Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

How and When Organizational Artificial Intelligence Adoption Impacts Employees’ Well-Being

Economics and Management School, The Department of Business Administration, Wuhan University, Wuhan, 430072, China

* Corresponding Author: Yuchao Pan. Email:

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(11), 1769-1780. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.070147

Received 09 July 2025; Accepted 11 October 2025; Issue published 28 November 2025

Abstract

Objectives: While organizations are increasingly adopting artificial intelligence (AI), its effects on employees’ well-being remain poorly understood. Drawing on social cognitive theory, this study aimed to examine the underlying mechanism through which organizational AI adoption influences employees’ well-being. Methods: A two-wave time-lagged research design was conducted with 262 Chinese employees employing a voluntary and anonymous survey. The survey included measures of organizational AI adoption, AI use anxiety, job insecurity, subjective well-being, and psychological well-being. The data were analyzed using SPSS 26.0 software and macro PROCESS. Results: The moderation analysis revealed that AI use anxiety moderated the association between organizational AI adoption and job insecurity (b = 0.19, standard error [SE] = 0.04, p < 0.001), indicating that organizational AI adoption was positively related to job insecurity when AI use anxiety was higher. The moderating mediation analysis further revealed that the indirect effect of organizational AI adoption on employees’ well-being via job insecurity was negative (for subjective well-being, moderated mediation index = −0.05, SE = 0.03, 95% CI = [−0.103, −0.005]; for psychological well-being, moderated mediation index = −0.04, SE = 0.02, 95% CI = [−0.089, −0.007]), indicating that organizational AI adoption would impair employees’ well-being by increasing job insecurity for employees with a higher level of AI use anxiety. Conclusions: AI use anxiety acts as a critical moderator in the link between organizational AI adoption and employee well-being. The finding supports the notion that a wide variety of boundary conditions may influence how individuals react to AI filling roles typically held by humans.Keywords

Artificial intelligence (AI) refers to intelligent machines or computerized systems that possess the capacity to learn, respond, and carry out a range of humanlike tasks [1]. Due to its promising capabilities, an increasing number of organizations are adopting AI to enhance productivity and reduce costs across business units. For example, intelligent financial services are used by financial departments and intelligent robots are employed by production departments. While this shift offers tremendous potential for enhanced efficiency and productivity, it simultaneously introduces intricate challenges, particularly concerning employee well-being. In response to organizational AI adoption, employees may, on the one hand, fear being replaced [2,3], which in turn can decrease their well-being in the workplace. On the other hand, AI can complement human intelligence [3]. Employees can use AI-powered technology (e.g., algorithms, virtual agents, and intelligent machines) to improve their efficiency and productivity in their work [4,5], which in turn will improve their well-being in the workplace. Empirically, researchers have obtained conflicting views about the role of organizational AI adoption in employees’ well-being. Some studies have found organizational AI adoption to be positively related to employees’ well-being [6,7,8], whereas other studies have shown organizational AI adoption to be positively related to employees’ well-being [9,10,11].

One explanation for these conflicting results is that researchers have often overlooked the boundary conditions that influence how employees react to AI filling roles typically held by humans. Cheng et al. found that employees with an external locus of control tend to view organizational AI adoption as a hindrance [12], leading to prevention-focused work behaviors. In contrast, employees with an internal locus of control view organizational AI adoption as a challenge, leading to promotion-focused work behaviors. Similarly, using a sample of knowledge-based workers, Huang et al. observed the double-edged sword effect of organizational AI adoption on well-being [9]. On the one hand, organizational AI adoption improved employees’ well-being through fostering their role breadth self-efficacy; on the other hand, it impaired well-being by triggering AI anxiety. Given the conflicting results about the effects of AI on employees, Yam et al. have called for much more research to examine the boundary conditions that shape how people react to AI [13]. Considering the role of well-being for human beings, this study focuses on how and when organizational AI adoption is related to well-being in the workplace.

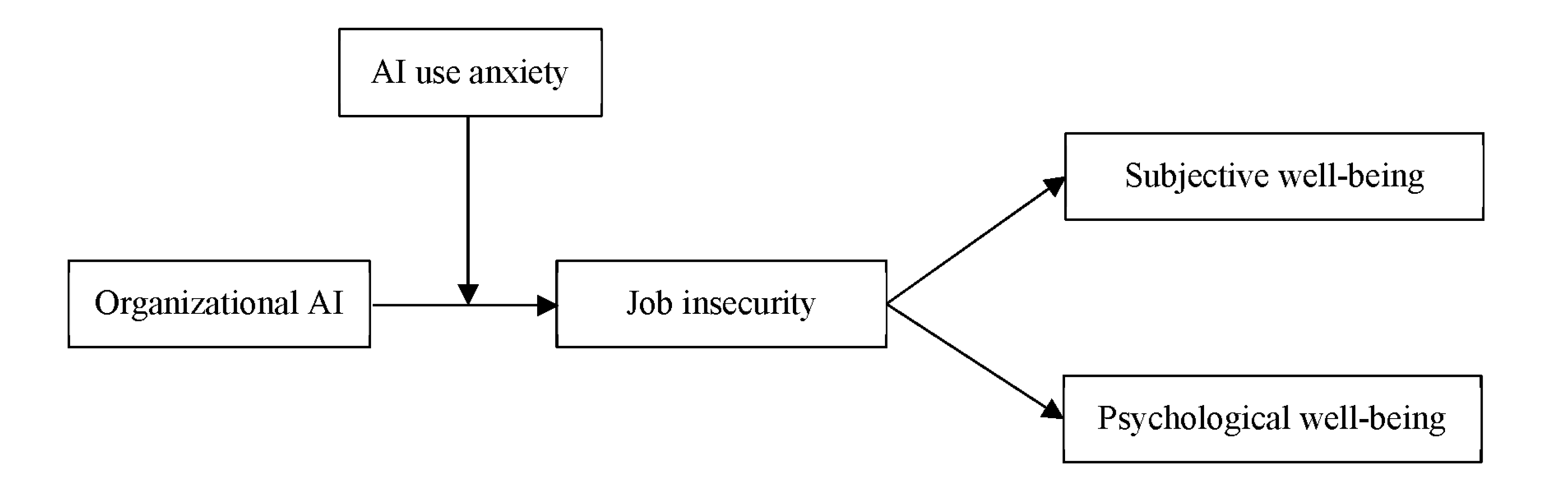

Social cognitive theory (SCT) proposes that the impact of external environments on individuals is largely contingent on individual differences [14]. Based on social cognitive theory (SCT), the present study argues that the impact of organizational AI adoption as an external environmental factor on job insecurity depends on employees’ anxiety about AI use. Accordingly, AI use anxiety conditions the indirect effects of organizational AI adoption on employees’ subjective and psychological well-being via job insecurity. The proposed model is showed in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Research model.

2.1 The Moderating Role of AI Use Anxiety in the Link between Organizational AI Adoption and Job Insecurity

As an area of computer science where machines are capable of performing human-like tasks, AI has two functions: replacement and augmentation. Replacement means that AI is capable of substituting humans by bearing intelligent tasks that were once limited to human beings. Augmentation means that AI is designed to assist and amplify human intelligence, working alongside individuals to enhance and complement human cognitive abilities rather than replacing them [15]. Organizational AI adoption is a substantial external environmental factor that induces employees’ cognitive evaluation process [16]. SCT suggests that the impact of external environments on people is largely contingent on individual differences, including individuals’ attitudes toward their environment [14]. Thus, attributes and, more importantly, an individual’s perceptions of them critically determine whether they are willing to let external environmental factors exert an actual influence on them.

Faced with organizational AI adoption, employees may develop either replacement fears or augmentation expectations, depending on their cognitive appraisal of the technology. AI use anxiety describes a worker’s anxious feelings about the practical use of AI at work and reflects individuals’ general disposition toward technological innovation [17]. Faced with organizational AI adoption, employees with less AI use anxiety demonstrate greater propensity to perceive and capitalize on the beneficial opportunities afforded by AI technologies [18], which in turn reduces their perceptions of job insecurity. Additionally, employees with less AI use anxiety may have a high desire to learn and equip themselves with new knowledge and skills to avoid being replaced by AI [19]. As such, employees with less AI use anxiety demonstrate a greater propensity to perceive organizational AI adoption as augmentation rather than replacement. In contrast, employees with high AI use anxiety have low confidence and motivation to make efforts to equip themselves with new knowledge and skills [18]. Thus, when faced with organizational AI adoption, they are inclined to consider it as a replacement, meaning a potential threat to their job maintenance or career sustainability [20]. Consequently, employees with higher levels of AI use anxiety are more likely to generate perceptions of job insecurity. Taken together, we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 1: AI use anxiety moderates the relationship between organizational AI adoption and job insecurity, such that the relationship is positive when AI use anxiety is high.

2.2 The Moderating Role of AI Use Anxiety in the Indirect Effect of Organizational AI Adoption and Employees’ Well-Being via Job Insecurity

SCT proposes that people’s cognitive perceptions shaped by external environments will lead them to display certain attitudes and behaviors [14]. Prior studies have demonstrated that perceptions of job insecurity have detrimental effects on employees’ subjective and psychological well-being [21,22,23]. Based on SCT, indirect effects of organizational AI adoption on employees’ well-being via job security are expected. SCT further states that individual differences will play a contingent role in the effects of external environments on individuals. Based on this theorizing, Hypothesis 1 argues that AI use anxiety moderates the relationship between organizational AI adoption and job insecurity. Combining the above arguments, and according to the moderated mediation model [24], this study proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: The indirect effect of organizational AI adoption on employees’ well-being via job insecurity is moderated by AI use anxiety, such that the indirect effect is negative when AI use anxiety is high.

3.1 Participants and Procedures

Data for this study were collected from four manufacturing companies in Wuhan that adopted AI devices (e.g., intelligent robot and intelligent financial services) extensively across operational workflows. With the help of the companies’ directors, a web-based survey was administered. A cover letter explaining the aim of the study and assuring the confidentiality and anonymity of the survey was sent to participants via e-mail. Employees interested in participating could respond through e-mail. Data were obtained at two time points, with a one-month interval to minimize common method bias [25] and to help establish causal relationships between key variables [26]. Identification codes were generated to match the participants’ responses across the two-time points. At Time 1, 600 questionnaires were sent, and participants were asked to report demographic variables, organizational AI adoption, AI use anxiety, and job insecurity. Of the 600 target participants, 458 submitted valid responses, yielding a response rate of 76.33 percent. One month later (at Time 2), a follow-up survey was sent to the 458 participants who had completed the first survey. Participants were asked to report on subjective well-being and psychological well-being. Fifteen cases were deleted due to a large number of irregular patterns of responses that had identical responses to a large number of consecutive questions, resulting in 262 valid cases and a valid response rate of 57.21 percent. In the final sample, 72.91 percent of respondents were male; their average age was 29.58 years (standard deviation [SD] = 4.71), and their average organizational tenure was 6.17 years (SD = 3.99). In terms of education, 81.30% held at least a Bachelor’s degree. Following Goodman and Blum [27], the present study conducted attrition analyses by regressing dichotomous indicators of missingness for Time 2 on study variables. Analyses showed no systematic dropout at Time 2. However, male and older employees were significantly less likely to participate in the second wave. Although this fact does indicate systematic dropout at Time 2, it is important to note that this dropout was related only to the control variables and did not depend on well-being [28].

This study was approved by the Committee for Scientific Research and Academic Ethics of Wuhan University (Approval Number: WU-2024589). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

All measures were administered in Chinese. To begin, two native Chinese speakers fluent in English independently translated the scales from English to Chinese. Any disagreements were discussed and addressed between them. A bilingual person specialized in English and vocational psychology was then paid to translate the Chinese materials back to English. Finally, the translated materials were sent to the companies’ directors to ensure that the materials were appropriate to the current context. Podsakoff et al. state that researchers can use different response formats to procedurally remedy common method bias [25]. Following Podsakoff et al.’s suggestion, the current study used different point Likert-type scales.

3.2.1 Organizational AI Adoption

Organizational AI adoption was assessed with a three-item scale used in the study by Wang et al. [29]. A sample item is “My company has been involved in the adoption of AI technology”. Participants were asked to respond on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the scale was 0.78.

The four-item scale developed by Park et al. was used to measure AI use anxiety [18]. A sample item is “Using AI for work is somewhat intimidating to me”. Participants were asked to respond on a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). In the current study, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) demonstrated that the AI use anxiety scale had a one-dimensional structure (χ2 (2) = 4.88, p > 0.05; comparative fit index [CFI] = 0.98; root mean square error of approximation [RMSEA] = 0.07; standardized root mean square residual [SRMR] = 0.02), and standardized factor loadings ranged from 0.72 to 0.93. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the scale was 0.81.

We used a three-item scale developed by Hellgren and Sverke to assess perceived job insecurity [30]. A sample item is “I am worried about having to leave my job before I would like to”. These were rated on a four-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the scale was 0.73.

We used the multidimensional scale of employee well-being developed by Zheng et al. to assess participants’ well-being [31]. This scale reflects two underlying dimensions, each measured with three items: subjective well-being (e.g., “I am satisfied with my work responsibilities”) and psychological well-being (“I feel I have grown as a person”). Participants were asked to respond on a six-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). Second-order confirmatory factor analysis demonstrated that the well-being scale had a higher-order latent construct overarching two factors (χ2 (7) = 9.64, p > 0.05; CFI = 0.95; RMSEA = 0.06; SRMR = 0.05). Standardized first-order loadings ranged from 0.76 to 0.93, and standardized second-order loadings ranged from 0.82 to 0.87. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the subjective well-being and psychological well-being subscales were 0.79 and 0.76, respectively.

The study followed Bernerth and Aguinis’ recommendations for selecting control variables [32]. Participants’ age, job tenure, marital status (1 = single, 2 = married), gender (1 = female, 2 = male), and education (1 = associate degree and below, 2 = undergraduate degree, 3 = graduate degree and above) were controlled for in this study because previous studies have shown that employees’ well-being is affected by these socio-demographic variables [33,34].

In this study, I used a variety of statistical methods to analyze the data. First, I used SPSS 26.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) for data sorting and descriptive statistics. Second, I utilized Mplus 8.3 (Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles, CA, USA) to conduct CFA to test discriminant validity among the variables. Maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors (MLR) was used. Third, I used marco PROCESS in SPSS (Model 1) developed by Hayes [35] to test Hypothesis 1. Fourth, I used marco PROCESS in SPSS (Model 7) developed by Hayes [35] to test Hypothesis 2. I set the significance level at p < 0.05 to evaluate the significance of each statistical test. All statistical methods were selected based on their applicability in this study, and the reliability of the results is ensured.

I first performed CFA with Mplus 8.3 (ESTIMATOR = MLR) to assess the distinctiveness of the latent variables (see Table 1). The findings demonstrated that the hypothesized five-factor model, distinguishing organizational AI adoption, job insecurity, and AI use anxiety, subjective well-being, and psychological well-being, fit the data well (χ2 = 120.04, df = 79, CFI = 0.96, RMSEA = 0.05, SRMR = 0.06) and performed better than the alternative models.

Table 1: Comparison of measurement models.

| Model | χ2 | df | CFI | RMSEA | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Five-factor model1 | 120.04 | 79 | 0.96 | 0.05 | 0.06 |

| Four-factor model2 | 264.46 | 83 | 0.83 | 0.09 | 0.10 |

| Three-factor model3 | 494.46 | 86 | 0.62 | 0.14 | 0.13 |

| Two-factor model4 | 382.36 | 88 | 0.73 | 0.11 | 0.11 |

| One-factor model5 | 556.89 | 99 | 0.57 | 0.14 | 0.13 |

To test the presence of common method bias more rigorously, following the advice of Podsakoff et al. [25], an unmeasured latent method factor was used. The result showed that the fit indices of the six-factor model did not fit better than the theorized five-factor model: χ2 = 87.27, df = 66, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.98; RMSEA = 0.04; SRMR = 0.05. Changes in model fit indices did not exceed the recommended cutoffs [36,37]: ΔCFI = 0.02, ΔRMSEA = −0.01, and ΔSRMR = −0.01, suggesting this study does not seriously suffer from common method bias.

4.2 Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

SPSS 26.0 software was used to calculate descriptive statistics. The means, standard deviations, and correlations of the variables are provided in Table 2. As shown in Table 2, organizational AI adoption is not significantly correlated with job insecurity (r = 0.04, p > 0.05), suggesting that the relationship may be contingent on the moderator. Job insecurity is negatively correlated with subjective well-being (r = −0.12, p < 0.05) and psychological well-being (r = −0.11, p < 0.05). These results provide preliminary support for the hypotheses.

Table 2: Descriptive statistics and inter-correlations among variables.

| Variables | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Organizational AI adoption | 4.27 | 0.92 | (0.78) | ||||

| 2. AI use anxiety | 1.86 | 0.80 | −0.18** | (0.81) | |||

| 3. Job insecurity | 3.00 | 0.65 | 0.04 | 0.02 | (0.73) | ||

| 4. Subjective well-being | 3.48 | 1.16 | 0.28*** | −0.27*** | −0.12* | (0.79) | |

| 5. Psychological well-being | 4.43 | 0.99 | 0.31** | −0.35*** | −0.11* | 0.63*** | (0.76) |

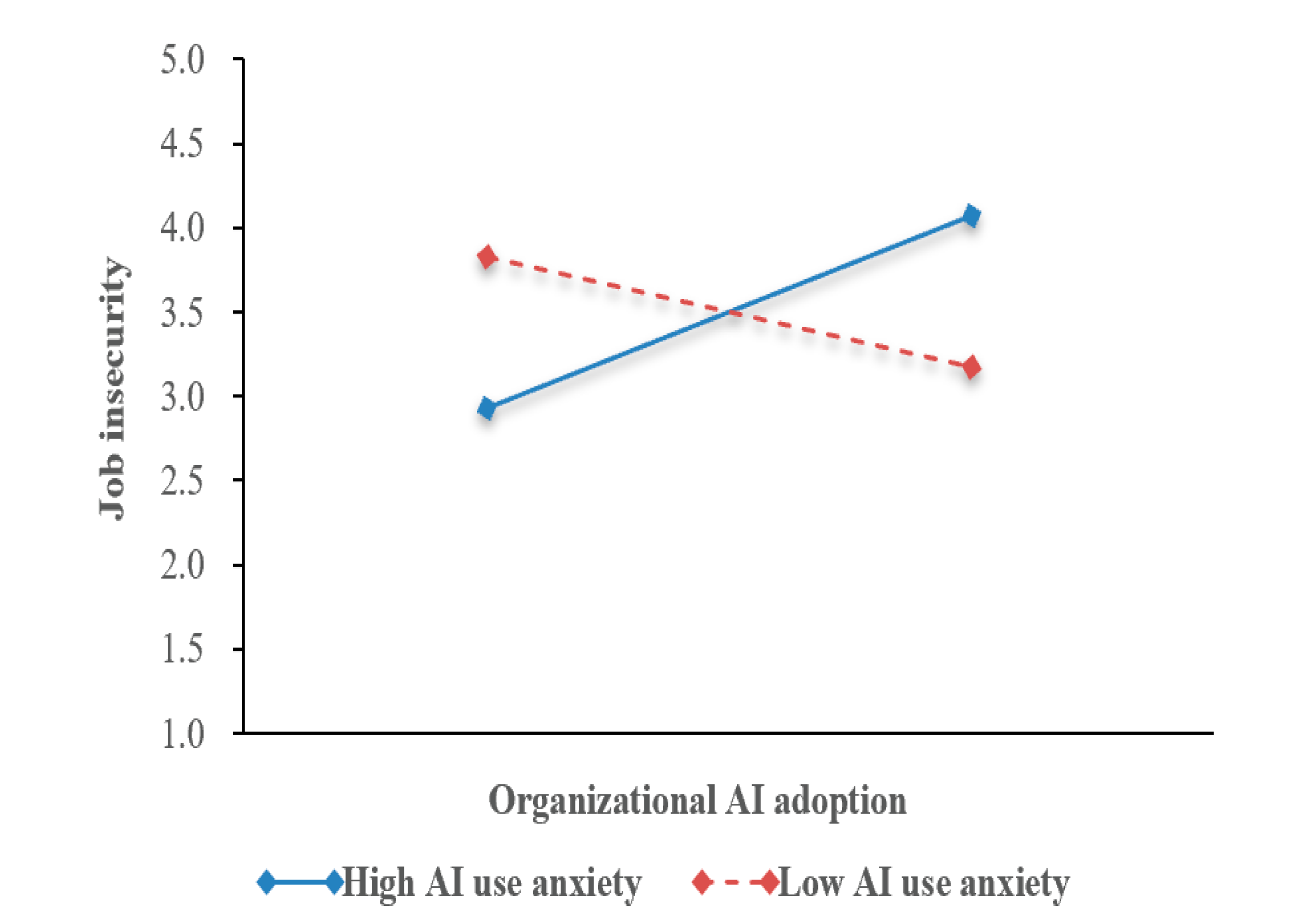

Hypothesis 1 proposed that AI use anxiety moderates the association between organizational AI adoption and job insecurity. The PROCESS 4.1 (Model 1) program was utilized to test Hypothesis 1, while controlling for demographical variables and setting the bootstrap random sampling to 5000 times. As shown in Table 3, after controlling for demographics, the interaction term between organizational AI adoption and AI use anxiety was positive and significant (b = 0.19, SE = 0.04, p < 0.001). The interaction effects explained additional variance in job security (ΔR2 = 0.007, ƒ2 = 0.075). The simple slope analysis further showed that organizational AI adoption had a positive and significant effect on job insecurity at a higher level of AI use anxiety (Mean + SD = 1.86 + 0.80, b = 0.19, SE = 0.06, t = 3.43, p < 0.01). However, the relationship between organizational AI adoption and job insecurity is negative at a lower level of AI use anxiety (Mean − SD = 1.86 − 0.80, b = −0.10, SE = 0.05, t = 1.98, p < 0.05). Fig. 2 clearly visualizes the moderating effect of AI use anxiety on the relationship between organizational AI adoption and job insecurity. Therefore, Hypothesis 1 is confirmed.

Table 3: The results of examining Hypothesis 1.

| Variables | Job Insecurity | Job Insecurity |

|---|---|---|

| Controls | ||

| Age | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| Gender | −0.12 | −0.12 |

| Education | 0.01 | −0.01 |

| Marriage status | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| Job tenure | −0.00 | 0.01 |

| Predictors | ||

| Organizational AI adoption | 0.03 | −0.31** |

| AI use anxiety | −0.73*** | |

| Organizational AI adoption × AI use anxiety | 0.19*** | |

| Adjusted R2 R2 change | 0.02 | 0.10*** 0.07*** |

Figure 2: The moderating role of AI use anxiety in the organizational AI adoption–job insecurity link.

Hypothesis 2 suggested that AI use anxiety moderates the association between organizational AI adoption and well-being via job insecurity. The PROCESS 4.1 (Model 7) program was used to test Hypothesis 2, while controlling for demographic variables and setting the bootstrap random sampling to 5000 times. For subjective well-being, the moderated mediation index was −0.05 with 95% CI = [−0.103, −0.005]. As illustrated in Table 4, the indirect effect is positive and significant when AI use anxiety is lower (b = 0.03, SE = 0.02, 95% CI = [0.010, 0.082]. However, the indirect effect was negative and significant when AI use anxiety is higher (b = −0.05, SE = 0.03, 95% CI = [−0.122, −0.003]. For psychological well-being, the moderated mediation index was −0.04 with 95% CI = [−0.089, −0.007]. As illustrated in Table 4, the indirect effect was positive and significant when AI use anxiety was lower (b = 0.02, SE = 0.01, 95% CI = [0.001, 0.059]. However, the indirect effect was negative and significant when AI use anxiety was high (b = −0.04, SE = 0.02, 95% CI = [−0.101, −0.003]. Thus, Hypothesis 2 is confirmed.

Table 4: Results of moderated mediating effect test.

| Dependent Variables | AI Use Anxiety | Effect Size | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | |||

| Subjective well-being | Lower (M − 1 SD) | 0.03 | 0.010 | 0.082 |

| Middle (M) | −0.01 | −0.052 | 0.009 | |

| Higher (M + 1 SD) | −0.05 | −0.122 | −0.003 | |

| Psychological well-being | Lower (M − 1 SD) | 0.02 | 0.001 | 0.059 |

| Middle (M) | −0.01 | −0.036 | 0.005 | |

| Higher (M + 1 SD) | −0.04 | −0.101 | −0.003 | |

The main aim of this study was to reveal the underlying mechanism through which organizational AI adoption impacts employees’ well-being in the workplace. Drawing on SCT, we proposed a research model positing the moderation role of AI use anxiety and the mediation role of job insecurity. The results illustrated that the relationship between organizational AI adoption and job insecurity depended on AI use anxiety. Specifically, organizational AI adoption was positively related to job insecurity for employees with higher levels of AI use anxiety, whereas a negative association was observed for those with lower levels of AI use anxiety. In addition, the moderated mediation analysis confirmed the moderation role of AI use anxiety in the indirect effects of organizational AI adoption on subjective and psychological well-being via job security. Specifically, organizational AI adoption was negatively related to employees’ well-being by increasing job insecurity for employees with higher levels of AI use anxiety. In contrast, organizational AI adoption was positively related to employees’ well-being by decreasing job insecurity for employees with lower levels of AI use anxiety.

5.1 Theoretical and Practical Implications

The findings revealed by this study have important theoretical and practical implications. First, the study deepens our understanding of how organizations adopt AI by explaining the relationships between organizational AI adoption and job insecurity and employees’ well-being. Prentice et al. called for investigations into how AI adoption influences outcomes from the perspective of employees [38]. Recently, we have witnessed the dramatically increasing interest in examining the effects of organizational AI adoption on employees’ workplace experience, such as job insecurity and well-being. However, conflicting results have been reported [8,9,10,11]. Given that, researchers have called for more studies to investigate the contingent effect of organizational AI adoption on employees’ reactions [13]. In response to this call, the present study examined the contingent role of AI use anxiety in the relationships between organizational AI adoption, job insecurity, and employee well-being. Second, this study offers a fresh theoretical insight into the mechanisms underlying the impact of AI adoption on employees’ well-being. To date, management literature on AI has predominantly relied on the technology acceptance model (TAM) and the unified theory of technology acceptance and use (UTAUT). These frameworks have been widely utilized to examine the adoption and implementation patterns of innovative technologies across diverse organizational contexts. In contrast, this study utilized SCT to frame job insecurity as employees’ cognitive appraisal of organizational AI adoption, with well-being serving as the resultant outcome. Furthermore, based on the SCT tenet that individuals’ responses to external environments vary by individual differences, this study revealed that employees’ AI use anxiety plays a critical conditional role in the association between perceived job insecurity and well-being. Thus, this study represents a meaningful attempt to integrate cross-disciplinary frameworks with AI research in organizational contexts.

Practically, this study provides valuable practical guidance for managers. The current study found that AI use anxiety played a critical contingent role in the relationships between organizational AI use, and job security and well-being. To effectively address the escalating issue of AI anxiety, organizations should develop anxiety reduction interventions to reduce employees’ AI use anxiety. For example, AI literacy training should cover AI awareness (i.e., sensitivity to the AI technological revolution), AI knowledge (i.e., the ability to understand the basic techniques and concepts behind AI in different products and services), and AI skills (i.e., knowing how to apply AI concepts in different contexts and applications in everyday life) [39,40]. Meanwhile, instead of letting employees figure out organizational AI adoption themselves, managers should proactively make sense of AI adoption, including sharing a benefit framework rather than a loss framework for AI. Bockstedt and Buckman revealed that when AI adoption was reframed as losses for performance, individuals would show high AI anxiety and aversion, which in turn harmed their AI adaptation [41]. In contrast, when AI adoption was reframed as benefits for performance, individuals would show high AI appreciation, which in turn fostered their AI adaptation.

5.2 Limitations and Future Research Directions

Despite the theoretical and practical implications discussed above, this study carried several limitations that suggest avenues for further research. First, all study variables were self-reported, raising concerns about common method bias. In the current study, AI use anxiety, job insecurity, subjective well-being, and psychological well-being all reflect intra-personal experiences and are not readily observed by others [42]. Self-report measures seem an appropriate choice in the current context. However, it is ideal to adopt an objective measure, such as actual AI tool usage metrics to assess organizational AI adoption. To mitigate common method bias concern, this study measured the independent variable (i.e., organizational AI adoption), the mediator (i.e., job security), and the moderator (i.e., AI use anxiety) at Time 1, and the dependent variable (i.e., subjective well-being and psychological well-being) at Time 2. In the current study, the relationships examined depend on a moderator (i.e., AI use anxiety). Prior research demonstrates that interactive relationships are not inflated by common method bias [43]. In addition, both Harman’s single-factor test and an unmeasured latent methods factor test demonstrated that common method bias does not seem to be a major concern in this study. However, to enhance the validity of mental health promotion recommendations derived from the results, an experimental research design to replicate the findings is encouraged. Second, the current study was cross-sectional in nature, and causal inferences cannot be drawn from the findings. Although the relationship examined followed a presumed causal order suggested by SCT, alternative explanations may exist. Consequently, a longitudinal research design that allows multiple data collection points [44] is needed to shed light on how organizational AI adoption influences job insecurity and employees’ well-being over time. Third, this study adopted a convenience sampling method to collect data in China, which could reduce the generalizability of the results. Thus, further research is needed to use stratified sampling across diverse contexts to replicate and extend the findings.

One interesting future research direction is to examine the effects of organizational AI adoption on a more comprehensive assessment of well-being outcomes. For instance, researchers can examine the effects of organizational AI adoption on social well-being or workplace engagement. In doing so, a more comprehensive framework for mental health in the AI era will be provided.

The second future research direction is to recognize other mediators (e.g., positive or negative emotions) and moderators (e.g., perceived organizational support) to understand the mechanism for the relationship between organizational AI adoption and employees’ well-being by drawing on insights from alternative theoretical frameworks such as the positive emotion broaden and build theory [45]. The experimental study by Hu et al. found that AI chatbots effectively reduced the arousal of negative emotions (e.g., anger, frustration, and fear), compared to the control group [46].

The third future research direction is to examine the role of cultural factors (e.g., collectivism or power distance) in employees’ responses to organizational AI adoption. Cultural differences would influence perspectives on self, others, and society, causing differences in attitudes toward AI [47,48]. For example, individuals with a high level of collectivism and power distance are more likely to adhere to social norms, fostering positive attitudes toward new technology adoption [49] when the new technology becomes prevalent. Thus, it is reasonable to suggest that collectivism and power distance may mitigate the effect of organizational AI adoption on individuals’ well-being via job insecurity.

Finally, it is necessary to examine simultaneously the roles of individual, environmental, and interpersonal factors (e.g., employee participation in AI implementation decisions, organizational cooperation strategies, career support from coworkers, and employment policies) in the relationship between organizational AI adoption and employees’ well-being by adopting a multi-level perspective. By doing so, we can help develop environment-or interpersonal-sensitive mental health promotion interventions for AI-integrated workplaces.

With a sample of employees from companies with comprehensive AI integration across operational workflows, this study found that AI use anxiety acts as a critical moderator in the link between organizational AI adoption and employee well-being. The findings support the notion that a wide variety of boundary conditions may influence how individuals react to AI filling roles typically held by humans, and they respond to the call for more research to investigate these boundary conditions. The results highlight the importance of anxiety reduction interventions to help organizations reap the benefits of adopting AI.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: The author received no specific funding for this study.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the first author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: The studies involving humans were approved by the Committee for Scientific Research and Academic Ethics of Wuhan University (Approval Number: WU-2024589). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Informed Consent: The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Malik A , Budhwar P , Patel C , Srikanth NR . May the bots be with you! Delivering HR cost-effectiveness and individualised employee experiences in an MNE. Int J Hum Resour Man. 2022; 33( 6): 1148– 78. doi:10.1080/09585192.2020.1859582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Koo B , Curtis C , Ryan B . Examining the impact of artificial intelligence on hotel employees through job insecurity perspectives. Int J Hosp Manag. 2021; 95: 102763. doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Siaw CA , Ali W . Substitution and complementarity between human and artificial intelligence: a dynamic capabilities view. J Manag Psychol. 2025; 40( 5): 539– 54. doi:10.1108/JMP-06-2024-0398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Yu X , Xu S , Ashton M . Antecedents and outcomes of artificial intelligence adoption and application in the workplace: the socio-technical system theory perspective. Inf Technol Peopl. 2023; 36( 1): 454– 74. doi:10.1108/ITP-04-2021-0254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Soulami M , Benchekroun S , Galiulina A . Exploring how AI adoption in the workplace affects employees: a bibliometric and systematic review. Front Artif Intell. 2024; 7: 1473872. doi:10.3389/frai.2024.1473872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Kim BJ , Kim MJ , Lee J . The dark side of artificial intelligence adoption: linking artificial intelligence adoption to employee depression via psychological safety and ethical leadership. Hum Soc Sci Commun. 2025; 12( 1): 1– 14. doi:10.1057/s41599-025-05040-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Kim BJ , Lee J . The mental health implications of artificial intelligence adoption: the crucial role of self-efficacy. Hum Soc Sci Commun. 2024; 11( 1): 1– 15. doi:10.1057/s41599-024-04018-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Liu H , Ding N , Li X , Chen Y , Sun H , Huang Y , et al. Artificial intelligence and radiologist burnout. JAMA Netw Open. 2024; 7( 11): e2448714. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.48714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Huang M . A study of the double-edged sword effect of organizational AI adoption on work well-being of knowledge-based employees. In: Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Management Science and Software Engineering (ICMSSE 2024); 2024 Oct 26; Shanghai, China. p. 169. doi:10.2991/978-94-6463-552-2_17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Soomro S , Fan M , Sohu JM , Soomro S , Shaikh SN . AI adoption: a bridge or a barrier? The moderating role of organizational support in the path toward employee well-being. Kybernetes. 2024. doi:10.1108/K-07-2024-1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Cambra-Fierro JJ , Blasco MF , López-Pérez ME , Trifu A . ChatGPT adoption and its influence on faculty well-being: an empirical research in higher education. Educ Inf Technol. 2025; 30( 2): 1517– 38. doi:10.1007/s10639-024-12871-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Cheng B , Lin H , Kong Y . Challenge or hindrance? How and when organizational artificial intelligence adoption influences employee job crafting. J Bus Res. 2023; 164: 113987. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2023.113987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Yam KC , Eng A , Gray K . Machine replacement: a mind-role fit perspective. Annu Rev Organ Psych. 2024; 12: 239– 67. doi:10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-030223-044504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Bandura A . Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA: Prentice-Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

15. Hassani H , Silva ES , Unger S , TajMazinani M , Mac Feely S . Artificial intelligence (AI) or intelligence augmentation (IA): what is the future? AI. 2020; 1( 2): 143– 55. doi:10.3390/ai1020008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Lin H , Tian J , Cheng B . Facilitation or hindrance: the contingent effect of organizational artificial intelligence adoption on proactive career behavior. Comput Hum Behav. 2024; 152: 108092. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2023.108092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Shoss MK . Job insecurity: an integrative review and agenda for future research. J Manag. 2017; 43( 6): 1911– 39. doi:10.1177/0149206317691574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Park J , Woo SE , Kim J . Attitudes towards artificial intelligence at work: scale development and validation. J Occup Organ Psych. 2024; 97( 3): 920– 51. doi:10.1111/joop.12502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Mandler G , Sarason SB . A study of anxiety and learning. J Abnorm Soc Psychol. 1952; 47( 2): 166. doi:10.1037/h0062855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Wen T , Mao S , Fan X , Wu J . The effect of performance pressure on employee well-being: mediator of workplace anxiety and moderator of vocational delay of gratification. Int J Ment Health Promot. 2025; 27( 4): 591– 606. doi:10.32604/ijmhp.2025.057726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. De Witte H , Vander Elst T , De Cuyper N . Job insecurity, health and well-being. In: Vuori J , Blonk R , Price RH , editors. Sustainable working lives: managing work transitions and health throughout the life course. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer Science and Business Media Dordrecht; 2015. p. 109– 28. doi:10.1007/978-94-017-9798-6_7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Karatepe MK , Hassannia R , Karatepe T , Enea C , Rezapouraghdam H . Specifying the psychosocial pathways whereby child and adolescent adversity shape adult health outcomes. Int J Ment Health Promot. 2023; 25( 2): 287– 307. doi:10.32604/ijmhp.2022.025706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Yang T , Long X . Post-COVID-19 challenges for full-time employees in China: Job insecurity, workplace anxiety and work-life conflict. Int J Ment Health Promot. 2024; 26( 9): 719– 30. doi:10.32604/ijmhp.2024.053705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Edwards JR , Lambert LS . Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: a general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychol Methods. 2007; 12( 1): 1. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.12.1.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Podsakoff PM , Mackenzie SB , Lee JY , Podsakoff NP . Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003; 88( 5): 879– 903. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Mathieu JE , Taylor SR . Clarifying conditions and decision points for mediational type inferences in organizational behavior. J Organ Behav. 2006; 27( 8): 1031– 56. doi:10.1002/job.406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Goodman JS , Blum TC . Assessing the non-random sampling effects of subject attrition in longitudinal research. J Manage. 1996; 22( 4): 627– 52. doi:10.1016/S0149-2063(96)90027-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Menard S . Longitudinal research. Newbury Park, CA, USA: Sage; 1996. [Google Scholar]

29. Wang YS , Li HT , Li CR , Zhang DZ . Factors affecting hotels’ adoption of mobile reservation systems: a technology-organization-environment framework. Tour Manag. 2016; 53: 163– 72. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2015.09.021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Hellgren J , Sverke M . Does job insecurity lead to impaired well-being or vice versa? Estimation of cross-lagged effects using latent variable modelling. J Organ Behav. 2003; 24( 2): 215– 36. doi:10.1002/job.184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Zheng X , Zhu W , Zhao H , Zhang C . Employee well-being in organizations: theoretical model, scale development, and cross-cultural validation. J Organ Behav. 2015; 36( 5): 621– 44. doi:10.1002/job.1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Bernerth JB , Aguinis H . A critical review and best-practice recommendations for control variable usage. Pers Psychol. 2016; 69( 1): 229– 83. doi:10.1111/peps.12103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Agrawal J , Murthy P , Philip M , Mehrotra S , Thennarasu K , John JP , et al. Socio-demographic correlates of subjective well-being in urban India. Soc Indic Res. 2011; 101: 419– 34. doi:10.1007/s11205-010-9669-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Waterman AS , Schwartz SJ , Zamboanga BL , Ravert RD , Williams MK , Bede Agocha V , et al. The questionnaire for eudaimonic well-being: psychometric properties, demographic comparisons, and evidence of validity. J Posit Psychol. 2010; 5( 1): 41– 61. doi:10.1080/17439760903435208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Hayes AF . An introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. New York, NY, USA: The Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

36. Chen FF . Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Struct Equ Model. 2007; 14( 3): 464– 504. doi:10.1080/10705510701301834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Hu X , Yan H , Jiang Z , Yeo G . An examination of the link between job content plateau and knowledge hiding from a moral perspective: the mediating role of distrust and perceived exploitation. J Vocat Behav. 2003; 145: 103911. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2023.103911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Prentice C , Nguyen M . Engaging and retaining customers with AI and employee service. J Retail Consum Serv. 2020; 56: 102186. doi:10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Kim JJ , Soh J , Kadkol S , Solomon I , Yeh H , Srivatsa AV , et al. AI anxiety: a comprehensive analysis of psychological factors and interventions. AI Ethics. 2025; 5: 3993– 4009. doi:10.1007/s43681-025-00686-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Ng DTK , Leung JKL , Chu SKW , Qiao MS . Conceptualizing AI literacy: an exploratory review. Comput Educ Artlf Intell. 2021; 2: 100041. doi:10.1016/j.caeai.2021.100041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Bockstedt JC , Buckman JR . Humans’ use of AI assistance: the effect of loss aversion on willingness to delegate decisions. Manag Sci. 2025. doi:10.1287/mnsc.2024.05585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Conway JM , Lance CE . What reviewers should expect from authors regarding common method bias in organizational research. J Bus Psychol. 2010; 25: 325– 34. doi:10.1007/s10869-010-9181-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Siemsen E , Roth A , Oliveira P . Common method bias in regression models with linear, quadratic, and interaction effects. Organ Res Methods. 2009; 13( 3): 456– 76. doi:10.1177/1094428109351241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Cooper B , Eva N , Zarea Fazl Elahi F , Newman A , Lee A , Obschonka M . Addressing common method variance and endogeneity in vocational behavior research: a review of the literature and suggestions for future research. J Vocat Behav. 2020; 121: 103472. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Fredrickson BL . The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am Psychol. 2001; 56( 3): 218– 26. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Hu M , Chua XC , Diong SF , Kasturiratna KS , Majeed NM , Hartanto A . AI as your ally: the effects of AI-assisted venting on negative affect and perceived social support. Appl Psychol. 2025; 17( 1): e12621. doi:10.1111/aphw.12621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Awad E , Dsouza S , Kim R , Schulz J , Henrich J , Shariff A , et al. The moral machine experiment. Nature. 2018; 563( 7729): 59– 64. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0637-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Yam KC , Tan T , Jackson JC , Shariff A , Gray K . Cultural differences in people’s reactions and applications of robots, algorithms, and artificial intelligence. Manag Organ Rev. 2023; 19( 5): 859– 75. doi:10.1017/mor.2023.21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Leidner DE , Kayworth T . A review of culture in information systems research: toward a theory of information technology culture conflict. MIS Q. 2006; 30( 2): 357– 99. doi:10.2307/25148735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools