Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Effectiveness of an 8-Week Game-Based Physical Activity Program in Reducing Post-Traumatic Stress among Children Affected by the 2023 Kahramanmaraş Earthquakes

1 Department of Physical Education and Sport on Disabilities, Faculty of Sport Sciences, İnönü University, Malatya, 44100, Türkiye

2 Department of Sport Management, Faculty of Sport Sciences, İnönü University, Malatya, 44100, Türkiye

3 Sümer Middle School, Physical Education and Sport Teaching, Malatya, 44090, Türkiye

* Corresponding Author: Burak Canpolat. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Enhancing Mental Health through Physical Activity: Exploring Resilience Across Populations and Life Stages)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(11), 1781-1795. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.069852

Received 02 July 2025; Accepted 27 October 2025; Issue published 28 November 2025

Abstract

Objectives: This study examines the effectiveness of an eight-week game-based physical activity program designed to reduce post-traumatic stress levels in children affected by the Kahramanmaraş-centered earthquakes that occurred in Turkey on 06 February 2023. Following the earthquake, millions of children experienced significant changes in their education and living conditions, adversely affecting their psychological health. Methods: The therapeutic effects of physical activity on post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are frequently emphasized in the literature, and this study specifically focuses on the impact of game-based exercises. The research employed an experimental design, involving 80 earthquake-affected children aged 10 to 13, who were randomly assigned to either an experimental group (n = 40) or a control group (n = 40). The experimental group participated in game-based physical activities three times per week for eight weeks, with each session lasting 60 min. Data were collected using the Child Post-Traumatic Stress Reaction Index (CPTS-RI), and pre-test and post-test comparisons were conducted. Results: Children in the experimental group showed a marked reduction in PTSD symptoms, with mean CPTS-RI scores decreasing from 2.60 at pre-test to 1.91 at post-test. In contrast, the control group’s scores remained virtually unchanged (2.59 at pre-test vs. 2.57 at post-test). Two-way ANOVA demonstrated significant main effects of group and time, as well as a significant group × time interaction (F = 114.88, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.42), indicating that the reduction was attributable to participation in the game-based physical activity program. These findings highlight not only the statistical significance but also the practical relevance of structured, culturally adapted physical activity interventions for trauma-exposed children. Conclusion: These findings suggest that regular, structured game-based physical activities can support the mental health of children following traumatic events such as earthquakes and reduce their stress levels. The study recommends integrating physical activity into post-disaster psychosocial support programs and highlights it as an effective, accessible, and enjoyable method to enhance children’s trauma coping skills. Accordingly, it advocates for the wider implementation of physical activity-based interventions in similar crisis situations.Keywords

Natural disasters such as earthquakes are not only associated with widespread physical destruction but are also recognized as some of the most psychologically distressing life events [1]. Due to their sudden and unpredictable nature, such disasters often trigger intense emotional responses including fear, helplessness, and uncertainty, which may lead to long-term psychological consequences [2]. Previous studies have shown that earthquakes can lead to a variety of mental health problems, including depression, among large segments of the population [3]. On 06 February 2023, at 04:17 and 13:24 local time, two major earthquakes with magnitudes of 7.7 and 7.6 struck Türkiye, with epicenters in the Pazarcık and Elbistan districts of Kahramanmaraş. These earthquakes were recorded as the most destructive in the country’s history, affecting an area of 108,812 square kilometers and impacting 11 provinces across the Eastern and Southeastern Anatolia regions. The province of Malatya, where the present study was conducted, experienced a significant loss of life and property as a result of the disaster [4].

Following the earthquakes, it was found that adult survivors experienced varying levels of depression—ranging from mild to severe [5]. However, the psychological effects of the disaster were not limited to adults. Approximately four million children were affected by the February 6 earthquakes, and the destruction or damage of around 576 schools across the 11 provinces severely disrupted children’s access to education [6]. This disruption, combined with the sudden changes in daily life and the experience of loss, increased children’s and adolescents’ vulnerability to various mental health issues [7]. Furthermore, a post-disaster report emphasized the scarcity of psychosocial support programs to help children and adolescents in the affected regions cope with the traumatic experience of the earthquake, highlighting a significant need for specialized professionals and interventions in these areas [8]. Additionally, an information bulletin published by the Turkish Psychiatric Association after the earthquake noted that children aged 2–5, 6–11, and adolescents aged 12–17 may exhibit different trauma-related symptoms [9].

Disaster psychology is a field that examines the psychosocial impacts of disasters such as earthquakes, floods, mining accidents, and acts of terrorism [10], and it is stated that post-disaster social work was initiated in the twentieth century by sociologists [11]. In Türkiye, studies on the psychological consequences of disasters began following the 1992 Erzincan earthquake [12] and gained momentum after the 1999 Marmara earthquake [13]. This is because individuals’ reactions following a disaster vary depending on the nature of the disaster and personal characteristics, and are generally categorized into different phases: the initial hours, the early days, and the end of the first week [14]. Based on these phases, psychological assistance to disaster survivors has been framed within the context of disaster psychology as both psychological first aid, recommended by the World Health Organization [15], and as individualized mid- and long-term treatment approaches involving psychosocial support interventions [14]. Within this context, the current study was conducted approximately one year after the earthquakes of February 6, 2023, during the months of March, April, and May. Although this timing might be considered a limitation of the study, it is important to acknowledge that earthquakes are natural disasters known to cause long-term psychological effects [16,17,18,19].

Regular physical activity and exercise can play a significant role in improving the physical and mental health of children following trauma. Research has demonstrated that physical activity is effective in reducing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and other psychological symptoms. Specifically, physical activity has been shown to enhance mental well-being in traumatized children by reducing symptoms of anxiety, depression, and PTSD [20,21,22]. Moreover, the combination of resistance and aerobic exercises appears to be particularly effective in alleviating PTSD symptoms [23]. Beyond natural disasters, regular exercise has also been found to reduce depressive symptoms and improve overall mood in individuals who have experienced other forms of trauma [21,22]. Additionally, exercise is known to contribute to cognitive recovery after traumatic brain injuries. [24,25]. It has also been reported that physical activity can reduce social anxiety and boost individuals’ self-confidence [26], and that engaging in physical activities integrated with nature can foster post-traumatic growth while lowering stress levels [27]. Finally, given the significant disruptions in sleep patterns observed among individuals affected by earthquakes [28,29], it is important to note that regular exercise has been shown to improve sleep quality and enhance general physical health in children [20,30].

Game-Based Physical Activity (GBPA) and Psychological Well-Being

Game-based approaches have become increasingly popular in educational settings [31]. In recent years, they have been increasingly employed as an active methodology to address issues related to social behavior and motivation among children and adolescents [32,33,34]. In this context, implementing physical activities in a gamified format for children was a crucial parameter in ensuring the sustainability of the intervention and in achieving the desired outcomes.

The impact of game-based physical activity (GBPA) on psychological well-being has been the subject of extensive research in recent years. Studies have shown that GBPA can significantly enhance psychological well-being in children, adolescents, and adults alike [35,36,37]. GBPA—such as exergames, augmented reality (AR) games, and traditional physical games—has been associated with substantial improvements in participants’ happiness, subjective well-being, and overall mental health [35,36,37,38,39,40,41]. These types of activities are linked to reductions in stress, anxiety, and depression. Notably, active video games (exergames) and AR-based games have demonstrated such effects, particularly among university students and young adults [37,38,40,41]. Furthermore, game-based activities have been found to improve self-esteem and promote positive emotional states in children and adolescents, while simultaneously reducing negative emotions such as tension, anger, and confusion [35,37,39]. GBPA has also been shown to enhance social interaction, attention, and memory [35,40].

The effectiveness of game-based physical activity in reducing PTSD symptoms can be theoretically explained by several mechanisms. Meta-analyses and randomized controlled trials indicate that GBPA significantly reduces PTSD symptoms in children. Specifically, children receiving group-based interventions experienced significant reductions in PTSD symptoms compared to controls, with a moderate effect size (g = −0.55). This effect was also observed across different types of trauma (natural disaster, war, abuse) and across various socioeconomic settings [42,43,44,45]. Game-based group therapies have been found effective in a variety of forms, including traditional games and cognitive-behavioral approaches [46,47,48].

The positive psychological and social effects of game-based physical activities for children are supported not only by research findings [42,46] but also by some positive psychology [49] and health behavior theories [50]. Indeed, as theorists such as Piaget, Vygotsky, and Erikson, who have pioneered approaches to children from past to present, have suggested, game supports multidimensional development for children, playing a fundamental role in cognitive, social, emotional, and physical domains [51,52,53]. Modern approaches, on the other hand, emphasize the effects of play on coping with uncertainty, learning motivation, and psychosocial resilience [54,55,56].

Within this framework, it is evident that earthquakes are natural disasters that leave profound physical and psychological effects on children, and that they can have particularly significant impacts in terms of post-traumatic stress. Interventions aimed at reducing post-traumatic stress levels are of great importance in facilitating children’s adaptation to life following such traumatic events. While physical activity is well known for its positive effects on individuals’ overall health, it also plays a crucial role in psychological recovery processes. In this context, the central research question of the present study is whether regular physical activity is effective in reducing post-traumatic stress levels among children affected by the earthquake. Accordingly, the study was conducted using an experimental design involving both an intervention and a control group.

This study was conducted to examine the effect of regular physical activity on the Child Post-Traumatic Stress Reaction Index (CPTS-RI) levels in children affected by the earthquake. The research employed an experimental design, one of the quantitative research methods. A pretest-posttest control group model was adopted within the scope of the study.

A total of 80 students (Experimental: 10.75 ± 0.74 years; Control: 11.1 ± 0.93 years), aged between 10 and 13, living in the same region affected by the earthquake, participated in the study. Participants were randomly assigned to either the experimental group (n = 40; 21 females, 19 males) or the control group (n = 40; 19 females, 21 males). The children were homogeneously distributed in terms of age, gender, and trauma level. Participants in the experimental group received a regular physical activity program, while participants in the control group did not receive any intervention. As of June 2025, all participants in both the intervention and control groups continue to reside in safe container settlement areas established for earthquake survivors.

The rationale for selecting children aged 10–13 is based on both developmental and methodological considerations [57,58,59,60]. This age group corresponds to late childhood and early adolescence, a critical period for psychosocial development during which trauma symptoms are quite evident but also responsive to structured interventions [58,59,61,62]. Additionally, the CPTS-RI scale has been shown to be reliable and valid in assessing PTSD symptoms in children at this developmental stage.

The study was approved by the Scientific Research Publications and Ethics Committee of the İnönü University with decision number 2/6 dated 08 February 2024. Participation was voluntary, and ethical guidelines were strictly followed throughout all phases of the study. Informed consent was obtained from the families, and participants’ personal information was kept confidential.

2.2 Child Posttraumatic Stress Reaction Index (CPTS-RI)

To assess participants’ post-traumatic stress levels, the CPTS-RI, originally developed by Pynoos and colleagues in 1987, was employed [63]. The validity and reliability of the scale in Türkiye were established by Erden and colleagues [64]. This instrument is designed to measure the intensity of post-traumatic stress reactions experienced by children and adolescents who have been exposed to trauma. The scale consists of 20 items, each rated by the participant on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 4, where 0 indicates “never experienced” and 4 indicates “experienced very often”. As a result, total scores range from 0 to 80, with higher scores reflecting more severe post-traumatic stress symptoms. The CPTS-RI evaluates trauma-related symptoms across emotional, cognitive, and behavioral dimensions, providing a comprehensive assessment of the negative effects experienced by children. Items on the scale assess symptoms such as intrusive memories related to the traumatic event, fear, avoidance behaviors, hyperarousal, and emotional responses. Due to its ability to capture a wide range of trauma symptoms, the CPTS-RI is widely used as a valid and reliable tool in both the diagnostic assessment of PTSD in children and in monitoring treatment outcomes. In this study, the CPTS-RI was administered to each participant twice: once before the intervention (pre-test) and once after the intervention (post-test). This pre-post evaluation enabled the researchers to assess changes in post-traumatic stress levels and determine the effectiveness of the intervention.

2.3 8 Week Game Based Physical Activity Program

The children in the experimental group participated in a structured physical activity program conducted over eight weeks, with sessions held three times per week, each lasting 60 min. The program was designed by the researchers involved in this study, consisting of game-based exercises tailored to be age-appropriate for the children. Given the lack of access to necessary equipment and transportation among the earthquake-affected children, the program—comprising educational, game-based physical activities as outlined in Table 1—was implemented in a manner that ensured consistent and regular participation.

Table 1: GBPA program applied for 8 weeks.

| Week | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Introduction, trust and group games | Balance and coordination games | Educational games based on teamwork |

| 2 | Sensory-motor skill games | Target-based games | Story-supported movement activities |

| 3 | Crawling, jumping, and catching games | Ball games and cooperation activities | Station-based activities |

| 4 | Movement with imitation and role-play | Rhythm and music-integrated games | Educational competitive games |

| 5 | Obstacle course and climbing activities | Attention and memory-enhancing games | Balance beam, rope jumping activities |

| 6 | Emotional expression games | Body awareness activities | Group problem-solving games |

| 7 | Outdoor orientation and exploration games | Team competitions | Game creation and leadership skills |

| 8 | Free and creative movement games | Mini tournaments and group evaluation | Symbolic ceremony and closing activities |

The program design, consisting of 24 sessions over eight weeks, each lasting 60 min, is based on evidence from physical activity and play therapy interventions that typically last between 6 and 12 weeks [26,65,66]. A frequency of three sessions per week was deemed optimal to establish routine and ensure consistent exposure while preventing participant fatigue. The 60-min duration was deemed appropriate to balance the children’s attention span with the need to include warm-ups, basic play-based activities, and cool-down phases. The program’s conceptual framework was informed by international literature on play-based interventions and was implemented in a format appropriate to the region’s culture, integrating traditional games and physical activities into educational practices and psychosocial support programs.

Conducted in a controlled environment by trained specialists, this program aimed to evaluate the effects of physical activity on trauma-related stress. In this context, children in the control group continued their normal daily routines and did not receive any structured interventions during the study. Due to logistical and ethical concerns in the post-disaster period, an alternative active control condition, such as participation in standard physical education or non-physical group activities, was not implemented. In particular, the lack of trained personnel and the need to prioritize immediate psychosocial interventions for the affected children made it impossible to organize parallel structured sessions for the control group. Therefore, a passive control design, consistent with similar post-disaster intervention studies, was adopted.

Table 1 summarizes the weekly and daily overall structure of the eight-week game-based physical activity program planned for the earthquake-affected children. The program consisted of three weekly sessions, each 60 min long, featuring enjoyable and interactive activities appropriate for the developmental stage of the participants. The first weeks focused primarily on fostering social bonds, group cohesion, and the development of basic motor skills among children. In subsequent weeks, games were added to the program, which fostered skills such as balance, coordination, rhythm, problem-solving, and leadership. The final week was dedicated to free-form activities that strengthened children’s self-confidence, such as mini-tournaments and closing ceremonies.

The program was designed to promote both physical development and psychosocial recovery following trauma.

2.4 Data Collection and Analysis

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics version XX (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Prior to conducting inferential analyses, the normality of the data was examined using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests, along with an evaluation of skewness and kurtosis values. The assumption of homogeneity of variances was tested with Levene’s test.

To assess baseline equivalence between the experimental and control groups, independent samples t-tests were applied to pre-test scores. To evaluate the main effects of group (experimental vs. control), time (pre-test vs. post-test), and the group × time interaction, a two-way mixed ANOVA was conducted. When the assumption of equal variances was violated, corrections based on the “equal variances not assumed” approach were used.

Effect sizes were reported alongside significance values: Cohen’s d was calculated for t-test comparisons, while partial eta squared (η2) was provided for ANOVA results. Effect size interpretation followed conventional thresholds (small = 0.01, medium = 0.06, large = 0.14).

All statistical tests were two-tailed, and the level of significance was set at p < 0.05.

2.5 Use of Artificial Intelligence

Artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted tools (ChatGPT, OpenAI, San Francisco, CA, USA) were used exclusively for language polishing and improving grammar/fluency in the preparation of this manuscript. No AI tools were used for data collection, statistical analysis, or interpretation of results. The authors take full responsibility for the scientific content of the article.

According to the results of the Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk normality tests presented in Table 2, all variables were found to conform to a normal distribution. Given that the sample size was below 50, the Shapiro-Wilk test was considered more reliable, and its results indicated that the significance values for all variables exceeded the 0.05 threshold. Although the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test showed a significant result for the post-test data of the experimental group (p = 0.024), the Shapiro-Wilk test yielded a borderline but acceptable significance value of 0.055. Therefore, it was concluded that this variable also followed a normal distribution.

Table 2: Normality test.

| Group | Test | Kolmogorov-Smirnov | Shapiro-Wilk | Skewness | Kurtosis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistic | df | Sig. | Statistic | df | Sig. | ||||

| Experimental | Pre-Test | 0.097 | 40 | 0.200# | 0.966 | 40 | 0.272# | 0.450 | 0.086 |

| Post-Test | 0.150 | 0.024 | 0.946 | 0.055# | 0.045 | −1.164 | |||

| Control | Pre-Test | 0.099 | 0.200# | 0.978 | 0.617# | 0.459 | 0.182 | ||

| Post-Test | 0.105 | 0.200# | 0.981 | 0.731# | −0.016 | −0.278 | |||

Furthermore, an examination of skewness and kurtosis values revealed that all variables fell within the range of −1 to +1, indicating symmetric distributions resembling a bell curve. These findings support the assumption of normality and justify the use of parametric tests for data analysis.

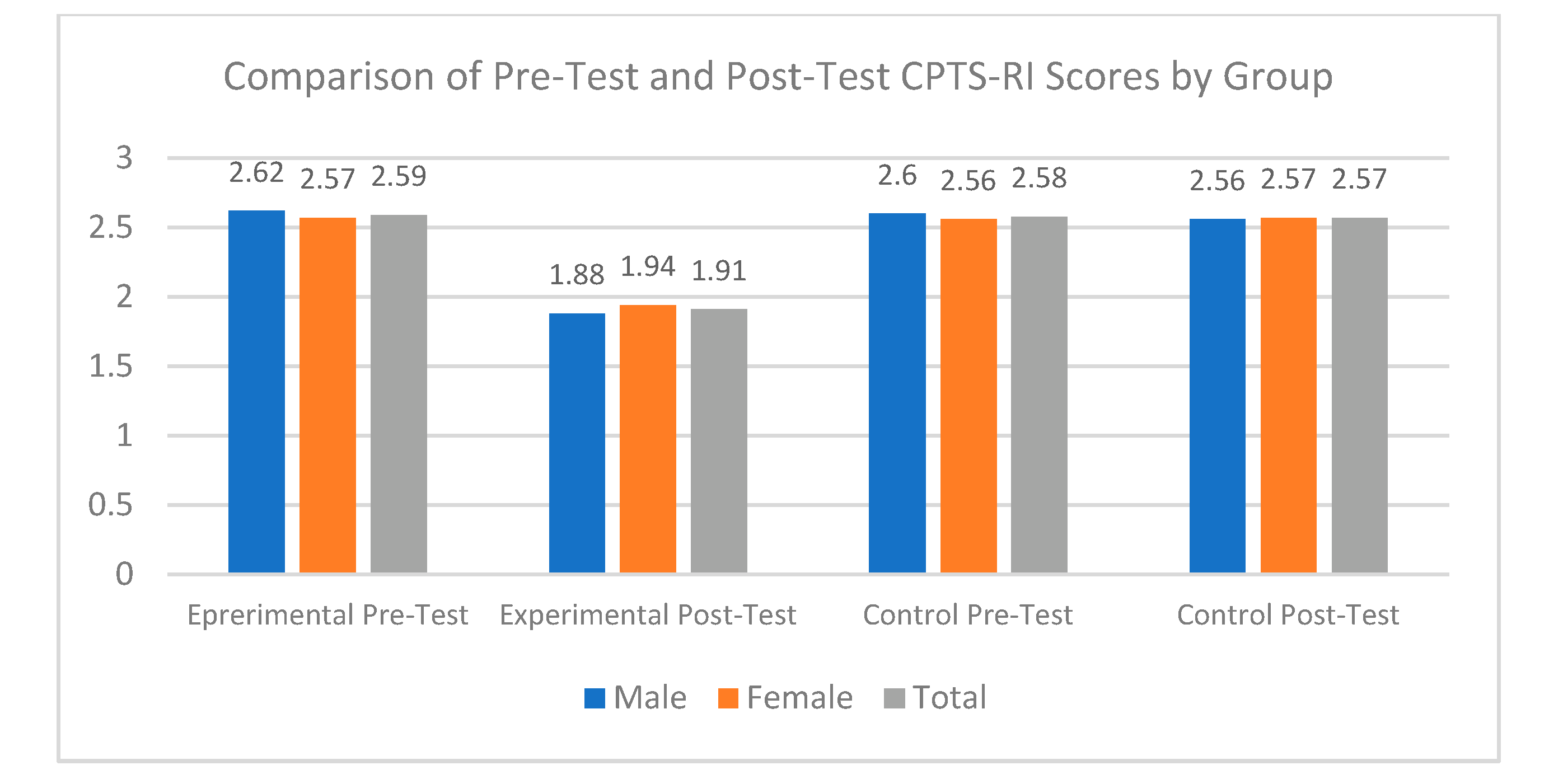

Table 3 and Fig. 1 present the mean scores and standard deviations of CPTS-RI (Child Post-Traumatic Stress Reaction Index) pre-test and post-test results for participants in the experimental and control groups. In the experimental group, the mean pre-test score for male participants was 2.6289, which decreased to 1.8816 in the post-test. Similarly, female participants had a pre-test mean of 2.5714 and a post-test mean of 1.9452. Considering the overall experimental group, the mean score declined from 2.5988 in the pre-test to 1.9150 in the post-test. These data indicate a significant reduction in post-traumatic stress levels among both male and female children in the experimental group. In the control group, the mean pre-test score for males was 2.6079, slightly decreasing to 2.5684 at post-test, while females showed a slight increase from a pre-test mean of 2.5667 to 2.5786 post-test. The overall mean for the control group was 2.5863 in the pre-test and 2.5738 in the post-test. While no notable changes were observed in the control group, the significant decrease in scores within the experimental group demonstrates the effectiveness of the intervention in reducing post-traumatic stress symptoms in children.

Table 3: Means and standard deviations of pre-test and post-test CPTS-RI scores of experimental and control groups.

| Group | Gender | Pre-Test | Post-Test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | ||

| Experimental (n = 40) | Male | 2.6289 | 0.2417 | 1.8816 | 0.1857 |

| Female | 2.5714 | 0.1479 | 1.9452 | 0.2048 | |

| Total | 2.5988 | 0.1975 | 1.9150 | 0.1961 | |

| Control (n = 40) | Male | 2.6079 | 0.2534 | 2.5684 | 0.2180 |

| Female | 2.5667 | 0.1653 | 2.5786 | 0.1609 | |

| Total | 2.5863 | 2.5863 | 2.5738 | 2.5738 | |

Figure 1: Pre-test and post-test CPTS-RI scores averages of experimental and control groups. (Note: Scores represent total PTSD symptom scale values; no units are applicable).

Table 4 presents the comparison of pre-test CPTS-RI scores and the differences in post-test scores between the experimental and control groups using an independent samples t-test. The Levene’s test for equality of variances indicated that variances were equal for the pre-test scores (p = 0.835). The t-test results showed no significant difference between the groups at pre-test (t (78) = 0.274, p = 0.785), indicating that the experimental and control groups had similar CPTS-RI scores prior to the intervention. For the difference in post-test scores, Levene’s test indicated unequal variances (p < 0.001), thus the t-test was evaluated using the “equal variances not assumed” row. The results revealed a statistically significant difference between the experimental and control groups at post-test (t (50.159) = −17.771, p < 0.001), with the experimental group demonstrating a significantly lower mean score compared to the control group (mean difference = −0.67125). These findings suggest that the intervention effectively reduced post-traumatic stress levels among the children in the experimental group.

Table 4: Independent samples t-test for pre-test and post-test-first test differences of control and experimental groups.

| Test | Levene’s Test for Equality of Variances | t-Test for Equality of Means | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | Sig. | t | df | Sig. (2-Tailed) | Mean Difference | Std. Error Difference | 95% Confidence Interval of the Difference | |||

| Lower | Upper | |||||||||

| Pre-Test | Equal variances assumed | 0.044 | 0.835 | 0.274 | 78 | 0.785 | 0.0125 | 0.0455 | −0.0782 | 0.1032 |

| Equal variances not assumed | / | / | 0.274 | 77.712 | 0.785 | 0.0125 | 0.0455 | −0.0782 | 0.1032 | |

| Post Test—Pre Test Difference Average | Equal variances assumed | 16.306 | <0.001 | −17.771 | 78 | <0.001* | −0.6712 | 0.0377 | −0.7464 | −0.5960 |

| Equal variances not assumed | / | / | −17.771 | 50.159 | <0.001* | −0.6712 | 0.0377 | −0.7471 | −0.5953 | |

As shown in Table 5, the evaluation of the group factor revealed a significant difference between the experimental and control groups (F = 106.486, p < 0.05). This indicates that the decrease in CPTS-RI scores in the experimental group, which received regular GBPA, was statistically significant compared to the control group. The difference between pre-test and post-test scores was also significant (F = 123.601, p < 0.05), demonstrating a marked reduction in CPTS-RI scores during the period of GBPA intervention. The interaction effect between group and test was found to be significant as well (F = 114.885, p < 0.05), indicating that the impact of GBPA on reducing CPTS-RI scores differed between the experimental and control groups. Partial eta squared values suggest a moderate effect size for group (η2 = 0.406), test (η2 = 0.442), and group * test interaction (η2 = 0.424). These results show that the combined effect of the test and group variables on participants’ post-traumatic stress reaction scores was significant, F(1156) = 114.885, p < 0.05, partial η2 = 0.42. In other words, being in the experimental or control group had a different impact on reducing post-test scores. Thus, the change in CPTS-RI pre-test and post-test scores between the experimental and control groups was significantly different.

Table 5: Two-factor ANOVA on the effect of group and test variables on CPTS-RI scores.

| Source | Type III Sum of Squares (SS) | df | Mean Square (MS) | F | Sig. | Partial Eta Squared (η2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 935.814 | 1 | 935.814 | 23,860.672 | <0.001* | 0.994 |

| Group | 4.176 | 1 | 4.176 | 106.486 | <0.001* | 0.406 |

| Test | 4.848 | 1 | 4.848 | 123.601 | <0.001* | 0.442 |

| Group × Test | 4.506 | 1 | 4.506 | 114.885 | <0.001* | 0.424 |

| Error | 6.118 | 156 | 0.039 | |||

| Total | 955.462 | 160 |

In our study, using the CPTS-RI, it was concluded that eight weeks of regular exercise led to a significant improvement in the experimental group compared to the control group. Other studies that examined post-traumatic stress reaction levels in children following the Kahramanmaraş-centered earthquakes using the same scale have reported similar findings. Düken et al. found that 100% of children exhibited symptoms of depression, 23% experienced severe trauma, and 77% showed very severe post-traumatic stress symptoms following the Kahramanmaraş earthquake [67]. Another study using the same scale reported high rates of depression and anxiety disorders among children [68], and similar emotional responses were observed in children affected by a 2011 earthquake in Van [69]. Research conducted after that earthquake also indicated that children suffered from severe trauma and sleep disturbances. It was noted that children experiencing trauma due to the earthquake had increased rates of sleep disorders [70]. In a study involving 292 children aged 8 to 15 affected by the earthquake, it was found that higher levels of earthquake exposure corresponded with increased stress responses, which in turn heightened anxiety sensitivity. Various recommendations were made to reduce this anxiety [71]. In light of these recommendations, it can be inferred that physical activity and sports may have a positive impact on the physical health that is often diminished due to trauma [72].

Research on the effects of regular physical activity on trauma levels in children indicates that physical activity provides positive social, emotional, and behavioral outcomes for children and adolescents following trauma [20,65,73]. Trauma-informed physical activity programs promote social, emotional, and academic improvements among youth [65]. These programs offer positive experiences, such as post-traumatic social bonding and psychological escape [74].

Physical activity enhances psychological resilience in individuals after trauma and reduces adverse psychological conditions, including anxiety, depression, and PTSD [20]. Additionally, physical activity may facilitate post-traumatic growth and stress reduction [27]. It can improve behavioral and emotional problems in children and support overall mental health [73,75]. Among children who have experienced trauma, physical activity has been linked to better working memory performance and fewer depressive symptoms [76]. Trauma-informed physical education aims to create safe and supportive environments, which can help children better understand challenges related to learning, relationship building, and behavior management [77]. Nature-integrated physical activities promote post-traumatic growth and assist in stress reduction [27].

While the positive effects of physical activity on traumatized children are emphasized, potential risks should also be considered. During physical activity, trauma-affected children may feel vulnerable, and instructors who lack full awareness of the deep fragility experienced by these children may inadvertently contribute to difficulties in learning, relationship formation, and behavior management [65,77]. This may lead to the re-experiencing of trauma.

In children affected by earthquakes, play therapy has been found to reduce post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and negative behaviors [78]. To cope with the traumatic effects that may arise following an earthquake, encouraging children to return to their daily routines and participate in play, cultural, and art-based activities can support their stress management [79]. It has been observed that children affected by earthquakes experience declines in motor skill levels and physical activity [80]. Addressing these adverse effects requires early diagnosis, psychosocial support, and physical activity, which play crucial roles [81].

Following the Wenchuan earthquake in China, a sand play therapy intervention was conducted with children and adolescents. Trauma scores recorded at 1 and 6 months post-intervention were significantly lower compared to those obtained at 12, 18, and 24 months [82]. Similarly, Valenti and colleagues concluded that amateur sports activities can alleviate psychological and behavioral problems caused by natural disasters [83]. In addition to amateur sports, both team and individual sports have been reported to reduce the negative and traumatic effects of earthquakes [84].

From this perspective, numerous studies indicate that applying physical activity alone or as an adjunct to existing treatments in CPTS-RI management is associated with symptom reduction [23,85,86,87,88,89,90,91].

This study has several limitations. First, due to the limited sample size, the generalizability of the findings to larger and more diverse populations is restricted. Additionally, since the CPTS-RI is a self-report measure, there is a risk of bias arising from social desirability or differences in participants’ understanding of the items. The effects of the intervention were assessed only in the short term, and the lack of investigation into its long-term impact and sustainability constitutes another limitation.

The absence of any intervention for the control group may have made it difficult to fully control for external factors. Furthermore, the non-standardized environment and conditions under which the intervention was delivered could have introduced variability in the implementation process. Considering cultural and social factors, the validity of the scale and the intervention might differ across cultures, which limits the comparability of the results obtained in the Turkish context with those from other countries.

Finally, factors such as participants’ momentary mood, external influences, and motivation levels during data collection may have also affected the results.

Therefore, it is recommended that future research employ larger samples, include long-term follow-ups, and be conducted in diverse cultural settings to address these limitations.

This study demonstrated that regular physical activity is effective in reducing post-traumatic stress levels in earthquake-stricken children. The eight-week physical activity program significantly reduced CPTS-RI scores in the experimental group. This decrease was not statistically significant in the control group. This study also demonstrated that regular physical activity is effective in reducing post-traumatic stress levels among children affected by earthquakes. The eight-week physical activity program significantly decreased CPTS-RI scores in the experimental group, whereas no statistically significant reduction was observed in the control group.

The findings suggest that physical activity may serve as a supportive factor for children’s mental health and contribute to psychological recovery following a disaster. Specifically, aerobic exercises and game-based activities were found to play a crucial role in lowering stress levels in children. Moreover, regular physical activity was observed to enhance social interaction, thereby improving individuals’ coping skills with trauma.

Accordingly, it is recommended that physical activity be incorporated into post-disaster psychosocial support programs. Designing structured physical activity interventions after large-scale traumatic events, such as earthquakes, should be considered an important approach to maintaining children’s well-being and strengthening their mental health. Future research should explore different age groups and examine the long-term effects of physical activity to gain deeper insights into its role in the psychological recovery process following trauma.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the Scientific Research Projects Unit (BAP) of İnönü University under project number SBA-2024-3449.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Burak Canpolat and Göktuğ Norman; methodology, Burak Canpolat; software, Burak Canpolat; validation, Yalın Aygün, Göktuğ Norman and Cemal Gündoğdu; formal analysis, Burak Canpolat; investigation, Şakir Tüfekçi and Cemal Gündoğdu and Taylan Akbuğa; resources, Burak Canpolat; data curation, Burak Canpolat and Yalın Aygün; writing—original draft preparation, Burak Canpolat; writing—review and editing, Burak Canpolat and Göktuğ Norman; visualization, Taylan Akbuğa and Şakir Tüfekçi; supervision, Cemal Gündoğdu; project administration, Burak Canpolat; field coordination and participant communication, Cemal Gündoğdu and Şakir Tüfekçi; physical activity program implementation, Burak Canpolat, Taylan Akbuğa and Yalın Aygün; statistical consultation, Burak Canpolat and Göktuğ Norman; funding acquisition, Burak Canpolat. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author, B.C., upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: The study was approved by the Scientific Research Publications and Ethics Committee of the İnönü University with decision number 2/6 dated 08 February 2024. Participation was voluntary, and ethical guidelines were strictly followed throughout all phases of the study. Informed consent was obtained from the families, and participants’ personal information was kept confidential.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Norris FH , Friedman MJ , Watson PJ , Byrne CM , Diaz E , Kaniasty K . 60,000 disaster victims speak: part I. An empirical review of the empirical literature, 1981–2001. Psychiatry. 2002; 65( 3): 207– 39. doi:10.1521/psyc.65.3.207.20173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Galea S , Nandi A , Vlahov D . The epidemiology of post-traumatic stress disorder after disasters. Epidemiol Rev. 2005; 27: 78– 91. doi:10.1093/epirev/mxi003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Shi X , Yu NX , Zhou Y , Geng F , Fan F . Depressive symptoms and associated psychosocial factors among adolescent survivors 30 months after 2008 Wenchuan earthquake: a follow-up study. Front Psychol. 2016; 7: 467. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. AFAD . 6 Şubat 2023 Kahramanmaraş (Pazarcık ve Elbistan) Depremleri Saha Çalişmalari ön Değerlendirme Raporu. 2023 [cited 2025 Oct 27]. Available from: https://deprem.afad.gov.tr/assets/pdf/Arazi_Onrapor_28022023_surum1_revize.pdf. (in Turkish). [Google Scholar]

5. Cengİz S , Peker A . Deprem sonrası yetişkin bireylerin depresyon düzeylerinin İncelenmesi. Trtakademi Trt Akad. 2023; 8( 18): 652– 68. doi:10.37679/trta.1277689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. UNICEF . 6 February–31 December 2023 humanitarian situation report No. 19. New York, NY, USA: UNICEF; [cited 2025 May 12]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/turkiye/en/media/17516/file/6%20%C5%9Eubat%20-%2031%20Aral%C4%B1k%20.pdf. [Google Scholar]

7. Yıldırım EA , Boztaş MH , Bülbül A . 6 Şubat Depremleri Hatay-Kahramanmaraş-Adıyaman Birinci Ay Alan Değerlendirmesi Raporu [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 Oct 26]. Available from: https://psikiyatri.org.tr/tpddata/Uploads/files/turk%C4%B0yepsikiyatridernegi6ayhataykahramanmarasadiyaman6ay.pdf. (in Turkish). [Google Scholar]

8. Ünüvar N , Özmete E . Kahramanmaraş merkezli depremlerde psikososyal Destek uygulamalari: elbistan ve kahramanmaraş İl merkezi saha çalişmasi raporu. Ankara, Turkey: Ankara Üniversitesi; 2023. (in Turkish). [Google Scholar]

9. Türkiye Psikiyatri Derneği Depremden Etkilenen Çocuklara Yönelik Bilgilendirme [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 Oct 26]. Available from: https://www.europsy.net/app/uploads/2023/03/Guide-for-Mental-Health-of-Children-Survivors-After-the-Earthquake.pdf. (in Turkish). [Google Scholar]

10. Karancı AN , İkizer G . Afet psikolojisi: Tarihçe, temel ilkeler ve uygulamalar. Turk Klin Psychol-Spec Top. 2017; 2( 3): 163– 71. (in Turkish). [Google Scholar]

11. Quarantelli EL . Disaster research. In: Edgar RJ , Borgatta F , editors. Encyclopedia of sociology. 2nd ed. New York, NY, USA: Macmillan; 2000. p. 681– 8. [Google Scholar]

12. Karanci AN , Rüstemli A . Psychological consequences of the 1992 Erzincan (Turkey) earthquake. Disasters. 1995; 19( 1): 8– 18. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7717.1995.tb00328.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Salcioglu E , Basoglu M , Livanou M . Post-traumatic stress disorder and comorbid depression among survivors of the 1999 earthquake in Turkey. Disasters. 2007; 31( 2): 115– 29. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7717.2007.01000.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Özkan B , Kutun FÇ . Afet psikolojisi. Sağlık Akad Derg. 2021; 8( 3): 249– 56. (in Turkish). [Google Scholar]

15. DSÖ . Psikolojik ilk yardim: Saha çalişanlari için rehber. Ankara, Türkiye: Türk Psikolojik Danışma ve Rehberlik Derneği; 2014. (in Turkish). [Google Scholar]

16. Stroebe K , Kanis B , Richardson J , Oldersma F , Broer J , Greven F , et al. Chronic disaster impact: the long-term psychological and physical health consequences of housing damage due to induced earthquakes. BMJ Open. 2021; 11( 5): e040710. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-040710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Yin Q , Wu L , Yu X , Liu W . Neuroticism predicts a long-term PTSD after earthquake trauma: the moderating effects of personality. Front Psychiatry. 2019; 10: 657. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Shui A , Mierau J , van den Berg GJ , Viluma L . The impact of induced earthquakes on mental health: evidence from the Dutch Lifelines Cohort Study. Eur J Public Health. 2023; 33( Suppl 2): ckad160.1186. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckad160.1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Lu WT , Zhao XC , Wang R , Li N , Song M , Wang L , et al. Long-term effects of early stress due to earthquake exposure on depression symptoms in adulthood: a cross-sectional study. Injury. 2023; 54( 1): 207– 13. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2022.07.047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Wang Z , Jiang B , Wang X , Li Z , Wang D , Xue H , et al. Relationship between physical activity and individual mental health after traumatic events: a systematic review. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2023; 14( 2): 2205667. doi:10.1080/20008066.2023.2205667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Perry SA , Coetzer R , Saville CWN . The effectiveness of physical exercise as an intervention to reduce depressive symptoms following traumatic brain injury: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2020; 30( 3): 564– 78. doi:10.1080/09602011.2018.1469417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Mizzi AL , McKinnon MC , Becker S . The impact of aerobic exercise on mood symptoms in trauma-exposed young adults: a pilot study. Front Behav Neurosci. 2022; 16: 829571. doi:10.3389/fnbeh.2022.829571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Jadhakhan F , Lambert N , Middlebrook N , Evans DW , Falla D . Is exercise/physical activity effective at reducing symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder in adults—a systematic review. Front Psychol. 2022; 13: 943479. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.943479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Piao CS , Stoica BA , Wu J , Sabirzhanov B , Zhao Z , Cabatbat R , et al. Late exercise reduces neuroinflammation and cognitive dysfunction after traumatic brain injury. Neurobiol Dis. 2013; 54: 252– 63. doi:10.1016/j.nbd.2012.12.017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Morris T , Gomes Osman J , Tormos Muñoz JM , Costa Miserachs D , Pascual Leone A . The role of physical exercise in cognitive recovery after traumatic brain injury: a systematic review. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2016; 34( 6): 977– 88. doi:10.3233/RNN-160687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Nilsson H , Saboonchi F , Gustavsson C , Malm A , Gottvall M . Trauma-afflicted refugees’ experiences of participating in physical activity and exercise treatment: a qualitative study based on focus group discussions. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2019; 10( 1): 1699327. doi:10.1080/20008198.2019.1699327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Noushad S , Ansari B , Ahmed S . Effect of nature-based physical activity on post-traumatic growth among healthcare providers with post-traumatic stress. Stress Health. 2022; 38( 4): 813– 26. doi:10.1002/smi.3135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Tang W , Lu Y , Yang Y , Xu J . An epidemiologic study of self-reported sleep problems in a large sample of adolescent earthquake survivors: the effects of age, gender, exposure, and psychopathology. J Psychosom Res. 2018; 113: 22– 9. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2018.07.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Geng F , Fan F , Mo L , Simandl I , Liu X . Sleep problems among adolescent survivors following the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake in China: a cohort study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013; 74( 1): 67– 74. doi:10.4088/JCP.12m07872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Antczak D , Lonsdale C , Lee J , Hilland T , Duncan MJ , Del Pozo Cruz B , et al. Physical activity and sleep are inconsistently related in healthy children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2020; 51: 101278. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2020.101278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Ferriz-Valero A , Østerlie O , García Martínez S , García-Jaén M . Gamification in physical education: evaluation of impact on motivation and academic performance within higher education. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020; 17( 12): 4465. doi:10.3390/ijerph17124465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Dicheva D , Dichev C , Agre G , Angelova G . Gamification in education: a systematic mapping study. J Educ Techno Soc C. 2015; 18( 3): 75– 83. [Google Scholar]

33. Morford ZH , Witts BN , Killingsworth KJ , Alavosius MP . Gamification: the intersection between behavior analysis and game design technologies. Behav Anal. 2014; 37( 1): 25– 40. doi:10.1007/s40614-014-0006-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. López-Belmonte J , Segura-Robles A , Fuentes-Cabrera A , Parra-González ME . Evaluating activation and absence of negative effect: gamification and escape rooms for learning. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020; 17( 7): 2224. doi:10.3390/ijerph17072224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Xin Z , Lim SP , Zhao H . The impact of sports games on the psychological health of middle school students. J Contemp Educ Res. 2024; 8( 3): 95– 100. doi:10.26689/jcer.v8i3.6400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Berglund A , Orädd H . Exploring the psychological effects and physical exertion of using different movement interactions in casual exergames that promote active microbreaks: quasi-experimental study. JMIR Serious Games. 2024; 12: e55905. doi:10.2196/55905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Andrade A , da Cruz WM , Correia CK , Santos ALG , Bevilacqua GG . Effect of practice exergames on the mood states and self-esteem of elementary school boys and girls during physical education classes: a cluster-randomized controlled natural experiment. PLoS One. 2020; 15( 6): e0232392. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0232392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Zhao Y , Soh KG , Bin Abu Saad H , Rong W , Liu C , Wang X . Effects of active video games on mental health among college students: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2024; 24( 1): 3482. doi:10.1186/s12889-024-21011-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Dese DC , Huwae A , Nugraha PAP . Effect of physical activity based on traditional games on the psychological well-being of elementary school children. J Maenpo J Pendidikan Jasmani Kesehatan Dan Rekreasi. 2023; 13( 1): 36. doi:10.35194/jm.v13i1.3150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Lee JE , Zeng N , Oh Y , Lee D , Gao Z . Effects of pokémon GO on physical activity and psychological and social outcomes: a systematic review. J Clin Med. 2021; 10( 9): 1860. doi:10.3390/jcm10091860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Hastürk G , Akyıldız Munusturlar M . The effects of exergames on physical and psychological health in young adults. Games Health J. 2022. doi:10.1089/g4h.2022.0093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Davis RS , Meiser-Stedman R , Afzal N , Devaney J , Halligan SL , Lofthouse K , et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis: group-based interventions for treating posttraumatic stress symptoms in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2023; 62( 11): 1217– 32. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2023.02.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Rolfsnes ES , Idsoe T . School-based intervention programs for PTSD symptoms: a review and meta-analysis. J Trauma Stress. 2011; 24( 2): 155– 65. doi:10.1002/jts.20622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Rafieifar M , MacGowan MJ . A meta-analysis of group interventions for trauma and depression among immigrant and refugee children. Res Soc Work Pract. 2022; 32( 1): 13– 31. doi:10.1177/10497315211022812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Pfeiffer E , Sachser C , Rohlmann F , Goldbeck L . Effectiveness of a trauma-focused group intervention for young refugees: a randomized controlled trial. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2018; 59( 11): 1171– 9. doi:10.1111/jcpp.12908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Rusmana N , Hidayah N , Asrowi A , Riduwan M . Reduce students post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms with traditional games: play therapy based on local wisdom. Int J Instr. 2023; 16( 4): 747– 70. doi:10.29333/iji.2023.16442a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Rusmana N , Hafina A , Ruyadi Y , Riduwan M . Trauma healing based on local wisdom: traditional games to reduce students post-traumatic stress disorder. Int J Instr. 2023; 16( 4): 37– 54. doi:10.29333/iji.2023.1643a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Rusmana N , Hafina A , Suryana D . Group play therapy for preadolescents: post-traumatic stress disorder of natural disaster victims in Indonesia. Open Psychol J. 2020; 13( 1): 213– 22. doi:10.2174/1874350102013010213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Benoit V , Gabola P . Effects of positive psychology interventions on the well-being of young children: a systematic literature review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021; 18( 22): 12065. doi:10.3390/ijerph182212065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Payne HE , Moxley VB , MacDonald E . Health behavior theory in physical activity game apps: a content analysis. JMIR Serious Games. 2015; 3( 2): e4. doi:10.2196/games.4187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Prins J , van der Wilt F , van der Veen C , Hovinga D . Nature play in early childhood education: a systematic review and meta ethnography of qualitative research. Front Psychol. 2022; 13: 995164. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.995164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Akiriza OF . The importance of play in child development and health. Newport Int J Res Med Sci. 2025; 6( 2): 171– 8. doi:10.59298/nijrms/2025/6.2.171178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Jean P . Physical world of the child. Phys Today. 1972; 25( 6): 23– 7. doi:10.1063/1.3070889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Andersen MM , Kiverstein J . Play in cognitive development: from rational constructivism to predictive processing. Top Cogn Sci. 2024. doi:10.1111/tops.12752.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Andersen MM , Kiverstein J , Miller M , Roepstorff A . Play in predictive minds: a cognitive theory of play. Psychol Rev. 2023; 130( 2): 462– 79. doi:10.1037/rev0000369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Sando OJ , Kleppe R , Sandseter EBH . Risky play and children’s well-being, involvement and physical activity. Child Ind Res. 2021; 14( 4): 1435– 51. doi:10.1007/s12187-021-09804-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Mills MS , Embury CM , Klanecky AK , Khanna MM , Calhoun VD , Stephen JM , et al. Traumatic events are associated with diverse psychological symptoms in typically-developing children. J Child Adolesc Trauma. 2019; 13( 4): 381– 8. doi:10.1007/s40653-019-00284-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Milot T , Ethier LS , St-Laurent D , Provost MA . The role of trauma symptoms in the development of behavioral problems in maltreated preschoolers. Child Abuse Negl. 2010; 34( 4): 225– 34. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.07.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Plümacher KS , Loy JK , Bender S , Krischer M . Psychopathological symptoms in school-aged children after a traumatic event. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2025; 19( 1): 12. doi:10.1186/s13034-025-00869-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Kolaitis G . Trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2017; 8( sup4): 1351198. doi:10.1080/20008198.2017.1351198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Arseneault L , Cannon M , Fisher HL , Polanczyk G , Moffitt TE , Caspi A . Childhood trauma and children’s emerging psychotic symptoms: a genetically sensitive longitudinal cohort study. Am J Psychiatry. 2011; 168( 1): 65– 72. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10040567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Macksoud MS , Aber JL . The war experiences and psychosocial development of children in Lebanon. Child Dev. 1996; 67( 1): 70– 88. doi:10.2307/1131687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Pynoos RS , Frederick C , Nader K , Arroyo W , Steinberg A , Eth S , et al. Life threat and posttraumatic stress in school-age children. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1987; 44( 12): 1057– 63. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800240031005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Erden G , Kılıç E , Uslu R , Kerimoğlu E . Çocuklar için travma sonrasi stres tepki ölçeği: Türkçe geçerlik, güvenirlik çalişmasi. Çocuk Ve Gençlik Ruh Sağlığı Derg. 1999; 6( 3): 143– 9. (in Turkish). [Google Scholar]

65. Berger E , O’Donohue K , Jeanes R , Alfrey L . Trauma-informed practice in physical activity programs for young people: a systematic review. Trauma Violence Abus. 2024; 25( 4): 2584– 97. doi:10.1177/15248380231218293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Woollett N , Bandeira M , Hatcher A . Trauma-informed art and play therapy: pilot study outcomes for children and mothers in domestic violence shelters in the United States and South Africa. Child Abuse Negl. 2020; 107: 104564. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Düken ME , Küçükoğlu S , Kiliçaslan F . Investigation of posttraumatic stress and depression symptoms in children who experienced the kahramanmaraş earthquake. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 2025; 31( 2): 165– 75. doi:10.1177/10783903241257631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Yakşi N , Eroğlu M . Determinants of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) among children and adolescents in the subacute stage of Kahramanmaras earthquake, Turkey. Arch Public Health. 2024; 82( 1): 199. doi:10.1186/s13690-024-01434-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Tanhan F , Kardaş F . Van depremini yaşayan ortaöğretim öğrencilerinin travmadan etkilenme ve umutsuzluk düzeylerinin İncelenmesi. Sakarya Univ J Educ. 2014; 4( 1): 102. doi:10.19126/suje.52552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Koçak HS , Kiliç FE , Kaplan Serin E . Post-traumatic symptoms and sleep problems in children and adolescents after twin earthquakes in Turkey. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2024; 18: e322. doi:10.1017/dmp.2024.307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Küçük F , Eryılmaz SE , Özdemir S . Relationship between post-traumatic stress reactions and anxiety sensitivity in children with earthquake experience. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2024. 13 p. doi:10.2139/ssrn.4981656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Bağci Uzun G , Arslan A , Arpacı MF , Demirel E , Karakaş N . Relationship between post traumatic stress disorder and hand dimensions and hand grip strength in children aged 8-12 exposed to earthquakes. Sci Rep. 2024; 14( 1): 29266. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-80340-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Borland RL , Cameron LA , Tonge BJ , Gray KM . Effects of physical activity on behaviour and emotional problems, mental health and psychosocial well-being in children and adolescents with intellectual disability: a systematic review. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2022; 35( 2): 399– 420. doi:10.1111/jar.12961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Massey WV , Williams TL . Sporting activities for individuals who experienced trauma during their youth: a meta-study. Qual Health Res. 2020; 30( 1): 73– 87. doi:10.1177/1049732319849563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

75. Ahn S , Fedewa AL . A meta-analysis of the relationship between children’s physical activity and mental health. J Pediatr Psychol. 2011; 36( 4): 385– 97. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsq107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

76. Aas M , Ueland T , Mørch RH , Laskemoen JF , Lunding SH , Reponen EJ , et al. Physical activity and childhood trauma experiences in patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorders. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2021; 22( 8): 637– 45. doi:10.1080/15622975.2021.1907707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

77. Quarmby T , Sandford R , Green R , Hooper O , Avery J . Developing evidence-informed principles for trauma-aware pedagogies in physical education. Phys Educ Sport Pedagogy. 2022; 27( 4): 440– 54. doi:10.1080/17408989.2021.1891214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

78. Mahmoudi-Gharaei J , Bina M , Yasami MT , Emami A , Naderi F . Group play therapy effect on Bam earthquake related emotional and behavioral symptoms in preschool children: a before-after trial. Iran J Pediatr. 2006; 16( 2): 137– 42. [Google Scholar]

79. Aral N . Depremin çocuklar üzerindeki etkileri. Çocuk Ve Gelişim Derg. 2023; 6( 11): 93– 105. (in Turkish). doi:10.36731/cg.1299175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

80. Okazaki K , Suzuki K , Sakamoto Y , Sasaki K . Physical activity and sedentary behavior among children and adolescents living in an area affected by the 2011 Great East Japan earthquake and tsunami for 3 years. Prev Med Rep. 2015; 2: 720– 4. doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2015.08.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

81. Bedriye AK . Determination and evaluation of effects of earthquake on school age children’s (6-12 years old) behaviours. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2014; 152: 845– 51. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.09.332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

82. Wang D , You X . Post-disaster trauma and cultural healing in children and adolescents: evidence from the Wenchuan earthquake. Arts Psychother. 2022; 77: 101878. doi:10.1016/j.aip.2021.101878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

83. Valenti M , Vinciguerra MG , Masedu F , Tiberti S , Sconci V . A before and after study on personality assessment in adolescents exposed to the 2009 earthquake in L’Aquila, Italy: influence of sports practice. BMJ Open. 2012; 2( 3): e000824. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-000824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

84. Çiçek H , Ayhan R , Şenol MR . Wushu-kungfu Türkiye şampiyonasına katılan depremzede sporcuların travma ve zihinsel dayanıklılık düzeyleri. In: Bulut M , Karacagil Z , editors. Sosyal Bilimlerinde Güncel Tartışmalar 12. Ankara, Turkey: Bilgin Kültür Sanat Yayınları; 2023. p. 443– 56. (in Turkish). [Google Scholar]

85. Rosenbaum S , Sherrington C , Tiedemann A . Exercise augmentation compared with usual care for post-traumatic stress disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2015; 131( 5): 350– 9. doi:10.1111/acps.12371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

86. Björkman F , Ekblom Ö . Physical exercise as treatment for PTSD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mil Med. 2022; 187 (9–10):e1103–13. doi:10.1093/milmed/usab497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

87. Mitchell KS , Dick AM , DiMartino DM , Smith BN , Niles B , Koenen KC , et al. A pilot study of a randomized controlled trial of Yoga as an intervention for PTSD symptoms in women. J Trauma Stress. 2014; 27( 2): 121– 8. doi:10.1002/jts.21903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

88. Huberty J , Sullivan M , Green J , Kurka J , Leiferman J , Gold K , et al. Online Yoga to reduce post traumatic stress in women who have experienced stillbirth: a randomized control feasibility trial. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2020; 20( 1): 173. doi:10.1186/s12906-020-02926-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

89. Nordbrandt MS , Sonne C , Mortensen EL , Carlsson J . Trauma-affected refugees treated with basic body awareness therapy or mixed physical activity as augmentation to treatment as usual-a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. PLoS One. 2020; 15( 3): e0230300. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0230300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

90. Hall KS , Morey MC , Beckham JC , Bosworth HB , Sloane R , Pieper CF , et al. Warrior wellness: a randomized controlled pilot trial of the effects of exercise on physical function and clinical health risk factors in older military veterans with PTSD. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2020; 75( 11): 2130– 8. doi:10.1093/gerona/glz255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

91. Whitworth JW , Nosrat S , SantaBarbara NJ , Ciccolo JT . Feasibility of resistance exercise for posttraumatic stress and anxiety symptoms: a randomized controlled pilot study. J Trauma Stress. 2019; 32( 6): 977– 84. doi:10.1002/jts.22464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools