Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

A Double-Edged Sword: A Scoping Review of the Mental Health Aspects of Parentification

1 Doctoral School of Education, University of Szeged, Szeged, 6722, Hungary

2 Department of Behavioral Sciences, University of Szeged, Szeged, 6722, Hungary

* Corresponding Authors: Istvan Berkes. Email: ; Bettina Piko. Email:

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(11), 1627-1643. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.071931

Received 15 August 2025; Accepted 05 November 2025; Issue published 28 November 2025

Abstract

Objectives: Parentification, a role reversal where children assume age-inappropriate duties in the family, is a significant childhood adversity often linked to disrupted developmental trajectories and poor mental health outcomes. Yet the complexity of parentification, influenced by various contextual factors, obscures a comprehensive understanding of its psychological consequences and its mental health aspects. The paper aims to map up-to-date research, synthesize key findings, and identify critical knowledge gaps. Methods: To that end, a systematic search was performed in Scopus, PsycINFO, PubMed, and EBSCO databases, and data was extracted and reviewed by two reviewers. The search yielded 29 studies, including 9 qualitative, 1 mixed, and 19 quantitative studies that examined the mental health aspects of parentification, from various countries of origin. Results: Parentification, often arising from contexts like parental illness or substance abuse, is linked to varied mental and physical health outcomes. These outcomes are strongly moderated by the adolescent’s subjective perception of their role and the presence of protective factors like strong sibling relationships. The review also identified a clear pathway for the intergenerational transmission of parentification, where a parent’s own history was found to impact their parenting cognitions. Conclusion: This review concludes that future longitudinal research should move beyond negative or positive outcomes of parentification and investigate the mediating and moderating mechanisms that play a crucial role in the outcomes. Furthermore, the absence of prevalence studies on parentification is a notable limitation, and as a result, the size of the affected population remains unknown. Further research is also needed to identify potential protective factors in various circumstances.Keywords

Parentification is a psychosocial phenomenon that involves emotional, physical, and social disruption in the child’s own development. These children frequently encounter significant psychosocial burdens, which are often associated with heightened stress levels and diminished well-being. While parentification is often linked to psychopathology, it can foster resilience and competence, creating a complex and sometimes contradictory picture. Therefore, the primary aim of this scoping review is to systematically map the current research, synthesize key findings on the mental health aspects of parentification, and identify critical gaps to assist future research.

1.1 Defining Parentification: A Conceptual Overview

Parentification is a role reversal where a child assumes adult responsibilities to care for a parent or family member instead of receiving care [1]. Boszormenyi-Nagy and Spark [1] defined it as a child fulfilling a parental role for which they are not developmentally prepared. At its core, parentification is a distortion of the family hierarchy and a violation of generational boundaries [1,2], a phenomenon also described as “role reversal” or the “parental child” [2]. This violation is considered a serious developmental challenge and a potential form of neglect or maltreatment, creating an adverse environment for the child [1,3]. The impact is explained by theories like attachment theory [4] and self-development models [5], which suggest that parentification hampers development and prevents the child from forming an autonomous sense of self because their own needs for comfort and support are unmet [5].

1.2 Forms and Contributing Factors of Parentification

Parentification is classified by its primary subtypes: instrumental and emotional [6,7]. Instrumental parentification involves performing functional duties like cooking, grocery shopping, or caring for siblings, whereas emotional parentification requires the child to meet the family’s emotional and social needs, such as acting as a confidant or mediating conflicts [7]. While they can co-occur, the emotional form is often considered more covert and harmful [7,8]. The direction of care is also crucial, as parent-focused versus sibling-focused parentification profoundly affects the child’s duties and development [8,9].

Parentification typically arises from compromised parental capacity, which leads to the dissolution of boundaries and a reversal of roles [3,6,8]. Key precursors include parental incapacity due to mental or physical health challenges like substance abuse, personality disorders, schizophrenia, and other serious mental or physical illnesses [9,10,11,12]. For example, adult children of alcoholics experienced significantly more distortion in generational boundaries [13]. Similarly, mothers with their own history of sexual abuse often look for emotional support from their children [14,15]. Research also strongly supports the intergenerational transmission of parentification, where parents with unmet needs from their own childhood unconsciously repeat these dysfunctional roles with their children [16,17,18].

Socioeconomic status (SES) is another critical factor. In low-SES families, financial hardship and parental absence can compel children to assume adult responsibilities [10,19]. Conversely, in affluent families, parental devotion to work or intense pressure for a child to succeed can create a form of emotional parentification, where the child must provide satisfaction and hide their own needs [20,21,22,23].

1.3 Developmental Consequences and Bimodal Outcomes

The impact of parentification is complex, leading to different potential outcomes that can significantly change a child’s development trajectory. The distinction between whether the experience is ultimately harmful [6,12] or beneficial [19] depends on the contributing factors and conditions, including the child’s age, duration of parentification, perceived fairness, and the nature of caregiving responsibilities. These various factors led to the conceptual separation of destructive and constructive parentification with different precursors and consequences [19,22].

1.3.1 Destructive Parentification and Associated Risks

Destructive parentification occurs when the role reversal is excessive, chronic, unrecognized, and developmentally inappropriate, thereby creating a strong violation of generational boundaries [1,2,24]. This form is characterized by a fundamental deprivation of childhood, as the child’s needs are unmet and they are faced with age-inappropriate tasks to assist their parents or siblings, often recalling their childhood with the feeling that they lost something [9,12]. The underlying mechanism of harm is often explained with attachment theory, which posits that the child’s own attachment needs are neglected, which in turn prevents the child from forming an autonomous sense of self [4,15]. The lack of unsatisfied needs often results in shame, and parentified children frequently develop masochistic or narcissistic personality characteristics [25].

The negative consequences are far-reaching and well-documented. A meta-analysis [6] and numerous other studies have established a link between destructive parentification and adult psychopathology [12,19,21,22,23]. Negative consequences include a higher risk for anxiety, depression, eating disorders, and PTSD symptoms [12,19,24], as well as poor relationship functioning, hindered identity development, and lower academic status [12,25,26,27]. The severity of these outcomes often increases with an earlier age of onset [28].

Emotional parentification, which involves serving as a confidant or mediator, is frequently identified as the most detrimental form, due to its covert nature and the significant psychological weight it places on the developing child [4,5,6,17].

1.3.2 Constructive Parentification and Potential for Positive Outcomes

By contrast, some research suggests that constructive parentification can foster resilience, competence, and empathy [29,30,31]. The critical factor differentiating destructive from constructive outcomes is the family’s response and circumstances. In this context, the family hierarchy is not entirely inverted, because the child is rather seen as a competent helper whose contributions are valued, but their fundamental needs as a child are still acknowledged and met. When the child’s caregiving is temporary, age-appropriate, and explicitly recognized and appreciated, the experience can lead to positive psychological changes, a concept aligned with posttraumatic growth [32,33,34,35].

When these conditions are present, the experience can foster personal growth, including resilience, competence, empathy, and strong coping skills. The positive trajectory through developing the ability to overcome manageable adversity leads to positive psychological changes [32,34,35].

A child’s subjective satisfaction with their role is a powerful moderator. Adolescents who report high satisfaction with their caregiving duties also report better physical health and life satisfaction [31,32,35]. Furthermore, protective factors, like proactive personality and strong sibling relationships, can buffer against potential harm and facilitate adaptation [18,30]. Some studies have found that instrumental parentification was linked with higher academic achievement [8,18,35].

1.4 Gaps in the Literature and Rationale for the Scoping Review

Despite its clinical significance, parentification literature has substantial limitations that necessitate a systematic review. A primary gap is the lack of research on its current prevalence, making it difficult to assess the scope of the issue. Methodologically, the field is based on over-reliance on biased retrospective self-reports, questionnaires that miss complexities, and non-representative student samples. This fragmented evidence highlights the need for more rigorous, prospective longitudinal studies that also consider sociocultural contexts and protective factors leading to resilience and positive outcomes. Therefore, this scoping review aims to map up-to-date research, synthesize its findings, and identify critical weaknesses to guide future inquiry.

2.1 Scoping Review-Literature Search Strategy

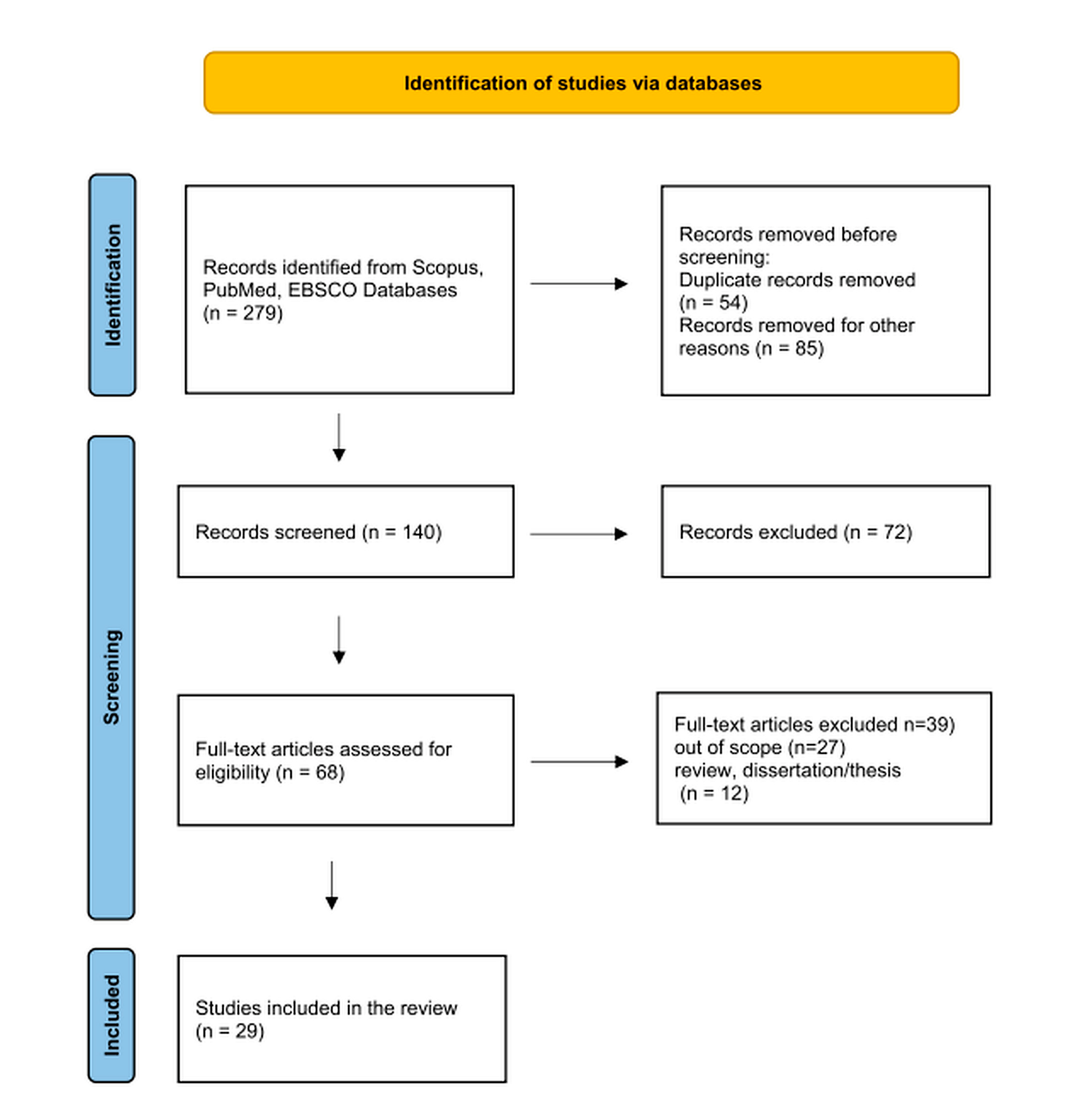

This scoping review was conducted and reported in accordance with the PRISMA-ScR guidelines (Supplementary Material S1) [36]. A comprehensive literature search was performed across three major electronic databases: Scopus, PubMed, and EBSCOhost, including PsycINFO. The search was conducted to identify all relevant articles published between 01 January 2018 and August 2025. The search strategy was designed to capture all relevant literature and combined two core concepts: (1) parentification and its related constructs, and (2) mental health outcomes. The following search string was used: (“parentification” or “role reversal” or “boundary dissolution”) and (“mental health” or “mental disorder” or “mental illness” or “psychological distress”). The initial search yielded 279 articles. After removing 54 duplicates, the remaining 225 unique records were screened based on the eligibility criteria detailed below.

2.2 Study Selection and Eligibility Criteria

The study selection process involved a two-stage screening procedure conducted by two independent authors. Any disagreements at either stage were resolved through discussion and, if necessary, consultation with a third author to reach a consensus. In the first stage, the two authors independently screened the titles and abstracts of the 225 unique records. Articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded. In the second stage, the full texts of the remaining potentially relevant articles were retrieved and assessed for final inclusion.

To be eligible for inclusion in this review, studies had to meet the following criteria:

- 1.Study Type: The study had to be a primary empirical investigation, employing quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-method designs.

- 2.Population/Exposure: The study must have explicitly investigated the concept of parentification, role reversal, or boundary dissolution in any population.

- 3.Outcome: The study must have measured or assessed at least one mental health outcome associated with parentification.

- 4.Language: The article was written in the English language.

- 5.Publication Status: The study was published in a peer-reviewed journal.

- 6.Timeframe: The study was published between January 2018 and August 2025.

- 7.Availability: The full-text version of the article was accessible.

2.2.2 Exclusion Criteria Studies Were Excluded for Any of the Following Reasons

- 1.Non-Empirical Work: Articles that were not primary research, such as theoretical papers, literature reviews, editorials, commentaries, case reports, or book chapters.

- 2.Irrelevant Exposure: Studies that focused on adverse childhood experiences (e.g., parental addiction, mental or physical illness) but did not explicitly measure or conceptualize these experiences through the lens of parentification.

- 3.Irrelevant Outcome: Studies that investigated parentification but did not examine its association with any mental health outcomes.

- 4.Language and Availability: The article was not in English or the full text could not be retrieved.

Out of the 225 unique records screened, 85 were excluded during the title and abstract review. The remaining 140 articles were further assessed, during which another 72 articles were excluded for not fully meeting the eligibility criteria (e.g., thesis, dissertation, other types of articles). This process resulted in 68 articles, and after the full text review, 39 articles were excluded for not meeting the eligibility criteria (e.g., no connection between mental health outcomes and parentification, parentification mentioned but mental health outcomes not measured, adverse childhood experiences mentioned but there was no connection to parentification). This process resulted in a final selection of 29 articles for inclusion in this review. The detailed process of literature search and study selection is illustrated in the PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: PRISMA flow diagram of this study.

Based on the eligible studies, parentification is a multifaceted phenomenon predominantly examined within contexts of parental substance abuse [37,38,39], severe physical illness [40,41], sometimes alongside positive features, such as child caregivers’ resiliency [42], mental illness [43,44,45], or family disruption like divorce [46,47,48]. Research consistently shows that children in these situations often assume developmentally inappropriate caregiving roles [37,38]. This experience is frequently associated with adverse mental health outcomes, including heightened symptoms of depression, anxiety, stress, and low self-esteem, which can persist into adulthood [40,47,49]. Qualitative studies describe the experience as a “relational trauma” leading to a “lost childhood”, feelings of invisibility, and profound sadness [50,51].

The impact of parentification, however, is not uniform and is shaped by various factors. The specific nature of the caregiving tasks matters; emotional parentification and tasks perceived as unfair are often linked to worse outcomes than instrumental caregiving [52,53,54,55,56]. Cultural context significantly influences the experience. In collectivistic cultures like Chinese families, filial responsibilities may be viewed as normative and can be associated with positive outcomes like life satisfaction, particularly when mediated by parental warmth [47,48].

Several factors can moderate or mediate the effects of parentification. Protective factors such as maternal warmth [47,48], perceived social support [57], proactive personality [58], and the ability to perceive benefits from the experience [42,59] can buffer against negative outcomes. By contrast, risk factors like high interparental conflict as a result of a parent’s depressive symptoms might cause the child to support one or both parents emotionally, which will not leave space for the child to express and cope with their own emotions [45]. The consequences of parentification can also be intergenerational, with a mother’s own history of unfair caregiving predicting lower self-esteem and parenting self-efficacy in her own parenting journey [60]. Ultimately, the research indicates that while parentification presents significant risks for mental health, the outcomes are complex and depend heavily on the type of caregiving [61], the family environment [62,63], cultural values, and available protective factors [64], or building psychological defensive mechanisms to cope with the hardships [65].

Based on a systematic analysis of the selected sources, the studies were classified into seven thematic categories. The tables below provide a comprehensive overview of the included literature, detailing the author, publication date, title, methodological approach, and the central investigation of each study. Importantly, these classifications overlap, with several studies fitting into more than one category due to their multifaceted nature. These overlapping studies, however, will be put in one category only.

Looking at the chosen literature, it was clear that a considerable amount of research has been conducted on contributing factors of parentification, such as parental substance or alcohol abuse. Table 1 focuses on this area, showing parentification in the context of parental substance abuse. The studies included here investigate the consequences of this environment, demonstrating that while it is often associated with neglect and low self-esteem, it can also produce bimodal outcomes where some children develop competence and coping skills.

Table 1: Parentification in the context of substance abuse.

| Author(s) (Year) | Research Method | Focus of the Study | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tedgård et al. (2019) [37] | Qualitative, in-depth interviews | To investigate the consequences of growing up with substance-abusing parents. | Parentification was associated with neglect, unmet emotional needs, feelings of insecurity, poor self-confidence, and internalized problems, although it fostered competence. |

| Silvén Hagström and Forinder (2022) [38] | Qualitative, longitudinal narrative analysis | To analyze children’s life-story narratives about growing up in an alcoholic family environment. | Bimodal outcomes were identified: some children saw themselves as vulnerable victims, exposed to neglect, violence, and abuse, while others became competent agents who developed coping strategies and acted as young carers. |

| Tinnfält et al. (2018) [39] | Qualitative, interviews with content analysis | To explore the experiences and coping strategies of 7–9-year-old children with an alcoholic parent. | Children reported feelings of sadness, trying strategies to manage the situations (fights between parents). |

| Kallander et al. (2018) [41] | Quantitative, cross-sectional survey | To investigate negative or positive outcomes of children caregiving for a parent with a physical/mental illness, or substance abuse. | Outcomes were mixed: better social skills and less household management predicted positive outcomes, while poorer social skills, more household management predicted more negative outcomes. |

| Fleitas Alfonzo et al. (2023) [63] | Quantitative, longitudinal survey | To examine gender as a moderator of the mental health effects of informal care among Australian adolescents. | Female caregivers reported stronger negative mental health effects and higher distress scores than their male counterparts. |

| Sakkopoulou and Tsiboukli (2024) [65] | Qualitative, individual interviews | To explore adult women’s recollection of childhood with parental substance misuse and its perceived effect on their adult relationships. | Key experiences included parental absence, violence, and assuming a „super-parent” role, leading to anxiety, helplessness, and low self-esteem in adulthood. |

Another significant contributing factor to parentification is the chronic parental or sibling illness, which requires long-term care. Table 2 puts the focus on families affected by parental or sibling illness or disability. Research in this area demonstrates the significant emotional and academic burdens placed on children and reveals that family conflict and the ill parent’s emotional state are often more predictive of adolescent distress than the physical illness itself.

Table 2: Parentification in the context of parental or sibling illness/disability.

| Author(s) (Year) | Research Method | Focus of the Study | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Levante et al. (2022) [57] | Quantitative online survey | To test a model where distress and parent-child relationship quality mediate the link between sibling-focused parentification and the adult sibling relationship. | Sibling-focused parentification predicted higher distress and a poorer parent-child relationship, which in turn negatively impacted the sibling bond. Social support served as a protective buffer. |

| Hanvey et al. (2022) [44] | Qualitative, semi-structured interviews | To explore the lived experiences of siblings who grew up with a disabled or chronically ill brother or sister. | Key themes included feeling invisible, experiencing psychological difficulties, guilt, and an inability to recognize their own needs. |

| Barr et al. (2025) [43] | Qualitative, semi-structured interviews | To provide a descriptive analysis of teenagers’ experiences with a critically ill parent. | Parentification was associated with academic, emotional, and physical consequences, including lower grades, increased stress, and fatigue. |

| Shinan-Altman and Levkovich (2024) [62] | Qualitative, phenomenological interviews | To explore the experiences of emerging adults who grew up with a sibling with depression. | Key themes included assuming parental roles, a lack of parental support and negative mental health impacts alongside personal growth and resilience. |

| DiMarzio et al. (2022) [45] | Mixed method: survey and video analysis | To evaluate how family processes (e.g., conflict, cohesion) contribute to parent-child role confusion in families with parental depression. | Interfamilial conflict and disruptions to the family system, rather than parental depressive symptoms directly, were associated with role confusion. |

| Chen and Panebianco (2020) [40] | Quantitative | To investigate the links between the physical and psychological aspects of parental chronic illness and adolescent psychological adjustment. | The ill parent’s emotional well-being was directly related to adolescent distress, not the physical illness itself. |

| Tam and Cheung (2025) [61] | Qualitative, in-depth interviews | To explore the lived experiences of parent–child dyads regarding parentification in Chinese families affected by parental depression. | The dyadic interaction and the resulting emotional distance, not just the parents’ depression, were central to the parentification experience. |

| Bowman Grangel et al. (2024) [49] | Quantitative, longitudinal study | To compare the effect on depression of caring for a parent versus caring for another family member. | Caregiving directed toward a parent was associated with a significantly higher risk of depression in adolescence compared to non-carers. |

Parentification is not merely about family dynamics, but it is closely related to society in a broader sense. Table 3 examines the crucial role of cultural and socio-demographic factors. These findings illustrate how the experience of parentification varies across different cultural contexts, with some responsibilities that are linked to higher self-esteem in certain situations but increased anxiety in others.

Table 3: Cultural and socio-demographic factors in parentification.

| Author(s) (Year) | Research Method | Focus of the Study | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbajal and Toro (2021) [52] | Quantitative survey | To examine how filial responsibility dimensions relate to mental health (depressive symptoms, self-esteem) among Latina college students, and the moderating role of bicultural competence. | Expressive caregiving was related to more depressive symptoms, while instrumental caregiving was related to higher self-esteem. Bicultural competence moderated these relationships. |

| Leung et al. (2023) [48] | Quantitative survey | To examine filial responsibility as a moderator between maternal distress and adolescent mental health in low-income Chinese single-mother families. | Instrumental filial responsibility intensified the negative effect of maternal distress on adolescent anxiety and depression, with some effects differing by gender. |

| Żarczyńska-Hyla et al. (2019) [53] | Quantitative survey | To examine the prevalence and socio-demographic correlates of parentification in Polish adolescents. | A high prevalence of emotional parentification and perceived unfairness was found, particularly among girls and older siblings. Parentification was linked to increased feelings of depression and anger. |

| Cho et al. (2024) [51] | Qualitative, semi-structured interviews | To understand the lived experiences of parentification among young Asian American adults within their sociocultural context. | Key themes included a sense of a lost childhood, a struggle for survival, and feeling out of place, which hindered self-exploration. |

The outcomes of parentification for children exposed to emotional and physical burdens in the family are not always negative. Table 4 demonstrates research on protective factors and positive outcomes. The studies in this section identify key factors that can reduce harm, such as maternal warmth, strong sibling relationships, and a proactive personality, while also presenting links between instrumental parentification and higher academic achievement.

Table 4: Protective factors and positive outcomes of parenification.

| Author(s) (Year) | Research Method | Focus of the Study | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Borchet et al. (2020) [54] | Quantitative survey | To explore the mediating role of sibling relationship quality on the link between perceived benefits of parentification and self-esteem. | A positive perception of caregiving benefits was linked to higher self-esteem. This relationship was partially mediated by the quality of the sibling relationship. |

| Monaco and Heesacker (2025) [59] | Quantitative survey | To explore correlations between parentification and relationship satisfaction, testing self-regard and attachment style as mediators. | Sibling-focused parentification correlated with lower life and relationship satisfaction. However, recognition of the benefits of parentification correlated with higher satisfaction. |

| Eşkisu (2021) [58] | Quantitative survey | To investigate proactive personality as a moderator in the relationship between parentification and psychological well-being/resilience. | A proactive personality acted as a protective factor; as proactivity increased, the negative effects of parentification on well-being and resilience decreased. |

| Borchet et al. (2021) [56] | Quantitative survey | To explore the relationship between parentification types, quality of life, and school achievement in early adolescence. | Instrumental parentification was positively related to academic achievement, while emotional parentification was not significantly related. |

| Połomski et al. (2021) [42] | Quantitative survey | To examine the relationship between parentification characteristics and resiliency in Polish adolescents. | Girls reported higher levels of both emotional and instrumental parentification. Boys reported higher resiliency and higher satisfaction with their family role. |

| Leung and Shek (2024) [47] | Quantitative survey | To investigate maternal warmth as a moderator between filial responsibilities and adolescent well-being in low-income Chinese single-mother families. | Filial responsibilities did not inherently harm adolescent well-being. Maternal warmth was identified as a crucial protective factor that positively influenced this relationship. |

Research clarified that the effect of parentification may be passed through generations. Table 5 explores the intergenerational transmission of these dynamics. This research demonstrates that a parent’s own history of parentification can negatively impact their parenting self-efficacy, cognitions about their children, though sibling parentification may function as a protective factor.

Table 5: The intergenerational transmission of parentification and trauma.

| Author(s) (Year) | Research Method | Focus of the Study | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nuttall et al. (2021) [60] | Quantitative longitudinal survey data | To examine associations between a mother’s own childhood parentification and her cognitions about self, parenting, and her child. | A maternal history of parentification was linked to lower parenting self-efficacy and more negative evaluative cognitions about her child, demonstrating a pathway for transmission. |

| Nichol et al. (2025) [64] | Qualitative, case studies | To explore the intergenerational transmission of trauma in relation to ACEs and AFEs, focusing on sibling resilience and parentification. | Sibling parentification can be a protective factor that fosters resilience and adaptive coping, potentially moderating the intergenerational transmission of trauma. |

Studies on parentification clearly demonstrated that the effect of parentification may seriously affect the life stages and circumstances of parentified children or adults. Table 6 examines parentification in the context of major life and family transitions like divorce. The literature here associates post-divorce parentification with increased depression and stress and frames the experience as a form of developmental relational trauma.

Table 6: Parentification in the context of life/family transitions and structure.

| Author(s) (Year) | Research Method | Focus of the Study | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wilkins-Clark et al. (2024) [46] | Quantitative survey | To examine how perceived parentification and parental affection after a parental divorce relate to emerging adults’ depression, anxiety, and stress. | Self-perceived post-divorce parentification was associated with higher levels of depression and stress. Parents’ different affection to siblings was also linked to more negative outcomes for the participant. |

| Schorr and Goldner (2023) [50] | Qualitative semi-structured interviews | To develop a theoretical model of the lived emotional experience of childhood parentification and its long-term consequences. | Parentification is framed as a developmental relational trauma, leading individuals to develop a “split self-structure” as a coping mechanism to manage adverse experiences. |

A noteworthy finding of the thematic analysis was that there was only one empirical study connecting parentification to somatic outcomes as well. Table 7 addresses the connection between parentification and physical health. This research finds that an adolescent’s satisfaction with their caregiving role is a key predictor of better physical health and life satisfaction, regardless of the level of responsibility assumed.

Table 7: Parentification in the context of physical health (and life satisfaction).

| Author(s) (Year) | Research Method | Focus of the Study | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tomek et al. (2024) [55] | Quantitative, large-sample survey | To identify adolescent parentification profiles and determine how they are linked to physical health and life satisfaction. | Adolescents in profiles characterized by high satisfaction with their caregiving role, regardless of the level of parentification, reported better physical health and life satisfaction. |

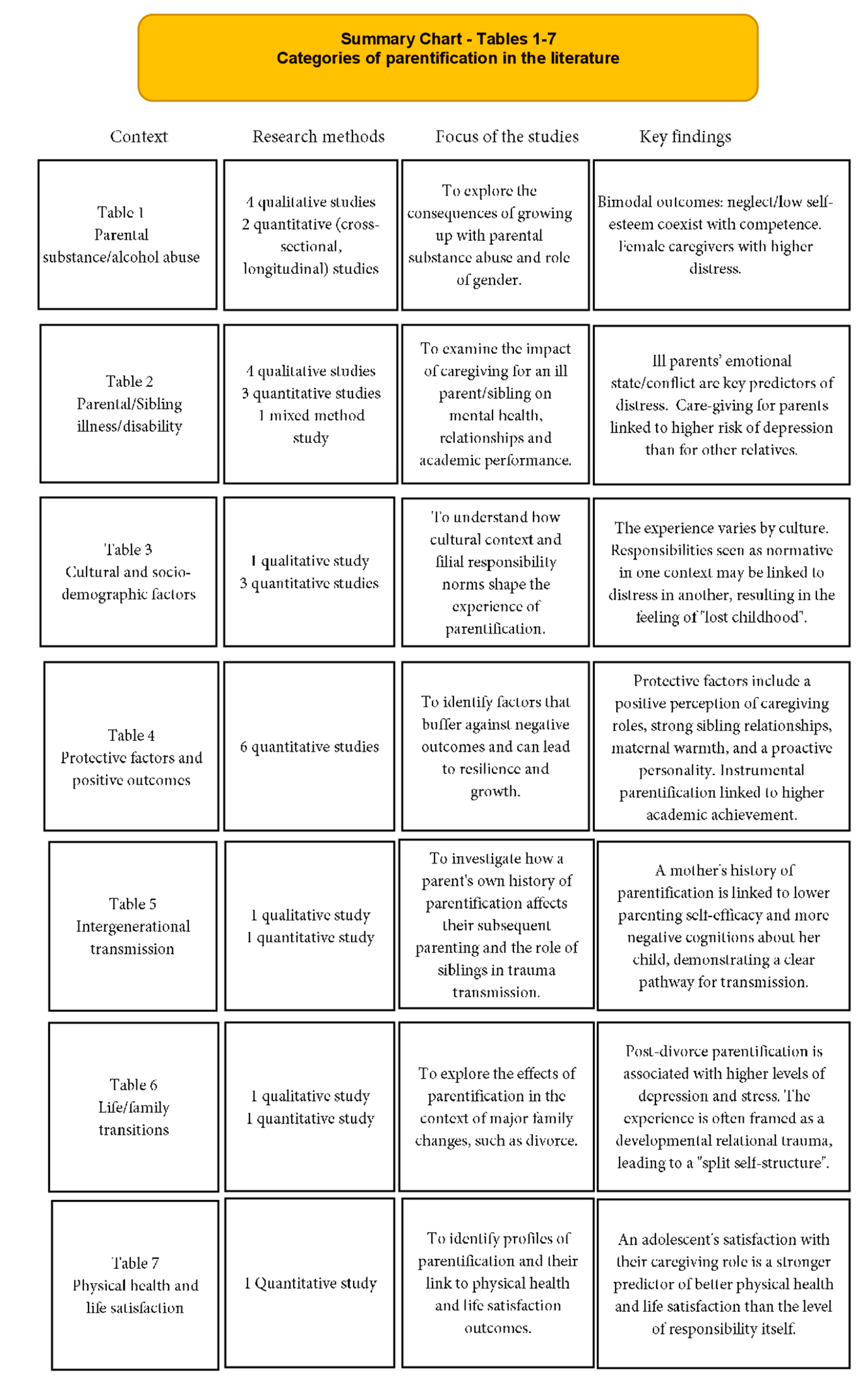

To provide a clear and accessible overview of the core findings, the detailed information from Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7 have been consolidated into the summary chart below (Fig. 2). This chart synthesizes the key context, methods, and findings from the reviewed literature.

Figure 2: Summary chart of Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7.

The reviewed literature reveals that parentification is a complex family dynamic, often initiated by challenging situations such as parental substance abuse, chronic illness, or significant family transitions like divorce [37,38,46]. These findings identify parentification as a significant, though often overlooked, form of childhood adversity. While broader meta-analyses on Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) have found a strong graded correlation between early stressors and later-life psychopathology [66], the literature synthesized in our review focuses on the specific relational dynamics of role reversal. Studies focusing on parental substance abuse consistently find that children in these environments suffer from emotional neglect, insecurity, and anxiety due to the physical or emotional absence of the parent [48,65]. The research in our review highlights bimodal outcomes, where some children become vulnerable victims of neglect and abuse, while others develop into competent agents with advanced coping skills, acting as young carers for their parents [38]. Similarly, parentification in the context of parental or sibling illness or disability is associated with significant emotional and practical burdens, including increased stress and fatigue [43]. Crucially, research indicates that it is often the ill parent’s emotional well-being and the resulting familial conflict, rather than the physical illness itself, that more strongly predicts adolescent distress and role confusion [45].

The consequences of parentification extend to measurable health outcomes and profound psychological experiences. Caregiving directed specifically toward a parent is associated with a significantly higher risk of depression in adolescence [49]. The lived experience is often so intense that it can be identified as a form of developmental relational trauma, compelling individuals to develop a “split self-structure” as a coping mechanism [50]. This focus on relational trauma distinguishes the parentification literature from many systematic reviews of “young carers”, where most studies found that young carers had poorer physical and mental health, on average, compared to noncarers [67]. This psychological toll is directly linked to well-being, with an adolescent’s satisfaction with their caregiving role emerging as a key predictor of their physical health and life satisfaction [55].

The experience and outcomes of parentification are not uniform but are strongly moderated by cultural and socio-demographic factors. For instance, while instrumental caregiving was linked to higher self-esteem among Latina college students [52], it increased anxiety and depression in the context of low-income Chinese single-mother families [48,61]. In Poland, a high prevalence of emotional parentification was found, particularly among girls and older siblings [53]. Qualitative studies further confirm these nuances, showing that for some Asian American young adults, parentification is linked to a sense of a “lost childhood” and a struggle for identity within their sociocultural context [51].

Despite these challenges, the literature also identifies significant protective factors and positive outcomes. A recurring finding is that the individual’s positive perception of their role and its benefits is strongly linked to higher self-esteem and life satisfaction [54]. Key protective buffers that can mitigate negative effects include maternal warmth [47], a proactive personality [58], and the quality of sibling relationships [54]. In some cases, parentification is associated with positive outcomes, such as higher academic achievement for those engaged in instrumental caregiving [56].

However, the picture of ACEs and parentification and their bimodal outcomes seems to be highly complex. A meta-analysis by Morgan et al. [68] found a clear and significant negative association between ACEs and levels of psychological resilience, concluding that youths with ACEs were less likely to display high resilience. Yet, a key strength of our scoping review is the synthesis of recent research that highlights a more controversial “double-edged sword” effect where parentification does not consistently reduce resilience. Our review identified studies where instrumental parentification was linked to positive outcomes, such as higher academic achievement and the development of competence and coping skills. This highlights the importance of examining the type and context of adversity, rather than just its absence or presence.

Finally, the research underscores the cyclical, long-term nature of these dynamics through studies on intergenerational transmission. There is clear evidence that a mother’s own history of parentification can negatively impact her parenting self-efficacy and her cognitions about her own child, providing a distinct pathway for the pattern to repeat. However, this cycle is not inevitable; sibling parentification, for example, can serve as a protective experience that fosters resilience and may help moderate the transmission of trauma to the next generation [64].

3.2 Limitations and Future Research

While this scoping review was conducted systematically following the PRISMA-ScR guidelines (Supplementary Material S1), several limitations should be considered when interpreting its findings.

First, the scope of the review was constrained by the search strategy. The search was limited to four major databases and articles published in English between 2018 and 2025. The search strategy, while being systematic, was intentionally focused on four major databases to cover core literature in health and social sciences. Databases such as Web of Science were not included due to the high degree of content overlap with Scopus. Similarly, ProQuest was excluded as its strength lies in indexing dissertations and theses, which constituted “grey literature”, outside the scope of this review. While this approach was strongly directed to peer-reviewed articles, we acknowledge it is not exhaustive. Future reviews may benefit from including more specialized databases to capture additional literature.

Furthermore, the review scope was confined to articles published in the English language. It was a necessity, based on the linguistic proficiency of the review team, to ensure that studies could be interpreted accurately and in depth. We acknowledge that this limitation may introduce a language bias, omitting significant research from non-Anglophone cultures where the concept of parentification may be understood differently. Consequently, the generalizability of the conclusions should be considered with this in mind.

Second, the limitations inherent in the primary studies included in this review affect the overall conclusions. The body of literature on parentification relies heavily on cross-sectional designs and retrospective self-report data, which are susceptible to recall bias and cannot establish causality between parentification and later mental health outcomes. Many studies also draw from non-representative samples, such as university students, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to the broader population.

To address the critical gap regarding prevalence studies of parentification, future research should follow a multi-step approach. First, it is necessary to develop and validate a standardized screening tool for parentification that can be used across diverse populations. With this tool, as a next step, researchers should conduct large-scale, cross-sectional surveys, using national samples, perhaps by integrating parentification modules into existing health surveys. This would provide the first reliable estimates of how many children and adolescents are affected. Finally, targeted prevalence studies should be conducted within specific populations, identified in this review, such as families affected by parental substance abuse, chronic illness, or divorce, to determine the prevalence within these vulnerable groups.

Finally, as a scoping review, the primary goal was to map the existing literature rather than to conduct a formal quality appraisal of the included studies. Therefore, the strength of the evidence presented in each study was not systematically evaluated, and the findings of this review should be interpreted as an overview of the current state of the research field rather than a quantitative synthesis of effects.

This scoping review identifies specific contexts where parentification is common, such as parental substance abuse or chronic illnesses. From clinical and public health perspective, these findings support the development of simple screening protocols for use in pediatric primary care, with simple, targeted questions about household responsibilities. It could help identify youth at risk before mental health outcomes emerge. For mental health practitioners, this review highlights the necessity of systemic interventions. Therapeutic methods like family system therapy should be employed to reorganize generational boundaries and address underlying family dynamics resulting in role reversal.

Parentification is often linked to poorer academic performance, so schools are also crucial in providing support. Educational policies could be developed to train teachers and school counselors to recognize the signs of parentification, such as increased stress, fatigue, or social withdrawal, and based on these, school-support programs could be organized by the schools or local educational authorities.

Finally, because cultural context significantly shapes the experience of parentification, all interventions must be culturally sensitive. Social programs should be tailored to the specific values and norms of the communities they serve to avoid pathologizing behaviors considered normative filial responsibilities in certain contexts.

This scoping review confirms that parentification is a complex, “double-edged sword” phenomenon with significant risks for mental health outcomes like depression and anxiety. The evidence shows that outcomes are not uniformly negative but are profoundly shaped by the type of parentification, cultural context, and the child’s subjective experience. The research also highlights a clear pathway for the intergenerational transmission of these dynamics.

Despite these insights, the field is hampered by methodological limitations, such as an over-reliance on retrospective data. This review concludes that future longitudinal research should move beyond negative or positive outcomes of parentification and scrutinize the mediating and moderating mechanisms that play a crucial role in the outcomes. Furthermore, the absence of prevalence studies on parentification is a notable limitation, and as a result, the size of the affected population remains unknown. Further research is also needed to identify potential protective factors in various circumstances. A deeper understanding of these pathways is essential for developing effective, targeted interventions to support vulnerable children and youth and mitigate the potential harm of this complex family dynamic.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: conceptualization, Istvan Berkes and Bettina Piko; methodology, Istvan Berkes; software, Istvan Berkes and Bettina Piko; validation, Istvan Berkes and Bettina Piko; resources, Istvan Berkes; writing—original draft preparation, Istvan Berkes; writing—review and editing, Istvan Berkes and Bettina Piko; visualization, Istvan Berkes; supervision, Bettina Piko. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.071931/s1.

References

1. Boszormenyi-Nagy I , Spark GM . Invisible loyalties: reciprocity in inter-generational family therapy. New York, NY, USA: Harper & Row, Inc.; 1973. [Google Scholar]

2. Minuchin S , Montalvo B , Guerney B , Rosman B , Schumer F . Families of the slums. New York, NY, USA: Basic Books; 1967. [Google Scholar]

3. Kerig PK . Revisiting the construct of boundary dissolution. J Emot Abuse. 2005; 5( 2–3): 5– 42. doi:10.1300/J135v05n02_02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Hooper LM . The application of attachment theory and family systems theory to the phenomena of parentification. Fam J. 2007; 15( 3): 217– 23. doi:10.1177/1066480707301290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Chase ND . Parentification: an overview of theory, research, and societal issues. In: Burdened children: theory, research, and treatment of parentification. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: SAGE Publications, Inc.; 1999. p. 3– 33. doi:10.4135/9781452220604.n1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Hooper LM , Decoster J , White N , Voltz ML . Characterizing the magnitude of the relation between self-reported childhood parentification and adult psychopathology: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychol. 2011; 67( 10): 1028– 43. doi:10.1002/jclp.20807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Greenberg R , Jurkovic GJ . Lost childhoods: the plight of the parentified child. Fam Relat. 1999; 48( 1): 101. doi:10.2307/585689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Borchet J , Lewandowska-Walter A . Parentification—its direction and perceived benefits in terms of connections with late adolescents’ emotional regulation in the situation of marital conflict. Curr Issues Pers Psychol. 2017; 5( 2): 113– 22. doi:10.5114/cipp.2017.66092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Aneta P , Schier K . The role reversal in the families of adult children of alcoholics. Arch Psychiatry Psychother. 2012; 14: 51– 7. [Google Scholar]

10. Burton L . Childhood adultification in economically disadvantaged families: a conceptual model. Fam Relat. 2007; 56( 4): 329– 45. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3729.2007.00463.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Earley L , Cushway D . The parentified child. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2002; 7( 2): 163– 78. doi:10.1177/1359104502007002005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Jones RA , Wells M . An empirical study of parentification and personality. Am J Fam Ther. 1996; 24( 2): 145– 52. doi:10.1080/01926189608251027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Goglia LR , Jurkovic GJ , Burt AM , Burge-callaway KG . Generational boundary distortions by adult children of alcoholics: child-as-parent and child-as-mate. Am J Fam Ther. 1992; 20( 4): 291– 9. doi:10.1080/01926189208250899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Burkett LP . Parenting behaviors of women who were sexually abused as children in their families of origin. Fam Process. 1991; 30( 4): 421– 34. doi:10.1111/j.1545-5300.1991.00421.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Alexander PC . Application of attachment theory to the study of sexual abuse. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1992; 60( 2): 185– 95. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.60.2.185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. MacFie J , McElwain NL , Houts RM , Cox MJ . Intergenerational transmission of role reversal between parent and child: dyadic and family systems internal working models. Attach Hum Dev. 2005; 7( 1): 51– 65. doi:10.1080/14616730500039663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Jacobvitz DB , Morgan E , Kretchmar MD , Morgan Y . The transmission of mother-child boundary disturbances across three generations. Dev Psychopathol. 1991; 3( 4): 513– 27. doi:10.1017/s0954579400007665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Barnett B , Parker G . The parentified child: early competence or childhood deprivation? Child Adolesc Ment Health. 1998; 3( 4): 146– 55. doi:10.1111/1475-3588.00234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. McMahon TJ , Luthar SS . Defining characteristics and potential consequences of caretaking burden among children living in urban poverty. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2007; 77( 2): 267– 81. doi:10.1037/0002-9432.77.2.267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Carroll JJ , Robinson BE . Depression and parentification among adults as related to parental workaholism and alcoholism. Fam J. 2000; 8( 4): 360– 7. doi:10.1177/1066480700084005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Hooper LM , Marotta SA , Lanthier RP . Predictors of growth and distress following childhood parentification: a retrospective exploratory study. J Child Fam Stud. 2008; 17( 5): 693– 705. doi:10.1007/s10826-007-9184-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Hooper LM . Expanding the discussion regarding parentification and its varied outcomes: implications for mental health research and practice. J Ment Health Couns. 2007; 29( 4): 322– 37. doi:10.17744/mehc.29.4.48511m0tk22054j5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Valleau MP , Bergner RM , Horton CB . Parentification and caretaker syndrome: an empirical investigation. Fam Ther. 1995; 22( 3): 157– 64. [Google Scholar]

24. Byng-Hall J . The significance of children fulfilling parental roles: implications for family therapy. J Fam Ther. 2008; 30( 2): 147– 62. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6427.2008.00423.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Wells M , Jones R . Childhood parentification and shame-proneness: a preliminary study. Am J Fam Ther. 2000; 28( 1): 19– 27. doi:10.1080/019261800261789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Mechling BM . The experiences of youth serving as caregivers for mentally ill parents: a background review of the literature. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2011; 49( 3): 28– 33. doi:10.3928/02793695-20110201-01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Borchet J , Lewandowska-Walter A , Rostowska T . Performing developmental tasks in emerging adults with childhood parentification—insights from literature. Curr Issues Pers Psychol. 2018; 6( 3): 242– 51. doi:10.5114/cipp.2018.75750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Sroufe LA . Attachment and development: a prospective, longitudinal study from birth to adulthood. Attach Hum Dev. 2005; 7( 4): 349– 67. doi:10.1080/14616730500365928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Byng-Hall J . Relieving parentified children’s burdens in families with insecure attachment patterns. Fam Process. 2002; 41( 3): 375– 88. doi:10.1111/j.1545-5300.2002.41307.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Walsh S , Shulman S , Bar-On Z , Tsur A . The role of parentification and family climate in adaptation among immigrant adolescents in Israel. J Res Adolesc. 2006; 16( 2): 321– 50. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2006.00134.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Toth SL , Cicchetti D . Patterns of relatedness, depressive symptomatology, and perceived competence in maltreated children. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996; 64( 1): 32– 41. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.64.1.32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Tompkins TL . Parentification and maternal HIV infection: beneficial role or pathological burden? J Child Fam Stud. 2007; 16( 1): 108– 18. doi:10.1007/s10826-006-9072-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Kaplow JB , Widom CS . Age of onset of child maltreatment predicts long-term mental health outcomes. J Abnorm Psychol. 2007; 116( 1): 176– 87. doi:10.1037/0021-843x.116.1.176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Walker JP , Lee RE . Uncovering strengths of children of alcoholic parents. Contemp Fam Ther. 1998; 20( 4): 521– 38. doi:10.1023/A:1021684317493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. van der Mijl RC , Vingerhoets AJ . The positive effects of parentification: an exploratory study among students. Psychol Top. 2017; 26( 2): 417– 30. doi:10.31820/pt.26.2.8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Scoping . PRISMA Statement 2018 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 10]. Available from: https://www.prisma-statement.org/scoping. [Google Scholar]

37. Tedgård E , Råstam M , Wirtberg I . An upbringing with substance-abusing parents: experiences of parentification and dysfunctional communication. Nord Alkohol Nark. 2019; 36( 3): 223– 47. doi:10.1177/1455072518814308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Silvén Hagström A , Forinder U . ‘If I whistled in her ear she’d wake up’: children’s narration about their experiences of growing up in alcoholic families. J Fam Stud. 2022; 28( 1): 216– 38. doi:10.1080/13229400.2019.1699849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Tinnfält A , Fröding K , Larsson M , Dalal K . “I feel it in my heart when my parents fight”: experiences of 7–9-year-old children of alcoholics. Child Adolesc Social Work J. 2018; 35( 5): 531– 40. doi:10.1007/s10560-018-0544-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Chen CY , Panebianco A . Physical and psychological conditions of parental chronic illness, parentification and adolescent psychological adjustment. Psychol Health. 2020; 35( 9): 1075– 94. doi:10.1080/08870446.2019.1699091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Kallander EK , Weimand B , Ruud T , Becker S , Van Roy B , Hanssen-Bauer K . Outcomes for children who care for a parent with a severe illness or substance abuse. Child Youth Serv. 2018; 39( 4): 228– 49. doi:10.1080/0145935X.2018.1491302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Połomski P , Peplińska A , Lewandowska-Walter A , Borchet J . Exploring resiliency and parentification in Polish adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021; 18( 21): 11454. doi:10.3390/ijerph182111454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Barr M , Thakur A , Thvar VK , Dupee D , Vasan N . Phenomenological description of the experiences of teenagers with critically ill parents. J Nurs Res. 2025; 33( 1): e370. doi:10.1097/jnr.0000000000000659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Hanvey I , Malovic A , Ntontis E . Glass children: the lived experiences of siblings of people with a disability or chronic illness. J Community Appl Soc Psychol. 2022; 32( 5): 936– 48. doi:10.1002/casp.2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. DiMarzio K , Parent J , Forehand R , Thigpen JC , Acosta J , Dale C , et al. Parent-child role confusion: exploring the role of family processes in the context of parental depression. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2022; 51( 6): 982– 96. doi:10.1080/15374416.2021.1894943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Wilkins-Clark RE , Wu Z , Markham MS . Experiences of post-divorce parentification and parental affection: implications for emerging adults’ well-being. Fam Relat. 2024; 73( 4): 2690– 708. doi:10.1111/fare.13013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Leung JTY , Shek DTL . Filial responsibilities and psychological wellbeing among Chinese adolescents in poor single-mother families: does parental warmth matter? Front Psychol. 2024; 15: 1341428. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1341428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Leung JTY , Shek DTL , To SM , Ngai SW . Maternal distress and adolescent mental health in poor Chinese single-mother families: filial responsibilities-risks or buffers? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023; 20( 7): 5363. doi:10.3390/ijerph20075363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Bowman Grangel A , McMahon J , Dunne N , Gallagher S . Predictors of depression in young carers: a population based longitudinal study. Int J Adolesc Youth. 2024; 29( 1): 2292051. doi:10.1080/02673843.2023.2292051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Schorr S , Goldner L . “Like stepping on glass”: a theoretical model to understand the emotional experience of childhood parentification. Fam Relat. 2023; 72( 5): 3029– 48. doi:10.1111/fare.12833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Cho S , Glebova T , Seshadri G , Hsieh A . A phenomenological study of parentification experiences of Asian American young adults. Contemp Fam Ther. 2025; 47( 2): 275– 87. doi:10.1007/s10591-024-09723-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Carbajal S , Toro RI . Filial responsibility, bicultural competence, and socioemotional well-being among Latina college students. Cult Divers Ethn Minor Psychol. 2021; 27( 4): 758– 68. doi:10.1037/cdp0000467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Żarczyńska-Hyla J , Zdaniuk B , Piechnik-Borusowska J , Kromolicka B . Parentification in the experience of Polish adolescents. The role of socio-demographic factors and emotional consequences for parentified youth. New Educ Rev. 2019; 55( 1): 135– 46. doi:10.15804/tner.2019.55.1.11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Borchet J , Lewandowska-Walter A , Połomski P , Peplińska A , Hooper LM . We are in this together: retrospective parentification, sibling relationships, and self-esteem. J Child Fam Stud. 2020; 29( 10): 2982– 91. doi:10.1007/s10826-020-01723-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Tomek S , Borchet J , Jiang S , Dębski M , Hooper LM . Patterns of parentification, health, and life satisfaction: a cluster analysis. Contemp Fam Ther. 2024; 46( 1): 21– 36. doi:10.1007/s10591-023-09668-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Borchet J , Lewandowska-Walter A , Połomski P , Peplińska A , Hooper LM . The relations among types of parentification, school achievement, and quality of life in early adolescence: an exploratory study. Front Psychol. 2021; 12: 635171. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.635171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Levante A , Martis C , Del Prete CM , Martino P , Pascali F , Primiceri P , et al. Parentification, distress, and relationship with parents as factors shaping the relationship between adult siblings and their brother/sister with disabilities. Front Psychiatry. 2023; 13: 1079608. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2022.1079608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Eşkisu M . The role of proactive personality in the relationship among parentification, psychological resilience and psychological well-being. Int Online J Educ Teach. 2021; 8( 2): 797– 813. [Google Scholar]

59. Monaco SB , Heesacker M . Perceived family benefits overshadowed parentification in predicting life satisfaction and relationship satisfaction. Am J Fam Ther. 2025; 53( 4): 426– 49. doi:10.1080/01926187.2025.2456713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Nuttall AK , Ballinger AL , Levendosky AA , Borkowski JG . Maternal parentification history impacts evaluative cognitions about self, parenting, and child. Infant Ment Health J. 2021; 42( 3): 315– 30. doi:10.1002/imhj.21912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Tam ATL , Cheung MC . Dyadic interaction of parentification in Chinese families of maternal depression: a qualitative study. J Marital Fam Ther. 2025; 51( 1): e12754. doi:10.1111/jmft.12754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Shinan-Altman S , Levkovich I . The experience of growing up with a sibling who has depression from emerging adults’ perspectives. Fam Relat. 2024; 73( 4): 2655– 70. doi:10.1111/fare.13024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Fleitas Alfonzo L , Singh A , Disney G , King T . Gender and care: does gender modify the mental health impact of adolescent care? SSM Popul Health. 2023; 23: 101479. doi:10.1016/j.ssmph.2023.101479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Nichol MR , Curley LJ , Sime PJ . The intergenerational transmission of trauma, adverse childhood experiences and adverse family experiences: a qualitative exploration of sibling resilience. Behav Sci. 2025; 15( 2): 161. doi:10.3390/bs15020161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Sakkopoulou A , Tsiboukli A . Recollection of childhood memories from parental drug and alcohol misuse in a qualitative study of women in Greece. Alcohol Treat Q. 2024; 42( 2): 153– 67. doi:10.1080/07347324.2024.2304193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Hughes K , Bellis MA , Hardcastle KA , Sethi D , Butchart A , Mikton C , et al. The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health. 2017; 2( 8): e356– 66. doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30118-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Lacey RE , Xue B , McMunn A . The mental and physical health of young carers: a systematic review. Lancet Public Health. 2022; 7( 9): e787– 96. doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(22)00161-X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Morgan CA , Chang YH , Choy O , Tsai MC , Hsieh S . Adverse childhood experiences are associated with reduced psychological resilience in youth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Children. 2021; 9( 1): 27. doi:10.3390/children9010027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools