimed to explore the relationship between rotating teachers’ emotional labor strategies and job performance. Methods: This study conducted a cross-sectional survey among 577 rotating teachers selected through stratified random sampling from primary and secondary schools in mainland China. Date were collected using the Teacher Emotional Labor Scale and the Teacher Job Performance Scale. Latent profile analysis (LPA) was employed to identify distinct categories of emotional labor strategies: indifferent, moderately engaged, naturally invested, proactively adjusted, and emotionally elevated. Results: Teachers in the naturally invested and proactively adjusted types demonstrated relatively higher job performance scores, followed by those in the emotionally elevated type. In contrast, teachers in the indifferent and moderate engagement types exhibited comparatively lower scores (F = 25.858, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.153). These findings indicate a practical significance, suggestion that flexible and adaptive use emotional labor strategies is strongly associated with enhanced job performance. Conclusion: This study demonstrates that rotating teachers’ job performance differs significantly across distinct emotional labor profiles, with balanced and adaptive emotional regulation emerging as a key determinant of higher performance. By identifying and characterizing individual-centered emotional labor profiles, the study advances understanding of how emotional regulation contributes to teachers’ professional effectiveness. These results underscore the importance of providing systematic and personalized support to help rotating teachers develop adaptive emotional regulation skills. Targeted guidance should enable teachers to appropriately express and adjust their emotions, thereby avoiding both excessive and insufficient emotional labor and promoting sustainable professional development.Keywords

In recent years, the promotion of high-quality and equitable development in compulsory education has become a central focus of educational reform in China. Teacher rotation has emerged as an essential policy instrument for optimizing the allocation of teacher resources, fostering educational equity, and promoting balanced development in basic education [1]. By facilitating teacher mobility, the government aims to address the shortage of qualified teachers in rural schools while leveraging the professional expertise and influence of high-caliber rotating teachers to drive transformation and holistic improvement in rural education. These efforts ultimately aim to achieve equitable and high-quality development in compulsory education. Since the Ministry of Education, the Ministry of Finance, and the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security jointly issued the document titled Opinions on Implementing Rotation of Principals and Teachers in the Compulsory Education Sector Within County (District) (OIRPTCESWC) [2], the teacher rotation system in China has largely become institutionalized.

Rotating teachers refers to those who participate in inter-school or inter-regional teaching exchanges under the national teacher rotation policy, serving as key agents in promoting educational equity [3]. As a key agent in the successful implementation of teacher rotation system, their job performance profoundly influences its overall effectiveness. Traditionally, the focus of the teacher rotation system has been on ensuring the equitable deployment of teachers to underdeveloped regions, while often neglecting the emotional experiences of rotating teachers as “real, individual people” [4]. In fact, rotating teachers frequently encounter many emotional challenges when they participate in the rotation system, such as feelings of interpersonal unfamiliarity arising from spatial transitions, cultural alienation caused by group differences, psychological loneliness due to shifts in social relationships, and inner disillusionment resulting from discrepancies between expectations and reality [5]. Such emotional experiences are pivotal to the system’s practical effectiveness. Without effective support, unresolved emotional issues may not only weaken teachers’ professional commitment but also erode their perception of institutional fairness within the teacher rotation system. Thus, overlooking the critical role of emotional labor undertaken by rotating teachers is both inappropriate and unacceptable. This study seeks to fill gaps in existing research by focusing on the emotional labor of rotating teachers and exploring the relationship between emotional labor strategies and job performance. The findings aim to provide insights and recommendations for enhancing the effective implementation of the teacher rotation system and advancing the high-quality, equitable development of compulsory education.

1.1 Teacher Emotional Labor and the Emotion of Rotating Teachers

Teacher emotional labor refers to teachers’ regulation and management of their emotions to convey feelings that align with the demands of teaching and learning activities [6]. Generally, teachers’ emotional labor encompasses three strategies: surface acting (SA), deep acting (DA), and expression of naturally felt emotions (ENFE) [6]. SA refers to the strategy of altering external emotional expressions without modifying internal emotional feelings; DA involves modifying internal emotional experiences to genuinely align with external emotional expressions; and ENFE refers to the spontaneous and authentic emotional expression that aligns with organizational expectations [7]. Emotional labor is not only a key aspect of teachers’ daily work, but also a critical component of their professional development [8].

Research on the emotions of rotating teachers can be categorized into two phases. The first phase primarily focused on the logistical aspect of how teachers could “be mobilized”, paying little attention to the emotional dimensions of their experiences. Studies during this period concentrated on topics such as the incentive mechanisms to encourage teacher participation in rotation programs [9] and their willingness to engage with the rotation system [10]. In the second phase, “emotion” or “affect” emerged as a distinct focus in this research domain, encompassing three main areas. First, scholars such as Wu [11] and Xue et al. [12] explored the emotional challenges faced by rotating teachers, including feelings of loneliness and frustration, arising from transitions between familiar and unfamiliar school environments. They argued these emotions could influence the implementation of the rotation system in daily educational practices. Second, researchers like Tian et al. [5] and Lang [13] emphasized the importance of emotional competence in overcoming these challenges, advocating for enhanced abilities in emotional recognition, expression, understanding, and regulation. Building on these studies, recent studies have further highlighted the role of emotional literacy—the ability to understand, regulate, and express emotions constructively—in promoting teachers’ well-being and professional relationships. Emotional literacy not only strengthens teachers’ emotional regulation but also enhances the positive impact of emotional labor on social capital and educational effectiveness [14]. Third, scholars like Huang et al. [4] drew attention to the emotional disconnect experienced by rotating teachers from rural life, schools, and communities. Although the focus on rotating teachers’ emotions has gradually shifted from a peripheral concern to a central topic, much of the existing literature remains conceptual and descriptive. The emotional labor of rotating teachers and its relationship with relevant variables remains underexplored both in depth and breadth.

1.2 The Relationship between Emotional Labor and Job Performance

According to Grandey’s theory of emotion regulation, job performance is a significant outcome variable associated with emotional labor [15]. Job performance refers to the outcomes of teachers’ behaviors in achieving the educational goals. It serves as a critical criterion for evaluating whether teachers effectively fulfill their educational and teaching responsibilities [16]. Assessing the job performance of rotating teachers offers insights into the effectiveness of the teacher rotation system. However, there is no consensus in research on the relationship between emotional labor strategies and teachers’ job performance. Some studies suggest that DA enhances job performance [17], while others argue that ENFE positively impacts job performance, SA negatively affects it, and DA shows no significant relationship [18]. Such inconsistencies may be attributed to methodological limitations in existing research.

1.3 Individual Differences in Emotional Labor Strategies

Most previous studies have adopted a variable-centered approach to examine the relationship between teachers’ emotional labor strategies and related variables, often neglecting individual differences in emotional labor types. In fact, teachers do not rely on a single emotional labor strategy; instead, they may simultaneously employ multiple strategies depending on their work context or personal preference [19]. Latent Profile Analysis (LPA) is an individual-centered statistical method that analyzes the unique characteristics of each subgroup, allowing researchers to explore the combinations of variables and the outcomes associated with specific groups. By identifying subgroups based on the properties and differentiation of explicit variables, LPA addresses the limitations of variable-centered methods and provides a more nuanced understanding of population heterogeneity [20].

Currently, some researchers have utilized LPA to explore the emotional labor strategy types. For instance, Gabriel et al. [21] identified five categories of emotional labor strategies among employees: non-actors, low-actors, surface-actors, deep-actors, and regulators. Hong et al. [22] found that kindergarten teachers’ emotional labor strategies could be classified into four types: active participation, moderate participation, low participation, and passive participation. Zhao et al. [23] categorized the emotional labor strategies of middle school teachers into four groups: high emotional labor, medium emotional labor, natural sincere, and low emotional labor. Building on these studies, the present research employs LPA to examine the underexplored group of rotating teachers, thereby addressing a significant gap in the literature and advancing the understanding of their emotional labor strategies.

In China, rotating teachers, as a special human resource, play a pivotal role in mitigating teacher shortages in rural or underdeveloped areas and fostering the equitable and high-quality development of compulsory education. Rotating teachers’ emotional labor plays an irreplaceable role during the rotation process, making it essential to acknowledge and harness the positive impact of emotional labor. Building on this foundation, this study aims to explore the subgroups of rotating teachers’ emotional labor strategies and their relationship with job performance from an individual-centered perspective. This paper contributes to the literature in three ways: first, it addresses the research gap by focusing on the emotional labor of rotating teachers, a group that has been underexplored; second, it employs LPA to capture heterogeneous emotional labor profiles, extending beyond traditional variable-centered approaches; last, it links these profiles with job performance, offering both theoretical insights and practical implications for improving teacher management and professional development.

2.1 Description of the Participants

A total of 594 rotating teachers in primary and secondary schools in mainland China were invited to participate in an online questionnaire survey. Data collection was conducted online via the free Questionnaire Star (also known as Wenjuanxing in China) service. Using response time as a criterion, 17 invalid questionnaires were excluded, resulting in 577 valid responses and an effective response rate of 97.1%. Prior to data collection, ethical approval for the research was granted by the Ethics Committee of Zhejiang Normal University (ZSRT2025235). All participants in the study signed informed consent forms. The questionnaire link was shared with some school liaisons, who then forwarded it to their colleagues and invited them to participate voluntarily. Before answering the questionnaires, participants read an introductory letter explaining that their participation was voluntary, their data would remain confidential, and it would be used solely for academic research. Participants then provided school and personal details before answering a series of questions. They had the flexibility to exit the survey at any stage. The demographic characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1.

Table 1: The demographic characteristics of the participants.

| Variables | N | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 146 | 25.3 | |

| Female | 431 | 74.7 | |

| Age | |||

| 30 years old or younger | 35 | 6.0 | |

| 31–40 years | 171 | 29.7 | |

| 41 years old or older | 371 | 64.3 | |

| Stage of education | |||

| Primary stage | 369 | 64.0 | |

| Secondary stage | 208 | 36.0 | |

| Teaching experience | |||

| 5 years or fewer | 21 | 3.6 | |

| 6–10 years | 63 | 10.9 | |

| 11–15 years | 79 | 13.7 | |

| 16–20 years | 107 | 18.5 | |

| 21–25 years | 127 | 22.0 | |

| 26 years or more | 180 | 31.3 | |

| Degree | |||

| Foundation degree | 15 | 2.6 | |

| Undergraduate degree | 511 | 88.6 | |

| Postgraduate degree | 51 | 8.8 | |

All respondents in this research filled out a survey booklet including the following questionnaires: Teacher Emotional Labor Scale (TELS) [6], Teachers’ Job Performance Scale (TJPS) [24], along with a section on sociodemographic information (e.g., gender, age, stage of education, teaching experience, and degree).

2.2.1 Teacher Emotional Labor Scale (TELS)

The TELS, adapted by Yin [6] from Diefendorff et al.’s [7] Emotional Labor Scale (ELS), demonstrates enhanced reliability and validity in the Chinese cultural context. The scale assesses emotional labor through three dimensions: SA (6 items), sample items include “I put on a ‘show’ or ‘performance’ when interacting with students or their parents”. DA (4 items), a sample item is “I try to actually experience the emotions that I must show to students or their parents”, and ENFE (3 items), a sample item is “The emotions I show students or their parents match what I spontaneously feel”. Participants responded on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from “completely disagree” (code 1) to “completely agree” (code 5), with higher scores reflecting greater use of the corresponding strategy. In this study, the scale exhibited strong internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.818), with α values of 0.909, 0.828, and 0.966 for SA, DA, and ENFE, respectively.

2.2.2 Teachers’ Job Performance Scale (TJPS)

The TJPS, developed by Motowidlo and Van Scotter [25], and adapted by Ma [24] for use in China, evaluates teachers’ job performance across three dimensions: Work Dedication (WD) (4 items), a sample item is “compliance with school rules and regulations”, Task Performance (TP) (5 items), a sample item is “willingness to take on challenging tasks”, and Interpersonal Facilitation (IF) (5 items), a sample item is “harmonious relationships with colleagues”. Consistent with the TELS, this scale employed a 5-point Likert scale in the current study, ranging from “completely disagree” (code 1) to “completely agree” (code 5). The TJPS demonstrated excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.958), with reliability coefficients of 0.919, 0.931, and 0.972 for WD, TP, and IF, respectively.

Two primary analyses were conducted in this study: descriptive statistics (e.g., independent samples t-test, cross-tabulation analysis, one-way ANOVA, etc.) were examined using SPSS Version 27.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) for Mac, and LPA was performed using Mplus Version 8.3 (Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles, CA, USA). Prior to these analyses, preliminary data screening procedures were conducted, including checking for normality, outliers, and missing data.

To determine the optimal number of latent profiles, a series of models with progressively increasing numbers of profiles was tested. The initial model specified two latent profiles, followed by models with three, four, five, six, and seven profiles. The best-fitting solution was identified by comparing the classification quality and relative parsimony of these models. The optimal model was characterized by the highest classification quality and a relatively smaller number of latent profiles.

According to the recommendations of Nylund et al. [26], the fit statistics used to evaluate the LPA model included Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC), Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), Sample-Size-Adjusted Bayesian Information Criterion (SSA-BIC), the Lo-Mendell-Rubin Likelihood Ratio Test (LMRT), the Bootstrap Likelihood Ratio Test (BLRT), Entropy, and class probabilities. Lower values of AIC, BIC, and SSA-BIC indicate better model fit, while significant LMRT and BLRT results suggest that the current k-class model provides a better fit than the k − 1 class model. Entropy measures classification quality, with higher values (ranging from 0 to 1) indicating better quality and values nearer to 1 reflecting greater classification accuracy [27]. Additionally, class probabilities exceeding 5% are considered relatively reliable. Based on these fit indices and theoretical considerations, the optimal number of profiles was determined, and each profile was then labeled according to its distinct characteristics.

3.1 Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis of Emotional Labor Strategies and Job Performance of Rotating Teachers

According to Table 2, rotating teachers reported a higher frequency of employing DA and ENFE compared to SA, suggesting that they invested considerable emotional effort during the rotation process. Additionally, the relatively high job performance scores indicate that rotating teachers generally have positive perceptions of their rotation outcomes. The correlation analysis identified significant associations between emotional labor strategies and job performance. Specifically, DA and ENFE showed significant positive correlations with all dimensions of job performance (p < 0.01), whereas SA was negatively correlated with all dimensions (p < 0.01).

Table 2: Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis of key variables.

| Variables | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Emotional labor strategies | 2.89 | 0.61 | - | |||||||

| 2 SA | 2.22 | 0.92 | 0.727** | - | ||||||

| 3 DA | 3.33 | 0.89 | 0.800** | 0.281** | - | |||||

| 4 ENFE | 3.63 | 0.95 | 0.348** | −0.286** | 0.412** | - | ||||

| 5 Job performance | 4.27 | 0.68 | 0.102* | −0.188** | 0.225** | 0.366** | - | |||

| 6 WD | 3.92 | 0.87 | 0.162** | −0.122** | 0.256** | 0.362** | 0.847** | - | ||

| 7 TP | 4.38 | 0.72 | 0.049 | −0.0177** | 0.159** | 0.279** | 0.919** | 0.666** | - | |

| 8 IF | 4.43 | 0.73 | 0.065 | −0.200** | 0.186** | 0.334** | 0.897** | 0.602** | 0.602** | - |

3.2 Types of the Rotating Teachers’ Emotional Labor Strategies

To identify the latent profiles of emotional labor strategies among rotating teachers, this study employed Mplus 8.3 for statistical analysis. Several unconditional LPA models with an increasing number of profiles were examined (i.e., two-profile, three-profile, four-profile, five-profile, and six-profile, see Table 3). The results suggested that the values of AIC, BIC, and SSA-BIC exhibited a decreasing trend, indicating a progressively better model fit. A comparison of LMRT values revealed that the three-profile model outperformed the two-profile model, the five-profile model surpassed the four-profile model, and the six-profile model was superior to the five-profile model. Meanwhile, the entropy value was highest for the five-profile model, suggesting it achieved the most accurate classification. Considering the overall fit indices, the five-profile model was identified as the optimal LPA model for emotional labor strategies among rotating teachers.

Table 3: Results of latent profile analysis (LPA) of the rotating teachers’ emotional labor strategies.

| Profile | AIC | BIC | SSA-BIC | LMRT (p) | BLRT (p) | Entropy | Class Probabilities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 20,688.544 | 20,862.857 | 20,735.874 | 1732.794*** | −11,180.402*** | 0.914 | 0.62/0.38 |

| 3 | 19,372.579 | 19,607.903 | 19,436.475 | 1329.033** | −10,304.272*** | 0.928 | 0.47/0.34/0.19 |

| 4 | 18,821.233 | 19,117.566 | 18,901.694 | 572.910 | −9632.290*** | 0.936 | 0.32/0.1/0.15/0.42 |

| 5 | 18,298.263 | 18,655.606 | 18,395.289 | 544.849* | −9342.616*** | 0.948 | 0.06/0.46/0.15/0.17/0.16 |

| 6 | 17,847.952 | 18,266.305 | 17,961.544 | 472.996* | −9067.131*** | 0.936 | 0.05/0.1/0.34/0.23/0.16/0.12 |

3.3 Naming the Types of Emotional Labor Strategies for Rotating Teachers

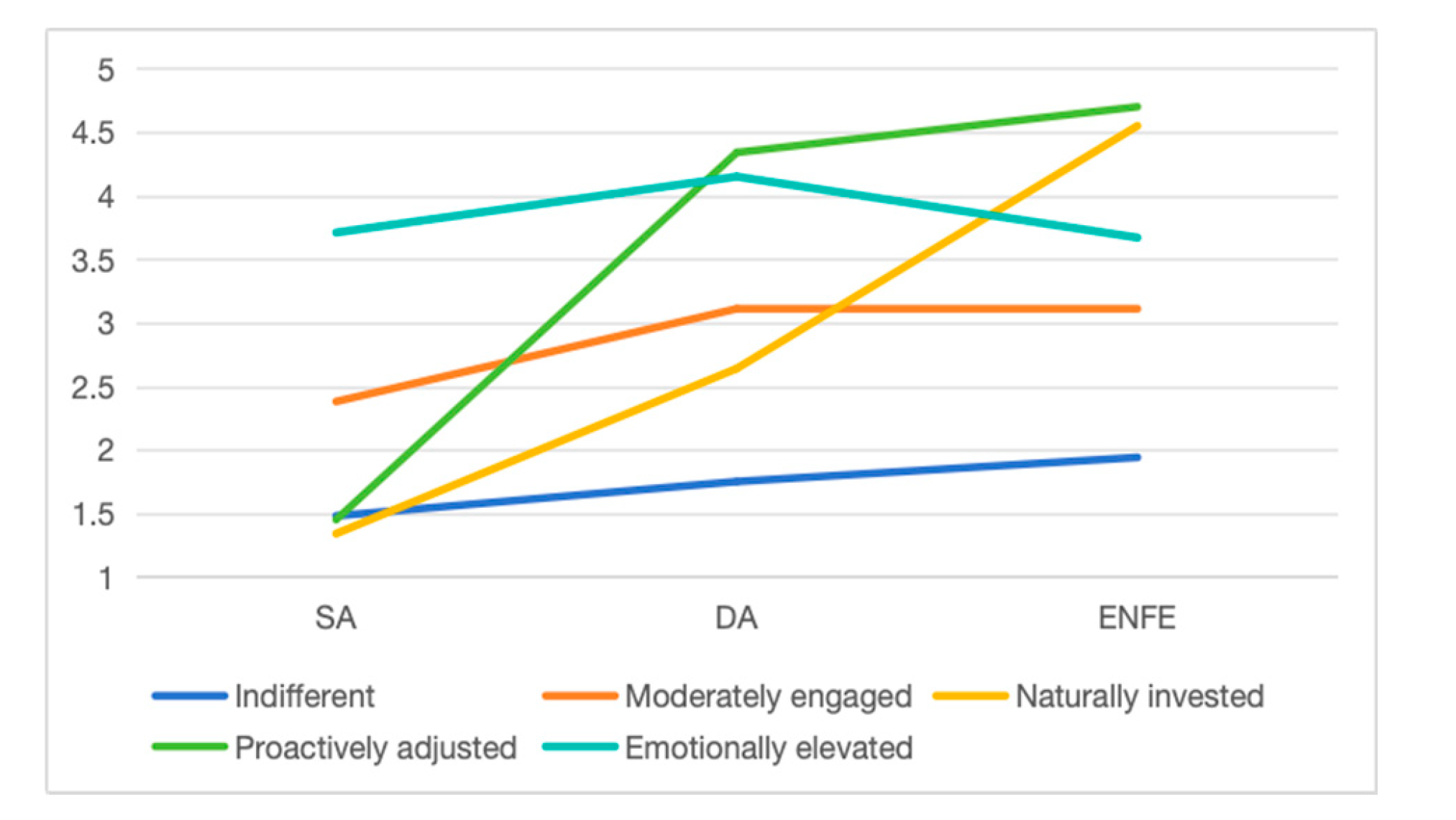

This study named the latent profiles based on the mean scores of the emotional labor strategy dimensions (see Table 4). Class 1, the indifferent type (n = 33), showed uniformly low scores in SA (Mean = 1.48), DA (Mean = 1.75), and ENFE (Mean = 1.94), indicating a minimal level of emotional engagement during the rotation. In contrast, Class 2, the largest group (n = 268), was labeled the moderately engaged type, with moderate scores in SA (Mean = 2.38), DA (Mean = 3.11), and ENFE (Mean = 3.12), reflecting a balanced but measured emotional effort. Class 3, the naturally invested type (n = 87), showed low scores in SA (Mean = 1.34) and DA (Mean = 2.64), but an exceptionally high score in ENFE (Mean = 4.55), indicating a strong preference for authentic emotional expression. Class 4, the proactively adjusted type (n = 100), exhibited minimal reliance on SA (Mean = 1.45) while achieving high scores in DA (Mean = 4.34) and ENFE (Mean = 4.70), reflecting deliberate avoidance of SA and an effort to align emotions with the demands of rotation. Finally, Class 5, the emotionally elevated type (n = 89), showed consistently high scores across all three dimensions: SA (Mean = 3.71), DA (Mean = 4.15), and ENFE (Mean = 3.67), indicating intense and multifaceted emotional engagement. Fig. 1 provides a visual representation of these distinct emotional labor strategy combinations, offering a clear overview of each profile.

Table 4: The number, proportion, mean scores and standard deviations (Mean ± SD) of rotating teachers’ emotional labor strategy types.

| Latent Profile | Number (Persons) | Proportion (%) | SA | DA | ENFE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indifferent | 33 | 6% | 1.48 ± 0.46 | 1.75 ± 0.55 | 1.94 ± 0.67 |

| Moderately engaged | 268 | 46% | 2.38 ± 0.52 | 3.11 ± 0.46 | 3.12 ± 0.45 |

| Naturally invested | 87 | 15% | 1.34 ± 0.41 | 2.64 ± 0.65 | 4.55 ± 0.50 |

| Proactively adjusted | 100 | 17% | 1.45 ± 0.45 | 4.34 ± 0.53 | 4.70 ± 0.42 |

| Emotionally elevated | 89 | 16% | 3.71 ± 0.58 | 4.15 ± 0.55 | 3.67 ± 0.85 |

Figure 1: Latent profiles of rotating teachers’ emotional labor strategies. Note: SA, Surface Acting; DA, Deep Acting; ENFE, Expression of Naturally Felt Emotions.

3.4 Analysis of the Differences in Emotional Labor Strategy Types Among Rotating Teachers by Demographic Variables

To explore individual differences in emotional labor strategy types among rotating teachers, this study conducted a cross-tabulation analysis using key demographic variables (e.g., gender, age, state of education, teaching experience, and degree) as independent variables and emotional labor strategy types as the dependent variables. The results (see Table 5) revealed significant differences in emotional labor strategy types among rotating teachers of different ages and teaching experience. Specifically, rotating teachers aged 30 or younger were predominantly classified as the moderately engaged type and the emotionally elevated type. In contrast, those aged 41 or older were most represented in the indifferent type, naturally invested type, and proactively adjusted type. Additionally, rotating teachers with fewer than 5 years or more than 25 years of teaching experience had a higher proportion in the indifferent type, possibly reflecting early-career hesitation or late-career emotional fatigue. Interestingly, teachers with 10 years or fewer and those with 16 to 20 years of experience were overrepresented in the emotionally elevated type, indicating a peak in emotional engagement during these career stages. By contrast, teachers with 21 to 25 years of experience predominantly belonged to the naturally invested type and proactively adjusted type, while showing the lowest representation in the moderately engaged type. This finding suggests a deliberate and well-defined approach to emotional labor strategies at this phase of their career.

Table 5: Tests of differences in rotating teachers’ emotional labor strategy types on demographic variables.

| Variables | Indifferent | Moderately Engaged | Naturally Invested | Proactively Adjusted | Emotionally Elevated | χ2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.686 | ||||||

| Male | 8 (5.5%) | 71 (48.6%) | 21 (14.4%) | 26 (17.8%) | 20 (13.7%) | ||

| Female | 25 (5.8%) | 197 (45.7%) | 66 (15.3%) | 74 (17.2%) | 69 (16.0%) | ||

| Age | 25.088** | ||||||

| 30 years or younger | 2 (5.7%) | 19 (54.3%) | 3 (8.6%) | 1 (2.9%) | 10 (28.6%) | ||

| 31–40 years | 7 (4.1%) | 90 (52.6%) | 17 (9.9%) | 24 (14.0%) | 33 (19.3%) | ||

| 41 years or older | 24 (6.5%) | 159 (42.9%) | 67 (18.1%) | 75 (20.2%) | 46 (12.4%) | ||

| Stage of education | 5.895 | ||||||

| Primary stage | 18 (4.9%) | 175 (47.4%) | 63 (17.1%) | 58 (15.7%) | 55 (14.9%) | ||

| Secondary stage | 15 (7.2%) | 93 (44.7%) | 24 (11.5%) | 42 (20.2%) | 34 (16.3%) | ||

| Teaching experience | 40.440** | ||||||

| 5 years or fewer | 2 (9.5%) | 11 (52.4%) | 3 (14.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (23.8%) | ||

| 6–10 years | 2 (3.2%) | 34 (54.0%) | 4 (6.3%) | 8 (12.7%) | 15 (23.8%) | ||

| 11–15 years | 3 (3.8%) | 44 (55.7%) | 10 (12.7%) | 11 (13.9%) | 11 (13.9%) | ||

| 16–20 years | 3 (2.8%) | 46 (43.0%) | 17 (15.9%) | 15 (14.0%) | 26 (24.3%) | ||

| 21–25 years | 6 (4.7%) | 52 (40.9%) | 25 (19.7%) | 29 (22.8%) | 15 (11.8%) | ||

| 26 years or more | 17 (9.4%) | 81 (45.0%) | 28 (15.7%) | 37 (20.6%) | 17 (9.4%) | ||

| Degree | 4.873 | ||||||

| Foundation degree | 1 (6.7%) | 8 (53.3%) | 3 (20%) | 2 (13.3%) | 1 (6.7%) | ||

| Undergraduate degree | 31 (6.1%) | 232 (45.4%) | 75 (14.7%) | 91 (17.8%) | 82 (16.0%) | ||

| Postgraduate degree | 1 (2.0%) | 28 (54.9%) | 9 (17.6%) | 7 (13.7%) | 6 (11.8%) | ||

3.5 Relationship between Emotional Labor Strategy Types and Job Performance of Rotating Teachers

A one-way ANOVA was conducted using the five latent profiles of rotating teachers’ emotional labor strategies as grouping variables and job performance as the dependent variable. The results revealed statistically significant differences among the five profiles in terms of overall job performance and its specific dimensions (see Table 6), indicating that different emotional labor strategy types are associated with distinct levels of job performance (F = 25.858, η2 = 0.153, p < 0.001). Post hoc tests showed that teachers in the indifferent types had significantly lower job performance scores compared to the naturally invested type (p < 0.01) and the proactively adjusted type (p < 0.001). Similarly, teachers in the moderately engaged type scored significantly lower than those in the naturally invested type (p < 0.001), the proactively adjusted type (p < 0.01), and the emotionally elevated type (p < 0.01). Additionally, the proactively adjusted type exhibited significantly higher job performance scores compared to the emotionally elevated type (p < 0.01).

Table 6: Comparison of the mean and standard error (SE) of job performance among rotating teachers with different emotional labor strategy types.

| Latent Profile | JP | WD | TP | IF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indifferent | 4.065 (0.155) | 3.576 (0.170) | 4.285 (0.167) | 4.236 (0.168) |

| Moderately engaged | 4.026 (0.039) | 3.611 (0.045) | 4.176 (0.043) | 4.208 (0.046) |

| Naturally invested | 4.562 (0.052) | 4.247 (0.084) | 4.646 (0.060) | 4.731 (0.048) |

| Proactively adjusted | 4.664 (0.054) | 4.428 (0.088) | 4.710 (0.056) | 4.808 (0.050) |

| Emotionally elevated | 4.324 (0.072) | 4.101 (0.087) | 4.398 (0.081) | 4.429 (0.073) |

| F-test | 25.858*** | 26.311*** | 15.224*** | 19.606*** |

| η2 | 0.153 | 0.155 | 0.096 | 0.121 |

| Post hoc tests | 3 > 1, 3 > 2, 4 > 1, 4 > 5 > 2 | 3 > 1, 3 > 2, 4 > 1, 4 > 2, 5 > 2 | 3 > 2, 4 > 1, 4 > 2, 4 > 5 | 3 > 1, 3 > 2, 4 > 1, 4 > 2, 4 > 5 |

At the dimensional level, significant differences were observed in WD (F = 26.311, η2 = 0.155, p < 0.001), TP (F = 115.224, η2 = 0.096, p < 0.001), and IF (F = 19.606, η2 = 0.121, p < 0.001) across the latent profiles. Post hoc tests further revealed that, in WD, teachers in the indifferent type scored significantly lower than those in the naturally invested type (p < 0.01) and the proactively adjusted type (p < 0.001), while teachers in the moderately engaged type scored significantly lower than those in the naturally invested type (p < 0.001), the proactively adjusted type (p < 0.001), and the emotionally elevated type (p < 0.001). In TP, teachers in the indifferent type scored significantly lower than those in the proactively adjusted type (p < 0.05), and those in the moderately engaged type scored significantly lower than teachers in the naturally invested type (p < 0.001) and the proactively adjusted type (p < 0.001). Teachers in the proactively adjusted type also scored significantly higher than those in the emotionally elevated type (p < 0.05). In IF, teachers in the indifferent type scored significantly lower than those in the naturally invested type (p < 0.05) and the proactively adjusted type (p < 0.01). Similarly, teachers in the moderately engaged type scored significantly lower than those in the naturally invested type (p < 0.001) and the proactively adjusted type (p < 0.001). However, teachers in the proactively adjusted type scored significantly higher in IF compared to those in the emotionally elevated type (p < 0.01).

4.1 Emotional Labor Strategy Types of Rotating Teachers

First, this study innovatively proposed five emotional labor strategy types of rotating teachers: indifferent (6%), moderately engaged (46%), naturally invested (15%), proactively adjusted (17%), and emotionally elevated (16%). This finding reveals the complexity of emotional labor and the flexibility in the use of strategies among rotating teachers. While previous studies have suggested that emotional labor strategies are mutually exclusive, implying that using one strategy excludes the others [28], the findings of this study show that SA, DA, and ENFE can coexist, which is consistent with the conclusions of Gabriel et al. [29], that emotional labor strategies can be used in tandem. Such insights might not have been revealed in a variable-centered approach, highlighting the advantages of the individual-centered approach used in this study.

Specifically, rotating teachers in the indifferent and moderately engaged exhibited uniformly low scores in SA, DA and ENFE, reflecting limited emotional engagement and a lack of enthusiasm for their work. More than half of the rotating teachers belonged to these two categories, suggesting that insufficient emotional investment is a widespread issue among rotating teachers, which warrants the attention of policymakers and school administrators. The naturally invested, proactively adjusted, and emotionally elevated each accounted for a comparable proportion of teachers, but their predominant emotional labor strategies varied. Teachers in the naturally invested primarily type employed ENFE, whereas those in the proactively adjusted type scored high in both DA and ENFE. These two groups demonstrate a proactive adjustment of emotional states to align their emotional expression with professional demands. Meanwhile, teachers in the emotionally elevated type frequently used all three emotional labor strategies. According to the conservation of resources theory, this type can is prone to significant energy depletion. The flexible use of emotional labor strategies is closely related to rotating teachers’ levels of emotional literacy and their organizational environment. Teachers with higher emotional literacy and sufficient organizational support are often more capable of effectively understanding, regulating, and constructively expressing emotions, thereby flexibly combining SA, DA, and ENFE in different contexts to better meet the multiple demands of teaching and organizational requirements [30]. Identifying distinct emotional labor strategy types and characteristics among rotating teachers assists in understanding their emotional needs and challenges, enabling the development of more targeted strategies to support their professional growth and well-being.

Second, this study identified a subgroup of rotating teachers whose SA scores exceeded their ENFE scores, a phenomenon not previously reported in similar research [31]. The rotating system requires teachers to transition from familiar schools to relatively unfamiliar ones. When faced with different colleagues and students, rotating teachers may find it challenging to quickly adapt and establish new relationships. Under such circumstances, they are more likely to adopt SA, employing outward expressions (e.g., tone, gestures) to display emotions, thereby facilitating the fulfillment of personal needs and organizational expectations within a short timeframe. From the perspective of the conservation of resources theory, teachers in unfamiliar contexts lack sufficient social support and emotional resources, and thus rely on SA to temporarily conserve or protect their internal emotional energy. Furthermore, many teachers perceive rotation assignments as compulsory tasks driven by external pressures, including career advancement opportunities, rather than voluntary endeavors. During the rotation process, teachers are frequently situated in unfamiliar contexts, occupying peripheral roles and interacting with their surroundings as temporary participants, which reflects their detachment from rotational responsibilities. Consequently, they are more likely to engage in SA, which is devoid of authentic involvement. This may account for the presence of subgroups in this study where SA scores exceed ENFE.

Lastly, this study identified significant differences in emotional labor strategy types based on age and teaching experience among the rotating teachers. A comprehensive analysis revealed that rotating teachers at the beginning of their careers often lack teaching experience and emotional regulation skills. As a result, they may struggle to accurately interpret the norms of emotional expression, leading to either insufficient or excessive emotional labor due to uncertainty in perceiving and expressing emotions. With the increase of age and teaching experience, rotating teachers are more likely to experience burnout, which may result in a greater reliance on SA to manage their emotions in the workplace. However, compared to other groups, these teachers tend to be more adept at recognizing organizational emotional expectations and more skilled in controlling and regulating their emotions. From the perspective of emotional literacy, younger teachers require additional training to enhance their abilities to perceive and regulate emotions, whereas experienced teachers need extra support to restore emotional energy and prevent burnout. Future educational practices should focus on supporting both novice, younger rotating teachers and those with longer teaching experience, helping them enhance their emotional labor capabilities.

4.2 The Relationship between Emotional Labor Strategy Types and Job Performance among Rotating Teachers

This study identified significant differences in job performance scores among rotating teachers employing different emotional labor strategy types. Overall, teachers classified as the proactively adjusted type and naturally invested type demonstrated relatively high job performance scores, followed by those in the emotionally elevated type, whereas teachers in the indifferent type and moderately engaged type exhibited comparatively lower scores. These findings suggest that job performance of rotating teachers is closely related to the flexible use of emotional labor strategies, indicating that targeted guidance on emotional labor strategies could help enhance their job performance.

First, rotating teachers in the naturally invested type and proactively adjusted type exhibited relatively higher job performance scores. As mentioned in the previous section, these teachers demonstrated lower frequencies of SA and relatively higher frequencies of DA and ENFE. According to the conservation of resources theory, SA involves an entire process of psychological adjustment, primarily relying on pretending or camouflage to meet organizational requirements. Such insincere emotional expressions lead emotional laborers into a vicious cycle of resource depletion, with little or no return on resource. In contrast, DA and ENFE, characterized by genuine and positive emotional expressions, are more likely to yield substantial resource returns and compensation [32]. Based on the analysis, rotating teachers in the naturally invested type and proactively adjusted type rarely experience psychological resources depletion and instead gain greater resource returns. Therefore, compared to the other three types, these teachers achieve higher job performance scores.

Second, rotating teachers in the emotionally elevated type achieved job performance scores second only to those in the naturally invested type and proactively adjusted type. Compared to these two groups, teachers in the emotionally elevated type demonstrated similar frequencies of DA and ENFE, but reported significantly higher levels of SA. Although the use of DA and ENFE enables these teachers to gain positive feedback and experiences, their excessive reliance on SA depletes substantial psychological resources. Consequently, the job performance of rotating teachers in the emotionally elevated type is lower than that of their counterparts in the naturally invested type and proactively adjusted type.

Lastly, rotating teachers in the indifferent type and moderately engaged type demonstrated relatively low job performance scores. Unlike the other three types, these teachers consistently exhibited low levels of SA, DA, and ENFE. According to the resource conservation theory, the limited use of SA by rotating teachers indicates reduced effort and energy expenditure. However, their similarly low engagement in DA and ENFE hinders the timely replenishment of their depleted resources. As a result, rotating teachers in the indifferent type and moderately engaged type show lower job performance scores compared to their counterparts in other categories.

4.3 Implications and Limitations

First, this study indicates that rotating teachers, as a unique group, exhibit significant individual differences in emotional labor, and different types of emotional labor strategies have differential effects on job performance. These findings suggest that future research should pay greater attention to the internal emotional experiences of rotating teachers and their dynamic changes, rather than focusing solely on policy or institutional analyses. When examining the emotional labor of rotating teachers, an individual-centered research perspective can be adopted to gain deeper insights into the fluctuations of teachers’ emotions during the rotation process and their relationships with job performance, psychological resources, and other key work-related variables, thereby providing new theoretical foundations for the application of emotional labor theory in dynamic educational contexts.

Second, implement personalized emotional regulation guidance to enhance the emotional management of rotating teachers. The results reveal that rotating teachers employ diverse emotional labor strategies, leading to varying levels of job performance. To address this complexity, personalized training and differentiated support are recommended. For teachers in the proactively adjusted and naturally invested types, offering additional career development opportunities and increasing recognition can motivate them to sustain high levels of job performance. For teachers in the emotionally elevated type, psychological support should be provided to reduce workplace stress and enhance resource recovery. Teachers in the indifferent and moderately engaged types require a harmonious work environment, greater emotional care, and stronger support for professional growth to foster a sense of ownership in rotational schools and boost work enthusiasm. At the same time, attention should be given to teachers at different career stages. For young, novice rotating teachers, training on emotional expression and regulation should be prioritized to improve their understanding of emotional expression norms. For older, more experienced teachers, greater care and support should be offered, along with increased autonomy in professional development. In addition, digital technologies can be integrated into teacher training, such as through online emotional management platforms and AI-based feedback systems, to provide rotating teachers with more flexible and data-driven support for emotional regulation. This approach can enhance their self-development awareness, strengthen their professional identity, and promote greater emotional engagement in educational practices. In conclusion, based on the unique characteristics of rotating teachers’ emotional labor strategy types, diversified management and care methods should be adopted to guide them in improving their emotional labor.

Third, rotating teachers should actively regulate their emotions to maintain an optimal level of emotional labor. Research findings indicate that both excessively high or low levels of emotional labor hinder satisfactory job performance: excessive emotional labor depletes psychological resources, while insufficient emotional labor reflects a lack of emotional engagement in work, both of which undermine efforts to achieve higher job performance. Therefore, rotating teachers should not only rely on support from policies and organizations, but also enhance their emotional awareness and self-monitoring. When encountering emotional challenges during the rotation process, they should proactively seek support from their organizations and colleagues, actively adjust their emotional states, and strive to express emotions in a reasonable manner. Effort should be made to reduce reliance on SA while promoting the use of DA and ENFE to improve professional effectiveness. At the same time, rotating teachers can enhance self-awareness, relieve stress, and build supportive networks through practices such as emotional reflection, mindfulness training, cognitive regulation, and peer experience sharing, thereby attributing more positive meaning to their emotional engagement. By leveraging digital tools such as mindfulness apps, emotion-tracking software, and virtual peer communities, the effectiveness of these practices can be further strengthened, helping rotating teachers maintain psychological well-being, boost work motivation, and achieve long-term professional development.

The current study has a number of limitations that warrant discussion. First, this study explores job performance differences among rotating teachers across latent profiles of emotional labor strategies based on cross-sectional data. However, this design limits causal inferences. Future research could adopt longitudinal approaches to assess profile stability, category transitions, and dynamic links to job performance. Second, although the participants in this study were drawn from cities and counties, providing a relatively broad geographical representation, the generalizability of the findings requires further validation. Future studies could expand the scope of investigation to include teachers from more diverse regions and contexts, thereby enriching the understanding of emotional labor strategies. Lastly, this study focused on outcome variables at the organizational level, offering insights into categories that could benefit organizational development. However, the study did not examine the individual-level impacts of emotional labor, which future research could explore to provide a more comprehensive understanding.

In the current dynamic and complex social context, teachers’ emotional competence not only directly or indirectly influences students’ socio-emotional and academic development, but also serves as an essential professional quality that enables teachers to navigate the complexities of teaching and interpersonal interactions. Based on an individual-centered perspective, this study employed LPA to explore the potential categories of emotional labor strategies among rotating teachers and their relationship with job performance. The findings highlight the existence of diverse emotional labor profiles among rotating teachers, which are closely linked to personal characteristics such as age and teaching experience, as well as to variations in job performance. These results underscore the importance of promoting adaptive emotional labor strategies to enhance teachers’ professional effectiveness. Future research could further explore the longitudinal effects of emotional labor strategies and develop targeted interventions. In particular, in the digital era, exploring how to leverage intelligent technologies to provide rotating teachers with more flexible and personalized support for emotional management and mental health represents an important direction for in-depth reflection and exploration.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the Postdoctoral Fellowship Program of CPSF (China), grant number GZ20232369. No part of the study (design, data collection, and curation analysis, manuscript preparation or publication) was influenced by the funder.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Huanfang Wang; methodology, Huanfang Wang and Fangfang Zhao; validation, Huanfang Wang and Xinyi Li; formal analysis, Huanfang Wang and Fangfang Zhao; investigation, Huanfang Wang and Ximeng Cui; resources, Huanfang Wang and Ximeng Cui; data curation, Huanfang Wang and Xinyi Li; writing—original draft preparation, Huanfang Wang and Ximeng Cui; writing—review and editing, Xinyi Li and Fangfang Zhao; supervision, Huanfang Wang and Weijian Li; project administration, Huanfang Wang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are openly available upon request from the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval: The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Zhejiang Normal University (ZSRT2025235). All participants in the study signed informed consent forms.

Informed Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, who were assured of their right to withdraw from the study at any stage.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Zhou CW , Du YY . Promoting the balanced development of urban and rural teacher workforce through rotational exchanges. Chinese J Educ. 2024; 11: 86– 90. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

2. Ministry of education, ministry of finance & ministry of human resources and social security, opinions on implimenting the mobilization of principals and teachers in the compulsory education sector within county (district) [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2025 Jun 1]. Available from: http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/A10/s7151/201408/t20140815_174493.html. [Google Scholar]

3. Zhu ZY , Xu XY . “Conform to local customs”: a case study on the emotional energy changes of primary school rotated teachers. Educ Res Mon. 2024; 9: 97– 103. (In Chinese). doi:10.16477/j.cnki.issn1674-2311.2024.09.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Huang L , Hao M . The absence of rural emotion among rotational teachers: representation, origins, and cultural formation. J Teach Educ. 2024; 11( 1): 22– 31. doi:10.13718/j.cnki.jsjy.2024.01.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Tian GX , Wang Y . Enhance teacher’s emotional ability and respond to the test of “job rotation and mobility”. Fujian Educ. 2022; 23: 64. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

6. Yin H . Adaptation and validation of the teacher emotional labour strategy scale in China. Educ Psychol. 2012; 32( 4): 451– 65. doi:10.1080/01443410.2012.674488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Diefendorff JM , Croyle MH , Gosserand RH . The dimensionality and antecedents of emotional labor strategies. J Vocat Behav. 2005; 66( 2): 339– 57. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2004.02.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Zhang Q , Yin J , Chen H , Zhang Q , Wu W . Emotional labor among early childhood teachers: frequency, antecedents, and consequences. J Res Child Educ. 2020; 34( 2): 288– 305. doi:10.1080/02568543.2019.1675824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Liao W . Subtle sensemaking large consequences: implementing three teacher policies in a Chinese context [ master’s thesis]. East Lansing, MI, USA: Michigan State University; 2018. [Google Scholar]

10. Liao W , Liu Y , Zhao P , Li Q . Understanding how local actors implement teacher rotation policy in a Chinese context: a sensemaking perspective. Teach Teach. 2019; 25( 7): 855– 73. doi:10.1080/13540602.2019.1689490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Wu X . Narrowing the gap: a Chinese experience of teacher rotation. Asia Pac Educ Rev. 2020; 21( 3): 393– 408. doi:10.1007/s12564-020-09630-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Xue E , Li J . The implementation of teacher exchange and rotation policy. In: Teacher education policy in China. Singapore: Springer; 2021. p. 15– 24. doi:10.1007/978-981-16-2366-0_3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Lang XQ . Pay attention to the value identification, emotional attitude and professional development environment of job rotation. People’s Educ. 2022; 12: 32. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

14. Alemdar M , Anılan H . Reflection of social capital in educational processes: emotional literacy and emotional labor context. Asia Pac Educ Rev. 2022; 23( 1): 27– 43. doi:10.1007/s12564-021-09701-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Grandey AA . Emotion regulation in the workplace: a new way to conceptualize emotional labor. J Occup Health Psychol. 2000; 5( 1): 95– 110. doi:10.1037/1076-8998.5.1.95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Cheng T , Zhu S . The relation between normal education and teachers’ job perfomance: impact mechanism and heterogeneity of teaching age. Educ Econ. 2023; 39( 5): 54– 62. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

17. Li H . The relationship between emotional labor and job performance of kindergarten teachers: the mediating effect of job burnout [ master’s thesis]. Chongqing, China: Southwest University; 2024. doi:10.27684/d.cnki.gxndx.2022.004200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Töre E . Effects of teacher emotional labor on job performance: mediating role of job satisfaction. Int J Educ Technol Sci Res. 2021; 6( 15): 945– 76. doi:10.35826/ijetsar.261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Grandey AA , Melloy RC . The state of the heart: emotional labor as emotion regulation reviewed and revised. J Occup Health Psychol. 2017; 22( 3): 407– 22. doi:10.1037/ocp0000067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Wang M , Bi X . Latent variable modeling using Mplus. Chongqing, China: Chongqing University Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

21. Gabriel AS , Daniels MA , Diefendorff JM , Greguras GJ . Emotional labor actors: a latent profile analysis of emotional labor strategies. J Appl Psychol. 2015; 100( 3): 863– 79. doi:10.1037/a0037408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Hong XM , Zhang MZ . Kindergarten teachers’ emotional labor types and impact on job satisfaction—based on the latent profile analysis of kindergarten teachers in six provinces in China. Teach Educ Res. 2021; 33( 1): 68– 74. (In Chinese). doi:10.13445/j.cnki.t.e.r.2021.01.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Zhao XY , You XQ , Qin W . The latent profile analysis of middle school teachers’ emotional labor strategies and the relationship with vocational well-being. J East China Norm Univ Educ Sci. 2023; 41( 1): 16– 24. (In Chinese). doi:10.16382/j.cnki.1000-5560.2023.01.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Ma YX . A study on organizational climate in colleges and universities and its relationship with teachers’ job performance [ master’s thesis]. Zhengzhou, China: Zhengzhou University; 2005. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

25. Motowidlo SJ , Van Scotter JR . Evidence that task performance should be distinguished from contextual performance. J Appl Psychol. 1994; 79( 4): 475– 80. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.79.4.475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Nylund KL , Asparouhov T , Muthén BO . Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: a Monte Carlo simulation study. Struct Equ Model A Multidiscip J. 2007; 14( 4): 535– 69. doi:10.1080/10705510701575396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Wang MC , Bi XY . Latent variable modeling and applications of mplus (advanced edition). Chongqing, China: Chongqing University Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

28. Austin EJ , Dore TCP , O’Donovan KM . Associations of personality and emotional intelligence with display rule perceptions and emotional labour. Pers Individ Differ. 2008; 44( 3): 679– 88. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2007.10.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Gabriel AS , Diefendorff JM . Emotional labor dynamics: a momentary approach. Acad Manag J. 2015; 58( 6): 1804– 25. doi:10.5465/amj.2013.1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Rezai A , Namaziandost E , Teo T . EFL teachers’ perceptions of emotional literacy: a phenomenological investigation in Iran. Teach Teach Educ. 2024; 140: 104486. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2024.104486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Huang S , Yin H . The relationships between paternalistic leadership, teachers’ emotional labor, engagement, and turnover intention: a multilevel SEM analysis. Teach Teach Educ. 2024; 143: 104552. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2024.104552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Johnson HM , Spector PE . Service with a smile: do emotional intelligence, gender, and autonomy moderate the emotional labor process? J Occup Health Psychol. 2007; 12( 4): 319– 33. doi:10.1037/1076-8998.12.4.319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools