Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Follow-Up Study on the Clinical Effectiveness and Satisfaction of an Online Mental Health Self-Care Program for Mothers in Korea

1 Department of Preventive Medicine, College of Korean Medicine, Kyung Hee University, Seoul, 02447, Republic of Korea

2 Department of Preventive Medicine, College of Korean Medicine, Daegu Hanny University, Daegu, 38610, Republic of Korea

3 Department of Clinical Korean Medicine, College of Korean Medicine, Kyung Hee University, Seoul, 02447, Republic of Korea

4 Department of Science in Korean Medicine, College of Korean Medicine, Kyung Hee University, Seoul, 02447, Republic of Korea

5 Department of Korean Medicine, College of Korean Medicine, Kyung Hee University, Seoul, 02447, Republic of Korea

6 Department of Preventive Medicine, College of Korean Medicine, Woosuk University, Wanju, 55338, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Authors: Kyeong Han Kim. Email: ; Seong-Gyu Ko. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Evidence-based Approaches to Managing Stress, Depression, Anxiety, and Suicide)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(11), 1695-1708. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.071014

Received 29 July 2025; Accepted 07 November 2025; Issue published 28 November 2025

Abstract

Objectives: This study aimed to evaluate the clinical effectiveness, durability, and acceptability of a Korean medicine-based online mental health self-care program for mothers. Methods: This non-randomized comparative study evaluated the clinical effectiveness, durability, and acceptability of a Korean medicine-based online mental health self-care program for mothers. Group 1 (regular version) included 120 participants who attended one live session per week for 5 weeks, while Group 2 (shortened version) included 30 participants who completed five recorded sessions within 1 week. A total of 112 participants (93.3%) in Group 1 and all 30 participants (100%) in Group 2 completed the program and surveys. Results: Within-group analyses demonstrated significant improvements for depression (ΔCESD-10 [Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale-10] = −2.38 ± 2.10, p < 0.001; Cohen’s d = 1.10), anxiety (ΔGAD-7 [Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale-7] = −3.82 ± 3.20, p < 0.001; d = 0.93), and stress (ΔPSS [Perceived Stress Scale] = −6.44 ± 4.50, p < 0.001; d = 1.12) in Group 1. Between-group analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) of postintervention scores showed significant differences favoring Group 1 in CESD-10 (p < 0.001) and GAD-7 (p = 0.025). These improvements were largely maintained through the 12-week follow-up (all p < 0.001), indicating both statistical and clinical significance. The average willingness-to-pay per session was 8562.5 ± 3609 KRW, and overall satisfaction was high. Conclusion: These findings demonstrate that the regular 5-week Korean medicine-based online program is effective, cost-effective, and capable of sustaining improvements in maternal mental health, supporting its potential use in community-based care strategies.Keywords

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) led to a global public health crisis in 2020, affecting both the physical and mental health of individuals. Recent studies have reported that around 20 percent of Korean adults were at high risk of depression by December 2020, which was approximately 4.8 times higher than before the outbreak [1]. The stress caused by COVID-19 was reported to be 1.5 times higher than that caused by Middle-East Respiratory Syndrome, and 1.4 times higher than that caused by earthquakes [2]. According to the literature, individuals affected by COVID-19 may experience depression, anxiety, and stress, along with severe mental disorders, including panic attacks, impulsivity, sleep disorders, and posttraumatic stress symptoms [2].

During the continued spread of COVID-19 in 2022, workplaces, schools, and daycare centers for children closed their doors. These major changes led to an increased caregiving burden in women [3,4]. Additionally, school closures led to an immediate increase in unpaid care. During the lockdown period, women spent significantly more time as caregivers than men, and more mothers than fathers reduced their working hours or rescheduled their employment due to childcare needs. Women who spent long hours doing housework and parenting were more likely to report increased psychological distress [5], as the closure of schools and childcare facilities disrupted regular work rhythms [6]. Anxiety levels were also higher among women living with children than among those without children [7].

Increased maternal care due to COVID-19 is a global trend. In Norway, mothers who strongly believed women are natural caregivers provided more care during the lockdown, and consequently reported poorer mental health [8]. In the United States, there have also been reports of increased stress among caregivers. High levels of caregiver burden and psychological distress can disrupt one’s daily life balance. Parents, particularly mothers, must often sacrifice their personal well-being to meet their children’s needs [9,10]. Similar burdens to those described above are also present in Korea [11]. Accordingly, various online healthcare programs have been initiated due to the COVID-19 pandemic; however, these are still in the infancy stages, and the advantages of face-to-face interactions cannot be overlooked.

Korean medicine refers to traditional medicine in Korea, wherein various complementary and alternative medicine treatments—such as acupuncture, moxibustion, and herbal medicine—are utilized. Currently, Korea is in the process of producing Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPGs) for Korean medicine at the national level, which aims to provide evidence-based and standardized healthcare services [12]. CPGs have already been developed for anxiety disorder, autism spectrum disorder, dementia, insomnia, and hwabyeong—a Korean culture-specific term that refers to anger syndrome with both psychological and physical symptoms, mainly occurring in middle-aged women [13,14,15].

Therefore, this study aimed to apply an online healthcare program developed using acupuncture, moxibustion, mindfulness meditation, tea, and aroma oil to reduce mental stress. An initial short-term evaluation of this program, focusing on outcomes from weeks 1–5, was previously reported in the form of a research letter [16]. In the present study, we extend this investigation by analyzing follow-up outcomes at week 17, and assessing participant satisfaction. This extended evaluation aims to provide more robust and practical evidence on the program’s effectiveness and feasibility as a long-term intervention for stress relief during the COVID-19 pandemic.

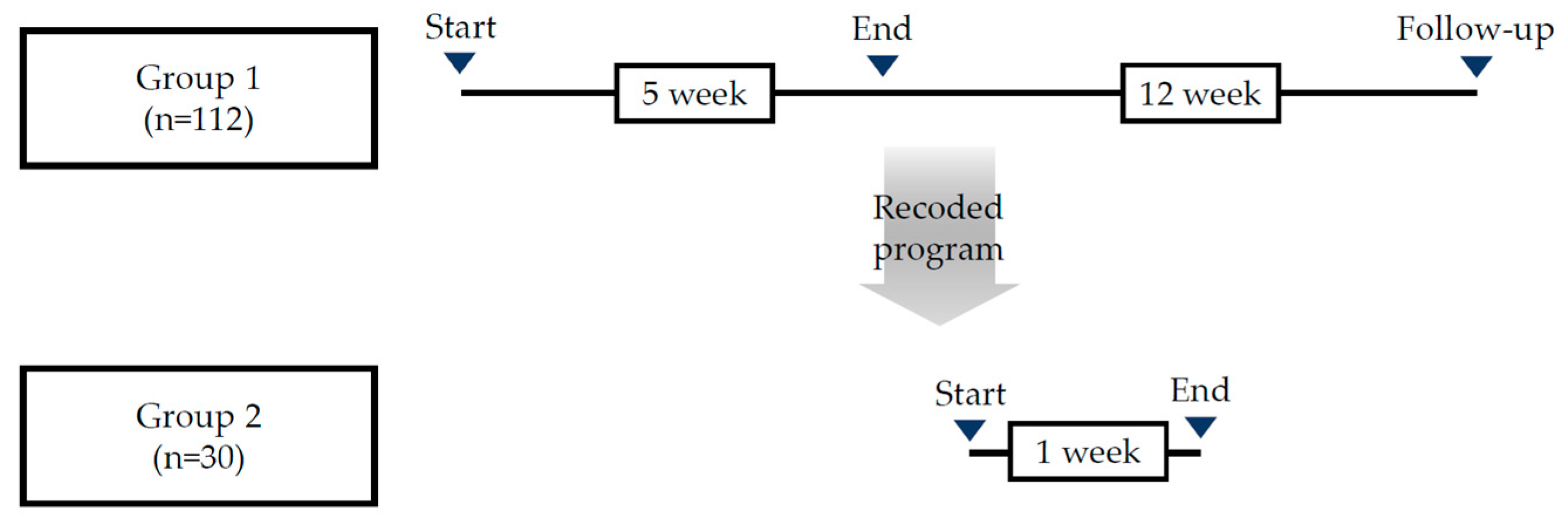

This nonrandomized comparative study evaluated an online mental health self-care program for mothers of elementary school children. All data, including demographic and health-related information, were collected directly from the participants of this study through online surveys administered before and after the program. The participants were assigned to either Group 1 (participating in the regular program [5 weeks]) or Group 2 (participating in the shortened program [1 week]). The program was conducted from 05 October to 04 November 2021. The regular program conducted classes in real-time, while the shortened program proceeded with recorded lecture videos. After the completion of all programs, postintervention tests were performed for participants (Fig. 1).

The protocol of this study was registered at CRIS (KCT0008298) and approved by the Woosuk University Institutional Review Board (IRB No.: WSOH IRB H2210-03). Written informed consent was provided by all the study participants.

Figure 1: Study design.

2.2 Recruitment and Eligibility of Participants

Participants were recruited over a 2-week period via the Korean Medicine Association of Chungcheongnam-do and online posters. Interested individuals contacted the researchers by phone or email and were screened for eligibility by a Korean medicine doctor following a preliminary survey. This preliminary survey included demographic questions and the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) to determine eligibility. All participants were informed of the study’s purpose and ethical considerations, and written informed consent was obtained. Participants received the necessary program materials as compensation. The inclusion and exclusion criteria for participant selection are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Inclusion and exclusion criteria for study participants.

| Selection Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| 1. Age between 20 and 70 years 2. Having children currently attending elementary school 3. Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) scores of ≥4 or ≤19 4. Voluntarily signing the consent form for clinical research 5. Willingness to cooperate during the research period and comply with restrictions | 1. Mental illness and difficulty in communication 2. Difficulty in communication due to being unconscious or critically ill 3. Conditions related to mental health requiring medications 4. Pregnancy 5. Participation in other clinical trials 6. Conditions that may affect the evaluation of this study according to the researcher’s judgment for reasons other than those listed above |

2.3 Sample Size and Assignment

The sample size (N = 150) was determined based on the study duration and budget. Participants chose either the regular or shortened version of the program based on their availability, and were assigned to groups at a 4:1 ratio, respectively.

2.4 Online Mental Health Self-Care Program

This program was based on the model proposed by Lee [17] for developing Korean medicine-based health promotion and community-linked programs. A draft was created through literature review—including clinical practice guidelines, related reports, and existing programs—and finalized through expert and public health center consultations. Two Korean medicine neuropsychiatrists reviewed the content. The full program development has been previously published and is available online [18].

Before the program began, participants completed an online pre-questionnaire and received the necessary materials by mail. They then joined live-streamed sessions with instructional videos and practiced independently. The program ran twice daily, 2 days a week, over four sessions. Each weekly lecture lasted approximately 30 min and addressed topics such as causes of stress, recognizing depression, self-understanding, coping strategies, and sharing stressful situations. A group chat was created for ongoing engagement and daily missions. The sessions were led by a professor from Woosuk University’s College of Korean Medicine, an experienced researcher in preventive medicine. All materials were reviewed by experts for quality assurance (Table 2).

Table 2: Program outline.

| Step | Main Program | Time | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Previsit | Consent form and pre-questionnaire | - | |

| Shipment of supplies | - | ||

| Week 1 | Education | Program introduction (10 min) Causes of stress (10 min) Korean medicine practice training (10 min) | 30 min |

| Training | Pellet, hot pack (10 min), meditation (10 min), tea | 20 min | |

| Week 2 | Education | Recognizing depression (30 min) | 30 min |

| Training | Pellet, hot pack (10 min), meditation (10 min), tea | 20 min | |

| Week 3 | Education | Knowing myself (30 min) | 30 min |

| Training | Pellet, hot pack (10 min), meditation (10 min), tea | 20 min | |

| Week 4 | Education | Improving oneself (30 min) | 30 min |

| Training | Pellet, hot pack (10 min), meditation (10 min), tea | 20 min | |

| Week 5 | Education | Sharing stressful situations (30 min) | 30 min |

| Training | Pellet, hot pack (10 min), meditation (10 min), tea | 20 min | |

| End point | Postintervention questionnaire | - | |

| Follow-up | Follow-up questionnaire | - | |

2.4.2 Interventions for Mental Care Program

The intervention combined Korean medicine-based physical, psychological, and lifestyle therapies into a structured program. Participants engaged in self-administered acupoint stimulation, mindfulness meditation guided by expert-created audio, psychoeducational lectures and exercises, and supplementary therapies (lavender oil and green tea) aimed at promoting emotional stability (Table 3).

Table 3: Interventions for mental care programs.

| Component | Description |

|---|---|

| Acupoint stimulation | Magnetic pellets were applied to LI4 and LR3 acupoints [19], and a hot pack was used on CV4 instead of moxibustion [20]. These methods allow participants to perform self-stimulation to alleviate anxiety, depression, and fatigue [21]. |

| Mindfulness meditation | A prerecorded guided meditation file was provided by a Korean medicine expert with >3 years of experience [22]. Participants practiced individually using the file. |

| Education | Sessions included understanding depression, recognizing stress symptoms, and learning coping strategies. Participants also practiced behavior change techniques and shared experiences. |

| Supplementary therapies | Lavender oil for aromatherapy [23] and green tea [24] were used to support mental and physical relaxation based on previous literature. |

For the evaluation tools, the 2019 Standard Guidelines for Mental Health Examination tool [25] and Clinical Practice Guideline of Korean Medicine; Hwabyeong [26] were referenced. The Korean versions of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale-10 (CESD-10) [27], Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale-7 (GAD-7) [28], and Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) [29] were used to assess depression, anxiety, and perceived stress, respectively. To assess the improvement of Hwabyung, both the Hwabyung Standard [30] and a Visual Analog Scale (VAS) [25] were used. The Hwabyung Standard consists of two self-report subscales—personality traits and symptom severity—developed to evaluate individual vulnerability to hwabyung and the degree of symptom manifestation. Additionally, in reference to the CPGs, core somatic symptoms of hwabyung were measured using a VAS focusing on five key symptoms: vexation, indigestion, heavy-headedness, hot flash, and irritability (Table 4).

Table 4: Outcome measurements.

| Period | Observational Study | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visit | Screeninga | Preprogram | 5 weeks (end point) | 17 weeks (follow-up) |

| Consent form | O | - | - | - |

| Demographic characteristicsb | O | - | - | - |

| Case and drug history | O | - | - | - |

| PHQ-9 | O | - | - | - |

| CESD-10 | - | O | O | O |

| GAD-7 | - | O | O | O |

| PSS | - | O | O | O |

| Hwabyung standard | - | O | O | O |

| Hwabyung VAS | - | O | O | O |

| Adverse events | - | - | O | O |

| Satisfaction | - | - | O | O |

All analyses were performed according to the intention-to-treat principle, with the level of statistical significance set at p < 0.05. The homogeneity of baseline characteristics between groups was assessed using independent t-tests for continuous variables, and the χ2 or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables.

Within each group, pre–post changes were analyzed using paired t-tests. Between groups, independent t-tests were first used to compare postintervention scores, followed by analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), with the corresponding baseline value as a covariate to adjust for initial differences. To correct for multiple comparisons across outcomes, the false discovery rate (FDR) was controlled using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure.

For the follow-up analysis in Group 1, repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to evaluate changes across three time points: baseline, postintervention, and at the 12-week follow-up (equivalent to 17 weeks from baseline). All analyses were conducted using jamovi (version 2.6.26).

This study evaluated the program’s effects after 5 weeks to evaluate the effects of the non-face-to-face Korean medicine program on stress and depression in women with elementary school children. Data from 112 participants (93.3%) who completed all sessions and both the pre- and postintervention surveys were analyzed. Some of the participants attended the same lecture two to three times; however, this was not the case for many participants, and the attendance rate differed weekly. Repeated attendance was therefore not included in the analysis. Regarding the shortened program, data from 30 participants (100%) who completed all five sessions and the postintervention questionnaire were analyzed.

3.1 Basic Information of Participants

Table 5 shows the general characteristics of the participants. No statistically significant differences were observed between the experimental (n = 112) and control groups (n = 30) regarding height, weight, or body mass index (BMI). The BMI distribution, number of children, employment status, history of depression diagnosis, year of diagnosis, and experience with antidepressants were also comparable between groups (p > 0.05 for all). Most participants were housewives with one or two children, and most had not been diagnosed with depression or taken antidepressants prior to the study.

Table 5: Basic information of participants.

| Classification | Group 1 (n = 112) | Group 2 (n = 30) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD)/N (%) | ||||

| Height (cm) | 162 (5.53) | 163 (5.97) | 0.745a | |

| Weight (kg) | 62.0 (10.8) | 59.3 (9.97) | 0.213a | |

| BMI | 23.5 (3.81) | 22.4 (3.54) | 0.144a | |

| Underweight | 10 (7.0%) | 4 (2.8%) | 0.739b | |

| Normal | 45 (31.7%) | 15 (10.6%) | ||

| Overweight | 24 (16.9%) | 4 (2.8%) | ||

| Obesity | 26 (18.3%) | 6 (4.2%) | ||

| Stage 2 obesity | 7 (4.9%) | 1 (0.7%) | ||

| Children | 1 | 35 | 13 | 0.462c |

| 2 | 54 | 12 | 0.4829b | |

| ≥3 | 23 | 5 | 0.4829b | |

| Job | Regular job | 25 | 4 | 0.4655b |

| Irregular job | 19 | 4 | 0.4655c | |

| Housewife | 68 | 22 | 0.4655c | |

| Diagnosis of depression | Yes | 15 (10.6%) | 5 (3.5%) | 0.647c |

| No | 97 (68.3%) | 25 (17.6%) | ||

| Diagnosis year of depression | 2017 | 1 | 0 | 0.656b |

| 2018 | 1 | 0 | ||

| 2019 | 2 | 0 | ||

| 2020 | 5 | 1 | ||

| 2021 | 6 | 4 | ||

| History of taking antidepressants | Yes | 11 (7.7%) | 3 (2.1%) | 0.725b |

| No | 4 (2.8%) | 2 (1.4%) | ||

A homogeneity test was performed on the dependent variables between the regular and short program participants. There was no significant difference in the prior symptom scores (Table 6).

Table 6: Symptoms prior to participating in the program.

| Variable | Group 1 (n = 112) | Group 2 (n = 30) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |||

| CESD-10 | 3.80 (2.30) | 3.83 (2.34) | 0.950 | |

| GAD-7 | 7.31 (4.36) | 8.47 (4.78) | 0.210 | |

| PSS | 20.77 (5.09) | 20.63 (5.66) | 0.900 | |

| Hwabyung standard | Personality | 34.18 (9.00) | 32.90 (10.89) | 0.510 |

| Symptom | 32.81 (13.24) | 31.50 (13.49) | 0.632 | |

| Hwabyung VAS | Vexation | 4.43 (2.74) | 4.63 (2.51) | 0.712 |

| Indigestion | 4.77 (2.98) | 4.47 (3.01) | 0.624 | |

| Heavy headedness | 5.74 (2.42) | 6.07 (2.53) | 0.518 | |

| Hot flash | 5.24 (2.78) | 5.87 (2.93) | 0.282 | |

| Irritability | 6.17 (2.77) | 6.50 (2.93) | 0.568 | |

3.2 Effectiveness of the Program

Within-group analyses showed significant pre–post improvements in Group 1 across the CESD-10, GAD-7, PSS, Hwabyung Standard (personality and symptom subscales), and all VAS items (p < 0.001 by paired t-tests). In Group 2, paired t-tests also indicated significant reductions in GAD-7, PSS, and several VAS scores; however, the magnitude of change was smaller than in Group 1.

Between-group comparisons of postintervention scores using independent t-tests revealed significant differences favoring Group 1 in the CESD-10, GAD-7, and selected VAS items (vexation, hot flash, irritability). These findings remained significant after ANCOVA, adjusting for baseline values, and significance was preserved after FDR correction across multiple outcomes (Table 7).

Table 7: Changes in CESD-10, GAD-7, PSS, Hwabyung Standard, and VAS scores.

| Classification | Group | Preintervention | Postintervention | pa | pb | pc | qd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | |||||||

| CESD-10 | 1 | 3.80 (2.30) | 1.42 (1.79) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 2 | 3.83 (2.34) | 2.90 (1.90) | 0.058 | ||||

| GAD-7 | 1 | 7.31 (4.36) | 3.49 (3.22) | <0.001 | 0.016 | 0.025 | 0.0495 |

| 2 | 8.47 (4.78) | 5.13 (3.45) | <0.001 | ||||

| PSS | 1 | 20.77 (5.09) | 14.33 (5.08) | <0.001 | 0.339 | 0.344 | 0.382 |

| 2 | 20.63 (5.66) | 15.33 (5.14) | <0.001 | ||||

| Hwabyung personality standard | 1 | 34.18 (9.00) | 28.07 (8.11) | <0.001 | 0.062 | 0.045 | 0.075 |

| 2 | 32.90 (10.89) | 31.20 (8.05) | 0.373 | ||||

| Hwabyung symptom standard | 1 | 32.81 (13.24) | 19.56 (10.28) | <0.001 | 0.068 | 0.055 | 0.079 |

| 2 | 31.50 (13.49) | 23.53 (11.33) | <0.001 | ||||

| (VAS) Vexation | 1 | 4.43 (2.74) | 2.63 (1.82) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 2 | 4.63 (2.51) | 4.00 (2.18) | <0.001 | ||||

| (VAS) Indigestion | 1 | 4.77 (2.98) | 3.17 (2.13) | <0.001 | 0.872 | 0.906 | 0.906 |

| 2 | 4.47 (3.01) | 3.10 (2.02) | <0.001 | ||||

| (VAS) Heavy headedness | 1 | 5.74 (2.42) | 3.69 (2.19) | <0.001 | 0.115 | 0.151 | 0.189 |

| 2 | 6.07 (2.53) | 4.37 (1.61) | <0.001 | ||||

| (VAS) Hot flash | 1 | 5.24 (2.78) | 3.10 (2.18) | <0.001 | 0.002 | 0.005 | 0.012 |

| 2 | 5.87 (2.93) | 4.50 (2.33) | <0.001 | ||||

| (VAS) Irritability | 1 | 6.17 (2.77) | 3.49 (2.25) | <0.001 | 0.006 | 0.005 | 0.012 |

| 2 | 6.50 (2.93) | 4.77 (2.13) | <0.001 | ||||

For the follow-up analysis, data from 80 participants in Group 1 (regular program) who completed all preintervention, postintervention, and 3-month follow-up questionnaires were analyzed. In Group 1, repeated-measures ANOVA across three time points (baseline, postintervention, and at the 12-week follow-up) demonstrated significant time effects for the CESD-10, GAD-7, PSS, Hwabyung Standard symptom subscale, and VAS scores for vexation, indigestion, and heavy-headedness (all p < 0.001). Post hoc comparisons indicated that improvements from baseline were maintained at the 12-week follow-up. Only the Hwabyung personality subscale and VAS items for hot flash and irritability showed partial rebound between postintervention and follow-up; still, scores remained significantly better than at baseline.

These results confirm that the regular 5-week program produced significant short-term benefits that were largely sustained for 12 weeks after completion (Table 8).

Table 8: Program results, including follow-up.

| Classification | Preintervention | Postintervention | Follow-up | pa | pb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CESD-10 | 3.98 ± 2.38 | 1.38 ± 1.66 | 1.43 ± 1.53 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| GAD-7 | 7.19 ± 4.12 | 3.41 ± 3.25 | 4.15 ± 2.55 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| PSS | 20.8 ± 5.45 | 14.99 ± 4.90 | 15.21 ± 4.3 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Hwabyeong Standard | Personality | 34.08 ± 7.90 | 28.16 ± 8.52 | 30.43 ± 7.12 | <0.001 | 0.001 |

| Symptom | 31.49 ± 12.54 | 20.74 ± 9.92 | 20.9 ± 8.94 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| VAS | Vexation | 4.50 ± 2.70 | 2.66 ± 2.00 | 3.23 ± 3.84 | <0.001 | 0.010 |

| Indigestion | 4.85 ± 2.93 | 3.21 ± 2.27 | 3.23 ± 1.72 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Heavy headedness | 5.79 ± 2.32 | 3.85 ± 2.30 | 4.09 ± 2.19 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Hot flash | 5.26 ± 2.75 | 3.19 ± 2.40 | 4.00 ± 1.89 | <0.001 | 0.003 | |

| Irritability | 6.31 ± 2.62 | 3.75 ± 2.39 | 4.90 ± 2.58 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

Satisfaction and recommendation scores were assessed at both the postintervention and follow-up points. As shown in Table 9, participants in the regular program (Group 1) reported higher satisfaction scores than those in the shortened program (Group 2) at both time points (postintervention: 8.74 vs. 8.07; follow-up: 8.81 vs. 7.77). Recommendation scores were also higher in Group 1 at the postintervention time point (8.82 vs. 8.10).

To further quantify satisfaction, participant responses from Group 1 were converted into a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Very bad, 5 = Very good). The average scores were 4.69, 4.49, and 4.81 for overall satisfaction, satisfaction with the schedule, and satisfaction with the non-face-to-face delivery method, respectively. Regarding willingness to recommend the program, the average score was 4.49, indicating high acceptability and satisfaction across all domains (Table 10).

Table 9: Satisfaction and recommendation scores by group and time point.

| Classification | Satisfaction (Postintervention) | Satisfaction (Follow-up) | Recommend (Postintervention) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | 8.74 ± 0.81 | 8.81 ± 0.75 | 8.82 ± 0.80 |

| Group 2 | 8.07 ± 1.01 | 7.77 ± 1.07 | 8.10 ± 1.37 |

Table 10: Detailed satisfaction ratings among regular program participants (Group 1).

| Question | Answer | N (%) | Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Are you satisfied with the overall program? | Very bad | 2 (2.4%) | 4.69 ± 0.72 |

| Bad | 0 (0%) | ||

| Normal | 1 (1.2%) | ||

| Good | 16 (18.8%) | ||

| Very Good | 66 (77.6%) | ||

| Are you satisfied with the operating hours and schedule? | Very bad | 2 (2.4%) | 4.49 ± 0.89 |

| Bad | 1 (1.2%) | ||

| Normal | 8 (9.4%) | ||

| Good | 16 (18.8%) | ||

| Very Good | 58 (68.2%) | ||

| Are you satisfied with the non-face-to-face online operation method? | Very bad | 1 (1.2%) | 4.81 ± 0.59 |

| Bad | 0 (0%) | ||

| Normal | 2 (2.4%) | ||

| Good | 8 (9.4%) | ||

| Very Good | 74 (87.1%) | ||

| Are you willing to recommend the program to others? | Very bad | 0 (0%) | 4.49 ± 0.57 |

| Bad | 0 (0%) | ||

| Normal | 3 (3.5%) | ||

| Good | 37 (43.5%) | ||

| Very Good | 45 (52.9%) |

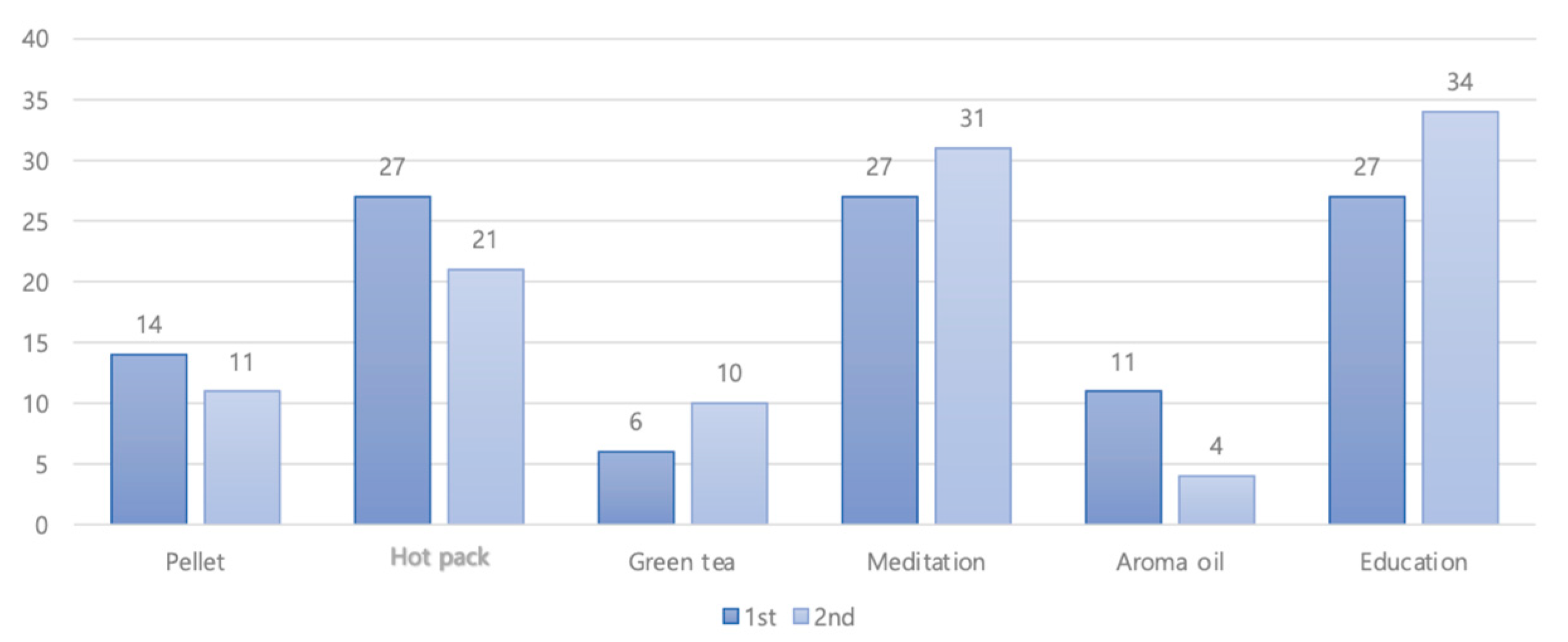

Participants were asked to rank the top two most preferred components of the program. As shown in Fig. 2, meditation (n = 27 first, n = 31 second) and education (n = 27 first, n = 34 second) received the highest combined preferences, followed by hot pack/moxibustion (n = 27 first, n = 21 second). Pellet stimulation (n = 14 first, n = 11 second), green tea (n = 6 first, n = 10 second), and aroma oil (n = 11 first, n = 4 second) were less frequently chosen. These results suggest that participants showed a strong preference for active interventions that engage the body or mind, such as meditation and education, compared to more passive or sensory components.

Figure 2: Satisfaction of the intervention.

Women’s mental health was disproportionately affected during the COVID-19 pandemic, with many reporting increased caregiving burdens and psychological distress [31,32,33,34]. These challenges were especially pronounced among the parents of young children, highlighting the need for accessible and sustainable mental health interventions. This study builds upon our previously reported short-term findings by providing extended data on follow-up effects, participant satisfaction, and economic acceptability [35].

To prevent COVID-19, the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and related societies are continuously issuing prevention rules and guidelines [36]. Additionally, guidelines and support centers have been established to protect mental health. To prevent a mental health crisis, acquiring reliable information, maintaining social networks, expressing emotions, and continuing daily life are considered important factors; however, most people have difficulty participating in the rapidly changing environment. Various health promotion programs have been launched to support this population [37]. The current study expands our prior work by incorporating a 3-month follow-up and additional participant-centered outcomes—such as willingness-to-pay and satisfaction—offering a more comprehensive assessment of the intervention’s real-world applicability.

A total of 112 (93.3%) and 30 (100%) participants from Groups 1 and 2, respectively, completed all procedures and surveys and were included in the analysis. This study confirmed that the online Korean medicine-based program effectively improved depression, anxiety, and stress in mothers. The primary finding is that the regular, live, 5-week program was significantly more effective at reducing depression (CESD-10) and anxiety (GAD-7) than the shortened, recorded, 1-week program, even after controlling for baseline differences (ANCOVA). This suggests that the program’s duration and live, interactive components are key factors for its therapeutic effect, rather than mere participation. Furthermore, the benefits of the regular program were not transient. Repeated-measures ANOVA demonstrated that these improvements were largely sustained at the 12-week follow-up, highlighting the program’s potential to foster long-term mental health maintenance by equipping participants with durable self-care skills.

This study has several limitations. First, as this was not a randomized controlled trial, the self-selection of participants into programs may have introduced selection bias; participants in the regular program might have possessed higher motivation. To statistically mitigate this limitation, ANCOVA was used to adjust for baseline scores when comparing groups; however, as this method cannot entirely eliminate bias, the results should be interpreted with caution. Additionally, the sample primarily included relatively healthy individuals with low baseline PHQ-9 scores, which restricts the generalizability of the findings to clinical populations with moderate to severe depressive symptoms.

Second, only the regular program group completed the 17-week follow-up, making it difficult to assess the long-term effectiveness of the shortened version. While both formats showed short-term improvements, the lack of sustained CESD-10 improvement in the shortened group suggests that program duration may play a critical role. Future studies should consider evaluating hybrid or intermediate-length formats to balance effectiveness and scalability.

Third, this study recruited participants during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the eligibility criteria required being a mother of elementary school children. Additional screening excluded those with severe mental illness, and collected prior diagnosis and treatment history. Nevertheless, it was not possible to determine with certainty whether the observed mental health difficulties had newly emerged in response to the childcare burden during the pandemic, or whether they reflected preexisting conditions.

Finally, while overall satisfaction with the program was high, the exclusive use of quantitative measures (e.g., Likert scale ratings) without qualitative feedback may limit a deeper understanding of participant experiences and barriers to engagement. Future research should incorporate mixed methods to better inform program refinement and implementation.

Despite its limitations, this study is meaningful as it is among the first to develop and apply an online mental care program based on Korean medicine for mothers with children. While several studies have explored online healthcare programs for mental health problems caused by COVID-19—such as exercise and online counseling using Social Network Service platforms in Taiwan [38], and an online exercise program developed for elderly people in Canada [39]—Few studies have investigated the parenting stress caused by COVID-19 in mothers with children. This study fills the gap by focusing on culturally tailored, accessible care for mothers, suggesting a need for further expansion and refinement of such targeted online programs.

This study confirms the utility of online Korean medicine programs. Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, health promotion programs using mobile devices were expected to increase, and the government attempted to develop an online healthcare program; however, existing Korean medicine-related programs were insufficient. Therefore, we developed a program by incorporating interventions that are easy and convenient to perform alone. We evaluated the effects of the program and confirmed the possibility that the Korean medicine program could be completed online. As it is a program optimized in the era of COVID-19, it is likely to be used in more regions in the future, and the interventions used in this program are expected to be included in mobile healthcare programs.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. 2020R1A5A2019413).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: conceptualization, Hyein Jeong and Soobin Jang; methodology and formal analysis, Hyein Jeong, Taek Gyu Kim, Chan Ho Ju, Hwimun Kim, Chunhoo Cheon, Su Yong Shin; investigation, Hyein Jeong, Soobin Jang and Bo-Hyoung Jang; writing—original draft preparation, Hyein Jeong; writing—review and editing, Chunhoo Cheon, Seong-Gyu Ko and Kyeong Han Kim; supervision, Seong-Gyu Ko and Kyeong Han Kim. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: The ethics committee of the Woosuk University Institutional Review Board approved this study (REC number: WSOH IRB H2210-03).

Informed Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from all participants after they were provided with a detailed explanation of the study procedures and information regarding the publication of the study results.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| Analysis of covariance | |

| Analysis of variance | |

| Body mass index | |

| Center for epidemiological studies depression scale-10 | |

| Clinical practice guideline | |

| Coronavirus disease 2019 | |

| Double-bounded dichotomous choice method | |

| False discovery rate | |

| Generalized anxiety disorder scale-7 | |

| Institutional review board | |

| Patient health questionnaire-9 | |

| Perceived stress scale | |

| Visual analog scale |

References

1. Kim SJ , Sohn S , Choi YK , Hyun J , Kim H , Lee JS , et al. Time-series trends of depressive levels of Korean adults during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic in South Korea. Psychiatry Investig. 2023; 20( 2): 101– 8. doi:10.30773/pi.2022.0178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Hossain MM , Tasnim S , Sultana A , Faizah F , Mazumder H , Zou L , et al. Epidemiology of mental health problems in COVID-19: a review. F1000Research. 2020; 9: 636. doi:10.12688/f1000research.24457.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Collins C , Landivar LC , Ruppanner L , Scarborough WJ . COVID-19 and the gender gap in work hours. Gend Work Organ. 2021; 28( S1): 101– 12. doi:10.1111/gwao.12506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Craig L , Mullan K . Parenthood, gender and work-family time in the United States, Australia, Italy, France, and Denmark. J Marriage Fam. 2010; 72( 5): 1344– 61. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00769.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Xue B , McMunn A . Gender differences in unpaid care work and psychological distress in the UK Covid-19 lockdown. PLoS One. 2021; 16( 3): e0247959. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0247959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Aslam A , Adams TL . “The workload is staggering”: changing working conditions of stay-at-home mothers under COVID-19 lockdowns. Gend Work Organ. 2022; 29: 1764– 78. doi:10.1111/gwao.12870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Avery AR , Tsang S , Seto EYW , Duncan GE . Differences in stress and anxiety among women with and without children in the household during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Public Health. 2021; 9: 688462. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.688462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Thorsteinsen K , Parks-Stamm EJ , Kvalø M , Olsen M , Martiny SE . Mothers’ domestic responsibilities and well-being during the COVID-19 lockdown: the moderating role of gender essentialist beliefs about parenthood. Sex Roles. 2022; 87( 1): 85– 98. doi:10.1007/s11199-022-01307-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Cluver L , Lachman JM , Sherr L , Wessels I , Krug E , Rakotomalala S , et al. Parenting in a time of COVID-19. Lancet. 2020; 395( 10231): e64. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30736-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Martinez-Marcos M , De la Cuesta-Benjumea C . Women’s self-management of chronic illnesses in the context of caregiving: a grounded theory study. J Clin Nurs. 2015; 24( 11–12): 1557– 66. doi:10.1111/jocn.12746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Bae EJ , Park KJ . COVID-19 pandemic: effects of changes in children’s daily-lives and concerns regarding infection on maternal parenting stress. Korean J Child Stud. 2021; 42( 4): 445– 56. doi:10.5723/kjcs.2021.42.4.445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Shin S , Moon W , Kim S , Chung SH , Kim J , Kim N , et al. Development of clinical practice guidelines for Korean medicine: towards evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine. Integr Med Res. 2023; 12( 1): 100924. doi:10.1016/j.imr.2023.100924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Lee JG , Lee JH . Study on the prevalence of Hwa-Byung diagnosed by HBDIS in general population in Kang-won province. J Korean Neuropsychol. 2008; 19: 133– 9. (In Korean). [Google Scholar]

14. Kwon CY , Shin S , Lee B , Seo JC , Nam JH , Park JH , et al. Disease-based evidence map for the second-wave development of evidence-based Korean medicine clinical practice guidelines in Korea. Integr Med Res. 2022; 11( 3): 100868. doi:10.1016/j.imr.2022.100868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Lin KM , Lau JKC , Yamamoto J , Zheng YP , Kim HS , Cho KH , et al. Hwa-byung: a community study of Korean Americans. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1992; 180( 6): 386– 91. doi:10.1097/00005053-199206000-00008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Jeong H , Jang S , Jang BH , Kim KH , Ko SG . Clinical effectiveness and economic evaluation of an online mental health self-care program for mothers in Korea: a non-randomized comparative study. Asian J Psychiatr. 2025; 106: 104444. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2025.104444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Lee S . Research on the development of Korean medicine health promotion programs and community linkage plans. Seoul, Republic of Korea: Korea Health Promotion Institution; 2014. (In Korean). [Google Scholar]

18. Jeong HI , Kim KH . Development of a Korean medicine online program on mental health. J Pharmacopunct. 2023; 26( 1): 77– 85. doi:10.3831/KPI.2023.26.1.77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Gentil D , Assumpção J , Yamamura Y , Barros Neto T . The effect of acupuncture and moxibustion on physical performance by sedentary subjects submitted to ergospirometric test on the treadmill. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2005; 45( 1): 134– 40. [Google Scholar]

20. Nadler SF , Steiner DJ , Erasala GN , Hengehold DA , Hinkle RT , Beth Goodale M , et al. Continuous low-level heat wrap therapy provides more efficacy than Ibuprofen and acetaminophen for acute low back pain. Spine. 2002; 27( 10): 1012– 7. doi:10.1097/00007632-200205150-00003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Lee YO , Kim C . The effects of hand acupuncture & moxibustion therapy on Elders’ shoulder pain, ADL/IADL and sleep disorders. J Korean Acad Community Health Nurs. 2010; 21( 2): 229. doi:10.12799/jkachn.2010.21.2.229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Goyal M , Singh S , Sibinga EMS , Gould NF , Rowland-Seymour A , Sharma R , et al. Meditation programs for psychological stress and well-being: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2014; 174( 3): 357. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.13018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Kim HJ , Jeong SH , Jeong HI , Kim KH . A literature review of aromatherapy used in stress relief. J Soc Prev Korean Med. 2021; 25( 2): 45– 60. (In Korean). [Google Scholar]

24. Williams JL , Everett JM , D’Cunha NM , Sergi D , Georgousopoulou EN , Keegan RJ , et al. The effects of green tea amino acid L-theanine consumption on the ability to manage stress and anxiety levels: a systematic review. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2020; 75( 1): 12– 23. doi:10.1007/s11130-019-00771-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. National Center for Mental Health. The 2019 standard guidelines for mental health examination tools. Seoul, Republic of Korea: National Center for Mental Health; 2019. (In Korean). [Google Scholar]

26. National Institute for Korean Medicine Development. Clinical practice guideline of Korean medicine; Hwabyung. Seoul, Republic of Korea: National Institute for Korean Medicine Development; 2021. (In Korean). [Google Scholar]

27. Andresen EM , Malmgren JA , Carter WB , Patrick DL . Screening for depression in well older adults: evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (center for epidemiologic studies depression scale). Am J Prev Med. 1994; 10( 2): 77– 84. doi:10.1016/S0749-3797(18)30622-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Spitzer RL , Kroenke K , Williams JBW , Löwe B . A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006; 166( 10): 1092– 7. doi:10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Cohen S , Kamarck T , Mermelstein R . A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983; 24( 4): 385. doi:10.2307/2136404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Kwon JH , Lee MS , Kim J , Dong-Kun P , Min SK . Development and validation of the hwa-byung scale. Korean J Clin Psychol. 2008; 27( 1): 237– 52. doi:10.15842/kjcp.2008.27.1.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Daly M , Sutin AR , Robinson E . Longitudinal changes in mental health and the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence from the UK household longitudinal study. Psychol Med. 2022; 52( 13): 2549– 58. doi:10.1017/s0033291720004432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. McGinty EE , Presskreischer R , Han H , Barry CL . Psychological distress and loneliness reported by US adults in 2018 and April 2020. JAMA. 2020; 324( 1): 93– 4. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.9740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Daly M , Sutin AR , Robinson E . Depression reported by US adults in 2017–2018 and March and April 2020. J Affect Disord. 2021; 278: 131– 5. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2020.09.065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Yang H , Ma J . How an epidemic outbreak impacts happiness: factors that worsen (vs. protect) emotional well-being during the coronavirus pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2020; 289: 113045. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Kim SJ , Lee S , Han H , Jung J , Yang SJ , Shin Y . Parental mental health and children’s behaviors and media usage during COVID-19-related school closures. J Korean Med Sci. 2021; 36( 25): e184. doi:10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Korean Center for Disease Control and Prevention . Guideline for preventing COVID-19 [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2025 Jul 1]. Available from: https://www.kdca.go.kr. [Google Scholar]

37. Jae J , Yong J . Mental health and psychological intervention amid COVID-19 outbreak: perspectives from South Korea. Yonsei Med J. 2020; 61( 4): 271– 2. doi:10.3349/ymj.2020.61.4.271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Tsai CL , Tu CH , Chen JC , Lane HY , Ma WF . Efficiency of an online health-promotion program in individuals with at-risk mental state during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021; 18( 22): 11875. doi:10.3390/ijerph182211875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Beauchamp MR , Hulteen RM , Ruissen GR , Liu Y , Rhodes RE , Wierts CM , et al. Online-delivered group and personal exercise programs to support low active older adults’ mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2021; 23( 7): e30709. doi:10.2196/30709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools