Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

An Investigation into the Association between Fear of Recurrence, Spousal Emotional Support, and Self-Disclosure in Patients with Cerebral Glioma

Department of Neurosurgery, Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital, Affiliated Hospital of Medical School, Nanjing University, Nanjing, 210000, China

* Corresponding Author: Lu Chen. Email:

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(11), 1681-1694. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.070461

Received 16 July 2025; Accepted 14 October 2025; Issue published 28 November 2025

Abstract

Objectives: Fear of recurrence (FoR) is a common psychological burden in cerebral glioma patients. Spousal emotional support and self-disclosure may help mitigate FoR, yet their roles in this population are unclear. This study aimed to explore the association between FoR, spousal emotional support, and self-disclosure in patients with cerebral glioma. Methods: Patients with cerebral glioma were assessed using the Fear of Progression Questionnaire-Short Form (FoP-Q-SF), Perceived Social Support Scale (PSSS), Distress Disclosure Index (DDI), and Acceptance and Action Questionnaire (AAQ). Pearson correlation analysis was conducted to examine the relationships among the scale scores, while multiple linear regression analysis was performed to identify factors influencing FoR in these patients. A structural equation model (SEM) was constructed to analyze the pathways of influence among FoR, spousal emotional support, and self-disclosure. Results: FoR was significantly negatively correlated with spousal emotional support, self-disclosure, and psychological flexibility (r = −0.3986, −0.3206, −0.4547, respectively; all p < 0.05), while spousal emotional support and self-disclosure were significantly positively correlated with psychological flexibility (r = 0.2457, 0.2776, respectively; all p < 0.05). Regression analysis revealed that self-funded medical insurance, unmarried/other marital status, lack of religious belief, and lower scores of spousal emotional support, self-disclosure, and psychological flexibility were risk factors for increased FoR. The SEM demonstrated an acceptable model fit. Psychological flexibility was found to mediate the relationship between self-disclosure and FoR, indicating that self-disclosure not only had a direct negative effect on FoR but also exerted an indirect negative effect through its positive influence on psychological flexibility. Conclusion: FoR is prevalent among patients with cerebral glioma. Spousal emotional support and self-disclosure were identified as independent influencing factors of FoR. While spousal emotional support directly affected FoR, self-disclosure influenced it both directly and indirectly through the mediation of psychological flexibility.Keywords

Gliomas of the brain are the most common primary malignant tumors of the central nervous system, characterized by high invasiveness and a high risk of recurrence, leading to a generally poor prognosis for patients [1,2,3]. In recent years, with the continuous optimization of comprehensive treatment strategies combining surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy, the survival time of patients with gliomas has been prolonged. However, fear of recurrence (FoR) is a prevalent psychological concern among patients with life-threatening or chronic diseases, characterized by persistent worry that the disease may recur or progress [4,5,6]. Studies have shown that up to 63% of brain tumor patients experience moderate to severe FoR [7]. In oncology, FoR has been shown to significantly impact patients’ emotional well-being, quality of life, treatment adherence, and overall prognosis [8,9,10]. For instance, in breast cancer survivors, elevated FoR is associated with increased levels of anxiety, depression, and healthcare utilization, even many years after treatment completion [11]. Similarly, in patients with melanoma, FoR has been linked to impaired psychosocial adjustment and reduced engagement in follow-up care [12]. These findings underscore the pervasive influence of FoR across various cancer populations. Despite its clinical relevance, FoR remains understudied in patients with cerebral glioma—a population uniquely vulnerable due to the tumor’s location, potential neurological impairments, and often poor prognosis. Given the aggressive nature of cerebral gliomas and their high recurrence rates, patients may experience heightened and persistent FoR, which could negatively affect their psychological state, coping strategies, cognitive functioning, and overall disease trajectory. Therefore, investigating FoR in this population is essential for understanding its broader impacts and for developing targeted interventions to support patient outcomes.

Emotional support from partners and self-disclosure are important psychological regulatory mechanisms, and their absence or insufficiency can significantly exacerbate FOR and related psychological distress [13,14]. A qualitative study exploring the meaning of FOR among cervical cancer survivors indicated that FOR is a challenge often discussed with partners and coped with by drawing on partner resources [15]. The lack of effective communication with partners may increase patients’ sense of loneliness, thereby amplifying FoR [15]. In patients with advanced lung cancer, reduced levels of self-disclosure were found to heighten uncertainty about the disease, which in turn elevated anticipatory grief [16]. Similarly, research on thyroid cancer patients demonstrated that insufficient self-disclosure reduced benefit finding and triggered negative emotions such as depression and anxiety [17]. Therefore, encouraging partners to provide emotional support and motivating patients to engage in active self-disclosure are important strategies to alleviate patients’ FOR and promote psychological recovery. Evidence shows that partners can support patients emotionally by offering comfort and encouragement, expressing love and care, providing companionship, and helping patients divert attention away from cancer, which enhances their quality of life and capacity for disease adaptation [18].

Moreover, active self-disclosure among cancer patients has been shown to significantly improve sleep quality, benefit finding, anxiety, and overall quality of life [19], while also enhancing their sense of well-being [20]. However, existing research has primarily focused on common cancer types such as breast cancer [21] and lung cancer [22], while studies specifically addressing glioma patients remain relatively limited. Therefore, this study aims to explore the relationship between FoR, spousal emotional support, and self-disclosure among glioma patients, as well as to examine the influencing factors of FoR. The findings are expected to contribute to a better understanding of the psychological state of glioma patients, improve their treatment adherence, and ultimately enhance treatment outcomes and quality of life.

According to the sample estimation method, the sample size should be at least 5–10 times the number of variables [23]. This study included 18 variables in total, comprising five dimensions from four scales—FoR, Perceived Social Support, Distress Disclosure, and the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire—together with 13 variables from the general information questionnaire. Therefore, a minimum of 90–100 questionnaires needed to be collected. Considering the effective response rate, the sample size was increased by 10%, resulting in an estimated range of 99–110, and the final sample size was determined to be 100.

A total of 100 patients with cerebral glioma, admitted to Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital, Affiliated Hospital of Medical School, Nanjing University between June 2022 and December 2024, were selected as research participants. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) age >18 years; (2) clinically and pathologically confirmed diagnosis of primary cerebral glioma; (3) awareness of their medical condition and treatment plan; (4) clear cognitive function with the ability to complete questionnaires and communicate normally (Mini-Mental State Examination [MMSE] score ≥ 24) [24]. The exclusion criteria included: (1) presence of severe physical illness, neurological disorders, psychiatric diseases, or other severe complications; (2) poor compliance.

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital, Affiliated Hospital of Medical School, Nanjing University (No. 2023-587-01). Informed consent was taken from all the patients.

The Fear of Progression Questionnaire-Short Form (FoP-Q-SF), developed by Mehnert et al. [25] and translated into Chinese by Wu et al. [26] (Cronbach’s α = 0.88), was used to assess patients’ levels of FoR. This scale consists of 12 items across two dimensions: physical health and social-family concerns. Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from “never” (1) to “always” (5), with a total score ranging from 12 to 60. Higher scores indicate greater fear of disease progression, with scores ≥ 34 suggesting psychological dysfunction. The Cronbach’s α coefficient for this scale in this study was 0.947.

2.2.2 Spousal Emotional Support

The “Significant Other Support” dimension of the Perceived Social Support Scale (PSSS), developed by Zimet et al. [27] (Cronbach’s α = 0.86), was utilized to measure the degree of perceived spousal support. This dimension consists of four items, each rated on a 7-point Likert scale, from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (7), yielding a total score range of 4 to 28. Higher scores indicate greater perceived emotional support. The Cronbach’s α coefficient for this scale in this study was 0.930.

The Distress Disclosure Index (DDI), developed by Kahn et al. [28] (Cronbach’s α = 0.92), was used to evaluate the level of self-disclosure among patients. This scale comprises 12 items, each rated on a 5-point Likert scale, from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (5), with total scores ranging from 12 to 60. Higher scores indicate a stronger willingness to disclose distress. The Cronbach’s α coefficient for this scale in this study was 0.930.

2.2.4 Psychological Flexibility

The Acceptance and Action Questionnaire (AAQ), developed by Kumar et al. [29] and translated into Chinese by Cao et al. [30] (Cronbach’s α = 0.88 for the Chinese version), was used to assess psychological flexibility. This scale consists of seven items rated on a 7-point Likert scale, from “never” (1) to “always” (7), with total scores ranging from 7 to 49. Higher scores indicate greater psychological flexibility. The Cronbach’s α coefficient for this scale in this study was 0.897.

A questionnaire survey was conducted among research participants to collect demographic data and scores from the FoP-Q-SF, PSSS, DDI, and AAQ. All research personnel underwent standardized training before data collection to ensure consistency and accuracy. Upon receiving the completed questionnaires, researchers immediately reviewed them for clarity and completeness, addressing any ambiguities or missing data on-site.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 26.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to assess the normality of measurement data. Normally distributed data were presented as mean ± standard deviation, i.e., mean ± SD, and group comparisons were conducted using independent/pairwise t-tests. Non-normally distributed data were presented as median (interquartile range), i.e., M (P25, P75), and analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical data were expressed as frequency and percentage, i.e., n (%), with group comparisons performed using the chi-square test. Pearson correlation analysis was used to examine the relationships among the scale scores, while multiple linear regression analysis was conducted to explore the factors influencing FoR. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was performed using the AMOS module in SPSS. Mediation effects were tested using the Process Process macro (Model 4). A significance level of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The overall model fit of the structural equation model was primarily evaluated using fit indices. The fit indices and criteria applied in this study were as follows: Chi-square divided by degrees of freedom (χ2/df) < 3; goodness of fit index (GFI), comparative fit index (CFI), normed fit index (NFI), incremental fit index (IFI), and Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) > 0.90; root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) < 0.08 [31,32].

3.1 General Information of Patients with Cerebral Glioma

Among the 100 patients with cerebral glioma, 19 cases (19.00%) were under 50 years old, while 81 cases (81.00%) were 50 years old or older. Additional basic information is shown in Table 1.

Table 1: General information about patients with cerebral glioma.

| Item | Cases (n) | Proportion (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | <50 | 19 | 19.00 |

| ≥50 | 81 | 81.00 | |

| Gender | Male | 60 | 60.00 |

| Female | 40 | 40.00 | |

| Residence | Rural | 55 | 55.00 |

| Urban | 45 | 45.00 | |

| Educational Level | Junior high school or below | 11 | 11.00 |

| High school or technical secondary school | 61 | 61.00 | |

| College degree or above | 28 | 28.00 | |

| Employment Status | Employed | 33 | 33.00 |

| Unemployed or retired | 67 | 67.00 | |

| Household Income (CNY/month) | <1000 | 19 | 19.00 |

| 1000~3000 | 63 | 63.00 | |

| >3000 | 18 | 18.00 | |

| Disease Duration | <6 months | 20 | 20.00 |

| 6–12 months | 32 | 32.00 | |

| 12–24 months | 37 | 37.00 | |

| >24 months | 11 | 11.00 | |

| Recurrence or Metastasis | No | 82 | 82.00 |

| Yes | 18 | 18.00 | |

| Family History of Tumors | No | 83 | 83.00 |

| Yes | 17 | 17.00 | |

| Medical Insurance Payment Method | Self-funded | 10 | 10.00 |

| Medical insurance | 90 | 90.00 | |

| Life Stress | No stress | 15 | 15.00 |

| Mild stress | 52 | 52.00 | |

| Moderate stress | 21 | 21.00 | |

| Severe stress | 12 | 12.00 | |

| Marital Status | Unmarried/Other | 37 | 37.00 |

| Married | 63 | 63.00 | |

| Religious Belief | No | 69 | 69.00 |

| Yes | 31 | 31.00 | |

3.2 Scores of FoR, Spousal Emotional Support, Self-Disclosure, and Psychological Flexibility in Patients with Cranial Glioma

In a sample of 100 patients with cranial glioma, the total score for FoR was measured as 33.74 ± 9.22, spousal emotional support was recorded as 13.54 ± 5.69, self-disclosure was assessed at 29.79 ± 10.13, and psychological flexibility was evaluated at 23.49 ± 9.27 (Table 2).

Table 2: Scores of fear of recurrence (FoR), spousal emotional support, self-disclosure, and psychological flexibility in patients with cranial glioma.

| Item | Number of Items | Score Range | Total Score (Mean ± SD) | Average Item Score (Mean ± SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FoR | 12 | 12~51 | 33.74 ± 9.22 | 2.81 ± 0.77 |

| Spousal Emotional Support | 4 | 4~27 | 13.54 ±5.69 | 3.38 ± 1.42 |

| Self-Disclosure | 12 | 12~55 | 29.79 ± 10.13 | 2.48 ± 0.84 |

| Psychological Flexibility | 7 | 9~46 | 23.49 ± 9.27 | 3.36 ± 1.32 |

3.3 Correlation Analysis of FoR with Spousal Emotional Support, Self-Disclosure, and Psychological Flexibility in Patients with Cranial Glioma

A significant negative correlation was observed between FoR scores and spousal emotional support scores, self-disclosure scores, and psychological flexibility scores (r = −0.3986, −0.3206, −0.4547, respectively; all p < 0.05). Additionally, a significant positive correlation was found between spousal emotional support scores and psychological flexibility scores (r = 0.2457, p < 0.05), as well as between self-disclosure scores and psychological flexibility scores (r = 0.2776, p < 0.05) (Table 3).

Table 3: Correlation analysis of FoR with spousal emotional support, self-disclosure, and psychological flexibility in patients with cranial glioma.

| FoR [r (p)] | Spousal Emotional Support | Self-Disclosure | Psychological Flexibility | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FoR | 1 | - | - | - |

| Spousal Emotional Support | −0.3986 (<0.0001) | 1 | - | - |

| Self-Disclosure | −0.3206 (0.0011) | 0.0914 (0.3658) | 1 | - |

| Psychological Flexibility | −0.4547 (<0.0001) | 0.2457 (0.0137) | 0.2776 (0.0052) | 1 |

3.4 Univariate Analysis of Factors Influencing FoR Scores in Patients with Cranial Glioma

Univariate analysis revealed that age, occupational status, recurrence or metastasis status, medical insurance payment method, marital status, and religious belief were significantly associated with FoR scores in patients with cranial glioma (p < 0.05) (Table 4).

Table 4: Univariate analysis.

| Item | FoR Score (mean ± SD) | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | −4.020 | 0.0001 | ||

| <50 | 26.58 ± 9.31 | |||

| ≥50 | 35.42 ± 8.47 | |||

| Gender | −1.652 | 0.1018 | ||

| Male | 32.55 ± 9.89 | |||

| Female | 35.52 ± 8.03 | |||

| Residence | −1.693 | 0.0937 | ||

| Rural | 32.36 ± 10.00 | |||

| Urban | 35.42 ± 8.06 | |||

| Educational Level | 1.990 | 0.1422 | ||

| Junior high school or below | 31.91 ± 11.81 | |||

| High school or technical secondary school | 35.20 ± 6.97 | |||

| College degree or above | 31.29 ± 11.95 | |||

| Employment Status | −2.039 | 0.0442 | ||

| Employed | 31.09 ± 10.06 | |||

| Unemployed or retired | 35.04 ± 8.63 | |||

| Household Income (CNY/month) | 1.967 | 0.1455 | ||

| <1000 | 36.16 ± 8.79 | |||

| 1000~3000 | 34.00 ± 8.85 | |||

| >3000 | 30.28 ± 10.62 | |||

| Disease Duration | 2.099 | 0.1054 | ||

| <6 months | 31.75 ± 9.65 | |||

| 6–12 months | 33.22 ± 9.49 | |||

| 12–24 months | 33.41 ± 9.09 | |||

| >24 months | 40.00 ± 6.60 | |||

| Recurrence or Metastasis | −2.291 | 0.0280 | ||

| No | 32.98 ± 9.64 | |||

| Yes | 37.22 ± 6.44 | |||

| Family History of Tumors | −1.814 | 0.0727 | ||

| No | 32.99 ± 9.52 | |||

| Yes | 37.41 ± 7.00 | |||

| Medical Insurance Payment Method | 4.631 | 0.0002 | ||

| Self-funded | 41.30 ± 4.83 | |||

| Medical insurance | 32.90 ± 9.27 | |||

| Life Stress | 1.184 | 0.3199 | ||

| No stress | 36.47 ± 8.43 | |||

| Mild stress | 34.31 ± 8.98 | |||

| Moderate stress | 30.95 ± 10.03 | |||

| Severe stress | 30.95 ± 10.03 | |||

| Marital Status | 3.749 | 0.0003 | ||

| Unmarried/Other | 38.00 ± 7.61 | |||

| Married | 31.24 ± 9.29 | |||

| Religious Belief | 5.566 | <0.0001 | ||

| No | 36.77 ± 7.82 | |||

| Yes | 27.00 ± 8.75 | |||

3.5 Multiple Linear Regression Analysis of Factors Influencing FoR Scores in Patients with Cranial Glioma

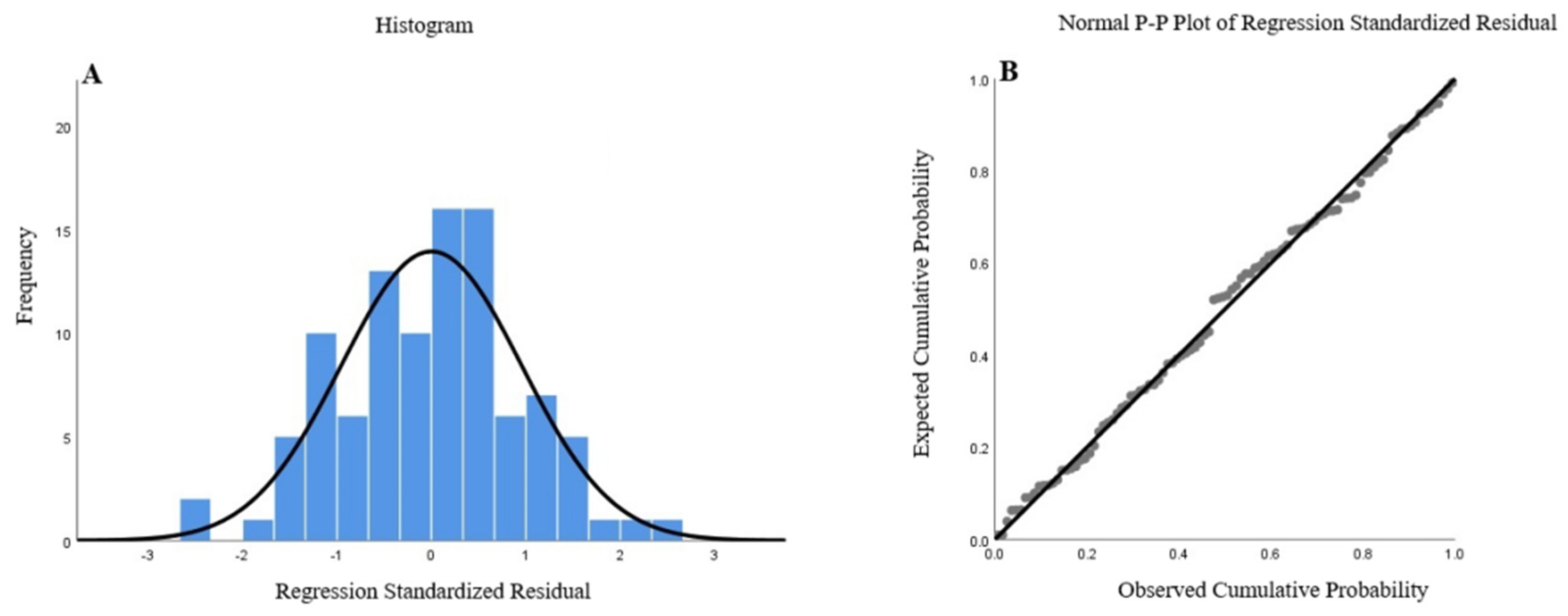

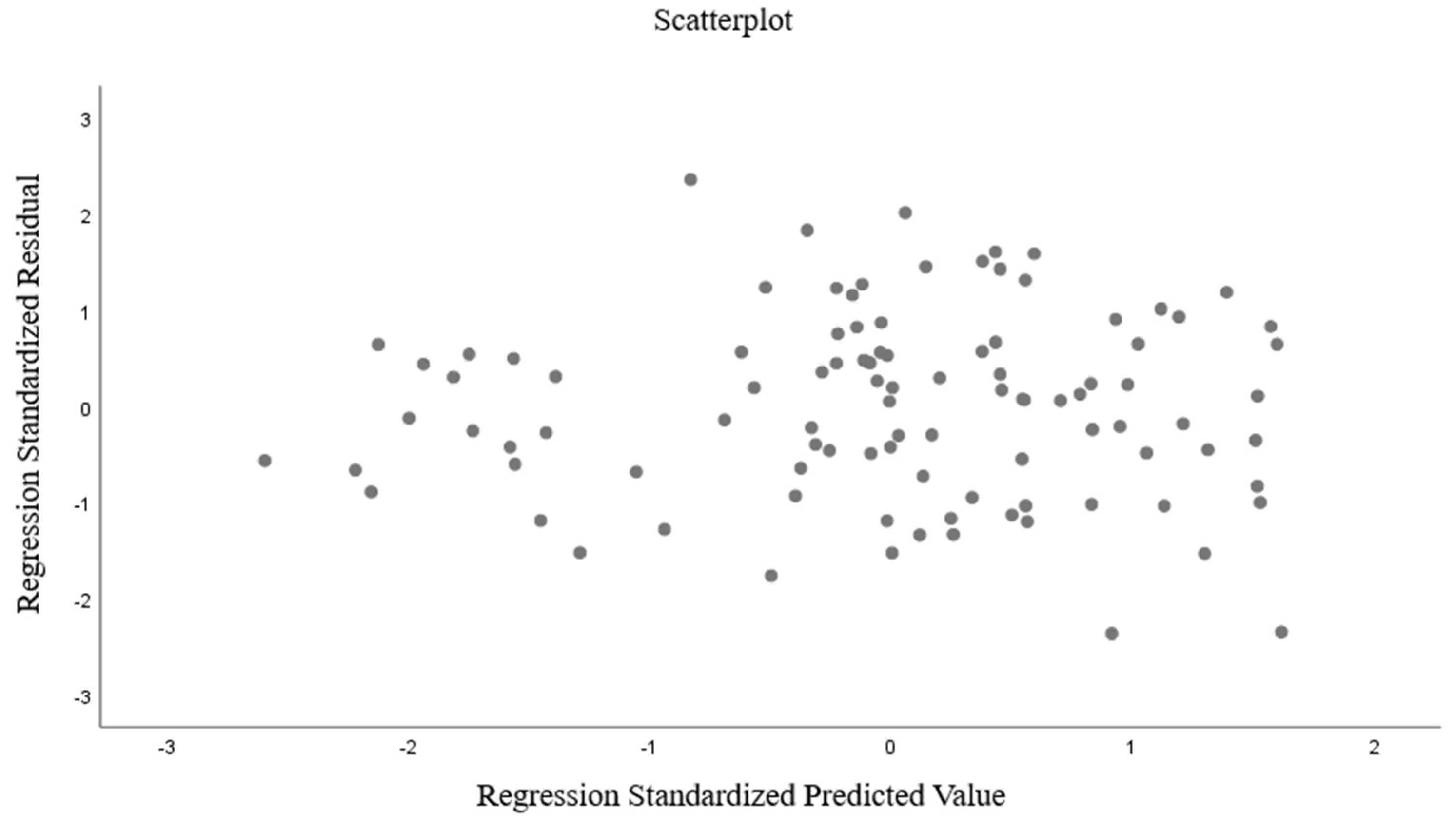

A multiple linear regression analysis was conducted using the total FoR score as the dependent variable, based on the previously identified univariate and correlation analysis results. The findings indicated that self-paid medical insurance, unmarried/other marital status, lack of religious belief, lower spousal emotional support scores, lower self-disclosure scores, and lower psychological flexibility scores were all significant risk factors for increased FoR in patients with cranial glioma (p < 0.05). The adjusted R2 of the regression model was 0.7533, suggesting that the included variables explained 75.33% of the total variance in postoperative cancer adaptation (Table 5). Additionally, the assumptions of multiple regression analysis were tested. The tolerance and VIF values were close to 1, indicating no multicollinearity (Table 5). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test yielded p = 0.200 (>0.05), suggesting that the residuals met the normality assumption, which was further supported by the standardized residual histogram and the normal P-P plot showing that the residuals approximately followed a normal distribution (Fig. 1). The scatter plot of standardized residuals versus standardized predicted values demonstrated that the variance of the residuals was relatively consistent across different levels of predicted values, meeting the assumption of homoscedasticity (Fig. 2).

Table 5: Multiple linear regression analysis.

| Influencing Factors | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | p | Collinearity Statistics | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | β | Tolerance | VIF | |||

| Age | 0.0475 | 0.0581 | 0.0603 | 0.8174 | 0.4158 | 0.8828 | 1.1328 |

| Employment Status | 2.8045 | 1.7751 | 0.1431 | 1.5799 | 0.1176 | 0.5862 | 1.7058 |

| Recurrence or Metastasis | 3.4294 | 1.8567 | 0.1429 | 1.8471 | 0.0680 | 0.8027 | 1.2458 |

| Medical Insurance Payment Method | −7.5145 | 2.2348 | −0.2446 | −3.3625 | 0.0011 | 0.9086 | 1.1005 |

| Marital Status | −5.6009 | 1.8049 | −0.2934 | −3.1032 | 0.0026 | 0.5379 | 1.8592 |

| Religious Belief | −4.9177 | 1.7616 | −0.2467 | −2.7916 | 0.0064 | 0.6152 | 1.6254 |

| Spousal Emotional Support | −0.2798 | 0.1252 | −0.1726 | −2.2344 | 0.0279 | 0.8055 | 1.2414 |

| Self-disclosure | −0.1412 | 0.0689 | −0.1551 | −2.0492 | 0.0434 | 0.8389 | 1.1920 |

| Psychological Flexibility | −0.1928 | 0.0785 | −0.1938 | −2.4554 | 0.0160 | 0.7716 | 1.2960 |

Figure 1: Normality test of residuals in the multiple linear regression model. (A) Histogram of standardized residuals showing an approximately normal distribution; (B) Normal P–P plot of standardized residuals indicating that the residuals closely follow the diagonal reference line, supporting the assumption of normality.

Figure 2: Homoscedasticity test of the multiple linear regression model.

3.6 Structural Equation Model Analysis of FoR, Spousal Emotional Support, Self-Disclosure, and Psychological Flexibility in Patients with Cranial Glioma

3.6.1 Construction of the Mediation Effect Model

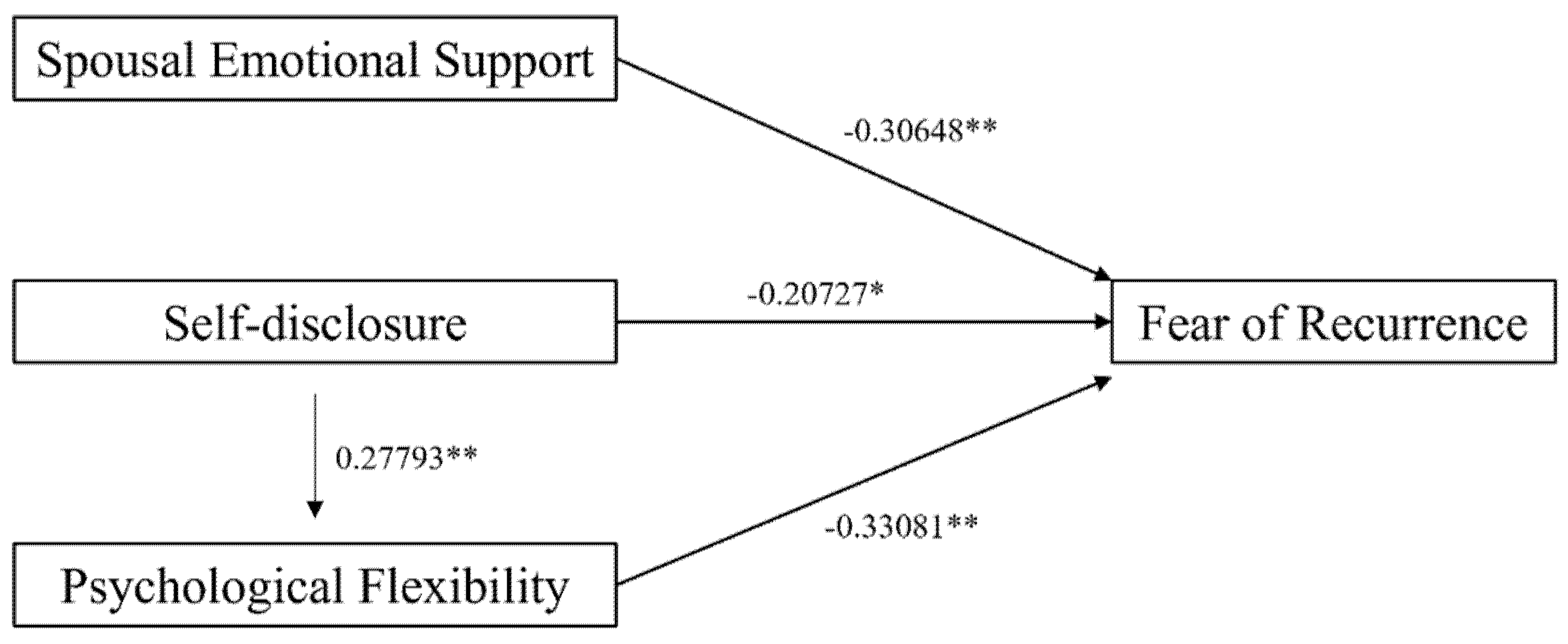

Based on the Pearson correlation analysis, significant relationships were observed among FoR, spousal emotional support, self-disclosure, and psychological flexibility in patients with cranial glioma. Drawing on these findings and relevant literature, a preliminary structural equation model was developed. In this model, spousal emotional support and self-disclosure were set as independent variables, psychological flexibility as a mediating variable, and FoR as the dependent variable. The model was further validated through goodness-of-fit indices and path coefficients to test research hypotheses and explore the relationships among these factors. The model fit assessment indicated satisfactory goodness-of-fit, with the following indices: χ2/df = 1.3632, GFI = 0.9510, RMSEA = 0.0606, TLI = 0.9378, CFI = 0.9689, NFI = 0.9003, and IFI = 0.9714. These results suggest that the structural equation model demonstrated an acceptable fit (Table 6).

Table 6: Model fit indices for the structural equation model.

| Indicator | χ2 | df | p | χ2/df | GFI | RMSEA | TLI | CFI | NFI | IFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment Standard | - | - | >0.05 | <3 | >0.9 | <0.08 | >0.9 | >0.9 | >0.9 | >0.9 |

| Value | 5.4529 | 4 | 0.2439 | 1.3632 | 0.9510 | 0.0606 | 0.9378 | 0.9689 | 0.9003 | 0.9714 |

| Compliance (Yes/No) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

The results of the path coefficient testing of the structural model showed that the standardized path coefficient of spousal emotional support on FoR was −0.30648 (p < 0.05), indicating that spousal emotional support had a significant negative effect on FoR. The standardized path coefficient of self-disclosure on FoR was −0.20727 (p < 0.05), suggesting that self-disclosure had a significant negative effect on FoR. The standardized path coefficient of psychological flexibility on FoR was −0.33081 (p < 0.05), demonstrating that psychological flexibility had a significant negative effect on FoR. The standardized path coefficient of self-disclosure on psychological flexibility was 0.27793 (p < 0.05), indicating that self-disclosure had a significant positive effect on psychological flexibility. See Table 7 for details. The standardized path coefficient diagram of the mediation structural equation model in this study is shown in Fig. 3.

Table 7: Path coefficient testing results of the model parameters.

| Path | Unstandardized Path Coefficient | SE | z (CR Value) | p | Standardized Path Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spousal Emotional Support → FoR | −0.48680 | 0.13334 | −3.65092 | 0.00026 | −0.30648 |

| Self-disclosure → FoR | −0.18480 | 0.07789 | −2.37259 | 0.01766 | −0.20727 |

| Psychological Flexibility → FoR | −0.32285 | 0.08493 | −3.80146 | 0.00014 | −0.33081 |

| Self-disclosure → Psychological Flexibility | 0.25391 | 0.08776 | 2.89327 | 0.00381 | 0.27793 |

Figure 3: Path coefficient diagram of fear of recurrence (FoR) with spousal emotional support, self-disclosure, and psychological flexibility. Values on the arrows represent standardized path coefficients, indicating the strength and direction of the relationships between variables. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

3.6.2 Significance Testing of the Mediation Effect

The above structural equation model demonstrated that psychological flexibility played a mediating role between self-disclosure and FoR. The results showed that the effect value of self-disclosure on FoR through psychological flexibility was −0.1000, with the 95% bootstrap confidence interval excluding zero, indicating a significant mediation effect. Additionally, the direct effect of self-disclosure on FoR was −0.1917, with the 95% bootstrap confidence interval also excluding zero, suggesting that psychological flexibility served as a partial mediator. This means that self-disclosure exerted a direct negative effect on FoR while also indirectly reducing FoR through its positive impact on psychological flexibility. The proportion of the mediation effect of psychological flexibility was 34.28% (Table 8).

Table 8: Significance testing of the mediation effect.

| Path Relationship | Effect Size | LLCI | ULCI | p | Proportion (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediation Effect: Self-disclosure → Psychological Flexibility → FoR | −0.1000 | −0.1941 | −0.0256 | - | 34.28 |

| Direct Effect: Self-disclosure → FoR | −0.1917 | −0.3572 | −0.0261 | 0.0237 | 65.72 |

| Total Effect: Self-disclosure → FoR | −0.2917 | −0.4645 | −0.1189 | 0.0011 | 100.00 |

This study reveals that FoR is prevalent among patients with cerebral glioma, with an average score of 33.74 ± 9.22, approaching the threshold for severe worry. FoR not only exacerbates anxiety and depressive symptoms but also contributes to functional impairment and increased healthcare costs [33,34]. Therefore, healthcare providers should pay close attention to patients’ recurrence-related concerns and implement more effective interventions to alleviate their negative emotions.

Previous studies have shown that social support, self-disclosure, and psychological flexibility are closely related to FoR. Spousal emotional support, as a crucial component of social support, can directly alleviate patients’ anxiety about recurrence by providing a sense of security and empathetic communication [35]. Increased frequency of self-disclosure may help reduce patients’ catastrophic thinking about recurrence through emotional externalization and cognitive restructuring [36,37]. Moreover, enhanced psychological flexibility enables patients to better accept the uncertainty of their disease, thereby reducing excessive worry about future risks [38,39]. In this study, correlation analysis revealed significant negative relationships between FoR and self-disclosure, spousal emotional support, and psychological flexibility. Furthermore, multiple regression analysis identified self-funded medical insurance, unmarried/other marital status, lack of religious belief, lower spousal emotional support scores, lower self-disclosure scores, and lower psychological flexibility scores as significant risk factors for FoR, further confirming the crucial role of spousal emotional support and self-disclosure in alleviating such concerns. The underlying reasons for these findings may be as follows:

- (1)Compared with self-paying cancer patients, those with medical insurance exhibited lower levels of FoR, which is consistent with the findings of Wang et al. [40]. Medical insurance can reduce patients’ out-of-pocket medical expenses and alleviate their financial stress to some extent, whereas out-of-pocket payment imposes a substantial financial burden on patients, leading to anxiety about treatment costs and future medical expenses, thereby intensifying FoR.

- (2)Some studies have found that married cancer patients exhibit higher levels of FoR [41]. However, contradictory findings have also been reported, indicating that single patients experience higher levels of FoR than married patients [42]. These inconsistencies may be attributed to differences in study samples among studies. In this study, unmarried/other marital status patients exhibited higher levels of FoR, which may be explained by their lack of a stable spousal support system, making it more difficult to cope with disease-related psychological stress.

- (3)Niu et al. [43] found that patients without religious beliefs experienced more severe FoR than those with religious beliefs. The results of this study are consistent with their findings, suggesting that religious belief may serve as a source of spiritual support, providing patients with confidence and courage to overcome the disease and thereby reducing fear and anxiety about cancer recurrence. In contrast, patients without religious beliefs may lack such spiritual support or a framework for finding meaning in coping with the disease, making it more difficult for them to accept the uncertainty of recurrence.

- (4)Low spousal emotional support scores indicate that patients do not receive sufficient emotional comfort and empathetic understanding from their intimate relationships, potentially leading to feelings of isolation.

- (5)Low self-disclosure scores suggest difficulties in emotional expression or a lack of effective emotional release mechanisms, resulting in the accumulation of negative emotions.

- (6)Finally, lower psychological flexibility scores reflect a diminished ability to adapt to disease-related uncertainty, making it challenging to adjust cognitive and behavioral responses to cope with recurrence-related fears. These factors collectively contribute to increased psychological stress, weakened coping resources, and an elevated risk of FoR.

The results of this study provide valuable insights into the psychosocial mechanisms underlying FoR. Further analysis revealed that psychological flexibility mediates the relationship between self-disclosure and FoR, indicating that self-disclosure not only directly influences patients’ FoR but also exerts an indirect effect through its impact on psychological flexibility. This phenomenon can be explained by the fact that self-disclosure, as a form of emotional expression, helps patients release suppressed negative emotions, alleviate inner anxiety and fear, and enhance self-understanding and emotional processing, thereby improving psychological flexibility [44].

Based on the principles of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), enhancing psychological flexibility can help patients accept disease-related distressing experiences (such as FOR and death anxiety), reduce experiential avoidance and catastrophic thinking, and strengthen their resilience and coping capacity when facing disease-related uncertainty and stress [45,46]. When patients enhance their psychological flexibility through self-disclosure, their ability to cope with FoR improves, reducing excessive anxiety [47,48]. Thus, self-disclosure not only directly affects FoR but also plays an indirect role through its modulation of psychological flexibility.

Additionally, during the construction of the structural equation model, it was found that the initial model showed signs of overfitting, which could affect its robustness and generalizability. Considering that SEM should follow the principles of theoretical guidance and parsimony, and based on a comprehensive assessment of the theoretical framework and modification indices, the pathway “spousal emotional support → psychological flexibility” was removed in the final model. After removing this pathway, the model fit improved significantly, suggesting that the effect of spousal emotional support on FoR is mainly direct rather than mediated by psychological flexibility. This finding aligns with the research of Sella-Shalom et al. [49], who concluded that spousal emotional support primarily alleviates patients’ anxiety through immediate emotional comfort and practical assistance rather than significantly altering long-term psychological traits such as psychological flexibility.

Based on these findings, it is recommended that psychological support should be an integral part of the treatment plan for patients with cerebral glioma, in addition to conventional medical interventions. First, patients should be encouraged to engage in self-disclosure, releasing anxiety and worries through emotional expression. The principles of ACT can be integrated into psychological interventions; for example, mindfulness practice can enhance patients’ present-moment awareness, acceptance training can reduce excessive control and resistance toward FOR, and value clarification together with committed action can help patients choose a meaningful lifestyle even in the face of illness. These strategies can enhance psychological flexibility and strengthen patients’ ability to cope with disease and negative emotions. Second, patients’ partners should be encouraged to actively accompany them throughout the treatment process and provide appropriate support. In summary, treatment programs should combine emotional counseling, psychological interventions, and spousal support to more comprehensively improve patients’ mental health and effectively alleviate FoR.

However, this study was conducted at a single center with a relatively small sample size and limited representativeness, and it was confined to a specific regional and cultural context, which restricts the generalizability and external validity of the findings. Future research with multi-center studies across different regions is warranted to further validate the reliability of the results.

In conclusion, FoR in patients with cerebral glioma is associated with spousal emotional support, self-disclosure, and psychological flexibility. Spousal emotional support, self-disclosure, and psychological flexibility scores were identified as independent influencing factors of FoR. Spousal emotional support directly impacts FoR, whereas self-disclosure not only has a direct effect but also exerts an indirect influence through the mediation of psychological flexibility.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: All authors contributed to the study design. Wei Zhu and Lu Chen were involved in the study design, data analysis, and manuscript drafting. Yan Song, Di Chen, Huimin Chen and Dingding Zhang participated in the study design, data collection, and manuscript revision. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [Lu Chen], upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital, Affiliated Hospital of Medical School, Nanjing University (No. 2023-587-01). Informed consent was taken from all the patients.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Xu X , Li L , Luo L , Shu L , Si X , Chen Z , et al. Opportunities and challenges of glioma organoids. Cell Commun Signal. 2021; 19( 1): 102. doi:10.1186/s12964-021-00777-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Song B , Wang X , Qin L , Hussain S , Liang W . Brain gliomas: diagnostic and therapeutic issues and the prospects of drug-targeted nano-delivery technology. Pharmacol Res. 2024; 206: 107308. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2024.107308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Bombino A , Magnani M , Conti A . A promising breakthrough: the potential of VORASIDENIB in the treatment of low-grade glioma. Curr Mol Pharmacol. 2024; 17: e18761429290327. doi:10.2174/0118761429290327240222061812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Ma H , Hu K , Wu W , Wu Q , Ye Q , Jiang X , et al. Illness perception profile among cancer patients and its influencing factors: a cross-sectional study. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2024; 69: 102526. doi:10.1016/j.ejon.2024.102526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Pizzo A , Leisenring WM , Stratton KL , Lamoureux É , Flynn JS , Alschuler K , et al. Fear of cancer recurrence in adult survivors of childhood cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2024; 7( 10): e2436144. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.36144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Taher R , Carr NJ , Vanderpuye N , Stanford S . Fear of cancer recurrence in peritoneal malignancy patients following treatment: a cross-sectional study. J Cancer Surviv. 2023; 17( 2): 300– 8. doi:10.1007/s11764-022-01238-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Du L , Cai J , Zhou J , Yu J , Yang X , Chen X , et al. Current status and influencing factors of fear disease progression in Chinese primary brain tumor patients: a mixed methods study. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2024; 246: 108574. doi:10.1016/j.clineuro.2024.108574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Yang Y , Sun H , Luo X , Li W , Yang F , Xu W , et al. Network connectivity between fear of cancer recurrence, anxiety, and depression in breast cancer patients. J Affect Disord. 2022; 309: 358– 67. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2022.04.119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Podina IR , Todea D , Fodor LA . Fear of cancer recurrence and mental health: a comprehensive meta-analysis. Psychooncology. 2023; 32( 10): 1503– 13. doi:10.1002/pon.6205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Kang DW , Fairey AS , Boulé NG , Field CJ , Wharton SA , Courneya KS . A randomized trial of the effects of exercise on anxiety, fear of cancer progression and quality of life in prostate cancer patients on active surveillance. J Urol. 2022; 207( 4): 814– 22. doi:10.1097/JU.0000000000002334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Yang Y , Qi H , Li W , Liu T , Xu W , Zhao S , et al. Predictors and trajectories of fear of cancer recurrence in Chinese breast cancer patients. J Psychosom Res. 2023; 166: 111177. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2023.111177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Russell L , Ugalde A , Milne D , Krishnasamy M , O Seung Chul E , Austin DW , et al. Feasibility of an online mindfulness-based program for patients with melanoma: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2018; 19( 1): 223. doi:10.1186/s13063-018-2575-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Waldenburger N , Steinecke M , Peters L , Jünemann F , Bara C , Zimmermann T . Depression, anxiety, fear of progression, and emotional arousal in couples after left ventricular assist device implantation. ESC Heart Fail. 2020; 7( 5): 3022– 8. doi:10.1002/ehf2.12927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Zhao H , Zhou Y , Che CC , Chong MC , Zheng Y , Hou Y , et al. Marital self-disclosure intervention for the fear of cancer recurrence in Chinese patients with gastric cancer: protocol for a quasiexperimental study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2024; 13: e55102. doi:10.2196/55102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Hamama-Raz Y , Shinan-Altman S , Levkovich I . The intrapersonal and interpersonal processes of fear of recurrence among cervical cancer survivors: a qualitative study. Support Care Cancer. 2022; 30( 3): 2671– 8. doi:10.1007/s00520-021-06695-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Zhang N , Li H , Kang H , Wang Y , Zuo Z . Relationship between self-disclosure and anticipatory grief in patients with advanced lung cancer: the mediation role of illness uncertainty. Front Psychol. 2023; 14: 1266818. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1266818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Zhang X , Huang T , Sun D , Liu M , Wang Z . Illness perception and benefit finding of thyroid cancer survivors: a chain mediating model of sense of coherence and self-disclosure. Cancer Nurs. 2025; 10: 1097. doi:10.1097/NCC.0000000000001347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Faraji A , Dehghani M , Khatibi A . Familial aspects of fear of cancer recurrence: current insights and knowledge gaps. Front Psychol. 2023; 14: 1279098. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1279098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Yao T , Li J , Su W , Li X , Liu C , Chen M . The effects of different themes of self-disclosure on health outcomes in cancer patients—a meta-analysis. Int J Psychol. 2024; 59( 2): 267– 78. doi:10.1002/ijop.13091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Lee H , Jeong Y . Self-disclosure in adult patients with cancer: structural equation modeling. Cancer Nurs. 2025; 48( 4): 289– 97. doi:10.1097/NCC.0000000000001302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Li Y , Fang C , Xiong M , Hou H , Zhang Y , Zhang C . Exploring fear of cancer recurrence and related factors among breast cancer patients: a cross-sectional study. J Adv Nurs. 2024; 80( 6): 2403– 14. doi:10.1111/jan.16009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Yang X , Li Y , Lin J , Zheng J , Xiao H , Chen W , et al. Fear of recurrence in postoperative lung cancer patients: trajectories, influencing factors and impacts on quality of life. J Clin Nurs. 2024; 33( 4): 1409– 20. doi:10.1111/jocn.16922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Ni P , Chen JL , Liu N . The sample size estimation in quantitative nursing research. Chin J Nurs. 2010; 45( 4): 378– 80. (In Chinese). doi:10.3761/j.issn.0254-1769.2010.04.037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Salis F , Costaggiu D , Mandas A . Mini-mental state examination: optimal cut-off levels for mild and severe cognitive impairment. Geriatrics. 2023; 8( 1): 12. doi:10.3390/geriatrics8010012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Mehnert A , Herschbach P , Berg P , Henrich G , Koch U . Fear of progression in breast cancer patients—validation of the short form of the fear of progression questionnaire (FoP-Q-SF). Z Psychosom Med Psychother. 2006; 52( 3): 274– 88. doi:10.13109/zptm.2006.52.3.274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Wu QY , Ye ZX , Li L , Liu PY . Reliability and validity of Chinese version of fear of progression questionnaire-short form for cancer patients. Chin J Nurs. 2015; 50( 12): 1515– 9. (In Chinese). doi:10.3761/j.issn.0254-1769.2015.12.021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Wu L , Chen X , Dong T , Yan W , Wang L , Li W . Self-disclosure, perceived social support, and reproductive concerns among young male cancer patients in China: a mediating model analysis. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs. 2024; 11( 7): 100503. doi:10.1016/j.apjon.2024.100503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Kahn JH , Hessling RM . Measuring the tendency to conceal versus disclose psychological distress. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2001; 20( 1): 41– 65. doi:10.1521/jscp.20.1.41.22254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Kumar CS , Subramanian S , Murki S , Rao JV , Bai M , Penagaram S , et al. Predictors of mortality in neonatal pneumonia: an INCLEN childhood pneumonia study. Indian Pediatr. 2021; 58( 11): 1040– 5. doi:10.1007/s13312-021-2370-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Cao J , Ji Y , Zhu ZH . Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the acceptance and action questionnaire-second edition (AAQ-II) in college students. Chin Ment Health J. 2013; 27( 11): 873– 7. (In Chinese). doi:10.3969/j.issn.1000-6729.2013.11.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Bentler PM . Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol Bull. 1990; 107( 2): 238– 46. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Hooper D , Coughlan J , Mullen MR . Structural equation modelling: guidelines for determining model fit. Electron J Bus Res Methods. 2008; 6( 1): 53– 60. [Google Scholar]

33. Prins JB , Deuning-Smit E , Custers JAE . Interventions addressing fear of cancer recurrence: challenges and future perspectives. Curr Opin Oncol. 2022; 34( 4): 279– 84. doi:10.1097/CCO.0000000000000837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Livingston PM , Russell L , Orellana L , Winter N , Jefford M , Girgis A , et al. Efficacy and cost-effectiveness of an online mindfulness program (MindOnLine) to reduce fear of recurrence among people with cancer: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2022; 12( 1): e057212. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-057212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Yang L , Liu J , Liu Q , Wang Y , Yu J , Qin H . The relationships among symptom experience, family support, health literacy, and fear of progression in advanced lung cancer patients. J Adv Nurs. 2023; 79( 9): 3549– 58. doi:10.1111/jan.15692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Hu C , Weng Y , Wang Q , Yu W , Shan S , Niu N , et al. Fear of progression among colorectal cancer patients: a latent profile analysis. Support Care Cancer. 2024; 32( 7): 469. doi:10.1007/s00520-024-08660-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Lyu MM , Chiew-Jiat RS , Cheng KKF . The effects of physical symptoms, self-efficacy and social constraints on fear of cancer recurrence in breast cancer survivors: examining the mediating role of illness representations. Psychooncology. 2024; 33( 1): e6264. doi:10.1002/pon.6264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Li H , Wu J , Ni Q , Zhang J , Wang Y , He G . Systematic review and meta-analysis of effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy in patients with breast cancer. Nurs Res. 2021; 70( 4): E152– 60. doi:10.1097/NNR.0000000000000499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Sevier-Guy LJ , Ferreira N , Somerville C , Gillanders D . Psychological flexibility and fear of recurrence in prostate cancer. Eur J Cancer Care. 2021; 30( 6): e13483. doi:10.1111/ecc.13483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Wang F , Shang L , Chang DY . Regression analysis of factors influencing fear of recurrence after radical resection of cervical cancer. J Med Forum. 2025; 46( 11): 1146– 50. (In Chinese). doi:10.20159/j.cnki.jmf.2025.11.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Ki P , Ha M . Fear of cancer recurrence in South Korean survivors of breast cancer who have received adjuvant endocrine therapy: a cross-sectional study. Front Psychol. 2023; 14: 1170077. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1170077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Yang Y , Sun H , Liu T , Zhang J , Wang H , Liang W , et al. Factors associated with fear of progression in Chinese cancer patients: sociodemographic, clinical and psychological variables. J Psychosom Res. 2018; 114: 18– 24. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2018.09.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Niu L , Liang Y , Niu M . Factors influencing fear of cancer recurrence in patients with breast cancer: evidence from a survey in Yancheng, China. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2019; 45( 7): 1319– 27. doi:10.1111/jog.13978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Li L , Zhong HY , Xiao T , Xiao RH , Yang J , Li YL , et al. Association between self-disclosure and benefit finding of Chinese cancer patients caregivers: the mediation effect of coping styles. Support Care Cancer. 2023; 31( 12): 684. doi:10.1007/s00520-023-08158-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Krok D , Telka E , Kocur D . Perceived and received social support and illness acceptance among breast cancer patients: the serial mediation of meaning-making and fear of recurrence. Ann Behav Med. 2024; 58( 3): 147– 55. doi:10.1093/abm/kaad067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Zhang Z , Leong Bin Abdullah MFI , Shari NI , Lu P . Acceptance and commitment therapy versus mindfulness-based stress reduction for newly diagnosed head and neck cancer patients: a randomized controlled trial assessing efficacy for positive psychology, depression, anxiety, and quality of life. PLoS One. 2022; 17( 5): e0267887. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0267887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Sihvola S , Kuosmanen L , Kvist T . Resilience and related factors in colorectal cancer patients: a systematic review. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2022; 56: 102079. doi:10.1016/j.ejon.2021.102079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Lucas AR , Pan JH , Ip EH , Hall DL , Tooze JA , Levine B , et al. Validation of the Lee-Jones theoretical model of fear of cancer recurrence among breast cancer survivors using a structural equation modeling approach. Psychooncology. 2023; 32( 2): 256– 65. doi:10.1002/pon.6076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Sella-Shalom K , Hertz-Palmor N , Braun M , Rafaeli E , Wertheim R , Pizem N , et al. The association between communication behavior and psychological distress among couples coping with cancer: actor-partner effects of disclosure and concealment. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2023; 84: 172– 8. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2023.07.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools